THE

MADNESS!

ISSUE #95, FALL 2025

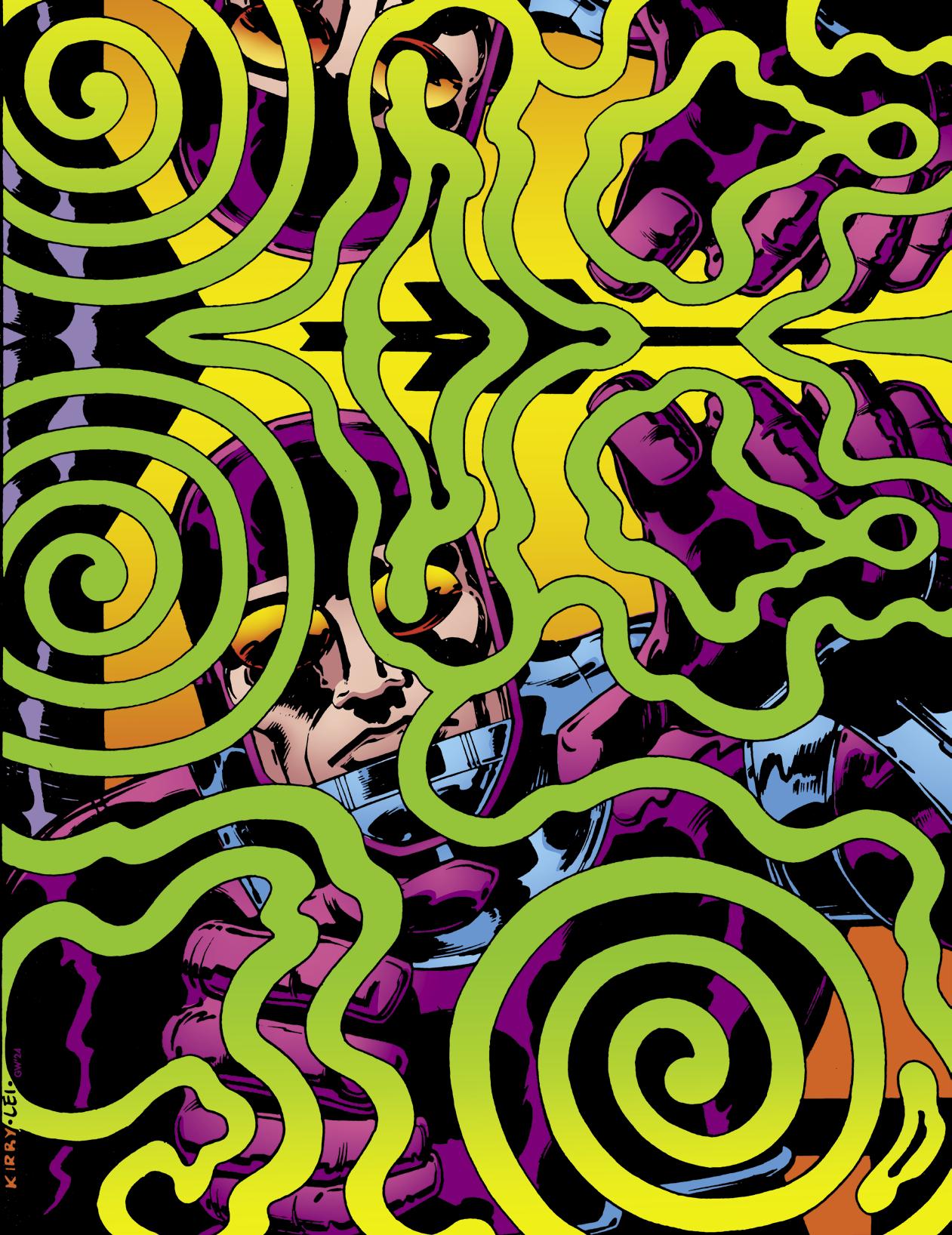

Cover inks: STEVE LEIALOHA (an unused Machine Man #6 cover) Cover color: GLENN WHITMORE

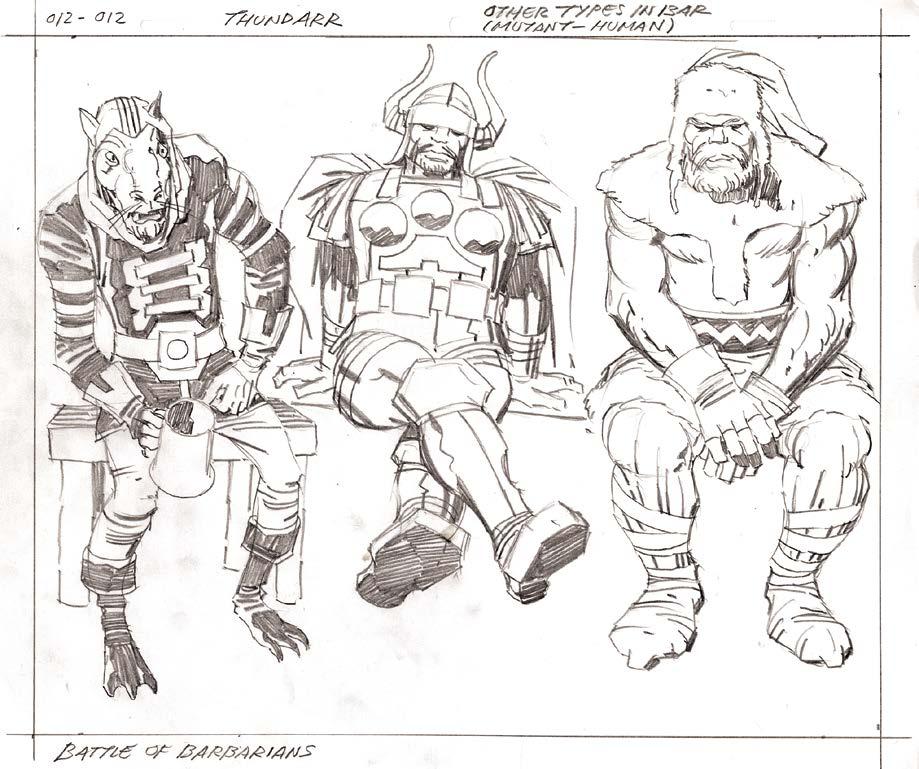

COPYRIGHTS: Aunt May, Balder, Baron Mordo, Beehive, Black Panther, Captain America, Daredevil, Dormammu, Dr. Doom, Dr. Strange, Eternals, Falcon, Fantastic Four, Fantastic Four: First Steps, Forbush Man, Galactus, HERBIE, Howard the Duck, Hulk, Ikaris, Iron Man, Klaw, Larnilla, Loki, Machine Man, Mr. Buda, Nick Fury, Quicksilver, Rawhide Kid, Sandman, Scarlet Witch, Sgt. Fury and his Howling Commandos, Silver Surfer, SpiderMan, Sserpo, Sub-Mariner, Thing, Thor, Wakanda, Warriors Three, X-Men TM & © Marvel Characters, Inc. • Big Bear, Black Magic, Challengers of the Unknown, Darkseid, Dingbats of Danger Street, Forever People, Goody Rickels, Kamandi, Losers, Madame Evil Eye, New Gods TM & © DC Comics • Destroyer Duck TM & © Steve Gerber and Jack Kirby Estates • Bullseye, From Here To Insanity TM & © Joe Simon & Jack Kirby Estates • Alaria, Captain Victory, Goozlebobber, Jacob and the Angel, Klavus, Mr. Mind, Personal images in “Color His World” section, Tracy’s Alien TM & © Jack Kirby Estate • 2001: A Space Odyssey TM & © Warner Bros. • Animal Hospital, Thundarr the Barbarian TM & © Ruby-Spears Productions

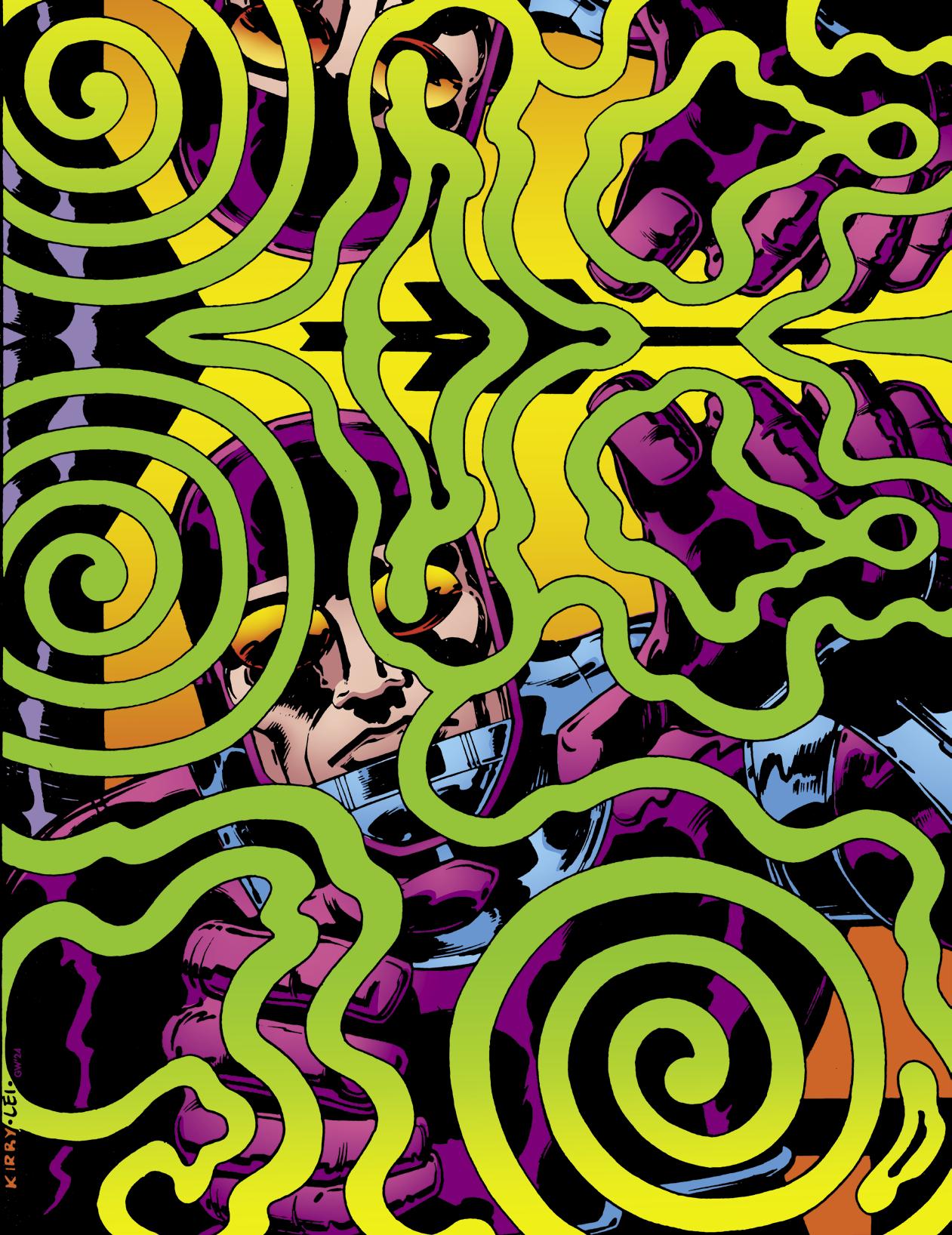

for Jack’s unused cover adorning this issue.

(above) Machine Man #6, page 13 (Sept. 1978). Panel 3’s crazy pattern was the basis

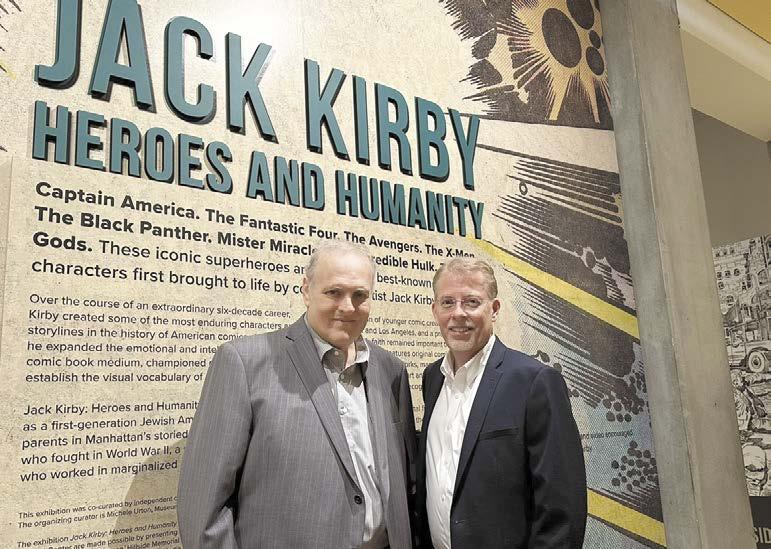

...Welcome to the Skirball, Y’all!

...and how an Alabama native traveled from North Carolina to Los Angeles, California for a once-in-a-lifetime Kirby exhibit, by editor John Morrow

Original art from these comics is on display at the Skirball:

2001: A Space Odyssey

Treasury Edition

Adventure Comics #73

Avengers #1

Black Cat Mystic #58

Black Magic #3

Black Panther #8

Boys’ Ranch #2 and #6

Captain America #112

Captain America Comics #5

Captain America’s

Bicentennial Battles

Captain Victory Special #1

Demon #2 and #12

Devil Dinosaur #4

Fantastic Four #5, 9, 28, 46, 51, 59, 74, 83, 94, 96, and #175

Fantastic Four Annual #2

Fighting American #1

In Love #3

Incredible Hulk #3

Journey Into Mystery #84, 107, and #112

Kamandi #3

Mister Miracle #4

OMAC #8

Our Fighting Forces #153

Police Trap #2

Rawhide Kid #32

Silver Star #6

Silver Surfer Graphic Novel

Sky Masters

Star Spangled Comics #7

Strange Tales #135

Strange World of Your Dreams #4

Super Powers V1 #5

Superman’s Pal, Jimmy Olsen #147

Tales of Suspense #98

Tales To Astonish #34, 35, 39, and #62

The Demon #7 and #16

Thor #139, 153, 155, 159, and #175

True Bride-To-Be

Romances #19

Warfront #28 and #34

X-Men (a full issue’s interior)

Young Brides #27

Plus:

New Gods concepts

Kirby family artifacts

Collages

Animation presentation

pieces and sketches

Personal works

Unpublished works

Growing up in Alabama, I spent ’most every summer of my youth wishing I could one day make it out to the San Diego Comic-Con and meet Jack Kirby— to no avail. I finally got there as an adult in 1991 and met Jack briefly, which inspired me to launch this magazine the year of his passing, 1994. The following year, I first exhibited at Comic-Con, where our booth was mobbed by Kirby fans, in what was a truly magical experience that still fuels me to this day.

After exhibiting at 30 of those cons, while it’s still an exhilarating experience being there, nothing has ever quite captured the excitement and emotions of that first 1995 Comic-Con trip—until now.

On April 30, 2025, I was in attendance at the opening of Jack Kirby: Heroes and Humanity at the Skirball Cultural Center in Los Angeles (adjacent to the famed Getty Museum). The exhibit officially runs from May 1, 2025–March 1, 2026, and if you can find a way, I implore you to see it before it ends. It’s worth the time and expense to make your way West whether you’re a Kirby fan, a comics fan in general, or just someone who appreciates a fascinating and well done exhibit. If you’re looking for a reasonably priced hotel for your trip, I can even recommend where I stayed, and mostly avoided the infamous LA traffic: the Hampton Inn & Suites Los Angeles/Sherman Oaks (about 10 minutes away from the Skirball, and 30 minutes from the Burbank airport, which I flew in and out of).

This is the big one, folks. Nothing like it has ever been assembled to my knowledge. I can not stress enough what an astounding experience it was to view it, especially on opening night.

After introductory remarks by Jessie Kornberg (President and CEO of the Skirball, shown above), at the conclusion of the private opening event, the public was allowed in to preview the exhibit before the official opening the next day. At times, the line just to enter the display that evening stretched to 30 minutes or longer.

The opening night was an invitation-only event filled with Kirby friends, family, fans, and well-heeled art collectors, many of which had loaned their art for the exhibit. After I zipped down to LA to pick up Mark Evanier, we arrived just in time for a quick walk-through of the exhibit before the formal proceedings began. Over hors d’oeuvres and drinks, we chatted with longtime friends including Lisa Kirby, Mike Thibodeaux, Glen David Gold, Mike Royer, Rand Hoppe, Tom Kraft, Charles Hatfield, Paul Levine, and so many others who’d been invited to attend.

This wasn’t the first such showing of Jack’s work; a solo museum exhibition took place 50 years ago. Jack Kirby: Comic Book Pioneer ran from September 15 to December 31, 1975 at Mort Walker’s now defunct Museum of Cartoon Art in Greenwich, Connecticut.

Since then, there have been some impressive exhibits of Jack’s work—namely Comic Book Apocalypse: The Graphic World of Jack Kirby at California State University, Northridge which ran from August 24–October 10, 2015; and KirbyVision, held at the Corey Helford Gallery in Los Angeles from June 29–August 3, 2024. But never has a major American museum devoted itself to displaying the original artwork of one comics creator, in an exhibit this large, with such a lengthy run.

There was so much to take in, and relatively limited time to do it opening night, that I opted to return the next day for a more leisurely stroll, so I could fully enjoy and appreciate what was there. I fortuitously arrived that next day just as a docent’s tour was about to take place, led by co-curators Ben Saunders and Patrick Reed, who offered some behind-the-scenes anecdotes of how the event came to be, in addition to additional history behind the art and Jack’s life, as you’ll see recounted here. At the end of the tour, I asked the roughly two dozen attendees how many of them previously knew about (and were fans of) Jack Kirby, and how many were learning about him for the first time that day. About half said it was their first exposure to Kirby, and that they came because of the Skirball’s reputation for putting on incredible exhibits—something that bodes well for this one serving its purpose of educating the non-comics-reading public about Jack. To a person, everyone seemed extremely impressed with the display, and what they’d learned about him.

The Skirball didn’t produce an Exhibition Catalog for the event, and licensing restrictions prevent us from showing most of the art here—nevertheless, I hope the following overview helps preserve it for posterity, and piques your interest to visit. Thanks go to comics historian Paul Duncan, and Randy Renaldo (creator of Rob Hanes Adventures, found at wcgcomics.com) for supplying numerous photos to supplement my own, and to the Skirball for the materials they provided as well.

So welcome to the Skirball, y’all—let’s get started! H

[below] Utilitas zothecas fermentet bellus saburre. Perspicax syrtes spinosus circumgrediet ut

Photo by Next Exit Photography

OPENING NIGHT PHOTOGRAPHY:

[row 1, l to r] Mark Evanier & John Morrow

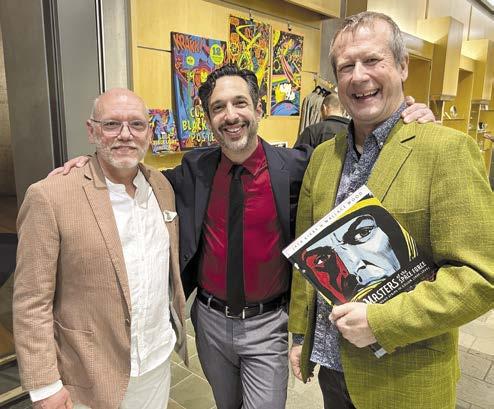

• Tom Kraft, Mike Cecchini, & Rand Hoppe

[row 2] Andrea & David Schwartz • Linda & Mike Thibodeaux

• Sara & Glen David Gold

[row 3] Tracy Kirby • Prof. Ben Saunders

Patrick A. Reed

[row 4] Kaia & Jeremy Kirby • Ray Wyman, Jr.

• Mark Evanier, Gabriella Muttone, & Mike Royer

Kirbyesque Skirball Curator’s Tour

Led by co-curators Ben Saunders and Patrick A. Reed on May 1, 2025 • Edited and transcribed by

Visit the Skirball Cultural Center • 2701 N. Sepulveda Blvd., Los Angeles

Closed Mondays • Tuesday–Friday, Noon-5pm • Saturday–Sunday, 10am–5pm

Get tickets at: https://www.skirball.org/tickets • Free admission on Thursdays

This exhibition was co-curated by independent curators Patrick A. Reed and Professor Ben Saunders. The organizing curator is Michele Urton, Museum Deputy Director at the Skirball Cultural Center. It runs through March 1, 2026.

The exhibition and its related educational programs are made possible by presenting donor Brandon Beck with additional support from Stephanie and Harold Bronson, Hillside Memorial Park and Mortuary, The Dennis and Brooks Holt Foundation, Marvel Studios, and U.S. Bank. Media sponsorship provided by The Hollywood Reporter.

PROFESSOR BEN SAUNDERS: The first thing that people are going to be seeing when they walk in is this wall-sized treatment from [“Street Code”], the only work of memoir that Kirby created. This is the Lower East Side of his memory. But the things that formed his imagination and the experiences that shaped him, that’s what we’re trying to convey in this initial opening space.

PATRICK A. REED: And we wanted to bring you sort of into Jack’s world. So you have his memory of the Lower East Side of New York City where he was born as a first generation Jewish American. We have video material here that provides a little more context. It gives you a sense of time and place; shows both his inspirations and his environment. And so we wanted to augment the text so we are not just filling the walls with words. We wanted to do a little bit of scene building and give you a sense of his environment.

SAUNDERS: The first artifact that you see is his first massive commercial hit, which is Captain America Comics #1. This often comes as a surprise even to people who think they are comics fans. A lot of people think this comic was produced in response to the war, but actually America did not enter the war until twelve months after this was printed. The date you’ll see on the cover says March, but that was actually the sell-by date, if you will. During this period, the comics would come out about three months before the date that is on the cover in an effort to keep them on the newsstand for as long as possible. So this actually came out in December of 1940, almost a full 12 months before Pearl Harbor, and it is a piece of popular propaganda that is attempting to make an argument for why America should become involved in the war. Two young Jewish

John Morrow

Americans, Joe Simon and Jack Kirby, who collaborated on this creation of this character, were obviously more aware than a lot of people in the United States at the time of the nature of the threat that they represented—which means it’s not just Captain America’s first appearance on the cover of American comic, it’s also Adolf Hitler’s first appearance on the cover of American comic book. We try then to offer a little more context for why they may have wanted to create it. Here’s an incredibly powerful and disturbing film that takes about seven minutes to loop through completely here. [A Night at the Garden, 1939, directed by Marshall Curry. It can be viewed at: https://anightatthegarden.com/] This is film of the Nazi rally that was held in Madison Square Garden in 1939. A lot of people are not aware that this happened or that there is film of it. You see the images of George Washington and the flag next to the swastikas. This is of course at a venue where Kirby would’ve gone to see sporting events and entertainments. It’s his neighborhood. So the Nazis came to town, and a few months later he had responded by creating an iconic American character whose job is to punch Nazis.

REED: Yeah, it’s worth noting this wasn’t just in his hometown, this was in his backyard. The old Madison Square Garden was one block away from the Fleischer animation studios where Jack had his first artistic job.

SAUNDERS: So with that, where the war does actually break out and Kirby enlists, we were incredibly fortunate to get this; his family has preserved his uniform [below], and so you can see what a feisty guy he was. [laughter]

REED: We then try to move you through again showing how Jack and his collaborator, Joe Simon, went from envisioning fighting artistically, to fighting the war in person on the front lines. And then you will see throughout the exhibition Jack’s war experiences. This was long before a PTSD diagnosis or anything was even conceived of. But throughout his career, he would revisit a lot of the themes, sometimes with very literal war stories, sometimes with more fantastical, otherworldly stories that he would tell. But there was always a very strong consciousness of the horror of war and the need to fight back against oppression, to stand up to Fascism.

SAUNDERS: At this point, there are other objects that you’re seeing. I think obviously the uniform has a real resonance, but anything that you see in a frame is a piece

Jack Kirby’s US Army uniform, Loan courtesy of Jeremy Kirby

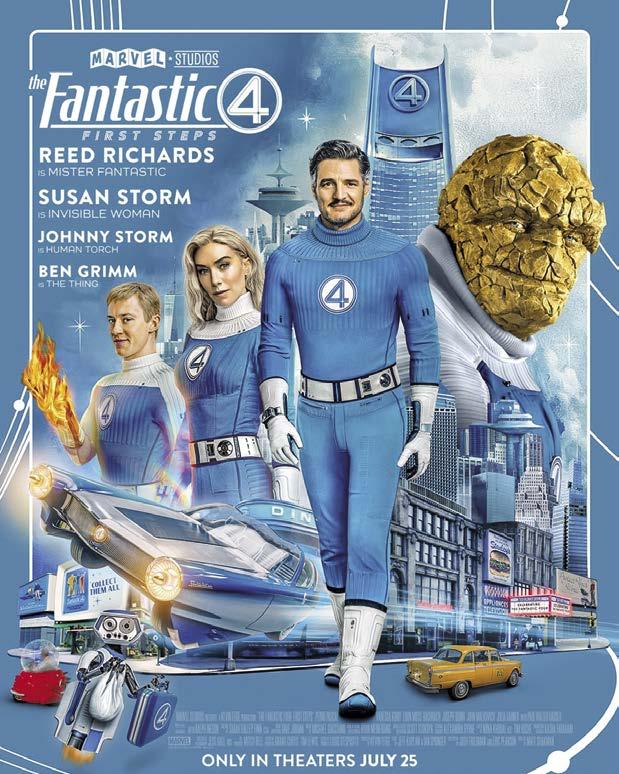

(below) Poster for the Fantastic Four: First Steps film, which this magazine’s editor thoroughly enjoyed. My capsule review: Saw it in IMAX and loved it! I think Matt Shakman nailed it with the retro art design. It felt like it was made for me/my generation, and Kirby fans. They spent the money for good GCI; Ben and Galactus looked fantastic! Vanessa Kirby as Sue stole every scene she was in. Pedro Pascal was fine as Reed; the mustache didn’t bother me, since he also had beard stubble. Johnny needed more screen time, but Herbie didn’t annoy me—and neither did having a female Silver Surfer.

The Real Fantastic “4”

by Will Murray

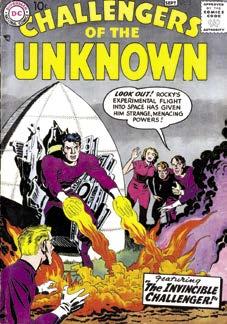

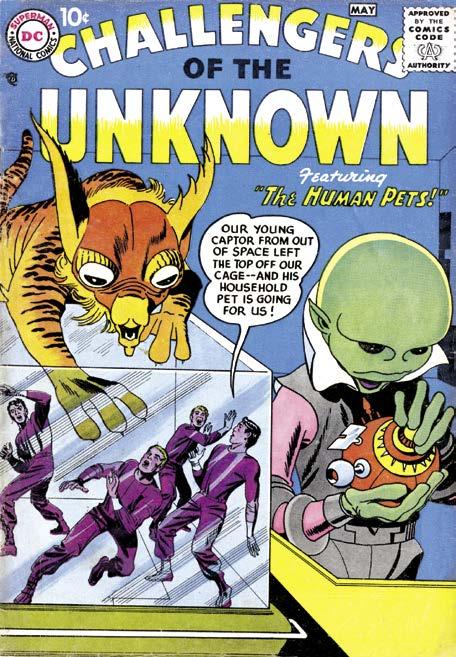

When Stan Lee and Jack Kirby bowed down to reader pressure to give the Fantastic Four distinctive costumes in issue #3, Kirby designed simple uniforms for the cosmic ray-mutated quartet, not much different from those worn by the Challengers of the Unknown, which he had created half a decade before.

“If you look at the uniforms,” admitted Kirby, “they’re the same. It kind of gets to be a habitual thing. My idea of a superhero is some guy who can engage in action. And you can’t engage in action in a business suit, so I always give them a skintight suit with a belt. If you notice, the Challengers and the FF have a minimum of decoration.”

These outfits were utilitarian uniforms not far removed from the astronaut flight suits they had donned in their first issue, and certainly an improvement on the nondescript outdoor garb and billed caps they wore when they penetrated the Mole Man’s redoubt, Monster Isle, later in that debut issue. These togs are obviously intended to be the FF’s regular action attire. While Reed, Ben and Johnny sport caps, Sue’s blouse is equipped with a hood, and Ben’s shirt has a huge collar that’s pulled up to half-conceal his monstrous features. They are also equipped with short boots

into which their pant legs are tucked paratrooper-style, like those worn by the Challengers in their earliest adventures. Why these prototype uniforms were absent in issue #2 is a mystery.

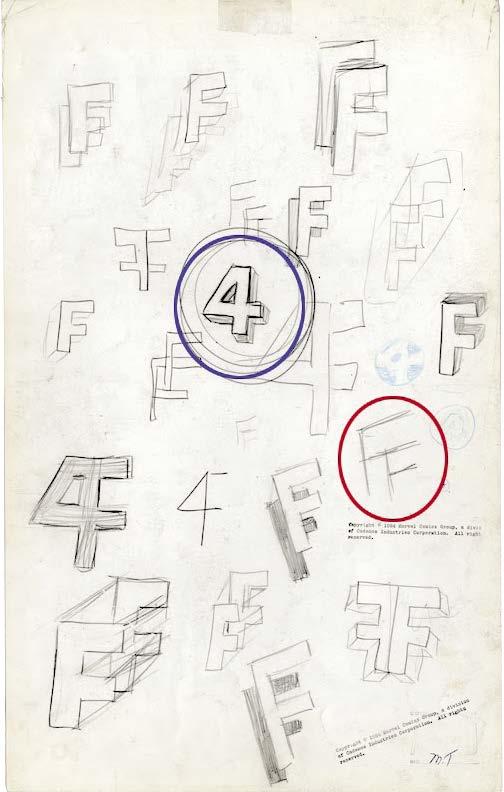

Initially, the FF’s official costumes consisted of two-piece blue uniforms accented by matching black gloves, boots, belt, and collar. To distinguish the Fantastic Four from the Challengers, Kirby gave them a simple numeral 4 centered in a circle on their chests. This was in the decades-old tradition of the superhero chest emblem, which went all the way back to the genre’s prototype, Superman.

On the back of one of the art pages for Fantastic Four #3 [above], someone—it’s unclear if it was Lee, Kirby, inker Sol Brodsky, or letterer Art Simek, but Greg Theakston believed it was Lee––sketched several preliminary test versions of the chest emblem, which included the letters “FF” in various configurations, as well as merged combinations of F’s and 4’s, most offset by striking drop shadows. Among these options, a 3-D “4” is circled, indicating it was selected as final choice. It appears that Kirby initially drew the new uniforms with interlocking F’s as the chest emblem. The elegantly simple numeral 4 was added in the inking stage. The newly-outfitted quartet also wore exotic-looking domino masks [see next page], but these were whited out before going to press.

Unsuspected by Fantastic Four readers was the fact that originally the 4 sign was not merely the simplified

MARGIN NOTES

My very first column for this publication was on Jack Kirby’s margin notes. Needless to say, it is an endlessly fascinating pursuit to investigate Kirby’s original artwork over the span of his career, but arguably more interesting during his time with Marvel. This is because he was working with Stan Lee, who had a final say in his product. Since at that point the King was not generally writing his own dialogue, the margin notes were a shorthand way for him to clarify the direction of his story and what he wished to be the dialogue of his characters.

For whatever reason, prior to 1965 the margin note process was not used. Therefore, we have no way of knowing the nature of the communication related to the direction of the story between Lee and Kirby. No full scripts exist, and the closest things to that are the outlines of issues of Fantastic Four #1 and #8.

However, it is clear that from approximately when the margin note method began to be employed, Kirby had more control over the direction of his product, and as a result his art and storytelling took a major leap forward into greatness.

It is enlightening to compare the original art to the printed comic, because we can see what changes have occurred after Lee’s interventions, and how they have impacted the plot. Sometimes the final product is at odds with Kirby’s intent as a plotter, and these discrepancies can clarify the actual nature and extent of the two men’s contributions.

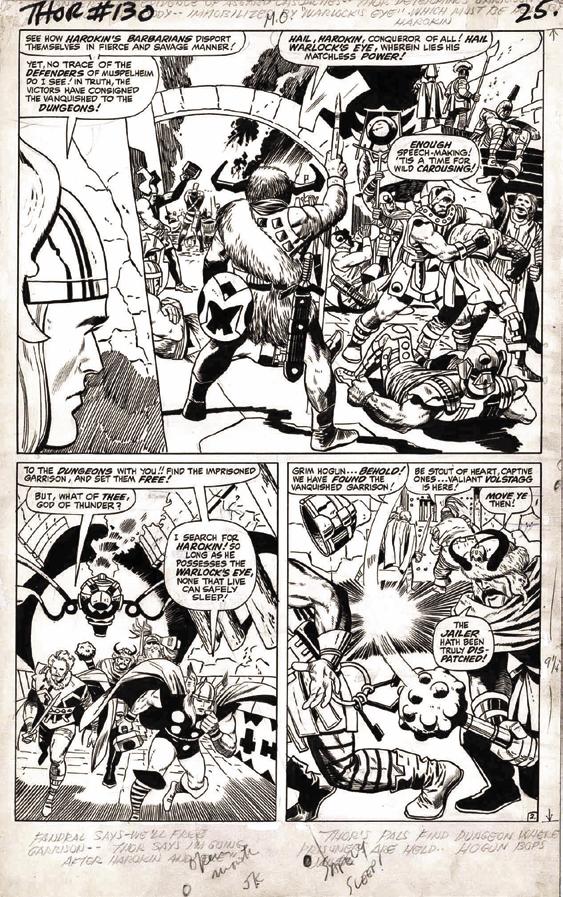

1 This Thor #130 “Tales of Asgard” page is a somewhat common example. As is often the case, between the trimming of the border and heavy-handed writing over the page, we see that much of Kirby’s notes is obscured. What we can make out tells us that the dialogue in the large first panel fairly accurately represents Kirby’s margin notes. However, we can see that in panel’s 3, Lee removes dialogue from Fandral and gives his line to Thor. In panel 4, Kirby’s notes suggest that in the background, Fandral and Volstagg have found the imprisoned garrison which the visuals clearly show, and Lee give appropriate dialogue to those characters. So in this case, both men make contributions to the story that are not essentially at odds with each other.

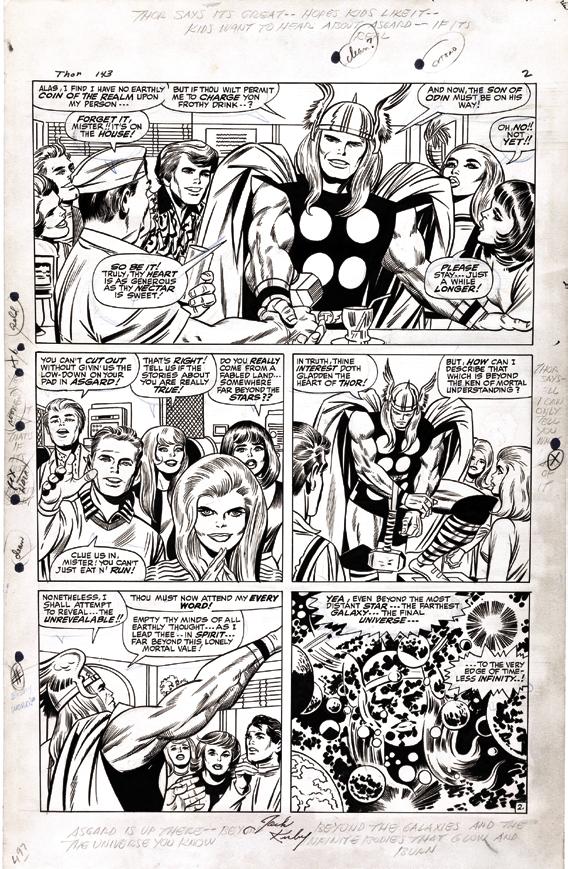

2 This page of Thor #143 again shows Lee sticking to Kirby’s margin notes more or less. In the first panel, Thor is seen enjoying a

beverage at a local soda fountain, and Kirby’s brief notes at the top margin indicate that the youths there want to hear about Asgard. Lee expands on this in his usual way, giving several of the kids dialogue to flesh out Kirby’s general directions. As usual, the page has been trimmed, so it’s difficult to make out what Kirby has written on the left margin (referring to something not being a publicity stunt). In the following panels, Lee’s script seems to overemphasize the impression that Thor believes Asgard to be beyond human comprehension, which is not something that Kirby’s notes imply Thor is saying.

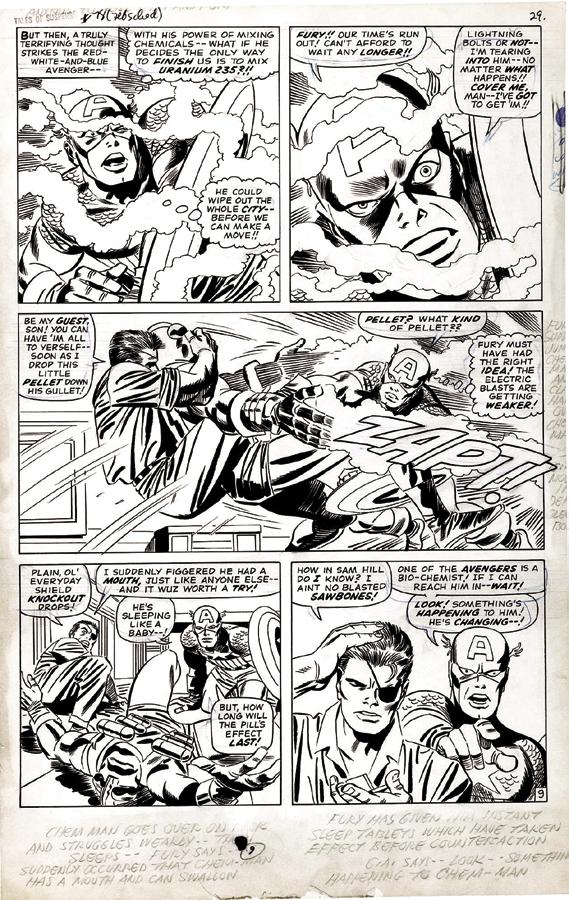

Based on the margin notes that can be made out, this page from Tales of Suspense #78 3 is another good example of Lee staying pretty close to Kirby’s intent. Although a good deal of Kirby’s writing has been trimmed from the right margin, one can still make out a portion of a sentence that probably reads, “Fury suddenly jumps Chem Man and clamps his hand over Chem Man’s mouth,” but the action on the page already makes this clear. Kirby’s bottom margin notes basically state that Fury has slipped the “Chem Man” a mickey, so Lee does a pretty good job putting that fact in the conversation between the two heroes in panels four and five.

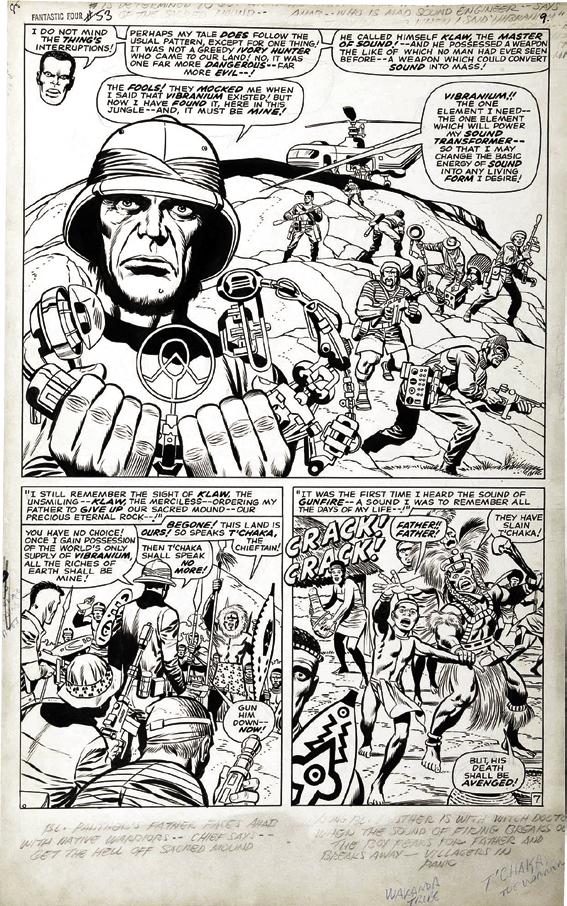

Next is a sample from Fantastic Four #53 4 worthy of mention because of the alterations that Lee clearly makes. In his margin notes, Kirby gives the villain the name Ahab, an obvious reference to the obsessive captain in Moby-Dick. He also draws the character very

much as Ahab is often depicted, with a gaunt face and a distinctive chin beard. Lee discards Kirby’s idea and names the villain Klaw. Kirby describes Ahab as a “Mad Sound Engineer”, which Lee alters to “Master of Sound.” However, Lee retains Kirby’s use of the word vibranium and changes the words “laughed at” to “mocked,” but essentially gives the villain the script that Kirby suggests. The captions and dialogue in panel 2 more or less follow Kirby’s intent, as T’Challa’s father orders the interlopers to leave. Kirby’s notes in the final panel indicate that young T’Challa hears gunfire from afar, and Lee’s dialogue maintains that perspective.

It is worth mentioning that the Panther’s narrative of Klaw’s villainy resolves in a way that does reflect Kirby’s initial use of the name Ahab. Klaw’s hand is damaged as a result of the young Panther using the villain’s own weapon against him. As Ahab loses his leg because of his obsessive pursuit of the “White Whale”, Klaw is maimed and eventually altered by his own obsession with the pursuit of vibranium. In removing the name Ahab from the story, Lee has essentially nullified Kirby’s symbolic resonance associated with that name.

5 This page from Fantastic Four #61 is notable because there are clearly notes from both contributors. It is likely that at the last minute, Lee’s note in the upper left has given more dialogue to Johnny in the first panel. Kirby’s notes are pretty faithfully followed in panels 2 through 4, although Lee gives Ben and Sue dialogue

Innerview

The King At Work

Interview by James Van Hise, originally presented in Comics Feature #44, May 1985*

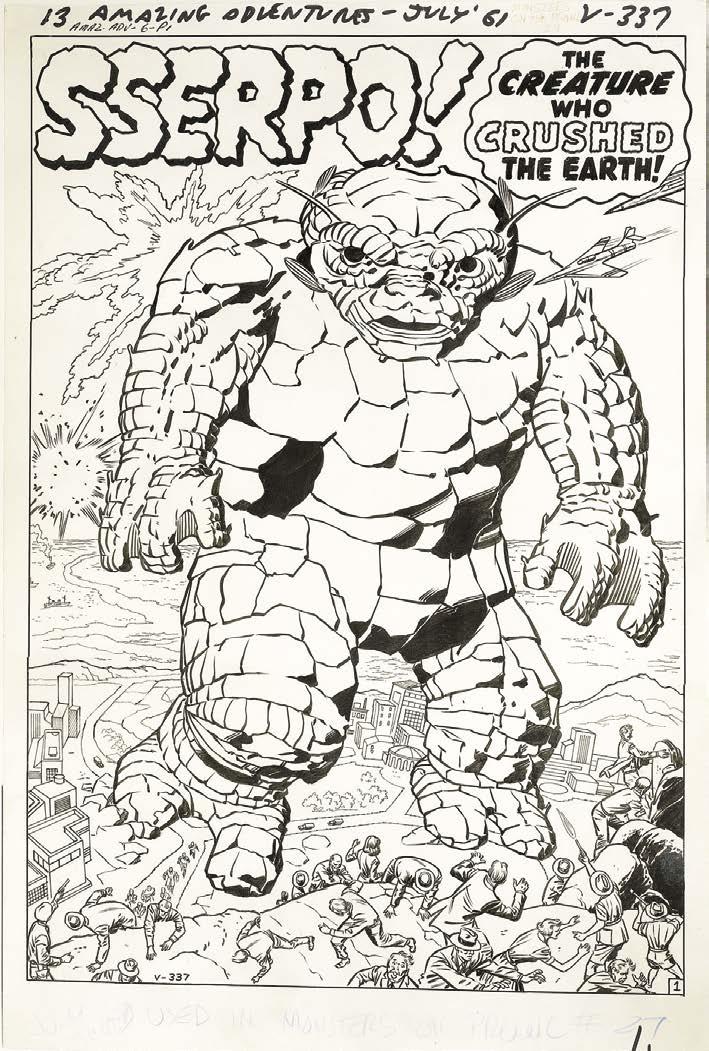

(below) Sserpo lives in Amazing Adventure #6 (Nov. 1961). He exhibits a rocky hide the same month a rather lumpy-looking Thing was debuting in Fantastic Four #1.

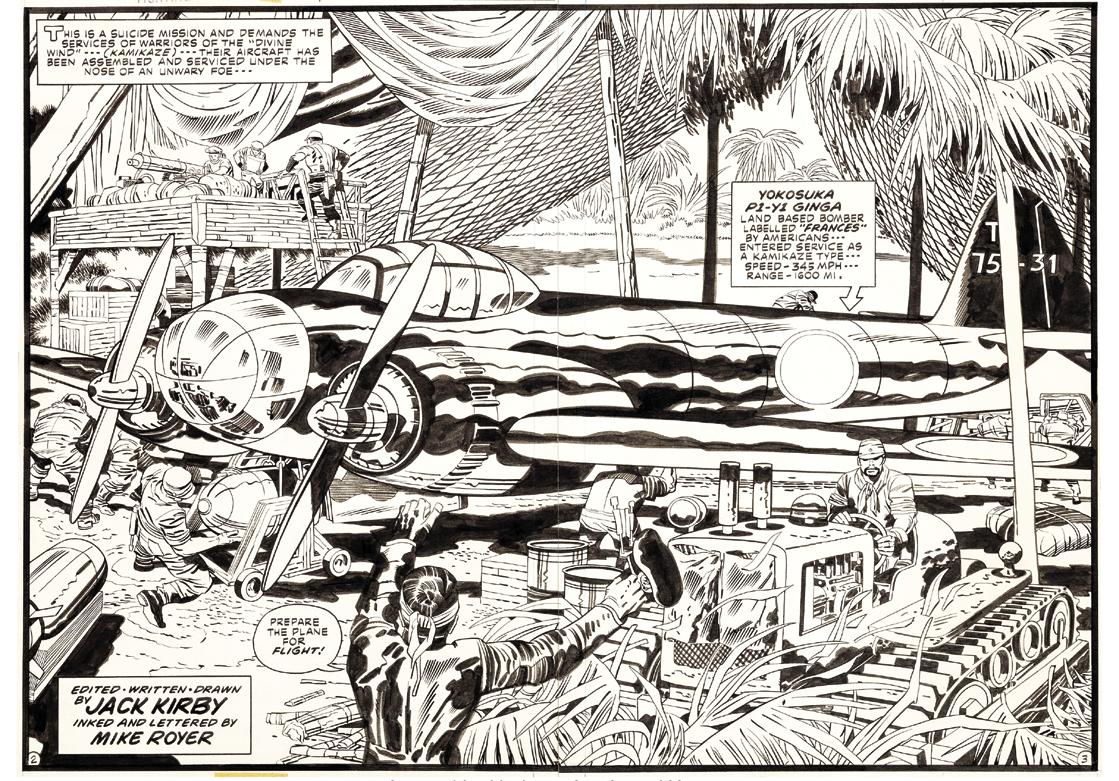

(next page) Original art for Our Fighting Forces #158’s two-page spread (Aug. 1975).

Without Jack Kirby, there may well not be a Marvel Comics today. Kirby helped create all of Marvel’s seminal characters: the Fantastic Four, the Hulk, Spider-Man, Thor, the X-Men, Captain America, and others. These heroes form the backbone of the Marvel line, then and now. In this, the 25th anniversary year* of the creation of the Fantastic Four, it is impossible to look back over Marvel’s creative history without giving credit to Kirby, their most powerful creative dynamo. Kirby lived on Long Island for 20 years, and it is a time he remembers with fondness.

“I lived in Long Island, in East Williston in central

Long Island. It was a nice town in which to raise children. I bought a house there. It was a lovely little town—you could walk across it in five minutes. I raised all of my children there.”

Unlike other Marvel staffers who worked at the office, Jack labored at home.

“I had a little dungeon-like basement, and I worked there,” he recalls. “I bought a big moose head for about five bucks, and put it up on the wall. If you patted that moose head, a big dust cloud would come out. It was a wonderful place to work because I could create the stories and the characters there. When you’re alone and you can think, that’s all an artist/ writer wants, and then you can reach out for new things. It’s not just a matter of telling stories and selling books, it’s a matter of not being static. I never remained static. I always looked for new things and new characters and new ways of telling a story.”

A Creative Philosophy

Describing the 1960 period of Marvel, Kirby explains that the monster books they were doing had become repetitious, and a new direction was needed.

“Marvel had monster books, romance books, and Westerns—and all of those weren’t working any more. They didn’t know what to do then. Nobody there could write them so that they didn’t remain static. Marvel was stagnant.

“I did a Rawhide Kid which sold better than all the rest. I did monster books which are still remembered and collected today. When I draw a monster book, I’m giving you the real thing, and you’ll enjoy it. That’s what I did for Marvel. But I felt that wouldn’t sustain Marvel, because it was the same old subject which had been used for quite a few years. Going back to the superheroes was the thing to do.”

Kirby states that there were no story conferences to discuss the new characters before he prepared them.

“I came in with presentations. I’m not gonna wait around for conferences. I said, ‘This is what you have to do.’ I came in with Spider-Man, the Hulk, and the Fantastic Four. I didn’t fool around. I said, ‘You’ve got to do superheroes.’ I took Spider-Man from the Silver Spider—a script by Jack Oleck that we hadn’t used in Mainline. That’s what gave me the idea for Spider-Man. I’ve still got that script.

“The Hulk I took from one of the monster stories I’d done. [Note: From Journey into Mystery #62] I took the Hulk name and made a superhero out of him because I felt it was realistic,” he explains. “There’s a Hulk in all of us. It was a natural. They were going to discontinue it after the third issue because they had no faith in it. The Hulk was saved when a couple of guys came

up from Columbia University with a list of 200 names, saying that the Hulk was the mascot of their dormitory. I said, ‘For God’s sake, don’t stop the Hulk now! We’ve got the college crowd!’ We’d never had the college crowd. They would never read a comic book before, but this time they were reading them because I was slanting them to a universal audience. My job is to do a comic book which attracts everybody. If I did a motion picture, I would have the same kind of challenge. My job was entertainment, and that’s what I did!”

Kirby feels that his approach is that he writes from the heart.

“I write from a people’s point of view. I write what I know about the next guy and what I know about myself. That puts a little realism in a story. Then I dramatize it for entertainment, and have a wonderful time at it. I think that anybody who gets the opportunity and the time to do it has a wonderful time.

“It’s not the heroics. It’s the humanity that counts,” Kirby asserts, “and that’s what I put in my stories. Of course, I don’t get gory. I don’t get sleazy. You don’t have to. It’s something that you’ll never find in my stories.”

Kirby drew on past experiences whenever he wrote or drew for Marvel.

“I was a PFC in a heavy weapons platoon,” says Kirby of his stint in the army in the second World War. “There was plenty of action. When a barrage came in, you thought that the world was gonna end. I saw things that made me turn off. Then, of course, the war became bearable. A lot of these things are reflected in my stories. I can dramatize what I felt. I did that in those stories. People began to mean a lot to me; my characters began to mean a lot to me. The Hulk, Spider-Man, Captain America, and all the rest—and, of course, the Howling Commandos… They were people and they were successful. Everything I did for Marvel was successful.”

Classic Characters—New and Old

In the fourth issue of The Fantastic Four, when the Marvel universe was still aborning, Kirby revived a character he had never been creatively associated with before: Prince Namor of Atlantis—the Sub-Mariner.

“I felt that Sub-Mariner was a powerful character and should be used. It had originally been done by Bill Everett. But those old characters, like the Human Torch, could be used. I used everything that was at hand, that Marvel had which could be used as a superhero.

“I brought Captain America back from the dead, and I made him human because Bucky was dead. He had to live with the fact that he no longer had Bucky. Those things happen. Having been in a war, I’ve seen that. The war changed me because I saw guys suffer— guys with wounds. I saw one guy walking through the train, and he was saying, ‘I understand my wife wants to talk to me? Where is she? Have you guys seen her?’ Of course his wife wasn’t there. He didn’t have his mind. He was in shock. This was on a train heading for the hospital at Verdun. I saw all that. I saw guys with half-faces, and I began to see people in every type of circumstance. And there were other sides, comic sides. I put all those facets into the war stories. My war stories for DC are still remembered.”

Kirby’s creations reflected the tone of the times in which they were written. That is why so many of them were, either directly or indirectly, products of the Atomic Age.

“I created the X-Men because of the radiation scare at that time,” says Kirby. “What I did was give the beneficial side. I always feel that there’s hope in the human condition. Sure, I could have made it real scary. We don’t know the connotations of genetics and radiation. We can create radiation, but we don’t know what it’s

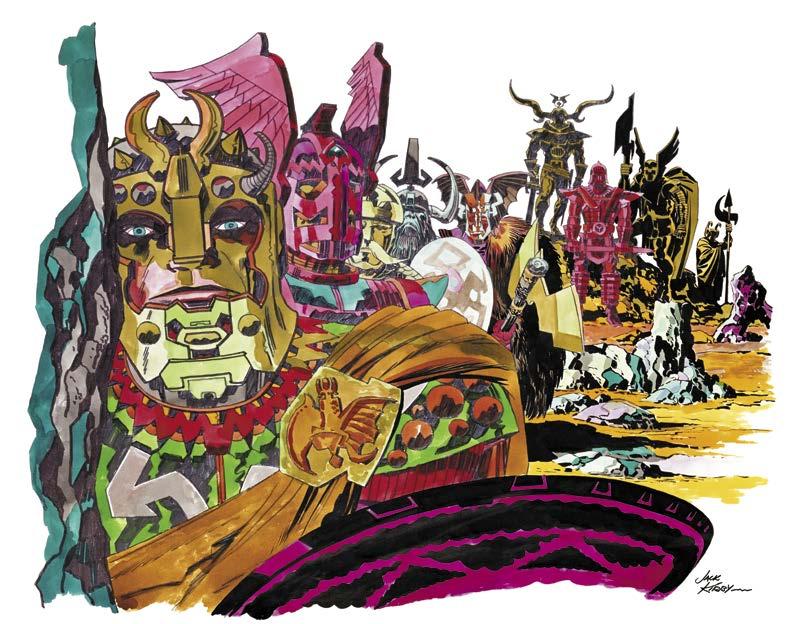

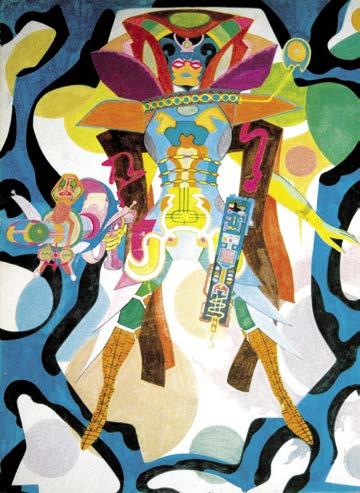

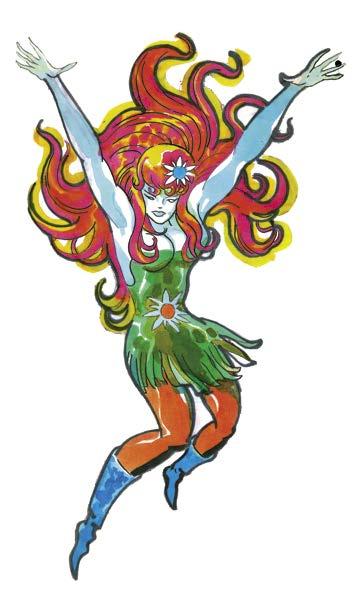

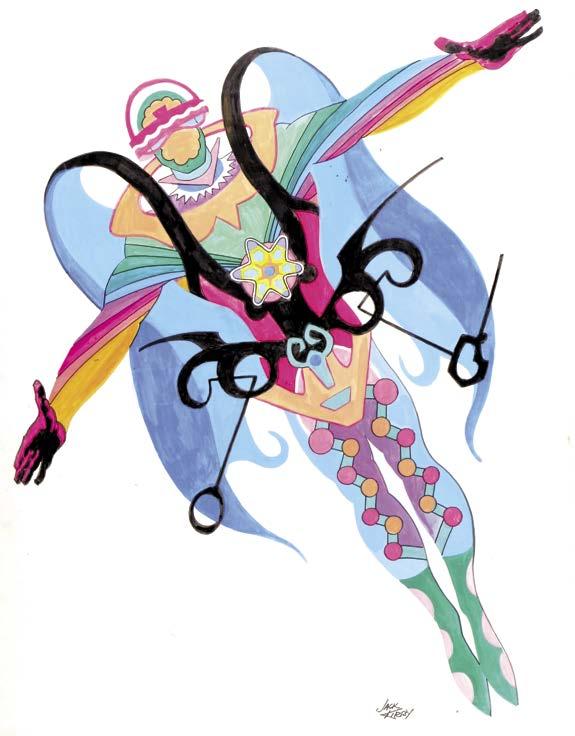

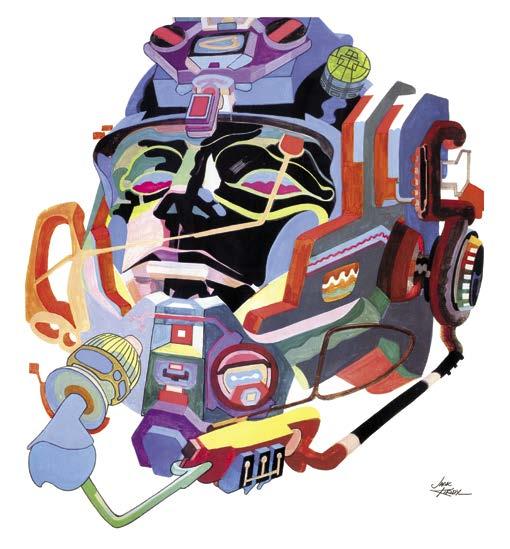

Kromatic Color His World

An eye-popping look at Kirby’s coloring, by John Morrow

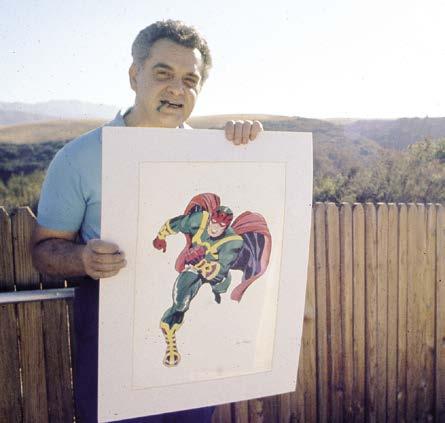

(below) You can see how much the Dr. Martin’s dyes have faded from this circa 1969 photo (probably taken within a couple of years of producing this drawing), and the same art decades later.

Jack Kirby’s art and storytelling were undeniably unique among comics professionals. But one aspect of his output has gotten little attention— surprising, since it’s so in-your-face. It’s his sense of color, which is every bit as idiosyncratic and powerful as his bombastic penciling style.

Growing up and living in New York until the late 1960s, Jack had ready access to its art scene. If you search for his artistic interests outside of comics historically, he was likely intrigued by the medium of collage as early as 1956, when fine artist Richard Hamilton included a Simon & Kirby Young Romance cover in his collage “Just What Is It that Makes Today’s Homes So Different, So Appealing?” By the early 1960s, collage became a regular part of Kirby’s repertoire, both personally and in his comics work (though in comics, it was frustratingly hampered by terrible black&-white-only reproduction). From there, the next step in his artistic evolution appears to be watercolors—Dr. Martin’s dyes, to be exact. Those dyes were only meant for commercial work that would be reproduced soon after use, and not for long-

term fine art display hundreds of years later, like the work of the Old Masters. As you can see by many of the examples presented here, the dyes faded relatively quickly, and it’s challenging to try to reproduce and restore these older pieces that have faded over time. Thankfully, photos of many of them were taken while the dyes were fresh and vibrant [above and left], so we can see them close to what Jack put down with his brush. Also, there are 12 fluorescent colors that are not meant for reproduction use [shown above], and Jack seems to have enjoyed using those in his work—and they tended to lose their vibrancy more quickly than other colors.

The psychedelic art movement of the 1960s looks to have caught Jack’s eye, including the work of Peter Max, known for his dazzlingly colorful creations. When asked about Max’s work in an interview for Train Of Thought #6, circa 1972, Jack replied, “Oh, I’m crazy about it. I think Peter Max has taken a greater step than Picasso. I think Peter Max has really taken a realistic stance as far as art is concerned. He’s made art less

harsh, and art more rich, and given it more form and more grace. I just can’t explain the kind of admiration I have for Peter Max.”

(It should also be noted that Picasso is considered one of the pioneers of collage art.)

Jack appears to have stayed in touch with the fine art world, as well as the pop art movement and commercial art. It’s unknown whether he was involved in the

decision to briefly call Marvel’s output “Pop Art Productions” in 1965, in the wake of Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein’s popularity.

Poster artists like Rick Griffin and Victor Moscoso likely influenced Jack also, at least in passing. Although he’d already moved to California by the time of the August 1969 Woodstock music festival in upstate New York, that important cultural landmark event—plus moving to California and being surrounded by rock concert posters and album covers— was bound to rub off on him, and he produced several psychedelic images during that era.

The Los Angeles Times eventually published Jack’s Pioneer Plaque illustration and essay alongside work by both Peter Max and Victor Moscoso in their September 12, 1972 West Magazine supplement.

Space-in Captain Victory: Zap-Out!

by Richard Kolkman

“This is how it will happen when the star worlds come to Earth!” comes the breathless opening of Captain Victory and the Galactic Rangers, Kirby’s cosmic comic book series for brothers Steve and Bill Schanes’ new Pacific Comics direct market title.

After his contract with Marvel ended in April 1978, Kirby’s books disappeared from newsstands. However, Kirby was still a restless working artist. An unstoppable creative force. A storyteller—bolstered by forty years in the comics industry. In addition to his new-found work in animation, Kirby started work on his own series—creator-owned. An investor wanted to sign Kirby to an idea for an imprint, Jack Kirby

Comics, in 1978. While the company never got off the ground, Kirby did produce the two-part, 48-page story of Captain Victory, inked by Mike Royer. Kirby explained in 1982, “Captain Victory is my answer to Steven Spielberg.” (The movie he’s referring to? Close Encounters of the Third Kind, 1977.) Distilled from an earlier movie screenplay by Kirby and Steve Sherman in 1976—“Captain Victory and the Lightning Lady”—it was the beginning of Kirby’s final creative freedom. The concept stayed in the files until it was offered to Pacific Comics.

Exploding amid much industry promotion, Captain Victory had a difficult journey into print. The terms were new in the comics business, favoring the rights of the creators: Full ownership of intellectual property, art returns, and a royalty rate. Not much, but it was a show of professionalism and respect. After 18,000 copies of the first issue were destroyed in a delivery truck accident, the issue had to be reprinted.

From such mundane beginnings, Kirby began to weave the story. Captain Victory/Captain Glory harken back to 1968’s Secret City concept art. Kirby never wasted a good idea, for he had hundreds of them. The overall concept is of a galactic protector, fighting to keep a galaxy safe from evil infiltration by “Insectons” (Homo Insectus). This is a well-used plot by Kirby. In Black Magic #31 (Aug. 1954), Simon and Kirby’s story “Slaughter-House” has Earth dominated by insect-like alien oppressors. Then later, in Journey into Mystery #124–125 (1966), Queen Ula menaces Asgard in “Tales of Asgard” as she commands her deadly, invasive “Swarm.” Still later, in New Gods, Mantis invades Earth, culminating in issue #9 and #10’s “Bug” infestation takeover. The hive mind always bothered Kirby because he respected the individual.

After no new Kirby comics for three years (1979–1981), I was stunned when I first saw Captain Victory #1 on the stands at Fool’s Paradise in Bloomington, Indiana (IU). Kirby had returned—and his name wasn’t even on the cover.

It didn’t need to be. Kirby may have been inspired by Close Encounters, but Captain Victory rode in on the tailwinds of Star Wars (1977) which spawned hundreds of imitators, all snapping at the big interstellar pie full of money. Seemingly, every franchise had to have a cute, impertinent robot sidekick. The Fantastic Four (animated) had HERBIE, Buck Rogers (TV) had Twiki, and on and on... Captain Victory, of course, has Mister Mind (Egghead), an annoying, super intelligent encephaloe—with a “mental hernia.” (It may have been the “fascinating ultimate” that caused it.) Kirby also had some overtly silly unpublished concepts at this time: “Star Cats” (parody), “The Astrals”, and “Deep Space Disco”—a blatant rip-off of the memorable “Cantina” scene in Star Wars

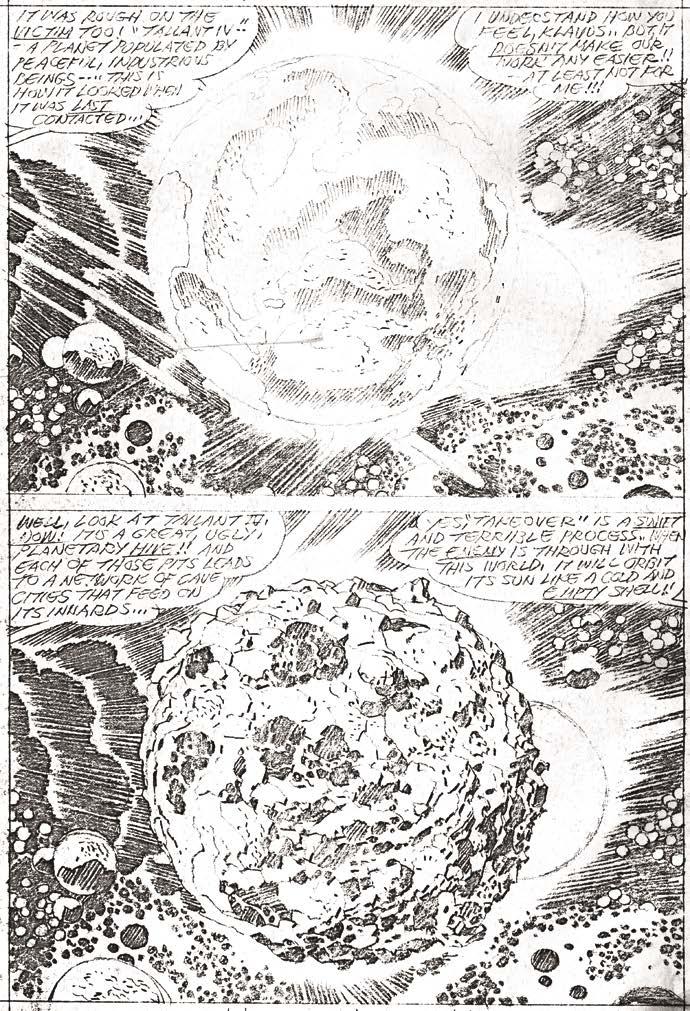

(below) Page 3 pencils from Captain Victory #1 (Nov. 1981), in a visual reminiscent of the opposing worlds New Genesis and Apokolips from the Fourth World.

Gallery 1 Losing Your Mind

A gallery of Jack’s maddest work, with commentary by Shane Foley

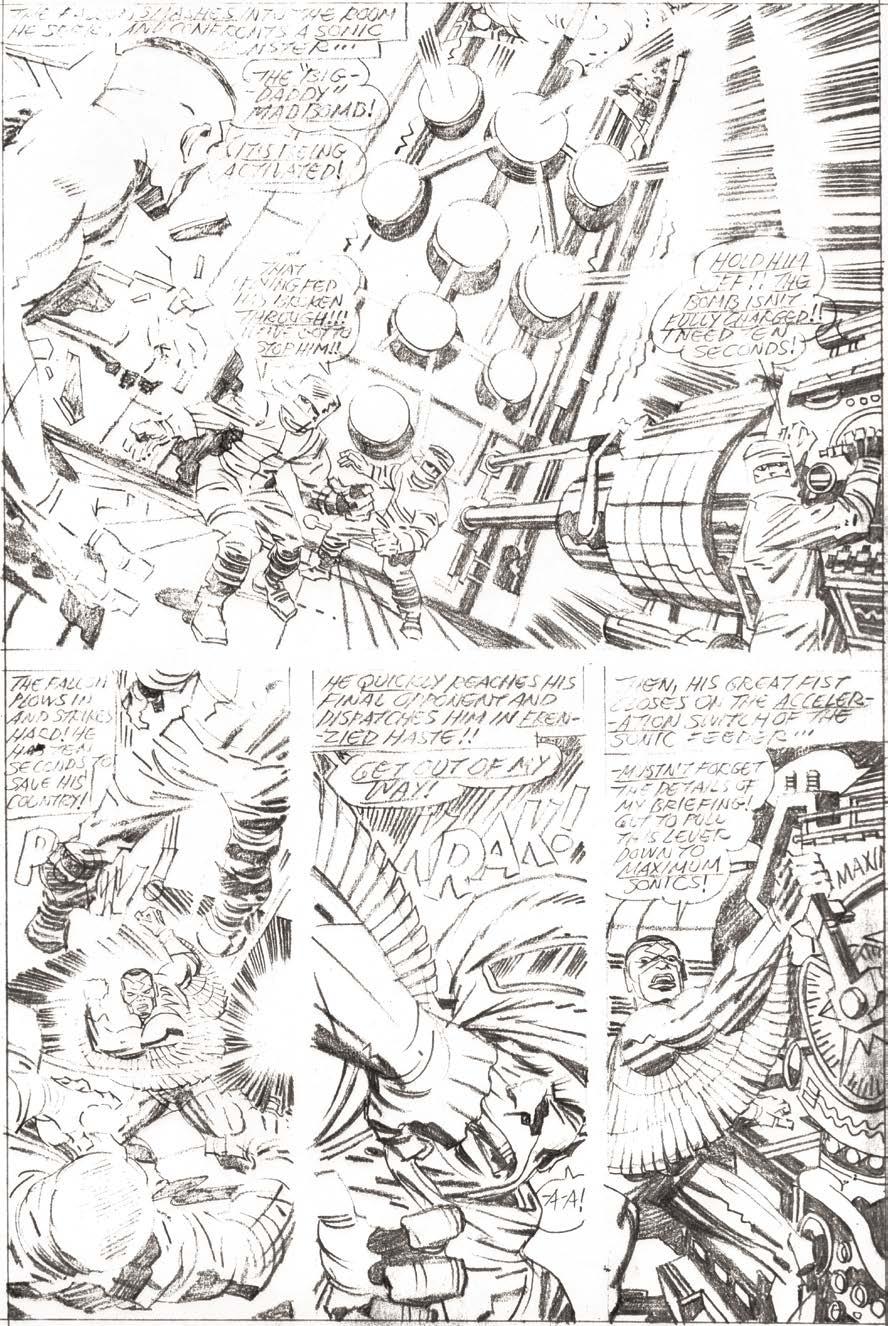

[right] Captain America #200, page 9 (1976):

Tilting the POV in the top panel is so simple, yet so dynamic. What made Jack do it? As usual, our commentary on his drawing is as much about his mind as his tremendous drawing skill. There are plenty of comic artists who wouldn’t have begun to think of such a storytelling option. Between this simple tactic and the flash lines, our minds quickly get the idea of the power the Falcon confronts.

[next page]

Captain Victory #9, page 12: (1983):

Notice the “alive” shadows in panel 5—all swirling snakelike around to give life and tension to a picture of a very still body. I love that little extra piece of shadow under Mr. Mind’s arm—that little swirl that joins the shadow of the body’s head to the right side of the panel. It looks like Jack added it as an afterthought. “Not enough action,” he must have thought.

WIncidental Iconography

An ongoing analysis of Kirby’s visual shorthand, and how he inadvertently used it to develop his characters, by

Sean Kleefeld

hen I first thought to write this issue’s column on Destroyer Duck, I felt it would be interesting, but fairly straightforward. In the early 1980s, both Steve Gerber and Jack Kirby were having separate, largely unrelated, ownership disputes with Marvel Comics. Gerber took formal legal action and created Destroyer Duck to both mock Marvel’s position, as well as raise funds for his legal battle. Jack was sympathetic and drew the first issue of the comic for free.

Gerber’s history and issues with Marvel are a lot deeper than that, of course, but since I’m here to talk about how Jack designed and drew Destroyer Duck, I can gloss over much of that—except, part of what I’d like to discuss here is how future artists took their cues from Jack’s designs.

“What’s to discuss, Sean? There were only seven issues, and Jack drew five of them.”

Yeah, well… it gets muddy after that pretty quickly. But I’ll get to that in a bit.

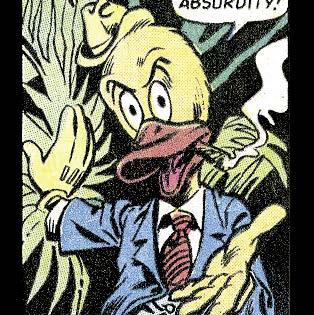

The concept of Duke “Destroyer” Duck is actually fairly straightforward. Since Gerber’s story is a direct commentary on how he created Howard the Duck for Marvel, Gerber set up Destroyer Duck as coming from the same world—Howard and Duke were even friends—so Jack’s design of an anthropomorphic duck stems at least in part from Val Mayerik’s original design of Howard [above left]. But Jack was never known for emulating others’ artistic styles, and indeed, it should be noted that Jack’s pencils on any of

Kirby’s art for the F.O.O.G. portfolio envelope, as penciled, and then inked by Alfredo Alcala (next page, top).

the duck bills that show up in the series are a bit awkward, and inker Alfredo Alcala did wind up touching up many of them to more closely match Howard’s bill.

(As an aside, I suspect Jack was aware of his “limitation” in drawing duck bills—I can’t find any other animal-based characters, from the High Evolutionary’s Ani-Men to any of the creatures encountered by Kamandi, in which he includes anthropomorphized ducks.)

Of course, this is still a humanoid duck filtered through Jack’s eyes, so Duke is considerably taller and more muscular than Howard. In fact, in his first issue, at one point we see Duke stripped down to a pair of boxers with all his feathers plucked [right], and he looks very much like someone slapped Howard’s head and feet on a par-for-thecourse superhero that Jack drew.

But that’s not Destroyer Duck’s primary look. He’s more often seen wearing a knitted cap

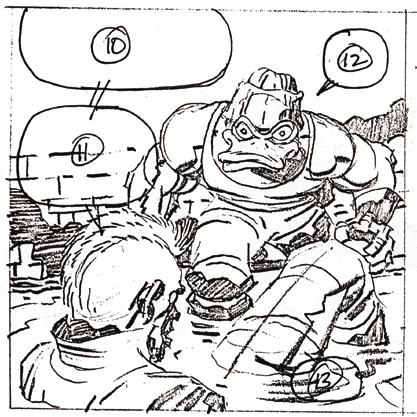

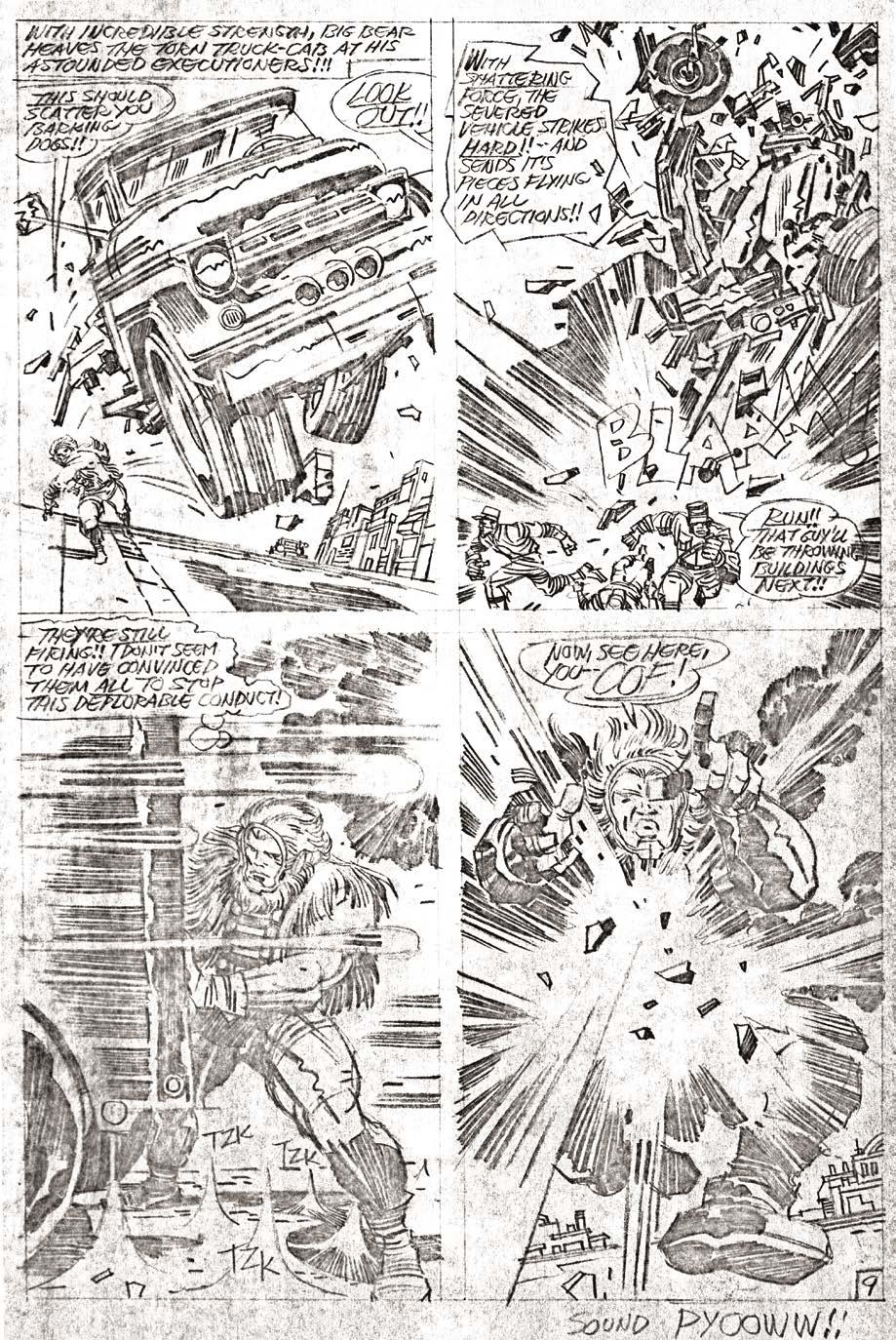

Gallery 2 Grin & Big Bear It

A little comic relief from a gallery of Jack’s funniest Forever People work, with commentary by John Morrow

[this spread] Forever People #8, pages 9–10.

[next two pages]

Forever People #9, page 7.

Forever People #7, page 10.

Of all the Forever People, Big Bear had the most personality. While being the strongman of the group, he was simultaneously the main comedic element of the strip, as evidenced by these pencil pages. They prove that Jack could set up a sight gag with the best of them. Make special note of the plethora of sound effects that Jack indicated for Mike Royer to letter across just these four pages:

BLAAM! TZK TZK TZK PYOOWW!! WHOOOOMM!

BAROOOM!! BAM!!!

RRRR VROOM!!

RRREEOW!! RRROWWR! POP! WHAMM!!

Kirby must’ve literally been hearing these noises in his head while visualizing these scenes!

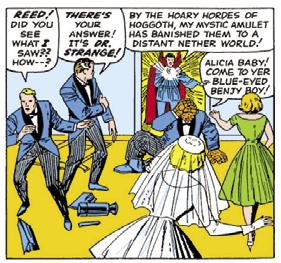

Whichcraft

Strange Strange

ever in one place too long, Kirby’s take on Dr. Strange popped up almost randomly—complementing Steve Ditko’s definitive version. Precursors of Ditko’s creation could be found in Marvel’s (then Atlas) pre-hero mystery titles. Witches, warlocks, wizards, and sorcerers begin here. Amazing Adventures’ Dr. Droom began his occult practices in the mountains of Asia, similar to Dr. Stephen Strange. Sazzik the Sorcerer completes the round-up of spell casters in Tales of Suspense #32. Also, the villainous Dr. Strange who confronts Iron Man in Tales of Suspense #41 (May 1963) is not our hero. After Ditko and Lee got rolling with Dr. Strange’s introduction in Strange Tales (an apt home) #110 (July 1963), Strange didn’t make his first cover appearance until #118 (March 1964) in a typical Ditko vignette. Kirby’s Dr. Strange cover appearances begin with #121’s vignette 1 (June 1964), which matches Ditko’s interior story content. Sometimes Strange shares half the covers with co-stars the Human Torch and the Thing; facing off with Mordo, Loki, Dormammu, or other baddies. Kirby’s Dr. Strange had a look of his own. Even though Kirby adapted to Ditko’s costume revisions, Kirby’s Strange had a narrow, angular head, similar to his take on Sub-Mariner. Who needs a model sheet? Kirby’s Strange appears on the covers of Strange Tales #121 1 , 123 2 , 125 3 , 126 4 , and 128 5 ; including a star turn at the mercy of Baron Mordo on the cover of #130 6 (with beautiful Chic Stone inking).

CROSSING OVER

plays a major part in Journey into Mystery #108 9 (Sept. 1964) helping Thor (from a hospital bed) battle Loki. Throughout these guest shots, Kirby and Lee are faithful to the character. In the 1960s’ Silver Age, it seems that Dr. Strange never crossed paths with the X-Men, Captain America, or Hulk. By 1965, after “Nick Fury, Agent of SHIELD” took the Torch’s spot Strange Tales, Kirby’s Dr. Strange basically disappears. And the counterculture was not left out: After Kirby’s Strange began appearing in the corner logo box on ST #142 10 (March 1966), he was appropriated by artist Greg Irons for the “Strange Happenings” concert at San Francisco’s California Hall by the Youngbloods.

Guest appearances were not always apparent. Dr. Strange works behind the scenes of Fantastic Four #19 (Oct. 1963), which is not revealed until later. Strange also helps the FF in #27 7 (which Jack redrew for Marvel Collectors’ Item Classics #19 in February 1969), FF Annual #3 8 (1965); and

Kirby also portrayed Dr. Strange on some outside projects: 1965’s Merry Marvel Marching Society (MMMS) Stationery Set 11 (inked by Marie Severin) and in a Marvel Superhero group illustration in September 1966’s Esquire magazine 12 (comics are cool on campus). Just before Ditko’s final issue (ST #146, July 1966), we get one final vignette (floating) head by Kirby on the cover of #144 13 (May 1966). In ST #161 (Oct. 1967), artist Dan Adkins swipes the splash panel creature from Kirby’s “The Big Hunt” in Harvey’s Alarming Tales #2 14 (Nov. 1957). Though Kirby drew a Dr. Strange promo icon for Marvelmania in 1969 15 , the good doctor does not appear in Kirby’s well-known Marvelmania self-portrait. I don’t believe any convention sketches or commissioned art of

Kirby’s Master of the Mystic Arts, by Richard Kolkman

Barry Forshaw

A regular column focusing on Kirby’s least known work, by Barry Forshaw

(below)

THE ART OF SIMPLICITY

Towards the end of his career, Pablo Picasso so refined his art that he could bash off a drawing which consisted of merely a handful of lines—and his instant artworks would often fetch the kind of stonking prices that many of his canvases accrued. Jack Kirby, of course, never enjoyed such prodigious financial success, even though he was similarly a master of economy (and it’s a crying shame that he never lived to see the immense cinematic success that his co-creations posthumously achieved). And if you want a classic example of this particular skill, just take a look at the cover of the very first issue of Challengers of the Unknown (published by DC in April/May 1958 with inking by Marvin Stein). It shows the four Challs imprisoned in a clear glass box while a bizarre giant-sized alien cat reaches into maul them. Take a look, however, at the figure to the right of them—another gigantic alien, this time a child, fingering what we later learn is a strange toy. The face of this creature consists of just about six lines, but these lines are perfectly chosen to suggest the otherness of the creature. Similarly, in the story that follows, the misbehaving giant is rendered in several different ways, but always with the economy mentioned above. Readers in Britain, however, were to be tempted by this issue without any real possibility of buying it. The adverts in DC comics for this issue found their way to the UK in the pickand-mix selection of books we randomly received in the UK, and we didn’t even know that it was in fact the first issue of the book after a tryout in Showcase (apart from anything else, there was no “No. 1” on the cover, as it was felt that young readers would only buy books that had managed to make it to four of five issues—this was some time before the words

OBSCURA

“Number One” on a cover made it particularly collectable). And, boy did we wish that we had American pen pals who could have sent this comic to the neglected readers of the UK! As ever, the grasp of human anatomy in Challengers of the Unknown #1 is as surefire in Kirby’s work as ever—and Marvin Stein’s inking does full justice (almost!) to it. I say “almost” because just round the corner was Wally Wood’s stint as inker on the book—astonishing work that blew away everyone else who ever inked The King’s work. In fact, I know I’m not alone in regarding the Kirby/Wood duo as the absolute apogee of comics illustration. Read it again and you may agree!

KIRBY’S SQUARE (AND TRIANGULAR) MONSTERS

Let’s face it—there is simply no argument. The comics illustrator who possessed the most surreal imagination (which he demonstrated throughout almost the entire history of the medium) was Jack Kirby. This statement is verified in a thousand small ways, often with throwaway panels that demonstrated time and again that he could come up with visual concepts to rival fine artists such as Dali and Tanguy when it came to visualizing things which had never walked the face of the Earth. Proof? Well, you could take a look at two Kirby creations over the years which (to my knowledge) no other artist attempted: monsters whose bodies were not shaped like anything in the natural world, but possessed either square or triangular shape. An early example of this comes from Kirby’s glorious period in the Harvey comics 1958 SF triumph Race for the Moon #2, in a story called “The Thing on Sputnik 4”. An object is found floating in space which turns out to be an organic creature but, bizarrely, it first appears in a triangular shape (rather like a large wedge of cheese) before transforming into the strange otherworldly creatures we see in the splash panel. In some ways, it looks like a forerunner of a creature that the

Barry Forshaw is the author of Crime Fiction: A Reader’s Guide and American Noir (available from Amazon) and the editor of Crime Time (www.crimetime. co.uk); he lives in London.

Challengers of the Unknown #3 (Sept. 1958).

(center) Challengers of the Unknown #1 (May 1958).

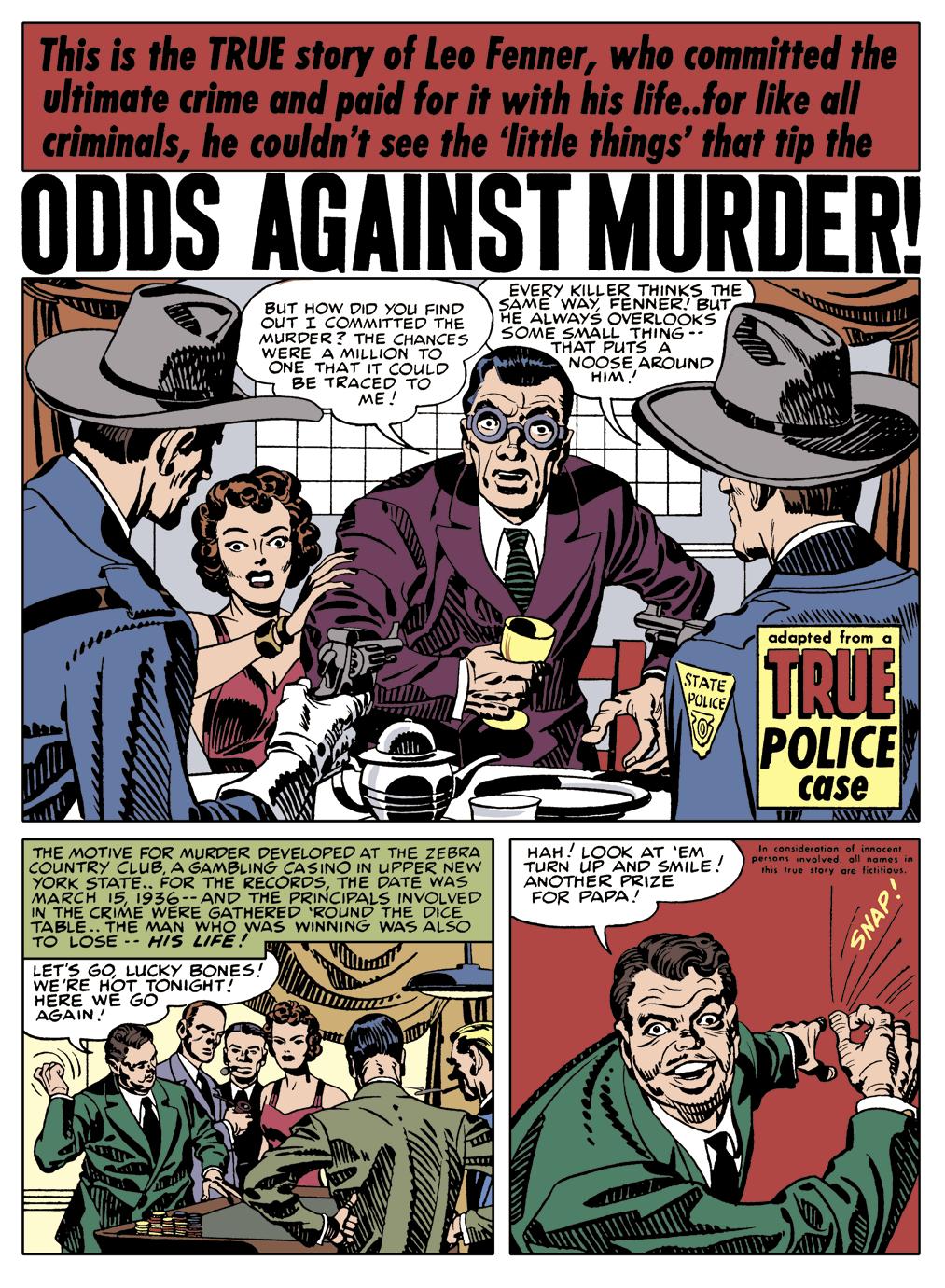

a never-reprinted

Here’s

classic Simon & Kirby story from Headline Comics #36 (August 1949): “Odds Against Murder” Art restoration and color by Christopher Fama.

Mark Evanier

JACK F.A.Q.s

Sample Headline

by John Morrow

A column answering Frequently Asked Questions about Kirby

WonderCon 2025 Kirby Tribute Panel

(right) Back row, l to

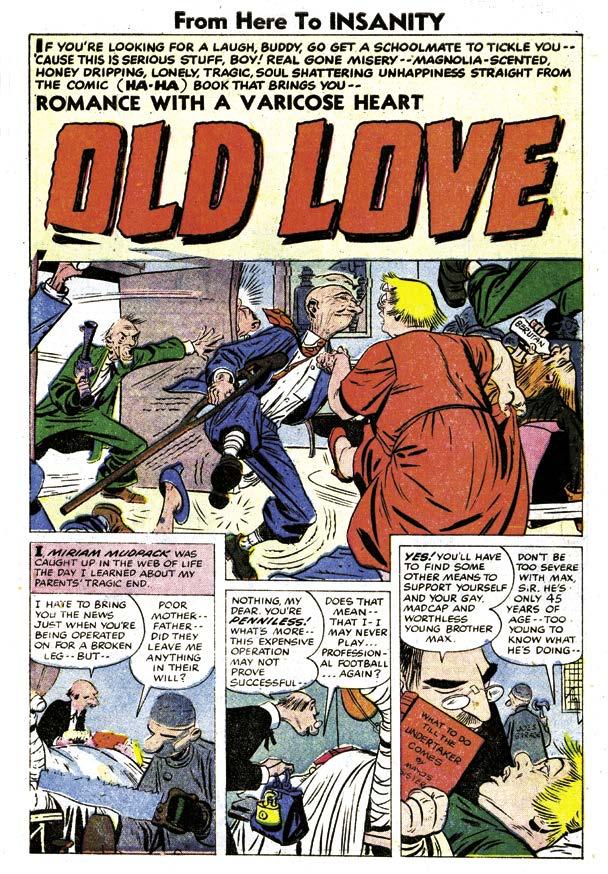

(below) From Here To Insanity #11 includes this 6-pager credited to Jack, but at most it’s got his rough layouts, and possibly some dialogue.

(next page) Thundarr the Barbarian character designs.

[This panel was held at the Anaheim Convention Center on March 30, 2025. Featuring Tracy and Jeremy Kirby, David Schwartz, Paul Levine, Rand Hoppe, John Morrow, and moderated by Mark Evanier. The transcript was copy-edited by John Morrow and Mark Evanier.]

MARK EVANIER: I always look forward to this Jack Kirby panel. If you look around the room, you’ll see, this is true: Jack Kirby fans are the smartest people at the convention, [laughter] the classiest people, the most imaginative people. I met Jack Kirby in July of 1969, and I thought I was just meeting one of my favorite comic book artists. I didn’t realize I was meeting a man who would change my life as much as he did, as he changed many lives,

as he changed many industries. He was an extraordinary man. Unfortunately, there aren’t that many people left who knew Jack Kirby. We’ve got some of them up here on the dais. He was smart, he was creative, he was giving, he was one of the nicest men you could ever possibly meet. They say, “Don’t meet your heroes, they’ll disappoint you.” Jack never disappointed anybody. I’m very pleased that we can do these panels and sit and talk—and I talk about Jack all the time. We might as well do it on the panel. This is my seventh panel at this convention. I think Jack’s been mentioned at every one of them, at some point.

One of the people who knew Jack, visited his house, helped him out, and was very instrumental in making him realize how beloved he was, is my friend here. This is Mr. Dave Schwartz, ladies and gentlemen. Welcome Dave. [applause]

We are honored to have two members of Jack’s family here, who are doing a lot to keep his name alive, and to tell his story, to make themselves available to people who want to know about Jack—and he was very proud of his family. This is Tracy Kirby, ladies and gentlemen, and this is Jeremy Kirby. [applause]

The convention’s program books said that we were going to have a man named Henry Holmes on this panel. Henry Holmes is one of the lawyers who helped Jack out over his career, and Henry couldn’t be here because his best friend is George Foreman [who just passed away on March 21, 2025], and he’s taking care of funeral arrangements and stuff at the moment, but we’ve got another lawyer for you. [laughter] This is the gentleman who is representing the Rosalind Kirby Trust Estate, whatever the name of it is—I’ve never gotten the name right. This is Mr. Paul S. Levine. [applause] Full disclosure: he is also my attorney, frequently. This is the man who made or makes most of our Groo deals.

Okay, next we have one of the founders, the person who runs the Jack Kirby Museum and Research Center. Would you welcome Mr. Rand Hoppe? [applause] And the publisher of the Jack Kirby Collector, a magazine that—every time I get an issue, I think, “Gee, I wish Jack was alive to see it.” I wish Jack was alive for an awful lot of reasons; that’s another one. And he’s got a company that you’ve probably stopped by their booth and bought one of everything they’re selling. It’s all good stuff.

r: Mark Evanier, David Schwartz, Jeremy Kirby, John Morrow. Front row: Rand Hoppe, Tracy Kirby, Paul Levine. Photo by Phil Geiger.

Mr. John Morrow.

[applause]

Dave, you haven’t been on too many of these panels with us. Now, something that I know about Dave is that I am completely unable, as long as I’ve known Dave, to make him laugh about anything whatsoever. [audience laughs]

DAVID SCHWARTZ: That is true. That is absolutely true. [pause, audience laughter] All right, I get it.

EVANIER: All right, tell us how you met Jack, Dave.

SCHWARTZ: I met Jack a number of times. I met Jack when I was in college in 1978 or ’79 or somewhere around there, where everybody was going to lunch, and I happened to be within earshot, and they invited me to lunch. I did not know Jack. I knew one of the artists who was going to lunch, and I was stunned that I was invited to come along to this lunch with Jack and with Roz, and it was delightful. I sat there next to Jack and I just listened to him the whole time. I didn’t say anything, but the accessibility of Jack was remarkable. Then flash-forward a few years and I was working in animation, and I ran into Jack at RubySpears when he was doing animation, doing conceptual animation. I said hi, and I had met them a few times. They remembered me, and then I started to become more friendly with them. And you probably know the name Michael Thibodeaux, but Michael was for a long time helping them out when they got their original art back, and even long before that, to bring people up who wanted to meet them. Because what would happen is people would want to come up and meet Jack, and Roz and Jack were happy to meet people, but were uncomfortable just having strangers come into their house. You guys, Jeremy and Tracy know this—and they would have Mike come up and be kind of a liaison, where he would bring people up there to visit, so that they had someone they knew go up [with them]. And I became part of that with Mike.

SCHWARTZ:

My favorite Jack Kirby comic? I can’t…

EVANIER: Well, you have to name one. [laughter]

SCHWARTZ: All right. All right! Fantastic Four #39. Okay? All right, I named something. All right, but that’s one of many.

EVANIER: Okay. What should people know about Jack? You must have a story about Jack we haven’t told here. I’m putting you on the spot here.

And so Mike and I would go up there a lot with people who wanted to meet Jack, and in every instance, they were more wonderful and inviting and friendly and accessible than anybody else I’ve ever met who had any kind of fame, or any kind of celebrity. And while you may think outside of this convention, there are people who are bigger names, etc. When we brought people up to meet Jack and Roz, it was like they were meeting the top level celebrities. These people were in awe of Jack. And it was just a very delightful thing to be in the presence of seeing so many people, enjoy so much to have that time with Jack and Roz.

EVANIER: What was your favorite Jack Kirby comic?

SCHWARTZ: No, that’s fine. I can remember how friendly and how open Jack Kirby was. Anyone who came up there to visit, Jack would be happy to talk with them and tell them a story about some of the artwork he had on the walls. Sometimes that story would change. [laughter] However, the story, everybody who came up there got a tour and got to hear all about the artwork. And when I say that story would change, it was because Jack would add to it or would come up with something else. It wasn’t that he was necessarily making up something. He wasn’t making something up that was untrue. He was just going deeper into what his feelings were about the artwork. And one of the things that really struck me, and I’ve said this before at least privately, is that at the time that Jack and Roz were having people come and visit them who were really into comics and really cared, there was no financial reason for them to be warm and friendly and open, and take time away from Jack doing his work. Obviously Jack was paid by the page. So when Jack took a few hours to visit with some fans, that was work he could have been doing to help his economic situation. And I know they always felt so connected to people who were finding real value in what Jack did with his work.

EVANIER: Did you hear a lot of World War II stories?

SCHWARTZ: Only just about every time. [laughter] Jack told these World War II stories, and more power to him, he was there. He was on the ground, he was in danger, and he recounted and remembered a lot of the things he went through. And yes, I heard a lot of them and they were very harrowing. I mean, it was not that long ago that he had been in these situations.

EVANIER: I was saying the other day on another panel, how much I thought World War II affected Jack and his whole approach to life after that. Tracy, you must have heard a lot of World War II stories.

TRACY KIRBY: Oh yeah. I mean, the joke was the number of Nazis would get larger and larger [each time he told a story]. [laughter]

EVANIER: No, excuse me, that’s the Trump administration. [laughter]

TRACY: It was always, like, five, and then twenty. So we’d always—I was young, and we’d always joke, but I mean he was very—.

EVANIER: How old were you when he started to tell you World War II stories?

TRACY: Well, he was always very cognizant about—the stories that I would hear would be a lot different than what the adults would hear, because when we’d sit down and talk, it would be more of a story, more about turning it into more of a Boy Commandos or Newsboy Legion story, something that’s just a little bit more adventurous, versus the reality of what was actually going on in war. Which I can understand, because I never was—I don’t ever recall actually sitting down and being like, “Oh my God, that’s crazy!” with what he would tell us. He never really told any kind of very harsh reality stories.

EVANIER: He didn’t tell you about the hookers and other people. [laughter]

TRACY: Yeah, he left some stuff out. [laughter]

EVANIER: Jeremy, what is your perception these days of how much fame Jack has? I see it’s growing and growing and growing.

JEREMY KIRBY: Yeah, I think it’s amazing. Just year after year, more and more people recognize not just the name, but the contributions, which I think is the most important thing—the creation of the character. One of the main things that I’ve noticed, is the fact of: it’s one thing to have name recognition, that’s fine. Unfortunately, he didn’t get as much of it when he was alive. But it’s amazing to see the actual contribution, recognition, what he meant to the creation of most of all of our favorite comic book superheroes. And I think that’s very important and it’s just amazing to see that grow.

EVANIER: Do people ask you a lot about his relationship with Stan Lee?

JEREMY: [pause] All the time, [laughter] but it’s different because when I was young, as I’ve kind of said before, I wouldn’t even mention who my grandfather was, because if I said my grandfather created or co-created a certain character, they’d immediately say, “Whoa, your grandfather is Stan Lee!” So just until probably my twenties—so going back until the late 1990s or early 2000s—that’s when I was older, so I didn’t mind trying to explain the difference. But now there’s more recognition. In my field of work, we do nothing with superheroes whatsoever, although I work with actual superheroes, law enforcement, those first responders that are helping out. But there are stories now where I’ll be talking to a police chief, and I’ll see a piece of art behind his desk. This literally happened. It was a piece of Kirby art. He was a huge fan. And starting to see that recognition now that I never saw maybe 10, 15 years ago, it is amazing. Yeah, it’s a big change.

IF YOU ENJOYED THIS PREVIEW, CLICK THE LINK TO ORDER THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DIGITAL FORMAT!

EVANIER: I get the question, “Who created these characters? Did Jack create them?” vs. “Did Stan create them?” And I have finally, over all these years, developed my stock answer, because I say, “These characters were created by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby, and I think Jack did least 75% of the creation in there, and maybe a lot more.” How would you answer that question?

JEREMY: I believe my grandfather, based on the recognition of his work throughout all the different [eras], whether it’s Silver Age, Golden Age, Bronze Age, then animation after that—I think his body of work shows for itself really the creative prowess that he had. And I don’t think that takes away from Stan Lee, because he also had a large body of work that he was responsible for. So I think there’s never going to be a full answer, but I can tell you, and I’m sure we’ll talk about: there is going to be an exhibit coming up with his artwork. And you’ll

COLLECTOR #95

KIRBY

MADNESS! Kirby’s most deranged work: Dingbats, Goody Rickels, Destroyer Duck, the Goozlebobber, Not Brand Echh, and wild animation concepts! Plus, a 1980s Kirby interview by JAMES VAN HISE, a look at Jack’s psychedelic coloring, Kirby’s depictions of Dr. Strange, Forever People art gallery, MARK EVANIER, a crazy 1950s Simon & Kirby story, behind an unused Machine Man cover inked by STEVE LEIALOHA!