Information and Subscriptions

Town & Country Planning is the journal of the TCPA (Town and Country Planning Association), a company limited by guarantee and registered in England, number 146309; and registered charity, number 214348.

Copyright © TCPA and the authors, 2025.

The TCPA may not agree with opinions expressed in Town & Country Planning but encourages publication as a matter of interest and debate. The views expressed in this journal are those of the contributors and advertisers and not necessarily those of Town & Country Planning, Darkhorse or the Editorial Advisory Panel. While every effort has been made to check the accuracy and validity of the information given in this publication, neither Town & Country Planning nor the publisher accept any responsibility for the subsequent use of this information, for any errors or omissions that it may contain, or for any misunderstandings arising from it. Nothing printed may be construed as representative of TCPA policy or opinion unless so stated.

Editor

Georgina Griffiths georgina.griffiths@tcpa.org.uk

Contributions

If you are interested in contributing an article, please contact the editor before writing, to agree topic and word count.

Editorial Advisory Panel

Peter Hetherington (Chair), Anna Aldous, Simin Davoudi, Clare Goff, Tomas Johnson, Charlotte Morphet.

Associate Editor

Julia Thrift

Subscriptions

£148 (UK); £178 (overseas).

Subscription orders and enquiries: t: +44 (0)20 7930 8903 e: tcpa@tcpa.org.uk

Town & Country Planning is sent to all TCPA members. To find out about joining the TCPA see: www.tcpa.org.uk/join

TCPA membership benefits include:

• a subscription to Town & Country Planning;

• discounts for TCPA events and conferences;

• opportunities to become involved in policymaking;

• a monthly e-bulletin;

• access to members’ area on the TCPA website.

Design

Darkhorse Design hello@darkhorsedesign.co.uk

Town & Country Planning is produced by Darkhorse Design on behalf of the Town and Country Planning Association and published six times a year. It is printed on paper sourced from EMAS (Eco-Management and Audit Scheme) certified manufacturers.

Advertising

Full page: £800+vat

Half page: £400+vat

Quarter page: £300+vat. Inserts: price on request.

Cover image Hazelmead co-housing, Bridport © Barefoot Architects

Contents

Regulars

140 On the agenda

Fiona Howie:

Healthy homes and safe spaces

143 Time and tide

Celia Davis:

A healthy home is a net zero home

Features

150 Building momentum for healthy homes

Rosalie Callway, Sally Roscoe and Clemence Dye on why the Campaign for Healthy Homes is more vital than ever at a time of change and uncertainty in the planning system

159 Homes for all

The government needs vision, cross-sector support and long-term statutory commitment to tackle the housing crisis, says Kate Markey

165 Embedding health into New Towns

A study tour of Bicester showed Charlotte Llewellyn how healthy outcomes can be built into new communities

172 Housing, health and economic growth: can we negotiate towards a healthier future?

Daniel Black advocates for holistic, long-term thinking in housing policy, rather than a rush to build new homes for short-term gains

179 The health impacts of permitted development rights

It’s time for government to revoke damaging planning deregulation so that local authorities can once again take the lead on creating healthy housing, says Sally Roscoe

186 Are we building healthy homes?

Georgie Revell on how (or if) the Healthy Homes Principles are currently regulated, and whether changes could be made to ensure that high-quality homes are built in future

194 Making the case for healthy homes at the local level

Many councils are working hard to embed Healthy Homes Principles into housing in their area, reveals Sally Roscoe

202 Tackling inequality in housing design quality

There are proven routes to success when it comes to creating well-designed, sustainable homes in challenging areas, explains Matthew Carmona

On the agenda It has been running since 2019, but the Campaign for Healthy Homes is just as relevant and important now as it ever was, says

Fiona Howie

Healthy homes and safe spaces

Safe communal spaces around homes, such as the peaceful courtyard and play areas of Agar Grove in London, are vital to residents' health and wellbeing

Fiona Howie

© Tim Crocker/Mae Architects

With a government arguing that it is overhauling the planning system to enable growth and remove burdens and barriers faced by developers, it feels that little has changed over the last five years.

As I have acknowledged before, the narrative about planning is positive from some ministers, but that is not being reflected in speeches from senior members of the Labour Party. Sadly, this means that a change in government does not mean an end to our Campaign for Healthy Homes. Indeed, with targets set for local authorities to give planning consent for 370,000 new homes a year, ensuring that new homes support people’s health, wellbeing and life chances feels as relevant as ever.

As this special ‘Healthy Homes’ issue highlights, maintaining momentum for long-running campaigns requires imagination and hard work. But the Planning and Infrastructure Bill provides a new opportunity for us to work with parliamentarians to try to table amendments and seek responses from government about the issue of housing quality. However, with Labour having a substantial majority in the House of Commons, securing amendments will be difficult. When we were first discussing the Healthy Homes Principles and developing the Campaign back in 2019, one of the most important elements for me was that this was about more than the individual home. People being safe in their own home is essential. As much of the Association’s work highlights though, the space around homes, and the neighbourhood that homes are within, also have profound impacts on people and the environment.

Two of the Principles relate to safety explicitly, namely fire and safety from crime. But the Association has also been involved in discussions recently about the importance of the design of public realm in keeping people safe. Often this has been in the form of bollards – the ugly concrete blocks outside Parliament come to mind. But, the national protective security authority (NPSA), a part of the MI5 that works to keep people safe from threats, has published the Public Realm Design Guide: Hostile Vehicle Mitigation,1 which provides tools and understanding to encourage a proportionate, but much more creative response. The hope is that sites that are vulnerable to vehicle attack can be protected through more aesthetic and multi-purpose solutions. It is worth noting that this guide is the third edition and was published in November 2023, yet awareness of it seems to have remained very low. The third edition has therefore been developed with the built-environment sector, rather than security sector, as the intended audience. As the guide now notes:

‘The opportunity exists for designers of the public realm to ensure that Hostile Vehicle Mitigation measures are integrated seamlessly into the environment, providing proportionate security whilst also creating appealing and functional places for people.’

While I recognise that this might not be relevant to all readers of the Journal, I encourage those involved in the planning, design and creation of public realm to have a look at the guidance.

Fiona Howie is Chief Executive of the TCPA.

Notes

1 Public Realm Design Guide: Hostile Vehicle Mitigation. Third Edition. Guidance. National Protective Security Authority, Nov. 2023. https:// www.npsa.gov.uk/public-realm-design-guide-hostile-vehicle-mitigation-0

Time and tide

New housing must be sustainable for the health of people and the planet, and we need to remove the ‘blockers’ to this inevitable future, says Celia Davis

Celia Davis

A healthy home is a net zero home

Five years after buying our first home in Bristol, my husband and I are nearing the end of a DIY retrofit journey. Hours of hard graft, a pandemic and a few bank loans later, our home is now a place in which we can lead a healthy life (although the process may have aged us).

The refurbishments included external wall insulation, solar panel and battery installation; underfloor and loft insulation; a new mechanical ventilation system; and draught-proofing to improve airtightness. The house is warmer, needs less heating, but stays cool in summer. We run on solar power in daylight hours (unless it’s very grey), but the battery can charge overnight and provide cheap energy when the sun is unobliging.

Predictably low energy bills feel great for the blood pressure. Other health benefits are less tangible, but our carbon dioxide (CO2) monitor tells a compelling story. Humidity is reduced (no more damp patches in north-facing corners), and CO2 is close to outdoor levels. The insulation means that we barely hear our neighbours, and ventilation reduces odours. Our experience

reveals the many ways in which an energy-efficient home is the essential foundation of a healthy home.

So, as a Bristol resident, it was disappointing to learn that the city council have weakened the net zero buildings policy in their Local Plan in response to the 23 December 2023 Written Ministerial Statement (WMS) on energy efficiency. This WMS seeks to tie local authorities to the carbon metrics used in building regulations, stifling more innovative policies that use energy-based metrics to drive down the energy demand of new buildings and more effectively reduce operational energy use.1 I fear that it will have a similar impact on other emerging Local Plans, meaning that across England, thousands will miss out on the health and cost benefits of living in the highest standard of energy-efficient homes.

The failure to regulate for lowcarbon homes is a result of successive governments being in thrall to the housebuilder lobby

Until building regulations deliver net zero homes, there is a clear rationale for planning authorities to set higher standards to accelerate carbon mitigation from the built environment, where this is deliverable. The failure to regulate for low-carbon homes is a result of successive governments being in thrall to the housebuilder lobby who, rather than adapt their business models in the face of the climate crisis, continue to pour resources into undermining policy progress for healthy, sustainable communities at the national and local level.

In Bristol, the Home Builders Federation (HBF) have objected to a raft of progressive policies – from affordable homes, space standards, urban greening and nature recovery, to net zero buildings and climate adaptation. Their familiar arguments can be summarised as ‘that’s not how we do it’

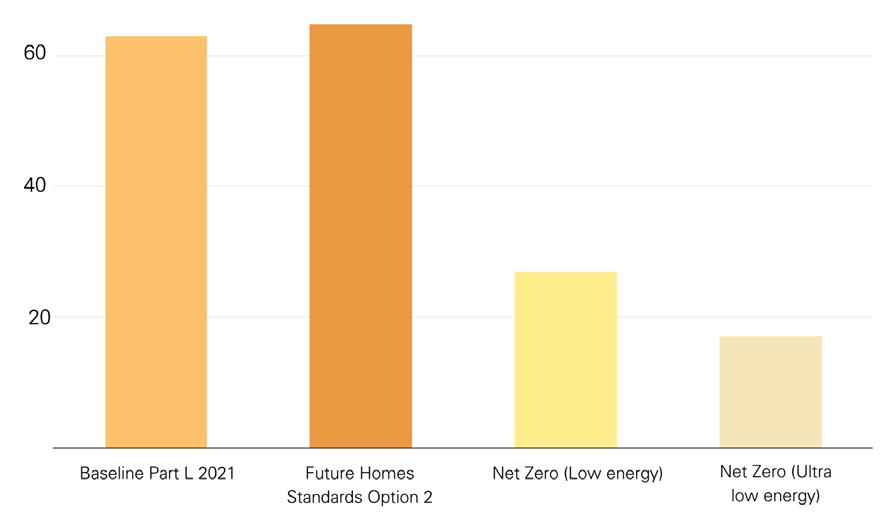

Indicative energy cost savings comparison by policy

Key insights from South East England

These figures are based on a typical semi-detached house

• Energy Use: Net zero policies show the lowest energy use compared to Baseline Part L and Future Homes Standard Option 2.

• Annual Costs: Net zero policies also yield the greatest cost savings.

Homes built to net zero standards substantially reduce both energy use and costs, creating financial benefit for future residents as well as emissions savings.

The cost savings of net zero buildings

Space Heating Demand (kWh/m2GIA/yr) – all scenarios

and ‘it’ll cost money’, and these are repeated at Local Plan consultations across England, with the intention to bring down policy standards to the lowest possible denominator.

At this year’s Futurebuild 2025 conference,2 this was made clear in stark terms at a session entitled ‘We the housebuilders, will provide the quality, affordable, net zero carbon, healthy homes in well-connected places that work for people of all ages’. The presenter from the HBF appeared to have misread the brief, launching into a tirade against environmental regulation and democratic oversight, setting out instead why ‘we the housebuilders’ flatly refuse to provide the high standard of homes our communities deserve. They accused local authorities of embarking on a ‘feeding frenzy’ of policy demands on nature and climate, and, alongside communities, of ‘opportunistically’ using energy and water constraints to block development. ‘The debate on housing has been dominated by arguments about quality for too long’, they said.

Annual energy cost by policy in £

This vitriolic attack on planning regulation reveals an ideological disdain for the right of authorities to democratically shape their places for the better. It also shows a disregard for the lives and long-term health of the people who will live in the homes that we are expected to trust the private sector to build. It all felt rather tone deaf at a conference showcasing gamechanging innovations in low-carbon building design; and alongside panellists presenting case studies demonstrating how nature and development can be integrated in practice, with powerful outcomes for people and wildlife.

West Carclaze garden village – proof that good-quality affordable housing can be built to high environmental standards © TCPA

Perhaps it’s time to turn the rhetoric of ‘builders’ and ‘blockers’ on its head

I wonder which housebuilders the HBF were representing here? There are many examples of developers – particularly smaller ones, but also some of the more enlightened volume builders – who, from Sheffield to Cornwall, from Cambridgeshire to Lancaster, can pick up a low-carbon, naturepositive brief and deliver it. Perhaps it’s time to turn the rhetoric of ‘builders’ and ‘blockers’ on its head. There’s only one destination for housebuilding in a climate crisis, and that is net zero and resilient homes that provide the same health and wellbeing benefits as my lovingly retrofitted house. The question is, how do we accelerate and promote innovation to make this mainstream, and how do we get the ‘blockers’ to our net zero future out of the way?

Celia Davis is Senior Projects and Policy Manager at the TCPA

Notes

1 For a fuller explanation see: https://www.tcpa.org.uk/resources/settinglocal-plan-policies-for-net-zero-buildings/

2 Futurebuild is an annual built environment expo in London focusing on sustainability. See: https://www.futurebuild.co.uk/

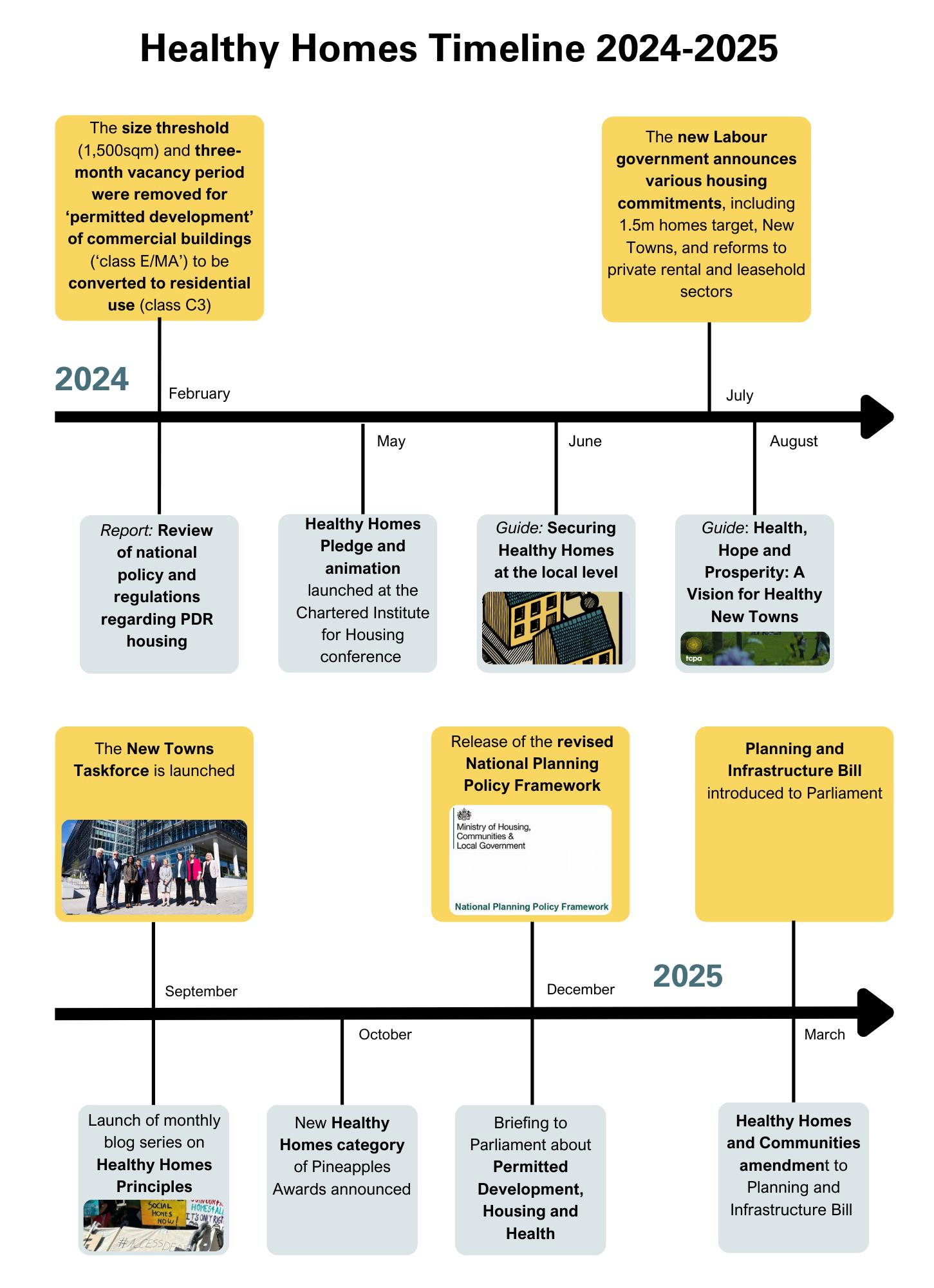

Healthy Homes Campaign

It is possible to create healthy and affordable homes in the right places, but some new housing is still shockingly bad. That is why the Campaign for Healthy Homes needs to continue its vital work.

Enterprise House in Merton. Permitted development rights allow former offices such as this one to be converted into housing without planning permission, but are these the healthy homes people need?

© Daniel Slade

Healthy Homes

Rosalie Callway, Sally Roscoe and Clemence Dye on why the Campaign for Healthy Homes is more vital than ever at a time of change and uncertainty in the planning system

Building momentum for healthy homes

Since 2019, the Campaign for Healthy Homes has sought to deliver primary legislative reform regarding the quality of all new homes, essential to deliver better health outcomes; and to promote industry-wide adoption of 12 Healthy Homes Principles.

The latest planning reform legislation, the Planning and Infrastructure Bill, was introduced in Parliament on 11 March 2025. It promises to deliver 1.5 million new homes by 2029, and this target is presented as a mechanism for stimulating the macro-economic growth of England. But what of the quality, affordability and long-term legacy of those future homes and communities?

There has been little progress on establishing a comprehensive approach to housing standards since the requirement to meet the Code for Sustainable Homes was dropped in 2015. Over the last decade, both Labour and Conservative governments have made a lot of noise about housing targets and so-called planning and regulatory ‘red tape’. The TCPA agrees that more homes are needed urgently, but we are concerned that a narrow focus on numbers will not lead to the resilient and healthy communities England needs now and for the future. Consequently, we remain committed to pressing for a more fundamental approach to standards for new homes and communities.

The second half of 2024 was tumultuous, with multiple announcements about the reform of regulations, policy and governance in housing and wider planning. The government pressed ahead with its Plan for Change and target for 1.5 million new homes. The obsession with seeing housing primarily as a means of delivering economic growth carries many risks. These include the question of how deliverable the

Appleby Blue Almshouse in London provides sustainable affordable housing for older people, with plentiful communal green spaces.

The project was joint-winner of the 2025 Pineapples Award for Healthy Homes

© Goddards

target is in practice, recognising that considerable market barriers (including skills, capacity and price-point pressures) undermine housing delivery. There is also the question of whether sufficient affordable homes will be built by the private sector alone.

The Campaign is concerned about the tenure, location and quality of new homes. Will they be genuinely affordable for those who most need them? This is why we are calling for affordability to be defined as it is by the Office of National Statistics – based on people’s average or below-average income levels, rather than by market rates.1,2

There is also the challenge of ensuring the quality of the new homes that will be produced. Permitted development (PD) changes in 2015 have meant that commercial and light industrial buildings can be converted into housing without requiring a full planning application. The TCPA has raised numerous concerns about some developers cutting corners in terms of the safety, quality and location of PD housing. Many are in isolated industrial estates or along busy main roads in dilapidated former office blocks, and some residents have described these as feeling like prisons. In opposition, Labour condemned the poor-quality homes produced under PD rules. However, when Healthy Homes champion Lord Nigel Crisp

Hazelmead co-housing in Bridport was joint winner of the 2025 Pineapples Award for Healthy Homes. Its car-free streets and communal green spaces foster a strong sense of community

© Rebecca Noakes/ Barefoot Architects

raised a question about these rules in Parliament before Christmas 2024,3 the Minister for Housing merely said that they would be kept ‘under review’.

Beyond PD rules, the Competition and Markets Authority has been highly critical of the standard of new-build homes being produced by volume housebuilders, and has identified a ‘significant minority’ who are producing homes that are structurally unsound.4 Others have criticised the use of nondisclosure agreements to disguise poor performance,5 as well as the disconnected locations of many new housing schemes, leading to car dependency and social isolation.6

Looking ahead

The Planning and Infrastructure Bill emphasises the need to clear the ‘blockers’ to delivering the national housing target, as well as to new national energy and transport infrastructure. In the rush to deliver new homes ‘at pace’ the government must avoid repeating the mistakes of the past. Cutting corners to achieve quick wins has been shown to have dire consequences. The Grenfell Tower fire remains the most shocking example of this failure to put people’s safety and wellbeing first. Cheap, unsafe cladding materials remain on thousands of flats around the country to this day. As Emma O'Connor, a resident on the 20th floor of Grenfell Tower, said on BBC Radio 4’s Today programme in February 2025:

‘You can’t speak about deregulation and say you’re going to keep your promises to Grenfell survivors and be believed, when deregulation caused the fire in the first place.’

The Planning and Infrastructure Bill, the anticipated new national housing strategy and the New Towns programme should prioritise creating places that support good health for people and the planet. We need to return to the original definition of sustainable development, which is all about health equality and equity. In the words of Gro Harlem Brundtland (former Director General of the World Health Organisation), it is:

‘development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs’.

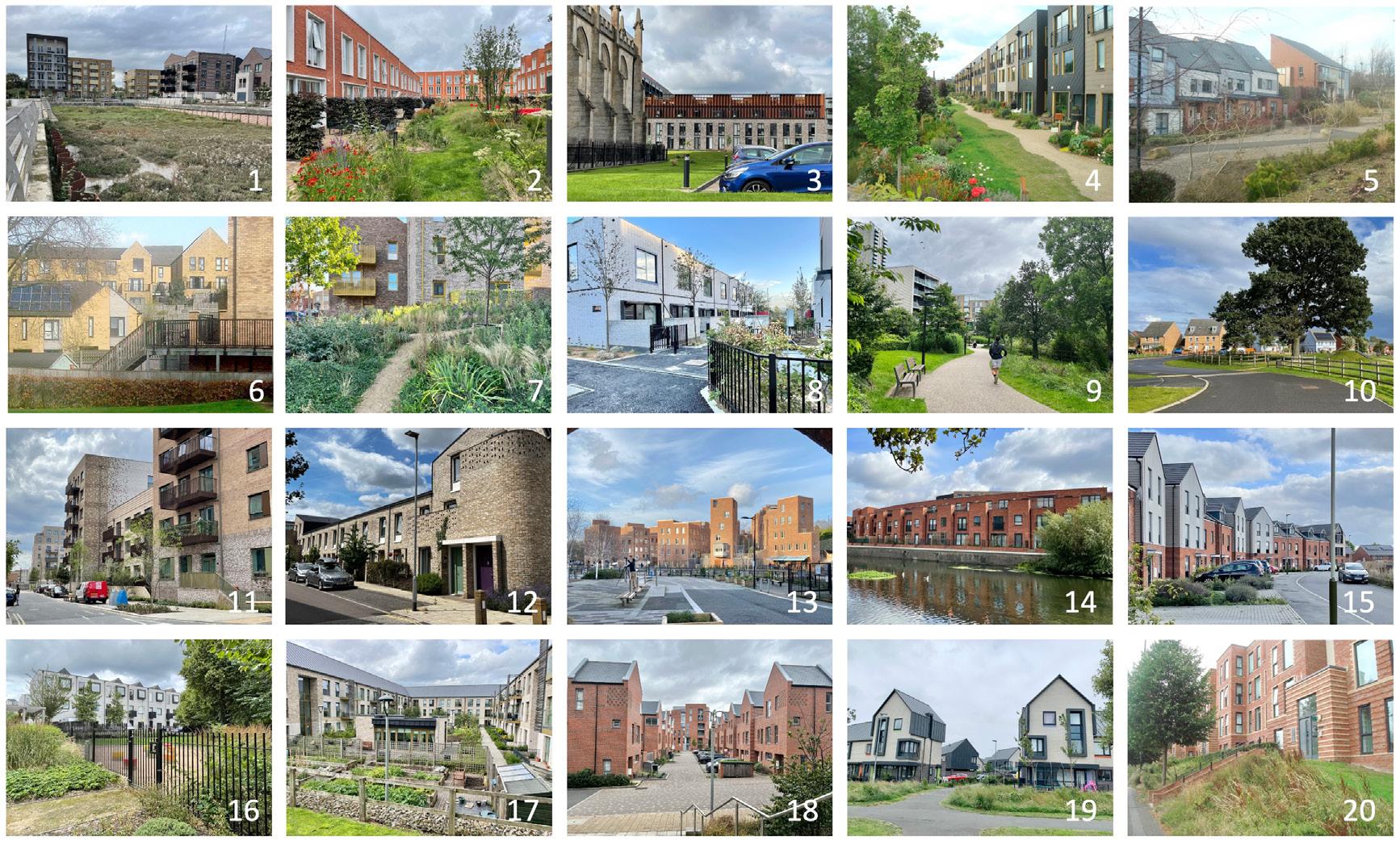

It is entirely possible to produce healthy and happy new communities that are inclusive, affordable and sustainably built. The Healthy Homes category of the Pineapples Awards,7 as well as our own research with the Place Alliance8 (see page 202), highlight excellent examples around the country, where developers and their clients have done just that.

The problem is that the current planning and regulatory system does not prevent poor-quality homes being produced by unscrupulous developers. The rules and lines of accountability to ensure even bare-minimum standards remain messy, confusing, under-enforced and easy to avoid. Because of this, the TCPA will continue to advocate for a more comprehensive approach, to not only protect people from harm but to actively promote better health outcomes for them.

Healthy

Homes Pledge

Launched in April 2024, the Healthy Homes Pledge has become a key mechanism for mobilising progressive organisations and individuals in support of the Healthy Homes Principles. It has more than a hundred signatories, including 58 organisations from local government, housing associations and urban design

It is possible for developers and clients to produce highly sustainable and affordable homes in challenging areas, such as the Climate Innovation

District in Leeds

© Wendy Clark

Healthy Homes

practices, as well as the Wates Group – the first large housing developer to adopt the Pledge. Leading industry stakeholders are advocating for and working to deliver healthier new homes.

Since signing up, Pledge supporters have also been working hard to address the Healthy Homes Principles and embed health considerations in new housing developments. An article in this section (see page 194) outlines the ways in which some local authorities have been adapting and applying the Principles in their local contexts. The Harlow Civic Society has been promoting ‘access to nature and local amenities’ through various events and advocating for affordable housing and liveable spaces that foster civic identity and community. Similarly, South West London Law Centres and Renters Rights London have been campaigning for affordable and secure housing for local tenants.

Many signatories are influencing policy at different levels. The Housing Learning and Improvement Network, a community of over 15,000 housing, health and social care professionals in England, Wales and Scotland, has focused on promoting more inclusive and adaptable housing, especially for older people.

Currently under construction, the new Sydenham Hill Estate in London has adopted the Homes Quality Mark, which meets all the Healthy Homes Principles

© City of London

Individual signatories describe working to influence district and county councils to adopt better policies, emphasising the need to reduce carbon emissions through development management. The Passivhaus Trust is helping to deliver high-quality housing by promoting the adoption of their Passivhaus standard throughout the UK. Their standard addresses many of the Healthy Homes Principles,9 including healthy indoor environments and affordability through lowering fuel bills.

Pledge signatories have also highlighted various challenges, including a lack of resources, upfront costs of implementation, skills or staffing limitations and, importantly, the absence of robust regulatory, monitoring and review processes. Despite this, the growing commitment among signatories demonstrates the Pledge’s potential to drive meaningful and comprehensive change that sets health as a central objective of future housing development.

A good home is a central foundation for people to thrive

Beyond new build

The Campaign has focused principally on achieving primary legislative change to improve the quality, affordability and location of new homes. However, we know that the greatest challenge remains the condition of existing homes. The latest English Housing Survey shows that some progress has been made towards meeting the Decent Homes Standard, which outlines 29 housing hazards that providers need to address. Particular progress has been made in the social rental sector, where it is mandatory to apply the standard.10 Nevertheless, 15% of homes are still not meeting it, and the survey found that rates of damp in homes are increasing. The Campaign is therefore pleased to be talking to like-minded networks about existing housing stock, including the Healthy Homes Hub, who are working with housing associations around the country to consider how the Principles might be applied to improve existing affordable homes.

Healthy Homes

The Campaign is based on common sense. A good home is a central foundation for people to thrive. We know that high standards for housing are achievable and affordable. Planning reform presents a huge opportunity for the government to positively introduce robust and comprehensive housing standards that will ensure that good homes are built for everyone, regardless of their income.

Rosalie Callway is TCPA Projects and Policy Manager, Sally Roscoe is TCPA Projects and Policy Officer, and Clémence Dye is TCPA Projects and Policy Assistant.

Notes

1 Housing affordability in England and Wales: 2024. Office for National Statistics, 24 Mar. 2025. https://www.ons.gov.uk/ peoplepopulationandcommunity/housing/bulletins/ housingaffordabilityinenglandandwales/2024

2 Private rental affordability, England and Wales: 2023. Office for National Statistics, 28 Oct. 2024. https://www.ons.gov.uk/ peoplepopulationandcommunity/housing/bulletins/ privaterentalaffordabilityengland/latest

3 Permitted development rights, health and housing. Parliamentary briefing. TCPA, 2024. https://www.tcpa.org.uk/resources/permitteddevelopment-rights-health-and-housing-parliamentary-briefing/

4 CMA finds fundamental concerns in housebuilding market. Press release. Competition and Markets Authority, Feb. 2024. https://www.gov. uk/government/news/cma-finds-fundamental-concerns-inhousebuilding-market

5 D Whitworth: ‘House builders should drop appalling gagging orders.’ BBC News, 13 Mar. 2021. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/ business-56376112

6 E Kiberd and B Straňák: Trapped Behind the Wheel: How England’s new builds lock us into car dependency. New Economics Foundation, 2024. https://neweconomics.org/2024/11/trapped-behind-the-wheel

7 ‘Healthy Homes award category – shortlisted schemes’. TCPA, Mar. 2025. https://www.tcpa.org.uk/healthy-homes-award-categoryshortlisted-schemes/

8 Tackling inequality in housing design quality. The Place Alliance, 2025. https://placealliance.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/full-report.pdf

9 ‘We can build healthy homes that cut carbon – so let’s get on and do it!’ Guest blog, TCPA, May, 2024. https://www.tcpa.org.uk/we-can-buildhealthy-homes-that-cut-carbon-so-lets-get-on-and-do-it

10 English Housing Survey 2023 to 2024: headline findings on housing quality and energy efficiency. Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government, Jan. 2025. https://www.gov.uk/government/ collections/english-housing-survey-2023-to-2024-headline-findings-onhousing-quality-and-energy-efficiency

Healthy Homes

The government has a chance to tackle the housing crisis and show what a housing system is for, but it will take vision, cross-sector support and long-term statutory commitment, says

Kate Markey

Homes for all

What does a home mean to you? A place of comfort and security, where you and your loved ones can put down roots and build a life? A legacy to pass on to future generations? Or perhaps a way to provide financial stability, whether as an investment for retirement or a career as a landlord? Housing can serve different purposes, but when the system fails to strike the right balance, the consequences can be harmful to many.

We are currently in the grip of one of the worst housing crises in a generation. A chronic shortage of affordable homes, rising rents, and record levels of homelessness have left millions struggling. Years of underinvestment in social housing, combined with the pressures of the cost-of-living crisis, have pushed the system to breaking point. The figures speak for themselves: over 1.3 million households in England stuck on social housing waiting lists,1 nearly £2.3 billion spent by councils on providing temporary accommodation in the financial year ending April 2024,2 and 164,040 children living in temporary accommodation in September 2024.3 A wellfunctioning housing system should provide the foundation for a stable and fulfilling life, yet for far too many, this basic right remains out of reach.

Healthy Homes

It takes thoughtful government policies – directly and indirectly linked to housing – to effectively work in parallel to give families a foundation for a healthy and stable life, satisfy financial markets and sustain private landlordism, while supporting our most vulnerable in society.

In 2024, the Nationwide Foundation partnered with the Church of England and leading voices across the housing space to call for a bold and long-term strategy for housing. Our Homes for All 4 report provides a powerful vision for good housing, designed by the coalition of housing providers, academics, campaign groups and tenants’ bodies, with 25 outcomes that indicate a well-functioning housing system.

This government has positioned itself to deliver the biggest housing revolution in recent history, including delivering 1.5 million new homes, a reform of renters’ rights, a planning legislation overhaul and investment in social housing, alongside restricting right to buy options.

A

The intention of Homes for All was not to offer a to-do list for government, but rather to cut through the complexity of our housing system with a set of clear indicators that – with the right policies – would illustrate a healthy housing market. The report groups its 25 outcomes into these four categories to reflect this complexity:

1. Better homes

2. Effective housing market

3. Better systems

4. Better policy and policymaking

Category 4, ‘Better policy and policymaking’, deserves a particular focus, as it demonstrates both the complexity of the housing system, and the fundamental problem of purpose. Successive governments have relied on short-term (politically attractive) policies, followed by a series of unintended and often dire consequences. The government’s Help to Buy scheme is a case in point. In 2022, a damning House of Lords report found that this scheme would have cost £29 billion in cash terms by the time it ended in 2023.5 Dubbed a ‘developer subsidy’ the scheme was criticised for failing to deliver genuinely affordable homes or value for taxpayer money. Perversely, it pushed up house prices in England by inflating prices by more than its subsidy value in some areas. Money that could have been spent more effectively on restoring social housing stock and increasing housing supply was wasted on Help to Buy.

The ‘Better policy and policymaking’ category puts forward a vision of what better, more effective housing policy might look like. Policy should be thoughtful and thought-through, drawing on evidence where it is available and mindful of uncertainty where it is not. It cannot be based on ‘one size fits all’ approaches and should reflect regional difference. Policy must be forward-looking, scanning the horizon for factors shaping the future of the housing system. Land, planning and housing institutions need to be restructured to make it easier to assemble land cheaply and bring it forward in a timely fashion; provide infrastructure to scale; masterplan new settlements; and make effective use of brownfield development. Supply policy should focus on creating successful places and

Healthy Homes

sustainable communities, as well as great homes. There needs to be recognition that interconnections between housing and other policy areas – such as health care, social care, finance, levelling up, and climate change – require a whole-ofgovernment effort, consistency and co-ordination. Effective monitoring and evaluation mechanisms need to operate at different levels to provide rapid feedback, understand impact, and allow for timely course correction.

To facilitate a sustained and long-term approach to better housing, Homes for All calls for a cross-party and independent statutory governance committee to scrutinise government efforts. There is an existing model to follow: The Climate Change Committee (CCC) is an independent, cross-sector public body that holds the government to account on its measures to meet the climate emergency. Such a committee need not slow the momentum of the government’s ambitions – a good housing system could and should be the engine of

We need a housing strategy that can be future-proofed, one that can weather the storm of political change

the economy. However, a whole-system-whole-government approach also involves long-term investment of the kind whose outcomes may not be felt for years to come. We need a housing strategy that can be future-proofed, one that can weather the storm of political change. An expert and independent committee would know this, providing sound reasoning, endorsement and strength. Such governance could make the difference between success and failure.

There is hope. The government’s housing strategy (due in spring 2025) is hoped to be cross-departmental, outcomesfocused and systemic. And it could span 10 years (two parliamentary terms). In early March 2025, a Homes for All event focused on comparing international housing strategies. Commissioned by the Nationwide Foundation, the interim evidence6 shows how other countries have failed and succeeded on this journey towards a long-term housing strategy. The key insights? Few strategies have been truly systemic, focusing instead on a particular aspect, such as quality, affordability, or homelessness. Some have put weight on engaging public opinion as part of the process (something not adopted by this government). Understanding and articulating the limitations (for example, of planning and health) has been critical to implementation.

Healthy Homes

There is an opportunity here to show true vision, demonstrate the trade-offs, articulate what a housing system is for. The government has a chance to demonstrate how to get housing right, with cross-party endorsement and longterm commitment in statute.

Kate Markey is Chief Executive Officer of the Nationwide Foundation, the charitable foundation supported by Nationwide Building Society. All views expressed are personal. Read more about Homes for All and the supporting coalition at www.homesforall.org.uk.

Notes

1 Social housing lettings in England, tenants: April 2023 to March 2024. Ministry of Housing, Communities & Local Government, 5 Feb. 2025. https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/social-housing-lettings-inengland-april-2023-to-march-2024/social-housing-lettings-in-englandtenants-april-2023-to-march-2024

2 ‘Council spending on emergency accommodation tops £2.2bn’. Press release. Crisis, 29 Aug. 2024. https://www.crisis.org.uk/about-us/crisismedia-centre/council-spending-on-emergency-accommodation-tops22bn/

3 ‘Children in temporary accommodation hits another shameful record as rough sleeping soars’. Press release. Shelter, 27 Feb. 2025. https:// england.shelter.org.uk/media/press_release/children_in_temporary_ accommodation_hits_another_shameful_record_as_rough_sleeping_ soars

4 Homes for All: A Vision for England’s Planning System. Report. Nationwide Foundation, Apr. 2024. https://homesforall.org.uk/wpcontent/uploads/2024/05/01_05_24_Homes-for-All_A-Vision-for-Englands -Housing-System.pdf

5 Meeting housing demand. Built Environment Committee Report. House of Lords, Jan. 2022. https://committees.parliament.uk/publications/8354/ documents/85292/default/

6 Listen to a recording of the Homes for All international comparisons interim findings, at https://homesforall.org.uk/webinar-whats-needed-forenglands-housing-strategy/

Healthy Homes

A study tour of Bicester revealed how healthy outcomes can be built into new communities, says Charlotte Llewellyn

Embedding health into New Towns

On 26 February, the TCPA hosted the New Towns Taskforce on a study tour and ‘policy sprint’ in Bicester, to explore how health can be embedded in the next generation of New Towns. The tour brought together members of the Taskforce and civil servants with experts from the planning, built environment, and public health professions. The aim of the day was to focus on the promotion of good health outcomes, not simply as a matter of individual equity, but as a fundamental component for any successful and thriving community, New Town, and country. The benefits of prioritising health range from reducing NHS costs to creating a population that can engage in all aspects of civic life, including education, culture, volunteering, employment and business generation.

Future health trends

To appreciate how New Towns can promote good health, it is essential to understand the health trends that will impact the UK’s population in future. These are:

• Growing population: England’s population will grow from 57.1 million in 2022 to an estimated 64.2 million in 2042.1

• Ageing population: Between 2000 and 2050, the number of people aged over 65 in the UK is expected to double.2

• Living longer in poor health: In 2040, people will spend on average 12 years in ill health.3

• Economically inactive: In 2023, over 8 million people between the ages of 16 and 64 had a long-term health condition that limited the type or amount of work they could do.4

• Mental health: One in four people in England will experience a mental health problem at some point each year.5

• Planetary health: Meeting national carbon and biodiversity targets, and ensuring a resilient natural environment, including efficient and clean water systems.

Lessons from Bicester

Bicester is strategically positioned in the Oxford and Cambridge Arc (an area between Oxford, Milton Keynes and Cambridge) and it has been recognised as a potential site for large-scale development since the mid-2000s. In 2007, it was designated as one of four Eco-towns, then in 2014 it became a garden town, and in 2015 it became an NHS Healthy New Town. The Cherwell District Council Local Plan 2011-2031 identified over 10,000 new homes on five strategic sites across Bicester, including North West Bicester, Graven Hill, and Kingsmere.6

Our morning study tour included some of these development areas, including Elmsbrook in North West Bicester. This is the first and only development in the UK built to meet the original principles of the Eco-towns Planning Policy Statement (PPS) 2009, which, according to the Green Building Council, has resulted in significant energy savings for residents.7 In addition, the Taskforce visited Graven Hill, which remains a unique

development opportunity, as the UK's largest self-and custombuild site.

While Cherwell District Council has a sustainable vision for the town’s growth, clear challenges are preventing this from being delivered. It became obvious that the two most significant constraints are the insufficient and unreliable funding for a strategic link road, and the capacity limitations of the local energy grid. These constraints have also impacted the lives of the existing residents, leaving people reliant on cars to access everyday amenities. Yet, while growth has been constrained, Cherwell’s ‘Everybody’s Wellbeing’ strategy demonstrates that healthy place-making in the town is ongoing; the council offers many activities, including pedal parties and establishing ‘health routes’ to promote active travel.

During the afternoon’s policy sprint, we heard from speakers with expertise in public health and the planning and delivery of New Towns and communities. It became evident that we already have the knowledge and insights needed to embed health into the next generation of New Towns. Ten high-level lessons emerged:

Apartments at Graven Hill, an evolving new community that offers self-build and custom housing options as well as sustainable new homes

© Rosalie Callway/ TCPA

1. Embed health from the outset: The NHS Healthy New Towns programme demonstrated the advantages of thinking about health priorities from the outset.9 Considering the health context of existing and surrounding communities and planning for future health helps to deliver inclusive health outcomes. When health is at the centre of the vision, goals and policy of a New Town, it helps to shape what is designed and delivered throughout the development.

2. Allow for flexibility: Planning and building New Towns takes decades. During this time good practice on issues such as the natural environment and health will evolve, and technological innovations may become outdated. The health needs of the community will change over time, too. A New Town programme must allow room for reflection and adaptation, not just as it is built out, but also as it matures as a town and community.

3. Work in partnership: Key partnerships must be created and nurtured from the start. Lessons from Bicester demonstrated the benefits of creating a health partnership to help link up the work of the key health actors in the area. This learning was further highlighted in the work of the NHS Healthy New Towns programme and the need to bring local community and anchor institutions into the process.

Elsmbrook –the UK's only development built to standards outlined in the 2009 Eco-towns Planning Policy Statement (cancelled in 2015)

© Rosalie Callway/ TCPA

4. Build community ownership: The creation of a New Town is a significant change process for any local and neighbouring community; New Towns are not merely tools for stimulating macro-economic growth, they must work for communities, as key partners in that process. Existing and new communities should therefore have a say in shaping their area's future. It is crucial to work with communities to understand their health needs and to put programmes of work in place to ensure community activation is successful.

5. Take an infrastructure-first approach: Where possible, essential infrastructure, including energy grids (or microgrids); water, shops, healthcare and sports facilities, and community spaces, should be delivered upfront, to ensure residents benefit from them from the start. During the visit, we heard of instances where essential infrastructure was delayed, and how this had eroded public trust. This slowed the delivery of further phases and made it difficult for new residents to live healthy lives, for example by increasing their reliance on cars to access amenities. The current use of Section 106 agreements to fund infrastructure, affordable homes and amenities greatly limits the extent to which these services can be delivered up front, as payment is usually made after initial phases of a development have begun.

6. Remember that health starts at home: The quality, accessibility, affordability and location of homes are key building blocks for creating healthy New Towns, as they shape people’s lifelong physical, mental and social health. The TCPA’s Healthy Homes Principles provide a comprehensive framework of what new housing developments should be striving for to ensure they have a positive impact on residents’ health.10

7. Adopt a ‘whole-life’ approach: It is essential that any New Town adopts an inter-generational, whole-life approach to its development; it should be designed with amenities that improve over generations, allowing people to thrive from childhood through to old age. This includes thinking about incorporating young voices into the planning process and enabling play.11 For older people, it includes providing agefriendly infrastructure and diverse housing options.12

8. Enable healthy life choices: Attention should be given to how places can work to make healthy choices the easiest and most affordable ones. A presentation on Northstowe in Cambridgeshire highlighted the importance of often-forgotten design elements that make public spaces more accessible, such as water fountains and public toilets. Additionally, Bicester showcased a range of projects that focused on community activation and enabling people to engage with their local surroundings, such as a local bike library.

9. Creating a whole place: Lessons from previous generations of new developments show the need to consider how a New Town can positively benefit the health and lives of both existing and new residents. By creating complete, compact and connected neighbourhoods, new developments can enable residents to fulfil their everyday needs within a short walk, wheel or cycle ride.

10. Think about legacy: A presentation about Ebbsfleet in Kent highlighted the need to consider the legacy and stewardship of a town from the outset – designing regeneratively, so that New Towns improve in quality and character over time. It is important that community assets are secured for the benefit of the local community in perpetuity. Planning for stewardship from the start can help to ensure a cohesive and high-quality stewardship model, rather than a patchwork of different management companies across a development.

A unique opportunity

It was clear from our day in Bicester that there is a wealth of knowledge and insights into how we can create healthy new communities that are resilient and can adapt and improve over time. The next generation of New Towns offers a unique opportunity to create exemplary new communities that work to tackle the concurrent health, housing, climate and nature crises. To achieve this, they must support regenerative and

distributive economies that ensure prosperity for all; a thriving community, and an environment that makes good health achievable for all.13

Charlotte Llewellyn is the TCPA Osborn Research Assistant.

Notes

1 National population projections: 2022-based. Release. Office for National Statistics, 2025. https://www.ons.gov.uk/ peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/ populationprojections/bulletins/nationalpopulationprojections/2022based

2 One hundred not out: a route map for long lives. The International Longevity Centre, Dec. 2023. https://ilcuk.org.uk/wp-content/ uploads/2024/01/One-hundred-not-out-report-final.pdf

3 Health in 2040: projected patterns of illness in England. The Health Foundation, Jul. 2023. https://reader.health.org.uk/projected-patterns-ofillness-in-england

4 ‘Health conditions among working-age people’. Webpage. The Health Foundation, Sep 2024. https://www.health.org.uk/evidence-hub/work/ employment-and-unemployment/health-conditions-among-working-agepeople

5 The Big Mental Health Report. Mind, Nov. 2024. https://www.mind.org. uk/media/vbbdclpi/the-big-mental-health-report-2024-mind.pdf

6 Adopted Cherwell Local Plan 2011-2031. Cherwell District Council, Dec. 2016. https://www.cherwell.gov.uk/info/83/local-plans/376/adoptedcherwell-local-plan-2011-2031-part-1

7 ‘Elmsbrook’. Webpage. UK Green Building Council, 2021. https://ukgbc. org/resources/elmsbrook/

8 Everybody's wellbeing strategy. Cherwell District Council, Dec. 2023. https://www.cherwell.gov.uk/info/277/everybodys-wellbeing

9 Putting health into place: executive summary. TCPA, Kings Fund, The Young Foundation, Public Health England, NHS, Sep. 2019. https://www. england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/phip-executive-summary.pdf

10 Healthy Homes Principles. TCPA. Mar. 2024. https://www.tcpa.org.uk/ resources/healthy-homes-principles/

11 Raising the healthiest generation in history, why it matters where children and young people live. TCPA, Dec. 2024. https://www.tcpa.org. uk/resources/raising-the-healthiest-generation-in-history/

12 One hundred not out: a route map for long lives. The International Longevity Centre, Dec. 2023. https://ilcuk.org.uk/wp-content/ uploads/2024/01/One-hundred-not-out-report-final.pdf

13 Health, hope, and prosperity: a vision for healthy new towns. TCPA, Aug. 2024. https://www.tcpa.org.uk/resources/health-hope-and-prosperity-avision-for-healthy-new-towns/

Healthy Homes

Daniel Black advocates for holistic, long-term thinking in housing policy, rather than a rush to build new homes for short-term gains

Housing, health and economic growth: can we negotiate towards a healthier future?

The government’s bullish house-building reforms are understandable yet worrying. Without long term health as the lodestar, we will get more identikit sprawl, more traffic, lifeless lawns, and few, if any, amenities.

Will the government's ambitious house-building targets lead to yet more urban sprawl?

© iStock

Is it any wonder we are a nation of ‘Nimbys’ (Not in my back yard)? New housing is needed, but this quantity-at-any-cost approach will burden a healthcare system that is already on its knees.

Arguably, it is not the fault of the government or the housebuilders. They are trying to get decent houses built, as best they can, within a system locked into outdated modes of delivery, while in a financial and social media straitjacket. So, what is to be done? How do we turn Nimbys into ‘Yimbys’ (Yes in my back yard), and do it quickly?

Hugh Ellis, the TCPA Director of Policy, called recently for a return to the ideals enshrined by Ebeneezer Howard in the Garden City Principles.1 This raises two critical areas of consideration; value and values and risk and negotiation.

Value and values

When Garden Cities were being promoted at the end of the 19th century, the UK was awash with money and largesse. Merchants were the Silicon Valley tycoons of their day (the former exploited India’s natural resources, the latter are exploiting the world’s data and attention, creating geopolitical turmoil in the process). Today, the UK is certainly not poor, yet, according to our measure of progress, gross domestic product (GDP), we are not rich enough, and this drive towards growth is dictating housing policy. How do we get out of this race to the bottom?

There is no simple answer. The world’s economic and socio-political systems are vast and complex, which is why uncertainty is fundamental to the consideration of whole systems.2 National housing policy may not be as complex as global macro-economics, but it is complex, nonetheless. In the TRUUD research programme (Tackling the Root causes Upstream of Unhealthy Urban Development), we identified 27 problem areas and 50 areas of potential intervention.3 Fundamental problems we identified included inherent shorttermism, and health being marginalised.4 We made seven key recommendations.5

1. Prioritise health (prevention) at the top of government.

2. Elevate quality alongside quantity.

3. Examine the role of law in determining urban health outcomes.

4. Study and improve public-private partnership.

5. Value planetary health in ways other than quantitively.

6. Negotiate complex trade-offs.

7. Make digital technology serve us, rather than the other way around.

Our evidence suggests that government acting to protect our health would be supported by the private sector if it was strategically coherent and fair. However, achieving this paradigm shift in priorities is easier said than done, and complex trade-offs are inevitable. Rapid change is needed, and those people and

companies whose practices need to shift will require support in this transition. For example, in another research project, we estimated the costs and benefits of reducing food waste, and found, unsurprisingly, that doing this is bad for (food) business.6 Yet there will be just as many winners too in these new systems of delivery, and we will all, ultimately, be better off.

This echoes one of the other key points in Ellis’s article: Schumpeter’s theory of ‘creative destruction’. From the spinning jenny to the dot-com bubble, technological revolutions are replete with cycles of boom and bust. Yet the Luddites and miners didn’t break the looms and strike because they were technophobes. They had lost their jobs and their communities.

People are not anti-technology or anti-housing, but they are pro-health, pro-nature and pro-fairness

Take the Garden City Principle of land value capture. One of the push-backs from a regional director of a volume housebuilder was: Why tax land? Why not tax the Big Tech companies who are avoiding tax?7 It’s a fair question. Ellis is therefore right to bring AI into this discussion. People are not anti-technology or anti-housing, but they are pro-health, pro-nature and profairness. This is about values.

Risk and negotiation

There’s a lot going on here. Thankfully, we’re not starting from scratch. Back in the 1990s, following several major threats to public health, including the BSE and Brent Spa crises, the Royal Society convened a group of leading thinkers to discuss a new approach to managing risk.8 The main debate was between the technocrats, who felt that risk can and should be quantified and managed/reduced, and the sociologists, who felt that risk is far more political and negotiable. An uneasy rapprochement was forged, but the debate continues.9 Their discussions featured frequent references to cultural theory, especially as applied to risk. This was pioneered in the 1970s by the British

anthropologist, Mary Douglas. A core concept of this theory was ‘grid-group’ framing, which enables us to distil, arguably, all the complexity of human nature and society into something manageable: the four ‘myths’ of human nature, and of nature (see Table 1). We are likely to have some of each myth within each of us. For example, I generally support autonomous, market-based solutions as the most efficient way to progress (individualist), but also want state intervention to secure our environment and future (hierarchist), as I do worry it's leading to collapse, and sooner than many think (nature can break down – egalitarian, hierarchist, fatalist).

Myth of human nature (how people behave, and think others should)

Hierarchist

Individualist

Top-down (i.e. state) intervention and control

Autonomy (i.e. market-based), survival of the fittest

Egalitarian Grass-roots, equal distribution

Fatalist Passive, leaving it all up to chance

Myth of nature (how they think nature behaves)

Self-rectifying up to a point; in need of some management to prevent breakdown

It's fine; it'll look after itself

Precious; prone to breakdown

Impossible to determine one way or another

If we apply cultural theory to the government’s current approach to housing delivery, it is facilitating (hierarchist) market-led delivery to kick-start business-as-usual (individualist) assuming nature will look after itself. There is also a general powerlessness at the prospect of AI (fatalist), and the concern of many that we are all headed for disaster (egalitarian). This not only allows simplification, it engenders respect for others’ points of view: there is no right or wrong, just different beliefs, values and world views. It recognises plurality, rather than suggesting there is only one right answer.

Table 1: Grid-group cultural theory re-framed10

Cultural theory has been developed over time to help with negotiation and reconciliation – a perennial challenge for government, who need to decide every day how to balance the demands of the ‘haves’ with the ‘have-nots’. It steers away from overly simplistic or ‘elegant’ solutions to complex problems, and more towards practical or ‘clumsy’ solutions.11 It’s been used in a range of different areas, such as engineering projects and insurance risk.

I wonder whether a cultural theory-based approach to stakeholder negotiation might be used, via citizens’ assemblies, in the development of strategic planning and housing policy, or to help different groups work with the new Environmental Outcomes reporting.12 Might we use it with planning jargon? For example, current government policy is clearly welcoming the Yimbys yet steamrolling the Nimbys. Cultural theorists might ask us to look for and involve the ‘Yiobys’ and ‘Niobys’ (‘yes/not in others’ back yards) too (see Table 2).

Table 2: Possible urban planning myths of (human) nature

Are these the urban planning myths of (human) nature?

Nimby Not in my back yard Not antidevelopment per se, but perhaps anti-social, and possibly pro-nature?

Yimby Yes, in my back yard

Yioby “yobbies”

Yes, in others’ back yard

Nioby “nobbies”

Not in others’ back yard

Pro-development, pro-social, pro-nature?

Pro-development, yet anti-social, anti-nature?

Anti-development, pro-nature?

Where would these fit in the grid-group framing?

Answers on a postcard..

Healthy Homes

Many quotes are attributed to Einstein, one of which is ‘make things as simple as possible, but not simpler’. This could apply here. The problems are complex, and we must work with that, but there are solutions.

Daniel Black is Programme Director of TRUUD (Tackling the Root causes Upstream of Unhealthy Urban Development) and Specialist in Urban Development for Planetary Health, Bristol Medical School, University of Bristol. All views expressed are personal.

Notes

1 ‘The NPPF and Ebenezer Howard’s inconvenient legacy’. Blog. TCPA, 26 Feb. 2025. https://www.tcpa.org.uk/the-nppf-and-ebenezer-howardsinconvenient-legacy/

2 Introduction to systems thinking for civil servants. Government Office for Science, 12 Jan. 2023. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/ systems-thinking-for-civil-servants/introduction

3 Phase 1 Report. TRUUD, Feb. 2024. https://truud.ac.uk/wp-content/ uploads/2024/02/TRUUD-Phase-1-Report.pdf

4 D Black, G Bates and R Callway et al: ‘Short-termism in urban development: The commercial determinants of planetary health’. Earth System Governance, Vol. 22, Dec. 2024, 100220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. esg.2024.100220

5 ‘We need to overcome short-termism if we are to make healthy places to live’. Blog. TRUUD, 17 Oct. 2024. https://truud.ac.uk/overcome-shorttermism/

6 D Black, T Wei, et al: ‘Testing Food Waste Reduction Targets: Integrating Transition Scenarios with Macro-Valuation in an Urban Living Lab’. Sustainability, 2023, Vol. 15 (7), 6004. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15076004

7 D Black, P Pilkington et al: ‘Overcoming Systemic Barriers Preventing Healthy Urban Development in the UK’. Journal of Urban Health, 2021, Vol. 98, 415–427. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11524-02100537-y

8 J Ashworth: Science, Policy and Risk. Royal Society, 1997

9 A similar debate has been ongoing in economics (see note 7, above)

10 M Thompson: Cultural Theory. Routledge, 1990

11 M Verwij and M Thompson: Clumsy Solutions for a Complex World. Governance, Politics and Plural Perceptions. Palgrave, 2006. https://link. springer.com/book/10.1057/9780230624887

12 D Black and E Kirton-Darling: ‘Environmental outcomes reporting –clearly inadequate, but does opportunity knock?’ Town & Country Planning, Nov-Dec. 2023, see: https://truud.ac.uk/wp-content/ uploads/2023/11/Environmental-outcomes-reporting-TCPA-Nov-23.pdf

Healthy Homes

It’s time for government to revoke damaging planning deregulation so that local authorities can once again take the lead on creating healthy housing, says Sally Roscoe

The health impacts of permitted development rights

Permitted development rights allow for the conversion of large-scale commercial and industrial buildings to residential use without requiring a full planning application.

Healthy Homes

In partnership with University College London, the TCPA has been conducting a three-year research study, ‘Investigating potential health and health equality impacts of planning deregulation’1 to explore how living in housing created using permitted development (PD) rights impacts the health and wellbeing of residents. As part of this, we have consulted a range of stakeholders from planning, public health and development control to understand how they are trying to improve the quality of PD homes.

Serious concerns

The experience of PD housing varies across the councils we have spoken to (and not all are fully against it), but a large majority of respondents raised profound concerns. One planning officer stated that:

‘PDR [permitted development rights] was about quick wins, a fast buck for dodgy developers. They are not going to be interested in investing in keeping properties up to date. They will be left until they need to be pulled down.’

PD rights can lead to dangerous and unhealthy housing for some of society's most vulnerable people

© Rob Clayton

Findings from Permitted Development, Housing and Health: A Review of National Policy and Regulations

Fragmented and complex rules

The TCPA’s role in the study is to examine the ‘levers’ available to local government to ensure that PD homes can support residents’ health and wellbeing. This began with a policy review, Permitted development, housing and health: a review of national policy and regulations.2 Overall, the review found that the current policies, guidance, and regulations are fragmented, complex, and inconsistent in what they require from homes created through permitted development (see Figure 1).

The current stage of the project is examining the effectiveness of local levers on shaping the quality of PD homes, using a three-pronged data collection process. This includes a survey of local authorities, six online roundtables, and to date, five semi-structured interviews with industry experts. Participants included local government officers from planning, public health, development management, housing, and environmental health, as well as various professional bodies. The survey received 49 responses, with all nine English regions represented.

Healthy Homes Principle

Do policies and regulations clearly address PD dwellings regarding delivery of the principle?

Unclear

Partially addressed Clearly addressed

Fire safety

Liveable space

Inclusive, accessible, adaptable

Access to natural light

Access to amenities, transport and nature

Reductions in carbon emissions

Safety from crime

Climate resilient

Prevent air pollution

Limit light pollution

Limit noise pollution

Thermal comfort

Affordable housing

Figure 1

Healthy Homes

Key concerns

Many local authorities raised concerns that varied standards and reduced regulatory requirements under PD are resulting in extremely poor-quality homes in problematic locations. This can have profound impacts on the wellbeing of residents, especially for vulnerable individuals living in temporary accommodation. One policy officer summarised the problem in this way:

‘The difficulty is, there are so many different classes within the GDPO [general permitted development order], it is a minefield for planning officers to know what conditions they can apply and then make a decision on whether it is appropriate and won't go to appeal... It would all be solved if we didn't have PD and everything went through the planning system.’

Several of the responding authorities pointed to the inadequacy of regulatory levers in shaping the quality of PD housing. This, along with significant resourcing pressures, reduced ‘prior approval’ timeframes and lower fees, makes it more challenging to properly scrutinise PD applications. When asked about the effectiveness of current levers on shaping the quality of PD conversions, survey responses varied, but the majority were negative or neutral (see Figure 2).

Survey question: How effective are the current levers (if any) in shaping the quality and location of homes through PD conversion?

© TCPA

Figure 2

If we do not address significant regulatory concerns posed by permitted development, then we risk condemning some of society’s most vulnerable people to living in slum-housing conditions

Participants agreed that there is a pressing need for clearer requirements to incorporate local health needs and evidence in decision-making processes related to PD housing. This is particularly true in relation to the prior approval conditions authorities can ask for. These vary by building use class and are currently limited to considering factors such as transport impact and flood risk, but miss many issues, for example, air quality and access to amenities and green space. The health impact of the development is not currently a prior approval condition – both in terms of potential individual health and broader community impacts. It is also noteworthy that concerns about PD rights vary regionally, and are associated with higher levels of PD housing in the South East and South West compared to the North East.

Another major concern was that local authorities are suffering ‘immense resourcing pressures’ and lack the capacity to adequately scrutinise housing produced through PD. This was a common theme from the survey, roundtables, and interviews (see Figure 3).

Critically, it was also noted that PD undermines any affordable housing contributions, as well as wider developer contributions to community amenities and services that would traditionally be secured through Section 106 agreements.

Healthy Homes

Survey question: What are the key challenges that can limit the effective management of the quality and/or location of permitted development

Lessons so far

Hugh Ellis, the TCPA’s Director of Policy, recently stated in The Observer 3 that PD has created a ‘free-for-all’ for developers. If we do not address significant regulatory concerns posed by permitted development, then we risk condemning some of society’s most vulnerable people to living in slum-housing conditions, when we could be creating decent and affordable homes for them.

Most of the people we spoke to for the study revealed that PD conversions are not producing decent-quality outcomes for residents or for the wider local community. They indicated that it would be far less complex and burdensome if we simply returned to the system as it was prior to the changes made in 2013 and 2015. The original PD scheme, established in 1943, was intended only for very minor changes and small-scale conversions, such as household extensions and barn conversions. It was never designed for permitting large-scale housing schemes of over 100 units, which have significant impacts to local area and communities.

Figure 3

conversion to residential use?

© TCPA

The government could change everything by revoking this damaging deregulation

Overall, the findings clearly show an urgent need for policy intervention to ensure that the existing housing stock produced through PD meets clear health and quality standards. The government could change everything by revoking this damaging deregulation and once again permitting local authorities to lead on creating safe, healthy, and sustainable communities for the long term.

Next steps

Throughout the study, representatives from local authorities raised significant concerns about the negative impact PD has on housing quality and on vulnerable residents, as well as the limitations of existing regulatory levers and challenges faced by resourcing constraints. These findings will be fully disseminated later this year, and the project will conclude in February 2026. Along with these research findings, the project will create a database of PD housing in England, which will be available to researchers and government organisations on request.

Notes

1 See the ‘Health Impacts of Converted Housing’ webpage, at https://www. uclpdhousing.co.uk/

2 Permitted development, housing and health: a review of national policy and regulations. TCPA, Feb. 2024. https://www.tcpa.org.uk/resources/ permitted-development-housing-and-health-a-review-of-national-policyand-regulations/

3 J Ungoed-Thomas: ‘Labour condemned for allowing ‘new generation of slum homes’ in England’. The Guardian, 14 Dec. 2024. https://www. theguardian.com/society/2024/dec/14/labour-condemned-for-allowingnew-generation-of-slum-homes-in-england

Sally Roscoe is the TCPA’s Project and Policy Officer.

Healthy Homes

Georgie Revell on how (or if) the Healthy Homes Principles are currently regulated, and whether changes could be made to ensure that high-quality homes are built in the future

Are we building healthy homes?

The Healthy Homes Principles spark important conversations about priorities and capabilities, and keep a focus on quality to ensure we build robust and sustainable homes that are fit for the future.

Access to amenities, nature and transport

Access to natural light Inclusive, accessible and adaptable

Principle 1: fire safety

Recent regulation on fire safety has significantly impacted both building design and construction. Changes such as the introduction of criteria for higher-risk buildings have meant a steep learning curve, but the impact of the new Approved Document B1 (AD-B), British Standards and the Building Safety Act 2021, will stabilise in time. In general, regulations are easy to incorporate in simple buildings but are challenging in complex layouts, such as where internal and external access is combined.2

Principles 2 & 3: liveable space, inclusive, accessible and adaptable

Since their introduction in 2015, nearly half of local authorities have adopted nationally described space standards (NDSS),3 which set minimum requirements for home size, some room dimensions, and storage. Local authorities can also require enhanced levels of accessibility with options in AD-M. Mandating national space standards would improve housing quality and equality. This change is likely to come, as proven by the 2021 requirement for NDSS in permitted development conversions – a positive step forward. A 2020 government consultation also found mandating Category 2 as a minimum was popular across the industry because it levels the playing field. NDSS and AD-M Category 2 are designed to work together, so if requiring one, you may as well include the other.

Looking further ahead, the 2023 London Housing Design Standards have set new best practice space standards, 5-10% larger than NDSS, to accommodate post-Covid lifestyle changes. London has previously led on space guidance, so this could influence future standards generally. It would be good to see national requirements for external amenity space too, which will be beneficial to all, particularly children and young people.4

Private amenity space, such as this winter garden in a laterliving home, is important for people’s health and wellbeing

© Levitt Bernstein

Principle 4: access to natural light

Daylight and sunlight assessments are required by many local authorities in new residential developments, to test natural light levels in both proposed and existing surrounding homes. Most assessments follow Building Research Establishment (BRE) guidance, British Standards, and CIBSE (Chartered Institute of Building Services Engineers) publications. BRE is quite inflexible, so can result in authorities routinely accepting a level of failure, particularly in built-up areas. There is a clear conflict between natural light and overheating, which is now covered by regulation in AD-O and often a planning requirement too. It is important that guidance for daylight and thermal comfort are regulated in the same way (see Principle 11).

Principles 5, 8 & 11: cut carbon emissions, climate resilient, ensure thermal comfort

Homes that include measures that reduce building service energy demands will lower operational carbon emissions and ensure thermal comfort during extreme weather. Understanding of sustainable design has advanced greatly in the last decade, and many planning authorities now ask for evidence through energy statements, plus flood risk and wind

Fixed shading prevents overheating but does not limit daylight or views

© Levitt Bernstein and Frank Grainger/ Origin Housing

Healthy Homes

microclimate testing. At a technical level, regulation updates (AD-O and AD-L) ensure a reduction on energy demands. The GLA (through the London Plan) also push developments to go further by requiring major developments to achieve a 35% on-site carbon reduction. These requirements are driving a move away from single-aspect flats and large areas of glazing and will prevent unusable balconies on tall buildings – all of which will improve homes for residents.5

While Passivhaus efficiency isn't yet the norm, our practice designs to these principles as standard, because a fabric-first approach is more viable, robustly tested and effective long-term. Decisions such as orientation and window proportions impact energy usage and reduce reliance on mechanical systems. The preference for passive design techniques should be the industry norm.

Affordable Passivhaus homes at The Bourne in Hook Norton, Oxfordshire – the scheme was shortlisted for the 2025 Pineapples Healthy Homes Award

© Charlie Luxton Design

Principle 6: access to amenities, nature and transport

In the last five years, the 15-minute neighbourhood concept has been much discussed, especially as, post-Covid, more people spend more time at home. Encouraging active travel and creating connections to green spaces and play areas and ensuring easy access to services and amenities will create strong communities. However, as the industry finds ways to build 1.5 million new homes, it is crucial that the focus is not only on local amenity but also transport connections to wider networks, to prevent communities becoming isolated, which will increase inequality. Area-based supplementary planning documents (SPDs) could help to ensure future communities are well-equipped and connected.

Principle 7: safe from crime

Secured by Design (SbD) is a voluntary national standard that can be required by clients or local authorities. It requires projects to be reviewed by a Design Out Crime Officer (DOCO) who should be consulted during the design development. The views of the DOCO and SbD principles go beyond regulation set in AD-Q for security of doors and windows. Input from a DOCO is most valuable in early design stages. At later stages, there may be issues complying with competing specifications, particularly when also achieving other building safety and Passivhaus requirements, specifically on flatted blocks. It is important to balance the need to secure homes and buildings without limiting the ability for residents to form a community, which is arguably the best form of security.

Principles 9 & 10: prevent air pollution and limit light and noise pollution

Internal and external pollutants affect health and wellbeing, and these issues become more acute as we build at higher densities. By ‘insulating tight and ventilating right,’ we can control external factors as assessed through planning requirements and building regulations. Best practice is to integrate passive systems to avoid reliance on complex equipment. For ventilation, designs might include openable panels separate from glazing for good views and better airflow. To reduce noise transfer between flats (a common cause of distress), bedrooms should be above bedrooms and avoid

Healthy Homes

direct connections to communal areas and entrances. The Code for Sustainable Homes (now replaced by the voluntary Homes Quality Mark) gave points for going beyond the requirements in AD-E for sound, and many developers still ask for this in their housing briefs. This could be included in updated versions of the approved document. Phasing out gas cookers and using VOC-free finishes will further improve indoor air quality.

Principle 12: genuinely affordable and secure homes

Across all sites, local authorities need to apply their housing targets flexibly to ensure that diverse types and tenures of homes are suitably placed. On sites less suitable for families, for example high-density housing in urban locations, local authorities could encourage mixed-tenure specialist housing types, for example adaptable homes for older people, or new forms of shared living. These should never be the predominant housing type but can offer site-specific solutions to help tackle the housing and health crises. Permitted development rights must also be reviewed and restricted to ensure homes are suitable and contribute fairly (through Section 106 agreements) towards the delivery of healthy neighbourhoods.

Georgie Revell is an associate at Levitt Bernstein. All views expressed are personal.

Notes

1 Approved Documents (AD) are referenced through with a lettered suffix

2 Editor's note: conversions of existing buildings to housing through PD avoid full planning application processes and skip the fire safety requirements of Planning Gateway One in the Building Safety Act. See: Permitted development, housing and health: a review of national policy and regulations. TCPA, 2024. https://www.tcpa.org.uk/resources/ permitted-development-housing-and-health-a-review-of-national-policyand-regulations/

3 S Özer and S Jacoby: ‘Space standards in affordable housing in England’. Building Research & Information, 2023, Vol 52 (6), 611-626 https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/09613218.2023.2253337#d 1e557

Marmalade Lane co-housing in Cambridgeshire has few physical boundaries outside, which allows communities to form organically and increases security (see Principle 7)

© Mole Architects/ David Butler

4 Raising the healthiest generation in history: why it matters where children and young people live. Report. TCPA, Dec. 2024. https://www. tcpa.org.uk/resources/raising-the-healthiest-generation-in-history/