TKTNK collage

2023

5th Edition, April 2023

For inquiries, contact bcarchitecturesociety@gmail.com Visit us online at https://issuu.com/tktnk

TKTNK is published by the Barnard + Columbia Architecture Society.

A

Open Activity ..........................................................................................................................................................................................

Feats of Architecture and Civil Engineering - Lowell Cerbone .....................................................................................................

Cabbage Vessels - Eris Gao .................................................................................................................................................................

Revolving - Thy-Lan Alcalay .................................................................................................................................................................

Minecraft: The People’s Architecture - Fred Avila Bravo ................................................................................................................

Breaking Cracking News - Ji Yoon Sim ..............................................................................................................................................

Materialogics: Vessels - Tina Wang ....................................................................................................................................................

Scaled Nostalgia - Ramona Delyser.....................................................................................................................................................

Highlighted Transparencies - Sophia Zhang .....................................................................................................................................

Supported in part by the Arts Initiative at Columbia University.

Supported in part by the Barnard + Columbia Architecture Department.

Comfort as Ornament - Georgia Dillane and Jharna Kamath ........................................................................................................

Hermit Crab Helmet - Dana Lee ..........................................................................................................................................................

Purple Emotions - Victoria Perez Giannone ......................................................................................................................................

What is a Shrinking City? - Eleanor Ding ...........................................................................................................................................

AD HOC ASSEMBLY - Xianming Zhou ................................................................................................................................................

Conversations in Architecture - Quinn Hughes ................................................................................................................................

MICRO to MACRO - Maeve Flaherty ..................................................................................................................................................

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Letter

the

from

Editors .......................................................................................................................................................................

-

Umpierre ............................................................................................................................................................. B+C Architecture Society...................................................................................................................................................................... 6 7 15 20 24 26 31 34 42 44 52 56 58 64 66 74 78 83 90 97 Printed by Barnes & Noble Press. collage 4 5

Vaivén - Victoria Perez Giannone ........................................................................................................................................................ Crescendo

Samira

A Letter from the Editors...

We are excited to present the first physical issue of TKTNK since the disruption of the pandemic in 2020. Both of us joined the Barnard + Columbia Architecture Society as sophomores in the fall of 2020, in the midst of the pandemic; living away from campus and attending classes online, the Society was an important point of connection for us. When the virtual format of studio courses limited our ability to collaborate and form creative relationships with our peers, this community became our substitute.

Over the past three years, the Society has generated meaningful work internally—group activities that ranged from silly to serious, trips to cultural institutions and important works of architecture in New York and beyond, analytical examinations of Columbia’s campus and the built environment with which we interact every day—but the products of these explorations rarely made it outside of our own circle. Thus, during the 2022-2023 academic year, the Executive Board made it our goal to be more accessible, open, and engaged with the broader Barnard+Columbia community. We have opened up many of our events to students outside of the Society and outside of the department. We secured funding to subsidize our museum trips, firm tours, and site visits in order to break down any barriers to participation. And now, we present the April 2023 issue of TKTNK, showcasing the ideas, art, and dreams of our design community.

This issue’s theme is collage, reflecting our desire to represent that community in all of its different permutations and combinations. We chose not to establish rigid boundaries for our content, instead seeking to provide a home for interdisciplinary exploration. We hope that the juxtaposition and layering of different mediums, modes, and methods of design will offer new insights that are only visible when they are brought together into one body of work. We look forward to the future creations of all of the designers and makers featured here, growing out of the kaleidoscopic collective to which they all belong.

Sophie Sebuh & Teresa Lawlor Co-Managing Editors of TKTNK

TKTNK Editors

Eris Gao

Fred Avila Bravo

Maeve Flaherty

Quinn Hughes

Ramona Delyser

collage 6 7

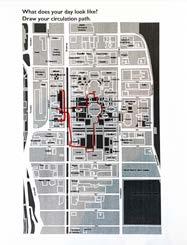

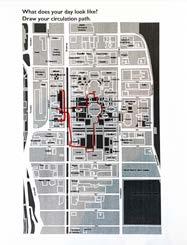

open activity workshop exercises created by the community collected by the TKTNK publications team

OPEN ACTIVITY collage 8 9

OPEN ACTIVITY collage 10 11

OPEN ACTIVITY collage 12 13

Feats of Architecture

FEATS OF ARCHITECTURE collage 14 15

WEST VIRGINIA

Feats of Architecture and Civil Engineering in the Hills of West Virginia

Lowell Cerbone

As a state that ranks #47 in economy and #50 in infrastructure, it might come as a surprise that the state of rolling mountains hosts some of the United States’ best examples of historic architecture and construction. In the media, West Virginia often gets a bad reputation as a state ravaged by the opioid epidemic, represented by a controversial senator, and denounced by celebrities as home to a population that is “poor, illiterate, and strung out”. While we shouldn’t ignore the state’s overrun foster system, suffering public school system, and generally poor economic status, let us also appreciate a few of its better attractions: a grand B&O railroad station in Grafton, a historic suspension bridge in Wheeling, and the incredible Palace of Gold in Moundsville.

On Main Street in Grafton, West Virginia, a town of just under 5,000 people, there sit two gems of architectural design. The B&O railroad station and the adjacent Willard Hotel are great examples of Beaux Arts architecture, the architectural style taught by the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, France, particularly in the mid- to late-19th century. Both structures sit on a slope that runs along the B&O railroad station and are faced with red brick and terra cotta trim. The station rises two stories on Main Street and three on the track, while the hotel rises five and one-half stories on Main Street and six and one-half on the track. The station features six white columns which surround its three main entrances, a massive entablature that sits atop the columns, and a parapet curve which contains a garlanded cartouche with the B&O logo. The hotel features a mansard roof with dormers that have been altered and a panel inscribed with the name of a prominent lawyer and entrepreneur of the area, John T. McGraw. Maurice Alvin Long designed both structures while employed in the railroad’s engineering office to be built in 1910.

In Wheeling, West Virginia, home to approximately 27,000 people, lives a bridge that was the first longspan wire-cable suspension bridge in the country and first bridge to span the Ohio River. The Wheeling Suspension Bridge was first built in 1849, destroyed by a tornado five years later, and rebuilt in 1856. The 1,010-foot bridge is supported by twelve iron cables

suspended from its towers. The cables are anchored to masonry walls built under Wheeling’s Main Street and rest on cast iron rollers that adapt to changes in temperature or transitory loads. This historic structure was designed by architects Charles Ellet Jr. and Washington Roebling. The bridge still serves as an example of pre-1900 bridge construction and is the oldest vehicular suspension bridge still in operation in the world.

Perhaps most surprising is the Indian palace, glittering gold against a backdrop of forested hills and farmlands in Moundsville, West Virginia, which earned its spot as one of CNN’s “8 Religious Wonders to See in the US.” The temple features 30 stained glass windows, 4 royal peacock windows, murals depicting ancient Indian classics, and walls and pillars accented with semi-precious stones and 22-karat gold leaf. The interior is lined with 24 pillars topped with sculpted lions, its walls are hung with oversized works of art, and its ceilings are adorned with crystal chandeliers and mirrored ceilings. Surrounding the temple are the award-winning Palace Rose Garden which features more than 150 varieties of roses; the Garden of Time which displays a variety of geraniums, marigolds, zinnias, salvias, and dahlias; and the Lotus Pond which attracts several swans. The highly-ornamented structure creates a beautiful contrast between the rugged simplicity of rural West Virginia and an opulent palace of material beauty. The palace was built by devotees in 1973 to serve as a home for Srila Prabhupada, an Indian Gaudiya Vaishnava guru and foremost Vedic scholar, translator, and teacher of the modern era. The devotees did the work themselves without any architectural design experience and often learned on the job.

Grafton’s B&O railroad station’s French architecture style that is rarely found in the US, Wheeling’s suspension bridge which stands as the last of its kind in the world, and Moundsville’s Palace of Gold built entirely by untrained workers are just a few of the many hidden gems in West Virginia. The too-often underrepresented state’s mountains are decorated with historic community centers, grand hotels, and relics of West Virginia’s once-booming manufacturing industry. Let West Virginia serve as a reminder that brilliant feats of architectural design can be found in the most unexpected places.

February 12, 2023

Works Cited

Chamber, S. (2019, June 17). B&O Railroad Station and hotel. SAH ARCHIPEDIA. https://sah-archipedia.org/buildings/WV-01-TA1

Ferrell, J. (2022, March 15). Uncover this peaceful palace in an unexpected place. Almost Heaven - West Virginia. https://wvtourism.com/palace-gold-moundsville/ Srila Prabhupada. Palace of Gold. (2021). https://www.palaceofgold.com/srila-prabhupada

Wheeling suspension bridge. ASCE American Society of Civil Engineers. (2022). https://www.asce.org/about-civil-engineering/history-and-heritage/historic-landmarks/ wheeling-suspension-bridge

FEATS OF ARCHITECTURE collage 16 17

C

B

A

C

B FEATS OF ARCHITECTURE

18 19

A. B&O railroad station and the adjacent Willard Hotel / B. Historic suspension bridge in Wheeling / C. Palace of Gold

A

collage

cabbage vessels

ERIS GAO

Material Logics

Julian Harake

Fall 2022

CABBAGE VESSELS collage 20 21

CABBAGE VESSELS collage 22 23

THY-LAN ALCALAY Systems and Materials

REVOLVING

collage 24 25

Todd Rouhe Fall 2022

REV OLV ING

EV OLV ING V OLV ING OLV ING LV ING VING ING NG G

My favorite days in elementary school were always the rainy ones. Ms. Tatum would teach math in the morning (the sky darkening with cottony clouds), then English grammar after break (the wind whistling through the classroom door), and by recess the drops began to fall, tapping gently at the roof over our twenty-something heads. Fearing for our health and for the structural integrity of school supplies in the hands of soggy children, Ms. Tatum kept us indoors where there were no soccer balls or jump ropes to play with, and no water to drench us. But then how should a third grader survive the half hour of confinement? With whatever Ms. Tatum had in the back drawers. She brought out puzzles, and board games, and coloring books, but best of all, the blocks! I shyly lay claim to the wooden blocks, of which not all were squares. There were hexagons and triangles and rectangular prisms all painted in primary colors. loved the deep clinking sound they made when they connected, and the process of figuring out how each piece fit or stacked. With them I could imagine the quiet city streets outside, all the houses and stores slowly darkening with dampness, lulled to sleep by the rainfall.

As I grew up I found new ways of building things: blanket forts, legos, and eventually video games. But no other video game was such a home to my creativity as Minecraft. Since its release in 2009, Minecraft has become an incredibly popular game, platform, brand, and community. As of 2023, the franchise is estimated to have over 140 million active players, $3 billion just in game-sale revenue, and a player age average of 24. Needless to say, Minecraft is far from being a little-known children’s game. Its success hinges on catering to a variety of audiences and interests.

Being a sandbox game, Minecraft allows for players to choose and seek out their own fun. Some players are obsessed with using redstone mechanics to build complex machines, or with spending hours exploring randomly generated landscapes, or even with mining thousands of blocks underground for the resources to slay monsters. But with such a diverse array of blocky materials, Minecraft is really the perfect game for builders. One only needs to spend a few minutes on YouTube’s gaming page to see video after video of Minecraft content creators that make a living out of recording gameplay. Many of them raised me.

Growing up, I didn’t have access to console games, let alone anything that would require a PC. This wasn’t particularly disappointing. I understood from a young age how hard my immigrant parents worked to make ends meet in the Bay Area – a notoriously expensive place to live. I didn’t particularly envy the gross looking zombie games, or the ones about stealing cars grandly, or the ones about stabbing people, etc. It wasn’t till got a hold of my dad’s Samsung and began watching people play video games online that I realized there were kinder games than the ones knew, designed to be creative outlets. spent much of my childhood watching Minecraft videos, experiencing the fun vicariously, and subconsciously learning the techniques for mimicking real-life architecture. Soon enough, I was able to have my own device to download the mobile version of Minecraft (now called Bedrock Edition). It didn’t have all the features that the computer version had, but it was enough. I spent hours after school making houses and gardens and churches and zoos, finally putting into practice everything I’d been watching on YouTube. The worlds I could build and stories I created to go with them gave me the perfect escape from whatever troubled me as a middle schooler. Over the years of playing the game, I became a better builder, and with each new update, the game grew up alongside me. I played all throughout high school, and even now as a CC student majoring in Architecture, I still find myself gravitating toward old game files when I want to avoid reading for Literature Humanities.

Though I’m not as avid of a user as I once was, I’ve come to understand Minecraft in new ways since starting college. Because of my socioeconomic background, I wasn’t raised with access to the same technology resources as some of my peers. A quick google search for computers and 3D modeling software is all it takes to realize how expensive those programs can be. But Minecraft I could afford, and it came with a slew of people sharing ideas, serving as each other’s creative muses, and constantly pushing the limits of the game and of themselves to ambitious ends. I know I’m not alone in having grown up with Minecraft as a tool that fostered my passion for architecture, and I’m certainly not the first low-income student to enter the world of urban design. My hope is that rather than putting such platforms in a box and dismissing them as childish, we recognize that not every creative person has equal access to every artistic medium, but that fact shouldn’t stop them from finding ways to create, nor should it make their art any less valuable. As architects, we should see the intricate beauty of all creative works, regardless of whether they’re shown to us in thousand dollar 3D software renders or in a school teacher’s wooden blocks.

FRED AVILA BRAVO

FRED AVILA BRAVO

MINECRAFT: THE PEOPPLE’S ARCHITECTURE collage 26 27

MINECRAFT: THE PEOPPLE’S ARCHITECTURE collage 28 29

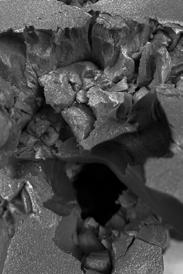

JI YOON SIM Systems & Materials Todd Rouhe Fall 2022 Design solution to a corridor-style office for a journalism organization. C BREAKING NEWS R C A N I K G BREAKING CRACKING NEWS collage 30 31

BREAKING CRACKING NEWS collage 32 33

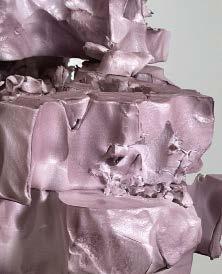

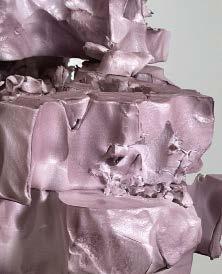

I thought I was a hardcore perfectionist.

As a student completing a degree in architecture, I can plan, sketch, and model with fine levels of formal resolution. I find joy in seeing the clarity and elegance of form bespeak my ideas, of course, through the representation of computer models in the perspective window.

Something was missing. As I become more adept at designing with digital tools, I wonder why those designs look like single objects trapped in frozen shape space. Then, I start to question the primacy of geometric rationalization in the design process. Curious to see what structural behaviors that calculations could not initially provide, I want to explore the nonlinear material behavior towards the design of decorative vessels.

Materialogic: Vessels is about making. It is a lineup of hand-made vessels unique in proportion, shape, and personality. Due to the intrinsic nature of the material – gelatin, food coloring, glycerin, bubble solution, and optionally cheesecloth – each vessel not only twist and curves but also droop, bond, and spread.

Materialogic: Vessels is about experiencing with

our hands and all our senses. These vessels are not single objects; they are informed by the spaces around them and amenable to individual experiences. Crumple one thin sheet: it is a bowl. Combine two porous sheets: it is a pencil holder. Stack three folded sheets: it is a bookend. The life cycle of these sheets is circular. The combination of materials can be used and reused by repeating the process of its heating. The sheet can be used as an adhesive when it is wet or used as a structure that permanently maintains its shape when it is dry.

The material sheet preserves its content but its properties are fascinatingly fluid. Materialogic: Vessels offers architectural design formal possibilities –dim in outline – that require releasing design ownership and letting the materials take a course of action that may not always make logical sense.

Should we disregard geometric rationalization? No.

Materialogic: Vessels does require deliberate mold-making in the replicating process but is more contingent on methods of fabrication.

There remains a lot uncontrolled, yet all came together in the most elegant display of architectural moments in Materialogic: Vessels.

MATERIALOGICS: VESSELS

TINA WANG

Material Logics

Julian Harake

Fall 2022

MATERIALOGICS: VESSELS collage 34 35

MATERIALOGICS: VESSELS collage 36 37

MATERIALOGICS: VESSELS collage 38 39

HIGHLIGHTED TRANSPARENCIES collage 40 41

SCALED SCALED SCALED SCALED

Looking around my 114 square-foot dorm room, I noticed the little arrangements I had made with the few things I brought from home. I wondered how my tastes would manifest on a larger scale in a home of my design. Having no experience and only my memories of Sunset magazine ranch houses to guide me, I began.

In this small sketch inspired by my bedside table, I imagined a shrine in front of large windows, behind which the pink paper potted flowers had grown to be smoke bushes. The shrine and smoke bushes were key features of my family’s life in my childhood home.

RAMONA DELYSER

I established a rough layout of the house and worked out the dimensions, ending up with a 1500 square foot home. The smoke bushes and wall of windows of the original inspiration still remain, but in a more practical way. Elements of homes I had loved as a kid integrated themselves into my design: a pass-through over the stove, garden beds by the carport, lavender like at my grandma’s house, bamboo along various walls, and wisteria over the patio.

While not everything is drawn in perfect convention and there are surely many improvements to be made, I found the process to be extremely rewarding. I was able to create a personal reflection of my memories. I enjoyed revisiting the residential architecture of my past that has shaped the way I understand and create spaces.

NOSTALGIA

SCALED NOSTALGIA SCALED NOSTALGIA SCALED NOSTALGIA SCALED NOSTALGIA SCALED NOSTALGIA SCALED NOSTALGIA SCALED NOSTALGIA SCALED NOSTALGIA SCALED NOSTALGIA SCALED NOSTALGIA NOSTALGIA NOSTALGIA NOSTALGIA

SCALED NOSTALGIA

collage 42 43

SOPHIA ZHANG

Material Logics

Julian Harake

Fall 2022

highlighted transparencies

HIGHLIGHTED TRANSPARENCIES collage 44 45

material experiments in bubble wrap modge podge, epoxy resin, rockite

Highlighted Transparencies is a project which explores the material and commercial dynamics of bubble wrap. In everyday use, bubble wrap is a secondary commodity used in the packing industry. It is not a product in and of itself; its sole purpose is to serve other fragile products during storage or shipping processes. As such, its presence is often something that is completely ignored or taken for granted - however, given the intensity of the flow of commodity goods across the globe today, the production, export, and use of bubble wrap is actually a massive undertaking and industry which contributes heavily to the presence of plastic and microplastic waste in the environment today. In this project, I attempt to call attention to bubble wrap as a commodity product by centering its form, texture, and material qualities, prioritizing its existence over the object it wraps around and stretches over.

Given the fact that bubble wrap itself is a highly malleable and elastic material, the development of the fabrication process for these vessels has been centered around the goal of “freezing” the bubble wrap in particular s tates of being while stretched and wrapped over existing vessel forms. This involves the layering of other casting and hardening materials, namely Modge Podge, epoxy resin and Rockite, to varying degrees and ratios. Because dried Modge Podge peels away easily from the plastic of bubble wrap, this material is what directly interfaces with the original material; resin and Rockite are then poured over the dried Modge Podge layer, taking on the texture of the bubble wrap as it cures. The original vase and bubble wrap are then taken out and peeled away from the inside of the vessel, leaving only the impression of the original material.

The Modge-Podge-resin-Rockite composite material takes on and emulates certain qualities of bubble wrap, such as its transparency, but is also different enough from the packing material in its solidity and rigidity that it creates a moment of dissonance and confusion for viewers as they question the material makeup of the vessel

rockite casting resin

rockite casting resin

modge podge elastic rubber bands plastic bubble wrap glass vase collage

[detach] 46 47 HIGHLIGHTED TRANSPARENCIES

material layers

collage 48 49 HIGHLIGHTED TRANSPARENCIES

HIGHLIGHTED TRANSPARENCIES collage 50 51

Comfort as Ornament:

THE CASE OF THE ANTI-FEMINIST FEMINIST JAIL

ORNAMENT AS COMFORT: THE CASE OF THE ANTI-FEMINIST FEMINIST JAIL

BY GEORGIA DILLANE AND JHARNA KAMATH

At 31–33 West 110th Street, less than ten blocks away from Columbia, lies Lincoln Correctional Facility, a minimum security men’s prison that closed in 2020. The site is the proposed home of the “Women’s Center for Justice,” a concept developed by Michelle Feldman of the Women’s Community Justice Association in conjunction with the Prison and Jail Innovation Lab at the University of Texas at Austin and the Justice Lab of Columbia University. The project attempts to propose a reformed solution for the imprisonment of “women and gender expansive people” once Rikers Island is closed, part of New York’s plan to replace the large prison with smaller, borough-based jails.

Although the project proposes a “‘Reentry at Entry’ model that focuses on therapeutic care, family unification, and skills building to break the cycle of incarceration,” the model proposes only reform and ethical imprisonment, something that fundamentally does not exist. The project does little to differentiate itself from a classical prison model, instead dressing it up with a variety of humane buzzwords.

Ultimately, it can be likened to form and function, utilitarianism and ornament: a beautiful jail is

still a jail. Prison design has long been the test site of violent architectural design. Architects have experimented with ways to incarcerate people, even before policing was invented (key word: invented). The prison itself acted as a form of structural policing, instilling fear and harm onto impressionable

COMFORT AS ORNAMENT collage 52 53

populations. Bentham’s panopticon was adopted for prison use and implemented into a structural tactic of violent surveillance. The abandonment of its physical design does not mean, however, that its legacy does not continually permeate strategies of surveillance as violence in the carceral state largely. The proposed “Feminist-Jail” acknowledges the violence of prison design, as it attempts to subvert the harmful structural qualities of prisons, all the while operating within the same prison industrial complex that upholds the prisons that they claim to distance themselves from. The “Women’s Center for Justice” is a prison. Plain and simple. As much as they will decorate it with a new reformist name and inclusive language (“ a first-of-its kind gender-responsive, trauma-informed facility”), it is a carceral space, within a carceral state.

Below, we pick apart their language of design, and what they qualify as innovative use “evidence-based practices,” to reveal the inherent violence that they try to cover up.

“Evidence-based

best practices” Reality

“Comfortable furniture made of natural materials that feel homelike and contribute to a normalized environment”

“Small groups of rooms with 12 or fewer residents to foster a sense of community”

“Center should have a ‘blue room’ where residents can decompress and participate in activities such as watching nature videos. Access to nature and natural elements can significantly improve residents’ behavior and mental health.”

“A separate building, miles away from the men’s jail, which will reduce the potential for re-traumatization.”

“Homelike” facilities are not the same as being at home.

Community is not fostered by forcefully assigning a group of people to a room.

Fails to consider how being incarcerated itself significantly harms one’s mental health.

former women’s correctional facility into a community center dedicated to women. Clearly what to do with the skeletons of the United State’s massive prison industrial complex is a continued project with a variety of solutions. The Anti-Feminist-Feminist Jail sees comfort as ornament instead of comfort as a fundamental piece of the places that shelter us. Proximity to the community does not negate the physical separation between prisoners and their families. A home-like environment is not the same as being at home.

“No blind spots, except in areas where privacy is important, to reduce the risk of violence, sexual misconduct, or the use of contraband.”

Being incarcerated is traumatizing in and of itself. Claiming that a solution to re-traumatization is physically separating the jail from another jail, avoids the reality that those working in a jail cause this trauma that they claim they want to avoid.

Surveillance.

List of practices taken from “A Safer New York City: The Women’s Center for Justice: A Nation-Leading Approach on Women & Gender-Expansive People in Jail.” Published by Women’s Community Justice Association in collaboration with HR&A, the Columbia Justice Lab and UT Austin’s Prison and Jail Innovation Lab.

Many of our current conversations tend to center the idea of architecture as care. Designers are expected to create for a wider audience, considering bodily ability, social dynamics, and environmental concerns along with more traditional ideas of form and beauty, to name a few. It must then follow that as designers, we need to unpack the implications of our work. Our involvement does not begin and end at the drafting board, but continues into what we create. If, as architects, we have always been so concerned with legacy, this includes the social, environmental, and ethical legacies of the things we create. Architecture is not a neutral discipline, and architects are complacent in upholding a harmful system, even if that form is a “beautiful” prison.

The Women’s Center for Justice is not the end of this conversation. Design firms like HDR have designed hundreds of jails and prisons, using the language of progress and reform to make themselves appear socially responsible. Evidently, HDR has received enough backlash for their involvement in “Justice Architecture” that they removed the page from their website (https://web.archive.org/ web/20201024123201/https:/www.hdrinc.com/markets/justice). Projects like the Women’s Building by Deborah Burke Partners seek to transform prisons into non-carceral institutions, turning an abandoned

COMFORT AS ORNAMENT collage 54 55

DANA LEE

Environment Studio

Lindsay Harkema

Spring 2023

HELMET hermit crab

A wearable helmet for extroverted people who hate talking to others, sometimes...

...and for introverts who love to talk to others, sometimes.

HERMIT

HELMET collage 56 57

CRAB

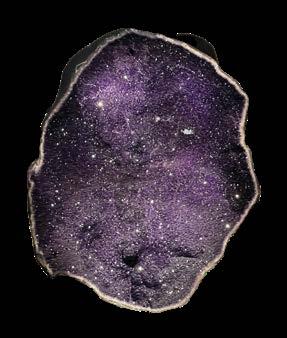

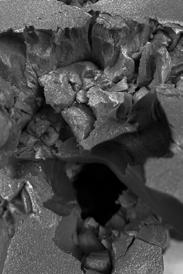

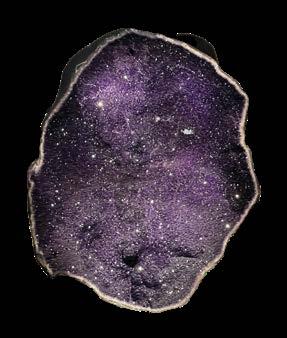

VICTORIA PEREZ GIANNONE Material Logics Julian Harake Fall 2022 PURPLE EMOTIONS collage 58 59

FIRE stab Reattach burn twist dig melt shape PURPLE EMOTIONS

the high

I started with a set material, XPS insulation purple foam. I choose several words that were violent, because at the beginning all I wanted to do was get rid of the foam form my dorm. I was attracted to burning it, stab it with pliers, with hammers, and so forth. This material is toxic when burnt, so I had to use caution, buy the right mask for safety, and find an outdoor spot to perform the actions. By using a lighter in different areas, I added depth into the material, creating different tonalities and controlling the randomness of the fire reaction into the material. By using the hammer and the pliers I create holes and areas of contrast (untouched areas) where you could get lost on what was untouched and what was the material. Reaching this level of contrast, while also making it look natural was important for me. Something in between disturbed and undisturbed.

After trying these couple actions, I remembered something I used to do about a year ago with this material to create curves. Using the wire cutter in the studio was how I achieved the smooth curves along the outside of my vessel structure. These made it look like a rock formation and it was a key step to see the “erosion” like cracks and layers. From plastic to natural looking, even with the purple color, the three vessels resemblance that of an amethyst crystal. Curiously enough, this mineral rock is belived to calm rage, fear, and anger.

A material that is from nature, with properties so different from purple foam and the plastic/toxic/ prefabricated world, can end up looking and feeling very similar. The first vessel, the circular one, I wanted to play with how people hold it in their hands and the very straight forwards perspective it had in the middle hole. The second vessel, which is divided in two in the center, has the idea that is a rock formation cracked open in the center, showing in detail the layers and unnatural “erosion” created by the fire and the hammer. The third vessel is a result of the second vessel, the interior shape of it created only by the material leftover from the action of stabbing. Showing the interiority as a shell is what I was trying to experiment with.

PURPLE EMOTIONS collage 60 61

and low of materiality...

Prelayering

fabricated Actions

Prototypes...

Wire Cut Curves

Burned by Flames

PURPLE EMOTIONS collage 62 63

Stab by hammer

Whatis a shrinking CITY?

Are there advantages to concretizing the definition of shrinkage?

Eleanor Ailun Ding

Shrinking Cities

Claire Panetta

Fall 2022

During one of the first sessions of the course, Bernt introduced the concept of a “shrinking” city in a vague yet straightforward manner: one that has “lost considerable population” (Bernt, 2019). Despite this,t as acknowledged by both scholars and fellow students throughout the semester, the definition of shrinkage has remained conceptually and linguistically unclear. But perhaps the obsession with establishing accurate definitions of shrinkage can shed light on its other immediate and hidden purposes. This paper will attempt to answer the question, “Are there advantages to concretizing the definition of shrinkage?” by presenting arguments for both sides.

The most straightforward argument in favor of concretizing the definition of shrinkage is that the fundamental premise of problem-solving is a thorough understanding of the issue at hand. But to claim this reasoning would be an over-simplification. In the same direction that Mumford’s 1937 “What is a City” demonstrated the importance of establishing principles for a city to position it appropriately within the sociological and urban fabric, the same is true of the significance of

defining shrinkage. Though it may seem counterintuitive to draw parallels between the concept of the city and the concept of shrinkage (as their matryoshka doll-like relationship seems more to be a nested one, rather than an adjacent one), both concepts share the same core of fundamental logic. The core being the inhabitants of that specific urban environment. Further, if “the city fosters art and is art; the city creates the theater and is the theater” (Mumford 1937, 29), then the city experiences shrinkage and is thus the shrinkage. And hence, the city must be established properly in order to produce optimal “functions of social existence” (Mumford 1937, 31), and shrinkage must be viewed correspondingly in order to better exemplify the myriad possibilities of urban life.

Despite this, it may also be proposed that there are difficulties in defining shrinkage in a consistent fashion. The first is the concept’s inherent nature. As previously mentioned, shrinkage is most conceptually alive within urban sociology, making it a dynamic that takes human and geographic factors into account and hence, making it inevitably fickle. Accordingly, one could argue

that it is counterproductive and futile to assign a fixed definition to an ever-changing construct. And therefore, concretizing a definition of shrinkage may not only impede its adaptability to factors such as time and the natural and built environment, but also reduce it to a unidimensional universal concept applicable to all cities experiencing population loss.

A comparison between Detroit, a city in the upper midwestern United States, and Qiqihar, a city in northeastern China, illustrates this logic. Although both cities are seen as the symbol of urban shrinkage in their respective countries, it is flawed to use a broad definition of shrinkage (such as the one proposed by Bernt, which is primarily focused on population loss). This is due to the fact that it disregards race and politics, which are undeniably critical components of both cities’ narratives of rise and decline. In contrast to Detroit, where systemic racial discrimination permeates every aspect of its urban history, from industry to policy to culture, this cannot be said of Qiqihar. Even though there are variations within the Chinese ethnicity, contemporary China remains racially homogeneous East Asian, particularly in the northeast. Thus, factors such as disinvestment initiatives and government policies are not racially motivated. Furthermore, economically, the rocket trajectory of China’s economy over the past fifty years places Qiqihar in a completely different position relative to its country’s overall economic framework than Detroit’s position relative to the United States. Such considerations demonstrate the disadvantages of standardizing a solid definition of shrinkage.

Finally the relevance of concretizing a definition can be contested conceptually and linguistically. One may then contend for the distinction between the principles of “define” and “interpret”. The act of defining shrinkage is arguably much more passive than its interpretation. Though a level of understanding is required for both in-

stances, its functions are fundamentally different. Defining a term is more akin to labeling, and thereby categorizing, while interpreting calls for the process of genuine care and embodiment. Thus, one is in pursuit of understanding, while the other has understanding as their ultimate goal. Consequently, in the case of shrinkage, perhaps the focus should shift away from the concretization of the definition and toward the active interpretation and accompaniment of the concept, to better accommodate the issue’s physical and urban landscape repercussions. To conclude, it is evident that the concept of shrinkage is extremely nuanced and difficult to define and comprehend. By juxtaposing the terms “shrinkage” and “city,” structural similarities can be discerned, shedding light on the value of establishing an idea’s guiding principles. However, when the nature of both shrinkage and “definition” is questioned, it is possible to observe the volatility of both concepts and how this affects the perception of the urban dilemma. Although the aforementioned points attempt to provide plausible arguments for and against the concretization of the definition of shrinkage, the immaturity and sometimes speculative nature of the reasoning should not be overlooked. Because, perhaps ultimately, the respondent’s own views and opinions regarding the phenomenon may provide the only true meaningful definition of shrinkage. Similarly, the only people who can truly experience the effects of urban shrinkage are those who live in the city that is shrinking.

Works Cited

Bernt, Mattias. 2019. “Shrinking Cities.” In The Wiley-Blackwell Encyclopedia of Urban and Regional Studies – 1st Edition, edited by Anthony M. Orum. Cary: Wiley-Blackwell.

Mumford, Lewis. [1937] 2015. “What is a City?” In The City Reader – 6th Edition, editewd by Richard LeGates and Frederic Stout. New York: Routledge: 110-114.

WHAT IS A

collage 64 65

SHRINKING CITY?

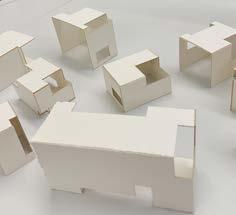

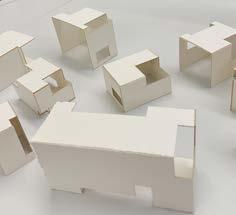

XIANMING ZHOU Systems and Materials Todd Rouhe Fall 2021

CENTER CENTER CENTER CENTER CENTER 12 3 AD HOC ASSEMBLY ––Projects from Fall 2021 Systems and Materials with Professor Todd Rouhe 12 ’’ 20 ’’ 29.75 ’’ 6 ’ 1 2 3 4 5 6 The Social System The chosen social system includes a group of students chatting in front of the law library. Every individual plays a role in changing the pattern of the social system as they spontaneously connect with or separate from each other. The ad hoc assembly could intentionally guide individuals to form groups that align with the pattern of the original social system, “reorienting” the space they occupy. Deconstructing the Prototype: ADIRONDACK BENCH The Adirondack bench is deconstructed into 6 components for reconstruction to accommodate possible interactions people might have with the ad hoc assembly. Possible Interactions Individuals could have different interactions with the Adirondack bench, which may function as a bench, a table, a stool, or a recliner, after various heights are determined based on the components of the Adirondack bench. AD HOC ASSEMBLY collage 66 67

ASSEMBLY AD HOC

Cu t will break the continuity of an obje ct , which could be used to indicate subgroups.

Rotation is a translational motion, which parallels the phenomenon that individual interac tions within the subgroup will not change its pattern

TO RTION transf ormation code: X Distor tion will either expand or shrink the obje ct , which is similar to the pattern that individuals within the social system will spontaneously fo rm several subgroups that will change over time.

Translating the Social Pattern

The group interactions within the social system can be categorized as three situations: union, rearrangement, and segregation. Then three transformation methods are corresponded to these situations: distortion, rotation, and cut. The ad hoc assembly is arranged based on the overall pattern of the social system, forming a sort of landscape within the social group that connects individuals.

Assembly

The number assigned to speci fi c components can be interpreted as the following:

Form (A-J) + Deconstructed components (1-6) +

Transformation methods (XYZ)

For example, A3YXXZ means In form A, component 3 is rotated, then distorted, and distorted again, and finally cut. Then, all the reconstructed components are assembled.

Reconstruction

After the Adirondack bench is deconstructed into several components, different transformation methods are applied to indicate the specific changes/interactions within the social system. The deconstructed components then will be reconstructed into new forms, labelled with a unique number to indicate the specific transformation methods applied to them.

Situation 1: UNION DIS

Situation

RO TA TION

code: Y

2: REARRANGEMENT

transf ormation

Situation 3: SEGREGA TION CUT trans fo rmation code: Z

CENTER CENTER CENTER RO TA TION DIST ORTION CU T RO TA TION CU T DIST ORTION RO TA TION DIST ORTION DIST ORTION DIST ORTION RO TA TION CU T CU T DIST ORTION CU T RO TA TION DIST ORTION RO TA TION DIST ORTION Fo rm A Fo rm D Fo rm C Fo rm E Fo rm G Fo rm H Fo rm I Fo rm J Fo rm F Fo rm B A3X B1X B2X C3 XX C4 XX D4X E5YZ F3X F4X F5Z H3X H4X I3 J4’XZ J4XZ

AD HOC ASSEMBLY collage 68 69

The Altered Social System

The ad hoc assembly will then diversify the interactions within the social group, either making them more organized or chaotic.

NO SLEEP

Cu t Va lle y Mountain

more complicated

simple fabrication method: cutting and folding.

Ad Hoc Assembly

Pattern Simplified Pattern with Cutting and Folding

Steps to Transform

1. Simplify the assembly 2. Unfold the assembly 3. Simplify the unfolded surface to fi nd patterns 4. Determine the cutting and folding lines 5. Fold the structure after cutting AD HOC ASSEMBLY collage 70 71

A Variance from the Ad Hoc Assembly... The ad hoc assembly can evolve into a

structure while applied with one

Simplified

Unfolded

Lines

the Ad Hoc Assembly

Exploded Diagram of the Structure Canopy Isometric View Right View Section Front View Base AD HOC ASSEMBLY collage 72 73

Michael

Abel

Conversations in Architecture

Founder of NYC based practice FOOD New York, DongPing Wong is one of the most exciting and innovative voices in architecture. With collaborators spanning from Les Benjamins, to Virgil Abloh, to Kanye West, to HYPEBEAST, Wong’s practice is on the frontier of multi-disciplinary design. I caught up with Dong-Ping over Dim Sum at House of Joy, just blocks from FOOD’s China Town office. This is an excerpt from a full interview available on the TKTNK Youtube.

Quinn Hughes: I think, from the student perspective, that’s one of the hardest things to learn. That the voice of the architect, is the balance between letting the site, and the client, and the program speak for itself, and letting your voice, you’re kind of architectural imposition on the space (speak), in a certain way. That’s that balance in a lot of instances, which I think is super cool to hear you speak to, that relationship. It’s not one approach every time, it has to happen organically.

Dong-Ping Wong: Don’t get me wrong, I fight with our clients all the time! But we’re always pushing back, they’re always pushing us back. There’s always stuff that we want to, do that physically, environmentally, cost wise, we can’t do. And that is a good lesson to learn. It’s a good ego check. It’s a good real world check. I’m honored that you even pick up on that through line through the work because, we’ve gotten to the point where I realized it but it’s never conscious in terms going into it. It’s just kind of like, you just want to do it. At least I just want to do it. I keep thinking, did an interview a long time ago, and I was like, the ideal feeling I try to achieve in the work doesn’t always happen. I grew up in San Diego and I grew up surfing. And when you’re surfing, there’s always moments. I mean, the majority of the time you’re just sitting there waiting for a wave and there’s this calmness, oftentimes where there’s no wave coming into us. It’s like flat horizon, especially when it’s like kind of overcast and it’s the grey/silver sky kind of blends and reflects off the water and blends in. And you’re sitting in this weird serene, void. But also, you’re like floating in water. And it’s really quiet. You have no media, you have no phone. But that feeling of just kind of being, in nature was always like, if I can find a way to always hit that moment where you snap into this weird zen moment, that’s always what we try to do. But I think that kind of being outdoors was always my favorite. I’m always happiest, usually, outdoors. Initially, the challenge was like, how do you do interior spaces and bring some outdoors in? And the Off-White store was one good example of that. And I think once we had success with that, we’re like, “Oh shit, we can do this, there’s methods to do this. It’s not an impossible Ideal.” Well, honestly, it’s as dumb as like, we just design places that I think we’d want to visit.

part of building an environment. Of course that is. It seems like often, GSAPP or the GSD aren’t writing papers about that, aren’t having labs dedicated to that. But of course, that’s such an intrinsic element. Could you talk about where like, Mahjong specifically but also that theme in the work of thinking about community comes from and what that process is like?

Dong-Ping Wong

QH: Yeah! And I think it seems simple, but it’s a level of mindfulness. Because, it’s about physical environment and it’s also about communal environment in a certain way, it’s a way of thinking about architecture, not isolated, but as responsible to nature, community, and physical ecosystem. I think something that seemed like a super cool throughline was, Plus-Pool a few years ago, and currently the work that’s being done, but also Mahjong. Which is of course, that’s architecture in a certain way. Of course, inviting people in to do things and make things that’s already existing is a

DPW: I mean, it’s interesting that you pulled Plus Pool and Mahjong together, because there’s a very clear line between the two, just from like an initiative point of view. Plus Pool was one of the first one of the first projects I thought up when I was like, “what’s the kind of work I want to do?” And instead of just doing competitions, let me just try to invent something and see what happens to it. Maybe it picks up a few eyeballs, and that’s it. But the idea was, “Can we like invent a project?” But that was very much, “What is the kind of work I want to do?” It deals with the natural environment, it’s outdoors, it’s for a bunch of people. That was also much more heroic. It’s a glittering piece of architecture in that “capital A” kind of way. So, years later, when we’re still trying to push Plus Pool, its a decade plus old, it was like, alright, I want to keep doing initiative stuff, we want to keep doing initiative stuff, we don’t want to do another decade’s worth of project that doesn’t get built yet, can we do something quick? And also, I think the big advantage is kind of “put your money where your mouth is”. We talk about community a lot, can we actually make a space people want to come to? It may look cool, but if nobody wants to come hang out, what’s the fucking point? So it started actually with Food Radio, and that was our first attempt. And that was after like, you know, we’re in Chinatown now, if we really believe that we want to learn how to be part of Chinatown, just put your shit out there. It may not work, it may work. What was interesting, it both worked and didn’t work in a way. It worked and it was great. The interviews were amazing, I thought, I learned a lot, people came by the space, it was super fun. It didn’t work, I would say, in the sense that the community of people that came by, were already our community. Like our friends, friends of friends, colleagues, people in the design world, architecture world. And we only had a handful of people that came by from the neighborhood. But it was like, look, we spent two months on it, we very quickly learned from real world experiences, you can’t just open a space and expect people to come by. You have to actually be a part of the neighborhood. You know? One of the things that brought people by was, as dumb as it was, Bella, who’s the director of the office, just walked across the local public library, and was like, “Hey, we’re doing a taco building workshop, if any of the kids want to come by.” And they came by. It was that simple. Well, like that’s not an architectural problem in the way that you learn how to deal with it. So that was really important for us to learn. Mahjong club, very similarly is like, as it leads into a more traditional architecture, my goal is maybe we can actually build out a community center project physically at some point, but I want to make sure also, if we ever get hired to do that, or can initiate that, we already are part of the community that it is for in some way. Or we’ve worked with them in some way, and so let’s start with just these events, and slowly build those events up. Even now it’s still majority friends and family. What’s nice now is, we’re starting to involve people that are a little bit out of our circle. Same age, same interest, but people we didn’t know before. We’re still not getting

Quinn Hughes

Photo: Tanya and Zhenya Posternak

Quinn Hughes

Photo: Tanya and Zhenya Posternak

CONVERSATIONS IN ARCHITECTURE

74 75

Photo: Dezeen

collage

like-, my dream was, I want to get like the old dudes playing mahjong in the basement that I walked by, and they’re like, “I want to come to this.” We may never get there, and that’s all good. But I know how far we have to go with that. But to your point, I also believe it’s fully architecture. It is the architecture part that I think it’s very easy to ignore as a designer. How do real people actually occupy this thing? How do you make sure they have a good time? Sometimes it’s like, well, just put on good music. It could be that dumb. It doesn’t have to be more complicated than that. Serve them some good food. That’s all you really need. You don’t have to have some crazy form. There’s no crazy shit. It’s good food, good music, get some people around, that’s it.

QH:It’s that willingness to be open. Once you’re there, it’s like, “Oh, of course”, in a certain way. I did debate in high school. I am working with (my high school’s team) now that my brother is there. And it’s like, oh, “how do we get these young 15-yearold kids to want to like come to debate? Oh, of course, you just bring pizza, you bring them Doritos.” (They’re) like, “Okay, I guess we’ll come to argue with each other.” I think that’s super cool to think in that way and be open.

DPW: Well also think, and I’m curious if you’re starting to sense this because you’re only a couple years in. But it’s like, the deeper you get into architecture education, at least at the high end academic, Ivy League, level, I do think the further away you get from just knowing how to talk to normal people. You have this whole other language, you have this whole other way of operating that is very removed from the people that end up using your space. And so luckily, I’ve been out of it for a while. Part of the reason why I was like, let’s learn how to just be neighbors. You know? That simple kind of stuff.

QH: I think it It’s with architecture, it’s super specific, because I think a lot of folks have that one moment, young, where it’s like, “Oh, snap architecture is just a word that I use for the cool stuff that like with my friends, when we’re designing sneakers on the Nike ID website that we’re never going to buy, or when we’re setting up our own rules for basketball, when we’re just hoping, because we only have three people and a fourth person comes.” Architecture is a way of describing that. It totally gets abstracted from that essence in a certain way. Hearing you talk and seeing the projects, when I was doing some research for the interview, I think what made you as a person super interesting is-, it’s one thing to be an architect, that’s already a risk, in a certain sense. You don’t necessarily know what the processes are to make money, and be sustainable, if you work for anyone. Then, there’s another level when you work for yourself. And you’re now responsible for your own money, and your own finances, and your own projects. But then to do that, and to do something like Plus Pool, where, when you were describing it, the traditional model of architecture, of being commissioned by a client, was flipped on its head, that seems super courageous to. To be like “we have to we what we want to see, we don’t know if someone’s gonna buy it, but we believe in it, and we work backwards.” Similarly, in a certain way, to mahjong or working with a young streetwear designer who’s just an artistic director for Kanye West with Virgil. Can you speak a little bit about-, of course that’s fun and super exciting, but it has to be a little bit scary, at least initially, when you just have the ideas. Can you talk about what that courage is like to keep going and moving forward, when it’s difficult in that process?

DPW: I will say weirdly, it gets it gets scarier the more established we get, in a way that is more psychological. It’s kind of like, the more you have to lose, the less risk averse you become. But generally, I feel I’m super privileged that had a very classical architectural training and education, that I worked at very classical architecture offices for a number of years before starting my own thing. And so, for the longest time, was like, “I know what that world is, and if I need to get a job in that world, I think I can get a job.” When I also know that I’ve got 40 years of this, or whatever, to look forward to, or not look forward to, however you want to put it. And especially with Plus Pool at that time, it was actually right after the 2008 recession. There wasn’t a lot of shit going on anyways. It was kind of like I literally have nothing to lose. I’m freelancing to pay some bills, I’m getting by. I’m not making a ton of money no matter what I do. I’m not getting the kind of work, nobody’s calling me for work, I guess, no matter what I do. And so at that point, Plus Pool actaully didn’t seem like a risk at all. If anything, it was like, a no brainer. Let’s just try this. And also, I mean, we put in a lot of work, with Archie and Jeff from PLAYLAB. We put a lot of work. But also, we had time to do it, It seems cool, it’s getting our brains out of just trying to survive from a business point of view post (recession), and we had no real expectations of where we’re going. So with Mahjong, the risk is not so much from a business point of view. It’s like, I don’t want to, misstep and create something that’s actually detrimental in some way to the neighborhood. Or harmful in some way. But at the same time, I won’t know what that is, until get to that limit. I can either do nothing, or, one of the reasons we put so much out there is like, I want to find a way to actually learn from other people that are doing work in the neighborhood. And be like, “this is what we’re about. You can either fuck with it or not, and if you don’t fuck with it, we’ll take that as a lesson and I might switch it up. And it also gives us, frankly, we made it an excuse just to call people up, and be like, “Can I talk to you? And can we do an interview.” I don’t know if it actually feels that risky. As dumb as it is, the only risk is like, okay, we got $10,000 right now, should we save it a little bit, or should we just put something?

I think that philosophy has always been like, if we have money, let’s spend it. Let’s either like, put it to the staff, let’s put it to an event, let’s do anything with that. Money will come and go. We’ll figure it out. It may mean that we’re not the best at building a business, but at the same time, I’m very happy that we’re not hoarding money or something. I think it’s one of those things, I started an office to pay bills obviously but that’s not why I started the office. I started the office mainly to try and figure out what kind of work I wanted to do, and find a way to do that.

Michael Able is co-founder of NYC architecture practice ANY, and Chief Design Officer at Frank Ocean’s jewlery line HOMER. Recenlty winning AIANY’s new practices competition, ANY’s work explores the intersection between architecture, media and culture. In January, Michael and I talked about SMLXL, writing, architectural education, and Lil Uzi. This is an excerpt from a full interview available on the TKTNK Youtube.

Quinn Hughes: I think that’s probably my favorite thing about school, in a particular way, is just finding different people who speak your language. And, think that’s what’s cool about architecture is that it draws from so many different backgrounds. It’s so rewarding to have those dialogues with people who come from different spaces, different thought processes. I’m super interested in a lot of what you spoken about, I’m really interested in the different medium exchanges that you’re referencing. Are there places that you feel like you’ve tried to most to look (at) when you’re when you’re-, not necessarily for inspiration, but when you’re looking at music, art, film, that you find yourself thinking about architecture? Other spaces, or artists or musicians that you find yourself engaging the most. Or is it as you see an array of different things?

Michael Abel: I think it happens subconsciously, you know? I try not to apply it so directly..but I do really think it is important to engage in all these other mediums and disciplines. It’s not to say you have to be an expert in everything but it’s important that you can meet experts, talk to them, work with them, and collaborate. It’s such a simple idea…the more you learn, the better. You just have to find ways to mitigate, translate and provide clarity to all of these ideas. Because the biggest risk is to be like “okay, I know everything about everything…now what?” And then you get this convoluted project. So I’m trying to think about output, which is why Casa Da Musica was an important project for me to see this summer. I do believe that was a physical manifestation of overexposure at a certain time…20 years ago.

QH: I see the word “sponge” often in your writing and stuff like that. I think that’s such a such a useful metaphor, immediately, because it’s drawing from other things to create one kind of unit, in a certain kind of way. Being open to those relationships, being open to those connections as an embrace.

MA: Yeah, I’ve been trying to toy with that idea, with “sponge” and “flipper”. The “sponge” one is kind of self explanatory. And then the “flipper” one is a little less self explanatory, but it came from this derogatory term that conservatives used with liberals to describe a “flip-flop politician”…which is describing a liberal politician to flip-flop on their ideals (or they change their mind). So they were against something five years ago, and then they’re for something five years later, and it’s derogatory because they’re saying it’s just because they want the vote. But if you spin its progress, or learning and things like that.

QH: I got to see the flipper presentation at Cooper Union in November of last year. And it was super cool to see that kind of rhetoric, and then immediately applied to the projects and ideas that y’all are working with now. I think the two of my favorite things were the meme of like, “I’m trying to learn the distinction between, post modernism and modernism.” And it’s like, “The these terms are generated by the Academy.”

I don’t I don’t know the particular language.

MA: “this binary is obsolete as fuck”

QH: Yeah!

MA: Yeah…I don’t know if we’ve applied it yet. We’re working on it. I don’t know even what we’ve shown you is-, you know… we’re very much a young practice…we are practicing and the scale of the projects don’t necessarily represent these ideas that we’re thinking about. When you give lectures like that at Cooper, you can talk about these kind of disciplinary ideas of where we want to go, and where we think the discipline should go. But then we work on projects that are, you know, maybe only a 2000 square foot building, or house, or restaurant, or something like that. And, I can’t say you can put all of those ideas in that, versus a concert hall in Porto, which is an extremely public project, in the best way possible.

QH: Yeah, I think it’s useful to be able to, like, use language in a particular way to think about design. Because I think the projects kind of exist on their own, but the conceptual framework that’s kind of used to create them develops.

MA: I’ve been thinking about lately that writing doesn’t need to be a representation of your architecture…it’s also another medium. It’s a trip wire to be like, “everything I write needs to be related to the architecture that I’m making.” My favorite architectural writing is more about disciplinary or cultural observations. Where they’re trying to understand what the world is…at an extremely large scale. And then, those observations are disciplinary conversations which will again seep into projects in small ways or big ways down the road.

QH: And I think, the best architecture is a reflection of how people are living lives in a very intimate way. And, I think writing is a really wonderful way to begin that investigation at a very simple, and foundational, and fundamental level, how are people interacting with each other, how to built environments reflect that? And I think writing is like-, it’s a very useful tool to be able to get from that place to actually creating form. That observation.

MA: Are you writing a lot in school?

QH: Of course! It seems like it’s half design, half writing, if not more. And, I think it’s super useful to get those juices flowing.

MA: You like it?

QH: I love it. I think because you’re always writing with someone. You’re writing in response to someone, especially in architecture.

MA: I think that’s it’s good and important. I’ve been writing again. It’ll probably take a long time, but I’ve been doing it.

* * *

* CONVERSATIONS IN ARCHITECTURE collage 76 77

moments of scale on and around campus

MICRO to MACRO

MAEVE FLAHERTY MICRO TO MACRO collage 78 79

MICRO TO MACRO collage 80 81

VAIVÉN collage 82 83

created by Victoria Perez Giannone

VAIVÉN collage 84 85

VAIVÉN collage 86 87

VAIVÉN collage 88 89

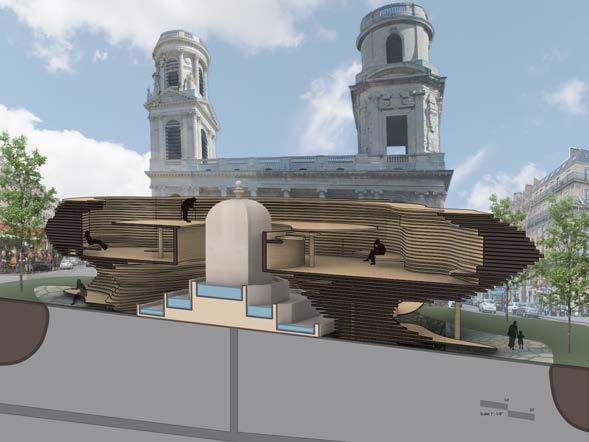

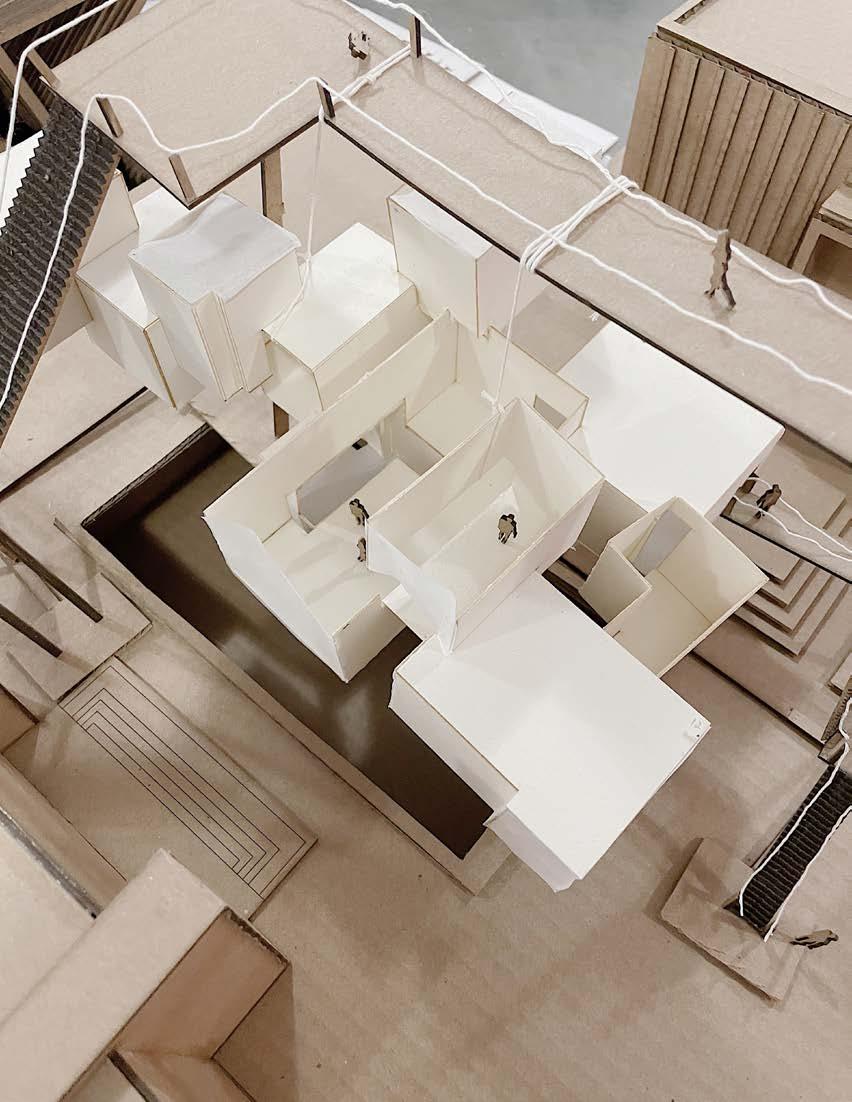

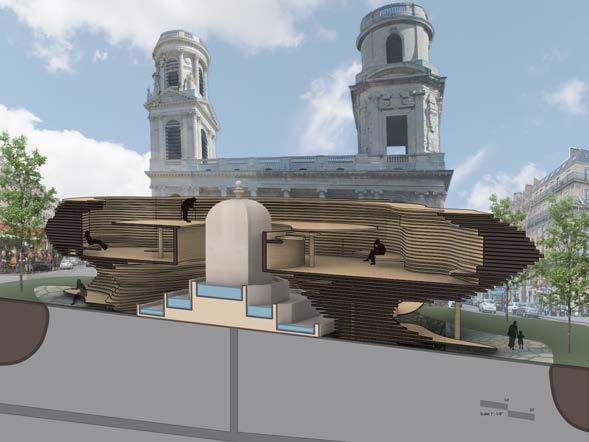

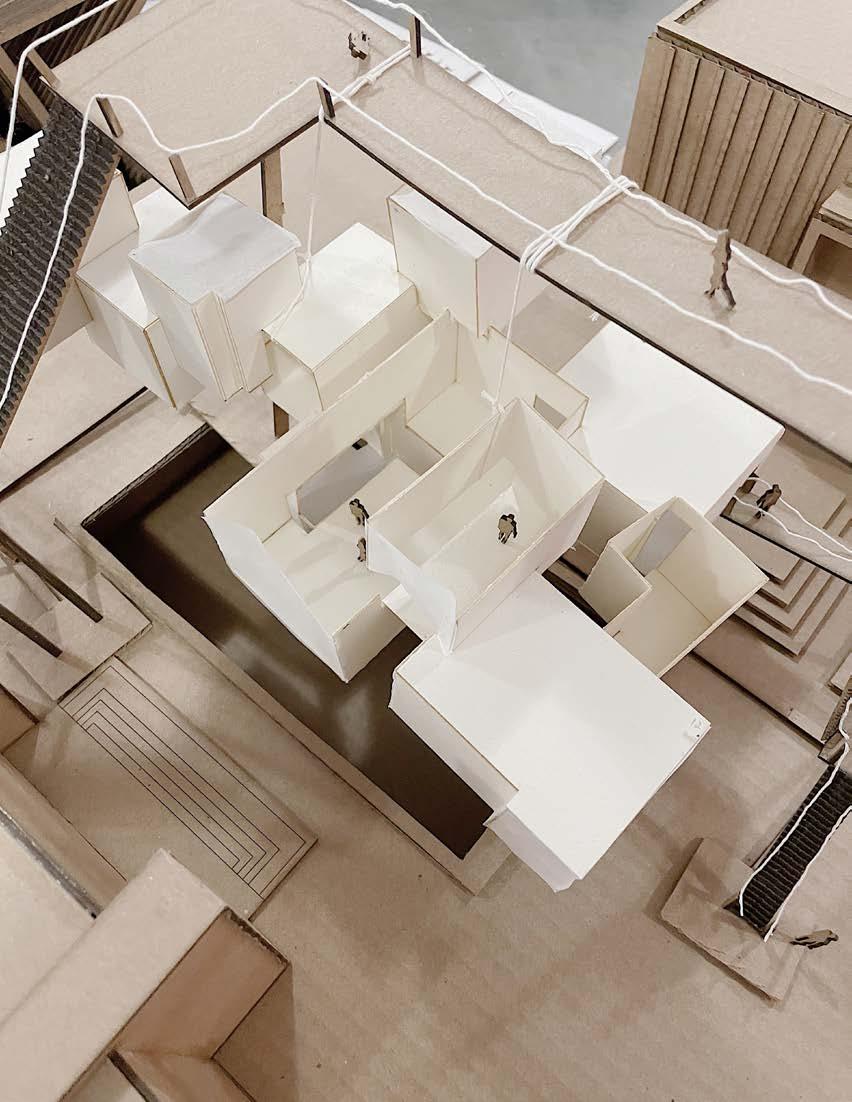

Crescendo

Tasked with repurposing Fontaine Saint-Sulpice in Paris, France, Crescendo examines sound and site activity to develop a space tailored to play with your senses. During a series of site visits similar to those conducted by Georges Perec, I observed peoples’ use of the plaza space surrounding the fountain and measured the duration of their activities and sources of sound. Crescendo features a similar double-helix staircase as in Chateau Chambord--revealing nooks within the walls of the top floor and on the exterior ground floor of the 65-foot fountain. This intervention incentivizes visitors to interact with the fountain for longer periods of time.

SAMIRA UMPIERRE

The Shape of Two Cities: New York/Paris Studio

Columbia GSAPP

Thomas Demonchaux

Spring 2023

100’ Rue Saint-Sulpice Rue de Vieux Colombier Rue Bonaparte RuePalatine Rue Henry de Jouvenel Place Saint-Sulpice Rue de Mézières des Canettes Scale: 1/32” 50’ Rue Saint-Sulpice Rue de Vieux Colombier Rue Bonaparte RuePalatine Rue Henry de Jouvenel Place Saint-Sulpice Rue de Mézières Rue des Canettes CRESCENDO collage 90 91

The third level brings you to the very top of the fountain. It exposes one to the heightened sounds of the waterfall and provides a top to bottom view of the fountain as well as a horizon of the site’s tallest buildings.

Crescendo utilizes three varying wall thicknesses to insulate sound. As you ascend the fountain, noise pollution from the waterfall and around the plaza are reduced to provide a space of refuge for visitors.

20’ Section West-Facing Sound Movement Insulation

CRESCENDO collage 92 93

CRESCENDO collage 94 95

B+C Architecture Society

Executive Board

Logan Shorthair, Co-President

Sophia Zhang, Co-President

Zoe Hyman, Secretary

Sophie Sebuh, Treasurer

Ryan Newberger, Events VP

Teresa Lawlor, Publications VP

Society Members

Amy Xiaoqian Chen

Anabella Advincula

Ava Frisina

Charlotte Lawrence

Catherine Mok

Dana Lee

Eris Gao

Fred Avila Bravo

Georgia Dillane

Grace Schleck

Hazel Lu

Isabel Canalejo

Jharna Kamath

Ji Yoon Sim

Lolo Dederer

Lowell Cerbone

Maeve Flaherty

Max Graves

Quinn Hughes

Ramona Delyser

Saeah Yu

Samira Umpierre

Sean Skaskiw

Sofiya Belovich

Victoria Perez Giannone Advisor

Simone Medley

B+C ARCHITECTURE SOCIETY collage 96 97

TKTNK: collage B+C Architecture Society, 2023.

FRED AVILA BRAVO

FRED AVILA BRAVO

rockite casting resin

rockite casting resin

Quinn Hughes

Photo: Tanya and Zhenya Posternak

Quinn Hughes

Photo: Tanya and Zhenya Posternak