Fruitslice Summer 2025 Issue

• Porch lights

• Open doors

• The Midwestern goodbye

• Sleepovers

• Found families gathering in handmade homes

• The soft power of staying

• Systems that turn housing into profit

• Minimalism as moralism

• Prioritizing wealth lining the walls of our houses instead of what we love

• “How it's always been done,” prioritizing mindless tradition over flesh and blood humanity

To the ones we are born into. The ones we're trying to find. The ones we make, and the ones we leave behind. The ones we’ve outgrown. The ones that haunt us. The ones we carry in our bodies.

To those who make homes in language, in lineage, in resistance.

To everyone who maintains the shared spaces we rely on—schools, hospitals, offices, labs, libraries, streets: custodians, sanitation workers, garbage collectors.

To the people building homes in wreckage—of systems, of relationships, of disaster. To those who squat with care and claim the abandoned. Who patch roofs, share stoves, and hold the line against displacement.

To those who understand that revolution starts at home. It starts with sharing and engaging in everyday domestic labor tasks.

To the couches we’ve crashed on. The doors that opened and the ones that slammed shut. To the ones who stayed. To the ones who couldn’t. To the ones who ran. To the ones who returned.

To the ones tending altars, building ramps, passing down recipes, and leaving porch lights on. To the ones who showed us how to change a tire, unclog a sink, or fix a bike chain.

To those who stock the food pantries.

To the children translating for their parents.

To those who plant gardens in concrete.

To the ones who host teach-ins, cuss out city council, link arms to block squad cars, stock medic kits, defend encampments, and show up for jail support.

To those who live: "we keep us safe” and “not in our house.”

To those who hold the line, hold the door, hold the baby, hold the broom.

You are the blueprint. You are the welcome.

This issue is for you.

Thank you.

Content Warning: This issue, and the contributors within, reconstructs what “home” looks like within a Queer context. To do so, Fruitslice Editors and contributors have had to reconcile fraught histories that are embedded in our homes, cultures, communities, and families. To properly reconstruct a Queer home, we have been faced with the task of tackling difficult subject matters, such as racism, colonialism, imperialism, christofacism, genocide, exploitation, cultural erasure, displacement, imprisonment, slavery, disordered eating/diet culture, fatphobia, childhood neglect/ abuse, death, violence, alcohol and drug use, natural disasters, misgendering, gentrification, classism, religious trauma, adoption trauma, mental illness, internalized Queerphobia, break ups, divorce, sexual violence, TERF ideology/gender essentialism, and family estrangement. These themes are intertwined with the concept of home and building stronger and more sustainable communities in the future. We hope you manage your discomfort as it arises and take care of yourself while reading this issue.

Home is not a neutral word.

It holds weight—emotional, historical, political. It is a site of origin and of rupture. It is where we are first named, shaped, and sometimes, where we are first exiled from. Queerness exists in tension with the state. Queerness is sometimes cast as clashing against tradition. When our bodies are relegated to scrutiny, home can become unsafe, unlivable, or unreachable. At the same time, home can be an inheritance—a space passed down from our loved ones, carried with us in food, music, language, and faith. For many of us, both things are true at once.

We build home in the in-between. In the silence after a slammed door. In shared playlists or guest room shelves. In public transit rides and side-street cigarette breaks.

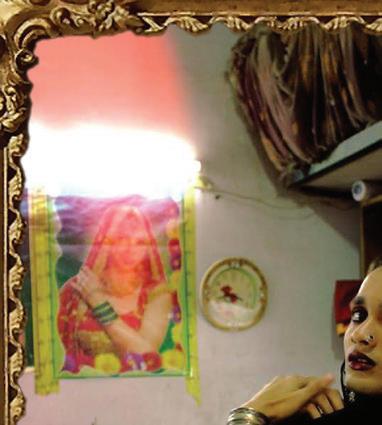

In the mirror (eventually, maybe).

It’s the chosen family dinner that runs until 3 AM, the group chat that never sleeps, the lover’s apartment where you finally learn to take up space. It’s the particular way your grandmother folded dumplings, carried now in your own clumsy fingers. It’s the pronouns that fit or a name that finally clicks.

Home is a deeply personal idea—the personal is political. And sometimes, the political is terrifyingly personal.

To speak of home is to speak of land, of displacement, of who gets to stay and who is pushed out. It is impossible to reflect on home without acknowledging the people for whom home has been violently taken: the millions of Palestinians facing occupation and forced displacement, the Congolese communities ravaged for resources, the Sudanese civilians made refugees by an ongoing genocide. Their struggles are not peripheral—they are central to the question of home. Any conversation about safety, belonging, and rootedness must include those who are systematically denied it. We are inseparably bound to the broader fight for liberation across all occupied and colonized lands as the project of home is often one of reclamation, reinvention, and resistance.

Amid loss, survival, and the slow work of repair—we still find evidence of home everywhere.

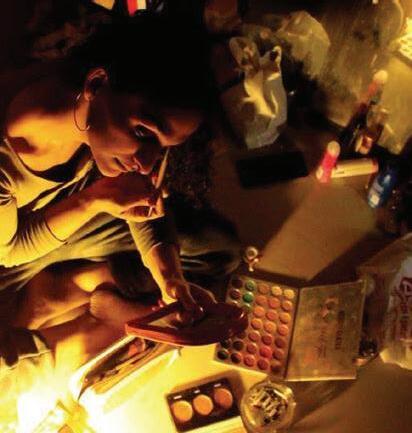

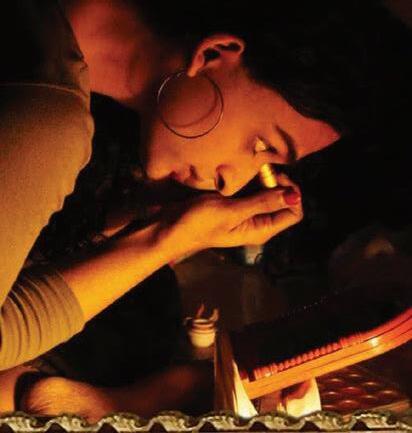

That’s what we’ve tried to gather here: stories of home in wedding altars built in onebedroom apartments, in Trans* joy documented on 35mm film, in friendships forged through shared grief, in the shape of a prayer passed down through generations. We see home in the way people reclaim their bodies through movement, medicine, adornment, or rest. We see it in the quiet endurance of making something—anything—where there was once only absence.

In the making of this issue, we’ve seen how the individual becomes a home they can extend to others in a multitude of ways. Home is a patchwork project—a quilt stitching together place and people. Home is a strange place we have yet to discover. Home is a place we can be welcomed into by others.

It’s not always permanent. It can be chosen. It can be cultivated. It can be found in the leftovers, the offcuts, the in-between spaces where we’re allowed to just be. It is not necessarily where we start—but it may be where we return. It may be where we land. Sometimes, it’s where we are brave enough to stay.

Wherever you are, wherever you’re reading from—this page, this issue, this moment—you’re home. And in this home, you are always welcome.

Copyright © [2025] Fruitslice Inc. All rights reserved.

Everything in this issue belongs to its original creators—the writers, the artists, the dreamers, etc. Fruitslice holds first publication rights, and the right to archive and distribute the work in its originally published form. Every effort was made to contact and properly credit copyright holders. Please get in touch with us regarding corrections or omissions. Reproducing or reprinting all or any part of this issue without prior consent (except in the case of brief quotations used in critical reviews and academic work) will be considered utterly disrespectful, generally uncool, and legally questionable—but we aren’t cops.

Alfie Nawaid

Andy Valk

Ann McCann

Anneliese M. Gelberg

Asher Perez

Ava Pauline Emilione

Bailey Bauer

bellze t

Brie Coleman

Cal O’Reilly

Caryl Townsend

Casper Orr

Kimberly Hall

Knock Off Bowie

Kota Ball

Kyle Raymond Fitzpatrick

Lia Turpin

Lorinda Boyer

Maia Brown-Jackson

Manda

Meg Streich

Micah B

Michael McFadden

Nell Kerr

Celeste deBardelaben

Chloe Oloren

Daisy Slucher

Daniel Rivera Stahlschmidt

Diane Nguyen

Djeneba Deby Bagayoko

Donica Larade

Eden Aphrodite

Emily Rose Miller

Fatima B.

Flossie Hedges

Franky (Frances) Cannon

Izy Carney

Josie Boyer

jp thorn

Kahlea Williams

Kam Bradley

Kate Netwal

Kathleen (Tac) Tacelosky

KD Hack

Kim Arthurs

Octavius Nightingale

Patricia Kusumaningtyas

Philip Kenner

Sabrina Skinner

Safara Louise Parrott

Sam Fitz Sarthak

Scott Pomfret

Sean O’Neill

Shannon Brown

Shelbey Leco

Shelley Lloyd

Taylor Michael Simmons

Theo Elliot

Vas Littlecrow Wojtanowicz

Victoria Ivie

Victoria Jamilé Hernández

V.M. Reilly

v.w.l.

Founding

Editor-in-Chief

Chloe Oloren

Ann McCann

Casper Orr

Em Buth

Editors

Kayla Thompson

Meg Streich

Starly Lou Riggs

ashley hunt

Azul Castro

Casper Orr

Eden Aphrodite

Kayla Thompson

Navreet Gill

Rowan Crosthwaite

Tess Conner

KD Hack

Azul Castro

Adam Mac

Casper Orr

Chloe Oloren

Danny LaVigne

Em Buth

Kam Bradley

Kahlea Williams

Kayla Thompson

KD Hack

Rhyker Dye

Tess Conner

Andi Rand

Azul Castro

Bailey Bauer

Chloe Oloren

Danny LaVigne

Em Buth

Rowan Crosthwaite

Starly Lou Riggs

Tess Conner

Bailey Bauer

Casper Orr

Chloe Oloren

Danny LaVigne

Em Buth

KD Hack

Rowan Crosthwaite

Casper Orr

Chloe Oloren

Em Buth

Bellze Tandoc

David Cruz

Layla Razek

Melanie Zhgenti

Nicole Hernandez Reyes

Manda

Executive Council

Ann McCann

Cam Reid

Caroline Gharis

Casper Orr

Chloe Oloren

Em Buth

Jason Wayne Wong

Kayla Thompson

Meg Streich

Melanie Zhgenti

Nicole Hernandez Reyes

Rhyker Dye

Starly Lou Riggs

Board of Directors

Founding Editor-in-Chief

Art Directors

Senior Designer

Project Management

Ann McCann

Chloe Oloren

Jason Wayne Wong

Chloe Oloren

Melanie Zhgenti

Nicole Hernandez Reyes

McKenna Gray

Bellze Tandoc

Danny LaVigne

Kim Do

Leilany Sosa

Submission Managment

Grant Coordinators

Bellze Tandoc

David Cruz

Layla Razek

ashley hunt

Elisha Sawyer

Kahlea Williams

Accountant and Financial Strategist

Creative Strategy and Operations

Website Design and Technical Support

Internal Community Director

Publicity Coordinator

Events Team

Luchia Liu

Social Media Marketing Lead

Social Media Team

Caroline Gharis

Casper Orr

Olivia Bannerman

Puzzle Designer

Rhyker Dye

Starly Lou Riggs

Beau Beatrix

Caroline Gharis

Hailey Green

Kim Do

Hannah Potter

Caroline Gharis

Chloe Oloren

Daisy-Drew Smith

Hailey Green

Melanie Zhengti

Nicole Hernandez Reyes

Micah B

We are Always in Jacksonville Words by Shelley Lloyd

Family Home Evening Words by Chloe Oloren

Ode to SGV Words and Photos by Victoria Ivie

Adopting “Home” Words by v.w.l

The Model Apartment Words by Kyle Raymond Fitzpatrick

I have never known home Words and Photos by Sarthak

Sweet Little Lies Words and Art by Sabrina Skinner

A record for living in queer time Words by Shannon Brown

Built, Not Found Words by Lorinda Boyer

Lalish, Duhola Village, Yazidi children and Khanke IDP camp

Words and Photos by Maia Brown Jackson

Carrie Bradshaw With A Baby Harness On: Notes On Nesting Words by Ann McCann

Welcome Home, Fellow Traveler Words by Octavius Nightingale finding some body Words by Diane Nguyen

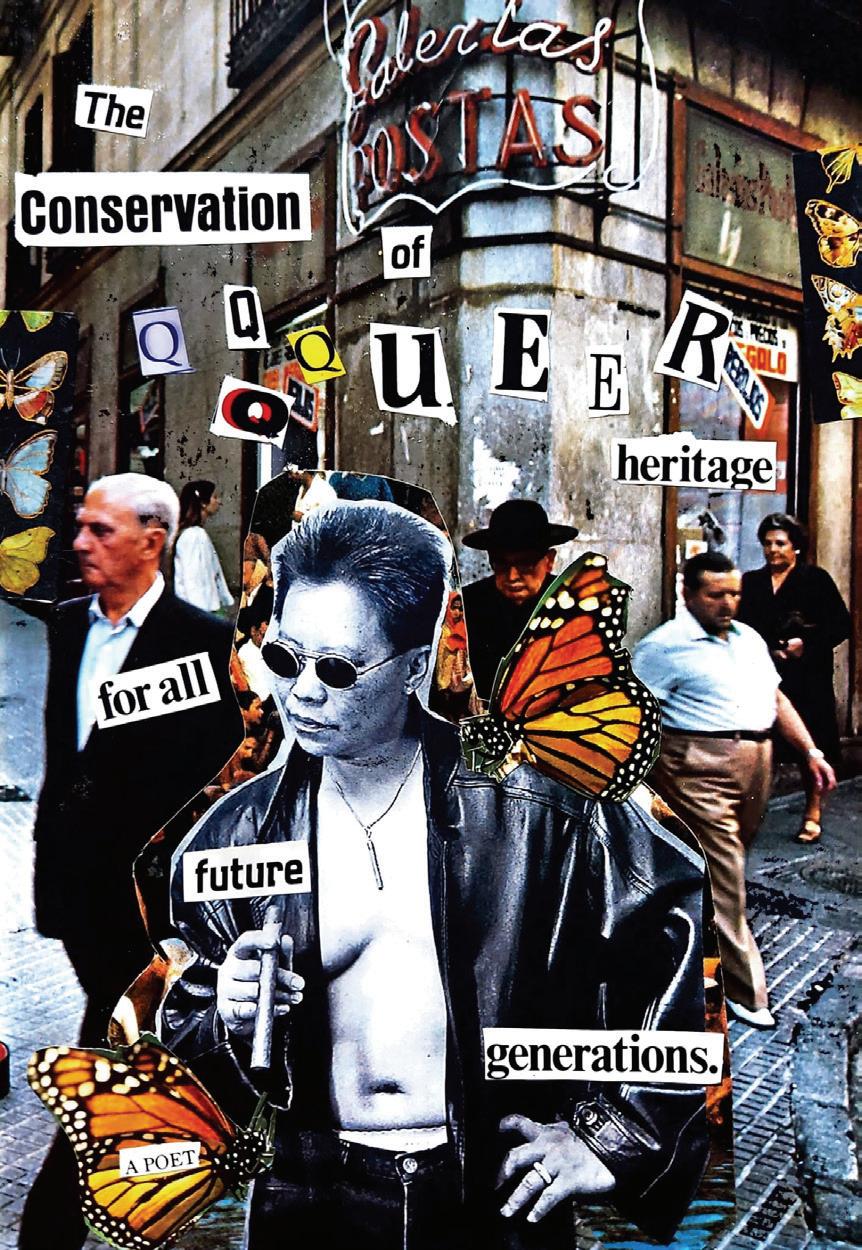

The Conservation of Monarchs Art by Victoria Jamilé Hernández

New Orleans Photos by Shelbey Leco

Watch out for the bones Words by bellze t.

People of the (African) house Words by Djeneba Bagayoko

Saturn Returns To Find You, As Garden Art by Kim Arthurs

Fervent for the Hunger Words by KD Hack

Swingers, Collateral, and the Sunset Strip Words and Photos by Celeste deBardelaben

Love Thy Neighbor, No. 1,2, & 3 Words and Photos by Sam Fitz

I Can’t Go Home To My Fatherland Words by Littlecrow Wojtanowicz

The Body Politic

Ghost Brook Words by Franky (Frances) Cannon

People Are Dying, I Hope I Can Change Art by Andy Valk

i’m doing this because i love u Art by Nell Kerr

Do You Know Me? Words by Lia Turpin Language

You Are Here, Not There Words by Safara Louise Parrott

As Close to Worship As We’ll Get Words and Art by Daisy Slucher

Welcome to East Hampton — No, Really, Welcome

Reality does not run along the neat straight lines of the printed page1—an unwelcoming welcome dinner in East Hampton, New York is where it comes to a head, which is hilarious because I only just got here.

The drama teacher corners me and tells me that my aunt has told the entire staff all about me—For gossip inflamed her with a passion2—all about my family. About my stepdad’s carport setup—three TVs, a fridge, an oyster pit, a bar, a smoker, four grills, two high top tables, and a pair of heaters—and how he and my mom never use the living room.

Anyway, he wanted to let me know that they all voted for Obama with a hard look in his eye.

And I’m wondering—still wondering over a decade later—what the hell it was that my aunt told her coworkers (my coworkers, our coworkers) about her redneck niece.

What a welcome. I have the rest of the school year to spend with these folks, faced with the doxa which has labeled me white trash before I opened my mouth.

registers, I find myself most drawn to the third affective register that surfaces in this passage: exhaustion.4

But I run off into the city whenever I can and wander around. I have a friend who lives here but I’m scared to call him.

He knows too much.

Too often we forget that we have the right to leave if we want to. We have the right to deny our use,

and, through this, close the wounds created by the world fed on the binary rhetoric.5

Where are we? Is this Jacksonville?6 When isn’t it? We always are.

L’atopie—

But must we choose between delight and dread? Are these our only options?3

And it lingers, through Doctor Who marathons and Talking Heads dance parties in my room like the constant buzzing in my ears now has meaning. Beyond these two

1 Sadie Plant, Zeros + ones: Digital Women and the New Technoculture

2 Roland Barthes, Roland Barthes

3 Cynthia Barounis, “Wretched Refuse: Disability, Disposables, and the Cripistemology of Camp”

4 Ibid.

5 Legacy Russell, Glitch Feminism

6 Jillian Weise, “Dream About The War on Opioids by Someone Who Uses Opioids, Responsibly, For Chronic Pain.”

(And I’m Not Good at Dodgeball)

Language itself is a violent thing.

Language reconstructs itself elsewhere under the teeming flux of every kind of linguistic pleasure.7

It’s 2004, I’m sitting in the sunroom of a stranger in Bracknell, England burning through my calling card and trying not to scream at the person on the other end of the line back in Jacksonville. My best friend broke up with his boyfriend the day before I left. The boyfriend I introduced him to and was friends with. Who he broke the heart of and put me in a horrible spot by doing so. There are a lot of things that I want to say during this call.

Not the least of which is that he is ruining my trip.

I’ll find an internet cafe when I get to London.

Queer silence clings to the potential that absence can do work.8

Our friendship lasted less than a year after I got back from England.

Memories in the Margin: Because Apparently I’m a Hoarder Now

Tickets, receipts, and business cards count as things at the same time that they count as subgenres of the document; they are patterns of expression and reception discernible amid a jumble of discourse, but they are also familiar material objects to be handled—to be shown and saved, saved and shown—in different ways.9

I keep a lot of things that I really ought just to throw out. In a book, I recently found an airline ticket: Indianapolis to Charlotte, American Airlines flight number 5487, Gate B10, Departing at 5:01 PM on March 30, 2018, Seat 15C, Group 8. I forgot about the actual events that would lead to the need for the old-school, printed-at-the-gate boarding pass in this day and age until I found it.

7 Roland Barthes, The Pleasure of the Text

What does it look like—or feel like—to salvage the unsalvageable?10 To hoard useless trash that should be taken away and thrown in the dumpster?

I remember going to Indianapolis, of course. It was a quick 24-hour trip to present at the Popular Culture Association conference and then back to Clemson.

I spent three of those hours virtually attending one of my graduate seminars. I presented at an impossibly early hour. I ate nothing but aloo gobi in an attempt to forestall any further cravings for curry when I got back to an Indian foodless Clemson.

8 J. Logan Smilges, Queer Silence: On Disability and Rhetorical Absence

9 Lisa Gitelman, Paper Knowledge: Toward a Media History of Documents

10 Cynthia Barounis, “Wretched Refuse: Disability, Disposables, and the Cripistemology of Camp"

But now I remember that it was the flight back from the conference that was an absolute nightmare. My flight was delayed long enough that I would have missed my connection in Charlotte if I hadn’t sobbed to the gate agent that I absolutely had to get on a flight, any flight, to Charlotte because my cats were home alone and were probably getting hungry (I wasn’t sure when Shauna had come over to feed them in the morning) until the Delta gate agent found an American Airlines flight she could get me on.

Never fly anywhere with me; if the flight out doesn’t get delayed and requires rebooking in order to make connections, the one back definitely will.

When I moved, I unearthed books I hadn’t seen since that unreal year in New York. Books that I had lovingly selected at The Strand. Books that had sat in the trunk of my car for years. Books on Oscar Wilde, books on Flannery O’Connor. Wilde’s love letter to Bosie. O’Connor’s prayer journal.

A ticket stub for a Placebo show.

The blank areas allow onlookers to reconcile their own reality as they grapple with the pagina; these are spaces to remember where one exists as a reader.11

Trash or Treasure? The Art of Dumpster Diving (Emotionally)

And pictures of my father, of Ocala, and Jaguars games when he would take me at the end of a visitation—or, more often than not, meet me at the park and ride in Mandarin. And we would spend five hours side by side but alone, both of us becoming one with the sea of teal. Me with gold glitter running down my face.

Pictures of Joyce and me at Warped Tour.

Memories of someone else, maybe.

Maybe I was trying to throw that me away finally. To throw her in the dumpster with those pictures.

When I left Clemson, I threw hundreds of pictures in the dumpster near my apartment alongside the listing cat tree and the lamp that refused to work except when it wanted to—usually in the middle of the night after I had gone to bed.

Pictures of high school winter guard competitions and trips to Orlando, Miami, Tallahassee, and Tampa, and seemingly everywhere in between.

A photographic map of Florida seen through a teenager’s eyes.

Along with the junk and the failure lives a camp cripistemology, created by returning to camp’s origins as a trash aesthetic and as a set of relations to and among discarded objects.12

But of course, I couldn’t get rid of it all, and no matter how long it has been since I legally became someone else (thirteen years last February),

I am still here, and they are still me.

A cripistemology of camp allows space for tears.

Tampa, Time, and Other Holding Patterns

As a kid, my hockey stick scraped against the rough pavement of our street.

Today the cold wind off the Hillsborough River steals my breath as my hands freeze around my beer and I wait to get inside the arena.

Yes.

I moved to Tampa for the hockey.

But—I’m not sure I ever lived there. I never unpacked my clothes in the three years I lived in my apartment. I never hung up my pictures.

I existed.

Back in Jacksonville: Home Is Where the Hurt Is

I’ve been reading Survival Strategies by Tennison S. Black and I’m being haunted by two stanzas from “I Was Born For Rainy Days But.”

because I left something of me13 I’ll just remix them—

Remixing is an act of self-determination; it is a technology of survival.14

but, anyway—

I waved up an exorcism of my origin—but I’m going back, anyway15

moving back to Jacksonville. Again.

A truck full of boxes and a nearly empty bank account.

Homecoming, Question Marks, and the Inevitable Crying

When I flew back home for the holidays from New York in 2013, I didn’t even make it back to the house before my mom and I made our way through three pitchers of margaritas at the La Nopalera in Mandarin.

It’s just down the road from the apartment my mom and I lived in before she met my stepdad.

It was snowing when I flew out of McArthur. I’m shedding layers the longer I sit across from my mom.

The idea that return is the same as homecoming is a myth.16

I want to cry.

I don’t know if it is because I’m happy I’m home, or if—

Words by Chloe Oloren

We never locked our doors in the house that I grew up in. Nothing to steal, nowhere to run. Besides, everyone was watching.

My neighborhood was a deliberately engineered social experiment. Mormonism had arranged our lives into “wards”— geographical divisions that determined (among other things) when you attended church, when you cleaned the building, and who monitored your spiritual progress. Every neighborhood in the world is theoretically divided into these mormon jurisdictions. Someone has certainly drawn a circle around your home on a map. You are someone’s spiritual responsibility, even if—especially if—you’ve never considered mormonism at all.

I remember someone once warned my mom to lock our car doors at night—not because of theft, but because it was a good year for home gardening and the neighborhood had a surplus of zucchini. People were leaving bags of them in unlocked cars. You can only make so much zucchini bread before you start to resent generosity.

In Utah, these wards are compressed—just a few streets long. The bishop, three doors down; the relief society president across the street; the seminary teacher, next door. Every backyard is a shared backyard, every child a little missionary-in-training. There was no real sense in being alone. I’d bike through the neighborhood, stuffing my T-shirt with cherries from trees that didn’t belong to us. Property lines existed only in theory.

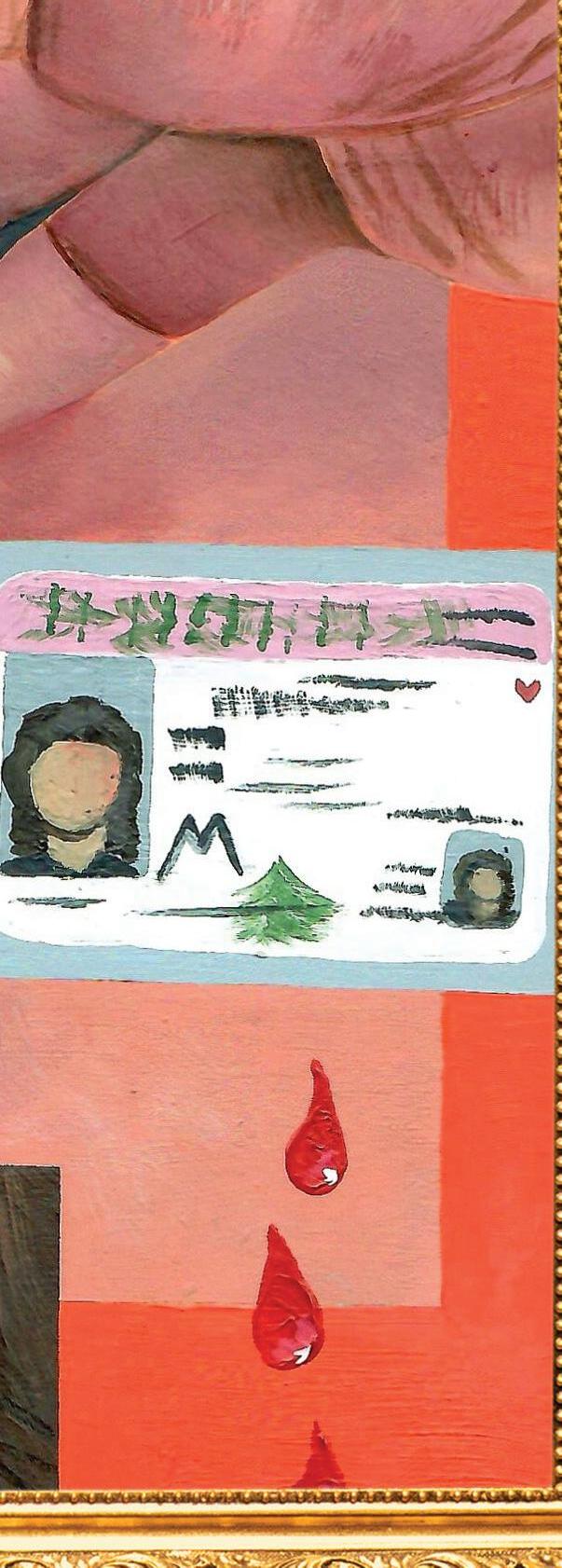

Art by Andy Valk

We all knew the name of the police officer in town because he had nothing better to do than chase teenagers for jaywalking or being out past curfew. Officer Thurston, otherwise known as “Thirsty.” As in “Thirsty” to get some high schoolers in trouble.

But the policing that regularly took place was much more insular, a pattern deeply embedded in mormon history. We all knew who was watching. The bishop. The relief society president. The ward gossip. But none of them were as powerful as the voice in your own head.

Utah was constructed to look like zion, feel like order, and erase whatever came before. The straight streets, the templecentered design, the imported flowers, and the artificial rocks—all of it serving the narrative of a divine plan rather than acknowledging the violence of settlement. Paradise requires both construction and erasure.

All of this—the wards, the self-surveillance, the cherries, and the gossip—wasn’t random or organic. It was designed with meticulous precision.

I started to wonder if I’d been planted too— if everything about me was being groomed to look natural, while nothing actually was. I carried a kind of low-grade nausea everywhere I went. I didn’t know why I felt disconnected, only that the world around me was seamless and I felt like a glitch. I kept thinking: it’s not supposed to feel like this. Everyone else seemed so at home. Why didn’t I?

Mormonism is a religion of order and bureaucracy. Mainstream mormonism today has lost most of its mysterious fantasy-sexcult energy from Joseph Smith’s time. Now, it’s mostly a corporation run by repressed conservative old white men, shaped by the red scare, and obsessed with paperwork. That obsession with control isn’t just spiritual, but extends to the land itself.

When Brigham Young stood on the hill with his wives and followers and declared, “This is the place”—a phrase now printed on everything from license plates to baby onesies—he was engaging in that most american tradition of declaring paradise on stolen land. The Ute tribes who already lived there weren’t just inconvenient obstacles to a divine real estate development; they were real people with their own complex civilization, spiritual practices, and relationship to the land. There is a horrifically brutal and often buried history between the mormon settlers and the Indigenous people they displaced. Popular books about pioneers celebrate the handcarts and the seagulls that saved the crops, but remain silent about things like the Circleville Massacre1, the Bear River Massacre2, and the forced relocations3. This selective remembering isn’t accidental—it’s as deliberate as the grid system of Salt Lake City.

The feminist scholars I would later read gave me language for this: epistemic injustice, the damage done when your experience is rendered unintelligible by dominant narratives. When you are told, repeatedly, that what you feel is wrong, impossible, or sinful. When the pain in your body is reframed as spiritual weakness.

Everything around me was organized around worthiness. Worthy to go to the temple. Worthy to be a missionary. Worthy to have the spirit with you. Worthy to have a loving husband. I didn’t know how to measure worth except that mine always felt precarious.

Then I had sex.

When I lost my virginity at 17, my bishop told me that sexual sin was second only to murder and I was no longer worthy to enter the temple.

I want to be precise about what this means. In mormonism, they baptize the dead. The living stand in for those who died without knowledge of the true church. We gather names from census records and baptize them by proxy. I had done hundreds of these by 17.

But when I committed adultery, I stained my worthiness. Every baptism I’d performed was null. Their souls, waiting in the spirit

1Paiute Indian Tribe of Utah, “The Circleville Massacre,” accessed May 24, 2025, https://pitu.gov/the-circlevillemassacre/.

2Darren Parry, *The Bear River Massacre: A Shoshone History* (Salt Lake City: Common Consent Press, 2019).

3Paiute Indian Tribe of Utah, “Chapter 4: Paiutes,” in A History of Utah’s American Indians, ed. Forrest S. Cuch (Salt Lake City: Utah State Division of Indian Affairs, 2000), https://historytogo.utah.gov/uhg-history-american-indians-ch-4/.

world, would continue waiting. I had failed them through my unworthiness. I’d ruined their only chance. Their eternal progress stalled because my body had betrayed them. I carried not just personal shame but cosmic responsibility.

I felt dirty. I felt heavy. I felt irredeemable. The mathematics of mormon damnation are precise. This is gaslighting elevated to theological principle: convince teenagers that their normal desires have metaphysical consequences. Create a system where salvation and damnation operate on an existential blockchain, where each transaction is recorded permanently, where forgiveness exists in theory, but the ledger never really clears.

I started to notice how everyone knew which families had a wayward kid, even if no one ever said it outright. Girls who dressed “too loud” got modesty talks in the bishop’s office. How no one ever swore— not just in front of adults, but ever. It was like the language itself had been scrubbed clean. Every interaction came with a kind of glossy politeness, but underneath it was simmering fear. A fear of stepping out of bounds. Of being seen in the wrong light. Of disappointing someone who might be watching.

What’s most difficult to explain to outsiders is how this system manufactures its own justification. When all measurements of worth are internal to the system, you can never appeal to external standards. When your community has created its own epistemology—its own process for determining what counts as knowledge— doubt itself becomes evidence of unworthiness rather than legitimate questioning.

It took years to realize that what I’d been raised in wasn’t a home, but a film set— perfect from the front, all scaffolding and emptiness behind. The manicured lawns and ordered streets weren’t signs of paradise, but control. Mormonism is about control— of land, of bodies, of narrative. The most tightly monitored communities are often the ones that boast about having nothing to hide. The most inescapable prisons are the ones we mistake for home.

We’re shaped by the first systems we live in, even as we learn to reimagine them. Freedom isn’t the absence of constraint, but rather the ability to choose which constraints give our lives meaning. What

I was seeking wasn’t boundlessness, but agency; not the absence of structure, but structures I had actually consented to.

The journey out of the system that raised and erased me required a complete ontological restructuring. I had to relearn what constitutes reality, what counts as evidence, what love looks like without conditions attached. I had to rebuild myself without the scaffolding of certainty.

Now I live in a house with doors that I can lock when I want privacy and open when I choose connection. I plant native flowers that grow wild and unplanned. I’ve drawn up new blueprints for a life where worth isn’t measured by compliance, and where boundaries are respected not as barriers but as the frames that make genuine intimacy possible.

Sometimes, I’ll feel that familiar sensation— that someone is watching, measuring, noting my failings in the cosmic ledger. But I’m learning that what they called sin was often just humanity. What they called faith was an oppressive structure created to keep us small. What they called zion was just a facade with darkness underneath it all.

I still believe in transcendence, just not the kind that requires uniformity. I believe in the sacred, just not the kind that needs constant policing. I believe in community, but the kind constructed through mutual recognition rather than mutual monitoring. For the first time, I understand what home actually means; not a perfect place where nothing is out of line, but a messy, honest space where I can finally, completely, be myself.

For 28 years, the San Gabriel Valley has been my home

Born and raised, I have an extreme love of the beautiful, nature-filled, diverse, and often overlooked small cities that make up the SGV.

Seeing the Eaton fire’s devastation to the communities of Altadena and Pasadena (aka Dena) firsthand has brought a new pain and meaning to “home.”

The place where I was born, where I had my heart broken more times than I can count, where I lost my dad and grandpa, where I made connections, broke my leg, was a caregiver, volunteered, learned to drive, and too many other memories to recount.

The SGV home is hurting, ravaged and working to repair.

to belong and be provided for.

Even while physical homes, and decades of memories that made up the buildings that hold so much value were turned to ash, SGV communities came together to provide fire victims a sense of communal home, a place to belong and be provided for. Hope, resiliency, strength, happy memories, and legacies—those are also the things that make Dena Strong.

These photos were taken while I was driving around the ruins of Altadena and parts of Pasadena, interviewing predominantly people of color who had lost so much to the fire. To the families who have shared their pain, loss, and worries for the future, thank you and I wish the best for you. May this area recover, rebuild, and keep the deep cultural history of so many SGV Black, Latine, and Asian families.

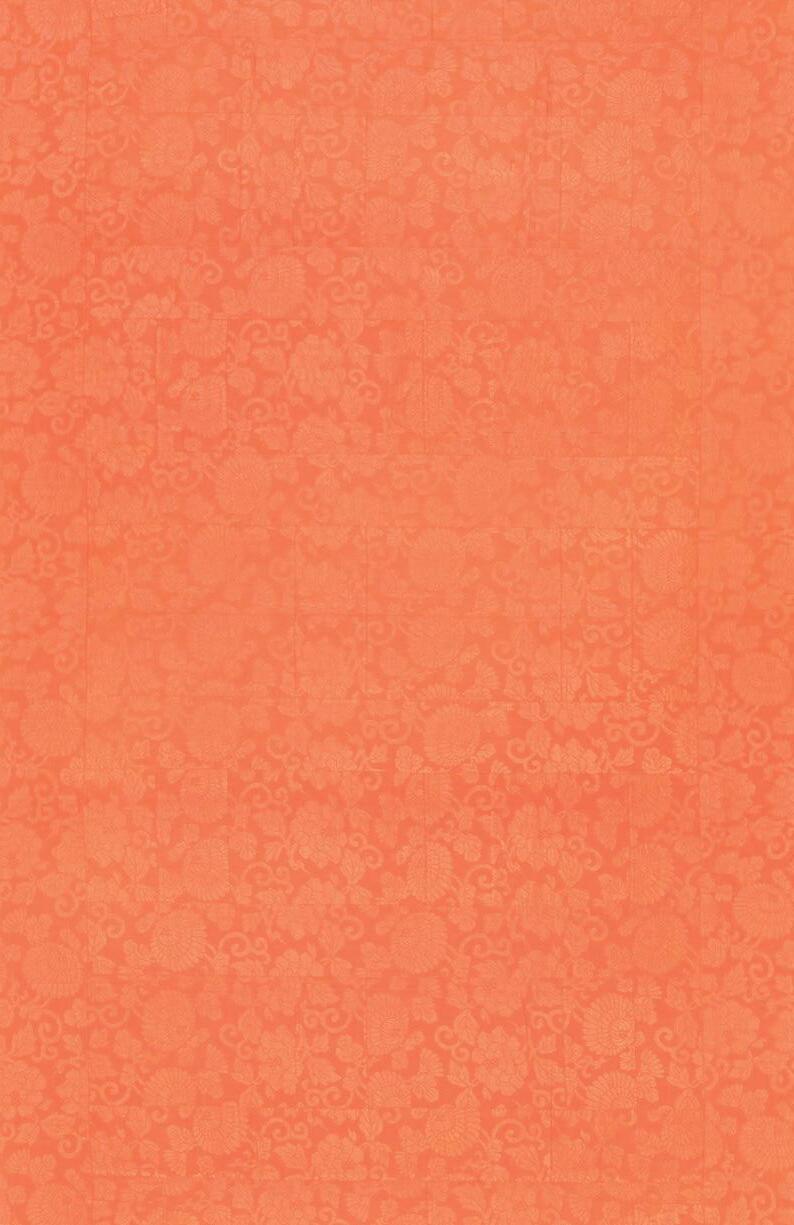

Words by v.w.l

She is pressed against the window and it is cold on her fabric skin. Nothing is outside. She is shivering. She never felt so frozen, so consumed at Home she’s not allowed to say that anymore because she is home. That’s what they tell her. No, she says. No. This can’t be home, not this place—please, not here. Where the glass is freezing and the palm is burning on her cheek. Where she spits out Mother like a curse and her brothers are her cousins and her uncle is her dad who is never home and her Mother is raising her hand again already, no patience, no limitations, and her sister’s—her real sister’s—tears water a feeling deep inside: a sickness they tell me is Home. Welcome Home. Welcome to your new* family*, welcome to your new name. Her hand, sewn up again, embroidered in unrecognizable letters. Frantically, I search the back of mine, praying the stitches are skin deep, that they have not touched me and have just branded this doll they call me, but is not Me. It is not Me. That name is not Mine, but they are in the Dollhouse and I am Outside of it, and they dress her in pink rose dresses and tie up her hair and call her theirs. And she looks at me, afraid. And I see through her eyes briefly, for just a moment, and all the threads I’ve unraveled tighten across my neck in an instant, and we are (un)done again. Mother says I am beautiful. I shower in the dark. I cannot see the doll, or the walls, and I am Outside again.

I am an hour away from that house and I can breathe. Oxygen burns my lungs; it is so foreign to me now. My voice is low. I try out being myself. I gift someone the truth. They use language for me no one else has used before, call me things I was told I could never be, wasn’t born to be. I can breathe.

I am thirty minutes away, and I can feel the tips of my fingers. They drum on my knee in the car. Basketball shorts hang loosely off me. My hair is short, cut at the root. No one says anything when I hold a boy’s hand. We are allowed to be friends. Allowed to be.

I am across the sea, and I can clearly see my face, my skin, my teeth. Winter cradles my face here in this faraway city. Even the snow is kind. Maybe He remembers. I try not to. Funny how something that once made me feel so dead now makes me certain I am alive.

I am across the country, and the sea knows my name. Savors it. Engraves it on breaking waves against the seawall. Stows it away in the roots of the mangroves. Reminds me of it when I come to the beach late at night to stare into the dark.

I am across the street and I am safe. The neighbors are walking their pigs. I walk behind their house, out of sight from the house’s windows. I am unseen. I am free, for the moment.

I am outside the front door and blood rushes to my face: a reflex. A knowing of what is behind the door. new*: but not really new—new in the way they look at you, new in name, but the same family you were in before the adoption (but also, not) family*: in the sense of blood and bone, of legal branding, of “Hi yes this is my Mom, she told me I had to call her that now.” Conditions may apply (if you ever wanted it to feel like home that is)

Orchard

Chlorine laps at the small of my back as I float face up. The backyard is so quiet this time of day. All the other kids are at school. Daddy is at work. I don’t know where my sister or nanny is. It is just me, the bees, and the pool on a hot day. I feel the depth of the water beneath me. The citrus trees are full of fruit again. Oranges, lemons, and grapefruits checker the mingling green leaves. Lizards scurry up the walls of the house, their tongues flicking the air. Inside, the tile floors are cool to the touch. It is quiet. Like no one is home at all.

The streets, too. Empty, and quiet. Across the street and four houses down lives my babysitter. Down the road and to the right, my best friend is home. I see the U-shaped driveway, the Blu Ray set we use when we visit. The backyard full of groundhog holes. His father with the icy blue eyes and cheery smile. His mother's silver car. To the left of my house, my school waits for me each morning, close enough to walk. Perfectly rock-shaped holes dot the sand along the fence where I waste time before school digging up anything I can. Imprints of my own making. Indents made by my hands and feet. These are my streets, my sand, my home, my pool. My body, floating in the water, watching the sky above. No one is here but me.

[blank]

I wake up to the sound of my parents' dogs barking. For a moment, it feels like I’m back in that place, but we moved years ago, and I am no longer a child.

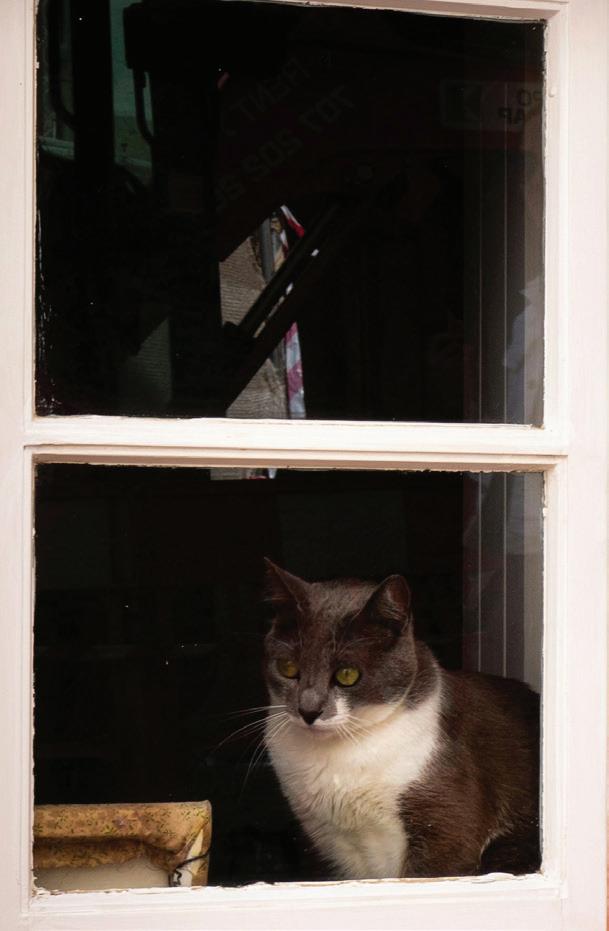

My arm brushes against my partner’s. Our cat is asleep on the end of the bed. When she notices I’m awake, she hurries to be in my face, asking rudely for breakfast. The morning is barely escaping into the gaps in our blackout curtains. Our room is small, smaller than our dorm was. The walls are almost bare, but over the last few months, our things have slowly taken over the space like Spanish moss. New curtains here, coat rack there, bookshelf covered in plushies and crystals in the corner. No one has come to wake me up. No one is yelling. It’s so quiet, it’s almost like no one is home.

But they’re home, here in bed with me. I roll over to wrap my arms around them. Immediately, they push me away and grumble back to sleep. Now, our cat is yelling at the door. There’s a feeling, one I haven’t felt since I was very young. A sense of ease. Of belonging. And I’m not even really “home” yet. I'm only resting here in this unfamiliar house that replaced our Dollhouse.

I lie awake and let the morning wash over me.

Words by Kyle Raymond Fitzpatrick

A little musing on dream homes and the Queer imagining of said homes.

It’s the yellow flowers in the bottom left corner of the fourplex that draws the eye. It’s the Edison bulbs on the square chandelier in the dining room. It’s the lack of a television. It’s the Spanish Colonial Revival style of the exterior meeting the craftsman style of the interior. It’s the serape draped over the boxy tangerine couch, the drip painting above the terracotta fireplace, the cherry walls whose corniced corners connect to the cherry beams on the ceiling.

It’s everything: it’s the model apartment, the apartment you imagine moving into when you’re older, the place you live when you no longer have debt and feel more adjusted, when you’ve abandoned your worries and are actually living the life you’ve been dreaming about. This apartment is a fact and a fiction on Sycamore Avenue, a few units north of your own apartment, occupying space in your mind for when you grow up.

You try to pass the apartment whenever you can, going out of your way to indulge the prickles to look in and around from the sidewalk. You most often find yourself luxuriating outside while walking with your dogs, idling there as you encourage their relief on the apartment’s climbing plants and fruiting bushes. You pretend to stare at your phone, looking over your sunglasses, and into the apartment. It’s the northeast corner unit, first floor, the building’s centerpiece that’s just left of center. You are eye level with the paned picture window that is flanked by column windows that offer glances of the front door and fireplace, although these views are obscured by the ruffles of vining plants stationed on the cutest miniature makeshift balconies, kind guards that climb from first to second floor.

You’ve never seen anyone in the apartment. It’s empty but markedly habitated, even if only by your imagination. In fact, you’ve seen yourself in the model apartment as a Gen X version of you with the Gen X version of your boyfriend and the Gen X version of your dogs and friends and family. You are having a wonderful dinner party, where everyone feasts on decadent foods you made using a stand mixer, served out of little white ramekins with indented grooves on the sides. Everyone drinks wine out of matching crystal stemware and eats

leafy salads from your garden off plates from a place like Heath. No one has a hyperrestrictive diet. With your guests, you are a portrait of the united nations. The party sits around a reclaimed wood table whose centerpiece is a mass of lit pillar candles that you don’t worry are a fire hazard. Words like business account and persimmon and Bryn Mawr and Marrakech are tossed around and no one feels alienated or dumb when they are used. There are no kids. Everyone is from the East Coast. Everyone has time to go to the gym. Everyone reads. Everyone has a clean, specific gender. One of the guests mentions a friend who passed away. Only red wine is drunk. There is no still water. Someone has a movie deal. Another sold a book. A home was just closed on. Everyone, in their own way and while, looks out the paned picture window at a shaggy twentythirtysomething standing with a few dogs at the edge of the lawn. You look out from the dinner table and think about how this young person must have it so much simpler than you do. You smile because, really, your gay reality is much less complicated than theirs. You are casually well-balanced, you think.

On another day in the apartment, you are having a quiet afternoon with a giant man. A husband. You share the boxy couch with him. The fireplace is on. The two of you are looking through big books and reading the new yorker from cover to cover. One of you is an architect. The other is an unspecified designer. It’s after work. You talk about what you heard on npr. A single mandarin is a suitable dessert. There is not a computer in the house. You talk about how lovely the apartment looks as the sun sets, but, in your Palm Springs house, the sunset would look all the lovelier. When is the next time you’ll have a weekend or week or month to get away to the Palm Springs house? This is a constant question you and your husband, the giant man, toss at each other until someone catches the idea to just leave, to get in the range rover and go, taking the always packed thom browne weekenders and the ralph lauren towels, getting out of town without needing to tell anyone or ask for anyone’s permission. You invite friends from New York and Miami and D.C. You’ll make a lamb roast. There will be martinis. A boys’ weekend. You will wear the penny loafers.

Another night, another dream, you are alone, with a cigarette. You smoke them casually, on cold nights like this. You drink a scotch with a single rock. Jazz music plays from a big rectangle that blends into the cherry walls. A giant candle flickers from the coffee table. It smells like roasted figs. You are wearing a robe. Your doorbell–a set of actual bells on a gold chain–rings. You open the heavy door. A man with a salt-andpepper beard gives you a hug. He is wearing a leather jacket. You help take his jacket off, pausing to squeeze his firm shoulders before letting go to put the jacket on a mirrored coat rack. You take his large hand and take him to the couch. You offer him a cigarette. He accepts, plucking one from the complicated European packaging, doing so in a knowing way that assures everyone this is not the first, second, third, or even fourth time he has done this. You both sit on the couch and talk about how lovely things are, how lovely the night is, how lovely each other’s eyes are. You offer him a cocktail, rising to the bar cart to prepare something for him. You take a long blink and look out the window. The night is black as violets, he says. Blacker than violets, you reply. You join him back on the couch, handing him his drink in a crystal tumbler. He takes a sip, licks his lips, and places the drink on a leather coaster. You wipe a drop of drink from his beard. Your robe falls open. He looks down and back up. He winks. The two of you laugh. You kiss a kiss that suggests this is the only thing that will happen during

You shake your head, looking up and down the street, since nothing is actually happening in this apartment. There are no people, just beautiful stuff that isn’t yours. You think this standing outside with your dogs, noticing the dusty doormat and dying potted plant on the apartment’s stoop. The velvet curtains are drawn more than usual. The lights always seem to be on during the day. The candles are never lit. There’s an untended stack of magazines by the window. Does anyone actually live in the apartment? Does anyone live the Queer lives you think they’re living behind those walls? These imagined lives in the model apartment, these fuzzy facsimiles of cinematic people from a late 1990s fantasy, are nonfictional, off living beyond these walls.

You walk back home. You wonder about the people you hope live there, these future selves in their present tenses. You walk up the woody stairs of your Spanish Colonial Revival building. You take your dogs off their leashes. You sit at a window facing the street, looking at the trees. You think. You pour a glass of wine into a milky, stemless cup. You stare at a painting on your wall. The sun sets, casting the room in pinks and oranges. You go back to the window. You catch eyes with someone younger, someone who was standing there, someone indulging a look. They walk away, quickly, eyes off in another direction.

I have never known home

but I know the walls that surround it, the moon light that never enters, the room that no one visits, and the thing that everyone forgets.

I have never known home or the grocery lists on the refrigeratorbut I know everything that wasn’t listed Jeevika December, 2023

like poems that you thought of reading or your mother’s favourite colour, or the note your father once wrote from the time he used to smile.

I have never known home, only the photographs of faces that don’t exist; Probably lying in the attic in that one closet

which no one really remembers the purpose of just that it was given by someone to someone else and has existed through time and space and parallels. Alas, the closet survived longer than the faces it holds.

Anonymous August, 2023

where I realised, for the first time that you will never see papa smile again or mama wearing her favourite shade of red or the faces locked inside the ancient closet or the ugly fact that you are twenty-five now or how you understand more than you know you aren’t home, and you don’t miss it either you are inside an apartment on another street where you only know how to breathe

I have never known home, I have only known all that hides underneath it and the street that lies outside the window and for now, that is all that you need to know.

April, 2023

Sabrina Skinner

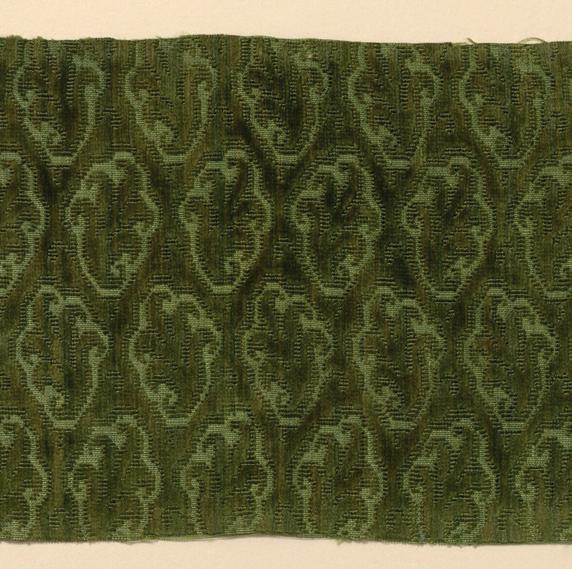

make reliquaries. Memorials, sculptures that exist alone or form altars; my work acts to contain disjointed memories, thoughts, and desires within the vessel of clay. Objects that are sired by personal metaphors, their creation immortalizes transient moments. From large installations to functional pottery, I connect interpersonal symbolism and popular culture through the depiction of surreal arranged imagery. Through the use of narrative devices to convey deeper meanings within the form, I illustrate personal stories within fantastical scenes. Drawing inspiration from historical forms, a sense of nostalgia and (dis)comfort remain in the familiar silhouettes of home and nature. By joining together abstraction and realism, an allegory of truth emerges. Where through odd collages of repeated symbols and mundane objects, the weight of memory takes shape.

By exploring subversive humor and subjective memory, my work is the embodied presence of a process driven urge for satisfaction and control. Self-indulgent attention is paid to texture and pattern, while a restrained color palette allows the form to remain visually powerful. Embodying a manner of holding, the lines between body and form blur. While texture invites touch as a way of preserving and cathartically acknowledging desires, negative space represents the duality of being “whole.” Raw and empty; reliquaries are filled by words unspoken, and truths unknown. This duality is further expressed within forms of growth and decay, opulence and the mundane, and the urban alongside the rural; each theme acknowledging the presence of conflict within the internal world. Clay, in its age and surety, is the material I’ve found that best expresses the innate and fluxing nature of human connection and our presence here on earth. Combining natural subjects and materials, later subverted by man-made objects—the conjunction of these parts express the turmoil of our ongoing and recurrent states of being. Thus, by making what was once fleeting, now solid and whole, I hope to preserve those experiences and feelings in their full authenticity; acknowledging the past, and taking back control of the narrative.

Ultimately, the sculptural forms I create are a collage of fragmented memories. Three dimensional, and heavily detailed—the clay is visually and tactilely familiar. Meant to portray a kind of vulnerable whimsy; my collaged arrangements (both the odd and the mundane) create an illusion which represents larger concepts of home, comfort, and uncertainty. Through their combined installation, these forms elicit a subjective, palatable experience; the captured moment of that final space. Thereby embodying shared sensory memories collectively to express the inherent ephemerality of our lives, the beauty found in decay, and the benefit of liminality.

Words by Shannon Brown

1. “Queerness is that thing that lets us feel that this world is

not enough, that indeed something is missing,”

(Muñoz 1).

It is the way that we lose time down by the river. All of us. I bring my lover first and kiss her when we get up to our ankles. We watch the 10 o’clock beavers slide out, troubling the smooth surface of the brown-blue expanse. 10 o’clock becomes whatever o’clock and our toes have gone numb. The wood is aromatic and freshly cut by the tooth. Kiss me on the bank like the animal I am. We will feel the fur rise between our fingers and cushion out the cold. The June moon is half-bitten and we are something new under it.

2. “...queerness is not quite here,” (Muñoz 22).

Our language pours from the nightstand and buzzes between us. The day begins at midnight and not at all. Obscure me into the morning that we call morning because the welcome light wanted for a name. We name it what do you want to do now? Whatever it is, it is unproductively, ridiculously, painfully, temporally, wastefully gorgeous.

3. “...the mark of the utopian is the quotidian,” (Muñoz 23).

Your body is like mine is like yours. Soft belly and blue eyes that look up at a low prairie cloud when they roil, like mussel purple against the iridescent nacre of a high-drifted one. Our time is on the side of a folk hill. Press the line of your spine into the softness of my belly. I will sigh hard and it will make you want to get up. Feel my air and know that I am the sturdy bank. Packed clay in white and gray layers, sweet humus and grasses. The river driftwood of my ribcage settles back into the dirt when you breathe.

4. “...queerness as horizon,” (Muñoz 19).

We are not quite here yet. Stitch your fragmented vision into mine while we walk. But it doesn’t feel like walking, not all the time. It feels like gliding and flapping and pushing our aching sky-bound muscles toward an elsewhere. We are on every dockside and harbourfront, wondering what that wave broke over way out there. We are storm-watching the flat canola field. We are the pearl, pushing through the fleshy present toward the thin daylight opening of our shell. We are. Hard and shining and here and not at all. Works Cited Muñoz, Jose Esteban, et al. Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity. Tenth Anniversary edition. New York University Press, 2019. https://doi.org/10.18574/9781479868780.

Words by Lorinda Boyer

Sandy and I waited until marriage was legal in our home state of Washington. We weren’t interested in chasing approval across state lines. We wanted to marry where our roots ran deep—where we lived, paid our taxes, and waved to neighbors who never asked questions. Some folks didn’t understand. “Why wait?” they asked. But we weren’t the ones who needed to move. The law needed to catch up to us. For Queer folks, belonging isn’t ambient— it’s constructed. Forged. We gather the rusted scraps of acceptance and weld them into shelter. Over and over. And there’s a kind of quiet defiance in holding out for what feels right. In saying: I belong here. I deserve this. Love, after all, shouldn’t require a passport. But the fight for legal recognition was only half the battle. The deeper reckoning was internal—carved from years of trying to be someone I wasn’t.

Eleven years later, I sit on the porch with Sandy, coffee in hand, toes bare against the wood, and I can still feel the twin weights I carry. Grief and joy. The religion that raised me told me I must pick their side, the right side. Blend in, straighten my spine—and my sexuality—and say all the right things. And I tried. God, I tried. I told myself to keep quiet, to blend in, to be grateful. I wore the smile like armor, married the man like it might save me, and swallowed the truth so hard it cut going down

But truth doesn’t stay buried. Not when it splinters like bone.

Mine started as a whisper—barely there, just a breath under the door. But whispers grow teeth. And one day, it didn’t knock. It blew the whole damn thing wide open.

Coming out wasn’t all confetti and Pride parades. It was messy. It was reckoning. I had to unlearn everything I’d been taught about what it meant to be good, to be loved, to be enough. But authenticity doesn’t negotiate. It doesn’t soften its edges for comfort. It demands space, it demands light.

Still, I carry joy around like currency. The quiet kind, hard-earned and deeply felt. The comfort of Sandy’s breath rising and falling beside me in sleep. The way our laughter fills the room without asking permission. I now carry a truth I didn’t always believe: My love is real. And it’s right.

In living as myself—a Queer woman, a wife, a survivor—I lost things. Predictability. Approval. A few people I once would’ve fought to keep. But I found my voice. I found peace in pieces—on porches, in protests, in the low hum of safety I now call marriage. I found color so rich and defiant it made the gray-scale years feel like a ghost I barely remember. That’s home. Not a place you stumble into, but one you build with trembling hands and stubborn joy.

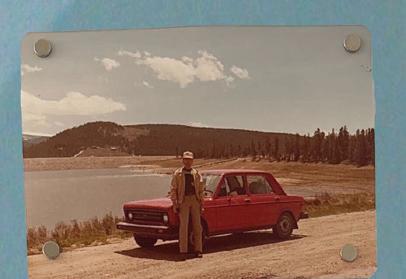

As a survivor, my skin itself is unsafe. I don’t truly feel at home anywhere. I long for it—I’ve searched the world. One of the places I felt most at home was in Iraqi Kurdistan, welcomed and embraced by the Yazidi survivors of ISIS genocide. These three photographs represent the different forms of home that the Yazidi from Shingal currently have:

Their village, destroyed by ISIS and rebuilt, somewhat, with barely any international aid, a place where many refuse to return.

The most holy place in their culture, where they are always welcome and meant to feel protected.

The IDP camps—overcrowded, unhygienic, fraught with conflict and violence and always in need of supplies.

These are the options they have for home. And still they are enduring. They are fighting. They are asking only that the world remember they exist as they continue, somehow, to have hope for their future.

Words by Ann McCann

If you followed my journey of online sperm-searching last year, you will have learned about my wife’s and my foray into the online world of free sperm donations and donors. In the world of capitalism, cash is king, and so it is in the world of sperm purchasing as well. With vials costing several thousands of dollars each at some clinics, and not typically covered by insurance, many turn to facebook and other online groups where donors supply their sperm for free. My wife and I found ourselves among them.

Now that you’re caught up to speed on our search for seed, I ask that you come back home with me. For me, home— which had sometimes been followed by the suffix -less—was usually somewhere I just came back to after work. Not much more, sometimes less. They were short-lived dwellings, of which I jumped to and fro out of necessity, or timing, or convenience. Now, it is where I work, where I spend my days and nights with my best friend, where I play with my pets, where I write, and lately, where I again daydream about being pregnant and caring for an infant alongside my wife.

Shortly after I wrote “Getting Strangers on the Internet Pregnant,”1 my wife and I had actually decided against children. Politics got scarier, we watched babies in Palestine die, our mutual mental health plummeted, and things felt too uncertain to entertain the idea of children. “But nothing has changed!” you might be screaming at the page. But that’s where you’re wrong. Two very important things changed: I am turning thirty, and we just finished rewatching Sex and the City. While I type, I’ve always fancied myself a Carrie,

but as I approach thirty, I find myself crying with Charlotte when she can’t get pregnant and screams about wanting a baby, and yearning when Miranda decides to keep her unexpected pregnancy. I cannot sleep one night, and my wife asks what’s on my mind. “I feel like I’m going crazy but I can’t stop thinking about babies and right now I’m freaking out because I can’t think of any boy names I like!” They get my beta-blockers and cold water, massage my feet, and tell me about their plan to start collecting vintage baby clothes. I calm down and fall asleep.

The next day we, again, make a tentative timeline and action steps towards getting pregnant. We decide which room will be the playroom. I don’t know if I-want-a-baby hormones are real or not, but my body has decided they are and—like a cat circling and scratching a cardboard box before giving birth—they begin making me need to nest in the most frenetic and insane ways. First, it starts with cleaning the “doom room” of half-empty boxes from moving over a year ago that will be a playroom in the future. I unpack, I let go, I check expiration dates on medication, I throw things away, I put all my tools in one spot, I use the top shelf of the closet. Then I sweep. Twice. Then I mop. By hand, with a cleaner and paper towels. The floors have been lived on. My feet are dirty, but the floor is clean. I wash the windows with real glass cleaner. Finally, I hang up my baby quilt that my great-grandma made for me on the wall. The same one I stared up at on my wall as a child myself.

We dream about a big brother followed by two girls. I unpack the last of the boxes from moving. We have two boy

names—just in case—and both girls’ names picked out and have discussed the order in which they will be used. We bring more plants into the home and start our balcony garden. I meticulously research different cribs and decide on one after several nights of google research and reading product reviews. We somehow put more art on the walls and discuss painting them because my wife and I see a shade of yellow on the walls of a friend’s house we both adore. When we tell them about the hard work of turning a Doom Room into a Nursery, they think we mean for plants and I have to find the self-assurance to correct them and tell them we mean for children—I can have a baby, I remind myself, I can raise a child, I can make this choice, I’m going to be a mother. I’m going to be a great mother. Later, my wife and I decide on the nursery room theme.

I’ve played room-tetris every night as I go to sleep, and imagine where bassinets and tummy time stations will go. I realize that our treehouse, surrounded by sun and the tree tops and birds and bees, will be the first home our children remember, and I think about rearranging the art on the walls. Our home is quiet and peaceful as I write this. Incense and candles burn, cats surround my writing perch, my wife quietly journals by my feet. I know it won’t always be this way, especially once children arrive, but it’s more than I’ve ever had before and everything I’ve always wanted.

“Are you writing? You look like Carrie Bradshaw right now, you must be writing.” My wife knows just what to say. Maybe I can be Carrie Bradshaw with a baby. Either way, I’m finally home.

Words by Octavius Nightingale

I haven’t gotten braids down quite yet. Smaller ones I can do, despite the painful lack of ribbon and twine and beads to decorate them. Sometimes, I manage a sort of half-up ponytail style, or a braid ‘round my shoulder—my split-end hair scratches and tickles, so it never lasts long. I once managed twin braids, but very quickly despised it.

I wonder if my ancestors had help with their braids. If, before battle or ritual or travel, they all sat together and wove strands of blonde and brown and black, ensuring that no one’s sight was infringed and that they all looked presentable should they die that day.

I grew up with short hair. It was as though my parents weren’t quite ready to leave the comfort of the ‘80s and ‘90s; they downloaded shows from that era for me, as well. My hair was lighter than it is now, chin-length and pin-straight. I cut it shorter in middle school, an attempt at becoming— or at least looking like—a “real boy.” I’m glad I failed. My hair grew back quickly, gentle waves colored like acorns and soil. I didn’t know what to do with it, even how to brush it. I looked to the past for answers.

For a long time, I deemed myself reprehensible—pale and masculine, I was a danger to those around me. The basis of this belief was the truth. If I asked, my parents would tell, and they rarely sugar-coated things. Before reaching double-digits, I was watching true crime and reading historical

fiction concerning Indigenous boarding schools. In my mind, I was an abuser waiting to happen. It was in my blood.

It took me a long time to realize where my blood really came from: a time and place far before the Mayflower and all it brought with it. I realized that I never truly saw myself as an American, or even an Oregonian. The mountains and forests and stars are far stronger and older than any line laid by human minds. It was then that I stopped seeing things so simply, and began to see myself as a forest, a skyscape, a constellation: ancient and holy beyond words.

My cousins tell stories. In these stories, I’m a retired knight living in an isolated sanctuary, having hung up the iron in exchange for incense. Perhaps those stories are true, in a way. Perhaps the blood of some Germanic Christian priest flows alongside that of a Scandinavian vitki, alongside that of Czech archers and Slovakian wanderers.

How much of my existence is an echo of someone else’s? Names and faces long forgotten, yet their blood flows in me, passing quietly through the veins of colonizers and abusers, waiting for someone ready and willing to get back on the path from which we were ripped so long ago. How many of my ancestors bore decorations like me? Silver rings engraved with charms of luck, leather cords bearing pendants of hammered steel in the shape of holy symbols, painted nails and inked skin. How

many of them hit bullseyes despite being unable to properly see their target? How many of them worshipped the gods of their ancestors despite or alongside Christianity? How many of them struggled with braiding their own hair, preferring to keep it down anyway? How many of them were me?

In my dreams, I press ink onto papyrus and skin and watch the stars and birds. I travel in search of stories and language, speak many tongues, and soak up every bit of knowledge I can find. I hold a sword forged for me alone, shoot arrows which always hit their target, and divine messages from the gods. I wear robes and tunics, douse my cheeks in starlight and let seedlings sprout from soil-colored waves, and ride a pale gelding. I live in a temple in the mountains, surrounded by starlight and birds.

In the waking world, I haven’t shot an arrow in well over a year. I sit behind a screen and write fantasy. Sometimes poetry.

There are no stars or snow where I live, somewhere between the coast and cliffs of Cascadia. I ride my bike and sing with birds and wait for the Dicentra formosa to bloom. I try hard to learn other languages, scrape up enough money to get another tattoo, and listen to music sung in a language my ancestors once spoke—still alive. I draw stars on my cheeks and sit in the sun. I sew something of a tunic out of old curtains and shuffle tarot cards. I braid my hair as best I can.

The path one is born on doesn’t have to be the one they follow. There is a sort of holiness in forging one’s own path—even more so when they use the remnants of the old. Peeking through the trees and fog to find conveniently forgotten paths and places, plucking histories from bloodlines and bird calls and starlight and sea. The past is never as far behind as believed.

Art by Victoria Jamilé Hernández

Whenever I write about my parents, I use the words “mother” and “father.” There is a gravity to them. They’re like the authoritative bell toll of a clock tower. Maybe it’s because it makes me feel like I have my shit together. Maybe I gravitate towards them because they let me be dispassionate; I keep them at this distance so I don’t have to immediately reconcile my diasporic trauma.

My father, steeped in shame as a victim of harsh racism, expedited the assimilation of our family. My parents gave my siblings and I tetherless English names removed from Vietnam or Laos. I can’t speak our mother tongues, and neither can my brothers. I can see my father’s rationale. Erasing any possible traces that marked us as different would spare us from the prejudice and hate he lived through when he sought refuge from what Americans dub the vietnam war.

This detachment has been with me for as long as I can remember. I am, of course, distanced from my Asiatic cultures. Estranged from being able to communicate with my limited-Englishspeaking grandparents. Mostly, I interface with what should be my culture through mispronouncing menu items in Asian restaurants. In effect, the conception of my identity is dissociated from my physical body. I inhabit a Southeast Asian skin, and yet I have no evidence that validates my body’s stake.

This detachment from the body repressed my Queerness for the majority of my life. There is an irony here: I went to an arts high school and attended two arts colleges. I’m sure there have been more closeted individuals in the world, but I like to think it took me three institutions and a children’s cartoon to pull out whatever was repressed inside of me.

I have always felt like I was piloting a fleshy vessel. Like a giant mech in a Japanese anime. If I was the sum of my thoughts and experiences and feelings, then I could detach myself from any physical body I inhabited. This logic certainly paralleled my father’s line of reasoning, that if we lived as Americans, then Americans we were.

In that liminal phase of gradually relaxing COVID-19 restrictions, I streamed She-Ra and the Princesses of Power with my then-partner. We’d always loved kids’ shows; we burned through Hilda and

Words by Diane Nguyen

Gravity Falls and Owl House. I think it was us nursing the hurt kids inside ourselves, letting them live and breathe and laugh and play in ways we never got to.

She-Ra was different for me. It was the first American cartoon with Queer and neurodivergent representation I’d ever seen. My heart melted for Bow’s dads, and I resonated with Entrapta’s one-track mind for tinkering. I cheered for Perfuma and Scorpia.

At the end of it, something clicked for me. I realized that I could tell the little kid inside of me that it was safe to come out now. And I remembered that kid watching Queer anime and wishing with her whole heart how much she wanted to be the women on screen. How much she’d always known and I didn’t. It was like I had finally noticed the ebb-tide, and noticed the people walking along the beach, and realized that I could walk there, too.

I have been transitioning (my mother calls it “transforming”) for three years now. The changes sneak up on me. Like how one day I notice my chest filling out my bra, or the parabolic curve emerging at my waist. I feel so intimately connected to the contours of myself. I don’t just live in the space between them; these outlines are me. I am no longer a ghost haunting these bones. I am corporeal, and I feel like I’ve finally arrived at a place I knew was inevitable.

I am on a video call with my mother and father. I haven’t called them in half a year, which for me isn’t atypical. Their love is encoded: my father asks how the car was running, and if my phone is working well for me. My mother asks about the food she sent. They reiterate a point they’ve made: I need to transfer the car’s title from their name to mine.

“He can do it at his leisure, I didn’t write a date on the form for that reason,” my mother says from off-screen to my father. I say that I know, and we say goodbye.

I walk into the living room and sit on the couch with Liv. She kisses my cheek and asks how it went. “Fine,” I say. “My mother misgendered me off-screen.” I shrug, signaling that I don’t want to talk about it. She fiddles with the wrong remote and I laugh, handing her the correct one. She presses play. “Starfleet is the only family I need,” says Captain Picard

Words by bellze t.

I was eating bangus today, and my mother told me to watch out for the tinik. This is the closest kind of intimacy I can expect from my mother—a warning about the bones that could bleed my mouth.

Conversations over family dinners are largely occupied with such talk: what each faroff cousin is doing now, when we need to buy groceries this week, the things we cannot consume. All to disguise an unspoken longing to return to somewhere else. I ask my brother to pass the soup.

I feel closest to home when I eat Filipino food. My body has been carved around lechon and sinigang and fish bones. I am a product of my ancestors’ bodies. My bones are their bones, made of what nourished them. But eating our food is as close as I can get to them. I become more aware of the distance between us and the hollow that exists to mourn our degrees of separation. My body has determined what our home is supposed to be like based on the food we eat and is dissatisfied with the loss of it. Eating is intimacy, but such closeness is haunted by people and places I will never truly know. We are only halfway to fullness, my body says.

When I stay at their university apartment, my Queer friends and I usually cook rather than go out to eat. We’re all children of Asian immigrants or immigrants ourselves. Cooking for each other makes me feel as close to them as possible. There is a closeness that I can only find in total consumption, the sacred nature of creating something and nourishing ourselves with it. From bánh xèo to hot pot to ramen, we fill ourselves with meals and memories and rebuild the kind of homes that we have been denied. We revel in sharing utensils. We wash each other’s dishes. We say: “Eat more; we need to finish this lettuce.” “Who left rice on the paddle?!” “Do you want more chili oil, garlic, or fish sauce?”

Then we talk about T, top surgeries, and phalloplasties. Awkward hookups, complaints about apartment hunting, and how worried we are about becoming our parents. We get drunk and laugh at ridiculous grindr messages and hinge profiles. This is it. This is what family conversations are supposed to sound like. The yearning for elsewhere isn’t gone, but we are building a better home that lets us be Asian and Queer.

It’s not a perfect replica of what home should be. All of us hail from distinct diasporas, so we alone cannot fill all of our cultural gaps. We aren’t able to touch the earth of our homelands and feel like it is made for us. The apartment is cramped, full of eight people. There isn’t adequate space on the windowsills for the plants, and the couch hasn’t had pillows all year. Yet as I lather pots, bowls, and the individual tines on forks, my body feels as right as it can be. We are all warm and alive and new.

I am standing at the kitchen sink, surrounded by people who aren’t ashamed to eat.

We are all untethered from our homelands because we would never belong. We’re too u.s. american to be Asian, too Asian to be u.s. american, and too Queer to fully be either. But we will not disinherit the hallmarks of our ancestors’ homes, rooted in distant lands.

Home starts with hungry mouths and ends with satisfied appetites. I refuse to suffer the undignified hunger that denies my Queer self and my Filipino self. I want to savor everything, bones and all.

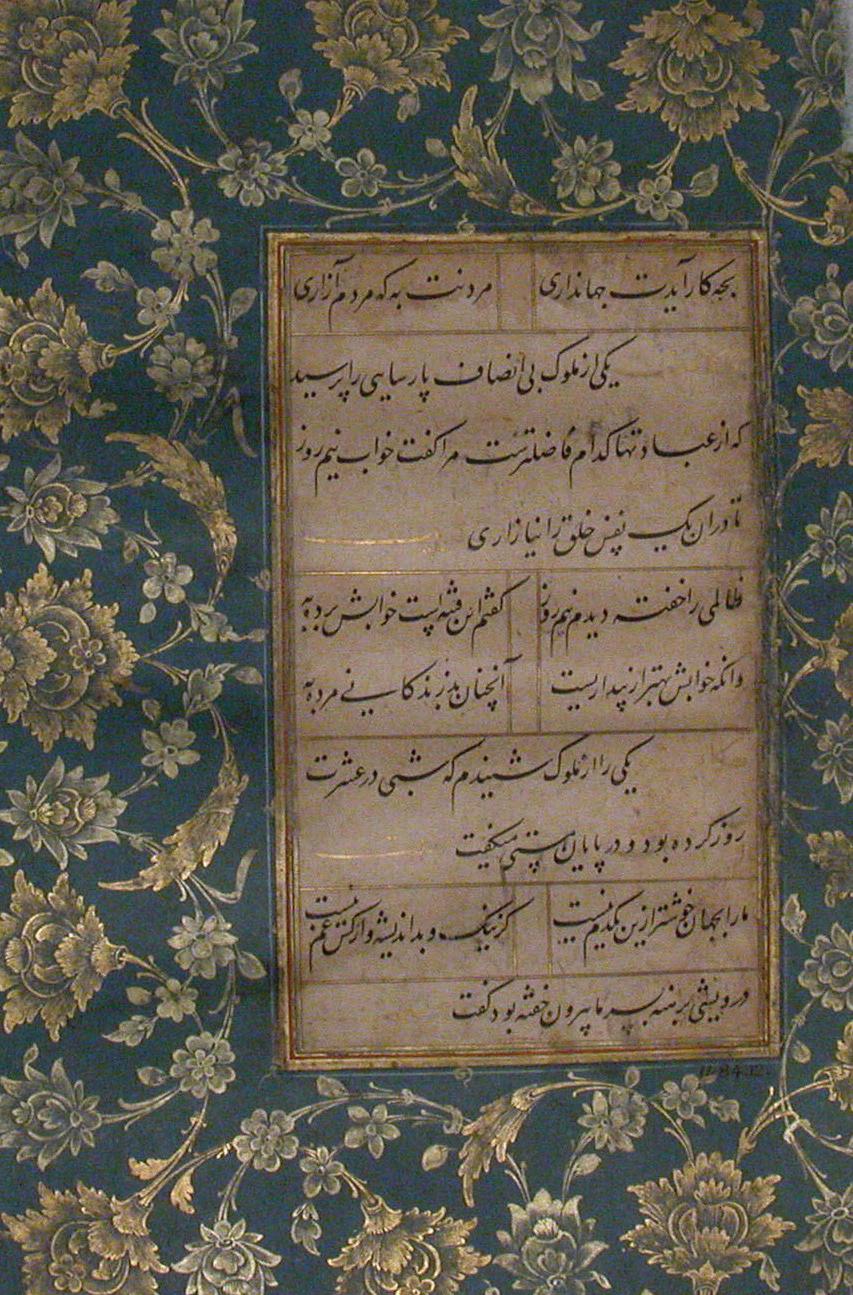

Words by Djeneba Bagayoko

Colonization did a number on all of us. From displacing entire populations, bending nature to colonizers’ will and uprooting trees and people, to demonizing ancestral cultures and practices. One of its most nefarious legacies is the redefinition of the concept of family. This redefining includes the imposition of crystallized gender binaries, the staunch LGBTQIA+ phobia in continental and diasporic African communities, and the so-called need to maintain (colonial) “family values.”

However, not all is lost. As a matter of fact, nothing ever was.

Though the forces of colonialism, imperialism, and slavery have been devastating, echoes of who we were before their arrival still live on—in our language, our architecture, and our world-sense.

c c c c

In continental Africa, and more precisely in the languages of Bamanankan (Mali), Jula (Ivory Coast, Burkina Faso) and Wolof (Senegal, Gambia, Mauritania), the terms for family are som g w, lum g w, and waa kër respectively. Their literal translation in English is people of the house. If you’re part of Ballroom or have watched Paris Is Burning, Pose, or Legendary, the translation might already be ringing a bell.

Ballroom culture uses the house as an embodiment of family. This value crossed over from the continent and holds true in the diaspora. Before we delve into it, a little history lesson: Black Ballroom culture emerged in the 1960’s in New York. Queer Black people faced discrimination from their white counterparts, so they separated from them and created their own underground Ball culture. Ballroom became a safe space for Black and Latine Queer folks. Ballroom is a world where those who are marginalized, discriminated against, and oppressed due to their gender and sexual identities are free to express themselves. Competitions—or walks—are a core aspect of the culture where different people and houses compete against each other to snatch trophies and have their name engraved in the pantheon of Queer legends. Ballroom culture restructured the concept and organization of the family, or better yet, it remembered the African way.

Houses are a social structure where Queer people who cannot depend on their biological family unit for acceptance find a home. They are led by house parents: mothers, mostly Butch Queens (Gay Men) or Femme Queens (Transgender Women) or fathers, who are mostly Butch Queens or Butches (Transgender Men). The name of the house parent becomes that of the house and the children. Houses often adopt names of famous designers, stylists, supermodels, or magazines. Some iconic houses include House of Prestige, the Kiki Royal House of Noir, House of Mugler, House of Xtravaganza, House of Pendavis, among others.

Other synonyms for family in Bamanankan are:

Denbaya = family from den (child), ba (mother).

Badenya = kinship (when siblings have the same mother).

Balimaya = used for relatives related by blood, friends, and people we love, respect, and hold in high esteem. It is also used in distressing situations to empathize with the other person (e.g. do not worry, my child).

They all center ba, mother.

It is mothers who pass down histories, take care of and spend more time with children. In many African American families, both within and without Ballroom, the mother and the grandmother are often the pillars of the house.

In Ballroom, people find solace, protection, support, food, a roof, and love in chosen families after their biological relations shun them. Although house fathers do exist, house mothers are more predominant. This is reminiscent of matrilineal family structures in Africa where the family is an extension of the mother. House mothers thus reinstate the practice of African matriarchy in their families.

As written by Marlon M. Bailey, “In Ballroom, your sex assignment or gender identity does not necessarily determine the role you play in the family. Ballroom members reconfigure what genders perform certain gender roles in this kin unit. Hence, Butch Queens can be mothers and fathers, some Butches are fathers, and many Femme Queens are house mothers.”

This flexibility in Ballroom kinship structures echoes practices found in many African cultures, where social roles are also fluid and contextual. On the continent, identity is often shaped by shifting markers like age and place. Roles can change based on how old you are (you can be the junior in one setting, but become the elder in another while maintaining your age), and whether you are in your lineage family or the one you married into. In African tongues like those mentioned above—and Yoruba—we don’t have gendered terms like “brother” and “sister.” Instead, we say younger sibling or older sibling. This is noted in more detail by Ifi Amadiume in Male Daughters, Female Husbands, and by Oyèrónke Oyĕwùmí in The Invention of Women, where both scholars highlight gender-inclusivity in African idioms and ways of life.

Across various continental and diasporic African communities, family is much more than the two-parent nuclear household. It includes grandparents, parents’ siblings, in-laws, other families and children in the neighborhood and friends. In countries like Mali, Senegal, Ivory Coast and Nigeria, compound houses are the architectural manifestation of how large and inclusive African families are.