EDITORIAL BUSINESS

Editor-in-Chief

Aisha Chaudhry eic@ubyssey.ca

Managing Editor Saumya Kamra managing@ubyssey.ca

Deputy Managing Editor Spencer Izen deputymanaging@ubyssey.ca

News Editors

Colin Angell Stephen Kosar news@ubyssey.ca

Culture Editor Julian Coyle Forst culture@ubyssey.ca

Features Editor Elena Massing features@ubyssey.ca

Opinion Editor Spencer Izen opinion@ubyssey.ca

Humour Editor Kyla Flynn humour@ubyssey.ca

Sports + Rec Editor Caleb Peterson sports@ubyssey.ca

Science Editor Elita Menezes science@ubyssey.ca

Illustration Editor Ayla Cilliers illustration@ubyssey.ca

Photo Editor Sidney Shaw photo@ubyssey.ca

Business Manager Douglas Baird business@ubyssey.ca

Account Manager Scott Atkinson advertising@ubyssey.ca

Lead Developer and Website Strategist Sam Low samuellow@ubyssey.ca

Web Developer Nishim Singhi nishimsinghi@ubyssey.ca

President Ferdinand Rother president@ubyssey.ca

Words

Julian

Editorial Office: NEST 2208 604.283.2023

Business Office: NEST 2209 604.283.2024

6133 University Blvd. Vancouver, BC V6T 1Z1 Website: ubyssey.ca Bluesky: @ubyssey.ca Instagram: @ubyssey Facebook: @ubyssey TikTok: @ubyssey X: @ubyssey LinkedIn: @ubyssey

The Ubyssey acknowledges we operate on the traditional, ancestral and stolen territories of the Coast Salish peoples including the xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam), Sḵwx̱wú7mesh Úxwumixw (Squamish) and səlilwətaɬ (Tsleil-Waututh) nations.

LEGAL

The Ubyssey is the official student newspaper of the University of British Columbia (UBC). It is published every second Tuesday by the Ubyssey Publications Society (UPS). We are an autonomous, democratically-run student organization and all students are encouraged to participate.

Editorials are written by The Ubyssey’s editorial board and they do not necessarily reflect the views of the UPS or UBC. All editorial content appearing in The Ubyssey is the property of the UPS. Stories, opinions, photographs and artwork contained herein cannot be reproduced without the expressed, written permission of the Ubyssey Publications Society. The Ubyssey is a founding member of Canadian University Press (CUP) and adheres to CUP’s guiding principles.

The Ubyssey accepts opinion articles on any topic related to UBC and/or topics relevant to students attending UBC. Submissions must be written by UBC students, professors, alumni or those in a suitable position (as determined by the opinion editor) to speak on UBC-related matters. Submissions must not contain racism,

sexism, homophobia, transphobia, harassment or discrimination. Authors and/or submissions will not be precluded from publication based solely on association with particular ideologies or subject matter that some may find objectionable. Approval for publication is, however, dependent on the quality of the argument and The Ubyssey editorial board’s judgment of appropriate content. Submissions may be sent by email to opinion@ ubyssey.ca Please include your student number or other proof of identification. Anonymous submissions will be accepted on extremely rare occasions. Requests for anonymity will be granted upon agreement from seven-eighths of the editorial board. Full opinions policy may be found at ubyssey.ca/pages/submit-an-opinion It is agreed by all persons placing display or classified advertising that if the UPS fails to publish an advertisement or if an error in the ad occurs the liability of the UPS will not be greater than the price paid for the ad. The UPS shall not be responsible for slight changes or typographical errors that do not lessen the value or the impact of the ads.

The Ubyssey periodically receives grants from the Government of Canada to fund web development and summer editorial positions.

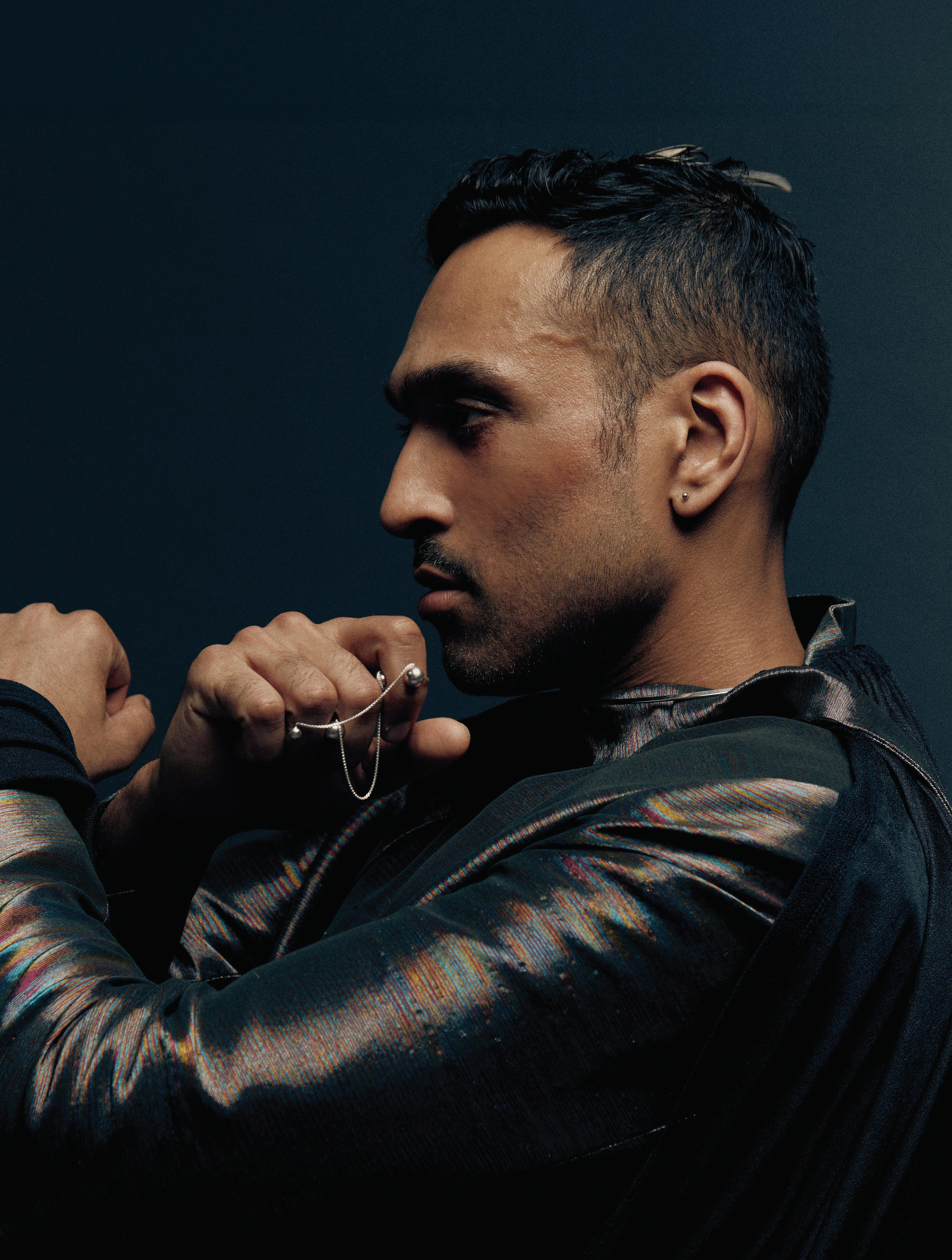

Dr. John Paul “JP” Catungal recalls the moment he was first approached by a stranger on the topic of his own Queerness. It was in the early 2000s, in a geography 241 classroom at SFU during Catungal’s pursuit of an undergraduate degree in geography and sociology.

“I remember vividly a classmate asking if I was Queer,” he said. “And that was the first time in a very public way … I mean it was a one-on-one conversation, but that was the first time I felt confronted — not in a bad way — about acknowledging to someone else my Queerness.”

Geography 241 was formative for Catungal in more ways than one. This was the class that led him to tackle questions of transgression and sexuality in writing for the first time, questions that would go on to define his academic life for years to come.

Drawing on the work of British poet-geographer Tim Cresswell, particularly his 1992 book In Place/ Out of Place, Catungal wrote a paper on schools and transgressive sexualities — those deemed “out of place” by establishment forces — for his class, taking as a case study the 1997 Surrey school board ban on select books depicting same-sex parents.

“I used that [ban] as a lens to think about schools and sexuality,” said Catungal. “When something is out of place, what does that reveal about how we understand place? Focusing on transgression allows us to actually identify the taken-for-granted norms that structure the world. If we say that something is out of place, we must have measures about what it means to be in place, right?”

The intersection of transgressive sexual identity with societally imposed norms got its hooks into Catungal. Now, 20 years later, he works as an assistant professor in critical racial and ethnic studies with UBC’s Social Justice Institute and was awarded a 2024/25 Faculty of Arts Killam Teaching Prize in recognition of his approach to mentorship and equity in the classroom.

The Killam Teaching Prize, one of many academic awards under the Killam Program umbrella overseen by the National Research Council, is adjudicated on the

faculty level at UBC via an extensive nomination process.

“[The nomination] requires a dossier, really, that includes statements of [candidates’] teaching philosophy and practices, the kind of assignments that you do [and] the way you might think about questions of equity and difference and accessibility in the classroom,” said Catungal.

The philosophy of equity-forward teaching and mentorship described in Catungal’s nomination portfolio runs through all aspects of his academic life, he said, inextricable from the qualitative lived-experience-based research that he has conducted throughout his career.

“My work as an academic across all areas of professional practice … is shaped by a commitment to advancing equity and elevating historically marginalized people’s agency and knowledge.”

Catungal’s commitment to the pursuit of truth and justice for marginalized peoples is reflected in his work on the HIV In My Day oral history project, an extensive database of interviews conducted with long-term HIV survivors and their caregivers between 2017 and 2020 aimed at recording and preserving personal histories of the epidemic from 1996 and earlier.

Catungal explained the people behind HIV In My Day — a multi-disciplinary group of community organizers, leaders and caregivers as well as academics mostly from SFU, UVic and UBC — designated ‘96 as the cutoff point for the scope of their research “because that was the year when more effective … therapies to manage AIDS became publicly available.”

Far from the extractive and stigmatizing methodologies that characterized early anthropological and sociological fields, the HIV In My Day project saw significant reciprocal collaboration with subjects.

One interviewee, playwright Rick Waines, became involved in the project as a transcriber after sharing his history with the researchers. He went on to write and produce In My Day, what starring actor Alen Dominguez called “a verbatim theatre piece” in a 2022 interview with The Ubyssey on the production’s debut at The Cultch’s Historic Theatre.

The play — narratively based

on stories shared by survivors during the HIV In My Day project — is set for another run at UVic’s Phoenix Theatre in March 2026. Catungal was involved in the Cultch production as chair of a Committee for Anti-Racism and Equity that he formed to help “ensure that the production of the play itself maintains its commitment to questions of equity.”

Catungal’s work is also influenced by his lived experience as a member of the Filipino diaspora in Canada. In a similar fashion to his work chronicling the HIV epidemic, he lent his expertise in 2023 to a project that used oral history as a tool of resistance to a rezoning plan that threatened several Filipino culinary institutions in Joyce Collingwood.

“Many of those businesses are businesses of significance to Filipino communities but also more broadly Asian and other racialized communities in East Vancouver,” said Catungal.

The lack of community consultation by developers and City Hall with the community on the impact of the project on these important businesses made it clear to many in the community that a more specific avenue for telling Filipino-Vancouverite stories was needed.

To address this, Heritage Vancouver Society, Sliced Mango Collective, UBC Asian Canadian and Asian Migration Studies, and the UBC Public Humanities Hub established Kuwentong Pamamahay (Tagalog for “Stories of Homemaking”), an oral histories database for Filipino Canadian stories.

Grassroots community projects like Kuwentong Pamamahay and HIV In My Day arising in resistance to overtures from repressive and marginalizing forces is central to Catungal’s academic perspective.

“I’m not just interested in the damage inflicted on historically marginalized communities, the violence they experience, the experiences of inequality that they live through but also their capacity to respond to them,” he said.

“Marginalized communities are far from passive actors in the world. They are great, courageous, creative movers of the world, and they intervene and adapt and imagine and create new worlds through the ways that they support each other.” U

If you stand on the shores of Chá7elkwnech (Gambier Island), you may be lucky enough to see a pod of orcas that have made the waters of Átl’ k a7tsem (Howe Sound) their temporary home. Each pod is intergenerational, typically consisting of an older female and her offspring. Even when the children start their own families, they often linger close to their mother’s pod as they travel through the sea.

The organizers of CampOUT! think Queer people and the whales may have something in common when it comes to creating a community.

Since 2009, CampOUT! has welcomed Queer, Trans, Two-Spirit, questioning and allied youth aged 14–21 from across BC and The Yukon to bring “campiness to camp.” During the five-day-long retreat at Camp Fircom on Gambier Island, they participate in activities aimed at building leadership skills, finding their people and increasing their understanding of Queerness.

CampOUT! originally began as a day camp hosted at UBC and was inspired by a similar program at the University of Alberta, Camp fYrefly. It has since expanded with the support of UBC’s Faculty of Education, SOGI UBC and the Equity & Inclusion Office, as well as funding from community partners like Foundry — an inclusive care network based in Vancouver.

The theme of this year’s camp season is “Find Your Pod: 16 Years of Queer Joy.” In light of

continued anti-Trans sentiments and many 2SLGBTQIA+ organizations having no choice but to close their doors, camp organizers wanted to highlight joy as an act of resistance and explore how members of the Queer community work to keep each other safe. Like the orcas, campers are also making themselves a home — even if only for a few days — and building their own pod of intergenerational Queer solidarity.

“Sometimes the word ‘community’ can be a bit overused or more aspirational, and many times, even when you’re part of a Queer community, you don’t necessarily have the support of the entire community,” said Camp Director Daniel Gallardo in an interview with The Ubyssey. “Finding your pod [means] you have supports that are reciprocal … We want to create those relations when camp happens.”

There’s a wide range of camp activities for people to explore — painting, cross-stitch and drag; workshops on sexual health,

disability justice and anti-fascism; or traditional outdoorsy camp activities and “gay sports,” as Gallardo put it.

Campers build their own schedule at the start of the week to match their interests, but regardless of what they choose, they can expect to learn more about anti-racism and Indigenous resurgence, which are woven throughout all of the programming.

For some of these lessons, white and BIPOC campers are separated into different “affinity groups,” in which they’ll attend sessions specifically tailored to their own identity and experiences.

“Specifically for white folks, it’s more understanding … how can they be in radical solidarity with BIPOC folks. I think for BIPOC folks, it creates a place for connection and sharing of strength and resistance and experiences and stories,” said Gallardo.

Even the logo for this year’s theme draws on these values. Gallardo commissioned x ʷ m əθ k ʷəy ə m and Ts’msyen artist Chase Gray to draw a pod of orcas breaking a yacht in half, a representation of how embracing Queerness goes hand in hand with breaking down capitalism, colonialism and other systems of oppression — or, in Gallardo’s words, “crashing the cis-tem.” Queer youth don’t typically have many older role models to turn to for guidance on questions concerning identity, but CampOUT! aims to change that. In addition to camp

Words by Elena Massing

Illustration by Adriel

Yusgiantoro

leaders, there are community mentors running the programming and people providing mental and physical health support.

“We’ve been able to build a community of more than 1,000 Queer youth. Many of them become part of camp in an intergenerational way. A lot of our campers become cabin leaders, who then become community mentors … One of our campers last year became one of our co-directors of camp,” said Gallardo.

Before becoming camp director, Gallardo was the drag mentor, running workshops that gave campers the chance to develop a drag persona, dress up and play with makeup. Gallardo talks about their ‘drag children’ — all 50 of them — with pride. One of their first drag children eventually became a cabin leader, and as a skilled seamstress, they’re now creating an outfit for Gallardo based on the season’s “Find Your Pod” theme.

Gallardo’s favourite moments of camp always happen right before the showcase on the last day, where campers show off their paintings, writing, crafts and, in this case, drag. With both Gallardo and the kids getting into full glam, it gets chaotic backstage — makeup strewn across the room, Gallardo screaming at the top of their lungs trying to track down their missing silver glitter and campers laughing.

“It’s one of the most rewarding and also heartfelt sharings because of how — even in so little time — how transformative it is to have 100 Queer people in the same space, and being able to in an intergenerational way.” U

Words by Lauren Kasowski

Photo by Veronika Kapitanchuk

In the corner of the fourth floor of Chinatown’s Sun Wah Centre lies the On Main Gallery hosting Varied Editions, a small but hearty exhibit in this year’s Queer Arts Festival (QAF).

The QAF — first started in 2008 — is a multidisciplinary art festival that incorporates exhibitions and events “presented by and for and about Queer arts,” according to Paul Wong, one of this year’s artists.

Wong, a Vancouver-based artist, recently finished his artist-in-residence term at UBC’s department of art history, visual art and theory and has been involved with the QAF since 2012.

Varied Editions is a curated gallery featuring work from six artists, focused on printmaking and its intersections with Queerness and activism.

“Borrowing its name from the printmaking technique where artists alter individual prints within an edition, the exhibition reflects on queerness as a shared yet uniquely expressed experience,” the festival’s website reads.

The exhibit is located in a small room but the works fill it intimately without making the space feel crowded.

Exhibition Curator Cheryl Hamilton’s collage of drawn and printed pieces featuring drag queens, fire alarms, smiles and bricks

audiences in the narrow hallway leading to the room. Hamilton embodied a non-digital method with her work, using torn cardboard and different types of paper.

“Printmaking is an old school and tactile form. You can see and feel the layers,” said Wong. “It has its limitations … and people in arts are constantly pushing the edges of those limitations.”

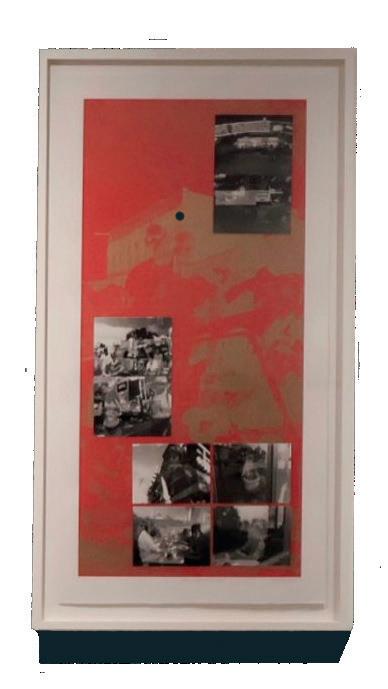

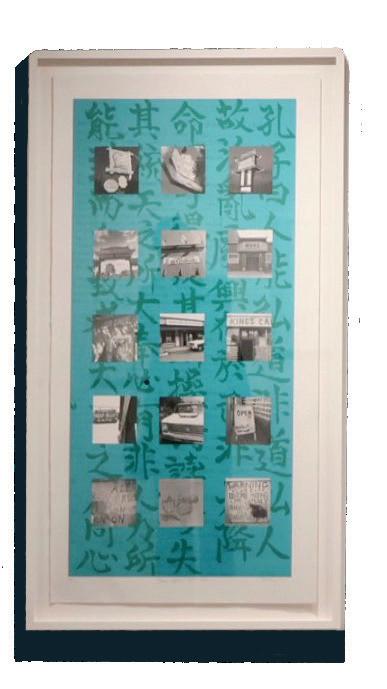

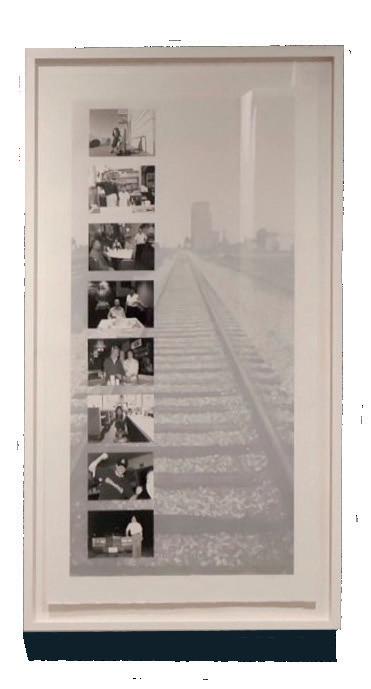

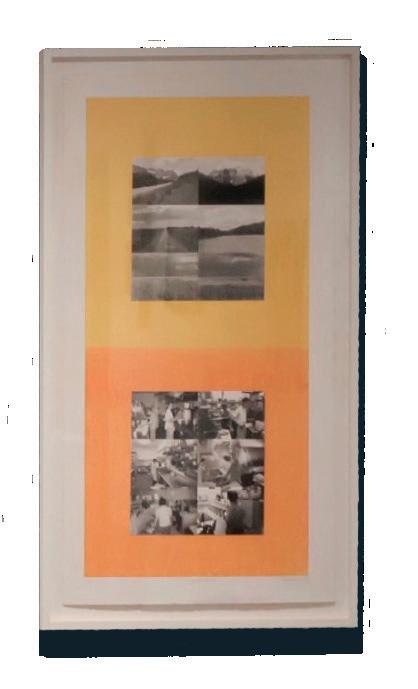

Wong’s displayed piece, “Chinese Cafes: The Five Energies,” was initially made for Them = Us, a photographic exhibition that travelled across Canada between 1998–2000 aimed at promoting diversity. Varied Editions is the first time “Chinese Cafes” has been unpacked since that viewing.

To create the piece, Wong glued blackand-white photographs to contact sheets, double-exposed prints, other photographs and even a cafe menu — blending various techniques of screenprinting and film photography. The final products are five differently coloured panels of intentionally scrapbooked layers.

“That, in a sense, [was] very experimental when I made that, and obviously still stands out as an interesting form and content,” he said.

The second panel particularly resonated with Queerness through its visual motif of reflections. On top of a red and gold

images that each had an element of reflection. The photos taken through a window or focusing on a silhouette spoke strongly to the theme of individual, yet shared, experiences of marginalization and Queerness.

“It’s about ways of looking,” said Wong.

The evolution of meaning in “Chinese Cafes” since its first exhibition was one of its most compelling dimensions — despite being made in the ‘90s, it still felt reflective of today’s society; something Wong agreed with.

“I don’t think it even matters,” he said. “I could have dated it today. I think Mark [Takeshi McGregor], the director of the Queer Arts Festival, was shocked that it was not a current work.”

The piece evolved from Wong deciding to follow different kinds of connection pathways — literal ones, like railways or highways, and metaphorical ones, like language-speakers and Chinese Canadian cafes. Wong went on a road trip through Western Canadian rural towns, photographing the people he met and stories he heard along the way in an attempt to highlight the ups and downs of the cafe industry and its intersection with immigrant culture.

“Mine is not specifically Queer in content except that I identify as being Queer,” he said. “I think that being out and proud as someone who identifies as a Chinese Cana

in their connections to Queerness, the pieces that were less overt proved the most thought-provoking. This exhibit offered much to ponder regarding Queer art — what it is, what it can be, how to push its limits and its role in fostering community.

“I think that this festival has been now going on for [17] years, that it continues to evolve in a kind of grassroots level, that it continues to provide access to artists and access to community, access to the public,” Wong said.

“I think that has [played], and continues to play, a very important role, particularly with the huge orchestrated dismantling of all types of ‘woke culture,’ as they say it from south of the border.”

According to the American Civil Liberties Union, there are over 595 anti-Queer bills tabled across the United States. But this trend is influencing rhetoric and legislation in Canada as well. In the past two years, Alberta and Saskatchewan have both passed legislation restricting Queer freedoms. Federal Conservative leader Pierre Poilievre promoted anti-Trans views during April’s federal election campaign.

“Now more than ever, this work needs to be made, needs to be seen and needs to be celebrated and discussed,” Wong said.

Varied Editions runs Tuesdays

Over the past two decades, many sport policy makers have increasingly prioritized demographic diversity within recreational sport. This has led to the improved representation of women, people with disabilities and racial minorities within the sporting world.

However, there has been one major blind spot. The needs of 2SLGBTQIA+ individuals have received comparatively limited funding and attention, with this community often being cast off and ostracized within sport.

This gap in accommodation is further complicated by ongoing challenges within sport organizations, where reluctance to engage with 2SLGBTQIA+ inclusion efforts persists, as people often assert that there is a lack of evidence demonstrating that 2SLGBTQIA+ exclusion is a problem in sport.

While UBC is certainly not exempt from this issue, progress is being made. People and groups across campus are working to make sports and recreation more accessible for all, moving inclusion forward and illuminating the barriers that still persist within institutional sports settings.

Helping foster inclusive recreation efforts at UBC is Alex Northey — who serves as the coordinator for physical activity within UBC Recreation — bridging both UBC Recreation and UBC Wellbeing through an emphasis on physical activity as a pillar of well-being.

When it comes to inclusivity, Northey emphasized that UBC Recreation doesn’t

Words by Jeff Lee Illustration by Ayla Cilliers

“We do have a dedicated inclusivity committee … we analyze programs, we go over training. We become trainers to then train staff on how to be inclusive,” said Northey.

One of the most visible examples of this commitment is found in the restructuring of intramural divisions to be more gender-inclusive.

“We did our naming convention change … [from] men, women and co-rec to a broader spectrum,” Northey said. “[Now it’s] open, which is inclusive to everybody … then we have our women and Trans women welcome space … [and a] mixed space, which [has] rules based on the maximum number of self-identifying men that can be on the field.”

In addition to the ongoing efforts at UBC Rec, student-led initiatives like KUS Pride and community organizations like the Bike Kitchen are carving out affirming spaces from within.

KUS Pride is a committee under the Kinesiology Undergraduate Society dedicated to “fostering inclusion and empowerment for 2SLGBTQIA+ students” within the School of Kinesiology.

KUS Pride runs a range of events aimed at representation, education and community-building. As Kyra McKinnon, one of KUS Pride’s volunteer committee members, explained, these include panels featuring “Queer and gender-diverse professionals or athletes or community members,” often organized around specific themes.

“We’ve done one on women in sport and research. So that one

have women — Queer — or not Queer talking about their involvement in athletics or in research around sport,” she said.

The committee’s goal with their events is to not only to uplift underrepresented voices, but also to give students hope for the future.

“It’s … open to everyone … [showcasing] Queer professionals [with] what they’re doing in their respective domains,” she said.

But McKinnon’s connection to this work isn’t just administrative — it’s deeply personal. Identifying as a Queer woman herself, she came into KUS Pride already aware of the social and institutional barriers many 2SLGBTQIA+ students face.

“I [got involved with] it knowing how hard it is for Queer students to exist … and not have a dedicated space.”

However, KUS Pride isn’t the only group trying to change that: the Bike Kitchen, UBC’s community bike shop, continues to create inclusive spaces for 2SLGBTQIA+ communities through its ongoing Access Nights for women, Trans and Queer people.

These events, held regularly over the past few years, offer a welcoming environment for individuals who may feel excluded from the traditionally masculine culture of biking to come in, learn and work on their bikes.

Zoé Kruchten, programs manager at the Bike Kitchen, emphasized that true inclusion begins with representation.

“The main inclusion aspect is having [women, Trans and Queer] mechanics and volunteers running the night,” she explained. “Historically, [that] has sometimes been hard because there is a lack of diversity among mechanics in general.”

For Kruchten, this visibility is essential, not only for those working behind the scenes, but also for those accessing the space.

“A really core part of inclusion is people coming into a space and seeing themselves reflected back in the folks who are running those evenings,” she said.

From an academic perspective, research at UBC also plays a critical role in understanding the nuanced experiences of 2SLGBTQIA+ students in physical activity spaces.

Naomi Maldonado-Rodriguez, a fifthyear PhD candidate at the UBC School of Kinesiology in the Faculty of Education, is contributing directly to this conversation through her research project “Perceptions of and Experiences with Physical Activity in UBC Sexual and Gender Minority Students.” As co-author of this study, alongside

fellow PhD candidate Ben Hives, Maldonado-Rodriguez and her research team sought to explore how physical activity spaces on campus can better serve Queer students.

“We did virtual and in-person focus groups with different students, and just [asked] them about their experience of physical activity — the kind of things that make them feel included or not as included, how physical activity makes them feel,” said Maldonado-Rodriguez.

One key issue that emerged from the research was the impact of social norms surrounding appearance and gender. For many Queer students, physical activity environments come with implicit expectations about how a “fit” or “healthy” body should look, or what people should wear in order to belong. These pressures can make movement spaces feel more alienating than inclusive.

“Clothing is so gendered in many different ways,” she said. “What might sometimes be under-appreciated or not even acknowledged as a decision [can] cause significant stress … [it] is how they show up into the spaces and how what they’re wearing maybe signals who they are, [or] expresses their gender and sexual identities.”

Throughout the process of this study, what became increasingly clear was that amidst the plethora of barriers 2SLGBTQIA+ students often face in finding an inclusive recreation space, solutions can be complicated.

“There were so many varied experiences with physical activity and what people want,” said Hives. “Some people wanted more group activity and shared experience and some people are just like, ‘Leave me alone, I just want to do my own thing.’ So, there isn’t really a one-size-fitsall solution. Rather, there are a number of solutions that should be implemented.”

Inclusion is not a one-time fix but a continuous process — one that requires collaboration between institutions, student groups and researchers alike. While a perfect solution to the discriminatory barriers facing 2SLGBTQIA+ students in sport may not be imminently possible, there are still countless groups and people across campus, like McKinnon, who have made a place for themselves.

“By being here and by giving this space to people — that’s doing enough anyways,” said McKinnon. “The events we do and infographics we post, learning things and teaching people, that’s all extra. It’s the fact that we have a designated space. That is enough.” U

Gender has been widely viewed as a binary concept in society — a belief that comes from cisnormativity and one that can affect paradigms about Transgender people themselves.

Transnormativity is an ideology that claims the validity of Trans people’s identities is based on their adherence to binary gender norms. For gender non-conforming people, beliefs like these can be alienating.

Even in Queer and Trans-centred research, strict views of binary gender norms have kept the experiences of gender non-conforming people on the backburner. Despite having different lived experiences, non-binary people are sometimes grouped with binary-aligned Trans people in research samples or don’t receive the same focus because they are separate from the gender binary.

While there is overlap between Trans and non-binary experiences, there’s still room for research surrounding their identities individually.

The studies that have focused on non-binary populations outline the variety in Trans experiences. For example, a study by Dr. Stef Murawsky at the University of Cincinnati shows non-binary individuals feel more existential uncertainty in their identities, which can create hesitation and a delay in accessing gender-affirming care.

Standardized gender-affirming care — such as facial feminization or masculinization — is also generally binary, meaning non-binary people will often seek more personalized care. Gender non-conforming people also feel the need to transition in binary ways due to medicalization and other external pressures.

“There’s a lot of non-binary folks under the Trans umbrella who want a more individualized approach,” said

Kai Jacobsen, a PhD student in UBC’s Interdisciplinary Studies program, in an interview with The Ubyssey. “Like, ‘I want some changes, but not all the changes that hormones might bring me.’”

“The effects of lower or higher doses of hormones, or particular combinations of medications, or different surgery options — there’s a big community demand for having those kinds of more expansive, individualized gender affirming care pathways available.”

Jacobsen has been involved in research showing that non-binary people experience more instances of being misgendered than binary-aligned Trans men and women. As a result, non-binary people also experience more distress, poor mental health outcomes, gender dysphoria and non-affirmation of identity.

Though there’s a clear difference in experiences, the amount of research on non-binary people can still be expanded.

“Because there wasn’t a lot of research literature to draw out, that analysis was really based on our lived experiences to kind of guide how we were analyzing and interpreting the data we had,” said Jacobsen, referring to their study on misgendering. As a Transgender and non-binary person themselves, their research is focused on the intersection of health systems, and social and structural factors shaping Queer and Trans health.

A focus on non-binary people is critical for Jacobsen who believes research samples should represent their epistemologies — that is, the priorities and lived experiences of non-binary people themselves. This is critical as it challenges popular assumptions that can illegitimize the experiences of non-binary people, like that they need to experience dysphoria in order for their identities to be valid.

Epistemic justice refers to an equitable and inclusive process of knowledge creation, utilization and dissemination, as it calls for a focus on marginalized voices. It is a critical lens Jacobsen aims to integrate in their own research around Trans and non-binary people accessing gender affirming care in Canada.

This framework has guided their research to concentrate on understanding the experiences of Trans and non-binary people who have been subjected to skepticism, ignorance and ableism from their care providers.

Jacobsen believes researchers, health care providers and other actors in health care and medical sciences need to recognize their gaps in understanding, while still being equipped with substantial knowledge about Trans and non-binary people.

The path toward non-binary inclusive research is vulnerable to institutional and societal challenges. Categorization in surveys is one barrier that might make doing statistics easier, but has nuanced implications for non-binary people.

“In quantitative research, there’s always this tension between wanting to give folks space to describe their gender in their own words or like, not force them to tick a box,” said Jacobsen.

They believe this is always going to be a work in progress.

“How do we produce knowledge that is meaningfully representative of folks’ diverse experiences, and also is legible to the government and policy makers, people who really rely on having usually binary, male and female data? … I think it’s possible, but hard.”

“As a Trans person in research … people just end up asking you, ‘What’s the best way to ask about gender in surveys?’ And I feel like my answer to that changes all the time.”

Jacobsen noted the resourceful -

ness of the Canadian Gender and Sex Research Equity Toolkit released by the Collaborative for Gender and Sexual Health Equity to help researchers navigate linguistic and methodological limitations to conduct more gender sensitive and inclusive research.

Jacobsen also said they were in the process of co-founding a non-profit organization which aims to bring the community needs of Trans, non-binary and Two-Spirit people to the forefront in health research in Canada. As the project is still in early development, they are currently working on a grant application to do community consultations.

The recognition of non-binary experiences as unique and worth accommodating is present in UBC projects like eSense Non-Binary, led by researchers at the Brotto Lab in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. e-Sense is an online platform originally geared toward cisgender women facing female sexual interest/arousal disorder, but which is now being adapted to non-binary individuals, widening their access to treatment.

Ultimately, non-binary participation throughout the research process is key to ensuring research seeks not only to advance scientifically, but to improve the lives of Trans and non-binary people.

“For a long time, there’s been cisgender medical researchers doing research on Trans people that really treats Trans and non-binary folks as the objects of research, rather than active participants of research,” said Jacobsen.

“I think the research is usually better when you have people with lived experience involved in designing it, interpreting the data … It’s easier to distribute the findings back to [the] community when [the] community was involved with it from the beginning.” U

In kindergarten, Joel Yi Xin Hung noticed how deep his voice was for someone of his assigned gender at birth. In elementary school, he would hang out with other guys in his class and strived to be like them. But it was during quarantine in his early high school years that Joel joined an online server with other Queer people and began coming into his identity.

“I think [Queerness] was something I’d always kind of thought of.”

On the surface, Joel is not someone that is “visibly queer.”

On a sunny June day at North-Arm Dyke, he was wearing a gradient of shades — off-white shorts, a grey t-shirt and a black hat. He sat on a bench in full sun as float planes took off from the Fraser River ahead and committed cyclists rode by on the trail behind.

“I try and just look like a normal guy,” he said. “Like the kind of guy you’d see on the street … you see me, and then you forget me.”

“The word passing is like you blend in.”

Joel understands passing as being seen “as the gender you identify as, but also as cis.” He looked out at the water as he spoke. “I think passing only applies to certain kinds of Trans

people, kind of like myself.”

As a Trans man, Joel is someone who falls within a binary Trans identity and passes regularly. He is able to use the men’s washroom with little issue, and in one instance, a fellow Queer classmate praised him for asking for their pronouns. Joel was confused by this, since it is standard within the Queer community.

“I [realized] I was perceived as cis,” he said, describing the mixed emotions that came with the interaction. “I’m passing, but at what cost? At the cost of being immediately accessible to … other members of my community.”

Joel spoke slowly to find the right words. He explained how at this stage of his journey, passing is something that he actively tries to do, sometimes falling into “cookie cutter [gender] presentation.”

“I don’t necessarily want to keep on adhering so strictly to gender presentation … but then there’s also this really intense feeling of dysphoria sometimes when I don’t pass almost perfectly,” he said. “It’s like self-inflicted pressure, but then also a desire to not conform as hard, because that’s almost the antithesis of Queerness.”

Joel hopes that as he grows more

The name “Pride Month” often evokes images of rainbow flags, sparkles and loud music. The irony in this literal parade — in screams for visibility and in flashy displays of Queer identity — is that there’s little dialogue about those who don’t look visibly Queer. In other words, people who “pass.”

When starting this project, the concept of gender passing seemed simple enough: it is the experience of being interpreted as the gender one hopes to be seen as. But as we interviewed people with different gender identities and at varying stages in their journey, it was clear that the term “passing” had different interpretations within the Trans community.

Here are some of the ways in which four Trans UBC students have expressed what passing means to them and, in the process, reflect on their own Queer journeys.

comfortable with his masculinity and starts to transition medically, he won’t feel as obligated to follow conventional gender presentation.

“As a Trans guy, you come into your own sense of masculinity … It’s like that term of a self-made man, right? Except it’s quite literally self made, whereas a lot of cis people don’t necessarily have to fight as hard for an identity.”

Joel emphasized the need to acknowledge a range of experiences, not only those experienced by different identities within the Queer community, but also the nuances of an individual’s experiences.

“The past self of a Trans person isn’t always necessarily null and void. That kind of upbringing will always shape … who I have become as a person, even if I don’t like to think or talk about it,” he said after describing being raised as a girl. “That was still me, but I can change … All people can change, and to change and to err and to figure things out is human.”

“I hope that’s what people are understanding, [gender identity] is so fluid and open.” U

There are two things Lyn Scatchard loves: sewing and flowers. In their most recent project, they decided to combine the two.

“This is supposed to be a rose,” said Lyn as they showed off a white sweater they were embroidering flowers onto. Sitting on a picnic bench in the Biodiversity Research Centre’s courtyard, the surrounding greenery was a fitting background for the flowers on Lyn’s sleeves. They explained how the flowers on the sweater convey certain meanings — hydrangeas represent pride, blue roses represent achieving the impossible and anemones represent sincerity.

“Eventually it’s gonna be anemones all down the arm … mostly blue on [one] side with a couple pinks, and then mostly pinks on the other side with a couple blues.”

In many ways, the sweater represents Lyn’s gender identity as a non-binary person. To them, being non-binary is “not quite a boy and not quite a girl, but kind of both at the same time.”

“I think there’s elements of being masculine and elements of being feminine that I enjoy … and there’s elements from both that I don’t enjoy. So I kind of end up in the middle.”

Lyn has never seen themselves as straight, but when they resonated with a Trans YouTuber and memes, they were surprised to realize they were also Trans. Initially they thought they were a Trans woman before realizing that non-binary was a more accurate

description for their identity.

To Lyn, passing means being per ceived as one’s true gender by strang ers. But as someone who exists in the “middle” of masculine and feminine, this is often not always possible in a binary world.

“If you meet a stranger and they look at you and see the gender you be lieve yourself to be, that’s passing,” they said. “For non-binary [people], there’s not quite an equivalent, because every one always makes their best guess.”

“In media, it’s always presented as you’re either a man in a dress, or you get a makeover and suddenly you’re completely the most beautiful person … and how that’s really not often the case where it’s more of an in-between.”

Instead, Lyn looks to cause “some sort of confusion” when strangers at tempt to gender them. “Or if someone calls me ‘sir’ and then the next person calls me ‘ma’am,’ close enough,” they said.

It’s a compromise but in an ideal world, Lyn just “want[s] to be known as me, as Lyn, non-binary.”

“My hope is that someone sees me and then recognizes that I’m at least some type of Queer, like I’m some variation of being LGBT.”

“[Queerness] is about being myself,” Lyn said. “I think the best way to describe that is by describing myself through labels that I feel comfortable with. So I am non-binary. I am a knitter … I am someone who likes plants. I like hanging out with my friends. It’s a diffi

For first-year geosciences PhD student BD Voss, passing had been about safety for most of their life.

Raised Mormon in Utah, then continuing their education in New York, Wyoming and West Virginia, BD’s gender presentation — or ability to choose and experiment with their presentation — was often constrained by their environment.

“I was often also in states where people are allowed to carry weapons, knives, guns — both concealed and open carry,” BD said. “In those kinds of environments, being able to pass as a binary gender is incredibly important for your safety.”

BD is non-binary, so passing for safety also meant being perceived as a gender they do not identify with.

“Especially while I was on testosterone, but before my

breast reduction surgery, I would often up pitch my voice and make sure that I sounded very feminine,” said BD. “Then once I got top surgery, it became a lot easier to pass as a guy, and then it was like, ‘Oh, I’m gonna use the men’s restroom when I go to a gas station.’”

happening in the United States, especially over the past decade, it’s not really left me with room to actually explore [passing] in a meaningful way.”

story, BD’s playfulness was ap parent — as they described their experiences they gestured wildly with their hands and took out a dinosaur cap to wear. While sitting in the Pacific Museum of Earth, BD began to rethink their relationship to passing, alongside what comfort in their body truly feels and looks like.

“I’m sitting here having to think about what it actually means for me to pass and whether or not I want to pass in the way that I am used to the idea of passing … Now it’s very much more about comfort.”

But for BD, intentionally exploring this comfort on their own terms requires time and emotional output. As a graduate student balancing research, teaching, volunteering and much more, exploring and “playing”

gender expression and their fear of “gender pain.”

“God, I miss wearing jewelry. God, I miss wearing makeup,” said BD. “But at the same time, I’m so scared [of what] is gonna end up happening, because if

Yuki Ichikawa recalls growing up in Lethbridge — a conservative city in southern Alberta — and finding a desire in herself to explore girlhood. From asking her dad questions like, “Do you ever wonder what it would be like to be a girl?” to sleeping in her sister’s Halloween costumes, she was constantly questioning the rigid social rules around her.

Around 2020, she transitioned socially and medically. What seemed like the last step in a decade-long process of coming to terms with her identity ended up being the beginning of her journey of discovery.

Transitioning introduced a host of other issues, including the complex phenomenon of passing.

“In the past, [I’ve had a] negative relationship with feeling a pressure to pass, pressure to be perceived as cis,” she said.

Yuki elaborates further on this pressure she has felt to present more femininely — wear makeup, dress a certain way — in order to pass as

identity and perception.

“In certain aspects, I’m very openly Queer and very openly Trans,” she explained. “But then in certain areas of my life, I do pass, and my Queerness and Transness is not visible. And I do have mixed feelings about that.”

With this comes a sense of dissonance as an advocate for the Trans community. Passing as cisgender, in some ways, does not advocate for the visibility of the community.

Yuki realizes her visibility is beneficial to people, but at the same time, she recognizes there are situations where disclosing her identity is not safe, as the environment might not be supportive or have deep-seated unconscious biases.

“My visibility has been beneficial for other people directly,” she said. “For other Trans people who might want to walk the same path [and] for cis people to realize that there’s Trans people in their spaces.”

“It would be nice if every cis person could have a Trans friend or a Trans co-worker

Yuki’s relationship with passing is ever-evolving. Over time, she has realized that as she settles into her identity, she no longer feels the need to pass. She doesn’t feel the same pressure to go the extra mile to prove her feminine expression.

“I’ve become more secure in my identity, in a sense, through passing; through having my gender affirmed by strangers,” she said. “It’s kind of cyclical in that sense … I think passing helped me become more comfortable with not passing.”

“I’m more comfortable now, expressing myself in ways that aren’t to maximize how well I pass to a cis person.”

Moving forward, Yuki is starting medical school at UBC in August and hopes to amplify Trans visibility in health care. Growing up, she did not have anyone who shared the same experiences as her that she could look up to, so she hopes to be that person for an upcoming generation.

Yuki is not just passing

In an exciting conference that I accidentally stumbled upon after 45 minutes of looking for a passably clean washroom on campus, UBC unveiled a new course to be integrated into its curriculum in celebration of Pride Month.

“We thought about consulting ‘real gay people’ about the sort of course topics they would find beneficial to the university’s curriculum, but that seemed too hard tbh,” said Leia Z. Bones, a prominent university alum and “like, the biggest ally ever,” according to her LinkedIn. I took a seat in the back row because they were giving out rainbow-shaped cookies (I love free snacks).

Bones, who has spearheaded over 10 different Pride T-shirt design teams across 4 discount stores and grocery superstores over the past 6 years (according to the conference program I used as a napkin to brush off my cookie crumbs), “believes in Queer inclusion!” This, written in large, bold, underlined font on the program’s first page, should perhaps not need such overt clarification as that’s like, the bare minimum, but I’m gonna keep my thoughts to myself and keep giving you the cold hard factual juicy yummy news.

“Drumroll, please…” Bones waited for seven minutes and forty-six seconds in order to ensure conference-wide percussive participation. “I am both humbled and honoured and humbly honoured to introduce the university’s newest course concept: ‘Corporate Allyship Principles for Dummies: Pride’ or ‘GAYS 350B’!”

The course will be available for registration immediately, after being added to Workday within “one week I guess. Or nine business years.”

GAYS 350B will be an interactive, hit-theground-running type of course taught by Bones and a lot of her friends who have gay friends, they swear.

“Students will have the unique opportunity to visit a number of offices across Vancouver where they will conduct real research on how corporate

Back in the good old days (2016), you could tell if someone was gay based on their appearance. But now, Queerness is all ambiguous and nonchalant. In the grand scheme of things, that is pretty good for the community — “growth” and whatnot — but it sure makes trying to hit on hot girls on campus a lot harder. Are you gay or do you just really love Clairo? Is your carabiner a functional thing, or what? The dating scene can be brutal, so here’s my foolproof guide on how to tell if someone is gay nowadays.

Stickers, stickers, stickers

Water bottle and laptop stickers are one of the most telltale signs of Queerness. Please note that not all laptop stickers are built equally. Sometimes, you’ll come across easy-to-spot Pride stickers. These come in all shapes and sizes. I personally have a frog in the bisexual colours, saying “my stomach hurts.”

Some stickers, however, may be more subtle. For instance, let’s consider the following: a toad in a cowboy hat riding a Minecraft skeleton. This can indicate bruh luh bruh, or it may just be a symptom of an unhealthy Minecraft YouTube phase that took place in 2020. And sure, a Pokémon laptop decal shouldn’t

instantly sound your homosexual alarm, but a sticker of that one guy from Team Rocket or my spiky-haired girl Misty? That’s the gay agenda being pushed.

Speed, I am speed

Next, ask yourself: how fast do they walk to class? Is your prospective crush walking at a reasonable place or are they rampaging down Main Mall like the ghosts of Chappell Roan past, present and future are chasing them down? One thing to consider here is how far apart their classes are. If they’re moving from Buchanan A to B at the speed of light, perhaps they might also be into cuffing their jeans and knowing way too much boygenius lore (Is that still a thing or am I getting old?). However, if they need to hustle all the way from Orchard Commons to the Chan Centre, they may just be trying to cram a 20-minute walk into 10. A good way to test this is to sit inconspicuously on the benches near IKB (do your best to take in minimal second-hand smoke) and try to get a sense of the direction they’re walking in. A less creepy way to do this is to approach your crush and ask for their schedule, but talking to people is scary, so choose your own adventure, I guess. (ATTN straight people. For your reference, the heterosexual equiva -

allyship is implemented within different workplaces, from mainstream retail stores to pyramid schemes,” Bones said. “There’s a lot to be done with the term ‘MLM.’”

At this, some probably AI-powered humanoid entities in uniforms started passing out various samples of “corporate-approved Pride products.” These included a rainbow button with a thumbs-up emoji and the word “ok” printed on it in Comic Sans, a seethrough plastic fanny pack that says “BE YOU!” in hot pink block letters and a flimsy cotton tote bag with nothing on it at all because, as Bones said, “gay people love tote bags, so the bags speak for themselves.”

“This is a real step forward for inclusion and diversity and stuff. I don’t think the university has any classes that will help students think critically about these relevant topics and issues,” said Bones.

When an anonymous audience member commented on their own experiences taking UBC Arts courses which discussed and explored gender, Queerness and sexuality in “enlightening, enjoyable and important ways,” Bones laughed.

“Arts courses! You’ve gotta be joking. Everyone knows those aren’t real.”

The audience member was then escorted from the conference, but was given what appeared to be a mildly uplifting poster of a cat and a free clicky pen on their way out.

Bones went on to describe more core elements of the course, including key topics such as “the importance of vaguely supportive phrasing,” “leveraging Millennial beige in rainbow product design,” “the art of changing the company profile photo to rainbow colours in June,” “performing the performative” and “weaponizing your incompetence.”

Because of its highly-involved hands-on nature, and also because Bones “can only handle all that PC stuff for so long,” the course has been specially designed to run only during the month of June and then promptly be forgotten about for the rest of the year. U

lent to the boygenius lore would be the Paul Mescal, Gracie Abrams and Daisy Edgar-Jones drama.)

Iced or nothing!

Lastly, we come to number three: the ultimate telltale sign of Queerness on campus. Are they drinking an iced coffee (or iced drink of choice) in the winter? If the answer is yes, then you already know what I’m going to say. Pack it up and go celebrate Pride. However, like every rule, there are exceptions: if their drink of choice is hot in the winter, either they have really poor circulation or they’re as straight as the curve these profs keep grading on. If iced or hot isn’t a clear indicator, you can also consider their beverage of choice. Classic Queer is an iced oat latte. Evil bisexuals will tend to go for a strawberry oat matcha. Lesbians studying criminology can’t resist a dirty chai (two shots if they’re feeling freaky). All of these drinks can be found at your

favourite niche local underground cafe, Blue Chip (not sponsored)! Please remember at the end of the day nothing defines you or your sexuality other than yourself. Own what you love and never be ashamed to be yourself. No matter how you dress, how much Clairo you listen to, how frequently your tummy aches or even if you played Beyblades as a kid, no one can define you other than you. U

Words by Maya Tommasi

Maya Tommasi (she/her) is a third-year political science student and The Ubyssey ’s external politics columnist. She is a trans woman and latine immigrant, and holds a previous degree in psychology with multiple years of research experience. You can find her on BlueSky or reach her by email at m.tommasi@ubyssey.ca.

Politics encroaches on all aspects of our lives. Powers at be is a column written by External Politics Columnist Maya Tommasi about the ways in which political power — corporate, federal, provincial, Indigenous and municipal — affects the lives of those who call themselves part of the UBC community.

Throughout history, science has been used to perpetuate systems of oppression and the marginalization of minority groups. As society changed during the Enlightenment to bring science to popular attention, so grew oppressive uses of it.

Scientific racism was used to justify slavery, eugenics, apartheid and genocide. While now discredited, diagnoses like female hysteria justified the institutionalization of women. Instances of that oppression are still with us today.

At the same time, we can acknowledge this without refuting that advancements in fields like medical science, as well as our broader understanding of the natural world, have inevitably led to the betterment of society. Our life expectancy, quality of life and potential are all greater today, often as a direct consequence of scientific advancement. This legacy of societal enhancement, specifically, as well as the heightened objectivity of empiricism, is what drew me into professional scientific research — the field I have worked in for the last six years.

Broadly, we tend to recognize both of these seemingly conflicting stories of science — its emancipatory potential as well as its historical shortcomings. With the increase of scientific rigour and broader ethical standards in the field, the belief goes, that science has moved beyond the excesses of its past.

While this is largely true — methodological improvements have made many historical excesses impossible, and science remains as close as we possess to an objective and unbiased tool for the pursuit of knowledge — modern science is not free of its marginalizing potential.

Higher methodological standards like ethics approval requirements for research projects and researcher certification are welcome. But they do not occur in a vacuum. Human input in judging the quality of a methodology and the interpretation of data will always be necessary; human biases still seep in. Science is not an infallible system.

When we talk about modern

science, we too often fail to recognize its discriminatory potential, and regard this as something of the past. And when it comes to the relationship between queerness and science, that potential is not an artifact of the past; we have long been pathologized by science.

In the field I work in — psychology — there is a long history of

ing label, recognizing our existence as that of a disorder — until 2012.

While those classifications have thankfully changed, the recency of them should remind us we are not far removed from the marginalizing past of science. To this day, queer — particularly trans — communities are marginalized within the medical system, with outright discrimination

pathologization of queer identities.

The DSM, the American Psychiatric Association’s standard classification of mental disorders and a centrepiece of our understanding of mental health, classified homosexuality as a mental disorder until as recently as 1973. Similarly, transness was still classified in the DSM as a “gender identity disorder” — an unnecessarily stigmatiz-

as well as institutionalized medical gatekeeping is a reality for many.

Crucially, even the best science does not address issues in how that science is disseminated. How specific research is interpreted and used in modern society is, to me, the biggest issue by far in our society.

Methodologically, science will always be imperfect. This is the case

not only because methodological perfection is impossible, but also as our attention to ethics rightfully increases, the ease with which high-quality data can be collected becomes more limited. The notion that science is an absolute and perfect source of knowledge is untenable — science is not, and should not be expected to produce absolute or perfect results.

This gets us to our current political climate: while trans issues have taken centre stage in many ways, the debate over health care is the most insidious, especially calls to ban certain medical interventions.

One of the most contentious subjects of that debate is the use of puberty blockers in teenagers — and while there are also attacks on surgery or hormone therapy, those are less common, and the attacks on them are vastly overexaggerating their use.

Puberty blockers are prescribed with the explicit intent of delaying the permanent changes to the body resulting from undergoing puberty. These changes — such as body hair, bone structure and breast growth — can cause serious and acute psychological anguish to trans people, known as dysphoria, risking a decrease in our quality of life and mental health outcomes. While a lack of prescription under appropriate circumstances will condemn children to these changes, it does not preclude them from happening; puberty will resume when medication ceases.

Yet, calls for banning puberty blockers — or vaguely gender-affirming medication — for trans youth are loud among federal and provincial politicians. The federal Conservative Party’s policy declaration says it would prohibit “life altering medicinal or surgical interventions” on minors to treat “gender confusion or dysphoria” to protect children’s mental and physical well-being. The People’s Party of Canada has proposed using the Criminal Code to “outlaw the mutilation of minors,” which is how they describe the effect of puberty blockers. Alberta Premier Danielle Smith’s government considers puberty blockers “not medically necessary,”

and National Post columnist Amy Hamm, a former BC nurse, has equated puberty blockers with chemical castration (Hamm rose to prominence after being fired for “discriminatory and derogatory statements” about transgender people).

In forming their criticisms of trans health care, some look to science to back up their claims. One of the best examples of this is Smith and Hamm’s — as well as pieces across a diversity of respectable outlets — use of the Cass Review, a report on gender-affirming care for children commissioned by England’s National Health Service in 2020.

The Cass Review examined most aspects of gender affirming care, and its most notable — and contentious — conclusions were about puberty blockers, finding that while there were multiple studies of the matter, there was an overall lack of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) to prove their efficacy.

The basic idea of an RCT is that participants are randomly assigned to either a treatment or control group — the “treated” one with the intervention and the one without, often using a placebo in its place — and their outcomes are compared. RCTs are often preferred because they minimize the effect of confounding variables, allowing researchers to directly investigate the effects of their treatment isolated from other factors.

While they are often called the “gold standard” in medical research, RCTs are not the only form of acceptable evidence and they can also be difficult to conduct. Chief among those difficulties are ethical concerns: restricting medication from a group that might need it exclusively for the sake

of having a control group is ethically questionable. This makes running many RCTs impossible and reliance on other forms of research not uncommon in medical sciences.

A Calgary physician noted in an interview with the CBC that while the Cass Review took issue with the lack of RCTs run on the use of puberty blockers in minors, even common medical interventions like prescribing painkillers or antibiotics for children with ear infections may lack evidence in the form of an RCT. The physician pointed out that exclusively relying on RCTs would be like saying to a pregnant person that, since there is no RCT-based evidence to support the care of people in pregnancy, care won’t be provided.

One need only imagine the implications of banning all medical interventions which lack RCT evidence to understand the problematic logic behind the Cass Review ’s concerns relating to trans health care.

After it was published, trans people, physicians, academics and advocacy organizations noted these flaws. Among those who rose to the defence of puberty blockers were the Canadian Pediatric Society, American Academy of Pediatrics and World Professional Association for Transgender Health.

But these criticisms of the review have not prevented it from being cited by those in power; the Cass Review was the basis for the then Conservative government issuing a temporary ban on puberty blockers in the UK, which has more recently been made permanent by the current Labour government. The argument is always the same: that “science” (a stand-in for the Cass Review) shows puberty blockers might not be the way forward, as

repeated beyond the UK and by the Premier of Alberta — whose government moved to ban, with exceptions, puberty blockers for teenagers under the age of 16 (puberty blockers are usually prescribed at a much younger age).

The point here is not that the main argument used by those calling to restrict gender-affirming care is reliant on fundamentally flawed evidence — though I do believe it is. I am not concerned with simple political point-scoring by suggesting ‘my evidence is better than yours.’ The point is that we recognize the context in which science is being used.

It seems clear to me that we live in a world which is fundamentally hostile towards trans people. And given how historically science has been used to entrench marginalizations in certain communities, overreliance on the Cass Review and other science which “proves” the harms of procedures that deviate from a traditional gendered norm, serves less as evidence for a genuine concern for trans people but more an explicit presentation of a persistent anti-trans prejudice.

Attacks on trans people are now part of our political life globally, ranging from banning us from using bathrooms, defining our gendered legal statuses, our participation in sports, our gendered medical care and even the ability of trans youth to socially transition. This exists in the context of the cissexist (belief that cis identities are more normal or legitimate than trans ones) society that we live in, where trans people experience substantially more violence, discrimination and poor mental and physical health outcomes.

In our modern world, research and science are often thought of as the gold standard for truth — “facts don’t care about your feelings,” an infamous political commentator would claim. And while I maintain that empiricism and scientific evidence are a reliable form of interpreting our world and creating policy, science is not infallible, especially if accepted uncritically.

Anti-trans actors, be it those who are vehemently engaged in transphobia or those who simply fail to recognize the underlying cissexism of our society — and in turn our thinking — will look to scientific data to argue positions which would further harm an already significantly marginalized community. This doesn’t have to happen in intentionally malicious acts; a review which leads to policy change in major democracies does seem like a compelling source of questions about these issues at home. But it is not solely because of the flaws of the Cass Review that these misguided questions can perpetuate harm against trans people — it is also the underlying dynamics of how our society sees and understands trans identities.

As consumers — and sometimes creators — of media and politics, it serves us to recognize the shortcomings of even our most potent tools. Nothing exists devoid of context; given a systemic and persistent discrimination of certain groups, even a tool as objective as science can still fail us, as it has many times before. U

This is an opinion article. It reflects the contributor’s views and does not reflect the views of The Ubyssey as a whole. Contribute to the conversation by visiting ubyssey.ca/pages/submit-an-opinion