Icouldnot be more pleased to share that on February 26, USA Today announced that the Toledo Museum of Art (TMA) had been selected the top museum in the United States. A panel of experts began the process by selecting 20 top museums in the country. Our nomination was the first for TMA in almost a decade. From there, a public vote determined the ranking of the top 10 museums.

That our museum was selected as the top museum in the country by public ballot—even though Toledo was one of the smallest metropolitan areas in the competition—speaks both to the deep love and respect that our community feels for the museum but also for the recognition we increasingly get outside of Northwest Ohio. We owe our victory to each of you who voted and to our local organizations that promoted our nomination, just as we also owe our win to the New York City art collector who promoted us on X, the Los Angeles gallerist who got out the word, and everyone in between.

It should come as no surprise that the museum is receiving such widespread support. It is an indication that we are delivering on our vision to become the model museum in the United States for our commitment to quality and our culture of belonging. Our community is responding; we are on track for yet another year of attendance growth. And the world is noticing that there is a different model brewing in Toledo, something that intrigues people without connections to our region but who share our care for culture and museums.

The USA Today recognition is a reminder that there is a broad consensus that a great museum both focuses on the best and creates an environment where anyone can feel welcome. The amazing team at TMA has operationalized that vision in impressive ways, and those are on full view in this issue of Art Matters.

A conversation with three members of our conservation team on p. 10 highlights the depth and breadth of their knowledge. The team is twice the size it was just two years ago. Vanessa Appelbaum, Emily Cummins, and Marissa Stevenson have extraordinary technical knowledge. Their responses underscore the community ethos they bring to their work, which is a distinctly Toledo trait.

Also featured in this issue on p. 24, the Guest Artist Pavilion Program (GAPP) brings artists from around the world and those in our own backyard

to work with glass in our hot shop. Every year, we feature a regional artist as an expression of our commitment to our artistic community, just as we work with artists like María Dávila and Eduardo Portillo, originally from Venezuela. Nearing its 20th year, GAPP has not only matured under the guidance of Alan Iwamura, our glass studio manager, and Diane Wright, our senior curator of glass and contemporary craft, it has hit its stride.

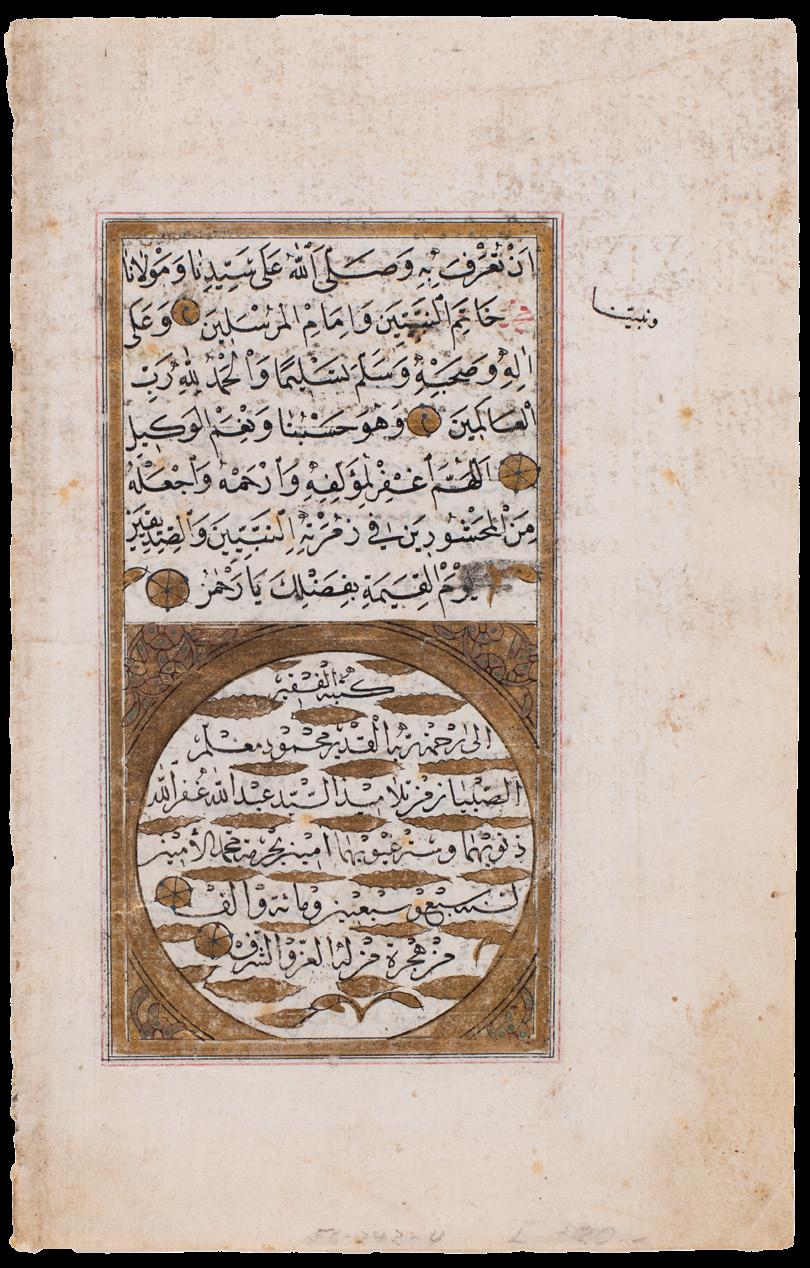

TMA’s holdings of works on paper, which range from ancient Egyptian papyri and eighth century Islamic calligraphy to modernist artists' books and contemporary digital photography, rank among the very best in our country. On p. 20, Tanya Pattison-Arraiza, our newest Brian P. Kennedy Leadership Fellow, profiles Unshelved:

An Artist’s Book Pop-Up Exhibit, an innovative display of Aminah Brenda Lynn Robinson’s important Ragmund Collection of Folkquilt Studies. The one-night-only event was conceived and curated by Jehan Mullin, TMA’s curatorial research associate in modern and contemporary art, and supported by the Wolfe Family Foundation. Watch for more pop-up events in the future.

Ranking among the best is always the benchmark for TMA curators and directors. No doubt the museum’s next temporary exhibition, Rachel Ruysch: Nature into Art, will do just that (see p. 30).

Curated by Robert Schindler, the William Hutton Curator of European Art, the exhibition will be the first-ever retrospective of Rachel Ruysch, one of the great Dutch painters of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries whose paintings routinely sold for more than Rembrandt’s during her life. Building around a remarkable Ruysch floral still life in TMA’s collection, this exhibition—a collaboration with the Alte Pinakothek in Munich and the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston—will advance scholarship, build on our history of important exhibitions on European painters, and delight audiences.

There is much to be proud of as a supporter of the Toledo Museum of Art, and all of it is directly attributable to you. The museum is entirely private, so these achievements are a function of your support. Thank you for all you do to help achieve our vision of becoming the model museum in this country. As you can see, we are well on our way.

Best regards,

Adam Levine

Edward Drummond and Florence Scott Libbey President, Director, and CEO

Spring Through Impressionism

Soft light, fresh color, fleeting moments—Impressionist painters captured the essence of Spring. Step into In a New Light: Impressionism & PostImpressionism in the Glass Pavilion to experience the season’s energy through luminous brushstrokes. See it before the exhibition closes on April 27.

Spring has a way of transforming the Toledo Museum of Art (TMA). The days grow longer, filling our galleries with warm light, and the snow-covered Glass Pavilion—so recently a winter wonderland— becomes a beacon of transparency, inviting visitors to see the world through a fresh lens. Outside, the museum’s gardens begin to bloom, mirroring the vibrant energy that Spring brings to our campus.

It’s a season of renewal, a time when nature unfurls its beauty—and a fitting moment to celebrate an artist who captured the essence of botanical life with extraordinary precision and artistry. This Spring, TMA is proud to present Rachel Ruysch: Nature into Art, a landmark exhibition dedicated to one of the most celebrated still-life painters of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

Ruysch’s breathtaking flower paintings are more than masterful compositions; they are windows into a world of scientific curiosity, artistic innovation, and global exploration. Each meticulously arranged bouquet bursts with color and life, featuring blossoms that, in reality, never bloomed together—an artistic illusion made possible through her deep knowledge of botany and her remarkable skill with oil paint.

At a time when women faced immense barriers in the art world, Ruysch defied expectations, securing prestigious commissions and earning widespread acclaim. Her work bridges the realms of art and science, capturing not just the beauty of nature, but the increasingly global networks that shaped her era.

As we welcome the arrival of spring at TMA, we invite you to step into Ruysch’s world, where art and nature intertwine in dazzling detail. Whether strolling through our gardens or exploring the brilliance of our exhibitions, this season is a celebration of the beauty that surrounds us—and the artists who bring it to life.

Jennifer McCary

In the quiet, meticulously organized conservation labs of the Toledo Museum of Art (TMA), art meets science in a blend of skill and knowledge. Recently, I sat down with the conservation team to reveal their insights on the intricate methodologies employed in art conservation and explore what’s next for conservation work at TMA.

Jennifer Art conservation seems to require both scientific knowledge and artistic skill. How do you balance these two disciplines in your work?

Vanessa You're right when you say that it is a balance. Art and science have a dynamic relationship in conservation. We focus on both physical and intangible aspects of cultural heritage and works of art. Using analytical technologies like microscopy, testing, and spectroscopy, we can understand materials and the condition of artworks. This helps us identify deterioration causes and stability of the works and confirm the best treatment methods.

“Conversations with curators about authenticity and artistic intent are critical. We often debate how much intervention is appropriate and how past alterations impact our decisions.”

Vanessa Applebaum Director of Conservation

However, we also need to consider artistic intent and the broader context of the work, which involves discussions with curators about the aesthetics and authenticity of the piece. Some of our treatments involve artistic skills like color matching and infilling.

Emily The concept of technical art history is crucial. It emphasizes understanding an object’s materiality rather than just its visual representation.

Marissa I would add that the analytical techniques we use can also reveal historical facts about the object. This information can enrich our understanding of the work's significance.

Jennifer Could you talk through a typical conservation process, including what it involves and how you decide which techniques or materials to use?

With bright eyes and wide grins, the room erupted in laughter at my question and Emily’s mixed humor in her response.

Emily Well, I'd first probably say that the word “typical” isn’t one we would use. Every treatment is unique. As an objects conservator, I always start with a physical examination. This first assessment often includes cleaning and solubility tests to understand the material and what can or cannot be used. I also talk with the curator early on to align aesthetic goals, allowing me to plan my treatment approach accordingly. I often work backward to understand and plot my path to get the result.

Vanessa Conversations with curators about authenticity and artistic intent are critical. We often debate how much intervention is appropriate and how past alterations impact our decisions.

Emily Vanessa makes an interesting point. We often look into the future when adding materials while also considering what has been done in

the past. Sometimes we find repairs that were done 100 years ago, and we debate if those repairs are something we should ethically leave in place. It can open a whole can of worms.

Marissa From a textile perspective, understanding the fiber content and weave structure is vital. These factors directly influence treatment methods. From a fiber standpoint, I do fiber microscopy to determine what the actual content is, the weave structure, what will change, how I will treat the object, how it will need to be cleaned, or what have you. Historically with textiles, it's a little different than what Emily and Vanessa described from their object conservation perspective because those past treatments become an incredibly integral part of its history, and sometimes they were done intentionally. For example, if we think of fashionable dresses from the eighteenth century, a lot of times they were altered later to create a different silhouette because the fabrics were so expensive. So, that becomes part of its legacy, and we wouldn't want to disturb that.

Jennifer What are some of the most innovative technologies or methods currently used in art conservation?

Marissa One exciting area is 3D scanning for documenting ephemeral works, especially textiles.

Vanessa We’re currently using 3D scanning technology for various objects in Classic Court to explore non-invasive mounting solutions. We want to minimize risk.

Emily In broader object conservation, test fitting pieces digitally before manipulating them minimizes risks and preserves the integrity of the work.

Jennifer Can you give an example of a particularly challenging conservation project you've worked on within our collection and how you've approached it?

Emily I am working on an Etruscan column Krater vessel with a complex repair history. It has various unknown adhesives and fill materials that complicate treatment. My approach involves documenting the existing repairs and deciding which can be undone or need to be preserved.

There are times we find the materials used are not the conservation-grade materials we would use now. There are also times when the repairs are done well enough that we realistically wouldn't need to undo and redo them from a stepping standpoint.

Stepping is a conservation term that identifies a misalignment of repairs where you get a stepped surface that is visually obtrusive and can affect attempts to visually integrate repairs.

Jennifer What role does science play in understanding the long-term preservation needs of different types of artworks, like glass, paintings, textiles, or sculptures?

Vanessa Science is essential for material analysis. Knowing what we are preserving helps inform our preservation plans. For example, understanding the composition of a piece allows us to predict how it might deteriorate in a given environment

or how it might react with other artworks nearby. There are some categories of art, like those made of brand new or proprietary materials, where you're not fully sure of how they will react. But if you can analyze something and get a good idea of what it is you're looking at, or if you see that it is similar to something more familiar, it helps you to prepare.

Marissa We are very diligent about testing materials that come into contact with artworks to prevent further degradation, and we test any material that hasn't been previously analyzed. We want to ensure materials won't off-gas harmful chemicals that could contribute to degradation.

Emily Environmental monitoring is equally important. Keeping items in optimal condition can significantly affect their longevity. We continuously monitor the temperature and relative humidity of the spaces that hold our art.

Jennifer Art conservation often deals with preserving the artist's intent. How do you navigate ethical dilemmas when a piece's original materials may no longer be available or usable?

Emily That question is one that we deal with more every day as modern materials are starting to age in real-time. Understanding the artist’s intent is crucial. Sometimes that involves reaching out to the artist or their foundation for guidance. The field is shifting towards conducting more artist interviews focused on conservation.

Vanessa Sometimes artists create works that aren’t meant to last forever, and then when it's over, despite its beauty, it's over. We must accept when artists choose not to have their works preserved, acknowledging the life cycle of the artwork and the intent of the maker.

Marissa Collaborating with cultural knowledge keepers ensures that our treatment aligns with the cultural significance of the objects we are working with.

Emily Yes! And I'll mention this because I think we often take it for granted, but we document everything through writing, photography, and audio recording to keep track of absolutely everything.

Jennifer How do you predict and mitigate potential future damage to artworks that are part of the museum's collection?

Vanessa Something dear to my heart is risk analysis and risk management, which we can use to our advantage when we are developing preservation plans while making works more accessible.

We can use our knowledge of materials and our access to networks of scientists and professionals to predict how something will age. This prediction is influenced by a lot of variables, including the environment that the art is in, the art being put on display, or it being sent on loan.

When you understand the variables that can influence deterioration of materials and art, you can then address them in advance to make sure you’ve mitigated any risks. This type of analysis helps

us understand if our gut reaction or perceptions of the risk are aligned with the real risk.

It might not be immediately obvious, but risk analysis is critical in conservation. We leverage our knowledge of materials and environmental variables to ensure our art is safe, while also allowing our visitors to enjoy it.

Emily I agree with all that and will throw in that Integrated Pest Management (IPM) is another preventive measure that helps us keep storage areas pest free.

Jennifer How do you see the relationship between sustainability and conservation?

Are there ways to reduce environmental impacts in conservation practices?

Emily This is a significant topic. In many ways, conservation practices have traditionally not been very sustainable. We use a lot of disposable materials, like nitrile gloves and packing materials. However, the field is starting to shift towards greener practices. For instance, we’re looking at using environmentally friendly solvents and evaluating whether strict climate control standards can be relaxed without compromising the integrity of the collection.

Vanessa Exactly. There’s emerging evidence suggesting that it’s not always about maintaining a narrow environmental range but rather ensuring consistency in environmental conditions. A more stable environment may be more preferable overall, particularly when you consider the amount of energy used to rigidly adhere to specific numbers.

Marissa It also depends on the specialty. In textiles, for example, many materials I use can be reused or washed, which helps reduce waste.

Jennifer Creating opportunities for a more sustainable and equitable built environment, while reducing embodied carbon is critically important to the museum as we continue to focus on our sustainability efforts. Thank you for your commitment to this.

Jennifer Have you ever discovered something surprising about a piece while conserving it?

Emily Absolutely! One fascinating discovery involved using multispectral imaging, which is a process where you photograph a work in 18 narrow bandwidths of light and then stack those images. We did this on the portrait of Victoria Dubourg by Edgar Degas because we were curious to know what was happening on the wall behind the sitter. This technique revealed an original landscape painting in the background that had been painted over. This kind of revelation is what makes conservation so exciting.

“One of my favorite aspects of this job is the depth and intimate relationship you develop with any artwork through treatment. Each piece offers a unique story and connection.”

Emily Cummins Associate Objects Conservator

Jennifer If you could work on conserving any artwork or artifact in the world, which would it be and why?

Marissa If I could choose, I would love to conserve one of the Muppets donated to the Smithsonian by Jim Henson. Working on something that has such sentimental value to many people would be a dream come true.

Emily For me, it’s less about a specific object and more about the treatment I like doing. One of my favorite aspects of this job is the depth and intimate relationship you develop with any artwork through treatment. Each piece offers a unique story and connection.

Vanessa I share a similar sentiment. But if I had to choose, I’d love to work on Byzantine icons. They raise interesting questions about materiality and immateriality. They were considered living images. Preserving them involves much more than just the physical aspects. Although I’ve studied them, I would love the opportunity to explore them more in the lab.

Jennifer Do you have a favorite art conservation fun fact or little-known trivia that always fascinates people?

Vanessa One interesting fact is about a product called a PLECO pen, which is an electrolytic pencil that can reverse tarnish on metals without removing any material. To me this is as close as we get to being magicians.

Emily I always tell people that when cleaning silver objects, remember that tarnish is the surface, not just something on it.

Vanessa I also like the fact that we can sometimes engineer things to be invisible to the naked eye, but that are very easily identified

under UV light. This is our way of leaving behind some hints for other conservators and future curators. As part of our ethical stewardship, we treat things in a reversible way.

Marissa I find it fun to involve our protective services team in the conservation process by asking them to spot where we’ve done treatments on textiles. If they can see it, I know I need to adjust my work.

Jennifer What is an unexpected skill you use in conservation?

Emily I’ve found that creative problem-solving is essential. It often feels like detective work, piecing together an artwork’s history based on visual evidence and documentation.

Marissa I would add that we all specialize in a specific area, but a broad understanding of different specialties is crucial because many objects involve multiple materials. This knowledge helps in treating complex works.

Vanessa I think ahead about various scenarios and what could happen in the future. This forward-thinking is especially important in contemporary art, where we may not have access to the artist down the line.

Marissa Being able to consider worst-case scenarios and then working your way backward with any object, whether it's considering storage, packing, or movement, can really mitigate any sort of potential problems.

Vanessa It’s true! We think decades into the future.

Emily And on a lighter note, I would say that I'm much better at insect identification than I ever expected to be.

Jennifer What advice would you give someone interested in entering the field of art conservation?

Vanessa It's never too late to pursue a career in conservation. I didn't know it was an option until after college. But you’ll need to take general chemistry and studio art classes to build a foundation.

Emily Don’t hesitate to reach out to professionals in the field. The conservation community is welcoming and loves sharing knowledge and guidance, especially with aspiring conservators.

Marissa Agreed! I have gotten internships by cold calling museums, so don’t be afraid to put yourself out there. There is typically an expectation that you have some experience entering graduate school. Even if you cannot get into conservation initially, any experience, even in adjacent fields, can be valuable.

Jennifer What upcoming conservation projects or initiatives at TMA do you think the community would find most exciting or engaging?

Vanessa The reinstallation initiative is huge for us. It allows us to examine our whole collection comprehensively and plan for better preservation strategies. For example, we have been doing a remarkably close examination of everything that is on display right now, and so far, have assessed 1,049 works of art in 32 galleries. We’ll be looking at art in storage next.

It will also be an opportunity to implement innovative mounting and storage solutions. We We have a lot of great challenges to figure out.

Jennifer Beyond their technical achievements, the conservation team, which is larger than just those interviewed, sees their work as part of executing our strategic objectives of broadening the narrative of art history and creating a platform for operational excellence, while simultaneously engaging and inspiring the community.

Through public programs, behind-the-scenes tours, and collaborations with partners, the team aims to demystify the conservation process and highlight its importance. Conservation is as much about people as it is about objects. As TMA continues to innovate and expand its conservation efforts, the team remains dedicated to their dual roles as scientists and artists. Their work is never static,

it evolves with technological advancements, shifts in cultural understanding, and the everchanging needs of the artworks themselves.

By building connections between disciplines, colleagues, and communities, the conservation team at the Toledo Museum of Art exemplifies the museum’s mission to integrate art into the lives of people—ensuring that these artworks and stories they tell endure for generations to come.

“A broad understanding of different specialties is crucial because many objects involve multiple materials. This knowledge helps in treating complex works.”

Marissa Stevenson Associate Conservator of Textile-Based Collections

Emily We’re also exploring ways to display analytical techniques we use in conservation alongside artworks. This could include interactive screens where you can see the reflectance transformation imaging, which is essentially like a topographical map image, so you can understand the surface quality of an artwork. This would help engage the public in the conservation process.

Marissa The glass fiber dress made by Libbey Glass Co. for the 1893 World's Fair is another exciting project. It presents challenges that require extensive research, treatment, and collaboration.

Beth Lipman (born 1971, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; works in Sheboygan, Wisconsin). Glass, wood, and metal. Purchased with funds from the Florence Scott Libbey Bequest in Memory of her Father, Maurice A. Scott, 2024.225a

Currently on view in Gallery 7 in the Glass Pavilion.

at the Toledo Museum of Art

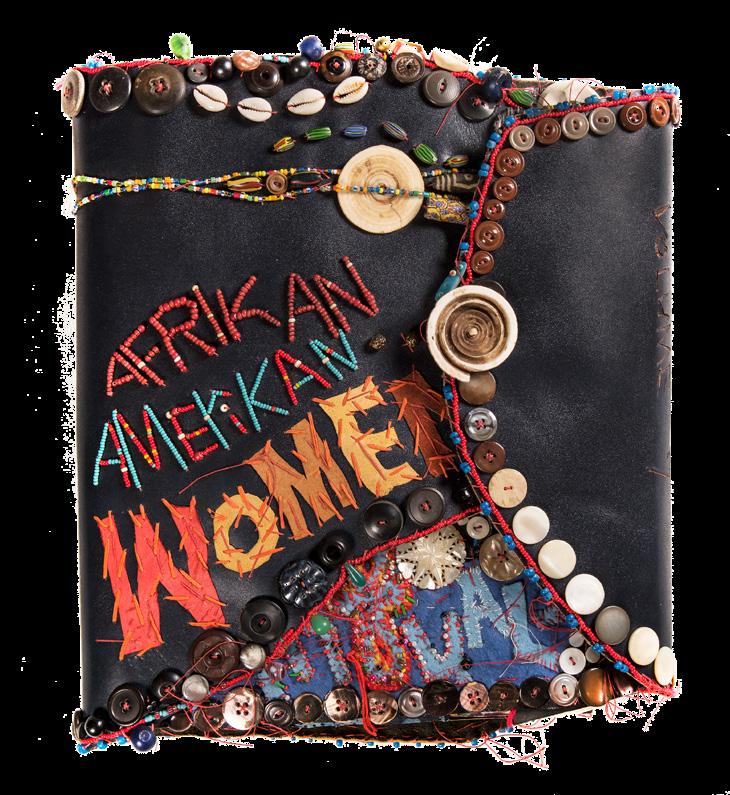

Ona cold January evening, the Toledo Museum of Art (TMA) invited visitors to step into a world where books transcend the written word. The inaugural Unshelved: An Artist’s Book Pop-Up Exhibit on January 17 shared the work of Columbus native Aminah Brenda Lynn Robinson, launching a new event series dedicated to artists’ books—works of art inspired by the idea, form, or function of a book. This series offers one-night-only exhibits in the Hitchcock and Stevens Galleries, giving visitors an intimate, up-close experience with these exceptional works.

Celebrated for her vibrant storytelling through mixed media, Robinson honors the lives of ordinary and extraordinary African Americans in her art. In 2013, TMA acquired her Ragmud Collection of Folkquilt Stories, a series of 10 handmade artists’ books created over two decades. These intricate volumes, composed of bright fabrics, delicate stitching, hidden pouches, and interactive fold-out pages, invite viewers to engage with history through discovery.

Guest Writer

Tanya Pattison-Arraiza, Brian P. Kennedy Leadership Fellow

What makes the Unshelved series special is its approach—the works are displayed without glass cases and brought to life by museum staff who carefully turn pages for visitors. The books in the Ragmud Collection are layered—some feature smaller books tucked inside, while others have pages that unfold across the table transforming storytelling into a tactile, immersive experience.

“I created Unshelved to activate our artists’ book collection, which is a significant part of TMA’s modern and contemporary holdings,” explained Jehan Mullin, project curator and curatorial research associate in modern and contemporary art.

“We wanted to bring attention to our remarkable collection of artists’ books, and we wanted to do so in a way that encouraged greater, more meaningful engagement with these works.”

Beyond the exhibit, visitors enjoyed a screening of Aminah Robinson: Voices that Taught Me How to Sing in the Little Theatre. Originally created

“We

are extremely careful, treating them as precious objects… The artist has a completely different relationship with them. She flips through pages without hesitation. To her, they’re living objects to be experienced in a physical way—to be read and enjoyed.”

Paula Reich Manager of Gallery Interpretation

for TMA’s 2010 exhibition on Aminah Robinson, the film captured the artist interacting with the Ragmud Collection, offering insight into her creative process. In addition, the TMA library and archives displayed a selection of artists’ books for visitors to handle, offering a rare opportunity to explore these works independently. Guests also received complimentary copies of the Voices that Taught Me How to Sing exhibition catalogue, extending Robinson’s legacy beyond the evening.

“When we began developing Unshelved, we couldn’t think of a better way to launch the series than with the work of the extraordinary Aminah Robinson,” said Jehan.

The exhibition also illuminated a challenge curators and conservators often face: how to balance preservation with engagement. Many artists’ books are designed to be handled, yet museums must protect these fragile works from damage. Typically displayed behind glass, books—like furniture and flatware—are often admired but not touched.

Unshelved sought to address this tension by carefully facilitating interaction under controlled conditions.

This dilemma is poignantly highlighted in Voices that Taught Me How to Sing, where Robinson interacts with her books in a way museum staff never would. “We are extremely careful, treating them as precious objects,” reflected Paula Reich, manager of gallery interpretation. “But, in the film, the artist has a completely different relationship with them. She flips through pages without hesitation. To her, they’re living objects to be experienced in a physical way—to be read and enjoyed.”

With Unshelved, TMA has created a dynamic way to share its collection of artists’ books, ensuring these extraordinary works can be both preserved and experienced as their creators intended. As the series continues, visitors can look forward to discovering more unshelved treasures that blur the line between books and art. Artwork:

2006, when the current Chair of the Board

Sara Jane DeHoff was asked to support the Toledo Museum of Art (TMA) Glass Pavilion, a structure that seamlessly merges history with innovation, she said yes with a catch. DeHoff provided support with a residency program as the condition. Since its opening, the Glass Pavilion has housed one of the most significant glass collections in the world. It has become a space also known as an incubator of creativity, where artists, scholars, and the public converge to explore the limitless possibilities of glass. Central to this experimentation is the Guest Artist Pavilion Project (GAPP) residency, a program designed to expand the dialogue between glass and contemporary art practices.

Since its inception, the GAPP residency has invited both established and emerging artists to push the limits of glass as a medium. The program welcomes those who work primarily in glass as well as artists from other disciplines interested in exploring its properties. Each residency is shaped by a unique interplay between the artist’s practice and the resources available at TMA, resulting in thought-provoking projects that engage both material and concept.

Artists selected for GAPP receive the opportunity to experiment freely, working alongside the museum’s skilled glass studio staff. Residencies typically last one to two weeks, with the flexibility to extend based on the scope of the artist’s project. In addition to hands-on studio work, GAPP artists share their creative process with the public through lectures, demonstrations, and collaborative engagements, fostering a dialogue that extends beyond the walls of the museum.

Over the years, GAPP has hosted a diverse range of artists whose work has redefined the possibilities of glass. Each artist approaches the material with a distinct perspective, leading to projects that range from large-scale installations like Pinaree Sanpitak’s The Hammock located outside the Glass Pavilion, to conceptual explorations of transparency, fragility, and transformation such as Saya Woolfalk’s Woods Woman, currently on view at Susan Inglett Gallery. In the past year, GAPP's impressive roster of resident artists has grown by far.

In February 2025, María Dávila and Eduardo Portillo, internationally exhibited fiber artists, explored the intersection of glass and textiles during their GAPP residency. Influenced by studies in China and India, their work reflects connections

between people, places, and materials. At TMA, they integrated glass into textiles, creating hollow, transparent structures that allowed fibers to be woven through and around glass. This juxtaposition of firmness and softness highlighted the intricate transparent nature of glass, casting dynamic shadows from light passing through forms and revealing the delicate details of the woven materials from different perspectives. Their work, though materially shifted, continued to explore imagined cosmos tied to their artistic journeys.

In November 2024, Toledo-based artist and designer, and member of the XY&Z artist collective, Adam Sanzenbacher explored the structural and optical properties of glass, creating sculptural forms that challenged perception and storytelling. While in his residency, Adam merged digital technology with traditional glassmaking, broadening the medium’s possibilities. Using CAD software and 3D printing, Adam developed interchangeable molds for efficient glass production, enabling modular and complex works. His innovative approach blended digital precision with handmade qualities, pushing the boundaries of craft. By integrating commercial production methods into studio glass, he highlighted technology’s role in expanding creative possibilities within a historically rooted art form.

Left:

Saya Woolfalk (born 1979), Woods Woman (Head). Fused glass with plant material, 2024. 11 × 7 × 3/4 in. Photo: Adam Reich, Courtesy of Leslie Tonkonow Artworks + Projects, NYC, and Susan Inglett Gallery, NYC. Created during Woolfalk's GAPP residency at TMA.

Above: Kristina Arnold, Hand Hold. Cast glass, 2024. 3 × 3/4 in. Created during Arnold's GAPP residency at TMA.

Right: GAPP Artist Beth Lipman at work in the TMA hotshop.

The GAPP residency fosters a space for creative risk-taking, enriching both the individual artist’s intentionality and the broader discourse on materiality. As TMA continues to champion the evolving field of glass art, the Glass Pavilion remains a hub for exploration, ensuring that the studio glass legacy continues to inspire new generations of artists and audiences alike.

Beth Lipman’s 2022 residency led to ReGift, a tribute to TMA’s founders, and the artwork transitioned from exhibition to acquisition. DeHoff recognized the need for a residency, but she also ensured that this initiative enriched artists’ practices, strengthened Toledo’s cultural fabric, and contributed to the broader art world.

Encourage artists to apply. If you know someone interested in the GAPP residency, have them reach out to Glass Studio Manager Alan Iwamura at aiwamura@toledomuseum.org for more information.

Saya Woolfalk

In August 2024, New York-based artist Saya Woolfalk joined the GAPP residency. Saya is known for using science fiction and fantasy to explore themes of women, race, and society through immersive multimedia works. During her residency, one key focus of her time with the glass team was the production of a series of glass busts, designed to complement and interact with ceramic heads she had brought on-site. These forms along with the flat glass works containing foraged plants from New York, reflected her interest in utopianism and hybridity while celebrating the possibilities of living—which she credits to her mentor Joan Fenrow. Saya’s residency deepened her exploration of identity and transformation, allowing her to collaborate with the glass team and expand the storytelling within her layered installations.

In February 2024, artist, educator, and chair of art and design at Western Kentucky University Kristina Arnold, brought her background in painting and community health to the GAPP residency, using glass to explore unseen forces shaping our environments. Inspired by Toledo’s rich glass manufacturing history, and former GAPP artist Beth Lipman’s ReGift, Kristina created 300 glass medallions during her residency, which were given to museum visitors. These pieces, produced through the mimicry of glass press technology, and the act of giving, fostered a sense of connection and community among museum staff and visitors alike. Kristina’s residency bridged personal expression with social impact, reinforcing the role of glass in storytelling and engagement.

Rachel Ruysch made a name for herself as one of the premier painters of Europe with a career spanning nearly seven decades. She achieved widespread fame and financial success while raising 10 children, winning the lottery twice, and transforming science into art through her breathtaking still-life paintings.

The first-ever major exhibition of her work, Rachel Ruysch: Nature into Art, will be on view at the Toledo Museum of Art (TMA) from April 12 to July 27. Featuring over 100 works—including paintings, botanical books and drawings, plant and animal specimens, and TMA’s own Ruysch masterpiece, Flower Still Life (1716-1720). The exhibition explores her extraordinary career and the intersection of art, science, and natural history.

“This exhibition is Rachel Ruysch’s moment to shine,” said Robert Schindler, William Hutton Curator of European Art at TMA. “Despite her fame during her lifetime, her story has not yet been fully told. Already facing cultural barriers due to her gender, Ruysch’s consistent output of paintings to major patrons and her exploration of biodiversity fueled by Dutch colonialism speaks to her curiosity and tenacity as an artist. What she created were more than just still lifes; they reflect the deep interest in documenting and understanding nature during the period often called the Scientific Revolution.”

Born in The Hague, Netherlands, in 1664, Ruysch’s artistic lineage ran deep. Her mother’s side of the family included a well-known painter and an architect. Ruysch also grew up surrounded by science. Her father, Frederik Ruysch, was a renowned botanist and anatomist, granting Ruysch access to Amsterdam’s botanical gardens, extensive collections of natural specimens, and the latest scientific discoveries of the time. Her paintings reflect this knowledge, depicting hyperrealistic flowers, plants, and animals—both native and newly introduced to the Netherlands through global trade and colonial expansion.

Frederik Ruysch’s groundbreaking work in anatomy and botany led to his appointment as head of the Amsterdam surgeon’s guild in 1667. His position brought the Ruysch family to Amsterdam, where the artist began her artistic training around age 15 as an apprentice to Willem van Aelst, one of the leading still-life painters of the time.

Under Willem van Aelst’s mentorship, Ruysch experimented with different formats of flower and fruit still lifes including a type pioneered by Otto Marseus van Schrieck called the forest floor still life, which placed flora and fauna around a single plant against the backdrop of a landscape. While Ruysch absorbed techniques from her teachers and peers, she quickly began to develop a style of her own—one that set her apart and caught the attention of patrons and poets alike. In 1685, Amsterdam poet Hieronymous Sweerts celebrated her talent, referring to her as “their flora goddess elect.”

Anna Ruysch, Rachel Ruysch’s younger sister, also trained as a still-life painter but had a far shorter career. And, as Ruysch became a household name in the Dutch art world, Anna Ruysch experienced a far shorter career. Only about a dozen paintings are attributed to her today.

Her compositions often mirrored her sister's, suggesting close collaboration in their early years. Around 1700, during the height of her sister’s career, it is thought that Anna Ruysch may have assisted her in producing still lifes. However, after Anna Ruysch wed in 1688, she accepted responsibilities in her husband’s paint business and did not continue as a professional artist. Her story serves as a reminder of the societal limitations that often dictated women’s careers during this period.

Dutch trade and colonial expansion brought a wealth of plant and animal specimens to Amsterdam in the 1600s. These exotic specimens fascinated

collectors and scientists alike. Many artists, including women, were hired to document the specimens in prints, watercolors, and paintings. Thanks to Ruysch’s scientific connections through her father, she had great access to these imported species. Her works often contained plants, insects, reptiles and amphibians from diverse climates and habitats that could have never existed together in the wild.

One particularly striking example is her depiction of the Pipa Pipa toad from Suriname, a South American colony. This species, known for carrying its young in pockets on its back, captivated European audiences and appeared in both a drawing and a painting, both featured in the exhibition.

“Ruysch’s paintings, especially those from the 1690s, demonstrate this moment where art and science are deeply entwined,” said Robert. “The biodiversity in her works is the product of Dutch trade, exploration, and exploitation of their colonies around the world.”

Rachel Ruysch: Nature into Art pairs her paintings with botanical and zoological specimens from local and national collections, illustrating the deep intersections between art and science at a historical moment of increasing global trade and colonization. Experts in botany and zoology have contributed to the exhibition, helping to identify the species in her paintings and their indigenous habitats.

“This exhibition is Ruysch’s moment to shine. Despite her fame during her lifetime, her story has not yet been fully told.”

Robert Schindler

William Hutton Curator of European Art at TMA

Ruysch’s talent and business acumen led to unprecedented success. Unlike many female artists of her time, she continued painting after her marriage in 1693 to portrait painter Juriaen Pool. Compared to her husband’s known works, Ruysch far outearned him. She was even more financially successful than some of the era’s most famous male painters, including Rembrandt. And she did this while raising 10 children. Sadly, only three lived to adulthood.

Despite her immense talent, Ruysch faced gender-based obstacles. She was denied entry into the Amsterdam guild of painters because she was a woman. Instead, she gained acceptance into her hometown’s guild of painters, the prestigious Confrerie Pictura in The Hague. Her husband served as her sponsor. Ruysch’s entry in the guild’s records includes her signature—tellingly, she continued to use her maiden name throughout her career:

“I the undersigned promise to pay this year to the gentleman of the praiseworthy Confrerie a silver ducation or three guilders and three stuivers.” Confirmed on 7 November 1699 Ruysch.

In 1708, Ruysch and her husband were appointed court painters to Johann Willhelm, an influential German duke who lived in Düsseldorf. For eight years, she produced exquisite floral compositions for the duke and his court. Their relationship was so close that Ruysch named her youngest son, born in 1711, Jan Willem after her patron, and the duke served as the child’s godfather.

As Ruysch’s career flourished so did her fortunes. In fact, she and her husband won the lottery twice! Their second win in 1723 was the equivalent of a modern-day fortune, securing their financial independence. Afterword, Ruysch painted less frequently, though later in life she resumed

creating smaller, more delicate works signed with both her name and her age, proudly marking her longevity and continued artistic prowess.

In 1749, at the age of 85, Ruysch was interviewed by Jan van Gool for his biographical compendium of Dutch artists. During that same visit, it is believed artist Aert Shouman drew a moving portrait of Ruysch as a dignified and emotive older woman. She died the following year at age 86, leaving behind a legacy of unparalleled achievement.

A collection of poems written celebrating her career was published in the year of her death, praising her skill and naming her “the heroine of art.” While she was never forgotten, her reputation gradually faded, like many women artists throughout history. Now, with Rachel Ruysch: Nature into Art, TMA is bringing long-overdue attention to one of the most important Dutch still-life painters with the first monographic show dedicated to her.

“For centuries, Rachel Ruysch’s still lifes have dazzled viewers,” said Robert. “This exhibition will finally place her in the spotlight, recognizing her immense contributions to art history.”

Rachel Ruysch: Nature into Art is organized by the Toledo Museum of Art in conjunction with the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston and the Alte Pinakothek in Munich. TMA’s exhibition design partner for the Toledo exhibition is Selldorf Architects.

The Toledo exhibition is made possible with the generous support of Presenting Sponsors Susan and Tom Palmer; Season Sponsors Taylor Automotive Family and the Rita Barbour Kern Foundation; Platinum Sponsor Todd and Jeannie Peters, and the Zenith Foundation; Silver Sponsor TMA Ambassadors; and additional funding from the Ohio Arts Council, which receives support from the State of Ohio and the National Endowment for the Arts.

At the height of her career, Rachel Ruysch often painted still lifes in pairs—one featuring flowers, the other fruit. Though visually distinct, these companion pieces were intended to be displayed together.

For example, the TMA fan-favorite Flower Still Life was painted by Rachel Ruysch between 1716-1720.

Its fruit still-life counterpart, Still Life with Fruit, Bird’s Nest, and Insects, was painted by Ruysch in 1716. The works remained together in an English collection until 1848, when they were sold separately.

The fruit still life was acquired by an English noble family and kept at Dudmaston Hall in Shropshire, England. Meanwhile, the flower still life passed through two English families and dealers before

finding a home at TMA in 1956. The museum was the first public institution in the United States to add a Rachel Ruysch artwork to its collection.

And now, for the first time in over 150 years, Flower Still Life will be reunited with its longlost pendant Still Life with Fruit, Bird’s Nest, and Insects in Rachel Ruysch: Nature into Art.

Seeing these works together invites new insights. How does pairing them change your perception of Ruysch’s artistry? What connections emerge when viewing these complementary compositions side by side? We don’t know which way the pendants were meant to hang. Would you hang them differently than we did?

On view through June 2025

Edward B. Green Building, Wolfe Mezzanine

Throughout time, artists have devised ways of illustrating complex stories through an economy of means. The works in this gallery all have in common a graphic approach to art making, the use of artistic shorthand, and reliance on their contemporary audience understanding of symbols and iconography.

From Greek mythology to family lineage, to political and social practice, we see ways of compacting stories using bold, elegant line, bright color, and compressed space. Overcoming challenges of form and dimension, artists and illustrators communicate succinctly to their contemporaries.

On view through June 29, 2025

Edward B. Green Building, Gallery 18

In 2023, TMA acquired an extraordinary assembly of eighteenth-century Indigenous Eastern Woodlands objects. This beautiful collection, featuring quillwork, beadwork, moose hair embroidery, and birchbark creations, presents a rare opportunity for visitors to explore the artistry and history of early America.

On view April 12-July 27, 2025

Edward B. Green Building, Levis

Rachel Ruysch: Nature into Art is the first major retrospective of one of Europe’s most celebrated flower painters. The exhibition showcases Ruysch’s masterful still lifes alongside botanical books, drawings, and natural specimens, exploring the connections between art, science, and global trade and colonization in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

On view April 16-July 6, 2025

Edward B. Green Building, Robert C. and Susan Savage Community Gallery

Muralist Chris "Chilly" Rodriguez brings his bold, vibrant artwork to a smaller scale in this exhibition.

Featuring neon colors, geometric and organic shapes, and a mix of realism and abstraction, his work aims to uplift and inspire joy in every viewer.

On view July 12-November 30, 2025

Edward B. Green Building, Canaday Gallery, Gallery 5, Gallery 9

Infinite Images: The Art of Algorithms explores the foundations of generative art, from early pioneers like Vera Molnar to contemporary artists working with algorithmic systems. Featuring digital and physical works, interactive experiences, and largescale installations, the exhibition reveals how artists collaborate with technology to challenge ideas of creativity, authorship, and automation.

The Toledo Museum of Art is proud to announce that Collectors Corner at the Museum Store will now be known as the Sanda Findley Collector’s Corner for the next two years, thanks to a generous gift from long-time museum supporter Sanda Findley.

A passionate advocate for the arts, Sanda has been a steadfast champion of the museum and its mission. Her support ensures that Collector’s Corner—featuring artwork by more than 200 regional artists—continues to thrive as a platform that celebrates local talent and their contributions to the creative community.

Visit the Sanda Findley Collector’s Corner to discover exceptional, locally made art, including works by TMA staff, such as Alan Iwamura, glass studio manager.

Give the gift of membership!

Looking for the perfect gift for a graduate, newlywed, or retiree?

Celebrate TMA’s April 1901 founding with special discounts on new memberships—perfect for sharing art with someone special.

Learn more at toledomuseum.org/membership.

P.O. Box 1013

Toledo, Ohio USA 43697

Forwarding Service Requested

On the Cover: