TheSummerOpiate 2025, Vol. 42

The Opiate

Your literary dose.

© The Opiate 2025

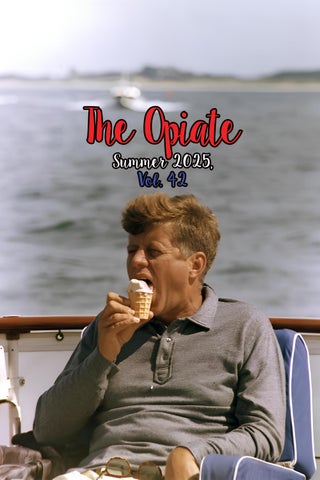

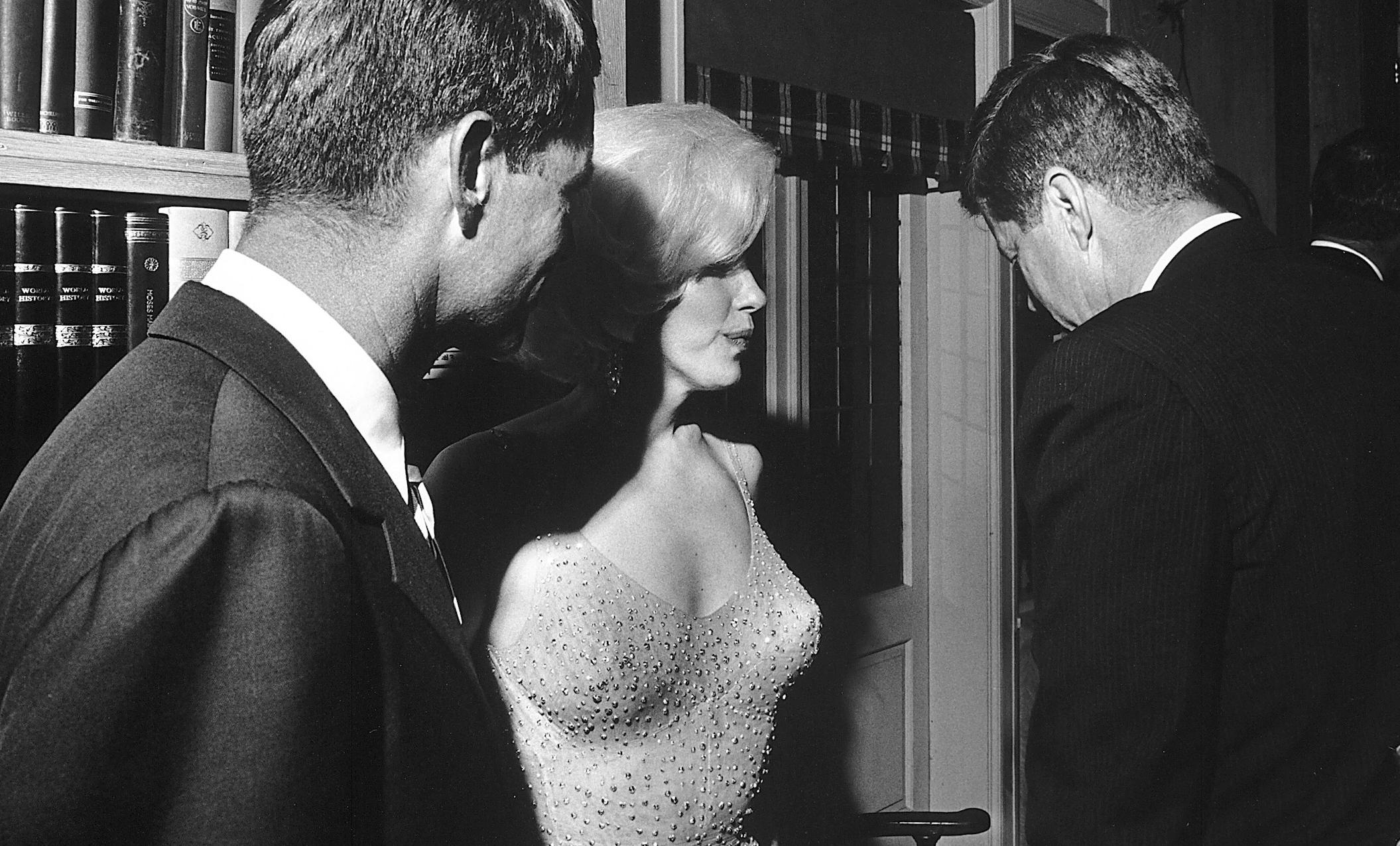

Cover art: John F. Kennedy eating ice cream on his yacht, Honey Fitz, on August 31, 1963 by Cecil W. Stoughton This magazine, or parts thereof, may not be reproduced without permission. Contact theopiatemagazine@gmail.com for queries.

“We’re half awake in a fake empire.”

-The National

“All a girl really wants is for one guy to prove to her that they are not all the same.”

-Marilyn Monroe

The Opiate, Summer Vol. 42

Editor-in-Chief

Genna Rivieccio

Editor-at-Large

Malik Crumpler

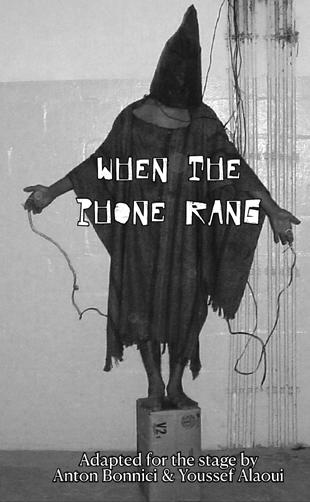

Editorial Advisor Anton Bonnici

Contributing Writers:

Fiction:

Steve Novak, “Addicted to Love” 10

Barry Fields, “Caretaking” 22

Antonia Alexandra Klimenko, “Synchronicity” 30

Arthur Davis, “Friends for Life” 46

Ken Post, “Lincoln Street” 56

Salvatore Difalco, “Conversations With the Cardinal” 63

Nonfiction:

Renshaw, “I’m Supposed to Smile as if God Knew That I Would be Troubled” 75

Poetry: John Tricarico, “Erased By a Mirror” 85

Priscilla Atkins, “À la Harpo, 1992” & “Jackie, Pat and Me” 86-89

Frank Freeman, “The Shock of Recognition” 90

Gaia Huaira Capizzi Candiracci, “Room-by-room eulogy of my first studio apartment, and the girl that lived in it,” “Only Threw This Party For You” & “Un Mondo a Parte” 91-96

Hedy Habra, “Vanishing Point” 97

Sophie Roy, “The Door Is Closed” 98-99

Kathryn Adisman, “Goodbye, America” 100-101

Xavier Jones, “May As Well” & “Shh!” 102-105

Jonathan Ukah, “Death Does Not Know How to Kill,” “I Saw My Ancestor in the Moon,” “Dead on Arrival,” “A Shadow of Himself” & “If I Could Have My Time Again” 106-110

John Grey, “Desert Time” 111

Onix N. Vanga, “B-1-gone,” “People” & “Conversations With the City” 112-115

Stephanie Watkins, “Carry On,” “River,” “Girl Under Water,” “Night Swimming” & “Silver Thread” 116-122

Jennifer LeBlanc, “Superbia, Pride,” “Invidia, Envy” & “Chart Reading II” 123-125

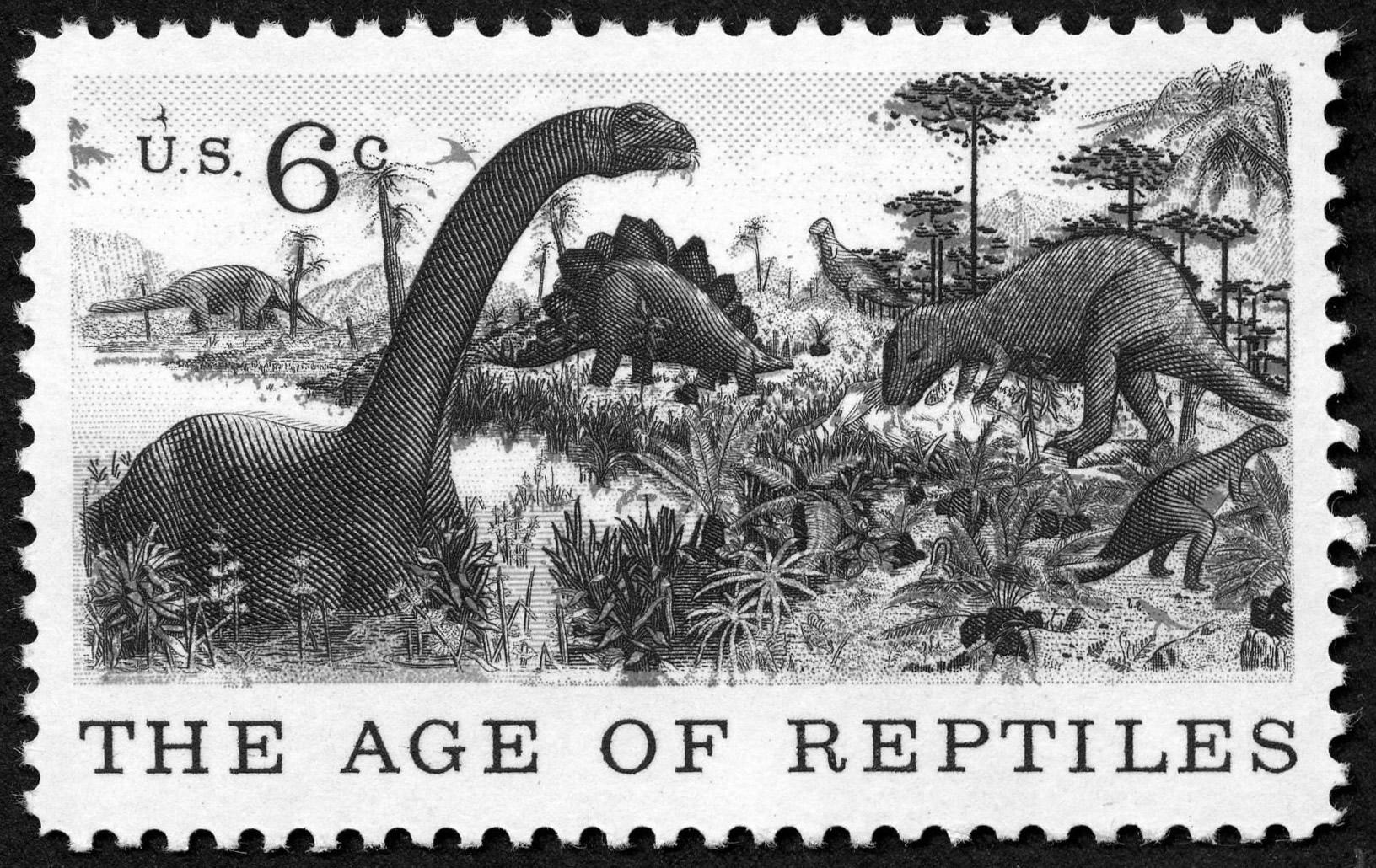

Robert Witmer, “Critique of Pure Reason,” “Perspectives,” “Put It On a Postage Stamp,” “Beloved, My Belated, Beloved” & “Where the Wind Blows” 126-130

Criticism:

Genna Rivieccio, “Lambs to the Slaughter: The ‘Kennedy Women’ of Maureen Callahan’s Ask Not: The Kennedys and the Women They Destroyed” 132

Editor’s Note

Depending on which member of a certain generation you ask, each one will offer a different “pinpointing moment” for when it all went tits up for the U.S. The moment, in other words, where it was no longer an “empire,” but a republic in perennial decline. A decline that has presently turned into more of a rotting decay. Those from the millennial generation might tell you this decline/ decay began on September 11, 2001 (or maybe even November of 2000, when Bush II shadily “won” the election against Gore). Gen X might tell you it was the Iran-Contra affair...or the suicide of Kurt Cobain. Gen Z, if they could lift their heads up long enough to see it, might tell you it was TikTok. But it‘s really the baby boomers who have far more “pinpoints” to offer, starting first and foremost with the assassination of John F. Kennedy on November 22, 1963 (followed at a close second by Richard Nixon‘s entire presidency).

And perhaps it‘s only right that the baby boomers should be the ones to more fully grasp the moment when it all went to shit since they, too, are the ones who got to experience the U.S. at the height of its sheen. One that quickly gave way to dullness when the economic boom that occurred after (and during) WWII busted, big time. Making it far less of a “breeze” to sell the so-called American dream. Which has always been, at its modern core, the promise of everyone being able to live a middle-class life. A.k.a. a “comfortable” existence. Even when James Truslow Adams first popularized the phrase, his explanation of it, despite favoring the ideas of freedom and democracy, still referred to the trappings of wealth that America had become known for. Ironically, of course, Adams’ summation of the American dream arrived in 1931, at the very beginning of one of the country’s most marked nadirs, economically and otherwise: the Great Depression. At the same time, the storm of that era was weathered by a president that continues to be regarded as one of the best (or at least most competent) in U.S. history: Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Alas, like many presidents who are a “product of their time” (that phrase designed to excuse away all shitty behavior), FDR hardly had a squeaky-clean track record vis-à-vis his treatment of those who have been placed in the “other” category in the U.S. ever since the moment it was colonized. But still, one must look to his

more avant-garde policies (even if Eleanor was secretly at the helm) for reassurance about his lasting legacy. This includes, needless to say (unless you’re talking to someone in Gen Z and afterward), his sweeping implementation of social programs that would make the likes of Donald Trump foam at the mouth. Indeed, perhaps more than any other modern president, FDR remains the one most closely associated with advocating for “average” Americans. Which is to say, working-class people with little give in the direction of “upward mobility.” The same can’t be said of another president who is often still put on the same pedestal as FDR: JFK.

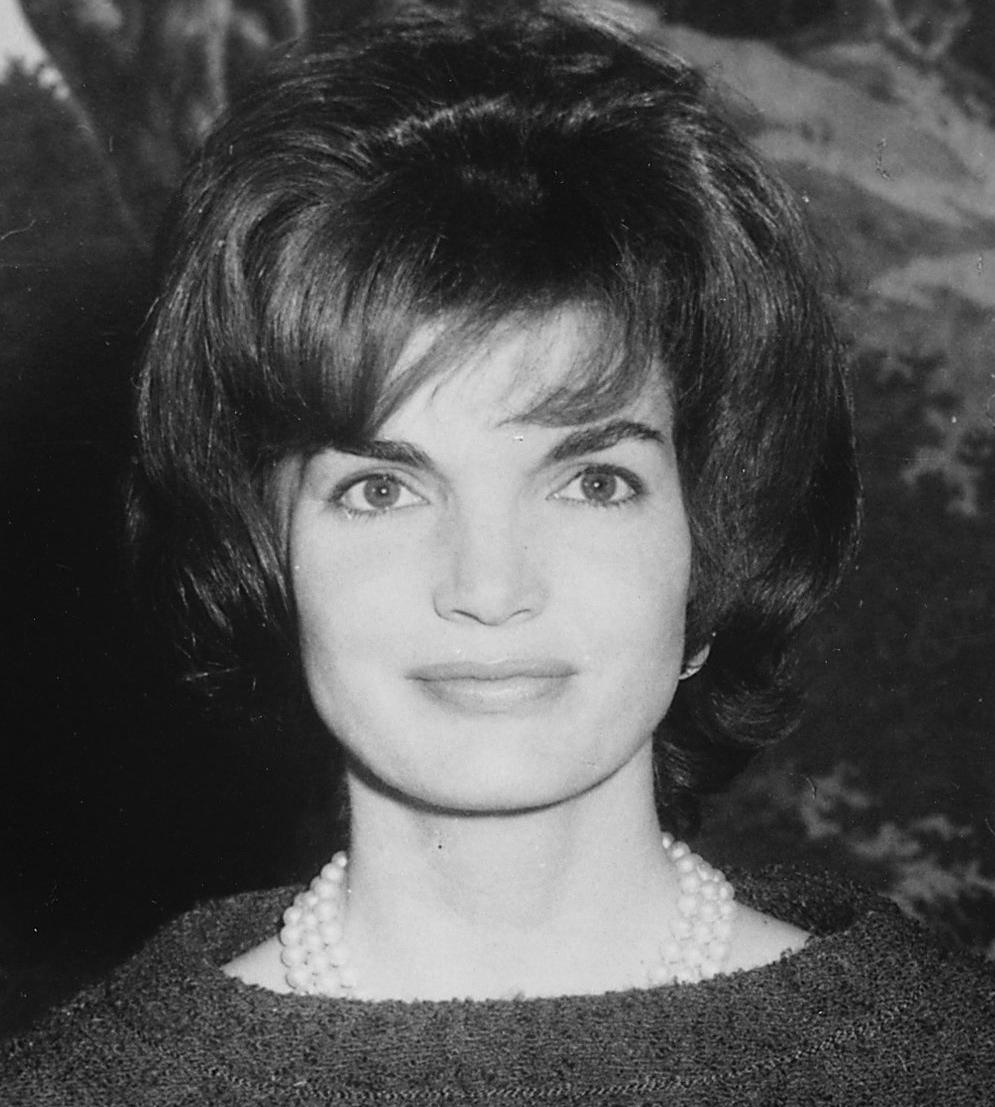

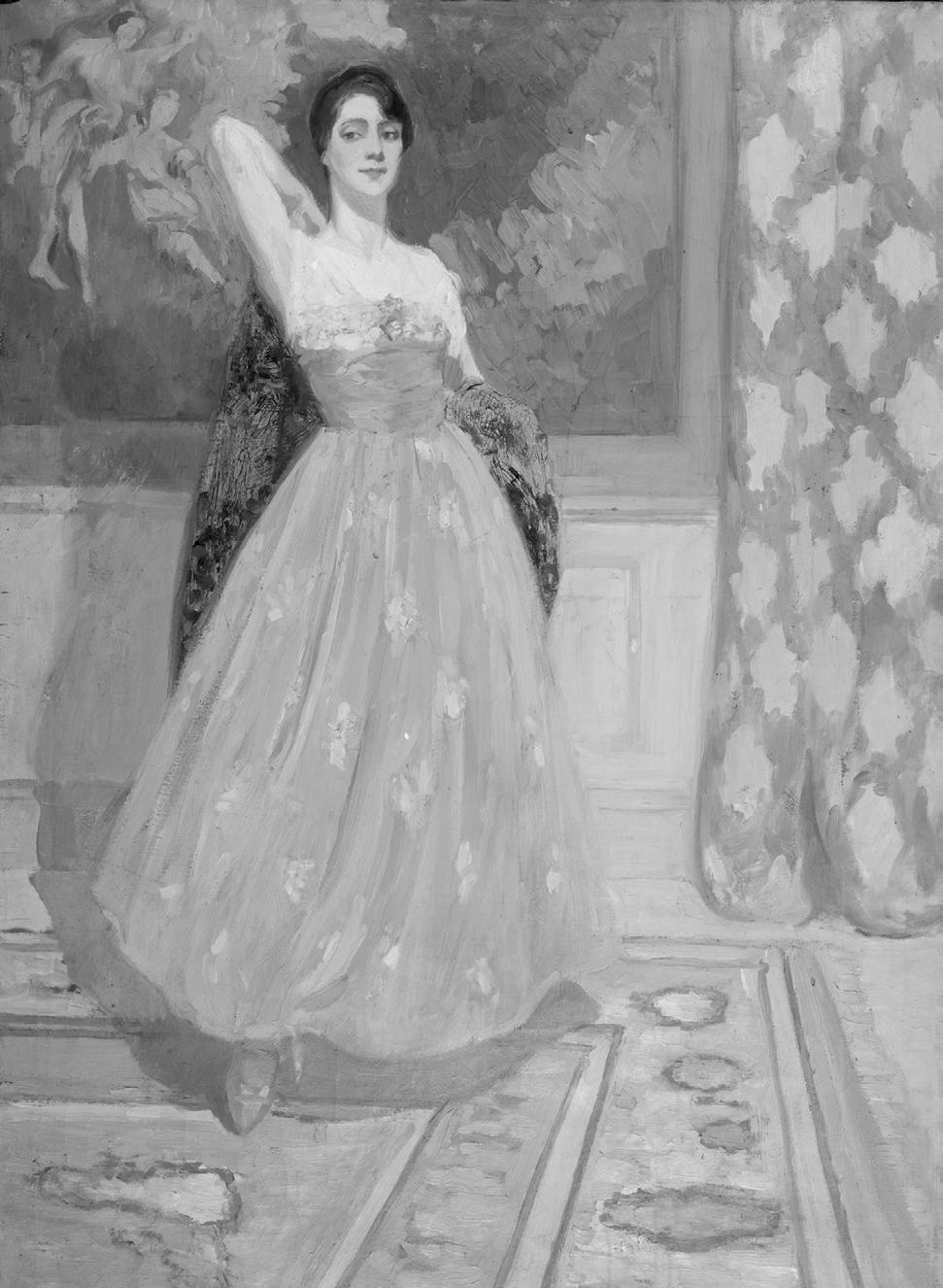

Though not by everyone. In fact, in the sixty-two years since Kennedy’s assassination, the reverence that was once assured by such a death (further compounded by being shot down in his prime) has waned. Not just because RFK Jr. has succeeded in totally decimating all “prestige” associated with the Kennedy name, but because, in reevaluating who Kennedy was as a person, it’s plain to see that the ethics, integrity and moral uprightness he built his image on was little more than a smokescreen. And one that was thickened by his “good looks.” Though, in truth, these alleged good looks merely served to corroborate that, for far too long, the U.S. had been saddled with old, graying men as their ruler, therefore making JFK seem like a “total snack” in comparison. Which just goes to show, when people’s standards are set low enough, you can make them believe something that’s just okay is actually amazing. As Cecil W. Stoughton managed to do with many of the photos he took of the Kennedys during his tenure as JFK’s White House photographer. To be sure, it’s Stoughton who can be held largely responsible for simultaneously glamorizing the Kennedys’ family life and making them seem so “relatable” in the process.

And yet, among all the many images he took of JFK, one that stands out in particular for its lack of a veneer (or “Kennedy shine,” as it were)---apart from the post-assassination image itself---is a photo that was snapped while “Jack” was aboard his yacht, the Honey Fitz, at the end of the summer of 1963 (specifically, August 31st). His last summer. Which is part of why the image is so poetic. So symbolically on the nose. For not only does it reveal a kind of foreshadowing of the demise of Kennedy, but also of the United States itself. That is, the United States that

The Opiate, Summer Vol. 42

was once known as a “land of promise.” For here you have the image of a man who has been totally deglamorized, stripped of all traces of his erstwhile glittering façade (paunch on display and everything). Eating an ice cream with the same aplomb as a grizzly bear and, accordingly, letting a glob of that ice cream drop onto his clothing. No fucks given. Sure, he still looks tan (sandblasted even), “vital,” but it’s obvious he’s in “letting it all hang out” mode. A mode that has been in activation for the president with increasingly fewer barriers since the Orange One took up the office for a second time at the beginning of 2025.

So yes, maybe the baby boomers have the more accurate “pinpoint moment” for when America, the concept, the shiny symbol, began its slow death that has been going on since at least 1963. As it continues its long-winded death rattle, some keep wondering, “When will you just die already?” Because perhaps the only thing worse than having a revelation about something---the curtain pulled back on a hard truth---is having a revelation about something and refusing to acknowledge it in a way that effects actual change. It seems that more and more Americans (read: the whites who are always late to understand how fucked things are due to their inherent privilege), regardless of their generational assignation, are finally seeing that America ain’t all it’s cracked up to be, and it never really was.

It is only through this collective realization that perhaps something can be done about it. Something to rebuild it. Of course, rebuilding requires tearing down everything that many are still too “precious” about to let go of (myself included).

Under construction,

Genna

Rivieccio July 2025

FICTION

Addicted to Love

Steve Novak

Sprawled in the dirt, Sarah and Troy rested in each other’s arms. Troy and Sarah. Having been separated for a time, they were back together, and would remain together until the end. They were in love and enjoyed a warm embrace.

It was impossible to guess the original color of Troy’s shirt, but the message advocating kale was still readable. Sarah wore a faded yellow sundress. A light breeze lifted the hem, threatening to reveal more of her thigh. In other circumstances, Troy would have felt some carnal excitement at the prospect, but not now.

Because at that moment, the pair lay in their own filth behind an abandoned house, both in a hallucinatory stupor. And they would very soon be dead. Because the warm embrace they enjoyed was not with each other, but with the heroin that flowed through their veins. Too much heroin. Too much poison. And while they loved one another, they also loved the high. And hated it. Because that was what had separated them.

For both, the cause of death would be recorded as a drug overdose, and for Sarah that was true. But not for Troy. No; Troy died from something else, something that couldn’t be detected by a post-mortem examination.

What killed Troy was a broken heart.

“We’re going to get married and have three children: two girls for you to spoil, and one boy for me to play ball with and build things with. I’ll work, and you can stay home and raise the kids.”

“We’ll both work because I want my own career, not to just be your plaything.”

“Okay, but you can still be my plaything even if you have your own career.”

Sarah and Troy dated all through high school and college, and had talked about marriage, but the time had never been right. While Troy excelled, Sarah struggled.

“You’ll find something, don’t worry. You’ve got plenty of time to figure out what you want to do.”

“I know. I just don’t want to be a burden on you.”

“A burden? Just the opposite. I’d never have gotten through school or survived those summer internships from hell if it weren’t for you. I don’t know what I’d do without you.”

Troy rose quickly through the corporate ranks.

“You are looking at the newest senior vice president at First United Bank.”

“Oh, honey, that’s wonderful! I knew you’d make it!”

“And,” Troy continued, “with that promotion comes a private office, my own parking stall and an administrative assistant.”

“Ooo, your own assistant?”

“Well, no. I have to share the assistant, but it’s still a big deal. Before, I had to do all my own grunt work, now I have some help.”

He was teasing, but he was proud of his accomplishment.

Sarah bowed and motioned him to the table with a flourish.

“Sit down, Mr. Senior Vice President. Dinner will be served shortly.”

“Thank you, my dear. The promotion is nice, but what would be even better is coming home and finding you here waiting for me. It’s going to be more work, but as long as I have you, it’ll be okay.”

Sarah smiled, but said nothing.

Maybe we can get married and start our family now, Troy thought. Soon. It would be soon.

Not long after he shared the news of his promotion, Troy took some time out of his always-busy day to book a weekend getaway. On a hazy Thursday afternoon in August, he was in the midst of searching for flights when his phone rang.

“Sarah’s in the hospital.”

It was Sarah’s mother. He knew by her tone the reason, and it

The Opiate, Summer Vol. 42

immediately deflated him.

“I’ll be right there.”

“This is the fourth, no, fifth time she’s been brought here.”

Sarah’s father was berating his wife when Troy entered the room. “I’m done with her. I don’t need this.”

Sarah’s mother sat on the edge of the bed holding her daughter’s hand. She didn’t reply. Sarah saw the pain in her mother’s eyes.

“First it was those Vico-dans, then the cough syrup—cough syrup, can you believe it?—and now this. What’s next? Where do you go from here?”

“...the pair lay in their own filth behind an abandoned house, both in a hallucinatory stupor. And they would very soon be dead. Because the warm embrace they enjoyed was not with each other, but with the heroin that flowed through their veins. Too much heroin. Too much poison. And while they loved one another, they also loved the high. And hated it. Because that was what had separated them.”

“I’m sorry! It won’t happen again, I promise!”

“You promised last time. And the time before that, and the time before that.”

Sarah’s father wanted to be angry, put on a show of being angry, but he was really just tired and frustrated.

“I know. I know. But this time it will be different. I’ll get help. I’ll go back to rehab.”

Troy stood silently at the foot of the bed, his head hanging, not looking at Sarah.

Sarah did go to rehab. Again. Six weeks later, she was released with optimism and anticipation of a brighter future.

“We talked about what made me relapse.”

Troy listened, knowing she was full of energy after her discharge and needed to talk.

“I was so happy to hear about your promotion, but it made me feel inadequate. More than inadequate; worthless. You’re doing so well, and I’m going nowhere. But that’s not what triggered me. It’s that I feel like I’m hindering you, holding you back. You’d be doing even better if I wasn’t an albatross around your neck.”

It pained him to hear that...because it wasn’t true.

“You’re not holding me back. It’s because of you I made it this far.”

Sarah reached out to stroke his cheek but stopped. She looked into his eyes. “I wish I could do more.”

He pulled her in for an embrace. “You do more than I could wish for.”

“Hmm. How about this? I’m going to get a job, a real job, I mean, and be the best girlfriend/fiancée/future wife you could ever hope for!”

“Okay, but you’re already more than I ever hoped for.”

They both felt optimistic, yet it was tinged with fear.

“Real” jobs for unskilled recovering drug addicts who have been in and out of rehab and arrested several times are hard to find. Sarah became discouraged.

“It’s okay, sweetie, there’s no hurry. Something will come along.”

On the pretense of going to job interviews, Sarah instead met up with friends. She drifted back into old habits and back toward the people who enabled and used her. She fell into despair. Two months after her release, Sarah shot up again in a friend’s basement. The real world was hard; getting high was easy. She hesitated, briefly, thinking of Troy and how let down he’d be.

“I shouldn’t,” Sarah said.

“It’ll ease the pain,” her friend reminded.

Troy and her parents suspected but held their tongues.

Is she at it again? Can’t anyone else see it?

She’s losing weight; she looks so thin. Am I the only one who notices?

They didn’t want to believe it. They pretended everything was okay. They felt guilty about their suspicion. Each thought they were alone in their mistrust. When her parents returned home after an evening out and found her unconscious in the flower bed in front of their house, they could no longer pretend.

Sarah disappeared the next day. Her father’s angry outbursts and her mother’s crying she could handle, but Troy’s quiet sadness

The Opiate, Summer Vol. 42

drove a stake through her heart.

***

“I love her. I have to help her. I know she just can’t give it up, and sometimes I think she wants to live that way, but somehow, some way, I’m going to help her through this.”

“Are you sure that’s what you want to do?”

“What do you mean?”

“You’ve tried helping her, for years now, and she’s right back at it. Don’t you think you’ve tried long enough?”

“Long enough? There is no ‘long enough.’ It’s a disease, and if it can’t be cured, it can at least be kept at bay. I’m not giving up on her, no matter how long it takes.”

“You know she has to want to change. You can’t do anything until she wants to change.”

Kevin knew it was a cliché and it didn’t help, but he didn’t know what else to say. No one knew what to say.

“She does want to. I know she does.”

Kevin hoped that was true. So did Troy.

***

“I found her.” Troy had called Sarah’s parents. They’d been worrying for several days. Troy took her to their house.

“She’s sleeping now. You should go and get some rest.” Sarah’s mother looked pale and thin, Troy thought, as she spoke.

“Okay.” He paused. “What about tomorrow? Somebody needs to stay with her. I have meetings all morning, but I can come in the afternoon.”

“I can go in late. Her father will go in early and come home at lunch. You get here when you can.”

“After that, we’ll take it one day at a time,” her father said. He spoke to his hands that were resting palms-up on the table. He didn’t have the energy to raise them to his face.

“We’ll get through this. She can overcome it if we help her. Let’s not get discouraged,” Troy urged, trying to keep his hopes up. But it was hard, even for him.

***

“Your favorite, buttermilk hotcakes and a side of eggs.”

“You are far too good to me, Miss Sarah.”

The periods between Sarah’s relapses, when she wasn’t using, were glorious. She and Troy were so happy together.

“I am, aren’t I?”

But there was always an unspoken fear. Will she stay clean? For how long? Even so, Troy didn’t only love her when she was clean. He loved her regardless. Dirty, incoherent or lashing out at him in her fog; he loved her.

“It’s hard on her since I got the promotion.”

“Why’s that? Is she upset you’re moving up and she still can’t find a job?”

“No, no, it’s not that. I’m working more, and longer hours. I’m not home as much, and even when I am there, I’ve often got work I brought with me.”

Kevin nodded. “Hmm.”

“She gets bored. And when she’s at home, her parents hover around and watch her. They’re only concerned, but it’s annoying. I couldn’t take that myself. And if she’s at my place, there’s only so much cleaning or cooking you can do. She doesn’t have any hobbies; she has trouble staying focused. And she doesn’t have any friends to speak of. At least not ones she can hang out with and do regular things.”

“Yeah, it’s not good for her to be around those, uh...”

“Users?”

“Yeah.”

“And when I’m done with work, I’m too tired to want to go out and do anything. I just want to sit in front of the TV for a while.”

“And she wants you to take her out?”

“Out, or at least do something with her. Play cards or games or something.”

“Uh huh. It’s tough.”

“It is. But I feel so bad. I want to do things with her. I want to take care of her. Maybe I shouldn’t have been so ambitious. Maybe I should have stayed in mid-management, in a nine-to-five, and had more time and energy.”

“But you can make her more comfortable now. She doesn’t want for anything. She doesn’t have to worry about anything.”

“That’s just it. She’s not comfortable. She does want, she does worry. Sarah wants me to be around more. She worries that I’ll get tired of her, that I’ll run off with some high-powered executive type. It doesn’t matter how much I tell her I love her and I’ll never get tired of her, if I’m not there to be with her... It tears me up. It rips my insides apart.”

“Sarah! Honey?!”

Sarah wasn’t in the kitchen when Troy got home. She wasn’t watching television. She was passed out on the bed in her clothes, disheveled, her hair a mess.

“Honey?”

It was no use trying to wake her. As gently as he could, he made her more comfortable and tucked her in. Then he lay down next to her and stared at the ceiling.

“Sarah!”

No answer.

She didn’t respond...because she wasn’t there. He didn’t call her parents because he didn’t want to worry them if she hadn’t gone home. He sat up waiting. She didn’t come in.

He left her a note in the morning before he went to work.

I love you!

Call me!

“Sarah? Honey?”

Sarah sat at the table. Slumped at the table would be a better description. She could barely keep herself upright.

“Can you eat a little more? Just a bite?”

Seeing Sarah grow thinner didn’t help Troy’s appetite. He felt ill watching her nibble at her food. It wasn’t so much the amount she ate, but how she ate it. She pushed the food around her plate slowly, poking at it, mashing it up. She’d put tiny bites in her mouth and chew in a way he thought resembled some sort of reptile.

“A little more. Please?”

When she wouldn’t eat any more, he’d help her to the couch and turn on the TV for her, or help her to bed. When he returned to the table, he’d stare at his plate for a while before dumping what was left.

“Troy, you on a diet?” a co-worker asked. “You look like you’ve dropped a few pounds.”

“No, not really. Just eating less.”

His friend Kevin noticed too. “You look like hell.”

“Thanks.”

“No, I mean you don’t look well. Are you okay?”

“I’m fine. Just tired.”

“I’m sorry I haven’t seen you in a while. What’s it been, a couple of months?”

“I guess.”

“It’s Sarah, isn’t it? She’s wearing you out. Seeing as how you look, I’m guessing she hasn’t improved.”

“No, not improving. If anything, she’s getting worse. I can’t get her to go rehab or counseling, and she seems to be getting in deeper, if that’s even possible.”

“So what are you doing?”

“Whatever I can. But my job’s kicking my butt on top of what’s going on with her. Sometimes I don’t see her for days, and I can’t relax or sleep when she’s gone. And when she comes home, about all I can do is try to get her to eat and keep her clean. I have to wash her, her clothes, the sheets, the blankets and just about everything else. She’s pretty nasty sometimes when she comes back. And sometimes she brings someone else, so it’s two or three times the nasty. I should have bought soap stocks.”

Kevin attempted a weak smile. He couldn’t do anything and had nothing to say, so he just sat looking at Troy.

“Sorry, you don’t need to hear this.”

“It’s okay. I’m just worried about you. And Sarah too, of course. What can I do for you?”

“Nothing. I don’t know. I don’t know what to do for me. Sleep. Sleep and peace are what I need, but I don’t see either one happening anytime soon. I just don’t know what to do.”

Kevin started to say something before he caught himself.

“I know what you want to say, but I’m not giving up on her. I love her.”

“I wish you wouldn’t do it, but if you have to, do it here where I can watch over you. I worry when you’re out there.”

Troy had heard of safe spaces and thought he could make one for Sarah. Provide her a place where she didn’t feel judged, so then maybe he could help wean her off it. He didn’t know if it would work, but he had to try.

“Nooo! I don’t want you to see me. I don’t want to do it, you know I don’t, and I don’t want you to see me do it.”

“But it’s worse when I don’t know where you are or if you’re going to come back. Do it here. Please. For me.”

Sarah hated what she did to him, but as hard as she tried, she couldn’t give up the drug.

The first time Troy watched her inject, he nearly vomited. It didn’t take long for him to get used to it. Sarah, however, had more difficulty. She felt anxious with Troy there. She couldn’t stand to see Addicted

him trying not to watch her. It ate her up inside worse than the drug did. So she snuck off. She slunk away. To places where he couldn’t see.

“There’s nothing else you can do.” Kevin tried not to sound callous, but he was frustrated that Troy couldn’t see what he saw: a lost cause.

“There is.”

“I want to try.”

“No! No, you can’t!”

“I want to. The only way I can understand you is to try it myself.”

“No! Please, no!”

Sarah was scared. What was Troy doing? She refused him. He insisted. She held her ground. She had ruined her own life; she wasn’t going to let him destroy his. She ran. Hid herself. Away from Troy, and away from the remnants of the life she once knew. This time, she didn’t come back.

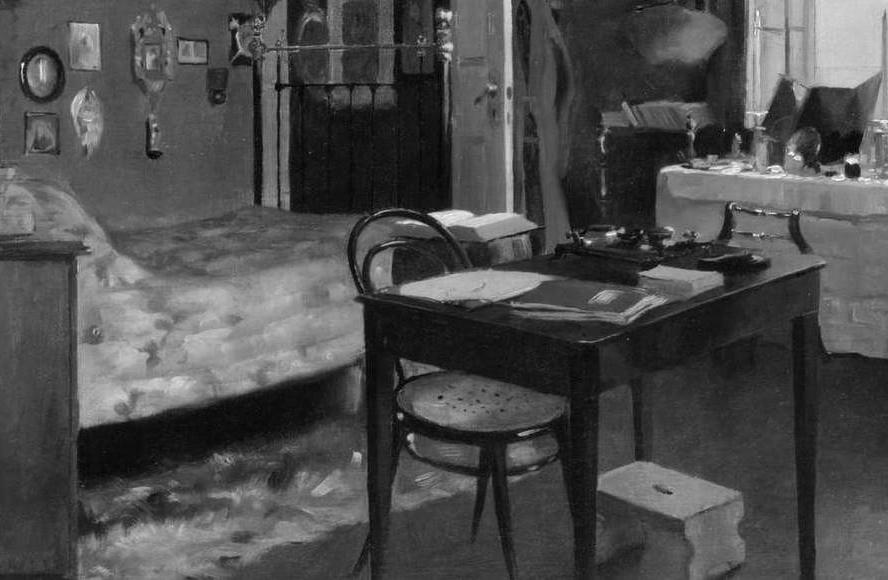

Sarah lived, if it could be called that, in a squalid room next to a dank and fetid alley on a little-traveled street. Below the level of the road, it felt like a tomb. Separated from the land of the living by a broken, ill-fitting door and a short flight of stairs, she was also separated from the one who loved her most. She prostituted herself for heroin and begged for food. She lived to get high. She got high to forget; to forget Troy and the agony she brought him.

Troy didn’t forget Sarah. He ached for her. He ached for her the way she ached for another hit. He searched. He contacted every agency and organization he could find, asking for help. He talked to the few friends of hers that he knew. At night, he roamed the streets.

After a fruitless month, he knew what he had to do.

“Do you know where I can get some heroin?”

He considered just asking people who looked like they might know. He realized, luckily, that wasn’t the way to go about it. He didn’t know about drugs, but he knew something else.

“Drinks? Sure! Where we going?”

He had never been social with his co-workers, but he began to accept their after-work invitations.

“Are you guys leaving? I’ll be right behind you, I’m just going to finish this.”

When those office gatherings broke up, he stayed until the later evening crowds materialized. And then until the late-night regulars trickled in. He became known all around town.

Friendly conversations led to rounds of drinks.

Addicted to Love -Steve Novak

“Troy! Good to see you, have a seat.”

Drinks at the bar led to after-hours parties.

“Hey, Troy, we’re going over to Sinatra’s, why don’t you join us?”

“Sure! Does he really have a karaoke machine at his place?”

“Where do you think he practices?”

“Sarah was scared. What was Troy doing? She refused him. He insisted. She held her ground. She had ruined her own life; she wasn’t going to let him destroy his. She ran. Hid herself. Away from Troy, and away from the remnants of the life she once knew. This time, she didn’t come back.”

Parties led to pot, coke and meth. Eventually, finally, for Troy, it led to heroin. H, smack, junk—the stuff he was really after.

“Yeah, man, give me a hit.”

The mellow highs of weed were soothing, coke was a thrill and meth was jarring. But heroin, it was like a locomotive coursing through his veins. Unfortunately, it was a locomotive on a circular track, never reaching a destination and always coming back around to start anew.

“You got any more? Hook me up, will you?”

Staying out all night shooting up and getting high did not help Troy’s career. It didn’t take long for his colleagues to notice his unkempt appearance and change of behavior.

“What’s up with Troy?” Aki asked, leaning back and peering around the corner after he had passed.

“I don’t know. He looks like crap, and I know he’s messed up

The Opiate, Summer Vol. 42

some work.”

His boss had words with him. HR counseled him. He denied everything. He had sick leave and vacation days stored up, and he used them all. He had a healthy bank account, but it was quickly being depleted.

“How much you got?” Troy would ask his source, while counting the cash he’d just pulled out of his pocket. “Give me all you’ve got.”

He stopped speaking with Sarah’s parents. He crept deeper into Sarah’s world, but he hadn’t found her yet. He still had one foot in the real world. He would have to give up that life completely if he wanted to find her. His boss accommodated him, unknowingly. He took his severance and hit the street.

“I got you, Boots. I just scored some.”

“Oh, thanks, man. I owe you one.”

“Maybe you can help me,” Troy said. “I’m looking for a woman.”

“You want some action? I know this chick who’ll give you some for a hit.”

“I don’t need that, I got a girlfriend.”

“Dude, you ain’t got no girlfriend. I never seen you with anybody.”

“She’s at home. Or was. I’m looking for her.”

In Troy’s clouded mind, he couldn’t tell the past from the present and he believed that past Sarah was present Sarah.

“I need to get me some too. Help me out, won’t you?” Boots’ mind was clouded too.

“You want me to give her a bump, so you can get a little something?” asked Troy.

“Help me out, man.”

“Okay, Boots, but I’ll go with you to make sure you don’t shoot it up yourself before you get there. But you gotta help me, I have to find someone.”

“Yeah, yeah, sure. Come with me. You’ll see. She ain’t no skank. She’s nice.”

“Okay, she’s nice. My girlfriend’s nice, too.”

“We gotta do it first,” Boots said to the woman, “then I’ll give it to you. I don’t want you to pass out on me.”

“Give it to me to hold, so you won’t cheat me. I don’t trust you. Not with your friend there. He want some, too? That’ll cost you two bumps.”

“He don’t want none. Says he’s got a girl.”

“Give it here anyway. I don’t trust you.”

Boots handed over the paper. The woman put it in her pocket.

“He gonna watch?”

“What do you care?”

Troy sat on the floor in the corner. He didn’t recognize Sarah. She didn’t recognize him.

After Boots got his relief, the three of them shot up together. At some point, Boots left and wandered away down the street. Sarah and Troy stared at each other.

***

“Let’s go home. I found you. Let’s go home.”

“Can we?”

They lay together on the mattress, Troy’s arm around Sarah, her head resting on his shoulder.

“I took some time off; I’m going to be swamped when I go in tomorrow.”

Troy believed he still worked at the bank.

“Tomorrow? Can’t you take another day? I haven’t seen you in so long.”

“Okay. One more day.”

They talked as if they’d been separated at the mall and ran into each other at the food court, rather than Troy’s months-long, drugfueled quest to find her.

“Do you have any more stuff? We should finish it before we go, then we’ll be done. Done for good.”

“Yeah, I’ve still got some. You’re right, we should finish it and be done with it.”

One more day.

“It’s so nice to be together.”

One more day.

“Okay, this will be the last time, then we’ll go home tomorrow.”

One day too many.

Violence comes with the lifestyle. Two men, in the right place, but not looking for love, arrived at Sarah’s room. They beat Troy mercilessly and raped Sarah repeatedly.

Deceit comes with the lifestyle. Heroin cut with impurities, cut with fentanyl, cut with broken promises, sells for the same price as pure.

***

Sarah and Troy. Troy and Sarah.

They lay in their own vomit and piss, and the muck it created. They held each other as they retched.

They finally found the peace they sought, together.

All you need is love.

Caretaking

Barry Fields

Anotice popped up on the car’s display screen. I looked down to read it just as an old woman stepped into the middle of the road. Jerking the steering wheel, I veered into the lane of oncoming traffic, almost hitting the car heading towards me, then pulled back to my side and stopped on the wide shoulder, shaking from the near miss. The woman kept standing in the road, blocking movement, unfazed by the blaring of horns or, for that matter, almost getting killed.

I ran back to her. “Hey. You can’t stand here.”

Traffic in the lane began to move again once I guided her onto the shoulder. I started to walk back to my car; the woman didn’t budge. I followed her gaze upward to some birds on a telephone wire.

“Let’s go.” My insistence made no impression, but she allowed herself to be led to the car, after which I sat her down in the passenger seat.

She still hadn’t uttered a word. With pure white, shoulder-length hair, deep furrows all over her face and sagging cheeks, she must have been in her nineties. She wore floral-patterned pants with an elastic waist and a sweatshirt in spite of the noontime warmth. She stared out the windshield impassively.

I’d almost hit her and thought I owed it to her to help. But I was pressed for time and the inconvenience rankled me.

“Where can I take you?” I asked.

Caretaking - Barry Fields

She didn’t respond, so I repeated the question in a louder voice. She turned toward me, her face still blank. “Home, mister.”

“Fine. What’s the address?”

She didn’t answer.

I started the engine, got off the busy road at the next light and pulled into a strip mall. “I need an address. You don’t have to tell me how to get there. Just the street and number.”

The woman stared at me and I spoke, volume turned up. “Do you know where you live?”

She shook her head.

Terrific. I’d driven three hours, on an important assignment for Rolling Stone to interview a band about their recent Grammy, and didn’t have much time. I exhaled my frustration audibly, which got no reaction from her.

“What’s your name?”

“Lydia.”

“Lydia what?”

“Smith.”

“Who do you live with?”

“Johnny.”

“Who’s Johnny?”

“Johnny.”

My exasperation got the better of me. “Come on, Lydia!” I almost continued yelling at her to quit acting dumb, but I could see her mind was gone. I felt like I’d committed an assault.

Sheepishly, I asked, “Is Johnny your husband?”

“My son.”

“Johnny Smith?” More frustration. She’d given me one of the most common names on the continent.

She spread her fingers and regarded her wrinkled hands. Her nails needed to be cut.

Information found no listing under her name, but had two John Smiths I decided to call. Not related. John could be a middle name, he could have a different last name, who knew what?

The thought of leaving her there crossed my mind, but it would have been wrong, like abandoning a lost child. I pulled back onto the street. “Lydia, I’m going to drop you off at the police station. They’ll be able to help you.” Google Maps showed it as being less than a mile away.

“No. Not the police. Not there.” She began trembling and crying and tried to open the door. “Not there,” she yelled hysterically, “Not there.”

“Okay, not there. No police.”

I considered unloading her onto a hospital. Let her be their

The Opiate, Summer Vol. 42

problem. But as far as I knew, she wasn’t sick. Just old. And it didn’t feel right. A year before, when my grandmother was sick without long to live, I visited her only once. In my thirties, I avoided her and the awfulness of her wasting illness. My parents told me I should spend some time with her, and my fiancée, Maggie, warned me that I’d regret it if I didn’t. The next time I saw my grandmother was at the funeral home. Maggie was right. I could have bonded with her during her final months and given her solace. I never got to say goodbye, to tell her I loved her. I still hadn’t forgiven myself.

“Half the family was gone now, the remaining two dwelling in a cheerless house. I stared at [the picture], struck by the mutability of life. Uneasy now, I recalled my grandmother before cancer drained the vitality from her. The possibility of my own vulnerability to time unsettled me.”

I called the band’s lead singer to say I’d be late for the interview. He said they were rehearsing and could wait another hour or two. With the pressure off for a bit, I still had no idea how to get her home. Would putting myself out to help a stranger provide redemption for the neglect of my own grandmother?

Figuring she couldn’t have walked too far, I drove back to the area where I’d first seen her. Her sobbing reminded me of my grandmother the one time I saw her during her illness, when narcotics couldn’t take away the pain and she wept the whole time. Lydia calmed down after I squeezed her hand and reassured her we weren’t going to the police. I searched in the console and handed her a fresh pack of tissues. She fumbled with it, couldn’t figure out how to open it and ultimately left it on her lap.

Caretaking - Barry Fields

“Are you hungry?” I asked.

“Are you?”

I looked up nearby lunch places and found Tony’s Deli. Lydia needed help getting out of the car, but walked steadily enough. I held the restaurant door open and she made a confident beeline for the dessert display. So she’d been there enough times to have a memory of it. I thought I was in luck, but the woman behind the counter didn’t know her, and no one in the open kitchen recognized her. I ordered minestrone soup and a grilled ham and cheese on focaccia. Lydia eyed the baked goods and pointed to a brownie.

“Don’t you want some real food? They have all kinds of sandwiches and soups and salads.” When I saw my grandmother, her inability to eat added to my distress. I dreaded a repeat with Lydia. Her index finger touched the glass. “That.”

I shrugged and the server took it as confirmation to put a brownie on a plate. Lydia wanted coffee. By the time my food came, she had inhaled half the brownie, breaking off pieces by hand and putting them in her mouth. She held the coffee cup in both hands as though guarding a treasure she feared someone would take from her.

Lydia had no trouble devouring the dessert. A relief. Crumbs dropped all over her sweatshirt and chocolate smudged her chin, which I cleaned with a wet napkin. I asked how she knew the restaurant, how long she’d lived in the city, where she grew up. She either answered, “I don’t know” or remained silent.

My writing career had taken off, and my wedding date was approaching. Riding high, I was helping Lydia as much to compensate for my past failure with my grandmother as I was to return her home safely. With her deteriorated mind and empty personality, Lydia belonged to an alien world. Although she piqued my journalistic curiosity, her condition couldn’t touch me.

I finished my sandwich and she was on her second brownie when an older couple passing by our table stopped.

“Hi, Lydia,” the woman said.

Lydia stared blankly at her.

“I’m Stephanie,” the woman nudged. “Do you remember me?”

Lydia bit into the brownie and concentrated on chewing.

The woman turned to me. “Who are you?”

“She wandered into the middle of the street nearby and I almost hit her. She doesn’t know her address and I’m trying to figure out how to get her home.”

“She lives on Elm Street between Third and Fourth. It’s less than half a mile from here. A blue house with two dogwood trees out front.” She must have seen me light up. “We’d take her, but we’re meeting friends for lunch.” She pointed to a couple sitting at a nearby

25.

The Opiate, Summer Vol. 42 table.

I thanked her.

Lydia finished the brownie and coffee. Holding the empty cup, she stretched her arm towards me. “More.”

She’d started to smell. She must have gone while sitting there. “You can have more at home,” I promised. It was a placation to get her outside.

The bulkiness of her pants suggested adult diapers. I placed a wad of paper towels on the front seat before she got in the car and rolled down the windows as soon as I put the key in the ignition.

We arrived a couple of minutes later. The house needed painting, one of the window panes had a crack in it and overgrown azaleas crowded along the fence. Lydia swung her legs out of the car and labored to get up. I helped her to her feet, walked by her side to the house and rang the doorbell.

A man opened the door and cried out, “Mom!” Wearing a t-shirt that was sweat-stained around the armpits, he was of medium height, practically bald and had a paunch. In his seventies, I guessed. Lydia stepped inside without a word.

I summarized what had happened. I’d done my part and was ready to go, but Lydia’s son had more to say to me.

“She left when I went into the backyard to turn on the sprinkler. She does that on occasion. Walks out on her own. Gets lost. I don’t know how to stop her unless I use a leash. Hey, please come in. Please. Please.”

His urgency turned the invitation into a plea. Fatigue had eroded his features and he had about two days’ worth of stubble. Interested to learn more about Lydia, I crossed the threshold and he closed the door.

“I don’t have a whole lot of time...” Then I suggested, “Can you install a deadbolt?”

He shook his head. “If I have to leave for some reason and there’s a fire...” He let the implication hang. “Thanks so much for bringing her home.” He patted her on the shoulder. No hug. “Can I offer you something to drink? Coffee?”

He guided the three of us into the kitchen. “I’m Greg, her son.”

“Steve. She said your name is Johnny.”

“That’s my older brother. He died several years ago. She gets confused.”

“She soiled her pants in the restaurant.”

Greg started the Mr. Coffee and left the room with his mom. The kitchen, like the rest of the place, needed maintenance, with a slowly dripping faucet, a buzzing refrigerator and chairs that looked

Caretaking - Barry Fields

like battered relics from the 1960s. Unwashed dishes cluttered the countertop. He’d left his computer open on the table and I read a cover letter. He was a computer programmer looking for part-time work from home.

I walked into the living room while the coffee pot slowly filled. There was a gas fireplace with the pilot light off and, above it, a mantel with some framed photographs. In one of them, I recognized Lydia as a woman in her fifties, wearing a bright summer dress with a matching smile. A man stood at her side with his arm around her, and two younger men—Greg barely recognizable and Johnny, I presumed—crouched in front of them.

Half the family was gone now, the remaining two dwelling in a cheerless house. I stared at it, struck by the mutability of life. Uneasy now, I recalled my grandmother before cancer drained the vitality from her. The possibility of my own vulnerability to time unsettled me.

Greg emerged from Lydia’s bedroom and stood behind me. “She’s resting.”

I pointed to the photograph. “What was the occasion?”

“Their anniversary.” He pointed. “That’s my stepfather.”

“They look like a happy couple.”

“They argued all the time.” He took down another picture, this one a portrait of a younger woman with pretty features and long, blonde hair topped by a black graduation cap.

“Lydia?” I asked.

He nodded. “My parents divorced when I was five. She had to work during the day and went to college at night to become a teacher. Then she went to graduate school while teaching high school. Johnny and I barely saw her for years. She wasn’t much of a mother.”

In the kitchen, Greg filled two ceramic mugs. He put a carton of half and half and a small bowl of sugar cubes on the table, adding some of each into his cup. I drank it black.

“Getting stuck with her wasn’t what I envisioned for myself. Her dementia’s so bad, she has no appreciation of what I do for her. How hard it is.”

I’d only spent an hour with her, but he didn’t have to tell me. Lydia and Greg were cellmates in a prison with only one escape. Greg’s world-weariness and the shabby surroundings troubled me as the illusion of my immunity to the future fell away.

“Once I left for college, I didn’t have a lot of contact with her. I guess it was payback for her not being there when I was growing up. I had to move in eight years ago when she couldn’t take care of herself anymore. Now I’m irritated every time I have to change her

diapers.”

Ashamed of my own earlier arrogance, I rushed to defend her. “She can’t help it.”

“Exactly.”

He stared down at his coffee and brought the cup to his lips. I had no solution for him, could do nothing other than witness his hopeless resignation. He reminisced about his marriage and the life he once had, then returned again to his oppressive present. His eyes moistened and I stared at the dregs in my cup to avoid embarrassing him.

He got up. Back turned, he wiped his eyes with his sleeve, walked to the counter and returned with the coffee pot to pour some more. I covered my mug with my hand, shook my head.

Lydia shuffled into the kitchen completely naked, holding the TV remote.

“Mom!” Greg shouted. “What the hell are you doing?”

She cowered and backed away, a hint of fear in her face.

“What do you want?” he barked.

She turned to me. “Who are you?”

Recovering, Greg said more gently, “That’s Steve. You got lost. He brought you home.”

She held out the remote towards me. “The TV won’t work.”

“Come with me.” Greg took her arm and returned with her to her room.

He had no right to treat her like that. Lydia had struggled to provide for her children and she’d wanted to better herself. I imagined I would have liked that younger version of her. Maybe Greg, too. Now they had only each other, caught in a duet, the same discordant song repeated over and over. The daily suffering they endured could be visited on anyone.

The sound of a game show suddenly blasted through the house, then muffled when a door shut. Greg reemerged and took his seat. He picked up his mug, put it down and again wiped his eyes with his sleeve. He looked out the kitchen window at the blank wall of the house next door. “I’m sorry. I shouldn’t get angry at her.”

“It’s okay.” But it wasn’t. None of what I’d seen was okay.

Greg seemed to shrink into himself, his self-pity hanging like a shroud over the room. The possibilities of his life had narrowed until only this—taking care of his mother with unending resentment and self-recriminations—was left.

A sick, hollow feeling came over me. Any words of encouragement I thought of sounded contrived.

“I’m sorry to trouble you with all this,” Greg said. “I shouldn’t.”

“It’s no bother,” I lied. I couldn’t remember ever feeling so bad

Caretaking - Barry Fields

for people. Life could crush any of us as inexorably as it had them.

Greg shook his head, stared at his coffee. “I don’t know how much longer...”

I shifted in my seat, pulled my phone out and looked at the time.

“Lydia and Greg were cellmates in a prison with only one escape. Greg’s world-weariness and the shabby surroundings trou- bled me as the illusion of my immunity to the future fell away.”

“I’m sorry. I’ve kept you here too long.”

“I have an appointment for work. They’re expecting me.”

At the door, Greg held out his hand. His grip was firm and he held on too long, as if reluctant to let me go. “Thanks for listening.”

Back in the car, I slumped against the driver’s seat, gripping the steering wheel until a couple of children playing noisily across the street broke my paralysis. I texted Maggie to tell her I’d be home late, then entered the band’s address into my phone.

Synchronicity

Antonia Alexandra Klimenko

It was in the sleep of winter, at that opaque hour that the pale moon trembles on the water, when his dark radiance in all its brilliance peeked through my doorway. I had already left the door ajar in anticipation of his arrival and was just about to turn on the evening lamp when his silhouette loomed large on the wall. Walls make wonderful screens for the silent movies of imagination, especially those backlit by candlelight. Projections, themselves, magnify—transporting one to a faraway place—one of spacious possibility. Perhaps it is because it’s such a small room that I so often “travel light,” not unlike a child with a flashlight, who, under the tent-like cocoon of bedsheets, creates a private world of her own. That is, until it’s time to turn out the light. Then, another kind of darkness begins––the invisible dark; and you either learn how to make friends with it or...you must find your own way back.

“Forgive my appearance,” he began—rolling his eyes as if to mock his own feigned embarrassment. “I’ve been up all night, and I’m afraid I look like I slept in my clothes,” he admitted with a rather disarming smile unfolding from the corners of his mouth. “But that’s because I slept in my clothes! The night before, too!” he boasted. Indeed, he smelled of damp wool, burnt candlewax and yesterday’s Camembert, and I smiled to myself as I took his half-broken umbrella and

Synchronicity - Antonia Alexandra Klimenko placed it next to mine. “By now,” he mused, tucking his shirttail into his trousers in the most endearing manner, “they and I are old friends!” Then he kissed me on both cheeks, imparting the memorable sting of a cold burn, before shaking off the rain and depositing his canvas bag in a corner by the door. “Thank you for...for inviting me,” he said graciously, turning in an elegant gesture to offer a single flower. A lily.

I was immediately drawn to his sophisticated blend of old- and new-world contradictions, having a particular penchant for puzzling out the obvious mysteries of life’s eternal paradox. More than handsome, he was charismatic; therefore, I gave less attention to the costume of his undress. I do recall that he was of a robust build, with dark penetrating eyes and a trim moustache overshadowed by razor-sharp stubble. His cheeks were flushed, his forehead pensive, his expression passionate. Here was a man who was achingly alive—the coiled spring of his vibrant energy all but humming the body electric! We had spoken just days after our dear Anya passed away, and I was struck then, as I was now, by the sense of our being two intimate strangers engaged in the flow of one uninterrupted conversation.

“’Gauguin...he’s my favorite. I love the primitiveness of him. If I had money, I’d go to Tahiti and run around naked in the sun.’ ’Funny, to think that it takes money to go to a place where you don’t have to spend it...or won’t have any to spend. Guess I’ll just have to settle for running around naked here.’”

“I’m happy you’re here, Sergio” I said, still trying to find a spot for the bottle of wine he had brought.

“Here...let me.” He wasted no time in uncorking the Bordeaux and pouring us each a glass. “Yes, at last!” he exclaimed with a sense of

The Opiate, Summer Vol. 42

relief as his eyes began their search.

Recovering from seizures of highs and lows and still deep in morbid rapture, I had told him that our visit would have to wait until I felt almost human. In all honesty, I felt almost guilty for calling him. Anya would have appreciated it, but she might not have liked it.

“I visited this room in my mind, you know. It’s exactly the way Anya described it.” He looked in the direction of the bookshelves. “But different, of course. You, too; the same, but changed.” He observed me with a sidelong glance. “Transcendent. Quite human!” he concluded.

“Really?” I felt absolved. “All too human, I’m afraid.”

His lips curved into a knowing smile. “Do you mind if I take a look around?” He sipped from his glass, already resting on one of the shelves.

I watched him out of the corner of my eye, freeze-framing (I like to think) the very instant he spotted the much coveted leather-bound journals, which he did with the most guarded interest. As it humbles one to have something just out of reach, I had purposely moved them to the top shelf, only inches from the ceiling. The humbler the better.

“Oh, please...be your guest,” I said, placing a plate of sliced apples, gruyère and a baguette on a tray between us. I’d wished it could have been more.

“It’ll do.” He surveyed the room, tilting his head in my direction as if to reassure me. “The space next door is of the same dimensions?” He flashed me a Cheshire cat grin. “So small you have to go outside to change your mind?” No doubt, it was an old vaudeville joke that had become part of his how-small-is-it repertoire.

“Small, but charming,” I replied, quick to defend my modest abode. I had almost forgotten he was interested in the chambre de bonne across the hall. As it was not yet ready to be seen, I had suggested that he take a look at mine. “As I said, it might not be available for another couple of weeks.”

“Oh, no worries,” he returned with a warm lilt that reminded me he was from Barcelona. “I’ll just stay with a friend close by.” His eyes fixed on mine, he added, “But, it’s always a bit of a problem. Well...it’s just that I’m a night person, that’s when I do most of my writing, drawing too. And, if I have something that I must do in the day, I burn the candle at both ends. How ‘bout you? You a night person or a day person?”

I inhaled the exotic lily—its petals delicate, its fragrance, pungent.

“I’m a ‘both’ person. I hate to miss a thing.” He nodded before emptying his glass. “You have a lot of interesting things here. May I?” he asked, picking up a bronze replica of Isis. “I love Egyptian artifacts,” he remarked, running his fingers over the small statue in a caress. “I

used to go to the Louvre all the time and spend hours there. They have a whole Egyptian section, you know.”

“It’s been a while.” I steadied Osiris, her companion statue, which threatened to topple over. The challenge of treasured possessions in a limited space.

“But, I like the d’Orsay better, I think,” he went on. “Gauguin... he’s my favorite. I love the primitiveness of him. If I had money, I’d go to Tahiti and run around naked in the sun.”

“Funny, to think that it takes money to go to a place where you don’t have to spend it...or won’t have any to spend. Guess I’ll just have to settle for running around naked here.”

“Let me know,” he said, slyly, over his shoulder, “I’ll bring my sketchpad.”

“You say that now,” I warned, bemoaning the decline of my once artful shape and form. I stared at my red-striped canvas armoire, which I likened to a circus tent and thought of my clothes that never went anywhere. “Sometimes I imagine that my clothes whisper to each other at night. She promised to take me to the opera, says one. She hasn’t fit into me in years, says another. I’m still wearing my price tag, says the third.”

He chewed vigorously on the cheese (which, I’ll admit, was a little rubbery) as I chewed on my own thoughts. His cheeks, I noticed, were a little rosier for the effort.

“It’s time that we never seem to have enough of,” I added, remembering our dearly departed in mid-sentence.

“Yes, but, who’s counting?!” he exclaimed, polishing off another slice of apple with a flourish.

“Time is the Great Imposter. Were it not for light and dark... there would be no ending or beginning. No need for measure.”

“No measure possible.”

Just then, my clock elected to “chime in” eleven times. The fact that it was only nine o’clock wasn’t noticed or, if it was, was not remarked upon. The truth being that it had always had a mind of its own, chiming precisely on the hour, however, as many times as it pleased.

“That’s a beautiful clock you have. It’s great that the ticker is still going.”

“Yes, I like things that work. What’s a clock without a heart?” I said, patting my pink Sèvres on its pointy little head with affection. He smiled. We had “a moment.”

“Have you seen the two at the d’Orsay?” he asked excitedly. “I was overwhelmed with their grandeur when I first saw them. The size of them!” He extended his arms and rotated them like the hands of a clock. “It used to be a train station, you know... People still coming and going...never staying. Anya and I used to go there at night and pretend that we might hide in those amazing art nouveau cabinets and emerge after everyone had gone and it was all locked up. Then, we’d play like

The Opiate, Summer Vol. 42

children and have the museum all to ourselves. You know, to live there for those few hours.”

He drew out each vowel, accenting the most significant word of each staggered phrase. His animated gestures—like cartoon caricatures that leap off the quickly turned page. I could see why Anya thought he might have enjoyed a triumph in the theater. As for myself, I wasn’t so sure. Unless he played himself...he would have so much to unlearn.

“We were close friends...then.” He tacked on that last word as if to say that perhaps they hadn’t remained so. “A lot of synchronicity

“‘A lot of synchronicity between us.

Like you and your clock.’ Ah, he noticed. ‘Like what, for instance?’ I was interested in hearing what might have happened between them. Anya, who had once been a bright light both on and off the silver screen, kept everyone pretty much in the dark when it came to personal affairs.”

between us. Like you and your clock.”

Ah, he noticed.

“Like what, for instance?” I was interested in hearing what might have happened between them. Anya, who had once been a bright light both on and off the silver screen, kept everyone pretty much in the dark when it came to personal affairs. Word was, he was a bit of a know-it-all, an artist that she picked up off the street and, as they were inseparable for a time, there was speculation about the nature of their relationship.

“Oh, like we would keep running into one another. Sometimes we’d see each other on one side of the city, and the very same day see each other, again, on the other side.”

“Synchroni-city,” I quipped, having always enjoyed wordplay.

Synchronicity - Antonia Alexandra Klimenko

“Or, I’d do a drawing of something...what was it? Oh yes, a drawing with the theme of separation and she would tell me that she had just been thinking about that. That you, in fact,” he said, coolly studying my face, “had just written something...about it in...your journal.” He raised his eyebrows as he observed me wince. “I can only imagine what’s in there.” His eyes darted to the distant “there” and back while his face betrayed his separation anxiety. A long pause settled in.

“One day, they will publish the silences between our words.” I was quoting myself.

“Yes...she...used that line on me...once... I thought at the time... she was echoing the heroine from some obscure play.” He looked at me point-blank.

“Obscure...yes,” I repeated, biting my lip. And my tongue.

“Or, I’d be thinking of her just as she would phone to say good night. Sweet dreams, she’d say. His voice broke almost imperceptibly. “Things like that. Do you mind if I smoke?”

“No,” I lied, not wishing to deprive him of that, too. “Go ahead.” I handed him an ashtray, expecting him to smoke a cigarette.

“Hash. It’s mild. You smoke?”

“On...rare occasions.”

He shaved some off, very deftly rolled it into the tobacco and, within what seemed only a few seconds, he was lighting up. “Here.” He produced the rather prodigious joint.

I waved my hand as if to say no thanks. But he held it out to me, not taking no for an answer. I inhaled and began to choke a little.

“Go ahead,” he encouraged, plucking a cranberry from the table’s centerpiece and popping it into his mouth.

I took another, inhaling very slowly. It was not as disagreeable this time as I began to relax into it. In fact, I could only smoke if I were relaxed and knew I didn’t have to go anywhere or do anything as my perceptions almost always unfolded in slow motion, making it difficult to function in the real world. It was like watching a movie for the first time. You’re so much more aware of things as they are happening, so much more present. After you’ve seen the movie again and again, you anticipate the next scene and it takes you out of the experience. Only, the trick, I said to myself, is to do it without the smokescreen.

By now, Sergio was checking out the CDs in my collection. He put on the soundtrack to Last Tango in Paris. It was a seductive selection. Slow at first, sultry, undulating. Of course, I knew the music would eventually become more frenetic and I was already anticipating it with some apprehension. As if he sensed my mood, he patted me on the shoulder. Then, he took his jacket off and hung it on the shoulders of the chair before pouring us both some more wine. It was impressive

how he made himself at home. I was beginning to feel like his guest and it made me feel both easy and a little un.

“Haunting...don’t you think?” He took another toke. I was slow to respond. “This music,” he continued, in an effort to prompt me.

“Yesssss,” I agreed, shivering from the cool night air, my voice trailing off even on a dry consonant. I had only just realized that my shawl had slipped off my shoulders and was dangerously close to the flame.

“The only things worth remembering are those you can’t forget,” he intoned.

His remark was haunting. I supposed it hinted of his companion and perhaps something yet unspoken. And it had a feeling of abandon about it. As if life were to be lived fervently.

“Don’t you think?” he insisted before swilling down half a glassful.

“If only we wouldn’t forget...to be worthy...of what we remember.”

“So tell...me...what do...you do? Again? Oh, I remember now,” he said, not skipping a beat, “you write other people’s memoirs.” His voice smacked of sarcasm. I found myself cringing—bracing for what was to come.

“Rearranging their sentences, no doubt, like dead furniture in the dark.” He made an awful face at the notion before he grinned, revealing a set of nicotine-stained teeth. The gap between the two in front he used, momentarily, as a cigarette holder. His next sentence dangled from his lips, eager to be lit from within, while his color increased in intensity. I lowered my pale gaze and turned to warm my hands over the flame of the candle—my own melting flesh retreating from my self-appointed guide, unwilling to cross a frontier that would surely leave a trail of scars and ashes.

“Better yet, what...do you...remember...that is...worth telling?”

He had the hiccups now, and his sentences had become broken—the sound of his voice like a smooth stone skipping across the surface of the Seine before sinking to the bottom. I took a swallow of the Bordeaux and was myself swallowed by an emptiness. Was I sinking or floating? It was as if a large jigsaw puzzle had spilled into my consciousness and the connecting pieces were missing. Sergio’s eyes flickered burnt-orange in the candles, his lips—lips that moved without sound—curled in the smoke without a face. A dialogue between the deaf and blind shadows emerged from other shadows. The visible darkness in the invisible light. I closed my eyes and remembered the impression she left on the white pillowcase—her sleep as deep as snow. Anya, now, a silent movie. Oh God, I realized, I’m stoned. With that, the

Synchronicity - Antonia Alexandra Klimenko clock chimed once, skipping midnight altogether. I was grateful. Sergio stood by the radiator, illuminated by the moon, looking out at the rooftops in the night sky.

What kind of moon... I wondered. Contained within the word moonlight are the words thin gloom. And I was thinking the thinner the better in this case.

“Is the moon fulllll tonight?” I asked with some trepidation. The word “full” had taken on another shape and was difficult to dislodge from my throat.

“Can’t see from here,” he answered, grumbling. “She’s unfaithful...secretive...” He shot me a meaningful glance. “Obscure!”

“Transcendent,” I added.

“Full...of it! Heh, heh, who can tell? At least with the sun, you know where you stand. Brrrrrr! With the moon...that old liar...with her, it’s hard to tell,” he scowled, returning to his seat and the warm lining of his jacket.

The wind whistled through the cracks; the drumbeat of the downpour pulsed like a heartbeat on the single tiny window through which raindrops, like teardrops, formed little rivulets.

“It’s damn cold in here,” he bellowed, rising from the chair again to close the skylight. “Fine if you’re a bi-polar bear. Heh, heh, heh,” he tittered. Then he plumped himself down on a pillow next to me, placing another behind his head—one with the stuffing coming out at the seams. “We could have had her stuffed and brought her here,” he mused, using his index finger to poke the stuffing back in.

“The stuffing that dreams are made of,” I quipped under my breath. Breath which was now visible.”

“She would have been happy here. Right at home.”

She was happy here. Made herself right at home. Ripped that pillow which she had meant to repair (as I am sentimental, I won’t either) wore my clothes, ate my food, borrowed my words and never brought them back. Dear Anya, who could never keep her promises. Darling Anya, who apologized so beautifully that one could forgive her almost anything. Almost. With a voice as clear as a mountain stream, she laughed with rippling abandon, provoking even the most modest of admirers. It was unclear who she was or where she came from, save for a slight accent, which hinted of Mother Russia. She told people she was an orphan, rarely spoke of her past. Her future just another dream on lithium.

No...she lived for now...as many “nows” as somebody else could afford. Despair as unfathomable as...

“Where are you? I’ve lost you.” He tapped me on the wrist with the lily—the yellow pollen clinging to my skin like the stain of sin.

The Opiate, Summer Vol. 42

“The trick is to be in the moment, not in the parentheses before and after—not in the rearview mirror reflecting upon itself.”

“I understand...really I do. Words, without the spirit to inhabit them, are, at best, mere apparitions, approximations, shadows of forgotten light...meteors that fall short...illusions of still more illusions. People are immortal. Got it.”

He reached for a silver flask inside his jacket. “Here, have some immortal vodka,” he urged, spilling as much of it outside the glass as in it. “Everything is immortal. Energy never dies. The past, the present, the future. Everything happens at the same time.”

“Simultaneously,” I whispered. Together, we lifted our glasses and drank the contents all in one audible gulp. “Did you know that contained within the word simultaneous are the words time is a lie?”

“Really?” he whispered back, wiping up the spilled vodka from the floor with our napkins and helping himself to the sleeve of my sweater with my ragdoll arm still in it to remove one last drop.

“Contained within the name Osiris, by the way, is the name Isis which shows you the far-reaching extent of his protection.”

Protective energy was to be wished for devoutly. Had I not wished to be encompassed in Sergio’s sphere of influence as much as I simultaneously wished to be just out of its reach? Had I not manifested a life lived through others?

“Is that what...you and Anya did a lot of? Staying in the moment?” I queried, in an attempt to deflect the focus from being directed toward the vicinity of my vicarious existence.

“Found another good hiding place, I see.” Clearly, it wasn’t just a line from the film; he was speaking to me. “You’re afraid. You’re always afraid,” he continued, parroting Brando’s character in the film.

After a few beats, I began, “When she and I visited...” Oh God, I wished I hadn’t accented the “I.”

“So, you would rather be comparing notes, I suppose,” he grumbled. “Yes, let’s get together and talk about our friend, Anya. How long did you know her for? Two minutes? What would you like to know? Yes, she’s definitely dead. Next you’ll be wanting to know if I did her...and how many times. What she said and then what I said... and then what she did and then what I did. And, WOW!” he turned up the volume. “I didn’t know that! That was REEAALLLY profound! What kind of bullshit is that? I say, get your own life! Don’t you believe you deserve one? WHAT ARE YOU WAITING FOR?!”

I hadn’t been prepared for his outburst, however admirably restrained. Nor how life had begun to imitate art and vice versa. What am I waiting for? Why are you keeping me? she had cried that evening when I had held onto her, lest she do something she would never live to regret. She was desperate now, and a bold move was just what she craved.

Synchronicity - Antonia Alexandra Klimenko

Everything about her was bold...her shocking red hair, her black fishnet stockings, which now had huge holes in them, her eyelinerrimmed, tear-stained raccoon eyes. I know he’ll be there! Please! she said, trying to break away. I have to look for him...I know I can find him! We always find each other. I know I can make him understand. If only I can speak to him, I know he’ll forgive me. Please, Mama! Please come with me, please make him understand. Sometimes I would go searching with her. I didn’t that night.

“His lips were not in sync and he was slipping into his native tongue. I began to experience him as a poorly dubbed foreign film. If only he had subtitles moving across his forehead. I might read what was on his mind. If only.”

I wasn’t her mother. She said she was an orphan. I hardly even knew her. Not that night. That night, I, an audience of one, watched her as she painted a smile on her face, like Gelsomina in Fellini’s La Strada. Watched her, as she faded into the shadows.

“Besides, I never even touched her,” he said quite matter-offactly. Clearly, not the version I had heard, but, knowing Anya, I almost believed him. “Not like that... She wanted to...but that’s another story.” Another surprise. His lips were not in sync and he was slipping into his native tongue. I began to experience him as a poorly dubbed foreign film. If only he had subtitles moving across his forehead. I might read what was on his mind. If only. His lips curled upwards with the smoke as he reached over to me. “Now, you,” he insisted, slowly running his fingers over my hand. “You touch me. I like you.”

“Oh, please!” I hadn’t fully recovered from the way he had mocked me only moments before, and though this gesture seemed

The Opiate, Summer Vol. 42

genuine enough, I wasn’t sure where he was going with it. And then there was...

“Anya,” I uttered her name, feeling suddenly protective of her, her memory.

“Okay, so you want to be stuck in the past all your life.” He looked around the room, steeped in history. His voice took on that

“Alright, so I would adopt him, but only for the night.

Only for the night, I promised myself. Is there not something to be said for accommodating a fellow traveler?”

sing-songy, taunting tone that echoes all the way from childhood back to some bad movie in surround sound as he added, “Look, we have the museum allllll to ourselllllves now.” And, of course, it came just as the music was climaxing. What, again? Oh my god, the CD was on instant replay. In Last Tango in Paris, right about now, she’s trying to get away from him.

“Noooooo,’’ I pleaded

“Si, si, si, si, si, si, si, si, si, si, si, si, si, si, si, si, si, si, si, si,” he all but crowed. “I’m like your clock. I chime when I please! And as many times as I please!”

The music at this point was a frenzy of insistent rhythms with compelling, furtive, sexual undertones of longing. I began to tremble, ever so slightly. Then, he moved in very close, waiting for his cue from the movie theme. “You’re alone...you’re all alone. Until you go right up

into the ass of death...right up into his ass...until you find the womb of fear... Then, maybe...you’ll find him.”

It was only a few lines from the film, but the delivery was all too real. The music was becoming more insistent; the air had become thick with damp wool and Camembert, and rich with uncertainty. I began to wish that I could linger forever in formlessness on some invisible ceiling, or perhaps escape with the smoke through the skylight. I trembled again as I pulled back from him. The expression on my face must have translated well because he himself was taken aback.

“Ah,” he said, genuinely shocked that I should feel frightened. Before I could protest, he wrapped his arms—arms that had once held Anya—Anya in all her many mood swings—around mine and was soon rocking me back and forth in them. I imagined it was a lot like being cradled in the giant pendulum at our favorite museum.

“Don’t you worry,” he winked, gently releasing me from his embrace, “I grow on you. You’ll see!”

“That’s what I’m afraid of.”

“I need to take a piss,” he announced, rushing out the door, only to poke his head back in. “If you look real close, you’ll see me hiding behind my zipper.”

Once he left the room, I turned off the stereo and began to rinse out the glasses in an effort to regain some sense of normalcy and more subtly indicate to him that our uninterrupted dialogue would have to continue without me... Let it come. Let it go. Let it come. Let it go. I took a deep breath and felt the air moving out and in, in and out of me. So many people coming and going...never staying, his words echoed in my brain. By the time I smiled, in retrospect, at his zipper line, he had already reentered laughing. Or rather, stood at the threshold while we exchanged places like the sun and moon in unspoken understanding. Breathing out, breathing in. Let it come, let it go. I wanted to tell him it was time for him to go and had prepared to do so when, on my own way back from les toilettes, I realized that he had already put on Billie Holiday. Her voice was warm and mellow and I found I had no objections. I was, in truth, relieved that the mood had changed. But to what? Ohhh, those lyrics:

Baby why stop and cling

To some fading thing That used to be

So if you can’t forget Don’t you worry ‘bout me

Some fading thing...that’s what I felt like, some fading thing. Also, I had the peculiar feeling that something was missing, although I

The Opiate, Summer Vol. 42

couldn’t quite put my finger on it. At least, not at first. Then, I noticed that the table was devoid of any color. Good grief! He had, in my short absence, raped the vines of all their cranberries. As he was in an altered state—“tripping,” as it were—could I really blame him? He simply had the munchies and couldn’t help himself. As he helped himself. You see, I was already making excuses for him.

“Look, I’ve missed the last metro. Can I spend the night here? I won’t bother you, I promise. And, I won’t take up much room, just that little piece of heaven over there,” he said, pointing to the unspoiled hardwood floor by the door, parallel to my bed.

“Charming,” I sighed. Oh God, how’d it get to be so late? I couldn’t believe it! My senses were reeling and my balance had become somewhat wobbly, to say the least. I lay down on the bed, Sergio stretched out at one end, myself at the other—the reconciliation of night and day. We remained very still until the end of the CD, and when all was quiet, he spoke in such a tender timbre.

“I was in love for the first time,” he recalled, lowering his eyes. “I had waited...a long...long time. Anya, god rest her soul, knew how I felt and she poisoned him against me. Now, I know you wouldn’t do that, would you?” He frowned. His fixed gaze seemed intent on challenging me, as if he already suspected that I, too, had warned her against him.

I was still a little shaken from our “last tango,” and surprised that I wasn’t surprised by his sexual orientation, which only further reflected his dual and all-encompassing nature. I shook my head in mute response and gently stroked his shoulder. I couldn’t help but feel compassion for him. How his loved ones had, in his estimation, betrayed him. Perhaps Anya, unable to save herself, had tried to save this man as I had tried to save her. Alas, the players were perfectly cast, the stage already set, but the karmic tapestry of this evening’s scenario was still being woven. A reminder to myself not to repeat the same old pattern.

It was then that a new thought threaded its way into the very fiber of my being: Oh God, perhaps I’m not any better than he is! With this revelation, I bowed my head and sighed a sigh that was, without a doubt, centuries in the making.

“I know you wouldn’t have done that to me.” This time he spoke with soft conviction. “You have a heart.” He looked crestfallen and spent. Neither of us spoke for a few moments. I wouldn’t be at all surprised if...she...told you about it. Perhaps you even...wrote about it.” His eyes turned expectantly to the journals.

“I don’t believe...she...did,” I said tentatively. Although...there is...one...” Was it too much for him to bear? Possibly more than the passing of Anya herself—guilt and regret being what they are. I had

done my best to capture her essence. Might it give him pause?

“You have...that one?” he asked, as if it were a popular selection on the hit parade. Anya had carried it off with her one day and had evidently shown it around. I was given to understand that it was received with great interest—something I had little desire to elicit. Having painstakingly painted and collaged many of the pages as I had with all the journals, it was, for me, a journey, a labor of love.

“May I...see it...? Please?” he persisted innocently now, and with just the right tone of reverence and humility that might, at last, gain him access to it. I took the step ladder out of its hiding place, retrieved the journal off the shelf where it had been leaning against all the others and handed it to him in slow motion. He fingered it with trembling eagerness, turning randomly to a page here and there. Ahhh-ing at one illustration of naked dancers—reminiscent of Matisse—gasping at another—a portrait of a soul illuminated from within. How else might a soul be illuminated, after all? And, finally Anya herself—her features awakening to the torment of ecstasy.

“An...irrelevant...masterpiece,” he mumbled, shaking his head in disbelief. Then he paused at the only entry which I had marked and quietly read my signature scribble to himself: