earth spirit Osamu Inayoshi

a solo exhibition

Contents

Foreward by Osamu Inayoshi - p5

‘Earth Spirit’, an essay by Howard Clegg - p6

Tsubo - p8

Hanaire - p10

Mizusashi - p12

Chaire - p14

Shuki - p16

Zara - p18

Sculptural Forms - p20

a solo exhibition

Foreward by Osamu Inayoshi - p5

‘Earth Spirit’, an essay by Howard Clegg - p6

Tsubo - p8

Hanaire - p10

Mizusashi - p12

Chaire - p14

Shuki - p16

Zara - p18

Sculptural Forms - p20

My pottery may seem very tricky to use and really awkward to drink from.

But if you just bring it to your lips once… Well… maybe it really is a little hard to drink from.

But Isn’t that better, don’t you think?

A little imperfect and hard to use…that’s what makes it charming, don’t you think?

In a world where people chase perfection, predictability and control, isn’t it a thrill to let that go? To give in to elements of chance, introduce challenge to your life, engage your senses with questions rather than quieten your mind with answers. This is what my work strives to do and my work gives to me.

I will be 50 soon.

If someone asked me if I’d want to start my life over again… I’d rather stay with this one. This is the life I want.

This life is truly the one I want.

It would make me very happy if you enjoy my exhibition and choose a work to add to your collection. Choose one that asks you questions, and see if you have answers.

Osamu Inayoshi, October 2025

“InJapan,therearespiritsineverypartofnature—and inOsamuInayoshi,anindomitablespiritofhisown.”

At The Stratford Gallery, we have long admired Osamu Inayoshi, a first-generation potter from Toyohashi, Aichi Prefecture. In Earth Spirit, we encounter the most accomplished stage of his practice to date. Across 100 works — including tsubo, hanaire, chawan, shuki, platters, bowls, and sculptural forms — Inayoshi’s mastery of material, form, and firing has reached unprecedented intensity. For those familiar with his work, this exhibition reveals a striking evolution: new forms, glazes, and natural firing outcomes that redefine his artistic language.

Inayoshi’s practice is inseparable from the history he reveres. Atsumiyaki, a 700-year-old ceramic tradition of Aichi Prefecture, provides both inspiration and framework. These underground kilns, long lost to time, produced iron-rich clays with subtle ash glazes, marrying functionality with quiet elegance. Inayoshi has reconstructed these kilns using archaeological research, confronting formidable challenges: one flooded, another collapsed after a single firing. Undeterred, he plans a third attempt, exemplifying a devotion to process and material that transcends the practical.

This commitment is evident in every piece. His chawan exhibit surfaces of rich, unpredictable coloration; shuki and tsubo balance utility with sculptural presence; experimental glazes interact with clay in previously unseen ways, producing subtle variations that reward contemplation. Even seasoned collectors will discover unexpected surprises, reinforcing that this is work one cannot simply assume they know.

Inayoshi engages clay as both medium and interlocutor. Every mark, every ash deposit carries centuries of memory, yet his work is not merely retrospective. Tradition becomes a living dialogue between maker, material, and fire. As a first-generation potter, Inayoshi has earned serious regard through technical mastery, rigorous scholarship, and persistent creative ambition. Earth Spirit captures this culmination: work that honors ancestry while asserting a compelling, contemporary voice.

Forms throughout the exhibition embody the dialogue between spirit and matter. Hanaire rise with subtle asymmetry; platters and bowls evoke natural phenomena; sculptural forms assert vitality while inviting reflection. Surfaces record transformation

— the interplay of flame, ash, and clay — creating objects that are as intellectually compelling as they are visually compelling.

Through Earth Spirit, we witness an artist whose pursuit of excellence is inseparable from the work itself. Each vessel carries the trace of Inayoshi’s persistence, discernment, and reverence. The exhibition is both culmination and beginning: a testament to a spirit rooted in tradition yet unflinchingly original.

ExploringAtsumiyaki:HistoryandRevival

Atsumiyaki, originating in Aichi Prefecture, is one of Japan’s most ancient ceramic traditions. Flourishing during the Kamakura and Muromachi periods, it is characterized by iron-rich clays and subtle ash glazes, producing robust yet elegant forms designed for daily use and ritual practice.

Archaeological studies reveal that Atsumiyaki kilns were ingeniously constructed underground, allowing precise temperature control over long firings. The resulting vessels carried the marks of flame and ash while achieving refinement and functional balance. Over time, this tradition waned, leaving only fragmentary evidence for contemporary potters.

Osamu Inayoshi’s work is transformative in this context. Fascinated by lost techniques, he has reconstructed underground kilns informed by scholarship. The first flooded; the second collapsed after a single firing. Undeterred, Inayoshi continues, translating centuries-old processes into forms resonant with contemporary sensibilities.

His chawan, shuki, and tsubo exemplify a philosophy that embraces unpredictability: each surface and glaze variation is an integral part of expression. Tradition is treated not as a fixed inheritance, but as a living dialogue between maker, material, and

fire.

Through Inayoshi’s work, the spirit of Atsumiyaki is renewed: vessels that honor ancestry, confront material and technical challenges, and reveal the expressive possibilities of clay as both utilitarian and sculptural. Earth Spirit offers collectors and admirers a rare opportunity to witness this dialogue, where past and present converge in tangible form.

Howard Clegg October 2025

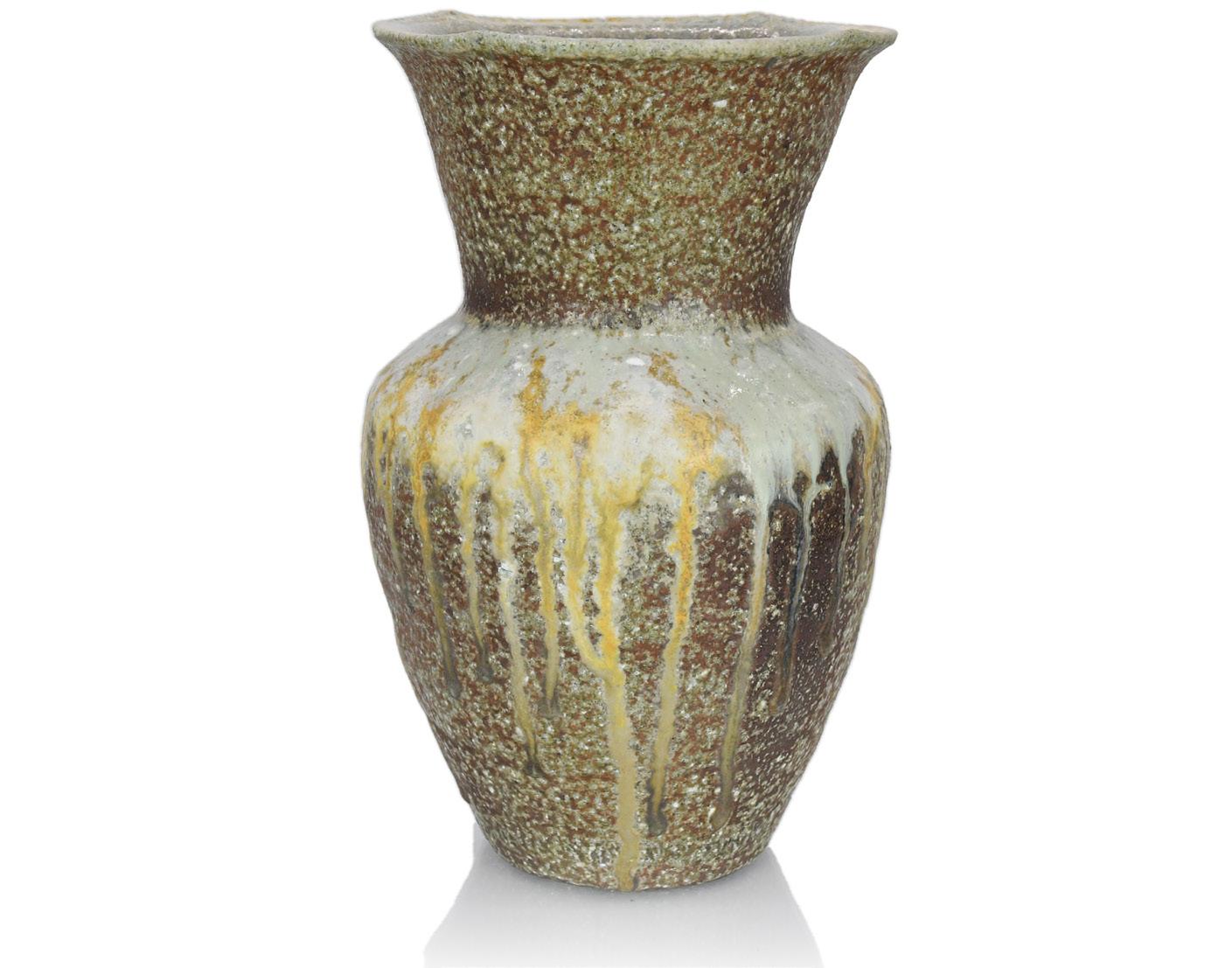

Few ceramic forms carry such dignity and universality as the tsubo. Originally conceived as a vessel of necessity — for storing water, grains, or tea — the tsubo has transcended its utilitarian origins to become one of the most revered expressions of Japanese ceramic art. Its voluminous body, narrow mouth, and balanced curvature embody both containment and release, simplicity and monumentality.

Across centuries, from ancient earthenware to Momoyama period masterpieces, the tsubo has been celebrated for the honesty of its form. Fired in wood kilns, its surfaces bear the fingerprints of flame and ash — natural patterns that transform each jar into a unique record of the firing process. Collectors and tea masters alike have long cherished tsubo for their quiet grandeur: objects that seem to breathe with the rhythm of the earth itself.

To live with a tsubo is to bring an elemental presence into one’s space. It is a vessel that stands without adornment, yet never empty — resonant with the memory of its making. In its generous curves and subtle asymmetries, it holds both function and metaphor: the idea of preservation, of holding within it the unseen energies of time and nature.

A fine tsubo asks little yet gives much — a reminder that beauty and purpose are one, and that silence can speak profoundly.

Among the many vessels born of the tea ceremony, few carry such quiet gravity as the hanaire — the flower vase. In the world of chanoyu, where each object serves both purpose and philosophy, the hanaire occupies a role of poignant beauty. It is the vessel that holds life itself, a space where nature enters the tearoom in its most transient form.

Historically, hanaire evolved from simple bamboo tubes and rustic jars to refined ceramic forms used to display seasonal blooms. In the tea room, they do not shout for attention; they invite contemplation. A single flower, a branch just past its prime — such arrangements remind participants of ‘mono no aware’, the Japanese awareness of impermanence and the bittersweet beauty of things that fade.

To own a hanaire is to participate in this lineage of mindfulness. Its emptiness is as meaningful as its occupation; it exists in readiness, its presence transforming when life is placed within it. Every mark, curve, and texture becomes a stage for renewal — a collaboration between the vessel, the flower, and the passing moment.

In Japanese aesthetics, the hanaire embodies grace through restraint. It is a reminder that beauty is not fixed, but fleeting; that form is animated by spirit; and that within simplicity lies profundity. A fine hanaire brings not only flowers to a room, but the soul of the seasons themselves.

The mizusashi, or fresh water jar, is a vessel of quiet authority within the tea ceremony. It holds pure water — the element from which the ceremony begins and to which it returns. While the chawan and chaire invite touch and intimacy, the mizusashi stands apart: poised, reserved, and profoundly symbolic.

Historically, the mizusashi reflects both purity and restraint. It is placed at the edge of the tatami where the host draws water for the kettle, an act performed with care and reverence. The vessel’s surface may be richly glazed or left bare to reveal the clay’s natural beauty. In either case, it must express calm dignity — a kind of silent balance between utility and grace.

For the artist, the mizusashi offers a canvas of proportion and stillness. It is a large form that must not impose; it holds power through humility. Many of Japan’s most celebrated traditions have produced mizusashi admired for their subtlety and spirit and many of those mizusashi are treasured national objects of cultural importance.

To own one is to hold a piece of that ritual lineage: a reminder that purity is both physical and spiritual. In a contemporary context, the mizusashi becomes an object of contemplation — a vessel that embodies composure, clarity, and the serenity and purity of water itself.

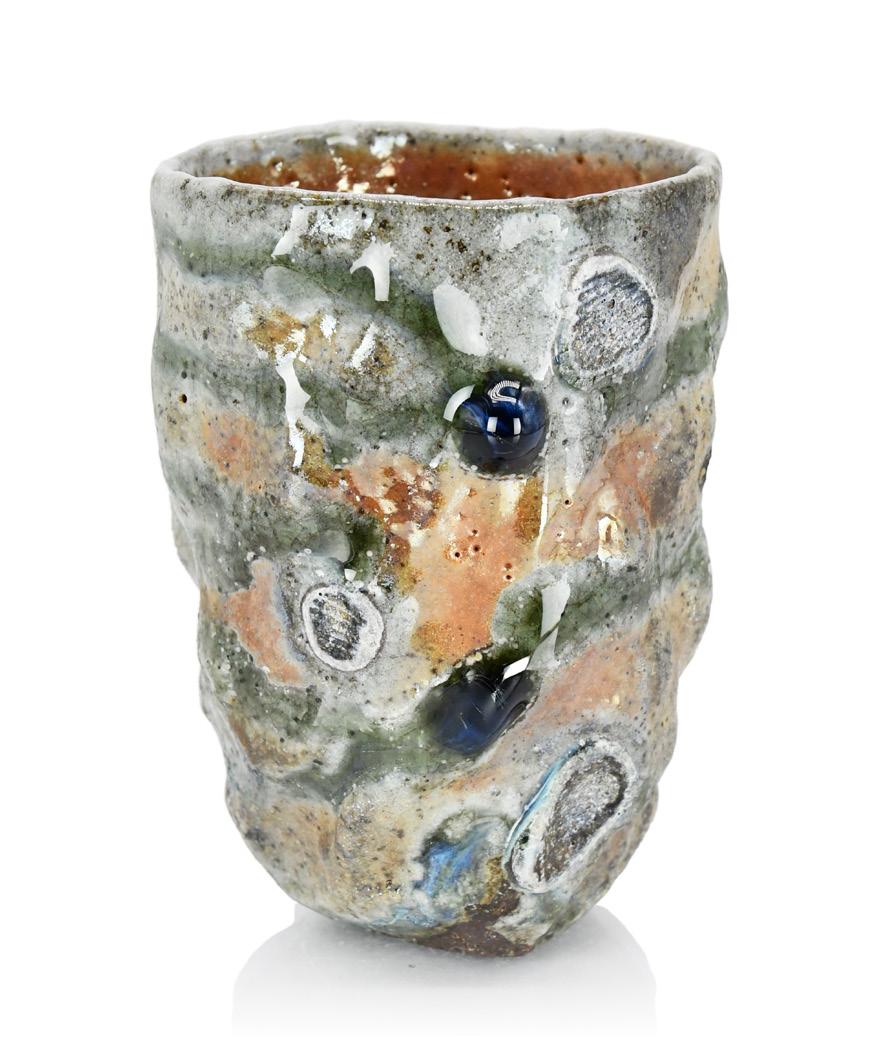

Shuki — vessels for serving and enjoying sake — hold a special place in Japanese culture. They embody hospitality, connection, and the quiet ceremony of shared experience. To pour for another and not for oneself is an act of respect; to choose a cup from a selection offered is a gesture of personal expression and taste.

In the finest dining traditions, guests are often invited to select their own guinomi from an array of cups. This moment of choice — tactile, instinctive, and aesthetic — heightens the ritual of drinking. The form, weight, and glaze of a cup all influence the character of the sake and the intimacy of the encounter.

Osamu Inayoshi’s shuki make that choice deliciously difficult. His works span a remarkable spectrum — from surfaces rich in molten movement and iridescent depth to others that seem to have emerged from the earth itself. Each piece holds the tension between ancient and contemporary, between controlled intention and the unpredictable voice of the kiln.

These vessels are not merely functional; they are meditations on fire, texture, and form. To hold one is to feel the dialogue between craft and nature, between restraint and freedom. Inayoshi’s shuki invite touch, reflection, and conviviality. They remind us that in Japan, beauty often resides in the moment of use — when art meets life in the simple, profound act of sharing a drink.

Within this new collection of Shuki from Osamu Inayoshi we are treated to vessels for Nihonshu (what we know as ‘Sake’ outside of Japan), Shochu (Japanese distilled spirits) and Beer cups.

Zara (sometimes spelled Sara), or platter, holds a distinguished place within the kaiseki dining tradition. Far more than a serving surface, it is a stage for culinary art — a vessel that frames the fleeting beauty of seasonal ingredients. In Japan, food presentation is an act of aesthetic mindfulness; the sara provides the canvas on which that mindfulness unfolds.

Historically, sara evolved from simple wooden trays to ceramic works of extraordinary refinement. During the Edo period, potters began producing sara that reflected the tastes of the tea masters — earthy, restrained, and sensitive to season. A well-chosen sara enhances not only the appearance of food but the entire sensory experience of dining.

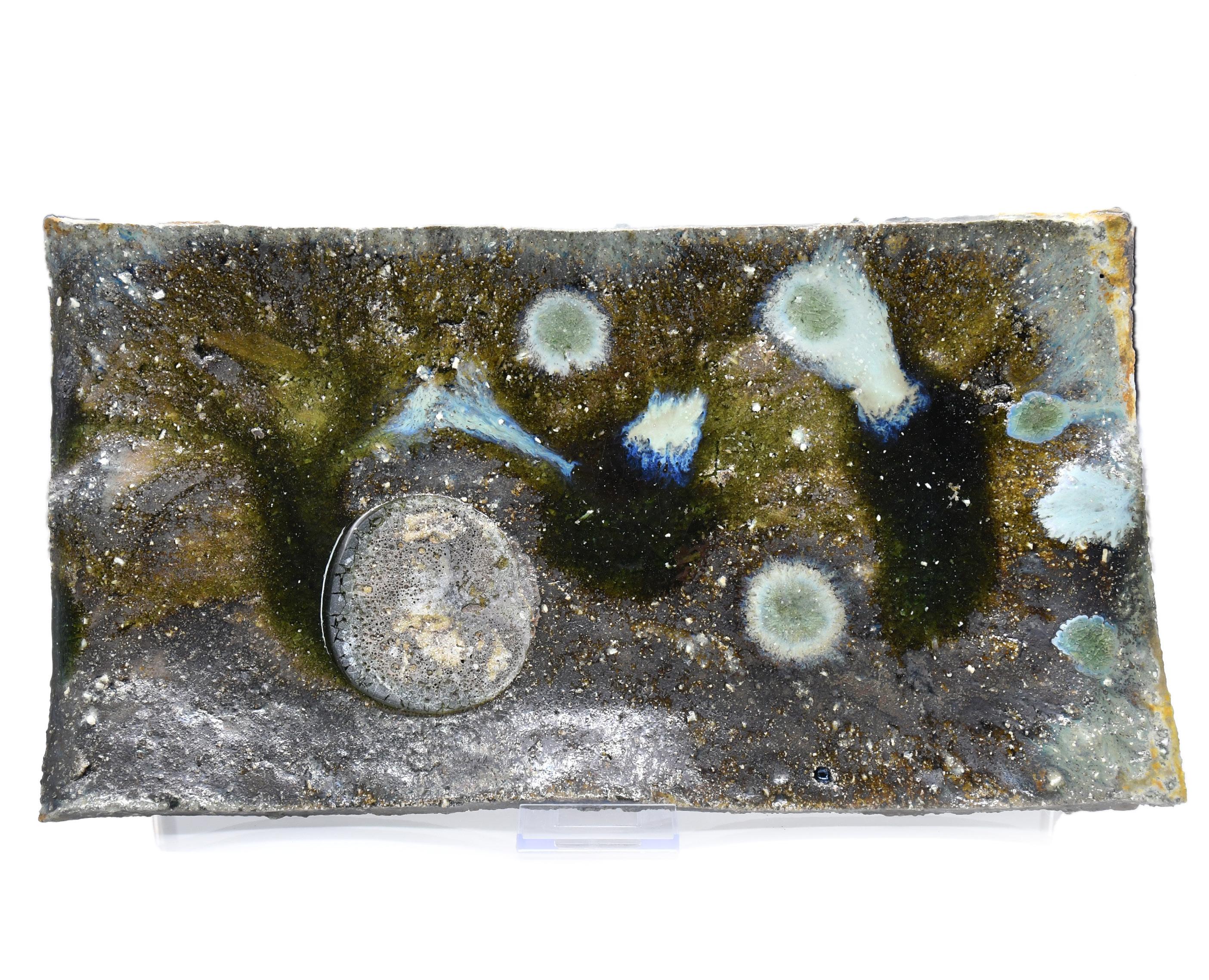

The best sara unite proportion, surface, and presence. Their expansiveness allows glaze and fire to speak in painterly ways: ash runs, iron spots, or shino blushes creating landscapes across the surface. In kaiseki, the sara anchors the visual rhythm of the meal, mirroring nature’s cycles through changing motifs and hues.

To live with such a vessel is to understand that beauty and use are inseparable. Whether holding food, fruit, or simply space, a fine sara brings harmony to its surroundings. It is a reminder that in Japan, art does not sit apart from daily life — it enriches it, quietly, with every meal.

While functional vessels have long defined Japanese ceramics, sculptural expression has occupied a parallel and equally vital tradition. From early Jomon figurines and ritual objects to the more abstract kiln-fired forms of the modern era, sculpture in clay has allowed potters to explore form, surface, and concept beyond utility. These objects bridge craft and art, embodying both technical mastery and aesthetic vision.

Osamu Inayoshi’s sculptural works continue this lineage, yet speak with a distinctly personal voice. Drawing inspiration from the natural geology of his region, his forms evoke rock strata, riverbeds, and eroded landscapes, each surface alive with texture and energy. The irregularities of clay and the unpredictability of firing are celebrated rather than restrained, producing pieces that pulse with vitality while retaining a sense of groundedness.

Accents of gold and subtle metallic finishes imbue Inayoshi’s sculptures with a quiet jewel-like quality, echoing the furyu aesthetic — an elegant blending of natural spontaneity and refined beauty. These touches of treasure do not dominate; they hint at hidden richness within the earth, amplifying the sense of discovery for the viewer.

To encounter one of Inayoshi’s sculptural pieces is to witness the meeting of elemental forces and human imagination. They invite touch, reflection, and contemplation, transforming space through presence. In their lively, natural forms, these works remind us that ceramic art can extend far beyond the functional, carrying the spirit of landscape, the thrill of material, and the quiet joy of aesthetic surprise.

October 2025

No part of this publication may be reproduced by any party without the written consent of The Stratford Gallery Ltd

All text and images © The Stratford Gallery Ltd

62 High Street, Broadway, Cotswolds, WR12 7DT

TheStratfordGallery.co.uk

01386 335 229 Art@TheStratfordGallery.co.uk