Welcome to Issue 15 of The Muse. As much as we would like to stop talking about the pandemic, we recognize that the challenges associated with the pandemic continue to persist across our global community and affects individuals in unique and uncertain ways. As pandemic-related restrictions are lifted, we hope that everyone remains mindful and courteous of the values and preferences of others.

Firstly, we would like to sincerely thank all our members here at The Muse for another year of dedication and interest in The Muse’s goals. Your commitment in reaching out to individual authors and artists, your ability to visually portray and present the works of others, and your interest in writing your own blog posts on novel topics, all demonstrate how universal the medical humanities is. To those who submitted works to Issue 15, thank you for your trust in The Muse in sharing your stories and for collaborating with us along the way.

Alongside our yearly initiatives, we also continue to partner with Keeping Six —Hamilton Harm Reduction Action League to produce their Quarterly Zines and share stories of harm reduction with our local Hamilton community. We also collaborated with McMaster’s ENGLISH 3NH3 class and the McMaster Child Health Conference to assist in sharing and supporting the works of students. We look forward to further collaborations in the future!

We would also like to thank McMaster University’s Office of the President, the Department of English & Cultural Studies, and the McMaster Alumni Association, for their continued sponsorship to The Muse. Their genorosity and belief in our mission allows us to share these unique stories around the world.

As another academic year draws to a close, we would like to say farewell to all our graduating members and we wish them the best of luck on all their future endeavours. We look forward to hearing from you about all your successes! We would also like to introduce our three new Co-Editors-in-Chief: Kelsey Gao, Kylie Meyerman, and Subin Park. They have been a monumental component of our team since the first day they joined, and we are all excited for their leadership at The Muse.

Yousef Abumustafa Alexandro Chu Editor-in-Chief Editor-in-Chiefpathological dreams i am enough here comes a square one a bed 3 poems mixing music, medicine & not "norwegian woods" trying to find my footing again art that speaks disappearing scrubs & sensory fatigue an ode to lost nerves reading diversity confined souls & avalanche being abnormal & nothing to do but wait angel poised the l(onely) companion frontliner's day quarantine & connection after snow a finger painter derailed by circumstance health care listening covid portrait fear of people because of asthma 1984 natasha verhoeff child health confrence abstracthoeff the guasha treatment peau, pear, pain resisting the ableist notions bubbles

Bidisha Chakraborty Jagoda Zwiernik

Les Epstein

Daisy Bassen Michele Mekel Gerard Sarnat Renata Pavrey David Sheskin Renee Cronley Renata Pavrey Renata Pavrey Chary Hilu Keon Madani Sergey Dobrynov Amy Bassin & Mark Blickley

Heba Khan Ges Jaicten Larissa Peters Vanesha Pravin Eric Lawson

Binod Dawadi Karen Boissonneault Gauthier

Pawel Pacholec Maid Čorbić DC Diamondopolous Natasha Verhoeff

Hua Huang Yannick De Serre Rose Ajdar Keith Buswell

AUTHOR Bidisha Chakraborty

AUTHOR Bidisha Chakraborty

The dreams I encountered are vulnerable, Or am I mistaken? Are they hallucinations? I am alone in the streets at night by the London Bridge Held breath, moistened eyes, probably crying The pathological error is recurrent Neither severe, nor apocalyptic

It is just a quintessential panorama I can be Ruthless but never Ruth* Something is clutching me back I want to kiss my emotions No! I am not vulnerable

The pathological error is recurrent Neither stupendous, nor awkward

Yes, my art echoes that of John Keats

I am mesmerized by the Nightingale’s phonetics, Linguistic disorders I carry French or Italian, I don’t know

The pathological error is recurrent Neither acceptable, nor rejected

Yes, I am a dreamer and not the only one Someday you will join us And the world will be as one** United with love and humanity

Yes, I am vulnerable A proud pathological dreamer Blessed to be apocalyptic, anointed with human perfumes.

*Ruth isa character from Harold Pinter’splay TheHomecoming, whereshewasa prostitutein literaland metaphoricalsense.

**an excerpt from thesong Imagine by John Lennon

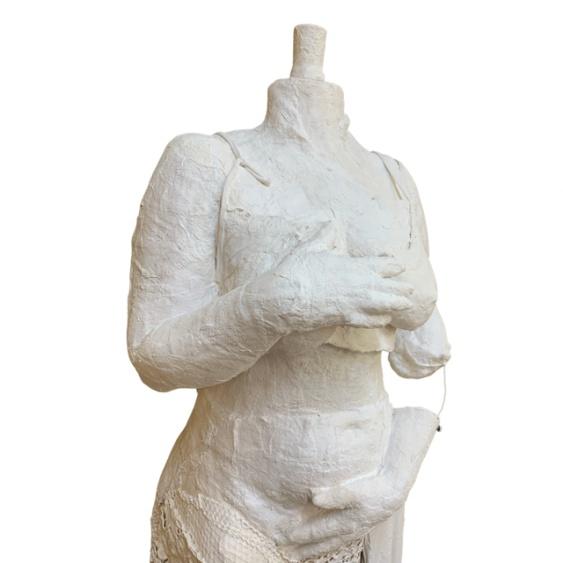

Bidisha Chakraborty is a post graduated student in English Language and Literature from University of Calcutta, former intern at Academic Researcher at Y.E.S Intercultural, Michigan (2020).Their area of interests prevails in creative writing and they have three international creative publications. They aspire to pursue their doctoral research in Romantic Literaturein their futureendeavors.Sculpture, 1.65 cm (plus7 cm stand)

I AM ENOUGH I am enough because I AM and that is enough. Each of my scars has a story and is a path to who I am now Each of my scars reminds me that appearance is a very fleeting thing.

It doesn’t matter where you come from. It doesn’t matter what you have experienced (or not experienced) in your life. Remember that you aren’t what happens to you. You are not the emotions that grips you. It only matters who You Are at Source. Don’t let your appearance define your worth.

EACH OF US IS ENOUGH. Just be there and let yourself be. Don’t judge, support.

Jagoda Natalia Zwiernik is a visual artist that has been living and working in Edinburgh, Scotland. She studied Interior Design & Architecture at the Institute of Visual Arts of the University of Zielona Góra and Faculty of Sculpture and Spatial Activities at the Academy of Fine Arts in Poznań, Poland. She is most inspired by people and their stories, as well as by social situation to which she feels obligated to respond. She has exhibited her artworks in Poland, Hungary, Italy ,Spain, Belgium and UK.

Morning and here’s a fine buffet of pills and the new guy comes as a square ingested by a Blue Ridge square, who has always fallen in line with the 14th century idea of esquarre and would have taken on the mantle of the second World War II idea that I must be a fuddy-duddy, hardly in tune with the latest swing. But, hey, Monk and Miles blow my mind so I insist to be square with all that groove.

I once took a seat on a rectangular bench in Bellevue, waiting in line for a bottle of calming magic. Each blue peacemaker had an oval look, a sapphire gleam. All afternoon the sun glanced over the tips of our tortured heads, our names left lingering in shadows. Whoever imagined a square remedy?

Square dances are fun. Four people mesh in kaleidoscopic fashion; my partners at Yorktown Junior High School most certainly preferred a plague rather than holding my hand. So, I’ll creep out after midnight and dance with farmer ghosts in the old city’s square where cattle once came to die.

I’m ready for my square one, Mr. de Mille.

Les Epstein a poet, educator and stage director living and working in Virginia's Blue Ridge Mountains. After years of devouring various treatments for Chrons Disease, a pill was prescribed to treat the onslaught of Acid Reflux. The reflux, the pill and copies of the Bacopa Literary Review and Slant which contained new poems by Epstein all came at once; despite all the activity he was taken by the odd shape of the new pill. Though suffering, humour seemed the right remedy- or at least a pathway to feeling better. "Here Comes a Square One" grew out of these early autumn events.

All it will do is keep her safe, I guess that’s enough you said As if you’d weighed the options On a scale, as if there were a scale Made to measure in calibrated grams How much a girl is, all the years She’s lived and all those to come stored Like the fat ivory bulb of a tulip, covered In its brown paper; thrust into the dark To draw power from earth, casts Of worms, the invisible return of the sun. Safe. Enough. Safe enough. A slant Rhyme you couldn’t hear, still guiding You to a decision she wouldn’t accept.

Daisy Bassen is a poet and community child psychiatrist who graduated from Princeton University’s Creative Writing Program and completed her medical training at The University of Rochester and Brown. Her work has been published in Oberon, McSweeney’s, Smartish Pace, and [PANK] among other journals. She was the winner of the So to Speak 2019 Poetry Contest, the 2019 ILDS White Mice Contest and the 2020 Beullah Rose Poetry Prize. She was doubly nominated for the 2019 and 2021 Best of the Net Anthology and for a 2019 and 2020 Pushcart Prize. Born and raised in New York, she livesin RhodeIsland with her family.

Living in Happy Valley, Michele Mekel wears many hats: writer, editor, educator, bioethicis, poetess, cat herder, and woman; and, above all, human. With more than 120 poems published, her work has appeared in various academic and creative publications, including being featured on Garrison Keillor’s The Writer’s Almanac and nominated for Best of the Net. Her poetry has also been translated into Cherokee. She is co-principal investigator for the Viral Imaginations: COVID-19 project.

Artwork by Aditya Kalra.

Connected by Bluetooth, I fully suspect the smart scale :: faithfully mounted with bare feet each morning, even before coffee :: and the fitness tracker :: ever present on my wrist, monitoring inhalation/exhalation :: gleefully gossip about my weight :: tittering over my sloth, wagering as to my BMI next week ::

How do the butter and the lemon both taste of yellow?

We counted chickens not yet hatched, too soon shedding masks and social distance. Not enough vaccines, and millions still in vials, our resolve fell months too early.

Death won this game of Russian roulette without even a single bullet in the chamber.

I sat on a rug biding my time Drinking her wine. We talked until two and then she said It's time for bed”*

but from everything recently seen plus read, you and your carpet have bad Norwegian scabies, so, cad, let’s sleep separately.

Buddha found suffering at the root; Jesus lived it through his electric kindling crucifixion.

If there's god(s), s/he's' way more than Yahweh and Allah, even beyond nature...

The bell rings. We open our lids. A lotus-kneed smiling Scandinavian begins a dharmette:

before I can focus on him, an Asian perches on the stairs, blocking my chair's sight line.

Adding insult to injury, she drops her clodhopper shoes, shattering the silence.

At first, seeds of upsetness pour from me, outraged someone so Eastern could be so oblivious, so insensitive.

Should I tap her right shoulder, fingers gently pleading, Please move a bit to the left?

Then my skittish practice seems to kicks in, making me too aware of the gratuitous story I'm building.

Realizing the irony of my ruthless expectation –that a yellow-skinned lady is more sangha atuned than a WASP or a Jew -- I laugh at myself.

And decide to just close my eyes again, relax back into the blond’s teaching about craving.

A staged invasion of love and compassion suddenly lifts me above his most intelligent design.

Beyond fundamentalist virgin births, resurrections, excommunications; further than atheist quarks and Darwinian quirks.

On a middle path rather than extreme. Momentarily not missing the forest for the trees. Deep inside a fleeting white light shines. I do my best to bless all sentient beings.

Gerard Sarnat is a Harvard-trained physician who’s built and staffed clinics for the marginalized and a Stanford professor and healthcare CEO. Currently he is devoting energy to deal with climate justice, and serves on Climate Action Now’s board. Gerry’s been married since 1969 with three kids and six grandsons, and is looking forward to potential futuregranddaughters.

by Shuxuan Cao on Pexels. Photo *Beatles’ Norwegian Wood (ThisBird HasFlown)

AUTHOR Renata Pavrey

AUTHOR Renata Pavrey

Renata Pavrey (MSc, CDE, UGC-SET) is a nutritionist, diabetes educator, and Pilates teacher. Marathon runner and Odissi dancer are her unofficial designations, when she's not discussing food, exercise, and medications. She readsa lot, and writesa bit, too.

Photo by Tomas Anunziata on Pexels.Art That Speaks is composed of images that utilize the format of a Scrabble board or crossword puzzle to provide a unique perspective on a variety of topical and fictional subjects.

David Sheskin made his first work of art at the age of 40. His initial efforts were pen and ink drawings. He then began to paint in acrylics and subsequently utilized sculpture, mixed media, collage and digital technology to create an extensive but diverse body of art. Sheskin’s images have been published in magazines and exhibited in both galleriesand museums.

What lies behind the sterile walls of a female dominated profession roots grounded in religious service “Say Little, Do Much”—St.Vincent de Paul reverberates into the modern nurse and echoes back insurmountable duties built from hands cut from auxiliary staff that were no longer in the budget but fits the ghosts into the census because the optics on paper matter and “if it isn’t charted, it didn’t happen” but the caregivers’ voices die out receding into the proper channels until they burnout into apparitions systemically faulted for disappearing with inhospitable aseptic technique then look on as enthusiastic graduates and a diverse array of foreign talent poached from the countries that need them vanish behind the sterile doors.

Renee Cronley, is a writer and nurse from Brandon, Manitoba. She studied Psychology and English at Brandon University, and Nursing at Assiniboine Community College. Her work has appeared in NewMyths.com, Love Letters to Poe, Black Hare Press, Dark Dispatch, Off Topic, and many other anthologies and literary magazines.

Artwork by Sabrina Sefton.

I hear partisan purple prose and see field hospitals.

I touch yesterday’s PPE and smell disinfectant.

I taste bitterness and feel nothing.

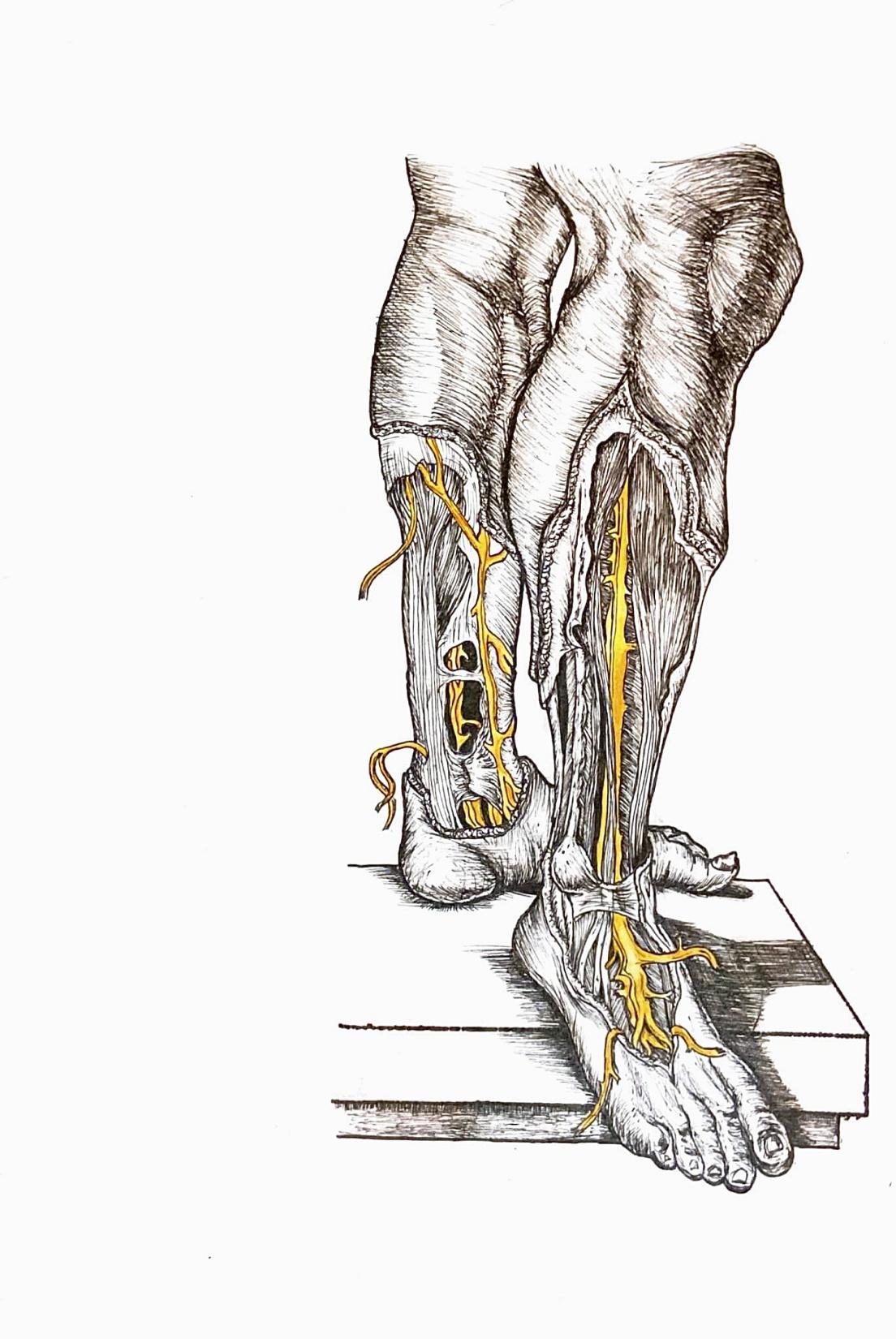

Who would have thought that right could go so wrong? Let down by my own leg, Can’t even walk in my own shoes;

Forget about someone else’s, You tingle and niggle, Let me know you’re there There, but unable to cooperate, or unwilling to with the rest of the body; Not walking the talk, Leading me only into Struggle and pain, Like a puppet with a broken leg I dangle helplessly, Nervous about my injured nerves

Renata Pavrey, (MSc, CDE, UGC SET) is a nutritionist, diabetes educator, and Pilates teacher. Marathon runner and Odissi dancer are her unofficial designations, when she's not discussing food, exercise, and medications. She readsa lot, and writesa bit, too.

Artwork by Sabrina Sefton.

The members of Read The World Book Club always look forward to their monthly book discussions. They spend the entire month reading the chosen book — selected in turn by different members — and can’t wait to present their thoughts and opinions at the eagerly awaited literary curation of ideas. The book picked for the month of April was The Reason I Jump by Naoki Higashida. Originally written in Japanese, the memoir has been translated into English by David Mitchell (popularly known for Cloud Atlas and Slade House, among other wellknown works). Priya had picked the title this month, because the book club was keen on discussing a nonfiction book. They had been reading a lot of translated fiction from classic and contemporary writers in the past few months, and were looking for something new and different to talk about.

The meeting has been scheduled at Sam’s place today, the last Sunday of the month (when all their book meets occur, to give everyone sufficient time to finish the book). Sam starts off by commending Priya on her choice of book for the month.

“It was nothing like I expected,” he informs her and everyone else.

“I, too, wasn’t aware that the writer was a thirteenyearold boy with autism when I picked up

this book,” Priya admits. “A Japanese language memoir sounded interesting, and it was David Mitchell’s name on the cover (as translator) that caught my attention.”

“We learned so much,” shares Geneve. “The Reason I Jump is certainly a oneofakind memoir that showcases how an autistic mind thinks and perceives. I hadn’t known much about autism earlier, because I personally don’t know anyone with autism. I’ve heard about it as a spectrum disorder, but until reading Naoki’s book I had no experience with people with autism.”

Many of the book club members reiterate Priya’s and Geneve’s thoughts. They dove into the book expecting something else and came out with insights and information like never before. Using an alphabet grid to construct words and sentences, the child author writes about his life with autism in a neurotypical world, and answers questions that people don’t have answers to, or never knew they needed to ask in the first place. Why do people with autism repeat words and phrases, why do they line up blocks and toys, why do they avoid eye contact, why do they jump and flap their arms? Questions upon questions from nonautistic minds, unanswered

Naoki Higashida was diagnosed with autism at age 5, wrote the Japanese book at age 13, and the English translation came out eight years later by British author David Mitchell, whose own child is autistic. Mitchell translated the book because he wanted to help others like himself and his wife — parents, siblings, teachers, caregivers — to understand and support their loved ones on the spectrum. Naoki’s honesty and generosity provide unique insights into not only his life with autism, but on autism as a whole and life itself. In teaching us to understand others, it helps us understand ourselves and our role in fostering better relationships in society. Written in the form of Q & As, the illuminating narrative structure is just like Naoki’s alphabet grid — understanding and empathizing with autistic behaviors that are communicated through so much more than words.

Like many people on the spectrum, Naoki has speech difficulties, but his story is a revelatory account of autism, beautifully translated onto the page in his own words and language. One of the book club members, Lata, points out that after reading the book she started looking up other literature

about autism spectrum disorders. “I came across the word neurodivergency and began reading up on it. Autism in Heels by Jennifer O’Toole was another book I read alongside The Reason I Jump,” Lata reveals. “The memoir is about the author’s journey of being diagnosed with Asperger’s Syndrome at the age of 35, and presents a firsthand account of autism in women.” Lata appreciated the insights she gained from both books, written across different ages and genders, and learning how wide and misunderstood the spectrum can be.

Like Lata, other members also researched books on autism when they realized how little they knew on the subject. More book recommendations started pouring forth — At Home in the Land of Oz by Anne Clinard Barnhill (the writer’s memoir of living with her autistic sister), Animals in Translation by Temple Grandin (an animal behaviour expert with autism talking about the autistic brain and the humananimal bond), The Color of Bee Larkham’s Murder by Sarah J. Harris (the protagonist is a child on the spectrum who witnesses a murder), The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Nighttime by Mark Haddon (a teenager with Asperger’s Syndrome out to solve the murder of the

neighbour’s dog), Odd Girl Out by Laura James (an autistic mom raising nonautistic children talks about the underdiagnosis of female autism), How Can I Talk If My Lips Don’t Move by Tito Rajarshi Mukhopadhyay (a nonverbal autistic who finds expression in reading and writing) an assortment of books on autism spectrum disorders across fiction and nonfiction, with a range of autistic characters in prominent roles.

As the list grew, the Read the World Book Club members realized that they were not as widely read as they had imagined. They had undoubtedly read a lot of books, but their reading habits were not diversified. Their reading choices were not inclusive of authors, characters and situations different from their own. By making a conscious effort to venture out of mainstream authors and popular bestsellers, they learned to appreciate the vastness of literature and its many forms. They learned how books can be educational and not just entertaining. They learned to look beyond their own lives and see and know human beings for who they are. They learned to appreciate the interconnectedness of humanity and what makes us human.

Armed with their list of new titles to read, Sam

concludes the book meeting with plans to ensure that their reading is more diverse from now on. “I, for one, am going to read Naoki Higashida’s followup book next,” Nick states, while alluding to Fall Down 7 Times Get Up 8 (a sequel to The Reason I Jump that Naoki wrote at age 24). “What book on neurodivergency are you going to pick up next?”

Renata Pavrey (MSc, CDE, UGC-SET) is a nutritionist, diabetes educator, and Pilates teacher. Marathon runner and Odissi dancer are her unofficial designations, when she's not discussing food, exercise, and medications. She readsa lot, and writesa bit, too.

Vladimir Mokry on Unsplash

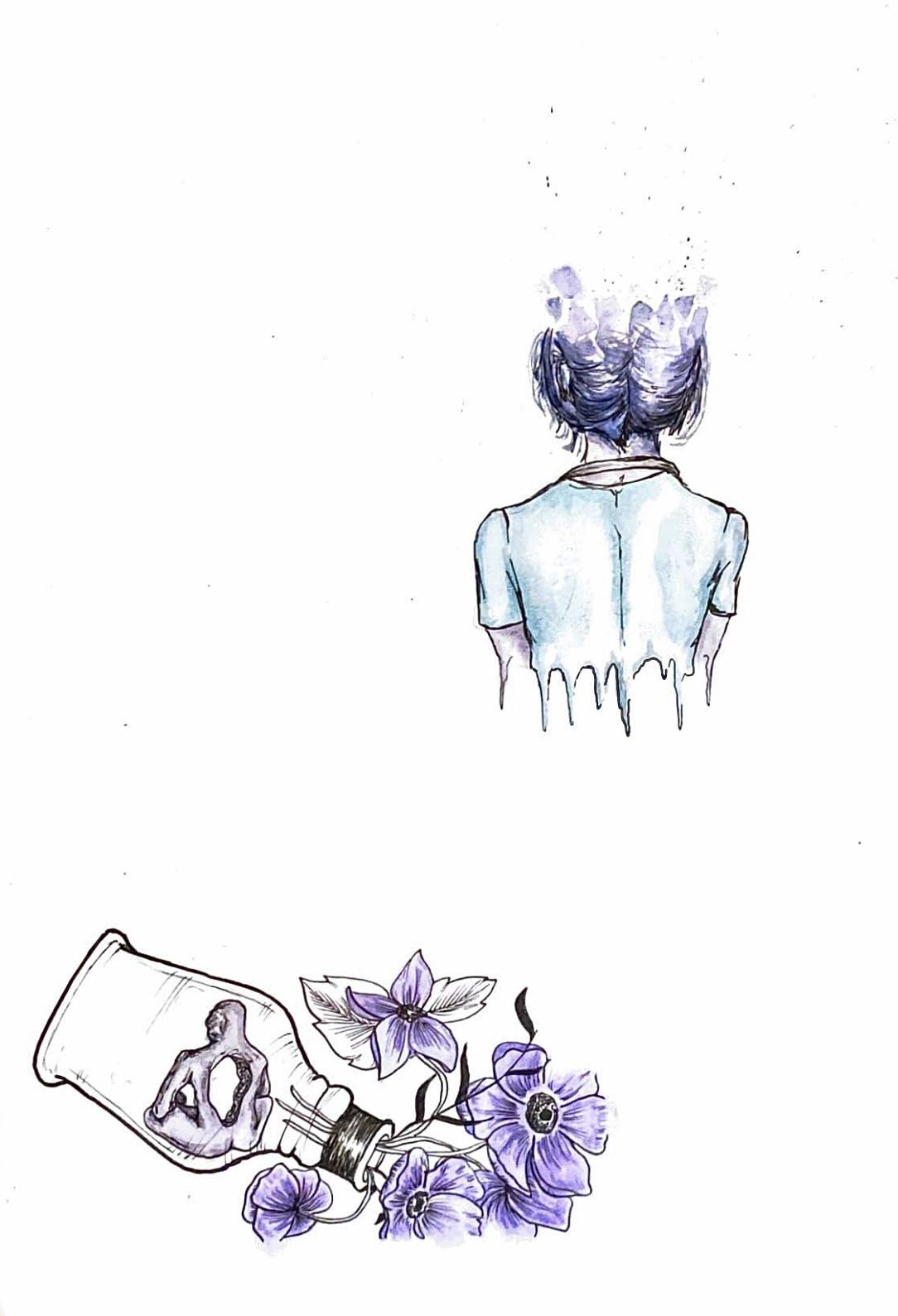

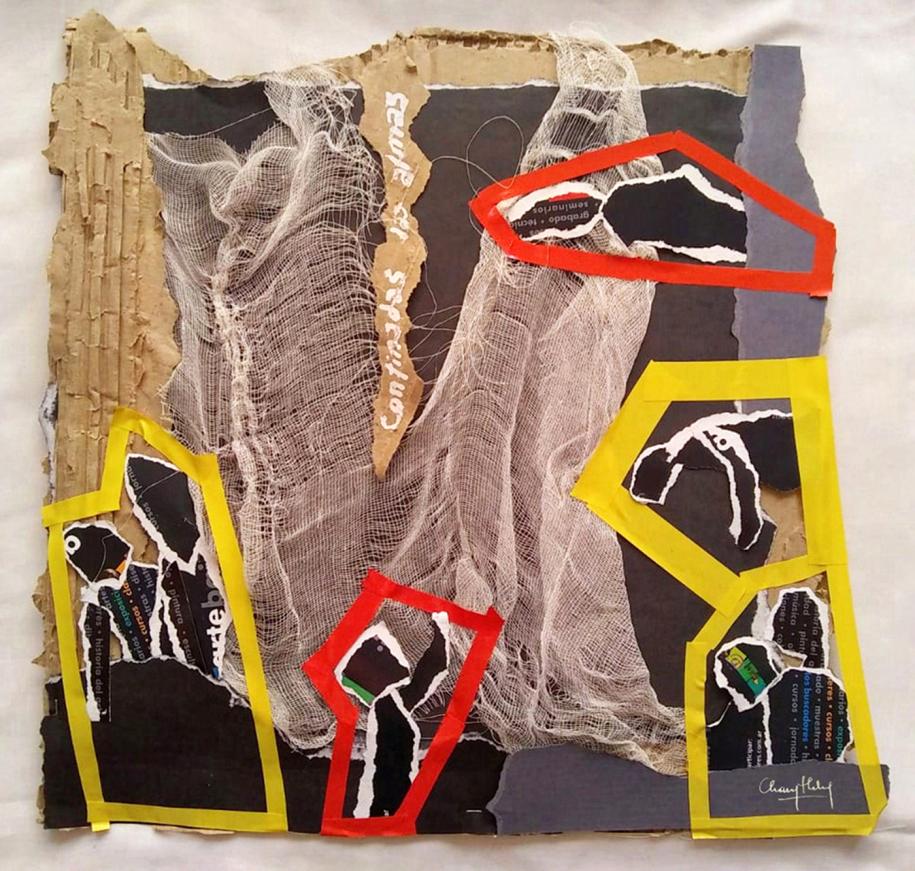

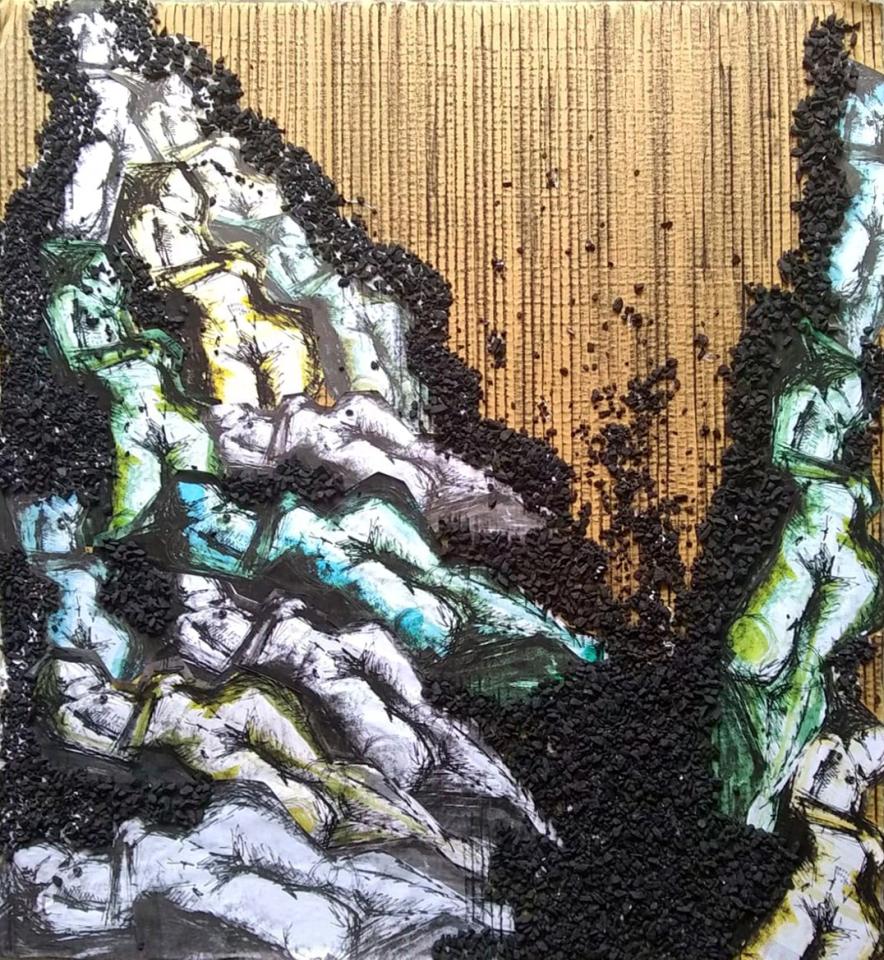

This work aims to capture and reproduce the moment when the rupture occurs in the world as we knew it, with its "normality" and the paralysis of everyday life.

Confined souls wants to represent that at the same moment, all over the world, souls are locked in their homes, while the outside world is torn by pain and uncertainty.

In terms of its format, the work expresses the absence of regular edges, where nothing is as we know it. The support of the work is not conventional, like the reality in which we had to live. We have no frame of reference, we stand on uneven ground.

Chary Hilu is an artist and teacher of fine arts from Argentina. He is a member of the Association of Visual Artists of Argentina and a graduate of the National School of Fine Arts in Buenos Aires (Argentina). His works are conceived as a response to the sensations, feelings and experiences evoked by extreme situations.

Suddenly we were swept away by an avalanche of stones that swept away everything in its path to leave us on a winding terrain, an uncertain terrain... a mountain between stones, buried under what was familiar and known to us. Suddenly, a great hole opened up in the earth, the hole of uncertainty, the enormous void that asks questions and questions what was our seemingly controlled reality.

In this flood of avalanches and depressions, the same image, the same human

figure that repeats itself, that takes different positions, different colors, different sizes, but in the end is the same, confronts us with the certainty that we all face this situation in the same conditions. Although we are in one way or another, we are all the same. Falling into the abyss seems to be the fate shaped by the weight of bodies. But a solid foundation, even if it is made of rubble, still supports us.

now. The internet told me what that label means. So many peo‐ple are like me. We have the same label, so we should be able to relate.

But I guess not, because I fulfill 3 out of 12 symptoms on the checklist, while my mother fulfills 4 out of 12 that are dif‐ferent from mine. My father has 6, but not all of them are the same as mine. We have the same label though. There’s an

I met someone who also has that broader label, but not the same category of abnor‐mality. It’s amazing how much we had in common. Despite taking different prescriptions, and being placed in different categories, we shared nearly identical experiences. I learned that it’s not only these two cate‐gories that share similarities, but most of the other labels also share core experiences.

tion, it’s just a guess. It might change, because they can never be sure. I could’ve gone to the same doctor as my friend with identical symptoms and I could've been put on their med‐ication. But I’m not because our doctors guessed differently. In grade 3, we learned that the Anishinaabe go on vi‐sion quests. It’s a spiritual jour‐ney said to provide sacred knowledge and strength from

the spirit world. It’s something that is praised and celebrated. But I guess if I were to tell a doctor that I set out to have vi‐sions to gain wisdom, it would be delusion. The visions them‐selves, hallucinations. They would put me on antipsychotics and call it a day. One less per‐son putting themselves and oth‐ers in harm’s way.

It is such an ambiguous fog that we have deemed to be science, Fact. I understand that sometimes science is theoreti‐cal, and changes constantly. My issue is that I have seen too many people receiving a label and a prescription because they are human. One of my friends is considered abnormal, they say it’s because they get nervous. My aunt’s stamp of abnormality is due to her sadness after her husband passed. My little cousin can’t sit still, so he has that label too. They're consider‐ing medication for a 6-year-old, because he is jumpy and gets excited. A 6-year-old is abnor‐mal because they don’t sit still. And that doesn’t even address the biggest problem with all of this. I’ve been this way since birth, and many of

the people I know have this broad label too. It is treated as something that most people ex‐perience and told that it shouldn’t be treated as strange. Throwing around labels and pathologizing behaviours is not healthcare, it's harmful.

But it’s still called illness

It’s still called disorder. It's still called disease. It’s still called dysfunction. It’s still called deficit. It’s still called disability. It’s still called abnormal, and we're still told that we need to be fixed.

Homosexuality stopped being diagnosed in 1973 based on a vote. Drapetomania used to be a diagnosis—a disease causing slaves to run away. Un‐til 2012, someone struggling with their gender identity, had gender identity disorder; It still exists, but they renamed it to gender dysphoria. Disease is a classification for some people to rationalize a difference that they don't understand. If some‐one is doing something abnor‐mal, or unlike the majority, they must be sick.

If somebody becomes dependent on a substance, they're sick, but if the substance they're dependent on was pre‐scribed, they're getting healthy.

Before the doctor looked at his 30-question checklist, I was normal.

Keon Madani is very passionate about mental health and illness because sometimes people treat it as such a black-and-white thing, when it's the complete opposite. Keon Madoni is trying to pursue a career in healthcare because the grey goop that people call "mental illness" is far from being complete. Their own journey took a lot of trial and error, failure, relapse, and hardship. They are very lucky to have the support system that they have, because they would not be where they are today without them.

The first time I drowned I was 6 years old.

When you drown your instincts tell you to kick and jump, you are desperate for oxygen. You’re gagged by water, and you can’t scream for help. They can’t see you, you’re down way too deep. You can only pray that someone realizes something is wrong.

And all you can do is wait. Waiting is the worst part of drowning.

You can only wait so long before involuntary spasmodic breaths drag water into your windpipe. The only thing that overcomes the agony of running out of air is breathing in water. The distance between you and the surface grows and blocks out the sunlight, as you become heavier and heavier with each hopeless gasp. Your lungs begin to burn and the pressure from within makes you feel like you are going to be torn apart. You know you’re a lost cause, but you can’t help but struggle. Eventually, your

lungs give out and you take a deep, deep breath. After that, it’s all black.

Then you awake on the surface, your chest compressed, and your lips pressed from CPR. You begin to throw up water and excruciating pain remains in your chest, but above all of that you can’t help but feel relief that you can once again breathe air and see the light.

The second time I drowned it was different. The second time was much, much worse.

I tried to hold my breath in absolute denial, but to no avail. I struggled to reach the surface, flailing my limbs towards the light for dear life, same as before. The water filled my lungs and anchored me to the bottom, same as before. The pain was excruciating and everything I tried felt helpless, same as before. And once again, a deep, deep breath in. Only this time it was different.

This time there was nobody

who could pull me out and resuscitate me. At first they tried, but I was too deep and too heavy. They gave up. Worst of all, this time I did not faint. I had to keep waiting.

Water used to be refreshing, it was a remedy for exhaustion, and it cleaned my wounds. But it feels like I’ve swallowed a grenade. I was aware of everything my body was feeling, it felt like the grenade had internally exploded and my body remained intact. There was no square inch of me that hurt less than the others, no redeeming instance that I could drag out and cling on to. The water that surrounded me swallowed my tears and muted my screams, as if it tried to eliminate even the slightest form of release that I could have had. I needed to get back, but there was not nearly enough strength in my body to swim back up. It dawned on me that I was not going to make it, but I held out hope that things would change.

There was nothing to do but to wait.

At a certain point, everything became numb, I was unmoving, and I could see that the ripples in the surface of the water had dissipated. Everyone had left and yet I laid there alone, immersed in a lifeless realm, devoid of sunlight and comfort. A maelstrom of thoughts and emotions had overcome me, I was inundated with anger, confusion, anxiety and hopelessness all at once. Will anybody come back? What have I done to deserve this? Am I going to die? I felt destroyed. I did not want to keep waiting. But I was in an impossible situation, so all I continued to do was close my eyes in hope that this would all stop.

I kept waiting. I stepped away from my body and looked down at myself. Looking at my hands, their dark tone had sunken to something ashen and lifeless. The water held me in its frigid claws and

robbed my skin of its usual warmth. I stared for a moment at my blue lipped face and my blank expression, gazing endlessly through nothingness. This was not the same face that I saw in the mirror every day, it was a hollow shell. Still though, tiny bubbles hung above me as if to signal that there was some hope in holding on.

So, I kept waiting.

I couldn’t handle this wait. Moving without pain, aches, was just one thing I used to take for granted. Sometimes I looked up to try and find the sun, hoping that it could magically shine through the endless depths of the water. To look up and see its golden arching rays that cascaded across the sky brilliantly, and warmly caressed my face, was nothing but a faded memory. I often tried to remember what it was to take in fresh air and feel replenished. If I could, I would take a deep, deep breath and suck in the air as if nothing had ever been so sweet. I miss my

family and my friends, there is so much I have to say that I cannot. And still I continue to wonder what could have been if I was able to make it out. But I didn’t.

And at some point, I don’t know when, I realized that I had to accept my new reality. It wasn’t happy or enjoyable, but it was life. I had to accept that I was going to live in this realm that was devoid of sunlight forever. I had to accept that nobody was going to come back for me. I had to accept that I was going to have to carry on breathing underwater. It was pointless to keep waiting. So, I stopped.

I stopped waiting.

Keon Madani is very passionate about mental health and illness because sometimes people treat it as such a black-and-white thing, when it's the complete opposite. Keon Madoni is trying to pursue a career in healthcare because the grey goop that people call "mental illness" is far from being complete. Their own journey took a lot of trial and error, failure, relapse, and hardship. They are very lucky to have the support system that they have, because they would not be where they are today without them.

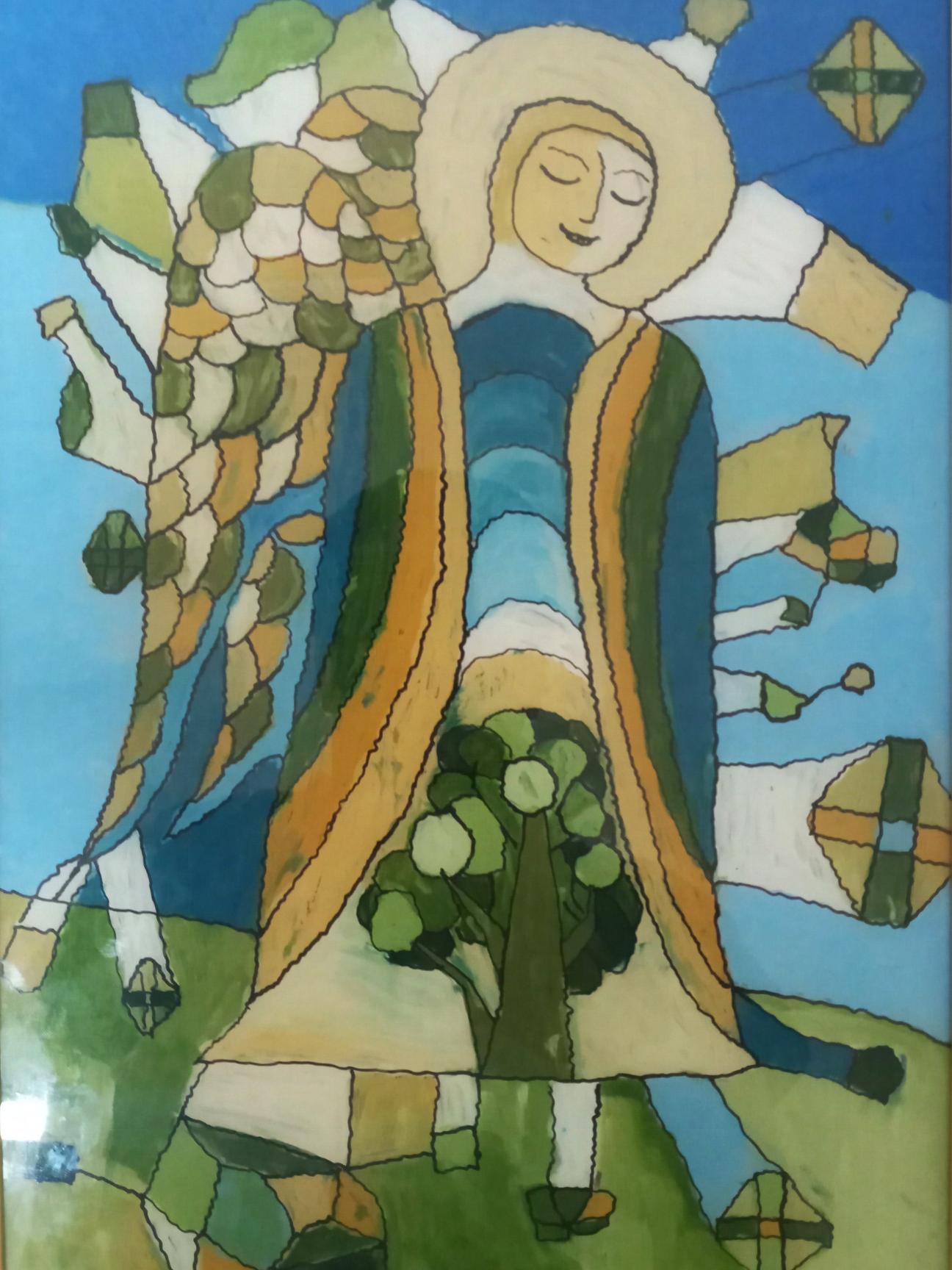

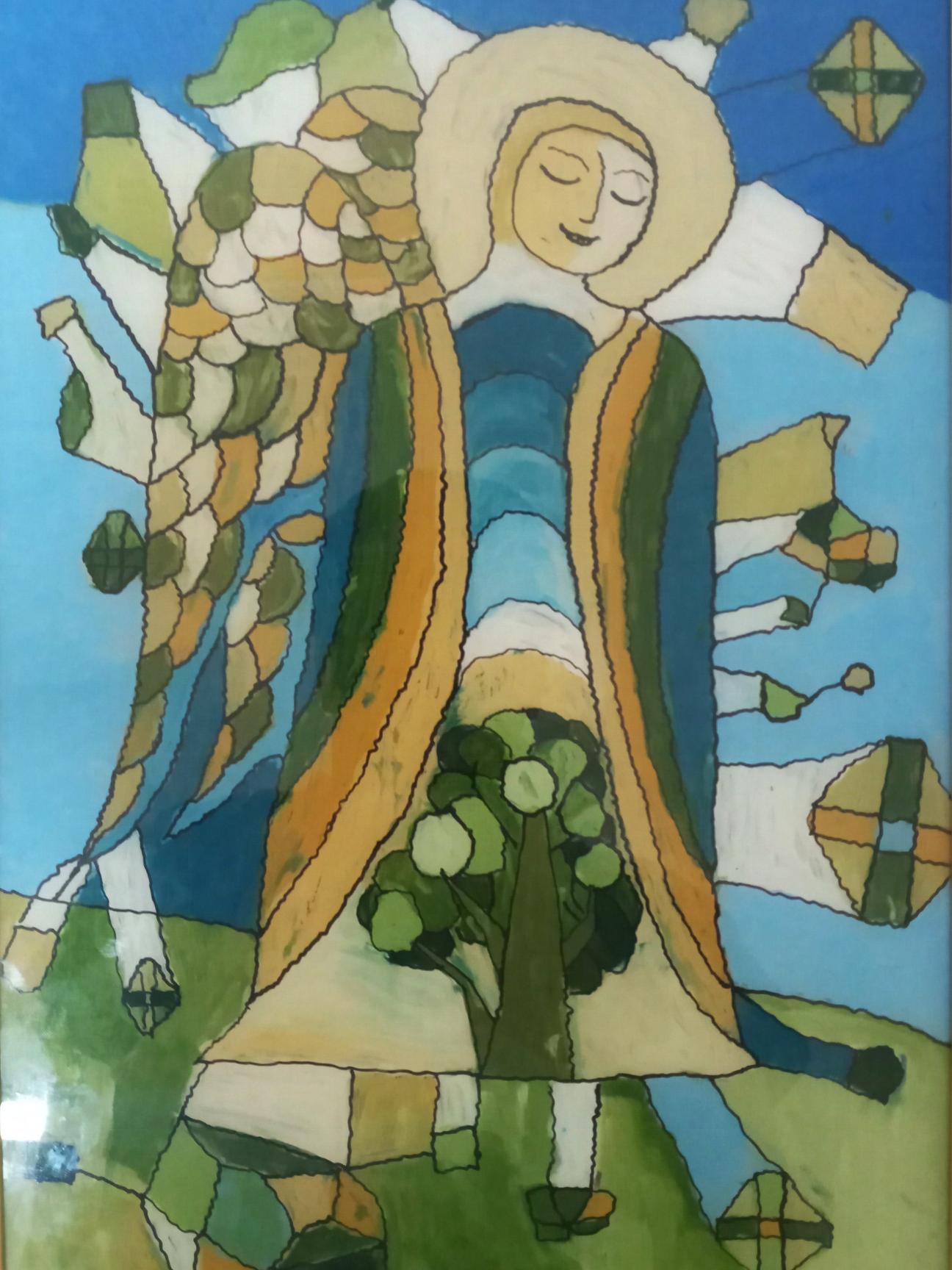

The work is done on glass with oil paints, size 20/30 centimeters. An angel is depicted, protecting us from everything, helping us recover and find the strength to fight.

a life rooted in self-confident quiet dignity allowing poised acceptance of an uncertain future

Loneliness expands within the cavities between my cardiac and pleural apices, asphyxiates the nostalgia-tinted dreams that these alveoli perfuse into my crimson streams.

My atherosclerotic vessels of hope have sunk— have become shipwrecks festered by liquid rust and it's starting to make sense why the most debilitating, dehumanizing sentence in prison is social isolation.

But what about us— the figuratively free,

in the forlorn cage of this vast world trapped alone, and only Loneliness steps forward to offer compassionate companionship; convinces you that you exist in the prison and presence of your intrusive thoughts; offers sensation in the numbness of existence, perception in the blindness of persistence.

Loneliness embraces you like a well-wisher only to plunge the sword of betrayal into your spine and while you pine for affection,

yearn for conversation and long for communication, Loneliness makes you tightrope on the barbed wire of sanity, only to have isolation tempt you into the alluring claws of insanity.

But you will find the softness in the hearts of the forsaken, their laughter in the midst of all this grief, the eloquence of the soliloquies sung in the suffocating silence the transience of their suffering in the face of their magnanimous resilience

Heba Khan is a mental health counsellor who has seen the deteriorating and insidious effects that loneliness has had on the vulnerable members of society. Heba Khan has also seen the way the pandemic and social isolation has impacted people across the world. This poem aims to capture the way that people that have endured trauma, grief and suffering have a desireto heal, havehopeand resilience.

On

When duty calls, has there been time to celebrate amidst the blood storms? No, she will do so anyway. In fact, her children at home are still waiting for the clock, whose hands are still paused since prepandemic times, to bring to them news that their mother can come back home. But, like a storm in the belly of Jupiter, it just does not end: an indelible mark on the surface of our histories, it has yet to end. So, she strokes her children’s heads with the gentle caress of a text that says, “I will be there soon, I will be there soon.” but she is not yet there, instead she continues her stride against the gravity of that Jupiterian storm, moving in retrograde from her clock at home, marked red as the blood she transfuses every single day for the sake of life.

Ges Jaicten is a Filipino poet and a student of literature, currently participating in workshops and submitting various writings online. In the past 4 years, their education has been provided by their mom who works tirelessly as a nurse in the UK. This submission is dedicated to her work in the field these past 2 years during the COVID-19 crisis.

by Marcelo Moreira on Pexels.

Palm Sunday is just a day. “Hosanna” can be cried out any day any time from anywhere: a crowd, a rooftop banging a whisk or a spoon on a copper pot or a metal mixing bowl or all alone, as the sun dips a prayer, blushing, while the healthcare professionals — weary-boned doctors and nurses, technicians and workers — slowly make their — Land Before Time near-extinction — way home.

Today, this one lies alone—desperate for a physical “other”. Another with her duplicate selves—young bodies—clinging, clamoring at her—all hours, minutes of the day. Neither can get away to different spaces, from their own unique voices vying for attention—at times soothing, other times terrifying. All the while down the street—a woman just wants the chance to see her 88 year old father—now in hospice— through a window.

The screens continue to warn, throw numbers while floating heads gather and pretend “it’s just as good”, “it works just as well”. Still. Any of us would trade places with Somebody. Except for the 36-year-old in the ICU, struggling to breathe while the only one who speaks to him is a stranger, her own breathing ragged and worn.

But that’s a distance—until it isn’t. When you can feel it crawl closer, closer to your circle, breathing on your neck. While you press the anxiety down for the sake of a touch.

Larissa Peters grew up in Indonesia and moved to California last year after living on the East Coast for over 10 years—in the middle of a pandemic. Being somewhat of a nomad, this is only one of the many cities she's lived in these last 40 years. Her poems have appeared in many places including Adelaide Magazine, The PlumTreeTavern and Rabid Oak.

Artwork by The Muse Graphics Member.

Larissa Peters grew up in Indonesia and moved to California last year after living on the East Coast for over 10 years—in the middle of a pandemic. Being somewhat of a nomad, this is only one of the many cities she's lived in these last 40 years. Her poems have appeared in many places including Adelaide Magazine, The PlumTreeTavern and Rabid Oak.

Artwork by The Muse Graphics Member.

For Kurt (1932 – 2018)

We’re in your room, waiting for you to wake.

Light filtering through the dirty glass Tufts of grass and twigs slash through snow, some tracks crisscrossing – what animals ran through here last night?

Snow grows whiter and whiter and whiter within our insteps, the light rich, the branches stir. When you stir, the day cuts you open: If I am not my body,

If I am not my mind, then what am I against time?

You wince from the bedsore on your sacrum and the nurse, stroking your head, uptitrates the morphine.

On a smartphone, we watch a video of a white cell expiring to understand what we can never see live –how the cell sprouts a strand of beads as a warning.

Invisible white blood cells are swelling and you look out at the sky, chalky white, with the roads plowed.

Yet strong winds dust the asphalt with snow and white blood cells, like drifts, are faithful to no curb.

It is the last time we will see you. Overnight, the freeze. The trees iced, people slip on ice, the soul slips from the body.

Only hours ago, you were swallowing apple juice, we held the cup, looking into the whites of your eyes.

Rigor mortis and the icicles dripping on the stoop, the mounds of snow that will grow dirtier and dirtier and, underneath, the grass slicked back.

What a world it will soon be of slush and patches of grass, of crocuses and daffodils in the snow, of hungry bees

It is still January. Your children sit by your side, but they have to leave, catch flights, fly home.

Venesha Pravin's book Disorder was published by the University of Chicago Press in 2015, and she is the recipient of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences' Sarton Poetry Prize and the Northern California Bookseller Association Golden Poppy Award. Currently, she teaches at theUniversity of California, Merced Artwork by The Muse Graphics Member.

AUTHOR Eric Lawson

AUTHOR Eric Lawson

I used to smear paint on these same walls for hours, oblivious, and perfectly content. Primary colors swirled together quaintly. Life imitating art imitating life, replicated. But somewhere along the way I started worrying about my posture and a 401k. And utilities and sodium and calories. And new school clothes for the munchkin. And rent and car payments and exercise. Yet at night I dream about feeling the wet textured slime oozing between my fingers. Creating a valley full of elk and squirrels. Or lily pads with frogs and ducks in a pond. A hellish forest fire blaze belching smoke skyward along the pale coastal highway. Infinite fractals spring forth from ancient man-made mythological and dark desires. The quest for more light is endless. How many stars must I chase only to ignore the closest sunlight on my face? How many solid relationships must I flee from because the idea of commitment is too stifling, too vanilla, and too final? How many screens must I view daily in order to quell my boredom and curiosity? I need to unleash something feral. I need a tangible tool in my hands. I need to entwine and breed with chaos. Verily, I vow to continue to map the constellations by torchlight while smearing finger paint on my cave walls.

Binod Dawadi is from Purano Naikap 13, Kathmandu, Nepal. He has completed his Master’s Degree from Tribhuvan University in Major English. He likes to read and write literary forms. He has created many poems and stories. Hedreamsto bea great man in hislife.

Photo by Edward Howell on Unsplash

Health is wealth your health is, Your all things your happiness, Sadness your difficulties and your, Happiness are impacting on your health, As well as your health impacts vin making, Such things,

In the world the greatest thing is wealth, Without health we can’t get our dreams, Our ambitions our goals, The wealth is nothing it can’t buy your, Health it can’t buy your time and your works,

Health is greatest thing in this world, This is because when you feel weak, As well as when you become sick, You can’t work, So love, care, protect your health,

Don’t take drugs and alcohols, They will destroy your body parts, They will destroy your body’s organs, They will seize your long life, As last your death will occurs,

Take only home made and, Don’t take jung foods. So love and care your health.

"Listening" is an image with any overlapping shots. Within e stethoscope is a forest of trees and branches making the ir we breathe. While we listen to the climate, we listen to ourselves. We live in tandem.

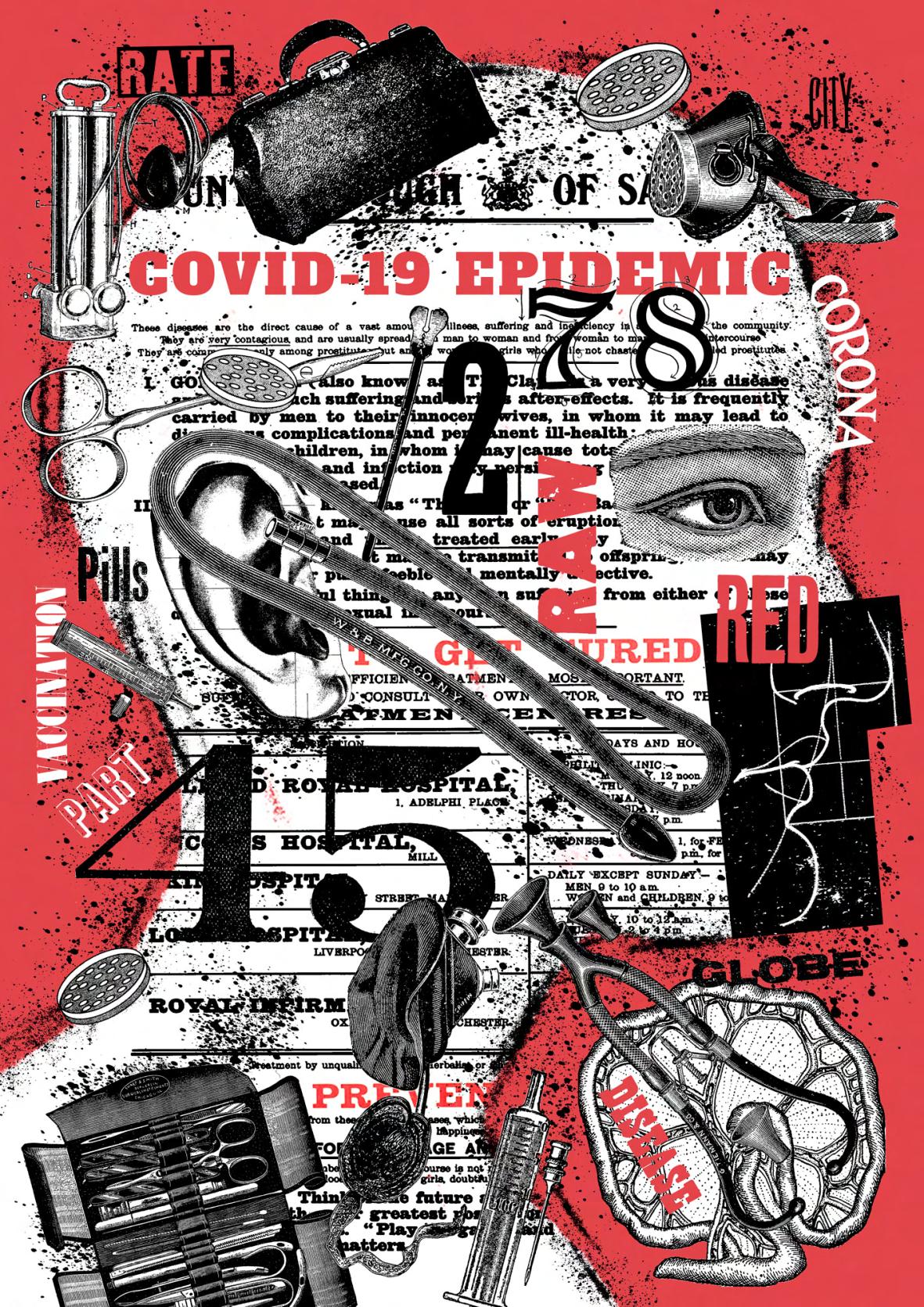

Pawel Pacholec works with collage technique putting emphasis on composition and esthetic outcome where each element is placed carefully into position. Their compositions are kept in the Dadaist style. They studied arts in the Academy of Fine Arts in Gdansk (Poland) and photography at the University of Arts in Poznan (Poland). They have been published in many magazines and have been exhibited in many countries including the USA, Canada, China, Australia, the UK, Ireland, Germany, and Spain.

ARTIST Pawel Pacholec

Pawel Pacholec works with collage technique putting emphasis on composition and esthetic outcome where each element is placed carefully into position. Their compositions are kept in the Dadaist style. They studied arts in the Academy of Fine Arts in Gdansk (Poland) and photography at the University of Arts in Poznan (Poland). They have been published in many magazines and have been exhibited in many countries including the USA, Canada, China, Australia, the UK, Ireland, Germany, and Spain.

ARTIST Pawel Pacholec

Maid Čorbić

Maid Čorbić

I remember as if it was yesterday when I was fat and I found out I had asthma. Of course, it was hard for me to be only nine years old when I found out about it. Although I had some symptoms, such as headaches or minor migraines, I didn't want to tell others lightly. I thought to myself that I might be worse off and that I definitely wanted to have peace in my life. I often wanted to play with others around me, but this world became so cruel that I could not have anyone, so I was often left alone. I frequently worried about whether I was different from others or whether it was a fate that I had to follow at such a young age. Asthma is very difficult in the life of someone who is ill, and I doubt that anyone can get out of it healthy. Over time, if left untreated, it becomes a very sick condition. I have had parents who are always eager to help their child, to be happier than ever before and have a normal, fast-paced childhood.

I had my first visit to the doctor when I was nine years old, and I remember that I often had to carry a pump with me, so I couldn't continue to talk properly. I often still imagined that I didn't have what I wanted, and those are the right people in my life. Life only made sense if I continued to believe in myself -that I could somehow get over all those diseases of the world properly. And at the doctor’s, when I came still, I was aware that my time had begun. And I had to be scared because asthma is severe. It leads to

AUTHORproblems and suffocation at night, which is why I struggled with it the most. I couldn't eat because of the pain, which I confessed to the doctor, and he of course advised me to be strong. He said that it was natural and that my condition was not worse than some others. This gave me the motivation to continue to fight more than ever for myself and to be the winner of my story in the end. I believed that happiness was hiding far away and that no one could stop me from dreaming some of my dreams that I had planned. I just wanted the world to be mine -- it is unfair that children get sick in any way. I was a dinosaur then, but even today I am a boy who always dreams of achieving something. And I believe that everything happens for a reason.

The doctor gave me some pills and pumps like I said, but I certainly felt uncomfortable. My concern was whether I would be generally accepted by people today or tomorrow and whether I would find a girl who still might have wanted to be with me. But she couldn't get over it. And I doubted more and more as I grew up if I could make myself something. But again, I remained strong more than ever - I would say that I was partially cured, and that asthma still accompanies me from time to time. And it usually happens when the weather is bad and cloudy. I am happiest when the sun is shining because I don't care what others will say. I was just

afraid if I was different from the others, I would have to be everything I am not. Because they still want me to be a kind of shadow of the past that will drive me to some tears that are paler and paler. Maybe my world was not as I dreamed, but I believed that it would be somewhere if I found it myself. So, I learned that asthma is a natural process of man and that no one and nothing can stop me from dreaming. Only I am the creator of what I dream and want.

I struggle with asthma because it is a disease that still destroys my lungs and I am not sure if everything is still okay with me, but I know that there are always good people somewhere who will understand the loneliness and care if I survive. Because, after all, the most precious thing of all is the one life I have, and I have to understand that time is money. Now that I often cough a lot, I remember that someone far away in the world has nothing to eat. Maybe that makes me realize that not everything is so black and that there is always some happiness around the corner. I feel happiness when I value myself and when I find people around me ready to help me when it is most needed. My life only makes sense if I find people for myself and if I had a magic wand, I would just want to not be sick anymore because it affects everything I want to become. And my dream is just to be a doctor who will treat others and say that, from my experience, asthma or another

disease does not care if you react in time, but also that we must be aware that life is short.

I often have to work through some challenging things, but also hope that one day I will be beaten again by an old man who will play football with his father who is my best friend and my mother who will help me whenever it is difficult. Because I know that they are my only comrades, always have been and always will remain; and everything else is fake. I'm used to having asthma and controlling it, but I'm afraid it will get worse and worse again. But there is justice and God, He looks at me whenever necessary and knows that I only believe in Him. And the asthma is still there, but I'm happy because happiness is anything but pain when you're young.

Maid Čorbić from Tuzla, 22 years old. In his spare time he writes poetry that repeatedly praised as well as rewarded. He also selflessly helps others around him, and he is moderator of the World Literature Forum WLFPH (World Literature Forum Peace and Humanity) for humanity and peace in the world in Bhutan. He is also the editor of the First Virtual Art portal led by Dijana Uherek Stevanovic, and the selector of the competition at a page of the same name that aims to bring together all poets around the world. Many works have also been published in anthologies.

by Sincerely Media on Unsplash.James, as the doctors and staff at St. Mark’s Regional Hospital in San Diego insisted on calling him, applied pancake make-up over the band-aid camouflaging the skin lesion on his chin. He was glad to be home, sur‐rounded by his Nippon fig‐urines, the ornate lampshades with exotic scarves draped over the top, and his trunk of over‐flowing satin and silk cos‐tumes, boas, several strands of pearls, and oodles of costume jewelry. His move to San Diego had been a windfall—the most money he’d ever made doing drag. He lived to entertain. On stage, he was Jasmine and loved. Standing-room only. Now he was sick. How long would he be able to afford his apart‐ment in Hillcrest?

The obituaries from three newspapers spread across the coffee table. Circled in black were the names of seven young men.

Jasmine wanted to live, to work again at Glitter Glam Drag. But James didn’t.

No can do, James. You’re not going to pull me down to‐day. It’s Pride. I’m going to party.

Donna was coming.

At St. Mark’s, the only person who bathed and dressed him, changed his sheets and consoled him, was Donna, the pretty dyke nurse who was now his source for food, medication, and shots —his entire life.

It was Sunday, her day off, and she promised to take him to Pride. Jasmine had never missed a parade, but James’s taunts of looking buttugly opened more scabs than he had on his body.

Jasmine dressed in black sweatpants and a gold lá‐may blouse, brushed her long stringy hair, pulled it into a ponytail, and clipped it with a rhinestone barrette. She ap‐plied red lip gloss and blue eye‐shadow.

When James fell ill and admitted himself to St. Mark’s Regional, the doctor asked how many men he had slept with. Was he kidding? “Honey, how many stars are there in the heavens?” Hundreds, thou‐sands, in parks, bath houses, clubs, from San Francisco to LA and San Diego. The doctor had kept a straight face when James answered. The nurse turned her back on him.

Gay liberation tore the hinges off closet doors. Men like him left the Midwest for the coasts and found a bacchanal of men, a confectionery of sex and drugs, a feast for the starv‐ing who thought they were alone in the world.

James’s life had been about dick and where to get the next fuck. Jasmine’s life was drag, antique stores, and Vogue Mag‐azine.

When his conservative, homophobic, fundamental

Christian parents caught him in his mother’s dress and high heels, they demanded, “Get out now and don’t you ever come back.” He promised them, “I’ll live up to your expectations. I’ll make the most of a trashy life.” Jasmine grabbed a green boa from the trunk and wrapped it around her neck. You think that’ll hide your Kaposi’s Sar‐coma, James baited. Jasmine tugged at the feathers that made her neck feel on fire.

Grace Jones’s, “Pull up to the Bumper” boomed from the ghetto blaster. Jasmine wanted to dance, but her legs ached. You can’t even walk, sucker.

“Shut-up, James.” Jasmine said, pulling herself up and moving to the window.

When he heard a car, he backed out of view. James never wanted Donna to know what she meant to Jasmine.

He held onto furniture as he made his way to the red vel‐vet couch and sat, poised, wait‐ing.

Donna knocked and opened the door.

“Well, don’t you look jazzy,” she said, pushing a wheelchair inside with a rain‐bow flag attached.

You’ll look like a sick bastard in that baby buggy, James bullied. Everyone will know you have AIDS.

“I can’t go.”

“It’s up to you.”

“Are we so pathetic we need a parade?”

“Yes.” Donna pinned a button that read, Gay by birth, fabulous by choice, on his blouse. “We need to pump our‐selves up. If we don’t, who will?”

“They want all queers dead. Looks like they’ll get their way.”

“Not everyone. “The Blood Sisters keep donating blood, and they’re delivering food and medicine.”

“Thank God for lesbians,” he said and wondered if gay men would do the same if les‐bians were dying.

Donna released the footrests on the wheelchair.

“I’m not going. Everyone will know I have AIDS.”

“You do, James.”

He looked away, not wanting to disappoint the woman who showed him so much compassion and strength.

“What if I run into some‐one I know?”

“You’ll know what to say.”

“Like I’m dying of pneumonia. Like all those fake obituaries,” he said, kicking the coffee ta‐ble. “Fucking closet cases. Even in death.” Jasmine felt the weepies coming on. James scolded, Be a man. Only sissies cry. But Jasmine was female, too. “In my obit, I want you to put that I died of AIDS. I want everyone to know.”

He held onto the seat of the wheelchair and winced as he pulled himself up. The smell of barbecue wafting in from the open door reminded him of summers back in Kansas City, his mom cooking the catfish that he and his dad caught in the Missouri River, his dog Corky —was she still alive?—joyful memories that always left a wake of loneliness.

Today was supposed to be happy, floats with dancing bare-chested boys, banners, dykes on bikes.

Donna shoved the wheel‐chair forward. “I’ve brought wa‐

ter and trail mix.”

“Poor substitute for pop‐pers and quaaludes.”

Donna laughed, pushed him outside, and shut the door. The ocean air breathed vitality into his frail body. He raised his face to the sun and began to gather life like flowers. A bouquet of drifting purple and orange balloons floated high to‐ward the swirling white splashes in a blue background. He heard applause and whistles as he watched a float pass by on Park Boulevard. “Go faster, Donna. I don’t want to miss anything.” For just one after‐noon he wanted to wave the rainbow flag and cheer the pa‐rade on and forget about him‐self and all the dying young men.

DC Diamondopolous is an award-winning short story, and flash fiction writer with over 300 stories published internationally in print and online magazines, literary journals, and anthologies. DC's stories have appeared in: Penmen Review, Progenitor, 34th Parallel, So It Goes: The Literary Journal of the Kurt Vonnegut Museum and Library, Lunch Ticket, and others. DC was nominated twice in 2020 for the Pushcart Prize and in 2020 and 2017 for Sundress Publications’ Best of the Net. DC’s short story collection Stepping Up is published by Impspired. She lives on the California central coast with her wifeand animals.

Background: Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental condition that impacts interpersonal skills and behaviour. Children and youth with ASD typically receive increased support at school. The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted education across the globe, resulting in school being delivered online. This may have had unique effects on children and youth with ASD but research on this topic has not been synthesized.

Aim: To investigate the following research question: what are children and youth with ASD’s experiences with online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic?

Method: Arksey and O’Malley’s five-stage scoping review methodology was used. Systematic searches of MEDLINE, PsycInfo, and ERIC databases were conducted to identify eligible articles.

Results: The database searches resulted in 34 unique articles of which eight were eligible for this review. Thematic analysis of the eligible articles revealed the following themes regarding children and youth with ASD’s online learning experiences: 1) Some preferred online learning while others preferred in-person learning 2) There is a lack of educational support for them and their families 3) Changes in eating behaviour were experienced 4) Adapting to schedule changes was particularly challenging.

Conclusion: Children and youth with ASD have had unique experiences with online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. To help with their transition to and experience with online learning, more educational supports should be made available to them and their families. Additionally, future research on this topic should be done with larger sample sizes and investigate factors that promote wellness and resiliency so that these factors can be maximized.

Artwork by Aditya Kalra.

In the past six years, I have been sick many times, and I have also used a lot of Chinese scraping therapy, or Guasha Treament. This is a selection of photos after 7 times, combined into a pop artwork.

ARTIST Yannick De Serre

Peau, Peur, Pain is an art piece made on Japanese paper. This inkjet printing on crumpled paper was enhanced with stitches: a technique that was learned during a medical rotation in a northern community. Pores are created from the crumpled texture and the choice of colour. The paper becomes like skin. With only one look, we can feel the pain. This piece was made during the pandemic... It's a crucial feeling we've all felt.

Hua Huang is a contract photographer of Tuchong.com, which is China's largest commercial photography agency. Starting their photography in 2001, Hua is an intermediate member of the China Folklore Photography Association, one of the most influential photography associationsin China.

Yannick De Serre holdstwobachelor'sdegrees–the first in Visual Arts and the other in Nursing. Since 2004, Yannick de Serre has been working as a registered nurse in the emergency department which has influenced his approach to art. He describes his art as personal, sensitive, yet rough in a manner that depicts the violenceof reality.

AUTHOR Rose Ajdar

AUTHOR Rose Ajdar

As a combination of art and science, at the heart of the field of medicine is something of a more humanistic nature which is the patientdoctor interaction (Sfakianakis).

Although medicine might treat one’s condition, it sometimes fails to provide the expected care. Since it is quite limited in understanding bodies as discrete beings, it abstracts patients to data, which can lead to feelings of desensitization or devaluation in patients (Boyer). Additionally, the dominating ableist notions can influence the medical field and cause

discrimination in interactions of medical professionals with individuals who are known as sick women (Hedva 8). As the barrier in understanding discrete bodies persists, the abstraction of patients remains inevitable; however, medical professionals can still prevent the devaluation of patients by distinguishing the concept of care from data collection. To value every patient, care should be the main focus of the medical professionals, and data collection should be supplementary rather than a means of clarifying care. A

focus on the notion of care is also important in resisting the ableist notions to honour who Hedva calls the sick women. A carefocused relationship between the medical professionals and the sick women can resist the ableist notions by valuing the humanity of the sick women.

The abstraction of patients to data is inevitable as both medicine and medical research are incapable of understanding people’s health condition simply by glancing at the human body in its entirety and the humanity that lies

within. Boyer emphasizes that, “Medicine hyperresponds to the body’s unruly event of illness by transmuting it into data”. To tackle this barrier, medicine sets the abstraction of patients as an objective to provide effective treatment. The abstraction process involves collecting numerical data from patients as well as assigning numerical values to sensations and pain. Next, the medical professionals analyze the data and choose treatment strategies which could potentially balance the numbers. As for medical research, its objective is to design or discover treatments. But due to a similar barrier, it uses technologized math to abstract the bodies of the human population to statistics that determine the likelihood of falling ill, staying well, dying, and healing for assessing the effectiveness of a treatment.

Though inevitable, the abstraction of patients has considerable consequences. The medical professionals can get so caught up in collecting data, that they can forget to take the time to hear a patient’s own narrative of their health. Hedva describes this by reflecting on the patientdoctor encounter: “The distance swims in the air that you both inhale. It distorts the exchange of two bodies in close proximity, making a little void that yawns open. It can feel like you’re speaking a language that your doctor not only can’t understand, but doesn't care to hear” (Hedva). If a doctor is too

focused on reading the collected abstract data instead of listening, patients can feel a dark vast distance between themselves and the doctor. They might view the doctor as a stranger with whom they have no chance of connecting. Many of these patients are sick women who have chronic illness or disabilities, and are confined to these uncertain yet longterm patientdoctor relationships with no trust and connectivity (Hedva). The distance they feel with their doctors while interacting with them is what can lead to feelings of devaluation in patients.

The consequences of abstraction can be minimized by directing the focus of medicine towards the abstract notion of care, and making the notion of data collection supplementary to care (Boyer). The notion of care involves an equal relationship between the doctors and patients, which has a foundation of mutual trust, and a resistant nature towards the dominating discriminatory notions. What Hedva says about the importance of trust in care is: “It’s the only force I can think of that might alleviate the vast distance between us, as well as the vast distances between the many parts of myself, not because it will diminish the distance, but because it will honor it. It will acknowledge that the distance is here”. Therefore, medical professionals and students should not assume their profession of medicine is

sufficient for gaining the trust of patients. Rather, they should attempt to establish a mutual trust by treating patients, including the sick women, as their equals. The equality in patientdoctor interaction is achieved by honouring the patients with all their parts and hearing them out. A trusting relationship with a foundation of equality which values the humanity of all the patients including the sick women, is the true notion of care which is capable of resisting against discriminatory ableist notions.

1. Boyer, Anne. “Data's Work Is Never Done.” Guernica,March30,2018.https:// www.guernicamag.com/anne-boyer-dataswork-is-never-done/

2. Hedva, Johanna. “Letter to A Young Doctor.” Triplecanopy, 2018. https://www.canopy‐canopycanopy.com/contents/letter-to-a-youngdoctor/#title-page

3. Hedva, Johanna. "Sick Woman Theory." Mask Magazine, 2016.

4. Sfakianakis, Alexandros. “Medicine Is the Sci‐ence and Art of Healing.” Otolaryngology, April 25, 2016. https://www.omicsonline.org/pro‐ceedings/medicine-is-the-science-and-art-ofhealing-43384.html

Rose Ajdar is a fourth year Life Sciences student at McMaster University. Rose was born in Toronto, Ontario and is originally from Iran. As someone who has always been interested in medicine and healthcare, Rose is aware that healthcare is a crucial element of our society. However, she believes true healthcare is something beyond taking blood tests and collecting samples from patients. True healthcare is indeed characterized by empathy and building trusting relationships that respect patients’ narratives and resist discrimination.

Photo by Pixabay on Pexels.These sculptures made of paper, fabric, and faux fur not only represent our minimal world view, but the stress of dealing with illness. Seeing friends contract HIV, followed by the COVID-19 pandemic, and

concluding with my father’s death due to brain cancer, I became enthralled by the concept of disease. Our psyche’s, represented by the wall, are riddled with loss and regret, pockets of disease

which gather and froth. This project is a way for me to cope with those feelings in ways only an artist can, through color and texture. Here we are, stuck in our bubbles while the real enemy eats us inside.

Keith Buswell graduated with a BFA in art University of Nebraska--Lincoln. He works with various printmaking processes such as screenprinting, intaglio and mono printing and dabbles in drawing and multimedia. He currently is a member of Karen Kunc’s Constellation Studios where he creates his prints. His work has been shown in the United States, Egypt, Dubai, France and Italy. Notably, Keith received the Perry Family Award in 2018 and second place in the 40 Under 40 Showcase in Annapolis, MD and third place at the Under Pressure print show in Fort Collins, CO. Originally from Council Bluffs, Iowa, he currently lives in Lincoln with his husband Brad and hisdog Max.

editors-in-chief

Yousef Abumustafa

Alexandro Chu blogs

Kylie Meyerman Karen Li Laura Ferlanti

Sierra Granger Arul Kuhad Daniel Kwan Logan Newton Arman Noormohamed Julia Sharobim Esther Su events Saud Haseeb Gracie Liu

media

ISSN 2563-7274 (Print) ISSN 2563-7282 (Online)

published Nov 2022 themusemcmaster.ca