16 minute read

Hilarian Discourse: Roman and Canon Law

Obscure areas of law you probably didn’t know about: interview by: christina akele roman law and canon law

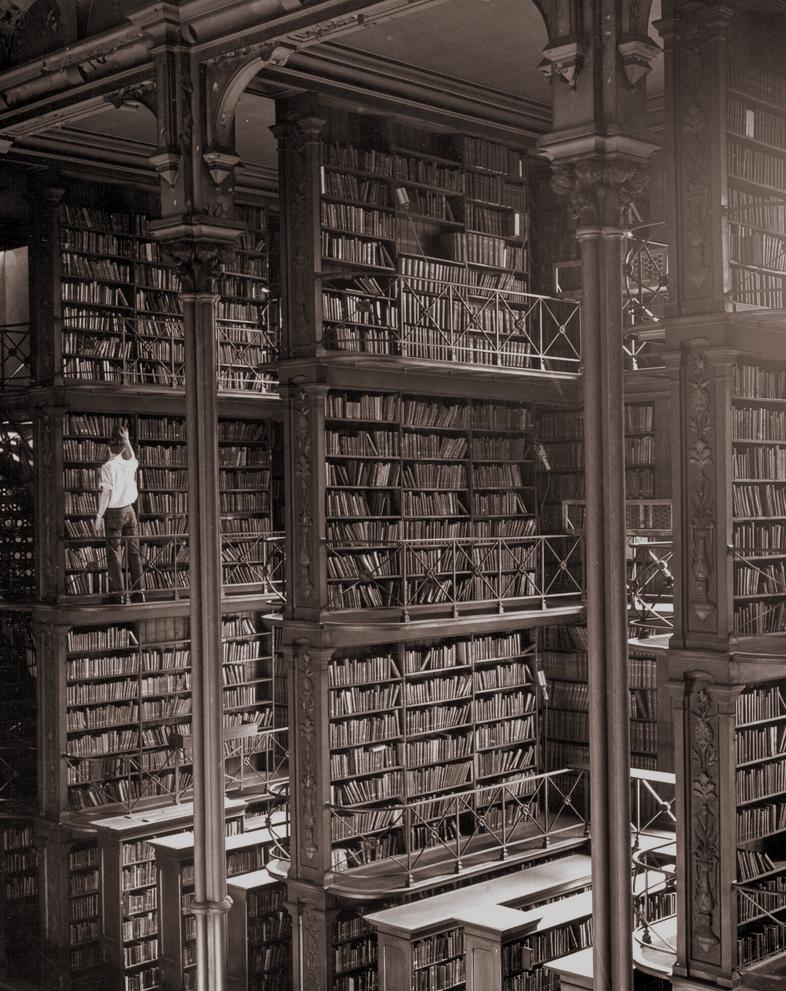

What is Roman law? What is Catholic canon law? We have probably heard of these areas of law. Perhaps some of us are even familiar with them and have strong opinion on either one. While both these systems may seem out-dated or irrelevant, they are certainly fascinating, revealing the basis of our current legal system in the case of Roman law, or providing us with legal context about current crises facing the Catholic institution. I sat down with Fr. Kevin Taylor to ask questions about these somewhat unknown areas of law. Fr. Kevin was asked by Archbishop Faulkner to study canon law in Rome at the Pontifical University of St. Thomas Aquinas between 1995 to 1997. As part of the course, he studied the Roman law system. He later worked as a judicial vicar in the Archdiocese of Adelaide between 2004 to 2012 as a canon lawyer and taught Roman law at the University of Adelaide between 1998 to 2000. roman law

Advertisement

CHRISTINA (C): How would you define Roman law?

FR KEVIN TAYLOR (KT): “Roman Law is the structure of law that was established by Emperor Justinian and it was then put in place throughout the Roman Empire, giving people rights and obligations. The rights went with those who were ‘free people’ – slaves had no rights – and so Justinian then wanted to order society. So, he gave [the people] obligations towards the State. From these rights, various issues started to arise that needed to be addressed. These were introduced into a legal system which took on a power of its own in many ways, and it developed a system where jurists were introduced. Jurists then would write arguments on a particular passage of law which then became a reference point and a teaching model.”

C: Why do you think that Roman law has informed so many legal systems in the modern world?

KT: “[Emperor] Justinian [who lived in Constantinople at the time] was the central figure in the study of Roman law. In about the 6th Century, he ordered the work containing the the laws to be brought together. This was going to govern the whole of the Roman Empire, which stretched from Turkey, all the way through to Great Britain. The Roman Empire needed to be administered justly and evenly. As lands were conquered, the need to put in place a legal system which made their subjects accountable to the Emperor, or to his representative, the Governor, became increasingly important.”

C: What were the original sources of Roman Law?

of the culture to continue. For example, the Jewish people [of Jerusalem] had a very strict legal system based on religious law. The Romans integrated that into their society and structure but made those laws accountable to themselves. Therefore, the Roman law assumed what was the common practice of the people, but tightened it and controlled it, so the people became subject to the Roman authority. Rome was the one who determined how the laws were interpreted… Roman law was constantly picking bits and pieces out of the cultures that it had conquered and was constantly adapting it and placing it under the subject of Rome.”

“As Roman law was imposed on the whole of the Empire, subjugating all the peoples to it, they adapted so that the conquered peoples were not seen to be in conflict with the occupying power. But these people also benefited from the structure and order imposed, therefore it was beneficial to maintain the structure – it’s like they kept the best parts of it. [Those under the empire] saw the best parts of [Roman law] and the good ordering of it. Rome was the one that could impose the penalties: criminals – executed, imprisonment, confiscation of lands, taking away of rights – all [punishments] were determined by the governing power [but] religious practices were generally not interfered with. Yet, when Rome withdrew, [these cultures] maintained the Roman Law but administered it themselves, calling it their law.”

C: How was Roman law structured as a legal system?

KT: “If you look at the structure of the Roman law, it is divided into sections dealing with the good ordering of life when it was codified. You had Persons, the rights of persons such as marriage. Only the ‘free’ could marry in Roman society, or [at least] those who were seen to be the upper part of society. Slaves could not marry [but] they could have children. However, the children would become part of the property of their master.”

“Then there was [the section of] Property and Ownership. As people earned properties and had rights to that (for example, growing their own crops) they had to pay tax. They had to pay for the water they used, they had to pay for what ‘services’ were deemed to belong to their territory. Again, [it was] at the discretion of the governing body to determine who could have that ownership and who could administer it. Documents of Ownership; Property; Possessions became essential, and these were drawn up by jurists and registered in case of disputes.”

“With Roman Law you begin to see that with these divisions, comes a structure for a legal system. You have: People and their rights, Property, Ownership, Possessions and Fidelity and Prescriptions, etc. The in Book 4 or 5 of Justinian’s code, you have Obligations to the State and to the Emperor and how you could lose those obligations and pay the penalty. Quite often it was not just the individual, but it was the individual and their family who paid, so everybody was part of the transaction…” “In those times women were seen as the possession of the man and she could be confiscated as part of the penalty, so the wife did not have any rights under the law, it was only the male and his line – the one who could hold possession and defend the Empire when called upon.”

in the Empire in a land that was being subjugated to Rome. So, for example, the Kings of the Germanic tribes would lose all of their rights, their people would be subject to Rome, the people would pay taxes and would have to hand over their sons to the Roman army, becoming dispossessed in many ways. This becomes the law of conquest. So, it is then seen as being a right of a conqueror, and in it becomes the right of the State. In this way we see how [Roman law] developed…it came out of practice. And the practice was how to subject these people to make them toe the line to be ‘Roman’. The more you won favour, or toed the line, the more rights you would be granted.”

C: How did the financial system work under countries under the Roman Empire such as Great Britain? Did they switch the currency that was used in Rome?

KT: “Yes, they used their own form of currency. They introduced their own documents of ownership and receipts so that people paid their tax to the local governor and it was remitted to Rome or to the Emperor so that he could continue building on projects [and cities].”

KT: “If we look at the Roman law and the structure, we still see that we have People, who have Rights, who have Obligations. We still see that penalties can be imposed for a crime. Or a deliberation is given in favour of one party over another. This all comes from the structure of Roman law and the rights of the individual and the obligations of the individual. Law is always changing and its always adapting, but the basic structure and principles have remained the same…that is the basis for many common law systems and civil law systems: people have Rights, Obligations and duties towards the State. If we want goods and services, [citizens] have to pay the taxes.”

KT: “Roman Law started the process with jurists. Because the Governor could not always be in every town of the province, he would have people who were there to administer the law. Generally, it became separate from the role of the Governor. The Governor represented the Emperor, and so the jurists studied the law and the rules of the society and often would write an opinion which would be shared throughout the Empire [so that everyone could be on the same page], keeping the laws uniform. But those opinions became the jurisprudence; the basis of which a case was determined. Here we see developing the whole sense of jurisprudence for our criminal system. We have this system where we can look at precedents of other cases, learn from it and apply it. In a real sense, this goes right back to Justinian and the Roman Law system.”

c: Were there judges and lawyers in the Roman legal systems like we have today?

KT: “There would have been judges. An individual would bring a case against their neighbour and a learned person would adjudicate it. That learned person would have their scribes who would then ask for the research to determine what needs to be done. The judge would listen to the arguments and then make the determination based on what

CANON law C: How (and why) did canon law begin to evolve?

KT: “Where canon law started to evolve was when Christianity became the religion of the State (and it came to be acceptable) from Emperor Constantine III. The Church was given parcels of land for its administration of its property and for the community and the administration of its charitable works. This then brought with it certain clashes with people who fell out with the Church…so it needed to have a system of resolving these disputes. Many of the lawyers who had studied the civil law, and were also embracing the Christian faith, were out to protect the Rights of the church and its properties.” “This probably started in regard to property, but it went on to the rights of individuals. As the system of Clergy developed, they [themselves] had rights. Who were [the Clergy] answerable to? Were they answerable to the Governor? Or were they answerable to the Emperor? Or were they answerable to the Bishop? So, the role of the Bishop becomes more and more equated with those of the Governor, and he would govern the clergy and keep good order in the Church community.”

c: What are the links between canon law and Roman law?

KT: “Canon Law embraces the Roman Law principles, but it is based in the theology of the Church. Going back to the example of marriage: marriage is a covenant between a man and a woman in canon law, whereas, in the Roman and civil law, [marriage] was a contract. Now, you can argue about covenant and contract. But the covenant takes us back to the Old Testament with the agreement between God and His people… In Church theology, a man and woman exchanging consent brings about the covenant of marriage. In civil law, it is the signing of the contract that brings about the marriage. So, the two go side by side. It is trying to create a balance but protect both rights.”

c: So, this would have spread throughout the Roman Empire?

KT: “Throughout Christendom.”

C: What are the sources of canon law?

KT: “Canon law really came about in a much similar way to Roman Law. There were decisions written by Popes to help various bishops throughout the world deal with problems that were coming up in the administration of their diocese. To try and bring that all together, the Pope asked for it to be codified, starting the process under a priest called Gratian and he brought them together in a treatise known as the ‘Decretals’. The Decretals then became like a textbook for bishops to deal with problems. St Raymond of Penyafort was another canon lawyer who brought them together under different headings” “These decretals were the forerunner to the 1917 Code of Canon Law. The Decre tals gave each bishop principles for deliberating arguments within the diocese. Then, a tribunal system started to develop around that. The tribunal was a group of lawyers who

C: Did that decision have any implications on the public life of citizens?

KT: “As these decisions came together, and brought together in this body of work, then it becomes more of a common practice and it becomes the thinking of the Church. Then, of course, it finds its way into the theology, into the thinking, into the determination of the Rights and Obligations of the Faithful, binding on all members of the Catholic Community. It becomes more and more of a system of law, but it is evolving all the time. Like Roman law, it is adapting to various cultures, taking good bits out of various cultures and embedding it in there, so that the rights of the people are looked after.”

KT: “If we look at the Roman law and the structure, we still see that we have People, who have Rights, who have Obligations. We still see that penalties can be imposed for a crime. Or a deliberation is given in favour of one party over another. This all comes from the structure of Roman law and the rights of the individual and the obligations of the individual. Law is always changing and its always adapting, but the basic structure and principles have remained the same…that is the basis for many common law systems and civil law systems: people have Rights, Obligations and duties towards the State. If we want goods and services, [citizens] have to pay the taxes.”

KT: “Roman Law started the process with jurists. Because the Governor could not always be in every town of the province, he would have people who were there to administer the law. Generally, it became separate from the role of the Governor. The Governor represented the Emperor, and so the jurists studied the law and the rules of the society and often would write an opinion which would be shared throughout the Empire [so that everyone could be on the same page], keeping the laws uniform. But those opinions became the jurisprudence; the basis of which a case was determined. Here we see developing the whole sense of jurisprudence for our criminal system. We have this system where we can look at precedents of other cases, learn from it and apply it. In a real sense, this goes right back to Justinian and the Roman Law system.”

c: You have mentioned the rights of people and how the canon law affects them. Throughout history (e.g. in Medieval Europe), did Canon Law apply to everybody? Or did it just work in conjunction with, for example, the common law system?

KT: “The easiest answer to that is to say that they went side by side… If it was a religious argument, the religious debate was given precedence. If it was a dispute over rights and obligations for the town, then the civil [law] would be the area to go to. Canon law has always had this principle in it that [it] bows to the civil law in matters of criminal intent and things like that. For example, to bring it into the current climate, over the abuse cases [in the Catholic Church], the Church has been accused of protecting its own. It certainly looks like that, but that is not what its intent was…The intention is that we

allow the civil law to take its course and deal with the matter. After that is concluded, we then conduct a canonical trial – a separate trial – but we might be able to ask for the evidence that was gained in the civil [or criminal] trial to assist us, but we would then look at it from the religious point of view. So, when people call for the defrocking of a priest who has been an abuser, we have to sit back and let the civil law finish, and that involves the penalty. When that is all concluded, then we are free to act because if we act before then, we are seen as interfering in the civil legal process. But if we do not act, we are seen as neglecting. So, we are in a no-win situation with that. But it is always the intent to allow the civil law to run its course before we start any canonical process.”

c: How do legal professionals in the field of canon law, particularly in the Roman Curia, respond to issues like the sexual abuse scandal in the Catholic Church and the institutional coverups of these offences?

KT: “The Roman Curia is applying the laws globally, internationally. The laws have to be read and applied to the facts of the case. What Rome has recently done, is rewritten a section on penalties and sanctions. They have updated a number of the canons and added another four or five canons so that it can actually move forward with stronger penalties and greater accountability in cases of abuse. That has happened under Pope Francis…in the last three years. They came into effect, probably, twelve months ago. So, it is always evolving and changing; the first codification was in 1917, followed by the review and renewal in 1983, and now we have had these extra updates.”

c: In a general sense, a lot of the time we find that the Catholic law can be seen as inconsistent with what the general public believes to be true or moral. How does canon law adapt to social, economic and cultural shifts?

KT: “The law is fluid. It is changing and adapting to the circumstances and is always in the process of evolving. To say that it is totally entrenched in the past is not quite true. Yes, some theological concepts are, but generally, as you apply it, it has got that flexibility.”

C: What are current changes being enacted in Rome in the Vatican, particularly regarding the Roman Curia?

KT: “At the moment we are waiting on a new document…where Pope Francis has restructured [the Roman Curia] to decentralise everything from Rome, putting it back into the diocese and calling or greater accountability (particularly in the area of abuse), to work with civil authorities, to have structures in place for child protection, etc. So [Pope Francis], is throwing it back to the local church…Pope Francis is trying to bring in a greater sense of accountability to make the system work, where we respect the religious law, but we also respect the civil law. So, a criminal does not get away with [the crime] and the Church is not seen as ‘covering-up’.” “[In regard to the sexual abuse cases], the Church has to acknowledge that there has been a culture of cover-up and say ‘yes, we’ve got it wrong. We’ve got to move forward and make it better for the next generation and the current victims.’”

decorate/colour/design this friendly coffee cup!

[This page has been unintentionally left blank]