Retro Robots (More) I Was the Zeroids’ Boss... for a Hot Minute

Retro Robots (More) I Was the Zeroids’ Boss... for a Hot Minute

BY MARK VOGER

It was a weird place in a weird time: Hollywood in the 1950s. “Peroxide” was a verb ... cars had fins ... and, in Edward D. Wood Jr. movies, men wore women’s clothing, buffalo stampeded for no apparent reason, and pie plates attacked Los Angeles.

Writer-director Wood (1924–1978) was the auteur behind 1953’s Glen or Glenda (propaganda for transvestism), 1955’s Bride of the Monster (drug-worn Bela Lugosi’s last hurrah as a mad scientist), and 1959’s Plan 9 From Outer Space (the gold standard for schlock), among other cinematic oddities.

To label these simply as “bad” movies misses the point; Wood’s way-out films have a logic and rhythm all their own. But what went on behind-the-scenes was crazier than anything you saw on screen, such as Wood’s predilection for cross-dressing; Lugosi shooting up between takes; or Swedish wrestler Tor Johnson’s broken toilet seats.

Wood’s entourage—referred to as his “menagerie” by Plan 9 hero Gregory Walcott—was a mix of weirdos, wannabes, and has-beens. Members included TV prognosticator Criswell (a favorite guest of Johnny Carson); Johnson (cueball-bald at 400 pounds);

The poster for Wood’s Plan 9 From Outer Space shows a caped figure representing Lugosi. © Reynolds Pictures.

scream queen Maila “Vampira” Nurmi (who had a 17-inch waist and 2-inch nails); not to mention hungry-for-work movie veterans (Lugosi, Lyle Talbot, Tom Keene, Kenne Duncan).

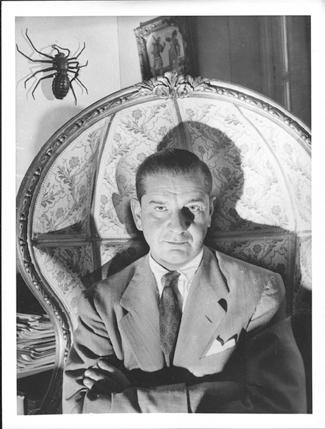

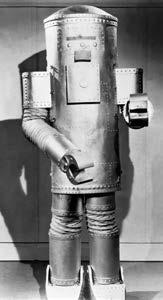

(ABOVE)

Edward Davis Wood Jr. was a writer, director, actor, ex-Marine... and enigma. © Screen Classics Productions.

After Wood’s heyday, such as it was, he slid into making, and sometimes appearing in, softcore films and writing sleazy “adult” stories and books. Sample movie titles from this period: The Love Feast (1969), Take It Out in Trade (1970), The Cocktail Waitresses (1973), Five Loose Women (1974).

For decades, Wood was a virtual unknown except to schlock aficionados. But in 1994, he was introduced to the mainstream via director Tim Burton’s oddly touching Ed Wood, starring Johnny Depp in the title role and based on Rudolph Grey’s interview-packed biography, Nightmare of

Ecstasy (1992, Feral House). Martin Landau snagged an Oscar for his portrayal of Lugosi in Burton’s film.

Wood’s life story seems to exemplify the axiom: Truth is stranger than fiction. What follows are my interviews with five people who worked in Wood’s films. All are now deceased, but their recollections endure as a revealing testament to a man whose films often elicit unintended laughs, while they evoke an undeniable fascination.

DOLORES FULLER (1923–2011)

It’s a beguilingly corny moment in Wood’s cross-dressing opus Glen or Glenda. Wood, as Glen, confesses to his fiancée Barbara (Dolores Fuller, Wood’s then-girlfriend) that he likes to lounge in pretty things. Barbara rubs her temples in anguish as she takes in the revelation. In a flash, she is awash in waves of understanding. Barbara peels off her fluffy white angora sweater, and passes it to Glen like some Holy Grail.

(To be honest, the sweater does look awfully comfortable.)

Indiana native Fuller confirmed the characterization of Wood as a charmer during our 1996 interview.

“He had a lot of charisma and effervescence,” Fuller said. “He was ‘up’ most of the time. Always on a project, and believing in it, in order to get anyone else involved to believe in it. But there were times when he had his disappointments.” Fuller and Wood lived together, which was not common for unmarried couples in the repressed 1950s.

“We had a nice home life,” she recalled. “I was cooking healthy meals. I worked a lot, though. I had about three different jobs. That kept me busy.” Fuller became aware of Wood’s preference for drag by degrees.

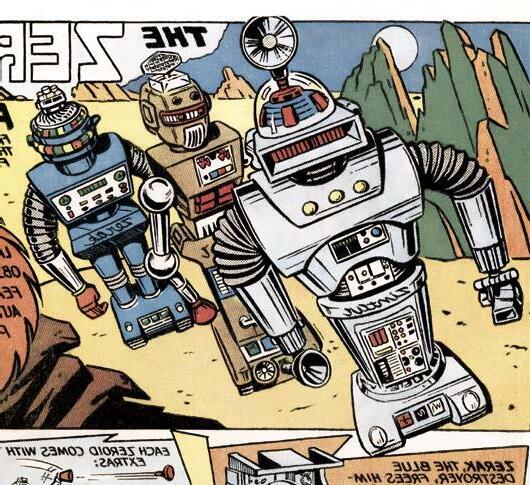

(LEFT) Dolores Fuller, the leading lady in Glen or Glenda, was then Wood’s live-in girlfriend. (ABOVE AND RIGHT) Fuller wrote the lyrics to “Beyond the Bend,” the opening song for Elvis Presley’s movie It Happened at the World’s Fair (1963) as well as the tie-in soundtrack album. © Metro-Goldwyn Mayer. © RCA Victor.

“He would be on the typewriter most of the time, and when he worked on into the night, he’d want to wear my angora sweater,” she said. “I didn’t mind that, because I thought no one would ever find out about it. And if it helped him write a good script, made his creative juices flow, then that’s our private business. Of course, Eddie had hidden the fact that he was a transvestite from me. Because, every day he asked me to marry him, and he was afraid that when I found out, maybe I wouldn’t.”

In retrospect, Fuller respected the bold stance of Glen or Glenda, which came at a time when society wasn’t as savvy about transvestism.

“It was way ahead of its time,” she said. “Eddie begged me to do Glen or Glenda. I didn’t want to do it at all. I told him to get another actress. But he said, ‘This will be my chance to make better movies. My next movie will be better, because I have this writer-director credit that I need so badly.’ So, I went along with him and did it, even though I didn’t want to.” Fuller had one caveat, though. Wood could have his precious writer-director credit, but she asked him to use a nom-de-plume for his acting credit.

As Fuller and Wood filmed Glen or Glenda, suddenly their respective roles changed from girlfriend/boyfriend to actress/director, an unusual feeling for Fuller.

“He told me to play the part just as I am,” she said. “Don’t even act. Let it be a documentary. And it probably comes through that I was very uneasy having my private life put on film.”

Case in point: The iconic scene in which Fuller hands her angora sweater to Glen was a reflection of the couple’s private life. Said Fuller: “The first time we recreated it on film, I took it off and threw it at him. Somebody saved the

cut; I’ve seen it. But then he redirected it so I handed it to him nicely.”

Fuller—who, it should be noted, wrote the lyrics to a dozen songs recorded by Elvis Presley—worked on Wood’s movies off-screen, too, as an uncredited wardrobe supervisor.

“I finished all of the women’s clothes for Eddie’s movies,” she said. “All of the girls’ clothes, every stitch of it, were things that I would pick out. Because I worked for Shipp Lingerie, Westwood Knitting Mills, and Evan-Picone. All I did was pick out the clothes I needed for the picture, and put their names on the screen.

“You know, these first three pictures, many people have said, would not have been made without my help. Because I contributed to his support. I loved it, because I was doing the work of my dreams, too, as well as Eddie’s dreams.”

CONRAD BROOKS (1931–2017)

In Plan 9 From Outer Space, 13th-billed Conrad Brooks had only four lines in a handful of scenes as one of three uniformed patrolmen. (You could call his character “Cop No. 3.”) Still, Brooks got to deliver the classic Woodsian line: “It’s tough to find something when you don’t know what you’re looking for.”

Brooks and his brother, Henry, first met Wood in 1948, when they hired him to shoot a western (“a home movie, really”) while they were trying their luck in Hollywood. “Ed had to do it his way,” Brooks told me in 1996. “My brother was supposed to direct

Wood company player Conrad

the movie, and Ed was going to be the cameraman. We paid him 60 bucks for it!”

Five years later, Wood put Brooks in Glen or Glenda, which starred Lugosi as the scientist/narrator in what was Wood and Lugosi’s first collaboration.

Recalled Brooks: “I thought Ed was kidding me when he says, ‘Connie, I’m going to do my first feature.’ When he mentioned Lugosi, I said, ‘Damned Ed Wood, up to his old tricks again, trying to kid us.’ ”

“But he did have Bela! He was my idol, and here we had Bela Lugosi on Glen or Glenda. My brother said, ‘This is too cheap of a movie for Bela Lugosi.’ You know, Bela was a major star, and he went for Ed Wood? And especially in that type of film: exploitation. But Bela just wasn’t getting any work. The guy was up around 72. He was considered pretty much over the hill.”

In April 1955, when Lugosi checked himself into Los Angeles County General Hospital for treatment of morphine addiction, Brooks again thought it was a scam dreamt up by Wood.

“At the time, when I read about it in the headlines, the first thing my brother said was, ‘I don’t believe it. I don’t believe it.’ We looked at each other. I agreed with him,” Brooks said.

“Eddie had this picture coming out called Bride of the Monster. So, my brother figured it out. He said, ‘I’ll bet Ed Wood put him up to that.’ We thought maybe Lugosi was on some drugs, and then Ed put him up to it. ‘Bela, turn yourself in and we’ll get a million dollars’ worth of publicity for Bride of the Monster, and this will help your comeback!’ ”

BY JIM BEARD

Everything you need to know about the show is right there in the opening credits.

Under cover of one of the most rockin’ musical themes of any television series ever, you see: aliens, spaceships, action, adventure, explosions, dashing heroes… and beautiful, sexy women.

None of it is by accident. Producers Gerry and Sylvia Anderson packed that opening with more hooks than a bait and tackle shop, hitting the viewer on multiple pleasure levels to ensure everyone knew exactly what they were in store for with UFO. And did we mention the beautiful, sexy women?

Set in the far-flung future of 1980—flashing the date several times rams the point home—the series presented science fiction television with maximum appeal, and there was no doubt from the visuals that women would play a big role in that attraction. They were front and center as the theme music beat its way into a viewer’s head, providing a curvaceous counterpoint to all the science fiction goings-on. The Andersons weren’t taking any chances on the score.

In terms of characterization and presentation, females fared no worse in UFO than any other show of its era, and perhaps even a bit better in some respects. Being set in the “future” of 1980, it attempted to present a more enlightened, progressive time, but in the end it very clearly chose its battles and erred on the side of beauty and sex appeal to rope in its intended audience. While perhaps somewhat forgotten or overlooked today, ask anyone who ever watched the show to cite what their first and foremost memory of it is, and the sure bet is that they’ll all have the same thought: the women of UFO.

But what is UFO? For the Uninformed Fan Objects among us, it’s simply one of the Grooviest SF TV Shows No One Knows About.

(TOP) Antonia Ellis as Lt. Joan Harrington and Gabrielle Drake as Lt. Gay Ellis. (ABOVE) Aliens invade Earth in this screen capture from UFO. © ITC.

Following a string of successes with crafting “Supermarionation” kiddie fare in the 1960s, i.e., adventure shows featuring elaborate puppets in lieu of human actors (The Thunderbirds were go way back in RetroFan #4 – RetroEd), the Andersons produced a feature film in 1969 called Doppelgänger (aka Journey to the Far Side of the Sun). Though met with indifferent reactions from critics and moviegoers, the film buoyed the husband and wife team enough for them to feel confident to accept a challenge from legendary producer Lew Grade to create their first entirely live-action television series for the British market—with an eye to also land it on American shores. That series became UFO

Along with artist-producer Reg Hill, the Andersons went with their strengths to conceive and craft the series: science fiction adventure with extensive model use. UFO premiered in both the UK and in Canada in 1970 with a full twenty-six episode season, and two years later fulfilled the team’s goal of shopping it to the US. By most accounts, UFO was another

UFO allowed the Anderson production team an all-out assault on viewers’ senses with fantastic set pieces, finely crafted models of spaceships and vehicles, weird alien plans, and one of the most unique fashion senses of any show up to that time. Essayed by Sylvia Anderson herself, the humans’ costumes were meant to represent something both familiar and “futuristic,” and the women in particular were often dressed for maximum sex appeal in outfits designed to showcase the female form. UFO was most definitely not a kids’ show. For the first time, the Andersons had produced a product for adults, and boy did it show.

Anderson success story, and in many ways the producing duo could be seen as the British equivalent of Tsuburaya in Japan, also masters of model work, such as on the multiple Ultraman series.

From its first episode, UFO told the tale of Earth’s invasion by mysterious aliens who arrived in traditional flying saucers from an unknown planet and conducted a kind of cold war of sabotage, subterfuge, espionage, and generally underhanded nastiness. In American TV terms, think Man from U.N.C.L.E. meets The Invaders. (More on Man from U.N.C.L.E. in RetroFan #15 – RetroEd) The humans had, though unbeknownst to the public at large, a clandestine government agency to protect them, SHADO, the Supreme Headquarters Alien Defence Organisation (in the original British spelling). The group was led by the surly and strict Commander Ed Straker (played by American actor Ed Bishop), a seemingly dispassionate whip-cracker with the constant weight of a crushing responsibility on his head. Under his command, a procession of SHADO agents put up with his displeasure while battling the aliens’ schemes on land, sea, and on the moon, a barren landscape which just happened to be the “front lines” of the ongoing conflict.

The aliens remained a mystery for the most part throughout the episodes. Having traveled across great lengths of outer space to allegedly harvest human organs for their own dying race, they threw considerable resources at Earth in the form of what was referred to by the human defenders as “You-foes,” swirling circular craft that made a distinctive sound that for some impressionable young viewers became a terrifying trill of impending doom. Regrettably, there seemed to be no females among the aliens, though in their bulky red spacesuits, who knew exactly what SHADO was up against with any given close encounter?

On Earth, in a secret base underneath a working film studio, women played a more-or-less supportive role in SHADO’s operations, watching screens and fetching coffee in their skintight uniforms, but on the moon they were integral to the group’s operations there. Dressed in odd purple wigs and slinky silver suits that could be edited down to swingin’ scanties for off-duty relaxation in co-ed dorms, the moon women appeared to be in charge.

As Lt. Gay Ellis, SHADO Moonbase commander, actress Gabrielle Blake could arguably be considered the face of the series. When the subject of UFO comes up, it’s her image that most people who remember the series think of. She also normally received fourth billing in the series’ credits during her time on it.

Born of British parents in India, Drake has described herself as something of an “exhibitionist” as a child, due to her love of theatrical productions and desire to attend the Royal Academy of Dramatics. Before winning the UFO part, she paid her dues in stage productions and guest spots on shows such as The Avengers, The Saint, and Coronation Street. (Be sure to grab RetroFan #26 for more on the UK Avengers – RetroEd) Genre fans will be interested to hear that Drake almost wound up on Doctor Who as the Third Doctor’s companion Jo Grant, but lost the part to the perky Katy Manning. (More RetroBrit fun in RetroFan #12 when we looked at Doctor Who. – RetroEd.) The UFO role really only lasted a few months when Drake was lured to other gigs during a break in the series’ production. Later, she became known for even stronger adult fare by shedding her clothes for several British so-called sexploitation films of the 1970s.

As Lt. Ellis on UFO, Drake offered a professional picture of a cool, compe-

BY DEBORAH PAINTER

Ron Ely’s Tarzan swung on his vine onto the small screen for the first time in 1966 and into the hearts of millions around the world. As the narrator for the premiere episode tells us:

Tarzan’s awesome warning cry is known to every living creature in the jungle. Hearing that cry, the antelope knows he is safe. The lion pauses. The crocodile seeks the safety of the water. The elephant comes to his friend, Tarzan of the Apes!

For those who have not read any of the Tarzan novels or comics, nor have seen the relatively recent 1984 Greystoke: The Legend of Tarzan, Lord of the Apes or the 2016 The Legend of Tarzan, here is a little background into the loincloth-clad fellow who battles bad guys and helps the oppressed with his immense strength, jungle savvy, and agility.

Tarzan creator Edgar Rice Burroughs’ own life prior to the success of his most popular literary character had been colorful, but not terribly successful. He was a former cattle drover and railroad policeman who had achieved some publishing success with the first of his John Carter of Mars series in All-Story Weekly in 1912.

He then wrote a story, “Tarzan of the Apes”, which was serialized in the pulp fiction magazine that same year. Book deals followed for both, and then motion picture deals for Tarzan. Soon, Burroughs and his family went from poverty, due to his mediocre career as a pencil sharpener salesman, to being the owners of a vast ranch in the San Fernando Valley. They named their ranch Tarzana. It’s now a bustling suburb.

Tarzan was born in a cabin built hurriedly by his parents, John and Alice Clayton (Lord and Lady Greystoke), when mutineers commandeered a ship in which they were sailing to British West Africa. They were marooned on a beach along the northern coast, probably where Gabon is today. They struggled there for a year, and Lady Alice gave birth to their son John. Fever took Lady Alice, and a bull great ape (Kerchak) invaded the cabin and killed her husband. Kerchak’s mate Kala found the baby in his crib and adopted him because her

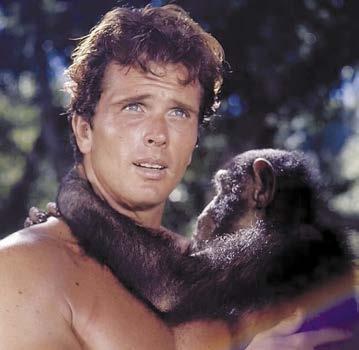

(ABOVE) Ron Ely as Tarzan. (LEFT) Tarzan’s first appearance in a pulp magazine. TM and © Edgar Rice Burroughs (ERB).

own baby had died. These creatures had their own language, and they named him Tarzan, meaning “white skin”. He grew to magnificent manhood among the great apes, desiring to be one hundred percent ape, but always knowing he was different. He visited the old cabin often, not remembering his parents, and taught himself to read by looking at picture books the Claytons had managed to salvage. He met an exploratory party, and fell in love with an American girl named Jane Porter. Thus began Tarzan’s journey of rejoining human society. John Clayton reclaimed his heritage and the Greystoke estate, and married Jane. They owned a plantation in Africa and had a son, and Tarzan continued to have adventures in Africa, Hollywood, and even at the Earth’s core.

(LEFT) Tarzana, California as seen from Nature Conservancy property in the Topanga State Park area. Here, Edgar Rice Burroughs built a ranch following explosive financial success.

Photo: Deborah Painter. (BELOW)

From the Tarzan episode “The Pride of the Lioness”. Tarzan has a conflict with a mother who does not want her doctor son to follow in his dad’s footsteps and live in rural equatorial Africa. Tribal chief Kanzuma (Davis Roberts) looks on. Banner Productions/NBC. Tarzan TM and © Edgar Rice Burroughs (ERB).

Tarzan understood the ways of human societies, and had a large vocabulary in most of his silent film appearances (well, according to the title cards, anyway). MGM changed that with their series starring Johnny Weissmuller. RKO, which owned the movie rights during the late 1940s, worked closely with producer Sol Lesser, and starred Gordon Scott as an increasingly articulate jungle lord in several films that were only moderate hits. Lesser wanted to produce a television show, but plans never came to fruition. MGM producer Al Zimbalist had just produced a remake of the original 1932 MGM Tarzan talkie which premiered to lukewarm responses.

In 1958 Sy Weintraub purchased the screen rights to Tarzan from Edgar Rice Burroughs, Incorporated. and produced many exciting films starring Gordon Scott, Jock Mahoney, and Mike Henry. Gone was the idea of a grunting Tarzan and gone were the films made on back lots in Los Angeles. Now the films were filmed in Brazil and Kenya. Along with the return to an original Burroughs concept of an educated Tarzan came the un-Burroughs concept of no Jane and no son. Weintraub wanted Mike Henry to star in his new TV series in development. However, Henry had been bitten by one too many chimpanzees and other semi-tame animals brought in for the films, and had contracted dysentery in Brazil. He opted out of signing to be in the new series.

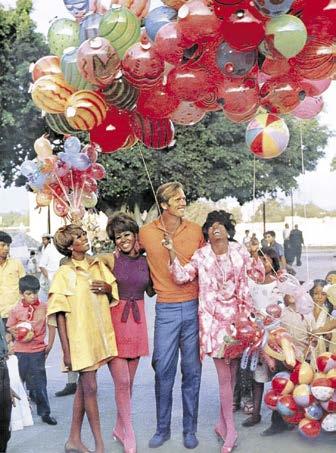

Ron Ely (center) strolls down a boulevard with Diana Ross, Cindy Birdsong, and Mary Wilson of the Supremes, balloons in tow, on location to film the Tarzan episode “The Convert.” Banner Productions/NBC. Tarzan TM and © Edgar Rice Burroughs (ERB).

Ronald Pierce Ely was signed to be the first TV Tarzan. He had already been cast as a Tarzan impostor for a planned TV

episode that never came to fruition, and so his career as Tarzan was born.

Ely was a very tall, lithe looking athlete who had played football at the University of Texas while majoring in radio and television arts. His early film career garnered him some attention for his small role in South Pacific as a pilot, and The Remarkable Mr. Pennypacker. He portrayed Mike Madison in the scuba adventure TV series The Aquanauts (a.k.a. Malibu Run), replacing actor Keith Larsen when he left the show. He also appeared in episode 16 of the horror series Thriller, “Waxworks”. Ely’s Tarzan, like the other Weintraub production versions of Tarzan before him, would be unattached. The theory was that this would make him more appealing to the females in the audience. They need not have worried; he was appealing enough already! Although Tarzan would have no wife or child of his own, he would be teamed with a boy named Jai (Manuel Padilla Jr.).

Just where did Jai come from? The character name had been given to an elephant boy who figured prominently in the Weintraub film Tarzan Goes to India. In the new series he would return, this time as an orphan very much like “Boy”

BY SCOTT SHAW!

“It’s hard to figure whether you’re eccentric or not. An eccentric is really a very practical person. They’re just trying to make their fantasies work.”

– Charles Addams

On Saturdays, when I was eleven years old in 1962, I’d take the bus to downtown San Diego to “scrounge” used bookstores for old comic books, pulp magazines, and paperbacks at inexpensive prices. Then, I’d walk over to the San Diego Public Library. It had a section of cartoons—not comic books, nor animation— but hardback collections of editorial cartoons and gag cartoons from slick magazines of the 1940s and 1950s. I was interested in all forms of cartooning, so I read them all. Since I was a Shock Theater “monster kid” of the late 1950s, a particular gag cartoonist immediately caught my attention—specializing in a hilariously creepy point of view of the world—Charles Addams. His work not only appeared in annual editions of The New Yorker’s Best Cartoons of the Year, but there were also collections of Addams’ gag cartoons for me to peruse. Sometimes I would stare at one of his gags for an hour or more, until I could detect his subtle and morbid gags, worth every minute spent.

Born on January 7, 1912—the same year the Titanic sunk— and raised at 511 Summit Avenue in Westfield, New Jersey, Charles Samuel Addams’ earliest memory was at eighteen months when he witnessed an old man getting run over by an automobile. He was an only child. Charles’ father, Charles Huey Addams, worked for a company that manufactured pipe organs and player pianos. His father eventually became an architect. Charles’ mother, Grace Spear Addams, was a homemaker, with a sense of humor that definitely had an influence on her boy. Besides his parents, Charles’ maternal grandmother Emma Louise “Grandma Spear” lived upstairs with them. Charles was a very happy and good-natured baby who loved to laugh. As a boy, he was well-liked, with the nickname “Chill.” At eight years old, Charles was caught breaking into someone’s house and drawing skeletons on its walls. His parents paid a fine for criminal damages. “It wasn’t really an arrest, but I like to think of it as one,” Addams recalled. “I know it would be more interesting, perhaps, if I had a ghastly childhood—chained to an iron bed and thrown a can of Alpo every day. I’m one of those strange people who actually had

a happy childhood.” He once quipped that “the only exciting thing that ever happened to me in childhood” was when the family dentist hanged himself in a swamp near Surprise Lake. However, Charles, like his mother, suffered claustrophobia. He dealt with it with a fascination for Iron Maidens—as a kid, he saw his first one at an antique shop, and immediately wanted to purchase it—and the graves in a local cemetery. “Maybe I was trying to scare myself,” Charles later explained.

“Laughs from the School.” By now, he was inspired by Percy (Skippy) Crosby and George (Krazy Kat) Herriman. But the more that he intended to become a serious illustrator, Charles’ natural sense of humor kept raising its goofy head to distract him from that goal.

Fortunately for us all, The New Yorker magazine arrived in 1925. Its founder and publisher, Harold Ross, guided his artists to achieve what would become one of the magazine’s most noted elements: the gag cartoon, consisting of a lively cartoon drawing with a single caption, with each supporting the other. Ross’ initial gag cartoonist stars were Peter Arno, Helen Hokinson, and Gluyas Williams. Sixteen-year-old Charles’ response was, “Well, that’s the magazine I want to work for.” The New Yorker immediately became his personal textbook to train himself for the job, while creating new material for The Weather Vane. In his 1929 yearbook, graduating from school to attend Colgate University, a liberal arts college in Hamilton, NY, his classmates said of Charles: “He amazed us.”

(ABOVE) Screen capture of a young Addamsdrawn skeleton found on a neighbor’s barn from an ABC LOCALish broadcast. © ABC Entertainment. (BELOW) Addams’ mother sought out cartoonist H. T. Webster for his opinion of her son’s work. Webster portrait by Boris Chaliapin. © TIME USA, LLC. All rights reserved.

Like most of us cartoonists, by the time he could hold a crayon, Charles was constantly drawing, inspired by his father’s skills with a pencil and urged onward by both of his parents. He was also highly impressed by the work of Gustave Doré, John Tenniel, and Arthur Rackham. His mom Grace brought samples of Charles’ cartoons and illustrations to Caspar Milquetoast’s cartoonist creator, H. T. Webster. Unfortunately, he told her that Charles was bereft of talent. But when he was thirteen, Charles won ten dollars in a drawing contest for a local chain of clothing stores. His artwork depicted a man being executed on high-tension wire, getting help by a Boy Scout wearing rubber boots while standing on a rubber mat, with “Be Prepared” as its caption. By the time Charles was in high school, he was the kid who was always doodling in class rather than taking notes, creating “funny-looking people” to share with his classmates for a laugh. Charles gravitated toward creative groups, such as the school’s Art Club, its literary magazine, The Weather Vane, and similar organizations. That magazine was especially important to Charles, of which he became its editor and wherein he contributed cartoons, illustrations, and stories, including a comic strip,

After a year at Colgate, Charles transferred to the University of Pennsylvania, only to learn that his art classes were for architects, not cartoonists. (At least he learned how to party at the school’s Theta Chi fraternity.) Next up was the Grand Central School of Art in New York City, which was full of 1,500 talents of every type of art, commercial and otherwise. In his spare time, Charles could also study the people and architectures of NYC.

Better yet, the offices of The New Yorker were near him. In 1931, Charles drew a bird’seye-view sketch of a window washer on a tall skyscraper and dropped it off at the magazine’s office at 25 West 45th Street without a return envelope. Months later, he visited TNY to retrieve his artwork, Charles was astonished to learn that it had already been published as a space-filler in the January 6, 1932 issue. Charles returned to the art school showing off his New Yorker check for $7.50. At only twenty years old, he’d already achieved his self-promised goal. Now all he had to do was make a second sale to The New Yorker, while competing with new New Yorker gag cartoonists such

as James Thurber, William Steig, George Price, and William Crawford Galbraith, as well as Arno, Hokinson, Williams, and many more. Their work demonstrated to Charles that in gag cartoons, “the idea is important.” And the more he drew, the funnier his gags became.

Three months after his first sale to The New Yorker, Charles’ architect father unexpectedly died from a brain hemorrhage at the age of 58. This made Charles feel that he should hurry to address the application of his art skills to an actual job. He left the Grand Central School of Art to take a job retouching crime scene photographs at True Detective magazine in NYC for $15 dollars a week. Charles personally liked the photos the way they were, “with just a tad more blood and gore,” he claimed.

Of course, in his spare time, young Mr. Addams was hatching more gag cartoons.

In The New Yorker’s January 4, 1933 issue, his second gag was published, featuring a hockey player who forgot his shoes. Four more were published in 1933, he was starting to get noticed... and then, Charles suddenly hit The Wall... suddenly unable to concoct a single gag for over a year while still working for True Detective.

In early 1935, Charles submitted a sketch of newspapers rolling off a printing press to The New Yorker. Within a row of Herald Tribunes, there’s a tabloid bearing the headline, “Sex Fiend Slays Tot.” After addressing a few notes, including changing the masthead to The New York Times, Charles’ finished cartoon was published on March 23, 1935.

Suddenly, The Wall evaporated as if it was never there and the “real” Charles “Chas” Addams had always been. Weirder. Wilder. Better. He began to experiment with diluted ink called a “wash.” It gave the characters and especially the lush backgrounds more dimension, and if needed, more atmosphere. He applied it to his next sale to The New Yorker, set on

a roller coaster, and printed larger than his previous gag cartoons.

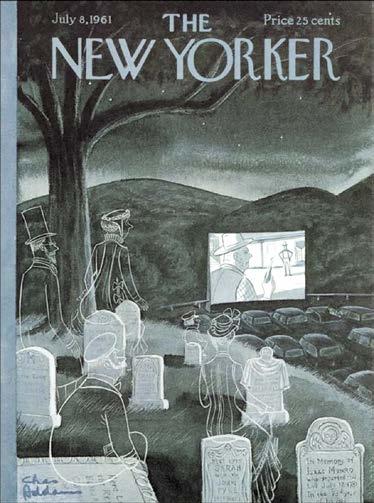

(ABOVE) Addams cover to The New Yorker (July 8, 1961). © Condé Nast. All rights reserved. (BELOW) Addams introduces a protoype Morticia in this New Yorker cartoon. Art © Tee and Charles Addams Foundation.

Now 23 years old, Charles was doing well enough selling cartoons to The New Yorker as well as to Collier’s magazine—to leave True Detective. By June 1935, every issue of The New Yorker contained one or more of his cartoons. Mr. Addams had finally achieved his dream as a genuine New Yorker artist. However, he wasn’t on staff; in fact, none of the artists were. And editors could be fickle, as well as the readership. Charles knew that creative freelancers can’t afford to feel comfortable. However, it must have been uplifting to realize that his work was influencing The New Yorker’s other artists. (They were never referred to as mere “cartoonists.”) Only a few of them could pull off the natural weirdness that emanated from Charles. However, his lack of security was beginning to slow down the gag-factory inside his cranium, but now that he was a The New Yorker regular, the magazine’s staff—mostly editors and writers, with only one artist—had a hand in creating the gags, very unusual in the gag cartoon business. (The only cartoonists who were free from this occasionally cruel process were James Thurber and William Steig.) Sometimes, the caption’s wording was changed, and the artwork was altered down to the smallest details. Other times, the cartoonists had to make an entirely new drawing. Sometimes the staff had a completely new concept. The results were indeed “better”, but the process itself was a bit intimidating. Even worse, Charlie had to share his pay with those who provided new gags. On the bright side, The New Yorker was granting reprint rights for Addams’ gag cartoons for other magazines, including Literary Digest, the Boy Scouts of America’s Boys’ Life, and overseas publishers. At least Charles received a slice of the royalties.

In the August 6, 1938 issue of The New Yorker [left], Charles Addams struck gold, although he wasn’t aware of it at the time. First, he would draw the pitch art, using a soft Wolff pencil

BY WILL MURRAY

One of the most popular television programs of the 1960s was one that nobody wanted to see air.

Nobody in Hollywood, that is.

“Everybody hated The Fugitive,” said Roy Huggins, creator of such popular television programs as Cheyenne, Maverick, and 77 Sunset Strip for Warner Bros.

After leaving Warner Bros., Huggins turned his imagination toward inventing something new. Since Westerns were still dominant on TV, he began with their popularity as a springboard. But he needed a new breed of hero.

“The thing that made Western characters interesting,” he said, “was that they were totally free… No one questioned them when they wandered from town to town… Money never changed hands…. They never made a commit ment to anybody. When they got bored with the town, they moved on.”

But Huggins didn’t want to create a modern cowboy star. He had something else in mind. “I knew that

(TOP) Title card for The Fugitive program. (ABOVE) Wanted poster for Richard Kimble played by David

audiences would not accept it if he were just a drifter. Suddenly it hit me: He had to be a fugitive… For a capital crime. If he’s caught, it’s his life.”

Coming up with a treatment was easy. The rest was hard.

Huggins had accepted an executive position with 20th Century-Fox Television. He presented his three-page Fugitive treatment to his superior.

“He looked at me as if he had just made the biggest mistake of his life,” recalled Huggins. “He wouldn’t even respond.”

Huggins thought the problem lay with the obtuse executive. But when he told others about The Fugitive concept, everyone was against it.

Abruptly, he decided to leave the business and enrolled in a graduate studies program at UCLA. While working on his thesis, Huggins received a request to meet with Leonard Goldenson, President of a struggling ABC-TV network. Goldenson was looking for something original, something that would help ABC get back into the ratings sweepstake game.

During the meeting, Huggins pitched The Fugitive He later recalled Goldenson saying that, “It was the most un-American idea anyone ever heard. They thought it was a slap in the face of American justice every week in prime time.”

The thinking of ABC brass ran that The Fugitive turned the concept of the good guys and the bad guys upside down. If the protagonist actually committed the crime, he could only be a bad guy. But if he was a true American, he would turn himself in.

Yet after those complaints were made, Goldenson spoke up, saying, “Roy, that’s the best idea for a series I’ve ever heard.”

The Fugitive received the greenest of green lights.

But there was a hitch. Huggins wanted to finish his degree. So he cut a deal to sell the premise to ABC as long as someone else produced it, and suggested a proven producer.

That person was Quinn Martin, who had just formed QM Productions. QM had signed an exclusive contract with United Artists Television. Part of that deal called for him to produce the pilot for The Fugitive, but with ABC-TV funding the project.

Martin turned to a writer named Stanford Whitmore, who had worked with him on the recently canceled New Breed. After reading Huggins’ presentation, Whitmore agreed to write the pilot.

Whitmore recalled, “It began [with] the train speeding through the night… And then the train wreck.

Embedded in Huggins’ treatment was the name, Richard Kimble, the fact that he was a physician, and that he had, on the night of his wife’s murder, seen a red-headed man running from his house—but no one believed him.”

The difficulties in launching The Fugitive did not end there. Several people pointed out that the

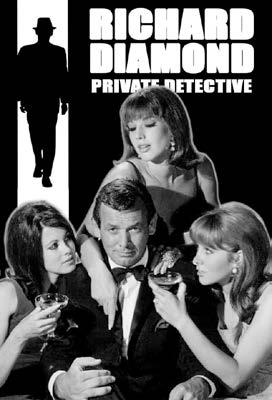

(ABOVE) Undated publicity photo of David Janssen. (LEFT) Previous to The Fugitive, Janssen starred in Richard Diamond: Private Detective (1956–1960). © 20th Television.

premise mirrored the 1954 murder of Dr. Samuel Shepard‘s wife. Dr. Shepard had claimed to have seen a bushy-haired man leave the murder scene. Nevertheless, he was tried and convicted, then sentenced to life imprisonment.

So they fine-tuned the concept. Changing the bushy-haired suspect to something else was needed. Something memorable. A disfigurement. But what?

“We quickly agreed,” remembered Whitmore, “that this man couldn’t be crippled in the sense that he would be slowed down for any possible confrontation.”

After kicking several ideas around, Whitmore suggested, “How about a one-armed man?” That sold Quinn Martin. The next hurdle was finding a suitable star.

WHO WOULD BECOME THE FUGITIVE ?

“Ben Casey had been on the air by then,” recalled Whitmore. “Vince Edwards had the dark look about him, and he was a big hit. But no matter what name they came up with, Quinn was adamant about David Janssen.”

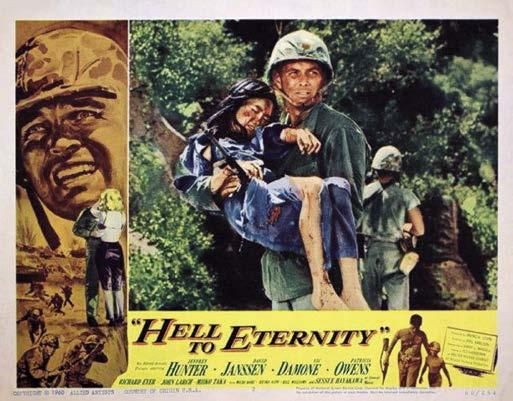

(RIGHT) Janssen starred in Hell to Eternity (Allied Artists, 1960) with Jeffery Hunter, Sessue Hayakawa, George Takai, and Vic Damone. © Allied Artists.

Previously, Janssen had starred as Sunset Strip private detective Richard Diamond on CBS, and

appeared in several movies and television programs. Ironically, he had turned down two prior opportunities to play popular TV doctors, Dr. Kildare and Ben Casey.

“I was freelancing after the Diamond series ended, and CBS asked me to consider doing Kildare,” Janssen related. “I said, no, that Lew Ayres was still thought of as the doctor and anyway, the series wouldn’t go. I sure was a great prophet! I said much the same thing about Ben Casey—I told them I didn’t want to play a doctor, and the whole thing sounded like a rather bad B-movie to me. That was short-sighted of me, but strangely enough, I’ve never been unhappy about the decision.”

(RIGHT) Dr. Richard Kimble on the run... because (LEFT) he was a “wife killer being sought” (more like hounded). © Paramount. Courtesy of IMDb.

Janssen agreed to play Dr. Richard Kimble—in return for a generous salary and a 23% ownership of The Fugitive.

The actor saw the new character as a step up from previous roles. “I’m not knocking Diamond; it was no more ridiculous than every other private eye series flooding TV a few years ago. This new series makes Diamond look like a character out of a cartoon strip. As the Fugitive, I’m an average human being, subject to human fears, and heroic only when forced into a corner. Quinn Martin—he launched The Untouchables—won’t settle for inferior scripts or two-bit actors. Every performance, even the bit parts, have meaning, and the dialogue studiously avoids clichés and platitudes.”

Martin had his eye on a specific actor to play Kimble‘s nemesis, Police Lieutenant Philip Gerard. Barry Morris had appeared on two episodes of The New Breed. Usually, he played bad guys.

As Morris related, “Quinn called one day to say he was sending over a script, and when it came, I looked at it, but couldn’t find a villainous part. I thought someone had switched scripts. Then Quinn called and asked me if I’d play Lieutenant Gerard. I was surprised, but said yes.”

Morse wondered, “Why me? And [Martin] said he didn’t want a cliché-type of man.”

The producer decided to emulate the approach he employed on The Untouchables—a semi-documentary noirish look and vibe, filmed night-for-night to give the series an aura of stark reality.

“The style is going to be like the movie The Big Sleep brought up to date,” Martin explained. “Then we add the ’63 Fellini feel.”

(LEFT) Paperback novelization of the pilot episode of The Fugitive (Pocket Books, 1964). (RIGHT) Dr. Richard Kimble revisited his story in the first season’s “The Girl from Little Egypt.” © Paramount. Courtesy of IMDb.

A pilot was shot. After fine-tuning the musical score and suggesting other details, ABC executives ordered a series. The show premiered on September 17, 1963.

The pilot episode was called “Fear in a Desert City.” The backstory of Richard Kimble’s escape from a train wreck while traveling to the death house was explained in the opening credits. When Kimble arrived in Tucson after stepping off a bus and taking a job in a saloon, most TV viewers did not realize that this was a modernization of the traditional Western hero who blows into town and becomes embroiled in local problems.

“All those were calculated to get sympathy for the hero,” explained Whitmore.

Kimble, a former pediatrician and Korean War medic now calling himself James Lincoln, had been on the run for six months in the series opener.

“I play an educated, cultured man—a doctor—who must constantly disguise his background,” Janssen related. “One week I am working as a truck driver, another as a farmhand. In each, I must take a different attitude—be convincing

BY DEWEY CASSELL

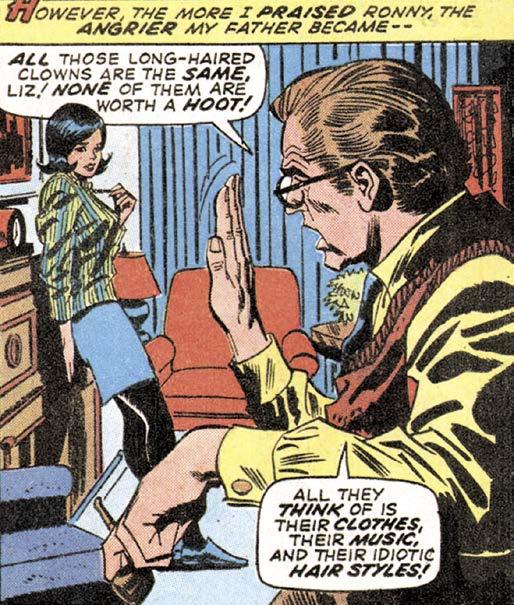

The late 1960s and early 1970s were an era of experimentation, from the Beatles’ White Album to the Apollo 11 moon landing. And it wasn’t limited to music or scientific discovery. The same was true when it came to comic books. In a concerted effort to reach a broader audience, Marvel Comics experimented with new genres like sword and sorcery, and old ones like romance comics. While rival DC Comics was still publishing Young Romance after twenty years, Marvel had left the genre and its readers behind. So, in 1969, Marvel launched two new romance comics. And you can’t have a romance comic without an advice column. Enter Suzan Loeb (née Lane), the subject of Dewey Cassell’s interview that follows.

Dewey Cassell: Did you read any romance comics or teen romance magazines when you were growing up?

Suzan Loeb: Of course! And mostly behind the closed door, because it was not something that was recognized as good reading material for a young girl—thirteen, fourteen years old—by her parents.

DC: I understand. Do you remember the titles, by chance?

SL: No, I have absolutely no recollection of the titles, but I will tell you that there was no sex in any of the magazines that I read, or any of the romance stories that I read. There was innuendo, there was hugging and kissing, but that’s as far as it went.

DC: It sounds like a reflection of the times.

SL: Absolutely. And we’re talking about the late Fifties, early Sixties.

DC: A great time for romance.

SL: Yes. And they were glossy-covered magazines.

DC: Did you ever read Dear Abby?

SL: Oh, my gosh, absolutely. Every day. And it was really interesting because when I was [later] given the romance

column assignment by Stan Lee, one of the first things that I thought about was do I have the credentials to be able to answer these questions? And I was laughed at by Sol Brodsky when I said, “Maybe I should contact Abigail and get some advice from her as to how to handle it.” And what I did, I realized, was not taken seriously by anybody in the office other than me and the people that wrote to me.

DC: Well, it was definitely taken seriously by the readers.

SL: Absolutely. And that’s why I took it so seriously and I was so concerned about giving advice to the readers who looked to me for answers, without having any kind of psychological background to make sure that I was not overstepping and giving incorrect advice. It was very important to me. I took it very seriously.

DC: When you were growing up, were you one of these people that friends typically came to ask for advice?

SL: Yeah, in those days, before handheld computers, before laptops, and before cell phones, as young women and young teenagers, we really had nobody else to go to except each other. So, when it came to discussions about going all the way with a boy, or petting, these were things that we would discuss not with the moms, but amongst ourselves. So, yes, I think equally people came to me for my views, but I also went to them to listen to what they had to say.

DC: It’s nice that you could rely on each other.

SL: Absolutely.

DC: But writing the romance column was not initially what you were hired to do at Marvel, right?

SL: That is correct. I was hired to do whatever was needed, which at that point was answering the telephone and sorting the mail. I did not have to make coffee, I did not have to run errands, pick up laundry, or pick up dry cleaning. It was whatever needed to be done in the office, and mostly it was answering phones.

DC: Did the phone ring a lot?

SL: Yes, constantly.

DC: Who was typically calling?

SL: Usually, fans of Marvel who wanted to know if I had on the shelf a first edition of this comic book or that comic book. That was most of what the phone calls [were], fans calling to ask for a comic book that they could not find on a shelf in a comicbook store [or newsstand].

DC: How old were you when you got hired at Marvel?

SL: I was probably around 22.

DC: I seem to remember you saying you had been working as a teacher.

SL: Yeah, I graduated college in ’67. I had taught in the inner-city school system in New York—in Harlem, actually— for a couple of years. I was in the first strike or the second strike, and was threatened on the picket line, which was when I left teaching.

DC: I don’t blame you. So, I think I remember you telling me that when you were in the course of interviewing with Marvel for the job, that they asked you to take a writing test of sorts?

SL: Well, Roy Thomas said, “I want you to write a ‘Stan’s Soapbox’.” I guess maybe at that point they were looking for someone to take over doing “Stan’s Soapbox”, which was, what, a one-inch by one-inch column? So, I answered the question, but obviously they weren’t thrilled with the way I answered it, because I never wrote another “Stan’s Soapbox.”

DC: But you did get a writing assignment out of it.

SL: Yeah, I got a writing assignment. Obviously, whatever letters came in, I answered. I typed them up, and typed the answers. I submitted storylines, too, because they were always looking for different storylines.

DC: You suggested storylines for the comics?

SL: Sure, of course. For the love comics. I stayed away from the superheroes. That was not in my wheelhouse. But when the romance comics came out, I submitted storylines for those.

(LEFT) Panel from “His Hair is Long and I Love Him!” in My Love #21 (January 1973) written by Stan Lee with art by Gene Colan and Frank Giacoia. (ABOVE) “Suzan Says” column from My Love #1 (September 1969). © Marvel.

“I pulled cotton at six years old and worked on the peanut farm and paper route.”

–Johnny Bench, former sport of baseball pro.

Is it too late to call Social Services?

Johnny Bench and Planters Peanuts became known to me about the same time during the late 1960s. Johnny Bench because of my brief flirtation with baseball card collecting, and Planters Peanuts due to my Dad’s brief flirtation with bringing treats home after work. These treats would sometimes be candy and sometimes they’d be a little plastic bag of Planters Peanuts. Planters Peanuts are still a favorite snack here at the Sanctum. And while I’ve enjoyed peanuts my whole life, it has never, ever occurred to me to ask from whence these little munchies came.

Arachis hypogaea is the fancy science name for the lowly peanut. How lowly is the peanut? Very low, as in underthe-ground low. It’s not even a nut, but rather a member of the legume family of plants (chickpeas, lentils, and alfalfa, etc.). But because it is used and served like actual nuts, it is often simply lumped in with that crowd.

Evidence of peanuts date back some 7,600 years. They are native to South America. Europeans looking for treasure found peanuts there, and they eventually made their way to the American colonies. Peanuts were used as feedstock beginning in 1870 the same year that Georgia returned to the Union after the Civil War. It was the last state to do so. Peanuts are the official state crop of Georgia, which is the birthplace of former president Jimmy Carter (who passed at the age of 100 just last year). Carter’s father owned a peanut producing farm

from 1928–1949 and after the elder Carter’s death, the future president then inherited a small portion of the land, becoming a (poor) peanut farmer losing a million dollars over the course of that career.

Fun fact: Jimmy Carter was the first American president to be born in a hospital. Fancy.

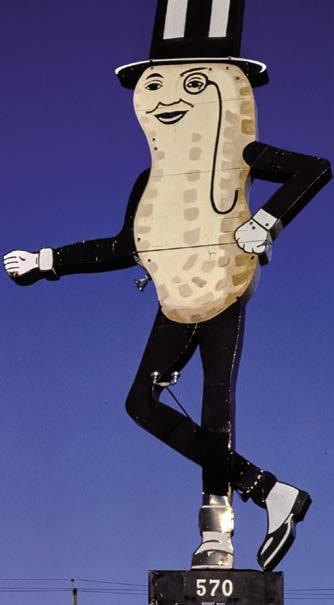

A Mr. Peanut figural sign at Swansea, Massachusetts in a 1984 photo by John Margolies. © Hormel Foods, LLC. Courtesy the Library of Congress.

(ABOVE) George Washington Carver with a peanut plant in his lab at the Tuskegee Institute via rare color footage circa 1941. Courtesy of the National Archives. (INSET) A drawing of former peanut farmer President Jimmy Carter as Mr. Peanut. Illustration by Neal Adams and published in Jimmy’s Coloring Book (Manor, 1976). Art © Estate of Neal Adams.

George Washington Carver (1864?–1943) encouraged cotton-growing farmers of the South to rotate their crops with peanut plants to help replenish the soil. He didn’t invent peanut butter (the Aztecs made a version of it 500 or so years ago) but he was a proponent of the use of peanuts in everyday life. It wasn’t until the 1930s that the popularity of peanuts for human consumption really took off. Previously, peanuts were largely considered animal feed, and only the poor ate them. As a result, the cheapest seats in a theater became known as the “peanut gallery,” because that’s where the peanut-eaters sat. Further promoting peanuts as a respectable food was the government’s request that Americans eat more peanuts during World War II so that more standard food could be sent to the troops. And, of course, Planters promotion of peanuts as worthy food helped boost the consumption as well.

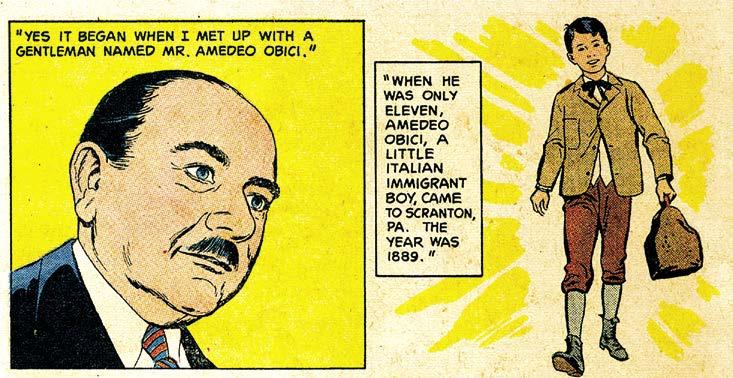

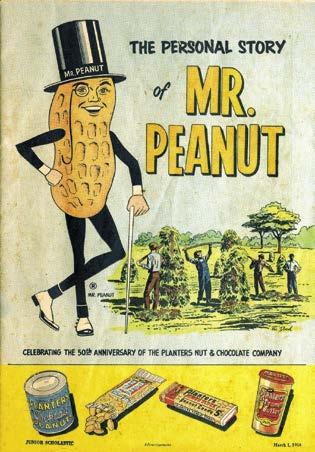

Few are likely to know the name Amedeo Obici, the founder of the Planters Nut Company. Like many tales of ingenuity and creation we’ve shared here at the Sanctum [See “The

Many Faces of Mr. Potato Head” in RetroFan #38 –RetroEd] vague and/or contradictory facts are fairly common. It’s not any different with Mr. Obici’s and his claim to fame as promoter, seller, and innovator of peanuts.

Amedeo Obici was born July 15, 1877 in Italy. His father died when Amedeo was seven. A few years later his uncle Vittorio Sartori, who had immigrated to the US with his family, invited him to come to America. Obici was only 11 years old when he traveled by ship (in steerage) leaving behind his mother and three siblings. When he arrived in Brooklyn, New York, he took a train bound for Scranton, Pennsylvania, where his uncle lived. He spoke no English. One version has Amedeo accidentally getting off the train in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, with a tag pinned to him. The tag had the name of his uncle. Some good Samaritans, not knowing who Vittorio Sartori was, took Obici to a nearby fruit stand owner, Enrico Musante, also an Italian immigrant.

(LEFT) As Obici’s roasted peanuts business picked up, he branded himself as “The Specialist.” © Hormel Foods, LLC.

American money. It was the nickels that caught his attention. This will be important later.

In the Nation’s Business version, no mention is made of Enrico Musante or his fruit stand with the peanuts or his daughter Louise (who is real, I assure you). But the basic fish out of water (with almost no money) storyline of a kid coming to an alien place is both frightening and hopeful. He came to make good, and he did.

Musante, a complete stranger, then did two, no, maybe three things that impacted Amedeo’s life: He employed him at his fruit stand, which also sold roasted peanuts, possibly tracked down Obici’s uncle, and had a daughter named Louise. More about her in a bit. Eventually, Amedeo did make his way to his uncle in Scranton about ten miles away.

Mr. Obici tells a slightly different story in the December, 1928 issue of Nation’s Business magazine. He traveled with an Italian couple across the Atlantic by ship. Once they reached New York, the trio boarded a train. The couple was going to Pittston, which is a town just before Scranton, but after Wilkes-Barre. Once the couple detrained at Pittston, the plan was for Obici to find a fruit stand—any fruit stand (!)— in Scranton where it was assumed he would be able to get help. Apparently enough fruit stand operators in Scranton were Italian that this seemed like a good idea. It worked. Connected now with family, he was employed by his uncle at his fruit stand (or tailoring business—honestly, history is so elusive), and began to learn both English and how to handle

Obici’s younger years did not include much formal schooling (only about three months’ worth). For young Italian immigrants of the day in industrial parts of Pennsylvania, schooling was often unfinished since getting work, usually in mines or mills, to help support family was paramount. Obici, who maxed out at about five foot, one inch, was a hard worker who grabbed his education on the fly. Over the years he would work at more fruit stands, a cafe, a bar, was a bellhop, and worked at a cigar factory for 80¢ a week (about $28 today, try living on that). Eventually, he rented a sidewalk space in front a saloon and set up his own fruit stand. Roasted peanuts were part of the product mix.

The peanut roaster Obici used was manually operated and required constant attention to avoid burning. Obici needed his hands free to tend to his fruit stand customers, so he attached a fan motor to the roasting equipment and roasted more peanuts more evenly in less time. There would be other improvements to the process of producing peanuts in the coming years as the still very young immigrant put more and more time to peanuts.

(LEFT) Amedeo Obici as a child and an adult as seen in (ABOVE) The Personal Story of Mr. Peanut comic book (1956). © Hormel Foods, LLC. Both courtesy of the Hagley Museum and Library.

BY JIM BEARD

Kids love robots.

Since at least the dawn of the 20th century, the young and the young at heart have been fascinated with the mechanical marvels that have populated not only prose, but also comic books, film, and television—not to mention the imaginations of scientists and inventors. In all those venues, robots have been near ubiquitous and more than fertile ground for both fantasy and speculation.

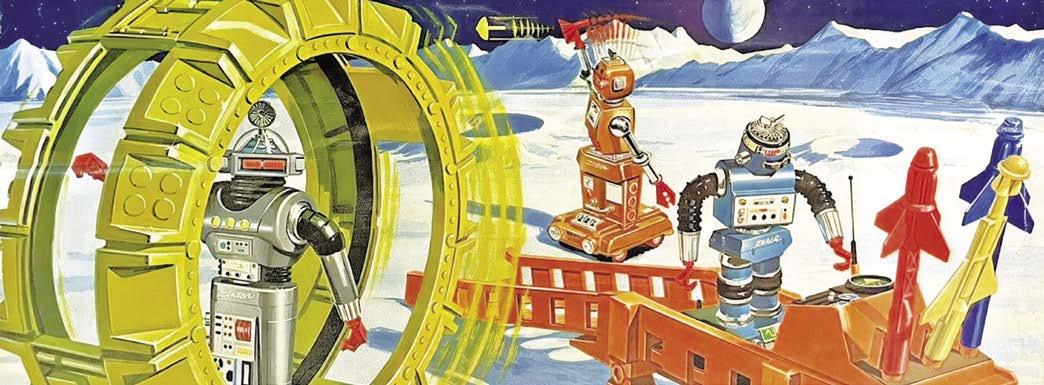

Banking on that fact, the Ideal Toy Corporation introduced a line of robot figures in 1968 that, while brief in its stay, proved an imaginative addition to not only the history of toys, but, here in the present, to the desire of collectors.

The Zeroids, “incredible automatons from outer space,” took hold of hearts and minds more than fifty years ago, and have never really let go.

In 1968, robots, outside of a few examples of real-world factory machinery, were generally a product of fiction.

The prime examples predating the Zeroids would have been the multitude of mechanical menaces in the classic pulp magazines of the 1930s and ’40s, Saturday morning serials, the iconic introductions of “Gort” in 1951’s The Day the Earth Stood Still and “Robby the Robot” in 1956’s Forbidden Planet, and the much later Lost in Space “B-9” robot in the 1965 television series.

In terms of kids’ playthings, the Zeroids could look to Japanese robot toys of the 1940s and America’s “Robert the Robot” toy in 1954 as their direct ancestors. While Robby and B-9 marked unique design elements that broke somewhat from the more angular, boxy looks of their pulp predecessors, in the late 1960s Ideal seemed to be more interested in fashioning its robot series

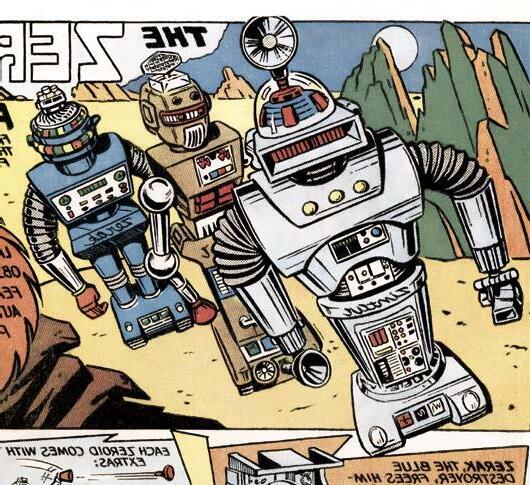

(ABOVE) Box art from the Solar Cycle and Missile Defence Pad Zeroid Action Set (Ideal, 1968). (LEFT) Zintar, the silver explorer. Zeroids TM Toyfinity. (ABOVE) Robot from Mysterious Doctor Satan (Republic, 1940). © Paramount.

DIAMOND COMIC DISTRIBUTORS

FILED FOR BANKRUPTCY IN JANUARY without paying for our December and January magazines and books, leaving us with enormous losses— and we still have to pay the expenses on those items, and keep producing new ones. Until payments from our new distributors begin in the Fall, we’re staying afloat with WEBSTORE SALES

Every new order (print or digital) and subscription will help TwoMorrows get through this, and emerge even stronger for 2026. Please download our NEW 74-PAGE 2025 CATALOG and order something if you can: https://shorturl.at/gA9Fv

Also, ask your local comics shop to change their orders from Diamond to LUNAR DISTRIBUTION, our new distributor. We’ve had to adjust our release dates for the remainder of 2025 while we wait for orders from our new distributor, so you may see some products ship earlier or later than originally scheduled. We should be back to normal by end of Fall 2025; thanks for your patience!

(LEFT) He always got a bad rap, Zerak the Destroyer. (RIGHT) Can you carry that over here, please, Zobor? Zeroids TM Toyfinity.

along more traditional lines. If anything, the Zeroids owed more design-wise to the “pepperpot” Daleks in England’s classic Doctor Who television series than to leggy lurchers like Gort and Robby.

In 1964, Hasbro’s “G.I. Joe” cemented the concept and term of “action figure” throughout the toy industry and kids’ play patterns, but the idea of a line of robot action figures was something singular at the time. With the Zeroids’ average height of five to seven inches tall, they would have made poor companions to G.I. Joe’s twelve-inch stature or even Ideal’s own foot-tall “Captain Action” changeable superhero, so the toy manufacturer may have had their eye on rival Mattel’s “Major Matt Mason” line of six-inch flexible astronaut figures—which lacked robotic characters—as a suitable play-date match for their new creations.

In all, the Zeroids would become one of the first—if not the first—action figure concept based, at first, purely on non-human characters. They were designed, primed, and readied to be the robots every kid would want to accessorize their fantasy-play. NASA’s Apollo project was hot thanks to moon-landing prep, and everyone, children most especially, were looking to the skies and dreaming of a future in space.

Kids got a colorful eyeful of the Zeroids in a comic book ad that ran in National Periodical Publications’ comic

(RIGHT) Zeroids trade ad from Ideal in 1969. Zeroids TM Toyfinity.

magazines in issues appearing on stands around August of ’68—Captain Action #1 for example, a joint production between Ideal and National. The ad, done in comic panel style, made it clear from the outset that the line was all about the characters. The Zeroids all had individual designs, names, jobs, and accessories, not to mention an actual planet of origin, Zero. The ad conducted a terrific, four-color tour of the three robots, and even gave kids ideas for increasing their play value.

The figures themselves weren’t just static pieces of plastic, much to Ideal’s R&D department’s credit. Based on a small motor, the company was already using in their “Motorific” race cars, the Zeroids could move on their own under battery power, and even manipulate objects to move and throw them. To make things even cooler for the kids, a plastic “automatic reversing tile” was included to send the figures into reverse the second they ran onto it with their treads. The idea was to give the Zeroids some variation in their movements so their youthful masters could use the robots to “haul, batter, ram, attack, launch, transport, fight—anything!” There’s some duplication in those breathless terms, certainly, but one has to imagine kids were eager to pit their Zeroids against each other at the drop of a robotic hat… or head, if that be the case.

IF YOU ENJOYED THIS PREVIEW, CLICK THE LINK TO ORDER THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DIGITAL FORMAT!

Another addition to the three-robot fleet was Ideal’s then-unique packaging. In an era when most kids—and moms—would normally trash the boxes and backing cards 1960s toys arrived in, the Zeroids asked for their packing crates to be kept and used. Each of the robots’ plastic “boxes” became workable tools, referred to as “control stations,” of one kind or another, as well as a nice way to store your new mechanical friend when playtime was over.

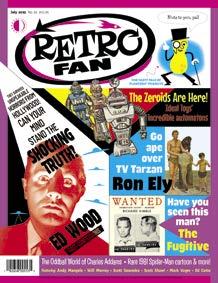

Can your mind stand the shocking truth of… ED WOOD CAST CONFESSIONS? Plus: Ideal Toys’ Zeroids, television Tarzan RON ELY, Planters® Peanuts’ Mr. Peanut, CHARLES ADDAMS, TV’s The Fugitive, the forgotten 1981 Spider-Man cartoon, and more! Featuring columns by ANDY MANGELS, WILL MURRAY, SCOTT SAAVEDRA, SCOTT SHAW, ED CATTO, and MARK VOGER

(84-page FULL-COLOR magazine) $10.95

Overall, perhaps the sassiest selling point of the Zeroids was who they were and what they did.

The Teamster of the tin-plated team was Zobor, a mostly gold colored guy with pincer hands and what looked like a reel-to-reel tape player on his chest. Zobor’s case became what Ideal labeled a “cosmobile,” that once set down horizontally allowed him (it?) to haul found objects like rocks and sticks. The comic ad told kids that “[n]o transporting job is