Ka Pili Kai

ALL THINGS RELATED TO THE SEA ∙ VOL 5, NO 2 ∙ KAU 2023 A publication of the University of Hawai‘i Sea Grant College Program Navigating Our Future: 10 Years,

Challenges

10

Ka Pili Kai (ISSN 1550-641X) is published biannually by the University of Hawai‘i Sea Grant College Program (Hawai‘i Sea Grant), School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology (SOEST). Hawai‘i Sea Grant is a unique partnership of university and government focusing on marine and coastal research, education, communication, and extension services.

University of Hawai‘i

Sea Grant College Program

2525 Correa Road, HIG 208

Honolulu, HI 96822

Director

Darren T. Lerner, PhD

Communications Leader

Cindy Knapman

Assistant Communications Leader

Heather Dudock

Ka Pili Kai

Editorial Team

Darren T. Lerner

Cindy Knapman

Rachel Lentz

Beth Lenz

Maya Walton

Layout and Design

Heather Dudock

Contributing Writers

Damond Benningfield

Liz Coley

Cary Deringer

Mark Marchand

Josh McDaniel

Lurline Wailana McGregor

Robin Meadows

Kristen Pope

Denice Rackley

Rayne Sullivan

Natasha Vizcarra

Outreach Publication Photographer

Andre P. Seale

Postage paid at Honolulu, HI

Postmaster: Send address changes to:

Ka Pili Kai, 2525 Correa Road, HIG 208 Honolulu, HI 96822 (808) 956-7410; fax: (808) 956-3014 uhsgcomm@hawaii.edu hawaiiseagrant.org

The University of Hawai‘i Sea Grant Program was established in 1968 and designated a Sea Grant College Program in 1972, following the National Sea Grant College and Program Act of 1966.

Ka Pili Kai is funded by a grant/cooperative agreement from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Project C/CC-1, which is sponsored by the University of Hawai‘i Sea Grant College Program, SOEST, under Institutional Grant No. NA18OAR4170076 from NOAA Office of Sea Grant, Department of Commerce. The views expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of NOAA or any of its subagencies. UNIHI-SEAGRANT-NP-21-04.

Welcome to our latest issue, dedicated to the United Nations Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development. Through this initiative, the world's attention is focused on the vital importance of the ocean, its immense biodiversity, and the need for its conservation and sustainable use. We invite you along on our journey, raising awareness, inspiring action, and championing ocean conservation to forge a sustainable, resilient future.

Together, we must include knowledge forms from across cultures to ensure the UN Ocean Decade becomes a transformative moment in history. As Pelika Andrade, our colleague, says: “We are invested in a growing collaboration between both Indigenous and western knowledge systems, both relevant and valuable in our journeys to ʻĀina momona, thriving and productive communities. As we find the courage to act, provisioned with tools, instructions, innovation, and faith, let’s remember to vision towards a future and not against a past.”

Darren T. Lerner, PhD Director, University of Hawaiʻi Sea Grant College Program

Aloha mai kākou, e nā hoa heluhelu. Ma kēia helu o Ka Pili Kai, hoʻohanohano ʻia ka United Nations Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development. ʻO ka manaʻo nui o ia kūkala, ʻo ia nō ka hōʻike ʻana i ka waiwai nui o ka moana, nā iʻa like ʻole, a me ke koʻikoʻi a me ka pono o ka hoʻomalu moana. Ke kono nei mākou i ka lehulehu e huakaʻi pū, e hoʻolaha aku i kēia ʻike, a e paipai i ka hoihoi e hoʻomau i nā hana e pono ai ka moana no ka pōmaikaʻi o nā hanauna o kēia mua aku.

Aia ka pono ʻo ko kākou hoʻokomo pū ʻana i ka ʻike o nā lāhui like ʻole i paʻa ke kahua o ia UN Ocean Decade. Penei ka ʻōlelo a ko kākou hoa, ʻo Pelika Andrade, “Ke kākoʻo nei kākou i nā hana kūpono e momona ai ka ʻāina me ka ʻike o nā lāhui ʻōiwi a me nā lāhui ʻē aʻe. I ko kākou ʻimi hoʻonaʻauao me ka manaʻoʻiʻo, ka wiwoʻole, a me nā lako kūpono, e hoʻomanaʻo kākou, mai kaukaʻi kākou i ka manaʻo kūʻē o ka wā i hala, akā, e nānā kākou i ka wā hou e hiki mai ana.

Translated by Alyssa Anderson, PhD Postdoctoral Fellow, Pacific Islands Climate Adaptation Science Center

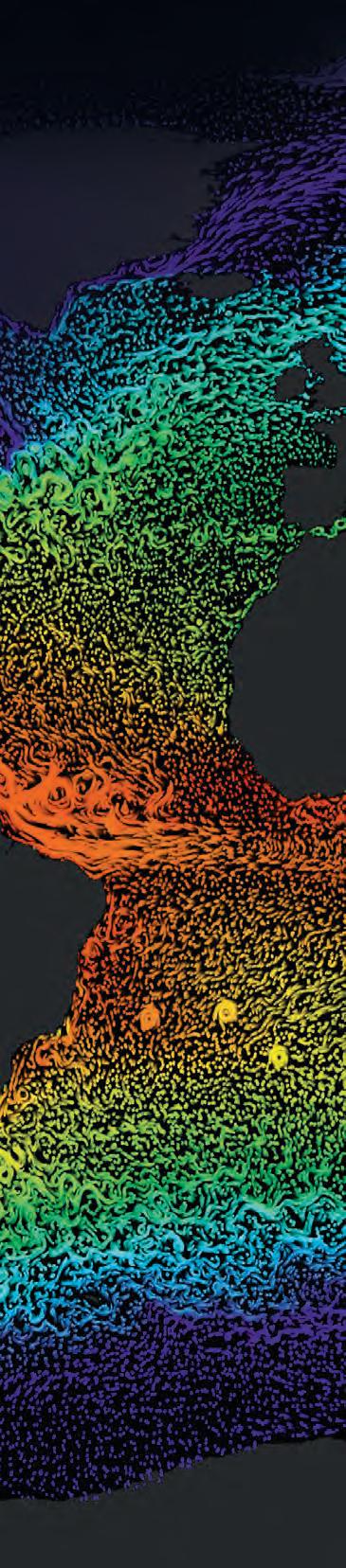

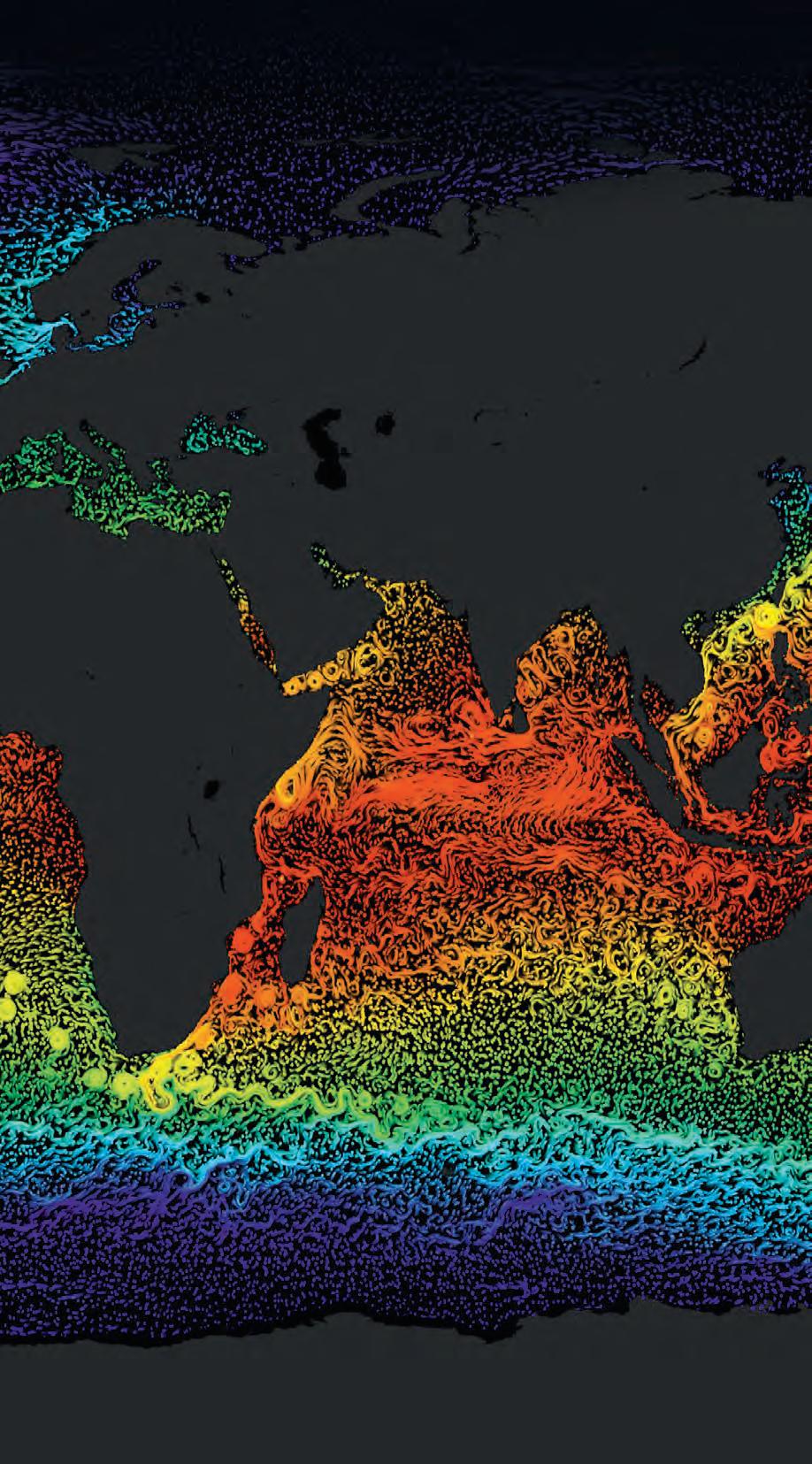

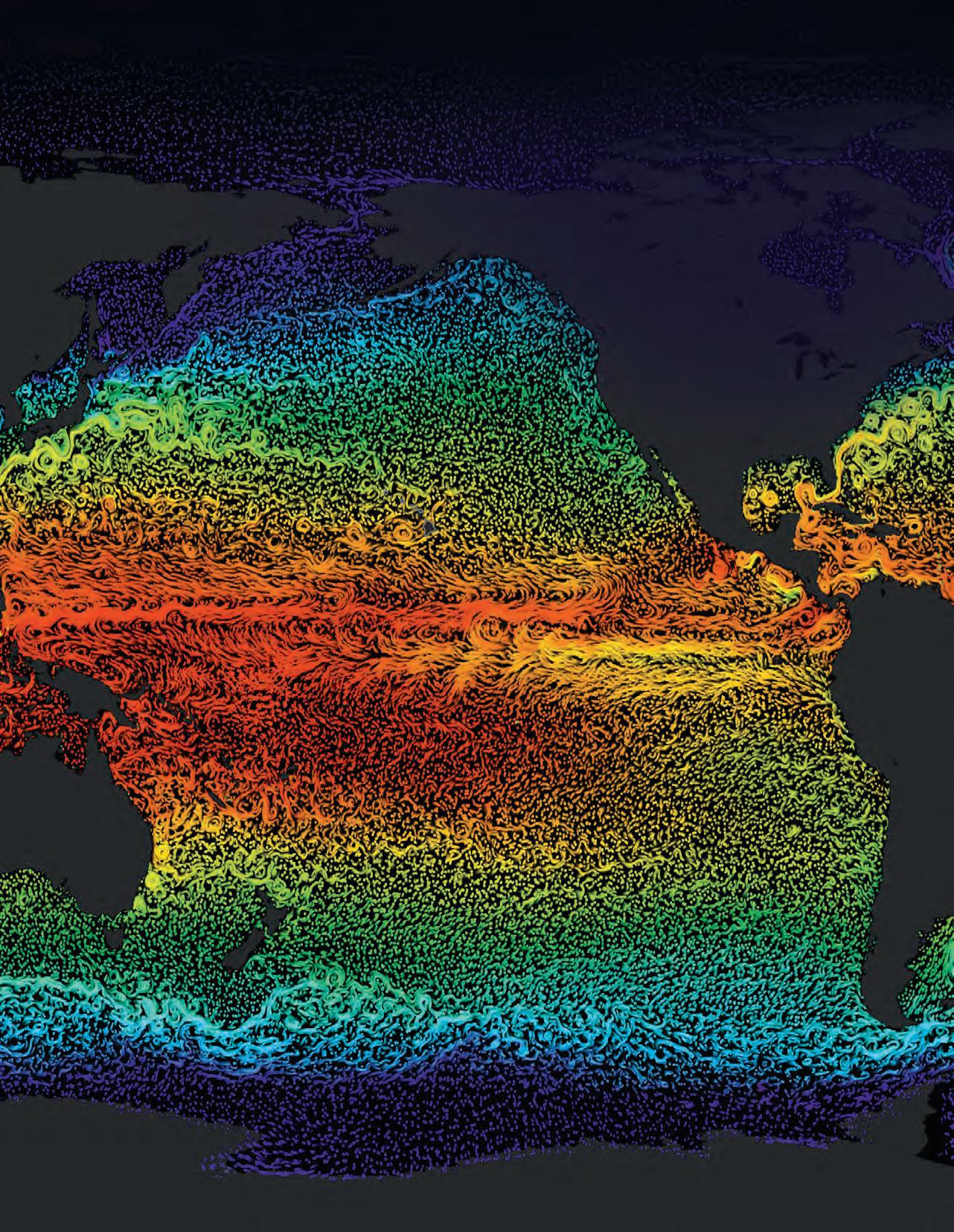

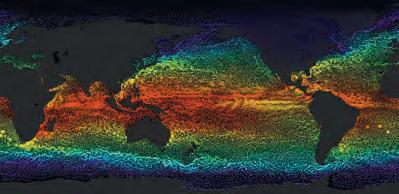

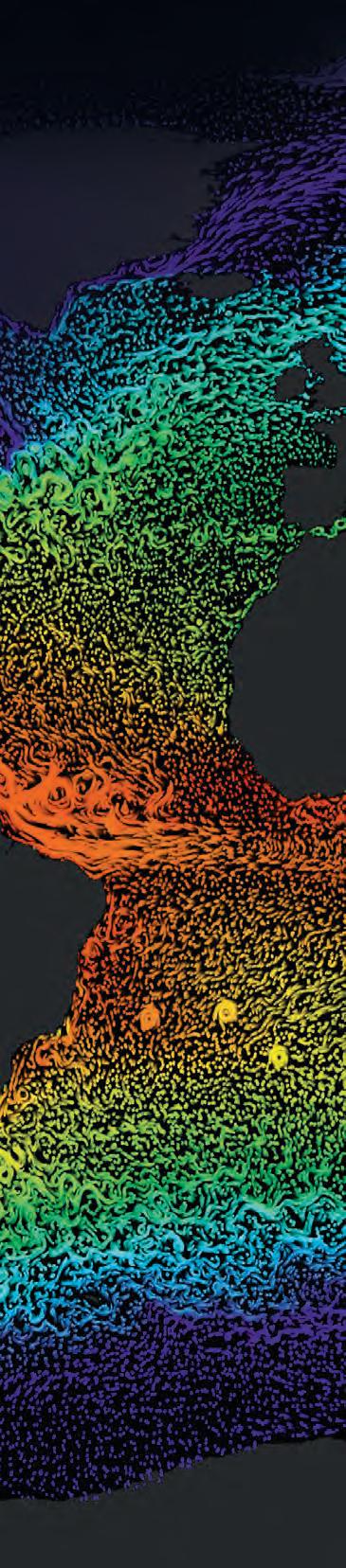

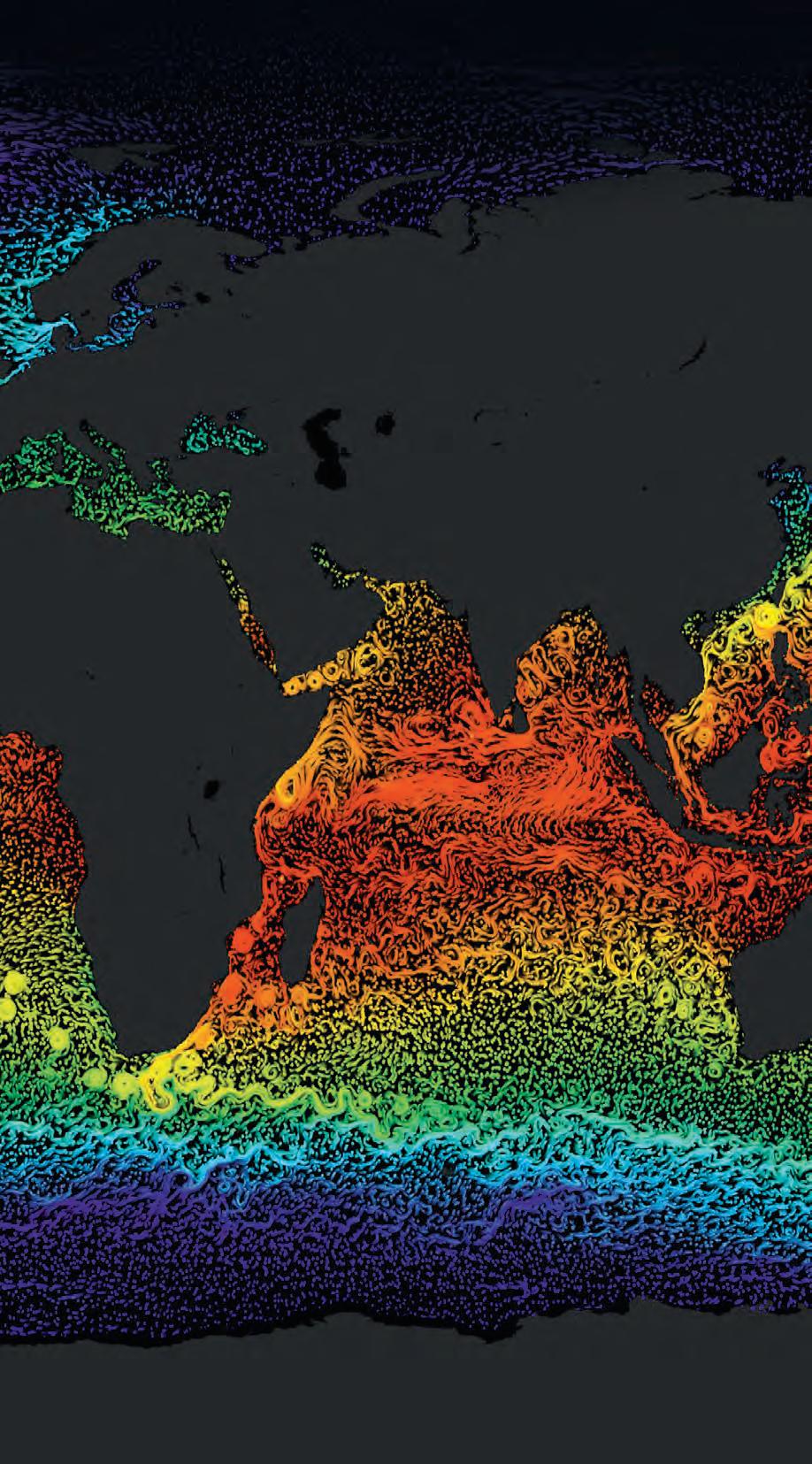

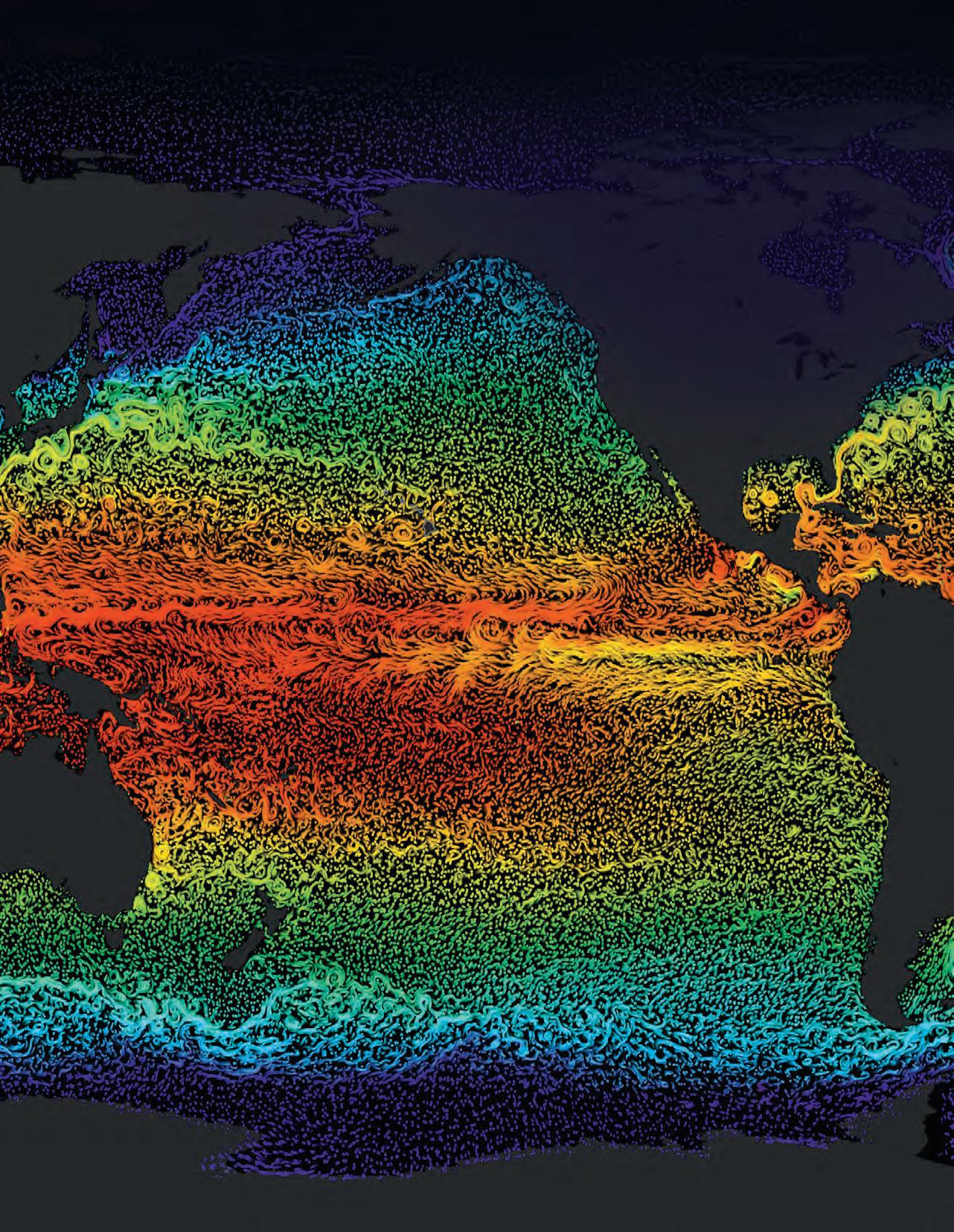

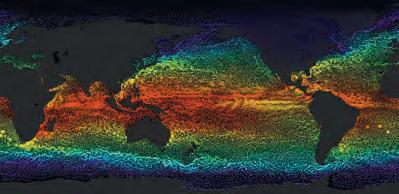

A warming climate appears to be altering global currents, reconstructed here from satellite and ship readings. This visualization shows ocean current flows on a flat map of the world. This simple flat map (cylindrical equidistant projection) is designed to be easily wrapped to a sphere. The flows are colored by sea surface temperatures with blues being cooler waters and yellows/reds warmer waters. Courtesy of NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center Scientific Visualization Studio

Visit: seagrant.soest.hawaii.edu/resources/ka-pili-kai

Ka Pili Kai • Kau 2023 Volume 5 • Number 2

E KOMO

THE COVER: Subscribe to Ka Pili Kai

MAI | WELCOME ON

1 5

10 YEARS, 10 CHALLENGES: INNOVATIVE OCEAN SCIENCE SOLUTIONS IN THE PACIFIC

by RAYNE SULLIVAN

HAUNTING THE NORTHWESTERN ISLANDS by DAMOND

BENNINGFIELD

HOPE FOR THE SEAS by

LIZ COLEY

SEAWEED SOLUTIONS FOR FEEDING THE PLANET

by CARY DERINGER

CIRCLING BACK TO HAWAI‘I’S ROOTS

by ROBIN MEADOWS

LOOKING TO THE OCEAN

by KRISTEN POPE

COMMUNITY RESILIENCE THROUGH EARLY WARNING SYSTEMS

by LURLINE WAILANA MCGREGOR

BUOYING THE PACIFIC ISLANDS TO ADVANCE EQUITABLE OCEAN OBSERVING SYSTEMS

by NATASHA VIZCARRA

by NATASHA VIZCARRA

MAPPING THE OCEAN FLOOR: ‘WE CAN’T PROTECT WHAT WE DON’T KNOW’ by

MARK MARCHAND

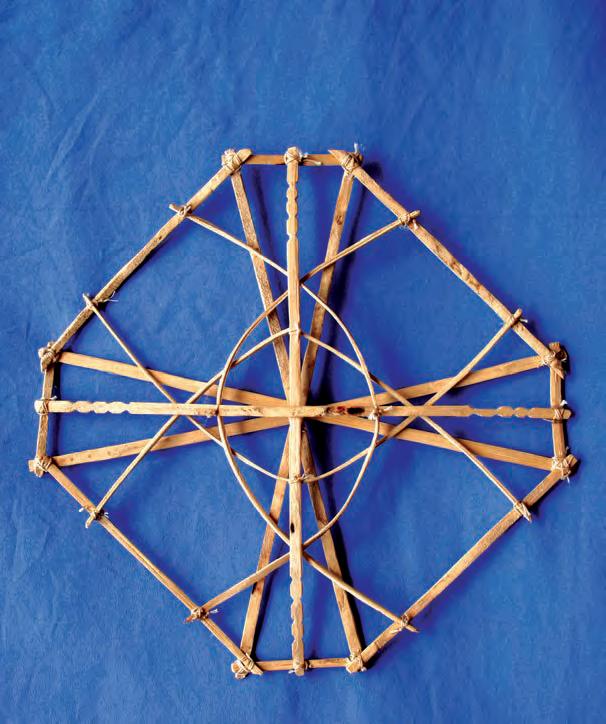

SETTING THE COURSE: WHAT INDIGENOUS KNOWLEDGE TEACHES US ABOUT SUSTAINABILITY

by JOSH MCDANIEL

INTIMATELY CONNECTED TO THE OCEAN

by DENICE RACKLEY

13 15 19 27

47

31 37 41 45

By Andre P. Seale

Contents

THE UNITED NATIONS OCEAN DECADE YEARS, 10 CHALLENGES

Innovative Ocean Science Solutions in the Pacific

by Rayne Sullivan

by Rayne Sullivan

With worsening ocean health, the Pacific and much of the world are facing a multifront threat to heritage and culture, livelihoods, security, health, and ultimately their very existence. In Palau, it is said that when there is threat to one mesekuuk (surgeonfish), all rally together to meet the threat in force.

In meeting this threat, the UN Ocean Decade rallies together people across domains and disciplines to develop impactful ocean science solutions for sustainable development centered on the interconnection between people and the ocean. This aim is further underpinned by the Decade’s vision: “the science we need for the ocean we want.”

Nowhere is the central role of the ocean better understood perhaps than in the Pacific. As children and custodians of the ocean, Pacific communities actively preserve and pass down an understanding of reciprocity with the ocean, inextricably linked to all those that have been and all those that have yet to be. This connection can be felt in the rhythms of the women of Gaua, Vanuatu drumming the waves (Ëtëtung) and heard in the Kumulipo (Hawaiian creation/genealogy chant) that tells of the emergence of the coral polyp as the first organism.

2

Acknowledging this interconnection between people and the ocean, the Ocean Decade outlines ten ambitious challenges to secure seven key transformative outcomes. These challenges encompass everything from a resilient ocean protecting both ecosystems and communities, to an accessible ocean where data and innovation are equitable both in their access and benefits.

The Ocean Decade is distinct from, but complemented by, the wide constellation of existing ocean governance and policies. Diverging from the recent Biodiversity Beyond National Jurisdiction treaty (BBNJ) or the 2050 Blue Pacific Strategy, the Decade focuses on capacity building for science and knowledge to advance the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (the 17 SDGs). In advancing the 2030 Agenda, especially SDG 14 “Life Below Water,” the Ocean Decade Alliance sets out to move beyond the conventional ocean science approach of identifying and assessing problems. Instead, the Decade will work on generating solutions through collaborative, science-backed networks of partners to align and mobilize financing, communications, influence, and research.

The Ocean Decade has been further galvanized by the swelling international attention and prioritization of the ocean-climate nexus. Within the UN process, ocean concerns were formally included in the Paris Agreement’s Preamble in 2015. These concerns later took center stage in 2019 at COP25 led by Chile. Known as the “Blue COP,” that meeting launched an Ocean-Climate Dialogue for ocean-based action, which was subsequently mandated as an annual dialogue by COP26’s Glasgow Climate Pact. At the recent COP27 in Egypt, this momentum culminated in several significant commitments. The U.S. and Norway launched the Green Shipping Challenge to advance zero-emission shipping. Emphasizing the importance of biodiversity and ecosystem services, private and public sector leaders launched the Mangrove Breakthrough, a project that strives to secure a $4 billion USD investment to restore mangroves around the world and protect 15 million hectares of mangroves by 2030. At COP27, Pacific nations worked tirelessly with other island nations to achieve historic progress including pushing for the inclusion of stronger

Corals in the Rock Islands of Palau, like this vibrant sea fan, are still thriving. By Alex Wang, Palau Blue Tours

Corals in the Rock Islands of Palau, like this vibrant sea fan, are still thriving. By Alex Wang, Palau Blue Tours

provisions in the Sharm el-Sheikh Implementation Plan that encourage countries to include ocean-based action plans in national climate goals.

Amidst this sea of challenges, Hawaiʻi and the Pacific remain a reservoir of inspiration, solutions, and resilience. In the Western Pacific, Palau’s National Marine Sanctuary (PNMS) is a model for innovative global conservation prioritizing local communities. The PNMS harnesses traditional practices such as the bul (moratorium placed on natural resources) and leverages international collaboration to align biophysical and social science for monitoring one of the world’s largest marine protected areas.

Working with partners to protect nature-based solutions through novel financial instruments, Hawaiʻi has become the first pilot site in the U.S. to implement an insurance policy to safeguard coral reefs and their restoration. Bridging Indigenous knowledge and equitable ocean conservation, the Office of Hawaiian Affairs’ new

ocean policy campaign aims to reaffirm the pilina (relationship/connection) between kānaka (Hawaiians) and ʻāina/kai (land/ocean) through intergenerational management of marine resources informed by Native Hawaiian knowledge and practice.

The ocean is our greatest shared gift, benefiting everyone but rightfully belonging to no one. Whether it's feeding 3 billion people, supporting industries that contribute $2.5 trillion USD each year to the global economy, or producing half of the oxygen we breathe, the ocean plays a central, multifaceted role in social, economic, and ecological health. Every community is an ocean community, and these solutions showcase how Hawaiʻi and the Pacific have and will continue to play an indispensable role in achieving the Ocean Decade goals.

Ka Pili Kai • Kau 2023 • hawaiiseagrant.org

4

Rayne Sullivan delivers a keynote address to business leaders at the Industry Action Event during COP27, held in Egypt in 2022. Courtesy of Rayne Sullivan

Understand and beat marine pollution

HAUNTING THE NORTHWESTERN HAWAIIAN ISLANDS

by Damond Benningfield

A diver with the Papahānaumokuākea Marine Debris Project (PMDP) cuts a tangle of fishing nets from the reef. Courtesy of PMDP

Ghosts haunt the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands. They glide in with the currents and tides, from all around the North Pacific Ocean. They destroy coral reefs and ensnare seals, sea turtles, and other endangered animals. They foul the beaches, present a hazard to boats, and cost millions of dollars to exorcise.

These ghosts aren’t of the Halloween, supernatural, jump-out-and-shout- “boo” variety. Instead, they’re of human fishing gear, fishing nets lost or abandoned at sea that congregate in the islands. Known as ghost nets, they’re part of a growing problem not only in Hawaiʻi but around the world: marine debris, which affects life in the oceans and beyond.

“It’s causing a real diminishment of the natural environment,” says Dr. Mary Donohue, program development and national partnership specialist faculty member at the University of Hawai‘i Sea Grant College Program and an international expert in the field.

Marine debris is so pervasive and is increasing so quickly that the United Nations made understanding and defeating the problem the first of ten UN Decade of the Ocean Challenges. The concern is bringing together scientists, policymakers, resource managers, and many others to outline the extent of the problem and suggest solutions for the coming decades.

6

The great bulk of marine debris consists of plastics. “Any type of plastic you’ve ever used, it’s out there, and more than 80 percent of it comes from land,” says James Morioka, chief scientist and executive director of the non-profit Papahānaumokuākea Marine Debris Project (PMDP), which collects ghost nets and other nasties from the monument twice a year.

A 2022 report by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine said that about nine million tons of plastic debris enters the ocean every year, “the equivalent of dumping a garbage truck of plastic waste into the ocean every minute.” If the current upswing in plastic production continues, the report said, the amount could reach almost 60 million tons by 2030. And since plastic is designed to be durable—no one wants their water bottle to spring leaks, after all—“most of the plastic ever produced since the beginning of time is still around,” says Donohue.

Plastic swept into the oceans by rivers, rains, and other avenues can float for years or decades, forming “garbage patches” that are carried around the world by currents. The largest is the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, which covers hundreds of thousands of square miles.

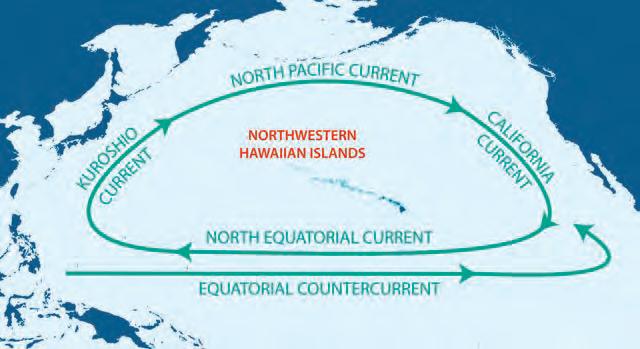

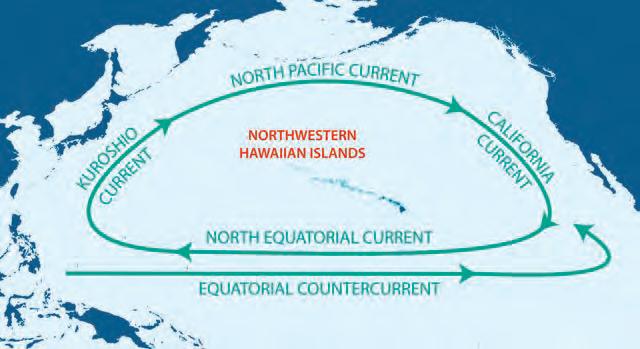

The Pacific patch is circulated by the North Pacific Gyre, a series of currents that swirl clockwise around the Hawaiian Islands. The northwestern islands are close to the northern boundary current, so debris from the garbage patch sweeps across them.

“The islands are uninhabited, yet this remote seascape is plagued with debris of all sorts, especially fishing gear,” says Mark Manuel, Pacific Island regional coordinator for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Marine Debris Program. “The islands act like a sieve or a comb. It’s pretty remarkable, in a bad way.”

The Northwestern Hawaiian Islands, which stretch about 1,250 miles from Honolulu, are contained within Papahānaumokuākea, the largest marine protected area

Four major currents form the North Pacific Gyre, which swirls around Hawaiʻi, bringing debris to the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands. Courtesy of U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

Members of the Papahānaumokuākea Marine Debris Project pull a tangle of old fishing net onto the boat during its November 2022 expedition into the monument. Courtesy of PMDP

in the United States and one of the largest in the world. It covers more than 580,000 square miles and is home to more than 7,000 species of birds, mammals, and other life, a quarter of which are found nowhere else on Earth.

Papahānaumokuākea, which is designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, is a place of special significance to Native Hawaiians, says Kaʻehukai Goin, a graduate student at the University of Hawaiʻi at Hilo, who has participated in two debris removal expeditions to the islands. “It’s a place of the gods; our islands and our genealogy extend from there. So to our people, it’s the concept of mālama ‘āina— to care for the land, the air, the water. You always take care of the ‘āina, because it takes care of you.”

Taking care of the islands isn’t easy. Scientists estimate that more than 50 tons of debris accumulate there every year, with a total of almost a million pounds currently stacked up on the beaches or in the adjoining lagoons and shallows.

On shore, the problem is plastics: bottles, bottle caps, cigarette lighters, sandals, sneakers, umbrella handles, toothbrushes, combs, helmets, toilet seats, and many other products. “I’m a toy collector, and I’ve come across several little green army men up there,” says Morioka, who

Ka Pili Kai • Kau 2023 • hawaiiseagrant.org 8

Albatross nest in marine debris at Midway Atoll (Kuaihelani) National Wildlife Refuge. Courtesy of Andy Collins, NOAA, Office of National Marine Sanctuaries

At Kauō (Laysan Island) in Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument, tides wash the debris ashore from the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, which flows past the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands. Courtesy of Susan White/USFWS

estimates he’s spent a total of three years in the islands. “I haven’t seen them in stores in probably 20 years, but I see them on shore. That’s pretty incredible.”

Birds and other critters become entangled in the debris and can’t escape. Others eat eroded bits of plastic, creating additional problems.

“It’s appalling how much of this sea turtles are eating,” says Dr. Jennifer Lynch, a research chemist and co-director of the Hawaiʻi Pacific University Center for Marine Debris Research. “We’ve seen them with up to 200 grams in their stomachs, like half a soda bottle full of plastic. They feel full, but there’s no nutrition. That reduces growth, so they’re more likely to be eaten by others.”

In addition, Lynch says plastics are “a cocktail of many, many different chemicals.” Studies have shown that ingesting them can affect reproduction, the quality of eggshells, hatchling growth rates, and other health aspects. And animals don’t have to eat the plastics directly to suffer the effects, Lynch notes. The chemicals can be ingested by everything from plankton to fish, then are transferred up the food chain.

By far the biggest problem in the islands, though, is ghost nets. They come from trawlers, deep-sea tuna fishing, and other operations. They often form tangled, twisted balls that can weigh tons.

Morioka got interested in marine debris when, while studying monk seals in the monument, he found an 11.5-ton net ball that contained two dead sharks, numerous turtle shells, and a tree. “I had a vendetta against that ball,” he says.

Almost none of the nets come from Hawai‘i. Instead, they’re carried by the currents from Japan, Asia, North America, Central America, and from fishing operations far from any shore, says Kevin O’Brien, founder of PMDP and a former NOAA employee. “The monument is highly protected; there’s no fishing allowed at all. So it’s not coming from Hawai‘i. I suspect that some of it is lost gear, and some is intentionally thrown overboard. There’s very little accountability out there in the mid-Pacific.”

Much of the gear consists of gillnets, walls of nets suspended from buoys that can stretch for hundreds

Ka Pili Kai • Kau 2021 • hawaiiseagrant.org 9

Wildlife is learning to cope with marine debris in the natural setting. While this turtle struggles through a discarded net, a seabird uses it as a convenient perch. Courtesy of PMDP

of yards. Other debris comes from abandoned fish aggregating devices (FADs), which are comprised of nets, sensors, and GPS systems. They’re set adrift to snare tuna. They amass their own ecosystems of smaller fish, then alert their owners when enough tuna congregate in the nets. The systems are cheap enough that it’s sometimes less expensive to abandon them than to retrieve them if they don’t bring in enough tuna. The GPS trackers can be switched off, so it’s impossible to determine their origin.

FADs and the other nets can ensnare humpback whales and other marine mammals offshore, carry invasive species and hazardous chemicals, and even pose a hazard to navigation. One study reported that similar nets off the coast of South Korea had entangled the propellers of hundreds of navy vessels.

Most significantly, they devastate coral reefs as they move into island waters. “It just bulldozes these habitats,” says Lynch. “One of these balls snags on a reef, smothers it, kills it. Then another wave comes along and pushes it farther toward shore and it does the same thing to the next patch.”

“It really shakes you inside to see the damage these nets can do,” adds Manuel. Return inspections of damaged sites show that the reefs don’t grow back.

In the late 1990s, NOAA launched a clean-up campaign to clear the nets from the monument. It staged one trip into Papahānaumokuākea per year, then cut back to one every three years, then dropped out completely. By then, O’Brien had started PMDP, which today ventures into the

Ka Pili Kai • Kau 2023 • hawaiiseagrant.org 10

The Papahānaumokuākea Marine Debris Project removes thousands of pounds of abandoned nets and debris from the shore. Courtesy of PMDP

monument twice a year, with a hoped-for increase to thrice, often enough to clear the backlog.

During the most recent trip, in November 2022, the crew spent 30 days at sea and collected more than 53 tons of junk, including 48 tons of ghost nets—32 from the reefs and 16 from the beaches.

Recovered debris has been repurposed in several ways, Morioka adds. H-Power has produced electricity from some of it. The Hawaiʻi Department of Transportation has tested an asphalt mixture that incorporates ground-up nets, and will become the main beneficiary of the debris in the years ahead. Others have made skateboards, sunglasses, building blocks, and even art.

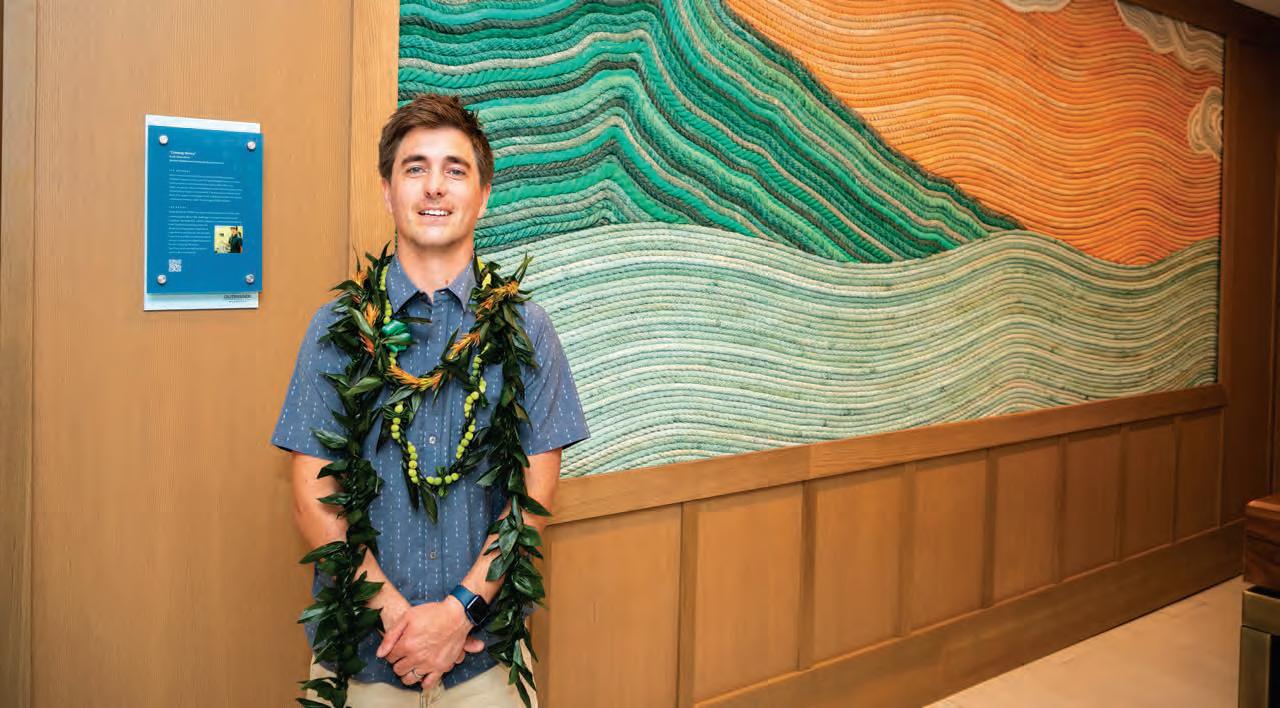

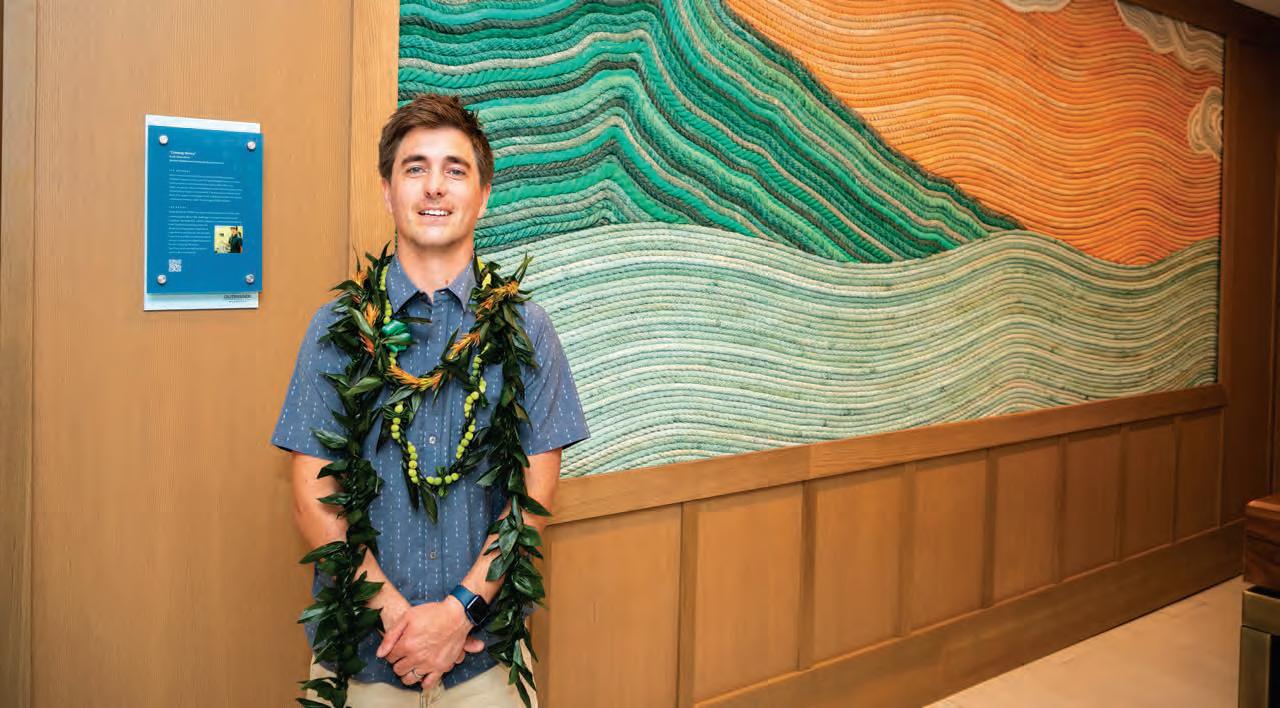

For example, Ethan Estess, a surfer, marine scientist, and artist who splits his time between Oʻahu and Santa Cruz, California has created artworks using tons of rope from derelict fishing lines, including a mural in a Waikīkī resort crafted using debris from the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands. “I’m trying to use art as visual storytelling to inspire change,” he

Left: A NOAA team removes old nets from coral at Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument. Courtesy of NOAA. Bottom: Mounds of rope from fishing nets recovered from the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands are being repurposed by local artists. Courtesy of Ethan Estess

says. “I want to draw people in with something that’s eyecatching, so they say ‘Cool!,’ but then they look deeper and get an understanding of the problem.”

Ultimately, though, clean-up efforts may only be applying a bandage. “It’s like cleaning up after a car wreck; the damage has already been done,” notes Lynch. “We need to prevent the damage in the first place.” This perspective is acknowledged in the framework of the UN Decade Challenge, providing an avenue for recognition of the plastics issue with an eye to addressing their input, not just the resulting debris.

NOAA and other agencies have proposed many steps to control the fishing net problem: attaching barcodes to every net, requiring fishers to weigh their equipment in and out with each trip, or paying to retrieve derelict gear. So far, however, “nothing has stuck,” says Morioka.

“I hope that one day [PMDP] won’t have to exist,” Goin says. “But it’s a process. We’ve come a long way since my first time in Papahānaumokuākea. There’s a lot more awareness, and that’s where we can make a difference. We want people to be more aware of what’s going on.”

That may someday exorcise the ghosts that haunt the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands.

Ka Pili Kai • Kau 2023 • hawaiiseagrant.org 12

Ethan Estess stands before a final product titled "Outrigger," made from the recovered net ropes. This artwork is on display in a Waikīkī resort. Courtesy of Ethan Estess

Protect and restore ecosystems and biodiversity

HOPE FOR THE SEAS

by Liz Coley

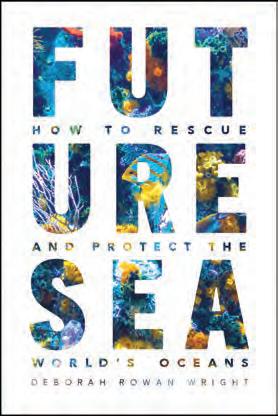

If “developing solutions to monitor, protect, manage, and restore” ocean ecosystems sounds like a challenge the human species is unprepared to face, author Deborah Rowan Wright offers good news in Future Sea: How to Rescue and Protect the World’s Oceans. Her treatment of the subject is well-researched, informative, clear, and very readable, no matter one’s prior knowledge. Unlike many disheartening books about our warming, depleting, and plastic-filled seas, Future Sea offers a thrilling new perspective.

Rowan Wright argues that international agreements are already in place to accomplish, in theory, what needs to be done. In their scope and intent, The Law of the Sea and many other international treaties apply protective rules and principles over 96 percent of the world ocean, across the commonly held “high seas” and individual countries’ economic coastal zones.

With a nod to realism, Rowan Wright’s concept of complete protection includes

13 Ka Pili Kai • Kau 2022 • hawaiiseagrant.org

Thriving reef ecosystems, like this one at Lalo (French Frigate Shoals) in Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument, are threatened by multiple hazards. By Greg McFall, NOAA National Marine Sanctuaries

responsible resource extraction alongside restoring ecosystem health. The capacity of ocean as a source for minerals and renewable food is immense, but we share it with millions of species and must practice sustainability as we feed ourselves and our industries. Rowan Wright shares examples of countries—the U.S. and Norway—who pulled a collapsing fishery back from the brink with good management, and others—Iceland—who persist in deep seabed trawling, refusing to join a major ocean floor ecosystem protection agreement. Successes and failures like these are specific and isolated. Unfortunately, to date, mediocre effort

is the norm. But that can change, Rowan Wright believes.

Rowan Wright details existing laws that already address this challenge, with the caveat that “Laws can’t do much on their own” but rely on coordinated oversight and enforcement. With global satellite surveillance, oversight is not the problem it once was. Without penalties, however, cheating is rampant. Some nations set fishing quotas above scientifically recommended levels. The High Seas commons are regularly abused with overfishing or indiscriminate netting. Industries dump waste along the shore as if it were our global trash bin. Rowan Wright suggests that coordinated global bodies, such as the International Criminal Court and the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea, take on the enforcement role, while local/regional experts develop conservation plans and monitoring methods.

Challenges to this vision of the “Future Sea” include the rise of autocrats and self-interested plutocrats, climate deniers in key positions, and the challenge of gaining unanimity on international commitments and actions. But local (and national) voluntary efforts make a difference. An increasing number of small and scattered marine reserves have created areas of replenishment and recovery, demonstrating how quickly an ecosystem can rebound, and showing positive effects on adjacent waters and commercial activity.

Rowan Wright’s recitation of the interviews she conducted is a Who’s Who of the world of conservation, climate science, and public policy. Reading this book, I felt I was in conversation with someone who had become expert by compiling the best of expert knowledge, experience, and opinion. She emerges with a positive mindset, drawing an analogy with the way the world came together in 1989 to address the hole in our ozone layer, a task more challenging than she realized before interviewing Dr. Stephen O. Anderson, co-chair of the Montreal Protocol. The point was that in spite of the complexity, as a world we figured it out and took action. This book gives me hope that our marine environmental problems aren’t too big to solve with such concerted thoughtfulness and collaboration.

Ka Pili Kai • Kau 2023 • hawaiiseagrant.org 14

The cover art for Deborah Rowan Wright's Future Sea, reviewed here, draws the reader into the beauty of the sea from the start.

SEAWEED SOLUTIONS FOR FEEDING THE PLANET

by Cary Deringer

To increase future sustainable food production while reducing methane emissions, scientists are turning to the ocean, specifically seaweed, for answers.

Food production needs will have to double to feed nearly ten billion people by 2050. However, production of protein-rich foods like meat and dairy poses dangers for the planet.

For grazing livestock, digestion involves fermentation within their rumens—the first of four stomach chambers. This intestinal fermentation forms methane, a potent greenhouse gas released into the atmosphere every time a cow burps.

Herds of cattle graze in open grasslands on Hawaiʻi Island. Courtesy of Shutterstock

Herds of cattle graze in open grasslands on Hawaiʻi Island. Courtesy of Shutterstock

But this seemingly harmless bodily output makes it up in volume. One cow’s burps amount to 220 pounds of methane annually. With one billion cattle burping globally, approximately 220 trillion pounds of methane are released yearly.

One species of red seaweed known to Hawaiians as limu kohu, or Asparagopsis taxiformis, “produces specialized halogenated compounds that directly influence methane

production in the rumen,” says Alexia Ackbay, founder and CEO of Symbrosia, a macroalgae aquaculture production and research startup on Hawaiʻi Island’s west coast.

Methane is short-lived in the atmosphere but is eighty times more potent as a greenhouse gas than equal amounts of carbon dioxide. Ackbay’s field research with local farmers is therefore promising. Their supplemental seaweed product, SeaGrazeTM, is expected to reduce methane by at least 70 percent per belch! Rapidly cutting emissions will drastically reduce atmospheric warming, buying time for clean energy efforts.

“This seaweed and other native species are bigger than just methane emission reduction,” states Ackbay. “It has cultural currency, first and foremost.” Symbrosia’s work ethic recognizes this plant’s relevance in Hawaiian

Ka Pili Kai • Kau 2022 • hawaiiseagrant.org 16

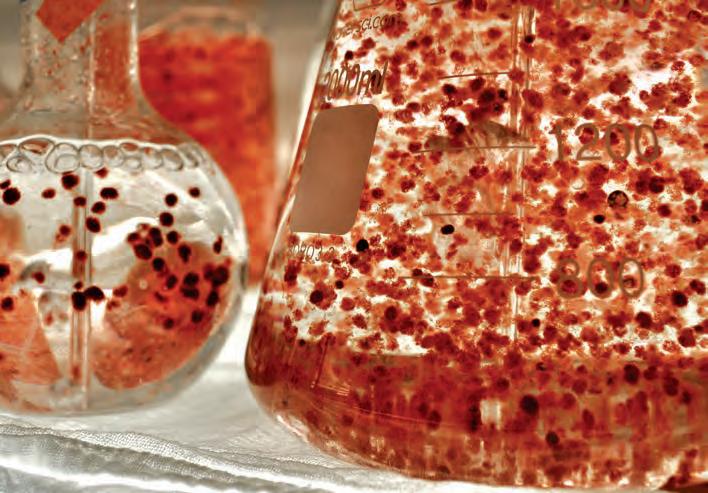

Top: Ermias Kabreab conducts research with dairy cows, adding a small amount of seaweed to cattle feed to reduce their methane emissions. Left: This ground-up macro red algae is mixed with the cows' feed, and preliminary results on emission reductions are promising. By Gregory Urquiaga, UC Davis

Kyler Shigematsu, a macroalgae technician, samples the red algae, limu kohu, being cultivated by Symbrosia. Courtesy of Symbrosia

Kyler Shigematsu, a macroalgae technician, samples the red algae, limu kohu, being cultivated by Symbrosia. Courtesy of Symbrosia

culture, aiding their understanding of the species and ensuring that their efforts remain pono (correct). “Not taking the first sample seen, or the largest, or more than 50 percent, and not harvesting roots,” Ackbay explains, “is how Indigenous practices and thought processes are incorporated. The continuity of the resource for the next seven generations is kept in mind.”

Todd Low, the aquaculture and livestock support services manager with the Hawai‘i Department of Agriculture, agrees. He is promoting such restorative aquaculture practices to support the ecosystem and economic services while improving ocean health. “That’s the push this year,” says Low. “Get funding to examine Indigenous seaweed, replenish nearshore stocks, and expand offshore growth potential.”

Seaweed aquaculture is globally relevant for producing protein-rich foods, and this growing industry is driven by scientific development and innovation. “We’ve developed, through natural selection and breeding, strains with advantageous traits for both aquacultural production and farm use,” states Ackbay. “There’s no genetic modification.”

Cows are proof. “Each animal is 8-10 times more productive,” says Dr. Ermias Kebreab at UC Davis’ Department of Animal Science. Reducing livestock numbers, while increasing food production, benefits humans and the planet. Combining restorative aquaculture practices with zero ocean impact brings those benefits full circle. “Only three ounces a day,” says Dr. Kebreab, are necessary to see these positive results.

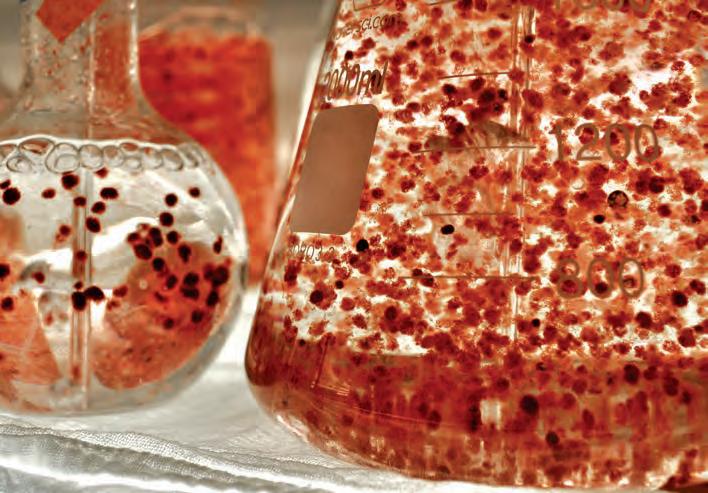

Symbrosia’s innovative macroalgae biotechnology improves production in photobioreactors—enclosed systems kept at controlled environmental conditions. “We work closely with coastal organizations and cultural practitioners,” says Ackbay.

Seaweed solutions to increase global food production, foster food sovereignty for Hawai‘i, and build climate resilience—that’s something worth ruminating on!

Ka Pili Kai • Kau 2023 • hawaiiseagrant.org

18

Top: Haeleigh Grajo, research assistant at Symbrosia, works on algal biotechnology using the limu kohu, pictured here, focusing on climate change mitigation and restoration. Courtesy of Symbrosia. Middle: Limu hoku naturally grows in coral reef systems. Courtesy of Hawai‘i Sea Grant. Bottom: Limu kohu is harvested and processed into feed for the cattle. Courtesy of Symbrosia

CLING BACK TOHAWAI‘ I

Develop a sustainable and equitable ocean economy

by Robin Meadows

by Robin Meadows

The Native Hawaiian philosophy of aloha ‘āina embodies a deep, abiding love for the land, sea, and connections between nature and people. Today, there is a large movement to reestablish Hawaiian roots. The new movement blends the longstanding wisdom of aloha ‘āina with a more recent school of thought called a circular economy, which reimagines people’s relationship with the natural world. Most economies today are linear, and are often described as “take, make, waste.” In contrast, a circular economy is a cycle of give, take, and regenerate.

’

SROOTS

Dr. Kamana Beamer of the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa’s Center for Hawaiian Studies calls aloha ‘āina the Hawaiian ancestral circular economy, adding that it mirrors the water cycle’s natural circular system. For example, the Hawaiian value of “mauka to makai” celebrates the link between mountains and sea, respectively. Caring for upland watersheds promotes ocean sustainability by, for example, curbing sediment runoff to keep coral reefs from being choked by silt. A circular economy also improves upon social equity by using regenerative practices that provide for all.

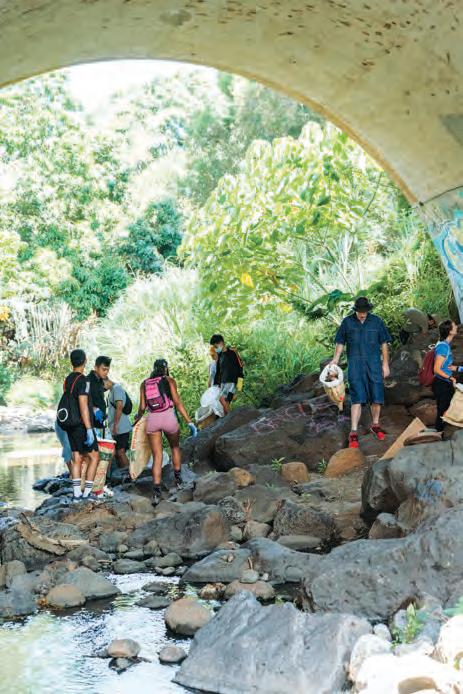

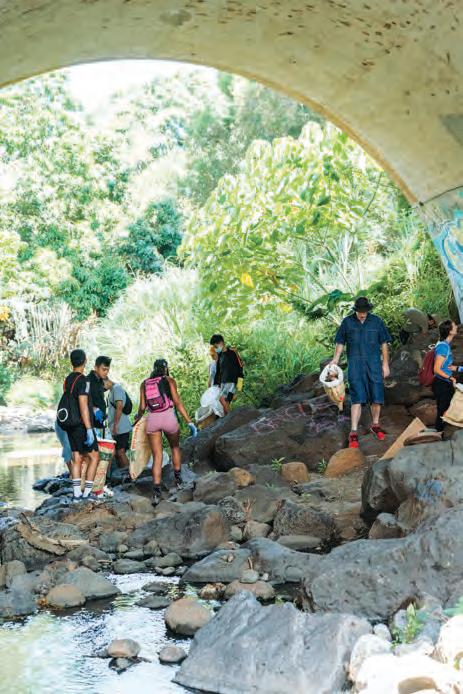

Volunteers collect trash by a Kaimukī stream during a watershed cleanup event organized by Sustainable Coastlines. By Kate Dolbier

Natural capital

In 2021 the Hawai‘i state senate voiced its support for a circular economy in a pair of resolutions. Senate Resolution 38 calls for a circular economy grounded in aloha ‘āina principles, and Senate Resolution 56 asks the state governor to convene a task force to support Hawai‘i's transition toward a circular economy by 2035.

Dr. Kirsten Oleson, a University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa environmental economist, is working to facilitate this transition by accounting for the benefits of healthy ecosystems to people and communities, from food to clean water to mental health. She is developing a new economic measure of these ecosystem services to apply to natural capital accounting, a method of systematically assessing the economic importance of nature by treating its goods and services as assets.

“It’s a way to make explicit the value of nature to people,” she says. “Nature is like a bank account—you can draw down the balance beyond the ability for it to regenerate.”

Natural capital accounting shows the worth of making deposits by protecting and restoring ecosystems.

For example, the contribution of coral reefs to people’s well-being is reflected in tangibles, such as commercial fishery catches, as well as intangibles, such as enjoyment and relaxation. Healthy reefs produce fish in greater abundance and, as research by Oleson and colleagues shows, also attract more snorkelers and divers. “They’re drawn more to places with high quality reefs than low quality reefs,” she says.

“There’s no way we can express the full value of nature,” Oleson continues. “But natural capital accounting keeps it from being left out altogether, as it has been. It gets it a seat at the table.”

Formal economic measures tracked by the state of Hawaiʻi currently include the value of goods produced, the cost of goods to consumers, and personal incomes. Oleson hopes the state will ultimately track its wealth of natural capital as well.

20

Below left: A volunteer helps remove unwanted roots, as part of the Sustainable Coastlines' watershed cleanup event. Right: Non-native albizia trees are felled and cut into sections to facilitate removal, opening up space for native plants to be re-introduced into the watershed system. Courtesy of the Albizia Project

Healing the land

In the meantime, many Hawaiians have already put circular economy approaches into practice. “Individuals can move faster than institutions,” says former University of Hawaiʻi System sustainability coordinator Matthew Lynch, whose

family has lived on O‘ahu for generations. For example, in 2017, he co-founded a nonprofit dedicated to removing an invasive tree called albizia, which was introduced to Hawaiʻi a century ago. Albizia trees alter watersheds by decreasing groundwater recharge and increasing

Matthew Lynch stands in front of the LIKA pavilion, a prototype built to illustrate the utility of a wood usually considered too brittle to build with. The structure was inspired by Indigenous Pacific Island designs and made entirely of albizia wood. Courtesy of Matt Lynch

Matthew Lynch stands in front of the LIKA pavilion, a prototype built to illustrate the utility of a wood usually considered too brittle to build with. The structure was inspired by Indigenous Pacific Island designs and made entirely of albizia wood. Courtesy of Matt Lynch

runoff, which pollutes streams with sediment that then discharges into the ocean. The nonprofit, called the Albizia Project, turns lumber from these non-native trees into wooden lamps, cutting boards, and serving platters. Just removing albizia is not enough, though. “If that’s all you do, one thousand will grow back,” Lynch explains. “We also need to repair the damage.” The nonprofit is piloting restoration at a site near Waiakeakua Stream on Oʻahu. After the albizia were cleared in 2021, they worked with volunteers to plant 190 native and endemic trees, including koa, kukui, loulu, ulu, and ʻōhiʻa ʻai.

The Albizia Project and its partners continue to care for these newly planted trees and are monitoring the return of the native forest at the stream restoration site. “We help heal the land, which helps heal ourselves,” Lynch says.

Composting food waste

Rafael Bergstrom, who began as a volunteer at, and now directs, the nonprofit Sustainable Coastlines Hawai‘i, also promotes ocean health by tending the land. In 2022, the nonprofit launched a large-scale composting program for food scraps at Full Circle Farm in Waimānalo, Oʻahu.

“We’re taking something that was waste and turning it into a resource,” Bergstrom says. “O‘ahu burns its food waste—that’s crazy.” Discarded food accounts for about 15 percent of the island’s total refuse.

The composting program transforms food waste from its beach cleanup events and other sources into a rich organic material that nourishes soil. “We have such degraded soils,” Bergstrom says. “It’s the legacy of

Ka Pili Kai • Kau 2023 • hawaiiseagrant.org 22

Full Circle Farm in Waimānalo, Oʻahu composts food waste in a retrofitted 20-foot shipping container that operates quietly and eliminates odors and pests, a model that Sustainable Coastlines hopes will spread across the island. By Rafael Bergstrom

industrial agriculture—sugarcane and pineapples—and pesticide testing.” Depleted soil can be so hard that water runs straight off the land and into nearshore waters, carrying nutrients that can cause reefsmothering algal blooms.

Full Circle Farm makes compost in a 20-foot shipping container retrofitted with a huge spiral blade that mixes and aerates food waste. This hastens decomposition while minimizing the unpleasant odors from anaerobic decay. The composter can process 1,000 pounds of food waste each day, and the dark, crumbly output is perfect for replenishing soil.

Bergstrom envisions local composting systems throughout the island. “Every farm, school, and hotel could compost,” he says. Decentralizing food waste management would cut down on transportation, reducing carbon emissions.

Top: Adding food waste to the large-scale composter at Full Circle Farm in Waimānalo, Oʻahu.

Bottom: Sean Anderson and two young helpers checking the temperature to monitor decomposition of a compost heap at Full Circle Farm in Waimānalo, Oʻahu. By Rafael Bergstrom

Top: Adding food waste to the large-scale composter at Full Circle Farm in Waimānalo, Oʻahu.

Bottom: Sean Anderson and two young helpers checking the temperature to monitor decomposition of a compost heap at Full Circle Farm in Waimānalo, Oʻahu. By Rafael Bergstrom

Fishing sustainably

Ashley Watts feeds people with sustainably harvested fish. Today, more than 60 percent of seafood in Hawaiʻi is imported. “It’s tremendously unsustainable,” says Watts, who grew up fishing with her family and has a background in marine biology. “Shipping has a big carbon footprint.”

Watts runs a Honolulu-based, community-supported fishery called Local I‘a, which provides subscribers with fish caught in Hawaiʻi. Local I‘a takes only what it can use from the ocean. “Some people fish all day but can’t sell it all, so it goes bad and is wasted. Our fishers know how much to catch and when to stop,” Watts says, adding that Local I‘a fishers also use lines instead of nets to catch fish selectively, rather than in whole schools.

Local I‘a offers fishers fair trade wages, ensuring that those doing the labor receive an equitable share of the profit. In addition, Watts pays a premium that encourages fishers to catch the non-native blueline snapper, which is bright yellow with blue stripes and was introduced when stocks of native red snapper plummeted in the 1950s.

The introduction was not a success and blueline snapper are now invasive. “People eat with their eyes, and they were used to red fish, not yellow ones,” Watts says. Local I‘a catches all sizes of blueline snapper and uses the little ones to make fish sauce. Now she’s also encouraging her fishers to catch blacktailed snapper, another non-native species that was likewise introduced in the 1950s in a well-meant but misguided attempt to shore up Hawaiʻi’s fisheries.

Ka Pili Kai • Kau 2023 • hawaiiseagrant.org 24

Left: Chef Robynne Maii holds fresh onaga from Local Iʻa that will be used at her award-winning restaurant Fête. Top: Onaga or long-tail red snapper harvested sustainably by Local I'a. Courtesy of Local Iʻa

Upcycle Hawaiʻi diverts plastics from landfills though creation of reclaimed products like these fused plastic zipper pouches. Courtesy of Upcycle Hawaiʻi

Upcycle Hawaiʻi diverts plastics from landfills though creation of reclaimed products like these fused plastic zipper pouches. Courtesy of Upcycle Hawaiʻi

Upcycling waste

To aid the shift from a linear to a circular economy, the Guam Green Growth Initiative has founded a new Makerspace and Innovation Hub in Hagåtña, Guam. The makerspace provides entrepreneurs with a gathering place, as well as tools and equipment from laser cutters to 3D printers for transforming waste products into marketable products. Makers then sell their creations onsite at the Green Store.

Hilo maker Mattie Mae Larson has seen waste as a resource since she was a child on Hawaiʻi Island. “I was a maker as a kid before it became a thing,” she says, explaining that she grew up in an artistic community where everything was reused. “There’s no such thing as trash; everything can have a second life.”

As a girl, Larson loved expeditions to Kamilo Beach, known as “plastic beach” for the mounds of plastic that wash up there. “We were excited to go there—it was a treasure hunt!” she recalls. “We played king of the plastic mountain and dressed up in our finds.”

It wasn’t until much later that Larson learned that “plastic is terrible for the planet.” Her epiphany came during a class at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, when a guest speaker cited plastic beach as an infamous example of environmental harm. Until that moment, “I didn’t realize it wasn’t supposed to be there,” Larson says. “That started me on a mission.”

After returning to her home island, Larson founded Upcycle Hawaiʻi, a company that repurposes plastic. Her team combs shorelines for the ropes and nets that pose the most immediate threat to marine life, unravels them, and melts the resulting colorful fibers into shrink wrap and other clear plastics that would otherwise be tossed. “Everything shipped to Hawaiʻi is wrapped in plastic,” she points out.

Upcycle Hawaiʻi transforms this unwanted plastic into products from zipper pouches and wallets to keychains and earrings. Since 2018, the company has kept nearly 1,000 pounds of plastic out of the landfill.

“I’m really proud of what I do, but it’s bittersweet,” Larson says. “Ideally, I’d like to be put out of the business of working with other people’s trash.”

A circular economy will help make this dream a reality in Hawaiʻi by, for example, recognizing waste as a resource and rejuvenating exploited ecosystems to promote ocean sustainability and equity.

Ka Pili Kai • Kau 2023 • hawaiiseagrant.org 26

Top: Mattie Mae Larson collecting plastic ropes and nets that washed ashore on Hawaiʻi Island. Bottom: Mattie Mae Larson unwinding a plastic rope for reuse in new products. Courtesy of Upcycle Hawaiʻi

LOOKING TO THE OCEAN

by Kristen Pope

Surrounded by the vast Pacific, thousands of miles from any large landmass, Hawai‘i is in the crosshairs of climate change, facing a multitude of impacts, including sea-level rise, increasing temperatures, and changes in precipitation. With so much at stake, it only makes sense for Hawai‘i to turn towards ocean-based climate solutions when developing its innovative policy to mitigate and adapt to climate change. The ocean is a natural thermostat and carbon sink, stabilizing our climate and has the potential to mitigate 21 percent of carbon emissions.

“For us in Hawai‘i, this is an island state, these are island communities. Life is inextricably tied to, and influenced by, the ocean, and we need to be thinking about that and bringing that into conversations and management decisions and mitigation strategies, or we won’t be successful,” says Dr. Eric Conklin, The Nature Conservancy’s (TNC) Hawai‘i and Palmyra marine science director.

Hawai‘i declared a climate emergency in 2021, the first state to do so. The state has established a number of ambitious climaterelated goals, including plans to have

Unlock oceanbased solutions to climate change

100 percent of its energy derived from renewable sources by 2045. The Hawai‘i Clean Energy Initiative provides a framework to reach these goals. In 2008, when the Initiative was first created, the state targeted supplying 60-70 percent of its energy from clean, renewable sources, but in 2014 the state introduced the more ambitious goal for total renewable energy.

Hawaiʻi has a number of technological advances underway to help unlock Earth- and ocean-based solutions to climate change, looking to a variety of renewable energy sources, including solar, wind, tidal, and hydroelectric power, and beyond. The state is experimenting with bioenergy, which taps

energy sources from organic materials, and for years has developed geothermal energy using the heat generated by its volcanic systems, especially on Hawai‘i Island. Prior to the 2018 eruption along Kilauea’s East Rift Zone which partly buried the plant, Puna Geothermal Venture was producing 31 percent of the island’s energy needs. After a hiatus for reconstruction, the plant is back up to providing nearly 20 percent of Hawai‘i Island’s electricity today.

Researchers in Hawai‘i are also studying how to utilize the ocean to produce power through hydrothermal and hydrokinetic energy. Hydrothermal energy derives from temperature differences between the ocean’s cold depths and warmer surface waters, while hydrokinetic power capitalizes on the energy associated with the natural movement of the ocean through wave and tidal action.

Kāneʻohe Marine Base on Oʻahu hosts a test site for hydrokinetic applications where researchers from a number of agencies and partners, including the University of Hawai‘i and the Hawai‘i Natural Energy Institute, are collaborating to bring these ideas to life. Dr. Patrick Cross is principal investigator for the Wave Energy Test Site (WETS), the nation’s first grid-connected wave energy test site, where three test berths of varying depths allow for pre-commercial testing of wave energy devices. They hope one day the technologies will provide electricity to remote areas, and power desalination, aquaculture, and even autonomous undersea vehicles.

“The reason to pursue wave energy is that it’s a really vast resource,” Cross says. “If you look at the amount of energy that’s stored in the waves globally at any given time, it’s just enormous. It’s a huge prize. There’s enough power out there to meet global electricity needs.”

While the ocean provides vast stores of energy, it also creates a challenging environment to capture that energy. The ocean is corrosive to equipment, and rough wave and storm conditions can cause weeks-long waits to repair damaged equipment, not to mention the costs of expensive and time-consuming transportation.

“I often hear people say: whatever you do on land, multiply it by ten to do it at sea. You’ve got to hire a boat and get out there; you may require divers; it’s very, very expensive,” says Cross.

While wave energy does not currently make a significant contribution to the state’s power grid, Cross notes that it tends to be fairly predictable about a week out. “It’s not at a level of maturity yet to play a role in today’s energy mix in Hawai‘i, but certainly when you think on the timescale of Hawai‘i’s 2045 goals, it very well could be.”

Ka Pili Kai • Kau 2023 • hawaiiseagrant.org 28

The BOLT Lifesaver, developed by Fred Olsen and deployed off the coast of O‘ahu at the Wave Energy Test Site (WETS), converts wave energy to power for offshore operations. The white box is the University of Washington’s Adaptable Monitoring Package, holding instruments and electronics to monitor the energy production. Courtesy of Pat Cross

While Cross’s team is working to harness the ocean’s energy, Dr. John Lynham, professor of economics at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, and colleagues are working to learn more about the benefits of marine protected areas (MPAs). Designating MPAs can contribute to both climate change mitigation and adaptation. Many coastal habitats protected by MPAs naturally sequester carbon, aiding the emissions battle, and many healthy coastal habitats, like coral reefs, provide natural protection from storms, which are predicted to become more frequent and intense with climate change.

In a 2022 paper in Science, Sarah Medoff, a graduate student of Lynham’s, and colleagues examined the “spillover benefits” from Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument, which is the largest contiguous, fullyprotected conservation area in U.S. waters. While fishing is prohibited in the monument itself, the researchers found the MPA served to enhance nearby fishing grounds for commercially fished species, like yellowfin and bigeye tuna, in addition to promoting broader benefits.

“Marine life in general was more abundant just outside the boundaries of the protected area,” Lynham says, noting that protecting these areas serves as insurance for the future.

“We know from decades of research that marine ecosystems that are closer to pristine, with high degrees of biodiversity, are better able to handle different impacts and different unexpected shocks,” Lynham says. “I think that will create a buffer or an insurance policy in the ocean against future climate change.”

MPAs also protect vital organisms too small to see. Dr. Jeanette Davis is a marine microbiologist, as well as an author and speaker who goes by the name “Dr. Ocean.” She studies marine microbes to find potential new drugs, and also analyzes DNA and RNA proteins that animals leave behind.

Healthy ecosystems are characterized by abundant life and diversity, like these schools of fish in Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument: (right) yellowfin tuna (by Jeff Muir), and (bottom) ʻūʻū (bigscale soldierfish), kihikihi (Moorish idols), and masked angelfish. By Andrew Gray, NOAA

Healthy ecosystems are characterized by abundant life and diversity, like these schools of fish in Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument: (right) yellowfin tuna (by Jeff Muir), and (bottom) ʻūʻū (bigscale soldierfish), kihikihi (Moorish idols), and masked angelfish. By Andrew Gray, NOAA

“There is a big misconception around marine protected areas that they are just protecting what we call the 'charismatic megafauna.' But the truth is, the great thing about having these marine reserves or protected areas is that it allows for lots of species richness and diversity overall,” Davis says. “The reserve or preserve is really all about protecting biodiversity, protecting communities, and also protecting areas of refuge for rare organisms.”

Along with environmental benefits, unlocking ocean-based climate solutions also involves numerous co-benefits. The state’s Clean Energy Wayfinders program, implemented

by the Hawai‘i State Energy Office and partners, builds community awareness about conservation and clean energy through community outreach and engagement, as well as sharing information about related job opportunities.

Working with community organizations, residents, schools, and groups, the Wayfinders help the state meet its clean energy goals by sharing information on energy efficiency and conserving energy, clean transportation, green careers, and more. By reaching out to community members to learn about their needs and concerns, the Wayfinders also hope to address inequities.

Incorporating traditional knowledge every step of the way is part of their process. “[It is of] critical importance [to be] guided by traditional practices and native Hawaiian management and values and practices,” TNC’s Conklin says. He insists that the work must be “done with, for, and by cultural practitioners in ways that are responsive to the threats of the future but acknowledges the importance and incredible knowledge of the past, and how the Hawaiian community is carrying that forward.”

By Shellie Habel,

Left: The aeʻo (Hawaiian stilt) and other native wildlife are returning to the wetlands being restored by Kākoʻo ʻŌiwi at Heʻeia, Oʻahu. By Sean Marrs, The Nature Conservancy. Bottom: Wetlands, like those at Waialeʻe on North Shore of Oʻahu, absorb and filter runoff after heavy rains, helping to reduce flooding and preventing sediments from flowing onto reefs.

30

Hawaiʻi Sea Grant

As an island no higher than two meters above sea level, Majuro Atoll is extremely vulnerable to high wave activity, which can come even under good weather conditions.

By Karen Earnshaw

By Karen Earnshaw

COMMUNITY RESILIENCE THROUGH EARLY WARNING SYSTEMS

by Lurline Wailana McGregor

Islands in the Pacific vary from tiny atolls, where the highest point of land may only be six feet above sea level (and even that is not land, but a bridge!), to steeply rising volcanic isles, where there is only a narrow band of habitable coastal land. Despite their geographical differences, both low and high islands are extremely vulnerable to rising seas and ocean inundation as seawater flows across entire atolls and coastal lands subside.

Ka Pili Kai • Kau 2023 • hawaiiseagrant.org 31

Challenge Six of the United Nations Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development calls for an increase in community resilience to ocean hazards. The challenge is two pronged: experts must first develop forecast and early warning systems that are appropriate to individual coastlines; and communities must be able to implement them effectively. Such ocean hazards as rising sea levels, King Tides, storm surges, and tsunamis put coastal communities around the world in jeopardy, but some of the most endangered coasts are on Pacific Islands.

Almost 95 percent of American Samoa’s population lives in coastal villages on Tutuila Island, where rainforests cover its mountainous interior. Prior to the September 29, 2009 earthquakes in the Tongan Trench that generated deadly tsunami waves, American Samoa’s sea levels increased less than one inch a year, or 9.5 inches every one hundred years, according to NOAA sea-level tracking data. After the earthquake, the sea level rose 9.8 inches in 11 years and Tutuila Island began subsiding at 0.63 inches a year compared to the global sea-level rise of 0.13 inches a year. As a result, coastal areas in American Samoa that were previously above sea level have become prone to inundation during high tides and storms.

“We’ve lost about a foot of combined relative sea-level rise vertical height since the tsunami, and that has pretty big impacts,” says Kelley Anderson Tagarino, a Hawaiʻi Sea Grant extension agent in American Samoa. Tagarino is working on a project together with Dr. Philip Thompson with the University of Hawaiʻi Sea Level Center to produce sea-level projections for American Samoa that will combine the effects of subsidence and climate change. “Getting tide gauges in place is really important in terms of getting good elevation data. You need ground control points but we only have the one, tiny edge, and so putting in tidal gauges is an important part of the puzzle.” There is only one tidal gauge in Pago Pago Harbor, which limits the data that can be used for tracking the rest of the five volcanic islands and two atolls that comprise American Samoa. All are inhabited except for Rose Atoll, a marine national monument and wildlife refuge.

Picturesque Pago Harbor and Pago Pago on Tutuila Island illustrates the vulnerability of development on high islands, which is constrained to narrow strips of land at ocean level. By valentine Vaeoso

Picturesque Pago Harbor and Pago Pago on Tutuila Island illustrates the vulnerability of development on high islands, which is constrained to narrow strips of land at ocean level. By valentine Vaeoso

32

Red crosses indicate the locations of the tide gauges and GPS stations at Apia, Samoa, and Pago Pago, American Samoa. Courtesy of CC by 4.0

“My thoughts are rolling out the Sea-level Rise Viewer to use as a tool for families and villages who want to take some action on their land,” says Tagarino.“It’s not going to be an approach like in the states where there are going to be setback notices and things like that. By traditional land tenure, you have to work directly with landowners and the chiefs and let them say what they want to do on their land. And then, hopefully, support them with options from technical experts and see if we can get funding for actual implementation of those things.”

As for tsunamis, the only option is to evacuate coastal areas as soon as a quake is felt since it will only take 14 minutes for the wave to hit. “In the 2009 tsunami it was actually school kids who had undergone training and alerted the villages to go up the mountain. As a result, peoples’ lives were saved,” says Monica Miller, news director at South Seas Broadcasting in American Samoa. “Since then, the general reaction is, even without being told to leave, that once they feel an earthquake, go to higher ground. Last month we had an example of that. It

was a tsunami advisory, not a warning. Once people started feeling the effects, there were postings on Facebook; the people in high risk areas took matters into their own hands and left.”

Resilience in the Marshall Islands

The Republic of the Marshall Islands (RMI) is one of the most isolated and low-lying nations on earth. King Tides and ocean swells exacerbated by a rising sea level are inundating coastal lands. Hilda Heine, president of the Marshall Islands

Roads around American Samoa, like this one on Ofu Olosega, Manu'a Islands, are often low-lying and coastal, putting them at risk from coastal hazards. By valentine Vaeoso

A 2009 tsunami caused substantial damage when it hit American Samoa, leaving debris along the narrow coastlines. Courtesy of National Park of American Samoa

Roads around American Samoa, like this one on Ofu Olosega, Manu'a Islands, are often low-lying and coastal, putting them at risk from coastal hazards. By valentine Vaeoso

A 2009 tsunami caused substantial damage when it hit American Samoa, leaving debris along the narrow coastlines. Courtesy of National Park of American Samoa

from 2016 until 2020, is acutely aware of the increasingly endangered atolls in the RMI and has been a strong advocate for addressing climate change and developing remedial actions.

“We don’t have a complete picture of the situation of coastal erosion in all of RMI,” says Heine. “We entered into an agreement with the World Bank to implement the Pacific Resilience Project – Phase II. The objective of the project is to strengthen early warning systems, increase climate resilient investments in shoreline protection, and provide immediate and effective responses to crises or emergencies. So far the implementation is not consistent; the COVID-19 pandemic interrupted progress on a number of the recommendations when expertise could not come into the country or when government officials could not visit outer island communities due to lockdown policies.”

Despite interruptions caused by the pandemic, Max Sudnovsky, a Hawai‘i Sea Grant extension agent in the Marshall Islands from 2018 through June of 2022, saw changes in the development and adaptation of early warning systems during the years he was on Majuro.

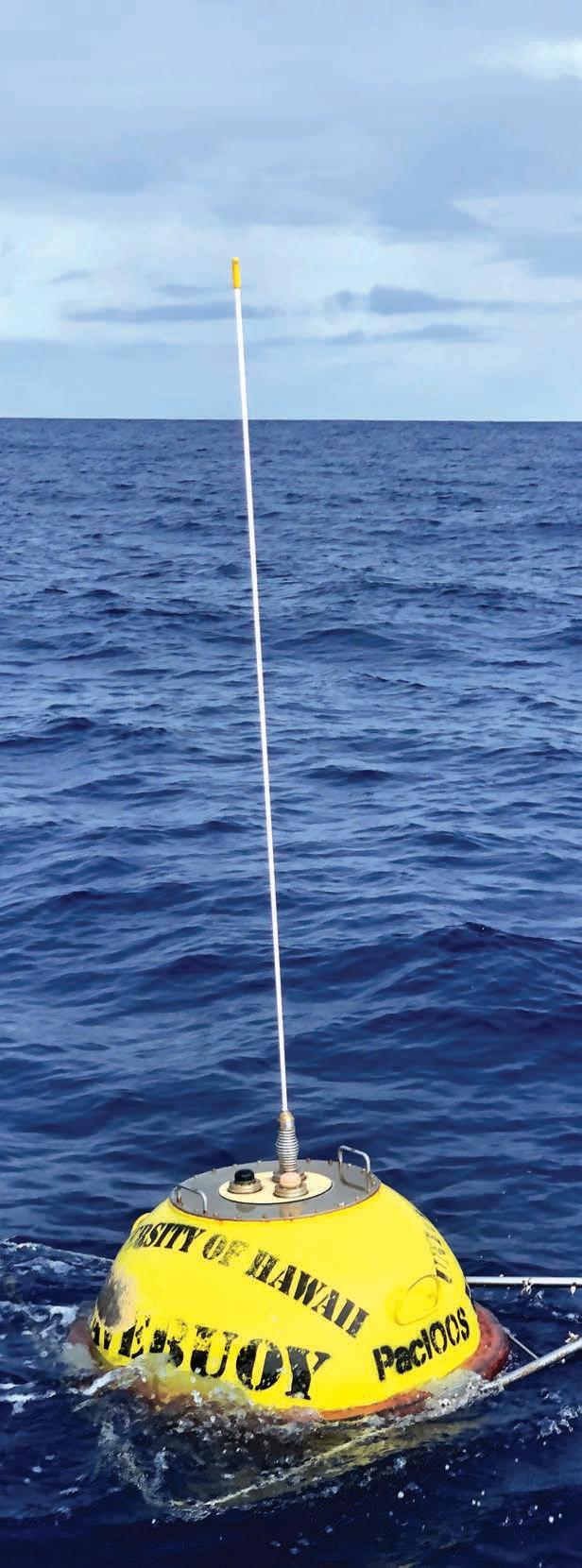

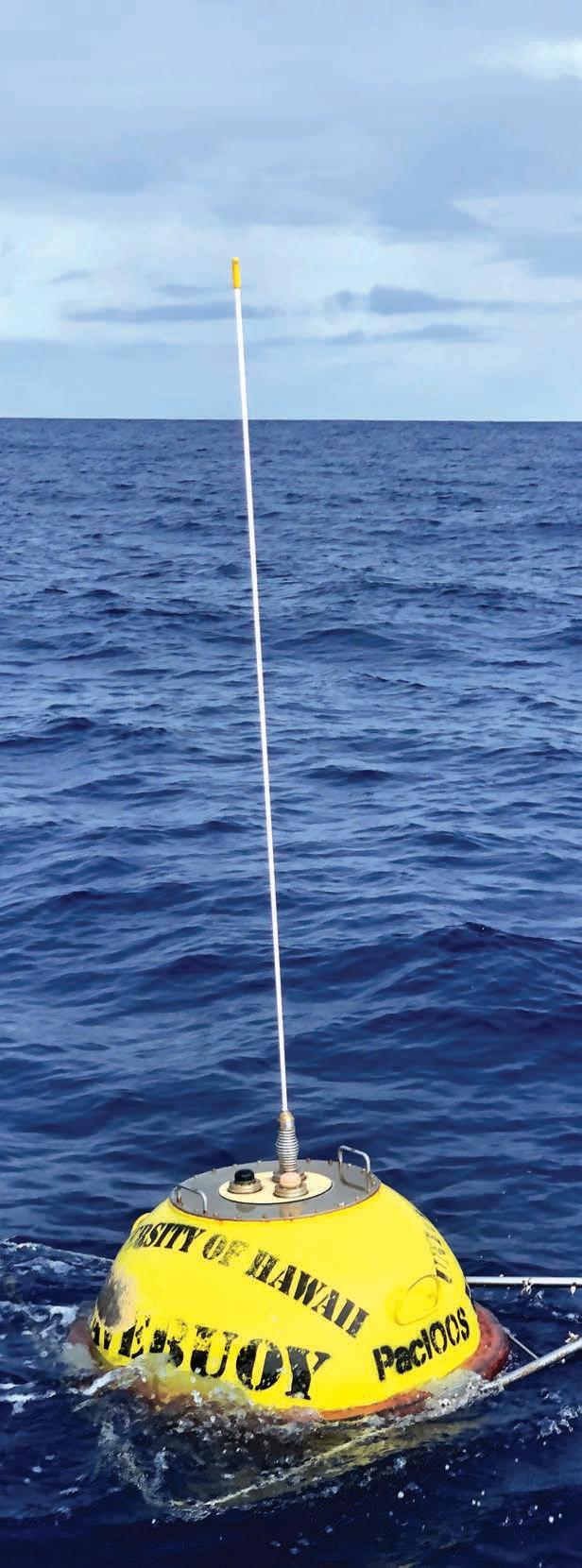

“There’s been a significant improvement from when I first arrived until now in community messaging regarding some of the threats like inundation,” says Sudnovsky. “The PacIOOS (Pacific Islands Ocean Observing System) has a wave buoy that provides very accurate data on wave run-up models and when there might be extreme events that can lead to inundation.”

“What PacIOOS has done has been phenomenally helpful to the Marshall Islands,” says Giff Johnson, journalist and editor of the Marshall Islands Journal “They do a wave runup, which gives you a seven day forecast of the possibility of high tides and storms, and whatever’s going on that the region has for causing inundation. And it has a very useful website, because as we approach the full moon cycle each month, particularly in January and February, when we have the King Tides, you can say, ‘okay, they’re predicting that the potential for inundation is for Friday, Saturday, Sunday’, like that. We’re sitting on a little place like this; it’s gonna flood, but you can prepare a little bit for it. The number of inundations

34

Despite protective seawalls, Majuro homes are often pounded by high westerly surf. By Hilary Hosia

With a lagoon to one side and open ocean on the other, the narrow strip of land that is most of Majuro Atoll faces an existential risk from rising seas.

By Chewy C. Lin

By Chewy C. Lin

that happen now are almost every month. I’ve lived here for 35 years now, and it used to be rare.”

The RMI has been proactive in developing a National Adaptation Plan for sustainable adaptation to climate change, addressing the circumstances and vulnerabilities facing the country. The plan reflects close consultation with local communities throughout the islands, merging science with traditional and local knowledge while informing communities about the importance of ecological and socioeconomic resilience.

Also recognizing the need to involve youth, community members founded an organization called Jo-Jikum, meaning “your home” in Marshallese. “It started out as an environmental group and now has become a climate organization, doing all kinds of workshops with young people to get them engaged, doing creative things that tell the story about low-lying islands, climate challenges, sea-level rise, things we’re seeing,” says Johnson. Some of the youth have worked their way up to becoming participants in international conferences.

“Our survival is paramount,” says Heine. “As a Marshallese, I have to be optimistic that RMI will survive climate change. To think otherwise is not an option and is counter productive.”

Jo-Jikum’s team members Magdalene Rose Johnson and Watak Lanwe participated at the 2023 University of Guam 14th Conference on Island Sustainability in partnership with the Blue Planet Alliance Organization. L to R: Hoku Roby, Nicole Yamase, Watak Lanwe, Magdalene Rose Johnson. Courtesy of Jo-Jikum

Jo-Jikum’s team members Magdalene Rose Johnson and Watak Lanwe participated at the 2023 University of Guam 14th Conference on Island Sustainability in partnership with the Blue Planet Alliance Organization. L to R: Hoku Roby, Nicole Yamase, Watak Lanwe, Magdalene Rose Johnson. Courtesy of Jo-Jikum

36

Majuro youth learn more about climate change with the Jo-Jikum team by traveling to the island of Elekan which, as of 2023, is submerged due to the effects of climate change. Courtesy of Jo-Jikum

BUOYING THE PACIFIC ISLANDS TO ADVANCE EQUITABLE OCEAN OBSERVING SYSTEMS

by Natasha Vizcarra

by Natasha Vizcarra

Expand the Global Ocean Observing System

Peter Perez, who heads a nonprofit preserving maritime culture in the Marianas Islands, holds up a Backyard Buoy. The buoy weighs 16 pounds, 7 ounces and can transmit data on sea surface temperature, barometric pressure, and various wind and wave parameters, all in real time.

Perez

Courtesy of Peter

On the eastern coast of Majuro Atoll, a banana-yellow sphere bobs with the waves. To beach combers, it looks inconsequential as it appears and disappears from view. But the yellow blob is actually a 440-pound data buoy and houses scientific sensors that are key in warning Marshall Islands residents ahead of dangerous storms and floods.

Nicknamed “Kalo” after a species of brown boobies that breed on the atoll, the buoy transmits wave and atmospheric data to a program in Hawaiʻi that uses models to churn out coastal hazard warnings and flood forecasts. These make their way back to the low-lying atoll nation through national and local weather services. Soon there will be more banana-yellow buoys around the Marshall Islands, only much smaller, lighter, and more affordable. Instead of being maintained by personnel in Hawaiʻi—as is the case with Kalo—the smaller buoys will be managed by the Marshallese. More data from these so-called “Backyard Buoys” promise improved forecasts.

Imbalances

“The Pacific Islands include some of the most underserved communities within the ocean observing world,” says Melissa Iwamoto, director of the Pacific Islands Ocean Observing System (PacIOOS) at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa. PacIOOS manages Kalo and 15 other buoys across the Pacific, and has worked hard to address such inequities in ocean observing systems.

The organization is one of 11 regional programs in the U.S. Integrated Ocean Observing System (IOOS) and one of many players in the Global Ocean Observing System (GOOS). PacIOOS recognizes that it serves islands extremely vulnerable to ocean hazards and climate change, so it has tried to lead in the global effort to address critical data gaps.

“The ocean is a big part of our planet, and if you want to observe that, it’s a vast area,” says Mathieu Belbeoch, manager of OceanOPS which tracks 10,000 observations per day coming from the GOOS networks. “Yet the

38

The Republic of the Marshall Islands, a nation of low-lying atolls, faces rising sea levels projected to affect 40 percent of buildings in the capitol city of Majuro, as well as freshwater supplies on all atolls. Courtesy of Asian Development Bank

observing system relies only on a few member states, with the U.S. doing half of the work.”

This imbalance has resulted in inequities in research priorities and funding. Belbeoch says, for example, that because northern hemisphere countries fund most ocean observing systems, oceans in the southern hemisphere have not received as much funding and haven’t been studied as much as they should be. The same gaps have overlooked remote island nations and territories in the Pacific. Bringing awareness to these and other such inequities is one reason this observation challenge is part of the UN Ocean Decade.

Equitable access

Backyard Buoys aims to address the inequity experienced by Pacific Islands by empowering Indigenous and other coastal communities to collect and steward their own wave data. Ajeltake Village, located on the southwestern portion of the Majuro Atoll ring, is preparing to deploy its first buoy, just off the village coast.

“You take care of what’s in your backyard. That’s why it’s named Backyard Buoys,” says Dolores Debrum-Kattil, who leads the Marshall Islands Conservation Society (MICS), PacIOOS’ partner in the atoll nation. “You take care of something that is providing safety for your home.”

Organizations that frequent the waters off Ajeltake have committed to help. Around 100 fishers from the Marshalls Billfish Club and the Majuro Urok (Marshallese for bottom fishing) Club will maintain the buoy during their monthly fishing tournaments.

“Sea safety is really big in the Marshall Islands,” says Dua Rudolph, MICS deputy. “It’s the way we find our food, and it means a lot for the billfish and urok clubs.” Surrounding communities have taken notice and now want their own Backyard Buoys. Some of them will get their wish, as PacIOOS is working with more communities to deploy the buoys.

Iwamoto would love to see more ocean observing systems working with community partners to help them realize their desire to take charge of their own data collection and analysis. “We hope Backyard Buoys can be one example for how to serve the needs of people and communities, especially in the islands,” Iwamoto says. “We are learning every day from our partners and hope to provide a model that others can learn from as well.”

Ka Pili Kai • Kau 2023 • hawaiiseagrant.org 39

Kalo, a PacIOOS wave buoy, is moored off the coast of Majuro Atoll in the Marshall Islands.

Photo by Max Sudnovsky

TIGER SHARKS HELP COLLECT OCEAN DATA

by Natasha Vizcarra

by Natasha Vizcarra

A constellation of hi-tech sensors make up the world’s ocean observing system. Satellites observe the ocean from space. Instruments measure from land, from ships, and from platforms at sea. Data buoys, Argo floats, and ocean gliders collect data from the sea surface to the ocean floor. Now, tiger sharks have joined other ocean animals in helping researchers survey parts of the ocean that humans and robots haven’t explored.

Researchers from the University of Hawai‘i’s Hawaiʻi Institute of Marine Biology (HIMB) have successfully collected ocean and animal behavior data from sensor-equipped tags attached to the sharks’ dorsal fins. The tags collect data on temperature, salinity, dissolved oxygen, and light levels at depth and transmit these to satellite and land-based stations whenever the sharks surface.

The data are distributed by PacIOOS to help augment observations on under-sampled regions of the ocean, and inform and validate oceanographic models. PacIOOS is the first group in the U.S. IOOS to incorporate fish telemetry and behavior as part of their data offerings.

“Nobody’s actually done this with a fish, in our case, sharks,” said Dr. Kim Holland, lead author of the study and head of the HIMB Shark Lab. “We demonstrated the potential for using sharks as ocean monitors.”

By Mark Royer

Ka Pili Kai • Kau 2023 • hawaiiseagrant.org

40

Top: Researchers attach a sensor tag to a tiger shark off O‘ahu. The size of a deck of cards, the tag collects and transmits data that allows researchers to learn more about the sharks and explore previously inaccessible parts of the ocean. Courtesy of PacIOOS. Middle: Researchers from the Hawai‘i Institute of Marine Biology attach a sensor tag to a tiger shark’s fin. By Mark Royer. Bottom: A tiger shark swims away after being tagged. The tags don’t harm the sharks, as they are designed to fall off after a few years.

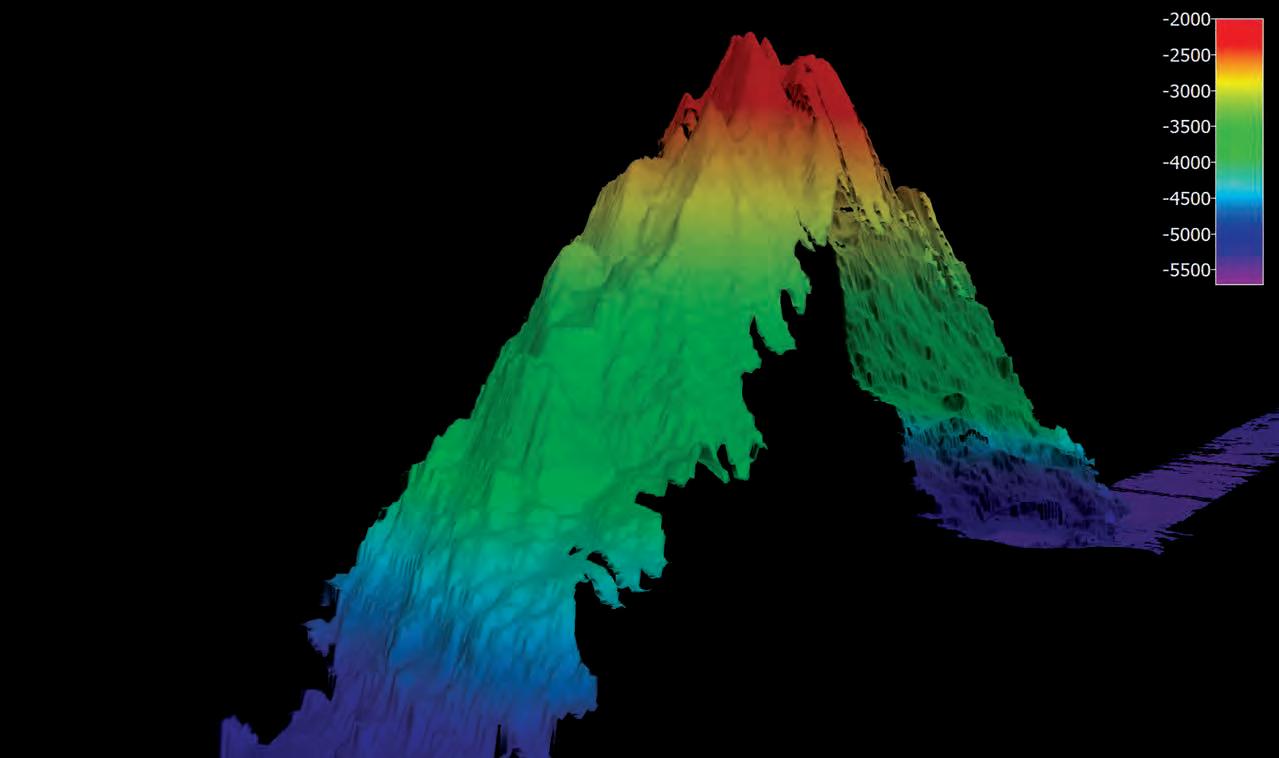

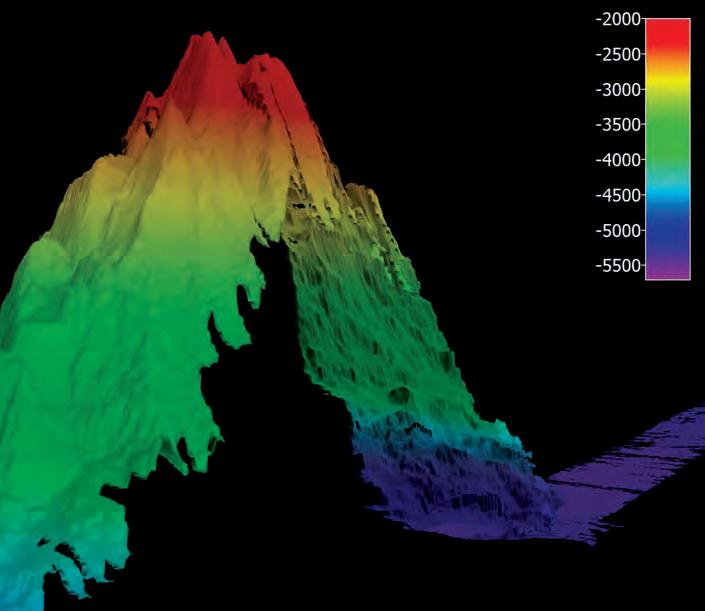

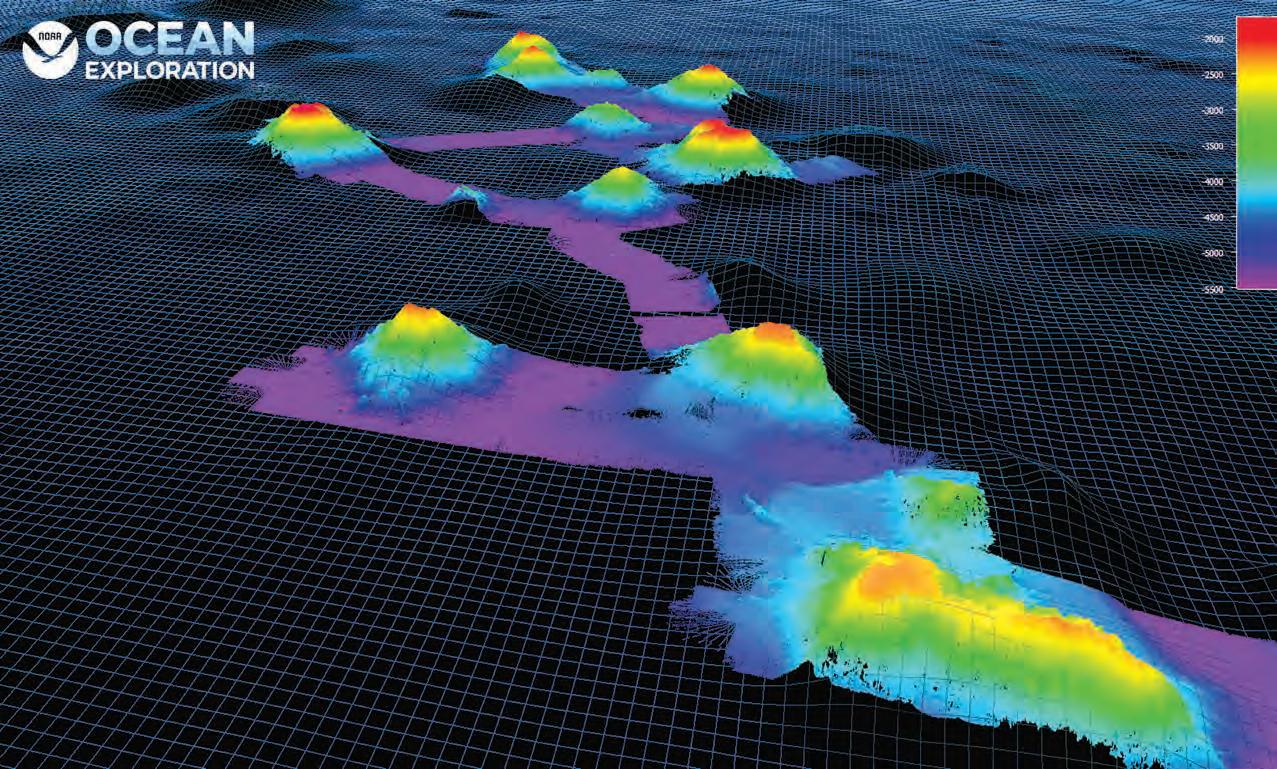

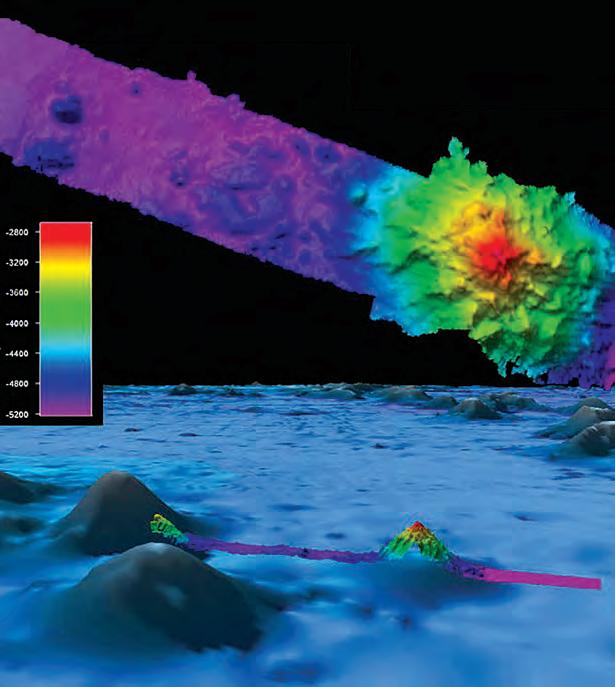

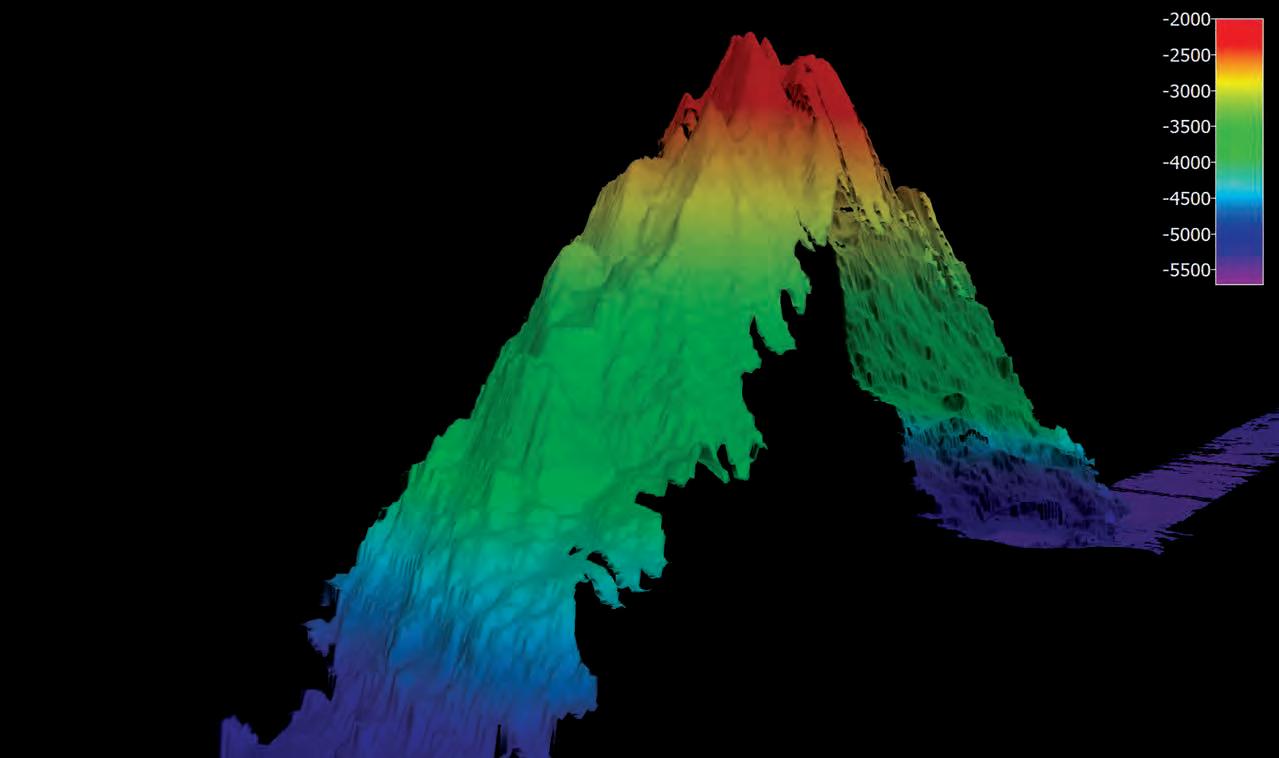

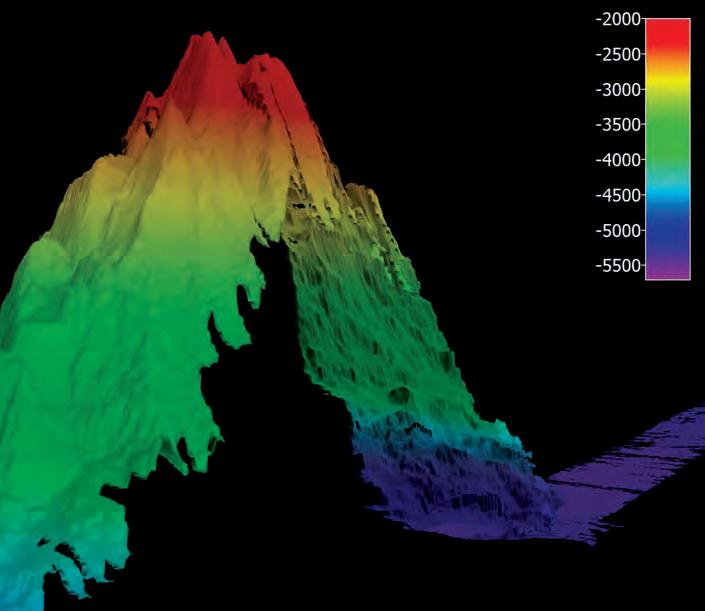

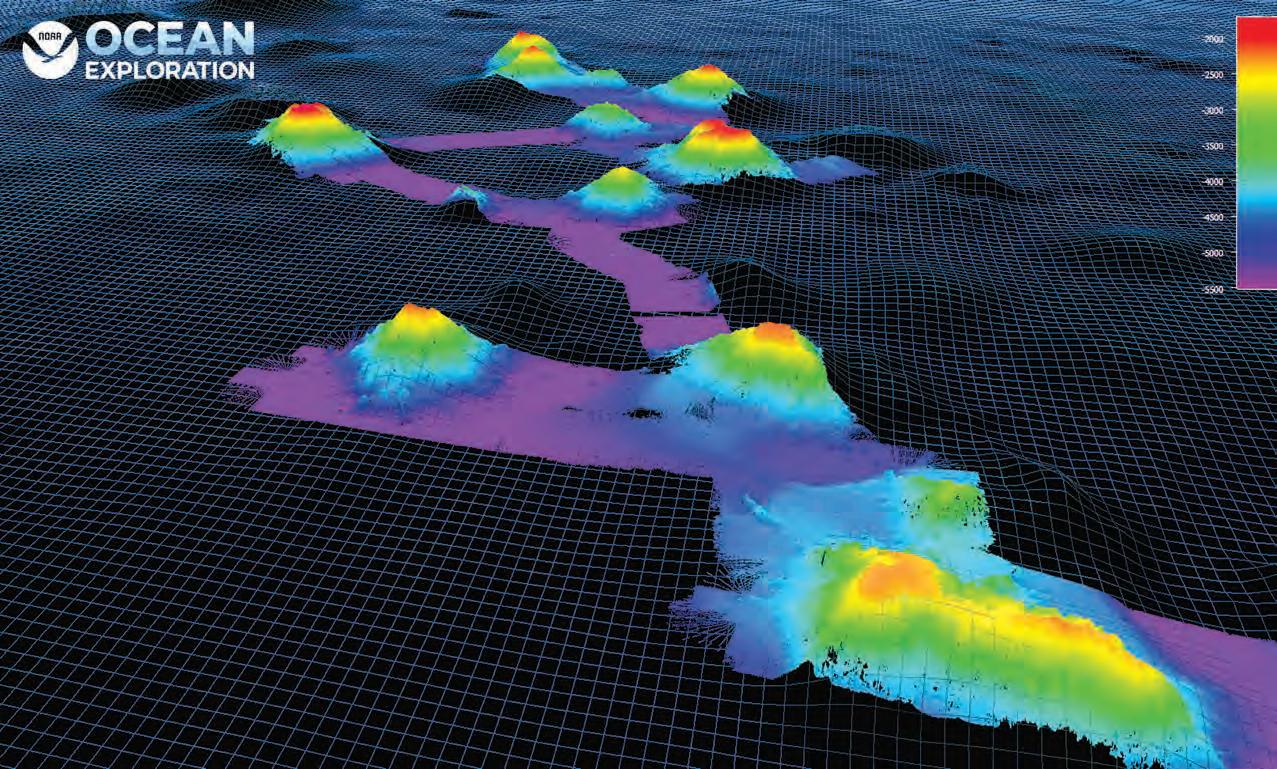

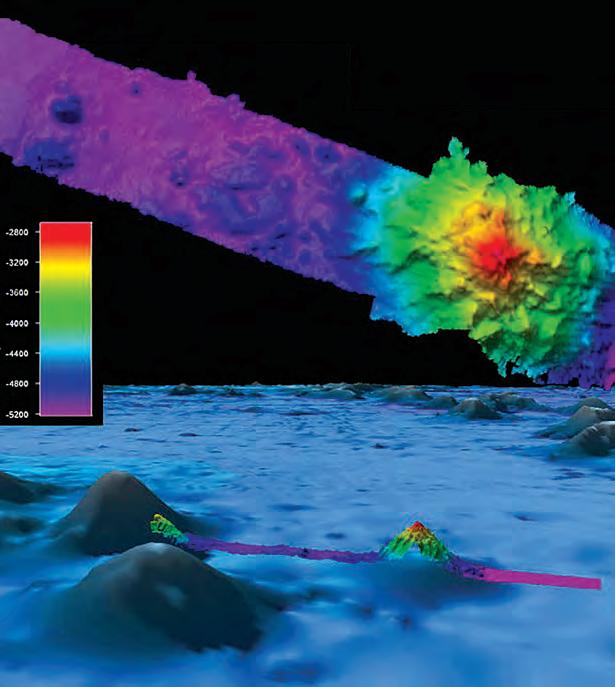

Using data from the Okeanos Explorer mission, 3D visualizations can illustrate the topography of seabed mountains, like this one off the Hawaiian Islands, opening up further research. Courtesy of NOAA Ocean Exploration

MAPPING THE OCEAN FLOOR: ‘WE CAN’T PROTECT WHAT WE DON’T KNOW’

by Mark Marchand

Acknowledging what we don’t know is often the first critical step in scientific research.

One important example of this principle is the seabed lying beneath 139.5 million square miles of water, covering over 70 percent of the Earth’s surface. Today, about 80 percent of the seafloor remains unmapped. If researchers and organizations around the world have their way, the creation of a new digital representation of four-fifths of this deep frontier will be completed in the next seven years.

Ka Pili Kai • Kau 2023 • hawaiiseagrant.org 41

Among those striving to meet the 80 percent mapping goal by 2030 are organizations such as the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), through its Decade of the Oceans effort, and scientists such as Shannon Hoy of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Ocean Exploration team. Hoy, an expedition coordinator teamlead for mapping missions aboard NOAA’s 224-foot long Okeanos Explorer research vessel, has spent about 500 days of her young career at sea helping to conduct ocean floor mapping. Creating the detailed floor map, she explains, requires far different technologies than those used to create topographical maps of Earth and other planets.

“We have increasingly detailed surface maps of other planets like Mars because we can use light-based technology, among other methods. With ocean research on our planet, we can’t use light, because it doesn’t penetrate far enough into water. We use advanced soundbased technologies similar to SONAR used for decades.”

Okeanos Explorer features four different types of sound emitters and receivers known as echo-locators, or sounders. By sending out sound waves and measuring return signals they are capable of sensing the floor up to 20,000 feet below the surface. The returning sound waves are used to create digitized, detailed maps with the help of computers. The ship also features a remotely controlled, dual-stage submersible vessel that can capture smaller-scale, higher-resolution imagery on the bottom.

Hoy and others involved in the mapping consider the effort critical to ongoing environmental research, even though it consumes a great amount of funding and other resources.

“We can’t protect what we don’t know,” she says. “Every time we add to the collective map with our partners around the globe, we learn more about how our world works, how human interaction affects the water column and the seabed. We simply find out more about the planet, for the benefit of all.”

Ka Pili Kai • Kau 2023 • hawaiiseagrant.org

42

While some sections of the ocean floor are well mapped, like these strips near New England, much is still not. Courtesy of NOAA Ocean Exploration

The effort of learning about this remote landscape requires many working on a variety of aspects of the project. Dr. Adrienne Copland, a physical scientist in NOAA Ocean Exploration and a 2017 NOAA Sea Grant John A. Knauss Marine Policy Fellow, spends time calibrating the onboard echo sounders, in addition to studying life in the deep.

“Animal life at those depths will respond to the sound waves differently than the seabed. When we see this, we can study these life forms by sending down submersibles to get closer, high-definition video images. They often end up unveiling life forms or animal behaviors completely new to us.

“One such incident involved a midwater shrimp eating a fish twice its size—from inside the fish’s stomach,” she says. “It was very graphic and interesting. The larger fish just flapped around and didn’t realize it was being eaten.”

On another trip, Copeland and her colleagues obtained video of a bright red jellyfish-type organism they had never seen before. “We were pretty sure it was a new species. We’ll often try to get a small sample of an animal like this to examine genetics, but in this particular case we weren’t able to retrieve some tissue.”

Closer to Hawaiʻi, similar imaging research but in shallower waters is helping scientists better understand ongoing threats to coral reefs that serve as critical wildlife habitats.

University of Hawaiʻi at Hilo assistant professor John Burns and his colleagues have successfully developed detailed three-dimensional imaging techniques to help scientists study coral reefs. Like creating a map of the ocean floor, Burns’ efforts will help generate a baseline.

“Without this detailed starting point that many scientists can use, we cannot track what’s happening to these reefs over time,” he says. “Is a pristine reef staying pristine?”

Threats to these reefs, which are among the most diverse environments in the world, are many, says Burns. They include climate change, sewage outfall, excessive recreational diving, and overfishing. When the reefs suffer, creatures who depend on them for habitats or live around them can fail.

“The biggest threat factors are related to humans,” he says. “We have forgotten how connected we are to coral reefs. Think about the discussions related to the Amazon rain forests. They might be far away from us, but keeping them healthy helps all of us. The same is true for these reefs.”

From better understanding the world some four miles beneath the surface of the ocean to tracking precious, living coral reefs in shallower waters, a better roadmap is under development to help us protect our planet and its myriad life forms.

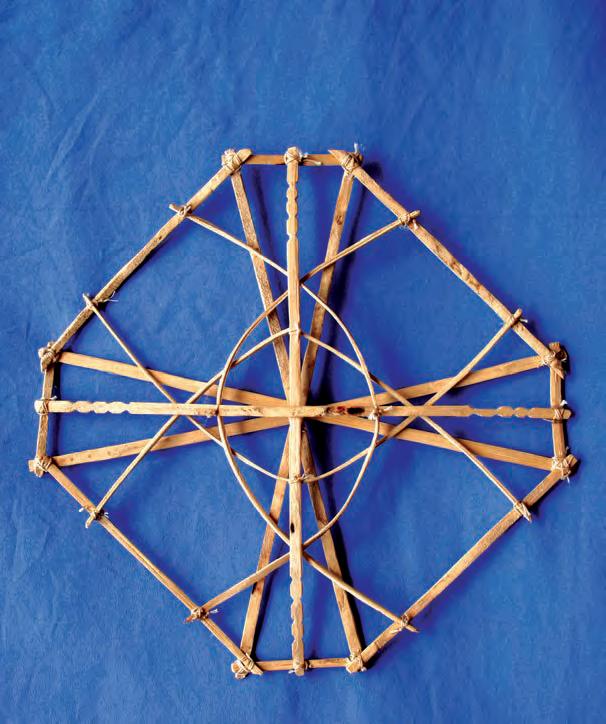

Ka Pili Kai • Kau 2023 • hawaiiseagrant.org 43