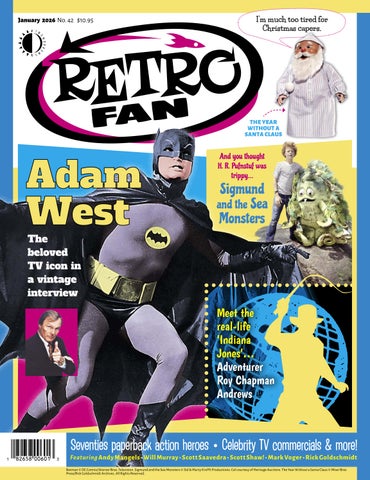

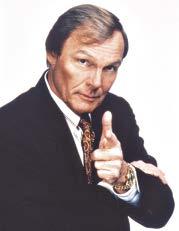

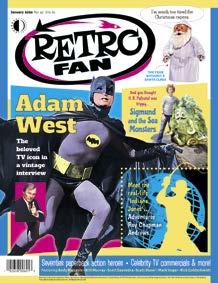

Adam West

Voger‘s Vault of Vintage Varieties

Andy Mangel’s Retro Saturday Morning Sigmund and the Sea Monsters

Scott Saavedra’s Secret Sanctum Before They Were Famous: Soon-to-Be-Stars in TV Ads

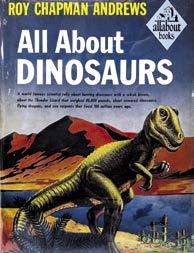

Oddball World of Scott Shaw! Roy Chapman Andrews: The American Museum of Natural History’s Indiana Jones

Will Murray’s 20 th Century Panopticon The Executioner

BY MARK VOGER

You leave work after a long, hard day. You’re starving, but your fridge is insufficiently stocked. You decide to pick up something on the way home.

Who among us hasn’t been in this situation?

It happened to Adam West, then a relatively unknown actor, on Jan. 12, 1966, a Wednesday. The exact date stands out because on that very evening, the action comedy Batman which West starred) was to premiere on ABC Television. How it would fare was anybody’s guess. For now, West just needed a bite of grub.

Recalled the actor: “I stopped at a market in Malibu, where I lived at the time, to grab a steak and a six-pack of beer for dinner. I was in a hurry and overworked. And I heard, at the check-out, ‘Come on! Hurry up! We’ve gotta get home to watch Batman! Faster!’ And I thought: Uh-oh, this could be the start of something.”

division of

(ABOVE) Adam West and Burt Ward in cartoon form as Batman and Robin in the opening credits to Batman (1966).

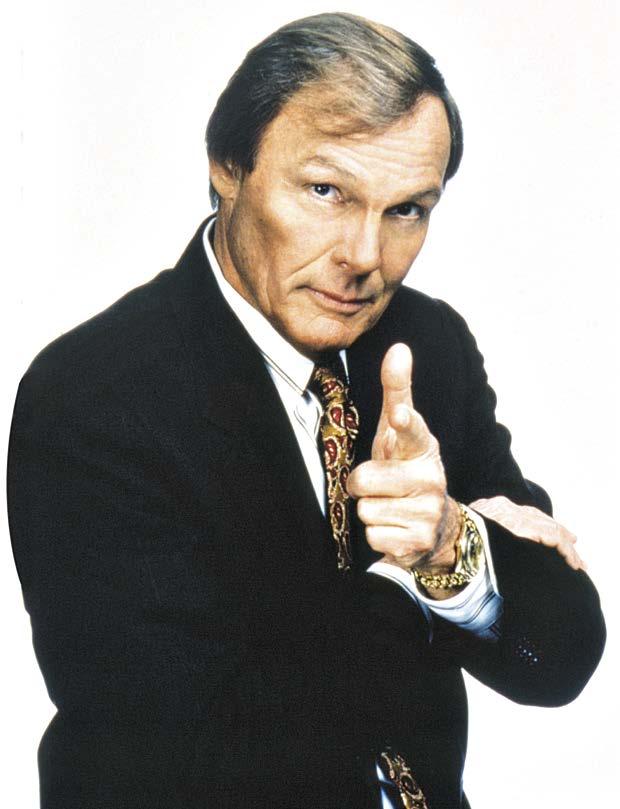

© Warner Bros. (LEFT) West in a promotional photo for Danger Theatre (1993).

© Universal Television, a

NBCUniversal.

Indeed it was. The debut episode—in which Batman (West) and his youthful sidekick Robin (Burt Ward) faced off against that giggling criminal mastermind, the Riddler (Frank Gorshin)—proved to be a ratings bonanza.

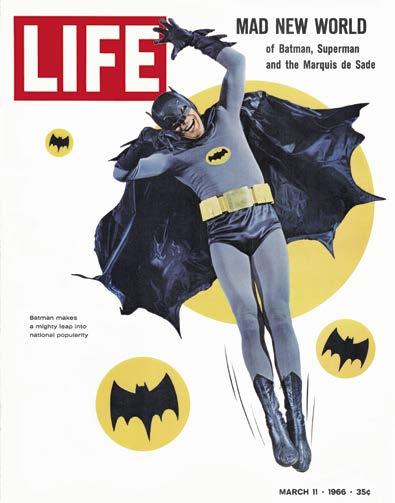

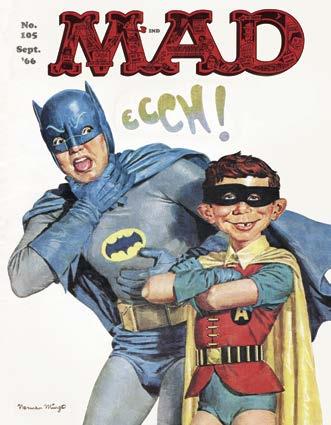

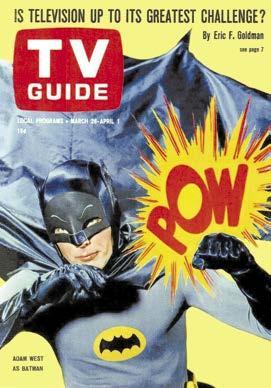

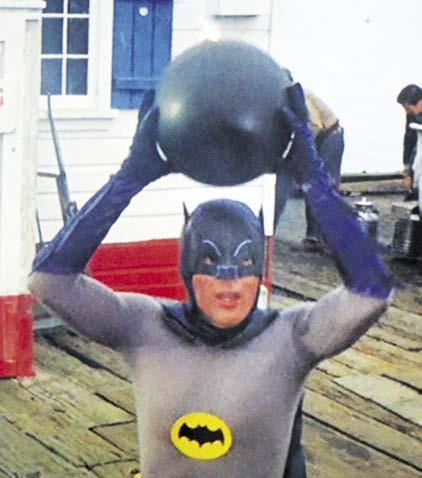

(LEFT) West had to do 18 jumps off of the Batcave’s atomic pile before Life photographer Yale Joel got what he wanted for this cover story (1966). Life © Dotdash Meredith. (CENTER) West (as Batman) meets MAD mascot Alfred E. Neuman (as Robin) on the cover of MAD #105 (September 1966). The painted art was by Norman Mingo. Mad and Batman © DC. (RIGHT) West threw a punch at readers on the cover of TV Guide (1966). TV Guide © NTVB Media.

Executive producer William Dozier mounted a color-saturated production fueled by screenwriter Lorenzo Semple Jr.’s hip script (with subsequent writers taking Semple’s comedic cue). The casting gods, too, were with Batman. West’s Bruce Wayne was a human mannequin, a grown-up Boy Scout. Ward’s Dick Grayson was the last gasp of well-behaved pre-hippie youth. Before long, Hollywood elite clamored for roles as “guest villains” on the TV show.

Batman exploded into a full-blown phenomenon, which the media termed “Batmania,” à la “Beatlemania.” There wasn’t a man, woman, or child in America who was unaware of the series. Store shelves burst with Batman-themed paraphernalia.

But without West, would Batman have rocked our world? Also considered for the role were Lyle Waggoner, Mike Henry, and Ty Hardin—fine professionals all, but come on. Dozier already had his amazing, colorful production built and the first scripts written. In the 11th hour, all he needed was for the perfect Batman to stroll through his office doors.

WALLA WALLA TO HOLLYWOOD

Can you name an actor who landed on the cover of both Life and Mad magazines in the same year? West had that honor. He was also granted a papal audience, and learned that Pope Paul VI was a Bat-fan.

An actor who could be both leading man and clown, West (1928–2017) was born Billy West

Anderson in Walla Walla, Washington. In his 1994 memoir, he was candid about his mother, Audrey, an alcoholic who West knew, even as a youngster, was not faithful to his father. Audrey had dreams of stardom, and once told West that but for his birth, she could have been Joan Crawford. Armchair psychologists might point to these events as the roots of West’s own issues with intimacy and commitment. West worked as a radio disc jockey in Walla Walla… spent a year with the McClatchy news agency… worked in an embryonic television facility at Fort Monmouth, N.J., while in the Army… migrated to Hawaii, where he made his film debut in the Boris Karloff movie Voodoo Island (1957) and hosted The Kini Popo Show on local TV… migrated to Los Angeles... and won promising early roles in The Young Philadelphians (1959), TV’s The Detectives (1961–62), and Robinson Crusoe on Mars (1964). In the end, a silly little TV commercial

Prior to Batman, West filmed a commercial for Nestlé’s Quik which caught the attention of producer William Dozier, leading to the role of a lifetime. © Nestlé S. A.

CANCEL CULTURE

(RIGHT)

Comedian Milton Berle, who later played guest villain Louie the Lilac, filmed a commercial for ABC Television with West in costume. © ABC Television. (ABOVE LEFT) West struck a deal to get more Bruce Wayne, hence more Adam West, into the movie Batman (1966). (LEFT) West as Batman can’t find a safe place to dispose of a bomb out of a Tom and Jerry cartoon in the movie Batman. (BELOW) Bruce and Dick play chess as doting Aunt Harriet (Madge Blake) looks on. © DC Comics. Images © Disney.

But when the TV Batman crashed in ’68, it really crashed. The once-hot series had entered into a death cycle of sinking ratings and production values. Did the lackluster ratings trigger the lower budgets, or vice versa? Either way, West’s final flap of the cape happened just in time for the hippies, with their marijuana and their Nehru jackets, to commandeer the culture. Overnight, the ’66 Batman became an anachronism.

Could West sense Batmania dying near the end of the series?

“You see, that’s when I started to really get restless and want out of the show, in the third season,” the actor recalled.

“It was a very glossy, expensive show to produce, and they were taking losses. So 20th Century-Fox said, ‘Well,

let’s get another season. We’ll have enough product to go into reruns, and then we’ll recoup. We’ll make some money.’

“Well, that was fine. But in order to do that and just get it out of the way and into reruns, they started to cut back, and I fought like hell. I wanted out of the show. We finally came to an agreement that we would try to make it as good as possible, for adults on a certain level. In other words, to keep the classic potential going, that this would be a television classic. Because I sensed that. And I think we did a fairly good job.”

There was also the matter of financial compensation for the use of West’s likeness on merchandise. “We settled once out of court, in 1975,” he said. “They were to have given us an ongoing accounting, and continue with payments. They never did. There was no more communication whatsoever. Look, this is Time-Warner. They’ve got, what, 290 lawyers. Even in small towns. If they want to cheat—I mean, cheating is kind of traditional, I guess. But I never collected on this stuff, really.”

What was West’s most cherished career souvenir from the show?

“I’ll tell you what it is,” he said. “I treasure the reaction people have to me wherever I go. Anyone would prize that. People are warm and funny and loving. I’ve had 40 years of this nonsense. People are wonderful to me. They trust me.”

Through the Seventies, West grabbed a lot of TV work, playing the Love Boat-Fantasy Island circuit as well as the Mannix-Murder She Wrote circuit. In what he called his “secret money out of Hollywood,” West appeared in costume at county fairs, rodeos, and car shows. (He was once shot out of a cannon in Evanston, Indiana.) He and Ward voiced Batman and Robin for Filmation’s animated series The New Adventures of Batman (1977). West, Ward and Gorshin suited up as Batman, Robin, and the Riddler for two regrettable live-action TV specials

Batmania ’66 Lays a Grey and Yellow Egg

BY JIM BEARD

When the Batman television series and its accompanying Batmania hit the homeland hard back in ’66, it spread its wings in many and varied ways as it flew from belfry to belfry…and perhaps one of the oddest, yet somehow unsurprising, manifestations landed smack-dab in the show’s source material.

You see, Robin the Boy Wonder grew up and became Batman, all to serve the greater Bat-good in those campy comic books of the day.

The Caped Crusader was everywhere in 1966; it was a rare corner of life indeed that didn’t fall under the shadow of the hero’s cape and cowl. Toys and games, kitchenware and other household items, apparel, and even foodstuffs weren’t safe from Bat-branding, but for the most part the image of the adult member of the Dynamic Duo that adorned the goods was recognizable to consumers—it took comics to produce an offshoot of Batmania that offered something new, something—we scarcely dare give it utterance—unique

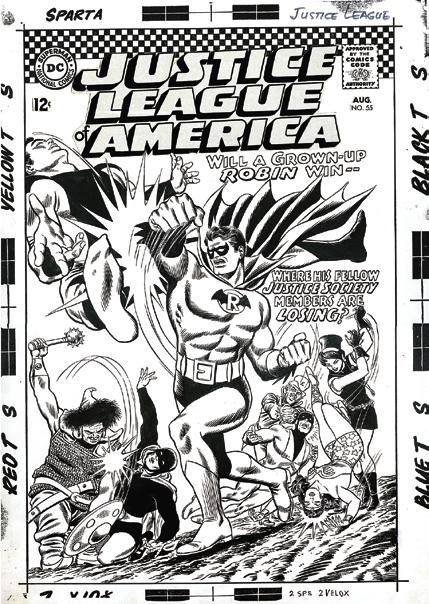

(ABOVE) The Grown-Up Robin of Earth-2 debuts in Justice League of America #55 (August 1967). Text has been digitally removed. (RIGHT) Cover art to JLA #55 by Carmine Infantino and Murphy Anderson. © DC Comics. Courtesy of Heritage.

Kids moseying past the newsstand and the drugstore comic book spinner rack in June of 1966 might’ve had their eye captured by a concept on a comic cover that would have felt both familiar and freakish. Oh, they’d already seen Batman dominating covers before—he was a TV star and entitled to it—but they had never seen anything quite like a “grown-up Robin” sporting a very Batman-ish costume as a member of Earth-2’s legendary Justice Society of America.

(For the uninitiated two or three among you, “Earth-2” is the parallel universe DC Comics whipped up back in 1961 to explain how characters like Superman, Batman, and Wonder Woman could still be hanging around in the “modern” era despite being “born” in the ’30s and ’40s. Earth-2 was where all the Golden Age heroes resided, and Earth-1 was the home of the costumed crumbums running around in the ’60s. Got it?)

Justice League of America #55, cover dated Aug. 1966, sported several figures in action poses, but none so grandiose, so masterful, so… dynamic as that of an overly muscular adult Robin giving a criminal the ol’ Zlonk! Zok! Zowie! just like his diminutive counterpart on the TV show. This “Boy” Wonder was thick as a brick, large and in charge, and decked out in a weird, way-out hybrid uniform,

The Immortal Lee Falk

BY WILL MURRAY

During the course of my nearly thirtyyear career interviewing celebrities for the Starlog group of magazines, I must have talked to hundreds of film stars, directors, and other luminaries. My favorite interviews were always with the creators of movies, TV shows, and comic books I grew up on. I could probably compile a fat book of such interviews.

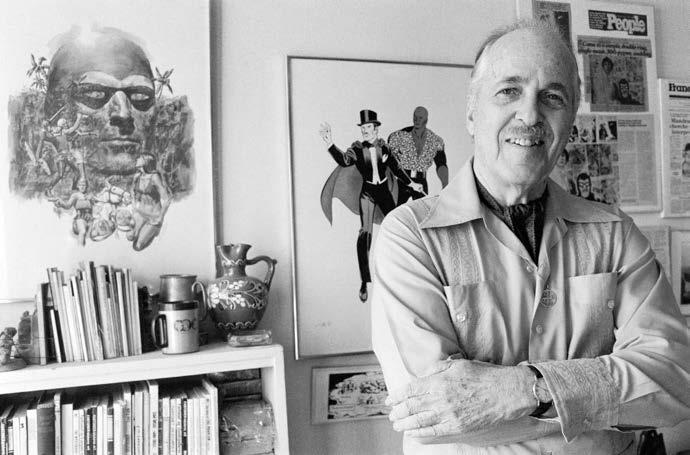

I had an opportunity to interview the great Lee Falk on the occasion of the imminent release of the 1996 Phantom movie starring Billy Zane and Catherine Zeta-Jones. It was a wideranging interview in which I delved into the origins of his immortal character, the Phantom, one of my favorites.

Falk was an amazing individual. He originated not one, but two long-running comic strips, Mandrake the Magician in 1934 and The Phantom in 1936—the first while he was still in his teens!

“I started Mandrake when I was a junior at the University of Illinois at the age 19,” he said. “Actually, I sketched the first Mandrake myself. I wasn’t a very good artist. In fact, I was a bad artist. But I thought it was fun and drew up a Mandrake. I didn’t think anything would happen with it.”

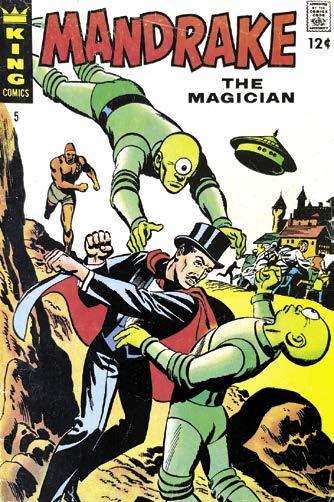

King Features bought it. Mandrake took off, especially after Falk hired Phil Davis, a tremendous artist in the same league as Flash Gordon’s Alex Raymond.

“Mandrake came out of the early interest in stage magicians like Blackstone and Thurston and

Cardini, who I adored,” declared Falk. “I’d seen them all as I grew up. Cardini was a very immaculate gentleman. He came out in full white tie and tails, top hat and cape, started doing marvelous card tricks, and made endless cigars and lighted cigarettes and pipes appear out of nowhere. I had this image of the magician as a very suave gentleman in a top hat.”

Mandrake was no mere performer, but a combination of supernatually-powered stage detective and rootless adventurer inspired by Sherlock Holmes and Marco Polo, who was assisted by an African prince named Lothar.

“People have often told me that I looked like Mandrake,” Falk once quipped. “Well, of course I did because I was alone in a room with a mirror when I drew the first two weeks of the strip.”

With his fantastic supernatural powers and otherworldly adventures, Mandrake quickly became one of King Features’ top strips. But it was the Phantom who achieved a kind of international immortality.

FIRST STEPS TO IMMORTALITY

Strangely, the opening storyline got off on the wrong foot. Initially set in New York City, the events swirled around heiress Diane Palmer and her playboy admirer, Jimmy Wells, as they tangled with a group of thugs. With its Manhattan setting and familiar title, the early episodes must have alarmed the publishers of The Phantom Detective pulp magazine, whose hero was a wealthy playboy who secretly fought crime as the Phantom, who often operated in disguise and sometimes wore a domino mask.

(ABOVE) Lee Falk at home. Photo courtesy of Will Murray. (LEFT) King Feature’s Mandrake the Magician #5, also showcasing Lothar, from 1967. Cover art by Fred Fredericks. Interior story and art by Gary Poole and Rya Bailey. TM Hearst Holdings, Inc.

When I asked Falk about his pulp influences, he replied, “I knew there was such things as The Shadow and The Phantom Detective. I don’t think I’ve ever read them. The only pulps I read in the old days were science-fiction. The old

Amazing Stories. I liked Weird Tales too. I used to read Lovecraft and those writers, you know. Of course I loved to read Edgar Rice Burroughs, not only his Tarzan but Mars stories. He was a real original, and an interesting man.”

Falk never mentioned any legal issues surrounding the strip, except to note that he briefly considered changing his hero’s name to the Gray Ghost, but ultimately decided that the Phantom was the most suitable title.

When asked about the change, this was his reply:

“The first few months he was Jimmy Wells, a very attractive playboy in love with Diana, who liked him as a friend and a brother. But she was in love with a mysterious masked man who appeared out of nowhere to help her during her first troubles. Of course, it was Jimmy, but I didn’t go to the trouble to reveal this. I’ve met people who read the strip then and they had guessed that Jimmy was the Phantom. Later on, I began to change the whole concept as I became intrigued with the whole mythical notion about the 400 years and twenty generations of Phantoms in the jungle. The more I got into that, I kept adding to this background, and I still do.”

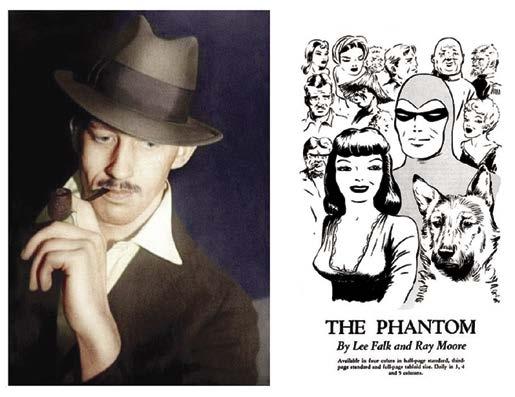

Although Falk himself drew the first two weeks of The Phantom, he preferred to simply script it. So he recruited an obscure artist who was destined to bring his hero to iconic life.

“Ray Moore was assisting Phil Davis in St. Louis,” Falk recalled. “I asked Ray if he’d like to draw The Phantom. Again, I had sketched out what I wanted. So Ray tried it, and again they bought that. So then I decided that my inclinations were actually toward writing rather than drawing. So I decided to stay with it. So when I was about 22, I had two strips going. And that was enough comic strips for me.”

The Phantom quickly evolved from its Manhattan detective-story milieu. With no warning, Falk dropped Jimmy Wells forever, and the action jumps to the South Seas where Diana Palmer gets mixed up with a pirate band called the Singh Brotherhood. Over the course of this story, the background of the Phantom is first revealed. It’s a story that Falk repeated virtually every year, a rote recap preceded by the phrase: “For Those Who Came in Late….”

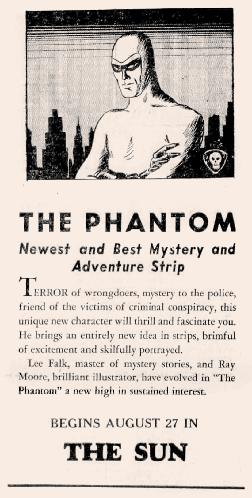

A vintage ad trumpeting The Phantom and its weekly Sunday comic strip appearances. The Phantom is TM and © King Features Syndicate, Inc., World Rights Reserved.

In 1525, Singh pirates captured a merchant vessel near India, slaughtering Captain Standish and his crew. The only survivor, his son, was washed up on shore, where he swore an oath on the skull of his father’s murderer to devote his life to stamping out the Singh Brotherhood. The lad became the first Phantom, and every eldest son of his line adopted the mask and costume of the Ghost Who Walks, creating the illusion of an immortal being dedicated to eradicating evil.

“It gradually developed,” Falk recalled. “But the more I did with it, the more intrigued I became with it. I kept adding to it. I included more background, including stories about his grandfather, or his great-grandfather, and stories dealing with the 17th century Phantoms. Then I began to tie the Phantom mythos with great historical events, like the father of the first Phantom, who was the cabin boy for Columbus. I had a whole story about how he and an Indian boy actually came to the North American continent and saw the Mayans and the Aztecs and so on. I’ve had stories about a 17th century Phantom who conquered a whole pirate city run by a pirate named Redbeard. He conquered Redbeard and his followers, tamed them, and made them into the first Jungle Patrol. The Phantom is the unknown secret commander. The reason for this is that it was founded 250 years ago by a Phantom, who was about the 7th Phantom, who was known as the Seventh.”

Even then, Falk continued to tinker with the strip. Originally his hero was named Christopher Standish. Later that evolved into Kit Walker, for the Ghost Who Walks. While the Phantom initially operated on foot, Falk added a white stallion named Hero so his jungle protector could get around more heroically. Over time, other elements appeared, including his skull ring; Devil, his pet wolf; and countless others. Piece by piece, a mythos was built up.

Ray Moore and his art.

TM and © King Features Syndicate, Inc., World Rights Reserved. Associated characters are © King Features Syndicate, Inc., World Rights Reserved. Courtesy of Will Murray.

“The Phantom came out of my boyhood interest in the gods and heroes of Greece and Rome, and the Scandinavian heroes, plus Robin Hood,” Falk

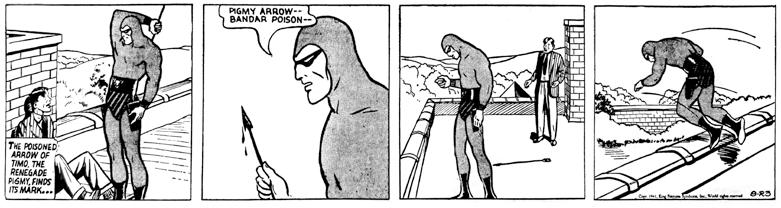

explained. “You know it’s kind of a Robin Hood get-up. Also, my interest in Tarzan. He’s been called a modern Tarzan. I adored Kipling’s Jungle Book. I’ve named the Phantom’s special crowd, the pygmies who live in the Deep Woods with him, the Bandar. I took that from Kipling’s Bandar-log, the monkey tribes that Mowgli is associated with.”

Despite his lack of superpowers, the Phantom is considered the first truly costumed superhero, stylistically the forerunner of all who came afterward. In different interviews, Falk provided varying accounts for its origins.

He told me, “It was an odd concept. Sort of a masked, hooded figure, like a medieval executioner. But he’s not an executioner. He’s a good guy. I thought of him as a jungle man.”

When I pointed out that the outfits of both Superman and Batman, who soon followed, were modeled after circus acrobat tights, he demurred.

“They remind me more of the Robin Hood type,” Falk corrected. “I think of Robin Hood in green, and he also wore tights. Those were the pictures I grew up with.”

The outfit Falk designed was minimal at first. There was no skull on the buckle of his gun belt, and the diagonal black stripes on his trunks were added as the outfit was refined. The empty eyes of the mask were inspired by the eerie look of classical Greek statuary, pupil and iris eerily blank.

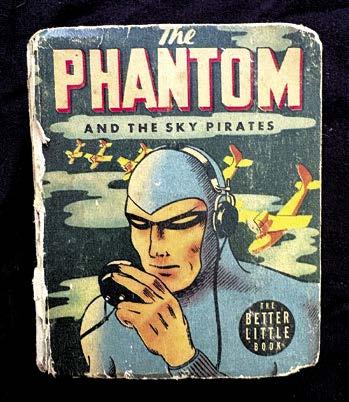

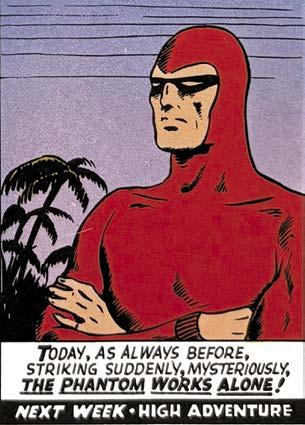

Because the Sunday strip did not come along until 1939, confusion arose when it came time to color the Phantom’s uniform. The early Phantom Big Little Books inexplicably chose red. The first U. S. comic book depicted him in brown. Other countries presented him haphazardly—apparently at the whim of the people involved in production.

Astonishingly, none of these colors hit the mark.

“I had this image of a guy climbing over roof tops, the mystery man, and later on through the jungle, in tights,” Falk explained. “But I never thought of the tights as being

(LEFT) In 1945 Better Little Books’ (a version of Big Little Books) The Phantom and the Sky Pirates reprinted panels from Lee Falk and Ray Moore’s daily Phantom strip and matched them with prose pages. (BELOW) For those who came in late… a reprinted origin of the Ghost Who Walks from the Pacific Comics Club Publication. Note the red Phantom outfit. TM and © King Features Syndicate, Inc., World Rights Reserved. Both from the Bill Catto Collection.

purple. I thought of them as gray. They put out a color page, and the tights were purple. They didn’t consult me. They just made it purple, much to my amazement. I would have changed it to a camouflage color like green. But it was out, and I didn’t change it. In Europe, the Phantom is red. Which is absurd, having a man run through the jungle in red. Both colors are no good, really.”

The explanation might be more than mere error. In those days, a pale purple was used to emulate gray. For decades, Batman’s outfit was similarly purplish until DC Comics demanded a better true gray hue from their printer. The anonymous original Phantom colorist may have gotten it as correctly as 1939 technology allowed!

Over time, the Ghost Who Walks eclipsed Mandrake the Magician, who gradually lost his supernatural powers and hence his invincibility, becoming a kind of super-hypnotist who defeated his foes with illusions.

“Perhaps The Phantom is more widely read than Mandrake because he is a better hero,” suggested Falk. “He is simple, straightforward—a colorful hero, a real man, but a hero. Whereas Mandrake appeals to the more imaginative readers. It takes a better imagination. I feel whenever you write fantasy, you lose half of your readers anyhow, and Mandrake is mostly fantasy. For that reason it has always been more difficult to write Mandrake. Every Mandrake story is a new gimmicky idea. It has to be very special. Otherwise, it becomes boring. He needs very special opposition and situations because he is a very special man.”

Part of The Phantom’s popularity is that it is a pure adventure strip. The action takes place around the globe, giving the hero an interna-

The Phantom is hit by a poison arrow in this 1941 daily strip. TM and © King Features Syndicate, Inc., World Rights Reserved. From the Bill Catto Collection.

FANTASTIC FALL PREVIEWS

Looking Back at TV Guide Special Issues of the Late 1970s and Early 1980s

BY ROBERT JESCHONEK

Once upon a television, every home in America seemed to have a copy of TV Guide magazine on the coffee table, sofa, or atop the TV set itself. Each week, a new issue hit the mailbox or landed in the grocery cart, its pages listing what shows could be watched at what times on which days.

And once a year, one very special issue—the Fall Preview arrived with a bang.

It still comes around, as do the regular weekly issues, and its mission is much the same: to preview the many new shows that the television networks (broadcast and cable alike) plan to run in the new TV season. (These days, the offerings of select streaming services are also included.) As in years gone by, you can still flip through and see which series look most likely to succeed… or barely squeak by… or flop.

But in decades past, like the 1970s and 1980s, the Fall Preview issue was more of an event. There weren’t as many news sources as there are today; no internet or social media to continuously deliver the latest scoops on upcoming entertainment. You couldn’t just use a search engine to find fresh updates on your favorite shows and stars.

Quite simply, if you loved TV, you loved TV Guide’s Fall Preview. You pored over every page in the slick color sections—half in the front of the magazine and half in the back—and devoured each profile of a new network series featured there. You marveled at the show concepts—some cool, some not so cool—and wondered if the stars in the accompanying color photos would be worth watching.

And as you combed through that very special issue, you thought about the shows and stars who’d gone before, some still raking in giant ratings, others long gone after a handful of episodes. Sometimes, the shows died young while the actors went on to great success; other times,

the shows succeeded, and the actors bombed out.

There was a lesson on every page, if you paid attention… and there still is. Looking back from the vantage point of today, the lessons can be even more illuminating. We can see how the past changed the future.

We can see how the shows and stars of yesterday became the enduring classics or forgotten flops of today and tomorrow.

MICHAEL KEATON AND ANDY KAUFMAN: FLOPS OF 1976

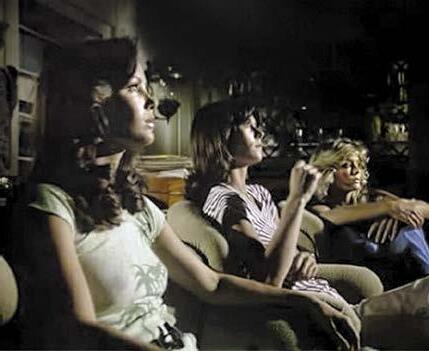

Could any show in the 1976–1977 TV season have had a bigger cultural impact than the ABC network’s Charlie’s Angels, the titillating adventure series that launched Farrah Fawcett-Majors, Jaclyn Smith, and Kate Jackson into the rarefied firmament of superstardom?

And yet, in the September 1976 Fall Preview issue, Charlie’s Angels was just another question mark on the fall schedule. It had just as much chance of success as other network shows previewed in that issue like Spencer’s Pilots, Ball Four, or Executive Suite… in a statistical sense, at least.

(ABOVE) ’Twas the season! In 1976, Fall meant it was time for the Previews issue. © TV Guide Magazine, LLC. (LEFT) Even the Angels were excited to watch the new shows in 1976.

TM Columbia Pictures, Inc. Courtesy of IMDb.

But the even odds of success didn’t last long. Charlie’s Angels turned out to be the metaphorical lightning captured in a bottle… though it wasn’t the only show to make a strong positive impression that season.

Quincy, an NBC show starring Jack Klugman as a crimefighting coroner, also had legs. It might not have made as big of a splash early on, but it ended up outliving Charlie’s Angels in the long run, broadcasting 148 episodes over eight seasons.

Not bad, though the diner-set CBS sitcom Alice, starring Linda Lavin, was the true champion of the class of 1976–1977 in terms of longevity. Alice went on to run 202 episodes over nine seasons… 87 episodes and four seasons longer than Charlie’s Angels

By contrast, All’s Fair, a political sitcom with a Norman Lear pedigree and the established star power of Bernadette Peters and Richard Crenna, lasted only one season of 24 episodes. Van Dyke and Company, a variety show starring the beloved Dick Van Dyke, only made it to 11 episodes.

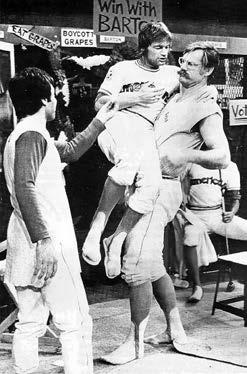

That isn’t to say the two shows didn’t make a mark. The cast of All’s Fair included a young, mostly unknown actor named Michael Keaton in a supporting role. As for Van

(RIGHT) Quincy, M.E. debuted in 1976 and ran for 8 seasons. Jack Klugman’s day-to-day activities as a medical examiner were different from most of his peers. Pictured here with Lynnette Mettey in an early Season 1 episode: “Hot Ice, Cold Hearts”. TM Universal Television. (BELOW) Jim Bouton and Ben Davidson clown around the locker room for Ball Four. TM Paramount Global. All images courtesy of IMDb.

Dyke, then up-and-coming comedian Andy Kaufman was a member of the regular troupe of performers backing the titular star each week.

Keaton, of course, went on to become a movie icon, starring in such films as Batman, Beetlejuice, and Mr. Mom. Kaufman parlayed his signature offbeat style into the role of Latka Gravas on the ABC sitcom Taxi (which premiered in 1978) and appeared in numerous TV shows and films until his untimely death in 1984 at age 35.

Big careers can grow from the briefest and least wellknown of TV shows… though it’s also true that some roles can be dead ends for talented actors. Whatever happened to the cast of Executive Suite, also featured in that 1976 Fall Preview issue? They may well have gone on to very fulfilling careers, but there seem to have been no Michael Keatons, Linda Lavins, or Farrah Fawcett-Majors among them.

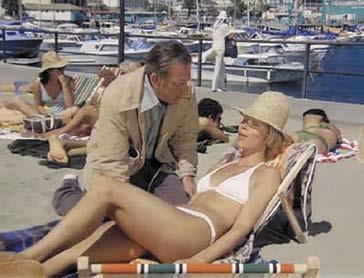

JAMIE LEE CURTIS: FAVORITE NURSE OF 1977

Some TV seasons have an embarrassment of riches in the hit department. Others… not so much.

Case in point, the 1977–1978 season brought us ABC’s The Love Boat (a cruise ship-based romantic comedy) and Soap

(ABOVE) Future star Andy Kaufman got his start on Van Dyke and Company, pictured here with Lucille Ball and Dick Van Dyke. © NBC. Courtesy of IMDb. (RIGHT) All’s Fair featured (LEFT TO RIGHT) Michael Keaton and starred Judith Kahan, Richard Crenna, and Bernadette Peters. © Sony Pictures Television.

(RIGHT) Executive Suite starring (LEFT TO RIGHT) Percy Rodrigues, Sharon Acker, William Smithers, and Mitchell Ryan. © MTM Television. (BELOW) All’s Fair starred Richard Crenna and Bernadette Peters, but Michael Keaton (FAR LEFT) appeared, too.

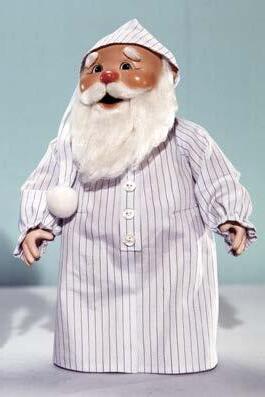

BY RICK GOLDSCHMIDT

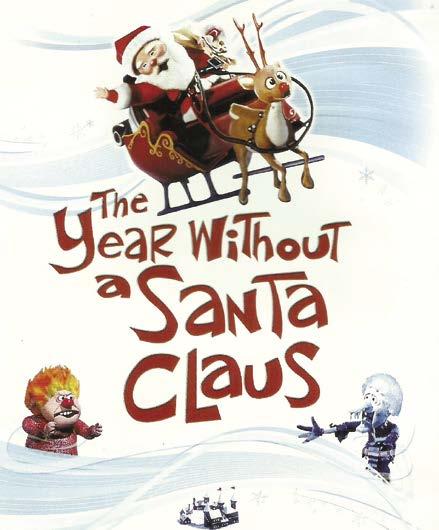

As the official Historian/ Biographer for Rankin/Bass Productions, I was asked two questions frequently, especially as I was starting out: “What was wrong with the misfit doll on the Island of Misfit toys?” and “What was the title of the Christmas special with the Heat Miser and Snow Miser?”

Rankin/Bass’ The Year Without a Santa Claus celebrated fifty years last year (2024) and with the work I have been doing over the past thirty-plus years, people are starting to know the special by name. In fact, my seventh book, which came out last year, focused on The Year Without a Santa Claus and ’Twas the Night Before Christmas, which also turned fifty.

What Was the Name of the Special with the Heat Miser and the Snow Miser?

The Year Without a Santa Claus premiered on ABC-TV December 10, 1974, and was sponsored by Parker Brothers games. The real mystery is why did it disappear from ABC-TV? They had a network goldmine in this classic holiday special. Everyone wants to watch the Heat Miser and Snow Miser for Christmas! ABC hung on to Rankin/ Bass’ Santa Claus is Comin’ to Town, but airs a badly edited version every holiday season. I have seen networks and big companies acquire Rankin/Bass specials and films over the years, and do all the wrong things with them. So this is no different.

(TOP LEFT) The Snow Miser. (TOP RIGHT) The Heat Miser. (ABOVE) The Blu-Ray version of a classic! © 2012 Rick Goldschmidt Archives/Miser Bros. Press.

Bass series on Saturday morning, which is where Michael started working for ABC, but they began airing many specials in prime time. Eventually, the relationship spawned many ABC Friday night television movies produced by Rankin/Bass Productions. Early on, Rankin/Bass provided content exclusively for NBC, as they had a friend there through business associate Larry Roemer, but they expanded to all three networks beginning in 1969 with Frosty the Snowman on CBS.

For this special, The Year Without a Santa Claus, Arthur took the Pulitzer Prize winning book by Phyllis McGinley and told Michael, “We want to turn this into our next Christmas special.” Michael green lit it and they were off! Usually, Arthur and Jules would base their TV specials on a classic song or Christmas carol, but this one was based on a short storybook, for which they would expand it considerably. This is a big part of the reason the title is not so memorable. The theme song is definitely not as memorable as the Miser Bros. songs, but more on that later.

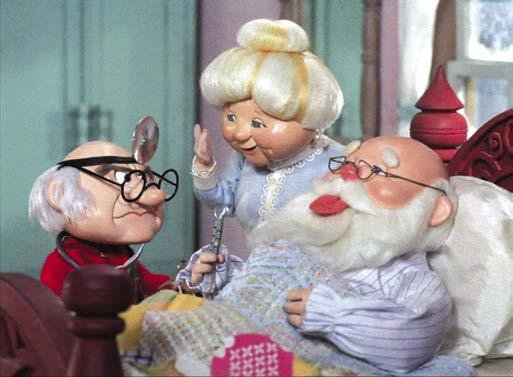

THE CHRISTMAS CAST

Arthur Rankin Jr. had a very good friendship with Michael Eisner at ABC. Not only was ABC running various Rankin/

For Santa Claus, Mickey Rooney would return to do the voice and singing. Rankin/Bass musical composer and dear friend, Maury Laws, would always say, “My favorite specials were the ones Mickey Rooney appeared in. He was very good for animation, and could pull off singing whatever song we threw at him.” Mickey did become the voice for Rankin/ Bass’ Santa Clauses, as he would return for the feature film

Rudolph and Frosty’s Christmas in July in 1979.

(LEFT TO RIGHT) Bob McFadden, famous as Frankenstein Jr, was Jingle Bells the elf in The Year Without a Santa Claus; Bradley Bolke, the voice of Chumley the Walrus in The Adventures of Tennessee Tuxedo, was Jangle Bells in this Rankin/Bass production; the Snow Miser himself, Dick Shawn! In the 1974 movie, Shirley Booth, best known as TV’s Hazel, was the voice of Mrs. Claus. The Television version of Hazel is © Sony Pictures Digital Productions, Inc.

I love Mickey as Santa, but my favorite was Stan Francis as Santa Claus in Rankin/Bass’ Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer. To me, he just captured Santa perfectly and was also the voice of King Moonracer. Stan, unfortunately, passed away during a performance in Canada in 1966. [See RetroFan #12 for more on Rudolph –RetroEd.]

My pal Vic from Fox-32 in Chicago asked Mickey about his work with Rankin/Bass Productions, and Mickey said, “Originally, I turned down the role for Santa Claus is Comin’ to Town. I really had no interest, but my agent persisted and I accepted, and boy am I glad I did. Over the years many have come up to me, telling me how much these specials have meant to them and having me sign things. Out of all the things I was in, these specials mean the most to my fans.” My late, great friend Producer Arthur Rankin Jr. said, “Mickey was a very good actor. He was always very excited about doing his part and he would grab me and crawl up my lapel. He was very, very good!”

Mrs. Claus, or Mrs. C, was played by Academy Award winning actress Shirley Booth, better known as TV’s Hazel! She won her Best Actress Oscar for Come Back, Little Sheba in 1953, and she won many other awards, including Emmy Awards for Hazel. The Year Without a Santa Claus was her final role in show business, so Arthur and Jules were lucky to get her. She joins many other veteran actors in supplying their final roles for Rankin/Bass, which include Richard Boone and Victor Buono.

Maury Laws said, “Many people knew her from her series Hazel, but forget she did many heavy roles in serious productions before that. She was a wonderful performer and did a great job at singing the songs we wrote for her.”

For elves Jingle Bells and Jangle Bells, Arthur and Jules recruited veteran cartoon voice actors Bob McFadden and Bradley Bolke. I became very close friends of both actors, and they shared everything with me.

Bob McFadden and I connected shortly after my first book, The Enchanted World of Rankin/Bass: A Portfolio (Miser

Bros. Press) came out in 1997. I didn’t know it, but Bob was very ill. He wanted me to document his career, and I have done that over the years. Besides Jingle Bells, he is well known for being the voice of Frankenberry, Milton the Monster (and all the other characters on that show), Cool McCool (and many in that cast, too), Snarf in Rankin/Bass’ ThunderCats and Baron Von Frankenstein in Rankin/Bass‘ Mad, Mad, Mad Monsters. He recorded all of these characters for me as voice mail messages, and his voice still nailed the characters. As a small boy, I remembered a Terrytoons cartoon that Bob did the voice for called Luno. Bob also recorded voices for many famous albums, including some with Rod McKuen (sometimes as Dor), and is on one of the best-selling records of all-time, The First Family, during the Kennedy Presidency. Bob passed away January 7, 2000.

Archives/Miser Bros. Press.

The North Pole’s Doctor, uncredited by name in the cast listing, was also voiced by Bob McFadden. © 2012 Rick Goldschmidt

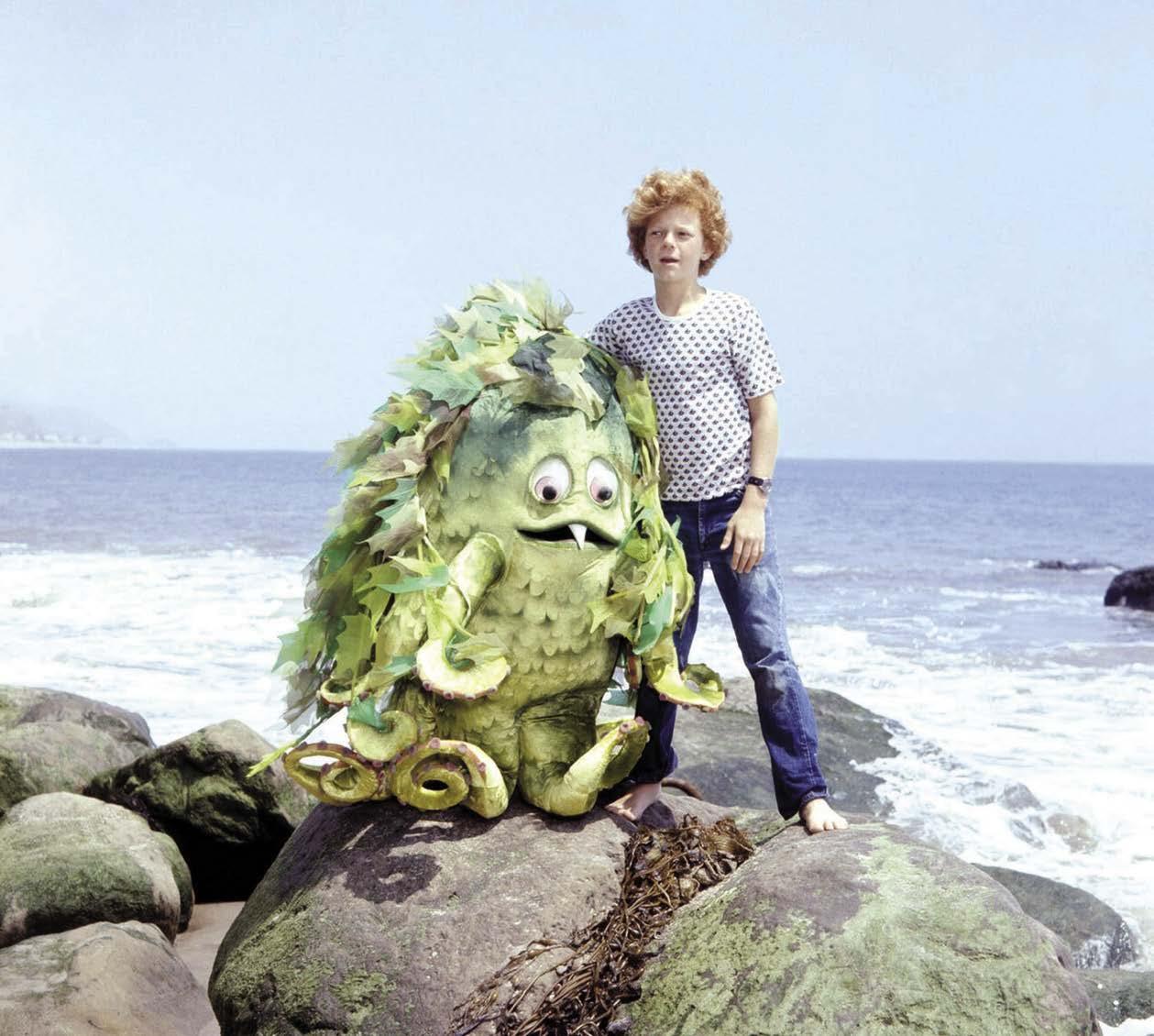

Billy Barty (in costume) as Sigmund Ooze with Johnny Whitaker as Johnny Stuart in Sigmund and the Sea Monsters. © Sid and Marty Krofft Productions.

BY ANDY MANGELS

Welcome back to Andy Mangels’ Retro Saturday Morning, your constant guide to the shows that thrilled us from yesteryear, exciting our imaginations and capturing our memories. Grab some milk and cereal, sit cross-legged leaning against the couch and dig in to Retro Saturday Morning! This issue, we’re finding out that the ocean hid weird adventures even on Saturday mornings, as we trawl through the saltwater and sand to review Sigmund and the Sea Monsters

Children’s television of the late 1960s and early 1970s was full of superheroes, adventure, music, and talking dogs… and then there was the weird worlds of Sid & Marty Krofft. Building a legacy on far-out candy-colored and counter-

culture shows, bizarre stories, puppets, and vaudevillian comedy actors, the brothers Krofft produced many hits… but none had thus-far lasted as long as the one which starred a little sea monster who couldn’t scare anyone…

THE KROFFT KALEIDOSCOPE

In the world of 1960s–1970s Saturday morning television, only a few companies ruled the roosts on the three networks: Hanna-Barbera Productions, Filmation Associates, DePatie-Freleng Enterprises, and Sid and Marty Krofft. Though Filmation had been dabbling with live-action among its animated offerings, the Kroffts would almost single-handedly keep live-action alive on Saturday mornings, first designing The Banana Splits for Hanna-Barbera in

1968, then debuting their hallucinatory (some would say hallucinogenic) hit H.R. Pufnstuf in 1969 (see RetroFan #16 –RetrodEd). Both were NBC series, and they followed them up with The Bugaloos in 1970–71, and Lidsville in 1971–72.

All the shows featured humans interacting with performers in elaborate costumes, as well as puppeteered objects or animals. Insect rock bands; hats that talked, danced, and sang; dragons; witches; and anthropomorphic clocks, houses, and vehicles all combined with a psychedelic tone that not only appealed to young imaginations, but also to those older viewers of the era that might be experimenting with mind-altering drugs and hallucinogens.

The costumed performers whom Krofft employed were mostly shorter/little people—and they were rightfully called “puppeteers” because they had to puppeteer their costumes and perform in them. Alumni for the shows included dancer and former Mouseketeer Sharon Baird, as well as Felix Silla, Angelo Rossitto, Johnny Silver, Harry Monty, Joy Campbell, and Patty Maloney. Famed little person actor Billy Barty was a Krofft mainstay, and he had helped spread the word to diminutive actors that helped them get hired by the Kroffts. The performers earned the SAG minimum of $420 a week.

Although Lidsville and H.R. Pufnstuf stayed in semi-regular reruns, the Kroffts were without a new show, although they continued to provide costumes and props for the syndicated series The New Zoo Revue. But a new FCC rule that took effect on January 1, 1973, meant that networks had to reduce the amount of commercials from 16 to 12 minutes per hour, and thus provide more content. The result meant that live-action shows—which were somewhat cheaper, and definitely faster, to produce—had an edge, and the Kroffts were back in the game.

A soggy chance encounter would lead to the Kroffts’ next success…

SIGMUND WASHES ASHORE

According to Sid Krofft in a 1999 EmmyTVLegends interview, “In La Jolla… I was down at the beach with a friend of mine, and we found this strange piece of seaweed that I had never seen before, wanted to bring it back to L.A. because nobody would believe it. And then in driving back to L.A. with my friend, I said, ‘My God, we were like two little kids playing on the sand with this piece of seaweed. I mean, wouldn’t it be a great concept for two kids to hide out a sea monster?’ I immediately gave him a name, you know, Sigmund, because he was such a smart piece of seaweed. And that’s where that concept came from. It came into the office, and we started putting it together. Si Rose was actually still working for us, doing all of our shows. And he helped put that whole concept together.”

Si Rose was a longtime comedy writer who had worked extensively with Bob Hope, before continuing on as writer, head writer, and producer on shows like Bachelor Father, How To Marry A Millionaire, and McHale’s Navy. He had joined the

The brothers who started it all: Sid and Marty Krofft. © Sid and Marty Krofft Productions.

Development art for Sigmund. © Sid and Marty Krofft Productions.

Krofft company in 1969 as a writer and executive producer on H.R. Pufnstuf. In 2005, Rose revealed on an interview for the Saturday Morning with Sid & Marty Krofft DVD that when riffing with the Kroffts on ideas for Sigmund, “I kind of modelled it all after All in the Family, where the papa monster was gruff and hated everything… and mama monster was a ding-a-ling… and the two sons were meatheads.”

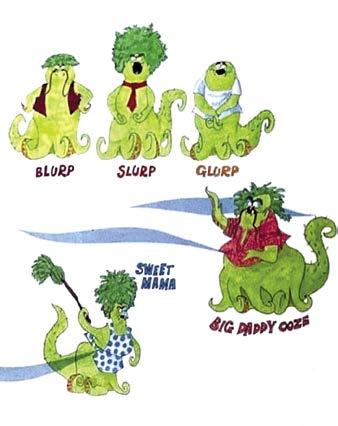

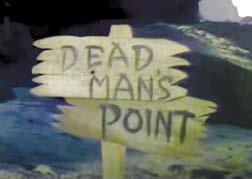

The show concept, mostly developed by Si Rose, found Sigmund Ooze, the least scary member of the Ooze family of sea monsters who lived in a cave at Dead Man’s Point. Belittled and ridiculed by Big Daddy and Sweet Mama, and bullied by big brothers Slurp and Blurp—all because he can’t scare humans properly—the dejected and sad Sigmund was found on the beach by a pair of teen boys. With their parents out of town—seemingly forever—Johnny and Scott Stuart brought Sigmund back to live at their secret clubhouse. Unfortunately, there, they had to contend with keeping the green buck-tooth creature out of sight of their housekeeper, Zelda Marshall, and her paramour, town sheriff Chuck Bevans.

Sigmund was indeed the opposite of his family, with a sweet and caring heart; it was only because of his looks that any human might actually be frightened if they were to interact with him. Another difference of the show was that rather than a single human star, Sigmund had the two teen brothers as protagonists, which allowed them to play off each other in the stories. And in an era of Saturday morning in which Action for Children’s Television was warbling about what would eventually be known as “prosocial content,” the Stuart brothers were nearly perfect role models; they cleaned their rooms and did their chores, recycled items from their neighborhood and the beach, and as often as possible—even though they had to hide a sea monster—they were respectful to the adults around them.

But who would play the siblings in question?

THE BROTHERS STUART… AND THE FAMILY OOZE

Casting Sigmund’s two leads was a critical matter. Oliver! film star Jack Wild had been essential to H.R. Pufnstuf’s success, and The Munsters star Butch Patrick was the darling of Lidsville. So Sid and Marty Krofft looked at what other

(LEFT) Not exactly ready for the Best Set Design Emmy! From the set of show. © Sid and Marty Krofft

(ABOVE) Writer and producer Si Rose. (RIGHT)

Sigmund had superficial similarities to previous Krofft shows just due to its pedigree, but this time instead of the “stranger in a strange land” discovering exciting, magical, or dangerous things, the show was set fairly firmly in a grounded human reality. Although the Ooze family “monsterland” cave was still unusual, the home and toolshed/clubhouse were normal. And instead of dastardly villains, the “bad guys” were mostly the Ooze family who, at their base, wanted Sigmund to live up to the family job. Even if Big Daddy was a brutish father, Sweet Mama cared more about her possessions than her children, and Slurp and Blurp were cowardly and thickheaded bullies.

The Stuart brothers, Johnny Whitaker and Scott Kolden, and their new slimy friend, Sigmund.

© Sid and Marty Krofft Productions.

“We needed a human side to it” said Rose on the DVD interview. “So we came up with the idea that the there’d be a family down at the beach, and there’d be some kids there. It sounded like a good setup. There was more opportunity here for real good story construction because there was a human side of life, and then what a monster is going through. Everybody’s got problems.” Indeed, as Sigmund was developed, the writers planned tandem stories that worked as a kind of funhouse mirror, giving viewers a chance to see a “normal” story and an Ooze-family parallel to it.

Before They Were Famous

Soon-to-Be Stars in TV Commercials

BY SCOTT SAAVEDRA

“And now a word from our sponsor…” – Early radio and television announcement

RetroFans likely recall having to sit through multiple “commercial breaks” —a cluster of 30–60 second advertisements—that punctuated nearly every broadcast on television. The common joke about these breaks centered on how quickly you could relieve yourself or put together a snack before the regular program resumed. There was no effective workaround for most of us. The number of commercials we viewers were subjected to varied. In the 1960s the average amount of commercial time was 8–9 minutes of ads. By the 1980s an hour of Prime Time could have 16–18 minutes of commercials.

This isn’t the first time we’ve looked at commercials here at the Secret Sanctum [See RetroFan #25 for commercial jingles and RetroFan #35 for coffee advertising –RetroEd], but this is our first extensive examination of the actors featured in the ads. Specifically, noted talent in the early stage of their careers. And it’s a good batch, but I have to admit, we barely scratch the surface here. There’s plenty more. Maybe

we’ll get to it someday. Unfortunately, the quality of most of the commercials available to us (via YouTube, Internet Archive, and Duke University’s Digital Collection) can be of poor quality. Corrections were made as best as technology allows (today), but be prepared for a bit of blurriness (your patience is appreciated).

A good television commercial performance in a popular campaign could change the arc of an actor’s career. The ad that put 1 Sandy Duncan on the map was for United California Bank (c.1969) touting the quality of its tellers. It was a terrific ad in its day—a young teller struggling to write down and pronounce a name completely foreign to her— but probably wouldn’t fly now. Duncan is a total charmer in the ad, and the camera wisely holds on her expressive face. Her co-star was Titos Vandis, a classic “oh, I’ve seen that guy” actor.

Duncan’s career quickly blossomed with her own TV series at age 23, movies, and stage work following the UCB commercials. She continued to do commercials for years.

Sandy Duncan

You Deserve a Commercial Break Today

Ronald McDonald, the mascot for the now ubiquitous McDonald’s fast food chain, starred in a series of regional commercials beginning in 1963. He was created and played by 2 Willard Scott, who would later go on to be the weathercaster for the Today Show from 1980–2015. Scott, who had previously played Bozo the Clown in the Washington, D.C. market, designed Ronald giving him a drink cup for his nose and two trays of McDonalds’ food as hat and belt.

Before his tenure on Seinfeld (1989–1998) as the self-centered George Costanza, 3 Jason Alexander performed in stage musicals. That experience served him well as he danced his way through this 1985 commercial for the long gone McD.L.T.

4 Megan Mullally (Will & Grace, 1998–2020) and 5 John Goodman (Roseanne, 1988–2018) are both excited about the new Egg McMuffin in the same commercial.

McDonald’s began their first national promotion campaign, “You Deserve a Break Today,” in 1971 with the utterly fantastic “Grab a Bucket and Mop” musical ad. Most notable pre-fame actors include 6 John Amos (Good Times, 1974–1979) and 7 Anson Williams (Happy Days, 1974–1984). Other solid character actors in the ad were 8 Robert Ridgely, 9 Johnny Haymer, and John Wheeler. 10 Howard Morris, Ernest T. Bass on the Andy Griffith Show (1960–1968) and a variety of characters on Your Show of Shows (1950–1954).

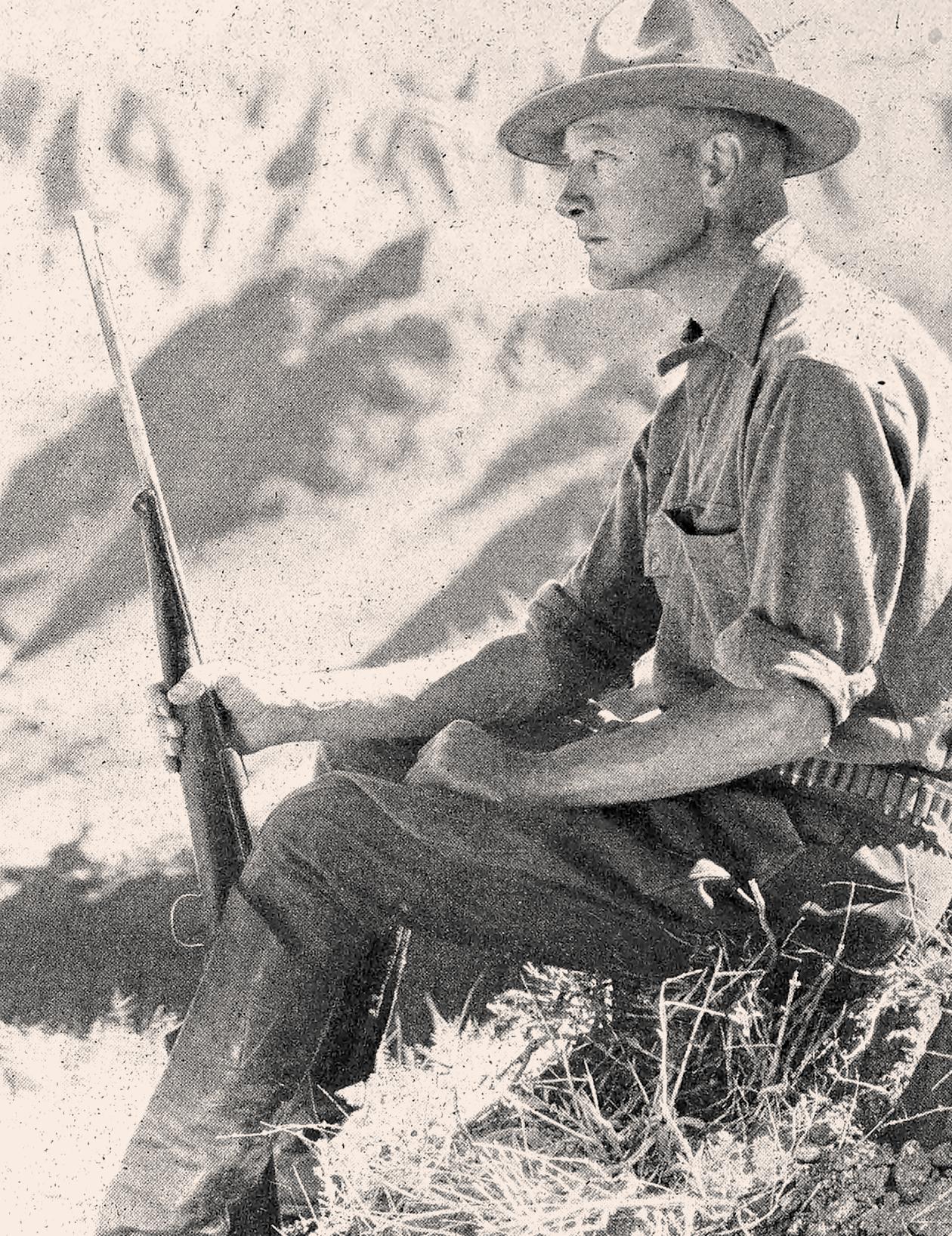

Chapman

armed, surveys his surroundings during an expedition circa late 1920s.

BY SCOTT SHAW!

Other than working in entertainment, what could George Lucas, Steven Spielberg, and I possibly have in common?

We all were approximately the same age as kids. And kids like us read Roy Chapman Andrews’ All About books published by Random House in the 1950s. Specifically, All About Dinosaurs (1953), All About Whales (1954), and All About Strange Beasts From the Past (1956). It’s also likely that we also read Andrews’ Quest of the Desert (1950) and Quest of the Snow Leopard (1955). Unfortunately, back when Roy was a young ’un, there weren’t any books about these for children.

(Of course, George, Steve, and I also probably read Famous Monsters of Filmland, but that’s not what this article’s about... although it’s certainly possible

Roy

Andrews,

that I’ll be writing about Uncle Forry and his pun-filled monster-mag sooner or later.)

Roy Chapman Andrews (January 26, 1884—March 11, 1960) was born in Beloit, Wisconsin, which was full of fields, woods, and streams. “I was like a rabbit, happy only when I could run out of doors. To stay in the house was torture to me then, and it has been ever since. Whatever the weather, in sun or rain, calm or storm, day or night, I was outside, unless my parents (Charles Ezra Andrews and Cora Chapman Andrews) almost literally locked me in,” wrote Andrews.

When Roy was nine years old, his father gave him a shotgun. He enjoyed hunting, which seems odd for a person who loved animals. This led him to master taxidermy, which brought in money for him after the annual hunting seasons. It was useful in his future. Museums acquired the bones and furs of animals to display by hunting them in the wild and rebuilding them to look live. It wouldn’t be long before he was hunting and creating taxidermy specimens for New York City’s most famous museum.

Bryan. He was a Democrat, and most of the audience were Republican. “The president of the college introduced him. Bryan rose and looked to the left with a broad smile, and then to the right, chuckling to himself; finally, he began to laugh outright, but still said not a word. The audience, too, began to smile, for his mirth was infectious. Then, just at the right moment, he told a very funny story. Everybody roared, and the hostility ended. His audience listened to him with sympathy and friendliness, even if without agreement. I never forgot that platform trick of Bryan’s and used it to my own advantage in later years.” Indeed, across his career, from convincing millionaires to finance expeditions to explaining paleontology to women’s clubs, Roy Chapman Andrews was a very successful speaker.

STEPPING UP

When he was young, Roy’s favorite book was Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe. According to Roy, “I used to think that nothing could be more wonderful to live on a faraway island, shifting for myself.”

Even as a child, he had always wanted to be three things: an explorer, a worker in a natural history museum, and a naturalist. Roy didn’t know how he was going to achieve those goals, but time would tell. Using his money from summertime jobs and taxidermy commissions, Roy financed the costs of attending Beloit College, “the Yale of the West.”

“I didn’t do a very good job in college, so far as studies were concerned, except in literature and science. Those things came easy, and I love them. But most of the other subjects bored me exceed ingly, and I worked just hard enough to get medium grades,” wrote Andrews. During his junior year at Beloit College, he lost his best friend, who drowned due to a stomach cramp. This accident had a hard effect on Roy, causing him to lose forty pounds and most of his hair, and left him with a nervous affliction for the rest of his life.

While attending Beloit College, Roy learned a valuable lesson in public speaking, due to a speech to the school’s students by William Jennings

In Roy’s senior year, Dr. Edmund Otis Hovey, curator of geology at New York City’s American Museum of Natural History, visited the college to speak about a recent volcanic eruption. The young man hounded his hotel until he could meet him one-on-one to show his boss, museum director Dr. Hermon Carey Bumpus, Roy’s taxidermied deer heads nearby. The doctor was encouraging and promised that he would mention Roy to the museum’s director. Eventually, the director wrote him that there were no positions open, but that he would be glad to see Roy if he happened to be in NYC. This excited him and his mother, but his father, a salesman, considered their belief in Hovey’s promise to be like “counting unhatched chickens.” Upon his graduation, Roy Chapman Andrews regretted his mediocre interest in learning, and forwent his parents’ gift for a fishing and camping trip. He told his mother, “It would be more of the same thing I’ve been doing. Just wasting time. I would enjoy it now. I want to go to New York and try to get into the Natural History Museum at once—next week.”

When Roy arrived in New York City from a somewhat small town, he was immediately comfortable. “All my fears vanished. I did not know a soul among the millions living there, and yet I felt sure that I should make friends and be happy; it was my city. I have never ceased to feel that way about New York.” He checked into a small hotel

Andrews as a young boy.

Roy Chapman Andrews, 1912.

1970s

Men’s Adventure Series

The Executioner

BY WILL MURRAY

In 1967, a 40 year old aerospace engineer made the courageous career decision to take the plunge into freelance writing. As a consequence, he would change the face of paperback publishing, as well as the destinies of dozens of other writers, but chiefly himself.

“It was a tough decision to make,” recalled Don Pendleton. “I’d already written seven novels, and a number of short stories and articles. I’d usually wait until everyone had gone to bed, then sit down at the typewriter for a couple of hours—and back in those days, I’d usually work 60 or 70 hours a week at my regular job.”

Initially, Pendleton struggled. In 1968, he penned a novel he titled “Duty Killer.” It was the story of Master Sergeant Mack Bolan, called home from Vietnam to Pittsfield, Massachusetts because his family had been slain by his father. Mafia loan sharks had pressured Mack’s sister into prostitution, and Bolan, Senior had snapped. The only survivor was his wounded younger brother, Johnny.

Bolan is no ordinary G.I. An exceptional Army sniper, he racked up 95 confirmed kills, earning him a chilling nom de guerre—the Executioner.

“Why defend a front line 8,000 miles away when the real enemy is chewing up everything you love back home?” he asked himself.

Fueled by a righteous vengeance, Bolan methodically tracks down the responsible Mafiosos and cold-bloodedly executes them, leaving with each cold corpse his calling card—an Army marksman’s medal.

Hunted by the law and the underworld alike, Bolan declares war on the nationwide Mob, proclaiming, “I am not their judge. I am their judgment. I am their executioner.”

Pendleton admitted to being influenced by Mickey Spillane’s I, the Jury. “He was the first to truly popularize the mean-bastard hero who still retained sentimental ideals about the worth of the human experience. Bolan is such a character.”

Pendleton’s other inspiration was Peter Maas’ 1968 The Valachi Papers, which told the story of Mafioso Joe Valachi, who was the first “made man” to break the Omertà code of silence, and unmask La Cosa Nostra for what it was.

“The story Valachi told, the way of life of the Mafioso was so blatantly anti-social, so brutal, it made a good black-andwhite comparison with what I wanted Bolan to be,” he recalled. Part 1

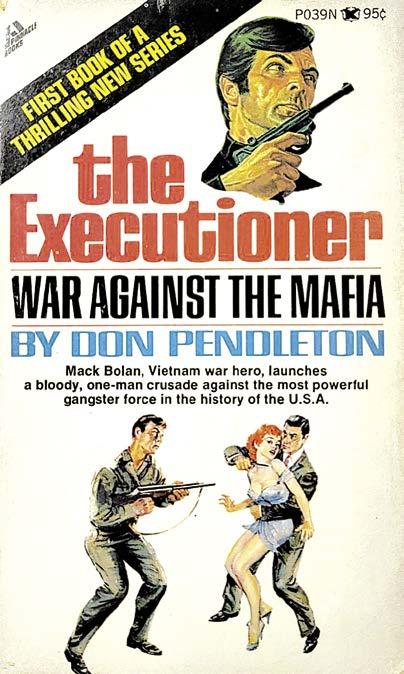

(ABOVE LEFT) The Executioner: War Against the Mafia by (LEFT) Don Pendleton (Pinnacle, 1971). TM & © Pendleton Estate. Cover courtesy of Worthpoint.

According to Pendleton, the character was also a response to the tumultuous 1960s social upheaval.

“I wrote the books to make money,” he admitted, “but beyond that every writer works from his belly. Bolan was created at the height of Vietnam. All the peace demonstrations were going on. If the American fighting man had been the middle man and all that, that would’ve been all right. But he came out as the punching bag. Guys were coming back from a year of hell in ’Nam to placards on the docks and air strips that said ‘Baby Killers.’”

Pendleton’s reaction was to turn a Vietnam-era soldier into a new kind of hero—an urban guerrilla fighter on a holy suicide mission.

“My idea was not a psychopath, not people who want to go out and slay and see blood flow,” he insisted. “My idea of a hero is someone who would really rather be doing almost anything but that, but takes it up as a calling, a service, hating it all the while. Now this is a hero, a truly courageous

person. Someone who loves the thrill of going out there and smearing blood is a psychopath.”

Although his outline pitch suggested the possibility of sequels, Pendleton thought this was just another novel in a career of turning out stand-alone stories. Yet it triggered a combustible chain reaction, thanks in part to his publisher, David Zentner.

Zentner, who published soft porn paperbacks and wanted to break into the mass market, saw potential in Mack Bolan’s paramilitary approach to the Mafia menace. Thinking that Bolan’s first campaign should not be his last, he published it in March 1969 as War Against the Mafia, the first release of the newly formed Pinnacle Books, and the initial installment in the Executioner series.

The early releases sold well enough for Pendleton to keep writing sequels, but financially, it was tough. “I think the closest to starving I ever came was during those early Executioner years,” the author recalled.

But in 1972, sales took off. Boston Blitz was released that year. This adventure, #12 in the series, brought Bolan back to his native Massachusetts to rescue his brother, who had been kidnapped in an effort to lure Bolan into a Mob death trap. Narrated with white-heat intensity, it was a tour de force—and the author’s personal favorite.

Readers were drawn to Mack Bolan’s uncompromising one-man war. Pendleton’s visceral style enjoyed a wide appeal among active military, veterans, blue and white collar working men—as well as women, who made up a surprising percentage of readers.

With the eleventh book, Gil Cohen was recruited to paint the covers, as well as new ones for reissues of the first ten titles, replacing original cover artist George Gross. Although Cohen himself posed as the Executioner, the artist visualized Bolan as actor Clint Eastwood, whose first Dirty Harry film was released in 1971.

“He more clearly personified Mack Bolan to me,” said Cohen. “I didn’t just try doing portraits of Clint Eastwood. But I tried to get a feeling of Clint Eastwood, so you’ll see the physicality of Clint.”

IF YOU ENJOYED THIS PREVIEW, CLICK THE LINK TO ORDER THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DIGITAL FORMAT!

The Executioner series did not exist in a vacuum. Mario Puzo’s best-selling novel, The Godfather, was also published in 1969. It was released as a movie in 1972, with ther Part II following two years later. The American public became fascinated by the Mafia.

Don Pendleton and Mack Bolan rode this tidal wave to the tune of four new releases every year, collectively selling millions of copies, and undoubtedly inspiring Hollywood to produce Dirty Harry, Death Wish, and similar violent vigi lante fare.

“I never expected the Executioner books to take off the way they did,” Pendleton admitted. “It’s just been a delightful surprise.”

But where big money was to be made, trouble was sure to follow.

Lured by a lucrative contract, Pendleton cut a deal with New American Library to take the series over to them. David Zentner was not happy. Neither was Bolan’s creator.

The Executioner: Boston Blitz (Pinnacle Books, 1972). TM & © Pendleton Estate.

RETROFAN #42

We profile TV Batman ADAM WEST! Plus: Sigmund and the Sea Monsters, Rankin/Bass’ The Year Without A Santa Claus, celebrity TV commercials, real-life ‘Indiana Jones’ ROY CHAPMAN ANDREWS, ’70s paperback heroes, and more! Featuring columns and contributions by ANDY MANGELS, WILL MURRAY, SCOTT SAAVEDRA, SCOTT SHAW, MARK VOGER, RICK GOLDSCHMIDT, and ED CATTO