The Opiate

Spring 2025, Vol. 41

The Opiate

Your literary dose.

© The Opiate 2025

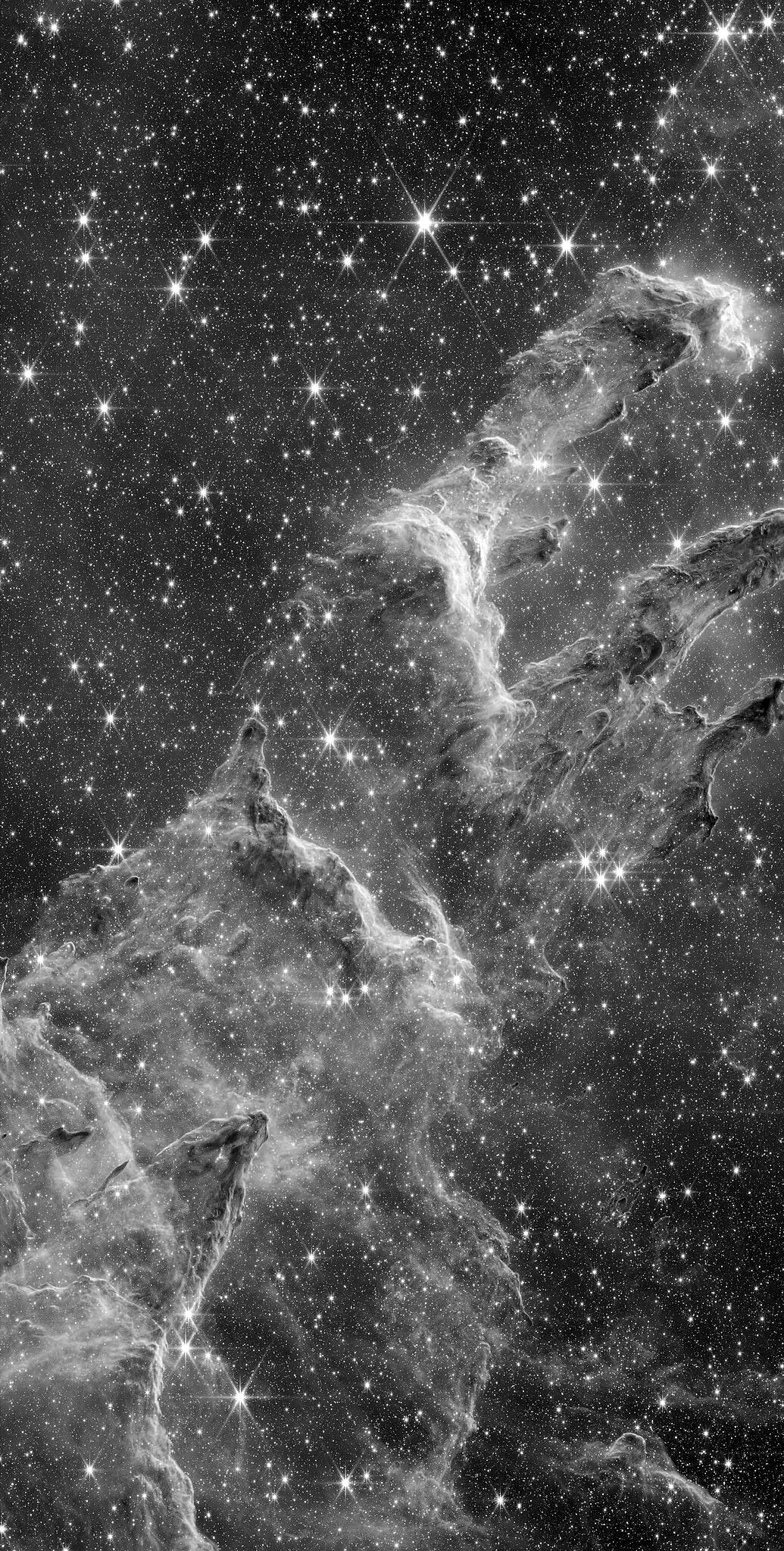

Cover art: Scene from the Palisades Fire, January 2025 by CalFIRE This magazine, or parts thereof, may not be reproduced without permission. Contact theopiatemagazine@gmail.com for queries.

“Live simply so others may simply live.”

-Mother Teresa

“Two kinds of Californians will continue to live with fire: those who can afford (with indirect public subsidies) to rebuild and those who can’t afford to live anywhere else.”

-Mike Davis

The Opiate, Spring Vol. 41

Editor-in-Chief

Genna Rivieccio

Editor-at-Large

Malik Crumpler

Editorial Advisor

Anton Bonnici

Contributing Writers:

Fiction:

Scott T. Hutchison, “Hard Lessons” 11

Debbie Miszak, “Girls’ Night Out” 15

Mike Lee, “The Last of Them” 29

Rich McFarlin, “Emily” 36

Johnny Allina, “Mushroom Chloe” 48

Barry Garelick, “Beanpole John” 54

Mary Lewis, “Alfred Under” 61

Nonfiction:

Alexander Lowell, “Mexico City Barber School Haircut” 68

Renshaw, “Letting You Know I’ve Arrived” 99

Poetry:

Kathryn Adisman, “March 2000” & “The Curse of Ingrid Bergman” 109-110

Ron Kolm, “Star-Spangled Nightmare” 111

Margaret R. Sáraco, “I Try Not to Grow Old,” “Letter to Adulthood” & “Death, Then Grief” 112-114

Steve Denehan, “Teal,” “And Hundreds Just Like Him” & “How I Tried to Leave You” 115-119

Dale Champlin, “The Music That Learns Us” 120

Mark Katrinak, “Highway Motel,” “Purple, Blue and Yellowing,” “Stones” & “Cosmetic” 121-124

Leanne Grabel, “Famous Film Director,” “Wool,” “Botox,” “America” & “Drawing a Pumpkin Wtih Mom” 125-131

DS Maolalaí, “The Hippie Across the Street” 132-133

Edward L. Canavan, “Breakdowns & Breakthroughs,” “Waste of Ages” & “Beyond Reason” 134-136

John Delaney, “Gobi Dream” 137

Megan Cartwright, “Metamorphosis” & “Unboxing” 138-139

Criticism: Genna Rivieccio, “Blasé About Trauma As Only a Californian Can Be: Darcy O’Brien’s A Way of Life, Like Any Other” 141

Editor’s Note

In the end, it always goes back to California. The geographic location that exhibits the gamut of weather and natural disaster phenomena (though there will forever be those holdouts who associate the state solely with nothing but “golden sunshine”). The place that shows the rest of the world what could happen to them if they’re not careful. Of course, it’s already much too late, even though the Golden State has provided numerous examples of what transpires when climate change exacerbates an already volatile and unpredictable Mother Nature.

And while, yes, the reaction to the extent of the devastation that Los Angeles experienced as the Palisades and Eaton fires raged (while other smaller fires raged at the same time as well) was unanimous heartbreak, as is what usually happens, most of those who weren’t directly affected have moved on to the next catastrophe of the day. Whether that’s bird flu, measles outbreaks, disastrous foreign policy decisions, etc., there’s plenty to choose from to keep the focus off how grave what happened in Los Angeles at the beginning of the year truly was. Not just another harbinger of climate change or the increasing incongruity of class disparity, but, in truth, of how so many of us are content to sit back and quite literally watch the world burn without doing much about it.

This is because, in all likelihood, we think to ourselves, “What can I really do about it anyway?” It’s easy to grow complacent and apathetic. Which is exactly why there’s been so much less resistance to a certain administration in the U.S. taking power compared to the first time it happened in 2016 (but officially, at the beginning of 2017). Not only less resistance, but blatantly and willingly voting that person in (this in contrast to what happened during the 2016 election)...essentially as a “fuck you” to both Democrats and, once again, the idea that a woman (Black, white or otherwise) could ever be “allowed” to be president in the United States (a name that has become increasingly oxymoronic, in addition to housing only full-stop moronic people).

The woman that vied for “the crown” (since the Orange One is

calling himself “the king” now) in the latest election is herself a California girl. And yes, there’s no denying that having her in office instead of the dolt that managed to win instead would have been a boon for “the land of milk and honey.” After all, it’s no secret that the state has sold itself many times over for the sake of federal funding (hence, its federal prison system being one of the most burgeoning in the nation). But now, no matter how kowtowing the state’s current governor, Gavin Newson, is to the Orange One, the latter has made it his personal mission to put the state on his list of ever-expanding vendettas just because both Newsom and the state itself has expressed frequent disgust for the führer

More jarring still were the additional post-election revelations that 1) swathes of formerly blue counties in California turned red and 2) a large pro-Trump voting bloc consisted of Gen Zers. The very generation that ought to have feared the outcome of a second Trump presidency the most. For it is their future (while Gen Alpha might not even have a future at all) that will be in the most noticeable dire straits as a result of the Orange Creature’s policymaking. As for the first revelation, it’s an additionally alarming statistic to come out of the 2024 election. That ten counties—Butte, Fresno, Inyo, Merced, Nevada, Orange, San Bernardino, Riverside, San Joaquin and Stanislaus—that voted blue in 2020 flipped in favor of the ultimate American grotesque.

Now, the voting map looks nothing like the California that once made conservatives “mockingly” (even though it’s actually a compliment) bill the state as “The People’s Republic of California.” A dig at its supposed ”communistic” government (and yeah, it’s easy to seem that way in a country as rigidly capitalistic as America). But such an “insult” is holding less and less water now (much like the Shasta Reservoir), with CA falling into the deep pit of redness that was once only reserved for the “flyover states.”

The one color of the state, however, that appears to be ever- constant is orange. As in the flaming orange of fire. An element that has always been synonymous with California. Except that, in the current conditions, it’s more dangerous and catastrophic

The Opiate, Spring Vol. 41

than it has ever been. Something that Mike Davis spoke to in his prescient 1998 essay, “The Case for Letting Malibu Burn.” In it, he discusses the absurdity of the long-standing approach to dealing with fire in Southern California, commenting, “‘Total fire suppression,’ the official policy in the Southern California mountains since 1919, has been a tragic error because it creates enormous stockpiles of fuel. The extreme fires that eventually occur can transform the chemical structure of the soil itself. The volatilization of certain plant chemicals creates a water-repellent layer in the upper soil, and this layer, by preventing percolation, dramatically accelerates subsequent sheet flooding and erosion. A monomaniacal obsession with managing ignition rather than chaparral accumulation simply makes doomsday-like firestorms and the great floods that follow them virtually inevitable.”

Here there is no denying that what Davis is talking about isn‘t “only” governmental mismanagement and ineptitude. What he‘s talking about is a willful state of denial (“state” meant literally [i.e., the state of California is the state of denial] and figuratively). An utter refusal to acknowledge reality, therefore ceaselessly engaging in the same behaviors that will continue to have increasingly dire consequences. That California (especially through Hollywood) has long embodied the crux of the “American dream” (or rather, the American delusion) only adds to its symbolic place within the deluded cultural consciousness of America and what it “means.”

When that batch of hellfire rained down on Los Angeles in January of this year, Mother Nature was putting none too fine a point on the fact that denial, or notions of “fake it till you make it,” can only get you so far before cold, hard reality seeps back in. Which reminds one of the 1934 quote from The Los Angeles Times that Davis places at the front of his book, Ecology of Fear: Los Angeles and the Imagination of Disaster: “No place on Earth offers greater security to life and greater freedom from natural disasters than Southern California.” Because, if you sell the lie hard and often enough, it will continue to be bought until the collective’s dying breath. Choked, no doubt, by the flames. Or, in the U.S. at large’s case, choked by another entity that happens to be orange as well. One that is also repeating the same lies (or “alternative facts”) over and over again despite everyone knowing, not so deep down, that the emperor has no clothes. But he‘ll more than likely still pretend that he does when he shows up to a “better and

brighter” Los Angeles for the 2028 Olympics. Burned to a crisp or not, the show must always go on in California, nay, the world.

Fearfully yours,

Genna Rivieccio March 2025

FICTION

Hard Lessons

Scott T. Hutchison

Junebee

freely declared that she visualized herself in the role of military sniper. My first-day-of-school icebreaker with sophomore English is to listen—to their fantasies and pipe dreams, to openly discover what brilliant thing they might want to do with their young lives. Junebee—with her bouncy brown hair and shiny braces—smiled broadly, saying she wanted to “plunk holes in the enemy.”

My classes sit in a Socratic circle, hearing various thoughts and opinions respectfully while skipping back and forth in a lively discussion, me facilitating. Nobody can hide in a circle—I see everybody. Sometimes, I have to work harder to teach the respect part. As Junebee finished, I detected a couple of eye-rolls, and one boy mumbled psycho under his breath. I applauded—told the class they needed to be supportive, announced that I believed Junebee could accomplish whatever she wanted. I made another pronouncement, too: I felt that way about all of them.

You’ve got to be honest and trustworthy to teach and navigate young people. I asked, “Does anyone here want to be dismissed? Or labeled ‘crazy’?” Some acted like that’s fine. And that’s fine. “Anybody want others thinking you aren’t in charge of yourself?” Nobody nodded in the affirmative. “Then how about we don’t lay that meanness

The Opiate, Spring Vol. 41

down on others while you’re in here? Lots of words we won’t use in this class. At year’s end, we’ll revisit this discussion, hear your thoughts on it all.” There’s fair control inside my classroom.

I shared my approaches with my student teacher, trying to load him up with non-book skills he’d need in the future. He only listened out of politeness; college indoctrinated him in the newest measures and methodologies. I represented old school crossing guard thinking. He wore the fresh-faced look of a twenty-year-old acolyte, speaking in the tongues of rubrics. I shook my graying head, told him, “Try saying good morning to each and every kid. Learn their interests. Talk about the madness of their worlds. Be even-handed, non-judgmental. With the texts you pick, always share good stuff—to hell with homogenized safe stuff. Deliver, with everything you’ve got—don’t be scared.”

“Junebee freely declared that she visualized herself in the role of military sniper. My first-day-of-school icebreaker with sophomore English is to listen—to their fantasies and pipe dreams, to openly discover what brilliant thing they might want to do with their young lives. Junebee—with her bouncy brown hair and shiny braces—smiled broadly, saying she wanted to ‘plunk holes in the enemy.’”

My student teacher didn’t like the sound of parents potentially coming for his head over something that might be construed as objectionable. He experienced the banning of a couple of books back when he was in high school—he admitted that, since everything’s on the internet, fighting certain kinds of people wasn’t the most important battle to take on.

I brought in powdered milk and a gallon of whole chocolate milk, along with two glasses, and set them down in front of him. I

Hard Lessons - Scott T. Hutchison

added dry powder and water to one glass, brown delicious density to the other. I feel people have a right—I said, “Your choice.”

When Junebee, as a senior, began stalking the halls and dropping targets in pools of blood on the school colors-painted linoleum, chance found me coming out of the restroom, just as everything broke. I was still wiping my hands with a paper towel—my faulty old hearing failing to fully process the booming noises. Then the school’s defenses kicked in: alarms, an automated announcement that warned, “Intruder in the building. There has been a report of an intruder in the building.” The assistant principal’s voice frantically cut off the recording: “Intruder in the English-Social Studies wing. Use your ALICE training. Go!”

As part of my student teacher’s introductory experience, I’d left him alone in the testy clutches of my creative writing seniors, flying solo while trying out his worksheets. The announcement catapulted the school’s kids and teachers into action. I was too slow to make it into anybody’s lockdown room: teachers had turned keys, closed shades, barricaded and hunkered down silently behind desks—a standard part of education prep these days. I was flooded with thoughts—what’s happening with my kids? Probably deep in prayer and text messaging and making Divine deal promises if chosen and blessed with escape. All I knew: I wasn’t there for them. I said to hell with covering and hustled toward my students.

Junebee stormed around a hallway corner, dressed in camo and face paint, heavy ammo strapped across her chest. Junebee held some kind of long gun with a scope, drifting it back and forth in sweeping, rhythmic, calculated arcs. Pulling up short, I did all I could do: backed up against the thin metal of purple and gold lockers. Junebee sidled toward me, leaving red footprints behind her on the brightly waxed floors. She stopped, looked me dead in the eye and winked. Then Junebee marched off to carnage and oblivion.

I dimly stumbled on, found my classroom and whispered, “Clear, open the door.”

One of my bravest girls—she’d grabbed keys off my desk and locked it—cracked the door open, and I slipped inside. They rushed me. I opened my arms, hugging each of my small, trembling students as they plunged into me.

My student teacher had pulled himself tightly into a corner— the kids jumbled and cried, telling me how they handled the securing of the room. I thought about the Junebee of two years ago, the Junebee

The Opiate, Winter Vol. 41

two minutes ago, saw her needing support, saw a cringing boy needing my veteran help.

I placed a hand on his shaking shoulder, silently transmitting the teaching basic stirring up in my chest in that moment: Remember, every kid wants to be liked, every kid wants to be respected. Every. Single. Kid.

We all spun our heads toward the pounding footsteps surging in our direction from out in the hall. My student teacher scrabbled in his backpack. He ripped at the zippers and pulled out some kind of handgun. The kids screamed as he began firing at the door.

I reacted, went old school. My teaching job was done. His would never begin.

Girls’ Night Out

Debbie Miszak

Wehad to boldly go to a club we’d never gone to before last Friday because Melanie didn’t want to run into anyone who knew her ex-boyfriend. Neither of us was supposed to mention Paul. Forgetting him was the Prime Directive.

For someone so concerned about how often the actors on the set of Star Trek: The Next Generation adjusted their uniforms and how distracting it could be to viewers, I couldn’t believe that she chose to wear the ill-fitting black tube top that she got for five dollars from Forever 21. She had to adjust it every five minutes. It started in the Uber on the way there. She kept grabbing the sides of it and hiking it up in a way reminiscent of someone mouth-breathing or picking their nose.

Melanie could get away with being a little vulgar and with being a Trekker (she told me I couldn’t call her a Trekkie—it’s derogatory) because she was Deanna Troi-level beautiful. She wore a Bajoran earring every day during our senior year of high school and still ended up on Prom Court. The fact that she spoke fluent Klingon was a cute icebreaker with guys instead of a red flag that she might insist on naming a future child James Tiberius or Kathryn Annika.

I liked Star Trek too, but mostly because Melanie and I would never have become friends if I didn’t give it a shot. I didn’t really get

the original series, and I didn’t have the attention span to follow the arcs in Deep Space Nine and Voyager, but I liked The Next Generation and most of the movies. That was good enough for her.

If Melanie was Deanna Troi, I was more like Tasha Yar: plain and forgettable. I said this to Melanie once and she disagreed, stating that no true fan could ever call Denise Crosby’s performance plain or forgettable. I didn’t say it, but we both knew that Denise Crosby asked to have her character killed off after the first season because she was sick of standing around on the bridge doing nothing.

“This place is supposed to be really cool,” she said, using the front-facing camera on her phone to help guide her as she slathered on a thick layer of pink, cotton candy-scented lip gloss.

“Yeah, I saw Kelly post about it on Instagram.”

“I did too. I asked her about it because I thought it was weird that she didn’t post any photos from inside. I guess they have a ‘no phones’ policy. They make you put them in one of those locked bags like when we saw that comedian last month.”

“Isn’t that kind of a safety hazard?”

Melanie shrugged. “It’ll be fine. It’s cool. It’s all about disconnecting from technology and living in the moment. What do you think people did before phones at bars?”

“They were kidnapped and murdered.”

“They don’t use phones on Star Trek,” she noted. “And before you say that’s because nobody could’ve anticipated phones when TOS was on, or even TNG, it’s true even now. If you turn on an episode of Picard, he never whips a smartphone out of his pocket.”

“Right, but don’t they always have their tricorders and communicators?”

“Tricorders and communicators don’t exist in real life.”

“But our phones are basically the same—”

“Don’t be lame. This is going to be fun!”

This was the resounding echo throughout the decade we’d been friends. When I didn’t want to toilet-paper Mrs. Mulligan’s house in ninth grade, even though she did always smell like a mix of the hardboiled eggs she brought for lunch and general disappointment, Melanie said I was lame, that it would be fun. The same thing happened when she insisted on sneaking flasks into our senior prom. Even now, she still didn’t know that mine was full of Sprite.

“I am lame,” I announced. I couldn’t look at her. “I’m incapable of having fun. You know this. Ryan knew it too. That’s why he’s in the fucking Bahamas with that new girl—who has the blonde hair extensions down to her ass that I told you about—even though we could

Girls’ Night Out - Debbie Miszak

never take a trip beyond Frankenmuth in the five years we dated. But, you know, they’ve been public for, like, a month so they deserve to go to an all-inclusive resort.”

Melanie snorted. “Would you even want to go to the Bahamas with Ryan?”

“God no. But that’s not the point. The point is that I don’t understand why she gets to go somewhere nice and I didn’t. Should I have been keeping one of those punch cards they give you for Blizzards at Dairy Queen every time I did something that earned a reward? Every time I made sure he got his homework done, remembered to call his mom, got him to act like a decent human being?”

“There’s something wrong with you, like psychologically.”

“I know.”

She laughed and elbowed me. “You just have to learn to use it to your advantage. Guys like crazy. It means you’ll be good in bed.”

Our silent, middle-aged Uber driver glanced at us in the rearview mirror. I grimaced. “That’s a stereotype.”

“It works for me.”

I felt the need to give her a reality check as I explained, “Guys don’t like you because you’re crazy. They just don’t notice because of everything else.”

She sighed and looked out the window. “Maybe you’re right. Men are so shallow. Do you think part of the problem with Paul was that he looked too much like Odo? Did I project too much of what I wanted him to be onto him? Should I have settled for someone who preferred Babylon 5 to DS9?”

“Don’t go down that road. We aren’t even supposed to say his name. The boyfriend formerly known as Paul doesn’t exist to us anymore, right?”

Melanie didn’t answer; she just continued to stare out the window. Part of me wanted to touch her—to place a hand over hers or even just nudge her shoulder—to comfort her, or to try and convey that even if I didn’t understand exactly what she was going through, I knew that it hurt. Instead, I just tried not to look at her for too long.

The driver slowed down in front of a windowless brick building that had been painted a dark purple. Dance music wafted onto the street as the bouncers let a gaggle of shrieking girls with matching bachelorette party sashes inside.

I didn’t think I looked terrible, but Melanie made a face when we got out of the car. It was the same face she made when I showed up to our first day of seventh grade in the white Skechers tennis shoes my parents bought instead of the matching Nikes she wanted us to have.

“You said you liked this when I bought it. I sent you a photo and you told me to buy it.”

“It’s just pinker in person, that’s all. Don’t be self-conscious, though.”

I pulled at the hem, feeling the faux silk fabric on my fingertips. I thought about how I should’ve worn something else. It was too bright, and it was too form-fitting, and if Melanie wore it, she would look great. But I wasn’t Melanie, and that was fine. I was fine. I’d been practicing positive affirmations and I said them in my head now: I am fun to be around! I have a healthy body that helps me do the things I want to do! My friends and family are better off because I’m in their lives!

“It’s more of a fuchsia,” Melanie decided.

I didn’t make eye contact with the bouncers or the spindlefingered goth lady who snatched our phones and locked them away. My eyes met those of a wizened, graying French bulldog on a Persian rug surrounded by an entourage. It directed its snout toward a deck of tarot cards. I never was much of a dog person, but I couldn’t help wanting to scoop it up and carry it around with me. Melanie pulled me toward the bar.

There were two open seats separated by a guy in a baseball cap. He looked older than us, and he had bags under his eyes like he might have a real job. I knew Melanie would make us sit next to him. One of her complaints about Paul was that he was too “immature” (read: he was still working at a gas station even though he got a degree in chemistry, but he wasn’t applying to grad school because he didn’t have the grades). Melanie, for her part, wasn’t working anywhere. She lived at home. Her parents were both physicians. She was a dancer with a brand-new BFA, but she didn’t want to dance professionally. It would have compromised her love for it to do it as a job. Anyway, she tapped Baseball Cap’s shoulder, and he moved down a seat. She took the one next to him, and I sat next to her. A bartender put a menu in my hands without a word.

Melanie turned toward Baseball Cap and giggled over his menu. I couldn’t hear her too well over the music, but between songs, I heard her say something that ended with, “Body Positivity Barbie.”

They both laughed.

Maybe she wasn’t even talking about me, but it still pissed me off, and I pretended not to hear her when she leaned over and giggled that I wouldn’t look so miserable if I got laid once in a while, and that she would make it her mission to help ensure that happened tonight.

The menu was printed on iridescent paper that made it difficult to read under the low lights. The cocktails were boring and expensive.

Girls’ Night Out - Debbie Miszak

Melanie leaned over to Baseball Cap and pointed at a sixteendollar old fashioned.

“What are they using,” she asked, “Romulan whiskey?”

He didn’t know this joke was a test in disguise, so he chuckled politely.

“Sorry, I’ve been watching a lot of Star Trek recently.”

“I grabbed his face, and he seemed shocked. He had that look men get when they think you’re going to kiss them, with their eyes somehow both dreamy and surprised, poised to close as they anticipate the contact of lips on lips. For a minute, I thought about doing it, about what kind of person I could become if, instead of insisting that I needed him to see what I saw, I just gave in and made out with him.”

Baseball Cap nodded. “I’m more of a Battlestar Galactica guy.”

Melanie perked up. “You know, Michelle Forbes, who played Ro Laren on Next Generation, was on BSG, and Ronald D. Moore, who worked on Next Gen, DS9 and Voyager, also worked on it. Oh, and he worked on Caprica.”

“Caprica was shit.”

“I know!”

They turned toward each other, and over the music I couldn’t hear them continue. It was better that way, and I had time to look at the menu and decide what I would order to make myself more fun to be around. I wished there was a drink that would turn me into Melanie, or at least something that would make me more than her gawky accessory.

The craft shots were unique. The first couple were ones I’d seen at other places, the obnoxious Blow Job and Blue Balls shots, which

The Opiate, Spring Vol. 41

Melanie used to make for us in our dorm out of contraband alcohol gifted to her by Paul and her other admirers over the age of twentyone, but the remaining three were new:

• Cute in the Dark

Melon Liqueur, Black Vodka, Pineapple Juice, Sweet & Sour

• Angry Feminist Vodka, Midori, Amaretto, Cranberry Juice, a Drop of Menstrual Blood

• Self-Loathing Slammer Tequila, Tabasco

“I’m going to order us a couple of Blow Jobs,” Melanie announced, once she remembered I existed.

I shook my head. “I don’t like the whipped cream.”

Melanie bought two for each of us and insisted on showing off for Baseball Cap by licking the whipped cream out of the glass when she was finished with each one. White specks remained at the corner of her mouth, and I handed her a napkin from a dispenser near us. I didn’t get it, but Baseball Cap seemed to appreciate her efforts. The next round was on him, he said.

“No, thank—” Melanie cut me off before I could refuse. No stranger had ever offered to buy me a drink before, and I felt like I’d been plopped into the middle of a cheesy public service announcement.

“We’ll try the Cute in the Dark. Two each, please.” She put her hand on his knee.

The bartender, a woman covered in thousands of dollars’ worth of tattoos, took our empty shot glasses and made the next set. Baseball Cap smiled and raised one to both of us. “To the start of a great night.”

We clinked our glasses together. Liquor slid down the back of my throat, and then I swallowed the next one and tried not to gag because I let too much of it hit my tongue. Still, the buzz was instantaneous, and I didn’t even have to pay for it. When Melanie asked me to dance with her, I couldn’t say no.

One of the reasons I agreed to going dancing was because Melanie was a classically trained ballerina and, therefore, she looked ridiculous when she tried to be sexy. All those years with Mrs. Golubeva beating precise movement and calculated grace into her via strict instruction and Russian swear words made Melanie win awards, and made me look like an object of desire.

“I move like Data,” she whispered into my ear, and gestured toward the impeccable freedom of the other girls, who flaunted their

strappy crop tops and long, balayage hair. “No, that’s actually too generous to me. It’s more like B-4.”

“You’re great. Just don’t pay attention.”

“Someone’s paying attention to you.”

I turned and glanced at a guy in a puffer vest a couple feet away. His eyes darted when they met mine, and he pretended to resume a conversation with his friend, who was turned away from him and grinding against some girl in a pleather mini skirt’s ass.

“I think I’m going to go talk to him,” I told her.

“Really?”

“Yeah.”

“Go do it!”

Melanie pushed me toward him as the first sign of hesitation crossed my face, and I stumbled off the dance floor. This time, when I looked at him, he didn’t look away. I put on my best “coquette” smile and promised myself that if he tried to sell me on Bitcoin, self-help methods he found on the internet to increase productivity or Quentin Tarantino movies, I would run.

“Hey,” he said.

“Hey.”

The silence made me feel like a balloon had deflated in my lower intestine. I looked at the French bulldog again as a handler massaged its stomach.

“Do you come here often?”

“This is my first time.” I couldn’t stop looking at the dog, which now ate kibble out of an elevated gold dish. I wanted to venerate it, to hold it close to my chest like a scapular. “Do you know what’s up with the dog?”

“What?”

“The dog!”

“What dog?”

I grabbed his face, and he seemed shocked. He had that look men get when they think you’re going to kiss them, with their eyes somehow both dreamy and surprised, poised to close as they anticipate the contact of lips on lips. For a minute, I thought about doing it, about what kind of person I could become if, instead of insisting that I needed him to see what I saw, I just gave in and made out with him.

I turned his head and pointed.

“Oh, that’s weird.”

“You don’t want to know more about that?”

“It looks like a gimmick to me.”

“That’s so cynical.”

“What?”

“I said you’re being cynical!”

“I can barely hear you. Can we go somewhere else?”

“Lead the way.”

He grabbed me by the hand and pulled me to a standing table in a corner. My heartbeat quickened when I realized the dog was outside of my line of sight. There was no time to cope with this distress because Puffer Vest decided to stand close enough for me to feel his breath.

“You think I’m cynical?”

“Yeah,” I said. “That dog is the best thing I’ve ever seen. I don’t even really like dogs. A German Shepherd bit me when I was five, and I still have a scar on my thigh.”

“Can you show me?”

I giggled. “Maybe.”

“I’m surprised you don’t think you’re cynical. You looked annoyed with your friend at the bar, and you ditched her pretty fast just now.”

“She’s fine, believe me.” I gestured to the group of other girls she’d joined. “Anyway, you abandoned your friend too.”

“He’s fine.” His friend, Red Shirt, had his hand on the small of some girl’s back in Melanie’s new group. There was another silence, but instead of dejection, I wanted to shove my tongue down his throat, if not for pleasure, at least to make the conversation stop.

“So, tell me about you,” he said.

“I just graduated. I write grant applications for Habitat for Humanity.”

“Do you like it?”

“I don’t know. It’s only part-time. But a job’s a job, you know?”

“For sure. Is it something you could see yourself doing five years from now?”

“Maybe. But I would want it to be full-time. It’s for a good cause.”

“You’re never going to make a ton of money as a do-gooder.”

“You’d get along with my parents.”

“When do I get to meet them?”

I laughed and moved in closer to him. “What about you?”

“I teach fourth grade at a charter school. You don’t need a teaching certificate. They just want to see a diploma. They don’t even need your—”

I couldn’t hear him as the DJ put on a dance remix of Tracy Chapman’s “Fast Car,” which felt off and made me want to be sick. A migraine brewed in the right side of my skull.

“What?”

“Transcripts! They don’t need transcripts! They just let you teach.”

“That doesn’t seem like a great idea.”

“The kids have a way better chance of success with us than they would at some underfunded public school.”

“You don’t think scammy charter schools might be part of the

Girls’ Night Out - Debbie Miszak

funding problem?”

“You’re missing my point. We’re short-staffed! It’s a great gig. You need a full-time job. It’s super easy. You’d be great.”

“Thanks, I guess.”

Puffer Vest used his eyes to gesture toward Melanie. “You look like the smart one, like, out of all of the girls here.”

Puffer Vest, with his great sensitivity, intuited that he’d said something wrong. “Hey,” he said, grabbing my waist and pulling me closer. I froze. “It’s okay, it doesn’t make me any less interested. Once you hit your late thirties like me, you start to realize that looks don’t matter as much. It was honestly refreshing to meet a girl at a place like this who isn’t completely brainless...”

Refracted light from the disco ball illuminated his black hair, which had the trademark dullness of cheap, boxed hair dye. Melanie made eye contact with me.

Before I could excuse myself, she yanked my arm and announced, “Sorry, I need a tampon!”

I wanted to cry. Maybe it was the liquor but, suddenly, I felt like I was back in her pink-walled room, plastered with One Direction, Selena Gomez and, of course, Star Trek posters as she shoved her iPod Touch camera in my face.

“High School: The Next Frontier,” she said with a slight lisp brought on by her retainer. “These are the voyages of two super epic BFFs. Their four-year mission: to explore strange new classrooms, to seek out new boys and places to hang out. To boldly go where no girls have gone before.”

I pushed the phone out of my face and hid behind a pillow.

She continued, “Captain’s log. Star date: June 14th, 2013, because I don’t know how to tell what the star date should be.” I snickered in the background. “I’m here with my amazing best friend, and first officer, Number One. We have just graduated from the eighth grade. What strange creatures will we encounter at John F. Kennedy High? Who will we become? Will we truly be best friends forever?”

That was my Melanie, and here she was again, loving me, wanting me. She didn’t even drag me to the bathroom. We just went back up to the bar. I craved her audacity.

“What’s wrong?”

“It’s nothing. Don’t worry about it.”

“He looked like a douche.”

“I know.”

“Don’t be upset. You put yourself out there. That’s a good thing.”

I nodded. My face burned along with the acid in my stomach, and if I could get past my bruised ego, I wanted to sit at the bar and eat something smothered in grease and salt. Melanie flagged the bartender over. I ordered pretzel bites, but I needed another drink.

23.

The Opiate, Spring Vol. 41

Out of curiosity, I asked, “What’s up with the Angry Feminist and the menstrual blood?”

The bartender sighed. “Yeah...” She snapped a piece of gum in her mouth and saliva droplets hit my wrist. “I really wish they didn’t put that on the menu. They’re just asking for a health inspection. It’s just grenadine that we pour out of this vagina bottle.”

She lifted a heavy, disconcertingly accurate crystal decanter in the shape of the female reproductive system. Melanie snorted. The

“Melanie could get away with be- ing a little vulgar and with being a Trekker (she told me I couldn’t call her a Trekkie—it’s derogatory) because she was Deanna Troi-level beautiful... The fact that she spoke fluent Klingon was a cute icebreaker with guys instead of a red flag that she might insist on naming a future child James Tiberius or Kathryn Annika.”

bartender glared.

We knocked back the drinks as she put them down. Baseball Cap slid in next to Melanie. She hit him on the arm like he was an old friend and told him about Puffer Vest, and he reached across her breasts to pat my arm.

“I would totally sleep with you, if it makes you feel any better.”

“Thanks. It’s so generous of you to make that offer, especially as you’re actively trying to fuck my friend. You’re so kind.”

Melanie smacked me on the arm and laughed to play it off as a joke, but I turned away.

“What’s her problem?” Baseball Cap asked. “I was just being polite.”

Girls’ Night Out -

Debbie Miszak

Melanie made a show of how she didn’t want to look at me. “She doesn’t have an alcohol tolerance. Don’t take it personally, she just can’t hold her liquor. This one time, back in college, I caught her throwing up from her fully lofted bed onto our white rug. She was such a mess.”

Sometimes I hated her. Part of me wanted to correct the record and tell Baseball Cap that Melanie was actually the one who did that, and that it wasn’t just Melanie, but Melanie and Paul (who I knew she would get back together with, so Baseball Cap shouldn’t bother getting his hopes up), and they were vomiting from the lofted bed together, and they kept me up with that all night before my Econ 201 final, which I almost failed.

It didn’t matter. I stopped listening and bought myself the sixteen-dollar old fashioned and stared at the dog. In addition to its security team and ornate rug, it had a teal collar, what appeared to be a memory foam dog bed and a wooden toy crate emblazoned with its name: Snugglemuffin. It looked back at me with stoic blue eyes and wagged its short tail.

“Melanie, I’m going to steal the dog.”

“What? No! You’re so drunk.”

“So are you.”

“I don’t even feel it.”

She adjusted her top and tripped off the barstool. When we got to the velvet-roped line, a bouncer stopped us.

“I need to make sure you don’t have any food on you. Snugglemuffin is on a very restrictive diet due to her advanced age, and we don’t want to compromise her health or psychic abilities.”

I nodded. Nothing was more important to me than her safety. Melanie rolled her eyes. The man turned out the pockets of my jacket and checked my purse. My attention turned toward the current client, Puffer Vest. He sat on his knees in front of her with his eyes closed. With great majesty, she stood and revealed a stomach the size of another small dog. Her snout rooted at Puffer Vest’s lap and ear. She backed into her former spot, extended one of her front legs and, with an outstretched paw, selected a tarot card: The Tower.

Melanie hated astrology, crystals and pretty much every New Age practice that I, as a recovering Catholic and lackadaisical agnostic, governed my life by.

“I find this highly illogical,” she said, in her best Spock impression.

“Shut up.”

A single tear rolled down his cheek, and he hobbled back to the

The Opiate, Spring Vol. 41

bar with a sullen expression on his face. The next person, a woman in brown leather pants, struggled to kneel before Snugglemuffin, whose handlers told her that she could prostrate herself if that was more comfortable. Either were acceptable displays of devotion.

Despite my best efforts to focus on Snugglemuffin and her majesty, I stared at Puffer Vest. He was drinking a Self-Loathing Slammer. Part of me wanted to go laugh at him, part of me wanted him to apologize and tell me that I was the hottest girl here and another, more shameful part of me wanted to just pretend he hadn’t offended me at all so that we could get on with trying to have sex with each other.

“Ma’am,” one of Snugglemuffin’s handlers called out. Snuggemuffin, my savior, launched me out of this trance. “Please step forward.”

I kneeled on the smooth rug and presented my palms for her to sniff. When she approached my ear, just as I’d seen her do to Puffer Vest, her presence made me feel, for perhaps the first time, truly beloved. Aside from treats, I got the sense there was nothing she would ever really want from me. She walked in a circle around the mess of tarot cards, and one of the handlers made a nervous expression. Snugglemuffin presented me with a card in her teeth. The High Priestess.

I leaned back toward Melanie. “She wants me to take her.”

“Don’t. I’m serious, don’t do this.”

Before she could snatch me away, I patted my thighs with my hands, begging Snugglemuffin to come to me. “I just want to pet her,” I told the guards.

“One pet,” the biggest guard conceded. “That’s it.”

She jumped into my lap and licked my face.

“That’s enough.”

“You’re right, I’ve had enough. Snugglemuffin, we’re going.”

She nestled into my arms and fixed her eyes on mine. I could hear her serene, gravelly voice in my mind saying that I was made for her, that I was a beautiful, loveable person, that I was way out of Puffer Vest’s league and that I didn’t need male validation to be a complete human being. As the burly guards attempted to rip her away from me, she remained glued to my body. We understood each other—belonged to each other in some predetermined way.

“Melanie, we have to run.”

The floor began to rumble as though the entire building were growling. I dropped Snugglemuffin from the shock, and she stared at me. A circle of guards and guests formed around the three of us. Red

Girls’ Night Out - Debbie Miszak

Shirt, Puffer Vest’s buddy, lunged at me. His stubby fingers grabbed at my ankles as he tripped on the slick floor, covered in spilled drinks from all the commotion. I kicked him with my heel, unbothered by his lackluster attempts. There would be no redemption for people like him on Snugglemuffin’s watch.

“You’re going to get us all killed.”

I rolled my eyes. “Wrong. Melanie, isn’t it always true that, usually, only the Red Shirt dies?”

Though frightened by my newfound power, or rather, the power invested in me by Snugglemuffin, Melanie nodded.

“This is my dog now,” I declared, vaguely aware that my words were coming out slurred. “You can all fuck off.”

Then, a sharp pang in my chest. Snugglemuffin wiggled in my arms. She wanted to get down. I placed her on the floor gently, recognizing that a dog this ancient must have terrible hips.

“You don’t want to come with me?”

She took painstaking steps toward my legs and nuzzled me. It wasn’t that she didn’t want to, she told me.

“I understand.”

I wanted to wash her paws with my hair, to anoint her, to show her proof of my conversion. Melanie caught me as a I began to weep and buckled at the waist. She grabbed one side of me, and Baseball Cap grabbed the other. They waved off the bouncers and took me out of the building. Puffer Vest gave me a timid smile, and I returned the gesture. I leaned against the cool brick wall once we got outside and tried not to smell Melanie’s bile as she threw up on the sidewalk.

“Thanks for your help,” Melanie said to Baseball Cap. “We’ll see you around.”

“‘See me around’? That’s all I get? I don’t even get your number?”

Melanie had already stopped listening and, still feral from the alcohol, tore the locked phone bag open with her teeth.

“God,” he said, digging for his car keys. “You’re both psycho bitches, and I didn’t even want to have a threesome, by the way. I was just being nice.”

Melanie laughed in his face before he turned to walk away. I didn’t even feel like he was a real person. He could say whatever he wanted. It didn’t change the gift Snugglemuffin had given me.

“Hi, Imzadi,” Melanie purred into the phone, using the near-sacred Betazed term used by Riker and Troi to call each other “beloved.” That’s who Paul was to her, I could feel it in my guts that she meant it. “Can you pick us up? We’re at that new place, the one in Ferndale. Okay, we’ll see you in a few minutes.”

27.

We sat down on a bench and watched the traffic lights change. The bride-to-be from the bachelorette party group puked into a cityowned garbage can and her tiara fell in. Her friends took photos of her and laughed, and she flipped them off.

Melanie looked at me. “When I have my bachelorette party, you have to promise to help me protect my TOS uniform, because we’re all going to be in Trek cosplay, and that’s my cutest one, and I only have one, and it’s dry clean only.”

“Of course.”

She grabbed my cold, sweaty hands. “When Paul and I get married, I want you to be my maid of honor.”

She threw her arms around me and, even though she smelled terrible, I hugged her back.

In Paul’s backseat, my impending migraine reached fruition. I rested my head on the window’s glass with closed eyes and waited for them to finish French kissing. It took three full minutes, but I could be patient.

Melanie turned toward me and said, with vomit-stained teeth, “Let’s do this again next weekend.”

The Last of Them

Mike Lee

Thewind blew down from the rooftops of MacDougal Street, carrying an array of waste paper and candy wrappers that fell peacefully like snow toward the ground. The sound of rap could be heard, bouncing from building to building, through alleys and cross streets. Lyvere guessed it was from the park, where NYU students and tourists rubbed shoulders with dope dealers and crackheads—the typical New York scene. He snared a flyer that advertised half-price glasses as it floated in front of him, wadded it and threw it into the gutter.

He and Thompson turned to check for oncoming traffic and crossed the street, passing a group of skinheads, one of whom mumbled.

Lyvere began to reply, but Thompson shot him a don’t-getinvolved look. He retracted and jerked his head away, moaning and sitting between two BMWs parked illegally on the curb. They paused in front of a coffee house, but decided against going in.

“There’s a place I go to on the corner,” said Lyvere. “It’s never crowded in the daytime.”

Thompson shrugged as they passed a homeless man curled up in a fetal position beside a stoop. Lyvere noticed he might not be alive, but they always look that way when asleep.

The Opiate, Spring Vol. 41

Thompson was wearing the gray tweed sports coat his wife had bought him the summer before he started his university position.

He hated the jacket at first, yet meekly went along once he got used to it. He realized it gave him a classical air that set him apart from the other young instructors. Even so, for Thompson, words and deeds—not fashion—made the man.

They stopped at the coffee house Lyvere recommended.

As they entered, Lyvere turned to Thompson. “Nobody seems to like this place except a few failed novelists and me. Even on Saturday, this joint is empty.”

Thompson looked at his feet and saw cockroaches scurrying across the checkered tile floor. On the wall, he noticed a mural of the Borgia family. He guessed that this was a dump and a mob hangout— one of the two remaining in the West Village. The place reminded him of a French art film.

They sat in what passed for a booth, a row of scratched marble-topped tables covered with over a decade’s worth of grease and cigarette burn marks. Thompson figured this was the perfect location for Lyvere to hang out.

The place was probably the scuzziest dump in Greenwich Village. Leave it to Lyvere to like it.

Thompson brushed off a seat and sat down, hoping in the back of his mind that his tweed wouldn’t get dirty. Lyvere removed his own sports coat (in green plaid) and flung it over a chair at an empty table to his left. He opened his shirt and wearily loosened the knot of his tie. He pulled out a pack of Marlboros and dropped them on the table. His wife made him quit before they got married. He still stole a few puffs occasionally, especially on trips like these.

Lyvere adjusted his glasses and removed a cigarette, lighting it with one hand as he always did. Thompson remembered that he had taught him that trick. He grabbed another cigarette from the pack and lit it off of Lyvere’s.

He looked up at the waitress, who he found charming, and ordered an iced cappuccino. Lyvere ordered the same.

Thompson almost choked on the smoke. He wasn’t used to it; thank God Lyvere didn’t switch to something awful. Instead, he looked up and saw Lyvere’s ubiquitous evil grin, another reminder of days gone by.

He had come to New York to work on some research regarding CLR James for a class on Caribbean literature, which the department chair had allowed him to take. As par for the course, Thompson was versed in a lot of Caribbean writing; he even corresponded with Andrew Stalkley and other writers in the field.

Unfortunately, he didn’t have the chance to meet CLR, as he

The Last of Them - Mike Lee

was affectionately known, before he died last summer. Thompson recognized him as a source of criticism. However, he was fashionable and so Thompson took it upon himself to teach his work.

He was an influential writer...perhaps one of the giants of his literary genre. CLR was also a Trotskyist and a pan-Africanist before it was even known to his community. So Thompson brought CLR, at least in spirit, to Greensboro, North Carolina.

Thompson had an affinity for CLR. The old man was an idealist, a committed activist and a survivor until the day he died. He was an

“He hated being told what to do, and he hated being told the truth. Of course, he always had the mirror in the bathroom to remind him of what he was; he definitely didn’t need Thompson to tell him. Maybe he was taking it all too seriously, but he realized he was asking for it.”

excellent author who only wrote one novel, long out of print, a brilliant essayist whose work languished in obscure Trot journals and a historian whose work on the Haitian Revolution was considered the finest in the field. To Thompson, CLR was the classic invisible man.

He was someone that the kids (he hoped) would like. A good counterbalance to the politically correct crap his contemporaries were currently teaching. He aspired to teach and had much to bring to the table. He felt CLR knew what he wrote would convince somebody that there was something more than spineless politicians and demagogues going for the lowest common denominator, with one grandstanding sore after another tearing away another layer from his soul.

So Thompson put in his hours at NYU and the public library; he dug up some old Trotskyist comrades of CLR living in Brooklyn,

The Opiate, Spring Vol. 41

interviewed them and spent most of his free time playing solitaire, trying hard not to think. It was the only thing he could do now that his migraines had worsened.

Antonio wrote to him around last Christmas and told him that Mike Lyvere had gotten married and moved to New York, giving his address with the attendant’s request that he write him. After all, it had been a year since he last talked to him; six years before that, they had only been occasionally in touch. But, of course, they still counted each other as friends; it was just that Thompson was too busy. And Lyvere, well, was Lyvere, the man with the broken writing hand.

So he wrote him a month before he went north, telling him he was coming up for a while for this research and hoped they would get together. Lyvere managed a reply. Yeah, sure. I’ll be happy to see you.

After three weeks, Thompson arrived and found the time to drop in on his old friend.

He met Lyvere at the steps of the research library. The first thing that surprised Thompson was that Lyvere looked the same. He had the same haircut, cropped short on the sides, though touched with a little gray, parted on the side, the bangs hanging over his forehead like Adolf Hitler. His face had softened, yet the sharp edges of his cheekbones still gave Lyvere the look of a bad character actor. He still wore ugly vintage sports coats with matching ties.

As for Lyvere, he felt ambivalent about meeting Thompson again. He thought they went off in entirely different directions over the years. He marked it from their senior year in high school. Thompson graduated, while he, Lyvere, dropped out. Thompson got to go to Houston-Tillotson and Fisk while he dawdled along part-time in a community college and washed dishes. Thompson got the degree, did the graduate work and hustled for the teaching position, while Lyvere engaged with radical politics, played music and worked as a third-rate journalist. He, Lyvere, paid his dues while Thompson worked his ass off. He felt guilty and a little jealous and wondered why Thompson would like to be reminded of his wasted youth.

Thompson was firmly in position while Lyvere was terminally spinning his wheels. Of course, he didn’t believe Thompson wanted to be reminded of that fact; hell, he didn’t want to be reminded of it. But when he saw Thompson sitting on the steps, he comprehended that, while everything had changed, nothing had changed the obnoxious asshole he knew years ago.

Thompson was still as before, although looking a tad less. When they rode the subway down to the Village, it struck Lyvere as painfully apparent that he had changed a lot. Sure, he was still

The Last of Them - Mike Lee

cynical as hell. The years, especially the ones he had spent in New York, had warped this aspect of his personality. Lyvere’s sense of humor had taken a walk on the wild side. The one-liners and wisecracks had become ugly, and his delivery had sped up. He knew Thompson had difficulty keeping up as he related every scrap of information from his head. He wondered if it was the excitement of seeing Thompson or some other undetected element that was making his delivery embarrassingly annoying. It was the wrong time to be self-conscious. Nevertheless, he was glad to see him.

Lyvere was right, Thompson noticed. Lyvere was always a loudmouth, full of useless bravado.

After about an hour, Thompson realized that Lyvere was turning into a carbon copy of his father, Louie, the wandering loser.

Maybe there was something genetic, a bad seed, in the Lyvere gene pool. History repeats itself, he chuckled, just like Spengler said.

The cycle is complete. For what it was worth, at least Lyvere had a good job and was maybe writing. But, intriguingly, the old man was at the same point in their respective lives.

Lyvere intuited what Thompson knew, and understood.

The thought of his father was with him when he went to bed at night and returned like a ghost whenever he looked in the mirror while he shaved every day for the last twelve years. When he took a chance, he dropped out of high school. Lyvere viewed it as an expected aspect of his baggage, and accepted Louie’s spectral presence as part of the life he had chosen for himself.

He realized the only way Louie Lyvere would ever truly “depart” was when Mike succeeded at something. It could be a month, a year or ten years, but, eventually, Lyvere would exorcise his father’s spirit from his life. On the other hand, thinking about his father lent him comfort. It reminded Lyvere that, no matter how things turned out for him, in the end, he was still better than the old son of a bitch. But as he grew older, and the excuses of being precociously bright were wearing thin with age, Lyvere began to worry.

Every night and every morning brought new fears; lately, his worries were death. That was brought on by thoughts of Eddie O’Day and that August weekend before their senior year. Even though he wasn’t responsible, remembering O’Day only made Lyvere feel worse. But he knew.

He was around. As Thompson used to tell him, Friends don’t clean up after idiots. And O’Day was an idiot, as were Irene, Miriam and many others except the two survivors here.

Lyvere held up his glass. “Here’s to survival.”

Thompson smiled. “Très cool, hombre,” he replied, clinking his glass against Lyvere’s.

“I have this awful feeling. Do you want to tell me something important?” Lyvere asked with a mocking concern.

The Opiate, Spring Vol. 41

“Like what? You have long known that you’re an asshole.” Thompson took a hard drag from his cigarette, blowing smoke in Lyvere’s face.

Lyvere angrily flicked an ash into the ashtray. “This isn’t the time to get ugly. I know I have problems.”

Thompson stared at the floor. “Sure. And you’ve had the tools to deal with them. I don’t understand why you never bothered to face them. I look at you, and it’s the same old Lyvere—the guy with a snarl.

“...they still counted

each

other as friends; it was just that Thomp- son was too busy. And Lyvere, well, was Ly- vere, the man with the broken writing hand.”

You are too maudlin for your age and seem to look for failure around every corner. New York hasn’t changed you, Lyvere. You are the same underachieving slob you always were in Texas. You’re a goddamn floater—and a con man, to boot. And to make matters worse, you’ve become a conniving wimp. And no, you are not like Louie Lyvere. No, man, you’ve become a carbon copy of Irene.” Thompson spat her name out.

Lyvere winced. He wasn’t expecting this, but, yet again, he knew it would come from somewhere. He hated the Irene analogy. He pounded the table and grabbed his jacket.

“I’ll pay the check,” Thompson said abruptly.

Lyvere didn’t reply as he just as abruptly walked out the door.

The Last of Them - Mike Lee

Thompson figured he shouldn’t try to follow him. He sighed and stared up at the mural in front of him. “God, that’s ugly.”

Lyvere crossed Bleecker and walked toward Broadway. This is stupid, childish and par for the course, but who cares? He hated being told what to do, and he hated being told the truth. Of course, he always had the mirror in the bathroom to remind him of what he was; he definitely didn’t need Thompson to tell him. Maybe he was taking it all too seriously, but he realized he was asking for it. Lyvere only felt worse. He walked to the subway station and took the A train back to Brooklyn.

Meanwhile, Thompson had reached the breaking point.

Alienating friends was a hobby. He felt alone again, just like twelve years ago. He sat in the coffee house, ordered another iced cappuccino and thought of suicide.

Even when he felt he was right, the words came out wrong. He should have understood that Lyvere was haunted by demons like himself.

What was funny to Thompson was the revolting irony that the demons chasing them were the same. Thompson was glad to see that Lyvere, in his sudden anger, had left his cigarettes behind. He took another, lighting it off the butt end of the one he had just finished smoking. There was only so much that could be done to accommodate the promises to quit, but he resolved to do it tomorrow before flying back to Greensboro.

Emily

Rich McFarlin

Isaw her through the window of the coffee shop, right there on Main Street, acting like she hadn’t been gone for well over a year. She had disappeared out of my life, out of my world, without warning, without fanfare, without...well, without anything, really. And here she was, right back in almost the same spot where I had first laid eyes on her some years back. I stood there on Main Street, people walking past me, almost as if I wasn’t there at all. I could sense that a couple of them looked at me out of the corner of their eye, staring at the man who was standing on the sidewalk in the early evening, staring through the window of the local coffee shop. I didn’t care. She was there, right where I first saw her, right where I first fell in love with her; my Emily. I finally roused myself out of my stupor and shook my head. I was still trying to wrap my head around what had just transpired, after all this time. I watched Emily, my Emily, sip daintily (the way she did just about everything) from the white and pink bone china cup. Emily had always been delicate, a real lady. She sipped her coffee from the cup, setting it down softly on the china saucer. My heart ached with sudden, newly invigorated love, a love I thought that I would never know again. I debated with myself about what my next step should be;

Emily - Rich McFarlin

should I go inside and surprise her, or wait here on the sidewalk, maybe catch her coming out of the shop? I was just about to move, to gather my courage and go inside when Emily set down her cup and rose from her chair. I watched her gather her things: her purse and the book she had been reading. She stuck them into the crook of her arm and started towards the door. I moved quickly down the sidewalk, trying to meet her as she came out. What a surprise this would be!

What would she say? What would she do? Would she throw her arms around me, smother my face with kisses and tell me how much she missed me? And what would she say about her absence? Had she been in an accident; had she been hurt? Had she possibly been hospitalized? Was that the reason she’d been gone for so long? Had she been lying in a hospital bed, lost in a coma, dreaming of being in my arms again? My stomach fluttered with the possibilities of our renewed love. I could feel my throat going dry. I almost lost my breath in anticipation of our reunion.

I saw her opening the door to the coffee shop and stepping down the three concrete steps, moving onto the sidewalk. I called to her from the side of the building, “Emily! Em! Hey, wait up!”

She never stopped, but kept walking away from me, away from our life together. I ran up to her, keeping pace at her side. I reached out, grabbing her by her bare arm. She felt soft and feminine, if that was at all possible. When I touched her, she pulled her arm away, recoiling from me.

“Hey! What the fuck, man! Don’t touch me!” she screamed, stepping away from me, almost as if she didn’t know me.

“Emily? It’s me, Bill. Where have you been? I mean, it’s been almost a year and a half! Where have you been, my sweet girl?” I tried reaching back out to her, but she pulled away again.

“What is wrong with you? I have no idea who you are, Bill. And my name is not Emily. Please leave me alone or I will call the police.”

With that, my Emily turned and walked away, leaving me standing on the sidewalk, more questions than answers at this point.

I remained fixed in my position, not quite sure what to do now that Emily had shown that she clearly did not remember me, or our relationship. I decided to follow Emily from a safe distance. I would see where she went, then determine what my next course of action would be from there. I followed her down Main Street, past the center of town. She turned up Bradford and headed north, away from downtown. At least she didn’t get into a car; that would have presented a bit of a problem, at least for me. My car was parked off Main; it would have been impossible to get down to it if Emily had gotten into a car and driven away. I would have lost her again for sure. As it was, she moved

The Opiate, Spring Vol. 41

quickly, particularly for someone who had been, up until just a few moments ago, somewhat of a ghost. I followed along, far enough away so that I kept her in sight, but close enough so that I could see where she was going.

I watched as she approached one of the small houses off Bradford, opening the gate of the white picket fence and closing it behind her, taking the pathway up to the front door (which was also white and in need of painting). The house was a small two-story that had been around since the late 1950s, painted and renovated over and over until it was sold to someone who had converted it from a home for a family into a rental for transients or college students. Emily was neither of those things so what was she doing here? As she approached the door, a light flickered on, illuminating the porch, and someone opened the front door. It was a man, standing in the foyer, wearing jeans and a flannel-print shirt. He said something to Emily, who leaned in toward him, kissing him on the lips! He put his arm over her shoulder, guiding her inside, and closed the door behind them. The porch light went off, leaving me in the dark about so many things.

I could not believe what was happening to me; in fact, I honestly could not believe any of this. First, Emily disappears almost two years ago, vanishing into thin air without a trace, without warning, without even the benefit of an explanation. I mourned her loss for months, trying my best to deal with not only her absence from my life, but her total disappearance. It’s one thing to have someone end a relationship, it’s another thing entirely to have them simply vanish without a trace. And Emily had vanished. She had left behind her clothes, her books, her friends and, most importantly, me. I had tried to find her, tried to understand what had happened. I had contacted the police, and then hired a private investigator after the police had come up empty. All to no avail. She had simply vanished, until now. Now, after months of anguish and heartache, she had turned up again, back in her hometown, back in my world. But she seems to not know who I am, has no idea of what I mean to her, of what we meant to each other. And who was this mystery man that she had kissed so easily and comfortably on the lips? Who was the flannel shirt wearer who welcomed my Emily home, never thinking that she might belong to another? Did he have something to do with her vanishing those many months ago? Did he brainwash her, kidnap her, seduce her into leaving me? Or was he an innocent in this macabre play? I could not believe that Flannel Man was a simple passerby, caught up in the drama of Emily by chance; no, of course not. He was a linchpin, someone who had somehow fostered her disappearance, taking her from my arms, from my bed, from my heart. And for that, he must pay. And with his demise, I would take back my Emily. Once she had been released from

Emily - Rich McFarlin

the tether of her captor, she would awaken and her eyes would be opened. She would see that it was I who had set her free from her prison, had released her from the cage that she was clearly asleep in... or simply too afraid to try to escape from. Then, once she was free, she would love me again. Yes, he must pay.

I went home and slept peacefully, knowing that my Emily would soon be mine once again. I woke to the sounds of birds chirping happily and the day beginning joyfully. Today was a day that would, as the old expression goes, be the first day of the rest of my life— correction: of our lives together. I dressed and went down to the café where, just last evening, I had once again found her. I ordered a vanilla latte and a bagel in anticipation of a long day ahead helping Emily move back home, out of the clutches of Flannel Man. I felt refreshed and energized after a good night’s sleep, filled with pleasant dreams of our reunion. My malaise from the past year had dissipated like the dew in the face of the first rays of the morning sun, and I found myself unable to stop smiling at everybody.

I finished my breakfast, taking the last of my coffee with me, and set off towards the house where my Emily was held, obviously against either her will or against the sharpness of her memories, somehow made to forget our lives together, our love for each other. Never fear; she would remember me again. I walked up to the front door and knocked, deciding that a direct confrontation was best; I would get to the bottom of the mystery! The man who opened the door was tall, at least six feet. He was younger than me, with a face hidden by a sparse brown beard. His eyes were green and sparkling, full of life and vigor, and, dare I say it, a touch of malice and deception. He was wearing jeans and another flannel shirt, this pattern in tones of green, which highlighted his eyes. I smiled at him.

“Good morning. I was wondering if we might have a chat.”

“I’m sorry, but who are you?” He cocked his eyebrow at me inquisitively, as if he had no idea who I might be. The gesture infuriated me, but, remarkably, I held my temper in check.

“I’m Emily’s husband.” I said it as calmy as possible, seething inside at having to explain to this stranger who I might possibly be.

“Again, I’m sorry, but there’s no Emily here. I believe you have the wrong house and the wrong woman. Now, if you don’t mind, I have to get ready to get to work.” He started to close the door on me.

“If you don’t mind, it will only take a second to explain. We can clear all of this up in a heartbeat and I won’t bother you again. Please. I’m quite distraught. You see, my Emily disappeared almost two years ago. Then, after just about giving up hope, I saw her last evening at the café down on Main Street. You can certainly imagine my joy at seeing her again! If you’d just allow me a minute to explain, I’m sure we can

The Opiate, Spring Vol. 41

work this out. Then, I promise, I’ll be on my way, never to darken your domicile again.”

He stared at me for what felt like a day; lifetimes passed in that look, galaxies swirled and broke apart, re-forming as new ones in the expanse of that stare while he decided our fates. He finally opened the door wider and motioned for me to enter.

“It’s one thing to have someone end a relationship, it’s another thing entirely to have them simply vanish without a trace. And Emily had vanished. She had left behind her clothes, her books, her friends and, most importantly, me.”

As I followed him inside, he turned and asked, “Can I get you some coffee? I was just about to pour myself a cup.” He took two steps into the kitchen, which was located just off what I can only assume was the living room. There was a couch, beige and stuffed, along with a Queen Anne chair with some obsequious pattern along the side, both facing the television, which was placed on a piece of furniture that appeared to be mahogany, with drawers and cabinet doors. Cozy, but unremarkable. Emily had certainly stepped down in her tastes since her departure from my home, furnished in the finest antiques and most beautiful décor money could buy, all done by a very highly paid and highly skilled designer. No matter; soon we would be together again and Emily would be home where she belonged.

I must say, I went through that door with the purest intentions. I would ascertain how and why Emily had come to be with this man,

Emily - Rich McFarlin

rather than at home with me. I would ask the right questions, listen calmy and logically to the answers, then allow Emily to explain herself when she arrived home. I was sure that, given what we meant to each other, and given that she was obviously persuaded by some means not altogether proper to be here, that she would see where she needed to be: home with me. But he had something else to say about it; he always has something else to say about things. He is extremely insistent about what he decides, and he decides most things. Again, I did not want things to escalate beyond a simple conversation, but alas, it was not to be.

“Hit him.” I heard him say in my head, like nails on a chalkboard. I grimaced from the pain of him, pushing his way to the forefront.

“HIT HIM NOW!” he screamed at me, pushing me to act as if it were me, and not him, that was the actor in all things. Let me be clear; I had no real choice in the matter. His voice was, as ever, insistent and overwhelming.

Flannel Man, whoever he was in Emily’s life, was thoroughly surprised, dare I say, shocked, when the hammer struck, causing his knees to buckle, almost as if he were a giant oak, hewn from its rooted moorings, swaying in the forest, about to be felled. I myself was stunned at the blow, at its viciousness; he dropped the two cups of coffee, shattering them on the wooden floor and spraying hot coffee all over the room. His hands flew to his forehead and he groaned, staggering back and forth. I was almost as shocked and dismayed as Flannel Man was, but he was not shocked at all. In fact, he was gleeful, as he always was at moments like this. I just stood there, horrified at what he had done once again.

How had it come to this? How had I allowed him to push me around, direct me, steer me to do what he decided needed to be done? I was no longer an autonomous agent in my own destiny, but simply a boat, directed by its captain towards rougher waters, peril be damned. Almost as if on cue, the hammer rose and fell again, its waffled-patterned front hitting the tall man on the top of the head, blood spattering like drops of rain, mixing on the floor with the hot coffee. He lifted his head, looking me in the eyes, resigned now to his fate.

“Why are you doing th—” and he struck again, over and over. He flipped the drywall hammer around, using the hatchet side, striking Emily’s captor on the head and shoulders as he lay slumped before us on the ground.

“No more” I whispered, trying to get him to realize that the

man was done, gone, passed from this world to the next, laid at the gates of Hades holding his two coins for the ferryman. He ignored me, raining blow after blow upon the dead man, pieces of him falling off from the hatchet’s sharp wit.

“NO MORE!” I screamed at him, trying to assert some semblance of control again. Of course, it was far too late for that sort of thing. But, alas, stop he did, chuckling as he wiped the hatchet side of the drywall hammer on the dead man’s flannel shirt.

He had to be taught a lesson. You do not simply take what belongs to another man and expect to suffer no ill consequences. His logic, of course, was as always, sound. The man had stolen from us, had taken from us, and therefore had to pay. The price was almost as dear as the object stolen. But now, how to persuade Emily that this was for the best, that we had only her safety and her release from the hand of her captor in mind when the first blow was struck. No worries; why would she not be overjoyed at having her release secured? Why would she not be thrilled to be set free so that she might, once again, come home to those who adore and worship her? The answer, of course, was that she would. We set about the task of cleaning up the large mess with sudden happiness and glee; Emily would see what we had done and rejoice in our great love. He was right again, as he always was. Once we were done, we sat down to wait, silent in our brooding.

Emily came home just as the last rays of the fall sun disappeared from the horizon, casting the world into that ethereal time when night and day have kissed one another, neither one willing to relent to the other’s dominance. The brilliant colors of the sunset ran through the windows in the front of the small house, filtered by the white lace curtains that had been hung from metal rods, now speckled with the splashes of Emily’s captor. In the sun’s dying embers, the dark mahogany tone of his blood took on an orange hue, speaking of his demise to any who would hear. I was sitting in the kitchen area, drinking a cup of tea that I had brewed, Earl Grey, which was Emily’s favorite. She came through the front door and called for him.

“Noah. I’m home, honey!” She set her bag down on the Queen Anne chair just inside and took two steps before realizing that something was not quite right. When she saw me sitting at her kitchen table, she knew something was wrong. “What are you doing in my house? Where’s Noah? Who the fuck are you?” She had stopped advancing into the house and was now backing up. I stood up.

“Noah’s fine. He’s using the bathroom.” I looked towards the bedroom, implying that Noah was in there, in the bathroom. “He and I have had a lovely conversation. He’s quite a good guy, your Noah.” I stood and took a step around the table. Emily stayed where she was, but her flight mode was fully active. I had to assuage that instinct, and

Emily - Rich McFarlin

fast, or I would lose her. “Look, there’s been a terrible mistake on my part. I’m so sorry. As I mentioned to Noah, my Emily disappeared almost two years ago, just walked out the door to go grab coffee and was gone. I’ve been a mess ever since. You, again, as I explained to Noah, look startlingly like her in almost every way. I showed him several photos and he could, of course, like any rational being, understand how I made that mistake. We’ve worked things out and, now, as much as it pains me, I’ll be going. My apologies for any inconvenience I’ve caused you.”

I was almost on top of her now; her danger signals briefly abated thanks to my talk of the made-up conversation with “her Noah.” When I reached her, she was almost calm, but not quite, her eyes darting behind me, hoping that Noah would come out of the bathroom and corroborate my story. I grabbed her quickly, spun her around and, pulling the hypodermic needle from behind me, stuck it in her neck. She struggled for a brief second, then fell into my arms, where she belonged. I held her there for a moment, smelling her freshness, her cleanness; whatever Noah had been to her, he had obviously allowed her to take care of herself. I sat her down on the couch, propping her up against the pillows. She’d be out for about an hour, which was plenty of time.

When Emily began to come around, she found that I had changed her outfit, dressing her in something more representative of her station in life, rather than the ripped jeans and concert t-shirt that her Noah had dressed her in. She was now wearing a pair of Brunello Cucinellis in taupe with a black Oscar de la Renta top, which matched the black Jimmy Choo pumps absolutely beautifully. A trip to Helena’s and my Emily would be back in the world from which she was taken as if she had never been missing for the last two years. She shook her head, trying to remove the muzziness from her brain and get clear-headed. She rubbed her face with her hands, trying to get herself awake enough to comprehend what was happening to her. I watched from the chair, watched her struggle with consciousness, until she realized that her clothes were changed.

“What the fuck? What did you do to...did you change my clothes, you sick fuck? What did you do to me?” She stood up and almost fell, the Jimmy Choos wobbling under her ankles that had grown unaccustomed to being in four-inch heels.

“I did nothing. You were born to this and simply forgot who you were, Emily. You were mine; you were taken by this Noah person and held here for God only knows how long before I found you! And now,