Marshall Rogers BrightestDaysandDarkestKnights

by Jeff Messer and Dewey Cassell

A SISTER REMEMBERS

Suzanne (Rogers) Schmachtenberger Interview

Conducted

2019 by Dewey Cassell

Transcribed by Steven Tice

DEWEY CASSELL: Are you younger or older than Marshall?

SUZANNE SCHMACHTENBERGER: I’m six years younger than Marshall.

CASSELL: So, my understanding is that Marshall was born in Queens. Is that right?

SUZANNE: Yes. I was born in Dobbs Ferry. In 1952 my parents moved to Ardsley, New York, so Marshall would have been two. I was yet to be born. And Ardsley and Dobbs Ferry are adjacent towns.

CASSELL: Tell me a little bit about your parents. I assume your father was William Marshall Rogers, Jr.?

SUZANNE: Correct. My mom was Ann Palmer-White.

CASSELL: What did your dad do for a living?

SUZANNE: My dad was a mechanical engineer, graduated from Pratt. He was from Paducah, Kentucky. And he worked for Johns Manville. That’s a mechanical engineer.

CASSELL: Did he do that all of his life?

SUZANNE: He did.

CASSELL: That’s unheard of these days.

SUZANNE: Well, he died young. My dad died, just like Marshall, of catastrophic heart failure. My dad was 57 when he passed away.

CASSELL: And what about your mother?

SUZANNE: My mom did not work outside of the home in the traditional sense. She was a “stay-at-home mom,” and I put that in quotes. My mother was a fabulous seamstress and sewed everything for everybody in the house, forever. And she did alterations in the house for a select clientele. She did that forever. We moved to Colorado in 1971. Right before we moved

to Colorado, she got a job, a part-time little something at Stretch & Sew, which was a big deal way back in the Seventies. She taught classes: how to sew and stretch. And so, when we moved here to Colorado, she did that for a little bit, until my dad died. My dad died 18 months after we moved here. We left home, came out to Colorado, and I’m going to say this tongue-in-cheek: where there were no shoe stores, and no good Jewish delis, and no friends, and then he died.

CASSELL: But you all stayed.

SUZANNE: Well, we did. We’d been here 18 months. By then I was a junior in high school. And if we moved back to New York, my mother said we couldn’t move back to Ardsley. I’m like, “Well, then why would I move?” I was 17, and in my own sad world, I didn’t think about how much my mother would have loved to have been back in New York. My mother grew up in Queens. So we stayed here. When we moved here, my parents and I, Marshall chose not to move with us. He was 21 when we moved.

I’ll tell you something about my parents: I had this mother who was a fabulous seamstress. I’m not exaggerating when I say that. She could look at anything and make it beautifully. Until she passed away, when I was 51, I never bought a winter coat, because she made them, and they were gorgeous. So that’s my mom—one of her many

CHAPTER 1

Marshall and his sister Suzanne, Christmas circa 1983. (courtesy of Suzanne Schmachtenberger)

talents and skills. My dad was an engineer by day, and a fabulous wood craftsman/carpenter by night. So he had his wood shop, and my mom had her sewing room, and they made all sorts of things.

CASSELL: What kind of things did your dad make?

SUZANNE: Well, we lived in an 1100 square foot house, and he put an 1100 square foot addition on our house, and then he did all the cabinetry inside the house. Do you remember FAO Schwarz? They had a bear house that I really wanted when I was very little, and he copied it for me. It looks like a tree stump, with a roof that comes off, with built-in bunk beds; it has a little fireplace, a little kitchen area, and it looked just like it came from FAO Schwarz; and I know that it didn’t, because I went to the basement unannounced and saw him making it. I was pretty sure there was no Santa, but that’s what solidified it. So Marshall and I grew up in a very normal house with two very talented parents.

CASSELL: So six years apart, did you play much together as kids?

SUZANNE: You know, semi. Marshall was always, always a really sweet person, at least always from my perspective, and he was a sweet big brother. As far as he could be inclusive of a little pain-in-the-neck, six-years-younger sister, he was always sweet about me tagging along, or telling me no, no way, go away. But, for the most part, he was just always very sweet to me, and inclusive in whatever he could be inclusive in. Not everything, certainly. But in the neighborhood we grew up in, there was a group of kids. His friends were all about the same age, plus or minus two years, and then there was the next wave of kids; we were the younger siblings

of all those kids. So we were all friends, a small group of friends, and then Marshall and his friends were all friends. And they would let us come play, like, football with them. That’s probably it. We just played football with them, and we did that a lot. Our yard and our neighbor’s yard was just perfect for a football field. He’s six years older than me, so there’s things that I never did with him, obviously. He went away to boarding school his junior year. He repeated his junior year. His grades weren’t as good as my parents thought they should be, and they thought that he should grow up to have a nineto-five type job. So he went away to Blair Academy, and I think that was ’68 to ’69. So when he came back, he and I ended up going to the same high school. The school district we were in was building a new middle school, junior high. I don’t remember what they were going to call it. So our school was seventh grade through twelfth grade. So he was a senior that year that I was a seventh grader. He drove me to school every morning in his Triumph TR3. He played football and he was good at football, so all the girls thought he was cute, and they were just delighted that he drove this TR3, and he would drop me off at the young kids section, the seventh and eighth grade wing, and there would be just a bevy of girls sitting in the window waiting to see Marshall in his TR3. And then he would drive past the school and go pick up his girlfriend, and then come back. But he was very popular. He was popular enough that I could sell his photographs, and I sold some of his socks to girls.

CASSELL: Oh, you’re kidding! SUZANNE: I am not.

CASSELL: I didn’t know he was an athlete. That’s interesting. SUZANNE: He was. And he was a wrestler. He was very good at wrestling. He would use me as a dummy. I don’t think I learned any wrestling moves. He was very good at pinning me.

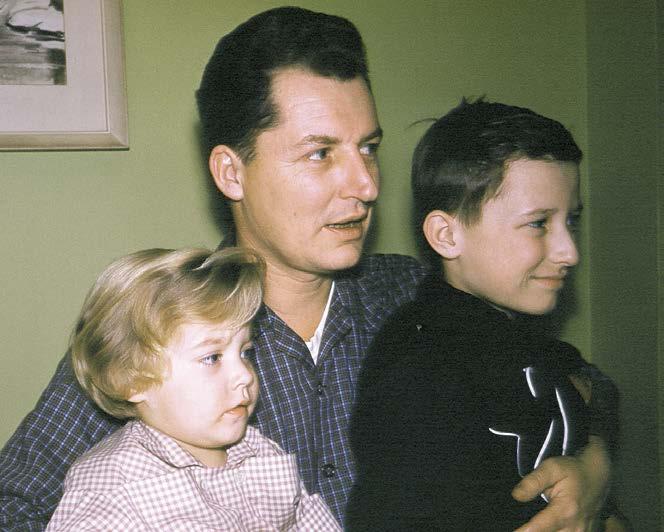

Suzanne and Marshall with their father. (courtesy of Suzanne Schmachtenberger)

Marshall played football at Ardsley High School. (courtesy of Suzanne Schmachtenberger)

CHAPTER 2

INDEPENDENT SPIRIT Arvell Jones, comic book artist

“I met Marshall in the early ’70s when I, Tom Orzechowski, my brother Desmond, Joe Wesson, Greg Theakston, Mike Kurcharski, and Richard Buckler worked on our fanzine Fan Informer. I really don’t remember much about our encounters (we were all pretty busy trying to break in to comics).

“He produced a couple of spot illustrations and a cover for the fanzine. I know he was passionate about getting into the field and he was a huge Batman fan.

“I remember him letting me know he was going to get to draw my co-creation of Misty Knight and he was excited to get my reaction. I was proud that he made it into the industry and I was alway excited to see his work.

“He was in some ways one of the most creative with design and style of any of us midwestern artists, which included Jim Starlin, Al Milgrom, Mike Vosburg, Keith Pollard, Terry Austin, Greg Potter, Sam De La Rosa, Aubrey Bradford, Mike Nasser (Netzer), Ken Stacey, and Don Vaughn. We were all very

happy with any of us getting an assignment and starting a career in the business.”

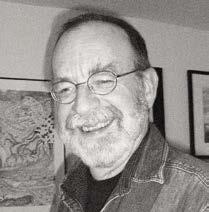

Michael Netzer Remembers the Early Days

Interview conducted by Jeff Messer

JEFF MESSER: When, where, and how did you first meet Marshall?

MICHAEL NETZER: I had been at Neal Adams’ Continuity studio for about three months when Marshall first visited the studio and liked it enough to ask about renting table space for drawing comics. I was also drawing the Batman/Kobra issue [DC Special Series #1 (1977)] when we first met. I had a table in the large back area that sci-fi artist Mike Hinge maintained and worked from. Neal had plans for one more room to be partitioned from the large space. So the next thing I knew, Marshall and I were sharing a newly constructed room tailor-made for us, with two tables and cabinets—and a nice black leather two-

Michael Netzer

seater that was tucked away in a corner of the back room. Being next to Larry Hama and Cary Bates’ rooms, a second hub of comics activity was growing in the back area of the studio.

Elite Avni-Sharon / Wikimedia Commons.

© Michael Netzer

Marshall was a tall and jolly fellow, while I was a lesser 5’-3” height—and he was about six years older than I (a quintessential expression of an odd couple). It was a different time and world back then—still alright to smoke cigarettes in the front room, but that was also about the time, early 1976, that more and more people began complaining about it. Marshall and I declared our room a smoking area. We hardly worked on a page without first rolling a joint on it. We worked together for a total of about three years.

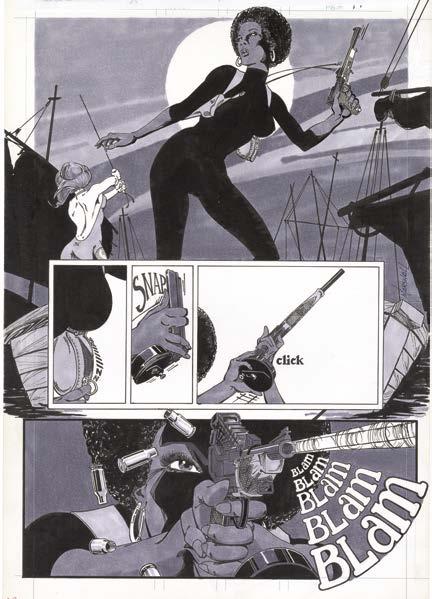

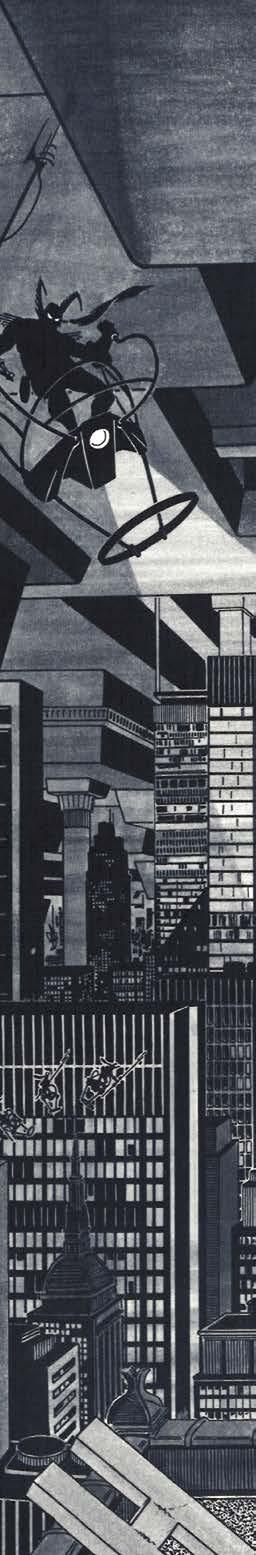

The Daughters of the Dragon in action from Deadly Hands of Kung Fu #32, 1977.

Arvell Jones Tenebrae

MESSER: What was it like in those early days, working to succeed in comics?

NETZER: One of the more intense life challenges has been to evolve from a would-be, to a good enough comics artist. Marshall seemed to feel the same way. We both worked our brains and arms off, spending between 12–16 hours daily on the board. We were very lucky to work closely back then, in a studio like Neal’s, which helped and energized the entire experience. We thirsted for criticism of our work, especially from the many seasoned pros whose advice could help improve the art in ways that we didn’t think of. The difference between our work was always a subject of discussion between us, and we had no problem criticizing each other.

Long before computers and the internet, reference photos were hard to come by. We basically had to dig through magazines or go out and buy them for reference. There were no shortcuts available, and if either one of us could finish a page in one day, we considered it a worthwhile achievement. It still boggles the mind that a beginning artist who had to work much harder to come up to speed, was making less money per hour than the guy sweeping the floor at McDonalds—in an industry that makes billions from the raw stories that creators produce for pennies.

The rest of the studio; the communal working environment; the proximity to top comics creators and projects in production, all made those first few years very significant for our ability to continue improving. A lot of hard work and a lot of comraderie defined those early days for the gang of grown-ups playing with kid toys that we were.

MESSER: What was Marshall like when you first met and were hanging out together?

NETZER: We were worlds apart in our life experience and approach to comics art, but we both influenced each other in very subtle ways. We hung out together by the force of group gravity. Marshall quickly became best friends with Chris Goldberg, a fan and later professional writer with whom I shared an apartment and who

frequented the studio. For the most part, I was actually the odd one out, trying to absorb the zany comics talk like a deer in the headlights. The bottom line was that the endless hours working together seemed to override anything else that differentiated between us. There was a wonderful and inspiring chemistry there. We were very involved in each other’s work because our approach was so different—and I believe we both appreciated the other’s influence.

Marshall was always pleasant to be with. I can hardly remember ever seeing him upset or despondent. He liked to talk about the essential storytelling element of our work—he preferred mood and design over the wave of semi-realism that swept the comics through the Adams era. More than any other artist I knew, he seemed to have a lot of courage to take this direction, mostly against the then-current tides that I myself was immersed in.

MESSER: When he got his break and did the art for Detective Comics with Terry Austin inking, they both suffered a backlash from Joe Orlando and DC editorial, who savaged the artwork. Were you privy to Marshall’s feelings about how he was being treated by editorial? And after the comics were a huge success, how did that change things for Marshall?

NETZER: Marshall was upset and apprehensive at first. Who wouldn’t be in that situation where your newly chosen vocation in life hangs in the balance? But we were able to talk it through and minimize the significance of editorial opinion so early on in the game. I had one such experience with an editor over a Princess Projectra back-up in a “Legion of Super Heroes” story, that had too many full-page splashes (I thought it worked and the editor finally agreed it was better to go with it than change it). The only thing Marshall could do was persevere and hope that more and more editors would recognize the appeal of the Batmanesque mood that he’d injected into the character. Once the tides changed, and Marshall’s star began to rise, he became far more secure in his approach to the work—and much less apologetic for the new look he brought to a favorite superhero icon.

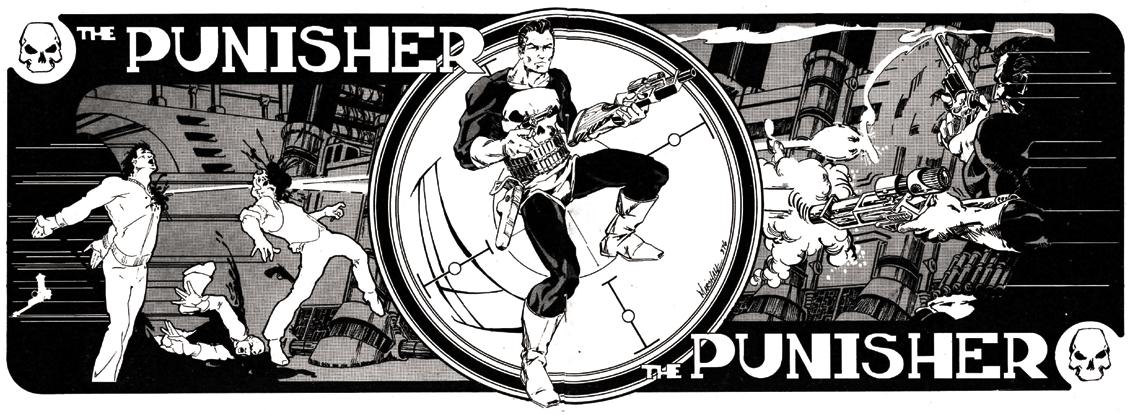

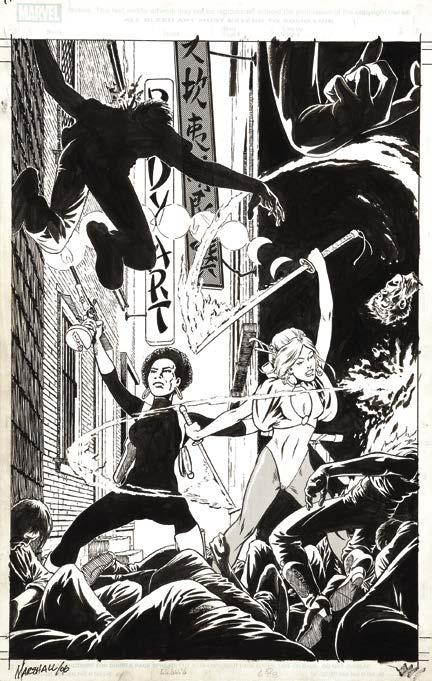

Punisher centerspread art by Rogers from Marvel UK’s Super Spider-Man #180, 1976. (courtesy Jason Schachter)

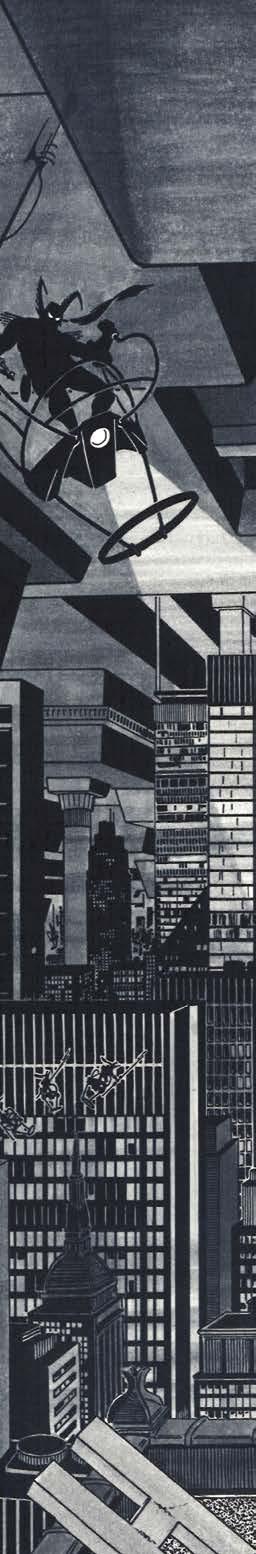

COYOTE

Rogers drew Steve Englehart’s newest creation for Eclipse. This was several years after they teamed up on Detective Comics, and followed a few smaller projects for Eclipse (Scorpio Rose and Cap’n Quick & a Foozle). In the rise of creator-owned comics, Eclipse was offering creator-ownership, and attracting some top talent, like Don McGregor, reprinting his Detectives Inc. collaboration with Rogers.

Rogers must have felt comfortable with the promise of ownership, as well as the creative freedom, which allowed for more adult themes, nudity, and an interracial relationship, which was, at the time, somewhat controversial.

Englehart’s Coyote was part superhero, part mystical character: a young Native American man who grew up in the desert outside of Las Vegas, and was imbued with magical powers that allowed him to shapeshift and teleport.

Coyote appeared serialized in Eclipse magazine, which was the fledgling company’s

attempt at their own sort of Heavy Metal or a classic Warren black-&-white magazine of the 1970s.

The series ran from issue #2 (published in 1981) through #8 (published in 1983), and was later collected as a graphic novel in January 1984, this time colored.

Englehart took the property to Marvel’s Epic line soon after, with new artist Steve Leialoha taking over art chores from Rogers on the first two issues, followed by a single issue by Jackson “Butch” Guice, and the rest of the run by Chris Truog. Issue #11 features a back-up story, with first time comics artist Todd McFarlane making his comics debut.

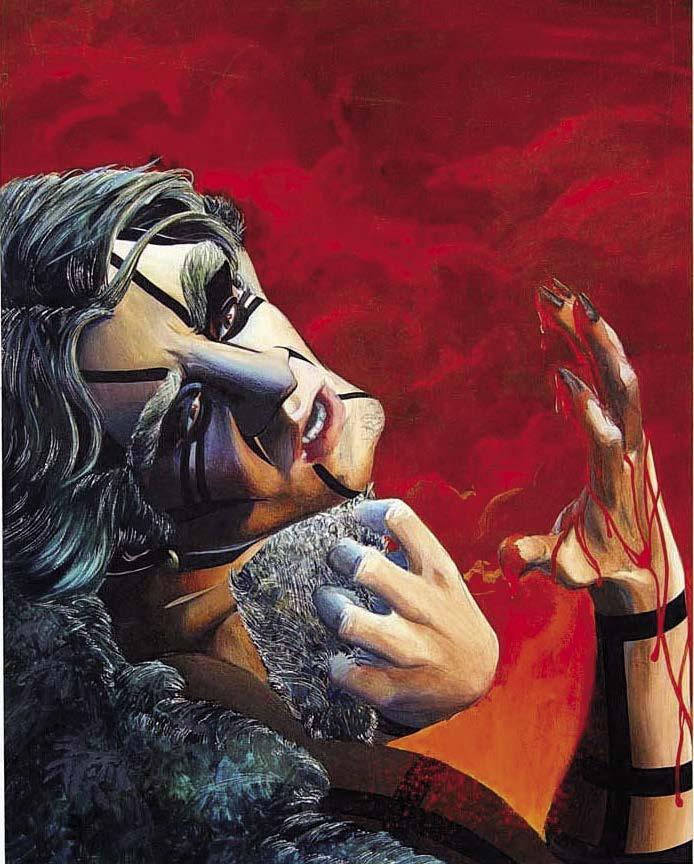

(Above) Coyote painting for the cover of Eclipse Magazine #8. (Left) Coyote splash page. (courtesy of Phillip Hester)

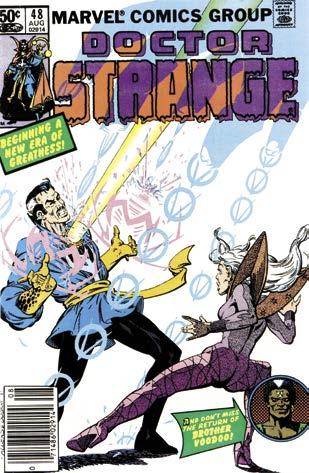

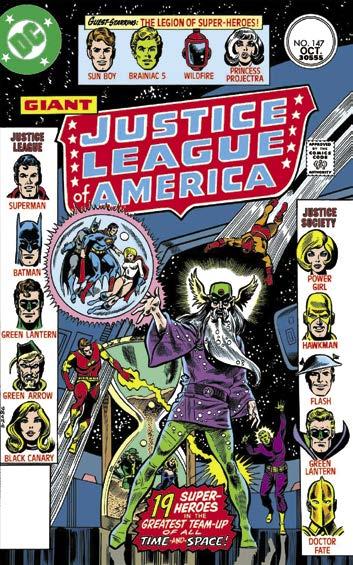

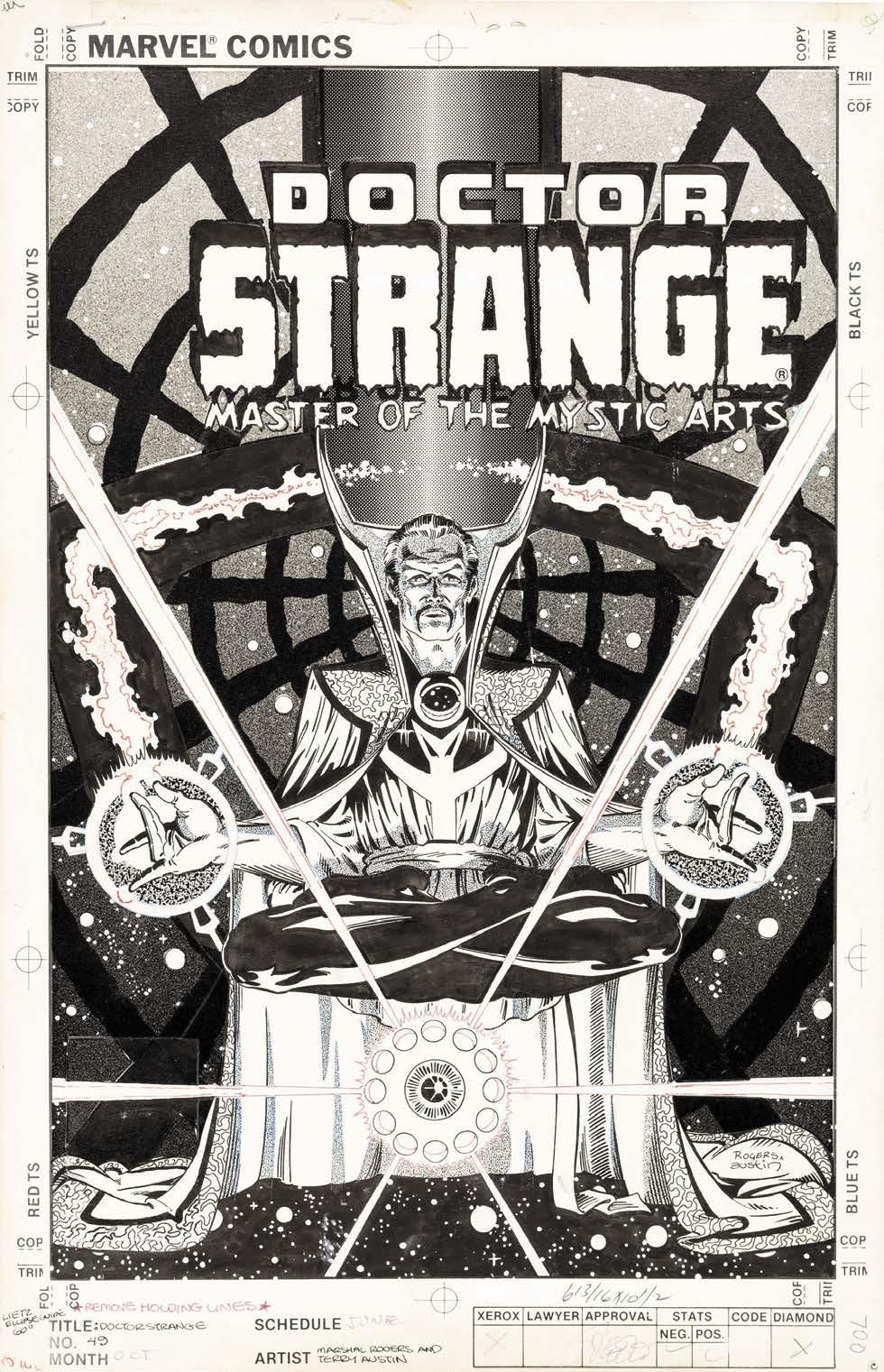

PUBLISHER: Marvel Comics

TIME PERIOD: 1981–1982

BOOK/COMIC TITLE and ISSUE NUMBER(s):

Doctor Strange: Master of the Mystic Arts #s 48–53

Marvel Fanfare #5

FORMAT: Comic book

OVERVIEW: Doctor Stephen Strange is a gifted but arrogant surgeon who has a car accident that costs him the use of his hands. Searching for a cure for his infirmity, Strange encounters the Ancient One. From a world defined by the practical application of skills and tools, he is thrust into a world filled with the abstract and fantastical, like it was taken straight from a dream—or a nightmare.

Created in 1963 by Steve Ditko, Doctor Strange first appeared in the pages of the split-book Strange Tales #110, alongside first the Human Torch and later Nick Fury, Agent of SHIELD. The book was rebranded Doctor Strange as a solo title with issue #169 and continued through the last issue, #183. The character then appeared in Marvel Feature and Marvel Premiere before Doctor Strange: Master of the Mystic Arts was launched in 1974.

KEY CHARACTERS:

Clea – Strange’s love interest and disciple in the mystic arts. Wong – manservant and confidant of Doctor Strange.

Baron Mordo – Strange’s oldest enemy, a former student of the Ancient One who turned to evil.

Nightmare – Recurring adversary of Doctor Strange who can invade and manipulate our sleeping thoughts.

SETTING(s): New York City, the Sanctum Sanctorum of Doctor Strange, various historical venues, and the supernatural world.

SYNOPSIS of KEY ISSUES:

Doctor Strange #49 – Doctor Strange defeats Baron Mordo by having his astral form inhabit the body of a cat.

Doctor Strange #51 – Features not only Dormammu and Adolf Hitler, but Nick Fury and the Howling Commandos.

Doctor Strange #53 – Having time traveled to the past, Doctor Strange (in his astral form) is witness to the first meeting of the Fantastic Four and Rama Tut. Meanwhile, Nightmare encounters a Gnit (or two) and Clea leaves.

Marvel Fanfare #5 – Clea saves Doctor Strange when he is attacked by the sorcerer Nicodemus. P. Craig Russell inked this issue, giving it a different feel than the Austin-inked stories.

BEST ISSUE: Rogers’ rendition of the Sorcerer Supreme on the cover of Doctor Strange #49 is a fan favorite and the battle with Baron Mordo is captivating, if brief, but the story in issue #53 has a wonderful blend of adventure, pathos, and humor in which Rogers excels.

MARSHALL ROGERS’ CONTRIBUTION: Although his tenure on the book was short, Rogers makes masterful use of different textures in his art and diverse page layouts, giving depth

TERRY AUSTIN

Terry Austin’s name as an inker frequently appeared next to Rogers’, most notably for their time together drawing Englehart’s Detective Comics scripts. And while few at DC seemed to be fans of those issues at the time, nor did they have faith in the art team, those comics would become some of the most iconic tales of Batman to ever be published.

Austin was gracious enough to agree to an interview about his relationship (creatively and personally) with Rogers. However, what started as a simple Q and A gave way to a vastly more entertaining and free-flowing series of essays of memories and misadventures. Austin wrote back in elegant, honest, and insightful essays.

Eighth Street and introduced me to one of the artists I most admired in comics!

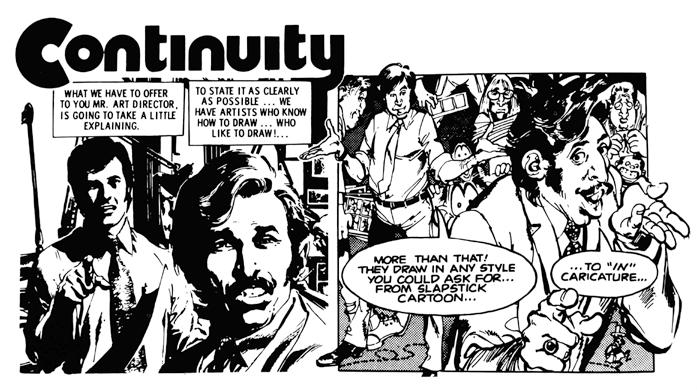

Neal glanced over my samples, cut me to ribbons in no uncertain terms, thrust a page of Bob Brown’s “Lilith” in my hands and said “Here’s a nice pen and here’s a nice brush and there’s a nice table—get to work!” That was how I joined the merry band of Crusty Bunkers at Continuity Associates.

It was instantly clear that Austin held Rogers in high regard—and that his essays should be included free of interviewer questions. Here’s Terry Austin’s tale:

FIRST PROFESSIONAL WORK, AND MEETING:

I had met Al Milgrom for maybe five minutes at a comic book convention in Detroit a year before I graduated from Wayne State University and moved to New York in order to try to get work in comics. Allen had looked at my work and said, “If you ever get out to New York, you should go up to Continuity and show your stuff to Neal Adams.”

So, I stumbled out of somebody’s office at Marvel a year later (having been thoroughly rejected once again) and Milgrom was standing there and, for some unfathomable reason, he remembered me and said, “Terry! Hey, did you ever go see Neal?” and he literally walked me down Madison Avenue to Forty

It was about a week later that I was sitting at that table, feeling my way along inking window sills and door frames on that “Lilith’’ job for one of Marvel’s black-&-white vampire magazines, that I learned Dick Giordano, Neal’s partner in Continuity Associates (which was actually a commercial art studio that used comic book artists to do commercial jobs for advertising agencies and such) was looking for someone to ink backgrounds for him on his comic book work.

Happily, I happened to be sitting closest to Neal when Dick asked him to suggest someone, and I became background inker/ assistant to one of the nicest, most knowledgeable guys in the business.

I absolutely loved inking backgrounds for good ol’ Dick on whatever he did for the next two or three years—stuff such as Bram Stoker’s Dracula, Stephanie Starr, Batman, the Elongated Man, Red Sonja, Thor and Conan. It was inking the backgrounds for Dick

CHAPTER 3

Terry Austin

From a promotional piece for Continuity Associates, featuring Neal Adams and Dick Giordano.

Immortalized on a billboard in Superman vs. The Amazing Spider-Man, inker Terry Austin makes a name for himself, 1976.

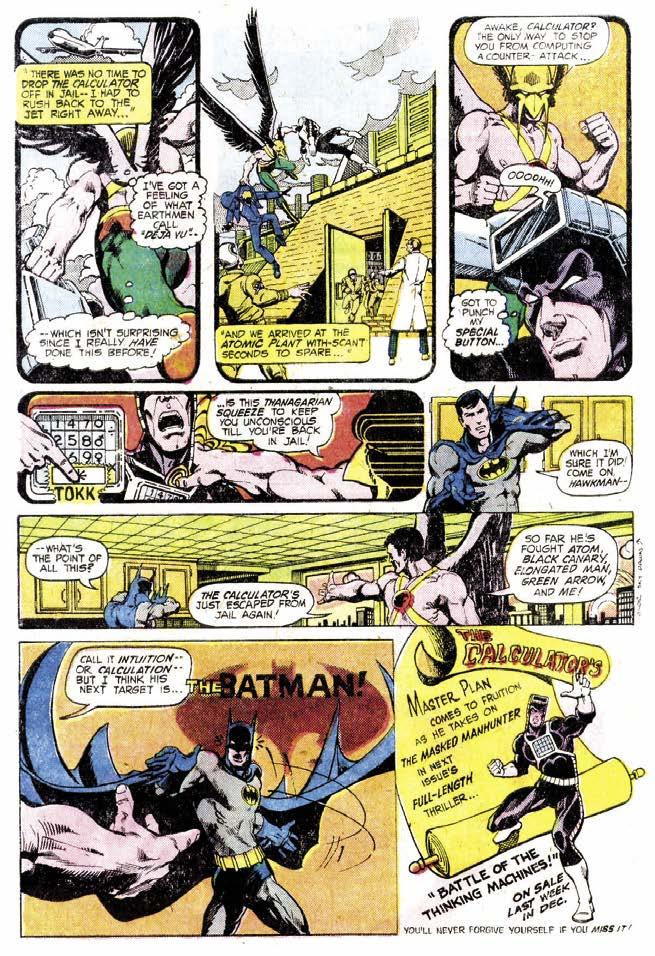

The first collaboration between Rogers and Austin: A Hawkman vs. the Calculator backup story in Detective Comics #467, 1977.

on the first DC/Marvel crossover project Superman Vs. The Amazing Spider-Man that brought me some added attention (completely unintended) as I had put my name in the backgrounds every couple of pages on a billboard advertising Austin Bread or some such, not realizing that everyone in the comic book industry would be reading that history-

making book and that they would be seeing the name Austin over and over, and pretty soon everyone would be asking, “Who the heck is this Austin guy who inked all of New York City in this comic book?”

With that job, and Dick’s taking on a couple of back-up jobs where he let me start inking figures and seeing to it that my name appeared in the credits, pretty soon some folks decided to give me a chance inking some of the back-up jobs at DC.

MR. AUSTIN GOES TO DC

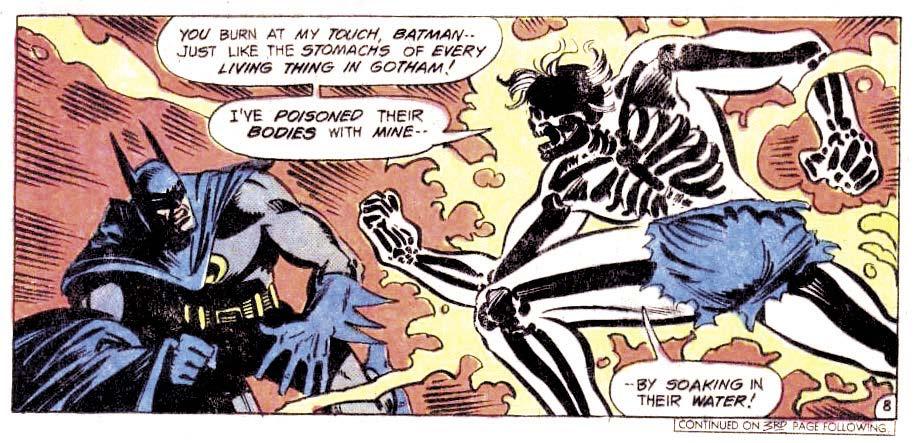

Julie Schwartz had assigned me the backup series in several issues of Detective Comics in which several DC characters who didn’t have their own titles each individually went up against a villain named The Calculator.

At the end of each chapter the hero would trounce The Calculator, and the bad guy would press a button on his vest which would somehow inoculate himself against being beaten by that hero again (ain’t comic book science wonderful?).

Written by Bob Rozakis, the first two chapters starring The Atom and Black Canary were penciled by Mike Grell. The third chapter featuring The Elongated Man was penciled by Ernie Chan.

Apparently I was working on that chapter when Marshall Rogers arrived in New York and, as everyone looking to enter the field of comic book art did in those days, made the pilgrimage to Continuity Associates to show their work to Neal. I found out later that Neal looked at Marshall’s work and said, “There’s a guy in the back who you ought to hook up with to ink your pencils.” All I knew at the time was that there was this new guy who came into my room, introduced himself, and seemed awfully interested in what I was working on.

Apparently he went up to DC (with an introduction from Neal) and told Julie Schwartz that he wanted to pencil The Calculator, having had the idea planted in his head by Neal that we could be a penciler/inker team.

In short order, Marshall was renting space in the back room at Continuity and penciling the next two chapters featuring Green Arrow and Hawkman slugging it out with The Calculator.

That would have been it for the nascent Rogers and Austin team, as the final chapter

of the saga of The Calculator was to be a book-length epic in which the villain smacked down the five heroes that had previously beaten him soundly (remember that handy inoculation) and went up against Batman himself, the star of Detective Comics, to be drawn by peerless professional Jim Aparo.

Marshall and I were told by the powersthat-be that Batman was too important a character to be trusted to a couple of bumbling amateurs, and we understood and prepared to move on.

In an unlikely occurrence that seemed to be right out of a 1940s movie where the star of the big Broadway show falls ill on opening night and the understudy goes on in their place and consequently become a Big Star, Jim Aparo got sick and at the last possible second, someone (Julie? Art Director Vinnie Colletta? Publisher Carmine Infantino?) decided to toss the all-important Batman job to the two new dumbells.

NOT EVERYONE WAS SOLD ON ROGERS AND AUSTIN ON BATMAN

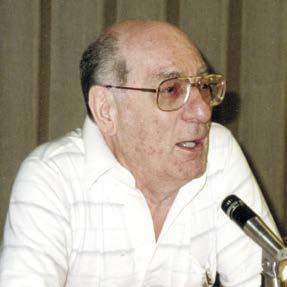

I do know who didn’t make that decision: Joe Orlando, who had some sort of position of power in the DC hierarchy, and who hated my work and Marshall’s individually—so team us up on a lead feature, and his hatred reached new levels of fury heretofore undreamed of by mortal men!

On the day that Marshall turned in his pencils on the Rozakis Batman job, we were both summoned to Joe’s office. We had both been subjected to Orlando’s screaming critiques of our meager efforts individually, but this tagteam event was a new event not to be looked forward to.

I always said in retrospect that I owed Marshall one for what happened that afternoon; for, after sitting in the hallway outside Joe’s office for a good 30 minutes listening to him scream at Marshall about what an idiot he was, and how his lack of talent would undoubtedly lead to the ruination of National Periodical Publications, and how he should feel personally responsible for all the men who would be fired and thrown into the street with their wives and children to starve thanks to the destruction of this classic character that could be laid directly at the door of his pitifully meager efforts—Marshall emerged, white-faced and clutching the

nearest wall for support, and it was my turn in the barrel. I say that I owed Marshall because I entered that office to find Joe spent from Marshall’s dressing-down. Soaking wet with sweat, beet-red and panting from his efforts to make a kid feel small, he had nothing left for me. I innocently asked, “What approach do you want me to take on the job?” and he panted, “It doesn’t matter—you can’t save this sh*t! Get the hell out of here!”

After that, we were told that we would never be allowed under any circumstances to touch Batman again, and we were next teamed on a two-part back-up for the low profile Jack Kirby-less Kamandi book on a story of the far-flung future where humanlooking bulldogs in business suits fought giant insects in a devastated London (which would eventually see print in Weird War Stories after Kamandi was canceled).

SO, WHAT DID JOE ORLANDO’S OPINION REALLY MATTER?

Some time later, I was in the DC offices when Paul Levitz approached me and said (in the charming fashion in which DC apparently

Joe Orlando at the DC offices in 1978.

(Photo by J. Michael Catron)

trained all their employees in order to keep the freelancers humble), “A bunch of people with no taste wrote in who liked your and Marshall’s Batman job, so we’re giving you Detective Comics.”

I ran back to Continuity and broke the happy/sad news to Marshall—happy because it was a kind of vindication that we were doing something different that people responded to, and sad because it meant we could look forward to more time in Joe Orlando’s office with his vitriolic spittle hitting us in the face.

OPPOSITES ATTRACT GREAT COLLABORATION

During the Continuity years, I can’t honestly say that Marshall and I were exactly friends. Our working hours usually didn’t overlap: I was a 9-to-5 type (with additional

hours of labor thrown in during the evening at home) while Marshall unleashed his muse during the overnight hours. He was part of the crowd who indulged in certain pharmaceuticals that you couldn’t find at your local apothecary; me, I’m such a square, I’ve never even tried coffee.

I don’t know how Marshall felt about it in those years, but I always felt (and hold onto your hats as a non-sports fan is going to attempt a sports metaphor) like the guys you were thrown together with on a project were teammates.

Oftentimes these were guys you never even met, as you were routinely separated by great distances, and long-distance phone calls in those days were prohibitively expensive, and thus rare. But I felt like we were all part of the same team, working toward the same goal—that of doing good work and producing good comics—and so if someone made a mistake or slacked off in one area, you were there to quietly compensate for whatever was lacking, and hopefully they would do the same for you should the occasion arise.

So, while Marshall and I weren’t geographically separated in those years, we didn’t socialize—didn’t ever share a meal or go out to a movie—but like strangers in time of war, we were bonded by our common struggle in the trenches as we fought to gain a foothold in the industry that we both loved.

It wasn’t until we reunited many years later for Batman: Dark Detective that I can confidently say that Marshall and I became close. With the maturity that comes with the passage of time and the culmination of life experiences, when we again came together with a common purpose, we talked, we truly collaborated, we shared, we commiserated, we laughed, we even toured together and thankfully, we finally became great friends! To have had that happen before Marshall passed away is a gift that I’m inordinately thankful for!

A CRACK AT THE BAT

The first two issues of the Batman story that Steve Englehart wrote full-script in its entirety before leaving the country were illustrated quite capably by Walter Simonson and Al Milgrom during the time that Marshall and I were in our DC-imposed exile from the character (years later, after several reprintings

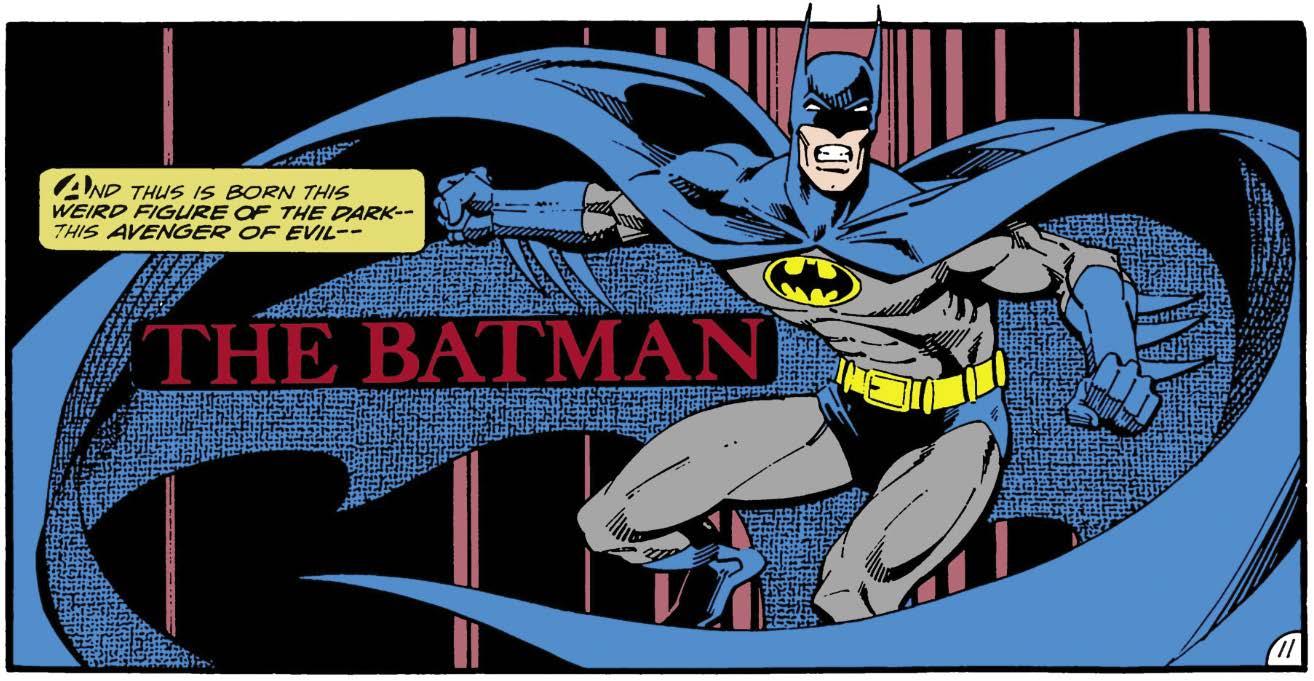

Fate gives Rogers and Austin their first shot at the Batman in Detective Comics #468, 1977.

of the whole story, Marshall and I offered to take a crack at those issues so that there would be a consistent look to the reprints, but were flatly turned down).

At first I wasn’t sure what to make of this story with this odd DC Doctor (Hugo) Strange that I had never heard of, and who the heck was Boss Thorne (keep in mind that the first two issues of the story by the other folks hadn’t been published yet), but certainly by the third or fourth part, I was aware that this Englehart guy was up to something quite extraordinary!

Looking back at those issues now, I can see myself still feeling my way along for the first three parts, still learning the craft. By the fourth issue, things are starting to gel, and by the fifth and sixth I see a new confidence in my approach and find little that I would do differently today (although zip-a-tone choices are always subject to second-guessing). I wish that it could have gone on longer but it just wasn’t to be…

As time went on, the book got later and later and as that happened, Marshall took shortcuts, putting down less on the pages in order to speed things up on his end. This was fine by me, as again, I thought of us as teammates, and if he was forced by circumstance to do a little less, I was there to backstop him

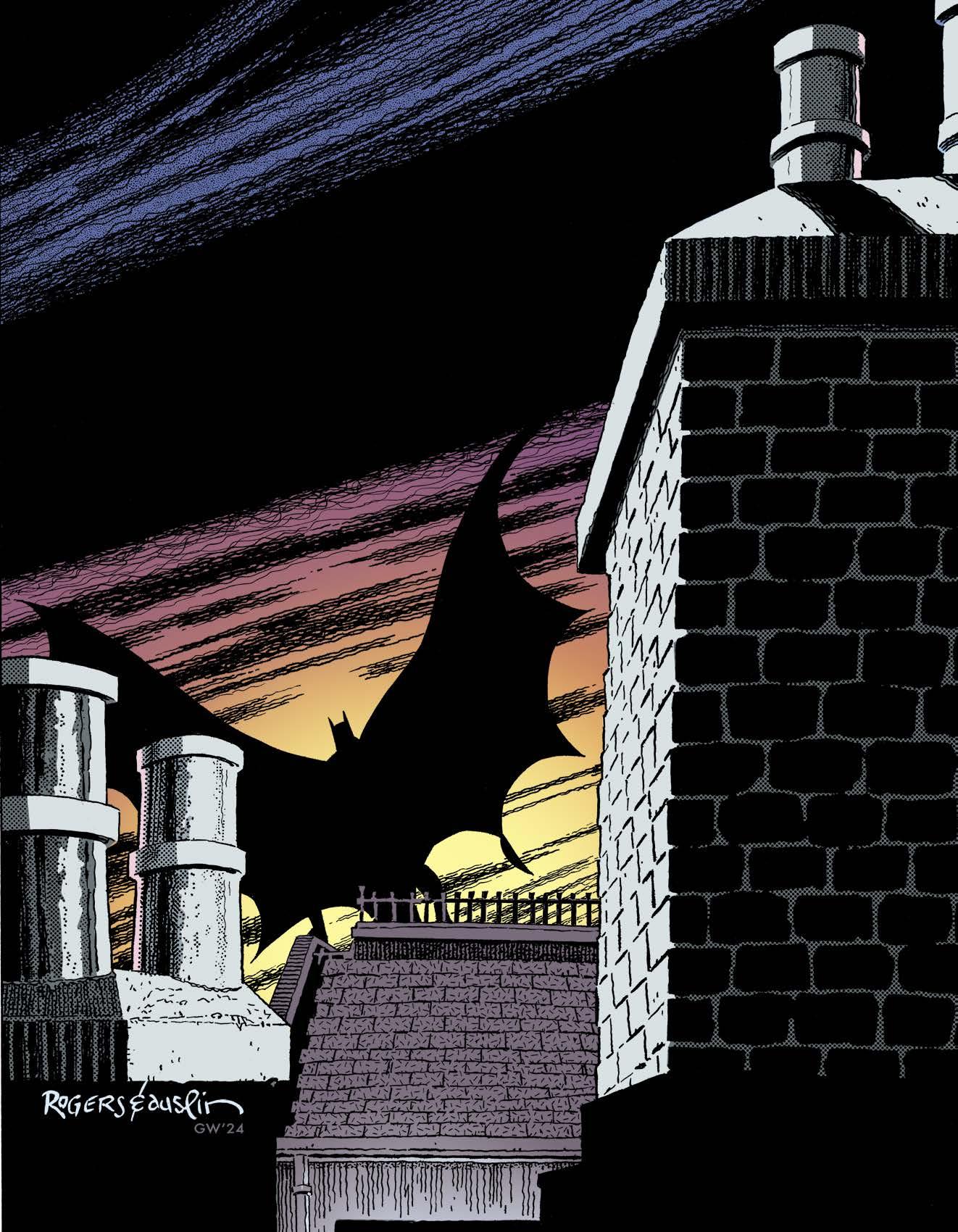

Cover of Detective Comics #471, the beginning of the Englehart, Rogers and Austin run on Batman, 1977. Below: Iconic image of Batman from that issue.

and happily contribute a little more.

One of the benefits of working in a studio like Continuity was there were older, wiser heads around to dispense advice and try to teach. My kind and benevolent mentor, Dick Giordano, was always attempting to hip me not just to artistic techniques, but also to the realities of the business of comics, saying things like, “I know you love what you’re doing and would probably do it for free, but you’ve also got to be realistic about it and don’t let the companies take advantage of you.”

In this instance he would see the pages as Marshall was producing them and again after I had inked them and he said, “You’re doing more of the work than an inker should do—you’ve got to ask for a raise in your page rate.”

Well, I wasn’t about to risk doing so as long as we were illustrating Steve’s wonderful scripts, but when I turned in the last pages, I explained the situation to Julie Schwartz, our Editor, and asked for a raise.

Julie seemed flustered and dragged me down to explain things to Art Director Vince Colletta. Vinnie seemed flustered and they both dragged me down to explain the whole thing over again to Joe Orlando (if you sense an “uh-oh” coming, give yourself a cookie for paying attention so far).

That’s where things went sideways. Keeping in mind that I wasn’t trying to get Marshall in trouble, imagine my horror when Joe started screaming, “Get Rogers on the phone and tell him to get his ass over here! By God, we’re paying him for pencils and I’m going to make damned sure that he’s going to give us pencils!” (Or words to that effect.)

With that, I was dismissed and wandered woozily down the hallway, thinking that Dick had never prepared me for this and feeling just awful that I had now gotten my teammate in trouble, and once again the wrath of Orlando was going to descend on him.

I did the only thing I could think of, which was to take a seat in DC’s reception area where I could see the elevator doors and wait there to warn Marshall.

Some minutes later, he arrived and I quickly explained what had happened and began to apologize as best I could while

warning him that he was going to be yelled at once again.

At that moment Julie walked past the door, did a double-take and hollered, “Marshall, get in here!” and Marshall and I exchanged a woeful glance as he walked away to what I could only imagine was going to be just short of his execution.

I went back to Continuity and waited terrified for Marshall to return. Return he did and when I asked him what had happened, he grinned and said, “They told me I’m doing a great job and gave me a big raise!” which seems mystifying unless you understand the pecking order in comics, and know that their mantra is that writers and pencilers are the important ones in the talent pool, and everyone else is expendable! I made the mistake of thinking that I was contributing something unique to the finished product and that the guys in charge would recognize its value.

Need I say that I quit the book at that point?

I walked away from the insanity that was DC and began doing more work for Marvel (where I was already inking John Byrne’s Uncanny X-Men) and where the people genuinely seemed happy to see you when you walked in the door.

The unfortunate part was I ran into Len Wein a day or two later and he broke out into a big smile and said how much he was looking forward to working with Marshall and I on Detective Comics, and I had to explain that it was nothing to do with him, but that I had had no choice but to quit the book. If I hadn’t already liked Len a whole lot, I certainly would have liked him even more as he looked absolutely stricken when I told him what had happened.

Before leaving the subject behind, I should probably mention the fact that other people (including my friends Berni Wrightson and John Workman) were treated well by Mr. Orlando and thought that he was a terrific guy. I have to believe that he saw nothing of worth in the efforts of either Marshall or myself and that his attitude toward us reflected the same.

MOVING ON FROM BATMAN

While we were working on our oft-reprinted Detective Comics run, Marshall was busy on some additional DC assignments, and

Vinnie Colletta

Julius Schwartz

box for coloring, I called Joey Cavalieri and asked what happened to Dave Stewart. “Oh, we couldn’t get him,” Joey replied, as if I was insane to even suggest such a thing.

As usual, Marshall pulled out his blue pencil to indicate which areas he would like to have me add a gray tone or texture in the inking.

Since my existing supply of zip-a-tone sheets was dwindling, I’d have to figure out some way to make my own (as they were no longer being commercially manufactured).

I believe it was Tom Palmer who put me on to my old X-Men teammate John Byrne, who had a supply of clear plastic sheets with glue on one side that he had used to print out his own lettering and affix to the original artwork on a project or two. John sold me a box full that he was no longer using and I was able to xerox my remaining zip-atone patterns onto these, the only problem being that the glue was a lot stickier than actual zip-a-tone sheets, which meant that once I applied it to the page, it couldn’t be lifted and repositioned, and it was a royal pain to remove the excess trimmed areas— but t’would suffice!

The next small bump occurred when Marshall decided that he had a better idea for the look of the Scarecrow’s mask than the one that he had penciled throughout the issue where he appeared. He mailed me a couple of drawings of the new version he envisioned and I was able to make the changes before the pages were inked.

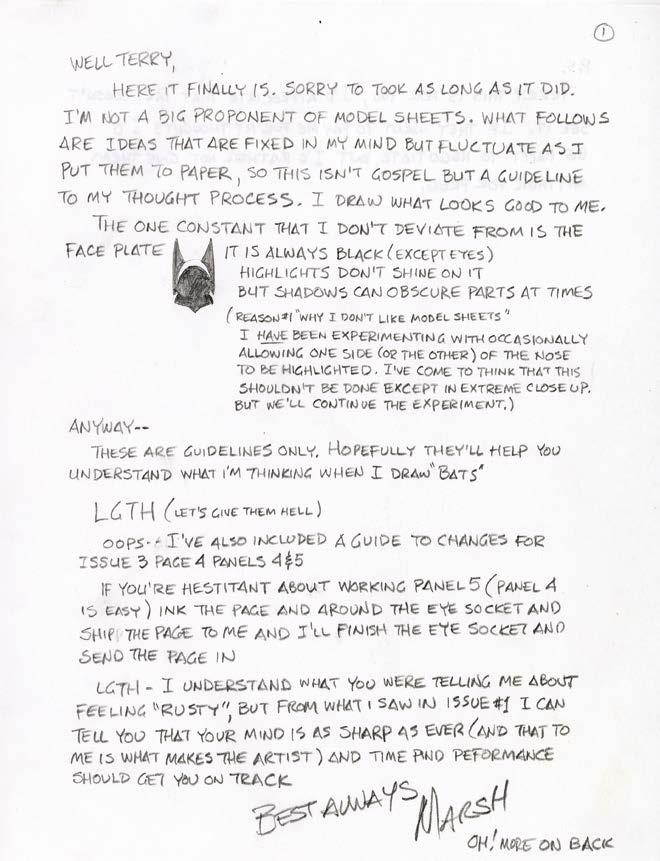

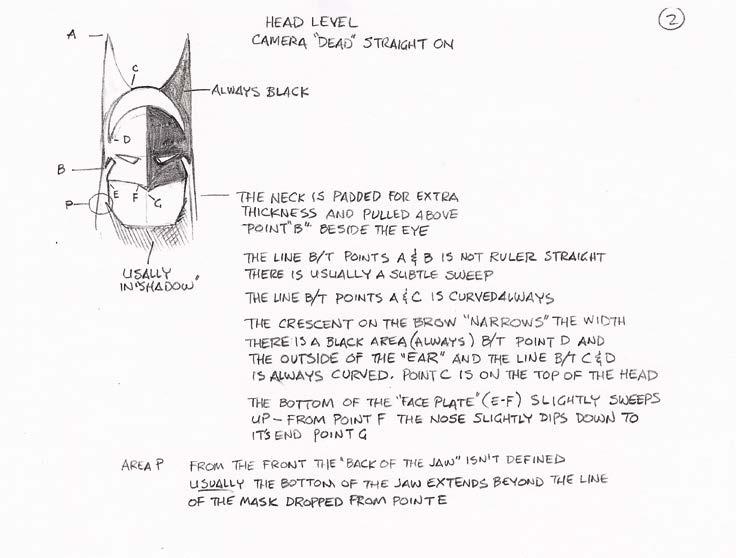

As an aside, one day while talking on the telephone, Marshall explained that it had taken him years to figure out the structure of the bat ears on Batman’s cowl and how they worked visually from different angles. Naturally I was keen to see the fruits of all this cognition for myself, and he generously sent along a page where he detailed his theories in pencil which I have kept to this day.

Notes from Rogers to Austin on his vision of the Batman’s cowl. (courtesy of Terry Austin)

ODDS AND ENDS

(1978 from DC Profiles #26, which appeared in Batman #295, Superman #319, and Superman Family #187)

Of all DC’S rapidly rising new stars, Marshall Rogers’ ascent has been swiftest of all. In less than a year, Marshall has gone from back feature artist to firststringer on Detective Comics and Mr. Miracle. Marshall almost didn’t make it to comics. His studies in art school concentrated on architecture, but after two years of studying designing parking lots and shopping centers, Marshall decided “the world wasn’t ready for another Frank Lloyd Wright” and left school seeking fame and fortune in the comic field.

Unfortunately, the comics world was not yet ready for Marshall Rogers. For the next two years, he worked in a hardware store while doing occasional illustrations for mass circulation magazines and sharpening his artistic skills.

Apparently, those two years did the trick. Marshall broke into comics, landing a stint penciling for Marvel’s British weeklies. Not long after, Marshall showed up at DC Comics, portfolio in hand, and was given his first assignment: a two part “Tales of the Great Disaster” story for Weird War Tales.

That was followed by some mystery stories, a Tales of Krypton piece and a four-part feature in Detective Comics featuring a new villain named The Calculator. His work on the latter led Editor Julie Schwartz to hand Marshall a real plum for a newcomer: penciling the book-length Batman versus the Calculator story in Detective Comics.

What came next surprised even Marshall. The powers-thatbe assigned Marshall to Detective as the regular penciler. And he almost immediately picked up the art chores on the newlyrevived Mister Miracle book as well.

“What I try to do,” Marshall told DC Profiles, “is first think of

what’s been done before, and then I discard that and try to approach it from a completely different angle.”

After looking over Marshall Rogers’ work, we’d have to say he’s found a different angle.

AWARDS

• 1978: nominated at the Eagle Awards for Favorite Artist, for Favorite Single Story for Detective Comics #472: “I am the Batman” with Steve Englehart, and for Favorite Continued Story for Detective Comics #471–472 with Steve Englehart

• 1979: Inkpot Award

• 1979: nominated at the Eagle Awards for Favorite Comic Book Artist (US), for Best Continued Story for Detective Comics #475–476 with Steve Englehart, and for Best Cover for Detective Comics #476

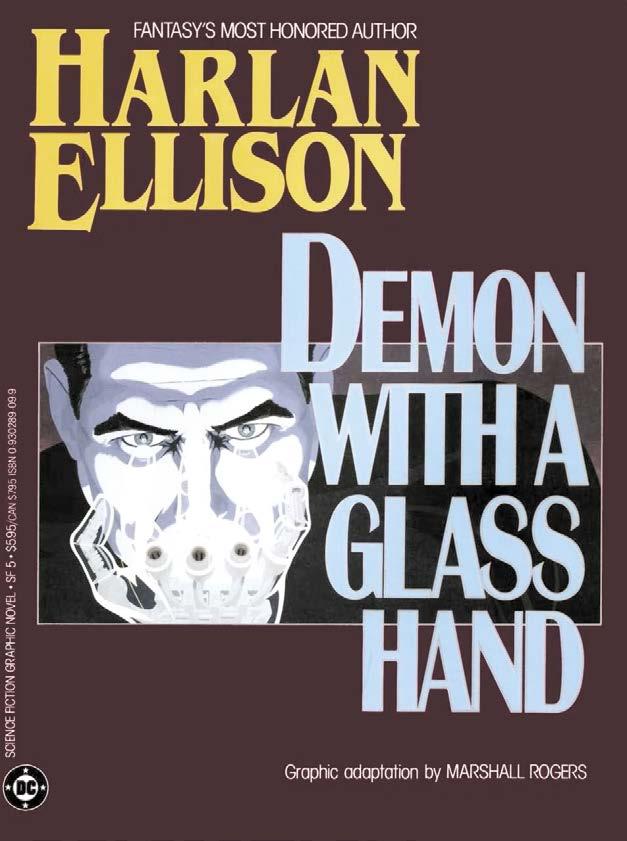

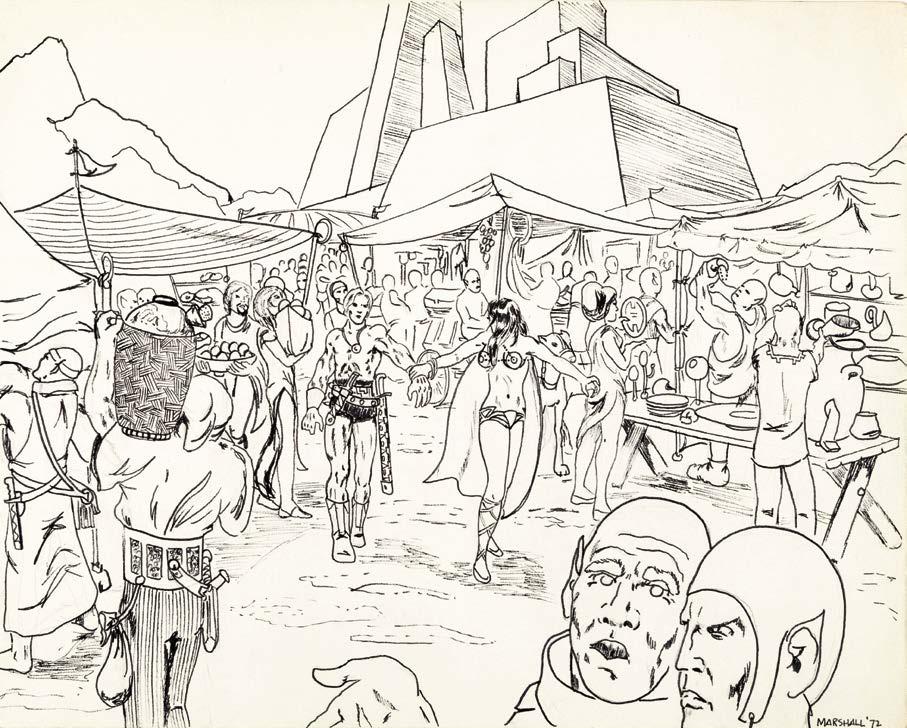

DEMON WITH A GLASS HAND

DC introduced a line of graphic novels based on classic science fiction, and teamed up some of their best artists to tackle the task of bringing epic ideas into a 52-page format. Marshall Rogers was given the task of adapting Harlan Ellison’s “Demon With A Glass Hand” story based on an episode of The Outer

CHAPTER 4

Photo by Sam Maronie

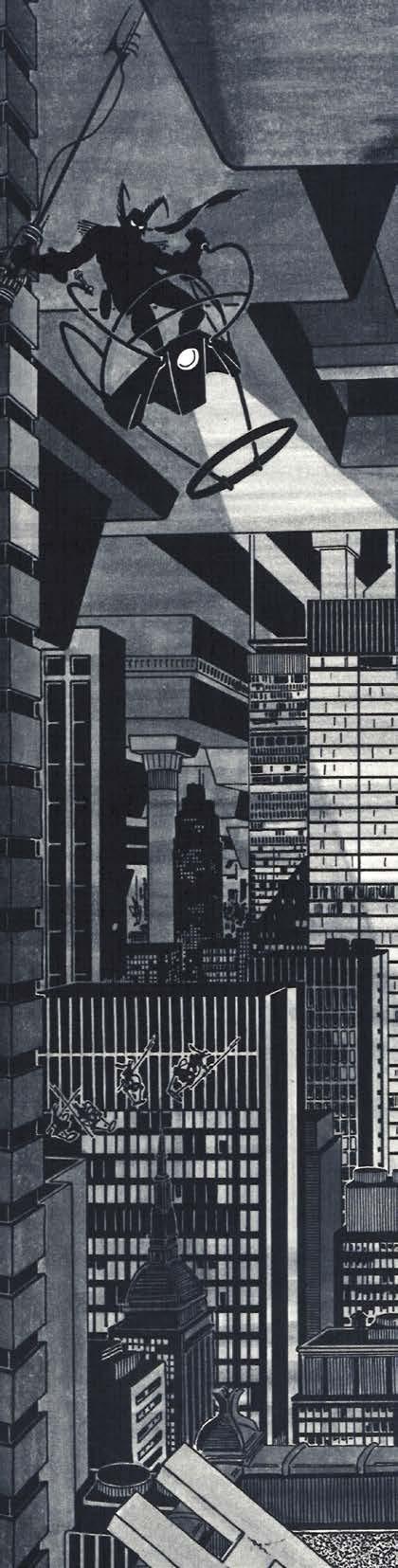

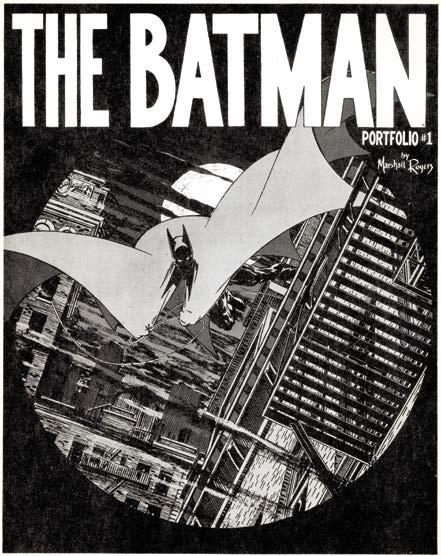

THE BATMAN PORTFOLIO

In 1981. S.Q. Productions released The Batman Portfolio #1 by Marshall Rogers. The limited (1,000 copies) full color, fiveplate portfolio was signed by Rogers, and featured an envelope with a black-&-white Batman illustration.

(courtesy Dave Lemieux)

Limits from 1964, written by Ellison specifically for actor Robert Culp. It became one of the definitive episodes of the series, and was named #73 in TV Guide’s 2009 “Top 100 TV Episodes of All Time.” However, Ellison was not a fan of Rogers’ work on his story.

[From a video posted on YouTube by routier1642 of a Convention appearance by Harlan Ellison in Sydney, Australia in 1996.]

MODERATOR: Were you happy with the adaptation?

HARLAN ELLISON: No, I hate it. Well, first of all, Julius Schwartz, one of my oldest friends— he was an editor at DC comics forever and ever and ever and ever; he’s now the editor emeritus—was doing a series of science fiction novel adaptations. And I gave him my original shooting script of my Outer Limits segment, “Demon With The Glass Hand”… it had additional material in it, additional scenes, it was much larger, and Julie asked me what artist I wanted to use. And I said Marshall Rogers, because Marshall Rogers had, shortly before that time, done a brilliant, brilliant series of Batman comics. They had been absolutely extraordinary in terms of design, in terms of use of color, in terms of just interior dynamics from panel to panel, and I thought he would be perfect for it. And so he was hired to do it. Now I’ve gotten conflicting stories about why it is not—I don’t think its particularly good, and I’ll tell you why… I heard he was not paid as much as he wanted, so he didn’t do as good a job.

Now, I find that a really—it’s a horrible reason for not doing your art. If you take a job, even if they pay you in pennies, if you accept the gig, dammit, you do your best work. Doesn’t matter how much you’re being—if you’re not happy with the payment, don’t take the job. Nobody’s breaking your arm to take the job, but if you do it, you don’t say, ‘Well I wasn’t paid a dollar, I was only paid a dime—so I’m only going to do it real fast.’ That is indefensible, and I lose all respect for the artist. And that’s apparently what happened with Marshall.

shots. When I do a script, I tell you everything that’s in the shot. I even pick out the music which I want to be played, which really annoys the crap out of directors. But then that’s my mission in life, to annoy the crap out of directors.

Harlan Ellison

I was not happy at all with… the storytelling itself… and he was working from my script. So all he had to do was draw the scenes as I had described them. I mean, I do a very complete script. I don’t just do master

MARSHALL’S QUOTES FROM THE ’80S

[Bill DeSimone managed to interview Rogers in the late 1980s for a research page, and got some great quotes from Rogers about the comic book industry at that time.]

Chain-smoking Camels, wearing a Cap’n Quick & a Foozle T-shirt under a sport jacket, Marshall Rogers sketched, autographed, and talked comics at a Fred Greenberg Convention on a September Sunday in Manhattan. New projects mentioned by Marshall included a “Shadow” fill-in written by Andy Helfer; a year-long stint on Silver Surfer, written by Steve Englehart; and a DC benefit book

Cover of Rogers’ 1986 graphic novel adaptation of Harlan Ellison’s Demon With A Glass Hand.

CHAPTER 5

ON JACK KIRBY

B. Cooke in March 2002 for The Jack Kirby Collector #35, and transcribed by LongBox.com Staff

JON B. COOKE: How far back do you recall Kirby’s work?

MARSHALL ROGERS: I grew up with Kirby’s work. He’s probably the reason I wanted to get into comic books.

JON: What work specifically?

MARSHALL: Everything, but it wasn’t until he started working with Marvel that I knew what the man’s name was. Then, once I realized who the guy was drawing that work, I realized I had probably first read him when he had done either the Shield or the Fly. I don’t remember exactly which of the two, but Jack’s work was so distinctive that even as a young kid, I recognized it: “Hey, this is the same guy that did the Fly.” I went back and I checked it out and looked at the art and realized, “Yeah, this was the same guy.”

JON: What was it about Jack’s work that was compelling?

MARSHALL: The dynamics, I guess, would be the best way to say it. Jack brought the work to life for me. It made it seem more than two-dimensional to me. One thing that I remember noticing was when some villain would uproot a building from a New York City block, the pipes and the guts of the building underneath were dangling down, as compared to Superman; when he lifted a building up, it had this nice clean flat

surface, you know—as if it was a toy placed on a chess board or something—but there was always rubble and junk coming out of Jack’s buildings whenever they were lifted up.

JON: Were you into his Atlas monster work? Did you look at those—like Tales of Suspense, Strange Tales, you know—the pre-Marvel hero stuff?

MARSHALL: A little bit, but I don’t honestly remember seeing it straight off the shelves. I was collecting comic books as a youngster, but I didn’t get right in on the very beginning of Marvel. I ended up running around the neighborhood trading to get back issues, so I don’t remember exactly if I started out with some of the monster books and had seen them, or had picked them up during trades, etc.

JON: Have you looked at the monster stuff since? Did you find anything of interest in there to this day?

MARSHALL: I guess, really, the monster genre was not my favorite genre, but I looked at everything and anything that Jack did at one point, that I could lay my hands on.

JON: You were born in 1950—so, generally speaking, you started picking them up around ’62? Were you about 11 or 12 years old?

MARSHALL: No, I was reading comic books earlier than that.

JON: I meant the Marvel stuff specifically. You said you didn’t get in on the ground floor necessarily.

Marshall Rogers Interview conducted by Jon

Jack Kirby

MARSHALL: I just missed it because a friend of mine had Amazing Fantasy #15 that Spider-Man first appeared in. Then I ended up buying the second issue of Spider-Man, but it wasn’t like I was hitting the newsstand every week to get them, so it was hit-and-miss in the beginning.

JON: Did you find Fantastic Four compelling the minute you encountered it?

MARSHALL: Yeah, and actually X-Men was one of my favorite titles. That was the one I really glommed onto because I always felt I had large feet and I really related to the Beast. (laughter) I wanted to be able to walk up the sides of a building. That was one of the things about Jack’s work, particularly in the beginning, that I think was the most attractive to me. The situations were more down-to-earth. They weren’t as fantastic as the DC stuff. It was Jack creating characters that would walk up the side of a building or shrink to the size of an ant. It was more basic fantasy elements rather than the fantastical type of elements. The Fantastic Four was certainly a departure from that, but his other stuff was even more compelling to me, and Thor would not necessarily be included in that. I think the work of his I found most compelling were the simple fantasy elements, like shrinking down to a real small size or being able to swing around a building as if you were on a jungle vine.

JON: Did you also clue into Stan Lee’s contributions to it?

MARSHALL: In the beginning I was attracted to the artwork. I realized Stan’s name from the signatures. When I got a comic book, I would basically flip though the pages just to see the artwork and then go back and read the story later on. Particularly with Jack’s work, you could tell what the story was without having to read the captions.

JON: The X-Men was a title on which he later did quite loose breakdowns. Could you still see the Kirby through the guys who inked and finished the penciled stuff?

MARSHALL: I could, and I was able to quickly tell as soon as Jack stopped contributing to it as a ghost, because the layout and dynamics just took a vast turn, and became very different.

JON: Prior to Marvel, did you collect comics? Did you save them or were you a reader?

MARSHALL: I was a reader.

JON: And once you got bit by the Marvel bug, did you continue to read DC comics or did you pass them by?

MARSHALL: I always went back to Batman, hoping to see that “something” that I’d always wanted to see, but—.

JON: You didn’t see it.

MARSHALL: No, I never did, you’re right.

JON: So did you remain with Marvel pretty much throughout your teen years?

MARSHALL: Well, I don’t know; about 15 or 16 I started getting interested in girls and losing interest in comics. Then once I got into college, I started to take up the interest again. It coincided with a serious interest in getting into the business.

JON: Were you losing interest in the comics just as Jack was getting into the Galactus trilogy, for instance, and when the cosmic comics came on, with the introduction of the Silver Surfer?

MARSHALL: The introduction of the Silver Surfer was a little bit earlier. I was still reading Fantastic Four on a regular basis when the Silver Surfer first appeared. I’m sure I was collecting because if I read it, I was putting it into my pile.

JON: Did you spark to the Surfer? Did you think he was cool?

MARSHALL: It was another interesting character, but a little too much like Superman. I prefer characters that have got fallibilities. I’m not a big Superman fan because at this point he can basically do anything, so where is the conflict in the storyline? It was really very much the same with Silver Surfer, even

A full-page of Darkseid from Mister Miracle #22. At the 1978 Atlanta Fantasy Fair (attended by TwoMorrows publisher John Morrow), Marshall commented that he hung the original art for this page by his front door to scare away salesmen.

(previous page) Rogers pencils and Terry Austin inks on a page from Detective Comics #468, featuring Bruce Wayne’s encounter with an old Kirby character, Morgan Edge.

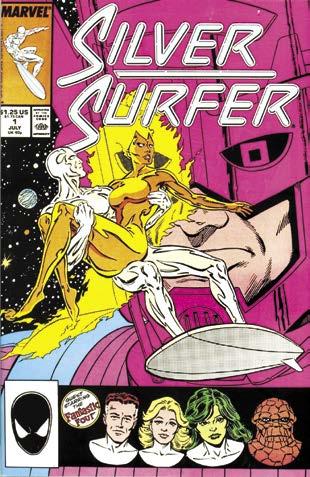

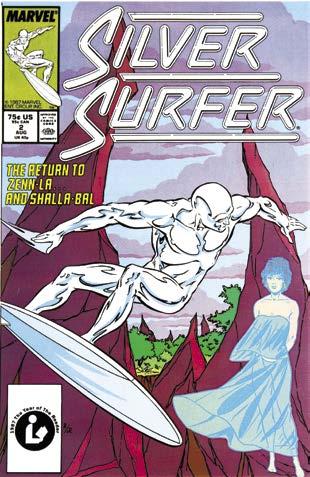

PUBLISHER: Marvel Comics

TIME PERIOD: 1987–1988

BOOK/COMIC TITLE and ISSUE NUMBER(s):

Avengers Annual #16

Marvel Age Annual #3 - Ad

Silver Surfer #s 1–12, 21

Silver Surfer print

FORMAT: Comic book

OVERVIEW: Marshall Rogers was not the first artist to draw the Silver Surfer. That distinction belongs to Jack Kirby, who penciled his debut in Fantastic Four #48. Reader response to the character was positive and after multiple guest appearances, the Surfer received his own title in 1968. But in spite of exceptional artwork by John Buscema, the book only lasted 18 issues, the last drawn by Kirby. What followed was another series of guest appearances in various titles, a 1978 solo graphic novel illustrated by Kirby and published by Fireside, and a one-shot drawn by John Byrne. Then in 1987, Marvel launched a new Silver Surfer title, the first not written by Stan Lee. It featured writer Steve Englehart and frequent collaborator, artist Marshall Rogers. The series was noteworthy in that the initial story broke with long-held tradition and, with the help of the Fantastic Four, enabled the Surfer to break through the barrier of Galactus and leave earth.

KEY CHARACTERS:

Galactus – devourer of worlds and his herald Nova.

Shalla-Bal – former love of Silver Surfer and Empress of Zenn-La. Mantis – Avenger and companion of the Silver Surfer in the battle against the Elders of the Universe.

SETTING(s): Earth, Zenn-La, and various locations throughout space.

SYNOPSIS of KEY ISSUES:

Silver Surfer #1 – The Fantastic Four help the Silver Surfer escape his confinement on earth and the Surfer rescues Nova from the Skrulls.

Silver Surfer #2 – The Surfer returns to his home world to find that his former love Shalla-Bal is now Empress and Zenn-La is being drawn into a new Kree-Skrull war.

Silver Surfer #3 – Origin of Mantis told.

Silver Surfer #7 – Mantis discovers that the Elders are plotting to kill Galactus with the soul gems.

Silver Surfer #9 – The Surfer comes to the aid of Galactus when the Elders try to kill him.

Silver Surfer #10 – Galactus meets Eternity.

Avengers Annual #16 – Korvac removes the protective silver coating from the Surfer.

BEST ISSUE: This is debatable as several are noteworthy, but the nod goes to Silver Surfer #1, watching Norrin Radd escape the confines of earth that have held him for so long.

MARSHALL ROGERS’ CONTRIBUTION: Rogers not only penciled

STEVE ENGLEHART

Steve Englehart Interview

Conducted 2020 by

Dewey Cassell

Transcribed by Steven

Tice

Additional Interview by Jeff Messer in December 2023

DEWEY CASSELL: There came a time when you ended up leaving Marvel and went to DC. I thought that might be a good place to start.

Steve Englehart

STEVE ENGLEHART: Yeah, although I did not meet Marshall until a year after that, and I didn’t see Marshall’s stuff. I mean, I went to DC, I wrote Justice League and Batman, and then I left the country, and so did not meet the artist who was going to do the Batman stuff, and did not even see it until all of it was published when Julie Schwartz sent me a package over in Spain. So I can start wherever you want to start, but, in terms of Marshall, I was unaware—I mean, the first time I was aware of Marshall was when I saw the printed material, and I didn’t meet him until I got back to America, so make of that what you will.

CASSELL: Okay. So when you went to DC, one of the things you particularly wanted to do was to write Batman. Did you already have the story in mind that you wanted to do?

ENGLEHART: No, not at all. I mean, the way I tend to work is, being a freelancer, I don’t make up stories until somebody’s paying me for them, so, when Jenette Kahn called me up and asked me to come over to DC, I had already made plans to go to Europe six months, whatever, down the line. So I said to her, “I can only give you less than a year before I leave town.” So she knew that going in, and she wanted me to do Justice League. She wanted me to do for the Justice League what I had done for the Avengers, which is how she put it. Give them characters, and give them stories, and all stuff that the Justice League didn’t really have at that point in time. And I said, “Yeah, okay, that would

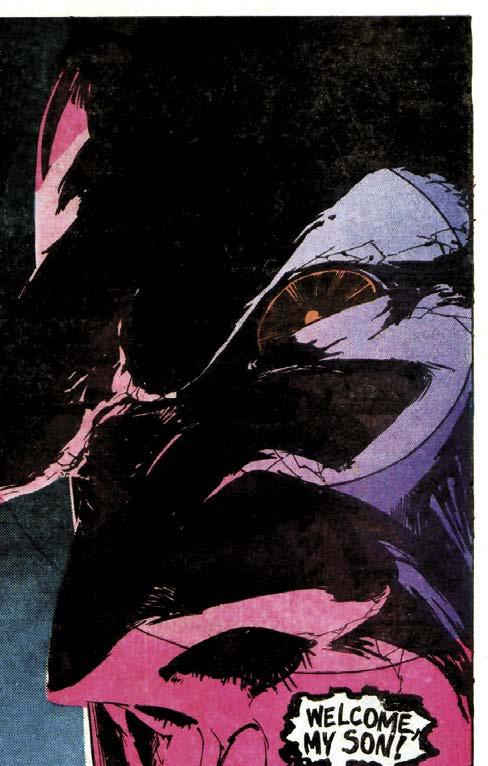

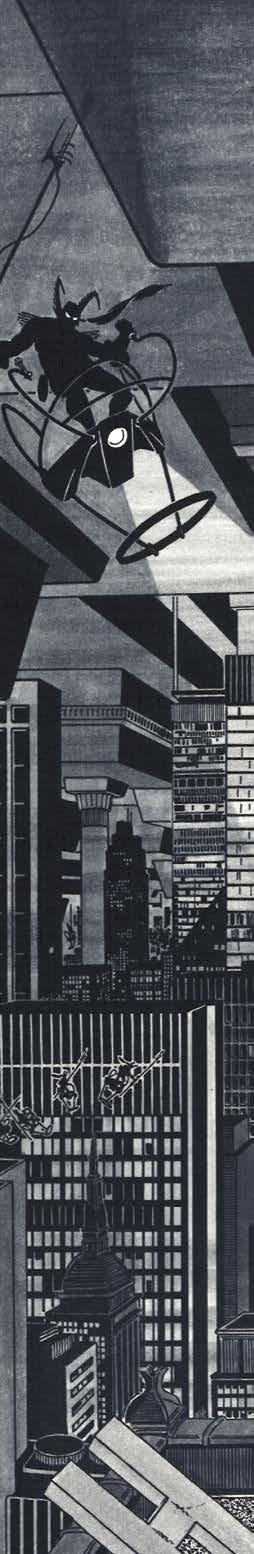

be fine. But I also want to do Batman because I’ve always loved Batman, and this is my one opportunity,” I thought, “to do Batman, so I want to do that.” And she said, okay, she could go with that. So it was at that point that I started thinking about the Justice League and Batman, and I think that was all I was thinking about at the beginning. Later on we did Mister Miracle, of course. So I sat down and started figuring out what I wanted to do. We can forget about the Justice League for this discussion, but for both of them I was figuring out what I wanted to do, and I sort of gradually built up what I thought was important to do in Batman, which is basically I wanted to do two things. One, I wanted to get back the pulp darkness from the original concept of the thing. If you’ve ever seen Batman stories from the first year of Detective Comics, the art is very dark, and he’s fighting vampires, and Hugo Strange with monsters, and all this sort of thing, and the early days of the Joker. I wanted to get that darkness and that pulp feeling back, because he was a modern day DC superhero like a lot of them were, and I thought, “No, Batman needs atmosphere.” And the other thing was make Batman an adult. I had always thought it just made no sense to me, even as a kid, that when Lois Lane or Lana Lang would saunter up to a superhero that the superhero would go, “No, I’m sort of above all of that,” and I thought, “I don’t think that’s how adults actually operate.”

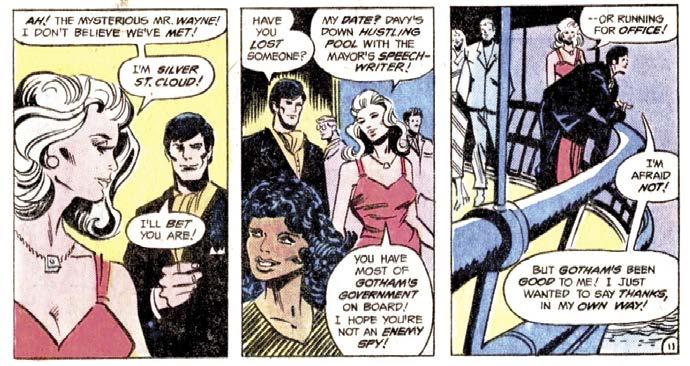

So Silver St. Cloud, I wanted a strong woman who could stand up to a strong character like Batman, Bruce Wayne. I wanted to know more about Bruce Wayne, that’s what that was sort of opening up. I wanted to know who the guy was inside of him. So I had those concepts. I went back and looked at the old stuff, found Hugo Strange and just sort of started putting stuff together. So we started out, of course, with Walt Simonson doing the art, and he was very enthusiastic

CHAPTER 6

about it, and Walt is Walt, and it was like, “Oh, that’ll be good.” Because there weren’t a lot of superstars left working at DC. Neal Adams had gone over to Marvel, Gil Kane had gone over to Marvel, Bob Brown had gone over to Marvel. So there wasn’t a deep bench of artists, and I was lucky at Justice League that I had Dick Dillin, because Dick Dillin wasn’t a superstar, but he was Dick Dillin, who had drawn the Justice League for a long time, and I thought it was cool to be doing that book with him. But on Batman, there was no telling who was going to do it. And then they said, “Oh, Walt’s going to do it.” He’s going to do layouts, and Al Milgrom was going to do finishes. So I started off doing the book Marvel style, which is where I would come up with a plot, and then give the plot to the artist, who would then be able to draw that plot as best suited him. It was an approach that I prefer, because I like to let artists—I wanted to be an artist when I got started. I like art. I don’t want to be telling an artist how to draw stuff, necessarily, so I want him to tell the story and let him draw it the way he wants to. The problem, as it turned out, was I only had a limited amount of time, so giving a plot to Walt, waiting for him to draw it—I mean, he wasn’t delaying it, he was doing what he was supposed to do, but I realized that I was not going to be able to do the entire series that way because I just would run out of time.

here, and you take who you get.” That’s the way it worked. Pretty much everybody I ever worked with back in those days was assigned to the same book. I just rolled with whoever was there. In any event, I started writing the scripts in advance, and I knew how many I could do, which was seven, total, based on the publishing schedule as it existed, before I would run out of time. And so I started at that point to really think about, “Okay, what are these last five scripts, how am I going to accomplish what I want to accomplish in these last five scripts?”

Midway through that, Julie Schwartz, the editor, said that the first couple of issues had sold so well that they were going to add an extra issue that summer, so all of a sudden I had eight, and that turned out to be good, because I had the same storyline, but I could let some scenes breathe a little bit more. I could open things up and add a few extra things here and there and make the whole thing just a little smoother. I mean, hopefully what I was going to do was smooth enough, but I could elaborate on things and let things go a little further.

So I needed to do the scripts in advance, which is the other approach to writing comics, where you’re doing, “Panel One: Batman says this, Silver says this. Two, blah, blah, blah.” And so, somewhere in there, and I can’t say that the two things were simultaneous, but when I said I can’t wait for Walt anymore and I’ll just go ahead and write the scripts, I’ve never known exactly why we switched artists at that point. I mean, Walt could have taken those scripts and drawn them. I think it was Julie Schwartz who decided that he wasn’t completely satisfied with what was going on. Back in those days, that was editorial’s decision. I mean, you didn’t go to an editor as a writer and say, “Oh, I don’t like this artist. Get a different artist.” It’s like, “No, dude. We’re running a machine

In any event, I wrote all the scripts, six more scripts, handed them all in, left the country. I had no idea who was going to draw them. I figured the odds were it was going to be a couple of journeymen. If they didn’t want Walt, there wasn’t much of a bench where they could go find somebody else that good. So I figured, my basic thought at that point was I am writing these scripts to be as good as they can possibly be on my end. I loved the Batman, I want to do that anyway, but I’m figuring that the art’s going to drag down the overall finished product, and I had learned over the years that most people can’t differentiate and go, “Wow, the story was really good, but the art sucked,” or whatever. They just go, “Oh, I didn’t like that book,” or whatever. So that’s all I knew. Then I went to Europe, and six months later I got a package in the mail, and it had all the issues in it. So I saw Marshall Rogers and Terry Austin’s work for the first time, and I absolutely, truthfully, I looked toward heaven and said, “Thank you, God.” I’m not religious in that sense, but that was the appropriate response to, like, oh, I really wanted this series to be good, and it is. So I was extremely happy about all that. And then, when I finally get back to America the following summer, I met Marshall and Terry for the first time. So that’s how we got there.

CASSELL: So when you opened that package and you’re looking at the artwork for the first time, what was it about it that pleased you? What is it that you think is appealing about Marshall’s style?

ENGLEHART: He and Terry both really loved the Batman as much as I did. And I’ve seen this over the years with a number of new artists. You can see that they’re good enough to get

Walter Simonson

Al Milgrom

Panel from Detective Comics # 469 illustrated by Walter Simonson and Al Milgrom.

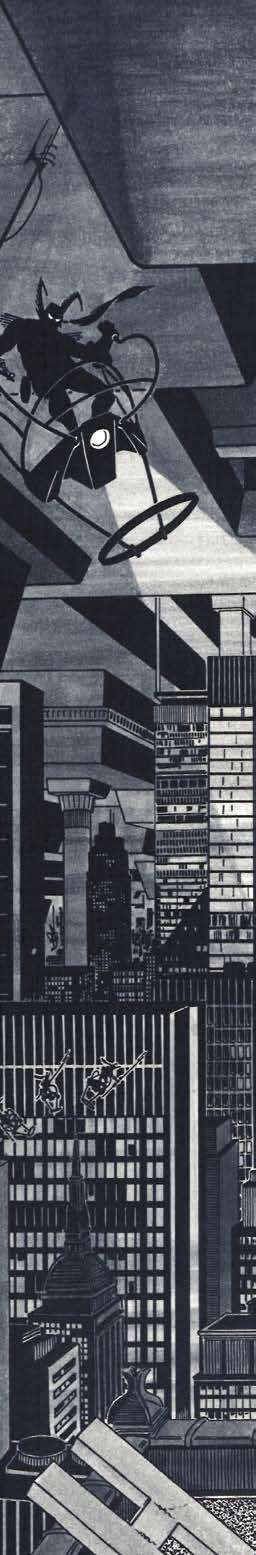

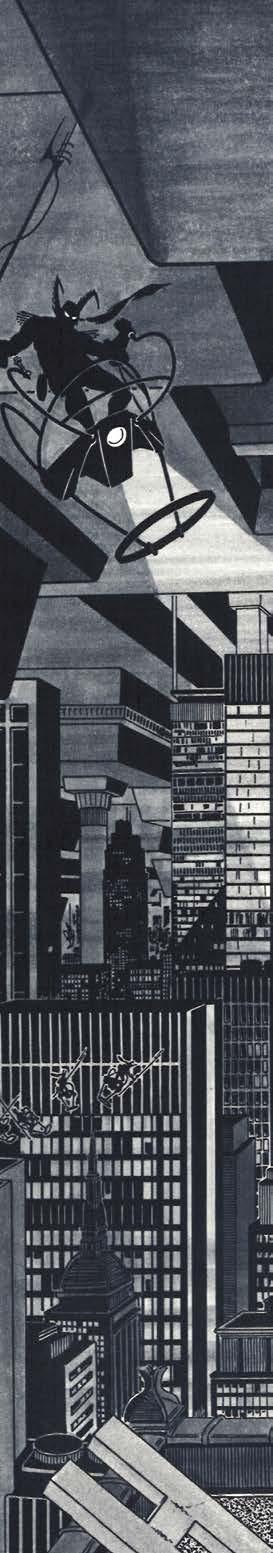

the job with the first issue, and then you could see they got better with the second issue, and then they got better with the third issue, because they’re really trying to take it as far as they can, and they’re getting more experience drawing, and all that different stuff. I mean, it just felt like Batman… Marshall understood the character. He understood Gotham City, which, again, I had thought about making Gotham City a big part of it. I mean, it was in the scripts, but I hadn’t said, “Oh, I’m going to specialize in Gotham City here.” But Marshall had studied architecture. He liked buildings. He didn’t mind drawing a very gritty Gotham City. And his characters were amazing. His Joker, his Penguin, Silver St. Cloud got a whole lot prettier when Marshall drew her. So there was nothing to criticize. Which, I don’t know who you’ve talked to, but Marshall and Terry, when we did the second run in 2004/2005, they told me—and I heard for the first time, that DC, their art director Joe Orlando, hated their artwork. Do you know this story?

CASSELL: No!

ENGLEHART: Every month they would get called into the office, and Joe Orlando would go on in detail and at length about how terrible this art was. It did not look like DC artwork. “You’re going to have to change it.” Terry says he once sat outside Orlando’s office for a half an hour hearing Orlando yelling at Marshall, and then Marshall came out white-faced and kind of shaken, according to Terry. I was astounded to hear this, thirty years after the fact. But DC’s the company that redrew Jack Kirby when they hired him. They are a corporation, and they have a corporate mentality. They didn’t think of, like, “Here’s an exciting new art direction.” They thought it ought to look like it was drawn by half a dozen other guys who work up here. And so that’s the first half. And then the other half is kudos to Marshall and Terry for not doing it, for not changing what they were doing. But apparently DC just really didn’t like it. Once it started appearing, it started selling like crazy, and then they said, “Oh, well, cool! We like this. Hey, why don’t you guys do Mister Miracle, too?” And Madame Xanadu we did, and other stuff once they decided that Englehart and Rogers was a saleable concept. So that’s probably all I know about the art. I don’t know if you’ve tried to talk to Terry… he’s the only one, obviously, who could tell you anything more about what working conditions were in that situation.

CASSELL: I want to talk a little bit more about the first series of stories. For example, about Silver St. Cloud, you mentioned that you wanted to have a more adult Batman, if you will, that was in a relationship. Did you base Silver St. Cloud on any particular person?

ENGLEHART: No. I could see who this woman would have to be. Good-looking, of course. Strong, a strong person, a strong woman. She needed to be a business-

woman, somebody who could move in Bruce Wayne’s Gotham City circles, etc. And the name Silver St. Cloud just comes from—I was trying to think of a Batman sort of name, and I could see silver clouds in front of the moon at midnight, that atmosphere that I was looking for. So that’s where the name Silver St. Cloud came from. But, no, I never base things on people. I mean, I probably have here and there, but in general, I don’t say, “Oh, I think I really like Scarlet Johansson, so I will do a Scarlet Johansson character.” No, Silver St. Cloud is her own person. I wanted her to be the girlfriend for Bruce Wayne. I knew I wasn’t going to continue on the series or anything, but that was the contribution that I wanted—because Batman, to me, I mentioned I wanted to know more about Bruce Wayne. Everybody else in superhero world gets their powers because they came from another planet, or they got bitten by a radioactive spider, or whatever. But Batman is a person who taught himself to be this good, so I wanted to know more about the person. I thought that was far more important than knowing about Clark Kent, for example. Clark Kent’s not a real person. Barry Allen, 83 Flashes in the past, he’s a real person, but we didn’t care so much about Barry Allen. We cared about the Flash. But I really thought Bruce Wayne was somebody that we needed to know. Silver St. Cloud, as I say, was a way of getting at that person who saw his parents murdered, and swore that he was going to do something about it, and taught himself to be able to do something about it, and so forth. That’s my rant on Silver St. Cloud.

CASSELL: I liked that you sort of gave him a reason to want to be Bruce Wayne. Because, otherwise, the Batman part’s a whole lot more interesting in some respects, right? It’s exciting, and it’s adventuresome. But you gave him a compelling reason to want to be the Bruce Wayne that Silver would want to be with.

ENGLEHART: Yeah, well, I like writing characters. I mean, the reason I write is to get inside all these different people’s heads. So it may be that Batman vs. the Joker in a lightning storm is more exciting than Bruce Wayne and Silver sitting in a restaurant having a conversation, but I

Bruce Wayne meets Silver St. Cloud in this panel from Detective Comics #470 by Simonson and Milgrom, 1977.

Batman takes on a maniacal Joker in this commission by Rogers. (courtesy of Albert Moy)

You can download all six scripts for the unproduced Dark Detective III at Steve Englehart’s website: www.steveenglehart.com

had just as good a time writing both of them. I mean, the way people took to Silver and so forth, she held up her end in the parts where she had to. If I had been continuing to write the thing—and I sort of have over thirty-year periods, because I don’t work things out that far in advance—I still don’t know whether that relationship would be able to survive the rigors of his being Batman. I didn’t have a problem bringing her back when I did the second one. That made sense to me. The third one, which was unpublished but can be downloaded off my website, they’re broken up. What does that mean to Bruce Wayne, to have this girlfriend that he can’t be with? So as I have done that run of Batman, the Marshall Rogers Batman stories, the relationship

between Bruce and Silver has progressed, has moved along. But I still couldn’t tell you whether they would end up living happily together in Wayne Mansion or whether it’d just be impossible to make that work. That’s what I like about writing stories is you find that stuff out, but we never got to the end, so we never found out.

CASSELL: Well, I think that evolution, if you will, is part of what makes it believable as well, because real-life relationships don’t stand still, so I liked the fact that it evolved. Like, in the second one, the Dark Detective, or what you refer to as Dark Detective II, the nature of their relationship changed via circumstances. It was something outside their control. I thought you handled that really well. The second thing I wanted to ask you about was, where did you come up with the idea for the Joker to want to patent these laughing fish?

ENGLEHART: Well, I wanted—I mean, back in the day, the Joker was a homicidal maniac, and as I recently figured out for the first time, that’s when I was doing an intro for their Greatest Joker Stories new book that’s coming out at some point. I don’t know what their publishing plans are now, but they were putting together eighty years of the Joker and they wanted me to write a thing about the history of the Joker, and I had always known that, in those early stories, every Joker story would end with the Joker dying or being caught and thrown in jail, and the next Joker story would begin with him having escaped death, although people didn’t know it, or breaking out of jail. So it was like they did continuity with the Joker until there were so many Batman stories being published in Batman, and Detective, and World’s Finest, and all the rest of this that they couldn’t keep it up. But I thought that was pretty cool. And what I realized was that made him not only a homicidal maniac, but it made him a serial killer, because he kept coming back. So the first serial killer in comics, probably. But he was supposed to be crazy. He was supposed to be a maniac. And we, from 1942 until 1976, he had been the clown at the Ha-Ha Hacienda, and he did funny things, and not even that. One of the best stories in the Fifties was him and Luthor teaming up to build robots, so it’s like, all of the atmosphere had been taken out of this guy. And, in fact, just before ’76, they had made a Joker series in which he was sort of like a bad guy, except he wasn’t really a bad guy because everybody else was a worse guy. It was just terrible. So I wanted to bring back the dark, scary Joker who was insane.

So then I thought, “Well, all right. I can’t just say, ‘Oh, yeah, he’s insane.’” I should think of something that an insane person would do, and, again, I’m a writer. Hopefully I’m not insane, but I have the desire to put myself inside the head of an insane person. And it was kind of like Silver St. Cloud or any of the rest of this. I figured out I want to do something in this ballpark, and laughing fish just sort of appeared. I mean, I didn’t see a fish and go, “Oh, I have an idea,” or whatever. It was like, that just sounded weird: laughing fish, it sounded like a weird thing to say. So I wanted the Joker to have a plot where you as the reader could go, “That’s nuts. That’s crazy.” But you could see how he could believe it, you know? He could talk himself into this kind of thing. And so that was kind of what that was about—laughing fish just sounded nuts, but the idea of copyrighting them, and going to the office and wanting to fill out forms and stuff—I mean, hopefully readers would go, “Gee, that’s really, he’s insane.” So that was what I was trying to accomplish there. But there’s no rosebud when it comes to the laughing fish. It just sounds cool, just like Silver St. Cloud sounds cool. I just sort of go on gut reaction, and does that do what I need it to do? I mean, at some point there’s me back here in the background sort of manipulating everything, but you’re not supposed to feel that or see that, right? A lot of it is like, “I’d like to go over here and do this. What’s the most comic bookly effective way to do that?” So that’s how we got there.

CASSELL: It worked very well. And I liked the way, too, that you worked into the stories—not just the Joker one, but the whole series that you wrote— these little Easter eggs for people, like naming characters after past Batman artists and writers, such as Giordano, Giella, Novick, and Friedrich. There were nice little touches along the way, too, for people that had been reading Batman for more than a couple of years.

CASSELL: Well, I thought it was great. It provided a little bit of humor, as it were; dark humor, mind you, but worked in there as well with this insane guy. As you said, he believed it, but at the same time it was kind of sickly humorous. I don’t know, I thought it was great. I thought it was a really clever way of presenting the Joker that was both humorous and enjoyable, and at the same time sort of scary and frightening.

ENGLEHART: Over the last 40 years, I’ve been asked to write about the Joker a lot. I hadn’t thought of this all the way through at the time, but I have had to think about the Joker a lot over the last 40 years. The Joker’s the kind of guy who says, “I want to rob a bank. But I’m not going to go in there with a couple of guns and a couple of goons and rob the bank. I want to rob a bank with laughing fish and parachuting out of the sky.” And then he makes it work. He figures out a way to do it. He’s not just walking in there tripping and like, “I’ve got some fish, let’s rob—.” No, the Joker’s so scary because he thinks like nobody else, but he does figure out a plot. He does figure out what he’s supposed to do. So all of that was, even just sensing that without putting it into words, but I knew that he needed to have a plot that made sense, you know? And then the rest of it came.

ENGLEHART: Yeah. Well, you know, I’m a big fan of most everybody in comics, especially including the guys who I really liked when I was just reading them and not yet doing them, so I wanted to—and here I was at DC for a year, so it was a chance to sort of tip my hat to DC people in the process.

DARK KNIGHT’S RETURN

CASSELL: So flash-forward 27 years. What afforded the opportunity to get back with Marshall Rogers and Terry Austin and take another stab at it?

ENGLEHART: Well, I should not skip over the 27 years, first. When those Seventies books came out, as I say, they sold like crazy. I mean, it was like a huge—it was everything Jenette Kahn could have wanted from me, to really put DC back on the map, to create new energy over there—and it sparked Michael Uslan to decide that he wanted to do a Batman movie based on those stories. And so, for the next ten years, they tried to make a movie out of those stories, and eventually they came to me and they said, “Nobody’s really been able to get that feel, that ambience that you had. We’ve had Hollywood guys doing it, but we need you to get involved in this movie.” So I went on and became basically a script doctor for that movie. And it was still the era when comic book movies were supposed to be funny. You were supposed to have a funny side to it, because you had to sort of let the audience know that you didn’t really believe in any of this stuff, or that comics were actually a thing, so the movies—Uslan and Tim Burton, who would do that; I mean, they all wanted to move it in a more comedic direction, and I was brought in because it was based on my stories, and so I was trying to emphasize the strengths, as I saw them, in my stories. So that movie, when it finally came out, was kind of a mix of the two concepts. It was more serious than movies had been to that point; it was less serious than they’d become. When that movie came out, it was when I was in the theater that I saw that Silver St. Cloud had had her name changed to Vicki Vale, and Boss Thorne had had his name changed to Boss Grissom. And why was that? So that DC wouldn’t have to pay me any royalties, me and Marshall and the rest of us, any royalties on this thing. And from that point on, from ’89 to 2004, me and Marshall were, like, erased out of the DC pantheon. I mean, they did not want us to do any more Batman because it would upset this. DC again

Jeanette Kahn

Michael Uslan

Dan Didio

Batman battles the Riddler in this Rogers page from the unpublished issue of Batman: Dark Detective II. Inks by Jouko Ruokosenmaki. (courtesy of Jouko Ruokosemaki)

being corporate, they like to go on the idea that everything just sprang from DC Comics, and didn’t like it when people started talking about the “Englehart/Rogers Batman,” or the “Alan Moore Watchmen,” or the Mike Grell (Green Arrow)… They wanted it all to look the same, and be the same, and just come from DC Comics. So, for two decades, we didn’t get to do Batman. I did a couple of Batmans here and there with other people, Marshall had the newspaper strip for a while, but for twenty years, basically, or 15 years, whatever it was, we went from having our stuff reprinted to having nothing reprinted. And when they finally did reprint it, they put it under the name “Strange Apparitions” so that nobody could find it.

I’m not a DC fan. I don’t like DC. They asked