The Pop-Up Pub is not popping off...

Shannon Murphy, page 4

The Pop-Up Pub is not popping off...

Shannon Murphy, page 4

Chat, are we cooked?

Estelle Anderson, page 14

Are a cappella groups making treble?

Olivia Zambrano, page 10

Dear reader,

This semester has gotten me all tangled up in time. The phantom of graduation lurks ever closer, and bright-eyed first-years remind me just how much time has passed since I first stepped foot on a college campus. I want to freeze these slippery days like an image to film — to create some barricade between me and the unrelenting watershed of change.

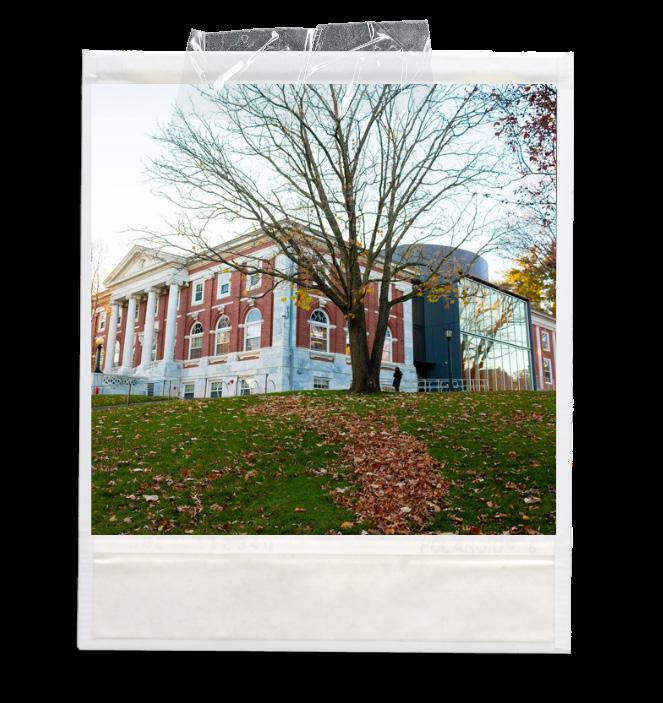

When I first arrived on this campus, five semesters ago as a sophomore, Tufts was teetering on a precipice of change. University President Sunil Kumar’s administration was freshly minted, life was finally coming to a new normal after the COVID-19 pandemic and the school was about to plunge into semesters of encampments and protests. My next three years blurred into a haze of administrative emails, midterms, helicopters flying overhead, finals, construction sites melting into refurbished buildings and a packed protest in Powderhouse Park.

Now, as the newest crop of students builds lifelong friendships, attends its first parties and dines at a freshly blue (!) Dewick, I’ve begun to wonder what

this current era of Tufts feels like for them. What kind of launchpad will they have for their college journeys? What’s it like to attend college after a chilling effect has set in on student speech; after diversity, equity and inclusion has died rather than still in the midst of an unceremonious collapse; and now that we’re more concerned with “No Kings” than COVID-19?

Most of all: What is Tufts culture now, as they understand it, absent the influence of past experience here? If we could distill Tufts University in fall 2025 into blots of ink on a handful of pages, what would it say?

I’ve set out to answer that grandiose question for this third edition of TD Magazine. Helping me do so is a brigade of wonderfully talented writers. Estelle Anderson grapples with the impact of artificial intelligence in our classrooms. Sadie Roraback-Meagher examines the nuances of Jewish life on campus. Olivia Zambrano dives into a cappella culture at Tufts, from group traditions to social dynamics. Shannon Murphy investigates the new Pop-Up Pub: what it is — and why you might not have been

there yet. And finally, Max Lerner explores how Tufts students actually engage with politics.

Throughout my time in college — in classes, on jobs and at the Daily — I’ve combed through thousands of pages of publications. It has become a personal obsession: The most ordinary information feels extraordinary when pulled from a microfilmed, century-old newspaper. These small, everyday details about life that necessarily work their way into every paragraph are, to me, often even more fascinating than the banner headlines above them. They are unintentional snapshots we take of our ever-changing culture.

That is my hope for this magazine: that someday, a few decades down the line, some Tufts student working on some project or other stumbles upon these pages and discovers something startling about our everyday lives — just as I have in the writing of so many Tufts students in our editorial history.

Pax et Lux!

Liam Chalfonte

Tufts Daily Magazine Editor, Fall 2025

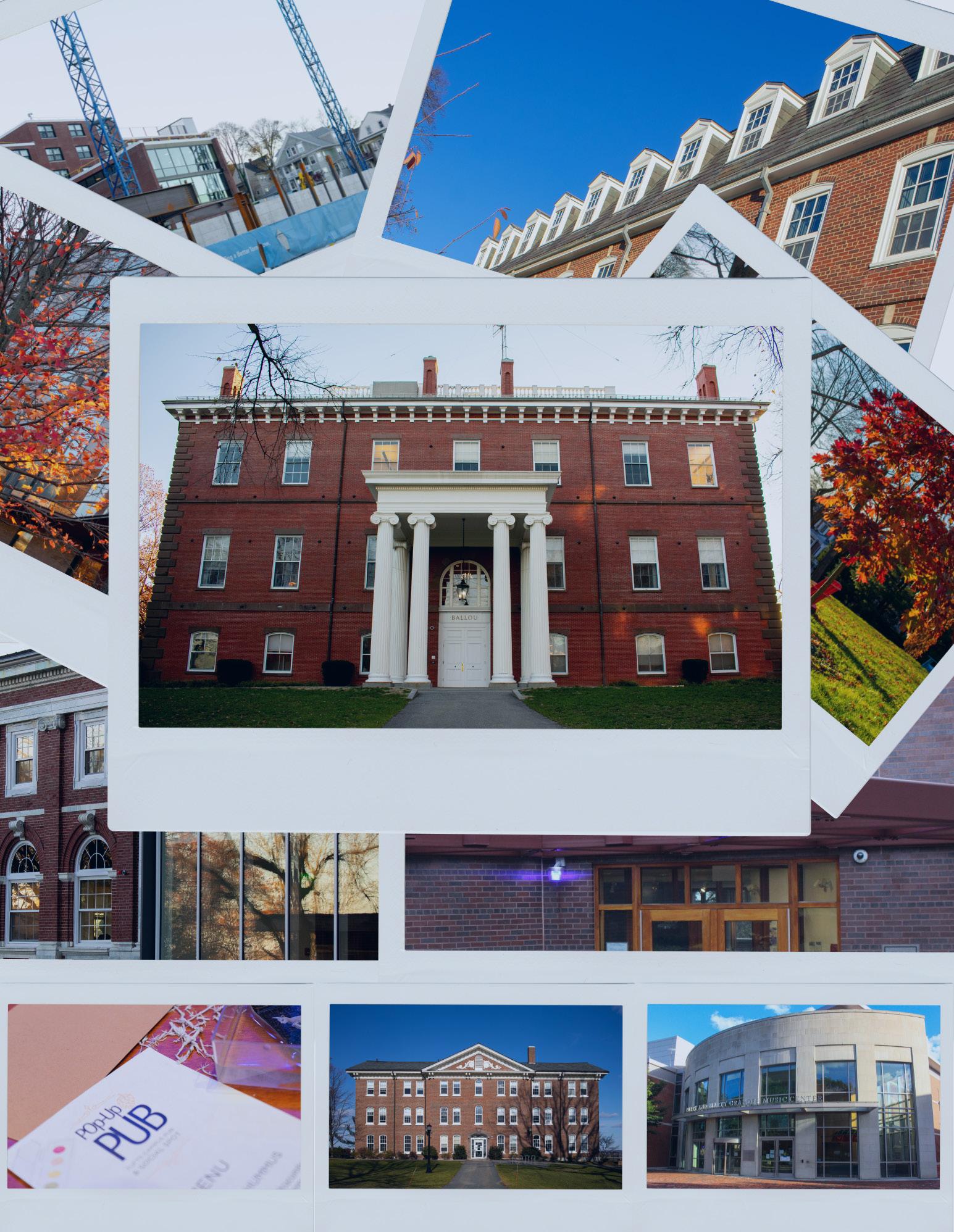

Is Thursday the new Saturday?

SHANNON MURPHY

It’s a Thursday evening, and the normally cozy, inviting Hotung Café is blocked off from the rest of the Mayer Campus Center. Deep purple mood lighting fills the space. The counter that serves vanilla lattes and chocolate croissants by day is now a fully stocked bar serving alcoholic beverages to those 21 and older. The café's glamorous alter ego that only comes out to play once a week from 5–9 p.m. is here: the Pop-Up Pub.

The Pop-Up Pub launched in November 2024 as a joint effort by the Tufts Community Union Senate and Tufts Dining, with support from the deans of the School of Arts and Sciences and School of Engineering, the chief student officer for AS&E and University President Sunil Kumar.

Conceptually, it’s a very attractive setup: a cool place for students to chill out, crack open a cold one or try a classic cocktail without ever having to step foot off campus. However, there is one small problem.

No one is there.

One Thursday around 6 p.m., I noticed the sliding doors separating the swanky little area of Hotung from the perpetually crowded Campus Center had been pulled shut. I walked around to the exterior of the building, only to find both doors suspiciously locked. I returned to my

friend, defeated because my plan to check it out had fallen through.

As I left the building about 20 minutes later, I decided to try again. This time, the door was open. I was greeted by manager Jasmine Allan, who, with a bright demeanor, answered my questions about the pub. Despite her enthusiasm, the loneliness of the pub itself was quite depressing. We took our place as the only people in the seating area.

Allan, a retail dining manager at the Campus Center, said the highest attendance she’s seen at an alcohol-serving Pop-Up Pub event is 13 patrons.

“I’ve heard a lot that [Tufts Dining has] tried [to increase attendance], and it’s just going nowhere,” Allan told the Daily. “A lot of the students [on the] marketing team just don’t want to come, don’t want to promote it or anything. It’s like beating a dead horse at this point.”

Allan believes that inadequate marketing strategies have contributed to the low turnout.

“In my opinion, advertising could be a little better, especially because you get so many new students,” Allan said. “And my first couple weeks of doing the pub, I have people coming and going ‘What is this? What’s going on?’ And then they’re like, ‘Oh this is really cool — this happens every week?’”

However, Allan is hopeful that the pub will grow in popularity and has spoken with groups such as Tufts Film Club and Jumbo Drag Collective about collaborating on events. She sees strong potential in the space, especially for movie nights and drag shows. But realizing that potential is another story.

“The idea is there, but bringing people in is tough,” Allan said.

According to Amy Hamilton, manager of strategic communications and marketing for Tufts Dining, the Pop-Up Pub is intended to enhance the student experience by fostering community and conversation on campus, but the space relies on student organizations and other campus groups using it for collaborative functions.

“Attendance has varied from week to week, with higher turnout when the Pub partners with a collaborator who brings their members,” Hamilton wrote in an email to the Daily. “These collaborations are most successful when the partner actively promotes the event.”

Hamilton explained that partnering with student organizations, who increase the attendance by bringing their members to the pub, is an essential part of its marketing strategy.

“There have been recent initiatives to boost attendance, but they rely on student groups to take the lead in organizing and promoting the events,” Hamilton wrote. “The Pub provides support and space, but a successful turnout depends on student involvement in planning and outreach.”

Still, programming options remain limited. If a group wants alcohol at their Thursday night pub event, they must, as Hamilton suggests, “get creative with their programming, like [with] trivia nights, interactive games, or a crafting activity.” The current liquor license at Hotung Café does not permit alcohol to be served alongside live entertainment.

Senior Rory Myers believes that having live music would boost attendance substantially. The Burren, a popular Davis Square pub, offers live music by college bands and alcohol on Thursday nights, putting the Pop-Up Pub at a competitive disadvantage.

“There’s already a major event going on for people who are over 21 on Thursdays,” Myers said. “So, already everyone wants to go to that. … [The Pub could be more popular] if it was on another day and they perhaps had, more exciting things available, perhaps even live music.”

Allan recognizes this competition as well. As a new manager, she is working on getting a new liquor license that she believes would solve this conundrum.

“I have had friends that are currently going to Tufts or have graduated and most of them have been like, ‘No, I’ve never been to the pub because it’s on a Thursday. I’m going to The Burren.’ Or something of that nature,” Allan said.

Myers had a similar experience. When I asked if he had ever been to the campus pub, he simply replied, “Nope.”

He had come across the pub once unintentionally and, put off by the lack of signage and promotion, promptly left. It felt slightly unusual because a campus pub at Tufts should be a big deal — students had been asking for one for years. And yet, it sprung up almost silently on the Tufts campus, like a mushroom through soil.

“I low-key didn’t know about it until this year,” Myers said. “There was, like, one sign outside the Campus Center. And I was like, ‘Oh, that’s

a little weird — I wonder what that is.’ And then I never went.”

Because Tufts is, well, not exactly known for its thriving party scene, Myers believes that an event run by the university would seem performative.

“It feels like more of an advertisement, that we have more of a social life [than we actually do],” he said. How do we make the Tufts pub not-lame? Myers said more student feedback would help.

“I think there’s ways to make it more interesting and that would involve talking with students,” he said. “And also perhaps loosening up some of the social rules they have in place outside of the campus pub.”

Hamilton noted that student input has been used to develop the pub, but responsibility falls on students to host collaborative events that reflect what they want it to be. Ultimately, the Pop-Up Pub is what students make of it.

“Student feedback has played an important role in shaping the Pop-up Pub,” Hamilton wrote. “We’ve heard consistently that students enjoy having a casual, social space on campus, and that interest increases when events are tailored to specific communities or themes. As a result, we’ve focused on collaborating with student groups to co-host events that reflect their interests and identities.”

Allan wants to be more engaged with students and incorporate their feedback into an iterative process, but her role gives her little direct access to student comments.

“I would love to have more of a way to [reach out to students directly],” she said. “So far we’ve just been utilizing a little QR code around dining [centers], but us as retail managers, we have no access to see any of that. It all goes to somebody else. So I would love to know what people think.”

And what do Jumbos really think?

“Tufts should have a dispensary,” Myers joked.

No Jewish experience is the same at Tufts.

On a chilly spring evening in 2024, 150 student protestors placed their arms around each other’s backs and gently swayed to avoid being broken apart by police. Tents where protestors had been sleeping for almost a month dotted the Academic Quad, where a large, makeshift wall constructed of plywood and paint stood tall. Despite the break from chanting “From the river to the sea” and “Apartheid kills, Tufts pays the bills,” the scene was tense. A mere two hours earlier, University President Sunil Kumar had issued a “no trespass order” to all students remaining in the encampment. Students anxiously waited to see whether their sleepy Massachusetts campus would erupt into the kind of violent confrontation between police and protestors seen at Columbia University and Univeristy of California, Los Angeles.

Such demonstrations at Tufts and other universities have been viewed by some as emblematic of the antisemitism Jewish college students have faced in the past two years. In the months following Oct. 7, 2023, activists and politicians alike have called on universities to take stronger action to protect Jewish students. Tufts later became one of 60 universities under investigation by the Department of Education following complaints of antisemitic discrimination.

Yet for many Jewish students, conversations regarding campus culture today have misrepresented their lived experiences. While many

SADIE RORABACK-MEAGHER

have endured antisemitism amid the campus turmoil, others have greater grievances against university administrators’ handling of protests and the administration of President Donald Trump's crackdown on free speech.

Over the past two years, many Jewish students have found their identities scrutinized by their peers and exploited on the floors of Congress as the President waged war against universities. Amid ever-increasing political tensions, Jewish

“Amid everincreasing political tensions, Jewish college students have longed for a simple dream: to just be college students.”

college students have longed for a simple dream: to just be college students.

I. Healing — ר

Two days after Oct. 7, 2023, Tufts’ Students Justice for Palestine sent an email praising the “creativity” of the Hamas attacks that killed 1,200 people in Israel. Soon, cries of “Glory to intifada” to the beat of a makeshift drum, echoed across campus, and the seeds of activism began to sprout. For Jewish students, the fall of 2023 blurred into grief,

confusion and frustration as they navigated both the tragedy of the attacks and the divided campus they found themselves in.

Junior Peri Karpishpan, a freshman at the time, recalled the difficulty of that fall. “It was tough. The idea that a bunch of people got murdered [or] taken hostage, some of whom … you know, and then you have a bunch of people celebrating it — that was hard,” she explained.

But Karpishpan also stressed that people should continue to protest, so long as such demonstrations don’t become disruptive or veer into antisemitism. “If somebody were to start a protest right now to end the war — for a ceasefire — I’d join it,” she said, “But [I] couldn’t join it now, because they’re gonna still scream ‘Long live the intifada’ … and imply that Israel shouldn’t [exist] at all.”

Tufts has since suspended its SJP chapter — a decision Karpishpan believes has made campus safer. Indeed, universities around the country have suspended or banned their SJP chapters, citing violations of school policies or incidents of antisemitism.

Yet for some Jewish students, curtailing Pro-Palestinian activism will not have the positive effect administrators may think it will.

Senior Meirav Solomon, national board president of J Street U, a student arm of the wider J Street organization that lobbies for a two-state solution, discussed how political polarization has further complicated the ability to process the conflict. “It can’t just be that

somebody makes a mistake and says the wrong thing … and we just shun them. … That’s not how we build the community that we want to build,” Solomon said. “We have to bring them in. We have to say, ‘Here’s how you hurt me.’” While Solomon believes many of the actions taken by SJP were harmful, she disagrees with the university’s decision to suspend the organization. “I think that every club has a right to exist on this campus,” she said. She believes it’s necessary to provide students with a path toward having these difficult conversations.

For Jews everywhere, the pain of the Oct. 7, 2023 attacks has been compounded by a renewed confrontation with Zionism and a concerning uptick in antisemitic incidents. For college students in particular, the ability to move forward came with its own unique set of challenges.

Solomon reflected on living in a dorm her sophomore year in the

aftermath of Oct. 7, 2023 knowing that the hallways could contain students with a constellation of different viewpoints, some of which were likely directly at odds with her own. She points out that, “as college students, you see news pundits all the time. They get to argue about Israel and Palestine, and … never have to see the other person they were arguing with on the show ever again if they don’t want to. … We have to live next to each other.”

Moving past the Oct. 7, 2023 attacks and to a point of normalcy has proven nothing but difficult for students. In the wake of campus turmoil, many Jewish students have been forced to censor their beliefs to avoid social ostracism. A study conducted by Tufts professor Eitan Hersh for the Jim Joseph Foundation found that one in four Jewish students nationwide feel the need to hide their Jewish identity to fit in on campus. The study also noted that

45% of Jewish students at elite college campuses had lost friends because of the conflict.

Sophomore Ely Cristol-Deman described feeling apprehension about sharing his Israel-forward views outside Jewish spaces, and expressed discomfort with the"Zionist" label.

Karpishan also noted the social risks that come with outwardly expressing Zionist views. She explained, “When you say you’re Zionist, you’re kind of f---ed no matter where you are, because that’s such a loaded term,” adding that, “You walk in the door and like, [people will think], ‘Oh, it’s a white supremacist. It’s a person who hates Arabs.’”

Even within Jewish spaces, finding catharsis has proven difficult for many Jews. In the wake of campus turmoil, Solomon found it challenging to attend services at Tufts Hillel, where she felt her views were judged. “It’s

one thing to pray with the people you disagree with, but it’s another thing to pray in a space that you know fundamentally wouldn’t allow for your ideas to be presented, or welcomed as genuine or valid,” she explained. Ultimately, Solomon turned to other outlets for spiritual fulfillment, attending off-campus synagogues and finding community through J Street.

II. Repair the World —

In Washington, the protests on college campuses prompted congressional hearings with university presidents, academics and students to better understand the situation at hand. While heading home from her brother’s bar mitzvah, Solomon received a call asking her to testify before the Senate about her experiences as a Jewish student. Although she was incredibly grateful for the opportunity, she said the experience encapsulated the high expectations placed on Jewish college students today.

“When I left the Senate testimony, I had midterms to get back to,” Solomon said, adding, “My primary job right now is to be a student. … It’s not to be telling US senators, ‘Please don’t cut my university’s research funding because you think that somebody holding a Palestinian flag is anti-Semitic,’ because it’s not, and I’m Jewish and I’m fine.”

Solomon also described how the media has poorly represented the experiences of Jewish students, further leading to misunderstanding. “Imagine watching somebody say that they’re telling everybody else your life story … and everything is wrong,” she said.

Much of the tension surrounding the conflict has only been exacerbated by the Trump administration’s response.

Cristol-Deman described the president’s current actions as the “political weaponization of the term antisemitism.” He noted that, for many Jews, watching Donald Trump suddenly seem to care about antisemitism — despite his association with Charlot-

tesville and Jan. 6 insurrection — feels frustrating and insincere. Karpishpan agrees, asserting that, “the idea that the way to solve [antisemitism on campus] is to get the government involved and threaten to withhold funding until the school caves … is not going to end well for anyone, and I certainly do not support that.”

In fact, roughly 60% of Jews disagree with the White House’s decision to freeze federal funding from Harvard and UCLA on the grounds of protecting Jewish students.

Cristol-Deman further expressed concerns that recent restrictions the university has placed on pro-Palestinian-related activism will ultimately cause people to blame Jewish

“If neither the president nor the university is doing an adequate job at protecting Jewish students, who is?”

people for suppressing free speech. “The far left is going to say, well, this was done in the name of Jews, and so the Jews are going to be scapegoated for it; at least that’s my cynical prediction.”

If neither the president nor the university is doing an adequate job at protecting Jewish students, who is? When asked, Solomon responded with a laugh. “You’re the first one to ask that,” she said. After reflecting, Solomon described the importance of J Street in protecting both Jewish and Muslim students. Solomon also noted how many of the organizations that Jewish students have relied on have ultimately failed to be there for students and, in some cases, betrayed their mission altogether.

Karpishpan believes that Jewish organizations, specifically Jewish on Campus — a group dedicated to writing about antisemitism and providing resources to help students address it — play a significant role in protecting the well-being of students. Cristol-Deman also credited Jewish communities such as Hillel with looking out for Jewish students during these tumultuous times.

III. Hope —

After two years of war — to the day — Hamas and Israel reached a ceasefire agreement on Oct. 8. All 20 living hostages were returned back to Israel in exchange for 2,000 Palestinian prisoners. The announcement of the ceasefire came during the Jewish festival Sukkot, a time marked by singing and dancing. For Jews around the world, the return of the hostages marked the end of what had been a long nightmare. Yet at the same time, reconciling with the Palestinian and Israeli lives lost has only just begun.

At Tufts, the two-year anniversary of the attacks was met with varied responses. “Bring them home” was painted on the cannon one day, hoping for the hostages’ return; “Free Palestine” was painted on the cannon the following day.

Still, this October was far more peaceful than the divided campus of 2023. Red and orange leaves covered the rolling hills of President’s Lawn, and the sounds of students chattering between classes filled the air. Grass has long since grown over the spots where tents once filled the quad.

Though doubts about whether the ceasefire will hold certainly remain, optimism for the future of campus life persists. However, the pressure placed on Jewish students over the past three years is still very real.

“Once I graduate, I’m so excited to not be a Jewish college student, and just be a Jewish young adult,” Solomon joked.

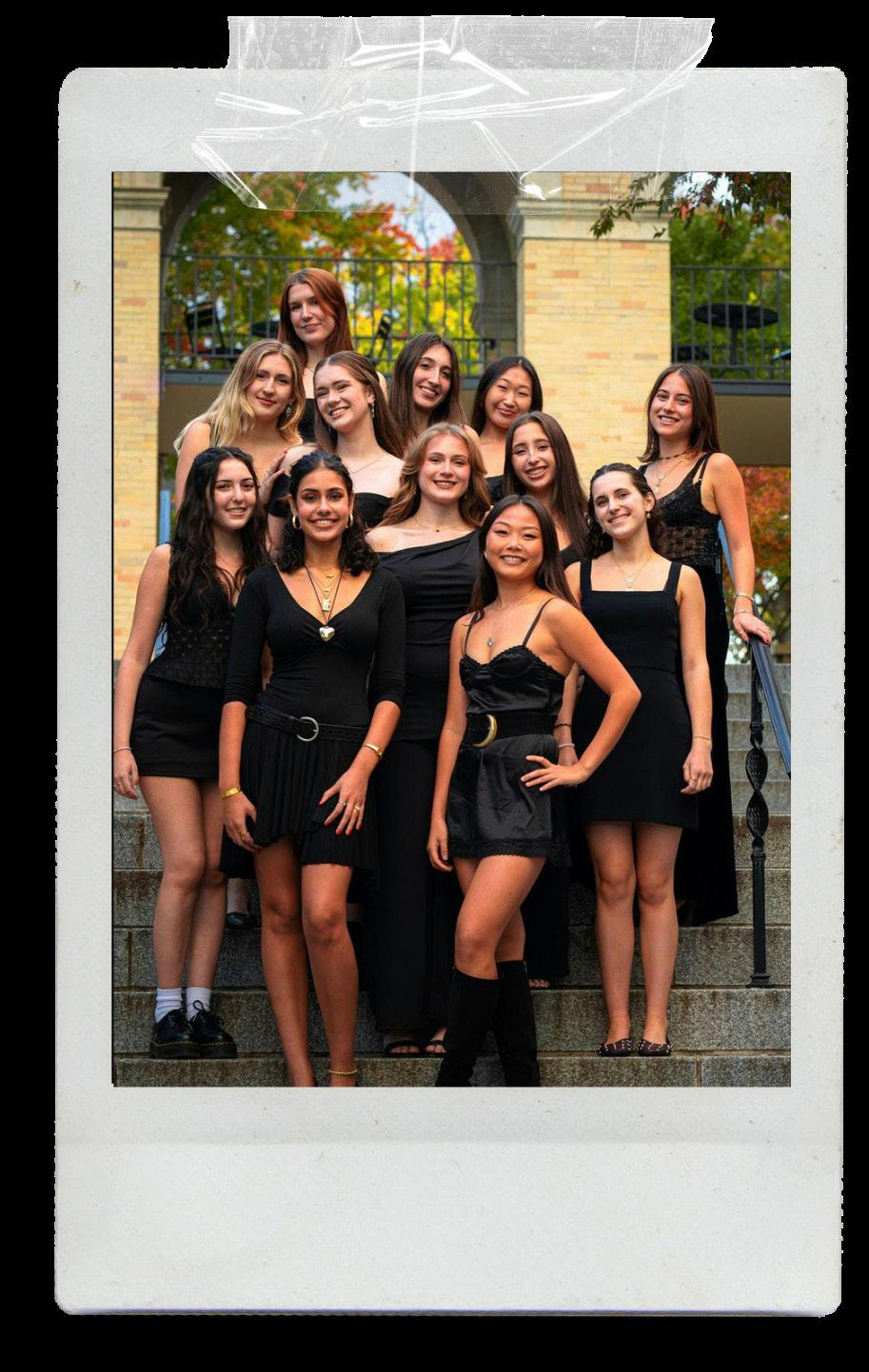

A look inside a cappella’s covert role in campus culture.

OLIVIA ZAMBRANO

If you’re a Tufts student, chances are you’ve met at least one member of an a cappella group — and didn’t even know it. Tufts is the proud home to 10 a cappella groups, each with a unique history, repertoire and membership. From Enchanted, which sings almost exclusively Disney music, to S-Factor, Tufts’ all-male group specializing in music of the African diaspora, Tufts offers no shortage of opportunities for students interested in entering the a cappella scene. Because of the sheer number of groups, each occupying its own musical niche, it can be difficult to grasp what a cappella culture actually looks like on campus. To find out, I decided to start at the source, and interview leadership from three groups on campus: the Jackson Jills, the Beelzebubs and Shir Appeal.

I sat down with senior Layla Hoffmann, president of the Jackson Jills, for a brief interview at The Sink where I learned a little bit about her experience entering the a cappella scene at Tufts and preserving the Jills’ legacy as a whole. Hoffmann’s passion for the Jills was infectious. From friendships with fellow members to fond memories from prior years, Hoffmann is immensely passionate about both a cappella and her leadership role, something that bled into every aspect of our conversation. She spoke at length about preserving the Jills’ legacy as the oldest femme-identifying a cappella group on campus — a history she sees as integral to its identity. This legacy of sisterhood

bleeds into every aspect of their on and off campus presence, with their extensive alumni network playing an enormous role in the Jills’ culture. Hoffmann emphasized that the sisterhood created between members spans generations. “We do an alumni brunch meetup in the spring,” Hoffman said, “and members will come in from [the] Jills’ class of '76 and I’ll just immediately have something to talk to them about.”

For the Beelzebubs — Tufts’ oldest a cappella group, although there is some friendly dispute between the Bubs and the Jills about who is ‘technically’ the oldest — legacy takes on a different meaning. Senior Anish Guggilam, president of the Bubs, acknowledges the role of both privilege and hard work in crafting the legacy the Bubs have on campus today. In response to a question about the Bubs’ legacy and its impact on how the group carries themselves, Guggilam resolves that “the Bubs have had kind of an iffy image on campus for a long time” — something that initially discouraged him from auditioning. However, “the

pressure of thinking that [they’re] trying to ‘resolve’ the Bubs image” is simply too “macro — [too] hard to control.” For the Bubs, changing whatever mystique they might have across campus isn’t a priority — rather the music, the members and their passion speak for themselves.

By nature of their character as the three oldest a cappella groups — the Beelzebubs, the Jackson Jills and the Amalgamates, have a unique relationship — one that comes with annual traditions, extensive alumni networks and a distinct image on campus. Both Guggilam and Hoffmann cited this connection. Hoffmann highlighted annual apple picking with the Bubs and the Mates as a standout tradition. “A lot of [our] traditions involve the Bubs and the Mates, because we’re the three oldest groups on campus,” Hoffman said. “[These traditions] started up years and years ago, and we just continue them.”

Guggilam echoed that closeness, commenting that the Bubs “[have] a lot of friends in the Jills” who they hang out with a lot.

That depth of tradition and alumni connection is not limited

to the oldest groups. Shir Appeal — Tufts’ all-gender Jewish a cappella group — also boasts strong traditions and alumni ties. Junior Henry Nova, business manager of Shir Appeal, proudly recounts a classic Shir Appeal tradition that occurs every autumn after they accept their new class of members: the Fall Retreat.

“Just after we accept the new baby class,” Nova explained, “we go for a weekend off campus to some members’ home and just spend a weekend bonding. It’s a really fun time where we get to know each other.”

As a myriad of a cappella groups have entered the previously Jills and Bubs dominated scene, the dynamics of a cappella culture have shifted. While Nova described relationships with other a cappella

groups far less frequently than Hoffmann and Guggilam, he’s certainly friendly with members of all the groups. He told me that he and his fellow Shir Appeal members “definitely have friends throughout the a cappella community,” waving Hoffmann over with a smile to introduce us.

Guggilam agreed, finding that Tufts’ a cappella community is full of like-minded, fun individuals. “Joining the Bubs … introduced me to a whole different side of campus,” he said. This sentiment parallels Hoffmann’s thoughts on the social dynamics of the a cappella scene, which seem to growing closer as the years go by.

“The community just gets closer and closer every year. … The people that join every year are more and more outgoing and are

wanting to build a community not just within their own group, but amongst each other,” Hoffmann commented.

Nowhere is that sense of unity more visible than the Riff-Off, Tufts’ annual a cappella competition. This academic year’s Riff-Off will be in the spring, so get excited — it’s a favorite for members and students alike. Guggilam finds that it’s “one of the only times, maybe the only time, that every group comes together and does something.” Seeing that each a cappella group on campus has roughly 10–15 members, events that host all 10 groups are few and far between.

Nova finds that “it’s a lot of fun collaborating with the other groups, not just at the Riff-Off, but [at] the other events that we

do on campus.” Although there might not be many collaborative events, it’s a highlight for members across groups.

The entire a cappella scene seems to exist within its own realm on campus, from members maintaining secret traditions, representing with members-only varsity-style sweatshirts and generally existing within their own social scene at Tufts. These secret traditions seem to be fairly common — in my interviews, I prefaced with the fact that I don’t expect to be let in on any memberonly traditions without even knowing if there even were any. To my surprise, both Nova and Hoffmann acknowledged the level of secrecy that exists within the a cappella groups. Nova notes that on their Fall Retreat, members “do lots of secret Shir Appeal traditions,” but didn’t

“A cappella appeared to be not just a bureaucratic student organization, but a tight-knit community of friends who all love to sing.”

let me in on any of them. Similarly, when asked about her favorite Jills traditions and their place in greater campus life, Hoffmann had to briefly pause. “I want to make sure I tell you the ones that I can tell you,” she said, before letting me in on a few.

Ultimately, the a cappella scene at Tufts presents members with the opportunity to bond over a shared passion and create a tight-knit —

and perhaps fairly exclusive — community.

Sitting down with Nova, Hoffmann and Guggilam enlightened me on what really goes on within the a cappella scene at Tufts. Although I had a vague grasp of the a cappella community prior to these interviews, my perception was far more removed. In each of our conversations, their passion for not only their art but their community shone through. A cappella appeared to be not just a bureaucratic student organization, but a tight-knit community of friends who all love to sing. More importantly, though, is the ever-changing nature of the a cappella scene as a result of the individuals that characterize these groups. As Hoffmann eloquently comments, “The culture of [a cappella] is able to live on despite the fact that it’s a constantly changing group. It still has that same core feeling to it.”

Students and professors determine whether AI is really intelligent.

Everyone at Tufts seems to have a metaphor for AI. One professor compared humans who religiously use ChatGPT to ‘barnacles eating their own brains.’ Another described AI as a “billion-dimensional glider,” an aircraft that transports people through new realms of discovery and innovation. Yet another envisioned it as a “fairy,” ready at a moment’s notice to wave its wand and solve students’ problems.

What’s with all the metaphors? AI represents infinite possibilities: optimism and pessimism, progress and backsliding, a supplement to human learning and the erosion of human intelligence. From ChatGPT to Claude to Gemini, AI technologies are constantly evolving. Perhaps we find it easier to think about AI in abstract, representative terms because we can’t quite put our finger on what it is yet. As humans, we are grappling with a technology that continues to divide, perplex and excite us.

Tufts is no exception. As a university that prides itself on intellectual curiosity, inquiry and creativity — on being the epitome of a tried-and-true liberal arts education — is there a place for AI in the classroom here?

James Intriligator, a professor of mechanical engineering, certainly seems to think so. As he shared his screen on Zoom to show off new ChatGPT prompts he was experimenting with, I could practically feel his excitement emanating from the screen.

“I think of [AI] like flying an airplane. It’s a whole new human experience … it opens up minds. It creates new

avenues of exploration. It creates possibilities and intersections that people miss,” he said. “Realistically, pretty much every job is going to be impacted by [AI] and I think the university owes it to the students to at least get them conversant in it.”

In his free time, Intriligator uses ChatGPT to create new languages, brainstorm policymaking strategies for politicians and even troubleshoot the broken cigarette lighter in his car. He frequently incorporates AI into his homework assignments. In one of his classes, students must use ChatGPT to brainstorm design improvements for various consumer products, documenting AI usage in an appendix.

Listening to Intrilligator speak, the skeptic in me couldn’t help but cry out: What about human creativity? Doesn’t asking AI to brainstorm these ideas mean that students aren’t exercising their own potential for original thought?

“I guess I think of it as a new form of thinking and brainstorming and creativity,” Intriligator said. “You still have to be creative and innovative and add the human touch to it, but you can do it at a larger level and faster. … It will take care of the number-crunching, detaily things that you don’t like doing.”

“Is there a risk that you’re losing a valuable learning experience by asking the machine? Potentially, yes,” Murphy said. “But I think that, at least with [coding], the trade-off is net favorable, because I had a lot of students who just never were able to even get to [a basic level of coding] in the course of my one-semester class, because they had never coded before.”

Yet as valuable as ChatGPT can be, Murphy is not that optimistic about students’ and professors’ ability to use AI tools with discipline. The temptation to turn to AI can be nearly impossible to resist, Murphy said, meaning more and more of his math students may use it as a substitute for putting pen to paper and developing core mathematical skills on their own.

“I don’t think the answer is to say, categorically, ‘You can’t use it,’” Murphy said.“Part of what you have to do in math is struggle. You have to work on hard problems for at least some number of hours. … I worry that if you can just go straight to [AI] and ask it for the answer, then you lose that experience.”

“ W hat about human creativity? Doesn’t asking AI to brainstorm these ideas mean that students aren’t exercising their own potential for original thought? ”

Like Intriligator, James Murphy, a mathematics professor, encourages students to use AI for certain assignments, especially homework that involves coding. Typically, Murphy explained, about half the students in his “Probability” and “Statistics” courses have no prior coding experience — a skill that can take rigorous time and practice to master. Allowing students to use ChatGPT helps break down that learning curve.

One of the challenges of incorporating AI into education is that each academic department at Tufts is impacted differently. AI technologies may naturally supplement the technical, data-based demands of STEM fields, but in the humanities, they are often seen as cataclysmic threats to the creative writing and critical thinking that the discipline is rooted in.

Jess Keiser, a professor in the English department described AI as a “cliché machine” that takes students’ inputs and produces wishy-washy writing and ideas. As I stepped into

his office in East Hall, I was met by a floor-to-ceiling bookshelf teeming with literature that he and his students dissect in courses such as “The Paranoid Imagination” and “Of Microscopes and Monsters.”

“[AI is] really good at just churning out fine prose that is essentially meaningless and thoughtless,” Keiser said. “In any kind of writing, there’s some of that — there’s throat clearing. But ideally, the writing and thinking one would want to do and see in a literature classroom is going to be more meaningful, thoughtful — not just boilerplate.”

If there’s any use for AI in the classroom, Keiser told me, it’s as a negative example of the writing style students should avoid. At the same time, he acknowledged that the quality of AI-generated writing has improved exponentially in recent years. AI may be a “cliché machine,” but Keiser argues it has become nearly impossible to tell whether a piece of writing was produced by a student or ChatGPT.

The English department is going to have to do a “serious rethinking” about what future assessments will look like, Keiser said. In some of his classes, he has already begun assigning more in-person exams as a way to prevent students from using ChatGPT. But for Keiser, the most effective response to the inevitability of AI might be even more drastic: “going medieval.” He envisions the creation of “writing labs” around Tufts, where computers are replaced with typewriters and students sit for several hours, clacking away, alone with their thoughts.

Jody Azzouni, a philosophy professor, has also returned to in-class exams. If a student wants to write an essay, they must meet with him multiple times to discuss their thesis, giving Azzouni a way to ensure students have wrestled with ideas themselves as opposed to offloading their thinking to a chatbot.

“What I’m trying to do is create a class that’s beneficial to the student

and is good for their brain health, too,” Azzouni said. “If there’s somebody who’s intent on gaming that — well, fine. I’m not a policeman. I’m gonna set things up as best I can, so that those who can profit by it in a healthy way will.”

These days, Azzouni kicks off his classes with a presentation titled “Your Brain on ChatGPT,” riffing on the ’80s “This is Your Brain on Drugs” commercial by Partnership for a Drug-Free America. I reviewed the presentation before our interview, startled by its slides with evidence that ChatGPT reduces neural connectivity and ability to remember passages we just read.

And yet, “This is Your Brain on Drugs” has become a meme in modern times, widely parodied and even said to have nudged more teens toward trying drugs. I couldn’t help but wonder if anti-AI campaigns will meet a similar fate.

In the humanities, where many professors have adopted firm stances against AI, Ester Rincon Calero stands apart. A professor in the romance studies department, she has embraced a hybrid approach: Students may use AI, but they must demonstrate they are still practicing writing, reflection and critical thinking.

“I think a minority of people are doing what I’m doing, but I love technology. I have always used technology,” Rincon Calero said.

Rincon Calero sees plenty of benefits to incorporating AI into her classes. For students who are too shy to attend office hours or speak to her after class, AI can answer their questions instead, while offering “unlimited” opportunities for feedback as they write essays or study for exams.

“Like everything, a lot of resistance [to AI] comes from the fact that there is a learning curve,” Rincon Calero said. “The faculty development is crucial. … For some people who are not familiar with technology, [AI] is daunting.”

In one of her Spanish poetry classes, students have the option to use the AI songwriting app “Suno” to create a song based on a Spanish poem and then write an essay reflecting on whether the result is representative of the poet’s style. She also encourages her students to use an AI platform called “Rumi” for feedback on their writing, as long as they incorporate the corrections by hand.

Because of the prevalence of AI, Rincon Calero believes students’ ability to demonstrate their knowledge ‘on the spot’ is more valuable than ever before.

“If you have used AI to prepare, I don’t mind, but you’re going to have to talk about it, which means your brain is going to have to process that information and discuss it in class,” she said. “I have increased dramatically [the percentage of] the final grade [composed of] participation in class.”

AI can be incredibly enticing, its allure almost magnetic. I often feel that pull myself. Even as I write this article, I am tempted to open ChatGPT, knowing a little AI assistance would give me more time to work on job applications, edit my essay due tomorrow or hang out with my friends as the end of senior year creeps closer.

Among my fellow Gen Zers, the refrain, “Just ask Chat” is increasingly common as AI becomes more ingrained into every facet of our lives. Peer out across the sea of laptops in a lecture hall, and you’ll spot at least a handful of screens open to ChatGPT, with students often asking it to answer questions raised during lecture. Like professors, students remain divided about whether to embrace AI with open arms, steer clear of the technology altogether or try to find a balance between these two extremes.

Junior Cecile Thomas, an English and psychology major, remains firmly anti-AI. As a writing fellow,

she is particularly concerned that ChatGPT may homogenize students’ writing styles.

“ChatGPT standardizes your voice and can inhibit some of that personality [from coming] through in your writing,” she said. “I feel like a lot of people I talk to are like, ‘I might as well embrace it, because it’s the reality.’ I personally don’t subscribe to that, because it’s your reality if you want it to be. I’m not choosing to make it my reality.”

Other students, especially those in STEM fields, see ChatGPT as a useful resource that can help them better understand class material while also easing their workload.

“[AI] is so convenient. You can upload your whole file into it. It can detect your handwriting. It’s so freaking smart that it’s honestly kind of scary,” junior Alexa Santa Cruz said.

For Raydris Espacia, a junior and chemistry major, a typical semester involves multiple six-credit classes, about 60 pages of reading per night and extensive work for her labs and recitations. Like many students, it sometimes just gets to be too much — which is where ChatGPT can step in.

structure where students watch online lectures for homework and then use class time for practice problems.

“A lot of people that I know struggled with not having the professor teach us in person [and] not being able to ask questions in person,” she said. “I feel like sometimes I’m not getting taught properly, and then it’s up to me to selfstudy. …There’s a lot of work that is expected outside of class that I don’t think professors are realizing is more work than they think.”

When I asked my interviewees what Tufts students use AI for the most, I was met with a range of responses. Students feed their lecture notes into ChatGPT to generate practice exams. They ask it to synthesize dense readings. ChatGPT solves students’ homework problems, clarifies ideas that the professor did not fully explain during lecture and even completes take-home quizzes.

AI is also increasingly becoming a substitute for office hours. Senior Will Soylamez, a teaching assistant for a computer science course, said that he and his fellow TAs are seeing more AI-generated homework submissions

“Among my fellow Gen Zers, the refrain ‘ Just ask Chat ’ is increasingly common as AI becomes more ingrained into every facet of our lives.”

“With all that combined … you don’t have the brain power to constantly be keeping up with assignments and lab reports,” she said.

It’s true that Tufts students tend to be the workaholic type, piling on as many classes and extracurriculars as their schedules can bear. But the workload is not always self-inflicted, Espacia explained. Often, the way professors structure their classes can increase the feeling of confusion that leads students to use ChatGPT as a crutch. For example, Espacia pointed to “flipped classroom” courses, a class

and fewer students showing up to office hours for support.

“I think in a weird way, [ChatGPT] doesn’t feel like cheating, necessarily. We all know we’re not supposed to use it, but … somehow with ChatGPT … it feels like a softer line,” Soylamez said. “I think that’s honestly part of the reason so many people use it.”

No matter their major or their stance on AI, however, the students I spoke with emphasized that it must be used with moderation.

“I personally don’t mind students using it, especially with facilitating

their learning, but ask questions in a smart way, minimize your impact and try your best to get [answers] for yourself,” Espacia said.

Santa Cruz, who is studying mechanical engineering, said many of her professors encourage AI usage both inside and outside the classroom. But that encouragement can sometimes have a reverse-psychology effect: The more professors allow the use of AI, the more students want to prove they can complete assignments on their own.

to professors across the university.

“The real gist of [the AI Taskforce] was to try to bring people together to understand the ways that AI is impacting our work, but also to build capacity, to think about how [we can] work together,” Carie Cardamone, a member of the Taskforce and an associate director at the Center for the Enhancement of Learning and Teaching, explained.

For now, the AI Taskforce’s guidelines will not be binding; instead, they’ll function as a set of suggestions

“ What’s the point of going to school if you can’t formulate your own thoughts?”

“A lot of our professors, especially my professors, are like, ‘Chat[GPT] is really great,’ but at the end of the day … you need to understand these basic fundamentals,” Santa Cruz said. “What’s the point of going to school if you can’t formulate your own thoughts?”

AI policies across Tufts’ academic departments exist as a patchwork of complex, often contrasting approaches. Some professors, like Intrilligator and Rincon Calero, are embracing AI and directly incorporating it into assignments. Others, like Azzouni and Keiser, are going to great lengths to wipe any traces of AI from their courses. As a result, walking between two classrooms on Tufts’ campus can mean encountering entirely different policies on AI usage and what a professor counts as plagiarism.

How should Tufts students navigate this kaleidoscopic landscape of AI rules? That concern was the impetus behind the creation of a new AI Taskforce, composed of approximately 30 faculty members from Tufts’ four schools. The Taskforce meets once a month to discuss the role of AI at Tufts and develop shared guidelines regarding AI use, which will eventually be distributed

that different departments can mold to their liking. Cardamone hopes departments will ultimately create shared “buckets” of policies — sets of policies a professor might adopt in a given department.

“There’s a shared understanding from all of our conversations around the fact that we want guidelines and not policies, and we want them to be broad and allow for academic freedom within space, but give us a scaffolding of common language and common considerations to understand when we’re making those choices,” Cardamone said.

One guideline under consideration would require professors to set crystal-clear expectations in their syllabi about how students may use AI. Rather than just prohibiting students from using AI, professors will be expected to explain why. For students like Santa Cruz, it’s useful when professors are specific about the types of assignments where they permit AI usage versus assignments where it is prohibited.

“I personally appreciate having the ‘okay’ and ‘not okay’ kind of structure,” she said.

There is a fine line between allowing professors to maintain autonomy over their classroom while also creating academic policies that remain consistent across the university. It’s

a balance Tufts will have to weigh carefully as more departments chart their own paths forward.

AI’s radical transformation of our society is undeniable. It is everywhere: in our Google searches, in our email auto-complete suggestions, in the deep-fake videos saturating our X feeds. We may not yet know what directions it is pulling us, but in the weeks, months and years to come, no one on Tufts’ campus will be able to avoid difficult conversations about how much we want to let this new technology into our lives.

Many professors view incorporating AI into the classroom as a responsibility they owe to their students, who are entering a precarious job market in which many employers will demand AI fluency.

The Tufts Career Center agrees, encouraging students entering the workforce to “view AI as a tool, rather than an adversary.”

For Rincon Calero, exposing her students to AI is meant to prepare them for life after graduation.

“The reality [students are] going to face when they leave Tufts and they go to a job is that they’re going to have to use AI to be more efficient. If they cannot be more efficient, then they’re going to struggle,” she said. Is that enough of a reason for even the most anti-AI student or anti-AI professor to consider giving in?

Where does Tufts — and higher education overall — go from here? Will AI lead to the cataclysmic, earth-shattering educational shift that many theorists predict, or is it perhaps all a bit overhyped?

Will an AI-driven society make us collectively realize the beauty of being human, of the creativity and hard work and thought processes that an algorithm might be able to simulate but that only ‘we’ are able to feel, viscerally, down to our bones?

I left with more questions than answers.

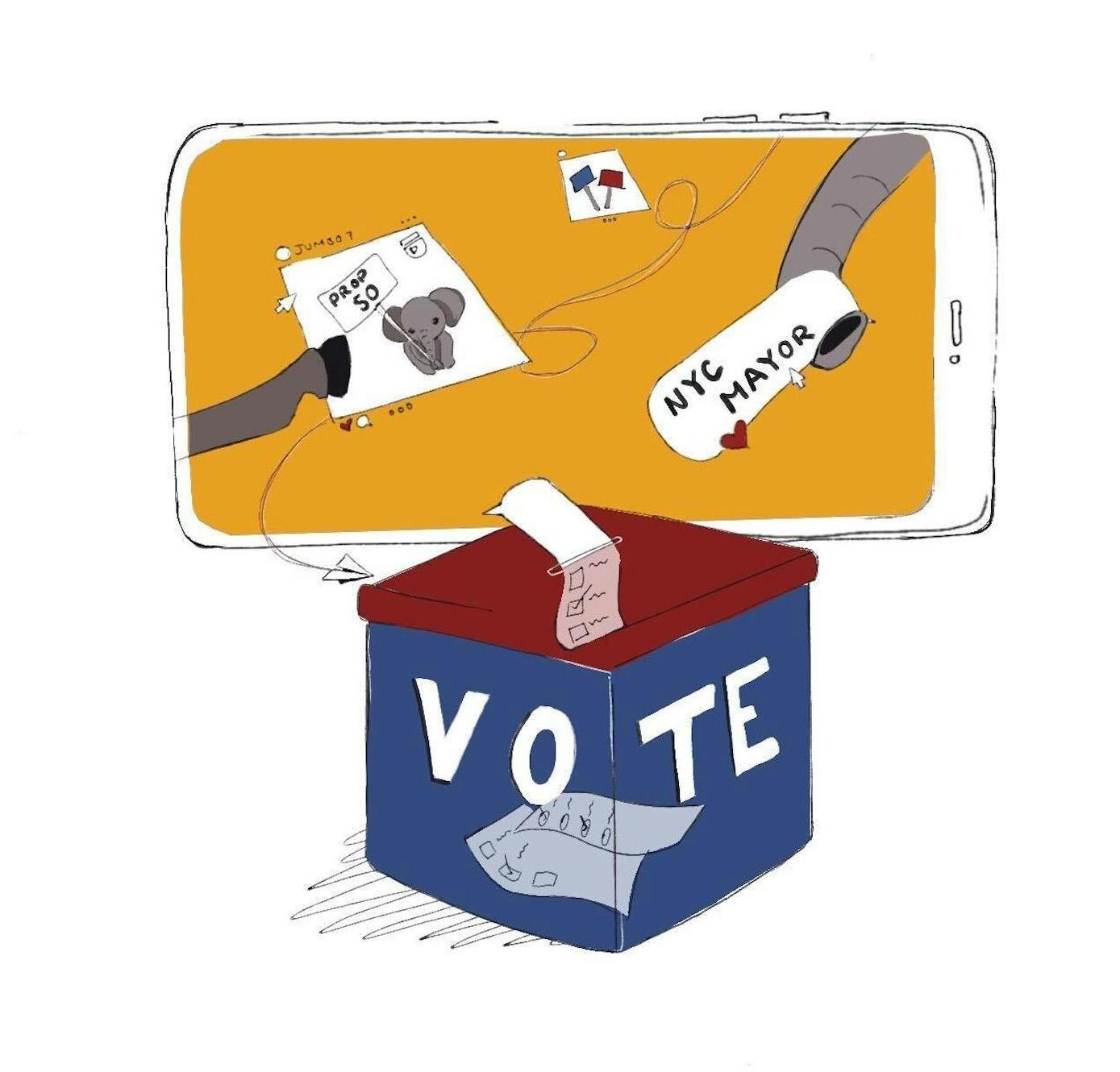

The youth vote isn’ t silent — politicians just aren’ t listening.

Max Lerner

With the holidays approaching, I find myself bracing for accusations of being the ‘woke’ sibling — the one who has been influenced, if not wholly indoctrinated, by the radical ways of his liberal arts college. In all honesty, this may not be far from the truth. But rather than being radicalized by some higher-education agenda, I’ve merely found myself among peers having conversations that reflect political awareness, intelligence and urgency. This bloc embodies a hunger for institutional change and a willingness to actually take action that, I would argue, form the bedrock of our ‘American experiment.’

This voting bloc, which consists of an election-swaying combination of political awareness and social mobilization — to say nothing of the fact that it almost exclusively contains first-time voters — has long been valued by political candidates. And yet, I, along with every student I spoke with, can’t ignore the tangible disconnect between our ideas, values and agendas and those of the policymakers governing our lives. With the future of our democracy at risk, Gen Z college voters — like us at Tufts — are a crucial group for a candidate to win over. We are a demographic with distinct voices and priorities.

And to put it bluntly: Gen Z is impatient. I am referring here to a sense of political impatience with the status quo. As Kamala Harris recently put it: “[Members of Gen Z have] only known the climate crisis; they missed substantial parts of their education because of the

pandemic. … It is very likely that whatever they’ve chosen as their major for study may not result in an affordable wage. … [Gen Z is] rightly impatient with … the tradition of leadership right now.”

The question, then, is whether current politicians have successfully engaged this hyper-political, essential, ‘impatient’ bloc of voters.

To answer that, one must first understand the issues that live in the heart of this voting bloc. Most emphatically, college-aged voters are simply looking for ‘action’ — for results. Our leaders are widely perceived as stagnant or misguided in their actions.

Avery Ohliger, a sophomore studying history, political science and ancient world studies, hails from rural Pennsylvania. He described watching a representative from his district who — after running on an anti-congressional stock trading platform — turned around to become an “egregious” participant in it.

“He lied to his entire constituency,” Ohliger explained.

Having been shaped by such experiences, Ohliger expressed disillusionment with politicians’ empty promises. “[Politicians] need to follow through on their promises,” he expressed. “One of the biggest issues is holding the people that we elect into office accountable.”

Lydia Du, a sophomore biology major and political science minor from New York City who plans to attend medical school, echoed that frustration. She said her interest in courses such as “Introduction To American Politics” has helped her track what she called “the erosion

of democracy.” Du echoed Ohliger’s sentiment — emphasizing her exhaustion with our current political leaders’ priorities.

“I feel like we talk about the economy all the time, and I get how it relates to affordability, but I could not care less about the stock prices,” she said with a frustrated laugh. “None of us can afford stocks right now. We’re worried about paying rent next month, [we’re] worried about the price of gas, the price of groceries — and then they’re talking about how all the AI companies are doing. I don’t care. I do not care at all.”

Du described becoming politically roused by the insurrection on Jan. 6, 2021, and the blatant desecration of the dignity of American politics. “Growing up in the U.S., there’s a pledge of allegiance every morning. Everyone knows that when the national anthem is playing at sports games, you’re supposed to be silent and reverent. So in my head, … places like the White House [and] the Capitol [felt] almost sacred.”

She continued: “Seeing a place that is such a pillar of your life … under siege like that was just so unfathomable.” College-aged voters like Du are tired of the lack of dignity and respect being shown toward both themselves and their country. “How did this happen?” she asked. “How did we end up here?”

From Ohliger’s perspective, the heart of the problem is political extremism and polarization — “[a] more extreme kind of politics.”

“We’re really in a problem where we get hung up on these political points where we’re going to … divide one side or the other,” he said. “[We will] not really actually come together on anything.”

Du concurred. “[Politics is] a lot, and it’s very divisive, especially [along] the party divide.” Du even described how the alarming state of modern politics has compelled the people around her to pay closer attention. “They’re like, ‘Wow,

things are so bad. I need to go find out what is happening,’” she said.

Despite frustrations, some students also described a growing sense of hope — one that was reignited on Nov. 4, the day of several key off-year elections. In New York City’s mayoral election, gubernatorial races in New Jersey and Virginia and California’s Proposition 50 vote, unprecedented voter turnout and major leftward shifts in many districts illuminated a resurgence of a galvanized progressive voting bloc.

So what is it about these candidates (or propositions) that motivated liberal voters to turn out in such great numbers?

Across my conversations, one answer emerged: candidates who connect directly with constituents. Junior William Brentani wrote in a statement to the Daily, “I feel like a lot of times politicians just don’t listen. Especially when they’re in safe districts, they often just do the bare minimum, which is really unfair to their constituents.”

Brentani, an international relations major from San Francisco, voted in a different key election this cycle: the Proposition 50 vote. Proposition 50, led by Democratic Gov. Gavin Newsom, is a redistricting proposal that could lead Democrats to gain more seats, created as a direct response to Texas’ attempted redistricting. Proposition 50 passed with overwhelming support, with some programs calling the election in mere minutes.

Proposition 50, landslide vote or not, was a bold response. “They thought we were going to write an op-ed, have a candlelight vigil, maybe do a rally,” Gov. Newsom said at a rally in San Francisco before the vote. “They poked the bear, and the bear is poking back.” However, in many ways this willingness to confront the federal government epitomizes much of what people think the democratic party lacks.

“Prop 50 is a lot bolder and riskier, and it makes me feel more excited about the future,” Brentani wrote.

Taking an aggressively anti-Trump stance seemed to be a successful strategy for several other candidates as well — with New Jersey being a particularly interesting case.

Junior Lula Duda, a New Jersey resident studying history, recalled Governor-elect Mikie Sherrill — then a Congressional candidate for New Jersey’s 11th district — visiting her high school years earlier.

Duda, then a middle schooler, jokingly recalled the experience: “I just remember being like, ‘Oh, I’m so jealous — the high schoolers got to meet this person who’s going to be in Congress.”

Sherrill would end up winning the congressional seat. However, just over a year ago, she announced her campaign for a new position: Governor of New Jersey, running in the general against the Trump-aligned Republican Jack Ciattarelli.

Sherrill’s victory was, like in California and New York City, unexpectedly resounding; she not only

won by a significant (and underestimated) margin, but she won the election with an unprecedentedly high turnout.

Few races, however, saw a more notable and tangible presence of this newly motivated voting bloc than New York City’s mayoral race, which not only saw millions of people vote but also ended with the election of a self-described democratic socialist mayor.

Du, a New York City voter, said “[Zohran Mamdani] has that … ability to connect with people.” She used his Veteran’s Day schedule as an example. “For the Veteran’s Day Parade recently, people are like, ‘Oh, the mayor-elect always goes to march in the parade — he didn’t do that. Instead, he went to go visit facilities that directly work with veterans, and [talked] to actual veterans instead.”

Authenticity, transparency and action - that is what these electoral victors have in common; that is what will win the college-aged vote. “It might take some time,” Du admitted. “But I think it’ll be okay.”

The Fifth-Year Master’s Degree program allows Tufts undergraduates to continue on to a master’s degree with the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences or the School of Engineering after completing their bachelor’s degree.

Students complete all requirements for both degrees. Some graduate coursework will be integrated during the bachelor’s degree, thereby shortening time and financial commitment to the graduate degree.

The deadline to apply is:

GSAS: December 15 (seniors); March 15 (juniors)

SOE: January 15 (seniors) gradadmissions@tufts.edu | 617-627-3395

Benefits of a Fifth-Year Master’s Degree

• Earn your bachelor’s degree and master’s degree together, usually within five years

• GRE scores not required

• Application fee and enrollment deposit are waived

• Only two letters of recommendation are required

• Generous scholarships are available*

The Fifth-Year Master’s Degrees are offered through the following programs:

Graduate School of Arts and Sciences

Art Education, MAT Biology, MS Chemistry, MS Child Study and Human Development, MA Classics, MA Creative Practice, MA Data Analytics, MS

Digital Tools for Premodern Studies MA Economics, MS Education: Middle and High School, MAT Environmental Policy and Planning, MS Mathematics, MS Museum Education, MA Music, MA Philosophy, MA

Sustainability, MA

Urban and Environmental Policy and Planning, MA

School of Engineering

Artificial Intelligence, MS

Bioengineering, MS

Biomedical Engineering, MS

Biophotonics, MS

Chemical Engineering, MS

Civil and Environmental Engineering, MS

Computer Engineering, MS

Computer Science, MS

Cybersecurity and Public Policy, MS Data Science, MS

Dual Degree Program: Tufts Gordon Institute degree + other Engineering degree, MS

Electrical Engineering, MS

Engineering Management, MS

Human Factors Engineering, MS

Human-Robot Interaction, MS

Innovation and Management, MS

Materials Science and Engineering, MS

Mechanical Engineering, MS

Offshore Wind Energy Engineering, MS

Software Systems Development, MS Technology Management and Leadership, MS