Park University International Center for Music Presents

Park University International Center for Music Presents

Friday, April 25, 2025 • 7:30 p.m. Graham Tyler Memorial Chapel

Dear Esteemed Patrons and Lovers of Music,

As we continue with our 22nd season at the International Center for Music at Park University, I find myself reflecting on the profound impact that music has on our lives. It’s not just the sound that resonates, but the emotion and dedication behind every performance that truly moves us. As Artistic Director and founder of this institution, I am continuously inspired by the exceptional talents of our students, faculty, and guest artists who pour their hearts into their craft. Kansas City is a remarkable place, home to a community that cherishes and supports the arts with unparalleled enthusiasm. Our concert series is designed to bring you closer to the magic of live music, offering an intimate and accessible way to experience the brilliance of our performers.

Our mission remains steadfast: to create an environment where musical excellence thrives, free from the distractions and financial burdens that often hinder artistic growth. At Park ICM, we are committed to nurturing the next generation of musicians with the same intensity and focus that shaped my own musical journey.

This season, we are proud to present a lineup that includes not only our extraordinary students and faculty but also internationally acclaimed guest artists whose contributions to the world of music are nothing short of legendary. In keeping with our mission, we will also introduce you to the newborn stars, the bright talents who represent the future of classical music. Each concert is an opportunity to witness the convergence of passion, discipline, and talent, creating moments that linger in the heart and mind.

I invite you to join us in celebrating the transformative power of music. Your presence and support are invaluable to us, fueling our drive to reach new heights of artistic achievement. Together, let’s create a symphony of shared experiences that transcends time and space.

With deep gratitude,

Stanislav Ioudenitch Founder and Artistic Director International Center for Music at Park University

P.S. Each performance is a manifestation of our shared love for music. Your presence and applause amplify our drive to elevate the art form further.

ICM Orchestra Spring Concert with Guest Conductor Barbara Yahr

Antonín Dvořák (1841-1904)

Franz Joseph Haydn (1732-1809)

Moderato

Adagio

Allegro molto featuring DIYORBEK NORTOJIEV, CELLO SOLOIST

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827)

Poco sostenuto – Vivace

Allegretto

Presto – Assai meno presto

Allegro con brio

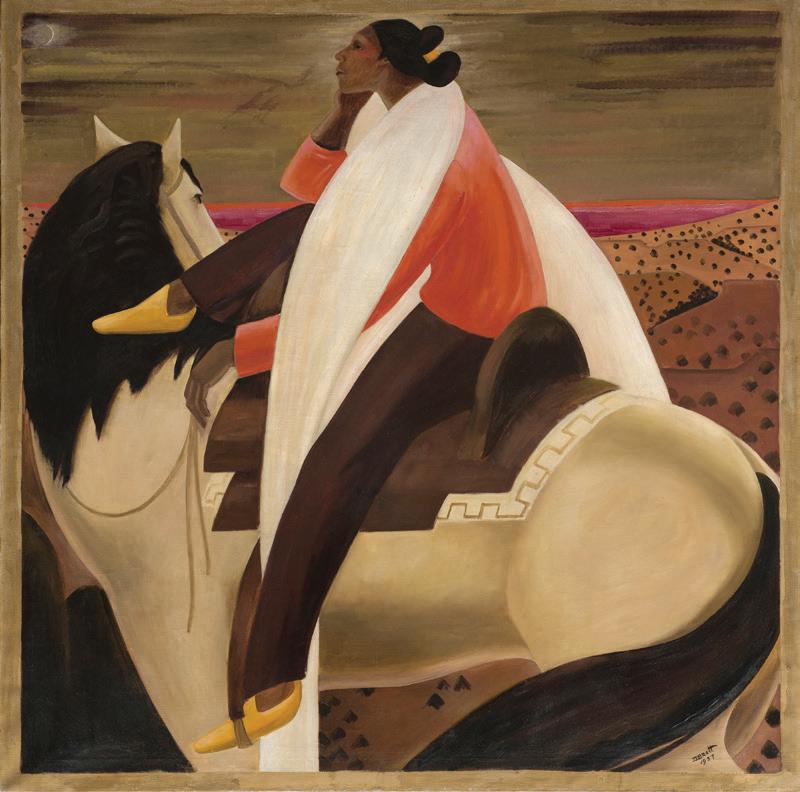

Photo: Claudine Williams

Now in her twenty-first season with the GVO, Music Director Barbara Yahr continues to lead the orchestra to new levels of distinction. With blockbuster programming and internationally renowned guest artists, the GVO under Barbara’s baton has grown into an innovative, collaborative institution offering a full season of classical music to our local community.

A native of New York, Ms.Yahr’s career has spanned from the United States to Europe, the Middle East, and Asia. Her previous posts include Principal Guest Conductor of the Munich Radio Orchestra, Resident Staff Conductor of the Pittsburgh Symphony under Maestro Lorin Maazel, and conductor of the Pittsburgh Youth Orchestra. She has appeared as a guest conductor with such orchestras as the Bayerische Rundfunk, Dusseldorf Symphoniker, Deutsche Kammerphilharmonie, Frankfurt Radio, Orchestra Sinfonica Siciliana, Janacek Philharmonic, New Japan Philharmonic, NHK Symphony Orchestra, Singapore Symphony, and the National Symphony in Washington D.C. She has also conducted orchestras in Anchorage, Calgary, Chattanooga, Columbus, Detroit, Flint, Louisiana, New Mexico, Lubbock, and Richmond, as well as the Ohio Chamber Orchestra, St. Paul Chamber, Rochester Philharmonic, Cincinnati Chamber Orchestra, New World Symphony, and the Chautauqua Festival Symphony Orchestra. She has also appeared in Israel conducting in both Jerusalem and Elat.

As an opera conductor, she has led new productions in Frankfurt, Giessen, Tulsa, Cincinnati, Minnesota and at The Mannes School of Music in NYC. In recent years, she coached the actors on the set of the Amazon Series, Mozart in the Jungle, conducted the Ridgefield Symphony Orchestra, the Chappaqua Orchestra, Orchestra 914, the Park ICM Orchestra, the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra musicians in a concert to benefit the Musicians of Steel fund and has returned for a third time to conduct at the Jacobs School of Music at Indiana University.

Originally from Reading, Mass., Steven McDonald, director of orchestral activities, has served on the faculties of the University of Kansas, Boston University and Gordon College. While in Boston, he conducted a number of ensembles, including Musica Modus Vivendi, the student early music group at Harvard University. McDonald also directed ensembles at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, serving as founder and music director of the Summer Opera and Independent Activities Period Orchestra, and conductor of the MIT Chamber Orchestra and the Gilbert and Sullivan Players. At the University of Kansas, McDonald served as assistant conductor of the KU Symphony, and was the founder and music director of the Camerata Ensemble of non-music majors, and of the chamber orchestra “Sine Nomine,” a select ensemble of performance majors. Additionally, he has conducted performances of the KU Opera. He has also served as vocal coach at the Boston University Opera Institute and at Gordon College.

McDonald served as music director of the Lawrence (Kan.) Chamber Orchestra from 2007-14, during which time the group transformed into a professional ensemble whose repertoire featured inventive theme programs and multimedia performances. In 2009, he was selected to conduct the Missouri All-State High School Orchestra, and in 2011 was the first conductor selected as guest clinician at the Noel Pointer Foundation School of Music which serves inner-city students in Brooklyn, N.Y. An avid proponent of early music, McDonald has also taught Baroque performance practice at the Ottawa Suzuki Strings Institute summer music program, and regularly incorporates historically informed practice into his performances. McDonald is a graduate of the Boston University School for the Arts, the Sweelinck Conservatory of Amsterdam (The Netherlands) and the University of Kansas School of Fine Arts.

Diyorbek Nortojiev, a dedicated cellist, is currently pursuing a Graduate Certificate in Cello Performance under the guidance of worldrenowned soloist and professor Daniel Veis.

Originally from Uzbekistan, Diyorbek’s musical journey began over a decade ago at the prestigious Glier School of Music in Tashkent, where he honed his craft under celebrated mentors such as Dadabaeva Nigora and Jakhangir Ibragimov.

His talent has gained international recognition, notably in 2024, Diyorbek was honored as the recipient of the Undergraduate Scholarship from the Kansas City Alumnae Chapter of Sigma Alpha Iota. In 2018 he showcased his skills at the IV S. Knushevitsky International Cello Competition in Saratov, Russia, and secured 1st prize at the II “Istedod” International Music Competition in Tashkent that same year.

In 2017, he also earned 3rd prize at the A. Jubanov International Competition in Almaty, Kazakhstan. Diyorbek has continued refining his artistry through participation in masterclasses with distinguished musicians such as Na Mula and Suren Bagratuni.

While passionate about solo cello repertoire, he also finds great joy in collaborating with chamber ensembles and orchestras, including the Kansas City Symphony where Diyorbek serves as a regular substitute.

Mumin Turgunov, concertmaster

Yuren Zhang

Soobeen Nam

Nathaniel Humphrey

Ilvina Gabrielian

Jose Ramirez

Alla Wijnands

Gina Buzzelli

Aviv Daniel, principal

Yin-Shiuan Ting

Vincent Cart-Sanders

Yiyuan Zhang

Grace Hemmer

Casey Gregory

Emma Andersen

Ben Lerman

Viola

Christian dos Santos, principal

Iana Korzukhina

Victor Diaz

Samin Golozar

Kathryn Hilger

Cello

Nikita Korzukhin, principal

Mardon Abdurakhmonov

Diyorbek Nortojiyev

Otabek Guchkulov

Ainaz Jalilpour

Jordan Procter

Bass

Kassandra Ferrero

Minjoo Hwangbo

Flute

Christina Webster

Gina Hart-Kemper

Oboe

Emily Foltz

Luis de Leon

Clarinet

Richard Galbreath

Katie Varadi

Bassoon

Austin Way

Luke Frith

Horn

Dwight Purvis

Adam Paxson

Trumpet

Jennifer Oliverio

Jena Vangjel

Timpani

Mark Lowry

Sometimes a slow movement is so rare and remarkable that it takes on a life of its own, separate from its source. From Handel’s Largo to Bach’s Air on the G String, Mahler’s Adagietto to Barber’s Adagio — these become so well-known that we begin to forget that they started out as parts of larger works. A composer might even separate a movement and promote it, or even publish it, as a distinct composition. Dvořák’s Nocturne in B major is one such work. It began its life as the slow movement (Andante religioso) of the early String Quartet in E minor, written in 1869 or 1870 and later known as No. 4. This was shortly before Dvořák left his post as violist in the Bohemian Provisional Theater Orchestra in order to focus wholly on composition.

Dvořák chose not to publish the prolix E-minor Quartet at the time, but he was so taken with the Andante that, in 1875, he adapted it for inclusion in his String Quintet in G major, Op. 77. This additional slow movement made the quintet too long, though, and in 1882 he adapted it once again as a work for string orchestra. This was published in 1883 as the Nocturne, alongside versions for violin and piano and for piano four-hands. Evidently it was performed in Prague with conductor Karel Kučera before receiving its “official” premiere in March 1885 at London’s Crystal Palace, on a program conducted by the composer that included the Symphony No. 7 in D minor.

Franz Joseph Haydn (1732-1809): Cello Concerto in C major, Hob. VIIb:1

Haydn is not often recognized as a composer of concertos, although we know of at least 20 such works for violin, cello, double bass, flute, horn, trumpet, and lyra organizzata (a sort of hurdygurdy). Several of these are lost (though perhaps not forever) or spurious. One that we were not sure of until the 1950s was the Cello Concerto in D major, composed in 1783 for the 1784 London premiere by soloist James Cervetto — he of the city’s Italian Opera Orchestra. Its authenticity remained uncertain until Haydn’s own manuscript was found in 1951, appearing to debunk the notion that it might have been the work of cellist Anton Kraft of the Esterházy Orchestra.

Quite a different case is that of the C-major Cello Concerto, now known as Hoboken VIIb:1, which was composed a full 20 years before the D-major Concerto and remained lost for two centuries. Scholars knew of the work because of its inclusion in Anthony von Hoboken’s Haydn catalogue, but it had become lost (as it turned out) in the vast archives of the National Museum in Prague. Enter the young Czech musicologist Oldřich Pulkert, who during the early 1960s was among those organizing and cataloging a huge cache of manuscripts “collected” from private archives of the former European nobility. Among these was the archive of the Radenín Castle in southern Bohemia, which contained works by Haydn, Dittersdorf, and others that had not been cataloged, or even viewed, in decades.

Photo: Emil Matveev

Fortunately, Pulkert knew his Haydn. When he came across the yellowed manuscript parts inscribed with the name Heydn, he might well have scoffed, for many a composition by lesser musicians of the Classical period has been attributed to a well-known master. But Pulkert was

familiar with the first volume of Hoboken’s then-new catalog of Haydn’s works, which had listed — in a section titled “Concertos for Violoncello” — a Concerto in C major that Hoboken had declared “lost.” When Pulkert glanced at the opening bars of the Radenín concerto, he realized that he had indeed found one of Haydn’s most delightful early works — lost for 200 years.

His discovery is still considered one of the most significant musical finds of modern times. In the ensuing years, the concerto has become a concert favorite, alongside the D-major Concerto. Unlike the later work, however — which is a fully “High-Classical” piece — the Concerto in C major is very much a product of the pre-Classic world of the 1760s, when the playful, coy, rococo utterances of the late Baroque still held sway.

Haydn was probably inspired to write the C-major Concerto through his friendship with Joseph Weigl, a first-rate cellist who had come to the Eisenstadt court in 1761 (where Haydn was already court composer and musical director). Not only was Weigl a close friend of Haydn’s, he also apparently shared a drafty Eisenstadt apartment with him and with court violinist Luigi Tomasini. Weigl was probably first to perform the piece; the modern premiere, in May 1962, featured cellist Miloš Sádlo and the Czechoslovak Radio Symphony led by Sir Charles Mackerras.

The concerto’s light instrumentation reveals its pre-Classical origins. The orchestral cello line is to be taken by the soloist when he is not playing the solo line; Esterházy court records reveal, in fact, the presence of only one cellist in the tiny chapel orchestra during this period: Weigl himself. The opening Moderato is cast in a three-part form that is as Baroque as it is Classical — a rudimentary sonata form, perhaps, complete with a modulatory middle section and a decisive return to the main theme. The Adagio spins out a quasi-operatic vocal line that reminds us that vocal music was central to the composer’s activities in the service at Eszterházá; it is easy to envision this tender melody as an aria for high tenor. The light-hearted wit of the Finale: Allegro molto presages the merry good humor that was later to form an important part of Haydn’s mature style.

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827): Symphony No.7 in A major, Op. 92

The Seventh Symphony embodies few of the myths that surround Beethoven. It is not “about” heroism (like the “Eroica”) or destiny (the Fifth), or nature (“Pastorale”), nor does it sing stentorian celebrations of universal brotherhood (“Ode to Joy”). Each of those works has a unique and specific place in Beethoven’s life and work, and in world art.

But like the light, cheerful Eighth Symphony, which was composed at the same time as the Seventh, the A-major Symphony seems to us today as mercifully free of outside associations as a 19th-century symphony could be.

It was not always seen this way — as simply a pinnacle of symphonic art. Previous commentators have heard in the Seventh everything from a “peasant’s round-dance” (Berlioz) to a “bacchic orgy” (Paul Bekker); from a “masquerade of a multitude drunk with joy” (Alexander Oulibicheff) to a “divine intoxication of the spirit” (Ernest Newman). Richard Wagner, in his high-blown way, waxed poetic on the Seventh: “All tumult, all yearning and storming of the heart, become here the blissful insolence of joy, which carries us away with bacchanalian power through the roomy space of nature, through all the streams and seas of life, shouting in glad self-consciousness as we sound throughout the universe the daring strains of this human sphere-dance. This Symphony is the Apotheosis of the Dance itself: it is Dance in its highest aspect, the loftiest deed of bodily motion, incorporated into an ideal mold of tone.”

It is striking how many of these reactions to the Seventh are associated with dance, drink, and celebration. Clearly the pervasive rhythmic “germs” throughout this masterly work contribute to the sense of dance; beyond this, many listeners have perceived a deep sense of joy (if perhaps drunken joy) throughout the Seventh, a sort of intrinsic

euphoria that is not easily explainable in terms of Beethoven’s biography.

The Seventh was begun in 1811, not long after the composer’s hopes of marriage to Therese Malfatti — probably the closest he ever came to becoming engaged — had been dashed by her rejection of his proposal. She was, by all reports, a delightful young woman, and although we’re not sure that Beethoven ever actually asked for the hand of the purported dedicatee of Für Elise, he did write a quite revealing letter to her around this time:

“Now fare you well, respected Therese. I wish you all the good and beautiful things of this life. Bear me in memory — no one can wish you a brighter, happier life than I — even should it be that you care not at all for your devoted servant and friend, Beethoven.” Resigned despair had become de rigeur for the composer by now, not to mention passiveaggressive irony.

Thus in mid-1811 the 40-year-old composer, who was in terrible health, retired to the spa at Teplice, Bohemia, to “take the cure”; on returning to Vienna that winter, he took up the Seventh with renewed vigor. That Beethoven could, in the face of illness and dejection, compose a work so filled with optimism is evidence of his resolve to turn his back upon the things of the world and to dedicate his life to his art and to the hopes that it held for him — as expressed in his famous Heiligenstadt Testament of 1802.

The Seventh was not performed until December 1813, in concerts at the University of Vienna that included the notorious Wellington’s Victory. Beethoven’s early biographer Anton Schindler reports that the performance on December 8th was “one of the most important moments in the life of the master, at which all the hitherto divergent voices, save those of the professional musicians, united in proclaiming him worthy of the laurel.” In a word, the symphony was a hit.

The Seventh begins with one of the longest, most ponderous

introductions in the history of the symphony. This Poco sostenuto is built on two themes, one introduced by solo oboe, the second by woodwind choir; because of its length, the introduction becomes a part of the overall structure of the movement in a rather unique way. The main body of the movement (Vivace) is based on a persistent dotted rhythm that pervades the movement in the way that the Fifth Symphony’s “fate motif” had done a few years earlier — but with far more amiable, even optimistic, intent.

The second movement, the famous A-minor Allegretto, is a set of variations on a chorale-like theme heard in the low strings at the beginning. Even more dancelike than the first movement, the Presto (scherzo) is alive with a jaunty energy. But Beethoven reserves his most vibrantly jagged music for the Allegro con brio, in which we hear, perhaps for the first time in the composer’s symphonies, the heavenly rattle of the late style — the noisy dissonances of a mind that was quickly growing deaf to the sounds of the real world and turning inward to more high-atmospheric wavelengths.

— Paul Horsley

Stanislav Ioudenitch, Founder & Artistic Director, Piano Studio

Behzod Abduraimov, Artist-in-Residence

Gustavo Fernandez Agreda, ICM Coordinator

Peter Chun, Viola Studio

Lolita Lisovskaya-Sayevich, Director of Collaborative Piano

Steven McDonald, Director of Orchestra

Ben Sayevich, Violin Studio

Daniel Veis, Cello Studio

Support the ICM, enjoy beautiful music and special events just for members.

Patrons Society members enjoy exclusive invitations to group events including meeting the talented ICM artists.

For more information on how to join our Patrons Society, scan the QR code with your mobile device camera.

The Park University International Center for Music’s Patrons Society was founded to help students achieve their dreams of having distinguished professional careers on the concert stage.

Just as our faculty’s coaching is so fundamental to our students’ success, our Patrons’ backing provides direct support for our exceptionally talented students, concert season, outreach programs and our ability to impact the communities we serve through extraordinary musical performances.

We are continually grateful for each and every one of our Patrons Society members. For additional information, please visit ICM.PARK.EDU under “Support Us.”

We gratefully acknowledge these donors as of April 4, 2025.

Brad and Marilyn Brewster *

Steven Karbank

Benny and Edith Lee

Ronald and Phyllis Nolan

John and Debbie Starr

Steven and Evelina Swartzman

Jerry White and Cyprienne Simchowitz *

Jeffrey Anthony

Brad and Theresa Freilich

Shirley and Barnett C. Helzberg Jr. *

Holly Nielsen

Steinway Piano Gallery of Kansas City

Gary and Lynette Wages

Vince and Julie Clark

Stanley Fisher and Rita Zhorov *

Susan Morgenthaler *

Rob and Joelle Smith *

Kay Barnes and Thomas Van Dyke

Lisa Browar

Mark and Gaye Cohen

Suzanne Crandall

Charles and Patty Garney *

Doris Hamilton and Myron Sildon

Colleen and Ihab Hassan

Lisa Hickok and Brian McCallister *

William and Regina Kort

Jackie and John Middelkamp *

Kathleen Oldham

Kevin and Jeanette Prenger, ’09 / ECCO Select

James and Laurie Rote *

Stanley and Kathleen Shaffer

Guy Townsend

John and Angela Walker *

Nicole and Myron Wang*

Phil and Barbara Wassmer *

* 2024-2025 Member

The Park University International Center for Music Foundation exists to secure philanthropic resources that will provide direct and substantial support to the educational and promotional initiatives of the International Center for Music at Park University. With unwavering commitment, the Foundation endeavors to enhance awareness and broaden audiences across local, national, and international spheres.

Vince Clark, Chair

Steve Karbank, Secretary

Marilyn Brewster

Lisa Browar

Stanley Fisher

Brad Freilich

Ron Nolan

Benny Lee, Treasurer

Shane Smeed

John Starr

Steve Swartzman

Angela Walker

Karen Yungmeyer

Park University International Center for Music Presents the

Park ICM in Partnership with NAVO Presents

IN CONCERT

Friday, January 24, 2025 • 7:30 p.m.

Wednesday, May 7, 2025 • 7:30 p.m.

1900 Building • Mission Woods, KS

Our season finale will feature the father-daughter duo, Stanislav Ioudenitch, piano, and Maria Ioudenitch, violin. Witness their exceptional musical chemistry as they present an all-French program. Maria has earned top honors at the Ysaÿe, Tibor Varga, and Joseph Joachim International Competitions, along with receiving special recognitions like the Joachim’s Chamber Music Award and a prestigious recording deal with Warner Classics. Scan

PARK UNIVERSITY INTERNATIONAL CENTER FOR MUSIC

PARK UNIVERSITY INTERNATIONAL CENTER FOR MUSIC

IANA KORZUKHINA

VIOLA RECITAL

May 1, 2025 • 7 p.m.

MUMIN TURGUNOV

SENIOR VIOLIN RECITAL May 5, 2025 • 7 p.m.

IN CONCERT

PIANIST MICHAEL DAVIDMAN IN RECITAL

ALI MAMMADOFF

GRADUATE PIANO RECITAL May 14, 2025 • 7 p.m.

APRIL 26, 7 : 0 0 P M

GRAHAM TYLER MEMORIAL CHAPEL

PARK UNIVERSITY CAMPUS

All recital performances held in the Graham Tyler Memorial Chapel, Park University, Parkville, MO.

C ON C E RT IS F R EE .

Concerts are free to attend. Show your support for these talented, young artists!

RESE R VATIONS AR E EN C O URA GED . SI G N U P HE R E .

I C M . P AR K . E D U

Imagine hearing — and seeing — every keystroke of a world-class piano performance in your own home. With spirio , you can enjoy music captured by renowned pianists, played with such nuance, power, and passion that it is utterly indistinguishable from a live performance.

Thousands of recordings by steinway artists are available at the touch of a button on the included iPad.

The library of music, videos, and playlists expands monthly and spans all genres. In addition to today’s greatest musicians, spirio delivers historic performances by steinway immortals , including Duke Ellington, Glenn Gould, Art Tatum, and many more.

- Becky N. Lowry, MD Physician Internal Medicine

For me, there’s nothing more rewarding than the meaningful connections I make with my patients. Maybe it’s growing up in a small town where those personal values remain strong. Or maybe it’s the belief, shared with all of my co-workers, that people come first. Whatever it is, the opportunity to provide care is a privilege I never forget. To schedule an appointment, call 913-588-1227 or visit KansasHealthSystem.com/Appointments.