The Middle Ages in Modern Games: Conference Proceedings Vol. 3

Edited by

Robert Houghton, James Baillie, Lysiane Lasausse, Vinicius Marino Carvalho, Juan Manuel Rubio Arévalo, and Tess Waterson The Public Medievalist

Part Five: Creating II: Adaptions and Settings 27

10: A Question of Class? The Three Estates as mechanic in Foundation 28 Philippe Dion

11: Adapting Medieval Indonesia at Sengkala Dev 29 Muhammad Abdul Karim

12: “In hac insula convenierunt reges…”: Situating the Medieval in the Backstory of The Knight & the Maiden 32 Andreas Kjeldsen

Part Six: Religion II: Revisiting Assassin's Creed 34

13: ‘Whose Holy Land?’ The ‘Christian Muslim frontier’ in Assassin’s Creed...................................35

Quinn Bouabsa Marriott

14: Christian and Muslim mentalities during the Third Crusade in Acre, Damascus and Jerusalem, represented in Assassin's Creed........................................................................................................37 Ricardo Santana

15: Assassin’s Creed: Disassociating religion from religious war......................................................40 Ryan Stacey

Part Seven: Medievalism, Colonialism and Capitalism 42

16: Teyvat’s Timeline: Exploring Medieval Fantasy Beyond Western Europe in Genshin Impact....43 Johansen Quijano

17: Before 1492: Building Medieval Environments for Immodern Games 46 Sarah Nelle Jackson

18: “There and Back Again”: the Rebooted, High tech Logic of Revivalism in Assassin’s Creed 49 Kevin Moberly

Part Eight: Geographies and Spaces 51

19: Medievalism and Chinese Gamers: A Case Study in a Broadcaster of Crusader Kings 52 Chenlin Shou

20: Hic abundant indigeni: Spatial Constructions of Indigeneity in the Dragon Age games 53 Sven Gins

21: A Geolocation journey into the past with Assassin’s Creed 56

Fern Dunn, Will Humphrey and Jason Veal

Part Nine: Labour and Resources 58

22: Work in Neomedieval RPGs 59

Krista Bonello Rutter Giappone and Daniel Vella 23: ‘Wood please!’ Resources in Digital Games about the Middle Ages 60

Jonas Froehlich and Tobias Schade 24: “The granary is full, milord!”: The Everyday in Stronghold 63 Tyla Thackwray

Part Ten: Bending and Breaking Genres 64 25: Fenlander: Exploring Life in a Medieval Landscape 65

James Baillie 26: Hex and History: Modelling the Middle Ages in Tabletop Wargaming 68 Stuart Ellis Gorman 27: Alternating Activations and Alternating Identities: A study of Medievalism within Modern Tabletop Wargaming 70 James Reah

Part Eleven: Modern Impositions 71 28: Gender and Sexuality between modern expectations and Viking narratives in Assassin’s Creed: Valhalla .............................................................................................................................................72 Joana Hansen 29: Medieval Nordic Culture and Mythology in Valheim 74 Jéssica Iolanda Costa Bispo 30: “Dan of the Dead”: Music and MediEvil 76 Karen M. Cook and Andrew S. Powell

Part Twelve: Ludological Theory 79

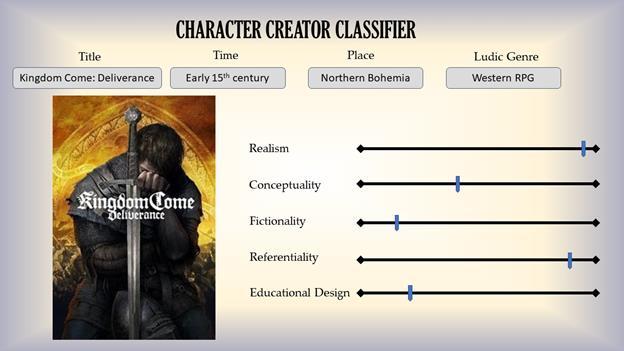

31: The Girdle and the Bottle: Exploring Ludoludo Harmony in Sir Gawain and Ocarina of Time 80 Andrew S. Latham 32: What Makes Crusader Kings, Skyrim, and Golden Sun Similar? Proposing a Descriptive “Character Creator” Framework for Medievalist Games 81

Adam Bierstedt

Part Thirteen: Religion III: Playing with Religion 83

33: Bradwen the Celt or Bradwen the Paladin? Two Worlds and Two Religions in Arthur's Knights: Tales of Chivalry................................................................................................................................84

Renata Leśniakiewicz Drzymała

34: “You are pure, you shall live!”: Religious fanaticism and the End of the World in the Medievalist world of The Witcher (2007) Video Game ....................................................................86

Juan Manuel Rubio Arévalo

Part Fourteen: Post Apocalyptic Medievalism .....................................................................................87

35: Nier Replicant’s perspective on medieval eschatology: Post apocalyptic setting as a critique of medieval tropes in Japanese RPGs 88

Albert de Vanves

36: Fallout 4: Medieval Ages in a post apocalyptic future 89

João Paulo da Silva Roque

37: Neo medievalism, Americana, and the Post Apocalypse: Honest Hearts, Ancestral Puebloans, and the Sorrows 90

Thomas Lecaque

Part Fifteen: Closing Keynote................................................................................................................92

38: Best Practices for Speculative Species Design 93

James Mendez Hodes

Introduction

The Middle Ages in Modern Games, Volume 3

Vinicius Marino Carvalho, @carvalho_marino, Universidade de São Paulo Robert Houghton, @robehoughton, University of WinchesterHistory games are an influential and dynamic genre of popular history. They have proven to be incredibly useful tools for education, research, heritage projects, and academic outreach. They can also be focal points for cultural criticism and analysis. This is especially true concerning the long tradition of medievalist games. Analysing how the Middle Ages is co opted by (often problematic) aesthetic, ideological and/or political discourses can be a window to understanding our present and its issues. History games operate in different epistemologies, mobilize distinctive genre conventions, and are often subject to commercial pressures. To understand them, we must consider their role as both historical discourses and cultural products.

These are the proceedings of the third Middle Ages in Modern Games Twitter conference. The event comprised papers from 44 scholars and game developers over four days between 7 and 10 June 2022 addressing a broad range of issues surrounding the use of the Middle Ages and medievalism within games of all sorts. This volume is a compilation and expansion of these papers and represents a range of work in progress across a diverse collection of approaches and disciplines. This year we were pleased to welcome a substantial number of new voices from across the world including many graduate students and early career researchers, alongside industry representatives. These collected papers highlight the emergence of many new approaches and ongoing projects which will be of great importance to the field in the coming years.

This year the organisation of the event and proceedings was expanded with the assistance of several new organisers and editors, namely: Vinicius Marino Carvalho, Tess Waterson, Juan Manuel Rubio, James Baille, and Lysiane Lasausse. The event was sponsored by Slitherine Games and Intellect Books and supported by The Public Medievalist and the Centre for Medieval and Renaissance Research at the University of Winchester.

Fortunately, there is increasing constructive dialogue between industry voices and scholars. This congress is a testament to this welcome development. Our sessions include speakers from both within and outside academia engaging with a wide variety of topics. Our papers include discussions on themes such as medicine, labour, religion, and geography in the context of medievalist games. Some sessions are entirely dedicated to modern impositions and the cross section between medievalism and contemporary discourses We also have sessions looking at the practical implementation of historical concepts in games. Topics include how to design game mechanics, create historical settings, address challenges of quantification, and incorporate ludological theory.

The papers of this volume represent a truly diverse set of topics and fields, but a few common themes may be tentatively identified across them:

1) There is a growing amount of discussion around the construction of games in theory and practice. This is partly a consequence of the very welcome participation of many developers this year including representatives from Slitherine, Polymorph Games, Sengkala Dev, Stark Raving Sane Games, and the Sugar Collective, but we have also seen a growing number of scholars thinking about game design in earnest. This overlap between industry and academia is increasingly important and we hope to foster closer collaboration in future years.

2) There has been a greater breadth of papers this year. New aspects of old favourites like Religion and Colonialism have been explored, but we’ve also seen clusters of papers around less commonly addressed issues like Illness, Labour, and the Apocalypse. This is really important and highlights the growth of the field.

3) These papers have also demonstrated a greater awareness of the state of the field than in previous years and within many publications. These are informal papers, but there have been plenty of references to other scholars throughout the presentations and in the discussion around them. There have been a handful of papers dedicated to theory, but these have been rooted heavily in existing methodologies and illustrated through practical examples.

All of this is a sign of a maturing area of scholarship. The introduction to our proceedings last year (volume two) presented medievalist game studies as an embryonic field, but this is increasingly inaccurate. A growing body of written scholarship and theory exist within this field and in multiple subfields. There are numerous conferences, events and centres focusing on this subject. The field is still varied and shifting, but it is increasingly unconvincing to address it as a brand new area of study.

A key next step is greater integration across disciplines and between the academy and industry. A lot of the papers this year represent a move in this direction, but we would all benefit from moving further out of our silos. Medievalist game studies is conducted by scholars from archaeological, literary, historical and media backgrounds amongst others but we have a tendency to talk past each other and as a result there has been a substantial amount of reinvention of the wheel. Moreover, scholars have often ignored developers to the detriment of their research.

In sum, it’s a really exciting time to be working on the Middle Ages or medievalism in modern games. This volume represents a small cross section of the excellent work being conducted within the field and we can’t wait to see what everyone comes up with next. We hope to see a lot of new and fascinating developments at the fourth Middle Ages in Modern Games Twitter conference next year.

Part One: Opening Keynote

I work on representations of gender in medieval historical narratives. Instead of examining whether they give ‘accurate’ accounts I consider how and why people and events are repackaged and the function of gender within this process. Recently I’ve focused on crusade texts. I take the same approach to modern medieval narratives. Instead of highlighting what games ‘get wrong’ we must acknowledge what they do well: their capacity to go beyond conventional academic formats and enhance our understanding of the past, as discussed in these books.

Medievalism is a well established field but gender hasn’t been substantially discussed (except Joan of Arc!) This is changing with studies focused on women including medieval games in @JLDraycott‘s collection and see also her volume with @KatExe on women in classical games. I must also highlight here my PhD students @CalumLeatham and @TesterPoppy working, respectively, on gender in Japanese dating games with Western European medieval settings and on the depiction of women in medieval video games in relation to design, mechanics and reception.

But masculinity in Medievalism is still lagging behind. It’s crucial to investigate modern depictions of medieval masculinity: some modern conceptions of masculinity (drawing on extremist ideologies) are made to appear ‘natural’ with reference to the Middle Ages. Blackburn and Scharrer state that young adults who favour violent games endorse traditional hypermasculinity, contending ‘game creators have a responsibility to vary the roles and actions… [of] male characters…to better reflect…performances of gender…in the real world.’

Masculinity in games isn’t only embodied by and experienced via male characters, but female too. It’s arguably now compulsory to have warrior women in medieval narratives: part of the wider rise of women action heroes, accomplished fighters equal to/better than men. Some historical settings offer more justification than others for women warriors. Sagas delineate them as a distinctive aspect of the Viking mentalité: both Vikings (tv) and Assassin’s Creed: Valhalla draw heavily on sagas ergo the inclusion of shield maidens makes sense.

But were shield maidens real? Were they a regular feature of Viking society? Debate continues to rage, especially focused on the Birka grave. Many argue that Viking warrior women always tell us more about the time when they’re portrayed than about actual Vikings.

Admirable women in historical media are now habitually those who adopt masculine qualities and accomplishments, including violence, often involving denigration of traditionally feminine traits or occupations: for example, Michael Hirst’s rationale for including Lagertha in Vikings. In Assassin’s Creed: Valhalla Eivor can be a woman or a man (although is canonically female) and the choice makes little difference: they dress the same and have the same story. Vikings influenced their appearance: exemplifying media informed/created popular perceptions of the past.

Female Eivor and similar depictions reflect the currency of shield maidens as an idea in Viking society but don’t represent the vast majority of Viking women or the distinctive forms of agency they possessed, resting on other attributes and activities than violence. For more detail see @sagaknitter‘s fantastic book highlighting the association between women and wise council, the value placed on

1: “I feel somewhat trapped. In this room, in this settlement, in this life”: depicting women and the experience of gender in medieval video games

women’s intelligence, also their management of household economies and the significance of their involvement in weaving and textile work.

There is a character in Assassin’s Creed: Valhalla who does more nearly embody real women’s occupations and status: Randvi (wife of Eivor’s foster brother Sigurd), the chief advisor in Ravensthorpe, a wise and capable manager and subject of a quest called (tellingly) ‘Taken for Granted’. At the start of this Randvi says ‘I feel somewhat trapped. In this room, in this settlement, in this life.’ She spends so much time overseeing Ravensthorpe’s affairs that she later refers to herself ironically as a ‘Table Maiden’. Eivor takes her outside for adventure!

During the quest (which leads to a potential romance, whether Eivor is male or female) Randvi experiences Eivor’s world, hunting and fighting bandits, having a drinking contest, then climbing a ruined tower. Eivor tells Randvi her adventurer’s heart had been hidden behind the table. Randvi replies revealingly: ‘I was rowdy in my youth: hunting, sailing. I was a wildling of the open air, before I became this staunch and stoic woman. Married off in service between two clans. A noble and worthy role, but not one I had ever imagined for myself.’ Randvi has status and authority, but the game also articulates the limitations of her situation, especially her status as a commodity. Like many medieval women Randvi has no choice in her husband and marriage is unfulfilling; hence she is attracted both to Eivor and adventure. Randvi’s dissatisfaction feels like an authentic expression of the frustration some women must have felt faced with patriarchal constraints. This is where games can shine; depicting inner lives of people, including women, not usually accessible via medieval sources.

But why does Randvi have to aspire to be a warrior? Why must that be the epitome of achievement for a female character? Why do women have to be violent and hypermasculine in order to be fulfilled and admirable? Actually, the same questions could be applied to male characters too! The inclusion of women warrior characters has value as a means of combatting sexist and misogynistic attacks which use ‘historical accuracy’ to criticise and deride moves towards equality and diversity of representation. Although such attacks are themselves denounced. Depicting historical women only in domestic roles, supporting male relatives is also problematic: by modern standards this reinforces reactionary stereotypes about the gendering of occupations, lately compounded by the pandemic and its impact on women’s careers. Thus, Eivor can be a woman but is still masculine; Randvi is a leader but resents having had to become a ‘worthy’ woman. So: how can such games include and centre women while avoiding the reiteration of essentialist patriarchal paradigms that prize masculinity over femininity?

Part Two: Illness and Medicine

2: Potion Craft: Between Occult Dark Master and Noble Artisan

Lysiane Lasausse, @nordllys, University of South Eastern Norway

Potion Craft: Alchemist Simulator (Potion Craft or PC from here) is an early access simulation game in which one roleplays as the town’s alchemist.1 The principle of the game is simple: make and sell potions. But promising: aspire to create the Philosopher’s Stone!

PC’s “Unique visuals inspired by medieval manuscripts and medical books” are not only aesthetically pleasing, they also contribute to the mediaeval feel and immersion in the game.2 It brings the player into mediaeval times, and mediaeval times into the 21st century. The art style, the parade of customers and the passage of time, all have a Bayeux tapestry feel to it. While there is no direct inspiration or connection between the Bayeux tapestry and alchemy mentioned in the devlogs (developers’ logs), the interrelation with the mediaeval is perspicuous.

The easily recognizable style fits well with the concept of alchemy, another famous trope associated with the mediaeval in a Western, particularly European context. While both the tapestry and alchemy are anchored in reality, they also have spiritual and mystic overtones in common.3 These overtones are presented in the game through the effects of the potions as well as the alchemical ingredients, but also the townspeople you interact with. Mana and necromancy potions, the Philosopher’s Stone and even a familiar face amongst your clients in the presence of a Geralt de Rivia look alike.

Fig. 2.1 Potion Craft

1 Potion Craft, niceplay games, 2021. https://www.potioncraft.com/

2 Ibid.

3 Que raconte la tapisserie de Bayeux ?, musée de la tapisserie de Bayeux, Bayeux, France. https://www.bayeuxmuseum.com/la tapisserie de bayeux/decouvrir la tapisserie de bayeux/que raconte la tapisserie de bayeux/ ; Alexander Roob, Alchemy & Mysticism, Bibliotheca Universalis, 2014.

Word spreads fast and as the town’s only alchemist, you will have to make some (im)moral choices: increase your renown as a purveyor of all potions, for any and all clients, or maintain your standing by shooing away hard working rogues in dire need of various poisons?

Another interesting aspect of the game is that most potions are not inherently good or bad: the moral dilemma relies on the client’s dialogue and their supposed intentions. Relying on text or speech is an interesting parallel to the historically obfuscatory language of mediaeval alchemists, namely decknamen, hermeticism and coded language. Historically, these elements contributed to the association of alchemy to mysticism and the occult and led to the practice of alchemy being forbidden in most of Europe (13 14th centuries CE), gaining a seedy reputation that would categorise it as a pseudo science for centuries.4

Fig 2.2 Potion Craft

Your reputation as an alchemist in the game, then, varies by the requests you accept, not by the potions you tinker with. If you provide for a client whose intentions seem nefarious, it will lower your shop’s reputation. The same potion for seemingly innocuous uses will, on the contrary, increase your standing. The shop’s features do not put your alchemical talents in question: you will still gain a sort of popularity, but with a different crowd. The mechanic (still a work in progress at the time of writing), suggests that there is a balance of good and bad to your craft, and it’s your responsibility to manage it, your shop’s popularity and income. The fourth devlog even suggests selling a high tier potion (which are more expensive to the client) to make your shady deals well worth it…!5

In a historical context, alchemy was both sought after and seen as threatening to the powers in place. Transmuting into gold would have crashed the economy, but having your own personal alchemist make you wealthier & potentially immortal was hard to pass up on. While the mysticism around alchemy lingers and thrives under pop culture, as is apparent in the game, it is also being rediscovered

4 Gabriele Ferrario,Understanding the Language of Alchemy: The Medieval Arabic Alchemical Lexicon in Berlin. Staatsbibliothek, Ms Sprenger, 1908; Lawrence M. Principe, The Secrets of Alchemy. Science History Institute, 2013. https://www.sciencehistory.org/distillations/the secrets of alchemy

5 Potion Craft devlog #4. Reputation, April 2021. https://store.steampowered.com/news/app/1210320/view/4706800454255234870

as an early science (related to chemistry for example).6 And if science hasn’t yet achieved the creation of the Philosopher’s stone, you can try your hand at it in Potion Craft!

6 Megan Piorko, Marieke Hendriksen & Simon Werrett, Alchemical Practice: Looking Towards the Chemical Humanities, 2022. Ambix, 69:1, 1 18, DOI: 10.1080/00026980.2022.2035572: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/00026980.2022.2035572

3: Medieval epidemics in modern videogames

Vinicius Marino Carvalho, @carvalho_marino, Universidade de São PauloToday I will be talking about the plague. Covid 19 spurred a lot of interest in past pandemics. We’ve witnessed great historiographical advances in the last couple of years, as well as the release of many independent games inspired by the Second Plague Pandemic. They may not be as flashy as big budget productions like A Plague’s Tale: Innocence. However, they are important to historian designers and educators because their principles are easy to replicate and our mistakes in creating our own games will probably echo theirs. Let us have a look at them.

A lot of these games (Strange Sickness, Mask of the Plague Doctor, Tales of the Black Death) are mechanically very similar. They tend to be RPGs or interactive fiction experiences offering bottom up perspectives of the plague and its impacts. Protagonists are usually common folk. As Kee et al. (2007) argued, it is a solid foundation for micro historical approaches. Exodus by Priory Games and Plague M.D. are management sims, a genre I have talked about in the past (https://twitter.com/carvalho_marino/status/1397862729843625985 ). Cursed Kingdom is as abstract as an agent based model. While fun, one could almost use it as a virtual laboratory.

Goals are important for a game’s historical validity (cf. Houghton, 2019). At first sight, games about epidemics have an easier time, as historical goals are easier to spot and fun to play with: investigate, contain, and/or survive the disease. But the reality is more complicated. All of the games grapple with the challenge of encouraging roleplay in a world that precedes modern medicine. Players have the benefit of hindsight not to make decisions they know to be useless or counterproductive.

The portrayal of faith is particularly problematic. Many of these games feature a dichotomy between “faith” and “science”. This is understandable given the current anger against Covid 19 denialism, yet also problematic as it ignores how intertwined spiritual and secular institutions were in medieval society. A notable exception is Strange Sickness, in which church and clergy contribute to plague responses. The game, which was made by historians, was featured in the 2021 edition of Middle Ages and Modern Games.

Some games address this roleplay conundrum with “meters” urging players to care for characters’ non physical necessities. Yet, the implementation often feels “tropey”. Jeremiah McCall’s point about the weight of genre conventions in historical game design comes to mind.

A common, well implemented topic in these games is the role of communication networks in spreading the plague. This has been particularly well done in Cursed Kingdom, in which the environment is a literal network. Yet, cost, length, and danger of particular routes is a theme present across many games on the list.

On the other hand, while these games address immediate plague related societal breakdown, they do not pay too much attention to long term consequences, and/or side effects of responses. An exception is Strange Sickness, but even there it is not essential for the gameplay. Indirect consequences are a major area of interest in current plague studies, as we increasingly understand that society shapes epidemics as much as epidemics shape society. Hopefully, future games about epidemics will make use of this new knowledge.

4: Exploring the Intersections of Illness and Otherness in A Plague Tale: Innocence

Blair Apgar, @BlairApgar, University of York

Blair Apgar, @BlairApgar, University of York

In the 2019 game 'A Plague Tale: Innocence' developed by Asobo Studio, 'otherness' is directly tied to illness. Set in Aquitaine during the 1348 plague outbreak, the game tells a complex tale of illness, isolation, and otherness during the Black Plague.

The story centres on Amicia de Rune and her younger brother, Hugo. Hugo has a hereditary illness connected to a familial trait (‘Prima Macula’) and has lived in quasi isolation while in treatment. Amidst a plague outbreak, Hugo is targeted by a fictionalized Inquisition. The plague’s devastation can be seen in a nearby village: empty streets, doors marked with white Xs to signal infected households, bloodied bodies strewn in the streets, a terrified populace immolating its residents. As outsiders, Amicia and Hugo are targeted as plague bringers.

After the village, the player encounters an ill, alchemic doctor named Laurentius who contracted the disease while helping the ill at a plague hospice. Rather than remain at the hospice, he retired to his farmstead, presumably to die. Such tactics were documented in contemporary sources, including Boccacio’s Decameron 7 Isolation (self and otherwise imposed) was a common tactic during outbreaks of the disease as a protective measure. The pope himself is reported to have fled to Étoile sur Rhône to avoid infection,8 and ordinances were passed in Pistoia to control travel to and from infected areas.9 While the game frames the village’s negative response to the outsider/player as part of an irrational one, any such decision would have been carefully considered and apparently, even legislated.

7 Boccaccio, Giovanni. Decameron, Book 1. ll. 25 27.

8 Horrox, Rosemary. The Black Death. Manchester University Press, 2013, 45.

9 Ibid., 194 201.

The game employs swarms of infected rats as the primary threat; without light their sole deterrent they quickly engulf and devour the player causing a ‘game over’. According to the game’s director, Kevin Choteau, the rats embody the looming threat of infection and death by the plague.10 By this rule, the player cannot both be infected and finish the game, positioning them as an outsider who traverses the world of the sick and who themselves cannot become ill. The player encounters few living infected people, bolstering the plague = death narrative. Contemporary estimates of fatalities reach as high as 7011 75%12 and characterize the illness’ efficacy as “healthy one day, dead and buried the next.”13 Letters from the papal court reveal the belief that even brief contact with the ill inevitably resulted in death.14 These accounts reveal the overt otherization of the ill and no doubt informed the game’s depiction of plague sufferers.15 By making the plague instantly deadly to Amicia, the game also perpetuates contemporary beliefs of the disease and creates two false groups: sick/alive. As a result, the ‘ill’ and the ‘dead’ are indistinct while the player remains unfazed by the illness that is laying waste to southern France. Though reflective of medieval attitudes, this dichotomy does nothing to reflect bioarchaeological data of the plague and its deadliness.

Though engaging gameplay, it flattens the experience of the plague and uncritically recreates the fearful stigma surrounding the illness and the medieval belief of the plague’s certain death.16

Fig. 4.2: A Plague Tale: Innocence

10 Parijat, Shubhankar. “A Plague Tale: Innocence Interview A Harrowing Journey.” GamingBolt, April 2, 2019. https://gamingbolt.com/a plague tale innocence interview a harrowing journey… .

11 Horrox, 20.

12 Ibid., 59.

13 Ibid., 55

14 Ibid., 42 43.

15 Boccaccio, Book 1. ll. 10 15.

16 DeWitte, Sharon N. “Mortality Risk and Survival in the Aftermath of the Medieval Black Death.” https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0096513… ; DeWitte, Sharon N., and J. W. Wood. “Selectivity of Black Death Mortality with Respect to Preexisting Health.” https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0705460105….

Part Three: Religion I: Aesthetics and Mechanics

5: The Witchfinder Aesthetic, from Early Modern Pamphlet to Warhammer

Tess Watterson, @tesswatty, University of AdelaideThe title ‘Witch Hunter’ evokes an immediate image for fantasy players/fans: he has varied assemblages of a long leather coat, belts, and ammunition, and one consistent accessory The Witch Hunter Hat. Sold as LARP gear and re enactment gear alike, the Witch Hunters Hat is a fantasy adaptation of the capotain hat of the 16th and 17th centuries and has its own place in popular imagination. The witch hunter and his hat are a very non medieval archetype that is very normalised in medievalist spaces, especially video games. Fantasy witch hunters are an infusion of many ideas (like wild west, gunslinger, outlaw, puritan, leather, and more), likely springing first from Robert E. Howard’s 1920s pulp fiction character, Solomon Kane, an Elizabethan puritan monster hunter.

The most well known “witch hunter” of the historical record is Matthew Hopkins, Witch Finder General. However, Hopkins was effectively an “amateur detective” in the 17th century, who titled himself ‘general’ with no context, and only lived to age 27. The popular visual image of him is from his own witch hunting pamphlet. The big names in witch persecution that were actually temporally closer to the Middle Ages are figures more like Kramer and Sprenger, Reginald Scot, or even King James VI. They represent far less aesthetically appealing figures for fantasy violence, but these were the authors of (almost medieval) witchcraft treatises. The concepts of a witch hunter ‘class’ in fantasy games is thus misleading, implying men like Hopkins represented an organised profession. Witch finding, particularly at the very end of the Middle Ages and start of the Early Modern period, was conducted more by communities, neighbours, or church groups, than by individual (or institutional) violently trained men. Less cool, more insidious.

The witch hunters of fantasy films are aesthetically in line with the filmic grimdark medievalism trend, such as Vin Diesel in the Last Witch Hunter or Nicolas Cage in Season of the Witch. Films seem to have kept puritan hats to era appropriate historical texts (usually not fantasy), like the 1968 Witchfinder General. Though, inversely, James Purefoy’s 2009 version of Elizabethan Solomon Kane has a bit of the grungy/gritty medievalism flavour.

In the world of roleplay games, however, the fantasy witch hunter thrives. CRPG Warhammer’s witch hunters are a playable class: state sanctioned, usually “Templars”, lone mercenary types that are proficient with violence (especially a pistol and rapier). The game lore frames them as grim, zealous, and disliked, but their violence is edgy and cool (and very cosplay able). In TTRPG Warhammer lore, there is even a “Hammer of the Witches” text written by a witch hunter character named Wilhelm Hasburg. Hammer of the Witches is the common translation of the title of the real Malleus Maleficarum, a treatise written by German Heinrich Kramer in the 1480s.

The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt ’s witch hunters are NPCs: soldier inquisitors sanctioned by the Church (and some rulers). They are framed as thugs and fanatics who are largely disliked, but with whom the PC works when needed that is, their violence becomes acceptable if the common enemy is uglier (The Crones). The Witcher 3’s journal entry on witch hunters describes them as “bloody butchers” who are capitalising on chaos. This depiction both frames witch hunters as real commanders of a force, and implies that only evil opportunists engaged in such practices.

The flattening of later ideas back into the medieval is often reflective of a desire to relegate anything uncomfortable to a pre modern past. With witch trials, it seems we also prefer to think of cloaked

cardinals and pistol wielding hunters as persecuting the innocent, as opposed to grappling with stories of everyday people, often betraying neighbours due to beliefs that modern audiences disparage as superstition. But fantasy witch hunters are also made into cool, dark, anti heroes to play. What image does this create of the witches they hunt? If magic is a real threat, the witch hunter's meaning is changed. This narrative obscures the complexity of community contexts in a historical period of widespread sociocultural instability and change, and has the potential to subtly reshape ideas about the real history of the witch trials.

6: Piety +2.5/Month: Quantifying Faith and Morality in Crusader Kings III

Robert Houghton, @robehoughton, University of WinchesterCrusader Kings III uses complex mechanics and roleplay elements to create a different experience from many strategy games. The game represents a deeper dive into the medieval world through its detailed consideration of economic and political issues alongside warfare while also providing gameplay which focuses on the strengths (and weaknesses) of individual characters and their position within complex relationship networks. In combination, these elements allow the game to portray many aspects including Faith and Morality more deeply than most medievalist strategy games.

Religion sits in a weird place in medievalist games (and medievalist media more generally). It's absolutely central to the modern perception of the period and shows up everywhere in the architecture, material culture, rituals, acoustics, story etc. of games across genres. Cathedrals for example appear across games such as Assassin’s Creed and Kingdom Come: Deliverance as key indicators of the period, and are adopted within fantasy works from Dark Souls to Skyrim with no link to Christianity.

But these uses of religion are typically shallow. We get churches and mosques without context, ritual without faith, and ominous Latin chanting for the sake of atmosphere. A few games go deeper as Lobitz has highlighted, the backstory of Dragon Age provides a surprisingly detailed parallel to the 1054 Great Schism for example. But mostly it's aesthetics without substance, often as studios are reluctant to engage with potentially controversial religious subjects and the accompanying possibly ruinous backlash.

Morality is one of the few themes with links to religion which is addressed in any depth by medievalist games. Roleplaying games in particular frequently make use of ethical choices, ‘karma meters’ and other mechanics to allow players to engage with moral issues, weigh difficult decisions, and live with the consequences through changes to abilities (in Baldur’s Gate for example) or story (as in The Witcher). But these systems are often blunt and arbitrary: Mass Effect was particularly notorious in this regard for neatly colour coding the ‘good’ and ‘less good’ dialogue choices within conversations, removing any requirement for thought or contemplation a factor compounded by the fact that the ‘good’ choice almost invariably led to better narrative and mechanical outcomes. Morality is likewise almost always stripped of any link to religion despite its very visible presence within many games Good is good because the devs say so.

Within strategy games like Civilization and the Total War series, these trends run into a set of mechanical needs and assumptions. These games need a model of society reduced to a series of values which works for any culture within the game. Food production, population growth, and the creation of armies are all abstracted and quantified indeed, must be abstracted and quantified in order for the game to function and to be remotely accessible to players.

This abstraction and numeration leads to the quantification of religion as a resource within strategy games often as a central element of these games In Civilization VI 'Faith' is produced by religious structures, citizens and a number of other sources to be spent on the construction of buildings or armies. Religious buildings within the game provide particular benefits: often boosts to happiness or access to new units. In this manner, ‘Faith’ acts in a similar manner to ‘Food’, ‘Production’ and ‘Gold’

and the less tangible ‘Science’ and ‘Culture: it is accrued and spent to gain advantages for the player’s civilization.

Morality is less visible, but still plays a role. Medieval II: Total War allows generals and rulers to acquire Dread and Chivalry for ‘evil’ and ‘good’ actions respectively. Hence, releasing captives after a battle will increase a character’s Chivalry, while executing them will boost their Dread. These can have an impact on their combat abilities: Chivalry boosts the morale of troops under the character’s command, while Dread lowers the morale of opposing forces.

But these systems are pretty shallow. Every faith and every culture has access to the same religious and moral mechanics. Civilization VI allows the creation and customisation of religions, granting the player the ability to attach beliefs to any given religion, gaining mechanical benefits which may be wildly divorced from doctrine. Hence it is perfectly possible for Confucianism to emerge as a religion with and emphasis on choral music, worship conducted in mosques, a system of tithes, and practicing crusades. Representations of morality are likewise typically basic and lacking in nuance. Beyond facilitating a clash of civilizations narrative, Christianity and Islam are functionally similar within Medieval II: Total War: Chivalry and Dread and the morality they represent are identical for every character regardless of faith.

Crusader Kings III is bound by similar core mechanical restrictions as Civilization and Total War, but still manages to create a more nuanced representation of religion and morality. Characters still accrue and spend Piety like any other resource, gaining Piety through their traits and Learning skill, alongside constructing religious buildings and taking pious actions, and can use this Piety to justify wars or sway religious characters. However, each religion has a different ideology with each faith viewing different attributes as virtuous or sinful. Hence Christianity values chastity while Norse praises vengeance and Yoruba focuses on patience. Morality is more complex and different religions can play differently.

More importantly though, the character driven play of Crusader Kings III centres these moral issues. Players do not simply collect ‘Faith’ for mechanical gain as is the case within Civilization. Instead, characters’ actions and traits build emergent personal stories and interactions. These are fairly rudimentary and can often be repetitive, but ultimately dictate that character with pious traits can play very differently from those with sinful ones. Morality and religion are complex and varied.

There are certainly problems and limitations with this system. The game is still abstract and limited in the variation and depth of issues it discusses Further, beyond some mechanical checks, there is nothing to stop players from ignoring the morality of their characters and its interaction with their faith’s doctrine. But the blurring of genre boundaries between Strategy and RPG within Crusader Kings III allows a deeper exploration of faith and morality and neatly dodges many of the pitfalls present in other games.

Part Four: Creating I: Mechanics and Roleplay

7: King of the Hill: Swiss Pikemen in Field of Glory II

Marco

Minoli, @piuemme, Slitherine Games.Field of Glory II: Medieval is a wargame at heart. Wargames are a perfect way of depicting historical events in an entertainment product while delivering perfectly accurate historical information. They are less prone to compromise in favour of pure fun elements. In the Rise of the Swiss DLC, the game covers a period of military evolution that’s often disregarded: the heyday of the mounted knights, confronted with the increase in the use of long pikes introduced by the Swiss Army.

From the late 1300s, some Swiss started to carry the long pike, and by the end of the fifteenth century, it had become the dominant weapon. The halberd was only retained by a small number of experienced soldiers to defend the banners. Soon, pike formations were adopted in many western European countries, notably in Germany by the famous Landsknecht, who were often supported by foot soldiers. Swiss pikemen quickly became a powerful contingent (around 8000 men in total) hired as mercenaries in Italy and France during the 14th and 15th centuries. The involvement of Swiss mercenaries guaranteed many victories, including the conquest of Milan by the French.

In the FoG II Medieval Rise of the Swiss module, the pikemen are represented with extremely accurate fidelity: pikemen formations are nearly invulnerable to front charges and can withstand any front charge from mounted knights and infantry units in open terrain. In the game, like in reality, pikemen formations need to protect their vulnerable flanks, which poses a number of tactical issues. These units usually also needed to push forward very heavily, which caused them to be exposed to encirclements and disruption. Field of Glory players are presented with a number of options to counter the pikemen's effectiveness: longbow and artillery firing from long ranges, mounted charges on the flanks, and the use of special sword and buckler formations.

Depicting pikemen tactics in a turn based battle game like Field of Glory II: Medieval allows a better understanding of its use and its efficacy against a specific type of formation. It’s also a perfect way to visualize how these units were used.

8: Exultet: playing liturgy, its context and their changes. A proposal

Arturo Mariano Iannace, @ArturoIannace, School of Advanced Studies, LuccaThe Exultet scrolls are a unique form of medieval liturgical manuscript originating in southern Italy. Containing the homonymous prayer to be chanted during Easter Vigil, what makes them such unique objects is the combination of text, images, and musical notation. The visual commemorations of authorities are wildly different between each other, ranging from symbolically charged representations of rulership, to simpler ‘vignettes’ showing rulers in the exercise of justice or some other of their governmental prerogatives.

Fig. 8.1: Image from the Exultet Scrolls

The proposal to be forwarded here concerns the attempt to translate into a tabletop game mechanic the intersection of political, liturgical, and cultural landscapes at which such unique liturgical and artistic objects emerged. The goal would be three pronged: to make this intersection understandable to the players; to look at emerging mechanics between players that may help shed some light on the history of the scrolls; and to raise awareness towards such objects. Each player would take the role of an ‘abstract’ actor: the ecclesiastical authorities, the secular rulers, the urban aristocracy. Each of them would receive a starting number of two resources: Legitimacy (L, to be summed as Total Legitimacy or TL), and Power (P)

Cards would represent iconographical elements or scenes: ‘The Ruler Enthroned’; ‘The Bishop with Saints Peter and Paul’; etc… Each iconographical element or scene would be taken from existing cycles. Cards will have L and P values, and a Symbolic Meaning/Ritual Efficacy (SM/RE) value, indicating, when

combined, if and how much the cycle being created by the players is still liturgically viable and effective. Too low a score, and the game would be lost.

Fig. 8.1: Proposed Gameplay

While still in need of proper design, this proposal shows how the three goals set at the beginning may be achieved by a tabletop boardgame design. However, some issues immediately rise to attention, and are in need of being addressed. First, how exactly to represent the iconographical elements or scenes on the cards is an issue that cannot be underestimated. Iconography is a matter of nuances, subtle meanings, where also minor modifications can have correspondingly higher impacts. Second, to represent liturgy and liturgical objects solely as tools for increasing/decreasing legitimacy, and for political statements, would mean opting for a reductionist approach, unable to render the true value of liturgy and ritual in pre modern societies.

It may be necessary for the case under analysis here, as the point is to show how a liturgical object was influenced in its history by competing interests and needs, and evolving contexts and circumstances for a given community. SM/RE attempts at addressing this issue. However, this last issue also opens the way for one consideration: could boardgames (instead of, for example, RPGs) be used to model and replicate rituals and liturgies, with their nuances, competing interpretations, varying performative role in pre modern societies?

9: Gender, (Un)freedom and Theft in the Gamification of the Lombard Laws

Thom Gobbitt, @booksoflaw, Österreichische Akademie der WissenschaftenThe Edictus Rothari, the first written phase of the early medieval Lombard laws, was issued in the name of the Lombard King Rothari (~606 52) from the palace in Pavia, on 22 November 643.17 Over the last few years, I have been slowly developing a table top “pen & paper” role play game (RPG), Langobard, adapted from this law code, for what might be considered “edutainment” purposes. The RPG brings together a group of interested players to explore the social, historical and legal implications of a selection of the Lombard laws through the medium of storytelling and semi improvisational communal theatre while, hopefully, having fun!

What I term the character Identity in the Langobard RPG are the core of predominantly qualitative traits, the ‘concept’, which are then further fleshed out through specialist traits such as skills, inventory, etc. In the Langobard RPG, the core traits of the Identity comprise a character’s Name, Gens (ethnicity), social Class (“free”, “half free” or “unfree/enslaved”) Gender, and Age. Here, I shall delve into the inspiration for the gamification of the laws, and the development of character Identity traits (or concept) from legal categories, focusing mainly on Class and Gender as revealed through a closer look at the Lombard laws on theft.

It is surely not a startling observation to note that, with the exception of a person’s name, these Identity traits as used in the RPG correspond closely to the types of legal categories used in the laws to specify individual legal actors, such as the perpetrator or victim of a crime, or a participant within some legal process or civil framework. In practice, these various legal categories overlap with each other, so separating them into distinct categories is somewhat artificial, and in both law and RPG the individual’s socio legal and interpersonal relationships are informed by the intersection of all such categorical traits, although of course in any given circumstance one or another may take more or less prominence. A fundamental point to recall, is that these categories are not universal, but instead are socially constructed and continually being developed and perpetuated.18

The typical legal actor imagined by the law givers who composed and issued the Edictus Rothari is the adult, free man: the homo liber/liberus [free man] or arrimannus [army man].19 The regular approach taken in the law code when addressing a given subject is to first outline the legal framework for the

17 Friedrich Bluhme, ed., ‘Edictus Langobardorum’, in Monumenta Germaniae Historica, vol. 4, Leges (Hannover: Hahn, 1868), 1 90.

18 The scholarship on ethnicity and gender in Lombard Italy is extensive, and I mention here only a few key studies that have informed my thinking: Ross Balzaretti, ‘“These Are Things That Men Do, Not Women”: The Social Regulation of Female Violence in Langobard Italy’, in Violence and Society in the Early Medieval West, ed. Guy Halsall (Woodbridge: Boydell, 1998), 175 92; Ross Balzaretti, ‘Masculine Authority and State Identity in Liutprandic Italy’, in Die Langobarden: Herrschaft Und Identität, ed. Walter Pohl and Peter Erhart, Forschungen Zur Geschicte Des Mittelalters 9 (Vienna: OEAW, 2005), 361 82; Ross Balzaretti, ‘Lombard Fathers’, Archaeologia Medievale 38 (2011): 45 57; Thom Gobbitt, ‘Poisoning, Killing and Murder in the Edictus Rothari’, in Medieval and Early Modern Murder: Legal, Literary and Historical Contexts, ed. Larissa Tracy (Woodbridge: Boydell, 2018), 333 49; Patricia Skinner, Women in Medieval Italian Society 500 1200 (Pearson, 2001); Walter Pohl, ‘Gender and Ethnicity in the Early Middle Ages’, in Gender in the Early Medieval World: East and West, 300 900, ed. Leslie Brubaker and Julia M.H. Smith (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), 23 43.

19 Balzaretti, ‘Masculine Authority’, 365, 368.

homo liber, and then detail the specific ways in which the legal and social circumstances changed according to the specific legal categories to which the individual belonged, that is perhaps if the person in question is unfree, a woman or both. A good example of this can be found in the laws on theft, and a comparative assessment of the changes they introduce illuminates a facet of what the Lombard law givers imagined it meant to be a man or woman, free or unfree, adult or child or what they thought those categories ought to entail.

The basic restitution for theft in the Lombard laws is that nine times the value of what was taken should be returned. In the case of the liberus this is augmented with a composition of eighty solidi, 20 or if he unable to pay this amount then a death penalty is set instead.21 In the case of the servus [enslaved man], the composition for the crime is half, forty solidi, or else death.22 For the aldia and/or ancilla [half free and enslaved woman, respectively], the penalty for the crime is, again forty solidi, however, here if the composition cannot be paid there is no death penalty.23 These laws, then, appear to establish an absolute difference between free and unfree in the composition due: the same crime by the free (man) is set at double that for the enslaved man or woman.

In the case of the mulier libera, like with and ancilla and aldia there is no death penalty, and there the laws establish a structural binary of male | female. Lombards, in the case of theft, at least, restrict the death penalty on gendered grounds.24 Moreover, the law on theft when committed by a fulcfrea [folk free] women also states that no other composition should be exacted by the victim beyond the nine fold return of the goods that were stolen,25 so the eighty solidi composition does not indicate being free, but rather being a free man.

However, theft when committed by a mulier libera includes a further element, that reveals the expected gendered identities and behaviour for free women. The act of stealing is referred to as an opera indecentem [unseemly deed], a judgemental statement on the activity that is not paralleled in the cases where the perpetrator is male and/or unfree. Moreover, the law also states that vitium [shame] should be imputed to the free woman who has committed theft.26 A somewhat comparable use of affective language can also be seen when a free man compels his puer [boy] or a servus to commit theft.27 As well as bringing age as a binary category of (male) child | adult into focus, the severe

20 A solidus was originally a coin weighing approximately 4.5 grams of gold. By the Lombard period it is a unit of account rather than an actual coin: Alessia Rovelli, ‘From the Fall of Rome to Charlemagne (c. 400 800)’, in Money and Coinage in the Middle Ages, ed. Rory Naismith, vol. 1, Reading Medieval Sources (Leiden, Boston: Brill, 2018), 65 66; Peter Spufford, Money and Its Use in Medieval Europe (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988), 18 19.

21 Edictus Rothari, No. 253: Bluhme, ‘Edictus Langobardorum’, 62.

22

Edictus Rothari, No. 254: Bluhme, 62.

23

Edictus Rothari, No. 258: Bluhme, 63.

24 The three grounds given in the Edictus Rothari where the death penalty can be legally applied to a (free) woman, are if she conspires against her husband’s life, commits bigamy, or is caught committing adultery. Respectively, Edictus Rothari, Nos 202, 211 & 212: Bluhme, 50 52.

25 Edictus Rothari, No. 257: Bluhme, 63.

26 The law does not elaborate on how vitium was imputed, and whether this shaming was simply a statement or if it comprised public acts In the Lombard laws of Aistulf, issued in 750 CE, punishment for a free man who conducted business with Romans without royal permission includes an act of humiliation in which his head is shaved and he must go about decrying his mis deeds. So a public act to shame a free woman theif is not beyond the imagination. Aistulf, No. 4: Bluhme, 196 97.

27 Edictus Rothari, No. 259: Bluhme, 63.

immorality of the circumstances is also stressed. The deed is described as inhonestum [dishonesty] and the compelling of the theft as being contra rationem [against reason]. In addition to offering the RPG setting copious materials for plot hooks and characters, these phrasings also offer insight into how Langobards understood the differences between male and female, free and unfree, child and adult.

In summary, for the unfree (and children), crimes are simply committed either of their own volition or under compulsion. Restitution must be made, but the moral implications for individual identity and/or society need not be elaborated on. For the free, however, the opportunity is taken to moralise, and this in turn reveals the normative gendered behaviours that Lombards (or law givers), expected of people in the upper echelons of society in the mid seventh century: (free) men should not act dishonestly and they should not act against reason, while (free) women conversely should not do things that are unseemly, and if they do they should then be subjected to shame. These affective terms provide a fertile ground for creating the underlying identities of characters in the RPG not by necessarily limiting what a character should be and can do through a static, dogmatic reading of the law, but rather by exploring Identity in the dialogue of character agency against the restrictions and expectations framed in the socio legal norms.

Bibliography

Balzaretti, Ross. ‘Lombard Fathers’. Archaeologia Medievale 38 (2011): 45 57.

. ‘Masculine Authority and State Identity in Liutprandic Italy’. In Die Langobarden: Herrschaft Und Identität, edited by Walter Pohl and Peter Erhart, 361 82. Forschungen Zur Geschicte Des Mittelalters 9. Vienna: OEAW, 2005.

. ‘“These Are Things That Men Do, Not Women”: The Social Regulation of Female Violence in Langobard Italy’. In Violence and Society in the Early Medieval West, edited by Guy Halsall, 175 92. Woodbridge: Boydell, 1998.

Bluhme, Friedrich, ed. ‘Edictus Langobardorum’. In Monumenta Germaniae Historica, 4:1 205. Leges. Hannover: Hahn, 1868.

Gobbitt, Thom. ‘Poisoning, Killing and Murder in the Edictus Rothari’. In Medieval and Early Modern Murder: Legal, Literary and Historical Contexts, edited by Larissa Tracy, 333 49. Woodbridge: Boydell, 2018.

Pohl, Walter. ‘Gender and Ethnicity in the Early Middle Ages’. In Gender in the Early Medieval World: East and West, 300 900, edited by Leslie Brubaker and Julia M.H. Smith, 23 43. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004.

Rovelli, Alessia. ‘From the Fall of Rome to Charlemagne (c. 400 800)’. In Money and Coinage in the Middle Ages, edited by Rory Naismith, 1:63 92. Reading Medieval Sources. Leiden, Boston: Brill, 2018.

Skinner, Patricia. Women in Medieval Italian Society 500 1200. Pearson, 2001. Spufford, Peter. Money and Its Use in Medieval Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988.

Part Five: Creating II: Adaptions and Settings

10: A Question of Class? The Three Estates as mechanic in Foundation

Philippe Dion, @foundationgame, Polymorph GamesToday we'll talk about the thought process of having an immersive mechanic in a sandbox game that responds to player actions rather than getting in the way. Our vision of Foundation is of an asymmetrical experience that encourages players to create villages full of unique monuments. We spent a lot of time finding the backbone that would justify player actions toward that goal while ensuring a high level of immersion.

Inspired by medieval France’s Ancien Régime, players get to please either the Labor, Kingdom or Clergy estates by raising the splendor of their village toward one, or many of them. This is achieved by constructing monuments like castles, markets and monasteries. Each Estate focuses on specific gameplay mechanics and unique strategies. The Labor path values villagers’ promotions and taxation; the Kingdom path focuses on helping the realm with soldiers; the Clergy path excels at trading luxurious resources like wine and herbs In the end, players are presented with various victory conditions, which are optional. A village can focus on a prosperous economy with just a small priory trading wine. Or it could develop a major outpost that will allow the Kingdom to shine on the military front. It’s a constant challenge to keep our game grounded. We are trying to find the right balance between being factual and fun. Sometimes, it’s facts that inspire us game mechanics. Other times, we’ll work to justify a game mechanic that we believe should be in the game

As for our narrative take on the Ancien Régime, we lay emphasis on equal representation of all three estates from the players' perspective. Another concern we have in mind is the approachability of storytelling in a city builder facing complex historical elements. In the popular history of High Middle Ages, the third estate is often poorly personified. Not much is told about their own story, but rather their rulers or other people of interest. Who is dedicated to the well being of the laborers? History tells of sympathizing dignitaries, leagues, communes, city states, and more people resisting the “upper estates” through extraordinary events. However, it is preferable to have relatively harmonious estates for players to be systematically independent. A certain degree of conflict between the estates is necessary to create interesting storytelling, as long as players start with a blank slate. Free from external pressure, they can then decide which aspect of the old regime will influence their city building most.

Foundation’s optimistic aesthetic helped in simplifying historical elements that would have gotten in the Player’s way. This includes difficult notions such as serfdom, extreme social inequality and dogmatism, which would have led to stark perceptions of the estates Our desire to streamline the Ancien Régime into a city building game is a careful balancing act between meaningful gameplay, engaging storytelling and historical immersion. We aim to use this harmony as the keystone upon which we build Foundation's future.

11: Adapting Medieval Indonesia at Sengkala Dev

Muhammad Abdul Karim, @Pedalahusa, Sengkala DevNowadays video games are very popular throughout modern society and we can’t separate the two easily. From 1972, Pong, become very popular28 and pushed video games to evolved not only in the sport genre, but across many genre and platform to fulfil the market demand: including the historical genre. Historical games are very interesting as the players can enjoy and learn about the past. Many historical games use the Medieval era as their background, but games set in this period are mostly set in Europe. But now with emerging indie game developers, players can find non Eurocentric medieval games including historical games from Indonesia.

The history of Indonesian game developers can tracked with Matahari studio founded in 1998 and dissolved in 2010.29 Several local developers were founded in the 2000’s and several of these developers made Indonesian historical games like Nusantara Online published in 25 Febuary 2010 by Nusantara Wahana and developed by Sangkuriang Studio and Telegraph Studio. This game set in Indonesia’s anicent era at Srivijaya, Majapahit, and Pajajaran era is a Massively Multiplayer Online Role Playing Game (MMORPG).

From the early 2010’s, more Indonesian developers founded either small or big studios including Sengkala Dev. Sengkala Dev was founded in November 2015 under name “Pedalahusa Project Developer” and later change to Sengkala Dev. We focus on historical strategy games set in Indonesia since there are not many historical strategy games set in Indonesia, and especially few from Indonesian developers. Our first project was Fall of Bali from November 2015 January 2017. We started the project called Perang Laut Maritime Warfare from May 2017 to June 2019. On 27 October 2021 this project was released on Steam. This game focuses on the history of Indonesia’s maritime world from the fifteenth century to the seventeenth Century. Dato of Srivijaya released on 16 December 2020 focuses on the rise of the Srivijaya empire from the seventh century to the tenth century.

According to the National History of Indonesia series, the official history of Indonesia, Indonesian historians call Indonesia’s medieval an ancient era/“masa kuno”.30 Another historian calls this period the “Hindu Budha” era since in this time, there were many Hindu and Buddhist kingdoms. So in general, there are no medieval era in Indonesia. But if we are looking for a period contemporary to the European Middle Ages, Indonesia’s ancient era is the answer. The ancient era start from the fourth century when inscription about the Kutai Kingdom founded . This era ended in middle fifteenth

28 Carl Therien (2012) Video Games Caught Up in History. Before the Crash: Early Video Game History. Detriot: Wayne State University Press.hlm 19 29 https://tekno.tempo.co/read/228418/game nusantara online sudah bisa dimainkan#:~:text=Nusantara%20Online%20adalah%20game%20yang,%2C%20arsitektur%2C%20sampai%20t ata%20busananya. (Accessed in 9 August 2022)

30 Sejarah Nasional Indonesia or National History of Indonesia is offical book published by Balai Pustaka and compiled by many notable Indonesia’s historian and archeologist. There are 6 books from pre history (first volume), ancient era(second volume), rise of sultanates(third volume), rise of colonialism(fourth volume), rise of nationalism and Dutch East Indies(fifth volume), Japanese occupation and Republic of Indonesia era(sixth volume).

century when the Majapahit empire collapsed while many Islam states rose across the archipelago like Aceh, Ternate, and Demak.

In the ancient era, there were many kingdoms in Indonesia archipelago but the most important in Indonesian history are the Srivijaya empire (7th to 13th centuries) and Majapahit empire (14th to 15th centuries). Srivijaya and Majapahit were geographically large and covered most of Indonesia. This has made Srivijaya and Majapahit important to Indonesian nationalism. In making Perang Laut Maritime Warfare, we initially randomized many maritime states through history but later, we decide the era of this game is late medieval into early modern.

As we did with our previous project, Pedalahusa Fall of Bali, we used many books and journals for reference since the scope of this era is very big. The key medieval kingdoms in this game are Majapahit and Srivijaya. We focused research on junk ships of that era. In the main campaign, Majapahit is in a strong position similar to the middle of the fourteenth century. In same time Srivijaya position is weak since that era is the last time this kingdom exists.

At the time of the game, Majapahit has become a late Hindu Kingdom which has substantial influence throughout the archipelago and Southeast Asia. The empire made use of a policy of “mitreka satata” with kingdoms in mainland like Khmer, Ayuthaya and Champa, supporting these kingdoms with their military power and prestige. In Perang Laut Maritime Warfare, Majapahit has knowledge of gunpowder allowing the use of cannons “cetbang”. This knowledge came from the failure of the Mongol invasion in 1293 and remained through Chinese cannons used by Majapahit in expending their influence through the archipelago.

While in producing Dato of Srivijaya, supported by funding from the Direcorate General of Culture Ministry of Education and Culture through the Facilitation of Culture Project/“Fasilitasi Bidang

Kebudayaan”, Sengkala Dev conducted diverse research about Srivijaya and the surrounding areas. This was very critical as we have sources about this ancient period, but we only have ancient Javanese and Sundanese materials and a complete lack of information about ancient Malay. The greatest challenge in this development was lack of information about Srivijaya before their expansion in 670. Sengkala Dev looked at the condition of East Sumatra which have lot of marshes and jungle for making buildings in this game. In the middle December 2020, we released this game but as we made it too fast, lot of problems emerged. We had big update for this game and released the latest version with better quality in March 2022 after 4 months development of new version.

Fig. 11.2: Screenshot of Dato of Srivijaya. Taken in 30 November 2021

After Perang Laut Maritime Warfare and Dato of Srivijaya, what next? Well, there are probably update for both projects in improving quality of the game and historical information as we continue reseatch into the ancient era. From late June 2022, Sengkala Dev is preparing a new project Fall of Bali in order remake this game with better quality than before.

12: “

In hac insula

convenierunt reges…”: Situating the Medieval in the Backstory of The Knight & the Maiden Andreas Kjeldsen

Hello all! I am the solodev of The Knight & the Maiden: A Modern Medieval Folk Tale, an upcoming narrative adventure game exploring themes of subaltern agency and subversion in a patriarchal society, inspired by the late Middle Ages. Although set in a secondary world, my ambition is to invoke a sense of the late medieval period (15th/early 16th C), and the game's backstory is a very important tool for establishing that appropriate mental and cultural space.

Part of this is of course reflected in the story as it happens in the game, which focuses on the ongoing political and personal consequences of “the Battle of Lethelsberg Pass”, a major event that is inspired by the real world battle of Agincourt and the Hundred Years' War.

However, the backstory in The Knight & the Maiden does not exist only to set up the events of the story, it also works “behind the scenes” in a more indirect way that adds colour and coherence to its mental environment, while not directly impacting the story itself.

Throughout the game, as the story progresses, the player will discover a large number of small “fragments” of information, often in the form of inscriptions, documents, passages from books, building remains, and various other found sources. Although some of these fragments are presented to the player in the course of various questlines, they are generally not otherwise connected to or relevant for the events of the game's plotline, which is intentional. Their purpose is to create a kind of ongoing “thick immersion” that continually hints at the presence of a larger game world, complete with its own “deep history”, existing just outside of the main character’s (and by extension the player's) immediate frame of reference.

Combined with supporting dialogue, the effect is intended to emulate a kind of “Ubi sunt” sensibility similar to that found in both early and late medieval poetry a sense of being surrounded by remains of a distant past, the original meaning of which is now lost.

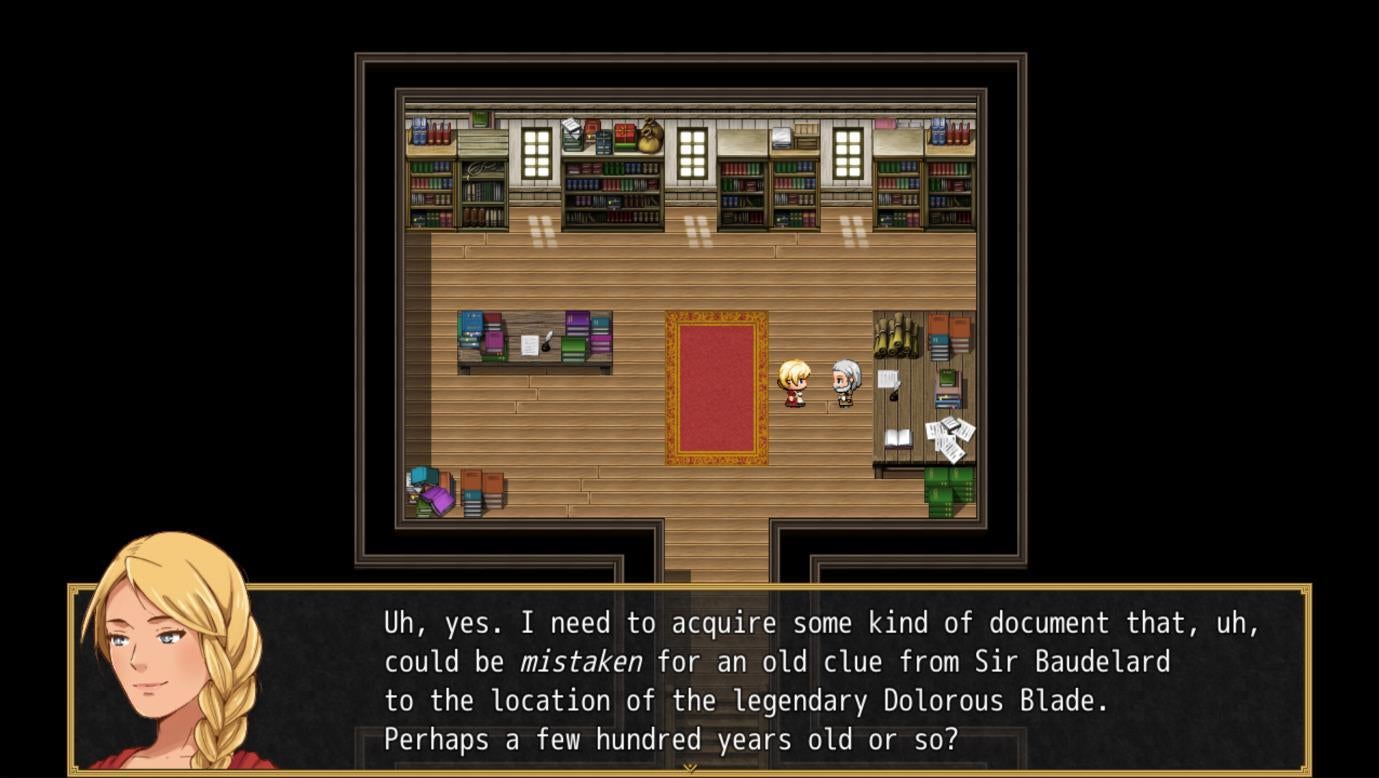

Finally, no discussion of the medieval sense of the past would be complete without including everyone’s favourite topic: The prevalence of forgeries among medieval documents, which are also going to play an important part in the story's plotline. Several puzzles will require the player to evaluate information derived from (potentially) forged manuscripts and yes, the main character also get to engage in a bit of creative forgery for her own subversive purposes as well.

Fig. 12.2: The Knight & the Maiden – Stark Raving Sane Games

In summary, the backstory works on three levels: 1) A recent past, which both drives the plot and is contextualised by it; 2) a fragmentary deep past, which builds the game’s medieval mental and cultural environment; and 3) the forged or manipulated past, which supports the themes of subversiveness. Using these methods, rather than being just “lore”, the game’s internal history becomes a crucial tool for establishing the late medieval character and atmosphere of its setting.

Part Six: Religion II: Revisiting Assassin's Creed

Assassin’s Creed

Quinn Bouabsa Marriott, @Quinn5566, University of LeedsExisting on cultural and religious boundaries, studies of ‘frontier societies’ have served as useful insights for historians, particularly for those looking at the cross cultural contact between Christians and Muslims, a ‘Christian Muslim frontier’. One of the earliest games to portray such societies is Assassin’s Creed. Set during the Third Crusade (1187 92), Assassin’s Creed presents the player with the rich, historical environment of the Holy Land. Exploring the cities of Damascus, Acre and Jerusalem, the player becomes acquainted with the depictions of both Christian and Islamic spaces.

Starting with Damascus, the city is framed as a centre for Islam, filled with mosques and minarets as well as inhabited by an exclusively Muslim population. Additionally, the city is illuminated with bright and clear colours, combining to evoke a nostalgic connection to the era of the Islamic Golden Age. Because the city is not the focus of this crusade and not subjected to any conflict in the game, a wider theme from popular culture can be inferred: that a lack of any European intervention allows Islam to preserve its scientific and prosperous nature.

Evidence of the opposite is apparent in Acre where, following its conquest by crusaders in 1191, the city experiences an immediate ‘de Islamification’. We are shown a clear lack of a Muslim presence, the population completely replaced by European Christians and the mosques and minarets left in ruin. Simultaneously, Acre is also ‘Europeanized’ with churches, mosques turned into churches, and the stereotypical use of gothic for the city’s cathedral of the Holy Cross. Furthermore, the area’s dark blue tones, combined with the scene of a war torn city, brings forth the popular image of a ‘Dark Age’ Europe. This leaves us with a simplistic, segregationist model of the frontier. This is influenced by the game’s use of a ‘clash of civilization’ narrative, where the romanticized conflict between King Richard and Salah ad Din has left Christianity and Islam in direct opposition.

Jerusalem, however, manages to break this simplistic picture of separated Christian and Muslim spaces, as it contains a mix of both. Although the population is entirely Muslim, and the city is under the control of the Ayyubids, we find the presence of both churches and mosques, and even a Jewish synagogue. On top of it's green ish tones a mix of the colours from Damascus and Acre the overall presentation of Jerusalem can lead to the suggestion that the developers intentionally presented the player with an initially black and white model through Damascus and Acre, only to introduce further nuance upon reaching Jerusalem.

Such portrayals of cultural exchange are surprisingly consistent with the scholarship. It was only a few years before the game’s release that historians like Christopher MacEvitt were increasingly questioning the segregationist model in favour of a much more multicultural approach in the relationships between Christians and Muslims.31 In more recent times, although the ‘multicultural model’ appears to be a lot more promising, scholars have also been careful not to fully accept it either,

13: ‘Whose Holy Land?’ The ‘Christian Muslim frontier’ in31 Christopher MacEvitt, The Crusades and the Christian World of the East: Rough Tolerance (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2003), pp.13 4.

concluding that the truth of the matter must lay somewhere between the two models.32 Regardless, the game should be credited for attempting to engage with the contemporary historiography.

Looking back at some of the developer interviews as well, this presentation of nuance can be further hinted at, the producer Jade Raymond stating that “we needed to capture the experience of living during this tumultuous time: the fusion of European and Middle East art and architecture, the hustle and bustle of medieval city life”.33 This point is reinforced in a YouTube video released by Ubisoft, titled ‘Assassin’s Creed: The Real History of the Third Crusade’, which affirmed their historical focus as on the cities themselves.34 This implementation of historical complexity serves as a great gateway into thinking about how the historiography can be implemented and engaged with in games.

This complexity, however, was a potential that was left unexploited, overshadowed by the prior mentioned use of the ‘clash of civilisations’ narrative. Enforcing the Third Crusade as a binary conflict, we find several preachers who lead the cities' people to either support the ongoing crusade or a jihad, Richard or Salah ad Din. By comparison, the cities' designs are superficial, and their significance is left unnoticed by the average player. Conclusively, this attempt to breathe life into the historical environment would have merited from much greater levels of engagement, requiring features that not only connected it to the game’s wider narratives, but incentivised meaningful interaction from the player.

32 Alan V. Murray, ‘Franks and Indigenous Communities in Palestine and Syria (1099 1187): A Hierarchical Model of Social Interaction in the Principalities of Outremer’, in East Meets West in the Middle Ages and Early Modern Times, ed. by Albrecht Classen (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2013), pp.291 310 (pp.296 7).

33 Magy Seif El Nasr, Maha Al Saati, Simon Niedenthal and David Milam, ‘Assassin’s Creed: A Multi Cultural Read’, Reflection and Review, 2 (2008), 1 32 (p.12).

34 Ubisoft North America, ‘Assassin’s Creed: The Real History of the Third Crusade’, YouTube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=er6z afGceQ&ab_channel=UbisoftNorthAmerica

14: Christian

and

Muslim

mentalities during the Third Crusade

in Acre, Damascus and Jerusalem, represented in Assassin's Creed

Ricardo Santana, @RafsRicardo, University of Lisbon IntroductionAssassin's Creed games have always been partially intended to represent a fictionalized version of various religious, political, and multicultural beliefs. The first title in the franchise, 2007's Assassin's Creed, is no different.

In this article, we will briefly analyze the possible perspectives that the Levantine populations had on the Third Crusade through the rhetoric used by some heralds represented in this game, and how their interpretations can mirror or contradict specific historical facts.

Damascus

In every district of the city, generic heralds can be found criticizing the crusade activity of King Richard I of England in the Holy Land and praising the efforts of Saladin and his armies to drive Christian forces away from Jerusalem through the idea of Jihad.

Although the concept of Holy Har was indeed present among the Syrians in this period, as it was instilled by the former emir Nur ad Din, the Damascenes did not really like Saladin's war efforts: he was often criticized by his people after the occupation of this city in 1174, accusing him of being a mere usurper of his predecessor. The Syrians also likely did not appreciate the sultan's military incursions, mostly due to being known as a weak general. (Graino 2022, 76 84).

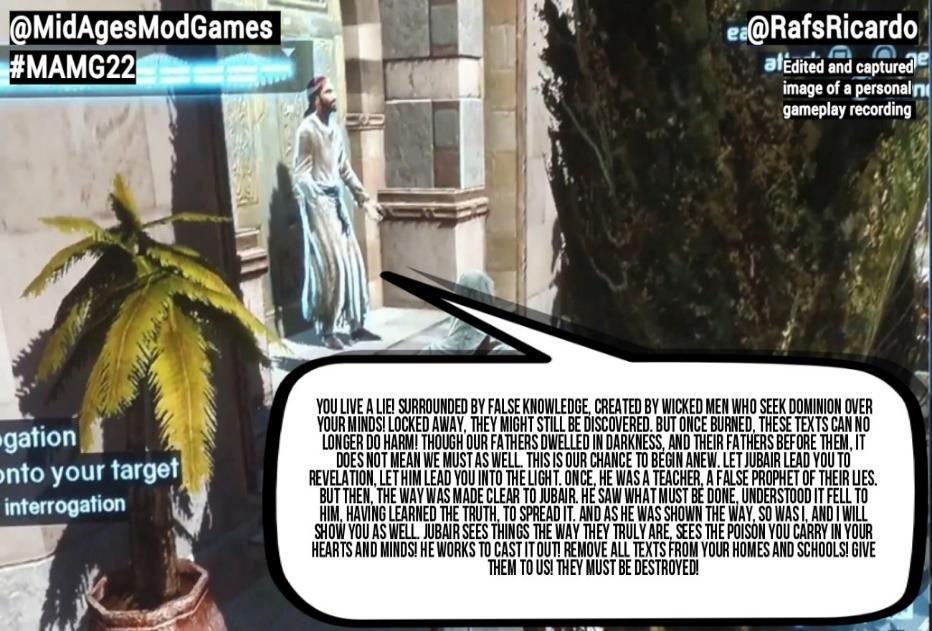

In the Middle District, during Memory Block 5, we see a herald spreading the ideology of Jubair al Hakim, the fictitious chief scholar of Damascus, who argued that the sharing of written knowledge in Levantine territory was the main cause of the ongoing war between Christians and Saracens. Because of this, he advocated that all local scriptures should be destroyed (see Figure 14.1).

This hatred towards local writings can be interpreted as a method of Eastern extremism (Komel 2014, 72 90). It may also be linked to a theory that Saladin ordered the burning of Fatimid scriptures, something that has not been historically confirmed.

Acre

During Altaïr's history, Acre is portrayed several times as a place in constant conflict (Dewi S 2018, 277). However, as the city's general preachers show, there may be a mentality of brief religious hope among the Christian population with the conquest of Acre by Richard I's army in 1191 (Corral 2022, 66 71).