FRUITSLICE

The wild, the untamed, the beautifully overgrown.

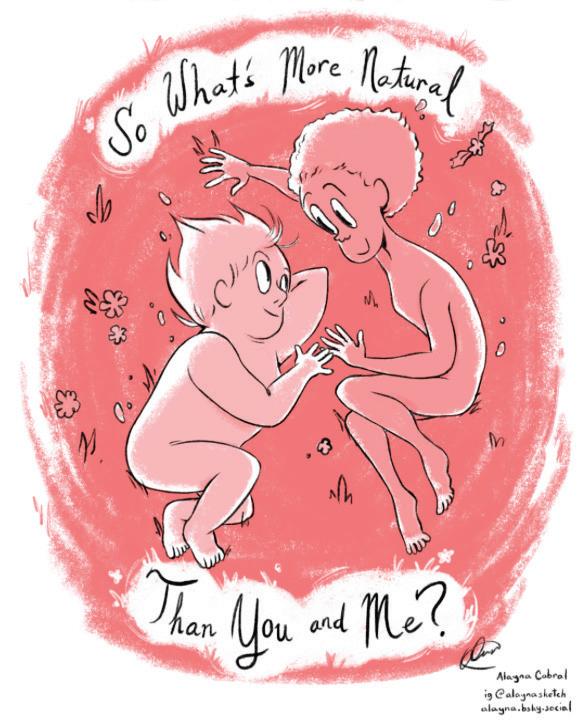

Queerness as a natural state of being.

Fluidity—in rivers, tides, gender, and identity.

Root systems and the magic of symbiosis.

The cycles of seeding, blooming, and decaying.

The myth that Queerness is separate from nature.

Colonial binaries that separate land from people.

Capitalism’s obsession with monoculture—in crops and in people.

The anthropocene, environmental racism, and Indigenous erasure.

Any united states president.

Any attempt to tame our wild.

This issue is dedicated to everyone across the planet whose homes, lives, traditional ecologies, friends, and families have been affected, warped, or destroyed by Climate Change in a system that manufactures consent to the degradation of land, air, body, and water.

This issue is dedicated to land and water protectors on Turtle Island and all over the globe, the original keepers of land, who hold kinship through tradition.

This issue is dedicated to those who recognize Queer ecology in their day-today lives: ruptures to the standing order that take the form of graffiti on luxury highrises, making plans for sustainable living on a local level, and caring for their fellow human beings.

This issue is dedicated to the Earth that spins and gives us a moment of life across the expanse of the Universe’s history.

This issue is dedicated to our houseplants.

This issue is dedicated to Queering our ideas of nature and naturalizing our ideas of Queerness.

This issue is dedicated to environmentalists, birdwatchers, gardeners, rock hounds, bushcrafters, foragers, farmers, wildlife photographers, scientists, stewards, outdoor recreational groups, wilderness therapists, and, of course, Gay people everywhere.

There are some who may benefit from an answer to the question: “What is Queer ecology?”, before immersing themselves into the worlds and words that explore this term in Fruitslice Issue 6. There are academic definitions and those that take the term to praxis. This issue features something that embraces both: a combination of the theoretical and the practical—what we desire, and how we enact growth and change in our own environments. Queer ecology (according to our fruit community) is the innate interconnectivity in the lush world of Queer people through an ecological lens.

There are many reasons why we, as a Queer publication, are interested in an ecological way of thinking. We are human animals, concerned with the health of the very delicate ecosystem that we inhabit. We are Queer people, often told that we are unnatural for answering a call from within. We are members of a community that is interlaced with other communities, forming a vibrant ecosystem that we want to observe, embrace, and steward. Many of us are LA residents, recently devastated

by large-scale wildfires. All of us are living on a changing planet. Our art and our love is made at the confluence of rapidly morphing landscapes. All of us know what it feels like to have the earth shift underneath you, to feel unnatural at home, and confront the strangeness that comes from within.

With this issue, we hope to illuminate the Queer ecological thought in art for our audience. We want you to see plants, dirt, sunlight, air, death, birth, bugs, animals, and life itself and know that Queer hands touch all of these things, and Queer artists have something to say about them all. And to that end, ecology is also not limited to gardens and plants—but all habitats and habits, from cityscape to inner microbial workings. From the infinitesimal to the infinite, we are all bound to each other, to ourselves, to this planet, to this Universe.

Much of the work in this issue delves into connection, while making space in all the little corners of the world. In that way, each piece seems to be connected to each other by virtue of being bound page to page. So we welcome you to wander safely into the heart of the ecosystem found right here.

Content Warning: This issue, and the contributors therein, spend considerable time reckoning with and examining the many ways Queer ecology shows up and manifests in our lives, thoughts, and work. In doing so, contributors and staff alike have addressed and explored topics including homophobia, transphobia, queerphobia, slurs (both reclaimed and weaponized), gender dysphoria, sex, sexuality, religion, ecological devastation (including the recent wildfires in LA), climate crisis, environmental racism, ableism, medical trauma, eugenics, the COVID-19 pandemic, colonialism and domination, enslavement, capitalism, settler ideology, citizenship status, mental illness, mentions of disordered eating and eating disorders, needles, blood, physical injury, death, decay, grief, and substance use, among others. These themes are all interwoven with both the Earth and our history and community. We hope you manage your discomfort as it arises and take steps to care for yourself.

Copyright © [2025] Fruitslice All rights reserved.

Everything in this issue belongs to its original creators—the writers, the artists, the dreamers, etc. Fruitslice holds first publication rights and the right to archive and distribute the work in its originally published form. Every effort was made to contact and properly credit copyright holders. Please get in touch with us regarding corrections or omissions. Reproducing or reprinting all or any part of this issue without prior consent (except in the case of brief quotations used in critical reviews and academic work) will be considered utterly disrespectful, generally uncool, and legally questionable–but we aren’t cops. :(

A Lapointe

AJ Dent

Alayna Cabral

Amber Jaitrong

Angel T. Dionne

Ann McCann

ashley hunt

Averie Bueller [APB Photography]

Azad Namazie

Bailey Bauer

Bennett Rine

Bethany Leigh Greenman

Bri Campbell

Brie Coleman

Caroline Brink

Casper Orr

Chloe Oloren

Chloe Parsons

Christine Leistner

Courtney Williams

Dejan Ann Kahilinaʻi Perez

Dominic Scicchitano

Eleri Denham

Em Buth

Emerson Hayes Jermstad

Emily Vance Brown

Emmye Vernet

Figueroth Lavalle

Gaby Bee

Gale Winegarden

gp

Grant Kanak

Jalisa Sousa-Silva

Jamayka Young

Jess Beaudin

Johanna E. Hall

Kam Bradley

Katie Hillard

Kota Ball

Layla Razek

Liv Soter

Mazerick Betko

McKenzie Janisz

Melanie Robinson

Micah B

Míša Štorková

Morgan Champine

Morgan Hyatt

Nat Deam

orion (aka puppy)

Roman Campbell

Rhyker Dye

Salena (@zonked_art)

Sanna Koskimäki

Shaniqua Harris

Shelby Pinkham

Sophie Mutiara Nova

Surya Du Preez

Taylor Michael Simmons

Tommy Rider

Tzushan Chu von reyes v.w.l

Yazmin Munoz

Zoe Grace Marquedant

Cam Reid

Kayla Thompson

Ann McCann - Non-fiction Lead

Cam Reid - Non-fiction Lead

Casper Orr - Non-fiction Lead

Em Buth - Fiction Lead

Kayla Thompson - Poetry Lead

Meg Streich - Non-fiction Lead

Starly Lou Riggs - Spotlight Lead

Ashley Hunt

Casper Orr

Ellie Allan

Kayla Thompson

SJ Wasachi

Tess Conner

Bailey Bauer

Cam Reid

Casper Orr

Em Buth

Kahlea Williams

Kam Bradley

Kayla Thompson

Meg Streich

Tess Conner

Starly Lou Riggs

Rhyker Dye

Andi Rand

Bailey Bauer

Em Buth

Kayla Thompson

Meg Streich

SJ Wasachi

Cam Reid

Kahlea Williams

Starly Lou Riggs

Casper Orr

Em Buth

Starly Lou Riggs

Meg Streich

Andi Rand

Bellamy Bodiford

Hamish Bell

Ky Tanella

Micah Brown

Michael Bednar

Natalie Walton

Nikolai Seraphina

René Zadoorian

Roman Campbell

Sarah Pennington

Timothy Arliss OBrien

Melanie Zhgenti

Nicole Hernandez Reyes

Nicole Hernandez Reyes

Roman Campbell

Averie Bueller [APB Photography]

Ann McCann

Ariel Tusa

Bellamy Bodiford

Cam Reid

Caroline Gharis

Casper Orr

Chloe Oloren

Em Buth

Jason Wayne Wong

Kayla Thompson

Meg Streich

Melanie Zhgenti

Nicole Hernandez Reyes

Nikolai Renee

Olivia Bannerman

Rhyker Dye

Starly Lou Riggs

Ann McCann

Chloe Oloren

Jason Wayne Wong

Melanie Zhengti

Nicole Hernandez Reyes

McKenna Gray Director of Development

Ann McCann

Caroline Gharis

Olivia Bannerman

Internal Community Director

Publicity Coordinator

Operations Chronicler

Events Project Manager

In-house Comic Illustrator

Rhyker Dye

Starly Lou Riggs

Casper Orr

Hailey Green

Ariel Tusa

Caroline Gharis

Dillon Parker

Daisy-Drew Smith

Hailey Green

Melanie Zhengti

Nicole Hernandez Reyes

Meg Streich

Your Favorite Transcendental Author Was a Homo Words by Casper Orr

Hua | Fruit | Word Words by Dejan Ann Kahilinaʻi Perez

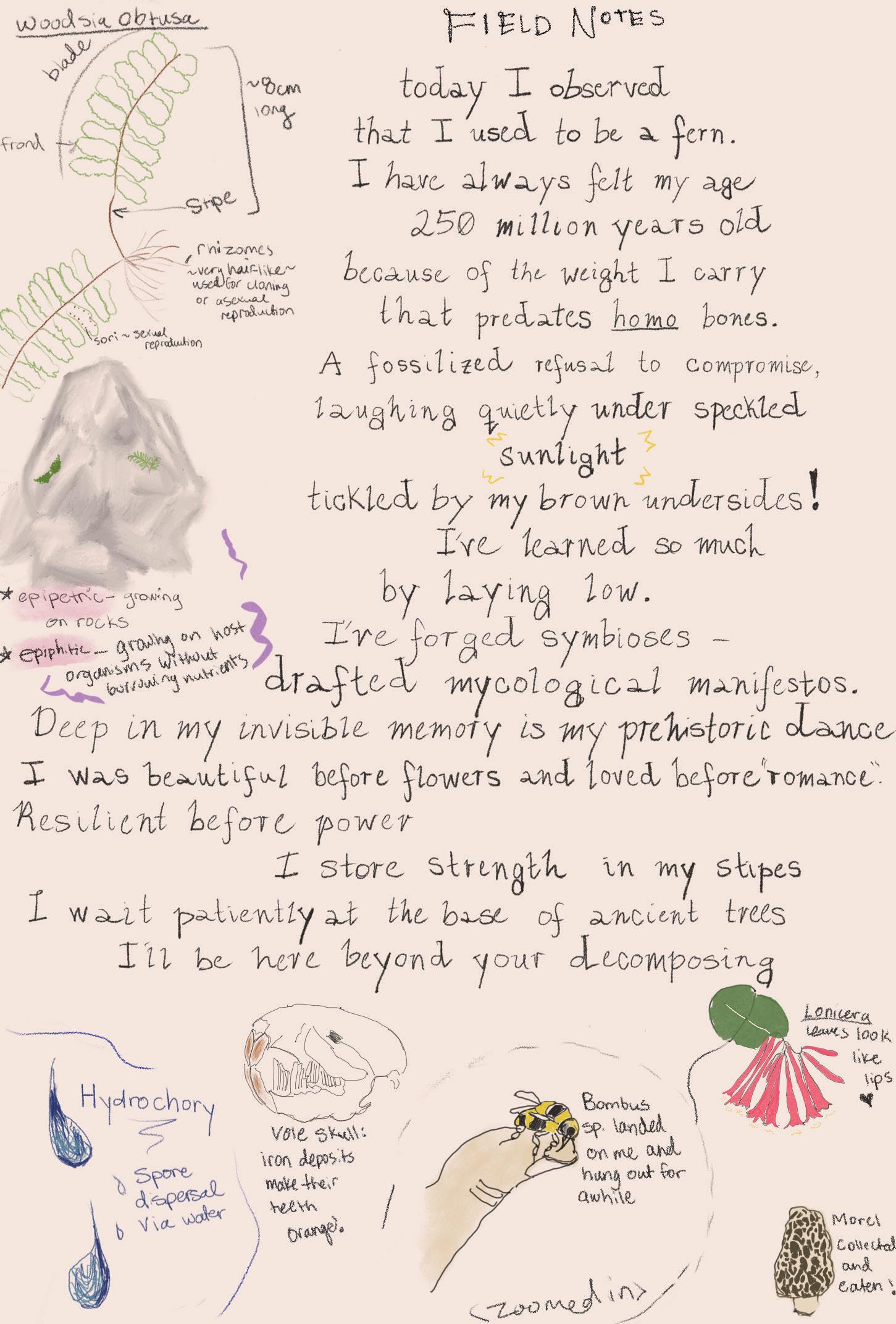

Echolands: Ethereal Landscapes of Becoming Words and Art by Salena (@zonked_art)

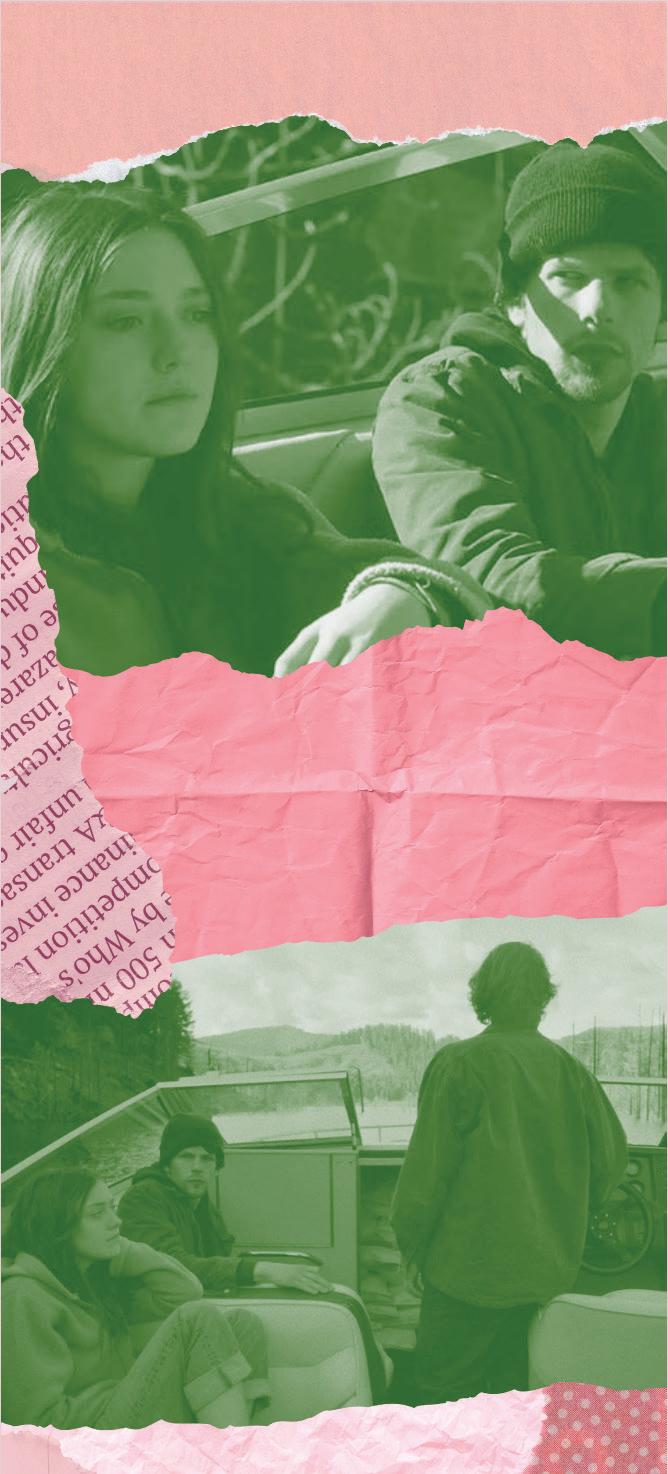

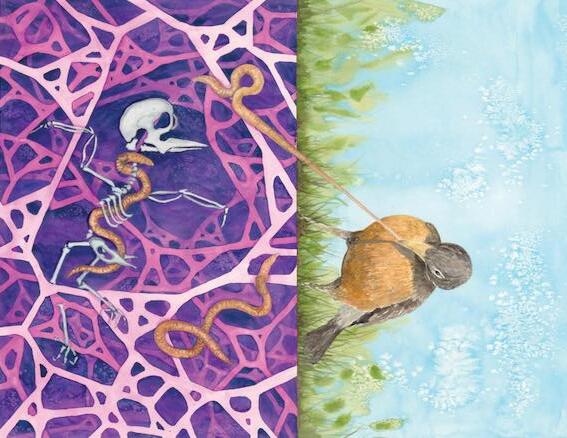

Within Barren Lands: Terra, Fear, and the EcoGothic Words and Art by Tommy Rider

To Refuse Order: Lessons from the Great Dismal Swamp Words by Jamayka Young

Displaced: Native Plant Narratives Words and Photos by Jess Beaudin

It’s the End of the World as We Know It, and That’s Okay Words by Bethany Leigh Greenman

Sparkle2 Words by Sophie Mutiara Nova

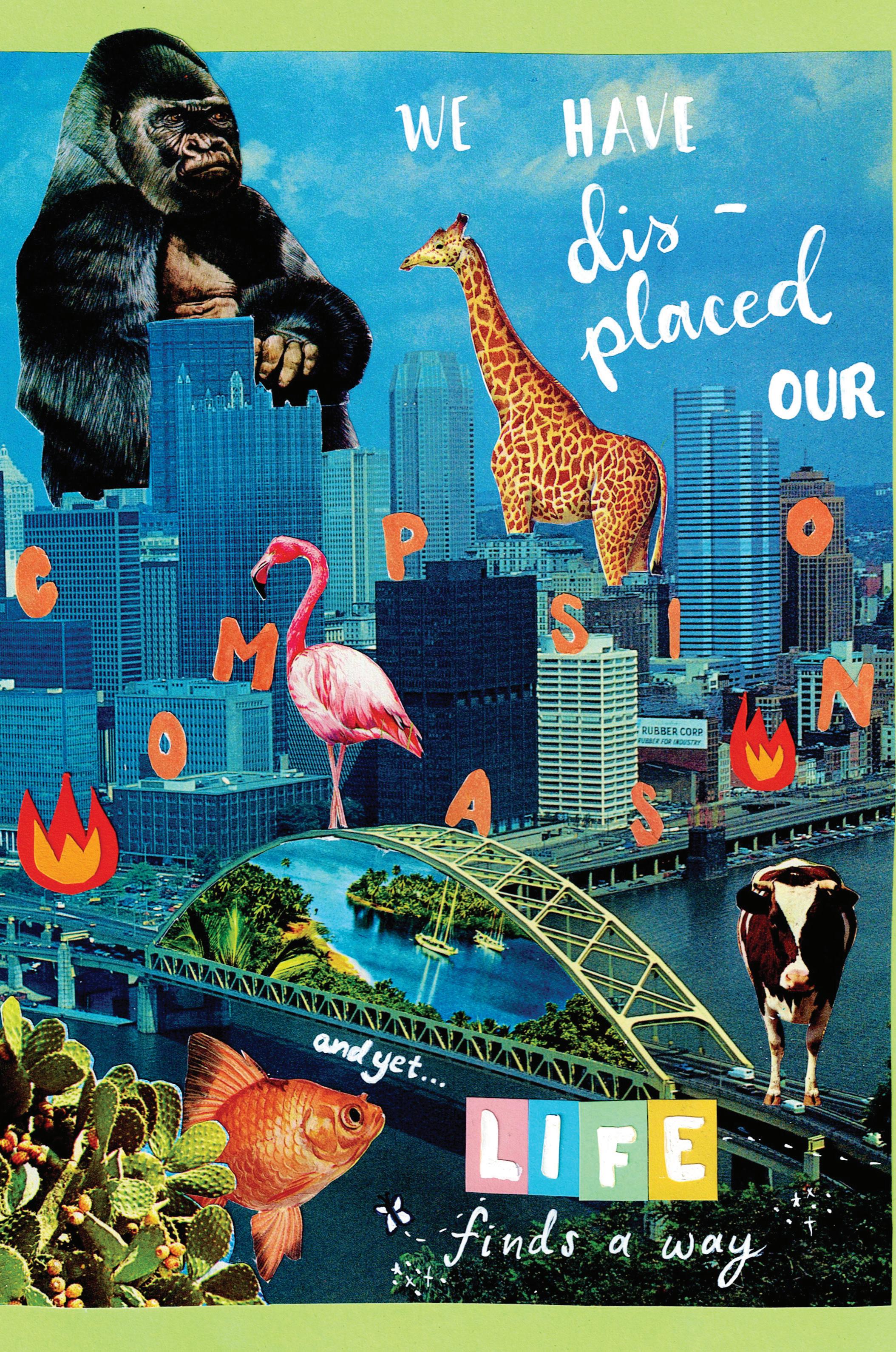

Displaced Compassion Art by McKenzie Janisz

Burning Questions: What LA’s Fires Reveal About Class and Climate Feral Words by Chloe Oloren

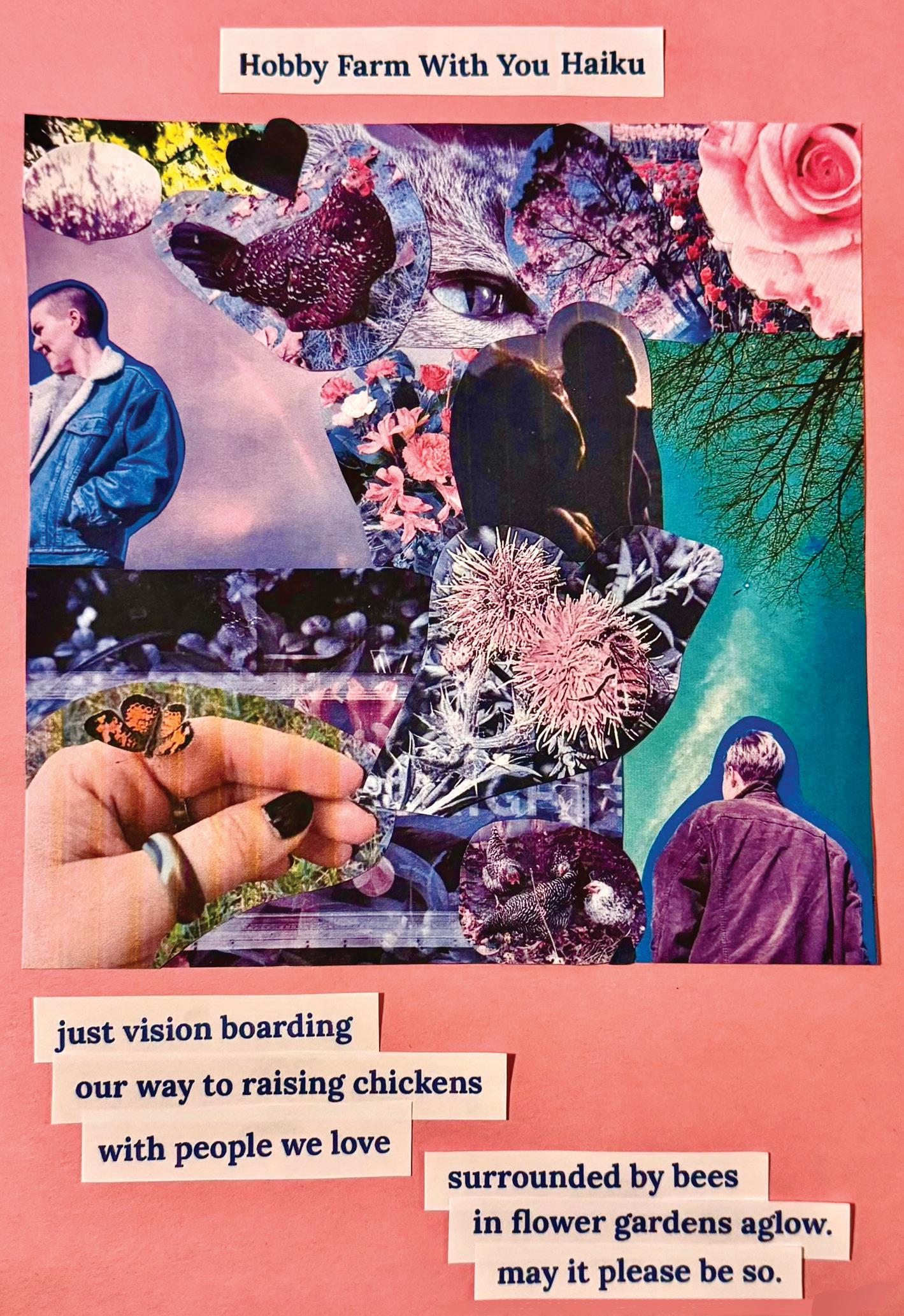

Small Queen, Hot Salad, and Question Party Words and Art by A Lapointe

Parasitology Words and Art by Míša Štorková

Reflections and Relationships

If You Are the Honey, I Am the Hum: How I Handle the Grief of the Bees and Ecological Decline Words by Ann McCann

Valley Girl, Riverside, 2010 Words and Photos by Kota Ball

The Land is a Friend Words by Emmye Vernet

Arrivals Words by Zoe Grace Marquedant

Mind, Body, and Bouldering: an exploration of ourselves and the rocks we climb

Words by Kam Bradley

Mangoes and Black Ants Words by Shaniqua Harris

The Birds and the Bees Art by Natalie Deam

On Growing In Tough Places Words by Kam Bradley

A Rage Room in the Garden Words by Christine Leistner

Forest Full of Names Words by Eleri Denham

Dig Deep: A Queer Perspective on Horticultural Therapy Words and Photos by Rhyker Dye

A Crip’s Reading of Heroes and Saints Words by Casper Orr

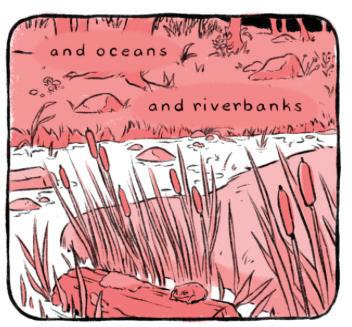

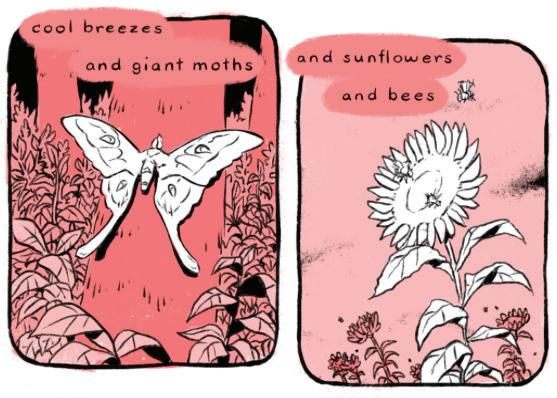

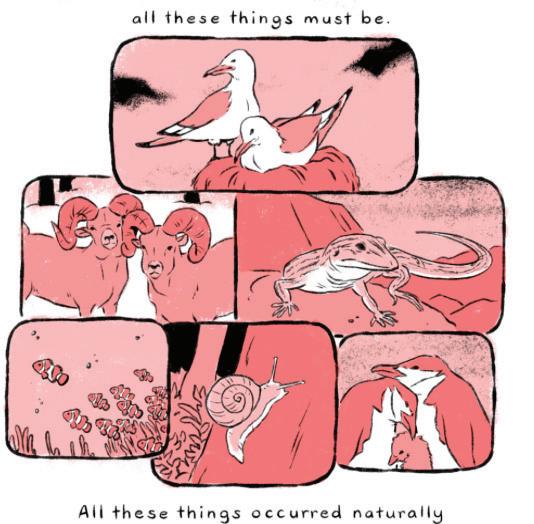

Natural You and Me Words and Art by Alayna Cabral

Cycles II Words and Art by Morgan Hyatt

Words by Casper Orr

Author’s note: Within this text I will be discussing numerous historical literary figures and their partners when applicable. However, these figures were not infallible people. Although I did not find it possible to mention their transgressions within the piece, I would like to be clear I am not attempting to white or pink wash the damage done by some of these artists and their lovers. Within this essay, I will be discussing figures such as Walt Whitman, Peter Doyle, and Ralph Waldo Emerson—all men who had perpetuated harm. Whitman was a pedophile and a racist, which was reflected in his writing. His partner, Peter Doyle, had been a soldier in the confederate army in the civil war. Ralph Waldo Emerson’s writing, despite being staunchly anti-slavery, had racist undertones. These men were not good men, but their influence on Queer nature writing has been undeniable. To understand just how far we’ve come, I feel it’s important to recognize the faults of our predecessors.

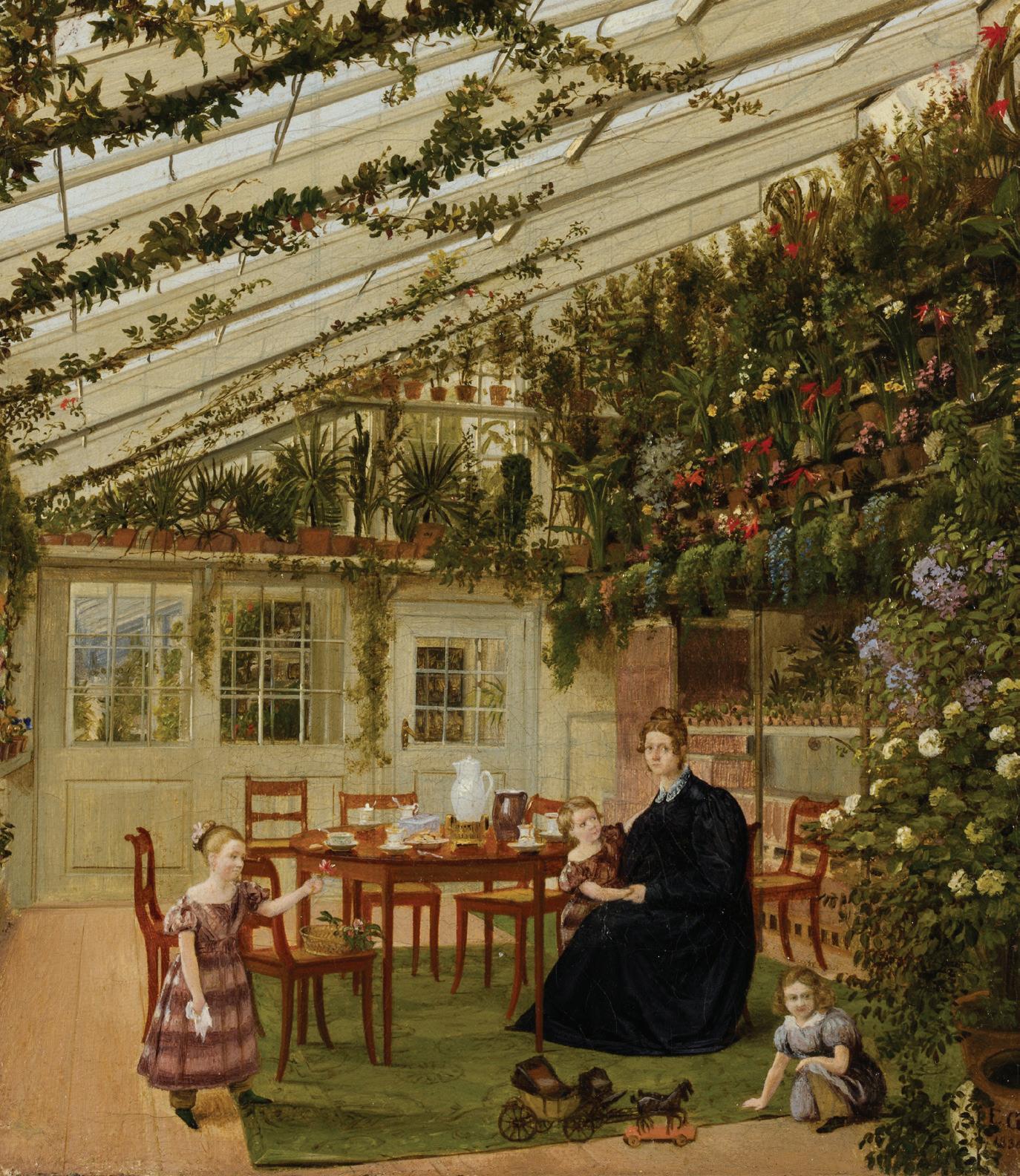

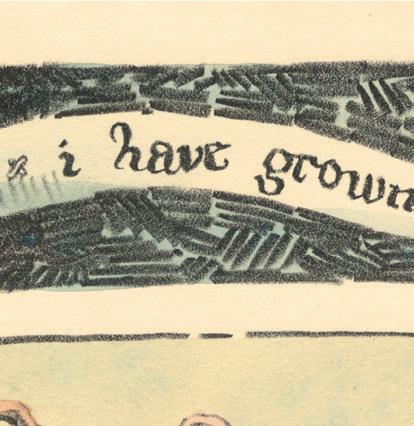

As Queer people, we have long been subjected to the narrative that our identities are “unnatural.” Even if we ignore the thousands of Homosexual animal relationships within nature, we can clearly observe this same affinity between the natural world and Queerness in different art and literary movements. In movements such as Romanticism, Modernism, and especially Transcendentalism, Queer authors flourished. Oftentimes, our favorite writers today set academia on fire with discourse; poetry that was so Gay, everyone and their mothers had to go outside and touch grass— I’m looking at you, Walt Whitman.

So what sparked this Queer relationship with the Transcendental movement? It’s hard to pin down, just as the true nature of Transcendentalism was, which was widely debated among artists within the movement. There was not one specific mold for the Transcendentalist to fit, no rigid rules or hard constraints assigned to the ideology. Mary Oliver best described the very nature of its philosophy in her collection of essays, Upstream, as being “hardly a proper philosophy” due to its loose and ambiguous ideas. It had the ability to mean something completely new to each individual. During the rise of the literary movement, from 1835-1855, this would have been an enticing opportunity for Queer creatives, sick of a society with no flexibility and little sympathy for those outside of their small, compact boxes with no room to breathe.

Although Transcendentalism was notoriously difficult to pin down, a key tenant in nearly all interpretations of this historically Queer literary movement is the unity of all creation; the idea that we are all connected. Perhaps this is why so many Queer artists flocked to Transcendentalism—a newfound feeling of normalcy without having to play a game with rules that actively disclude them.

Take Thoreau, for example, one of the most notable figureheads of the movement. Largely labeled as a “reluctant heterosexual” in modern academia (though this has only shifted within the past few decades), Thoreau’s work included an abundance of homoeroticism, which encouraged his contemporaries to speculate on his sexuality. Not to mention that he was very close with his mentor and friend, Ralph Waldo Emerson. In fact, it’s speculated that Thoreau had a deep attachment to both Ralph and his wife. However, unlike many other of his Queer peers, Thoreau was reported to have an emotionally detached quality to him, which most likely led to his writing excluding any explicit conversation around his personal desires. It is theorized that Thoreau’s nature—selfisolating and “rarely tender”—was a product of his feeling unable to express his desires, becoming increasingly closed off the older he got, the longer he was forced to hide these fundamental parts of his identity away.

Transcendentalism grew a following of revolutionaries, tired of living in a system with

strict binaries. Anti-gender essentialist and Butch icon Margaret Fuller, most well known for her novel, Woman in the Nineteenth Century, was among many Transcendentalists disillusioned with industrialism and patriarchal structures. Throughout Fuller’s entire career, she wrote about women, specifically the relationships women have with one another. In fact, 19th century women’s literature was rife with romantic engagement between women and an exploration of sexuality. Transcendental literature was no exception. In Fuller’s memoir, Memoirs of Margaret Fuller Ossoli, her readership gets a better understanding of her proclivity towards the depiction of women’s relationships.

The scene rose before me, very unlike reality, doubtless, but majestic and wild. I was the little Harry Bertram and had lost her,-all I had to lose,-and sought her vainly in long dark caves that had no end, plashing through the water; while the crags beetled above, threatening to fall and crush the poor child.

In this recollection of her first love, Fuller unveils a Queering of social norms. She loves this woman, but she feels she cannot express her love for her as a woman. She can only express her desires through the emotions of a man.

And we can’t ignore Walt Whitman, one of the Queerest writers of the movement. Most notable—and controversial—for Leaves of Grass, Whitman set academia ablaze with his explicit homosexual writing. The “Calamus” poems celebrated the “manly love of comrades,” a love that Whitman was quite familiar with. Scholars have long theorized that the Calamus poems were inspired by Whitman’s long term romantic partner, Peter Doyle. Although Whitman never came out as Queer to his speculating contemporaries, letters written by him and Peter were published five years after his passing. To get a better understanding of their relationship, we can take a look at what Doyle had to say about their relationship in a letter to a friend:

We felt to each other at once…He was the only passenger, it was a lonely night, so I thought I would go in and talk with him. Something in me made me do it and something in him drew me that way. He used to say there was something in me had the same effect on him. Anyway, I went into the car. We were familiar at once—I put my hand on his knee—we understood. He did not get out at the end of the trip—in fact went all the way back with me.

Their relationship was uncommonly open for its time despite Whitman’s denial, but was this really necessary? The couple had several photographs taken together, posed together affectionately during an era in which photography was still a luxury must could not attain. Not only did they partake in several of these luxuries of the time, but they had them together.

Transcendentalism and Queer nature writing didn’t end in the 19th century; it’s still alive today. To take a look at modern Transcendentalism, I want to look at authors Mary Oliver and Gabriela Mistral, two of the most innovative and gameshaking modern Transcendentalists.

A beloved contemporary within the Transcendentalist movement that is unfortunately often left out of the literary canon is Gabriela Mistral. Mistral was born in Chile in 1889 under the name of Lucila Godoya Alcayaga, later taking on the name she is most well known by to publish her poetry under. Her poetry focused on advocacy for the rights of women, children, and the impoverished. She not only stood beside the marginalized communities within her home country, but she defended communities across the globe. Although activism and radical political ideologies were always a key tenant to Transcendentalism, first wave authors tended

to write close to home. Gabriela Mistral was a revolutionary off of paper as well, later becoming a Chilean diplomat to advocate for the rights of women worldwide.

Not only was Mistral’s poetry a form of advocacy, but it was a way for her to process her Queer identity within a conservative society. She wrote extensively about forbidden loves, and while these poems were not explicitly Queer, her relationship with Doris Dana was. It was her poetry written about Queer love that won Mistral a Nobel, making her the first Latin American woman awarded a Nobel Prize for literature.

As previously stated, the Transcendentalist philosophy is not exactly concrete and means many different things to many different people. In the inception of Transcendentalism, its stance on organized religion was not an exception to this shape-shifting principle. Most authors agreed that the first and foremost authority of any person was

the individual who may decide on whether or not they believe in a god. Most Transcendentalists gave credence to those who searched for a god on their volition without outside influence, while other great thinkers were on a different page; god was personal experience, reaching ever closer to divinity. This was not something that religion could assist one with. Mistral was not only on a different page, but reading out of an entirely different book.

Growing up Catholic, Gabriela Mistral was a part of the Secular Fransciscan Order, the third branch of an order that followed the practices and observances of Saint Francis of Assisi. Her involvement with religion and the church was a great change seen within the Transcendentalist movement, as was her incorporation of her faith in her writing. In short, this third branch of the Franciscan Order commits itself to the service and advocacy of marginalized communities, adoration for natural creation, a belief in the unique value in each individual, and a faith in the personal god. Despite Transcendentalism historically being antithetical to organized religion, the overlap in these philosophies are great, both seen intertwined within poems such as “Tiny Feet” and “Decalogue of the Artist;”

II.There is no godless art. Although you love not the Creator, you shall bear witness to Him creating His likeness.

X. Each act of creation shall leave you humble, for it is never as great as your dream and always inferior to that most marvelous dream of God which is Nature.

– Gabriela Mistral, Decalogue of the Artist (Commandments 2, 10)

With a new wave of Transcendentalism established by Gabriela Mistral, anything had officially become possible. Mary Oliver, author of “Wild Geese,” saw this and ran. In

Citations

Lybarger, Jeremy. “Walt Whitman’s Boys.” Boston Review, 3 Mar. 2024

her collection of essays, Upstream, Oliver writes several essays dedicated to her Transcendentalist inspirations, including Whitman, Emerson, and Wordsworth—all men who were involved in sexually transgressive art. While these authors shaped Oliver’s voice, second wave Transcendentalism was no longer Whitman’s literary movement.

After coming out as a Lesbian and leaving the church and her husband, Mary Oliver left the Midwest and moved to New York where she met her life partner, Molly Malone Cook, in the late 1950s. Both as a child and a professional poet, Oliver sought comfort in Transcendental literature. Growing up Queer in the rural Midwest and surviving sexual abuse at the hands of her father as a young girl, the words of Whitman, Emerson, and Wordsworth were what helped her cope with such a painful childhood. Oliver fell in love with the Transcendentalist philosophy and its reverence for nature, pioneering the second wave of the movement with a focus on healing.

Unlike the originators of Transcendentalism, Oliver set out to make poetry more accessible to readers. Through her interpretation of Transcendentalism’s key tenant of a unity of discovery through nature and art, she strove to create art with as few barriers as possible to truly connect all of creation through art. Through this initiative, Oliver not only pioneers a new wave of Transcendentalism, but poetry as a whole. Poetry that we all have a home in.

Transcendentalism is no longer what it was in 1835, when its canon writers were predominantly male and white. Now, Queer writers of all backgrounds are starting to thrive and grow in the field of nature writing; Eduardo C. Corral, Akwaeke Emezi, Janalyn Guo, Petra Kuppers, and so many more. Modern Queer writers continue the tradition of weaving Queerness and nature into one concept, inextricable from each other.

Porter, Lavelle. “Should Walt Whitman Be #cancelled?” JSTOR DAILY, 17 Apr. 2019

Murray, Martin G. “Pete the Great”: A Biography of Peter Doyle, 1994 Painter, Nell Irvin. “Ralph Waldo Emerson’s Saxons.” JSTOR, Mar. 2009

Marcus, James. “Thoreau in Love.” The New Yorker, 11 Oct. 2021

Boylan, Jennifer Finney. “If I Had Loved Her Less: On a Queer Reading of Henry David Thoreau and the Daily Performance of Manhood.” Literary Hub, 13 Sept. 2021

Kiffer, Selby, and Halina Loft. “Literally in Love: The Story of Walt Whitman and Peter Doyle.” Sotheby’s, 25 July 2019

Young, Mathilda. “Celebrating the Legacy of Poet Walt Whitman This LGBTQ History Month.” HRC, 17 Oct. 2019

Wood, Mary E. “‘With Ready Eye’: Margaret Fuller and Lesbianism in Nineteenth-Century American Literature.” American Literature, vol. 65, no. 1, 1993, pp. 1–18. JSTOR

“Gabriela Mistral.” The Library of Congress

Habib, Yamily. “The Latina Lesbian Love Story That Inspired A Nobel Prize.” Latina Media Co, 1 Dec. 2021

Words by Dejan Ann Kahilina i Perez

The word for “word” in Hawaiian is the same word we have for “fruit”—Hua.

Hoooo—like the first whisper of dusk from the forest outward—to that ahhhhh—the sigh of relief once gentleness reaches you. To speak our language is to literally engage in the fruits of our ancestors labor. Hua, fruit, words.

Most histories in american textbooks start with Pacific histories at the beginning of the first time a white manʻs boot hit the sand. When in all fullness, the peoples have surpassed open water sailing long before the white man challenged his fear of the ocean. Our peoples have fear of the ocean as well, but in reverence. Most cultures in the Pacific have names, gods, a creation story that begins in the depths to the shore, to the forest, to the mountain peak, to the sky. Pacific worlds have always transcended what was documented of us.

My present day privilege of Queerness will always be tied to Hawaiʻi’s history, because both my awareness of my Queerness and Hawaiʻi’s moʻolelo saved my life.

The fact that same-sex partners are in our moʻolelo, that there were words to describe us: ʻaikane. That there was always a third-gender: māhū. This all happened pre-contamination, precolonial disease, and will continue as there is an infallible survivance in our cultures as evidence through the robust amount of folks identifying as māhū, as using the old moʻolelo of aikāne to describe their love current love stories, as the Hawaiian language continues to be taken up by another kanaka, grown or keiki alike.

“Colonialism will not be the final moʻolelo of our people, so long as we know that our culture and language are beautiful parts of who we are,” Hawaiʻi Poet laureate Brandy Nālani McDouggal provided in a TedxMānoa talk almost 12 years ago, and this statement still feeds. Colonialism threatened to take our stories away, and at one point, was nearly successful. Following the illegal

overthrow of our Queen Liliʻuokalani in 1896, the white businessmen began pushing erasure after erasure: no language, no dance, no culture. Schools began to mandate the physical torture and humiliation of Hawaiian students using Hawaiian language. If you ask our elders today of those days, though, you can hear them remember how the language still thrived and where: at home over the table, in the whispers into their grandbabies hairs, in their dances in backyards for birthdays and graduation.

They thought they had forced fruit to spoil and rot when they forced my ancestors the flesh out of our mouths, but all along, they were hiding the seeds in their cheeks, under their tongues, waiting for the right moment to plant again into trees that their grandchildren could nestle under the roots once again.

Hua, it means fruit, it also means word, in Hawaiian. It also refers to the reproductive organs of each body—the kūleana, responsibility, to think of the next generation. Biological reproduction and procreation is not all that matters, as the poem “Sons” by the late activist Haunani-Kay Trask makes clear. She forged a pathway beyond offering biological children to her nation, slyly reproducing as Haumea did: through the forehead, through thoughts, through thoughts passed on and on and on and on. It is under Haunani and so many other groves I stroll through when I am lost, it is the hua I reach for, and it is the seeds I save.

Kūleana—the word for responsibility and privilege—holds the most promising seeds. I am still only learning my language after three generations of not having it spoken fluently in my family. I am still learning to teach in the way that is through a forest and not a fire, savoring the stories of the needs of new roots. I am still learning what love means. Yet, I do not fear. I am in the forest, and fruits are speaking.

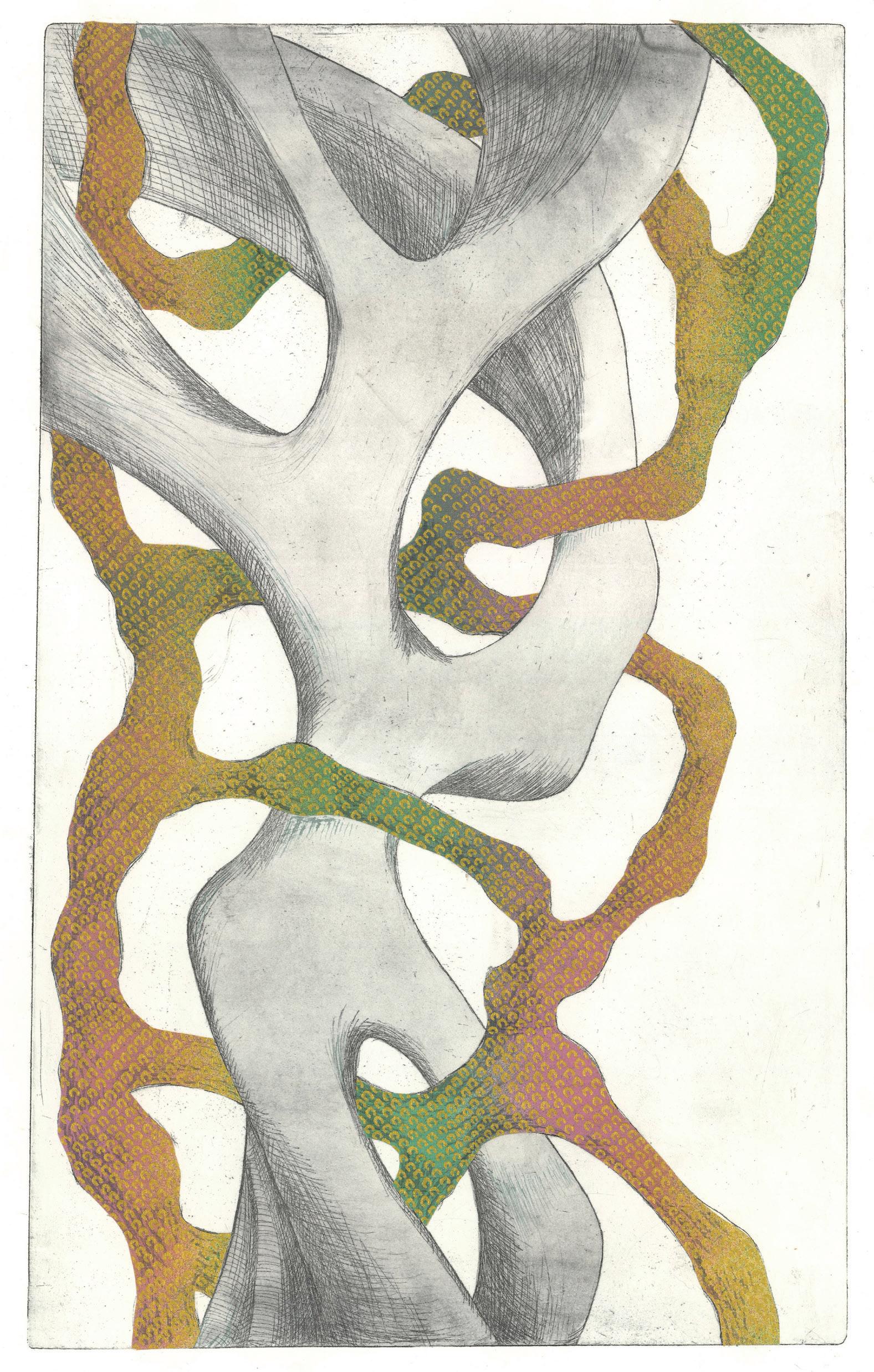

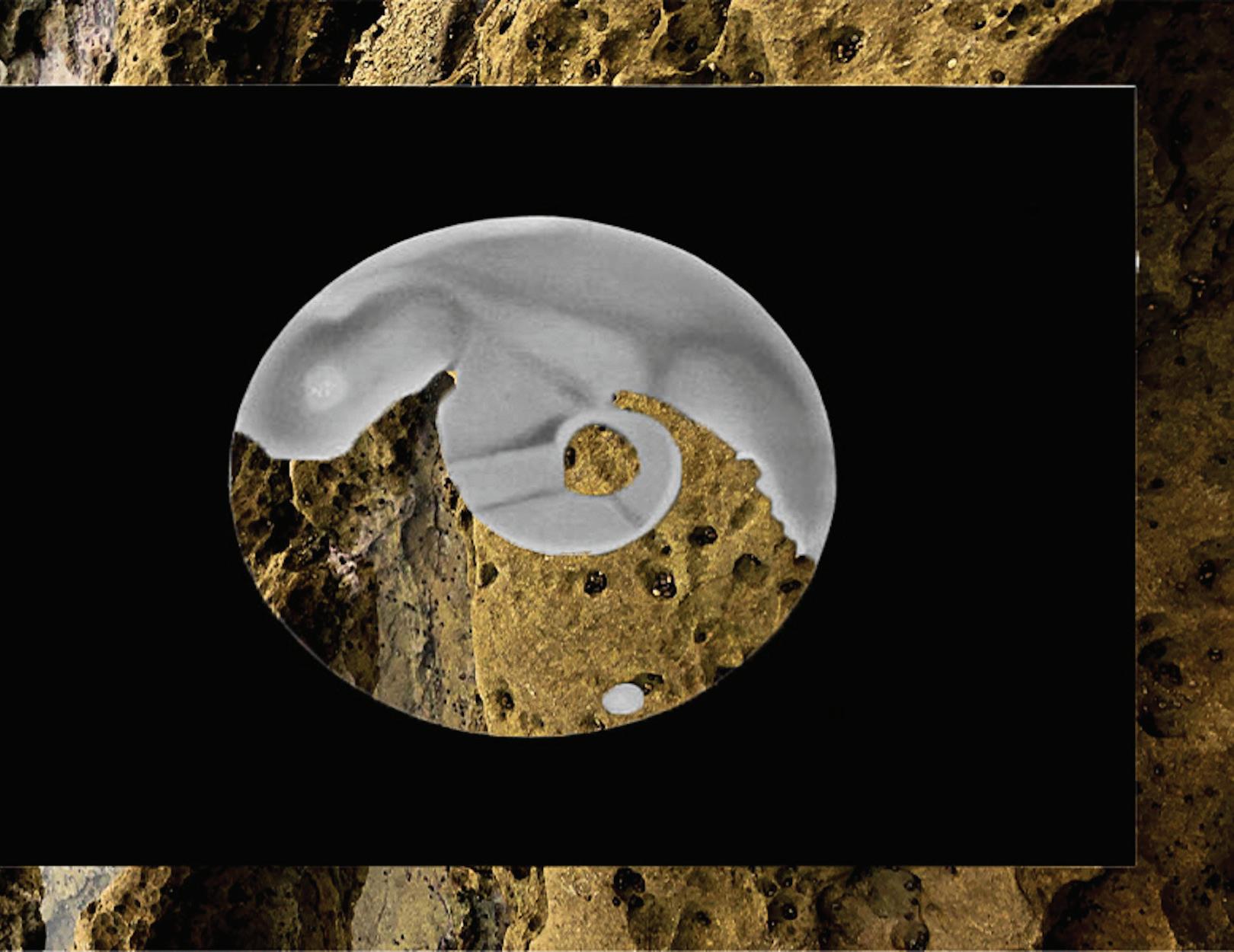

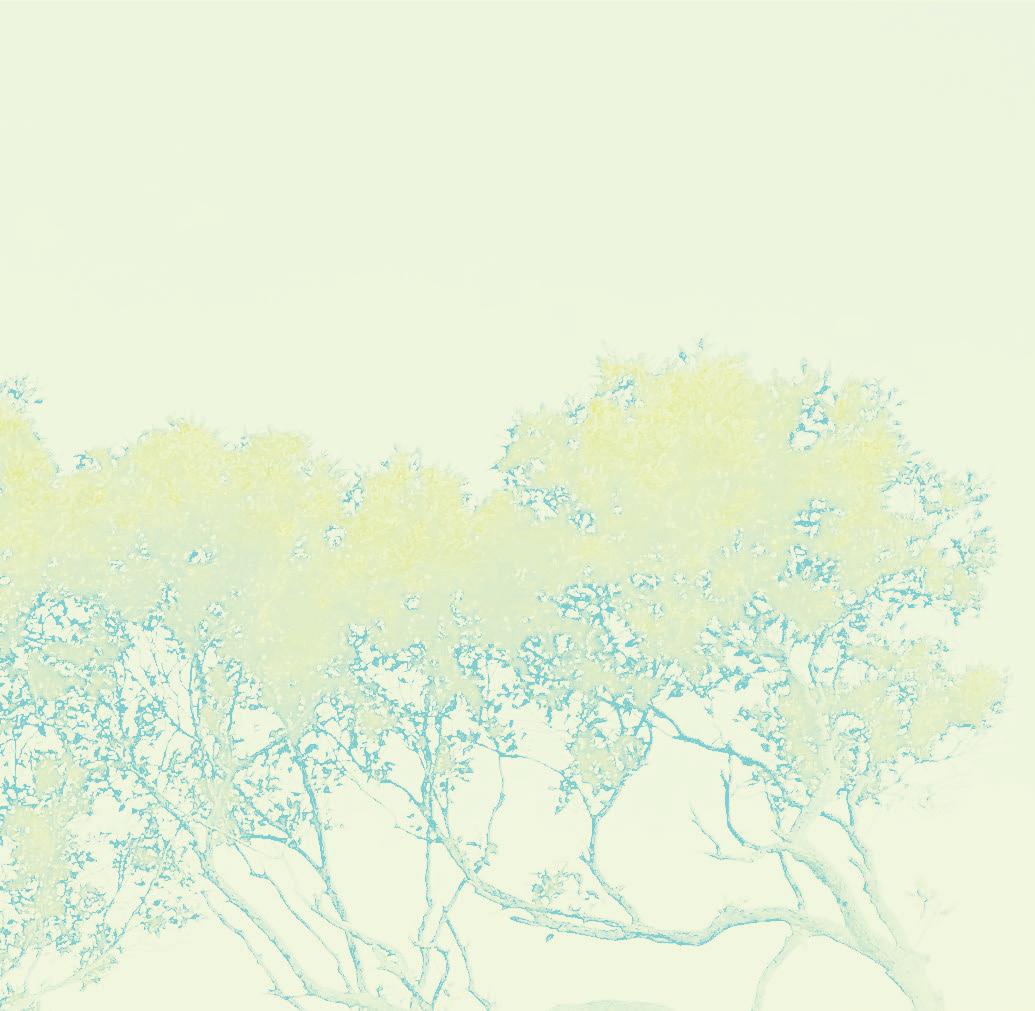

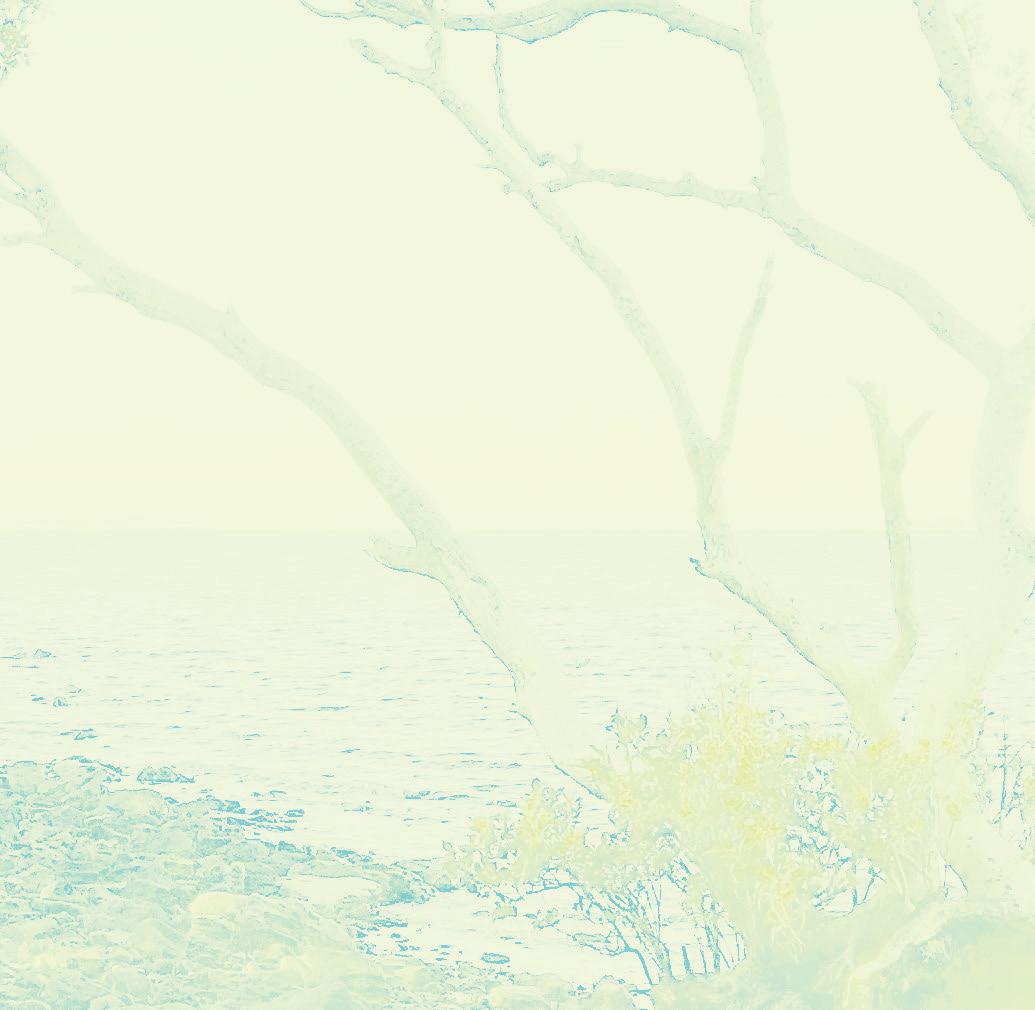

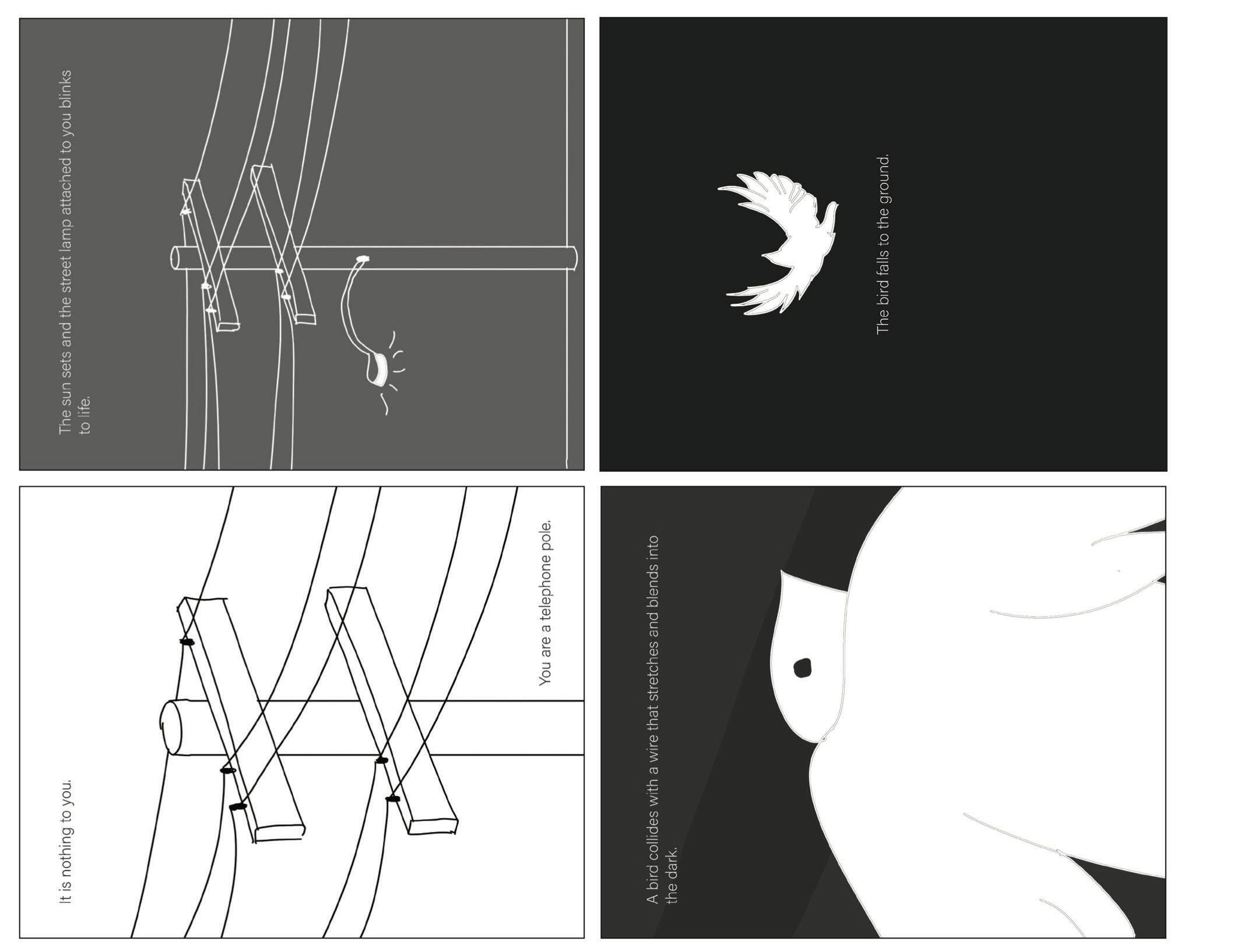

by Salena (@zonked_art)

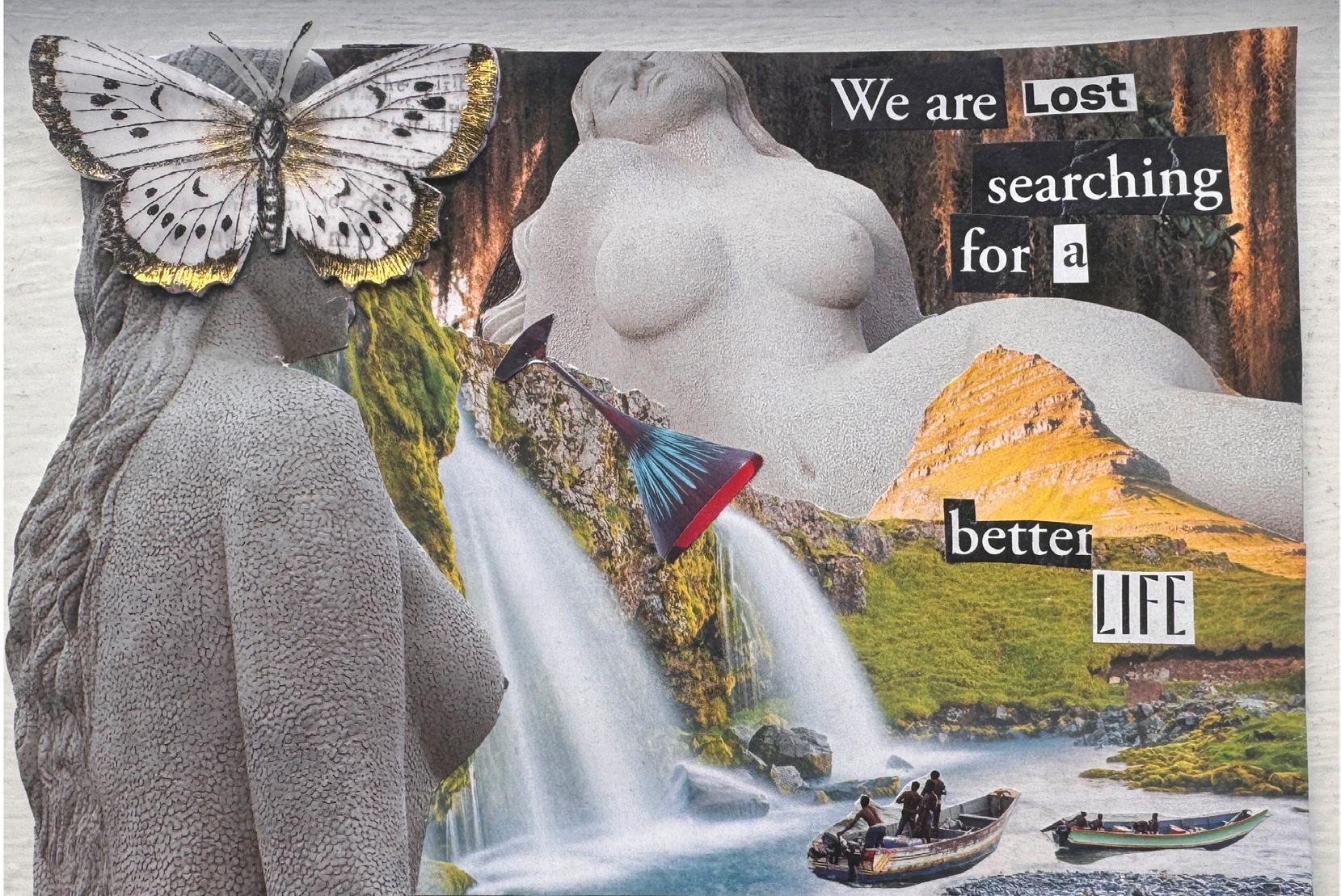

This series embodies Queer ecology by reimagining landscapes as spaces of radical becoming, where human and non-human forms merge in soft rebellion against rigid binaries. It challenges hierarchical constructs, celebrates diversity in all its forms, and invites viewers to consider ecosystems as inherently Queer—dynamic, interconnected, and constantly evolving. Through poetic visuals, the series suggests that to reclaim harmony with the earth, we must also embrace our own multiplicity and fluidity.

Rider

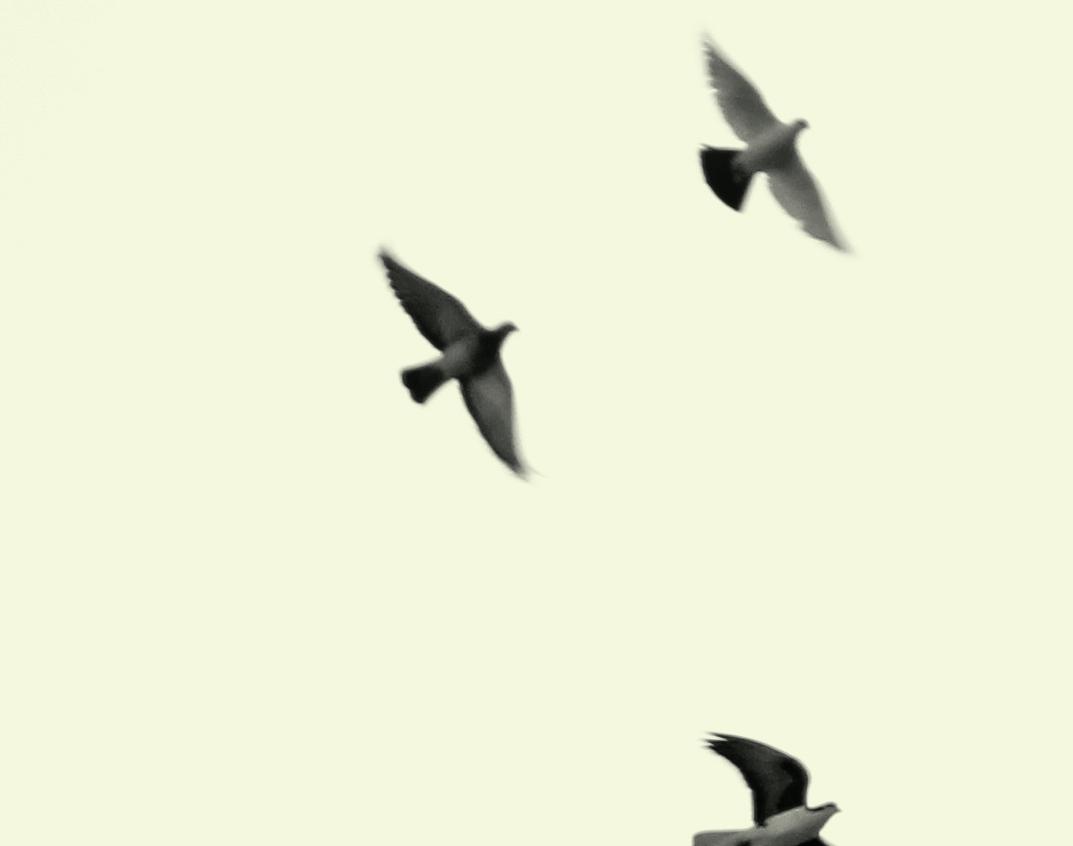

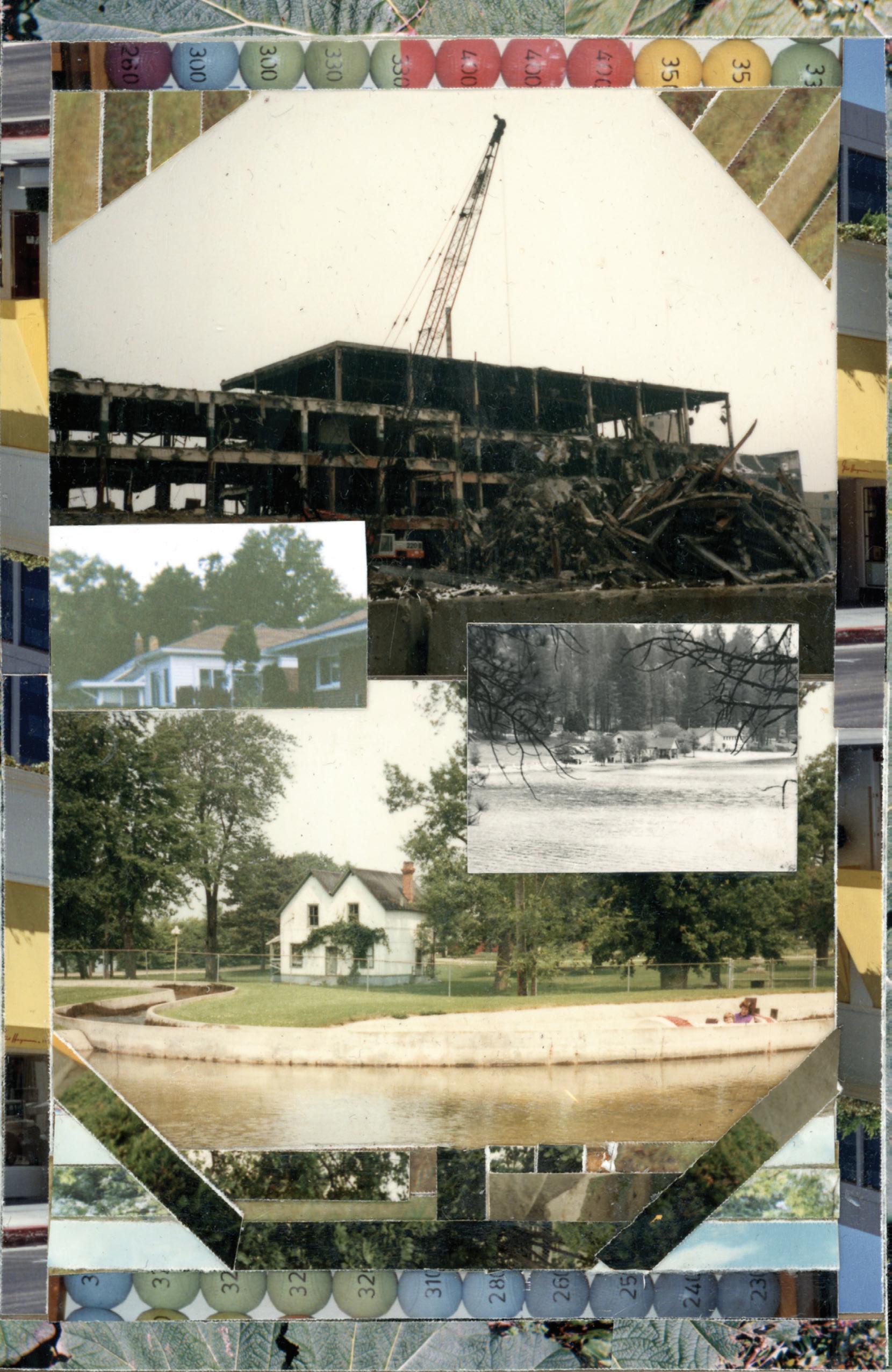

“EcoGothic” is a term that was first legitimized in an anthology under the same name, edited by Andrew Smith and William Hughes in 2013.1 This anthology is considered the first book to examine the Gothic through theories of ecocriticism and is heavily related to Canadian Gothic subcategories focusing on colonization, decolonization, wilderness, sublime landscapes, and romanticism (Hughes, 2018; Sugars, 2014). I would argue that if landscape is as highly political as ecocriticism would suggest, then the Gothic depiction of Canadian wilderness can also be understood through a similar lens.

In this work, I propose that we understand the land not as an inanimate or fixed background for human experience, but as one of the characters in the creation of personal and national narratives. Representations of the land can be understood as having the power to create feelings of fear, and even paranoia in the viewer. As Cynthia Sugars (2014) argues in “Canadian Gothic,” this reconstruction of the land is important as it facilitates us in shifting the question from the conventional Gothic approach of “Who am I” to an approach that shapes the Canadian ecoGothic of “Where is here?”

My research on the ecoGothic genre has largely been through visual creation centred on the use of photography. This work was created in response to the dominant visual culture in Canadian, specifically Albertan, culture and colonial history. This research became the foundation for building and creating a new understanding of the ways identity impacts our relationship with the land. My art exhibition, Within Barren Lands, is a visual representation of this research creation, and acts as a space where I can invite the viewers to consider their place in land, horror, and identity outside traditional academic articles.

As Sugars (2014) and Edwards (2005) state, Gothic history within Canada was created by settlers to legitimize the settlement of the colony and create a fake claim through developing new folklore and superstitions while ignoring established mythology from residing Indigenous Peoples. They further claim that colonists were haunted by the lack of spiritual identity, showing they had no connection to the land outside occupying it. In comparison, the “Old World” Gothic, which often referenced medieval Europe, referenced a deep connection to the history and oppression on the land (Angelis & Savolainen, 2016; Launis, 2016). Thus in the “New World,” spectres haunting the settlers would have proved they had historical antiquity; “[g]hosts, in this context, are not objects of fear, but of fulfillment. To be haunted is to have one’s place as a historical subject validated” (Sugars, 2014, p. 69). This allowed the Canadian Gothic to develop in such a way that promoted fear of the wilderness (Edwards, 2005; Murphy, 2013). The terrain became a monster, an amalgamation of anything deemed as the dangerous “Other” to the status quo and the nation’s current fears (Ancuta, 2015; Angelis & Savolainen, 2016). The “Other” is an individual or group of people who are viewed as and treated as though their inherent nature is alien and different to oneself. Through dominance hierarchies the act of othering often resorts in not only social ostracisation but systematic violence.

1Stylized as “ecoGothic” within the anthology, it is the combination of “ecocriticism” and “Gothic.”

Although serving the same purpose of furthering colonial agendas, visually the promotion of settling Canada focused more on selling the land to settlers as “empty” (Frye, 2002; Sikora, 2016; Sugars, 2014). This narrative claimed that the land needed cultivation and white domination, while still in awe of the sublime wilderness. Both the fear and fetishization of the landscape furthered a national agenda and allowed land to become a tool of propaganda to, regardless of the framing, position the white settler as the pitiable victim of the untamable landscape, and brave cultivator in the New World (Angelis & Savolainen, 2016; Bondar, 2013).

After establishing the land as a threat, the Canadian Gothic further separates the untamable landscape from society (Ancuta, 2005; Sikora, 2016; Sugars, 2014). This binary thinking of man vs land then scaffolds into excluding marginalized people from the dominant group whether it be by race, class, gender, etc. (Murphy, 2013). To “Other” an individual or group of people is to separate yourself from them, to dehumanize and see them as a threat to the norm of social rules and traditions or physical wellbeing (Ancuta, 2005). The Gothic utilizes this through a process known as monsterization, having the “Other” transform mentally and/or physically into a beast which the audience and hero can no longer relate to or empathize with. Often in ecoGothic it is the land that is corrupting an individual, contaminating them and making them inhuman (Ancuta, 2005; Sikora, 2016; Sugars, 2014). This subtext then communicates to the audience that the “Other” is corruptible, dangerous, and a threat to the status quo. In this context, Canadian Gothic functions as a tool to further demonize and disenfranchise groups while still manipulating the narrative of the land.

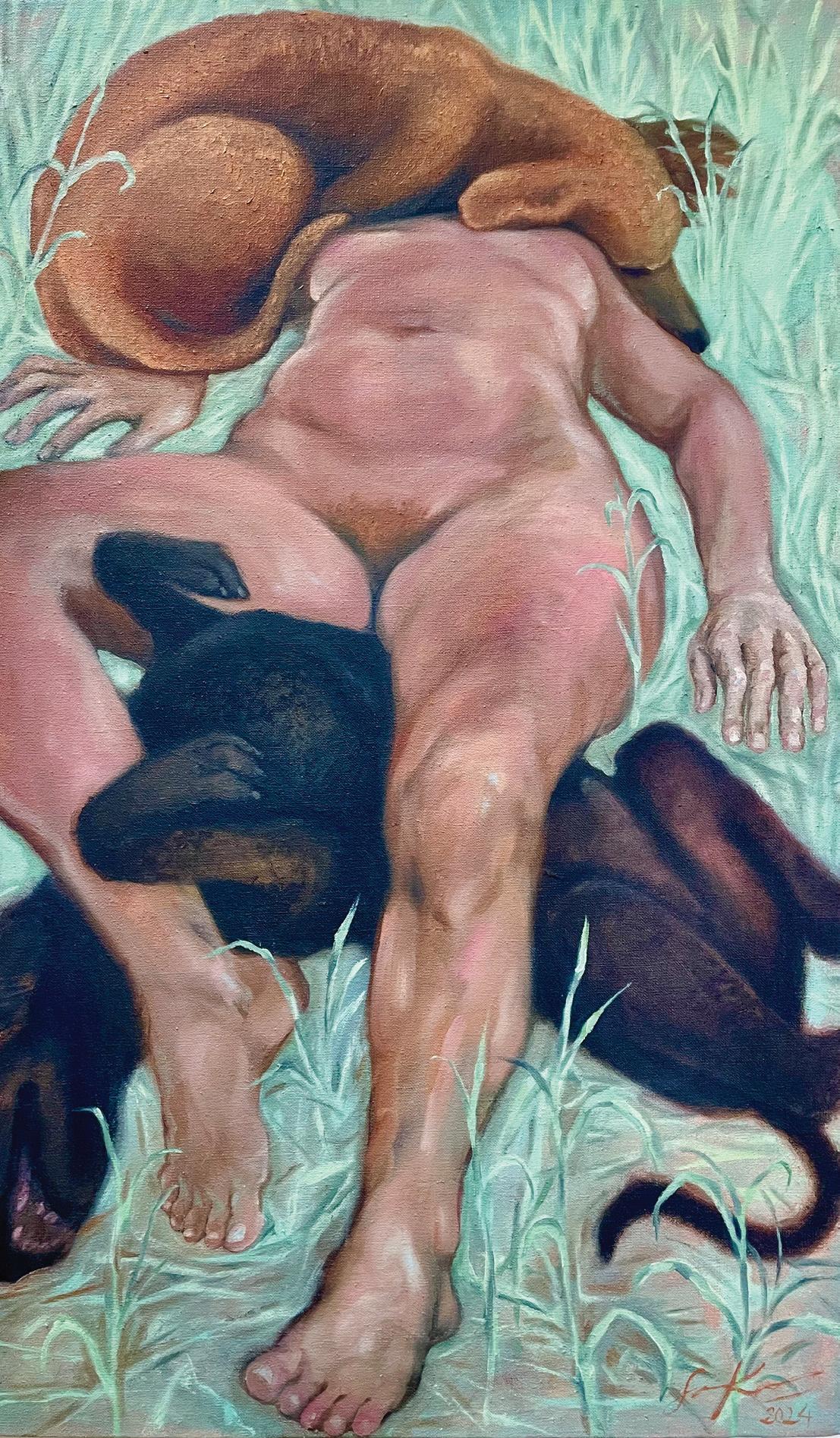

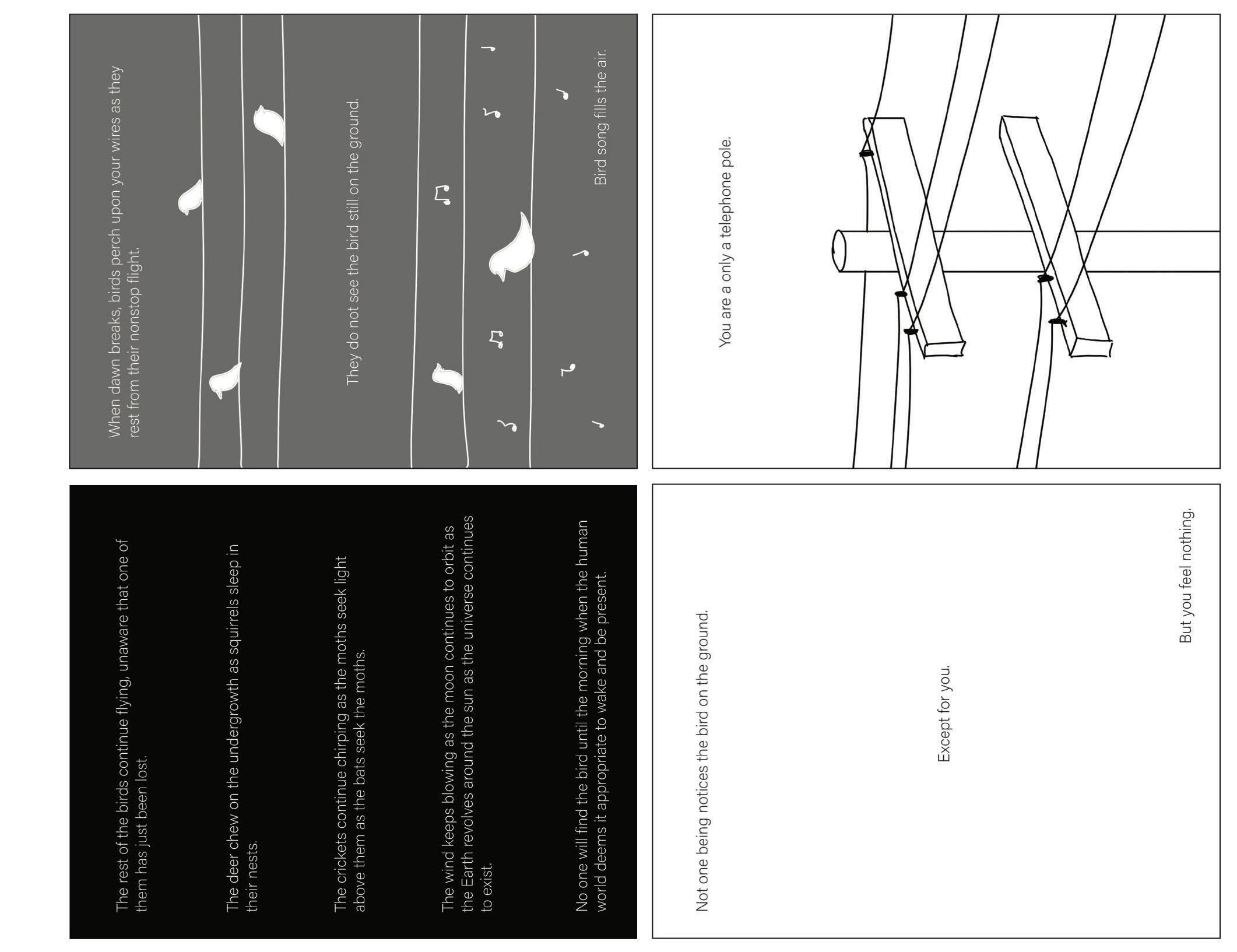

Artist Statement

The settlement of Canada and the subsequent literature, art, film, and culture created have shaped an identity around land and what it means to experience it. As an Albertan artist, I see my work as a dialogue with the subliminal nature of the landscape. My artwork has been grounded in examining how the land is used to simultaneously uplift and outcast people, animals, and wilderness. In this work, I blur the lines between the viewer’s many possible identities: as aggressor, victim, and voyeur, to question any comfort the viewer might feel while engaging with the work from one of these many points of identification. I highlight photography’s capacity to present both a subtle and inaudible threat, through the colonial tool of representing a landscape as a fixed object contained by border, as well as presenting it as a character within itself filled with a tense atmosphere to induce a fictional paranoia. Instead of ignoring the history of the ecoGothic narrative and romanticism of land within the Canadian canon, the research builds on them as a criticism and repossession of the conversation. I have strived to fully embrace the ugliness of the Gothic as a statement of love for the land and people. To be seen as the “Other” is something anyone is capable of experiencing, making no one safe from becoming a perceived monster.

Instead of humanizing these experiences to invoke audience empathy, my research is focused on asking the audience to reconsider what it means to be the threat, and what it means to experience land. The landscape is an active agent in relation to the audience instead of scenery—allowing the viewer to have a conversation with instead of about.

The findings of this research are summarized in a body of visual work including pieces created through film and digital photography, found objects, oil painting, and silkscreen printmaking. A solo exhibition took place in The Little Gallery at the University of Calgary from September 23rd to October 4th, 2024. In this show, the bulk of the documentation of the landscape was represented through projected slides of photographs. This display method is an alternative to traditionally hung and framed prints; it is both a reference to analog mediums and faux documentation, as well as a horror motif in the contemporary art scene. The slides do not allow for a deep examination of the photographs, as they are timed to flip to the next image before a meaningful understanding of the previous can be attained. Street signs printed on and shot imply violence alongside paintings and prints of roadkill and farm animals, both inviting the audience to consider if they are a threat or threatened. As an exhibition, the aim was to further invoke this consideration of paranoia and occupation. While the title Within Barren Lands offers a false sense of security, suggesting there is no danger lurking in the landscape, the trust between the audience and work is lost because the land displayed is visibly inhabited (by either flora, fauna, or monster), a parallel to the false narratives spewed by the colony.

Throughout this research, I extensively studied key concepts of the ecoGothic and noted a consistent theme within Gothic monsters. These act as a form of catharsis, where the status quo is constantly threatened by both the taboo and by alienated groups based on the current social-political climates. I argue that using the Gothic to explore contemporary Canadian issues, rather than focusing exclusively on antiquity, is a natural progression of the invocation of monsters and folk tales. This work sought to explore and define Albertan ecoGothic through visual and artistic means based in photography. The research challenged me to reconsider how I defined and experienced wilderness, belonging, home, and what it means to have a relationship with the land. This is a topic I will continue to explore, both through research-creation and, in the future, by expanding the research methods to include the exploration of archival material related to specific local areas and towns in Southern Alberta. While an important first step, this project has also become the foundation of a larger body of work and dialogue that I hope to continue to investigate.

References

Ancuta, K. (2005). Where angels fear to hover: Between the gothic disease and the meataphysics of horror. Lang. Angelis C., & Savolainen M. (2013). The ‘New World’ gothic monster: Spatio-temporal ambiguities, male bonding and Canadianness in John Richardson’s Wacousta. In P. Mehtonen & M. Savolainen (Eds.), Gothic topographies: Language, nation building and “race” (1st ed., pp. 217–234). Taylor & Francis Group.

Bondar A. F. (2013). Bodies on Earth: exploring the sites of the Canadian ecoGothic. In W. Hughes & A. Smith (Eds.), EcoGothic (pp. 72–86). Manchester University Press.

Edwards, J. D. (2005). Gothic Canada. The University Of Alberta Press. Frye, N. (2002). The bush garden: Essays on the Canadian imagination. Hughes, W., & Smith, A. (Eds.). (2013). EcoGothic. Manchester University Press. Hughes, W. (2018). Key concepts in the Gothic. Edinburgh University Press. Launis, K. (2013). From Italy to the Finnish woods: the rise of Gothic fiction in Finland. In P. Mehtonen & M. Savolainen (Eds.), Gothic topographies: Language, nation building and “race” (1st ed., pp. 169–186). Taylor & Francis Group.

Murphy, B. M. (2013). The rural Gothic in American popular culture: Backwoods horror and terror in the wilderness. Palgrave Macmillan. Sikora, T. (2013). ‘Murderous pleasures’: the (female) Gothic and the death drive in selected short stories by Margaret Atwood, Isabel Huggan and Alice Munro. In P. Mehtonen & M. Savolainen (Eds.), Gothic topographies: Language, nation building and “race” (1st ed., pp. 203–216). Taylor & Francis Group.

Sugars, C. C. (2014). Canadian Gothic: Literature, history, and the spectre of self-invention. University Of Wales Press.

Words by Jamayka Young

Photo by Yazmin Munoz

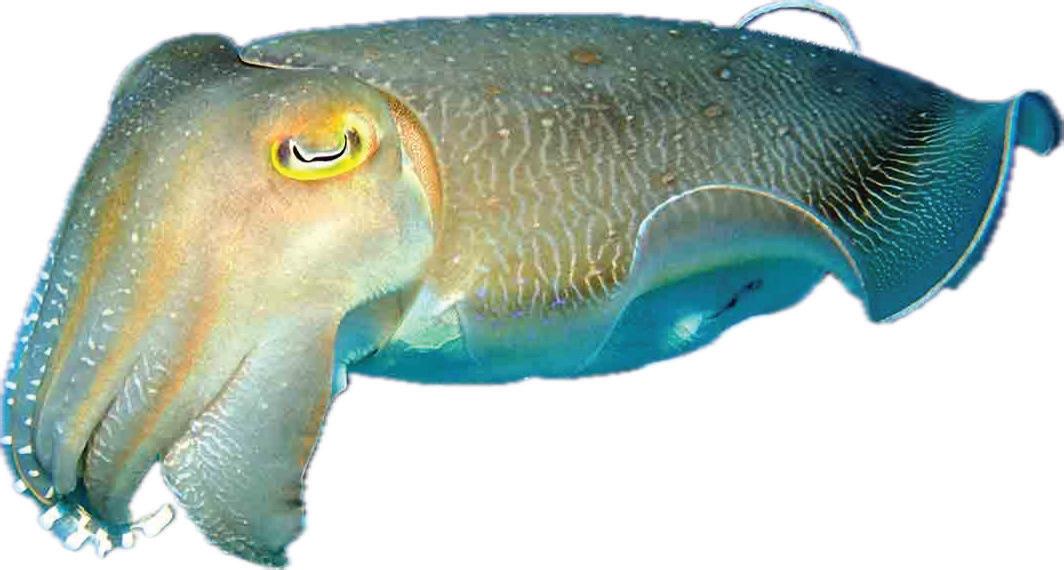

The Great Dismal Swamp, the largest remaining swamp on the East Coast of the United States, stretches across the Mid-Atlantic, from the Southeast of Virginia to the Northeast of North Carolina. The swamp serves as a relic of the original wetland of more than 1.2 million acres that has since been dwindled down to just 1/10th of its original size.

The swamp was named Dismal by William Byrd II, a slaver and plantation owner in colonial Virginia, after his visit to the swamp in 1728. Upon seeing the thick bogs, swampy marshes, and massive mauls of migrating black bears he remarked that the area was a, “miserable morass in which nothing can inhabit” (Blaakman, n.d.).

This statement was declared in direct opposition to the thousands of escaped formerly enslaved Black people, or Maroons, who had found their freedom amongst the impenetrable landscape, alongside the many Indigenous tribes who had been hunting in the region for millennia.

The term Maroon comes from the Spanish term “cimarrón” meaning feral or untamed. As the colonists attempted to bring the Indigenous population and the enslaved Africans under heel, they simultaneously attempted to tame the landscape.

The terrain made safe harbor for those escaping the unthinkable violence of chattel slavery and the encroachment of European settlement. For many escaped slaves fleeing north, the swamp was a critical stop on the Underground Railroad.

For other former slaves in search of freedom beyond the control of white men, they chose to take up permanent residence in the swamp, trading with Native people, enslaved people, and occasionally even white people living outside the autonomous communities they built. Maroonage was not just an escape from bondage, but a chance to truly live as free, not reliant on the tenuous benevolence of northern colonial governments.

While teeming with crocodiles, black bears, and other dangerous creatures, the dense, uneven landscape made it difficult for slave hunters and their dogs to navigate—a significantly more attractive option than the horrors the Maroons escaped from. One such Maroon who found refuge in the swamp, Tom Wilson, remarked “I felt safer amongst the crocodiles than the white men”(Youssef, 2017).

William Byrd was in the swamp scouting the land in order to lay the groundwork for a new capitalist venture. The Dismal Swamp Company, founded in 1763, was a land-speculation company. Byrd schemed with the powerful class of Virginia plantation owners, including George Washington, with the intention of draining the swamp in order to uncover and sell the land beneath it.

Draining the swamp would kill two birds with one stone. Simultaneously increasing the wealth of the growing capitalist class in the early United States, and furthering the settler colonial project of complete domination over the land, over the Native population, over the enslaved.

The ever-growing scale of the colonial project and its violent, slave-labor fueled exploitation of stolen lands had begun degrading the soil. This made virgin land an increasingly valuable commodity.

This viewpoint was in opposition to many Indigenous groups of the region. The capitalists imagined land as a commodity that could be owned by one man or company, rather than the commons of a community. And like any other commodity, it was something that could be used up and discarded when it lost its value. That value was the cash crops grown by the enslaved to be sold in European and American markets.

Outside of the monetary value the land could bring to the slavers, it also served another end. Under the colonial ideology the settler glorifies himself, imagining his role in the world as divinely ordained to manage the rabble, to instill order over the otherwise unruly, casting the world in the image of his pristine, white god.

Marshlands like the Great Dismal Swamp act as the antithesis to this manicured environment, a liminal in-between, an unmanageable space refusing definition, defiant as the Maroons that inhabit the wetlands, refusing their assigned roles as slaves. The Great Dismal Swamp serves as an example of resilience in the face of capitalist, colonial suppression and an outpost of anti-colonial resistance.

The United States continues to be governed by an ideology that demands endless productivity and perfect order. One that attempts to stamp out “deviance” from prescribed order—Queer folks, Disabled folks, immigrants, people of color, and others that subvert the enforced myths of a heterosexual, white, Christian nation. Spaces like swamps, full of disorder, unsteady the ground this empire was built on. The Great Dismal Swamp, in all its liminal landscapes and Maroon encampments, teaches us to refuse definition, to refuse binaries, to refuse refinement, to be unruly.

Citations

Blaakman, M. A. (n.d.). Dismal Swamp Company. The Digital Encyclopedia of George Washington. https://www.mountvernon.org/ library/digitalhistory/digital-encyclopedia/article/dismal-swamp-company

US Fish and Wildlife Service . (n.d.). Great Dismal Swamp National Wildlife Refuge. FWS.gov. https://www.fws.gov/refuge/great-dismalswamp/about-us

Youssef, S. (2017, August 15). The Great Dismal Swamp. https://99percentinvisible.org/episode/great-dismal-swamp

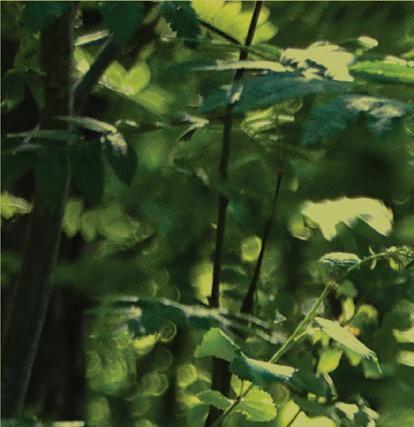

Words ad Photos by Jess Beaudi

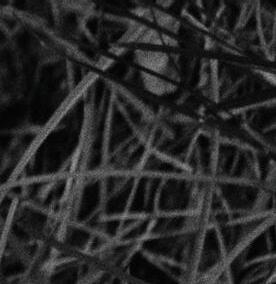

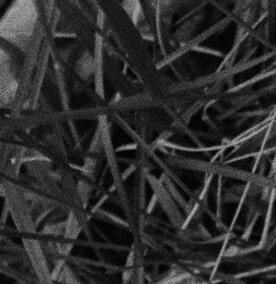

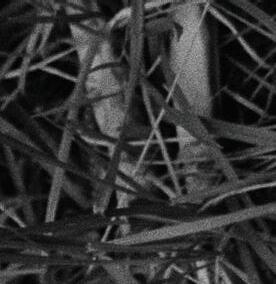

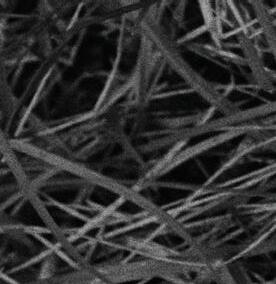

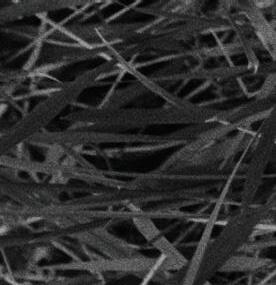

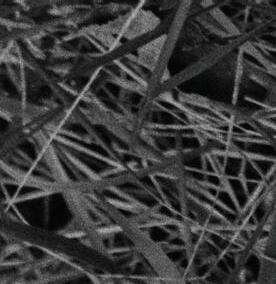

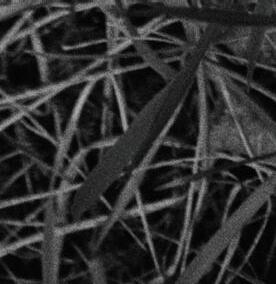

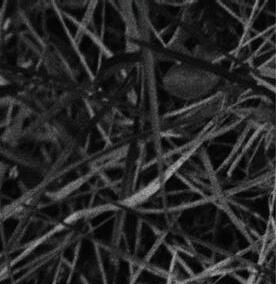

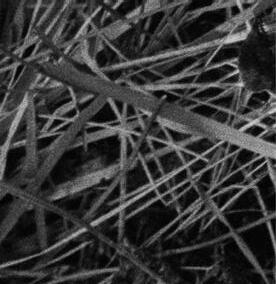

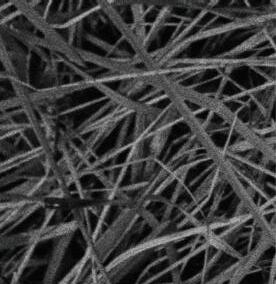

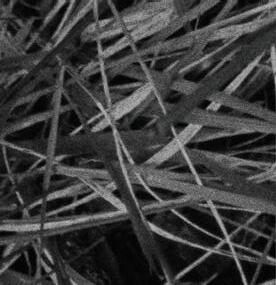

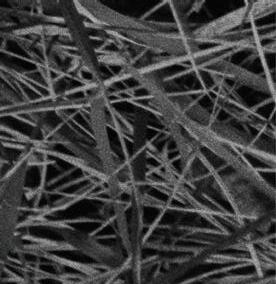

Photoseries;double-exposedfilmdevelopedwithplant-basedfilm developerofsageandchokecherries.6images,1600x1667px.

Displaced: Native Plant Narratives aims to highlight gaps in community and land management that are being exacerbated by an influx of construction in Secwepemcúl’ecw, the traditional territory of the Secwepemc people (so called Kamloops, B.C., Canada), and reflect on the ways we can learn from and work with nature in our communities. In 2022, the City of Kamloops signed a Memorandum of Understanding with the provincial housing authority to create over 500 new housing units. Landscaping plans for any given site must be approved before construction begins, but these plans often overlook preserving the biodiversity of the site. This land management mis-practice mirrors the ways in which Queer and minority communities become displaced as a result of city expansion and gentrification. With proper consultation, indigenous seeds can be saved, and plants transplanted to a temporary home, before being replanted around the new-build in an effort to preserve the site’s ecology. Unfortunately native landscapes are often replaced with ornamental, and sometimes invasive, plants. There is a lack of responsibility in our province to ensure biodiversity and Indigenous ecologies are preserved. Similarly, there is not enough protection for minority communities who get priced out of the neighbourhoods they have lived in for decades. Displaced uses double exposures to illustrate the lasting imprints both the natural world and human intervention leave on one another, and remind the viewer of nature’s ability to persevere, should we work with it, rather than against it. This series photographs each indigenous plant species’ leaves, and their seed heads or fruit, to initiate a conversation of the regenerative properties of our natural environment. The seeds of each species, which the plants produce in abundance, ensure they continue to populate the area as the seeds are spread by wind and animals. These plant species seem to appear spontaneously across the region, much like construction sites have begun appearing in recent years, and pockets of Queerness can be found across a city, even after they have been removed or pushed out of their core neighbourhoods. Displaced asks how communities can embrace the ideas of regenerative ecologies when planning their construction process. How can our governments ensure minimal harm to our natural environment and our communities when mandating construction? To further the idea of responsibilities we have to the land and our communities when developing it, the images in Displaced have been developed with plants indigenous to the areas of construction: chokecherries and sagebrush. Traditionally, developing film uses a toxic chemical process that contributes to ecological degradation. By developing film with organic chemistry, I have taken responsibility for the adverse ecological impacts of my work, and have done my best to minimize these effects. The process of creating film developers from the native environment, which can be returned to the land after use, engages with the feedback loops of nature and community we disrupt with expansion, and how we can choose to work with and re-enter these cycles instead of stopping them entirely.

Words by Bethany Leigh Greenman

Art by Azad Namazie

Cities are ecosystems.

I read that once in school when I was assigned an essay to analyze. Since encountering it, the idea has shaped my worldview. The concept of a massive center for gathering, working, playing, singing, dancing, gathering, working, playing, moving, shaking, being—an ecosystem. A living, breathing ecosystem, with all parts working together in, ideally, harmony.

If cities are ecosystems, Queer people are subecosystems. In every city, we find each other and we keep each other alive. Not only that, we give each other reasons to stay alive. We create clubs and bars, we produce drag shows, we organize movie nights for Paris is Burning because oh my God, Jonathan, you are simply not allowed to be gay without having seen this!

We become each other’s family. It doesn’t matter that I’m mad at Neha, I’m still going to help her move in the middle of the night because her landlord is a bitch. On Christmas, Onyx, Marly, and I are seeing Nosferatu since none of us can go home. Halfway through a game of dreidel, it hits me: this is home now. The realization nearly makes me fall over with gratitude.

There have been flashpoints in my life that have brought the larger city ecosystems into focus— Hurricane Sandy in my beloved homestate of New Jersey, the start of the COVID-19 pandemic when I lived in cozy Boston, and most recently, wildfires lighting up the rambunctious Los Angeles skyline. Nothing has made me feel the pulse of the living, breathing ecosystem that is Southern California quite like the current disaster.

My emotions about the response to the wildfires have been a tangled-up ball of yarn. Unspooling it has shown me I am grateful for what we have, but I need more. On one hand, it is a relief to finally see air purifiers being distributed and widespread efforts amongst organizers to normalize respirator-wearing. On the other hand, it is disheartening to know that, had we as a city not chosen the path of denial of the ongoing pandemic, we would have been in much better shape when the flames began. We already would have normalized respirator-wearing. Air purifiers would be in every home and building. We would have been ready.

Regardless, the mutual aid groups that formed in response to the pandemic have picked up the slack of government. MaskBlocLA, MaskBlocLongBeach, AirGasMicLA, and CleanAirLosAngeles have been distributing N95 masks and air purifiers all over the county. Never mind the fact that many of the members of these groups are Disabled and immunocompromised, the very people who have been shut out of public life because of others’ refusal to mitigate the risk of COVID. The very people others have mocked, ridiculed, or ignored out of discomfort. These “shut-ins” are still serving the people because they know the urgent need will not be met otherwise.

Crises bring out the best in us. Acute crises, that is. In the weeks following a new threat, people band together, offer what they can, and look out for one another. Hell, many donation centers can no longer accept clothes because people have given so many! However, as the crisis goes on, people grow weary. They start to wonder if all this is really necessary, and my God, when do we get to move on with our lives? These people want us to live like it’s 2020 forever, and we simply cannot do that! Sorry you lost your house, but why should that mean I can’t go to brunch? Yes, “the vulnerable will fall by the wayside,” as Dr. Anthony Fauci so eloquently put it, but that’s life. I need to get back to normal. Those who have to stay home because of that will simply have to stay home. If you lost your home, figure it out. Tough, but whatever. You were dealt a bad hand, suck it up. Don’t make me think about it. My empathy has an expiration date.

Eugenics. Survival of the fittest. The idea that we must allow those most vulnerable to perish while the strong prosper and carry on the human race. There is a reason why Disabled people were

the first ones the third reich targeted: they are the easiest to identify as “dead weight.” The “weakest,” according to the capitalist idea of strength that defines it as economic productivity.

To me, Queerness does not exist without community. Perhaps being gay does, but not being Queer. Queerness is a departure from the individualist norm, which necessitates that it center collectivism.

Bisexual and Trans* people are more likely to develop long COVID than their cisgender, heterosexual, and even gay counterparts. This is in large part theorized to be because of the social stigma these groups face in medical settings. Can we call ourselves a community if we allow our fellow members to slip through the cracks of the medical industry in this way?

“Ecology” is most basically defined as the study of organisms and their relationships to each other and their environments. As an organism myself, my relationship to other organisms and my environment has lately been challenging.

In March of 2024, I got COVID-19 for a second time. I got it from my partner at the time while taking care of her. I knew it was stupid to believe a negative rapid antigen test and continue being unmasked around her, but I was in love and didn’t care. Besides, I had gotten COVID once and it was very mild; surely, I’d be fine. I was not prepared for what would happen to my body.

I was unable to stand for days, and when I finally could, it was only with great effort and for short amounts of time. It took even longer to return to walking. I experienced intense congestion, headaches, nausea, dry-heaving, chills, fever, sweating through my shirts, muscle aches, and extreme fatigue. I spent my days coughing up yellow, green, and even gray mucus, haunted by the feeling that I might legitimately be dying. Twice, I almost visited the ER.

For two months, walking was a struggle that resulted in shortness of breath, and I could only do that for ten minutes at a time. I experienced brain fog in the form of being unable to process time as I once had; suddenly, it seemed to mean nothing at all to my mind. I had to take two months of unpaid time off work. I no longer felt like I knew myself.

I am embarrassed this is what it took for me to genuinely take COVID seriously again. Sure, I always maintained masking on public transit and in stores, but I stopped masking in bars and at parties. I returned to indoor dining. To an extent, I went “back to normal.” I did so while knowing on a certain level that I was not living in accordance with my professed values, which made my actions worse. Everything I do now is to

try to pay off the debt of the incalculable harm my actions did during that time.

Community is not only bars, clubs, and movie nights. It is doing the hard work, and volunteering alone does not cover it. Community requires looking inwards and facing where we have fallen short. Before my second infection, I know I did. I’m sure I still do in ways I do not yet realize. The work is ongoing. We owe each other commitment to that work, or how can we claim to be a community at all? Maya Angelou said it best: ‘[W] hen you know better, do better.’ Too many of us are looking the other way, scared of what we know deep down, and what it requires of us.

As humans, we like stories. They’re part of how we understand the world around us and how we define ourselves within it. I sometimes tear up thinking about cave paintings, proof even the earliest humans wanted to leave their mark on their world. Wanted to be understood by those around them. There is nothing more human than that, no stronger reason to build community. At its heart, community is a place where people go to feel understood and ensure their lives have meaning beyond themselves. We seemingly most often can do this by gathering around a real or metaphorical fire and telling those with whom we wish to connect a story.

As a playwright, I see the pandemic has not followed the comforting narrative the favored Aristotlean story offers: old world order, intrusion, rising action, crisis, falling action, new world order. We are stuck in crisis, the moment in a play after which nothing can ever be the same. Nothing will ever be the same after the pandemic, even after it ends. It is time we all be brave enough to face that and what it means for our lives.

There are other story styles, ones that lend themselves better to the stories of Queer people than a form created for white, property-owning men such as Aristotle. Brechtian, Absurdist, Naturalist; the list goes on and on. I suggest we, as Queer people, reject the Aristotelian narrative of the pandemic, and instead embrace episodic structure. We recognize we have existed in every space and time; we, as a people, are the constant. Everything else changes, but our existence never has and never will. Using this as a center can help us recognize the changed world around us now. Yes, the new world of the pandemic and climate change is scary. The only way to survive it, though, is to accept reality and turn towards each other.

The revolution will be scrappy and exhausting. The revolution will center Disabled people. The revolution will be worth it.

The revolution is now, if you are willing to face it.

Words by Sophie Mutiara Nova

As a mixed Indonesian and queer artist—I think there’s an element of sparkle to being queer. Like glitter embedded in one’s pores—sometimes there are situations where I let the glitter shine fully, and other times, I turn the spotlight down for safety. But the glitter is always there—as present as the stars in the sky even when the sun shines so brightly during the day.

Glitter remains within skin, even after you scrub it off. Embedded into pores, mixed with longing, sweat, desire—the glitter tells a story of where you’ve been and who you hoped to be with at the end of a long night—caught in smoky nightclubs and eyeing a newcomer across a bar in (dis)comfortable quietude. Someone looks at you when your gemstone-covered iris stares into a stranger’s. The longing is too deep and the silence too long.

Too many questions not asked.

Too many moments not taken.

Too many (mis)understandings.

And you scrub off dead skin cells in the shower and watch the glitter, the sparkle, as it shimmers down the drain.

Mom stays up all night, knowing where you’ve been but not talking about it; it’s more peaceful not to talk about it. But she cares—she loves you. She cries when you tell her that some days it’s hard to live. She says she wants you alive even if you’re a butterfly and the world she understands consists of moths lost at an extinguished flame—she accepts you, she tries… even if she does not understand.

So, when you come back home from the bar/the club/the intimate domicile where you are allowed to worship the natural desires of your body—she stands in the doorway with glittering eyes and sighs in relief that no harm came to you tonight. That no bigot took to physical blows, and instead, resorted only to words that ran like sewage water down your back.

Your mom asks you quietly, sudah mandi? because she does not know how to ask if you fell in love with someone tonight. That she cannot comprehend. It is a sin; she says in the same breath she whispers: but I love you—sayang kamu.

You scrub off the sparkle, but still, it remains on your fingertips when you brush your hair out and wear it down. You search up “how to dress cishet” because your culture is tied up in a church group. You learn and relearn words from Bahasa Indonesia by echoing the penitent murmurs and supplications and psalms of old grandmas and grandpas around you. Surga. Naraka. Bapak kami. You turn your palms inward like a prayer but it’s really to hide the glitter and make the other churchgoers comfortable. You don’t bring the nightclubs and glitter into this space. There is a time and a place for you to shine, but now you must be dim. Safe. Quiet.

You put on a batik dress that feels natural in a different way on your body. With glitter-speckled fingertips, you spoon golden cubes of rice, nasi kuning, to your lips and swallow as someone asks why you aren’t bringing home a husband. Saya belajar, you smile dutifully, I’m studying (how to be ****). You cannot tell them that as you progress in life, the quote, unquote “normal” path turns wavier than oceans beneath a moonlit tide.

You cannot tell your elders of last night’s date—how their lips felt on yours beneath the stars on a witching night, the small of your back pressed against their car and glitter in their eyes. You cannot tell them how their piercings sparkled when you confess, may I? Tattoos are a road map on their skin as you dared to fall in love and get your heart broken (again) but that’s okay because it’s better to have loved in medias res than not at all, right?

You write of love because you’re a fucking Pisces sun and Pisces moon and, what’s your birth chart? –breathe— you’re tired of writing stories that end in trauma. You’re tired of writing as catharsis and therapy. You’re tired that writing feels like you cut yourself with a gemstone pen knife and let the glitter bleed onto obstinate pages. And you wish to god(s)? That shivers didn’t run down your spine when you wrote this because it is ultimately a love story.

And you remember, as you stare into the cup of coffee that simultaneously gives you acid reflux and the will to live….

...the glittering specks in the eyes of a golden-haired lover who tries to cross a divide bravely and falls short despite their ultimate effort. They cannot understand that you are same/but/not. A grandmother who asks you what “gay” means in Bahasa Indonesian/English and you can only smile and laugh and twist the piercings in your skin and apologize because you didn’t want to be a bad child—you didn’t want to be bad, but the world said you weren’t good. Nobody directly told you—but they told you in other ways when the group of men passed you and laughed asking: What is it ( !@#$% REDACTED )? And you were afraid they’d hurt you.

The universe holds you in her arms and sings you to sleep and says that if dolphins and penguins and every animal Genesis created beneath her full moon was Queer that you could be Queer too. Queer.

Q.U.E.E.R. Quiet Ultimate Everything Everyone Rests in the soul of the world.

Glitter rests on your fingertips as you press them to her/their/his/zer/xer/ ad infinitum lips and you embed the glitter into their skin and beg for forgiveness.

I didn’t mean to scare you.

In memento mori

I’m sorry if I did.

I rest in the scent of melati/jasmine beneath the celestial beauty of bulan/moonlight, and I whisper to the god(s)? above that I deserve good things and love and someday may love find me. Yet for now I kiss the glitter in your skin, and I pray that within my eyes you see my mother, my grandmother, my ancestors before/in/after me. As my mother tells me, you are like a son to me, even as she insists, she is my daughter (maaf-but I’m trying). And we laugh as we cook bubur ayam in a beat-up rice cooker (I don’t know who caused that dent on the side) and I stare at my reflection in a knife’s edge and smile because I see it in the corner of my eye…

SACROSANCT + SPARKLE

(in refrain)

-kami berdoaAmin.

The Climate Crisis isn’t the Great Equalizer it’s often portrayed as—it’s the ultimate expression of class warfare, and Los Angeles is its deadly theater.

The day our landlord told us we had to move, we watched burnt pages from a children’s book drift through our yard like apocalyptic confetti. We hovered between browser tabs—zillow listings on one side, evacuation alerts on the other—while Los Angeles burned at both ends. We couldn’t help but notice the bitter irony of it all: our landlord forcing us out while a natural disaster threatened to make the decision moot. “I guess he can’t sell the house if it burns down,” we joked, imagining his greed and nature’s fury competing to see who could claim the home first. But that wasn’t really funny since either way he’ll be making money. Most importantly though, it’s not accurate. To frame this as a race between human greed and natural disaster misses the truth: this disaster isn’t natural—it’s manufactured. It’s the product of a system that prioritizes profit over people, one that allows utility companies to neglect infrastructure maintenance while real estate developers continue to push deeper into fire zones, creating ever more dangerous conditions. But even more insidious than the neglect itself is the way in which these disasters actually feed into the very greed that created them. For landlords like mine, the destruction caused by these fires isn’t just an unfortunate side effect—it’s an opportunity. Each displaced family becomes another desperate bidder, driving up demand—and landlords capitalize by hiking rents ever higher. They quite literally benefit off the suffering of others.

Long before the first luxury development broke ground, the Tongva and Chumash peoples lived in careful relationship with fire in these lands for millennia by using controlled burns to prevent massive destruction and sustain the ecosystem. This approach embodied what we might now recognize as a Queer ecology. There is a refusal of the binary between “wild” and “managed” land that embraces cycles of death and rebirth, and practices forms of kinship that honor the intricate relationships between humans, flames, forests, and future generations. The violent displacement

of Indigenous peoples by colonial forces—a process that continues to this day—marked the start of a rigid new order that seeks control rather than collaborate with the land. This was the first act in Los Angeles’s long drama of a profit-driven environmental crisis.

In the 1920s, real estate moguls like Harry Chandler and Moses Sherman carved up these fire-prone hillsides into luxury developments, setting the stage for today’s inferno. Their contemporary heirs maintain this deadly algebra of profit over safety. Developer Geoffrey Palmer continues to pour millions into fighting rent control while his cheaply-built luxury apartments rise like vertical kindling. Meanwhile, billionaire Rick Caruso hires a private firefighting team to protect his Palisades Village shopping complex, even as the undocumented workers who staff his retail empire face the risk of deportation at evacuation checkpoints. And when the flames approach, insurance giants like state farm and allstate abandon working-class neighborhoods, canceling policies and refusing to issue new ones, leaving residents vulnerable unless they can somehow afford $12,000 annual premiums— three times the amount of the average Angeleno family’s monthly income.

Our landlord’s eviction notice arrived as fires tore through Palisades and Eaton Canyon, areas where Southern California Edison’s aging power lines— known to pose extreme fire risks—remain in place. Despite repeated warnings and the company’s knowledge of these risks, SCE has delayed upgrading infrastructure, leaving communities vulnerable to disaster. Meanwhile, their lobbyists have continued to fight against legislation that would require underground power lines in fireprone areas. Their excuse? Undergrounding is “too expensive”—even as their executives’ stock options continue to grow. Leaving power lines above ground may be cheaper for the company, but it imposes devastating costs on the public. The recent fires have caused an estimated $250 billion to $275 billion in damages so far, with insured losses alone reaching up to $30 billion. These catastrophic expenses far exceed the initial savings SCE might gain from avoiding infrastructure upgrades, and the financial burden these disasters often falls on taxpayers.

While we face this ever-worsening Climate Disaster, leaders like Mayor Karen Bass have defended cuts to the fire department, citing budget constraints while funneling resources into less immediate issues. Her decisions to prioritize other funding—at times for law enforcement or real estate initiatives—have left Los Angeles unprepared for the inevitable crises that come with a profit-driven environmental system. Bass’s choices mirror the broader systemic failure: a city where corporate lobbyists and real estate developers dictate the future, while public safety and Climate Resilience take a backseat.

Los Angeles reveals its priorities in stark numbers: while the LAPD’s budget swells to $1.3 billion for 2024-2025, the fire department remains chronically underfunded. The city’s solution? Exploit prison labor to fill the gap. Behind the headlines about heroic firefighters battling infernos lies a darker truth: many risking their lives to protect Beverly Hills mansions are incarcerated people earning $2-5 per day, plus $1 per hour when fighting active fires—barely 0.5% of the $91,000 annual salary their professional counterparts earn. The cruel irony compounds: the same system that deems these individuals capable of protecting multimillion-dollar homes bars them from firefighting employment after release due to their criminal records.

At the end of the day, the consequences of the Climate Crisis are felt most acutely by those with the least to lose. The myth of “Climate Change as the Great Equalizer” is shattered when some Angelenos retreat to homes with hospital-grade air filtration systems or charter private jets to escape the smoke while others face impossible choices: risk losing wages by skipping work in hazardous conditions, or risk losing everything in an evacuation they can’t afford. Even evacuation itself is a privilege—first, you need the means to leave: a reliable vehicle, money for gas, the ability to miss work without losing your job. Then comes the question of where to go: you need a destination, money for hotels, some kind of safety net beyond the reach of disaster.

As smoke blankets the city, the ultra-wealthy aren’t just buying their way out of the crisis— they’re planning their escape route while leaving everyone else out of the equation entirely. While Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos pour billions into space colonization, working-class communities face worsening air quality, increasing “natural” disasters, and disappearing resources. The very people whose companies and investments contribute the most to environmental destruction are the ones orchestrating their exits from the mess they’ve created. As they accelerate Climate

Change with their unchecked industrial practices and resource exploitation, they simultaneously shield themselves from the consequences. “Ecological wealth,” once thought of as simply having access to clean air and water, is now about possessing the resources to insulate oneself from climate disasters or escape them altogether.

Climate Disaster is deliberate, profitable, and preventable. Now before you start queuing up Bo Burham’s ‘Funny Feeling’ to cry-sing “it will be over soon”, remember: While the wealthy prepare their escape pods, Queer and Trans organizers are at the forefront of building solidarity networks stronger than any firebreak. Drawing on decades of experience relying on chosen family networks and mutual aid systems when mainstream institutions failed them, LGBTQ+ leaders are doing what government agencies won’t. Organizations like the Queer Ecojustice Project are fostering resilience by combining ecological justice with Queer liberation, creating mutual aid networks that protect the most vulnerable. In Appalachia, Pansy Collective—a Trans-led artist group—mobilized swiftly during Hurricane Helene, providing essential supplies and support to affected communities faster than national relief efforts. Asheville’s Firestorm Books, a Queer feminist collective, served as a critical resource hub during the same disaster, coordinating emergency aid for displaced residents.

These efforts echo the care ecologies forged during the AIDS crisis, where LGBTQ+ communities banded together out of necessity and compassion. As we continue to build these networks and rely on each other in the face of Climate Disaster, we are divesting from a system of harm and creating a community-driven future that embraces the kind of radical interdependence Queer communities have long practiced. Each act of solidarity, whether it’s providing food, organizing rides, or securing emergency housing, is a step toward a more resilient, collective way of living.

The next time the Santa Ana winds blow, let’s hope that they’ll carry not just ash and smoke, but the rising heat of organized resistance.

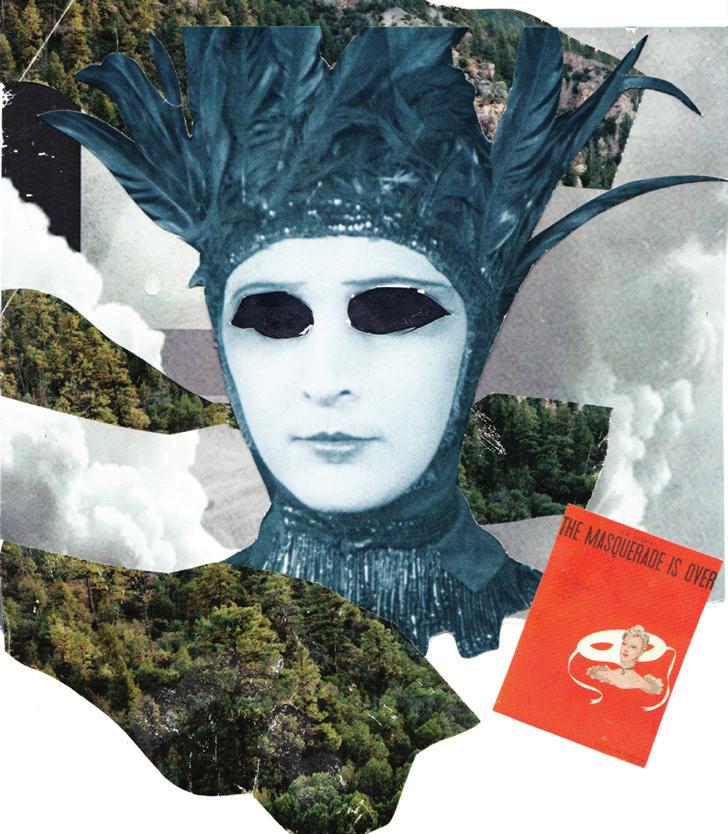

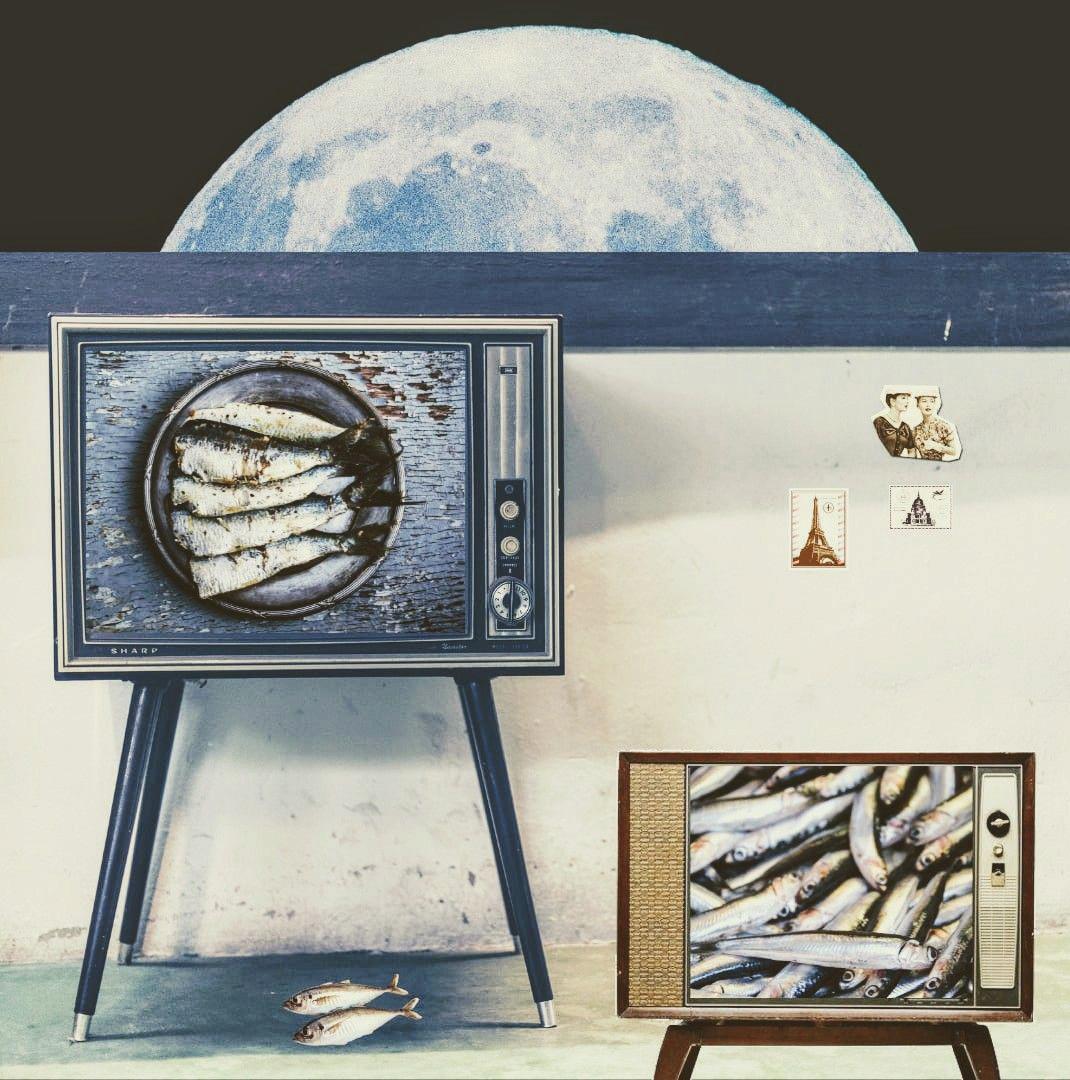

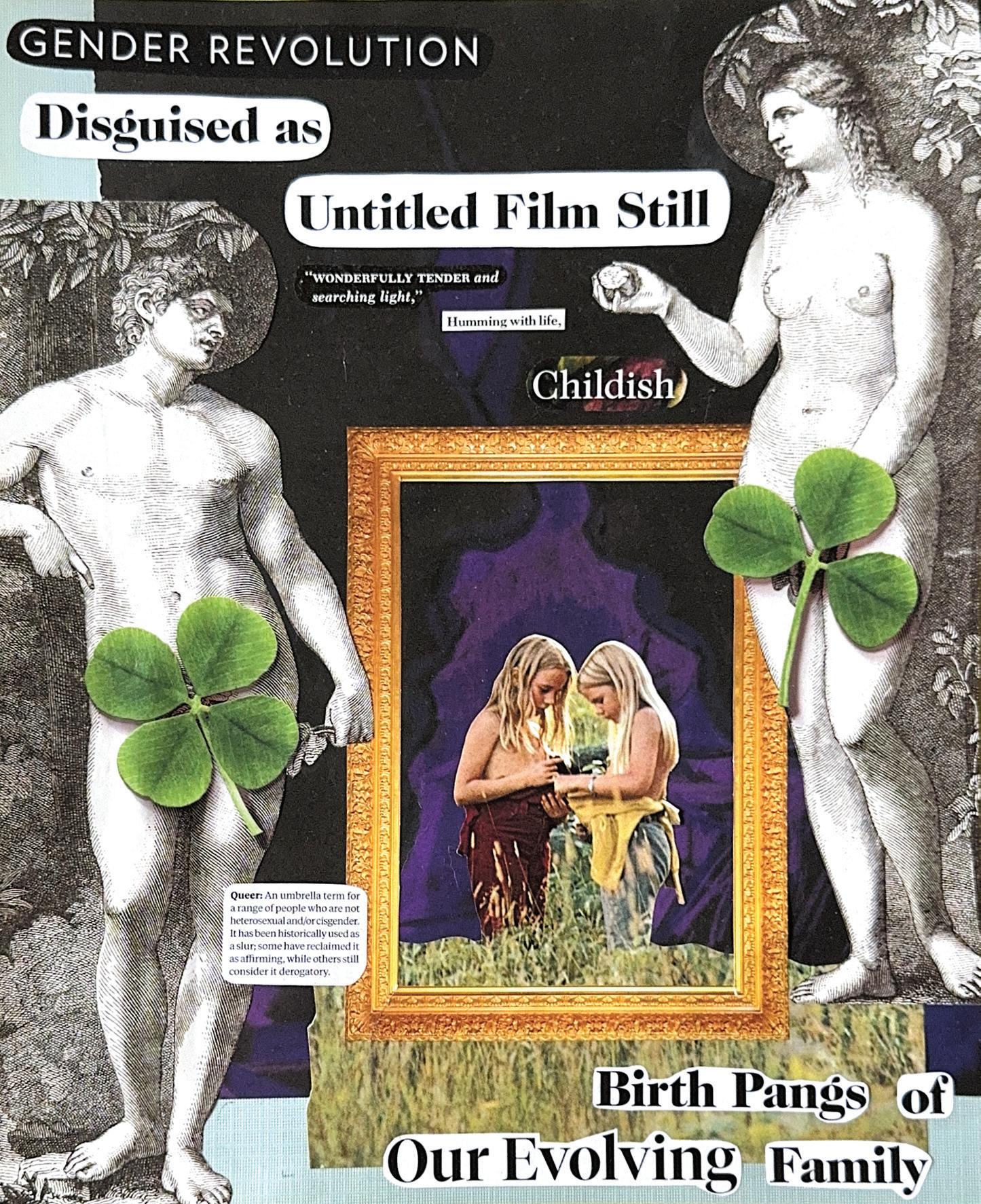

“Feral” is a digital collage exploring the connection and history of the perception of “otherness.” This piece juxtaposes myths and beliefs that degrade and dehumanize, with reality and protest. There is a strong connection between Queers and creatures—why is that? Perhaps we see ourselves in the unloved, the cast aside, and the mistreated. I’ve combined pieces of newspapers, online articles, antique photographs, and protest propaganda, aiming to find the root of our connections with “pests” and “vermin.” We all know people with strong connections to creatures, i.e. bug collectors, friends with tattoos of possums or raccoons or pigeons, bone scavengers, etc. Our histories are so interwined with those who are tossed aside by society and seen as weird, creepy, or dirty. We can find strength in standing with those who mirror us. This can be explored indefinitely—the connections of class, race, species, liberation, exploitation, commodification, extermination, domestication, and the general “inconvienence” of our existance. I encourage you to resist by existing. By living. By loving.

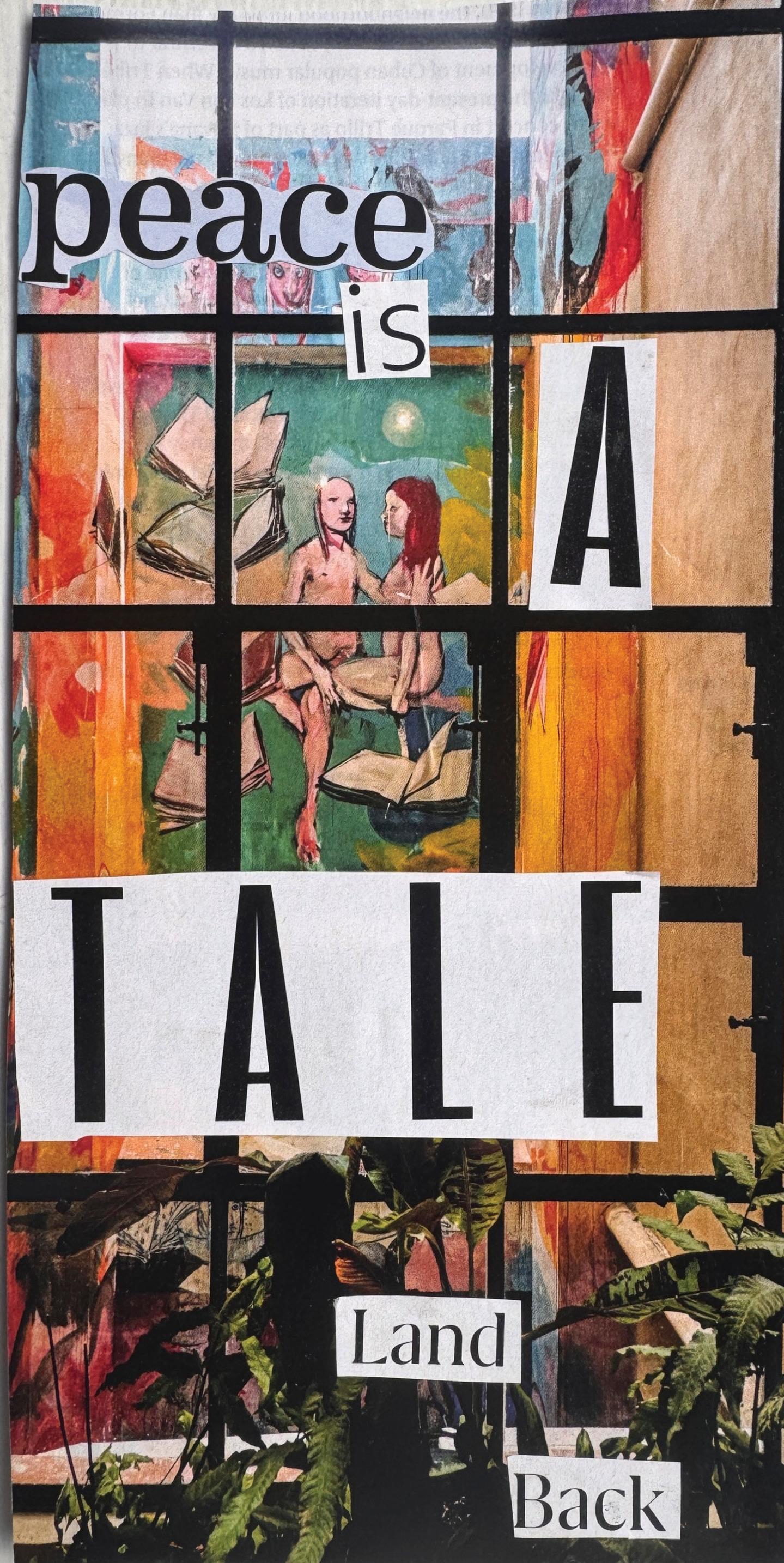

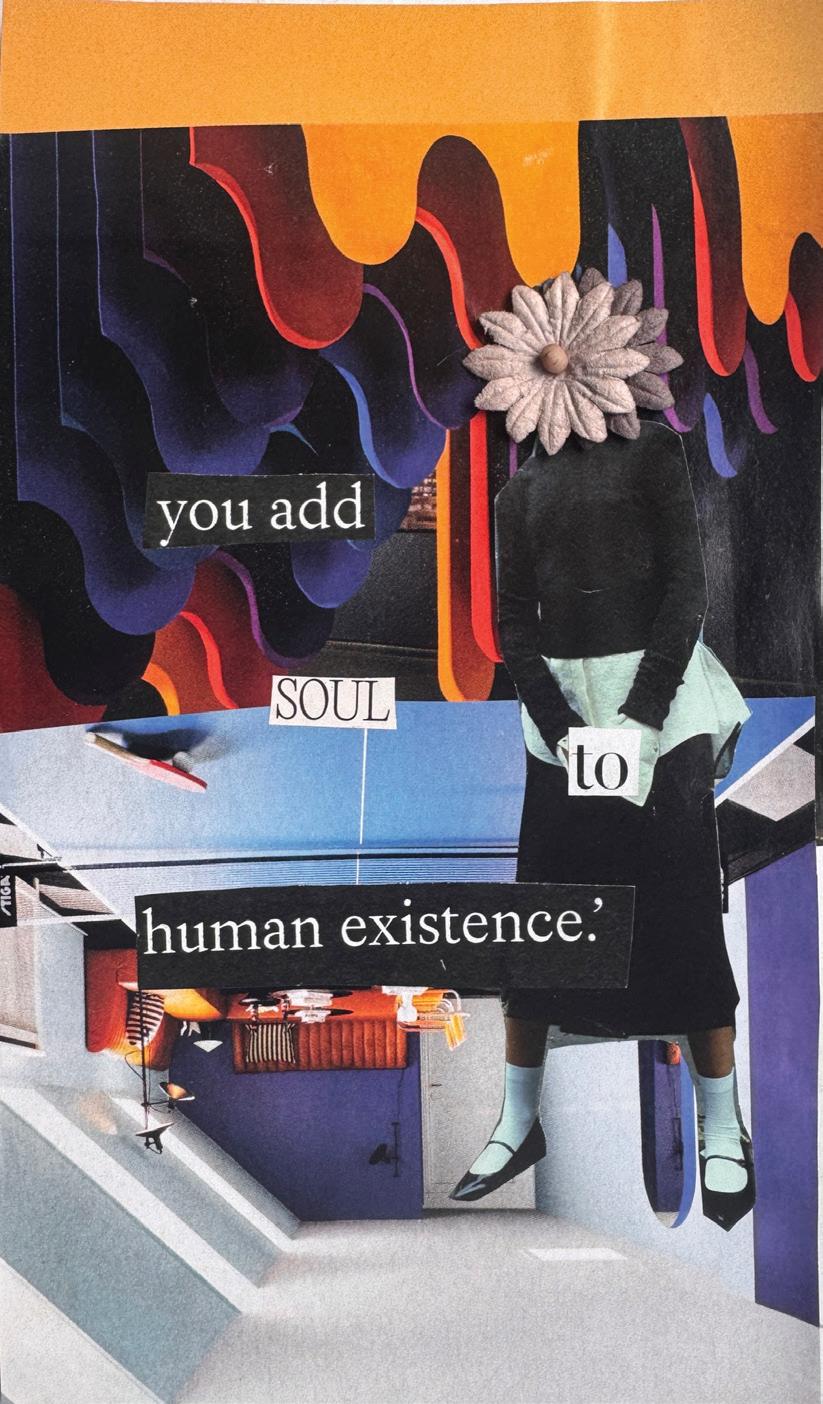

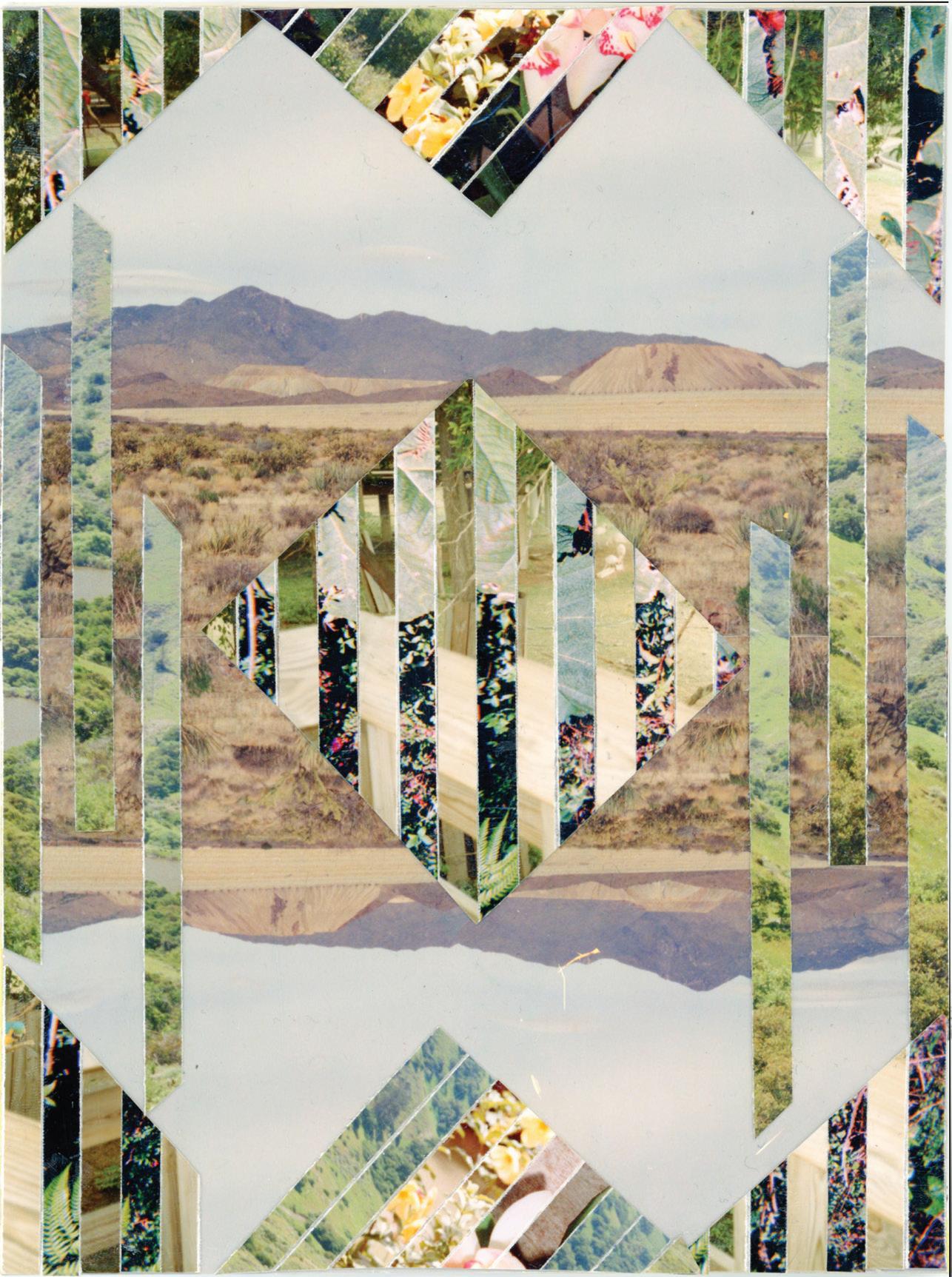

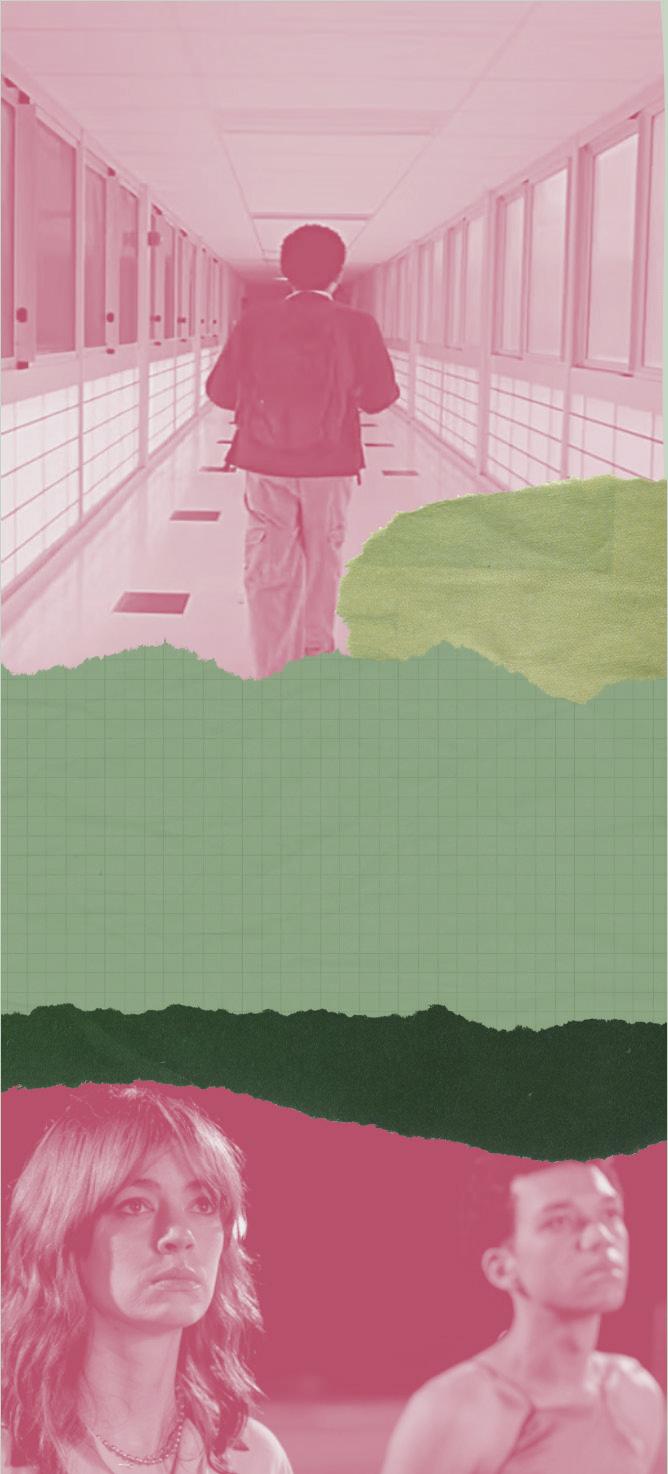

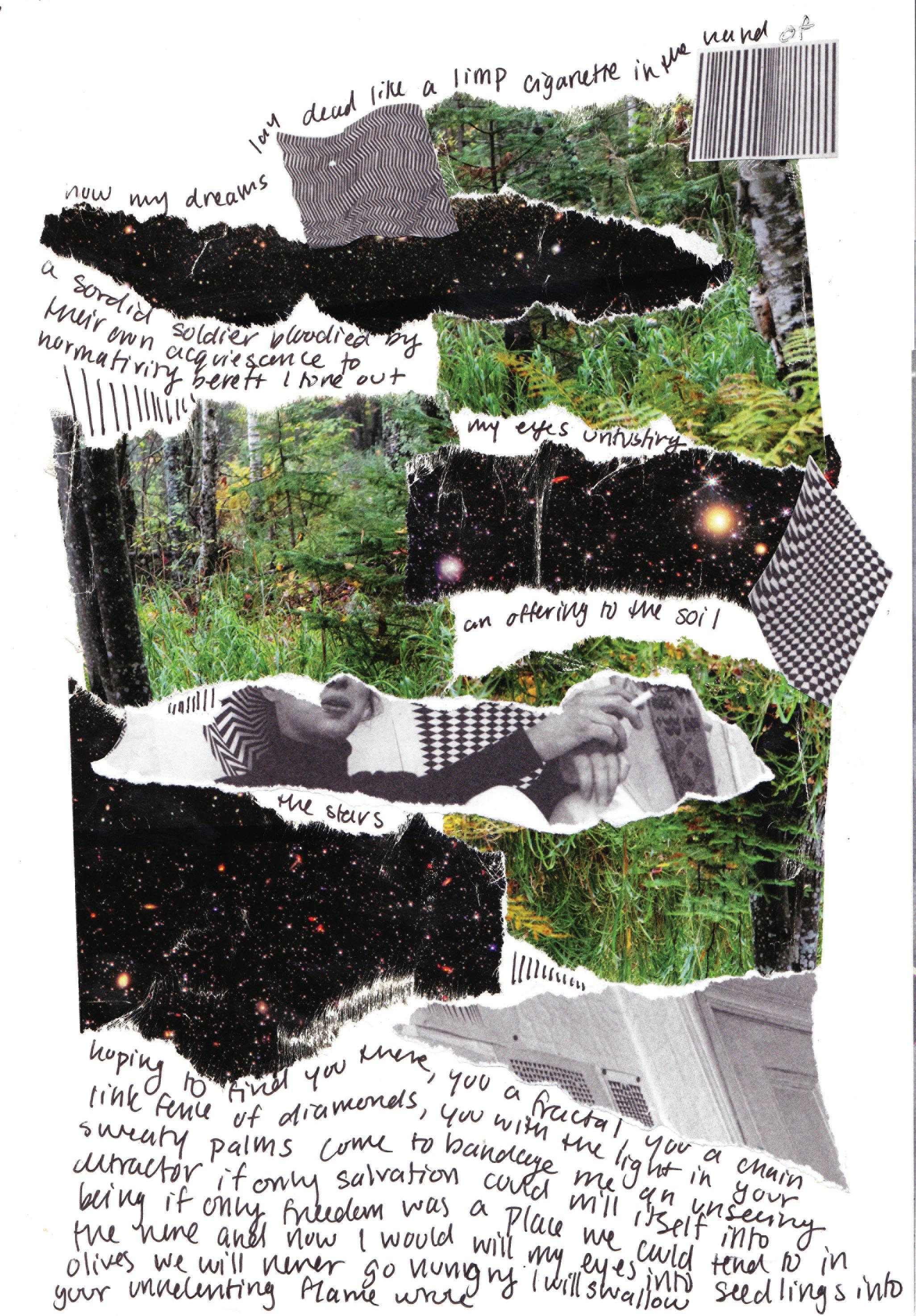

Trans people build community and identity by reclaiming their environments. These found photo collages are an example of direct reclamation, using existing imagery to construct a new habitat. My community, my art, and my identity are all built by shredding the ideas presented to me as “whole” and “normal,” reshaping them into what works for me, and using only what I need to nurture me physically, spiritually, and artistically. Just as the uniquely harsh conditions of a desert climate shape the evolutionary functions of its resident species, so too does the hostility of the modern world force Trans people to develop ways to survive and adapt in a society that wants us dead.

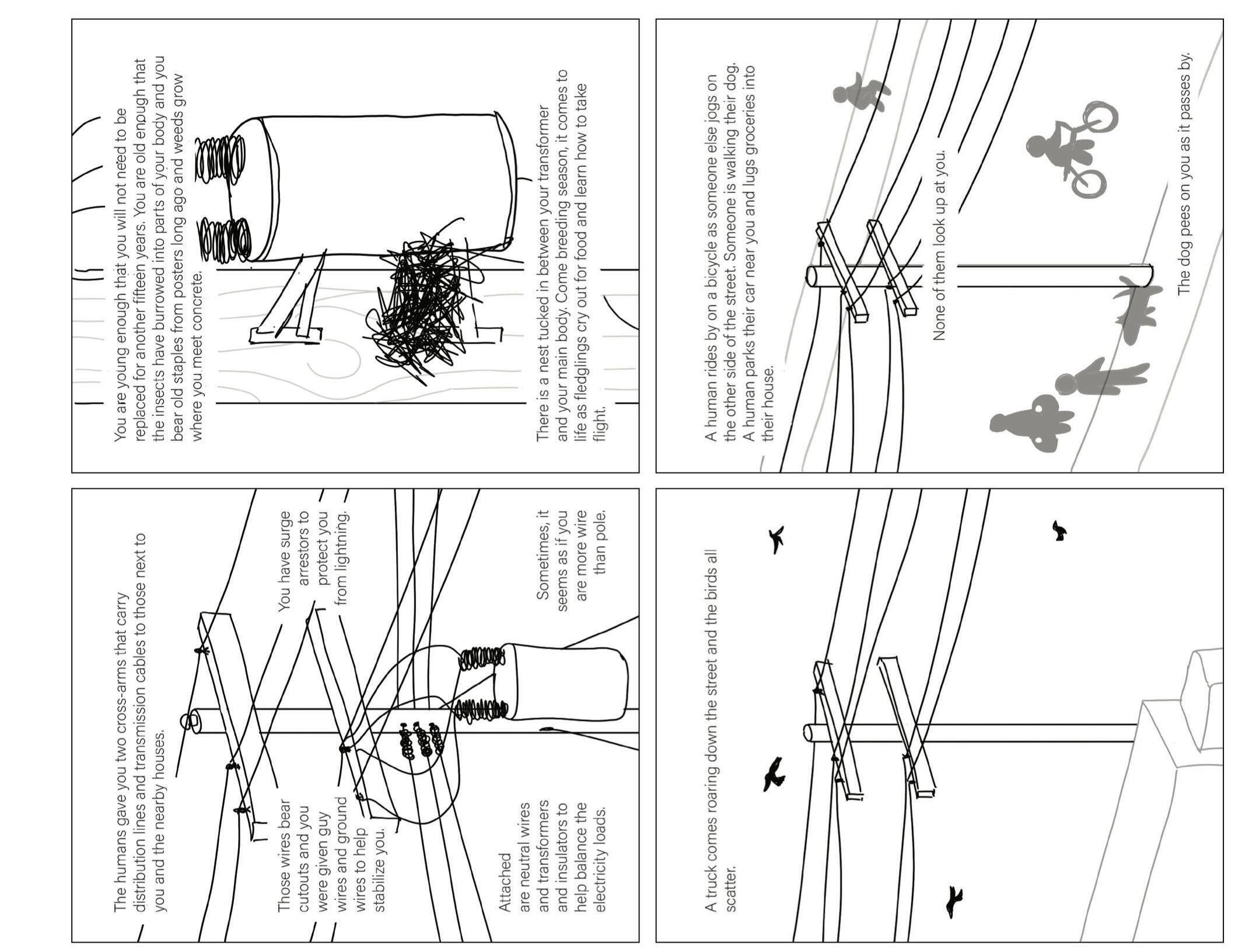

In order of appearance: “Small Queen” “Hot Salad” “Question Party”

01 - “nature chews on me”

IMAGE DESCRIPTION: a grainy, black and white print made up of human teeth x-rays and text reading “nature chews on me”. The text is in white over the background, giving it an appearance of negative space carved out from the image.

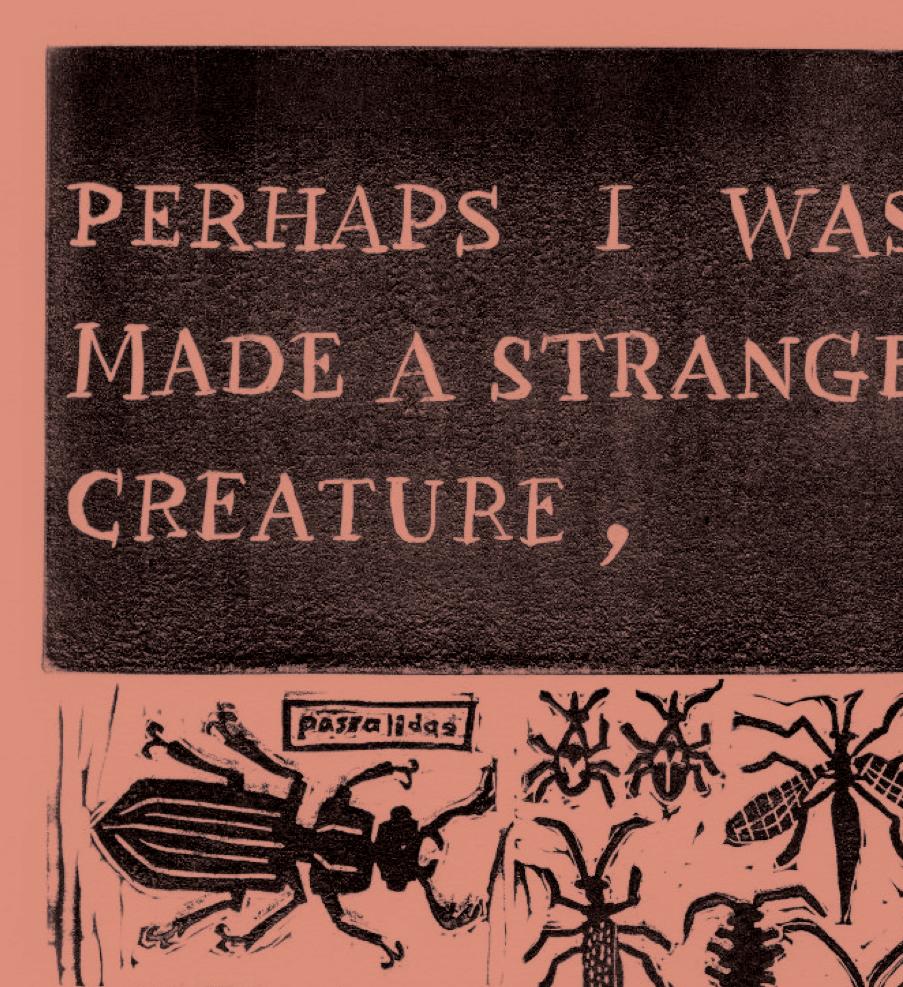

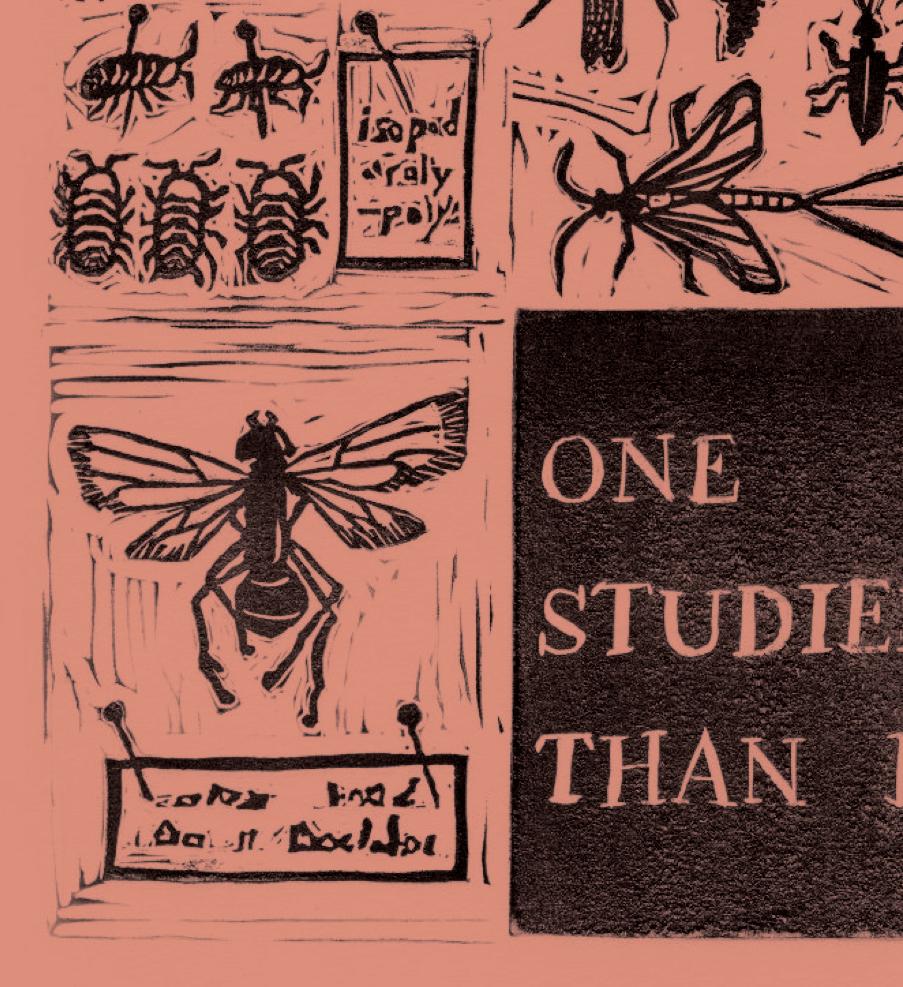

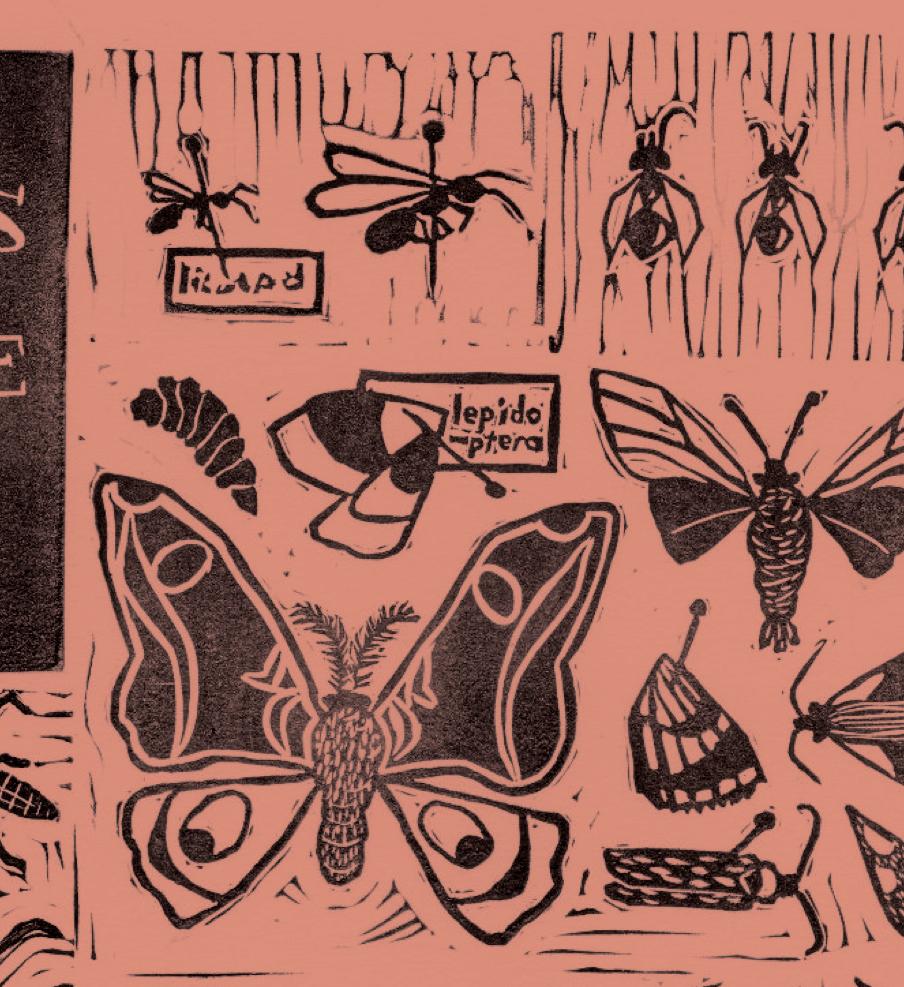

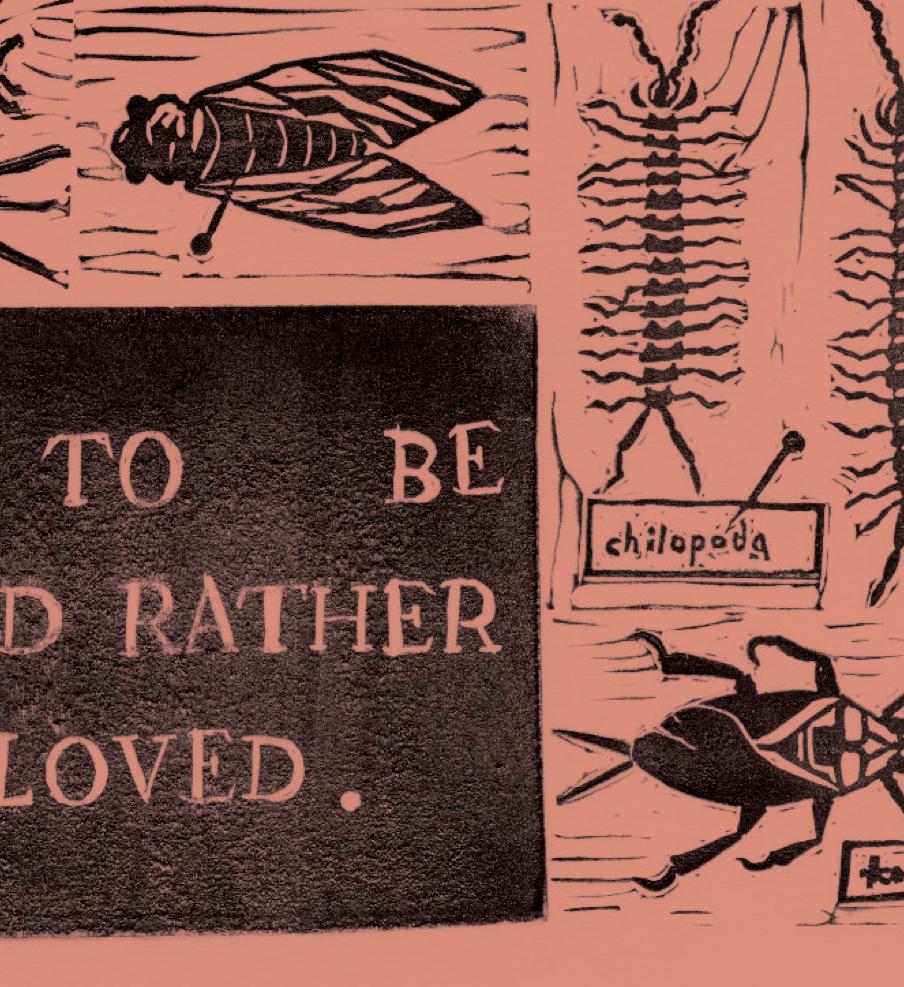

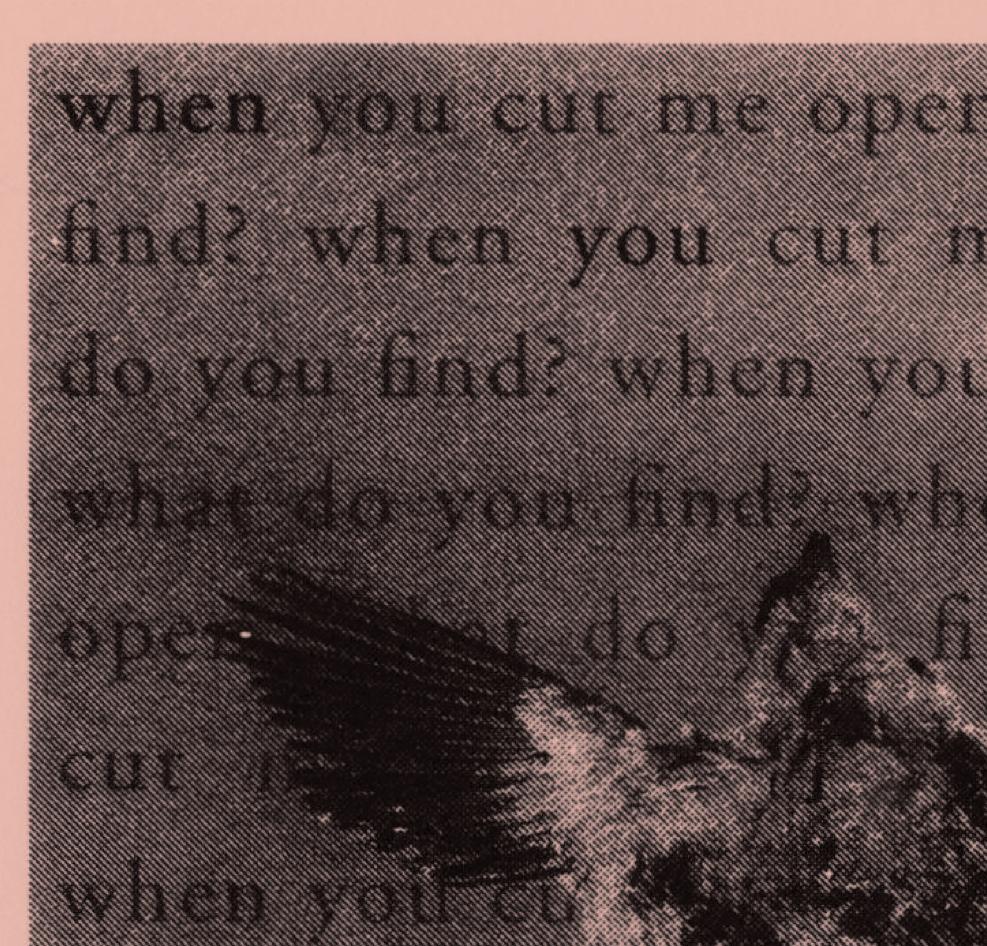

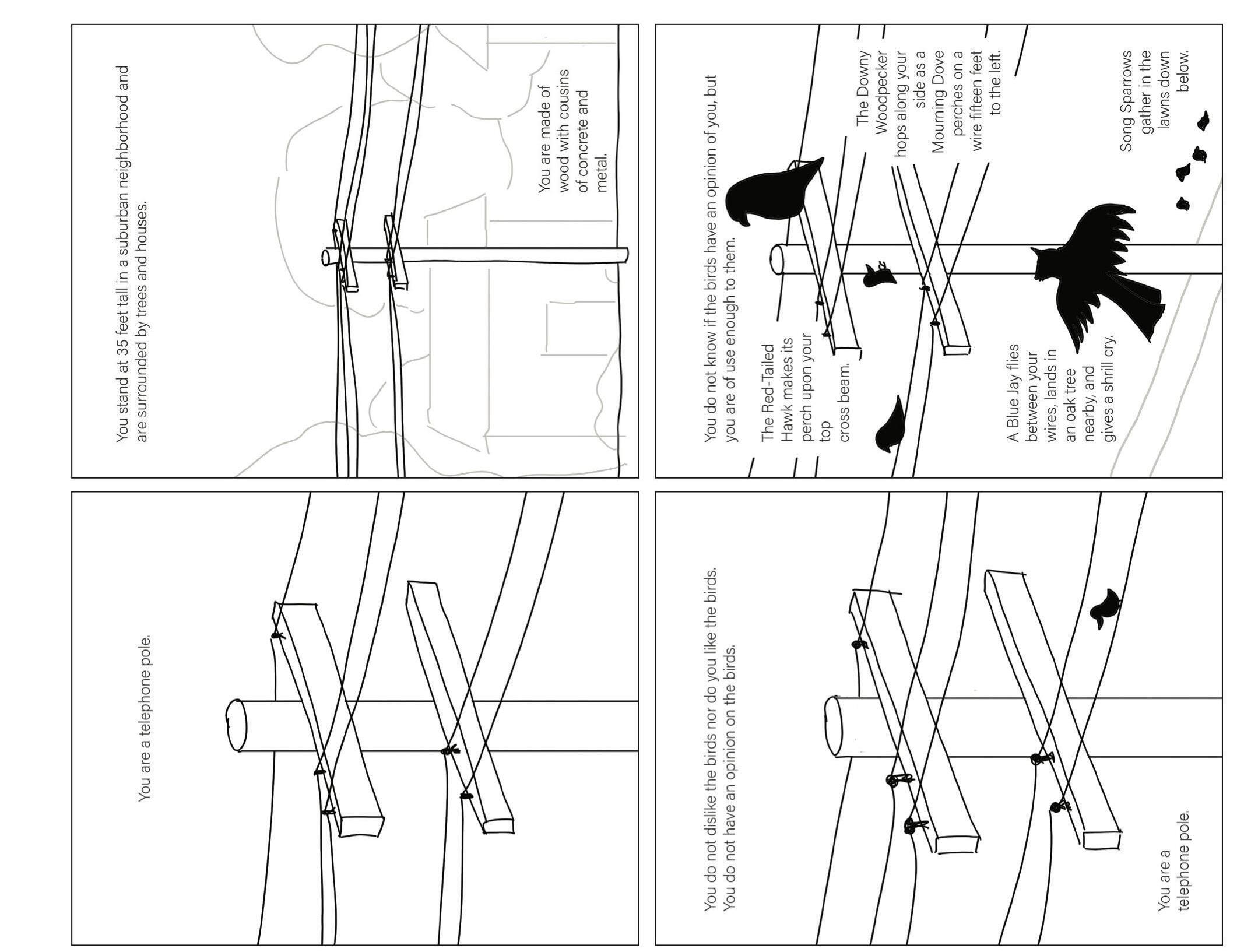

The series Parasitology is one which uses specimen imagery, EcoCrip theory, and personal reflection to examine the Disabled experience. As a physically Disabled and Trans person, I have always felt drawn to the aesthetic of a cabinet of curiosities in an empathetic sense. Historically, cabinets of curiosities have often exhibited body parts of “othered” individuals, specifically the physically Disabled, Gender-Nonconforming, and People of Colour. The basis of this work is photography, and I have worked to challenge the idea of photography as a “documentative” practice. To give my prints an explicit subjectivity, I abstract my images to give them a grimy, grunge aesthetic. Through poetic text, I challenge the typical voyeuristic gaze often projected onto “oddities”. In this way, I am the specimen, and through me, the specimen now has a voice. To make these connections, I draw on my

IMAGE DESCRIPTION: a tiled together square block print in black ink on white paper. Most of the image is made up of rectangles, each with a different type of insect exhibited, with labels and pins. In the top left hand corner and bottom center are two blocks with the text carved into them; “PERHAPS I WAS MADE A STRANGE CREATURE, ONE TO BE STUDIED RATHER THAN LOVED.”

experiences as a Disabled and Trans individual, where I have often been a subject of study and unsolved anomaly within the medical system

Overall, this series is one which utilizes imagery of scientific and collectable specimens while prompting the viewer to ruminate on the prevalence of the “othered” body in a cabinet of curiosities.

Within EcoCrip theory and Queer Ecology, parallels are drawn between “othered” individuals and the fluidity of the natural world. Similarly to how nature defies the boxes we impose on it, Queerness and Disability lie outside of normative societal boundaries. Within western cultures, nature is studied and thought to be an inanimate object in such a way which strips it of any dignity; it is dehumanized similarly to how medical speculation dehumanizes Disabled and Trans individuals. Many decomposers, scavengers, and other “gross” creatures are deemed undesirable, leading to them being pushed out of sight or even exterminated.

Ironically, the reason for the prevalence of these creatures is because they thrive around humans and 02 - “Perhaps”

IMAGE DESCRIPTION: a grungy, dark, greyscale print in black ink on white paper. The central image is a bird specimen, with its abdomen cut open and wings spread out to the sides. Repeating text makes up the background, reading “when you cut me open, what do you find?”. The background tone is quite splotchy and dark, making the text difficult to read at times.

in urban areas; think rats, bedbugs, and pigeons. Yet, they are thought to be leaching off of humans. Disabled individuals specifically are often referred to as parasites on society, and because of this connection, I have used “disgusting” specimens within this series. The title Parasitology comes from this idea, as well as the concept within EcoCrip theory, that Disabled people are important members of society, parallel to the unloved members of ecosystems, such as parasites. The disgust and violence which “gross” specimens evoke is ultimately ironic, as they are integral members of their ecosystems, much like Trans and Disabled people. My series Parasitology uses text and specimen imagery to equate Disabled and Trans individuals such as myself to reviled, but necessary, creatures.

Words by Ann McCann