DRAWN TO GREATNESS

Wayne Boring & The Early “Superman” Artists Who Followed Joe Shuster

PART II

by Eddy Zeno

(with the interviewing aid of Mel Higgins)

Original Graphic Design by Jeff Weigel

[Continued from Alter Ego #193]

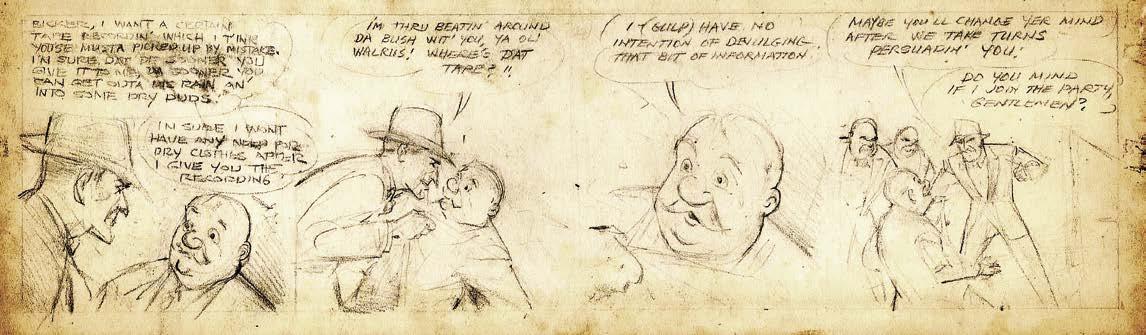

XII . Professional Embellishers: Stan Kaye & George Roussos

Although Stan Kaye and George Roussos fully illustrated and colored their own comicbook stories starting in the 1940s, they are chiefly remembered for embellishing the pencils of others.

George Roussos was born in Washington, DC, to Greek immigrants. He and two sisters became orphans at an early age. After his parents’ death, Roussos attended public school in Queens, New York, while residing in the Brooklyn Orphan Asylum. In 1939 he began working in comics by lettering for the Spanish language version of the Ripley’s Believe It or Not newspaper strip. Understanding Greek thanks to the legacy of his late parents, George stated that the similarity of the two languages carried him through. Roussos was married twice. He had four children.65

Stan Kaye was born in Brooklyn to parents who immigrated from what is now Poland; his father died from complications related to tuberculosis (TB) before he was two years old.66 Originally named Stanley Rawinis, he took the surname of Kalinowski after his mother remarried.

Stan attended a different high school in Queens than George Roussos. By 1941, if not before, he and half-brother Jerome “Jerry” Kalinowski changed their last name for the final time. There is a note of explanation in the clan’s archive from Jerry’s wife: “The Great Depression resulted in a scarcity of employment opportunities, particularly when combined with the prejudices of family origins. All were contributing factors in Stan and his brother, Jerome, ultimately changing their surname from Kalinowski to Kaye.”

Kaye’s future wife Marion Jensen67 left her Wisconsin home to study at New York’s Tobé–Coburn School for Fashion Careers (currently the Wood Tobé–Coburn School). After meeting on a blind date at the end of 1944, Stan and Marion married the following

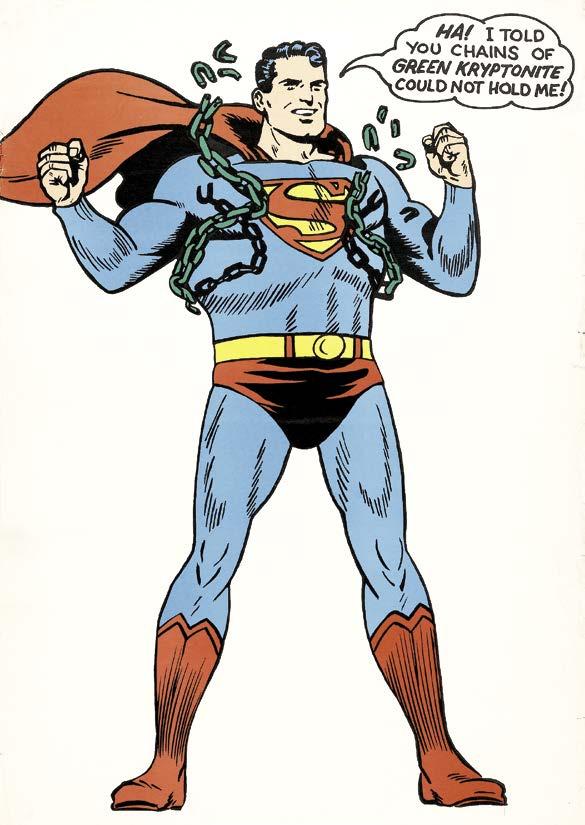

Unchain

My Heart!

year.68 They had five children together.

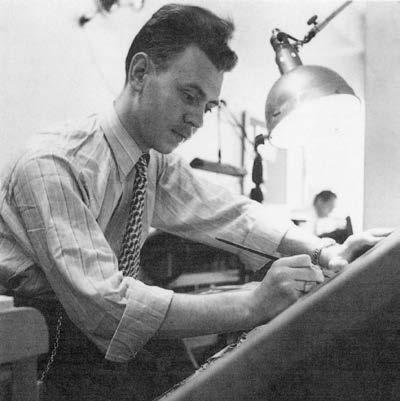

Mel Higgins interviewed a group of Stan’s relatives in 2009. In addition to the sources footnoted above, the Kaye family history was verified by youngest son Paul and his wife Diane. Oldest child Howard described his father as stocky and with curly black hair—at first. Stan’s widow Marion remembered that her future husband was already balding when they met. The artist was five feet seven inches tall.

One Classically Trained…

After high school Stan Kaye attended sign-painting school in the mid-1930s. He went on to assist painter William Mackay with murals for the American Museum of Natural History and studied under Harvey Dunn at the Art Students League of New York. Harvey Dunn was part of the famous Brandywine School of illustrators, which stemmed from his tutelage under Howard Pyle. Pyle also taught N.C. Wyeth, Frank Schoonover, and other great illustrators of the early twentieth century. Dean Cornwell, known

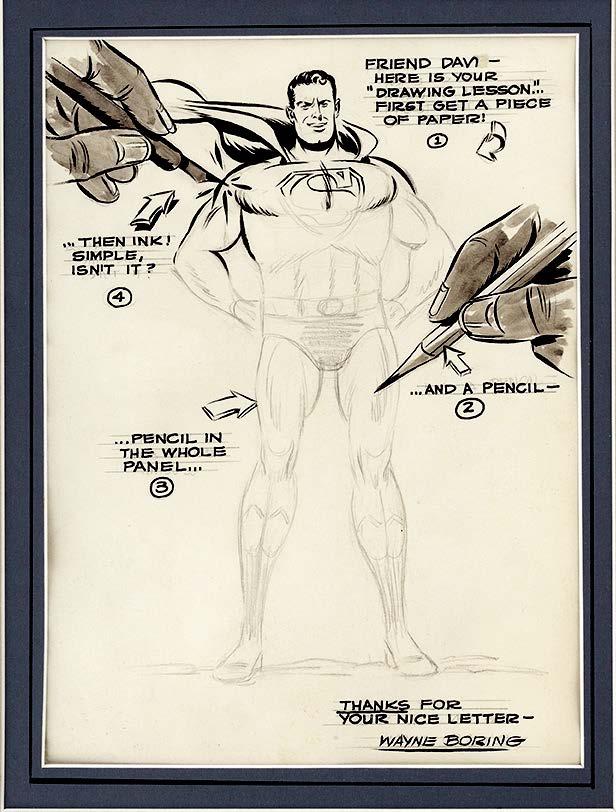

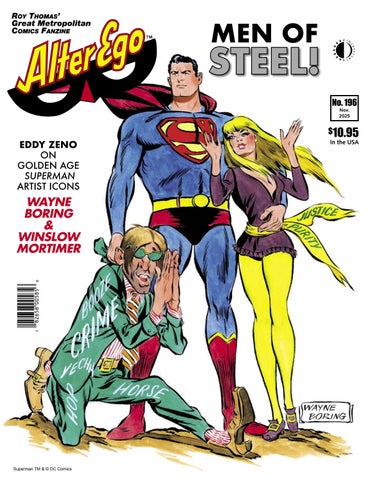

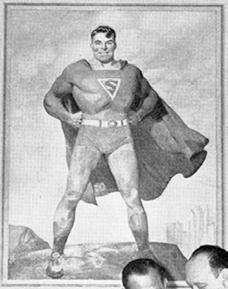

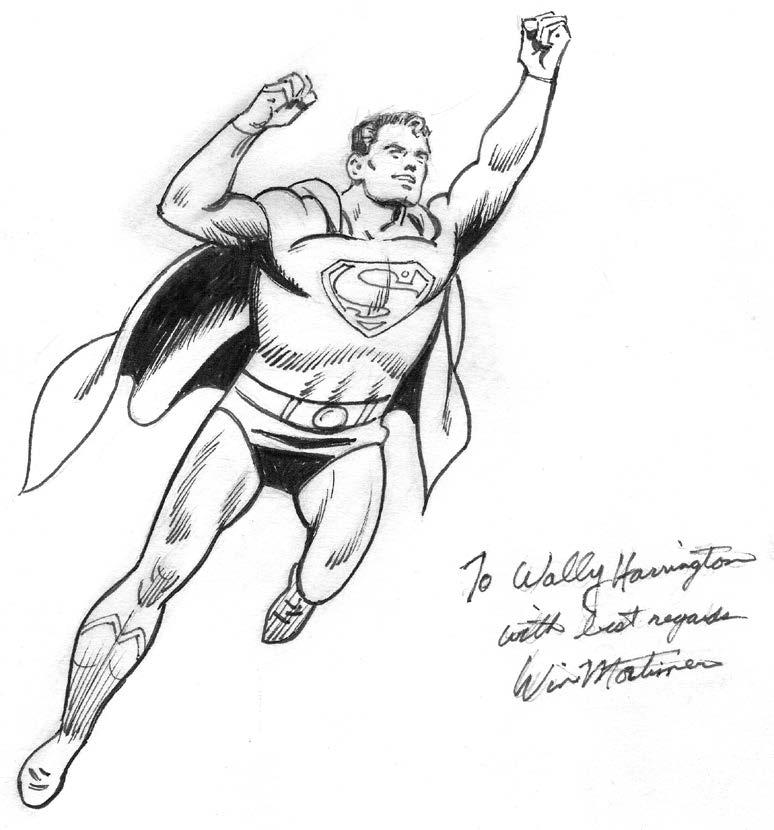

Our cover artist Wayne Boring drew (and colored) this iconic pose of the Man of Steel in 1966, for fan/researcher Glen Cadigan. It’s one of the relatively few photos or pieces of art accompanying our presentation of the second half of Eddy Zeno’s book Drawn to Greatness that was provided by someone other than the author himself. Unless otherwise acknowledged, all visual elements depicted on pp. 3-60 were provided by Eddy. [Superman TM & © DC Comics.]

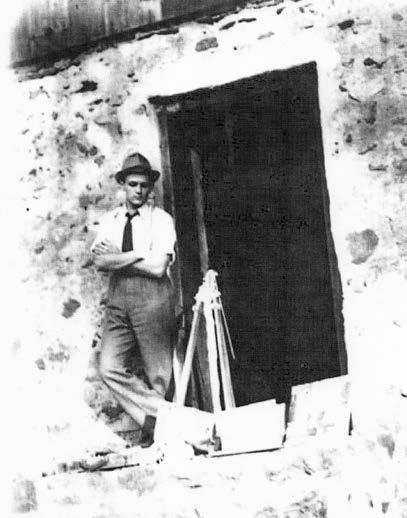

Howard Kaye, artist Stan Kaye’s oldest son, believes the above photo was taken “when [Stan] was studying with Harvey Dunn…. The one showing him posing by a doorway is probably from his 20s, during his photography days. He spent a lot of time taking pictures in the coal mines of Pennsylvania.”

as the “Dean of Illustrators,” studied under Dunn; he likewise taught at the Art Students League. Kaye would come to be employed by Cornwell, painting murals as he had done earlier with Mackay.68

The young artist became draft-exempt during World War II when doctors found scar tissue on his lungs; he had been asymptomatic and was unaware of having had TB. The military’s loss was DC’s gain. Stan’s earliest known comicbook work was a spot illustration done for a one-page text story in Superman #11 (July-August 1941).

…The Other Self-Taught

George Roussos verified that Stan Kaye studied under Dean Cornwell, as well as being George’s first mentor: “He helped with illustrations. I would do an illustration every week with opaque colors, and he would correct it for me…. I was interested to learn because I had no schooling [in art] except the things I learned by myself.”69 Interviewer Jim Amash once asked longtime production man Jack Adler: “In the early days of your DC employment some artists, like George Roussos and Stan Kaye, colored their own features. Would you have any involvement with their work?” “Not at all,” was Jack’s easy response.70 George obviously learned well from Stan.

Adler further mentioned Roussos: “He was a good artist and I liked him. He was very easy to work with. He was very reluctant to push himself; had he been a little stronger, he’d have gone much further than he did.”

70 Perhaps that is why George hung around the fringes in Batman and Superman’s formative days.

Roussos ended his career as a colorist. Longtime Marvel and DC Comics inker Dave Hunt, a generation younger than George, worked side-by-side with him in what was known as the Marvel Bullpen. Hunt enjoyed “chewing the fat” with Roussos and called him a “funny guy.” Dave remembered: “At that time, in the early 1970s, George Roussos was coloring the Marvel Comics covers, and he was really good. George was one of the original guys who worked with Bob Kane on ‘Batman.’ He was really in on the ground floor of comics. George lettered the earliest stories and did the backgrounds.” Once, when Dave casually asked how to correctly pronounce the name of Superman’s mischievous nemesis Mxyzptlk, Roussos immediately called his old writer friend and Batman co-creator Bill Finger for the answer.71

Known as a kind and generous man, the old pro could be eccentric. Dave Hunt again: “George was a recluse. He actually built a fortress out of boxes in the office, and he would color behind this screen. You didn’t see him, but he was back there.”71

Comicbook Weekend

Late-in-life work habits notwithstanding, Roussos got around. For instance, he was part of a weekend famous in the annals of comicbook lore. By early 1941, paper, like many supplies that would soon put the country on a war footing, needed to be returned if it went unused. That is why Lev Gleason, publisher of the already successful character Daredevil (not the Marvel Comics super-hero with that name who appeared later), had to use his surplus paper by putting out another comicbook immediately. At least that’s one version of the story.72 A more mundane account is that if Gleason didn’t use his stash to print something fast… “his distributor wouldn’t advance him the money to pay the bill.”73

Think Ink!

A young George Roussos at the drawing board (from the Comic Vine website)—and his lavish brushwork for the “Air Wave” splash panel from Detective Comics #77 (July 1943), which demonstrates how he earned the nickname “Inky.” Script by Joe Samachson. Panel courtesy of Doug Martin. [Page TM & © DC Comics.]

Sonrise

Cartoonist/writer/editor Charlie Biro, who worked for Lev Gleason, recruited his friend Jerry Robinson, and Jerry brought in buddies to help. Their task: write and fully illustrate an entire 68-page comicbook in 2½ days, between Friday and Monday morning. George illustrated a story catered to his interests by writer Dick Wood. Stated Robinson: “George Roussos did a mystery strip; he liked dark stories.”72 The character Roussos co-created was named Nightro.

To complicate matters, a nor’easter hit the city that weekend. After drawing straws, one of the famished artists wandered the paralyzed streets for hours before finally finding an open bar. Someone there took pity by letting him purchase a dozen eggs and a can of beans. Having no stove, the comicbookers ripped down several bathroom tiles to form a makeshift hotplate on the wooden floor. Using a T-square

and keys in lieu of a can opener, they punctured the can and lit newspapers to heat the beans and fry the eggs. The work was turned in on time.

The Sketchbook

In the early days Roussos asked artists whom he admired to draw in his sketchbook; lifelong friend Jerry Robinson was one of them. Robinson began his career by providing vital art assists to Bob Kane before becoming a major “Batman” illustrator of that era. George was hired to help Jerry. Later statements relayed by Robinson hint at Roussos’ importance: “George and I really sweated it out trying to make some of Bob’s drawings work.” Also: “George and I used to have fun with Bob’s habit of drawing gangsters pulling out a gun like it came out of their left shoulder. Whenever we could we tried to change his drawings to make them looser and a little more naturalistic.”38

Robinson stayed little more than a year in Bob Kane’s studio before he and writer Bill Finger went to work directly in the DC bullpen. That was in mid-1941. George left Bob Kane’s employ to join them.38 Roussos’ fellow “Superman” contributors Fred Ray, Jon Small, Win Mortimer, Stan Kaye, and even Joe Shuster (after the Clevelander relocated to New York) worked in the bullpen at varying times, each man drawing whimsical works in George’s sketchbook.

So did artist Charles Flanders. Roussos assisted Flanders on the Lone Ranger newspaper strip; he helped other creators on several different comic strips as well.

Johnny Craig, Al Feldstein, and Frank Frazetta drew in the sketchbook, too. Like them and other well-known contributors to Entertaining Comics (EC), Roussos illustrated comicbook stories around 1950 for the innovative company.

Mort Meskin and Jack Kirby, two of the fastest artists in comics, sketched in George’s book. No doubt influenced by Meskin’s early style, Roussos earned the nickname “Inky” for his prodigious spotting of blacks during comics’ Golden Age. It was not unusual for Inky to embellish Mort’s graphite on comicbooks published during the 1940s, ’50s, and into the ’60s. Toward the

An Artist Of Power

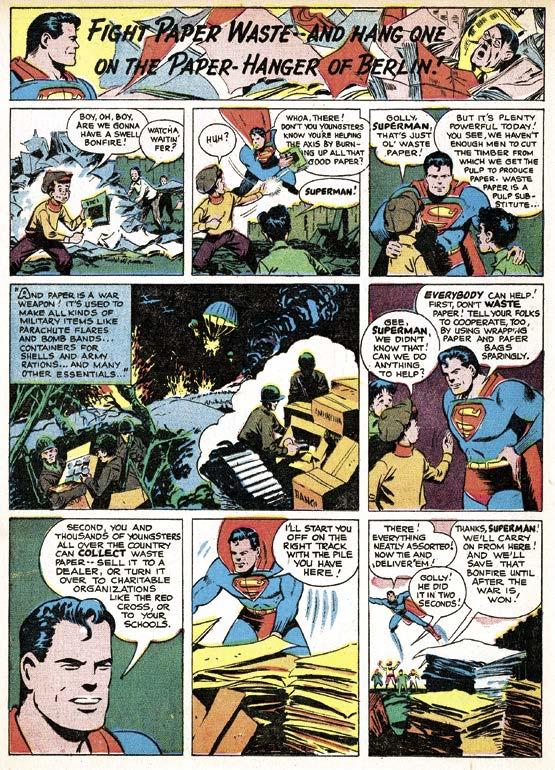

A wartime public service page by George Roussos, featuring the Man of Steel, that appeared in various DC comics that bore a cover date of April 1944. It was probably written by editor Jack Schiff. [Superman page TM & © DC Comics.]

Sketch As Sketch Can!

A sketch by Joe Shuster done for Roussos’ legendary sketchbook. Courtesy of Heritage Auctions, via Eddy Zeno. [Superman & Batman TM & © DC Comics.]

The

painting confirmed his readiness for the role.

The idea to pair Kaye with Boring was born from necessity. According to DC Comics’ Supergirl Archives, Vol. 1 (2001), when Wayne was asked to take over the Superman Sunday art chores in addition to his already doing pen, pencil, and brush work on the dailies, Stan became the Sunday page inker. The gig morphed into both men being partnered together on nearly every subsequent assignment.

Comicbook illustrator Curt Swan spoke about how Stan Kaye embellished not only Wayne’s pencils but his, too, for several years: “He’s another fellow with whom I got very close—and his family and children. We worked together and collaborated on covers at the office many times. I found [Stan] to be a true friend. He was again a very professional artist and quite knowledgeable about art. As a matter of fact, there was one time when he was asked to act as a curator at a museum in New York City [Swan later noted that the museum job offer was actually in Washington, DC], but he didn’t follow through on it…. He turned it down because

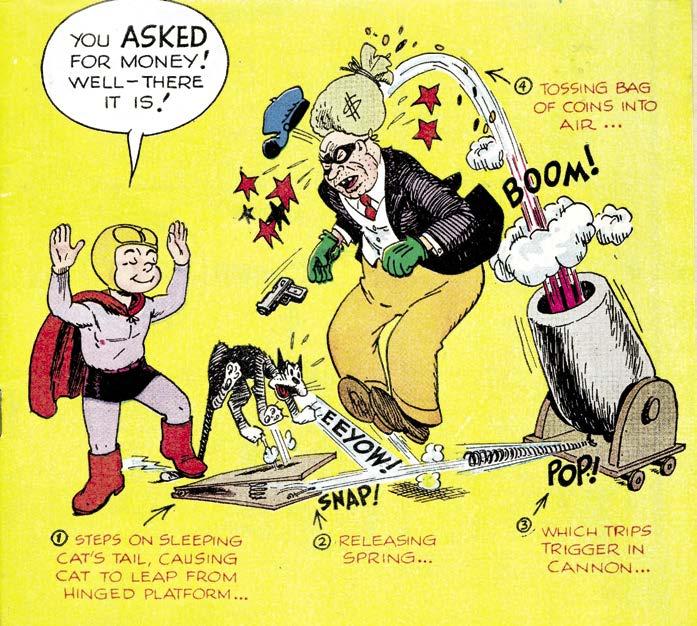

Genius Jones Does A Rube Goldberg

Cover scene penciled and inked by Stan Kaye for More Fun Comics #109 (April ’46)—and (at right) a blowup of the artist’s subtle signature thereon. Scripter unidentified. [TM & © DC Comics.]

This Means Ward!

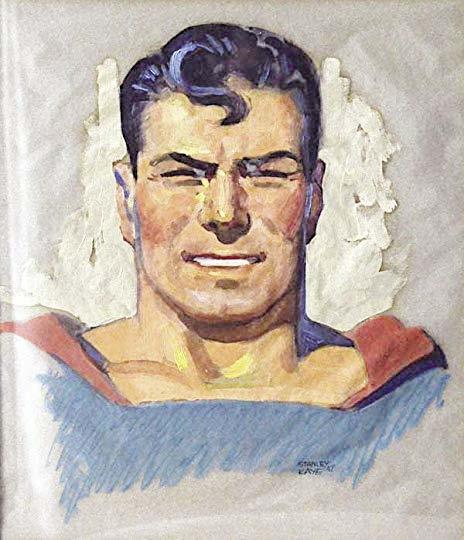

Stan in 1942 was inspired to paint his own closeup version of Superman (top right) after seeing artist H.J. Ward’s large canvas of the hero (top left) that hung for many years in the DC offices. The Ward art was, in turn, later retouched and updated by artist Joe Szokoli (above center), who also appropriated Fred Ray’s distinctive “S” logo. [TM & © DC Comics.]

Year Santa Didn’t Need A Sleigh

The combo of Kaye (penciler) and Roussos (inker) handled the cover of Adventure Comics #113 (Feb. 1947). Together the two cartoonists’ work was almost ephemeral, with a gentleness that was highly attractive. [TM & © DC Comics.]

to work with Joe and Jerry. What was left of the Shuster Shop would now be focused on Funnyman. Marvin was now teaching at the School of Visual Arts (SVA) in New York City, and Joe’s studio was nearby. Stein remembered: “Joe was editing Superman comic art for DC Comics and was also busy preparing a lawsuit against the publisher for control of Superman. He was too busy to work on Funnyman. He would just change a face or two, or a figure or a layout.”78

Shuster was never too preoccupied to appreciate good work. Mel Higgins spoke to Larry Englehart by phone on August 16, 2008. Englehart carried an idea for a newspaper strip he had wanted to do ever since high school when he attended SVA. The year was 1959. A buddy gave Larry Joe’s phone number, and by 1960 Shuster was penciling a few comic strip samples to pitch to the newspaper syndicates. Their proposal came to naught, but a friendship ensued. Joe never bragged, and so it stood out to Larry when Shuster, without meaning to do so, revealed his generous nature. A dozen years prior, after Marvin had done a particularly nice job interpreting a “Funnyman” script, Joe mentioned giving Stein something he could little afford—a large cash bonus.

Like Marvin Stein, John Sikela would follow Joe Shuster to his and Jerry Siegel’s next hoped-for mega-hit. Sikela helped on later issues of the Funnyman comicbook as well as working on the short-lived newspaper strip that followed. Next to Joe himself, John remained most adept at keeping the Shuster look, especially on dames and crooks. Other assistants would join Sikela and Stein for the first time, making this version of the Shuster Shop both old and new.

Dick Ayers and Ernie Bache were the new guys. Bache, usually inking others’ graphite lines, had skill as a penciler, too. He started in advertising. Ernie’s comicbook work began at Quality Comics, and by the mid-’60s he was mostly working at Charlton Comics. Bache, a heavy smoker, passed away in his sleep in 1968.

When Tarzan newspaper strip artist Burne Hogarth founded the School of Visual Arts, Dick Ayers joined the beginning group

of students. Interviewed by Shaun Clancy for The Comics Journal in 2012, Ayers reminisced: “As I’m going into my class for about the first evening, there’s a fellow and on his notebook is ‘Bache.’ Bache is my middle name. So that made me stop and talk to him. I got more interested, and then I found out he worked for Joe Shuster right nearby, and then would go to the school there, too... which is what I did for quite some time. I penciled Funnyman.” Dick continued: “I was so happy to get that and I worked in the studio. Joe Shuster was in the art department, and he would more or less finish up what I drew to get it into his style.”84

It was at Joe’s behest that new recruit Ayers became the lead penciler on a “Funnyman” tale.85 He wished to utilize Dick’s penchant for portraying action to showcase the clowning crimefighter’s crazy stunts. In 1994 Ayers remembered of Shuster: “He mostly kibitzed our work, touching up a facial expression here or there. Joe did tell us that he modeled Funnyman after the popular movie comedian Danny Kaye and to think of him when we drew the character.”78

After his success in the Shuster Shop Joe sent Dick Ayers to see Vin Sullivan for his first direct assignment. Seems that drawing the offbeat Funnyman with his fake-nose secret identity prepared Dick to render another comedian’s famous schnozzola. In 1948 Ayers was the principal artist (both as penciler and inker) on three issues of Jimmy Durante Comics. Unfortunately, the title was discontinued due to poor sales after only the second issue; the last one went unpublished. Ayers would later work on other features for Magazine Enterprises, including his most famous co-creation, “Ghost Rider.” This was in summer 1949. Though the Funnyman newspaper strip started months earlier, Dick stated it was also sometime in 1949 that Shuster called him back to the studio to become the next penciler of the Funnyman dailies.85

By the mid-1950s, in addition to his work at ME, Dick Ayers was illustrating stories for Charlton Comics and Atlas (Marvel Comics), often with Ernie Bache inking. For Marvel, Dick would go on to greater things, including inking Jack Kirby’s pencils and drawing Sgt. Fury and His Howling Commandos for a decade. The artist and sometime-writer later freelanced for DC Comics and did much else. Mr. Ayers’ career extended well into the 2000s.

Dropped

For Joe and Jerry, lightning had not struck again. Funnyman as a comicbook lasted six issues (with cover dates of Jan.-Aug. 1948). The subsequent newspaper comic strip dailies and Sundays started in October 1948. Toward the end, Reggie Van Twerp, a mid-1930s character of Siegel and Shuster’s, was resurrected as the new lead, while Funnyman was dropped from his own feature. It was a futile attempt to save the strip. The dailies and Sundays ended,

Vin Sullivan

First editor of “Superman,” “Batman”—and (at left) “Funnyman.”

Stormy Weather

(Below:) In 1960 Shuster began to work up a newspaper comic strip titled Stormy Summers, with Larry Englehart as writer. Alas, their proposal remained unpublished. [Art © Estate of Joe Shuster.]

and sandwiched as he was between Jack Burnley and Curt Swan, Mortimer’s style was transitional. His self-inked illustrations were indicative of an emerging trend among the commercial stylists working on the soap-opera newspaper features of the 1950s and ‘60s.

A circa-1956 newspaper article written for Carmellites (Carmel is in Putnam County, NY) celebrated one of their own: “‘David Crane’ follows in the soapy footsteps of those other vocational do-gooders, Rex Morgan, M.D., Steve Roper, wholesome news photographer, and Mary Worth, motherly meddler.” Less over-embellishment and a sharper line

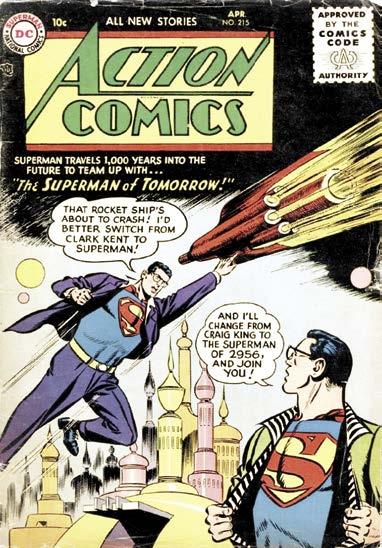

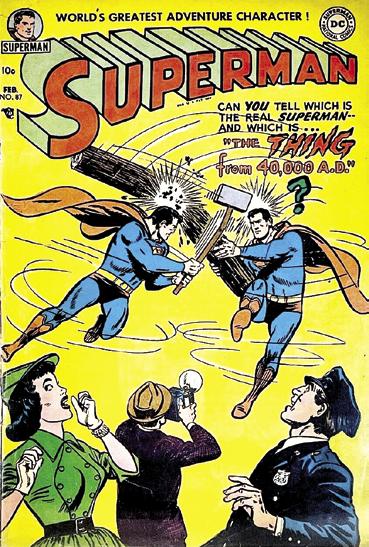

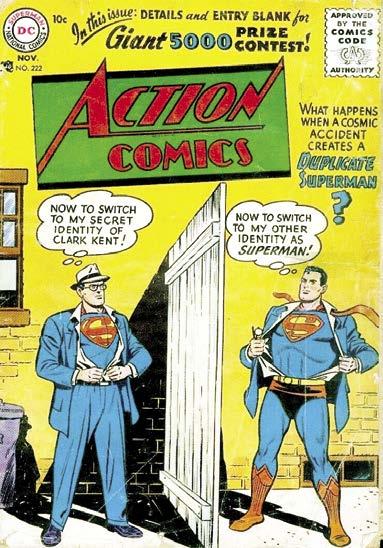

(Below:) Selling twice as much hero on newsstands, Winslow Mortimer’s cover for Superman #87 (Feb. 1954; inker uncertain) can be seen sandwiched between Wayne Boring’s Action Comics #215 (April 1956; inked by Stan Kaye) on left and Al Plastino’s Action #222 (Nov. 1956). In these examples, Win placed emphasis on the bystanders, Wayne on his city of the future and a rocket ship’s distress, and Al on the duplicate champions donning and doffing their Kent suits in opposite stages of dress.

A Trio Of Titans

Courtesy of the GCD. [TM & © DC Comics.]

Win Mortimer & Friend

A photo of a youngish Win that appeared in Batman: The Sunday Classics: 1943-46, from DC & Kitchen Sink Press (1991)—and one of a series of commission drawings the artist penciled and inked late in his career, this one reproduced courtesy of Wally Harrington. [Superman TM & © DC Comics.]

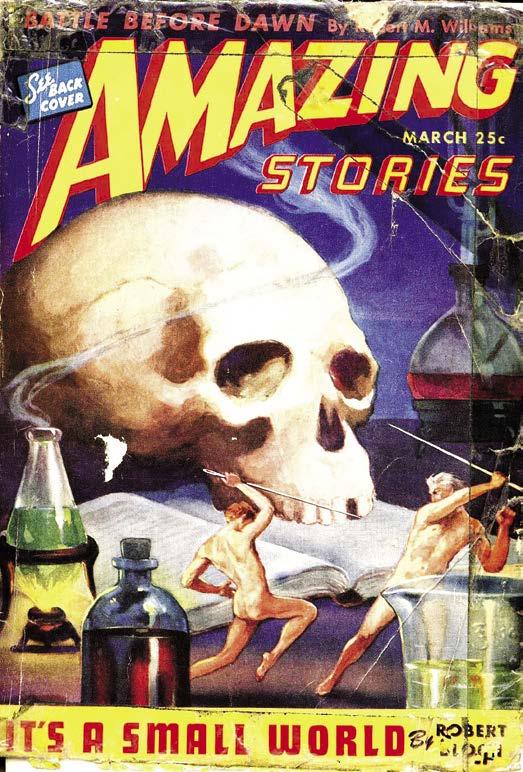

and beakers

Amazing!

chemical potions,

both the men and women of Krypton wearing identical uniforms and football helmet headgear. This was a harbinger for what came 40 years later when writer/artist John Byrne designed garb that was indistinguishable for each of the planet’s inhabitants; their craniums were covered as well.

Along with Wayne Boring, artists Al Plastino and Curt Swan became the three chief successors to Joe Shuster. While Al and Curt, like Wayne, rendered memorable versions of how Jor-El and Lara’s son rocketed here from a doomed world, they are better known for other things. Alfred John Plastino drew the origins of the Legion of Super-Heroes, Brainiac, Metallo, Supergirl, and the Parasite. As the plots became more intricate and the emotions of heroes and villains deepened, Douglas Curtis “Curt” Swan portrayed what are fondly remembered as some of DC Comics’ best two- and three-part novels. Before the arrival of new key characters and longer yarns that permitted greater emoting, however, it was Wayne Boring who shepherded Superman through a science-fiction renaissance!

Beginning in the latter 1940s with stories reaching farther into space, the character’s origin became more crucial to his development. After all, if he hadn’t traversed them as an infant, the adult Superman might not have been able to amble so comfortably among the stars.

Many think of Mr. Boring’s first chance to illustrate Kal-El’s journey to Earth as occurring in Superman #53 (July-Aug. 1948).

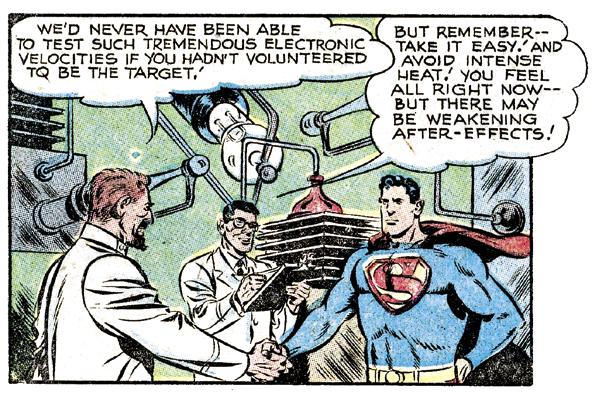

Lab Work

Coils and ray tubes. In contrast to St. John’s work, Wayne Boring seems better suited to portraying massive electrical devices. Panels from a Superman color Sunday from 1954. Script uncertain. [TM & © DC Comics.]

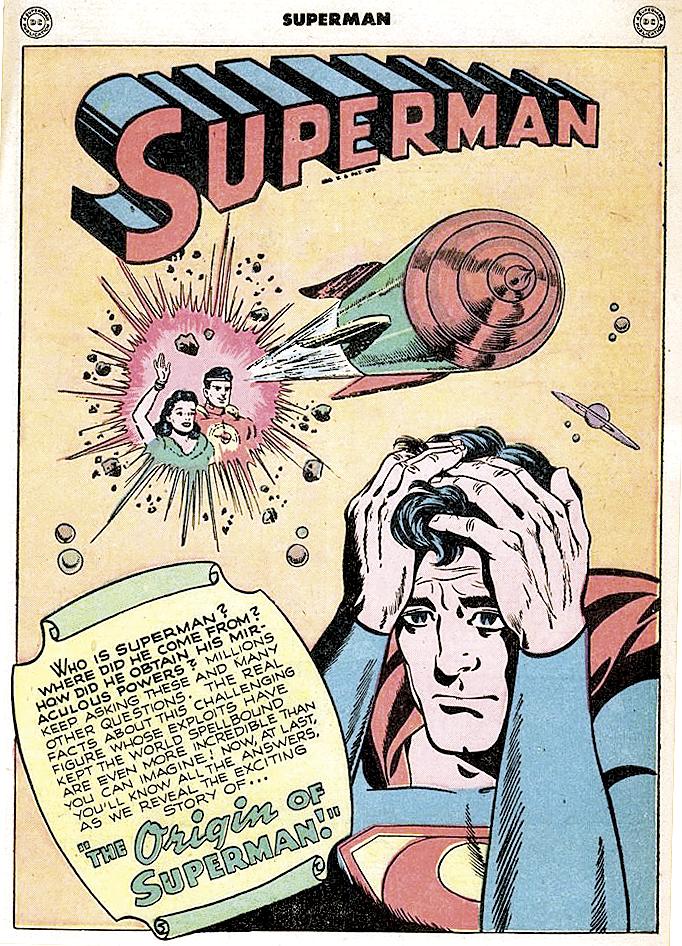

Tales Retold

Boring’s splash for Superman #53 (July-Aug. 1948). Inked by Stan Kaye. Script by Edmond Hamilton. [TM & © DC Comics.]

That’s

Flasks

with

smoke rising from delicate glass. J. Allen St. John’s cover for the March 1944 issue of Amazing Stories pulp magazine, published by Ziff-Davis. [TM & © the respective trademark & copyright holders.]

But, thanks to IDW’s commitment to publishing the heretofore un-reprinted Superman dailies and Sundays (continuing the prior efforts of Kitchen Sink Press), an older origin story by Wayne resurfaced. Winding up a series of WW II-related themes, on November 18, 1945, the Man of Steel (with Wayne Boring as chief artist) helped a returning soldier settle back into civilian life. A blurb in the last panel expounded, “Many readers have written in to ask: ‘Who is Superman? Where did he come from? How did he acquire his incredible, fantastic super-powers?’ So, starting next week – The answers! In THE ORIGIN Of SUPERMAN!” What better time for the country and for Kal-El to make a fresh start?

Nine successive Sundays, beginning on November 25, 1945, took Krypton from tremor to explosion, from orphaned infant to being adopted by the Kents, and from a boy exploring his powers to his first assignment at a major metropolitan newspaper. At the beginning, barrel-chested Jor-El looked both tough and regal at the same time. Focusing on the Superman newspaper strip for most of the 1940s, Wayne’s style was maturing beyond his days in the Shuster Shop.

By the time Superman #53 appeared, the nine Sunday strips of three years earlier were redrawn as a ten-page comicbook tale. Fewer panels were dedicated to Clark Kent’s journalism career

and more to the vital portions of the myth. Jor-El’s meeting with the Science Council to exclaim “Gentlemen… Krypton is doomed!” grew from one panel to seven; the Kents instilling their moral code in son Clark doubled from two panels to four. Bill Finger typed the script, borrowing heavily from Jerry Siegel’s (attributed) 1945 newspaper effort. The irony that Batman’s co-creator would follow Siegel to write some of Superman’s most iconic tales is often overlooked.

Re-Energizing The Franchise

Superman #53’s cover-featured origin story commemorated the hero’s 10th anniversary as a published phenomenon. It also symbolized a new beginning for the Man of Steel’s editors… and for Wayne Boring, too. This was after Siegel and Shuster’s failed lawsuit, when their creator credits were yanked, and they were coldly booted off the character.

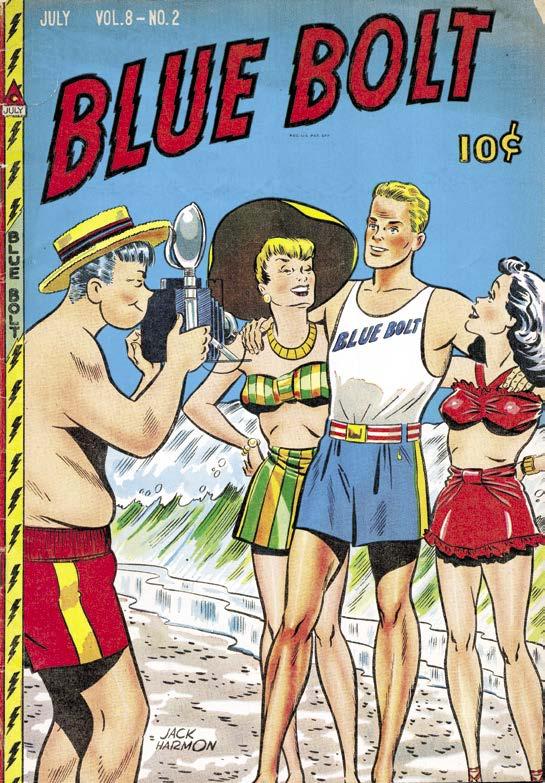

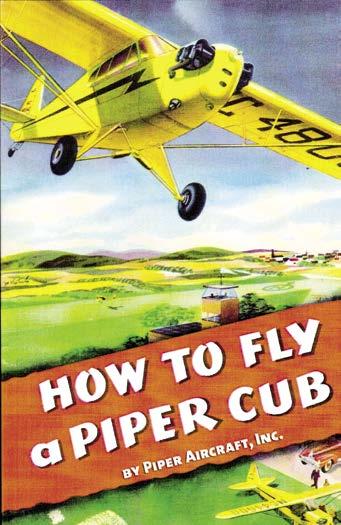

You’ll Believe A Piper Cub Can Fly! Wayne illustrated (and Stan Kaye inked) the 1945 giveaway booklet How to Fly a Piper Cub. Like many of his comicbook and comic strip contemporaries, Boring’s connection to the advertising agency Johnson and Cushing got him the job. [© the respective copyright holders.]

During the grievance there was an interesting aside. Because Wayne was being sued along with the publishers, the opposing attorney told him: “You’re no longer drawing Superman!” Boring wasn’t overly concerned: “I didn’t care about it. Not really. I also worked for Johnstone and Cushing, an advertising agency. I got 600 bucks for a half-page, which Stan Kaye would ink for me. Remember How to Fly a Piper Cub? I did that.”8 What Wayne failed to mention during a 1984 interview was that he was also hedging his bets by taking a job with the Novelty/Premium Group of Comics. Between issues cover-dated Fall 1945 and April 1948 he drew several covers and stories featuring the characters Toni Gayle (in Young Cole Detective Tales) and Blue Bolt (in the title of the same name). Boring moonlighted under different aliases, the favorite being “Jack Harmon.” Wayne’s father John went by his middle name of “Harmon”; the artist concocted his pen name from that.

At DC, with the Shuster Shop no longer supplying the art, Wayne was reassigned from doing the newspaper dailies to being a comicbook mainstay. (He would continue to pencil the Sundays and his byline eventually replaced Jerry and Joe’s.) Though he’d been drawing Superman and Action Comics covers, he was asked to do interior stories, too. Boring must have very much liked working on both the Sunday comic strips and on comicbooks. With a new sophistication to the art, his version of Superman became the house style.

Near the end of the 1948 origin sequence, Wayne dressed reporter Clark Kent in a suit that looked slightly large. In a fitting way, the grown son was drawn less broad-shouldered than his real dad. Perhaps subconsciously, the artist was not yet ready to

Like A Bolt From The Blue

Using the alias “Jack Harmon,” Wayne Boring’s version of “Blue Bolt the American” resembled… himself, on the cover of Blue Bolt, Vol. 8, #2 (July 1947). From Curtis’ Novelty comics group. [TM & © the respective trademark & copyright holders.]

Once A Cartoonist, Always A Cartoonist

With Charlie Roberts acting as proxy, Boring mailed 16 works featuring the Man of Steel to be sold at the 1985 San Diego Comic Con Art Show. Twelve of the items were Superman dailies from the 1960s, original art from near the end of the newspaper strip’s run. If a daily merely featured Clark or other secondary characters, Wayne would obliterate part of the strip with whiteout and draw a flying Superman therein. He was not worried about maintaining the integrity of a piece if he could make it more saleable; Boring had that in common with many artists from his generation.

After shipping the dailies along with four original comicbook pages, Wayne wrote: “Are all the copyright signs on everything? Julius Schwartz and all of his minions will be there, so do not take any crap from them as my agent. This material has been returned to me from DC for sale as I wish. The release is on the back of most of it.” The Man of Steel originals, both dailies and full pages, were priced at $75 each.

Another venue through which Boring solicited Superman

dailies was the Comics Buyer’s Guide (CBG). Formerly known as The Buyer’s Guide to Comics Fandom, CBG was once a weekly tabloid for comicbook and newspaper strip fans. Wayne’s 1986 ad touted that dailies were still available at $75 apiece. He also offered “old mag covers painted on wood panels” for $400 or “watercolor paintings of favorite old covers” for $140 (postage and handling separate). The artist divulged his Pompano Beach, Florida, address so collectors could contact him directly.

One of his last projects for DC saw print in All-Star Squadron #64 (Dec. 1986). It was a homage to the 1942 Superman #19 story titled “Case of the Funny Paper Crimes.” The inker was Tony DeZuniga; the writer and editor was again Roy Thomas.

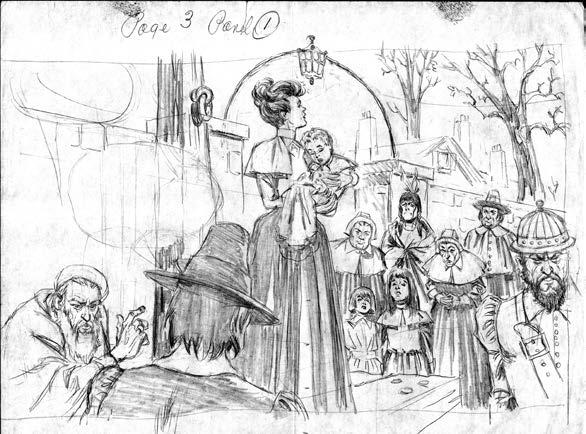

There are pencils for an unpublished adaptation of Nathaniel Hawthorne’s novel The Scarlet Letter, done late in the illustrator’s life. Later still was the unfinished “Jasper Stone, Star Spanner.” Jasper Stone was a sort of Superman story in reverse. Clark Kent lookalike goes to a distant planet where he is the weakest being before a weird chemical bath grants him great strength. Boring outfitted Jasper with a skirt like the one Magnus Robot Fighter (Gold Key Comics’ hero set in the year 4,000 A.D.) sported as futuristic attire. Besides being penciled, inked, and lettered by Wayne, he is believed to have been writing it, too, when he suffered

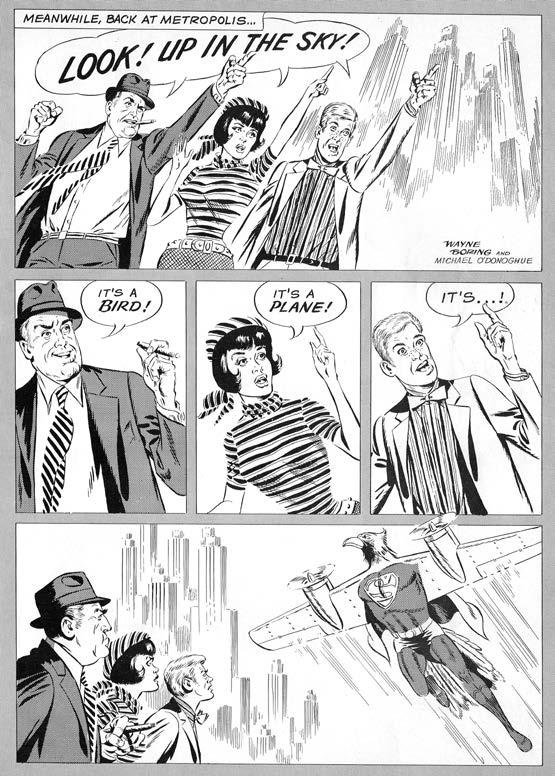

“…It’s BirdPlaneSuperman!”

Appearing in the June 1971 issue of National Lampoon, this spoof was perhaps the first time since exiting “Superman” that Wayne Boring had been paid to illustrate his erstwhile friends. [© National Lampoon or successors in interest; Superman TM & © DC Comics.]

The Secret Origin Of Secret Origins #1

The Ordway-Boring cover of Secret Origins #1 (April 1986). Writer/editor Roy Thomas got Wayne B. to pencil a figure of the Golden Age Superman in action, à la 1938’s Action Comics #1… then Jerry Ordway both inked that image, and drew several super-heroes watching, in an homage to the cover of All-Star Comics #8 (Dec. 1941-Jan. 1942). [TM & © DC Comics.]

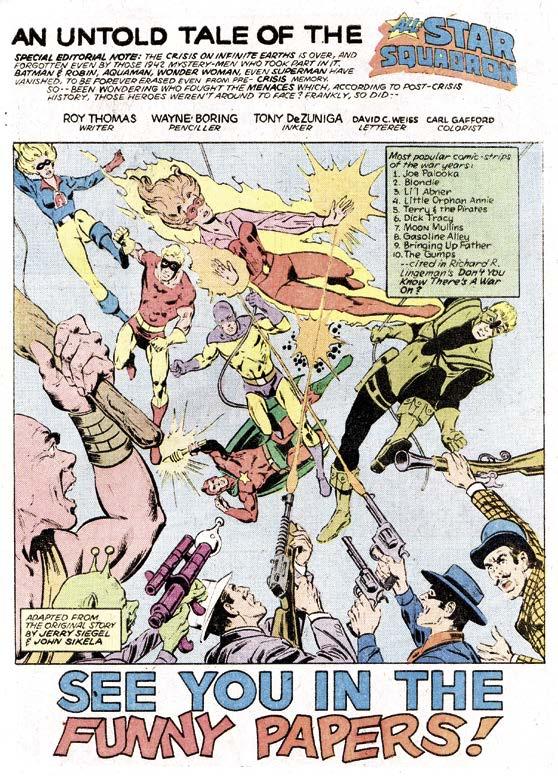

“See You In The Funny Papers!”

All-Star Squadron #64 (Dec. 1986) saw Boring penciling and Tony DeZuniga inking an “untold tale” of DC’s 1940s super-heroes battling newspaper comicstrip villains brought to life by a baddie called Funny-Face. It basically retold a story from Superman #19 (Nov.-Dec. 1942), only with other masked crusaders taking the place of the Man of Tomorrow, since he, Batman, Wonder Woman, Green Arrow, and Aquaman had been rendered “retroactively non-existent” by the events in the 1985-86 limited series Crisis on Infinite Earths. Script by Roy Thomas. Thanks to John Joshua. [TM & © DC Comics.]

a fatal heart attack in 1987.

A final CBG ad was posted in the 1990s to sell Boring’s remaining Superman dailies. The vendor this time was the late artist’s wife. Pop culture writer Sam Maronie bought a couple of originals and made a friend, as he and Lois became “sort of pen-pals.” In his book Tripping through Pop Culture, Sam described Lois Boring as “a feisty old gal in her 80s, very opinionated and full of energy. She was a real firecracker.” After flying to Florida to attend one of the annual Orlando Cons, Maronie made a side trip to take Mrs. Boring to dinner. He rejoiced when she pulled an item from a condo closet and, without quibbling, Sam paid Wayne’s widow more than he should have for a large Superman portrait in oil on Masonite. A key selling point was that it was the final painting completed by her husband before his death. Maronie wrote that he would not let the airline attendants touch the art on the flight home; nor would he place it in the overhead bin. Protecting the bulky thing with guarded grasp, Sam concluded: “I felt much like Lucille Ball in the I Love Lucy episode when she dressed the giant round of cheese like a baby so she could smuggle it on board the airplane from Europe.”118

Honors

To celebrate DC Comics’ 50th anniversary in 1985, Mr. Boring was acclaimed in a one-shot comic book titled Fifty Who Made DC Great. In 2007, twenty years after his death, the artist was elected to the Will Eisner Hall of Fame at Comic-Con International. If there is a comicbook Valhalla for deceased Superman contributors, the pantheon is perhaps even now seated at a banquet table while imbibing flagons of wine. And, having long ago made their peace, one can visualize Wayne Boring chuckling at Mort Weisinger while rubbing in the fact that (with a shard of poetic justice) Mort received the same accolade three years after Wayne did, in 2010.

The Art Team Of Boring & Kaye

Having died in 1967 and thus gone long before him, Mr. Boring never forgot his chief embellisher. After attending Miami Con III on May 2, 1980, Wayne wrote to Charlie Roberts: “Interesting aside—a kid asked me to sign 10 Actions in mint condition, of date ’56. I was astounded at the quality of Stan Kaye’s finishes. Stan was working for Dean Cornwell at that time, for nothing, on Cornwell’s murals, as mentioned in that wonderful book you sent me, 50 Illustrators. The kid with the Actions was highly incensed at my offer to buy him out! They were not for sale at any price, he said.”

Dave Sim referred to a 1950 newspaper article in which Boring said that he never read more than a panel ahead when illustrating a “Superman” tale: “To read the script over and then draw it, knowing the answer, would spoil it for me and make it seem too much like work.” In addition, Sim got the artist to update his thoughts on the man who made his workload seem lighter: “I draw off the cuff, penciling twenty pages per week. I did a Sunday and daily ‘Superman’ per week and twelve pages for the Superman magazine per month. Plus, I did a ten-page Action story per month, pencils only. Stan Kaye inked and made me look really good.”107

Under Boring’s entry on the “Eisner Awards” link, the

“My Baby Wrote Me A (Scarlet) Letter!”

Wayne Boring’s pencils harmonized with the primitive theme of Nathaniel Hawthorne’s classic The Scarlet Letter in these panels from pages of a neverpublished adaptation done in 1975. [© Estate of Wayne Boring.]

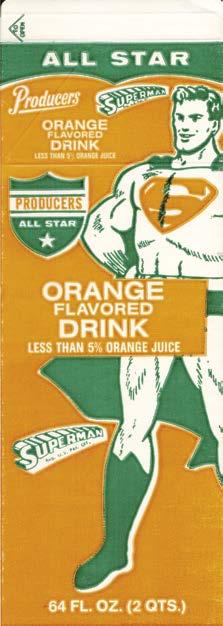

Three—Though Not In 3-D

Permutations of a classic Superman drawing by Wayne Boring—from a pinup (above left) through a flopped/reversed ad for an orange drink to the cover of Three-Dimension Superman (1953). Though the latter version has been slightly retouched and is often credited to Curt Swan, Eddy Zeno feels it is actually lifted from the cover of Superman #53, the 1948 tenth-anniversary issue. Inking quite possibly by Stan Kaye.

A statement Boring made brings clarity to the confusion: “Yes, I did the [Superman #53] cover. It bears little resemblance to my original, though, because it has been worked over by editors who think they can draw and by the kids in the bullpen.” (From a circa-1973 article by Dave Sim.) [TM & © DC Comics.]

only other name mentioned is Kaye’s, cited as his long-time embellisher.119 Perhaps Wayne would have received the honors he did without Stan’s accompaniment, but that is not a certainty.

Pencilers, Inkers, & Company Mandates

Going back more than 70 years, near the end of Superman’s first decade, any semblance of loyalty to Kal-El’s co-creators was in tatters. Those in charge asked Stan Kaye and George Roussos to provide pen and brush to several artists’ graphite, both mainstays and those who were newly assigned. Attempting to provide an evenness to the artwork, Stan’s—and for a while George’s— panache and consistency supplied a house look the editors preferred.

As the lawsuit with Jerry and Joe was concluding, frayed ties became severed. The editors’ next step, like what had been done earlier on the newspaper strip, was to embolden Superman’s appearance in comicbooks. They replaced those with a cartoonier bent like Pete Riss, Ira Yarbrough, and Sam Citron with sleeker pencilers: guys like Win Mortimer, Wayne Boring, Al Plastino, and eventually Curt Swan. Certain stories with fully finished art, including a couple by Riss, were discarded and redrawn for publication by Boring. With his Superman inking assignments dwindling, George Roussos found work elsewhere. Stan Kaye still

had plenty to do as Wayne Boring’s complement (and before long as Curt Swan’s inker, too). He chose to stay.

The Ink on Superman’s Face

With the end of Shuster’s reign, it was up to Stan Kaye to maintain consistency in the Man of Steel’s visage. Not that hard when inking a Superman face penciled by Pete Riss or Win Mortimer. Even when asked to embellish the offbeat, hard-todomesticate pencils of Ira Yarbrough, Kal-El might sport a “Stan Kaye face” now and then.

Like Yarbrough, what Wayne Boring laid down on Bristol board shone through, bravura too robust to obliterate. At least that was almost always the case. Bob Rozakis wrote that Stan Kaye’s inking overpowered Boring’s essential style on his covers but not his inside stories. Indeed, on rare occasions, Wayne’s Superman was misidentified as being drawn by Curt Swan when the figure was transposed from a cover to adorn a souvenir card, commercial product, or advertisement.

Commonalities when Stan Kaye gentrified Superman’s face included narrowing the width, downsizing the nose, and taking some jut out of the chin. Since Stan did not usually do this, and since the editors were most concerned with the covers and how to generate increased sales, it may have been under their instructions. Not just Stan but other bullpen artists and staffers may have sometimes done the deed.107

Wayne was most appreciative for what his two-decades embellisher normally did with his pencils, but he said he did not care for those instances when there was deviation from his intent.

Buoyant Inks & Pencils With Verve

Some who harbor mind images of Wayne Boring’s grand poses might agree; his super-hero templates needed counterbalance.

(Top:) Powell’s “Mr. Mystic” splash from Eisner’s Spirit Section #143 (Feb. 14, 1943) from The Star-Ledger (Bottom:) Mr. Mystic’s cast from the Star-Ledger’s Spirit Section #40 (Feb. 3, 1941). [TM & © Estate of Will Eisner.]

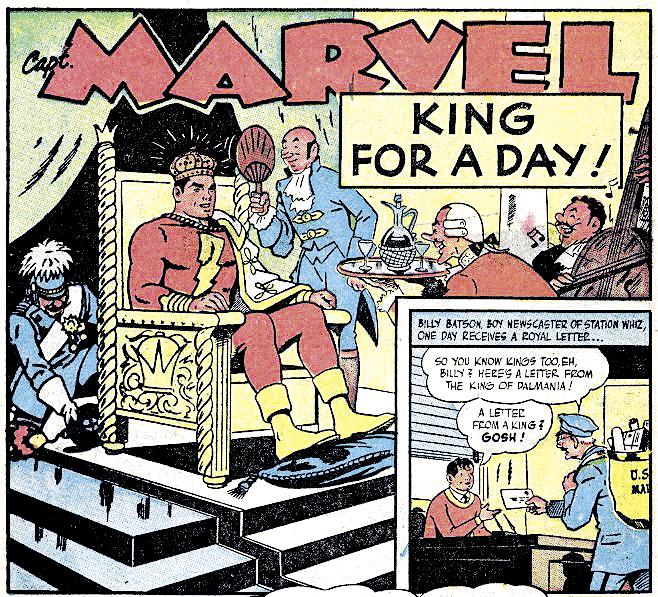

Captain Marvel & The One-Shot Villains The Top One-&-Done Wrongdoers Of The World’s Mightiest Mortal –Part I

by Carl Lani'Keha Shinyama

INTRODUCTION

For many of us, the true end of the Golden Age of Comics came in 1953—the year that Fawcett Publications shut down their comicbook division, following a long-drawn legal saga with National Comics Publications that resulted in Fawcett agreeing to never again publish Captain Marvel and all related characters.

Captain Marvel was the preeminent and greatest super-hero of the Golden Age, with a staggering 892 appearances on his résumé across all titles; when Fawcett put the “Big Red Cheese” on ice, it marked the true end of the era.

Of course, many comics pundits may dispute my claim about Captain Marvel as the king of the Golden Age, because it was Superman who godfathered the era. In truth, the original Golden Age version of Superman—who, for all intents and purposes, was wildly successful during that era—could not hold a candle to Captain Marvel’s popularity and demand for stories. Indeed, by the end of 1953, Superman was a distant second with 541 of his own appearances, also across all of his titles. This wide disparity between Captain Marvel and Superman was a testament to the commercial triumph that was the World’s Mightiest Mortal.

Superman, along with the original Golden Age Batman, were more or less in a class all their own (exceeded only by Captain Marvel, of course). Indeed, in those days, Batman was the only leading super-hero besides Superman and Captain Marvel to have over 500 appearances, with 540 of his own across all titles by the end of 1953. No other franchise-leading super-hero had more than 300 appearances. For that matter, very few—like Green Arrow (206) and The Flash (254)—had more than 200.

Much in the same way that Captain Marvel’s virtual ubiquity on the comicbook newsstands put him over his competition, Dr. Sivana, the World’s Wickedest Scientist, was the undisputed preeminent Golden Age super-villain, with a prodigious 149 appearances to his name.

That number is astounding; even the Golden Age Lex Luthor and The Joker could do no better than 37 and 62 appearances,

respectively. So far and ahead of his peers was Dr. Sivana that no other recurring arch-nemesis did half of his numbers, a claim that not even Captain Marvel could make.

Even against Captain Marvel’s own rogues gallery, Dr. Sivana far surpassed any of the other recurring villains in the stable. Mr. Mind is in second place with 25 Golden Age appearances, thanks to the sprawling 25-issue epic, “The Monster Society of Evil” (although the worm was no more than a mysterious disembodied voice in the serial’s first several chapters). No other Captain Marvel villain had more than twelve appearances, a number owned by the ancient subhuman, King Kull. All of Captain Marvel’s villains had their number of appearances no greater than a single digit. Mister Atom and Ibac had only three and five, respectively.

(Captain Nazi is not included in my examination because— even though he began as a Bulletman and Captain Marvel villain, and even though he had 23 appearances in the Golden Age—he ultimately became a Captain Marvel Jr. villain with all but two of his appearances in the pages of Junior’s own stories.)

Dr. Sivana’s numbers may be arguably more impressive than Captain Marvel’s because super-heroes, by default, are intended to be recurring characters and featured in all of their stories. Meanwhile, super-villains, owing to the variety of adventures that super-heroes are meant to have, are far more likely to be intended as one-offs, shuffled in a never-ending merry-go-round of alternating miscreants.

True, Dr. Sivana was always intended to be Captain Marvel’s foremost opponent, which necessitated that he be a recurring villain, so he had a built-in advantage against most of his peers. However, Sivana’s longevity and appearances were never fully guaranteed. C.C. Beck once stated that Fawcett eventually wanted to get rid of Dr. Sivana:

“The publisher also once wanted to drop Sivana, claiming the old rascal was becoming a more interesting character than Captain Marvel. The editors paid no attention to so silly an order and kept him alive and cackling.”

Actually, He Was Circulation King For Several Years! Captain Marvel, King of the Golden Age! Splash from Whiz Comics #75 (June 1946) by Otto Binder, C. C. Beck and Pete Costanza. [Shazam hero TM & © DC Comics.]

The Clockwise Kings Of Anti-Captain Marvel Villainy Captain Marvel faces Dr. Sivana for the first time, in Whiz Comics #2 (Feb. 1940), actually the first issue of Fawcett’s flagship comicbook title (script by Bill Parker, art by C.C. Beck)—

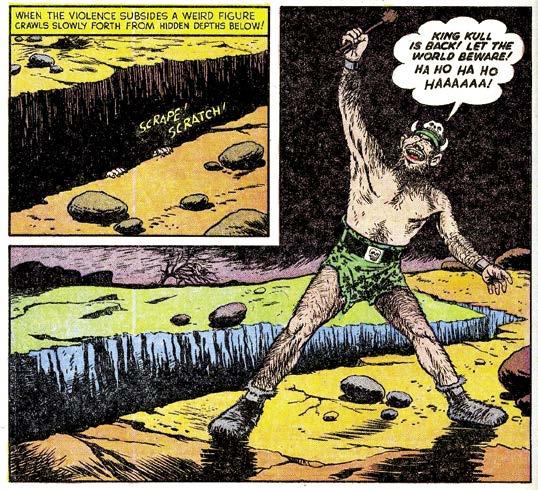

Mr. Mind and his Monster Society of Evil menaced the World’s Mightiest Mortal for 25 straight issues, including Captain Marvel Adventures #35 (May ’44), with script by Otto Binder and art by Beck & staff— —and, in the final few years of Cap’s Fawcett run, the subterranean superbaddie King Kull popped up in an impressive dozen stories. Here’s a panel from his first appearance—“The Return of the Ancient Villain”—CMA #125 (Oct. 1951) by Binder, Beck, & Pete Costanza. [Shazam hero, Dr. Sivana, Mr. Mind, & King Kull villain TM & © DC Comics.]

IF YOU ENJOYED THIS PREVIEW, CLICK THE LINK TO ORDER THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR

Sivana’s remarkable appeal happily kept him appearing regularly in Cap’s four-colored pages, yet one mathematical fact remains: 149 is far less than 892. That meant the Doctor did not appear in 743 of Captain Marvel’s own adventures, which, conversely meant that, by the end of 1953, Captain Marvel had a vast line-up of numerous one-and-done villains that never got to see life past their own story.

ALTER EGO #196

Concluding our presentation of EDDY ZENO’s book on the early SUPERMAN artists from ALTER EGO #193—with a focus on style-setting WAYNE BORING and classic cover illustrator WINSLOW MORTIMER! Featuring a fabulous, previously unprinted cover by BORING! Also: FCA (Fawcett Collectors of America), MICHAEL T. GILBERT in Mr. Monster’s Comic Crypt, and more! Edited by ROY THOMAS

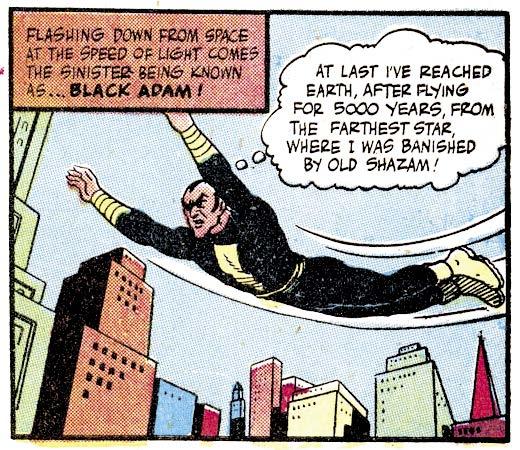

Of course, a small handful of the Fawcett one-shot villains were resurrected after DC Comics revived Captain Marvel and the rest of his Fawcett compeers in 1972. The most prominent of these was Black Adam, whose only Golden Age appearance had been in The Marvel Family #1, where he returned to Earth after being banished to the farthest star in the universe for 5,000 years to do battle against the Marvel Family—which ultimately led to his death. I chose not to include such a renowned one-and-done villain in favor of more abstruse candidates that were equally deserving of more than their single appearance.

In the task of paring the list down to ten, I also wanted to avoid overly-gimmicky characters who can only be dealt with in one type

But, Boy, Has He Made Up For It Since 1972! Black Adam—the foremost one-and-done Fawcett villain. Panel from The Marvel Family #1 (Dec. 1945): “The Mighty Marvels Join Forces” by Binder, Beck, & Pete Costanza. [Black Adam TM & © DC Comics.]