CARE CARE

In reflecting on care, I can’t help but to think about when we need it most—both in the beginning and end of our lives. When we arrive into this world, we are in our most vulnerable state. Materially speaking, we are fed, clothed, and cleaned. We are closely monitored when we venture out to the bus stop on frigid Tuesday mornings. After a long night out with family or friends, we fell asleep in the car and miraculously appeared in our bed—tucked in the perfect amount beneath our throw blankets and stuffed animal pile. Care in this season of our lives was defined by a safety blanket. For every slip, fall, and tear, someone was there to mend our wounds and affirm that our bruises were, by no means, a limiting factor to our joy.

As we approach the end of our lives, a similar level of attention is paid to our existence. The meals are still prepared for us; the clothes are neatly folded and stored away without moving an inch. Perhaps we are in a facility where we are under the supervision of nurses and CNAs, who keep track of our weight and bowel movements. Family may only come to visit every now and then. They supplement our diet with prune juice and multivitamins housed in the large cardboard boxes from Costco. While there are no more playdates with classmates, the very existence of people in our orbit magnifies the sliver of hope in our psyche. Their words of affirmation contour the creases of our lips into a gentle smile, and we are once again residing in the warmth we last felt in our youth. We are no longer an individual body, but rather a careful compilation of the truth, love, and light that people have poured into us over the course of a lifetime.

This spectrum of life, marked by our genesis and expiration, brims with potential—the chance for something new. But this prospect only comes to fruition through the act of care. Care is dynamic, vibrant, and everlasting. It is not an additive, and cannot be confined to a mere daily dose of good vibes that bring us to live another day. For marginalized populations throughout history, care was a bold act of survival. The Black Panther Party was notable for organizing illustrative strings of mutual aid. In responding to a system that expelled them, the Black Panthers asserted the necessity of community-oriented initiatives that shocked the system and introduced new modes of resistance and hope in the process.

Our current moment is defined by the attempted erasure of the very identities that have cultivated historical abolitionist movements. While there are imminent efforts to disregard the ways in which the carceral state thrusts harm upon its inhabitants, it’s high time that we attune ourselves to the levels of care that fashioned those that came before us. Beyond a staunch refusal of any intervention that calls for the eradication of our nation’s reckoning with systemic injustice, it’s a call to action to turn inward and ensure that those in our community are being fed, clothed, and loved. Care is not a novel concept, it’s something baked within each and every single one of us—just waiting to emerge.

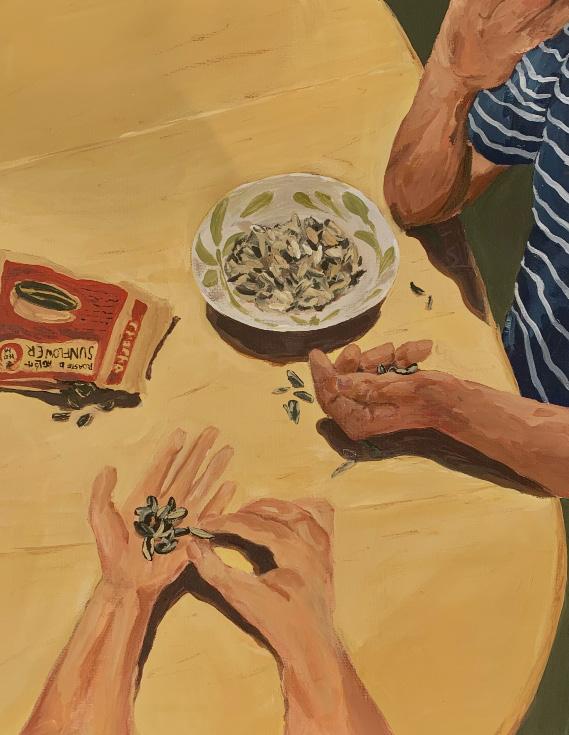

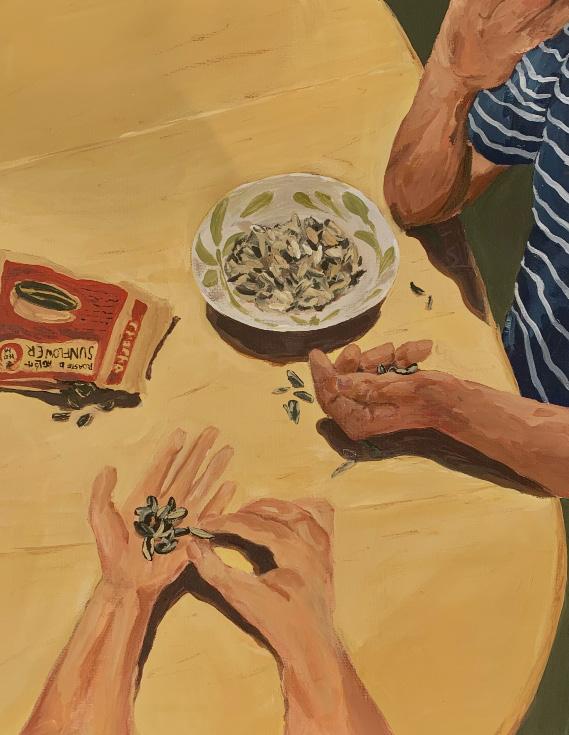

As we careen through the hurdles and barriers that construct our carceral state, we must embody the level of collectivity we wish to establish long-term. Leaning on each other in times of both light and darkness is a necessity to ensure that our liberation is truly sustainable. Care does not have to reflect large, grand acts of kindness. In fact, I would argue that it’s the seemingly menial offerings of comfort that illuminate care in its three dimensions. It’s the silence on the phone, as you carve out space for your friend to unabashedly vent about their week. Showing up to that recital that was mentioned that one time a while back. Dropping off groceries or a freshly cooked meal unannounced. Care is a fervent reminder of the love that stitches the beautiful tapestry of our world, a warm embrace amidst the coldness of our moment.

Thank you for taking the time to read this edition. I hope that you go forth and care with the strength, velocity, and boldness that takes us into a future that enshrines this value.

Sincerely,

Varughese letters from

Co-Editor-in-Chief of the MJLC

Landis

the editors

To the dreamers, revolutionaries, and readers in between,

I welcome you to the Madison Journal of Literary Criticism’s Spring 2025 edition, Care. Whether you’re an avid consumer of our literary content, or a new reader gazing through the lens that abolition affords us, I trust that you will find within the contents of our magazine value and resonance to bring into your life.

Our journey to this semester’s theme, care, has been thoughtfully cultivated over several semesters, spanning over two years. Through our previous editions, we’ve understood how to be conscious of the structure of our carceral state, the imaginative capacities of our own minds, and processes of protest not only to resist, but revolutionize. As a lofty stone left yet unturned, we now focus on care.

The word “care” comes from the Old English caru or cearu, meaning “sorrow, anxiety, or concern.” This eventually traces back to the Proto-Indo-European root g̑ā̆r, or gal, meaning “to cry out” or “call,” often in connection to grieving or lamenting. Care, however, should not be thought of as a remedy to an ailment. The MJLC defines care as the means to be an abolitionist by practice, and, by the same token, what prompted our desire to effect change in the first place. Care itself is grounded in our work, in abolition. Regurgitating the maxim to “care about one another” is seemingly common convention, yet care, as a custom, is almost entirely absent from most of our daily lives. Our tangible aim is to bring the practices of the world we want to live in into the world of today, right now.

One can easily be swept up by the onslaught of terrible news, delivered daily, showcasing the utter horrors our species is not only capable of, but shameless in committing. Yet, I often find myself justifying the belief that humans are born innocent, and only turned toward greed, corruption, and other vices by external forces. I’m convinced that there must be some good in all of us, that no one is wholly evil. The very quality of humanity which we desperately desire seems to be squeezed out of all of us from our very birth. After all, we all want the biggest piece of pie for ourselves, fighting over it, not unlike hungry school children. What’s missing from the adult world is any reasonable guide for engaging with one another, of which even the kindergarteners have us beat—in using simple platitudes such as “the golden

rule,” a general proposition that we’re all created equal and deserve to be treated equally.

Compassion, working in practice, is primarily predicated upon the upbringing and education of the youngest generations. Thus, when moral obligations fail to hold against one another, we are responsible. Each failure brings us one step farther from our own liberation, something unattainable as long as our material and monetary attachments, and perceived differences persist. From our active and constant monetary valuation of everyone and everything, to the belief that nationality and citizenship determines moral worth and the very right to live, we implicitly and explicitly devalue fellow human lives. Imagining a world without currency or borders may sound disastrous, but a world lacking compassion appears to be emptier in all respects.

My final point will be brief: care is not a transaction. There is no expectation to return good deeds. That isn’t to say we don’t benefit from kindness secondarily, or that we shouldn’t want to move our societies at large towards more open methods of empathy. We may even do it for our own self-fulfillment, but that very fulfillment is necessary to societal living, one where we all must be empowered to “cry out” when a fellow human being faces suffering, abuse, and neglect. Care to be able to demand for change where change is due.

We don’t seem to exist for ourselves, but for others. Our bonds do not chain us. Rather, they fuse us, and, by the definition of the word, “join or blend to one single entity.” It’s thinking about each other, choosing altruism over apathy, that moves us towards a common purpose. So care for another, not because you’ve put yourself in their shoes, but because they are nothing less than a human being worthy of being cared for. Because what is kindness but the end of a spool of yarn, waiting to be unraveled, strands to be knit, weaving each of us together into the tapestry of humanity?

And with that, I hope you enjoy the MJLC’s Care

Jonathan Tostrud

Co-Editor-in-Chief of the MJLC

Spring ‘25 - Care

and uncertainty is something that I, along with other victims of chronic illness, are not strangers to. It is also a common theme in literature. Literature is something I find solace in on my bad days. It is something that makes me feel understood when others do not grasp what I am going through. Writers such as Franz Kafka and Samuel Beckett have explored confusion and uncertainty through characters trapped in situations that have no clear solution. In their works, discomfort with the unresolved becomes a tool to reflect on existence itself. And, similarly, chronic illness challenges the idea of a definitive end, revealing that life does not always have simple answers or moments of resolution. Instead of a narrative with a hopeful and conclusive ending, we are presented with a never-ending story, one in which the process of adaptation and acceptance becomes the real challenge. Confrontation with uncertainty is what shapes our understanding of the human experience. Uncertainty requires us to reexamine what it means to persist both in literature and in life itself.

Yet, despite the struggles, living with a chronic illness has shown me that care itself goes beyond medical treatment; It also lies in the small gestures that preserve human connection: the friend who adjusts plans without asking, the professor who grants a day of absence without requiring proof, the family who understands when words weigh too much. These acts reject the idea that those who cannot contribute fully and efficiently are burdens, an idea that has brutally plagued me for many years and I am sure that I am not the only one. These gestures of understanding and support have reminded me that true humanity is found in empathy, in recognizing the invisible struggles of others. Empathy is not just about offering help when it’s needed, but about being present without expectations, about supporting someone without

expecting a payment in return. This form of care has allowed me to redefine my own sense of worth. Finally, I am learning to see myself beyond what I can or can’t do. I am beginning to move through the feelings of betrayal by my own body. Instead of focusing on what I lack and on what was, I have begun to value what I already am and who I can be. I have come to understand that existence itself is worthy of respect and love, without the need to meet other people’s standards. My existence alone is worthy of respect because I am a human being, just like everyone else.

A meaningful life isn’t just about how much we produce or how busy we are. It’s also about maintaining our well-being, being present for the people who matter, and knowing when to step back and recharge. Living with a chronic illness has taught me this firsthand. There are days when pushing through isn’t an option—when symptoms make even simple tasks exhausting. I’ve had to learn that rest isn’t a luxury; it’s a necessity. Ignoring that reality only leads to burnout and setbacks. Taking the time to care for ourselves and others doesn’t mean rejecting hard work or ambition; it means recognizing that we can’t pour from an empty cup. True strength isn’t just about endurance—it’s about knowing when to slow down so we can keep moving forward.

Nada Dorado Puede Quedarse

Lorren Richards

The weather changed and my fridge stopped working. I told myself it was a good excuse to order out. Yes, include plasticware. I’ve cleared the freezer-back of soggy boxes.

Nothing new’ s built to last says Mamita, or something to that effect.

I don’t know as much Spanish as I should, just enough to dream about her telling me to keep my spoons in the fridge, my cups in the freezer.

In “Pleasures of the Imagination” (1712), Joseph Addison stretches the boundaries of experiencing nature by suggesting that the natural world is not merely a spectacle to behold, but rather a source of powerful inspiration that humans can actively engage with. By evoking images of “an open Champain Country, a vast uncultivated Desart, huge Heaps of Mountains, high Rocks and Precipices, [and] a wide Expanse of Waters” (Addison 540), Addison emphasizes nature’s ability to stimulate the imagination and provoke a sense of awe. Yet, in our contemporary world—in which forests are cleared, deserts industrialized, mountains flattened, and waters depleted—where can we find the same kind of inspiration? How can we connect with nature when so little of it remains relatively untouched? On the one hand, we might turn to earlier depictions of the environment and draw inspiration from accounts of the natural world in literature, artwork, and other media. However, this approach relegates us to engaging with nature through a secondary lens and suppresses the individual relationship to nature that Addison and later thinkers, such as Denis E. Cosgrove, emphasize in their essays.

Perhaps, then, a more satisfying alternative is to broaden our vision for what it means to engage with nature—a process that involves redefining the very essence of what we consider “natural.” In the Anthropocene, an era in which human influence has profoundly reshaped the planet, we must redefine nature in ways that allow us to still access it meaningfully. One way to do this is through poetry that highlights instances of urban nature—seemingly ordinary but often overlooked moments of the natural world in everyday, human-dominated spaces. Although this reimagination of nature does not make climate preservation measures any less necessary, it can work in conjunction with conservation efforts to rebuild our access to the environment.

Before analyzing how we can engage with nature in the current environmental crisis, we must define what exactly “nature” and “the Anthropocene” mean. While Addison does not provide a clear definition of nature in his essay, his allusions to geographical features and untouched landscapes suggest that he imagines nature as something removed from human development. This interpretation aligns with the Oxford English Dictionary’s definition from

Emily Aikens

the eighteenth century, which describes nature as “the phenomena of the physical world collectively; esp. plants, animals, and other features and products of the earth itself, as opposed to humans and human creations.” However, in the twenty-first century, it is nearly impossible to separate humans and their actions from the natural world. As a result of human impact’s pervasiveness, we have entered what scientists refer to as “The Anthropocene Epoch,” an unofficial geological period in which human activity has become a dominant force in shaping the Earth’s environment. The Anthropocene is not merely a result of humans cutting down a few trees or drying up a few rivers. According to Paul Crutzen, the geologist and meteorologist who coined the era’s name, human activities have become so widespread that they disrupt natural cycles and put the Earth at risk for destruction (Crutzen, Steffen, and McNeill 614).

Scientists debate when exactly the Anthropocene began. While Crutzen believes that the epoch began as a result of the Industrial Revolution, other scientists trace its origins back to 1610 with the collision of the Old and New Worlds (Lewis and Maslin). But regardless of the debate over the

starting date, most scientists agree that the world has existed firmly within the Anthropocene epoch since 1950. By this period, the climate was experiencing what scientists have named “The Great Acceleration,” a term that refers to the sharp increase of harmful carbon emissions fueled by human activity. Since then, the situation has only become more dire; the Environmental Protection Agency projects that, unless humans take swift and drastic action, the Earth’s temperature will likely rise almost 8.6°F by 2100, leading to an increase in floods, droughts, heatwaves, and other destructive natural forces.

With these definitions and contexts in mind, I will now turn to examining Addison’s “Pleasures of the Imagination.” In his essay, Addison argues that nature is pleasurable not only when we experience it directly but also when we think about it conceptually. To clarify this distinction, he divides these pleasures into two categories: Primary Pleasures of the Imagination and Secondary Pleasures of the Imagination. The former refers to the experience of observing nature directly—the awe one feels when standing atop a mountain or gazing at a vast landscape, for example. In contrast, the Secondary Pleasures of the Imagination arise from ideas of natural objects. According to Addison, these ideas either “are called up into our Memories, or formed into agreeable Visions of Things that are either Absent or Fictitious” (Addison 537). In other words, there are several ways that these pleasures can manifest. For instance, imagine someone

Spring ‘25 - Care

standing in front of a beautiful meadow. While the direct visual experience engages the Primary Pleasures of the Imagination, Addison would argue that the individual in the meadow might also recall other beautiful sights they have seen and reflect on the very concept of beauty itself. These abstract ideas, which emerge from a blend of memory and inspiration drawn from nature, constitute the Secondary Pleasures of the Imagination. But one need not even be in front of a natural scene to engage these pleasures. For example, if someone were to look at a beautiful painting of a mountain, the Secondary Pleasures of the Imagination might conjure images of other mountains that the viewer has seen within their lifetime and the feelings associated with those experiences.

Thus, while both Primary and Secondary Pleasures can be activated by observing nature, the Secondary Pleasures are far more versatile, as they allow individuals to engage with nature even when they cannot physically be in a natural environment. Although Addison’s philosophy provides a compelling account of humans’ relationship to nature, we must acknowledge that Earth’s environmental landscape has changed greatly since Addison’s time. If human impact on the climate continues along its current trajectory, untouched natural spaces will become increasingly rare. As a result, access to scenes that Addison would have identified as capable of exciting the Primary Pleasures of the Imagination may be significantly diminished. While we can still access the Secondary Pleasures of the Imagination by

engaging with poems or artwork depicting nature, we must ask whether such a relationship with the natural world can fulfill us in the same way as direct observation of nature. Indeed, Addison argues that artistic imaginations of nature can be more pleasing than nature itself when he writes, “The Mind of Man requires something more perfect in Matter, than what it finds there, and can never meet with any Sight in Nature” and that “the Imagination can fancy to it self Things more Great, Strange, or Beautiful than the Eye ever saw” (Addison 569). Consider the artwork of famous landscape artist John Constable, for instance. Currently housed at the Yale University Art Gallery, Constable’s Hadleigh Castle, The Mouth of the Thames—Morning after a Stormy Night (1829) depicts a vast landscape from the perspective of the artist standing at the top of a mountain. From thick clouds in the distant sky, beams of light stream down in diagonal lines that almost perfectly mirror the sloping mountains and lines of trees below. By organizing the painting around these diagonal lines, Constable exaggerates the formal qualities shared by various elements of the landscape. Additionally, he juxtaposes his rugged application of pigment on the land with linear brushstrokes on the water to augment the expansiveness of the scene (Taylor). Through these stylistic choices, Constable manipulates an already beautiful landscape so that it appears ever more visually pleasing than nature itself—a strategy that fulfills Addison’s requirement for something so perfect that it transcends the limitations of material existence.

Just as a painter or a poet chooses which aspects of a natural scene to highlight in their work, the observer of nature engages in their own artistic process by selecting a viewpoint and lingering on certain elements they see—a process that engages both the Primary and Secondary Pleasures of the Imagination.

What, then, does all this mean for the larger question of how we engage with nature in the Anthropocene? In order to formulate an answer, we must consider the connections between Cosgrove’s definition of landscape and Addison’s Primary and Secondary Pleasures of the Imagination. While one might assume that the Primary Pleasures of the Imagination have a universal effect—for example, that all viewers of Niagara Falls feel a shared sense of awe— Cosgrove’s argument complicates this. According to Cosgrove, even when individuals observe the same scene, each person creates a distinct visual landscape in their mind. This means that everyone experiences their own, unique version of the Primary Pleasures of the Imagination. On top of that, each person develops unique manifestations of the Secondary Pleasures of the Imagination, as the ideas these pleasures evoke differ depending on each person’s unique experiences and memories of nature. However, as mentioned earlier, Primary Pleasures nevertheless remain preferable to the Secondary Pleasures given that nature’s vastness and intensity can never fully be captured through interpretive media. By combining the theories of Addison and Cosgrove, we arrive at the

Spring ‘25 - Care

conclusion that direct engagement with nature is essential for deriving a unique worldview, for it allows the viewer to interpret the world through their own lens, first through the Primary Pleasures of the Imagination and then by transforming those experiences into unique ideas through the Secondary Pleasures. While it is true that we can generate original thoughts based on others’ depictions of nature, these thoughts are inevitably removed from the raw, direct experience of nature itself. As such, relying solely on others’ representations of nature to excite our Secondary Pleasures of the Imagination cannot fully sustain our relationship to the natural world.

That said, the situation is not without hope. As Cosgrove argues, areas completely untouched by human influence are increasingly rare, if not entirely extinct. However, this does not mean that human-altered environments are devoid of natural value. By reimagining these spaces, it becomes possible to see them as part of the natural world in their own right. In Reimagining Urban Nature: Literary Imaginaries for Posthuman Cities, ecocritic Chantelle Bayes suggests that literature can play a vital role in this reframing when she writes, “written narrative can allow for alternative ways of thinking to emerge, thus enabling us to question some of the more damaging conceptions of the nonhuman and to reimagine the urban as a more-than-human space” (Bayes 42). In practice, this reframing consists of adopting a flexible definition of nature

and then using writing as a tool that can illuminate, and even romanticize, things that we might not appreciate as part of the natural world. As Bayes puts it, “the narrative text becomes a way of linking the conceptualization of nature with the everyday lived experiences of a wider audience.” Especially in the busy, urban settings that Bayes focuses on in her book, it can be difficult to pause and notice instances of nature— phenomena as simple as pigeons resting on street signs or ivy growing on the sides of buildings. However, by engaging with literature that draws attention to these details, we can reimagine our world as teeming with nature.

Given its ability to “encourage reader empathy by facilitating roletaking and transportation,” fiction is prioritized by Bayes as the most effective genre for allowing people to reimagine urban environments as containing nature (Bayes 225). However, poetry may be an even more powerful medium for this purpose, as it engages both the visual and aural senses. A strong example of poetry’s ability to highlight nature in unexpected places is Amy Clampitt’s “Times Square Water Music” (1987). By meditating on a puddle of water in a New York City subway station, the poem reframes a mundane sight as a remarkable manifestation of the wild in an urban setting. Instead of merely stating that water drips from the ceiling, Clampitt imagines it as a “musical / miniscule / waterfall.” This ekphrasis not only allows the reader to visualize the scene but also stimulates the ear. Specifically, the repetition of the “all” sound mimics the flowing

individual, direct relationship to nature that the Primary Pleasures require. However, I then considered the possibility of expanding the definition of nature to include manifestations of the natural world in urban settings. Although it can be difficult to reframe phenomena like puddles in a subway station as natural, I built on Bayes’ argument about the power of narrative texts to demonstrate that poetry can help call our attention to the underlying beauty of such scenes. While increasingly few people have access to pristine landscapes, everyone has access to ordinary scenes of urban nature, such as street puddles or pigeons searching for food. Once we learn to recognize these scenes as natural through reading poetry like Clampitt’s “Times Square Water Music,” it will become easier to find our own examples of these scenes, create a direct relationship with them, and stimulate the Primary and Secondary Pleasures of the Imagination. This reframing of nature doesn’t replace the need to protect traditional, untouched landscapes, but it does provide a more inclusive path to reconnect with the environment in a time when ecological access is limited. Moreover, this heightened attention to urban nature has the potential to serve broader conservation efforts. By using poetry as a model for learning to appreciate and value the non-traditional nature around us—whether small, urban, or overlooked—we can generate care for the environment that can extend to larger, more fragile ecosystems. In this way, poetry becomes not only a tool for helping us notice instances of

Spring ‘25 - Care

nature but also a vehicle for fostering broader environmental awareness and advocacy.

Works Cited

Bayes, Chantelle. Reimagining Urban Nature: Literary Imaginaries for Posthuman Cities. Liverpool University Press, 2023. JSTOR, https:// doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv33b9qcd. Accessed 8 Dec. 2024.

Bond, Donald Frederic, and Joseph Addison. The Spectator. Oxford UP, 1965.

Clampitt, Amy. “Times Square Water Music.” 1987.

“Climate Change Indicators: Weather and Climate | US EPA.” US EPA, 27 June 2024, www.epa.gov/climateindicators/weather-climate.

Constable, John. Hadleigh Castle, The Mouth of the Thames— Morning after a Stormy Night. 1829, Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven.

Cosgrove, Denis E. Social Formation and Symbolic Landscape. Univ of Wisconsin Press, 1998.

Damian Taylor, ““As if every particle was alive”: The Charged Canvas of Constable’s Hadleigh Castle”, British Art Studies, Issue 8, https://doi.org/10.17658/ issn.2058-5462/issue-08/ dtaylor.

Graham, Jorie. “Are We Extinct Yet.” To 2040. Copper Canyon Press, 2023.

Lewis, S., Maslin, M. “Defining the Anthropocene.” Nature 519, 171–180 (2015). https:// doi.org/10.1038/nature14258.

“Nature, N.” Oxford English Dictionary, Oxford UP, September 2024, https://doi.org/10.1093/ OED/1850732511.

Steffen, Will, et al. “The Anthropocene: Are Humans Now Overwhelming the Great Forces of Nature?” Ambio, vol. 36, no. 8, 2007, pp. 614–21. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/ stable/25547826. Accessed 8 Dec. 2024.

Evie Erickson

RES for you

its representation in art. In tragedy, the audience finds meaning through reuniting with the world and humanity in the aesthetic.

When an individual discovers a disorderly passion in art, they get a glimpse into the Dionysian, which sets forth how beauty and pleasure can be experienced in the face of pain and sorrow. Within this glimpse, Nietzsche claims that an individual can see her modern existence, with all its perfection, rationality and moderation but beneath that a “hidden substratum of suffering and of knowledge.” Both the Dionysian and Apollonian were necessary for a fulfilling experience, as embodied in Greek tragedy. The Dionysian must be

balanced by Apollonian elements to maintain a sense of illusion, or a filter, which makes the tragedy consumable. The viewer can feel pain through an actor or song, and from this, experience an ecstatic and cathartic release because this art is representative. They cannot and should not experience all that the Dionysian world consists of, for in modernity they are too removed from that stagnant, instinctual state to relate to it completely. Additionally, we have seen how life that is predominantly Apollonian is equally, although differently, flawed. Tragic art is fulfilling to the viewer because its dialectic, as presented to them in the majesty of theater or song, or in moderation, evokes and reconnects one with lost

but essential instinctual feelings; they are understanding life in a romanticized fashion.

The depth and profound nature of this reconnection is expressed by Nietzsche, by way of Schopenhauer. Nietzsche compares the meaning one derives from aesthetic beauty with a newfound close relationship with the “primordial being.” I suggest that this association with a primordial being is symbolic of the intense unity one feels in experiencing the aesthetic. Within this symbolism, the universe is imagined as a figure embodied by a primordial god-like being. What initially may seem dramatic is reasonable, for when viewers are engaging with a tragedy, they are experiencing a breakthrough, a moment of awe or ecstasy, the sublime, and relief from the absurd . Nietzsche pictures himself as one of the Greeks experiencing tragedy, trying to imagine “how the ecstatic tone of the Dionysian festival sounded in ever more luring and bewitching strains into this artificially confined world built on appearance and moderation, how in these strains all the undueness of nature, in joy, sorrow, and knowledge, even to the transpiercing shriek, became audible.” He enthusiastically describes the release of previously suppressed instinctual feelings from their restraints. Through experiencing the aesthetic, the world now feels comfortable and familiar, like

home. The totality of life is realized as primal unity–whose lack thereof caused loneliness within the viewer–is now tangible and, as loneliness fades, the viewer is reunited with their place in the world.

Since tragic art reunites the audience with the world and their existence, it follows that the artist crafting the tragedy should experience this as well. If tragic art contains this sense of universality, must not the artist composing the tragedy contain this feeling? If the art connects one to the universal and the social, then it follows that the artist producing the art must also be involved with the universal. Similar to the experience of viewing art, Nietzsche argues, to create tragic art, one must surrender themselves to the Dionysian, so they can feel the contradiction between the instinctual and rational, and then reproduce it, so it is present in the art as a representation of itself. As they have surrendered their subjectivity in the Dionysian process and can identify their oneness with the world in the art they have made, similar to the audience, this creative experience provides a sense of peace for the artist . Nietzsche claims that artists giving into the Dionysian is not only beneficial, but necessary in the creation of profound art. Consequently, the very act of producing art is interconnected to the experience of unity. Due to its ability to reunify

one with the world and their existence, I argue that the creation and showing of tragic art is an act of service and care. The individualism inherent to modernity and the Apollonian is broken down in art as it forcibly connects one with the Dionysian and feelings of unity. Tragic art challenges the carefully calculated preconceptions one has of themselves and of their lives. The familiarity of loneliness is confronted with a Dionysian underbelly of emotion. It’s something of an act of bravery to truly commit oneself to that fundamentally life-altering experience. But, as we’ve seen, that experience of the aesthetic or of tragic art is crucial to finding meaning in our existence. For these reasons I propose that becoming acquainted with tragedy is an act of caring for oneself. As we’ve seen from the role of the artist, the creation of art requires sacrificing one’s subjectivity to the objectivity of primal unity, therefore its conception is a selfless one. The essential beginning of art is in sacrifice, and this sacrifice is given for a sense of oneness that remains with the art. The continued practice of making art then must be demonstrative of a continuous desire to look beyond oneself, to connect with the world and with others. Therefore the process of creating art is imbued with care.

Nietzsche’s The Birth of Tragedy provides a profound explanation for the great beauty and power that tragic

The essential beginning of art is in sacrifice, and this sacrifice is given for a sense of oneness that remains with the art. The continued practice of making art then must be demonstrative of a continuous desire to look beyond oneself, to connect with the world and with others.

“

art has. I used his ideas as a foundation to argue that tragic art unifies people with the world through its distinctive connection to oneness through the labor of the audience and artist, and thus inherent to their ability to lead a fulfilling life are acts of care. Engaging with tragic art brings relief and purpose to an artist and audience not without labor from both of them. Tragic art is paramount to finding meaning and cultivating care for ourselves and those around us in the context of a lonely, painful modern existence.

Nietzsche, Friedrich. The Complete Works of Friedrich Nietzsche: The Birth of Tragedy. Edited by Oscar Levy, Translated by WM.A. Haussmann. The Edinburgh Press, 1923 bibliography

Plans for the Apocalypse

If Susie likes apples and Jerome only eats oranges and a train leaves Albuquerque at 12:46pm headed toward Chicago at 65 mph and the world explodes and you’re one of the remaining humans who remake the rules, what would you do with time?

The sand pours through our fingers at an irregular clip, immeasurable unlike the hourglasses some timemaster metered out precisely.

A sandbox in the desert is like a pool next to the beach. Sand, sand, more sand. Sand that whips up with the fierce wind into a vortex storming across the landscape. It catches us on our walk back to the house, pelting us, blinding us, filling our shoes. We shriek in its midst and laugh long into its wake.

Time stops when our laughter does. We go quiet, lie down, or stare at the bigness of the New Mexico sky, the clouds with their magical moving edges. Briefly. Then we’re back to cackling.

There is no backwards here. In other words, there is no place where we all began nor the various crossroads at which we picked different directions. There is no time to which you can return where we weren’t already together, which must be how we see in each other all that needs seeing.

How do you want to be seen? Ask me again. Ask every question that pulls at the boundaries of me until I’m lying in a pool of myself surrounded by old magazines. Then ask me to find a mouse and tiny bats, and I won’t sleep until I do.

I won’t get out of the hot tub with you until the full moon crests the roof. I won’t leave this chair until we’ve witnessed every color of this big sky sunset. I won’t let Susie have the apples or Jerome eat the oranges if it will stop my train from departing Albuquerque.

Build me an owl kingdom and I will manufacture time there into a matter that does not draw us away from each other.

Build me an owl kingdom and meet me there before the world explodes.

Marisa Lanker Paniello

Arrhythmia

Alain Co & Emiland Kray

Arrhythmia is a collaborative artist book by Alain Co and Emiland Kray. The content of this book explores the clinging nature of past trauma and how those cycles persist within the lived realities of each artist. Pulled directly from the journals of Co and Kray, the text within this book shows hopelessness, violence, loneliness, worry, and fear in their most vulnerable states. This book was created with the intention that sharing these inner monologues could be a moment of recognition and comradery for individuals who suffer the same thoughts, harmful patterns, and compulsions.

The Madison Journal of Literary Criticism

EEEEEE JACK DUDEK THE RIDE

They shouldn’t have been in the car at all. There was a plane ticket in Zasha’s name, purchased by his mother, that now had to be refunded for mileage points.

Van Halen had been on the speaker for at least an hour. It was one of the only artists Zasha and his mother could agree on, the perfect intersection between his metal abominations and her 80s pop. Any conversation between them existed only in their heads, but they did chime in with David Lee Roth’s interludes in ‘Hot for Teacher’: I don’t feel tardy. Gimme somethin’ to write on!

Sometime after the change onto the Queen Elizabeth Way, Zasha started to feel a guilty irritation at the silence but couldn’t figure out how to fix it. Eventually, his mother did it for him.

“You want me to pick up something on the way home?”

It annoyed him how pleasant she was being about the whole thing—as if he wasn’t ruining her weekend.

“Lloyd? Rin Thai? Could get you some of those chicken jammers,” she persisted.

“Don’t worry about it,” Zasha said. “I can make myself something when we get home.”

“Even with no border traffic we won’t be back till nine or ten,” she said. “Just let me know. We can stop wherever you want. If it’s open.”

Zasha looked out the window, even though there was nothing to look at. It was all Canadian wasteland; the endless grey ribbon of highway that took him where he needed to go. Whether it was time to go to school or to come home.

Today he was coming home.

The video call had started as their usual check-in. The two of them would talk on Facetime every couple of weeks and rarely ever between. He told himself this was so they would have more to talk about, but he knew it was something else. Every week he was away from home it got more difficult to speak and think about home, to try and make himself into a person who could talk to the woman who knew him before he knew himself.

She had begun with her worries. Usually they were about grades and schoolwork, but today she was only concerned about him. It was a bad sign. Zasha hated how she knew right away when things were wrong. He knew he shouldn’t have confided so much in her when he still lived at home.

She could tell what misery looked like on him but she couldn’t do anything about it now and that only made things worse for both of them.

“I know you don’t want me asking,” she started. “But are you doing okay?”

Zasha nodded. I’m fine never worked for her and he had nothing more convincing.

She focused on something behind the camera. “You know I don’t care about the grades or anything else as long as you’re healthy and happy.”

“I know that.”

“Do you talk to anyone out there, you know, professional?” She asked. “I know you had those counselors in high school and I wonder if MSU has some too. I heard they’re even free for students.”

“I’ve looked into it,” he lied. “The schedules just didn’t line up with classes.”

Spring ‘25 - Care

“Okie-dokie,” she said. Of course she knew, but she wasn’t going to push him on it and that was enough right now. “Why don’t you come home for a little while?”

“I can’t—” he started.

“I’ll pay for the flight. Don’t worry about anything.” He hated the unflinching niceness she extended when things were wrong. When he was in high school they would fight every Sunday evening and have to storm off to their separate rooms before one of them apologized hours later. Her politeness, offering hundreds of dollars for his well being, was an acknowledgment that she knew he couldn’t fight back.

The rest was easy. Professors were all too accommodating when presented with the words medical leave of absence, and nobody asked any questions except how long it was going to be. ‘At least for the semester’ was his answer, and that was enough. The scholarship office confirmed the money would still be there when he returned.

Zasha wished somebody was as annoyed as he was. The same people who had demanded papers be turned in on the due date, no extensions, were suddenly willing to make concessions indefinitely. Everything that had sent him into fits of despair days ago didn’t matter to anyone anymore.

Two weeks before he was scheduled to fly, he and his mom had another call. He couldn’t remember afterward what it was that set him off, but while she was speaking he started to uncontrollably, violently

cry in front of her for the first time since he was a child.

“Honey, what is it?” she asked.

He couldn’t look at her for several seconds. The wetness in his throat and on his face was overwhelming and his breath came out in short, shallow gasps.

“I don’t think I can travel alone,” was all he could say. “I don’t think I can do it, I don’t- I can’t do it.”

Concern flooded her face. “Do you want me or your dad to come get you?”

The weight of this childishness buried and paralyzed him. After all the distance, the escape from home, hooking up with strangers his parents would never hear about, he was back here. Crying to his mother while she offered to come pick him up.

He nodded and wiped his nose.

“Don’t worry about anything,” she said. “I’ll figure out when I can come get you, okay? It’s going to be okay.”

Zasha sipped water and tried to calm himself down.

“Do you hear me? It’s all going to be okay.”

It didn’t take long to pack, his suitcase filled with chinos and Carhartt sweatshirts cushioned in toiletries. 88_ 92_ 96_ 100_104_108_ 5_ 7_ 9_ 11_ 13_ 15_

SANCTUARY EMMETT KRONER

Interior

Jessie Burton

I can guess what you’re thinking Rose, and yes, I asked Ma about the flowers and tried everything in my power to stop her from buying them. Despite my constant remarks that “we got no money,” she did her usual thing and “made things work.” She made the rash decision to sell the carousel just so you can be buried covered in a blanket of roses.

We didn’t know the day of the funeral would feel so lifeless. In our nightmares, this day would be bright and colorful, a day made to remember you the way we did——beautiful, impulsive, and snide, but the only hints of color were the scarlet roses that seemed to suck out everything in the world that made it worth living. All was black and white except for you, your casket adorned with vibrant roses, acting as a shield from all the dread this world harbors.

I stood next to Ma during everything. I didn’t cry—my tear ducts were dry. Not because I don’t love you. Ma cried passionately, her dark wrist pressed against her chest, crumbling the same wet tissue she held for the past four hours. She blamed the meds; she blamed the health care system and all its racism, but she also blamed herself.

“She would have such a big head if she knew everything had gone her way,” I told Ma. “I mean, she already did, physically speaking…”

“You and your jokes. You betta hope Rose don’t hear that,” Ma grimaced as she wiped away her tears.

We stayed near the Smith’s funeral home for a half an hour more once you were in the ground. Everyone left except for the immediates. I held cousin Lila’s hand as we waited out front for our mothers to make their way back from the cemetery. The two of them together looked like war weary soldiers drenched head to toe, struggling to march through the mud as if coming from battle.

We used to trash on Auntie Jules all the time. I mean, I still do, but this day she was helping by taking extra care of Ma. She dressed like you’d expect. Flabs of skin pooled out of the fabricless pockets of her dress, and she struggled to walk in those Grimace-colored pumps you broke your ankle in during 2nd grade. But she was quiet today, watching over her sister without a single general out-ofpocket comment. Jules guided Ma through the day, as she could barely keep herself up.

It was odd to see how much they differed from their usual selves.

“Does heaven have carousels?” asked Lila, as we watched them walk towards us. “They do,” I said.

“Good. Rose said she loves them.”

I peered down at Lila. A cute bunny tail held her comb-slicked, frizzy hair back. Playing with the pocket of her polka-dotted dress, she continued to gaze at the cemetery where you were buried.

The weight of everyone’s sadness was confusing to the child. Before the service, I had to entertain her, and we drew pictures in the back room of the church while everything settled. Her drawing was basic—a stick figure of you and Pop, frolicking among the swirling clouds of heaven as Pumpkin chased after y’all wagging her fluffy tail.You probably know this already, being up there and all, but Pumpkin is still alive so now I am concerned she knew something I didn’t. But, anyway, underneath everything was a large square with too many windows to count. Next to it was a circle with little shapes and lines through them. It was our diner, the old carousel just to the side. Ma, Jules, Lila, and I all stood disproportionately, holding each other’s little hand nubs. My smile was my entire face and my eyes were emotionless dots at the top of my shaved head. Sure, the piece lacked detail, but it was still impressive. So impressive that I didn’t have to pretend to know what anything was. I vowed to support her art career then on.

“Girl, stop playing with your pockets!” Auntie Jules snapped, giving Lila a little nudge on the shoulder. The baby pouted, her thin eyebrows squirming around. She looked like you and Ma when y’all are hiding something.

Lila dragged out a small Polaroid and gestured to me.

The photograph shined, bringing a soft warmness to my cheeks. It was a picture of you, me, and her on the diner’s carousel when it was actually working. I was on the puffin holding

baby Lila while you sat on the panda like you always did because, god forbid, you allow your brother the opportunity. Grudges aside, you looked happy. Elated even. I knew the photo was five years old because of my haircut and the baby I held. It was during your edgy Fall Out Boys era when you attempted to do your own silk presses. The lead singer is half black, right? No way in hell your hair could make that work.

You looked a mess, girl. But, I loved it. Something inside me bubbled, and I laughed and gestured the picture to Ma and Auntie Jules.

“I warned her,” Ma said, holding the Polaroid with shaking hands. She breathed in and out.

I turned to Lila and asked, “Where did you get the pic?”

“Rose gave it to me. She gave it to me last Christmas. As a gift. She told me to give it to you after she is put in the box.”

As we rode back home, I eased into confronting Ma one last time.

“Excuse me, Mrs. Harris,” I said politely in a British accent (don’t you dare put this down). “May I ask thee a question???”

Ma rolled her eyes, giggling as she reached over to the passenger seat and did her usual “stop talkin’ nonsense face push.” Her hands were rough yet gentle as her palm pressed against my cheek.

“Talk normal.”

“Won’t you miss the carousel?” I said.

“We don’t have the money for all that maintenance,” Ma said, voice cracking like an old radio going out of signal. “All ‘em customers barely used it and then it broke, so that company down on Wilson Street is gonna buy it. They already gave us the cash, you know that.”

“But can’t we pay them back off or something? We’ve done stuff like that. Maybe keeping it around

might be good for us. I mean, those customers didn’t use it, but Rose and I did, especially Rose. There are so many memories attached to it so I don’t see how you can just throw it away like it’s nothing—” The car jerked.

Ma’s voice became gravelly. “Like I said, it doesn’t work, and we don’t have the money to keep fixin’ some nonsense like a carousel. So put that talk somewhere else.”

The rest of the drive home was silent.

“We goin’ to Vegas, baby,” Auntie Jules said, waving around an envelope. It was Saturday night, only an hour before we closed. Only the usual customer, Ron (gross), was there, so it gave me the opportunity to hide in the corner booth and fold the cloth napkins to look extra presentable, like Ma prefers.

Ma and I have been working hard at the restaurant. Vince, too! During the day, Ma holds down the fort until Vince and I come back from school to be her servers as she cooks. It’sbeen getting oddly busy in the afternoons. I don’t know if the whole town of Belcrest knows you died, but there is this odd sort of pity that covers the tips left on the tables.

Sometimes Ma puts on makeup and her nice house dresses, but since the funeral she mainly wears her pajamas. None of the customers seem to care—she’s in the back, after all. I don’t want to sound like a jerk and ask my mother to dress up, but it’s a noticeable change.

“Why?” I asked Auntie Jules. “How did you get money—”

“What?” Ma’s voice bellowed.

The diner’s ceiling, adorned with marionettes and colorful trinkets, served as Ma’s backdrop as I watched her make a grand entrance from the kitchen. She wore that red striped pajama set from Target, making her resemble a large toddler. With the nearing toy train circling above on the ceiling rail, someone would have thought she was ready to grab hold of it at any moment and go Choo choo.

“What is all this racket, girl? It’s too late for this.” Ma reclined back onto the red shiny booth. I scooted over to give her more space.

“We leaving Jennie! To Vegas!” Jules cheered. “I got plane tickets, a hotel, and some spending money.”

“Now, how the hell did you—”

“We gotta be at the airport at 7:32 am on March 31st, so the boys can handle the restaurant for the week.” Jules pointed a manicured finger at me.

“Who the other boy?” Ma asked. She did not continue to question where Jules got the money or the specificity of the time of departure. But I could see the glint in her eye. The same sparkle I saw in your eyes when we applied for colleges.

“Vincent,” I said dubiously, still very concerned about the money Jules had in her possession. Ma closed her eyes, filling the room with a soft grumble. “You know I don’t trust that boy.”

I groaned. “Why did you hire him?”

“Because your sister told me too! I thought she liked him or something. But now he’s been pulling all that nonsense. And I made a fool out of myself tryin’ to get his parents to let him work here.”

I grabbed the stack of nearby napkins and began suffocating myself with them. “He’s made one mistake. He is a good person, Ma! He enjoys working with us… he is just a bit, well, dumb?”

“Bit-dumb-my-ass! I know he stealin’ my money. He betta be happy that I ain’t gone up to his mother and tell her what he did. She’d crumble seein’ me in her yard.”

“He isn’t stealing your money,” I muttered. The accusations reddened my cheeks. “It was one time. One time he miscalculated, Ma! He’s just a bit dumb, like I said.”

“And handsome,” Jules chirped.

“Miscalculated!” I reiterated.

“Seems to me the only time he miscalculates is when he is around my money.” Ma smacked her lips. “He lives up there in that castle . He thinks he can come up here and mess around with the common folk for “experience.” One thing for sure, my-black-ass ain’t takin’ none of it.” She slapped her hand onto the table, bringing order to the court. “Anyway Jules, keep talking. First, where the hell did you get that money?”

I sighed in relief.

The day came. Turns out Jules, like Pop, did some gambling and this time, things actually turned out okay. After learning this, I was originally against Ma taking a trip to the city of sin to indulge in the same ventures that nearly destroyed the Harrison family before; however, I am quite mature since your passing and had granted her this ONE vacation until I graduated high school. I mean, Jules did promise this was the last time, and Ma deserved some relaxation time. So I woke up around 5 am and hopped directly out of bed to help with their suitcases. Ma and Jules were to only be gone for a week, but they had fivestacked in the back of the Honda—I’m pretty sure one was just full of shoes.

“Remember to disinfect the sink after washing that chicken,” Ma said. She shut the trunk about three times until it closed. “We don’t need a Gubb Diner incident in this family. Also, update the food calendar and clean off the carousel after closing. Them guys down on Wilson are gonna come and pick it up in two days. All ‘em animals lookin’ real dirty.” She went into the car and slammed the door. The window went down, and she hollered, “Watch that boy, Vincent too!”

“Got it, Ma!” I saluted.

The one thing that bothered me was Ma didn’t give me a hug, but as she pulled away, her soft eyes held a strength, a fear of never seeing her son again, that touched me.

Silently, I promised to be safe and sound.

Once they pulled out of the driveway, I started my tasks. My first action was waking Lila, who’d stayed overnight. Lila laid in your bed surrounded by your stuffed animals. Lila had Mr. Jenkins nestled against her right armpit and Bubs against her left. Two bunny ears stuck out under her head, and I knew that was under there suffocating. I could have hidden all the stuffies knowing how you didn’t even let me touch them despite them being gifted to both of us on our birthday, but Lila has been anxious. She’s catching on that you’re no longer with us, so everything that was yours, she latches on to.

I poked her cheek until her eyes fluttered open. “Gotta get to work, sis!” Lila sprung up and hugged my arm, squishing her face into my shoulder. I patted her head, shaping her matted curls into

a more uniform shape. “Let’s go get you ready.”

So I did my usual task plus one. Drove us to the diner. Made her breakfast. Lila sat with a fat stack of pancakes, something her mother didn’t let her eat.

“Are you gonna eat, too?” Lila asked between each chew. “Mama said breakfast is an important day.”

“Nah. First off, something is wrong with that quote. It is supposed to be the most important meal of the day, and I have too much to do,” I said. Ma had left a complete list of things I needed to do before the diner opened at 9 am. I went one by one, starting with taking out the trash, then wiping down the counter, then preparing coffee for our regulars. Fortunately, Vince came in half an hour early and assisted with some tasks because I had to assemble ingredients.

I know you might be angry that Vince didn’t attend the funeral, but you know what his parents are like. They don’t let him out of the house unless it’s for sports, school, or work. They’re the type of people who looked us in the eyes only after finding out we brought cold lunches to school rather than eat the free hot lunches—so this should be no surprise to you.

Anyway, Vince wanted to be there. I promise. Every time he looks at me, I know he sees you and regrets not being there. You’re his best friend.

“Vince. I am counting on you today, okay? No mistakes!” I said, glaring up at him. It was hard being stern with him because, well, he is him. It was hard to take him seriously when his hair was shaved clean. Apparently, it’s a swim team thing so instead of those beautiful red curls, he looked like an overly pasteurized egg. Since the moment he came in, I tried not to make any comment, but that smile and those cheekbones mixed with that shiny bulb of a head made it difficult. Whenever our eyes met, the urge to giggle became irresistible.

“What?” Vince huffed.

“Nothing.” I jumped and slapped the top of his head. “Get to work!”

We worked nonstop.

Remember four years ago when it was just you, me, Vince, Ma, and Pa on Saturdays? There were five of us! FIVE! Now there’s only two of us, plus a kid who keeps wanting to help but keeps getting in the way. Vince toppled over her, dropping a plate of chicken and waffles. The whole day was a mess. Our last customer, Ron (ugh), left at 9:45pm so we could finally close up shop. Lila laid in one booth covered in her Elmo blanket and watched videos on her tablet. I tried making her go to sleep, but she said she couldn’t until she was back in your room strangling Moop.

Vince was drenched in sweat. Being the only server the entire day, he was moving so much. We could have switched off, but he doesn’t know Ma’s recipes like we do. Fortunately, he’s an athlete. Endurance is his game.

“I’m so tired,” Vince grumbled, flapping his collar. His neck was beet red and speckled all over.

“Me too,” I said, scrubbing my hands. “The smell of onions won’t go away.”

Approaching me, Vince took my hand and brought it to his nose. “Smells fine to me,” he sniffed. My hand just dangled there, the limpest wrist in existence.

I pulled away, smelling my hand once more. “Nope,” and I kept scrubbing, and kept scrubbing.

Once we completed Ma’s list and finished cleaning, only two things remained: the carousel and the food calendar! Upon hearing “carousel,” Lila leaped from the booth. I gave her a bucket and a mop while Vince carried out a bunch of the old blue towels and Dawn soap.

Our usual inky blackness met us as we exited the diner through its side door, the one by the carousel. The rain unleashed the smell of manure and grass. A big silhouette stood firm against the dark background. A gentle moonlight perfectly highlighted the carousel, the small brass ball on top glittering and casting its reflection on the neighboring oak.

I went and plugged it in, lights coming on underneath. A milky way of stars splattered the underside of its canopy. It was cloudy outside, but clusters of glowing orbs made up for it, making the night seem clear and bright. A joyous melody played as the animals rotated, the polar bear’s yellowing fur catching my attention. Since you left us, I have only come out to see the carousel two times, and each time I somehow missed this discoloration. She seemed to have withered over the years, her white painted coat crusting away.

Bringing my hand up, I felt the bear as it passed. It was uneven and full of cracks, as if she’d been fighting for life out in the cold. I am unsure how tough real polar bears have it, but I felt her history—a difficult, turbulent life of freezing winters and nurturing cubs— protecting them from orcas or whatever is out there in the snow. Polar bears are awesome.

Vince lifted Lila up to the operation board. She dramatically pressed a red button, and the carousel halted, yet the lights and music continued. It was just as beautiful still.

We filled the bucket with water and began disinfecting everything we could touch. Lila enjoyed wiping down the animals. She was ecstatic giving each of them names. She named the Moose Vince, named the puffin Rose, and named the seal after me. I was not sure if I agreed with this settlement because I thought that if you were a puffin, I would also be one since we’re twins, but Lila was adamant about her decision and even threatened me with the mop and a lawsuit when I tried to say otherwise.

By 11:30pm everything looked brand new–that is an overstatement. It felt new, as if the year of neglect that covered each animal no longer remained, and now the animals, lights and music had a new beginning.

The three of us sat on the ride against the center structure just to catch our breath. We sat in silence as the slow music of the carousel continued to play as we looked out to the field into the unknown. I didn’t want to move from this spot.

Lila took out her Elmo blanket, and we all made ourselves comfortable. Lila sat on my lap and Vince and I were shoulder to shoulder. We looked up at the stars that moved above us.

“You okay?” Vince asked as he turned to me. His voice lacked its usual strength. “Not sure.” I said. “Not sure.”

Vince took my hand and squeezed it. “It’s okay to be unsure.”

I stroked and patted the rough wooden floor. “She’s ready to leave.” I leaned my head on Vince’s shoulder. “I’ll see her again. I’ve just got to wait.”

Vince caressed my head, wiping the tears that now flooded my cheeks.

Isolation in Grief

Electra Sullivan

In this digital photograph is Electra’s father, who represents the heaviness of loss and self-reflection. With these emotional ties, the image embodies care of the mind and spirit.

“Craftivism,” a term popularized by activist and writer Betsy Greer, is the intersection of “crafting” and “activism” (Greer 8). Essentially, it is the crafting of objects to create community and facilitate social and political change. Since its inception, craftivism has been a means to express joy, care and anger. Trans and queer activists have adopted the term to craft materials to express queer joy and resilient community in the face of abandonment and oppression by the state. Craftivism, while certainly involving anger, centers joy and love for the self and community.

One of the most famous queer craftivist projects is the NAMES Project AIDS Memorial Quilt created in 1987, which memorialized thousands of people who died from AIDS and offered a way for the queer community to mourn. In this work, I look at the Norfolk Trans Joy Community quilt, a more recent example of craftism that continues the political legacy of the AIDS Memorial Quilt. The Norfolk Trans Joy Community quilt was created in 2023 by trans people and allies in Norwich, England, to offer trans

people a sense of community and to highlight trans joy in a society that is continually working to criminalize the trans body.

NAMES Project AIDS Memorial Quilt

One of the most notable works of craftivism is the NAMES Project AIDS Memorial Quilt. The government response to the AIDS crisis early in the epidemic was incredibly flawed and lacking, with Ronald Reagan’s administration staying almost completely silent on AIDS until 1987 (Oritz 89). Their only comments minimized the scope of the epidemic on the queer community, who were seen as immoral by the conservative Reagan administration (90) . Reagan’s administration abandoned queer people to fend for themselves during the AIDS epidemic, which left the care for themselves in their communities’ hands.

The NAMES Project AIDS Memorial Quilt, created in 1987, was crafted in mourning and in protest to the government’s abandonment of queer people. The quilt initially consisted of 1,920 squares, each memorializing a person who died of AIDS, made by themselves or those who loved them (“The History of the Quilt”). Cleve

Jones, who conceived the initial concept, hoped that it would serve not only as a communal form of healing in dealing with the great loss the community was feeling, but also to publicly shame the government for their apathy and failure to recognize and provide support to the queer community (“AIDS Memorial Quilt”). People combined their anger towards the government with their love and sadness towards losing someone close to them and channeled it into a quilt devoted to honoring those lost in the epidemic. On this topic, scholar Daniel Fountain writes in their essay “‘Queer Quilts’: A Patchworked History,” “Although the blocks can be exhibited independently of one another, the idea is that each panel –each life– would never be isolated or alone, even in death” (“The Norfolk Trans Joy Community Quilt Zine” 7). The Reagan Administration had abandoned the queer community, and many people with AIDS found themselves ostracized from their families and society. The quilt offered comfort that many people were deprived of. The AIDS quilt simultaneously allowed queer people to come together as a community and mourn those they had lost, while also showing that the government did not acknowledge the scope of the epidemic.

of male and female.” This hierarchy separated art from craft. Art forms of knitting, embroidery, quilting, etc., come to mind over the more “masculine” and therefore legitimate mediums of writing, painting, etc.., Associations with craft and queerness are tied, that they’re both seen as lower and not as legitimate than their more recognized counterparts (Fountain). However, Artist Ben Cuevas owns this association, writing of their personal connection to the link of crafting and queerness stating, “by knitting with my male body, and referencing that in my work, I’m queering gendered constructs of craft,” (qtd in Chaich & Oldham 137). Recognizing and reclaiming the connotations of queerness and craft, queer communities use this connection to materially render queer and trans experiences, including expressing joy and love for their community.

Implications of ‘Crafting’

The conventional definition of crafting is gendered as one that is feminine and therefore lower (Fountain). Fountain writes “that the development of a hierarchy of the arts coincided historically with a similar one between the categories

Quilting as a community practice was adopted by queer communities because quilting—as well as the act of gifting quilts—is a layered expression of love and care. Quilting teacher and writer Thomas Knauer in his essay “The Gift of a Quilt is an Act of Love” discusses the symbolism present in giving quilts, “warmth — once a literal protection against the elements — is also a symbolic means of protection, and our desire to protect is a reflection of the love we feel for another.” In other words, the gift of a quilt tells someone that they love and care for them, that in a literal sense you never want them to be cold and alone. Additionally, people make quilts to express love—the gift of a quilt involves incredible amounts of patience and care. In

make this a reality for transgender people. Despite the onslaught of cruelty thrown at trans people, they use craftivism as a means to express joy and challenge the narratives against them. An interviewee for the Norfolk Trans Joy Community Quilt Zine, K, said, “As much as I want to express my anger, trans joy is defiant. It can’t be legislated out of existence, defanged or sold. It doesn’t have one look and it contradicts itself. Its complexity is powerful, trans joy is a protest in itself” (Norfolk Trans Joy Community Quilt Zine 21). Anger is not absent in craftivism, as it is a response to injustice and abandonment of marginalized groups. However, joy is present in craftivism as well, which is a poignant form of protest against oppression. In other words, joy and anger are not mutually exclusive categories rather they mediate both ager and joy in the act of quilt making as both a form of political resistance and as an expression of love.

Even when not being portrayed as dangerous, trans people in mainstream narratives are subject to the trauma associated with being trans, such as the violence inflicted on them: suicide, and survival sex work to name a few. While these are all real issues affecting the trans community, hyperfocusing on these issues in the media creates a false narrative that trans people are joyless, which the Trans Community Quilt rejects. Alex, another person interviewed for contributing to the quilt said, “It helps to combat the tragedy of trans lives in lots of mainstream media, even in sympathetic cases.” (The Norfolk Trans Joy Community Quilt Zine 18). Instead of fetishizing trans

people through the lens of tragedy, the quilt highlights the joy in being transgender. Contributors expressed joy in their quilt squares in a variety of ways—such as memorializing achievements, or taking a more humorous approach. One square, made by a person named K, uses humor to express joy. Their square says “Orange you glad trans people exist?” Another square features embroidered rendering of the contributor’s chest nine months post top surgery. The quilt rejects the narrative that trans people are dangerous and tragic, but rather spotlights the joy for self and community in being transgender.

The Norfolk Trans Joy Community Quilt is not an American project, but it speaks to the importance of joy and care in queer communities, which America currently needs. The Trump administration has forsaken trangender people, but they and their communities still exist. The creation of the Trans Community quilt held recurring workshops for queer community members to gather and create. Workshops included free materials and instruction for creating the squares in addition to providing a safe community space for community members. Even today, the quilt creates opportunities for community building, exhibiting at various queer and trans events across England. Brannick and BigsbyBye wanted their project to inspire people to understand and contribute to their shared history (5). The quilt is therefore owned by the queer and trans community in addition to being made by and for the community.

As seen in the Norfolk Trans Joy Community Quilt,, craftivism is

The Madison Journal of Literary Criticism

joy and resistance. It expresses joy for the self and community and resistance to the state. Craftivism as a protest tradition has been practiced through the decades, with a notable queer example being the NAMES Project AIDS Memorial Quilt, which has inspired others such as the Norfolk Trans Joy Community Quilt. More research into craftivism, especially within more niche intersections, such as quilting and the trangender community, is needed by scholars. Resisting popular narratives of trans suffering, the Trans Joy Quilt reframes the trans experience around trans joy and community rather than suffering—especially pertinent to the coming years, in which it will likely be more and more difficult to publicly be queer and trans. defanged or sold. It doesn’t have one look and it contradicts itself. Its complexity is powerful, trans joy is a protest in itself” (Norfolk Trans Joy Community Quilt Zine 21). Anger is not absent in craftivism, as it is a response to injustice and abandonment of marginalized groups. However, joy is present in craftivism as well, which is a poignant form of protest against oppression. In other words, joy and anger are not mutually exclusive categories rather they mediate both ager and joy in the act of quilt making as both a form of political resistance and as an expression of love.

Even when not being portrayed as dangerous, trans people in mainstream narratives are subject to the trauma associated with being trans, such as the violence inflicted on them: suicide, and survival sex work to name a few. While these are all real issues affecting the trans community, hyperfocusing on

these issues in the media creates a false narrative that trans people are joyless, which the Trans Community Quilt rejects. Alex, another person interviewed for contributing to the quilt said, “It helps to combat the tragedy of trans lives in lots of mainstream media, even in sympathetic cases.” (The Norfolk Trans Joy Community Quilt Zine 18). Instead of fetishizing trans people through the lens of tragedy, the quilt highlights the joy in being transgender. Contributors expressed joy in their quilt squares in a variety of ways—such as memorializing achievements, or taking a more humorous approach. One square, made by a person named K, uses humor to express joy. Their square says “Orange you glad trans people exist?” Another square features embroidered rendering of the contributor’s chest nine months post top surgery. The quilt rejects the narrative that trans people are dangerous and tragic, but rather spotlights the joy for self and community in being transgender.

The Norfolk Trans Joy Community Quilt is not an American project, but it speaks to the importance of joy and care in queer communities, which America currently needs. The Trump administration has forsaken trangender people, but they and their communities still exist. The creation of the Trans Community quilt held recurring workshops for queer community members to gather and create. Workshops included free materials and instruction for creating the squares in addition to providing a safe community space for community members. Even today, the quilt creates opportunities for community building, exhibiting at

Lorren Richards

Pulled Apart

Anneliese Burke

Sydney Ziemniak

Subverting Gender Roles in Contexts Medieval and Modern

Julian of Norwich was an anchoress in the Middle Ages who saw a series of divine visions, which she detailed in A Book of Showings after contemplating them for over fifteen years. In chapters 58, 59, and 60, “Jesus as Mother,” Julian employs maternal imagery to describe Christ’s compassion and warmth while opposing the patriarchal society of her lifetime, a critique that remains applicable today. With an emphasis on affective piety, Julian not only diminishes the gender hierarchies of the medieval period but also invites contemporary readers to consider a more inclusive interpretation of religious leadership. By reorienting traditional roles of the divine, Julian challenges modern dichotomous standards of masculinity and femininity, presenting Christ as a spiritual leader who values empathy over dominance.

Julian first draws on affective piety to highlight Christ’s humanity. An influential practice during the Middle Ages, affective piety emphasizes a highly sensitive devotion to Christ, inviting believers to deeply empathize with his suffering. Julian compares the relationship between humans and Christ to an equal marriage, writing that “in the knitting and in the oneing he is our very true spouse and we his loved wife and his fair maiden, with which wife he was never displeased” (227). By referring to humans as the “loved wife” of Christ, Julian places mortals on the same level as God, encouraging an emotional attachment to the divine rather than a fearful one. The term “knitting” suggests an interweaving of two separate threads, reinforcing that Christ and his believers are linked in a relationship of mutual love. Similarly, Julian’s word choice of “oneing” conveys unity, breaking down the traditional hierarchy in which Christ rules over humanity in favor of an intimate, reciprocal bond. In her metaphor of Christ as a “true spouse” who is “never displeased” with his followers, Julian further challenges the traditional model of marriage as an arranged relationship of male dominance and female subjugation. Rather than Christ

Spring ‘25 - Care

being a punitive ruler or a possessive spouse, Julian argues he views his followers with mutual love and equality.

Julian then depicts Christ as a mother, challenging traditional patriarchal views of leadership by equating his sacrifice with the physical and emotional labor of motherhood, arguing for a more compassionate and inclusive model of divinity. Julian highlights the passion of Christ when she states, “[O]ur very Mother Jesu, he alone beareth us to joy and to endless living, blessed moot he be. Thus he sustaineth us within him in love and travail, into the full time that he would suffer the sharpest thorns and grievous pains that ever were and ever shall be, and died at the last” (Julian 229). By emphasizing Jesus’s intense suffering, Julian employs affective piety with an appeal to Christians’ emotions. In referring to him as “Mother Jesu,” she prompts readers to compare the grievous pains that mothers endure, such as pregnancy and childbirth, to the suffering Jesus experienced to save his believers. Her parallel between the burdensome aspects of motherhood and the passion of Christ reminds believers that the crucifixion was a sacrificial act of love for humanity. Further, Julian redefines both acts—Jesus’s suffering and mothers’ pain—as voluntary, intentional love, rather than mere obligations. In a Medieval society that saw motherhood as an inevitable responsibility for women, Julian’s portrayal of Christ as a motherly figure who chooses to undergo suffering offers a radical reimagining of divine authority. Like Jesus’s conscious acceptance of the crucifixion to redeem humanity, maternal love involves a willing undertaking of emotional and physical labor. Her interpretation challenges the traditional assumption that suffering is an unavoidable burden of motherhood, instead depicting it as an expression of active, selfless love.