REACHING

INTRODUCTION CONTENTS

“Success is not final, failure is not fatal: it is the courage to continue that counts.”

- Winston Churchill

We are thrilled to present Issue 18 of the Disputes magazine, our Next Gen edition. This edition dives into the themes of: Corporate Disputes, ESG, International Arbitration & Class Actions. Each theme offers an insight into the current trends and hot topics in the ever-changing nature of legal conflicts. As always, we extend our sincere thanks to our Corporate Partners, contributors, and readers for their support in bringing this issue to you.

Do keep an eye out as we continue to offer various engaging events in the Disputes Community.

The ThoughtLeaders4 Disputes Team

Paul Barford

Founder/ Managing Director

020 3398 8510

email Paul

Danushka De Alwis

Founder/Chief

Operating Officer

020 3580 5891

email Danushka

Amelia Gittins

Senior Strategic Partnership Executive 020 3059 9797

email Amelia

Chris Leese

Founder/Chief Commercial Officer 020 3398 8554

email Chris

Maddi Briggs Strategic Partnership Senior Manager 020 3398 8545

email Maddi

CONTRIBUTORS

Meera Shah - Bond Solon

Hannah Gannage-Stewart - Bond Solon

Hannah Howlett - Burford

Capital

Ben Dinoit - Burford Capital

Farrah Sbaiti - Ogier

Raedean Simpson - Ogier

Marc Kish - Ogier

Oliver Payne - Ogier

Yulia Barnes - Barnes Law

Catriona Campbell - Clyde & Co

Caleb Sturm - BRG

Hannah Jackson - BRG

Chris Wenn - Burges Salmon

Mona Yue - CANDEY

Jesler van Houdt - CANDEY

Rosalind Meehan - Weil, Gotshal & Manges

Amy Waddington - Weil, Gotshal & Manges

Hayley Lund - Weil, Gotshal & Manges

Seth Kerschner - Weil, Gotshal & Manges

Matthew Morton - Weil, Gotshal & Manges

Faiza Alleg - CMAP

Rupert Wheeler - 23ES Chambers

Syedur Rahman - Rahman Ravelli

Faye Summers - Rahman Ravelli

Matilda Lloyd Williams - Byfield

Amr El Sawaf - Charles

Lyndon Limited

Vishnuviraj Dhir - Charles

Lyndon Limited

Kassia Pletscher - Baker Botts

John Hays - Ankura

Magdalena Osmeda - KKG

Legal

Airlie Goodman - Mayer Brown

EUROPEAN COLLECTIVE REDRESS CIRCLE 2025

We are delighted to have concluded the European Collective Redress Circle 2025 in Cascais, Portugal. Over the past day and a half, we welcomed leading practitioners for a unique programme that combined high-level discussions on collective redress with the opportunity to enjoy the Portuguese sunshine.

Our sincere thanks to this year’s Advisory Board –for their guidance and expertise in shaping the event.

We are also grateful to Greg Haber and Niamh Tattersall (Verita), and Paul de Servigny and Phoebe Dubois (IVO Capital) for their valued support and contributions.

And, thank you to all who joined us. The Circle’s success lies not only in bringing together Europe’s leading practitioners, but in the collaborative and engaged spirit of its participants.

We look forward to continuing the conversations – and to welcoming you again next year.

FINANCIAL SERVICES – THIRD ANNUAL CONFERENCE 2025

This morning at the Financial Services – Third Annual Conference 2025, held at One Whitehall Place, we heard from a distinguished group of practitioners and experts as we explored some of the most pressing issues in financial services litigation.

We began with a Keynote Address: Judiciary Attitudes to Financial Service Disputes, delivered by Mr Justice David Waksman, Judge of the

Commercial Court, who shared his perspective on the evolving approach of the judiciary to disputes in the sector.

Following the keynote, the day featured a series of in-depth sessions, exploring key developments in litigation, regulation, and ESG.

Thank you to all speakers and attendees for an engaging and insightful afternoon

Upcoming Events

Sovereign & States Litigation Summit USA

23 - 24 September 2025 | Kimpton Hotel Monaco Washington, D.C., USA

The Family Business Disputes Forum 2025

30 September 2025 | One Whitehall Place, London

International Arbitration & Enforcement Forum 2025

8 October 2025 | Carpenters' Hall London

UK Class Actions - The 5th Annual

14 - 15 October 2025 | Saddlers' Hall, London

The European ESG Litigation Forum

4 November 2025 | Hôtel Mövenpick, Amsterdam City Centre

Corporate Disputes 2025 - 5th Annual Forum

2 December 2025 I Central London

Sovereign & States Disputes and Enforcement Summit 2026

5-6 February 2026 | Plaisterers' Hall, London

The ESG Litigation Summit 2026 - The 4th Annual

12 March 2026 | One Great George Street

For Partnership enquiries please contact Ben Jobson on +44 (0) 20 3059 9525 or email ben.jobson@thoughtleaders4.com

The Witness Familiarisation Specialists

Witness evidence can make or break a case. Give your clients the support they need to mitigate the risk of a poor performance at court.

Bond Solon’s team of specialists are experts in understanding the specific requirements of a case. Over the last 30 years, our essential pre-hearing service has helped over 250,000 witnesses achieve a positive outcome at the hearing stage.

Working with our clients, we create bespoke training and interactive workshops that will build witness confidence - allowing them to perform at their very best, taking chance out of the equation.

What Do You See As The Most Important Thing About Your Job?

The content development function in a business is often “lumped” with Marketing or seen as ancillary to Marketing rather than a standalone function. However, whereas Marketing tends to be more product driven and sales led, the creation of informative and on-the-pulse content goes beyond just increasing brand awareness and engagement. A wellconsidered content strategy can position a business as a thought leader in their industry. This objective is at the forefront of my mind with every piece of content I write or commission.

What Motivates You Most About Your Work?

I am and have always been a very curious person with a relentless thirst for knowledge. A significant part of my role as Content Manager involves horizon-scanning across our diverse industries for news/ developments that are relevant to our clients. That is what drives me most about my job – adding value beyond our primary function as a training provider.

If A Film Was To Come Out About Your Life, Who Would Play You?

In the absence of an A-list doppelganger, I’d say my daughter, Blake, who is the split of me but better looking.

60 SECONDS WITH... MEERA SHAH CONTENT MANAGER BOND SOLON

What Is Your Favourite Part Of Your Working Day?

Much of my work can be quite solitary – whether it’s horizonscanning, writing or editing content or working on the content strategy. So aside from the morning dog walk (the best way to start the day), I’d say catching up with our Marketing Manager, Marie about a project we are working on together or discussing content ideas with one of our business unit directors.

What Songs Are Included On The Soundtrack To Your Life?

Anything by Enya – she was my mum’s favourite singer.

Who/What Inspired You To Be Who You Are Today ?

Without a doubt my mother. She passed away when I was a teenager, but she still inspires me almost twenty years later.

What Is A Quote That Best Describes You?

“You may encounter many defeats, but you must not be defeated. In fact, it may be necessary to encounter the defeats so you can know who you are, what you can rise from, how you can still come out of it.”- Maya Angelou.

What Would You Be Doing If You Weren’t In This Profession?

Funnily enough, I’m already doing it! I’m a bestselling author of psychological suspense novels –Mira V Shah is my pseudonym.

What Do You Like Most About Your Job?

Probably the autonomy. Our content development team consists of me and one freelance content editor. So aside from input from our MD, Marketing and our business unit directors, I have a lot of autonomy in developing the content strategy for the business. I’m a former lawyer (commercial litigation) so I also appreciate that all my years of education (and practice) haven’t been a complete waste!

What Is Your Favourite Takeaway Dish?

Roti King’s dal and roti – if you’re London based or visiting London, you must try it (they have restaurants in Euston and Battersea Power Station).

JUDGE HIGHLIGHTS THE DANGERS OF A NEW EXPERT “ANCHORING” THEIR OPINION TO THAT OF THE PREVIOUSLY INSTRUCTED EXPERT IN RECENT HIGH COURT CASE.

Authored by: Meera Shah (Content Manager) - Bond Solon

The recent High Court case of Skykomish Ltd v Gerald Eve LLP [2025] EWHC 1031 (Ch) has highlighted some very important considerations for experts who have replaced another expert in a case – namely that the “new” expert report must be fully independent.

Read on to explore the finer details of the case and the dangers of a new expert “anchoring” their opinion to that of the previously instructed expert.

The background of the case

The dispute concerned a valuation of a site that was, at the time, a derelict building. This property was to be demolished and replaced with student accommodation.

The Claimant provided mezzanine finance with a profit share, relying on a valuation of the property provided by the Defendant.

The development eventually sold for a considerably lower sum and the Claimant recovered nothing from its investment.

The Claimant brought proceedings against the Defendant, alleging that the valuation it had relied upon had been carried out negligently.

Deputy Judge, Richard Farnill commented that this was the “source of three difficulties”:

The Expert Witness Evidence

The Claimant’s valuation expert was instructed in less-than-ideal circumstances, in that she was the third expert hired from the same firm. The first instructed expert left the firm, and the second instructed expert had to withdraw because he subsequently realised that he lacked the requisite experience.

1. Timeframe.

As she was the third valuation expert appointed by the Claimant, her report was “obviously prepared in a short time frame” and therefore, “contained multiple errors”. Whilst some were immaterial, others were much more significant. For example, an error in her calculations resulted in her valuation being understated by £460,000. Although the Deputy

Judge gave the expert full credit for acknowledging the errors when they were pointed out to her in cross-examination, he made it clear that “candid admission upon discovery is not the way the system is supposed to work.” took the view that had she had more time, she would have presented a more accurate report.

2. Anchoring.

The expert was the third expert from the same firm. Whilst the Judge accepted that she was not doing so consciously, her evidence did not appear to be fully independent and was compromised by her defending of what he coined the “house view”. He provided two examples in his judgment of instances where instead of carrying out the work herself, the expert relied upon the data of the previous experts. In concluding that her evidence was influenced by the earlier work of her colleagues, he stated that “the power of random anchors has been demonstrated in some unsettling ways”.

3. Conduct.

The Judge criticised the expert for at times acting like an advocate for the Claimant’s case. In answering the questions that were put to her, she went out of her way to mention details that undermined the credibility of the Defendant even though they that no relevance to the opinion she had been instructed to provide. Had the expert been instructed in a less hurried manner she might have been more aware of her legal duties and responsibilities as an expert.

Summary

The Skykomish case presents key learnings for lawyers instructing experts from in-house expert groups but also those who have appointed an expert to replace a previously instructed expert in a case. The primary consideration, as for all experts, is that their opinion must be fully independent. But it is also crucial that they have enough time to review all the facts of the case before providing their opinion, to avoid any unnecessary and damaging inaccuracies.

In this case, the Claimants expert’s “anchoring” to the opinion of the previously instructed experts and the critical errors in her report had a detrimental effect – leading to the Judge having “reservations about significant parts of her evidence”.

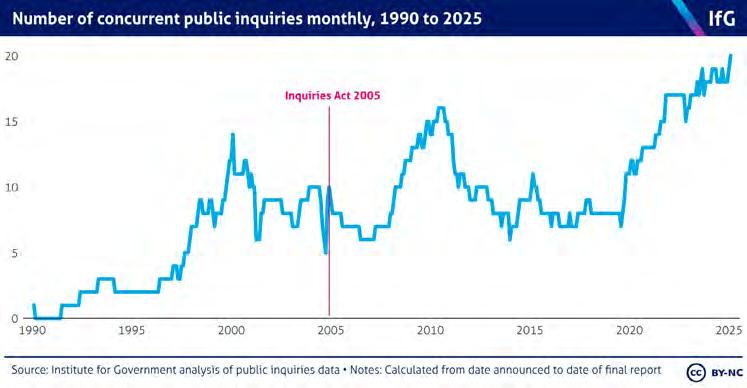

PUBLIC INQUIRIES ARE ON THE RISE ARE YOUR CLIENTS PREPARED TO GIVE EVIDENCE?

If it feels as though the frequency of public inquiries has increased in recent years, that’s because it has, significantly.

There are currently 20 ongoing public enquiries in the UK, with two of those announced just this year. Among them are the already underway UK Covid-19 Inquiry, Post Office Horizon IT Inquiry, the Thirlwall Inquiry and the inquiry into the Nottingham attacks. These highprofile investigations call on witnesses, and experts in various fields, to piece together what happened and why, and how to prevent similar events occurring again in the future.

With the frequency of inquiries increasing, the likelihood that emergency responders, public bodies, and other witnesses will be called to give evidence is also greater. Therefore, it is critical that these parties are competent and confident to carry out their roles to best practice standards.

What Is A Public Inquiry?

A public inquiry is an official investigation conducted by an independent body to examine a particular event or set of events that gave rise to matters of public concern. During a public inquiry many individuals can be called to give evidence.

There are two types of public inquiry: statutory and non-statutory. Under the Inquiries Act 2005, a statutory inquiry can compel testimony from witnesses and demand the release of other forms of evidence.

The Ministry of Justice states the primary purpose of an inquiry to be “preventing recurrence” of whatever matter of public concern arose. How this is achieved varies from inquiry to inquiry, but it will likely involve making recommendations. Specific terms of reference will outline the remit of a public inquiry and will address the questions that the inquiry is expected to answer.

It is also possible for a non-statutory inquiry to be converted to a statutory inquiry, which is what happened with the Post Office Horizon IT Inquiry.

Why Have Public Inquiries Increased In Recent Years?

Figures from the Institute for Government show that prior to June 1997, there were never more than three inquiries running at the same time. In stark contrast, the current 20 is the highest number ever to run concurrently.

Moreover, between 1990 and 2025, 88 public inquiries have been launched, compared with only 19 in the 30 years before 1990.

Alongside the increase in the number of inquiries, the Institute For Government has identified a long-term shift away from other forms of investigation such as royal commissions.

The arrival of the Inquiries Act 2005 goes some way to explaining changes. It streamlined the process for setting them up and gave ministers greater discretion to launch them, making it easier than it had been.

However, societal changes also play a big role. As the internet has evolved, spawning social media, alongside the emergence of 24/7 news, there is a

greater awareness of matters that affect the public, and with it a greater demand for accountability.

Various events have led to a growing distrust of public bodies, such as the government, police, and the NHS, fuelling yet greater demand for matters of public concern to be investigated and prevented from reoccurring. As such, this is likely to be a continuing trend.

In September 2024, The House of Lords Statutory Inquiries Committee made several recommendations related to following up and implementing the findings of public inquiries.

It was suggested that a joint committee of both Houses of Parliament should be established to publish inquiry reports and government responses in one place, and then to monitor the implementation of inquiry recommendations.

In February 2025 the government accepted many of the recommendations. As such, scrutiny is likely to continue beyond the inquiry itself, and those with a role to play in civil protection may find they are required to provide ongoing updates on the status of inquiry recommendations.

How Can Bond Solon Help Witnesses Prepare To Give Evidence In Inquiries?

For over 30 years, Bond Solon has provided witnesses with essential support and guidance prior to giving evidence in any type of legal forum, regulatory hearing, meeting or interview. Our band 1 ranked services (Chambers & Partners) are designed for both factual and expert witnesses, whether they have given evidence numerous times or are giving evidence for the first time.

Our large pool of lawyers – stemming from all practice areas and with extensive experience of preparing witnesses for testimony – have worked with over 250,000 witnesses to help build their confidence and enhance their ability to give evidence that will stand up under cross-examination. These include witnesses called to give evidence at many high-profile inquiries over the years, including but not limited to the Grenfell Tower Inquiry, the Manchester Arena Inquiry, the Edinburgh Tram Inquiry and the UK Covid-19 Inquiry. Bond Solon believes that no witness should be disadvantaged by not understanding the process or be taken by surprise when giving evidence. Our training sessions address these potential pitfalls head-on, equipping witnesses with the understanding, skills and confidence needed so that they can navigate the process successfully, helping mitigate risk and achieve the best possible outcome. To enhance our interactive and innovative training offering, we have developed a collection of virtual reality courtrooms, including an inquiry-specific virtual courtroom.

SOLAR FIELD CONSTRUCTION DISPUTES ARE HEATING UP

HOW UTILITIES AND CONTRACTORS CAN MANAGE COST OVERRUNS AND SCHEDULE DELAYS

As a surge in utility-scale solar projects converges with shifting trade policies and regulations, new threats to project budgets and completion dates arise when demand for solar energy is at an all-time high.

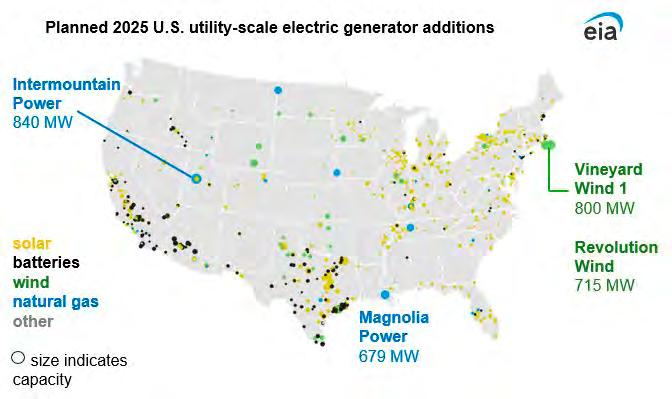

An unprecedented demand for solar energy infrastructure in the United States is on a collision course with trade and policy shifts, setting the stage for a surge in project risk that stakeholders must consider to mitigate exposure to cost overruns, delays, claims, and disputes.

electric-generating capacity in 2025. This is an increase of 30 percent and 94 percent, respectively, in new capacity compared to 48.6 GW in 2024 and 32.4 GW in 2023.

Figure 1: Locations of New Electric Generating Additions in United States

The continuing artificial intelligence (AI) boom and cryptocurrency computing needs have led to record-breaking demand for electricity consumption in 2025 and 2026, much of which will come from energy generated by solar facilities. According to the US Energy Information Administration (EIA), the US power grid is expected to add 63.0 gigawatts (GW) of new utility-scale

The industry expects an average of 43 GW will be added to the power grid in the United States each year through 2030, suggesting that the demand for solar energy is here to stay for the foreseeable future.

The EIA forecast that over 50 percent of new electricity generation capacity this year in the United States will come from solar fields. This projection includes a 30 percent increase in battery storage capacity that can temporarily store the energy generated from solar facilities.

At the same time, changing trade policies and tariffs threaten to disrupt supply chains and cause complications that may lead to time and cost impacts. Changes to anti-dumping and countervailing duties on critical materials from abroad may alter supply chains to ongoing projects. In addition, changing tax credits and tariffs may significantly affect the expected cost of larger solar projects. These factors may result in cost increases, time impacts, and red tape to solar projects, introducing an elevated likelihood of claims and litigation if left unaddressed.

Demand for solar power is expected to remain consistent in the coming years; however, it appears that energy providers and their construction contractors may need to find ways to work through some challenges to keep up with demand. Below we discuss factors that parties to the construction of a solar field may consider when contemplating strategies to manage and mitigate risks.

Known Drivers of Cost Overruns and Schedule Delays on Solar Projects

• Supply chain interruptions or complications: These could mount in light of new tariffs and regulations, inhibiting developers’ abilities to source materials abroad. This could be significant, as nearly all USmade solar panelsuse at least some components from overseas.

• Permitting problems: Solar developers may face opposition to or rejection of permits due to zoning ordinances, environmental concerns, historical preservation rules, or community pushback.

• Weather: Heavy rains, excessive snow, hurricanes, wildfires, and tornadoes all can cause intermittent and continued delays to the solar field construction process.

• Interconnection issues: A lack of standardization in interconnection procedures among new facilities and existing grids can make planning and coordination increasingly difficult.

• Sufficient workforce: Shortages of qualified working personnel can halt progress and result in delays, rework, cost overruns, and even litigation.

• Design modifications: Solar developers often must revise engineering designs, whether relating to compliance with new environmental regulations, differing site conditions, shifting weather conditions, or supply chain bottlenecks. Delays may follow if not managed closely.

• Unexpected environmental regulations: A South Carolina judge recently issued a stay in a lawsuit in which plaintiffs argue that a manufacturing plant poses environmental and safety risks to nearby properties and schools.

These factors can lead to delays and significant cost impacts that, if not addressed ahead of time or timely, can quickly result in claims and litigation related to pricing changes, breaches of contract, and noncompliance with environmental and zoning regulations.

Best Practices for Utilities and Construction Contractors to Mitigate Risk

Energy utilities and construction contractors alike would do well to consider the following best practices:

• Put the right team in place, including engineering designers and contractors that understand solar projects, reliable subcontractors that have access to quality labor, and material and equipment providers that have ample experience with utility-scale solar projects.

• Perform sufficient planning with stakeholders to account for unique site and project conditions that address site layout and logistics, supply chains, work sequencing, and safety protocols.

• Procure quality equipment and materials that may not be as susceptible to weather conditions and likely will perform better and for longer periods.

• Sufficiently prepare the site ahead of construction activities to ensure functioning and compliant stormwater management systems exist to prevent flooding and soggy ground conditions.

• Optimize project scheduling by developing a reasonable schedule of work, including subcontractors and material suppliers in the schedule development and update process; and by identifying alternative work sequences should unexpected conditions or events occur

• Maintain clear and open lines of communication among all parties, including regular communication between the general contractor and the utility regarding unexpected issues so that solutions are developed timely as a team.

• Be prepared to implement contingency plans if unexpected events occur. This may include procuring alternative labor sources if existing subcontractors encounter labor shortages; or having alternative equipment and material suppliers available in case of price fluctuations or supply chain complications.

• Maintain a complete understanding of environmental regulations and requirements regarding protected waterways and species, permitting, stormwater management and erosion and sediment controls, and disposal of hazardous materials.

• Begin the grid interconnection coordination process early Some utilities have undeveloped or inconsistent protocols for the connection of new solar facilities to the existing grid. Contractors and utilities alike would do well to begin the interconnection conversation early.

• Maintain sufficient quality control protocols to timely identify variances from required work standards and specifications. Addressing quality issues sooner may prevent cost overruns, delays, claims, and costly litigation.

• Mitigate weather delays through sufficient research of historical weather patterns and accounting for similar conditions in initial project timelines, maintaining flexibility in working days and shifts to mitigate weather impacts, and maintaining clear records of actual adverse weather conditions.

• Implement “lessons learned” after the completion of each project to capture project successes and challenges that can be referenced ahead of the next project. This allows teams to quickly leverage previous experience instead of reinventing the proverbial wheel for each project.

As demand for solar energy continues, utilities and contractors will have plenty of partnering opportunities in the coming years. But numerous complications now pose a threat to bringing these projects in on time and within budget. With the right planning and risk mitigation techniques, all parties can take steps to manage the time and cost impact of these risks.

What Do You See As The Most Important Thing About Your Job?

I genuinely love what I do. I’m motivated by doing work that’s interesting and meaningful, especially when it’s part of a team effort. I enjoy contributing to something that has real impact, and I find it satisfying when we deliver well together. It’s that combination of engaging work and good collaboration that keeps me going.

What Is Your Favourite Part Of Your Working Day?

Probably not surprising, but one of my favourite parts of the working day is when I get positive feedbackwhether it’s from clients, colleagues, or managers. It’s not about recognition for its own sake, but more about knowing that the work has landed well and made a difference. It’s a great motivator and a reminder that the effort and collaboration are paying off.

60 SECONDS WITH... MARZENA MEESON ASSOCIATE DIRECTOR

What Inspired You To Be Who You Are Today?

I’d say it’s a mix of people and experiences. I’ve been lucky to work with some brilliant colleagues and leaders who’ve set high standards and encouraged me to stretch myself. Moving to new places has also played a big part as it’s taught me to adapt and find my footing in unfamiliar situations. Most importantly, my family inspires me every daythey remind me of what matters and keep me grounded.

What Is A Quote That Best Describes You?

One that comes to mind is: “Life is a journey to be experienced, not a problem to be solved.” (Winnie the Pooh) I try to keep that in mind - staying open to new experiences and finding small joys in everyday life.

What Would You Be Doing If You Weren’t In This Profession?

I recently volunteered as a (temporary) tattoo artist at my sons’ school fairdefinitely not my calling! If I weren’t in my current profession, I’d probably be a dog walker. I love animals and walking, so it feels like the perfect combination - outdoors, active, and full of enthusiastic, happy clients.

What Is Your Favourite Takeaway Dish?

I enjoy spicy food and seafood so my favourite takeaway dish is probably a Thai green curry with prawns - full of flavour and just the right amount of spice.

FROM VERDICT TO VICTORY

ENFORCING FOREIGN JUDGMENTS IN DUBAI

The UAE has long been a hub for cross-border business and international investment, and that role has only deepened since Burford completed its first deal involving judgment enforcement in the region in 2018. Dubai in particular continues to be a key destination for global commerce and finance. Also, international conflicts, relaxation of UAE visa requirements and various other factors have led to an influx of ultra-high-net-worth individuals in recent years.

It is therefore unsurprising that judgment creditors are increasingly looking to recognize and enforce their foreign judgments there. From an international enforcement perspective, the Dubai courts have historically been considered unpredictable and opaque. However, based on our firsthand experience funding cases in the region, discussions with local firms and our analysis of local court data, this perception appears to be unwarranted — or at least outdated.

The UAE is a signatory to judicial cooperation treaties covering several Middle Eastern countries and it has bilateral arrangements in place with a number of other jurisdictions (including France, China, Kazakhstan and India) which govern the process for recognizing those judgments locally. Where no formal agreement exists, recognition and enforcement will be governed by the principle of reciprocity. We are aware of at least seven foreign judgments that have been recognized via this route in the last two years and where the lower court’s decision has been upheld by the Dubai Court of Appeal or Cassation Court (Dubai’s highest court). These include judgments from Canada, England, Switzerland, Russia, Singapore and the United States, with the Dubai courts also considering the recognition of judgments from jurisdictions such as Belarus, Palestine and the British Virgin Islands (BVI).

Requirements For Recognition Of A Foreign Judgment

For a foreign judgment to be recognizable in Dubai, it must meet the following criteria, codified in its civil procedure law and reinforced and endorsed in the case law:

1. UAE jurisdiction: The UAE courts must not have exclusive jurisdiction over the dispute.

2. Foreign court jurisdiction: The foreign court must have had (nonexclusive) jurisdiction to determine the dispute and the judgment must have been issued in accordance with all local laws and rules.

3. Finality and enforceability: The judgment must be res judicata in the jurisdiction which rendered it (and a certificate to that effect will typically be required).

4. Proper service and representation: The defendant must have been properly served and have had the opportunity to be represented.

5. No conflict: The judgment must not conflict with a judgment or order previously issued by a UAE court and must not violate UAE public policy.

Lessons Learned From Unsuccessful Attempts At Recognition

While the Dubai courts have recognized foreign judgments with a range of underlying causes of action, they do not appear willing to enforce foreign declaratory judgments or foreign bankruptcy orders. The Dubai Court of Appeal has recently refused to recognize:

Recent Success Stories

The Dubai courts have shown a willingness to enforce a range of foreign judgments, from complex commercial disputes to personal matters. For example, the Dubai Cassation Court recently upheld the recognition of a summary judgment from Ontario, Canada, based in part on a restitution order from a New York securities fraud case. This ruling was significant from an international enforcement perspective in particular because the Dubai court agreed to enforce a judgment (the Ontario judgment) that was itself based on an earlier judgment (the New York order) because it still met all the criteria for enforcement of a foreign judgment, and there was clear participation from both parties. This approach to recognition goes further than we have seen a court willing to go in several other jurisdictions.

The Dubai Cassation Court has also upheld the recognition of an English family court judgment for the division of assets, which was consented to by both parties. The judgment debtor sought to resist recognition both on public policy grounds, by arguing that the couple had not been formally divorced under the laws of the country where they were married (not England) or under Islamic law, and also by contending that the Dubai courts had exclusive jurisdiction over the Dubai property covered by the division of assets order. The court held that there were no public policy issues because the defendant had consented to the English order and the Dubai courts did not have exclusive jurisdiction, and that the English judgment was not a new ownership claim, but rather the enforcement of an existing obligation.

• An application by a BVI courtappointed liquidator to liquidate a BVI company in Dubai, on the basis the BVI order was declaratory in nature.

• An application by a Russian Trustee in Bankruptcy to enforce a Russian bankruptcy order that included language permitting a worldwide search for assets and enforcement up to the value of the debt ($31M), on the basis that a foreign bankruptcy proceeding cannot be enforced in the same way as a foreign judgment and requires a treaty or legislative provision.

• A judgment debtor’s successful resistance to enforcement of a Polish judgment, on the basis that he was not properly served with the judgment or given sufficient opportunity to be represented (at the time of the original Polish proceedings, the claimant had been unable to locate the defendant, so the Polish court had appointed a judicial guardian to represent him in the proceedings. The Dubai court found that the Polish judgment did not expressly confirm that the defendant had been represented in accordance with Polish procedural law or that the requirements for service of process had been met, as seen in condition 4 above).

It is clear the Dubai courts also expect and will insist on strict and explicit adherence to the five criteria outlined above.

Legal

Finance Can Assist With Asset Recovery

Legal finance providers like Burford have a proven track record in successfully funding and managing multi-jurisdictional enforcement campaigns involving sophisticated asset tracing and recovery strategies in Dubai, the broader UAE and around the world. This includes funding the successful recognition and enforcement of foreign decisions in the UAE and vice versa. For example, when Cessna Finance faced complex and risky enforcement proceedings due to a UAE-based counterparty’s default on aircraft leasing agreements, Burford was able to create a hybrid “money now, money later” assignment deal that gave Cessna immediate capital while transferring the cost, time and risk of the enforcement campaign to Burford. Burford’s global recovery and enforcement team routinely assists clients whose commercial litigation and arbitration matters require considerable resources and specialized legal expertise.

Burford offers bespoke legal finance solutions to support lawyers and their clients, including traditional litigation funding of fees and expenses as they are incurred and more tailored “money now, money later” assignment deals (such as in the Cessna case), where a client receives immediate capital while Burford assumes all enforcement responsibilities, including appointing specialized legal teams, conducting detailed asset tracing and managing international enforcement efforts.

DETERMINING FAIR INTEREST RATES WITHOUT EXPERT EVIDENCE CAYMAN ISLANDS COURT RULING IN RE XINGXUAN TECHNOLOGY LTD

In a landmark decision, the Grand Court of the Cayman Islands has set a new precedent by determining a fair interest rate of 6.39% in the long running case of Re Xingxuan Technology Ltd, without relying on expert evidence. The Court also awarded indemnity costs to the dissenter.

In its written reasoning for the judgment handed down on 25 March 2025, the Court confirmed that in appropriate cases, the fair rate of interest can be determined without expert testimony in section 238 fair value proceedings.

Managing associate Farrah Sbaiti and associate Raedean Simpson in Ogier’s Dispute Resolution team acted for the dissenter.

Background

Following an unopposed trial on 17 July 2024 of the section 238 fair value petition in Xingxuan Technology Ltd (Xingxuan), the Court handed down its fair value judgment on 9 September 2024.

The judgment determined that the fair value of the dissenter’s shares was US$318.69 million

– approximately 659% higher than the merger consideration offered by Xingxuan.

Once the Court indicated that it would hear counsel in relation to interest, costs and any other consequential matters arising from the fair value judgment, the dissenter asked the Court to consider its application for interest and costs on the papers and without an oral hearing. The Court provisionally agreed to this request but reserved the right to require expert and/or factual evidence to be filed, and/or an oral hearing, should it be considered appropriate.

After the written submissions and supporting materials were filed, the Court required the dissenter to file evidence formally confirming:

1. the basis for the proposed company borrowing rate

2. its belief in the reasonableness of the prudential investor rate methodology adopted and the accuracy of the final rate relied on in the written submissions filed

How Did The Court Determine A Rate Of Fair Interest In Xingxuan Technology Ltd?

1. Determining a fair rate of interest without expert evidence

The Court considered the English courts’ approach to the calculation of statutory pre-judgment interest on compensation for actionable loss, as summarised by Justice Segal in the most recent section 238 interest decision, iKang.

The Court noted that pre-judgment interest is routinely assessed without expert evidence. It also stated that as a commercially rational remedy, interest in section 238 cases should be determined using a process which is appropriate, proportionate and cost-effective, in accordance with the overriding objective.

The Court also noted “higher level” support for the existence of a positive duty to make the substantive law effect in an efficient manner, from the recent Privy Council decision in Re Changyou. com Limited (Changyou). The decision confirmed that section 238 must be read in a way that is compatible with, and which gives effect to, section 15 of the Cayman Islands Constitution, providing peaceful enjoyment of property and prompt compensation in the event of interference (such as compulsory acquisition).

The Court determined that it would not be a commercially-rational remedy if a dissenter had to incur disproportionate costs to recover an interest award.

Justice Kawaley, the assigned judge to the proceedings, considered that both economy and proportionality have increased significance in the context of a case such as Xingxuan, which he referred to as “section 238-lite” –particularly in circumstances where there was uncertainty over recoverability of the fair value and interest awarded.

The Court concluded that there was no invariable mandatory legal requirement that the entitlement to an award of interest on compensation awarded by a court must be supported by expert evidence in every case. Having concluded that interest can be determined without expert evidence in appropriate cases, the Court then moved on to considering whether the fair rate could be determined justly without expert evidence in this particular case.

2. The fair rate of interest applied

The written reasons helpfully summarise the key cases considered to develop the application of the “mid-point approach” for determining the fair rate of interest, and the underlying methodologies for determining the company borrowing rate and the prudent investor rate. The Court accepted the dissenter’s central submission that the core principles governing the approach to assessing the fair rate of interest under section 238 are clearly and firmly established.

The Court accepted Xingxuan’s factual evidence that the appropriate company borrowing rate was 4.35%, based on the interest rate applicable to an intercompany loan, the terms of which were documented in the company’s disclosure

in the proceedings. The Court concluded it did not need expert evidence to arrive at its decision on the company borrowing rate.

In relation to the prudent investor rate, the Court provided several reasons for its decision to accept the dissenter’s proposal to apply the iKang methodology (under the objective standard of an ordinary prudent investor) without expert evidence being adduced. In particular, the fact that the approach was substantially based on expert evidence adduced by Xingxuan in iKang made the risk of serious prejudice to the company in this case unlikely and the dissenter’s inability to enforce was to be balanced against any risk of unfairness to the company of proceeding without expert evidence.

The Court applied the same asset allocation of 45% equities, 45% bonds and 10% cash, and the same asset class indices (ETFs) for the assumed returns, as applied in iKang under the objective prudent investor standard. It was noted that the entire interest period in iKang fell within the interest period (representing approximately 70%) in Xingxuan. The Court determined that the prudent investor rate at 8.43% which was considered to be broadly consistent with the primary prudent investor rate in iKang (taking into account the longer interest period in Xingxuan and market movements during the extended period). Consistent with the previous authorities, the Court held the fair rate of interest was 6.39% which was the mid-point between the company borrowing rate of 4.35 % and the prudent investor rate of 8.43%.

3. The interest period in Xingxuan

As Xingxuan had not made an interim payment to the dissenter, the relevant interest period for the purposes of the fair rate of interest calculation was 29 September 2017 (the date of Xingxuan’s fair value offer) until 5 February 2025 (the date of the Court’s decision on interest).

In considering the dissenter’s application for costs to be taxed on the indemnity basis, Justice Kawaley examined Xingxuan’s conduct – particularly its absence from the litigation stage – and the actions and omissions leading to the company being debarred from contesting the proceedings.

Xingxuan’s failure to engage new attorneys and its breach of its obligation to pay the interim payment ordered by the Court amounted to improper and/or unreasonable conduct which, despite occurring (or manifesting itself) at a late stage in the proceedings, infected the proceedings as a whole and justified an award of costs to be taxed on the indemnity basis.

Conclusion

The circumstances in Xingxuan, which include a company in breach of a court order for an interim payment and subsequently debarred from participating in the proceedings, are plainly unusual. In most section 238 cases all parties will take an active role in what are usually heavily contested proceedings. Therefore, it is often impossible or impractical for expert evidence on interest to be dispensed with. However, the decision in Xingxuan reinforces the Court’s willingness to approach applications with pragmatism, proportionality and efficiency. In appropriate circumstances, the Court may be receptive to determining applications on the papers and without an oral hearing, and without expert evidence being adduced, in order to best serve the interests of justice and facilitate a just outcome.

4. Costs awarded to the dissenter

The Court had no difficulty in concluding that the dissenter was entitled to its costs of the proceedings, in circumstances where it had obtained a fair value award far in excess of what Xingxuan had offered.

The Court’s reference to the recent Changyou decision also indicates that the Court is likely to deprecate poor conduct and delay in section 238 cases to an even greater degree and make appropriate orders to uphold and give effect to what is now an accepted constitutional right to prompt payment of adequate compensation where shares are compulsorily acquired under the Cayman Companies Act. The Court has helpfully indicated that adjustments to the relevant statutory provisions and/or the Court Rules may well be required to prevent the integrity of the statutory scheme (which is now enshrined as a constitutional right) being undermined and/or abused in future cases. This would no doubt be a welcomed development for dissenting shareholders concerned about a company’s ability or willingness to meet a fair value and interest award.

“Extremely

THE END OF THE SHAREHOLDER RULE?

AABAR HOLDINGS S. À R.L. V GLENCORE PLC AND OTHERS

Authored by: Yulia Barnes (Managing Partner) - Barnes Law

In a ruling set to change the practice of shareholder litigation in the UK, the Supreme Court on 7 February 2025 rejected Aabar Holdings’ application to appeal directly, following a High Court decision that excluded the application of the ‘Shareholder Rule’ in English law. The appeal is now listed for hearing by the Court of Appeal on 26 January 2026. This article considers the impacts of the ruling on legal privilege, investor claims, and investigations, against the broader legal challenges facing Glencore.

Aabar Holdings S.à.r.l. (‘Aabar’), a Luxembourg entity owned by the Government of Abu Dhabi, brought proceedings against Glencore plc and three former directors. Aabar claimed to be the successor to Commodities S.à.r.l., the beneficial owner of Glencore shares between 2011 and 2020.

In 2022, following a UK Serious Fraud Office (SFO) investigation, Glencore admitted to multiple bribery offenses and was fined a record £281 million. Aabar and other institutional investors claimed they had been misled by Glencore’s public filings and suffered losses. Aabar’s claims were brought under sections 90 and 90A of the Financial Services and Markets Act

2000 (FSMA), and included claims in deceit and negligent misstatement.

Before addressing these allegations, the High Court was asked to determine whether Glencore could assert legal professional privilege against a shareholder, based on the historic ‘shareholder rule’.

The shareholder rule, derived from 19th-century law, once allowed shareholders to inspect company documents, including privileged ones. Aabar argued this rule remained valid, but Mr Justice Picken held that it had not survived the evolution of corporate law following Salomon v A Salomon & Co Ltd [1897]. He confirmed that shareholders do not have a proprietary interest in company property sufficient to override privilege.

government launched an inquiry into the refinery’s insolvency, drawing attention to Glencore’s role in the domestic energy market.

The High Court granted Aabar permission to appeal with a leapfrog certificate, but in February 2025, the Supreme Court declined to hear the appeal. The case will now be heard by the Court of Appeal in January 2026. The central issues are whether the shareholder rule still exists in English law, and whether a company can assert privilege against its shareholders.

The case could redefine investor litigation in the UK. The reaffirmation of legal privilege strengthens the ability of companies to obtain legal advice without fear of disclosure to shareholders. However, investors lose a potential avenue for accessing documents critical to proving misrepresentation or misconduct.

The judge also dismissed the applicability of joint interest privilege. Aabar argued it shared a legal interest in Glencore’s legal advice due to its shareholding, but the Court ruled that neither shareholding nor aligned litigation interests established joint privilege. Privilege, it reiterated, belongs to the company.

Concurrently, Glencore was under scrutiny globally. It had paid over $1.5 billion in fines to authorities in the UK, US, and Brazil for bribery and market manipulation. These scandals raised questions over Glencore’s governance and transparency, leading to further investor claims.

In 2025, Glencore was again in the spotlight following the collapse of the Lindsey Oil Refinery, with which it had a supply and offtake agreement. The UK

Parliament may eventually need to legislate. While FSMA provides investor remedies, it does not override privilege. If upheld, the ruling may prompt calls for reform to allow limited disclosure rights in cases involving regulatory breaches.

By contrast to some US jurisdictions where shareholders can inspect internal documents under certain conditions, English law prioritises the sanctity of privilege. Only statutory intervention is likely to shift this balance.

Practically, the ruling reinforces that privilege belongs to the company, regardless of shareholder interest. It sets boundaries on joint interest privilege and reiterates the Salomon principle of corporate separateness. Claimants must now rely on standard disclosure or inference rather than attempting to pierce privilege.

If the ruling is upheld, it may represent a significant turning point in the balance between corporate confidentiality and shareholder transparency in English company law.

MILIEUDEFENSIE ET AL V SHELL IMPLICATIONS FOR FUTURE CORPORATE CLIMATE LITIGATION IN EUROPE

by: Catríona Campbell (Associate) - Clyde & Co

Introduction

‘Climate litigation’ refers to cases brought before judicial bodies which feature climate change law, policy or science as a material issue in the case. Following almost universal ratification of the 2015 Paris Agreement – under which States agreed to take action to mitigate greenhouse gases (GHGs) and limit global warming to under 2 degrees, and well below 1.5 degrees – litigation has emerged as one of the main tools used by NGOs and other activists to hold accountable those seen as responsible for dangerous climate change.

Oil Majors, seen as most closely associated with contributing to the climate crisis, are often targeted in these claims, which generally seek damages for loss caused by corporate harm to the environment. Despite the fact more than 250 strategic climate cases have been filed against companies across the globe since 2015,1 uncertainties remain regarding the extent of corporate responsibility on climate change.

As part of the increasingly large body of corporate climate litigation, the Hague Court of Appeal issued a muchanticipated judgment in November last year which helped to clarify the obligations of private actors, particularly in Europe. The decision concerned Shell’s appeal of a landmark 2021 ruling which had ordered Shell to reduce its CO2 emissions. At the Court of Appeal, the 2021 decision was overturned.

find that Shell was required to reduce its CO2 emissions by 45% by 2030 compared to 2010 levels. These arguments were based on those used successfully in a seminal case which found that the Dutch government had an obligation under human rights law to reduce GHGs by at least 25% by the end of 2020.3

Although based on tort law, Milieudefensie is unusual in comparison to other similar climate litigation, as the claimants are not seeking damages. Instead, they seek to force a change in direction from the oil company, in order to “stop causing serious harm to the climate”.4

Background

The case was brought in 2019 in the Hague District Court by the NGO Milieudefensie, six other NGOs, and over 17,000 Dutch citizens.2 The Claimants requested the Court to

In 2021, the District Court found that, under Dutch tort law (based on a standard of care incorporating international human rights law and standards), Shell was required to reduce its CO2 emissions by 45% by 2030, in line with the Claimants’ request; this order was immediately effective. The required reduction applied to emissions produced by: Shell’s own operations (Scope 1 emissions); the operations of its suppliers (Scope 2 emissions) and; its customers (Scope 3 emissions).

1 Grantham Research Institute, ‘Global trends in climate change litigation: 2025 snapshot’, p.18, available at: https://www.lse.ac.uk/granthaminstitute/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/ Global-Trends-in-Climate-Change-Litigation-2025-Snapshot.pdf

2 Milieudefensie et al v Shell, ECLI:NL:RBDHA:2021:5339

3 Urgenda Foundation v Netherlands, ECLI:NL:HR:2019:2007

4 Milieudefensie, ‘Frequently Asked Questions about the climate lawsuit against Shell’, available at: https://en.milieudefensie.nl/climate-case-shell/frequently-asked-questions-aboutthe-climate-lawsuit-against-shell

This marked the first time a corporation was legally recognised under international law as having a duty of care to protect citizens from dangerous climate change by shaping its policies and curbing GHG emissions. It was also the first ruling to mandate emission reductions across a company’s entire value chain, and the first to hold a corporation accountable to the goals of the 2015 Paris Agreement.

Although a Dutch decision applying Dutch law, the 2021 judgment had a major effect on climate litigation, particularly in Europe, and was oft-cited by applicants in various jurisdictions. For example, claimants relied heavily on the decision in an ongoing claim in Italy against the major multinational energy company ENI (more on that later).

However, on 12 November 2024, the Court of Appeal overturned the landmark 2021 decision, dismissing Milieudefensie’s claims against Shell, and ordering the NGO to pay Shell’s legal costs.5 The Court of Appeal ruled that, whilst Shell has a legal duty to “counter dangerous climate change” and reduce emissions, specific reduction requirements like the 45% target, particularly in relation to Scope 3, are not legally enforceable. Although Shell has a legal obligation to reduce its emissions, the rate of emissions reduction cannot be specified or imposed by a Court. The Court seemed to accept that Shell has legal obligations to reduce Scope 1 and 2 emissions, but found that Shell was already on track to reduce these by more than 45%.

The decision ultimately turned on scientific and economic arguments: first (the scientific argument) that it was inappropriate to impose a sectoragnostic 45% emission reduction target on Shell, a company with a very specific emissions profile and business model; second (the economic argument), that ordering Shell to reduce Scope 3 emissions would not, in practice, reduce the supply of global oil and gas since another supplier would simply substitute Shell in the market.

Hollow Victory For Shell?

The Court of Appeal’s decision was hailed as a success for Shell, and beneficial to other Oil Majors – Shell said it was “pleased with the court’s decision”, which was “the right one for the global energy transition”. 6 Yet Milieudefensie described it as “big step forward for the climate”. Such competing claims are a common occurrence in climate litigation; however a case is decided, it tends to be described as a victory for the side which the commentator supports. Which party’s statement is more accurate? There is no doubt Shell won this particular case, but is it really a victory for the Oil Major in the long term? There are several of the case which point to a different conclusion:

• 1.5 degrees target: whilst the target under the Paris Agreement to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees is non-binding, and only applicable to States, it has gained such normative strength that the Court of Appeal considered it relevant to Shell’s obligations. EU companies, and some other companies doing business in the EU, will also soon be required to publish a transition plan consistent with the 1.5 degree target under the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive.7 This creates risks for Shell and other Oil Majors that they are breaching their duty of care if emitting in a way which goes beyond this target, which could be argued in future litigation.

• Reduction targets: Milieudefensie requested that Shell be obligated to reduce its Scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions by 45%. This was based on general scientific consensus – particularly from reports of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) – that global emissions must reduce by 45% to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees. The Court said this was not specific enough to Shell so the Court did not have sufficient certainty to require Shell (or the oil and gas industry in general) to meet this target. However, the ability of scientists to attribute emissions to specific polluters is improving all the time. Scientific consensus will likely coalesce around a specific target for the oil and gas industry based on the harm caused by its emissions, and in the future it may be the case that the science develops sufficiently to show that Shell should actually meet a higher reduction target than 45%, based on its emissions. This could then be confirmed in a future case.

• Corporate human rights obligations: the Court of Appeal confirmed that major emitters like Shell are required to respect human rights – a major finding, given that human rights obligations are generally considered to apply only to States. Whilst particular to Dutch law, it may be an important catalyst for future litigation seeking to hold Oil Majors accountable under human rights law and standards.

• Future oil and gas projects: in obiter comments, the Court suggested that new oil and gas projects may be incompatible with Shell’s obligations to reduce emissions. This means that Shell could be targeted in litigation seeking to prevent new projects on this basis.

As such, the decision opens new pathways for, and arguments in, litigation against Shell and other Oil Majors (and potentially other corporations which contribute substantial amounts of GHGs to the atmosphere). Because of this, it is seen by many commentators as a hollow victory for Shell, which may come back to bite in future.

5 ECLI:NL:GHDHA:2024:2100

6 Shell,’ Shell welcomes Dutch Court of Appeal ruling’, available at: https://www.shell.com/news-and-insights/newsroom/news-and-media-releases/2024/shell-welcomes-dutch-courtof-appeal-ruling.html

7 Article 22 of the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive

What Next?

Regarding this specific case, in February this year Milieudefensie stated that it was filing an appeal to the Dutch Supreme Court, arguing that it has a “strong case against Shell”.8 The Supreme Court is being asked to reinstate the District Court’s finding that Shell has a specific reduction obligation, stating that only a specific target will make sure Shell takes “real action”.9 This carries the possibility that the highest appeals court will overturn some of the findings made at the Court of Appeal, so it will be very interesting to see what happens on appeal. Shell has already moved its headquarters out of the Netherlands, after the 2021 decision (although it gave other reasons for doing so); this regulatory arbitrage is a risk that applicants take when filing climate cases.

More broadly, NGOs pursuing climate litigation against corporations are unlikely to be put off by the decision in the Dutch Court of Appeal. Milieudefensie has already filed a different claim against Shell which relies on the Court of Appeal’s comments. In seeking a court order to stop Shell from investing in new oil and gas fields, Milieudefensie stated “The Court of Appeal has provided

clear indications that Shell’s currently planned investments in new oil and gas fields are at odds with its legal obligation to take into account the negative consequences of a further expansion of fossil fuel supply”.10 In the aforementioned case against ENI in Italy,11 which follows similar arguments as Milieudefensie’s case against Shell – that EU law and Italian law impose a duty of environmental protection on corporates – the Supreme Court of Cassation recognised the procedural admissibility of climate change cases before civil courts in a seminal decision last month.12 In a case against German utility giant RWE decided earlier this year (which is explored in more detail elsewhere in this edition), the Court, although it dismissed the claim, found that corporate liability for climate-related harm is possible in principle.13

There is no doubt we are going to see more claims against Oil Majors (and others who facilitate them), likely employing successful arguments used in Milieudefensie. Courts seem increasingly open to finding that corporates have obligations in light of dangerous climate change; climate litigation against them is certainly not going away, particularly in Europe.

8 Milieudefensie, ‘Why we’re taking our Shell climate case to the Supreme Court’, available at: https://en.milieudefensie.nl/news/why-we2019re-taking-our-shell-climate-case-to-thesupreme-court

9 Milieudefensie, ‘Why we’re taking our Shell climate case to the Supreme Court’, available at: https://en.milieudefensie.nl/news/why-we2019re-taking-our-shell-climate-case-to-thesupreme-court

10 Letter available to download at: https://en.milieudefensie.nl/news/this-is-our-letter-to-shell

11 Greenpeace Italy et. Al. v. ENI S.p.A., the Italian Ministry of Economy and Finance and Cassa Depositi e Prestiti S.p.A.

12 Decision available to download at: https://climatecasechart.com/non-us-case/greenpeace-italy-et-al-v-eni-spa-the-italian-ministry-of-economy-and-finance-and-cassa-depositi-eprestiti-spa/

13 Luciano Lliuya v. RWE (2015) Case No. 2 O 285/15 (Essen Oberlandesgericht)

EMERGING THEMES AND THE ONGOING EVOLUTION OF CLIMATE LITIGATION

Summary

This article highlights a selection of some of the domestic and international cases and developments which demonstrate the evolution of climate change litigation, before considering some emerging themes which we are tracking.

The Supreme Court held that the Council was required to assess, as an indirect effect of the well expansion project (and the prepared environmental impact assessment document should have considered), the “downstream” environmental impacts of greenhouse gas emissions arising from the combustion of the extracted oil.

The judgment has the potential to impact the scope of environmental impact assessments where there is a direct link between the project and the creation of downstream emissions. This link manifests itself most clearly in fossil fuel projects.

Following Finch, a number of decisions have emerged which consider the judgment, in particular:

Litigation In The UK

In the UK, judicial review has become an established method for parties to challenge governments and public bodies in relation to climate change. Some of the recent judicial review decisions include:

R (Finch on behalf of the Weald Action Group) v Surrey County Council [2024] UKSC 20 - a judicial review of a planning permission granted by Surrey County Council to expand oil production from a well in Surrey.

• Friends of the Earth v Secretary of State for Levelling Up, Housing, and Communities [2024] EWHC 2349 (Admin) – the first planning decision successfully challenged through judicial review on climate change grounds, following Finch; and

• Greenpeace Limited & Uplift [2025] CSOH 10, a case which concerned planning consents for two North Sea oil fields, which saw the principles in Finch being applied by the Scottish Court of Session.

In a separate judicial review challenge, Friends of the Earth, ClientEarth, Good Law Project v Secretary of State for Energy Security and Net Zero [2024] EWHC 995 (Admin) marked a key decision where it was found that the Secretary of State’s decision to approve the government’s Carbon Budget Delivery Plan was unlawful, as it was based on a number of irrational assumptions.

International Litigation

On the international stage, a number of judgments have emerged, alongside cases where judgment is awaited.

Two ongoing international cases (involving events occurring in Brazil and Nigeria respectively) are being heard in English courts. They address the principle of parent company liability (i.e. whether a parent company is responsible for the acts of its subsidiaries) and the accountability of environmental harm allegedly caused by their subsidiaries abroad.

BHP and others v Municipio de Mariana and others is a class action lawsuit concerning the collapse of the Fundão dam in Brazil, and the subsequent escape of millions of cubic metres of toxic waste. The claimants seek up to £36bn in compensation. Bille and Ogale Group Litigation (also known as Alame and others v (1) Shell plc; (2) The Shell Petroleum Development Company of Nigeria Ltd), centres on claims by residents of the Ogale and Bille communities in the Niger Delta against the parent company of the Shell Group, Shell plc, and its Nigerian subsidiary, SPDC. The claimants allege that leaks from the defendants’ oil infrastructure have caused extensive damage to the local environment.

In Europe, we have seen a number of cases of note:

• In the Dutch courts, Milieudefensie et al v Shell plc sought to clarify the duties owed by Shell under Dutch and human rights law to mitigate their contribution to climate change. The Dutch Court of Appeal confirmed that Shell had a duty of care to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions but allowed Shell’s appeal on whether it had a specific emissions reduction obligation (i.e. to reduce emissions by 45% by 2030). Milieudefensie is currently appealing this decision to the Dutch Supreme Court.

• In the case of Verein KlimaSeniorinnen Schweiz and others v Switzerland, the European Court of Human Rights found that Switzerland had failed to comply with its obligations under the Convention regarding climate change – in so doing violating the applicants’ rights to life and private life (Articles 2 and 8).

Further afield, we have been following with interest developments in climaterelated litigation in Australia, particularly in relation to cases concerning decisionmaking processes for fossil fuel projects (such as Waratah Coal).

ICJ Advisory Opinion

On 23 July 2025, the International Court of Justice (“ICJ”) rendered its advisory opinion on the obligations of States in respect of climate change. The opinion confirms that:

• Climate change treaties and international laws oblige States to ensure the protection of the climate system and other parts of the environment from anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions; and

• Breach of such obligations constitutes an “internationally wrongful act” which may require (amongst other things) the offending State making “full reparation to injured States in the form of restitution, compensation and satisfaction”.

The opinion marks a significant development in international climate law, emphasising that climate obligations are more than simply aspirational targets. It follows another key advisory opinion from the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea (ITLOS) in May 2024, which confirmed that greenhouse gas emissions constitute “marine pollution” under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, whilst noting that States have obligations to prevent, reduce and control emissions.

• Preventing or delaying climate action – A significant amount of litigation has emerged to challenge climate-related financial disclosure rules and voluntary climate pledges. In parallel, “just transition” and “green v. green” cases test how climate mitigation and adaptation projects can be balanced with fairness, procedural integrity and biodiversity protections.

• Planning reform – In the UK, the government is progressing amendments to the planning regime related to judicial reviews of Development Consent Orders and National Policy Statements, particularly in relation to Nationally Significant Infrastructure Projects. The aim of these changes is to reduce delay and costs associated with judicial challenges of projects. Accordingly, we may see a reduction in judicial review challenges, particularly those relating to significant infrastructure.

Overall, it is clear that the coming years will be crucial in any assessment of the utility of litigation as a tool to mitigate climate risk in a difficult political and economic environment.

Key Trends

There are a number of broad themes emerging regarding the development of climate change litigation which we are following. These include, by way of example:

• An appetite to hold businesses to account – A significant proportion of cases filed globally in 2024 target companies or their leadership, with particular focus on those operating in industries with high global greenhouse gas emissions. Given that corporate actions and decisionmaking have such a crucial impact upon greenhouse gas emissions and the climate system, we may see an increase in climate-related commercial claims being brought between businesses or against businesses and the state.

• Political dynamics – A wave of claims followed the arrival of the new US administration at the start of this year, with further litigation which seeks to promote or challenge climate action expected. In Europe, proposed revisions to sustainability regulations are also creating uncertainty.

4 STONE BUILDINGS

4 Stone Buildings has consistently been ranked as one of the top sets at the Bar in our core areas of expertise. Since few business disputes or problems lend themselves to rigid categorisation, we apply our core areas of expertise in a wide variety of different legal and commercial contexts.

Arbitration

Banking and finance

Commercial litigation

Commercial chancery

Company law

Civil fraud

Financial services

Insolvency

Offshore

A set at the very top of the Commercial Chancery Bar.

- Chambers UK

FROM RISK TO RECKONING

THE EVOLVING LANDSCAPE

AND FUTURE

OF CLIMATE LITIGATION AGAINST COMPANIES –A UK FOCUS

In July 2025, the International Court of Justice advised that countries are legally obligated to curb emissions and protect the climate. The advisory opinion highlights the global emergence of climate litigation1 and the increasing pressure put on States to adopt climate friendly policies. This development will inevitably impact companies as well by influencing policy requirements and stakeholder expectations. The United Kingdom’s (UK) robust legal framework, active civil society, and growing regulatory pressure have made it a focal point for climate litigation. This report examines trends, notable cases, and future outlooks for climate litigation targeting companies in the UK.2

Fiduciary Duty And Governance Cases

To date, ClientEarth v. Shell plc has been the most impactful case on the influence of climate considerations on fiduciary duties in the UK3. ClientEarth, as a minority shareholder, brought a derivative action against Shell’s board of directors, 1

alleging a failure to adopt a climate strategy aligned with the Paris Agreement and UK law. The High Court dismissed the claim, stating that ClientEarth had not demonstrated a prima facie case that the directors were not acting in the best interests of the company (permission to appeal rejected).

Despite this judgment, the case set a precedent for shareholder activism and clarified the high bar for such claims in the UK, guiding civil society actors in developing more robust future claims. Precedents such as ClientEarth v Shell show that stakeholders are holding companies to account through litigation for how they deliver on their climate promises.

As climate litigation and regulatory scrutiny intensify, companies that fail to meaningfully consult investors, communities, employees, and other stakeholders risk lawsuits, enforcement actions, and loss of trust. Engaging stakeholders in the development and execution of climate strategies is now a critical component of sustainable business.

Greenwashing And Misleading Claims

Between 2022 and 2024, the UK’s Advertising Standards Authority (ASA) increased its scrutiny of environmental claims in advertising. This stricter enforcement resulted in several high-profile rulings, including against HSBC in 2022 for adverts that gave a misleading impression of the bank’s climate impact by promoting its green finance initiatives while omitting key information about the bank’s significant

science of climate change, mitigation and adaptation efforts, and loss and damage.” This definition does not capture cases where climate change is a motivating factor or where climate change mitigation or adaptation is impacted by the outcome of the case, but the legal arguments and judgments are not framed in terms of climate science or climate

fossil fuel financing. The cases illustrate that absolute claims like “eco-friendly,” “sustainable,” or “carbon neutral” must be substantiated with robust evidence and that all material environmental impacts, both positive and negative, must be disclosed clearly and prominently. Failure to provide all significant information and a balanced account is consistently ruled to be misleading.

While these claims carry limited financial risk, with the impact restricted to companies no longer being able to show misleading advertisements and ensuring that similar claims are not made again, they do pose the risk of reputational damage.

Further, the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) has intensified its scrutiny of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) and sustainability claims, particularly in relation to green finance products. The FCA has initiated enforcement actions against firms making misleading claims about their climate-related credentials and is under increasing pressure from activist organizations to ensure robust supervision of climate-related risks. This heightened regulatory focus is expected to drive greater accuracy in ESG-related disclosures and product labelling.

Polluter Pays Actions

There is growing interest in holding companies accountable for their contributions to climate change, including through tort-based claims. While polluter pays actions against companies have not yet been successful in the UK, there are key developments in this field that can impact companies in the future.

First, with the UK Supreme Court’s decision in Finch4, a precedent has been set for judges to recognise the impact of downstream emissions on the climate. It will be interesting to watch whether the Finch judgment increases companies’ liabilities for their climate impact by encompassing downstream greenhouse gas emissions.

Second, internationally, courts are increasingly open to considering polluter pays actions. In the Lliuya v RWE case tried in Germany,5 the court held that civil claims based on climate-related risks can be brought against companies and that the assessment of these risks falls within the purview of courts rather than merely being a political issue. This German judgment may influence how UK judges assess the merits of climate litigation arguments when brought in the scope of UK proceedings.

Conclusion

As States are increasingly held accountable for their climate impact, this is likely to directly and indirectly affect companies by broadening director and fiduciary duties and by ensuring that companies take responsibility for their environmental impacts. By implementing a climate strategy, transparent communication and cooperating with stakeholders, companies can mitigate the financial and legal risks of climate litigation and emerge as leaders in the environmental transition inevitably required of all companies.

TWO UNIQUE EVENTS AT THE SAME VENUE

OVER TWO CONSECUTIVE DAYS

FIRE Americas

22-23 September 2025

Washington, D.C., USA

23-24 September 2025

Washington, D.C., USA

Maximise your time to Washington, D.C., through attending both events!

Together, these events will draw a diverse group of litigation and disputes lawyers specializing in enforcement, arbitration, disputes and asset recovery. This unique scheduling provides the perfect opportunity to meet the right professionals at each event and expand your network across both gatherings. Don’t miss this chance to connect and collaborate.

CURRENT TRENDS IN CLIMATE LITIGATION: WHAT DO CORPORATES NEED TO KNOW?

On 23 July 2025, the International Court of Justice (“ICJ”) delivered an advisory opinion on countries’ climate change obligations. The ICJ, which is the United Nations’ principal judicial organ, found that countries are obligated under both treaties and customary international law to ensure protection of the climate system from greenhouse gas (“GHG”) emissions. More significantly, the opinion potentially opens the door to claims against countries that fail to act in accordance with these obligations, which include regulating companies within their jurisdictions.

ICJ DECISION

ICJ recognized that countries’ climate change obligations encompass activities relating to the production and licensing of, and subsidies for, fossil fuels. According to the ICJ, a nation’s failure to take appropriate action to protect the climate system from GHG emissions — including through fossil fuel production, the granting of fossil fuel exploration licences or the provision of fossil fuel subsidies — may constitute an internationally wrongful act attributable to that country.

US Update

For fossil fuel companies in particular, the ICJ’s advisory opinion opens the door to potential new areas of climate change legal risk. This is because the

In time, this may result in increased climate change regulation focused on the fossil fuel and other carbon intensive sectors, and other avenues of litigation by which private individuals, NGOs, climate activist organisations and governments can scrutinize corporate behaviour in such sectors with respect to climate change. As the full consequences of the opinion, which is technically non-binding on countries, remain uncertain, we summarise the state of play in climate litigation, comparing key cases and their potential effects upon companies in the US, EU and the UK.