TREASURES FROM THE SPECIAL COLLECTIONS RESEARCH CENTER TEMPLE UNIVERSITY LIBRARIES

THE BOOK

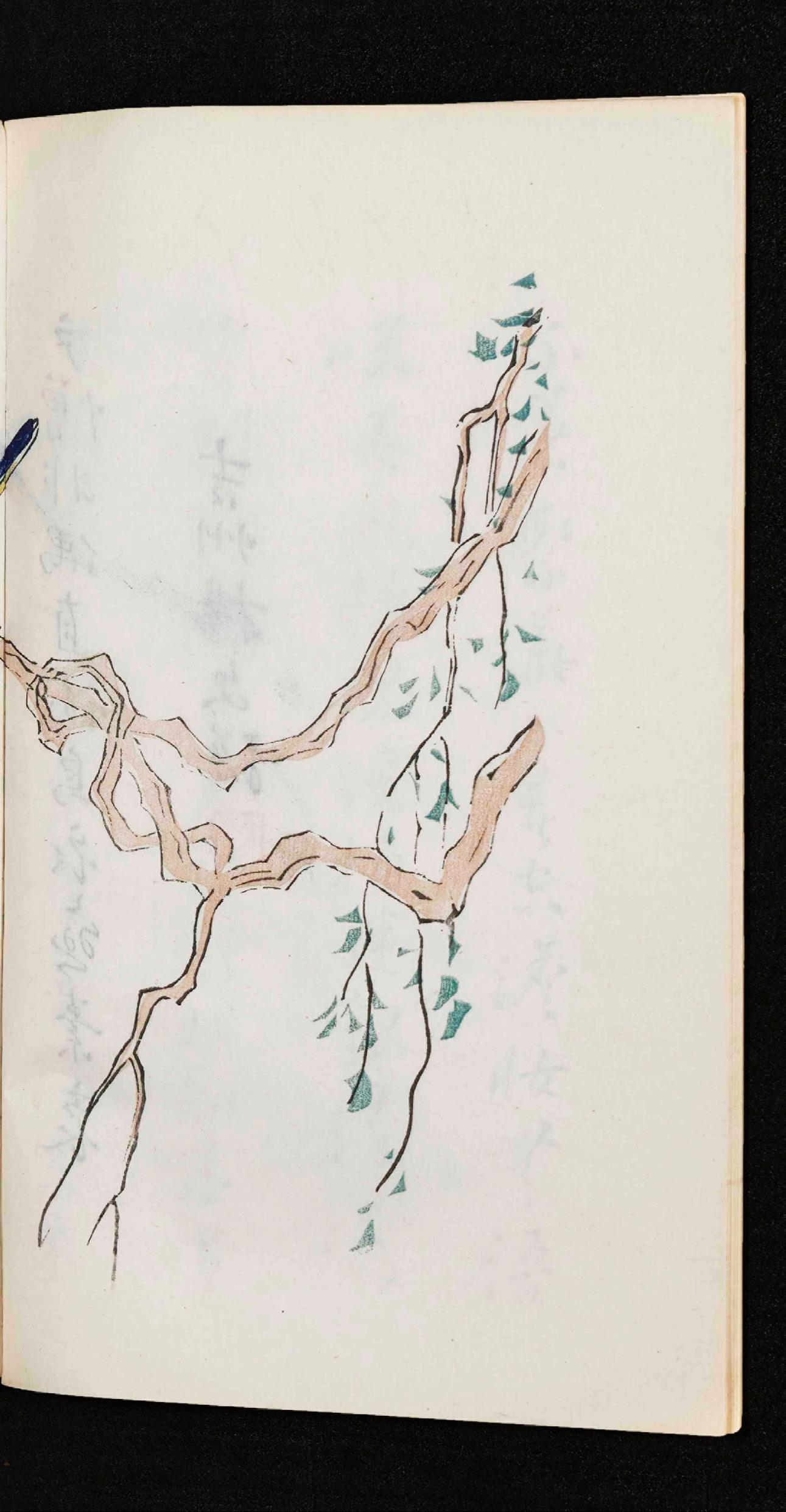

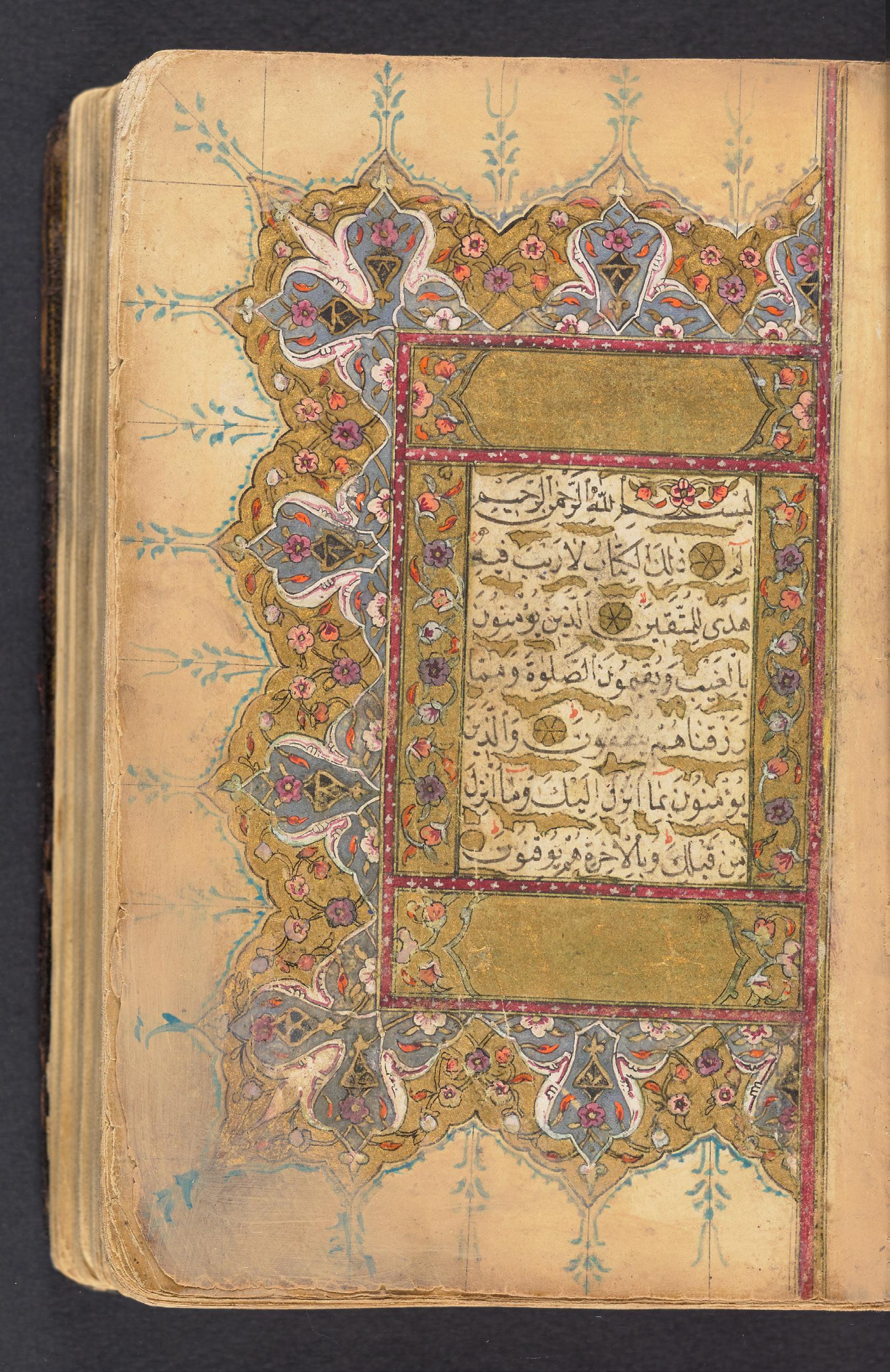

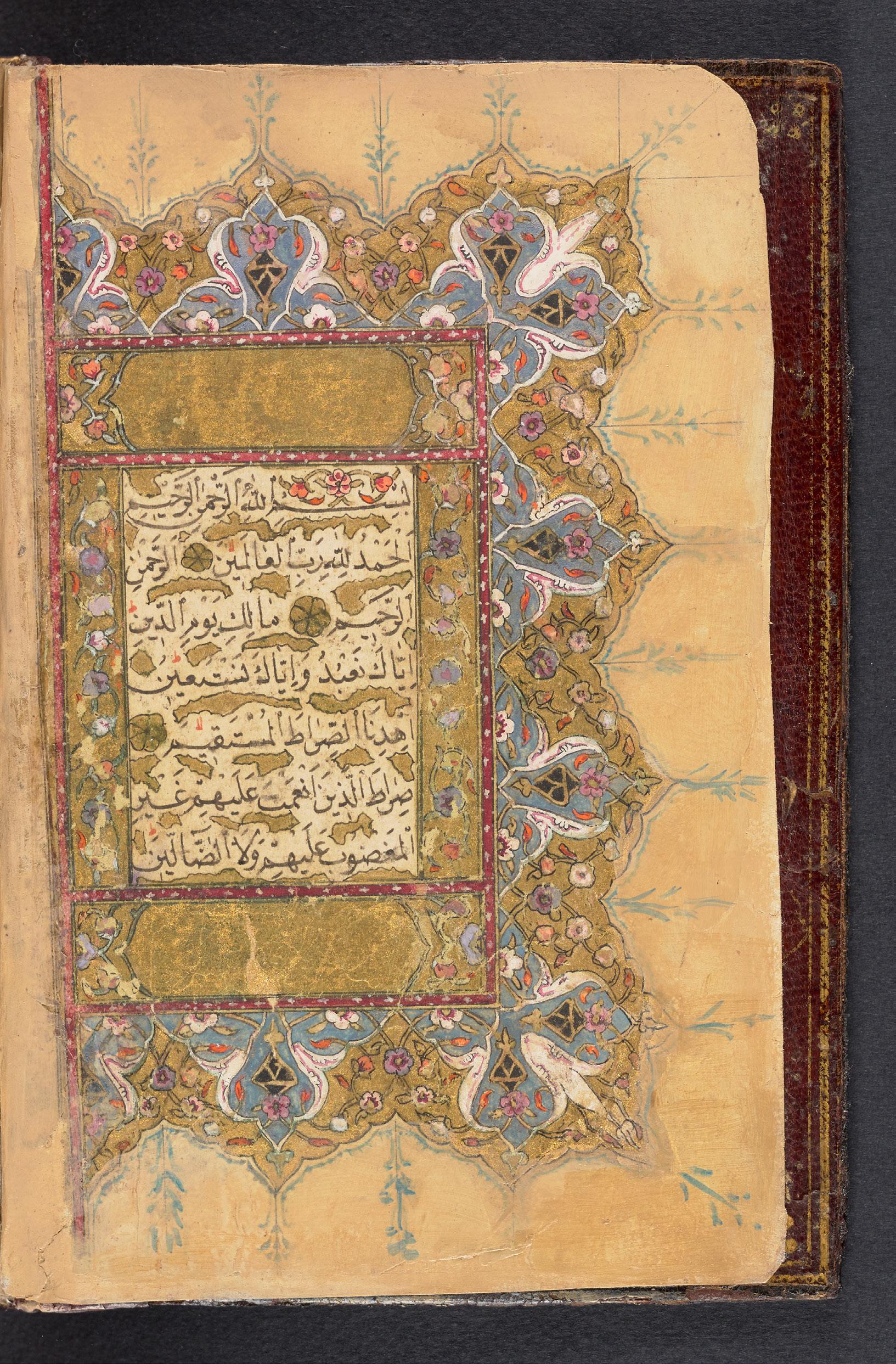

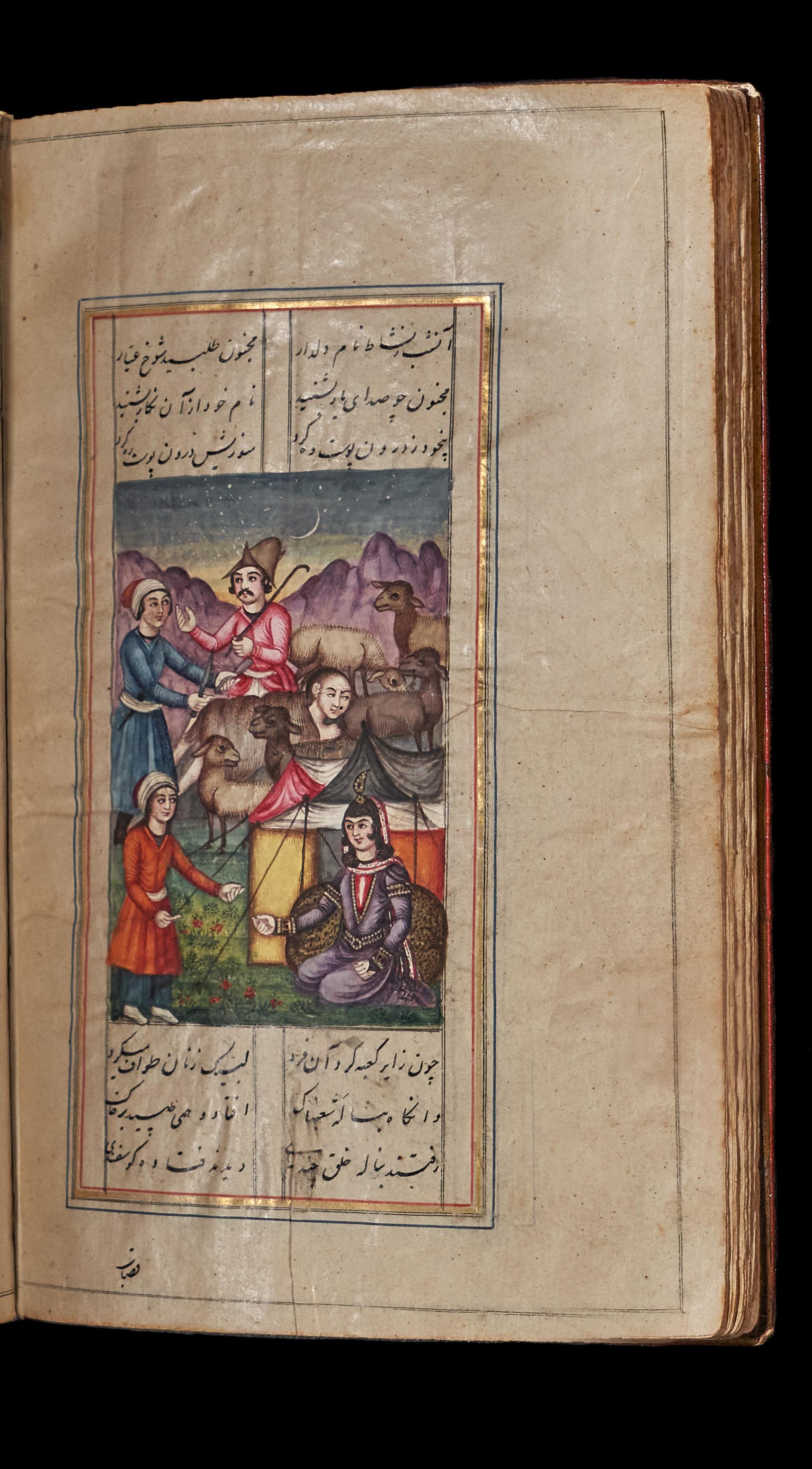

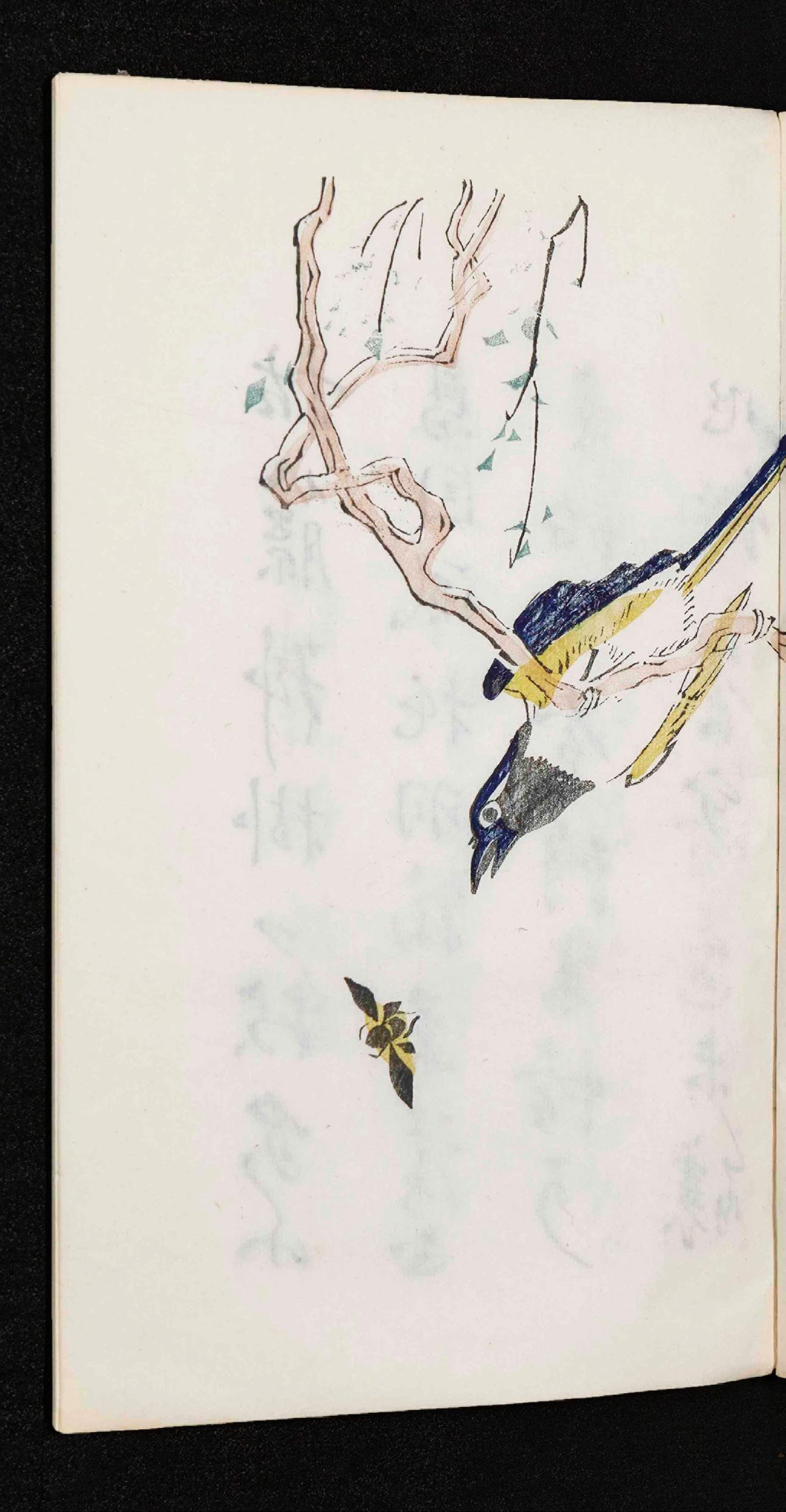

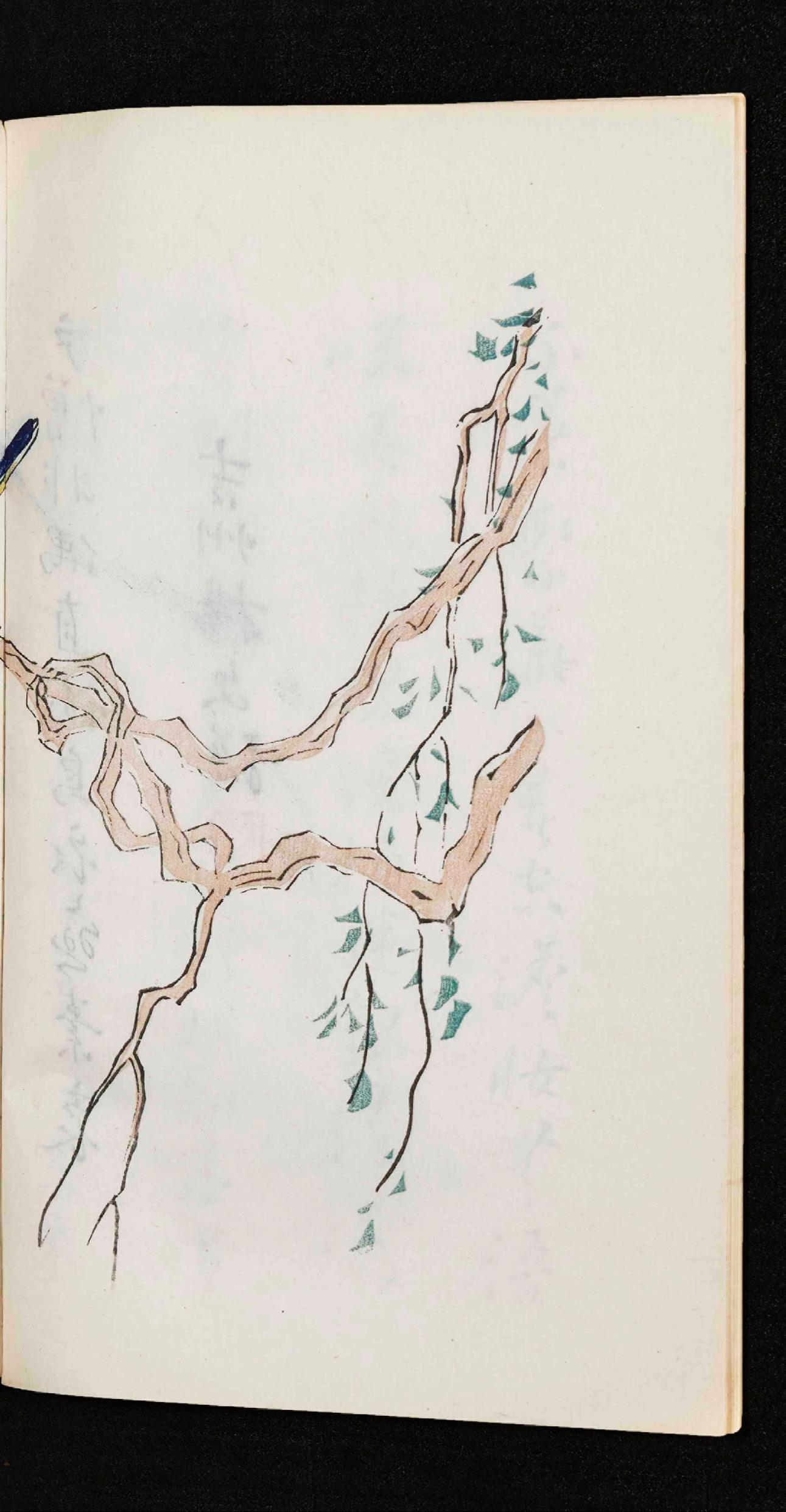

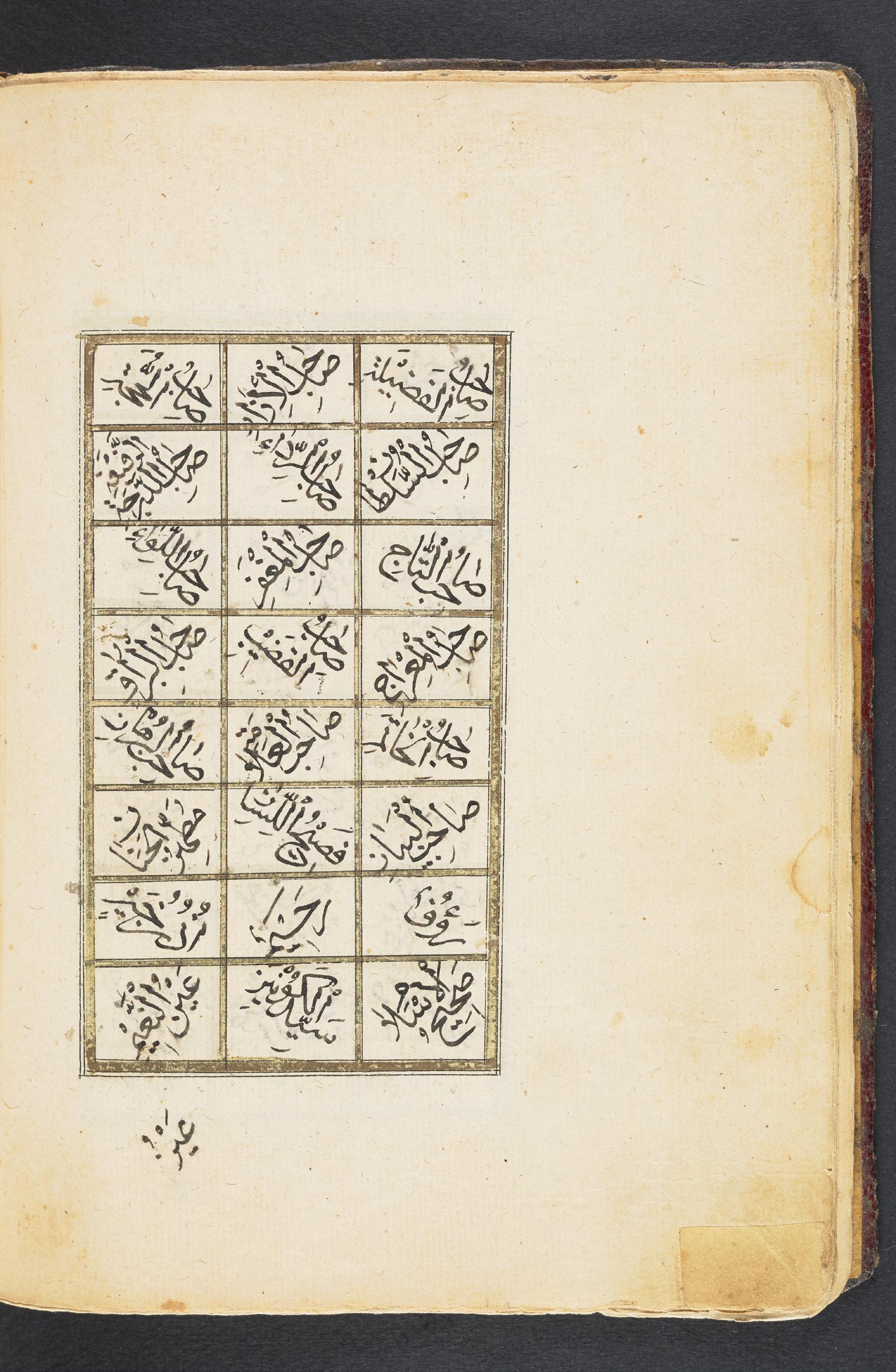

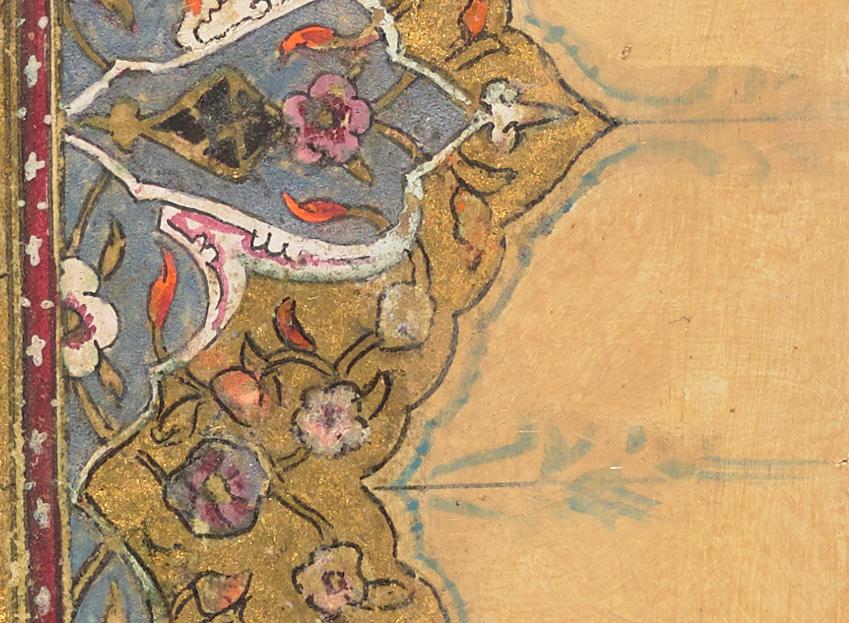

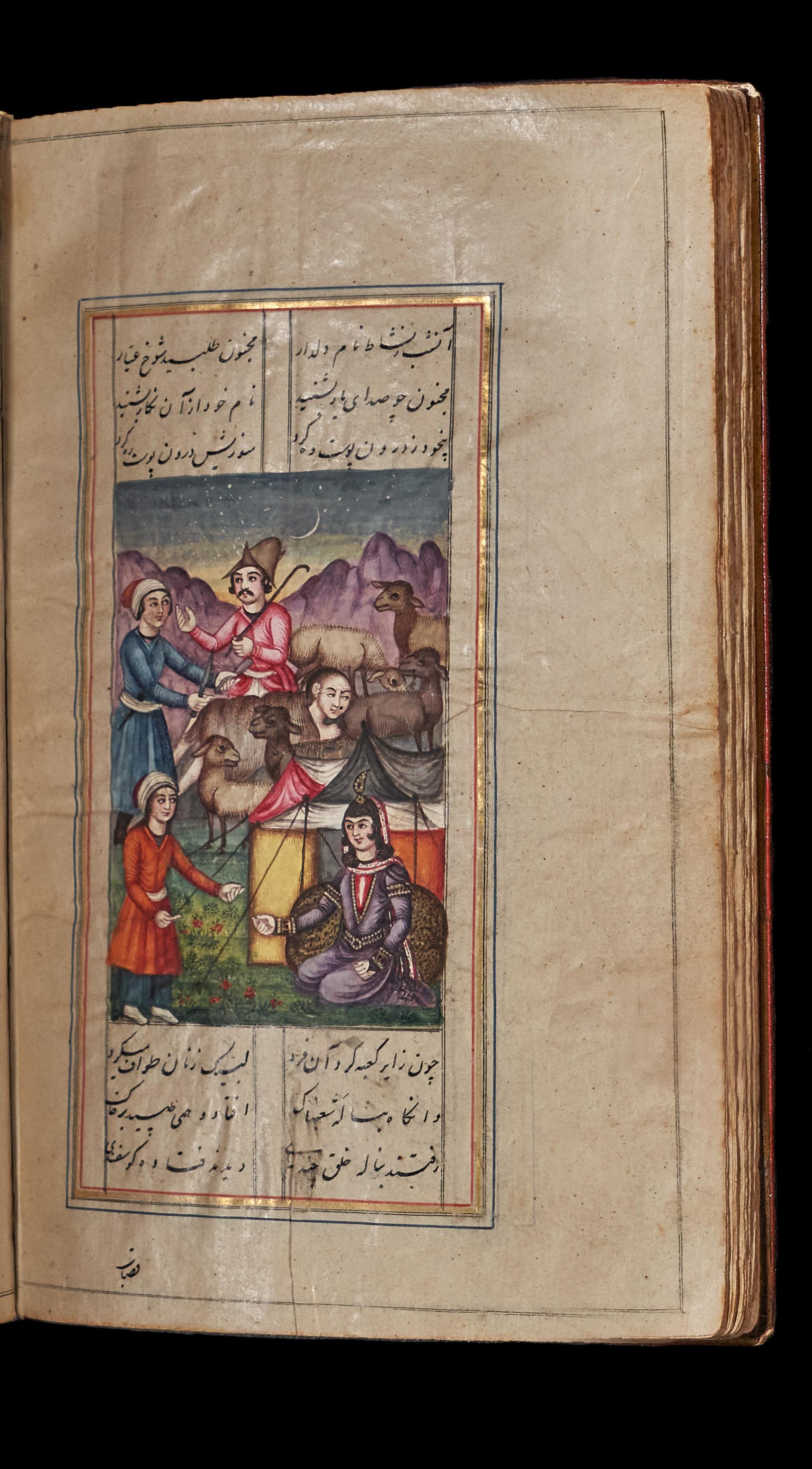

This manuscript from 1839 is an exquisitely illustrated rendition of the Persian epic poem Layli and Majnun, originally composed by the poet Niẓāmī Ganjavī in 1188. The poem tells the tragic love story of Layli and Qays, who fall in love only to be forbidden to see one another by their disapproving families. Qays goes mad and flees into the wilderness, thereafter, becoming known as Majnun (mad one). The two later attempt to reunite, but both die before they are able to realize their relationship.

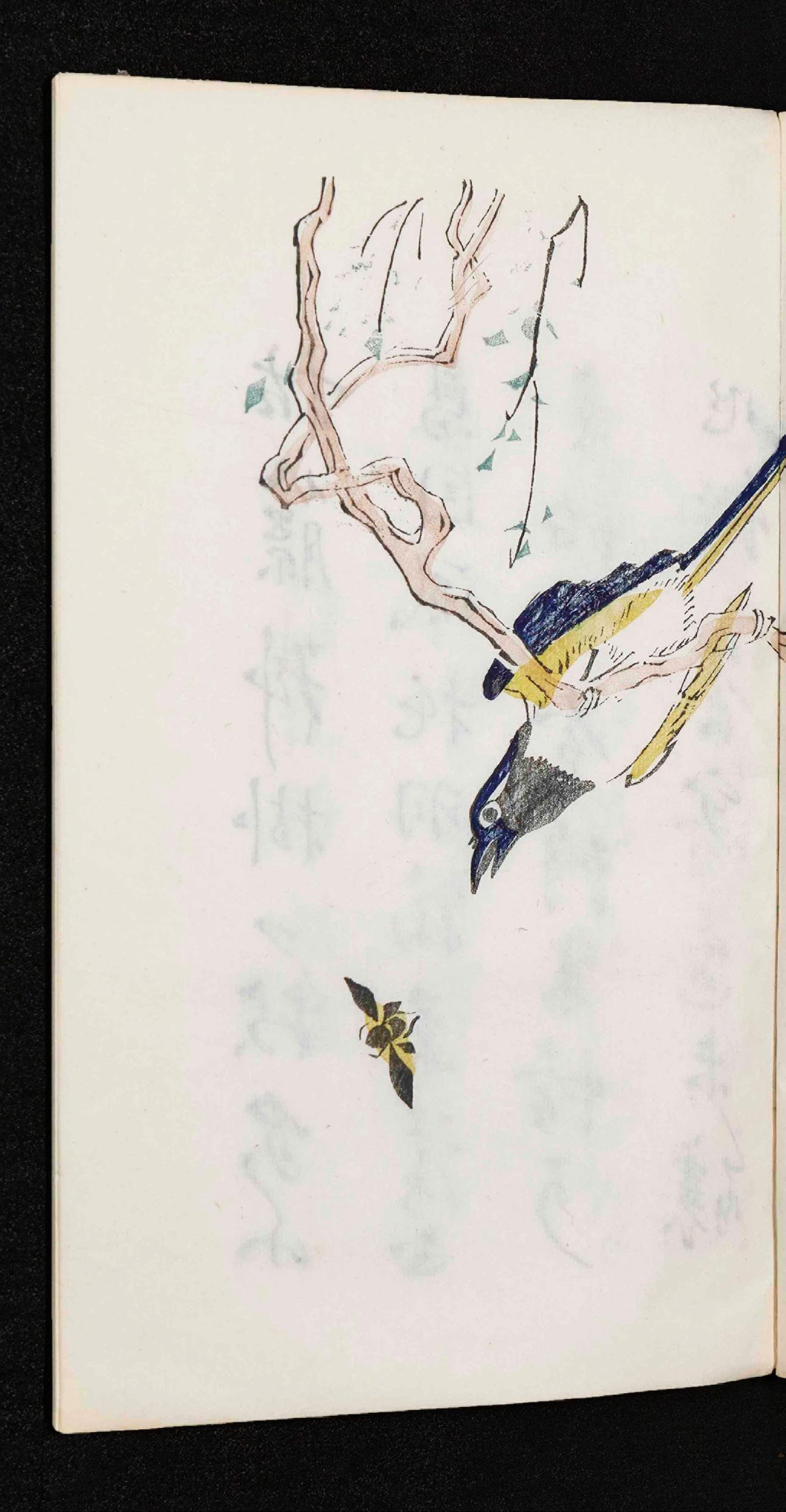

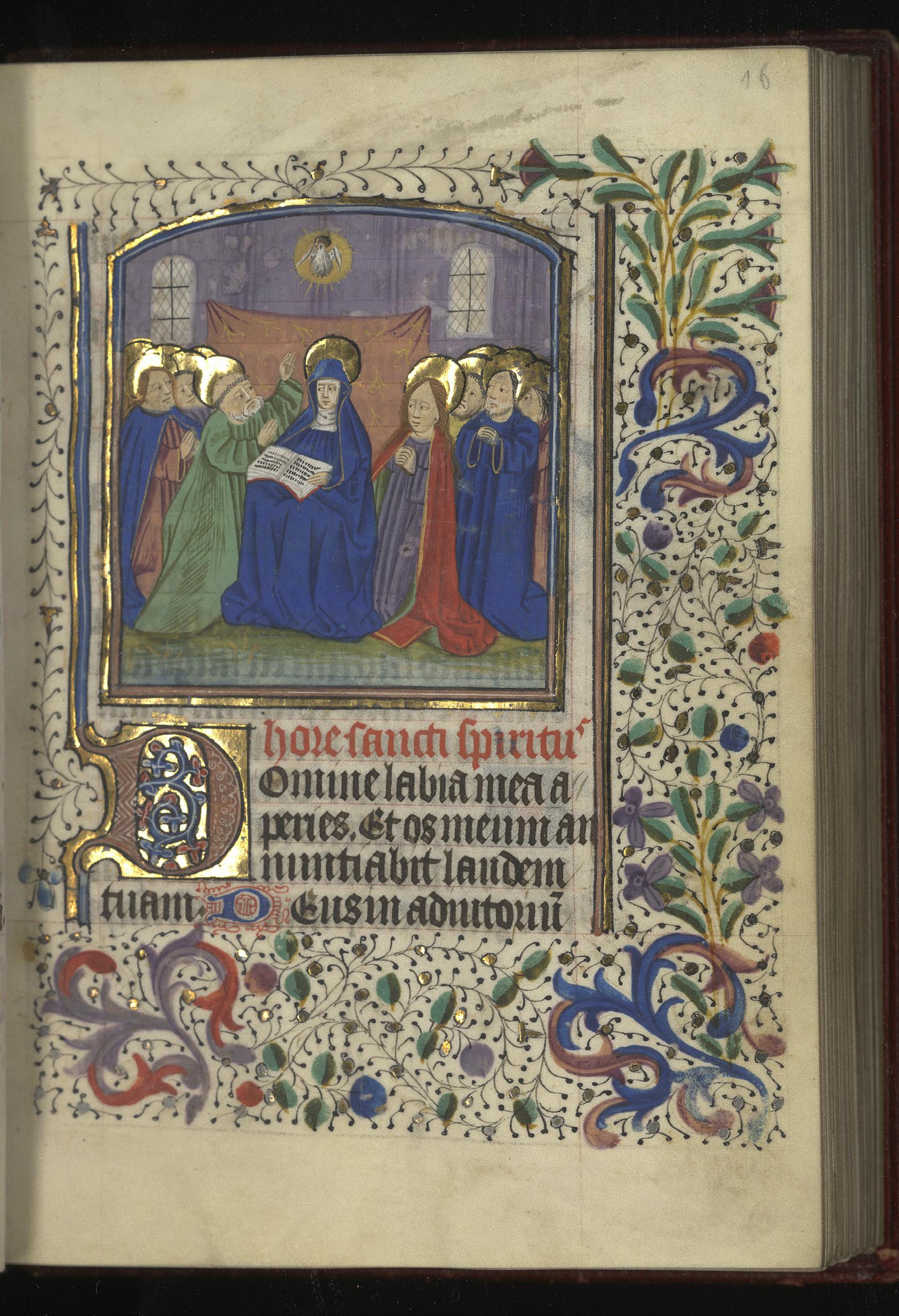

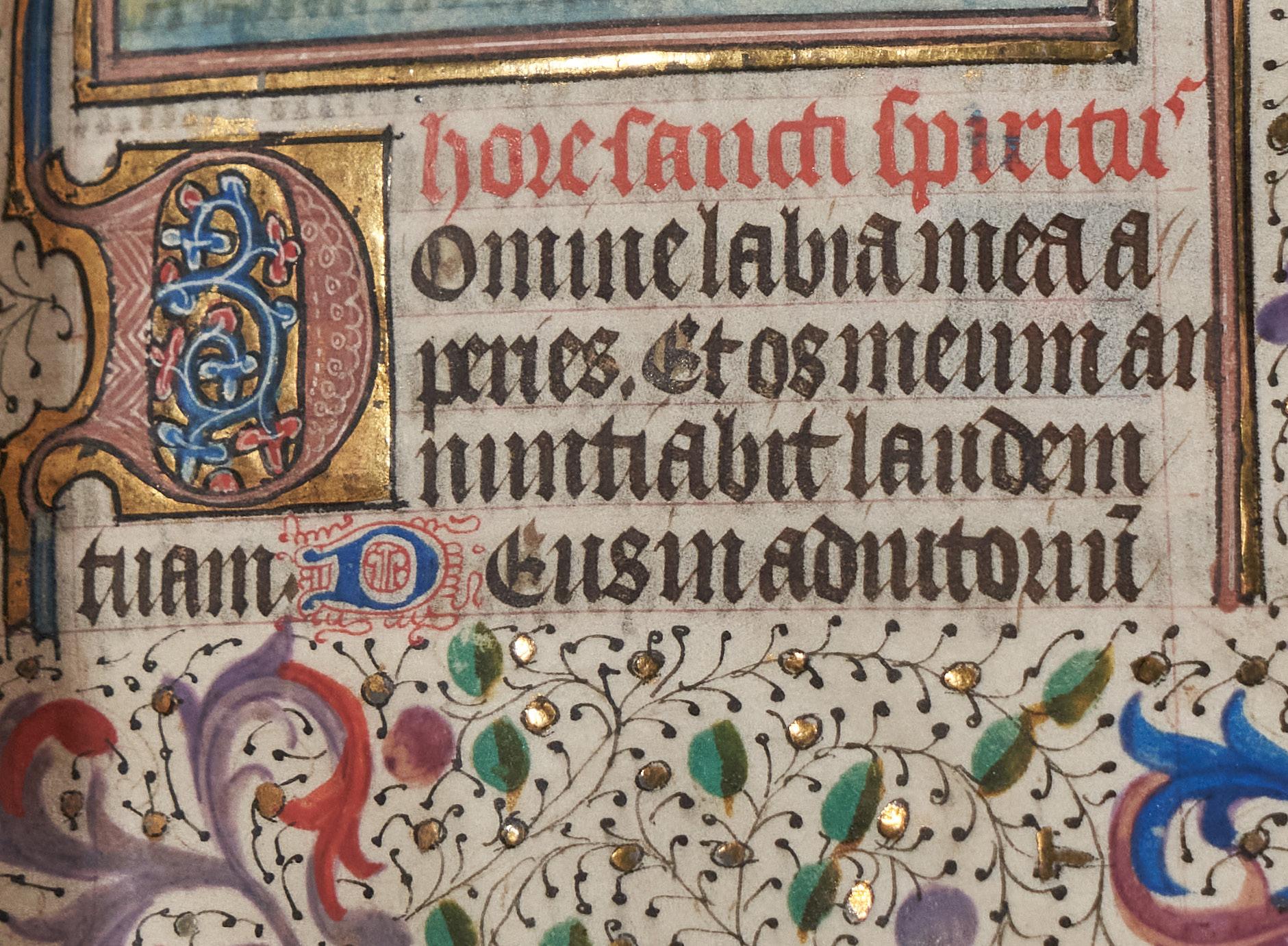

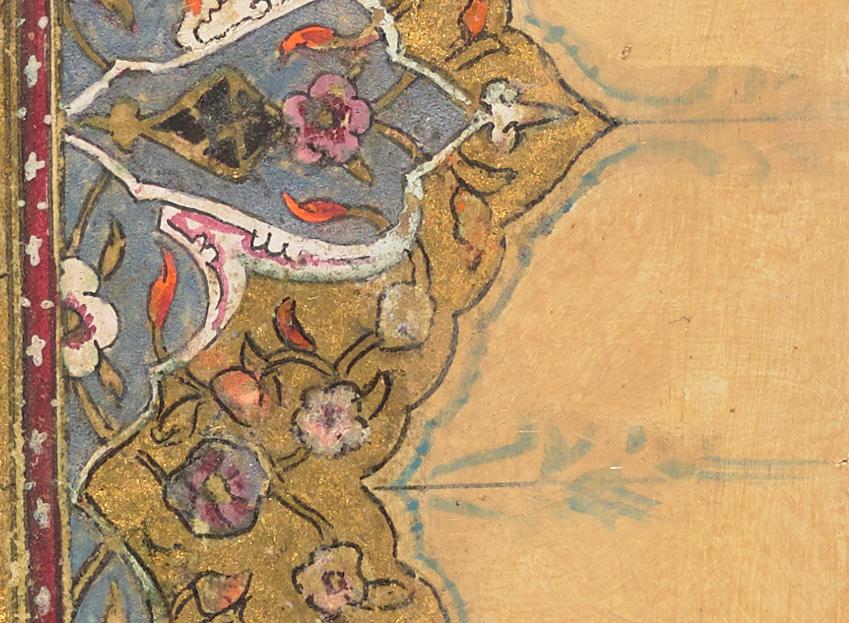

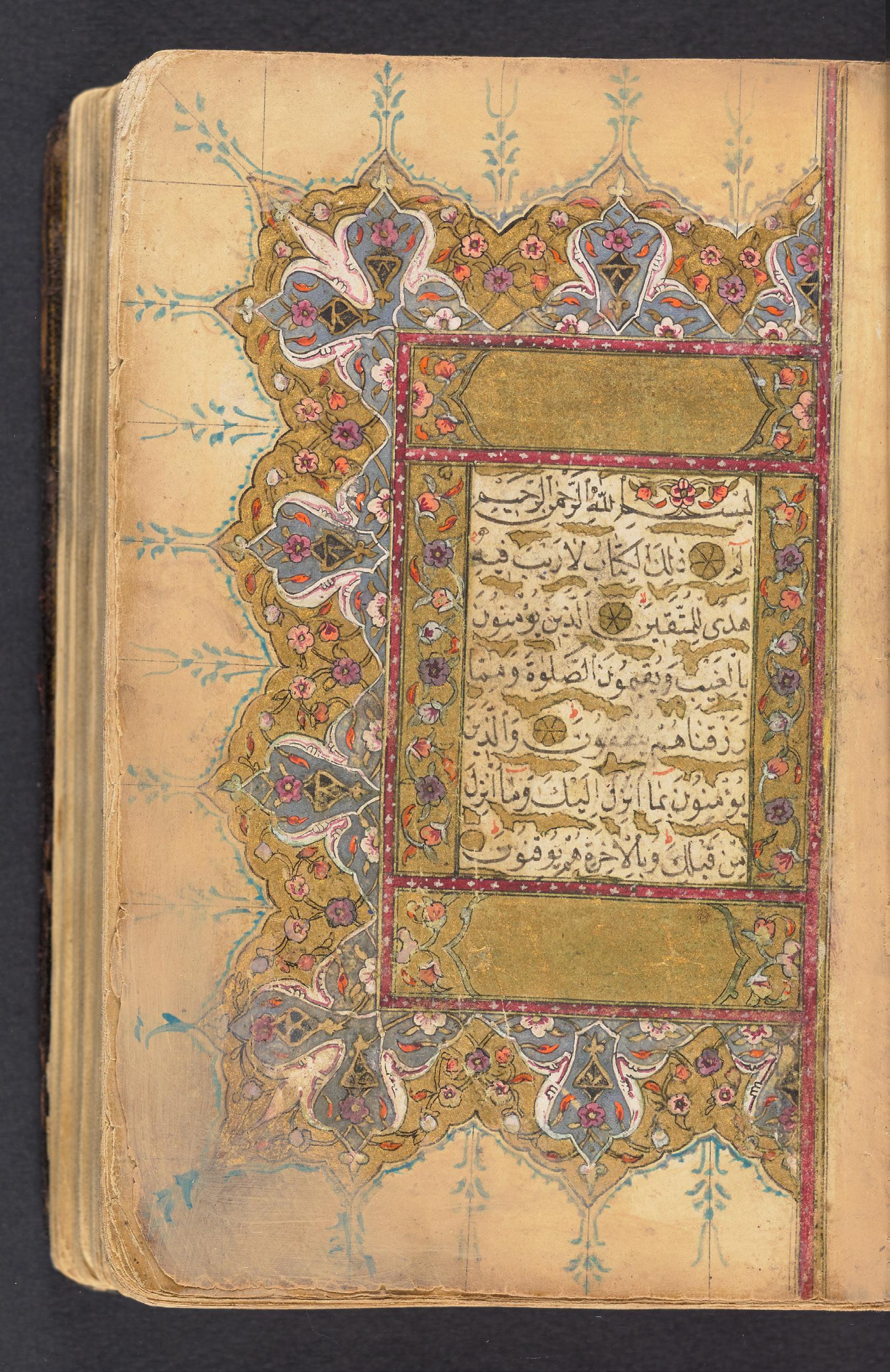

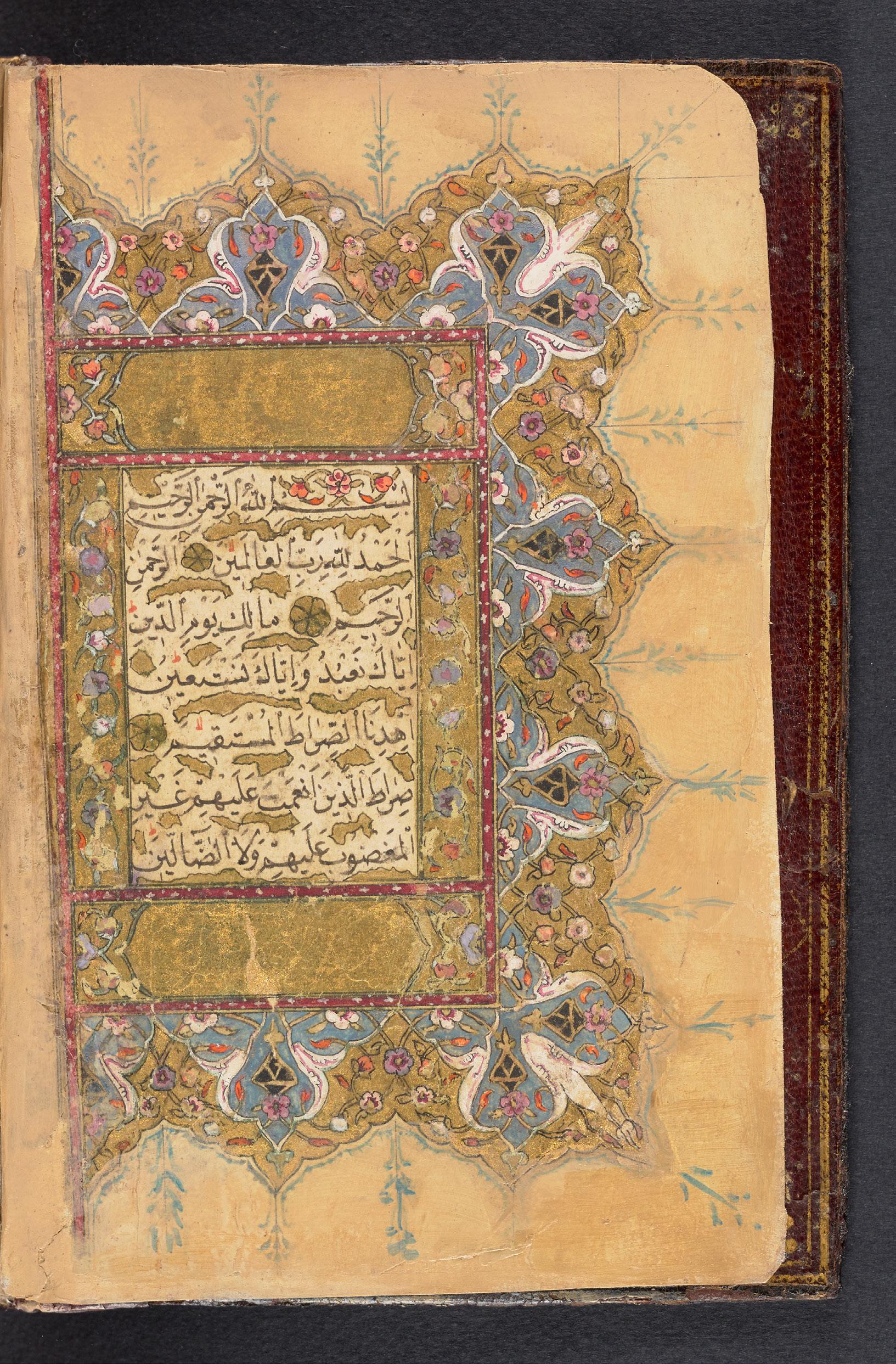

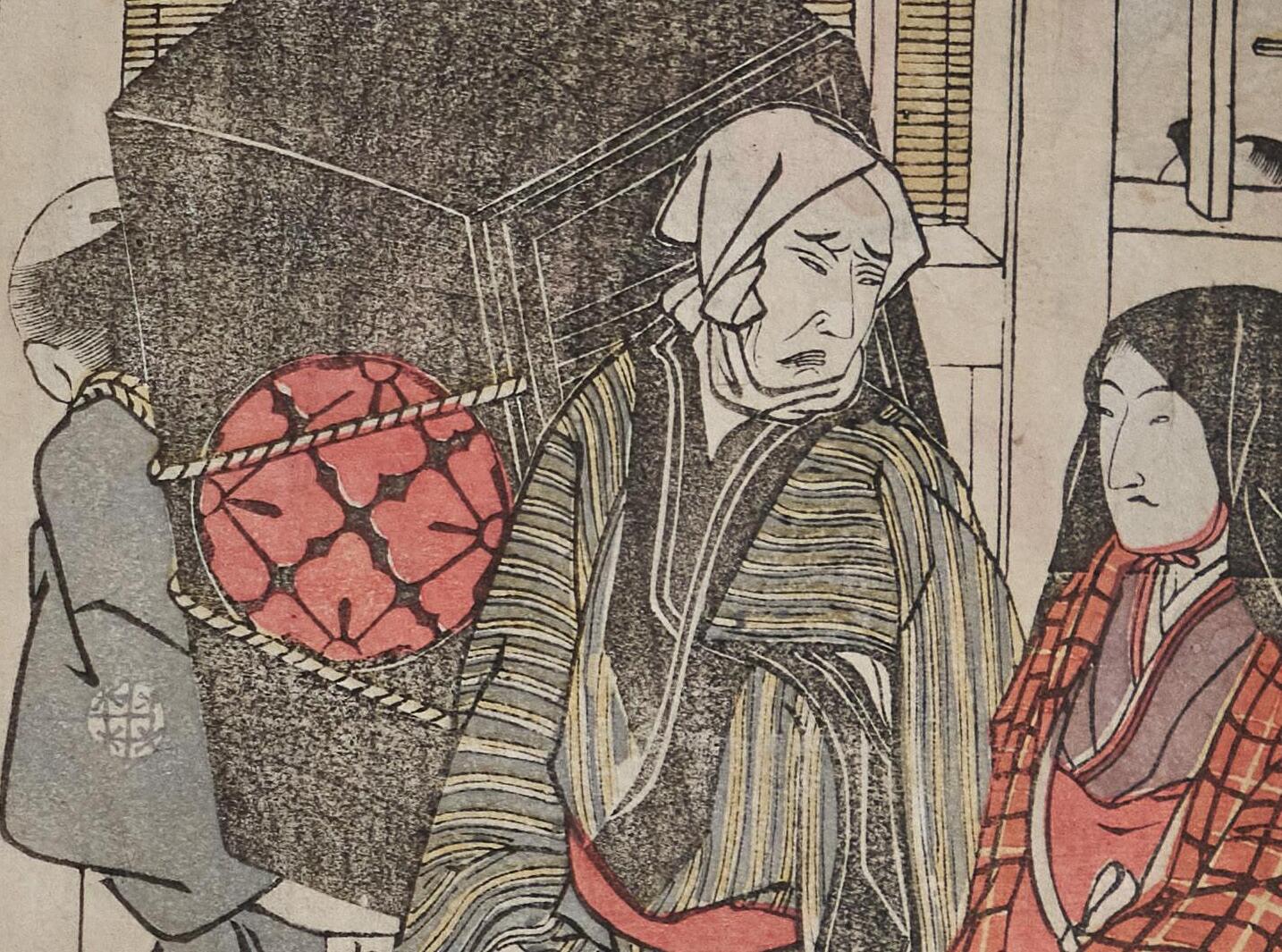

This manuscript offers multiple modes of readership, including purely visual ones. For example, while the text of the poem is written in columns in black ink, a single phrase is occasionally centered on the page in red ink. Even non-readers of Farsi will likely understand that this is a chapter title, and gives a sense of the story’s pacing. Additionally, the ruling lines that divide the space of the page closely resemble the digital guides still used to create book layouts today. Because the visual conventions used in this manuscript persist in contemporary graphic design, we can interpret it across both time and language barriers. Another way to read this manuscript is through its brilliantly colored, extraordinarily detailed illustrations. These are in the Qajar style of Persian art, with an emphasis on portraiture and saturated colors derived from Western influences. However, certain conventions of earlier Islamic painting styles prevail, including a diagrammatic, rather than distance-based, approach to perspec-

tive. In this illustration, we see Majnun hiding among a flock of sheep and peering at Layli in her tent. By rendering all characters at roughly the same scale regardless of their distance from the viewer, the artist gives equal weight to the perspectives of the two lovers and creates the sense that Majnun is lost in the crowd.

TREASURES FROM THE SPECIAL COLLECTIONS RESEARCH CENTER, TEMPLE UNIVERSITY LIBRARIES

TREASURES FROM THE SPECIAL COLLECTIONS RESEARCH CENTER, TEMPLE UNIVERSITY LIBRARIES

Edited by Joseph R. Kopta

Edited by Joseph R. Kopta

Managing Editors: Ana Matisse Donefer-Hickie, Emma P. Holter, Jackie Streker, and Rachel Vorsanger

With contributions by Daniel Cappello, MeiLi Carling, Ivy D’Agostino, Bradford Davis, Sophia Dell’Arciprete, James Rose Dewitt, Ana Matisse Donefer-Hickie, Müge Durusu-Tanrıöver, Emily Feyrer, Emma P. Holter, Bryan C. Keene, Angela Lorenz, Robin Morris, Dot Porter, Alice M. Rudy Price, Natalia Purchiaroni, Mike Ray, Mario Sassi, Jackie Streker, William Toney, Ha Tran, Kimberly Tully, Rachel Vorsanger, Ashley D. West, Byron Wolfe, Yaqeen Yamani, and Özlem Yıldız

Forewords by Susan E. Cahan and Joseph P. Lucia

This catalogue is published in conjunction with the exhibition The Art of the Book: Treasures from the Special Collections Research Center, Temple University Libraries, on view at Charles Library, Temple University, Philadelphia, from April 12 to July 15, 2024.

The Art of the Book project is a collaboration between the Tyler School of Art and Architecture and Temple University Libraries. It has been coordinated by Joseph R. Kopta and Kimberly Tully, together with graduate students from the Tyler School of Art and Architecture, Temple University.

The exhibition, catalogue, and public programming have been made possible by Temple University Libraries, the Tyler School of Art and Architecture, Temple University’s General Activities Fund (GAF), the Jackson Fund for Byzantine Art, the Center for the Humanities at Temple (CHAT), the Art History Department and the Art Department at Tyler, and two anonymous donors.

Edited

by

Joseph R. Kopta

Managing Editors: Ana Matisse

Donefer-Hickie, Emma P. Holter, Jackie Streker, and Rachel Vorsanger

Project Manager: Jackie Streker

Designers: MeiLi Carling, Mike Ray, and Ha Tran

Design Assistant: Emily Feyrer

Photographs of works of art in the Special Collections Research Center, Temple University Libraries are by Sophia Dell’Arciprete, Natalia Purchiaroni, William Toney, Byron Wolfe, Yaqeen Yamani, and Temple University Libraries, unless otherwise noted.

Photography credits appear at the end of the volume.

Typeset in Moret Variable Book, Byker, and Panel Sans Mono

Printed on 100 lb. smooth text

Printed by Fireball Printing, Philadelphia

Published by the Tyler School of Art and Architecture

Temple University

2001 N. 13th Street Philadelphia, PA 19122

Copyright ©2024 to the individually contributing authors and artists. All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner without written permission from the individual artists or authors, Temple University Libraries, or the Tyler School of Art and Architecture.

ISBN 979-8-218-38322-0

Note to the Reader:

All dates in the catalogue are in BCE or CE. As the works in this catalogue represent multiple language traditions, an effort has been made to simplify common forms of names and places in English. For this reason, diacritical marks of words in foreign languages have been avoided and common English spelling used. Catalogue entries provide objects’ geographical origin when it is known. Unless otherwise noted, dimensions are indicated as height by width by depth in centimeters. Every effort has been made to track provenance as accurately as possible. For provenance details of objects in the Special Collections Research Center, Temple University Libraries, see the online catalogue at library.temple.edu/scrc for the most up-to-date information. Many of the objects in this publication have been digitized and are available at digital.library.temple.edu.

2 Acknowledgements

4 Forewords

Susan E. Cahan, Joseph P. Lucia

6 The Art of the Book: An Exercise in Interdisciplinary Collaboration

Bradford Davis, Ivy D’Agostino, Ana Matisse Donefer-Hickie, Emma P. Holter, Robin Morris, and Rachel Vorsanger

8 Introduction to the Special Collections Research Center Collection

Kimberly Tully

10 Embodied Text and Image: The Codex in the Middle Ages and Today

Joseph R. Kopta

14 A Look at a Book

18 Economics & Labor

Emma P. Holter

30 Before (the Art of) the Book

Müge Durusu-Tanrıöver

34 Visualizing Science

Ana Matisse Donefer-Hickie

44 Printing in Early Modern Germany

Ashley D. West

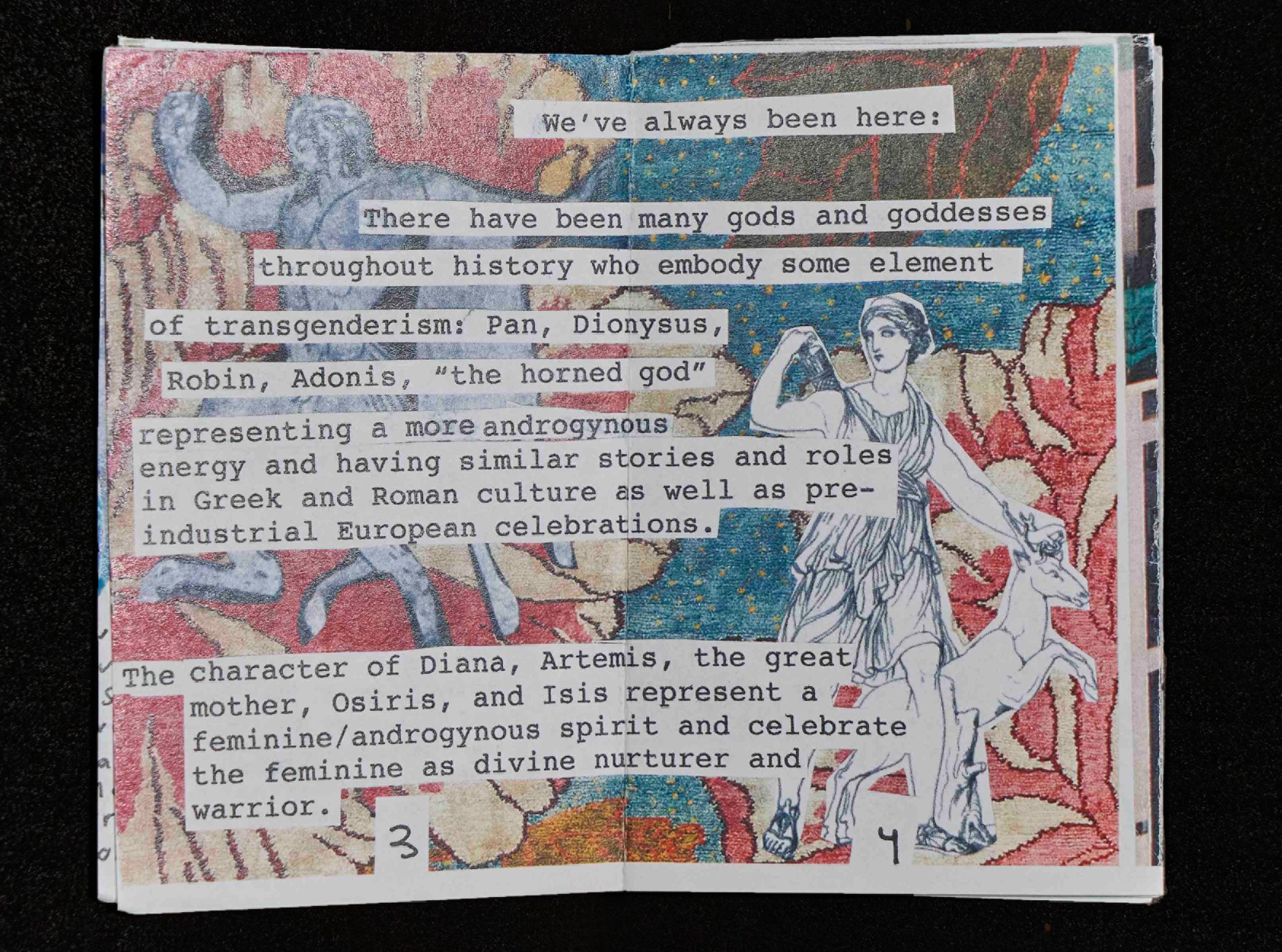

50 Embodied Perspectives & Identities

Rachel Vorsanger

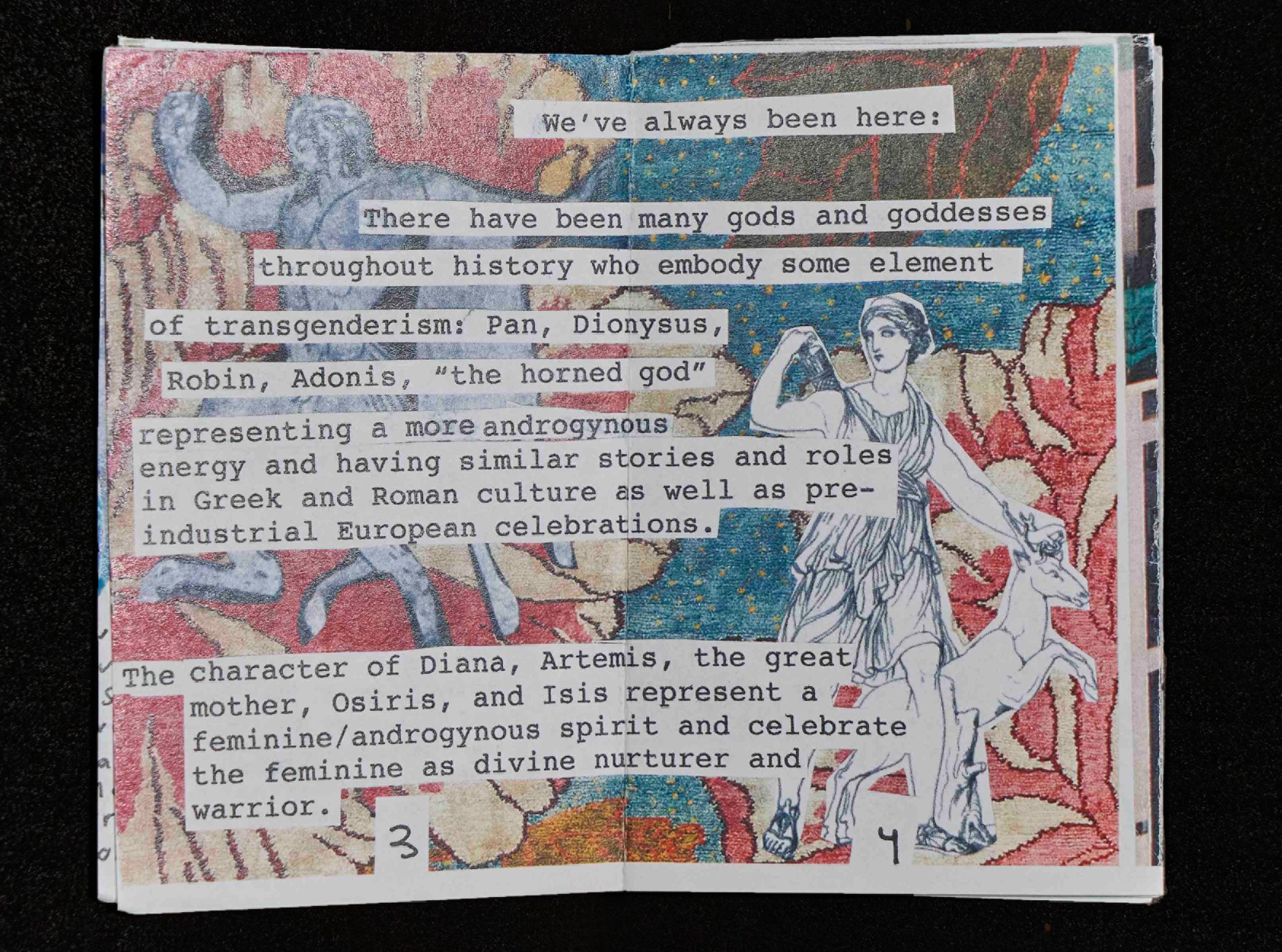

64 Sex Ed: A Love Story—An Interview on Zines

Ana Matisse Donefer-Hickie

with James Rose Dewitt

Table of Contents

68 Performance, Music, Visual Arts Daniel Cappello 80 The Artistic Book Alice M. Rudy Price 84 Marking Time Emma P. Holter 94 Paleography: The Shape of Writing Mario Sassi 106 An Encounter with the Ottoman Book Özlem Yıldız 110 Poetry, Philosophy, & Thinking Robin Morris 122 Manuscripts and the Digital Humanities: Bridging the Past and the Present Dot Porter 126 Dynamic Book Structures Rachel Vorsanger 138 Work for Curious People: An Interview on Artist Books with Angela Lorenz Robin Morris 142 Problematic Perceptions Daniel Cappello and Ivy D’Agostino 148 A Vision for the Future of Manuscript Curation and Book History Bryan C. Keene 152 Contributors 154 Photography Credits

TREASURES FROM THE SPECIAL COLLECTIONS RESEARCH CENTER, TEMPLE UNIVERSITY LIBRARIES

The Art of the Book: Treasures from Special Collections showcases a variety of artworks housed in the Special Collections Research Center at Temple University’s Charles Library. Organized through a curatorial collaboration between graduate students from the Tyler School of Art and Architecture, the exhibition and this catalogue examine how the format of the book has been treated across time and geography. A key question at the heart of this exhibition is, what constitutes a book? The diverse examples featured in this show challenge our preconceived notions and expand our definitions of this type of object. Melding illustration, painting,

object-making, calligraphy, and storytelling, the objects featured in The Art of the Book transmit a robust sense of the time and place in which they were created. Many of these books function as repositories of memory that simultaneously reflect the values, history, and available technologies of the particular cultural moment in which they were created. The thematic groupings of these treasures display the variety of ways in which artists from across the globe have dealt with similar subject matter and content. The essays in this catalogue endeavor to unveil the hidden histories and complicated entanglements behind each of the objects on display.

x | The Art of the Book

The Art of the Book began as a conversation in 2022 between us—an art historian of medieval manuscripts and a curator of rare books—about how the collection at Temple University Libraries could be used in an instructional setting to teach the history of the book as an art form; how best to feature the extraordinary collection of rare books, manuscripts, artist books, and zines at the Special Collections Research Center (SCRC); and how to supervise students in the theory and practice of an exhibition project. Drawing upon our complimentary expertise and our love of book objects, we began our collaboration in early 2023 with the public program A Look at a Book, in which members of the Tyler School of Art and Architecture—both faculty, graduate students, as well as the occasional guest scholar—presented, in 25-minute segments, a single object from the SCRC in a virtual platform. These presentations were recorded and subsequently uploaded for permanent viewing.

On the heels of the successful A Look at a Book program, we considered how best to pursue an exhibition project driven by students. This manifested in the graduate seminar, Problems in Medieval Art: Curating the Codex, a hybrid course combining the history and theory of the art of the book, intensive object study of books in the SCRC, theory of collecting and displaying, and a practicum on mounting an exhibition. Students across Tyler departments took on the role of conceiving, curating, and executing the exhibition project, together with the involvement and invested partnership of the Library.

The resulting exhibition, catalogue, web presence, and public programming was the result of this endeavor, with the graduate student curators from programs of Art History, Ceramics, Graphic and Interactive Design, and Sculpture. We would first and foremost like to congratulate the student curators on the success of their project: Daniel Cappello, MeiLi Carling,

Acknowledgments

Ivy D’Agostino, Bradford Davis, Ana Matisse Donefer-Hickie, Emma P. Holter, Robin Morris, Mike Ray, Ha Tran, and Rachel Vorsanger.

We are extremely grateful to the guest scholars who lent their expertise to the seminar and informed the ideas of the project in its infancy, including Bryan C. Keene, John T. McQuillen, Dot Porter, Mario Sassi, Emily Shartrand, and Ashley D. West.

We are also thankful to the scholars and artists who contributed essays and interviews to our catalogue, giving additional context to the works in the exhibition, including James Rose Dewitt, Müge Durusu-Tanrıöver, Bryan C. Keene, Angela Lorenz, Dot Porter, Alice M. Rudy Price, Mario Sassi, Ashley D. West, and Özlem Yıldız.

Byron Wolfe very generously coordinated his MFA students in a photoshoot producing beautiful new images of many exhibition objects featured in this catalogue, with photographs by Sophia Dell’Arciprete, Natalia Purchiaroni, William Toney, and Yaqeen Yamani. Jackie Streker was an excellent Research Assistant and Project Manager that kept the project on track across the finish line.

Additional colleagues, supporters, and friends, both at Temple University and elsewhere, aided in numerous ways, including Andrea M. Achi, Yasmine Amory, Mitos Andaya Hart, Julián Bértola, Erin Rose Boyle, Doug Bucci, Keia D. Carter Simmons, Theresa Davis, Maggie Downing Dunkle, Jane D. Evans, Emily Feyrer, Craig Fineburg,

Brenda Galloway-Wright, Marci Green, Morgan Griffith, Jordan Hample, D. Harland Harris, Josué Hurtado, Lynn Jackson, Nic Justice, Lydon Frank Lettuce, Ugo Mondini, Henry Morales, Ann Mosher, Wanda Odom, Alpesh Kantilal Patel, John Pyle, Paul Rardin, Katy Rawdon, David M. Rhoads, Mario Sassi, Paolo Scartoni, Kaitlyn Semborski, Courtney Smerz, Evan Weinstein, Stuart Whisnant, Brian E. White, and Sara Wilson.

We are indebted to our deans, Susan E. Cahan and Joseph P. Lucia, for their support of our collaborative project. We are extremely grateful to the entities and individuals who have financially supported The Art of the Book. The exhibition, catalogue, and public

programming have been made possible by Temple University Libraries, the Tyler School of Art and Architecture, Temple University’s General Activities Fund (GAF), the Jackson Fund for Byzantine Art, the Center for the Humanities at Temple (CHAT), the Art History Department and the Art Department at Tyler, and two anonymous donors.

Joseph R. Kopta

Assistant Professor of Instruction, Art History Tyler School of Art and Architecture

Kimberly Tully Curator of Rare Books

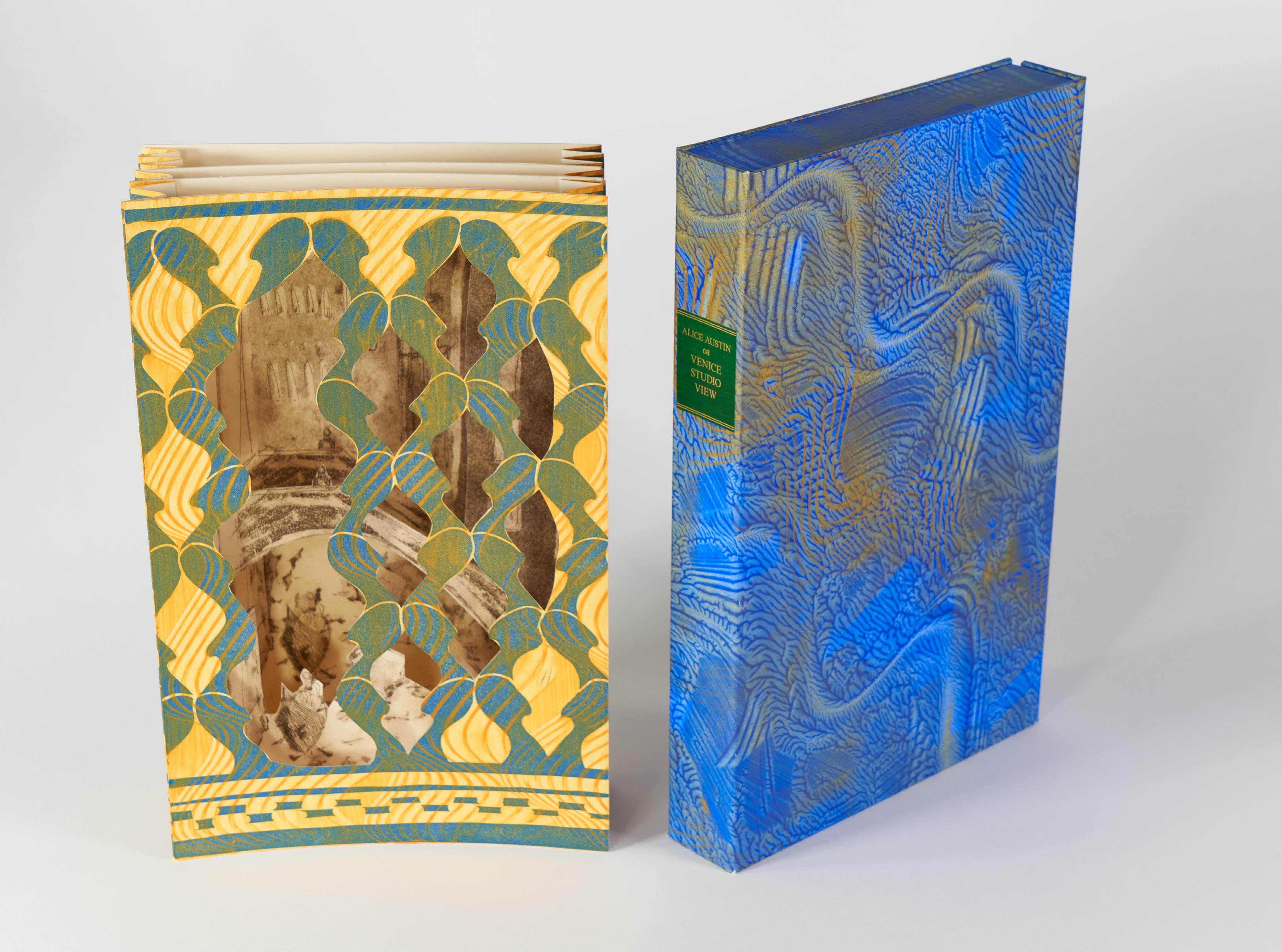

Special Collections Research Center Temple University Libraries

April 2024

| 3

Forewords

4 | The Art of the Book

Susan E. Cahan, PhD Dean, Tyler School of Art and Architecture

The Art of the Book reflects the essence of cross-disciplinary collaboration at the Tyler School of Art and Architecture and Temple University. This publication, exhibition, and programming result from months of research and teamwork among a range of Tyler graduate students as they sought to determine what defines a book.

They found that close study of historical objects provides a deeper understanding of the world today, just as the present creates new lenses through which past works can be considered. Through examination of diverse objects from ancient cuneiforms that mark the beginnings of recorded history, to luxurious and labor-intensive medieval manuscripts, to sculptural artist books and subversive zine publications, The Art of the Book is a testament to the power of books to tell stories, build communities, discover histories, and challenge worldviews.

I warmly acknowledge the faculty and staff who provided leadership and contributions to this project that embodies this sense of community and social justice. I am deeply grateful to Joseph R. Kopta, Assistant Professor of Art History at Tyler and Kimberly Tully, Curator of Rare Books at the Special Collections Research Center, for their vision and guidance. Finally, my deepest appreciation goes to the student curators, photographers, designers, and scholars who brought this project to life.

Joseph P. Lucia Dean, Temple University Libraries

Academic libraries are at their core catalysts for connection, for interaction and partnership, for imagination and historical (re)discovery. They connect people and ideas, people and books (both as physical objects and as digital entities), people and the diverse discourses of knowledge and culture. Any library that is viewed only as an inert repository of stuff is a morgue. Any library entered, engaged, and activated by people is a social nexus for thought, reflection and expression, a site for learning, inquiry, and exploration. At Temple, we are committed to the ideal of the engaged library. And The Art of the Book is a true exemplar of engagement fully realized.

In spite of our relatively short institutional history and our public mission, we are privileged in our Special Collections Research Center to have acquired over the years an impressive array of holdings that span the range of human inscription from cuneiforms and medieval manuscripts, incunabula and touchstones in printing history, to contemporary artist books and subculture zines. We value those items not for their rarity but rather for the way they stimulate mind and imagination when they are touched, explored, and interrogated in ways that give them new life and current resonance.

It is especially gratifying that this project is the result of a collaboration between our Curator of Rare Books Kimberly Tully and Tyler Assistant Professor of Art History Joseph R. Kopta. In the library, we often speak about partnership with faculty, educational impact, the unique value of bringing students at all levels into direct contact with the deep history and complex materiality of print culture. At a moment when networked digital affordances obfuscate handiwork and the hands of the maker, this project has drawn a group of graduate students–artists and thinkers –into the complex and various history of books and bookmaking with an intensity of focus that I am sure has been revelatory and enlightening for all involved. I am doubly proud that we are able to share this work with our campus community through an exhibition, a symposium, and this catalogue. I express my thanks to all who made this project come to fruition.

| 5

The Art of the Book: An Exercise in Interdisciplinary Collaboration

What makes a book? What makes an exhibition? This project is framed by these two questions—one of content, and the other of process. The Art of the Book is the result of a semester of work in the 2023 graduate seminar “Curating the Codex,” uniting Tyler School of Art and Architecture students from Graphic & Interactive Design, Sculpture, Ceramics, and Art History—a variety of professional backgrounds that embrace diverse disciplinary perspectives and priorities. To synthesize this multitude of viewpoints on exhibition development, the first half of the seminar focused on skill-building exercises, discussions, and conversations with experts in the field, which established a common ground from which the team could begin to build an exhibition that aligned with our respective approaches to art and the material culture of the book.

Books emerged from these dynamic conversations as objects as multitudinous as we are, defined as everything from “externalizations of ideas” and “vessels of knowledge,” to “records of journeys,” “entanglements,” and “manifestations of care,” used both for disseminating contemporary ideas

and safeguarding the ideas of the past.1 They are (sometimes) accessible repositories of memory, which simultaneously reflect the values, history, available technologies, and complicated entanglements of the particular cultural moment in which they were created. This expansive definition, focusing on function over format, was easily reflected in the Special Collections Research Center’s rich collection of manuscripts, codices, tablets, scrolls, zines, and artist books, from which the treasures that this catalogue and its accompanying exhibition explores have been drawn.

As you will see as you read through this book, each of us “adopted” two to four works to research, resulting in the entries that make up the content of this catalogue. These short case studies explore each work in more depth, but the research invested in their writing also formed the basis of the thematic groups that structure both catalogue and exhibition display. Thus, the framing essays that accompany each group grew from our explorations of the objects themselves, rather than from an overarching argument superimposed upon them.

This organic conceptual development, which responded to the stories we unraveled in each of the objects, was reflected in the exhibition workflow we developed over the course of the semester. Disrupting the traditional structure of an exhibition team, which strictly divides the labor of curation, exhibition design, education, graphic design, and editorial, our work on The Art of The Book was organized into flexible steering committees—the responsibilities and members of which adapted as the needs of both the students and the project changed. This unusual team structure allowed us the flexibility to both play to our strengths and to experiment with areas of exhibition planning we might not have had the opportunity to work in otherwise.

Though much of the project was developed through these discussions between graduate student artists and scholars, we would be remiss to ignore the integral role of Dr. Joseph R. Kopta. His expertise, encouragement, and imagination in framing the course made this exhibition project possible, and the student team owes him a heartfelt thanks. Profound thanks are also due to Kimberly Tully, whose care

6 | The Art of the Book

and attention to both the works in the exhibition and the students in the course provided much needed groundwork for our thinking. As we hope will become clear throughout this catalogue, The Art of the Book challenges preconceived notions of what a book can be, but the organization of the project also challenged standard definitions of curation, research, and design by focusing on true collaboration, integration, and mutual support.

Research Committee: Bradford Davis, Ivy D’Agostino, Ana Matisse Donefer-Hickie, Emma P. Holter, Robin Morris, and Rachel Vorsanger

Branding Committee: MeiLi Carling, Mike Ray, and Ha Tran

Catalogue Design Committee: MeiLi Carling, Robin Morris, Mike Ray, and Ha Tran

Gallery Design Committee: Daniel Cappello, MeiLi Carling, Bradford Davis, Mike Ray, and Ha Tran

Object Grouping Committee: Daniel Cappello, Ivy D’Agostino, Emma P. Holter, and Rachel Vorsanger

Public Programs & Access Committee: Daniel Cappello, Bradford Davis, Emma P. Holter, and Robin Morris

Web and Digital Presence Committee: Ana Matisse Donefer-Hickie, and Rachel Vorsanger

1. All quotes are drawn directly from notes taken during class discussion.

Introduction to the Special Collections Research Center Collection

Kimberly Tully

The Special Collections Research Center (SCRC) is the principal repository for and steward of Temple University Libraries’ rare books, manuscripts, archives, and University records. We collect, preserve, and make accessible primary resources and rare or unique materials, to stimulate, enrich, and support research, teaching, learning, and administration at Temple University. The SCRC makes these resources available to the general public as part of the University’s engagement with the larger community of scholars and independent researchers.

The books featured in this exhibition are representative of the breadth and strength of the SCRC’s print holdings and were acquired through a variety of both historical and current collecting strategies. Founded in 1967, the Rare Book Collection documents the history of printing and publishing, printmaking and illustration, typography and book design, and literature and language and supports teaching in the history of the book and book arts. In addition to rare and first edition printed books

dating from the fifteenth century to the present, the collection also includes early manuscripts and examples of ancient writing technologies. Particular strengths of the collection include private press and fine printing, herbals and botanical illustration, seventeenth and early eighteenth century AngloAmerican social and religious tracts, history of business and trade, and the history and development of lithography. The SCRC has also actively expanded its teaching collections to include non-Western books and manuscripts that illuminate the global history of book cultures and better reflect the diversity of Temple’s student body and Temple University Libraries’ users.

The SCRC houses several other print-based collections, most notably the Contemporary Culture Collection and the Science Fiction Collection. Established in 1969, the Contemporary Culture Collection (CCC) is a source of primary research materials documenting the social, political, economic, and cultural history of minority groups, the counterculture, and the fringe in North America dating from the 1960s to the present. In 1972, Temple University Libraries established the Science Fiction Collection, which traces the evolution of science fiction and fantasy writing and illustration

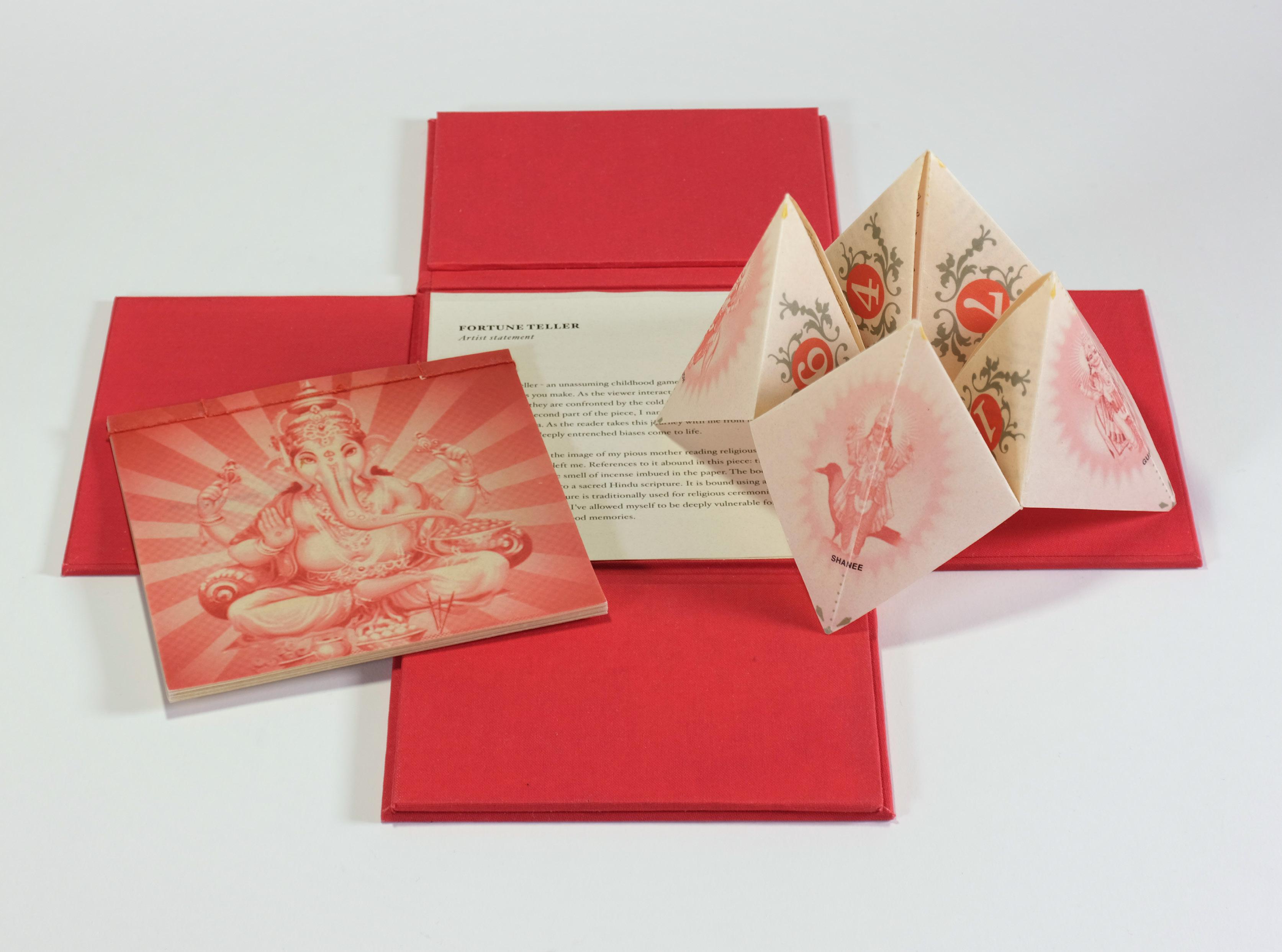

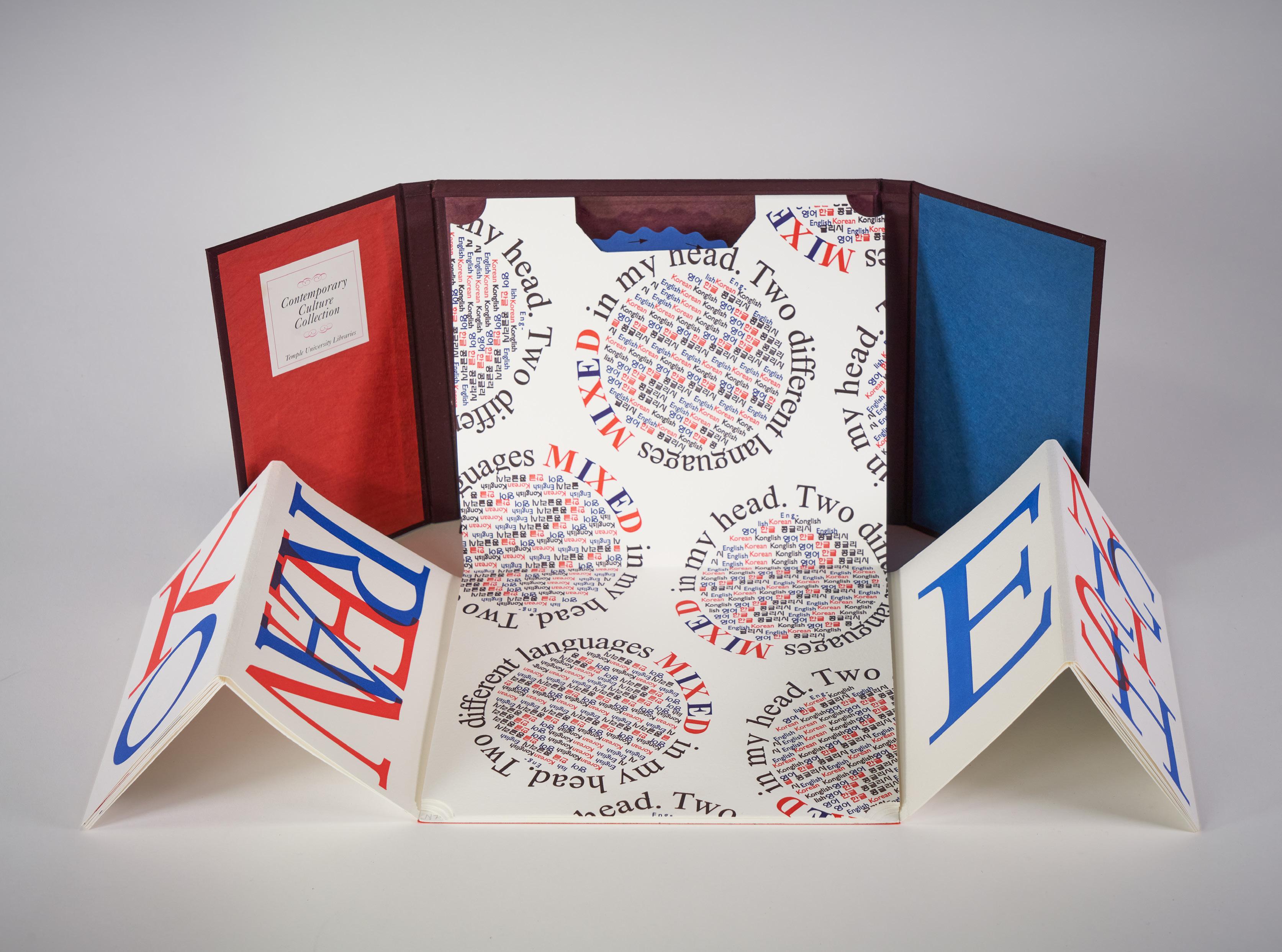

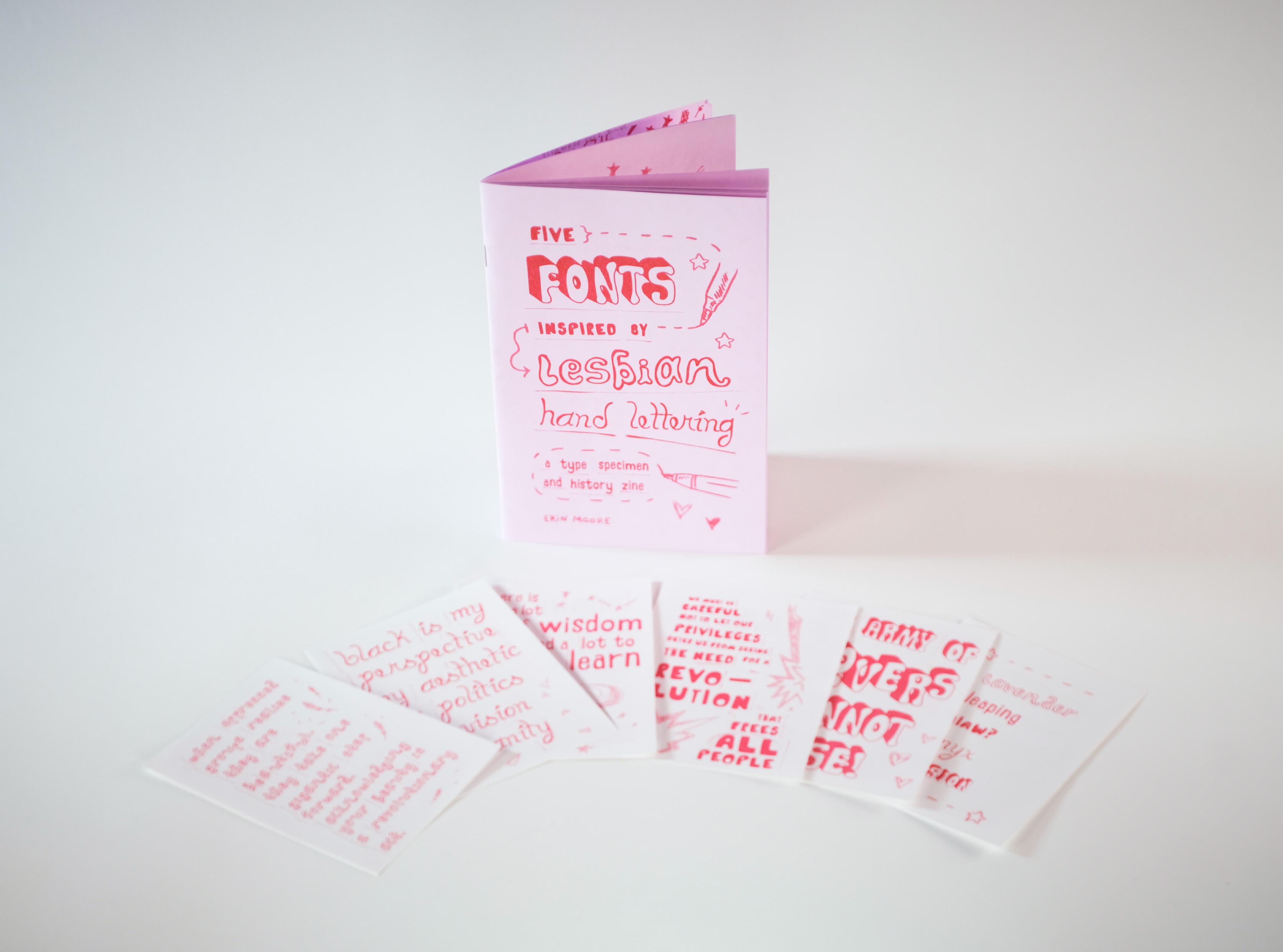

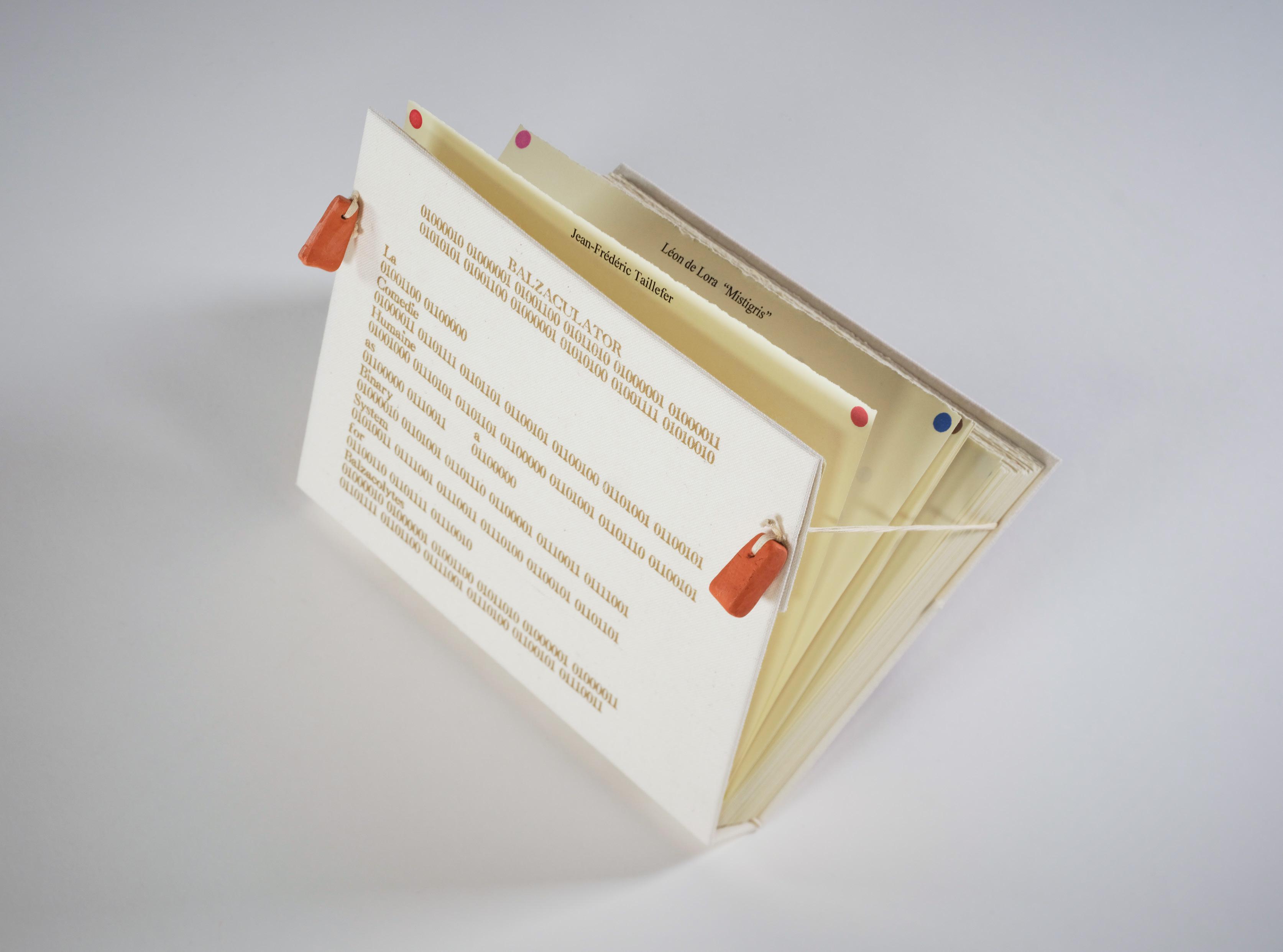

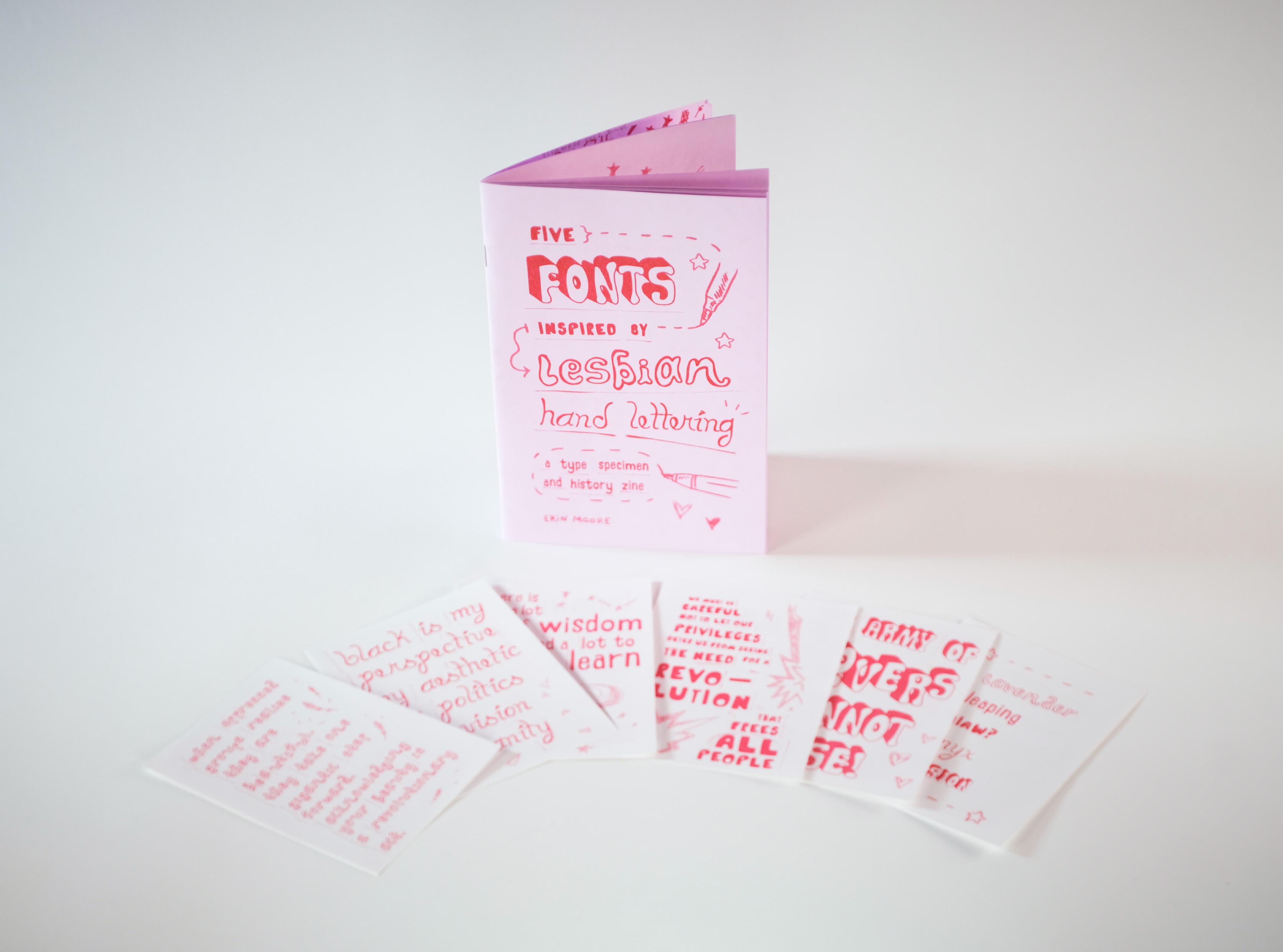

from the late nineteenth century to the present. In recent years, the SCRC has focused on collecting contemporary artists’ books, works of art in book form that challenge the traditional notions of what the codex can be, and zines, self-published DIY publications. Our rapidly expanding collection of artists’ books builds on earlier acquisitions from the 1980s and 1990s for the CCC and features a variety of book structures, materials, and printmaking techniques. Our fast-growing zine collection is one of the most highly-used collections by our faculty and students in the classroom and by researchers in our reading room. Both collections feature the work of book artists and creators from underrepresented and marginalized communities.

All of the collections mentioned above are “living” collections used regularly in the SCRC’s instruction and outreach initiatives and activities, as well as by individual researchers from the Temple community and beyond. This exhibition collaboration with the Tyler School of Art and Architecture’s faculty and graduate students reflects this dynamic use of our rich collections.

8 | The Art of the Book

Embodied Text and Image: The Codex in the Middle Ages and Today

10 | The Art of the Book

Joseph R. Kopta

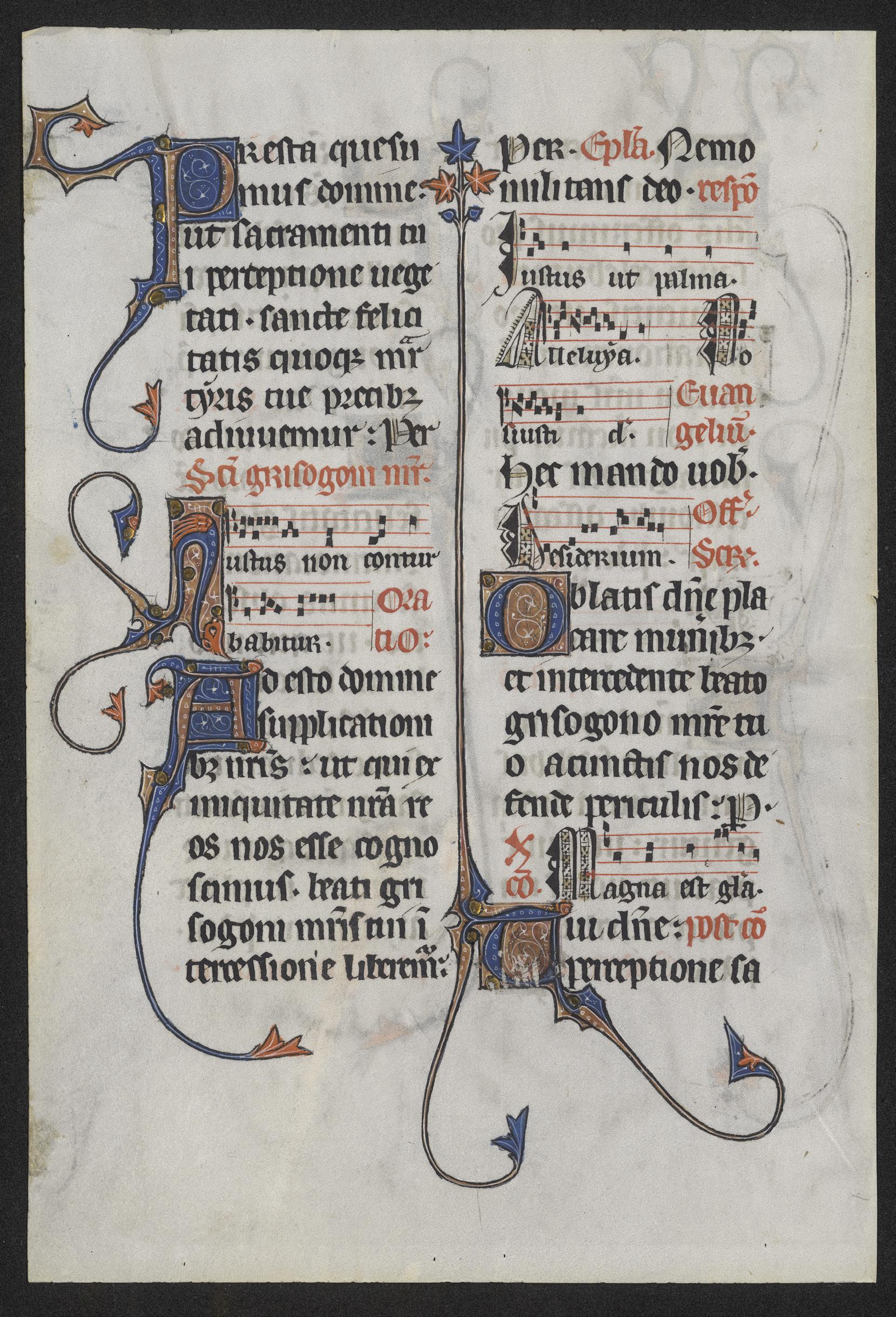

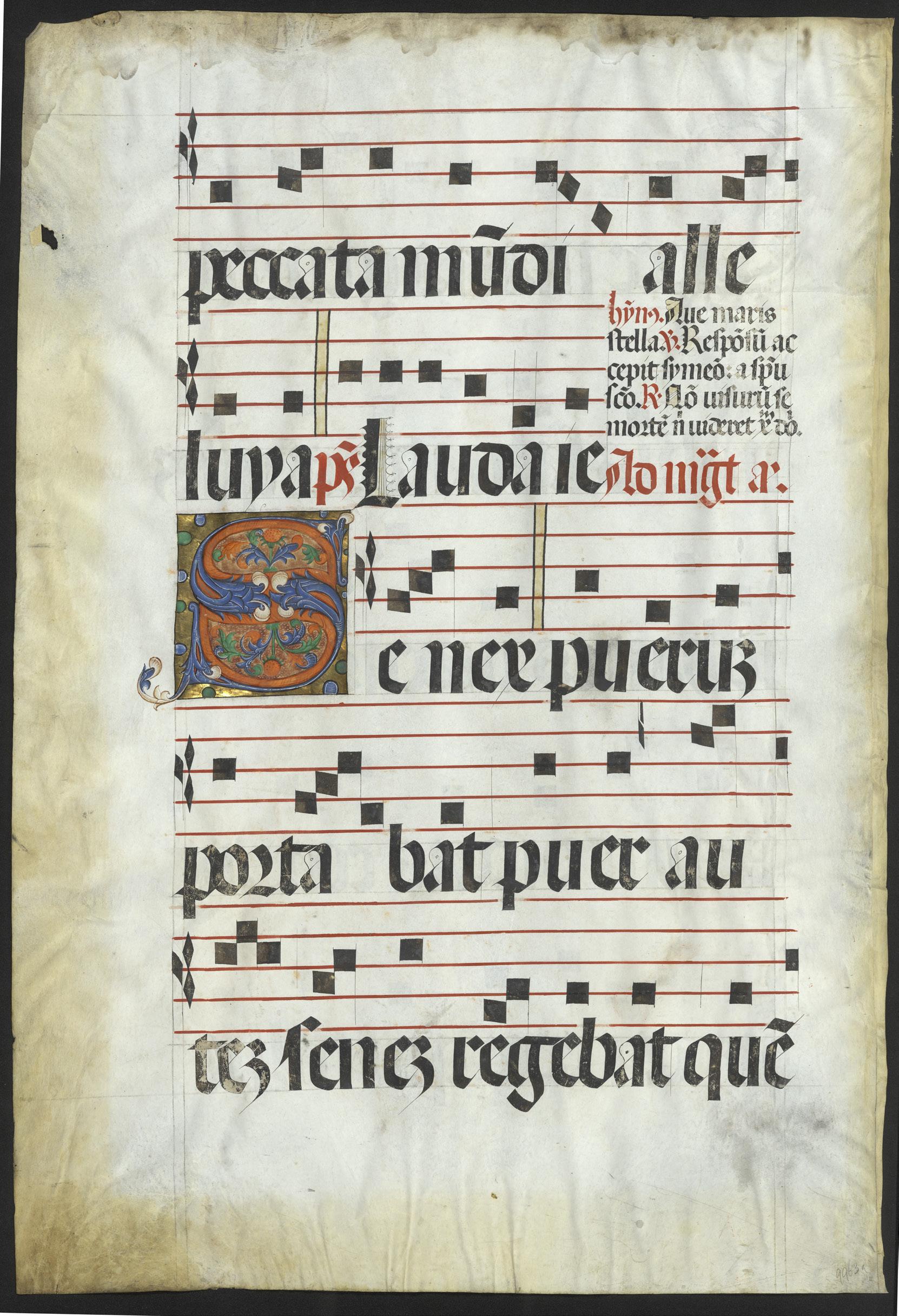

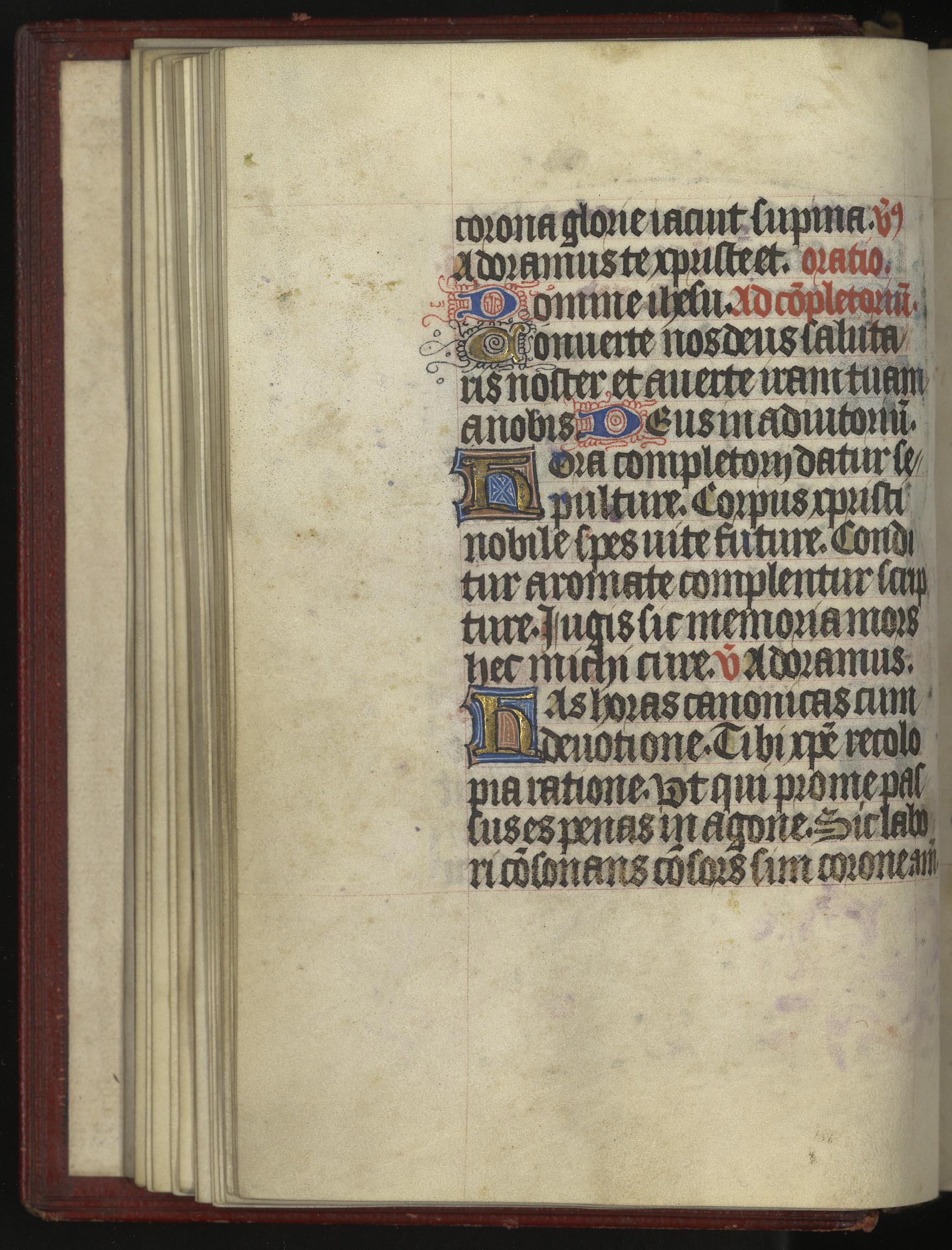

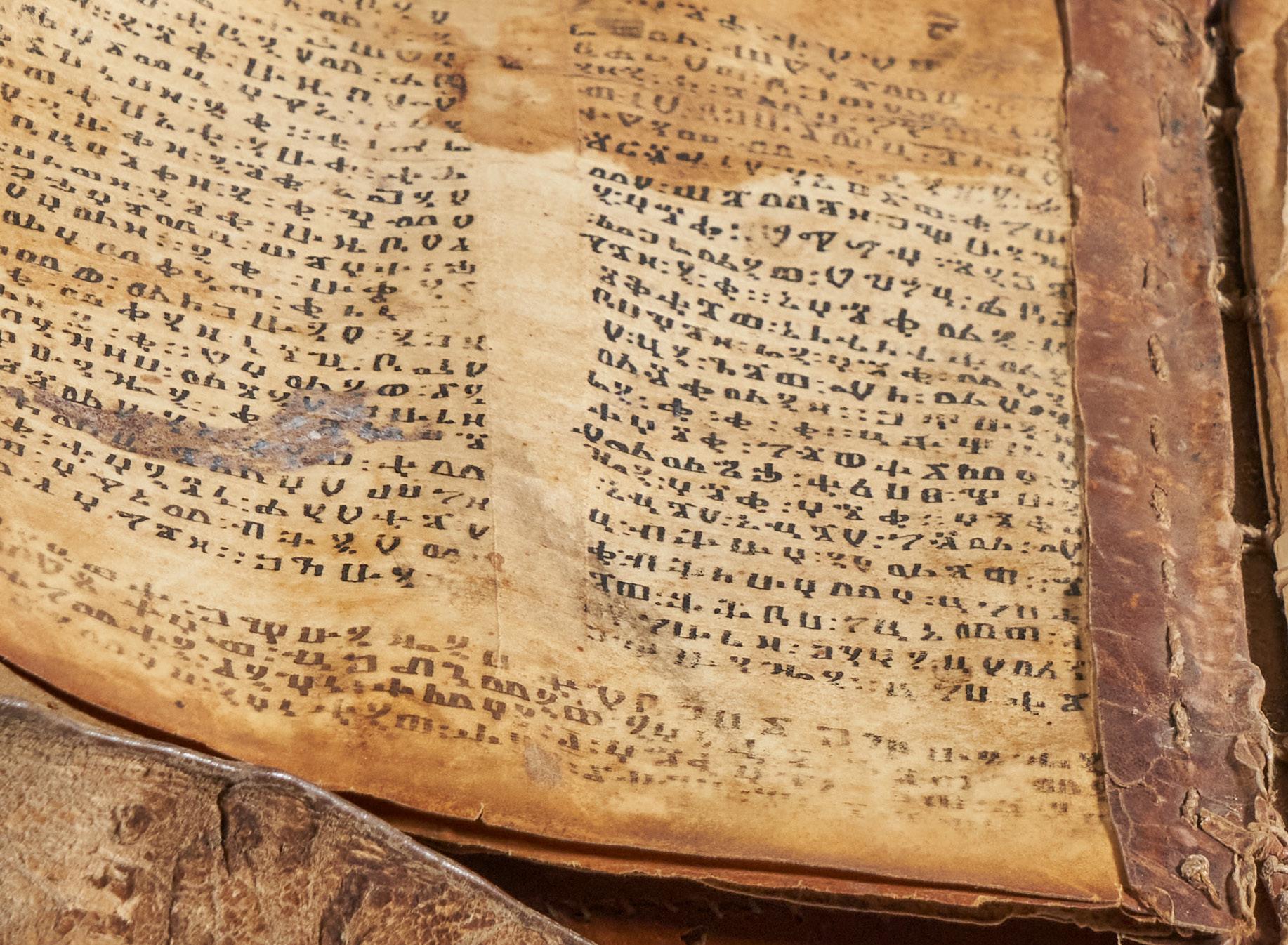

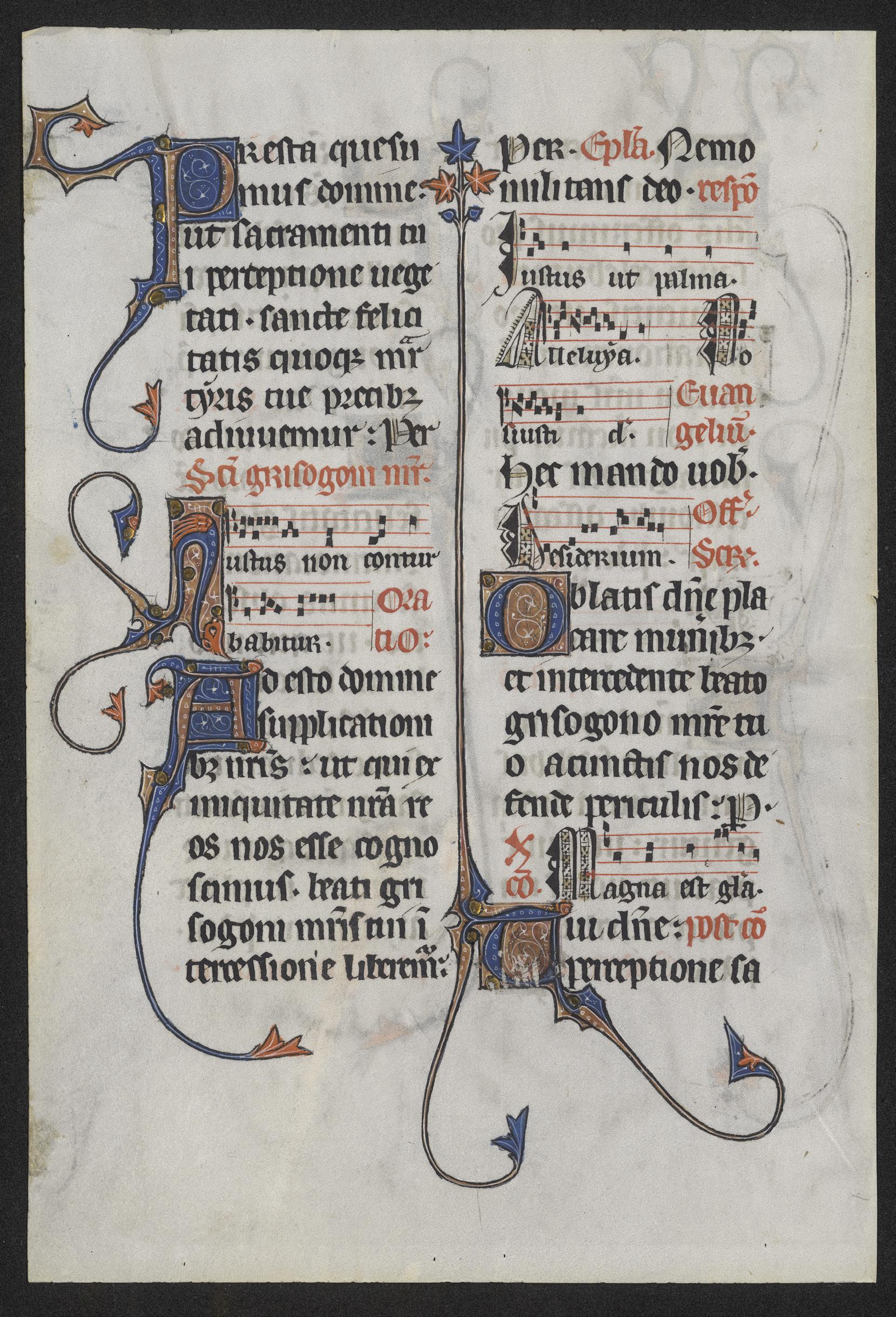

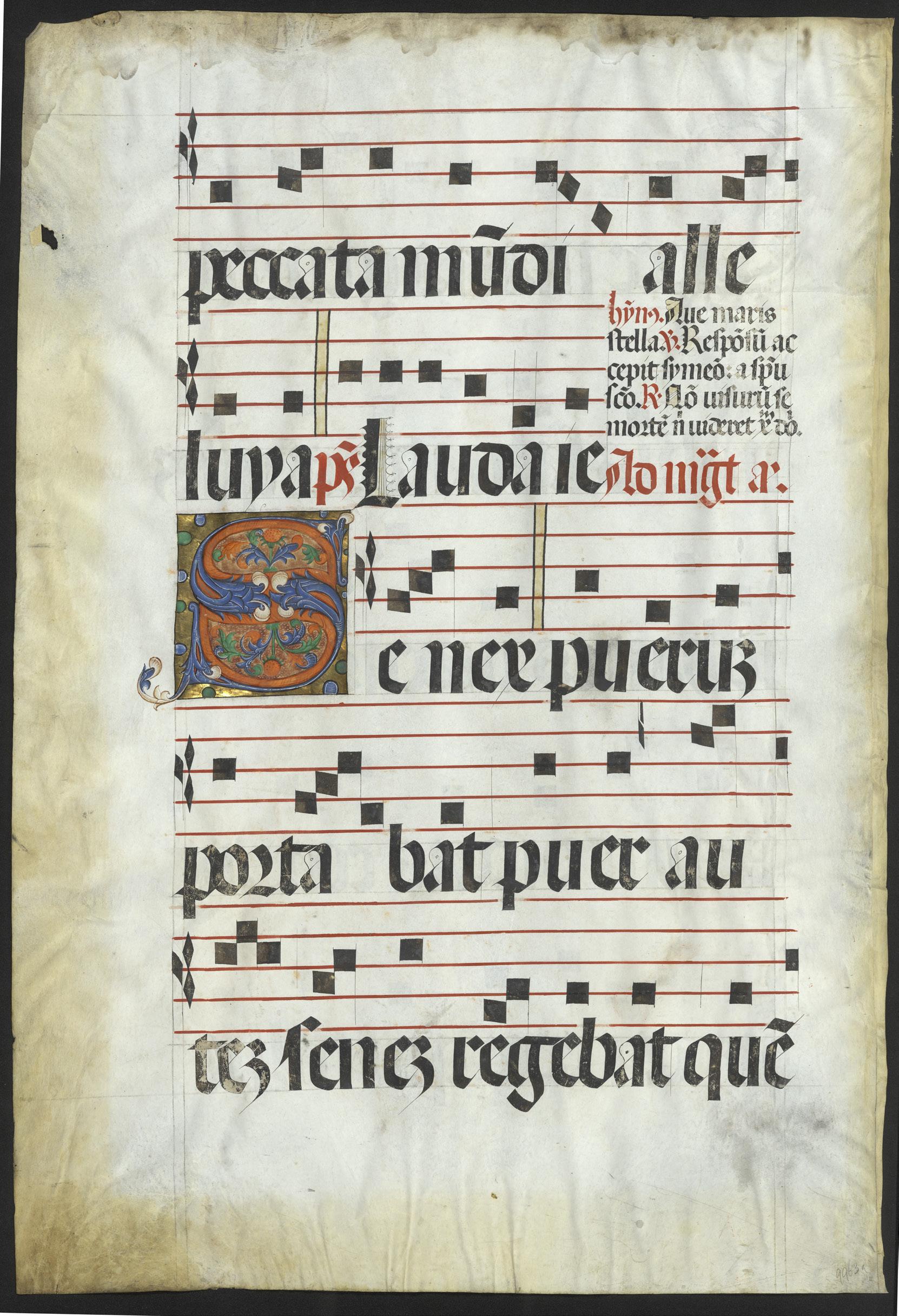

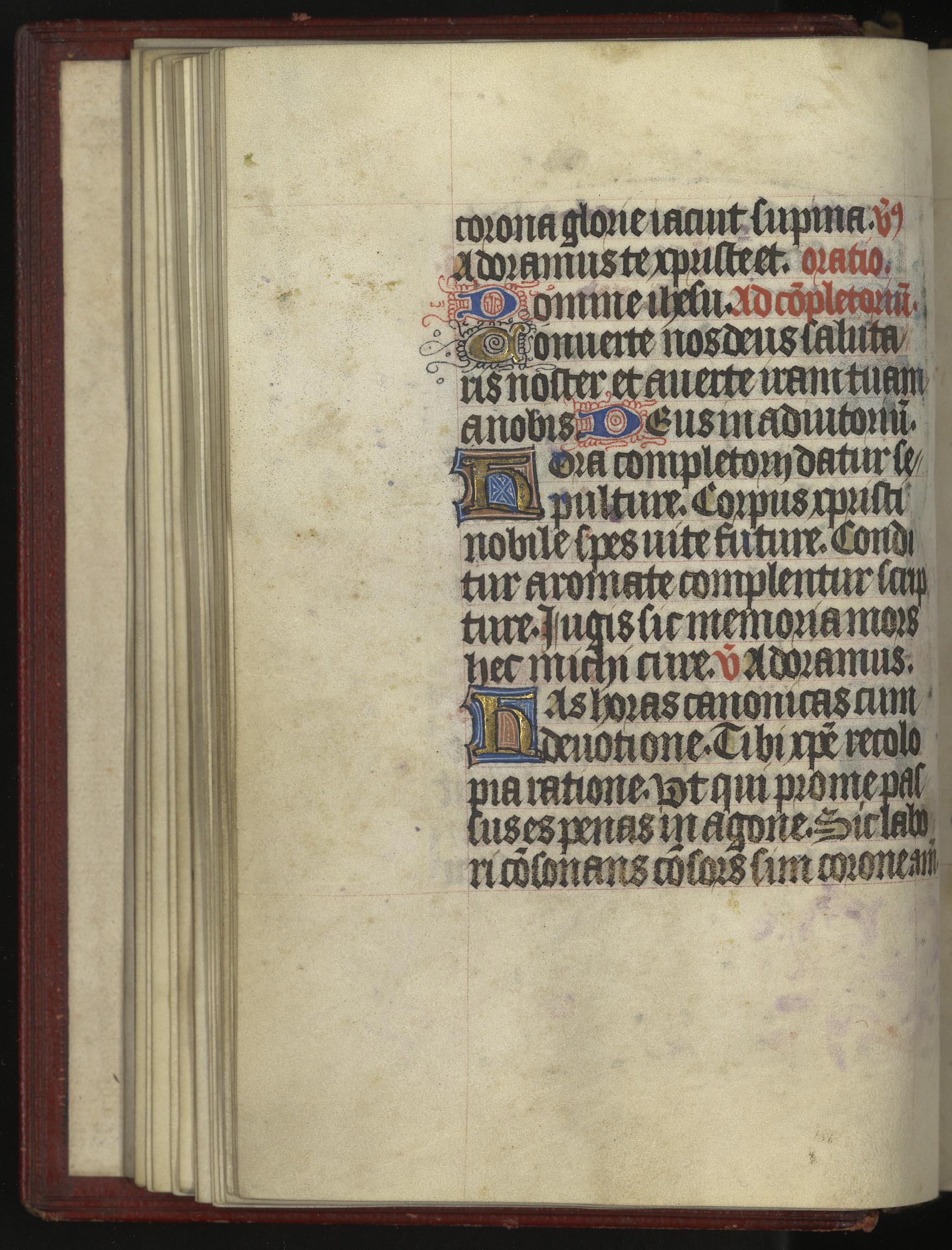

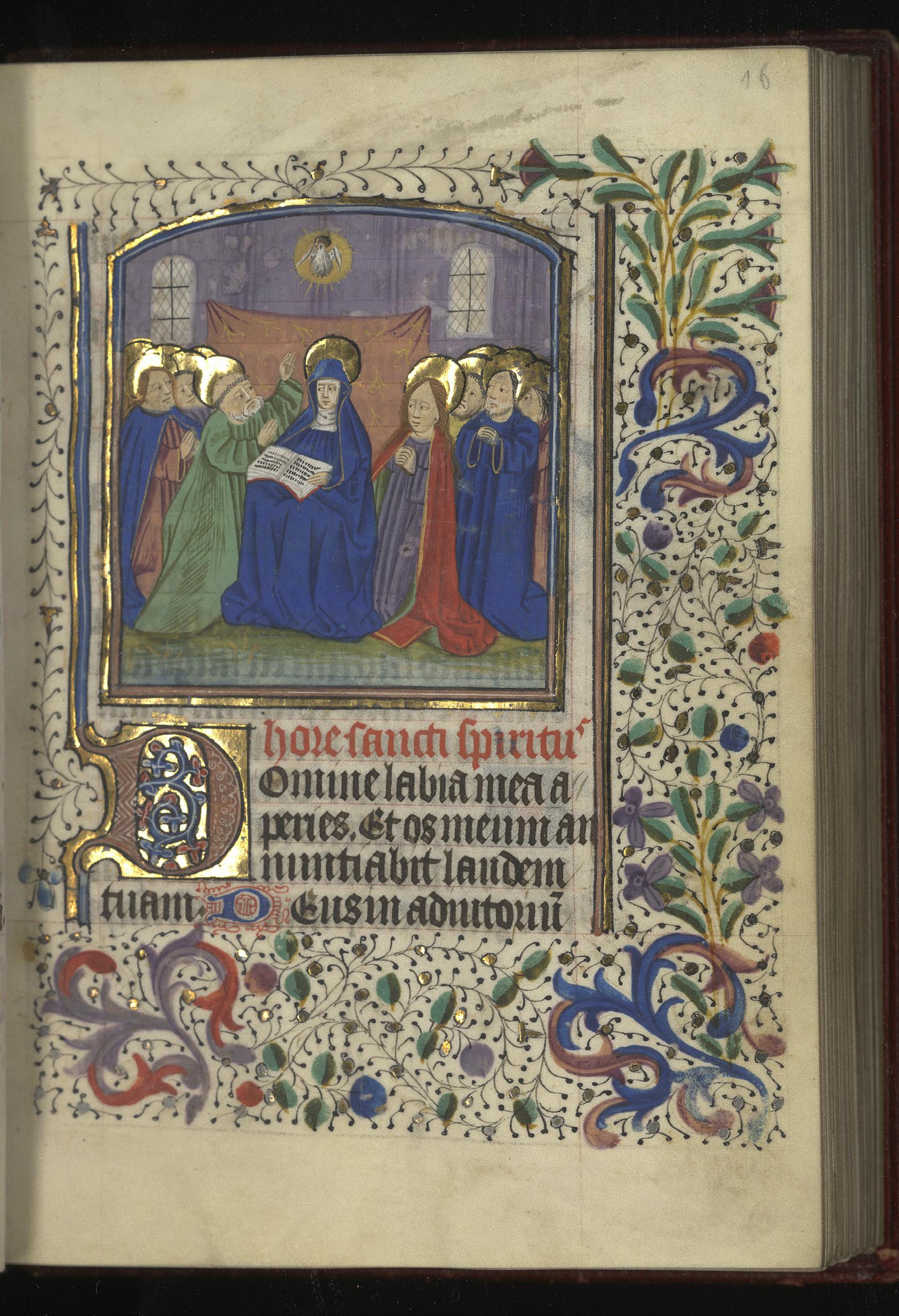

Around the world, codices are packed with knowledge and meaning. The codex, or the structure composed of pages bound together on one side at a spine (what we usually refer to when we call something a “book”), is a complex, expensive object, requiring careful planning by its makers and patrons before and during its design and execution. Profoundly different in cost and means of production from a mass-produced modern paperback, the value of a premodern codex is difficult for modern users of books to grasp. Preserving and transmitting knowledge through texts and images, the materials of a manuscript (a book written by hand), and the great effort of its multi-step production, demonstrate that it is both valuable and requiring of careful planning.

The codex first appeared in the early Middle Ages, largely eclipsing (although not entirely replacing) scrolls, ostraca, and wax tablets from antiquity as formats for conveying information in image and text.1 Its compact, sturdy form was advantageous, as well as the use of both sides of pages (recto and verso). Likewise, its bound structure allowed information encoded into its pages to be indexical and easily accessible, a system of reference different from the sequential access of a scroll.2

Although many other supports were used (including papyrus, wax, wood, ceramic, and paper), the great majority of medieval manuscripts were made from parchment, or animal skin. The number of animals required for a manuscript project and the long process of cleaning, depilating, stretching, and drying the parchment is an indication that a manuscript’s value was intimately tied to its materials.3 The making of text and images on the

laboriously prepared surfaces of manuscripts was complex, involving mapping out eventual pages and their sequencing for later binding on large expanses of parchment. Both ink and pigments had to be collected and made.4

Text pages were ruled and then inscribed with inks. Some surviving partially complete manuscripts show that the next step involved the adhesion of gold leaf applied to the surface using a mordant. Following this, the scribe or artist painted the illuminations. Finally, the manuscript makers assembled these large sheets of parchment into quires, which were then bound and stored.5

Medieval book makers and users cared about their manuscripts, and placed a high value on the materials required for their construction. This appreciation is visible in the manuscripts themselves; even the unobservant user would have been aware of the codex as a rare and vulnerable object, materially embodying tremendous labor. Additionally, something of the great worth placed on a manuscript, and its elevation as a prized object in medieval societies, is evident in tantalizing textual references. One such reference by the ninth-century Theodore the Studite6 lists penances for transgressions of monastic duties by librarians, users of books, and manuscript scribes.7 For the librarians—the caretakers of the Monastery of Stoudios’ precious library in present-day Istanbul—and borrowers, he indicates:

If anyone takes out a book and does not take good care of it; or if he touches the book of another without the permission of him who has taken it out; or if, grumbling, he seeks a book other than that which he has already taken, let him touch no book whatsoever the whole day.

If the Librarian does not show proper solicitude [for the books], shaking and re-stacking and dusting each one, let him eat no cooked food.

If anyone is found hiding a book in his cell which, without good excuse, he does not give back the moment the Librarian strikes [the gong], let him stand in the refectory.

Likewise, the great cost of materials, the importance of staying true in the copying of a text, and the respect of other scribes is revealed in Theodore’s rules for those working in the scriptorium:

If anyone makes more glue than is necessary, and wastes it by letting it sit too long, fifty genuflections.8

If anyone does not take good care of the quire [in which he is writing], as well as the book out of which he is copying, putting both away at the proper time, and does not retain the spelling, accentuation and punctuation [of the original], one hundred and thirty genuflections.9

If anyone recites by heart [anything] from the book out of which he is copying, let him not attend Church for three days.

If anyone reads more than is written in the book out of which he is copying, let him eat no cooked food.

If anyone breaks his pen out of anger, thirty genuflections.

If anyone takes up the quire of another without the consent of him who is writing in it, fifty genuflections.

| 11

If anyone does not follow the instructions of the Chief Scribe, let him not attend Church for two days.

If the Chief Scribe distributes the work with partiality towards anyone; or if he does not carefully maintain the pieces of parchment and the tools for binding, lest any of the things used in this work be ruined, let him do one hundred and fifty genuflections and not attend Church.

For modern audiences, Theodore’s list begins to nuance how profoundly medieval bookmakers held their manuscripts dear. When it comes to the extraordinarily high cost of producing a manuscript,10 the default assumption in modern eyes seems to be that its expensive materials and the great effort of its making are a display of conspicuous consumption on the part of patrons and book owners.11 While this is certainly true—and explicit dedicatory inscriptions and colophons do survive, which ensure that a patron, monastic institution, or collection was recognized or associated with a manuscript—it is a reductive position in that it negates the specific meanings and, indeed, the power that certain ideas and materials had for medieval book users themselves.

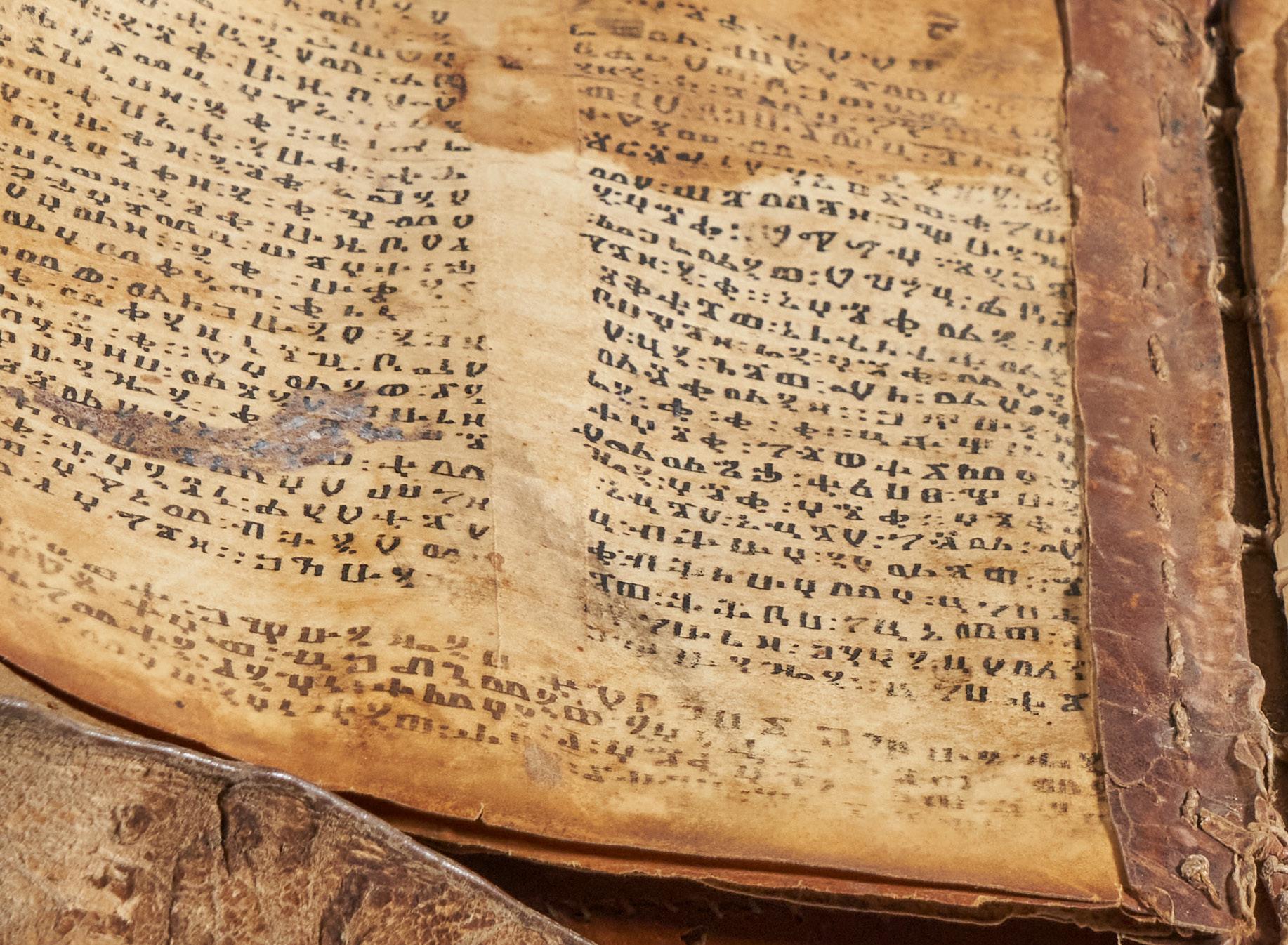

The medieval manuscript, with its intricate illuminations, calligraphy, and bound parchment, exists as a testament to the profound role of the book as both a vessel and transmitter of knowledge and ideas. The codex format laid the foundation that would allow the book to grow into various creative forms through the early modern period into our contemporary world. The wide adoption of moveable type in the fifteenth century—a technology that existed for centuries in China and Korea, and which was later independently innovated by Johannes Gutenberg in Mainz—revolutionized the production of books, making

them more accessible and less costly to produce than their handwritten predecessors.12 However, handmade codices, far from disappearing, flourished around the world; as witnessed in bookmaking in the Ottoman, Safavid, and Mughal cultural spheres, the hand-written manuscript continued to be of supreme value.13 Such was also the case in Ethiopian and Southeast Asian bookmaking traditions, where painting and writing texts by hand continued to be paramount.14

Rather than diminishing the value and artistic potential of the book, the technological inventions of modern printing in all its forms—including moveable type, relief printing, engraving, and lithography— might better be understood as paving the way for an explosion of creative bookmaking. In Japan, mokuhanga or relief woodblock printing allowed the dissemination of thousands of books. In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, a renewed appreciation for the craftsmanship of the medieval codex inspired publishers such as the Kelmscott Press, which printed books that were not merely texts but works of art in their own right—emphasizing that even in an age of increased accessibility, a book could still be a rare and beautiful object.15

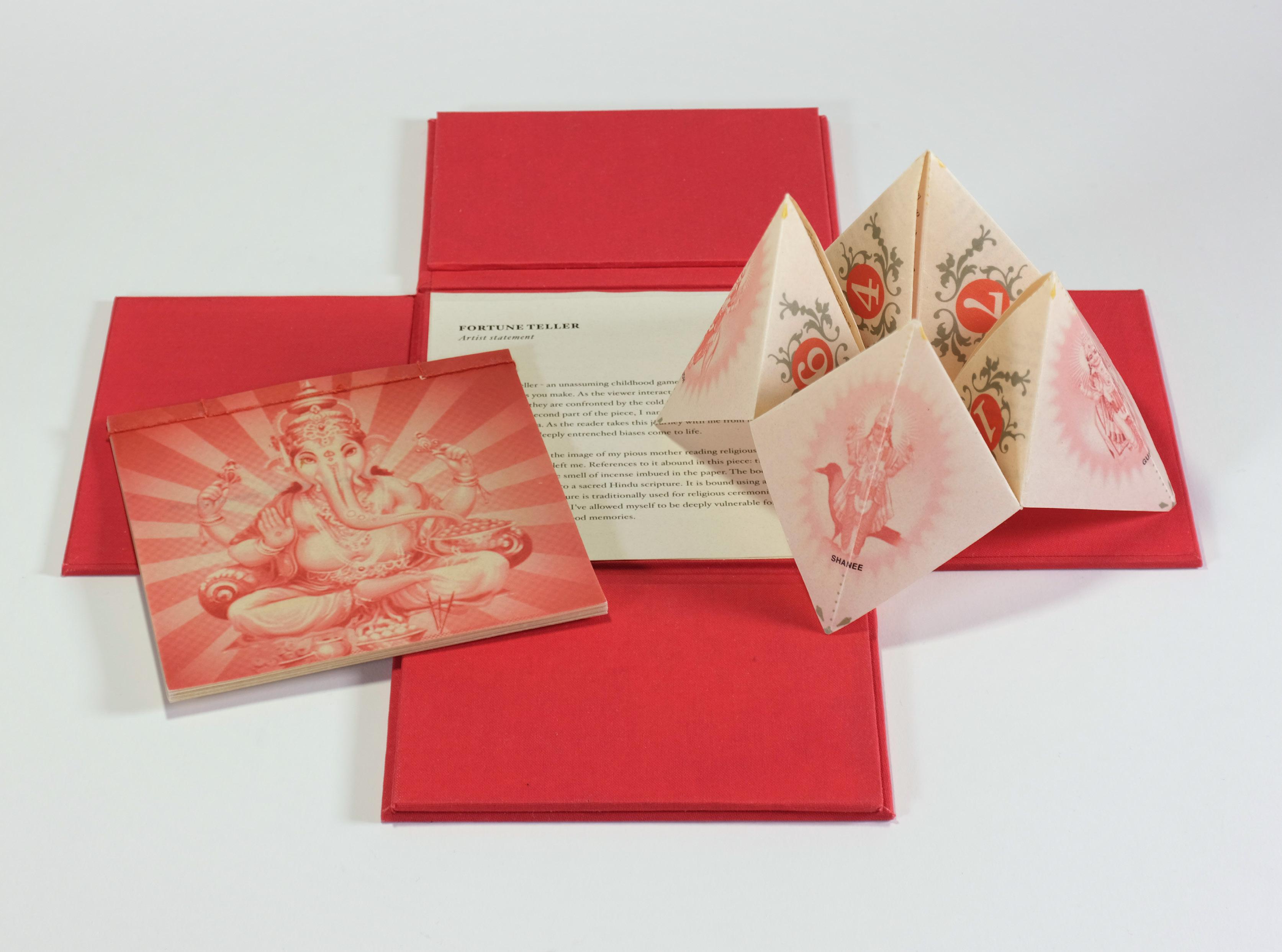

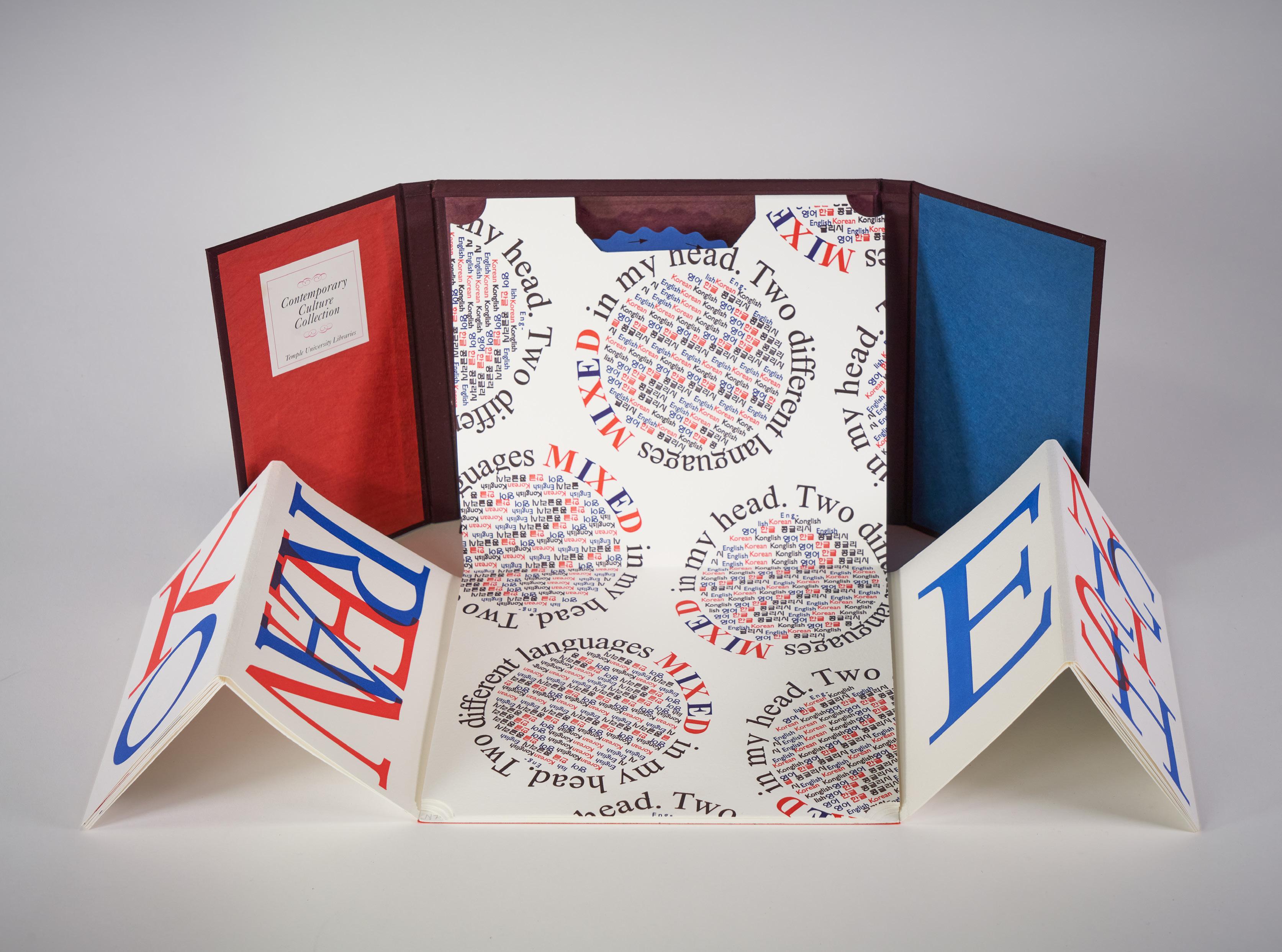

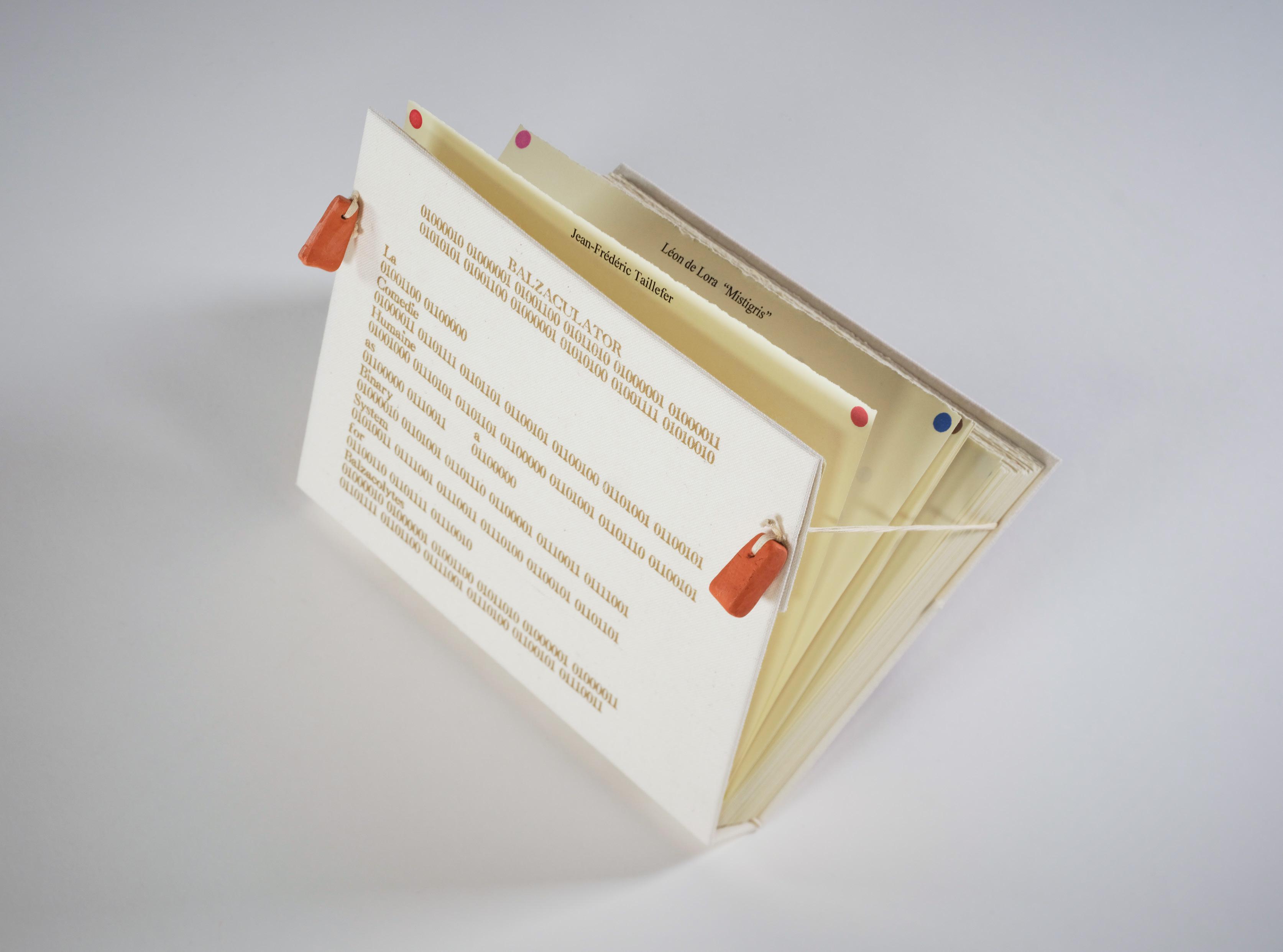

The tradition of the artistic book has continued to be explored through the twentieth and into the twenty-first century. Modern and contemporary artists, including those represented in this catalogue, have taken the format of the codex and pushed its boundaries, experimenting with its structure, materials, and the very concept of what a book can be.16 Embracing a wide range of forms—from pop-up books to those made of fabric and even books that incorporate digital elements—such artist books reflect an ongoing dialogue between tradition and innovation. These works often challenge the reader’s perception of what constitutes a book, inviting a deeper engagement with the text and images contained

within. Contemporary artist’s books likewise often explore the book as an object of interaction, not merely a passive vessel of information.17 By altering the structure of the codex—through unconventional binding techniques, foldouts, and sculptural elements—artists invite readers to engage with the book in a physical, tactile manner that harkens back to the (oftentimes) intimate experience of handling a medieval manuscript. This physical engagement adds layers of meaning, making the act of “reading” an affective experience that encompasses sight, touch, and sometimes even sound.

Despite vast technological changes that have transformed how we produce and consume information,18 the enduring legacy of the codex is evident in the continued vitality of the book object as a creative form. As the works in this catalogue from across the globe19 demonstrate, even in a digital age, the book remains a powerful medium for expression and cultural exchange. Rather than follow a chronological or geographic narrative of the codex’s transformation as an elite, handwritten object of the Middle Ages to the innovative artist’s books of today, this catalogue and the accompanying exhibition consider the diverse and myriad ways that the art of the book convey meaning for those who make and use them. The thematic groupings chosen by the student curators, ranging from “Marking Time” to “The Shape of Writing,” “Economics and Labor” and “Visualizing Science,” “Performance, Music, Visual Arts,” “Poetry, Philosophy, and Thinking,” “Dynamic Book Structures,” “Embodied Perspectives and Identities,” and “Problematic Perceptions,” moves towards a global understanding of the book as more than a repository of text and image, but a means of human interaction, identity, and as agents of social justice.20

12 | The Art of the Book

The collection of objects in The Art of the Book underscores the adaptability and enduring appeal of the codex as a repository of creativity and continuing transmitter of ideas. Far from becoming obsolete, the book continues to be infused with meaning, its form

and content constantly reimagined by artists who respect its history while pushing its boundaries into new realms of possibility.

1. See the essay by Müge Durusu-Tanrıöver, “Before (the Art of) the Book” in this volume on the early history of writing.

2. Contrary to popular belief, scrolls did not disappear in the Middle Ages, and continued to be used and valued; see e.g. Memorandum de operationibus in this catalogue.

3. For a discussion on issues of materiality in medieval manuscripts with particular attention to the Byzantine world, see Joseph R. Kopta, “Materiality and Materialism of Middle Byzantine Gospel Lectionaries (Eleventh–Twelfth Centuries CE),” PhD diss. (Temple University, 2022).

4. Raymond Clemens and Timothy Graham, Introduction to Manuscript Studies (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2007), 18–34. For monographs on western medieval manuscript production and history, see Jonathan J. G. Alexander, Medieval Illuminators and their Methods of Work (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992), and Christopher de Hamel, A History of Illuminated Manuscripts, 2nd ed. (London: Phaidon, 1997).

5. Clemens and Graham, 49–64.

6. Jeffrey Featherstone and Meridel Holland, “A Note on Penances Prescribed for Negligent Scribes and Librarians in the Monastery of Studios,” Scriptorium 36, no. 2 (1982): 258–260; also referenced in Nancy Patterson Ševčenko, “Illuminating the Liturgy: Illustrated Service Books in Byzantium,” in Heaven on Earth: Art and the Church in Byzantium ed. Linda Safran (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1998), 186–228, at 190.

7. For a view on the authenticity of this text, see Hans–Georg Beck, Kirche und theologische Literatur im byzantinischen Reich (Munich: C. H. Beck, 1959), at 494.

8. Featherstone and Holland, “A Note on Penances,” question whether this rule applies to a bookbinder requiring glue, or to the shoemakers of the preceding section. For a brief but useful overview of Byzantine bookmaking, see Berthe van Regemorter, “La reliure des manuscrits grecs,” Scriptorium 8, no. 1 (1954): 3–23.

9. An early text proposing the systematic identification of Byzantine manuscript centers through copying and textual transmission, and a review of the state of the field at the time, is found in Jean Irigoin, “Pour une étude des centres de copie byzantins,” Scriptorium 12, no. 2 (1958): 218–27, 219.

10. Nicolas Oikonomides, “Writing Materials, Documents, and Books,” in The Economic History of Byzantium ed. Angeliki E. Laiou, (Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks, 2002), II:589–592, at 591, while not indicating the source of these numbers, claims that the price of a manuscript in the tenth century on average cost 21–26 gold nomismata against the cost of a cow (3), a warhorse (12), and a mule (15), or the annual salary of an official protospatharios (72).

11. This is a point raised also with regards to marble by Fabio Barry, Painting in Stone: Architecture and the Poetics of Marble from Antiquity to the Present (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2020).

12. See the essay by Ashley D. West, “Printing in Early Modern Germany,” in this volume on the European transition from manuscript to printed book in Northern Europe.

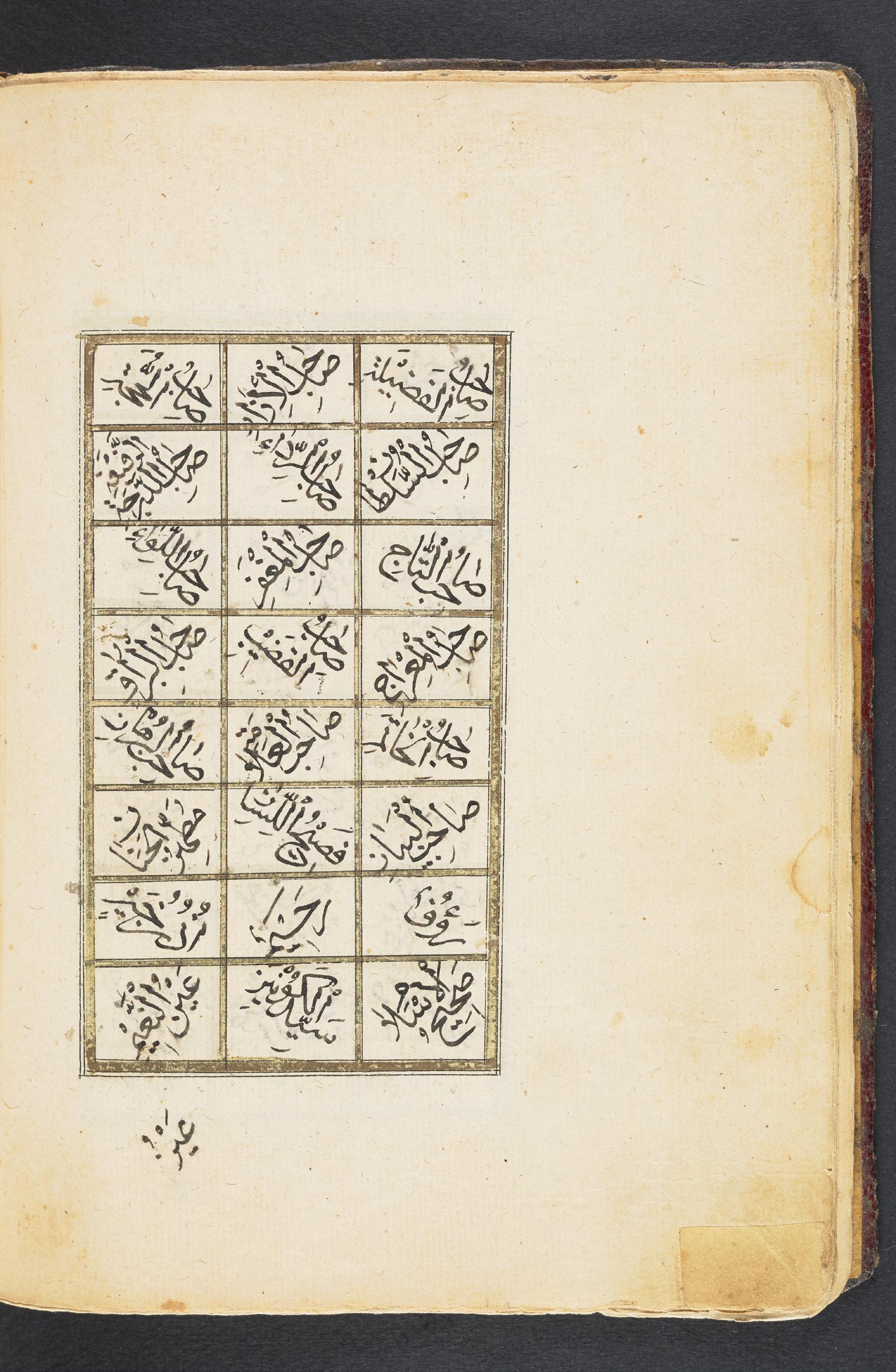

13. Özlem Yıldız discusses this tradition in the Ottoman context in “An Encounter with the Ottoman Book” in this volume.

14. These are by no means the only examples of manuscript cultures in the modern world.

15. In this volume, Alice M. Rudy Price, “The Artistic Book,” explores the nineteenth- and early twentieth-century tradition of artists’ books and presses.

16. See especially the “Dynamic Book Structures” section of this catalogue for innovations in the structure of the book object.

17. Interviews with artists James Rose Dewitt and Angela Lorenz in this volume explore the mediums of zines and artist books in terms of issues of accessibility, expression, process, and defining the book objects.

18. See Dot Porter’s essay, “Manuscripts and the Digital Humanities: Bridging the Past and Present,” in this volume for issues of the manuscript object in the digital world.

19. Scholarship that emphasizes a global history of the book is transforming the understanding of this object type; see e.g. Bryan C. Keene, ed., Towards a Global Middle Ages: Encountering the World through Illuminated Manuscripts (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2019).

20. I am grateful to Bryan C. Keene for visiting my graduate seminar early on and sharing their experience in the curation of premodern manuscript collections with an eye towards social justice, which helped frame the conversations that the student curators enjoyed through the semester. Some of Bryan’s thoughts are summarized in “A Vision for the Future of Manuscript Curation and Book History” in this volume.

A Look at a Book

A Look at a Book is a video series and public program hosted jointly by the Art History Department at the Tyler School of Art and Architecture and the Special Collections Research Center (SCRC), Temple University Libraries. In this virtual series, we explore the wonderful collection of rare books, manuscripts, zines, and artist books housed in Temple’s SCRC. Each week, via Zoom, scholars open a different artifact from the collection, flip through its pages, and share the knowledge within. This virtual series is open to the public and occurs weekly during the academic semester. Recordings of this series are on view in the gallery at Charles Library for the duration of the exhibition.

To view past episodes of A Look at a Book visit stellaonline.art/look-book.

A Look at a Book is a collaboration between the Art History Department at the Tyler School of Art and Architecture and the Special Collections Research Center (SCRC), Temple University Libraries. It is jointly organized by Joseph R. Kopta, Assistant Professor of Instruction, Art History, and Kimberly Tully, Curator of Rare Books, SCRC.

14 | The Art of the Book

Economics & Labor

Cuneiform Tablet Recording Sailors’ Wages

Dogale issued by Doge Girolamo

Priuli to Pandolfo Guoro, Captain of Famagusta, Cyprus

Libro de thesorero Diego de Salzedo para deste ano de 1571

Memorandum de operationibus

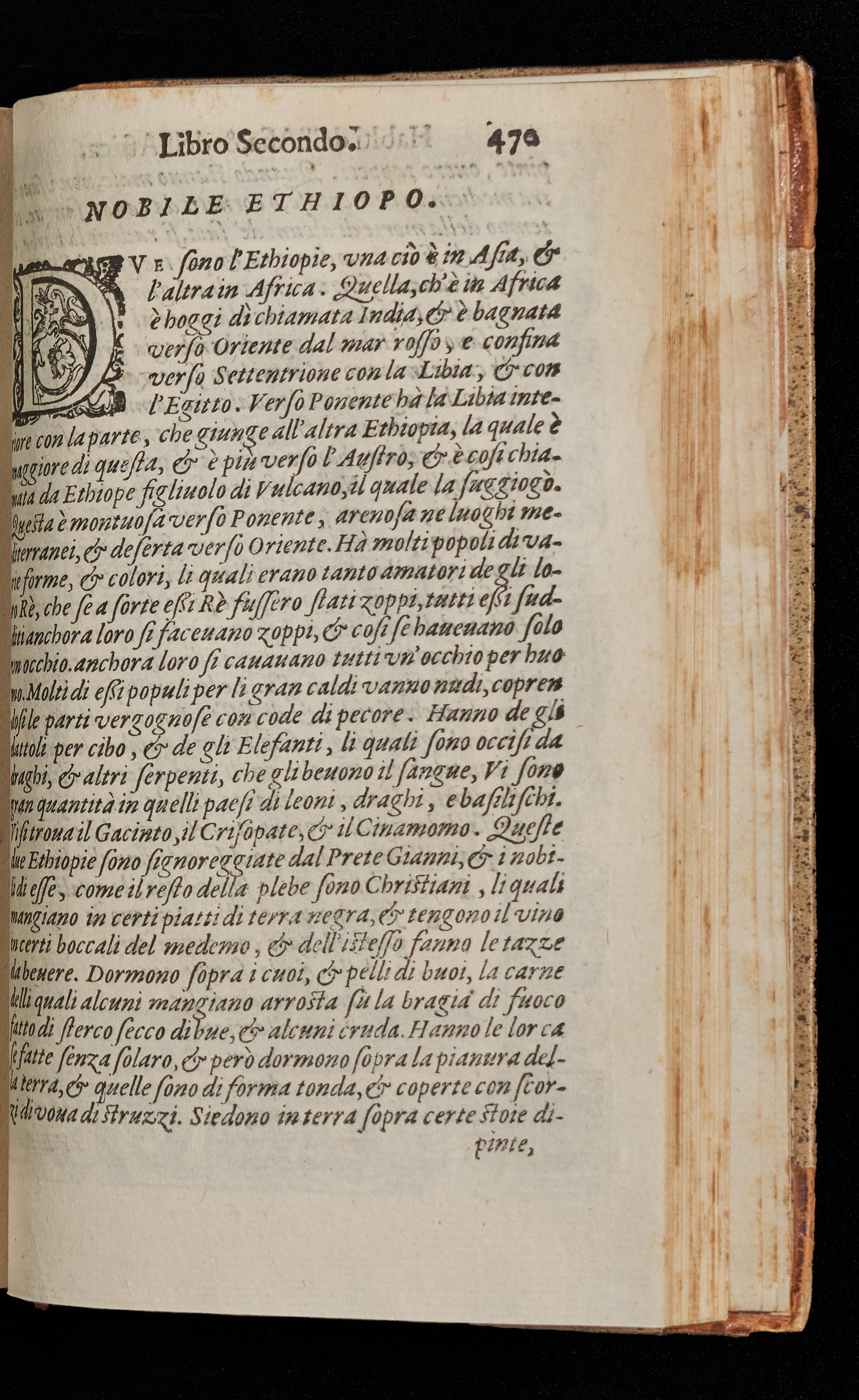

Questo e ellibro che tracta di marcantie et usanze di paesi

One of the strengths of the Special Collections at Temple University is the number of rare books and manuscripts relating to the history of business, economics, and labor. Most of the books included in this subsection entered the collection through the generosity of Dr. Harry A. Cochran, who from 1939–1960 was the Dean of the School of Commerce (now the Fox School of Business). Cochran’s personal collection of rare books focused thematically on the history of commerce and the many forms that it took throughout the centuries and across the globe.

The oldest object in Special Collections is sourced from Cochran’s collection: a 4,000-year-old cuneiform tablet from the ancient Mesopotamian city of Ur that was used to document the labor and wages of sailors. Similarly, a parchment scroll from fourteenthcentury England, Memorandum de operationibus accounts the distribution of wages.

Several of the other notable mercantile texts date to the Renaissance in Southern Europe, such as the Book of Trade and Customs of Countries, a business manual written in vernacular Italian from fifteenth-century Florence that detailed the trade practices and customs duties of over 195 cities in the Mediterranean world. Another example is a painting that once illustrated the first page of an employment contract issued by the Doge of Venice to one of his senators in 1560 CE. A final example is a sixteenth-century ledger that records taxes levied by the Spanish imperial crown upon what is now Peru. This orderly financial account documents the extraction of natural resources from land that the Spanish

had recently colonized and the theft of precious materials from a civilization they had enslaved.

While these books are presented in different formats, they all served utilitarian purposes. These objects demonstrate the ways in which labor, currency, and economics have been a fundamental component of our collective history for millennia.

Emma P. Holter

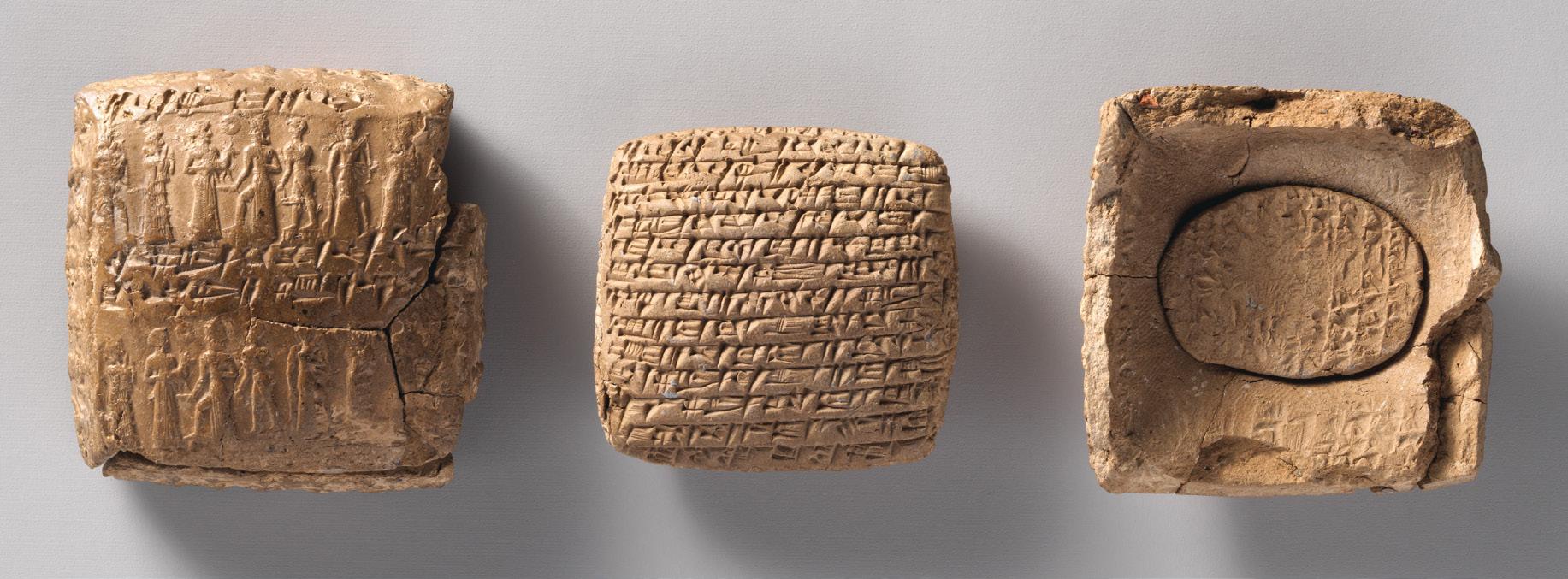

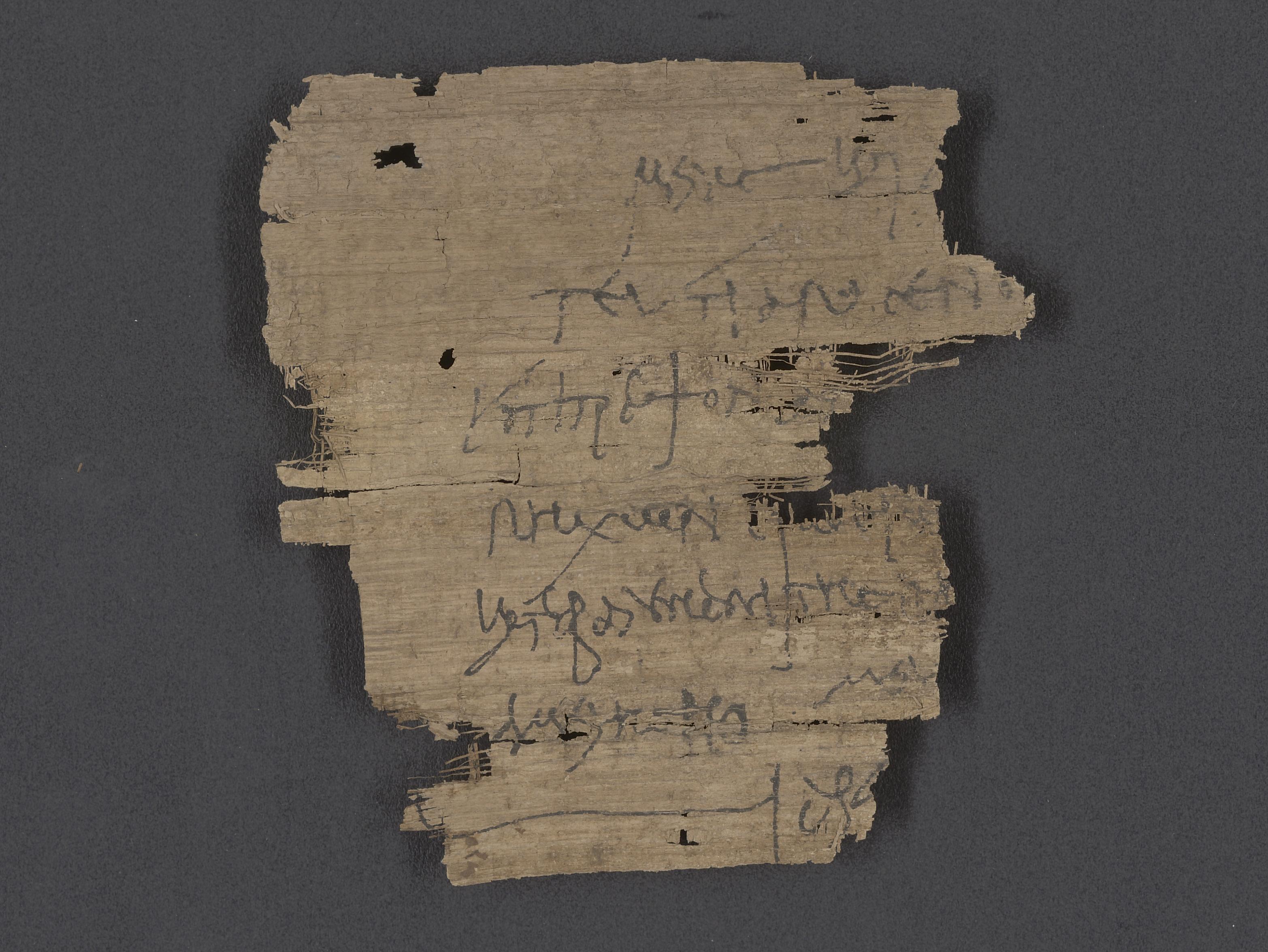

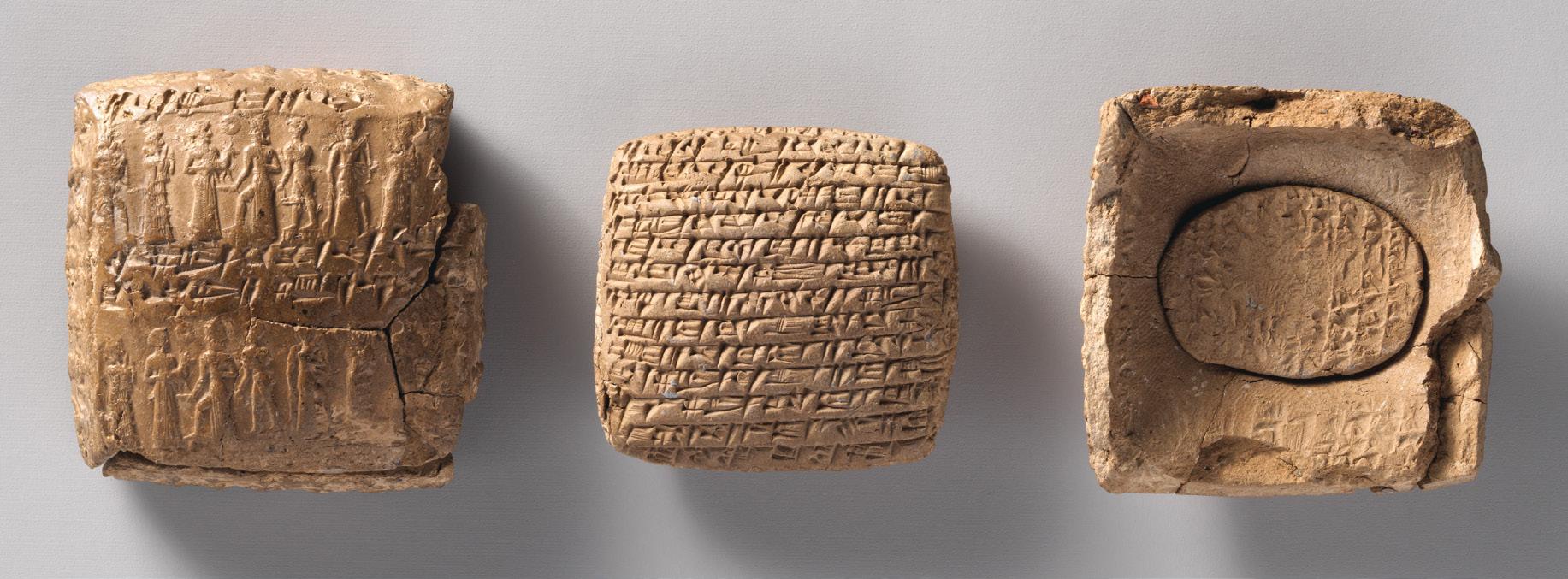

Cuneiform Tablet Recording

Sailors’ Wages

Ur-dingir-ra

Ceramic earthenware

4 x 4.3 x 1.5 cm

ca. 2150—2000 BCE, 3rd Dynasty of Ur (Neo-Sumerian Period), Sumeria (present-day Iraq)

SCRC 47 Cochran

Roughly 4,100 years ago, Ur-dingir-ra, a Sumerian scribe, sat down to “balance his accounts.”1 Recorded in soft wet clay that has dried and hardened, this diminutive tablet was the result. It describes payment to a sailor for services rendered.

Ur-dingir-ra, like other scribes in ancient Mesopotamia, used a dual system of mark-making to record the information on the tablet’s surfaces. First, he rolled out a “notarial” impression using a cylindrical seal into the surface of a small lump of clay. This seal includes three figures in a typical image called a “presentation scene.” At left, a standing goddess presents a human figure to a seated deity at right, identifiable as such by his conical cap; both standing figures raise their hands in veneration of the seated god. The cylinder seal also impressed three registers of text in a writing system called cuneiform (“wedge-shaped”).2 This Sumerian-language text is read by rotating the tablet 90 degrees counterclockwise from the figures. In this new position, reading from left to right, and top register to bottom, the inscription gives the scribe’s name: “Urdingir-ra, Scribe, Son of […].” Analogous to a modern-day notarial document, the impression has been made multiple times on both sides of the tablet, certifying the transaction of wages paid as witnessed by Ur-dingir-ra.3

Atop the now-impressed clay tablet, Ur-dingir-ra then pushed a reed into the still-soft clay to write the actual transaction—in this case, a payment of barley made to a sailor as wages, along with an indication of the year. Was this tablet created and then handed to the sailor? Or was it created by the scribe and set aside as a record of payments made? We will likely never know, but as a so-called wage tablet, we might do well to think of this object less as a receipt, and more as a Sumerian bureaucratic way of tracking expenses.4

Bradford Davis

1. I am grateful to Müge Durusu-Tanrıöver for lending her expertise as I was writing this entry.

2. C. B. F. Walker, Cuneiform (Berkeley and London: University of California Press and British Museum, 1987); Jean-Jacques Glassner, The Invention of Cuneiform Writing in Sumer (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003).

3. The entire process of making and reading the object in its Sumerian context has been explained by Müge Durusu-Tanrıöver, “Cuneiform tablet recording sailors’ wages, Ur III,” A Look at a Book, episode 9, April 19, 2023, stellaonline.art/look-book

4. Hans J. Nissen, Peter Damerow, and Robert K. Englund, Archaic Bookkeeping: Early Writing and Techniques of Economic Administration in the Ancient Near East (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1993).

Economics & Labor | 21

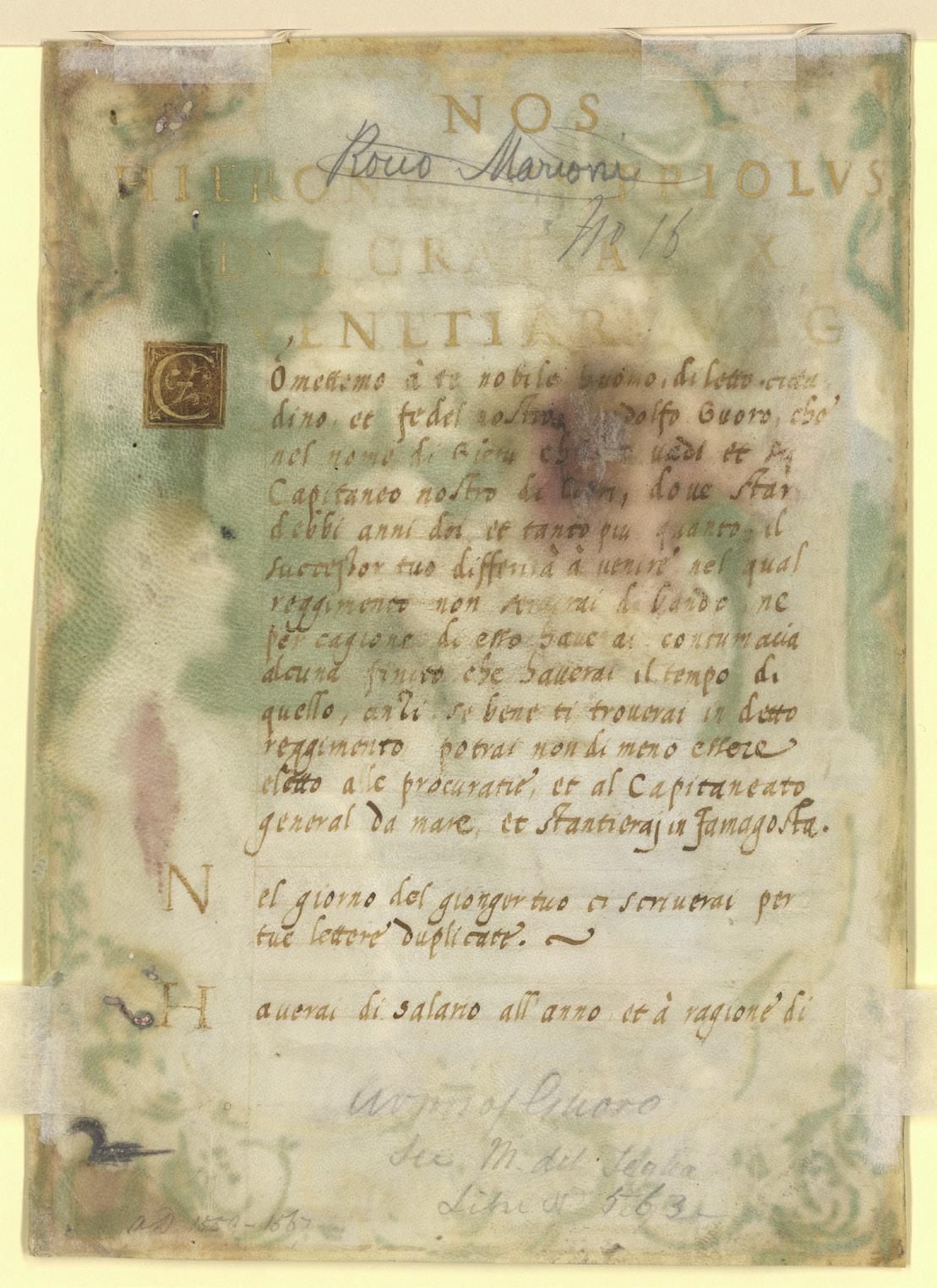

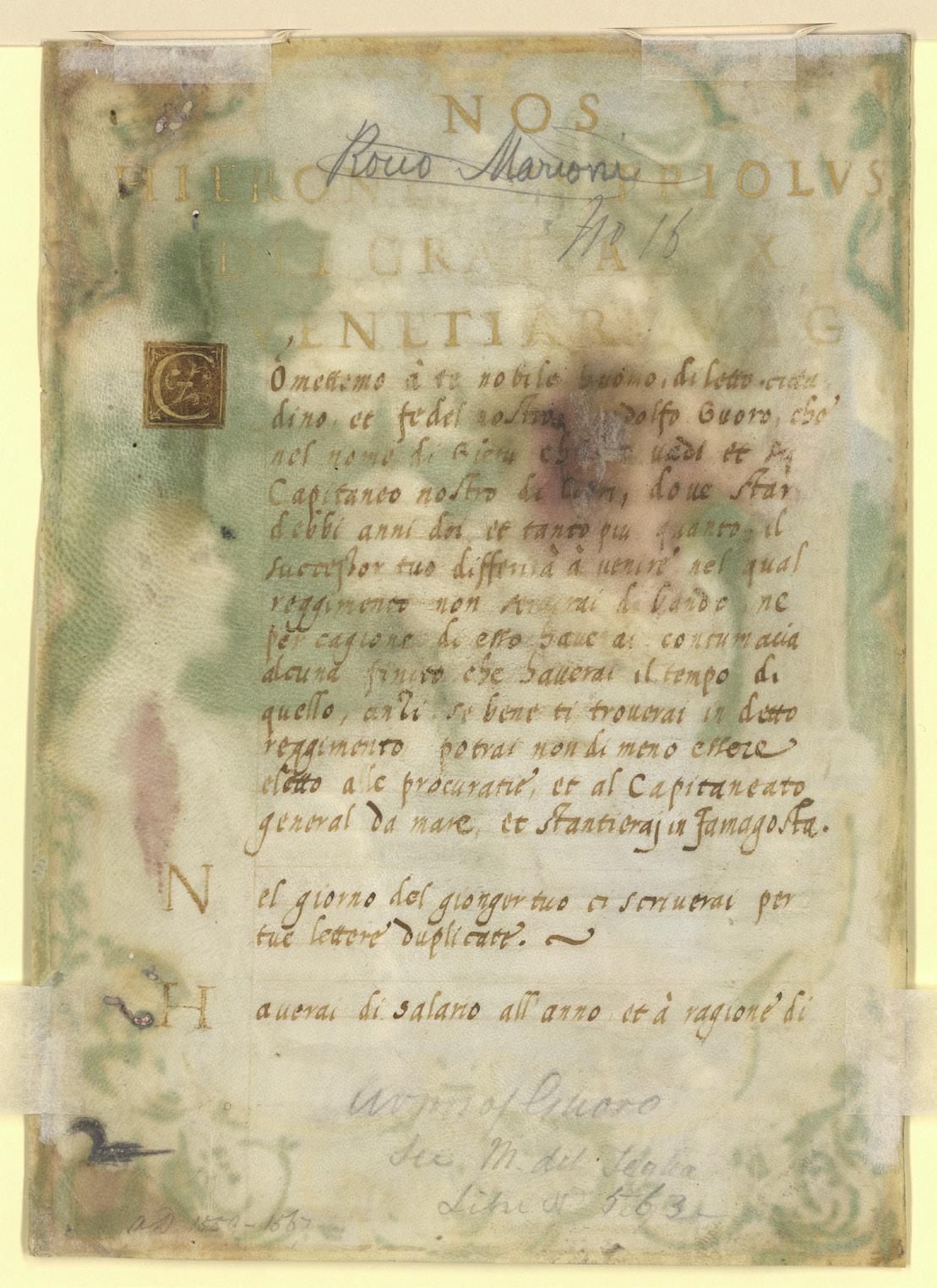

Dogale issued by Doge Girolamo Priuli to Pandolfo Guoro, Captain of Famagusta, Cyprus

Attributed to Master To. Ve. Illumination on parchment

22.7 x 16.2 cm

1560-61 CE, Venice, Venetian Republic (present-day Italy)

SCRC 375

22 | The Art of the Book

Dressed in the sumptuous red velvet garments of a Venetian senator, Pandolfo Guoro kneels in adoration before Christ. Despite the religious subject matter of the illumination, this image once decorated the opening page of a secular, official document, a dogale Dogali transmitted power from the Doge of Venice to an individual and outlined their legal obligations, responsibilities, and functions. This particular dogale was issued by the Doge Girolamo Priuli to nominate the Venetian senator Pandolfo Guoro as the capitan of the city of Famagusta in present-day Cyprus. Around 1560, when this legal document was drawn up, Cyprus was a strategically important stronghold in the Venetian empire because it was a stop for pilgrims en route to the Holy Land, and close to trading partners in Alexandria and Damascus. Much like a job description, the dogale would have outlined the role’s expectations, responsibilities, and functions for Guoro before he accepted his post and set sail for Famagusta. The details of his appointment begin with an inscription on the back of this image. However, one key piece of information is missing that would have been quite important to Guoro: his salary. The final line on the verso of this document states, “You will have the annual salary of…,”1 but the crucial number is nowhere to be found. Presumably the amount would have been included on the following page, but unfortunately that detail has not come down to us.

It is uncertain who painted this illumination, but based on the style of the decorative frame, scholars have likened it to the work of Master To. Ve. whose workshop was actively illuminating dogali between 1550 and 1570. There are two examples of dogali signed by Master To. Ve., now in the Fitzwilliam Museum and the Cini Foundation, that have very similar decorative frames around the illumination.2

Emma P. Holter

1. “Haverai di salario all’anno et à ragione di”… Transcription by Mario Sassi.

2. Consuelo Dutschke, “Leaf from a Dogale,” in Leaves of Gold: Manuscript Illumination from Philadelphia Collections ed. James R. Tanis (Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2002), 222–23. Cat. 77.

Economics & Labor | 23

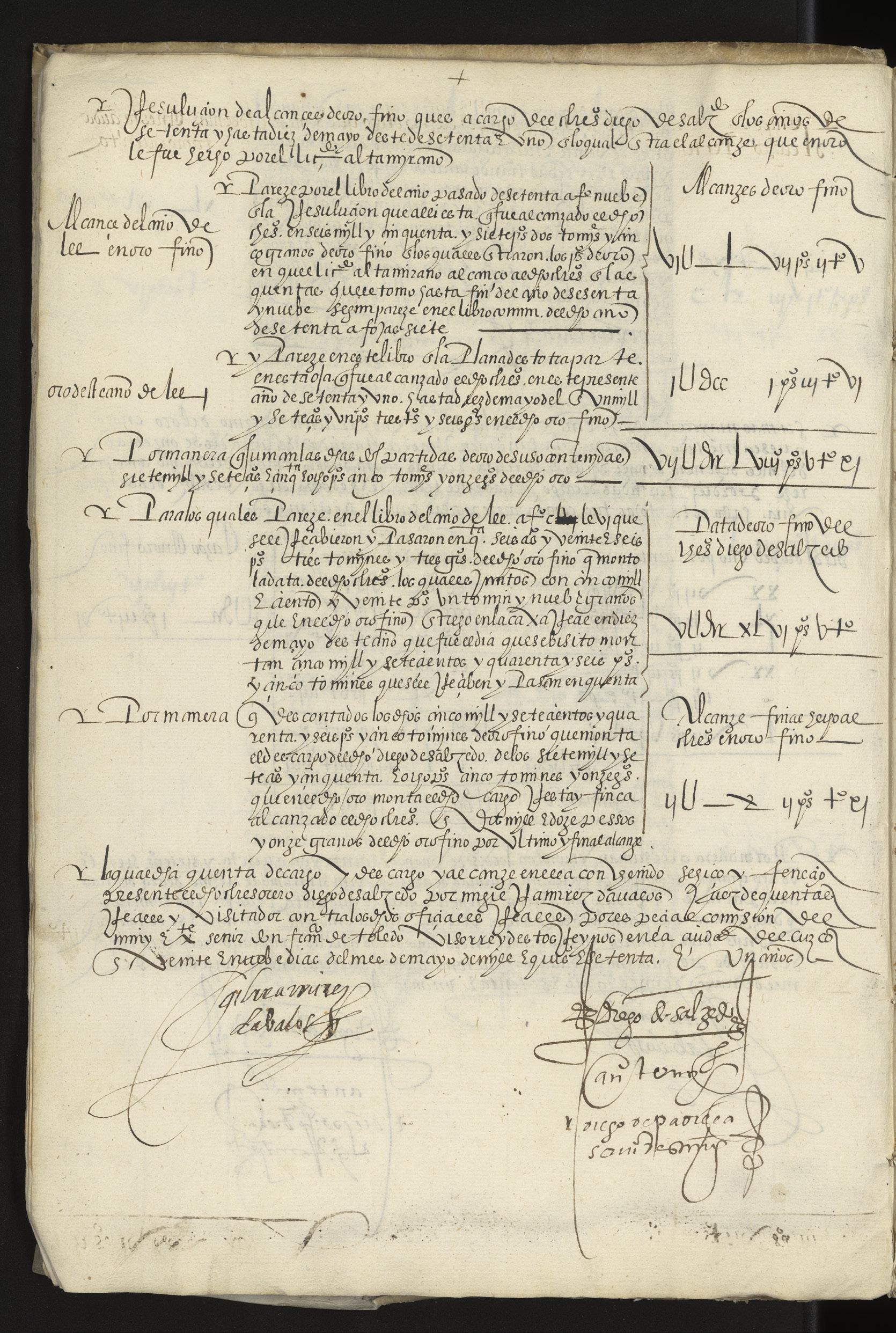

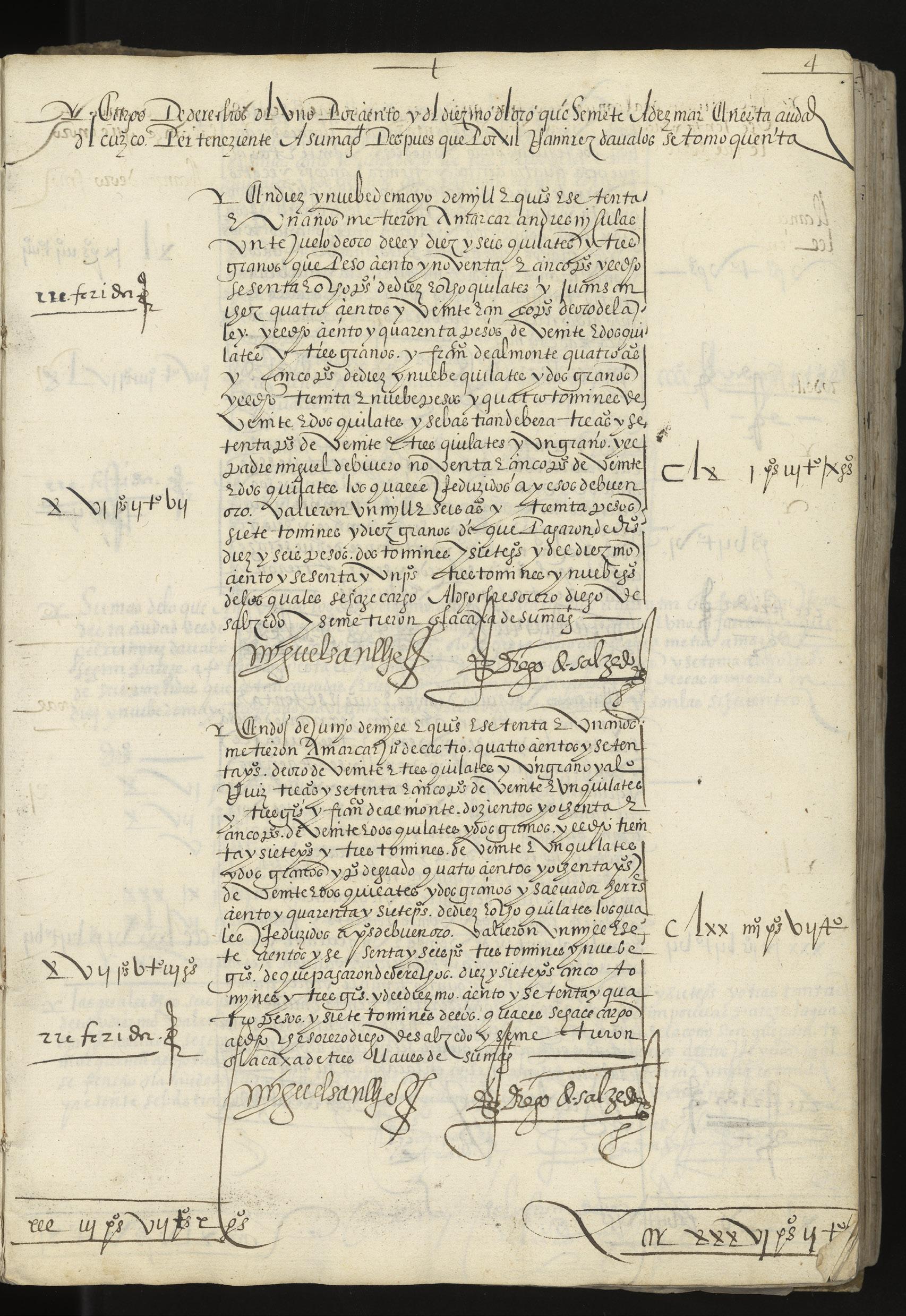

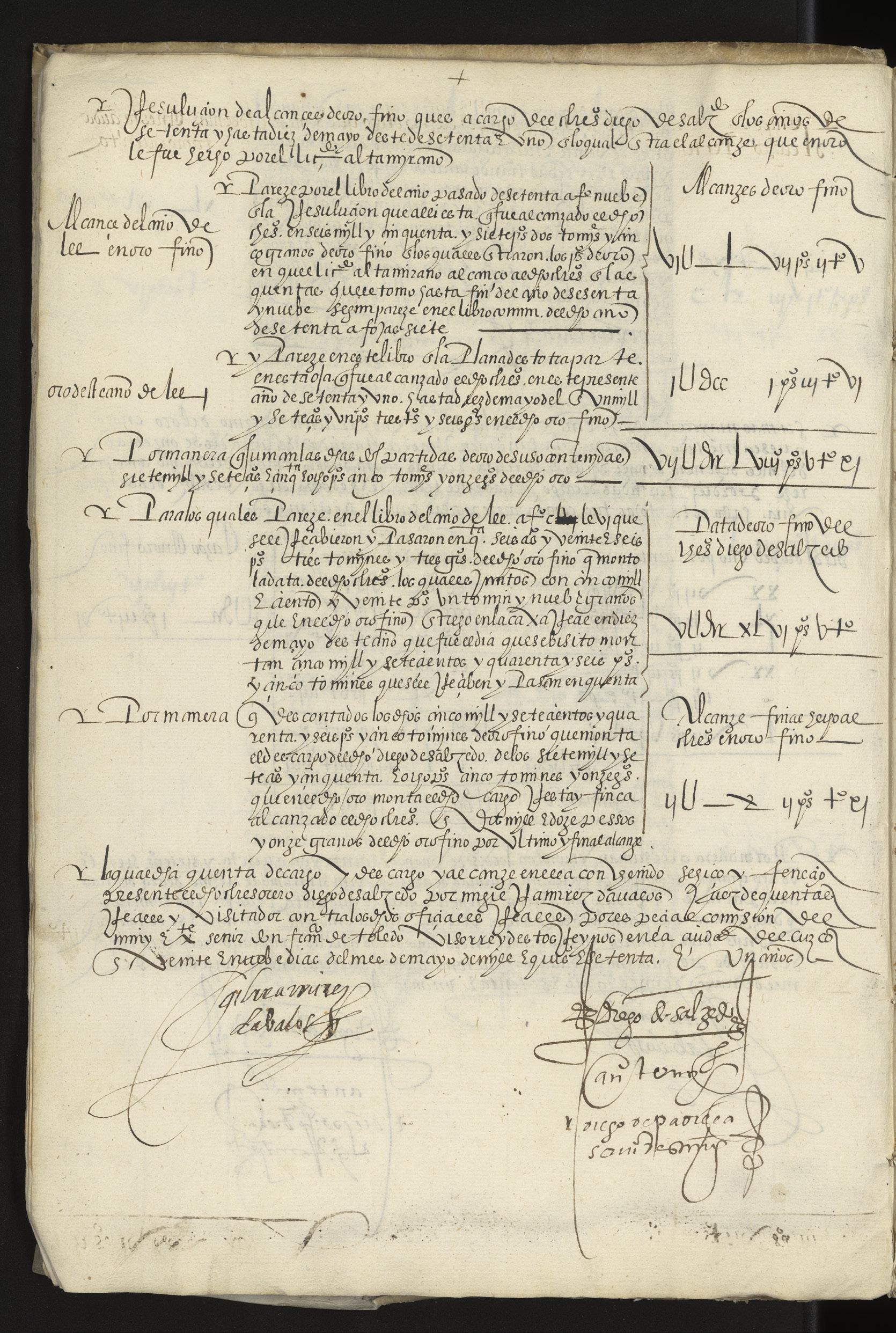

At first glance, this object may seem as simple as it appears: a plain, leatherbound notebook used to keep track of financial accounts. The entries on its thin paper pages are evenly spaced and neatly organized, with figures and sums appearing at regular intervals throughout its margins. Yet this ledger’s utilitarian design both facilitates and masks its true purpose: to aid the Spanish Empire in systematically subjugating and exploiting the indigenous peoples of Peru for its own political and financial gain.

Almost forty years before the creation of this ledger, the Spanish soldierexplorer Francisco Pizarro led his army of conquistadors in storming and pillaging Cuzco, the capital of the Inca Empire. Pizarro encountered overwhelming quantities of gold, silver, precious stones, fine cloth, and other valuable goods throughout the city, especially in the Temple of the Sun, which held the treasures of Incan kings.1 Shortly after this conquest, the Spanish Crown established the Viceroyalty of Peru. For close to three centuries, Spain implemented a system of colonial rule in which it mined Peru’s plentiful mineral resources, particularly silver, on the backs of the local population it enslaved.

Diego de Salzedo, the author of this ledger, was part of that matrix of oppression. As a Spanish royal treasurer living in Cusco, he worked within a fiscal system (the real hacienda) that collected royal taxes,2 disbursed funds throughout the colonies, sent surpluses back to Castile, and ensured the financial interests of the crown.3 Salzedo recorded these and other transactions in exacting detail in this ledger, which spans the year 1571 CE. The glimmering treasures Pizarro encountered in person appear in Salzedo’s ledger in black ink, reduced to sums and figures, as a numerical cost of colonization.

Rachel Vorsanger

1. Pedro De Cieza De León, The Discovery and Conquest of Peru, ed. Alexandra Parma Cook and Noble David Cook (Durham: Duke University Press, 1998), 317–21.

2. Known as “royal fifths.” The royal fifth consisted of a large quantity of gold ingots and four llamas of gold, and eleven gold women. Ibid.

3. Herbert Klein and John Jay TePaske, Introduction. The Royal Treasuries of the Spanish Empire in America, vol. 1 (Durham: Duke University Press, 1982).

24 | The Art of the Book

Libro de thesorero Diego de Salzedo para deste ano de 1571

Ledger of the Treasurer, Diego de Salzedo, for this year of 1571

Diego de Salzedo

Paper manuscript bound in limp vellum with bands of leather

30.5 x 21 cm bound to 31.3 x 21.5 cm

1571 CE, Cuzco, Viceroyalty of Peru (present-day Peru)

SCRC 560 Cochran

Economics & Labor | 25

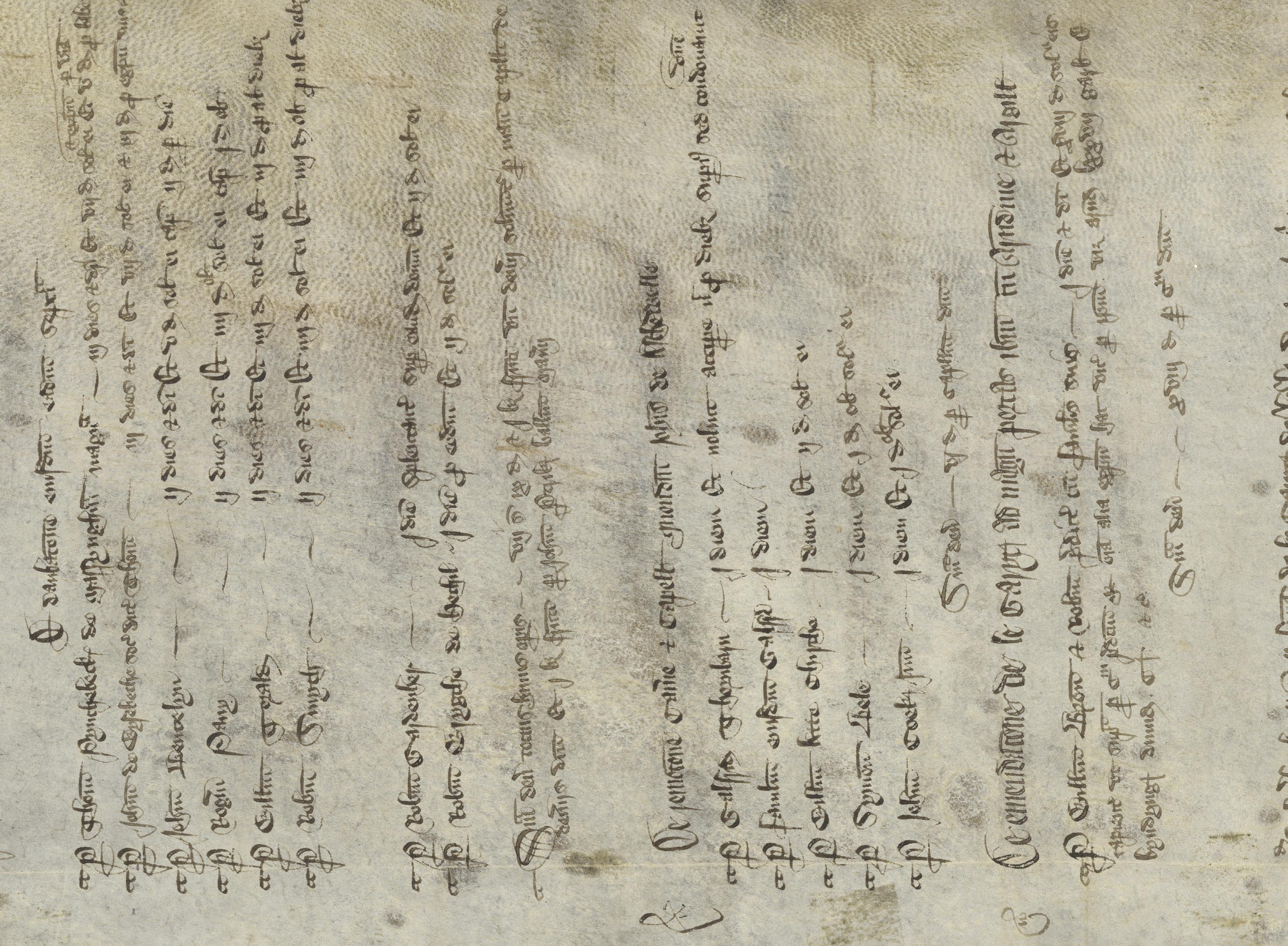

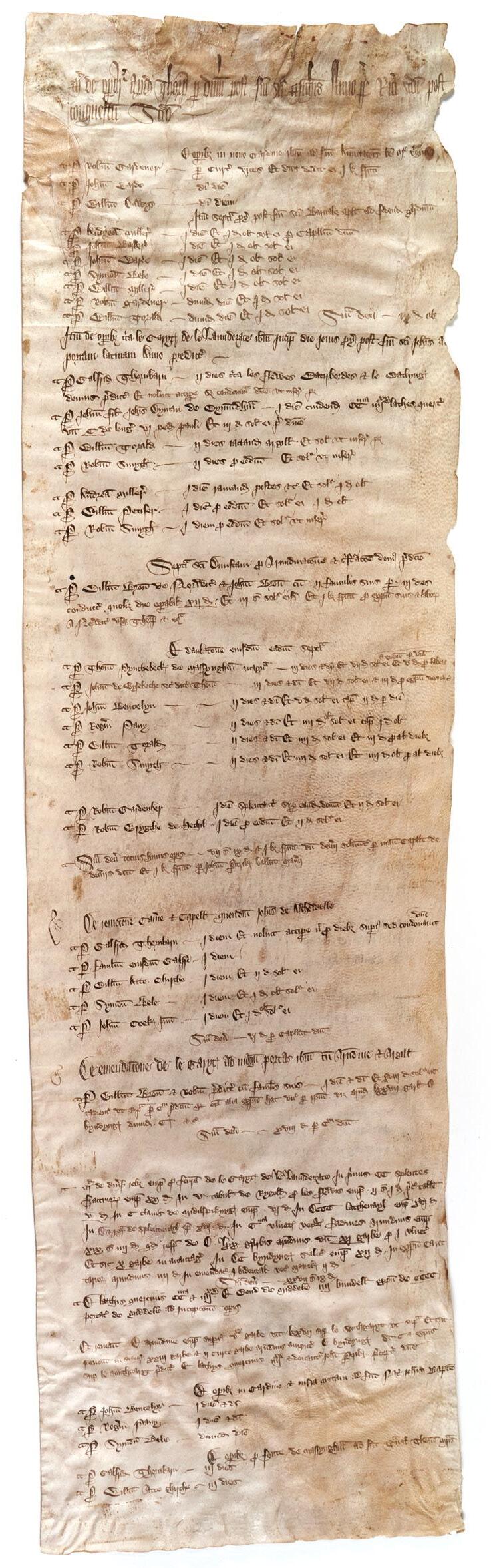

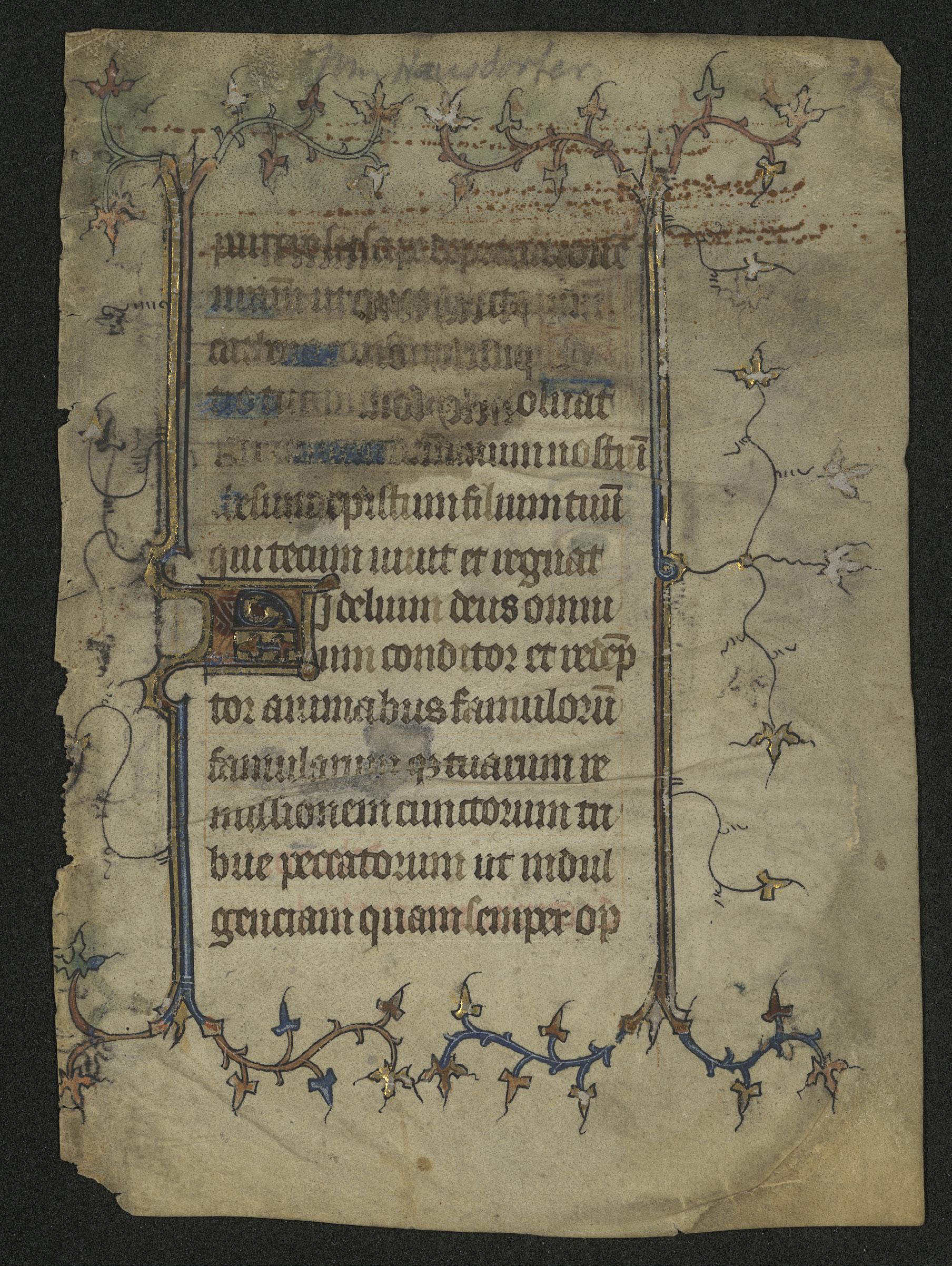

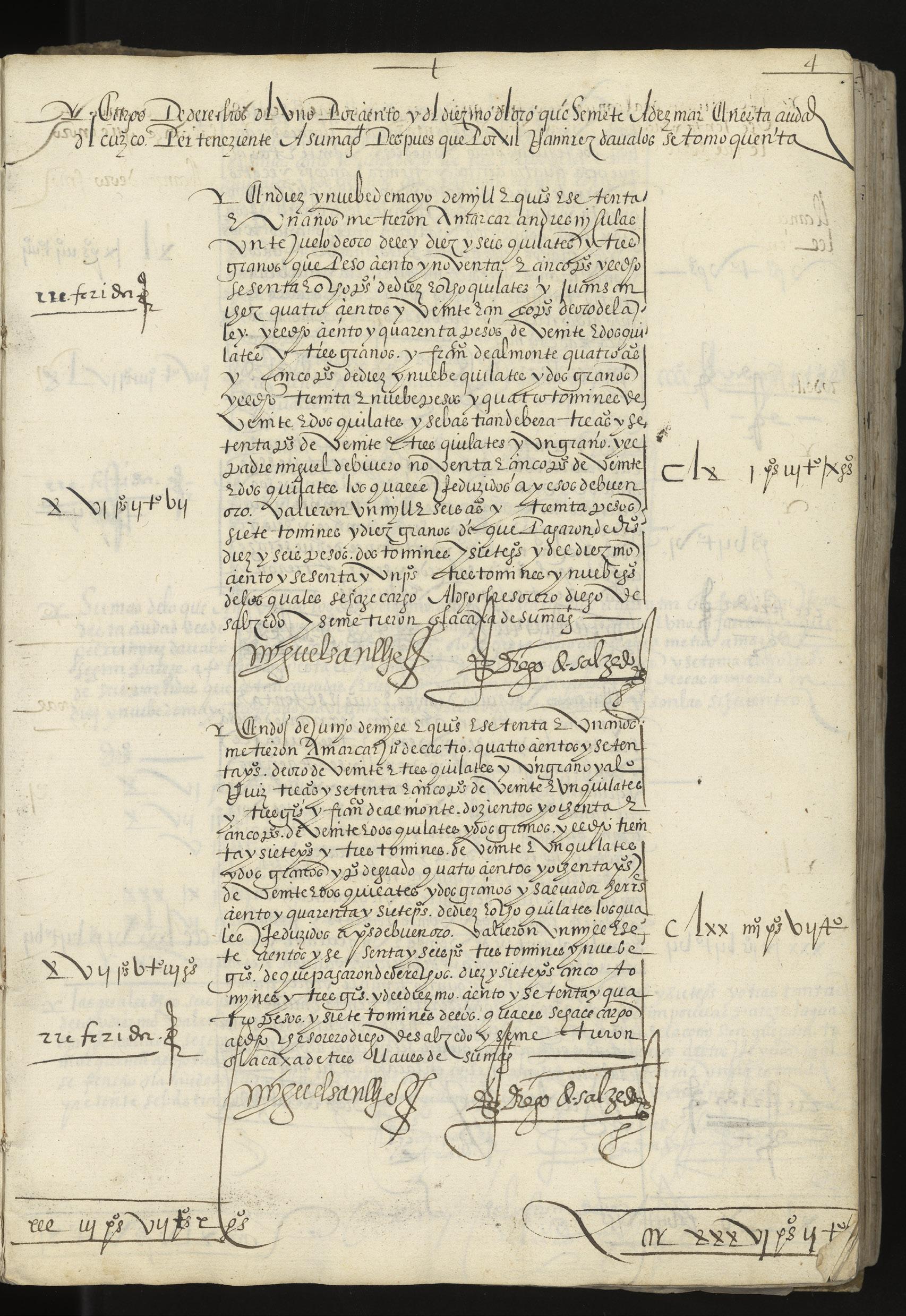

Memorandum de operationibus

Memorandum de operationibus apud Thorp per dominicam post festum Sancti Michaelis anno regni Ricardi Secundi post conquestum secundo

A Memorandum of the Proceedings at Thorpe on the Sunday after the Feast of St. Michael in the Reign of Richard II after the Second Conquest Ink on flattened parchment roll

70 x 20 cm

1378 CE, Ashwellthorpe, Norfolk, Kingdom of England (present-day United Kingdom) (SPC) MSS BH 057 COCH

26 | The Art of the Book

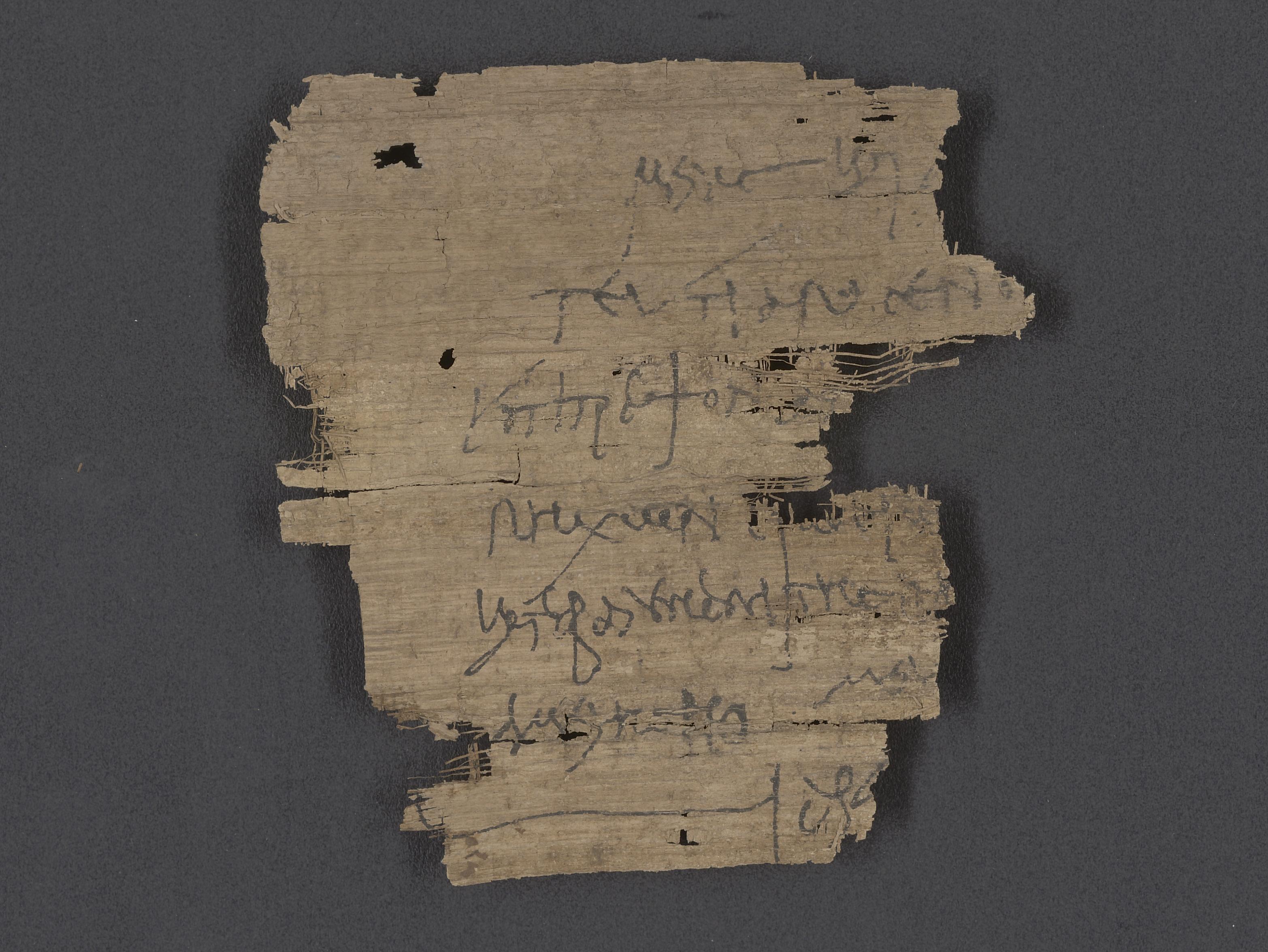

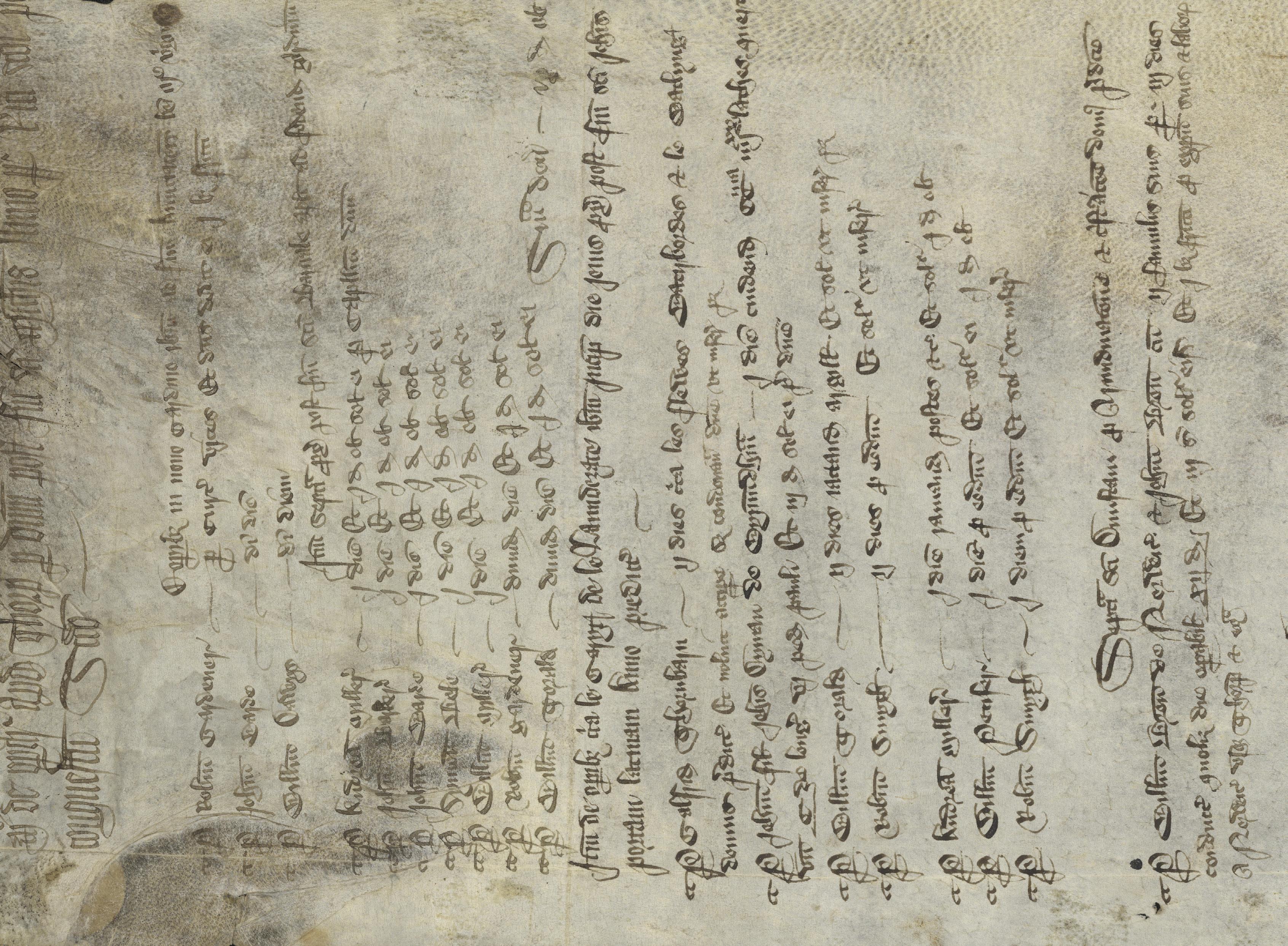

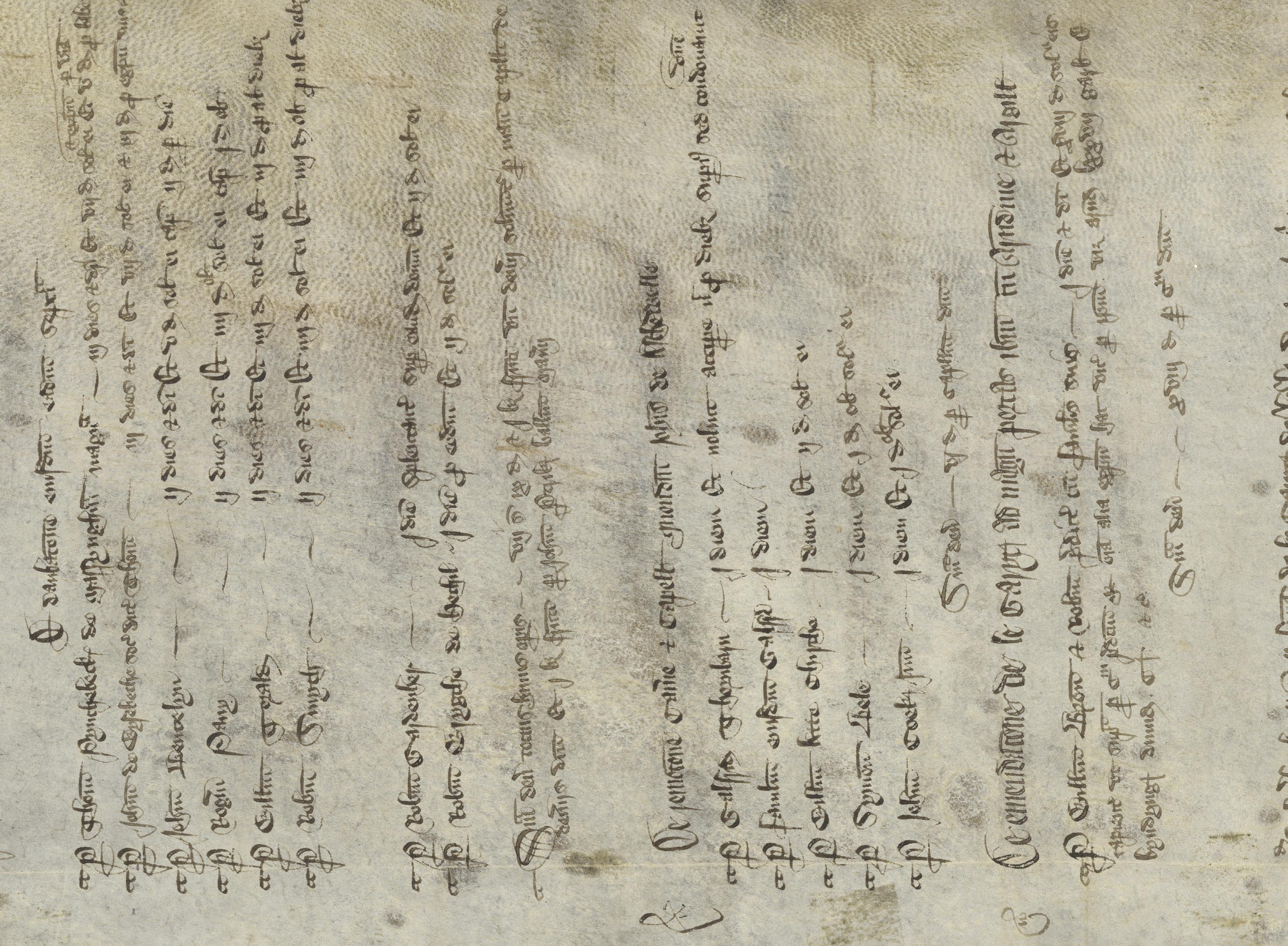

This flattened roll is an accounting record from Ashwellthorpe (abbreviated as Thorpe in the document), a community in the county of Norfolk, England. It was drawn up during the second Regnal Year of Richard II (beginning June 1378 CE), and records work completed and wages paid through the Sunday after the feast of Saint Michael (September 29, 1378 CE). Memoranda like this were often written in Latin until the early sixteenth century and used Roman numerals instead of Arabic numbers.

Accounting in late-medieval England was important, as the legal system and government relied heavily upon written evidence. This roll was made at a particularly violent and disruptive period in English history during the Hundred Years’ War, which had already been underway for nearly half a century. King Richard II, just eleven years old when this document was written, was a firm believer in royal prerogative (the authority and privilege afforded to monarchy) and as such, limited the power of the aristocracy, upon which a king would normally rely for military protection.1 Instead, Richard employed a private retinue, whose members’ salaries would likely be recorded in a way similar to this roll.

The format of this long document, measuring 70 centimeters in height, is related to the way it was kept: it would have originally been rolled up for storage, held shut with something like a string, and unrolled when needed for reference, either in sections or in its entirety.2 This opisthographic roll (one which is used on both sides) has its text oriented vertically, indicative of a medieval origin, rather than horizontally, as scrolls in antiquity were arranged. Although the format of the codex was common for the preservation of text by the late Middle Ages, rolls continued to be used and valued. One especially important genre that used the roll format was the Genealogy, such as the well-dispersed medieval text Genealogia Christi by Peter of Poitiers.3 For business records like this Memorandum, the length of text to be recorded would not always be known at the outset. Since scrolls can be extended by connecting additional lengths of parchment to one end, it is a format that can easily accommodate growing contents.

While the difference in physical construction and activation between a roll and a codex often leads us to discount rolls as books, rolls function identically to the codex, preserving and transmitting knowledge for posterity.

Ivy D’Agostino

1. James L. Gillespie, ed., The Age of Richard II (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1997).

2. Peter Beal, “scroll,” in A Dictionary of English Manuscript Terminology, 1450–2000 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008).

3. Sonja Drimmer, “The Rollodex: An Experiment around the Prepositional Paradigm through Peter of Poitiers’s Genealogia Christi,” The Journal of the Walters Art Museum 76 (2023), https://journal.thewalters.org/volume/76/essay/the-rollodex-an-experiment-around-the-prepositional-paradigm-through-peter-of-poitierss-genealogia-christi/.

Economics & Labor | 27

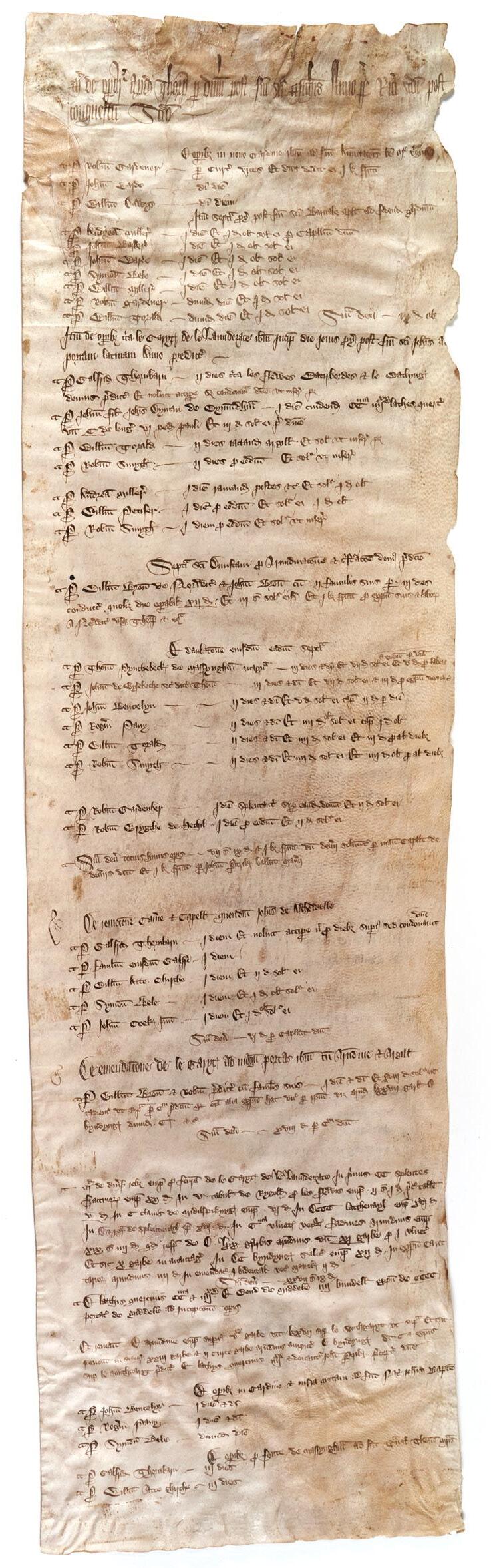

Questo e ellibro che tracta di marcantie et usanze di paesi

Book of Trade and Customs of Countries

Giorgio di Lorenzo Chiarini, author

Ludovico Bertini, scribe

Ink on parchment manuscript with blind-tooled and stamped leather binding and two closing straps

17 x 12.5 cm

July 1481 CE, Florence (?), Republic of Florence (present-day Italy)

SCRC 541 Cochran

28 | The Art of the Book

Businessmen in fifteenth-century Florence had to navigate a complex network of trades, customs, exchange rates, and a lack of standardization in units of measure, weight, and currency. In order to parse this tangled web, they consulted books such as the Tracta di marcantie et usanze di paesi. This business manual, written in vernacular Italian, details the trade practices and customs of 195 locations in the Mediterranean world—a testament to the interconnectedness of Western Europe, North Africa, and the Eastern Mediterranean five hundred years ago. Remarkably, the name of the author of this text, Giorgio di Lorenzo Chiarini, and the scribe who transcribed it, Ludovico Bertini, are both preserved in this codex.1 Originally, the title page would have been decorated with a small miniature painting and the coat of arms of the patron or owner of this book.2 For reasons that remain unclear, those details have been removed, cut out, and obliterated from the page at some point in this book’s long history.

Emma P. Holter

1. Written by Ludovico Bertini, Florence, 1481 CE (colophon, fol. 100r); formerly owned by Matteo di Lorenzo di Francesco, Scarperia, 1591 CE (ownership note, fol. 100r); formerly owned by Sir Thomas Phillipps, Phillipps mss. no. 6994; purchased by Temple University from Wm. H. Robinson, 1951 CE (dealer’s label inside front cover; Catalogue 81 (1950) Item 115).

2. Nicholas Herman, Making the Renaissance Manuscript: Discoveries from Philadelphia Libraries (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2020), 256–57, Cat. 77.

Economics & Labor | 29

Before (the Art of) the Book

Cuneiform tablet with a small second tablet: private letter ca. 20th–19th century BCE, Middle Bronze Age, Anatolia, probably from Kültepe (Karum Kanesh), clay, 4 x 4.3 x 1.7 cm, 2.2 x 3 x 0.7 cm. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1983. 135.4a, b

Müge Durusu-Tanrıöver

In many parts of the eastern Mediterranean, writing first emerged as a tool for recording and stock-taking. The earliest written artifacts so far known from Mesopotamia (i.e. the land between the rivers of Tigris and Euphrates, today part of Syria, Iraq, and Türkiye) come from the site of Uruk. There, clay tablets dating to ca. 3400 BCE were discovered in an archive of economic texts in the Eanna temple complex, containing lists and inventories inscribed with proto-cuneiform signs.1

What follows is, literally, history. The combined power of the accessibility and the cheapness of the medium (fine clay just left to dry in the sun afterward to become permanent) and the gradually increasing versatility of the cuneiform script that could render both words and syllables made this early writing technology the dominant choice in ancient Western Asia for more almost three and a half millennia. In Mesopotamia, cuneiform was continuously used to record first Sumerian, a language isolate, and then various dialects of Akkadian, a Semitic language. Second millennium

BCE archives found in central Türkiye yielded thousands of clay tablets bearing texts mainly in Hittite (an IndoEuropean language) and Akkadian. At this point, writing had already evolved beyond recording transactions or state business, and was used for epics, rituals, or ways to make sense of the universe, i.e. divination. In the first millennium BCE, inscriptions were carved in eastern Türkiye’s highlands in Urartian, while Assyrian king Ashurbanipal compiled his library of tens of thousands of tablets in the capital city, Nineveh. Later, Persepolis’s funerary monuments boasted Old Persian, Elamite, and Akkadian; all recorded in cuneiform.

From its earliest days, the development of the cuneiform writing in Mesopotamia was intertwined with the rise of cities, state, and administrative technologies.2 Clay tablets or their envelopes were often sealed with cylinder seals, carved objects that could impress a visual narrative endlessly as they were rolled on clay tablets. In other words, writing—a tool we tend to identify with the liberation and democratization of knowledge—started out as a tool for stock-taking and control in the ancient world. Even when it was opened to documenting various genres of text including fiction, cuneiform writing continued to be a technology taught in schools attached to temples, and tried to be gatekept as an exclusive practice intended for a stratum of the society that would move on to become scribes, bureaucrats, and high-level priests. Furthermore, as archaeological excavations of the last two centuries tended to focus on monumental structures and large cities, the cuneiform corpus we have is almost entirely yielded from state-related contexts.

The more than 3000-year journey of cuneiform, however, also instills hope, as it demonstrates that tools of oppression can ultimately be claimed by the oppressed. Merchants learned and used cuneiform to ask for tax breaks from states. Vassal kings denied their overlords’ requests for more resources to be sent to the imperial center in cuneiform. Local writing systems evolved and countered the exclusivity of cuneiform with graffiti carved over monuments. The incentives for the conceptual leap using an abstract system of signs might have been record-keeping and control, but the results fulfilled much broader needs that ultimately made writing a technology claimed by all levels of the society.

1. Hans-Jörg Nissen, “Uruk: Early Administration Practices and the Development of Proto-Cuneiform Writing,” Archéo-Nil 26 (2016): 33–48.

2. This is by no means endemic to Mesopotamia. Linear A in Crete, Linear B in Greece, and hieroglyphs in Egypt all demonstrate the same trajectory.

Visualizing Science

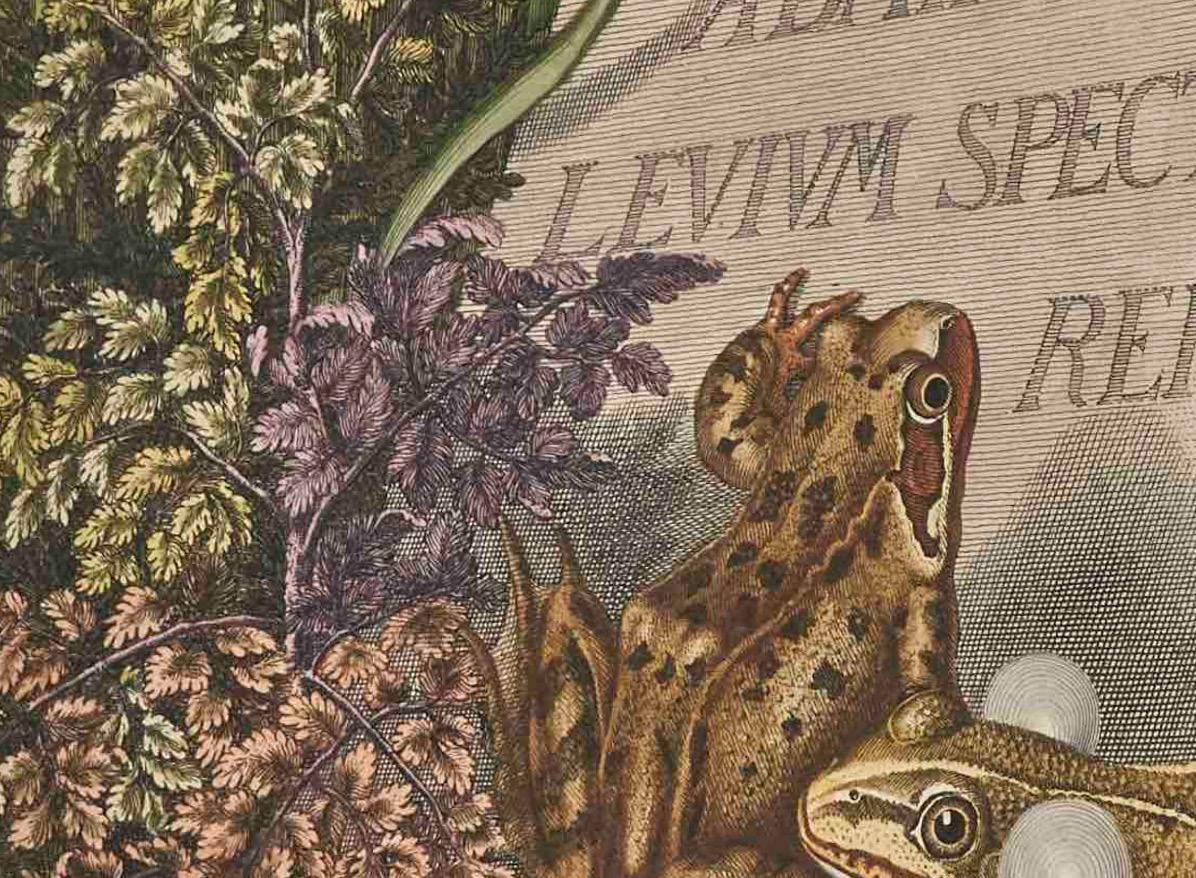

Historia Naturalis Ranarum Nostratium, oder, Die naturliche Historie der Frosche hiedigen Landes

Individual cut Leaf from Der Gart der Gesundheit

Textbook on curing small-pox, fever, cold, and red eyes

Cosmographia Petri Apiani

The production of texts and images is central to investigations of the natural world. To observe and synthesize empirical phenomena into scientific theory almost always involves graphic visualizations. The process is not straightforward, however, as scientific “theory often struggles to reflect the dynamic nature of living phenomena,” a difficulty reflected in the challenge of visually representing natural processes.1 Scientific images, then, might be understood as partial constituents of the relationship between scientific theory and the reality it hopes to explain. As tools for conveying information, images display visually salient features of the observable objects under investigation, be they toads, onions, tumors, or stars.

Historian of science Ottavio Bueno points out that, “scientific images… are generated in order to provide evidence regarding the sample under study.”2 Thus, in the process of scientific imaging, it is those features chosen to be visually salient, with an eye towards providing evidence to support certain theories, that construct empirical understandings of phenomena. Rather than direct, uncomplicated representations of reality, scientific images are constructed, informed by the cultural beliefs, values, and practices of those producing them.3 In this way, they are not so different from artistic representations, and the interplay between science and aesthetic considerations are part and parcel of the construction and interpretation of scientific knowledge.

Varied in the time and place of their writing and publication, the books in this section nevertheless all negotiate this central tension in human efforts to make sense of our environment.

From the marks on the bodies in the Thai folding manuscript that signify an ailment’s severity, to the volvelles of Peter Apian’s Cosmographia they are all exercises in the various ways science was visualized, framed, and filtered through the cultural concerns of their makers. The representational strategies that art makes available to science thus leave their mark on these pages, and in our understanding of their contents.

Ana Matisse Donefer-Hickie

1. Gemma Anderson, John Dupré, and James G Wakefield, “Drawing and the Dynamic Nature of Living Systems,” eLife 8 (March 27, 2019).

2. See Otavio Bueno, “Interpreting Scientific Images: Aesthetic Considerations at Work,” in On Art and Science: Tangle of an Eternally Inseparable Duo, ed. Shyam Wuppuluri and Dali Wu (New York: Springer, 2019), 104, who draws on Noel Carroll’s theory of images as “detached display.”

3. Jan Golinski, Making Natural Knowledge: Constructivism and the History of Science (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005).

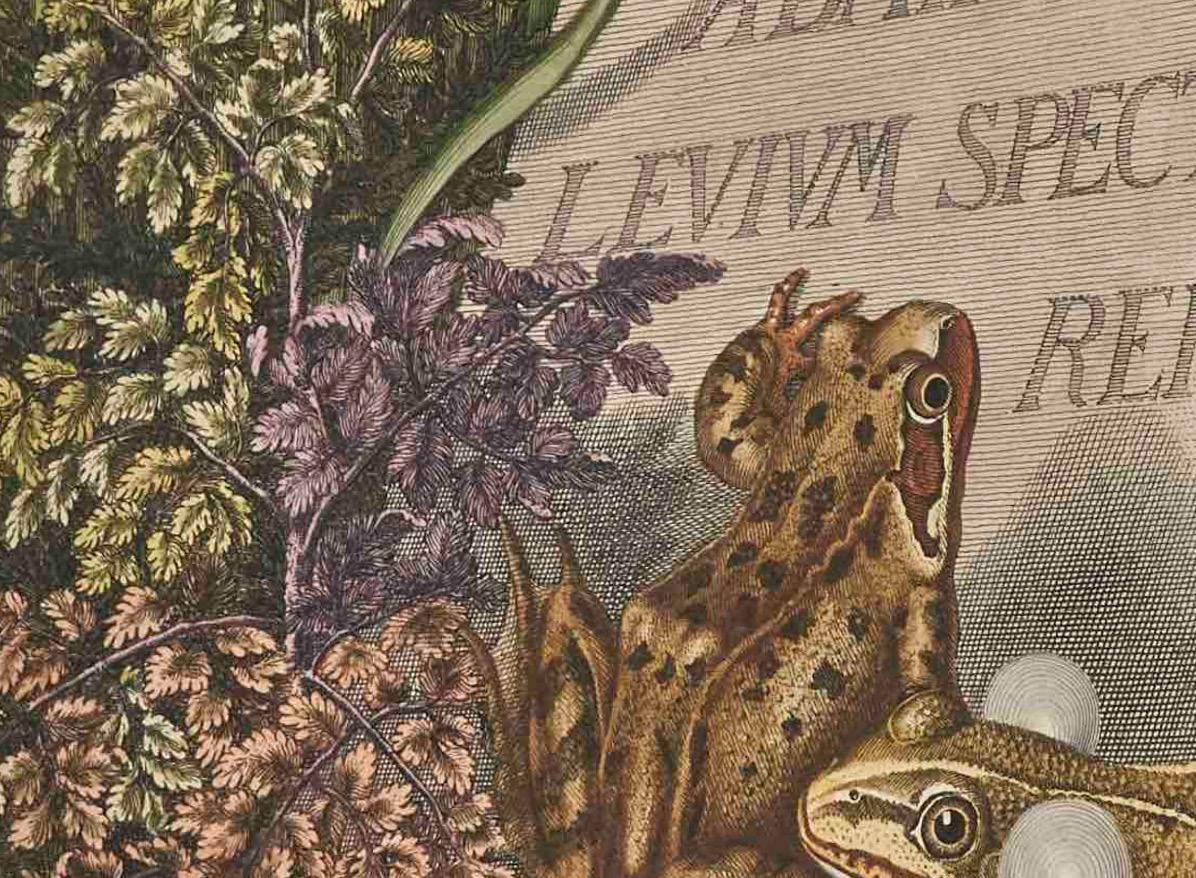

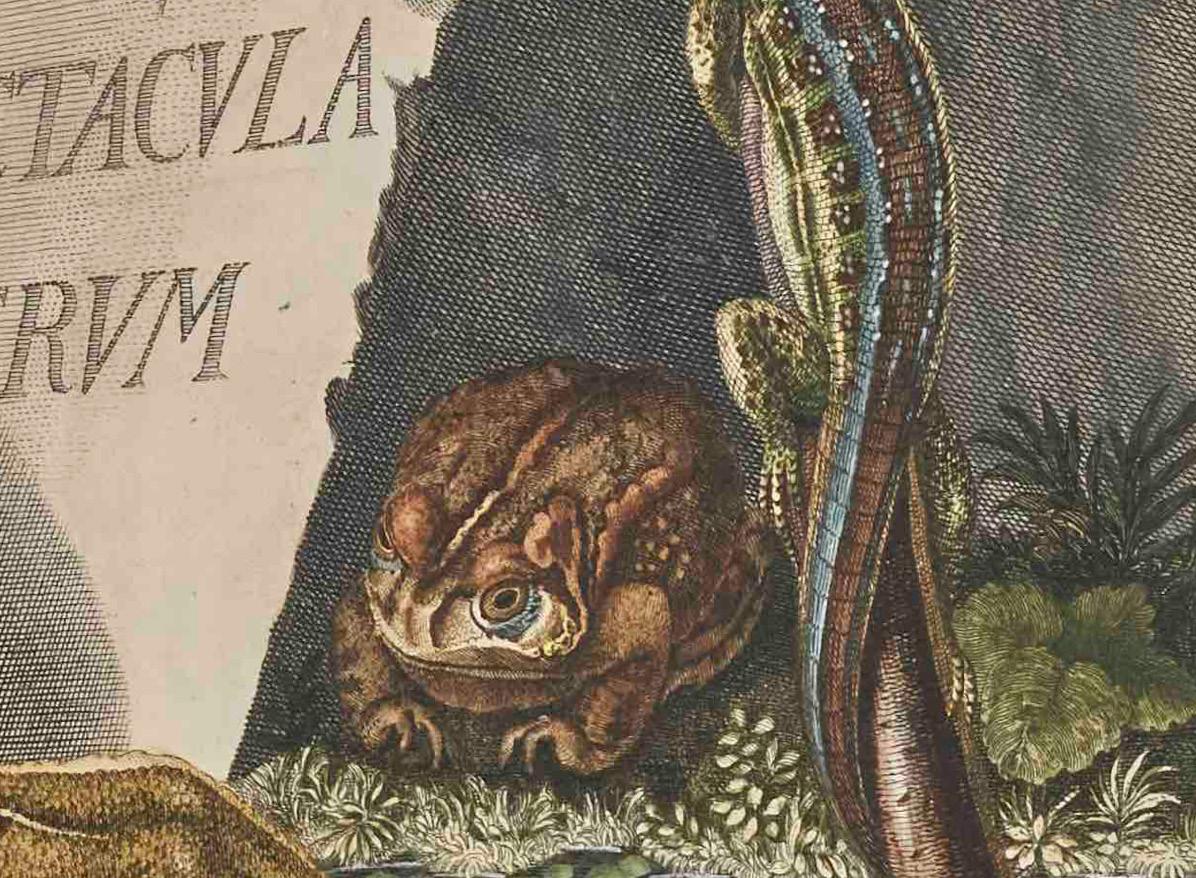

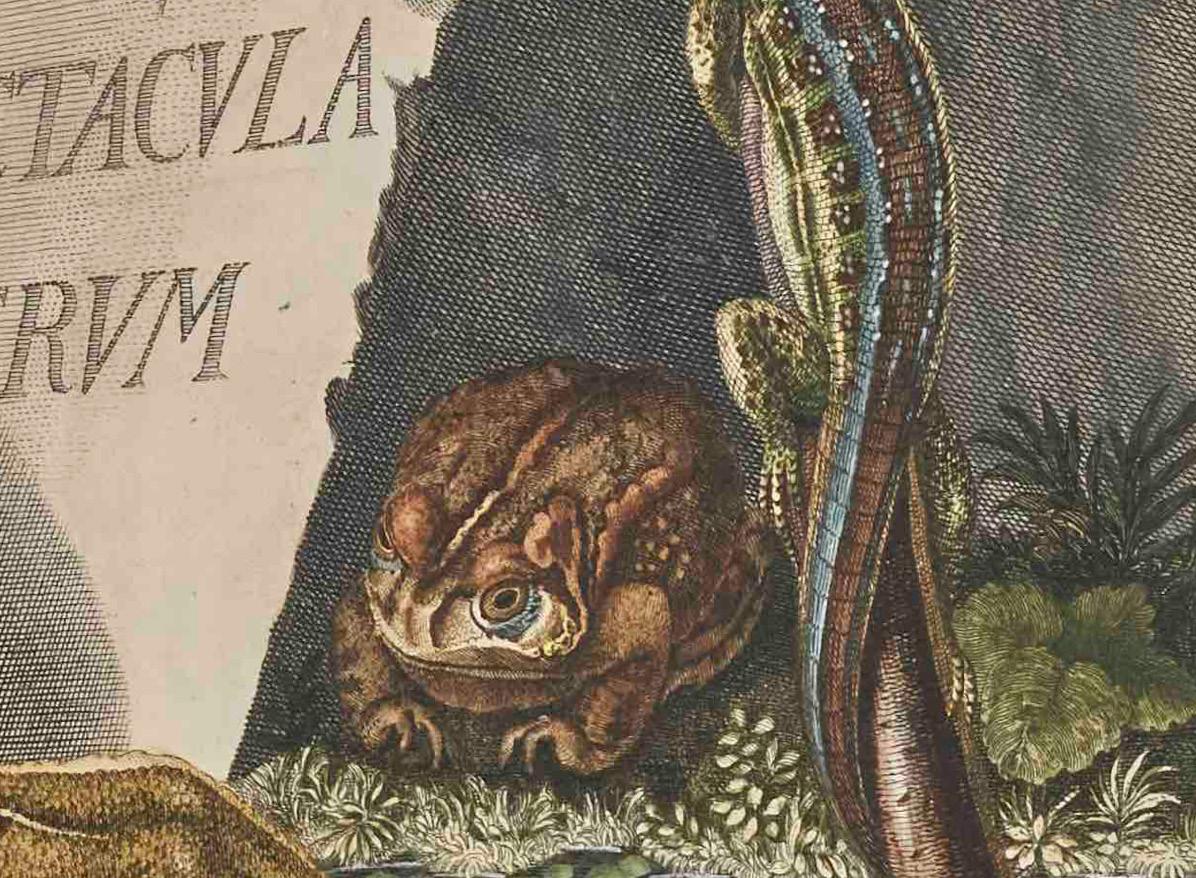

Published at the height of the Enlightenment, this text is known as the first major published work that accurately describes amphibian life cycles.1 The text, written in both Latin and German, describes the behavior and reproductive biology of the frogs and toads found around Nuremberg. The 24 hand-colored plates depict both live frogs in the acts of reproduction and frogs in the process of dissection, pins and all, laid open to reveal their anatomy. An aristocrat from the German-speaking principality of Arnstadt-Schwarzburg, Rösel von Rosenhof’s noble status allowed him the freedom to both study art and practice He was a portrait and miniature painter at the Danish Court in Copenhagen, but is better known today for his later work on bugs, salamanders, and frogs. His interest in insects and amphibians drew upon Maria Sybilla Merian’s (1647–1717 CE) ecological writings and illustrations based on her close observations of insect behavior. Despite Rosenhof’s several illustrations of frogs within the natural environment, like Merian, his observations of frog development were made at home, where he collected and raised the amphibians Also like Merian, this remove did not impact the success of Rosenhof’s work. Many of his illustrations and descriptions were used by Linnaeus as the basis for his influential classification system.

There is tension, however, between Rosenhof’s accuracy and the aestheticized design of his engravings. In plate VIII, for example, Rosenhof has arranged exquisitely detailed frog organs as if they were a set of jewelry: hearts glistening like garnets, fat curled like gold wire, and ovaries glittering like jet beads. This stylized depiction drawing on artistic convention that is incongruous with the true appearance of viscera suggests just how closely art and biology are linked.

Natural Histories: Extraordinary Rare Book Selections from the American Museum of Natural History Library ed. Tom Baione (New York: Sterling Publishing, 2012), 38. The SCRC copy was formerly in the collection of David

Dance of the Dung Beetles: Their

Historia Naturalis Ranarum Nostratium, oder, Die naturliche Historie der Frosche hiedigen Landes

A Natural History of the Frogs of these Lands

August Johann Rösel von Rosenhof, author and illustrator

Typis Iohannis Iosephi Fleischmann, printer

Paper, hand-colored copper engraving

43.5 x 32.5 cm

1758 CE, Nuremberg, Holy Roman Empire (present-day Germany)

QL668.E2 R6

Visualizing Science | 37

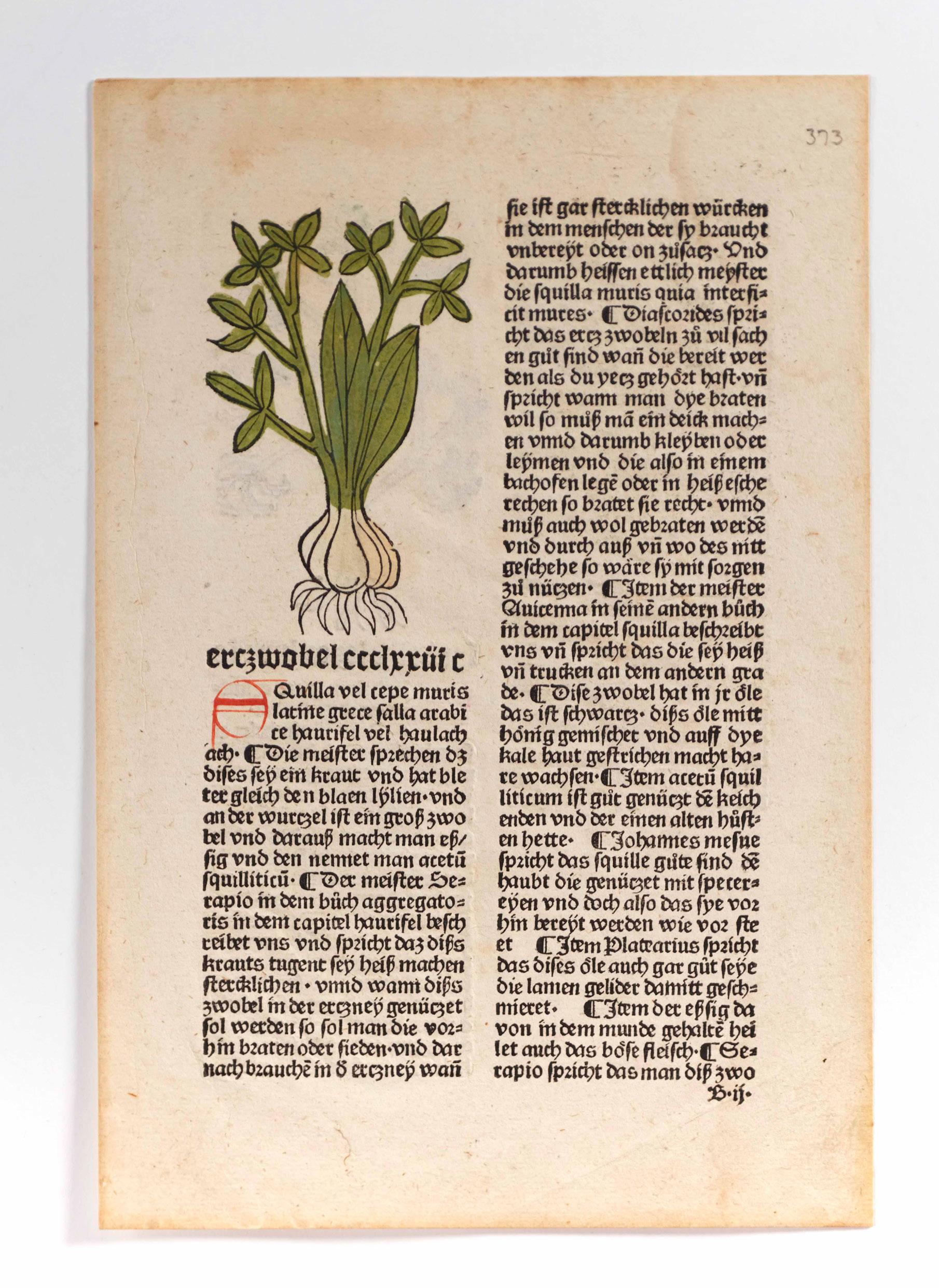

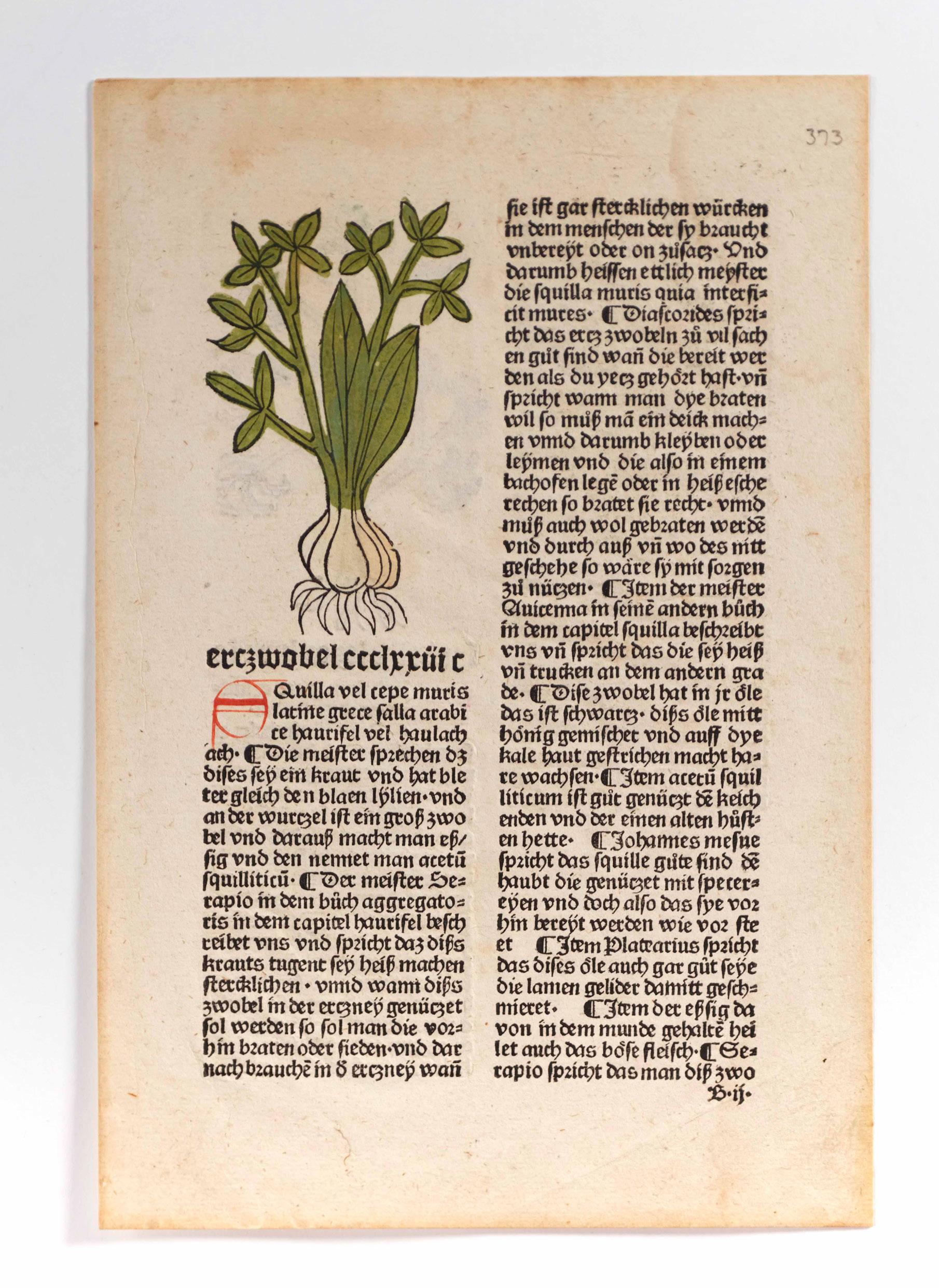

Individual cut Leaf from Der Gart der Gesundheit

The Garden of Health

Attributed to Johann Wonnecke von Kaub, writer

Johann Schönsberger, publisher

Woodblock printing on paper, ink

26 x 17 cm

1486 CE, Augsburg, Holy Roman Empire

(present-day Germany)

QK99.A1 G37 1486

This page is one of twenty-five in the SCRC collection that come from an edition of Der Gart der Gesundheit, or The Garden of Health Gart der Gesundheit is an herbal, or a medico-pharmaceutical text describing the medicinal virtues of plants. The pages in the SCRC collection include a large variety of plants including Liverwort, Strawberries, Masterwort, Wormwood, Spinach, and Sandalwood.

The Gart der Gesundheit is a complicated text, reprinted many times between 1484 and 1541 CE. Its precursor, called the [H]ortus Sanitatis, was published in Mainz by Peter Schöffer, with the Gart der Gesundheit following soon after, in 1485 CE.1 This leaf, which is laid out in two columns with hand-colored woodcuts and handwritten initials atop each chapter, was most likely cut from a copy of the 1486 edition printed by Johann Schönsberger in Augsburg.2

The information in some of the Gart der Gesundheit’s chapters is cited from the writings of historical authorities like Galen, Pliny, Serapion, and Dioscorides (referred to as the “masters”), while others recount local folk remedies. Chapter 207, for example, describes the usefulness of roses to women for making “menstruation easier.” Chapter 154, on Elecampane (inula helenium, also known as horse-heal or elfdock), cites Dioscorides’ description of the herb: “sharp with long light leaves and a stem that is not too small.”3

The woodcuts are less descriptive, and served more as mnemonics for people already familiar with the appearance of these plants than as guides to identification.

Ana Matisse Donefer-Hickie

1. Christian J. Bay, “HORTUS SANITATIS,” The Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America 11, no. 2 (1917): 57–58.

2. Johannes von Cuba, Gart der Gesundheit (Augsburg: Johann Schönsberger, 1486). Bayerisches Staatsbibliothek 2 Inc.c.a. 1771 b.

3. “Auch diss den frauwen menstruum behendigklich”; “Diascorides beschzeibet uns das diss seyein kraut scharpff und lange licht an den bletern umid hatt ein jtarn der ist nicht zu Klein.”

Visualizing Science | 39

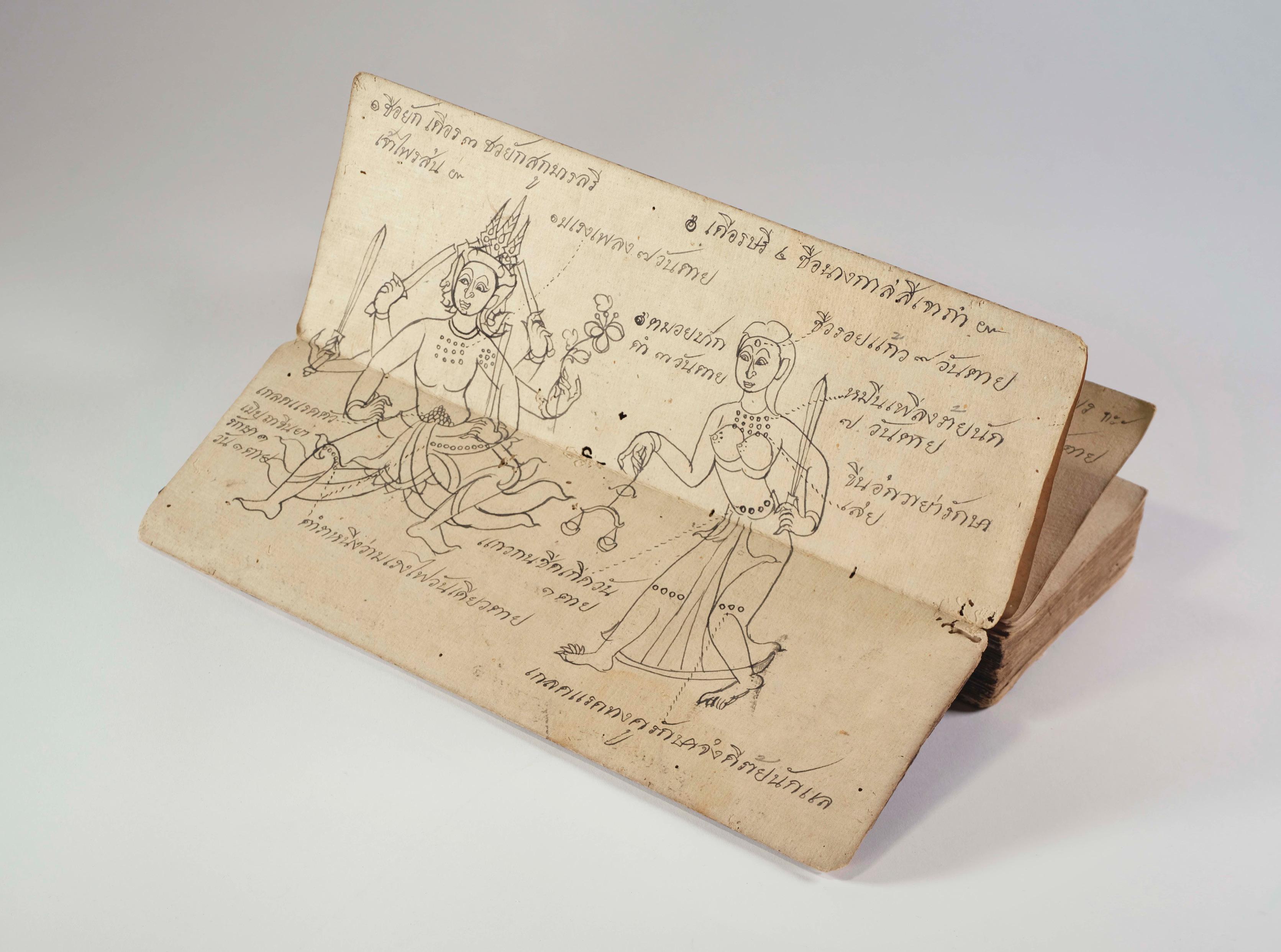

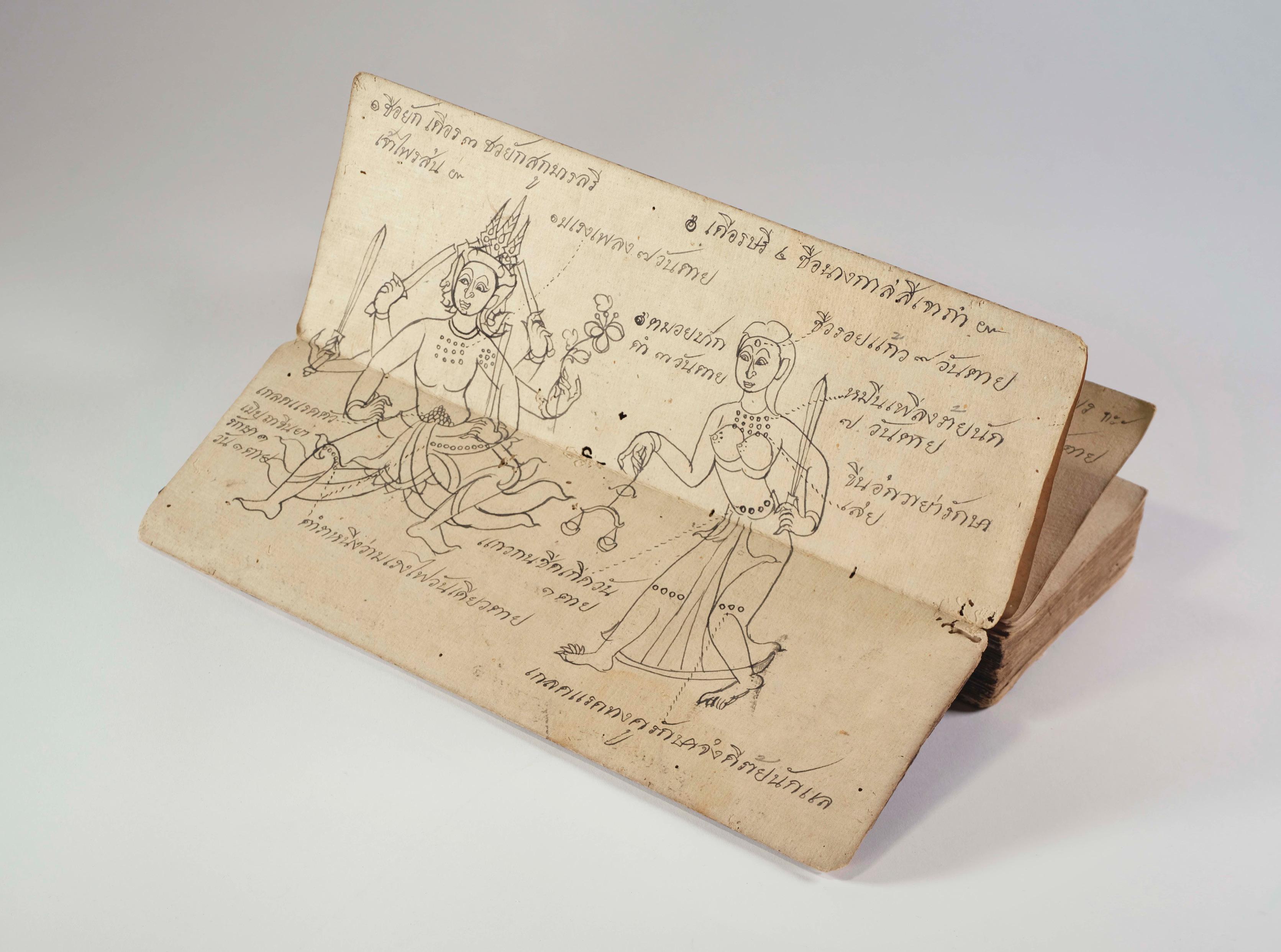

Textbook on curing small-pox, fever, cold, and red eyes

From the Thai Folding Manuscripts collection

Khoi paper, ink

11.5 x 34.5 cm

ca. 19th century CE, Kingdom of Siam (present-day Thailand)

SCRC 219

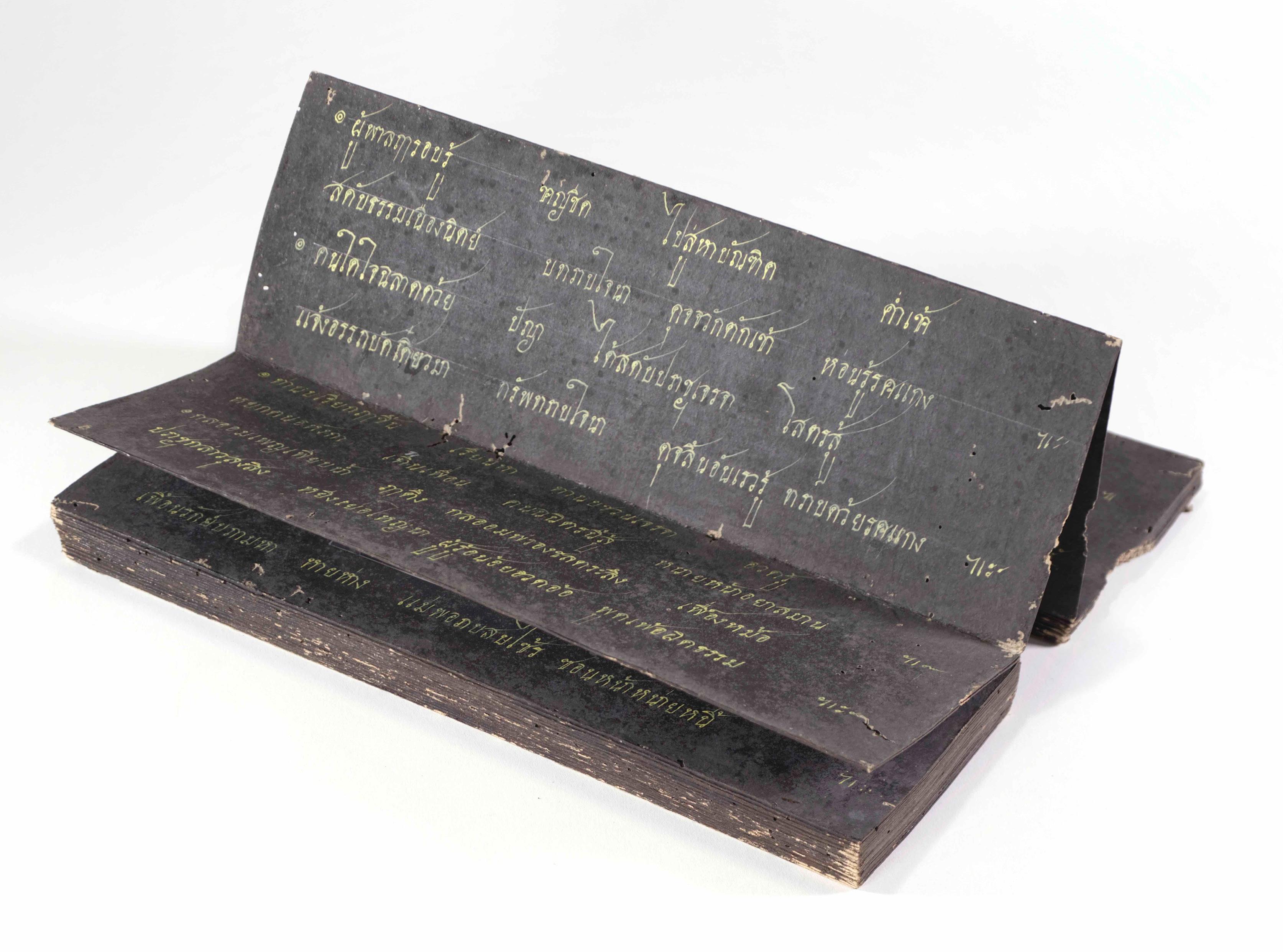

The three objects in the SCRC’s Thai Folding Manuscript collection can all be classified as samut khoi, a type of paper-folding manuscript characteristic of nineteenth-century Thai tradition.1 Each of the three objects was created for a different purpose; the medicine manuscript featured here is an example of a medical divination manual that provides instructions for curing diseases. Both the proverbs and poetry manuscripts are primarily textual, with the exception of a few detached folia that feature drawings of floral forms with text incorporated in their shapes.

Thai manuscripts’ concertina folding format allows the reader to flip through each page in opposite directions and access information through two different channels, challenging the Western expectation of a book. As observed in the proverbs and poetry lesson manuscripts, samut khoi were also commonly dyed black, creating a dark ground for text written in gold ink.2

The medicine manuscript, titled Textbook on curing small-pox, fever, cold, and red eyes, likewise follows the samut khoi format. Medical manuals of this type often include both written records of different types of diseases and illustrations to aid healing practices.3 Said illustrations are either presented as geometric patterns or as diagrams that identify tumors on the human body. Because medicine was informed by astrology, the time of year and the geographical location of the patient were also essential for a diagnosis.4 The illustrated human-like figures in this manuscript with varying numbers of limbs bear markings that signify the type and severity of a patient’s ailment, disease, or malignancy.5

Ha Tran

1. Joshua Kueh, “Tai Manuscripts in the Southeast Asia Rare Book Collection at the Library of Congress: Siamese Manuscripts and an Early Printed Book,” Research Guides, Library of Congress, last modified September 13, 2022, https://guides.loc.gov/tai-manuscripts/siamese-manuscripts.

2. “Figuring out Folds: Conserving a Thai Buddhist manuscript,” Chester Beatty Library, June 13, 2019, https://chesterbeatty.ie/conservation/figuring-out-folds/.

3. Henry Ginsburg, “Medical Divination,” in Thai Manuscript Painting (London: British Library, 1989), 28–30.

4. Kueh, “Tai Manuscripts.”

5. Ginsburg, “Medical Divination,” 28.

Visualizing Science | 41

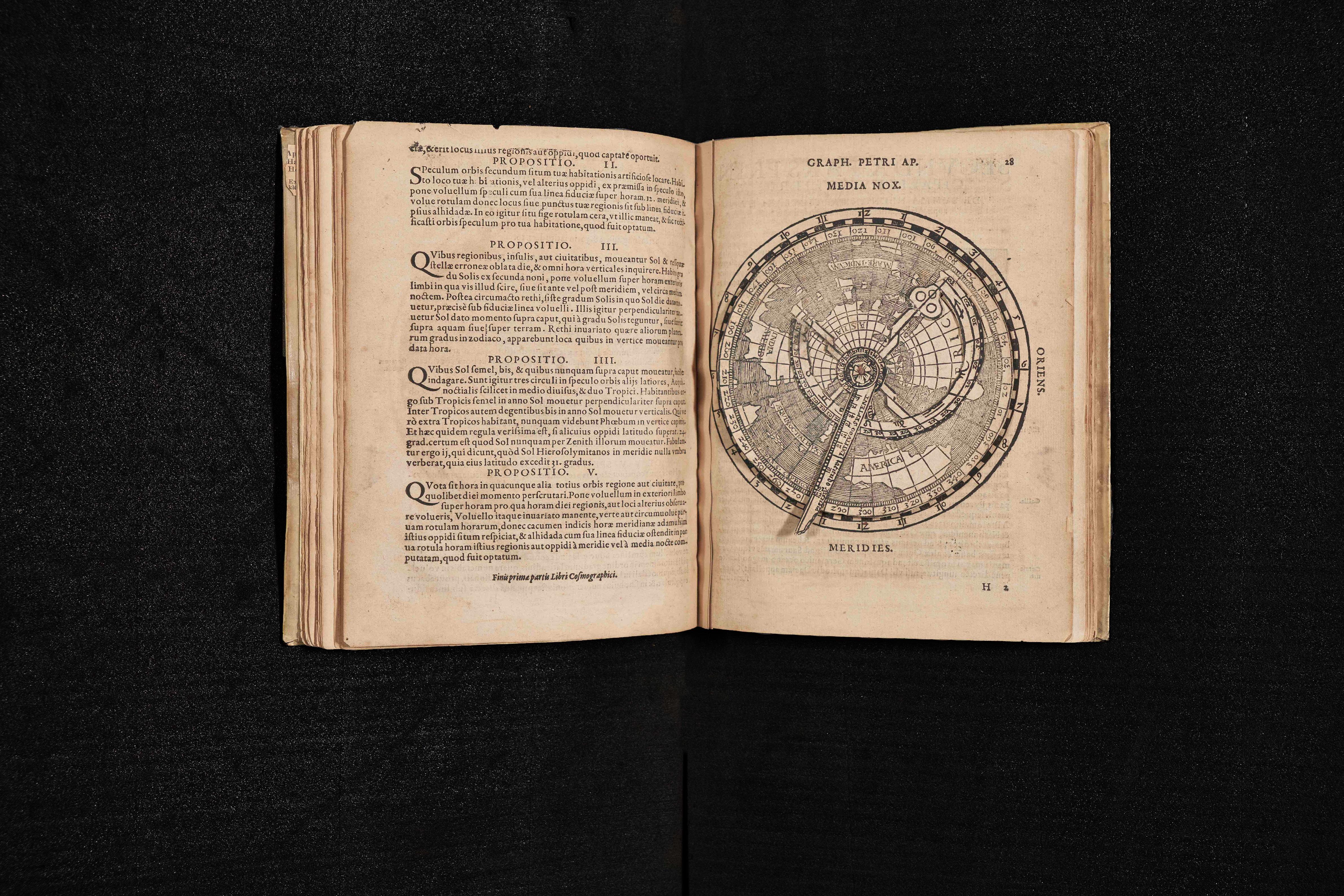

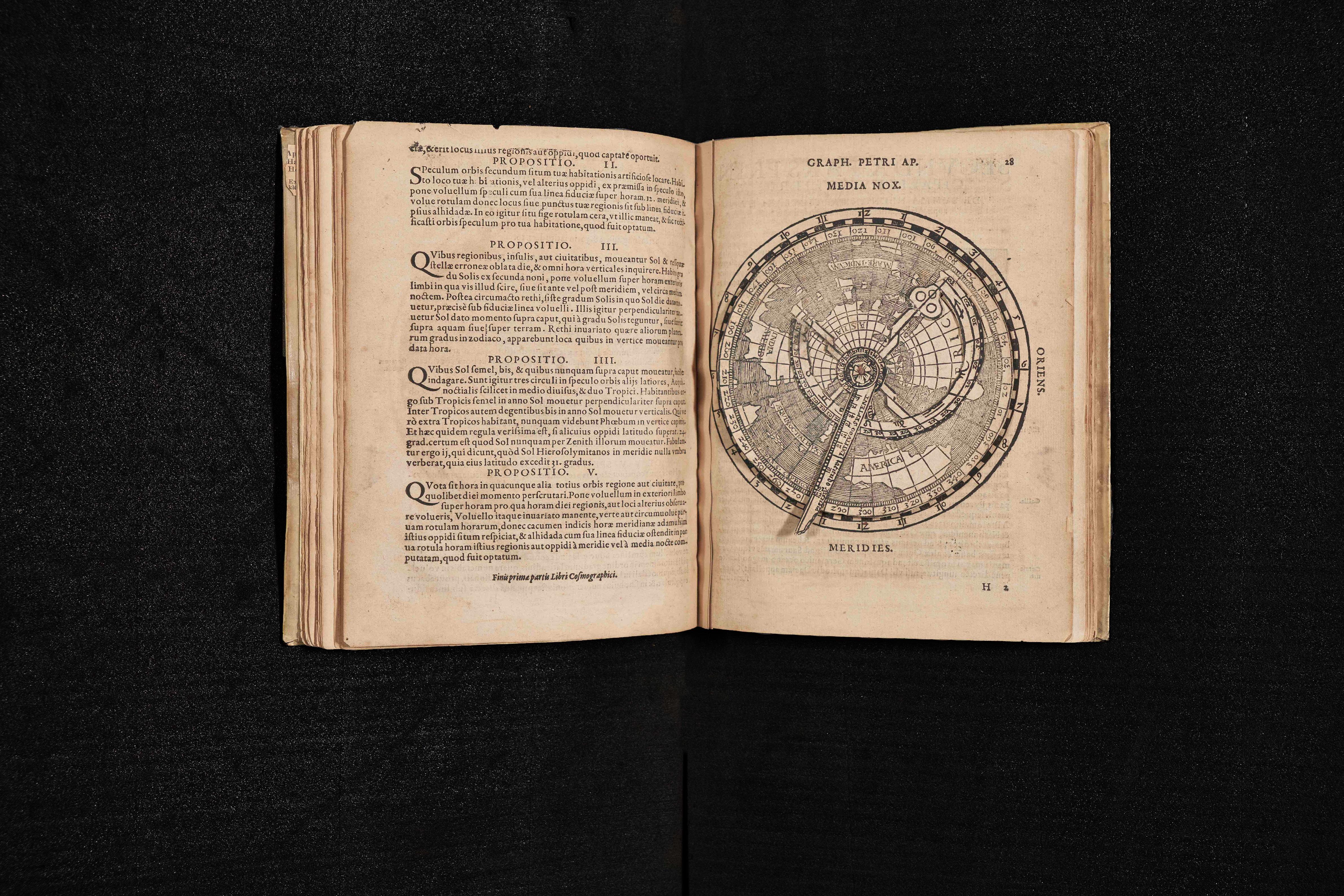

Cosmographia Petri Apiani

Cosmographia, or A View of Terrestrial and Celestial Globes

Peter Apian, author

Gemma Frisius, editor

Arnold Birckmann, Coloniae Agrippinae Press, publisher

Ink on paper

20.5 x 16 cm

1574 CE, Antwerp, Habsburg Netherlands (present-day Belgium)

GA6 .A53

42 | The Art of the Book

Peter Apian’s Cosmographia is a printed book on astronomy and navigation that includes several maneuverable diagrams and dials that were tools used to observe, measure, and calculate the movement of the cosmos. Apian’s text was first published in Landshut in 1524, but this edition was printed in Antwerp in 1574 with Gemma Frisius’s additions and corrections. The sixteenth-century astronomical and cosmographical text incorporated volvelles, or scientific instruments made of paper that the user could revolve to aid in mathematical calculations. Volvelle comes from the Latin verb volvere to turn, pointing to the interactive nature of this book. The one illustrated here features a terrestrial globe with a dial for calculating the movement of the cosmos throughout the calendar year. The text describes techniques for surveying, mapping, and triangulating one’s position in relation to the stars, and includes descriptions of each of the continents (including the Americas), a table of the latitudes of major European cities, and descriptions of techniques and instruments for making celestial observations—all of which encouraged readers to become amateur astronomers.1 The 1574 edition of the book also describes cosmological phenomena with illustrations of comets and eclipses of the moon.

Emma P. Holter

1. Margaret Gaida, “Reading Cosmographia Peter Apian’s Book-Instrument Hybrid and the Rise of the Mathematical Amateur in the Sixteenth Century,” Early Science and Medicine 21, no. 4 (2016): 277–302.

Visualizing Science | 43

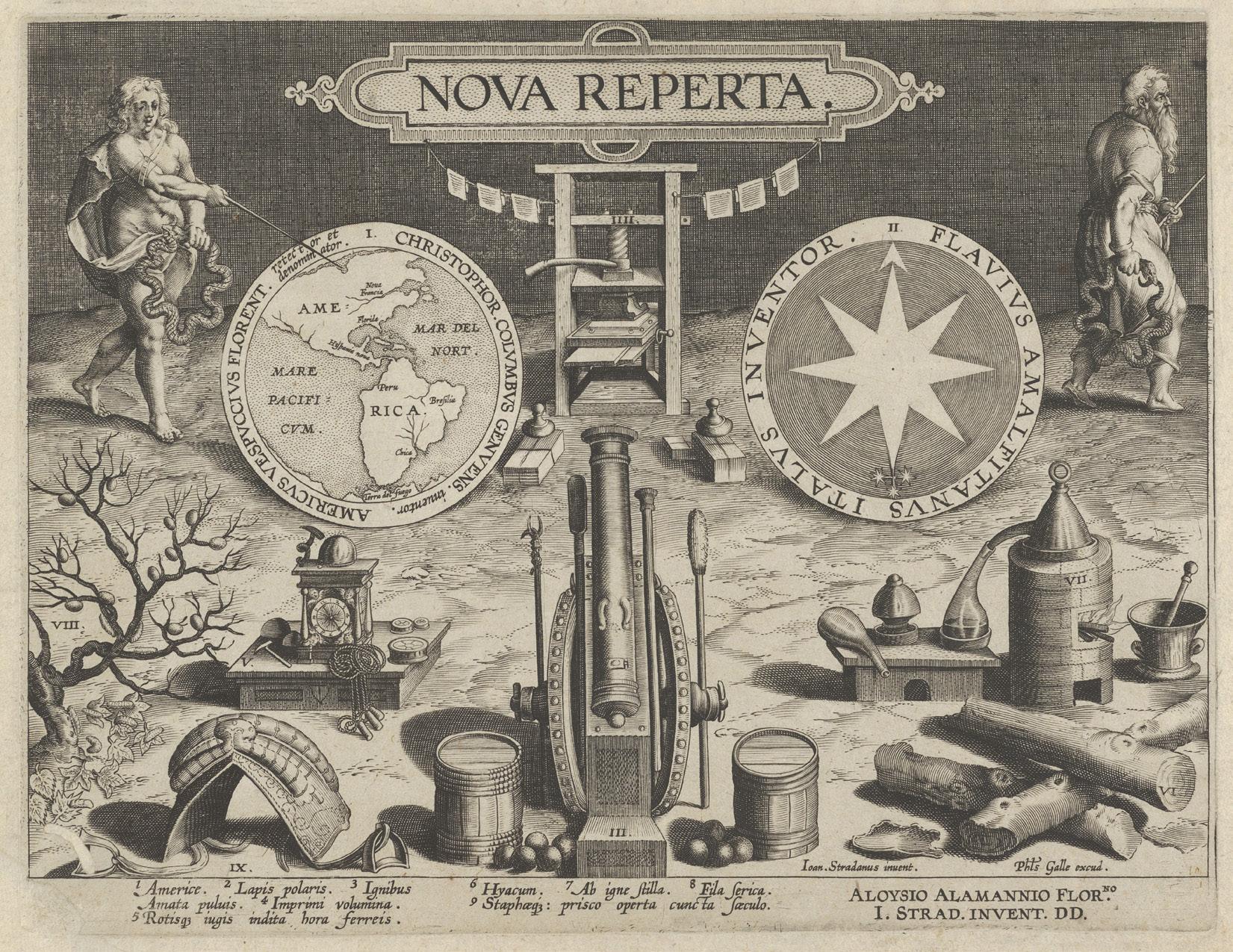

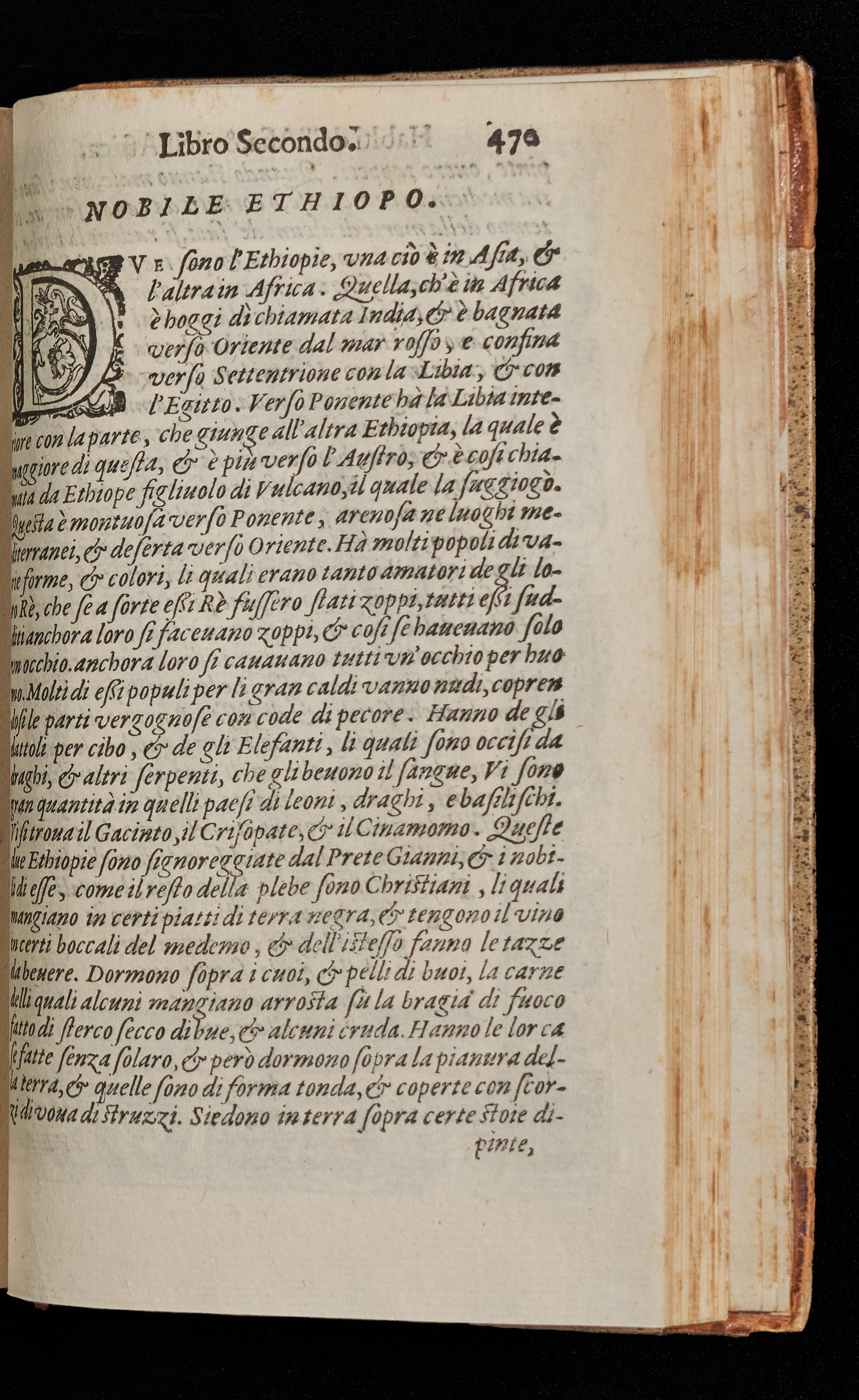

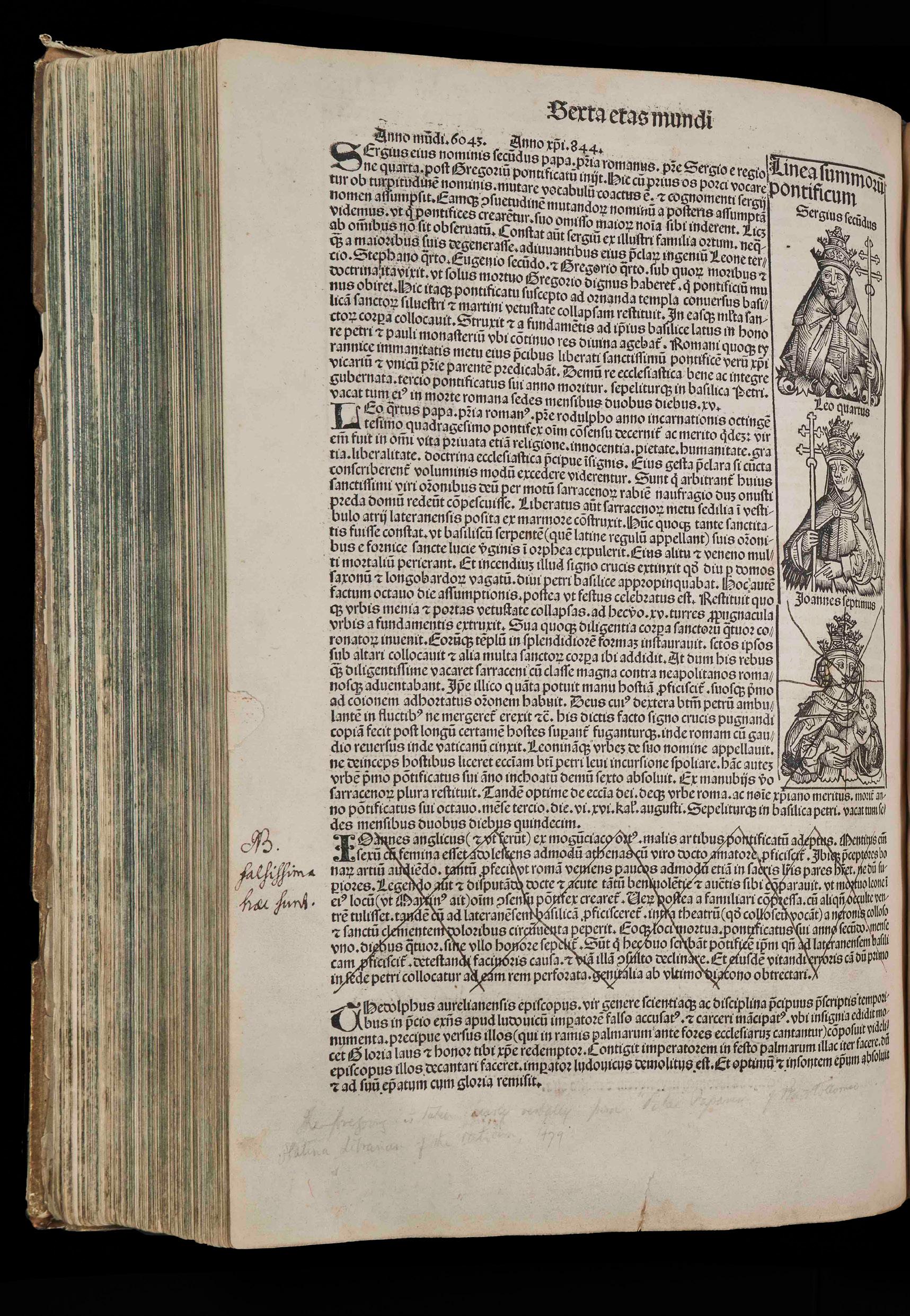

Printing in Early Modern Germany

Ashley D. West

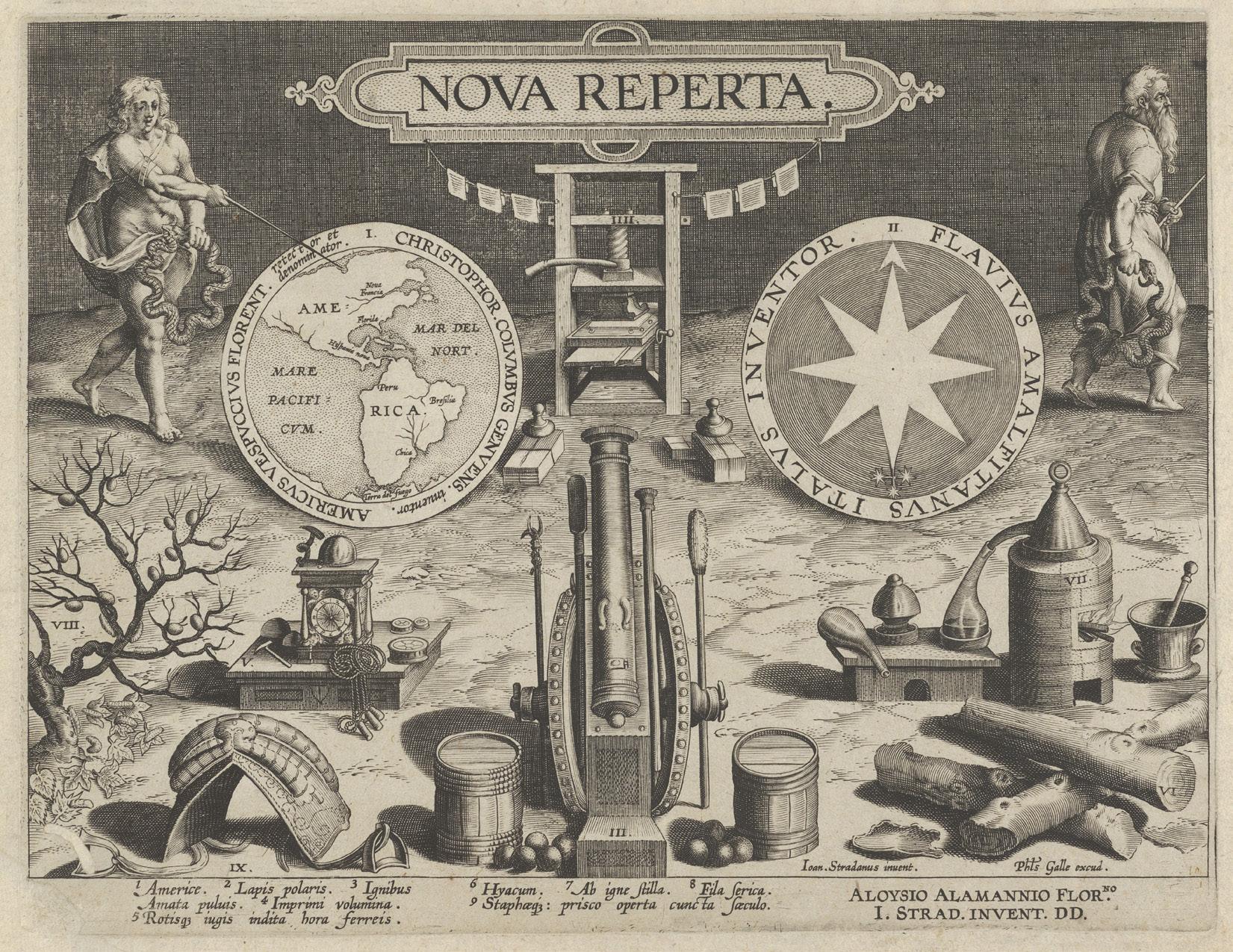

The title plate of Johannes Stradanus’ book of ca. 1590 CE, the Nova Reperta (New Inventions of Modern Times) prominently features at its center an image of a printing press, with newly printed sheets printed with movable type hanging to dry like a banner behind it. The press shares the page with other ‘inventions’ and technologies of the Renaissance period highlighted in the rest of the book: the compass; clock; saddle with stirrups; distillation process; the domestication of the silkworm; guaiacum wood (from the Americas and used to treat syphilis); gunpowder; and a canon, whose shaft points likes a finger upward to the image of the press above it, as if suitably singling it out above all else as the invention that made the book itself possible in its printed form.

Scholars have described Johannes Gutenberg’s invention of the printing press in Mainz, Germany, ca. 1440 CE—along with movable type (metal cast forms for printing language)—as constituting a media revolution.1 But to what extent is that an accurate assessment, both from our own twenty-first-century vantage and historically from that of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries? What were the benefits and consequences of early printing in Europe, as well as some of the concerns?

Like many of the ‘inventions’ on Stradanus’ title plate (gunpowder and compass included), Gutenberg’s printing press and movable type were not, in fact, ‘pure’ Renaissance European inventions, but rather might be thought of as useful adaptations of existing technologies from older crafts and cultures. Print—if we think of it in its most basic terms as a ‘replicating technology’ and process of making repeatable impressions onto a surface— goes back at least to ca. 3100 BCE to Mesopotamian cylinder seals.2 The invention of movable type for repeating forms—though without a mechanical press—took place as early as the mideleventh century in China and Korea, first made in wood and ceramic, and by the early thirteenth century, in bronze.

Gutenberg’s printing press enabled the mechanical reproduction of text using a system of cast lead metal movable type to print on paper with greasy ink. One impact of Gutenberg’s printing press and movable type—in conjunction with the wide availability of paper on which it relied3—was an increase in the output of book production and a decrease in the number of laborhours to do so. According to one scholar, “A man born in 1453, the year of the fall of Constantinople, could look back from his fiftieth year on a lifetime in which about eight million books had been printed, more perhaps than all the scribes of Europe had produced since Constantine founded his city in A.D. 330.”4 It was an innovation that allowed for the dissemination through time and space of repeatable texts, and could be combined with printed images if desired. The press and book printing were also important catalysts for the development of printed images as an art form. Woodcuts could be combined with movable type as a print relief medium: as many as one-third of books printed in Europe before 1500 CE were illustrated with graphic images.5

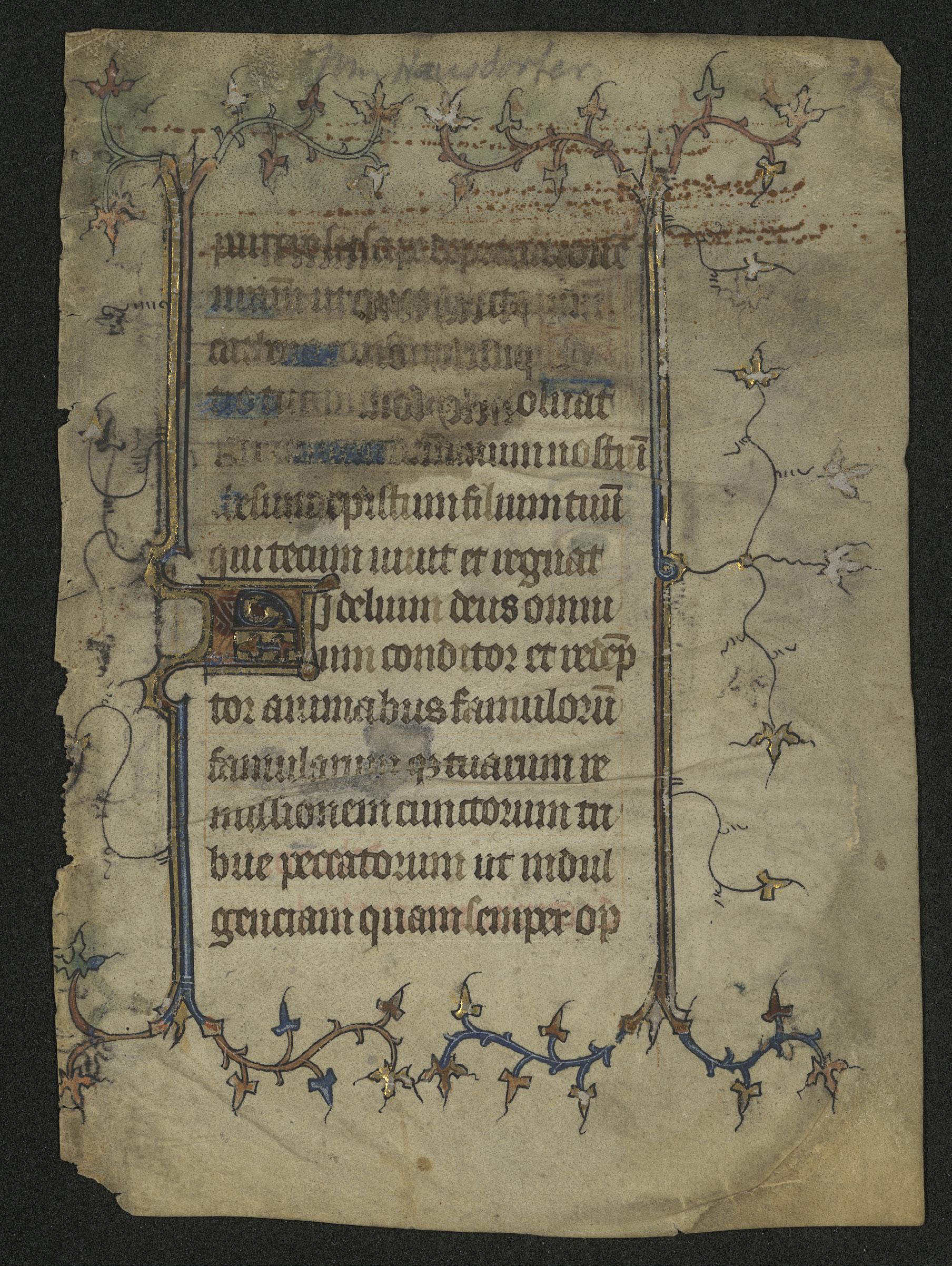

Even so, printing did not suddenly supplant manual scribal copying and hand-illumination. There was a long period of overlap of manuscript traditions and printing, and of mixing hand-done aspects of manuscripts with mechanical ones.6

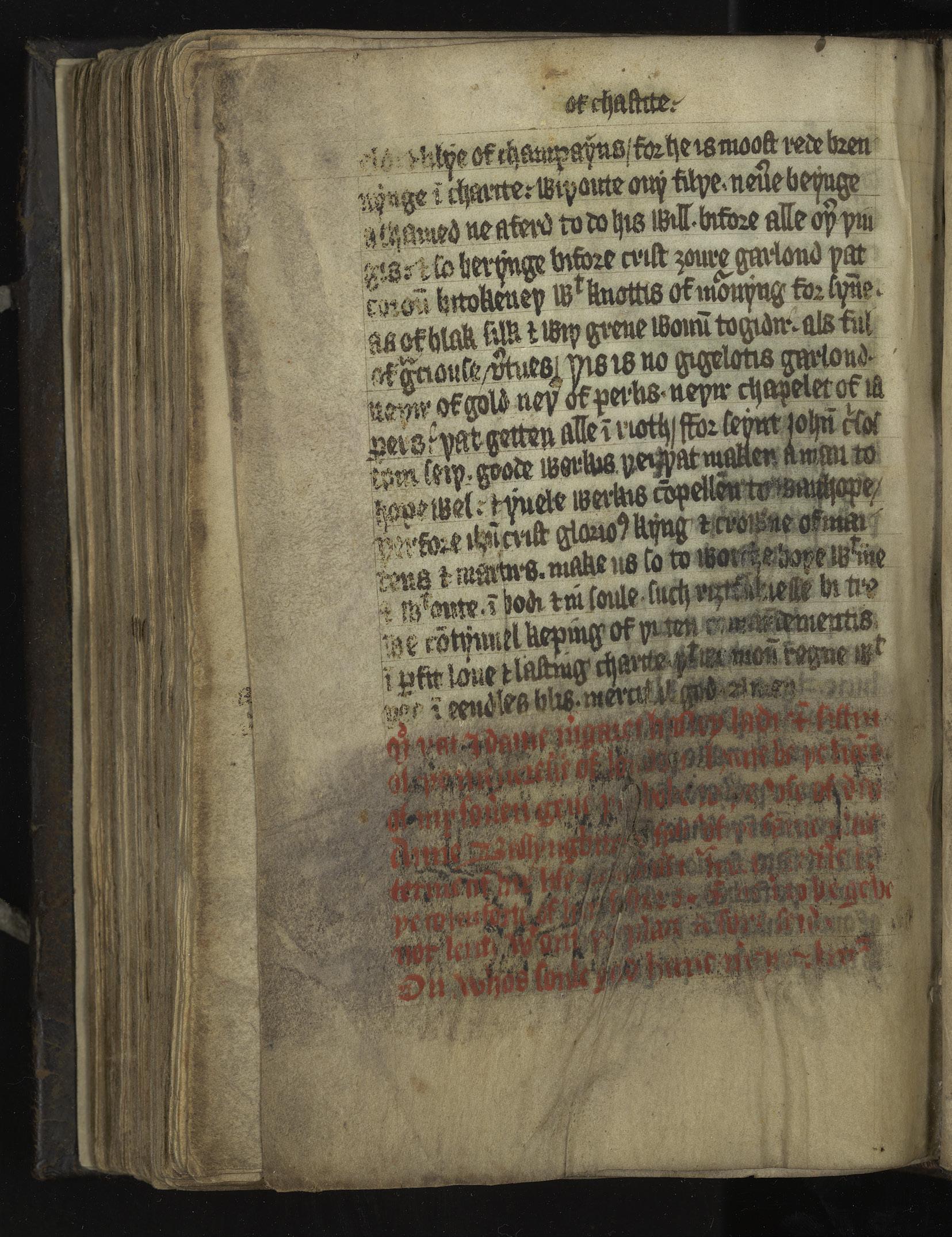

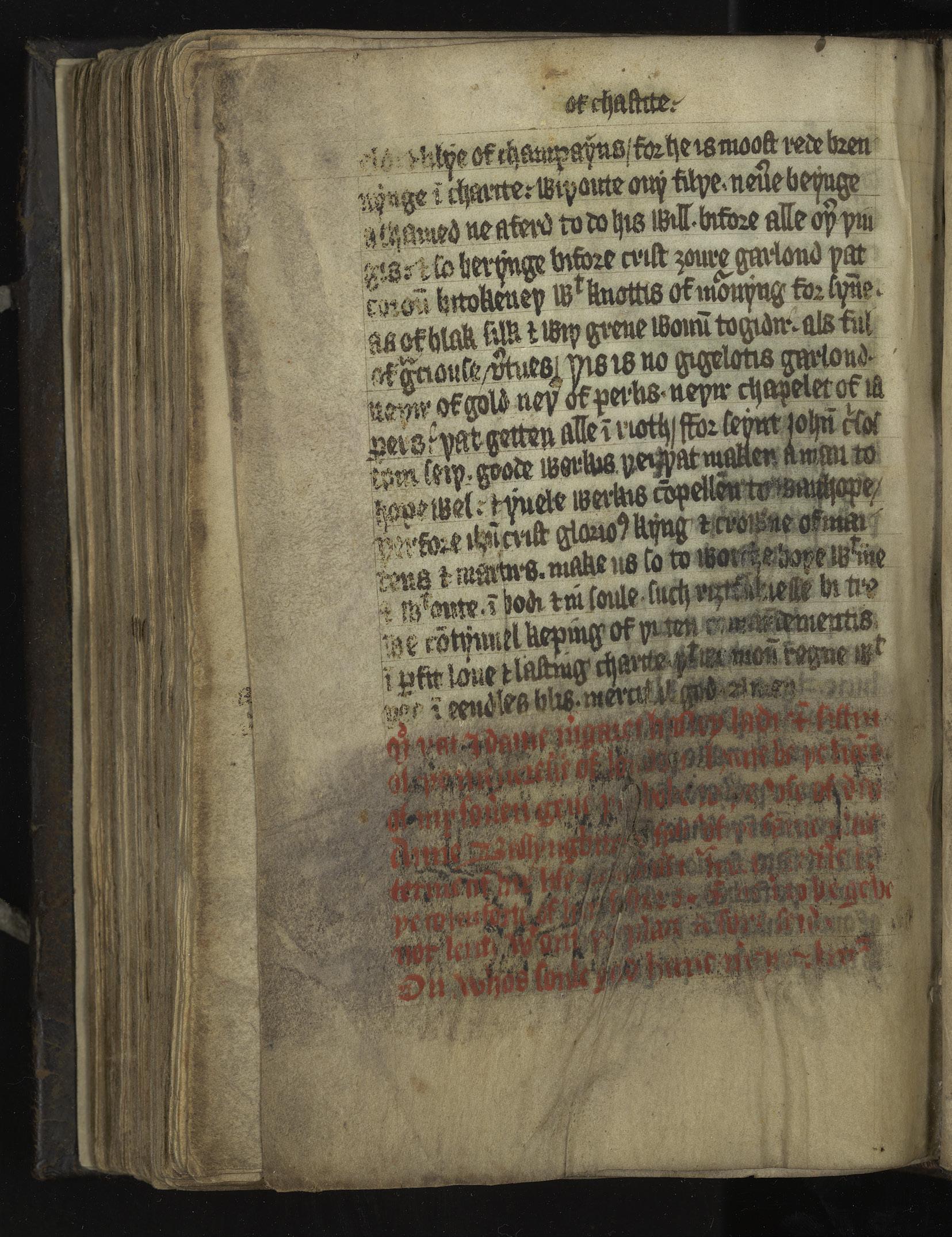

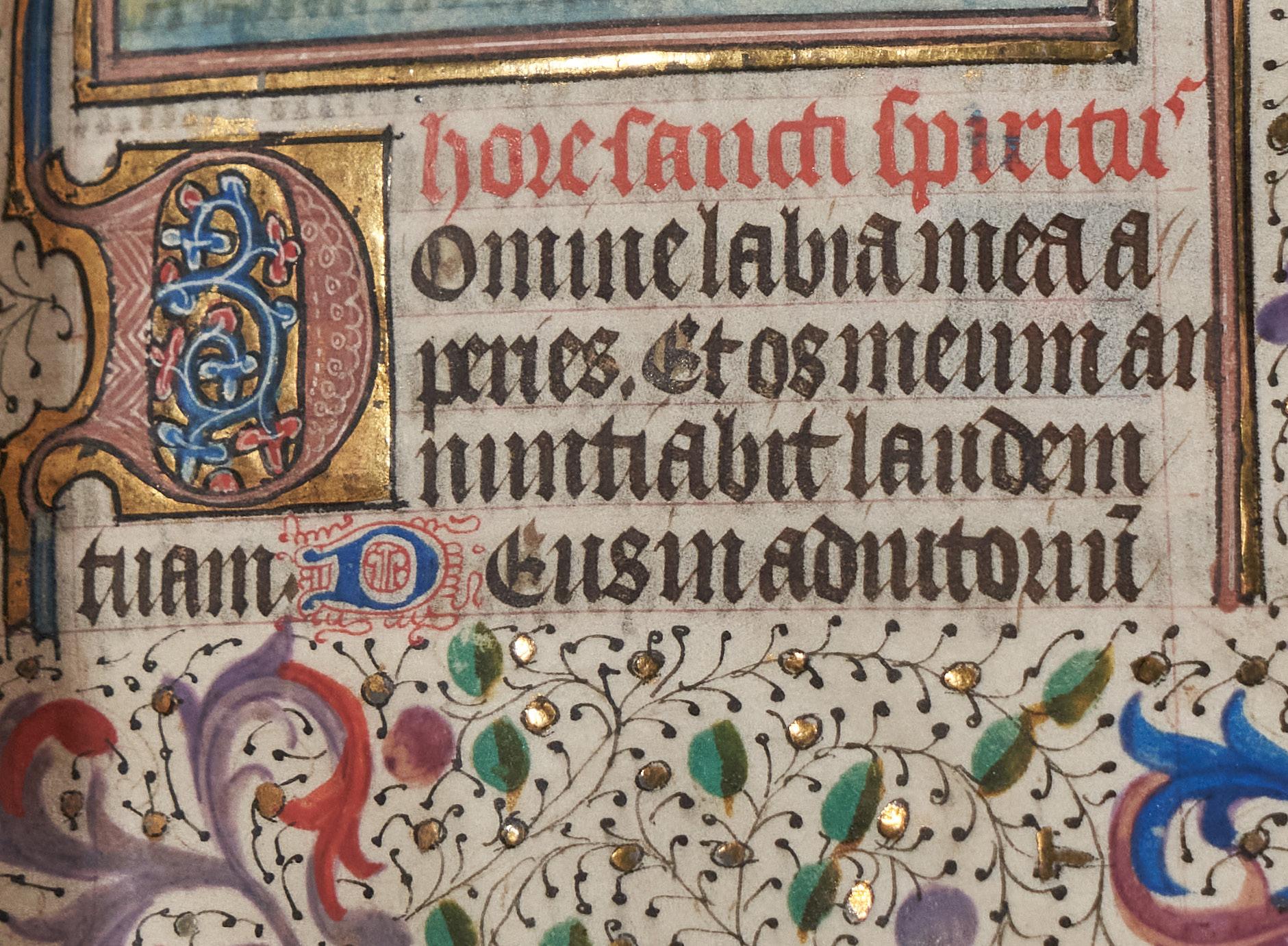

Many early printed books (called incunables if printed before ca. 1500 CE) deliberately imitated the visual effects and reading techniques established in the manuscript tradition: using rubrication (i.e., red ink) to tag a letter at the beginning of a sentence or section; catch words at the end of a page anticipating the first word on the following folio; and hand-illuminated or printed marginal decorations or historiated initials.

Among the earliest to take positive advantage of the printing press to produce and disseminate books, as well as single sheets and pamphlets, was the Protestant Reformer Martin Luther, who published his vernacular translation of the New Testament (Wittenberg, 1522 CE) as part of his effort to give educated laypeople direct access to Scripture.7 Fellow reformers utilized the press to publish loads of pamphlets on Lutheran beliefs and anti-papal polemics. Key printing centers and printers beyond Wittenberg and Mainz included Anton Koberger of Nuremberg;8 in Augsburg: Gunther Zainer, Anton Sorg, and Johannes Schönsperger; in Venice: Erhard Ratdolt, who developed new typographic forms to