At Rajah & Tann Asia, we are more than 1,000 strong across leading firms in ten countries, united by a shared commitment to excellence and regional insight.

From headline-making cases to cross-border collaborations, you will gain exposure to the legal challenges shaping Asia today.

We are lawyers who know Asia –are you ready to take the first step with a winning team?

Find out more - Scan the QR code or visit https://www.rajahtannasia.com/joinus

‘Substantive Legitimate Expectation’ Works – An Analysis of the Normative Concerns of the Doctrine in Singapore and Proposing a Deference-Modulated Model of Substantive Legitimate Expectation

Standing at Crossroads: The Growing Convergence of Standing Rules in Singapore and the UK

Wei Pheng Koon

We, The Jury… Analysing the Role of Jury Systems in Relation to Justice and Fairness

Nickolaus Ng

Filling the Gaps in Reproductive Wrongs: Loss of Genetic Affinity and its Potential in UK Law

Anni Huang, Cheryl Soong, Wesley Gordon Harrison and Zun Yin Ngo

Drawing the Line: Fixing Normal Baselines under Article 5 UNCLOS

Delaney Lim

Identifying and Navigating the Constitutional Penumbra of Fundamental Liberties in Singapore

Isaac Tan Kah Hoe and Bonnie Yeo Lu-Anne

Alliancing for Singapore’s Complex Road and Tunnel Projects: A Better Way to Build the North-South Corridor?

Joyee Goh

Dear Readers,

This year, we celebrate the 27th anniversary of the United Kingdom Singapore Law Students’ Society (“UKSLSS”) and the publication of the 20th Edition of the Singapore Comparative Law Review (“SCLR”). I would first like to begin by commending and thanking our Editor-in-Chief, Choon Wee Yeo, and the larger editorial team for their conscientious efforts in ensuring that this year’s edition embraces new perspectives across various jurisdictions, upholds the publication’s comparative uniqueness, and provides students with a valuable platform for academic research. Its success is a cumulation of their collective dedication.

Throughout this year, the UKSLSS has remained resolute in its mission to serve as a pivotal bridge between Singapore and Singaporean law students studying in the United Kingdom. This has been realised through a wide range of career events, strengthened sponsorships, and the diligent efforts of our editorial team.

In the spirit of fostering community, we proudly inaugurated the Legal Careers Helpdesk, which combined our annual Vacation Scheme Helpdesk and Bar Careers Talk into a singular, consolidated event. This initiative not only streamlined support for our members but also provided an opportunity for engagement with numerous alumni who graciously participated. I would like to extend my heartfelt gratitude to our coordinators, Nicole Lim and Andrew Ng, whose unwavering commitment was integral to the success of this event. The UKSLSS is steadfast in its endeavour to cultivate a supportive environment, one that offers a genuine sense of community and reassurance to our members. This was exemplified by the Chinese New Year dinners organised by our university representatives across the UK, reinforcing our shared mission of connecting members to their roots.

In continuation of the work of our predecessors, we have prioritised career-centric initiatives by expanding our sponsorship portfolio. This year, we witnessed a commendable increase in sponsor partnerships and successfully forged strategic collaborations with the Judicial and Legal Services, and the Singapore Institute of Legal Education (SILE). We are privileged to

count among our sponsor firms one Bronze sponsor, eleven Silver sponsors, and two Gold sponsors. The UKSLSS London chapter hosted numerous in-person recruitment events, including the Rajah & Tann Meet & Mingle as well as our inaugural event in partnership with the Judicial and Legal Services across London, Cambridge, and Oxford.

Beyond event organisation, we have sought to enhance student support through collaborations with our sponsor firms on feature articles. These contributions aim to broaden access to pertinent information and afford students valuable insights into Singapore’s legal landscape, thereby reinforcing their connection to developments back home.

Back in Singapore, over the summer months, the Society has continued its operations in tandem with events hosted by our sponsor firms. This year, we were honoured to welcome Freshfields as a new sponsor and Clifford Chance as our newest Gold sponsor, each hosting their respective Open House events. Additionally, the UKSLSS organised its annual Freshers’ Tea, providing a warm welcome to incoming members and equipping them for their forthcoming legal journey abroad. Finally, our flagship event, the Singapore Legal Forum, was executed on 23rd August 2025, featuring the Honourable Justice Kristy Tan as Guest of Honour.

Finally, let me take some moment to reflect on the 20th edition of the Singapore Comparative Law Review. It is once again the Review’s distinct privilege to have former Chief Justice Chan Sek Keong as its patron, as we proudly mark thirteen years under his invaluable patronage and mentorship. I extend my sincere appreciation to him for penning the foreword and for providing insightful reflections on each of the articles featured in this edition.

This year’s edition stands out for its diversity, notably including a law student from an Australian university for the first time a testament to the Review’s uniqueness and creative spirit. We are also pleased to have established a connection with our counterpart society in Australia and collaborated on a blog article. While this direction may be somewhat unorthodox, it embodies our hope to continue forging relationships with other Singaporean societies around the world, thereby nurturing a culture of belonging and fostering closeness among our members. After all, in an increasingly globalised legal environment, cultivating these bonds is essential for both personal growth and collective strength.

I shall leave Choon Wee to provide a detailed introduction to the contents of this year’s edition. However, I wholeheartedly commend the authors and editors for their steadfast dedication to

the development and promotion of legal thought and reasoning. The quality and calibre of the articles have risen considerably, encompassing a broad spectrum of topics with depth and originality. I invite everyone to engage with this edition with an open mind and to appreciate the considerable thought and effort invested by our student contributors.

On a personal note, I would like to express my deepest gratitude to the Executive Committee for their tireless efforts and commitment in ensuring another successful year for the UKSLSS. From the bottom of my heart, I could not have achieved this without each and every one of you. It has been a privilege to meet and work alongside such dedicated individuals, and I sincerely hope our paths cross again in the future.

It is my hope that you enjoy this year’s edition of the Review and take to heart that the study of law is an ongoing journey of continuous growth, reflection, and learning. The pursuit of legal knowledge is never complete, and it is through persistent inquiry and open-mindedness that we refine our understanding and contribute meaningfully to the legal profession.

The path through law is long and demanding, but I trust that the UKSLSS has provided a source of support and comfort as you begin this journey. I eagerly anticipate witnessing the unique journeys you each undertake, whether within the legal field or beyond, and I hope that you find success and fulfilment in whatever path you choose to follow.

Yours sincerely,

Alyson Lim Shi

25th President of the United Kingdom Singapore Law Students’ Society

Dear Readers,

It is with great pleasure that I present to you the 20th Edition of the Singapore Comparative Law Review, the flagship publication of the United Kingdom Singapore Law Students’ Society (“UKSLSS”).

From its humble origins as Lex Loci in 2006, the Review has evolved significantly over the years, adapting to the ever-changing interests of authors and readers. This milestone edition is no exception. For one, it reinforces the progress made by the 19th edition, which featured the debut participation of law students from Singapore universities as authors. This year, I am proud that among the list of authors stands Joyee Goh, a law student from the University of Melbourne. This Review is unique because it offers the amalgamation of different perspectives, bringing depth and flavour to our understanding of the law in the contemporary world. For the first time in the Review’s history, we not only hear from Singaporeans educated in English law or Singaporean law, but also in Australian law. This growing involvement strengthens the Review’s comparative nature, and I hope that we may all appreciate and cherish the unique diversity which this Review holds.

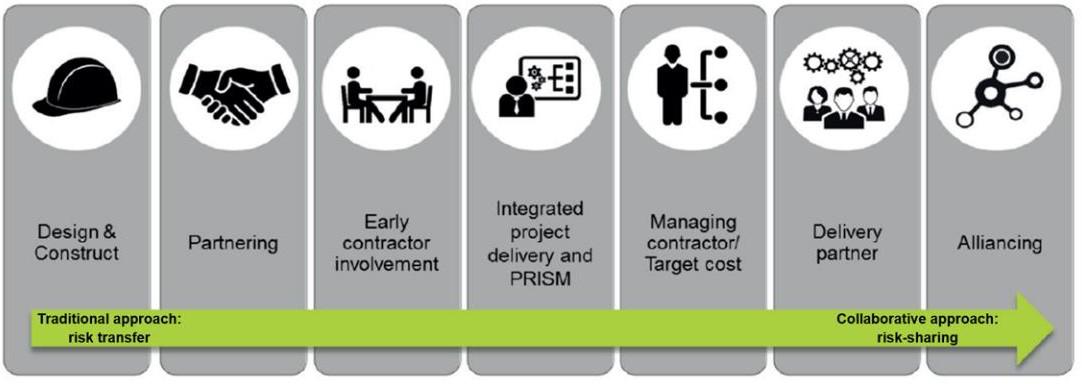

Joyee’s submission is not only a testament to the growing inclusion of perspectives but also the developing acceptance of ideas and interests in this Review. Her submission, titled “Alliancing for Singapore’s Complex Road and Tunnel Projects: A Better Way to Build the North-South Corridor?”, explores alliancing as a method of contracting which has not been used in Singapore. Together with Nickolaus Ng’s submission titled “We, the Jury… Analysing the Role of Jury Systems in Relation to Justice and Fairness”, which advocates for a jury-less system, the 20th edition highlights a review of the law beyond a traditional academic focus and inches towards a more holistic analysis of the broader legal frameworks and methodologies. The importance of doing so is clear - law exists not in a vacuum but in conjunction with commercial and practical realities. Providing a deeper understanding of wider topics enables a lawyer to better understand the implications of the law, especially in this turbulent world. I hope that you may enjoy the insights offered by these articles as I do, and I invite you to celebrate every author’s efforts as we continue to allow ideas to flourish in the Review.

Indeed, a proud feature of this year’s edition is the variety of topics covered. Although seemingly public law-heavy, with four out of ten articles covering constitutional and administrative law issues, the remaining six articles present a great assortment, ranging from comparing Singapore’s Workplace Fairness Act 2025 and the UK Equality Act 2010 to the interpretation of Article 5 of UNCLOS. Despite the overwhelming number of pitches received favouring public law issues (almost 70%), the Review remains true to its steadfast mission of introducing a balanced range of thought-provoking issues to readers, straddling between public and private law topics. I hope that for future editions, more authors may consider exploring private law issues, lending further strength to the robustness of the Review. Nevertheless, the editorial committee stays simultaneously committed to ensuring authors’ interests are reflected, irrespective of the spread of areas of law covered.

It is with a heavy heart that I bid farewell to this journey. A few thanks are in order.

Firstly, I would like to thank former Chief Justice Chan Sek Keong for once again gracing this Review with his foreword. His dedication to the Review has remained unwavering throughout the years, and I am sure every author and reader will benefit from his feedback. Personally, I will treasure his stimulating insights on how the Review should grow, and I am grateful for his authentic expressions.

Secondly, none of this would have been possible without the support of our sponsors. The lives of members of the UKSLSS continue to thrive because of the backing of our sponsors.

Lastly, I am eternally indebted to the hard work and dedication put in by all the authors, editors, managing editors and Executive Committee of the UKSLSS. The editorial committee has worked tirelessly since the start of 2025 to draft, edit and redraft the articles countless times. Their work, like all works, will continue to fall short of the standards of perfection, but I am thankful for their professionalism, grit and humility in seeing through this tall order with me.

I hope that as you read through these pages, you will find something meaningful and memorable. And most importantly, revel in the perpetual journey of learning about the law.

Thank you.

Yours sincerely,

Choon Wee Yeo Editor-In-Chief of the 20th

Singapore

Comparative Law Review

Left to Right: Choon Wee Yeo (Editor-In-Chief), Clarise Chan (Marketing Director), Hui Ling Tay (Finance Director), Alyson Lim Shi (President), Rebecca Kyi Thanthar (Vice-President), Chrisllynn Siah (General Secretary), Natasha Mok (Sponsorships Director)

Jia Hao Koh

Editor-In-Chief

Choon Wee Yeo

Managing Editors

Jun Xiang Wong

Editors

Aiko Yeo

Davon Pung

Lim Yee Rei

Nickolaus Ng

Alysa Lee Mynn

Julius Goh

Min Sittman

Seraphine Lai

Kang Zi Yuan

Amelia Neo

Junwei Huang

Natasha Wong

Sit Jie Ren

It is with great pleasure that I write the Foreword to this year’s issue of the Singapore Comparative Law Review (“SCLR”) 2025. It was in 2013 that I first wrote the Foreword for that year’s issue when it was called Lex Loci The title was interesting for its ambiguity in that the lex loci of the review could be UK or Singapore, or even both.

As every Singaporean law student knows, or should know, the legal system of Singapore was established by the 1826 Charter of Justice under which English statutes of general application existing in 1826 and the common law of England were introduced in Singapore, Malacca and Penang, subject to local circumstances. As Singapore was a ceded, and not a settled territory, the qualification was necessary to ensure that English law (with its different racial, religious cultural, social or political values) would not be applicable if it were to cause injustice to the local inhabitants.1 English law assumes that a ceded territory would already have a lex loci (the law of the place). Singapore island then had a small population of Malays and probably some Arabs or Indians or even Chinese.

From 1826 to the 1950s, the Singapore judiciary was populated wholly by English judges. From 1955 up to 1981 local lawyers, mainly government legal officers, educated in English law by English law teachers in English law schools, were appointed as judges. However, the first local Chief Justice appointed in 1963 was a private practitioner. Until the late 1980s, the Privy Council was still the apex court of Singapore, and therefore the development of common law in Singapore was ultimately still in the hands of English judges. During this period, utmost deference was given by local judges to English case law, especially the judgments of the House of Lords and the Privy Council. Hence, Singapore common law was virtually a carbon copy of English common law.

1 See Lord Denning in Nyali v Attorney General [1956] 1 QB 1.

Change in judicial attitudes came 25 years later in 1981 with the appointment of the first local law graduate (of the NUS law school established in 1956), and a new Chief Justice in 1990 and the progressive restriction of appeals to the Privy Council. From the early 1990s, the younger local judges felt that Singapore should develop a common law with Singapore characteristics to reflect Singapore’s national values, and to depart from English law in appropriate circumstances.

It was in this environment that Parliament, in deciding to cease reliance on English commercial legislation pursuant to section 5 of the Civil Law Act, reset the foundation law of Singapore by enacting the Application of English Law Act 1993 (“AELA”) in two steps. First, it abrogated all English statutes of general application existing as at 1826, and re-enacted as part of Singapore those statutes that were deemed essential as Singapore’s foundation laws. Second, the AELA provided that the common law of England so far as it was part of the law of Singapore immediately before 12 November 1993, continues to be part of the law of Singapore The premise of this provision is that the common law of England, once received in Singapore under a court decision, becomes the common law of Singapore (just as the common law received in such manner in Malaysia or any other common law jurisdiction, becomes the common law of that jurisdiction). These separate streams of the common law continue to share the legal, ethical or moral values of the mother common law, but which may be developed to accord with the cultural, religious, social, economic and political values of the receiving jurisdiction

In this context, the SCLR has, since 2006, provided a valuable platform for our UK law students to write on developments in the written and common law of England and Singapore law. According to the editors of the 2013 issue, “the purpose of Lex Loci is to reflect the interest the community [of Singaporean law students in the United Kingdom] has for Singaporean jurisprudence and development in Singapore’s legal scene, and to make its own contribution to academic discussion in areas members are passionate about”.

The current issue of the SCLR contains 10 articles, four of which are focused on constitutional and administrative law, in the areas of (a) locus standi, (b) substantive legitimate expectations, (c) proportionality in constitutional law, and (d) judicial review. Notably, these essays are from students reading law in Cambridge and Oxford.

There is one essay each on (1) the justice and fairness of the jury system; (2) Article 5 of UNCLOS; (3) loss of genetic affinity; (4) mental disorder and voyeuristic offences; (5) the Singapore Workplace Fairness Act 2025 compared with the UK Equality Act 2010; and (6) “alliancing” in the construction industry.

My comments on these articles are as follows:

– AN ANALYSIS OF THE NORMATIVE CONCERNS OF THE DOCTRINE IN SINGAPORE AND PROPOSING A DEFERENCE-MODULATED MODEL OF SUBSTANTIVE

Author: Kai Zhen Tek (University of Cambridge) (Chan Sek Keong Award for Best Article)

Procedural legitimate expectation in judicial review of executive decisions has been recognised by the courts in Singapore for a long time. In Chiu Teng @ Kallang Pte Ltd v Singapore Land Authority (“Chiu Teng”), the High Court recognised substantive legitimate expectations (“LSE”) as an independent ground of judicial review of administrative action, in the interest of good governance. In SGB Starkstrom Pte Ltd v Commissioner of Labour [2016] SGCA 27 (“Starkstrom”), the Court of Appeal reviewed Chiu Teng and expressed its deep concerns about the applicability of LSE in Singapore as it would involve reviewing the merits of executive action, of which the courts might lack institutional capacity, and doing so might blur the separation of powers.

This commentator agrees with the principle in Chiu Teng If good governance requires the Government to keep its promise in a matter where it has legitimate authority or power to make the promise, then the Court should hold the Government to its promise, especially whether the promise has relied on it to his detriment. This principle should apply whether the promise or representation concerns a procedural right or a substantive right.

In Tan Seng Kee v Attorney-General [2022] SGCA 16 (“Tan Seng Kee”), the Court of Appeal did an about turn and applied the LSE to dismiss Tan’s appeal that section 377A of the Penal Code was invalid for inconsistency with the constitutional right of equality before the law and equal protection of the law under Article 12 of the Constitution in criminalising male/male acts

of gross indecency in public or private, but not similar acts in similar circumstances between male/female and female/female actors.

However, the Court shut down Tan’s appeal and dismissed it on the ground that he was not at risk of being prosecuted under section 377A as the Attorney General, as the Public Prosecutor (PP), had made a public statement that all male homosexuals in Singapore would not be prosecuted for such offences, if committed in private. The Court of Appeal held that Tan had acquired a SLE, which he had not asked for, which immunised him from being prosecuted.

In this article, the author discusses the normative basis for recognising SLE as part of Singapore law, and how the Court overcame its concerns expressed in in Starkstrom and finds the Court’s reasoning inadequate, and that the level of deference given by the Court to the PP’s “representations” (in light of the prevailing religious and political attitudes to section 377A) obscures key principles underlying the doctrine of SLE. The author concludes as follows:

“In sum, while it is a step in the right direction to recognise the legal effects of the representations made by the AG, the recognition of SLE in Singapore administrative law is done in a hasty manner. The exceptional and limited circumstances of the recognition does not absolve the court of the responsibility to ensure that the English doctrine is incorporated in a principled manner. Raising the convenient argument that deferring to the conclusion reached by the AG and Parliament, any recognition of SLE does not violate SOP and the review/merits distinction, the Court in Tan Seng Kee omitted important discussion of the normative underpinning of the doctrine which compel us to recognise it in the exceptional context. While the outcome is commendable, the judicial reasoning can be imprecise and unsatisfactory at times, eschewing neater ways of explaining that are in line with administrative orthodoxy.”

The author does not explain why if the recognition of SLE in Tan Seng Kee was done in a hasty manner, and the judicial reasoning unorthodox, it was a step in the right direction, presumably for the development of administrative law in Singapore. Also, it is hard to commend the outcome to Tan and his other appellants as there is no evidence that they desired it since their primary ground of appeal was that section 377A was inconsistent with Article 12. What can be said is that a great deal of thought and deliberation was invested in the decision

to give a “one off” recognition to the SLE, without opening the door to a merits review of executive acts or decisions. What the Court did not appear to have considered was giving effect to the AG’s “representations” to the relevant “representees” was to enable the AG to suspend the operation of section 377A which he had no power to do, and neither has the Court to declare that section 377A was unenforceable, if the Public Prosecutor chose not to enforce it. It should not be forgotten that the appeal in Tan Seng Kee involved the constitutionality or otherwise of legislation, and not the legality of an administrative decision. An executive decision by the AG, even one made in his discretion as the Public Prosecutor, cannot trump the people’s constitutional right not to be prosecuted for an offence under an unconstitutional law.

Tan Seng Kee is an unusual case where the Court of Appeal could easily have decided whether or not section 377A was inconsistent with Article 12 of the Constitution. A previous Court of Appeal and four other High Courts have decided likewise. Yet, the Court chose to vest Tan with a SLE to neutralise Tan’s appeal that section 377A was unconstitutional under Article 12, without having to decide whether it had any merit, unlike Tan’s other arguments under Article 9 and 14, which were examined in great detail. If Tan’s arguments based on Article 12 had no merit, it would have been simpler to decide it had no merit. This is only one of the many unusual features in the litigation on whether 377A was inconsistent with Article 12.

Authors: Zoe Toh (Singapore Management University), Elizabeth Lim (Singapore Management University) (Joint Runners-Up for Best Article)

This is an interesting and well researched article on the medical causes of voyeurism, its growth in Singapore, its criminalisation and punishment up to 2020 under section 377BB of the Penal Code, and the case law in Singapore. The authors also compare the legislative regime and the case law in Canada and the UK and observe that despite the best efforts of the relevant governments to check this form of criminal conduct, voyeurism has continued to rise. However, given the ease with which voyeurism and voyeuristic-related offences can be committed under section 377BB, Singapore had 467 cases in 2021 which increased to 519 cases in 2024. This increase of about 10% over 4 years seems relatively small, and shows that such offences are under control in Singapore, and supports the authors’ conclusion that section 377BB is an efficient law in checking the spread of voyeurism in Singapore.

The authors also discuss voyeurism as a form mental disorder or a sexual control impulse disorder. Voyeurism is considered under two categories: those with behavioural preferences (a disorder of atypical sexual preference) and those with incapacitating conditions (which include Compulsive Sexual Behaviour Disorder). This part is technical and is relevant to how offenders should be sentenced, for which a useful discussion on the principles and practice in the three jurisdictions is provided, such as general and specific deterrence, rehabilitation and incarceration as deterrence.

An innovative feature of this article is that the authors did what may be called “field research”. They conducted an e-mail interview with Dr Cheow Enquan of the Institute of Mental Health (22 October 2023) in which they asked Dr Cheow to answer 12 questions. His answers to the questions are confidently stated and easy to understand. When asked whether “the court/criminal justice system has a good understanding of the mechanism of voyeuristic disorders”, Dr Cheow’s reply is that

“The court is not required to have a good understanding of mental disorders including voyeuristic disorder. This is why they need forensic psychiatrists to assist them as expert witnesses in order to understand the disorder and come to the correct considerations for sentencing.”

Dr Cheow’s covering email response and his interview answers provide a good understanding of the inherent problems faced by the courts in assessing expert evidence called by the parties.

Author: Jun Xiang Wong (University of Cambridge) (Joint Runners-Up for Best Article)

This article discusses the scope of the Workplace Fairness Act 2025 (“WFA2025”) in prohibiting “employment decisions” that discriminate against employees or applicants on the grounds of certain protected characteristics, which are (a) age; (b) nationality; (c) sex; (d) marital status; (e) pregnancy; (f) caregiving responsibilities; (g) race; (h) religion; (i) language ability; (j) disability; and (k) mental health condition. Currently these characteristics

constitute more than 95% of discrimination complaints received by the Ministry of Manpower (“MOM”) and the Tripartite Alliance for Fair & Progressive Employment Practices (“TAFEP”).

In comparison, the Equality Act 2010 (“EA 2010”), prohibits discrimination in employment on the basis of the following protected characteristics under the EA 2010: (a) age; (b) disability; (c) gender reassignment; (d) marriage and civil partnership; (e) pregnancy and maternity; (f) race; (g) religion or belief; (h) sex; and (i) sexual orientation.

The author points out that although the WFA2025 has a longer list of protected characteristics than the EA2010 and many of them are the same or overlap, detailed examination of these characteristics show that the WFA 2025 is likely to have the effect of providing less protection to workers in Singapore. It is difficult not to agree with the author especially in relation to categories (c) gender reassignment, (d) partnership; (g) religion and belief, and (i) sexual orientation, having regard to the existing case law on similar characteristics under the Constitution, making the WA2025 extremely deficient in these respects. The author points out that the WFA2025 provides certain exceptions which make it possible for employers to discriminate workers on (a) minimum age requirement, or “reverse ageism”; and (b) nationality (non-citizen and non-permanent resident workers who constitute the bulk of Singapore’s work force (66.6% in 2024).

Since the WFA 2025 is not yet in force, it will not be known whether the author’s concerns and views will prove to be correct when the legislation is implemented. Nevertheless, this article has provided a very useful discussion of the scope of the WFA 2025 which may or may not live up to its name.

Authors: Priyansh Shah (London School of Economics and Political Science), Jia Hao Koh (London School of Economics and Political Science) (Honourable Mention)

This article reviews the arguments for and against the introduction of proportionality review in Singapore’s constitutional rights jurisprudence, against the backdrop of English administrative law which does not permit such form review due the fundamental principle of parliamentary

supremacy. The authors argue in favour of such form of review in Singapore as neither principle nor precedent blocks its application, and that “the narrow drafting of constitutional rights and the principle of separation of powers” are not impediments to its acceptance as part of Singapore law The authors however recognise the “political climate” that may inhibit the courts from developing administrative and constitutional review in this direction, and therefore the courts might have to adopt a strategy of “maxi-minimalism”, which the authors describe as follows:

“Maxi-minimalism, articulated in proportionality review through the reading down of the necessity and balancing limbs in line with the Constitutional text so as to allow greater deference to Parliament, allows the vindication of junzi while also presenting future opportunities for Singaporean constitutional law to grow into a true guarantor of norms of justified governance.”

This commentator agrees with the authors’ thesis that proportionality review should be accepted as part of Singapore law. Its application encourages good governance, in terms of equity and fairness, and also serves to preserve and protect fundamental liberties from excessive dilution.

It is not clear from their review whether the authors have paid sufficient regard to the significant difference between proportionality review of legislative acts and executive acts. The latter is premised on a law that is constitutionally valid. The former challenges the constitutionality of that law. Reliance is made to Chee Siok Chin and others v Minister for Home Affairs and another [2006] 1 SLR(R) 582 as authority that proportionality review is not part of Singapore law. There, V K Rajah J said:

“Needless to say, the notion of proportionality has never been part of the common law in relation to the judicial review of the exercise of a legislative and/or an administrative power or discretion. Nor has it ever been part of Singapore law.”

However, note the following caveats on the authority of this statement: (1) it is obiter since there was no argument on proportionality in that case, nor was it necessary for the disposition of the appeal; (2) no authority was cited in support of this statement; (3) in relation to executive actions, the Court of Appeal’s decision in Dow Jones Publishing Co (Asia) Inc v Attorney-

General [1989] 1 SLR(R) 637, was not referred to. There, the Court did not reject the proportionality argument advanced by the appellant, but held that it was not applicable on the facts. The argument was that the Minister ’s order curtailing the daily circulation of the AWSJ in Singapore from 5000 copies to 400 copies for an indefinite period was a disproportionate penalty to inflict on the AWSJ for refusing to give the Government the right of reply. The Court said:

“Apart from making this submission in general terms, he has not suggested what would have been a proper restriction, assuming that the doctrine of proportionality applies to a case of this nature. This court has observed in Chng Suan Tze ([27] supra) that disproportionality as a ground of judicial review contains within it an element of unreasonableness or irrationality. The underlying basis of the restriction order is the need to make it difficult but not impossible for the AWSJ to communicate its unwanted views to its Singaporean readers in Singapore. What is an appropriate restriction is, in our view, purely a matter for the judgment of the Minister. The court has no right to interfere with the Minister’s decision in that respect unless it is made in bad faith or perversely. In the instant case, we are not prepared to substitute our judgment for that of the Minister in determining whether the restriction made against the AWSJ is out of proportion to its infractions.”

Proportionality review of legislation, i.e., section 377A, was argued as part of the reasonable classification test in Ong Ming Johnson v Attorney-General [2020] SGHC 63. The High Court reviewed the case law from India, Malaysia, US and Hong Kong, and found that it was accepted as such in India (in Om Kumar v Union of India AIR 2000 SC 3689, and, Anuj Garg and others v Hotel Association of India and others (2008) 3 SCC 1); in Malaysia (in Sivarasa Rasiah v Badan Peguam Malaysia & Anor [2010] 2 MLJ 333); in Hong Kong (in Secretary for Justice v Yau Yuk Lung Zigo (2007) 10 HKCFAR 335, and, under Article 25 of the Basic Law of the Hong Kong SAR); the USA (in Romer v Evans 517 U.S. 620 (1996)).

Nevertheless, the High Court found these authorities to be of limited assistance in establishing the applicability of a proportionality-based approach in Singapore law, without giving any meaningful explanation, other than citing Chee Siok Tin as having established the law in Singapore, and stating that “proportionality review would necessarily involve a review of the legitimacy of the object of a statute, and enable the courts to usurp the legislative function and

act like a “mini-legislature”, which the Court of Appeal cautioned against in Lim Meng Suang CA (at [82]).

In Xu Yuanchen v Public Prosecutor [2023] 5 SLR 1210, another High Court reiterated that proportionality review had no place in Singapore’s constitutional jurisprudence, citing Chee Siok Tin at [83]. The Court also said at [84] “Besides the forgoing difficulty, adoption of proportionality analysis would contradict the principle of separation of powers, which is well established in Singapore constitutional law: Jolovan Wham …at [27].” It is not clear why proportionality review contradicts the separation of powers, as the Court provided no explanation. In fact, Jolovan Wham at [28] states “that it is unequivocally for the Judiciary to determine whether that derogation falls within the relevant purpose”, i.e. it is up to the courts to decide whether any impugned legislation is inconsistent with the Constitution. This principle does not mean that legislation disproportionate to its purpose or without any rational relationship to its purpose, and which abridges constitutional rights is not unconstitutional.

The Court also stated at [75] that “Thus, the analysis for the constitutionality of pre independence laws under Art 14 was no different from that for post-independence laws – ie, via the framework under Art 14(2)(a).” This statement is also contestable. The Court did not refer to Article 162 which provides for the continuation of all existing laws which shall be construed with such modifications, adaptions and exceptions to bring them into conformity with this Constitution. This means that if proportionality review is applicable to postindependence legislation, it should equally apply to pre-independence statutes because the purpose of Article 162 is to ensure that all legislation conform to the Constitution.

VK Rajah J’s observation that the proportionality review of legislation has never been part of the common law was correct as the courts were subject to parliamentary supremacy under the UK unwritten constitution. That leaves no room for any kind of substantive judicial review of the constitutionality of any UK Act of Parliament. Indeed, after the UK became a member of the European Union, the English courts had to apply proportionality review of English legislation by legal force of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) under which proportionality review of legislation of member states was available.

By parity of reasoning, proportionality review ought to be available under the Singapore Constitution in respect of any law passed by Parliament. It is not an alien import, but inherent

in the nature of constitutional protections of fundamental liberties or rights. There is no constitutional impediment to the Judiciary, in exercise of its judicial power under Article 93, to apply proportionality review to Acts of Parliament. Likewise, the Judiciary does not need to rely on the common law to review the legality of executive acts on grounds of illegality, procedural impropriety or breach of natural justice, or breach of constitutional rights. Applying Occam’s razor, breach of constitutional rights is the simplest explanation justifying proportionality review as inherent in Singapore’s legal system.

Author: Wei Pheng Koon (University of Cambridge)

The article discusses the divergence between English law on (a) personal locus standi and (b) representative locus standi.

In respect of (a) English law requires a claimant to demonstrate a “sufficient interest” , an approach Singapore initially adopted, but was later discarded in Tan Eng Hong v AttorneyGeneral in favour of a “rights-based standing rules”. Under this approach, the claimant must show that the state violated an identifiable constitutional right.

In respect of (b) English law is “generally branded” as being more expansive than Singapore law. Since Lord Reed observed in Fleet Street Casuals that “technical rules” of standing should not prevent “a pressure group, like the [claimant], or even a single public-spirited [party]” from getting a court to “vindicate the rule of law and [getting]…unlawful conduct stopped”, representative locus standi, particularly associational and public interest standing, have flourished in the English context. In contrast, Singapore courts do not accept representative standing. Such locus standi may only be claimed if the applicant can show a personal connection to the case.

The author attributes Singapore’s narrow approach in both kinds of locus standi to their deference to the executive - the so-called green light theory of administrative law, whilst the UK is “perceived” to have adopted a red-light approach towards administrative law The author challenges this thesis of divergence in locus standi by reference to three areas where the approaches of “both jurisdictions” measured, characterised by moderate, controlled expansion,

which he calls “structural convergence” (the arrangement of various rules of standing in both jurisdictions); (b) “doctrinal convergence” “in their shared emphasis on rights”; and (c) “evolutive convergence” (neither jurisdiction is wholly red- or green-light, placing both jurisdictions more closely together in a middle “amber-light” zone rather than at one or the other extreme end of a red-light/green-light spectrum).

My short comment on the author’s thesis is that it reflects substantially the legal position in Singapore and that despite Tan Eng Hong and Vellama, the Singapore courts will remain conservative in according locus standi to challenge legislative or executive actions. This judicial culture will take time to change, if at all. Whether the principles will develop retrogressively or progressively, and stand still, depend very much on the current composition of the Court of Appeal. It is likely that a larger leeway will be accorded to constitutional challenges than administrative challenges. Vellama could be interpreted a case of both personal as well as a representative locus standi, as the complainant was a constituent who alleged that she, along with other constituents, had been unlawfully denied the constitutional right to vote unless a by-election was called.

Author: Nickolaus Ng (University of Birmingham)

This article seeks to present the inherent biases of jurors in decision-making, during preevidence presentation, during evidence presentation itself and during deliberations, and concludes that judge-based systems without juries would better serve the goals of fairness and legal consistency, offering a more stable safeguard against prejudice in adjudication. It is not clear what the purpose of this article is in a Singapore context since jury trial has been abolished a long time ago, and is unlikely ever to be revived.

Authors: Anni Huang (Singapore Management University), Cheryl Soong (Singapore Management University), Wesley Gordon Harrison (Incoming student at Singapore Management University), Zun Yin Ngo (Incoming student at National University of Singapore)

In this article, the authors examine the decision of the Singapore Court of Appeal in ACB v Thomson Medical Pte Ltd and Others [2017] 1 SLR 918 (“Thomson Medical”) that genetic affinity is an intangible right and loss of it (“LOGA”) is compensable in damages under Singapore law. The authors argue that the Singapore decision is applicable under English law should a similar case arise in the UK, due to their similarity in importance of genetic ties.

The authors also consider other kinds of mishaps in IVF, such as (a) where the mother selects A (not the husband), but gets the sperm of B, LOGA may not be an appropriate as a basis of a claim for damages. Suppose the mother selects CG (a chess grandmaster) as the donor, instead is given the sperm of GC (a Go champion) In such a case, would the LOGA by the mother be compensable? The second type of case is where a chosen donor has no genetic deficiencies or disorders, but the mistakenly substituted donor has some genetic deficiencies, which the mother is unaware of until later in the child’s life. Is there any LOGA by the mother, since the mother’s main objective is to have a healthy donor? What kind of harm has the mother suffered? If the mother suffers mental injury, psychiatric or psychological, from such negligence, what is the measure of damages? The authors conclude by asserting that the courts should be open to reforming the LOGA framework to address these emerging realities of modern reproductive technology, so that deserving claimants are not left without recourse.

Aside from restating how the Court of Appeal came to recognise LOGA as a novel head of claim for damages in tort, the authors have nothing else to say about whether the claim could have been dealt with in a different way that is consistent with logic and social reality. The Court accepted (at [150] of the Judgment) that ABC and her family had suffered anguish, stigma, disconcertment, and embarrassment in their social interactions with friends or other people, because the child’s skin tone was different from that of the parents. She did not say that she had suffered any psychiatric or psychological harm.

What then was the genetic affinity that the Court found that she had lost, and that it was a serious and compensable loss? This is how the Court describe the LOGA:

“127 [ABC’s] desire to have a child of her own, with her Husband, is a desire that is a basic human impulse, and its loss is keenly and deeply felt, even if it is difficult to put into words. Her desire (and therefore her loss) was for “genetic affinity”

128 … the desire for genetic affinity is complex and multi-faceted. It is, at its core, a desire for identity bounded in consanguinity. The ordinary human experience is that parents and children are bound by ties of blood and share physical traits. This fact of biological experience – heredity – carries deep socio-cultural significance. For many, the emotional bond between parent and child is forged in part through a sense of common ancestry and a recognition of commonalities in appearance, temperament, and physical appearance. For yet others, genetic continuity and biological lineage is deeply important to religious and cultural belonging This interest in affinity does not exist only at the bilateral level (between parent and child), but also multilaterally – it affects the parents’ relationship with their extended relations; the child’s relationship with his/her siblings; as well as the family’s relationship with the wider community of which they are a part.

129 … [ABC] has suffered, among other things, a loss of “affinity”, and the chance to have a family structure which comports with her aspirations . As a consequence of what has taken place, the Appellant’s welfare has been detrimentally affected in myriad of significant ways.

135 “[ABC’s] interest in maintaining the integrity of her reproductive plans in this very specific sense – where she has made a conscious decision to have a child with her Husband to maintain an intergenerational genetic link and to preserve “affinity” – is one which the law should recognise and protect. And given that interests are the “positive aspects of damage”, we hold that the damage to [ABC’s] interest in “affinity” is a cognisable injury that should sound in damages.”

It is clear from this description that the person who actually suffered a loss of genetic affinity was the child and not the mother. What ABC lost was a child that did not have the genes of her husband, but only her own and those of a stranger. Such a loss could be traumatic for ABC, and could cause her psychiatric, psychological or something other kind of mental anguish. If for example her husband was of the same race as the substituted donor, the child would probably be born with the same skin colour or tone. In that situation, there might be no social stigma or embarrassment, although the loss of a child with her husband’s genes would still be felt by her.

However, from this perspective, can it be said that the real victim of the mishap was the child, and not the mother? The mother might be able to have another child with her husband’s genes. But the child would forever have the genes of someone who was not her father. She had truly suffered a loss of genetic affinity to her father in that respect. In a traditional conservative Chinese family, what was lost was more than affinity: it was lineage based on her father’s bloodline. Is such loss compensable in law? How is it to be compensated in law, except by plucking a figure from the air?

In Thomson Medical, the Court awarded damages at 30% of upkeep costs. How did that come about? The Court held that damages should be awarded on the basis of the mother’s loss of expectation that she would give birth to a child with her father’s genes, and not those of a stranger. However, this consideration does not tell the Court how to quantify the loss or damage. The Court acknowledged there was no precedent to guide it, this difficulty, and held as follows:

“148 In the circumstances, we consider that we should benchmark the eventual award as a percentage of the financial costs of raising Baby P. Although we have determined that this is not an appropriate case in which to award upkeep costs as such to the Appellant, the financial costs of raising Baby P are not, in our view, wholly irrelevant as, absent such costs, there would be no other criterion or standard by which to assess the quantum of damages that ought to be awarded. This approach would have several advantages. First, to the extent that one of the purposes behind the grant of damages for non-pecuniary loss is to provide solace to the claimant, we consider that an award which is benchmarked against upkeep costs would achieve this purpose. Second, any such award would not be derisory but would instead produce a substantial award that offers “reasonable compensation”. Indeed, we note that such an approach is not wholly without precedent

149 . Our approach of using the latter as a benchmark for assessing the magnitude of the former does not derogate from what we have said about how the obligations of parenthood are incapable of being regarded by the law as loss Whilst it is perhaps not theoretically elegant, the approach of benchmarking the present award against upkeep costs is practical (provided one always bears in mind that the quantum of full upkeep costs is but a benchmark) and it prevents the court from having to pluck a figure out of thin air, so to speak. In any event, a theoretically

elegant result would, in any event, be elusive in the extreme, given the nature and complexities of the issue and the attendant difficulties that arise from such a controversial area of the law.

150 As we have explained above at [102], the award of full upkeep costs would amount to giving the Appellant an indemnity for the costs of raising Baby P. This would not, in our judgment, be appropriate compensation for the loss which has been suffered. However, it is also neither logical nor desirable to award the Appellant a merely nominal sum because to do so would be to make a mockery of the value of the interest at stake. It is clear that the damages to be awarded should therefore lie somewhere between these two extremes. On the issue of precisely where along the spectrum it should fall, the facts and circumstances are of the first importance. In our judgment, it is clear that substantial damages ought to be awarded to the Appellant. Whilst (as we have already noted), the Appellant and her Husband have accepted Baby P as their own, the reality of the situation cannot be denied (see, especially, the anguish, stigma, disconcertment, and embarrassment suffered by the Appellant and her family as expressed in the Appellant’s affidavit (reproduced above at [131] and discussed at [132]–[135])). In the circumstances, we are of the view that the Appellant ought to be awarded 30% of the financial costs of raising Baby P as compensation, which is an amount that, we consider, properly reflects sufficiently the seriousness of the Appellant’s loss and is just, equitable, and proportionate in the circumstances of the case.”

The Court did not explain why it assessed damages at 30% and not some other figure, say 20% or 50%. In other words, the assessment of damages appears to be wholly subjective. Hence, it is not possible for any reasonable person to say that the Court was wrong in any sense of the word, but it is possible to say that in another similar case, the percentage is unlikely to be the same, since the Court did not say that 30% was a conventional sum.

There were two other possible claims that the mother did not seek in Thomson Medical. One would be a refund of the cost of IVF treatment, including hospitalisation costs on the basis of a total failure of consideration since. The other could be for pain and suffering in giving birth to a child which she had not contracted for.

Author: Delaney Lim (University of Oxford)

In this article, the author argues that the orthodox interpretation of Article 5 of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (‘UNCLOS’) - that the normal baseline is considered ambulatory and recedes with sea-level rise - imposes unfair burdens that low-lying coastal and small island States like Singapore, and that the rules of treaty interpretation under Articles 31 and 32 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties (‘VCLT’) are applicable to interpret Article 5 to permit States to fix their normal baselines.

The argument is developed as follows: (1) a normative reappraisal of how Article 5; (2) the application of the general rule of interpretation under Article 31(1) VCLT to argue that the normal baseline is defined by reference to a charted line that States are not obliged to update to reflect coastal recession, (3) the application of Article 31(3)(c) VCLT, showing its consistency with the principles that the “land dominates the sea” and that boundaries must be stable; and (4) confirmation of the preceding interpretations by reference to widespread State practice that supports the permissibility of fixing normal baselines.

This article thus submits that the ambulatory interpretation of Article 5 is neither legally required nor normatively desirable in the face of climate change-induced sea-level rise. Instead, it argues that States may lawfully fix their normal baselines – an essential step to preserving legal certainty and ensuring equity for vulnerable coastal States.

Without reference to the cogency of the first three lines of argument, it is interesting to note that in respect of the fourth line of argument, Singapore up to today does not appear to have expressed any concern in any public statement with the effect of Article 5 in relation to fixing her normal baselines. Given her close relationship with the birth of UNCLOS, Singapore would be expected to the first state to raise the problem discussed in this article. Is there a real problem under international law on Article 5?

Having said that, this commentator agrees with the author that an interpretation of Article 5 UNCLOS permitting States to fix their normal baselines (unless international law and practice is clear on this issue) is therefore desirable, and so much the better if it is doctrinally defensible

A state should not lose the size of its territorial sea because of a rise of the sea resulting from climate change caused by industrial nations with vast land areas.

Authors: Isaac Tan Kah Hoe (University of Oxford), Bonnie Yeo Lu-Anne (University of Oxford)

The authors explore how fundamental liberties guaranteed under the Singapore Constitution can be interpreted more substantively by reference to case law on similar fundamental liberties or rights under the in the US Constitution, and UK’s unwritten constitution.

The first section provides an outline of the general characteristics of Singapore’s approach to judicial review, identified as (a) constitutional supremacy; (b) autochthony; and (c) green light approach. It is not clear to this commentator what the purpose of the outline is. Constitutional supremacy entails that Parliament must not enact any law and the Executive must not do any act inconsistent with the Constitution. Autochthony means that the Singapore courts will develop the legal system and the common law of Singapore with Singapore characteristics. The article does not point out that the green light theory could only apply to judicial review of executive actions, and not legislation because of the doctrine of parliamentary supremacy.

The second section considers the principle of separation of powers and argues since the specific scope of legislative power is not substantively laid down within the Constitution, there exists constitutional penumbras that “provide space for the judiciary to adopt a stronger interpretation of rights without unconstitutionally infringing on legislative power”. The authors say that the concept of constitutional penumbras has not received much attention in court, with the interference by the judiciary in legislative matters taken to be an almost-certain violation of the separation of power. This statement is difficult to understand, since by the term “constitutional penumbras”, the authors refer to the meaning and scope of the fundamental liberties in Articles 9 (“life”, “personal liberty”. and “in accordance with law”), 12 (equality before the law and equal protection of the law) and 14 (“freedom of speech, assembly and association”), 15 (“freedom of religion”), 49 (filling of vacancies in Parliament) and expression. Practically all the constitutional litigation to date have been on the penumbral meanings of the fundamental liberties and other constitutional rights.

Further, the authors argue that there is a considerable penumbra in the interpretation of the separation of powers from the constitution, and that “the laws surrounding the scope of judicial and legislative power are especially vague”. These statements are confusing and not easy to understand, since Articles 38 (legislative power), 23 (executive authority, which implies the existence of a legal power) and 93 (judicial power), as worded, are neither vague nor ambiguous. The legislative power authorises Parliament to make laws. The executive power authorises the Executive to execute them, and the judicial power authorises the courts to adjudicate disputes arising from such laws or executive acts. Each constitutional organ must act within its own sphere of power, and must not intrude into the domain of the other powers, but each of those acts must not be inconsistent with the Constitution.

Because the Constitution is the supreme law, Parliament may not make a law inconsistent with the Constitution. Likewise, the Executive may not act outside the law enacted by Parliament or in contravention of the Constitution. If the court declares a statute inconsistent with the Constitution, the statute is invalid to the extent of its inconsistency under Article 4 (constitutional supremacy). There is no question of the court intruding into the legislative power of Parliament, because under constitutional law, Parliament has no power to enact an unconstitutional law. The authors’ confusion in this regard is discernible from the following statement in another part of the article:

“The law regarding the arbitrary test thus remains open-ended. Nonetheless, Tan Seng Kee shows the constitutional penumbra inherent in rights adjudication. Even in Singapore, the courts recognise that the separation of powers does not present an absolute bar to the infringement of legislative power by the courts, especially when the circumstances are absolutely necessary”.”

The judicial power does not intrude into the legislative power or the executive power in constitutional or administrative law adjudication on the validity of a legislative act, or the legality of an executive act. It is implicit in the separation of powers under the Constitution, the function of the judicial power is check abuse or misuse of the legislative or executive power by Parliament or the Executive, as the case may be.

In not clarifying penumbra approach or its elements, the authors may have made the subject seem more complex, and less easy to understand, than it actually is.

The third section assesses the court’s scope of judicial review of fundamental liberties by reference to both legal positivism (i.e., the validity of a law is determined by its source and not moral content) and natural law (law must have a moral content, and a wicked law is not a law). The authors argue that the legal community would benefit from being able to navigate this constitutional penumbra through an exploration of alternative approaches to constitutional interpretation. Ultimately, the authors favour the positivistic approach for Singapore, given Singapore’s characteristics of judicial review, and also allow judges to avoid making their own moral subjective judgments.

The authors discuss a series of judgments of the courts of various jurisdiction in connection with Articles 9, 12 and 15, from Singapore, the UK, USA, and EU to argue that the fundamental liberties enumerated in the Singapore Constitution can be interpreted more substantively, yet in a calibrated way, including the inevitable use of moral reasoning by the courts to broaden the scope or to the fundamental rights from legislative dilution or executive transgression.

In summary, the authors’ arguments largely favour giving an expansive or liberal interpretation to constitutional rights, and a narrow interpretation to legislative and executive restrictions of constitutional rights. However, the authors also acknowledge that the Court of Appeal said in Jolovan Wham at [33], “In the final analysis, it is imperative to appreciate that a balance must be found between the competing interests at stake ” This commentator does not foresee any rebalancing in the near future that would favour the authors’ position.

Author:

Joyee Goh (University of Melbourne)

This article discusses a new type of collaborative methodology that has been used in the construction industry in the UK and Australia since the 1990s called “alliance contracting” or “alliancing”, but which has not been used in Singapore. It differs from the traditional EPC contract in that

“[Alliance’ contracting is a project delivery method where all parties, including owners, contractors, and sometimes even designers and consultants, form an

alliance to work collaboratively. This approach prioritizes shared goals, open communication, and risk-sharing among all parties. The alliance agreement is drafted and structured to avoid “win-lose” scenarios, foster “win-win” approaches, and typically includes pain and gain-sharing mechanisms.”

[https://constructionfront.com/alliance-contract/]

This article is useful for contractors, but not lawyers, and therefore a review is unnecessary.

This year’s issue of the SCLR could have benefitted from more subject matter, and even more areas of law. The new issue should contain a larger spread of articles on the development of private law in Singapore, although it is to be expected that student interest will continue to focus on public law issues. Still, I have learned much and enjoyed reading some of the articles. I thank the editorial board once again for giving me the opportunity to write the Foreword to this year’s issue of the SCLR.

Chan Sek Keong

Patron

16 August 2025

At Clifford Chance, our people are at the heart of everything we are and everything we do.

Our ability to excel on behalf of our clients; the quality of work; our international capabilities; collaborative and supportive working culture; our innovative mindset – they are all driven by our people. Joining us means sharing our ambitions and realising your potential.

We run two summer internships, each lasting four weeks, with eight interns per intake.

During the four-week scheme you will follow the life of a lawyer at Clifford Chance closely –you will sit in two different practice areas, working with our lawyers on real, live client projects.

You will learn about the business side of law and the opportunities available to you from our partners, business professional teams and our trainees from Singapore and around the world.

2026 Internship Dates:

Intake 1: 1 Jun – 26 June 2026

Intake 2: 6 July – 31 July 2026

Applications for our 2026 internships open on 8 September 2025 and will close on 23 January 2026

2027 Internship Dates:

Intake 1: 31 May – 25 June 2027

Intake 2: 5 July – 30 July 2027

Applications for our 2027 internships open on 7 September 2026 and will close on 22 January 2027

Our unique Training Programme is 26-months in duration and will first provide a Practice Training Contract in Singapore through Cavenagh Law LLP. Following your admission to the Singapore Bar, you will then undergo the Post-Qualification Training Programme conducted by Clifford Chance.

Applications for our 2028 Training Programme will be open on 1 July 2026

To learn more, speak to our graduate recruitment team at: atrecruitment.singapore@cliffordchance.com or visit our Singapore Graduate Page.

ambitious motivated passionate trustworthy well-rounded

Kai Zhen Tek*

Chan Sek Keong Award for Best Article

Abstract

The Singapore Court of Appeal recognised the ground of substantive legitimate expectation (“SLE”) in Tan Seng Kee v Attorney-General [2022] SGCA 16 (“Tan Seng Kee”), despite casting doubt on its applicability in the earlier case of SGB Starkstrom Pte Ltd v Commissioner of Labour [2016] SGCA 27 (“Starkstrom”). How were the normative concerns highlighted in Starkstrom overcome? What is the normative basis of recognising the doctrine in the Singapore constitutional setting? This article sets out to scrutinise the Court of Appeal’s reasoning in Tan Seng Kee and argues that the Court engaged in preliminary understanding of how the SLE doctrine operates, leaving important questions unanswered. In view of conflicting dicta regarding the normative impact of recognising the doctrine on important constitutional principles like the separation of powers, in order to render the doctrine more palatable, the Court exercised a large degree of deference. While the outcome may be correct in the present case, it is argued that the lack of discussion on why deference is displayed obscures key principles underlying the doctrine of SLE. Focusing on the separation of powers (“SOP”) principle and the merits/review distinction, it is argued that recognising SLE does not necessarily violate SOP nor the merits/review distinction if modulated by deference with a principled basis. Good administration is also identified as the most appropriate basis for the

* University of Cambridge, Trinity Hall, BA (Hons) In Law, Class of 2026 I am profoundly grateful to the reviewers from the editorial team for their comments on earlier drafts of this article. All errors that remain are my own. E-mail for correspondence: kztek01@gmail.com.

recognition of SLE. The article ends with a discussion of the doctrinal test of the doctrine, focusing on the elements of detrimental reliance and reasonable reliance which are missing in the English jurisprudence.

Despite the concerns that recognising the doctrine of “substantive legitimate expectation” (“SLE”) may allow the courts to engage in substantive reviews of the administrator’s discretion 1 , the English administrative law has long recognised the validity of substantive legitimate expectation in R v Devon Health Authority ex parte Coughlan2, on the basis that the degree of unfairness caused to the applicant similarly “amount[s] to an abuse of power” where the “legitimate expectation of a benefit which is substantive”. 3 However, Singapore has been hesitant in receiving the doctrine4 , citing similar concerns reflected in earlier English cases such as the need to adhere to the distinction between review and appeal5, and the compatibility with important constitutional principles like separation of power.6 Decided before Starkstrom, the possibility of receiving the doctrine reached a “high point”7 in the Singapore High Court case of Chiu Teng @ Kallang Pte Ltd v Singapore Land Authority (“Chiu Teng”) 8 which declared that substantive legitimate expectations ought to form an independent ground of judicial review of administrative action.9 In a significant turn of event, the Court of Appeal utilised the doctrine to recognise the legal effects of statements made by the Attorney-General regarding the non-enforceability of Section 377A of the Panel Code in the case of Tan Seng

1 Such concerns are best exemplified by Hirst LJ’s dictum in R v Secretary of State for the Home Department, ex parte Hargreaves [1997] 1 All ER 397 at 921: “Mr. Beloff characterised Sedley J.'s approach [recognising SLE] as heresy, and in my judgment he was right to do so” and Pill LJ at 924 “The claim to a broader power to judge the fairness of a decision of substance, which I understand Sedley J. to be making in Reg. v. Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food, Ex parte Hamble (Offshore) Fisheries Ltd. [1995] 2 All E.R. 714 , is in my view wrong in principle.”

2 [2000] 2 WLR 622.

3 Ex parte Hamble (n 3) 645E

4 Court of Appeal (Singapore’s highest appellate court)’s ruling in SGB Starkstrom Pte Ltd v Commissioner of Labour (“Starkstrom”) [2016] 3 SLR 598

5 Starkstrom (n5) [56] – [58]

6 Starkstrom (n5) [59], [62]

7 Kenny Chng, ‘An uncertain future for substantive legitimate expectations in Singapore: SGB Starkstrom Pte Ltd v Commissioner of Labour’ [2018] PL 192.

8 Chiu Teng @ Kallang Pte Ltd v Singapore Land Authority [2013] SGHC 262.

9 Chiu Teng (n9) [112] – [119]

Kee v Attorney-General [2022] SGCA16 (“Tan Seng Kee”), concerning a constitutional challenge to Section 377A of Singapore’s Penal code. 10

In view of recent developments, this article proceeds in Part II to analyse the key cases in Singapore that set out the doctrinal law on legitimate expectation and the concerns expressed by the courts in receiving the doctrine. It is observed that despite differences in the fundamental constitutional arrangements and “autochthony”11 or doctrinal divergences between the English and Singapore administrative law 12 , there are similar normative concerns surrounding the doctrine of legitimate expectation. By analysing each of the three significant cases that build on the doctrine of legitimate expectation, I critique the Singapore courts’ reasoning for being cautious in receiving the doctrine.

In Part III, I analyse the application of the doctrine in the latest Court of Appeal case in Tan Seng Kee and argue that its application is consistent with the “paradigm”13 cases of legitimate expectation in English administrative law. Focusing on (i) the SOP principles, referencing the distinction between ‘pure’ versus ‘partial’ notion of the SOP principle and the concept of “constructive breaches”; and (ii) the merits/ review distinction in judicial review, I defend the SLE doctrine and argue that recognising it does not necessarily involve violating these principles, which is also the Court’s position in Tan Seng Kee. However, in that case, the judicial reasoning in arriving at these correct conclusions is slightly flawed and left important questions unanswered – both doctrinally and normatively This results in an awkward position where though the SLE doctrine is recognised in the exceptional circumstances, it has unclear normative basis and doctrinal test. Though immaterial for the current ruling, the strength of the protection consequently offered to the appellants ought to be higher Referencing Elliott’s

10 [117]

11 Chuan Limin, ‘Autochthony and Conformity in Singapore Administrative Law’, [2023] 35 SacLJ 1.

12 Indeed, Chuan argues that “[a]”dministrative law is a unique field of law in so far as sensitivity to local context, local institutional peculiarities and socio-political values are critical to its functionalism within the modern administrative state”. This is supported by Chan Sek Keong CJ in an extrajudicial lecture where he stated “[o]ur ultimate objective is to build up a large body of local jurisprudence, so that local decisions can be cited first instead of English decisions”.

13 Jason Ne Varuhas, ‘In Search of a Doctrine: Mapping the Law of Legitimate Expectations’ in Matthew Groves and Greg Weeks (eds), Legitimate Expectations in the Common Law World (Bloomsbury Publishing 2017)

works14 on deference and the SLE doctrine, I argue that greater recognition can be given to the doctrine if the courts apply a context-sensitive analysis as modulated by deference which is justified on a principled basis.

In Part IV, I take a closer look at the doctrinal test set out by the court for SLE, focusing on the two elements which do not appear in English jurisprudence – detrimental reliance and reasonable reliance.

The brief facts of Chiu Teng relate to whether the circulars published by the Singapore Land Authority (“SLA”) setting out the calculation method of a differential premium for increasing the permissible use of land (as contracted for in state leases) will be calculated constitute sufficient representation for a legitimate expectation to arise. 15 While the Court held that the statements published on the SLA website are qualified due to the Terms of Use 16 and hence did not amount to unequivocal representations, the circulars “did contain unequivocal and unqualified statements”.17 As the Court held that the doctrine of legitimate expectation “should be recognised in our law as a stand-alone head of judicial review”18, the Court further set out a doctrinal test and held that the applicant had relied on the representations and suffered detriment. 19 The element which was not satisfied is the reasonableness of relying on the representation given that the applicant is an “experienced property developer”. 20

14 Mark Elliott, ‘From Heresy to Orthodoxy: Substantive Legitimate Expectations in English Public Law’ in Groves and Weeks (eds), Legitimate Expectations in the Common Law World (Hart Publishing 2016)

15 At [6]. Indeed, when read in context where the SLA referred to a “transparent system of determination of differential premium” (at [1] of the circular published in 2000) which aims to “provide greater certainty to landowners”, it seems like there is indeed unequivocal representations made, as the Court has found.

16 Chiu Teng (n9) [120], which includes a “wider disclaimer”

17 Chiu Teng (n9) [122]

18 Chiu Teng (n9) [119].

19 Chiu Teng (n9) [121]-[124].

20 Chiu Teng (n9) [125]-[129]

Two crucial points are worthy of analysis: 1. How did the Judge weigh the arguments against recognising SLE as an independent ground of review; and 2. The doctrinal test set out, and how its elements differ from the UK jurisprudence?

First, the Judge countered the submission that recognising the doctrine may violate the separation of powers principle from a precedent point-of-view. It is emphasised that such concerns are not noted in the majority’s judgment in Australia in Ex p Lam. 21 As a matter of constitutional principles, the submission that Singapore’s and Australia’s written constitutions “demarcate the powers” and therefore, allowing the judiciary to enforce substantive legitimate expectation would be “tantamount to judicial overreach” is also rejected 22 since the UK constitution also recognises the separation of powers 23 , and “upholding …legitimate expectations is eminently within the powers of the judiciary."24 The need for the judiciary to weigh the public interests in resiling from the representation against the private interests of the representation being satisfied can be done without “arrogating to itself the unconstitutional position of being a super-legislature or a super-executive.”25

On the other hand, though not explicit, the Court seems to recognise the normative rationale of recognising SLE as the principles of good administration.26 This is aligned with the recent English jurisprudence which points to the principles of “good administration”27 as grounding the concept of legitimate expectation. This is re-emphasised in the latest Supreme Court jurisprudence on the matter in Re Finucane’s Application for Judicial Review28 Indeed, this is reflected at [112] of Chiu Teng where the Court posed the question:

21 Chiu Teng (n9) [108]

22 Chiu Teng (n9) [109].

23 The Singapore Court citing Lord Keith’s dictum in Regina v Secretary of State for the Home Department; ex parte Fire Brigades Union [1995] 2 AC 513

24 Chiu Teng (n9) [113]

25 ibid [113].

26 As recognised by the Court of Appeal in Tan Seng Kee at [126], though the phrase “principles of good administration” was not explicitly referred to

27 R (Nadarajah) v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2005] EWCA Civ 1363

28 [2019] UKSC 7: “A recurring theme of many of the judgments in this field is that the substantive legitimate expectation principle is underpinned by the requirements of good administration”

“If private individuals are expected to fulfil what they have promised, why should a public authority be permitted to renege on its promises or ignore representations made by it?”

However, as Jhaveri argues29 , it is indeed unclear what the normative foundation of SLE is. This is best evident by the lack of guidance for the judicial balancing test, and for the “choice of priorities and principles” that are in conflict. On the one hand, citing from Bibi30 , Jhaveri highlights that there is “value in holding authorities to promises which they have made, thus upholding responsible public administration and allowing people to plan their lives sensibly”. On the other hand, this is balanced with the need to ensure flexibility and to preserve the administrative authority conferred by parliament for “the possibility in the future of coming to different conclusions”.31 The key question here is “who makes the choice of priorities and what principles are to be followed” (emphasis in original). The normative critique that it is not for the judiciary to be answering these questions on the choices of priorities would be more convincing if the Court analysed to the doctrine to this level of details. Put differently, the articulation as to why it is not for the courts specifically to perform this weighing test could have been more precise, given the possible abuse of powers by the executive in resiling from clear, unequivocal promise and the lack of adequate considerations of the harm suffered by relying on the promise.

Indeed, citing Forsyth who argues that "[p]ublic trust in the government should not be left unprotected" 32 , Chen argues that the need to uphold trust in public administration underpinning the doctrine “resonate with the governmental ethos in Singapore.”33

29 Swati Jhaveri, ‘The doctrine of substantive legitimate expectations: the significance of ChiuTeng@Kallang Pte Ltd v Singapore Land Authority’ [2016] PL 1, 4: Jhaveri argues that it is “[i]t is not clear from Chiu Teng, why administrative law needs to protect substantive legitimate expectations created by administrative decisions and neither is the rationale for recognising the doctrine in Singapore”.

30 R(Bibi) v Newham LBC [2002] 1 WLR 237

31 Swati Jhaveri, ‘The doctrine of substantive legitimate expectations: the significance of ChiuTeng@Kallang Pte Ltd v Singapore Land Authority’ [2016] PL 1, 4

32 Christopher Forsyth, ‘The Provenance and Protection of Legitimate Expectations’ (1988) 47 CLJ 238, 239

33 Zhida Chen, Substantive Legitimate Expectations in Singapore Administrative Law: Chiu Teng @ Kallang Pte Ltd v Singapore Land Authority [2013] SGHC 262, 26 SACLJ 237 (March 2014) at [12], citing Lee Hsien Loong v Singapore Democratic Party [2009] 1SLR(R) 642 at [102]-[103].

Second, it is noteworthy that the formulation of the doctrinal test for legitimate expectation in Chiu Teng differs slightly and includes more elements to be satisfied as compared to English administrative law.

The UK test for substantive legitimate expectation is articulated in Coughlan. There are two stages to the analysis: