A publication of Ideas from Robert Menzies College

The times where I have been moved to tears while gazing at an art work are seared to my memory.

I recall sitting in front of The Beheading of Lady Jane (left) painted by Paul Delaroche, that hangs in the National Gallery in London, transfixed by the immense 2.5m by 3m canvas. The fragility of the nine-day queen dressed in near-wedding white, blindfolded, kneeling and guided to place her head on the executioner’s block stands in stark relief to the certainty of the executioner and his axe. Another is Portrait of Doctor Gachet (top) painted by Van Gogh, which hangs at Musée d'Orsay in Paris. Doctor Gachet, Van Gogh’s attending doctor during the final months of his life, is painted eyes down despondently gazing into the mid-distance behind the viewer, his head resting on a closed fist with his elbow propped on the table. Other museum goers moved around me, whilst the colours, the despaired look, the tragedy of what’s to come (Van Gogh’s inevitable death), and the genius of Van Gogh melted into my tears.

Portraits that paint the tragedy of the human condition creates an emotional connection between the viewer and the object. I had never thought, though, that paintings of landscapes could move me to emotional wonder until I saw the works

of the Group of Seven at the Art Gallery of Ontario at three-thirty on new year’s day, 2025. The paintings were housed in a set of galleries where the walls stretched double-storied and ended at a frosted glass ceiling. I could not move. I kept pointing in childlike astonishment and stopping my friend to gaze at tiny splashes of hidden colours. In the white gallery space iceberg after iceberg seemed to float in soft ambient light.

Formed in 1919, a year after the end of the great war, the Group of Seven consisted of Canadian artists Franklin Carmichael, A. Y. (Alexander Young) Jackson, Frank Johnston, Lawren Harris, Arthur Lismer, J. E. H. MacDonald, Tom Thomson, and Frederick Varley. In the 20s, the artists devoted themselves to depict Canadian life from small town to snow-capped icebergs. Their styles are distinctly post-impressionist with sharp lines and bends of the Art Nouveau. Light is delicately reflected in a bubbling stream in flecks of yellow, naked alien boughs foreground transcendent mountains, spikes of foliage in red, orange, maroon, and amber, all combined to give glimpses of Canada through the eyes of seven people. Early critics called them “Hot Mush School” with work “more like a gargle or gob of porridge than a work of art;” the Toronto Star considered their work as “a Dutch headcheese having a quarrel with a chunk of French nougat.” This critic could not but stand frozen in place, gasping, “The blues, they’re so blue.”

The Group of Seven’s collective work demonstrates the theme of this issue, Exploration: Unknowns Near and Far. The group ventured artistically beyond the art movement impacting the transatlantic and explored the cusp of the new. They (re)depicted

"The Group of Seven," The Art of Story, https://www.theartstory.org/movement/group-of-seven/ 1 1

landscapes that have existed long ago, and will continue to exist long after, in styles and strokes that were invigorating and filled with new life. The rough tundra and dense birch woods lay far in rural Canada, yet existed in a place that was home. Seeing new in the old, seeing old in the new, capturing the old with the new, capturing the new with the old. Finding insight in the far and the near. Exploration can appear and reappear in many forms. The unknown may exist on the other side of the world or on the empty pages of a diary at your local coffee shop. It is there, if we seek for it. In Rev. Dr. Peter Davis’ words, “exploration always begins—with curiosity.”

This Winter issue of Vera Cogitate first launches us into the frigid unknowns of Antarctica; Rev. Dr. Peter Davis reflects on his recent trip to the only continent that is primarily a desert. He discovers the awe of massive ice-shelves and consequences of climate change, tiny planktons and their impact on major eco-systems. Readers are advised to watch the video of the trip first (there’s a QR code on the article for you to scan) and feel the experience.

From Antarctica we travel to Indonesia, Mexico, and The Quiet Between Bird Songs - a series of poems collected by Sebastian Perez. Naufal Irfansyah, Natalia Soriano, and Bree Coulston, three RMC Residents, were asked to write poems in their native language with an English translation on this theme. Naufal Irfansyah’s poem, Senya, reminisces on the twilight of love – transient, beautiful, where every sunset might be the last sunset. Natalia Soriano’s El galopar del caballo reflects on the tranquillity of battle inspired by Joan of Arc. The pair of poems, The Quiet Between Bird Songs and Epilogue – A New Beginning, seek to find a “sacred space” and beginnings in the midst of dark noise, real or metaphorical. This section begins with my reflection on translating poetry.

After global poetry, this issue returns to the human body, with an essay by Monaal Madan, a student of medicine. He introduces Multiple Sclerosis, a debilitating disease that he is researching, and the ways in which it affects human lives.

Three disparate themes, as you dive from ecological, literary, to medical, yet “Exploration always begins— with curiosity.” It is a curiosity that takes courage to enter into a space that we are unfamiliar with, whether the space is within or without. William Blake’s verse from Auguries of Innocence, seems an apt quotation to guide us,

“To see a world in a grain of sand And a heaven in a wild flower, Hold infinity in the palm of your hand And eternity in an hour.” 2

May you explore the unknowns and find the truths you seek.

Sam Wan B.Ed (Primary) USYD, MDiv AUT Dean of Academics | Editor – Vera Cogitate. Macquarie Park, May 2025.

2

William Blake, “Auguries of Innocence,” Poetry Foundation, https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/43650/auguries-of-innocence

Youtube Video MS Roald Amundsen Antarctic Trip 2025

It’s hard to know where to begin after that. Even now, watching that footage —penguins diving, ice shifting, the silent landscape—I find myself

catching my breath. This journey wasn’t just a travel opportunity. It was the fulfilment of a long-held dream—my wife’s dream, since she was a child, to go to Antarctica. And in chasing that dream together, something shifted in both of us. We stepped into a world that feels untouched and yet profoundly vulnerable.

The theme of this collection is ‘Exploration: Unknowns Near and Far.’ And that’s what Antarctica gave us—profound unknowns, both external and internal. Unknowns in scale and sound and stillness. Unknowns that made us feel small and fragile.

In this essay, I’d like to explore some of those unknowns: the ancient geology beneath the ice, the fragile web of life it sustains, the signs of change unfolding before us, and the international efforts to protect what is shared by all and owned by none.

But I want to begin where exploration always begins —with curiosity.

After the video, many people imagine Antarctica only as a place of snow and ice. But below the surface, the continent has a complex structure and a major role in shaping global systems.

Antarctica is the coldest, driest, and windiest place on Earth. The lowest temperature ever recorded was minus 89.2 degrees Celsius, at Vostok Station. And even though it looks like a frozen world, it’s officially classified as a desert.

But beneath the ice, Antarctica is a continent—one with mountain ranges, valleys, volcanoes, and tectonic activity. The Gamburtsev Mountains, completely buried beneath the ice, are roughly the size of the European Alps. Under Denman Glacier in the region. If it melts completely, it could cause a global sea level rise of about 1.5 metres.

Most of the continent—about 98%—is covered by ice. But that ice holds information. Over time, snowfall compresses into layers of glacial ice. Scientists drill into these layers to extract ice cores, which contain air bubbles from hundreds of thousands of years ago. These samples tell us about past climates—how much carbon dioxide was in the atmosphere, what temperatures were like, and how stable the environment was.

Antarctica also drives major ocean currents. Because it’s a continent surrounded by ocean, the water flows all the way around it. This forms the Antarctic Circumpolar Current—the strongest ocean current on the planet. It connects the Pacific, Atlantic, and Indian Oceans, distributing heat, oxygen, and nutrients around the globe. It’s a key part of the global ocean conveyor belt, which helps regulate Earth’s climate.

In winter, sea ice grows to cover about 19 million square kilometres. In summer, it shrinks to about 3 million. That seasonal expansion and retreat helps form dense, cold water that sinks and flows into the deep sea. As it sinks, it carries oxygen and carbon dioxide with it—essential for ocean health and climate stability.

Antarctica is also the source of large tabular icebergs that break off from ice shelves and move with ocean currents. These icebergs often look like floating cliffs. As they erode and roll, they change shape, and eventually break down into smaller pieces.

But warming temperatures are changing all this. Sea ice is thinning. Glaciers are retreating. Melting freshwater affects ocean salinity and current strength. If the West Antarctic Ice Sheet were to melt, it could raise global sea levels by 5 metres. If the entire Antarctic Ice Sheet melted, sea levels could rise by over 50 metres. These aren’t short-term risks —but the long-term consequences are significant.

So while Antarctica might seem isolated, it plays a critical role in global systems—climate, ocean. Currents, and sea level. And the geological structures beneath the ice aren’t just features of the past. They’re part of a changing present.

Antarctica may appear frozen and lifeless from above, but its marine ecosystem is one of the most productive on Earth. It operates on

seasonal rhythms, intricate food webs, and a foundation that—quite literally—keeps the planet breathing.

...WHILE ANTARCTICA MIGHT SEEM ISOLATED, IT PLAYS A CRITICAL ROLE IN GLOBAL SYSTEMS—CLIMATE, OCEAN CURRENTS, AND SEA LEVEL.

At the base of this ecosystem is pack ice, which forms each winter as seawater freezes. Sea ice does more than mark the changing seasons. It shapes the structure and function of the entire Southern Ocean. As ice forms, it pushes out salt, increasing the density of the water beneath it. This cold, salty water sinks, driving deep ocean currents that bring nutrients up from the sea floor. As the ice melts in spring and summer, it releases fresh water into the ocean, forming a lighter layer on the surface. Trapped inside the melting ice are bacteria, phytoplankton, and zooplankton—the building blocks of life in the ocean.

This melting triggers what’s called an ice-edge bloom —a massive increase in phytoplankton, which are microscopic, single-celled algae that photosynthesise like plants. These blooms are visible from space and drive the entire food web that follows..

Phytoplankton are small, but their impact is enormous. They are responsible for producing at least 50% of the Earth’s oxygen supply—more than all the world’s forests combined. In other words, every second breath you take is made possible by plankton in the ocean. So when we talk about the importance of this region, we’re not only talking about

penguins and icebergs—we’re talking about oxygen, climate, and life as we know it

These phytoplankton feed zooplankton—tiny drifting animals that include the most important species in this region: Antarctic krill. Krill are small—about 6 cm long—but they’re central to the Southern Ocean

https://dialogue.earth/content/uploads/2022/02/kril

food web. They can live for 5–6 years, survive winter by grazing on algae under sea ice, and control their position in the water column—diving to avoid predators and rising at night to feed.

Krill form enormous swarms—so dense they can turn the ocean red or orange. There can be thousands of individuals in each cubic metre of water, and the total biomass is estimated to exceed 300 million tonnes. Almost every major marine predator in Antarctica eats krill: penguins, seals, whales, and seabirds.

Baleen whales, such as blue, fin, and humpback whales, migrate to Antarctic waters in summer to feed. A blue whale—the largest animal on Earth— can consume up to 4 tonnes of krill per day, filtering them through keratin baleen plates. Humpback whales use a strategy called bubble-net feeding, working alone or in groups to corral krill into tight

clusters before lunging up through the centre with mouths wide open.

Penguins are also efficient hunters. Six species live in the Antarctic and sub-Antarctic regions, but only Adélie and emperor penguins are true Antarctic residents. They pursue prey—mostly krill, fish, and squid—using streamlined bodies and powerful flippers. Their feeding patterns can even be seen in their droppings: pink guano means a krill-based diet; white suggests fish.

Seals play multiple roles in the ecosystem: Crabeater seals are specialist krill-eaters and one of the most numerous large mammals on Earth.

Weddell seals dive under the ice to hunt fish and squid.

Leopard seals, top predators, feed on penguins, smaller seals, and krill.

Squid are both predators and prey. There are over 50 species found south of the Antarctic Polar Front. Ranging from 15 cm to 4 metres in length, they begin life eating crustaceans and switch to fish as they grow. Because they avoid nets and are hard to track, much of what we know comes from the stomach contents of whales and seabirds.

At the very top of the web are orcas, or killer whales. There are several types in the Southern Ocean— some specialise in fish, others in seals and whales. They hunt cooperatively, sometimes knocking seals off ice floes or chasing young whales during their migration. And while most attention goes to animals near the surface, the seafloor ecosystem is equally rich.

So what may seem like a frozen, silent ocean is in fact a highly active, deeply interconnected system. From microscopic diatoms to blue whales, from deep-sea worms to penguins diving under the ice— this is one of the most efficient, productive ecosystems on the planet. And it all starts—with phytoplankton. With ice. And with light.

WHAT MAY SEEM LIKE A FROZEN, SILENT OCEAN IS IN FACT A HIGHLY ACTIVE, DEEPLY INTERCONNECTED SYSTEM... ONE OF THE

There are sea stars, urchins, brittle stars, and large sponges—some over two metres wide and hundreds of years old. In deep, undisturbed areas, animals grow slowly and live longer.

Many Antarctic species are endemic, found nowhere else on Earth. Some show signs of polar gigantism, growing much larger than their temperate relatives due to cold, oxygen-rich water and fewer predators.

Even after death, the cycle continues. Organic matter sinks to the seabed as marine snow, feeding benthic communities. Over time, this becomes sediment—which, through upwelling, fertilises the next generation of plankton.

To many visitors, Antarctica still appears wild and untouched. But if you stay long enough —or know what to look for—the signs of

human impact become clear. There are old whaling stations, rusting remains of sealing outposts, and scattered scientific bases. But more concerning are the changes that aren’t immediately visible—like microplastics in the snow, or glaciers quietly retreating over decades.

Antarctica is warming. The continent has seen a long-term temperature rise in average air temperature of around 0.5 to 0.6°C, and the Antarctic Peninsula is warming even faster—3°C since the 1970s. In 2020, a record 18.3°C was measured.

This warming is reshaping the continent. Ice shelves are thinning, retreating, and collapsing—like Larsen B, which disintegrated in 2002, releasing 720 billion tons of ice. Glaciers are also retreating, forming meltwater lakes, waterfalls, and calving more frequently.

These changes are disrupting life: Krill numbers fall in low-ice years, impacting penguins, seals, and whales.

Adélie penguins, which rely on krill and ice, are declining.

Gentoo and chinstrap penguins, more adaptable, are expanding south.

New species—like king crabs and fur seals— are moving into warming waters.

There are more visible signs too: penguins panting in the heat, flowering plants spreading further south, and melting snow turning slushy and stained with algae.

ANTARCTICA DOESN'T STAY IN ANTARCTICA. IT'S A SIGNAL. AND IT’S GETTING LOUDER.

Sea ice is changing rapidly. After decades of stability, Antarctica lost as much sea ice in two years as the Arctic did in three decades. The four lowest summer sea ice records have occurred recently—2017, 2022, 2023, and 2024—and winter sea ice is no longer recovering as expected. Sea ice is essential —it supports krill, buffers ice shelves, reflects sunlight, and regulates ocean circulation. Losing it affects ecosystems and climate globally.

Antarctica is changing fast. It’s warming, melting, and shifting. And that matters—not just here, but everywhere. This continent regulates ocean currents, stores vast amounts of carbon, and its phytoplankton produce over half the world’s oxygen.

What happens in Antarctica doesn't stay in Antarctica. It's a signal. And it’s getting louder.

28b-cc6ba0

antarctic-region-dpla-189a0b713d3fcf59ef9299f2c8abd

https://boudewijnhuijgens.getarchive.net/amp/media/

Despite its isolation, Antarctica is not untouched. People have been coming here for over a century—for science, for survival,

and increasingly, for tourism.So how do we protect a place that belongs to no one, but matters to everyone?

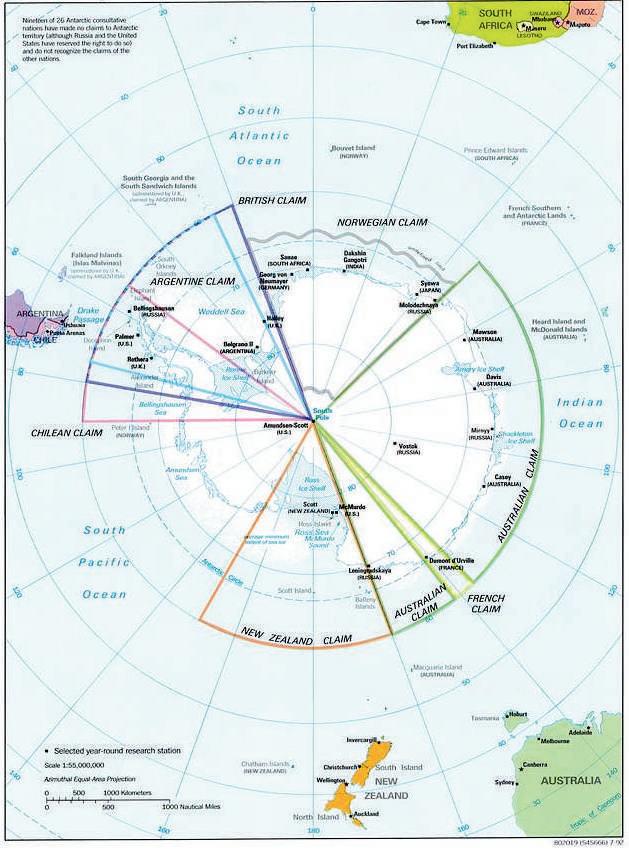

The Antarctic Treaty

In 1959, at the height of the Cold War, twelve nations came together to sign the Antarctic Treaty. It came into force in 1961 and remains one of the most remarkable international agreements ever made. At a time of global division, it created a continent set aside for peace and science.

The Treaty applies to everything south of 60° South latitude. It froze all territorial claims, meaning no one could enforce sovereignty, and no new claims could be made. It banned military activity, nuclear testing, and weapons deployment. Military support for logistics is allowed—but no military operations. To build trust, countries are allowed to inspect each other’s stations and ships.

Over the past 60 years, the Treaty has evolved into a wider system—including environmental protection agreements. One of the most important is the Protocol on Environmental Protection, which bans mining and designates Antarctica as a ‘natural reserve, devoted to peace and science.’

These agreements are based on consensus. That means every decision must be agreed on by all parties. Any one country can block a proposal. So, progress takes diplomacy, patience, and mutual respect. Most of the real discussions happen in quiet conversations outside formal meetings—person to person, culture to culture. It’s slow, but it works.

ANTARCTICA AS A ‘NATURAL RESERVE, DEVOTED TO PEACE AND SCIENCE.’

Tourism in Antarctica has grown dramatically. To manage this, a group of tour operators formed the International Association of Antarctica Tour Operators (IAATO). It’s a rare model: tour companies voluntarily working together to regulate themselves. IAATO sets rules for safe, environmentally responsible travel—things like:

Limiting the number of visitors at any landing site

Keeping safe distances from wildlife

Biosecurity measures to prevent introducing new species

Speed limits for vessels

Shared scheduling tools to prevent overcrowding

IAATO doesn’t have legal authority—but its success depends on cooperation and shared values. It’s an example of what protection can look like when there’s no single government in charge.

We came to Antarctica expecting distance —and instead found connection. We found ice that breathes, oceans that

regulate the planet, and plankton that help produce the air we breathe. We found that this place, which looks so far from everything, is tied to the fate of everything.

The video of the trip showed some of the wonder. The rest—the history, the science, the urgency— you’ve read now in words. Antarctica is beautiful, yes. But more than that, it is foundational. It shapes our climate, reflects our choices, and asks us questions about what kind of future we want.

We are no longer explorers in the heroic age. We are stewards in an age of limits. The unknowns we face today are not just out there in the distance. They are within us—questions of restraint, cooperation, and care.

Antarctica gives us a model of what’s possible with nations setting aside claims, companies regulating themselves, scientists sharing data, and people working together in fragile places, not to conquer, but to understand.

So the question we leave with is this: In the face of change, in the face of the unknown—what kind of explorers will we be? Will we continue to treat wonder as a resource to consume? Or as a responsibility to honour?

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Li_Bai_JingY%C3%A 8Si.jpg

TRANSLATIONS... CONVEY THE ORIGINAL MEANING OF A TEXT FROM ONE CULTURE TO BE UNDERSTOOD BY LANGUAGE USERS OF A DIFFERENT CULTURE.

Line two forms a couplet with line one through the use of “疑是.” The ambiguity of these two words lies in the absence of a pronoun. If we assume that the subject is an implied first person, it can be translated as a verb “to think/consider” with a sense of uncertainty, e.g. “[I] consider whether it *(the moonlight) [is] frost on the ground.” Alternatively, we can consider the second line as a conditional clause

Line three and four work as a couplet with parallelism, both begin with an adverbial phrase followed by a verb then the object. The is subject of the clause is the implied persona, as the noun cannot take the verb. The direction of up is natural, as the moon lies above, thus tracking the source of moonlight from lines one and two. Line three, then, also works in thematic parallel to line one, as both engage in regarding the light and the literal. Gazing down of the head is a natural figure of speech in Chinese to symbolise contemplation, thus line four uses 低頭 not only in antithesis to the line before but to reinforce the verb 思 思 means to think but has a lexical focus on memory, dreaming or hope; thus

It is possible, but unlikely, to break the clause into two with cadence so that the first half is a verbal phrase (舉頭 | 望明⽉).

https://cdn2.picryl.com/photo/1250/12/31/lian g-kai-li-bai-strolling-91145d-1024.jpg

7

6

4

Returning to translation, interpretation occurs in the act of translating. How can a twenty character, five by four structure written in 8th

century Tang Dynasty Chinese be rendered into twenty-first century English to impact the current audience? Below, I have chosen three translations from various sources to provide translation examples.

Moonlight illuminates [the space]* before my bed, as if frost blanketed the ground. I lift my head and see the glowing moon, and, head sinking, I think of home.

5

My casement veils glowing pools of moonbeams, Perhaps on the ground is simply frost it seems; Lifting my head I gaze up at the gleaming moon, Bowing my head I ponder my homesick dreams.

I saw the moonlight before my couch, And wondered if it were not frost on the ground. I raised my head and looked out on the bright moon; I bowed my head and thought of my far-off home.

Yvonne Ye, "《静夜思》 https://yyeintheplacetobe.wordpress.com/2016/06/23/%E3%80%8A%E9%9D%99%E5%A4%9C%E6%80%9D%E3%80%8B-ove translation-and-analysis/

5 “Quiet Night Thought,” Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Quiet_Night_Thought

Li Po, "On a Quiet Night Night),” Favorite Poem Project: https://www.favoritepoem.org/poems/on-a-quiet-night/#:~:text=I%20saw%20the% 20frost%20on%20the%20ground.

One difficulty of translation lies in render the poem into a discernible syntax that retains the original meaning and flows poetically in another language. All three translations above (hencefore T1, T2, and T3) choose to rearrange the syntax into standard english sentential structure of Subject, Verb, Object (SVO) with minor stylistic variations. On the basis of syntax, T1 and T3 deviates the most from the original. T1 rearranged line one and moves the original leading prepositional phrase (“before my bed”) to the end of the line. It retains the original line’s subject, “moon,” followed by the addition of a verb, “illuminates,” and an object, “[the space].” The action of “being illuminated” is implied in the original when the prepositional phrase (before bed) is in apposition to the noun (moonlight). T1 makes the superfluous addition of “[the space]” as the object, with the translator justifies it because “it doesn’t make grammatical sense in English.” The parallelism is also lost in the last couplet as the translator tries to connect the two lines as one broken line.

T3’s deviation lies in its anglicisation of Chinese verse. The translator of T3 repositions the entirety of their translation with the first-person pronoun as the subject: “I saw,” “[I] wondered” (in an ellipsis), “I raised,” and “I bowed.” Indeed, the majority of interpretations concludes an implied first-person persona who is himself that of the poet Li Po. In recitation history, performances of Chinese scribal poetry convey the verse as if it flows out from the reciter; hence, the horizon of reader, persona, and author are collapsed as one. However, though it may be argued that T3’s insertion of the first-person pronoun creates the connection needed between reader and persona, the subtly of the original is lost through the redacting hand of individualistic autonomy. The forcefulness the inclusion, combined with decision of using simple past tense, refocuses the text into a factual recount. Rather than nuance inference of events in the original that pedagogically allows the reader to engage in the pedagogy of imagination before unleashing this potential in the final memory of home, this rendering’s use of the past tense reduces the potential built in the original.

While on the topic of tense, verbs do not conjugate to distinguish time or aspect in Chinese, e.g. go, went, gone; rather, tense is determined through particles of speech or context. The original poem has no indication of tense. All three renderings, T1 in the present tense, T2 in the present continuous, and T3 in the simple past, are plausible. However, in choosing these tenses, T1 remains static with the reader as observer, T2 has the effect that the moment is occurring at the same time for both persona and reader, and T3 positions it as a memory (as mentioned above). T2, as a whole, seeks to represent the original as closely as possible. The structure follows the A/A/B/A rhyming pattern, and lines one and two have similar meters,

u /u / u-u / u /u u/ u-u / u u-u / u /

while lines three and four both have eleven syllables. Syntactically, the translation matches phrase with phrase: line one begins with the prepositional phrase (“casement” being a possible translation for “床”) and ends with the main clause; line two begins with the adverbial phrase without a verb, “perhaps” (T1 does similarly with “as if,” whilst T3 turns it into a conditional verbal phrase, “and wondered if”), then the object is in the prepositional phrase (on the ground) followed by the subject (frost). Lines three and four both start with prepositional phrases (“舉 頭” and “低頭”) in present participle, with the addition of a possessive pronoun modifying head (“my”), followed by adding the implied subject of the firstperson singular to turn the clause into SVO.

All three poems effectively communicate the meaning and sense of the original. Where quality and variation differ lie in the choice of

syntax and tense which alters the perspective and, subsequently, the rhetorical function of the translation. In my opinion, T3, translated by Lewis S. Robinson, deviates the most and inhibits the intention of the original; T1, translated by Yvonne Ye, conveys the sense of the poem, but ultimately falls short in choice of phrasing. Translation two, which surprisingly comes from Wikipedia, I find to be closest to the text in meaning, sense, structure, syntax, tense, perspective, and rhetorical function. This comes to show that, perhaps, with the power of collective knowledge, it is okay to “just wiki it.”

TThough Chinese is my first language, I have lost the ability to read or write since moving to Australia as a 5-year-old. However, it would be hypocritical for a poet to remain an armchair critic without having a go at translating the poem. So I’ll end this piece with my humble attempts at translation, with the aim to convey the sense, the poetics, and the rhetorical intent as close as possible.

Yonder sill moonlight runs Aground, or frost-bright glow?

Regard above – thy moon, Reminisce afar – my home.

8

Robinson completed a PhD in "Double-Edged Sword: Christianity and Twentieth-Century Chinese Fiction" (1982, published in 1986) from the University of California, under the East Asian Languages and Cultures within the core department for East Asian Humanities. He has published other works, including “The Bible in Twentieth-Century Chinese Fiction” in the monograph Bible in Modern China (1999). This translation was published in 1978 by Hong Kong Commercial press.

Yvonne translated the poem as a 19-20 year old when she undertook the Light Fellowship with Yale University that sends students on exchange in Asia.

Collected by Sebastian Perez Currently studying BMus MQ

di puncak bukit aku terdiam memandang kota yang dilahap malam langit menari dalam warna jingga dan emas di atas laut biru yang luas

mataharipun perlahan undur diri memberikan ruang bagi malam untuk bermimpi seperti hadirmu yang tak pernah memaksa namun mengubah pandanganku tentang apa itu indah

kau hadir sekejap namun membekas menyisakan hangat yang sulit lepas karena bagiku, kau adalah senja tak pernah datang terlalu cepat, tak pernah pergi tanpa bekas

Naufal Irfansyah

at the hilltop I sit in silence watching the city swallowed by night the sky dances in hues of amber and gold above the vast and endless blue sea

the sun slowly takes its quiet leave giving space for the night to dream like your presence—never forceful yet changing my view of what beauty means

you appear briefly, but the warmth remains a trace of light I cannot explain for to me, you are the sunset never arriving too soon, never leaving without a trace

El galopar del caballo — luchaba rítmicamente con el del agua. Su cabello hasta los hombros— y su mente, luchando por una tregua.

El estallido de la batalla — silenciaba el cantar de las hadas. Ella ansiaba su espada empuñar — pero, junto al palpitar el fuego, esperaba.

Paciente para doblegar su as — y de oro, teñir las cruzadas. La sangre tan sagrada como la guerra — alababa gloriosa a su corazón.

Al contrincante aterra y a lo vano destierra — poniendo fin a una era y moldeando a fuego, una generación.

El fuego que ahora enfriaba sus pies — una vez, su alma refugiaba.

Natalia Soriano

The horse’s gallop –battled rhythmically against the water. With her hair at her shoulders –and her mind, fighting for a truce.

The battle’s outbreak — silenced the fairies’ song. She longed to wield her sword— but, beside the fire’s heartbeat, she waited.

Patient to subdue her ace — and the crusades, tint with gold. Blood as sacred as war — praised her heart with glory.

It terrified her foe and banished the vain — welcoming the end of an era and forging, through fire, a generation.

The fire that now cooled her feet — once, once a haven to her soul.

Natalia Soriano

I ride the storm beneath a sky of fire, where swords clash—echoes of my soul, a journey carved in shadows, yet made whole, each step a whisper in the winds of desire.

The ocean calls with secrets in its tide, its waves like voices, crashing in the dark— reminding me that I am more than a spark; I am the sea itself, where dreams reside.

I feel the flames—they burn into my chest, ripping through the cage that once held me so tight. Freedom’s song, now rising, calls the night, as wings unfurl, to face the coming test.

Beneath the sun, the battlefield appears, the galloping of hooves, the hearts that race— and in the dusk, I find my sacred place, a place beyond all doubts, beyond all fears.

For I am not the drop lost in the sea, but the ocean in a single grain of sand, held gently in a quiet, unseen hand— forever seeking what it means to be free.

The sky turns red, the sun begins to fall, yet in the dusk, a bluebird starts to sing— its song, a promise of wings, free and bold, reminding me that after storms, we unfold.

Roses rise from dreams on trembling wing, their petals whispering the truth of fire— the strength we gain from trials we must endure, to bloom beyond the ash, and spread our wings.

Bree Coulston

I followed no map but the hush of the wind, where the earth split open to speak in flowers, and rivers ran like veins through the body of the world.

The forest did not ask who I was. It simply opened— like a question left unanswered for years.

The trees held the light in their trembling hands, and I, too, began to glow with a kind of knowing that needs no name.

I met myself in the quiet between two bird songs, in the soft ache of a mountain too old to boast its beauty.

The sky—endless, unfamiliar— taught me to walk without fear into places that do not promise arrival.

And there, beneath the eyes of stars who have seen every version of me— I did not find answers, but something softer: a beginning.

Coulston

Monaal Madan

Currently studying MD MQ, BBioSci (Hons) Monash, GCertHlthProm Flinders

Multiple Sclerosis (MS) is a long-lasting disease in which the immune system mistakenly harms myelin, the thin

protective layer that surrounds nerves in the brain and spinal cord. When this insulation breaks down, nerve signals slow or stop, causing problems with vision, movement and sensation. MS cannot yet be cured, but modern treatments can reduce attacks and delay disability. About 2.8 million people worldwide live with MS, including roughly 33 000 Australians. It usually begins between the ages of twenty and forty and affects women about three times more often than men. Rates are higher in countries farther from the equator, suggesting that lower sunlight and vitamin D levels increase risk. Genes also play a part, though no single gene causes the disease.

ABOUT 2.8 MILLION PEOPLE WORLDWIDE LIVE WITH MS, INCLUDING ROUGHLY 33 000 AUSTRALIANS.

Early signs are often subtle. Blurred vision in one eye, pins and needles in a limb, a brief electric-shock feeling down the back when bending the neck, or sudden unsteadiness can all be first clues. These symptoms may fade, then return months later, which makes diagnosis difficult.

Doctors confirm MS by showing that nerve damage has appeared in different parts of the central nervous system at different times. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans reveal small white scars, called plaques, where myelin has been lost. A spinal-fluid test often shows extra immune proteins, and a neurological examination documents objective changes. Conditions such as neuromyelitis optica must be ruled out.

When a flare-up limits daily activities, high-dose intravenous steroids speed recovery. For ongoing control, disease-modifying medicines such as injectable proteins, tablets or monthly infusions cut the number of attacks and slow long-term damage. Regular exercise, adequate vitamin D and avoiding smoking also help. Physiotherapists, occupational therapists, bladder specialists and psychologists work together to manage symptoms and keep people studying, working and active.

Research is advancing quickly. Scientists are testing drugs that may regrow myelin, exploring stem-cell treatments for severe cases and developing simple blood tests to track nerve injury. Continued investigation is essential to give people with MS a better future.

“TO SEE A WORLD IN A GRAIN OF SAND AND A HEAVEN IN A WILD FLOWER, HOLD INFINITY IN THE PALM OF YOUR HAND AND ETERNITY IN AN HOUR.”