2022, Issue 1

1 Art Matters

2

From the Director’s Desk

Insights and remarks from Adam Levine, Edward Drummond and Florence Scott Libbey Director and CEO

6

Inside the Issue

A reflection on the new direction of Art Matters

8

Curatorial Roundtable

Thought-provoking conversation around the vision for the TMA collection

14

In the Studio: Tiff Massey

A studio visit with TMA’s 51st GAPP artist-in-residence

20 Georgia Welles

A tribute to one of Toledo’s most generous and influential arts advocates

22

A Seat at the Table: The Museum Café’s History in Photos

Pictorial moments of time-travel through the TMA archives

26 The Material Curiosity of Matt Wedel

An in-depth look at the artist’s boundary-pushing ceramics, on view at TMA this fall 32

On View & Upcoming 34

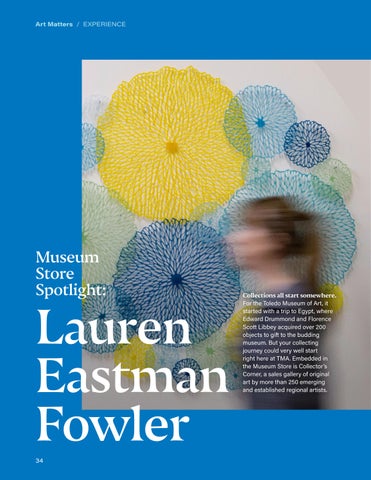

Museum Store Spotlight: Lauren Eastman Fowler

A profile of one of the many artists featured in the Collector’s Corner of the Museum Store

36 Classes & Workshops

1Toledo Museum of Art

ThinkDiscoverExperience

From Director’stheDesk

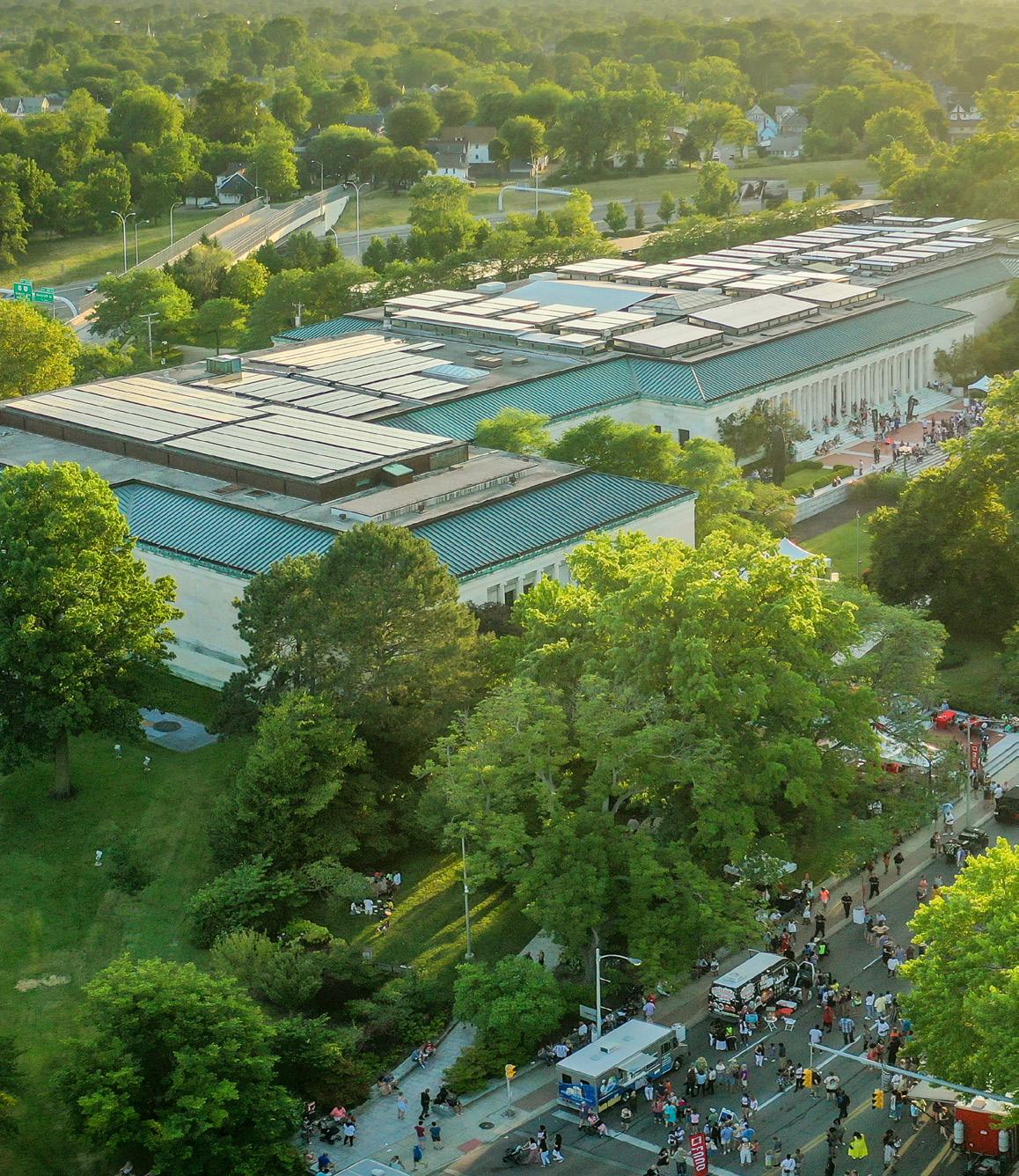

I hope this has been an energizing summer for you. At the Toledo Museum of Art (TMA) we’ve used this time advancing our strategic plan, which has included refresh ing the Art Matters publication you have before you. I hope you enjoy what we have created.

The past few months felt as if they moved at warp speed here at the Museum, and in my conversations with many of you, you have expressed similar sentiments. The feeling of time’s acceleration is, I think, a reflection of people

Adam Levine Edward Drummond and Florence Scott Libbey Director and CEO all,

2 Art Matters / INTRODUCTION

Dear

moving around more freely these past few months than over the past two years. Trips deferred have been taken. Friends and family seen only over Zoom for two years are being hugged again. COVID will remain a presence in our lives, to be sure, but people are beginning to come together once more.

As people reconvene, I have been struck by the fact that in virtually every space I find myself, someone tells me how proud they are that TMA is “world class.” When I go out to meet and speak with local groups—whether at Rotary clubs, neighborhood meetings, or over meals—there is an obvious pride in this Museum for its outstanding and differentiated collection. I also have been inspired by the number of times people reference formative experiences with the

Museum throughout their lives, from childhood into adulthood. It is incredibly meaningful to play a part in this community’s growth and exciting to see the ways that the Museum is growing itself.

Indeed, it is impossible to talk about the impact of COVID without also acknowledging the ways in which we have grown through this painful and disruptive experience. These years have been a challenge, but one from which we have learned, adapted, and evolved. Institutions are like people in this way—at TMA, we have grown considerably these past few years, adapting to the realities of COVID but also evolving to better serve our audiences in the 21st century.

Growth is natural, but it is also true that, like people, institutions have

DNA—fundamental characteristics that remain constant no matter how an institution evolves. At TMA, that DNA includes a steadfast commitment to quality. Artistic excellence is a bedrock principle of all we do here, and it is exciting to see our curatorial and collections team seeking quality more broadly. Whether in our acquisition of a 6th century silver plate from ancient Persia or our acquisition of artworks by southern African American artists from the Souls Grown Deep Foundation, superlative artworks are produced in every culture at every moment in human history. Growth at TMA in the realm of quality means that we will continue to pursue remarkable works across time and space, making our collection—already one of the greatest in the country— continuously better.

This edition of Art Matters, with its refreshed format focused on deeper coverage of our thinking and institutional decision-making, in many ways illustrates how we have grown to get to where we are now. The stories within leave me feeling excited about TMA’s future and the possibilities for this institution and our community. They also demonstrate the impact of your support—everything captured in these pages is made possible by you, our members and supporters. Our commitment to quality and our culture of belonging emerge because of and to serve you. You have my deepest gratitude.

3Toledo Museum of Art

AdamSincerely,Levine

4 Art Matters / THINK Think

5Toledo Museum of Art Think

6 Art Matters / THINK

Inside the Issue

The Matter of Matters

Since its very first issue in summer 2004, this publication has taken many forms. For this newest iteration, we looked to its title for inspiration.

“Matter” as a noun can mean a subject or a topic, and we will assuredly be discussing matters of art. However, “matter” as a verb signifies that something has importance, weight, and value. It is in considering matters as a verb that we identified a statement we want to make as a Museum with this publication and beyond, without ambiguity.

Art Matters.

It’s something we believe passionately as a staff. It drives us each day as we fulfill the various roles it takes to ensure everyone in Toledo and our surrounding communities can enjoy a worldclass art museum. And we hope that this publication will be one of many ways we make this belief in the power of art visible.

Our mission is to integrate art into the lives of people, and when this is done in a meaningful way, it can be transformative. Art can broaden how we see the world, foster a deeper understanding of perspectives outside of our own, and inspire awe and curiosity. Whether it’s within the walls of

the Museum or in the pages of this publication, we aim to provide experiences with art that are important and relevant to you. Art brings us together, and together we can build a more vibrant, flourishing Toledo.

This next chapter of the publication is structured around three actions— think, discover, and experience. We’ve carefully crafted each article to help you think in new ways, discover new points of access, and open doors to new experiences—all through the lens of art.

From a roundtable with our curatorial team and a studio visit with this past spring’s Guest Artist Pavilion Project (GAPP) artistin-residence Tiff Massey to a pictorial account of the museum café’s history, this issue’s offerings stem from research, exploration, and conversation. Art Matters is ultimately a vehicle to share stories that connect you with artists, ideas, communities, and all of us here at the Toledo Museum of Art. With each piece, we hope you’ll feel your own connection to our source of inspiration: the steadfast belief that art matters.

7Toledo Museum of Art

A RoundtableCuratorial

Implementing a Collecting Strategy befitting the Model Museum

8 Art Matters / THINK

The Toledo Museum of Art’s curatorial team sat down with Director Adam Levine to discuss their work with the Museum’s growing collection. As they prepare for a major reinstallation of all TMA’s collection galleries in the coming years, they discuss the joys and challenges of rethinking the stories we tell.

Pictured below (left to right):

Jessica Hong, Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art

Erin Corrales-Diaz, Curator of American Art

Robert Schindler, William Hutton Curator of European Art

Diane Wright, Senior Curator of Glass and Contemporary Craft

Adam Levine It’s great to see everyone. I wanted to get us started by talking through what brought you here to TMA. This team has grown tremendously, with both Erin and Robert joining us within the past 12 months.

Erin Corrales-Diaz Well, I can kick things off by talking about what brought me here to TMA in 2021. There are many reasons, but the one that I think really stands out to me is the structure of the curatorial department. In other institutions I’ve been to—I think this is still quite the tradition—folks are very siloed in terms of their media. Here I get to look at many different things, beyond just painting and sculpture, which allows me to extract interesting and distinct stories that haven’t been told in the history of American art before.

Adam Do you think that’s a turn the field is taking in general?

Erin I do think it’s a turn that the field is taking, but TMA is really ahead of that. Like I said, I haven’t been at places that have that sort of curatorial structure. I thought to myself, I want to be at a place that is thinking like that.

Robert Schindler I think it’s helpful that we have a small curatorial team here. It’s growing, but it’s still a relatively small group of people, which makes collaboration and communication much easier than if you have a curatorial staff of twenty-plus. Although what attracted me initially was something entirely different. Toledo, for somebody working in the field of European art, just has a spectacular collection. Working here only became more intriguing because of what TMA is trying to accomplish. There is such ambition, energy, and sense of direction here that is really intriguing to be part of.

Adam That is an interesting transition to both Diane and Jessica, because I think from a collection standpoint, Diane’s entry point would probably be like Robert’s, whereas for Jessica, she’s still very much building out the contemporary collection.

9Toledo Museum of Art

Diane Wright Yes, similar to the collection that attracted Robert, the glass collection here at Toledo is larger than life, so it’s always been on my radar. But I had other experiences working with remarkable glass collections and I wouldn’t have moved here exclusively for that. It was also the opportunity, kind of along the lines of what Erin was saying, to work with more in the collection. I was ready to branch out and to do more with the craft field with mediums like ceramics, textiles, and jewelry. I wanted to think more broadly and expansively.

Jessica Hong And then for myself, one of many things I was drawn to is the deep community investment in the institution, and the institution’s commitment to access in return. Admission is free and we have always been free— that’s novel for a lot of museums in the country. How the museum was dynamically positioning itself was also a draw. It’s not in this fixed, permanent state, but instead it’s liv ing and evolving continuously. This of course has its challenges, but it also allows for greater possibility in helping shape the direction that the museum can potentially go.

Diane Shaping that direction was important for me as well. During my interview process, I would ask very specific questions and I would get this answer that at the time felt kind of vague, but now feels like what drew me into this role. It was this mindset of “give us your biggest idea and we’ll see what we can do with it.” That’s very much the culture here—we can put an idea out there and see what we can do.

Robert I felt that, too. At my first check-in with Adam, he asked me, “what can we do better?” That’s really encouraging for someone who’s coming in with fresh eyes and ideas, especially regarding a monumental task like broadening the narrative of art history. I don’t think there’s any institution in the country that knows exactly how to do it, but we’re inching our way towards an understanding of what exactly we mean by this as a group.

Jessica When I think of broadening the narrative, I often want to say narratives. There’s a multiplicity of narratives across time periods, cultural contexts, geographies, and even media. It allows us to celebrate the multifaceted aspects of these narratives and the ways they are always shifting. So maybe by not defining what broadening the narrative is in any finite way, there’s a lot of expansive possibilities there.

Diane I think if there was an easy definition to land on, everybody would be doing it.

Adam The ambiguity is in fact intentional here. Broadening the narrative lives within the museum as a policy, not as a procedure— how we broaden the narrative is for the curators to define—and we know there’s a real chance to be leaders in this project. We’ve already demonstrated that with the global view of our reinstalled Cloister. Our team has visited 108 museums in the past year, so there’s been an awful lot of looking. And if we’re observing that the field is trying to figure it out, there really is the opportunity for us to be a model.

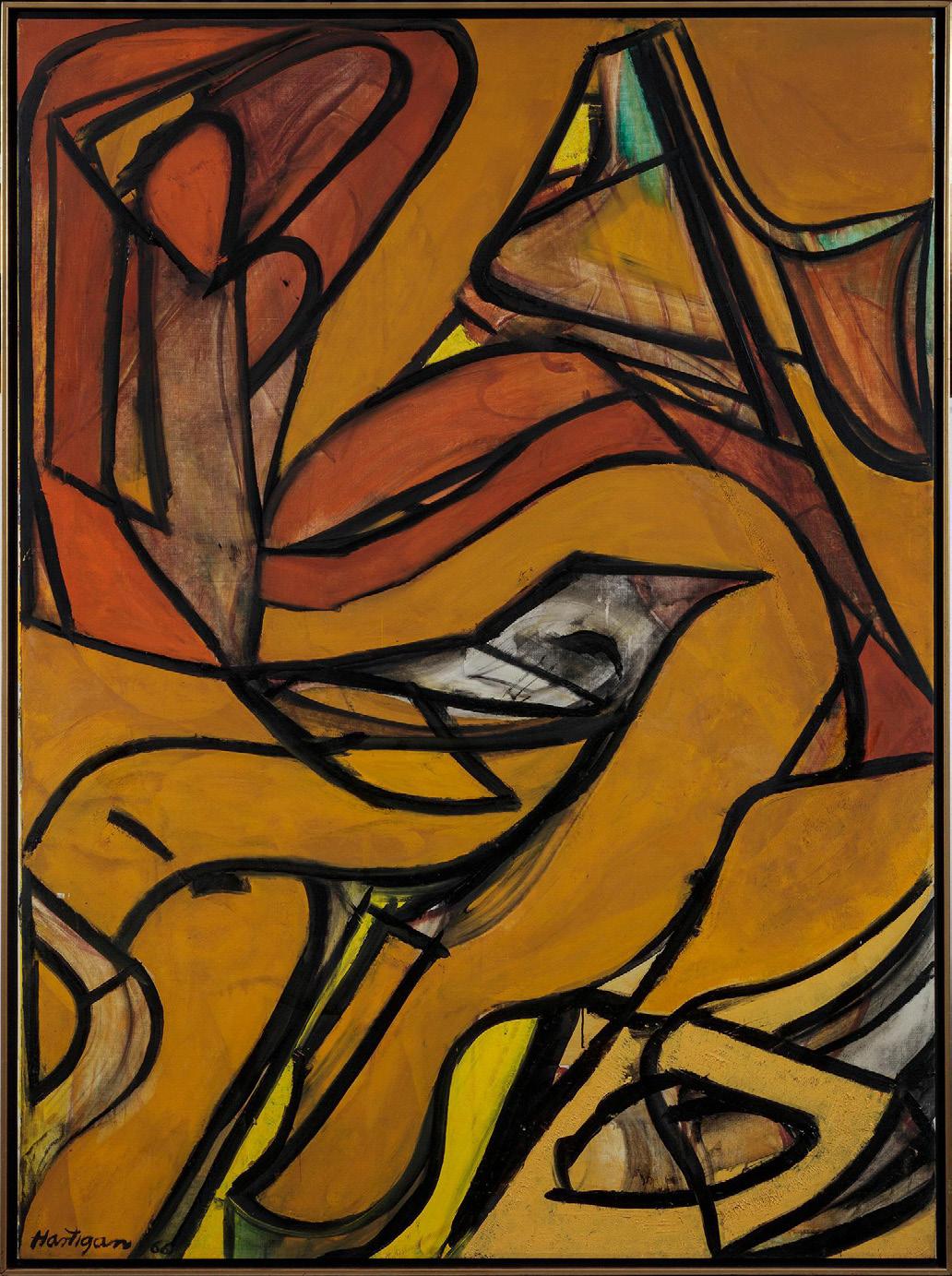

Grace Hartigan, Harvester, 1966, oil on canvas, Purchased with funds from the Libbey Endowment, Gift of Edward Drummond Libbey, 2022.23

On view: Gallery 5

10 Art Matters / THINK

Toledo Museum Art

Toledo Museum Art

11

of

On view: Gallery 7

Erin It’s also important to think about what it means in practice to expand narratives from a public standpoint. When I go into the American galleries here now, it’s only a limited sample of the art that exists. So to expand this, we can think about increasing representation in terms of geography, race, gender, but we can also think about the reinterpretation of objects. For example, we have a Paul Revere tankard. You could talk about Paul Revere in his workshop, or you could talk about the fact that silver came from the Peruvian Potosí mine, got made into coins which were then circulated throughout the world, which then got melted down and reformed by multiple hands in Boston to create this tankard that you now drink your beer from. Suddenly you’ve exposed a much wider narrative.

Adam I do want our visitors to know that they shouldn’t come to TMA and drink beer out of the tankard!

Erin Thankfully it’s in a vitrine!

Adam But that’s exactly it, Erin. It’s the difference between histories versus history. There are all these histories that aggregate up into history per se. The ability to take the same objects and leverage different dimensions of them, reconfiguring them to tell different histories, will fundamentally create a different overall history. We can have all sorts of pluralism within this. But people are going to interpret what this team does collectively as a single narrative. It’s our obligation to recognize that institutional power, but it’s also a huge oppor tunity to be a better model of how to wield it.

Zilia Sánchez, Sin título [Untitled], 1962/1990 (restored 1971), acrylic on stretched canvas, Purchased with funds from the Florence Scott Libbey, Bequest in Memory of her Father, Maurice A. Scott, 2022.10

12 Art Matters / THINK

Robert We’re really in the early stages of rethinking these histories as we prepare to reinstall the galleries in a few years. In my case for historical European works, there still is much to be learned. Erin mentioned the silver tankard—in the case of a piece of European furniture made of Ebony, for instance, it may not have occurred to me to think about where that material comes from and the histories that it implies. So I am developing new expertise and exploring new perspectives in order to look at many of the objects in our collection in different ways. There’s a certain humility to gain from it because it exposes my own blind spots.

Jessica In addition to the research, part of what I’ve been trying to do is experiment with gallery refreshes. As curators, we contextualize and recontextualize objects in our collection over time, and ask ourselves, how can we situate them in different ways in our gallery spaces? These smaller experiments have been critical, and I use the term experiment intentionally, as we start to gear up for the larger reinstallation to come.

Erin We’re also working on an interpretive strategy—interpretation is how we present information to the public. It’s exciting to take something like a museum label and rethink what more it could be beyond the basic information. What if we did something totally innovative? Just because something has always been done one way doesn’t necessarily mean it’s the best way.

Robert There’s an opportunity for more access points to informa tion, too. Through interpretation we can both provide answers but also ask questions.

Jessica And in addition to different forms interpretation, it’s important we ask ourselves whose voices we’re prioritizing. Working in the contemporary space, I try to prioritize the artist’s voice, but then build upon that to ensure the way a work can be interpreted is left open and allow for more voices. There’s a lot of entry points that the publics can engage with along with the artist’s intent. I think artists do understand that their work lives beyond themselves as it continues its journey through different contexts.

Diane Ultimately, these things contribute to a larger moment of self-reflection and criticality for us because we’re all looking at what we’re doing now, both at TMA and in the museum field, and figuring out how to better realize our potential for growth.

Robert This is challenging work, but I think it is important to say that I’m having fun in this process. I’m really enjoying what I’m doing, and I get the sense that’s shared amongst all of us. Not the least, we want TMA to be a place where visitors can feel the joy that we find in our work, and they can experience joy themselves.

Adam That’s the perfect note to end on, Robert. Two major barriers to museum visitation are a negative past experience and not feeling invited in the first place. So when we think of endeavors like reinstalling our galleries, that’s really what this is all about. A positive visitor experience will come from our ability to exhibit the greatest art from all over the world, developed by a team that truly enjoys what they do, in a space that intentionally welcomes everyone. These are the efforts that will get us where we want to be—the model museum for the 21st century. ■

On view: Gallery 4

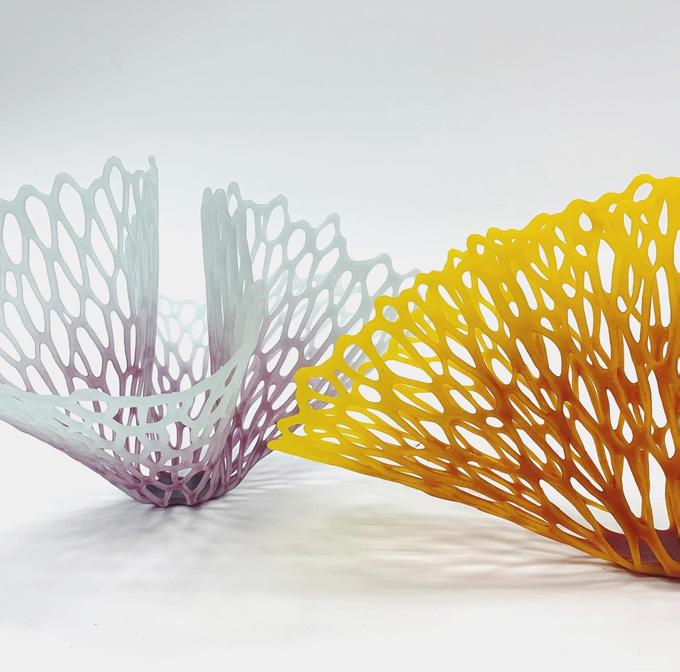

Nadège Desgenétez, Flow, Body Scape, 2016, glass, metal, Purchased with funds given by Rita Barbour Kern, and Gift of Richard C. and Betty G. Veler, by exchange, 2022.25

Nadège Desgenétez, Flow, Body Scape, 2016, glass, metal, Purchased with funds given by Rita Barbour Kern, and Gift of Richard C. and Betty G. Veler, by exchange, 2022.25

13Toledo Museum of Art

14 Art Matters / THINK In the Studio:Tiff Massey

We joined past Guest Artist Pavilion Project (GAPP) resident Tiff Massey in her Detroit studio to discuss her practice and what led her to experiment with glass.

Since its opening in 2006, the Toledo Museum of Art’s Glass Pavilion has uniquely combined its role as the home of one of the world’s great glass collections with its place as a working glass studio. The GAPP artist residency is part of the Museum’s efforts to support working artists and encourage them to explore the medium of glass without restriction. In April, Detroit-based interdisciplinary artist Tiff Massey joined us as the 51st GAPP artist in residence.

Massey’s work has been widely exhibited in national and international galleries and museums and garnered numerous awards, including a 2015 Kresge Arts in Detroit Fellowship, the 2019 Art Jewelry Forum Susan Beech Mid-Career Artist Grant, and the 2021 United States Fellowship in Craft.

Art Matters Could you tell us a little bit about your background as an artist and the path that got you to this point? Because we know it wasn’t linear.

Tiff Massey Not at all. So, I have to talk about high school here. I went to an all-girls Catholic school, and they had a jewelry class. That was the first time that I’d gotten an introduction to using a torch as a tool. I enjoyed it, but I had no idea that it would lead to anything. So, in college, I went and got a biology degree because I wanted to be a veterinarian. They had an art requirement to graduate, and I was like, oh, well they have jewelry for non-majors.

At first, it was just to break up the monotony of the biology and the chemistry classes. I was falling in love with the medium, but I wasn’t about to change my major. I graduated with my degree in 2005, but after that, I had to get back to art. So, I ended up at the Cranbrook Academy of Art to get my master’s.

That was the best program that I probably could have ever been in. The conversations I could have with other artists in my program were essentially the start of a lot of the patterns that emerge within

my own interdisciplinary practice. I make so many different things, and I’m not trying to limit myself to doing things one way.

And that’s very indicative to, like, how I grew up in Detroit. Like you don’t want to go out and some body’s got your same outfit on.

AM We’re glad you brought that up—the way your work is so rooted in that sort of uniqueness and self-expression. Could you talk further about the connection between what we choose to wear and identity in your work?

TM The Detroit state of mind is that you do want to be seen. All of those aesthetics that I see in the city, they scream in my work.

In terms of identity, there’s tons of identities that I am talking about in stories and narratives and histories. And they’re very much wrapped up into the diaspora because I’m not really interested in any other culture’s conversation. I’m really specific at this point who I’m designing for—who this conversation is for. It sucks to go into spaces where you don’t see any type of representation. So, when you see my work as a Black person, you’re going to be like, “Oh, hell yes! This is for me.” I am

15Toledo Museum of Art

Massey artist.thecourtesyImage

focusing on Black design, Black conversations, Black histories. But I know also what I am saying in my work about self-expression is cross-cultural.

AM Speaking of identity, we noticed the number of times you position yourself as a Detroiter. We were wondering if you could talk a little bit about place and the role it plays in your work.

TM I don’t think I could be anywhere else in the world doing what I’m doing. Detroit is a special place. I mean, you name it, it’s probably been invented here, right? Cars, techno, Motown, industry. I am very, very proud to be a Detroiter and half of it is because the whole world came from Detroit.

But the whole world also likes to talk about what’s going on in Detroit and have been very critical about things. So you kind of become an ambassador for Detroit speaking on the city’s behalf. We’re all so influenced by where we come from. If I didn’t grow up in Detroit and I didn’t see these people stunt ing on Sunday for church or at the club, I wouldn’t be making the same kind of work I’m making now.

AM: We’ve read about how you’ve gathered inspiration from 1980s hip-hop and jewelry, and in your dad’s interest in custom jewelry as well, as a way for him to show up and express himself in his community. What bridged the gap between this being part of your upbringing and something you wanted to explicitly bring to your art?

TM My father was one of my first style influences. The thing is, I didn’t even know I could be an artist when I was pursuing metalsmithing. It was fun using all the tools—especially the torch. At first, I just asked myself how I can adorn bodies specifically. I was only thinking about jewelry.

supposed to speak on behalf of all Black jewelers. It was like, because there aren’t enough opportunities in this world for Black jewelers, I’m the only one they know. But when I got this award, they gave me a platform, and I used that platform to repeat all those questions back to the audience so I wasn’t the only person going home with that experience. I told myself moving forward, we are going to talk about adornment in my way. I didn’t want to limit the work to being discussed in arenas where they want to have the same conversation with the same people.

AM And as you moved into this new art space, it seems like you became intrigued by large scale. You moved from something that we normally think of as small, something with which we adorn ourselves, and you’ve made it larger than life.

TM I was increasing scales of works while I was a student at Cranbrook, but I also wanted to take the wearability out of my work so I wouldn’t be called a jeweler. I experienced a lot of racism in the contemporary art jewelry world. In 2019, I was awarded the Art Jewelry Forum’s Susan Beech Grant, which is a very significant award in the jewelry world, and when I was doing a Q&A, I was consistently being asked questions that made me feel like I was

AM In talking about these sorts of experiences you’ve had, it is striking how these materials and objects that are so traditionally associated with conceptions of beauty, or things that we wear to make ourselves feel good and empowered, also become a means to address histories that are objectively not beautiful at all. They are actually very painful and complicated.

TM When I was at Cranbrook specifically, I knew I wanted to talk about the appropriation of the Black experience. I just didn’t know how to. I had to ask myself, what was the visual language that was going to match what I am investigating.

They wanna sing my song but they don’t wanna live it. That was the name of my first exhibition. What we wear can say a lot about how we feel, and I just want people to feel me—to see my experience. That’s why the jewelry is heavy. This life is heavy.

“”TheDetroit

state of mind is that you do want to be seen. All of those aesthetics that I see in the city, they scream in my work.

16 Art Matters / THINK

AM We want to start thinking about glass now and when it starts to come into play.

TM My first glass piece was Bitch, Don’t Touch My Hair!! I wanted it to be neon, and of course, neon is glass. So that was my first introduction.

My work often focuses on how Black women adorn themselves, and specially hair adornment. I knew I wanted to make beads on a large scale. I would always get my hair braided and I would put beads on the braids. I thought glass was

the perfect medium for this, and I wanted to experiment. That’s what led me to the GAPP residency.

AM So, the GAPP residency opened up this opportunity for experimentation and for you to expand your practice?

TM Exactly. Once I got to the residency, I went and got all kinds of sidetracked and made all this other work that had nothing to do with what I wanted to do, but it ended up being something completely unique that I want to keep working on.

AM It’s one of the things we’re proud of—being able to give artists the opportunity to explore freely during their time. We’re so glad you could discover something new about your practice, and we can’t wait to see where it goes. ■

Massey,Tiff Hair!!MyTouchDon’tBitch

17Toledo Museum of Art

Neon.2019,

18 Art Matters / DISCOVER Discover

19Toledo Museum of Art Discover

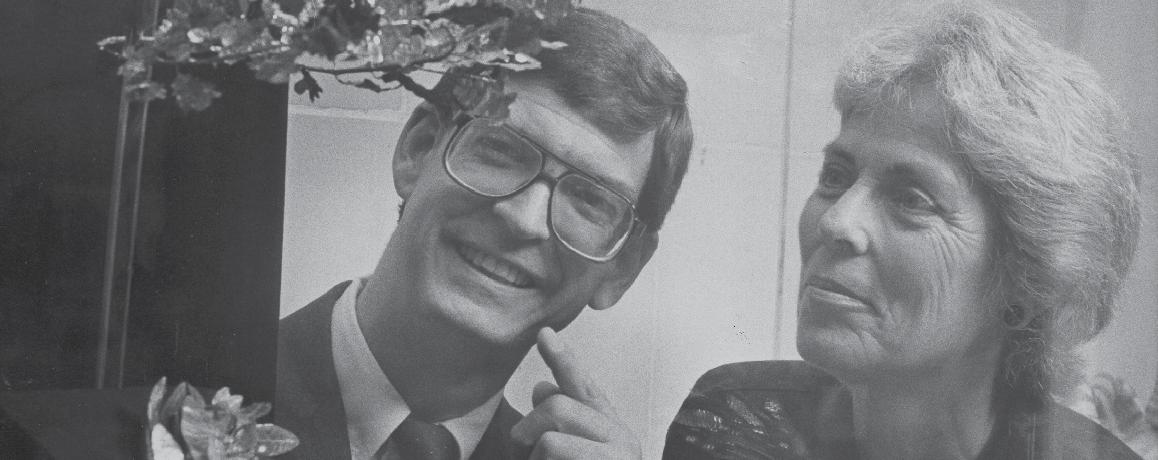

Georgia Welles

An Ongoing Legacy of Generosity

Kind, warm, passionate about the arts, and truly transformative for Toledo—that’s how those who know Georgia Welles describe her.

Welles is a longtime supporter of the Toledo Museum of Art. The generosity of Welles and her late husband, David, is so great that it rises to the level of the Museum’s founders, Edward Drummond and Florence Scott Libbey. Together, the Welles founded the sculpture garden; led the $60 million capital campaign to fund the construction of the Glass Pavilion; and started the Georgia Welles Apollo Society, a group of donors who annually pool their dues to purchase art for TMA’s collection. The group has purchased more than fifty works of art since its founding in 1986— acquisitions that would not have been possible without Georgia’s visionary efforts.

Georgia and David Welles both grew up with parents who deeply appreciated the arts. The couple began collecting art for themselves in the 1960s and developed an ex ceptional contemporary collection. In a 2006 interview with The Blade, Toledo’s local newspaper, Georgia

credited her collecting approach to “a gut feeling.” She likes artworks that make her “laugh or smile, that bring joy, [and] are interesting.”

Welles paired her gut feeling with her desire to gather works she felt could someday grow TMA’s collection. When purchasing art, she would often speak with experts in the field or the Museum director about what works met TMA’s qual ity standards. But over the years, she’s developed a skill for identi fying art that grows in value while nurturing relationships with leading international galleries and artists.

In May 2022, Welles promised a remarkable gift of more than seventy works of art to TMA from her personal collection, including pieces by Magdalena Abakanowicz, Richard Diebenkorn, Anish Kapoor, Martin Puryear, and Kara Walker.

“This generous gift from Georgia Welles is transformative for our collection,” said Adam Levine, TMA’s Edward Drummond and Florence Scott Libbey director. “By opening up her collection to our curators and allowing us to select so many exceptional works of art

that fill gaps in our collection, she has enabled us to take a crucial step toward our collecting goals.”

After Georgia Welles’ children identified the works they would like to retain, the Museum’s curators chose art from the Welles collection that support TMA’s strategic initiative to broaden the narrative of art history. Among the works gifted are a major painting from Richard Diebenkorn’s celebrated Ocean Park series, Ocean Park No. 32 (1970); Roxy Paine’s large-scale outdoor sculpture, Untitled Tree [Ohio] (2003); and Martin Puryear’s Bound Cone (1973).

The works, part of Georgia’s estate, will be transferred posthumously. Welles’ lifelong commitment to TMA has contributed substantially to a world-renowned collection that visitors will be able to enjoy for generations to come.

curatorTMApastwithWellesGeorgiaarchives.TMAtheCourtesyLuckner.Kurt

20 Art Matters / DISCOVER

Toledo Museum of Art

Roxy Paine, Untitled Tree [Ohio], 2003, stainless steel and stained glass. Photo: Natalie Tranelli

Martin Puryear, Bound Cone, 1973, oak and rope. Photo: Natalie Tranelli

Toledo Museum of Art

Roxy Paine, Untitled Tree [Ohio], 2003, stainless steel and stained glass. Photo: Natalie Tranelli

Martin Puryear, Bound Cone, 1973, oak and rope. Photo: Natalie Tranelli

21

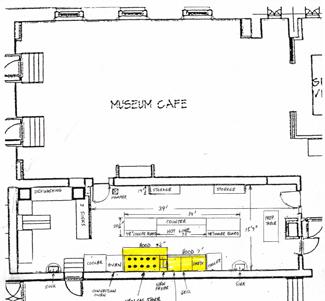

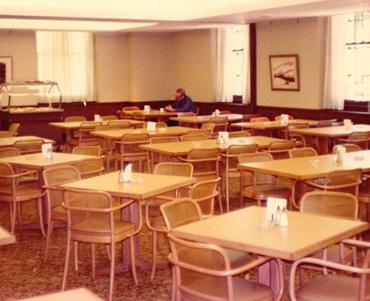

A Seat at the Table

The Museum Café’s History in Photos

If you’ve spent a long day perusing the galleries of the Toledo Museum of Art, it’s likely that you’ve stopped midday to enjoy lunch at the café. But as is the case with many spaces in TMA’s century-old building, the café has looked very different over the years.

Thanks to Museum Archivist Julie McMaster, we can peek into how the café has transformed from multi-purpose dining rooms to cafeteria-style hall to the sunny, full-service restaurant we know today.

22 Art Matters / DISCOVER

1930s

In 1933, when two wings were added to the building, the need for classroom space in the center core of the building lessened. With this newly available space, roughly located where the café stands now, multiple dining rooms and a kitchen existed. In one private dining room, staff had a place to eat lunch. A designated lunchroom also existed for school children to eat during their visit. And finally, a formal dining room was available for dinners with trustees and donors, as well as staff festivities like the holiday party, pictured here.

1970s 1980s

By the ‘70s, the dining spaces were transformed to a café experience so visitors to enjoy a meal during their visit. At this time, having the food served cafeteria-style was the most efficient use of space. The café staff cooked and served the food to the visitors and staff as they moved through the line, much like a school cafeteria.

2011–2012 saw significant changes to the café that transformed it into the space with which we’re now familiar. At this time, the café transitioned from cafe teria-style service to a full-service dining experience, with ordering at the front as well as table service.

Director Brian Kennedy envisioned a new look for the space. He wanted to feature the Museum’s history in the café by allowing people to be able to look at the historical images while waiting in line to place their order. The staff at the Glass Pavilion also created a new sculpture to sit at the café entrance.

In the early 1980s, when the Herrick Lobby and Canaday galleries were installed, a new kitchen area was created in a hallway next to the Little Theater to support the catering of events.

The café also saw some furniture and floor upgrades.

23Toledo Museum of Art

2011–2012 archives.TMAthecourtesyimagesAll

24 Art Matters / EXPERIENCE Experience

25Toledo Museum of Art Experience

The Material Curiosity of Matt Wedel

26 Art Matters / EXPERIENCE

When we walk the earth each day, how often do we really think about the ground below us? For artist Matt Wedel, the answer is “Clayfrequently.isafoundational material because it’s below our feet,” Wedel said. “There’s smell; there’s touch; there’s moisture; there’s texture—it’s this experiential curiosity of material.”

Matt Wedel: Phenomenal Debris, opening at the Toledo Museum of Art on November 5, invites visitors to join him in this curiosity. The exhibition marks Wedel’s first large-scale solo show in a major art museum and includes ceramics and drawings that span more than ten years of his career. The result is a celebration of color, clay, and humanity.

Wedel’s respect for his medium and its agency in his practice are evident. In creating his work, he leans on the way clay behaves. The result is simply a manifestation of the questions he asks the material. In this way, his ceramics document a conversation between earth and hand—often to an unpredictable end.

“You are contending with the results that come out of the kiln, which are usually many degrees, or at least a few, off from what you intended,” he said. “So, it’s really the material that teaches you what your work is, versus you dictating the outcome.”

And clay is a foundational material for Wedel in more ways than one. Ceramics run in the family. His father—to whom Wedel attributes his love and fascination with how materials behave—worked as a functional potter in Colorado for more than forty years. Equally significant to his practice was his mother, who passed along her sensitivity to touch and love of growing food. He calls what he gained from both of his parents “gifts” that are significant to his practice today.

Matt Wedel, Flower Tree, 2018, whipped porcelain. Courtesy the artist and L.A. Louver, Los Angeles. Photo: Jeff McLane.

Toledo Art

... it’s really the material that teaches you what your work is, versus you dictating the “”outcome.

27

Museum of

Curiosity

28 Art Matters / EXPERIENCE

Wedel took these influences to the School of the Art Institute of Chicago to pursue his undergrad uate degree, where he layered a larger framework of art history onto his functional knowledge of ceramic craft and appreciation for the tactile. In Chicago, his stud ies were rooted in the theoretical, providing a philosophical structure on which he could build. But when Wedel enrolled in graduate school at California State University, Long Beach, he experienced a new level of intensity.

“In grad school, it became physical,” he recalls. “I needed to act on that theoretical framework I developed as an undergraduate. I now saw other artists who were physically pushing themselves, almost into states of delirium.”

He was forced to contend with the idea of the consistent, devotional labor it takes to make something as an artist. And with the increased demand to produce in graduate school came a desire to experiment—a hallmark of the work Wedel creates today. Wedel is renowned in his field for pushing the boundaries of ceramics. His material curiosity translates to an exploration of the margins of possibility to better understand the medium. But to take the risks necessary to explore, one cannot be afraid to fail.

Many of us are inclined to hide our failures. Wedel, on the other hand, embraces them.

Toledo Museum of Art

Matt Wedel, Lemon Tree, 2018, ceramic. Courtesy the artist and L.A. Louver, Los Angeles. Photo: Jeff McLane.

LawMcKinleyPhoto:

Toledo Museum of Art

Matt Wedel, Lemon Tree, 2018, ceramic. Courtesy the artist and L.A. Louver, Los Angeles. Photo: Jeff McLane.

LawMcKinleyPhoto:

I see [failure] as a gift instead of a“”burden.

29

“Those failures, the cracking and tearing apart, give clues about how a material functions and how chemistry and gravity work,” he said. “There was this point in grad school where I was moving a large sculpture into the kiln and the base started to crack. As I inspected what was happening, the whole thing just crumbled and crushed me to the ground. I remember pulling my shoes out of the rubble.”

At first, Wedel didn’t want his professor to find out about the incident. His instinct was to sweep the shattered pieces into a bucket and hope that nobody would notice the mistake.

“I remember really regretting that I didn’t take more time to absorb all the information that was there, all the ways in which it cracked, all the weak points. That’s been a huge lesson, to see moments of failure as opportunities for knowledge. They offer things that challenge your thinking continuously and allow you to not be stagnant in your practice.”

That lesson became pivotal in what Wedel has created since graduate school. He has grown to see his practice as something that thrives on mistakes. Just as he sees the ways in which his parents have influenced his way of thinking about the world as gifts, mistakes are acknowledged in the same way.

“External forces of failure, like falling asleep and over-firing your kiln, I see that as a gift instead of a burden.”

Matt Wedel, Fruit Landscape, 2017, stoneware. Courtesy the artist and L.A. Louver, Los Angeles.

Photo: Jeff McLane.

30 Art Matters / EXPERIENCE

Wedel uses a technique called handbuilding, in which he creates forms with clay without a wheel. Throughout his prolific career, Wedel has used his hands and his fearlessness in the face of failure to create a practice that’s uniquely his own. He pushes boundaries, explores new ways of handling the material, and reimagines the application of color and glazes to the surface to achieve astonishing and imaginative results.

Wedel currently works from his home studio in Albany, Ohio—a small village outside of Athens. The circumstances that brought him to the region demonstrate the significant role family has consistently played in his life. When Wedel and his wife, Coral, were expecting their first child, they moved from Los Angeles to Ohio to be close to Coral’s mother and prioritize a safe and healthy birth over their careers. The couple had already endured the devastating loss of a child they were expecting.

This formative experience ultimately catalyzed the move across the country, but characteristically, Wedel and his growing family embraced the gifts that stemmed from the change of scenery. His new studio in the Ohio countryside has allowed him to work with a significantly larger kiln. With ample space to create, Wedel treats scale as yet another boundary to push. He now has the ability to create works of near-monumental proportions, using his hands to build ceramics that often tower over his own stature. Working at this scale introduces more

risk, more physicality, and more opportunities to fail and rebuild from that failure.

Wedel finds the delicate balance between fatherhood, tending to their home and land, and life as a practicing artist. Since moving to Ohio, Wedel and Coral have welcomed two children. Nestled into a landscape the couple cultivated together, new projects continue to bloom and flourish in his studio.

“I think it’s assumed that the career path of the artist sometimes negates the caretaking of one’s surroundings,” said Wedel. “We all grapple with that in different ways, our expectation to be caretakers alongside the drive to follow our own pursuits.”

Wedel’s outlook reflects his dialogue with the material. Just as he questions the boundaries of clay, he questions our own self-imposed boundaries. How do we prioritize our pursuits and not take away from other areas of our lives? Who says we can’t be multiple things in our lives with equal commitment?

Many of Wedel’s works test the medium of clay to the point where the final work looks as though it is on the brink of collapse. But in the end it stands, a testament to the balance the artist has found in his practice and in his life. In the artist’s own words, his work is the phenomenal debris that is shed from being human.

■

31Toledo Museum of Art Wedel,Matt Portrait McLane.JeffPhoto:Angeles.LosLouver,L.A.andartisttheCourtesypaper.onpastel2017,,

On View Upcomingand

32 Art Matters / EXPERIENCE

In addition to Toledoexhibitionstheseformarkcollectionever-changingourgalleries,yourcalendarstheopeningofinspiringnewattheMuseumofArt. Wedel,Matt LandscapeFruit theCourtesystoneware.2018,,McLane.JeffPhoto:Angeles.LosLouver,L.A.andartist Company,GlassLibbey Dress threads.glassspun1893,,UNACC.1A-B.1925Libbey,ScottFlorenceofGift

State of the Art: Revealing Works from the Conversation Vault

Sept. 24, 2022–Feb. 5, 2023

A work of art—like a person—changes as it ages. Varnishes and adhesives can become yellow and brittle; cracks may appear; surfaces may fade or tarnish; and materials can begin to fall apart. Conservators work to identify problems and perform treatments to improve the condition of the art. This exhibition opens the “conservation vault” to give visitors a glimpse of art works that largely have been out of sight in storage, in some cases for decades. All are in need of conservation.

Learn about some of the inherent condition challenges that works of art face and the crucial role that art conservators play in keeping the Museum’s collection safe and looking its best for generations to come.

State of the Art: Revealing Works from the Conservation Vault is sponsored locally by season sponsor ProMedica and presenting sponsors Susan and Tom Palmer, with additional support from Taylor Automotive and Bill and Cathy Carroll. The show is also made possible in part by the Ohio Arts Council (OAC).

Matt Wedel: Phenomenal Debris

Nov. 5, 2022–Apr. 2, 2023

Monumental, colorful, and expressive, Matt Wedel’s ceramics are a full celebration of what’s possible with clay. Matt Wedel: Phenomenal Debris brings together a large selection of the artist’s ceramics and drawings spanning over a decade of his career. Wedel is renowned in his field for pushing the boundaries of ceramics, resulting in objects that recall familiar forms while also springing from his own imagination. The exhibition marks the first large-scale solo show for the artist in a major art museum.

Wedel’s practice is grounded in the exploration of human psychology. With experimentation playing a pivotal role, he challenges himself to embrace chance, possibility, and failure. The resulting works are a story of creation and destruction. In Wedel’s own words, his work is the phenomenal debris that is shed from being human.

Matt Wedel: Phenomenal Debris is organized by the Toledo Museum of Art and curated by Diane Wright, senior curator of glass and contemporary craft. This exhibition is sponsored locally by season sponsor ProMedica and presenting sponsors Susan and Tom Palmer, with additional support from the TMA Ambassadors and the Ohio Arts Council (OAC).

Wedel,Matt Portrait andartisttheCourtesyporcelain.2018,,McLane.JeffPhoto:Angeles.LosLouver,L.A.

33Toledo Museum of Art

Collections all start somewhere. For the Toledo Museum of Art, it started with a trip to Egypt, where Edward Drummond and Florence Scott Libbey acquired over 200 objects to gift to the budding museum. But your collecting journey could very well start right here at TMA. Embedded in the Museum Store is Collector’s Corner, a sales gallery of original art by more than 250 emerging and established regional artists.

34 Art Matters / EXPERIENCE FowlerEastmanLaurenSpotlight:StoreMuseum

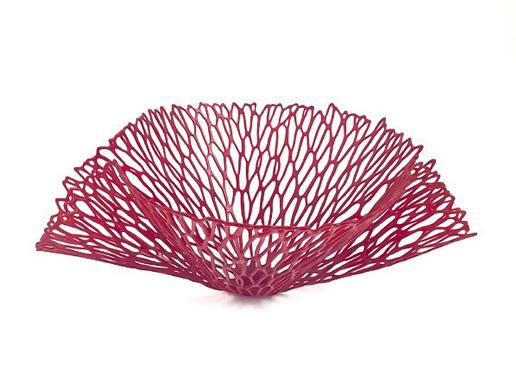

One of those artists is Lauren Eastman Fowler. Born in Ohio and raised throughout the Midwest, Fowler has developed a unique practice that is influenced by both the natural world and by her family history. Her grandparents were prized Dahlia growers, so it is no surprise the artist found inspiration in the flower’s delicate petals and cellular structure. Initially, she created these forms in porcelain, but over time she began to experiment in glass. The medium gave her enough versatility to explore different shapes, colors, and surface textures.

Working with glass in its pow dered form, she manipulates her work over the course of several firings in the kiln. Her work today has evolved beyond its source inspiration to become reminiscent of many complex forms in nature, such as coral, bone, or the veil of a

Inmushroom.celebration

of 2022, designated by the United Nations as the International Year of Glass, the Museum Store provides an opportunity to support the work of artists like Fowler. The Store stocks several of her original pieces, and she will also be collaborating with TMA this year on the 2022 limited edition ornament for the holiday season. You can shop these works and more in person or online at tmastore.org .

35Toledo Museum of Art

artist.thecourtesyimagesAll

Classes Workshopsand

Glass Art Workshops

Seasonal Object

Learn to create objects made of glass under the guidance of a TMA studio artist during this hands-on workshop at the Glass Pavilion.

Seasonal Object workshops are one hour on:

Fridays

6 p.m. and 7 p.m.

Saturdays

12 p.m., 1 p.m., and 3 p.m.

Tickets are $42 for members and $52 for nonmembers.

Pick Your Own Project

What you create is up to you! You’ll pick your own object to create from our list of projects under the guidance of a TMA studio artist.

Pick Your Own Project workshops are one hour on:

Sundays

12 Ticketsp.m. are $42 for members and $52 for nonmembers.

Teacher WorkshopsDevelopmentProfessional

Learn strategies to guide student inquiry, inspire creativity, and connect problem-solving and design through these workshops for pre–K and K–12 educators. These two-hour workshops connect art to Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math.

All workshops are $20, and include Gallery activities, handson artmaking experiences, and teaching resources.

Art & Science

Oct. 20, 2022, 4–6 p.m.

Art & Technology/Engineering Nov. 10, 2022, 4–6 p.m.

Art & Math Dec. 8, 2022, 4–6 p.m.

STEAM—Bringing It All Together!

Jan. 19, 2023, 4–6 p.m.

Teacher Professional Development Workshops are supported by Patricia Timmerman

Art Classes

Explore your creativity at the Toledo Museum of Art! For more than a century, this community resource has offered classes for every age, every experience level, and every schedule. Find inspiration from the Toledo Museum of Art’s vast and vibrant collections through classes for youth aged 3–18 and adults in drawing, sculpture, mixed media, metal, glass, and more!

For more information visit tickets.toledomuseum.org

36 Art Matters / EXPERIENCE

Art Matters Staff Director of Brand Strategy: Gary Gonya Feature Writer and Editor: Morgan Butts Design Team: Aly Krajewski and Mark Yappueying Send comments, questions, or inquiries to Morgan Butts mbutts@toledomuseum.org © Toledo Museum of Art. All rights reserved.

ON THE

Beggar’s Pond

The artist’s process was rhythmic and performative in nature. He often painted on the floor, moving around the canvas create the emotive strokes of color that result in the composition’s dynamic visual experience.

On view: Gallery

38 P.O. Box 1103 Toledo, Ohio 43697 Forwarding Service Requested © 2022 Toledo Museum of Art The Toledo Museum of Art • 2445 Monroe Street • Toledo, Ohio 43620 • 419.255.8000 • toledomuseum.org K ikuo Saito (Japanese-American, 1939–2016) 2002, Acrylic on canvas

COVER

to

4 Non Profit Org. US PAIDPostage Toledo, OH Permit 86