A beginner’s guide to identifying and growing trees from seed, and starting a Community Tree Nursery Includes the updated Good Seed Guide with extra content online

A beginner’s guide to identifying and growing trees from seed, and starting a Community Tree Nursery Includes the updated Good Seed Guide with extra content online

Trees are essential to human life. It’s impossible to overstate how crucial they are. They produce the oxygen we breathe, store carbon in their trunks and roots, protect soils from erosion, reduce flooding and air pollution, and provide medicines, materials, food and shelter for millions of species on Earth, including us!

Growing a tree from a seed is an easy, simple act and can help reconnect us to our shared natural world. This guide has been produced by a team of experienced tree growers who want to share their love of trees and how to grow them, including:

n The Tree Council is a national charity bringing people together for the love of trees, inspiring and empowering communities to take meaningful action. www.treecouncil.org.uk

n Moor Trees is an independent charity dedicated to restoring native woodland on Dartmoor and in South Devon, improving the environment and connecting people with their forest heritage. https://moortrees.org

n Cornwall Council is working with people, organisations and communities to increase tree cover by 8,000ha as part of the Forest for Cornwall programme. www.cornwall.gov.uk

n Norfolk County Council represents the people of Norfolk and its environment, making Norfolk a great place to live and work. www.norfolk.gov.uk

Anybody can grow a tree almost anywhere. Why don’t you?

The Tree Grower’s Guide 2022 was created for you by:

The Tree Council

Registered charity no: 279000

Jon Stokes

Clare Bowen

Louise Bowe

Jackie Shallcross

Gemma Woodfall

Moor Trees

Registered charity no: 1081142

Adam Owen

Darryl Beck

Norfolk County Council

Emma Cross Cornwall Council

Ben Norwood

On behalf of SLYGAS:

Sophie Stafford (Editor)

Dylan Channon (Art Editor)

Neil Aldridge (Photographer)

Illustrations by

Stuart Jackson Carter

Photographs by Neil Aldridge, Rose Summers and Georgia Taylor, unless otherwise stated

ISBN 978-0-904853-19-3

Copyright:

Text p2-131 © The Tree Council 2022

Text p132-193 © Moor Trees 2022

Text p194–273 © Norfolk County Council 2023

04 TREE SPECIES BY PAGE

Why you should grow trees from seeds

06 TREES ARE WONDERFUL

Why you should grow trees from seeds

08 WHAT TREES SHOULD I GROW?

Things to consider when choosing a tree

12 HOW TO COLLECT SEEDS OR TAKE CUTTINGS

Where, when and how much seed to collect

16 HOW TO PROCESS SEEDS

Nuts, fleshy fruits, winged seeds, cones or pods – how do you extract the seeds?

22 HOW TO STRATIFY SEEDS FOR GERMINATION

Get the best results from natural and artificial stratification

28 HOW TO SOW SEEDS AND PLANT OUT

From germination to growing, it’s time to get your seeds in the ground

32 HOW TO IDENTIFY TREES AND THEIR SEEDS Our grower’s guide to identification by species

138 HOW TO GET GROWING

Give your trees the best start in life

146 HOW TO GROW YOUR TREES ON

How to nurture strong young trees

152 HOW TO PROTECT YOUR PLANTS

Protection from the weather, wildlife and diseases

156 HOW TO MOVE YOUR TREES

Lifting, bundling and transporting

164 ENHANCING AND RESTORING LANDSCAPES

How to design a woodland and make sure your trees make a difference beyond the nursery

180 A BEGINNER’S GUIDE TO PLANTING

Ways to plant your woodland or hedgerow

188 HOW TO NURTURE YOUR TREES

Ensuring your trees thrive during the early years

194 CASE STUDIES

A range of case studies illustrating how different Community Tree Nurseries are growing trees

234 BIOSECURITY CASE STUDY

Examples from Salhouse to help improve your nursery’s biosecurity

122 HOW TO AVOID PESTS AND DISEASES

The biosecurity and growing practices that will help

PESTS AND DISEASES

Our A–Z guide to diseases and their symptoms 126 HOW TO AVOID DAMPING OFF

Keep your seedlings safe from sudden death

128 HOW TO START A COMMUNITY TREE NURSERY

Expert advice on running your own nursery

238 INFRASTRUCTURE

Fencing, irrigation and other essentials

246 HOW TO MANAGE VOLUNTEERS

Best practice for working with volunteers

252 PLANNING AND TREE DISTRIBUTION

Creating a blueprint for your organisation, including marketing and legislation

260 HOW TO RAISE FUNDS

Covering costs and applying for grants

264 ORGANISATION STRUCTURE

Which is the best legal structure for your nursery?

266 GLOSSARY

268 USEFUL RESOURCES

Acacia, false Robinia pseudoacacia P 111

Alder, common Alnus glutinosa C 98

Alder, grey Alnus incana C 99

Alder, Italian Alnus cordata C 99

Ash Fraxinus excelsior WS 87

Ash, manna Fraxinus ornus WS 88

Aspen Populus tremula CUT 119

Beech Fagus sylvatica N 44

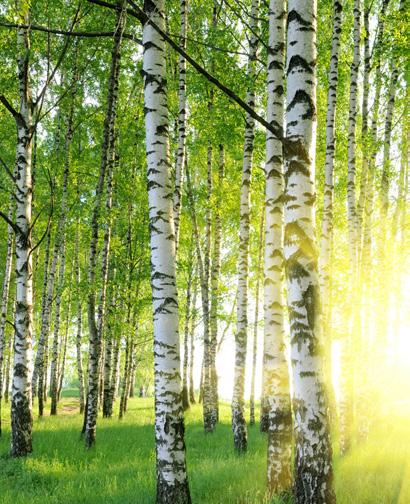

Birch, downy

Betula pubescens C 101

Birch, silver Betula pendula C 100

Blackthorn Prunus spinosa FF 70

Box

Buckeye, sweet

Buckthorn, alder

Buckthorn, purging

Buxus sempervirens FF 59

Aesculus flava N 46

Frangula alnus FF 73

Rhamnus cathartica FF 72

Buckthorn, sea Hippophae rhamnoides FF 74

Butcher’s broom

Ruscus aculeatus FF 60

Cedar of Lebanon Cedrus lebani C 104

Cherry, bird Prunus padus FF 69

Cherry, wild

Chestnut, horse

Chestnut, Indian horse

Prunus avium FF 68

Aesculus hippocastanum N 45

Aesculus indica N 46

Chestnut, sweet Castanea sativa N 47

Crab apple Malus sylvestris FF 79

Daphne

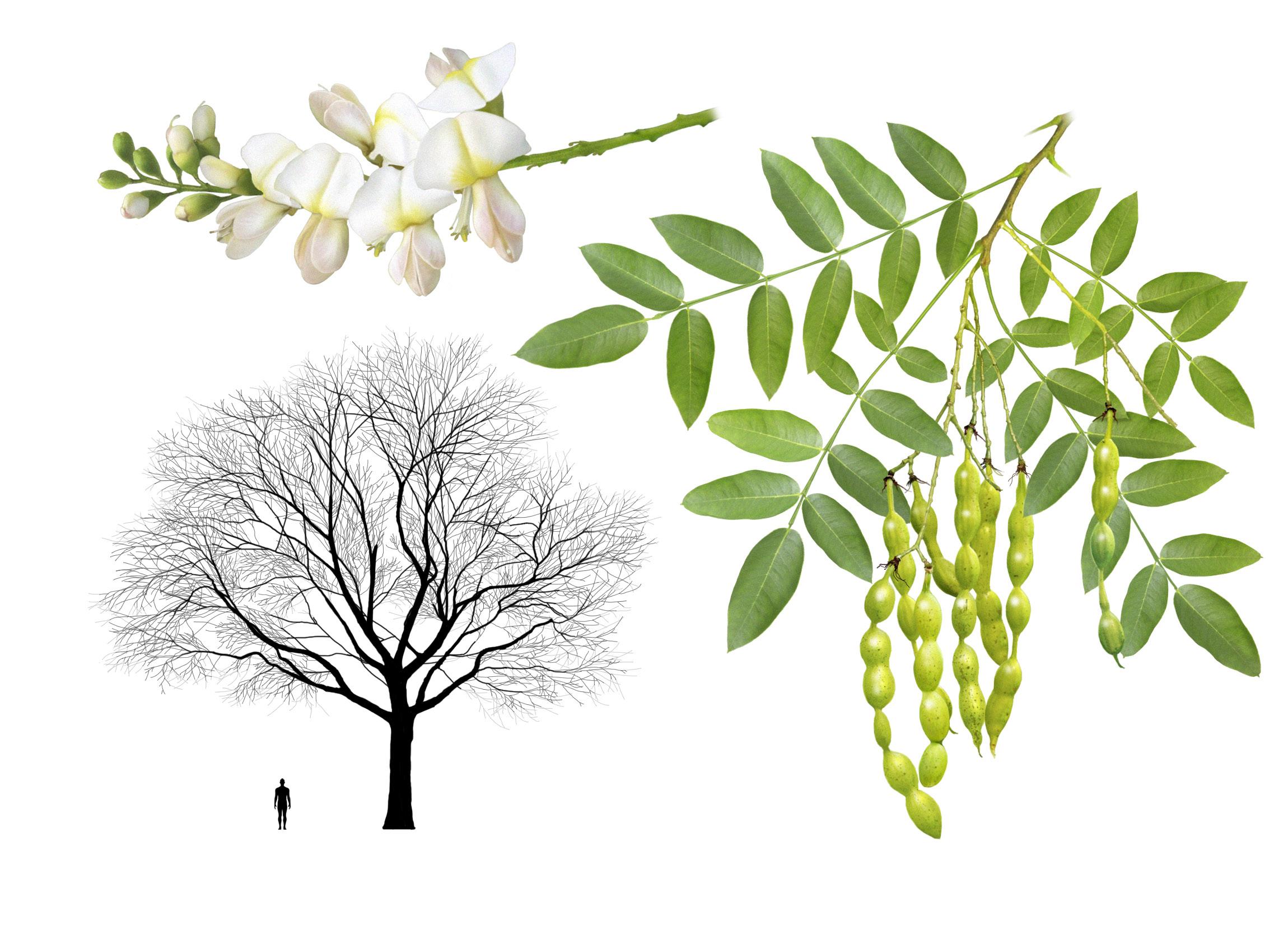

Daphne mezereum FF 77

Dogwood Cornus sanguinea FF 57

Elder Sambucus nigra FF 78

Elm, wych Ulmus glabra WS 95

Guelder rose Viburnum opulus FF 55

Handkerchief tree

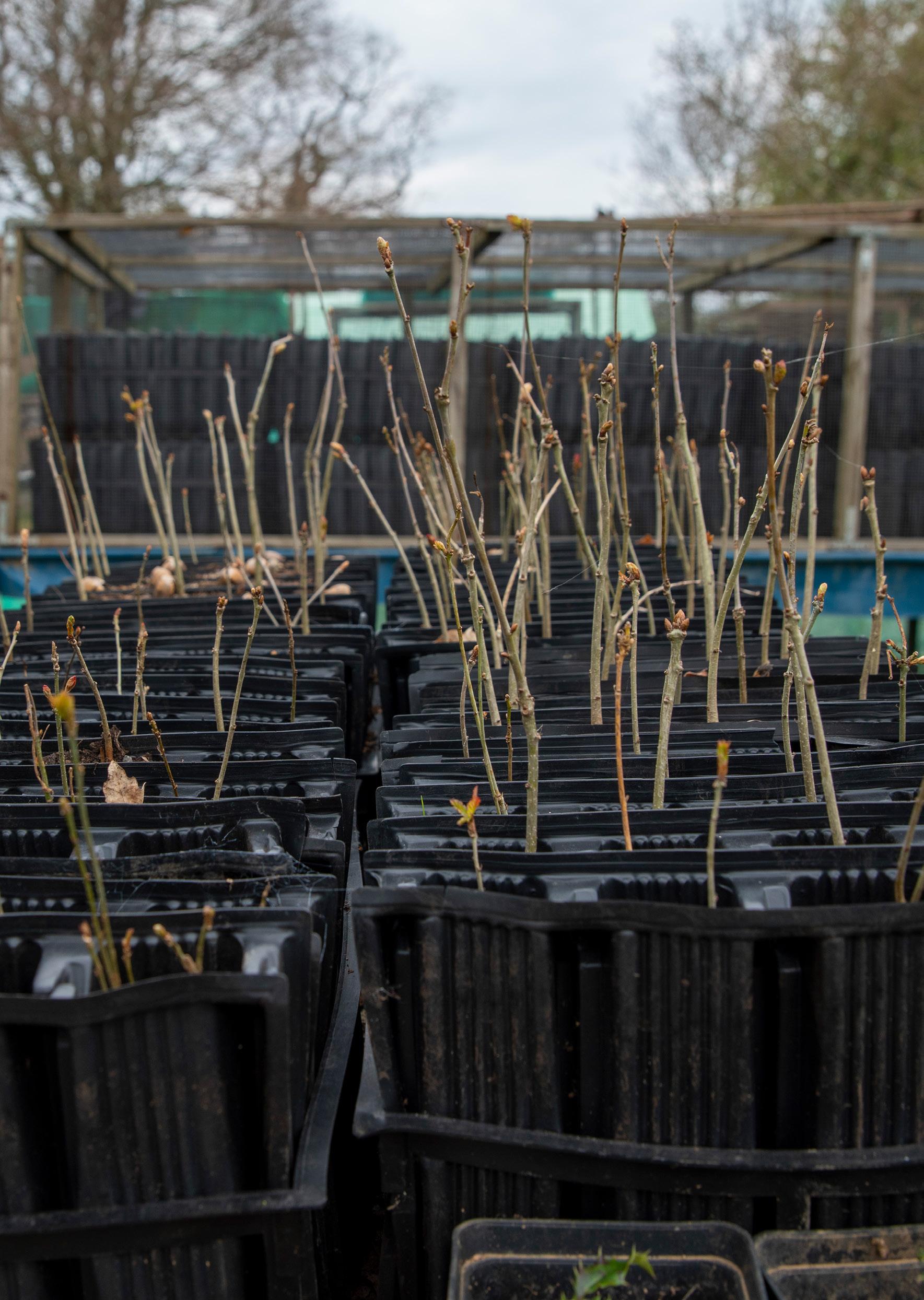

Davidia involucrata N 49

Hawthorn Crataegus monogyna FF 53

Hawthorn, Midland Crataegus laevigata FF 54

Hazel Corylus avellana N 42

Hazel, Turkish Corylus colurna N 43

Holly Ilex aquifolium FF 51

Honey locust Gleditsia triacanthos P 110

Hornbeam Carpinus betulus WS 91

Indian bean tree Catalpa bignonioides P 109

Judas tree Cercis siliquastrum P 108

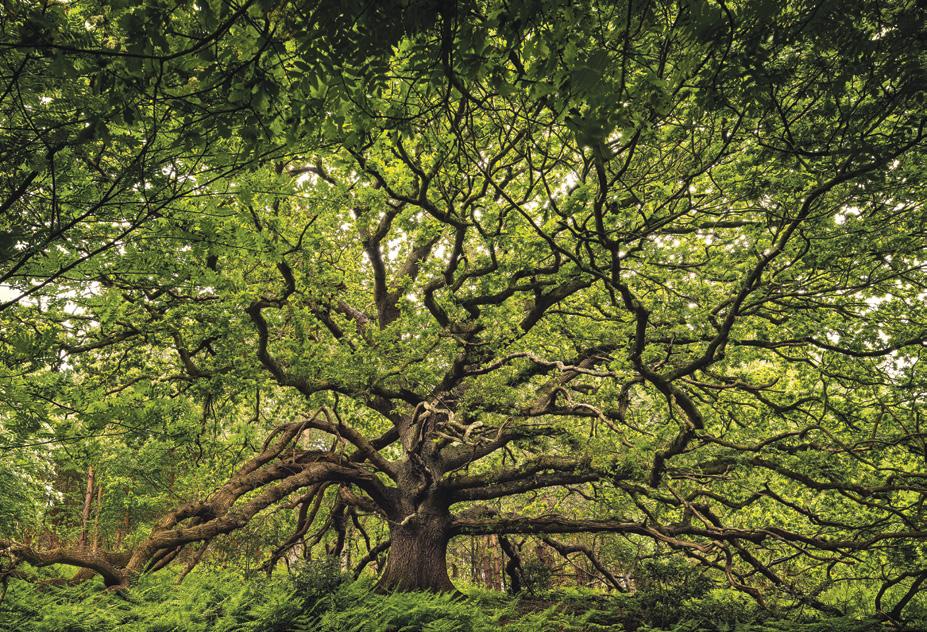

Trees give us oxygen, store carbon, stabilise the soil and support wildlife, so let’s get growing!

Richard Griffin/Shutterstock

The trees in our woodlands, hedgerows, gardens, streets and parks create a rich, diverse landscape for us all, and are often crucial to our sense of place. They provide homes for wildlife, improve the quality of the air we breathe and help us tackle climate change. They contribute to our wellbeing, help us to celebrate events or mark moments in time, and soften and beautify the places where we live, work and play.

Show them some love

The great thing about growing trees from seed is that anyone can do it – and it’s incredibly satisfying. Seeing a tiny seed we’ve pressed into the soil sprout and grow into a beautiful tree is the ultimate in feel-good. It’s also a great way to give back to your environment. Not every seed you plant will become a magnificent tree or a landmark in a wildlife hedgerow, but, with care, many of them can. Most trees will outlive us, so we plant for future generations, just as our ancestors did for us.

Whether you’re starting off with a few pots on your patio or balcony, growing a whole new woodland or setting up a Community Tree Nursery enterprise, we’ve covered everything you need to know in this guide to help you grow healthy young trees. You’ll find clear expert advice –including

n To grow trees that will thrive locally,

n To increase numbers of rare native species,

n To produce lots of trees cheaply,

n To grow a specific tree that may be difficult to buy.

step-by-step guides, illustrations and growing calendars – on what species to grow and how to collect, handle, stratify and germinate the seeds. You can also find some helpful demonstration videos online at www.treegrowersguide.org.uk

Once you’ve germinated and grown your first tree from seed, you may become hooked and find that every time you go for a walk, you are looking out for seeds and fruits to harvest. By raising a wide range of local trees from seeds – including unusual species that many commercial nurseries don’t usually grow – you can help to fill the gaps in supply and promote diversity. And all you need as you wander around is a paper bag and a pencil.

Remember, many trees are easy to grow from seed, just give it a go and see what happens.

Happy growing!

Different trees have different purposes and needs. Choose what to plant based on the space you have and what you want from your trees.

If you’re going to grow your own trees, you want to choose the right ones. The trees may be for your own planting project or to pass on to others in your community. Either way, growing suitable species is important as you don’t want to spend time and effort growing trees that won’t find a home. If you’re planning to pass on your newly grown trees, make sure you have identified somebody who is happy to take the type of trees you’re growing before you start.

Growing trees is a long-term commitment and you need to select species that are suitable for the space where they will be planted. It’s important to understand the size a tree will be when fully grown, and how quickly it will reach its maximum size. It’s not unusual to see small front gardens overwhelmed by massive trees that were probably planted by people who didn’t realise how big the young trees would get.

Horse chestnuts, for example, are easy to grow and when they are just a few years old, they make

Be sure you know how much space your young trees will need to grow before you start digging

beautiful small trees with characteristic handshaped leaves that are attractive to children and adults alike. However, within a few years, these fast-growing trees can become too big for a small garden, their dense canopies casting heavy shade that blocks out the light.

As well as size and speed of growth, there are other things to consider when deciding what trees to grow. If space is limited and you only have room for a small tree, look for a species that will provide interest throughout the year. Try to pick a tree that has attractive flowers, good autumn leaf colour or berries, and interesting bark that can be appreciated during the winter.

In small spaces, also think about the overall tree shape. Look for a species that is columnar in shape or narrows towards the top (fastigiate) with an upright or dense branching structure.

If space is limited and you only have room for a small tree, look for a species that will provide interest throughout the year.

If you have a larger garden or space to grow trees, then consider the ultimate size of the trees and space them out accordingly. Look at the height and spread they are likely to achieve in 20 years and give them room or you may need to remove some of the trees later on.

Alternatively, if you’re planting groups of trees, woodlands or shelterbelts (trees planted to block the wind) for example, you can deliberately plant at higher densities and then thin the trees out as they become crowded, leaving only the best and strongest specimens standing.

If you want to encourage wildlife, or are

planting in rural locations, select native species. Ornamental trees with fleshy fruits are good for birds. Do some research online, contact your local Wildlife Trust or local authority Tree Officer as they may be able to give you advice on species choice and any rare species particular to your area.

If you’re still not sure what to grow, look at which trees grow well in your neighbourhood, particularly if you live in exposed or coastal areas where trees will need to be adapted to very specific climatic conditions.

Some trees can grow well in large pots or containers, but all thrive and reach their best potential when grown out in a suitable location.

The UK has a wonderful variety of unique habitats, which support special wildlife. It’s important to plant trees where they will enhance a habitat, not damage it or make it unsuitable for sensitive species that may be dependent on certain conditions. For example, shading caused by trees planted on heathland could adversely affect rare heath wildlife, including plants, insects, birds and reptiles, which is already in decline.

Wetlands such as marshy grassland, bogs and fens support wildlife that can’t survive elsewhere and saturated soils store a huge amount of carbon. Planting trees in wetlands dries them out, and can cause a decline in biodiversity and the release of sequestered carbon.

Decisions about planting should only be made when it’s possible to assess the habitat you aim to plant into, though some important habitats are not always obvious to an untrained eye. Some grasslands that look unimpressive in winter, for example, may be vital for wildlife, bursting with wildflowers, bees and birds in spring and summer. Even bare earth is important for certain insect species, such as solitary bees, butterflies and reptiles. Assessing the habitat is especially important if you’re looking to establish new woodlands, so always seek good ecological advice before embarking on large-scale plantings.

Our handy guide to getting out into your local area and collecting the seeds you’ll grow into new trees

Tree seeds come in a huge range of sizes, shapes and colours designed to maximise the tree’s chances of survival. They are living things that, if treated with care throughout the collection, processing, storage and dormancy periods, will germinate and grow into strong, healthy trees.

All trees have different growth rates and germination characteristics, and need individual treatments and processes to enable a consistent successful germination rate.

When collecting native tree seeds, look for areas of ancient woodland and old hedgerows that harbour mature specimens. You can also harvest seeds from orchards, parks and arboretums, in fact anywhere that trees grow and have plentiful seeds. Don’t forget to ask for the landowner’s permission before collecting any seeds. Visit the site a few weeks before you plan to collect the seeds, in order to check on their quality and quantity. You’ll find the most tree seeds where there is plenty of light, and this is also where flowers are most likely to be in bloom. This includes around open areas, woodland edges, glades, woodland clearings and old hedges.

When collecting seeds, avoid trees that look diseased. Indicators that a tree may not be healthy include stained bark, the appearance of ‘bleeding’, large areas of dead branches or bark falling away. Leaves may also be withered or an unusual colour. Compare the tree to one of the same species nearby to see if one looks healthier. If in doubt, find another tree to collect seeds from.

Collect seeds from as many trees of the same species as possible (between 20 and 50+ trees is ideal) to achieve maximum genetic diversity.

Seeds must be fertile to germinate, so the best place to harvest them is places where there are groups of trees, and therefore cross pollination and fertilisation are likely.

Very few trees produce good crops of seeds every year. Keep an eye on the quality and quantity of seeds developing on the parent trees. Check the seeds are ripe before you collect them.

When ripe, seeds should be picked directly from the tree or gathered from the ground. You can use any suitable container to take your seeds home, but don’t store them in plastic bags as the seeds become too moist, and this reduces their chances

Collecting spindle seed capsules

of germination. Put the seeds from different species of trees in separate bags, labelled clearly. The ideal situation is to collect seeds from trees that are growing well in your area, and are therefore obviously suited to local conditions. Think carefully before collecting seeds from trees that are hundreds of miles away from where you will be planting. Trees adapt to the local conditions, so seeds collected in Sussex may not produce healthy trees in Perthshire, for example.

Timing is everything

Don’t collect the first seeds to fall from a tree, as later seeds are more likely to be of better quality. Watch carefully and be ready to act promptly when the seeds ripen – delaying too long may mean squirrels, jays and other wildlife beat you to the harvest! That said, always leave some seeds behind, as they are an important winter food source for wildlife.

Climbing trees can be dangerous, so only collect seeds you can reach from the ground. Use gloves if you are collecting seeds from spiny trees or bushes. If you want to collect seeds from the lower branches of trees, pick them by hand or use a hooked stick to carefully pull branches down to within reach.

It’s a good idea to create a seed collection calendar, and site cards detailing the seeds’ location and landowner’s contact details for future years.

Trees such as willows and poplars grow better from cuttings than from seeds. When seeds are difficult to obtain, cuttings can also be taken from alders, elders, hazels, hollies and mulberries. Generally, cuttings should be taken in late autumn or early winter. These cuttings should be set upright in moist, well-drained soils. Poplars and willows root so readily that anyone can plant them with a good chance of success.

Taking a willow cutting

1. Generally cuttings should be taken in late autumn or early winter.

2. Find a new branch that is about as thick as a pencil and has lots of buds on it.

3. Take your cutting from the branch just above a fork, using a pair of secateurs.

4. Cut the branch into 20cm lengths, each containing at least two buds.

5. Make the lower cut square-on to the branch, just below a bud. The top cut should be made at an angle about 1cm above the top bud.

6. Store the cuttings by burying them in moist sand or peat-free compost, in a cool, dark place such as a garage or shed.

7. Dig a hole with a trowel or spade and plant the cutting, so that only 5cm of it remains above the ground. The best time to do this is between mid-January and March.

8. By late spring, the cutting should have produced at least two or more sprouts. Cut off all but the strongest sprout on each plant. In the autumn, it can be transplanted to its final destination.

If you plan to sell seeds you’ve gathered or trees you’ve grown, you need to know about the Forest Reproductive Material (Great Britain) Regulations. These regulations are a control system for seeds, cuttings and planting stock that is used for forestry purposes in Great Britain. They help to ensure biosecurity (security from pests and diseases) and genetic diversity and quality of tree stocks across the UK. The regulations ensure that tree-planting stock is traceable throughout the collection and production process to a registered source of ‘basic material’. For example, seeds must be traceable back to the tree from which they were collected so that buyers can have information about the trees

or seeds they buy and their genetic quality.

If you intend to sell your seeds or trees, you must register as a Forest Reproductive Material (FRM) supplier before you collect tree seeds, cuttings and grow trees.

If you are collecting seeds for sale from the 50 controlled species, which include alder, beech, birch, hornbeam, oak, poplar species including aspen, small and large-leaved lime and wild cherry, you’ll need to notify the Forestry Commission of your intention to collect seeds at least 14 days before the collection date.

You can find out more here: www.gov.uk/guidance/marketing-forestreproductive-material-for-forestry-purposes

n Many nuts have a hard or spiky green outer shell, inside which there may, or may not, be a seed. Examples include walnut, horse chestnut and sweet chestnut. If a hard or spiky outer casing exists, carefully remove it without damaging the nut inside.

n Other nuts, such as oak, beech and hazel, have a hard casing that does not need to be removed.

n You can identify viable seeds using the ‘float test’. This involves putting the seeds in a bucket or bowl of water. Those that float are unlikely to have viable seed inside and should be discarded.

n Nuts will produce a radicle, which is the first root. This process is called ‘chitting’. Chitting can be encouraged by keeping the seeds in a bucket of leaf mould and gently turning them so they do not become too damp and start to rot. Once you see

the radicle start to sprout, gently remove the seed and plant it.

n These seeds can be direct sown into a suitable mix of soil and compost– see page 21 for an example mixture.

n Remember, squirrels, jays, voles and other small mammals love nuts and will remove them from the earth and from pots. Always protect the seeds you’ve planted by covering your pots or troughs with wire mesh to keep unwanted guests out.

Sprouting acorn

When handled with care, tree seeds will fulfil their potential to germinate, grow and develop into healthy plants

Most tree seeds are contained in some kind of fruit – good examples are apple pips and cherry stones –from which they need to be extracted and then cleaned. Different tree fruits require different processes to remove the seeds. The method you should use depends on the type of fruit or seeds you have collected – nuts, fleshy fruits, winged seeds, cones or pods.

Once you have separated your seeds into types, you need to know whether they should be either stratified for the winter or sown immediately into pots or seedbeds. All the information you need can be found in the guide from page 32

Don’t be disappointed if not all your seeds germinate, but by manually processing the seeds you can optimise germination and reduce the time it takes for them to grow.

n Trees that produce fleshy fruits are the most time-consuming to process, as much of the fleshy material needs to be removed. In nature, animals, microorganisms and weathering will break down the surrounding flesh from the seed.

n Fleshy fruits or berries can have stones, like blackthorn, hawthorn and wild cherry, pips like crab apple and guelder rose, or tiny seeds like rowan.

n The stones, pips or seeds need to be extracted from the fruit, as this can inhibit germination or increase the likelihood of diseases affecting the storage and viability of the seed.

n To remove the flesh, place the fruits in a bowl of water and gently squash with a potato masher or similar equipment to break the flesh. Then a rotating motion can be used until the fruit is separated from the seed. Viable seeds will sink to the bottom and the residue of the fleshy fruit can be discarded.

n For rowan and mulberry, put the berries in a sieve and gently squeeze them with your fingers under running water to release the seeds.

apples should be cut open with a knife to remove the seeds. Rinse the seeds and then dry

n Crab apples are easily scored around with a sharp knife. The apple can then be broken in half and the pips removed. Do not cut through the pips!

n For spindle seeds, you need to remove the pink outer shell. Inside there can be multiple seeds. These are covered in a bright orange skin, which needs to be removed and can be gently peeled off.

n For many fleshy fruits, using a rough surface such as a paving slab or purpose-made scarifying board (a wire mesh attached to a wooden block) can speed up the seed-cleaning process significantly.

n The seeds should be rinsed to remove any remaining flesh and reduce the likelihood of pests and diseases affecting them during storage. The seeds can then be surface dried and stored dry or stored in slightly moist coir (coconut husk compost), or in an equal mixture of compost and sand. The best methods for different tree species are covered on page 32 onwards.

n The seeds of all fleshy fruits need to be stratified over the winter. For our easy-to-follow guide to stratification, see page 22

n Winged seeds are usually collected from the tree when they are still slightly green. These include the seeds of field maple, sycamore, ash, lime, hornbeam and wych elm.

n They need to be dry before they are stored, especially if they are collected when damp from morning dew or rain.

n To dry them, the seeds should be laid out and turned every two days until they are dry.

n Store them in paper bags and check them every week until you are ready to stratify them. How long you wait to stratify will vary from year to year, depending on the temperature and the species of tree. For guidance on this, see the relevant tree Seed Guide from page 32 onwards.

n Winged seeds can be planted with the wings left on.

n It can speed up germination if the seed is removed from the outer casing, especially for hornbeams.

n Wych elm is best collected in summer and should be sown immediately after collection.

n Trees that have cones include Scots pine, redwood, alder and birch.

n Put ripe cones in a paper bag to dry out naturally for a few days – but avoid direct heat from, for example, direct sunlight, a radiator or a fire.

n When the cones are dry, they will open up and release their seeds, which are then ready to be sown.

n Alder seeds are contained in cones, which should be harvested once they turn from green to black. The seeds can be shaken from the cones and stored dry in paper bags until you are ready to sow them.

Alder produces catkins and cones

n Though technically not a cone, the catkins of birch are easy to process. Collect them during dry weather when they are brown and ripe. They can simply be rubbed gently to get them to separate, and the seeds stored in paper bags.

n Alder and birch seeds can be stored dry. Four weeks before sowing, soak them in cold water for 24 to 48 hours and leave them to surface dry. Then place them in a plastic bag, mixed with some moist horticulture sand, and place them in a fridge.

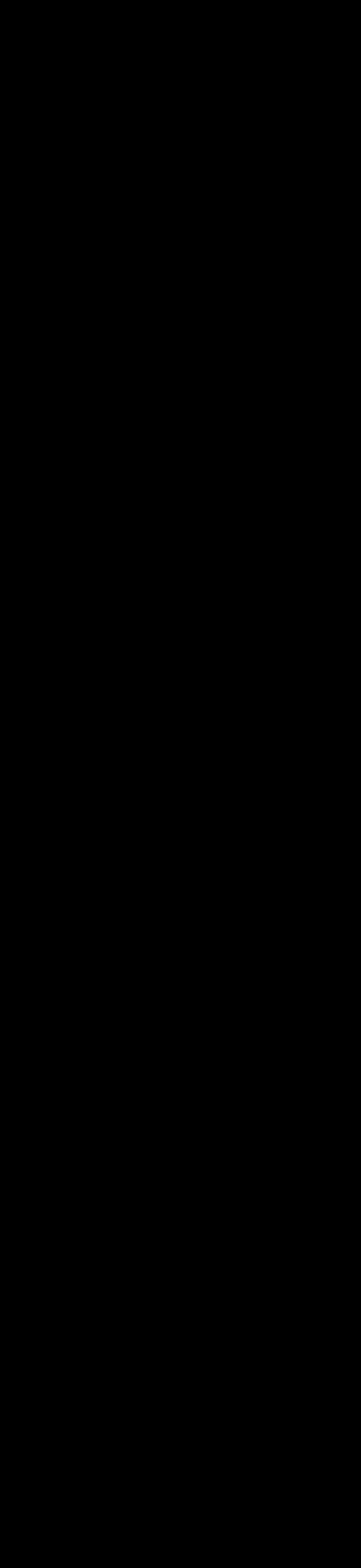

n Trees that have seed pods include laburnum, Indian bean tree and false acacia.

n Collect the seed pods when they are ripe, and place them in a paper bag, out of direct sunlight, to dry out naturally for a few days.

n When the pods are dry, simply break them open to remove the seeds.

Stratification is necessary to prepare pine seeds for germination

Some seeds require treatment that simulates natural conditions to germinate properly. You can do this naturally or artificially...

Very few tree seeds will germinate (shoot or sprout) without exposure to the cold over the course of at least one winter. Other species take even longer, needing the following summer plus another winter before they start to show signs of life.

This is because of a natural defence mechanism built into the seeds called dormancy, which ensures they don’t grow during the winter, when young seedlings might be killed by the cold.

Tree growers have developed a technique called ‘stratification’ that mimics this natural process: dormancy is broken by rising temperatures after a period of cold in order to allow germination

(when seeds develop their first roots and shoots) to begin. There are two types of stratification to consider – natural and artificial.

1. Choose your container

Look for a container with a minimum depth of 30cm and a surface area of about 30x60cm. We recommend the metal troughs used to feed livestock, but a dustbin, bucket or large pot will work equally well for small-scale growing. The depth is key as it supports an even temperature distribution that helps stop the seeds

from remaining frozen during periods of very cold temperatures. Make sure there are drainage holes, and add a layer of coarse gravel or similar to the bottom of the container to aid drainage.

2. Create your stratification medium

Some seeds need to be in contact with a moistureretaining medium before they will germinate. There are a variety of suitable stratification mediums you can try.

One recipe we use is to combine equal measures of peat-free potting compost (fresh or recycled) with a coarse-particle material, such as barkchips, perlite, sand or grit. You can also re-use waste material by partially filling deep containers with a reasonably large volume of homemade compost, which saves money and introduces beneficial microorganisms. However, homemade compost will contain the seeds of weeds, so add a thick (5cm) layer of purpose-made seed compost or one-part new potting compost and one-part sand on top, to act as a natural weed-seed suppressant.

Seeds can be stratified in layers, either singly near the surface or in multiple layers. Seeds such as field maple are best placed in a single layer. Depending on how much time you have, you can stratify seeds one by one or scatter them by hand (known as ‘broadcast sowing’). Aim to space the seeds apart by at least twice their size, so they have enough space to grow.

Compost improves soil quality enabling it to better retain air, nutrients and moisture. This leads to healthier roots, which in turn enable healthier growth

Cover the seeds with a 1.5cm-deep layer of seed compost or a 1:1 mix of compost and sand. Alternatively, if you have many large seeds, such as hazelnuts or acorns, it may be beneficial to stratify them to make the best use of your nursery space. Mix the seeds into a stratification medium and place this in a bucket or large pot. The viability of seeds is hard to know, but potentially it could be quite low, so make sure you stratify lots of seeds to avoid disappointment.

Water the container with a watering can fitted with a rose or a hose on the fine shower setting. It is essential to keep the mixture moist, but not saturated. Take a pinch between your thumb and forefinger – if you can squeeze out a drop of water, it’s moist enough. Finally, cover the container with a fine wire-mesh lid to keep out birds and rodents. The container should be positioned so it is kept cool and exposed to the elements.

4. Check for germination in spring

In spring, tip out the stratification mixture and remove any seeds that are ‘chitting’ (showing small shoots or roots). These seeds are germinating and are ready for sowing. Any seeds that haven’t germinated should be put back into the mixture. Keep checking them every week over the spring, so that you can remove and sow any that start to germinate.

Once the seeds start germinating, it’s important to sow them quickly, as the new shoots are delicate and fragile. If they get too large, they can easily be damaged during planting.

If any seeds haven’t germinated by the end of the spring, don’t be disheartened. It can take two winters for natural stratification to break the dormancy of some seeds, such as hazel, wild cherry, hawthorn and small leaved-lime, but check that the seeds haven’t rotted before continuing to stratify them.

Once the seeds start germinating, it’s important to sow them quickly, as the new shoots are fragile. If they get too large, they can be damaged during planting.

Put your seeds in a plastic bag or sealable container with some coir, or compost mixed with sand

Artificial stratification creates a controlled temperature and moisture environment for seeds, and can speed up germination. Natural winter temperatures vary and one of the risks associated with the climate crisis is the potential for reduced seed germination due to warmer winters. One way to artificially stratify tree seeds is to place them in a domestic fridge, to ensure they receive a consistent cold period to help break dormancy. Harvested seeds should be processed to remove any flesh to prepare them for fridge stratification.

1. Choose your container

Select a suitable container to store your seeds in, such as a small plastic storage container with a lid or a press-seal bag. A press-seal bag has the advantage of fitting into a much smaller space, which is useful if you are planning on fridgestratifying a large number of seeds.

Bags also allow easier control of ventilation and moisture content, as they can be adjusted.

Artificial stratification creates a controlled environment for seeds, and can speed up germination.

2. Prepare your stratification medium

Fill your bag or container with a medium that holds moisture, normally a mix of compost and sand – see suggested recipe on page 23. Coir (coconut husk compost) is also good. It’s easy to control the moisture level and it’s an almost sterile medium, reducing the risk of pests and diseases infecting the seeds. Start by ensuring your media is just moist. If using coir, squeeze a handful until it stops dripping.

3. Mix your seeds with your medium

Mix your chosen seeds and medium together, ensuring that each seed is in contact with the

medium, and some seeds are visible against the side of the bag or container. This can aid with checking seed health.

Ensure each bag is clearly labelled with the tree species, date and approximate seed number (and/or weight). It’s a good idea to record when the seeds have gone into the fridge and when you plan to take them out. Setting electronic reminders may be useful. The seed containers can now be put in the fridge for several months depending on the species.

4. Check your seeds

Seeds should be checked regularly for health and moisture – at least weekly at first, then this can drop to fortnightly until they start to show signs of germination. At this point, you need to increase the regularity of checking to every few days. Open your containers and look for signs of mould. Use your fingers to judge if any water needs to be added to maintain moisture levels. If there is any mould visible, see if it can be rubbed off. Give the seed a gentle squeeze and if it is still firm, it’s likely that the mould is just growing on any remaining fruit pulp and is not likely to be a cause for concern. If the seed feels soft, it should be discarded, and the remaining seeds checked thoroughly.

Some species may germinate in the fridge, and these seedlings need to be removed and potted carefully. Having grown in a cold environment, they will be very soft and may damage easily. Be careful not to damage any other seeds, which may just be starting to germinate.

5. Deal with ungerminated seeds

Ungerminated seeds can be put in a sheltered area. Transferring them from their small container to a deep and wide one will allow for more even temperature and moisture distribution, which will prevent the seeds from being damaged by extreme weather.

After one to two years, you may choose to discard them or spread them on cultivated ground, where any remaining viable dormant seeds could germinate in the future.

6. Decide how long to keep your seeds in the fridge

The calendar on each tree species page offers a timeline for collecting, stratifying and sowing native tree species. For each tree, the exact timing of the different stages may vary from year to year, and in different parts of the country. Trial and error, and excellent record keeping, will help you build up local knowledge to maximise successful germination.

Once the seeds start germinating, it’s important to plant them straightaway

Now your seeds are germinating, it’s time to give your young trees the best start in life. Here’s our advice for sowing success

Now your seeds have experienced the required cold period for the species, whether by natural or artificial stratification, any that are germinating can be removed from the stratification medium and sown. Alternatively, you can remove and sow all the seeds when 10% of them have chitted, in the hope that this is indicative that the remaining seeds are now close to germination.

Small seeds such as those of birch and alder should be scattered on the surface of the compost or soil, together with the medium, and covered with a thin layer of your chosen seed-potting compost. Larger seeds are usually sown singly and covered with soil or compost to about one-and-a-half times their average length.

Sow your seeds in potting compost in a suitable container such as a pot or root trainer, or outdoors in a seedbed.

An ideal method for growing a single tree is in a single pot or clean, recycled container, such as a milk or juice carton with the top cut off. Pierce small holes in the bottom to allow water to escape. Fill it with peat-free potting compost and sow either a single germinating seed, or a pinch of small seeds.

As the tree grows, water regularly to ensure the compost doesn’t dry out. Feed during periods of active growth with liquid plant food.

After a few months, the young tree may outgrow its pot, so the tree should be transferred to a larger container or planted out in the ground.

Root trainers are small, moulded plastic cells. They come in hinged packs with four or five cells in each row, allowing you to open them up to

examine how your young trees are developing. Five or six rows of these root trainer packs can be placed together in a tray, allowing 20 or more trees to be grown in a small space. Root trainers can be obtained from most garden centres and shops or from specialised stockists.

As with containers or pots, fill root trainers with peat-free potting compost and in each one, sow either a single germinating seed or a pinch of small seeds. As the trees grow, water them regularly. Add plant feed during active growth.

When the young trees have grown well-developed roots, they are ready to be planted out.

A seedbed is a mini tree nursery. To create one, first prepare the soil to ensure it is free draining and if necessary add some coarse grit to the soil to improve drainage. Either sow your seeds over the surface of the seedbed before covering them with a layer of soil, or sow in a drill – a shallow groove scraped out to the required depth – and cover with soil. Use a protective fence to keep rabbits and rodents away from your seeds and

If needed, protect young trees with biodegradable guards or re-use your existing plastic guards

As the young trees grow, water them regularly. Trees growing in seedbeds can be left for a year or more before being planted out.

Wherever you sow your seeds, you’ll need to ensure they don’t get waterlogged. If you’re using containers, ensure there are holes in the bottom to allow water to escape. If you’re using outdoor seedbeds with heavy soils, dig in sand and grit to improve drainage and prevent waterlogging. Germinating seeds need shelter from hot sun, cold winds, frost, birds, mice and other animals. A shady spot against a wall is ideal. Make sure you water your containers regularly, especially in summer. Occasionally, give the seedlings some liquid plant feed and weed containers and seedbeds – try to avoid pulling up any young trees by mistake!

Young trees can be grown in root trainers for up to three years to establish a set of good deep roots

When your seedlings have grown into small trees (at least 20cm tall), they can be moved to their final growing locations. This should be carried out during the winter planting season, normally the middle of November to the end of March.

There are many potential places where trees can be planted, including gardens, communal and public open spaces, road verges, parks, hedgerows, woodlands and churchyards. However, it’s vital that you secure the landowner’s permission before you start planting, and make sure there’ll be enough space for your tree when it reaches maturity. Choose well-drained sites

where the ground is not too hard. Test this by seeing whether you can push a trowel or spade into the ground simply by leaning on it.

If voles, rabbits, hares, squirrels, deer, livestock, lawnmowers or strimmers are a threat in the area, it will be wise to protect your newly planted tree from bark damage. There are a range of options, depending on the type of site you are planting and whether you’re planting individual trees or a hedgerow. They include tree guards (protective tubes that fit round tree stems) in various shapes and sizes, wire netting and wooden fencing. Protecting your young trees increases the environmental impact and financial costs of your planting. Guards have to be manufactured and transported, and they’re often left in-situ long after the saplings have matured. Plastic guards will ultimately break down into plastic litter and microplastics, polluting the environment. If possible, try to re-use old plastic guards or consider biodegradable alternatives, such as those made from cardboard or wool. Always remove guards from trees and hedgerows when they are no longer needed, and re-use or recycle them.

If you are planting a young tree from a root trainer, use a spade to make a slot in the ground. Widen the slot by wiggling the spade backwards and forwards and then put the tree and its soil in the centre of the slot. Carefully push the sides of the slot back together using your foot to close the slot, and firm the soil around the tree.

It’s best to transplant a bare-root tree from a seedbed when it is at least 20cm tall. Dig it up with a spade or fork, ease the tree from the ground and shake to remove loose soil. Make sure the new hole

Make sure the root collar is the same height as the ground

you dig for your tree is big enough to enable you to spread out the roots and, equally important, plant the tree so that the root collar – the point from which the roots grow – is at the soil surface. Fill the hole with soil, remove any air pockets and firm the tree down.

If you don’t plan to plant the tree immediately, wrap the roots in plastic to protect them and keep them moist. Don’t dig up more trees than you need at a time. Don’t leave any plants, particularly those in bags, exposed to direct sunlight or wind.

If you’re planting a young tree from a pot or container, ensure the hole is deep enough to take all the soil and roots. If required, use a little extra peat-free compost or fine soil to pack around the tree. Moisten the compost before removing the tree from its pot or container. When planted, the surface of the soil from the pot should be level with the soil around it.

All trees and seeds have distinctive features that help with identification –you just need to know what to look out for. Our simple ID guide is here to help.

The species included in this guide are either native to, or commonly found in, the British Isles. We have divided their fruits and seeds into the main groups described in more detail on pages 16–21, with the addition of some trees that are best propagated by cuttings.

n Nuts Trees and shrubs that produce genuine nuts, as well as those that produce nut-like seeds (e.g. oaks and beech).

n Fleshy fruits Trees that produce berries and fruits (e.g. holly and yew).

n Winged seeds Trees that produce seeds with ‘wings’ (e.g. field maple and sycamore).

n Cones Trees with seeds contained in a cone (e.g. pines) or conelike structures (e.g. alders and birches).

n Pods Trees that produce pods, which often resemble the pods of peas (e.g. laburnum).

n Cuttings Trees, such as willows and poplars, do produce seeds but are most easily propagated by taking cuttings from the parent tree.

For each species of tree, this guide provides:

n Key facts about the tree.

n A silhouette showing the shape of a mature specimen.

n Key identification features for the leaves and seeds, and some flowers.

n Other species with which the tree may be easily confused.

n ‘Right tree, right place’ – our helpful, at-a-glance guide to help you decide which trees are best suited to your space.

n Instructions about how to collect tree seeds and grow them.

n A calendar of when to collect, store, stratify, sow, take cuttings, grow and plant out each species.

The calendars are subject to growing conditions and climate. Planting timings are subject to the young tree being the optimum size, as indicated in the calendar. For example, planting when height is more than 20cm and root collar is more than 5mm.

Native

These tree species colonised the UK after the last ice age, before the land separated from Europe.

Non-native

These tree species are believed to have been brought to the UK from other parts of the world.

Deciduous

These tree species shed their leaves with the seasons.

Evergreen

These tree species do not shed their leaves seasonally.

Mature small trees

Mature small trees grow up to 10m tall.

Mature medium trees

Mature medium trees grow 10–20m tall.

Mature large trees

Mature large trees grow more than 20m tall.

Dioecious

These species have separate male and female trees. Pollen from the male tree is needed for the female tree to produce viable seed.

For a full explanation of terms, please see the Glossary.

Good park tree

These tree species are often large and planted in parks and large gardens for their attractive foliage or stem colour, stature and interest.

Good woodland tree

These tree species grow well in a crowded, wooded environment.

Good autumn colour

These tree species provide attractive colours in their leaves and/or stems in autumn and winter.

Good for wildlife

Particularly beneficial for a range of native wildlife, providing food and habitat.

Good street tree

Often found as street trees in urban settings, due to their ability to tolerate a variety of conditions.

Good for hedges

Form excellent hedge habitat and respond well to intermittent pruning if needed.

Good for wet habitats

Grow best in wet soils.

Toxic berries

Fruit can be toxic to humans and/or animals.

Top tip Many species have multiple benefits, we’ve selected just a few.

Top tip The calendars are a guide only. Please consider the specific requirements of each tree species.

A good time of year to gather seeds.

Store seeds in a suitable container and in a cool place before stratification. STORE

Treat seeds to break dormancy. This may take several years in some cases.

Sow seeds ready to grow.

A good time of year to take cuttings.

Grow seedlings until they are ready to plant. This may take several years in some cases.

Lift and plant trees in the winter, between November and March.

to brown

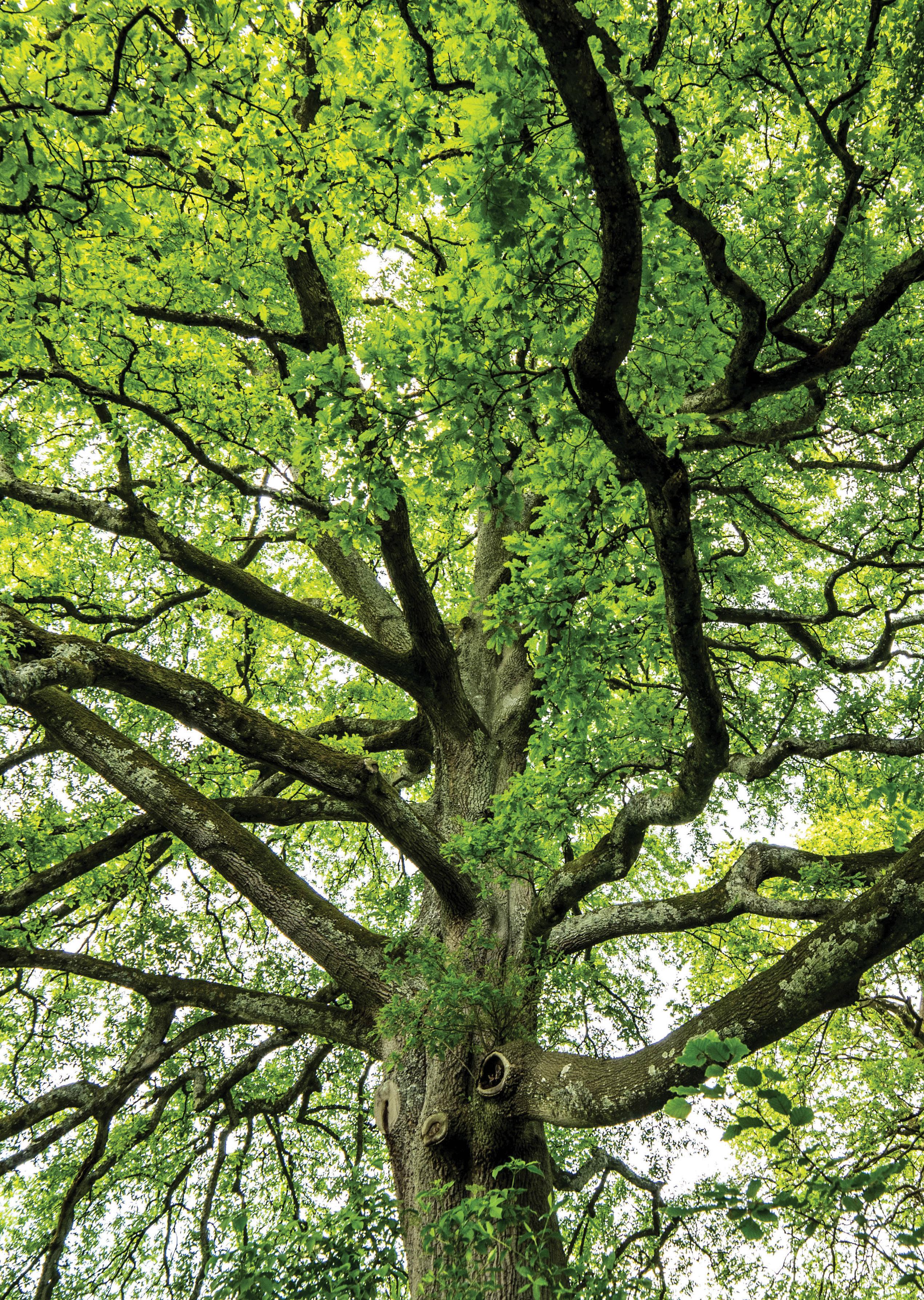

The English oak grows best on deep, fertile clays and loams, but tolerates a wide range of soils. Some trees, such as Lincolnshire’s Bowthorpe Oak, are thought to be more than 1,000 years old. English oaks can support more than 2,000 species, more than any other British tree. They also provide an important food source and roosting sites for birds and mammals.

The purple hairstreak butterfly breeds solely on oaks, and small groups can often be seen fluttering over the treetops in summer. Easily confused with: Sessile oak, Turkey oak and other oak species

Long, yellow hanging catkins distribute pollen into the air

Quercus petraea

Seed Guide

Collect the acorns from the tree, or very soon after they drop – usually from late September. The first to fall should be avoided, as they are often diseased or deformed and unlikely to grow. Separate acorns from their cups and float them in water; plant the ones that sink. To avoid your acorns drying out – which will kill them – sow straightaway in a seedbed to a depth of 2–3cm or singly, in pots, covered by a thin layer of compost. Protect from predators throughout the winter. Roots will grow during winter and the shoots will emerge in late April.

Leaves have distinct stalks

Acorns have no stalks, hence the name ‘sessile’, which means unstalked

Root collar>5mm

The sessile oak thrives in the west of Britain. It prefers areas of high rainfall and grows best in deep, well-drained clays and loams. Some trees may be more than 1,000 years old. Its branches are not closely spaced, which allows light to reach the forest floor. As a result, sessile oak woodland supports a rich ground flora, and a wide range of insects and birds, which feed in the spaces between the trees. Pied flycatchers and redstarts thrive here, jays and badgers love their acorns and caterpillars eat their leaves. Easily confused with: English oak, Turkey oak and other oak species

Seed Guide

Collect the acorns from the tree, or very soon after they drop – usually from late September. The first to fall should be avoided, as they are often diseased or deformed and unlikely to grow. Separate acorns from their cups and float them in water; plant the ones that sink. To avoid your acorns drying out – which will kill them – sow straightaway in a seedbed to a depth of 2–3cm or singly, in pots, covered by a thin layer of compost.

Protect from predators throughout the winter. Roots will grow during winter and the shoots will emerge in late April.

The Turkey oak was introduced from southern Europe in the early 18th century. It grows on light soils as far north as Scotland and is often planted in parks and gardens. The tree seeds freely and grows fast, and has become widely naturalised. Turkey oak is not as valuable to native wildlife as English and sessile oaks. It also plays host to a species of Cynipid wasp (Andricus quercuscalicis) that destroys English and sessile oak acorns. The trees should, therefore, only be planted very selectively.

Easily confused with: English oak, sessile oak and other oak species

Seed Guide

Collect the acorns from the tree, or very soon after they drop – usually from late September. The first to fall should be avoided, as they are often diseased or deformed and unlikely to grow. Separate acorns from their cups and float them in water; plant the ones that sink. To avoid your acorns drying out – which will kill them – sow straightaway in a seedbed to a depth of 2–3cm or singly, in pots, covered by a thin layer of compost. Protect from predators throughout the winter. Roots will grow during winter and the shoots will emerge in late April.

Quercus x hispanica

These large, evergreen oaks are a natural hybrid between cork oak and Turkey oak. The nature of the hybrids is variable and the trees can exhibit a variety of characteristics of both parents.

The tree takes its name from William Lucombe, who grew a number of seedlings in his nursery in Exeter around 1762. The hybrid between the species is frequent in the wild in south-west Europe and can be found growing in Britain, particularly in the south-west where it originated. One feature that aids identification is its pale grey bark, which forms corky ridges. Easily confused with: Other oak species

The acorn cups have coarse bristles

The evergreen leaves are alternate with triangular, pointed lobes

Seed Guide

Collect the acorns from the tree, or soon after they drop, usually from late September. The first to fall should be avoided, as they are often diseased or deformed and unlikely to grow. Separate acorns from their cups and float them in water; plant the ones that sink. To avoid them drying out – which will kill them – sow straightaway in a seedbed to a depth of 2–3cm or singly, in pots, covered by a layer of compost. Protect from predators over winter. Roots will grow during winter and shoots will emerge in late April. As it’s a hybrid, the seeds will not produce a tree identical to the parents.

Acorn cups are saucer-shaped

Leaves have deeply cut, triangular lobes

Acorns are nested in

Some leaves have holly-like spines

ilex

Red oak is a non-native species that can flourish on poor, dry soils and tolerates drought and urban conditions, as well as exposed locations with saltladen winds. Though liked by birds and insects, red oak doesn’t support as many species as native oak. Easily confused with: Other oak species

Holm oak was brought to Britain more than 400 years ago and grows well on a wide variety of soils. It can tolerate salty conditions and so can be found along coastlines, where its evergreen leaves are adapted to retaining moisture in hot weather. Easily confused with: Holly

Leaves resemble sweet chestnut

are bristly

Vigorous non-native oak, which can be very fast growing in the UK. As the name suggests, the leaves bear more of a resemblance in shape to sweet chestnut than to oak, and develop distinctive yellow and brown colours in autumn. Easily confused with: Sweet chestnut

Seed Guide for these oaks

Like most oaks, seed production is cyclical with heavy crops produced every two to five years. Acorns quickly lose viability if allowed to dry out, so it is best to sow them straight away in an outdoor seedbed. Germination will take between 120 days and a year. Seedlings produce a deep taproot and should be planted in their final location no later than after two growing seasons in the nursery.

For the calendar for these oaks, see English oak

Soft and hairy leaves have saw-toothed edges with a drawn-out tip

Grows to be a mediumsized tree

Long, yellow, male catkins appear in the depths of winter

This deciduous tree is found in woods and hedges across Britain. It can reach a height of 15m and grows on a range of soils, including chalk, limestone, mildly acid and clay. Male catkins appear in January or February. Hazel is usually coppiced to produce thin, flexible poles that are used for fencing, hurdles, pea and bean sticks, and thatching spars. Coppiced hazel woodlands are rich in wildlife, as the regular cutting allows light to reach the woodland floor, benefitting flowers and butterflies. Over 106 invertebrate species have been found on hazel. The nuts attract squirrels and hazel dormice.

Easily confused with: Elm, lime, mulberry, Turkish hazel

Seed Guide

Collect the first nuts in autumn as they ripen from green to brown, but be careful the squirrels don’t beat you to it. Sow immediately in a pot or seedbed. Protect from predators and severe frost. You can also place the hazelnuts in buckets of coir (a light material that does not stick) and leave covered outside over winter. Then in spring, carefully pick out the nuts that are germinating and sow them in a pot or seedbed.

Long, yellow male catkins appear in early spring

Leaves similar to hazel, but slightly more heart-shaped

Long, bristly bracts around the fruit (bristly cups)

Corylus colurna

Turkish hazel is a fast-growing, non-native tree with high ornamental value, a regular pyramidalshaped crown, and bright-green leaves that create a beautiful spectacle in autumn. In recent years, the tree has been a popular choice for urban areas, avenues, streets and parkland, where it is often preferred to lime because it does not sucker or suffer from aphid drop. Drought resistant and wind tolerant, it prefers hot summers and cold winters. It is an easily grown tree that does well in most soils. Easily confused with: Lime, hazel

Seed Guide

Collect the first nuts in autumn as they ripen from green to brown, but be careful the squirrels don’t beat you to it. Sow immediately in a pot or seedbed. Protect from predators and severe frost. You can also place the hazelnuts in buckets of coir (a light material that does not stick) and leave covered outside over winter. Then in spring, carefully pick out the nuts that are germinating and sow them in a pot or seedbed.

*Height>20cm,

The seeds are contained in a brown, prickly husk called beechmast (nuts)

The seeds are shiny brown conkers in spiky cases

brown spindles

The distinctive hand-shaped leaf has five to seven leaflets

The dominant native species on chalk and limestone, beech prefers well-drained soils, but can be found in heavy clays. It has been widely planted in parks and gardens as well as in hedging. Beech is well known for its excellent autumn colour, but the early ‘spring green’ of the leaves is also highly attractive.

The wood is strong and tough and was used for tool handles and flooring. The beechmast (nuts) make good pig feed, and are widely eaten by mice, squirrels and birds. Bats like to roost in holes in the trunk or among tangles of exposed roots.

The dense shade cast by beechwoods means

they have a restricted but specialised flora, including bird’s-nest orchid, the rare ghost orchid and various helleborines.

Some 94 species of invertebrates have been found in beech trees, including the lobster moth and barred hooked-tip moth. Easily confused with: Hornbeam

Check the first fall of beechmast in autumn – they may be empty. Collect only plump, ripe nuts from the ground. Sow immediately in a pot or seedbed, and protect from predators and severe frost.

Large, white, candle-like flowers have yellow spots that turn red with age or pollination

Aesculus hippocastanum

The horse chestnut was introduced into Britain from the Balkans in the early 17th century, and is now commonly found on village greens and in streets, parks and gardens.

It tolerates a wide range of conditions including dry sandy soils, wet clays and chalk, but prefers moist well-drained soils.

Its familiar nuts – conkers – are the essence of autumn and popular with schoolchildren. They provide food for deer and other mammals, while the flowers provide pollen for insects, particularly bees.

A new pest species has recently arrived in

YEAR 1

the UK – the horse chestnut leaf miner moth. The caterpillars eat chlorophyll from within the leaves, leaving brown spots and reducing the tree’s health. The long-term effects of this are currently unknown. See page 94 for more information.

Seed Guide

Collect plump, ripe, healthy looking nuts from the ground in autumn. Take the nuts out of their spiky casing, float them in water and only plant the ones that sink. Sow immediately in a pot or seedbed, and protect from predators and severe frost.

*Height>20cm, Root collar>6mm

Flowers in June, six weeks after horse chestnut

The seeds are dark brown conkers in smooth, leathery cases

The husks surrounding the conkers always lack spines

The leaf is made up of usually five, but sometimes seven, leaflets

Aesculus indica

Introduced to the UK from the Himalayas, Indian horse chestnut has dark-coloured conkers that are formed in spineless husks. It will grow in a variety of soils, but only becomes a large tree in loamy, well-drained soils. The species has little autumn colour.

Aesculus flava

Sometimes known as yellow buckeye, sweet buckeye has been grown in parks and gardens for its yellow autumn leaves. A native of south-eastern USA, sweet buckeye can grow in a variety of soils. Cream-coloured flower spikes, or ‘candles’, can be less impressive than those of horse chestnut.

Large, spear-shaped leaves with saw-toothed edges

The sweet chestnut was probably introduced to Britain by the Romans, who had a liking for chestnuts. The species is now widely established in Britain, being actively managed as coppiced woodland, especially in the south. The species prefers deep, moist sandy soils and drained clays, but doesn’t do well on very wet or lime-rich soils.

The strong, tough wood is good for fence posts and props, and the chestnuts are edible when roasted.

The tree provides good nest sites for birds such as woodpeckers and nuthatches, and nightingales often live in coppiced sweet chestnut woodlands.

Brownish twigs with orangeyred buds

Long, male catkins are often upright and have a distinctive, unpleasant smell

The oldest sweet chestnut in the country is the famous Tortworth chestnut, an amazing tree thought to be over 1,200 years old. This ancient hulk looks more like a small woodland rather than an individual tree.

Collect plump, ripe, healthy looking nuts from the ground in autumn. Take the nuts out of their spiky casing, float them in water and only plant the ones that sink. Sow immediately in a pot or seedbed; and protect from predators and severe frost.

Seed Guide

Collect plump, ripe, healthy looking nuts from the ground in autumn. Take the nuts out of their casing, float them in water and only plant the ones that sink. Sow immediately in a pot or seedbed, and protect from predators and severe frost.

Round, green fruit contains a wrinkled brown nut that only ripens in long, hot summers

Juglans regia

The walnut was probably introduced into Britain by the Romans and has subsequently become widespread in southern and central England, especially in hedgerows. Further north it is found largely in parks and gardens.

The tree grows best on moderately fertile, well-drained soils and will grow on chalky soils. It dislikes wet or shallow soils, or peat.

Cut twigs reveal a distinctive chambered pith

Leaves are alternate and sharply toothed

Each large leaf has seven leaflets that get larger towards the tip

Green male catkins appear in May and June

Fruit ripens from green to red-brown

Often called the ‘king of timbers’, this hardwood was used to make aeroplane propellers and is still used for cabinet making, decorative veneers and rifle butts.

The foliage of walnut gives off a scent similar

to shoe polish, and a sprig kept in a jar is said to deter flies. The walnut itself is widely eaten by humans, either pickled or raw. Rooks also like them and many trees grow from walnuts buried and forgotten by these birds.

Easily confused with: Ash, elder, rowan

Seed Guide

Collect the fruits from the tree or ground as soon as the husks darken or turn black. Remove husks and sow immediately in a pot or seedbed; protect from predators and severe frost.

Also known as the dove tree, this medium-sized deciduous tree is a native of China. It arrived in Britain in 1902, brought by the plant hunter Ernest Wilson after a dangerous journey in which his boat sank in rapids and his guide was an opium addict.

Its English name is derived from its spectacular white ‘handkerchief’-like flowers, which have made it popular in parks and gardens. The fruit is a hard green nut containing three to five seeds.

Growing well on moist, well-drained soil, this is a tree that likes full sun or partial shade, protected from strong winds.

Seed Guide

Collect the nuts from the tree in October, when they turn reddish-brown and before they split open. Each nut will contain three to five seeds. Place the seeds into polythene bags containing sand or perlite (a lightweight granular material that aids water retention). Keep in a warm place for four to six months, then store in a cold place for three months. After this time, the nuts will have split and young roots will have emerged. Plant these young seedlings out in late autumn.

Only female trees have bright red berries

Shiny, evergreen leaves have a waxy upper side and spiny edges

The holly is a widespread and distinctive native tree that grows on almost any soil. It tolerates shade well, and often grows as the understorey in woodlands, but also likes open situations and occurs widely in hedgerows.

There are male and female holly trees, which leads to one of the most commonly asked questions – ‘why doesn’t my holly produce berries?’ This will either be because the tree is male, or because there are no male trees in the area to produce pollen to fertilise the female.

The berries are eaten by birds, and the foliage

by deer and rabbits. Holly is also the foodplant of the holly blue butterfly, but only nine other invertebrate species have been found feeding on this tree.

Collect the ripe, red berries from the tree in winter. Remove the seeds from the flesh and wash them thoroughly. If the flesh is hard to remove, soak the berries for a day or two. Stratify the seeds for one or more winters. Select and sow germinating seeds each spring.

*Height>20cm,

Needles are dark green on their upper side and lighter green underneath

The red, fleshy fruit contains a single dark seed, which is poisonous

The spines on hawthorn are slightly longer than on Midland hawthorn

Fleshy, red haws contain a single seed

The oldest tree in Britain is probably a yew growing in the churchyard of Fortingall, Perthshire, which is thought to be thousands of years old. Many other ancient yews can be found in churchyards throughout Britain.

In the wild, yew trees prefer lime-rich soils and can, along with beech, become the dominant woodland type.

Historically, yew produced the finest longbows, enabling archers to fire arrows long distances.

The wildlife value of this species is limited, as the tree casts deep shade and few plants grow beneath it. The tree itself supports a limited

number of insects, though some birds eat the red flesh of the berries – known as arils – through the winter. The seed contained within the red flesh is poisonous.

Seed Guide

Collect fruit from the tree when the outer berry is a bright red colour. Remove the flesh and stratify the seeds for at least two winters. Select and sow germinating seeds in early spring of the second and successive years. Yew seeds take a long time to stratify, and the seedlings are also very slow growing, so do not be concerned.

Leaves have deeply divided lobes

flowers grow in clusters with a single style (female organ)

The hawthorn grows throughout Britain, apart from the extreme north-west of Scotland. It tolerates a very wide range of soils, except peat, and is probably best known as a hedgerow plant. Hawthorn has a high wildlife value, as its flowers provide nectar for spring insects while its berries provide excellent food for small mammals and birds, especially thrushes. Usually thought of as a hedging plant, hawthorn can grow to become a lovely medium-sized tree if left uncut.

The ‘May blossom’ of hawthorn is associated with stories and rituals. Regarded as symbols of hope, their scent was thought to revive the spirit

and drive off poisons, while wearing a sprig of hawthorn could protect you from lightning. Easily confused with: Field maple, Midland hawthorn

Seed Guide

Collect the red berries once they are ripe, from autumn onwards. Remove the seeds from the flesh and wash them thoroughly. If the flesh is hard to remove, soak the berries for a day or two. Stratify the seeds, occasionally for one, but usually for two winters. Select and sow germinating seeds each spring.

Midland hawthorn is the rarer of the two native hawthorn species, being found on heavy soils in shady woodlands, usually in the southeast of Britain. This species grows into a small tree more regularly than hawthorn and can be found growing along roadsides and in gardens. Many ornamental forms have been created, including ‘Paul’s Scarlet’, which is often seen in cities.

As with hawthorn, the wood has been used for tool handles and walking sticks.

The stems of Midland hawthorn are often contorted, improving the walking sticks one can make from the tree. While the flowers provide

nectar for spring insects, the berries provide excellent food for small mammals and birds, especially thrushes.

Easily confused with: Hawthorn, field maple

Seed Guide

Collect the red berries once they are ripe, from autumn onwards. Remove the seeds from the flesh and wash them thoroughly. If the flesh is hard to remove, soak the berries for a day or two.

Stratify the seeds, occasionally for one, or more usually two, winters. Select and sow germinating seeds each spring.

The twig has opposite buds

Each bright berry contains one seed and grows in a cluster

Large, white, outer flowers are sterile

The opposite leaves have three to five lobes and are hairy underneath

Viburnum opulus

This multi-stemmed shrub or small tree grows to a height of four metres. It is found naturally in woodland, scrub and hedgerows.

The main stems carry the flower buds, which develop into flowers in June and July. The flower heads have large, sterile, outer flowers with smaller, fertile, yellow inner flowers.

Once pollinated, the plant develops bright red berries in the autumn, each containing a single seed. The berries are eaten by a range of birds, which distribute the seeds in their droppings at a distance from the parent plant.

The combination of colourful berries and leaves

YEAR 1

that turn a vivid red in October have made guelder rose a popular ornamental shrub for gardens. There is a wide range of ornamental varieties. It is commonly found growing on moist, limerich soils. As it needs light to flower, this is not a shade-loving species.

Easily confused with: Wayfaring tree

Seed Guide

Collect the ripe, red fruits. Remove seeds from the fruit and wash thoroughly. Stratify the seeds for one winter or two. Select and sow germinating seeds in the first or second spring.

The twigs are grey brown and somewhat hairy with opposite buds

This small, deciduous, multi-stemmed shrub or small tree occurs naturally in Britain, and can reach a height of six metres. It occurs in hedgerows and scrubby areas, as well as along woodland edges.

The flower heads occur at the ends of the stems, and consist of clusters of small, white flowers. Once pollinated by bees and other insects, the fruits begin to ripen from July to September. As they ripen, the clusters of berries turn from green through red to black. The berry contains a single seed, which is dispersed when it is eaten by birds. The wayfaring tree grows well on lime-rich

The young twigs are green and turn red as a result of sunshine

Opposite leaves turn deep red in autumn

The berries change from red to blueblack as they ripen

soils, but not where the soil is waterlogged. Easily confused with: Guelder rose

Seed Guide

Collect the ripe, blueish-black fruits. Remove the seeds from the fruit and wash them thoroughly. Stratify the seeds for one winter or two. Select and sow germinating seeds in the first or second spring.

This medium to large, native, deciduous shrub or small tree grows naturally across much of Britain, except for northernmost Scotland. It can grow two to six metres high and is commonly found in scrub habitats alongside riversides, woodland edges and hedgerows. It tolerates a wide range of soils, but prefers a sunny, well-drained location.

Small flowers can be seen in spring at the end of twigs in dense clusters, which are followed by small, black berries in autumn. Dogwood leaves provide food for wildlife including micro-moths, while its berries are eaten by birds and mammals. Easily confused with: Ornamental dogwood species

Seed Guide

Collect the ripe, black fruits in autumn. Remove the seeds from the flesh and wash thoroughly. The seeds are deeply dormant: they may germinate after one winter following stratification, or two. Germination can be improved by keeping stratifying seeds at room temperature for two months, before putting them outside for the remainder of the winter. Select and sow germinating seeds in the first or second spring. The seedlings will be ready for planting out in two to three years. Dogwood can also be propagated by taking cuttings of shoots or roots.

of small, pungent-smelling white flowers

A large, semi-evergreen shrub growing up to four metres high, found throughout the UK. Native to Europe, it can be found growing naturally in hedgerows, woodlands and scrub, particularly in southern England and Wales, and is often used in hedgerows in urban areas.

Wild privet tolerates a wide range of soils, but prefers well-drained, calcareous soils.

It has clusters of small, white flowers on branch tips from June onwards. Small berries ripen in the autumn to black, and often survive through the winter. The berries are a good food source for birds, particularly thrushes.

The fruit is a small capsule containing black seeds

poisonous, matte black berries in autumn

Buxus sempervirens

Flowers are small and white. They appear in clusters at the junction of the leaves and stem

Small, shiny, evergreen leaves grow in opposite pairs

Seed Guide

Collect the small, black fruits in autumn, before the birds have eaten them all. Each berry will have between one and four seeds that are deeply dormant. Cold stratify the seeds for 8–12 weeks, then they can be planted in deep pots or trays. Growth in the first year is usually 15cm–40cm. Allow them to grow for one or two years, before planting them in a permanent position. Can also be propagated by cutting.

Easily confused with: Box and cultivated varieties

This shrub or small evergreen tree can reach a maximum height of about nine metres. It is a native of western Europe and is probably a native of England though, as it was planted extensively in Britain by the Romans, it may have spread naturally from gardens in Roman settlements.

Box can be found growing wild in southern England, the most famous site being Box Hill in Surrey, and in the Chilterns.

The evergreen leaves persist for five or six years, which is why the species is frequently used for hedging and topiary.

Because the dense and fine-grained wood is

very close to ivory in texture, it has been used extensively for turning and inlay. Easily confused with: There are many cultivated varieties of box

Seed Guide

The tree’s fruits are three-celled capsules, with each cell containing two seeds. They split along six lines, expelling the shiny, black, smooth seeds. Collect the seed capsules when they are ripe and keep them in a paper bag until they open. Sow in a pot or seedbed immediately, or stratify through the winter to improve germination rates.

Small, green-yellow flowers occur on the upper surface of the leaf like stem extensions

A low, evergreen, native shrub up to one metre tall, butcher’s broom is widespread in England and Wales, with a few populations in Scotland and Ireland. It can be found growing in deep shade, in woodlands and hedgerows, on rocky cliffs and ground near the sea. Butcher’s broom favours poor, well drained soils, making it useful as a shrub layer in woodlands.

It produces tiny, green-yellow flowers from September, which bloom from January to late April. Green berries form over the summer, turning red in autumn. They’re not popular with birds and animals, so they remain on the plant

through the winter into the next spring. As a result, distribution by seeds may be limited, and most plants spread by underground rhizomes.

Collect the berries from September. Germination can be improved by keeping stratifying seeds at room temperature for two weeks, before putting them outside for the winter. Sow thinly in early spring in light shade in a greenhouse. Germination may take 12–24 months. Prick them out into individual pots in the following spring, and grow on for another year before planting out.

Shiny, brown twigs have scattered, wart-like lenticels (raised pores that allow gas exchange)

Ripe, rounded, red fruits have only a few small or medium-sized lenticels

White flowers grow in clusters

Dark green leaves have densely white, hairy undersides and are unlobed

The whitebeam is a native tree that prefers chalk and lime-rich soils, but also tolerates other soil types. Its ability to withstand pollution means it is widely planted in urban areas. However, such trees are often ornamental forms of the wild species and are unlikely to produce a reasonable crop of seeds.

The tree’s hard, tough wood was used to make machinery cogs. Its overripe berries can be turned into jelly to accompany venison.

As with all Sorbus trees, the berries are eaten by birds, while the flowers attract insects and the white caterpillar of the tiny moth Argynesthia

sorbiella feeds on the shoots and flower buds. Easily confused with: Some Sorbus species, particularly Swedish whitebeam

Seed Guide

Collect bunches of fruits when they turn crimson. Remove the seeds from the flesh and wash thoroughly. Stratify the seed, usually for one winter. In cool autumns, germination can be improved by keeping stratifying seeds at room temperature for two weeks, before putting them outside for the winter. Select and sow germinating seeds in spring.

Orange-red fruits that are longer than they are wide, with only a few spots

Sorbus intermedia Sorbus devoniensis

Introduced from Scandinavia, this medium-sized tree is now widely planted in Britain. It generally grows to a height of 10 metres, though 18 metres has been recorded. The leaves are lobed, sometimes deeply. The white flowers produce orange-red or occasionally red ripe fruits in the autumn.

Seed Guide

*Height>20cm, Root collar>4mm

This rare, native, deciduous tree grows only in Devon. It grows in hedgerows where it favours soils layered over shales, grits and slates, rather than lime-rich soils. Believed to be a hybrid of wild service and whitebeam, this tree is able to clone its seeds without fertilisation.

Collect bunches of fruits when they turn orange-brown. Remove the seeds from the flesh and wash thoroughly. Stratify the seed, usually for one winter. In cool autumns, germination can be improved by keeping stratifying seeds at room temperature for two weeks, before putting them outside for the winter. Select and sow germinating seeds in spring.

For the calendar, see whitebeam (left)

Each leaf consists of numerous pairs of

Rowan is a tree of mountains, woodlands and valleys throughout Britain, growing on a wide range of soils including chalk, acidic and even peat. It has been widely planted in parks, gardens and streets due to its striking red berries – which occur as early as July – and its attractive foliage in autumn.

The tree has excellent wildlife value, providing fruit for thrushes and blackbirds, which help rowan to colonise new areas by eating and dispersing the seeds widely.

Easily confused with: Ash, elder, walnut

Seed Guide