THE UBYSSEY

Úxwumixw (Squamish) and səlilwətaɬ (Tsleil-Waututh) nations. racism, sexism, homophobia, transphobia, harassment or discrimination. Authors and/or

‘I want to see the weird in you’: Mila Zuo’s refreshingly honest take on cinema

Bernardo Sampaio de Saboya Albuquerque Contributor

being attracted to something — or someone — that falls outside the norm.

errors that do not lessen the value or the impact of the ads.

Dr. Mila Zuo wasn’t always going to study film — but after taking a pornography course at UC Berkeley, she was hooked. She credits the course’s professor, Dr. Linda Williams, as being one of the first people to open up her mind to the possibilities of film analysis as a discipline.

“She taught it really rigorously. We read Foucault and watched really graphic films and we were able to bring together conversations, and I was amazed that this was a form of academic study,” Zuo said.

Infatuated with critical analysis of film, Zuo went on to UCLA to pursue a master’s and a PhD — and eventually found herself on the other side of the classroom.

Zuo now teaches in UBC’s theatre and film department. She also makes her own films that embrace scandal and sexuality. They’re far from the level of intensity of the hardcore porn she first studied as an undergrad, but they’re definitely not afraid to get a bit weird.

Zuo’s academic interests culminate in her book Vulgar Beauty: Acting Chinese in the Global Sensorium, which has received significant acclaim, including the Association for Asian American Studies’ 2024 Outstanding Achievement award in the media, performance, and visual studies category.

The book, according to Zuo, draws on her attraction to “unsolvable, unanswerable questions.” For her, these inquiries manifest while thinking about how the concept of beauty influences film aesthetics, particularly within the realm of Chinese cinema.

Vulgar Beauty centres the experiences of Chinese women in contemporary media, from film to stand-up comedy, and how they challenge Western beauty ideals. That’s why she thinks the word “vulgar” best represents the work: it captures the shock that comes with

“The experience of [beauty] is ephemeral, but beauty is rooted and anchored in an object life, which is not only the way a physical body looks or presents itself, but it’s also the clothing and the environment that surrounds a person … It’s not just the individual human subject, but it’s the vulgar setting around them,” Zuo said.

“When I’m thinking about Chinese stars or racialized stars, for me, [vulgarity] has a particular meaning in the sense that there’s something that is disruptive about … beauty that doesn’t adhere to conventional standards, whether that’s white supremacist criteria [or] ableist criteria. It’s a shock to the system.”

Alongside her written work, Zuo is also a filmmaker who has produced works like Carnal Orient, her first horror short which provided a bold critique of Asian fetishization by featuring white male diners at a stereotypically Asian restaurant where things slowly start to get bloody.

Sticking with shorts but transitioning in genre, Zuo’s most recent film, Kin, delves into the racial tension and white supremacy she observed while teaching at a university in the United States during the beginning of Donald Trump’s first term as president.

Rey Chow’s 1995 essay “The Fascist Longings in Our Midst” was “crucial inspiration for what the film became,” Zuo said.

“In this essay, she makes this really provocative claim [that] fascists don’t think that what they’re engaged in is a project of hate. They think [it’s] a higher ideal of love. So actually, in their minds, they’re about purity. They’re about love for the nation [and] detoxification of all the contaminating figures that pose a threat to this idea of purity.”

Currently, Zuo is embarking on her most ambitious project yet. Mongoloids, her first feature-length film, combines elements of doc-

umentary and fiction, exploring her own family’s trauma stemming from China’s Cultural Revolution. The process is daunting yet exhilarating.

“As a child, I didn’t hear much about my family’s history. But the older I got and the more questions I asked, little tidbits of information came out,” Zuo said. “I know that this topic can be seen as still quite controversial, especially in China, so we do have to be really careful.”

Zuo was awarded a Killam Research Fellowship this year to work on the project, so she’ll be taking time off from teaching to shoot scenes in China. She plans to have her parents physically re-enact their own memories — there can be a thin line between finding closure and falling back into trauma, but she hopes she’ll be able to help them find a sense of catharsis in doing so.

“It’s a very tender subject, but both sides of my family were persecuted in different ways, and so [I’m] getting my parents to give testimonials,” she said.

“But the other aspect of this is my own questions around trauma … to query whether I have inherited some of these traumatic experiences or memories, and if so, how? As a mother too, this question of intergenerational trauma spans multiple generations now.”

Venturing into the world of documentaries is uncharted territory for Zuo — she’s terrified, excited and unsure of how this whole plan will pan out. But the filmmaking philosophy that she sticks by is to embrace the unknown or uncomfortable.

“There is truism in some of these clichéd pieces of advice … To share something — I hate the word ‘authentic,’ but you know what I mean — you really need to figure out who you are and [what] makes you different from other people,” she said.

“I don’t want to see the thing that makes you like everybody else. I want to see the weird in you.”

The Ubyssey periodically receives grants from the Government of Canada to fund web development and summer editorial positions.

Zuo’s filmmaking philosophy is to embrace the unknown or uncomfortable.

MEHNAJ SYED / THE UBYSSEY

In May 1982, The Ubyssey published a piece outlining the timeline of government cuts to employment funds which led to students finding less summer work.

As Lapu Lapu Day tragedy vigil is held on campus, mourners

look to systemic change for healing

Lauren Kasowski & Spencer Izen Staff Reporter & Opinion Editor

Editor’s note: This article contains descriptions of violence that some readers may find upsetting.

Campus community members gathered for a vigil on April 30 in front of the UBC Bookstore to commemorate the victims and families affected by the LapuLapu Day Festival tragedy. In addition to holding space for grief, many speakers made calls for justice and action to prevent a similar tragedy.

Organized by Sulong UBC and UBC Kababayan, the vigil opened with a prayer at 2:30 p.m. Students, staff, faculty and university administrators were joined by a larger crowd of those looking to pay their respects.

“We gather carrying grief so heavy and we gather carrying names and faces we love,” said a speaker who introduced themselves as Daniel.

“Names and faces that should still be here with us today,” he continued.

Statements of solidarity were heard from Sulong UBC, UBC Kababayan, UBC Sprouts and the UBC Central American Student Association, all reiterating calls for community care and justice.

“It’s important that all facts and answers are brought to light without delay and that accountability must be established,” said

a representative from Sulong UBC.

On April 26 just after 8 p.m., a man drove a black Audi SUV down a closed section of Fraser Street and into festival attendees celebrating Filipino heritage. The BC Prosecution Service has since charged Kai-Ji Adam Lo with eight counts of second-degree murder.

As of press time, 11 people have been killed and dozens more injured while several remain hospitalized in varying condition.

Among the victims was Kira Salim, a New Westminster teacher-counsellor and a former administrative staff at UBC’s School of Music as recently as 2023, according to an online statement made by the school.

New Westminster Schools said Salim’s work “and the great spirit they brought to it, changed lives.”

“The loss of our friend and colleague has left us all shocked and heartbroken,” wrote New Westminster Schools in a statement posted to its website.

Candles were lined along the base of the platform where the speakers stood. A representative from Sulong UBC said, “this tragedy was preventable,” and that “accountability must be established.”

Burnaby city councillor Maita Santiago addressed the various ongoing investigations regarding the tragedy.

“I hope that as we grieve, we also come together and rise [and]

leave no stone unturned,” Santiago began, before extending her call for listeners to focus on learning lessons from the tragedy in place of assigning blame.

“Every single facet of this horrific tragedy needs to be examined, from the lack of mental health supports, to what more the city [could have] done to what more the police [could have] done ... to what more ... could have been done on that day by people that directly had the capacity … to do something,” she said.

“We’re going to have more festivals. We need to. We’re going to gather again,” Santiago said in culmination.

In the hour before the vigil, Premier David Eby announced the government was initiating a review of the Mental Health Act: a provincial law governing involuntary treatment for mental health issues.

Lo was being supervised by Vancouver Coastal Health under the authority of the Mental Health Act at the time of the attack. However, the health authority has said they had no knowledge of any “recent change in his condition or noncompliance with his treatment plan that would’ve warranted him needing to be hospitalized involuntarily,” according to reporting done by the CBC.

The province has been facing a constitutional challenge to the legislation since 2016, which Eby cited as the reason the review was not initiated earlier, despite

agreement among the BC NDP, BC Conservatives and BC Green Party that a review is needed.

The province’s review will be led by Minister of Health Josie Osborne and Dr. Daniel Vigo — the chief scientific advisor for psychiatry, toxic drugs and concurrent disorders to the government of BC and an associate professor in UBC’s department of psychiatry and School of Population and Public Health respectively.

The province declared May 2 an official day of remembrance.

Dr. JP Catungal, a UBC assistant professor of critical racial and ethnic studies, also gave a few words at the vigil, at times with a tearful voice.

“We’ve lit too many candles and we’ve laid down too many flowers before, and here we are yet again,” said Catungal. “We continue to fight for our futures — not just for survival, not just for resilience, but for our genuine collective flourishing.”

Catungal closed his remarks with a poem titled “the garden on fraser and 41st” written by UBC alum Sol Diana.

“On Saturday, our home was turned into a crime scene,” Catungal read aloud, “on Sunday, we laid flowers to rest and turned Fraser and 41st into a garden.”

Christian Sanchez, a member of Sulong UBC, helped organize the vigil to “put [his] grief into action.”

“A vigil for the victims here at UBC is very [much] needed because there’s a lot of Filipino students here, a lot of Filipino workers that are very integral in the functioning of this campus,” Sanchez said.

Cass Del Rosario, a member of UBC Kababayan, also helped organize the vigil and said it was “really nice to see a lot of people come out.”

“And it wasn’t just students,” said Del Rosario.“It was staff, it was faculty — it was the greater community. So it meant a lot for them to make space for us and for our collective loss.”

Both organizers emphasized the vigil’s focus on calls to action.

“The Filipino community is looking for answers as to why this happened,” said Sanchez.

“It’s really important for us to know that a thorough investigation is going to be had, that everything that was preventable in this tragedy is addressed and taken accountability for,” he said.

With increasing scrutiny coming onto the way the municipal, provincial and federal governments address mental health in the wake of the tragedy, Sanchez claimed much attention has been paid only to the mental health of the accused. But for Sanchez, an investigation — and subsequent change — needs to be more holistic.

“For us, true healing for us actually comes from systemic changes. U

“We continue to fight for our futures — not just for survival, not just for resilience, but for our genuine collective flourishing,” said UBC assistant professor Dr. JP Catungal.

SIDNEY SHAW / THE UBYSSEY

Two Allard Law educators among 2024 BC King’s Counsel appointees

Simon Jian Contributor

On May 6, two educators at the Peter A. Allard School of Law were appointed as King’s Counsel (KC) — one of the highest legal designations in the province.

Among the 19 lawyers announced by the Ministry of the Attorney General to receive the initials are Allard lecturer Salima Samnani and adjunct professor Jon Sigurdson.

“The Allard Law community is incredibly proud of Professor Salima Samnani and Justice Jon Sigurdson, and we’re thrilled to see their many important contributions to the legal profession and legal education recognized with this distinction,” wrote Allard Law Dean Ngai Pindell in a statement to The Ubyssey.

The KC designation is a recognition of a person’s excellence in the practice of law, including outstanding work in legal education and leadership among the legal community.

For Samnani, the recognition was deeply impactful.

“I was quite taken [aback] when I got the news,” Samnani wrote. She is co-legal services director at the Indigenous Community Legal Clinic, where she balances legal advocacy with mentorship, guiding law students as they serve Indigenous clients in the Downtown Eastside.

Before UBC, Samnani worked as associate counsel for the BC Missing Women Commission of Inquiry and later as counsel for the Union

AMS LAWSUIT //

of BC Indian Chiefs at the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls.

She also served as a Tribunal Member at the Civil Resolution Tribunal — an administrative tribunal that adjudicates small claims, strata, co-op, societies and collision accident disputes.

“This award means a lot to me professionally as I have worked really hard to embody the ethics

of what it means to be in a helping profession … I have faced many barriers in bringing this goal to fruition, but I persevered and am so pleased.”

She aims for her teaching to reflect trauma-informed, feminist, anti-racist and decolonization frameworks.

“Her thoughtful teaching and mentorship has helped equip our students with the knowledge and

skills to make a meaningful difference in the lives of their clients,” read Pindell’s statement.

Sigurdson served on the BC Supreme Court from 1994 until his retirement in 2017. In addition to his decades on the bench, Sigurdson teaches Charter Litigation at Allard.

“Justice Sigurdson has been a valued advocate and a consistent supporter of the law school,” wrote

Pindell.

“The enthusiasm he inspires in his students … is just one example of the continuing positive impact he has had on BC’s legal community.”

Appointments to KC are made by the Lieutenant Governor on the advice of the Attorney General. Approximately 3.5 per cent of practicing BC lawyers currently hold KC. U

AMS sued by removed VP AUA for wrongful termination

Aisha Chaudhry & Colin Angell Editor-in-Cheif & News

Editor

Previously-removed VP academic and university affairs (AUA) Drédyn Fontana is suing the AMS for wrongful termination and aggravated damages.

According to the notice of claim obtained by The Ubyssey from the Provincial Court of British Columbia, Fontana is seeking a total claim of $32,824 — $21,531 in severance pay, $11,136 in aggravated damages and $156 in filing fees.

These numbers do not include court-ordered interest.

“We intend to dispute the claim and defend the AMS’s actions in court,” said AMS President Riley Huntley in a written statement to The Ubyssey. Huntley also wrote that Fontana “personally” delivered the claim to him.

“I’d like to see … some accountability taken,” said Fontana in an interview with The Ubyssey following the filing of the notice of claim.

Fontana was removed from office in November 2024 by an AMS Council vote following an investigation by the Executive Performance and Accountability (EPA) Committee into the former VP AUA, citing poor performance, non-confidence, inability to complete his goals and misrepresentations to Council as the reasons for his removal.

“I’d like to see … some accountability taken,” said

The notice of claim reads that Fontana never received severance pay or notice of termination.

It further claims that he was removed due to “an internal procedural process” not related to his competency as a worker, and he was not given the opportunity to remedy his performance.

Commenting on this, Fontana

said there were “problems” with bias in AMS Council and the investigation that he believes “were not properly addressed.”

“If there were concerns about my performance, a performance improvement plan would be put in place and then I would be able to address those concerns,” said Fontana.

“That didn’t happen,” he continued.

Fontana also claims the way the AMS and its representatives acted during and after termination was “malicious and harmful” to Fontana’s reputation.

The claim specifically cites the email sent out by previous AMS President Christian ‘CK’ Kyle

on February 12 about Fontana’s removal which was sent to the entire student body.

Huntley wrote that the decision to dismiss Fontana was made “in accordance with the AMS Bylaws and Code of Procedure,” and was voted on by “elected student representatives.”

During an investigation conducted into Fontana’s removal, The Ubyssey obtained a report titled “Inquiry Report: Drédyn Fontana Vice President, Academic and University Affairs,” purportedly created by the EPA Committee detailing their inquiry process into Fontana’s performance.

At the time, the AMS would not confirm the authenticity of the document but did respond to The Ubyssey’s reporting by standing behind Fontana’s dismissal.

The document said the committee found it “premature to make a determination on the progress of [Fontana’s] goals due to the number of ongoing goals and multi-year goals.” Despite this suggestion, AMS Council voted to terminate him.

In his statement, Huntley wrote that he cannot “comment on specific terms under which Drédyn left” due to privacy legislation.

“We do, however, believe that we have acted fairly and followed all laws in relation to this case,” wrote Huntley. U

“I have worked really hard to embody the ethics of what it means to be in a helping profession,” said Allard lecturer Salima Samnani.

Fontana in an interview with The Ubyssey.

MILES DEACON / THE UBYSSEY

ISABELLA FALSETTI / THE UBYSSEY

Art meets activism at the Music, Art and Architecture Library

Jodie Buan Contributor

Nestled in glass display cases by the entrance to the Music, Art & Architecture (MAA) Library in IKB is the latest exhibition from the library’s curatorial team.

Rise Up! Sights, sounds and spaces of protest features materials from the MAA Library collections, the Rare Books and Special Collections and the university archives. The exhibition explores forms of protest performance and presentation, highlighting the aesthetics of resistance across space and time.

The centrepiece of the exhibition is Christopher Cook’s photo book Black Lives Matter opened to a page with a photograph entitled Streamed. The image shows a man holding a sign above his head that reads ‘THE REVOLUTION WILL BE STREAMED.’ It was captured on film during the marches across the US in 2020.

“The particular protester is referencing a very specific phrase from the Civil Rights Movement but has adjusted the words to reflect the current movement,” said Sara Ellis, curator of Rise Up! and the art and visual literacy librarian at the MAA Library. “There very much is one individual there, but then you can see, everyone, the crowd, is behind and it’s this interesting juxtaposition.”

The phrase printed on the activist’s sign is an interpolation of American artist and activist

Gil Scott-Heron’s poem “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised,” first recorded in 1970. It invites reflection on the role of social media in propagating change in the modern era. Scott-Heron’s words remain relevant in the modern day. This past February, Kendrick Lamar echoed the poet at the start of his Super Bowl halftime show, saying, “the revolution is about to be televised.”

“I think, for myself, photo books

HELEN AND MORRIS BELKIN ART GALLERY //

“We do try to have exhibitions that highlight materials from our branch … that are reflective of past histories, movements, events and also responsive to the current moment,” said Ellis.

The conversations Ellis had with her fellow curators, MAA Library head Paula Farrar and music librarian David Haskins, were a highlight of their collaboration. These allowed the curators to learn from one another’s areas of expertise.

“I think … sometimes the specific connections when you’re planning on paper might not be super evident. But then, as you actually see the material in front of you, it’s like, ‘Oh, actually, these two things are really speaking to each other,’” said Ellis.

can be really important for capturing a very specific moment and capturing a very specific feeling or emotion, or a particular message,” said Ellis. “I think when you have a photograph that really does invite further questions and further investigation, that’s something that really appeals to me.”

last year’s Climate Action Week. This time, Rise Up! encompasses a wide range of social movements beginning in underserved and marginalized communities, rooted in history yet pertinent to modern times. Some of these protests occurred here on campus. For instance the exhibition included photographs of Tent City: a protest encampment built by students along Main Mall in 1966 to demand adequate housing.

Other pieces on display at the library include photographs of an exhibition entitled Not for Sale! by the Architects Against Housing Alienation collective at the 2023 Venice Biennale and the sheet music for “The People United Will Never Be Defeated!” — a piano composition by Frederic Rzewski — alongside a CD recording of the piece performed by UBC Professor and pianist Corey Hamm. Nearby, another photo book — open to a page showing the NAMES Project AIDS Memorial Quilt — rests atop the AIDS Quilt Songbook.

The Rise Up! exhibition will be displayed in the MAA Library until the end of summer, with new exhibitions planned for the upcoming fall semester. U

Impos(s)able Impositions: MFA exhibition at the Belkin

Fahmia Rahman Contributor

Impos(s)able Impositions — this year’s annual master of fine arts (MFA) graduate exhibit at the Hellen and Morris Belkin Art Gallery — encompasses the lives and experiences of its artists in various mediums such as photography, print, sculpture, film and performance art.

The exhibit invites select graduate students from the MFA program to showcase the artworks they have developed throughout their degree. This year’s exhibition features works by Solange Adum Abdala, Mahsa Farzi, Vanessa Mercedes Figueroa, Sarah Haider and Yuan Wen.

While the artists developed their work independently, Belkin curator Melanie O’Brian said “materially, they have this kind of interactivity … they’re all dealing with memory and the body.”

Haider’s piece, entitled “Pouring from an Empty Cup” is displayed on a large white wall next to the entrance. Sixteen letters span the space, each addressed to significant people in the artist’s life. Beside each letter is a piece of canvas with a scent that ties it to the letter. Through each letter and its associated scent, Haider offers the viewer a deeply personal insight into her life, laying her memories bare and allowing strangers to read personal correspondence with her family, friends and partner.

Haider uses this piece to communicate the experience of moving through space geographically and immigrating to a new country, while still feeling connected to one’s home. Through her inclusion of the scented canvases next to each letter, she shows how memories are intrinsically connected to smell.

In a large room at the other end of the gallery, Wen’s beautiful, in-

The MAA Library’s previous exhibition, The Heat Is On: Creative responses to climate action in Music, Art and Architecture coincided with tricate, woven bamboo sculptures, elements of her piece entitled “Following this Wave,” hang from the ceiling. Light shines from above the sculptures, creating beautiful patterns and shadows across the floor. There is something remarkable about standing under the sculptures and looking up at them. Wen explained that the artwork speaks to her cultural identity.

“I choose material from my

hometown and really closely relate to my childhood memory and [a] really different lifestyle in rural China,” said Wen. “My thing is [to] connect some memor[ies], connect some differences between futures, between nations, or maybe between different lifestyle[s], like … capitalism here [versus] my hometown, [a] quiet peasant community.”

Wen’s decision to use bamboo as her material comes from bamboo

not being limited to landscaping. In her hometown, she said, bamboo is used to “do everything — [to] cook, make tools and make furniture.” As such, the artist draws on a long and personal history of bamboo as a versatile material when she uses it to make her sculptures. Creating this bamboo installation was a process of experimentation for Wen, because she is not a master of bamboo weaving. Rather, she took some craft courses and examined patterns in bamboo woven objects from her hometown to understand the practice of weaving with the material.

Figueroa said that she uses film sculptures and performance art as a “reflection of how racialized, feminized bodies such as [her] own move through space.” She specifically focuses on the labour undertaken by feminized bodies. Like Haider and Wen, Figueroa draws on her memories and experiences to inspire her works. Her piece in Impos(s)able Impositions, entitled “Wow Factor III,” is based on her experience as a marketing coordinator in a chain liquor store where they told her that she “was doing a great job but that [she] had no wow factor.”

Impos(s)able Impositions is on display at Belkin Gallery until June 1. If you can’t make it to this one, don’t worry! The Belkin hosts MFA grad exhibitions every year, and they have other exciting exhibitions and events being held this summer and in the fall. U

Rise Up! is the latest exhibition from the MAA Library’s curatorial team.

“Chalo k Chalen! (Lets Go!)” by Sarah Haider.

COURTESY PHOEBE CHAN / UBC LIBRARY

COURTESY HELEN AND MORRIS BELKIN ART GALLERY

Conversation in translation

EDITORS’ NOTE

In a world where the luxury of swift translation is only a WiFi connection away, it can be all too easy to think of language barriers as a solved issue. For millions, though, the question of communication across linguistic and cultural divides remains a daily struggle.

This year, The Ubyssey’s Asian Heritage Month supplement highlights both the enduring challenges of interpretation in the multilingual Asian world, as well as the innovative steps that Asian care workers, activists and artists take to bridge systemic linguistic gaps. We spoke with Canadian medical interpreters on how their work allows people to access life-saving health services, heard from Asian singers paving the way through genres that weren’t built for them and searched UBC’s archives for the forgotten origins of cherry trees on campus.

Contributors reflected on feelings of comfort and alienation in their relationships with language, telling stories of stumbling through words that are supposed to feel natural and trying to find comfort through prayer in the wake of the Lapu-Lapu Day tragedy. Others took a look at the translation of customs and colours across the borders of Hong Kong, Taiwan and Vietnam.

Read these stories, parse their meaning. If they speak to you, in Tagalog, Hoisanese or English, tell your friends in whatever language rolls smoothly off your tongue.

HONG KONG STUDIES INITIATIVE BRINGS ASIAN INDIE FILM TO UBC

By Julian Coyle Forst

“Are you blue or yellow?” It’s a question that many Hong Kong residents will have answered in the past. Wrapped in code and tied to the unique socio-political position of the island nation, the phrase is at the heart of Hong Kong’s politics today.

On May 6, as the final event in their Asian Independent Cinema Showcase, UBC’s Hong Kong Studies Initiative (HKSI) screened two independent films that approached this question and the issue of independent cultural identity in the contexts of Hong Kong and Taiwan.

These two films were MT’s Cyclone and Chan Cheuk-sze and Kathy Wong’s Colour Ideology Sampling.mov. The screenings took place in a lecture hall of the Aquatic Ecosystems Research Laboratory and were followed by a virtual Q&A with the directors.

The HKSI’s Asian Independent Cinema Showcase, held four screenings throughout the first months of 2025 and was aimed at platforming smallscale productions from Asian filmmakers for a Vancouver audience.

Cyclone and Colour Ideology Sampling.mov were stylistically disparate, but both approached ideas of sovereignty in the shadow of the People’s Republic of China (PRC). The

first, Cyclone, was a shorter stylistic documentary record of the 25th anniversary of Hong Kong’s handover from the UK to the PRC; a day which coincided with the landfall of Typhoon Chaba.

Cyclone opened with rushing air and bubbling water — close-up shots of electric fans and boiling pots anticipated the coming storm.

Hong Kongers split their time, celebrating beneath gathering clouds and preparing for the floods. Dialogue was sparse, mostly confined to a short interview with a woman sharing thoughts on the handover. The question of Hong Kong’s relationship to mainland China loomed over the film like its titular cyclone.

During the Q&A, MT said the film was created for a competition that called for shorts filmed and set over the course of a single day. The variety of shots and filming locations were impressive, especially for such a small-scale production, with MT himself claiming surprise at how cohesive the final product turned out to be in the edit. It was shot, he said, in collaboration with friends and colleagues positioned all around the city to gather footage of the festivities and storm preparations.

The second documentary, Colour Ideology Sampling.mov,

was longer and more explicitly politically minded than the expressionist Cyclone. Through case studies documented in Hong Kong and Taiwan, Chan and Wong explored the significance of specific colours in the political contexts of the two nations.

Though the political landscapes of Hong Kong and Taiwan are both to an extent shaped by overtures from the giant to their north, the char- acters and colours of their political parties are distinct. The film followed a group of Hong Kong politicians visiting Taiwan during the 2019 presidential elections, and was interspersed with presentation sections where Wong and Chan discuss the footage and the significance of colour as symbols of political ideology.

The film was concerned with issues of translation and interpretation in both language and colour. At a few points, for instance, the difference in dialect between the Hong Kong and Taiwanese politicians led to comedic confusion and laughter from the audience.

But ideological translation between the two political environments proved an even bigger struggle. In Hong Kong, for instance, the colour blue represents conservative proPRC sentiment in opposition to democratic yellow. In Taiwan,

however, blue is the colour of the Kuomintang (KMT): the established centre-right party that fought the communists in the days of the Chinese Civil War. As such, many Taiwan- ese voters view them as the obvious anti-PRC ticket, which can lead to confusion for those with connections to both places.

The film’s central politicians ran into one upper-class Hong Kong woman at a KMT rally who voted blue in her native city for the party’s conservative values, but support- ed the Taiwan KMT for their resistance to mainland China. She scorned the communists as tyrants for threatening Taiwan yet called the protestors in Hong Kong a gang of riot- ers. Her case rendered a complex tangle of class, solidarity and nationalist zeal between the two islands crystal clear.

The Q&A section also became caught up in questions of translation when, while responding to a question on his plans for a follow-up to Cyclone, MT asked the hosts to interpret for him as he switched to Cantonese to better express his thoughts. Barring a small mishap when the hall’s projec- tor overheated and shut down mid-talk, this was a fitting close to an evening where the languages of colour, cultures and politics took centre stage. U

— Elena Massing & Julian Coyle Forst

One hundred years ago, in 1925, the mayors of Yokohama and Kobe presented five hundred Ojochin cherry trees to the Vancouver Park Board in honour of Japanese-Canadian veterans of WWI. The cherry trees were planted around the Cenotaph Memorial in Stanley Park and marked the start of cherry trees in Vancouver.

Today, there are around 43,000 cherry trees in Vancouver. The history of the city’s cherry trees — fascinating in its own right — has been written about, such as in Nina Shoroplova’s A Legacy of Trees, which focuses on the history of cherry trees at Stanley Park, and Fiona Tinwei Lam’s piece on the Uyedas, a family who donated 1,000 cherry trees in 1935 only to later become part of the 22,000 Japanese-Canadians forcibly interned during WWII.

Lesser known, however, is the history of cherry trees at UBC.

The oldest cherry trees on campus are likely at Nitobe Memorial Garden. Fifty trees were shipped over from Japan as a symbol of Japanese-Canadian friendship for the garden’s opening in June 1960. Of this generation — found mostly in Nitobe but also between Lower Mall and University Boulevard — there are likely 45 cherry trees left today, according to Douglas Justice, an associate director of UBC Botanical Garden.

The other cherry trees on campus were planted in subsequent waves in the 1970s and 1980s, such as those on West Mall near the Kenny Building. The cherry trees from the 1960s are mostly from Japan but, according to Justice, in the mid1970s the Department of Agriculture introduced strict importation rules over virus fears. Cherry trees have since been sourced from inside Canada.

The cherry trees’ history at UBC is not limited to waves of planting; cherry trees have often been cut down in favour

of campus infrastructure.

Justice said the path beside the Beaty Biodiversity Museum used to have some, as did the path between the Swing Space building and Main Mall, before the Earth and Ocean Sciences building opened in 2012. Most saddening, perhaps, is the three cherry trees that lived on the grassy hill southwest of the old Student Union Building (SUB), now known as the Life Building. According to Justice, the three great white Taihaku cherry trees were planted when the old SUB opened in September 1968, but were cut down in 2015 to make way for the Nest.

If the history of cherry trees on the main campus seems like an unpleasant combination of infrequent planting and too-frequent chopping, then the south campus provides more hope, or at least a sense of thoughtfulness and consideration.

In 1973, a plot of cherry trees near the UBC Farm was planted and co-managed by the Faculty of Land and Food Systems (then called the Faculty of Agriculture), the BC Landscape and Nursery Association (then called the BC Nursery Trades Association) and the BC Landscape Plant Improvement Association Orchard, which no longer exists, but is recorded in Botanical Garden Science periodical Davidsonia as having managed the south campus orchard.

Justice said the Faculty of Land and Food Systems used to run field schools at the cherry plot, with students deflowering some ornamental cherries to protect the fruit cherries from pollen-borne viruses.

Justice said thermotherapy was also practiced at the south campus cherry plot — a method used to propagate cherry cultivars that are virus-indexed. Cultivars are a variety of a given plant produced by breeding, with virus indexing being a process of determining whether a tree has a virus through

a combination of ‘test’ and ‘indicator’ plants. The Trades Association in particular would graft from the cherry orchard onto their stock to then sell throughout the province.

Of the 10 rows originally planted at the south campus plot, there is now only 1 left. This row, those on campus and those in Vancouver more generally, said Justice, all remain at risk from viruses and infrastructure projects.

And yet, hope remains. There has been a nascent focus on conserving our cherry trees. Justice said he was one of the only people interested in urban forestry or dendrology and epidemiology at UBC in the 1990s. Today, however, the Faculty of Forestry has an urban forestry department and he notes an increasing interest in cherry trees amongst the community, such as the Vancouver Cherry Blossom Festival founded in 2005.

Douglas himself has documented 55 cherry cultivars across Vancouver, and has tried to propagate all of them. There is still work to be done — Douglas laments the loss of three cherry cultivars that could not be propagated, and that there is not enough funding to be able to virus-index cherries at the Botanical Garden. With importation rules still in place, it is likely those three cherry cultivars will be lost, and Vancouver, come spring, will be that little bit less bright. U

HISTORY IN BLOOM

By Rory Maddinson

A HEALTHY UNDERSTANDING

By Elena Massing

“Because it’s convenient and doctors are busy, rather than asking the patient questions and asking that the family members interpret what they say … they just have a conversation with the family members and the patient has no agency.”

on this work.

“We’re doing all this work on the ground in response to these community needs, but how do we advocate for this at a more official or structural level to happen, so that it’s not falling on the hands of translators and kids and family members to do this?” Lee said.

“In an ideal world, those types of things should be sustained by those governments and institutions internally, as well.”

Cheung emphasized that governments should be working with grassroots organizations as often as possible because they know best — and without support, they may shut down or reduce capacity like Bảo Vệ Collective or the Hua Foundation.

He also believes there’s a space for academics in the conversation. The Hua Foundation has had a long-standing partnership with ACAM, in part because Lee graduated from the program herself.

“People will sometimes raise the critique of academics [being] completely separated from the community — all theory, no practice, no action. I’d like to think that ACAM is slightly different in that regard,” Cheung said. Lee said that working with scholars has given the organization access to grants and experts with knowledge in certain areas that they wouldn’t otherwise have.

“How do we advocate for this at a more official or structural level to happen, so that it’s not falling on the hands of translators and kids and family members to do this?”

— Christina Lee, Hua Foundation director of community capacity and strategic initiatives

Cheung also noted that academics, especially those in the ACAM program, are constantly collecting race-based data and doing research on how racialized communities might be impacted by certain health-related issues in different ways.

“Without that, the government does not know what communities are most impacted by the pandemic or by whatever public health crisis is happening,” Cheung said.

“We also have to understand the reasons why some communities were particularly impacted.”

He hopes to see the government prioritize reaching out to academic units and grassroots organizations going forward.

“Working with scholars [and] community organizations at the same time … can allow us to create plans and protocols that would really best serve communities in a conscientious, thoughtful and ethical manner.”

Shortly after the LAP launched, the City of Vancouver instituted an administrative policy for language accessibility. There’s still much more work to be done and many other languages to uplift, but Lee believes it’s a step in the right direction.

“I think even the staff that worked on it will admit that it’s not perfect, but it’s the first step in terms of building a tangible policy that supports language accessibility across multiple departments,” she said. “[It] was really exciting to see something like that come to fruition.” U

— Young Joe, medical interpreter

AWIT NATIN AY ‘WAG NA ‘WAG MONG KALIMUTAN

“Don’t ever forget our song”

My family moved from Makati to Delta, BC in 2023. Until then, I had been just another person in the crowd. Back home, I blended in — tall for some, I guess. I spoke a localized version of English without thinking and ate my grand mother’s adobo recipe every week. I was Filipino — so was everyone else. I had never been an immigrant. Since I arrived, being Fili pino in Vancouver has meant being constantly reminded that I do not belong. My head turns sharply every time I hear Taga log. I stare transfixed when I see people who look vaguely Filipino and beg my parents to speak to me in Tagalog at home to give me a break from the harsh yammer ing of English I hear every day.

My parents left everything they’d ever known to start over. The foundation of my identity as a Filipino immigrant is rooted in survival instincts; in the way I attend a Filipino mass to remember the prayers my grandparents recited as I laid beside them, in the fake accent I use to blend in with my peers and in the food we cling to like our lives depend on remembering the taste of garlic. I didn’t have many friends when I moved to Vancouver, let alone friends who’d be willing to eat Filipino cuisine. So when LapuLapu Day, April 26, came around, I was elated to invite my friend to come with me to the block party in South Vancouver.

By Arianna Aportadera

Lapu-Lapu Day was a haven. The day set aside to celebrate the beloved Indigenous hero who fought Magellan is one of the few moments that the Filipino community of Vancouver comes together to celebrate our history and culture. It symbolizes the solidarity of cultures uniting in BC and honours the heritage of Filipino-Canadians. It’s a special day that allows us to feel seen, to celebrate being Filipino together.

As I walked onto 43rd Avenue, my neck relaxed. I was surrounded by the bustling noise reminiscent of home. In one corner, I

aroma of garlic spread across the palengke. This was the smell of my Momsy’s kitchen. I was fine. Children clung onto their mothers’ skirts, trying their best not to get lost in the sea of black hair. By Plato Filipino’s booth, I spotted a stack of chicken skin for $8 and rushed over to buy a box. A true Filipino, I soaked each piece in vinegar before popping it in my mouth, indulging in the cholesterol my mother hated. My friend walked to the other side of the palengke to buy us jollof rice from a Ghanaian pop-up. It reminded me of my Tita Asia’s paella with a hint of pineapple. Language upon language surrounded us, creating a new environment of multicultural celebration.

While beautiful, Lapu-Lapu Day is another reminder that I don’t really belong here. It’s like being in a liminal space. I can smell the food my grandma would cook for me when I was sick but I also remember how hard I’ve had to search for any sense of community.

My friend and I arrived at the festival at around 6 p.m. We missed the bus and ended up arriving later than we expected. We left at exactly 7:24 p.m. I told

senior high school strand, when I chose UBC and when I chose to summer in Vancouver instead of back home, I’d kept faith in my choices. And now something was telling me to leave. As the sun sank low, we took a few last pictures and headed to the R4.

My father began calling me at 9:28 p.m. I didn’t answer until two phone calls later, confused at why so many people were ringing my cell.

“Where are you?” he asked, angry at my late response.

“I’m on the bus, why?”

“Are you still at the Filipino event?”

“No, why?” I asked. He hung up.

A few minutes later, my father sent me a link. It was a video of ambulances and police officers on 43rd Avenue, the same street where we had taken pictures earlier. People huddled in small circles, loudly arguing in a variety of Filipino languages. The sound of the sirens from emergency vehicles drowned out the screams of people at the crime scene. I did not know what I was looking at. I thought it was a small car crash that knocked over a food truck or two. I didn’t realize a massacre had just occurred.

A slow trickle of Instagram infographics followed the event. Plato Filipino and many other Filipino businesses closed for a few days afterward. St. Mary’s Parish, Bayan BC, UBC Sulong and UBC Kaba immediately released statements of solidarity. The community had taken a deep breath and was too fragile with grief to exhale. We were all trying to make sense of what had happened — to move with sensitivity and care. What happened that night was devastating. Lives of loved ones were lost and families were torn apart, all because of one decision made that night. I cannot speak for them. I was not there when it happened. I can only speak about what it was like to be part of the crowd before the sirens — hearing the children laughing, families sitting by the curbs eating street food and what it means to carry the aftermath as a member of this community.

St. Mary’s held a prayer vigil on May 2. I attended with my mother and my grandmother who held her rosary close to her chest and muttered ‘Hail Mary’ with a heavy heart. We prayed the five sorrowful mysteries, each ending with one ‘Our Father,’ ten ‘Hail Mary’s,’ one ‘Glory Be’ and ‘O My Jesus.’ This was Catholic-rooted resilience in our time of need.

My community was not supposed to grieve that night. We were supposed to dance, to eat until our mothers’ nagging of “high cholesterol” echoed in our minds. In the wake of LapuLapu Day, we are left with questions, fear and an overwhelming love for our community. We deserve to come together without the threat of grief or danger.

The image of those children clinging to their mothers’ skirts plays over and over again in my mind. I hope they made it home okay. As I remember Lapu-Lapu Day, I cannot help but wonder: is this what it means to be Filipino — to carry both loss and survival with us everywhere we go? U

SPENCER BRITTEN MARKS ASIAN HERITAGE MONTH AND PRIDE MONTH WITH NEW RECITAL MEMOIRS OF A GAYSIAN

Chinese-Canadian tenor and UBC alum Spencer Britten is set to debut their recital Memoirs of a Gaysian at the Canadian Opera Company in Toronto on May 27. The recital explores Britten’s experiences growing up at the intersection of Asian and Queer identity, with music by Hong Kong-born Canadian composer Alice Ping Yee Ho and Benjamin Britten, famed English composer and ancestor of Spencer Britten. The recital also includes pieces by other composers with a focus on Queer and Asian musicians and writers.

Originally from Port Moody, BC, Britten began singing as a child and pursued undergraduate and master’s degrees in the UBC Opera program, experiences that Britten said “really influenced the beginning of [his] love of opera.”

As a part of both the AsianQueer community and the opera world, Britten frequently explores the potential for openness and change in their field.

The adjacency of Asian Heritage Month in May and Pride Month in June inspired them to cele- brate both identities with the creation of Memoirs of a Gaysian.

According to Britten, Queer Vietnamese-American composer Dylan Trần’s recital Ba– poems from Ocean was inspirational in the production of Memoirs of a Gaysian

“[Trần’s work] was a starting point … because it came across my path at such an important time for me when I was rediscovering what I needed in life,” he said.

Memoirs of a Gaysian, for Britten, is both a challenging contemporary art work and an emotional journey wrapped up in ideas of Queer solidarity.

“[The recital involves] a lot of Queer love, Queer heartbreak and strength,” said Britten.

“There’s one song in there by an American composer [Ben Moore] and it really speaks towards … the strength of the Queer community. Honestly, I don’t know how I’m gonna get through that

SPEAK FREELY

The room filled with the laughter of my family. They rocked in their seats and patted one another as their laughter bounced off the walls of the echoing drawing room. Once they had dried their tears, they turned back to me.

“Say it again!”

I pressed my arms against my sides as I felt a rush of blood to my cheeks. I was unused to the sweltering days in India where I was now visiting my extended family. They sat staring, waiting for me to ask for ice cream again in my subpar Punjabi; to embarrass myself in exchange for relief from the heat. When I did — using English grammar with Punjabi shabads, words, out of nervousness — they laughed again before directing me to their freezer.

The memories of hot summer days playing with my cousins and enjoying the lands of my heritage are speckled with moments like this — perspiring faces filled with anticipation to hear me mess up speaking Punjabi because of my “Canadian-ness.” When I would speak Punjabi in Canada, I was met with the same laughter and judging glances for similar reasons.

Growing up, I had two first languages: English and Punjabi. The elder members of my family spoke Punjabi to me and I spoke to my cousins and friends in English. I was fairly fluent in

both until I started school and began learning English grammar conventions and sentence structures. This new focus on learning English resulted in a dwindling fluency in Punjabi.

I spoke Punjabi frequently enough at home but the effects of prioritizing English at school eventually seeped through. The Punjabi alphabet and phonology are very particular; certain sounds have similar articulations that are sometimes only deducible if you have the ear for it. When I mispronounced a word or made the wrong sound because of these similar articulations, I was met with laughter and pushed to repeat what I had said before getting support on correcting myself.

Seeing the frequency of my mistakes, my parents enrolled me in a program at a Punjabi language and cultural school so I could practice, memorize and improve my speaking. Even though I could read and, sort of, write, I was still burdened with an Anglo accent and involuntary code-switching when I combined English and Punjabi to create sentences that my family could not understand. It made me feel less South Asian and more removed from my own culture and ethnic community.

Eventually, I stopped speaking Punjabi entirely. Instead, I spoke to my parents in English to avoid

song without crying because it’s so meaningful and powerful, and I hope that translates to the audience as well.”

Personal resonance is threaded throughout Memoirs of a Gaysian. When performing Alice Ping Yee Ho’s opera Chinatown, a story about two families of Chinese immigrants in Vancouver, Britten sings in Hoisanese — the dialect their family speaks at home.

“It’s a Queer love story as well,” said Britten, “so that resonated really closely with my heart.”

Opera has not always included representation of the intersection between Asian and Queer identity. According to Britten, it can be difficult for Queer folks to see themselves in the traditional stories that opera tells.

Contemporary pieces like Memoirs of a Gaysian then create an inclusive space for the expression of diverse human experience. With this recital, Britten hopes to bring a new perspec-

being criticized or laughed at again. I was still made fun of for not speaking Punjabi and even had some family members tell stories of my mispronunciation as anecdotes, though it was better than giving them a new story to fuel my insecurity.

At school, however, it was different. Being raised in a community where the majority of residents are South Asian immigrants meant that a lot of my friends faced similar language problems. There were some like me who were criticized and ridiculed for trying to speak their parents’ native language. Others couldn’t speak it at all. We connected through the similarities of our experience and enjoyed our languages more because of it.

We cracked jokes in dialect and had full conversations in our languages. When students immigrating from South Asia joined our classes, they didn’t condemn us for our anglicized accents. Although they found it amusing, they were just happy they could communicate in dialect with us. There were times when we made fun of each other for misspeaking or forgetting an English word and using the dialect counterpart, but these were contrasted with the norm we established when we approached each other with a kindness that we could not find elsewhere.

We found solace in our shared

By Yujia Huang

tive into opera that represents the Asian-Queer community while touching the heart of a broader audience.

“I know there’s a lot of resistance to change in all aspects of life, but especially in the opera and classical musical industries, there seems to be a lot of resistance,” Britten said. “Hopefully, by doing more work like this, people become more accustomed to opening their minds and seeing things from a different perspective.”

In addition to the recital’s debut in Toronto with follow-up performances planned in Philadelphia and New York City, Britten hopes to bring Memoirs of a Gaysian to their hometown of Vancouver. Outside of stage performance, Britten is devoted to a social media campaign to promote opera in a fun way and challenge the elitist stereotype of opera. Readers can find more about the tenor’s work on their website, YouTube channel and Instagram account, @ spencerbritten U

By Shubhreet Dadrao

experiences and enjoyed the freedom of speaking to each other without judgment.

I am still grateful that I can speak Punjabi even if I’m laughed at for it by my own family. It’s unfortunate, but I’ve gotten used to it over time and improved as I began to speak it more, which also meant that I was made less fun of.

But with the community I had built at school with my friends and classmates — with people who spoke subpar Punjabi, Hindi, Urdu and Farsi; they made me feel like I was enough. Though I held a different kind of South Asian identity because I was also Canadian, I realized that didn’t make me any less South Asian.

Now I confidently speak Punjabi and English without worrying about being made fun of. After experiencing a community made up of second-generation South Asian Canadians and children of immigrants, I know who I am in my language and I wouldn’t know myself without it.

The cultural knowledge and connection we hold through language is as powerful as it is daunting. Although language for me was a point of tension and sometimes pain, it was also an escape and an opportunity to build community. I am more myself because of it. U

LUCKY MONEY AND SKY REPORTS: INSIDE VIETNAM’S LUNAR NEW YEAR

By Jeff Lee

Many countries celebrate Lunar New Year, but in Vietnam, Tết Nguyên Đán is considered a “mega event” holiday.

Think of it as if Christmas, New Year’s, Easter, and Thanksgiving all made a group chat to plan one giant, spectacular bash. It’s a time for reflection, reconnection and resolutions, all wrapped in centuries of culture and tradition.

Tết transforms everyday routines into meaningful rituals. Buying groceries? Suddenly an event. Cleaning the house? A spiritual cleanse.

The word “Tết” comes from the Vietnamese term “tiết,” meaning “season,” highlighting how deeply the festival is tied to nature’s cycles. Historically, Tết began thousands of years ago as a break for hardworking farmers after a long stretch in the rice field — a chance to rest, party and prep for the year ahead.

Originally brought to Vietnam through Chinese colonialism, the Lunar New Year festival has since becom a symbol of Vietnamese cultural sovereignty and blossomed into a holiday overflowing with food, rituals and togetherness. Tết isn’t just a new calendar page. It’s a fresh start for people’s homes, family and spirit.

Preparing for Tết is a big deal: homes are cleaned and decorated, special foods like sticky rice cakes (bánh chung and bánh tét) are made, and everyone dresses in their finest clothes. There’s a belief that the first days of the new year set the tone for the rest of it, so people strive to keep spirits high, avoid bad luck and express hope for health, prosperity and happiness.

In Vietnamese homes, the air carries the scent of peach apricot blossoms, and the streets come alive with vibrant decorations and bustling markets. People visit friends and neighbours, exchange gifts and offer good wishes. The symbolism is everywhere, from kumquat trees, which represent unity and togetherness, to traditional folk songs urging people to “remember to come home at Tết.”

Although Tết officially spans only four days of public holiday, don’t be fooled — the celebration starts early and stretches across two to three weeks, from the 23rd of tháng Chạp to at least the 7th (some say the 15th) of tháng Giêng. It kicks off with the kitchen god zooming off to the Jade Emperor to spill the tea on people’s household behaviour. The symbolic cây nêu pole is planted and later taken down to mark the festival’s end. In cities, Tết is everywhere: homes, parks, temples, flower markets, you name it.

In an article in the Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, the late anthropologist Patrick McAllister writes, “Most of these are sites of social activity all year round... but this activity is transformed and intensified [by Tết].”

Growing up in Vancouver, far from Vietnam, the shift into Lunar New Year always arrived in a quieter form. When I’d see the lanterns appear along the city’s streets, I knew the season had begun. They were hard to miss; bright red, round and glowing softly above sidewalks and store windows.

At first glance, they were just decorations: golden, swaying slightly in the winter

wind. But something about their glow always stopped me. Maybe it was the contrast — the soft, warm light cutting through the cold gray sky. Or maybe it was the feeling that these lanterns weren’t just for show. They carried meaning.

I’d pause under them, usually while walking through the city in late January or early February. I didn’t always know what the words on the lanterns meant. They were usually written in Vietnamese or Chinese characters, brushstrokes that looked elegant but unfamiliar. Still, I found them fascinating. The curves, the shapes, the way the ink seemed to flow across the surface, it all felt intentional and meaningful, even if I couldn’t translate it. There was a kind of beauty in just looking, in knowing that those words carried wishes for luck, happiness or prosperity.

Sometimes I’d reach up and touch the lanterns when they hung low enough. The material was thin and slightly rough, like a mix between fabric and paper. It crinkled a bit under my fingers if there was wind. The designs, gold patterns of dragons, flowers and traditional symbols felt delicate, almost as if they would be rubbed off if I wasn’t careful.

These intricate decorations reflect the spirit of Tết as an exuberant celebration of renewal. When the festival begins, Vietnam lights up with bright red and yellow

decorations, lively markets and festive activities. Red is especially important because it symbolizes luck and happiness, which is why red envelopes filled with lucky money are given to children and elders alike.

I’ve had a few Vietnamese friends who introduced me, in small but memorable ways, to the traditions of Tết. One winter afternoon in middle school, after a chaotic snowball fight, I went over to a friend’s house for a playdate. As I was getting ready to leave, his mom handed me a small red envelope and said it was for Lunar New Year. I remember sitting in the car, peeling it open and finding a crisp $10 bill inside.

At the time, I was mostly thrilled about the money, already dreaming of what I’d spend it on. But looking back, I wish I had taken a moment to really notice the envelope itself. The unique gold patterns, the texture of the paper and the care with which it was given. That simple gesture was more than just a gift; it was a glimpse into a rich cultural tradition I didn’t fully understand then, but deeply appreciate now. U

Opinion: Resilience is more than grit

This is an opinion article. It reflects the contributor’s views and does not reflect the views of The Ubyssey as a whole. Contribute to the conversation by visiting ubyssey.ca/pages/submit-an-opinion

Anita Aboni Contributor

Anita Aboni is a graduate student in human development, learning and culture at UBC, where she explores the intersections of resilience, social-emotional learning and educational psychology. She has a background in teaching and educational research.

Have you ever felt like the only way to succeed was to push through everything alone? Like you had to grind harder, sleep less and never ask for help?

Many university students know this pressure intimately — to appear strong and self-sufficient, no matter the cost. But real resilience isn’t about isolation or endurance. It’s about adaptation, relationships and systems that support us when we stumble.

Too often, resilience is portrayed as a badge of honour earned through suffering. The dominant “grit” narrative in education reinforces this, glorifying those who persevere no matter what. But grit, in isolation, is a narrow and misleading concept. Resilience is not just about willpower or endurance; it’s about how people adapt and recover with the support of their environment.

And yet, students are still taught, explicitly or not, that to be resilient is to be invulnerable.

I know this from experience. I grew up in a small village in Ghana where girls’ education was undervalued. I walked long distances to school, studied by candlelight during frequent power cuts and struggled with the constant uncertainty of financial hardship. When I moved to the city after high school, I worked menial jobs and lived without stable housing for six months. There were days I went hungry, unsure if I’d ever set foot in a university classroom.

But it wasn’t perseverance alone that got me through. At my lowest point, my Grade 5 teacher contacted me out of the blue. He reminded me that strength isn’t about staying silent — it’s about knowing when to reach out. With his encouragement, I began to hope again. That single moment of care planted the seeds for future support. Later, peers offered me meals and notes. Professors connected me to financial aid and wellness resources. These gestures were simple, yet they were lifelines.

Today, I am pursuing a master’s of education in human development, learning and culture here at UBC — a testament not to solitary grit, but to the power of connection.

In education policy and popular culture generally, resilience is still often equated with individual toughness. Studies show that resilience isn’t built in isolation;

it grows through connection and care. One long-standing study found that even a single strong relationship can significantly buffer the effects of chronic stress. School environments that integrate social-emotional learning and provide accessible mental health resources have been shown to improve both emotional wellbeing and academic performance. Resilience isn’t just a personal attribute — it’s also the product of an ecosystem that includes mentors, safe spaces and second chances.

When I first arrived in Vancouver, I experienced a new kind of isolation — one that came from being in a foreign country, navigating a new academic culture and missing the family networks that had always grounded me. I felt like I had to prove myself repeatedly. But in those early days, I also discovered that UBC had resources I could lean on.

I visited the Wellness Centre, spoke with academic advisors and found professors who were kind enough to listen.

I also joined a writing group organized by the Graduate Student Society. At first, I attended just for the quiet space, but soon I found a sense of belonging, accountability and the encouragement to keep going even when I

doubted myself.

These moments reminded me that the strongest people are often those who know how to ask for help and how to create space for others to feel safe doing the same. It is in these moments where resilience lives — when someone listens, shares or simply believes in you.

It grows when we stop treating failure as a flaw and start treating it as a step. Educators have shown that students benefit most when failure is framed as an opportunity for learning, not as a mark of inadequacy.

Asking questions, revisiting material and seeking support aren’t signs of weakness — they’re the foundation of growth. None of this diminishes the value of effort or determination. But when resilience is framed purely as grit, we risk shaming those who can’t push through alone. We discourage help-seeking. We reinforce harmful myths of meritocracy that obscure systemic inequities. In one podcast interview, an education journalist spoke about how the myth of unrelenting perseverance often isolates students and perpetuates cycles of burnout and self-doubt. And the danger of this myth is real. I have met students who internalize failure as personal de -

promoted, so that students see them as a natural part of their educational journey. UBC could further strengthen this by training “mental health champions” in each faculty — students who are equipped to direct peers to appropriate support. Instructors could also integrate “wellness checks” into their courses, providing a space for students to share concerns without fear of judgment.

Faculty, too, have a powerful role to play. Instructors who normalize setbacks, openly discuss their own academic struggles and offer flexible deadlines or checkin opportunities send a powerful message: learning is not linear. Supportive pedagogy is resilience-building pedagogy. When students feel seen and supported by their instructors, they are more likely to stay engaged, ask for support and persist through difficulty.

This also means challenging our assumptions about who needs support. Students from historically marginalized backgrounds — first-generation, racialized, disabled or low-income — may carry heavier burdens and encounter more barriers. For them, the story of grit alone is not only insufficient, but also harmful. Real equity in education requires that we build structures that acknowledge those burdens and actively work to alleviate them.

Resilience is not something we reserve for motivational posters and commencement speeches. It should be woven into the fabric of campus life. Let’s build spaces where students can speak openly about challenges without fear of judgment. Let’s celebrate the courage it takes to keep going — and the courage it takes to pause and ask for support.

ficiency when, in fact, they were never given the tools or support they needed to succeed.

We need to broaden our understanding of resilience. It is not something you earn by suffering in silence. It is something that grows in connection. Universities must take this seriously. When institutions invest in culturally-responsive counselling, create accessible mentorship programs and embed wellness into curricula, they aren’t offering “extras.” They are cultivating resilience. This means universities must go beyond surface-level support and embedding wellness into the very structure of campus life.

At UBC, resources like the Wellness Centre, the Peer Support Program, the UBC Student Assistance Program (through Aspiria) and Here2Talk offer students a chance to seek support without stigma. For example, UBC Peer Support volunteers provide confidential, peer-to-peer support, creating a safe space for students to share their struggles without judgment. During UBC Thrive, students can attend workshops, participate in wellness activities and learn practical strategies for mental health.

But access alone is not enough. These services must be visible, easily accessible and consistently

We all play a part. Support your peers. Check in on friends. Small acts like sharing notes, offering a listening ear or pointing someone toward resources, can change a person’s path. I still think of the friends who gave me food when I had none. Or the librarian who stayed open five minutes longer so I could finish a paper. These moments matter more than we know.

And to the students who are struggling: you don’t have to be a hero. You don’t need to be perfect. You need to know that your worth isn’t measured by how much you can endure alone. You need to know that asking for support is courageous. That failure is not final. That support is not conditional.

Let’s stop valorizing the myth of unbreakable independence. Let’s create a culture of care, where vulnerability is met with compassion, where setbacks are reframed as growth and where support is both given and received freely. Let’s teach students that resilience is a web, not a wall. Wherever you are in your journey, remember you don’t need to be unbreakable to be strong. Resilience is not about how much you can endure — it’s about how you recover, who you lean on and how you keep learning. None of us are alone — and all of us are enough. U

“Resilience grows in connection”, writes Anita Aboni.

LUA PRESIDIO / THE UBYSSEY

Take my unsolicited advice (or else): UBC survival tips from a recent grad

Akanksha Pahargarh Contributor

What is senior year for, if not reminiscing? As I wrap up my undergraduate career, I can recognize I’ve learned a lot. From how to properly party to how to properly study, these four years have taught me invaluable lessons. Lucky for you, I’m not selfish! I present to you five things I’ve learned at UBC.

IT’S DAMP OUT HERE

It’s going to rain. You’re going to be caught without an umbrella. The only question to ask is, “How long do you have to sit in your soaking wet clothes before you can change?” Unfortunately for me, there were some three-hour lectures that definitely saw me at my wettest. The good thing, however, is that’s plenty of time to dry before you have to step out in the rain again!

(The other good thing is that the “wet look” is trending right now, so rocking damp denim is super cool and not at all a torturous and evil punishment I wouldn’t wish upon my worst enemies.)

YOU CAN GET FROM ONE END OF CAMPUS TO THE OTHER IN TEN MINUTES

DO YOU EVEN TIP BRO? //

others, you’re fresh out of luck. There’s just no way you’re going to make it. Get used to finding a seat while everyone is staring at you to get out of the way. Sorry, it’s inevitable.

GOING TO WRECK BEACH WILL NEVER BE WORTH THE WALK BACK

I don’t care how pretty the beach is or how amazing the parties are — the walk up those stairs will never be worth it. Unless you love walking up stairs — who actually does? — don’t ever think you won’t end up huffing and puffing, stopping at some point during that cruel walk back to question all the life choices that led you there.

DINING HALL RATS ARE YOUR FRIENDS

BMX bike or develop the ability to teleport over there, but as I’ve learned the ins and outs of campus, I’ve realized UBC is actually quite gracious for giving us those 10 minutes. So kind of them. So generous. I am so thankful. Really.

BUT ALSO, SOMETIMES, YOU WILL NOT GET THERE ON TIME

I’m not gonna lie, I just lied. That second piece of wisdom is definitely an exaggeration. For most classes, you’ll be fine! For

Okay, fine. This one may be a coping mechanism, but that doesn’t mean it can’t be true. Remy the rat and all his friends are just there to help the chefs. That’s the story we’re going with. DO NOT CHANGE THE STORY.

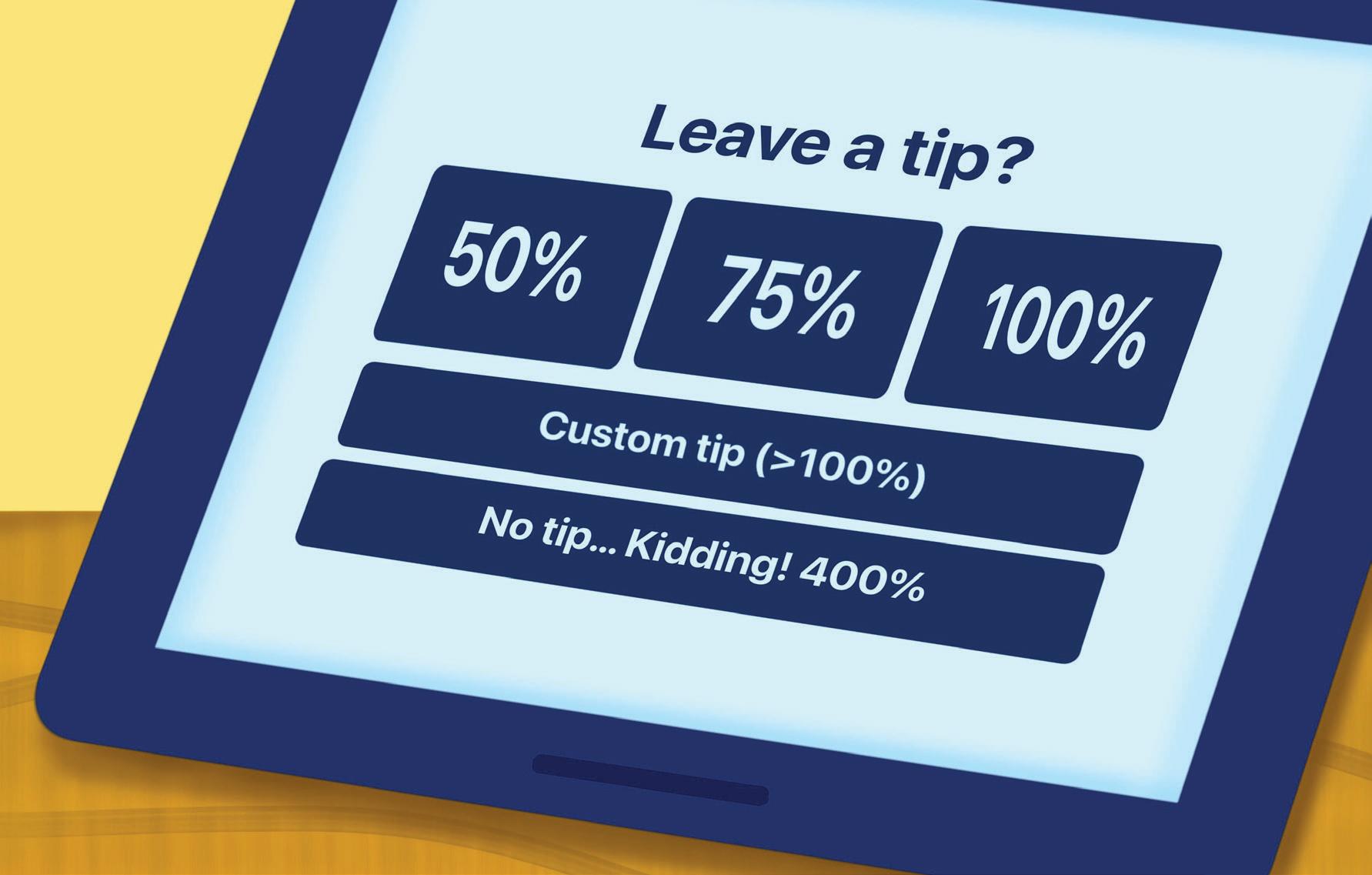

New tipping initiative to solve all of UBC’s financial woes

Kyla Flynn Humour Editor

Everyone knows UBC is broke — not in the actual sense of being broke, but in the way your rich friend says they’re, like, soooo broke because they could only afford a four-anda-half star resort for their reading week Mexico trip, whilst you’re planning to spend your break battling the spider infestation your landlord has let fester inside of your couch cushions for months.

I am sure you are beside yourself with worry at this breaking news, but rest assured — all will be well. Just like your IG baddie bestie, UBC will live to throw back unlimited spicy margs another day. In a recent announcement, UBC came up with what experts are calling a “super lit” solution to all their financial woes.

Their plan, which will be implemented in late summer 2025 (though if it’s anything like the new Rec North’s timeline, that’s mega bullshit), involves a campus-wide redesign of lecture hall door mechanics. Partnering with tech giants like The Evil Guys Who Invented 18 Per Cent Minimum Tip on Take-Out, UBC will require students to select a tip option before exiting every lecture hall, classroom and academic flex space.

Much like the old-fashioned parking garages of yore, where the little yellow rod thing keeps you from driving away until you pay the ticket thing, or the more familiar skytrain entry/exit gate system, virtually

Back in first year, I found it quite daunting to have class in the Anthropology and Sociology building immediately followed by another class all the way over in the Forestry building. Often, I thought I’d have to leave my class early or all doorways, entryways and other access points to academic spaces will be equipped with comparable technology.

In a statement to The Ubyssey, Khash Grabbe, a retired money launderer who now serves as the UBC Facilities Planning Department’s budgetary advisor, said, “Look. We need money. The kids have money. I mean, obviously they do. They can afford luxurious expenses like tuition and sensible footwear. One thing

about me? I go where the money goes. I know it. I can smell it. They call me Khash ‘Knowswherethemoneyis’ Grabbe for a reason.”

When asked about the inspiration behind this new development, Grabbe made several references to something called the “UBC Reddit forum” which I personally have never heard of.

Grabbe additionally spoke to a number of his proposal’s important features. Students will be able to use

debit, credit or any currency loaded onto their UBC card, including PayForPrint money and flex dollars, in order to tip their profs. Tipping options will be based on class size, in reverse of what would be typical in a restaurant setting. Students will be expected to tip an automatic gratuity for classes smaller than 40 students, and the percentage will increase proportionately as that number decreases. “That way, we’re discouraging students from seeking genuine

In conclusion, I came here as a kid, but I leave a much smarter and wiser woman. To any incoming UBC students reading this — good luck! You’ll need it. U connections and relationships with both one another and their professors by guaranteeing a student-bodywide preference for larger class size,” said Grabbe. Unburdened by “friendships,” “trivial socialization” or an “emotional support network,” students and faculty alike will have more time to do what’s important in this world: work!

When asked for their thoughts on this new system, fourth-year pogo-sticking student Tom Foolery said, “It’s no big deal. I usually hop out the window anyway.”

Grip P. Strength, a fifth-year dirt-eating major and president of UBC’s Jumping and Climbing Enthusiast Club, entered The Ubyssey’s office through its second floor window to provide his opinion on the matter.

“This new policy sounds like a great opportunity to teach more people about free climbing and the pure ecstasy that is a commitment to the unconventional movement lifestyle. I project this will be my club’s most lucrative recruitment year yet. The people yearn to scale Buchanan Tower. They crave fee avoidance and evasion.”

The funding collected via this initiative is expected to be distributed amongst professors, TAs and whoever Grabbe “is vibing with” that week. This arbitrary monetary distribution system is set to replace regular pay by 2026. Overall, this groundbreaking initiative is being hailed as a big win for the anti-financial security crowd. U

These four years have taught me invaluable lessons.

“Look. We need money. The kids have money.”

SIDNEY SHAW / THE UBYSSEY

ELITA MENEZES / THE UBYSSEY

Frictionless fuel: How UBC researchers detected hydrogen’s superfluidity and what it could mean for sustainability

Harleen Randhawa Contributor

Imagine a liquid that moves endlessly, without resistance — so smooth that it seems to defy the laws of physics. For the first time, researchers at UBC have observed this rare phenomenon in a molecular system.

Superfluidity is a unique state of matter in which a liquid flows without friction. An object placed in this liquid can move freely within it, not experiencing resistence. This intriguing behaviour occurs at temperatures close to absolute zero, but had previously only been observed in helium.