SINGAPORE COMPARATIVE LAW REVIEW 2023

The United Kingdom Singapore Law Students’ Society (UKSLSS)

Law Journal

The United Kingdom Singapore Law Students’ Society (UKSLSS)

Law Journal

Over the years, I have been writing a foreword to this review annually to give my personal reflections on the articles published by Singapore students studying law in UK law schools. It was more than a privilege to have been asked to do so, as I regard it as a learning experience for me in many ways. Governments need to change the law by legislation to keep up with social and, currently, technological advancements that impact the lives of the people. Even the common law of England has to receive a cleaning over from time to time because existing precedents no longer represent current social or moral norms. This is where this law review has a useful role in disseminating the latest UK legislation or changes in common law to law students and lawyers in Singapore. The articles in this issue continue to serve this purpose. In no particular order, I offer my comments on the 11 articles published in this year’s review.

(1) In Between Two Fearns: A Comparison of Private Nuisance in Singapore and UK, Matthew Lee has written a thoughtful and well-argued piece on why English law on nuisance post Fearn v Board of Trustees of the Tate Gallery [2023] should not be followed since Singapore law on private nuisance as applied in Tesa Tape Asia Pacific Pte Ltd v Wing Seng Logistics Pte Ltd1 is more in tune with the social conditions in Singapore, since more than 80% of the population live in flats and condominiums. Given this reality where people have no choice but to live in close proximity with one another, mutual understanding and tolerance, give and take, and live and let live should be the norms of social behaviour and interaction in such an environment in Singapore.

(2) In Acquiring Air India: Turbulent questions for the Competition and Consumer Commission of Singapore, Tarun Rao thinks that the acquisition of Air India by Tata may pose distinctive questions for the Competition and Consumer Commission of Singapore (CCCS) in its oversight of Singapore’s merger control regime. The CCCS has experience in addressing competition issues in the airline industry, having approved a joint venture between Lufthansa and Singapore Airlines in 2016. However, Rao considers the legal issues to be different and that the CCCS might look to the approach of the UK CMA in approving a similar kind of merger between Asiana and Korean Air by securing appropriate undertakings to ensure that competition will not be substantially reduced. It would appear from Rao’s study that the reduction in competition caused by the Air India takeover by Tata is only in the premium segments of the market. The problem then is whether this is sufficiently important to businessmen travelling between India and Singapore for the CCCS to secure appropriate undertakings from the parties, and what these undertakings may be. Rao does not suggest an answer to the problem.

(3) In A Handshake is a Promise, Joshua Ng and Priyansh discuss the old problem of the need for consideration for a valid contract under Singapore law, centring on the distinction between Foakes v Beer (1884) 9 App Cas 605 (‘Foakes’) and Williams v Roffey Bros & Nicholls (Contractors) Ltd [1991] 1 QB 1 (‘Williams’). The authors discuss the two Singapore judgments in Sunrise Industries India Limited v PT OKI Pulp and Paper Mills [2023] SGHC 3 (‘Sunrise’) and Ma Hongjin v SCP Holdings Pte Ltd [2020] SGCA 106, and argue that Sunrise demonstrates that consideration serves a primarily evidentiary function in Singapore law, serving as a marker that parties have willingly struck a bargain after negotiation. However, this is not perfectly mirrored in English law although consideration also serves an evidentiary function, it is to evidence that parties have agreed to the bargain in a fair manner. The authors do not say that this distinction is determinative of the outcome in any particular case.

(4) In Beyond ChiuTengand TanSengKee: the necessity of substantive legitimate expectation in Singaporean constitutional jurisprudence, Samuel Soh speculates on whether the current Court of Appeal is likely to recognise substantive legitimate expectation (“SLE”) as an independent ground of judicial review, given that the Court had applied it only to the exceptional (actually unique) situation in Tan Seng Kee. Soh does not find it difficult to imagine that the current Court of Appeal “may soon decide in favour of expanding the doctrine” because “Singaporean courts have displayed a remarkably consistent ability to shape and evolve the law for practical reasons.” The article concludes that the gradual expansion of SLE, and substantive judicial review more generally, should be welcomed by the judiciary.

(5) In Divide and Conquer: New Modes of Territorial Acquisition in Public International Law, Ning Teoh discusses the traditional modes of territorial acquisition in international law, being (a) original acquisition via occupation of terra nullius, i.e., abandoned land or land that has never belonged to anyone, and (b) derivative acquisition, whereby a state gains title by defeating a former owner via prescription, accretion, cession, or annexation, in the context of the ICJ’s decision in the Pedra Branca case.

In that case, the ICJ rejected Singapore’s argument that Pedra Branca was terra nullius, and concluded that the Johor Sultanate possessed original title over Pedra Branca which arose “... since it came into existence in 1512 [and] established itself as a sovereign State with a certain territorial domain under its sovereignty in this part of southeast Asia”.

Teoh points out that this categorisation, particularly original acquisition, is adequate to deal with post-colonial states. How did Malaysia acquire original title to Pedra Branca in 1957 when its predecessor state, the Federation of Malaya, was granted independence by Britain? The ICJ answered the question by holding that the British had always recognised the sovereignty of the Johor Sultanate, and that the Johore Sultanate had original title since 1512. The ICJ also held that the Johor Sultanate exercised control over Pedra Branca because the Orang Laut, who recognised the Sultan as their ruler, visited Pedra Branca (which was an uninhabitable rock island). The ICJ accepted these elements as further substantive evidence supporting Malaysia’s claim of ‘original title’.

Teoh criticises the ICJ’s analysis as it “ignores the tension between terra nullius and ‘original title’, thus failing to address the place of the former in contemporary international law.” When addressing ‘original title’ of Pedra Branca, the Court merely repudiated Singapore’s argument by establishing the Johor Sultanate’s authority over the surrounding islands, much like how it dodged the question in the dispute between Indonesia and Malaysia over the Sipadan and Ligitan Islands. …Hence, the relationship between terra nullius and ‘original title’ remains unclear.”

Teoh has made an interesting argument which is also logical. It is also a consequential argument because if Pedra Branca was terra nullius before 1512, so would Middle Rock and South Ledge. Perhaps, if only for academic reasons, the ICJ decision deserves another look.

(6) In Comparing Trade Union Laws & Labour Protections in the UK and Singapore, Khai Xing Chew uses the UK’s government’s new anti-strike bill to make a comparison with the UK’s trade union movement (which traditionally has been confrontational and disruptive) with that of Singapore’s more collaborative trade union movement which is a partner of the well-known tripartite model which has brought industrial peace and economic development to Singapore, and not least, financial benefits and rewards to trade union members. It is therefore not surprising that Chew finds Singapore’s collaborative model desirable, as it is able to promote and protects workers’ rights while also balancing the national objectives such as economic and social stability.

(7) In Doctors do not always know best - The vital triage of mediation as a viable alternative to litigious claims, Nickolaus Ng Cong Hin2 discusses the law on medical negligence in Singapore generally and advocates the economic and social advantages of mediation over litigation in respect of claims for medical negligence. He also refers to the role of the Government in promoting mediation in such claims.

(8) In Unfair Terms and Exemption Clauses in Consumer Contracts: The Need to Regulate Unfair Terms in Singapore? Zachary Lee highlights the differences in the way the Singaporean and UK courts determine when an exemption clause in a consumer contract is “unfair”, referring to specific examples in different types of consumer contracts, and the extent of protection from exemption clauses that is available to consumers. Lee concludes it is desirable for Singapore to adopt certain features of the UK’s legislation for better consumer protection, in particular providing greater clarity on the court’s jurisdiction in nullifying an unfair contract term.

(9) In The race to rescue: Evaluating the rollout of cross-class cramdowns in the UK and Singapore, Timothy Ang compares the insolvency restructuring regimes in the UK and Singapore which are both attractive jurisdictions for companies looking to restructure their debts. He evaluates the extent to which the “cross-class cramdown” (an ugly expression) has made the UK and Singapore’s laws more debtor-friendly. He argues that even though debtor-friendliness (and the parallel rescue culture) disfavours creditors, it is not necessarily undesirable if it is managed and carefully balanced. He favours the UK’s approach in giving courts discretion in deciding to apply a cramdown this allows the regime to test common law tests’ outcomes, and adjust them

with legislation if necessary, whilst maintaining the flexibility that the stakeholders of a company in distress need.

(10) In Digital Market Regulation: Lagging Behind? Liew Li Ren points out that while the CCCS has updated its guidelines in 2022 to keep pace with the concerns about the “unprecedented concentration of power amongst a small number of digital firms”, it may fall behind UK’s proposed Digital Markets, Competition and Consumers Bill (DMCC), which if passed, would implement drastic reforms to UK competition law. Liew provides an overview of the provisions in the Bill, and concludes that whilst foreseeability is an element in evaluating present or future market position, the DMA is backwards-looking (e.g., it examines whether the relevant thresholds of active business users were met in each of the last three financial years) while the DMCC is forwards-looking (e.g., the CMA is required to carry out a ‘forward-looking assessment of a period of at least 5 years’). Necessarily, this exercise requires a degree of speculation, including a counterfactual assessment on ‘expected or foreseeable’ developments due to the absent designation of SMS and other developments that ‘may’ affect the undertaking’s conduct in carrying out the digital activity. Liew argues that Singapore should have a new law specific to digital market regulation that allows the CCCS to have a broad ambit to intervene in the fast-evolving digital space while retaining the ‘old’ rules of competition law for other industries. Control measures like the countervailing benefits exception in the DMCC or the judicious employment of public and expert consultation before action would temper agency appetite and assuage industry concerns.

(11) Finally, in AI Regulation for the AI revolution, Dorian Chang endeavours to answer whether current AI law as a legal framework is adequate, and has the necessary tools to effectively deal with the most pertinent legal issues that Artificial Intelligence ("AI") development brings, including: human rights infringements of AI bias and (lack of) AI fairness, (intellectual) property right infringements of AI-generated content, inter alia. These two broad legal issues would be contextualised within recent developments in AI, including the advancements within the field of generative AI.

It is a full analysis of the current issues and problems that is worth detailed study. He refers to the four regulatory apparatus available which provide synergies when applied in parallel, and can be divided into the two main objectives of AI regulation - bulwark and empowering regulation, each serving different objectives (protecting rights and preventing stifling of innovation respectively) within AI regulation. As to the form AI regulation should take, the problem is whether AI regulation should be in the form of blanket AI-specific regulation (like the proposed AI Act) or decentralised sector-specific regulation (like the US’s incumbent approach). He prefers a middle ground. A baseline blanket regulation covering only the most fundamental issues, coupled with sector-specific mandatory or voluntary guidelines, could be the ideal fix.

To conclude, this issue shows a slight shift in focus. There are more articles on regulatory issues than private or public law issues. That is good, as it shows that our law students are becoming more aware that more legislation is needed to meet the problems of a globalised world (in spite of the perceived need to “decouple” certain parts of it in the interest of national security). The

editorial board should be commended for bringing together the contributors to produce another useful product.

Chan Sek Keong Patron15 August 2023

2022-2023

Ning Teoh

Rachel Lim

Ong Zi Kee

Singapore Comparative Law Review

Editorial Committee

Editor-in-Chief

Luke Zhang

Managing Editors

Titus Soh

Evan Chou

Associate Editors

Samuel Soh

Yinno Teh

Rachel Tan Chia Shang En

Suriani Zaini Abdullah Charmaine Annabelle

Liew Li Ren

This year we celebrate the 25th anniversary of the United Kingdom Singapore Law Students’ Society (“UKSLSS”) and the publication of the 18th Edition of the Singapore Comparative Law Review (“SCLR”). I would like to begin by extending my appreciation to our Editor-in-Chief, Luke Zhang, and the larger Editorial Team behind this year’s Edition for another successful publication, to which I am pleased to write an address for.

Over the course of the last two and a half decades, the UKSLSS has moved from strength to strength. Established under the auspices of the Government of Singapore in 1998, the UKSLSS has been for many years a fully-fledged and thriving Law Society for all Singaporeans reading Law in the United Kingdom. Over the years, a whole generation of law students have been a part of the UKSLSS family, the first of whom are now senior members within the legal profession and beyond.

Our mission has remained the same through all these years - keeping our members close to home, through the organisation of both social and professional events. This year has been a particularly successful one for the UKSLSS. As we fully transitioned away from the pandemic and its associated restrictions on live events, the Academic Year 2022-23 saw a record number of activities held by the Society. Recruitment teas were held throughout the year with our sponsor firms; with lawyers from Allen & Gledhill, Rajah and Tann, WongPartnership, Drew & Napier, and Baker McKenzie Wong & Leow flying up to the United Kingdom to meet with students. The presence of firm events in the UK emphasises the deep relationship we have with our partner firms, and underscores the continued investment these firms actively make in the futures of our members.

With students back home in Singapore, firm events continued, with Rajah and Tann, Shook Lin and Bok, and TSMP holding firm events in consecutive weeks. Our portfolio of partners continues to grow, with successful collaborations with many more local and international firms beyond those mentioned, and to deepen our ties with institutional stakeholders, such as the Singapore Legal Service, the Singapore Judicial Service, the Singapore Institute of Legal Education, the Law Society, and the Ministry of Law.

Outside firm events, the UKSLSS continues to run activities which have become a mainstay of the Society’s annual calendar. The Vacation Scheme Helpdesk, held annually in November, brings together Singaporeans in practice as solicitors in London to advise our members on their own paths; while the Bar Careers Talk, held annually in December, brings together Singaporean barristers for the same purpose. Perhaps the most ambitious (and a novel addition to this year’s calendar) were the Chinese New Year Lunches, whereby our University Representatives organised and hosted meals across the United Kingdom, in all the cities in which the Scheduled Universities are located. Other mainstays of our calendar include our Annual A&G-UKSLSS Junior Moot, a Freshers Tea for our incoming first-years to meet their seniors before flying up, and of course our flagship event, the Singapore Legal Forum, at which this 18th Edition of the SCLR is scheduled to be published, just to name a few.

Finally, I come to the subject matter of this address, the 18th Edition of the Singapore Comparative Law Review. In the course of the last eighteen years, the Review has gone from strength to strength; drawing on the unique position of Singaporean Law students studying in the United Kingdom to analyse comparative legal issues across the two common law jurisdictions. It is once again the Review’s privilege to have former Chief Justice Chan Sek Keong as its patron, as we mark eleven years under Justice Chan’s valuable patronage and mentorship.

This year marks the second year of my involvement with the SCLR. Last year, I had the privilege of sitting as Editor-in-Chief of the 17th Review, to which I composed a Foreword. In that Foreword, I commented that it was not merely enough for one to be well-acquainted with the substantive law, though that will certainly occupy centre stage in a practitioner's life. Instead, the study of Law as a lifelong discipline, I thought, demanded more from us. It forces us to ask not what the law is, but what the law should be. Legal scholarship plays an important role in the facilitation of these debates, without which the law cannot do without.

Indeed, in a field of study so closely linked to a particular (and competitive) profession, there is a dangerous inclination towards over-focusing on one’s career-based goals. It should not be forgotten that the true value of a legal education lies not in the substantive content of the degree - certainly, practitioners will be quick to tell you that practice is vastly different from education - but rather in the manner in which a legal education trains you to write, to argue, and to think. That is the true value of a legal education, and it is what distinguishes the student of law from his contemporaries.

I shall leave Luke to properly introduce the contents of this year’s Edition, but I heartily commend the Contributors and Editors to this year’s edition of the Review for their contributions to the development and promotion of legal thought and reasoning. On a more personal level, I thank my Executive Committee for all the effort they have put in for another successful year for the UKSLSS.

It is my hope that you should enjoy the contents of this edition of the Review as much as I have, and to never stop questioning and determining for yourselves what the law should be, rather than taking for granted what it already is.

Legal academic writing, and the study of law more broadly, is ultimately a process of growth, of looking into yourself, and of escaping the prison of your own mind. The journey into the Law is long, but I borrow the words of Hugo, a poem from the last lines of Les Misérables. “It happens calmly, on its own / The way night comes, when day is done”.

I look forward to seeing where your paths shall take you, both within and outside the law.

Yoursfaithfully,

EthanJeremiahTeo 23rdPresidentoftheUnitedKingdomSingaporeLawStudents’SocietyI am proud to present the 18th edition of the Singapore Comparative Law Review on behalf of the United Kingdom Singapore Law Students’ Society. Traditionally, the former Chief Justice Chan Sek Keong has served as the patronage of the Review, offering his valuable and thought-provoking insights regarding the articles presented herewith. This year, we are once again honoured and privileged to have Justice Chan’s valuable patronage and tutelage as we enter a new decade of publication under his mentorship. The Review is also immensely grateful for the support of our sponsors. Without their support, this publication would not be possible.

Since its original inception as Lex Loci in 2006, the Review has rebranded itself with a strong focus on comparative law between the two common law jurisdictions. The strength of this publication lies herein, through the unique experiences of Singaporean students studying law in the United Kingdom, who have experience and knowledge of the law within both jurisdictions. These writers are perfectly placed to produce well-thought analysis of comparative legal issues between these two jurisdictions. This underlying philosophy remains to underpin this year’s edition of the Singapore Comparative Law Review. This 18th Edition of the Review contains eleven academic articles written by Singaporean law students studying in various universities in the United Kingdom.

As we emerge from a post-COVID world amidst turbulent global economic outlook and geopolitical tensions, the law remains steadfast in development. As law students, we are familiar with the ubiquitous nature of the study of law and how it permeates each and every field. It is not uncommon to find the recent developments of the law to be exciting; rather, it is the very nature of law for there to be constant developments and evolution. As students of the law, we are proud to be part of this process, to write and catalogue legal developments as we provide our unique insights and perspectives to new questions.

Indeed, Singapore and the United Kingdom both occupy the privileged space of being key players in a globalized world. As Justice Chan poignantly addressed, despite deglobalization trends stemming from the recent ‘decoupling’ rhetoric, legal regulations nevertheless permeate the global world. This edition of the Review focuses on this aspect of the law. As corporations remain an integral part of the global economy, so too will legal regulations be prevalent in keeping companies in check.

Understanding legal concepts on their own is not enough in today’s age. As good lawyers, we must understand the principles underpinning the law, forcing us to understand not only what the law represents in the present, but also what form the law should take in the future. This skill will no doubt facilitate a practitioner’s journey throughout their legal career. Academic debates thus stand hand-in-hand with legal practice. To the busy readers who do not have the time to keep up to date with such developments, it is my aspiration that this Review will aid you in furthering your knowledge

I am extremely proud of my talented editorial team for all their effort in producing this year’s edition of the Singapore Comparative Law Review, without whom this project would surely not be a success. Further, I would also like to especially thank my predecessor and the current President of the UKSLSS, Ethan Teo, for contributing his rich editorial experience and guiding me along the way. Last but not least, I am eternally grateful to my teammates in the Executive Committee for their support throughout the past year

I invite you, my dear readers, to walk with us on this long road that the law paves - the same road trodden by our predecessors since the conception of civilization. We have come a long way indeed since the days of Gaius and Ulpian, as we aspire to carry on their legacy. As we embark on this never-ending journey together, I invite you to think and ponder the legal issues contained within this Review

As malleable as the law is, it is only useful if jurists like ourselves constantly engage with its rich content. If this Review has served as a fine accompaniment in your journey in the law, I take pride in knowing that we have succeeded in our purpose.

Yours sincerely,

Zhang Qiwei, Luke Editor-In-Chief of the 18th Singapore Comparative Law Review

This article seeks to critically compare the law concerning the tort of private nuisance in Singapore and in the UK, especially in light of the recent development in Fearn v Board of Trustees of the Tate Gallery [2023] (henceforth referred to as “Fearn”).

The article will first set out the law in Singapore as regards private nuisance, the UK’s approach to private nuisance, how Fearn changed the law in the UK and finally the normative value of the UK’s position post-Fearn and what, if anything, one jurisdiction could adopt from another.

To satisfy the requirements of private nuisance, the claimant must prove these four elements on the balance of probabilities:

(a) the conditions of and/or activities of the defendant on the land interfere with the claimants use and enjoyment of the neighbouring land;

(b) the defendant's interference was unreasonable;

(c) the claimant has possessory rights over the neighbouring land; and

(d) the damage is proved.

For the sake of comparison, only grounds (a) and (b) are of relevance. For the most part, grounds (c) and (d) are well-settled areas of law and consistent between the UK and Singapore. Rather, grounds (a) and (b) are where Fearn has changed the law of private nuisance in the UK and so will be the main area of discussion in this article.

For the claimant seeking to prove a prima facie case of private nuisance against the defendant, the starting point would be proving an interference with his land by the use of the defendant’s land. To prove an interference, the claimant must show that the use of the defendant’s land had

interfered with the use and enjoyment of the claimant’s land. Interferences can be broken down into two groups based on their resulting consequences.

The first form of interference is the causation of physical damage to the claimant’s land by a particular activity or the creation of dangerous state of affairs on the defendant’s land. Damages are immediately actionable upon the materialisation of physical damage to the claimant’s land.1 The second form of interference affect the claimant’s enjoyment of his land. This could take the form of excessive noise,2 noxious smells3, or infringement of the claimant’s right to light.4 In the absence of physical damage, if the impact on the claimant’s enjoyment of land is merely temporary or for a short duration, the courts will be unlikely to find an interference with the claimant’s land.

For liability to established, not only must there have been an interference with the claimant’s land by the defendant, that interference must have been objectively unreasonable. After all, the claimant’s use and enjoyment of land must be balanced against the right of the defendant to lawfully enjoy and conduct activities on his own land. To determine whether the interference was unreasonable, five main factors are considered by the Singaporean courts.

If the defendant had conducted an unsafe activity on his land which resulted in physical damage to the claimant’s land, that will be grounds for holding the defendant’s interference as unreasonable. In Tesa Tape Asia Pacific Pte Ltd v Wing Seng Logistics Pte Ltd, 5 the defendant had stacked several rows of containers up to seven tiers high near the perimeter fence separating the claimant’s premises. A gust of wind blew over the containers, causing them to fall onto the claimant's land and damage the claimant's property. In that case, the stacking of so many containers so close to the claimant’s property on the defendant’s premises was considered inherently unsafe and therefore amounted to an unreasonable interference with the claimant’s land once physical damage to the claimant’s land materialised.

1 Hygeian Medical Supplies Ple Ltd v T1i-Star Rotary Screen Engraving Works Pte Ltd (1993) 2 SLR(R) 411.

2 Halsey v Esso Petroleum Co Ltd (1961] 1 WLR 683

3 Ibid.

4 Colls v Home & Colonial Stores Ltd [1904) AC 179

5 Tesa Tape Asia Pacific Pte Ltd v Wing Seng Logistics Pte Ltd. (2006) 3 SLR{R) 116

When the defendant’s use of land was potentially beneficial to the public, the courts would weigh the social costs of the defendant’s activity against the benefits conferred to the wider public.6 While a publicly beneficial use of land by the defendant does not automatically outweigh the private interests of the claimant, the claimant should not have to bear interference with his interests beyond what one can reasonably expect individuals to bear without compensation.

Notably, this is not the position in English law. Public costs and benefits are only considered when considering the remedy to the nuisance.7 Where the activities of the defendant that constitute nuisance may confer public benefit, such as the strengthening of national defence through fighter pilot training in Dennis v Ministry of Defence, the English courts will not consider public benefit when ascertaining whether the activity constituted unreasonable interference. That issue is relevant only to the grant of remedy, such as damages in place of an injunction.

Where the defendant’s interference with the claimant’s property results in material physical damage, locality tends to be less relevant to assessing the reasonableness of the interference. Where it is relevant is if the interference affects the claimant’s enjoyment of his land. Under those circumstances, locality becomes relevant as the hypothetical claimant who suffers only “sensible discomforts”8 as a result of the trade or general business that occurs in that place should not be able to complain; the public interest requires that business should continue per usual.

Rarely, a defendant may maliciously interfere with the enjoyment of the claimant’s property. Activities conducted just for the sake of annoying or otherwise causing some sort of deliberate reduction in amenity to the claimant’s land is an illegitimate use of land and so constitute an unreasonable interference with the claimant’s use of his land.9

6 Antrim Truell Centre Ltd v Her Majesty The Queen in Right of the Province of Ontario [2013] l SCR 594

7 Dennis v Ministry of Defence [2003] EWHC 793 (QB)

8 St Helen's Smelting Co v Tipping (1865) 11 HLC 642; 11 ER 1483

9 Hollywood Silver Fox Farm Ltd v Emmett [1936] 2 KB 468

For the defendant whose activities conducted on his land potentially interfere with the use or enjoyment of his neighbour’s land, a duty is owed to his neighbours to take proper precautions and to ensure that the nuisance is reduced to a minimum. This includes measures such as restrictions on hours of operations and putting up of noise barriers where practical to do so. If, however, the defendant’s land is exceptionally susceptible to damage, his claim is likely to fail. In other words, if the damage caused to the claimant’s land was due to the hypersensitivity of the claimant’s activities or land to the defendant’s actions, the interference is unlikely to be unreasonable. Only if an ordinary claimant would have also suffered damage to his land as a result of the defendant’s activities can the interference by the defendant be said to be unreasonable.

To summarise, the Singaporean claimant must first prove to the court that the defendant’s activities had interfered with the use and enjoyment of his land. Following which, the court will, with reference to the five factors, decide whether the interference was unreasonable and impose liability accordingly.

To understand the change brought about by Fearn, we must first see what the law was pre-Fearn Before Fearn, interference that did not result in physical damage to the claimant’s land could only be determined with reference to the violation of some protected interest or right held by the claimant. In other words, there was no “test” for what actions could constitute nuisance. Rather, nuisance would only be established if there was interference with a claimant’s protected interest by the defendant. These interests included an interest in not being exposed to bad smells, 10 unreasonable vibrations11 or noxious fumes and smoke.12 Essentially, any examination of whether the actions of a defendant constituted nuisance had to be made with reference to a closed list of recognised, protected interests held by the claimant. Courts would very rarely have “opened” the list to recognise a new category of protected interest.

10 Adams v Ursell [1913] 1 Ch 269.

11 Hoare v McAlpine[1923] 1 Ch. 167

12 St Helen’s Smelting v Tipping (1865) 11 HLC 642; 11 ER 1483

In fact, there had been a history of courts being unwilling to recognise new protected interests. In AG v Doughty, 13 the courts refused to recognise that the claimants held a protected interest in the form of a right to a view while Bradford v Pickles saw the courts refuse to extend the right to ordinary above ground water flow to percolating, underground water flow beneath the claimant’s land. Indeed, in Fearn itself, the lower courts had refused to recognise that the claimants held a legally protected interest in not being exposed to constant, oppressive visual intrusion from the thousands of visitors that visited Tate Gallery’s viewing platform. Safe to say, the courts had always been reluctant to extend existing protected interests to cover new situations, much less create new ones where a novel situation may have demanded it.

Only having established the aforementioned invasion of the claimant’s interest can the court begin to assess whether such interference with the claimant’s enjoyment of land was unreasonable. The old “reasonable user” test asks what the normal person would find reasonable to have to put up with and whether the defendant’s actions go beyond that line. Similar factors such as locality,14 nature of the defendants conduct as regards malice15 and the hypersensitivity of the claimant’s land to damage 16 are all taken into consideration, the key difference being that public interest is straightforwardly not considered when determining whether the interference was unreasonable but rather the type of remedy granted to the claimant. The difference between how Singapore and UK define unreasonable interference are rather small and, in any case, not the main topic of discussion in this article. In the interest of brevity, I shall not expound further on this area.

The recent case of Fearn has opened the once closed list and judges no longer need reference to violation of some legally recognised right or interest held by the claimant in order to find interference. Rather, the court will now ask itself this question: Has the defendant’s use of land caused a substantial interference with the ordinary use of the claimant’s land?17 Fearn introduces a new two-step test for the courts to determine whether the defendant’s actions are sufficiently serious to constitute private nuisance.

13 [1752] 28 ER 290

14 Sturges v Bridgman (1879) LR 11 Ch defendant 852

15 Hollywood Silver Fox Farm v Emmett [1936] 2 KB 468

16 Robinson v Kilvert (1889) LR 41 ChD 88

17 Ibid at [21]

1) Has the defendant’s use of land has caused a substantial interference with common and ordinary use of land by the claimant?

2) Is the defendant’s use of land common and ordinary?

1. Substantial interference

Fearn at [22]-[23] has drastically lowered the bar for what can be considered interference. According to Fearn, substantial interference is any interference exceeding a minimum level of seriousness and to be assessed objectively by the standards of an ordinary or average person in the claimant’s position. The court no longer has to examine the actions of the defendant with reference to a violation of some legally protected interest of the claimant. Instead, any action can constitute interference so long as the reasonable person in the claimant’s position would agree. Not only has the bar as to what constitutes interference been lowered, the once closed list of interferences, only ascertainable with reference to a specific list of legally protected interests that first had to be violated, has now been opened to allow for any action to constitute interference.

The reason for this change was explained by the majority earlier in the judgement.18 According to the majority, the previous method of establishing interference with reference to a closed list of protected interests was unhelpful as “there is no conceptual or a priori limit to what can constitute a nuisance”. In fact, the majority felt that “anything short of direct trespass on the claimant's land which materially interferes with the claimant's enjoyment of rights in land is capable of being a nuisance.”

Normatively, such an approach is far more prudent for the court to adopt as it creates greater flexibility and adaptability when deciding novel cases. The common law may very well have never envisaged the possibility of certain types of interferences being physically possible to begin with, making the approach of equating interference with a violation of some legally protected interest underinclusive and incapable of dealing with new situations that arise as technology and society progress. The majority quite rightly point out that the focus of the law on public nuisance is compensating “interference with the utility or amenity value of the claimant's land” due to “something emanating from land occupied by or under the control of the defendant”. Hence, the reformulation of the test for interference is normatively desirable and accords greater flexibility to

the courts to deal with novel situations and recognise new forms of interference hitherto unprotected by the common law.

While it should be noted that judges were theoretically always free to recognise new protected interests in the law, the cases previously discussed has shown conclusively that the old framework for determining interference made judges unwilling to “open the list” and accord legal recognition to a new interest that arose. Hence, while the change brought about by Fearn may not appear significant on paper, in practice, its value in granting more flexibility to the courts cannot be understated.

Not only must there be an interference, but the interference must also affect the common and ordinary use of the claimant’s land. The majority in Fearn, citing Fleming v Hislop, 19 opined that nuisance is “what causes material discomfort and annoyance for the ordinary purposes of life to a man's house or to his property". In other words, the common law of private nuisance prioritises general and ordinary use of land over more particular and uncommon uses.

This cuts two ways. Straightforwardly, if the interference of the defendant negatively affects the claimant’s ability to enjoy his land in a common and ordinary manner, the claimant should be compensated accordingly, or the defendant ordered to end his interference. This points to the heart of what each of the legally protected interests decided under the old law were trying to protect: the ordinary and common use of his land by the claimant. Bad smells and noxious fumes are undoubtedly interferences with the common and ordinary use of the claimant’s land by the defendant, and are best expressed as such, as opposed to piecemeal violations of separate protected interests such as an interest against living with bad smells or with the presence of noxious fumes respectively.

However, this also means that interference by the defendant with an extraordinary and uncommon use of his land by the claimant are not protected by the law. This ensures that defendants are not unfairly held responsible for damage that materialises due to an uncommon, extraordinary use of the land by the claimant that makes his land more susceptible to damage by the defendant. Instead, it preserves the Robinson position that only interference which would have resulted in damage to land used in an ordinary manner is protected by the law.

The principle of protecting common and ordinary use of one claimant’s land does not stand alone but instead in conflict with another principle: reciprocity between neighbours and give and take. The defendant also has a right to the common and ordinary use of his own property as well. Equal justice and fairness require recognition of the defendant’s rights to the common and ordinary use of his own land such as freedom to build structures and carry out everyday activities. Cases such as Hunter v Canary Wharf20 and Southwark LBC v Tanner21 protect these activities as common and ordinary use of land. Only if the defendant’s land was used in an uncommon and extraordinary manner would the claimant’s right to common and ordinary use of his land be favoured over defendant.

The newly defined second stage of the test replaces the old “reasonable user” test formulated by Bramwell B and restated by Lord Goff in Cambridge Water v Eastern Counties Leather 22 Fearn at [18][21] explains that while “unreasonableness” has always been used to describe interference that amounts to nuisance, it is not “unreasonableness” itself that leads to a finding of liability. Rather, the common law of nuisance seeks to protect the right to common and ordinary use of land by its owner and stop any interference with it caused by an uncommon and extraordinary use of the adjacent land. In fact, Fearn at [29] points out how Lord Goff’s remarks in Cambridge Water have been misconstrued to say that “unreasonableness” is itself the test for interference amounting to nuisance. In reality, Lord Goff was trying to point out that the true focus of the law of nuisance is protecting “common and ordinary use and occupation of land and houses”.23

While it can be noted that interference with common and ordinary use of land is itself unreasonable, the label of “unreasonableness” is underinclusive as it only looks at the impact of defendant’s activities rather than the way it comes about. The effect of defendant’s activities could very well be unreasonable interference with claimant’s ordinary and common use of land. However, the principle of give and take and reciprocity between neighbours requires that claimant put up with defendant’s activities, respecting defendant's right to common and ordinary use of his own land.

20 [1997] AC 655

21 [2001] 1 A.claimant. 1

22 [1994] 2 AC 264

23 Ibid at [299]

When it comes to interference, the bar in Singapore is admittedly higher than that in the UK. Where the UK takes an expansive approach to interferences to the point where nearly anything could reasonably constitute substantial interference post-Fearn, the subsequent stages of the test limits actionability to ensure that no defendant is unfairly held liable for any interference with the claimant’s property regardless of circumstances. In Singapore, the defendant’s actions only constitute interference where they cause physical damage or reduction in the claimant’s enjoyment of his land.

Ultimately however, I submit that the difference between the two jurisdictions’ definition of interference is rather artificial. In practice, whether an interference is considered substantial by the reasonable person in the UK will likely be analysed with respect to the two categories of interference laid out in Singapore’s law. In other words, only interferences that cause physical damage or reduction in the amenity of the claimant’s land would be considered substantial in the eyes of the reasonable person in the UK to begin with. Hence, the test laid out in both jurisdictions are fairly similar.

More salient would be the different approach each jurisdiction takes to determining the actionability of the interference. The consideration shared by Singapore and the UK’s pre-Fearn law in determining the unreasonableness, and hence actionability, of the interference are the purposes of the defendant, the nature of the activity and nature of the land. Post-Fearn, only nuisance which stems from an uncommon and extraordinary use of defendant’s land which affects the common and ordinary use of claimant’s land will be actionable.

On one level, the difference between the two approaches seems artificial. Would not all interferences with claimant’s common and ordinary use of land by defendant’s extraordinary and uncommon use of his land be ipso facto unreasonable? However, nowhere in the pre-Fearn “reasonable user” test is there any mention of common and ordinary use of land. Rather, it simply asked what objectively a normal person would find reasonable to have to put up with. One argument may be that the reasonable person should have to put up with all forms of ordinary and common use of his neighbour’s land.

However, an ordinary and common use of land can create interference which even a normal person may find unreasonable to put up with. The facts of Southwark LBC v Tanner illustrate this best. In that case, the absence of noise insulation between flats meant that the claimant was constantly exposed to the noises created by the common and ordinary use of the defendant’s flat above. In fact, it was said that “For the most part, they(defendant) are behaving quite normally. But the flats have no sound insulation. The tenants(claimant) can hear not only the neighbours' televisions and their babies crying but their coming and going, their cooking and cleaning, their quarrels and their love-making. The lack of privacy causes tension and distress”.

Clearly, nobody would find it reasonable to put up with interference to the duration and extent described in Southwark. Yet, the majority found such interference not to be unreasonable. This ostensibly supports the position of all ordinary and common use of land being reasonable but would be ultimately misleading. Throughout Southwark, the court focused almost entirely on the use of the land rather than the reasonable user test, making reference to unreasonableness only once but how the defendant used his flat multiple times throughout the judgement. Implicit in Southwark is the notion that hidden behind the fiction of the “reasonable user” is simply the equal protection of defendant and claimant’s right to common and ordinary use of their land.

Other judgements support this claim as well. Bramwell B in Bamford v Turnley24 saw the role of the tort of private nuisance as protecting “common and ordinary use and occupation of land and houses”. He even relied on the ‘rule of give and take, live and let live’, implying that the law had to protect both defendant and claimant’s rights to the common and ordinary use of their land. Later, in Cambridge Water, 25 Lord Goff came up with the “reasonable user” when referring to Bramwell B’s principles, ultimately giving credence to the notion that implicit behind the reasonable user test was always the notion of common and ordinary use of land. This was later used by Lord Leggatt to justify the change brought about by Fearn at [246], holding that Lord Goff’s used the term “reasonable user” as a shorthand for someone who uses his land in an ordinary manner rather than being a new, standalone test to be applied. The reasonable user test had taken on a life of its own ever since its inception in Cambridge Water. While it generally has been applied correctly, it fails to reflect the true purpose of the tort in protecting common and ordinary use of land rather than limiting what the reasonable person can be expected to bear. More broadly, reasonableness as a concept operates at a high level of abstraction and can be understood

differently by different judges leading to inconsistent application in the law. The change in the law brought about by Fearn provides greater clarity to the courts through a simpler test.

The minority in Fearn argue that the new approach distorts the tort of public nuisance and the need to balance the competing interests by placing the burden of avoidance of friction between neighbours on defendants. However, this seems misguided as the new test seeks to protect the defendant’s common and ordinary use of land as well and in fact absolves the defendant of liability where his activities constitute common and ordinary use of his own land. More interestingly, they argue that the emphasis the emphasis on common and ordinary use of land may hinder land development and prevent innovation. However, I submit that the law should protect the common and ordinary use of land over a novel one. Even if the novel use creates great potential public benefit, not only is there no guarantee that this benefit would materialise but development should be undertaken in such a way as to not interfere with the defendant’s ordinary and common use of land. If anything, Hunter v Canary Wharf26 protects the freedom to build and develop land in an innovative manner as a common and ordinary use of land so long as it is conveniently done without undue inconvenience to neighbours. Hence, I submit that the concerns of the minority are likely overblown and adequately accommodated for in the case law and in the new test.

The law of private nuisance in Singapore has by and large followed the law in the UK up till Fearn The question then becomes whether it would be normatively desirable for Singapore to follow the UK’s approach to public nuisance. I submit that normatively, the vastly different societal landscapes between the UK and Singapore makes the unreasonable user test more desirable in Singapore from a policy perspective.

The UK as a whole has had a long history of protection of land ownership and the use of one’s land, best represented by the Sir Edward Coke’s most famous saying that “an Englishman’s home is his castle”. English jurists from the 16th to 18th century have long prioritised the proprietary rights of landowners and the protection of one’s land from unwarranted interference such that even "[t]he poorest man may in his cottage bid defiance to all the forces of the crown. It may be frail - its roof may shake - the wind may blow through it - the storm may enter - the rain may enter - but the King of England cannot enter."

Ultimately, the English conception of land as tiny fiefdoms or castles to which the owner has ultimate control is justified by the UK’s legal history and past struggles with totalitarian monarchs seizing land for the crown’s purposes. Consequently, the emphasis on protection of landowner’s rights against unlawful trespass has bled over into the law of public nuisance, with English law normatively favouring the right of landowners to common and ordinary use of their land, even if at the expense of some interference with their neighbour. In this conception, the odds of an activity within the common and ordinary use of one’s land creating substantial interference is fairly low and so justifies greater protection of common and ordinary use of land as a subset of broader landowner’s rights.

However, the story is different in Singapore. Unlike the UK, land use tends to be in the vertical rather than horizontal dimension and the population density is much higher. Common and ordinary use of land is much more likely to create substantial interference to one’s neighbours if reasonable steps are not taken to minimise their impact. The smaller size and greater population density of Singapore justifies the need for “unreasonableness” as the test for interference constituting nuisance as the closer proximity to one’s neighbours elevates the importance of reciprocity and consideration. Thus, better protection is afforded to the enjoyment of one’s land in a more densely populated nation like Singapore if the standard of nuisance is what a reasonable person can be expected to bear as opposed to whether the interference affects common and ordinary use of land. Interference to the extent of Southwark would be far too much for the reasonable man to bear in Singapore even if one’s neighbours were acting within the common and ordinary use of their land. The standard of “unreasonableness” in private nuisance is arguably fossilised in statute by the Community Disputes Resolution Act 2015. Section 4(1) of the Act stipulates that a person may not by act or omission, directly or indirectly, and whether intentionally, recklessly or negligently, cause unreasonable interference with his neighbour's enjoyment or use of the latter's place of residence. Not only is the standard of unreasonableness explicitly captured by the act, it imposes strict liability on land owners interfering with their neighbour’s enjoyment of land even if the former’s use of land was common and ordinary i.e., it imposes a positive duty on land owners to be considerate and take reasonable steps to not interfere with their neighbour’s enjoyment of land, even if they were using their land in a common and ordinary way. While the English courts would object to such an approach, the architectural and geographical landscape in Singapore warrants greater consideration for one’s neighbours over wholesale protection of landowners’ rights.

Ultimately, it is policy reasons that justify the standard of unreasonableness in Singapore and the evaluation of nuisance with respect to what the reasonable man can be expected to bear rather than ordinary and common use of land alone. Such an approach better suits the needs of Singapore, a far more densely populated country than the UK, where most of the population lives in blocks of flats with many neighbours in close proximity as opposed to cottages on little parcels of land which can operate as tiny fiefdoms with little to no interference with one’s neighbour. Hence, I submit that while it is legally principled and normatively justified for the UK to eschew the “reasonable user” test and shift its focus to ordinary and common use of land in Fearn, societal differences in Singapore make her better suited to the “reasonable user” test to ensure greater consideration between neighbours in a more densely populated society that lives in close proximity with each other within high rise flats.

The acquisition of Air India by Talace Private Limited, a holding company of Tata Sons Private Limited, has posed distinctive questions for the Competition and Consumer Commission of Singapore (CCCS) in its oversight of Singapore’s merger control regime. The merger carries the possibility of creating a significant reduction in competition within the air travel market connecting Singapore with major Indian cities such as Mumbai. The existing framework by which the CCCS requires airlines to make certain undertakings proves inadequate in addressing the implications of this acquisition, with limited precedents for the CCCS to consider in reaching a well-informed decision. The United Kingdom and Singapore share a similar merger control regime and an identical statutory test. Recently, the United Kingdom’s Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) approved a merger between Korean Air and Asiana Airlines which shared some of the characteristics with the acquisition of Air India by Tata Sons.1 The decision reached by the CMA therefore suggests a potential avenue for the CCCS to adopt in addressing the competitive concerns arising from the acquisition of Air India. This article aims to explore the legal context surrounding merger control in Singapore and the United Kingdom, as well as the commercial landscape within which the mergers of Air India-Tata and Asiana-Korean Air occurred. Additionally, it will address the competitive concerns associated with these mergers. Finally, this article will conclude with an examination of undertakings accepted by the CMA and additional concerns that will pose a challenge to the Air India acquisition.

Merger control in Singapore is governed by the Competition Act 2004, which provides the basis for most of the substantive law relating to anti-competitive behaviour by companies in Singapore.2 Prior to the enactment of the Competition Act 2004, there was no statutory basis for merger control or the regulation of anti-competitive behaviour. The introduction of a statutory basis for

1 Julie Masson, “CMA approves Korean Air/Asiana Airlines with slot divestments” (1 March 2023) Global Competition Review < https://globalcompetitionreview.com/article/cma-approves-korean-airasiana-airlines-slotdivestments> accessed 16 July 2023.

2 Competition Act 2004 (Singapore).

regulating merger control and anti-competitive behaviour was motivated both by economic policy reasons, and by Singapore’s obligations under international treaties.3

By contrast, English law governs anti-competitive practices and merger control through the Competition Act 19984 and the Enterprise Act 2002,5 respectively. The latter focuses specifically on merger control, granting the CMA the authority to investigate mergers and acquisitions that have the potential to threaten healthy competition within markets.

The United Kingdom and Singapore share similarities in their merger control regime, with the Singaporean Competition Act 2004 being after provisions under English law.6 An essential aspect to any merger control regime is the substantive test used to decide if a proposed merger between two companies or entities should proceed or if such a merger should be prohibited or restricted. In determining if a merger between two entities should be allowed, competition authorities worldwide usually rely on either a market dominance test or a substantial lessening of competition test. 7 The former asks if a merger would create or strengthen a dominant position and is predominant across much of the European Union, while the latter has been adopted by competition authorities in Singapore and the United Kingdom. Both the CCCS and the CMA follow the same threshold in determining if a merger should proceed, namely if there is a ‘realistic prospect’ of the merger resulting in the significant reduction in competition.8 9

Air India is India’s flag carrier and one of the largest airlines in the domestic and international air travel markets in India. A state-owned enterprise of the Indian Government from 1953 until 2022, the airline had in recent years suffered considerable financial losses and a poor reputation among

3 Daren Shiau, 'Chapter 10: Singapore', in Katrina Groshinski and Caitlin Davies, Competition Law in Asia Pacific: A Practical Guide, (Kluwer Law International; Kluwer Law International 2015) 573 - 633.

4 Competition Act 1998 (United Kingdom).

5 Enterprise Act 2002 (United Kingdom).

6 Burton Ong, 'The Origins, Objectives and Structure of Competition Law in Singapore', World Competition Law and Economics Review, (Kluwer Law International; Kluwer Law International 2006, Volume 29 Issue 2) 269 – 284.

7 OECD (2005), "Substantive Criteria Used for the Assessment of Mergers", OECD Journal: Competition Law and Policy, Volume 6/3.

8 Section 54 Competition Act 2004 (Singapore).

9 Section 22 Enterprise Act 2002 (As amended by the Enterprise and Regulatory Reform Act 2013) (United Kingdom).

consumers.10 Following several failed attempts at privatisation, the airline was sold in 2022 to Talace Private Limited, a holding company owned by Tata Sons. 11 Subsequently, the CCCS announced the commencement of a Phase 1 review of the acquisition, noting that the merger had the potential to result in a substantial reduction in competition. The CCCS also announced a further in-depth Phase 2 review of the acquisition.12

Tata Sons is one of India’s largest conglomerates, operating businesses across several industrial sectors, including Vistara, a joint venture with Singapore Airlines. In May 2023, Vistara was the third largest airline in India’s domestic air travel market with 9.0% market share, holding a similar share of the market to Air India with its 9.4% share of the domestic air travel market.13 Both airlines are considerably behind low-cost heavyweight IndiGo which held 57.5% of the market share.14 The highly consolidated nature of the passenger air travel market in India means that mergers between airlines could result in them obtaining significant market power. Given the high barriers to entry in the industry, it would be difficult for a new entrant to enter the market, potentially resulting in diminished competition at the consumer’s expense.

In India’s international air travel market, the combined market share of the top five airlines with the largest international operations is approximately 55%, indicating a more diverse landscape compared to the domestic market.15 Behind the seemingly diverse international air travel market in India, there exists fragmentation, allowing airlines to exert notable market power on specific routes, such as those connecting Singapore and various Indian cities. At the time of the announcement of a Phase 2 inquiry by the CCCS, some competing airlines such as IndiGo were

10 Astha Oriel, “Tata Group Reclaims Air India After 68 Years” Outlook India (27 January 2022) < https://www.outlookindia.com/business/tata-group-reclaims-air-india-after-68-years-news-47918> accessed 17 July 2023.

11 Ibid.

12 “CCCS Raises Competition Concerns on the Acquisition by Talace Private Limited of Air India Limited” Competitor & Consumer Commission Singapore (3 June 2022) < https://www.cccs.gov.sg/media-andconsultation/newsroom/media-releases/talace-air-india-merger-competition-concerns-3jun2022> accessed 17 July 2023.

13 Directorate General of Civil Aviation (India), “Market share of airlines across India in financial year 2022, by passengers carried” in Handbook on Civil Aviation Statistics 2021-22 (DCGA, 2022).

14 Rajesh Naidu, “InterGlobe on recovery path as market share improves” The Economic Times (1 June 2023) < https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/markets/stocks/news/interglobe-aviation-on-a-path-to-recovery-amidimproving-market-share/articleshow/100625653.cms?from=mdr> accessed 17 July 2023.

15 Directorate General of Civil Aviation, “Market share of major airlines in India in financial year 2022, based on international traffic” in Handbook on Civil Aviation Statistics 2021-22 (DCGA, 2022).

already operating other flights between Singapore to other Indian cities including Chennai and Kochi.

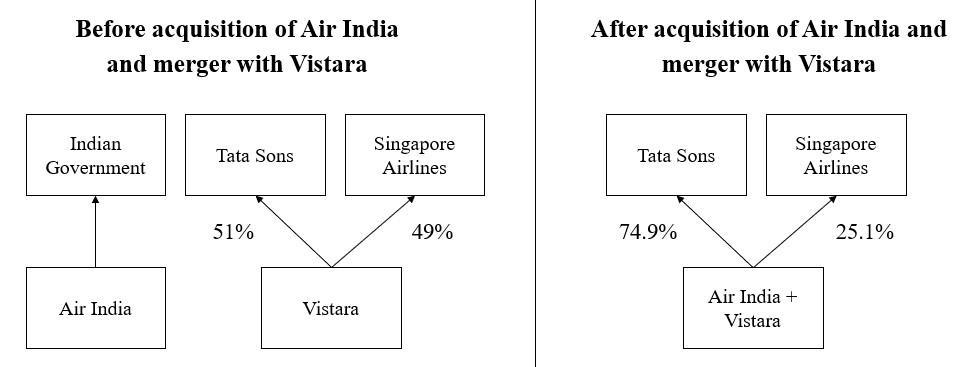

Nevertheless, given the complexity of the Singapore-Indian air market, this article will focus its analysis on one of the most important routes between Singapore and India the SingaporeMumbai route which connects Singapore to India’s financial capital. Until April 2023, Singapore Airlines, Vistara, and Air India were the only operators of direct flights on this route. Vistara, being a joint venture between Tata Sons and Singapore Airlines to capitalise on the latter’s public image, would naturally be disinclined to offer stiff competition to its joint venture parent Singapore Airlines. More significantly, following the announcement by the CCCS of a Phase 2 merger review, Tata Sons has since announced its intention to merge Vistara and Air India. Singapore Airlines has approved this merger of Vistara and Air India, intending to take a 25.1% share of the new entity.16

The CCCS’s press statement notes the need for the CCCS to determine whether Singapore Airlines would be able to compete against Air India on routes between Singapore and major Indian cities.17

The 25.1% share that Singapore Airlines can expect to hold in Air India would be a strong disincentive against competition.

16 Saurabh Sinha, “Tatas & Singapore Airlines agree to merge Vistara into Air India by March 2024; 25.1% stake for SIA in 'new Al'” The Times of India (Mumbai, 29 November 2022)

< https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/business/india-business/tatas-singapore-airlines-agree-to-merge-vistarainto-air-india-by-march-2024-25-1-stake-for-sia-in-new-ai/articleshow/95855970.cms> accessed 10 May 2023

17 CCCS, “CCCS Raises Competition Concerns on the Acquisition by Talace Private Limited of Air India Limited” (3 June 2022) < https://www.cccs.gov.sg/media-and-consultation/newsroom/media-releases/talace-air-indiamerger-competition-concerns-3jun2022> accessed 5 May 2023.

In addition to the high cost of entrance, further barriers to entry for new competitors seeking to enter the Mumbai-Singapore route due to limitations on available slots. Airports worldwide commonly employ the practice of allocating ‘slots’ to effectively manage capacity and ensure optimal utilisation of airport infrastructure by airline companies. Typically, airlines are limited to operating flights out of airports only where they hold allocated slots. These slots can effectively be a barrier to new competitors, preventing other airlines from running passenger flights to an airport even if they have the available staff, capital, and other necessary resources.18 Mumbai airport, due to its insufficient capacity and the presence of only one runway, has suffered a perennial shortage of available slots, restricting the ability of competitors to enter the Singapore-Mumbai passenger air travel market.

The acquisition of Air India by Tata Sons, occurring in the backdrop of an existing joint venture with Singapore’s flag carrier Singapore Airlines, poses a challenge to competition in the SingaporeIndia air market. The objectives of merger control aim to foster commercial activity while ensuring competitive markets, which may be jeopardised by the proposed acquisition of Air India by Tata Sons. At the same time, the consolidation of different airlines, each of which was suffering from profitability issues, might improve efficiencies and deliver cost savings that could be passed onto consumers. Given regulatory scrutiny, the outcome of a competition enquiry would be determined by the commitments which merging parties could offer to the CCCS and whether such commitments would mitigate the risk of a substantial reduction in competition.

To assuage the concerns of the CCCS, Tata Sons would likely be required to make certain commitments to address the competition concerns raised by the CCCS. These commitments are a common feature in regulators overseeing mergers and alliance agreements between competing airlines.

The CCCS has experience in addressing competition issues in the airline industry and specifically in evaluating the efficacy of commitments made by airlines seeking to assure the CCCS that markets would remain competitive. In addition to the Competition Act 2004, the CCCS also

18 Mihir Mishra, “Flying in and out of Mumbai to get costlier due to scarcity of landing slots” The Economic Times (Mumbai, 31 Mar 2016) https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/industry/transportation/airlines-/-aviation/flyingin-and-out-of-mumbai-to-get-costlier-due-to-scarcity-of-landing-slots/articleshow/51624716.cms?from=mdr accessed 11 May 2023.

relies on its Airline Guidance Note in regulating the market for passenger airline and air-freight services.19

An example of such a scenario where airlines made such commitments to the CCCS to secure its approval was in a joint venture between Lufthansa and Singapore Airlines in 2016.20 The alliance agreement between Lufthansa and Singapore Airlines, the flag carriers of Germany and Singapore respectively, had the potential to cause a substantial reduction in competition on routes connecting Singapore to various German and Swiss cities including Frankfurt, Munich, and Zurich.21 At the same time, both Singapore Airlines and Lufthansa highlighted the positive impacts for their customers, including cost savings, access to more destinations, and improved connectivity from the utilisation of each other’s resources. 22 To address competition concerns, both Singapore Airlines and Lufthansa made various voluntary commitments to the CCCS, which included increasing seat capacity on flights between Singapore and several German cities. 23 The CCCS responded favourably to such commitments, recognising that these commitments would mitigate competition concerns and ensure that the cost savings achieved by the merger were achieved.24

The CCCS’s treatment of the Lufthansa-Singapore Airlines alliance offers some guidelines to the sort of undertakings Tata Sons would have to offer, however it is limited in some key respects. This is because the approach of the CCCS in this case, and the underlying law which governs alliance agreements, is distinct from that governing merger control, with a higher threshold being imposed on mergers which the CCCS reviews. The commitments that were offered by Lufthansa and Singapore Airlines directly mirror the possible commitments identified by the CCCS in its Airline Guidance Note.25 The CCCS in its Airline Guidance note adopts a more relaxed approach

19 CCCS, “CCCS Guidance Note for Airline Alliance Agreements” (5 September 2018) < https://www.cccs.gov.sg/public-register-and-consultation/public-consultation-items/public-consultation-on-ccsdraft-guidance-note-for-airline-alliance-agreements> accessed 6 May 2023.

20 Competition Commission of Singapore (‘CCS’), “CCS Consults on the Proposed Joint Venture between Deutsche Lufthansa AG and Singapore Airlines Limited” (5 April 2016) < https://www.cccs.gov.sg/media-andconsultation/newsroom/media-releases/proposed-jv-between-lufthansa-and-singapore-airlines> accessed 5 May 2023.

21 Ibid.

22 Singapore Airlines, “SIA and Lufthansa Group Forge Extensive Partnership Involving JV On Key Routes” (11 November 2015) < https://www.singaporeair.com/en_UK/br/media-centre/pressrelease/article/?q=en_UK/2015/October-December/11Nov2015-1739> accessed 17 July 2023.

23 CCS, “CCS Accepts Capacity Commitments by SIA and Lufthansa in Clearing their Proposed Joint Venture” (12 December 2016) https://www.cccs.gov.sg/media-and-consultation/newsroom/media-releases/ccs-acceptscapacity-commitments-by-sia-and-lufthansa accessed 5 May 2023.

24 Ibid.

25 CCCS, “CCCS Guidance Note for Airline Alliance Agreements”.

to the regulations of airlines, and this likely has its origins in the differences between Section 34 and 54 of the Competition Act 2004. 26 While Section 34 concerns the creation of agreements which are designed to stymie competition, Section 54 imposes a far higher threshold, permitting the prevention of mergers where there is a ‘realistic prospect’ of a substantial lessening of competition.27 This is likely reflective of the far more permanent nature of mergers in contrast to alliance agreements whose contents are limited to the agreement itself between airlines.

The extent of control and cooperation which would occur following the acquisition of Air India is far greater than that envisaged in the alliance agreement between Lufthansa and Singapore Airlines. The previously discussed merger of Air India and Vistara, alongside the considerable stake held by Singapore Airlines in the merged entity, represent a considerable disincentive for competition. The existing precedent for approaching agreements between airlines therefore does not provide a sufficient framework for the CCCS to approach the acquisition of Air India and its merger with Vistara. Given the lack of existing precedent, it is worth referring to other jurisdictions, notably the United Kingdom, which can provide a framework for the CCCS in approaching this merger.

To examine what the approach of the CCCS can and should be towards the acquisition of Air India as well as possible undertakings which might be acceptable to the CCCS, it is worth examining the approach of the United Kingdom’s CMA towards a similar merger. The CMA had, following the announcement of a merger between Asiana and Korean Air, expressed concerns relating to a substantial reduction in competition in the market for passenger transport between the United Kingdom and the Republic of Korea.28 Nevertheless, following a series of undertakings by Korean Air, the CMA concluded that these promised undertakings would be enough to address concerns relating to the substantial lessening of competition.

The announcement of a merger between Asiana and Korean Air occurred in the backdrop of the COVID-19 pandemic, with both Asiana and Korean Air having come under financial pressure before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. The merger of the two airlines, bitter rivals in the

26 Competition Act 2004 (Singapore).

27 Ibid.

28 CMA, “Anticipated acquisition by Korean Air Lines Co., Ltd of Asiana Airlines Inc.”, ME/6924/21 (14 November 2022).

Korean market, was spearheaded by a Korean state-owned bank which sought to create a single large airline able to compete globally.29 Regulators in Singapore were sanguine on the merger, approving it following a Phase 1 inquiry. This was due to the continued presence of Singapore Airlines in the market for flights between Singapore and Korea which would limit the probability of there being a substantial lessening of competition. Contrastingly, in the United Kingdom, regulators were more concerned about the prospect of a substantial lessening of competition, particularly given that the United Kingdom’s flag carrier, British Airways, has stopped running flights between the United Kingdom and Korea.30 Following the merger, the merged entity would have a monopoly on the market for direct flights between London’s Heathrow Airport and the Incheon International Airport near Seoul.

These fact patterns, although different from the Singapore-Mumbai air travel market in some key regards, are sufficiently similar. It would therefore be useful for regulators in examining how the CMA, under the United Kingdom’s competition law, approached the prospect of a substantial lessening of competition.

In response to the CMA’s concerns, Korean Air and Asiana made several undertakings to ensure regulatory approval for the merger. Following a Phase 2 inquiry, the CMA was able to conclude that these undertakings would ensure that even following the merger, there would not be a substantial lessening of competition. These undertakings were primarily concerned with Korean Air and Asiana, facilitating the entry of a new competitor into flights between Heathrow Airport and Incheon International Airport.31 In the context of the agreement between Korean Air and the CMA, this new competitor was to be Virgin Atlantic, a competing airline whose flights were primarily to destinations in the United States, the Caribbean, the Middle East, and South Asia. Operating a flight between London and Seoul would mark a significant milestone for the firm’s operations in East Asia, where the airline has only one other route between London and Shanghai.

Facilitating the entry of a new competitor required several other commitments from Korean Air, including a commitment to make some of their slots available for Virgin Atlantic,32 in addition to

29 Kim Jaewon, “Korean airline merger faces debt burden and antitrust concerns” Nikkei Asian Review (30 November 2020) https://asia.nikkei.com/Business/Business-deals/Korean-airline-merger-faces-debt-burden-andantitrust-concerns accessed 11 May 2023.

30 CMA, “Anticipated acquisition by Korean Air Lines Co., Ltd of Asiana Airlines Inc.”.

31 CMA, “Decision on acceptance of undertakings in lieu of reference”, ME/6924-21 (3 March 2023).

32 Ibid.

a codeshare agreement, providing ground handling services, and a frequent flyer cooperation programme, among other requirements. In commercial terms, the agreement entered between Korean Air and the CMA would require Korean Air to provide much of the required facilities and infrastructure, both physical and otherwise, for Virgin Atlantic to use in its flights between London and Seoul.

The undertakings accepted by the CMA for the merger of Asiana and Korean Air offer a promising solution for allowing the acquisition to proceed. These undertakings would require Tata Sons to, after the merger, facilitate the entry of a new competitor into the market. There are few airlines which would be able to enter the market, with the two likely candidates being IndiGo and SpiceJet, both low-cost carriers which account for the two largest airlines in the Indian passenger market.

33

At the time the CCCS commenced its inquiry, the market for air-travel between Singapore and Mumbai was limited to just Singapore Airlines, Vistara, and Air India. However, in the year since the commencement of the inquiry has seen some indications of this changing. Low-cost carrier IndiGo, the main competitor to Air India in India’s domestic market, announced the commencement of flights to Singapore in March 2023,34 therefore being a competitor on the Singapore-Mumbai route following the conclusion of the merger of Air India and Vistara. It would stand to reason that with IndiGo already seeking to enter the Singapore-Mumbai passenger air market, that IndiGo could serve as an additional competitor in the market. While IndiGo’s position in the Singapore-Mumbai route is still nascent, an undertaking by Tata Sons to support IndiGo, including through the provision of slots and other required resources might assuage the competition concerns of the CCCS. Such an undertaking by Tata Sons to provide the necessary slots to a new entrant to the market, which in this context, would be IndiGo, might help assure the CCCS that the merger would not have the effect of a substantial lessening of competition.

34 Len Varley, “IndiGo boosts flight services from Mumbai” (AviationSource News, 20 March 2023) https://aviationsourcenews.com/airline/indigo-boosts-flight-services-from-mumbai/ accessed 20 May 2023.

There are some limitations however, to the extent to which the entry of IndiGo or Spicejet, being low-cost carriers, can prevent there from being a substantial lessening of competition in the market, even if Tata Sons was required to facilitate their entry into the Singapore-Mumbai route.