EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

Roger

PUBLISHER

John

DESIGNER

EDITOR

Michael

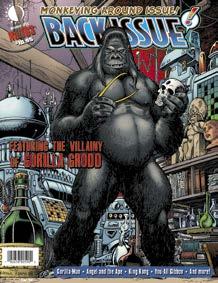

COVER

Arthur

(Originally appeared in Who’s Who in the DC Universe #3. Scan courtesy of James Sharland.)

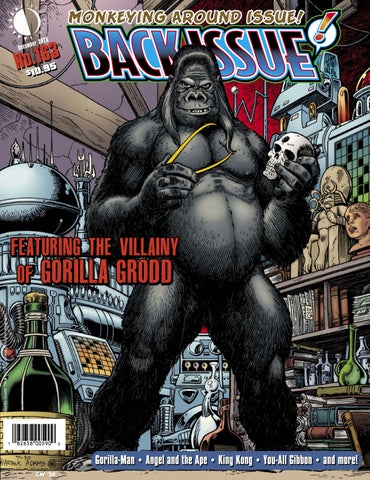

COVER

Glenn

COVER

Michael

PROOFREADER

Kevin

SPECIAL

Jeff

Arthur

Mark

Phil

Grand

Heritage

John

Paul

Ed

Brian

Jeff

Dandy Don Simpson Draws King Kong

Simpson discusses adapting the King Kong novel

ON THE BAD GUYS:

and O’Brien: Monkeying Around With Arthur Adams

Adams expounds on his gorilla from another dimension

BACK ISSUE™ issue 163, December 2025 (ISSN 1932-6904) is published monthly (except Jan., March, May, and Nov.) by TwoMorrows Publishing, 10407 Bedfordtown Drive, Raleigh, NC 27614, USA. Phone: (919) 449-0344. Periodicals postage paid at Raleigh, NC. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to Back Issue, c/o TwoMorrows, 10407 Bedfordtown Drive, Raleigh, NC 27614.

Roger Ash, Editor-In-Chief. John Morrow, Publisher. Michael Eury, Editor Emeritus. Editorial Office: BACK ISSUE, c/o Roger Ash, Editor, 2715 Birchwood Pass, Apt. 7, Cross Plains, WI 53528. Email: rogerash@ hotmail.com. Eight-issue subscriptions: $108 Economy US, $128 International, $39 Digital. Please send subscription orders and funds to TwoMorrows, NOT to the editorial office. Cover artwork by Arthur Adams TM & © DC Comics. All Rights Reserved. All editorial matter © TwoMorrows and Roger Ash , except Prince Street News © Karl Heitmueller Jr. Printed in China. FIRST PRINTING

by Brian Martin

You might think that the basic premise of a beautiful young girl and a 500-pound ape who operate a detective agency might limit the scope of treatments it could receive. However, in their history, DC has published three different series titled Angel and the Ape , while the characters continually popped up in the DC Universe, and even had a batch of stories appear within another title. Each iteration had a decidedly different tone, one that frequently reflected the time they were published as well as the sensibilities of the individual creators involved. Let’s step inside the cage and see what’s what. Though it might be a good idea if you brought a banana with you, just in case. Sam Simeon is quite civilized, but he is still an ape!

THE ODD COUPLE

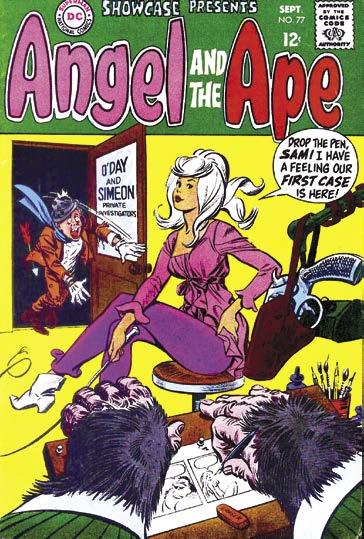

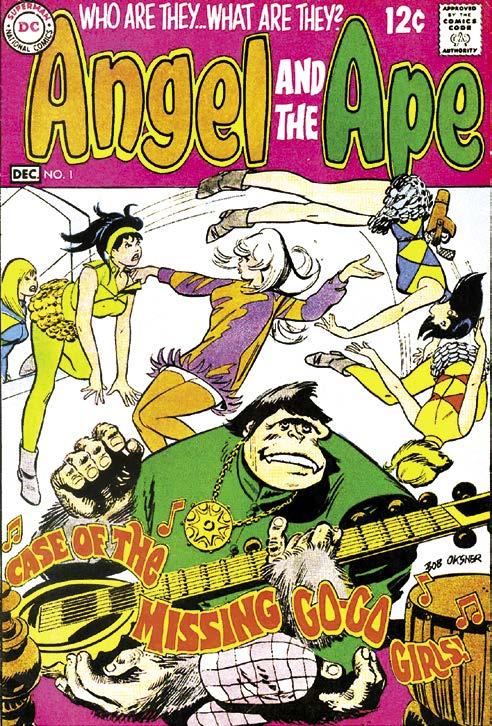

As with many DC series in the Silver Age, Angel O’Day and Sam Simeon appeared in an issue of Showcase, #77 (Sept. ‘68) in this case, before they graduated to their own series. Titled Angel and the Ape, the series had a dynamic that was odd, even for that era. In fact, over the logo on the cover of the first few issues of the series were the words, “Who are they… What are they?”

Illustrated by Bob Oksner and Tex Blaisdell, the authorship of the initial story is a little murky. E. Nelson Bridwell was definitely involved, but various sources cited at comics.org add the names of Al Jaffee, Howie Post, and Bob Kanigher to the mix. Bridwell, along with John Albano, were the main writers for the rest of the series with Sergio Aragones, Henry Boltinoff, and Oksner contributing.

OPEN FOR BUSINESS

From the very start, that being the cover of the Showcase issue, the premise of the series is established. We arrive with O’Day and Simeon Private Investigations open and ready for business. The cover to issue #1 also illustrates that though Sam is the five-hundred-pound ape in the room, Angel, the aforementioned beautiful young girl, was always able to handle herself physically as well.

The detective business does not appear to be too lucrative, however. From the Showcase cover and the initial pages of their first issue, we learn that Sam is a working comic book artist and Angel models for him. As an in-joke for comic fans, Sam works for an editor named Stan Bragg whose depiction may have stirred echoes of another highly placed individual working for another Marvelous publisher. The relationship between Sam and Bragg (as well as Bragg’s secretary’s crush on Sam) would be a subplot for most of the early issues.

Other elements of the series that would persist through the initial run appear here, with some being played with by other creators as time

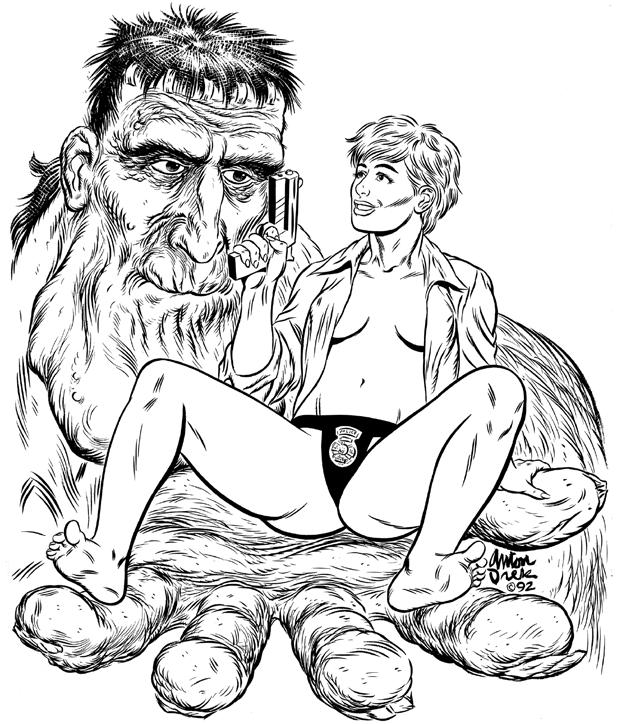

An unpublished Angel and the Ape cover for for the Vertigo issue #1 by Arthur Adams.

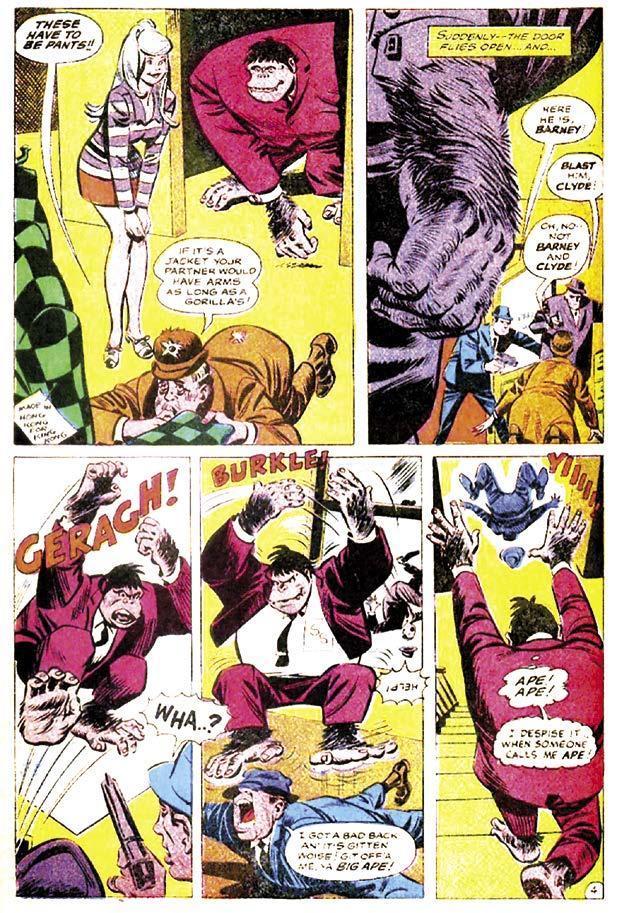

(top left) The first appearance of Angel and the Ape from Showcase #77. (bottom left) Angel and Sam meet their first client. (right) Angel and Sam get their own series.

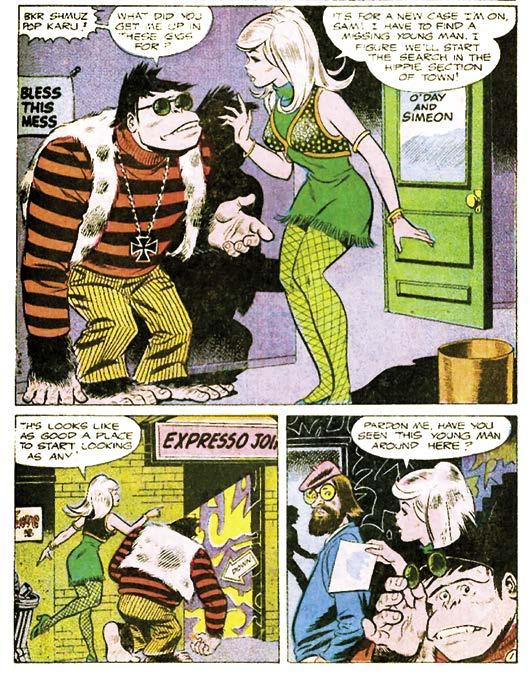

progressed. Sam speaks ape talk and Angel is the only one who can understand him. In the comic world at least, we readers were provided with translations. A lot of comedic situations are also brought about when people, for some reason initially unaware of the fact, suddenly realize that Sam is an ape. Also, Angel is most often the one who solves the cases, with Sam providing the muscle and timely rescues.

Though the dynamic of the pair obviously categorizes this as a comedy series, they were not given exceptionally outrageous cases (at least by comic book standards) to solve. While adhering to standard comic tropes, the mysteries depicted were grounded in reality and had logical conclusions. Smuggled rocket plans, kidnapped go-go girls, a circus using their talents for crime, and someone trying to murder an old man and the requisite mysteries surrounding the divestment of his fortune, all figure into the first few issues’ plots.

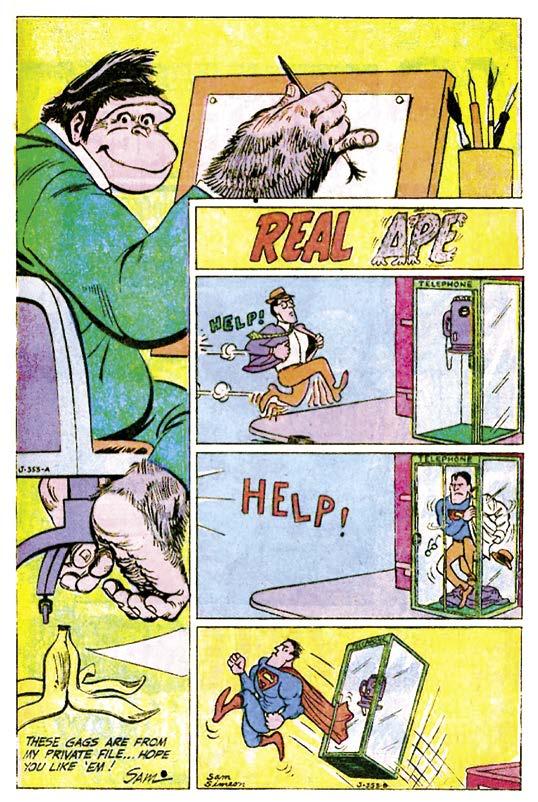

Beginning with full length mysteries, by the fourth issue, the comic began to feature multiple stories in each issue, with some of them being short, even one-page gags. Of these gag strips, most of them were presented as being actual comics that Sam had drawn!

WOOD YOU INK THIS FOR US?

With the second issue, comics legend Wally Wood began inking many of the stories. A noted expert on depicting the female figure, it is no surprise that he was recruited. From the start, the stories had utilized Angel’s physical attributes, mostly for comedic purposes, and Wood’s skills are used to their utmost, especially in issue #3, where the depiction of Angel in a skimpy nurse’s outfit almost vaults

continued on page 7

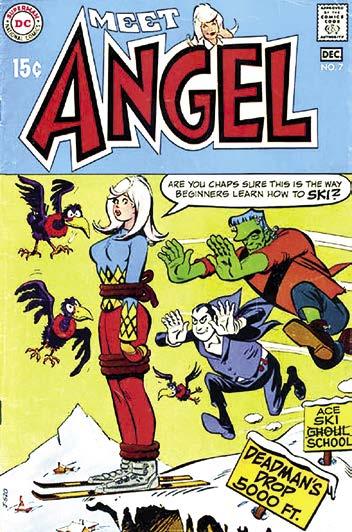

(top right) One of “Sam’s” gag strips from issue #5. (bottom right) Sam the hippie from issue #5. (left) With the final issue, Sam is completely gone from the cover.

continued from page 4

the tale into the category of Good Girl art. After that, there was no shortage of pictures of Angel in short dresses and nightwear, nor a dearth of men willing to comment on those outfits. Of course, the artwork never went beyond this small slice of cheesecake, the Comics Code still in full force at the time. There might have been a few sales lost however since all of the covers depicted Miss O’Day as almost completely… covered.

The shift in focus toward the distaff member of the pairing did become even more evident when the logo to issue #4 was altered to read, “Meet ANGEL and the Ape” with Angel in much larger print, though the official title did not change—a tactic emphasized even further when the seventh and final issue was retitled simply Meet Angel both on the cover and on the indicia inside

BEATNIK IT!

Running when it did, the series was sure to feature elements of the counterculture prevalent at the time. Beatniks, the aforementioned go-go girls, peace and love; all were featured, sometimes tangentially, sometime integrally to the story. Sam in hippie regalia in issue five is… something to behold.

Added to the shorter stories, the last three issues harkened back to comics’ earlier days by including text stories that did not feature the star characters. Running two pages each in issues five and six, and a single page in seven, the stories are certainly a bit of an anomaly for the time. Those three comics also, for some unknown reason, all showed cartoon versions of Count Dracula and Frankenstein’s monster on their covers, with neither a hide nor hair (nor bolt, nut, or fang) of them being found inside the comics.

Along with the title change for issue seven, the contents of the comic were evidence the book was floundering. It contains eight distinct tales, only one of which ran as long as eight pages, with that tale itself featuring only Angel. Whether the change in story structure after the third issue was due to dropping sales or creators having difficulty crafting full length stories for the duo, the switch really left no room for character development and a plot, especially since there was a requisite amount of humor needed. The issue is basically a collection of gag strips. So, with that seventh issue dated November-December 1969, Angel and the Ape met the case they could not solve: Cancellation. It does appear that the axe may have fallen rather suddenly though.

by Doug Zawisza

Gorillas, man! Or Gorilla Men? Gorilla-Men? Gorillas-Men?

Whichever way you peel the metaphorical banana, let’s take a look at the trio of Gorilla-Men generated by the Marvel media machine. Like the history of these hairy apes itself, this article is heavily influenced by the most prominent of this banana-loving bunch, the most prolific of mangorillas, resilient enough to survive for over 80 years. Which Gorilla-Man holds such prestigious recognition? Read on.

A mercenary, a secret agent, an Avenger, a turncoat, and an agent of Wakanda. And that’s just a sliver of what one of the silverback bruisers known as Gorilla-Man has accomplished. Ken Hale is the most famous of the characters to bear the Gorilla-Man brand, but he’s not the only one.

Influenced by masterful, Marvelous storytellers, the legend of the Gorilla-Man stretches far and wide, as all good legends do, ranging from the age of Atlas to modern-day scenarios brought to prominence merely by asking the question “What if...?” Born of the era when apes moved comics off the shelf, Gorilla-Man is one powerful primate packed with potential. The literal gorilla in the room, Gorilla-Man added primate pathos to every tale, regardless of which version of the bustling beast appeared. A foil for the Avengers and Defenders, a Silver Age sci-fi flashback, or colleague of goddesses, aliens, robots, and spies, Gorilla-Man’s adventures should not be overlooked.

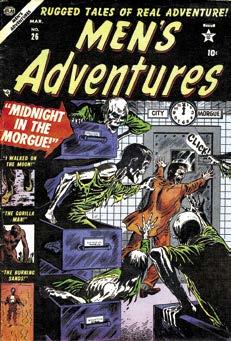

TO FACE THE CHALLENGE OF THE GORILLA MAN

In the final pages of Men’s Adventures #26 (March 1954) from Atlas Comics, Ken Hale becomes the first of the Marvel menagerie of Gorilla-Men. Simply titled “Gorilla Man,” this story caps off an issue that literally spans to the moon and back.

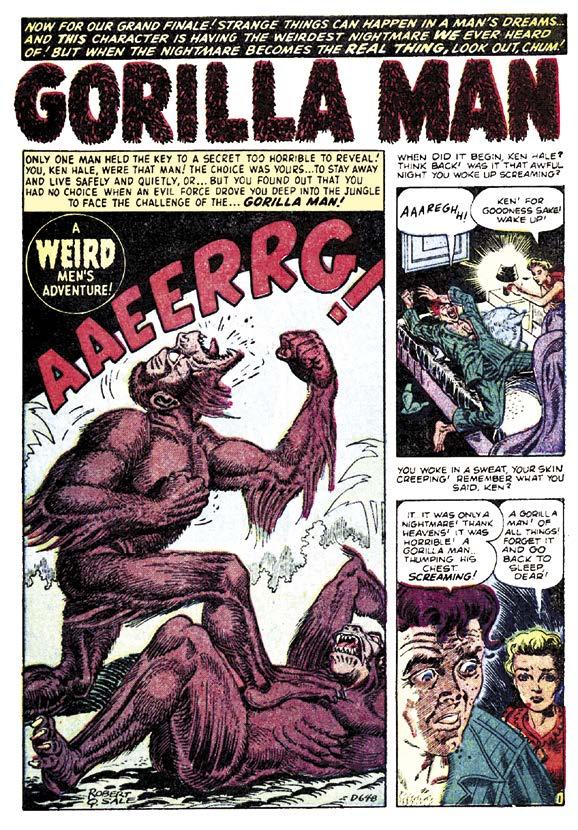

Attributed to Stan Lee as the writer and drawn by Robert Q. Sale, the origin story of Gorilla Man (initially without hyphen) is launched from the fevered nightmares of “an ordinary, unadventurous citizen.”

It would be a while until comic fans would see Ken Hale swing back into action, though, as two more gorilla-monikered-men stole the brand for a bit. Ken Hale’s return awaits you, gentle reader, later on in these very pages.

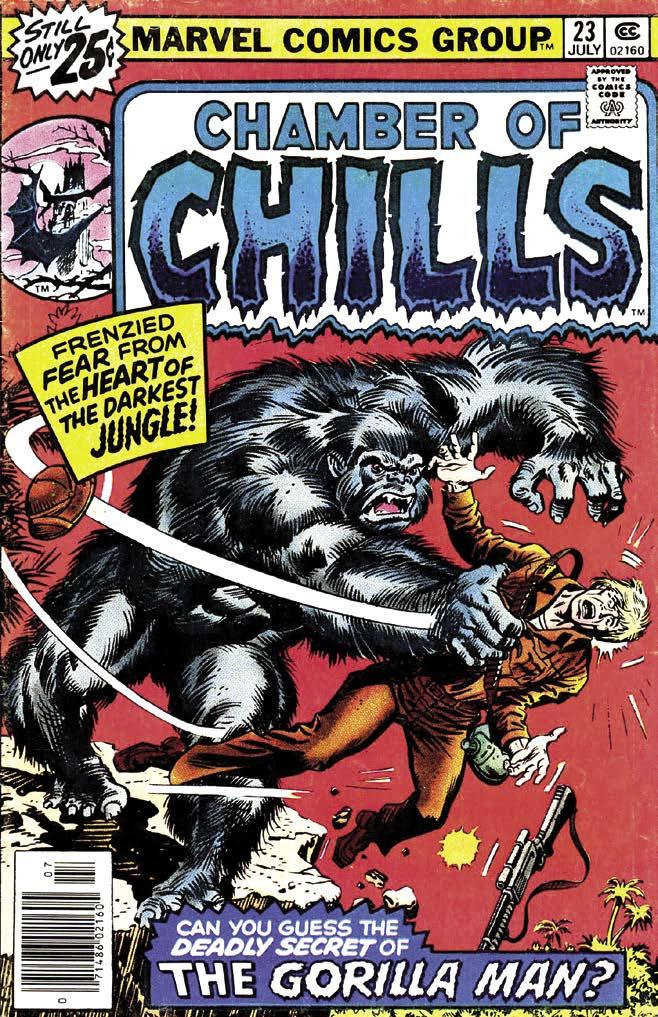

When “Gorilla Man” was reprinted in Chamber of Chills #23, Ken Hale made it onto the cover.

TM & © Marvel Characters, Inc.

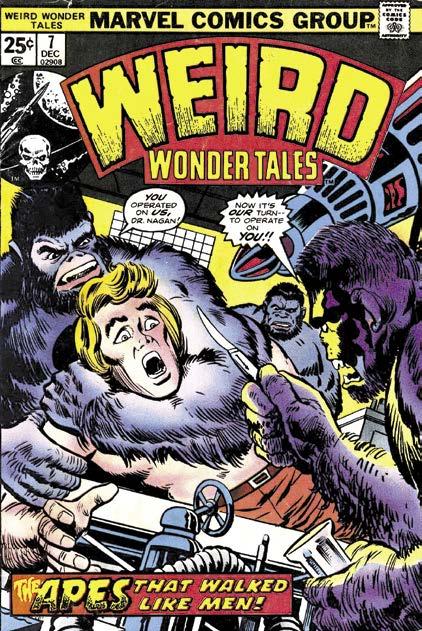

(bottom left) Ken Hale is haunted by a Gorilla Man in his dreams. By story’s end, he will learn a horrible truth. (top) Like Hale before him, Dr. Arthur Nagan is featured on the cover when his first story is reprinted.

(bottom right) Nagan is hoisted on his own petard and becomes a bizarre Gorilla-Man.

TM & © Marvel Characters, Inc.

IT WALKS ERECT

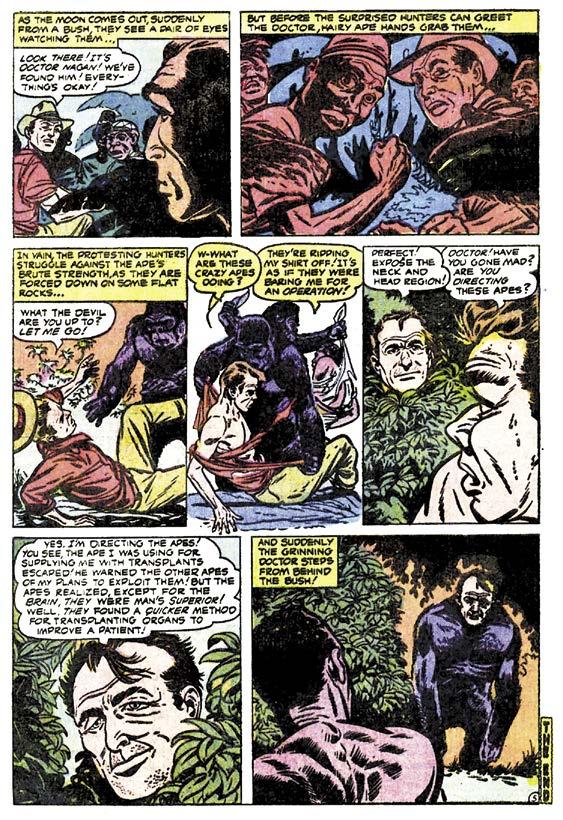

Anchoring Mystery Tales #21 (September 1954) as the finale (what is it with gorilla-man adventures bringing down the curtain?) the tale “It Walks Erect!” opens in an operating room featuring a lung transplant from dog to sheep. Not sure what makes a dog more dispensable than a sheep, but let’s just roll with it.

The five-page adventure packs comic book science with crazed science fiction into a story so meandering that it feels like a Mad Lib scrambling away from its own tail that is lit on fire.

Written by Paul S. Newman (not that one) and drawn by Bob Powell, this story decidedly flips the script, changing the transformation of gorilla and man into a hybrid chimera. Successful in transplanting a dog’s lungs into a sheep, Doctor Arthur Nagan decides to move up the evolutionary ladder. His next surgery delivers a healthy ape organ to replace the “sick internal organ” of a doomed man. Specific organs remain unnamed, but Nagan has found a schtick here and decides to continue growing his practice.

Proclaiming, “Apes are the best source of transplants,” Nagan goes to Africa to stock up on plundered spare ape parts for his burgeoning entrepreneurship in ape organ eviction (and re-conscription). His surgical mind slipping crazily towards the mad scientist end of the spectrum, Nagan starts poaching apes in a quest to infinitely

by Tom Powers

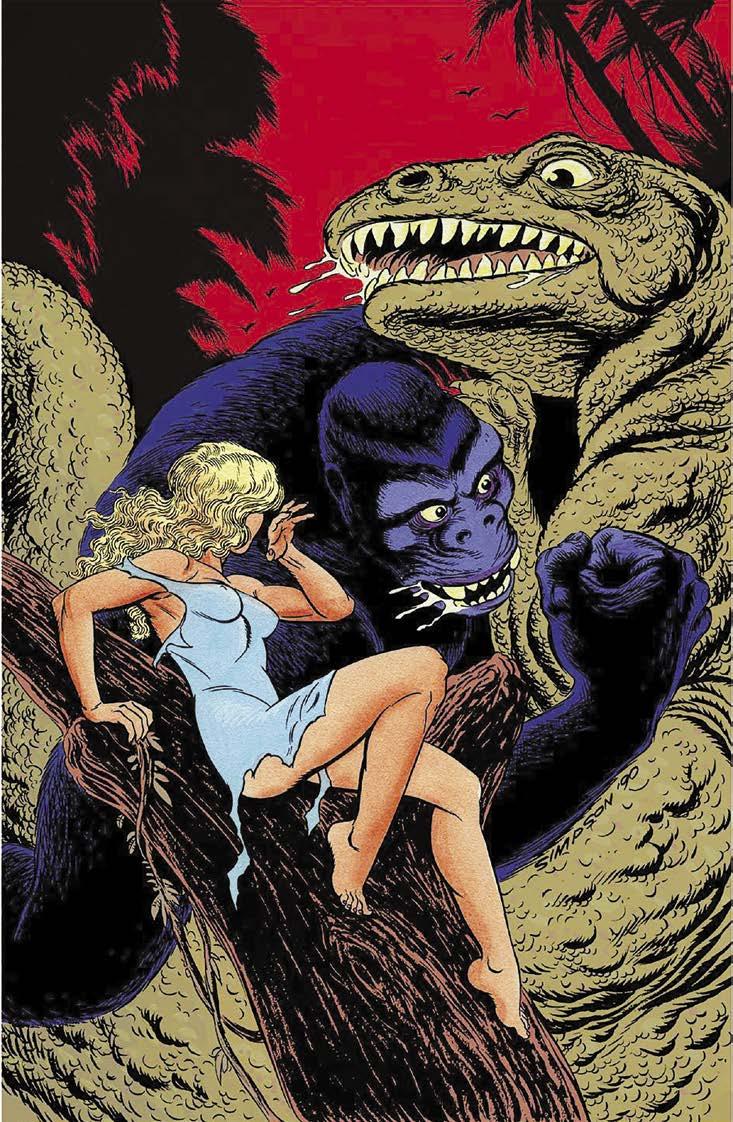

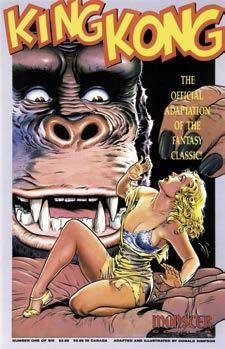

Don Simpson illustrating King Kong captivating words alone should sell anyone who is a fan of either larger-than-life figure. With his spectacular 1991-92 six-issue King Kong adaptation of the 1932 novelization of RKO Radio Pictures’ 1933 film for Fantagraphics’ Monsters imprint, Simpson offers a fresh, epic spin on the classic tale of a stunning beauty being unwillingly swept off her feet by a mutated large simian beast. By skillfully depicting the gritty Depression-era streets of New York City and the dizzying heights of the Empire State Building, as well as the Skull Island natives’ village and the monster-filled jungle nightmares beyond their protective wall, Simpson demonstrates his adept knowledge of these disparate worlds and adds new character beats to this tragic— yet wildly entertaining— tale, which we discuss in the following conversation.

TOM POWERS: Don, why did you choose to illustrate a comic book adaptation of King Kong?

DON SIMPSON: It’s not something I would have necessarily gone after or tried out for. I had an existing relationship with Fantagraphics from having participated in Anything Goes! #2 (Dec. 1986) with “In Pictopia” (scripted by Alan Moore). Also, I knew Thom Powers—quite a coincidence— a young man from Detroit who became an assistant editor at Fantagraphics. I had submitted the first fourteen or so pages of Wendy Whitebread to Thom after Denis Kitchen had turned it down. Thom had no immediate use for it, but he had me in his Rolodex.

POWERS: So how did this project end up being a part of Fantagraphics’ Monsters imprint?

Don Simpson’s cover for Amazing Heroes #183 featuring Kong. (inset) Dave Stevens’ cover for the first issue.

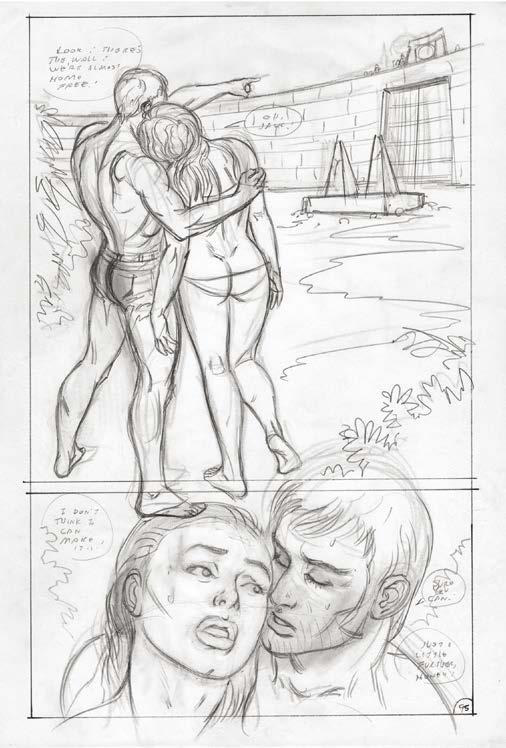

(left) A Kong-like image of Simpson’s creator-owned characters Forbidden Frankenstein and Wendy Whitebread. (right) Simpson’s pencil layouts for a page with Ann and Driscoll.

Forbidden Frankenstein and Wendy Whitebread TM & © Anton Drek. King Kong TM Merian C. Cooper Estate. Artwork © Don Simpson and Richard Merian Cooper. All rights reserved.

SIMPSON: At some point, Fantagraphics got the King Kong rights and decided to launch a separate imprint. They wanted to reserve the Fantagraphics imprint for their arty titles, Love and Rockets , Eightball, and so on—although they had put out Dalgoda and Anything Goes! , ostensibly more “commercial” projects, under the Fantagraphics imprint. Now they wanted to make it clear with Monster Comics that this was emphatically a lowbrow, commercial endeavor. Almost immediately after, they launched the Eros Comix imprint for explicitly sexual comics. The two were a pair, and Thom was doing a lot of the groundwork for both.

Gary Groth had been a fan of King Kong for a while and thought it would make a good comic. The idea was to get various superstar covers—the Dave Stevens piece already existed, I understand— and they wanted to get various artists in the EC tradition to do the covers. They needed somebody to adapt the story and draw the insides, and as a writer, artist, and letterer, I was one-stop shopping, and relatively cheap. (laughter)

POWERS: Like your Megaton Man-related one-shots and Border Worlds series for Kitchen Sink Press, your adaptation of King Kong is illustrated in black and white. Working in this format, what pens and inking techniques did you employ? Also, did the fact that the original 1933 movie is in black and white influence your approach to this adaptation?

SIMPSON: There was nothing really different in my toolbox or approach. I used Winsor & Newton

Series Seven #3 sable brushes, Hunt #102 crowquill pens, Zip-A-Tone or other brands of dot screens. I had used DuoShade on some of Border Worlds, but that was rather tricky and unstable stuff; it was basically a photochemical process, but it could not be fixed like a photograph, so it wasn’t lightfast. I found that out the hard way on Border Worlds #7 (Aug. 1987), where I hung some of the pages on the wall as I was drawing the book, and they washed out before I turned them in. So I decided not to use that technique again—I had probably also run out of my supply of DuoShade board. So, it was just my standard tools.

In terms of drawing, I had been doing a good bit of mainstream freelancing by that point, so I had developed a “straight” adventure style or at least as close as I would ever get to it. It still had a certain goofy element to it, particularly when I drew Kong himself; I could never really shake the gorilla-suit feeling. People didn’t necessarily love my interpretation of Kong at the time. But, as I say, I never would have tried out for Kong; I was asked to do it. It came to me.

POWERS: When I first contacted you about this interview, I asked you if your “urtext” was either the original King Kong screenplay or the novelization by Delos W. Lovelace (which is based on a story by Edgar Wallace and Merian C. Cooper), and you responded with the latter. Interestingly, since Lovelace’s work is an adaptation of the screenplay and your six-issue miniseries is an

by John Kirk

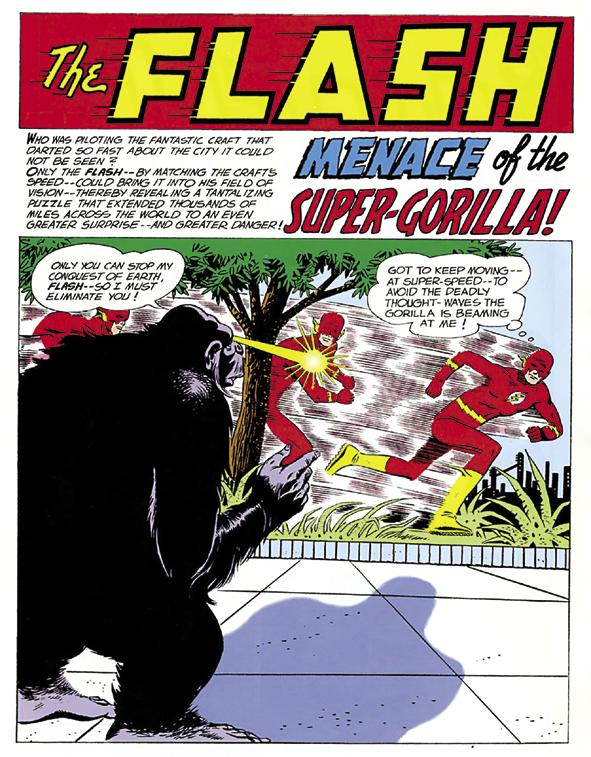

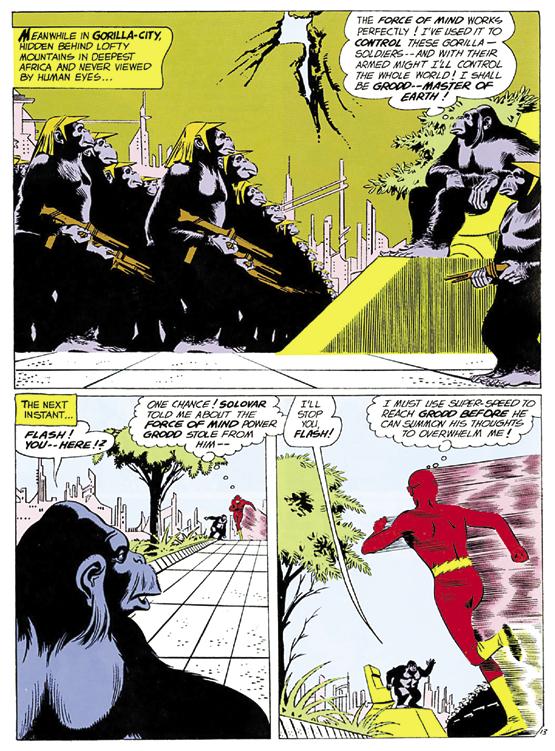

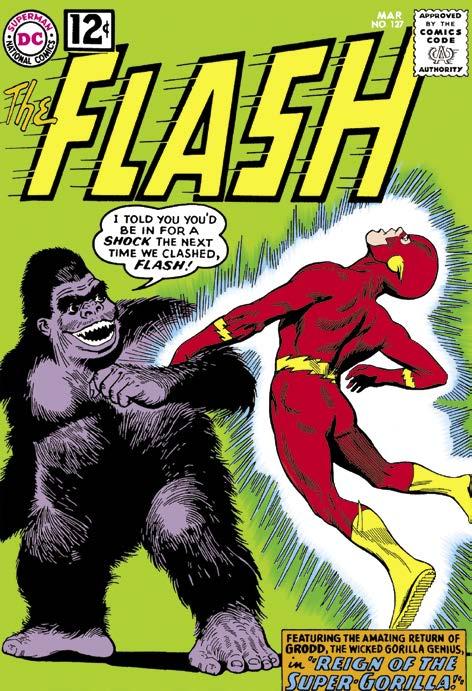

In 1959, John Broome and Carmine Infantino delighted the readers of The Flash with a new adversary that seemed not just perfect for the age, but also in line with the gimmicky characters the Flash seemed to attract: Gorilla Grodd. Not simply satisfied with a guy who could walk through mirrors or another who could control the weather, Broome and Infantino’s Grodd was a trope typical for the 1950s, a gorilla, but one with telepathic powers and a carnivorous appetite for both human flesh and power. But despite Grodd’s timely trope-heavy origins, Grodd managed to sustain himself throughout the decades to remain one of the greatest villains the Flash had ever encountered, but also a constant threat to other heroes in the DC Universe. He maintains this well into the 21 st century in reboots, canonical changes, and even appearances in video games as well as animated and live action television shows. If there’s one thing that can be said for Gorilla Grodd, whatever his background or ambitions, he’s a character who will never go away and will always be welcomed in facing off against the heroes in the DC Universe.

EARLY YEARS—GRODD STANDS ALONE

The 1950s saw a renewed interest in gorillas around the world. Jane Goodall’s work with primates in Kenya in the ‘50s, along with literature that was rich with primate characters—resting on a foundation of Tarzan of the Apes, King Kong, and Mighty Joe Young before him—meant gorillas and other primates would be natural sources for characters in comics.

It’s May 1959, and readers are treated to an introductory page of the Flash dodging deadly thought waves aimed at him by a menacing gorilla with an aptly named title at the top of the panel: “Menace of the Super-Gorilla.” However, this is a bit of a clumsy tease. Grodd proves hardly the menace that he promises to be and with information provided by Solovar, the leader of an unknown Gorilla City hidden somewhere in Africa, is easily dispatched by the Flash.

It’s a bit of a humble and abrupt beginning. The story starts with an actor friend of the Flash’s alter-ego, Barry Allen, Fred Pearson. Playing the role of a gorilla in an unnamed production, he is unnerved by the fact that he cannot account for his activities in the evening after his performances. He contacts his best friend who, in his alternate identity as the Flash, can look into the issue.

A dinner conversation reveals that before his performances, Fred is knocked unconscious

Grodd finally get his own comic. Francis Manapul’s powerful cover to Grodd of War #1.

TM & © DC Comics.

(left) Readers got a first glimpse of Grodd in Flash #106. (right) Flash faces Grodd in Gorilla City.

and with news reports about the amazing presentations of the ape persona he portrays, he has no recollection of the act. He begs Barry to look into it. Of course, he agrees, but he also reveals that there was a suggestion in his mind about “hiding out.” Barry Allen agrees to look into this and, in the course of his investigations, encounters a strange craft that can rival the Flash’s super-speed.

This, of course, ties into an American cultural motif of the 1950s: the encapsulation of a villain motif in the form of a threatening ape. With King Kong and Mighty Joe Young in the collective cultural memory, the idea of a threatening gorilla was a welcome prospect for a villain. There is no explanation for Grodd’s motivations. Readers know where he is from, but there is very little backstory development. All we know is that this one gorilla, out of a race of advanced gorillas in Africa, wants to dominate an obscure city somewhere in the United States.

entrusted with sensitive information: the fact that there is a secret advanced society of gorillas living in Africa.

This is all window-dressing. But Grodd makes for a decent foe with an acceptable background (for the time), and the simple motivation of conquest is enough to make him a villain who will return to menace the Flash in future issues.

Mark Waid, longtime writer of The Flash and other DC titles, had these thoughts on Grodd’s origins.

Of course, Broome and Infantino had the innovative sense to contribute a secondary nemesis for Grodd in the form of Solovar, the “good” gorilla. Despite how easily the Flash was able to dispatch his enemy in a matter of 22 pages, there is a tremendous amount of information to absorb about Grodd—like his origin, a potential ally for the Flash in Solivar, and that Flash is now

“At the time, DC had this belief that kids loved seeing gorillas on the covers of comics. Looking back at actual sales figures, this may have been more of an internal myth than reality by the early 1960s—by the mid-‘60s, they provided no spike at all—but there’s no way to know for sure. Regardless, that’s my best guess as to Grodd’s origins.”

Grodd runs the delicate balance between campy and threatening in this story. Part of this relates to the infatuation pop culture had for gorillas around this time, and to an extent, that infatuation continues today. However, first appearances of a character are also often awkward in their beginnings. While Grodd is defeated very quickly, the story not only serves to introduce Grodd to the DC Universe, but it establishes that Grodd is a major villain, not only super-strong, possessing

telepathic powers, but also has access to and control of superior technology. He is intent on world domination and the Flash has not seen the last of him.

Issues #106–108 are considered to be somewhat of a trilogy. #107 sees Solovar contacting the Flash to warn him that Grodd managed to retain some of his mental energies, enough that he escaped from imprisonment in Gorilla City and is hiding in an underground lair with a race of bird-people under his control. As we saw in the prior issue, Grodd used a hi-tech multi-purposed vehicle to not only cross the ocean but could also travel by air and through the earth. In #107, Grodd has a “Devolutionizer Ray” showing that he doesn’t simply rest on his other talents and that technology would become a key factor in his schemes. He is defeated and returned to his cell in Gorilla City.

Issue #108 sees Grodd escape yet again. His mind control over his vehicle (now given a name—the quadromobile) allows him to summon it to his location and crash through the cell. He escapes Gorilla City and uses a variation of his Devolutionizer to change his form into a human. He assumes a new identity of a reclusive millionaire scientist and creates a way to give himself telekinesis. However, only his human brain can harness this power and the stress of being human forces his body to change shape back to a gorilla. His gorilla brain can’t adapt to the power of telekinesis and the Flash is able to defeat his enemy once more. In the process, the Flash also wins Man of the Year beating out Grodd’s human persona!

After #106–108, Grodd also shows up in #115, 127, 155, and 172. Grodd is firmly established as one of the Flash’s most popular villains with a mandate of taking over cities, the USA, or other places in the human world.

right) Flash faces Grodd in human form in issue #108. (left) You can’t keep a bad gorilla down. (bottom right) The cover to the final Broome/ Infantino Flash. TM & © DC Comics.

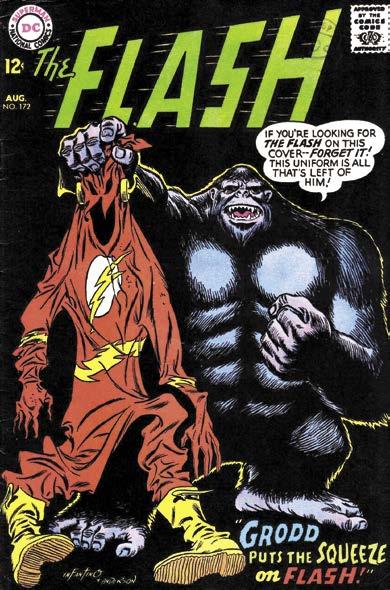

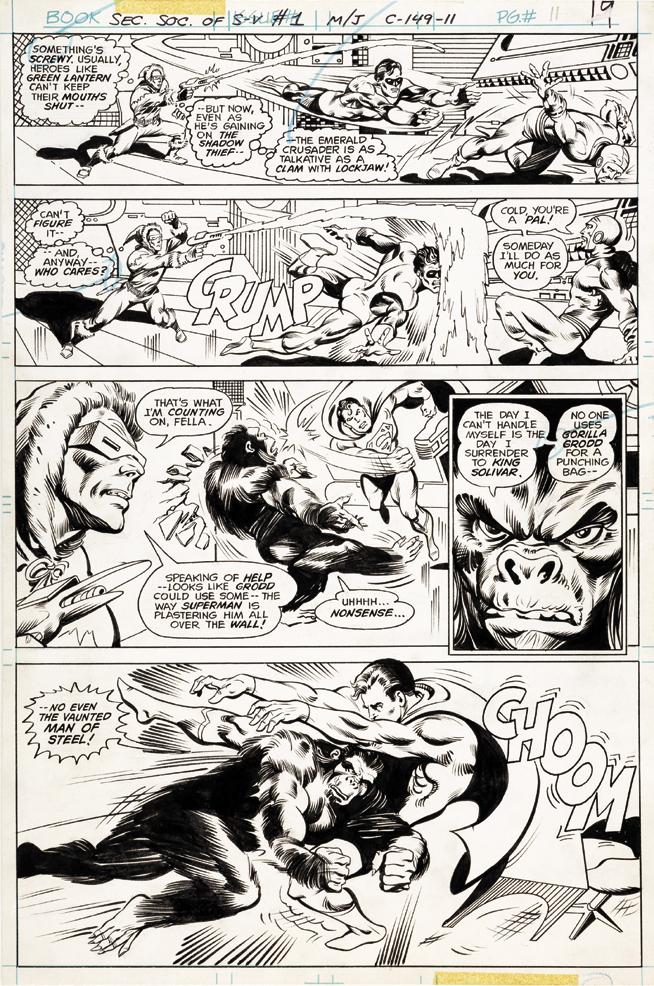

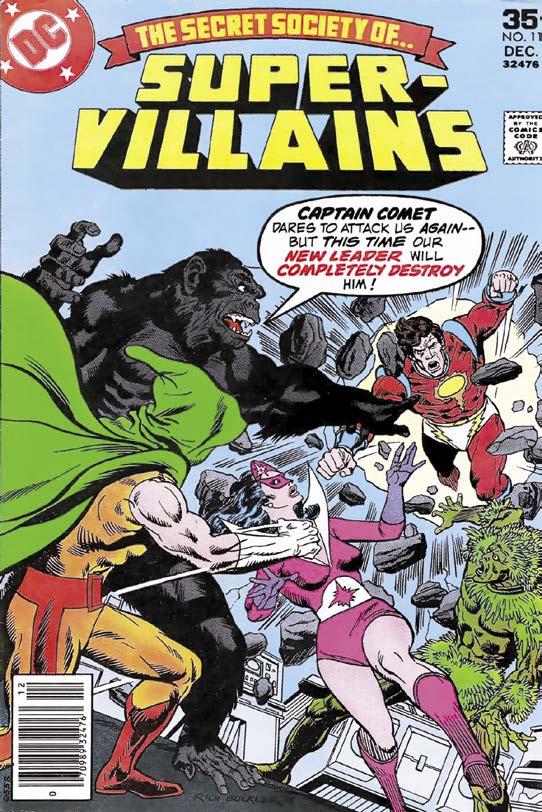

(left) Grodd is second to no one. Original art by Pablo Marcos and Bob Smith from Secret Society of SuperVillains #1. Original art scan courtesy of Heritage Auctions (www.ha.com). (right) Grodd defeats Kalibak. Now that’s one strong ape.

make him a dominant force on the team. In fact, Grodd even abandons Copperhead when he proves unable to measure up to the task they were to complete.

In the second issue, Grodd takes center stage by deceiving Captain Comet, who will prove to be the group’s recurring nemesis. This sets him up for further opportunities of leadership and, throughout the course of the series, actually manages to take control of the group through virtue of his advanced brain and mental powers. Grodd is re-invented into a more powerful adversary than when we were first introduced to him in 1959.

This stage of Grodd’s history features moments of transition that represent significant character growth in the late ‘70s. While Grodd could have been seen as kitschy or camp in his origins, these later appearances make him more of a serious threat. For instance, the repetition of constant imprisonments in Gorilla City no

longer occurs with a fixed base of operations. Grodd become more bestial in his rage, calculated in his planning.

In The Secret Society of Super-Villains #4 (written by David Kraft), Grodd’s voice becomes more prominent as he makes demands of his teammates, asserting not only his superior power, but his place. During this time, Grodd proves himself powerful enough to defeat not only Sinestro and the Wizard but also Kalibak of Apokolips.

The stakes are raised in these stories. The secret power behind the inception of the SSoSV is none other than Darkseid. With his involvement, Grodd is no longer tackling heroes on his own–he is besting peers, asserting control within the machinations of an interplanetary tyrant like Darkseid, while also avoiding interference by other villains and guest appearances of superheroes like Captain Comet on a routine basis. Grodd’s new ability of being a consistent menace puts him on a new threat level.

It wasn’t unnoticed by the readers. In the letters column, “The Sinister Citadel”, readers were pointing out how the combat portions of the stories are dominated by Grodd. By issue #10 (Gerry Conway, Rich Buckler, and Dick Ayers), Grodd not only also has a dominant seat at the table, but even a secret master plan that will allow his world-conquering ambitions. He takes control of the group, subjects Captain Comet to an intense battering, and even bends the will of Star-Sapphire to his own. Grodd is taking control and manipulating his allies like a true villainous mastermind, graduating from his previous status as merely a petty criminal nuisance.

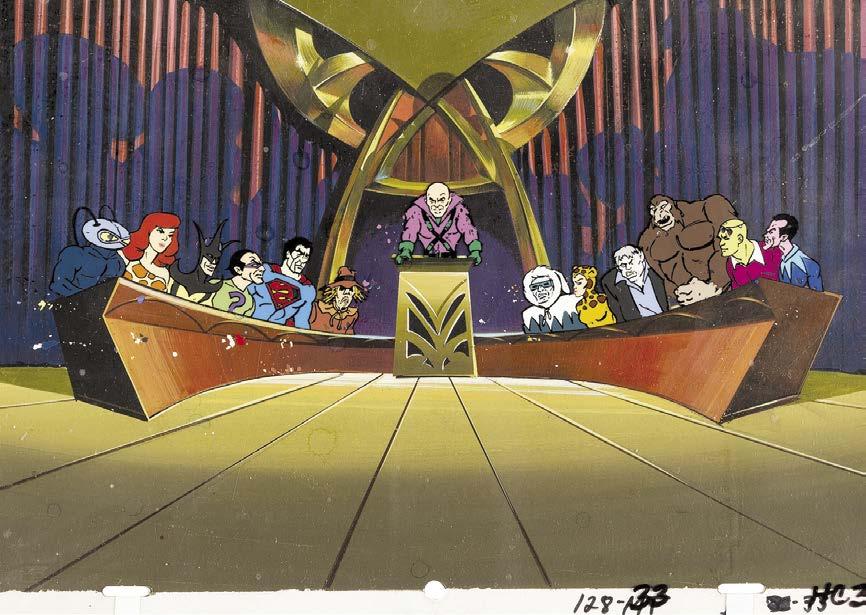

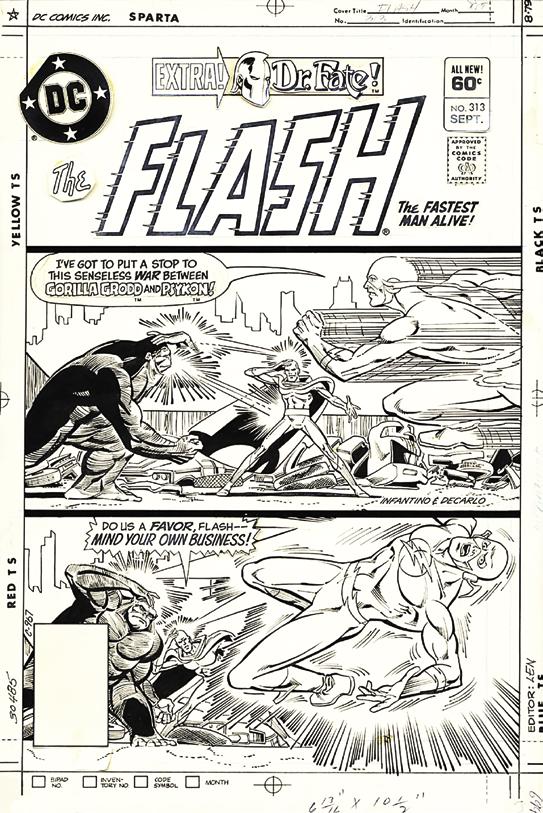

(top) Grodd sat head and shoulders above the rest of the Legion of Doom in Hanna-Barbera’s Challenge of the Super Friends cartoon. (bottom left) Secret Society of Super-Villains allowed Grodd to shine. (bottom right) Grodd still took time to menace the Flash. Original art by Carmine Infantino and Mike DeCarlo. Original art and animation cel scan courtesy of Heritage Auctions (www.ha.com). TM & © DC Comics.

I have known of artist and writer Scott Shaw! since the mid-1970s and became a personal friend of his by the 1990s. He has drawn the covers for three of my books: the two books on The Monkees singing group and an upcoming book called TV Animation That Time Forgot . His artwork has appeared on a couple of The Monkees’ actual albums including doing the cover design for their Justus album, released in 1996.

He has worked in animation at Hanna-Barbera and more specifically doing TV commercials featuring The Flintstones for Post’s Fruity and Cocoa Pebbles cereals and numerous Hanna-Barbera comic books for Marvel, Harvey, and Archie. He drew Rocky the Rhino for many a Rhino Records catalog and his version of Rocky has appeared on many Rhino Records. He was one of the founders of the San Diego Comic Convention and also the cocreator and original artist for Captain Carrot and his Amazing Zoo Crew for DC Comics. Besides The Monkees, Shaw had been “monkeying around” with other characters, namely You-All Gibbon and Urban Gorilla as well as other Wild Animals. I caught up with Shaw as he was putting the finishing touches on an upcoming Svengoolie comic book.

When this all-ape or all-gorilla issue of Back Issue magazine was mentioned to Shaw, he got very excited and said, “I look forward to that issue because I just bought a collection of all of the Detective Chimp stories. That’s why I collected Rex the Wonder Dog, because I like that chimp.” Shaw has regularly shown various comic book covers at his Oddball Comics presentations at various conventions, sometimes showing particular focus on DC Comics’ fondness for purple apes on their covers. He explains his fascination and love for the beasts, “If I had the money, I’d buy any comic with a gorilla or a dinosaur on the cover. Sometimes they were terrible, and sometimes they really were worth the money, like Kona, Monarch of Monster Isle , for example. It had gorillas and dinosaurs and everything else. As a kid, those are the two things I was most interested in: jungle animals and dinosaurs.”

This love led to Shaw’s first simian creation, the junk food eating ape named You-All Gibbon. Shaw explains, “I’ll tell you how I created him, because it’s interesting. I’ve had a relationship with the San Diego Zoo since I was three years old, and when I was 14, I became the President of the Junior Zoological Society for the San Diego Zoo. My dad got me a job as a groundskeeper, where I had a little picker and a burlap sack, and I put all the trash in there.

And here’s our star, You-All Gibbon.

TM & © Scott Shaw.

(left) You-All’s in a sticky situation and (right) we meet his annoyng nephew. (opposite page) You-All and his nephew must thwart a seriously nepharious plan.

TM & © Scott Shaw.

“When I was doing that job, a guy that was a noted health nut, no pun intended, was a guy named Euell Gibbons. He was advertising cereal at the time. He was in a lot of commercials, and when I was there one day, he showed up at the zoo and was walking around handing people acorns. I didn’t see anything behind him saying you have to promote your cereal. I think he just did it to impress people.”

By the time Shaw met Gibbons, Gibbons was already known for capitalizing on the growing return-to-nature movement in 1962. His resulting work, Stalking the Wild Asparagus, was an instant success. Gibbons followed it up with the cookbooks Stalking the Blue-Eyed Scallop in 1964 and Stalking the Healthful Herbs in 1966. He was also widely published in various magazines, including two pieces in National Geographic. His commercials for Post Grape-Nuts came later.

Shaw continues, “I was offered to work on this new comic called Quack that Mike Friedrich came up with, immediately after Frank Brunner started doing the Howard the Duck comics. He made him the star of the book drawing Howard the Duck, just with a different name, right? It was not very creative. I always like doing funny, stupid stuff, and I kept thinking about Euell Gibbons, and thought, well, I could have a gibbon. That’s a monkey. I like watching the gibbons at the zoo

because they’re very acrobatic. I thought, what if, instead of healthy food, he likes junk food, and eats all the crap. So that’s how I came up with You-All Gibbon, the junk food monkey. It was a very flimsy concept, but I milked it because I figured, well, this guy’s an idiot, so we can just wander in a different situation, right?

“I also really disliked John Denver for some reason. My first wife liked John Denver, and I did that to piss her off. I forget what I called him, but he was an orangutan. That was his nephew. I figured species go out the window when you’re doing funny animals, right? Then I put a character in there that I used a lot after that was a parody of Hunter Thompson, called Pointer Toxin.

“The three of them went on these adventures. I think the first issue just kind of established him, and they went into the jungle to find some idol or something. The second one, I had him fight giant boars. I think the Pig Boy was in those, too. It became a continued story that I never finished for Quack

“Years later, Pacific Comics called me; somebody had flaked out on them, and they needed something to fill in so they could print the comic. I had that book that Sergio Aragonés and I were going to print ourselves until we found out that we didn’t have the money to print it, and it just kind of sat in our drawer.

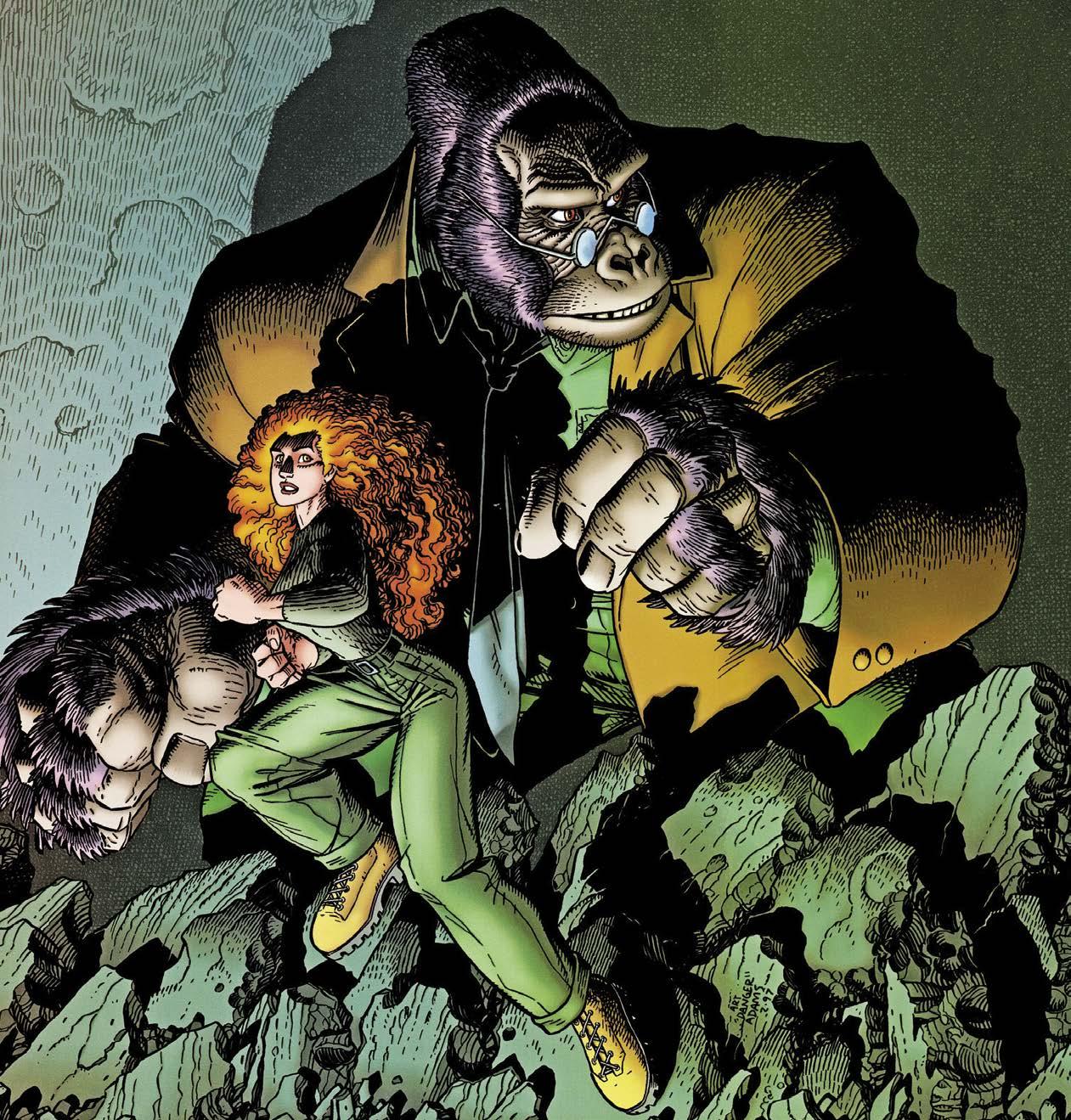

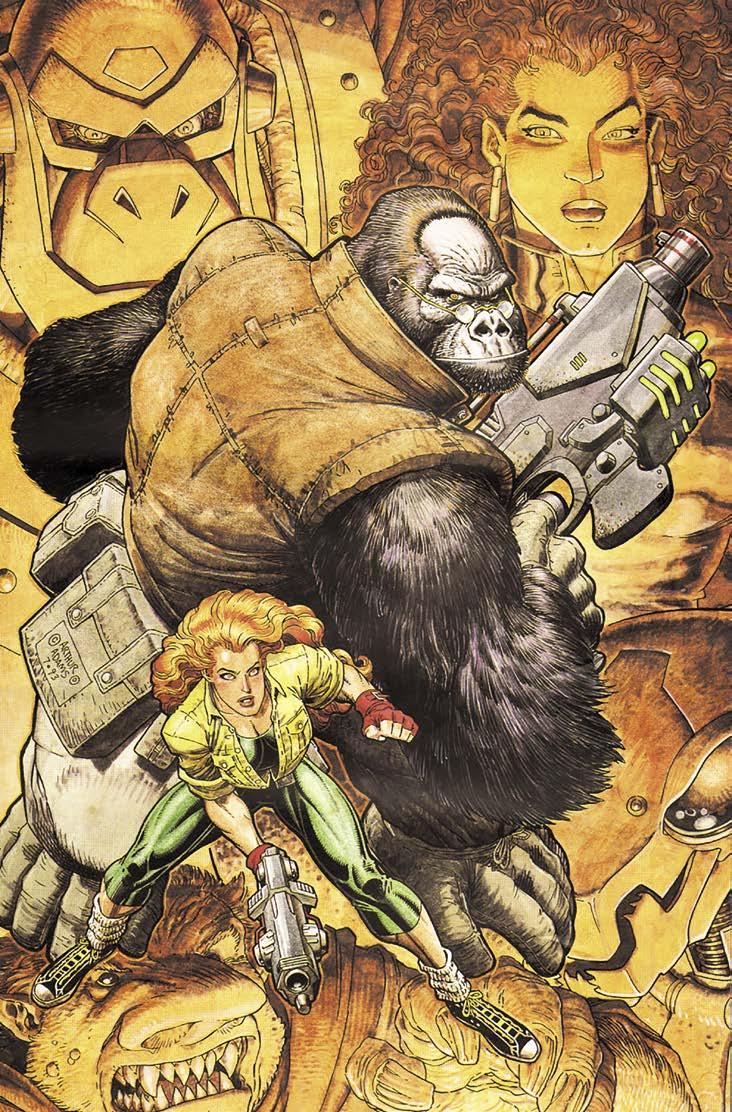

(left) Adams’ first color illustration of Monkeyman and O’Brien became a 1993 print for San Diego Comic-Con.

(right) A fine question that we hope to answer.

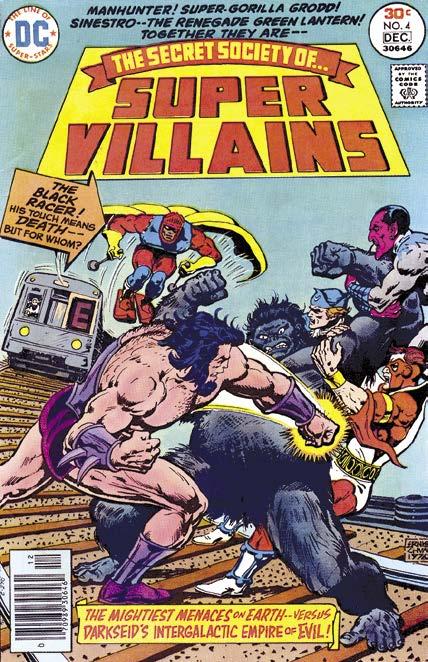

Artist Arthur Adams burst onto the comic book scene in 1985 with his stellar work on Marvel’s six-issue miniseries Longshot written by Ann Nocenti. After that miniseries he worked on some of Marvel’s biggest titles including Uncanny X-Men and Fantastic Four . He illustrated the iconic cover for Classic X-Men #1 (Sept. 1986). He even worked on DC’s big guns in Batman #400 (Oct. 1986), Action Comics Annual #1 (Oct. 1987), and Wonder Woman Annual #1 (Nov. 1988). While he had those issues and more under his belt, he wasn’t done giving fans some incredible comic book artwork.

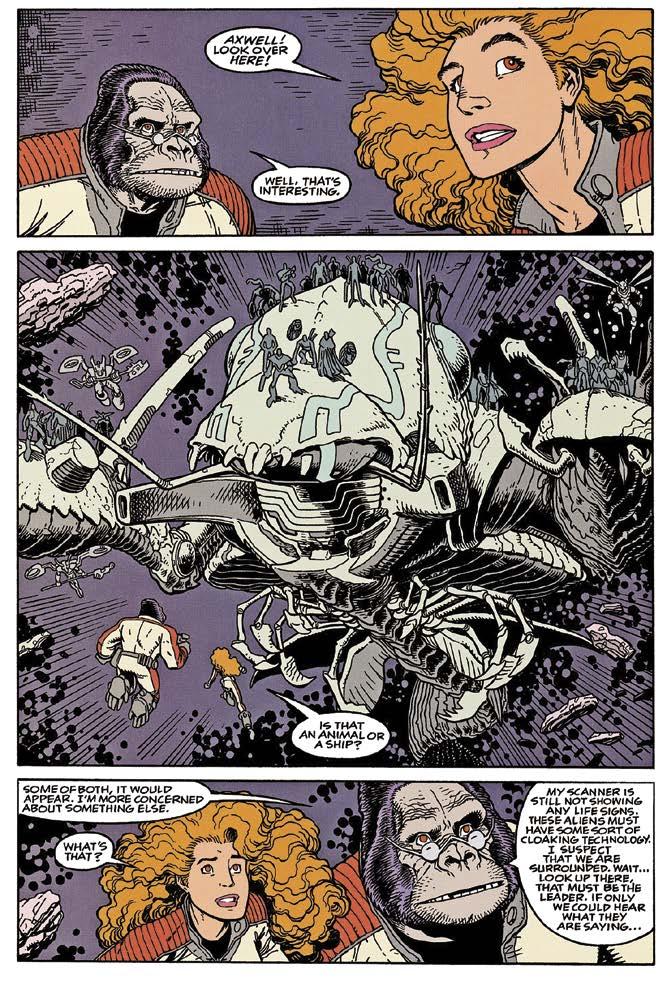

However, in 1993 Adams showed he was more than just an artist as he did double duty on his creator owned Monkeyman and O’Brien as he wrote

and provided the artwork for the comics. Monkeyman and O’Brien featured the adventures of Axwell “Ax” Tiberius and Ann O’Brien. The former is an intelligent, talking gorilla from another dimension that was accidentally brought to Earth by O’Brien. Together they teamed up to save the planet from intergalactic threats as well as monsters from our world. The stories were a fun mix of sci-fi and adventure with some outstanding artwork to boot. Come along as BACK ISSUE monkeys around with Arthur Adams in this exclusive interview about Monkeyman and O’Brien.

BACK ISSUE : Where did the original idea for Monkeyman and O’Brien come from?

ARTHUR ADAMS: It’s not terribly complicated. I got a call one day in the early ‘90s from Erik Larsen who very, very kindly invited me to pitch a story idea or a book idea to Image Comics. This was very early on for Image and I did like the idea of owning what I created and not giving it to Marvel or DC.

I had never really thought about making up my own stuff though. I was mostly just so enamored by all the things that already existed. I was already so happy just playing in that playground. I was content working on Marvel stuff and the little DC work that I had done at that point.

Never is an overstatement though. Of course, I had made up some of my own types of characters when I was a kid for myself and my friends. But during my professional life I hadn’t thought about making up my own stuff. So anyway, Erik Larsen invited me to participate in Image. When he called me, he also asked me to pass this invitation along to Mike Mignola. He said we want him involved in Image as well. Unfortunately, that never went anywhere for Mike with them.

ADAMS : [Dark Horse Publisher] Mike Richardson asked if I was interested in doing more Monkeyman stories and doing them in a different format. I liked doing them in that format. I regret that I didn’t do more of them. It wasn’t a full issue, but it was a way to condense the storytelling and still make it attractive.

BACK ISSUE: There was a potential Saturday morning animated series for Monkeyman and O’Brien from FoxKids. How did that come about and why didn’t it get made?

ADAMS: Well, the Fox series, ultimately it just didn’t work out. I kind of remember but I don’t think it’s my story to tell.

However, there were other attempts to get Monkeyman animated and even a movie. The first attempt was with Disney. The boss of Disney at the time was Michael Eisner. Mike Richardson from Dark Horse was talking to Eisner regularly and Eisner really liked Monkeyman and he was keen on doing it as a movie. But they had just bought the rights to Mighty Joe Young. When that movie came out, it didn’t do very well so they weren’t too keen on doing another giant gorilla thing.

But they were still interested in doing Monkeyman as an animated cartoon. But we couldn’t come to terms. This was the mid-‘90s and they were very excited about it being a Disney project, but they didn’t really want me involved at all. This was 30 years ago so those guys are long gone (presumably). My involvement wasn’t necessary, and they made it known.

After both Disney and Fox, the next attempt that actually got a little bit further was for Cartoon Network. Cartoon Network actually got to the point of doing character designs and those were looking a little rough. I had just been invited to step in and do some character design and reference for them. That’s about when that project fell through.

So, three times, there’s been three attempts so far. Oh, I just remembered another one. There was a fourth attempt by a Korean company. They were very excited and we had multiple conversations and as soon as we started talking money, they disappeared.

BACK ISSUE: Wow! If only just one of them had gone through to production.

ADAMS : I don’t know. It would have been curious anyway. There was a Savage Dragon cartoon, but I don’t remember anything about it really and I know I watched at least some of it. Was there a Youngblood cartoon? I think there was briefly. No, it was Wild C.A.T.S. There was a lot of Saturday morning stuff at the time. The shows probably made more of an impact on younger people than they did on me.

Of those cartoons that actually made it to the networks, the only thing I recall, the only one that I have any fond memories of, was Big Guy and Rusty. I think

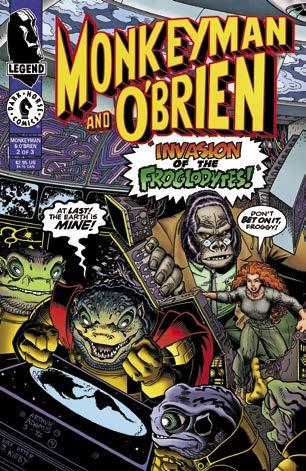

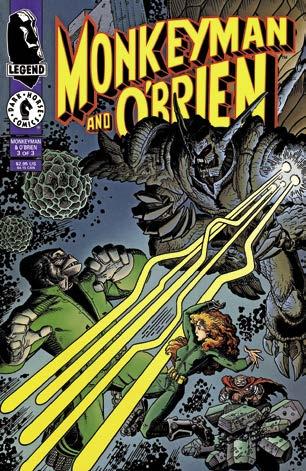

(top) Issues #2 and 3 of Monkeyman and O’Brien’s own series. (bottom) You never know what you’ll encounter in a Monkeyman and O’Brien adventure.

TM & © Arthur Adams.

by Ian Millsted

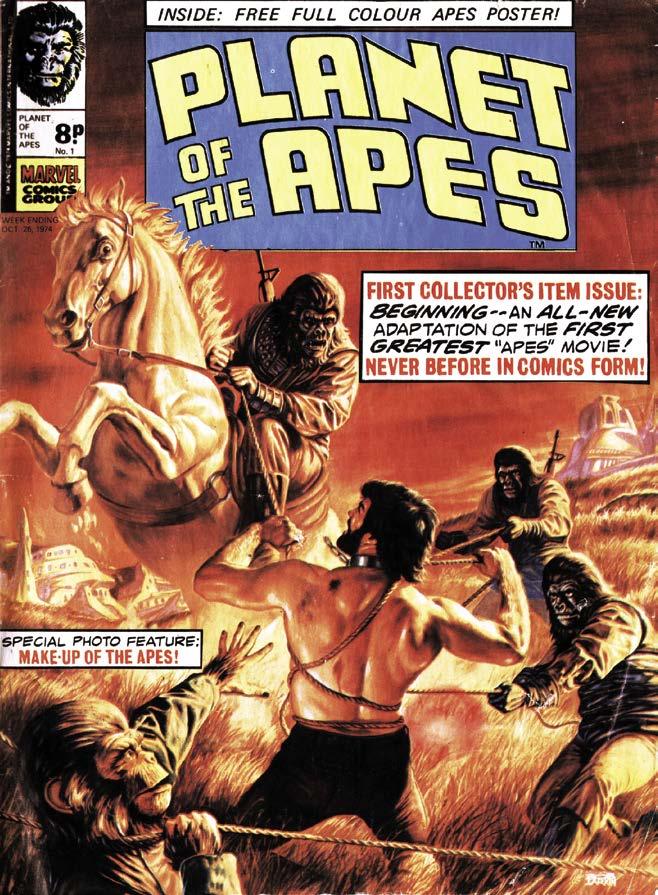

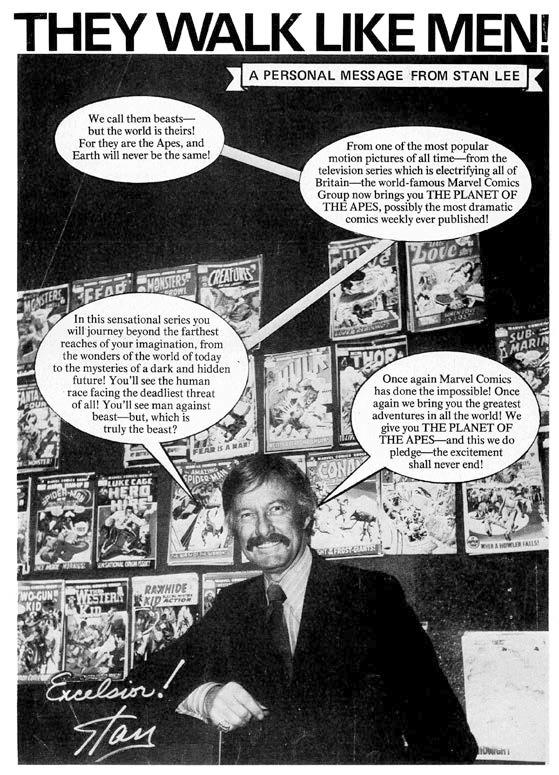

Two nations divided by a common love of great apes, might be how, in hindsight, we examine the British iteration of a comic magazine dedicated to, and mostly reprinting, Marvel’s Planet of the Apes monthly magazine. The handling of the Apes stories is an interesting spotlight into the different markets the two countries comics publishers operated in. More than that, the popularity of the respective source material also shows the variation in tastes on opposite sides of the Atlantic Ocean. As well as keeping an eye out for the statue of liberty we are also likely to find art previously unpublished in the US. Marvel’s monthly Planet of the Apes magazine debuted in 1974 with a cover date of August 1974 but had actually gone on sale in June. This was a point where the original five Apes films had been around long enough to not only have had a decent audience in the movie theatres, but had also started to gain more viewers with broadcasts on network television. The television series did not air until September 1974. Consequently, the stories in the magazine were either adaptations of the film series, or original stories riffing around that milieu. This was quite different in the UK. While the films had been popular in cinemas none of them had yet been shown on British television. This was common practice at the time – there was an agreement that television rights would not be sold until five years after they had been released on the big screen. Often it was longer before television viewers got to see them. In the case of the 1968 Planet of the Apes , it received its first UK television screening in March 1977 on the ITV network (the only rival to the BBC at the time). In contrast, the television series was first shown

This dazzling Bob Larkin cover set the tone for the UK version of Planet of the Apes ©2025 20th Century Studios.

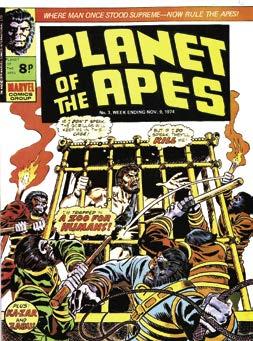

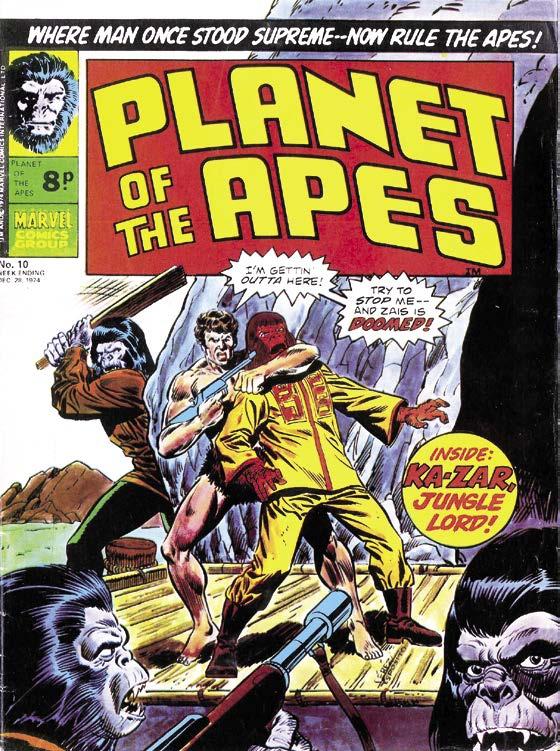

suit to introduce the series to the British audience in Planet of the Apes #1. (right) A George Perez-drawn cover to issue #10 of the series.

in October 1974, just four weeks after the US screenings. Even more of a contrast was the difference in popularity. While US viewers didn’t take to the TV show, which only lasted thirteen episodes on CBS, UK viewers loved it, and it did well in the ratings here. The fourteenth episode was shown in the UK before ever being broadcast in the US. So, when Marvel launched their Planet of the Apes British weekly comic, there was a keen audience of, mainly, boys, who were already fans of the concept. It’s just that the concept they were familiar with was the one from the television show. However, eight to fourteen-year-old boys are nothing if not adaptable and, given a slice of good storytelling with plenty of action, they are likely to forgive being served with something a little different from what they were expecting.

The first issue of the UK Planet of the Apes was cover dated 26 October 1974 and would have been on sale six or seven days before that. At that point, there were only two stories available for reprinting. One was the “Terror on the Planet of the Apes” serial which had started in the first US issue. The other, the option that was selected, was the comics adaptation of the first movie. This was a logical choice in terms of story and chronology but had one problem in that no actual apes appear until some way into the narrative. So, where most British Marvel comics contained three ten-page stories, often splitting one US comic

over two issues, Planet of the Apes #1 opted to print just the Apes story. The stunning painted cover by Bob Larkin was a reprint from the second US issue. Inside, readers were treated to a personal message from Stan Lee followed by twenty-five pages of the Doug Moench/George Tuska/Mike Esposita adaptation. Patient ape-fans had to read until the penultimate page before the first ape appearance. There was also a text feature on the film makeup, also reprinted from the first US issue.

IF YOU ENJOYED THIS PREVIEW, CLICK THE LINK TO ORDER THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DIGITAL FORMAT!

It was the second issue (2 November 1974) in which the first new art was seen. The cover by Ed Hannigan was drawn specifically for the British comic and unseen in the US title. Hannigan went on to produce quite a few further covers for the title. The other aspect of note in the second issue was the introduction of supporting features. In order to stretch out the limited supply of US comics material, the Apes story was reduced to ten pages and the rest of the issue was filled out by reprints of Creatures on the Loose #16) and Astonishing Tales #1). The Planet of the Apes film adaptation continued through #11 with new Ed Hannigan covers on issues 3,4 and 5. Ron Wilson drew new covers for issues 6 to 8. George Perez drew the original cover to #10. In addition, there are new splash pages created in issues 3, 5, 7, 9 and 11. Some insight into which artists were used for the new covers and splash pages is offered by Jeff Aclin, who was one of those involved at the time.