SkyTrain rally builds support for extension

GRSJUA on community through performance

Vancouver’s artists are in trouble

The NDP’s false choice

Women’s soccer keeps winning

SkyTrain rally builds support for extension

GRSJUA on community through performance

Vancouver’s artists are in trouble

The NDP’s false choice

Women’s soccer keeps winning

Editor-in-Chief

Aisha Chaudhry eic@ubyssey.ca

Managing Editor Saumya Kamra managing@ubyssey.ca

News Editor Stephen Kosar news@ubyssey.ca

Arts & Culture Editor

Julian Coyle Forst culture@ubyssey.ca

Features Editor Elena Massing features@ubyssey.ca

Deputy Managing & Opinion

Editor Spencer Izen deputymanaging@ubyssey.ca opinion@ubyssey.ca

Humour Editor Kyla Flynn humour@ubyssey.ca

Sports & Recreation Editor Caleb Peterson sports@ubyssey.ca

Research Editor Elita Menezes research@ubyssey.ca

Illustration & Print Editor Ayla Cilliers illustration@ubyssey.ca

Photo Editor Sidney Shaw photo@ubyssey.ca

Digital

Editor Sam Low samuellow@ubyssey.ca

Business Manager Scott Atkinson business@ubyssey.ca

Account Manager Ben Keon advertising@ubyssey.ca

President Ferdinand Rother president@ubyssey.ca

Editorial Office: NEST 2208 604.283.2023

Business Office: NEST 2209 604.283.2024

6133 University Blvd. Vancouver, BC V6T 1Z1

Website: ubyssey.ca Bluesky: @ubyssey.ca Instagram: @ubyssey.ca

TikTok: @theubyssey LinkedIn: @ubyssey

LAND ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The Ubyssey acknowledges we operate on the traditional, ancestral and stolen territories of the Coast Salish peoples including the xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam), Sḵwx̱wú7mesh Úxwumixw (Squamish) and səlilwətaɬ (Tsleil-Waututh) nations. sexism, homophobia, transphobia, harassment or discrimination. Authors and/or submissions will not be precluded from publication based solely on association with particular ideologies or subject matter that some may find objectionable. Approval for publication is, however, dependent on the quality of the argument and The Ubyssey editorial board’s judgment of appropriate content. Submissions may be sent by email to opinion@ ubyssey.ca. Please include your student number or other proof of identification. Anonymous submissions will be accepted on extremely rare occasions. Requests for anonymity will be granted upon agreement from seven-eighths of the editorial board. Full opinions policy may be found at ubyssey.ca/pages/submit-an-opinion It is agreed by all persons placing display or classified advertising that if the UPS fails to publish an advertisement or if an error in the ad occurs the liability of the UPS will not be greater than the price paid for the ad. The UPS shall not be responsible for slight changes or typographical errors that do not lessen the value or the impact of the ads.

organization and all students are encouraged to participate. Editorials are written by The Ubyssey’s editorial board and they do not necessarily reflect the views of the UPS or UBC. All editorial content appearing in The Ubyssey is the property of the UPS. Stories, opinions, photographs and artwork contained herein cannot be reproduced without the expressed, written permission of the Ubyssey Publications Society. The Ubyssey is a founding member of Canadian University Press (CUP) and adheres to CUP’s guiding principles. The Ubyssey accepts opinion articles on any topic related to UBC and/or topics relevant to students attending UBC. Submissions must be written by UBC students, professors, alumni or those in a suitable position (as determined by the opinion editor) to speak on UBC-related matters. Submissions must not contain racism,

The Ubyssey periodically receives grants from the Government of Canada to fund web development and summer editorial positions.

SIDNEY

“This is a global problem. We see

Gaza as the worst symptom of this, and I’m very afraid when I look at Canadian discourse ... that we’re not treating this as the outrage that it is.”

Spencer Izen

Deputy Managing Editor, Opinion Editor

Two weeks before Canada recognized the State of Palestine, UBC was visited by Dr. Deirdre Nunan.

Nunan is an orthopaedic surgeon and a graduate of the Northern Medical Program in Prince George, a partnership between UBC and the University of Northern British Columbia. For much of the past decade, she’s been doing humanitarian work internationally. This summer, she spent three weeks in Gaza — her sixth trip there — having spent the equivalent of two years in the occupied territory since 2019.

On Sept. 8, Nunan delivered her “Health Report From Gaza” to a packed audience at the Frederic Wood Theatre. The event was hosted by BC Physicians Against Genocide with the support of several campus units and groups, the Jewish Faculty Network, geography department, Middle East studies program and Climate Justice Centre among them.

Nunan’s report also introduced viewers to her colleagues and their stories: Dr. Hassan, Dr. Aseel, Dr. Jamal and Dr. Wesam, a “brilliant surgical partner.” I spoke with her a few hours before she delivered it.

Here’s what we discussed — edited for length and clarity.

The Ubyssey: You have done a lot of humanitarian work internationally in the past decade. What’s different about Gaza?

Dr. Deirdre Nunan: It’s the concentration and the intentionality. And the avoidability.

I have been to other places in the aftermath of a conflict, seeing the longer-term results rather than being within an area that is actively under attack.

It’s certainly not the first time I’ve been somewhere where there are ongoing attacks, but never so many, never in such a small area, and never in such a short time.

What was happening in the other places that you’ve worked, where there have been ongoing attacks?

In 2019, I was in Gaza when there was a three-day period of more intense aerial strikes from the Israeli military. I was on the outskirts of the conflict between Turkey and the Kurdish military and the north of Syria. In Iraq, there were some peripheral attacks outside of the urban area in Mosul when I was there. In Afghanistan, there were some suicide bomb attacks by ISIS on buses.

Things were happening in the area, but not this relentless, constant, ongoing bombardment.

I anticipate tonight’s talk is not the first event that you’ve delivered like it. What are the moments you want to stay with people?

I want to focus tonight on attacks on health-care institutions and healthcare personnel. I feel like in Canadian society we are starting to accept the unacceptable. We’re starting to treat things as inevitable, and we are not taking a step back and recognizing that some things are simply wrong. There are some things that are simply not defensible in terms of international humanitarian law. Societally, when we start to accept the unacceptable, it’s a slippery slope.

It’s not only Gaza. Gaza is the worst affected in terms of attacks on health care, but since 2023, we’ve been seeing ever-escalating attacks on health-care institutions and healthcare personnel around the world in different environments.

The worst attacks are happening in Palestine, but attacks are also happening in Myanmar, Sudan, Democratic Republic of Congo, and Ukraine. These are all places where we have started to lose any sort of sense of the sanctity of health care and the protection for patients and the wounded and the places that can OUR CAMPUS

treat them.

This is a global problem. We see Gaza as the worst symptom of this, and I’m very afraid when I look at Canadian discourse, when I look at Canadian media, that we’re not treating this as the outrage that it is. When we accept the unacceptable, we establish new tolerance for norms, and that’s not a world I want to live in. I don’t think that it’s a world that Canadians really want to live in, but unless we push back against the normalization of something that should never be normalized, that’s exactly the kind of world we’re going to let be created for ourselves.

What manifestations of attacks on health-care institutions and personnel are you most concerned about?

Globally, we’re seeing the erasure of the protected status of a health-care institution, or the use of very specious arguments against maintaining the safety of health-care institutions. Under international law, only in very particular moments can a health-care institution lose its protected status. But what we see in Gaza is that every single Israeli attack on a health-care institution is always justified, is always claimed to be necessary military action against Hamas or another armed group said to have a presence in hospitals. I see very little pushing for evidence for this. Few are asking, ‘What is this actual presence?’ ‘Does it meet the threshold for removing the protected status of this institution?’ ‘Were the other requirements followed, including giving warning to the hospital, allowing evacuation for patients, making sure that the reaction is proportional and that the damage done is not out of proportion to the risk that was posed by what was happening in that hospital that was used as a justification for attacking it, and the provision of ongoing health care for people that are deprived of health care when you attack a hospital or when you kill healthcare workers?’ That’s the big picture. We’re not looking at the true meaning of international law regarding the security and safety of health-care workers.

Elif Zaimler, Trinity Sala & Will Gust Contributors

Community leaders at the AMS SkyTrain rally on Oct. 1 called on the provincial and federal governments to support the construction of a SkyTrain extension to UBC’s Point Grey campus. Despite the rain, event organizers reported over a thousand attendees at the rally held outside the Nest.

The rally is one component of the AMS’s advocacy plan to push for provincial and federal support for the project. By the time the rally took place, the first stage of the plan — a petition calling on the provincial government to release the extension’s business case and for all levels of government to fund it — had over 15,000 signatures.

At the plaza outside the Nest, students, volunteers, media and community members gathered before speeches began. While some people in the crowd were just passing by or were there for the free barbecue provided by the AMS, dozens gathered in front of a stage holding signs distributed by volunteers. AMS VP External Solomon Yi-Kieran, the event’s main coordinator, led the crowd through a series of chants, before they started their speech.

Yi-Kieran thanked the signers of the SkyTrain petition and participants of the rally for their assistance in achieving one of the goals of the AMS’s SkyTrain campaign, generating media attention.

“Thanks to you, we got the SkyTrain in the news. There’s so much media here today. We generated so much attention that the premier released a statement about the importance of the SkyTrain just today,” they told the audience.

In the statement, Premier David Eby recognizes the “potential the UBC Extension has,” and commits to working with key partners including the federal government,

to advance the project’s planning work. The Ubyssey received the same statement from the premier’s office.

Yi-Kieran also outlined some of the AMS’s demands of the provincial and federal governments.

“We want to see the provincial government finally release the business case so that we know what the plan for the project is,” they said, emphasizing the urgent need for the extension. “Most importantly, we want to see the provincial and federal governments come together and put a combined funding agreement into the 2026 budget.”

The Ubyssey contacted the Prime Minister’s Office for a com-

ment on the SkyTrain campaign but did not receive a response by publication.

According to UBC’s latest Transportation Status Report, 79,000 daily transit trips were made to and from campus during fall 2024, accounting for 52 per cent of all trips to UBC. Despite the reliance on public transportation and years of advocacy by the AMS, a UBC SkyTrain extension has been under consideration by the provincal government since 2008.

“92 per cent of people in Metro Vancouver support the SkyTrain to UBC. So why hasn’t it been built yet? Maybe it’s because it has been years since we came out as a com-

munity, united in our voice and called for the SkyTrain to finally be built,” said Yi-Kieran.

They stated that the AMS’s advocacy plan aims to take their demands to Vancouver City Hall and “all the way to the legislature in Victoria.”

UBC President Benoit-Antoine Bacon also declared his support for the campaign at the rally.

“I’m proud to stand here with all of you to bring the SkyTrain to UBC. This is certainly a priority for the university as well, as much as it is for all of you. We’re all pushing hard for the SkyTrain to UBC,” he said.

Bacon’s speech was followed by Vancouver City Councillors Lucy Maloney and Sean Orr.

“All of [Vancouver City] Council is committed to this. This isn’t a partisan thing. You know who else is on board? The Musqueam, the Squamish and the Tsleil-Waututh,” said Orr.

Maloney said the councillors were “in Victoria, asking the minister for transport [and] the premier to extend the SkyTrain out to UBC.” She then asked the audience to participate in the introduction of the motion in discussion at Vancouver City Council on Oct. 8.

“We need to keep the pressure up so that the provincial and federal governments make sure they prioritize funding for [the] UBC [extension] right now,” added Maloney.

The last new speaker was Michelle Scarr, director of strategy and operations at the transit advocacy non-profit Movement. The organization was previously behind the ‘Save the Bus’ campaign that was on campus earlier this year in March.

Scarr said that Movement collaborated with the AMS over the petition for the SkyTrain to UBC, and that students can get governments to act on the SkyTrain extension.

“I hope that you, as a transit rider, recognize the power we have,” she said.

Despite years of seemingly unproductive advocacy to build the extension, its proponents are still optimistic about their campaign’s efforts.

“You don’t just ask once for something. You ask multiple times, and you ask in different ways: in person, meetings with ministers, meetings with government, petitions and motions by City Hall,” Orr told The Ubyssey in an interview after his speech.

Students at the rally told The Ubyssey that a UBC SkyTrain would be convenient and accessible for students who do not own a private vehicle and depend on public transportation to get to UBC.

One student named Paige believes the extension would open up a lot of transit possibilities for those without private vehicles or alternative modes of transportation.

“I feel like Vancouver is not a very accessible city for a lot of people, especially if you don’t have a car. It’d be nice to see the SkyTrain expanded,” they said.

Yi-Kieran said they were confident with the AMS’s planned lobbying of Vancouver City Council. They stated city council were “really supportive” of the SkyTrain extension. However, they emphasized that lobbying the provincial government would be more difficult.

“The challenge is when we go to Victoria, making sure that we are sitting down with MLAs and presenting all of the arguments … [we are going to] do our hardest work there,” they said.

“The biggest risk is people go, ‘it’s in the planning,’ and it’s really going to be about emphasizing that we can’t accept that it’s still in the planning stage. We can’t accept empty promises. We need tangible progress.” U

Sophia Samilski News Reporter

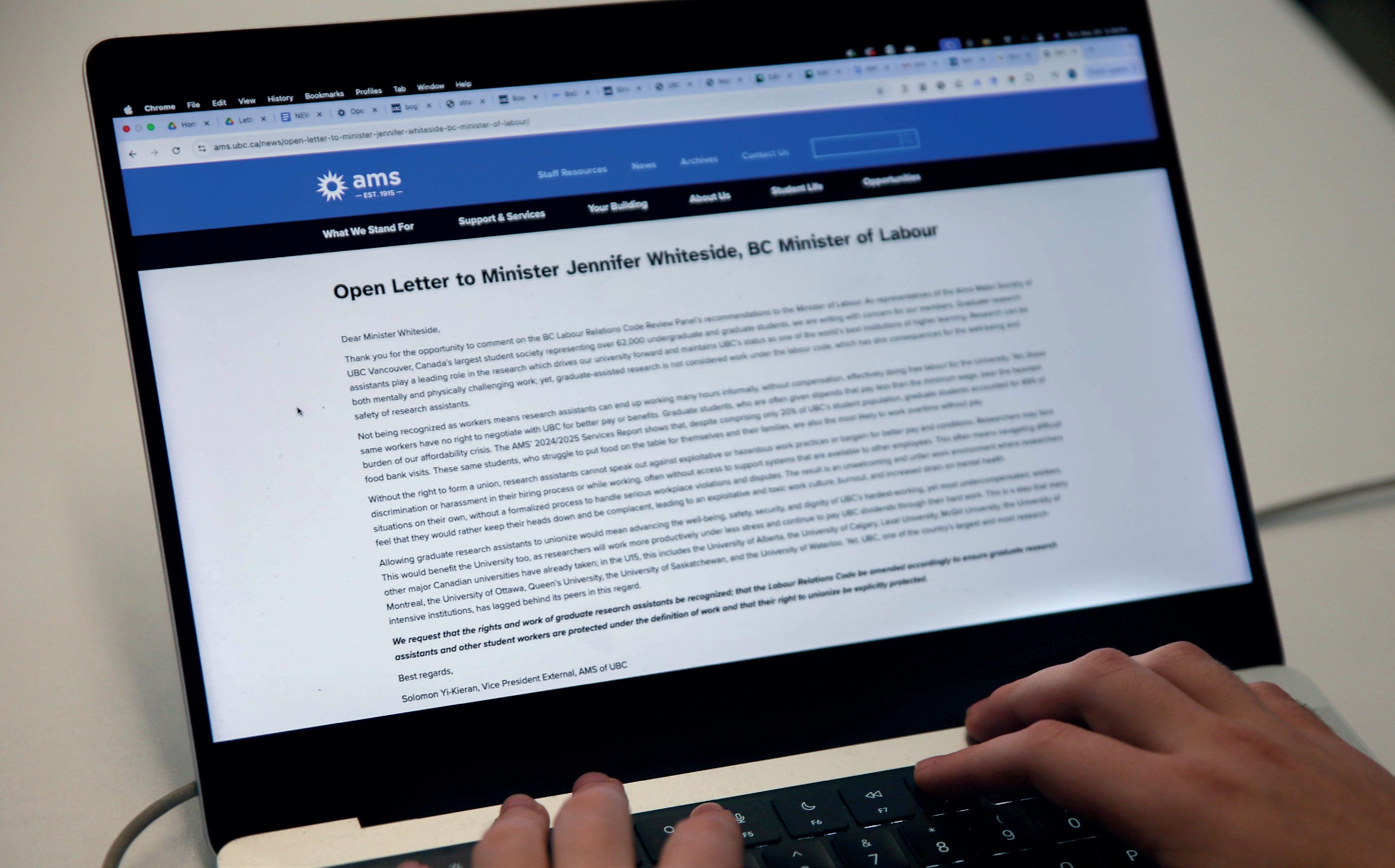

The AMS sent an open letter to B.C. Labour Minister Jennifer Whiteside on Sept. 17 urging the government to recognize graduate research assistants (GRAs) as workers under B.C.’s labour laws, giving them the right to unionize.

The letter comes months after British Columbia’s Labour Relations Board dismissed CUPE Local 2278’s — the Canadian Union of Public Employees local chapter representing groups of academic workers at UBC — bid to expand its bargaining unit and unionize roughly 3,200 GRAs at UBC. They did so on the basis that GRAs do not meet the definition of employees in the Labour Relations Code.

Graduate research assistants launched their unionization drive with CUPE 2278 in 2022 after reporting unfair working conditions, low pay and long hours, all without rights to negotiate better pay or benefits with the university.

“The fact that thousands of students at UBC are unable to be counted as workers or unable to unionize is a huge issue,” AMS VP External Solomon Yi-Kieran said in an interview with The Ubyssey . “It’s a huge injustice, and it does make it harder for a lot of students to afford their education, to afford living in the city and to continue doing the research they love.”

The AMS’s open letter was sent just days before the public consultation on proposed changes to the Code closed on Sept. 19.

“Research can be both mentally and physically challenging work; yet, graduate-assisted research is not considered work under the labour code, which has dire consequences for the well-being and safety of research assistants,” Yi-Kieran and AMS President Riley Huntley wrote in the letter.

The three-month consultation period allowed stakeholders, the public and other interested parties to provide feedback to the Labour Relations Code Review Panel, whose recommendations will be reviewed by the Ministry of Labour.

“Our hope is to see the panel include ensuring that student workers are able to be afforded the rights and protections that other workers get,” Yi-Kieran said.

In addition to the AMS, CUPE 2278 has submitted feedback to the Labour Relations Code Review Panel, calling for the code to recognize GRAs as employees.

“If the language of the labour code is going to be so that GRAs cannot qualify as workers under the code, then our next best option is to change the labour code,” the president of CUPE 2278, Drew Hall said in an interview with The Ubyssey Brad Spencer, communications

director of the Labour Communications Office, told The Ubyssey in an email that the Ministry of Labour confirmed it had received the AMS’s open letter. However, the government could not comment on the matter while the Labour Relations Code (LRC) remains under review by the LRC Review Panel.

“All feedback from workers, student organizations, and stakeholders on the LRC will be considered in the current LRC review process,” he stated.

CUPE 2278’s GRA fall 2022 unionization drive was built on several years of student interest. The local union already represented various academic workers, including teaching assistants, but sought to expand its bargaining unit.

The campaign came just months after the provincial government passed Bill 10 — the Labour Relations Code Amendment Act 2022, which lowered the threshold for automatic union certification. If 55 per cent or more of employees in a proposed bargaining unit sign union cards — a legal document indicating their support for union representation — the union can be certified without a vote.

After eight months of organizing, the union applied to add GRAs to its unit, with more than 55 per cent of GRAs signing union cards — enough to qualify for automatic certification under the

revised labour code. But in May 2023, UBC challenged the application. The university argued that GRAs do not meet the definition of an “employee” under the Code; instead, they are students who receive financial support to pursue their academic studies.

UBC maintained that GRAs were ineligible for inclusion in CUPE 2278’s bargaining unit.

“When we learned that UBC was objecting to this application, I think a lot of us were a bit appalled,” said Hall.

“This was a historic organizing drive … thousands of people signed union cards. For UBC to come and object to that decision and say that research assistants are not workers felt like a slap in the face.”

UBC’s objections led to a months-long hearing before the Labour Relations Board, where both the university and CUPE presented their cases. On March 31 this year — nearly a year after the Board’s original target decision date of April 2024 — the Board dismissed CUPE’s application. CUPE 2278 has since appealed the Labour Relations Board’s decision.

“The delays, no matter the cause — are only further hurting these precarious workers and making it harder to organize.”

Vice-President of CUPE 2278

Jessica Wolf told The Ubyssey

Emily Tang, president of the Graduate Student Society, said

that the society remains committed to working alongside CUPE 2278 to advocate for the fair treatment, protection and recognition for all student workers.

“We have always known that the fight for student worker rights does not begin or end with a single decision. This is part of a broader and ongoing movement,” she said in an email to The Ubyssey Hall, Tang and Yi-Kieran all said that GRAs not being counted as workers and not being able to unionize leads to a more exploitative workplace. Yi-Kieran pointed out that the situation can be even more dire for international students, whose ability to stay in the country is conditional on being in school.

“In many cases, a GRA may be hesitant to raise concerns out of fear of jeopardizing their academic progress or relationship with their supervisor,” Tang stated.

“It’s not just about the wages … but also having a mechanism where you can be protected in the cases where there is abuse of power or harassment or discrimination,” Hall said.

CUPE 2278 has since begun bargaining its expired collective agreement with UBC.

“We will be fighting for more protections for teaching assistantships in the face of [reduced hours and budget cuts], while GRAs continue to go without any sort of protection,” Wolf said. U

Elena Massing Features Editor

When Larry Grant showed his wife the first two chapters of Reconciling: A Lifelong Struggle to Belong, his new memoir, she said that reading it felt exactly like listening to him speak. Coming from someone who has spent more than a few decades hearing his stories, this wasn’t intended as a compliment — but it’s exactly what Grant and Scott Steedman, his co-author, had been aiming for.

Reconciling is presented as fragments of conversations between Grant and Steedman, most of them rooted in different geographical locations that hold weight in Grant’s life. The first starts on Musqueam Reserve No. 2, where Grant stands on a bank of the stɑl’əw, the Fraser River, not too far away from UBC’s Point Grey campus. Grant spent most of his childhood growing up on the reserve, and still lives there today.

Even though Grant didn’t attend UBC as a student until after he had retired from working the trades, he’s now an adjunct professor and the Elder-in-Residence at the First Nations House of Learning. However, he knew the campus long before he started teaching here.

A lot has changed since Grant was a kid. He and his friends would harvest kelp along Wreck Beach to sell to merchants who used it in food or medicine. There was also herring roe, smelt, salmon and oolichan to be caught, sometimes even mussels, clams and crabs — they’re all long gone from the area now. Even the beaches themselves didn’t always look like this. Before clean sand was shipped in to make the area more desirable for swimmers and other beachgoers, it was more of a marshland, with high grasses and diverse wildlife.

“For Larry, the real connection to all this land is the hənq̓əmin̓əm language,” writes Steedman in Reconciling. “Every little nook and cranny has a hənq̓əmin̓əm name from before contact.”

Grant’s mother, Agnes Grant, was one of the last fluent hənq̓əmin̓əm speakers and was deeply invested in learning about Musqueam traditional stories and rituals. People came to her for help figuring out the name for a certain plant in hənq̓əmin̓əm, and she knew the genealogy of the main Musqueam families — with certain hereditary names came certain fishing and hunting privileges, so people would also pay her visits to discuss protocol.

Agnes had no desire to get married, but she caught the attention of Hong Tim Hing, a Chinese immigrant who had paid the head tax and entered Canada under a fake name. After some negotiation, Agnes’s father gave permission for the two to get married. They later had children together, Grant being the second of four.

The Musqueam and Chinese communities became “intertwined” because “Indigenous people were denied integration within the surrounding community, and the Chinese were denied citizenship,

denied access to a lot of land,” Grant says in Reconciling. Neither group could enter professions in fields like health care or law; Indigenous people couldn’t even access post-secondary education unless they were pursuing theology. At the time, the local Indian agent — one of several federal bureaucrats who tracked and controlled Indigenous people across Canada until the position’s elimination in the 1960s — wanted the Musqueam to adapt to “Canadian ways” by doing more farming instead of fishing or hunting, and the Chinese immigrants happened to have a background in farming.

“So these two marginalized groups—one with a background in farming but no land, the other with land but no tradition or desire to farm it — found one another,” writes Steedman.

Racial tensions plagued every aspect of society during Grant’s earlier years. He went to Lord Strathcona Elementary, a fairly multicultural school where slurs of all kinds were constantly thrown around. On top of that, he lived the challenges of two distinct communities: on the one hand, his dad’s side was affected by the head tax forced upon Chinese immigrants, and on the other side of the family, he witnessed the effects of residential schools, the Indian Act and the Potlatch ban.

In the eyes of the law, however, Grant wasn’t Indigenous. “Indian” status was patrilineal, and Agnes had married a non-status man. “It was a really odd mindset for a child to

understand,” Grant says in the book.

“It was like you didn’t belong anywhere. The Canadian government didn’t recognize Chinese as citizens at that time, and didn’t recognize us, other than as bastard, half-breed children of our mother.”

In one way, at least, this was fortunate — it made Grant and his siblings ineligible to attend residential school. Many of Grant’s cousins were sent to St. Mary’s Indian Residential School in Mission City, and Grant’s wife is a residential school survivor as well. Unlike others in his life, Grant was encouraged to embrace his Indigenous ancestry. Agnes was diligent about educating him on his culture and language, and urged him to hold onto it. As he grew up, however — this was at the peak of World War II, when he was surrounded by more pressure than ever to adopt a “Canadian mindset” — he stopped speaking hənq̓əmin̓əm.

In 1998, Grant’s family encouraged him to enroll in the hənq̓əmin̓əm classes that UBC was developing. “Rediscovering a half-forgotten language after all that time was a strange, complicated experience, one that slowly rebuilt his connection to the far-away world of his mother and her upbringing in another century, when everyone spoke hənq̓əmin̓əm and saw life through that lens,” writes Steedman. There were times when the words wouldn’t come to him, but Grant slowly started to remember the language. He was always the oldest in the classroom and wasn’t afraid

to correct his younger peers or the professor.

He was eventually asked to co-teach the courses, which he still does to this day alongside linguistics PhD candidate Fiona Campbell. Dr. Patricia Shaw, the founder of UBC’s First Nations and Endangered Languages program, thought Grant’s ancestral knowledge should be appropriately recognized, and she insisted that Grant be hired as an adjunct professor.

Grant never even attended university, and instead spent four decades working in the trades as a highly-skilled auto mechanic and longshoreman, among other things. But maybe repairing connections with language and the trades have something in common, at least in Grant’s case: “That’s what he’s done since he was a child, with gutters and furnaces and diesel engines, but also with culture and language: fixing things, helping people out,” writes Steedman.

Shaw was absolutely right: Grant’s ancestral knowledge is valuable, not just from a linguistic standpoint, but in how much he remembers — at least a century’s worth of information, experienced firsthand and observed from those before him — about the lands we’re on now, from the shores of Wreck Beach to the streets of Chinatown. Steedman told me that he was stunned by the scope of Grant’s understanding of the land, even the areas he doesn’t see very often. It was even more surprising to him when he considered

the fact that Grant had spent the majority of his time on the reserve, somewhat detached from life in the city except for a few periods when he lived in Chinatown.

For Grant, the Musqueam reserve is home, but so is Vancouver’s Chinatown, and so is Sei Moon village in Southern China, where Grant once shared wordless tea with relatives he barely knew existed. These places are all home to him now, but the process of accepting them as such has taken nearly a lifetime.

“When Larry talks about reconciliation, he uses the verb: reconciling, a process we’re all going through, Indigenous and settler, immigrant and Canadian-born. ‘I have been reconciling my whole life, with my inner self,’” writes Steedman.

Grant is still living with the hurt and trauma of spending most of his life having his identity stripped away from him, then given back, then taken again. It’s taken a while for him to come to terms with who he is.

“I’ve got to the point where every day I thank my father for coming all this way, and for meeting my mother,” Grant says. He’s had to come to terms with the fact that his own father was a foreigner in his country — and that’s a part of who Grant is, too. “It’s taken me years to accept that, to be able to say it out loud. If you can’t do that, you can’t reconcile,” he says.

“And once you’ve sorted that out, it’s a lifelong journey to maintain it, without judging. Then you can help others.” U

Julian Coyle Forst Arts & Culture Editor

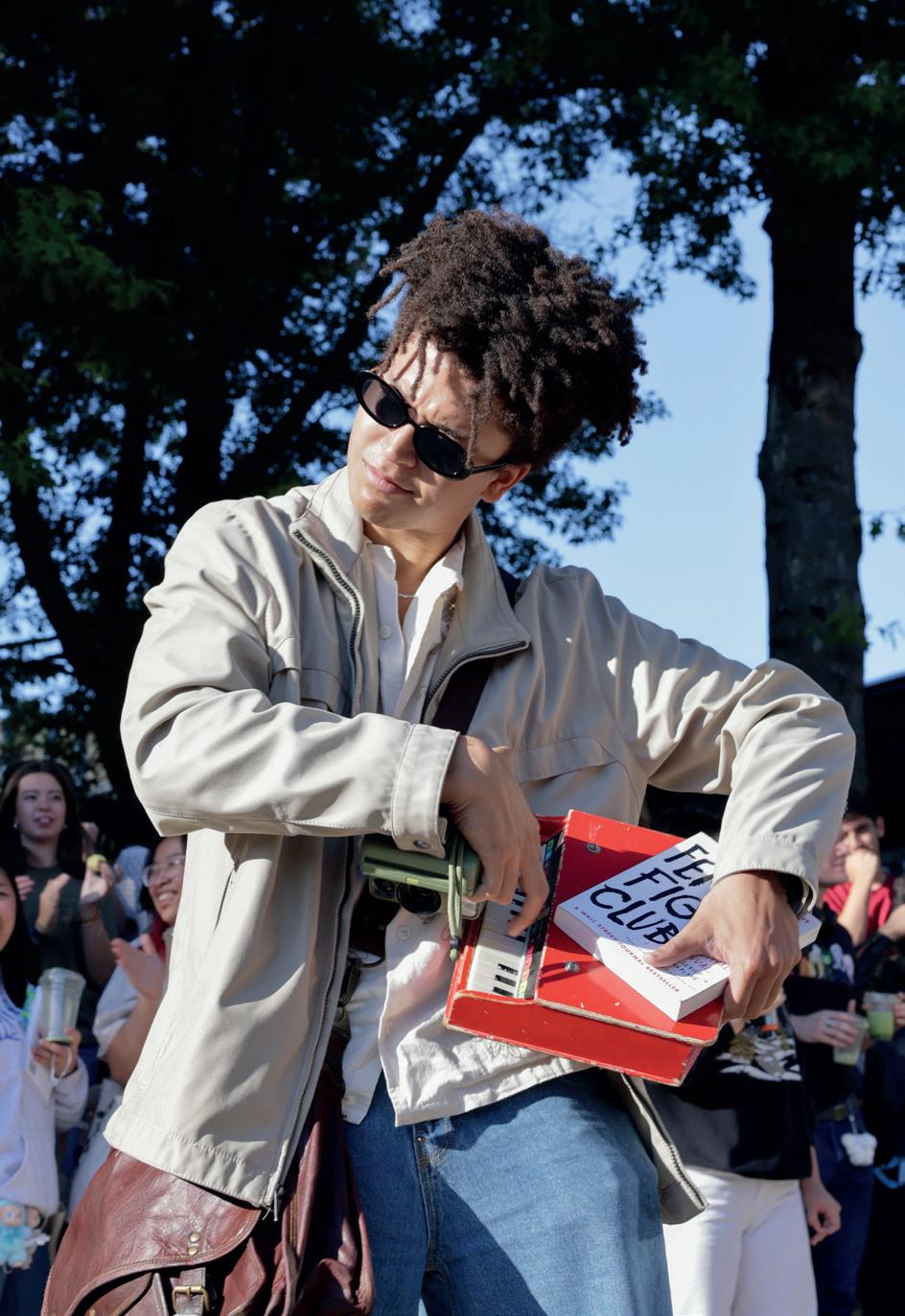

Two-dozen students stand shoulder-to-shoulder against the Pride wall outside the Nest on Sept. 22. They wear flannels, overalls, denim jackets and satchel bags. They hold matcha lattes, vinyl sleeves and books by Judith Butler. Speakers on the balcony above blast Clairo’s “Bags” on repeat. No, this is not the Indigo Starbucks on Granville and Broadway — this is the Gender, Race, Sexuality and Social Justice Undergraduate Society’s (GRSJUA) performative contest.

You know the scene — contests like this popped up as an offshoot of 2024’s celebrity lookalike contests over the summer in New York, Seattle and Jakarta, among others. They’re a send-up of semi-stylish, fake feminist men who show off Sally Rooney paperbacks like colourful plumage to attract mates. After a similar contest at Fortune Sound Club this August, GRSJUA Social Events Coordinators Nayis Majumder and Justina He saw an opportunity to bring discussions about gender to the mainstream in a fun and accessible way.

“We wanted to bring that community aspect to UBC and to be able to share that there’s merit in concepts of performativity,” said Majumder, who originally pitched the idea after seeing footage of a performative contest in a Sydney, Australia laundromat.

As new hires this year, He and Majumder didn’t know if the idea would be well received. “A lot of the GRSJUA’s previous events were more serious, more safe-space

oriented …” said He. “I said to Nayis, if you want to pitch it to [the other execs], you can, but we’ll see how they react.”

Their worries turned out to be unfounded — Co-Presidents Tanay Suresh and Ruby Gulati were already searching for ways to broaden their community outreach efforts. They jumped at the idea and the team got to planning.

Two weeks later, a crowd gathered by the Pride wall. Modest at first, it would swell to around 300 people throughout the event, spilling into the plaza and onto the stairs outside the Nest. Around 30 contestants of mixed genders milled about, chatting over blaring bedroom pop. One held a sign reading “6’7” by the way”; another showed off a wallet chain strung with Labubus like trophies of war. Another told anyone who’d listen how he didn’t even know there was a performative contest happening today.

From an alcove at the top of the stairs, Majumder MC’d while He corralled contestants on the ground. The first event was “Flying Feminism” — contestants perched their feminist literature of choice on their head, walked a few paces and did a hop. The droves of mascs who ended their performative journey at this step was an intended effect, said Majumder.

“We had a small discussion between us like, ‘If [the contest] is really popular somehow, what’s the way we can cut down our contestants to select the most performative people there?’”

Flying Feminism was initially on the backburner, with the team unsure if they would need to use it,

but the massive turnout convinced them they’d need to winnow things down.

“The first inkling that we got that this was going to be bigger than any of us imagined was when we posted our poster on our Instagram. That got like 20,000 views and 700 shares,” said He. “I was super anxious, like, ‘Oh my god, what if campus security comes to shut us down?’”

Despite these anxieties, the team managed the crowd well, asking people to avoid obstructing the stairs and create an opening for contestants. Majumder had some prior experience managing events — though perhaps none this large. The team also had some guidance from a masked mentor who had played this game before.

“I was pretty inspired by Pea Man,” said Majumder. “I went to his event in my first year, and I was like, ‘Oh my gosh, this is what community is about’ … I ended up DMing Pea Man, who helped me through quite a bit of the organizing process.”

Though the audience for the performative contest didn’t quite match the hordes who turned out last year to watch a guy in a green ski-mask eat 2.5 kilograms of peas outside the Nest, it was still a handful, which led to some chaos when it came to enforcing the rules of the contest.

“Only when I was reviewing the footage that we got did I notice that one of our top five contestants actually got eliminated in the first round,” said He. “There was definitely stuff that, if we had more time, more manpower, more resources, we could have fine-tuned. But … for the amount of time and effort that we

had on hand to plan this thing, I’m really happy with the turnout and how it went.”

By the time the last Plath hit the floor, the pool of contestants had dwindled to around 12. He lined them up and went down the ranks asking each one to introduce themselves. The level of commitment to the bit on display from each performer was incredible. The very first contestant in the line stepped forward and launched into a speech about the gender pay gap and the importance of respecting women. He didn’t make it two sentences in before stopping in his tracks and squinting into the audience: “Hey wait a minute, is that – Is that Period Cramps!!?”

At this, a guy in a red shirt with red fabric tied around his head launched himself at the performative man. The two brawled dramatically, the battle raging back and forth until our contestant valiantly vanquished his bloody foe and returned humbly to his place in line. Things continued in this vein throughout the contest — one performative masc threw tampons into the crowd, another marked their page in their Didion with a menstrual pad. One guy just stepped forward and started giving a land acknowledgement.

As the games unfolded — namethat-woman, gender theory trivia with questions from the audience, pin-the-matcha-on-the-Labubu — flannel-wearer after septum piercer were eliminated and sent home. The final two performers (both named Luca, by the way) paraded in front of the crowd and the audience voted by applause to crown the smaller of the two the most performative person at UBC.

Though the tone of the event was obviously playful and silly, the team was glad that the contest could raise awareness of the real concepts of performativity and gender that impact all of our lives. Co-President Gulati praised He and Majumder’s guiding of the contestants towards more critical thought throughout the event.

“They did a really good job of starting with simpler questions — ‘What kind of milk do you like with your matcha?’ — [but] then we got to some pretty [complex questions].”

The team was pleasantly surprised by the quality of audience questions during the trivia event, as well as the level of critical thinking displayed in some of the contestants’ answers.

“Just knowing that even that person who may have stopped by for [only] a few minutes may think about this a little more critically, made our entire space super happy,” said Gulati.

After the event, the GRSJUA handed out pamphlets explaining some of the concepts behind performativity and offering critiques of the trend of men co-opting women’s interests. It also featured a list of recommended readings for those wanting to “up their performative game.”

On the back of such a successful event, the GRSJUA is currently hiring social events assistants to help them organize similar ones in the future. They’re also gearing up for their annual mutual aid initiative in late November and organizing vendors to feature in the final event of this year’s ARTIVISM. U

‘Who am I to correct a woman?’: A day in the life of a performative man

Mason Carter Contributor

How does a performative man manage to perform all day? Are they constantly frolicking between classes or pondering the political and economic state of the world? For some, a performative man is an archetype they try to avoid on campus or dating apps, but for me, it’s my lifestyle.

*“Sofia” by Clairo begins playing*

As I open my eyes to my sweet queen Clairo’s beautiful melodies, I sit up in bed and look around my room. I catch sight of my poster of the Midwest Princess herself (that’s Chappell Roan, for all you less-than-cultured men out there). I lock eyes with her, take a deep breath and think to myself, “I think I can do this if I try.”

I jump out of bed, ready to make a big change. A change for the better. A change to de-centre myself and re-centre women, really. I step into my jeans and attempt to grab my belt from my desk, but my pants fall. Sigh. This is the cost of jeans so nonchalantly oversized that they fit three Ultra Peachy Keen Monsters in the pant leg, I guess. My jeans fall three times before I can securely fasten them to my waist with a peace sign belt buckle, but as wise woman and feminist scholar Kelly Clarkson once said, “What doesn’t kill you makes you stronger!”

I attach Sappho — my Labubu — to my hip with a carabiner I got climbing last week. I look down at her tiny UBC English department hoodie with bittersweet nostalgia, knowing she won’t be repping that for much longer.

Today’s the day I set my life on

the right trajectory. Since coming to UBC, I’ve spent my days in the Rose Garden writing poems about the inequalities women are forced to face daily. But, I realize, my heartfelt words and tear-stained pages are not enough — today is the day I become someone fully invested in being the change I wish to see in the world. It’s time I move toward action and allyship, for real.

I couldn’t imagine making such a life-changing decision, though, without the sweet nectar of the Okumidori variety of the Camellia sinensis tea plant, or as casual drinkers would call it, “matcha.” I ride my longboard to the Nest to grab my green goddess from Blue Chip — without strawberries, of course, as a true connoisseur would. With a sip and a smile, I finally feel ready for my meeting with… Arts Advising.

As I make my way to Brock Commons South Room 2060, I grow anxious. Every time I enter a conversation, I fight an uphill battle; the expectations for men are so low that it takes forever for anyone to trust that I’m truly “just one of the gals!” To calm down, I take a restorative breath and mist my face with my organic rose water. Skin dewy, I’m feeling more prepared already.

I sit down with my academic advisor. Without hesitation, I blurt out, “I want to change my major!”

Concerned, my advisor asks what I hope to study instead.

“I need to major in interdisciplinary studies in English with a focus on the philosophy of gender equality, also known as feminism,” I tell her, eager to hear her excitement about this new development in my academic quest toward pulverizing the pa -

triarchy. My advisor informs me that, sadly, that isn’t a major.

“Exactly, and that’s the problem!” I yell as I stand up. I flip the documents she has scattered across her desk and storm out. Wow, that felt good. Maybe I should major in performative arts instead. I consider going back to inform my advisor, but I decide not to ruin the integrity of the statement gleaned solely from my art.

I pull my headphones out of my pocket, spend five minutes getting the knots out of the wires, then begin my cruise back across campus. I’m riding through a crowd of people when suddenly I get pulled into a cluster of wellgroomed gentlemen.

“He’s definitely in the competition,” a lady who grabs me mutters.

I’m definitely not in the competition, I think to myself, but who am I to correct a woman?

The next thing I know, I’m in a line with all of these stylish guys. I look around and keep thinking about how I’d totally wear all of these outfits.

Bored, I pull my most recent read out of my satchel, Feminist Fight Club: An Office Survival Manual for a Sexist Workplace, and the crowd roars in applause. It’s weird, but I agree that sexism in the workplace is a real issue we need to work on. I look down to open my book, but realize that all the guys in the line are also reading. From Sylvia Plath to Jane Austen, I see a plethora of thought-provoking, iconic literature. These are my type of people, an example of what men should be.

A mic is handed to me and I’m told to introduce myself and talk about why I believe women’s

rights are important. Finally, a platform for me to preach my learnings. I explain how I am

currently working toward getting a degree in interdisciplinary studies in English with a focus on the philosophy of gender equality for that exact reason. The crowd’s response is electric. I’ve never felt so accepted. The other quality men, one by one, give their names and champion the abolition of the patriarchy and instating a matriarchy.

Would it be weird if I asked for their Instagrams? I need more guy friends.

The lady with the mic announces that it’s time to decide the winner. I, for one, am pretty sure we are all winners because an opportunity to preach about such issues of paramount importance is never a loss.

One by one, the announcers point to us, and the crowd cheers. My anticipation is building … But I don’t win.

But really, doesn’t that make me the real winner? Only an egocentric testosterone-driven male would actually want to be crowned a performative man; this isn’t a performance. To be such a standout example of a man is hard. To refuse external validation and live for the cause itself is the noblest journey. As sung in my favourite musical, The Greatest Showman, “This is brave, this is bruised, this is who I’m meant to be, this is me,” and I’m not changing for no one. U

to

For the first time in its 107-year history, the Vancouver Symphony Orchestra (VSO) saw its musicians go on strike.

This September, the Vancouver Musicians’ Association — the union representing musicians throughout mainland BC — announced that over 97 per cent of the VSO musicians had voted in favour of a strike against their employer, the Vancouver Symphony Society. According to the union, VSO musicians are paid 30 per cent less than their counterparts at the Toronto Symphony Orchestra, Orchestre symphonique de Montréal and Ottawa’s National Arts Centre Orchestra.

The VSO musicians walked off the job on Sept. 25 after serving a 72-hour notice. On Oct. 4, the Vancouver Musicians’ Association and the Vancouver Symphony Society announced that, after months of negotiation and two days of “intense mediation,” they had come to an agreement.

The strike, however, is just one example of a deeper issue affecting all types of creatives living and working in Vancouver. It’s always been difficult to make a living off of art, but there are signs that artists are currently being forced out of their studios — and the city as a whole — at an alarming rate, putting Vancouver’s cultural identity in a state of limbo.

In July of this year, Councillor Pete Fry brought a motion to Vancouver City Council on behalf of the Arts and Culture Advisory Committee calling for an urgent investment into Vancouver’s arts and culture infrastructure. It shines light on some of the funding and space-related issues that artists are facing and offers the city some areas they might want to tackle in order to make Vancouver a liveable city for creatives. Councillor Sarah Kirby-Yung brought forward a reworded amendment to the motion with many of its original components removed — including the suggestion to increase the minimum for operating grants — which was passed by the ABC Vancouver majority.

Over 40 people signed up to speak at that meeting in support of the motion. All of the biggest names of the Vancouver arts world showed up, like Bard on the Beach’s Christopher Gaze, Arts Club’s Peter Cathie White, and the Vancouver Folk Music Festival’s Fiona Black. It seemed that no matter how big the organization was or what discipline they practiced, all were in agreement: something needs to change now.

Duncan Watts-Grant was the third person who volunteered to speak in that meeting. News of the motion being brought to Council had happened to cross his inbox and he immediately signed up to share his thoughts. He was “gobsmacked” to see 47 of his colleagues do the same — there are never this many people interested in speaking on an arts and culture motion, he said.

“Off the bat, [that] speaks to two things: one is how rare it is that everyone agrees on something. No one spoke against it, which I think is amazing and never happens.” He joked that he once had a government representative tell him that arts and culture is “one of the worst industries for all getting on the same page” — there are so many different disciplines that all need different resources to succeed. “I think the scale of having that many people come out … to me, [that’s] an indication of the precarity of the situation right now for arts organizations and for artists in our city.”

For around two-and-a-half years now, WattsGrant has been the Vancouver Fringe’s executive director. He just wrapped up his third festival last month. The Fringe is an acquired taste — its

lineup of shows is completely uncurated, so it’s often quite strange — but Watts-Grant fell in love with the festival during his stage managing days. Although he trained as a singer and graduated from UBC’s opera program in 2016, he’s found his place in the technical and administrative sides of the performing arts. Before the Fringe, he was at the VSO for a number of years, working in community engagement and school operations.

Watts-Grant had a rocky start to his leadership role at the Fringe. Around the one-year anniversary of him taking on the job, he had to launch an emergency fundraising campaign to keep the festival afloat; they knew they would be able to run it in 2024, but the following years were up in the air. They set a goal of $80,000 over four months, and in the end, they raised $55,000 in three months, with the number of donors jumping from 165 in 2022 to over 700. The festival was also named in the federal budget to receive $300,000 over two years. This was a big moment for Watts-Grant, a self-proclaimed “political geek” who has that page of the budget printed out and framed on his wall. That campaign stabilized the festival. However, Watts-Grant pointed out that in recent years, finances have been especially rough for the entire arts and culture industry as the number of people giving to arts initiatives has gone down across the country. “Sponsorship has really dried up. It doesn’t exist in the way it existed before the pandemic,” he said. While Watts-Grant is grateful for the exponential increase in donors accumulated over the course of their funding campaign, he is sure there will continue to be financial challenges at the Fringe going forward.

There’s a traditional model of arts funding that many Canadian organizations have relied on at some point: one-third of their money is from government, one-third is from private giving, and the last third is from revenue. But as expenses and income have fluctuated over the years, Watts-Grant has found it difficult to rely on this model for any sense of stability.

When Watts-Grant took over the festival in 2023, he described there being a “hangover,” funding-wise. They were still receiving emergency money from the government as a result of the pandemic, so around 65 per cent of funding was coming from the government. “You don’t need to walk into that organization to know, ‘Oh, no, this is not sustainable whatsoever. We are not going to have this money in a year or two,’” he said. “And it was true.” Most governments cut back their emergency funding the following year, but Watts-Grant said the province has maintained different forms of funding in some way, which has been a huge help.

Money from all levels of government now sits closer to being 45 to 50 per cent of the Fringe’s total funding, including contributions from CMHC-Granville Island (their presenting sponsor) and grants offered by the BC Arts Council, the Canada Arts Presentation Fund and the City of Vancouver. These are very static, however; Watts-Grant noted the amount they receive from the city hasn’t changed since the Olympics took place in Vancouver 15 years ago — so this funding, when calculated against inflation, has gone down by 47 per cent.

The last funding chunk consists of earned revenue, but that doesn’t really work for the Fringe. “As an organization, we have a really strange business model, because we give all [box office profits back to the artists],” said Watts-Grant. It’s a different beast altogether.

The Vancouver Fringe, like most iterations

of the festival run in other cities, uses a lottery system to decide who gets the chance to participate. Anyone from experienced playwrights and comedians to people who have never staged a show in their lives could end up on a Fringe stage. Artists who are drawn in the lottery get to have a show in the festival with about 80 per cent of their production costs covered. According to Watts-Grant, each artist only paid $750–$850 to participate this year — it costs the Fringe an average of $4,000–$5,000 to cover the venue and production costs for one show. The festival tacks $5 onto every ticket sold, which only end

way, but … it’s a different way [of] operating.”

The festival’s ticketing model, in a way, is under constant threat. But at the end of the day, Watts-Grant doesn’t see it changing anytime soon; there’s an “alchemy” in making Fringe special and possible, and he doesn’t really know what the festival would be if it ever strayed from its model. In fact, keeping ticket costs low is crucial in a time when artists are fighting for people’s attention. The Fringe’s biggest competitor isn’t another theatre company — it’s streaming services. “Our competitor is Netflix,” Watts-Grant said. “Our challenge is convincing

“A lot of people, me included, get into running these spaces because you don’t want to see them disappear, or you want to continue to work on your art in a space that works. You don’t get into it to do administrative tasks or negotiate insurance premiums and things like that. These are things that accidentally happen to you as you go along.”

- Brent Constantine, executive director of Little Mountain Gallery

up costing between $15–$20 in total. The small fee is put toward paying box office staff and supporting theatre improvements, while the rest of the ticket cost goes toward the artist, which is mandated for all Canadian Fringes by the Canadian Association of Fringe Festivals. What the Fringe offers artists is an almost unbelievable opportunity, allowing them to take (very expensive) risks in front of a real audience. Watts-Grant’s mission is to find a way to give artists everything they want, but of course, there are constraints to that.

“I don’t think it’s happenstance that k.d. lang gave her first major concert at the Edmonton Fringe or Kim’s Convenience started at the Toronto Fringe. There is a real history of artists getting their start at these festivals,” Watts-Grant said. “But at the same time, from a funding perspective, it makes for a very challenging balance sheet when you’re returning that revenue back to artists. We wouldn’t want to operate any other

people to leave their houses and come and see something.”

There’s no arts organization that isn’t going to have some version of this funding problem — Watts-Grant joked that festivals like Fringe are run on “duct tape and dreams.” Most organizations find ways to make it work, but at a certain point, they will have used up every trick in the book and have no other option than to close their doors. The Vancouver Mural Festival (VMF) is one of the more notable examples of this happening. Over the course of nine years, the festival gave lesser-known visual artists an opportunity to cover Vancouver in over 400 murals, but it was forced to shut down at the beginning of 2025 due to financial hardship.

Pacific Theatre announced earlier this year that the company would be going on a hiatus starting in January of next year. The company operates out of the Chalmers Heritage Building, now owned by Holy Trinity Anglican Church.

Built in 1912, the site has become unsafe for long-term use and will need major structural upgrades adding up to $500,000. Pacific Theatre’s scaled-back fall programming will end with a performance on Dec. 23, after which they will have to leave the space for an indeterminate period of time to reassess the direction of the company’s future.

The Concord Pacific Dragon Boat Festival was also cancelled due to the FIFA World Cup being partially hosted in Vancouver next year. FIFA does not allow cultural and sporting events in the city to take place within a certain radius of the stadium, effective from the beginning of June to the end of July, despite there only being matches scheduled June 11–19. Watts-Grant pointed out that the 2025 Council motion had a suggestion to explore small taxes or surcharges on things like liquor, sales, empty buildings and hotels — which would be especially important at a time like this, had it been passed.

“Are we losing a piece of unique cultural identity to Vancouver because of the major event?” Watts-Grant asked. “I want major events to come to the city. I want cruise ships to come to the city. I want tourists to come to this city. We run our festival [in] one of the top four tourist destinations in Vancouver, and I love that we bring tourists to our festival at the same time. I really want to see that investment into local arts and culture because I think we have a vibrant story to tell … It’s just not represented at a city or a provincial level.”

Even though people might not be travelling to a city for its arts and culture events, they’re an asset to have once tourists are here and searching for something to do — but it’s hard to preserve that cultural identity unless we invest in it. Vancouver’s underground music and visual arts scene is where a lot of our local talent gets their first chance to showcase their work. It’s the first stepping stone into the creative world, shaping what Vancouver’s art looks like and who gets a chance to participate in creating it.

Ana Rose Carrico is the executive director and co-founder of the Red Gate Arts Society, which has been around for decades, she said, in

collection of artists and musicians working out of a three-story building in the Downtown Eastside. The top floor was the recording studio JC/ DC — which hosted the New Pornographers, among other big names — the second floor was artist live-work spaces, and the bottom floor was a gallery and performance venue.

Things “really took off” when they got an eviction notice because the building was being condemned. She said they had tried to behave pretty cautiously before then, but when they got the notice, they figured it was time to do everything they had been scared to do because they didn’t want the landlord’s attention.

After leaving that first building, they realized that they needed to make some structural changes in order to properly advocate for themselves, so they became an official non-profit organization. Their mandate is to provide a studio space for emerging artists that’s as affordable as possible, as well as access to performance and gallery spaces. Red Gate’s current home is now a one-story building along Main Street that holds artist studios, a performance space, a tattoo shop, a screenprinting shop, and a gallery. It isn’t a forever home, Carrico said, but at the very least, it’s a long-term lease. She also mentioned how they managed to get grant funding for the first time — she feels it’s “bizarre” that they’ve gotten to a point where they’re getting money from the government. “It seems like a miracle, almost,” she said. “We’re constantly struggling, and yet much more stable than a lot of other places.”

Red Gate is one of the city’s more established DIY venues. Other underground performance spaces haven’t been so lucky — keeping track of DIY venues in Vancouver is like playing a game of whack-a-mole, Carrico said. But it used to be that for every venue that shut down, another would pop up. Now she’s noticed it seems like only one opens for every two that are forced to call it quits. Smilin’ Buddha Cabaret shut down a few years ago; Grey Lab saw its last show this August; and 648 Kingsway closed down briefly last year after announcing they would be facing a 40 per cent rent increase, before reopening under a different team.

When a new venue appears, Carrico empha-

similar position, like Green Auto and the Birdhouse. “Generally, if I have some kind of human resources [or] grant, I just reach out to them,” she said. “The more we communicate, the less we have to experiment individually.”

Carrico used to be the station manager at CiTR and has some experience navigating the intricacies of arts organization bureaucracies, which she’s noticed a lot of artists seem to struggle with. She sees herself as a translator, of sorts, between the people on the creative and business sides of the arts and culture industry. “[Bureaucracy is] kind of its own language. That is really intimidating,” she said. “It feels really opaque, almost intentionally so.” People like her are essential to preserving the essence of DIY spaces, because when a space closes down, Carrico has too often seen it return feeling a bit too “corporate,” taken over by people with more resources and a better understanding of how to effectively communicate with various institutions.

“The smaller things are artist-run. There has to be accommodations made for that. We need translators, and ideally it would be representatives of the city who are coming from that sector,” she said. “[People] who are understanding, who know what kind of support artists need.”

Brent Constantine is the executive director of Little Mountain Gallery, a comedy club in the heart of Gastown. He has a background in arts infrastructure planning; he graduated from the University of Alberta with a master’s in urban planning and previously worked for the non-profit organization Arts Habitat, where he worked on redeveloping spaces for artist use.

Constantine didn’t start Little Mountain Gallery. As he put it, he’s “just the most recent person to inherit the curse of running it.” It was founded in 2006 as an artist collective by Ehren Salazar and taken over by comedian Ryan Beil in 2013, who then transformed it into a comedy-only venue once it became a non-profit in 2016. Little Mountain Gallery used to operate out of a 1930s automotive garage off Main Street. It was riddled with safety hazards and became the subject of many noise complaints, which almost got the venue shut down in 2010 — their zoning permit didn’t quite allow them

shows at the venue and had heard Beil was losing time and interest in running it, Constantine stepped in as director. However, they were forced to leave the building at the beginning of 2022 due to redevelopment. “We just ran the space as best we could,” he said. “We knew that we were going to lose the space, which is very common in the city … Artists reuse space. It’s never designed for the artists inside and the shows that are happening, so you kind of make do with the space that you have.”

This struggle to find spaces that can actually host artists and their work is what prevented Little Mountain Gallery from being able to reopen until the spring of 2024 in their Gastown location. It took around three years of searching for what they needed in terms of square footage, affordability and location, which Constantine said was difficult with the budget they had. Much like the garage, their new building wasn’t designed to be a theatre either; it now hosts two stages where they can run shows simultaneously, but took quite a bit of remodeling to get to this point.

With minimal budgets, organizations like Little Mountain Gallery can’t access buildings that are actually intended for the work that they do. “Purpose-built space is quite rare, especially for smaller [organizations]. It doesn’t exist,” Constantine said. The main factor in whether a building could work is the price tag, and functionality almost always has to become an afterthought. Even in older spaces — and regardless of the area — there aren’t caps on commercial rents the way there are on residential properties, and the triple-net-lease means that occupants are paying property taxes on top of their rent. Artists may think they can afford a space without truly understanding all of the factors that go into it.

“A lot of artists are not experts in space. They’re not experts in lease creation or legal aspects or city zoning, and they shouldn’t be. You shouldn’t have to have that,” Constantine said. “A lot of people, me included, get into running these spaces because you don’t want to see them disappear, or you want to continue to work on your art in a space that works. You don’t

doesn’t reflect what the building is currently used for, but its highest potential. Red Gate is zoned for a brand-new six-story building, so they’re currently being taxed as that, rather than as the older one-story building they actually are. Around a third of their monthly rental fee goes toward property taxes — Carrico said she’s been trying to work with the city to get exemptions for cultural spaces.

In January 2020, Red Gate was facing a drastic increase in property taxes that destabilized their future in their current space. The organization published an open letter explaining how their potential developed value had quadrupled in just four years due to this “highest and best use” principle. They had already been paying $30,000 annually in property taxes, and this increase would add another $18,000 on top of that; they made an agreement with the landlord to defer charges until the end of January, at which point they would be forced to pay over $9,000.

“Even though we are a non-profit cultural organization in an old low-rise building, we are being taxed at the same rate as the adjacent for-profit corporate megaliths,” Red Gate organizers wrote at the time. Shortly after this, the city granted Red Gate $27,000 in one-time funding as part of a new initiative to save affordable spaces for artists.

Finding spaces to operate can also be a headache, thanks to Vancouver’s zoning requirements. These are regulations around land use, including restrictions on which businesses can operate in a given location. Constantine explained that artists are often moving into re-purposed spaces, many of which used to be commercial spaces, like a hair salon or a restaurant. To use it for creating or performing, occupants must request to flip the business from commercial use to a different purpose.

People he knows have gone through this re-zoning situation — they signed leases and began operating, but because they did not have the current zoning permit, they couldn’t receive a proper business license. “So the city comes to you and says, ‘Well, what you’re doing is illegal.’ Is it? I mean, technically, I guess it is. You don’t have a business license because you can’t get a business license because the restrictions on your use of this space are so onerous.”

The City of Vancouver’s cultural services are doing what they can, from Constantine’s perspective. But the reality is that there is still so much unmet need in the city when it comes to renovation and development projects. “Even when there’s a lot of interest and there’s a lot of momentum to put something together, those timelines that the city puts in place — from applying for a development permit to getting it approved — can sometimes kill a project,” Constantine said. It took a long time to get Little Mountain Gallery’s new space off the ground because of all the back-and-forth between the city, the architect and himself, since it took weeks — and additional expenses — to make minor changes to floorplans and then get them approved. A space just down the street from Little Mountain Gallery is going through the same thing now, Constantine said; people have been trying to turn it into a dance studio, but they’ve been sitting on the space for about four years, paying to keep it open as the city reviews their plans.

Constantine interacts with a lot of other organizations about their space-related issues through his role with the Arts and Culture Advisory Committee, which he’s been doing for the past two years. He was part of the team that put together the recent motion with Councillor Pete Fry, and worked with former Councillor Christine Boyle on an earlier arts and culture motion that went to Council last year.

The 2024 motion passed unanimously. It called on the City of Vancouver to make progress on the action items outlined in Making Space for Arts and Culture: Vancouver Cultural Infrastructure Plan, which was approved in 2019 and outlines the city’s long-term vision to address space-related challenges faced by artists. Making Space was later incorporated into Culture|Shift, the city’s 2020–2029 strategic direction for arts and culture-related issues, which the 2025 motion drew on for its recommendations.

In writing the 2025 motion, Constantine said that they were aiming for it to be fairly open-ended. They weren’t necessarily saying that certain things had to happen or had to

be done in a specific way; the phrasing leaned more toward drawing attention to obstacles arts organizations are facing, and asking for further research to be pursued to determine the feasibility of these initiatives. It was also oriented toward action led by the city — there was only one point about liaising with the province — while the amendment written by Kirby-Yung focuses on redirecting issues to other levels of government.

Constantine was disappointed to see ideas within the scope of the city’s responsibilities not make the cut, like the creation of an Arts, Culture & Creative City Navigator to reduce artists’ barriers to accessing city services. He pointed out that the city already has solid plans, like Culture|Shift, that they’ve agreed upon, but he has yet to see any real progress on those goals. “I think a lot of cities have these plans, and they sit, sometimes, without any action behind them, or a lot of time, they don’t have any specific metrics

iam Berndt, a cultural space planner at 221A, hears from some organizations who are facing eviction, and some who are ready to grow their organizations but can’t because the market is too competitive. The CLT was largely inspired by a 2019 report that came out of the Eastside Arts Society, which found that over the course of a decade, 400,000 square feet of studio space had been lost to redevelopment, while studio rental rates also increased by 65 per cent. Artists and cultural workers are being pushed out of the city, and the CLT would try to solve this by purchasing and managing land for artist use, giving them opportunities for long-term leases and paths to ownership — kind of like how a condo works. “And then, what’s baked into the CLT is that if they were to sell their unit, it can only be sold to another non-profit entity,” Berndt said. “I think another reason why [the CLT is] important is because its mandate keeps that land

“Vancouver [gets] this terrible reputation as a ‘No-Fun City.’ It’s not something I agree with, but we run this risk of not having artists who want to create art, and at the same time, arts organizations who can’t afford to create art or can’t operate in the space that they’re operating in”

- Duncan Watts-Grant, Vancouver Fringe executive director

for measurement,” he said. “We have a motion from last year that the whole council supported. Nothing has come out of that.”

There are still aspects of the amended motion that could be productive changes for the arts and culture industry, as long as these initiatives are seriously pursued. “Here’s what Councillors can do,” Constantine said. “You have a motion from last year, and you have this motion now. So push [for] these aspects that you voted for, [that] Council voted for.”

“All we can hope for is that by showing that level of support to Council … nothing will be cut in 2026. We tried to get some stuff added, but maybe that amount of support will just not have anything changed for the worse. I don’t think that’s going to happen either, though.”

One part of this year’s motion that Constantine specifically highlighted was the Cultural Land Trust. He’s sat on some grant adjudication committees, and pointed out that they don’t typically invest in spaces that the artist will lose after a year or so — even a long-term lease might not be worth it if it takes hundreds of thousands of dollars just to get the space to a functional condition, only to get kicked out shortly after. In order for art spaces to be sustainable, there needs to be a path to ownership, and a land trust may be the best way to go about that.

The Cultural Land Trust (CLT), led by Vancouver-based non-profit 221A, was one of the initiatives on the motion that the ACAC suggested gathering more data on; there are hopes that one day, the city might consider investing $20 million in seed funding for the project.

Since 2018, 221A has been acting as a fiscal sponsor of the preliminary research stages of the CLT, which they eventually hope will be an independent entity, separate from 221A. Mir-

out of the speculative market. It forever will stay non-profit, and the key is to make a governance system where the leaders are accountable to the communities who use those spaces.”

The concept of a land trust isn’t new. “It kind of emerged as a model of ownership or land stewardship during the mid-century when disenfranchised Black Americans came together to create a village and to gain a security of tenureship,” Berndt said. An arts-specific land trust is also something that’s already proven to be successful in cities like London, Seattle and San Francisco, among others. In a land trust, she explained, the non-profit itself becomes the owner of the land, giving its membership a say in how it is managed. “[It] becomes a place that’s stewarded and developed through the interests of its membership,” Berndt said. “It decentralizes power.”

Berndt likes that the land trust is not a rigid formula — there are lots of different applications and potential business or governance models. Her research for 221A primarily investigates how, at different points of purchase, the land trust can honour the sovereignty of the Indigenous nations whose lands it’s on. One of 221A’s priorities with this project is to meaningfully engage with marginalized communities and create a model that serves them. “The voices that are sometimes not heard can be heard through this model, and then it directly becomes actualized in the way the land is stewarded directly, instead of having to go through levels of bureaucracy and lobbying,” Berndt said.

Larger affordability and cost of living concerns don’t just negatively impact studio spaces — they’re pushing artists out of the city altogether.

When asked about their thoughts on the fu-

ture of arts and culture in Vancouver, every single artist I spoke to brought up being concerned about a ‘brain drain.’ This refers to how the cost of living is pushing more and more artists out of Vancouver. If artists can’t afford to live in this city, they aren’t going to be able to participate in festivals or play in local shows, and someday, any semblance of cultural identity that Vancouver has will vanish.

When Carrico and others from Red Gate got evicted from their first building, they went down to CRAB Park to burn a bunch of paintings (why they were doing this in the first place is a long story, she told me, related to the intricacies of the world of fine art). Looking back at a photo from that day, Carrico realized that out of the nine people in it, only three of them still live in Vancouver. The rest of them made their way to Toronto, Berlin, Montréal, New York — any place that prioritizes arts and culture more than Vancouver seems to.

“Vancouver [gets] this terrible reputation as a ‘No-Fun City.’ It’s not something I agree with, but we run this risk of not having artists who want to create art, and at the same time, arts organizations who can’t afford to create art or can’t operate in the space that they’re operating in,” Watts-Grant said. This is a phrase that came up a lot during the speeches in that July Council meeting: ‘No-Fun City.’ Carrico sees this as a self-fulfilling prophecy — people refuse to believe in the city because it’s perceived as being boring, so they leave the city and then it truly does become lifeless. “We’re just not going to have a cultural ecosystem here if that happens,” she said. “I refuse to let my hometown become a post-cultural wasteland, but it really is bashing your head against a brick wall in a lot of ways.”

This growing sentiment that Vancouver doesn’t have a voice to contribute to the artistic world means creatives don’t always take it seriously as a place to grow their craft. “The Vancouver artistic community [is] sort of self-loathing,” Carrico said. “You haven’t really made it until you make it somewhere else. It doesn’t matter how big you are in Vancouver, because it’s just Vancouver.” Artists don’t even really need to travel internationally, WattsGrant said; many are moving to places within Canada, like Alberta and Manitoba, where the cost of living is lower and the arts scene is better supported by the government. This isn’t a good sign for the Vancouver Fringe, which relies on young, new artists who are just starting to find their way in the arts and can barely support themselves.

“The loss of venues [and] organizations bleed[s] immediately into artist experience, because if they don’t have a place to work, you feel the immediate effects of artists not being able to afford to stay in the city,” said Watts-Grant. “If artists aren’t able to continue to produce work here, are they losing the opportunity to train and get better? Do we lose cultural relevancy as a country?”

While Vancouver may have large arenas and stadiums, these venues are inaccessible for most artists. Carrico sees this as having a particularly bad impact on youth engagement in the arts, since a musician playing a big concert at Rogers Arena doesn’t have the same relatability factor as a musician just a couple years older than them playing at a small venue. “Nothing works like that,” Carrico said. “No natural cultural growth works like that. You can’t just package everything and hand it to them from this unattainable place.”

But at the end of the day, Constantine believes there will always be someone who will dedicate their life to turning a dank hole into a theatre. Art will find a way, but it’s a shame to think about how many less voices might be heard, or how much richness of the viewing or listening experience is lost, when you don’t have the proper environment for creativity to flourish to its full potential.

“We need more activity. We need more things for people to do. We need more places for people to experiment. There’s no compromising on that. In my opinion, it’s absolutely essential,” Carrico explained. “You can see that in any culture in the world, they have music, they have art. This is obviously something that we desperately need as human beings … It just shouldn’t be an afterthought, and it feels very much like it is right now.” U

Naomi Brown Contributor

The Hatch Art Gallery’s newest installation, Indigenous Symbols and Signifiers, has an interactive component where visitors can write or draw on pieces of cloth and pin them around a question on the wall, which asks, “What symbols represent belonging in your culture?” Situated between large digital prints, paintings depicting birds and fishermen, laser-cut wooden shapes and framed beadwork, the web of intercultural symbols grows as visitors of different backgrounds add to it.

Showcasing the work of six artists, Indigenous Symbols and Signifiers launched on Sept. 17 and is open until Oct. 9, 2025. Born from a collaboration between the Faculty of Arts and the First Nations House of Learning, with funding from the UBC Strategic Equity and Anti-Racism Enhancement Fund, the exhibition’s call for artists asked students to visually represent symbols of belonging, cultural identity and traditional knowledge.