town & country planning

The Journal of the Town and Country Planning Association

May–June 2024 Volume 93 • Number 3

• Special issue - 125 years of the TCPA

• Harnessing Towns and Cities for Better Growth

• Diagnosing delay in Planning: Dobry at 50

• Codes and Communities

In 2024 we’re celebrating 125 years of the Town and Country Planning Association – and the 120th anniversary of Town & Country Planning.

Copies of Town & Country Planning published between 1904 and 2005 are archived and free to view at: archive.tcpa.org.uk.

information and subscriptions

Town & Country Planning

The Journal of the Town and Country Planning Association ISSN 0040-9960 Published bi-monthly May-June 2024 • Volume 93 • Number 3

Town & Country Planning is the Journal of the Town and Country Planning Association (TCPA), a Company Limited by Guarantee. Registered in England under No. 146309. Registered Charity No. 214348

Copyright © TCPA and the authors, 2024

The TCPA may not agree with opinions expressed in Town & Country Planning but encourages publication as a matter of interest and debate. The views expressed in this journal are those of the contributors and advertisers and not necessarily those of Town & Country Planning, Darkhorse or the Editorial Advisory Panel. While every effort has been made to check the accuracy and validity of the information given in this publication, neither Town & Country Planning nor the publisher accept any responsibility for the subsequent use of this information, for any errors or omissions that it may contain, or for any misunderstandings arising from it. Nothing printed may be construed as representative of TCPA policy or opinion unless so stated.

Editorial and Subscriptions Office

Town and Country Planning Association

17 Carlton House Terrace

London SW1Y 5AS

t: +44 (0)20 7930 8903

Editorial: philip@darkhorsedesign.co.uk

Subscriptions: tcpa@tcpa.org.uk

Editor Philip Barton | philip@darkhorsedesign.co.uk

Design hello@darkhorsedesign.co.uk

Contributions: Articles for consideration are welcome. Material should be submitted to the Editor, preferably by e-mail and in Word-readable form. Reproductionquality illustrations are welcome.

Advertising: Rates (not including VAT): Full page £800. Inserts from £400 (weight-dependent). Half page £400. Quarter page £300. A 10% reduction for agents.

Subscriptions: £125 (UK); £152 (overseas). Subscription orders and inquiries should be addressed to: Subscriptions, TCPA, 17 Carlton House Terrace, London SW1Y 5AS t: +44 (0)20 7930 8903 e: tcpa@tcpa.org.uk

Payment with order. All cheques should be made payable on a UK bank. Payment may be made by transfer to:

The Bank of Scotland (account number 00554249, sort code 12-11-03). Mastercard and Visa accepted.

Town & Country Planning is also available through TCPA membership. See the TCPA website, at www.tcpa.org.uk, for membership rates, or e-mail membership@tcpa.org.uk for details.

TCPA membership benefits include:

• a subscription to Town & Country Planning;

• discounted fees for TCPA events and conferences;

• opportunities to become involved in policy-making;

• a monthly e-bulletin;

• access to the members’ area on the TCPA website.

Town & Country Planning is printed on paper sourced from EMAS (Environmental Management and Audit Scheme) certified manufacturers to ensure responsible printing.

Town & Country Planning is produced by Darkhorse Design on behalf of the Town and Country Planning Association and published six times a year.

Town & Country Planning May-June 2024

Town & Country Planning May–June 2024 • Volume 93

regulars features

132 On the Agenda

Fiona Howie:

Celebrating 125 years of supporting people and places to thrive

134 Time and Tide

Hugh Ellis: Looking backwards for future inspiration

137 Snakes and Ladders

Sue Brownill, Debbie Humphry and Jason Slade: Communities, garden cities and Kropotkin

142 Bird’s Eye View

Catriona Riddell: The role of strategic planning in delivering sustainable development

148 Obituary – Patsy Healey

178 Legal Eye

Bob Pritchard: Compulsory purchase – reports and reforms revisited

180 Going Local

David Boyle: Space in the middle – localism for the regions?

182 Green Leaves

Danielle Sinnett:

From garden cities to green infrastructure

Special issue: 125 years of the TCPA

187 Personal Provocations

Baroness Hamwee

Kate Henderson

Ian Wray

Richard Simmons

Charlotte Llewellyn

Peter Hetherington

Iain White

Olivier Sykes & John Sturzaker

Nick Green

Feature articles

149 Harnessing Towns and Cities for Better Growth

Nicholas Falk and Richard Simmons on how a 'considered reset of how we do development' could transform the economy and reinvigorate urban life

157 Planning Provocations: The Green Belt

Janice Morphet on agreeing a secure future purpose for maintaining the Green Belt

163 Codes and Communities

Jeff Bishop on the National Model Design Code requirement to engage with communities

168 The Expansion of Permitted Development Rights will Result in More Poor-quality Homes

Sally Roscoe, Rosalie Callway and Julia Thrift on how the latest regulatory changes entirely ignore the evidence about the poor quality of homes produced through permitted development rights

173 Diagnosing Delay in Planning: Dobry at 50

Gavin Parker and Mark Dobson on the perennial issue of time taken in decision making in planning

Town & Country Planning May-June 2024 131 contents

• Number 3

Cover illustration by Clifford Harper.

on the agenda

TCPA Chief

Executive Fiona Howie

reviews the TCPA's work since its centenary in 1999

celebrating 125 years of supporting people and places to thrive

As someone who has only been closely involved with the TCPA for the last five years, I am very mindful that I am not best placed to reflect on the Association’s 125 year history and all that has been achieved. I am delighted, therefore, that this edition features so many contributions from people who have been part of the Association’s history and made it what it is today. As speculation continues about the timing and potential impact of the next UK general election, it is lovely to be able to take a moment to pause and reflect on this organisation’s great history and heritage.

As part of doing that, I looked back at how Town & Country Planning marked the Association's centenary. The July 1999 edition, which is available on the Association’s journal archive website,1 featured contributions from eight TCPA vice presidents.2 The contributions are an interesting mix of reflections on those individuals’ involvement in the organisation, thoughts on what had been achieved and what needed a focus for the future. I particularly enjoyed the Rt Hon. John Gummer, who was still an MP at the time and is now a peer,3 stating that ‘of course, [the TCPA] has not always been right or even successful, but it has always been challenging and worthwhile’. I wonder if our current cohort of Conservative MPs would say the same!

The Association was very sorry to receive news in January of the death of one of its former chairs, Mary Riley. We were pleased, therefore, to be able to include in the last edition an obituary to highlight and commemorate her remarkable achievements.4 Mary was still one of our vice presidents at the time

of her death and her passing made reading her contribution to the centenary piece even more poignant. Her contribution included:

‘After 100 years are we still relevant? The problems this country faces in land use and the environment are more intense now that [sic] in Howard’s time, and the local and human issues within them have become more explicit. We have a function to be objective, to seek solutions, and to express them. We must continue.’

This feels as true today as it no doubt was 25 years ago. The journal frequently carries articles focused on tackling the health, housing, climate, economic and nature crises. I frequently write about my belief that the Association and what we are trying to achieve in terms of supporting people, places and the planet to thrive, is as relevant today as it ever was. As Mary urged us to, we continue to seek and express solutions. But as John Gummer noted, we are not always successful in securing the changes we believe are necessary. Inevitably, this can be frustrating for staff, trustees, our members and the people this impacts – but we will persevere. In doing so, however, we must also continue to think about how we make our messages resonate with decision makers and those across the built environment sectors.

Both Mary and Ralph Rookwood included reference in their pieces to the TCPA, in partnership with the Housing Associations Charitable Trust, setting up The Neighbourhood Initiatives Foundation. The establishment of the Foundation drew on the experience of work undertaken in Birkenhead, Wirral and later in Lightmoor, Shropshire, becoming recognised nationally as the leading body in providing local communities with practical techniques for being more effectively involved in local decision-making.

This links to my hopes for the TCPA as we look ahead another 25 years, in anticipation of the Association’s sesquicentennial. Seeking influence at

Town & Country Planning May-June 2024 132

on the agenda

the national level and working with local authorities to share best practice and encourage ambition is a critically important part of our work. However, so too is seeking to empower people to have real influence over decisions about their locality. This is a key route for the Association to try to tackle inequalities. At times this work focuses on trying to improve processes – such as our work last year to try and influence the Levelling Up and Regeneration Bill as it passed through parliament. But we are also trying to do more work directly with communities to enable and support change on the ground. We have examples of where we are doing this through Planning Aid for London; our involvement in a project to try and secure new affordable housing in Belfast, and our work in Peterlee New Town. I want us to be able to build on that work and learn lessons. My hope is that the Association will be able to secure sufficient funding to scale up this important, impactful work to make a real difference to people’s lives and the communities in which they live, work and play.

Finally, I want to thank you – our members and subscribers. At times people forget that the TCPA is a small organisation with a long and important history, and an incredibly wide remit. We are grateful for your support now and, I hope, in the future.

• Fiona Howie is Chief Executive of the TCPA

Notes

1 Over 100 years of past editions of the Association’s journal, along with minute books and FJ Osborn’s correspondence are available at https://archive.tcpa. org.uk/

2 See ‘Now we are one hundred’. Town & Country Planning, 1999, Vol. 68, Jul., 216-218

3 The Rt Hon. The Lord Deben was elevated to the House of Lords in 2010

4 G Bell: ‘Obituary – Mary Riley’. Town & Country Planning, 2024, Vol. 93, Mar./Apr., 85

The TCPA’s vision is for homes, places and communities in which everyone can thrive. Its mission is to challenge, inspire and support people to create healthy, sustainable and resilient places that are fair for everyone.

Informed by the Garden City Principles, the TCPA’s strategic priorities are to:

Work to secure a good home for everyone in inclusive, resilient and prosperous communities, which support people to live healthier lives.

Empower people to have real influence over decisions about their environments and to secure social justice within and between communities.

Support new and transform existing places to be adaptable to current and future challenges, including the climate crisis.

TCPA membership

The benefits of TCPA membership include:

• a subscription to Town & Country Planning;

• discounted fees for TCPA events and conferences;

• opportunities to become involved in policy-making;

• a monthly e-bulletin; and

• access to the members’ area on the TCPA website.

Contact the Membership Officer, David White t: (0)20 7930 8903

e: membership@tcpa.org.uk

w: www.tcpa.org.uk

TCPA policy and projects

Follow the TCPA’s policy and project work on Twitter, @theTCPA and on the TCPA website, at www.tcpa.org.uk

• Affordable housing

• Community participation in planning

• Garden Cities and New Towns

• Healthy Homes Act campaign

• Healthy place-making

• New Communities Group

• Parks and green infrastructure

• Planning reform

• Planning for climate change

Town & Country Planning May-June 2024 133

time & tide

Hugh Ellis - to drift blindly into a dystopia or to strive for better - which?

looking backwards for future inspiration

‘One can only hope that the present crisis will lead to a better world’ – Albert Einstein in a speech at the Albert Hall, 1933

For 125 years the TCPA has held the flame of the utopian tradition. That tradition goes far beyond how we currently practise town planning to an ambitious programme for the entire reconstruction of society to achieve the conditions where people can thrive in the context of equality and social justice. The Garden City ideals were underpinned by the work of John Ruskin and William Morris which generated a deep concern to value nature both as a practical necessity for our survival but also for the way that it enriches the human spirit.

The relationship between these high aspirations and the TCPA’s often highly technical work on climate change can be hard to discern. Why have we spent more than 30 years focusing on the challenges of the growing climate crisis? Perhaps most obviously because climate change is clearly the greatest barrier to achieving all the values which have guided 125 years of the TCPA’s history. No planet no progress is an obvious reality. But the forces which have led to climate change also illustrate profound mistakes that humanity has made in the way we regard each other and the planet upon which we depend. We got into this mess because of a delusional attitude to nature based on endless extraction and consumption with no regard for obvious environmental limits. The reckless production of greenhouse gases is just one example of this disregard, the current shocking level of species extinction is another. This is a failure of a set of core beliefs which have dominated western thinking for 500 years and have led us to the brink of disaster.

The climate crisis is useful in illustrating the practical consequences of these delusional beliefs. Our failure to resolve that crisis represents all that's wrong in the current way we have chosen to organise ourselves. An obsession with short

termism, a refusal to acknowledge the reality of scientific evidence and a staggering failure to prepare ourselves for the future which is lapping at our doorsteps. All of this is set in a context where those with the least responsibility for climate change will be the most badly affected both in the UK and internationally. Our current desperate state shows a systemic failure to recognise the importance of nature to our well-being and of how distorted our democracy has become when it is more concerned with divisive trivia than our basic survival. We don't need to read any fiction to imagine a perfect dystopia, we are living through it’

We must be extremely careful in suggesting that there is any hope to be found in our current circumstances in case we fall into the very delusional assumptions that got us into this mess. But the history of the TCPA shows that hope can emerge from the darkest times.

During the Second World War the challenge was even more extreme for the civilian population and yet what emerged was one of the greatest periods of social progress in British history. In both cases the TCPA and the Garden City movement refused to surrender to the crushing negativity that conflict always generates. Instead, even amongst the height of the destruction, the TCPA’s moral obligation was fulfilled by beginning to plan for ambitious reconstruction.

It is that constructive and practical idealism which is so essential to navigating the intensifying climate crisis. So, let’s ask ourselves where we will be at the end of the next 125 years, the year 2150? The reality of our future is defined by two scenarios. The first is the most obvious and depressing. The politics of far-right nationalism along with the manufactured and appalling conflicts which we see around the globe delay effective action to radically

Town & Country Planning May-June 2024 134

reduce greenhouse gases emissions condemning humanity to a desperate battle for survival. The scale of the climate damage will mean many of our world cities are underwater and the death toll from severe weather and starvation will run into the hundreds of millions. Rich nations and rich people will survive but the impact upon the poorest and most vulnerable will be extreme. It will be the ultimate dystopia in which the long-term prospects of humanity will be very bleak.

‘We don't need to read any fiction to imagine a perfect dystopia, we are living through it’

The second future will be defined by the same kind of systemic social transformation that accompanied the industrial revolution. It will have led by 2150 to a zero-carbon society in which overall global carbon dioxide concentrations have fallen below 400 parts per million and climate stability is beginning to return to the planet. That has been achieved by the

record deployment of all forms of renewable energy coupled with technological advances in battery storage. But these technological fixes will have been accompanied by a new moral philosophy of development comprising four core beliefs. That the purpose of social organization is to support the human thriving in all its diversity and underpinned by equality. That we recognise the indivisible relationship between nature and human well-being. That we have a circular economy which no longer depends on the extraction of primary resources nor the exploitation of human labour but seeks a fair and sustainable distribution of wealth. We have vibrant democracy which gives clear rights and meaningful agency to all citizens under an effective system of both global and local governance. Which of these two outcomes is most likely? In the UK context the breathtaking intransigence of the current government on climate policy points clearly towards disaster. On adaptation and mitigation, they have no credible strategy nor any political will to adopt one. They have failed in the most basic task of any government, which is to protect the basic security of its citizens. They have created a highly effective platform for systemic

Town & Country Planning May-June 2024 135 time & tide

Short-termism will lead to long-term harm

Freepik

failure in which the average citizen will pay a very heavy price.

We should not pretend that achieving the second outcome will be easy. Whilst the technologies are all available to us, our current politics will have to be transformed to secure a positive future. But there are two things that are absolute necessities for our survival. The first is that unbreakable human spirit when confronted with crisis that allows us to overcome the most enormous odds to achieve miraculous success. Our greatest enemy is losing that spirit and wallowing in understandable but dangerous demoralisation. The second vital element is that we have a strategic plan for national reconstruction which sets out the necessary transformation in the way we organise all aspects of our society in order to achieve a just transition to a zero-carbon society. Our survival will not be secured through the chaos of market forces or hoping for the best. It will be secured through visionary strategic plans with clear tactical outcomes.

‘Our survival will not be secured through the chaos of market forces or hoping for the best’

Our collective choice is clear, we can drift into the climate crisis unprepared, ill equipped and repeating and reinforcing the trends of inequality which blight human relations. Or we can face the future with practical realism and a determination to shape a new society defined by fairness and opportunity. That choice is in our hands, but time is running out fast. Our generation must make choices that will define the future of humanity. It is a heavy responsibility – a test not just for us but for the whole of our democracy. How should we meet the future? With realism but also with optimism and excitement. The future is in our hands, we just need to reach out and take it.

• Dr Hugh Ellis is Policy Director at the TCPA. All views expressed are personal.

Town & Country Planning May-June 2024 136 time & tide

Renewable energy generation is key to our utopian future. Green hydrogen production facility, Japan

The Government of Japan

snakes & ladders

How can anarchist theory help planners? Sue Brownill, Debbie Humphry and Jason Slade explain

communities, garden cities and Kropotkin

Over its 125-year history, a key thread of the work and philosophy of the Town and Country Planning Association has been the championing of what could be termed community planning. Although difficult to define, community or community-led planning (CLP) is an approach to planning and placemaking which is about, amongst other things, communities being in control, the inclusion and recognition of a wide array of ‘planning’ expertise and knowledge, local self-determination to determine and deliver appropriate and needed development, and the governance and mechanisms required to enable this, including the ownership of assets. To a large extent throughout its history, this approach has been intertwined with themes and ideas that the TCPA is perhaps better known for –its commitment to Garden Cities and more latterly to healthy cities and support for public participation in the more formalised planning system. So, the 125th anniversary is a perfect opportunity to highlight this important strand of the Association’s work in more detail and to explore the implications of bringing it into the spotlight both for the history of the TCPA and planning more broadly, but also for debates about where we are today and where we may go in the future.

As part of our recent project on the Hidden Histories of CLP,¹ which involved the TCPA as a partner, we examined Town & Country Planning and its predecessors (now available online as a fantastic resource) and spent some time looking at the TCPA’s physical collection of publications and documents, with this aim in mind. We also spoke to people involved with the TCPA, past and present. What we found is a long tradition of focusing on communities and planning, a fascinating history of the evolution of different approaches to CLP and a plethora of projects, debates and action. In particular, we were guided by a conversation with

Hugh Ellis, Director of Policy at the TCPA, to explore the changing dynamic over time between two approaches; one focused on community selfdetermination: ‘communities doing it for themselves’; and another on promoting community and public involvement in decision making in the more formal, state-led planning system. As evidence from the archives shows, the balance between these elements ebbs and flows over time, reflecting changing contexts and ideas about planning and debates within the TCPA itself.

One hundred and twenty-five years is a long time. So, in what follows we focus upon key time periods that help illustrate this shifting history. These are: the early years of the Association in the 1900s, the late 1940s, the 1960s and early 1970s, and the late 1980s. We conclude with some reflections on the present day.

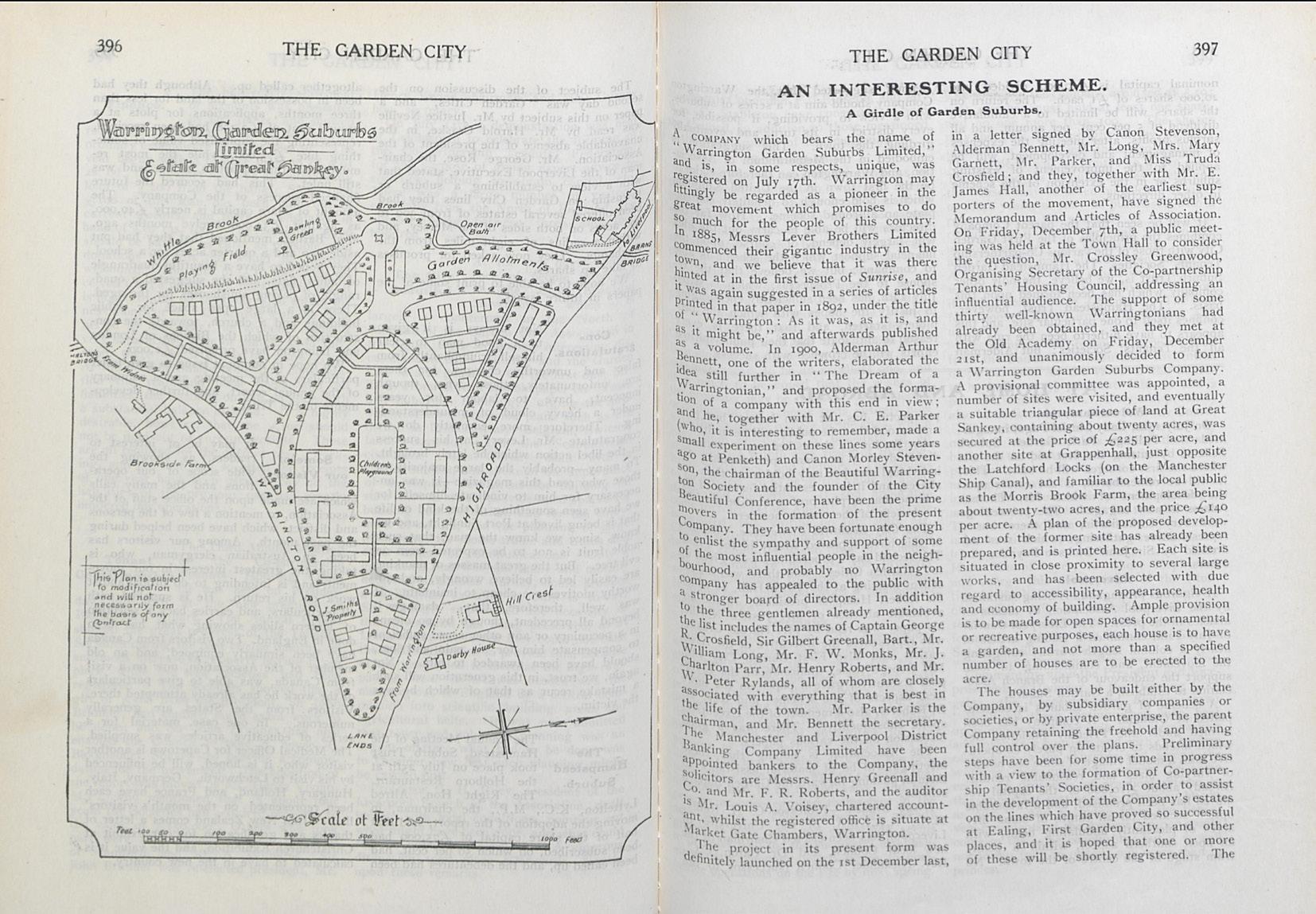

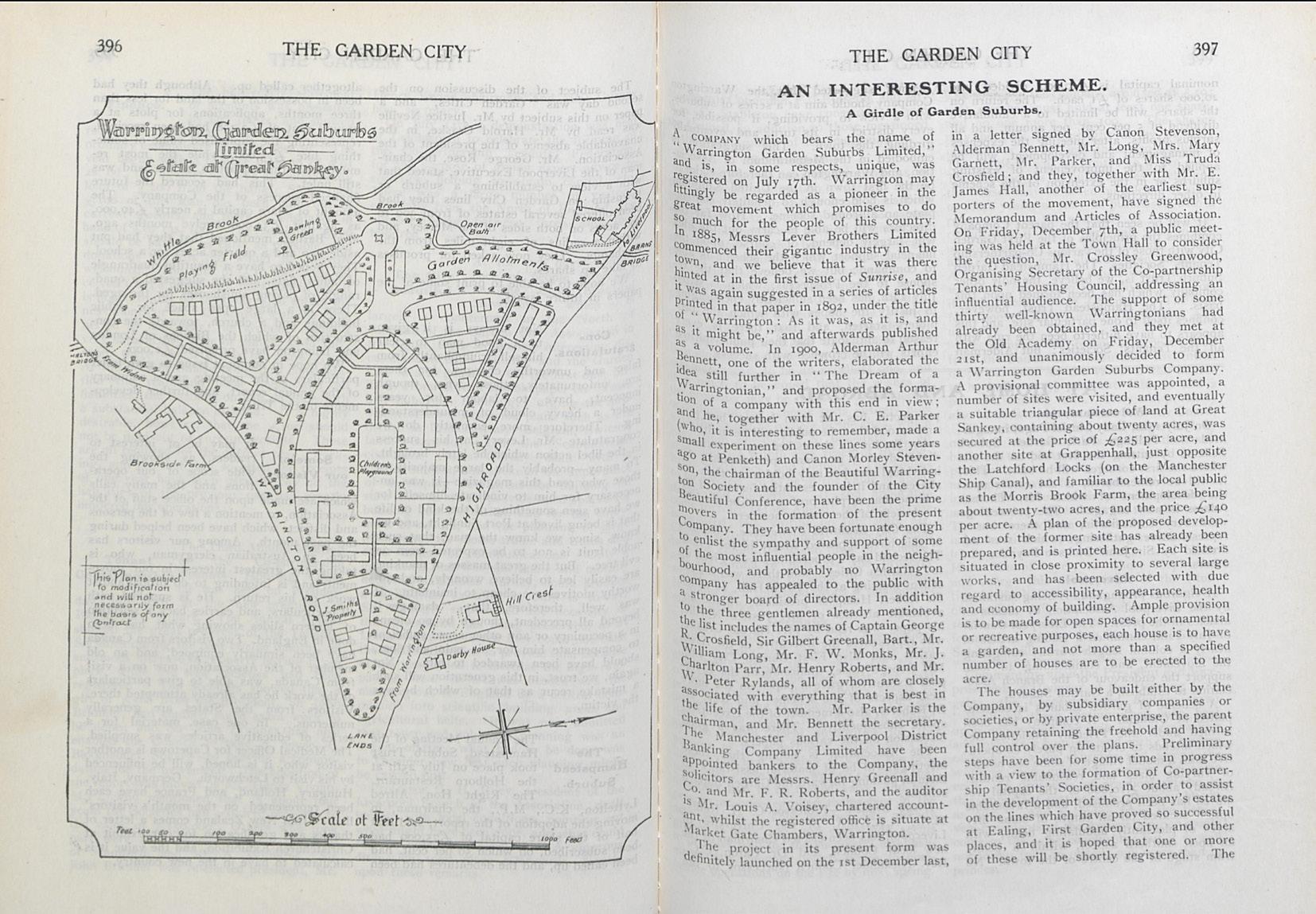

The 1900s: origins

For the first postcard from history, we go back 120 years to the start of the Association’s journal, then called ‘The Garden City: The Official Organ of the Garden City Association’. This was the early days of the Garden City movement, just after Ebenezer Howard’s book was published in 1898 and during the time that Letchworth Garden City was being built (starting in 1903). Inevitably, Garden Cities and Letchworth feature heavily in the editions but what also struck us were an array of articles and letters that link Garden Cities to an approach in which communities have a significant amount of control. For example, there are a number of pieces on the links between Garden Cities and what is termed ‘co-partnership and co-operative housing’, including one in January 1906 detailing on-going schemes in Woolwich and Ealing. In August 1904, an article appears on co-operative communities in the United States as a precursor to Garden Cities and in 1907 (p. 217) and 1908 (p. 484) the Co-operative Society writes about a co-operative Garden City. In 1905, a letter Howard wrote to the Daily Mail about co-operative housekeeping is reproduced, which argues for shared facilities to be provided within housing schemes – what we might today understand as co-housing.

In many ways this should not be too much of a

Town & Country Planning May-June 2024 137

surprise. The admiration that Howard had for the anarchist ideas of Peter Kropotkin is well known. These, rather than more popular perceptions of anarchism as brick-throwing and structurelessness, influenced the principles of self-determination and mutual ownership that are evident in how Letchworth was established, including the reinvestment of profits into the community.*

As Hugh Ellis told us:

‘the origins of that, therefore, go right to the heart of Letchworth, [that is] the principle of self-organisation, communities doing it for themselves… it is about communities making decisions and then owning those decisions through the mechanism that Howard set up.’

Therefore, these two elements – the idea of Garden Cities and the mechanisms to achieve them – together have to be seen as foundational to the Garden City movement. It is this element of the relationship between planning and communities that takes centre stage in the Association’s Journal at this time. This is to some extent understandable during a period when there was little in the way of national planning legislation and limited opportunities for consultation and public participation. Nevertheless, the richness of the debate; the number of examples that appear, and the obvious enthusiasm around the country for collective solutions are all apparent.

The 1940s: New Towns and planning systems

By contrast, the pages of Town & Country Planning in the 1940s reflect a move to a more

‘formal’ and state-led solution, centred around the New Towns programme and the Town and Country Planning Act 1947. The articles often explore participation in this more formalised planning system rather than the land-based and community control elements of the 1900s. This could in some senses reflect a more pragmatic and deliveryfocused view of Garden Cities and New Towns given the development of state-led interest and funding – a view shared by the then editor of the TCPA Journal, Frederic James Osborn (FJO). It could reflect in part the issues and obstacles experienced in establishing the early Garden Cities, but it could also arguably be seen as an ironing out of the more ‘difficult’ aspects of mutualism, anarchism, and collective provision in the original conceptions of Garden Cities.

This is not to say that there is complete silence on CLP related issues. For example, in March 1940 (p. 29) there is a critical commentary on current planning and in August 1940 (p. 69) community planning is mentioned. However, this is very much in the sense of planning facilities for the community, that is the planner considers the physical/land-use elements but needs to work with ‘students of social democracy and social relations’.

Individual examples of ‘good practice’ in participation such as the Knutsford Plan get a good write-up. In 1946 (pp. 110-114), there is a long article about the Middlesbrough Plan, focusing upon the participatory approach of Max Lock and his team, with multiple photographs showing workshops that prefigured the Planning for Real® of the 1970s and 1980s. In the same year, on page 78, there is an article on neighbourhoods in planning and on page 124 there is even one on planning and marriage guidance, talking about the impact of places on personal relations!

Reflecting the lobbying interests of the TCPA at the time, there is also considerable commentary on the 1947 Town and Country Planning Bill and Act. However, this often focuses more upon the involvement of a relatively well-off population than on the basic principles. Nevertheless, FJO also uses the pages of the TCPA Journal during this time to build support for more education about planning –one of his key concerns – which was to become a recurring theme in TCPA work in later years.

1968 and all that

The 1960s represent a pivotal moment in the history of community action and planning and it is interesting to see how this is reflected in the archives. At the start of the decade, the TCPA Journal is still edited by FJO and the focus remains

Town & Country Planning May-June 2024 138 snakes & ladders

Cover of one of the first editions of The Garden City, a precursor of Town & Country Planning

firmly upon the New Towns, state-led industrial restructuring and planning, with Garden City ideals looming large. At this time concerns appear about community focus and how this element may have been neglected in planning for the New Towns, with suggestions for how this might be remedied. But the arguments do not return to the original intertwining of the Garden City movement with a CLP approach. The focus upon the participation of people within the formal system remains but it is framed in a context of how to accommodate an increasingly well-educated and affluent citizen with ever more leisure time. As well as the right to

‘The admiration that Howard had for the anarchist ideas of Peter Kropotkin is well known.’

participate and be heard democratically, ‘he’ may want a second home and the ability to access the countryside easily in ‘‘his’ motor car(s)’ [sic].

This concern with participation in the formal system continues towards the end of the decade. The Skeffington Committee into participation in planning was set up in 1968 and FJO does not hold back from criticising the make-up of the committee:

‘It astonishes me that the official committee… with a membership of twenty-eight, contains nineteen councillors and officers of government and only five that can be regarded as representing unofficial citizens and their voluntary associations. There is no representative of the TCPA, which has surely done more than any other body to stimulate public participation in planning. Nor are there any members of local civic societies… It is a remarkably ill-balanced committee for its highly important purposes.’

(Town & Country Planning, 1968, Vol. 36(6) Jun., 285)

The TCPA submission to the committee is also printed in full. But again, this is about participation in the formal planning system. The late 1960s are often seen as witnessing an upsurge in community action and advocacy planning. However, new movements and campaigns – for example, around motorways and slum clearance – which might be expected to deserve increased coverage are surprisingly sparsely covered in the TCPA Journal. There is a new section called People and Planning but this covers consultation issues and not necessarily CLP.

Yet, there are some signs of change. Firstly, there

is increasing coverage of some growing movements, such as adventure playgrounds in London and a focus upon children in the cityinfluenced by Colin Ward, later Director of the Education Unit at the TCPA. Secondly, the issue of how communities can get their voices heard through self-organisation is featured, with civic societies and civic trusts being particularly prominent. Thirdly there is the recurring issue of information and education for planning. There is also evidence that the framing of planning from a TCPA perspective is very much in terms of a focus on social matters. Articles refer to the dangers of an overly economic focus and the need for planners to have a social science training. Therefore, the possibilities for a rebalancing of the relationship are put in place.

1970s to mid 1980s: CLP to the fore?

This section covers a relatively long and busy period, when the social, economic and political context and the evolution of the work of the TCPA come together in a way that puts CLP in the vanguard.

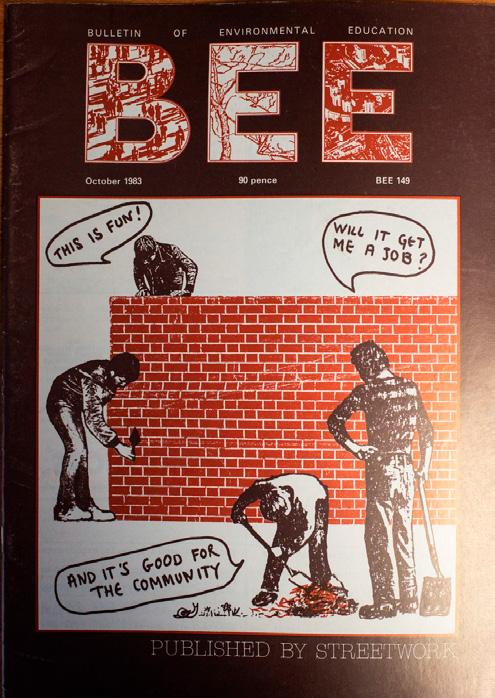

Although coverage of community issues in the Journal ebbs and flows in the early to mid 1970s, there is evidence of growing support and activity around CLP. This includes the growth of Colin Ward’s work around adventure playgrounds and articles and books that re-explore an anarchist approach to planning. In January 1971, the Planning Aid service was launched, with the aim of levelling the playing field for people who are traditionally excluded from, or without the resources to engage effectively with, the planning system. This was also an effort to further democratise planning. Nevertheless, it is only from 1974 that a regular series of Planning Aid case notes appears in the TCPA Journal.

With the arrival of Colin Ward and his deputy, Tony Fyson, in 1973 there is a change of tone in Town & Country Planning. The framing of articles betrays an ebbing confidence in the potential, inevitability and desirability of top-down, ‘technical’ solutions. For example, the circulars produced in 1971 to implement recommendations in the Skeffington Report are heavily criticised. In parallel with this more forceful critique of ‘official’ participation there is a renewed focus upon community-based initiatives. The first time a community plan is referred to is in April 1971 (p. 227) – the Golborne Community Plan in North Kensington. Alternative technologies and rural self-sufficiency are explored through the Dartington model, whilst we have reports on the first

Town & Country Planning May-June 2024 139 snakes & ladders

snakes & ladders

community-claimed city farms in London. Insurgency, self-help and co-operativism re-emerge, with coverage of the contestation at Coin Street;² community enterprise under the Westway in London; Walter Segal’s self-build houses;³ housing co-operatives in Glasgow and Nottingham, and workers co-operatives in Mondragon, Spain.⁴

During this time the focus of the TCPA upon planning education steps up a gear. This is reflected in extensive coverage of environmental education. In May 1972 (p. 261), the National Association for Urban Studies was formed, with the aim of promoting urban studies and facilitating participation in planning decisions. In 1973, with Colin Ward as founder editor, the TCPA started to publish the Bulletin of Environmental Education (BEE), which promoted urban environmental studies programmes. Then, in 1974, the Council for Urban Studies Centres was formed to encourage the establishment of urban field studies centres.⁵ Editions of BEE in the TCPA archive make for fascinating reading. Continuing this theme of opening planning up both democratically and in terms of expertise, the TCPA also set up technical aid centres, such as in Manchester, which worked with communities particularly in inner city areas to address their planning issues. In Issue 74, a Citizen’s Guide to Town Planning is referred to. In addition, the work of Tony Gibson, including publication of books by the TCPA such as Us Plus Them, and the work on Planning for Real® in Birkenhead, Wirral and later in Lightmoor, Shropshire put these principles into practice.

Speaking about this time Hugh Ellis remarks that with this work:

‘They're reinventing the Kropotkin proposition and saying ‘well actually we don't really need planners as a profession. You know what, why do we need these people, what we want to do is take back direct control for communities.’

Participation is not being promoted for its own sake but for how it can open up and be linked to a wider programme of enabling democracy. In addition, these alternative mechanisms of delivery in many ways splice those two strands of participation and CLP.

The wider sector played a significant role during this time. The TCPA was able to tap into and become part of a network of groups, individuals, projects and organisations – all arguing and working for advocacy planning, self-determination and community control. Many of these, including some TCPA initiatives, were funded through local and central government programmes such as the Urban

Programme, which was targeted at inner cities. However, it is noticeable that the 1970s ends with an editorial about how urban studies centres and other community groups are beginning to close.

Into the 1980s, CLP issues are now firmly on the TCPA Journal’s agenda – given a heightened significance by the changing and highly polarised political context. The national government was hostile to planning as a participatory state activity but, alongside this there are examples of local government pursuing a quite different agenda (such as in London and Sheffield). The battles between local and national manifestations of the State are well-evidenced in the Journal, with the community’s potential role placed front and centre stage and clear calls for decentralisation in a range of spheres.

Key examples such as Coin Street, Liverpool and London Docklands are covered. There is also discussion of the legal and financial basis for supporting community initiatives and critiques of policies that prevent this. Planning Aid goes on the road with its mobile unit and develops along more critical and political directions – one example of this being the support for the Divis community’s campaign in Belfast for the demolition and rebuilding of their estate.⁶ The Divis exhibition hosted by the TCPA in London in 1985, covered by the TCPA Journal seems to have been quite influential in this shift within the TCPA.

In May 1980, Colin Ward writes further about the continuation of Howard’s Kropotkinism and about how CLP appeals ‘to philosophies of both the

Town & Country Planning May-June 2024 140

Cover of Bulletin of Environmental Education (BEE), October 1983

political right and the post-Marxist left’ (p. 161).

TCPA Director, David Hall, talks more openly about the need for ‘‘bottom-up’ planning and the third Garden City Initiative’, which has a ‘manifesto’ that enshrines CLP within it (October 1980 p. 326). In another article (Why we need community planning (March 1987 pp. 89-90)) David Hall talks about community planning zones and the overall need to support CLP. After the 1987 general election, Gibson puts forward a neighbourhood manifesto (July-August p. 298).

There is therefore clear evidence of the foundational elements and the different approaches to participation coalescing at this time, but funding cuts for services such as Planning Aid and local groups, as well as the continued shift in planning towards a more market-oriented and less democratic process, as documented in the TCPA Journal, made this difficult to sustain.

Into the present day

It would be too simplistic, and it is not our intention, to say that the period from the mid-1970s to the mid-1980s was a ‘golden age’ for CLP and the TCPA’s approach to it, from which there has been a steady decline. Nor are we implying that CLP represents an unproblematic practice that deserves uncritical support. Instead, we hope we have shown through this examination of the pages of the TCPA Journal and collection of publications, the long history of the TCPA's support for communities and how this has changed and evolved over time.

In this way the 1970s and 1980s arguably represented a context within which it was possible to bring together the different strands of the TCPA’s work and those different approaches to communities in a sustained and balanced way. Space and the scope of our project unfortunately precludes as detailed an exploration of the following 40 years, but as we approach the present day our work has identified an enduring commitment within the TCPA to communities along with the same ebb and flow of coverage and the continuing shift in balance between different approaches.

New concerns have emerged particularly around health, the environment and climate change alongside the continued promotion of Garden City principles. The focus upon democratic involvement and participation has persisted since the Raynsford Review.⁷ And significantly the TCPA is continuing to work with and support initiatives such as Incredible Edible and another alternative community plan in Belfast on the Mackies site,⁸ which took to realise those foundational principles of community

self-determination and control, as well as exploring the collective mechanisms currently available to deliver Garden Cities.

Moving forward, it is important not only to recognise CLP as a discipline but to embed it within all areas of planning practice; in effect to intertwine foundational elements with practical approaches. Within this perhaps one of the most significant lessons is the need to press for the reintroduction of the national networks of support and funding that proved to be such a crucial part of ensuring an effective mix in the past. But we also hope that we have shown how the creative tension between these approaches has sparked debate and led to different possibilities and outcomes emerging throughout the longstanding relationships between the TCPA and communities. May this continue for at least the next 125 years!

• Prof. Sue Brownill is at Oxford Brookes University. Dr Debbie Humphry is at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. Dr Jason Slade is a Lecturer at the University of Sheffield. All views expressed are personal. Copies of Town & Country Planning published between 1904 and 2005 and other documents relating to the TCPA's history are available to view free of charge here: archive.tcpa.org.uk

Notes

1 See: https://www.peoplesplans.org Grant number AH/ T00729X/1

2 ‘Small Scale Utopia. The Coin Street's Case’. Blog. a+t architecture publishers, 19 Jan. 2009. https://aplust.net/ blog/_small_scale_utopia_the_coin_streets_case/

3 ‘Walter Segal’. Webpage. Wikipedia®, 2 Oct. 2023. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Walter_Segal

4 ‘Mondragon Corporation’. Webpage. Wikipedia®, 30 Oct. 2023. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mondragon_ Corporation

5 B Scott: ‘Environmental education in England 1960 to 1979 - a pen picture’. Blog. University of Bath, 18 Oct. 2020. https://blogs.bath.ac.uk/edswahs/2020/10/18/ a-sketch-of-environmental-education-in-england-1960to-1979/

6 L Petersen: ‘Life and Death in Divis Flats: The Enduring Symbolism of a 1960s Belfast Housing Project’. Webpage. War & Peace in Northern Ireland, 2 Jun. 2023. https://posc284.posc.sites.carleton.edu/uncategorized/ life-and-death-in-divis-flats-the-enduring-symbolism-ofa-1960s-belfast-housing-project/

7 'The Raynsford Review of Planning'. Online resource. Town and Country Planning Association, Nov. 2018. https://www.tcpa.org.uk/resources/the-raynsfordreview-of-planning/

8 See: https://www.takebackthecity.ie

Editor’s Note: *It is notable that this approach continues to this day because Letchworth Garden City is managed by a community benefit society – a type of co-operative, owned by its members.

Town & Country Planning May-June 2024 141

snakes & ladders

bird’s eye view

Catriona Riddell asks: despite faltering progress, is regional planning making a political come-back?

the role of strategic planning in delivering sustainable development

As someone who has worked and lived in the South East of England for over 30 years, and played key roles in how it is planned during this time, the history of London’s post war planning journey and its influence on the wider ‘city region’ has always been of interest. Looking back at Sir Patrick Abercrombie's post war vision and the London County Council’s Greater London Plan 1944, it was clear that making London a healthier and happier place to live and work in was key. These were integrated plans which looked at what type of housing was needed, how this would work from a transport perspective, where employment land should be located and what was needed to support healthy living, particularly in relation to providing adequate greenspace.

To create this vision, Londoners were asked what they wanted and needed. In a film made to promote the plan,1 it was made clear that planners:

‘had to learn what people were thinking and what they wanted… to know what sort of homes they lived in and how and where they spent their leisure hours.'

There was recognition that supporting community cohesion mattered:

‘A city exists because men have realised that by living together, they can enjoy many advantages. The idea of people living in communities has formed the basis of our plan.'

A large part of the Greater London Plan 1944 was implemented and continues to play a critical role in how London and the wider areas are planned today- the Green Belt and the M25 being two of the key planks.

The view that healthy homes are just as important as the bricks and mortar that hold buildings together is still core to today’s London Plan 2 The scale of change envisaged within the city itself was not fully realised in the post war era, mainly due to lack of funding, but the philosophy of a plan based on human and community needs as opposed to ticking a box on housing numbers still has a clear legacy. Cities continue to be where most of the UK’s population live and work, despite the impact of the 2020 pandemic and the availability of technology that allows remote working. They are also where investment in public transport is prioritised and as such, continue to be favoured by successive governments for supporting national growth, especially the capital, which remains a ‘world city’.

In developing his vision for Greater London, Abercrombie also acknowledged the importance of ensuring that London worked as part of the wider South East. The post war new and expanded towns programme and investment in transport systems connecting them, was part of this and many of these areas remain vital to supporting London’s economic role today. Some, however, are now taking on an economic life of their own, recognising that, with the right vision and investment, they have their own economic potential and no longer need to rely fully upon their relationship with London. For example, Milton Keynes is increasingly looking north towards the midlands and to Oxford and Cambridge, and South Hampshire is increasingly looking to build its own economy and its relationship with places along the Dorset coast. A formal regional approach to strategic planning emerged as a result of the post war recognition of the role wider regions would play in the economic future of England’s cities. It may have been triggered initially by the need to support the managed population growth of London, but it was part of a national industrial strategy that recognised the value planning played in growing the nation’s economy and ensuring that the growth of one city or part of the country was not at the expense of another.

Town & Country Planning May-June 2024 142

It was the start of levelling up.

A pivotal point in the history of planning in England and the need for a strategic approach across all regions came in the first half of the 1960s. It was evident by then that there was no clear plan for how the government envisaged employment growth to be distributed across the country and the role of migration and immigration in supporting this. It also became clear that without a national strategy for growth, there was a risk that a disproportionate amount of investment would go to the South East and not support any wider redistribution of growth, especially to the North.

The Conservative government at the time, with Sir Keith Joseph in charge of housing and planning, initiated the South East Study which had three main purposes: to provide for the growth of population in the South East region; to relieve the pressure on London; and to make enough land available to end the housing shortage in the South East. The study was a pilot for other regional studies and was published in 1964, just before the general election that returned a Labour government. To capture the importance of this study, not only for London and the South East but also for the nation's

economy as a whole, it is worth looking at one particular debate in Parliament from the 4 May 1964.3

The main speech came from Michael Stewart, MP for Fulham and shortly to become the new Labour government’s Secretary of State for Education and Science. He argued that, whilst a need to plan for the growth of London on a 'city region' scale was evident, there were a number of weaknesses in how the approach to planning for growth in the South East would be implemented as a result of the study.

Concerns were raised that the plans for the South East were being prepared in a silo, not only in relation to what the government’s approach to economic growth nationally was but also in terms of the lack of cohesion across different government departments and ministerial priorities. There was a clear disconnect between what the government was doing on transport, especially in relation to the plans for new and expanded communities in the South East and implementation of the Beeching Report recommendations4 which would see rail stations closed where population growth was being directed.

Town & Country Planning May-June 2024 143

bird’s eye view

iStock

View across city of London from Muswell Hill

‘…we cannot study this problem of the South-East satisfactorily until we know a little more about the Government’s policy on the distribution of employment and its influence upon the distribution of population… what ought to have preceded the southern study was at least a sketch plan by the Government of how they see the distribution of employment and population in the next 20 years… first and foremost, we must have a national physical development plan for the whole country, at least in broad outline, before we can hope to plan sensibly at regional levels.’

The Labour Party also pointed out that implementation of the study would require resources to support planning staff in the local planning authorities which were then the county councils, and that a ‘pooled’ regional resource would be needed. Resources would also be needed to support infrastructure and to find the land to deliver the new homes needed, with concerns raised about the hope value and land value increases that would inevitably result from the study’s proposals.

The market-led approach to growth promoted by the Conservatives was also challenged by Michael Stewart who argued that increased public ownership (including of land) and state interventions, especially in planning, were essential components for managing growth successfully and that the government had to play a central part in this. Planning should be seen as a force for good, not a restrictive tool on growth.

‘There is the liberty of the individual to be able to do his work in happiness, able to get from his home to work and from his work to play and to have a chance of planning and choosing his own life. We cannot get that kind of liberty by a negative approach alone. It has to be done by positive and constructive planning. Government activity today is an instrument through which liberty can be created and must be created.’

To counter the opposition’s criticism of the government’s approach, Sir Keith Joseph pointed out that this was an attempt to recognise the value of the South East as the economic engine of the country, whilst balancing the need to support other parts of the country. There was also a very clear view that the physical growth of London outwards was not part of the strategy and that the metropolitan Green Belt therefore had a critical role to play.

A Strategy for the South East – planned London overspill schemes as at June 1967, p. 165

‘We must relieve the pressure on London; we must hold the green belt; and we must provide enough land to meet the housing shortage while preserving the maximum possible amount of undeveloped land in the South-East… We must achieve all these objectives without harming the rest of the country and without damaging the investment priorities which, for some years, have been promised to Scotland and the North-East. Since the South-East makes a great contribution to the national prosperity, we must also achieve all this without in any way hampering or crippling the prosperity of the South-East, which is a national asset.’

This was the genesis of a formalised approach to strategic and regional planning in England, recognising for the first time that a planned approach was needed in the interests of maximising the economic potential of the country as well as balancing the needs of the capital with the rest of the country. It was the first time it was recognised that changing the way the country works both inter and intra-regionally required a long term approach, one that could also be responsive to changes over time. It was also the first time that it was acknowledged that change on this scale could not happen without the appropriate interventions at different levels of government, the right resources and implementation over a long term.

A Strategy for the South East ⁵ and other regional strategies that emerged from this process in the

Town & Country Planning May-June 2024 144

bird’s eye view

late 1960s were taken forward through the governance and policy infrastructure of the new Labour government and not the Conservative government that initiated it. Vitally, these were seen as economic vehicles and were therefore managed through the regional planning councils of the

regional economic boards established by the Department of Economic Affairs.

Although there was no national spatial plan within which these all fitted, they were primarily there to implement the government's national industrial strategy and the sum of the parts had to add up. This meant that the global economic role London and the South East played was supported but not at the cost of other parts of the country.

‘We are not putting forward expansionist plans for the South East at the expense of other regions; this report is a sober assessment of what needs to be done if the region is to continue to make its contribution to the country’s economy. Entry into the Common Market could well increase the importance of this contribution. Some of the region’s problems are formidable, for example, the urban renewal of areas of London, the construction of major transport systems, the development of new large city regions and the protection of the lovely countryside in many parts of the region; but they must be tackled if the region is to continue to play the important part in the national economy which it is vital for us all that it should do.’

Town & Country Planning May-June 2024 145

Diagrammatic presentation of A Strategy for the South East, p.85

bird’s eye view

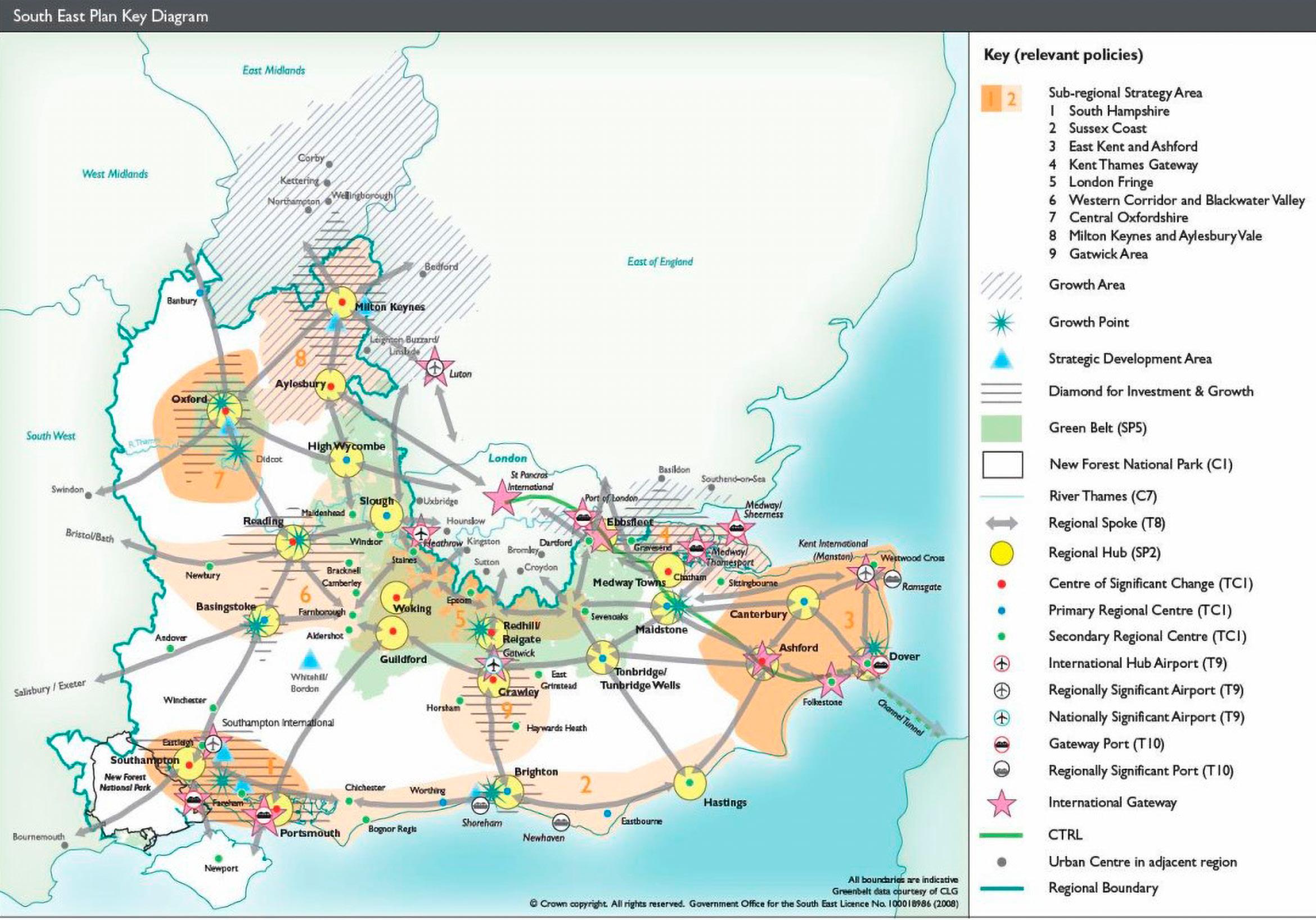

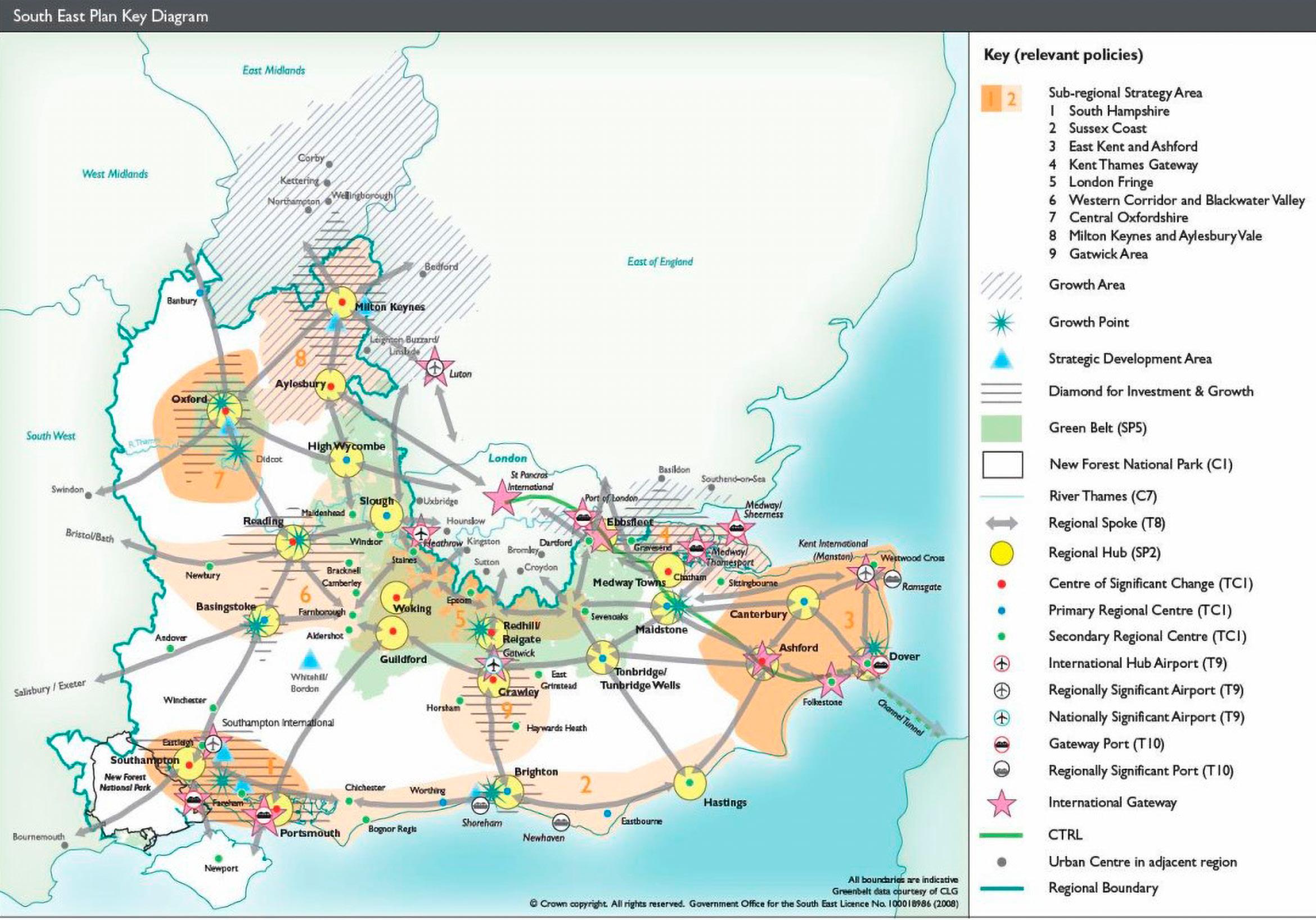

South East England Strategy 2008 – key diagram

Strategic spatial planning continued to play a key economic role through successive models at both the regional and sub-regional levels during the next four decades until it was dismantled by the Liberal Democrat and Conservative coalition government in 2010. It is important to revisit history and learn from both the good and the bad. As we move closer to a general election and a potential new government, it is also important to consider what we have lost as a result of the changes made to the planning system since 2010. So many of the challenges we face today are still the same as in the 1960s; how we plan for city growth without expanding their geographical spread and ensure they are sustainable (and the role Green Belt policy plays in this, where relevant); how we ensure we have an integrated approach to growth with housing an important but not exclusive issue; how we invest in infrastructure; and in the planning resources needed to manage plans for growth.

Probably the most significant change in how we use planning since the demise of regional planning in 2010 is its role in supporting economic growth and in planning long term. The irony is that the Conservative government of the 1960s initiated one of the most important changes in how we plan in history, recognising the need for state intervention to support economic growth, yet it was the Conservative governments from the 2010s that destroyed this. From David Cameron’s branding of planners in local authorities as the ‘enemies of enterprise’ in 20116 to Boris Johnson’s attack on planning in his 2020 White Paper,7 planning has lost its way in its role to support economic growth. Today, planning is seen as something that restricts growth, that prevents things from happening. Politicians at all levels do not want to take on planning responsibilities because of this; it is just too hard.

It is 60 years since that significant debate and we have never needed a positive and proactive approach to strategic planning across England as much as we do today, to tackle global economic and climate challenges; deliver the investment needed to support healthy and happy places, and to level up the socio-economic disparities. Despite the attempts to spread growth across the country in the 1960s, regional inequalities have grown progressively worse. The absence of an effective approach to strategic planning over the last 14 years has taken its toll and successive reports have acknowledged this, including the 2020 Raynsford Review which concluded that: '…the decision taken in 2010 to abolish regional plans and the organisational and intellectual

capital they contained was a major mistake and has made the job of producing sustainable growth much more complex.’⁸

More recently, a report by Harvard University with Ed Balls (Economic Secretary to the Treasury (2006-2007)) as one of the main authors, set out ten recommendations to get Britain’s economy growing again.9 Amongst other things, it recognised that the cities and regions outside of London and the South East have to play a much bigger role; that a national ‘Growth and Productivity Strategy’ was needed, and that all parts of the UK should have devolved systems of governance with mayoral combined authorities as the preferred model, thereby reducing reliance on centralised policy and interventions.

The second recommendation of the report sets out what the ‘Growth and Productivity Strategy’ should focus on. This includes a recommendation for sub-regional bodies (combined authorities): ‘to adopt a statutory spatial economic development strategy, which local spatial development plans should conform to. These strategies should be agreed by a qualified majority vote of local authorities, and should include plans for infrastructure including transport, energy and water, and an overall housing target. If they can’t agree, mayors should have the power to impose a plan. Mayors should be able to ‘call in’ decisions from local authorities if they do not confirm to the spatial development strategy.’

The current government appeared to recognise the vital role that strategic spatial planning needs to play in supporting economic growth and levelling up disparities in the 2022 Levelling Up White Paper This stated that a: ‘well-directed spatial strategy would address two market failures at source – the first affecting leftbehind places, the second afflicting well-performing places… That is the essence of levelling up.’10

This was lost in translation, however, through the Levelling Up and Regeneration Act, which makes no real attempt to bring an effective approach to strategic planning back into the mix. Arguably, it has weakened the few mechanisms we have to deliver cross boundary cooperation by repealing the legal duty to cooperate and putting in place a yet unknown policy tool.11

The Labour Party may well form the next government and although we do not know yet in any detail what role strategic planning will play in this, we do know that it will be a core part of a

Town & Country Planning May-June 2024 146

bird’s eye view

Labour government planning system. Matthew Pennycook MP, the Shadow Housing and Planning Minister, made this clear in the recent Westminster debate on planning reform.12

‘There is no way to meet housing need in England without planning for growth on a larger than local scale. However, this Government, for reasons I suspect are more ideological than practical, are now presiding over a planning system that lacks any effective sub-regional frameworks for cross-boundary planning… If we are to overcome housing delivery challenges around towns and cities with tightly drawn administrative boundaries we must have an effective mechanism for crossboundary strategic planning, and a Labour Government will introduce one.’

So much has changed in the 60 years since we started on a formalised approach to strategic planning but the need for something that helps support long term sustainable growth in the interests of the country as a whole remains the same, if not even greater given the wider global challenges we face as a country. There is a chance that this might happen in the near future, but it will depend upon a government that recognises the true value of planning as a positive tool for supporting sustainable growth and not the negative regulatory tool it has become over the last decade.

• Catriona Riddell is Director of Catriona Riddell & Associates, a TCPA vice-chair, and Strategic Planning Specialist for the Planning Officers Society. All views expressed are personal.

Notes

1 The Proud City – a plan for London (1945) Directed by Ralph Keene. London, England: A Greenpark Production in association with the Film Producers Guild Ltd for the Ministry of Information. Available to view at: https://archive.org/details/ProudCity

2 See https://www.london.gov.uk/programmesstrategies/planning/london-plan

3 The South-East Study. HC Deb 04 May 1964, vol. 694, cols. 919-1050. This was a key debate on the results of the pilot regional study, for the South East, which had been commissioned by the Conservative Government, with Sir Keith Joseph leading as Minister for Housing and Local Government. https://api.parliament.uk/ historic-hansard/commons/1964/may/04/the-southeast-study#S5CV0694P0_19640504_HOC_245

4 ‘Beeching Cuts’. Webpage. Wikipedia. 9 Mar. 2024 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Beeching_cuts

5 A Strategy for the South East – A first report by the South East Economic Planning Council. HMSO, 1967. Digitised by the University of Southampton Library Digitisation Unit, available at: https://archive.org/ details/op1267945-1001/mode/2up

6 D Cameron: Speech to Conservative Spring Conference, Cardiff, 6 Mar. 2011. https://www. newstatesman.com/politics/uk-politics/2011/03/ enterprise-government-party

7 Planning for the Future. White Paper. Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government. Aug. 2020. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/ media/601bce418fa8f53fc149bc7d/MHCLG-PlanningConsultation.pdf

8 ‘Planning 2020 'One Year On' - 21st Century Slums?. Town and Country Planning Association, Jan. 2020, p.20. https://www.tcpa.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/ Raynsford_Review_one_year_on_WEBSITE-1.pdf

9 N Weinberg, D Turner, E Elsden, E Balls, A Stansbury: A Growth Policy to Close Britain's Regional Divides: What Needs to be Done. Mossavar-Rahmani Center for Business and Government and Harvard University, Feb. 2024 https://www.hks.harvard.edu/sites/default/ files/centers/mrcbg/working.papers/Final_AWP_225.pdf

10 Levelling Up the United Kingdom. White Paper. CP 604. Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities. 2 Feb. 2022. https://assets.publishing. service.gov.uk/media/61fd3ca28fa8f5388e9781c6/ Levelling_up_the_UK_white_paper.pdf

11 The statutory requirement for local planning authorities to work together on strategic matters was introduced by §110 of the Localism Act 2011, which inserted §33A into Part 2 of the Planning and Compulsory Purchase Act 2004. This was the main strategic planning mechanism to replace strategic (regional) planning. However, it has been highly criticised over the years as being ineffective because it is not a ‘duty to agree’. Indeed, the Government’s Local Plan Expert Group in 2016 concluded that: ‘local plans are rarely coordinated in time and, whilst the Duty to Cooperate may encourage joint working between pairs of authorities, it is not sufficient in itself to generate strategic planning across wider areas… Apart from calls to revise [Strategic Housing Market Assessments], the call to facilitate strategic planning was the most frequent point made by respondents to our consultation – respondents in both the public and private sector – who recognise that some issues of agreeing the distribution of housing needs may prove intractable without a wider plan.’ Local Plans Expert Group: ‘Report to the Communities Secretary and to the Minister of Housing and Planning’. Mar. 2016, S18-S19, p.3. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/ media/5a81813aed915d74e33fe924/Local-plans-reportto-governement.pdf

12 Planning Reform. HC Deb 13 Mar. 2024, Vol. 747, Col. 110WH. https://hansard.parliament.uk/ commons/2024-03-13/debates/65995D50-E335-444C8065-405F91548338/PlanningReform

Town & Country Planning May-June 2024 147 bird’s eye view

Professor Emeritus Patsy Healey OBE FBA FAcSS

1 January 1940 – 7 March 2024

Patsy Healey was professor emeritus at the School of Architecture, Planning and Landscape, Newcastle University and Founding Editor of the journal Planning Theory and Practice, jointly published by Taylor & Francis and the Royal Town Planning Institute.

Patsy joined Newcastle University in 1988 as the third Chair of Town Planning, having previously held posts at Oxford Brookes University. She led the then Department of Town Planning through a transformative period, and significantly enhanced its international reputation.

As a founding member and former president of the Association of European Schools of Planning, Patsy went on to become a leading figure in the world of planning education and research. Her work and innovative ideas helped influence policy and planning practices and demonstrated her commitment and dedication to shaping cities and building communities. This is aptly illustrated in her final book Caring for Place – Community Development in Rural England (2023)

Patsy’s contributions to planning theory, education and practice are internationally recognised as reflected in her various accolades. She was a Fellow of University College London; an Honorary Fellow of the Association of European Schools of Planning and held an honorary degree from Chalmers University in Gothenburg, Sweden.

In 1999 Patsy was awarded an OBE for services to planning. In 2006 she was presented with the highly prestigious Royal Town Planning Institute Gold Medal. In 2009 she was made a Fellow of the

British Academy. In addition to her academic achievements, Patsy has made major contributions to her local community in her capacity as Chair of the Glendale Community Trust in Northumberland, always championing the ethos of the collective and the power of local civil society initiatives.

A truly remarkable academic, Patsy is held in great affection by her colleagues, former students and peers. Her generosity, kindness and care for others were second to none. Patsy has inspired a community of planners in the UK, and beyond, and she will undoubtedly continue to inspire future generations of planners through the legacy of intellectual contributions that she leaves behind. She will be greatly missed.

An online Book of Remembrance1 is available for anyone who wishes to leave a message.

Reproduced with the kind permission of Newcastle University

Note 1 https://rememberancebook.net/book/patsy-healey/

Town & Country Planning May-June 2024 148 obituary

Alchetron.com

harnessing towns and cities for better growth

Nicholas Falk and Richard Simmons explain how a ‘considered reset of how we do development’ could transform the economy and reinvigorate urban life

Town & Country Planning May-June 2024 149

Masterplan for Eddington, North West Cambridge AECOM

The next government must tackle low productivity in our cities before it can make real progress on its vital mission to boost the UK’s miserable economic growth. We propose four steps to revive conurbations as economic and social powerhouses, creating places that add extra value by promoting wellbeing and sustainable living, not just short-term financial rewards.¹

1. Learning from what works

2. Restoring spatial planning

3. Using stations as development hubs

4. Innovation in finance and tenure

Both major political parties advocate building many more homes faster to solve the housing crisis and boost economic growth. The Conservatives have shifted from mandatory targets and George Osborne’s Garden Cities to brownfield development. Labour intends to ‘bulldoze’ the planning system and build 1.5 million homes in five years.²

Yet neither party seems willing to address the fundamentals. The bulk of UK output comes from cities whose performance is generally poor compared with their continental equivalents.³ Fractured local government; failure to devolve decisions to the most appropriate level, including the abolition of regional planning; the dominance of volume house builders, and a finance system biased

towards property all contribute to the lowest per capita economic growth rate and the highest house price inflation in Europe.⁴ This malaise has persisted for at least four decades.⁵

We need a considered reset of how we do development, especially in areas with the greatest growth potential. Housing can only play a positive role in getting Britain moving if it is combined with measures to improve local infrastructure – with a strategy to intervene where government and its partners can make most difference.⁶ Reinvigorating urban life through targeted investment will boost productivity, promote wellbeing and help us meet environmental goals such as restoring natural capital.

Rather than simply axing planning controls, we must learn from what worked in the past and what still works in much of Europe – focusing on building better, well-connected neighbourhoods, not just new homes, and tapping financial institutions for development partnerships. Finally, to be sustainable, growth needs to follow models closer to those of the foundational economy,⁷ doughnut economics⁸ and the circular economy⁹ rather than the market theories espoused by most think tanks.10

1. Learning from what works

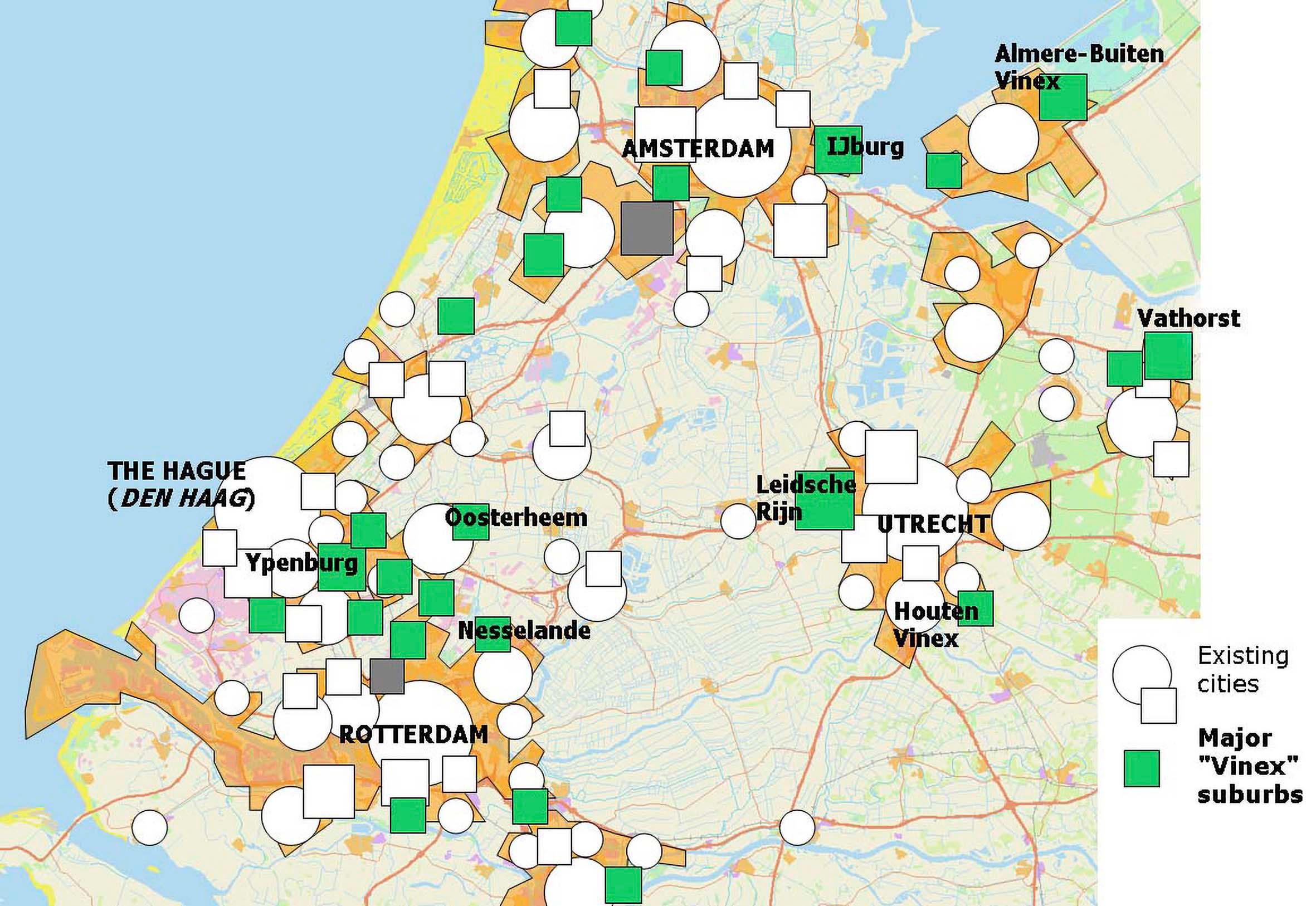

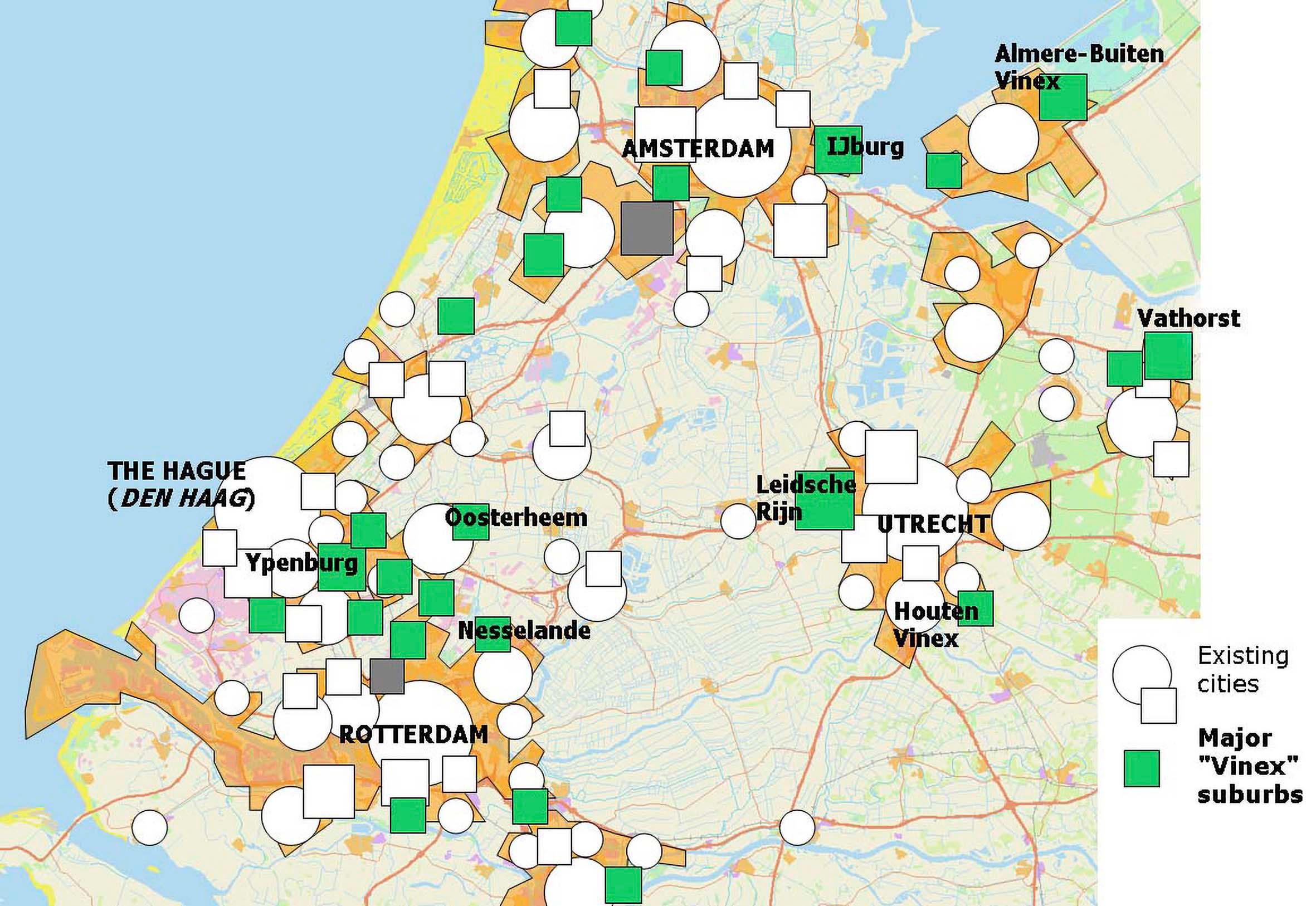

The immediate solutions lie in rebuilding our capacity to deliver results quickly. Policies like the Dutch VINEX programme prove local leadership and

Town & Country Planning May-June 2024 150

Vinex suburbs, Randstad, The Netherlands

Nicholas Falk

devolution of powers pay off. Across The Netherlands, 95 urban extensions increased the housing stock by 7.6% over ten years.11

With over 10,000 homes, the urban extension of Vathorst in the mid-sized town of Amersfoort is one of the most popular places to live, kicked off by a new railway station. Amersfoort was the Academy of Urbanism’s European City of the Year in 2023.

But we should also learn from closer to home. Historically, both major political parties sparked urban growth using innovative mechanisms. This included Development Corporations under Labour in the post war New Towns – a model adapted by the Conservatives for urban regeneration in the 1980s and now for housing growth. Partnerships conceived by the Tories in the City Challenge programme were adapted by Labour to administer and deliver successive rounds of the Single Regeneration Budget programme. English Partnerships and regional development agencies created thriving housing markets and quality regeneration in places like Ancoats, Manchester and in the centre of Nottingham.12 Labour’s approach to urban renaissance, recommended by the Urban Task Force led by Richard Rogers, was starting to deliver before the financial collapse in the US housing market precipitated a change of government.

A more recent example of smarter growth can be seen at Eddington, North West Cambridge. Inspired by a study tour to the Netherlands and Germany, Cambridge University decided to lead development of its own land into a place ‘designed for twenty-

first century sustainable living’. A bond issue raised £350 million, enabling advance infrastructure investment, which included an innovative sustainable urban drainage scheme. The first phase included 700 homes for staff, 700 market homes and 350 rooms for post-graduates – all designed by leading architects – plus shops and community facilities. The scheme shows the value of proactive planning by a progressive landowner in securing innovation.

‘Housing can only play a positive role in getting Britain moving if it is combined with measures to improve local infrastructure’

These domestic successes have three common elements: a coherent change strategy; a budget to build confidence, and skilled, dedicated teams. All three are singularly lacking in most places nowadays. Generations of politicians and professionals from the 1970s to the early 2000s had economic, planning and infrastructure delivery skills to broker change. The skills required to work in small multidisciplinary teams; focus upon outcomes not inputs; manage large urban development programmes and build partnerships that engage investors and communities are in short supply. Rebuilding a cadre of energetic and knowledgeable practitioners and leaders is a first priority.

Town & Country Planning May-June 2024 151

Vathorst, Amersfoort, The Netherlands

Nicholas Falk

2. Restore spatial planning

It is time to replace our tortuous adversarial planning system with an integrated model of strategic spatial planning for housebuilding and infrastructure linked to a ‘green’ economic base. This can provide a strong sense of shared ambition, bringing stakeholders on board to ensure smoother delivery of better placemaking. URBED’s report for Sheffield’s growth as a Garden City illustrates how a well-visualised plan can win support from business, developers, local people and environmentalists, offering a model for spatial planning from city to neighbourhood.13

The digital revolution should make it much easier to bring together different sources of data at a sub-regional level in the manner that the Digital Planning Task Force has recommended.14 The Royal Society for the Arts’ Urban Futures Commission recommends strengthening data and modelling capabilities. Spatial science can map social and natural capital and travel patterns to identify the best growth points. It might also be used to assess the extra wealth created through effective strategic plans, rather than relying upon the sometimes dubious claims of site promoters. It helps local partnerships turn plans into places by evaluating the impact of different options and scenarios on a multiplicity of objectives. Cambridgeshire did this in the Structure Plan that has shaped its growth to date. Greater Cambridge is now using Bioregional’s innovative carbon calculator to optimise site selection.15, 16

The technology is there. What about the art of urbanism? When it called for an urban renaissance, Lord Rogers of Riverside’s multidisciplinary Urban Task Force (UTF) learnt from how European cities like Rotterdam rebuilt themselves after the Second World War.17 The UTF report drew upon a lot of accrued wisdom about how to shape places for the better. English Partnerships and the Housing Corporation complemented this with comprehensive advice on delivery in a companion to their Urban Design Compendium 18 Both are still useful.

Whatever one thinks of standard house types, the creation of beautiful neighbourhoods has been a challenge, as housing audits have revealed.19 Yet there is long history of providing advice for developers and local planning authorities. The Commission for Architecture and the Built Environment (CABE) played an important role before its effective abolition in 2011. Its advice is still available online.20 The 2009 World Class Places strategy, introduced by Gordon Brown’s Labour government, was ditched by the Conservative/ Liberal Democrat coalition in 2010.21 The de facto hiatus in design policy that followed was, thankfully, ended by the Building Better Building Beautiful report, Living with Beauty. This was followed by the National Design Guide, the National Model Design

Code and an updated National Planning Policy Framework mandating design coding.22 If there is a hole in skills, it is in writing effective codes.

Richard Simmons undertook a review of a small sample of developer-written codes in 2023 for a non-governmental organisation and found a wide variation in quality – from detailed roadmaps to justifications for standard estate and house design without even a controlling diagram. The Office for Place, university design schools and architecture and built environment centres are trying to fill the skills gap, but all is dependent upon local authorities having the ambition to raise quality standards.

3. Using stations as development hubs

Even with the growth in working from home, connectivity that cuts travel times remains key to raising productivity. It takes twice as long to get to work in Birmingham as in French cities such as Lyon.23 Grand projects have inherent flaws, which lead to cost and time overruns.24 They need to be broken into incremental steps where transport and housebuilding can be joined together, and private investment mobilised.25 One opportunity is to make the most of underused railway lines, as Manchester and Croydon have done, by transforming them into tramways rather than pursuing grand projects like HS2.