Ridge Project Board of Directors and Executive Director

Corlis Dallas Clark is virtually a life long resident of the south Macon County, Alabama community. She is an alumna of the historic South Macon High School (also called the Macon County Training School). After graduation, Ms. Clark completed coursework at Tuskegee University. She earned Lab Technician credentials from Alexander City Jr. College and went on to begin a career with the U.S. Postal Service as a Rural Route Mail Carrier. Her career spanned 30 years. After retirement in 2007, Ms. Clark worked as an adjunct data collector and instructor with an agriculture and nutrition program for youth that was housed at Tuskegee University. Ms. Clark is a member of the Sweet Pilgrim Baptist Church, Roba, Alabama.

Gary Cox is an accomplished technical support professional with extensive experience the IT system environment as a systems administrator and specialist. His professional experience also includes business manager and financial reporting specialist.

Dr. Cedric G. Sanders is a descendant of ancestors from Creek Stand in Macon County, Alabama. He is an Instructional Designer in the University of Georgia’s Finance and Administration Department. Dr. Sanders’s research focus is African American men’s experiences in obtaining graduate level academic degrees in higher education. His dissertation, “Counternarratives of African American Male Doctoral Students at Predominantly White Institutions,” highlights the significance of this work and the need for intentional mentorship support, and meaningful interventions to increase the enrollment of African American men in higher education. He obtained his Ph.D. in Learning, Leadership, and Organizational Development with an emphasis on adult education from the University of Georgia. Dr. Sanders is a former police officer. In addition to a doctoral degree, he holds a Bachelor of Science degree in Psychology and a Master of Science degree in Adult Education Instructional Technology, both from Troy University.

Mary Jo Thompson is an educator, curriculum, and cross curriculum development specialist. She is a former teacher with the Lee County, Alabama School System. Ms. Thompson holds a Bachelor of Education degree from Auburn University and a Master of Education degree from the University of West Georgia.

Dr. Shari L. Williams is a Public Historian, independent scholar, and the Ridge Project’s Executive Director. She is the first African American woman to earn a Ph.D. in History from Auburn University. She is descended from Pace, Berry, Hubbard, and Ellison ancestors from Macon County, Alabama. Her research interests include the past, present, and future of rural historic landscapes and cultural traditions in Alabama’s Black Belt with an emphasis on social history through the lens of race, gender, and class. Her interest in the Modern American South and Public History began with her non-profit volunteer work in historic preservation in Macon County. She was inspired through this work, to establish The Ridge Macon County Archaeology Project Dr. Williams currently serves on the Board of Directors of the Black Belt African American Genealogy and Historical Society (BBAAGHS), and as Vice President on the Board of Directors of the Alabama Folklife Association (AFA)

17

“The People of Creekwood”

by Shari L. Williams, Ph.D., and Zion (Zee) McThomas, Auburn University

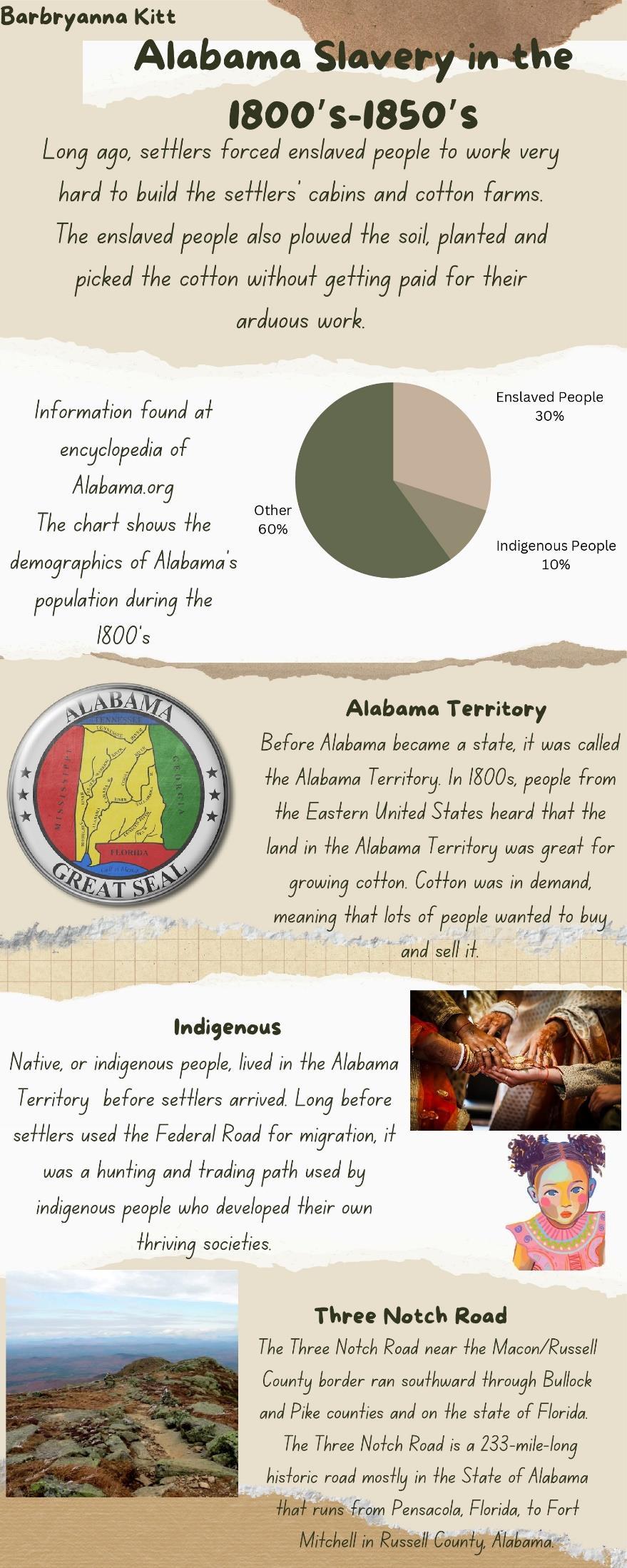

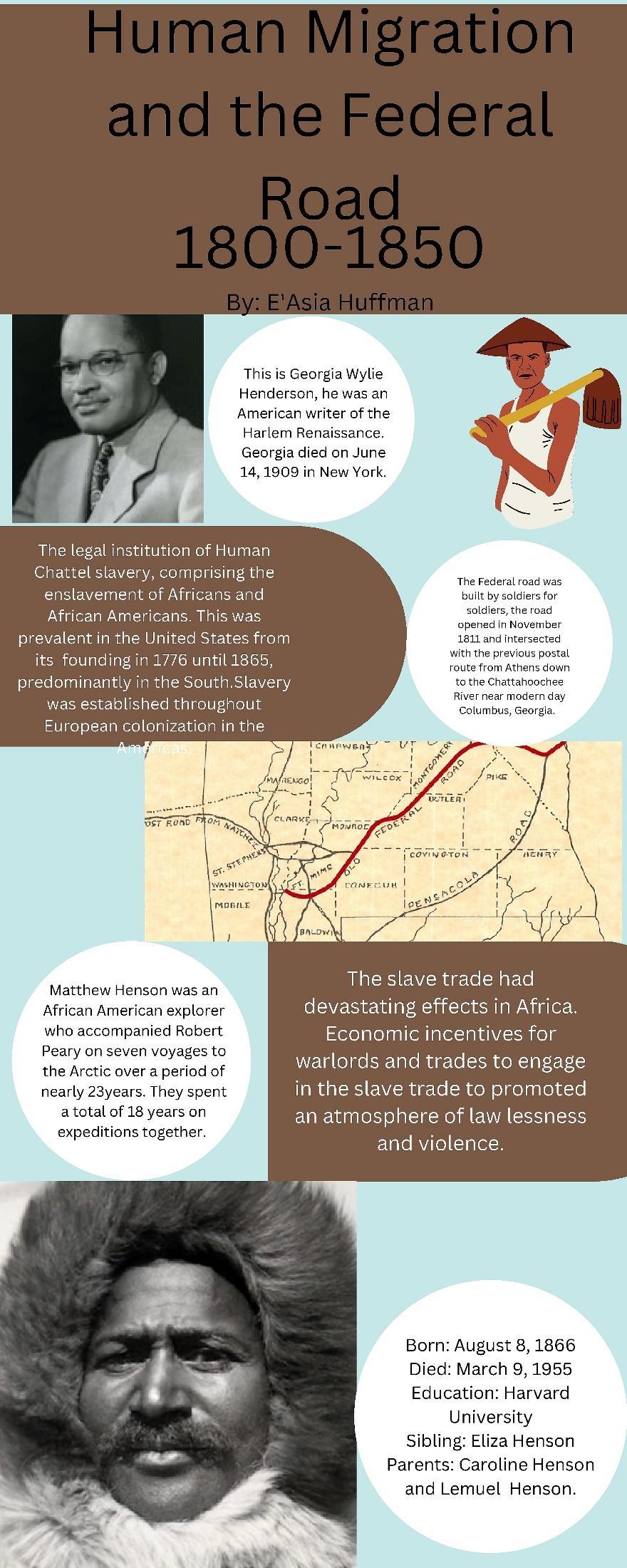

INTRODUCTION: ALABAMA FEVER DRIVES COTTON AND SLAVE ECONOMIES

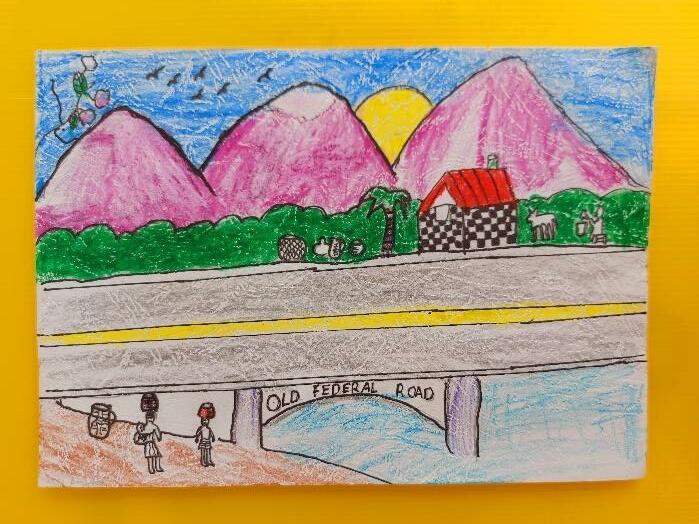

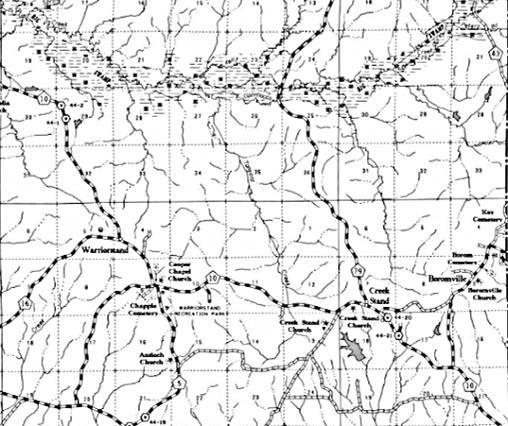

Alabama Fever, the name for white settler mass migration from the eastern United States into Alabama, peaked after the Creek Nation ceded the last of its territory in eastern most Alabama in 1832 with the signing of the Treaty of Cusseta. A travel writer named George William Featherstonhaugh crossed this densely forested territory in January 1835 as he traveled eastward on the rutted and perilous Federal Road from Montgomery, Alabama to Columbus, Georgia. After crossing Persimmon Creek in Macon County on his way to Creek Stand and Warrior Stand, both stagecoach stops on the Federal Road within fifteen miles of the Macon Russell County border, Featherstonehaugh wrote that he passed by 1,000 exhausted enslaved people “trudging on foot” with their white owners.1

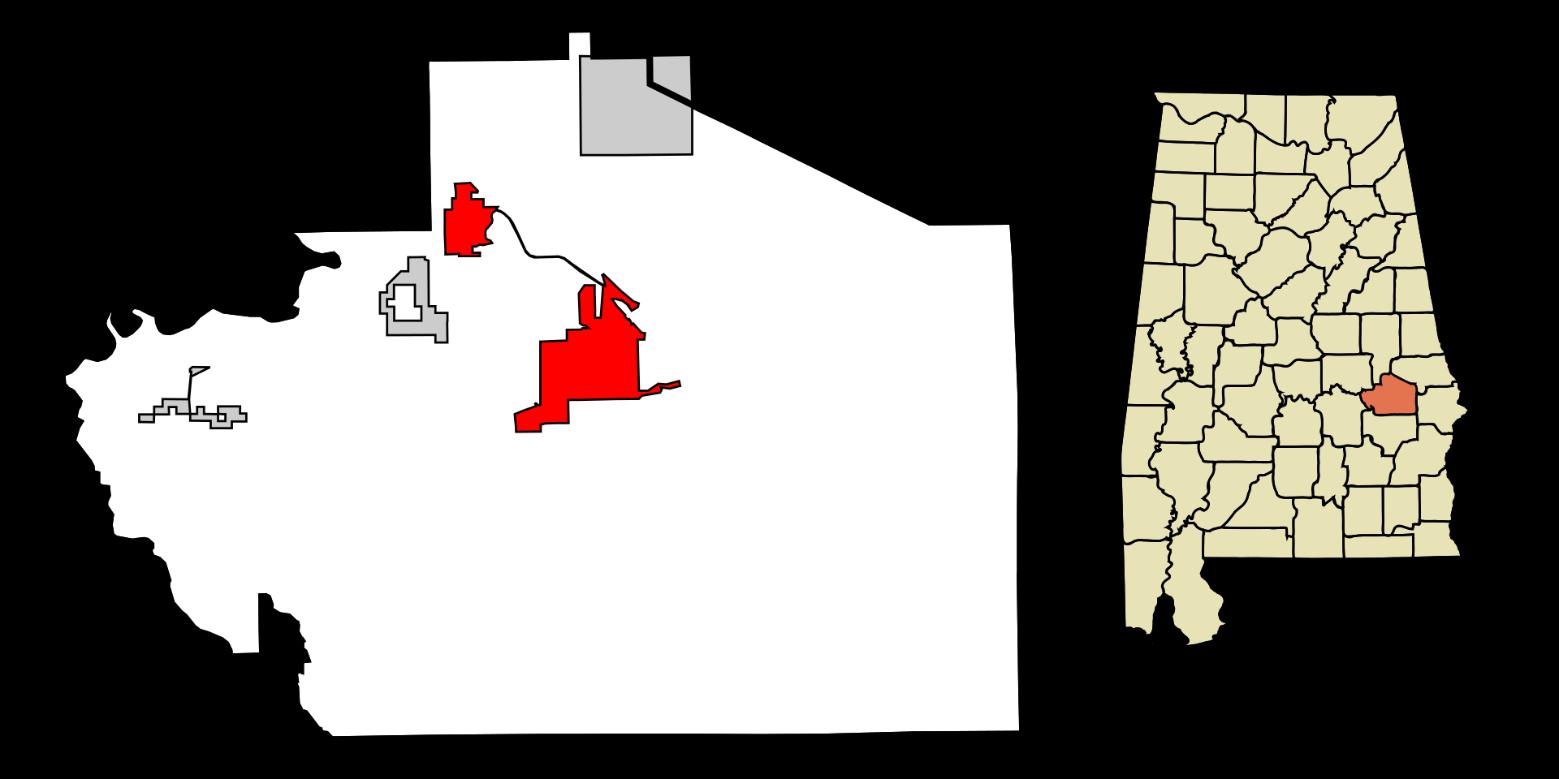

James Pace, an African American Civil War veteran claimed that in 1835 he forcibly migrated through vast frontier land to arrive in Macon County, Alabama with his mother Ailsy, his father, and an older brother and younger sister. If James recalled this experience correctly, he would have observed the same dense forests as Featherstonhaugh as he entered former Creek territory while traveling on the Federal Road from Georgia across the Chattahoochee River into Alabama. James and his family eventually arrived at the site that was to become the sprawling 1,200 acre plantation known as Creekwood located in Creek Stand, Macon County, Alabama located near the present day juncture of Macon County Roads 10 and 79. The plantation, owned by the planter and enslaver Stephen Pace (1802 1872), included several contiguous land parcels located north and south of the plantation house. On the north, the plantation land was located near the city of Tuskegee along the Opintlocco, Big Swamp, and Kelly Creeks that furnished an “abundant water supply” to Macon County.2 Today, the plantation house, known today as the “Creekwood Estate,” remains on its original site. The Federal Road that carried James and his family to Alabama, tells many stories, some good, some bad, and some ugly, from the perspectives of indigenous, enslaved, and free peoples.

As the U.S. population spread westward, the Creek Nation experienced tremendous pressure from the national government to conform to a civilization plan and adopt European culture, for example, row crop farming methods and slave owning. This pressure caused a complex schism within the Nation between conformists and resistors. In 1830, the U.S. government enacted the Indian Removal Act which set the stage for the forced removal of the Creeks to lands west of the Mississippi River. In 1832, the Creek Nation succumbed to pressures exerted both diplomatically and militarily by the government because of this policy. The Creeks ceded the last of tribal lands east of the Mississippi River in east Alabama totaling five million acres, with the signing of the Treaty of Cusseta on March 24, 1832. Macon County, and the adjacent counties of Barbour and Russell came into being in 1832 as a direct result of this major land cession.

Alabama Fever provided the impetus for nineteenth and twentieth century social and economic change in Macon County that mirrored changes over time within a State that depended primarily on cotton agriculture and an enslaved black labor force to drive prosperity and growth. An example is found in the proportion of the black population to the white population. In response to a growing global cotton economy, cotton planters and yeoman farmers migrated westward to the Alabama Territory, leaving behind soils in the eastern states that were depleted of their nutrients from intensive cotton farming in favor of fertile Alabama soils. Planters and farmers took enslaved people with them and imported enslaved people marketed and sold during the domestic slave trade in cities like Montgomery, Alabama, and Columbus, Georgia. In 1840 when James Pace was about ten years old, Macon County’s population consisted roughly of 5,369 free whites and 11,247 enslaved persons. In 1850, those numbers increased to 11,286 free whites and 15,605 enslaved blacks In 1860, Macon County’s population consisted of 8,624 free white people and 18,176 enslaved African Americans.3

1 Jeffrey C. Benton, ed., The Very Worst Road: Travellers’ Accounts of Crossing Alabama’s Old Creek Indian Territory, 1820 1847, (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1998), 119.

2 Alabama and Motisi Associated Engineers, “Macon County Sanitary Sewerage Facilities CDBG: Environmental Impact Statement,” Engineers CH2M Hill, Montgomery, , Waugh, Alabama, 1982, Chapter 2, Section 4, pp. 2 9. Accessed April 19, 2022, https://books.google.com/books?id=Edk3AQAAMAAJ&pg=PA9&lpg=PA9&dq=Opintlocco&source=bl&ots=1IsifIbwoa&sig=ACf U3U1rUH5SQJ6H78SnPgPZaKAnlBKAHw&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwi9m rytaH3AhUNd98KHe4yA8QQ6AF6BAgZEAM#v=onepage&q=Opintlocco&f=false

3 United States Census Bureau, “1840 Census: Compendium of the Enumeration of the Inhabitants and Statistics of the United States,” 52 53, accessed August 22, 2022, https://www.census.gov/library/publications/1841/dec/1840c.html, and United States Census Bureau, and “1850 Census: The Seventh Census of the United States ,” 421, accessed August 22, 2022,

Despite the existence of a majority black population in Macon County, rigid race social and political relations based on white dominance prevailed. In 1850 a total of 16 free blacks were counted on the census, but by 1860 the number dwindled to one which suggests renewed enforcement of Alabama’s Act 44, a law that banned free blacks from residing in the state.4 Even with the opening of the Tuskegee Normal School in 1881 and its subsequent growth and prominence, white social, political, and economic dominance would continue throughout the first four decades of the twentieth century. African Americans in Macon County as a bloc successfully challenged this dominance with the Tuskegee Merchant Boycott 1957 1961 when they fought against racial gerrymandering of city boundaries that excluded all but a handful of eligible black city residents from voting in Tuskegee’s municipal elections. Blacks resisted in the form of a selective buying campaign whereby city and county blacks refused to shop at the establishments of whites who supported gerrymandering. Their activism resulted in the 1960 landmark Supreme Court voting rights case Gomillion v. Lightfoot, which overturned the gerrymander and restored voting rights to Tuskegee’s eligible black voters.5

PART ONE: WESTWARD EXPANSION TO EMANCIPATION

The Tuskegee Boycott followed a consistent pattern of social, political, cultural, and economic tension and conflict in Alabama that reflected divided views along racial and cultural lines about who should control land. The earliest example is the long standing conflict during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries between the Muscogee Creek Nation and the national government over lands possessed by the Creeks in Alabama and Georgia. Politicians, land speculators, wealthy planters, and yeoman farmers who believed in territorial expansion to the west adhered to a belief system that prefigured “manifest destiny,” the popular belief in the mid 1800’s that aggressive and continuous westward expansion across the North American continent by white people was God ordained.

Stephen Pace, the prosperous planter from Harris County, Georgia took advantage of the 1832 cession as he planned his own relocation to the west. In 1840, Pace resided in Harris County, Georgia and owned thirty three enslaved persons. In 1850, he owned fifty three enslaved persons. Sometime during the next five years, Pace decided to seek his fortune in Macon County. In 1855, he began acquiring land parcels in Macon County and by 1860, he resided there at Creekwood. The number of enslaved persons owned by Pace in 1860 had increased to seventy seven, most of whom no doubt constructed the plantation house, seventeen slave cabins, barns, a gristmill, kitchen, and other structures on the plantation. Their labor on “perhaps the richest lands along Big Swamp Creek,” made possible a substantial and successful agricultural enterprise that generated wealth for Stephen Pace and his second wife Mary (maiden name Gregory), daughters Mary, Georgia, and Anna, and sons John, Thomas, and Elkanah. Enslaved laborers tended livestock including milk cows, horse, mules, oxen, cattle, sheep and pigs, and produced crops of wheat, rye, corn, oats, and cotton.6

Before the Civil War ended, Ailsy, her son James, and his siblings who likely belonged to the community of the enslaved at Creekwood, blended with another enslaved family headed by a man named Jim Pace. Jim was born in 1813 in North https://www.census.gov/library/publications/1853/dec/1850a.html, and Joseph C.G. Kennedy, Population of the United States in 1860; Compiled from the Original Returns of the Eighth Census Under the Direction of the Secretary of the Interior, (Washington, U.S. Government Printing Office, 1864, “Classified Population of the States and Territories, by Counties on the First Day of June 1860, 3, 7, accessed August 22, 2022, https://books.google.com/books?id=e8RLAQAAMAAJ&pg=PA1&lpg=PA1&dq=%22Classified+Population+of+the+States+and+Te rritories+by+Counties+on+the+First+Day+of+June+1860%22&source=bl&ots=j4e5kCGnk4&sig=ACfU3U1lqBTybLSJ7 F_CwaM0OgJ2U itw&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjI6sqgjO76AhW RjABHY2WC54Q6AF6BAgFEAM#v=onepage&q=%22Classified%20Population%20of%20the%20States%20and%20Territories%2 0by%20Counties%20on%20the%20First%20Day%20of%20June%201860%22&f=false/.

4 Ibid, “1850 U.S. Census”, and Population of the United States in 1860, and Equal Justice Initiative, “Alabama Legislature Bans Free Black People from Living in the State,” accessed October 20, 2022, https://calendar.eji.org/racial injustice/jan/17

5 Shari L. Williams, “Tuskegee Boycott,” Encyclopedia of Alabama, accessed October 21, 2022, http://encyclopediaofalabama.org/article/h 4275

6 Mary Mason Shell, “National Register of Historic Places Registration Form,” Section 8, pages 1 2, accessed March 14, 2022, https://npgallery.nps.gov/GetAsset/bff173cc 7c5c 4c8b ae66 1a57b01b4c58

19

Carolina. Jim’s first wife Beckie born nine children: Nat, Andina, Sarah, Harriett, Jim, Jr., Henry, Adaline, Sandy, Eliza, and Arch. Beckie died before Emancipation, and Jim remarried to Ailsy by 1866. Ailsy presumably was a widow.7

Stepbrothers James and Henry named Stephen Pace as their enslaver in affidavits and depositions they recorded after serving from 1865 1886 in the Union Army’s United States Colored Troops (USCT) Infantry. Both men joined Wilson’s Raiders troops as they approached Columbus, Georgia after waging a tactical campaign across Alabama to destroy Confederate supply and munitions depots and other material assets of the Confederacy. James and Henry Pace both filed applications for Union Army pensions and the application files of both men include few, but precious details about their lives as chattel slaves. Regarding his enslaver, James Pace attested,

I was born in Harris County Georgia July 1830. My parents were brought to Tuskegee when I was five years old and I grew up on a plantation near the town. I was living on this place when the war began and enlisted when I was quite a way. No records were kept of births of slave children except by their owners. I am unable to get access to these records if indeed they be still in existence. My master told me a number of times before his death that I was born in July 1830 and I have always understood that this was correct.8

Anna Pace Fort, daughter of Stephen Pace substantiated James Pace’s sworn statement in a General Affidavit also found in James Pace’s pension file:

James Pace was a slave of my father, Stephen Pace. I have been told that he was born July 10, 1831. I am not sure of his age however, but think he is between 76 and 77. The bible in which the names and ages of my father’s slaves were recorded is supposed to have been destroyed by fire fifteen or more years ago.9

In his pension deposition, the stepbrother Henry Pace who was born in 1840 stated, I was born, so I was always told, in Harris Co. GA. Was born the slave of Mr. [first name redacted in original document] Ardis but he sold all of us before I can remember and when I can first remember I was living near the little village called Ouchee [Yuchi] in this county I suppose. Where I can first remember I belonged to Steven Pace and lived near Ouchee no you misunderstand me. Mr. Ardis moved from Harris Co. Ga to Ouchee in this state and kept me until I was about seven or eight years old then he sold us all to Steven Pace. My parents were Jim and Beckie Pace. Mr. Ardis owned them both and sold them and their 9 children to Steven Pace and all of us belonged to Mr. Pace or his children until death or emancipation.10

Stephen Pace Federal Road Migrant from Harris County, Georgia

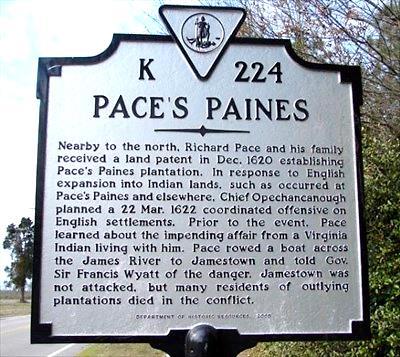

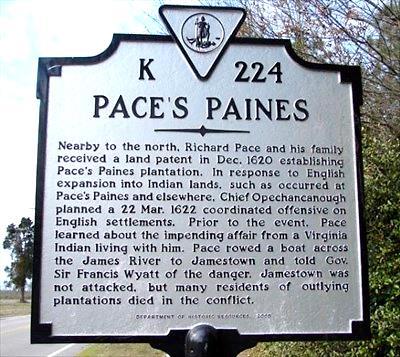

Stephen Pace, the planter and enslaver from Harris County, Georgia was born in 1802 in the Edgefield District of South Carolina, a descendant of one of the earliest immigrant families in the U.S. His father was William Pace, born 1773 in North Carolina and his mother was Mary “Polly” May, born 1770 in North Carolina. They named their son after his paternal grandfather, Stephen Pace, born 1747 in North Carolina. This Pace line descended from Richard Pace, born 1583 in England. Richard Pace, of colonial Jamestown, Virginia, was an original land grant settler. Richard Pace established the Pace’s Paines Planation and is credited with saving the lives of Jamestown’s white settlers from a Powahatan Indian attack in 1622. Supposedly a Powahatan youth named Chanco who lived with the family warned Pace about the impending attack. Pace reportedly rowed a boat across the James River to Jamestown to alert the governor of the impending raid in time for settlers to evacuate and escape the attack.11

7 National Archives, Pace, Henry Pension File, VC 2463.364. James Pace stated the following in his 1911 deposition for Henry Pace: “Henry and I are no kin but his father had my mother for his wife after Henry’s mother died.”

8National Archives, Compiled Military Service Record, Private James Pace, 136th USCT Infantry, Company K, Box 23, M1999.

9 Ibid., James Pace Service Record.

10 Pace, Henry Pension File

11 Freda Reid Turner, Pace Society of America Bulletins, Volume, II, (Wolfe Publishing: Fernandina Beach, Florida, November 1999), 1 4.

William Pace migrated with his family from Anson, North Carolina to Putnam County, Georgia. His son Stephen married Mary McCoy Ardis (1st wife) in 1827 while living in Putnam County. Mary died and Stephen married Mary C. Gregory in 1850. Shortly thereafter he made his way to Harris County, Georgia.12

According to Henry Pace, Stephen Pace purchased his family when Henry was a small boy and then migrated to Salem, Lee County, Alabama around 1851 when Henry was seven or eight years old.13 In 1852, Stephen Pace began purchasing Macon County land parcels to establish his plantation. In February 1852, he purchased land in sections 25 and 35 of Township 16N, Range 25E totaling 320 acres. In February 1855, he purchased 320 acres in section 26 of the same township and range.14

Henry Pace stated that Stephen Pace relocated to Macon County, Alabama around 1854. Although sources estimate Creekwood’s construction date to be between 1841 and 1850, it was 1855 when Pace purchased the parcel of land that became the location of Creekwood. Pace purchased this parcel from James M. Davis and his wife Jane Ellison Davis where he and enslaved laborers built the Creekwood Plantation house. On March 24, 1855, James and Jane Ellison sold forty acres to Stephen Pace for $650 located in the SE1/4 of the NW1/4 of section 7, T15N, Range 26E. This is the parcel where Creekwood is located. Pace also purchased from James and Jane Ellison “all the portion of land north of the Old Federal Road in the E1/2 of the SW1/4 of section 7 in the same township and range.”15 These records contradict James Pace’s testimony that he and his family arrived as slaves in Macon County in 1835 and lived near Tuskegee on the Stephen Pace plantation until 1865 when James went off to war unless James grossly miscalculated the timeline. In 1857, Stephen Pace purchased forty acres located in the NW1/4 of the SW1/4 of section 7, Township 15N, Range 26 E from Richard Burt for $400.16

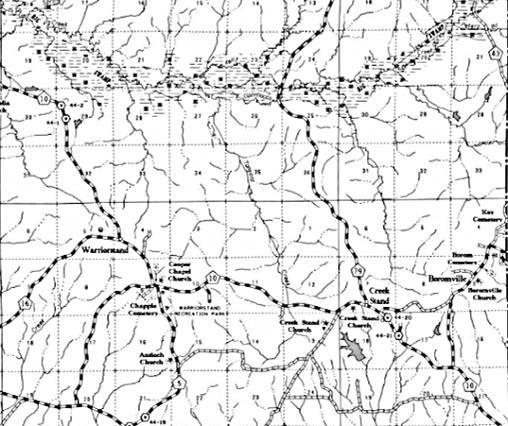

The image below shows the parcels in Township 15N, Range 26E, Section 7 that Pace purchased in 1855 and 1857.

12

13 Pace, Henry Pension File. Henry Pace stated that Stephen Pace, “Carried us to Salem where he lived about three years then moved here to about 3 miles east of Warrior Stand and kept me there until I went off with the raid.”

14 Macon County, Alabama Deed Book O Feb. 3, 1852, John Ellison and Eliza D. Ellison and James Ellison and Jane A. Ellison to Stephen Pace, pages 110 111. Feb. 19, 1855, James Ellison and Jane A. Ellison to Stephen Pace, pages 112 113.

15 Macon County, Alabama Deed Book O March 24, 1855, James M. Davis and Jane E. Davis to Stephen Pace, pages 108 109. Pace and his family are included in the historical summary of the National Register nomination form in Section 8 which provides the historical backdrop for their emigration to Macon County, and in the section that gives architectural details about Creekwood. A 1974 publication entitled Macon County Preliminary Inventory of Historic Assets: South Central Alabama Region states that the barn near the mansion was a “stand” or waystation along the Federal Road. It also states that Stephen Pace was the original owner, having acquired the land by trading liquor for it with unidentified Creek Indians. It claims that Pace obtained most of the lumber for the mansion from Columbus, Georgia and that it was transported to the site by an oxcart, and that enslaved people performed construction labor.

16 Macon County, Alabama Deed Book O, Richard M. Burt to Stephen Pace, October 10, 1857, pages 109 110.

21

“Married,” Weekly Columbus Enquirer, Columbus, Georgia, August 13, 1850, accessed October 21, 2022, newspapers.com.

Map not to scale Creekwood Plantation house NE1/4 of N1/2 NW1/4 of N1/2

1857 NW1/4 of SW1/4

1855 SE1/4 of NW1/4 1855 All the portion of land north of Fed Rd in E1/2 of SW1/4 SW1/4 of S1/2 SE1/4 of S1/2

Pace purchased land again in 1858 and 1859. In 1858 he purchased 20 acres in Section 36, Township 16, Range 25, and in 1859, he purchased 160 acres in Section 18 of Township 15, Range 26. The map below shows all the parcels of land that Pace acquired between 1852 and 1859.

SECTION 7 TOWNSHIP 15N RANGE 26E

23 Pace Hill R25 R26 T16 T16 T15 T15 R26 R25 1855 1852 1852 1858 1855 1859

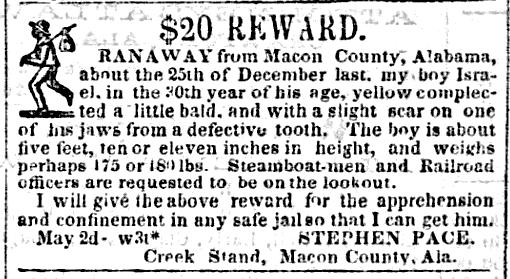

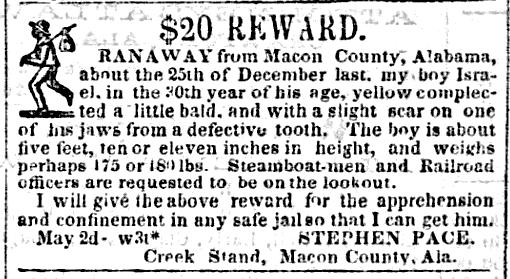

Few records exist to describe Stephen Pace’s temperament or his treatment of the enslaved persons at Creekwood. In April 1859, Pace placed a runaway slave advertisement in the Columbus Daily Times. He offered a reward for the capture and confinement of an enslaved man named Israel.

Columbus Daily Times, (Columbus, Ga.), April 30, 1859, Vol 5, no 131, page 2

The Hatcher & McGehee slave trading firm located in Columbus, Georgia recorded in its “Negro Book” that Stephen Pace purchased an enslaved man named John for $1,000 in September 1859, perhaps to replace Israel.17 Stephen Pace’s name appeared again in documents produced after the Civil War. He signed as a witness in 1865 to a summary of an agreement made between Manervy, the “former servant” of James Ellison. The agreement or contract, shown below specified the conditions for work and wages for Manervy’s employment with Ellison.18

17 Callie B. McGinnis transcription, “Hatcher & McGehee Negro Book pages 16 17,” Muscogiana, 4, nos.3&4 (Fall 1983), 59.

18 Alabama, Freedmen’s Bureau Office Records 1865 1867, Montgomery (Subassistant Commissioner), Roll 25, Fair Copies of Contracts Vol. 2, 1865, pp. 184 185, accessed June 24, 2017, familysearch.org.

24

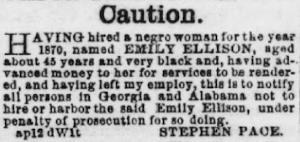

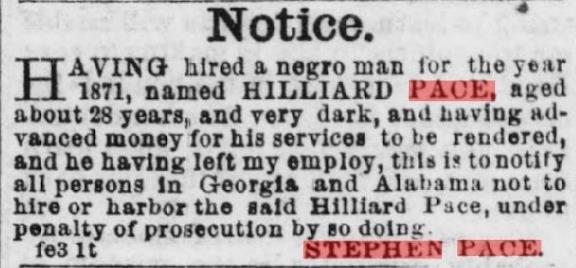

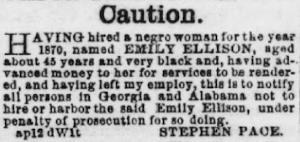

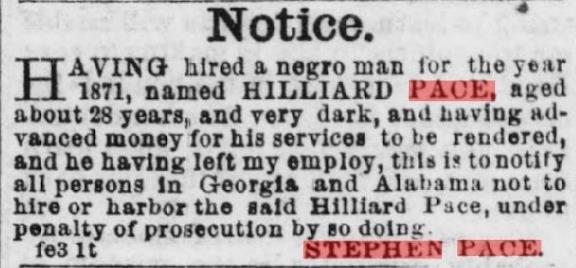

In 1870, Pace ran a notice for several days in the Daily Sun newspaper, Columbus, Georgia, to order potential employers to refuse to hire an African American woman named Emily Ellison who allegedly absconded with advanced wages without fulfilling her labor contract. He ran the same notice in 1871 in the Weekly Sun, Columbus, Georgia, against a man named Hilliard Pace.

These advertisements invoke an image of Stephen Pace as a strident planter who held elitist beliefs about the obligations of wage laborers. But the advertisements do not reveal the working conditions or treatment by Pace that Emily Ellison and Hilliard Pace experienced.

Right: Stephen Pace headstone. Photo by J.B. Chrismond, Findagrave.com, accessed October 20, 2022, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/73837963/stephen pace

Pace died in 1872. His family buried him in the cemetery adjacent to the tiny present day replica of the original Mount Zion Methodist Church that settlers built around 1850. The church replica and the cemetery still occupy the property which is located on Macon County Road 10 less than one mile from Creekwood. A remnant of the original Federal Road skirts the church property’s northern boundary which runs parallel to Macon County Road 10.

25

Left: Original Mt. Zion Church. Photo courtesy of Larry Floyd.

Circa 1896 photo of members of the Lloyd family. Lt. Col. William Bailey Lloyd purchased Creekwood in 1874 from the John Pace, Executor of his father Stephen Pace’s estate. Source: National Register Nomination Packet compiled by Francis. Jacques Bouilliant Linet, 1988.

The planter Stephen Pace’s wife second wife, Mary (maiden name Gregory), died in 1880 in Lee County, Alabama. Several Pace children remained in Macon County and the region. Other siblings, like their father, migrated to lands elsewhere to seek prosperity. Thomas Pace migrated from Creek Stand to Cedartown, Polk County, Georgia and became a prominent citizen there. Pace Street in Cedartown is named after Thomas Pace. The son Elkanah also migrated to Polk County, Georgia. The son John married Sarah Dawkins. Their son Mathew Downer Pace served Troy University from 1891 to 1941 as Professor of Mathematics, Dean, and President.

Ties between Creekwood and the descendants of its original owner Stephen Pace seem to be long ago severed. John Pace, executor of his father’s estate, sold Creekwood to Lt. Col. William Bailey Lloyd in 1874. This sale coincided with the Pace family’s apparent break with the property and the legacy it holds. The Lloyd family sold the property in 1983 to Francis Jacques Bouilliant Linet and his wife. In 2020, Bouilliant Linet’s widow sold the property to the current owners. In writing about Creek Stand, the settlement town nearest to Creekwood, the journalist J.M. Glenn stated in 1953 that

26

“Creek Stand is now largely a memory.”19 He described Creek Stand’s decline and fall from memory in terms of the outmigration of the descendants of early white settlers and his own memories of the place extending back to 1879.20 Glenn counted among those in Creek Stand’s historical memory the Creek Indians, the famous itinerant Methodist preacher Lorenzo Dow, and the French General the Marquis de Lafayette, noting how they all at one time traversed the Federal Road. He excluded the African American descendants of the enslaved and freedmen from the historical memory of Creek Stand and the Federal Road. Yet, those descendants had engaged since Emancipation in building a community of schools, churches, and fraternal organizations having been highly influenced by Booker T. Washington’s ideals for black self determination and landownership.

PART TWO A FEDERAL ROAD COMMUNITY OF SELF DETERMINED FREED PEOPLE

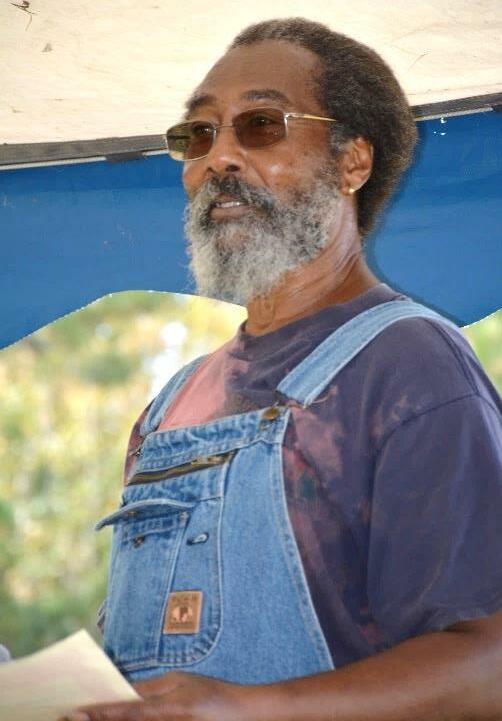

Golden Henderson, a now deceased keeper of oral black family history in Creek Stand claimed that the persons enslaved by Stephen Pace and his nearby Pace relatives, all chose the surname Pace after Emancipation. Henderson claimed that four distinct, non blood related African American Pace family lines descend from African American male Pace patriarchs.21 The claim that these family lines are not blood related is yet to be proven. Several black heads of household who chose the surname Pace appeared on the 1870 census. They include Abraham Pace, Ben Pace, Isaac Pace., James Pace, (son of Ailsy), Jim Pace (husband of Beckie then Ailsy), and Steve (a.k.a. Steven/Stephen) Pace.22

The table below shows several African American Pace families that resided in Macon County’s Precinct Four in 1870 and 1880. Precinct Four includes Warrior Stand and Creek Stand. Today, some descendants of Jim, Ben, and Steve Pace still reside within 200 miles of Creekwood, with the closest known relatives living in Tuskegee. The number of family members who know of the connection to Creekwood is slowly increasing but most descendants are scattered throughout the United States and the world and it is likely that most are unaware of their ancestors’ connections and contributions to Alabama Fever settlement and the existence of Creekwood.

19 J.M. Glenn, “Glimpses of Yesterday: Tales of Old Creek Stand,” The Tuskegee News, September 17, 1953.

20 Ibid.

21 Golden Henderson interview, Shari Williams, Creek Stand, Alabama, October 26, 2009.

22 1870 and 1880 United States Federal Census Records.Henry Pace and Nancy Thomas marriage information provided during Frankie Julkes Freeney interview, Shari Williams, Columbus, Georgia, 2000. Also, Gilbert Pace and Ellen Marshall in Alabama, U.S., Select Marriage Indexes, 1816 1942, and Beedie Boram in Denis Pace, U.S. Social Security Applications and Claims Index, 1936 2007. Eliza Brudlere (presumed to be Breedlove) in Lizzie Pace, Alabama, U.S. Deaths and Burials Index, 1881 1974. Also, Jane Brown and Jim Pace in the Alabama, U.S. Select Marriage Indexes, 1816 1942, Steve Pace and Sallie Thomas in Nancy Buelah Pace, West Virginia, U.S., Deaths Index, 1853 1973, Ben Pace and Eady Burt in 1880 United States Federal Census. Residing in the household is Lou Burt listed as mother in law of Ben Pace. Census, Marriage Indexes, Social Security Index, Deaths and Burials Index (Alabama and West Virginia). All sourced on Ancestry.com.

27

1870 Census 1880 Census

Head of Household Last Name

First Name and Spouse by maiden name (MNU=maiden name unknown)

Year & State Born Per 1870 Census

X X Pace Jim (Ailsy MNU) 1813 NC

X X Pace Hilliard (Winney MNU) 1840 GA

X X Pace Reuben (Charlotte MNU)

1830 GA

X Pace Andy (Lucy MNU) 1847 GA

X X Pace Isaac (Hattie Foster(?)) 1835 GA

X X Pace Jake 1840 GA X X Pace Henry (Nancy Thomas) 1825 GA

X X Pace Gilbert or Gilliard (Ellen Marshall)

1835 GA X X Pace Margret or Margaret 1825 GA

X X Pace Emanuel (Beedie A. Borom)

1851 GA X Pace Abram (Eliza Breedlove) 1815 GA X X Pace Henry (Matilda MNU) 1830 GA X Pace Jimmie (Jane Brown) 1835 X Pace Sandy (Louisa MNU) 1848 GA X Pace Tildy 1845 X Pace Steve (Sallie Thomas) 1830 GA

X X Pace Frank (Lucinda MNU) 1835 GA X Pace Ben (Eady Burt) 1833

Formerly enslaved people who adopted the surname Pace possibly wanted to maintain a connection to each other, or to the white Pace family, or both. Oral histories told by descendants of the freedman Steve Pace provide a less harsh characterization of Stephen Pace the enslaver and offer possible reasons for this surname choice among the formerly enslaved. As told by family historians, the formerly enslaved Steve Pace supposedly was pious and “favored” by his enslaver. Records are elusive to establish Stephen Pace as the enslaver of Steve Pace. Some African American Pace descendants say that after Emancipation, Steve Pace’s enslaver gave him “forty acres of land, a covered wagon, and a big

28

house.”23 Other family members say that he purchased 480 acres of land for $1 per acre. But the first deed record found for Steve Pace indicates that he purchased 80 acres in 1877 for $500 from Elkanah Pace.24 Three years later, John Pace held a sale of his father’s estate and Steve Pace purchased a broad axe, a chop axe, a box of sundries, a handsaw, a box of old irons, a crosscut saw, a safe, four chairs, an old wash pot, a table, and a bedstead.25 His purchases totaled $12.65. How Steve Pace came to possess this disposable cash within five years of the Civil War’s end is unknown, except that he and several other black farmers with the surname Pace, owned or rented farms by 1880.

The tables below provide information from the 1880 Agriculture Census for Precinct 4, Warrior Stand, which included Creek Stand and surrounding areas. In the absence of any known journals, diaries, or personal papers that belonged to the Pace freedmen, property records provide some clues about how each fared economically within fifteen years of Emancipation in terms of land owned or rented and the value of farm production.

Beat 4 Enumeration District 117, Warrior Stand

Page # Name Owned Rent ed for fixed money rental

#Im proved Acres

#Un im proved Acres

Farm Value Farm Imple ments & Equipment Value

Live stock Value

Est. value of all farm pro duc tion 19 Joe Pace X 80 22 $800 $10 $50 No figure listed 22 Ben Pace X 150 250 $800 $75 $200 $225 22 Frank Pace X 150 150 $1500 $15 $75 $325 24 Sandy Pace X 72 40 $500 $10 $100 $300 25 Emanuel Pace X 72 40 $150 $10 $150 $300 26 Steve Pace X 40 40 $240 $50 $275 $950 28 Henry Pace X 40 No figure listed

$200 $5 $75 $299 23 Family oral history as told by Jewel Garlington, descendant of Margaret Pace Berry, daughter of Steve Pace. 24 Deed Book B, Macon County, Alabama, 151. 25 Stephen Pace in the Alabama, U.S., Wills and Probate Records, 1753 1999, Macon County, Alabama, accessed October 21, 2022, https://ancestry.com.

29

Page # Name Owned Rent ed for fixed money rental

# Im proved Acres

#Un Im proved Acres

Farm Value Farm Imple ments & Equip ment Value

Live stock Value

Est. value of all Farm produc tion

3 Henry Pace X 25 No figure No figure No figure $15 $150

3 Jim Pace X 200 150 $3500 $100 $300 $800

22 Pace & Herbert (Steve Pace & George Hubbard)

X 800 870 $1200 0 $96 $50 $1500

24 Sandy Pace X 40 No figure No figure $15 $150 $300

The Agricultural Census for Macon County’s Warrior Stand Precinct Four indicates that Steve Pace owned 121 improved acres and 40 unimproved acres in 1880. The 1880 census also reported that Steve Pace owned acreage jointly with George Hubbard, another formerly enslaved man from Creek Stand. They jointly owned 800 improved acres, 800 unimproved acres, and 70 other non improved acres. The Agricultural Census reported in 1880 that Ben Pace owned 150 improved acres, and 150 unimproved acres. Joe, Frank, Emanuel, Sandy, Reuben, and Jim Pace, and possibly two different men each named Henry Pace rented the land they farmed in 1880.26 Land and tax records for these men do not reveal if or how they were kinfolk, except for Sandy (brother of USCT veteran Henry Pace) and Jim, who were stepbrothers.

After the Civil War, many freedmen were able to acquire land through the Southern Homestead Act of 1866. Even with this law, African Americans still faced opposition from entities such as the Ku Klux Klan and the federal government. The demise of the Freedmen's Bureau and the withdrawal of federal troops in 1877 from the South led to immense difficulties for African American landowners.

Plessy V. Ferguson's decision of “separate but equal” policies laid the foundation for Jim Crow laws to emerge during the late 19th century but the biggest issue that contributed to the African Americans’ loss of land was the practice by former masters of conveying property to freedmen through informal arrangements without documentation to prove that the land now belonged to its black inhabitants. This meant that relatives of the former master or just anyone who actually purchased the land could force the black inhabitants to leave. If the black inhabitants would not leave, angry white mobs would beat and/or murder them in order to secure the land for themselves.

In some cases where a legal, documented sale occurred between a former enslaving family and a freedman this threat still existed. According to Golden Henderson, Steve Pace faced this threat around 1915. Between 1876 and 1915, Steve Pace owned an aggregate 480 acres spanning three sections in Township 15N, Range 26.27 Henderson stated that all the Paces were smart people and nobody took their land or beat them out of their money. He said that Steve Pace was independent and industrious. One day while Steve Pace was “up on a hill cutting bushes, a white man rode up and declared that he was going to take Steve’s land. Steve told the man, “You a damn lie!” The incensed white man jumped off his animal and

26 U.S., Selected Federal Census Non Population Schedules, 1850 1880, accessed October 11, 2021, https://ancestry.com.

27 Deed Book B, 151, Deed Book 5, 121, and 190 191, Assessment of Taxes on Real Estate and Personal Property, 1877, 1879, 1899, 1885, 1889, 1893, 1894, and 1896. All records, Macon County, Alabama.

30 Township 16 Enumeration

Warrior Stand

District 117,

approached Steve to fight. Steve raised the ax and struck the man, nearly breaking his shoulder. The altercation angered the white community. Steve Pace “went walking” for a while, which means that he disappeared until it was about time for the taxes on his land to be paid. Henderson explained that Pace came back, paid the taxes and then on the same day, deeded all his land to his children. He claimed that later, when the children’s land was sold, it was never against their will. They always had control. Henderson stated that Steve Pace deeded 32 acres to each of his children, except that the son George Washington Pace acquired 40 acres total because after the land was equally divided, there were eight acres remaining and George Washington purchased them from his siblings.28

Deed records substantiate Henderson’s story about the division and deeding of Steve Pace’s land among his children in 1915 but they do not confirm that Steve Pace conveyed the properties. Instead, deed records show that the Pace siblings engaged in multiple land conveyances on April 30, 1915 that involved the sale of 32 acre land parcels from sibling to sibling for $1.00 each.29 Steve Pace and his children did encounter land loss against their will despite Henderson’s claim that they never lost control of the land they owned. The Tuskegee News advertised a tax sale in 1886 of Steve Pace’s land totaling 240 acres. Pace owned a total of $8.25 in taxes.30 Whether Pace paid the taxes is unknown, but in 1897, he sold one of the imperiled parcels to his wife Sallie.31 Several Pace children defaulted on mortgages during the 1920s. In 1915, the same year that multiple land conveyances took place between the Pace siblings, The Tuskegee News advertised the mortgage sale of Steve Pace, Jr and his wife Mattie Pace. The couple evidently defaulted on a loan with mortgagees Banks and Davis. The advertisement does not include the terms of the mortgage, but it was likely a crop lien. Crop liens were common arrangements between black farmers and a lender whereby farmers put up their crops, livestock, and sometimes their land as collateral against a cash loan that enabled them to purchase seed and equipment to plant and harvest a crop. Perhaps Steve Pace took out the mortgage, but died in 1915, and it fell to Steve, Jr., and Mattie to make good on the loan.

Heir property also posed a typical threat to African American landowners. Heir property ownership involves land that has multiple owners who are descendants of a deceased family member whose estate did not clear probate. In other words, the descendants can use and/or live on the land but a clear title to the land does not exist. When land continues to be passed down without a deed or will attached to it, confusion breaks out as more heirs are born into the family. The heirs lose out on potential federal benefits and are vulnerable to partition sales by third parties. These partition sales could net lower revenue than what the descendants expected. Often, unsuspecting the heirs lose their land in the process.

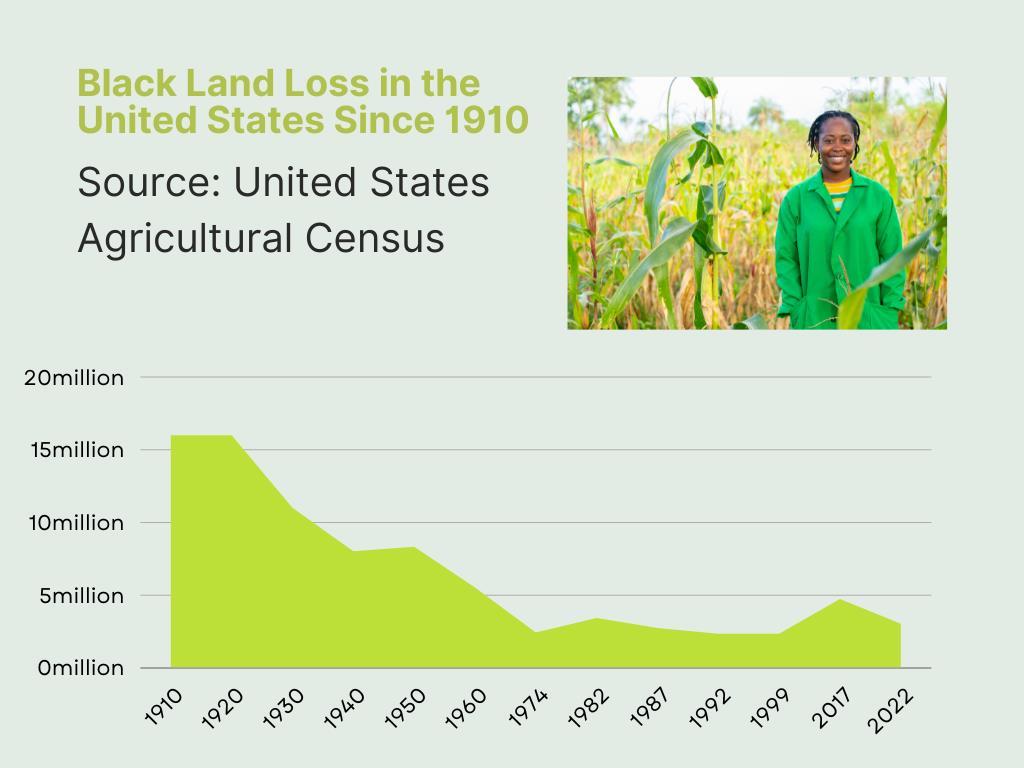

Source: Zion McThomas

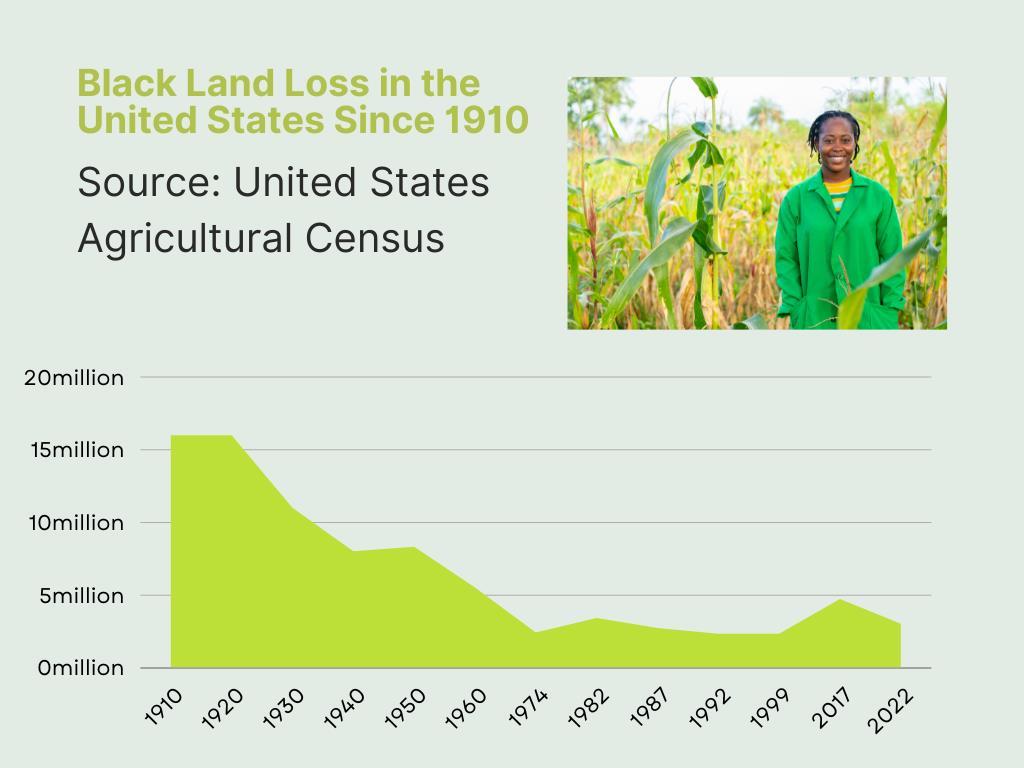

Heir property ownership is one of the main causes of black land loss historically in the United States. Other causes include systemic racial discrimination in the inequitable administration of government farm programs.32 In 1910, Black Americans owned 16 million acres of land and

28 Golden Henderson interview, 2009.

29

Deed Book 16, Macon County, Alabama, 264 (Ned Pace et al to Margaret Berry), 266 (Ned Pace et al to Lula Myhand), 268 (Ned Pace et al to Joe Pace), 270 (Ned Pace et al to George W. Pace), 381 382 (Pace heirs to Ned Pace), 514 515 (Margaret Berry et al to Anderson Pace), 522 (Mary Holmes to Albert Pace. Some Pace family historians counted Albert as sibling).

30 The Gazette, Tuskegee, Alabama, May 1, 1886.

31

Deed Book 5, Macon County, Alabama, 190 191.

32 U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, “Equal Opportunity in Farm Programs: Excerpts from an Appraisal of Services Rendered by Agencies of the United States Department of Agriculture,” CCR Special Publication Number 3, March 1965. This publication outlined findings of racially discriminatory practices by the USDA Cooperative Extension Service, the Farmer’s Home Administration, the Soil Conservation Service, and the Agricultural Stabilization and Conservation Service.

31

in 2017, Blacks only accounted for 4.5 million acres of land owned. Between 1910 and 1997, over 90% of Black landowners lost their land.

African American land ownership fluctuated between 1865 and 1930. The introduction of Jim Crow laws during the late 19th century produced restrictive farm contracts and limited the voting rights of African Americans. This caused issues of discrimination and financial inequality for Black landowners and farmers. Farm education and advocacy by Booker T. Washington and the Tuskegee Institute provided new ways of self sufficiency for Black farmers. Dr. Washington taught crop diversification and extension agents such as Thomas M. Campbell taught Black farmers and landowners a way to keep their crops from being undersold. Agents launched a movement of communal dependency between farmers and other African Americans within Macon County.33 Food insecurity and lack of support from the local, state, and federal government inspired Dr. Washington to host meetings during the late 19th century and into the 20th century. Groups such as Tuskegee Farmers Conference and the Colored Farmers’ National Alliance and Cooperative Union (CFNACU) created a safe space for Black farmers and landowners to learn more about the trade from other farmers across the Black Belt, protect their assets, and provide for their families. The emergence of small Black owned banks and Black institutions such as Tuskegee, The Agricultural and Mechanical College for Negroes (Now Alabama A&M), and The State Normal School in Montgomery established more opportunities for African American land ownership during this time period.34 African American landowners surrounding Creekwood benefited and thrived from Booker T. Washington’s and Tuskegee Institute’s promotion of self sufficiency through land ownership, construction and management of rural schools, and a gospel of thrifty and moral, independent living.35

In the midst of some successes, African Americans were still migrating north or to urban centers like Birmingham and Atlanta to find better opportunities during the first and second waves of the Great Migration (1910 1970). The African Americans who stayed in the rural areas and became landowners and farmers faced legal and environmental opposition during this time. Environmental opposition speaks to the natural infestations and weather issues of the early 20th century. There was the boll weevil invasion of 1916 and weather almanacs recorded severe thunderstorms destroying cotton crops in Alabama and Mississippi. The USDA’s report on climate change and agriculture reported that “high temperature extremes increased 10 fold in the first three decades of the 20th century (1900 1929)”36 The topography of the soil has also changed drastically since 1900 as farms have become bigger and include many types of crops.

Along with the continuation of Jim Crow laws, the years following World War I dismantled the upward climb to economic freedom for Black farmers and landowners. Most Black farmers and landowners produced cotton as their main crop. This did not fare well economically for African Americans who were in debt. The storekeepers would tell Black farmers to produce only cotton because of its store value. However, this overproduction drove the price of cotton down and African-American farmers made little to no money from it.37 During World War I, the loss of cotton business from transatlantic sales crushed the pockets of Black farmers and landowners. This left many with no means of income to pay the mortgage and/or taxes on their land as was the case with Steve Pace, Jr.. 1916 proved to be a very difficult year for farmers and landowners as severe rainstorms and the boll weevil invasion led to many farmers abandoning their farms altogether.38 With all of these troubles coming to a head with the stock market crash in 1929, many black farmers and landowners could not afford to own land and did not have the means to own land.

33 United Stated Department of Agriculture, “Black Farmers in America: 1865 2000,” (Oct 2003): 8.

34 Marable, Manning, “The Politics of Black Land Tenure:1977 1915 ”Agricultural History 53, no.1 (Jan 1979): 142 152, accessed October 8, 2022, https://www.jstor.org/stable/3742866.

35 Shari L. Williams, Silent for Awhile, But Not Idle: African American Self Determination Ignites Educational Opportunity in South Macon County, Alabama 1906 1967, (Williams: Columbus, GA, 2017). This publication describes the rural school building program initiated by Clinton J. Calloway of Tuskegee Institute and documents Paces from the Warrior Stand Precinct who patronized and participated in drives to build schools and fund teachers to extend the school year. Also, the historic marker at the Creek Stand A.M.E. Zion Church in Creek Stand, Macon County which acknowledges the church’s adjacent historic cemetery, lists Steve Pace, his son George Washington Pace, and other freedman from the area as founding church trustees. 36 USDA. “Climate Change and Agriculture in the United States” United States Department of Agriculture (Feb 2013): 111.

37 Ibid., 144 38 Ibid., 148 50

32

From 1840 to Emancipation, the planter Stephen Pace acquired great wealth through his purchases of land and the labor of enslaved persons. In 1860, seventy seven enslaved people sustained the wealth and comfort of the white Pace family. That year, Stephen Pace reported real property valued of $12,000 and personal property valued at $57,000.39 Pace plantation records and family Bible do not exist to reveal the names of all persons who were enslaved Creekwood. Stephen Pace died in 1872 after Emancipation so his estate records do not include an inventory and appraisement of enslaved people that could reveal the names of Creekwood’s enslaved population. Population and agricultural census records, oral histories, newspaper accounts, and probate records nevertheless offer clues about the lives of those who we know and speculate lived as enslaved persons at Creekwood and those who descend from Creekwood’s enslaved population. The diaspora of Creekwood’s enslaved extends worldwide and one member of that diaspora offers a story of their resilience.

Through his art, authorship, and sculptures, Dr. Lorenzo Pace is working to increase knowledge among the African American Pace descendants and the general public about Steve Pace, his great great grandfather and the family’s legacy of enslavement and freedom. Oral historians on the Steve Pace line claim that Steve inherited the lock that shackled him during slavery and that he passed the lock down to his son Joseph Pace, who then passed it to Julius Pace, Dr. Pace’s paternal uncle. Dr. Pace acquired the lock in 1991 during the repast for his father’s funeral. but he resisted the charge from his 80 year old Uncle Julius to be the heir and steward of the Steve Pace slave lock. Back home in his Brooklyn, New York studio, Pace questioned this turn of fate. He asked, “Why did the family entrust me with this responsibility? What good can I do with this icon of enslavement? What does Steve Pace, the slave, have to do with me?” Unwilling to bother with resolving these questions at the time, Pace stuck the lock into a closet and tried to forget it.40

In the same year that Dr. Pace inherited the Steve Pace lock, a forgotten African burial ground was rediscovered at the construction site of a federal office building in Lower Manhattan, New York City. In 1992, the New York City Parks Department and the Office of Cultural Affairs publicized the intent to commission an artist to design and erect a monument to commemorate the site. Pace interviewed for the job and received the commission after spending six months meditating in his studio and researching African arts and culture. He presented a design for a 60 foot tall black granite sculpture that was inspired by the female form of the African Chi Wara antelope. The monument, called “Triumph of the Human Spirit,” was unveiled in 2000 in the center of Foley Square Park in Manhattan. Pace buried a replica of the Steve Pace lock at the base of the monument and inscribed the base with a message to honor his parents and his great great grandfather Steve Pace. He also buried a lock replica at the base of the historic cemetery marker at the Creek Stand A.M.E. Zion Church.

39 Stephen Pace in the 1860 United States Federal Census, accessed October 21, 2022, https://www.ancestry.com.

40 “Dr. Pace on Legacies: Contemporary Artists Reflect on Slavery,” accessed 10/21/2022, https://lorenzopace.com.

33

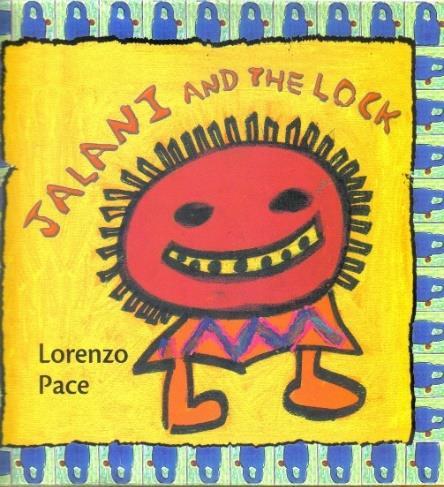

As these events transpired, Pace’s eight year old daughter posed the tough question, “Daddy, are we from slaves?” In response, Pace crafted an age appropriate response in the form of a book about Jalani, a small boy who is kidnapped from Africa and then shackled by locks and chains as a slave in America. After Emancipation, Jalani passes the lock that shackled him on to his children so they and their descendants will always remember his journey and be proud of the family’s legacy. The book, entitled Jalani and the Lock, was published in 2001 by Rosen Publishing Company, New York City. It was honored as "One of the Best Children's Books for 2001” by the Los Angeles Times and was a 2001 "Skipping Stone Award" recipient. The book is included in the collections of 247 libraries throughout the United States, has been published in Dutch, English, French and Spanish, and is found in library, school and government collections in France, South America, West Africa, and The Netherlands. Dr. Pace has exhibited the lock at the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute, Birmingham, Alabama, and other venues.

Previous Page: photo top page: Pace Family slave lock Photo middle right: Triumph of the Human Spirit monument. This page: Cover of book Jalani and the Lock Courtesy of Lorenzo Pace

34