An illustrated guide to agroforestry in the UK and routes to market for its products

Treesform the backdrop of our agricultural landscape in Britain, and yet for a large part of the last century, the value they add to our agricultural systems, both financially and ecologically, has been overlooked.

Agroforestry is a practical, time-tested approach to land management that integrates trees with crops and/or livestock to create more productive, sustainable, and resilient farming systems. In the UK, while the concept may seem new to some, our landscapes are already rich with agroforestry elements – from hedgerows and orchards to wooded pastures. Yet, there remains huge untapped potential for farmers to benefit more fully from these systems.

This guide aims to introduce various agroforestry systems that could be integrated with your land, and show the ways that trees could enhance productivity, reduce costs and generate revenue. Whether you're a livestock farmer, arable grower, smallholder, or land manager, agroforestry offers opportunities to do more with your land, naturally.

Jon Stokes, director of trees, science and research, The Tree Council

Trees on Farms 2025 was created for you by:

The Shared Outcomes Fund

Trees Outside Woodland Project

The Tree Council

Registered charity no: 279000

Jon Stokes

Jackie Shallcross

Cornwall Council

Ben Norwood

Shropshire Council

Nick Rowles

With thanks to Defra and Natural England

Design by Tom Dale of The Tree Council

The illustrations in the illustrated guide are by SJC Illustration.

Photographs by Indigo Creative unless otherwise stated.

The Shared Outcomes Fund Trees Outside Woodland project is a £4.8m, five-year programme of action research into effective and economical ways of establishing new non-woodland trees. It is funded by HM Government and delivered in partnership by The Tree Council, Natural England, the Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs, Chichester District Council, Cornwall Council, Kent County Council, Norfolk County Council and Shropshire Council.

This document provides general guidance about agroforestry believed to be correct at the time of writing. The authors do not accept liability for any loss incurred as a result of relying on its contents. Individuals, organisations, landowners and land managers should seek independent professional and legal advice where necessary.

‘There really is no excuse not to plant more trees’

The Duke of Richmond, owner of the Goodwood Estate, home to one of the largest lowland organic farms in the UK

In the face of climate change, market volatility, and evolving agricultural policies, UK farmers are increasingly exploring agroforestry as a strategy to enhance their farms.

At its simplest, agroforestry is farming with trees. It is the intentional integration of trees into agricultural systems to provide ecological and economic benefits to the farm.

Unlike mixed farming, which combines crops and livestock, agroforestry weaves trees into the picture – offering a richer, more dynamic use of the land which enhances production.

At its core is a recognition that trees can add more to farms that they take. They can shelter livestock, support pollinators, protect and enhance soils, improve crop yields, manage water, and diversify farm outputs.

In the UK, many farmers already

practise agroforestry without calling it that. Hedgerows, tree-lined fields, shelterbelts, grazed orchards, and even scattered trees in pasture all form part of this broader system. Yet, by approaching these elements strategically – choosing the right species, spacing, and purpose –farmers can unlock far greater benefits. Whether the aim is to improve soil health, generate a new product, or create more climate-resilient land, agroforestry provides a toolkit for farming with nature that has been tested for generations.

Inside these pages you will hear from farmers who have tried various agroforestry systems and are now reaping benefits.

While agroforestry is not a panacea for British agriculture, there is a growing body of evidence that trees help to build more resilient and productive farming systems.

Farmers and landowners experimenting with trees on their farms are finding they offer benefits beyond environmental stewardship and aesthetics.

A study by the University of Reading found that integrating trees into arable systems can boost crop yields by protecting against wind damage and improving soil moisture retention.

At Wakelyns Farm in Suffolk, research by the Woodland Trust and the Organic Research Centre found that implementing agroforestry practices like alley cropping (see page

22) led to crop yields comparable to those from land one-third larger.

“Agroforestry is broadly about farm resilience and boosting production,” says Ben Raskin, head of agroforestry at the Soil Association. “It’s a way of increasing tree cover while still producing food. If we get it right, it enhances your farming systems and creates resilience against climate change.”

And, while carbon sequestration often makes the environmental case for trees on farms, for Raskin it is not the primary reason that he is an advocate. “The carbon sequestration bit is useful, but I tend not to focus on it – it’s more of an added bonus. The immediate benefits to farming hugely outweigh the potential to offset carbon emissions,” he says.

Those immediate benefits are tangible: improved soil health, shade for livestock, reduced wind erosion, and diversified farm income. One study from the Organic Research Centre shows that agroforestry systems can boost crop yields by 10–30% through improved microclimates and soil health, while also reducing costs like veterinary bills or supplemental feed during heat stress.

However, as Raskin points out, agroforestry isn’t a one-size-fits-all solution. “It looks different on every farm, and that’s the challenge,” he says. “Soil varies, climate varies, livestock and crops vary. The best thing you can do is make it as flexible as possible and keep your options open.”

Flexibility is key, especially when considering the long-term nature of trees.

“You design something with the current paradigm, but things can shift massively. When you’re planning, imagine: what if I change from cows to sheep? What if I stop doing arable?” he says.

An iterative approach – testing ideas

Much of Britain’s agricultural land already incorporates trees. For Raskin, a first step is to work with these pre-existing trees

on a small scale before investing heavily – also buffers against the slow learning curve associated with tree planting. “With trees, it takes a decade to really start to learn what’s doing well and what isn’t,” he says. “If you did it all in year one and then realised ten years later it wasn’t quite right, that’s much worse than doing less and seeing what works by year five.”

Helen Browning OBE, organic farmer and CEO of the Soil Association, has applied this exploratory model on her land. After acquiring Lower Farm – a 200-acre parcel with heavy clay soils –she decided to trial a range of agroforestry systems. “I had long wanted to do more with trees but had been restricted in doing so as a tenant,” she says. “Since I couldn’t find many larger-scale examples in the UK to learn from, we thought it best

Agroforestry systems can boost yields by up to 30%

to trial a number of different approaches, so that we and others could learn from our experiences.”

While the capital costs and uncertainty about long-term markets were concerns, the immediate benefits became clear.

“Firstly, just how much more beautiful that farm is.” she says. “It was just a bowl of clay, relatively featureless, and now it’s a wonderful place to spend time.

"We also have so many opportunities for diversification of the business already emerging.”

For many farmers, the decision comes down to economics.

Evidence shows that integrating trees can improve net returns over time. Cranfield University researchers estimate that over 30 years, silvoarable systems can sequester up to eight tonnes of CO2 per hectare annually while also improving yields by 10-20% thanks to reduced

wind damage and enhanced soil moisture retention. More immediately, trees shield crops from wind stress –research, again from Cranfield University, suggests that shelterbelts can increase wheat yields by up to 5–10% – and can help livestock stay cooler, reducing lost milk production. “In dairy, if cows get too hot their metabolism shuts down and milk production drops,” says Raskin. “With trees providing shade, milk production goes up.”

The initial cost of introducing these systems can seem hard to bear, but, recent modelling by The Soil Association and Finance Earth has shown that once the break-even point has been reached, you then have a long period where the investment can be recouped many times over. Raskin says: “The most important takeaway in that research for me was that the difference that grant funding and carbon payments make is negligible – apart from funding covering planting costs. By far, the most important financial aspect was the improvement to your farm – whether that’s increased crop or livestock productivity, increased animal

welfare, reduced vet bills.

“What I find persuades farmers is discovering that this is going to affect your bottom line positively.”

A major barrier is the perception that trees compete with crops or livestock. “A lot of farmers have seen trees as either irrelevant or a problem: the hedge you have to spend money cutting, the tree you have to drive the combine around,” says Raskin. “But historically, trees were an integral part of the farm economy, and now the science is catching up.

and thicker could attract pollinators, beneficial predators and provide more shade.

“I'd hear that planting trees means you lose forage but now we know that most forage species actually grow better in partial shade.”

Trials from the European AGFORWARD project support this: pastures with scattered trees often yield the same or better biomass than open grassland while also supporting biodiversity.

The first step, says Raskin, is to map inputs and outputs on the land, identify challenges and then ask whether a tree could be a solution. “Whether it’s reducing vet bills, increasing yield, protecting crops, managing straw inputs, or even growing your own fence posts, by asking at every step, ‘could trees help here?’ you’re creating an opportunity to find a new way of doing things that could be beneficial,” he says.

The secret to success, Raskin suggests, is to start small and learn by doing.

“Even planting 20 trees teaches valuable lessons,” he says. “And it’s not necessarily even about planting more trees. The first step is to look at what you’ve already got and see if you can manage it differently to give more benefit to your farm.” For example, letting a hedge grow taller

Browning echoes that advice: “So much depends on your own situation, but the main thing is to spend some time looking at what others have done, and think about what might work for you. While it’s sensible to get started ASAP, given how long trees take to become productive, it’s also best to have enough time to look after the trees you have planted, rather than overdo it and have half of them die.”

Silvoarable systems can sequester 8t CO2 per ha annually

Looking ahead, agroforestry could open up new business opportunities and collaborations on farms. “Agroforestry creates room for specialists and new businesses within the farm ecosystem,” Raskin says. “Not every farmer has to do it all – partnerships work.”

In a landscape marked by climate uncertainty and market flux, agroforestry stands out as a way to build resilience and diversify income. It’s not a silver bullet, but by taking small steps and learning from others, UK farmers can sow the seeds of a more sustainable – and potentially more profitable – future.

Trees can provide additional sources of trace minerals and proteins for browsing

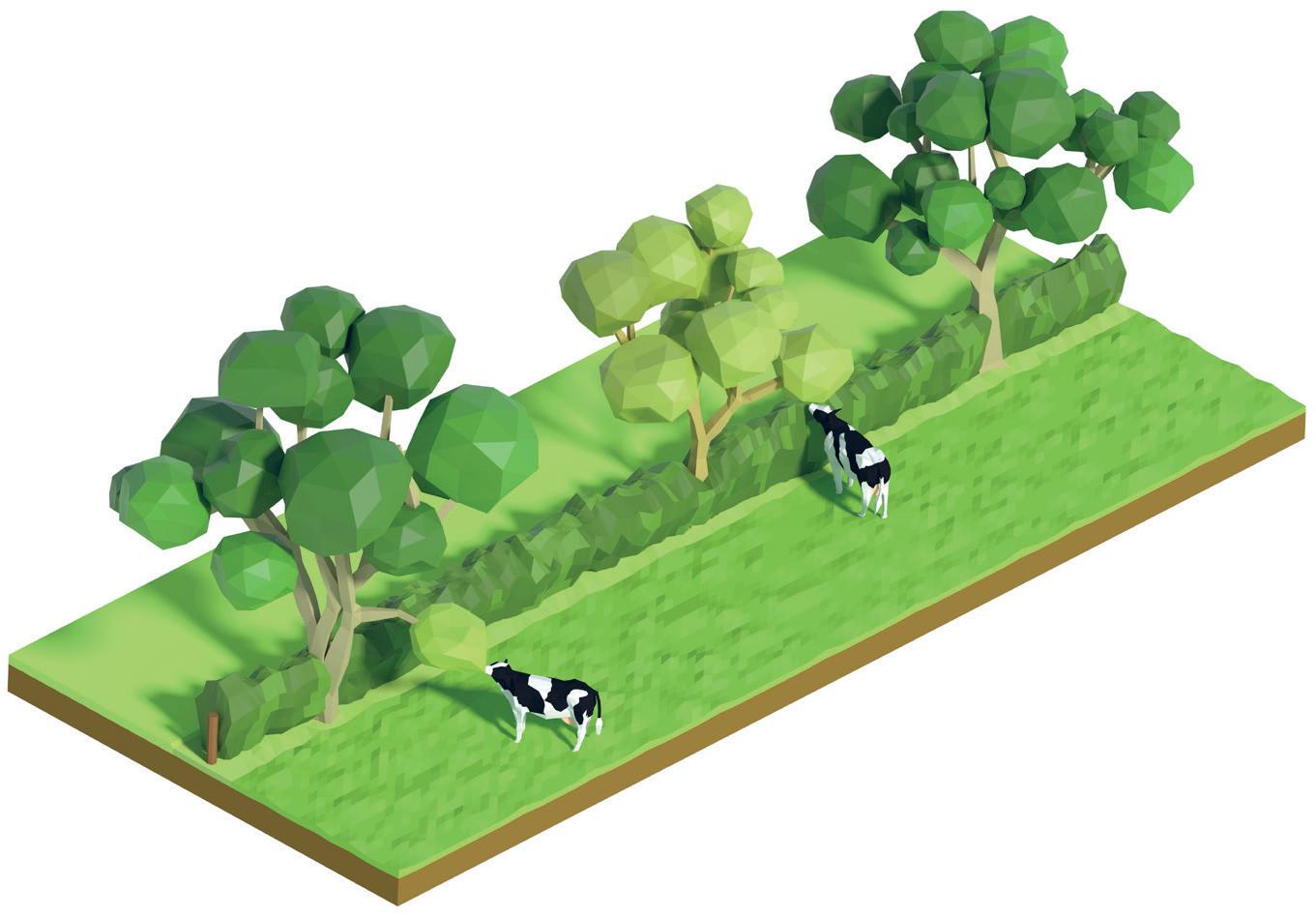

Hedgerows and open-grown hedgerow trees are a classic feature of the British landscape and are a relatively easy way to incorporate trees into productive farming systems whilst delivering a multitude of benefits both to the farm, the farm business and the wider environment.

Hedgerows are linear agroforestry features traditionally used to mark field boundaries, but they also serve vital ecological, agricultural, and cultural roles. They provide shelter for crops and livestock, act as windbreaks, support a high diversity of wildlife, and help reduce soil erosion and water runoff. Properly managed hedgerows can be a source of woodfuel, nuts, fruits, and even specialty products. Management practices like coppicing,

laying, and maintaining a diverse structure are important to maximize benefits. Including larger trees (called standards e.g. oak or beech) when planting hedgerows enhances their ecological value and landscape character, though it may require more complex management. Hedgerows are one of the most familiar and accessible forms of agroforestry in the UK, offering both productivity and ecosystem services.

l Shelter provision for livestock

l Help to maintain, restore or enhance the cultural heritage of the farmed landscape of Britain

l Carbon sequestration through maturing canopies and root systems

l Crops such as firewood, fencing material and forage products

l A sustainable method of maintaining field boundaries

l Ditching: to improve in-field water management and boundary integrity

l Fencing to aid establishment

l Typical hedge planting density: Five stems per metre

l Inclusion of open grown maiden trees every 10 to 20 metres

Widening hedgerows can create important wildlife corridors between other isolated habitats across the landscape

l Refuge for wildlife and habitat connectivity

l Well positioned hedges can protect water courses from sedimentation and point source pollution

In-field copses can be used as anchor points for holistic / mob grazing systems

Field corners and copses on a farm can be an easy way to increase tree cover without impacting significantly on the existing field management.

Field corners and small woodland patches (copses) are ideal spots for planting trees to maximize biodiversity and utility on less productive land.

These areas can host native tree species for conservation, provide shelter for livestock, or be managed for woodfuel, timber, or

recreational uses.

Incorporating trees into these areas enhances landscape connectivity, reduces nutrient runoff, and may support pollinators or pest predators.

They represent a low-risk entry point for farmers new to agroforestry.

l Shelter provision for livestock

l Carbon sequestration through maturing canopies and root systems

l Increased biodiversity when using flowering tree and shrub species

l Maximises productive area when using marginal land

l Timber crop through pollarding, thinning or coppicing

l Fencing to aid establishment

l Typical stem spacing approximately 2–3m apart

l Impacts of deer browsing in local areas will need to be considered

l Can be any shape or size

l Initial planting can be denser and thinned as trees mature

l Cultivation of soil to encourage natural regeneration where possible

Field corner plantings, when connected by hedgerows, help to improve the connectivity of the landscape for wildlife

l Grouping smaller field corner plantings across different fields helps to make larger wooded areas whilst reducing the impact on an individual field

l Good opportunities to use native species such as oak, birches, hazel, hawthorn and elder

l Can provide important nectar sources for invertebrates

l Provides habitat refuges in the wider landscape

l Can be used to buffer water courses and other sensitive areas

When integrated with arable crops trees can provide a range of benefits both direct – soil nutrient cycling, diverse crop options – and indirect – limiting soil erosion, creating alternative sources of income.

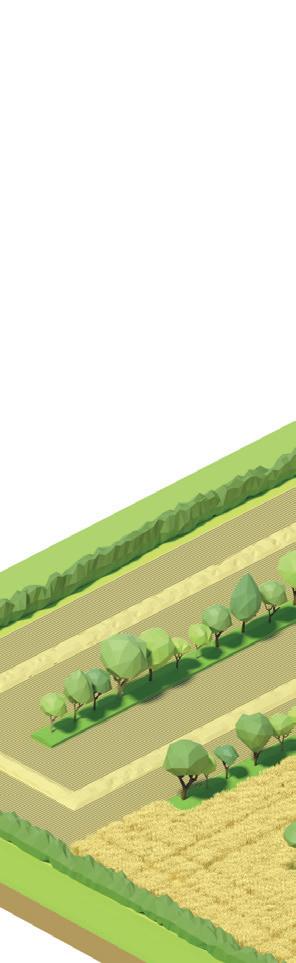

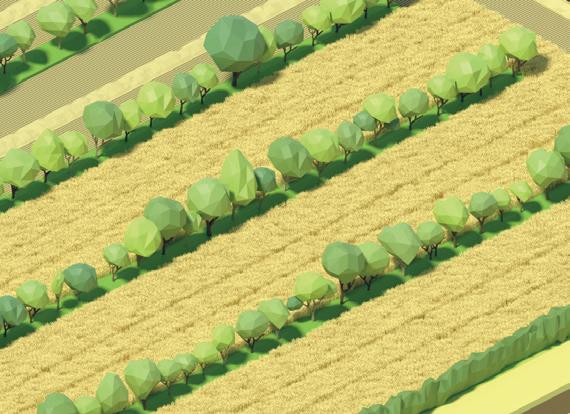

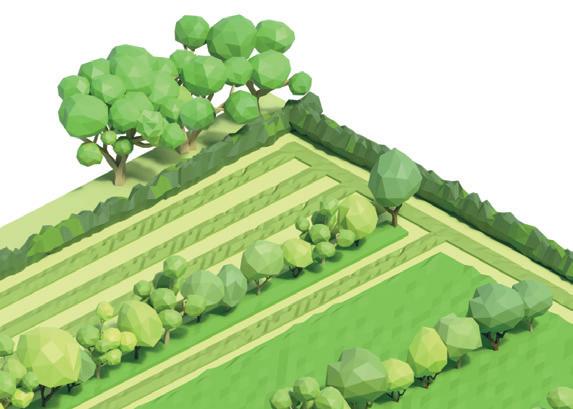

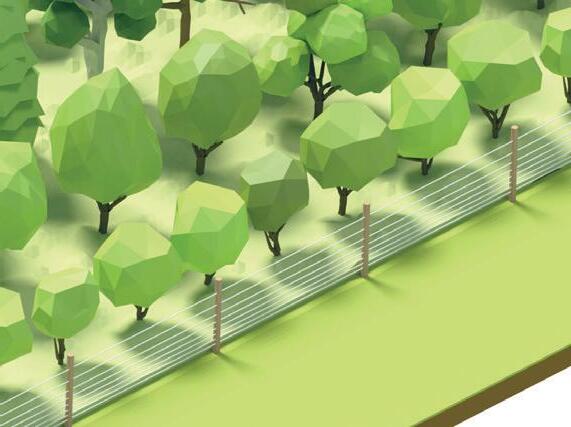

Arable alley cropping involves planting rows of trees at regular intervals within crop fields, allowing arable crops to be grown in the alleys between them.

This system improves resource use efficiency by combining tree and crop production, and trees may provide timber, biomass, or fruit/nuts.

Alley cropping can reduce crop damage from weather extremes, reduce erosion, and

enhance biodiversity, while crops continue to yield effectively.

Successful implementation requires careful spacing to accommodate machinery and to reduce competition.

Tree root systems and canopy management must be considered carefully to minimize competition with crops and optimize light and nutrient availability.

l Shelter provision against extreme climatic conditions and drying winds

l Alternative crops contributing to income diversification

l Carbon sequestration

l Supplementary crops (woody products) and browsing provision

l More diverse cropping helps reduce / spread the risk of pest and disease issue

l North South planting orientation for arable situations

l Protection of trees typically on an individual basis

l Variable densities along rows depending on species choice and management objectives

l Tree species choice can be multipurpose to provide fruiting / timber / soil conditioning benefits

l Alley width should be around 24m, allowing multiple machinery passes within each alley

Flowering and fruiting species can provide important nectar sources for invertebrates

l can

Creation of ‘beetle banks’ can be invaluable habitats whilst providing important sources of predators for pest species

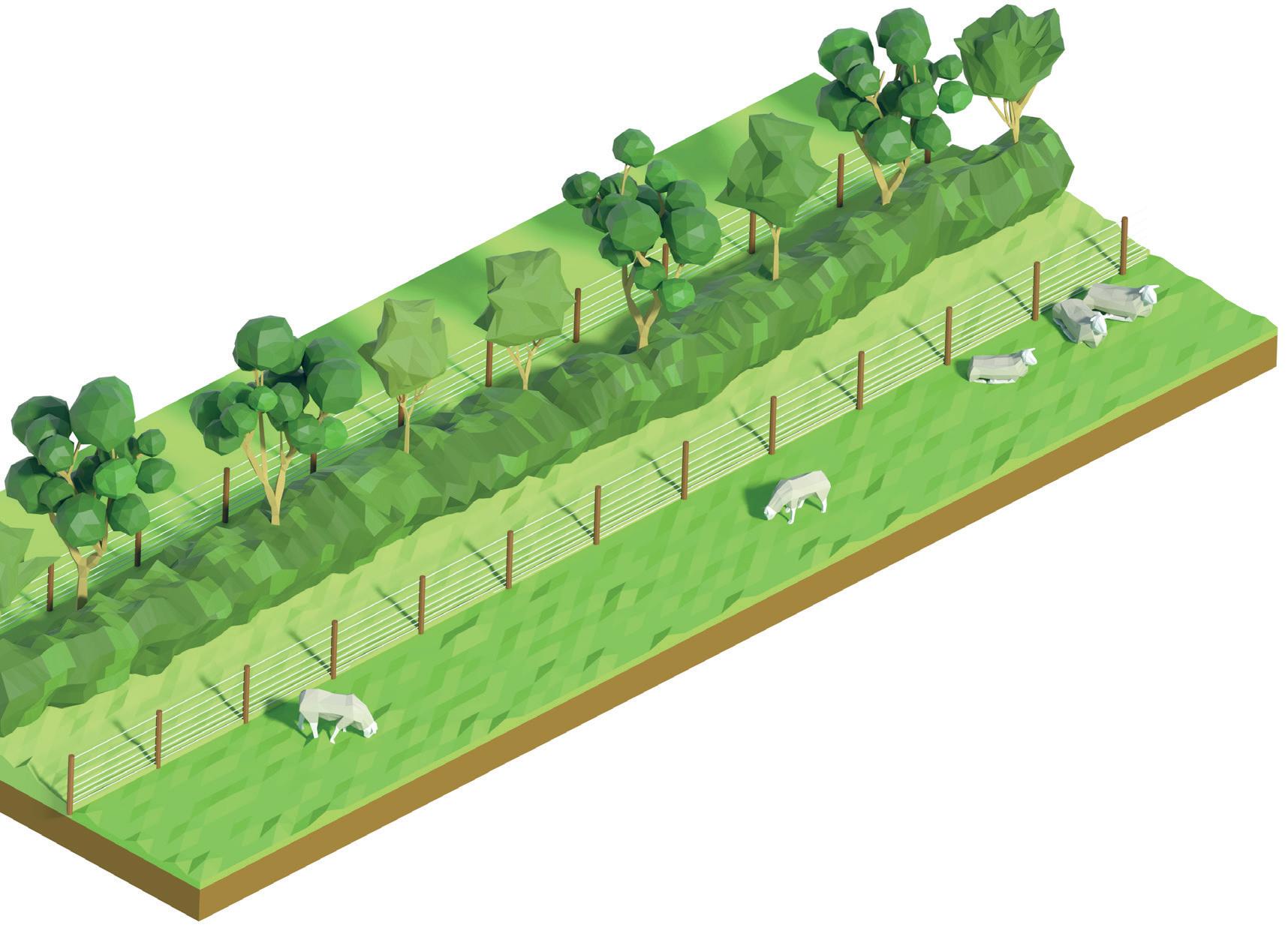

Alley cropping with pasture involves planting rows of trees at intervals within grazed grassland, allowing livestock to graze the alleys between tree rows.

This approach merges the benefits of silvopasture with structured tree layouts typical of alley cropping.

Trees may be selected for timber, fodder, or shade, and the system can help improve animal welfare and reduce stress by providing

Trees are planted in set rows to complement the underlying grassland management. The trees are intentionally managed to supply additional products – timber, fruits, tree hay –and services, such as increasing nutrient cycling and mineral deposition, aiming to enhance productivity.

shelter from the wind and sun, thus boosting productivity.

Tree rows must be designed to allow machinery access for grass cutting or weed control and to prevent overgrazing or damage to young trees.

The spatial arrangement can also influence biodiversity and soil health, making this system an effective strategy for sustainable intensification on livestock farms.

Shelter provision against extreme climatic conditions

Carbon sequestration

Can be integrated into holistic or mob grazing systems

Supplementary crops – woody products – and browsing provision

Allows hay or silage cropping to continue

Protection of trees through electric or permanant fencing systems

Variable densities along rows depending on species choice and management objectives

Inclusion of beetle banks as part of integrated pest management solutions across the farm

Lends itself to holistic / mob grazing

Tree species: Multi purpose fruiting / timber / browse

Management systems: Pollarding for tree hay

Management systems: Pollarding for

can l

benefits

Flowering and fruiting

species can provide important nectar sources for invertebrates

Creation of ‘beetle banks’ can be invaluable habitats whilst providing important sources of predators for pest species

Parkland is a classical and more formal approach to landscape tree planting, often suitable for restoration of historic areas.

Mimicking the style can also be a good way to establish new trees in the landscape in modern farmed environments.

Parkland-style silvopasture blends elements of wood pasture with formal landscape design, featuring widely spaced trees in grazed grassland, often for aesthetic and conservation value.

These systems typically include mature or veteran trees, and livestock such as sheep

or cattle graze beneath them. They provide multiple benefits: shade and shelter for animals, enhanced biodiversity, and potential production of timber or fruit. Management includes protecting young trees from livestock damage and planning for long-term tree regeneration.

l Carbon sequestration

l Shelter provision

l High-value biodiversity

l Leaves of different species can provide important minerals, proteins and fats for browsing livestock

l Open grown trees can help livestock cope with heat stress

l Typical stem density: fewer than 50 stems per hectare

l Tree protection is often bespoke.

l Cactus Tree Guards are a new cost-effective alternative to wooden fencing

l Species selection can be mixed and often informed by historic contexts

l Historic resources such as the OS 1st Edition mapping can aid design and layout

l A UK Priority habitat with potential for high biodiversity value

l Allows creation of other complimentary priority habitats such as species rich grasslands

l Encourages open grown trees to develop in the landscape

Wood pasture is an important priority habitat and a system that has been used for thousands of years in the British Isles.

Wood pasture describes landscapes where cattle or ponies graze amongst open-grown or pollarded trees with scrub and open habitats. Some of the trees are likely to have significant decay habitats and deadwood with fungi, invertebrates and lichens. It is a traditional land use practice still seen in Epping, Sherwood and the New Forest, combining ecological conservation with light agricultural use. This system supports high levels of biodiversity, offers shade and shelter to livestock, and creates visually rich landscapes.

l Flowering and fruiting species can provide important nectar sources for invertebrates

l Dead wood and decay habitats are essential for wood pasture, especially those found on and within still-living trees

l Deadwood and decay, especially within still-living trees

l Carbon sequestration

l Provision of browse – traditionally cattle or deer

l Supporting animal welfare by encouragement of natural foraging behaviours

l Timber crops by pollarding or coppicing

l Shade and shelter provision helping reduce thermal stress in a changing climate

l Clumps of dense scrub with scattered trees and shrubs

l Aim for open-grown trees set within a scrub and open habitat mosaic

l Protection for new trees: fencing or individual guards

l Native species such as oak, hazel, rowan, crab apple and hawthorn

l Initial planting can be denser and thinned as required

l Light soil poaching can encourage natural regeneration, helping reduce establishment costs

Scrub and deadwood are important components

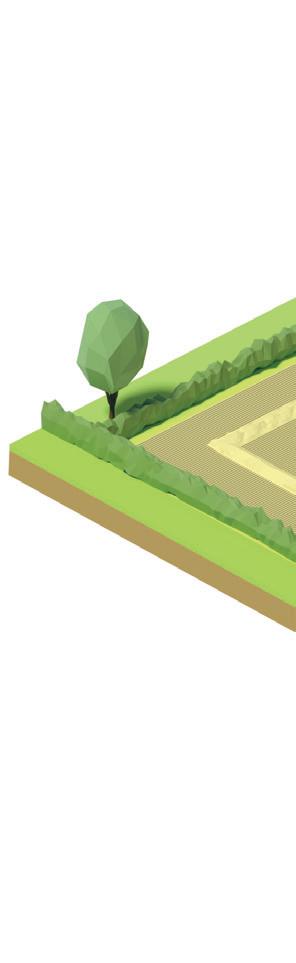

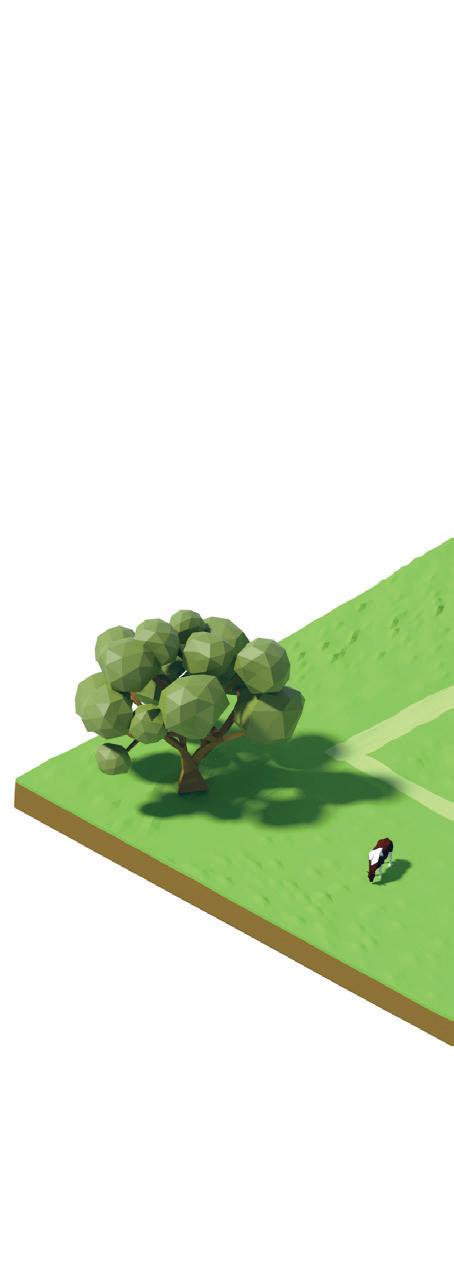

Traditional orchards differ from more modern commercial orchards by their use of vigorous rootstocks. They are managed extensively with little or no use of chemicals such as pesticides, herbicides, and non-organic fertilisers and they are a UK priority habitat.

Traditional orchards consist of widely spaced, fruit and or nut trees grown over grassland, historically managed for both fruit production and biodiversity. Prime traditional orchard habitat consists of grazed grassland with fruit trees of varying age, with an abundance of standing and fallen dead and decaying wood.

These orchards are low-input systems and often feature heritage fruit varieties. They support high levels of wildlife and may be used for grazing or hay production. Though less commercially intensive than modern orchards, traditional orchards are valued for cultural heritage, ecosystem services, and potential for premium or niche market products.

l Shelter provision

l High value biodiversity

l Shade provision for livestock in times of heat stress

l Varied habitats including species rich grasslands

l Encourages naturalistic behaviours in livestock (animal welfare)

l Crop diversification (fruit/nut production, beekeeping, grazing by sheep or cattle only)

l Young trees require protection –typically bespoke

l Range of planting patterns and spacing to integrate with management requirements (e.g. Grid or quincunx)

l Vigorous rootstocks (M25 & M111) should be used for a traditional orchard

l This guide is focused on planting a new orchard, but it is worth mentioning that a traditional orchard, when mature will look far less regular than depicted here, with dead wood, trees of various age etc.

can vary between 7–10m depending on root stocks and species used

l Allows creation of other complimentary priority habitats such as species rich grasslands

Other crops can be planted beneath a non-traditional orchard

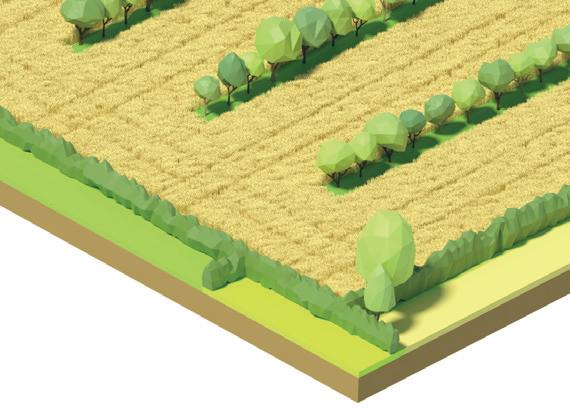

Non-traditional orchards can be under-planted with crops or grazed by animals such as sheep, cattle or pigs and differ from more modern commercial and traditional orchards by their use of vigorous or semi-vigorous root stocks and land sharing.

Non-traditional orchards differ from traditional orchards in that they are more focused on productivity – either through more dense planting with smaller rootstocks, or through diversification of the land use for grazing or production of other crops underneath the fruit or nut trees.

Chemical inputs such as fertilisers or pesticides can be used in non-traditional orchards, and the system often requires more intense management.

One example is a linear orchard incorporated with an alley cropping system, as illustrated above.

l Shelter provision

l Biodiversity

l Shade provision for livestock in times of heat stress

l Varied habitats including species rich grasslands

l Encourages naturalistic behaviours in livestock (animal welfare)

l Crop diversification (fruit/nut production, beekeeping, grazing)

l Young trees require protection –typically bespoke

l Range of planting patterns and spacing to integrate with management requirements (e.g. Grid or quincunx)

l Vigorous rootstocks (M25 & M111) or semi-vigorous (MM106 & Quince A)

l Stem spacing can vary between 5–10m depending on root stocks and species used. This illustration below is of vigorous rootstocks

Chickens can also benefit from grazing under trees in a non-traditional orchard, but they can damage the grassland underneath if not managed carefully - consider your objectives when deciding on grazing animals.

l A habitat with medium biodiversity

l Could allow creation of other complimentary priority habitats such as species rich grasslands (if grazed lightly by cattle or sheep)

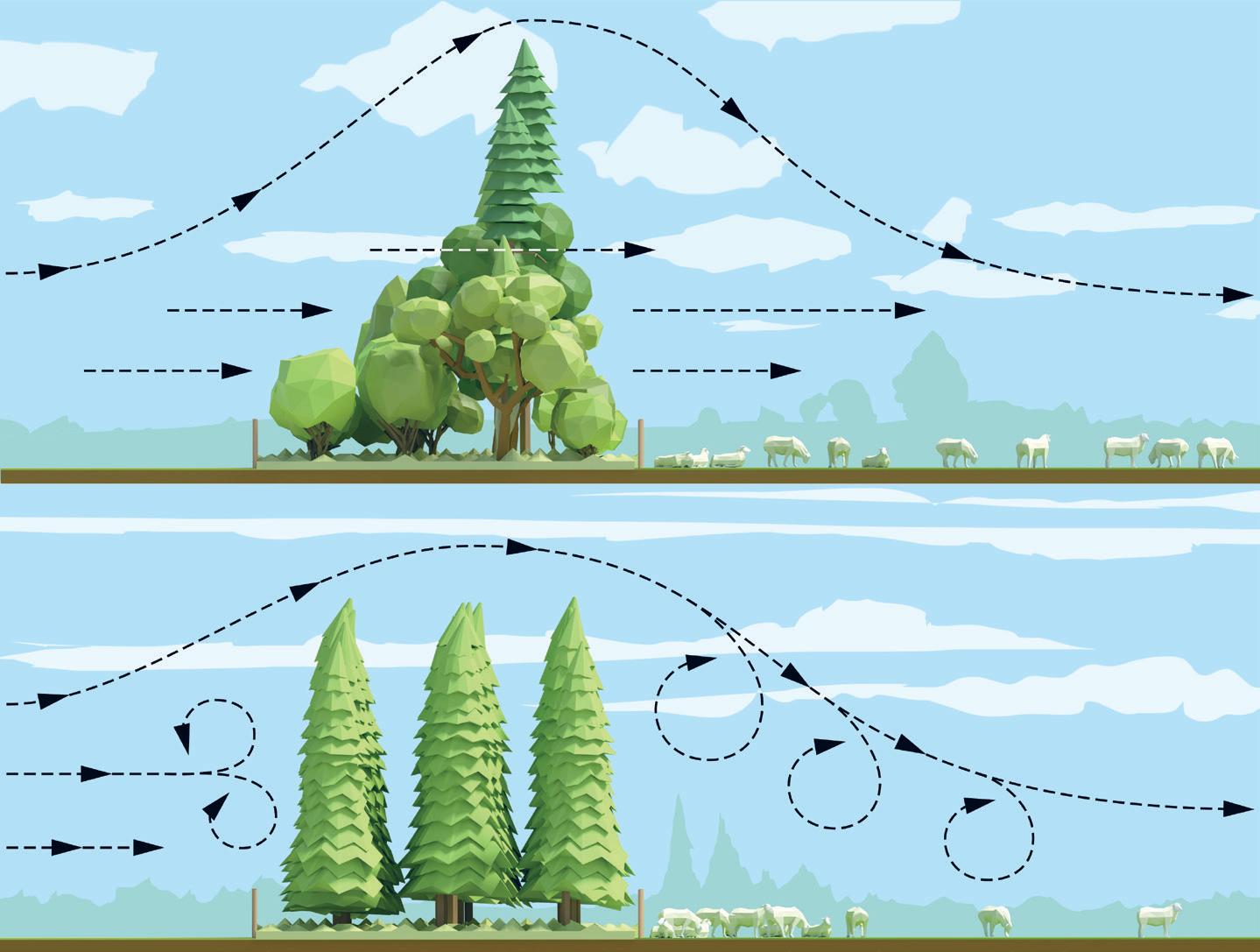

Permeable barrier

Semi-permeable barrier

Turbulence

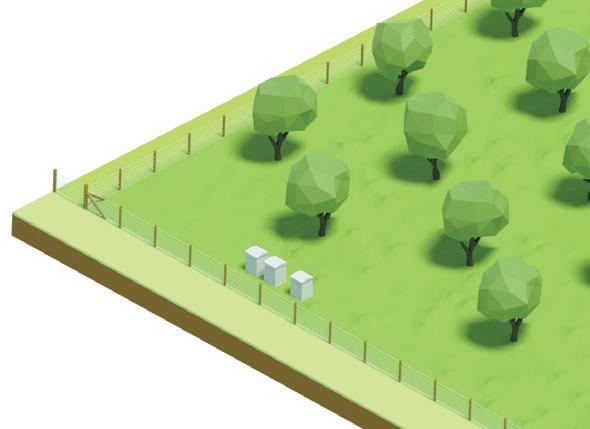

Shelterbelts are a flexible way to provide protection against the impacts of prevailing wind. Helping to moderate the climate conditions in a field or across farms, a carefully designed shelterbelt will bring a range of benefits when established.

Shelterbelts are rows of trees or shrubs planted to reduce wind speed across fields, protecting crops and livestock. They can improve microclimates, reduce soil erosion, and enhance yields by minimizing plant stress.

Design considerations include species selection, row orientation (typically perpendicular to prevailing winds), and spacing to balance protection with minimal shading or competition.

Shelterbelts also serve as habitats for wildlife and can produce additional income through biomass or wood products.

l Shelter provision for both livestock and crops

l Increased productivity from reducing cooling and drying winds

l Creates additional timber crops

l Helps to reduce surface water runoff

l Carbon sequestration

l Range in tree and shrub species will create desired porosity in the canopy

l Trees are typically protected with fences and individual tree shelters

l Plantings will need to be thinned over time

l Widths are usually between 5–20m

l Slower growing species on the leeward side

vary between 1–2m between stems

can extend to 20 times the height of the tallest tree

refuge for wildlife and enhances habitat connectivity

l Well positioned shelterbelts can protect water courses from sedimentation and point source pollution

These

interventions

have

our milk and beef “ ”

saved me money and increased profitability while keeping my animals healthy and improving the quality of

Tim Downes runs a 405-hectare organic dairy and beef farm with his wife Louise and his parents. Since converting the farm to organic in 2000, Downes has made it his mission to integrate trees into the farm’s landscape – not just for biodiversity, but as a key strategy for animal health, soil quality, and profitability.

Downes’ family has always valued trees. His father had previously planted field corners and margins and riparian barriers that have proven valuable. Today, though, Downes is carrying that legacy forward and utilising trees to boost the health of his livestock and his farm, saving money and increasing profitability.

One of Downes’ most impactful interventions has been planting trees for browse. “I did a lot of research into

l Farm size: 405 hectares, mostly pasture, some silage

l Livestock: 300 dairy, 150 beef cattle

l Trees: 70 willow trees and other species in silvopasture system; walnut trees for fly control; field-corner planting

l Impact: Reduced vet bills, increased profitability, higher milk and beef quality

which species would be good for grazing livestock,” Downes says. Supported by the Woodland Trust, he planted a dedicated browsing area with willow, cherry, sweet chestnut, and other native trees.

Willow, rich in salicylic acid (the active ingredient in aspirin), proved especially valuable. “We wondered whether that would work,” Downes says. “We planted a load of willow that went really well.”

The result? Healthier cows, lower vet bills, more biodiversity, and increased profitability.

Browsing these trees offers livestock not just forage but also natural medicine. Willow’s aspirin-like compounds help manage pain and inflammation, while tannins and secondary compounds from other trees act as natural anti-parasitics.

“We’re organic and antibiotic-free, and the willow really helps with that,” Downes says.

Beyond the cows’ health, trees on Downes' farm create microclimates that improve grass growth and retain soil moisture – key benefits in a grazingbased system. “Providing shelter with trees means higher growth and more nutritious grazing,” Downes says. “It’s a win-win.”

Back in 2009, Downes established a silvopasture system: 70 willow trees in seven rows. This integration of trees and grazing has allowed him to outwinter some animals, reducing housing costs and improving animal welfare. The benefits extend to water management. Trees planted near watercourses prevent nutrient leaching.

“Any field corners unmanageable for machinery have been planted up with cherry and oak,” Downes adds, turning unproductive land into valuable habitat and shelter.

Downes’ farm is a patchwork of

broadleaved copses (oak, beech, ash) alongside infield and hedgerow trees. A small area even features ginkgo and scholar’s tree –reflecting his experimental approach. Walnut trees by the milking parlour keep biting flies at bay, improving animal comfort.

Established woodlands provide another benefit: biomass heating. “We haven’t bought heating oil for the farmhouse for over seven years,” he says.

For Downes, trees are not just an environmental asset – they’re a key pillar of profitability. “These interventions have saved me money and increased profitability,” he says. “They’ve also improved the quality of our milk and beef.”

Downes has plans for more trees on his farm but admits that sometimes finding labour and time in a busy schedule is difficult. Still, he’s determined. “For the health of your farm, for future generations, planting trees is really important,” Downes says. “Whether for timber, nuts, or animal health, planting trees is a wonderful thing to do.”

We’ve added another crop and increased resilience. We’ve seen a 25% gain in productivity despite losing some arable land, and losses due to extreme weather have been reduced by 50% “ ”

Whitehall Farm, near Peterborough, has become renowned in the agroforestry world as a benchmark for successful silvoarable systems.

When tenant farmer Stephen Briggs took on the tenancy of the 120-hectare farm in 2007, he had a mission. “The objectives for us were to reduce soil degradation and erosion from wind, improve biodiversity and provide more habitat, and importantly add value – we had to make money while achieving this,” Briggs says.

Inspired by his time working in Africa, where he was introduced to agroforestry, and further fuelled by a Nuffield Farming Scholarship that took him around the globe, Stephen set out to build a system that would heal the soil, bring nature back, and secure the farm’s economic future.

l Farm size: 120 hectares (52 hectares agroforestry)

l System: Silvoarable alley cropping

l Trees: 4,500 apple trees

l Impact: 25% higher total productivity (cereals and fruit), increased biodiversity, increased weather resilience

l Tree products: Fresh fruit and juiced apples sold direct at farm gate

“We decided to plant 52 hectares – nearly half the farm – in a silvoarable system,” he says. “It’s been 18 years now, and the trees are well established and the system is thriving.”

In an alley cropping design, 4,500 apple trees of 13 varieties – half heritage, half modern – were planted, creating 24-metre alleys. Between the rows of trees grows cereal crops, which benefit from the shelter the trees provide. 18 years on, the experiment is bearing fruit.

“Even though we’re price-takers with Harvesting

cereals, because of the extra crop, the fruit yield makes us about 25% more productive than a monoculture,” says Briggs. “Plus, in extreme weather, the system is more resilient.”

“A few years ago, we had a hot, windy summer,” he says. “Open fields lost up to 20% of the grain to wind, but in the agroforestry alleys, we only lost 10%. That’s a 50% reduction in loss.”

Briggs’ hopes for increased biodiversity have also been fulfilled, and not just anecdotally. Whitehall has had university researchers on the farm every year for over a decade tracking this growth.

He has also found – counter to his intuition – that his cereal crop yields at the edges of the alleys often outperform those in the middle thanks to improved water drainage in winter and better retention in summer, and aided by mycorrhizal fungi from the trees.

Stephen coined the phrase “3D farming” to describe the synergy between trees and crops. “Farmers harvest sunlight, but cereals stop photosynthesising in June or July. Apples pick up in April or May and carry on until November or December,” he explains. “It’s adding a second income stream on

the same land.”

If you’re only farming the surface of your field, he says, there is a whole other plane that you’re not using – the vertical one – and trees help you tap into that.

One common worry about agroforestry is machinery access. Stephen tackled that head-on: “We standardised our machinery to six metres and developed a controlled traffic farming system. It fits perfectly in our 24-metre alleys. It’s efficient, and it works.”

Starting the agroforestry system gave Briggs the impetus to open a farm shop to sell the produce, and now all the apples produced at Whitehall Farm are sold this way.

And the apples don’t just sell as fruit – they’re juiced and bottled by a local processor, increasing the value by 300%, and both have proven popular with locals. “Every year, we sell out of everything,” Stephen says.

Stephen’s agroforestry system has changed more than just the bottom line. “We’ve definitely reduced soil degradation issues,” he says. “But more importantly, we’ve built resilience –against drought, heat and wind. With the weather extremes we’re seeing, that’s invaluable.”

I’d seen what other farmers were doing. Planting for shelter and browse and the effect that was having –increased productivity, higher welfare and lower vet bills, and thought that was the obvious next step

Nestled in the Shropshire countryside, Moor Farm is a 350-acre mixed regenerative farm where beef, pigs, chickens, and a farm shop come together under the stewardship of Daniel Roberts and his wider family.

Having come to farming late from a background in music, he and his wife now have a regenerative approach to the farm that’s been in her family for over 100 years. This shift is revitalising the landscape, and transforming the farm’s bottom line. And trees are playing a key role in this change.

Roberts married into the farm, joining full-time in 2016, and since then, he’s been on a mission to balance profitability with sustainability – a shift that’s reshaped everything from livestock management to orchard planting.

l Farm size: ~350 acres

l Beef cattle (grass-fed), pigs, small poultry operation

l Trees planted: 60-tree orchard, livestock shelter planting, ongoing hedgerow restoration

l Tree benefits: Livestock welfare, pig feed, orchard sales, community engagement, biodiversity boost

At the end of 2019, a year which on the surface had seemed successful, Roberts discovered the business had made a loss – so something drastic was needed. “We just thought, ‘we can’t go on like this,’” he says.

The first change was slashing the feed bill for the cattle by going 100% grassfed. Immediately, the health of the cattle improved, and he also noticed a surge in biodiversity on the farm. Next was improving the farm’s treescape.

The farm boasts a patchwork of well-established hedgerows, copses and

scattered trees. Roberts has introduced new trees, too, thanks to Shropshire Council’s Trees Outside Woodland scheme.

Four years ago, he began by planting rowan, walnut, and field maple to create shelter for his cattle. “It’s a welfare thing,” Roberts explains. “Shade and shelter are key for healthy cows, and they love it.

“I’d seen what other farmers were doing planting for shelter and browse and the effect that was having – increased productivity, higher welfare and lower vet bills, so that was an obvious next step.”

Despite challenging weather, and some curious calves looking to supplement their diet with the tender saplings, about two-thirds of those trees have survived.

Two years ago, Roberts then planted a 60-tree orchard of apple, plum, and pear trees. Located beside the pig paddock, the orchard is more than just an aesthetic addition. “It’s a bit of an experiment,” Roberts says. “Free apples to sell in the shop, and windfalls to feed the pigs.”

"The orchard’s beginning to produce fruit already, and every tree is thriving", he says. "Less than an acre of land will soon yield fruit, pig feed, and a community draw, all from what was once an underutilised strip of land".

For Roberts, trees are more than a

landscape feature—they’re a financial ally. “We sell the apples in the shop, so that’s higher profit margin. And the pigs get healthier, and their meat will improve.” Even the woodland walk he planted near the farm shop – intended as a visual screen – has become a community favourite.

He’s quick to point out that what started as an ideological move – more trees, more biodiversity – now looks like a business strategy. “If you do what you think you should be doing, it often ends up being profitable,” he says.

For those considering planting trees, Roberts’s advice is simple: “Just get on with it.” He urges farmers to visit other farms to see the real-world benefits – like reduced vet bills thanks to natural shade, shelter and browse – and to tap into the myriad free or subsidised planting schemes. “There’s no downside,” he insists. “Nature has had this all sorted for millions of years, and we’d do well from tapping back into those systems.”

Moor Farm continues to evolve. Roberts’ focus now is filling gaps in hedgerows, planting more trees, and building a resilient, wildlife-friendly farm. “I just want it to look nice,” he admits, “but it’s also about seeing the biodiversity explode – rare birds, insects, flowers. It’s all there when you let nature in.”

In this section of the guide we describe ten products that can be produced from trees on farms. Each is introduced along with its routes to market, an analysis of financial and non-financial benefits*, and useful resources.

Apples are consumed globally and are the dominant fruit grown in the UK. They can be eaten raw, used in cooking and baking, juiced, dried, or processed to make cider. Small orchards are common in many parts of the UK, but commercial large-scale apple production is concentrated in Kent, Worcestershire, and Herefordshire.

The area of apple orchards in the UK decreased by 13% between 2016 and 2022, but there was a 17% increase in the volume of apples produced and marketed.

Apples are categorised based on their intended use: cooking, dessert, or cider production.

Dessert apples make up 71% of all apples produced in the UK, but there is still a significant reliance on imports.

In 2022, domestic production accounted for 47% of the total supply of apples in the UK. Therefore, there is demand for apples and their subsequent products that are grown and produced in the UK.

Local juice or cider processing

Supermarkets

Wholesalers

Food industry

Farmgate sales, seasonal markets

Local retail outlets

Grower collectives & cooperatives

Local restaurants

Juice or cider

l Supermarkets account for 70% of UK-produced fresh apple sales.

l High dependency on wholesalers can lead to low profit margins – selling at farm gate is a solution.

l Producing value added products such as cider and juice increases profitability.

l Production costs have increased by 20-27%, but revenue has not increased in-line with these costs.

Apple trees can reduce soil erosion, increase water and air quality, sequester carbon, deliver aesthetic value, provide community building and nutritional benefits, as well as wildlife and biodiversity benefits.

This section presents a possible financial analysis for an apple orchard based on the 2023 Agriculture Budgeting and Costing Book (ABC), without government incentives and final firewood revenue.

l Yield and price: the figures shown are estimates for a typical crop year for Gala apples consisting of 3,500 trees from an established orchard. Both yield and price can vary considerably, particularly with the variety and density of trees.

l Crop depreciation: tree density can range from 750 to 4,000 trees/ha depending on the system. Higher densities are now more common and have greater initial establishment costs, earlier production and higher yields.

l Labour: harvest labour is based on £100 per tonne and includes supervision – much of this will be casual labour. Packing labour is based on a cost of £200 per tonne. Packing can potentially be done at scale off-farm to reduce cost.

l Transport & storage: assumed cost £80 and £40 per tonne respectively.

l Marketing: includes sales commission and any co-op levies. The range of marketing costs can vary largely depending on the marketing strategies opted for.

Pears are widely grown in the UK. The fruit can be eaten raw, used in cooking and baking, juiced, dried, or processed to make cider. The dominant areas of commercial pear production in the UK are the SouthEast, and the West and East Midlands.

The area of pear orchards in the UK decreased by 4.8% between 2018 and 2022. Production value has varied annually from 2016 to 2022.

There are many varieties of pears in the UK, but few are commercially grown. The Conference pear variety accounts for a total of 90% of UK commercial production, due to its good disease resistance and self-fertility. Other popular varieties include Comice, Concorde, and Williams.

The UK relies heavily on imports to meet domestic demand for pears. In 2022, domestic production accounted for only 14% of the UK’s total pear supply. Therefore, there is demand for pears and their subsequent products that are grown and produced in the UK.

Local juice or perry processing

Supermarkets

Wholesalers

Food industry

Farmgate sales, seasonal markets

Local retail outlets

Grower collectives & cooperatives

Local restaurants

Juice or perry

l Annual pear yields depend on the weather, pests and diseases.

l Pears can be grown in arable, pasture, and lowland orchard systems with moderate fertility and well-drained soil types.

l Pear trees are tolerant to high temperatures, but they are very sensitive to waterlogging.

Non-financial benefits

Benefits can include reduced soil erosion, increased water and air quality, carbon sequestration, aesthetic value, community building, nutritional benefits, as well as wildlife and biodiversity benefits.

This section presents an example financial analysis for a pear orchard based on the 2023 Agriculture Budgeting and Costing Book (ABC), without government subsidies or firewood value.

depreciation @ 4.35% share of establishment cost 996

& crop production

l Yield and price: Notable variations may occur, particularly influenced by factors such as variety and grade-out. Significant discrepancies are also expected between different producers and orchards. The table above is grounded on the ‘Conference’ variety, which accounts for the majority of the pear crop in the UK.

l Crop depreciation: The tree populations commonly range between 900 and 3,000/ha, depending on the system. The indicated cost pertains to a density of 2,750 trees/ha, amounting to £22,900/ha. This cost encompasses expenses related to trees, fertilisers, chemicals, labour for planting, as well as stakes and ties, spread over two years for establishment, followed by 23 years of cropping.

l Labour: The labour costs associated with the harvest, inclusive of supervision, are set at £100 per tonne while packing labour is estimated

at £200 per tonne. It is important to note that these costs may vary significantly across different crops and producers.

l Transport & storage: It is presumed that storage costs amount to £80/t and £40/t, respectively. This assumption is based on the provision of on-farm storage facilities. However, it should be noted that contract storage rates typically range higher, between £100 and £150 per tonne.

l Packing materials: The predominant practice involves conducting packing activities off-farm. The associated expenses encompass the provision of trays, film bags, and other materials required for the presentation of products in supermarkets.

l Marketing: Includes sales commission and any co-op levies. The range of marketing costs can vary largely depending on the marketing strategies opted for.

“If you add the fruit yield to the cereal yield, we’re about 25 per cent more productive than just the monoculture

”

At Whitehall Farm near Peterborough, apple trees grow in linear orchards –part of a 52-hectare agroforestry system that’s now over 15 years old. In long alleys between cereal crops, 4,500 trees of 13 apple varieties – a mix of heritage and modern dessert varieties – are producing more than just fruit.

“We sell the fruit fresh, and also juice it, bottle it and sell it as a value added product,” says farmer Stephen Briggs.

“We send the apples off as fresh fruit and it comes back in a bottle. We sell everything every year.”

All the produce from the apple trees is sold directly to customers at the on-site farm shop – an enterprise Briggs had long considered, but starting the agroforestry system gave him the reason to build.

“Off the back of putting this system in we built a farm shop – it’s something we’d wanted to do and this gave us the impetus to do it.”

While fresh apples sell well, turning them into juice has proven even more profitable. The juicing is done by a third party, and the bottles are returned for sale at the farm gate.

l 20-25 tonnes of apples per year (5t/ha)

l Orchard space: 4ha of tree strips on 52ha arable land

l Sale price: 50p/kg fresh, £4/ litre as juice

“It increases their value by 300%. We’re also able to sell our apples direct at retail value, which is so much more profitable.”

Every apple is used, every bottle sold. It’s a streamlined, small-scale supply chain that gives the farm full control and maximum return.

The trees are planted at 85 per hectare, in 24-metre-wide alleys – a design tailored to the size of the farm’s machinery, and cereals grow between the trees, creating a system that’s productive and resilient.

“We’ve now got two crops from the same space. We harvest one, then later in the year we can harvest another.”

In a changing climate, Stephen says the apple trees protect against extremes of wind, rain and heat, helping hold on to grain when high winds hit, and boosting crop performance at the tree edges.

“If you add the fruit yield to the cereal yield we’re about 25% more productive than just the monoculture.”

Organisation

British Apple and Pear Ltd (BAPL)

National Fruit Collection

FOUR ELMS

Groombridge Farm Shop

Speyfruit Ltd

Roughway Farm

Hayles Fruit Farm

Pomona Fruits

Brogdale Farm, Kent

Westons Cider

Dunkertons Cider

Gwatkin Cider

Birmingham Wholesale Market

British Independent Fruit Growers Association

Services

BAPL is a not-for-profit organisation that represents commercial growers

Part of an international program protecting plant genetic resources

Grower, supplier and apple juice producer

Retail and online sales

Fruit and vegetable trader

Website

britishapplesandpears.co.uk

nationalfruitcollection.org.uk

Grower and supplier of apples

Grower, cider and juice producer, and farm kitchen services

Apple trees supplier and maintenance services

Brogdale Collections is the home of the National Fruit Collection and works to provide access and education

Cider manufacturer

Cider manufacturer

Cider manufacturer

Wholesaler Trade union

fourelmsfruitfarm.co.uk

groombridgefarmshop.co.uk/

speyfruit.co.uk/productcategory/fruit-veg/fresh-fruit/ apples

roughwayfarm.co.uk

haylesfruitfarm.co.uk pomonafruits.co.uk

brogdalecollections.org westons-cider.co.uk

dunkertonscider.co.uk

gwatkincider.co.uk

birminghamwholesalemarket. company bifga.org.uk

The UK has a long tradition of growing hazelnuts, also known as cobnuts. The nuts can be eaten raw, used in cooking and baking, or processed to make hazelnut oil, nut butters and spreads.

The UK grows a few hazelnut varieties with the Kentish Cob being the most popular. Other established varieties include Gunslebert, Butler, Cosford Cob, and Nottingham Cob. The primary area for hazelnut production in the UK is in Kent, but trees can be established on arable land or in lowland areas with fertile soil and good drainage.

The UK nut market size (including peanuts) was estimated at £1.39 billion in 2025, and is projected to reach £1.59 billion by 2028.

The annual UK market for dried hazelnut kernels was estimated to be £15 million in 2022. However, this demand is met primarily through imports, with £12.7 million worth of hazelnuts being imported into the UK in 2022. Therefore, there is potential for increased market demand for hazelnuts and their

subsequent products that are grown and produced in the UK.

l Hazel trees generally thrive in moderately fertile soils with good drainage as they are sensitive to waterlogging

l Full height of 4-5 m is reached in 5 to 10 years

l Hazel trees remain productive for 70 to 80 years

l Can be successfully integrated with other farm activities such as arable cropping or livestock grazing in an agroforestry system

Supermarkets Wholesalers

Food industry

Other benefits of planting hazelnut trees can include reduced soil erosion, windbreak function, increased water and air quality, carbon sequestration, nutritional benefits, as well as wildlife and biodiversity benefits.

This section presents an example financial analysis for hazelnut production in the UK based on Nix 2023 and data from the Centre for Alternative Land Use from 2006 (CALU 2006). The establishment cost is based on 400 trees per hectare. After the first year, the maintenance cost will depend on the planting conditions.

Trees typically start producing nuts six years after planting and the average annual yield is estimated to be around 2.5 tonnes/ha. Hazelnut trees enter their peak production phase after ten years, where the average annual yield increases to 3.5 tonnes/ha. The values below exclude government incentives and firewood values at the end of the rotation.

Note: No income assumed during year 1 to 5; *Hazelnut price is assumed £5.5/kg (nutsinbuk.co.uk); fruiting hazelnut cultivars for orchard planting range in cost from ~£20 to ~£30

Walnut trees are not native to the UK, having been first introduced by the Romans. Walnut wood is highly sought after for its characteristic grain pattern and aesthetic appeal. While they were initially valued primarily for their timber, the nuts have since been recognised for their culinary value.

The average person in the UK, consumes about £19 of nuts (including peanuts) per year, equating to a market size of approximately £1.25 billion in 2023, which is projected to reach £1.59 billion by 2028.

Similar to other nuts, market demand for walnuts is met primarily through imports, with approximately £10.4 million worth being imported into the UK in 2022.

Therefore, there is potential for increased market demand for walnuts and their subsequent products that are grown and produced in the UK.

Sweet chestnut is another tree that has multiple products, producing both nuts, high value timber, and fencing

Food industry

Carpentry, furniture, musical instruments

l Walnut trees thrive in fertile soils with good drainage

l Minimum pruning is required

l Sheltered sites are preferred for good tree establishment

l While it varies between cultivars, walnut trees can grow up to 30m high and 18m wide making them suitable for high-quality timber production

l Wood from walnut trees is typically harvested after 60 years

Benefits include diversification, aesthetic value, reduced soil erosion, increased water and air quality, carbon sequestration, and nutritional benefits for livestock. The trees also deter biting insects which can improve animal welfare

Here we present an example financial analysis for walnut production in the UK based on 2019 data from The Agroforestry Handbook. It excludes government incentives for production, other crops produced on the land, and the value of timber at the end of the rotation.

The financial analysis is based on 27 trees per hectare, for example in a silvopasture system. After the first year, the maintenance cost will depend on the planting conditions. The trees typically start producing walnuts five years after planting and the average annual yield is estimated to be between 0.14-0.40 tonnes per hectare. Walnut trees enter their peak production phase after ten years, where the average annual yield increases to 1.0-3.5 tonnes/ha.

“Website sales are time-efficient, which is important when you're running a very busy farm

”

Alexander Hunt and his family have been farming trees in the Kent countryside for more than 60 years, so he knows his walnuts from his cobnuts.

The farm’s two businesses – Kentish Cobnuts and The Walnut Tree Company – sell both nut products and nut trees grown from seed, a diversification that Hunt started 40 years ago.

They now sell a range of nut products through their online business, and up to 14,000 nut trees a year, as well as offering an advisory and consultancy service to those wanting to add nut trees or orchards to their farm or land.

“Introducing fruit and nut trees to your land has little impact on productive land but gives another chance to diversify, giving you another product to sell while bringing other benefits in biodiversity, resilience, and image,” says Hunt.

Their farm is planted entirely with cobnut and walnut orchards – about 15 acres in total. Some of the trees on the farm are over a century old, and still productive. One cobnut orchard, planted in 1900, is still yielding around two tonnes per acre – double what many

l Crops: Cobnuts & walnuts

l Products: Whole nuts, valueadded nut products; bare-root trees, accessories

l Sales channels: Website (65%), farmgate, trade, events

l Land area: 15 acres in nut orchards

l Tree sales: ~14,000 per year

commercial growers achieve.

“A lot of people grow commercially at half that yield, and the difference is down to our pest control,” he says.

For the nut products, the farm works with a team of local makers to produce value-added items such as roasted nuts and confectionery, and some have been with them for over 25 years.

“That helps with the marketing to keep it local.”

The business sells through a combination of trade, farmgate and food events, but since the pandemic, online sales have surged, now making up around 65% of turnover.

“It’s great that the website brings in such a high volume of our sales, because all the customers are coming to us, rather than us having to go out and find them. This is time-efficient, which is important when you're running a very busy farm.”

Organisation

Gustav Heess

Eden Products Ltd

The Walnut Tree Company

Prime Timber

Nuts in Bulk

Veda Oils

VB Wholesale (UK) Ltd

Kentish Cobnuts

HBS Food UK

Horticulture magazine

Gardeners’ world

Tree shop

Sun Burst Snacks

Services

Supplier and manufacturer of oil

Supplier of walnut shell product

Advisory service and tree supplier

Purchaser of English walnut logs and timber

Online wholesale and retail supplier

Manufacturers and supplier

Wholesaler and retailer

Supplier and grower of hazelnuts, and consultancy and advisory service

Manufacturer

Resources for growing hazelnut trees

Resources for growing hazelnut trees

Bareroot Supplier

Manufacturer, wholesaler, and Retail supplier of nuts

Website heessoils.com/en edenproductsltd.co.uk walnuttrees.co.uk

primetimber.co.uk/englishwalnut

nutsinbulk.co.uk vedaoils.co.uk

vbwholefoods.co.uk

kentishcobnuts.com

hbsfoods.co.uk

horticulture.co.uk/hazelnuttree

gardenersworld.com/howto/grow-plants/hazel-treecorylus-avellana

tree-shop.co.uk

sunburstsnacks.co.uk

Timber refers to felled wood in its unprocessed state (roundwood) and all its subsequent processed forms such as planks and beams. The majority of UK timber is sourced from dedicated tree plantations and woodlands.

Softwood is largely sourced from coniferous tree species, while hardwood is largely sourced from deciduous and broad-leaved tree species. The majority of timber produced in the UK is softwood, which is primarily prcoessed in sawmills for timber, but also for wood fuel, in pulp mills and for exports. Hardwood produced in the UK is typically used for wood fuel. In 2022, UK timber production was estimated to be worth £2.7 billion.

Agroforestry systems offer opportunities to produce high-quality timber alongside other farm outputs, supporting both economic diversification and landscape resilience. Silvoarable and silvopastoral systems, for example, can include valuable timber species such as walnut, oak, cherry, or ash, providing

long-term income potential with relatively low maintenance once established. Though returns may be realised over decades, tree crops can appreciate in value significantly over time, especially when grown for furniture-grade timber or speciality uses such as veneer, tool handles, or construction.

(Buyer bears the cost of felling)

(Farmer bears the cost of felling)

l Selecting suitable tree species, managing long hardwood growth cycles, and navigating land tenure issues are the main challenges associated with timber production.

l Softwood tends to yield more than hardwood; however, hardwood can command higher prices, especially in niche markets, depending on tree type and quality.

Benefits can include agricultural diversification, reduced soil erosion, increased water and air quality, carbon sequestration, insulation properties, circularity, versatility, aesthetics as well as wildlife and biodiversity benefits.

Due to the vast array of tree species cultivated for timber production, with varying growth durations and end uses, financial analysis for all species is not feasible. Subsequent sections delve into the finances and considerations associated with a selection of specific timber production systems. It is important to note that government incentives for timber production and revenue generated from selling high quality timber from specialist trees are not included below.

Indicative prices for a selection of popular tree species and indicative establishment costs for UK timber production in general are provided in the tables below.

Poplar (domestic)

Poplar (export)

Ash logs

Oak logs – milling timber

Firewood

Softwood saw logs

Cricket bat willow

Ash hurley sticks

£25 - £40/t

£60 - £80/t

£3 - £5 per hoppus foot

£3 – 15 per hoppus foot

£24 - £32/t

£55 - £80/t

£500 - £700 per tree

£200 - £230/m3

Wood fuel is an important source of renewable energy that humans have used since ancient times. It can be used in different forms such logs and firewood, wood chips, pellets, briquettes and charcoal.

The UK firewood supply is derived from commercial forestry, small-scale woodland, and agroforestry including the use of hedges.

In recent years, the demand for UK-grown firewood has increased. The UK produced 2.3 million green tonnes of firewood or fuelwood in 2022. Imported firewood for the domestic sector reached 198,000 tonnes in 2022.

Agroforestry systems such as coppiced hedgerows, shelterbelts, and alley coppice can provide a steady supply of firewood while supporting biodiversity and landscape function. With energy prices rising and interest in renewable heating sources growing, there is increasing potential for well-managed farm woodfuel systems to contribute to both onfarm energy security and local markets.

l Producing firewood is relatively easy and the time investment can be financially worthwhile.

l Firewood trees can be grown in unused farmland and hedgerows.

l If there is local demand, better revenue can be generated through self-processing and distribution.

l The sale of wood-burning stoves was 40% higher in 2022 than 2021.

l Extra income can be generated from hedge coppicing grants.

Benefits can include soil erosion prevention, carbon storage, energy independence, renewable resource, water and air quality enhancement, community engagement, versatility, wildlife and biodiversity benefits.

This section demonstrates a sample financial analysis based on the 2018 data for Racedown Farm in Dorset, England and firewood produced from their hedge. It considers a 220m hedge where the tree species mix was 25% thorns, 25% sycamore, 5% ash, 10% hazel, 10% holly, 10% willow, 5% field maple, 5% oak and 5% bramble. The revenue can reach £6.9 per metre of hedgerow excluding governmental support.

* The current hedge coppicing grant is £5.33/m (Natural England, 2025)

1: A sample of flailing costs were taken from a number of farms and averaged. These costs varied considerably and were dependent on a number of variables, the most significant of which was hedge size.

“We’ve made this financially viable with no special kit. If you’ve got a chainsaw and a bit of time, it's doable ”

Ross Dickinson didn’t set out to become a firewood entrepreneur. But on his family’s 400-acre grassland farm in Dorset, he’s turned a problem into a profit by managing hedges not just as wildlife corridors, but as crops in their own right.

“Hedges won’t survive unless they have value to the farmer,” says Dickinson. “If they can bring in an income – great. But they need to at least pay their way.”

For years, Dickinson’s hedges were flailed annually, as on most farms. But that meant cost without direct financial return, and declining hedge health. In 2018, he and his son Euan began converting sections to a 15-year coppice rotation – cutting the hedge to ground level and allowing it to regrow.

The results have been impressive.

The Dickinson farm has around 12 miles of hedges under rotation, all contributing to their small-scale firewood business. Processing is done in gaps between other jobs. And there’s a ready market for sustainable local fuel.

“We use some of it ourselves—we’ve got eight burners across four houses.

From just 220 metres of mixed hedge—including sycamore, hazel, ash, willow and thorn—they produced:

l 9 tonnes of saleable firewood logs

l 6 tonnes of “ugly sticks” (unsplit logs for camping and open fires)

l 99 nets of “cobs” (mini-logs for compact stoves)

l 263 nets of kindling

But we also sell about 175 tonnes of logs a year, and we’re always sold out by spring,” he says.

Most of this was sold locally, some even via an honesty-box system on the farm. Altogether, this hedge generated £1,530 profit, or £2,410 if environmental grants were included, which equates to £10.95 per metre over the 15-year cycle.

Ugly sticks, far left, branches and hazel rods for cobs, and logs, top right

This system isn’t just about the income – it also avoids the annual cost of hedge flailing (around 35p per metre), improves biodiversity, and enhances the farm’s eligibility for future environmental payments.

“Perhaps above all, if hedgerows can be seen as economically viable, they’ll have a much more secure future,” Dickinson adds.

Organisation

Logs Online

Firewood Centre

Lekto Wood Fuel

Farm Woodland Forum

Devon Hedge Group

Forest Research

Scottish Forest Agriculture and Horticulture Development Board (AHDB)

Soil Association - Agroforestry handbook

Website

logsonline.co.uk/about-us

firewoodcentre.co.uk

lektowoodfuels.co.uk

agroforestry.ac.uk

devonhedges.org

forestresearch.gov.uk

forestry.gov.scot/forestrybusiness

ahdb.org.uk

soilassociation.org/ farmers-growers/low-inputfarming-advice/agroforestryon-your-farm/download-theagroforestry-handbook

Agroforestry Research Trust

Department for Environment Food and Rural Affairs (Defra)

European Agroforestry Federation

Forest Research

Grown In Britain

Woodland Trust

agroforestry.co.uk

gov.uk/guidance/funding-forfarmers

euraf.isa.utl.pt/welcome

forestresearch.gov.uk/toolsand-resources/statistics/ forestry-statistics

growninbritain.org

woodlandtrust.org.uk

Cricket bat willow (Salix alba var. Caerulea), indigenous to the United Kingdom, is used in the production of cricket bats owing to properties such as its lightweight nature, robustness, longevity, and a resistance to fracturing. Willow trees are characterised by rapid growth and they can be managed within agroforestry systems.

The cricket bat willow tree was introduced to the British Isles in the early 1700s. Now, the cultivation of cricket bat willow in the UK is geographically concentrated, with Essex accounting for 50% of the production, followed by Norfolk and Suffolk at 25%, and the remaining 25% dispersed throughout the country.

These trees are typically cultivated in proximity to water bodies, in marshy field extremities, and in low-lying wetland areas. Beyond their commercial value, cricket bat willow trees contribute to carbon sequestration,

riverbank stabilisation, and the enhancement of ecological diversity and conservation.

Willow trees can grow well on otherwise unproductive land offering a means to enhance farm revenue.

The integration of willow cultivation into agroforestry systems can present a supplementary income stream through the sale of willow biomass for fuel, timber, sports equipment, and basketry materials. Specifically, select willow cultivars, when meticulously managed, are utilised in the production of cricket bats.

Online sales

l Use of otherwise unproductive low lying wet heavy soils.

l 100 trees per hectare.

l Can be grazed with sheep seven years after planting.

l Guaranteed buy back when trees are mature from cleft manufacturers.

l Fast-growing, high-value investment with proven returns after 15-20 years.

l Sale price of a well-maintained tree can reach up to £500. Establishment and maintenance cost can be minimal.

Benefits can include wetland utilisation, carbon sequestration, flood mitigation, biodiversity benefits, productive use of marginal land, renewable resource.

The foundational expenses associated with the establishment of willow cultivation are relatively nominal. The preliminary costs encompass approximately £25 per plant, accounting for the trees, protective guards, soil preparation, and the planting process.

Several national willow timber merchants offer trees for free, predicated on a reciprocal agreement to purchase the mature stems. The maintenance expenditure is estimated at £1 per biannual pruning session for each tree, culminating in a total of £36 per tree over the standard 18-year rotational period.

The average market value of a harvested cricket bat willow tree is approximately £375, with exceptional specimens commanding prices up to £500. Notably, the income from the sale of timber from the ownership of commercial woodland is exempt from income tax and corporation taxthe exemption only applies if the timber cut or felled is not altered or transformed prior to sale.

Demand for UK-grown basketry willow remains steady, driven by artisan crafts, eco-packaging, and heritage restoration. While the market is niche, highquality willow can command premium prices.

Basketry willow is traditionally grown in low-lying areas with moist, fertile soils such as peatlands and riverbanks, and is well suited to agroforestry systems like riparian buffers, hedgerows, and coppiced alleys.

These fast-growing willows—typically coppiced between November and March— can reach heights of 1–3 metres in a year, regenerating new stems ideal for weaving. Common varieties include black maul (Salix triandra), continental purple (S. daphnoides), flanders red (S. alba fragilis), angustifolia (S. elaeagnos), and goldstones (S. purpurea).

Baskets crafted from willow range from laundry, log, and storage baskets to picnic hampers, drinks baskets, presentation boxes, and decorative items. Willow products are widely used in domestic and recreational contexts, including bicycle baskets, pet beds, trays, trugs, and even fish traps.

With growing interest in sustainable, locally made goods, UK-grown basketry willow has strong appeal for artisan markets and offers multifunctional value in agroforestry, contributing to soil health, biodiversity, and farm diversification.

makers Willow suppliers

Wholesale manufacturers and traders Basketry manufacturers

Retail use, wholesale and online sales in the UK

l Grown in low-lying areas with damp soil, grows quickly and coppiced to allow re-growth of new stems.

l The height of the harvested basketry willow can be 1- 3 m.

l Once harvested, willow rods are sold in bolts / bundles of particular height, size, quantity, and colours.

l Fast growing, high value investment with proven returns after 15-20 years.

l Sale price of a well-maintained tree can reach up to £500.

Basketry training in research institutions

Training & educational activities

Retail use of basketry products

Export of basketry products overseas

Non-financial benefits

Benefits include wetland utilisation, erosion control, biodiversity support, phytoremediation, water treatment, renewable resource, natural fencing, agricultural diversification.

According to reported sale figures as a foundational benchmark, an analysis of the economic feasibility of cultivating basketry willow across a hectare was conducted. This assessment presumes the presence of 15,000 willow plants per hectare, with a harvesting cycle commencing from the second-year post-plantation and extending over three consecutive years.

An estimated average yield of 10 rods per annum for each plant is projected, with a distribution of rod sizes categorized as follows: 30% measuring three feet, 40% between 4 to 6 feet, and the remaining 30% ranging from 7 to 9 feet. This estimation framework is employed to ascertain the financial viability of the basketry willow cultivation.

We’re seeing benefits to soil, wildlife, and cutting our energy bills as well as generating an extra income stream”

At Wakelyns, a pioneering agroforestry farm in Suffolk, willow was planted for short-rotation coppice as one part of five agroforestry trials from 1994, and now produces several revenue streams.

The farm’s willow plots (mainly Salix viminalis) are now thriving as part of a diverse system that also includes hazel coppice, fruit and nut trees, and hardwood timber.

“Most is grown to be harvested for hedge-laying binders and willow structures, with the residue chipped for biomass and mulching, and we also have an area of mixed varieties grown for basketry,” says David Wolfe, who co-owns and co-manages the farm.

While the willow grown for binders and biomass is managed by the Wakelyns team, Willow Phoenix, a separate on-site enterprise, uses the basket willow for courses, weaving, and bespoke products.

“We only need about four person-

Coppiced willow forms part of a complex agroforestry system at Wakelyns

Wakelyns grows and harvests all its own willow for:

l Hedge-laying binders (£1.20 per rod, with around 80p profit each)

l Biomass and woodchip for mulch and heating the farmhouse

l Basketry willow, which is cut by hand for craft courses and products

days per year to harvest the binders we sell,” Wolfe says. “And Willow Phoenix harvest what they need, often with their course attendees.”

And Wolfe isn’t only seeing financial benefit from the coppiced willow trees. They are an important part of the agroforestry system at Wakelyns, providing wind breaks and shade, helping with water management and creating habitats as part of a major biodiversity contribution.

“Recent soil sampling by Rothamsted Research suggests they may also be adding nitrogen to the soil,” says Wolfe.

“It’s an easy win – the trees provide so many benefits, create profit for two businesses on our site, and save us money on heating costs and mulch.”

Organisation

J.S. Wright & Sons

English Willow

Chase Cricket Bats

Musgrove willows

Coates English Willow

Basketmakers’ Association

Owen Jones

Woven Communities

Ruthin Craft Centre

Highland willow

Willowbrook

Service

Cricket bat willow suppliers who work with landowners to supply and grow willow

Cricket bat willow suppliers who supply saplings free of charge and guarantee purchase at maturity

British-based cricket bat manufacturer

Grower and supplier

Grower and basket manufacturer

Promotes basketry and related crafts, including trainings

Basket maker

Basketmaking communities in Scotland

Centre for applied arts and basketry crafts

Willow weaver and basket maker

Basketry willow farm

Website

cricketbatwillow.com

englishwillow.co.uk

chasecricket.com

musgrovewillows.co.uk

coatesenglishwillow.co.uk

basketmakersassociation.org. uk

oakswills.co.uk wovencommunities.org

ruthincraftcentre.org.uk/ exhibitions/basketry-2

highlandwillow.co.uk

willowbrookbasketfarm.com

Biochar is a carbon-rich product that is produced through heating biomass such as wood in a closed environment with little or no air present. When biomass is heated in an environment without oxygen, it can produce biochar, syngas and liquid oil.

Biochar – a stable, carbon-rich material produced by heating organic matter in lowoxygen conditions – offers multiple benefits and can be produced with the product of any agroforestry system.

When used as a soil amendment, it can enhance soil organic matter, improve nutrient retention, and boost water-holding capacity. Studies have also shown increased microbial activity, better crop yields, and potential reductions in greenhouse gas emissions by reducing nitrous oxide released from soil through denitrification.

Biochar can be used as a soil or compost additive and even as a livestock feed

supplement to support productivity in cattle, pigs, poultry, and fish. It has been shown to improve digestion, help fight disease and promote weight gain.

Due to these various benefits, the use of biochar is increasing with a projected annual market growth of 15.5% from 2023 to 2030, according to Fortune Business Insights.

It can be derived from various outputs of agroforestry systems, such as wood, and can be made using low-value remnants and byproducts from other wood-based processes. This allows it to serve as a value-added alternative to selling woodchips, kindling, and other low-revenue wood materials.

l Shortening the supply chain can minimize the cost of production.