July/ August 2023

SIMPLY RED

How to integrate and balance red artificial light within the built environment

RECLAIM THE STREETS (ONE YEAR ON)

Revisiting the challenges around lighting, crime, and safety at night

PARKS AND RECREATION

Why are so many urban parks still so poorly lit and maintained at night?

Professional best practice from the Institution of Lighting Professionals

The publication for all lighting professionals

Modular (2X2) refractive lenses in PMMA with 5 optical distributions available. Shield in flat tempered glass with impact resistance IK10 and prismatic IK07. Upper

Discover More asdstreetlighting.com +44 (0) 1709 374898 sales@asdlighting.com Optical package consists of 8 geometries. Enclosure protection: IP66, IK08. Transparent or prismatic glass screen. Luminous flux from 350lm to 4,500lm per light source.

Lumen output between 1,500 and 15,000. Can be ordered with or without the blade. The blade is a customisable aluminium screen that separates the brackets, filters light and can be laser-cut to specific designs or colour tinted.

frame shaped bell in aluminium with threaded connection G 3/4″.

RECLAIM THE STREETS (ONE YEAR ON)

The connections between lighting, crime, safety and perceived safety are complex and multifaceted. What’s important, argues Clare Thomas, is to recognise that there is no singular user that public spaces should be designed for, we can’t simply ‘design out’ crime, and lighting on its own won’t resolve societal issues

PARKS AND RECREATION

Lit well, urban parks can not only be safe spaces for women but year-round wholecommunity hubs, for people of all ages. So, why, as a conference recently asked, are so many still so poorly lit and badly maintained? Lighting Journal spoke to Elettra Bordonaro to find out

SAFE PASSAGE

The importance of welldesigned and maintained artificial lighting in making parks feel safer for women and girls after dark has been emphasised in recent research by the University of Leeds. But it is also clear that better lighting is not the only answer

CREATING A MORE ‘LEGIBLE’ PUBLIC REALM

A recent ILP event, ‘City Signs & Lights’, brought together academics and lighting professionals to consider how public realm lighting can be better integrated into – and even lead – urban design and placemaking. Graham Festenstein reports

DECLARATION OF INTENT

Lighting Urban Community International (LUCI) marked May’s International Day of Light by publishing an ambitious ‘LUCI Declaration’ outlining how municipalities and lighting professionals may need to rethink their approaches to urban lighting over the next decade

WHAT ARE YOU LOOKING AT?

A research project is testing the assumption that, when researching lighting for interpersonal evaluations on subsidiary roads, we should focus on the face. Khalid Hamoodh and Professor Steve Fotios of Sheffield University report

SIMPLY RED

Millennia of evolution have shaped how we see, perceive and think about red light. Understanding this will allow us all better to integrate and balance red artificial light within the built environment and public realm, a recent ILP ‘How to be brilliant’ led by BDP’s Colin Ball and Lora Kaleva concluded

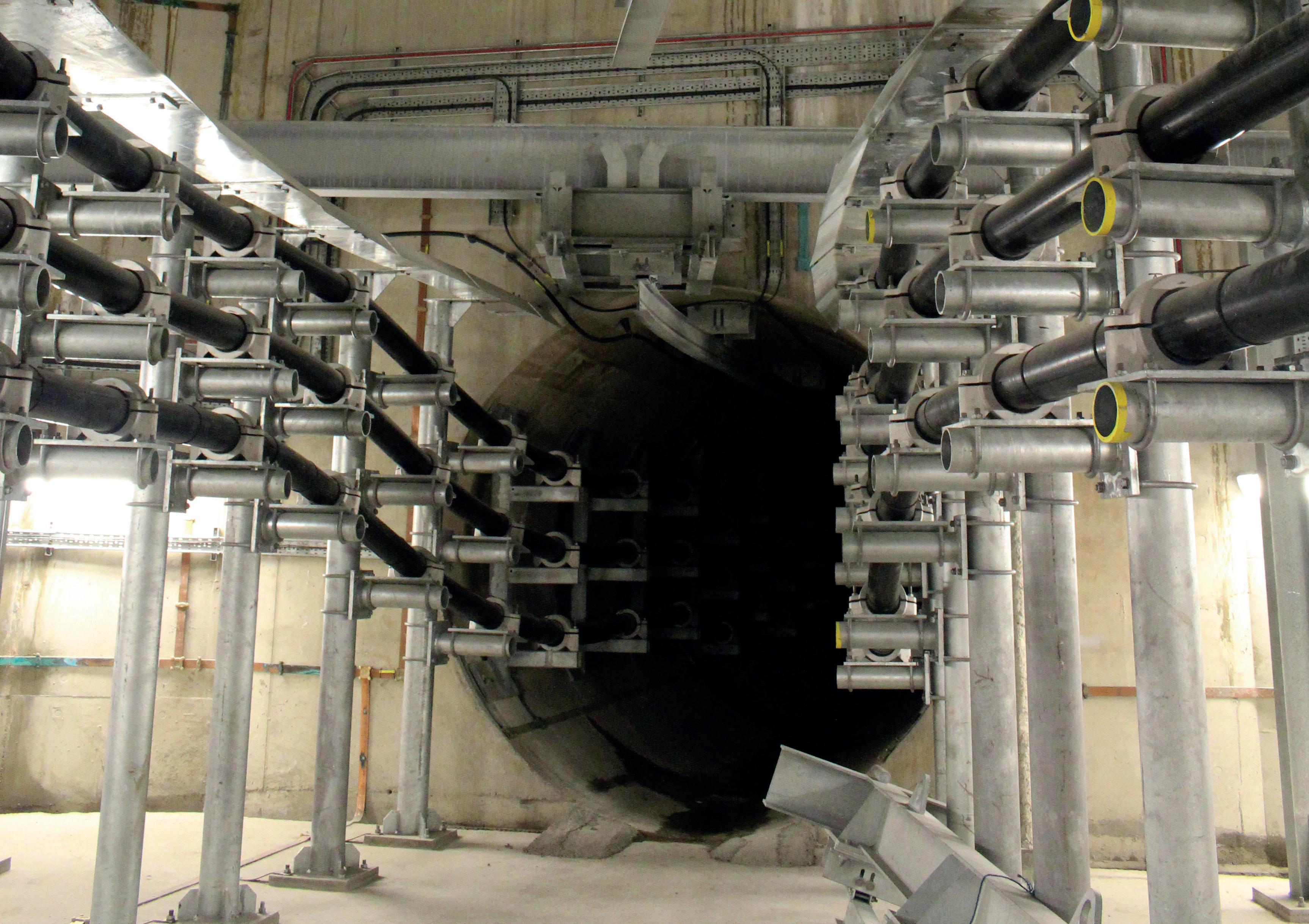

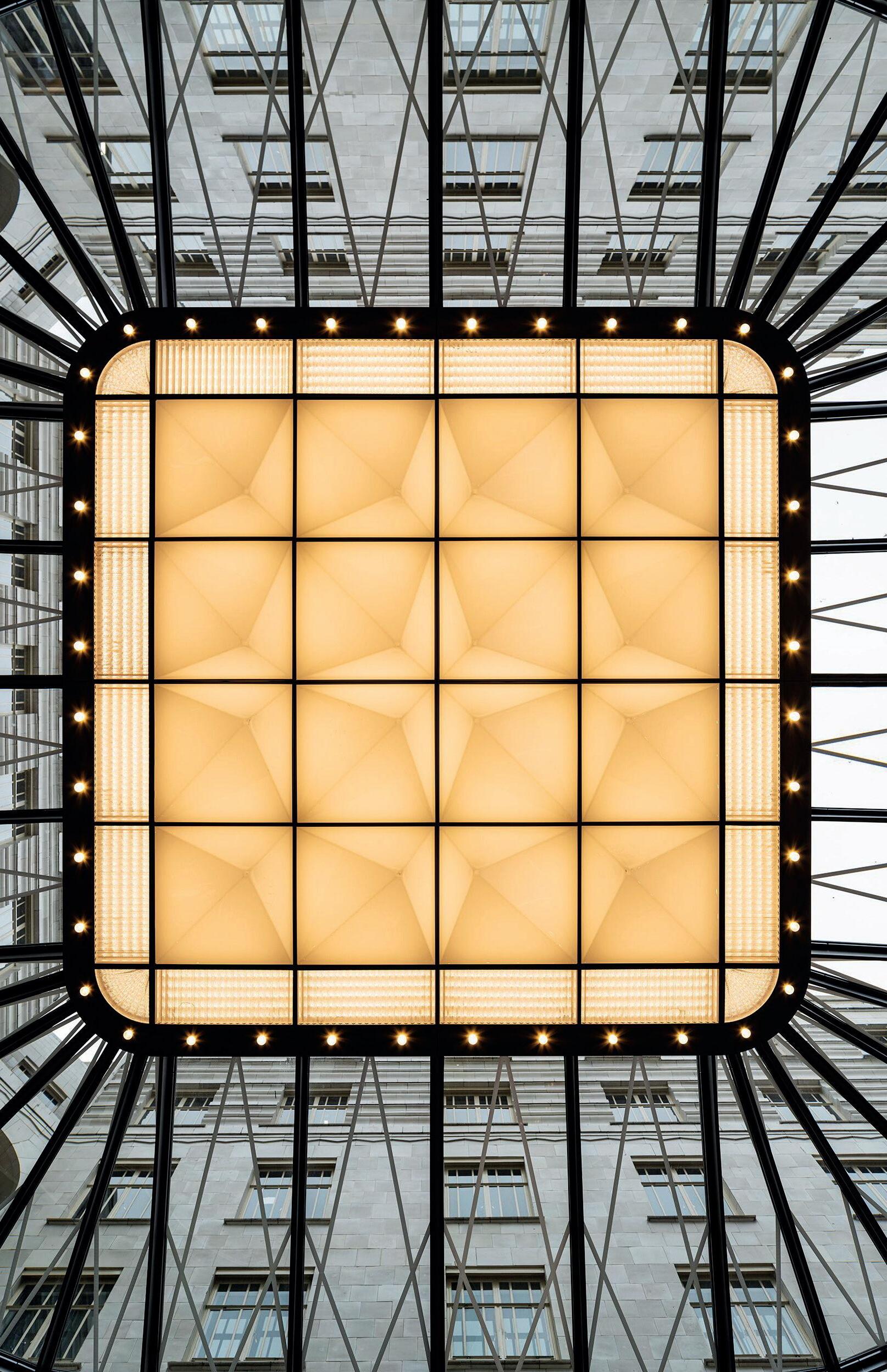

PEARL IN THE SHELL

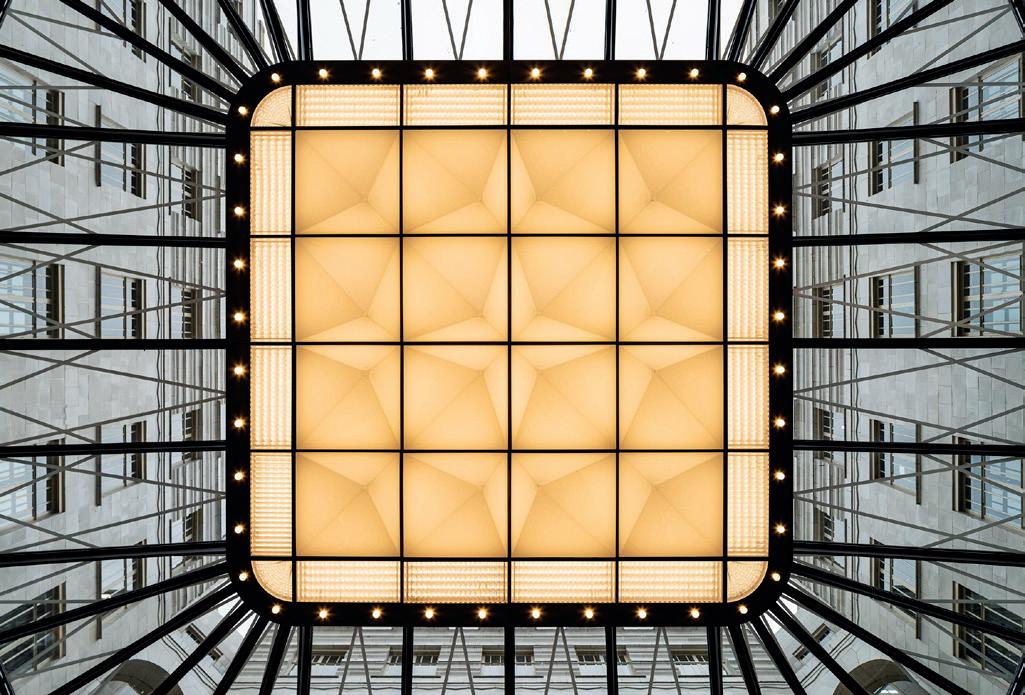

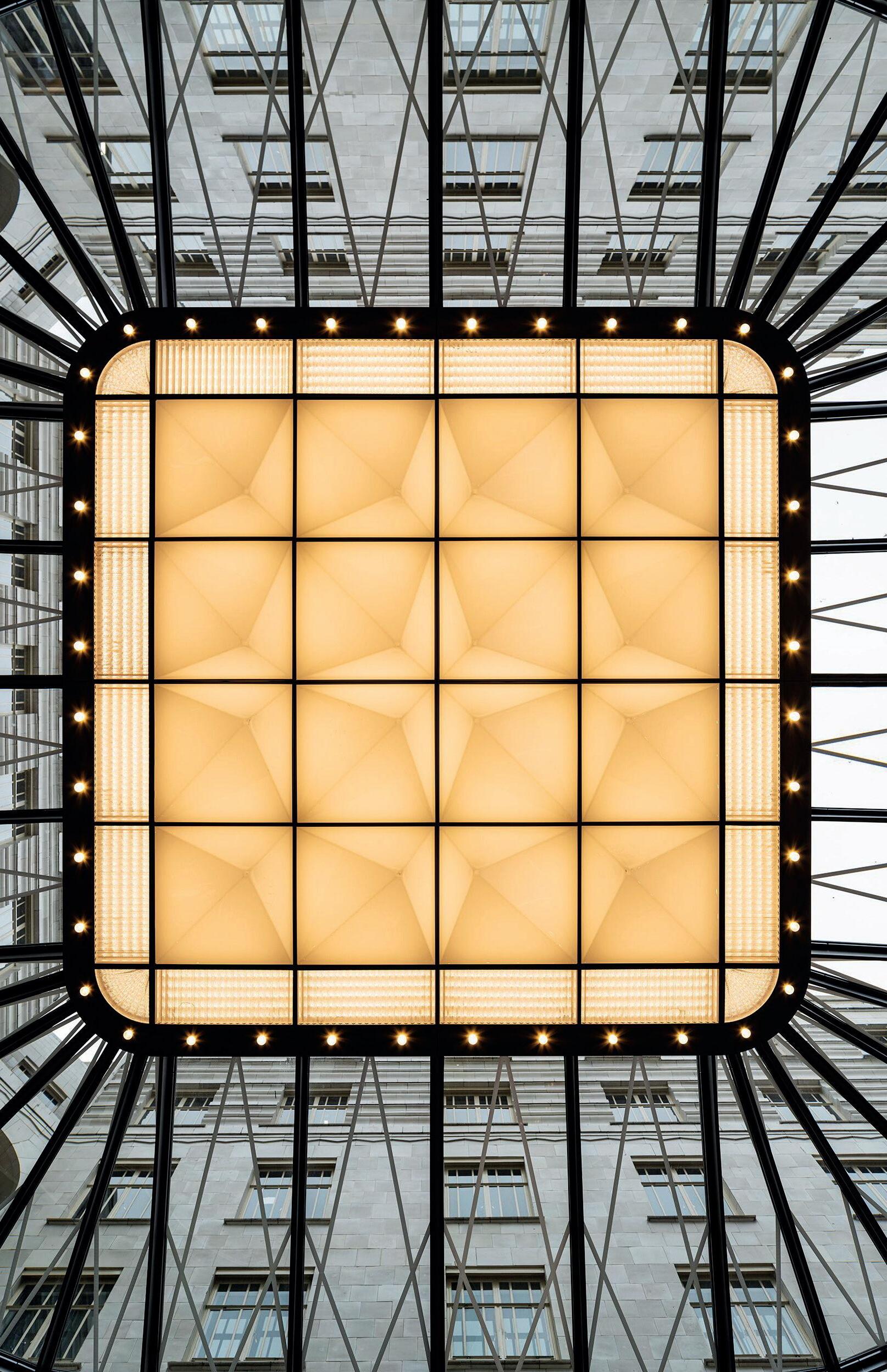

The new lighting scheme for 80 Strand, formerly Shell Mex House, in London draws inspiration from its Art Deco heritage while also bringing a sense of contemporary cohesion to its communal spaces

SKILLED WORK

With an ageing workforce and not enough young people choosing it as a career, the highway electrical industry is facing something of a skills crisis. Making better use of apprenticeships, especially the highway electrical apprenticeship, needs to be an urgent priority for the industry, argues Greg Jarvis

EURO VISION

With 2,500 luminaires, two kilometres of LED tape, 17,500 individual light sources, 37 immersive lighting environments and 79,000 individual lighting cues, May’s Eurovision Song Contest in Liverpool was a massively complex lighting challenge

AS GOOD AS OLD

For too long, lighting has been obsessed with promoting and selling new product and has shown little interest in repurposing fittings or caring what happens to them. That has to change, writes John McRae. Lighting now has no choice but to wean itself off ‘new’ as the default solution to every problem

EMERGENCY PLANNING

The phasing out of fluorescent lamps during this year is likely to put a renewed impetus into LED retrofit projects. As Andy Davies argues, while clients are thinking about upgrades and perhaps have labour on site, it makes sense also to be talking to them about the importance of revisiting their emergency lighting

‘I ENJOY BEING ABLE TO MAKE A DIFFERENCE TO PEOPLE AND PLACES THROUGH LIGHTING’

It is the turn of the YLP’s new chair Ryan Carroll to put himself in the Lighting Journal spotlight, discussing his route into the industry and how others can be encouraged to follow suit

CLIVE LANE: 1943-2023

Former Institution President Clive Lane sadly passed away in May. His widow Sheila reflects on his life and significant contribution to lighting over many years

COVER PICTURE

Boxpark Croydon, showing its ‘even carpet’ of 30 lux of pure red light, as designed by BDP. Turn to page 38 where BDP’s Colin Ball and Lora Kaleva have discussed how to integrate and balance red artificial light within the built environment and public realm, as part of a recent ILP ‘How to be brilliant’ event. Photograph by David Barbour

Contents 46 06 64 28 www.theilp.org.uk JULY/ AUGUST 2023 LIGHTING JOURNAL 3 LIGHT UP, DRIVE OVER EMINERE™ INGROUND anolislighting.com 06 38 46 50 54 56 60 64 62 12 18 24 28 34

AIR3 20,000-56,000lm M1-M3,C1-C5 AIR1 500-4,500lm P1-P6,C3-C5 AIR2 3,000-24,000lm P1-P3,M2-M5,C3-C5 SiCURA 500-8,000lm P1-P6,M3-M6,C3-C5 www.indolighting.com w +44(0)2030511687 info@indolighting.com

Volume 88 No 7

July/ August 2023

President Rebecca Hatch IEng MILP

Chief Executive

Justin Blades

Editor Nic Paton BA (Hons) MA

Email: nic.cormorantmedia@outlook.com

LightingJournal’scontentischosenand evaluatedbyvolunteersonourreaderpanel, peerreviewgroupandasmallrepresentative groupwhichholdsfocusmeetingsresponsible forthestrategicdirectionofthepublication. Ifyouwouldliketovolunteertobeinvolved, pleasecontacttheeditor.Wealsowelcome reader letters to the editor.

Graphic & Layout Design

George Eason

Email: george@matrixprint.com

Advertising Manager

Emma Barrett

Email: ebarrett@matrixprint.com

Published by Matrix Print Consultants Ltd on behalf of Institution of Lighting Professionals Regent House, Regent Place, Rugby CV21 2PN

Telephone: 01788 576492

E-mail: info@theilp.org.uk

Website: www.theilp.org.uk

Produced by Matrix Print Consultants Ltd

Unit C, Northfield Point, Cunliffe Drive, Kettering, Northants NN16 9QJ

Tel: 01536 527297

Email: gary@matrixprint.com

Website: www.matrixprint.com

© ILP 2023

The views or statements expressed in these pages do not necessarily accord with those of The Institution of Lighting Professionals or the Lighting Journal’s editor. Photocopying of Lighting Journal items for private use is permitted, but not for commercial purposes or economic gain. Reprints of material published in these pages is available for a fee, on application to the editor.

If there is a common thread running through this month’s edition, it is how lighting – good lighting especially – colours our perception of the public realm and built environment. My use of the word ‘colour’ here is deliberate, given our review of Colin Ball and Lora Kaleva’s ‘How to be brilliant’ event on the colour red, from page 38. As their seriously wide-ranging talk showed, millennia of evolution have shaped how we see, perceive and think about red light – and this process is still going on.

Moreover, from blue light being the topicdejourtwo decades ago with the arrival of LED, it is now red that is becoming not just better understood but much more prevalent. This direction of travel may only accelerate as the use of bat-friendly redder lighting gathers pace, especially in the public realm.

Yet, as Colin highlighted, there is a tension here that feeds into perhaps the other key conversation within this edition: lighting and safety at night, especially for women. Very red lighting, after all, can bring with it problems around visibility, contrast and definition at night as well as the perceived safety of spaces.

As Clare Thomas makes clear from page six, better lighting is of course not the only answer to safety at night: lighting is not able to resolve the problem of male violence, of community deprivation and crime, of societal tensions. But understanding how well-specified and designed lighting can make a difference – understanding how to press the buttons of decision-makers and budget holders and understanding who lighting professionals need to work and collaborate with – can all help.

Equally, as Elettra Bordonaro emphasises from page 12, it is vital lighting professionals get boots on the ground when it comes to designing for safety. That can mean co-designing with communities. It can also simply mean being prepared physically to visit these spaces at night or at dusk (and in different seasons) to understand them properly rather than making lighting decisions from the office or in front of a screen. It means thinking ‘safety’ when designing for wayfinding or traversing a space – so, for example, not having overgrown or narrow corridors. This is echoed in our review of Leeds University’s ‘Whatmakesaparkfeel safeorunsafe?’ research report, from page 18.

On the plus side, the fact the Leeds research acted as a springboard for a high-level conference on this issue in May – where Elettra was a speaker – does illustrate the greater priority and urgency this subject is being given. It is also welcome there appears to be growing recognition that well-lit public spaces – whether urban parks or otherwise – can create something of a virtuous circle of ‘levelling up’. Better illuminated, planned and cohesive public spaces will be more used and vibrant, in turn helping to (as Elettra puts it) ‘activate’ such spaces, so generating wider community, economic and societal benefits.

Finally, this whole debate feeds into the public realm conversations at the heart of, first, LUCI’s ‘LUCI Declaration’ on urban lighting (as we report from page 26) and the recent ILP/Leicester Urban Observatory ‘City Signs & Lights’ event on the public realm, as Graham Festenstein discusses from page 24.

As Graham makes clear, lighting has a central role to play in creating a more ‘legible’ public realm at night. A public realm where the social as well as the functional benefits of lighting are understood, where individual and community safety is prioritised, and where the importance of lighting in promoting heritage, architecture and cultural engagement is recognised.

As Graham writes: ‘We need to be developing better strategies for urban lighting and using lighting masterplanning to… create, ultimately, a much more cohesive approach to the design of public spaces at night.’ Quite right.

Nic Paton Editor

SUBSCRIPTIONS

ILP members receive Lighting Journal every month as part of their membership. You can join the ILP online, through www.theilp.org.uk. Alternatively, to subscribe or order copies please email Diane Sterne at diane@theilp.org.uk. The ILP also provides a Lighting Journal subscription service to many libraries, universities, research establishments, non-governmental organisations, and local and national governments.

Editor’s letter

JULY/ AUGUST 2023 LIGHTING JOURNAL 5 anolislighting.com LESS WIRES, MORE WIRELESS LIGHTING SOLUTIONS FOR HERITAGE BUILDINGS

RECLAIM THE STREETS (ONE YEAR ON)

The connections between lighting, crime, safety and perceived safety are complex and multifaceted. What’s important, argues Clare Thomas, is to recognise that there is no singular user that public spaces should be designed for, we can’t simply ‘design out’ crime, and lighting on its own won’t resolve societal issues

By Clare Thomas

By Clare Thomas

JULY/ AUGUST 2023 LIGHTING JOURNAL 6

It’s a year since Lighting Journal pub lished my article ‘Reclaim the streets’ (June 2022, vol 87 no 6). In it, to recap, I explored the complex relationship between lighting and safety. With ongo ing pressures on local authority revenue budgets, including the energy crisis, now seems a good moment to revisit some of those topics and ask whether decisions are being driven by funding rather than need.

My original article built on a white paper delivered at the Highway Electrical Associa tion’s (HEA) conference back in 2021, a sub sequent webinar for LDC Ireland in Febru ary and ongoing discussions with fellow industry professionals and customers. It culminated with some great workshop dis cussions at last year’s ILP Professional Lighting Summit in Bristol.

As discovered during the LDC webinar, lighting and its potential for improved public safety/crime reduction is a topic that triggers intense discussion, which is reflected when you carry out further background reading on this topic.

Safety and the potential for crime reduction is a topic that has been consistently linked with public outdoor lighting for over 30 years. Whilst it is generally acknowledged that improved lighting definitely improves perception of safety, there is still ongoing debate around whether improved lighting actually enables or hinders crime.

To cite just some examples of recent research, UCL in March 2022 published a study on how street lighting may enable rather than hinder crime, with an article subsequently also published in Lighting Journal [1]. Research led by the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine has considered the effect of reduced street lighting on road casualties and crime in England and Wales [2].

Going back a bit, Farrington and Welsh (2007) have looked at the links between lighting and crime reduction (as also cited within Safer Streets documents), with the original study updated in 2021, but which still seems to suggest lighting can be an effective tool in this context [3]

WHAT CAN LIGHTING DO?

So, let’s start by considering what lighting can do. Lighting significantly affects how a space or place feels and is used. Is it welcoming, or not? Does it look attractive after dark?

Lighting and safety

Is it somewhere to stay and socialise, a quick route for an essential journey, or somewhere to avoid? And what is clear is that perceived safety is an important topic for everyone.

A YouGov poll was carried out in the UK in May 2021 (‘What would make the UK safer for Women?’) [4]. From a timing perspective this poll was carried out shortly after the shocking murder of Sarah Everard, when there was a real public outcry and movement for women to reclaim the streets.

Looking at the top 12 results, better-lit streets polled highly for both men and women. From a physical intervention, CCTV also polled highly for both sexes, however these was more of a gender difference. The other point to note is that, actually, the rest of the recommendations were societal rather than infrastructure changes, as shown in figure 1 on the left.

This was followed up by an Office for National Statistics study in early 2022 ‘Perceptions of personal safety and experiences of harassment’ [5]. Between 16 February 2022 and 13 March 2022, respondents were asked how safe they felt when walking alone both during the day and after dark in:

• a quiet street close

• a busy public space;

• a park or open

• using public transport on their own, in their local area.

to home;

space; and

0 25 50 75 Men Women 100 76 89 37 49 45 57 58 62 65 78 69 81 69 82 73 84 73 84 77 85 79 88 Tougher sentencing for sexual harassment, sexual assault and domestic violence Making the police take reports of sexual harassment more seriously More victim support to encourage women to report crimes committed against them More resources for investigating and prosecuting crimes against women If men did more to criticise their male friends for bad behaviour they displayed to women Making schools teach boys about acceptable behaviour towards women More CCTV cameras in public places Better education for women on how to stay safe A government campaign telling men what is and is not acceptable behaviour towards women Having undercover police officers in bars, clubs and popular night spots Better lit streets

Figure 1. Interventions that would make streets safer for women, according to a May 2021 YouGov poll

www.theilp.org.uk JULY/ AUGUST 2023 LIGHTING JOURNAL 7

This page and pages 10 and 11: the Dodder Greenway Bridge in Dublin, with lighting by Urbis Schréder. The scheme aims to balance active mobility with safety and ecology

Lighting and safety

Those who reported feeling very or fairly unsafe in any setting were asked whether this had affected their behaviour. Respondents were asked about experiences of harassment in the previous 12 months.

In addition, people who reported feeling very or fairly unsafe in any setting were asked whether they had stopped doing any activities as a results. Some of the findings are illustrated below.

The ONS study was released just before a new tranche of Safer Streets funding was released (round 4) which took the total to £120m since its original launch in 2020.

Underpinning the Safer Streets Fund is the Crime reduction toolkit, which was updated in 2022. This document is published by the College of Policing and advocates taking a structured process to understand and tackle the root causes of local problems [6].

Improved street lighting is recommended by the college as an effective form of situational crime prevention for tackling both neighbourhood crime and a physical environment intervention to help reduce violence against women and girls (VAWG) in public spaces [7].

Additional design guidance is provided within The Police Crime Prevention Initiative’s Guide to Lighting and the Secure by Design guides [8]. These refer back to BS5489-1:2020-2 and set out a ‘good lighting system’ as ‘one designed to distribute an appropriate amount of light evenly with Uniformity Values of between 0.25 and 0.40 using lamps with a rating of at least 60 on the Colour Rendering Index.’

The first round of Safer Streets funding was focused on so-called ‘acquisitive’ crimes, such as theft, burglary or robbery. Of the initial 52 bids, street lighting interventions were delivered to 29 as part of public space initiatives (as opposed to home security initiatives).

Evaluation of the initial funding round was published in January this year, and initial findings showed that, whilst there was minimal impact on acquisitive crime, there was a definite reduction in concerns from local residents [9]. The report does acknowledge, however, that the impact was being measured during Covid-19 and therefore further/ongoing evaluation needs to be carried out.

In essence more evaluation needs to be done to confirm whether the initiatives, including lighting treatments, actually made an impact or not.

SHOULD WE BE LIGHTING OR NOT?

Why is this relevant when we’re discussing lighting for safety? Firstly, people make choices about where to go and how to get there and in some instances those decisions are based on perception.

This is where we need to be clear about whether we should be lighting or not. For instance, we have seen Safer Streets funding being used to light previously unlit parks. There are times when this can make sense. For example, if a park is often used as a pedestrian shortcut, or for sports training after dark, lighting can make a huge difference, as it did on our project in Finsbury Park.

However, done wrong, you are, in the words of one customer ‘leading people to an ambush point’ and disrupting the natural rhythms of flora and fauna. This topic was explained really well by Elizabeth Harrison and Paul Brownbridge LightingJournalearlier this year when they looked at Northumbria’s Safer Parks Strategy (‘Tackling violence’, February 2023, vol 88 no 2). It is also a topic that is looked at in more detail in the

During the day After dark Disabled Not disabled % 100 100 80 80 60 60 40 40 20 20 0 0 % Park or other open space Park or other open space Quiet street close to home Quiet street close to home Using public transport on your own Using public transport on your own Busy public space Busy public space

2021 In a quiet street close to your home In a quiet street close

In a busy public space such as a high street In a busy public space such as a high street In a park or other open space In a park or other open space Using public transport on your own Using public transport on your own 2022 During the day After dark 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 During the day After dark Female Male % 100 100 80 80 60 60 40 40 20 20 0 0 % Park or other open space Park or other open space Quiet street close to home Quiet street close to home Using public transport on your own Using public transport on your own Busy public space Busy public space

to your home

Figures 2-4. Some of the key findings from the ONS ‘Perceptions of personal safety and experiences of harassment’ study. Figure 2 shows that, during both time periods, adults felt less safe walking alone in all settings after dark than during the day. Figure 3 shows that women felt less safe than men in all settings. And figure 4 shows that disabled adults felt less safe in all settings than non-disabled adults

Figure 4

Figure 3

JULY/ AUGUST 2023 LIGHTING JOURNAL www.theilp.org.uk 8

Figure 2

Lighting and safety

following two articles of this edition.

Key questions in this context need to include: where do you want to encourage people to go, or not? Do you make a more populated route more inviting, meaning more people are around to potentially witness a crime? Or do you want to deter the use of less populated routes?

This is why, to my mind, it doesn’t make sense to light playgrounds after dark. Toddlers and primary school children are in bed and, in those instances, lighting could simply make them attractive locations for antisocial and criminal behaviour.

This brings us on to what lighting can’tdo. In my view, lighting – on its own – doesn’t prevent crime. It has to be aligned with a wider strategy for that neighbourhood. Lighting isn’t just a ‘thing’, it is a service, and how and where it is provided makes a huge difference.

We’ve also realised when working on safety-driven projects that there are a lot of stakeholders. Local authorities, police, business improvement districts, developers, architects, lighting designers, residents’ associations, community safety teams and so on… reaching a decision is hard. You can’t please everyone; there will never be a perfect solution. But what we have found is engagement and communication helps make intelligent choices.

Furthermore, you need collaboration across all of these functions to deliver sustainable schemes; the wider environment will impact on both actual and perceived safety.

Sight lines and the environment, too, have a huge impact. A well-lit alleyway will still feel intimidating if trees and shrubs are overgrown. The foliage will provide areas to hide and cast shadows. Will the lighting integrate with CCTV, and what other considerations are there to be taken into account?

IMPORTANCE OF ‘SEEING’ THE SPACE

Critically, you’ll only identify those issues by being on the ground, by ‘seeing’ the space, and understanding the lighting.

I’ve written previously about the danger of just relying on ‘the numbers’, the current lighting standards, to deliver the right lighting scheme. So, if we’re working to the guidance provided in BS5489-01 (2020) crime is

one of the criteria that should be used to help select the appropriate lighting class [10]. However, it’s extremely rare that detailed crime information is provided at a locational basis because of the potential for victim identification.

So, decisions on the lighting class are then made without this piece of data — and in many cases without actually visiting the site either before or after.

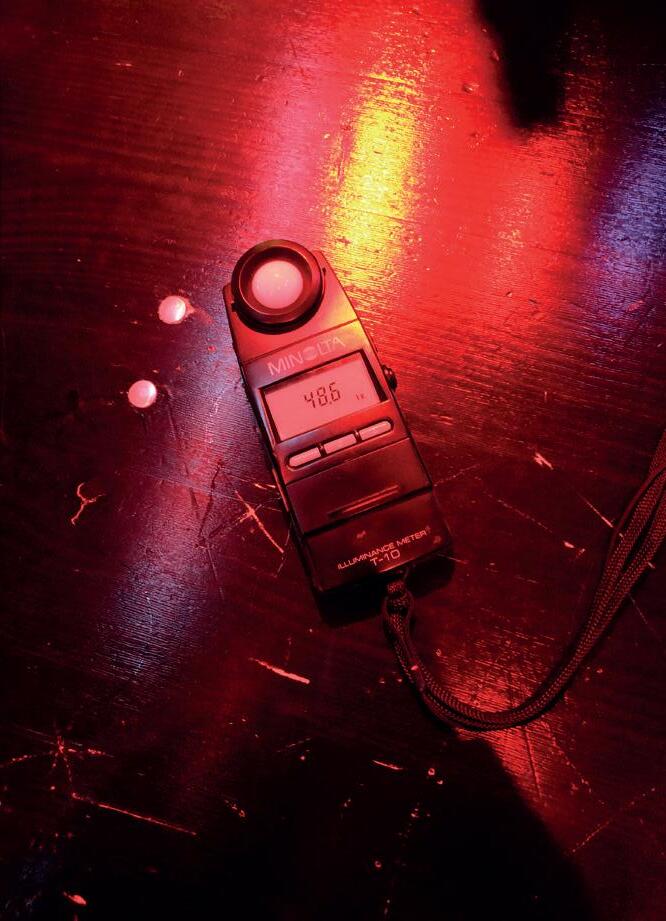

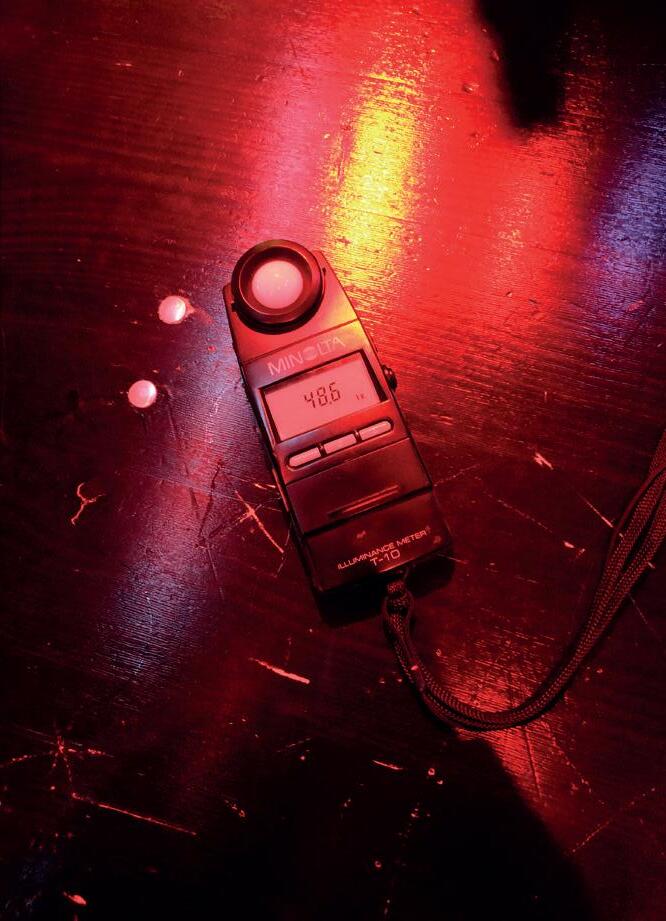

Over the years, at Urbis Schréder we’ve carried out many site visits and light level checks in nice – and less nice – parts of cities and towns all over the UK and Ireland. In some instances, we’ve gone out after dark to measure actual lighting levels and found the ‘numbers’ achieved aren’t even

www.theilp.org.uk

JULY/ AUGUST 2023 LIGHTING JOURNAL 10

the numbers that the end user thought they had. In any discussion about safer streets, there is no substitute for being there and experiencing the space, both before and after.

In many cases, the reported issue with lighting being poor or unsafe isn’t actually down to the lighting but other environmental factors. A good example of this was from a recent visit to west London to carry out a review of areas and streets where the residents and community safety officers had raised concerns regards poor or inadequate lighting.

In one particular location the measured lighting level was actually fine, but the perception was awful. Why? The location felt really dark because of a massive illuminated digital advertising hoarding right in your field of view, which effectively wiped out any night vision, hence the reported resident concerns.

In another location an alleyway was reported as being poorly lit and it had been flagged as a mugging hotspot. When we went to visit, the lighting was actually OK,

although one of the luminaires was partially obstructed by overgrown foliage from a private garden. The second point to consider was that the actual crime location was just outside the alleyway, so overall lighting intervention on its own would not have materially affected crime outcomes for that location.

So how do we put this into practice? Lighting for safety means making intelligent choices about the space. That means engagement with all the stakeholders and aligning any lighting approach with other environmental interventions. We should also consider a layered approach, and think also about vertical / surround illumination. Arup in its paper ‘Perceptions of Night-Time Safety: Women and Girls’ has articulated this really well [11]

To light or not to light? Where do you want to encourage people to go, or not? Do you make a more populated route more inviting, meaning more ‘eyes on the street’ and deter the use of less populated routes? What is important is making an informed decision? How do we make sure we are not letting money drive the decision-making process?

Over time, what we’ve learnt at Urbis Schréder is that good uniformity is more important than higher lighting levels when it comes to safety, and contrast should be minimised.

Bright spots contrasting with dark shadows in between do not create a reassuring walk home. In addition, excessive light levels have a negative impact on the environment and, of course, waste energy.

Control or remote lighting management is essential, as it allows you to tailor the lighting level to different tasks at different times. But it is also important to provide an instant override if needed or requested by attending services.

Communication matters, too. It is important to engage with all stakeholders – and that means having open dialogue with non-lighting people.

CONCLUSIONS

As a final thought, of course we can change the lighting within a space. But how do we know whether the lighting has had a positive or negative – or even any – impact? Therefore, we need more engagement

Lighting and safety

with and analysis of the data before and after. What would be interesting would be to get feedback on the impact of interventions. Fundamentally, we need more evidence and research into this topic so that we, as lighting professionals can support and provide advice on good practice.

We also need to monitor unintended consequences, such as crime displacement, and ensure we think really carefully about the diverse nature of modern cities. The focus on VAWG (violence against women and girls) has made everyone more aware of the topic. But everyone – young people, the elderly, BAME citizens, LGBTQIA+ individuals – all have a different experience of walking through the city after dark.

There is no singular user that public spaces should be designed for: such spaces therefore have to be for everyone. And we can’t simply ‘design out crime’ with the one tool we have at our disposal, we need that stakeholder engagement. Moreover, lighting won’t resolve societal issues.

Good street lighting can create spaces where people want to congregate, make them feel safer and create a welcoming environment for everyone. Done right, lighting complements the utility and distinguishing characteristics of the local environment.

It helps people work, play and move around – and yes, it can make people safer. But this will only happen if it’s part of a holistic approach to urban life, and one where stakeholders realise there are no instant fixes.

[1]‘Street lighting may enable rather than hinder street crime’, UCL, March 2022, https://www.ucl.ac.uk/news/2022/mar/street-lighting-may-enable-rather-hinder-street-crime; ‘Light fingered’, Lighting Journal April 2022, vol 87, no 4 [2] Edwards P et al (2015), ‘The effect of reduced street lighting on road casualties and crime in England and Wales: controlled interrupted time series analysis’, Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, vol 69, issue 11, https://jech.bmj.com/content/69/11/1118 [3] Welsh B C, Farrington D P, Douglas S (2007). ‘The impact and policy relevance of street lighting for crime prevention: A systematic review based on a half-century of evaluation research’, Criminology & Public Policy, DOI: 10.1111/1745-9133.12585, https://prohic.nl/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/389-StreetLightingEffectivenessPreventingCrimeSystematic Review.pdf; ‘Effectiveness of Street Lighting in Preventing Crime in Public Places’, (2021) Swedish National Council for Crime Prevention, https://prohic.nl/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/327-StreetLightingEffectivenessPreventiongCrimePublicSpacesSystematicReview.pdf [4] ‘What would make the UK safer for women, according to women?’, YouGov, May 2021, https://yougov.co.uk/topics/politics/articles-reports/2021/05/10/what-would-make-uk-safer-women-according-women [5] ‘Perceptions of personal safety and experiences of harassment, Great Britain: 16 February to 13 March 2022’, Office for National Statistics, May 2022, https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/crimeandjustice/bulletins/perceptionsofpersonalsafetyandexperiencesofharassmentgreatbritain/16februaryto13march2022 [6] ‘Crime Reduction Toolkit’, College of Policing, https://www.college.police.uk/research/crime-reduction-toolkit [7] College of Policing: ‘Interventions for situational crime prevention’, https://www.college.police.uk/guidance/neighbourhood-crime/interventions-situational-crime-prevention; ‘Physical environment interventions’; https://www.college.police.uk/guidance/interventions-reduce-violence-against-women-and-girls-vawg-public-spaces/physical-environment-interventions; ‘Street lighting’ https://www.college.police.uk/research/crime-reduction-toolkit/street-lighting [8] Secured by Design, https://www. securedbydesign.com/guidance/design-guides [9] ‘Safer Streets Fund evaluation’, Home Office, January 2023, https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/safer-streets-fund-evaluation [10] BS 5489-1:2020 – TC ‘Design of road lighting Lighting of roads and public amenity areas. Code of practice’, BSI, May 2020, https://knowledge.bsigroup.com/products/design-of-road-lighting-lighting-of-roads-and-public-amenity-areas-code-of-practice/tracked-changes [11] ‘Perceptions of Night-Time Safety: Women and Girls’, Arup, https://www.arup.com/projects/perceptions-of-nighttime-safety-women-and-girls

JULY/ AUGUST 2023 LIGHTING JOURNAL 11

Clare Thomas is head of Logic at Urbis Schréder

www.theilp.org.uk

PARKS AND RECREATION

Lit well, urban parks can not only be safe spaces for women but year-round whole-community hubs, for people of all ages. So, why, as a conference recently asked, are so many still so poorly lit and badly maintained?

By Nic Paton

It is estimated that, across the UK, as many as 27,000 parks give our nation much-needed access to nature within urban areas. As we perhaps felt most keenly during the lockdowns of the pandemic, our green spaces are invaluable places for exercise, play, socialising and relaxing, good for both our physical and mental health.

Yet, especially as night falls or dusk settles, and particularly in the winter months when it can be dark by late afternoon, many of our parks and public spaces can become much less welcoming, threatening or even unsafe. This is especially the case for women, and in

particular for lone women after dark.

Last year, a survey by the Office for National Statistics found that women feel considerably more unsafe than men across all types of public settings, especially after dark [1]. As many as four out of five UK women (82%) report feeling very or fairly unsafe after dark in a park or open space compared with two out of five men (42%), the same study concluded. Research by Girlguiding, meanwhile, has found that more than half of girls aged 11-21 (53%) do not feel safe outside alone [2]

It was against this rather depressing backdrop that, in May, Leeds University brought

together a wide range of high-level speakers, including academics, politicians, safety specialists and lighting professionals to discuss the subject of ‘Women and Girls: Safety in Parks’.

The university’s Dr Anna Barker and Professor George Holmes were among the speakers, and their research on what makes a park feel safe or unsafe is looked at in more detail in the next article. There were presentations from Tracy Brabin, the Mayor of West Yorkshire and Marina Milosev of the London Legacy Development Corporation, who spoke on her experience of lighting the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park and Detective Superintendent Vanessa Rolfe of West Yorkshire Police, among others.

PERCEPTION OF SAFETY

One critical aspect of this conversation, of course, is the role that light and artificial lighting can play in creating safer spaces and, as importantly, creating the feeling –the perception – of safer spaces. This was something emphasised in a presentation at the conference by Elettra Bordonaro, co-founder of lighting design consultancy Light Follows Behaviour.

Back in 2020, Elettra, as regular readers may recall, discussed in these pages how social housing can sometimes end up with ‘poorer’ second-tier lighting solutions because some local authorities feel it is just, well, social housing (‘Social value?’, July/ August 2020, vol 85 no 7).

Catching up with Elettra after this latest conference, it was clear that, from her perspective at least, some developers and local authorities have an equally long way to go to understand the ‘value’ (in all senses of the word) of properly lighting their park infrastructure.

‘In some places I’ve worked, the solution after there has been a serious incident in a park is simply to switch off the lighting, which is a totally bizarre response,’ she tells LightingJournal. ‘Equally, I’ve experienced councillors who feel that, because they’ve

JULY/ AUGUST 2023 LIGHTING JOURNAL 12

Lighting and safety

“solved” the lighting in one park, that’s it, job done; now it’s just a case of copying and pasting that approach across the rest of their part estate. But it really doesn’t work like that.’

What, then, is the answer? The first thing local authority teams and decision makers and lighting professionals need to understand is why having good lighting in parks is so important, not just to women but to anyone who uses parks after dark, Elettra argues. It’s not just about the individuals who are using the space (although that is important), it’s what a well-lit and well-maintained park also says about the vibrancy of a community, its cohesion and integration – and its night-time economy.

‘It’s about understanding how the wider park environment connects with and feeds into perceptions of safety, and how these need to link to and complement the surrounding more urban environment. It’s about, very simply, understanding the space you’re dealing with, at all times of the day and in different seasons. And, within all that, understanding if, with the right lighting, you can improve things,’ Elettra explains.

Elettra highlights how, at Light Follows Behaviour, night walks and community workshops – almost community co-design –are often an integral part of the design process. ‘We work to understand the situation in that particular park first. With some councils, they maybe don’t want to light up the park at night; they may be worried about obtrusive light or light pollution or energy costs or flora and fauna,’ Elettra adds.

www.theilp.org.uk JULY/ AUGUST 2023 LIGHTING JOURNAL 13

Lighting and safety

That, of course, highlights one of the most important tensions here: balancing safety with ecology and overly obtrusive, polluting light. As Elettra recognises, you of course want your scheme to be well-specified, installed and directed. ‘You don’t want a million lux flooding the space (and, in fact, a really bright and glary lighting scheme can be intimidating at night too). Yes, too, you need to consider the local ecology of the area, especially bats and insects.

‘However, at the same time, especially with urban parks, you need to recognise you’re going to be designing near areas that are brightly lit anyway; whatever you do there is probably going to be an element of skyglow, light from high-rise blocks, from retail units, from traffic and so forth spilling into the space,’ she adds.

CLEAR WAYFINDING

When it comes to safety and perceptions of safety in these sorts of spaces, clear wayfinding is absolutely imperative. ‘As a woman in a park at night if you can see, clearly, what the route is through the park, that is going to make such a difference,’ Elettra explains. ‘That there aren’t unexpected dark patches, or dead ends, or places where, say, all of sudden you find you’re on a badly lit, narrow path between bushes or trees. So, it is absolutely critical that the lighting designer effectively collaborates with the landscape architect.’

Within this, clear (and often illuminated) signage is also an important part. ‘What we’re looking to achieve is soft lighting that makes you feel comfortable both on the path and within the surroundings. You can and should of course try to leave parts of the park dark, but at least ensure you have a network of safer routes that people are going to feel safe to run on and walk on at night. Routes through parks are sometimes almost the only connections between neighbourhoods,’ Elettra recommends.

Furthermore, as touched on earlier, there’s the context of the park in different seasons to be taken into consideration. It is important to understand that it is not necessarily ‘night’ per se that is the issue here and more simply ‘after dark’. After all, in the UK a park in the middle of winter, is dark by 4pm. It will be – and feel – very different to a park at 11pm on a warm summer’s evening.

As Elettra explains: ‘Is the feeling you have at 8pm in winter comparable to the feeling you have at 10pm in the summer? No, it’s probably not. There will probably be many

more people around at the point of the summer than there will be in the winter. So it is not only lighting related; it is also related to things such as facilities, to other people in the park.

‘Moreover, within this, it is important to recognise that “after dark” is not “late night”, especially in winter. In winter, it can encompass the school run, commuter rush hour, after-school or after-work activities (or travelling to and from them), and community engagement events (or, again, travelling to and from),’ she adds.

HOLISTIC COMMUNITY APPROACH

This, in turn, brings us back to the importance of thinking about the space you have in the park in the round, how the park – and the lighting within it – connects to, colours and contrasts with the wider urban community around it.

‘If along and around the park you have lit activities, if you have spaces where families and children are going to feel welcome –especially year-round activities – those

JULY/ AUGUST 2023 LIGHTING JOURNAL www.theilp.org.uk 14

London’s Shadwell Estate, where, as part of the Peabody IMPROVE programme, Light Follow Behaviour’s lighting scheme focused on giving its residents an improved outdoor experience, including in terms of safety and wayfinding

Talk to us about making the right connections. Get in touch at logic@urbis-schreder.com Smart integrated solutions that protect and prioritise .

is YOUR hollistic

to making the right

dark skies safety Urbis Schréder

-

approach

choice

Lighting and safety

spaces automatically are going to feel safer,’ Elettra points out.

‘Thinking about your park space holistically in this way – so maximising how and when it is used all year around – is also probably going to lead to wider economic, social and community benefits, more community engagement and involvement, more cohesion, too. You’re much more likely to “activate” the space,’ she advises.

Extreme glare/contrast from badly specified or positioned light sources can be bad not just for light pollution but for damaging night vision and creating dark, intimidating spaces around the periphery, Elettra also highlights.

Furthermore, poor semi-cylindrical illumination can lead to spaces that have poor facial recognition, spaces where there is a risk of people looming at you out of the darkness – and this is something Khalid Hamoodh and Professor Steve Fotios discuss later in this edition.

‘Extreme darkness on main corridors and extreme darkness at the edges of spaces can both be issues. I’d argue we can often be a bit more sophisticated in the way we are lighting up the space within an urban park,’ Elettra argues.

‘We can look at vertical lighting and the way that we are perceiving colour rendering in the space. People often say colour rendering is not that important in urban spaces, but I think it is. If I need to detect the colour of a shirt or to make out someone’s face as they’re approaching me, for example.

‘Having good uniformity, good colour rendering means people can, simply, see better, with a lack of uniformity leading to the opposite. It means they may be more attracted to the place, to the space, because it is acting a like a beacon.

‘You can see through it; you can see there is a destination you can reach at the other end. In that sort of space, you’re going to feel that much safer. Which comes back to coordinating with the landscape architect, the playground design, the planners and so on,’ she adds.

CONCLUSIONS

Councils, Elettra argues, need to be encouraged to look at their green urban spaces holistically, to see ‘safety’ as not just ‘a women’s issue’ but, if you can crack it, as a way of turning your urban parks into lively, friendly, outdoor community hubs all year round, spaces that will benefit the whole community as well as the night-time economy.

‘With good lighting just one (if important) part of this transformation. You can’t, and mustn’t, look at a site in isolation; context is everything,’ she points out.

Good, ongoing, effective maintenance needs to be an important adjunct to this.

‘Good park lighting is also, normally, well-maintained park lighting. That will, and should, mean council teams and/or lighting department teams being prepared to visit their parks after dark, winter and summer, to see, know and understand what’s going on on the ground. Rather than women having to find out for themselves – the hard way,’ Elettra argues.

Finally, while universities such as Leeds are clearly doing valuable research in this area, there is an argument for the development of more lighting guidelines specifically to address these issues, Elettra emphasises.

‘We need better analysis of what works and what doesn’t from a lighting perspective in urban parks after dark; we need, too, better planning and design to become the norm,’ she says in conclusion. ‘Maybe this is the something the ILP could consider down the line, or SLL, or maybe both?’

• Turn to page 18 for an analysis of the Leeds University safer parks research and page 34 for a discussion on Sheffield PhD student Khalid Hamoodh’s research into facial identity recognition.

[1] ‘Perceptions of personal safety and experiences of harassment, Great Britain: 16 February to 13 March 2022’, Office for National Statistics, May 2022, https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/crimeandjustice/ bulletins/ptionsofpersonalsafetyandexperiencesofharassmentgreatbritain/ 16februaryto13march2022 [2] ‘A snapshot of girls’ and young women’s lives’, Girlguiding, https://www.girlguiding.org.uk/girls-making-change/girls-attitudes-survey/

JULY/ AUGUST 2023 LIGHTING JOURNAL www.theilp.org.uk 16

Don’t Switch to Solar

It isn’t right for every project.

BUT when the calculations work…

It’s light without ongoing energy costs. Without trenching costs. A permanent or temporary lighting and energy storage solution that can also be used to power CCTV and other Smart City sensors.

Challenge us – see if a solar solution could work for you. acrospire.co

SAFE PASSAGE

JULY/ AUGUST 2023 LIGHTING JOURNAL 18

women and girls’ views on what would make parks feel safer and more accessible public places. Indeed, research shows that welldesigned lighting can play a role in reducing fear and increasing use of space as well as reducing crime, providing opportunities for more equal access to public spaces and assisting women to foresee and respond to potential harms,’ it added.

The women interviewed by the academics agreed on eight areas:

By Nic Paton

Improving lighting in Britain’s parks, especially urban parks, would significantly help women and girls to feel safer in these spaces at night. Yet, by itself, better lighting is not a panacea solution, as it still leaves untouched the structural and cultural factors that underpin violence and harassment against women.

This is one of the key conclusions from a University of Leeds research report, ‘What makes a park feel safe or unsafe?

Theviewsofwomen,girls,andprofessionalsinWestYorkshire’[1]

The report, led by the criminal justice professor at the university Dr Anna Barker and co-authored by colleague conservation specialist Professor George Holmes, was the springboard for last month’s ‘WomenandGirls:SafetyinParks’conference at Leeds, as discussed in the previous article by Elettra Bordonaro.

The study, conducted across West Yorkshire in 2022, carried out interviews with 67 women aged 19-84 years, 50 girls and young women aged 13-18 years, and 27 professionals from parks and urban design services in local government and police.

Worryingly, most of the women and girls believed their local parks were unsafe. More than half felt they were very unsafe.

Lighting, it was also clear from the findings, does have a pivotal role to play in improving safety and perceptions of safety in these spaces, especially in the darker winter months.

PARKS ‘INACESSIBLE’ TO WOMEN

As the research stated: ‘Women and girls avoid parks after dark because they do not feel safe. In certain seasons with shorter days, parks without lighting become inaccessible to many women in early mornings and from late afternoons.

‘Lighting is very important to some

1. Well-used parks generally feel safer because of increased passive surveillance (or the visibility of staff, volunteers or other users) and more opportunities to seek help. Facilities, activities, mixed uses and staffing throughout the day all help to support this sense of busyness.

2. The presence of other women in parks will often be reassuring and signal it is a safer place but women-only areas were not felt to be the solution.

3. Organised group activities supported women to feel safer and extended their use of parks, though the choice and timing of activities could often be expanded.

4. Fences or walls around the edges of parks limited escape and visibility, whilst openness of spaces felt safer by enabling women to spot dangers earlier and, if necessary, take action.

5. Women generally felt safer ignoring than challenging unwanted comments and attention in parks, so as to avoid escalation and unsafe situations. Yet, they also recognised that leaving male harassment unchallenged simply perpetuates injustice.

6. Seeing other users of a similar identity in parks will often feel reassuring, though there was agreement that a diversity of users suggested parks were inclusive.

Lighting and safety

7. Women felt they could not rely on other park users to intervene in instances of harassment, but wellused parks did increase the probability of bystander intervention.

8. Mobile phone apps where women allow trusted contacts to track their journeys can be useful in parks but bring with them an unwelcome trade-off of freedom for safety.

PERSPECTIVES OF PROFESSIONALS

By comparison, while the professionals interviewed by and large had similar views on how to support women to feel safe in parks and what makes parks feel unsafe, they disagreed with the idea that noparks are safe for women and girls after dark.

Signs of disorder, people behaving inappropriately or unpredictably and using drink or drugs make women feel unsafe in parks, they agreed. Busier parks were and felt safer. Parks needed to be designed with

The importance of welldesigned and maintained artificial lighting in making parks feel safer for women and girls after dark has been emphasised in recent research by the University of Leeds. But it is also clear that better lighting is not the only answer

www.theilp.org.uk JULY/ AUGUST 2023 LIGHTING JOURNAL 19

Roundhay Park in Leeds

Lighting and safety

facilities and amenities that appealed to women, girls and families, thereby signalling parks as safe places.

Visible staffing helped, as did physical interventions, such as lighting and CCTV. Cutting down overgrown vegetation to reduce hidden areas, raising canopies and lowering shrubs could also be beneficial, but had to be balanced between accommodating natural or wooded areas.

In all, 89% of the professionals interviewed felt parks in their area of West Yorkshire were very or fairly safe for women and girls. Yet this compared with only 37% of women and 22% of girls interviewed.

Returning to lighting, there was a feeling among many of the participants that authorities could do more to support women’s independent use of parks. This needed to include better lighting, more visible security, more help points, and more staff presence.

LIMITATIONS OF LIGHTING

However, the researchers also had feedback to suggest badly designed and lit parks simply amplify the risks women can feel anywhere, especially after dark. Therefore, lighting parks in itself will not make parks feel safer, as it won’t stop men hurting women.

‘Lone men in parks are a potential threat, especially given the level of violence against women in society, and aspects of women’s identities, such as age and sexuality, makes them more at risk. But we must shift the burden from women to stay safe; authorities need to do more about harassment, and men’s behaviour has to change. For now, it feels safer using parks with friends or family, ignoring unwanted comments and avoiding secluded and thickly vegetated areas of parks,’ the report argued.

A further view argued that some parks are safe for women, just not ones that are secluded or have thickly vegetated areas and not after dark, as they are designed for daytime use.

Women will by and large avoid parks with bad reputations for drinkers, drug users or groups of men and boys. In this scenario, the answer is probably a higher staffing and police presence as much as it is infrastructure changes, the report highlighted.

In some instances, women identified wellused active travel routes through dark parks as safe because there were lots of people using them, including women.

This, the report emphasised, ‘illustrates that lighting and other physical design interventions should not be standalone solutions but part of a wider strategy to increase use of space and improve passive surveillance to engender feelings of safety.’

NEED TO BALANCE WITH ECOLOGY

The report, however, also recognised that in parks and green spaces there is a need for lighting to be balanced with the ecological needs of the space.

‘Lighting entire parks or all parks across a locality is not practical. Professionals felt that lighting interventions could be appropriate in parks subject to resourcing and opportunity,’ it stated.

‘Hence, decisions should be about where and which parks would benefit from lighting. Notably, women perceived lighting to be important in relation to other “popular” active travel routes, which are well used during the daytime but not after dark in part because of safety concerns and a lack of sufficient lighting.

‘Relatedly, girls pointed out that some facilities in parks are lit, such as MUGAs [multi-use games areas], but not the paths to/from them,’ the report added.

In terms of recommendations, while these were wide-ranging, the report did advise that local authorities should be including specific actions to improve safety and feelings of safety in parks after dark in their park management strategies. This needed also to be considering areas of parks

or routes through parks where there is a need for safe public use.

As it advised: ‘Local authorities and parks managers [should] consider where in parks artificial lighting would add value in supporting park use, active travel and feelings of safety as part of a wider strategy that considers the ecological needs of the site. Where lighting cannot be provided, alternative routes should be signposted.’

As well as local or council-led solutions, the report called for more central government funding to improve the safety of women in parks.

Dr Barker, an associate professor in criminal justice and criminology in the university’s School of Law, said: ‘Overall, we found that women and girls want parks and play spaces to be better designed and managed to be well-used, sociable places that offer a range of activities and facilities that are more welcoming to them.

‘This needs to be the focus of funding and interventions in order to break down the barriers to women and girls using and feeling safe in parks,’ she added.

Professor Holmes, professor of conservation and society in the university’s School of Earth and Environment, said: ‘We found that women and girls’ views on feeling safe in parks were shaped by broader societal issues such as misogyny, harassment and threats of violence.

‘As well as the specifics of park design such as overgrown vegetation, visibility and lighting, we recommend that changes to these spaces must be part of a holistic approach to address root causes of women and girls’ feeling unsafe in public spaces,’ he added.

[1] ‘What makes a park feel safe or unsafe? The views of women, girls, and professionals in West Yorkshire’, December 2022. Dr Anna Barker and Professor George Holmes (University of Leeds). With Dr Rizwana Alam, Lauren Cape-Davenhill, Dr Sally Osei-Appiah and Dr Sibylla Warrington Brown, in collaboration with West Yorkshire Combined Authority. Funded by the Home Office (Safer Streets Fund). Available at: https://eprints.whiterose. ac.uk/194214/1/Parks%20Report%20FINAL%207.12.2022.pdf

JULY/ AUGUST 2023 LIGHTING JOURNAL www.theilp.org.uk 20

Locked service position

Internal retention safety wire

Quick release connections

Aligning spirit level

Removable luminaire head

Preliminary TM66 score: 2.8 excellent circularity.

Contact us: info@holophane.co.uk www.holophane.co.uk TM THE ALL NEW

CONTRACTOR FOCUSED FEATURES

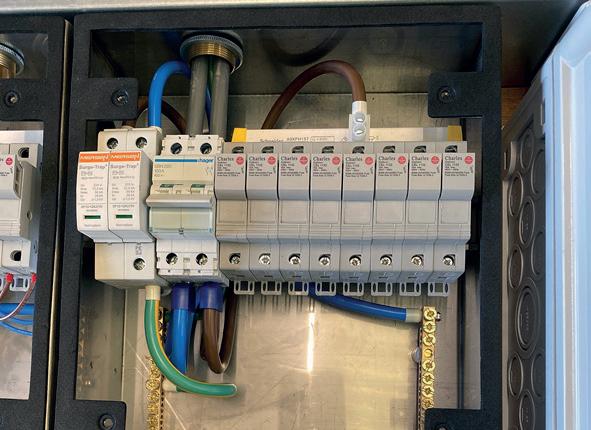

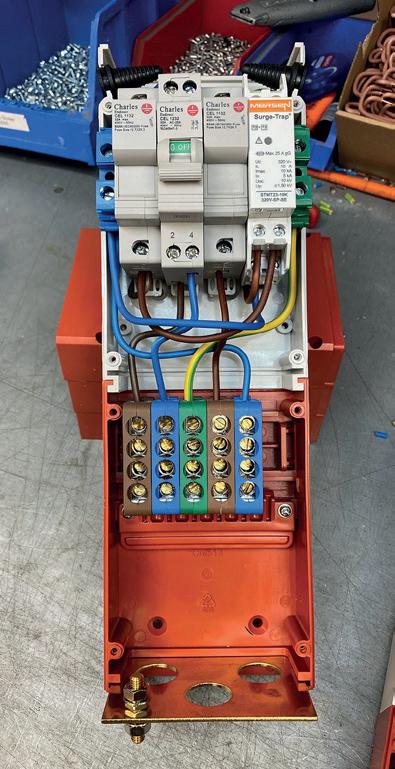

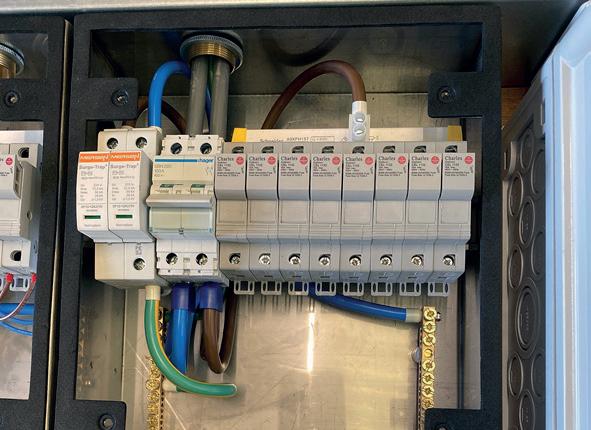

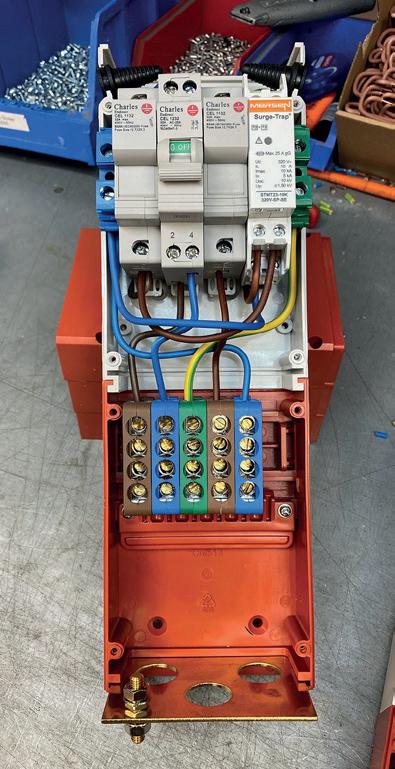

3 Capability to supply power to Slow, Fast and Rapid charge points.

3 Complete bespoke design service by expert team.

3 Can be pre-wired for your specific project.

3 Supplied tested & certified ready for installation.

3 Each pillar comes with full technical document pack.

3 New MEGA range designed to meet client demand for larger pillars.

DISTRIBUTION CABINETS FOR EV CHARGE POINTS

Wessex Way, Wincanton Business Park, Wincanton, Somerset BA9 9RR Reg no 1855059 England CharlesEndirect.com +44(0)1963 828 400 info@charlesendirect.com

CharlesEndirect.com +44(0)1963 828 400 info@charlesendirect.com Wessex Way, Wincanton Business Park, Wincanton, Somerset BA9 9RR Reg no 1855059 England For a limited time we have up to 20% off Festive Isolators use code CEL20 when requesting a quotation offer expires 31st July 2023

CREATING A MORE ‘LEGIBLE’ PUBLIC REALM

A recent ILP event, ‘City Signs & Lights’, brought together academics and lighting professionals to consider how public realm lighting can be better integrated into – and even lead – urban design and placemaking

By Graham Festenstein

Earlier this year, the ILP collaborated with the Leicester Urban Observatory on ‘City Signs & Lights’ – the first of a series of events to discuss the lighting of public space from a planning perspective, with an emphasis on the integration of lighting with signage and wayfinding, along with the potential for public art to play a role in urban design and placemaking.

The Leicester Urban Observatory is a collaboration between urban practitioners at Leicester City Council and academics at three local universities: De Montfort, Leicester, and Loughborough.

It aims to establish and develop a combined centre of excellence in urban studies and planning for Leicester. Three speakers took part in the event: Grant Butterworth,

head of planning for Leicester City Council; Dr Sean Clark, a digital and multimedia artist who has an interest in community projects and illuminated work; and myself on behalf of the ILP (as I am a lighting designer and consultant specialising in urban lighting).

The evening was introduced by Dr Robert Harland, lecturer in visual communication

JULY/ AUGUST 2023 LIGHTING JOURNAL 24

and reader in urban graphic heritage at Loughborough Heritage. We were joined for discussion by an audience of lighting professionals, planners and architects.

LIGHTING TO SUPPORT PLACEMAKING

The importance and potential of lighting to support placemaking and wayfinding within the public realm is often overlooked, with an over-reliance on street lighting to comply with standards and a design brief. This, in turn, too often precludes proper integration with landscape, architectural design and way-finding strategies.

The ILP as an Institution promotes collaboration between designers, engineers and other consultants involved with public realm design to ensure all users of public space are served, so creating comfortable, legible and safe places that are easily navigated.

Traditionally, the dialogue between lighting designers and planners has been fairly limited, leading to priorities that often do not do justice to the life and community that goes on during the hours of darkness, darkness that in the winter can of course begin as early as 4pm in the afternoon.

Lighting is often seen as a technical engineering exercise executed at the end of a project rather than one integral to the design

Public realm lighting

from the start as it should be. The way a space looks, feels and performs at night is fundamental to success of our urban communities.

The purpose of this and the further events to follow is to bring together lighting designers and engineers with planners and the other disciplines involved in public realm design to better understand how lighting can be supported and strategies developed to achieve these aims.

LIGHTING FOR VISUAL AMENITY

Grant Butterworth started the evening with a discussion around the planning priorities for lighting for visual amenity, protection of the environment and ecology through sensitive and properly considered lighting and the economic benefits of lighting through marketing, tourism and business promotion.

He went on to consider the social benefits of lighting, community safety and the promotion of heritage, architecture and cultural engagement through community events and cultural festivals such as Diwali, which of course is especially pertinent in Leicester, and how all of these areas of discussion are interlinked and the role of the local authority in delivering and managing them.

Grant used examples of Leicester’s

architectural feature-lighting grant scheme to illustrate some of his points along with images of lighting in public spaces.

These included examples of poor lighting, in particular some digital displays demonstrating the potential harm that can be done through bad lighting and when it is not regulated properly through the planning process.

Grant’s concluding statements can be summed up as follows: ‘Lighting can generate and reveal beauty… It can be a valuable and valued community resource. It can protect… It can harm and annoy… So it does need to be managed. Understanding the design process from all technical disciplines is a key objective .’

LIGHTING AND FESTIVALS

Sean’s presentation, meanwhile, discussed a number of public art installations and installations for cultural festivals he has produced, many involving an element of community engagement and or interactivity.

In particular, he discussed his involvement in the ‘Light up Leicester’ light festival. Sean’s work is interested in using technology to explore connectedness, often in a simple yet innovative way and light, lights or illuminated elements figure prominently in much of his work.

www.theilp.org.uk JULY/ AUGUST 2023 LIGHTING JOURNAL 25

Public realm lighting

When working in the public realm, he explained, he is interested in how his lit installations, or the way people interact with his installations, respond to the space or environment they are located within. For example, how they may be connected to or lead people across the city or react to specific locations.

Sean outlined how he is very keen to explore the use of technology on a city-wide basis to create city-wide installations that connect people and places across the pubic realm. As he explained, in his artwork, he is inspired by systems’ theory, the nature of interactivity and creative explorations of flow, connectedness and communication.

LIGHTING AND URBAN SPACE

Finally, for my own presentation, I discussed the role of lighting in placemaking and creating what I termed as a ‘legible’ public realm at night.

In particular, my discussion brought together a number of themes from the other presentations to demonstrate how lighting can be better integrated with urban design. In essence, how using elements of architectural or landscape feature lighting, street and area lighting, public art and lighting for wayfinding can deliver public spaces that are more comfortable and easier to understand.

How, too, lighting can be used to make spaces more navigable, using visual cues to

orientate and create destinations that promote footfall and permeability.

My presentation highlighted the importance of vertical illuminance on building façades or other structures, either through controlled light spill or with designed architectural lighting; how this, again, helps legibility and how, without it, the sense of a space can be dissipated.

To my mind, an urban space is often defined by the buildings that surround it and, if this is lost, the character and identity at night can be lost. Lighting can benefit the night-time economy and can bring social benefits, so potentially reducing anti-social

behaviour and promoting sustainability through community living.

I believe there is clear potential to develop design integration further through the use of lighting controls and smart city technologies. We need to be developing better strategies for urban lighting and using lighting masterplanning to draw together all of the threads discussed by all three speakers to create, ultimately, a much more cohesive approach to the design of public spaces at night.

The evening was then rounded off by a discussion with the audience that demonstrated the need to dig deeper into the interesting topics and differing perspectives raised. I certainly look forward to exploring these questions further as the collaboration between ILP and the Leicester Urban Observatory develops over the coming months.

But let me leave the final word to Robert Harland. The event, he argued, was a first for the Leicester Urban Observatory. ‘Conceiving the idea and making it happen with the ILP set in place not only the opportunity to hear from highly specialised lighting professionals and practitioners, spanning planning, design, and arts, but the event also provided a template for future events of this kind,’ he said.

‘These may involve other professionals who contribute to the way people and places interface. The academic underpinning of Stephen Carr’s CitySignsandLights policy study from Boston in the early 1970s underpinned the talks, and emphasised importance of lighting as a communication tool in cities,’ Robert added [1]

[1]

‘City Signs and Lights’, Stephen Carr, 1973, https://www.goodreads.com/book/ show/81760.City_Signs_and_Lights

Graham Festenstein CEng FILP FSLL runs Graham Festenstein Lighting Design and is the ILP’s Vice President – Architectural

JULY/ AUGUST 2023 LIGHTING JOURNAL www.theilp.org.uk 26

Leicester at night and (below) during Diwali

DECLARATION OF INTENT

LUCI, Lighting Urban Community International, marked May’s International Day of Light by publishing an ambitious ‘LUCI Declaration’ outlining how municipalities and lighting professionals may need to rethink their approaches to urban lighting over the next decade

By Nic Paton

By Nic Paton

JULY/ AUGUST 2023 LIGHTING JOURNAL 28

This year’s UNESCO International Day of Light took place on 16 May and, as every year, saw events taking place around the world to highlight and celebrate the role light plays in science, culture and art, education, and sustainable development.

LUCI, Lighting Urban Community International, the international network of 70 cities that shares best practice and innovation on urban lighting, marked the occasion by publishing its ‘LUCIDeclaration’

This is a series of recommendations for how we might adapt – in fact may need to adapt – urban lighting strategies to climate change; to new patterns of work, leisure and mobility; to evolving technologies; and to respond to the growing pressures on the planet’s biodiversity over the next three, five to 10 years.

With the ILP being one of LUCI’s 40 partner members, it therefore seemed a good opportunity to look at how the organisation is suggesting lighting professionals may need to be responding to these challenges in the coming years. After all, as LUCI president and deputy chair of the City Board of Jyväskylä, has put it in the declaration: ‘We have an unprecedented opportunity to better light our cities together.’

SEVEN FUTURE GOALS

The declaration, first, sets out seven highly aspirational goals for the future of urban lighting. These are:

1. Embracing net zero lighting. This is making that point that, if we genuinely want to hit net zero – and soon – replacement to LED alone is not enough and a too narrow scope for the future of urban lighting.

Urban lighting of the coming decades, LUCI argues, will need to be about

Urban lighting

applying design and planning approaches that enable us to achieve more with less light. This will need to include developing sustainable lighting masterplans, preventing excessive private outdoor lighting, and using dimming strategies, such as dimming in response to traffic.

Equally, it may mean embracing offgrid solar lighting and the removal of light in particular time periods and areas, where socially acceptable. Circularity, too, will need to become a prerequisite within tenders.

2. Minimising light pollution for all living beings. Light pollution, the declaration recognises, is a growing issue worldwide and is affecting all light-sensitive species, people and animals alike.

Here, the solutions are likely to be more reduction in the number of sources, in on-time, in intensity and in tuning the spectrum. Limiting the use of ‘cold’ white LED light will become increasingly important. ‘Where traffic volumes are not predictable, adaptive dimming technology should be applied to provide light only when and where needed,’ it recommends. Dimming can (and probably should) become more widespread, especially as people often don’t notice or don’t mind.

‘At master plan level, applying dark infrastructure is commended. A design approach should help us translate these strategies into lighting schemes that work for both people and nature,’ the declaration says.

However, this will, it concedes, require a major change in mindset. ‘We need to reconsider existing lighting policies, to allow more customised lighting

scenarios that respond to our needs with as little light as possible. Finding new norms and standards that offer the right constraints with enough flexibility will help us change in a responsible and acceptable way,’ the declaration recommends.

3. Supporting health and wellbeing. This goal emphasises the role urban lighting has had for centuries as a key enabler of public social life after dark and preserving security. Too often, however, this has led to urban lighting that is harsh and glary, motivated by the assumption that more light equals safer spaces, yet in the process making urban spaces less inviting, accessible and pleasant.

Therefore, LUCI argues that the future of urban lighting needs to be projects and masterplans that find the right balance – a better balance –between safety and security considerations on one side and health and wellbeing on the other.

‘We should be open to ongoing research on the influence of light on our mental wellbeing. Let us closely follow research on the possible influence of light on sleep-wake cycles, and ensure urban lighting has minimal negative effects on our health in this respect,’ the declaration recommends.

‘We need to encourage projects and strategies where urban lighting aims to strengthen the bond between people and the places they share. For maximum benefits, light- and urban planners should collaborate more closely, and bring the night-time experience on equal footing with the day-time experience in the full urban planning process,’ LUCI adds.

www.theilp.org.uk JULY/ AUGUST 2023 LIGHTING JOURNAL 29

Urban lighting

4. Progressing through public dialogue. This goal is about recognising the inherent tension between public and private urban lighting. As the declaration makes clear: ‘We recognise that private lighting can contribute to urban nightscapes in a positive way. However, private, mainly commercial, lighting is also responsible for an important share of light pollution, for example from uncontrolled overly bright LED screen advertising.’

One solution, as LUCI points out, is having and using clear public design guidelines, or ordinances with maximum light levels. But an important ethical question then emerges: who has the right to light the city nightscape?

This, the declaration argues, is where cities should give precedence ‘to light expressions that are sustainable and relevant to the community’. It will also mean dialogue with communities, user engagement and co-design, and the need for commercial conversations to ensure cities get the best hardware, software, and services. ‘Cities are in the driver’s seat and we should become more explicit in asking the tools and information we require in our tenders,’ LUCI recommends.

5. Realising the full potential of community engagement. Taking goal four a step further, this is about emphasising the value of citizen participation and engagement. As the declaration makes clear: ‘Community engagement is an essential part of placemaking. Such involvement goes beyond our residents: it includes professionals active in public space as well.’

Community-led approaches, LUCI argues, will increasing need to be part of

LED replacement programmes (especially ones that change the lighting colour); the competing uses around public space for sleep, work and play; or the gathering of data by smart lighting systems.

6. Harnessing the transformative power of light art. This goal is about emphasising the increasingly important role that light festivals have within public spaces these days, especially during the darker winter months. ‘They delight us and bring us together literally and figuratively. Light art can mean even more for the city,’ the declaration outlines.

‘Light art festivals as well as permanent light art installations can serve as test-beds for new urban concepts and allow local communities to experience new dimensions of urban space. We are only at the beginning of exploring these modes of expression,’ it adds.

7. Creating synergies beyond lighting. This final goal articulates the need, especially in the future, to make urban lighting about much, much

more than just the lighting. As has already been highlighted, successful urban lighting strategies are about meeting net zero targets, reinforcing community cohesion and engagement, boosting the night economy, supporting innovation and so on

As the LUCI Declaration argues: ‘Lighting can and should be a key enabler of city-wide night-time strategies, and more. Given these diverse benefits, we should strive to connect lighting much more to other urban policies.

‘Done in the right way, new synergies can be found, also in terms of funding. The scope of urban lighting is becoming broader and broader. Disciplines involved in sustainable urban design, such as social sciences, information and communication technologies, urban planning, ecology and lighting professionals need to team up and collaborate more intensively,’ it adds.

This aspirational talk is all well and good, and eminently laudable, of course. But what this vision of the future for urban lighting actually look like in practice, on the ground? This is precisely what the second part of the declaration attempts to articulate, outlining a series of themed chapters on reducing light pollution, creating healthier and happier cities after dark, transitioning towards a community-driven approach, and outlining the possible future of light festivals.

There isn’t space here to look at all these in their totality, but let’s try to tease out a few of the key insights.

URBAN LIGHT POLLUTION

On light pollution, first, the declaration outlines how municipalities, lighting designers, engineers, planners and architects will all need to work on reducing the quantity of light sources, reducing on-time, focusing light to where it is needed, reducing brightness, and tuning the spectrum.

JULY/ AUGUST 2023 LIGHTING JOURNAL www.theilp.org.uk 30

These pages and main image previous page: light festivals in Amsterdam and (opposite) Nabano no Sata in Japan

It will require better selection of luminaires, ideally ones with a properly tailored light distribution to avoid spill light and waste of luminous flux. This will likely require work around optics, lenses, and suitable accessories, such as proper shielding. There will need to be a greater emphasis on designing for glare-free environments and environments with a generally lower level of light.

Within this, there will gradually be a greater need for more planning for dark infrastructure in the city, in other connected areas without light barriers, more integration of adaptive street lighting technologies, more (and more connected) trials and pilots, and the formulation of city-wide design guidelines to prevent light pollution.

HEALTH AND HAPPINESS

On creating happier and more healthy cities after dark, the declaration advocates for municipalities and lighting professionals to be closely following research about the extent of urban lighting’s impact on people’s sleep-wake cycles. This needs to include lighting from advertisements, indoor private lighting, and the increased exposure to

screens, as well as public lighting. As the declaration states: ‘It is the sum of all exposure that counts.’

Preventing light trespass into people’s homes is likely to become a more important urban lighting topic, LUCI predicts. ‘We have heard citizens ask for the “right for darkness” during night walks, and this signal should be taken seriously,’ it recommends. ‘We, as cities, have a role to play when it comes to raising awareness about the impact of lighting on health, for example through prevention programmes and public engagement. Co-design with citizens is a fruitful way to incorporate their needs and wishes for darkness in projects.’

CONNECTED COMMUNITIES

The third themed chapter, on transitioning towards a community-driven approach, emphasises the importance of seeing lighting as a social medium. ‘Good urban lighting helps provide a sense of place, by highlighting meaningful elements, creating atmosphere, and supporting activities,’ LUCI argues.

Yet, urban lighting is also in transition. ‘The great challenges facing cities in terms of carbon neutrality, reduction of ecological impact, and rising energy costs urge us to reconsider how we should light public space,’ the declaration outlines.

‘Social and economic trends in the city, such as changing work and leisure patterns, and demographic trends change the use of, and demands on, public space. At the same time, the tools for lighting are evolving. How can we give shape to urban lighting of the future in such a way that both the environment and local communities benefit?’ it asks.