Town & Country Planning

Town & Country Planning is the Journal of the Town and Country Planning Association (TCPA), a Company Limited by Guarantee.

Registered in England under No. 146309.

Registered Charity No. 214348

Copyright © TCPA and the authors, 2024

The TCPA may not agree with opinions expressed in Town & Country Planning but encourages publication as a matter of interest and debate. The views expressed in this journal are those of the contributors and advertisers and not necessarily those of Town & Country Planning, Darkhorse or the Editorial Advisory Panel. While every effort has been made to check the accuracy and validity of the information given in this publication, neither Town & Country Planning nor the publisher accept any responsibility for the subsequent use of this information, for any errors or omissions that it may contain, or for any misunderstandings arising from it. Nothing printed may be construed as representative of TCPA policy or opinion unless so stated.

Town and Country Planning Association

17 Carlton House Terrace London SW1Y 5AS

t: +44 (0)20 7930 8903

Editorial: Georgina.Griffiths@tcpa.org.uk

Subscriptions: tcpa@tcpa.org.uk

Editor

This issue was edited by Philip Barton. Subsequent issues will be edited by Georgina Griffiths: Georgina.Griffiths@tcpa.org.uk. If you are interested in contributing an article, please contact the editor before writing to agree topic and word count.

Design hello@darkhorsedesign.co.uk

Advertising

Rates (not including VAT): Full page £800. Inserts from £400 (weight-dependent).

Half page £400. Quarter page £300. A 10% reduction for agents.

£148 (UK); £178 (overseas).

Subscription orders and enquiries should be addressed to: Subscriptions, TCPA, 17 Carlton House Terrace, London SW1Y 5AS

t: +44 (0)20 7930 8903

e: tcpa@tcpa.org.uk

Payment with order. All cheques should be made payable on a UK bank. Payment may be made by transfer to: The Bank of Scotland (account number 00554249, sort code 12-11-03). Mastercard and Visa accepted.

Town & Country Planning is also available through TCPA membership. See the TCPA website, at www.tcpa.org.uk, for membership rates, or email membership@tcpa.org.uk for details.

TCPA membership benefits include:

• a subscription to Town & Country Planning;

• discounts for TCPA events and conferences;

• opportunities to become involved in policymaking;

• a monthly e-bulletin;

• access to members’ area on the TCPA website.

Town & Country Planning is printed on paper sourced from EMAS (Environmental Management and Audit Scheme) certified manufacturers to ensure responsible printing.

Town & Country Planning is produced by Darkhorse Design on behalf of the Town and Country Planning Association and published six times a year.

Erratum

Amy Penrose, who contributed the article ‘From housing targets to the grey belt’ in Vol. 93, No. 6, pp. 372–373 of Town & Country Planning, is an associate at law firm Farrer & Co.

4 On the agenda

Fiona Howie highlights the importance of play to children’s health and wellbeing.

7 Time and tide

Celia Davis discusses the potential benefits and pitfalls of proposed flood performance certificates.

55 Created equal Anna Zivarts on being a disabled non-driver in the USA.

62 Legal eye

Bob Pritchard highlights growing concerns about development and water neutrality.

13 New Towns, new homes

Georgie Revell looks at innovative designs for medium-density homes.

19 The NPPF and Ebenezer Howard's inconvenient legacy

Hugh Ellis asks what Howard would make of the new NPPF.

28 Lessons from Northstowe

Nicholas Falk asks why, even in areas of high value and high demand, it can be so difficult to deliver growth.

30 Planning for urban greenspaces

David Adams, Mike Hardman, Peter Larkham and Rob Lamond look at recent urban greenspace initiatives.

42 Could pension funds invest more to boost affordable housing?

Tony Zeilinger suggests a win-win for lower-income households.

47 The role of artificial intelligence in wildfire prevention

Carsten Brinkschulte says AI could help protect forests from wildfires.

On the agenda

Title

Fiona Howie, TCPA chief executive, highlights the importance of play to children's health and wellbeing – and introduces this journal's updated design

In the first edition of 2024,¹ I highlighted an inquiry into children, young people and the built environment by the then Levelling Up, Housing and Communities Select Committee.

Opportunities to play close to home, known as 'doorstep play', are especially important for young children

© istock

The inquiry considered how better planning, building and urban design in England could enhance the health and wellbeing of children and young people, while also benefiting the population as a whole.

Over 100 pieces of evidence were submitted to the inquiry. However, the dissolution of Parliament in May 2024 meant that the select committee ceased to exist. To prevent this work from being wasted, the TCPA reviewed the evidence and published, Raising the healthiest generation in history,² which makes recommendations about how to improve children and young people’s health and wellbeing in England through the built environment.

A key theme from the evidence was access to and attitudes towards play. Play is an essential part of every child’s life as it supports social, emotional, intellectual and physical development. However, many children in England now face barriers to accessing safe playspace, with access even more restricted in areas of deprivation. An important emphasis in the evidence was that societal attitudes towards children playing in public have also changed and children playing outside of designated playgrounds is often now seen as antisocial behaviour.

Another key theme of the evidence is the need for effective cross-government collaboration. Despite an increasing understanding of the impact of the built environment on children’s health and wellbeing, the report highlights that children’s needs are rarely considered by national and local government outside of education and social care. This need for cross-government action is then reflected in the recommendations, which are

targeted at six different government departments, plus the Prime Minister. They include, for example, calling for revisions to national planning policy and guidance, but they also call on the Secretary of State for Culture, Media and Sport to create a national play strategy, and the Secretary of State for Transport to make sure that the update to Manual for Streets reflects children and young people’s needs.

Finally, we hope that readers enjoy this journal’s updated design. Changing such a valued publication is daunting. But, as the digital archive of the journal³ shows, its design has evolved over time. With the retirement of long-standing editor, Nick Matthews, in 2023, change became inevitable. We also wanted to make the whole publication more accessible and this required changes to fonts and layouts. We hope that existing and new readers will find that the evolution of the design of the journal better enables you to enjoy the continued highquality content.

Notes

Play is a serious matter, vital to children's health and wellbeing

© istock

1 F Howie: ‘2024 – what lies ahead?’. Town & Country Planning, 2024, Vol. 93(1), Jan–Feb., 2–3

2 Raising the healthiest generation in history: why it matters where children and young people live. TCPA, Dec. 2024. https://www.tcpa.org. uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/Raising-the-healthiest-generation-inhistory-Accessible-version.pdf

3 See: https://archive.tcpa.org.uk/archive/journals

Time and tide

Celia Davis, senior projects and policy manager at the TCPA, discusses the potential pros and cons of the proposed flood performance certificates

Celia Davis

At the time of writing, communities across England and Wales are reeling from Storm Bert. In places like Pontypridd, South Wales, the devastation is unhappily familiar after Storm Dennis flooded the same valleys just a few years ago. In Northamptonshire, shocking images showing hundreds of flooded caravans reveal the increased vulnerability to climate impacts of those forced into unsuitable accommodation in the face of the climate crisis.¹

Embattled farmers across England, still recovering from economic losses caused by last winter’s floods, are already seeing this year’s yields reduced as severe downpours hammer harvests.²

This pattern of disaster and recovery is the ‘new normal’ as the climate crisis takes hold. And as this reality unfolds, the question of long-term resilience must be at the forefront of the mind of all those involved in planning and managing our built and natural environments. However, we are worryingly far from this in practice.

Earlier this year TCPA research, commissioned by Flood Re, asked how effectively the English planning system was delivering flood resilience measures in new housing developments.³ It reviewed the practice of two local authorities with significant flood risk challenges, to understand how they used conditions to secure flood resilience measures. Two case studies were used to understand how flood measures are treated between planning permission being granted and build-out. This review unearthed a profusion of procedural issues that allow flood resilience measures to ‘fall through the net’ of regulation.

The question of long-term resilience must be at the forefront of the mind of all those involved in planning and managing our built and natural environments

One issue is that local authorities are often reliant upon weak and out-of-date evidence, even in areas where significant flood events have been experienced in recent years. This leaves them vulnerable to underestimating risk when considering planning proposals and the mitigations that might be required. The oversight of flood risk conditions and the delivery of agreed

mitigations appears to be inconsistent from one authority to the next – influenced by local resources and capacity. This is particularly true for surface water flooding, where the Environment Agency has a limited role. Schemes are subject to very little scrutiny in terms of compliance with flood risk requirements, and there is limited capacity to take enforcement action.

The study demonstrates the pivotal role of conditions in securing flood resilience measures for new development. However, this reliance creates vulnerabilities and means that flood resilience is often limited to delivering only minimum policy requirements (to meet the test of ‘necessity’ for a legally sound condition) and are further weakened because they are not being executed consistently and effectively in practice. Mitigations are often described in flood risk assessments as aspirational rather than necessary, making them hard to secure by way of conditions, and leading to interventions designed to address residual flood risk (such as property flood resilience measures and emergency evacuation plans) remaining undelivered.

The institutional complexity of flood risk management is illustrated in the research by a disturbing example of sewerage from an over-700-home development overflowing into fields and a nearby watercourse. The water company did not raise any infrastructure capacity issues during the planning process despite clear constraints. This is understandably of concern to the local community, a number of whom have reported increased instances of flooding and wastewater backup at existing properties since the scheme was built out.

The many avenues through which changes can be made to proposals after planning permission has been granted are a symptom of an overly complex system which makes it very challenging to understand what flood resilience measures have actually been delivered – something that a potential buyer would clearly wish to understand. This lack of transparency is also of great concern to an insurance industry cognisant of the increasing vulnerability of property assets to climate impacts. In response, there appears to be a growing voice for property-level interventions such as a flood performance

certificate (FPC) for housing. The concept is similar to the energy performance certificate (EPC) – it would explain the risk a property is exposed to, state the resilience features a property has in place, and identify measures that would improve a property’s resilience to flooding.⁴

This would enable homebuyers and insurers to understand the resilience (or vulnerability) of their property to flooding and, importantly, it would help homeowners understand how to use and manage the property flood resilience measures in their home. It would also provide, in the case of new-builds, a strong incentive for developers to deliver higher levels of protection.

The location of a home has the single biggest bearing on its flood resilience

There’s a clear rationale for this, particularly for new developments. And there is a need for more honest communication with communities about the potential risks they face from flooding. But there are wider risks that must be avoided for such a scheme to work effectively. With an EPC, a homeowner has considerable control (albeit within their financial constraints) over their rating because they can usually implement retrofit measures to improve energy efficiency. In contrast, many of the factors that influence a property’s flood resilience are far beyond the influence of individual householders.

This is because the location of a home has the single biggest bearing on its flood resilience. A homeowner has very limited control over funding for strategic flood defences, rewilding efforts upstream, or the management of sustainable drainage systems. So, there is a risk that communities could find themselves with poor ratings on a flood performance certificate by virtue of where they live. And we know that there is significant crossover between social deprivation and vulnerabilities to climate impacts – so the onus on householders to improve property resilience must consider those without the financial means to improve their home’s performance.

An FPC would focus upon property-level interventions. We can undoubtedly design buildings to respond to flood risk better by using property flood resilience measures that provide safeguards when flooding does occur, but we must be careful not to bank on consumer-focused solutions to address fundamental failures in our approach to land use planning. The TCPA’s recent research into flood resilience points to a broader need for more fundamental changes to the operation of the planning system to better protect communities, which must be driven by an overarching reprioritisation of planning to address the climate crisis, particularly in the context of a target of 1.5 million homes. The planning system needs urgent review so that climate resilience is given stronger priority in plan-making and planning decisions. This overarching priority must then be supported by procedural reforms that ensure resilience is delivered through all stages of the planning process.

Celia Davis is senior projects and policy manager at the TCPA

Notes

1 The lawful use of Billing Aquadrome is as a twin-unit caravan site. A BBC Panorama investigation revealed that some of the caravans have been sold for permanent residential occupation. https://www.bbc.co.uk/ programmes/m001x7pb

2 E Grimshaw, N Jewers: ‘Farmers’ warning as food crops lost to floods’. Webpage. BBC News, 7 Oct. 2024. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/ cgmgxxz2e29o

3 Full report available here: https://www.tcpa.org.uk/wp-content/ uploads/2024/08/TCPA-Delivering-Flood-Resilience-Report-Sept-2024.pdf

4 Flood Re’s roadmap for Flood Performance Certificates is available here: https://www.floodre.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/21594-Flood-PerformanceCertificates-Roadmap-16pp_AW1_Digital_PD-1.pdf

Georgie Revell considers designs for homes and places that could work at the higher densities likely in the next New Towns.

New towns, new homes

Pre-election, the government published imagery of their vision for the next generation of New Towns. The images were disappointingly nostalgic and pastiche, but they were suggesting, quite sensibly, that handsome-looking mansion block typologies could be part of the solution to create thriving and sustainable new communities. Although the autonomy of a house can never be rivalled by living in a shared building, mid-rise, medium-density housing has the potential to provide homes that are genuinely attractive to all sorts of households. They can make the most of the benefits of low-density houses and higher-density buildings with shared facilities to create attractive, sustainable homes. Designs for homes at this density must be specific – they are neither houses nor high-rise blocks – and the standards and guidance should reflect this. Some ideas that could be considered are:

minimum internal areas

New Towns are likely to stipulate Nationally Described Space Standards¹ which set different minimums for a one, two and three-storey home for any number of people (i.e. a twobedroom home for four people must be 70 sqm for one storey, 79 sqm for two storeys and 84 sqm for three storeys). These numbers have been sensibly calculated to take account of additional circulation areas, but sadly have resulted in flats being the only option when maximising housing numbers. There are significant benefits to maisonettes or duplexes as they offer more privacy and separation, which is important in multi-person households. Setting the minimum area as the same for a single and two-storey home would encourage more duplex homes, and, in flatted developments, offer nine sqm more space, which could be used flexibly; a separate utility room to avoid washing machine noise and a self-contained study for example.

Homes in a typical block are difficult to modify because moving walls or services requires consent and may be prohibited. Stand-alone houses are much more attractive in this respect as freeholders are able to extend and remodel to suit different lifestyles or people over time. It is possible, however, for joined homes to be more flexible by designing non-load bearing partitions and adding extra soil vent pipes and accessible service runs. To echo most houses, these homes should be dual aspect to afford residents options for sunnier or cooler rooms, with good views or increased privacy. A House for Artists, designed by Apparata architects and built in London, demonstrates ultimate flexibility for residents of this mid-rise block, who can create the home they want within the footprint of their apartment.

For many, the biggest draw of a house is a garden. Gardens on the same level as the home can't be provided at higher densities of course, so usable, attractive balconies and terraces must be the alternative. London’s minimum sizes and proportions (five sqm for up to two people plus one sqm per additional person) are a good start, but they don’t really compare. Providing larger homes with two balconies, ideally with different orientations, would offer something different to a garden. Perhaps space off the living room is used mainly by children, while the balcony off the bedroom is for evening drinks/gym equipment.

Providing larger homes with two balconies, ideally with different orientations, would offer something different to a garden

There are huge benefits to well-designed communal space, and it can be the best asset of a shared block. However, all too often, stairways, corridors and courtyards detract from the living environment rather than complement it (all while residents are paying for their upkeep). Developments should minimise shared circulation spaces and give this space to the homes instead, which is easily possible at medium density. This will have the added benefit of more front doors onto the street, which improves street activity and a sense of place. A relaxation on the requirement for M4(2)² would be required for this (likely to become a national minimum in time); however, the policy will allow for flexibility on site-specific and viability grounds, which should always be considered.

The Malings in Newcastle upon Tyne, is an example of well-conceived medium-density housing at 136 dwellings per hectare. The approach is one of stacked houses where ‘every square metre is part of someone’s home’. Every home has a front door onto the street and a sizable garden or terrace. The small communal garden is used as allotment space and is well overlooked. Other shared areas for bicycles and bins save space in the homes or gardens and are well used.

Sutherland Road in London is another example of medium-density housing which provides a mixture of houses, maisonettes and flats. The communal access areas are open and varied, providing space for residents to personalise and use as extensions of the living space.

Delivering 370,000 homes per year is a tall order (over the last 20 years we have averaged 190,000). While we grapple to meet this, we must remember that solving the housing crisis is not just a numbers game. Homes are about happiness, comfort and physical and mental health and wellbeing. New Towns present the perfect opportunity to deliver a vibrant new community, usable and attractive to all. With creative, progressive and intelligent design standards, ‘gentle’ density can offer genuinely lifetime homes and deliver the housing numbers to make these communities thrive.

Georgie Revell is an associate at Levitt Bernstein. All views expressed are personal.

Notes

1 A set of guidelines for homes in England. Although optional, they have been widely adopted since their inception. Technical housing standards – nationally described space standard. Department for Communities and Local Government. Apr. 2015. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/ media/6123c60e8fa8f53dd1f9b04d/160519_Nationally_Described_Space_ Standard.pdf

2 The Building Regulations 2010, Approved Document M: Access to and use of buildings, Volume 1: Dwellings. M4(2) Category 2: Accessible and adaptable dwellings. HM Government, 2015, pp. 11–22. https://assets. publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5a7f8a82ed915d74e622b17b/BR_PDF_ AD_M1_2015_with_2016_amendments_V3.pdf

a radical yet practical economic model

As we face another year of radical planning reform, Howard’s genius for imagining a compassionate future remains a demanding inspiration, argues Hugh Ellis

The NPPF and Ebenezer Howard's inconvenient legacy

Last year ended with a flurry of announcements around planning reform, devolution and local government reorganisation and with a new planning bill expected at any moment. At the time of writing – January 2025 – only the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) has been published.¹ However, before rushing into detailed textual analysis of this document, it is interesting to reflect on what an organisation like the TCPA, founded on Howard’s Garden City ideals, is to make of this its overall objectives?

The problem with Ebenezer Howard is that he offered a vision of a different kind of compassionate society which placed social justice and the environment at the heart of a holistic vision of better lives. And these lives were to be led in a fiercely democratic context in which people were to have real power to participate genuinely in the decisions that shape their communities. These ideas were interlocking and indivisible and unmistakeably socially progressive. The movement which those ideas inspired then had the audacity to make that vision a practical reality by building one of Europe's

largest co-operative communities at Letchworth Garden City. The Garden City went on to be one of the most culturally significant ideas of the 20th century, inspiring, among other things, the New Towns programme. But perhaps the movement’s biggest contribution was to provide the moral foundations of British town planning.

It is precisely this moral concern for progressive and holistic social change, in which town planning is seen as an embedded part of progressive democratic politics, which is now so inconvenient for the way that the TCPA navigates its response to planning reform. For example, what is most striking about the new NPPF is the lack of any overall vision for our collective future. Sustainable development is not the guiding thread of national planning policy, not least because any internationally recognised definition of sustainable development is effectively marginalised in the opening paragraphs of the document.² In fact, the NPPF is a market-led investment strategy designed to maximise GDP (gross domestic product) growth, predicated on the assumption that democracy and the environment get in the way of profit maximisation. In this development model it is important that the worst excesses of environmental and social harm are mediated, but only when this does not compromise the needs of private investors.

Here it is worth noting that this model has both an intellectual pedigree and a powerful set of advocates at the heart of the new government. The chair of the Chancellor's Economic Advisory Council is the highly respected LSE (London School of Economics) economist, John Van Reenen. Van Reenan has been at the heart of the government’s economic policy³ and it is significant that he has written about and endorsed some of the most influential views of the Austrian political economist, Joseph Schumpeter, particularly on the importance of ‘creative destruction’ and entrepreneurship. Schumpeter also held highly elitist views about democracy and was dismissive about the capability of the average electorate. This may partly explain why we see the government enthusiastically endorsing AI (artificial intelligence), despite the human cost this will have in terms of loss of work. It also helps explain the radical proposals to restrict local democratic accountability of planning decisions.⁴ It is, perhaps, significant

The NPPF and Ebenezer Howard's inconvenient legacy

that there is no sense of a traditional Keynesian approach in the new government. There are no proposals for a Rooseveltstyle ‘New Deal’ programme, of which Schumpeter was so critical. Instead, our future depends on private capital, providing both public goods like housing, and the tax revenues to mediate, in part, the problems caused by the extractive and unsustainable practices upon which the majority of private sector investment depends. Under this model, housing is means to a macro-economic end, not the foundation of human wellbeing.

Under this model, housing is means to a macro-economic end, not the foundation of human wellbeing

Howard’s genius was to stand this traditional economic model on its head by putting the wellbeing of people and the environment at the centre of decision-making and then creating an economic framework to support that ambition. Part of the enduring appeal of the Garden City development model is its ability to blend mutualised economics, a passionate commitment to nature, and vibrant democratic and participative governance. Howard would have been simply bewildered at the current rhetoric of politicians which pitches nature and people against each other. They are, quite obviously, an indivisible concept. Whether you want to describe this as the value of ecosystem services or simply the tangible benefits nature brings to our physical mental and spiritual wellbeing, we have to accept that our survival depends on the resilience of the natural world. Housing, as Ruskin said, ‘should be an ornament to nature and not its disfigurement.’⁵

The introduction in planning policy, after 1987, of the sustainable development model echoed the Garden City's ambitions for an integrated approach to social and environmental progress. It was also a reaction to the critical social costs and widespread environmental collapse created by both traditional neoliberal economics and soviet-style socialism. Since that point, there has been almost five decades of detailed thinking around; the need to integrate rather than trade off social, environmental and economic objectives; the importance of respecting environmental limits; and the centrality of empowering communities to shape their own future. There has also been the development of progressive economic ideas, including the promotion of a circular economy, foundational economics, and the generation of social value, which all reflect both the need for resource conservation and a fairer distribution of wealth.

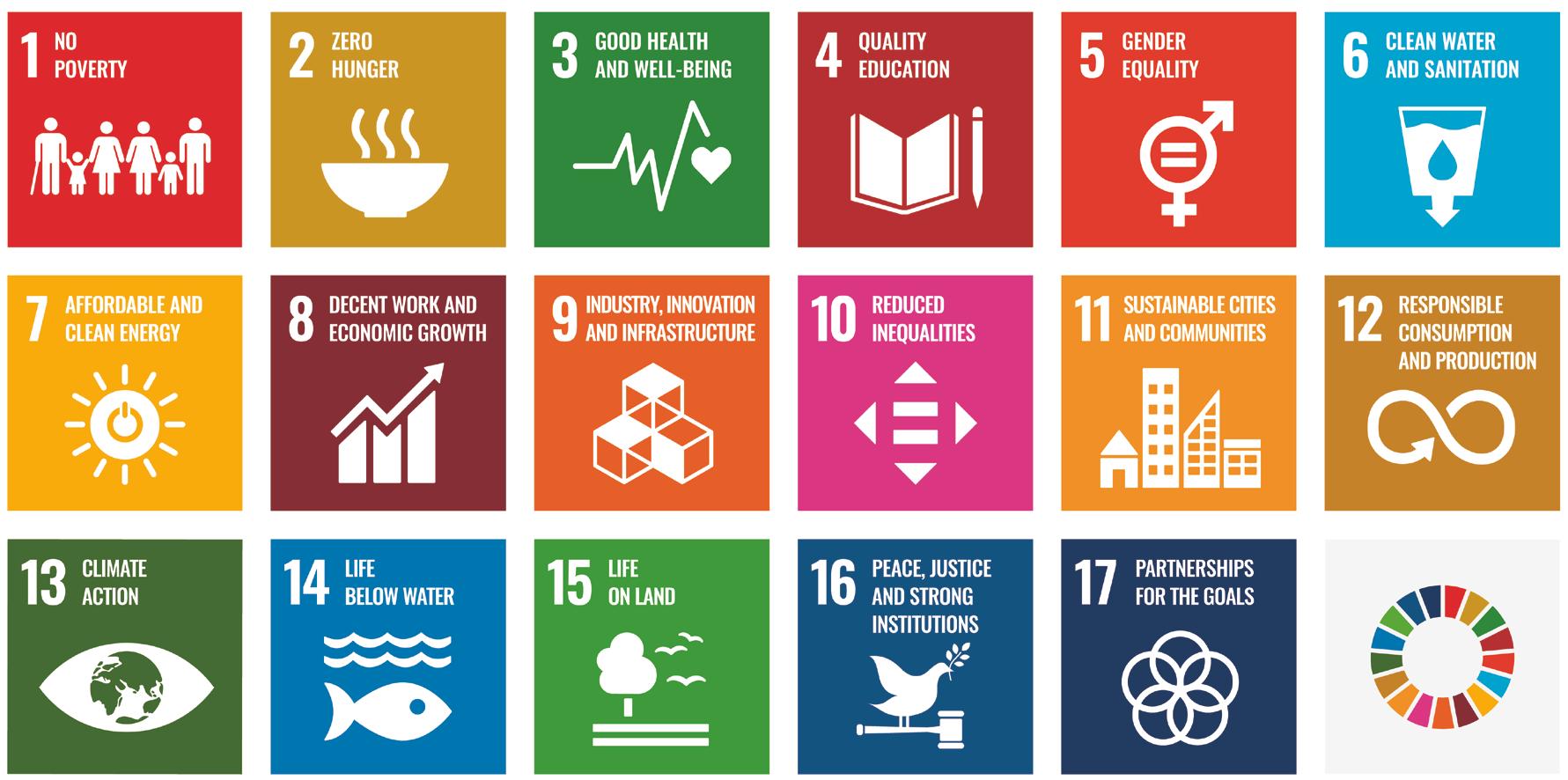

The NPPF requires sustainability ‘at a high level’, but not when making planning decisions

© United Nations www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment

The content of this publication has not been approved by the United Nations and does not reflect the views of the United Nations or its officials or Member States

The NPPF and Ebenezer Howard's inconvenient legacy

Much of this thinking culminated in the publication of the United Nations’ 17 sustainable development goals⁶ (see image on previous page), which the NPPF so expertly ensures can never be applied to any planning decision. It is also striking that none of these sustainable development concepts are represented in the ‘presumption in favour of sustainable development’⁷ which is the operational heart of the NPPF.

Continually applying the same failed approach to the development of our nation while expecting different results will not work. Planning, or what's left of it, was not a barrier to housing or infrastructure. As the TCPA has consistently pointed out,⁸ a chronic lack of investment in homes for social rent, along with a complete reliance on the private sector to build the right quantity of homes, in the right place, at affordable prices, are the real cause of this crisis. In recent years, far more planning permissions for homes were granted than the number of homes that were built. Simply continuing to increase the number of planning permissions will fuel land speculation, but do nothing to ensure that more new homes are actually built.

However, it would be foolish not to accept that, for the time being, that argument has been lost. Neither should the TCPA be in the business of defending the status quo, because the lack of ambition and vision in national policy has a much longer history. Prior to the introduction of the NPPF in 2012, national planning policy was shaped by Planning Policy Statement 1.⁹ This made it clear that planning should champion social justice and inclusion, along with participative decision-making. It was swept away in 2012 and replaced by the NPPF. It is striking that the latest version of the NPPF, the first NPPF to be issued by a Labour government, completely ignores both of those agendas. The government’s focus on GDP growth on its own will not meet the needs and aspirations of England’s diverse communities The NPPF suggests a future defined by appealled housing, data centres, and new energy infrastructure – but gives no suggestion of what that future England will be like to actually live in. This is even more stark in the context of a nation which has no urban policy and no sustainable

development strategy – in fact no sense at all of what the experience of walking down a street in an English community in 2050 will look and feel like. Articulating a vision of the future is more than just window dressing; it is fundamental in establishing a sense of confidence, and that is key to generating hope and combating extremism.

Articulating a vision of the future is more than just window dressing

The lack of imagination and diversity in economic policy is in stark contrast to Howard's conception of the Garden City, which created space for a vibrant private sector to contribute to the social value of the community. The critical difference between that, and what is on offer in the new NPPF, is that it didn't rely on the private sector to meet people's foundational needs in terms of homes and utilities. In the same way, the TCPA’s basic criticism of the NPPF is not that it focuses on GDP growth, but that it refuses to leave space for any other form of economic activity and community development. There is no meaningful content to encourage the multiple examples of mutualised and co-operative activity which the TCPA highlighted in its publication Practical Hope,¹⁰ ideas which are providing the only point of hopefulness in many communities across the UK. It is helpful to understand the scale of the challenge in advocating the Garden City and sustainable development models when these approaches are so at odds with the economic orthodoxy of the government. But this orthodoxy has severe limitations which will ultimately guarantee its failure. For example, it assumes that people and democracy can be ignored and marginalised without a major political and practical costs. In fact, England is a densely populated nation with some strong democratic tendencies. Building without democratic consent will reinforce community resistance, which will be expressed through the law and through protest, undermining everyone’s, including investors’, confidence in the system. It is significant that HM Treasury also assumes that nature is infinitely capable of absorbing GDP growth when the evidence is plainly to the contrary. What was needed from the

The NPPF and Ebenezer Howard's inconvenient legacy

new government was a form of economics which can meet the challenges of the climate crisis already playing out in many of our communities. Zero-carbon energy infrastructure is vital for this nation, but so too are the billions necessary to create flood-resilient communities, without which there is no viable economy. The reality is that the private sector will not, and will never, provide the income streams necessary to provide for all the public goods key to our survival. To solve that problem at least two things are necessary: a national government with the ambition of Roosevelt’s ‘New Deal’; and a much stronger commitment to the fine-grain mutualised economic instruments that can build the resilience of people in places after the damage of austerity.

the problem with technocratic, centralised solutions is that they ignore the reality of the human condition

It is more than ironic that the chair of the Chancellor’s Economic Advisory Council is a professor at the LSE, an institution founded by Beatrice and Sydney Webb, who also founded the Fabian movement. Ultimately, that movement was defined by a technocratic assumption that a rational Whitehall, applying command-and-control principles, could drive progressive social change. As a movement it was rudely dismissive of the Fellowship of the New Life¹¹ which inspired the Garden City ideals. For the Fabians, any discussion of hopefulness and utopia was the business of sandal-wearing cranks. But the problem with technocratic, centralised solutions is that they ignore the reality of the human condition and the diversity of our communities. They are emotionally illiterate, and as a result they fail to offer any inspiration for better lives in a hopeful future. If progressive politics will not offer such a vision, then we can be certain that the far right will. That is

why, despite the challenges of advocating the Garden City ideals, those ideals remain fundamental to our collective future and profoundly important in the defence of our democracy.

Dr Hugh Ellis is the TCPA’s director of policy

Notes

1 National Planning Policy Framework: Policy Paper. Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government, 12 Dec. 2024. https://www.gov.uk/ government/publications/national-planning-policy-framework--2

2 The interaction of paragraphs 7 and 9 of the NPPF mean the sustainable development goals are ‘high level’ goals and ‘not criteria against which every decision should be judged’. Coupled with a weak legal duty that planning should only ‘contribute to the achievement’ of sustainable development, and the absence of any text on environmental limits or the precautionary principle, the NPPF’s sustainable development commitments are rhetorical, rather than operational policy.

3 Heather Stewart: ‘He’s one of the best’: the economist shaping Rachel Reeves’s growth plans’. The Guardian, 17 Jan. 2025. https://www. theguardian.com/business/2025/jan/17/economist-shaping-rachel-reevesgrowth-plans-john-van-reenen

4 Planning Reform: In defence of democratic planning. TCPA, Dec. 2024. https://www.tcpa.org.uk/planning-reform-in-defence-of-democraticplanning/

5 John Ruskin: Sesame and Lilies. Two Lectures delivered at Manchester in 1864. Leopold Classic Library, 2016

6 See: https://www.undp.org/sustainable-development-goals

7 National Planning Policy Framework: Policy Paper. Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government, Dec. 2024, Paragraph 1. https:// www.gov.uk/government/publications/national-planning-policyframework--2

8 Our shared future: A TCPA White Paper for Homes and Communities. TCPA, Jan. 2024. https://www.tcpa.org.uk/resources/our-shared-future-atcpa-white-paper-for-homes-and-communities/

9 The 2005 PPS1 was not perfect but was a coherent and progressive framework operationalising the UK sustainable development Strategy. See archived content: https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/ ukgwa/20120919122719/http:/www.communities.gov.uk/documents/ planningandbuilding/pdf/planningpolicystatement1.pdf

10 Practical Hope: Inspiration for Community Action. TCPA, Oct. 2024. https://www.tcpa.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/A5ls-20pp-PracticalHope-ICAction-Aug24-v11.pdf

11 The Fellowship first met in 1883 and included a group of Utopian thinkers including Edith Rees, ‘Miss Owen’, the granddaughter of Robert, Ramsay Macdonald, Edward Carpenter, Havelock Ellis and many others. The Fabian society splintered from the Fellowship, led by the Webbs and Bernard Shaw. Howard knew all these personalities but was influenced by the Fellowship’s desire to experiment in practical Utopias.

Unlocking smarter growth is hard. Even in Cambridge, where demand is high, great architecture and places co-exist with mediocrity and unfulfilled plans. The ratio of house prices to incomes is so high that it is a brake on economic growth and causes social distress. Many blame planning. Yet continual meddling by government and changing regulations often cut red tape lengthwise.

Certainly, infrastructure can be a real constraint.1 But in reality it is the peculiar British housing and political system – not planning alone – that is holding us back. The story of just one large scheme is instructive.

Northstowe New Town, seven miles north of Cambridge, was allocated for development in the 2003 Cambridgeshire Structure Plan and is now linked to Cambridge by a guided busway. Twenty years after the site was allocated, only 1,500 homes have been built. In 2023, none were built, and today community facilities are lacking. It still has the potential to be a great place to live. But why do large schemes take so long to be built in the UK, even when public sector land is released?

During the first 12 years of the Northstowe project, Homes England had nine changes in accounting officer and five different chairs, and there were 14 different housing ministers – all of whom had a different view about what Northstowe should look like, and all of whom failed to learn from experience.

Plans were produced, then changed. There were disagreements between landowners and developers. Property recessions and builders’ bankruptcies took their toll. All the while, residents had to live on building sites in places lacking promised community facilities because there were too few people to make them viable.

Housing supply in the UK has become far too dependent on relatively few volume house builders. They prefer to build standard house types on smaller sites in desirable, low-risk greenfield locations. They avoid complex brownfield sites or untried markets. They rely on the public sector removing the risks and require higher returns before they will build out sites with planning permission.

The Competition and Markets Authority report2 will be one year old just a few days after this issue of Town & Country Planning hits the doormats of its subscribers. Its findings are sobering and must be addressed if the fundamental structural changes needed to deliver sustainable housing growth are to be achieved.

Dr Nicholas Falk founded URBED (Urban and Economic Development) in 1976 and is now Executive Director of the URBED Trust, which is sharing experience and promoting innovation in placemaking. All views expressed are personal.

Notes

1 N Falk: Land for Housing: Sharing the Uplift in Land Values from Growth and Regeneration. URBED Trust, 2019

2 Housebuilding market study: Final report. Competition and Markets Authority, 26 Feb. 2024. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/ media/65d8baed6efa83001ddcc5cd/Housebuilding_market_study_final_ report.pdf

David Adams, Mike Hardman, Peter Larkham and Rob Lamond look at some of the recent urban greenspace initiatives designed to address climate change, biodiversity loss and the nature crisis

There are repeated and sustained calls for policies, funding initiatives and endeavours to address ongoing concerns regarding the impact of climate change, biodiversity loss and the general depletion of nature.1 These are globally significant issues and positive, sustainable planning interventions can play an important role in creating better places for flora and fauna, people, and the wider environment. Such global ambitions expounded in the United Nations Sustainability Goals need locally implementable actions, and many policy measures and initiatives have been developed to resolve the ‘nature crisis’.2

However, in the UK, the Environment Agency,3 the State of Nature Partnership4 and other significant bodies recognise that, despite a growing need for action, more concerted effort is needed to halt the decline in quality of natural environments and engender improved nature-friendly decision-making that can provide significant social, environmental and economic benefits. The 2023 State of Nature report (produced by a consortium of conservation and research organisations) revealed distressing levels of decline in plant distribution between 1970 and 2019 across England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland.5 As part of wider sustainability efforts, the report encourages retention of ‘the greening of urban spaces’ as an important policy objective when taking decisions about housing and other infrastructure. Indeed, in the recent general election all the main political parties emphasised the importance of this in their manifestos.

Designing, creating and managing urban greenspaces is important in achieving such laudable and much-needed goals. And the recent expansion of urban greening interventions and greenspace provision is designed to encourage physical activity, leisure, and social exchange for all demographics.6

Urban greenspaces in England can provide an estimated £6.6m

of ‘health, climate change and environmental benefits every year’.7 Even being close to greenspace can bring economic benefit, too. Analysis of one million property sales in England and Wales between 2009 and 2016 revealed that living within 100 metres of a park, community garden, playing field and other open spaces can boost house prices by an average of £2,500.8

Despite these and other benefits, there is a turnover of green open sites; some of these, including school playing fields and community gardens, are sold for development, raising UK government concerns that any loss of such public land should be mitigated by other improvements to sports provision.9 Much urban greenspace is inadequately funded and susceptible to governmental pecuniary restrictions. For example, the local government ‘bankruptcy’ situation continues to bite, and many local authorities in England and Wales could struggle to manage and resource greenspaces under their jurisdiction. In February 2024, the Local Government Association (LGA) found that 48% of local authorities say they plan to significantly reduce the levels of funding devoted to maintaining parks and other greenspaces.10 Ultimately, greenspace and areas of nature and biodiversity in built-up areas become more restricted over time.

Inequality of access to greenspace remains an issue, too. The Environment, Food and Rural Affairs parliamentary committee noted that the most affluent 20% of urban wards have as much as five times more accessible green space than those in deprived areas.11 A further example relates to children’s access to greenspace. A recent Guardian investigation found

Main Feature Title

that children at the top 250 English private schools have more than ten times the amount of outdoor space as those who go to state schools.12 Hence difficult questions surround how to plan for equitable, inclusive and sustainable urban greenspace.

Urban greenspace and opportunities for growth

There remains exceptional opportunity to create innovative, scalable planned interventions that deliver more greening across the urban matrix. In the UK, legislation is now in place to encourage the natural habitat of new developments by ensuring that they contribute to a minimum 10% boost in terms of the quality of the local natural habitat.13 This provides a direct means of conditioning and measuring improvements to biodiversity as part of the development process. Likewise, there are vibrant green networks working across spatial scales and sectors, including Social Farms & Gardens,14 with its support for city farming and community growing at a national level, to Sow the City15 and public exhibitions, such as Carrot City,16 which involve students, educators, housing providers and others in shaping the built form and enable creative greening. At the sub-regional scale, the West Midlands Combined Authority’s Natural Environment Plan encourages partner organisations to promote urban meadows, and biodiversity on under-used spaces, thereby supporting climate mitigation and adaptation.17

Yet, given the ongoing debates surrounding the provision of green, blue and grey infrastructure in cities, there are other possible options to help create more liveable and equitable cities. First, creating improved policy mechanisms, incentives and support for small domestic gardening, community gardens or other growing spaces as part of new development opportunities. There are many precedents for this, from micro to macro scales. This could include more efficient use of rooftops for planting and recognising how gardens and the boundaries/ corridors between them encourage flora and fauna to flourish. For example, a recent study in New York provided evidence that city-scale rooftop farming could produce 38% of the city’s mixed green needs.18 Although this does not necessarily account for all of the dietary desires of increasingly diverse urban populations, this and similar examples point to the potential growing capacity of intensive roof-top farming to meet food demands.

Much promising work exists around the potential of repurposing those underused or ‘stalled’ informal greenspaces that exist in many urban contexts.19 These include sites such as vacant land, disused car parks, public transportation corridors, abandoned development proposals, or under-utilised open spaces, that could be suitable for various forms of productive urban growing in the short or longer term. Yet there is also scope to develop stronger legal, economic and policy mechanisms that encourage repurposing of those relatively underexplored sites. There are other options. For example, the biodiversity and nature potential within and at the edge of cities can be explored in ways that foster stronger humannature connections, while providing access to local urban food networks.

Although the spectre of green gentrification looms large in these discussions, bringing nature closer to the sites where most people live, work and socialise can yield positive socioeconomic benefits among diverse urban publics. For example, the Wildlife Trust’s Wild at Heart programme, designed to connect older people with the natural environment in Sheffield and Rotherham, helped boost physical and mental wellbeing, while also reducing NHS inpatient admissions, accident and emergency attendances and outpatient appointments and hence resulting in significant financial saving.20 Extending community orchard schemes offers further options to improve human connections with greenspaces, particularly in new-build developments at the edge of settlements, while maintaining a productive urban-rural interface.21 A range of organisations already support these and similar approaches. These include Incredible Edible, founded in Todmorden, West Yorkshire, helping to stimulate an international network of community gardens, and Manchester’s City of Trees, which has planted more than 140 orchards, and supported the extensive planting of street trees and hedgerows.22 Similarly, in Birmingham, initiatives such as Martineau Gardens, close to the city centre, encourage an appreciation of urban food growing, while enhancing biodiversity and sustainability.23

Delivering more housing remains a pressing national and local issue and was a central theme in the recent UK general election. Indeed, the new Labour government re-emphasised their commitment to this, and are pushing forward legislation to enable rapid growth of housing. The LGA argues that England needs 250,000 more houses a year, nearly double the 130,000 currently being built.24 A target closer to 300,000 is commonly cited as a more realistic figure; and large-scale strategic growth, through a fresh generation of New Towns, is being mooted as part of the solution.25 But building more housing alone cannot deliver wider benefits. More new development is also often seen by local communities as a threat to the character and appearance of areas. Although recent legislation should ensure a change in landscaping practices, new-build housing developments in and around urban areas are often characterised by large areas of hard landscaping and impermeable boundary features. While these often provide flexible live-work options and private sanctuaries away from the real and imagined dangers of urban life, such estates are routinely criticised for promoting sedentary, unhealthy lifestyles, and a general underappreciation of possible environmental features.26 But better design could deal with these problems and reduce NIMBY (not in my backyard) anti-development responses that stymie housebuilding, particularly with the new government’s ambition to radically scale-up housing developments.27

Alongside the need for suitable, well-maintained infrastructure (roads, doctors, schools, shops, and other community facilities), improved landscaping and food growing need to feature strongly in political and public debate around managing the requirements for new development. Emboldened policy initiatives, shifting public attitudes and strong civic leadership are key. Improved building types, estate layouts, densities and locations are all important. Inspiration can be taken from an array of different green champions. Elsewhere, our recent research28 points to possible options for change, carrying the potential of scaling up innovative urban greening. Instead of expanses of impervious hard surfaces, vegetation could provide permeable options; a wider roll-out of green roofs could be encouraged on flat-roofed structures,

such as garages, parking and/or common areas. Where feasible, timber, concrete and wooden fences could be replaced by hedges using native, fruit-bearing mixed species shrubs and/or trees, encouraging the movement of animals and invertebrates, while improving the nutrient cycle. These healthy hedgerows can provide shelter for wildlife, while protecting the soil and contributing to flood management. This could include productive edible hedges with sloes, elders, damsons, apples and similar species. New hedgerows connect with existing ones, while rear garden hedges combine to create new green networks, as imagined below.

More ambitiously, new developments might centre around working farms and/or inclusive local growing spaces. There is precedent here, too. These ambitions resonate with earlier suburban ideals seen in many countries for housing to be arranged around communal green spaces – sometimes productive ones.29 Recognising the significance of the countryside spaces and natural systems is important here, rather than focusing on the layout of buildings, roads, and infrastructure, and the displacement or management of protected/marketable species. Such thinking would help to build sustainable and resilient food networks across productive residential schemes, embedding food systems planning into new and existing (sub)urban landscapes.

© David Adams

New layouts could centre on farm production and/or gardening activity, with varied land uses, including fields and infrastructure set aside for growing. Early responsibility for designs could form part of the landscape plan and contract of works agreed by the developer, landowner, local authority and relevant contractors. Other options could include developer contributions and/or service charges for planting, installation and aftercare arrangements. Service charges could be paid by residents to those property management companies that often maintain communal areas and shared services on new properties. There is also an opportunity here to partner with organisations, such as community interest companies and social enterprises (see, for example, Manchester Urban Diggers30), who could co-ordinate the day-to-day operations of such spaces.

This holds the obvious potential for the creation of sustainably designed buildings, fostering a sense of ownership and empowerment among residents in maintaining these green spaces. Underpinned by effective planning frameworks, political will and public support, these productive schemes would be capable of delivering environmental public goods; these approaches hold the potential to serve local and wider markets. This would reduce reliance on global supply chains, while boosting resilience to unexpected events, food price shocks and socio-economic/political disruptions, as illustrated below. They would become embedded in wider initiatives to identify suitable official and unsanctioned growing spaces. This could involve an analysis of existing urban sites capable of supporting agricultural production (part 1 of the image overleaf); the building of new edge-of-settlement sites (part 2) (these should have the capacity to grow food and support the main settlement, while foodstuffs could be ‘exported’ to nearby urban areas and beyond) and this could result in a network of interconnected food-growing urban areas (part 3).

The kind of model discussed here may not necessarily result in the efficient delivery of high volume housing to satisfy the needs of politicians, investors, developers and some potential occupiers. Some residents may not wish to be associated with food production and the potentially unsettling sights, smells and sounds of agriculture. Potential investors may also be discouraged by the lifestyles promoted in such models; and some developers would be reluctant because it diverges too far from established modes of practice and may therefore risk profitability. Inventive, co-operative ownership models that help maintain the ecologically-minded ethos may also be needed.

Arguably the most politically palatable and expedient model could involve the use of stronger planning instruments built around a stronger community buy-in, and the design and application of criteria can be created relating to scale, contribution to housing need, local support, commitment to quality, and consideration of infrastructure. Examples of such developments do exist elsewhere in parts of the US, northern Europe and elsewhere. There is still much to learn from urban food-growing schemes and greenspaces already embedded into residential designs. There are wider messages here. Planning has a vital role to address the challenges stemming from shifting climates, and the loss of nature. The initiatives outlined in this paper should give hope. Building sustainable homes, bringing together commercial property, the public realm and community assets that build and sustain authentic places are necessary and achievable. The design briefly outlined in this article and discussed at length elsewhere would maintain and protect biodiversity, establish a deeper human connection with local history, culture and ecology, and encourage forms of residential development centred around existing and/or improved agricultural initiatives.

Arguably the most politically palatable and expedient model could involve the use of stronger planning instruments built around a stronger community buy-in

Dr David Adams is a Lecturer in Urban Planning at the University of Birmingham. Prof. Peter Larkham is a Professor of Planning at Birmingham City University. Prof. Michael Hardman is a Professor of Urban Sustainability at the University of Salford. Rob Lammond is Head of Strategy and Analysis at the West Midlands Combined Authority. All views expressed are personal.

Notes

1 Global Land Outlook Second Edition: Land Restoration for Recovery and Resilience. United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification, Bonn, 2022. https://drive.google.com/ file/d/1NfxqrezhaB30eh1FUPrXpka4-SQAjBWp/view?pli=1

2 P Jones: ‘Tackling the nature crisis in the UK’. Town & Country Planning, 2023, Vol. 92(6), Nov-Dec., 419-423

3 V Griffiths: ‘The connection between the climate and nature crises’. Blog. Environment Agency, 3 Nov. 2021. https://environmentagency.blog.gov. uk/2021/11/03/the-connection-between-the-climate-and-nature-crises/

4 State of Nature 2023. State of Nature Partnership, Sep. 2023. https:// stateofnature.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/TP25999-State-ofNature-main-report_2023_FULL-DOC-v12.pdf /

5 See: https://stateofnature.org.uk/

6 F Kleinschroth, S Savilaakso, I Kowarik, PJ Martinez, Y Chang, K Jakstis, J Schneider, LK Fischer: ‘Global disparities in urban green space use during the COVID-19 pandemic from a systematic review’. Nature Cities, 2024. Vol. 1, 136-149. Full text available at: https://www.nature.com/ articles/s44284-023-00020-6

7 ‘Natural England unveils new Green Infrastructure Framework’. Press release, Natural England, 2 Feb. 2023. https://www.gov.uk/government/ news/natural-england-unveils-new-green-infrastructure-framework

8 ‘Urban green spaces raise nearby house prices by an average of £2,500’. Webpage. Office for National Statistics, 14 Oct. 2019. https://www.ons. gov.uk/economy/environmentalaccounts/ articles/ urbangreenspacesraisenearby housepricesbyanaverageof2500/2019-10-14

9 ‘Register of decisions of playing field land disposals’. Webpage. Department for Education. 16 Apr. 2024. https://www.gov.uk/government/ publications/school-land-decisions-about-disposals/decisions-on-thedisposal-of-school-land

10 ‘Local government budget setting surveys 2024/25’. Webpage. Local Government Association. 28 Feb. 2024. https://www.local.gov.uk/ publications/local-government-budget-setting-surveys-202425

11 Oral evidence: Urban green spaces. HC 164. Environment, Food and Rural Affairs Committee. 5 Dec. 2023. https://committees.parliament.uk/ oralevidence/13954/pdf/

12 H Horton, P Duncan, Z Hunter-Green, B van der Zee, A Gregory: ‘Revealed: students at top private schools have 10 times more green space than state pupils’. Webpage. The Guardian, 16 Jun. 2024. https:// www.theguardian.com/environment/article/2024/jun/16/revealed-privateschools-have-10-times-more-green-space-than-state-schools

13 ‘Understanding biodiversity net gain’. Online guidance. Defra, 22 Feb. 2024. https://www.gov.uk/guidance/understanding-biodiversity-net-gain

14 Social Farms & Gardens. Website. 2024. https://www.farmgarden.org.uk/

15 sow the city. Website. 2020. https://www.sowthecity.org/

16 Carrot City: Designing for Urban Agriculture. Website. 2017. https://www. torontomu.ca/carrotcity/

17 West Midlands Natural Environment Plan: 2021–2026 – Protecting, restoring and enhancing our region’s natural environment. West Midlands Combined Authority, Sep. 2021. https://www.wmca.org.uk/ media/5102/natural-environment-plan.pdf

18 Y Harada, T Whitlow: ‘Urban Rooftop Agriculture: Challenges to Science and Practice’. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 2020, Vol. 4(76), 1-8. Full text available at: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/sustainablefood-systems/articles/10.3389/fsufs.2020.00076/full

19 M Hare, A Peña del Valle Isla: ‘Urban foraging, resilience and food provisioning services provided by edible plants in interstitial urban spaces in Mexico City’. Local Environment, 30 Jun. 2021, Vol. 26(7), 825–846. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/ pdf/10.1080/13549839.2021.1922998?casa_token=hQR13WR33m0AAAAA: 6wOrrgavBxHeWeSHeCDgtMTBWDRtSww9NWxsVt3qR-G5UCcaWgCKcl kLYtrObYSQstdlAeXqqJbRBA

20 A Natural Health Service: Improving lives and saving money. The Royal Society of Wildlife Trusts, 2023. https://www.wildlifetrusts.org/sites/ default/files/2023-07/23JUN_Health_Report_Summary_FINAL.pdf

21 ‘Bringing orchards into the heart of urban communities’. Webpage. The Orchard Project. https://www.theorchardproject.org.uk/

22 City of Trees. Website. 2024. https://www.cityoftrees.org.uk/

23 Martineau Gardens. Website. https://martineau-gardens.org.uk/about-us/

24 ‘House building in England’. Webpage. Local Government Association. https://www.local.gov.uk/topics/housing-and-planning/house-buildingengland

25 A Reiter, C Murray, J Oliver: ‘How many homes does England really need to build?’. Financial Times, 21 Feb. 2024 (subscription required). https:// www.ft.com/content/32846f68-52fd-40e1-9328-0fe6bb3b9c19

26 Lord Taylor of Goss Moor, S Essex, O Wilson: ‘Solving the housing market crisis in England and Wales: from New Towns to garden communities’. Geography, 2022, Vol. 107(1), 4-13. https://www. tandfonline.com/ doi/full/10.1080/00167487.2022.2019492?casa_ token=P1QLSggP6L8AAAAA%3AbXFso8d82AdFB0 q7-83CI0cpZ0mYn92 4994SRS7HHz1rtHcHuLZ2JCz-UmBBBUWarrXpNBHeaajI6w

27 T O’Grady: NIMBYism as Place-Protective Action: The Politics of Housebuilding. 29 Sep. 2020. Full text available at: https://files.osf.io/v1/resources/d6pzy/providers/osfstorage/ 5f7370d268d85003b88a45e5?action=download&direct&version=2

28 D Adams, PJ Larkham, M Hardman: ‘Edible Garden Cities: Rethinking Boundaries and Integrating Hedges into Scalable Urban Food Systems’. Land, 12 Oct. 2023, Vol. 12(10), 1915. Full text available at: https://www. mdpi.com/2073-445X/12/10/1915

29 D Nichols, R Freestone: Community green: rediscovering the enclosed spaces of the garden suburb tradition. Routledge, 2024

30 Urban Diggers website available here: https://www.wearemud.org/

Throughout our working lives, most of us in the UK contribute to pension savings through an employer’s workplace pension scheme and, in parallel, make national insurance contributions towards our state pension. It’s just something that we do, and as employees, we expect these deductions to be taken from our earnings so that we can have some retirement income when we get older. As far as the state pension is concerned, self-employed people are also required to do this.

In the post-Second World War years, a part of these pension funds was invested in new shopping centres and other commercial development, while the government invested in council housing and new and expanded settlements. Replacing bombed-out homes and slum clearance were national priorities. Since the 1980s, however, state investment in social housing of most types has fallen sharply. Right to Buy was first considered by Labour governments but only became a firm

policy when the Conservative government introduced the Housing Act 1980. This led to the substantial depletion of the UK’s social housing stock. By 1995, some two million councilowned homes had been sold. In 2022, then prime minister Boris Johnson extended the Right to Buy scheme to up to 2.5 million housing association tenants.1

With demand for more homes remaining strong for the foreseeable future, could pension funds invest more in the new construction and renovation of affordable housing stock? Could the rapidly growing auto-enrolment funds, whose main pension savers are low- to moderate-income earners, become more proactive in allocating a small but visible proportion of their funds to affordable housing proposals?

The UK government’s Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government defines affordable housing as ‘homes for sale or rent … for people whose needs are not met by the private market’.2 Affordable housing is a key element of the

Could pension funds invest more to boost affordable housing?

government’s plan to end the housing crisis, tackle homelessness, and offer aspiring homeowners a step-up onto the housing ladder. Within this frame of reference, institutional investors can invest a small proportion of their funds in such schemes. Such activities are different from the direct mortgage offers of retail banks and building societies to householders, which are covered by other regulatory lending controls.

Low- to moderate-income households find it much harder to build up big enough savings for mortgage deposits and remain longer or permanently in rented accommodation. Many of these are in the privately rented sector, where security of tenure can be uncertain, property maintenance poor, and rents high relative to available income. Some 4.6 million households3 live in privately rented properties – approximately 19% of all households in England. London has a higher proportion of private renters (29%) compared with the rest of England (17%). This has affected many, particularly those within the so-called millennial, Gen Z, and, in planning cycle terms (and soon in housing development cycle terms), the upcoming Alpha generations.Affordable housing schemes tend to offer improved security of tenure, better property maintenance, improved affordability and sometimes the opportunity for occupants to take equity shares and eventually the option of a full mortgage.

Contributing to workplace pension saving schemes is a current disposable income sacrifice that leads to longer-term retirement income benefits. Most workplace pension savers accept and trust that their contributions are being invested well and that their savings pots will grow and appreciate. For most savers, this happens in the background through passive awareness and trust. The pensions industry calls this inertia. What if the auto enrolment savers’ fund managers could convert some of this inertia into ‘engagement’, albeit indirect, by providing opportunities for more of these savers to become affordable housing occupants? In this way, through investment circularity, pension savings contributors could indirectly consume part of their pension wealth before they start to draw down their pension pots in later life.

Since their introduction in 2012, AE (auto enrolment) pension savings schemes have increased the proportion of employees paying into workplace saving schemes from around 30% in 2011 to approaching 79% by 2021.3 The number of employees currently registered within an auto enrolment scheme is more than 11 million.2 Auto enrolment pension savings under management are around £85 billion.3 Within the next 10 years, the wider UK-defined contributions pensions saving scheme market, which includes AE schemes, could have over £1 trillion in assets under management. Then there are public sector schemes, such as the Local Government Pension Scheme, which had more than £260 billion in assets under management in 2023. This is projected to grow to some £500 billion within 10 years. These schemes have many savings members within the low- to moderate-income bands who struggle to gain a place on the owner-occupation ladder.

In this way, with the interplay of other factors, such as lower interest rates and more recently proposed planning reforms, could affordable housing supply be boosted more significantly within the next five to seven years? Pension funds and their institutional investors do not necessarily need to seek out individual housing associations or other property developers and then create and manage loan packages. There are established institutional mechanisms, such as The Housing Finance Corporation (THFC),4 that repackage pension fund assets into loan instruments for the affordable housing sector. THFC also specialises in creating loan products to retrofit existing affordable housing stock, improving energy efficiency and other protections to reduce the impact of climate change. For institutional investors and their pension savers, receiving income streams from such developments is a positive and circular economy benefit, which can help improve the wellbeing, resilience and financial stability of harder-pressed households.

Could pension funds invest more to boost affordable housing?

Over the coming years, further AE scheme reforms are likely to be introduced to include lower income wage earners. This will make enrolment easier for younger workers, those working for several employers, gig-economy workers, and (increasingly) self-employed workers who haven’t set up their own companies. Many of these earners would welcome opportunities to access affordable housing at some stage(s) of their lives.

All of this strengthens the case for a greater focus by UK pension funds, particularly the auto enrolment sector, upon making more of their funds available for affordable housing schemes. The question is: what percentage of their funds can be directed towards such activities while mitigating risks and ensuring adequate returns for pension funds, particularly auto enrolment schemes, with their inclusive, saver community focus?

Tony Zeilinger was an appointee to the first two Nest Members’ Panels between 2012 and 2018. All views expressed are personal.

Editor’s note

The Members’ Panels allow Nest to take into account the views of its members. Nest is the National Employment Savings Trust, the UK’s largest and partly publicly funded auto enrolment pension savings scheme.

Notes

1 ‘Right to buy extension to make home ownership possible for millions more people’. Webpage. Prime Minister’s Office, 10 Downing Street, 9 Jun. 2022. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/right-to-buyextension-to-make-home-ownership-possible-for-millions-more-people

2 Fact Sheet 9: What is affordable housing? Guidance. Homes England, 2 Nov. 2023. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/new-homesfact-sheet-9-what-is-affordable-housing/fact-sheet-9-what-is-affordablehousing

3 ‘Employee workplace pensions in the UK:2021 provisional and 2020 final results’. Office for National Statistics. 20 April 2021. https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/ workplacepensions/bulletins/ annualsurveyofhoursandearningspensiontables/ 2021provisionaland2020finalresults

4 The Housing Finance Corporation. Website. https://www.thfcorp.com/

© Dryad Networks

Carsten Brinkschulte explains how artificial intelligence is helping to protect the world’s forests from wildfires

Currently, nearly every industry is exploring the use of artificial intelligence (AI). Wildfire detection is no different. Finding ways to detect and tackle wildfires is incredibly important. Trees play a vital role in absorbing carbon dioxide, arguably making them the most effective force to halt or reverse climate change effects. Wildfires release huge amounts of carbon dioxide and other harmful greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. As carbon dioxide (CO2) is released, temperatures rise, and the risk and frequency of wildfires grows. Billions of dollars a year are spent on fighting wildfires, protecting trees, natural habitats, infrastructure and, of course, people. By using AI to enhance wildfire detection, we can significantly lower wildfire risks by enabling us to detect and extinguish them in their early stages, before they have a chance to spread out of control. By reducing reaction time, we can not only mitigate the risk, but also save costs: extinguishing a small fire requires dramatically fewer resources than trying to contain a megafire.

If we want to counter the growing threat of wildfires with the help of technology, we need to look at different aspects of interacting with wildfires. Firstly, predicting where wildfires will occur can help to position response resources and raise awareness of the increased risk. Secondly, when a fire starts, alerting the fire fighters as soon as possible increases the chance of extinguishing it before it spreads out of control. Lastly, using technology, we could aim to improve efficiency or one day even automate the response to wildfires.

Calculating the risk can help us achieve reasonable prediction accuracy

Although predicting the exact start location of a wildfire is challenging, calculating the risk can help us achieve reasonable prediction accuracy. Currently, fire risk is determined predominantly based on weather information obtained from satellites and, where available, enhanced with data from local weather stations. Fire risk is then calculated on a rather coarse scale (e.g. with 1 km² resolution) and published on news channels to alert the public of a heightened threat by wildfires. More advanced calculations are based on VPD (vapour pressure deficit), which is the difference between the amount of moisture that’s actually in the air and the amount of moisture that air could hold at saturation. From a wildfire perspective, consistently elevated VPD means that ecosystems can more easily ignite and spread fire, leading to the larger, higherseverity wildfires.

Calculating fire risk levels by taking into account various sources of information (satellite, weather stations and potentially, local sensors) and then mapping the risk on a fine-grained scale is a complex and tedious task, which can be automated and enhanced in accuracy and resolution with the help of AI. Of course, adding more fine-grained information such as soil and air moisture levels measured by sensors embedded in the forest would help to take into account the microclimate of the forest. In the future, we might be able to push this even further if we could find a technical solution for measuring the fuel moisture (grass and needles), rather than just the soil moisture.

How does AI-enhanced fire detection work?

Unlike traditional methods of fire detection that rely on human observation, AI-based wildfire detection works by leveraging machine learning algorithms to analyse data from various sensors and identify patterns that indicate the presence of a fire.

The machine learning models used for fire detection are trained on large datasets that include both fire and non-fire scenarios to accurately identify fires based on the characteristics of smoke and other factors. The models are also rigorously trained to reduce the prevalence of false positive fire alerts.

The role of artificial intelligence in wildfire prevention

Improving camera detection with AI

Camera detection works by using a camera on a watchtower overlooking a large area of forest. Traditionally, these watchtowers were occupied by people keeping a lookout, but they are increasingly being monitored by cameras. In the context of wildfire detection, cameras are used to capture images of the forest above the canopy and analyse them for the presence of smoke. However, this method faces several challenges, one of the main ones being the occurrence of false positives. Agricultural machinery might throw up dust during field ploughing, for example, and even wind farms can be mistaken for smoke plumes from a large distance. Weather conditions, such as haze or fog, can also make it difficult for cameras to accurately identify smoke, and the time of day, particularly dawn, dusk and night-time, can affect the visibility of smoke in images.

By continuing to improve machine learning algorithms via increased amounts of data, AI-enabled camera detection can reduce false positives and improve the accuracy of smoke detection. However, a key restriction remains that cameras typically cannot see what’s happening under the tree canopy. This is an important limitation, as most human-induced fires start at the forest floor and smoke only breaches the canopy once the fire underneath has already grown quite large. The process can take up to several hours from ignition,

Cameras are used to capture images of the forest above the canopy and analyse them for the presence of smoke

in particular if the fire starts as a smouldering fire, for example as a result of a discarded cigarette. While infrared technology could help to complement the shortcomings of optical cameras, the resolution of these camera systems is typically too low to provide usable images for detecting fires at a great distance.