Summer (2024)

A publication of Ideas from Robert Menzies College

Editorial: In Search of Self and Other

Essay: The Future in the Other

Poetry: Sarah Roux

Culture: Diaspora LitFic

“Aoratos kai akataskeuastos-” an exercise in theological imagination.

Martin Buber wrote: “In the beginning was relation.”

I’d been intrigued with that ever since I came across that in my graduate studies. In what beginning was relation? In the Universe’s? God’s? Philosophy? In whose beginning? My beginning? Yours?

Wherever the beginning lay, I think Buber is right. The fabric of our reality is bound in relationshipscall it an ecosystem, call it marriage, friendship, food chain, nuclear reactions - there are relationship between one and another, or in Buber’s words, the I and Thou.

I’d been intrigued with that ever since I came across that in my graduate studies. In what beginning was relation? In the Universe’s? God’s? Philosophy? In whose beginning? My beginning? Yours?

Wherever the beginning lay, I think Buber is right. The fabric of our reality is bound in relationshipscall it an ecosystem, call it marriage, friendship, food chain, nuclear reactions - there are relationship between one and another, or in Buber’s words, the I and Thou.

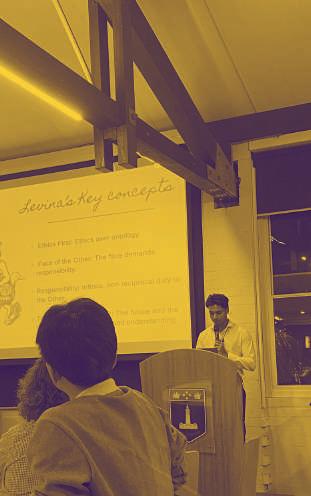

At our first Vera Cogitate: a Symposium of Ideas, we had the opportunity to hear from residents at Robert Menzies College who shared their thoughts on the nature of Self and Other related to their disciplines or interests. These have been edited and re-formed into the pieces we have in this edition of Vera Cogitate. Stefan Thottunkal, current Medical Student, shared about his own experience as a trainee doctor providing care. He explored how Levinasian ethics interact with the I and Thou of doctor/patient relationships. Sarah Roux shares her poetry exploring the intersection of relationships between herself, animals, nature, and others in her life. Her expertise in music and prose has allowed her to transform her experience into

pieces that engage the human soul. Josephine gives a vivid analysis of Diaspora Lit-Fic, where the other in the self is seen in contrast as people wrestle with their immigrant cultural identities. She dialogues with the novel Martyr and teases out the edges of our own otherness. Finally, I explore the nature of self and other in the opening verses of the Hebrew bible, considering its implication to the experience of disability. When we acknowledge that there is an other beyond ourselves, that they too, like us, are in search of another we begin to learn to embrace the reality of the other. When we recognise the self in the other and the other in the self, then we can begin to consider the relationships that exist in our communities.

May these pieces inspire you to consider the true person within and the true people in your midst.

Sam Wan B.Ed (Primary, USYD), MDiv (ACT) Dean of Academics | Editor – Vera Cogitate. Macquarie Park, April 2024.

https://www.flickr.com/photos/bracha-ettinger/124819595

StefanThottunkal

B. Health Science Hons. (Australian National University), Current M.D. Student (Macquarie University)

TTraditional bioethics—grounded in principles such as autonomy, beneficence, nonmaleficence, and justice—serves as the

foundation for contemporary medical ethics. However, these principles, while essential, may fall short in capturing the profound, almost existential, nature of the doctor-patient relationship.

Levinas’s ethics, centered on the encounter with the Other, offers a radical departure from duty-based ethics and invites physicians to engage in an infinite responsibility for the patient that transcends professional duty.

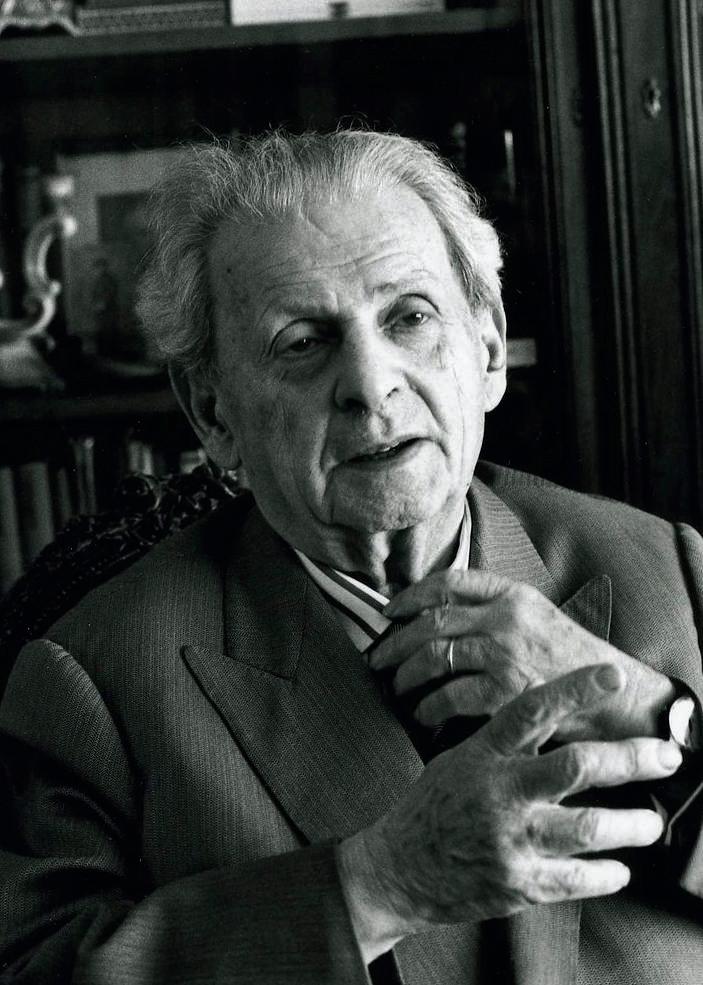

Emmanuel Levinas once said, “The very relationship with the Other is the relationship with the future.” This profound statement invites us to delve into the intricate web of identity, belonging, and humanity. As a medical student, the consideration and exploration of these themes is crucial given the demands of medical school. The delicate balance between personal and professional responsibilities, the negotiation of time for self, patients, family, and spirituality, forms essence of our being and our sense of interconnectedness with others.

For Levinas, the face-to-face encounter with the other commands a response; it is an ethical call that precedes any

conceptualization or predefined notions. This encounter disrupts the self’s autonomy and selfcenteredness, opening the self to responsibility and care for the Other.

In Levinas’ view, the Other is not merely an object within the world but a presence that transcends our understanding and categories. This transcendence is crucial because it introduces a future that is uncontrollable and beyond prediction by the self. The Other, in their alterity, represents a horizon of possibilities and ethical demands that force the self beyond its immediate present and into a future of ethical responsibility.

In the context of medicine, the patient represents the Levinasian Other. Their vulnerability—whether physical, emotional, or existential—creates an ethical demand that the physician cannot escape. The doctor’s response to this demand is not simply to follow professional guidelines or to act in accordance with principles like beneficence and autonomy, but to engage in an ongoing, unceasing care for the Other. The patient, in their suffering, becomes a face that interrupts the physician’s world and imposes a call to ethical action that transcends duty.

PHYSICAL, EMOTIONAL, OR EXISTENTIAL—CREATES AN ETHICAL DEMAND THAT THE PHYSICIAN CANNOT ESCAPE.

Levinian ethics fundamentally calls upon us to define our meaning through others. This question of identity for clinicians has both Who Am I? deeply personal and universally aspects. For example, within myself, I am also a human being with my own aspirations, fears, and desires. I am bound by my oath to serve my patients with utmost dedication.

On the other, I am an individual who seeks personal growth, familial closeness, and spiritual fulfillment.

In this regard, my professional identity does not stand in isolation but is deeply intertwined with my personal life. I must negotiate how much of myself I am to give to my patients and colleagues in addition to my family and friends.

To a great deal the compassion I extend to my patients is a reflection of the love I experience in my personal relationships. However, the realities of the time commitments it takes to study medicine means this love is very rarely reflected in the form of time, our most valuable asset. Every day is a step in a journey to acquire enough knowledge to one day benefit patients. Medicine is limitless, and knowledge on any single sign or symptom can make or break a diagnosis and consequently alter the course of a patient’s life. Thus, how can one stop and compromise on our ability to meet the ethical duty to the other.

IN THIS REGARD, MY PROFESSIONAL IDENTITY DOES NOT STAND IN ISOLATION BUT IS DEEPLY INTERTWINED WITH MY PERSONAL LIFE. I MUST NEGOTIATE HOW MUCH OF MYSELF I AM TO GIVE TO MY PATIENTS AND COLLEAGUES IN ADDITION TO MY FAMILY AND FRIENDS.

he demands of medical school and the consequent transition from scholar to medical student is a challenging time for Identity in the Other

Tmost. Many of us were at the top of our classes and now are mere average. This transformation forces us to question and reconsider our identities, and how

we view ourselves. Whilst fitting in hobbies, extracurricular activities and travel can help us find meaning, Levinian ethics advocates for finding meaning through our interactions with others.

As medical students we can often feel useless to others. We lack the knowledge and scope to make significant changes to the medical management and treatment for patients. Thus, often times we can feel like an observer instead of healer. But lending a compassionate ear and actively listening to patient’s vent is a form of healing. Instead, we can reframe this perspectives to the fact that we are not burdened by the responsibility of management at this point of time. We can perform thorough histories, take as much time as patients need to explain their conditions to them in ways they understand, and get to the bottom of how they feel, their epistemology, and what their wishes are.

Expression of shared humanity can be expressed through the small acts of kindness that often go u

nnoticed such as the gentle reassurance to a worried patient. Or offering an extra pillow and blanket or adjusting their bed to their comfort. For many patients, in particular the frail and elderly, seemingly forgotten by time and yearning for connection in the isolated hospital bed, they are happy talk to anyone about anything, even if it is just about their ailing health, their conditions worsening with the passage of time. We can connect to patients through hobbies and shared interests and show them that their clinicians are people just like them. It is through these little actions that we can find our shared humanity and redefine ourselves as healers of the soul.

Outside of shared identity, I find that it is the differences that truly enrich my interactions with others. Each person’s unique background, culture, opinions and experiences provide a broader perspective that challenges my assumptions and broadens my understanding. These differences are not obstacles but opportunities for growth and learning. They remind me that my view of the world is limited and that there is always more to learn from others.

Asignificant challenge for doctors is balancing their infinite responsibility to each individual patient with the realities of

the healthcare system. Time constraints, resource limitations, and systemic pressures can make it difficult to fully realize the Levinasian ethical ideal. In addition, the responsibilities outside of practice, towards that patient every doctor worries. They who are awaiting urgent results and have worrying symptoms but are not currently sick enough to present to the ED. They exist on a knifes edge for deterioration; undermining one’s ability to be fully present when spending time with loved ones. Ultimately, infinite responsibility threatens erasure of oneself.

It is moreover challenging to contend with the vast resources required for optimal healthcare within our current paradigm. Data suggest that the global health care sector is responsible for between 4.4 and 5.2 percent of the world's greenhouse gas emissions (Moutinho, 2024). In the US, the healthcare sector was found to be responsible for 12% of the overall national acid rain emissions, 10% of greenhouse gas emissions and 7% of all total water use in commercial and institutional facilities (Piscitelli et al., 2023). However, transitioning away is not simple as sterility warrants single use plastics for procedures and hospitals need an uninterrupted supply of energy for heating, cooling, and ventilation. High rates of water use is needed to properly maintain hygiene and treat wastewater due to the environmental risks associated with excreted drugs. However, being conscious of our impacts on others and using this as a rationale to identify ways to cut down, we can creatively work on solutions. For example, to address overpacking; pre-assembled kits which contain all the necessary medical supplies for specific procedures, such as cannulation and suturing, but extra components that are often not. Because packs are created sterile, these unused medical consumables are disposed. Thus, awareness can lead to simple tailoring of packs or creating devices that can pack custom kits on site, can easily reduce waste. Investing in battery based generators and powering solar energy are other key modes to

improve sustainability. Overall, the prospect of infinite responsibility is not a direction to destroy oneself, but a call to consider the global community, engage in systemic advocacy, and devise more creative solutions.

Given Levinas’ call to systemic engagement, it is crucial to critically appraise the advent of AI in clinical practice.Theoretically AI

systems, through machine learning and data-driven algorithms, can assist physicians in making decisions that are evidence-based, efficient, and precise. However, from a Levinasian perspective, is incapable of encountering the face of the Other, inherently rendering it inappropriate within the clinical setting.

AI lacks the human capacity for empathy, emotional responsiveness, and moral judgment; qualities that form the foundation of Levinas’s ethical framework.

AI systems are built on probabilities and statistical models, which foster an ideology of care that is efficient but detached from the ethical dimension of caregiving. For instance, AI might suggest optimal treatment strategies based on data, but it cannot comprehend the existential fear or suffering that a patient experiences. The patient’s vulnerability, as seen through Levinasian ethics, requires more than just a treatment plan; it calls for a human presence that acknowledges and responds to the patient’s deeper ethical needs and desires.

Furthermore, Levinas would argue that AIs use in medical decision-making risks reducing patients to mere data points, stripping them of their uniqueness and humanity. Trained mostly on western data, emerging evidence has already identified the potential for AI models to widen the health disparities faced by marginalized populations such as CALD groups. Ultimately, the infinite responsibility a physician bears toward a patient is grounded in the recognition of the patient as a singular, irreplaceable Other. AI, in contrast, operates by categorizing and generalizing, which runs counter to Levinas’s

insistence on the irreducibility of the Other. The ethical encounter cannot be replicated through a machine, no matter how advanced. While there may be a purpose for AI as an adjacent clinical reasoning tool, development in this field requires careful consideration of automation bias and the perverse incentives to replace clinicians for machines.

verall Levinas’ applications are multifold. He challenges individuals and societies to consider how their actions today impact Conclusion

Othe futures of others, particularly those who are marginalised or vulnerable.

The emphasis on the Other can lead to an untenable level of self-sacrifice, potentially neglecting the self’s needs and rights for doctors. The practicality of his ideas in complex social and political contexts where competing ethical demands are commonplace, is challenging to contend with.

However, I argue that Levinas does not advocate for the erasure of the self but rather for a reorientation of the self’s priorities and creativity. The ethical relationship with the Other enriches the self, offering deeper meaning and purpose that transcend individual desires. Furthermore, in practical applications, his philosophy encourages a balance between self-care and ethical responsibility, fostering a more compassionate and just society.

References

Moutinho, S. (2024) ‘Doctors prepare for the “Enormous health consequences” of climate change’, Nature Medicine, 30(9), pp. 2382–2385. doi:10.1038/s41591-024-03160-x.

Piscitelli, P. et al. (2023) ‘How healthcare systems negatively impact environmental health? the need for institutional commitment to reduce the ecological footprint of medical services’, Epidemiologia, 4(4), pp. 521–524. doi:10.3390/epidemiologia4040043.

Sarah Roux Currently studying B.Psych (USYD)

Iam a student currently in my final semester of undergraduate psychology. Music and poetry are mediums that I enjoy exploring. I first started

learning piano as a young child and creative writing has been an important outlet for me for many years. Sometimes words can create beautiful images that remind me of a sense of joy and lightness. Playing music, I’ve found, is a wonderful way to connect with both the self and others. When we share music together, we can both have an individual and a collective experience which can be a powerful source of healing. I’ve chosen to share, for this piece of writing, some poetry that I hope you enjoy. The music of the everyday is a source of inspiration for many poems I write.

Sunlight on a bed of ivy, The gentle movement of oak leaves, The sound Of a skateboard, The rhythm of walking, Laughter:

Such is feeling the buoyancy Of piano keys beneath my fingertips, A sound that resonates through and warms me, Resting deep within the centre of my heart.

As the breeze dances through the leaves, I am A moon that turns, Moves and feels pulled to the ocean, Such that I breathe With the ocean, Long, deep breaths, And I smile at the moon because there is always This constancy of change, This circle of life and something To learn each day.

Watching the wagging tails Of dogs and their cantering movements, Sensing in all directions, I give thanks and see A halo in this afternoon light, One that surrounds Each dog, Completely.

The moon beams With a wide Open smile, A place of centredness, Of clarity.

The moon beams And I feel A little dizzy, Contemplating How in all directions, Space exists.

Moon beams In garden paths Are Like quiet Passages Of light Of time And I seek To observe These beaming Moments, Just watching How the light changes:

First as dawn arrives, The moon

Beams through Little leaves, An illumination: Each one a tiny moon, An essential piece Of this plant Which surrounds, Like a wreath, Or a blessing

A statue Of a woman Who smiles, A wide, open smile

As she looks out And sees herself

Reflected in the light That is everywhere.

Blue algae shimmers, Dazzling wave-like forms on sand, Residues of peace.

Essentially, I know there To be a light Inside That means It holds true It holds you Through windswept Rain

Along the beach It carries you Forward, Lighting the way.

The chorus of little birds, High in register, A whistling sound, One that echoes, Is so clear, Clear as the droplets Of dew Perched on bushes Of tiny white flowers, Of honey-coloured flowers, Perhaps it is the fairy-wrens who are calling Me into deeper connection With myself, A fairy, perhaps, Or to the centre of me, A place that feels magical.

DISPARATE DIASPORA: IMPORTANCE OF DIASPORA VOICES IN

Kayla Josephine Wibowo

Currently studying B. Psychology & Cognitive Scienc University)

Literary fiction, as a definition agreed upon by many, separates itself from other genres of fiction usually by being character-driven as

opposed to plot-driven. It takes place in a grounded or realistic setting, and often, their stories make compelling statements about our real-world. In this essay I’d like to shine light on an even smaller section of fiction, namely literary fiction (litfic) written by members of a diaspora.

What is diaspora literary fiction? In this essay, I’m differentiating it from international or translated litfic, in that it

was written in English by people of non-anglophone cultures who usually reside in anglophone countries or among anglophones. Nowhere is it an official term, but people have used it to refer to works of literary fiction written by a person who lives out of their homeland. But why is it different to other kinds of literary fiction, and why should it be? In particular, is it necessary to make a differentiation between it and translated literary fiction? In this essay, I argue that diaspora litfic plays a drastically

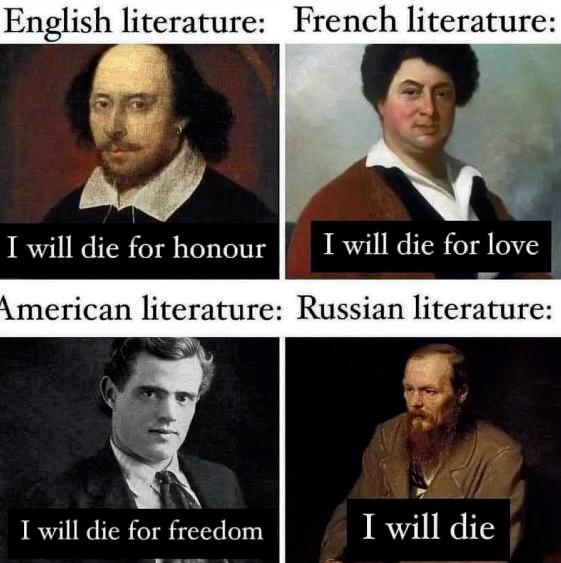

different role, with implications I believe are important to address. The best way to illustrate these differences is by identifying the common themes under each subgenre. For example, popular literature often heralded as “classics” often share common themes. Among the most beloved are of love, freedom, the meaning of life, and other abstract and complex emotions. To illustrate my point, you can imagine these themes being on the top part of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, instead called the “Hierarchy” of literary themes. Stories that explore these concepts are indulgent in a way that emphasises specific dimensions of the human condition.

“CLASSICS” OFTEN SHARE COMMON THEMES. AMONG THE MOST BELOVED ARE OF LOVE, FREEDOM, THE MEANING OF LIFE, AND OTHER ABSTRACT AND COMPLEX EMOTIONS.

https://www.reddit.com/r/memes/comments/r7ldud/russian_literature/

Readers love these stories because they provide an exaggerated, but possible, alternate reality— beautiful art to escape into. On the other hand, I’ve noticed that most translated works made popular by the international community also tend to cover certain themes. Colonialism, poverty, discrimination, postcolonial life… among other bitter things. Why is this so, and what are the implications of this?

The answer may be an obvious observation to many. On one hand, I agree that it is important for international readers to read these fictive stories as a gateway to learning history that they otherwise wouldn’t be familiar with. As global citizens, we have an active duty to be aware of how our modern history has shaped different cultures. After all, no nation lives in a vacuum.

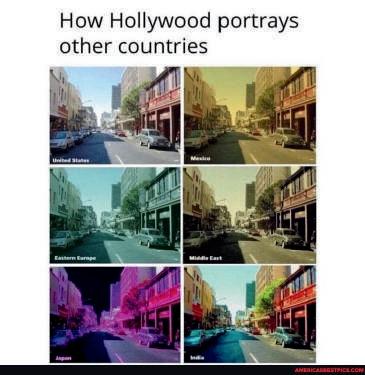

https://www.reddit.com/r/interesting/comments/1bf8rpd/how_hollywood_uses_filters_an d_colors_to_portray/

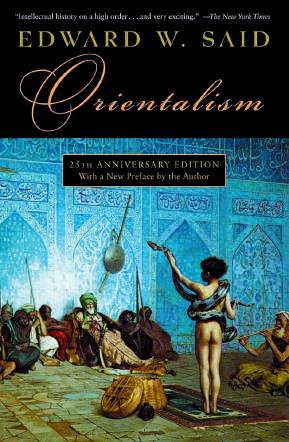

On the other hand however, the trend that translated fiction—especially from developing countries—only becomes popular if it’s about suffering has harmful implications on how we perceive people coming from those cultures. I speculate that our disconnect from other, non-Western cultures’ cultural dimensions have led to inaccurate stereotypes. Stereotypes that are shamefully evident in the media we enjoy. Our experiences shape our truth. I know I’m definitely not one of the first hundred people or

so to state that the media we consume affects our perception of other people. There is a “narrative,” if you will, that mainstream media has put most culture under. Edward Said explored more into this in his book Orientalism, which has largely influenced my making of this essay. I’m not saying that all cultural narratives that come under international spotlight is harmful. Instead, I argue that international spotlight only deems non-Western narratives worthy of attention when it is of suffering. Perhaps a lot of us, including myself, hold an implicit belief that nonWestern, non-individualist, non-consumerist cultures can’t possibly create complex and enlightened literature that’s even comparable to other modern classics. Therefore, the only thing these cultures can tell us of is their suffering. This brings me to my main argument. In this globalised world, we don’t have to rely on solely translated literature or historical films to connect with other cultures. We live among diasporas, or maybe we’re even a part of one. Culture, like other dimensions of the human experience, is ever-evolving and becomes influenced by these diasporas. Thus, diaspora litfic can be used as a gateway to understanding other cultures without the exotified lens we unconsciously hold them up to.

I recently read one of these diasporic books, titled Martyr! by the Iranian-American poet and author, Kaveh Akbar. Our main character is Cyrus Shams, a 29 year-old Iranian-American who shares the experience of many diasporic people. After the loss of his mother, his father moved himself and Cyrus to Indiana, raising his son alone in a foreign country, just barely speaking the language. Cyrus was raised to speak only English at home (“For practice,” his father

father, his mother, uncle, and Persian historical figures, something that would be much harder to do if he didn’t identify with them so strongly. It also helps that Cyrus is an incredibly well-read person that he is able to notice these distinctions on a deeper level between himself and other Americans. His perspective of the diasporic experience includes a life that many readers can probably imagine themselves living—coloured vibrantly with his

MAYBE IT WAS THAT CYRUS HAD DONE THE WRONG DRUGS IN THE RIGHT ORDER, OR THE RIGHT DRUGS IN THE WRONG ORDER, BUT WHEN GOD FINALLY SPOKE BACK TO HIM AFTER TWENTY-SEVEN YEARS OF SILENCE, WHAT CYRUS WANTED MORE THAN ANYTHING ELSE WAS A DO-OVER. CLARIFICATION. LYING ON HIS MATTRESS THAT SMELLED LIKE PISS AND FEBREZE, IN HIS BEDROOM THAT SMELLED LIKE PISS AND FEBREZE, CYRUS STARED UP AT THE ROOM’S SINGLE LIGHT BULB, WILLING IT TO BLINK AGAIN, WILLING GOD TO CONFIRM THAT THE BULB’S FLICKER HAD BEEN A DIVINE ACTION AND NOT JUST THE OLD APARTMENT’S TRASHY WIRING. (AKBAR 2024: 1)

said) and, to be as American as possible. All of this comes at a cost of his Iranian roots. Though Cyrus mainly writes poems in English, his cultural identity is often at the centre of his art. He has a less-thansatisfying grasp of his mother tongue, Farsi, yet writes beautifully in English. This, in particular, is something I personally identify with, and I believe many others do as well.

Cyrus suffers a dissonance between his cultural identity, that he desires to embrace, and his actualbehaviour. It’s true that he’s not as “Persian” as he would’ve been, had he been raised back in Tehran, however, culture is not restrained to a physical place. He inherited the values, spiritualism, and even historical heroes from his father. Despite the other parts of his Iranian-American experience that he feels discounts his “Persian-ness,” his cultural identity ultimately shows through his art. The book follows Cyrus as he starts writing his “Book of Martyrs,” and in it he includes poems about his

Persian heritage. Essentially, I want to emphasise that diaspora humanises. Translated literature is necessary and important, however it should not be our sole understanding of that culture. Diaspora literary fiction does this in a way that may be more universal, especially for those living in anglophone countries. This is important because unfortunately, the world of knowledge currently revolves around what is written in English.

I’d like you to put this book on your TBR list for next time, especially if you’re considering to diversify your reading. It’ll do more to battle bad generalisations of other cultures, and it’s always good to recognise the privilege that comes with living in an anglophone country, which this book highlights very well. Again, with our privilege, the first best thing we can do is to acknowledge it, and use it well.

Sources

Martyr! by Kaveh Akbar, page 1, First edition UK 2024, published by Picador.

“ AORATOS KAI AKATASKEUASTOS: ” AN EXERCISE IN THEOLOGICAL IMAGINATION.

Sam Wan

B.Ed (Primary, USYD), M.Div (ACT, SMBC)

Published with permission, Forthcoming Stimulus 2024 December

Words evoke images, imaginations drawn from the past. Bare wildernesses may conjure images of barren fruitfulness; endless sea, empty lostness; and chalky bone, death. Then wilderness, waters, and bone may become symbols of the unknown and finality.

Consider another approach – an exercise in imagination. With the experience of a gardener, bone may be imagined as life-giving food for roses; an archaeologist, a grave may tell living stories of the past; and the prophetic imaginations of Ezekiel, bone have the potential of life (Ezek 37:1-14). Imagination’s fingers, grasping past experiences, have the power to shape our present reactions and relationships and the trajectory of future engagement. The exercise of imagination has the power to change lives – “our action emerges from how we imagine the world.” Consider these following words:

How were they imagined? Which of the following ideas appeared alongside images of impairment: Condition, partner, beautiful, brokenness, injustice, worthy, hospital, godly. How humans imagine impairment form the ethics and relationships not only with others who experience impairment but to all human experience as we are vulnerable and limited. Even our imaginations are limited and impaired. Within our limited experience, a theological exercise of imagination allows Christians to contemplate our condition sub specie aeternitatis, for to exist in God’s creation we are only limited by God’s imaginations.

See James K. A. Smith, Imagining the Kingdom: How Worship Works, Vol. 2 of Cultural Liturgies (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2013), 49; Karen Swallow Prior, The Evangelical Imagination: How Stories, Images & Metaphors Created a Culture in Crisis (Grand Rapids, MI: Brazos Press 2023), 12.

Smith, Imagining the Kingdom, 63; sa. Prior, The Evangelical Imagination, 7.

G28:19; Gal 3:28), but the gospel is never transcultural, it exists in situ. God’s gospel can equally be reimagined to alienate and disable people. Within the wider western culture imaginations of standards of beauty, meritocracy, hyper-cognitivism, and ableism have the potential to shape scriptural interpretation, transform Christian social imaginations, affect the proclaimed gospel message (embodied and spoken), and Christian ethics towards people with impairment. It is not only chimerical transformation of social imagination that leads to alienation of impairments, but the very lack of social imagination of impairment that alienates. Brian Brock reflects on this:

“MOST CHRISTIANS WANT TO BE WELCOMING OF ANYONE WHO COMES TO CHURCH. BUT WHEN IT COMES TO DISABILITY, CHRISTIANS OFTEN FIND THEMSELVES NOT KNOWING [OR NOT BEING ABLE TO IMAGINE] WHAT TO DO. NOT KNOWING [, OR IMAGINING,] WHAT TO SAY. FEAR OF DOING THE WRONG THING MAKES IT EASY NOT TO DO ANYTHING.”

How can Christians, whether able-bodied, neurotypical, impaired, or neurodiverse, sanctify our minds, and imagine the imaginations of God?

od’s gospel creates a kingdom imagination of welcoming and discipleship for all regardless of ability, race, gender, (Matt 3 3 4 5 6

Samuel Wan, "‘Lovely in [Impaired] Limbs, and Lovely in [Impaired] Eyes All His:’ A Practical Theology Reflection on Beauty, Disgust, and Aesthetics for Christian Engagement with Disability and Impairment," Missiology: An International Review 52.3 (2024).

Hans Reinders, Receiving the Gift of Friendship: Profound Disability, Theological Anthropology, and Ethics (Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co. 2008).

John Swinton, "Disability, Vocation, and Prophetic Witness," Theology Today 77.2 (2020): 186-197, doi:10.1177/0040573620920667; Cristina Gangemi, "Ways of Knowing God, Becoming Friends in Time; a timeless conversation between disability, theology, Edith Stein and Professor John Swinton," Journal of Disability & Religion 24.3 (2020): 332-347, https://doi.org/10.1080/23312521.2020.1750537.

Brian Brock, Disability: Living into the Diversity of Christ’s Body (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic 2021), 135.

TThe entry point for this particular exercise is shaped by David Whyte’s insight: “a beautiful question shapes a beautiful mind. And so the

ability to ask beautiful questions — often in very unbeautiful moments — is one of the great disciplines of a human life.” In moments of impairments, often perceived as unbeautiful and unknown, asking a beautiful question has the potential to shape a beautiful imagination. The question I posit to ask is Jesus’ question when faced with impairment: “What works of God may be on display?” (c.f. John 9:3) This exercise will ask Jesus’ beautiful question vis-à-vis the triptych of seemingly unbeautiful moments in the opening chapters of Genesis to reimagine impairments in our lives.

1. TOHU VABOHU

“In the beginning when God created the skies and the earth (i.e. all creation), And now the earth was tohu vabohu…” (Gen 1:1-2)

As the reader considers the creation of the earth the author guides our eyes to the miraculous

appearance of our world ex nihilo in the first clause, then in the second clause eyes are cast upon the state of the earth – it was tohu vabohu – a state that will form our first exercise of theological imagination. “Without form/formless and void/empty” is the common rendering in English but has semantic contradictions. Formless can mean inexistence, undefined, or unordered; however, something undefined or unordered may still be in existence not inexistent. Had the author wanted to describe a non-existent world the phrase veha-arets lʾ hayetah (‘and the earth was not’) could have been used. Empty can mean inexistence, uninhabited, meaningless, unvaluable, or purposeless; yet, somewhere uninhabitable does not necessarily lack purpose, nor meaningless lack value.

Tohu vabohu has also been connected with chaos, deriving from chaoskampf theory posited by Higher Criticism where Genesis

was connected with Babylonian cosmology and tohu vabohu became the chaos monster that Yahweh defeats. Subsequent research has disproved this, but shadow of chaos lingered. For example,

"David Whyte: Seeking Language Large Enough," Krista Tippett and David Whyte: On Being with Krista Tippett, https://onbeing.org/programs/david-whyte-seeking-language-large-enough/.

The hendiadys of shamyim ve-eres indicates all that exists e.g., Hamilton, “the universe.” Victor P. Hamilton, The Book of Genesis: Chapters 1-17, NICOT (Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans 1990), 103, 117 n.2; sa. Bruce K. Waltke, Genesis: A Commentary (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Academic 2001), 59.

Ex nihilo can be argued from the use of bara in Genesis 1:1. See John Calvin, Genesis (Carlisle, PN: The Banner of Truth Trust 1578, repri. 1979), 70. Gerhard Von Rad, Genesis: A Commentary, TOTL (Philadelphia, PN: The Westminster Press 1972), 49. Henri Blocher, In the Beginning: The Opening Chapters of Genesis, trans. David G. Preston (Downers Grove, ILL: Intervarsity Press 1984), 63.

The earth that is described here is not pre-creation, for as Ouro shows the author uses a “circumstantial wav…’joined to the subject “the earth” and not to the verb.” Sa. LXX. Roberto Ouro, "The Earth of Genesis 1:2 Abiotic or Chaotic? Part 1," Andrews University Seminary Studies 35.2 (1998): 265, c.f. Victor P. Hamilton, The Book of Genesis: Chapters 1-17, NICOT (Grand Rapids, MI.: Wm. B. Eerdmans 1990), 116. NIV, NLT, ESV, KJV, NASB, CSB and JPS. Other translations also retain a similar essence e.g., Luther’s 1912: “wüst und leer,” or “Chaos vor der Weltschöpfung” (1. Mos. 1,2). "formless," Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/formless. Tohu is used in scripture to describe something in existence e.g., the wilderness (Deut 32:10), a city (Isa.24:10), a plea (Isa.29:21), or a plumb line (Isa.34:11). Bohu is only used in conjunction with tohu (Jer 4:23).

"empty," Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/empty.

Hermann Gunkel, Creation and Chaos in the Primeval Era and the Eschaton: A Religio-Historical Study of Genesis 1 and Revelation 12, trans. K. William Whitney Jr. (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans Publishing Company 2006), 78. Sa. Translations of Isaiah’s usage in John Oswalt, The Book of Isaiah: Chapters 1-39 NICOT (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans 1986), 615.Brevard S. Childs, Isaiah, The Old Testament Library (Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press 2001), 257.

David Toshio Tsumura, "The Chaoskampf Myth in the Biblical Tradition," Journal of the American Oriental Society 140.4(2020), doi:10.7817/jameroriesoci.140.4.0963; David Toshio Tsumura, Creation and Destruction: A Reappraisal of the Chaos Kampf Theory in the Old Testament (Winora Lake, IN: Wisenbrauns 2005); Rebecca S. Watson, Chaos Uncreated: A Reassessmnent of the Theme of ‘Chaos’ in the Hebrew Bible, BZAW (Berlin: Walter de Gruyter 2005); W. Robert Godfrey, God's Pattern for Creation: A Covenantal Reading of Genesis 1 (Phillipsburg, NJ: P&R Pub. 2003), 26.

Christopher Watkin’s popular work describes tohu vabohu in three contradictory ways, immaterial: “dark, cold, silent void;” material and uncontrollable: “monster of chaos;” and as a form of divine punishment: “the unmaking of society” and “utter desolation.” He concludes that “the thundering message is that in the absence of all form, fullness, and light there can be nothing good,” and tohu vabohu needs to be “overcome.” What is the impact to moral imaginations when our cosmological fabric is portrayed as a moral struggle or chaos needing divine intervention? If tohu vabohu existed prior to the fall and is not good, how is God imagined? Is he utilitarian – creating something not good so that his goodness may be revealed? Is he Machiavellian – economically ‘good’ but immanently a moral ambiguity? When our lives, bodies, and minds unorder and decay, how do we conceive order and disorder, purpose, emptiness, and fullness? Are impairments something chaotic to be overcome or needing divine intervention?

TTohu vabohu in its theological, literary, and linguistic context shows the original state of the earth as “not… the earth that they are all

VABOHU familiar with.” It is unknown, unfamiliar and unordered and not disordered. Chaos, a concept borrowed from Greco-Roman origins and loaded with semantic baggage of chance, malevolence, anticreation, disorder, should be an avoided description. How then should we consider tohu vabohu? At this point, the LXX’s imagination is helpful, “hē de ge en aoratos kai akataskeuastos” (Gen 1:2), rather than ascertaining the element it translates its purpose. Tohu is translated as aoratos: that which is known and exists but unseeable or immaterial (Rom 1:20, Col 1:15, 1 Tim 1:17, Heb 11:27). The earth in Genesis 1:2 is imagined by the LXX as “invisible and unprepared,” or perhaps, “awaiting to be revealed/seen and prepared/adorned/filled.”

Thomas L. Brodie, Genesis As Dialogue: A Literary, Historical, and Theological Commentary (New York, New York: Oxford University Press 2001), 131.

Christopher Watkins, Critical Biblical Theory: How the Bible’s Unfolding Story Makes Sense of Modern Life and Culture (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan 2022), 65.

Watkins, Biblical Critical Theory, 65. Watkins, Biblical Critical Theory, 72. Though Watkin’s work seeks to exposit scripture via a critical apologetic by shoehorning a plethora of meanings to make a critical point against culture, has Watkins allowed the tail of critical theories and to wag the imagination of the text? Tsumura, Creation and Destruction, 33, 34.

Watson, Chaos Uncreated 13; sa. M. Vail Eric, Creation and Chaos Talk: Charting a Way Forward (Eugene, OR: Pickwick Publications 2012). Walter Bauer et al., A Greek-English lexicon of the New Testament and other early Christian literature (Chicago, ILL: The University of Chicago, 2000), 95. Plato considered the Harmony (Plato, Phaedo, 85) and justice, virtue and the soul as aoratos (Plato, Sophe, 247b).

“Darkness was over the face of the deep and the Spirit of God hovered over the face of the sea. Then God said…” (Gen 1:2-3a).

The sea in ancient literature is an uncontrollable place, the dwelling place and playground for the gods. Poseidon uses it to keep Odysseus from home and lurking within are the Kraken, Leviathan, and Scylla. After the earth is described as tohu vebohu in Genesis 1:2, waiting to be revealed and prepared, its element is shown: the earth is sea, dark and having unknown depth. The earth as sea is part of God’s creative act and have no sentience or moral compass. Yet, the chaos motif continues to impact popular Christian portrayals of the sea e.g., Evangelical scholar Benjamin Gladd writes, “the sea [is] the embodiment of death, rebellion, and chaos… the storm on the “sea” of Galilee symbolizes a demonic horde’s attempt to thwart the gospel’s spread.”

The sea may be separated (Gen 1:6-9), used for God’s judgement (Gen 6-7), and a place for the dead (Rev 20:13), but it remains an element not an entity, with no moral responsibility. It is incapable of love just as it is incapable of evil. Rebecca Watson summarises,

“NOWHERE IN THE OLD TESTAMENT… IS THE SEA MANIFESTED AS A PERSONAL BEING, AND NOWHERE DOES YAHWEH ENGAGE IN CONFLICT WITH IT. SO GREAT IS HIS SOVEREIGN MASTERY OVER HIS CREATION, THAT SOMETIMES HE STIRS UP THE SEA

Returning to the Genesis 1:2, though the earth is uninhabitable as sea awaiting to be revealed “the Spirit of God hovered over.” Even on the precipice of Genesis 1:2, before God speaks, he is present in the foreign and uncontrollable – perhaps the sea is not so scary after all.

The Gospel of Mark reimagines Genesis 1:2 in two bookends (4:35-41 and 6:45-52) that extends faithful imagination in the face of

the unknown. In the first scene, Yahweh-incarnate hovers over the sea on a boat asleep (Mk 4:38); in the second, he hovers over the sea ambling past the disciples (Mk 6:48). In both, Jesus’ presence ought to be sufficient for their faith prior to the stilling of the storm (4:40, 6:50), but the disciples’ fear (4:40, 6:50) led to imaginations a ghostly omen (6:49) and abandonment (4:38). If the readers’ eyes are quick to focus on Jesus stilling the storm (4:39, 6:51) as the crux of the scenes, we leap over the precipice of Genesis 1:2 too soon and do not notice his presence “over the face of the sea.” Prior to the calming, God’s will and work in cultivating faith was already present in his presence, it was fear’s imaginations that stripped faith away. The moral imagination needed is for believers to have faith that God does not abandon them but hovers over all elements. In the face of impairments that seem to strip away our values of autonomy, intellect, function and relationship, and propel us into uncontrollable, it is natural human response to fear. As a means of protection, humans respond in fight, flight, fawn or freeze, and our prefrontal cortex, responsible for higher brain function, shuts off. In these states our potential for alternate imagination weakens and we return to beliefs held fast.

Chaoskampf theory associated tehom with the Babylonian God Mummu Tiamuatu and mayaim with Yam. C.f. Ouro, "The Earth of Genesis 1:2."; Roberto Ouro, "The Earth of Genesis 1:2 Abiotic or Chaotic? Part 2," Andrews University Seminary Studies 37.1 (1999).

Gladd could be using metaphoric language when he describes the sea as “embodiment of evil,” but it is unhelpful to attribute to the sea a bodily and potentially sentient form. "Sleep like a King: Why Jesus Slept Before Calming the Storm," Benjamin L. Gladd: The Gospel Coalition, https://www.thegospelcoalition.org/article/jesus-slept-calming-storm/. Watson, Chaos Uncreated, 4.

“Why are you still afraid? Do you still have no faith?” (4:40) shows the intention that the disciples ought to have had faith in the moment. Likewise, when the narrator comments “They were completely amazed, for they had not understood … their hearts were hardened,” (6:51-52) indicates that had they understood they would have faith.

Deppe writes that Christ’s slumber is Christological revelation, it is “a teaching parable on how to deal with an existential awareness of the absence of God.” Dean B. Deppe, The Theological Intentions of Mark’s Literary Devices: Markan Intercalations, Frames, Allusionary Repetitions, Narrative Surprises, and Three Types of Mirroring (Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock 2015), 311.

Bill Hughes, “Fear, Pity and Disgust,” in Routledge Handbook of Disability Studies, eds. Nick Watson, Alan Roulstone and Carol Thomas (London: Routledge, 2012), 70, doi:10.4324/9780203144114.ch6.

See Bessel van der Kolk M.D., The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma (London: Penguin Books 2015).

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/f/f3/Rembrandt_Christ_in_the_Storm_on_the_Lake_of_Galilee.jpg

THE MORAL IMAGINATION NEEDED IS FOR BELIEVERS TO HAVE FAITH THAT GOD DOES NOT ABANDON THEM BUT HOVERS OVER ALL ELEMENTS.

30 30 If imaginations have been trained to see the stilling of the storm as the work of God, we may be unable to imagine God’s real presence in the midst of the uncontrollable, unable to hear Jesus’ voice, “take courage, it is I… do not be afraid.” (Mk 6:50). Though impairments, long-term illnesses, and mental health challenges will bring the unknown and the unpredictability into our midst is fear preventing faith settings to take courage in taking bold the first step and asking: how does this person show me the presence of God and work within me the work of God, and how do I do likewise? Is fear a major factor in preventing imagination: theological, ecclesiological, practical, pastoral, and discipleship?

“Y“Yahweh God formed the man of dust from the ground.” (Gen 2:7)

“For you are dust, and to dust you shall

return.” (Gen 3:19b)

Human bodies derive from dust and returning to dust, this final dust is incapable of form and unable to embody our Spirit. Breath gives way, bones disintegrate, returning back into the earth, the sea, and into the unknown. Life is tragic in the sense a Tragedy (e.g. Orpheus and Euridice, Hamlet, or Sophie’s Choice) – a narrative that moves towards increasing “limitation, frustration, challenge, and suffering.” On a molecular level, cells generate, degenerate and regenerate, but degeneration is certain. The second law of thermodynamics state that entropy will always increase with time. A movement towards increasing limitedness, suffering and pain is what it means to be a “vulnerable” existence – a human existence – but it is not the totality of existence. “Existence,” disability theologian Thomas Reynolds wrote, “is tragic in its gratuity;” to paraphrase, “life is a blessing/gift in a tragic form.”

31

Thomas L. Reynolds, Vulnerable Communion: A Theology of Disability and Hospital (Grand Rapids, MI: Brazos Press 2008), 131.

31

Reynolds, Vulnerable Communion. 132

Even the crucifixion, a most tragic moment of degeneration, destruction, and vulnerability was not wasteful. Even the tragedy of the cross is gratuitous when it is revealed that it is the atonement for the world (1 Jn 2:2) and divine victory over all (Col 2:15). Yet, from the perspective of Mary at the foot of the cross gazing out into the horizon of every tomorrow, hidden behind locked doors as the disciples cowered with fear, gratuity might be the last thing to imagine. Fear opines in the face of dust and death: what caused this emptiness? How can I change it? Faith beautifies the moment with the question: “What is the work of God that may be on display?” (Jn 9:3)

The danger for Christians baptised in liturgies of praise rather than sorrow’s laments, existing within a society that has a penchant for therapeutic, middleclass expectations, is that we are uncomfortable in inhabiting the darkness of good Friday. Our imaginations in the dark, form shapes and futures that are based on fear rather than faith, unable to imagine the theology of the cross in the midst of our pain, where

“THERE IS ALWAYS CERTAINLY ... GRACE…FOR THOSE WHO IN DARKNESS ARE COMPELLED TO WANDER.”

In seeking for relief and to relieve, we imagine divine work only in the resolution or denouement and disable our imaginations to conceive the work of God in the midst of the limited and impaired lives of everyone before us.

Adam was abandoned by his parents because of his genetic condition, Bartsocas-Papas Popliteal Pterygium syndrome. His deformities included “no eyelids, no fingers, severely webbed legs, a cleft

palate and lip, as well as an absent nose.” A missionary couple felt called to adopt him and later reflected,

“INSTEAD OF TAKING US FROM THE MISSION FIELD, ADAM’S LIFE EXPANDED OUR MISSION FIELD. WE BEGAN TO SEE OTHERS IN NEW WAYS. WE LEARNED HOW TO RELATE TO PEOPLE IN NEW WAYS… HURTING PEOPLE WOULD SEE ADAM AND BE COMFORTED. JADED PEOPLE WOULD HEAR ADAM’S STORY AND THEIR WALLS WOULD COME DOWN…. WE SAW THE NAME OF JESUS GO FORTH IN PLACES AND IN WAYS WE HAD NEVER SEEN BEFORE.”

SStanding at ground zero of sickness and impairment, existence may dip into the tragic. Yet, though there are tragic

moments, tragedy does not have the curtain call. Reynold explains,

“DISABILITY IS MADE NEITHER BY GOD NOR BY CHAOTIC FORCES CONTRARY TO GOD’S PURPOSES. IT IS PART OF A VULNERABLE WORLD WHICH GOD LOVES. BUT NEITHER IS DISABILITY NECESSARILY TRAGIC… THE CULT OF NORMALCY TURNS DISABILITY INTO TRAGEDY, WITH THE TRAGEDY SOCIAL IN NATURE, AND ‘SINFUL.’”

See G. Geoffrey Harper and Kit Barker, eds, Finding Lost Words: The Church’s Right to Lament (Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock: 2017).

Reynolds, Vulnerable Communion. 132

Author’s translation of the original in Joseph Czarnecki, Last Traces: The Lost Art of Auschwitz (New York: Atheneum, 1989), 174.

J. M. Paul, “Unformed Yet Ordained,” in Disability in Mission: The Church’s Hidden Treasure, eds. David C. Deuel and Nathan G. John (Peabody, MASS: Hendrickson Publishers, 2019), 46.

Paul, "Unformed Yet Ordained," 52-53. Reynolds, Vulnerable Communion, 169.

Impairment is vulnerable and beloved, limiting and human, tragic at times but never wasteful.

For even death is never wasteful and death’s trajectory, in John Donne’s Holy Sonnet X, is not a period but a semi colon. The rot of our flesh and the dust of our bones take part in returning nutrients back to the earth. Ultimately dust shall be re-formed into a resurrected body that eternally sustains our spirit and consciousness (1 Cor 15:20-57; 2 Cor 5:110). To borrow from Martin Luther King Jr., the arc of existence may often dip into the tragic it bends towards goodness. When the ingredient of time is added, tragedies become comedies – a narrative where, despite the pain and disorder, all’s well that ends well. When the ingredient of God’s time is added, human tragedies become gracious comedies. How long is the time that turns tragic dip into comedy’s delight? How long is the time between the cross and the garden? Though comedy’s bend may be difficult to perceive in the everyday filled with toe scuffs, optometrist appointments, and carer’s bills, but like the bend of the earth divine comedy is perceivable ‘already and not yet.’

How wide is the space between tragic dip and comedy’s delight? The size of a mustard seed, the size of faith (Matt 13:31-32). It is apt to finish with Eugene Peterson’s words as he reflects on dust in Genesis 2, 33

“And death shall be no more; Death, thou shalt die.” “Holy Sonnets: Death, Be not Proud,” John Donne: Poetry Foundation, https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/44107/holy-sonnets-death-be-not-proud Tom Wright, Surprised by Hope: Original, provocative and practical (La Vergne, TN: SPCK 2004), 114-117.

As Julian of Norwich wrote, “All shall be well, and all shall be well, and all manner of thing shall be well.”

See discussion of kairos in Wan, "‘Lovely in [impaired] limbs, and lovely in [impaired] eyes all his,’” 13-14. Geerhardus Vos, Biblical Theology: Old and New Testaments (Edinburgh: Banner of Truth Trust, 1975).

THERE IS NOTHING WRONG WITH A DESERT THAT A LITTLE RAIN CAN’T FIX. DRY LAND IS NOT INHERENTLY BARREN; THE DIRT ITSELF IS NOT EVIL. WE ARE AFTER ALL “FORMED…OF DUST FROM THE GROUND” (GENESIS 2:7). AND NO ONE’S LIFE IS APART FROM THAT BASIC GROUND FROM WHICH GOD CAN BRING HIS PURPOSES TO BLOSSOM. THERE ARE STRETCHES OF TIME WHEN NOTHING IS GROWING, BUT ALL THE WHILE NUTRIENTS ARE IN THE SOIL AND SEEDS EMBEDDED JUST BENEATH THE SURFACE. A MOMENT WILL COME WHEN THE NECESSARY MOISTURE WILL BRING FAITH TO FLOWER.

EUGENE PETERSON, AS KINGFISHERS CATCH FIRE: A CONVERSATION ON THE WAYS OF GOD FORMED BY THE WORDS OF GOD (UK: HODDER & STROUGHTON 2017), 159.

“TO APPROACH THE OTHER IN CONVERSATION IS TO WELCOME HIS EXPRESSION, IN WHICH AT EACH INSTANT HE OVERFLOWS THE IDEA A THOUGHT WOULD CARRY AWAY FROM IT. IT IS THEREFORE TO RECEIVE FROM THE OTHER BEYOND THE CAPACITY OF THE I, WHICH MEANS EXACTLY: TO HAVE THE IDEA OF INFINITY. BUT THIS ALSO MEANS: TO BE TAUGHT.”