Park University International Center for Music Presents Thursday, November 13, 2025 • 7:30 p.m.

Park University International Center for Music Presents Thursday, November 13, 2025 • 7:30 p.m.

At Park University’s International Center for Music, our purpose is simple yet profound: to shape the future of classical music by nurturing extraordinary talent and sharing it with the world. Each season, our students — rising artists from across the globe — come to Kansas City to learn, perform and inspire. Their artistry enriches our community, connecting hearts through music and leaving a lasting impact far beyond the stage.

This season, we invite you to witness their brilliance alongside renowned guest artists and faculty who join us in advancing our mission. Every performance you attend supports not only world-class music, but also the dreams of the next generation of great musicians.

Thank you for believing in the transformative power of music and for being part of this remarkable journey with us.

With gratitude,

Stanislav Ioudenitch Founder and Artistic Director International Center for Music at Park University

Andante moderato

Andante non troppo e con molto espressione

Andante con moto

MEPHISTO

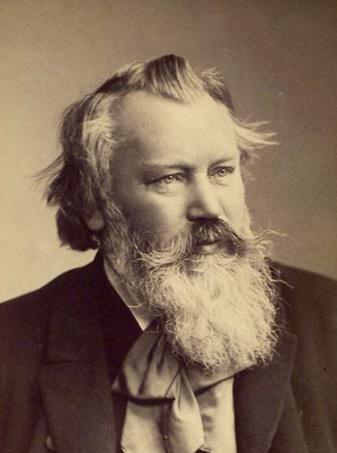

Johannes Brahms (1833-97)

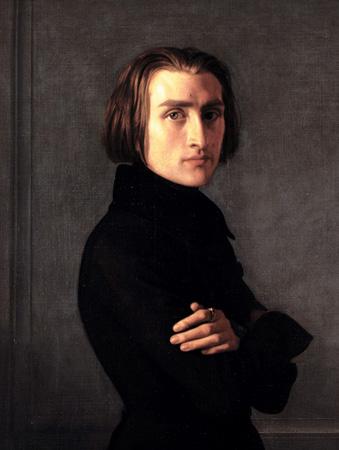

Franz Liszt (1811-86)

Ali Mammadoff (Graduate Certificate in Piano Performance)

Allegro molto

Andante sostenuto

Tempo giusto

Felix Mendelssohn (1809-47)

Béla Bartók (1881-1945)

Dmitry Yudin (Graduate Certificate in Piano Performance)

Allegro Maestoso

Andante Cantabile con espressione

Presto

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-91)

Intermezzo in B minor

Intermezzo in E minor

Intermezzo in C major

Rhapsody in E major

Johannes Brahms (1833-97)

Tatiana Dorokhova (Master of Music in Piano Performance)

Sergei Rachmaninoff (1873-1943)

Allegro agitato

Non allegro—Lento

Allegro molto

Jiarui Cheng (Bachelor of Music in Piano Performance)

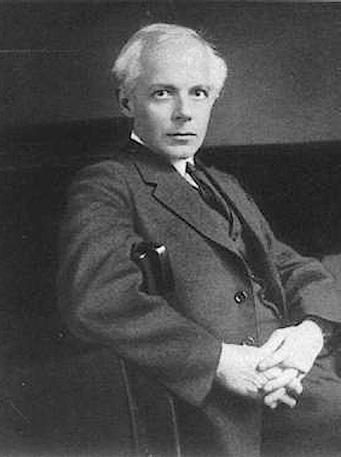

Praised by The Examiner (Independence, Mo., newspaper) as a “piano protege” and an “award winning talent,” Ali Mammadoff has been captivating audiences around the globe with his virtuosity, depth sensitivity and individuality. His exceptional talent has taken him all over the world, appearing numerous times as a soloist and with orchestras in the U.S., England, France, Germany, Italy, Turkey, Ukraine and his home country of Azerbaijan. His breathtaking performances have won Mammadoff prizes at international competitions as a pianist and a composer.

Born in Baku, Azerbaijan, the future musician began to show curiosity in piano at the age of 5. After beginning studies at the Bulbul Secondary Special Music School in Baku, he found early success winning local competitions, orchestrating and performing his own works. At 16, Mammadoff made a commitment to music. A fan of jazz, Mammadoff wanted to pursue a career as a jazz pianist, but finding it best as a hobby, his talent and passion for classical music brought him to the Manhattan (N.Y.) School of Music. After spending six years in New York, his journey continued at the University of Missouri - Kansas City.

At the age of 24, as a part of the “New Names” project, Mammadoff appeared for the first time with a symphonic orchestra performing one of the most difficult concertos in piano literature, Rachmaninoff’s “Piano Concerto in D Minor, Op. 30.” In October 2023, Mammadoff participated in a world concerto tour project by pianist Stanislav Ioudenitch, Park University International Center for Music founder and artistic director, celebrating Rachmaninoff’s 150th birthday anniversary featuring the composer’s complete piano concerti. In summer 2024, Mammadoff recorded a complete set of 24 preludes and fugues from the second set of “The Well-Tempered Clavier” by Johann Sebastian Bach, which will be published soon.

Currently, Mammadoff studies at the Park ICM under Ioudenitch, gold medalist of the 11th Van Cliburn International Piano Competition in 2001.

Dmitry Yudin was born in Moscow on May 16, 2001. In 2008 - 2019, he was Professor Lydia Grigoryeva’s student at the Moscow Gnessins School of Music.

Dmitry has taken part in a number of national and international competitions and festivals, winning prizes and audiences at numerous international events.

Dmitry has given solo recitals across Russia and abroad. His performance record includes concerts with orchestras like the Baltic States Youth Symphony Orchestra, Baltic Music Academy Symphony Orchestra, Musica Viva Moscow Chamber Orchestra, National Philharmonic Orchestra of Russia, St. Petersburg State Academic Symphony Orchestra, Tomsk Academic Symphony Orchestra.

Since August 2019, Dmitry has been studying with Horacio Gutierrez at the Manhattan School of Music where he was awarded full scholarship. During the pandemic, he gave several virtual solo recitals at MSM. In February 2022, Yudin became the winner of the MSM Eisenberg-Freid Concerto Competition with Prokofiev’s Piano Concerto-2. He performed the Concerto with maestro George Manahan in September 2022.

In 2023, Yudin played the recital in Boston after winning HMA Foote Award, won third prize in New York Concert Artists Auditions in August, and the second prize in Wideman Concerto Competition in Shreveport, Louisiana (December, 2023). Among Yudin’s last musical accomplishments is the Second Prize in the Geza Anda International Piano Competition (Zurich, Switzerland, 2024).

Currently Yudin studies at International Center for Music at Park University under 2001 Van Cliburn Gold medalist Stanislav Ioudenitch.

“An innate musical involvement and understanding is always evident in her interpretations,” said pianist Dina Yoffe, describing one of Tatiana Dorokhova’s performances.

Dorokhova is a pianist of striking sensitivity, virtuosity and stylistic insight. Her repertoire spans from the Baroque to the present, and her interpretations reveal a deep understanding of musical language and cultural context.

From an early age, Tatiana’s artistry drew attention from leading musicians, and despite her youth, her performances consistently left a lasting impression on audiences worldwide. Today, she performs across the U.S. Europe and Asia, captivating listeners with the depth and sincerity of her playing.

Born in Volgograd, Russia, into a family of musicians, Dorokhova began piano lessons at the age of 6. She went on to study at the Moscow Conservatory under Alexander Mndoyants, a laureate of the 5th Van Cliburn International Piano Competition, later becoming his teaching assistant.

In 2023, she joined the International Center for Music at Park University, studying with Stanislav Ioudenitch, gold medalist of the 11th Van Cliburn International Piano Competition. Under his guidance, Dorokhova became a laureate of several prestigious international competitions, including the Gurwitz (San Antonio, Texas), Santa Cecilia (Porto, Italy) and George Enescu (Bucharest, Romania).

She has performed with orchestras led by Stanislav Kochanovsky, Christian Reif and Scott Yoo. Dorokhova’s recordings were featured in the Anthology of Russian and Soviet Piano Music, released by the iconic Melodiya label. Her debut solo album “Liebestod” was released on the KNS Classical label in October.

Cheng began studying both piano and painting at the age of 3 in his hometown of Nanjing, China. While both disciplines shaped his early development, his connection with music gradually became the defining force in his life. From a young age, he was drawn not only to the sound of the piano, but to the expressive freedom it offered. “I really love the feeling of being on stage and creating the music somehow spontaneously.” He describes performance as an act of real-time storytelling and emotional honesty.

He’s performed extensively across China, Europe and the U.,S. Most recently, in June, Cheng participated in the world-renowned Van Cliburn International Piano Competition. He was awarded second prize at the Scriabin International Piano Competition and was a prize winner at the Isangyun International Piano Competition where he performed as soloist with the Tongyeong Music Festival Orchestra. He has also appeared with the Aspen Conducting Academy Orchestra as winner of the Aspen Concerto Competition, the Cleveland Orchestra after winning the CIM Concerto Competition and the Shanghai Conservatory of Music Symphony Orchestra as part of the Conservatory’s 70th anniversary celebration concert.

For Cheng, “music is a form of truth that begins where language ends.” He draws inspiration from the complexity and vulnerability of human experience: “The emotional depth found in relationships and in life itself —whether it’s joy, sorrow, love or struggle — profoundly shapes how I understand and perform music.” He says his artistic journey continues to be fueled by a desire to communicate something honest and timeless.

Cheng currently studies in the International Center for Music with ICM founder and artistic director Stanislav Ioudenitch (who won the Cliburn event in 2001). He has earned an artist certificate from the Cleveland Institute of Music under the guidance of Kathryn Brown and studied with Jin Tang at the Shanghai Conservatory of Music

In the summer of 1890, the 57-year-old Brahms rather impulsively declared that the Op. 111 String Quintet would be his final composition. He wrote to his publisher that he had “thrown a lot of torn-up manuscripts into the river.” But inspiration struck again in March 1891, when Brahms met the clarinetist Richard Mühlfeld. He wrote four chamber works for him that would become treasures of the repertoire. Still, Brahms was not going to neglect the piano during this stage of his life. Beginning in 1891, he produced four sets of character-pieces (Op. 116, 117, 118, and 119) that plumb emotional depths and heights that few had explored. Though they have been described as “autumnal” in character, Brahms’ lifelong friend and musical advocate Clara Schumann found rays of hope in them. Both Op. 116 and Op. 117 were composed during a brief stay at Bad Ischl in 1891, and when Brahms sent a copy of Op. 117 to Clara, she wrote back: “In these pieces, at last I feel musical life stir again in my soul.” Brahms described these as “three lullabies for my sorrows,” a reference perhaps not only to friends he had lost recently but also to his own declining health, and that of Clara.

Photo: Damian Gonzalez

Brahms has inscribed in the score of the first of these Intermezzi (Allegro moderato) two lines from the Scottish ballad Lady Anne Bothwell’s Lament: “Balow, my babe, lie still and sleep! It grieves me sore to see thee weep.” The piece is cast as A-B-A, with a dark central section and an embellished repeat of the opening material. The second (Andante non troppo e con molto espressione) presents a melancholy theme in B-flat minor that is accompanied by a rippling series of descending figures; a central section in major lifts the mood, with the repeat of the B section morphing into a coda that brings us back to the tristesse of the opening. The final Andante con moto opens with a mysterious theme in octaves that again touches on a deep sadness that some have said was inspired again by lines from a ballad: “Oh woe! Oh woe, deep in the valley.”

As the archetypal tale of man grappling with the Devil over his soul, the Faust legend has received a rich and varied array of tellings through the centuries from Goethe’s milestone of 1798 to the 19th-century operas by Gounod and Boito and all the way to Broadway. Part of the tale’s attraction lay in the fertile dramatic possibilities inherent in the characters of Faust (with whom many of us can identify), Mephisto (the one who causes us to make bad choices), and the lovely Marguerite (Gretchen, who makes the struggle worthwhile). During the 1850s Liszt was especially fascinated by the Faust legend as told by the Hungarian-German poet Nikolaus Lenau (1802-1850) and in 1859 he began an orchestral work initially intended as a series of episodes from Lenau’s 1836 Faust. He completed only two: The Midnight Procession and the work known to us as the “Mephisto” Waltz No. 1, though its full title is more expressive, The Dance in the Village Inn. To illustrate this scene, the composer has extracted the appropriate passage from Lenau’s original and reproduced it in the printed score:

“There is a wedding feast in progress in the village inn, with music, dancing, and carousing. Mephistopheles and Faust pass by, and Mephisto induces Faust to enter and take part in the festivities. Mephisto snatches the instrument from the hands of a lethargic fiddler and draws from it indescribably seductive and intoxicating strains. The amorous Faust whirls about with a full-blooded village beauty in a wild dance; they waltz in mad abandonment out of the room, into the open, away into the woods. The sounds of the fiddle grow softer and softer, and the nightingale warbles his love-laden song.” From 1859 to 1862 Liszt conceived of three versions of this Waltz No. 1: one for orchestra, one for piano duet, and a solo piano piece (dated September 1, 1859 and dedicated to Karl Tausig) that is distinctive enough to be considered a separate composition

As World War I progressed, Béla Bartók and his colleague Zoltán Kodály found the countryside growing hostile to the sort of folksong collection that had occupied them in the early years of the 20th century. Yet as travel became restrictive, Bartók became more productive as a composer,

producing several of the works for which he is best known—The Wooden Prince, the Piano Suite (Op. 14), the Second String Quartet, The Miraculous Mandarin, Bluebeard’s Castle, and numerous sets of folk songs. Many of these works explored a dark inner world of life during wartime, yet at the same time Bartók the composer was responding to the modernist challenges of composers such as Claude Debussy and Arnold Schoenberg. One rather quirky composition stands out among these, the Three Etudes, Op. 18, which although a mere eight minutes long still stands as one of the most difficult piano works of the early-20th century.

Bartók was one of the most accomplished keyboard virtuosos of his generation, having studied with István Thomán (1862-1940), one of Liszt’s most significant pupils, at Budapest’s Royal Academy of Music. It was also Bartók who, together with Russians such as Prokofiev and Rachmaninoff, helped redefine pianistic virtuosity for the 20th century. Bartók composed the Three Etudes in the summer of 1918 at his house outside Budapest and performed them on a recital of April 1919. The melodic, contrapuntal, and rhythmic difficulties were such that even the composer would later admit, in 1934, that he could “no longer play the Three Etudes—I haven’t played them, ever or anywhere, since 1918.” Additionally, he refused to perform any of the especially thorny works from this period in provincial communities where the audiences “have not been trained to listen,” he wrote. “These works only frighten the unprepared public.” The fast-slow-fast structure of the Three Etudes suggests that they were designed as an organic whole. “One can hear through the course of the work a rising level of musical complexity,” writes Paul Wilson, “which reaches its climax in the first half of the third study.” The first Etude (Allegro molto) is a toccata with rapid leaps of octaves and ninths, pitted against outbursts of clusters. The Andante sostenuto begins as a dreamy Debussian fantasy, then trundles toward a series of fiendish chords that seem to anticipate Messiaen. The final Tempo giusto looks toward the percussive hyper-virtuosity of Bartók’s most challenging works.

Mendelssohn’s “grand tour” of Europe from 1829 to 1834 had a profound impact on his musical outlook, eventually inspiring such works as the “Italian” and “Scottish” Symphonies and the Hebrides and Calm Sea and Prosperous Voyage Overtures. But even before these travels, the romance of Scotland had cast a strong spell

on the composer—through the poetry and “Scottish” novels of Sir Walter Scott: The Heart of Midlothian, Rob Roy, The Bride of Lammermoor. In 1828 Mendelssohn drafted a piece based on what he imagined Scotland to be like, which would become the Fantasy in F-sharp minor. Not having experienced the Highlands himself, he had read the stories and listened to the folk songs.

In 1829 the composer was calling the piece Sonate écossaise or Scottish Sonata in his correspondence, but when putting final touches on it in 1833, he decided to publish it as simply Fantasia. Having by then experienced the real Scotland, perhaps he no longer felt that the piece captured its spirit quite as accurately as he had imagined. It stands as one of the composer’s most striking early piano works, and while it does convey the nomadic feel of a “fantasy,” it retained a clear three-movement structure. After a harp-like introductory flourish, the Andante presents a tender folklike theme, followed by a second subject and a development of both themes. The Allegro con moto is a scherzo-like interlude, and the ferocious Presto suggests the swashbuckling energy of a swordfight.

Mozart’s earliest European travels were as a wunderkind performer and would-be composer. From the age of six, he and his gifted sister, “Nannerl,” were paraded—by their eager father, Leopold—through courts and castles in Munich, Vienna, Prague, Mannheim, Paris, London, The Hague, Amsterdam, Utrecht, London, Rome, Milan, and many other cities. From the age of 17, however, Mozart’s travels abroad were more specifically aimed at finding a permanent post outside of his dreaded hometown of Salzburg. When he requested of the Archbishop Colloredo that he be released from his Salzburg post, the old sourpuss responded by firing both him and his father. Leopold enjoined his son to find a position significant enough to enable him to support the entire family.

During much of 1777 and 1778, the teenaged Mozart sought employment at Mannheim, Munich, Augsburg, and (especially) Paris. He was in the French capital from late March through September 1778 but received no offers. In early July Mozart’s mother, Anna Maria—who had accompanied her son on this trip—grew gravely ill and died. It was a dark period for Mozart, but one that produced several works that we treasure today: the Symphony No. 29 (“Paris”), the Flute and Harp Concerto, K. 299, the two masterful Violin Sonatas, K. 304 and 306, and the

Sonata in A minor, K. 310. The latter is particularly striking in character; some have speculated that its sturm und drang is related to Anna Maria’s failing health and death, but our knowledge of its chronology is not complete enough to establish that. The opening Allegro maestoso is imbued with a ferocity that was virtually unprecedented in Mozart’s instrumental music: Its fiery histrionics yearn toward opera. The tender Andante cantabile con espressione sports a dramatic central section in minor; the Presto is fleet and edgy.

Brahms Rhapsody in E-flat major

The set that Brahms published as Opus 119, composed at Bad Ischl in 1893, consists of three Intermezzi and a final Rhapsody. The opening Intermezzo explores a devastating emotional landscape, while it also hints at the edges of diatonic tonality in a manner that feels ahead of its time. Brahms described it to Clara thus: “The little piece is exceptionally melancholic and ‘to be played very slowly’ is not an understatement. Every bar and every note must sound like a ritardando, as if one wanted to suck melancholy out of each and every one … of these dissonances!” The second Intermezzo (Andantino un poco agitato) exists in a more agreeable emotional realm, with a central section of modulatory ingenuity; it concludes with a coda that alludes back to the upbeat B section. The C-major Intermezzo (Grazioso e giocoso) is cheerful almost to the point of seeming ironic. This witty mood turns to outright joy in the final Rhapsody (Allegro risoluto), a discursive exploration of moods, keys, and textures.

(Horowitz version)

The early part of the 20th century was a decisive time for Rachmaninoff and his family. Growing political unrest in Russia was making life more and more difficult at home, and in 1906 the composer resigned his post as conductor at the Bolshoi and settled temporarily in Dresden. The family would spend parts of the next several years in the glittering Saxon city but still spent time in the stately solitude of Ivanovka, the family’s country estate—until the upheavals of war and revolution would make it impossible for them to return to Russia altogether.

The next several years saw a flurry of activity. There were concerts in Paris, successful premieres of his Second Piano Concerto and Second Symphony in Russia, an invitation to the United States, where Rachmaninoff conducted, played recitals, and performed his new Third Piano Concerto—in one instance with the New York Philharmonic and conductor Gustav Mahler. During return trips to Russia, he completed the Liturgy of St. John Chrisostom and conducted the premiere of his choral symphony The Bells after Edgar Allen Poe. In Rome, couple’s two daughters grew ill with typhoid fever, necessitating a trip to Berlin for medical treatment. Back in Ivanova in the fall of 1913, the composer completed the Second Sonata that he had begun in Rome—a piece whose sonorities still seem to echo the bell-like sounds of the Poe “symphony.”

The Sonata was dedicated to his boyhood friend and former classmate, Matvei Pressman. Rachmaninoff performed the new work numerous times in Russia from October through December, beginning in Kursk on October 18th and finishing the tour in Moscow and St. Petersburg. (In 1931 he created a more concise, and somewhat clarified, version of the piece.) There is nothing quite like this sonata. The first movement alone (Allegro agitato) seems to contain the whole universe, combining the composer’s exceptional lyric gifts with sonorities that possibly few people in 1913 realized the piano could produce; much of the thematic raw material for the whole sonata is contained in the exposition. The slow movement (Non allegro) is infused with nostalgia but contains a certain reserve that separates it from the more opulent sentiment of the concertos. The finale (Allegro molto) again returns to the bell-like sonorities and continues the “cyclic” return of themes from the first movement, culminating in an edge-of-your-seat coda that is as bracing as anything in piano repertory.

Stanislav Ioudenitch

Founder & Artistic Director

Piano Studio

Behzod Abduraimov Artist-in-Residence

Gustavo Fernandez Agreda

ICM Coordinator

Shmuel Ashkenasi

Distinguish Visiting Artist, violin

Peter Chun, Viola Studio

Christine Grossman Orchestral Repertoire, viola

Lolita Lisovskaya-Sayevich Director of Collaborative Piano

Steven McDonald Director of Orchestra

Ben Sayevich

Violin Studio

Daniel Veis

Cello Studio

The Patrons Society makes it possible for Park International Center for Music students to pursue their dreams of professional careers on the concert stage.

Our Patrons provide essential support for scholarships, faculty, and performance opportunities, ensuring world-class music thrives in Kansas City and beyond.

We are deeply grateful for the generosity of each member listed below.

Richard J. Stern Foundation for the Arts - Commerce Bank, Trustee *

Ronald and Phyllis Nolan *

Jerry M. White and Cyprienne Simchowitz

EXCEPTIONAL

Brad and Marilyn Brewster *

SUPREME

Commerce Bank *

Brad and Theresa Freilich

Barnett and Shirley Helzberg

Benny and Edith Lee *

John and Debra Starr *

EXTRAORDINAIRE

Joe and Jeanne Brandmeyer *

Thomas and Mary Bet Brown *

Vincent and Julie Clark *

Stanley Fisher and Rita Zhorov *

Stephen L. Melton *

Mira Mdivani/Mdivani Corporate

Immigration Law Firm *

Susan Morgenthaler

Rob and Joelle Smith

Nicole and Myron Wang *

Andrew and Peggy Beal *

Lisa Browar *

Rich Coble and Annette Luyben *

Paul S. Fingersh and Brenda Althouse *

Patty Garney *

David and Lorelei Gibson *

Ihab and Colleen Hassan *

Ms. Lisa Merrill Hickok

Robert E. Hoskins, ‘74

Walter Love and Sarah Good *

John and Jacqueline Middelkamp *

Patrick and Teresa Morrison *

Holly Nielsen *

Charles and Susan Porter *

James and Laurie Rote *

John and Angela Walker *

Barbara and Phil Wassmer *

Joyce Weiblen *

John and Karen Yungmeyer *

* 2025-26 Member

We gratefully acknowledge these donors as of October 21, 2025.

Your gift brings world-class music to life.

Your gift makes an impact by:

Supporting scholarships that bing gifted students from around the world to Kansas City

Sustaining performances that connect our community to international artistry

Advancing communication and outreach that inspires the next generation of musicians

Annual Gifts - Every contribution, no matter the size, fuels our students’ success

Patrons Society - join with a commitment of $1,000 or more annually and enjoy the unique opportunities to connect more deeply with Park ICM

Sponsorships - support a concert, artist or special event and receive recognition for your leadership.

Planned Giving - leave a legacy through bequests, estate plans or endowed funds

Together our donations sustain Park ICM’s mission and ensure that the music continues for generations.

Park University International Center for Music

The annual “Intimate Christmas with the ICM Orchestra” returns for its fourth year and features a wide range of festive music.

Don’t delay – secure your seats today to guarantee your presence at this enchanting musical affair! It’s an evening that not only delivers exquisite music but also fosters a profound sense of unity and community, embodying the true essence of the holiday season.

Friday, December 5, 2025 • 7:30 p.m.

Graham Tyler Memorial Chapel Dr. Steven McDonald conducting

Make it an evening! Visit charming Parkville, Missouri for dinner before the concert.

Tickets are FREE with reservation. Scan Here!

22, 2026

PRESENTED BY PARK UNIVERSITY

Don’t miss this rare opportunity to witness the magnificence of the International Center for Music’s award-winning artists. It will be a night to remember as two virtuosos, Stanislav Ioudenitch and Behzod Abduraimov, come together to perform Francis Poulenc’s captivating Concerto for Two Pianos and Orchestra with the Kansas City Chamber Orchestra. Immediately following the performance, meet the artists at a dessert reception.

KAUFFMAN CENTER

FOR THE PERFORMING ARTS