3 minute read

cabbage vessels

Eris Gao

Material Logics

Advertisement

Julian Harake

Fall 2022

Fred Avila Bravo

My favorite days in elementary school were always the rainy ones. Ms. Tatum would teach math in the morning (the sky darkening with cottony clouds), then English grammar after break (the wind whistling through the classroom door), and by recess the drops began to fall, tapping gently at the roof over our twenty-something heads. Fearing for our health and for the structural integrity of school supplies in the hands of soggy children, Ms. Tatum kept us indoors where there were no soccer balls or jump ropes to play with, and no water to drench us. But then how should a third grader survive the half hour of confinement? With whatever Ms. Tatum had in the back drawers. She brought out puzzles, and board games, and coloring books, but best of all, the blocks! I shyly lay claim to the wooden blocks, of which not all were squares. There were hexagons and triangles and rectangular prisms all painted in primary colors. I loved the deep clinking sound they made when they connected, and the process of figuring out how each piece fit or stacked. With them I could imagine the quiet city streets outside, all the houses and stores slowly darkening with dampness, lulled to sleep by the rainfall.

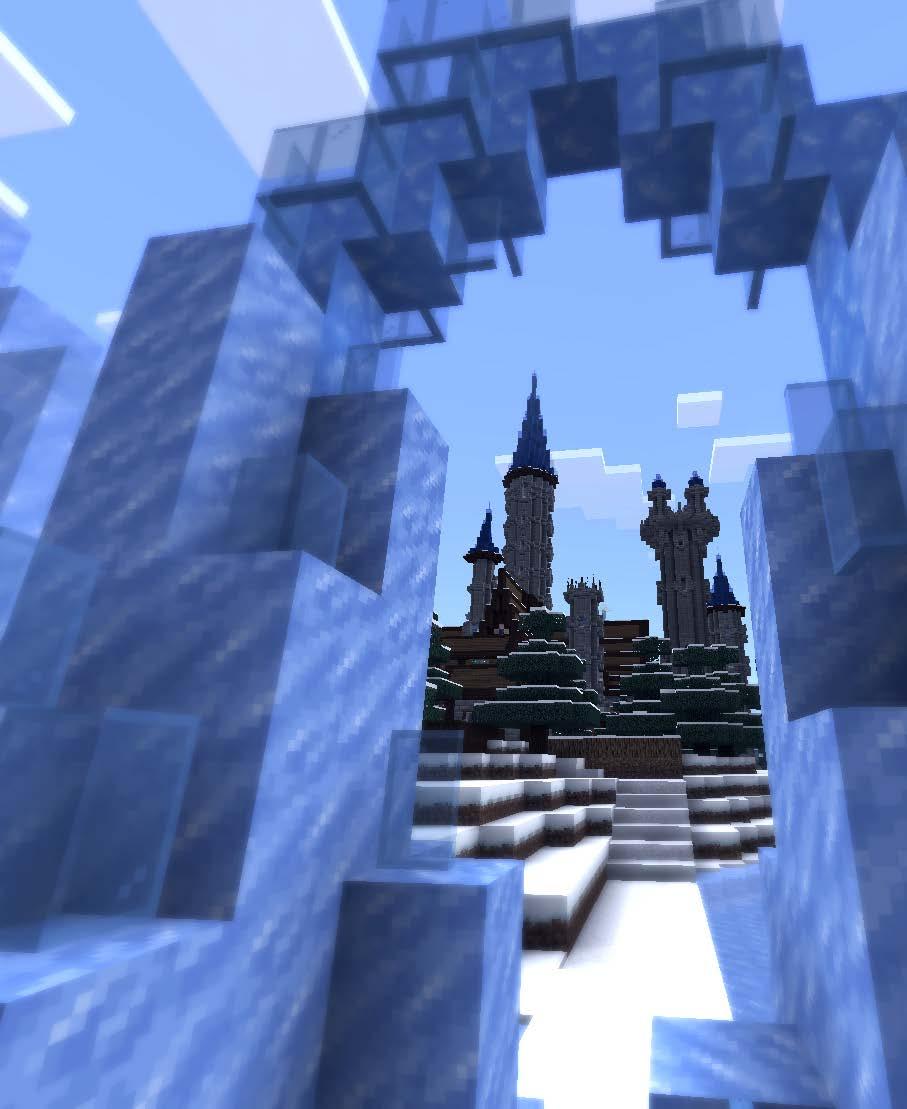

As I grew up I found new ways of building things: blanket forts, legos, and eventually video games. But no other video game was such a home to my creativity as Minecraft. Since its release in 2009, Minecraft has become an incredibly popular game, platform, brand, and community. As of 2023, the franchise is estimated to have over 140 million active players, $3 billion just in game-sale revenue, and a player age average of 24. Needless to say, Minecraft is far from being a little-known children’s game. Its success hinges on catering to a variety of audiences and interests.

Being a sandbox game, Minecraft allows for players to choose and seek out their own fun. Some players are obsessed with using redstone mechanics to build complex machines, or with spending hours exploring randomly generated landscapes, or even with mining thousands of blocks underground for the resources to slay monsters. But with such a diverse array of blocky materials, Minecraft is really the perfect game for builders. One only needs to spend a few minutes on YouTube’s gaming page to see video after video of Minecraft content creators that make a living out of recording gameplay. Many of them raised me.

Growing up, I didn’t have access to console games, let alone anything that would require a PC. This wasn’t particularly disappointing. I understood from a young age how hard my immigrant parents worked to make ends meet in the Bay Area – a notoriously expensive place to live. I didn’t particularly envy the gross looking zombie games, or the ones about stealing cars grandly, or the ones about stabbing people, etc. It wasn’t till I got a hold of my dad’s Samsung and began watching people play video games online that I realized there were kinder games than the ones I knew, designed to be creative outlets. I spent much of my childhood watching Minecraft videos, experiencing the fun vicariously, and subconsciously learning the techniques for mimicking real-life architecture. Soon enough, I was able to have my own device to download the mobile version of Minecraft (now called Bedrock Edition). It didn’t have all the features that the computer version had, but it was enough. I spent hours after school making houses and gardens and churches and zoos, finally putting into practice everything I’d been watching on YouTube. The worlds I could build and stories I created to go with them gave me the perfect escape from whatever troubled me as a middle schooler. Over the years of playing the game, I became a better builder, and with each new update, the game grew up alongside me. I played all throughout high school, and even now as a CC student majoring in Architecture, I still find myself gravitating toward old game files when I want to avoid reading for Literature Humanities.

Though I’m not as avid of a user as I once was, I’ve come to understand Minecraft in new ways since starting college. Because of my socioeconomic background, I wasn’t raised with access to the same technology resources as some of my peers. A quick google search for computers and 3D modeling software is all it takes to realize how expensive those programs can be. But Minecraft I could afford, and it came with a slew of people sharing ideas, serving as each other’s creative muses, and constantly pushing the limits of the game and of themselves to ambitious ends. I know I’m not alone in having grown up with Minecraft as a tool that fostered my passion for architecture, and I’m certainly not the first low-income student to enter the world of urban design. My hope is that rather than putting such platforms in a box and dismissing them as childish, we recognize that not every creative person has equal access to every artistic medium, but that fact shouldn’t stop them from finding ways to create, nor should it make their art any less valuable. As architects, we should see the intricate beauty of all creative works, regardless of whether they’re shown to us in thousand dollar 3D software renders or in a school teacher’s wooden blocks.