LOBSTER SEASON: Steady catch, stable price

BY CLARKE CANFIELD

The 2024 lobster season has brought Maine fishermen something they haven’t experienced in recent years: A sense of normalcy.

After several years of volatile price swings for their catches, unpredictable harvests, and increased costs for everything from bait to fuel, this year is shaping up to be unusually ordinary, lobstermen say.

With the fall harvest still to come, fishermen so far have reported steady if unspectacular catches, stable prices, and a ready supply of bait. As they head into the home stretch, fishermen are hoping for a strong catch for the remainder of the season.

Kristan Porter, who fishes out of Cutler in Washington County, said the lobster season in his neck of the woods has started sooner than usual in recent years, with shedders showing up in traps weeks earlier than their customary time. This year, however, the shedders began arriving at their usual time, a welcome change from the recent past.

“In the past few years it’s been a few weeks early, but this year seems to be a little more normal and hopefully [the catch] holds on later,” said Porter, who’s president of the Maine Lobstermen’s Association. “The jury’s still out. It’s still early, but

CHARGED UP—

August was pretty decent. We’ll see what happens after that.”

At Fifield Lobster Co., a lobster dealer in Stonington, owner Travis Fifield said this year for the most part has been steady—prices are up a bit, fuel

costs are down somewhat, and the offshore catch has been picking up.

“I’ve been telling people it’s an average sort of middling year,” he said.

TOURISM SEASON: Slow start, strong finish

BY DORATHY MARTEL

With the leaves beginning to turn, Maine businesses that cater to tourists are shifting their focus from peak occupancy to peak color. Looking back at

the June-through-August season, the consensus seems to be that business has been about like last year, or maybe a bit better.

According to the Maine Office of Tourism’s 2023 Summer Visitor Tracking Report, there were 8,537,000

visitors to Maine last summer. In the course of 42,380,000 visitor days, their direct spending totaled $5.1 billion.

• 30% were from New England

• 23% from the Mid-Atlantic states

• 6% from Canada

• 2% from other countries

• and the balance from the rest of the U.S. The Office of Tourism has not yet released 2024 data.

On Aug. 28, the Maine Turnpike Authority posted on its website a prediction that there would be 1.1 million transactions on the Maine Turnpike from Friday to Monday of Labor Day weekend, up 0.9% from 2023.

The Inn, owned by Greg and Lauren Soutiea, is located in Spruce Head, just south of Rockland. They’ve lodged “a lot of French Canadians this summer, but the bulk of our visitors are from New England,” Bedell said.

“Guests are saying it’s so darn hot in Florida, Georgia, Texas…”

Several coastal businesses have reported similar trends this summer.

Jillian Bedell, marketing manager for the Craignair Inn, said, “It was a busy summer here at the Craignair.”

She noted that in addition to the inn being a destination in itself, “We’re a point on the way. Folks are eager to get outside.”

For some, the climate plays a role in the decision to come to Maine.

“Guests are saying it’s so darn hot in Florida, Georgia, Texas. I get more guests wondering if there are more places to go… scoping out Maine for the future.”

For many seasonal businesses, finding workers has been difficult in recent years—in part because housing is so expensive. The Craignair Inn’s

continued on page 8

When you can’t get there from here

Islesboro

to raise road, plan for bridge at Narrows

BY JACK BEAUDOIN

The town of Islesboro will be moving ahead with a twopronged approach to maintain a vital road connection between the island’s northern and southern communities after four 100-year storms damaged the roadway over the last 12 months.

The Main Road crossing the Narrows—a low-lying stretch of land at the midisland’s belt—was briefly severed by the Jan. 10 winter storm. Its protective riprap seawall was overtopped by high tides and wave action, cutting off emergency services, ferry access, and other down-island services to residents living up-island.

While the island’s road crew and contractors patched the roadway back together once the tide receded, the following January 13 storm undid much of their work.

“The road was impassable not just at the height of the storm, but for at least a half-day until local contractors could come in,” said select board chairwoman Shey Conover. “Those January storms were a huge wake-up call. The destruction we saw and experienced bolded, underlined, and accelerated our plans to develop a more resilient solution.”

“It just ripped the road right out,” Town Manager Janet Anderson agreed. “If they can’t cross it—can’t get a firetruck or ambulance through—a lot of people are worried about that.”

Now armed with a $75,000 Maine Infrastructure Adaptation Fund grant awarded to the town on Aug. 8, Islesboro officials hope to advance engineering plans that call for a slightly higher roadway in the near-term (phase one) and a bridge in the next decade (phase two).

While the recent winter storms highlighted the fragility of the road connection across the Narrows, Islesboro residents have long fretted about the Main Road’s vulnerability to the elements. Nearly 10 years ago, in 2015, the town won its first grant to study the flood risks at the Narrows and Grindle Point, another vulnerable area on the island.

A subsequent 2017 report recommended adaptions such as hardened seawalls, nature-based features such as marsh creation, and warning systems. It also led to the formation of the town’s Sea Level Rise Committee (SLRC).

But it wasn’t until the fall of 2022, when Islesboro enrolled in Maine’s Community Resilience Partnership Program, that infrastructure planning accelerated. Joining the program garnered a $50,000 Community Action Grant from Maine’s Community Resilience Partnership program, which in turn enabled the town to the hire Shri Verrill of Sunrise Ecologic in 2023. An ecological restoration and watershed protection specialist, Verrill was charged with advancing the Narrows adaptation plan.

In early 2024, Verrill and the SLRC selected GZA Geotechnical Engineering to move the plan into the design phase. After six months

of analysis funded by a new Coastal Communities Grant from the state, GZA prepared about a half-dozen alternatives for the town’s consideration. Each scenario was designed in three sections: north, middle, and south Narrows.

“All of the short-term, phase one alternatives were consistent about raising the road and rebuilding the stone revetment in the south and middle sections of the Narrows,” Verrill said. But they differed about how high the revetment should be raised, how wide, and what materials should be used to provide barriers to reduce the force of wave actions during storms occurring at high tide. One proposal, for example, called for manmade reef balls to be anchored in the intertidal area east of the roadway, at the south and middle Narrows, that could lead to the development of new intertidal habitats that could help protect the shoreline.

Based on community feedback, Conover said, the SLRC recommended—and the select board agreed to—an alternative Verrill dubbed “short, wide and with a berm.” It would raise the road 2 feet immediately, maintain a planted slope of protective vegetation, and rebuild the stone revetments on the east side of the road.

“Those have been protecting the road for 40 years, but the January storms showed us that they are failing,” Conover said. “Stones are smaller, breaking up, and in the storms are becoming projectiles.”

Conover hopes it could be fully completed by 2027.

Verrill said that while the planning process may seem long to outsiders, it’s been exemplary in terms of involving the public in decision-making.

“It’s important that people are able to see the vision,” she said, explaining the value of the series of presentations and public input meetings leading up to the adoption of the current two-part plan. “They need to feel it in their gut and provide their consent.”

One question that came up frequently among community members was if the 2-foot increase was sufficient. After all, the Maine Climate Council has recommended managing for at least 1.5 feet of sea level rise by 2050 and preparing for a possible rise of up to 3 feet over that time.

Conover, who also chairs the Sea Level Rise Committee, said any height increase would require an increase in the roadway’s width, which could then impact the salt marsh on the road’s west side. Minimizing potential damage to the marsh was one of the values many community members expressed in the meetings.

“If the road goes up, it has to go wider,” Conover said. “So we felt that the 2-foot increase—which is consistent with state projections for 2050— was the most likely to receive permits.”

Conover also said some townspeople wondered if it didn’t make more sense to skip right to a bridge. But she argued that the engineering, permitting, and funding processes required would push that solution back to 2031—and probably beyond. Up-island residents can’t wait that long for a resilient, dependable road.

“With the current storms we’re getting, we need to do something as quickly as possible,” Conover said.

“If we continue to get four 100-year storms within a 12-month period, it will be a very taxing experience until the bridge is built,” Verrill agreed.

As for phase two—the bridge across the Narrows—Verrill said most of the planning and design remains incomplete. At this point, engineers envision the bridge being built from the southern end of the Narrows, and west of the current roadway. There are also discussions about a bridge option for the north Narrows, which also would likely be placed west of the existing roadway.

“There are conceptual drawings, but not designs, for what we are calling phase two,” she said. While it would guard against the possibility of relative sea level rise of 3.9 feet by 2100, the bridge—or bridges—would be built on pilings that would encroach on the salt marsh.

“There’s no way around that” said Verrill, who is a salt marsh ecologist by training. “But those impacts will be minimized at every opportunity.”

As for Anderson, the town manager, phase two remains little more than a possibility unless federal construction grants can be secured.

“Townspeople are committed to this—until they see a price tag,” she observed. “If they’re asked to come up with $20 million to build it, I don’t think that would fly.”

After the storms: Downeast coast rebuilds

Owners remain committed to staying on the shore

BY JACQUELINE WEAVER/ THE MAINE MONITOR

The owners of Chipman’s Wharf, a seafood market, lobster buying station, and restaurant in Milbridge, had a brutal awakening after the powerful January storms wiped away their 106-foot wharf.

The proprietors—brothers Chris and Jason Chipman and their wives—had insurance that would have covered damage to the pier from fire or an airplane crash, but not storms.

The two families are still reeling from the shock.

The Maine Coast Fishermen’s Association estimated at least 60 percent of Maine’s working waterfronts were heavily damaged or destroyed in the January storms.

Since then, many coastal businesses have had to decide whether to abandon their enterprises or rebuild, hoping to fortify their properties against future major storms—in some cases with a cash infusion from the state.

Earlier this summer, Gov. Janet Mills announced the state would provide $21.2 million in grants to help working waterfronts rebuild. The Chipmans applied for assistance when it was required that a wharf service at least 20 fishermen, which has since been lowered to ten.

“The damage to the working waterfront had to have a significant impact to the community,” Amity Chipman said.

Island Institute, publisher of The Working Waterfront, helped the families rebuild the wharf.

At Rest Ashoar cottages in Prospect Harbor, a village in Gouldsboro, Ashley and Jacob Knowles were heartsick as they watched three of the five cottages they just finished renovating get lifted by waves and pelted with water.

Ashley said insurance only covered damage to the siding because the cottages, which for a century have been perched over the water, were not “permanently affixed.”

“The reason they were not ‘permanently affixed’ is because there were no foundations to fix them to,” Ashley Knowles said. “The buildings were 100-yearold, non-conforming properties due to the proximity to the ocean, which prohibited us from putting foundations in.”

The Knowles have moved the five cottages back 80 feet from the shoreline and each now rests on a slab. They repaired the siding—the only thing their insurer covered—and replaced appliances, doors, and windows that had water damage.

“Every single porch had to be completely redone,” said Ashley. “There was dirt, seaweed and mud. Some of the doors blew open so the water got inside.”

Jacob Knowles, a lobster fisherman and social media celebrity, said the builder, who was a relative, worked quickly and was able to prepare the cottages for the rental season. He said the repairs were covered by their savings and equity lines. Ashley Knowles said they applied to the state for assistance but have not heard back.

After Rest Ashoar opened to renters in May, there has been a steady stream of bookings, with some guests renting all five cottages so extended families can vacation together.

Ashley Knowles said the storms had a silver lining: Ocean water washed up so far back that the properties now have extensive sand beaches, where visitors can lounge and gather around fire pits.

“I prefer how it is now than how it was then,” she said.

Meanwhile, over in Winter Harbor, friends Larry Lawfer and Gene Kelley watched their investment in the Donut Hole—a former breakfast spot that hovers over Henry’s Cove—tip into the water as wind and waves battered the local landmark.

Seaweed and water traveled across the property, the road, and up to the doorstep of the local supermarket, Winter Harbor Provisions.

The two purchased the property less than a year earlier with the idea of renting it and using it themselves. Photos of the building toppling into the water spread online as a testament to Mother Nature’s unforgiving nature.

“It took them nine hours to lift it up,” Lawfer said of the rescue effort by a local contractor, Dale Church.

Like the Knowles, Lawfer and Kelley knew they had to rebuild: “Our first question was what are we going to do,” Lawfer said. “We never discussed just letting it go away. We only discussed how we were going to save it.”

Once the cottage was returned to land, the owners saw the structure consisted of three shacks put together at different times that weren’t connected by a single platform.

“We gave it a solid bottom,” Lawfer said.

They also added insulation and upgraded the plumbing, as well as hired a firm to conduct mold remediation. Lawfer said the current structure is stronger, sturdier and nicer with new shingles, and grass where there was once just scrub and gravel— and it opened to renters late last month.

Lawfer said they have not received assistance from the state.

“We applied for everything we could, but I don’t think we qualify because it’s not a primary residence,” he said.

For Chipman’s Wharf, Amity Chipman said the state will pay up to $271,000, or roughly half the cost of the $540,000 repairs, once the project has been completed.

“It’s expensive, we’re dealing with time constraints and working around the tides,” she said.

She said the new wharf will be shorter and higher. Instead of a support system of pilings, there will be crib work and poles, and concrete on the surface. The Chipmans have also poured a concrete barrier on the south side to serve as a breakwater. The overall structure will be 42 inches higher than the previous wharf.

Amity Chipman said state officials want proof they are building a more resilient structure and have made many suggestions.

“It definitely was traumatic,” she said. “We spoke with an engineer and are just rebuilding in the hopes it will never happen again. When we drive down there and don’t see that pier…” Her voice trailed off.

This story was produced by The Maine Monitor, a nonprofit and nonpartisan news organization. To get regular coverage from the Monitor, sign up for a free Monitor newsletter at TheMaineMonitor.org.

Machias dike repair awaits plan

DOT to host delayed hearing in October

BY JOYCE KRYSZAK/ THE MAINE MONITOR

One recent late August evening, a few tourists gathered on the deck of Helen’s Restaurant overlooking the Machias River.

The summer holdouts tugged sweaters closer and steadied their glasses while trapping napkins that threatened to fly away. This time of year, the river’s breezes grow colder and lustier, as if crying out to Machias Bay and the open sea just around the bend.

Come winter, the sea and the bay will answer back with a roar, if last winter’s violent storms are any warning.

“We were like a little island,” said Julie Barker, co-owner of Helen’s Restaurant, a tidy, white-clad building perched at the edge of the river with the Machias dike in its dooryard. “We were surrounded by water until the tide receded.”

Over the past six years, catastrophic storms with surging tides dumped floodwaters in Machias far surpassing the base flood elevation, classifying the events as 100-year floods. Last winter alone, three floods overwhelmed the dike and much of the surrounding downtown, including forcing the town hall to move, a change that has become permanent.

Meanwhile, the erosion on the century-old dike—a significant cause of that flooding—remains inadequately mended. After 15 years of studies, hearings, and back-and-forth plans, the public still awaits a Maine Department of Transportation decision about how it will fix the problem—a dike that keeps crumbling and flood waters that keep coming.

The DOT’s decision, or even the status of the environmental impact assessment needed to arrive at a decision, has been delayed yet again—now the public hearing is not expected until fall.

‘No’ to Yard South

To the editor:

There is a brief opportunity to save waterfront on Portland Harbor, currently zoned industrial, for future marine commercial use. A 30-acre parcel that borders South Portland’s Bug Light Park and boat ramp to the east and an oil tank farm to the west is being considered for rezoning.

The current owners seek to build 1,000 residences, a mixture of six highrise condos overlooking the park and Casco Bay, luxury single family homes, and 10% affordable housing, and call it “Yard South.”

The soil, contaminated from years of use as a World War II shipyard, is full of “urban fill,” used to elevate land. The property sits in a flood zone. When the sea rises and storms surge, it will leach contaminates. Heavy high-rise structures will sink. South Portland taxpayers

Originally scheduled for the spring, the public hearing was pushed back, then pushed back again this summer. Beyond references to additional talks among stakeholders, and the public hearing possibly sometime in October, town and state officials remain tight-lipped.

“This is a complex project involving many different issues and stakeholders. I don’t expect to have anything new to add before the public hearing,” said Paul Merrill, DOT’s director of communications, in a written response to questions.

Four years ago, DOT published a “Purpose and Need for Action” report, detailing studies dating to 2016. Since then, flood waters have exceeded the base flood elevation eight times, each one chomping at the dike’s foundation.

The agency must give the green light for any plan to go forward because the dike spans Route 1, a federal highway.

But DOT’s draft assessment still hasn’t been made available to the public. Coupled with the public hearing repeatedly being pushed back, Downeast residents and other stakeholders are left in the dark, speculating on when a replacement dike will be built.

Residents and other stakeholders are left in the dark, speculating on when a replacement dike will be built.

Last November, after portions of the foundation washed away, DOT had to temporarily close the dike, which carries Route 1 over the Machias River at the nexus of Middle River and Machias Bay. Residents were forced to take lengthy detours until a temporary span was erected that month.

A permanent solution is no closer and many experts say the DOT’s preferred, “in-kind” replacement plan won’t prevent or even mitigate flooding.

Merrill, in a June email, wrote that DOT’s “draft EA (environmental assessment) analyzes alternatives and identifies the fully gated replacement culverts as the (DOT’s) preferred alternative.”

Merrill added that the Federal Highway Administration would be at a future public meeting to discuss the environmental assessment soon after it is published. The FHWA will review public comments then make its final findings.

For the last two years, representatives from various private, non-profit groups and government agencies have met as members of the Machias Downtown Resiliency Group to develop a flood mitigation plan. They have worked with DOT and voiced concerns about the agency’s preferred dike replacement plan.

Downtown Machias isn’t the only focus of concerns about the prospect of another violent storm season. The Downeast Salmon Federation and other conservation groups, including Maine Coast Heritage Trust, are in a race to restore salt marshes along the coast, including the Schoppee salt marsh just around the corner from the dike.

The marsh also gets ravaged by violent storms. Tidal surges routinely overtop the adjacent Downeast Sunrise Trail that straddles the marsh and the river. The constant deluge compromises the delicate balance of a crucial natural resource.

Last winter was literally the breaking point.

The trail was largely washed away along the river. It was closed, then reopened once repairs were completed by DOT earlier this summer.

Bigger rip rap was put in along the dike and the trail, new culverts installed, and the rebuilt trail was

letters to the editor

will be left to pay for all infrastructure repair and contamination clean up.

Fishermen, seaweed farmers, lobstermen, ferries, boating building companies, and other maritime industries should take this opportunity to make their voices heard. As a group, you will be heard by state government officials in addition to South Portland’s city council and its planning department. Once this waterfront is re-zoned to residential, the potential to increase Casco Bay’s working waterfront is forever lost.

The South Portland Planning Board is basing their determination on the city’s 2012 Comprehensive Plan, which does not account for rising seas, temperature increases, and rain flooding due to climate change. Seven City Councilors, not voting residents, have the final say as to whether this development will be rezoned and built. Oh, and try not to cough—the adjacent oil tank farm regularly exceeds what the EPA allows for cancer-causing

topped with a thick bed of crushed stone. A wide, neatly manicured berm was also added.

Flood mitigation experts say it all amounts to window dressing, with the Downeast Salmon Federation’s Charlie Foster arguing culverts won’t hold back the force of the sea.

The Downeast Salmon Federation designed a plan that includes installing a bridge over the most vulnerable parts of the trail. Foster said they have several grant applications pending, totaling roughly $30 million, to pay for the project and the group is confident it will receive the grants because the state and federal governments have made salt marsh restoration a priority.

Foster and others say the best solution for the Schoppee Marsh, as well as for Machias residents and businesses, would be to replace the dike with an elevated section and add a series of gated culverts to allow a gradual release of waters into Middle River.

Foster acknowledged it would be expensive, and cost has been a major consideration for DOT, but believes the project could easily be funded with the grant money available through the infrastructure law and from other sources. But he said they need to act fast because that money will dry up soon.

“It’s not going to be a permanent thing,” said Foster. “A lot of that extra money is based on the bipartisan infrastructure law … and you’re only looking at a couple more years of that kind of surge of money.”

Costs also are a concern for residents who have to brace for the worst.

Julie and David Barker, who own Helen’s Restaurant, spent about $5,000 this year shoring up the banks below the restaurant with more prodigious rip rap. They also pay an extra $2,000 for flood insurance.

benzene carcinogens to be emitted. The City’s decision will be made soon. Please make your voices heard. Visit “No Yard South” on Facebook.

Pamela Thomas South Portland

Blue Hill photograph

To the editor:

I’m the adjutant and finance officer for Duffy-Wescott Post 85 in Blue Hill with a family association of the town for almost 100 years and a full time resident of the town for ten.

The photo on page 9 in the September issue shows what was then known as Main Street but that now is referred to as Tenny Hill Road. The building shown was the third version of a building on that site. The first was a wood structure for the Blue Hill Academy built in 1803, the second built in the same location,

but a brick structure, and the one shown depicts the 1909 version that added the buttresses and some other modifications. It is currently undergoing its fourth “modification,” as long as money allows us to complete it.

At that time, Tenny Hill was dirt as were many of the roads in town and as I vaguely remember, it did not get paved (nor did South Street) until the early 1960s. The utility poles on the right carry telegraph and phone lines and those on the left carry power, so this was taken after about 1913 or so. A lot has changed, including the width of the road. Many on that road lost much of their front yards.

The building has experienced much, though in 1889 its purpose was modified when the Blue Hill-George Stevens Academy opened its doors as the secondary school for the area.

Butler Smythe Blue Hill

Building a better waterfront Castine replaces harbor deck with new material

BY TOM GROENING

Like many waterfront towns, Castine was hit hard by the January storms. One of its many specific victims was a harbor dock, an area about 40-feet by 40-feet, popular with tourists for its proximity to parking, views of the anchorage at the mouth of the Bagaduce River, and of Maine Maritime Academy’s State of Maine training vessel when it’s in port.

The Castine Town Dock, as it’s known, was destroyed by those storms as high water lifted the decking off the joists. The ragged remains were removed soon after.

But even as the storm raged, Harbormaster Scott Vogell was planning the rebuild. Rather than return the decking—which was the typical wood, an estimated 3-3/4-inches thick by 8-inches wide—Vogell inquired about new materials.

Two products were found—ThruFlow and Titan Open X. As the names imply, both are designed to allow rising seas to rise up through the deck without tearing it off the joists.

Vogell was the project manager on the work, conferring with the town harbor committee, and Islesboro Marine Services was hired to rebuild the dock. They decided to go with Titan Open X for decking, but there were other changes made to the structure.

Pilings were replaced, and the carrying beams now have 4-inch by 18-inch steel plates on both sides which are then lag-bolted to the pilings. The joists were set 2-feet on center, which allows more water to rise up through without encountering resistance.

But the game changer was the Titan Open X decking, which Vogell says allows more water to pass through it than the decking that it replaced.

“That has 37% or 38% of the water that hits it, it

goes up through it,” he said. And unlike wood, “This stuff sinks. The fact that it’s not buoyant” helps keep it attached to the joists.

Castine tapped $500,000 from a contingency fund to repair the dock, as well as to address other damage caused by the storms, Vogell said, including washouts at Fort Madison, which is now a waterfront park; Water Street; and a road just outside the village area. Adjacent to the Castine Town Dock is the Acadia Dock, which also will be repaired soon, he added.

The town dock project cost about $175,000. Perhaps surprisingly, using the Titan product for decking material was comparable in cost to using the traditional wood, Vogell said.

Being proactive helped the town recover, he said, and get the seasonally busy waterfront up and running.

“I had boats in the water by April 18,” he said.

We asked, you answered

Newspaper reader survey shows your interests

BY KIM HAMILTON

EARLIER THIS YEAR, Island Institute asked our readers for your thoughts and opinions about The Working Waterfront newspaper and the weekly online digest of Working Waterfront stories. As we consider ways to improve and expand our connections to those who share our deep commitment to the people and places that make the Maine coast unique, your input was instructive and practical.

Since our first issue in April 1993, this newspaper has provided wellresearched, insightful, and local stories and perspectives on critical community conversations. We bring the flavor of life on the Maine coast to you through our long-standing contributors, and we work hard to unpack some of the most complex issues shaping our coast— from the lasting imprint of last-year’s storms to the heroic efforts across small, peninsular and island communities to adapt in the face of extraordinary change. We share the hopes, tragedies, solutions, and humor, too, that define our remarkable corner of the world. As everyone knows, the environment for local news and journalism

rock bound from the sea up

is changing. You have more options on how and when you receive your news and analysis. We learned from more than 850 of you, however, that this newspaper remains your touchstone for all things related to the Maine coast.

We also learned that there is room for innovation, especially as we work to engage new generations in the solutions and opportunities ahead.

Thank you for valuing what we take great pride in producing and for taking the time to respond. Thank you, too, for continuing to support Island Institute so we can bring the extraordinary, the complicated, and the unusual from the docks to your doorsteps.

Here are some highlights from the survey results:

You seek and trust the content provided by The Working Waterfront

• 83% of readers regularly access The Working Waterfront, far more than any other source of news.

• Readers trust us for news and information on Maine’s coast by a 5:1 margin over other sources, such as

broadcast media, daily newspapers, and more local sources.

• 65% of readers report reading every edition of the paper, with 80% reading all or most all of the content.

You especially want content about climate and the economy, but not exclusively

•You want unique coverage (64%) with a local flavor (62%) as your preferred content types.

• 82% of readers are interested in climate and sea level rise issues.

• 57% percent are looking for information related to the environment, land use, and sustainability.

• 45% of readers are interested in issues related to Maine’s economy and marine economy.

• 43% are looking for information on housing and related issues.

• There are gender differences in responses, with women showing a stronger preference for stories about climate and environment along with stories about arts/ culture/lifestyle and schools. Men showed a stronger interest in stories about maritime history.

Public, private don’t always play nicely

The community must remain involved

BY TOM GROENING

IMAGINE THE REACTION to a town renting out offices in a public library built through the beneficence of Andrew Carnegie a century ago. Or a John D. Rockefeller-donated carriage trail in Acadia National Park being turned into a for-profit go-cart track.

It’s not quite as dramatic as all that, but a nettlesome controversy has been brewing in Belfast since the University of Maine announced it would be selling its Hutchinson Center, a sort of annex to the state system, which, when built in 2000, featured the best technology, more than a dozen classrooms, an auditorium, and a bright and spacious lobby ideal for hosting lunches.

(Full disclosure: Island Institute, publisher of this newspaper, has used the center for its conferences.)

Credit-card lender MBNA, which was later purchased by Bank of America, paid to construct the facility as a gift to the University (it was named for a former president of UMaine) and to Belfast, where the company had recently expanded.

The sale is not out of left field. During and since the pandemic, the Hutchinson Center has seen less

Our older readers have an affinity for print, but not entirely

• 80% of our readers who responded are over 65 years old.

• These readers prefer the print edition of the paper to digital formats (74% prefer printed copies).

• 64% of readers do access stories online (usually delivered to their email inbox).

Island Institute remains committed to publishing The Working Waterfront as a trusted source of news and information for Maine’s island and coastal communities. We plan to incorporate this reader feedback to deliver the content you are most interested in, both in digital and print formats. You’ll be hearing more from us in the months ahead as we dive into some of the most compelling stories shaping our coast.

Kim Hamilton is president of Island Institute, publisher of The Working Waterfront. She may be contacted at khamilton@islandinstitute.org.

in nonprofits

use as much of non-campus, postsecondary education has gone online. And in-person learning is not likely to come back.

The building and grounds, which are on Route 3, require substantial upkeep, so UMaine officials say they’re trying to be fiscally responsible in selling this property.

But Belfast civic leaders have argued the Hutchinson Center was a gift to the community to support public sector endeavors like education, and now the University is cashing it in and leaving town. And to further stoke the fire, the University is selling the facility to a church, which wants to use it for worship services and to start a private school. UMaine rejected two public group bids which, admittedly, offered less money.

Having the Hutchinson Center become private isn’t going to destroy Belfast’s character, nor is it going to sharply hamper education in the community. But the move suggests a betrayal of the benefactor’s intent, and it raises important questions about the role of nonprofit institutions: Is their value understood? Can there be too many in a community? Does their existence weaken the private sector?

Long before I worked for the nonprofit Island Institute, the Rockland newspaper would regularly run stories and opinion pieces about what some saw as too many nonprofits in the downtown, the Institute among them, along with the Farnsworth Art Museum and others.

The argument was that they didn’t pay property taxes on their large Main Street buildings. But consider the impact employees of those nonprofits— most of whom don’t live in Rockland— have on the local economy.

The Farnsworth in particular can make the case for impact very easily. Visitors must put a colorful round sticker on their chest to signify they’d paid for admission, and you see those stickers on people all along Main Street, going out to lunch, shopping at stores, browsing at art galleries.

Institute employees spend money at Main Street businesses, which in turn helps their owners pay their property taxes.

On a recent visit to Eastport, I noted that the Tides Institute, a homegrown nonprofit there dedicated to culture, arts, and history, was establishing an exhibition and restaurant space in the Masonic Hall.

That building had, in the last several years, been home to a couple of forprofit restaurants, both of which did not continue in business.

On that visit, I asked someone who has lived in the community for decades about the wisdom of having a nonprofit taking over a building that might again be home to a restaurant. She replied that despite hard work and high hopes, no restaurant could seem to make it there, so why not draw visitors with art and culture?

If there is a lesson to be learned in the Belfast situation, maybe it’s that the community should be sure to have a seat—or seats—on the governing board of a larger institution like UMaine. Boosters have worked hard to persuade the University to hold onto the Hutchinson Center, but that effort may have come too late.

Tom Groening is editor of The Working Waterfront. He may be contacted at tgroening@islandinstitute.org.

SHADY SUMMER STREET—

This photograph from the Library of Congress is labeled only as “street in York Village,” and dated at 1908. Do readers have information on the street name? Are the trees still standing? Email editor Tom Groening at tgroening@islandinstitute.org.

Neighbors helping neighbors on islands

Affordable housing efforts reflect unified resources

BY LIZA FLEMING-IVES

Twenty-five years ago, residents of Vinalhaven asked the Genesis Community Loan Fund for help. Without local options, their aging neighbors were often forced to leave the island for care in mainland facilities, separating them from their homes and families.

Genesis support helped open the Ivan Calderwood Home in 2001, enabling residents to remain in their island communities.

The project revealed a larger issue Genesis has focused on ever since: Maine’s coastal and island communities need resources to create and sustain affordable and accessible homes for year-round residents—not only for older adults but for individuals and families which include school-age children and service providers and other workers.

Through our lending and guidance, in partnership with MaineHousing, Genesis is helping expand affordable housing throughout rural Maine, including on islands, where neighbors are helping neighbors, often as

Island Institute Board of Trustees

Kristin Howard, Chair

Doug Henderson, Vice-Chair

Shey Conover, Secretary, Chair of Governance Committee

Carol White, Chair of Programs Committee

Kate Vogt, Treasurer, Chair of Finance Committee

Bryan Lewis, Chair of Philanthropy Committee

Megan Dayton, Ad Hoc Marketing & Comms Committee

Mike Boyd, Clerk

Sebastian Belle

John Conley

David Cousens

Mike Felton

Nathan Johnson

Emily Lane

Nadia Rosenthal

Michael Sant

Mike Steinharter

Donna Wiegle

Tom Glenn (honorary)

Joe Higdon (honorary)

Bobbie Sweet (honorary)

John Bird (honorary)

Kimberly A. Hamilton, PhD (ex officio)

volunteers. They are organizing, fundraising, identifying housing sites, and overcoming logistical challenges that “unbridged” places face when the only way there is by boat.

Islanders with different experiences, skills, and ideas are stepping forward to create plans and projects to ensure their communities can retain services, support, and connections.

With no one-size-fits-all housing solution, they are responding creatively with a diversity of project types: building new homes, rehabilitating existing structures, bringing in modular units customized to fit on ferries, and reusing what works—one example is the former ferry-crew quarters that will become a new home.

This year, with financing and/or guidance from Genesis and funding from MaineHousing, nine of 15 eligible coastal islands have launched or completed projects to create affordable housing for year-round residents. Here are some examples:

• Chebeague Island Community Association’s newest housing project to support island families will be

a multifamily building with threebedroom homes, developed through modular construction.

• On Cliff Island, a project is in progress to rehabilitate two three-bedroom homes to help ensure the community remains accessible to individuals and families at a range of income levels.

• To meet the needs of year-round residents of all ages, Cranberry Isles Realty Trust has led projects that have built two single-family homes on Great Cranberry Island and created four homes on Islesford. New projects will increase the total number of newly created affordable homes on the Cranberry Isles to ten.

• A project on Isle au Haut aims to adapt a single-family home into a duplex, and rehab two single-family homes, including one that has lacked a septic system or running water.

• Islesboro has plans to construct two new single-family homes for yearround residents.

• North Haven plans to expand its yearround housing stock by rehabilitating two existing properties and creating accessory dwelling units (ADUs) to provide flexible housing options.

THE WORKING WATERFRONT

Published by Island Institute, a non-profit organization that boldly navigates climate and economic change with island and coastal communities to expand opportunities and deliver solutions.

All members of Island Institute and residents of Maine island communities receive monthly mail delivery of The Working Waterfront. For home delivery: Join Island Institute by calling our office at (207) 594-9209 E-mail us: membership@islandinstitute.org • Visit us online: giving.islandinstitute.org

• On Peaks Island, Home Start has secured a project site to develop a multifamily building offering three homes.

• Vinalhaven Housing Initiative has plans to convert former ferry-crew quarters into a three-bedroom home and construct another onebedroom home.

Each project showcases the determination of island communities to secure homes that are affordable, accessible, energy-efficient, and climate-resilient. And what’s the even larger goal? To help sustain year-round island communities that have relied on innovation and cooperation for generations.

Across the state and beyond, communities can learn from Maine islanders who are overcoming tough challenges to create housing for their neighbors. Genesis is proud to be a partner in this work.

Liza Fleming-Ives is executive director of the Genesis Community Loan Fund and has worked with island and coastal communities for nearly two decades, helping to bring together resources to create affordable housing.

Editor: Tom Groening tgroening@islandinstitute.org

Our advertisers reach 50,000+ readers who care about the coast of Maine. Free distribution from Kittery to Lubec and mailed directly to islanders and members of Island Institute, and distributed monthly to Portland Press Herald and Bangor Daily News subscribers.

To Advertise Contact: Dave Jackson djackson@islandinstitute.org (207) 542-5801

www.WorkingWaterfront.com

LOBSTER SEASON

continued from page 1

Lobstermen in far-flung places like Matinicus and Criehaven have reported robust catches, said Sam Belknap, director of the Island Institute’s Center for Marine Economy. Elsewhere, landings have been steady and prices seem to be a little higher than last year.

Lobstermen welcome a return to normalcy, said Belknap, who had a student lobster license when he was in high school. His grandfather was a lobster fisherman, as is his father. With shedders arriving close to the traditional time of year and stable prices for lobster, it’s easier for fishermen to run their businesses.

“By and large, this year has been as close as I can recall to the way it used to be when I was growing up,” he said.

TOURISM SEASON

“In recent years the only thing that’s been steady has been the uncertainty.”

Lobster by far is Maine’s most valuable commercial fishery, bringing in hundreds of million of dollars to the state’s thousands of lobstermen.

The catch first topped 100 million pounds in 2011 and peaked at 132.6 million pounds in 2016. Since then, there’s been a downward trend, with landings coming in at 93.7 million in 2023—the smallest harvest since 2009.

While lobster prices always fluctuate, the price swings have been particularly wild in recent years. Prices went from an average of $4.21 a pound in 2020 to $6.71 in 2021 before crashing to $3.95 in 2022, according to the Department of Marine Resources.

The catch first topped 100 million pounds in 2011 and peaked at 132.6 million pounds in 2016.

Prices rebounded to $4.95 a pound last year and appear to be higher this year. Fishermen lately have been getting over $5 a pound and the price has been holding. Chris Welch, a lobsterman in Kennebunk, said he was receiving $5.50 a pound for new-shell lobsters, and $6.75 a pound for old-shell, in late August.

“We had a good [price] drop in the spring that got us all nervous, but prices have rebounded to a comfortable spot for this time of year,” he said.

There’s also been no shortage of bait, with strong catches of menhaden (also

known as pogies) off the Maine coast fortifying the supply. Besides herring and menhaden, lobstermen often use frozen fish, such as rockfish, as bait. The prices, too, appear to be about the same as last year’s prices, and cheaper than several years ago when there was a bait shortage, Welch said.

While things overall appear steady, the lobstering varies along Maine’s long ragged coast. What is true in southern Maine may be different from what’s happening along the midcoast or eastern regions of the state.

Bob Baines, who fishes out of Spruce Head, said the fishing in his area of Penobscot Bay has been spotty. “It’s not bad fishing, but there aren’t lobsters in places where you’d expect lobsters. I don’t know, ask me around Thanksgiving and I’ll tell you then.” He added: “We’re plugging along I guess is the best way to put it.”

continued from page 1 and cook it themselves,” which saves customers money versus driving to a restaurant and eating out.

owners have mitigated that problem by purchasing property that they rent to staff at below market rates.

Said Bedell, “We’ve been lucky and we’ve been smart. Retention is high here.” Providing affordable housing is part of the reason. “We don’t want to lose the younger demographic,” she said.

Amity Chipman of Chipman’s Wharf in Milbridge said their business has been steady, too.

Chipman’s is a seafood market and lunch grill founded by Chris and Jason Chipman, both of whom are lobster fishermen.

“I think we’ve had as much traffic, probably a little more than last year,” Amity Chipman said.

Some things have changed compared to prior years, however.

“There are fewer families—smaller parties. What people have been spending has been down. People are mindful of what they’ve been spending,” she said.

Also, Chipman’s has seen more international travelers in recent years, she noted. “We do have several people who come from the U.K., Canada, Asian populations.”

Especially since COVID, Chipman said.

“We’ve finally been discovered. Bar Harbor is so busy, people are staying here and traveling to the islands. A lot of people are staying here and traveling through and going to Lubec.”

She said that the increase in Airbnb and other such short-term rentals in the area has helped. With no large hotels in the Milbridge area, having the Airbnb option enables people to “come to the seafood market and go back

Bar Harbor Chamber of Commerce Executive Director Everal Eaton, too, spoke of the summer of 2024 as on par with recent seasons.

“It started slow but picked up. Talking to a lot of our lodging facilities, they are looking at a strong year,” Eaton said.

Visitors come “from all over at different times of year,” he said. “A lot of national and a little bit of international.” Their reasons range from a desire to eat lobster and visit Acadia National Park to simply seeing “the picturesque view of the town.”

Debbie Hoverson of Searsport Shores Campground said this summer has been “good but less busy. Nobody knows why. Election year? The economy?”

Searsport Shores, owned by Astrid and Steve Tanquay, is an oceanfront campground located on Route 1 in Searsport. Most of their clientele lives within four or five hours of Maine.

“A lot of New England people— Boston, Vermont—but also people from Michigan, Indiana,” Hoverson said.

They come, Hoverson said, “Because of this park. It’s a very unique campground. It’s got art, nature. People tell us, ‘This is the best site that I’ve ever been at.’”

Moderate this season may have been, but there is still leaf peeping ahead— and the prognosis is good.

“This summer was one for the record books! An abundance of daily sunshine with just the right amount of rainfall has set the stage for a breathtaking foliage season,” according to Gale Ross, spokesperson for the Maine Department of Agriculture, Conservation and Forestry. Coastal Maine’s colors are expected to peak in mid to late October.

Acadia is still an economic driver

A new National Park Service report shows that 3.8 million visitors to Acadia National Park in 2023 spent $475 million in communities near the park. That spending supported 6,600 jobs in the local area and had a cumulative benefit to the local economy of $685 million.

“I’m so proud that our parks and the stories we tell make a lasting impact on more than 300 million visitors a year,” said National Park Service Director Chuck Sams. “And I’m just as proud to see those visitors making positive impacts of their own, by supporting local economies and jobs in every state in the country.”

“People come to Acadia National Park to experience the beauty of its amazing landscape and recreate on its historic carriage roads and hiking trails,” said Superintendent Kevin Schneider. “We’re proud that Acadia National Park not only offers visitors extraordinary experiences but significantly supports local businesses.”

The National Park Service report, 2023 National Park Visitor Spending Effects, finds that 325.5 million visitors spent $26.4 billion in communities near national parks. This spending supported 415,400 jobs, provided $19.4 billion in labor income and $55.6 billion in economic output to the U.S. economy. The lodging sector had the highest direct contributions with $9.9 billion in economic output and 89,200 jobs. The restaurants received the next greatest direct contributions with $5.2 billion in economic output and 68,600 jobs.

Farnsworth shows coastal Wyeths

College intern explores, curates art

The Farnsworth Art Museum is presenting The Wyeths: Impressions of Coastal Maine, beginning Oct. 26 through Dec. 31. The exhibition presents paintings by N.C., Andrew, and James “Jamie” Wyeth, inviting viewers into the serene and evocative landscapes of Maine’s Midcoast, including Rockland, Tenants Harbor, and Port Clyde.

These communities, which have long served as a wellspring of inspiration for the Wyeth family, are reimagined in the watercolors and oils of three generations of painters.

This summer, curatorial intern and exhibition guest curator Sarai Marshall visited some of these iconic locations for the first time. Her own impressions of the coast are thoughtfully interwoven into her interpretation and presentation of the works on display.

This exhibition marks a milestone in the Farnworth’s Eddie C. and C. Sylvia Brown Institute for Museum Studies Program and exemplifies the program’s goal of introducing career paths to the next generation of museum professionals. Marshall, a senior at Morgan State University majoring in art history, was among three students who completed the inaugural internship program.

“We are thrilled to showcase this exceptional exhibition and celebrate the work of the Wyeth family,” said Christopher J. Brownawell, executive director of the Farnsworth Art Museum. “Sarai Marshall’s fresh perspective adds a unique dimension to the presentation, reflecting our ongoing mission to support emerging talent in the museum field.”

“I am incredibly grateful for the opportunity given to me by the Eddie C. and C. Sylvia Brown Institute for Museum Studies program and the Farnsworth Art Museum,” Marshall said. “The internship was a wonderful experience and introduction to coastal Maine. Learning more about the Wyeth’s was a large part of my role and I look forward to sharing my initial impressions of coastal Maine through this exhibition.”

The Wyeths: Impressions of Coastal Maine will be on view at the Farnsworth Art Museum from October 26 through December 31, 2024. For more information about the exhibition, visit the website.

Island Institute funded for lobster work

SBA grant supports community resiliency work

ISLAND INSTITUTE has landed a $1.4 million grant from the Small Business Administration to support Maine’s lobster industry and enhance the economic resilience of the coastal communities dependent on this vital fishery.

This congressionally directed spending request championed by Sens. Susan Collins and Angus King will launch the Future of Fishing, a collaborative effort designed to expand economic opportunities for Maine’s coastal communities, building on Island Institute’s longstanding partnerships to advance a diversified, climateforward marine economy in Maine.

“This funding is not just an investment in the lobster industry, it is an investment in the communities that have built their lives around these waters,” explained Kim Hamilton, president of Island Institute. “We are immensely grateful to Sens. Collins and King for their unwavering support and recognition of the importance of Maine’s island and coastal communities. With this support, we can begin implementing transformative changes that promise a sustainable future for the coast.”

Maine’s fishing communities face historic challenges, such as rapidly warming waters, more frequent and severe storms, costly regulatory changes, and rising business costs. These communities, and the men and women that work on the water, are the backbone of Maine’s seafood sector,

a sector responsible for more than $3 billion in total economic output and more than 33,000 jobs statewide.

“Island Institute provides critical support to those who make up Maine’s iconic lobster industry, helping to ensure our coastal communities continue to thrive amid climate and economic challenges,” said Collins.

“From Damariscotta to Eastport, this federal funding will support Island Institute’s efforts to promote business development and resiliency in communities along Maine’s coast,” she said

“The lobster industry is a cornerstone of Maine’s culture and identity, fueling livelihoods and the economy,” said King.

“The hardworking men and women who power the fishery are seeing firsthand the impacts of changes in weather and the water, so we have a responsibility to empower them through boosting collaborative efforts and informationsharing across the industry. When we invest in the lobster fishery, we make an investment in the future of Maine for generations to come.”

The three-year project will offer business and career training programs for rural fishing communities and families, including business management assistance and training, opportunities to explore diversified on-the-water income streams such as aquaculture endeavors, and assistance finding financial resources and educational opportunities for current and future generations.

Training technicians to work on electric outboards

BY YVONNE THOMAS

s a K-12 island educator for 20 years, I often witnessed the joy of students learning and it is something I miss, now that I work primarily with adults. I know adults feel happiness when they learn something new, but it’s usually a more muted response, especially in formal settings like classrooms and

development sessions.

Recently, I got to be with a group of adults who were highly engaged and excited to be teaching and learning together. This is a rare privilege and was one of the highlights of my summer.

The topic was electric outboards and the course was created with boat yard technicians in mind, but designed for a wide range of levels of familiarity with the content. It was offered in Rockland at Mid-Coast School of Technology in July and in Farmington at Foster Career and Technical Education Center in August. After over a year of planning and course development, it was thrilling to finally came to run the courses. Nearly 100% of participants

rated the course as good or excellent overall and all successfully completed the course.

My role was to coordinate the partners involved—Kennebec Valley Community College, the two hosting technical centers, and Island Institute. Then I got to sit back and watch the magic instructors Dan Hupp and Joel Rowland created with their students.

The 23 students were a surprisingly diverse group that included a few women, some in their 20s and 30s, and a number of Mainers born and raised in other countries. Several students had deep experience with the content and generously shared their knowledge.

A couple of oyster farmers interested in using electric outboards on their farms attended, as well as some who were experienced mariners, but new to the world of battery power and electric outboards.

would veer off into the inspirational and aspirational aspects of the subject.

Students got to experience the benefits of electric outboards, including the clean and quiet operation…

“The best part of the course was the open dialogue and mix of skills/knowledge,” one student noted. The format of the two-day bootcamp-style course included lecture on the theory and principles of electricity and electric propulsion fundamentals. The discussions were at times quite technical, but then

In the afternoon, students alternated between labs and sea trials. The sea trials were in a rigid inflatable boat powered by an Elco electric outboard motor and were done in Rockland Harbor during the Rockland class and at a lake during the Farmington class. The concept of “seeing is believing” is a powerful teaching tool. Students got to experience the benefits of electric outboards, including the clean and quiet operation, and to see how much power the battery for our electric outboard had. Our set up was not designed for high speed, but it was very steady and even after being out on the water for a couple of hours, we were able to track our use on an app and found that we’d used very little of the battery’s total capacity.

During the lab time, students worked on improving cable crimping skills, getting to know their digital volt-ohm meter, wiring electric panels, and learning about circuit boards. The opportunity to apply theoretical learning in the morning to the labs and sea trials in the afternoon created comradery and connection among both students and instructors.

FULL INVENTORY READY FOR YOUR WATERFRONT PROJECTS!

• Marine grade UC4B and 2.5CCA SYP PT lumber & timbers up to 32’

• ACE Roto-Mold float drums. 75+ sizes, Cap. to 4,631 lbs.

• Heavy duty HDG and SS pier and float hardware/fasteners

• WearDeck composite decking

• Fendering, pilings, pile caps, ladders and custom accessories

• Welded marine aluminum gangways to 80’

• Float construction, DIY plans and kits Delivery or Pick Up Available!

The electric boat course is part of Island Institute’s effort to reduce greenhouse gas emissions in the marine economy by promoting the electrification of Maine’s working waterfront. Deploying demonstration electric boats to several Maine harbors and marine businesses and supporting shoreside infrastructure are key aspects to this work.

And so is the electric boat course. We will be offering a third round of the course sometime this fall in Washington County.

If you would like to receive registration information about the next round of course, please contact me at ythomas@gmail.com.

And the next time you are at a working waterfront, scan the boats for electric motors—and smile if you see some, knowing that there are now a few more folks who can maintain and repair them!

Yvonne Thomas is a senior community development officer at Island Institute, publisher of The Working Waterfront.

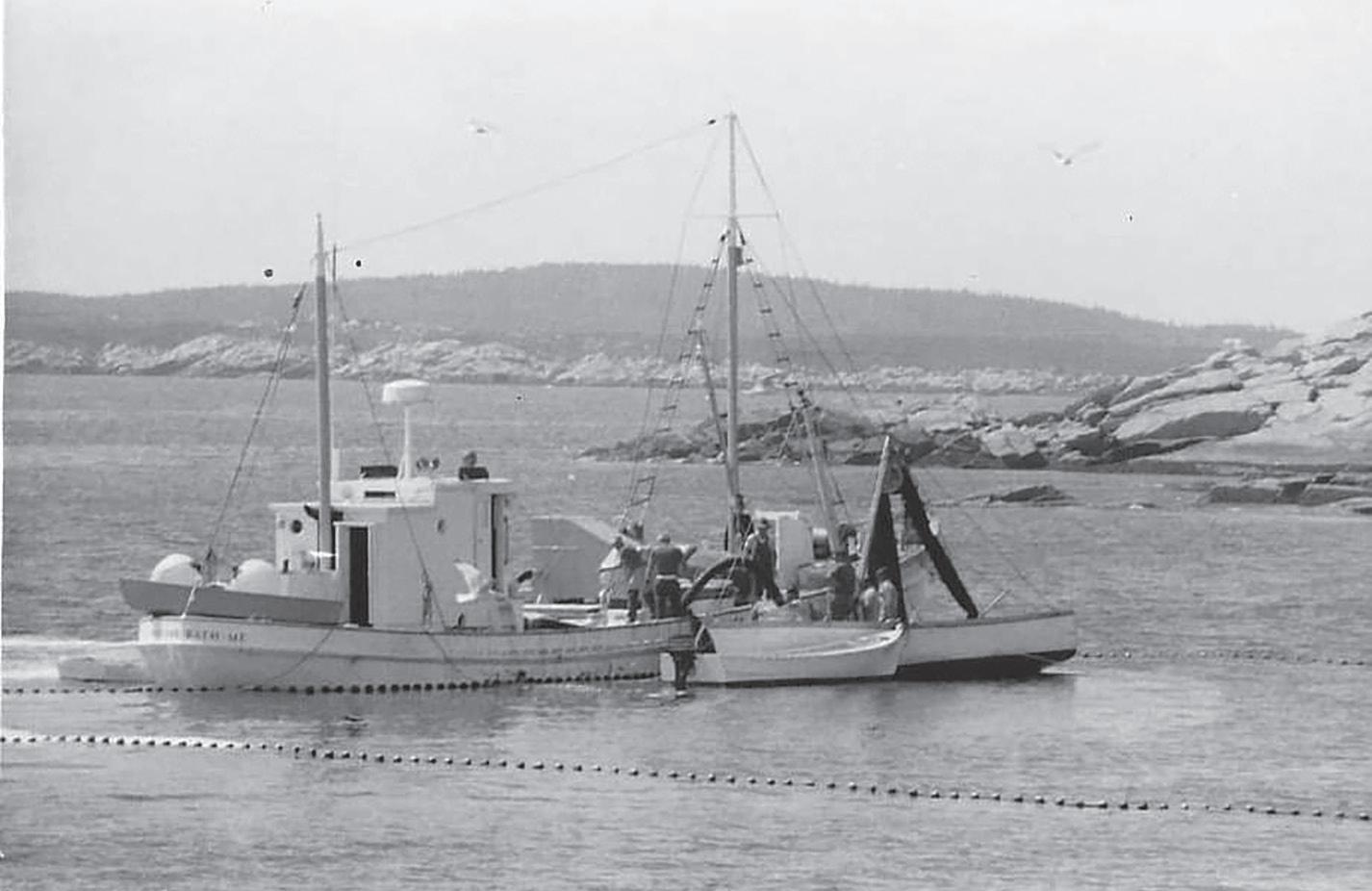

Lest we forget…

Sardine carrier Jacob Pike’s fate reminds us of fishery history

BY BUZZ SCOTT

If you know anything of the history of Maine’s sardine industry you understand the significance of the loss of the iconic Jacob Pike, which sank in the New Meadows River during the back-to-back January storms. The vessel was raised in early September and faces an uncertain future.

Her sinking was heartbreaking. She had fallen into disrepair and passed from owner to owner, with each hoping to rebuild and get her back in use.

Built in 1948 by Wallace and Newbert in Thomaston, the Pike is 81.5-feet long, one of the largest and most elegant carriers to work the Gulf of Maine.

She and her sistership Pauline were among the most well-known carriers, hauling herring from the late 1940s to the mid-1980s. At one time, hundreds such boats transported herring to the sardine factories that dotted the coast from the Canadian Maritimes to the shores of Massachusetts.

The sardine industry shut down in the mid 1980s when the taste for sardines turned to tuna. Factories closed, carriers were abandoned, and some were simply taken out to sea and sunk. The loss of these magnificent vessels is a loss of Maine’s culture, heritage, and history.

As kids growing up in the 1960s and 1970s, some of us were taught by the men who ran these vessels. They were family, they taught us the meaning of hard work, and they passed down stories that helped mold us into people of the sea.

I fear with the loss of these vessels we will also lose our ability to stay people of the sea and teach our children how to be the same. The Gulf of Maine needs people who understand it, love it, and be stewards for our waters and planet.

Campbell “Buzz” Scott grew up on Matinicus Island and has worked in marine trades for decades. He runs the marine educationfocused nonprofit OceansWide.

Our Island Communities

BACK TO SCHOOL—

As they prepared to work with Island Institute’s Teaching and Learning Collaborative, teachers in island one- and two-room schools attended two days of workshops at the Island Institute’s Rockland offices. Each pointing to the islands on which they teach, are (from left): Heidi Donnelly and Mary Train (Chebeague), Jenny Baum (Cliff), Terry Wood (Monhegan), Kipp Quinby (Isle au Haut), Laura Venger (Frenchboro), and Ashley Greenleaf (the Cranberry Islands).

PHOTO: JACK SULLIVAN

Island Institute welcomes five new Fellows

Community service program in 25th year

Island Institute’s flagship fellowship program, which is celebrating its 25th year, welcomes five new Island Institute Fellows, two new community partners, and five continuing Fellows. The program brings recent college graduates to island and coastal towns to work for two years on a community’s public priorities.

THE NEW FELLOWS ARE:

Thomas McClellan will work with Monhegan Plantation on a working waterfront resiliency project as the island replaces its public wharf and shores-up other waterfront access areas. The island will redesign for sea level rise and increased storm surge pressure. Originally from Maine, McClellan recently completed a degree in Sustainability and Oceanography at Dalhousie University in Nova Scotia.

Taylor Rossini will be the Swan’s Island Fellow working with the Society of Education Board as it launches a redesign plan for the island library. The town envisions the library transitioning into a community hub that will still provide library services, but with broader offerings. One such offering will be digital literacy training with the hope of providing on-island business owners, including lobstermen, with technology training and support as federal fishing rules and regulations change. Rossini joins Island Institute from Delaware where she was completing her master’s degree.

Erin Dent is the St. George Fellow, working with the town’s comprehensive planning committee, assisting in reviewing and interpreting data and anecdotes the committee has collected from the community. She will then lead in the writing of an updated plan. Once the plan is completed, Dent will focus on a priority area identified in the plan. Dent has come to Maine from Texas.

Lucia Daranyi is the Deer Isle and Stonington Fellow working with the Adult & Community Education program, which is moving to allow for more offerings. Daranyi will join staff to assist with this growth, primarily through outreach and engagement, and she will collect stakeholder feedback. The organization sees a need to help those making career transitions or whose jobs, like lobstering, will require

new technological skills for tracking and reporting. Daranyi grew up on Peaks Island.

Mark Gorski will be joining Peaks Island Home Start, the island’s affordable housing non-profit. Part of the city of Portland, the island will soon implement new zoning regulations that will change lot size, and distance/height from sea level, as well add rules spurred by population growth and climate factors. Gorski’s responsibility is to understand the new code, communicate it to the Peaks Council, homeowners, and support Home Start. Gorski arrives in Maine from New York where he worked in the city’s office of management and budget in its community development unit.

RETURNING FELLOWS ARE:

Alice Cockerham, who works with Hancock County Planning Commission assisting towns with

comprehensive and resilience planning.

Morgan Karns who works with MDI Biological Labs to collaborate with some islands in a statewide initiative to test drinking water for heavy metals and plastics, partnering with the Maine Seacoast Mission.

Lavinia (Livy) Clarke is the Machias Fellow, working on the Sunrise Trail Coalition, engaging DownEast communities to realize the trail’s potential in alternative transportation, recreation, and community building.

Grace Carrier is the Brooklin Fellow, working with the town’s climate response committee. Alongside committee members, she connects individuals, business owners, and municipal leaders to energy and cost saving programs.

Claire Oxford is the North Haven Fellow, working with town staff and committees to shore-up the island’s working waterfront from recent and future storm surge and sea level rise.

‘Island girl’ returns to teach on Isle au Haut Kipp Quinby started in island’s one-room school

BY SARAH CRAIGHEAD DEDMON

Kipp Quinby’s new job is a sort of homecoming. In September, she took over as the teacher of Isle au Haut’s one-room school house, the same room where she attended school as a child.

In fact, all of Isle au Haut’s children have attended the same wooden schoolhouse, ringing the same outdoor bell from a rope inside the classroom for at least 100 years. The school serves students ranging from Pre-K to 8th grade. Last year’s student population was two, but this year it has more than tripled, to seven students.

“We were playing the game octopus [tag] today and there were just about enough of us to make that happen,” said Quinby.

Quinby is well-prepared to teach children on an island. As a young girl, she lived with her family on Peaks Island, where she received her first commercial lobstering license at the age of six, later working as a teenage sternman. Quinby’s family relocated to Isle au Haut when she was a child, as part of the island’s affordable housing program, which offers below-marketrate rentals to families wishing to establish themselves on the island.

“My Dad saw an ad for the housing program, and he asked my mother if she would divorce him if he wrote for more information,” Quinby said, laughing. “She said no, and he said, ‘You should see its harbor!’”

In addition to the island’s exceptional harbor, almost half of Isle au Haut is part of Acadia National Park and a favorite summer attraction for campers and hikers. Quinby,

her parents, brother, and sister made the move and became part of Isle au Haut’s year-round population, which rises and falls, but averages around 50 residents.

One of those residents, Lisa Turner, is now in her 30th year as the Isle au Haut teacher’s aide. Like Quinby, Turner attended school there, and as far as anyone can tell, this is the first time two Isle au Haut graduates are working together to run the school.

Before applying for her teaching position, Quinby reached out to Turner, who served as a teacher’s aide when Quinby was a student.

“She said, ‘I think we’d work pretty well together,’ which is what I thought, too,” recalls Quinby. “She is very supportive, and she wants me to do a good job, and I want her to be proud of me.”

After graduating from the little white and green schoolhouse in 8th grade, Quinby’s high school education came in forms as unique as the island.

returning to Maine and attending the College of the Atlantic (COA), in part with a scholarship from Island Institute.

“COA offers one major: Human Ecology,” said Quinby. “It’s a flexible curriculum, so I received the equivalent of a degree in marine ecology and teaching.”

“She is very supportive, and she wants me to do a good job, and I want her to be proud of me.”

“We had a retired bishop on the island who taught me Latin and literature, and we had a carpenter who did boat design as lessons in geometry,” she said. “We are so lucky with the folks we have out here. It was also the early stages of a University of Maine distance education program.”

Quinby attended her senior year in Finland as an exchange student before

It’s difficult to imagine two degrees better suited to Quinby’s professional life, on and alongside the ocean. Today, she’s the owner of Island Girl Oysters, a sea farm located in the Blue Hill Salt Pond, where Quinby, with help from her sister, raises oysters. And for the past 12 years, she’s worked full-time in her family business, Ocean Resources.

“We collect and prepare marine specimens for schools and labs, so we do a lot of things prepared in formaldehyde and offer system coloring, where we might inject the arterial system one color and the venous system another,” said Quinby.

Speaking of the benefits to be found in a one-room schoolhouse, and also in a small island community, Quinby

Casco Bay Lines names new GM

Warnock has workforce, U.S. Navy background

Casco Bay Island Transit District, also known as Casco Bay Lines (CBL), has appointed John Warnock as the general manager following a unanimous vote by its board of directors. Warnock began work July 22.

“I am thrilled to return to Maine and get to work leading Casco Bay Lines,” Warnock said. “I look forward to starting out by riding the boats to meet captains and crew and Casco Bay islanders. My focus will be on safety first, on excellent service to islanders, good employee relations, and sound fiscal management.”

A search committee comprised of board members from Peaks, Long, Great Diamond, and Cliff islands worked with a recruiting firm to evaluate 75 applicants. The committee interviewed seven candidates and brought two in to visit Casco Bay Lines. Semifinalists rode boats to Peaks and Long islands and met with residents of several islands as well as three

members of CBL senior staff and the union president.

“Hiring the right leader to put CBL on track for the future is important to the islanders we serve and to captains, crew and staff,” said Jean Hoffman, chairwoman of the search committee.

“As a veteran of many searches, I can attest to the rigor and fairness of our process. John Warnock brings a history of learning, exceling at new challenges, effective management, and helping companies leverage technology to improve productivity and lower costs.”

Warnock will lead a team of management, marine, and shoreside personnel which grows from 40-plus year-round to 90 in the busy summer season. He will be responsible for leading day-to-day operations and long-range planning.

CBL’s mission “is to provide sufficient dependable, reliable service in a safe and secure manner, as affordably as possible, to preserve our year-round island communities.”

Nate Mills, president of the CBL union and senior captain, cited Warnock’s “strong operational background and commitment to safety” and said they will benefit “both our team and the community we serve.”

Warnock had worked at Worldwide Counter Threat Solutions based in Virginia, where he helped clients with strategic planning and communications, process improvement, and IT transformation. Most recently, as a strategic communication analyst, he provided analysis and interpretation of federal and military codes, laws, operations orders and directives, as well as effective communications, staff collaboration, and program management.

Previously, Warnock was at NGROUP Performance Partners, an organization that does workforce management and helps companies leverage technology to increase productivity and lower costs.

At the Navy Operational Support Center Norfolk, he was in charge of

says the intermingling of generations is a gift.

“In the classroom, there’s a lot of modeling that happens, and learning to be responsible for folks who are younger than you. It’s a valuable skill and it’s served me really well,” Quinby said.“Living on an island, where there are fewer options, I think it opens us up to realizing that potential friends and partners in different projects don’t exist in a single age bracket,” she said. “We can have friends of all ages, from just starting to do things, up into the 80s.”

2,500 reserve sailors in 123 units who were responsible for getting the right people on the right missions for their 25 “customers” and then managing those assets on each mission. Warnock served in the Navy for 29 years.

For more information about Casco Bay Lines, visit: www.cascobaylines.com.

book reviews

Tom Moore, unleashed

Poet blends real and surreal—and has fun doing it

Unleashed

and Other Poems

By Tom Moore Moon Pie Press, 68 pages

REVIEW BY CARL LITTLE

THE TITLE OF this book, Unleashed and Other Poems, and its cover, which features a painting by Sheep Jones of a figure walking a fish on a leash, reflect a new direction for Tom Moore, former Belfast poet laureate: an unplugged sense of humor. At the same time Moore adventures into metamorphosis via a curious creature kinship that enlivens several poems.

The title poem, prompted by the Jones painting, finds the poet swimming alongside a bass after removing its leash. The

matter-of-fact quality of the account of exploring Belfast harbor and beyond— “The water’s a bit/cooler out here, clearer too”—brings to mind the synthesis of the real and the surreal found in the poetry of Russell Edson and Gregory Orr.

In “A Plague of Grackles” Moore considers a group of these birds descending on seeds he has scattered.

“They must have texted/all their cousins because by noon there are/hundreds,” he writes, before describing a kind of Hitchcockian moment when the birds attack him. He ends up joining the flock, his “new comrades,” and appreciating their “raucous puns.”

Several poems are outand-out funny.

scents on an early morning walk. “Light bodied./Almost floral. Must be Olive, the eye doctor’s/Cavalier King Charles.”

A few poems complain.

“Cacophony in B Sharp Major for Blades and Blowers” takes aim at neighborhood noisemakers.

“Nothing Sucks Like an Electrolux” pays tribute to a ’67 vacuum cleaner, transforming it into a “bad-ass” babe, “leggy and ready to roll.”

In “Dirigo, Olfacio, Mingo” (Latin for “I lead, I sniff, I pee”), a dog samples

Inside an islander’s mind

Poems follow unconventional, random form

REVIEW BY DANA WILDE

STEVE LANGAN, the author of the poetry collection Bedtime Stories, keeps a residence on Cliff Island. This is helpful to know when you read his book, because the best poem in the collection, for my money, is “Island,” which is helped if you can picture a day visit to a Casco Bay island.

It’s also helpful to know that Langan is an expert in public health administration and a founder of the University of Nebraska Medical Center’s Seven Doctors Project, where healthcare workers use creative writing to deal with their profession’s stresses. He also holds an MFA in creative writing from the vaunted Iowa Writers Workshop, which might be the most useful background fact when reading his poems.

For these poems can be hard to follow for readers unfamiliar with the poetry workshops. While most of the sentences are quite plainly stated, at the same time, the sense of one thought often does not follow conversationally on the previous thought.

One of the shorter poems, “Modern Man Is Monstrous, Let’s Not Forget,” begins: “Seems like any time I have a minute/to relax here goes somebody all dressed up/on TV talking about the end of time.” These ideas are in themselves quirkily disconnected.

But then the next sentence, with no indication of how it fits, says: “I saw a photo of Michel Foucault today.” The poem concludes on how difficult it can be to make a sandwich.

This can be hard to make sense of, for some readers. But it’s not uncommon in the workshops for poets to understand their purpose is to disrupt conventional meaning.