List of Figures

INTRODUCTION

In the digital age, platforms like X (formerly known as Twitter) have emerged as dynamic arenas where traditional gender norms are both reinforced and contested. These online spaces offer users opportunities to engage in discourse through satire, irony, and direct critique, reflecting a broader cultural shift toward questioning patriarchal structures. Among the voices contributing to this discourse is @Ketso28, whose posts explore themes of masculinity, marriage, and power, often in provocative and ambiguous ways.

This essay applies a postmodern theoretical framework to explore how gender is performed and contested on X. Eckert and McConnell-Ginet (2013) argue that gender is not a fixed identity but a process socially constructed and sustained through everyday symbolic practices. Butler (1990) furthers this by suggesting gender is “an identity tenuously constituted in time, instituted in an exterior space through a stylized repetition of acts” (p. 140). These ideas align with Derrida’s theory of deconstruction, which proposes that meaning is always deferred and never fixed.

Shruti Jain (2020) extends this into the digital realm, noting that platforms like Twitter foster feminist resistance through humour and micro-activism. Rob Cover (2019) highlights how online platforms function not merely as mirrors of the self, but as performative stages where identity is curated and made visible. As this essay demonstrates, tweets by users like @Ketso28 perform gender in ways that both reinforce and subvert dominant ideologies, revealing the potential of social media to destabilise normative scripts and stage alternative expressions of gendered identity.

THEORETICAL OVERVIEW: REIMAGINING GENDER

Postmodern and poststructuralist theory challenge essentialist understandings of gender and identity. Central to this critique is the idea that gender is not biological but constructed through discourse, performance, and social norms. Butler (1990) formalises this as gender performativity, describing it as “a stylized repetition of acts” (p. 140), where individuals enact social scripts perceived as natural. These performances are constrained yet potentially disruptive.

Rob Cover (2019) shifts this discussion into the digital sphere. He explains that social media platforms like X are not merely reflective but are active stages for identity performance. As Cover states, “online articulations should not be seen as a representation... but a site at which we perform” (p. 7). Unlike transient offline performances, online ones leave behind searchable archives, challenging the idea of stable identity.

Digital performances, shaped by audience feedback, reveal identity as incoherent and socially constructed. Cover notes that digital environments both amplify normative expectations and provide conditions for resistance, offering playful, fluid, and contradictory explorations of gender and sexuality. Jain (2020) supports this, calling platforms like X “spaces of feminist resistance” where humour and storytelling become political acts. Hashtags, memes, and tweets thus serve as vehicles for both reinforcing and critiquing gender norms. Together, these perspectives frame X as a performative, contested space where identity is fluid, public, and multiply enacted.

BACKGROUND AND CULTURAL CONTEXT

The theoretical insights discussed above become particularly noticeable when situated within the South African cultural context, where traditional gender roles remain deeply embedded in social practices. In many South African traditional weddings, the handing-over ceremony involves uncles and the rakgadi (aunt from the father’s side), who instruct the bride on how to be a good wife and treat her husband well. This practice, known as ba laya ngwana , is deeply rooted in the cultural norms of the Bantu and Nguni people (Wedbuddy, 2023; South Africa Online, n.d.). These instructions emphasise the wife’s role in maintaining the household and supporting her husband, thereby reinforcing patriarchal gender roles (South Africa Online, n.d.).

Ketso’s tweets challenge these norms, highlighting the tension between modern digital discourse and traditional practices (Gender Study, 2024). By engaging with themes of masculinity, marriage, and power in provocative and often ironic ways, these digital performances expose the contradictions between inherited cultural expectations and contemporary expressions of gender identity. This juxtaposition underscores how platforms like X can serve as sites of both cultural continuity and resistance, where traditional scripts are not only performed but also questioned and reimagined.

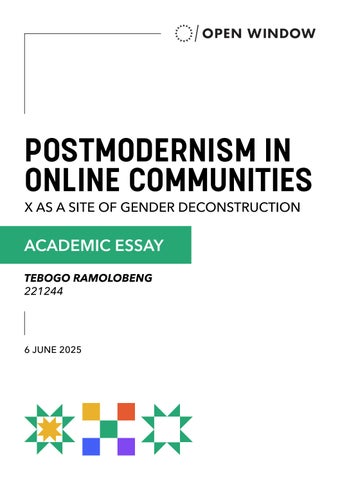

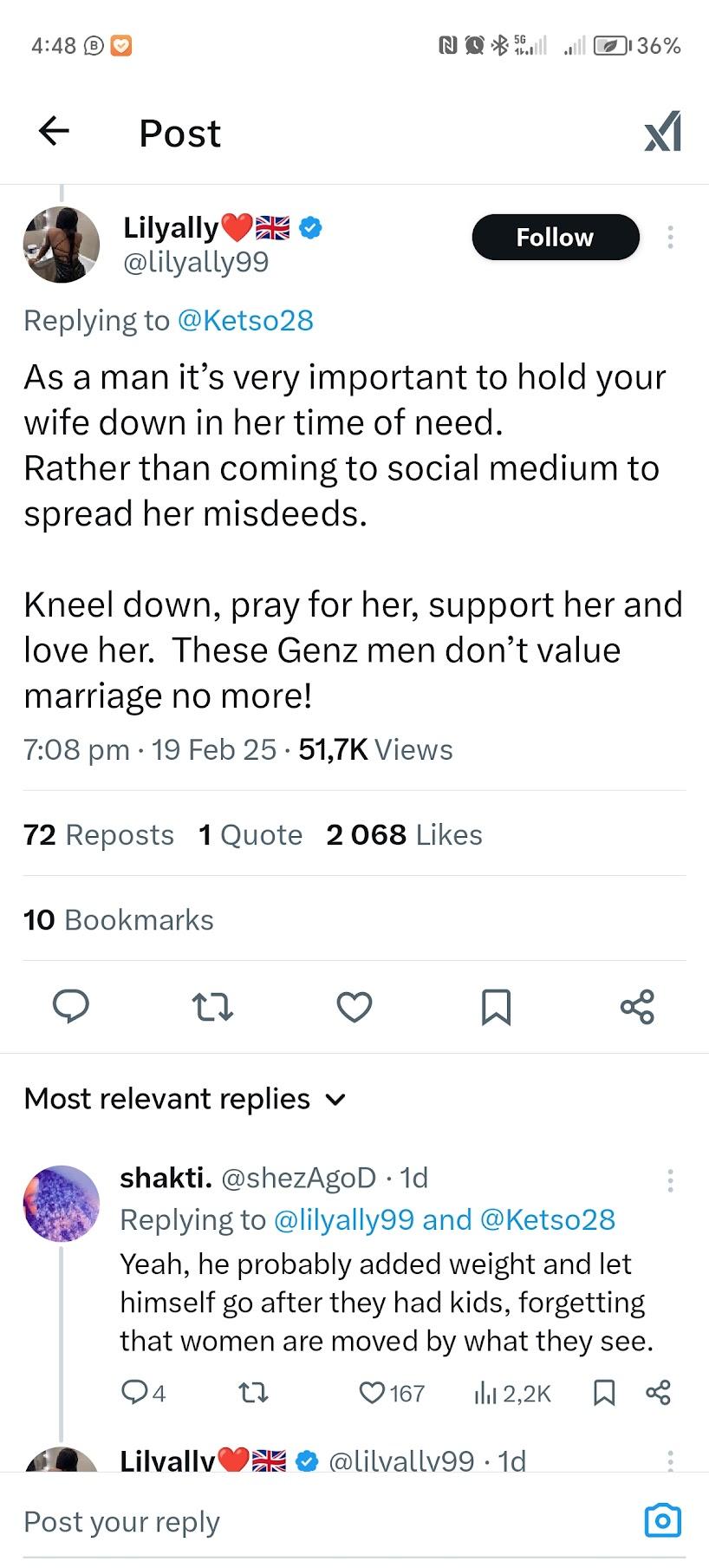

Note: Twitter post by user @Ketso28.

Screenshot of tweet about polygamy by @Ketso28.

02 03

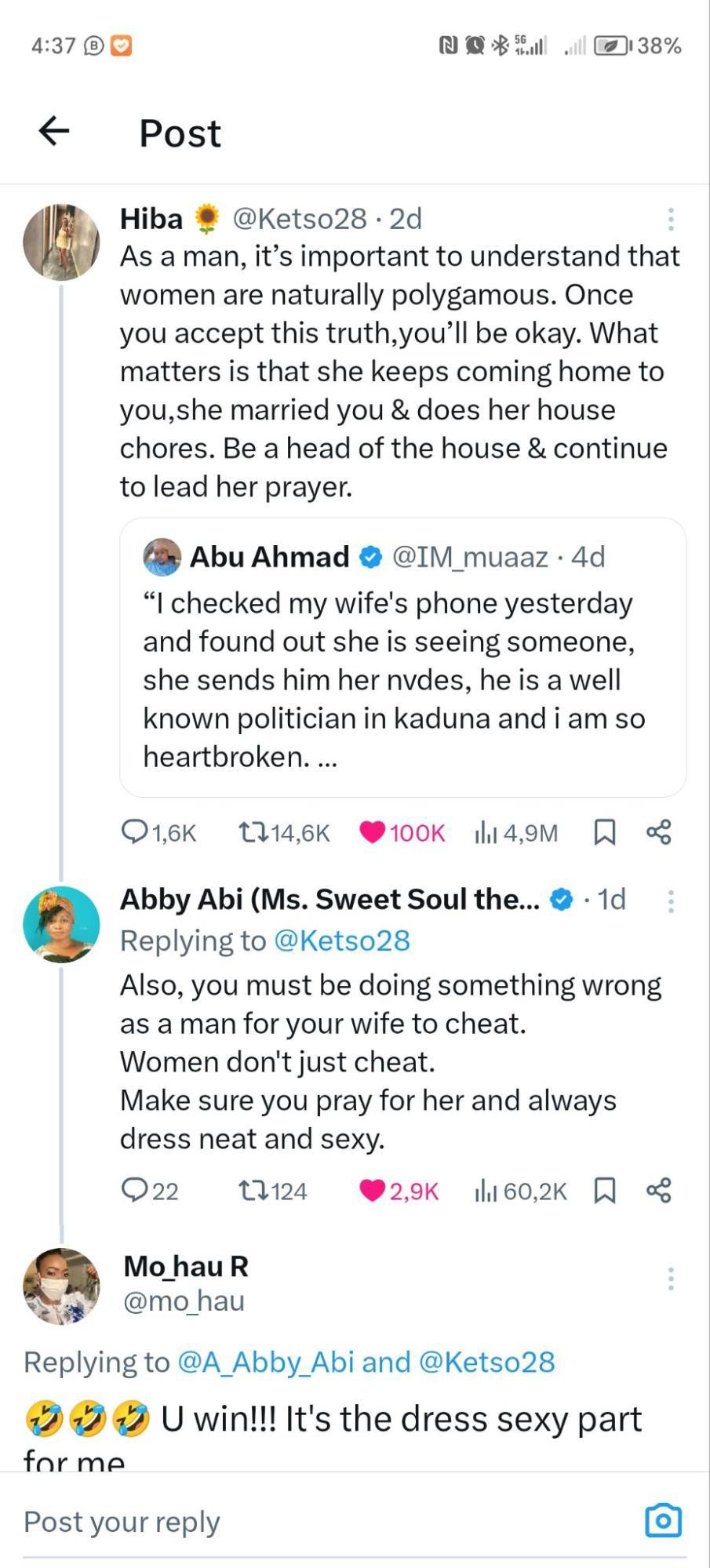

Screenshot of tweet about women’s privacy.

Note: Twitter post by user @Ketso28.

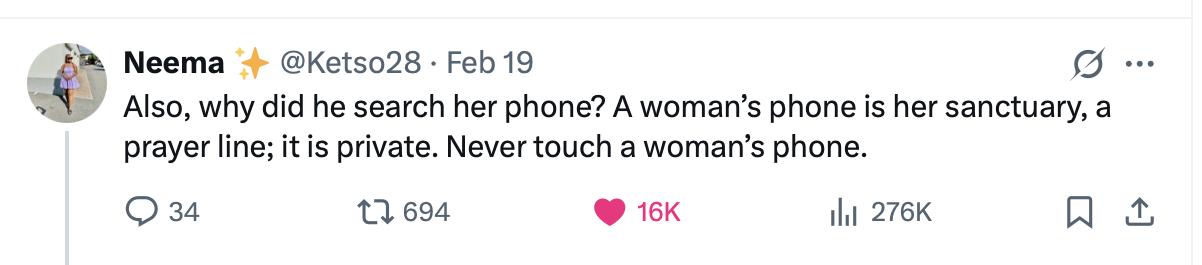

Screenshot of tweet on male leadership in marriage.

Note: Twitter post by user @Ketso28.

ANALYSIS: PERFORMATIVE GENDER IN KETSO’S TWEETS

In one tweet, Ketso writes, “As a man, it’s important to understand that women are naturally polygamous. Once you accept this truth, you’ll be okay.” This statement exemplifies the performative nature of gender by framing polygamy as an inherent trait of women. As shown in Figure 1, the tweet appears to reinforce traditional gender norms, yet it simultaneously exposes their arbitrary and socially constructed nature. From a postmodern perspective, this essentialist claim can be deconstructed as a cultural narrative rather than a biological truth (Cover, 2019, pp. 97–99).

Another tweet, illustrated in Figure 2, highlights gendered notions of privacy and control. Ketso suggests that women’s privacy is sacred and inviolable, yet the framing implies a need for male oversight. This reflects patriarchal discourses that position women’s autonomy as conditional and subject to male interpretation. The tweet reveals how digital performances can simultaneously idealise and regulate femininity, exposing the contradictions within dominant gender narratives (Cover, 2019, pp. 100–102).

In Figure 3, @Ketso addresses male authority and submission in marriage, stating: “It’s also very important for a husband to know his place & do his job properly. A wife will rarely go out to cheat if you’re giving her money, being a good head & leading her into submission.” This tweet speaks to performative masculinity that relies on maintaining perceived authority. It reinforces the idea that male leadership and financial provision are essential to marital fidelity, reflecting traditional gender roles. However, by framing submission as a consequence of

Note: Twitter post by user @Ketso28.

Screenshot of tweet about husbands standing by their wives.

05 06

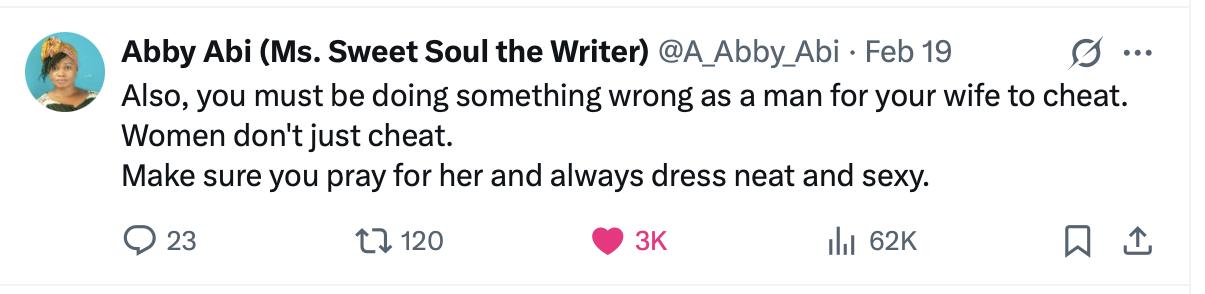

Screenshot of tweet implying infidelity tied to male performance.

Note: Twitter post by user @Ketso28.

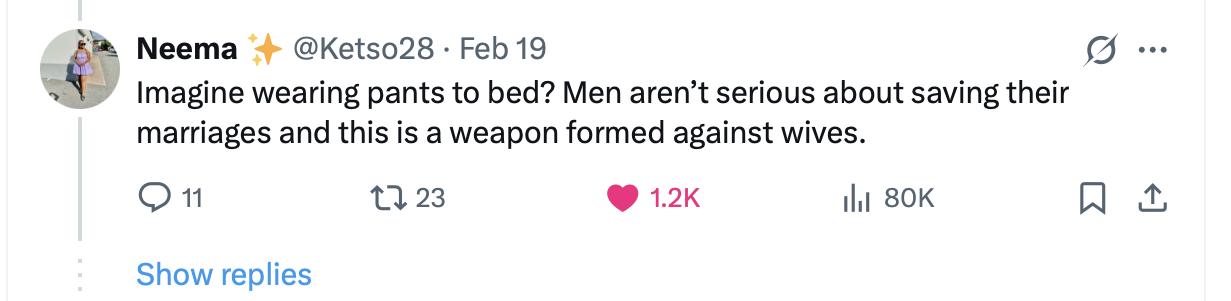

Screenshot of tweet about husbands wearing pants to bed.

Note: Twitter post by user @Ketso28.

male performance, the tweet also exposes the fragility and constructed nature of these roles (Cover, 2019, pp. 103–105).

In Figure 4, Ketso tweets, “It’s very important for a husband to stand by his wife in such difficult times.” This statement underscores the role of the husband as a source of spiritual guidance and emotional support within the marital relationship. While the sentiment appears compassionate, it simultaneously reinforces traditional gender roles by positioning the husband as the moral and spiritual leader. Within a religious context, this framing aligns with patriarchal values that assign authority and responsibility to men, particularly in times of crisis. As Cover (2019, pp. 106–108) notes, such digital performances often reproduce longstanding cultural scripts, even as they are shared in contemporary, participatory spaces like X.

In Figure 5, Abby Abi’s critique of men’s accountability for their wives’ actions reflects a victimblaming narrative often directed at men within traditional relationship frameworks. The tweet implies that a husband’s failure to fulfil his marital duties—such as providing leadership or financial support—justifies a wife’s infidelity. This framing minimises women’s agency and reinforces gender stereotypes by suggesting that male inadequacy is the root cause of female transgression. As Cover (2019, pp. 109–111) argues, such digital expressions reveal how patriarchal discourses can be internalised and reproduced, even when they appear to critique male behaviour.

Figure 6 presents another example of performative masculinity, with the tweet: “Imagine wearing pants to bed? Men aren’t serious about saving their marriages and this is a weapon formed against wives.” This statement ties men’s physical appearance and domestic behaviour to marital success, implying that even seemingly trivial choices carry symbolic weight. The tweet reflects societal expectations that men must perform masculinity in specific, visible ways to maintain their roles as desirable and responsible partners. As Cover (2019, pp. 112–

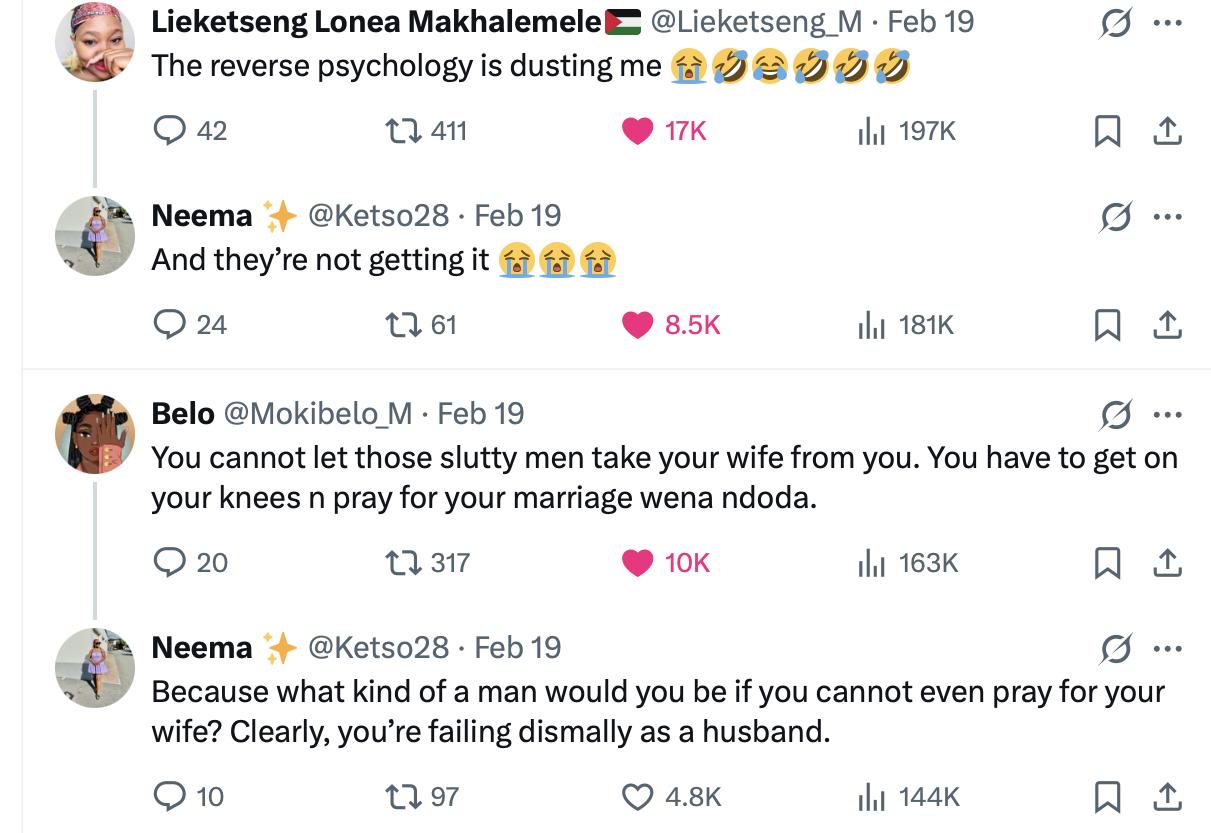

Screenshot of tweet about slutty men and marital threats.

Note: Twitter post by user @Ketso28.

114) notes, such performances are shaped by cultural scripts that define masculinity through control, presentation, and relational success.

Belo’s statement “You cannot let those slutty men take your wife from you,” speaks about sexual double standards enforced within patriarchal societies where women’s sexual behaviour is heavily policed (Cover, 2019, pp. 115-117). This tweet highlights societal expectations requiring men to control their wives’ sexuality to prevent infidelity, reinforcing power dynamics based on gender.

Responses from others towards Lieketseng Lonea Makhalemele’s views, such as “The reverse psychology is dusting me…,” show public reactions demonstrating how views are received and contested (Cover, 2019, pp. 118-120). These responses illustrate tensions between traditional and emerging counter-narratives within digital discourses.

These tweets collectively reveal the complex landscape surrounding digital gender discourse, illustrating how patriarchal narratives, when exposed to scrutiny, reveal their internal contradictions and performative nature (Cover, 2019, pp. 121-123). By engaging with these tweets, users participate in deconstructing, challenging, and redefining societal expectations regarding gender.

CONCLUSION

This essay has demonstrated how X functions not merely as a communication platform, but as a dynamic site of ideological performance where gender identities are actively constructed, contested, and reimagined. Drawing on postmodern and poststructuralist theories particularly the work of Butler, Derrida and Cover—it has shown that gender is not a fixed essence but a performative and socially mediated process. Through the lens of digital identity theory, we have seen how platforms like X amplify the visibility and complexity of these performances, enabling users to both reinforce and subvert dominant gender norms.

The case study of @Ketso28’s tweets illustrates how digital discourse can simultaneously uphold and challenge patriarchal ideologies. By engaging with themes such as masculinity, marital authority and sexual double standards, these tweets reveal the contradictions inherent in traditional gender scripts. Moreover, the public responses to these tweets highlight the participatory nature of digital identity construction, where users collectively negotiate meaning and resist normative expectations.

Ultimately, this analysis affirms that digital platforms are not neutral spaces but are shaped by power, visibility and cultural discourse. As such, they offer fertile ground for the deconstruction and reconfiguration of gender. In an era where identity is increasingly mediated through digital interaction, platforms like X will continue to play a critical role in shaping how gender is understood, performed and transformed.

REFERENCES

Butler, J. (1990). Gender trouble: Feminism and the subversion of identity. Routledge.

Cover, R. (2019). Emergent identities: New sexualities, genders and relationships in a digital era. Routledge.

Davis, M. (2020). Digital media and social norms. Cambridge University Press.

Eckert, P., & McConnell-Ginet, S. (2003). Language and gender. Cambridge University Press.

Eckert, P., & McConnell-Ginet, S. (2012). Constructing, deconstructing and reconstructing gender. Language in Society, 41(3), 285–311. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047404512000207

Ferguson, A. (n.d.). Butler, subjectivity, sex/gender, and a postmodern theory of gender. MIT Workshop on Gender and Philosophy. http://web.mit.edu/philos/wogap/ESWIP02/Ferguson. pdf

Gender Study. (2024). The impact of culture on gender roles and identities. Gender Study https://gender.study/psychology-of-gender/culture-impact-gender-roles-identities/

Jain, S. (2020). Cyberfeminist practices in the digital age [Unpublished manuscript]. Academia.edu. https://www.academia.edu/118419194/Gender_Performativity_in_the_Age_ of_Social_Media

Masutha, K. (2021). The modern customary marriage – can the handing over of a bride be waived? De Rebus. https://www.derebus.org.za/the-modern-customary-marriage-can-thehanding-over-of-a-bride-be-waived/

Soergel, A. A. (2024). Researchers explain social media’s role in rapidly shifting social norms on gender and sexuality. UC Santa Cruz News https://news.ucsc.edu/2024/05/social-mediarole-in-growing-gender-and-sexual-diversity.html

South Africa Online. (n.d.). Marriage in Tsonga society https://southafrica.co.za/marriage-intsonga-society.html

Wedbuddy. (2023). 16 South African wedding traditions and rituals https://wedbuddy.com/ south-african-wedding-traditions/

@Ketso28. (2025, February 19). As a man, it’s important to understand that women are naturally polygamous. Once you accept this truth, you’ll be okay [Tweet]. X. https://x.com/ Ketso28/status/1892079515955765723

© 2025 The Open Window