Spring 2024

Co-Editor in Chief

Ria Dhingra

Anna Nelson

Managing Director

Landis Varughese

Graphics and Layout

Emily Wesoloski

Cree Faber

Managing Editor

Ella Olson

Publishing Director

Sophia Smith

Operations Assistant

Quinn Henneger

Treasurer

Jonathan Tostrud

Social Media Manager

Eleana Anderson

Fiction/Prose/Poetry Editor

Ray Kirsch

Wll Hicks

Nonficton Editor

Aspen Oblewski

Mary Murphy Stroth

Art Editor

Lexi Spevacek

Academic Essay Editor

Mina Ankhet

Celeste Li

Special Thanks

Lacey brooks

Chloe Henry

The MJLC Study Group

Letter From The Editors

Speculative Fiction: The Importance of Dreaming of a Socially Just World

Coffee (Prose) - Mason Koa

A Classical Analysis On Gender Fluidity In A Modern World (Art) - Hailey Johnson

Spring Of Conciousness (Prose) - Evan Randle

Swimming Pool By Desert Landscape (Art) - Daniel Miter

Apocalypse (Prose) - AS

Soñando Con Más (Poetry) - Nilvio Alexander Pungil Bravo

Designing The Dream Neighborhood - MJLC Staff

Energy Of Tomorrow (Art) - Jacqueline Wisniski

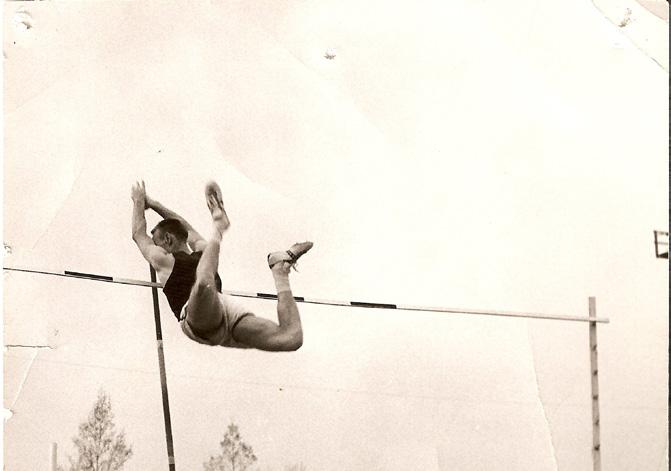

Raising The Bar (Poetry) - Larry Hollist

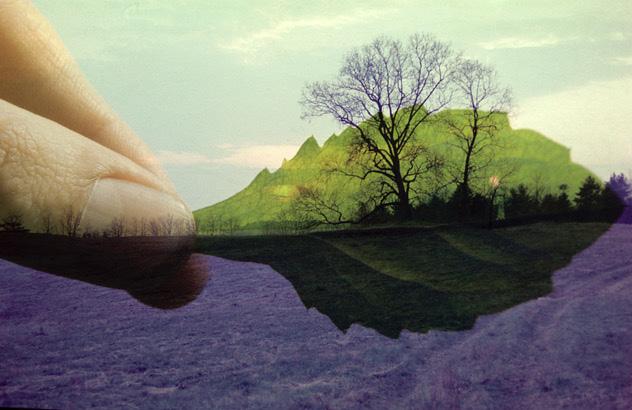

Landscape With Held Leaf (Art) - Charter Weeks

Armored Flesh (Academic Essay) Chyna Evans

Kansas City Dreaming: AWP - MJLC Staff

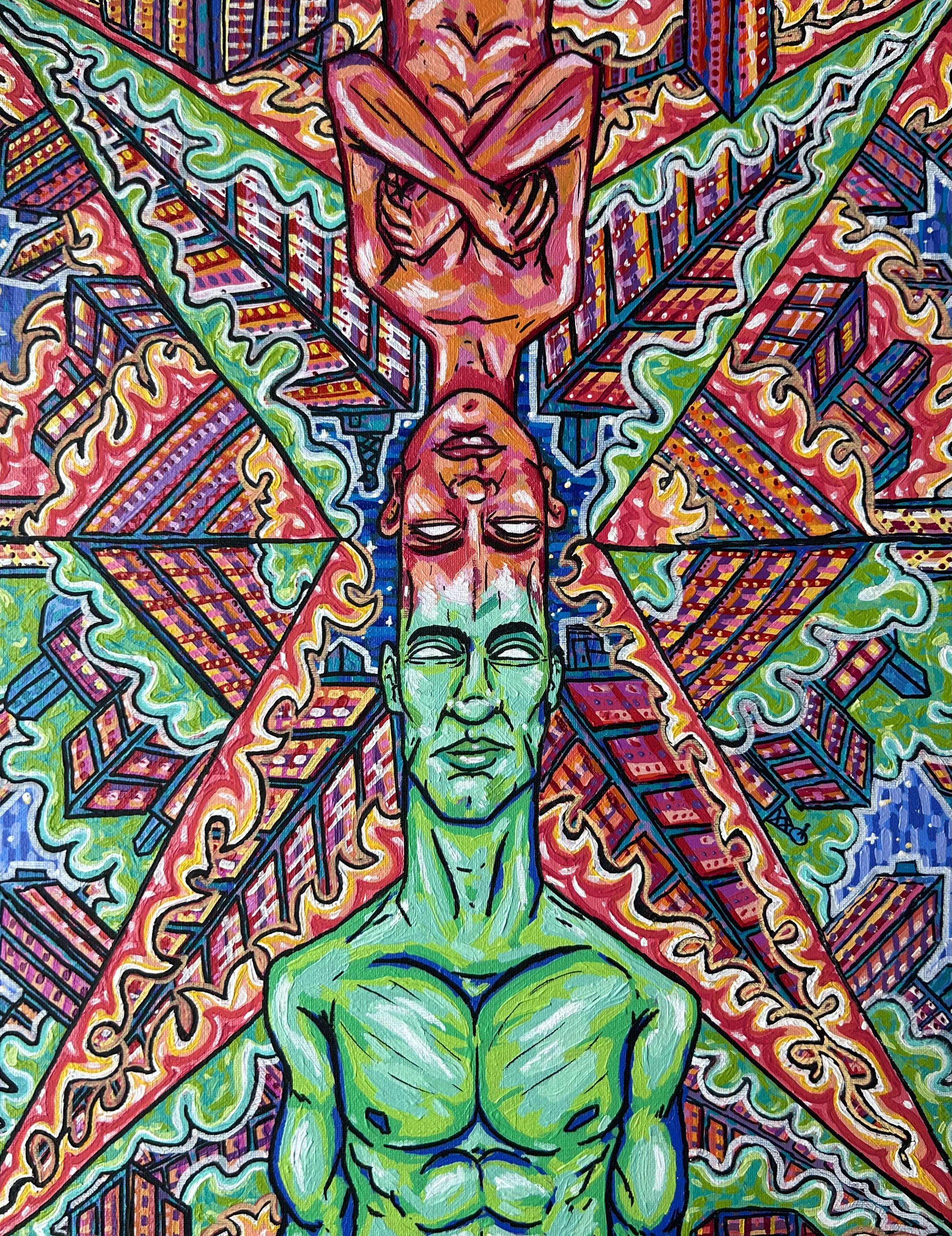

Technicolor Dream (Art) - Katie Hughbanks

The Ballad Of Antione Featherfluffer, And Cupid (Nonfiction) - Leah Johnson

Explorer (Art) - Riley Haller

I’ll Never Be A Butterfly (Poetry) - Boden Williams

Dewdrop Waltz (Art) - Katie Hughbanks

Abolition Isn’t A Blueprint - Ria Dhingra

In Her Gentle Gaze The Little Butterfly Falls On The Stele (Art) - Steve Qi

The Day The World Will Collapse - Ray Kirsch

One Of Many (Nonfiction) - Lily Spanbauer

Ethereal Connections (Art) - Shashwot Tripathy

The Death Of Hemingway (Prose) - Taylor Root

Wooden Canoe In Pool, Lone Pine, CA (Art) - Daniel Mirer

Idyllic Dreams And Dystopian Nightmares - Mina Ankhet

After Listening To Copland’s Appalachian Spring (Poetry) - John Muro

In Reverie (Art) - Erika Lynet Salvador

Green World Dreaming (Academic Essay) Mackenzie Dimond

poor Madeline (Poetry) - Holly Hartford

Dream Or Nightmare? (Art) - Chloe Henry

Nostalgia (Prose) - Annika Thiel

Haley And Emma (Art) - Meg Bierce

I Hold You (Poetry) - Victor Stoesz

Calling Out Barbie - Aspen Oblewski

For You (Art) - Gabriel Lange Salud

Speculative Thinking

Sweet Dreams: Moth StorySLAM - MJLC Staff

Dream Time (Art) - Charter Weeks

Different Worlds (Art) - Charlotte Knihtla

If I Could Be Eve (Poetry) Nicole King

Ashes And Dreams (Prose) - Aelia Chang

A Dreamy Double Bill (Nonfiction) - Lance Li

You Start To Slowly Roll Your Wrists And Ankles… (Art) - Emiland Kray

Whisper In The Wind (Art) - Erin Murphy Stroth

The MJLC Dream Reading List

Following our transformation of the Madison Journal of Literary Criticism into an abolitionist study group and magazine, this Spring 2024 edition sets out to further expand our mission of social and literary critique. This edition captures the process of dreaming in its multitude of forms and emphasizes how imaginative creativity is required to both envision and work towards an abolitionist future.

As our study group this semester engaged with topics of radical design, ideal theory, utopias/dystopias, speculative fiction, and questioned the role of visionary planning in relation to social change, our publication conveys their multiple interpretations of “dream.” This edition showcases how individual dreams and aspirations can break apart social constructs and transfigure into collective desires. From poetry about Eden to essays about the Iranian Revolution and 2023’s Barbie, this collection examines dreams through the various mediums of essays, art, fiction, journalism, and poetry. We are honored to share the work of these talented artists. In creating this collaborative publication, we are grateful to our study group for their ingenuity, our contributors for their work, and our staff for their dedication.

Dreaming is a future-directed process that we do from a present reality. And it requires us to look differently at our past dreams as well. In our study group, we often use the idea of form and function to look at historical patterns. We recognize that while America has moved between forms of enslavement to disenfranchisement to segregation and mass incarceration, the function of oppression remains strong. So while we see change—past dreams come to life—we also see the need to dream bigger.

And there is inherent difficulty in this dreaming. Today, in the midst of genocide, an impeding election, and post-pandemic world that has illuminated longstanding carceral failings to more individuals, dreaming of a better future is for some a privilege and for others an inherent survival strategy. To dream is to not only consider what can be better, but to grapple with what is wrong now—a heavy burden to consider, experience, and reckon with. There is weight in questioning every system we rely on and the compliance our own practices have in perpetuating systems of harm. There is weight in feeling

responsible for what is to come in the future, to have a dream of a kinder world without being able to articulate the steps on how to get there.

And despite the difficulties of dreaming, continuing to dream and act in accordance with those ideals is how we keep moving. The power of dreaming lies not just in its promises for the future—we dream for the act of dreaming itself. We dream to persevere. Over the years, countless abolitionists and trailblazers have been told their dreams are not possible. Yet, we keep dreaming. Yet, change continues to happen.

Dreaming is a practice of untethered hope. The very act is radical. It takes place in the mind, the one feature of the body that can never be surveilled or regulated. Doing so in community, dreaming together, is something that the creation of this publication has taught us the importance of. Our group’s biggest success is that we are still here—meeting every Tuesday for two years now, discussing the carceral, coming up with solutions, and acting in initiatives. Together, we create art and publish narratives often ignored in mainstream media. Together, we continue. We take care of one another. We take breaks and fill in for others when they do the same. We view dreaming as a collective activity where the burden of responsibility in social change is shared by all of us.

Dreams are a sort of lived reality. This was once our dream. The MJLC. A dream that would never have been possible without our community. Together, we have passed campus legislation, organized teaching events, started a podcast, created a platform for stories, and cultivated an environment for regular critical discussion. This is living proof of the change that comes from dreaming. Thank you all for dreaming with us these past two years. We are honored to have served as your Editor in Chiefs and ridiculously excited to see where this dream takes the rest of the team, our study group, and our community.

Keep asking questions. Keep creating. Keep dreaming of more.

With love, always, Ria Dhingra & Anna Nelson

Co-Editorsin Chief

by Ray Kirsch and Will Hicks

by Ray Kirsch and Will Hicks

It’s downright impossible to imagine next Thursday without participating in speculation. In some way, people engage in creating fiction for themselves every day: theorizing about traffic conditions, dreading tomorrow’s statistics homework, and deciding whether or not to bring an umbrella to work. These, of course, are small fictions, but they invariably contribute to tomorrow’s world. Speculative and visionary fiction, though, tend to focus on the less mundane. They dream of worlds void of discrimination or debilitating illness and entice readers to imagine what if, just for a moment, the world could be different than it is. It’s an immense genre, broader

than any one person can imagine. We interviewed Dr. Sami Schalk to get her perspective on this expanding field.

Dr. Sami Schalk has taught in the Department of Gender and Women’s Studies at the University of Wisconsin–Madison since 2017. She has taught countless Gender and Women’s Studies classes, focusing on disability and writers of color, as well as visionary and speculative fiction. As a creative writer herself, Dr. Schalk enjoys exploring social justice issues that her students are interested in; through her visionary and speculative fiction course, students from any major can deep-dive into a topic of their choosing. Dr. Schalk has published two books, Bodyminds Reimagined (2018) and Black Disability Politics (2022).

What exactly is visionary and speculative fiction and what is its significance?

Dr. Sami Schalk: Speculative fiction is this big umbrella term that really refers to any kind of fiction that is non-realist in some way. I like that term because as an academic, if you write about science fiction, people who are science fiction experts have very strict definitions of what science fiction is. It has to have a depiction of futuristic science and technology in it. But speculative fiction has this broader term that can be more magical—realistic things that are a little more fantasy and also include things like alternative histories.

Steven Barnes, for example, has a series that’s an alternative history of what if Africa had colonized the world and what that [would] look like instead. I like that term because I like things that also have more magical elements or things that blend the science fiction with magical elements in them. That happens with a lot of African and Caribbean speculative fiction writers. They incorporate these other kinds of magical elements and ancestral, spiritual sorts of things inside of it.

The term visionary fiction specifically comes from the work of adrienne maree brown and Walidah Imarisha, who edited a collection of short stories which we read from frequently in [Gender and Women’s Studies 359] called Octavia’s Brood. It’s inspired by the work of Octavia Butler. [Visionary fiction] has this list of specific things that have to be involved. It has to be approaching it from a social justice perspective, has to be focused on identity and marginalized identities, has to think about change coming from the bottom up, change being collective, and it has to be invested in hope. It has to be hard and realistic, but hopeful. It’s not a utopia. It’s not where everything has already been solved. We know that creating change is hard. It is intended to kind of fuel us in some way.

[Visionary fiction] is really a term that they developed, when they came up with the book, through working with organizers. They did these writing workshops with organizers and activists, some of whom did not identify as writers at all, to think about what it would mean to write a story about how we organize, how we create change, or what this better future looks like. This sort of fiction allows us to start to imagine it as the writers and as readers right to also say, “How would that work? What would that look like?” That’s kind of the point of this genre; now, we can go and identify things like

Butler’s work that was written well before this term was developed, but we can see that strain.

For me, my research, and in my teaching, I’ve realized that that’s the kind of speculative fiction that I’m most interested in reading. Teaching is that which inspires folks to think about how to do things differently, whether it is around abolitionist work, racial justice work, or disability justice work.

In the introduction to your book Bodyminds Reimagined, you briefly mentioned how you originally disliked speculative fiction and that it was Octavia Butler, a prominent Black science fiction author, who brought you into it. What about her works changed your mind?

SS: I read Kindred first, and then I read Parable of the Sower. I teach Parable of the Sower every time I teach [GWS 359]. It was the first time that I felt like I was reading science fiction that was directly speaking to social issues I cared about—and there was a representation of disabilities. My research interest is in disability and race; I was really excited about the way that disability was being represented.

So often, in our speculative fiction, it’s on these polar ends: either we’re in utopia where disability no longer exists and everyone’s able-bodied and ableminded all the time, or [we’re] in our like, dystopian, apocalypse version [where] everyone is disabled.

What role does reimagination and dreaming play in social justice activism?

SS: I think it allows us to imagine that things can turn out differently than what we have seen in our lifetime. Being able to give folks places of hope is really important. For my most recent book, I interviewed some activists. One of them works within the prison industrial complex, specifically with deaf and hard of hearing folks and ensuring that they have access to be able to speak to their loved ones but also to their lawyers. One of the things that this person was talking about was that when you’re addressing these huge systems, you have to have a different metric of success, right? For this person, their metric was like, “how many families have I reconnected?”

What I really liked in these stories is that sometimes the hope is like, “I’ve changed one person, I’ve changed my community, or I’ve figured out one way to resist and maybe it’s going to make a bigger difference down the line. But for now, at least I have

taken back some of my power.” That’s what I think is really important about these sorts of stories—the ability to dream is that it gives us that inspiration to be like, “I can keep going on, I can keep fighting back against this”—because it’s really easy for us to feel defeated by these systems, especially at the very large macro level.

How do you define abolition? Do you see a connection between the work you’re doing [in and outside of class] and abolition?

SS: I consider myself a person who’s learning and following [about abolition]. It feels new. I would say within the last like seven years, and I’ve really been able to dive more deeply into what it means. I come to the work mostly through disability justice work— thinking about institutions and incarceration, including psychiatric institutions and learning about the fact that so many folks with psychiatric disabilities are in prisons. It becomes one of the spaces [where] many disabled folks are being held.

For me, abolition is not just getting rid of prisons and jails but all systems of containment, coercive control, [and] punishment. For me, that expands into my teaching in the sense that I try really hard to have a classroom that is not punitive-oriented—I try not to be a police person in the classroom—to really allow students to show up in the ways that they need and be understanding about that. Moving away from systems is one of the ways that I see myself working toward that in my teaching, even [though] I don’t always necessarily teach about abolition directly. It often shows up to these other methods of moving us towards better and more free systems.

How would you respond to people who find that focusing on the speculative side, or the “what could have been” rather than the “what is,” is a waste of time?

SS: I think that there are folks who are gonna focus on the “what is right,” and I think that’s important. We also need folks who are imagining, where do we go from here? What comes next? What are the steps? What are the things that we want to move towards? We know these systems continue to morph

and change. There’s so many students that say, “Well, slavery [has] ended” or “The Civil Rights Act was passed. Therefore, it’s over.” These systems continue to shift.

We have to keep looking forward to think about what’s the actual horizon that we’re trying to get to when we need those folks that are pushing us towards better and better horizons. We don’t want to become complacent and to say, “Well, that’s good enough.” We know that there are still folks who are being marginalized, oppressed, harmed, and killed.

Ideally, what does an abolitionist world look like for you?

SS: A world where folks are not incarcerated, or otherwise contained against their will, a world where folks have support for their mental health needs, for their daily human needs. I think that an abolitionist world, it’s also a world where folks have housing, have access to food and education, and the bare minimum of life circumstances that we know actually leads for folks to end up in engagements with the prison industrial complex because of the fact that they don’t have their basic needs met. I think about the deinstitutionalization movement with the disability rights movement, where there was a push to end these institutions that were housing and people with disabilities—not just psychiatric disabilities, but disabilities of all sorts. The movement was to end them because they were causing harm to people; people were not being supported.

We know that we can’t just dismantle the existing kind of institutions of harm; we also have to create these other systems of support. For me, those things have to go hand in hand.

He tells me he has the same dream every night. He says, “Let me tell you this dream I’ve been having.” Then he tells me. Every morning.

I push his coffee forward on the counter. He stares at it and smiles weakly. He stands there, still in his pajamas.

The dream goes like so:

He is in bed. He is trapped. There are many of him in the labyrinth. Each room is a mirror, many a man trapped. Everywhere he goes, more mirrors of him, watching. The rooms are striped.

He goes to a big white box; a real nice big white box, he says. He waits in line to reach the box, more mirror men in the way. Then there’s a hole in the box and a young guy in the hole, and the young guy says, he says, “Good morning, fella, have some coffee.”

But the coffee is bad. So damn bad, he tells me. By this time, tears are strolling down his face. He rants. He rants, the coffee was so bad in the dream. He rants that they only used coffee because the bitterness covers up the taste of the small eggs inside. The little eggs, stale-white with a gloss. When he drinks the coffee, they hatch. They hatch, and they hatch into big dark monsters. Giant shadows that creep up the walls, clawing for the windows. He says he tried to open the windows so the shadows could leave, but no, the mirror men stop him and grab him and put him back in line with the striped rooms. The shadows are angry and get bigger and bigger, he tells me.

Sometimes, they get so big and swallow him whole. Then all there is to see is blackness. So he takes his empty coffee cup and gives it back, the shadow still with him. He walks to his room, and the darkness whispers to him, “We gotta get out of here, friend. That guy, he doesn’t like us. He isn’t like us, like you and me.”

“You’re right,” he says, and he breaks free, running from all the mirror men and striped rooms and he realizes that they’re all chasing him through the maze. Even the rooms, bounding after him like gray tigers. They roar and he keeps running. He gets to a gate, and climbs over, panting.

But there are more men. They grab him by the arms and into the striped rooms, the tigers. He screams, he tells me, but the men only shake their heads, muttering, “again, again, again.”

I stand there, checking behind him to make sure the others in line aren’t getting impatient. They aren’t. They never do.

He continues, saying they force him back into the room, the stomach of a beast. He says he cries and goes to sleep. Oh, the shadows are still with him, hatched from the eggs, whispering back and forth, lulling him to slumber.

Then he wakes up from his dream, he says, and now he’s here.

Shaking, I see him reach his forefingers into the coffee, and pull out two glossy eggs, slightly dissolved. He crushes the cup in his hand and, warm liquid seeping over, says to me,

“They can hatch in hell.”

Sometimes I felt as though my mind was as trapped in my body as my body was in prison. It yearned for more yet could not find it; it was a key without a purpose. I had tried to subdue my mind on many occasions (as I had before my conviction, albeit for entirely different reasons and in completely different ways) to no avail.

Yet, through a letter sent to many of us inmates from some social justice organization, my mind detected the faint image of a lock – perhaps my brain could not wholly turn it, but it could try to wriggle it loose enough to peer into the light beyond.

They called it astral projection. It was a way to position oneself while in the boundaries between consciousness and rest, to experience a life unlike one’s own—or, in my case, a life that could have been.

The logical, cynical edges my brain had developed over my adult years refused such a notion. If this advocacy group was at all refutable or helpful, then the letter would have never been allowed 1 to fall into my lap. Besides, such a concept was impossible – a waste of the little effort I had left to spend. But within my innermost thoughts, a voice whispered desperately:

Maybe. Just Maybe. Anything but this—anything more.

A few hours later, I sat crosslegged in my bare prison cell. The cell wasn’t empty because I was disorderly or anything of the sort, but because I didn’t want anything in it. Possessing anything in prison seemed duplicitous to me, even if it was a bed.

The process was strange, and while I could potentially describe it in its entirety, I didn’t write this story as a

manual or how-to. Unless this gets published and sent to prisons across the country, I don’t think anyone who would need to do this would have access to this account, anyway.

I took a few deep breaths in and tried not to gag from the musty scent that corroded my nostrils. My mind worked harder than it had in years; the rust and grime that built up over ages of doing nothing of value or meaning were slowly shaken off.

And I imagined, No,

I dreamt.

I stood on a hardwood floor that had been impulsively cleaned, a completely transparent glass window, a vista of a thick forest, and the mystifying sense that I had all the time in the world to explore life. My kid’s toys were strewn about me (I’d pick them up later; a sterile environment was bad for the mind, anyway), and my wife’s sky-blue sandals were tucked into a homemade rack.

No (DRINK). No glasses. A plastic cup of water in my hands, though. That sounded nice. I tried to imagine what my kid’s face would look like now, trying to imagine them as they gleefully ate the food I prepared. Maybe I’d have a job, too, instead of being a stay-at-home dad—perhaps then I wouldn’t have ended up here.

I suppose, though, it might have only made things worse if I had. Entering a monochrome life was easier when I knew only a few pigments. I leaned forward and cracked some god-awful dad joke: something about what aliens use to show their movies in a theater. My kid — who I was able to see grow into a talented but angsty tween —

facepalmed with an exaggerated groan. My wife, meanwhile, smiled endearingly – she needed some levity from her well-paying yet stressful job, and wasn’t too picky about how clever the methods were. I was making a fool of myself, but at least they seemed happy I was there.

After some extended parable, my hand reached out to douse my scratching throat and temporarily froze. There wasn’t any (DRINK) in it, was there?

Not the kind of (DRINK) that got me into this in the first place. Not the kind that had the officers tell my wife and kid never to see me again, even though it would take the devil himself whispering in my ear to hurt them. Not the kind that, during my first nights, where I had deluded myself into thinking I’d really feel again, I desperately begged for while clutching the sheets of my stone-like bed.

No, it was water. And it cooled my throat, my mind, my soul. I kept drinking and drinking and drinking, feeling as though the proverbial—and sometimes literal—chains binding me were made of sugar, fading away, and loosening my shoulders.

Drip. Drip. Drip.

When I woke up, my heart felt empty – I wasn’t sure why. Maybe it was still stumbling from the rug pulled alongside my opening eyelids, or maybe because it had experienced the first faintest touch of happiness it had in years.

Maybe it was both, but at least I could look forward to tonight.

Yuan, humans are social creatures; we bear responsibilities towards society.

You’ve grown four centimeters taller since last year.

On your own, you couldn’t have grown even a centimeter. These four centimeters are the grace of fruits and vegetables, grains of rice, and the labor of workers. You should be grateful. You must strive for betterment, have ambition, and hold lofty ideals. First, start with the attitude you bring to completing your homework. Why settle for mediocrity in your compositions? Yuan, Yuan? What are you thinking about?

Her voice pulled me back to the office. It was just us, the desks, chairs, and white walls. The setting sun filled the room,

water rushed into a sealed glass box. I knew I had to say something; occasionally, I felt this pressing need to speak. Yet, silence wouldn’t spell the end of the world, which in its final moments, would be filled with noises of things that must be said. I had to say something, as if leaving a blank on the test paper was against the rules.

I’m wondering, when it would rain this year.

She sighed, handed me back my composition, and told me to leave without looking at me again. I’ve heard this tone too many times, hiding in different mouths, within different sentences. But it always conveyed the same meaning: give up. It frightened me. The answers I’ve guessed on tests have never been right, unforgivably wrong,

even. I often wonder, am I fundamentally flawed as a person?

I bid her goodbye, closed the door, and in a daze heard her mutter: What’s the use of rain? There’s nothing left in the fields anyway.

Since that year, it indeed never rained again. The first year, I watched the disappointed sky and finished winter, the clouds murky like an unclear piece of jelly. The second year, the sky lost all its moisture, and the clouds turned into dry, cracked riverbeds. People stopped believing in weather forecasts. They said there would be rain, there would be rain, but the guest never came. Weather forecasts loved stating probabilities as certainties, but rain divorced probability and never looked back.

During the winter break, I wrote only one weekly journal, from the start to its end. I wrote: it didn’t rain this year; nothing happened. It didn’t rain last year; nothing happened. It won’t rain next year; and nothing will happen. The teacher didn’t talk to me about my journal, didn’t even spare me an extra glance. I was left in the winter wasteland to grow however I might.

The third year still had no rain. But I only guessed half of it right; filling in answers on a blank test paper, I was never completely correct. The third year had no rain, but it had a cat. We met in the vast, dirty belly of the world.

The cat was an urban legend that often went like this: red eyes, white fur, fat as a ball. If you satisfied his intellectual needs, brought him a book (not textbooks or shopping magazines), a box of videotapes (not horror films), a record (Bach preferred), he’d grant all your wishes, complete a year’s worth of math homework for you, make you the top student for a year, or get you the unpublished video game early. He lived in a drain in front of a convenience store.

I always thought he was just a legend. Then one day, perhaps my smartest day, I realized: who would let a legend live in a sewer?

I told him about the revelatory moment. He gently laid his paw on my hand.

I visited him with Nietzsche’s “Thus Spoke Zarathustra”. He had a bookshelf with a glass door, an old record player, a yellow construction lamp, and a vintage sofa. He was reading Hawking’s “The Grand Design” under the lamp, legs tucked under his belly. The book was open to a page with a goldfish illustration. Children’s book pictures are so lovely! He awkwardly explained.

I handed him the book, he glanced at it, then shoved it beneath his belly.

I want my dad to come back and see me.

He moved his belly aside with pity, pushing the book back inch by inch.

I have an electronic piano at home. A wall full of bookshelves, each book no worse than this one. I have many, many old movies at home. You can play, read, and watch anything you like, it doesn’t matter even if you break them, I just want my dad to see me...

I’m sorry, I wish I could help, he said thoughtfully. I can’t do it. It’s not about the reward. Once a wish involves relationships between people, everything becomes impure and complicated. I’m still learning, still understanding...

So when will you understand?

Hard to say. It might take a long time, until you’re old and dead. Or it might be soon, maybe tomorrow, I might understand by then.

The next day, I went to see him again. He was still on the page with the goldfish, silently covering it up when he saw me.

I already told you, don’t you understand...

I interrupted him.

Come over to my place to watch a movie.

Almost no living sound exists underground, the echo rolls over in this massive cave, repeating, come over to my place to watch a movie. I didn’t have the courage to say it a second time; I was too useless, weaker than the shadow of a sound. He didn’t answer. The echo, like a satellite off its course, played the only official language over this planet’s 500 million square kilometers, talking to itself until the end, becoming metallic trash floating in the vacuum.

He finally spoke. Alright, preferably a movie with lots of little fish.

The satellite shed tears of radio waves.

“Later” is a powerful word. All possibilities, good and bad, one hundred percent and one in ten thousand, both live within this word. Later, he moved to my house and lived on the carpet. Later, I started playing the piano. I didn’t learn much, just a bit, then casually left it. I’m like a leaking bag, losing things along the way. I know, I can hear those sounds. But I never looked back to pick them up. What for? I’m an

bag, why to pick things up just to lose them again? But I started playing the piano. I stumbled through “Mary Had a Little Lamb,” he darted across the piano keys on his short legs, playing chords better than me. I gradually got better too. Like a baby afraid of falling, unwilling to stand and walk until someone reaches out and says, come here, I’ll hold you, you won’t fall. I slowly stood up, walked with a stumble, faster and faster, finally ran into the wind. He said to me, panting: See! Things will get better when two people are together. I believed it from the bottom of my heart, even though last winter I wrote in my journal: Nothing will happen. Meaning, neither good nor bad things will come. This winter would be an empty bag.

We began to share our lives with each other. What could I say? I’ve only lived for fourteen years. Nothing was worth mentioning in those fourteen years. I mean, the things I’m going through, every fourteen-year-old around the world is experiencing. It could be a collective pain of a huge group, but no one wants to talk about it; or someone seriously talks about it, and everyone laughs, saying you guys are so humorous. Or everyone gets angry, saying you’re ungrateful, living better than any previous generation. Besides, could I speak for all the world’s fourteen-year-olds? Does everyone at fourteen feel life is just to be gotten through, like a long, useless class, whether

you pass or fail, you’ll graduate sooner or later. My own issues are trivial. Speaking out is a shame, as if flaunting one’s frivolous self-importance. But I told him. I even told him about my dad. My mom died giving birth to me. He raised me until I was six, then went to work far away. He only had a monthly obligation of one thousand dollars to me. I resented him, like resenting a kite that escaped in the strong wind. I dreamed of him walking in a heavy snow. I chased after him, calling, dad, dad. But the snow swallowed the sound and exhaled light. We were in a place of absolute silence, so quiet that even the possibility of communication was lost. I cried, shouting dad, dad, not knowing if my voice was hoarse or if the sound couldn’t escape. In this place, only silence could be deafening. He walked so fast. I was only six, I couldn’t keep up. I saw him about to walk into a place I couldn’t reach. I squeezed all the air out of my lungs, shouting da--d-- He turned around, looked at me. The sun shone on us, and for the first time in my life, I felt so warm. We looked at each other from a distance, like strangers, all barriers fallen away between us. We were as light as two sheets of paper, standing in the sun’s first ray. So warm. Together, we melted into the snow.

I wish I could make your dream come true.

I’m two hundred and ninetyfive years old this year. He looked at me, a bit annoyed. You’re not surprised at all!

I quickly said, wow!

Never mind, never mind. Do you really want to hear? It’s a long story! Think of the Arabian Nights. Two hundred and sixty-four stories, told over a thousand and one nights.

Go ahead.

I come from a planet without fish... I traveled over a hundred years, by that planet’s time. I know where I’m ultimately going, not to Earth. To death. He said. I want to die. I live to fulfill others’ wishes but can’t satisfy my own. I was born unfree. My wish is to die as a free being.

Before finishing his story, he won’t die, won’t leave, won’t go to a bigger, stranger planet. In a dream, I saw someone breaking into my house. I heard someone say, so this is the cat. The one from the sewer who grants people’s wishes. I heard someone say, is there really such a thing? Are there miracles in the world? They grabbed him by the neck and put him in a cage. They said, anyway, this city needs this cat. I told myself to wake up, wake up. I ran desperately in the snow. I was only six, I was only six, I was so tired, but for the first time, I ran with all my might. I thought, things shouldn’t be like this. He’s different from my father. My father and I never Prose

What about you?

started, but there was finally a possibility between him and me, please don’t take him away. Please don’t take away this precious seed. I thought, I’ve lived fourteen years, fourteen years. Nothing good happened in fourteen years. Now it’s time, there should be something good. Two people together, there should be something good. He’s lived two hundred and ninety-five years, seen more than half of the Galaxy. He can’t be wrong. The year before last, it didn’t rain. Last year, it didn’t rain. But this year, this winter, please leave me some rain. I ran to the end of the snowfield, there was nothing there, only a wall as tall as the sky. I pounded it desperately, my heart thumping loudly. This wall separated me from a cruel, merciless world. Protected me from courage and love. But I’ve never hated it more. They took him away. I knelt down, face against the wall, crying, my heart’s chamber filled with moist tears. Like a dam hit by a flood, it finally collapsed with a bang.

When I woke up, I was in an empty house.

I walked out onto the street. Two light rails crossed paths. In the cross-section, between the carriages, distance disappeared. The encounter finally became possible, and finally became a disaster. I watched them crash into each other’s bodies, against the gray winter sky, the huge sound of metal collision and the

explosion. The bridge crashed down in front of me, unfamiliar stars hitting my heart. The crowd suddenly converged in one direction, as if deceived by the moon’s gravity. I followed the crowd, where was I going? Who was I looking for? I finally saw him. He was on the stage in the city center square. In the eyes of the swirling crowd. He stretched out a paw, asking for a microphone. He coughed into it, like a stone falling into water, silencing the noisy crowd. I looked at him through the throng of heads. He spoke.

Today, I can only bless you. I wish everyone’s dreams come true, except mine. I wish all your dreams, unrelated to love, hate, hope, and despair, come true.

I pushed through the crowd towards him. Today, there was no rain; money and gold fell from the sky. I walked past the dead coming back to life, the blind seeing, one miracle after another. I approached the cage, touching his snow-white forehead through the gap. He said to me: I’m two hundred and ninety-five years old, Yuan. Two hundred and ninety-five years have their own pride. I’ve always wondered, why you... You’re so small, only fourteen. You’ve never left this city, never stepped out of this hamster wheel. You’ve never been to the Milky Way. You don’t even have something bigger and farther in your heart. Why you?

I finally understood what’s between people. At the same time, I understood I could never satisfy you. I’m sorry. He licked my palm.

I said no, no, you’ve already fulfilled my wish. I looked at him, at the miracle that arrived earlier than everyone else. Everything happened this winter, fourteen years of absence suddenly arrived. This was the first time I was happy about my mistakes. This wasn’t a futile winter. Both good and bad things happened.

I looked at him for a long time, I said, I hope your wish comes true...

He smiled and said, thank you, Yuan. I saw his head burst into a small red flower. I hugged the cage, kneeling in kneedeep wealth of human world. The blind saw, the deaf heard. The dead emerged smiling from their urns. Some were busy crying, some were busy laughing, some busy living, some busy dying.

I heard the sound of water running above the sky, the long overdue finally arrived. The first drop of the great flood fell from the sky; dropped into my eyes.

Tu silencio bajo una mirada seria y pensativa donde los mundos se unen bajo la manta poética y soñadora vuelan los sueños, los pensamientos eternos, gritando al universo, por qué? con el corazón abierto de par en par atravesando lo desconocido como flecha fugaz de estrellas que llueven mientras se visualiza un mundo eterno intacto sellado por cicatrices.

El tejido de nuestra realidad con hilos de confusión, nace ahí el poder de la imaginación, la medicina de los soñadores y de algunos necios.

Cada sección tiene un vínculo que nos define quienes somos y a donde vamos.

En ella existe una visión dormida sin límites donde un mundo nuevo se alinea.

Soñar es ver y oír más allá de nuestros sentidos como humanos. Hay que desafiar las cadenas de la tradición que nos ata con cada acción y palabra. El viejo pensar son como cenizas que vuelan con el viento.

El ave fénix despega y vuela, portando en si las esperanzas.

En los sueños encontramos el futuro que anhelamos crear.

El cambio está tejido de amor, paz, comunicación, armonía y no de odio ni rencor.

El pasado es tejido por el presente y entrelazado como bailarines nocturnos.

Soñar es tejer una nueva historia de la inmensa creación de la vida.

Entonces, soñaremos de nuevos sistemas con instituciones reinventadas que inspiren y empoderen ideas frescas y verdaderas sacadas del corazón.

Soñemos con un sistema en que la política no sea el poderío del mundo.

¡El mundo nos pertenece!

En el corazón de cada soñador existen semillas de un profundo cambio, la visión del mundo amable, llena de amor y esperanza que riega sus tierras con abundancia.

Sueñen todas estas almas, sueñen como guerreros con valentía y así dejar volar su imaginación, porque los sueños abrirán las puertas de un futuro prometedor.

Poetry

Your silence under a serious and thoughtful gaze where worlds unite under a poetic and dreamy blanket dreams fly, the eternal thoughts, screaming into the universe, why? with a heart wide open, piercing the unknown like a fleeting arrow of stars that rain down while visualizing an eternal world, intact yet sealed by scars.

In the fabric of our reality, woven with threads of confusion, lies the power of imagination, the medicine for dreamers and fools. Each section has a link that defines who we are and where we are going. In it exists a vision, dormant and boundless, where a new world aligns.

To dream is to see and hear beyond our human senses. We must challenge the chains of tradition that bind us with every action and word. Old thinking is like ashes that fly with the wind. The phoenix rises and flies, carrying within it our hopes.

In dreams, we find the future we long to create. Change is woven from love, peace, communication, and harmony, not hate or spite. The past is woven by the present and intertwined like nocturnal dancers. To dream is to weave a new story from the vast creation of life.

So, we will dream of new systems with reinvented institutions that inspire and empower fresh and genuine ideas drawn from the heart. Let’s dream of a system where politics are not the world’s dominion. The world belongs to us!

In the heart of every dreamer exist seeds of profound change, the vision of a kind world full of love and hope, watering its lands with abundance. Let all these souls dream, dream-like warriors with courage, and let their imaginations fly, for dreams will open the doors to a promising future.

When you hear the word “design,” what do you think of? Fashion? Graphic arts? Architecture? How awful the construction of a freeway over a walkable city is? Our favorite Shark Tank product: a fruit slicer, an avocado storage container? Design—“to create, fashion, execute, or construct according to plan”—is the process of dreaming, of imaginatively creating something tangible (“Design”). Innovation, invention, involves creating something in response to a need or problem. When “designing” a good product, one must consider the market and what will sell. That being said, designers themselves not only view design as a physical product, but as a creative, imaginative, process.

As an experimental art movement emerging in Italy in the 1960s, Radical Design was initially a subversion of traditional art forms. However, in the context of functioning as an abolitionist collective and artistic anthology, like the Madison Journal of Literary Criticism, talking about the radical capacities of art and design— looking specifically at fashion, architecture, institutional design, and magazine layout—allows us to envision, to “dream,” to design, an abolitionist future. As the MJLC aims to promote literary criticism as an everyday tool for navigating social narratives rather than an academic discipline, treating radical design in a similar fashion encourages everybody to consider how to create the sort of future we dream of having.

Thinking like a designer allows activists to approach social justice and an abolitionist future imaginatively. The creative capacities required to design something itself is a radical way of thinking in a world that promotes complicity over creation. Thinking like an artist, “outside the box,” is itself a radical praxis. Furthermore, categorizing the modern day, the status quo, like the carceral state as an institution that is intentionally designed empowers everyday people to critically question both why and how carceral practices are upheld and reinforced. The status quo is a dynamic series of overlapping designs, not a static monolith. As such, it is possible to re-design it. Thinking like a designer allows one to question accessibility in graphic mediums, the inclusivity of architecture, and the limitations of institutions such as the credit and labor market.

This past semester, the MJLC staff and study group considered design, discussing topics such as automatic hand sanitizer dispensers and Apple watches being created with a lightskinned audience in mind, failing to function properly on darkerskinned individuals. Or, how bright fluorescent lights in schools and hospitals, while harmful for individuals, are installed for surveillance purposes, making it easier for faces to be picked up on security cameras. And, the Brutalist design of the campus Humanities building, an infamous location known for its confusing

hallways, hidden bathrooms, and lack of windows. Essentially, in questioning pre-existing design, our team actively engaged with design rather than passively being subject to it.

To expand on this notion, not only did we question design but designed ourselves. The following reflections from MJLC staff, in tandem, showcase our team’s “dream neighborhood,” with each staff member focusing on a particular element of a fictionalized neighborhood they would either create or deviate from pre-existing design. Our team considered: What do the houses look like? Are there community facilities? What is our relationship with neighbors? How does the landscaping look? We questioned what is carceral about suburbia and aimed to change it for the better.

In this exercise, rather than considering a “market” we considered humanity, designing for people we loved. We attempted to envision a world that improves conditions rather than tries to profit from them.

Designing is putting dreams into action, a prerequisite way of thinking for a revolutionary future. We are proud to share our preliminary ideas, our dream design, of a neighborhood with all of you, an activity inspired by the Stedelijk Museum of modern and contemporary art and design, located in Amsterdam.

Growing up, my mother had a large, rectangular garden in our backyard in Southern Minnesota. She grew berries, green beans, and a variety of flowers. Whenever the green beans were ready to be picked, my three siblings and I would sit at the counter, each with a knife and cutting board in front of us. We each received a bucket of freshly-washed green beans and an empty bowl to place them in afterward. Every year, we’d place bets as to which sibling would accidentally snag their skin with the knife. Every time, we were reluctant—but still did it regardless.

Last semester, I read several articles and books about collective gardening. One of those novels included the Parable of the Sower by Octavia E. Butler, wherein the main character, Lauren, created the philosophical idea of Earthseed which is about collective change and consciousness. But Earthseed was not just fictional, it has inspired the creation of real-life communal spaces for people to garden and create produce together. The Black Farmers Collective and the Earthseed Land Collective are two examples of collective spaces that do more than just gardening or farming; they also explore relationships to land and sustainability.

Understanding and embracing our relationships with land, farming, gardening, etc. is vital to imagining a dream neighborhood. In a collective, dream neighborhood, there can be the sharing of food, space, and land to ensure that everyone in the neighborhood has access to healthy, locally-grown food. There could be countless gardens, collective farming spaces, physical spaces dedicated to preparing the food. Collective gardens offer endless opportunities, from what is grown to which meals are made, to the community we get to share them with.

AESTHETIC BEAUTY AND ORNAMENTATION ARE THINGS WE SHOULD DREAM FOR MORE OF. BEAUTY INTEGRATES THE BUILDING INTO THE COMMUNITY—IT OFFERS DIGNITY TO RESIDENTS WHO WOULD OTHERWISE BE VISIBLY AND SOCIALLY SET APART

Sophia Smith

As a kid, my mom would take my siblings and me to the Bay View public library at least once a week. We sometimes went even more often in the summer when school was out, trying to cradle as many books as possible in our arms. I think I took the accessibility of the library for granted, how information, stories, “how to’s,” art, and movies were all freely given with no expectation of reciprocity. Now, as a college student, I need my student ID to enter most of my university’s libraries. I have to pay an arm and a leg for a textbook. Education is given under the condition that a transaction will be completed—money for ideas. In our designed dreamscape, I would require public libraries in every neighborhood. Public libraries are places for all peoples to gather. There are no expectations of payment—you go in, check out a book, and enjoy. Anyone could have a library card, no ID or fee required. Our public libraries would have educational elements as well. Classes and workshops would be offered, giving people the opportunity to learn skills and gain knowledge that would otherwise be gatekept. Education would be accessible for all, just as books and information are accessible in public libraries, making libraries even more of a central gathering point for people. We would also hold events outside of educational purposes. We could even host book swaps and art events like scrapbooking or collaging, which would not only provide creative opportunities to citizens, but also act as a way to bring the community together. Libraries would be a safe haven for all and offer childcare to parents who want their children supervised in a safe, welcoming environment when they go to work. They would be a reliable place for learning and creating, with no transaction required.

Every so often, I slip into a reverie, reminiscing about how some of life’s most intimate moments transpire in parks, from youth through adulthood. As a child, I would construct sandcastles and get blisters from the monkeybars. Colorful balloons bobbed in the wind and laughter permeated the air as our community celebrated birthdays, holidays, and graduations. During my teens, we would weave dandelion flower crowns during the day and ride the swings after dark, exchanging secrets and heartfelt confessions in peaceful seclusion. Perhaps, in times of rebellion or pain, we would enshroud ourselves in plumes of nebulous smoke, crossing our fingers that no one saw. As an adult, the lush, lofty trees offer shelter from the sweltering summer heat, perfect for reading a book or hosting a picnic. In retrospect, what made these memories whimsical and magical was having a peaceful refuge from the inorganic isolation—fences, property lines, and walls—that divides urban neighborhoods. The parks of my childhood were home both to residents and roamers: the children, the elderly, the artists, the naturalists, the lost, the lonely, and the loved.

These memories are a testament to the importance of green spaces, which provide safe spaces for recreation, socialization, and celebration. Accessible green spaces offer multifaceted benefits, including improvements in mental, physical, and emotional well-being. Immersing ourselves in nature not only facilitates processing complex emotions such as grief and loss, but uplifts our spirits. Green spaces encourage people to leave their homes, socially bond with others, and pursue active lifestyles, which are especially important since a lack of walkable neighborhoods deters communities from engaging in these activities due to safety concerns. They also provide habitats for wildlife and native plants, an act of restoration that can mitigate the effects of pollution and depletion, allowing us to connect with the earth.

I grew up in a city where, if you didn’t have a car, you couldn’t get very far. Having my own was a privilege that shaped a lot of my opportunities—I had a reliable way to get to school and work, I could see members of my social circle whenever I needed them, and I was generally independent. After living in Madison without a car for a few years, I’ve had to find new ways to grocery shop, commute to work, and be an active community member. That’s why, whenever I see a city bus, I loudly proclaim I love the bus! to anyone who will listen. Now, is the bus a perfect experience? No, and I don’t pretend that it is. It can get crowded, it can get loud, and sometimes it can smell a little funky. But will it affordably get you from one place to another? Absolutely. It also gives you a chance to get to know your fellow community members, even if it’s through wishing someone a nice day or offering one another a smile. Well-organized bus routes also keep more cars off the streets, minimizing carbon emissions and dangerous road traffic. The bus, like trains or bike paths (which I also love), can keep communities cleaner, more well-connected, and safer. That is why my dream neighborhood would include the infrastructure for convenient, collective, and sustainable public transportation.

As a child, I was almost unilaterally restricted from screens of any kind, so I relied a lot on my brother and my neighbors for entertainment. I was fortunate in that way. We could run across backyards, explore the forest behind them, play in the creek, or play sports in the nearby fields. Most people, however, don’t have all of this. Their neighborhoods instead are bisected by busy roads or have no trees, parks, or small public spaces. It’s a shame, and it severely impacts the ability and desire of both children and adults to socialize with their neighbors. Where should the children go to play when they either don’t have a yard or don’t have easy access to a recreational public area? Or when houses with a “yard” have maybe 30 feet of poorly grown grass gated by a decaying, wooden fence?.

A neighborhood, ideally, should have less emphasis on individual property and more emphasis on community-maintained common areas. Maybe that means a garden. A baseball field. A grassy field. These convictions of mine didn’t stem from random thoughts. I’ve been to Montreal, Paris, Munich, and each of these major cities had within them beautiful parks humming with activity. It’s rare to see a bridge in the summer that isn’t lined with couples chatting on the railings. It’s rare to walk the city streets and not see at least one that doesn’t allow cars through.

In Montreal a guide pointed out to me a street which had at one point been much narrower and said: “This is where the kids used to play and the elderly would watch.” There had clearly been an introduction of the concept of community through areas allowing public congregation, and people were clearly happier for it. Neighborhoods can exist without community. I’m sure some of you experienced that personally. If I were allowed to dream, though, I would prefer to dream of a neighborhood that feels like a collection of the people and places inside of it.

When I was younger, the neighborhood I grew up in felt cut off from the rest of my home town. The area around me didn’t encourage neighborly comradery—there weren’t any open or shared spaces within walking distance, sidewalks or smooth pavement didn’t exist, and some homes were even further separated from the neighborhood by impenetrable walls. People kept to themselves and only really talked to each other to share a complaint about a change in the neighborhood. Community spaces such as parks and libraries were a far distance from my home, and places like the grocery store even more so. Access to these places were severely limited to me as a child—I couldn’t drive and the public transportation system couldn’t service my needs, so I was isolated from my peers and my community. Fortunately, my parents owned a car, so, if they were available, they could take me to these places. If they weren’t able to, the community was virtually inaccessible to me. As a child, these were relatively low stakes. I didn’t have to worry about purchasing food or other necessities or worry about getting to school because my parents would take me. The ownership of a car made these things simple, things I didn’t think twice about.

When arriving in Madison, one of the first differences I noted was the proximity of the people. As a college town, everything is either walking distance or a bus ride away. Madison is a walkable city, a walkable campus, because the average college student isn’t expected to have an automobile. An assumption made in my own hometown, that without the privilege of owning a car, a person would be stifled in their own community.Walkable cities challenge this by designing infrastructure that enables inhabitants to access necessary locations outside their immediate vicinity, such as those for socializing or purchasing essentials, and therefore perpetuates a society of care, connection, and inclusivity.

Look, I’m not an ecologist—or a writer, on that note—but I think the idea of biodiversity is something that we’ve all learned from high school biology classes or picked up from reading an article. The lawns we commonly see in suburban neighborhoods or city boulevards aren’t that. Most of us visualize the same thing when we think of lawns. Many of us can just take a look outside our windows and see the flat stretches of what is most likely a cool-season Kentucky bluegrass if you live in Wisconsin.

The idea of these sweeping, flat turfgrass lawns originated from wealthy landowners in colonial America who were emulating European elites; without modern machines, the upkeep of lawns was only possible for those who could afford the labor-intensive process.

Besides the disheartening homogeneity of lawns, the monoculture of grass harms biodiversity and the practices required to maintain it (e.g., pesticides, excessive watering, etc.) are often detrimental to the environment. According to the National Wildlife Federation, 50-70% of residential water is used for landscaping. In a dream neighborhood—unburdened by homogeneity, the “keeping up with the Joneses” attitudes perpetuated today, and the looming threat of changing climate—yards and natural spaces flourish with a variety of native plants through natural processes and humans caring for the land.

When I think of a dream world, it always includes opportunities and spaces for art and creative expression. Music, in particular, is a big part of my life, and I’ve experienced firsthand the power live music has to bring a community together. Official venues have the resources to bring bigger acts and hold larger events; but in many communities, including Madison, these venues have been bought out by larger corporations, with less revenue from ticket and merch sales funding the artists themselves. Local DIY venues exist and function well as spaces to appreciate and experience local music, but these rely on community members having the time, space, and resources to host shows, as well as the willingness to risk noise complaints. My ideal neighborhood provides spaces for musical acts of all genres and sizes, embracing the local scene and cutting out the corporate presence in larger venues.

Art history and architecture are big passions of mine. I hold a lot of bitterness towards capitalist production standardizing everything—in this case, obviously, architecture. One is unable to ignore the cold severeness of the buildings in our communities, especially in affordable housing projects. This endeavor towards affordability has trampled the experiential aspect of design for its residents; we have created impersonal fortresses for living spaces, prioritizing cost over beauty. Specifically in the 20th century, following the movements of Art Nouveau and Art Deco, we see the emergence of Bauhaus. Among many other factors like industrialization, it’s characterized by an ideological rejection of ornamentation, which is seen as wasteful. This can be observed more concretely in the essay Ornament and Crime by architect Adolf Loos, who declares, “for ornament is not only produced by criminals; it itself commits a crime.” He argues ornament is unnecessarily wasteful, with regards to both time and capital. On a human level, this is a rejection of the artisan and craftsman in favor of industrial mass production.

I don’t like to sound like I’m denying the merits of art movements like Bauhaus, the much-hated Brutalism, and the starkness of contemporary architecture as a whole. These movements are a product of and commentary on the environment they are built in—as are all art movements—reflecting the relations between production and society under capitalism. On a technical level, this simplicity is a benefit with regards to ease of production for affordable housing, and the virtues of this austerness can be seen on a larger scale in Communist China. I love and fervently defend the legitimacy of modern and contemporary art, and I find rejection of these movements inherently fascistic. However, aesthetic beauty and ornamentation is something we should dream for more of. Beauty integrates the building into the community—it offers dignity to residents who would otherwise be visibly and socially set apart as previously-homeless “charity-cases” from “the projects”. We should grow beyond simple efficiency; after all, one deserves to live with dignity.

While I often applaud the ingenious invention of shared living like Airbnbs or hostels, both of these communal systems function within a capitalist structure of profit prioritization. These inventions once began as an alternative to private ownership and encouraged better usage of inconsistently occupied housing. However, they have since devolved into gig economies that promote tourist spending over long-term housing. Furthermore, they exacerbate capital inequalities between those who lack shelter and those with disposable incomes.

Communal living, however, is rich in options for interpretation, many of which are already being explored by architects, activists, and artists. In doing so, these designers are reimagining the meaning of a home and family. You may already be aware of mixed generation housing that combines living spaces for parents, children, and grandparents, or even apartments that mix single bedroom strangers together in communal kitchens, living rooms, and rooftops. Other, lesser known options have begun to combine immediate families under one roof who share weekly cooking, cleaning and even child rearing responsibilities. And while many of these are, in fact, “efficient” products in terms of energy and expenses, they are good products because they produce good amongst the people who use them. Many of these options not only foster a more intimate level of respect in relationships, but recategorize the idea of property and ownership into a shared, interdependent context. While this may seem too beatnik for some, many contemporary designers are still taking the time to acknowledge the benefits of “private” spaces that provide residents the necessary time and place to be alone, independent, and in control. The beauty of this practice is that the interpretation of which spaces are more beneficial as communal versus private is variable to different experiences. The way that people define their “best” living style should be up to their flexibility, their boundaries, and their choice. To those who are willing to provide us options beyond the prescribed status quo and those who question and reimagine how homes, families, and living spaces can be structured—thank you neighbor!

Providing housing to those without a home is something that I believe is not only necessary for a “dream” neighborhood, but our moral obligation as human beings. No matter where I go—whether it be at home in Madison, on a school trip in the United Kingdom, or on vacation in Greece—I am disgusted by the lack of assistance given to unhoused individuals. We must do better to care for everyone around us. I believe that we are often blinded and have yet to realize how lucky we truly are; you, holding this magazine and reading this spread, are incredibly lucky. And now it’s time to start giving back to the community. This ideal neighborhood would benefit from more shelters, food pantries, and other resources that would create a better living situation for those in need. I think that this topic has become so important to me since transferring to UW–Madison because many people living in extreme poverty congregate around the State Capitol building. I’ve held many jobs in buildings around, and even inside, the Capitol and become furious every time I remember that people in power sit comfortably at their warm desks as their interns fetch them a coffee while there’s no space offered to the people stranded in the cold and asking for food.

Extending a helping hand is so easy. Maybe you aren’t in the position to change laws or open your own shelter, but you can always do more. Donate those old blankets you don’t use anymore, buy an extra sandwich for the person outside of the coffeeshop you visit, and lobby for the rights of unhoused individuals. Don’t rest until all of us are sleeping comfortably at night.

Suburbia—isolated from any true community and responsible for perpetuating the nuclear family—is characterized by identical, sterile houses that only connect to other cities through highways that have been built by destroying majority-Black neighborhoods. As one of the core tenets of Western capitalism, suburbia is destined to die.

I have lived the majority of my life in one of these suburbs—40 minutes away from Milwaukee, Wisconsin, rightfully nicknamed the “Cedarbubble.” Like most suburbs, it is a closed-off, majority white, car-centric town where I can’t even get to the “downtown” area a mile away without needing to cross a roundabout. Like all other suburbs, the Cedarbubble has a racist history that continues to exist in new ways to this day. The Cedarbubble is part of the Milwaukee Metropolitan Area, one of the most segregated metropolitan areas in the country due to the disparities between inner city Milwaukee and its surrounding suburbs.

These suburbs, since their creation after World War II (which, to note, was a complete shift in how living spaces had been built for centuries) have direct ties to the carceral state and its isolationist, settler-colonial capitalist values. This all lies in the core idea that suburbs rely on growth in order to stay alive. In contrast to most urban spaces, which have been built to have necessities within walking distance, suburbs were designed with expansion in mind. Suburbs involve building unnecessarily larger and distanced developments that are fated to deteriorate and fail over time. So, by design, suburbia is destined to die sooner or later if growth does not continue.

Once suburbia dies, everything else in our dream neighborhood can prosper: efficient and sustainable public transportation, cooperative living, libraries, sidewalks, open spaces, green spaces, cultural areas, and so much more! While suburbia is destined to die, it is our decision to decide how soon that death will come. This death is the first domino that needs to fall in order to allow these dream neighborhoods and all of their components to flourish everywhere.

Jonathan Tostrud

Every time I’m out at night, I look to the sky. The night sky, and the ability to spot stars that are thousands of light-years away, has always mystified me. On a clear night in Madison, you might see a handful of stars and make out a constellation or two. Madison is a 7 on the Bortle scale, which is a scale ranging from 1-10 designed to measure light pollution. For context, the stars observed in our sky would appear similar to the same stars next during a full moon in a light-free location. And this thought inspired me to consider how we interact with, and consume, everything around us. Pollution is a guaranteed by-product of daily life, and keeping track of and limiting unnecessary waste is how an ideal neighborhood can prosper, connecting us to nature and integrating it into every choice we make. By extension, caring for our local environment is self-care, providing direct and indirect benefits to both ourselves and our loved ones. In our city, there are no bright lights casting smoggy reflections into the clouds at night. In our city, everything consumed is carefully relocated, either through composting, repurposing, or any of the 3 R’s drilled in my generation’s heads since we were children. In our city you can see the stars.

After a couple years at university, I know the “college house” is no joke. Picture a mismatched modge podge of Target Essentials lamps, IKEA sofas, Amazon bed frames, and any odd assortment of beat-up coffee tables, nightstands, and bookshelves whose lore includes some version of a laborious trek from a mile away where it was left in the rain on the side of the road by somebody else. When I moved into my first apartment, it was the first time I ever really considered the investment that is furniture: sofas, mattresses, and armchairs don’t come cheap.

In a broader sense, the “college house” is an echo of a much larger issue in society. The American Dream enforces the need for a white picket-fence house with shiny floors and modern designs, upholding pressure for the everyday citizen to own and fill a house with all of the glorious things that money can buy. Except as inflation skyrockets and the wealth disparity increases, the accessibility to quality furniture for the middle and lower classes grows smaller and smaller. Consequently, a new market of affordable furniture has been created, deemed “fast furniture.” Made with cheap, environmentally destructive material in order to lower prices, these products create a new moral quandary in regards to our planet; but as the only financially supportable option many Americans are left with no choice but to invest. On the other hand, America has become the land of the outdoor storage shed. According to StorageCafe, over 38% of Americans have some sort of self-storage unit—which is a tasteful way to say that as a collective, we have a bunch of stuff that we don’t need.

In order to address both consumerism and the lack of accessibility to quality furniture, I envision a communal place to both drop off unwanted furniture and take furniture as needed. Not only would it provide a place for unwanted, landfill-bound items collecting dust, but the surplus of material would allow a place for those unable to buy furniture to collect it. There would be no price tags, no monitoring, no comparison—why would we need it? Often, one person’s trash really is another’s treasure.

Childhood for me was rooted in recreation, from mindlessly prancing through my neighbors’ backyards with my sister to playing badminton with my dad in our driveway. There’s something so innocent and creative about the childhood recreational activities that were once staples in our lives. Whether it’s decorating the sidewalk with chalk illustrations, making mystery potions out of grass and dirt, and playing silent ball with the deflated football—finding value in the mundane, and generally living outside of what your elders deem acceptable, epitomizes childhood. You can get away with playing a magical game of wizards at the creek adjacent to your house or shooting hoops with your neighbor down the street because you “don’t know better.” Yet eventually, you stop engaging in these activities as you grow up in favor of more “practical” activities, like math homework.

Capitalism, as a system, necessitates that we sacrifice these very experiences of recreation and leisure, almost entirely, for the sake of accumulating profit. You are always in school studying, getting a degree, perhaps getting another degree, to get a job, perhaps multiple, and over the course of your life these moments where you refrained from obeying by the rules of society remain just that: moments. What if these recreational experiences in our youth—times when we convinced ourselves that the mixture of grass, dirt, and dandelion fuzz was actually a magical healing potion, or that the water in the nearby creek was actually the secret ingredient for transforming into a mystical being—were just integral experiences in helping us develop our understanding of creativity and care? What if you did know better? What if it’s these very moments of recreation, leisure, where you are able to grow closer to yourself, your people, your world, that sets you up to be the best version of yourself?

An integral part of the dream neighborhood for me would be spaces for us to revert ourselves back to this childish mindset where the rules didn’t matter. I want there to be a space for art, specifically lots of concrete and chalk. I want there to be a majority of green space, accompanied by various equipment, including but not limited to basketballs, footballs and jump ropes. I want there to be bubbles, lots of them.

This setup is intentionally minimal, because as kids we weren’t given every material possession. Yet, I would argue that we were truly given the world in its entirety, an empty canvas waiting for our craft to inhibit it. Ultimately, reverting back to these moments of care, genuineness, and creativity would be the core of my neighborhood.

I used to have really bad nightmares as a kid. My first defense was hiding under the covers, blocking my sight so I couldn’t see the shadows in the corner of my room. Next, I had my mother check under my bed for monsters—surveying the space nightly. Finally, I closed the door before bed, locking out the terrifying unknown. None of it worked. Not really. I still never managed to feel safe in that space between restless consciousness and unsettling dreams.

One night, I remember my mother, frustrated but silent, walking me to my bedroom and crawling into bed beside me. I remember the reassuring sound of her breathing, the warmth of her skin next to mine, how truly safe, loved, I felt in her arms. After that night, I started sleeping with my door open—it helped knowing she was just down the hall.

In the modern-day surveillance state, I think a lot of us have conflated the feeling of security with that of safety. That locking up, boarding our windows, adding sharp points to the tops of our fences, cameras to our doorbells, and alarms to our homes will somehow protect us from all that is menacing, make us safer. It’s a response that parallels how I fought off nightmares as a child. A safe neighborhood seems to be one with the budget for the most security—Ring Doorbells, ADT, and neighborhood police. Linguistically speaking, it all makes sense—even when we literally lock up our money, we call the box it’s stored in a “safe.”

But security is not the same as safety. You can have a million alarms and still feel scared going to bed. Ultimately, I believe safety is the feeling of crawling into a loved one’s arms, not locking up and trusting nobody. Safety is rooted in connection, in love, in “knowingness.”

In my dream neighborhood, the residents would all take the time to know one another, trust one another—and it would make us all feel safer, requiring less security. Much like communal living, a truly safe neighborhood would not be bound by the physical structure of a house. It would be the ability to walk alone at three a.m. because you know everybody around you. It would be checking in when you hear shouting next door instead instinctually of calling 911. It would be knowing everybody’s name, sleeping without a lock or an alarm, or a baseball bat under your bed. Hell, it would be the theoretical ability to sleep with your front door swinging open if you wanted it to.

These days I sleep with the windows open. That ability is a privilege in itself. It’s because I feel safe. And when I study in my favorite coffee shop and get up to use the bathroom, I leave my belongings, my laptop, and my open drink out on the counter. It’s because I trust the people around me. Little privileges—rooted in the small communities that form in coffee shops and libraries and friendships—can be expanded and replicated on a larger, neighborhood scale and make collective spaces safer for all.

THE CREATIVE CAPACITIES REQUIRED TO DESIGN SOMETHING ITSELF IS A RADICAL WAY OF THINKING IN A WORLD THAT PROMOTES COMPLICITY OVER CREATION.

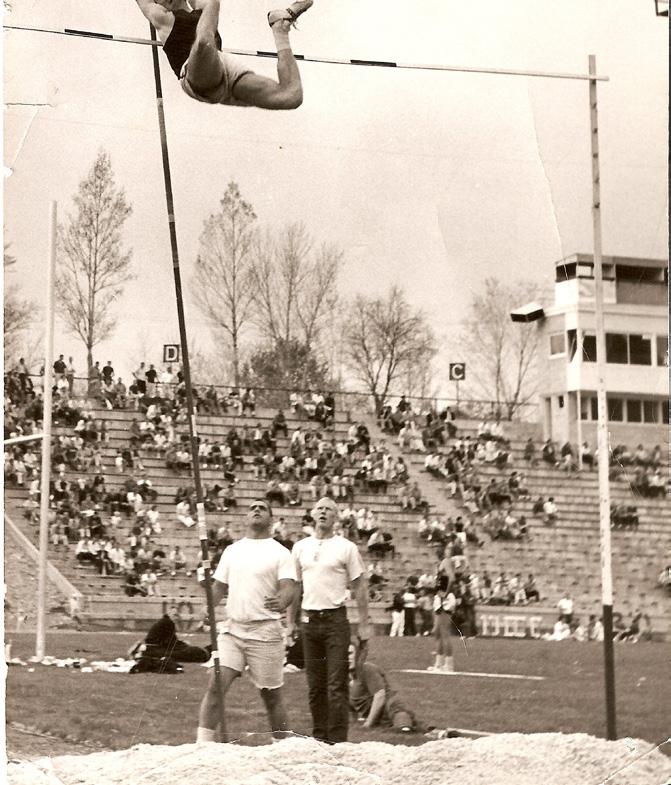

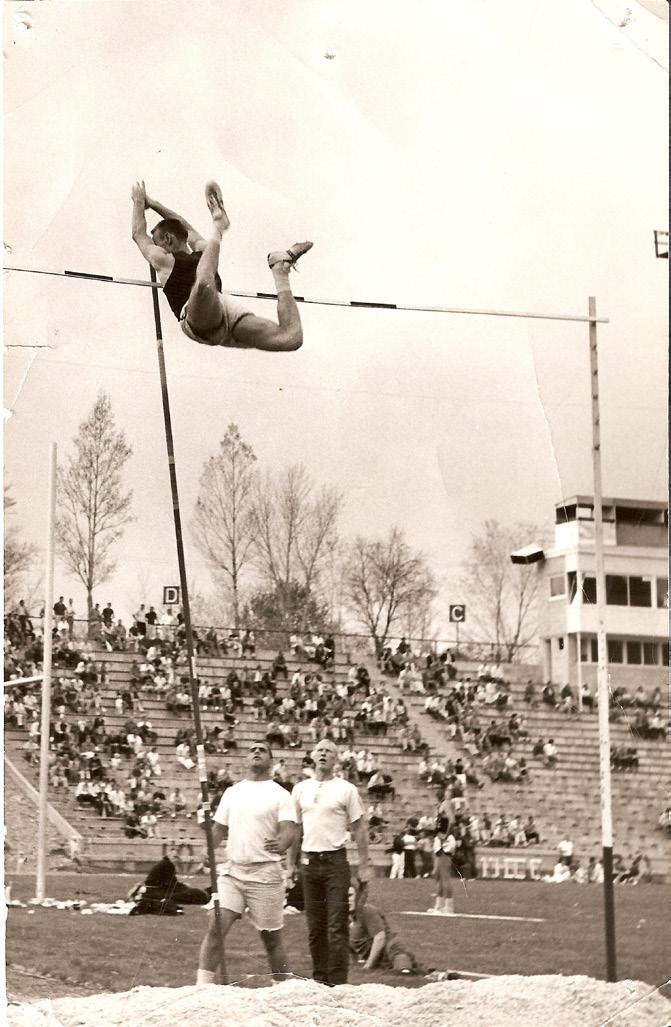

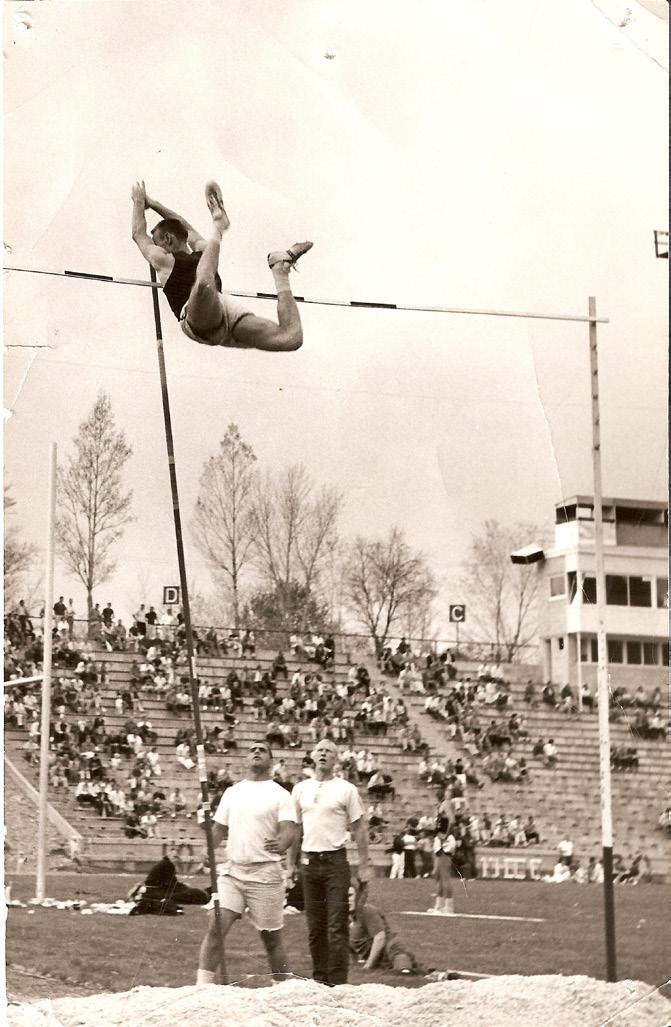

1956: my dad cleared the height of 14’ 2” with his metal pole into a pit of saw dust. He set the pole vault record for Utah State University. But that was not high enough to go to the Olympic trials.

Cornelius Waterman held the world record then of 15’ 7 ¾”

1956: African Americans in Memphis walked to work, part of the bus strike in the early days of the modern-day fight for Civil Rights.

Since 1956 the pits changed from sawdust to foam, from landing feet first to landing on one’s back, and the poles changed from metal to fiberglass.

The change made the technique so different that my dad felt he could not coach the new method.

The world record has gone from 15’7 ¾” to 20’ 3 ¼”. Nearly five feet.

Since 1956 we have gone: from separate but “equal” to Brown vs. Board of Education,

from poll taxes and poll tests to the civil rights and voting rights bill, from Redlining to equal housing,

and from White and Colored: water facets, rest rooms, and restaurants, to no outward signs.

If we are not moving forward we are going backwards.

So, raise the bar Higher and Higher until we cannot imagine going back.

CW: BDSM, sexual themes, killing deer and handling deer carcasses in the analyzed text

Described as a “memoir in verse,” Kayleb Rae Candrilli’s What Runs Over depicts their rural upbringing with an abusive father while navigating gender identity and sense of self. Through a mixed-genre narrative, Candrilli, using available gendered language, creates a trans narrative by breaking down the binary between masculinity and femininity, blurring the lines of a gendered self. Through their use of the poetic form, using imagery both violent and gentle; dominant and submissive; domestic and wild, Candrilli creates space for gender subjectivity, resisting notions of the gender binary.

In our contemporary, metamodernist moment, there seems to be a renewed sense of literary exploration in terms of explaining what our current cultural