The Trojan Horse of Design

VALUE-FRICTION,

IDENTITY, AND DECOLONIAL

PRACTICE IN SOUTH AFRICA

ACADEMIC ESSAY

ROUXAN POTGIETER

231013

24 OCTOBER 2025

IDENTITY, AND DECOLONIAL

ROUXAN POTGIETER

231013

24 OCTOBER 2025

As a gay, agnostic industrial design student from a (self-proclaimed) non-traditional (yet) Afrikaner background, my journey through South African creative education has been defined by a search for authentic expression within complex cultural expectations. This personal position, that of a misfit within multiple contexts, has fundamentally shaped the way I approach design. Over the past three years, my practice has evolved from simply satisfying brief requirements to creating projects that intentionally serve other misfits, and in doing so, I have found myself challenging the very systems meant to evaluate design.

This transformation is best represented by my project, BoardCity, a single-player educational game designed for children who, like I was, prefer solitary learning. To analyse this journey, I turn to two theoretical frameworks. Arjun Appadurai’s (2006) theory of the “politics of value” provides a lens to understand the friction my work generates. Appadurai (2006) argues that value emerges through specific social contexts rather than from objects themselves, stating that “the diversion of commodities from specified paths is always a sign of creativity or crisis, whether aesthetic or economic” (p. 418). Complementing this, Walter Mignolo and Rolando Vazquez’s (2013) concept of “decolonial aestheSis” offers a way to frame my practice as a form of critical intervention. They suggest that “aestheTics … colonised aestheSis” by imposing a universal standard of taste, and that decolonial practice involves a confrontation to “decolonise the regulation of sensing.”

My central argument is that my background has led me to create work that operates at the margins of institutional systems of value. While this creates friction, I argue that this friction is an indicator of the gaps between different value systems, a tension that reveals as much about the system’s limitations as it does about the complexities and potential blind spots of my own approach.

In simple terms, Appadurai argues that what we consider valuable is not innate to an object but is decided by the invisible rulebooks of different social groups. Appadurai’s work helps us see that design education, like any social field, is a system of value with its own rules for what constitutes good work. These systems are not neutral. Crucially, Appadurai notes that when objects defy these systems, interesting things happen. He writes, “The diversion of commodities from specified paths is always a sign of creativity or crisis, whether aesthetic or economic.” (2006, p. 417) and that “The diversion of commodities from their customary paths always carries a risky and morally ambiguous aura.” (2006, p. 418). This concept of “diversion” is key to understanding my experience with BoardCity; the project was diverted from the expected path of a typical student submission.

Furthermore, Appadurai explains the dissonance between creator and evaluator through a knowledge gap: “The production knowledge that is read into a commodity is quite different from the consumption knowledge that is read from the commodity ... these two readings will diverge proportionately as the social, spatial, and temporal distance between producers and consumers increases” (2006, pp. 419-420). The “production knowledge” embedded in my work (being its technical complexity and educational intent for solitary learners) was starkly different from the “consumption knowledge” applied by assessors working within a fixed rubric. This phenomenon is what I now understand as value-friction: a disconnect between production knowledge (expertise and concept) and consumption knowledge (the evaluative frameworks).

Mignolo and Vazquez build on this by focusing on power and perception. They suggest that alongside political and economic control, colonialism also imposed a hierarchy on our very senses, thus, dictating what is considered beautiful, valid, or worthy of being called art. Mignolo and Vazquez’s framework adds a geopolitical and ethical dimension to this

analysis. They differentiate between “aestheTics” (with a T) being the Eurocentric, normative philosophy of beauty, and “aestheSis” (with an S) being the broader, embodied capacity for sensing and creating meaning. Decolonial aestheSis, then, is “a confrontation with modern aestheTics ... to decolonize the regulation of sensing” (Mignolo & Vazquez, 2013). It is not about replacing one universal standard with another, but about opening space for plurality. They argue that “decolonial aestheSis is not just an indictment of the universal validity claim of modern/colonial aestheTics, but that it asserts itself as an option” precisely because it “does not seek to regulate a canon, but rather to allow for the recognition of the plurality of ways to relate to the world of the sensible that have been silenced” (Mignolo & Vazquez, 2013).

Together, these theories provide a powerful lens: Appadurai explains the mechanics of the value-friction I experienced, while Mignolo and Vazquez help me understand its decolonial significance within a South African context.

Mignolo and Vazquez’s concept of decolonial aestheSis has helped me understand my own position: I’m not rejecting South African identity, but rather exploring what it means to practice design here without being confined to predetermined aesthetic expectations. My design practice navigates complex questions about authenticity in post-apartheid South Africa. As someone with strong affinities for Western modernism, I’ve had to consciously consider what

it means to contribute authentically without feeling obligated to incorporate expected visual languages. Rather than seeing my aesthetic preferences as contradictory to my local context, I approach them as one legitimate strand in South Africa’s diverse “rainbow nation” tapestry. However, this stance is not without its tensions, and a critical self-reflection is necessary. My preference for Western modernism, while authentic to my formation, means my work sometimes remains within a hegemonic design tradition I claim to repurpose. I must constantly question if I’m truly delinking or simply replicating Eurocentric values in a new context. There is an inherent paradox in using a Western aesthetic to pursue a decolonial agenda. Furthermore, I risk romanticizing my outsider status. In reality, I operate from a position of significant social and educational privilege, and my critique could be seen as a performance of rebellion that doesn’t fundamentally threaten the system. This self-awareness is crucial to an honest reflection.

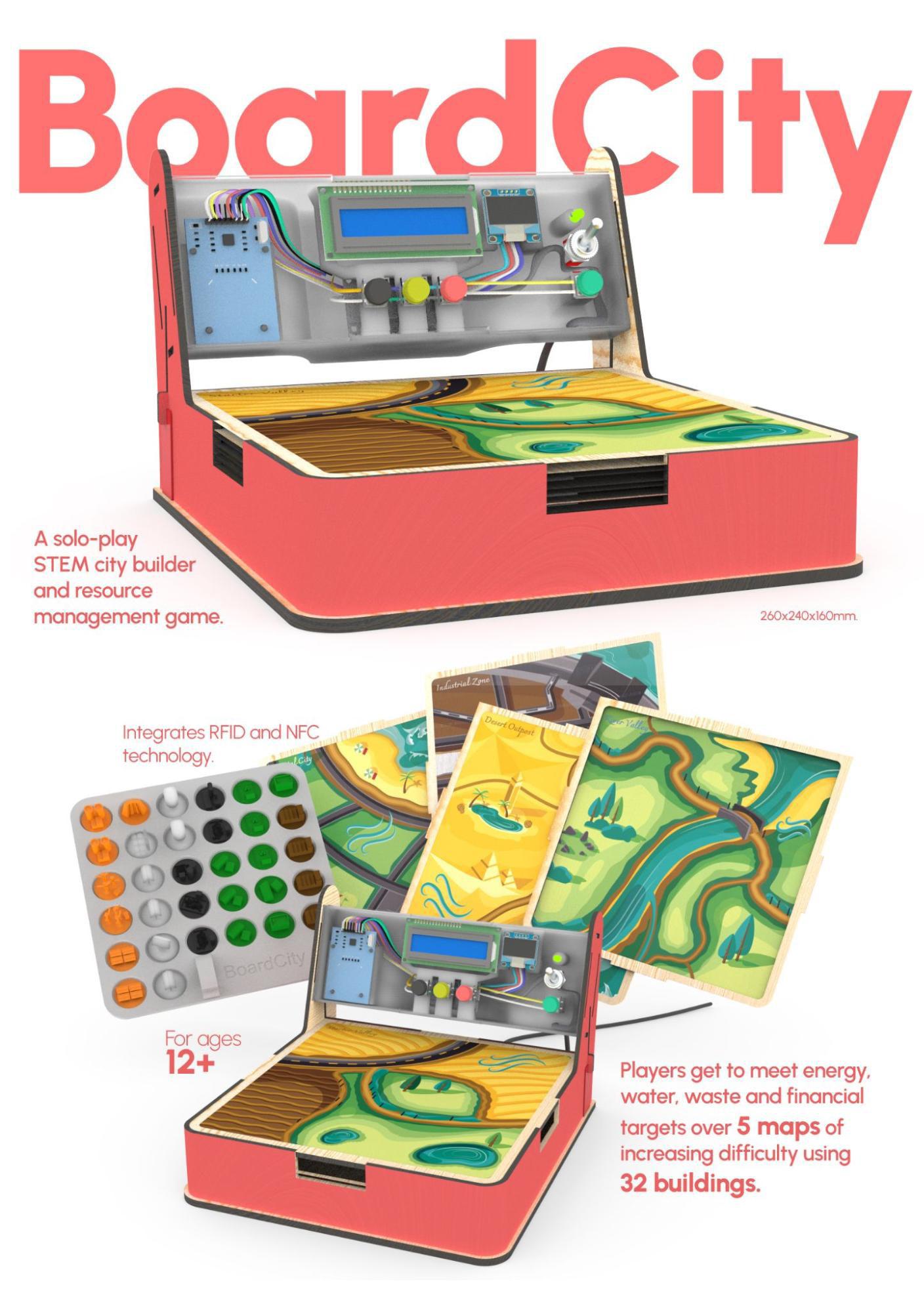

BoardCity (figure 1), an RFID-powered city management game, was designed explicitly for solitary-by-choice children, directly reflecting my own childhood experiences. Its success was viscerally confirmed during user testing when a child became deeply immersed, stating he would prefer it to his phone. This moment represented a powerful form of value to me and the child. That moment was what Mignolo and Vazquez might call a “decolonial healing”, encouraging a way of learning that is often marginalised.

Yet, institutional assessment focused largely on superficialities, such as the casing’s colour, while overlooking the project’s technical and educational innovation. Ironically, it still received high marks. This outcome may seem contradictory, but it actually aligns with Appadurai’s insight: the “production knowledge” I embedded diverged from the assessors’ “consumption

BoardCity Technical Poster

Note: Rouxan Potgieter, 2025.

knowledge”, creating value-friction. The project functioned as a “diversion” from the expected path, carrying the “risky and morally ambiguous aura” Appadurai describes (2006, p. 418). The high grade, then, becomes a kind of “Trojan horse of change” (Appadurai, 2006, p. 418). It is proof that the work succeeded not by conforming, but by subtly infiltrating and bending the system of value from within.

This infiltration became most evident when I discovered that BoardCity, and other projects like my first-year UX work and my sheet-metal project, Lumin, were being used as exemplary works for junior students. This created stark dissonance: the institution publicly upheld its consumption knowledge through direct feedback, yet privately validated my production knowledge by leveraging it as a pedagogical standard. Through Appadurai’s framework, I now understand that the system can desire the innovative output of a diverted commodity while remaining unable to formally endorse the disruptive process that created it. The “Trojan horse” had just passed through the gates, and it was now actively shaping the institution’s own teaching arsenal, even as the system maintained its official narrative.

This success, however, forces me to confront a deeper question about my methodology. My strong-willed approach, encapsulated by the phrase “if I like it blue, I’ll make it blue”, could be a limitation. In prioritising my own aesthetic judgment, do I risk becoming a solitary author rather than a collaborative designer truly serving user needs? Similarly, my motivation to excel “out of spite” can be a powerful motivator, but it may also lead to designs that are more about proving a point to critics than solving a problem with empathy. This friction, therefore, is not solely the institution’s failure; it also reveals my own evolving understanding of what it means to be a critical designer.

Reflecting on this journey, I’ve come to see value-friction not as an obstacle, but as a defining feature of my design practice. Appadurai’s idea that diversion acts as a “Trojan horse of change” (2006, p. 418) reframes my work as quiet but deliberate resistance. My work thus pushes against inherited norms without stepping entirely outside them. Mignolo and Vazquez add ethical clarity: my practice becomes part of a broader effort to “decolonize the regulation of sensing” (2013), making space for creative expressions often left unrecognised in dominant regimes. I don’t position myself as a rebel outside the system, but as someone fluent in its language. I leverage that fluency to highlight its blind spots.

This experience also reminds me that systems are remarkably adaptive. As I have seen, institutions can absorb disruptive ideas without fully acknowledging their origins. Such a manoeuvre protects their sense of order even as it proves that change has already entered their gates. Recognising this helps me frame my own position with humility: as both participant and gentle agitator in a process of slow, internal transformation.

Moving forward, I am committed to continuing this approach while remaining more consciously reflective about my privileges and blind spots. I want to design with technical ambition for specific communities while staying open to learning from the friction these choices create. This balance allows me to contribute meaningfully to South African design while staying true to my authentic voice and values, even as I continue questioning what authenticity means in our complex cultural landscape.

Appadurai, A. (2006). Commodities and the politics of value. In B. Ashcroft, G. Griffiths, & H. Tiffin (Eds.), The post-colonial studies reader (2nd ed., pp. 418-420). Routledge.

Mignolo, W., & Vazquez, R. (2013, July 15). Decolonial aestheSis: Colonial wounds/Decolonial healings. Social Text Online. https://socialtextjournal.org/periscope_article/decolonialaesthesis-colonial-woundsdecolonial-healings/

© 2026 The Open Window