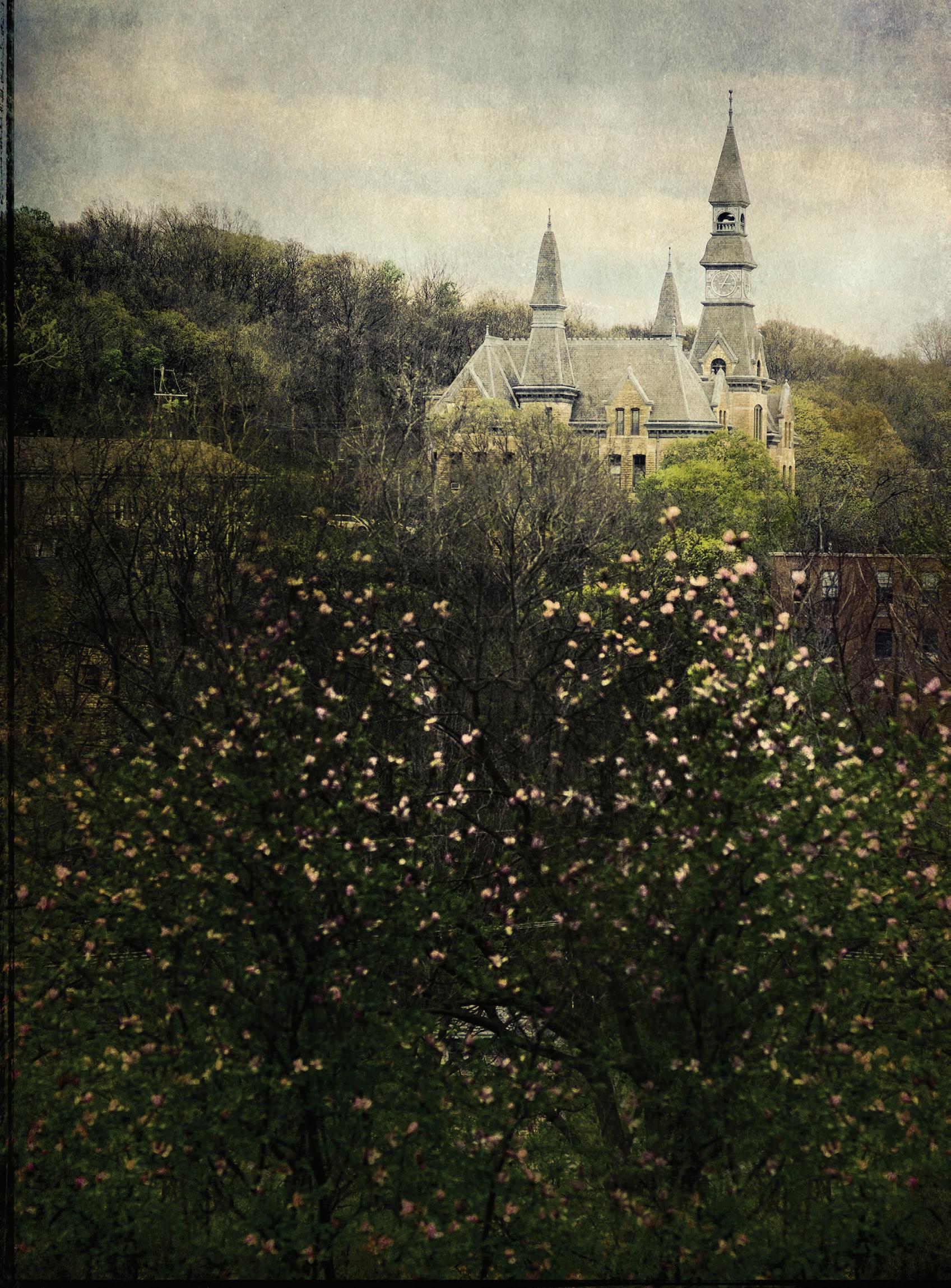

Park University International Center for Music Presents

FALL CONCERT WITH GUEST CONDUCTOR TIM HANKEWICH

Friday, October 3, 2025 • 7:30 p.m.

UN

Park University International Center for Music Presents

FALL CONCERT WITH GUEST CONDUCTOR TIM HANKEWICH

Friday, October 3, 2025 • 7:30 p.m.

UN

At Park University’s International Center for Music, our purpose is simple yet profound: to shape the future of classical music by nurturing extraordinary talent and sharing it with the world. Each season, our students — rising artists from across the globe — come to Kansas City to learn, perform and inspire. Their artistry enriches our community, connecting hearts through music and leaving a lasting impact far beyond the stage.

This season, we invite you to witness their brilliance alongside renowned guest artists and faculty who join us in advancing our mission. Every performance you attend supports not only world-class music, but also the dreams of the next generation of great musicians.

Thank you for believing in the transformative power of music and for being part of this remarkable journey with us.

With gratitude,

Stanislav Ioudenitch Founder and Artistic Director International Center for Music at Park University

Timothy Hankewich, conducting

Iana Korzukhina, viola

Jiarui Cheng, piano

Felix Mendelssohn (1809-47)

Grave-Allegro

Andante

Allegro Vivace

Paul Hindemith (1895-1963)

............................................................

Langsam

Ruhig bewegt

Lebhaft

Choral: Für deinenThron tret ich hiermit (“I now approach Thy throne”)

Iana Korzukhina, viola

...............................................

Allegro

Andante

Allegretto

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-91)

Jiarui Cheng, piano

George Frideric Handel (1685-1759)

Larghetto e staccato

Allegro

Presto

Largo

Allegro

Menuet

GROSSE FUGE, OP. 133, arr. Felix Von Weingartner

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827)

Overtura: Allegro

Fuga: Allegro

Meno mosso e moderato

Allegro molto e con brio

Hankewich, music director of Orchestra Iowa (based in Cedar Rapids), begins his 20th season as music director of the state’s premier symphony orchestra. He has earned an outstanding reputation as a maestro whose classical artistry is as inspiring as his personality is engaging. Prior to joining Orchestra Iowa, Hankewich served as resident conductor of the Kansas City Symphony for seven years and held an appointment as artistic director of the Philharmonia of Greater Kansas City for three years. He also served as an artist-in-residence at Park University for three years, prior to the start of the International Center for Music in 2003. He has also held staff conducting positions with the Oregon Symphony, Indianapolis Symphony and the Evansville Philharmonic.

Recent guest appearances have included performances with the Jacksonville, Victoria and Hamilton symphonies as well as a tour throughout the Czech Republic and Slovakia. In September 2014, Orchestra Iowa released its first commercial recording, featuring composer Michael Daugherty’s “American Gothic.”

Hankewich helped lead Orchestra Iowa through a catastrophic flood in 2008, raised it to new heights of artistic accomplishment and financial security. He helped restore the organization’s damaged performance venue, aided in the reconstruction of its offices and helped implement a new business model, allowing the orchestra to grow. Because of these achievements, he has advised boards of other orchestras on how to achieve meaningful artistic and financial health in the wake of a crisis.

Winner of the prestigious Aspen Conducting Award in 1997, Hankewich has enjoyed appearing as a guest conductor, leading Orchestra London the Kitchener-Waterloo Symphony, as well as the Windsor, Santa Rosa, Indianapolis, Oregon and China Broadcasting symphony orchestras.

A native of Dawson Creek, B.C. Hankewich married to his wife Jill, a pharmacist. He graduated from the University of Alberta, earning a Bachelor of Music degree in piano performance under Alexandra Munn, and a master’s degree in choral conducting under the direction of Dr. Leonard Ratzlaff. He earned a doctorate degree in instrumental and opera conducting from Indiana University, where his primary teachers were Imre Pallo and Thomas Baldner.

Korzukhina was born in 1995 in Arkhangelsk, Russia. In 2013, she enrolled in St. Petersburg College, and in 2022, she graduated with honors from the RimskyKorsakov St Petersburg State Conservatory.

She has participated in various competitions as part of string and piano quartets during her studies. In addition to participating in chamber ensembles, she performs solo. A laureate of international competitions, she has participated in master classes under Herman Tsakulov, Yuri Bashmet, Pavel Romanenko, Yuri Afonkin, Vladislav Pesin and Shmuel Ashkenasi.

Since 2021, she has performed with orchestras such as the St. Petersburg State Academic Symphony Orchestra, the Kazakh State Symphony Orchestra and the Symphony Orchestra 1703 in Russia, as well as in various festivals.

In 2024, Korzukhina began studying for a master’s degree in the Park University International Music Center with Chung-Hoon Peter Chun.

Cheng began studying both piano and painting at the age of 3 in his hometown of Nanjing, China. While both disciplines shaped his early development, his connection with music gradually became the defining force in his life. From a young age, he was drawn not only to the sound of the piano, but to the expressive freedom it offered. “I really love the feeling of being on stage and creating the music somehow spontaneously.” He describes performance as an act of real-time storytelling and emotional honesty.

He’s performed extensively across China, Europe and the U.,S. Most recently, in June, Cheng participated in the world-renowned Van Cliburn International Piano Competition. He was awarded second prize at the Scriabin International Piano Competition and was a prize winner at the Isangyun International Piano Competition where he performed as soloist with the Tongyeong Music Festival Orchestra. He has also appeared with the Aspen Conducting Academy Orchestra as winner of the Aspen Concerto Competition, the Cleveland Orchestra after winning the CIM Concerto Competition and the Shanghai Conservatory of Music Symphony Orchestra as part of the Conservatory’s 70th anniversary celebration concert.

For Cheng, “music is a form of truth that begins where language ends.” He draws inspiration from the complexity and vulnerability of human experience: “The emotional depth found in relationships and in life itself — whether it’s joy, sorrow, love or struggle — profoundly shapes how I understand and perform music.” He says his artistic journey continues to be fueled by a desire to communicate something honest and timeless.

Cheng currently studies in the International Center for Music with ICM founder and artistic director Stanislav Ioudenitch (who won the Cliburn event in 2001). He has earned an artist certificate from the Cleveland Institute of Music under the guidance of Kathryn Brown and studied with Jin Tang at the Shanghai Conservatory of Music.

Your gift makes an impact by:

Supporting scholarships by bringing gifted students from around the world to Kansas City.

Sustaining performances that connect our community to international artistry.

Advancing education and outreach that inspire the next generation of musicians.

Annual gifts - every contribution, no matter the size, fuels our students’ success.

Patrons Society - join with a commitment of $1,000 or more annually and enjoy unique opportunities to connect more deeply with the ICM.

Sponsorships - support a concert, artist or special event and receive recognition for your leadership.

Planned Giving - leave a legacy through bequests, estate plans or endowed funds.

Originally from Reading, Mass., Steven McDonald, director of orchestral activities, has served on the faculties of the University of Kansas, Boston University and Gordon College. While in Boston, he conducted a number of ensembles, including Musica Modus Vivendi, the student early music group at Harvard University. McDonald also directed ensembles at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, serving as founder and music director of the Summer Opera and Independent Activities Period Orchestra, and conductor of the MIT Chamber Orchestra and the Gilbert and Sullivan Players. At the University of Kansas, McDonald served as assistant conductor of the KU Symphony, and was the founder and music director of the Camerata Ensemble of non-music majors, and of the chamber orchestra “Sine Nomine,” a select ensemble of performance majors. Additionally, he has conducted performances of the KU Opera. He has also served as vocal coach at the Boston University Opera Institute and at Gordon College.

McDonald served as music director of the Lawrence (Kan.) Chamber Orchestra from 2007-14, during which time the group transformed into a professional ensemble whose repertoire featured inventive theme programs and multimedia performances. In 2009, he was selected to conduct the Missouri All-State High School Orchestra, and in 2011 was the first conductor selected as guest clinician at the Noel Pointer Foundation School of Music which serves inner-city students in Brooklyn, N.Y. An avid proponent of early music, McDonald has also taught Baroque performance practice at the Ottawa Suzuki Strings Institute summer music program, and regularly incorporates historically informed practice into his performances. McDonald is a graduate of the Boston University School for the Arts, the Sweelinck Conservatory of Amsterdam (The Netherlands) and the University of Kansas School of Fine Arts.

STEVEN MCDONALD, MUSIC DIRECTOR

Mumin Turgunov, concertmaster*

Yuren Zhang

David Brill

Noelle Naito

Sun-Young Shin

Aviv Daniel, principal*

Yin-Shiuan Ting

Vincent Cart-Sanders

Yiyuan Zhang

Ilvina Gabrielian

Jose Ramirez

Viola

Victor Diaz principal

Iana Korzukhina

Kathryn Hilger

Chung-Wen Lee

Nikita Korzukhin, principal*

Diyorbek Nortojiev

Mardon Abdurakhmonov

Fedor Solonin-Oliichuk

Ainaz Jalilpour

Otabek Guchkulov

Bass

Kassandra Ferrero, principal*

Minjoo Hwangbo

*=soloists in Handel

Lithograph by A. Weger_ LeipzigHaussmann

by Paul Horsley

Berlin in the early 19th century must have been a heady place for a prodigy bursting with intellectual curiosity and musical ambition. The young Mendelssohn, whose family moved to the City on the Spree in 1811, grew up among the most prominent literary, musical, and artistic figures of the day: from the poet Heinrich Heine to the scientist Alexander von Humboldt, from philosophers Hegel and Schlegel to the violinist Ferdinand David. “Europe came to their living room,” wrote one musician of the Mendelssohn household.

In 1819 Felix’s father, Abraham, placed his son under the tutelage Carl Friedrich Zelter, director of the Berliner Singakademie and a central figure in Berlin’s musical life. It was Zelter who eventually introduced Mendelssohn the pianistic wunderkind to Goethe, in whose Weimar home the boy performed in 1821. “Musical prodigies ... are probably no longer so rare,” Goethe wrote to Zelter, “but what this little man can do in extemporizing and sight-reading borders on the miraculous, and I could not have believed it possible at so early an age.”

Several of Felix’s most beloved works date from these early Berlin years—from the Octet for Strings (written at age 16) to the Overture to A Midsummer Night’s Dream (age 17) and the String Quartet Op. 13 (age 18). Most remarkable of all, perhaps, are the 12 string symphonies he composed in 1821 and 1822, aged 12 and 13—the first seven of which already show an assured command of texture, harmony, and thematic development. The youth had already written quite a bit of music by this time, but these string symphonies showed an ever-advancing sophistication of structure and melodic idiom. Like Beethoven before him, and Brahms after him, Mendelssohn used smaller-scale compositions to pave the way for larger works—in this case, for his first “real” symphony, the Symphony No. 1 in C minor of 1824.

Yet these string symphonies are no mere exercises: they are polished and forceful, and they show influences from the music of Bach, Handel, and the Classicists. The Fourth begins with a sort of “French overture,” complete with dramatic dotted rhythms that lead to the ensuing Allegro. The Andante spins forth a simple and songful melody, teased and elaborated with subtlety, and the Allegro vivace resembles nothing so much as the vibrant finale of a Baroque suite.

Hindemith was not just a composer: He began his career as a virtuoso violist and for many years he was considered perhaps Europe’s finest performer on the instrument. He was also considered one of the chief representatives of the avant-garde of the Weimar Republic and was thus one of the first composers to be denounced in the 1930s by the new Nazi regime. Known for orchestral and chamber works that systematized unique harmonic methods, Hindemith (who was also a professor at the Berlin Hochschule) had become a central figure in Germany of the 1920s. Yet he had hoped to withdraw into his art—to become, like the title character of his opera Mathis der Maler, invisible and apolitical.

He was, of course, in far too visible a position for this, and when performances of the opera were prohibited and Hindemith protested, he was relieved of all of his official duties. Seeing a dark future for Germany, he spent the latter part of the 1930s in a sort of nomadic existence, mostly in Switzerland, before settling in the United States in 1940. It was in January 1936 that Sir Adrian Boult invited the composer to perform his viola concerto Der Schwanendreher with the BBC Symphony Orchestra. (Now a pillar of the viola repertoire, the concerto was still new, having received its premiere just three months earlier in Amsterdam.)

The British premiere was to take place on January 22; alas, King George V died on the 19th and the concert had to be canceled. The BBC’s producer felt that Hindemith should somehow be involved in the on-air musical tributes to the deceased regent, and when nothing suitable could be found, the composer decided to create a new piece. The next day, from 11 a.m. to 5 p.m., he sat in an office that the BBC provided and created Trauermusik (Funeral Music). Scored for viola and strings, it was performed that evening in the studio, live on the air to all of Britain with the composer as soloists and Boult conducting.

Just 15 minutes long, the Trauermusik consists of four short movements that are performed continuously. The viola sustains a plaintive but assertive melodic thread, supported by a lush cushion of strings; Hindemith quotes briefly both the Schwanendreher and the Symphony he created from the Mathis opera, and he concludes with a tune regarded as Bach’s deathbed chorale: “Vor deinen Thron tret’ ich hiermit”—known in England as “All People That On Earth Do Dwell.”

Photo: Emil Matveev

“Boult was, by English and his own personal standards, quite beside himself, and kept thanking me,” Hindemith wrote to his publisher, Willy Strecker. “My various pupils are now busy writing articles about the affair; they are very proud that the old man [Hindemith was 40] can still do things so well and so quickly.” the Norwich String Orchestra in March 1934.

The composer has indicated, in the printed score, which early works he has cited — songs and piano works dating from 1923 to 1927, two per movement. In each segment, a vigorous theme is paired with a somewhat reflective one, after which the spirit of both is skillfully combined. The Boisterous Bourée is both elegant and kinetic, while the Playful Pizzicato reveals unusually savvy harmonic writing. The Sentimental Saraband grows from a plaintive tune from 1925 (its mournful sophistication seeming remarkable for a boy of 12), while the Frolicsome Finale (Prestissimo con fuoco) demonstrates a grown-up feel for expansiveness and pacing.

When Mozart arrived in Vienna in 1781 he found that his fame had preceded him. The public demand for his pianism was so great that instead of symphonies he decided to write piano concertos. It was through this form, which was still emerging as an official genre (thanks partly to the brilliant works for fortepiano of J.C. Bach) that Mozart was able to show off both his solid compositional craftsmanship and the brilliant pianism that he had acquired at the Salzburg court.

The 15 concertos he produced between 1782 and 1786, together with Nos. 26 and 27 from 1788 and 1791, arguably constitute the composer’s most important body of instrumental music. “These concertos are symphonic in the highest sense,” writes the scholar Alfred Einstein, “and Mozart did not need to turn to the field of the pure symphony until that of the concerto was closed to him.”

The first of these works were the three concertos that Mozart composed in late 1782 for his Lenten concerts of 1783: K. 413, K. 414, and K. 415. “They are very brilliant, pleasing to the ear, and natural without being vapid,” Mozart wrote to his father of the concertos. “There are passages here and there from which the connoisseurs alone can derive satisfaction, are written in such a way that the less learned cannot fail to be pleased, though without knowing why.”

The A-major Concerto, K. 414, is one of the most graceful of Mozart’s creations, with an elegant Allegro opening and a dashing Allegretto as finale. Between these movements is an Andante of deep affect: It sets a tune by none other than J.C. Bach himself—the news of whose death in 1782 in London had evidently just reached Mozart. It is a fitting tribute to the composer who contributed perhaps more to the developing Classical style than any other of J.S. Bach’s sons.

The Scherzo trips over itself with joyous energy, and the Larghetto provides a moment’s rest with a plaintive tune of ingenious design. The Finale (Allegro vivace) is perhaps the most “Bohemian” movement, both in character and in rhythmic design; it also refers to previous themes by way of rounding out the whole.

George Frideric Handel, 1726 By Balthasar Denner

Major, Op. 6,

Best known to modern audiences for his oratorios, in the 18th century Handel was known throughout Europe as a composer of opera and of chamber music. He is regarded today as a “synthetic” artist who, like Bach, took the best elements of German, Italian, French, and English music and fused them into a unique style. As an instrumental composer, Handel was celebrated for concertos, trio sonatas, and solo works; his output is vast, much of it unknown by today’s audience, and it includes dozens of instrumental suites (including the famous Water Music and Royal Fireworks Music) and at least 18 concerti grossi—works that pit a body of soloists against the whole orchestra.

The Concerto Grosso in D major, Op. 6, No. 5, which bears the number HWV 323 and was written in 1739, begins with a quirky violin solo that seems to announce tidings of joy. indeed, this concerto is known as the St. Cecilia Concerto because its first, second, and sixth movements contain music from Handel’s Ode for St. Cecilia’s Day (HWV 76). This cantata on a text by poet John Dryden contains a phrase that sounds remarkably similar to the concerto’s opening: “The tuneful voice, was heard from high: Arise! Arise! … and music’s power obey!”

The Concerto contains six movements and thus adheres to the more expansive model of the church concerto rather than to the more concise three-movement Vivaldi model. It opens with a stately “French overture” fanfare, which leads directly into an energetic Allegro. The Presto third movement is filled with mirth, while the Largo introduces a sudden shift of mood—pastoral sentiment bordering on

sadness. The dashing Allegro resumes the concerto’s joyous tone, and a surprisingly discursive Minuet brings the concerto to a garrulous close.

Composers rarely make good decisions when they second-guess themselves. For an 1889 performance of his Fifth Symphony in Hamburg, Tchaikovsky famously trimmed music from the last movement, which apparently neither he nor Brahms had liked initially. Anton Brucker’s revisions of his symphonies, generally created at the suggestion of well-meaning friends or colleagues, were rarely “better” than the originals—they were simply different.

More controversial still, perhaps, is Beethoven’s String Quartet in B-flat major, Op. 130, which was composed in 1825 with a massive 16-minute Grosse Fuge as its sixth and final movement. When the Schuppanzigh Quartet gave the piece its Viennese premiere in March 1826, both audience and critics found it bordering on the incomprehensible. With this piece, as the great biographer Maynard Solomon has written, “Beethoven had tried to carry his audience with him into a realm which their training and sensibility would not permit them to enter.”

Part of the problem lay in the finale, a complex “double fugue” of unprecedented density. Beethoven’s publisher, Artaria, who had purchased the rights to the work, entreated Karl Holz (the second violinist of the quartet and a Beethoven friend) to convince the composer that the finale was impractical. Surprisingly, when Holz suggested to the composer that he provide a more compact ending and publish the fugue separately (for additional remuneration, presumably), Beethoven agreed. The Grosse Fuge was printed as Op. 133. As with much of his late music, Beethoven seemed to be composing more from a spiritual place than a practical one. Within his silent world he heard sounds that had never been written down before—and which today, 200 years later, we find utterly sublime.

In 1933 the Austrian conductor, composer, and critic Felix Weingarten (18631942) created an arrangement of the fugue for string orchestra, which reveals a deep understanding of the original. Like many 20th-century “reworkings” of classics, Weingartner’s version strives toward making a distinctive artistic statement while confirming the greatness of the original. He has enhanced the dynamic compass considerably and he has expanded the range—for example, by supporting the lower tones of the cello with double bass in some passages.

Park University International Center for Music presents

ICM faculty will perform with principal string members of the Kansas City Symphony

Thursday, October 23, 2025 • 7:30 p.m.

1900 Building • Mission Woods, Kan.

Join us to experience the artistry of this special event!

The next performance in the Park University International Center for Music’s season will be on Thursday, Oct. 23, as members of the ICM faculty will perform with principal string members of the Kansas City Symphony in a side-by-side concert.

This concert replaces the originally scheduled performance by violinist Shmuel Ashkenasi, who was forced to cancel his appearance due to health reasons.

The Patrons Society makes it possible for Park International Center for Music students to pursue their dreams of professional careers on the concert stage.

Our Patrons provide essential support for scholarships, faculty, and performance opportunities, ensuring world-class music thrives in Kansas City and beyond. We are deeply grateful for the generosity of each member listed below.

SUPERLATIVE

Ronald and Phyllis Nolan *

Jerry M. White and Cyprienne Simchowitz

EXCEPTIONAL

Brad and Marilyn Brewster *

SUPREME

Brad and Theresa Freilich

Barnett and Shirley Helzberg

Benny and Edith Lee *

John and Debra Starr *

EXTRAORDINAIRE

Joe and Jeanne Brandmeyer *

Thomas and Mary Bet Brown *

Vincent and Julie Clark *

Stanley Fisher and Rita Zhorov

Stephen L. Melton *

Susan Morgenthaler

Rob and Joelle Smith

Nicole and Myron Wang *

Lisa Browar *

Rich Coble and Annette Luyben *

Paul S. Fingersh and Brenda Althouse *

Patty Garney *

Ihab and Colleen Hassan

Ms. Lisa Merrill Hickok

Robert E. Hoskins, ‘74

John and Jacqueline Middelkamp

Patrick and Teresa Morrison *

Charles and Susan Porter *

James and Laurie Rote

John and Angela Walker *

Barbara and Phil Wassmer *

John and Karen Yungmeyer *

* 2025-26 Member

We gratefully acknowledge these donors as of September 8, 2025.

Your gift brings world-class music to life.

When you join, you invest in:

Scholarships that open doors for gifted young musicians. Performances that connect Kansas City to the global stage. Community outreach that inspires the next generation.

Membership begins at $1,000 annually. Patrons enjoy unique opportunities to experience the music more deeply and are recognized throughout the season for their generosity. Scan the QR code or visit ICM.PARK.EDU to learn more.

International Center for Music at Park University, he began with transform exceptional students into masters themselves. Other time to their students like they do at the Park ICM.

“These featured soloists from Park University’s Inter national Center for Music represent not only the quality of perfor mance in Kansas City, but the future of it, too.”

Park International Center for Music

Stanislav Ioudenitch

Founder & Artistic Director

Piano Studio

Behzod Abduraimov

Artist-in-Residence

Gustavo Fernandez Agreda

ICM Coordinator

Peter Chun, Viola Studio

Lolita Lisovskaya-Sayevich

Director of Collaborative Piano

Steven McDonald Director of Orchestra

Ben Sayevich

Violin Studio

Daniel Veis

Cello Studio

Shmuel Ashkenasi

Distinguish Visiting Artist, violin

Christine Grossman Orchestral Repertoire, viola