Impact Report 2024

The

The

The

We

Brain research to improve lives

Brain diseases account for many of the most urgent health challenges of our time. At The Florey, our researchers, support staff and students are working towards a world where advances in the treatment and prevention of mental illness and brain disease mean that everyone has the chance to enjoy full and healthy lives.

The stories of research impact told in these pages are a sample of a wide array of leading-edge research undertaken at The Florey. Building on a long history of fundamental discovery science, our teams cover the full spectrum of research, from laboratory studies to clinical trials and the development of new tests, treatments and devices. We are united by our desire to improve the lives of those affected by neurological disorders.

As we celebrate the achievements of our researchers, we acknowledge our many collaborators, as well as the patients who volunteer to participate in research studies. We are grateful for the generosity of the individuals, trusts and foundations whose donations are a critical source of support for our research. We extend this gratitude to the Victorian Government.

It is our hope that these stories of research impact fill you with optimism for the future. A future where

sepsis is no longer a leading cause of death; one in which precise diagnosis of epilepsy is made in weeks as opposed to years, and effective therapies are initiated immediately.

We are on the road to ending the “postcode lottery” by delivering benchmark outcome data for people with stroke, setting standards for best practice care. We are charting the course to a future where research into the drivers of addiction, brain cancer, multiple sclerosis and motor neurone disease leads to the development of better treatments.

Our studies to improve the diagnosis of dementia and our efforts to develop new approaches to prevention and treatment offer hope of lessening its devastating impacts. Research that has uncovered links between autism in boys and prenatal exposure to a chemical contained in plastics will strengthen the global call for the harms of plastics to be understood and controlled.

These stories provide insights into what drives our researchers. We learn about Montanna Waters, whose experience of caring for two girls with developmental epilepsy inspired her to pursue doctoral research that aims to help them. These human connections and the desire to advance brain research to improve lives are at the heart of all that we do at The Florey.

Professor Peter van Wijngaarden Executive Director & CEO, The Florey

A new research structure

Research Priorities

Our research priority areas are depicted below. Each of our researchers has a main focus on one of these areas, but they share knowledge across disease boundaries. Their mission is to advance understanding of brain disease and mental illness, to develop better ways to detect, treat and ultimately to prevent them.

Research Methods

Researchers at The Florey have expertise in a range of methods including laboratory research, clinical studies, and research to develop new tests and treatments. They work with researchers in Australia and abroad, advancing brain research to improve lives.

Research leaders

Associate Professor

Nithianantharajah

Dr Leigh Walker

Professor Scott Ayton

Dr Rebecca Nisbet

Professor Chris Reid

Associate Professor Snezana Maljevic

Professor Brad Turner

Dr Thanuja Dharmadasa

Professor Yugeesh Lankadeva

Dr Connie Ow

Frontier therapy

Incisionless procedure for movement disorder

After decades of living with an uncontrollable tremor, Richard Mulcahy was fed up. He was tired of his hands shaking so much he couldn’t write properly, frustrated that he couldn’t use a knife and fork, and challenged by everyday activities like trying to button his shirt.

“I couldn’t eat soup without spilling it everywhere. Shaving became more difficult, even with an electric shaver, it was bouncing over my face because of my hand movement. Writing and typing were really hard and my head tremor meant people thought I was a really old man,” says the former MP and businessman.

Richard’s condition, known as essential tremor, began in his 20s. Thanks to a collaboration between The Florey and the Austin Hospital, Richard’s shaking is a thing of the past.

MRI-guided focused ultrasound (MRgFUS) is a relatively new technology rapidly becoming a treatment of choice for essential tremor.

“The procedure reversed all of my disabilities in a matter of hours. Most medical procedures require a recovery period, whereas with focused ultrasound in the MRI, the effects are immediate. It’s a dramatic procedure. I’m glad I’ve been the beneficiary of this treatment.”

The technology platform enabling Richard’s treatment is within The Florey’s Heidelberg brain imaging facility, adjacent to the Austin Hospital. It’s utilised by Austin

“They fixed the shakes on my left side. They’re gone completely, and so is my head tremor ... That was the day my life changed. The procedure was miraculous.”

specialists working alongside Florey imaging experts who scan the patient’s brain to identify a precise target the size of a rice grain deep within the brain.

Patients are awake throughout the incisionless treatment. While they are undergoing an MRI brain scan they receive a series of short, precisely focused bursts of ultrasound, which gently heat the target tissue.

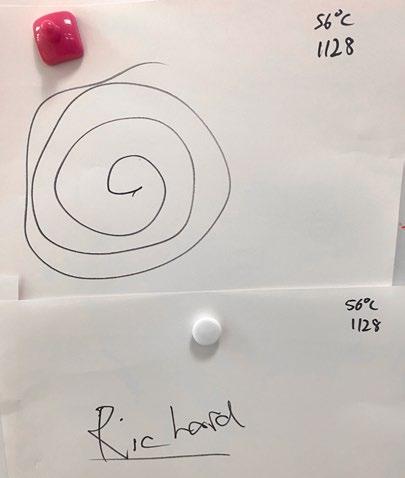

Richard Mulcahy

– Richard Mulcahy

With pin-point accuracy, the heat deactivates the misfiring circuit of nerve cells in the thalamus that cause the tremor. After each ultrasound burst, the patient is asked to draw a spiral and write their name. Just one hour after the treatment began, Richard’s spirals had changed from zig zags to smooth circles and his writing was legible.

Associate Professor Wes Thevathasan – Neurologist at Austin Health and Head of The Florey’s Movement Disorder Group – was part of Richard’s treatment team, with neurosurgeon Kristian Bulluss.

“I’ve done quite a few of these procedures now, and the outcome is rapid, dramatic, and transformative for the patient.

“The only alternative treatment for severe tremor like Richard’s is deep brain stimulation through electrodes implanted in the brain. However, that requires open brain surgery, and a 5-day stay in hospital.”

The $6m MRI scanner and focused ultrasound equipment is the only such platform in Australia within a research institute. It was jointly funded for research purposes by The Florey, the University of Melbourne, and the National Imaging Facility (NIF) – under the Australian Government’s National Collaborative Research Infrastructure Strategy – and the Victorian Higher Education State Investment Fund.

NIF Chief Executive Professor Wojtek Goscinski said MRI technology like this is crucial to developing precision therapies. “We’re proud to support The Florey in providing precise real-time visualisation of brain structures. Seeing the human brain in detail enables doctors to provide more effective treatments.”

Associate Professor Thevathasan said: “By combining The Florey’s advanced brain imaging research expertise, Austin Health’s clinical experience and the NIF network, we’re making a real difference to patients’ lives. We’re embedding MRgFUS in the public health system, so more patients can benefit from this remarkable procedure.”

“By combining The Florey’s advanced brain imaging research expertise, Austin Health’s clinical experience and the National Imaging Facility network, we are making a real difference to patients’ lives.”

Associate Professor Thevathasan talks to Richard during his procedure

– Associate Professor Wes Thevathasan

Before the procedure

After the procedure

Brain cancer

Collaboration is key to finding answers to brain cancer

A precious parcel navigates its way across a busy Melbourne street.

Inside a tiny vial lies a half-centimetre cube of brain tissue, freshly extracted from a cancer patient undergoing surgery to remove a tumour at the Royal Melbourne Hospital (RMH).

In fewer than 15 minutes, the cells from the tissue are in labs at The Florey and under a microscope, bathed in a special solution to keep them alive.

Here, a minuscule wire inside a pipette with a tip only one micron – or one thousandth of a millimetre – is carefully inserted into one of the cells under a microscope.

This highly specialised ‘patch clamp’ technique records the cell’s electrical activity, offering unique insight into how healthy brain cells and cancer cells communicate. Research like this demonstrates the power of the Parkville precinct, where doctors and researchers work

in parallel to pioneer new ways to diagnose, treat and prevent disease.

The project is led by Head of The Florey’s Neural Networks Group Professor Lucy Palmer, in conjunction with RMH Director of Neurosurgery Professor Kate Drummond AM, and RMH Neurosurgery Registrar Dr Heidi McAlpine.

Together, the trio is exploring the complex cellular interactions that are involved in glioma, a type of brain cancer.

Around 2,000 Australians will be diagnosed with brain cancer each year, and fewer than one in 4 is alive 5 years later.

“Our research suggests that the interplay between healthy and cancerous cells might be important for tumour progression,” Professor Palmer said.

The team is one of only a handful of groups globally that is taking this approach to brain cancer research.

From left: Professor Lucy Palmer, Professor Kate Drummond, Janet Micallef

By monitoring the ‘conversations between these cells’, the researchers can better understand how brain cancer cells use this communication to drive tumour growth and alter the brain’s structure.

“Cell by cell, we create visual pictures of cancers by filling them with fluorescent markers,” Professor Palmer said.

Their research shows that increased electrical communication between the healthy and cancerous cells facilitates tumour growth.

They are also examining how cellular changes in the brain due to the cancer’s presence could be used to find new therapeutic targets.

“In its healthy state, the brain maintains a beautiful equilibrium, firing electrical commands only when necessary.”

Professor Drummond, a pioneering neurosurgeon and researcher, said there was a pressing need to improve our understanding of glioma and to develop better diagnostic tests and treatments.

She emphasised the critical importance of partnering with patients on research, in this case using living human tissue from people who have brain cancer.

“Each patient at the RMH is asked if they’d like to consent to donate their tumour tissue for medical research, and in my experience it is rare for people to decline,” Professor Drummond said.

“Our patients, many of whom are facing a challenging diagnosis, are extraordinarily motivated to find a better way to treat brain cancer.”

For individuals like Janet Micallef, who lives with brain tumours, innovative research projects like these bring a renewed sense of hope for better treatment options.

In 1984, at the age of 16, an observant optometrist noticed pressure and swelling behind her eye during a routine test.

“Next thing I knew, I was seeing a neurosurgeon,” Janet recalls.

When the neurosurgeon inspected the CT scan of Janet’s brain, it was revealed she had a tumour in the

“Research like this demonstrates the power of the Parkville precinct, where doctors and researchers work in parallel to pioneer new ways to diagnose, treat and prevent disease”

– Professor Kate Drummond

third ventricle, right behind the eye, causing swelling and pressure.

Over 4 decades, she’s had 8 brain surgeries and has been treated by some of Victoria’s finest neurosurgeons, including Professor Drummond.

She describes her experience with a wry sense of humour, remarking that every seven years her tumours develop “an itch” and grow.

Janet’s tumours are benign but can be life-threatening and require urgent treatment.

Doctors remain puzzled as to what causes her tumours to grow.

Janet lives with this uncertainty, but copes by living in the moment, allowing herself to be anxious only in the time between her routine MRI scans and her follow-up appointments, where she finds out if there has been any tumour growth.

Each surgery takes its toll. Janet lives with fatigue, brain fog and memory loss.

Yet, she is determined to live a full life, raising two children, working in the public service until her retirement and setting up a support group called Grey Matters to help people in similar situations.

“I hope that with research like this, the way brain tumours are treated in the future will change for the better,” she said.

A neuron filled with red dye stands out within cancer tissue

Childhood epilepsy Care work inspires search for epilepsy cure

Before she was a Florey PhD student, researcher Montanna Waters was interested in genetic conditions.

While studying biomedical science, she looked for experience outside the lab to better understand the nature of these disorders.

Montanna worked with families whose children required complex medical support.

“Being a carer has given me a much deeper understanding of the impacts of the diseases that I research in the lab,” she reflects. Montanna began working with the Williams family – parents Danielle and Danny, and daughters Jaeli and Dali, both of whom live with a rare form of severe genetic epilepsy.

The first sign that something was wrong was Jaeli’s subtle eyelid ‘flutters’. She was diagnosed with epilepsy at 14 months of age – while Danielle was expecting their second daughter, Dali.

Jaeli’s seizures became more serious and more frequent, with as many as 52 seizures per hour.

When Dali was 13 months old, Danielle noticed that she too had eyelid ‘flutters’. “My heart just sank. I knew exactly what we were in for.”

Both girls faced daily seizures, sleeplessness, speech and behavioural problems, and intellectual disability.

“It’s like a game of whack-a-mole. You hit one problem and another comes up. It’s never ending,” Danielle said. Montanna recalls first meeting the girls. “A seizure is not a nice thing to see. It’s confronting. But I now know the girls very well and I adore their strong personalities.”

The girls are now aged 15 and 13. They’ve endured more than 400 medical appointments, 57 blood tests, 2 lumbar punctures, seen 20 different health specialists and trialled 23 anti–seizure medications, some with harmful side effects.

In February 2016, following exhaustive genetic testing, the girls were diagnosed with a variant in the SYNGAP1 gene, associated with seizures and neurodevelopmental disorders.

“Finding a cause was a big relief. Once we had a name, we had an enemy, and we could mobilise to fight it,” says Danielle.

Working with Professor Ingrid Scheffer, Director of Paediatric Epilepsy at Austin Health and Honorary Research Fellow at The Florey, they connected with other families whose children had genetic epilepsies and founded the Genetic Epilepsy Team Australia (GETA).

In 2017, Danielle and Danny established the SYNGAP Research Fund Australia.

Danielle and Dali Williams

“I’m investigating the early neurodevelopment of children with genetic epilepsies. Most research centres on seizures and their treatment, but I want to see if genetic variants cause changes in the brain before seizures occurred.”

– Carer and PhD student Montanna Waters

They also met neuroscientist, and then-Florey Director, Professor Steven Petrou. “Steve was pioneering gene therapy for epilepsy, so together, we lobbied the government for funding,” Danielle says.

Their proposal resulted in significant funding for The Florey. “This was a big win, it meant that Steve could focus his efforts on precision medicines for genetic epilepsy,” says Danielle.

Meanwhile Montanna, still caring for Jaeli and Dali every week, decided to pursue neuroscience research at The Florey. “I’m investigating the early neurodevelopment of children with genetic epilepsies.”

Under the leadership of Associate Professor Snezana Maljevic, Montanna sheds light on early brain changes that may explain the behavioural and intellectual difficulties children with epilepsy face.

Remarkably, Montanna’s research involves cells that Jaeli donated to The Florey.

“We isolated cells in the lab from a small sample of Jaeli’s skin and, using a series of genetic instructions, we ‘reprogrammed’ them into stem cells. The beauty of stem cells is that we can use chemical messengers to instruct them to become neurons. These neurons can be grown into tiny clumps, called mini-brains.

“She is one of the best support workers we have. Who better to work on finding a treatment for our kids than someone who knows them?”

– Danielle Williams

SYNGAP Research Fund Australia, founded by the Williams family, currently supports the research of Associate Professor Maljevic and Montanna Waters. syngapaustralia.org

By studying these neurons and mini-brains we can understand the ways the SYNGAP1 gene variants cause problems.”

Montanna has since met other families whose children have genetic epilepsies, many of whom have generously volunteered to donate skin cells for their research.

“It always strikes me how passionate they are about getting involved in research, because they see their children suffering every day.”

While Montanna hopes that her work ultimately leads to a cure for this condition, she appreciates that even small improvements could make a “world of difference” for children like Jaeli and Dali, who Montanna still cares for every fortnight.

Danielle says that The Florey is a source of hope for the families of children with SYNGAP.

“If you have all these complex and intense symptoms –it’s really hard to get through the day. But knowing that researchers at The Florey are working hard to make a difference is enough to keep us going,” Danielle says.

“To think that something may come out of it, like a gene therapy for our children, that is really special.”

Jaeli with Montanna Waters

Environment and brain health

Plastic exposure linked to autism

Plastic chemicals are now so widespread that no matter how hard we try, it’s almost impossible to avoid them altogether. In fact, it’s likely that we’re all absorbing, digesting or inhaling plastics daily.

As Florey-led research shows, these synthetic substances even affect children’s brains before they are born.

Professor Anne-Louise Ponsonby – an epidemiologist and public health physician – and molecular neuroscientist Dr Wah Chin Boon, are at the forefront of work to understand the many ways plastics affect children’s neurodevelopment and mental health.

Their research draws on more than 30 studies conducted over a decade, including the Australian Barwon Infant Study – a group of 1074 children in the Barwon region of Victoria who have been studied since their birth. In a major advance, The Florey team discovered that exposure to the plastic bisphenol A (BPA) in the womb plays a role in autism in some boys. “We found that boys with a particular genetic variation that leads to lower function of the enzyme aromatase, whose mothers had higher levels of BPA exposure in pregnancy, were 3.5 times more likely to have autism symptoms by age 2, and 6 times more likely to have an autism diagnosis by

age 11, compared to boys whose mothers had lower levels of BPA,” Professor Ponsonby said.

“In laboratory studies, we found that BPA is able to reduce the activity of aromatase, which controls neurohormones and is especially important in male brain development,” said Dr Boon, whose team also looked for ways to reduce the harmful effect of BPA.

“We found that a naturally occurring fatty acid has the potential to lessen the harmful effect of BPA on the brain in mice. Research is ongoing to develop and test this as a treatment,” Dr Boon said.

With the support of the Medical Research Future Fund and the Minderoo Foundation, the team is exploring the health effects of a range of different plastics during pregnancy and early life. Their findings have informed regulators, as well as the United Nations Global Plastic Treaty.

Professor Ponsonby is grateful to all the families who voluntarily took part in the team’s studies.

“Through their generosity, we’re building a clear picture of how plastics affect our community, and we’re contributing to stronger global regulations on plastics.”

Dr Wah Chin Boon and Professor Anne-Louise Ponsonby

“There is a growing body of evidence that female and male brains are fundamentally different. We are working to understand these differences with the goal of providing tailored treatments for women.”

– Dr Leigh Walker

Hunger hormone may drive female binge drinking

Florey research has shown that a hormone that makes us hungry may also drive excessive alcohol consumption in women.

Dr Leigh Walker, Florey Deputy Head of Mental Health Research, investigates the neurobiology of decision-making, particularly in relation to anxiety and addiction.

“There is a growing body of evidence that female and male brains are fundamentally different. We are working to understand these differences with the goal of providing tailored treatments for women, and people assigned female at birth, with alcohol use disorder,” Dr Walker said.

Although there is evidence that rates of alcohol misuse and alcohol use disorder in women are rising, sex as a biological variable has only recently gained traction as a critical factor in addiction.

“Most drug development research involves tests in male subjects only. It’s important to find out what’s happening in females too, and as we’re learning, it’s not always the same.”

Dr Walker, with researcher Amy Pearl, found the hormone ghrelin not only drives hunger but in females, it also drives alcohol consumption.

“We found that switching off the receptor that tells the brain it is hungry reduces binge drinking in female, but not male mice,” they said.

While more work is needed to test whether this “off switch” will work in humans, if it does, Dr Walker sees a future where women may be able take a drug that targets their ghrelin receptor to combat risky drinking and alcohol use disorder.

In earlier work with Dr Xavier Maddern, Dr Walker found that when a chemical called CART is removed from the brain, males drink more alcohol and females drink less. The researchers identified that CART makes alcohol taste bitter to females, unless the drink is sweetened.

“Ultimately, if we can work out how male and female brains differ, it will open unprecedented opportunities to treat disorders of the brain in women, including alcohol use disorders,” Dr Walker said.

Florey commercialisation

Advancing neuroscience from bench to bedside

At The Florey, we are committed to translating world-class neuroscience into real-world outcomes.

The mission of The Florey’s Commercialisation team is to help researchers translate scientific breakthroughs into new diagnostic tests, devices and treatments to improve lives.

This commitment to innovation is reflected in the success of our recent spin-out companies, which are attracting international attention and securing funds to bring pioneering technologies to the clinic. We are proud to feature our lead projects here.

“At Phrenix, we are driven by the urgent need for new and effective treatments for brain and mental health conditions. We want to translate cutting-edge neuroscience into realworld solutions to transform lives. Phrenix is reimagining how we develop next-generation medicines for brain and mental health.”

– Associate Professor Jess Nithianantharajah

Bio Inc

Co-Founder and CEO: Associate Professor Daniel Scott, The Florey’s Drug Discovery Innovation (DDI) Group Head

Co-Founder and CSO: Dr Christopher Draper-Joyce, DDI Group Head

Co-Founders: Dr Riley Cridge and Dr Lisa Williams, former Florey students and DDI lab members

Alkira Bio has pioneered a new way to develop drugs (antibodies) for disease processes that have been hard to target with conventional approaches. This platform technology has promise for a wide range of diseases. Founded in 2022 and supported by CUREator, Australia’s national biotech incubator, Alkira Bio has made rapid progress. The company recently secured seed funding from Curie.Bio (USA) to advance the development of its lead therapeutic program.

Centron Bio Pty Ltd

Co-Founder and CSO: Florey medicinal biochemist, Associate Professor Fazel Shabanpoor

Centron Bio has a mission to get drugs across the blood-brain barrier to their site of action. They create a selective gateway by linking drugs with their proprietary “peptide shuttle”. The company, cofounded by Professor Brad Turner, is raising funds to develop this innovative technology with the potential to revolutionise the treatment of brain diseases.

Alkira

L–R Phrenix

co-founders: Dr Greg Stewart of Monash Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences (MIPS), Florey Associate Professor Jess Nithianantharajah and Professor Chris Langmead (MIPS).

Phrenix Therapeutics Inc

Co-Founder and Vice President of Translational Biology: Florey Associate Professor Jess Nithianantharajah, Head of Mental Health Research

Phrenix Therapeutics is an innovative biotech company developing next-generation treatments for psychiatric and neurological disorders. Founded in 2022 as a spin-out from Monash University and The Florey, Phrenix received initial support from CUREator and follow-on investment from leading venture capital firms, including Curie.Bio (USA) and Brandon Capital (Australia), to advance its promising therapeutic pipeline. The company’s success shows the power of collaboration in scientific discovery and translation.

PanAscea Pty Ltd

Co-Founder: Head of Stroke and Critical Care Research, Professor Yugeesh Lankadeva

Co-Founder: Florey neuro-cardiovascular scientist, Professor Clive May

PanAscea’s lead program is a treatment to reverse multi-organ failure in patients who have sepsis. It is

estimated that sepsis accounts for approximately 20 per cent of all deaths. The treatment is undergoing Phase 1b clinical trials in intensive care units around Australia, with the support of the Medical Research Future Fund.

Their research has the potential to make a significant impact on global health, and the PanAscea team is seeking funding to fast-track this.

FeBI Technologies

Co-Founder: Associate Professor Gawain McColl, Molecular Gerontology Group Head

Co-Founder: Dr Nicole Jenkins, of the Molecular Gerontology Group

FeBI has developed a diamond-based quantumsensing technology that accurately measures iron stores in the blood.

The technology enables early detection of iron deficiency and may be used to improve the management of chronic health conditions. The team is seeking seed funding.

Ending stroke postcode lottery Stroke

Mike Lugg was home alone when he suffered a lifethreatening stroke, at the age of 77.

“It was very fuzzy. I was stuck between my bed and a chest of drawers. I tried to lift myself back up but I couldn’t.”

An ischaemic stroke, caused by a blockage in a brain artery, had paralysed Mike’s left arm but he managed to press his medical alert bracelet with his right hand. After that, time passed in a blur.

“I remember the sirens, the ambulance and then people in my apartment. I remember the trip to the Royal Adelaide Hospital, and medical staff asking me questions.”

Fortunately, he was in good hands. The Royal Adelaide is one of 67 hospitals around Australia that contributes stroke data from patients such as Mike to the Australian Stroke Clinical Registry (AuSCR).

The registry is led by The Florey on behalf of a consortium including the Stroke Foundation, Australian and NZ Stroke Organisation, and Monash University.

The AuSCR was established in 2009 to monitor treatments provided in hospitals across Australia, and in doing so, help improve the speed and quality of stroke care and patient quality of life.

When a stroke occurs, millions of brain cells die every minute. Time is of the essence, especially the time it

takes for a patient to undergo the surgical removal of the blood clot from the brain (thrombectomy).

For Mike, that time was only 44 minutes. For many, it can be much longer, with half of eligible patients nationally treated in more than 100 minutes.

“That afternoon, I was sitting up in bed talking to people, and it was like nothing had ever happened –I’ve lived a perfectly normal life since,” Mike says.

Not all patients have such a positive outcome. Stroke remains a leading cause of death and disability with many survivors experiencing loss of movement, sensation and mental function. The AuSCR data also show that half of all stroke survivors experience chronic pain, mood changes, and face challenges with usual activities and experiences.

Royal Adelaide Hospital neurologist, Dr Jackson Harvey, who was part of Mike’s treatment team, says the sooner someone is treated, the more of the brain is preserved and the better they do in the long-term.

“For Mike to walk out of the hospital 2 days after his stroke shows the importance of getting to hospital,

“The impact of the Australian Stroke Clinical Registry and the National Stroke Targets are that stroke care will no longer be a postcode lottery.”

– Professor Cadilhac

Dr Jackson Harvey (left) from Royal Adelaide Hospital and Mike Lugg

“For Mike to walk out of the

hospital 2 days

after his

stroke

shows

the importance of getting to hospital, and how powerful these treatments are if we get them to patients quickly.”

– Dr Jackson Harvey

and how powerful these treatments are if we get them to patients quickly.”

The AuSCR Executive Director and Florey researcher, Professor Dominique Cadilhac, says data from across Australia are invaluable to helping healthcare providers benchmark their stroke services and identify areas for improvement.

“The registry is fundamental to having standardised data so we can reliably compare hospitals. Individual hospitals have improved through activities like developing quality improvement action plans, providing additional education to staff, and streamlining processes across different hospital departments. More patients are now accessing stroke units and getting involved in their own discharge care planning,” Professor Cadilhac says.

In 2023, the AuSCR was a key source of information to guide the establishment of National Stroke Targets. These targets have been endorsed by the Australian Government, peak bodies and key stakeholders.

“The National Stroke Targets are a call to action for everybody involved in stroke care to make sure that all patients receive life-saving stroke care, regardless of where they live in Australia,” Professor Cadilhac says.

“The impact of the Australian Stroke Clinical Registry and the National Stroke Targets are that stroke care will no longer be a postcode lottery”.

In 2024, the Australian Government provided funding for the AuSCR to build a new data platform, increase the number of participating hospitals, and develop a sustainable funding approach with state and territory governments. This support will go a long way to embedding the registry within the Australian healthcare system.

For Dr Harvey at Royal Adelaide Hospital, the targets set a clear benchmark.

“AuSCR’s data just keeps getting better and more informative, and having a standardised and coordinated registry means Australia is among the leading nations for stroke therapy,” he says.

Understanding progressive MS Multiple sclerosis

Florey researchers have shown that inflammation could be connected to the death of neurons in people with multiple sclerosis (MS).

“If we could understand the underlying genetic drivers of MS, we might be able to develop new treatments,” said Associate Professor Justin Rubio, who’s been working on the problem for 25 years.

This dedication, and the efforts of a multidisciplinary team of researchers and clinicians, has led to the discovery that inflammation appears to speed up the rate of change (mutations) in the genetic code (DNA) of neurons and that this may contribute to their death.

“If we can understand the processes that are killing neurons in MS, then we might be able to stop the disease from progressing,” Associate Professor Rubio said.

A joint Florey and University of Melbourne team studied brain tissue generously donated by the family members of people who had suffered from MS.

They investigated areas of brain inflammation and contrasted those with unaffected brain areas.

Fellow Florey researcher and key collaborator, Professor Trevor Kilpatrick, said the discovery was significant because it was the first to show that inflammation could be connected to the death of neurons in MS via accelerated mutation of their genetic code.

“This brings us a step closer to a treatment for progressive MS.”

“The team found that inflammation in the brain due to MS speeds up mutations in the genetic code of neurons, potentially impacting their survival.”

– Associate Professor Justin Rubio

Parkinson’s disease

Advancing stem cell transplants

Deep inside the brain, in an area no larger than a thumbnail, a cluster of cells makes dopamine, a chemical messenger crucial for controlling movement and motivation.

Finding ways to replenish or replace dopamine stores has long been the holy grail for scientists searching for therapies for Parkinson’s disease.

“We know that by the time a patient with Parkinson’s disease shows symptoms, they have already lost 80 per cent of their dopamine cells,” Florey Deputy Director Professor Clare Parish said.

For decades, stem cell replacement therapies have been a glimmer of hope on the horizon for people living with the common neurological condition.

Professor Parish’s Stem Cells and Neural Repair Group is a world leader in creating and utilising stem cells to study and treat Parkinson’s disease.

“We can take a skin or blood cell and reprogram it, so that it can turn into any type of cell in the body, including dopamine cells,” Professor Parish said.

“These cells offer the potential for an ethical and endless supply for transplantation.

“Trials of this therapy are underway overseas, but our lab is focused on developing next-generation stem cell technologies for brain repair.”

The team utilised stem cells that were engineered to hide them from the immune system, essentially providing the transplanted cells with invisibility cloaks, so they are not rejected from the body.

“One of the biggest risks with transplants is the body rejecting the implanted cells, so recipients rely on

“Stem cell therapies have been a source of hope for people living with Parkinson’s disease.”

– Professor Clare Parish

immunosuppressant drugs which have unwanted side effects and long term complications,” she said.

“Invisibility cloaks would enable the transplanted stem cells to avoid detection by the immune system, allowing them to survive.”

Another benefit of this approach is that it overcomes the need to ‘match’ for transplants to each patient. This would allow the generation of pools of dopamine cells ready for treatment.

The Florey team is also developing a technology that creates an optimal environment in the brain for transplanted cells to thrive.

“We can use a ‘good virus’ to deliver a protein into the brain to help the transplanted cells make better connections with surrounding nerve cells.”

The protein serves a dual purpose as it has also been shown to slow the progression of Parkinson’s disease. Professor Parish is optimistic that this research may play a role in turning the promise of stem cell therapies into a reality for the 8.5 million people living with Parkinson’s disease.

A similar approach could also benefit people affected by other neurological disorders, including Huntington’s disease, epilepsy and stroke.

Professor Clare Parish

Motor neurone disease

MND: daring to hope

Florey researchers are using a word that has been missing from conversations about motor neurone disease (MND): that word is hope.

MND, also known as Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) or Lou Gehrig’s disease, affects more than 2,500 Australians. Every day in Australia 2 people are diagnosed with MND and 2 people die from the disease. At the moment, the average life expectancy after diagnosis is only 2 years.

In the past 25 years, almost 200 drugs have shown promise in the laboratory based on animal research, but almost all have failed in human clinical trials. There is an urgent need for more effective treatments for the disease.

Recognising that the decades-old approach to drug development isn’t working for MND, a team of Florey researchers began developing a new approach using human motor neurons grown in the laboratory.

“We simply had to find a more efficient and effective way forward. We started by inviting 100 people who have MND to donate skin samples. We then turned those samples into stem cells, so we could transform them into the nerve cells affected in MND,” says Professor Brad Turner, Head of Neurodegeneration and Immunology Research.

“While we await human clinical trials of the drug combination, we are filled with hope for the future”

– Dr Chris Bye

The breakthrough came when The Florey team was able to demonstrate that the cells get “sick” in the laboratory dish, just as they do in people with MND.

The Florey’s high-throughput drug screening platform, established in collaboration with FightMND, has now identified a combination treatment is more than 6 times more effective at keeping affected nerve cells alive in the laboratory than the leading treatment used in the clinic.

Dr Chris Bye leads the the project. “We use advanced robotics to test thousands of existing medications, searching for a drug or drug combinations that are effective at slowing or stopping MND.”

The Florey platform takes weeks instead of months to gauge a drug’s effectiveness.

And the beauty of the model is that because they’re working to repurpose drugs that have already been proven safe for humans, if they identify a drug that is effective, the team can launch straight into clinical trials. This is especially important given the short life expectancy of people affected by the disease.

“So far, we’ve identified 3 drugs which, when delivered in combination, appear much more effective than those currently used for the disease.”

– Dr Chris Bye

MND researchers (from left) Katherine Lim, Dr Chris Bye and Dr Elizabeth Qian

Alzheimer’s disease

Faster dementia diagnosis

Diagnosing Alzheimer’s disease has long been like assembling a jigsaw with many missing pieces.

Confirming a diagnosis takes time, causes anxiety and delays patients’ access to services and interventions.

New breakthrough technologies are now available to diagnose Alzheimer’s disease faster, but the challenge is making these accessible to all Australians.

A major new research program led by The Florey’s Head of Dementia Research, Professor Scott Ayton, is designed to do just that.

The Enhanced Dementia Diagnosis (EDD) study will develop a new standard for diagnosing Alzheimer’s disease. The study will recruit 500 patients suspected of having the disease and offer a range of diagnostic tests to determine the best testing strategy.

“Working with clinicians, consumers and researchers, we’re trialling diagnostic tools in real-world settings to enable fast, accurate and equitable dementia diagnosis across Australia,” Professor Ayton said.

Skilled dementia specialists diagnose Alzheimer’s disease accurately only 70 per cent of the time. New blood tests are up to 95 per cent accurate but are not yet in widespread use due to cost and awareness barriers.

The EDD study will give people suspected of having dementia rapid access to the latest diagnostic tools, including the new blood test, advanced MRI and amyloid positron emission tomography (PET) scans and a cognitive function test.

Professor Ayton said that early and accurate diagnosis also helps patients make appropriate lifestyle choices and prepare for their future care needs.

Western Australian man Steve Rule had long suspected that he may develop Alzheimer’s disease; his father and his two siblings died with it.

At the age of 68, Steve enrolled in a research study and discovered that he had a build-up of amyloid plaque in his brain, a tell-tale sign of the disease.

“What was important to me was to consider the drug trials available as soon as possible,” Steve said.

“I have now completed 6 months of infusions, as part of a drug trial, and I am hoping for the best.”

As well as being an active research participant, Steve has been a dementia advocate, participating in advisory councils and research foundations.

He shares his experience of living with Alzheimer’s disease with the EDD team. Steve describes how one of the biggest influences of Alzheimer’s disease on his daily life is that his thoughts don’t always get committed to memory.

“Early diagnosis is crucial because once brain damage occurs, it cannot be reversed.”

– Professor Scott Ayton

Steve Rule with Nellie

“I might think that I want to make a coffee, but when I get to the kitchen, I can’t remember why I’m there.”

He uses diaries, openly discloses his disease to people, and relies on the support of his family and friends to deal with these challenges. He also tries to adhere to a healthy diet, exercises regularly, and maintains social connections. Steve has 3 children and 3 grandchildren.

“One of the hardest things I had to do was to sit down with my children and let them know that they may also carry the gene that increases their risk of Alzheimer’s, so they could make their own decisions about genetic testing and starting a family.”

An era of prevention

The groundbreaking Australian Imaging, Biomarker, and Lifestyle (AIBL) study has made world-leading contributions to our understanding of Alzheimer’s disease over almost 2 decades.

Through meticulous testing and tracking of more than 3,000 participants in Melbourne and Perth, The Florey and its partners have uncovered important insights into the disease.

After 40 years in the field, Professor of Dementia Research Colin Masters AO is optimistic that we are now on the verge of an era focused on prevention.

“I never thought I’d live to see it. When I began my research in the 1970s, we did not understand the natural history of Alzheimer’s disease. Thanks to observational longitudinal studies like AIBL, we have insights into its onset and progression, we understand how we might prevent it.”

A breakthrough, to which Professor Masters contributed, was the discovery that beta-amyloid plaques accumulate in the brains of people who have Alzheimer’s disease.

This silent process is thought to begin many decades before symptoms emerge. Pioneering the best approach to detecting amyloid beta was Florey Professor Chris Rowe, an expert in Positron Emmission Tomography (PET).

Thanks to his research contributions, specialised PET scans for amyloid beta became the gold standard for diagnosis and prognosis.

Now aged 74, positivity is a key part of Steve’s advocacy work, where he tries to challenge societal perceptions of the disease.

“I try to show people that you can be positive, it’s a bump in the road and you just have to work out the things that will help you along the way. My life has been very happy to date, and I believe that can continue in the long term.”

In addition to improved diagnostics and treatments, his hope for the future is that people with Alzheimer’s disease will be able to live a life free from stigma.

“… most importantly, we understand how we might prevent it.”

– Professor Colin Masters AO

The AIBL study also played a key role in developing blood tests that are now up to 90 per cent effective in detecting the disease.

“We now have blood tests comparable to PET scans in detecting Alzheimer’s disease, several of which were validated in studies at The Florey.”

Moreover, AIBL research has identified genetic and lifestyle factors that influence cognitive decline in the disease. It also showed how the apolipoprotein E (APOE) gene increases the risk of developing late onset Alzheimer’s disease.

The study has contributed to drug treatment trials for early stages of Alzheimer’s disease with researchers and pharmaceutical companies relying on its data and clinical samples to develop and test new therapies and tests.

Several new treatments targeting amyloid and tau-related toxicity are available overseas, but are yet to receive approval in Australia.

“It may take time for these therapies to become available, with much still to learn about the right timing and dosage, but we are heading into an exciting new era where it will be possible to treat, and perhaps even prevent, disease,” Professor Masters said. He thanked AIBL participants for their support in advancing Alzheimer’s disease research.

Streamlining epilepsy diagnosis and treatment

Imagine waiting 20 years for an accurate diagnosis of a condition affecting almost every aspect of your life.

For many people with epilepsy, this has been the stark reality.

But a groundbreaking research project that utilises artificial intelligence to integrate advanced brain imaging, genetic testing and clinical information is transforming the diagnostic and treatment journey for people with this common neurological condition.

Australian Epilepsy Project (AEP) lead, Professor Graeme Jackson, said the team is pioneering a new model of care for epilepsy patients to provide rapid access to advanced diagnostic tools.

Professor Jackson, Florey Deputy Director, said predicting seizure recurrence, medication effectiveness, and patient prognosis is currently challenging.

Australian Epilepsy Project (AEP)

The AEP is setting a new standard of care that simplifies the journey from diagnosis to treatment.

Epilepsy is the most common serious brain disorder globally. One in 25 Australians will be diagnosed with epilepsy at some stage in their lives.

“If you ask your neurologist after you have had your first seizure how likely it is that you are going to have another, they may as well flip a coin for the answer.”

It’s also difficult to predict a person’s response to antiseizure medications. As a result, patients often endure a lengthy trial-and-error approach to treatment, experiencing continued seizures and medication side effects.

The aim of the AEP is to improve the lives of people with epilepsy through building a ‘digital twin’ of each patient’s brain.

The AEP provides the treating neurologist with indepth information about their patient, including more detailed images of the brain, visualising networks of neural communication, and providing new insights into brain function in epilepsy.

In a subset of patients, the approach will streamline the identification of abnormalities in brain structure that may benefit from surgery. This is important, as the average time from seizure onset to surgical treatment in these patients is 22 years.

“If your daughter or son has their first seizure, you wouldn’t imagine that it might take more than 20 years for the cause to be identified,” Professor Jackson said.

“The AEP aims to change this by setting a new standard of care that simplifies the journey from diagnosis to treatment.”

For patients like Will Campbell, the project has been life-changing.

Will Campbell

Throughout his teen years Will experienced subtle symptoms like dizziness, a metallic taste in his mouth and sudden emotional swings – all features of temporal lobe epilepsy.

Will’s epilepsy went undiagnosed for years.

“Over time, my symptoms changed in frequency, intensity and nature, and I developed episodes with an overwhelming sense of déjà vu, a feeling of dread, and a narrowing of my vision,” Will said.

He also had periods where his short-term memory was impaired.

“Suddenly I’d find myself in a different room of the house and I didn’t know how I had got there.”

One day, a friend observed him having a seizure and suggested that he see a specialist.

When he was seen by epilepsy specialist, Dr Moksh Sethi, Will received a swift diagnosis, with the assistance of the AEP.

“Unfortunately, it is not uncommon for people’s symptoms not to be recognised for several years,” Dr Sethi said.

“Seizures do not always involve collapse and a loss of consciousness.”

“Over time, my symptoms changed in frequency, intensity and nature, and I developed episodes with an overwhelming sense of déjà vu, a feeling of dread, and a narrowing of my vision.”

– Will Campbell

Fortunately for Will, Dr Sethi had access to a range of advanced diagnostic tests through the AEP that are not routinely available.

Dr Sethi said medication was unable to control Will’s symptoms, but thankfully, AEP brain imaging at The Florey identified a small structural abnormality in Will’s brain that was driving his seizures.

“Around one in ten of my patients referred to the AEP have been found to have critical brain lesions that could not be seen in their prior brain scans. These have been uncovered thanks to the project, providing patients with a surgical treatment option,” Dr Sethi said.

Neurosurgeons successfully removed the damaged section of Will’s brain in 2024.

Before the surgery, he was experiencing seizures up to 5 times a day.

“If your daughter or son has their first seizure, you wouldn’t imagine that it might take more than 20 years for the cause to be identified.”

– Professor Graeme Jackson

While he remains on medication, he is currently seizure-free.

Will’s diagnosis has given him renewed optimism about his future, and he hopes to start a medical degree, inspired by his own experience.

Epilepsy is the most common serious brain disorder globally. One in 25 Australians will be diagnosed with epilepsy at some stage in their lives.

Professor Jackson said eligible patients, like Will, can sign up to the project directly and be connected to local neurologists, or clinicians can refer their patients to the AEP.

The project is demonstrating that it’s possible to deliver most of this world-class healthcare in the home, with saliva genetic tests arriving by post, and neuropsychology testing completed online.

Patients then attend any one of a number of specialist epilepsy hubs for advanced imaging scans, which are interpreted by a neuroradiologist with special expertise in epilepsy.

“The AEP is pioneering the healthcare of the future,” he said.

“If we want to give Australians the best chance of reducing or eliminating their seizures, we need to change our ‘bricks and mortar’ health system and move away from postcode medicine, where the treatment you receive depends on where you live, and shift into the digital and data era.”

Importantly, Professor Jackson said the new model of care the AEP is developing has the potential to transform care for a wide range of common neurological conditions.

Lifesaving Florey sepsis drug

“It was like turning on a light; all of a sudden, their organs started switching back on,” Associate Professor Mark Plummer recalls.

The Head of Research and Innovation in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) at the Royal Adelaide Hospital describes the striking impact of The Florey’s pioneering breakthrough therapy for sepsis on his patients.

Here were two critically ill people on the highest level of life support, showing signs of recovery within hours of receiving a “mega-dose” of sodium ascorbate.

“Their kidneys and hearts began working again while we were at their bedside,” he said.

“They both survived and were discharged home from hospital.” It’s preliminary data from trials like these that is raising hopes we could soon have the world’s first treatment to reverse the devastating impact of sepsis on the body.

Each year, around 11 million people die from sepsis. This condition occurs when the body’s immune system has an extreme response to an infection, leading to lifethreatening falls in blood pressure and multiple organ failure.

If successful, The Florey-patented drug could become a low-cost treatment, administered directly into the patient’s bloodstream.

The pioneering research led by Florey Professors Yugeesh Lankadeva and Clive May has shown

that a mega-dose of sodium ascorbate reversed the devastating impact of sepsis on the brain, cardiovascular system and kidneys. This has been shown to be effective in preliminary human trials.

Professor Lankadeva said that while the drug infusion contains the same amount of ascorbate as more

“… The Florey is working on a new therapy to combat sepsis caused by uncontrolled infections to save millions of lives worldwide, and that’s very exciting.”

– Professor Yugesh Lankadeva

Associate Professor Mark Plummer

First Nations people at higher risk of sepsis

Darwin resident Yvette Clarke is determined to ensure Northern Territory residents and health professionals understand the early signs of sepsis through education and awareness campaigns.

She wants to prevent tragedies, like the death of her nephew, Thomas Snell, a fit, healthy boy who died from sepsis after contracting influenza at the age of 13.

Yvette has heard too many sepsis stories ending in heartbreak and loss. Like the mother who almost lost her baby to sepsis, and is traumatised to talk more than a decade later, and the parents of a toddler who died from sepsis.

She is positive about The Florey therapy’s potential but stresses the importance of early sepsis identification, so that people receive timely medical care.

“I keep going because of the stories I hear, I want everyone to know the signs of sepsis.”

– Yvette Clarke, founder of isitsepsis.org

than 2,000 oranges, it has a neutral pH that makes it possible to deliver it safely in a hospital setting.

The potential treatment is in Phase 1 b clinical trials that will involve 50 patients recruited across Victoria, South Australia, New South Wales and Queensland. The trial will focus on safety and the drug’s ability to normalise blood pressure.

Associate Professor Mark Plummer said sepsis is the main cause of death in ICUs in Australia and worldwide. “It’s deeply saddening to see so many people die before our eyes,” he said.

“All we can do is to use antibiotics to combat the infection, but we don’t have any treatments to reverse organ damage.

“The role of the ICU team is to support the failing organs, to allow time for the body to recover.”

Associate Professor Mark Plummer has the task of seeking the consent of patients’ family members for their participation in The Florey trial. “I’m speaking to families on the worst day of their life, when their loved one has gone from being fine to critically ill,” he said.

Thomas Snell, Yvette’s nephew, a fit, healthy boy who died from sepsis after contracting influenza at the age of 13.

He hopes that The Florey research will lead to the firstever treatment to reverse multi-organ dysfunction in sepsis, which would be a breakthrough in ICU care.

If there are positive results from the current trial, the research team will be launching a larger double-blind, randomised controlled trial involving 300 patients from around Australia. The trial will include the Northern Territory, where sepsis rates are 4 times higher than in other states and territories.

Professor Lankadeva reflects that The Florey is named after Australian scientist Sir Howard Walter Florey OM, who shared the Nobel Prize for his role in developing penicillin.

“Penicillin was one of the biggest medical breakthroughs of modern medicine – it has allowed doctors to treat bacterial infections, saving countless lives,” Professor Lankaedeva said.

“Now, almost a century later, The Florey is working on a promising new therapy to combat sepsis, with the potential to save millions of lives. It is fitting that this drug discovery was made in the institute named in honour of Sir Howard Florey.”

Levelling Up

Advancing women in science

Philanthropy is a force for social change – and now, it is transforming the future of women researchers at The Florey.

The Florey is home to many leading women researchers. Traditionally, women have been underrepresented in senior roles, and medical research is no exception. It’s a gap that has remained stubbornly unchanged for many years. Research points to systemic barriers such as unconscious bias, limited leadership and networking opportunities, and challenges balancing work and life demands as key contributors to this situation.

The Levelling Up program is made possible thanks to the Naomi Milgrom Endowment, generously established by Australian business leader and philanthropist Naomi Milgrom AC. The program will provide $150,000 for resources, mentorship, financial assistance, and leadership coaching for women researchers seeking promotion at The Florey.

The program will support personalised career development strategies, funding to attend

conferences, professional training, research support, grant writing assistance, and childcare support. Through these initiatives, participants will overcome barriers, build leadership skills, expand their networks, and advance their careers.

Beyond individual support, Levelling Up aims to foster a thriving, interconnected community of women leaders at The Florey – creating a culture where mentorship, collaboration and long-term professional growth are embedded in the research environment.

The program has clear goals for promotion rates, career satisfaction, grant success and greater diversity in leadership. Through annual progress reviews and a strong focus on accountability, Levelling Up will ensure lasting, meaningful change.

By investing in the advancement of women in science, Naomi Milgrom’s visionary philanthropy is helping The Florey build a more inclusive, equitable, and innovative future.

With this program The Florey is taking a critical step towards building a more inclusive and equitable academic community, and improving research and health outcomes. By addressing systemic barriers and providing targeted support, this program will help ensure that women researchers have the tools, resources, and networks they need to thrive – now and into the future.

The Florey family Florey Future Fund

One in five Australians is affected by neurological and mental health conditions.

For many, current medications and treatments do not work. Every day, world-class researchers at The Florey are working to find new ways to diagnose, treat and prevent these conditions. None of this would be possible without the generous support of our donors.

The Carl and Wendy Dowd Professorial Fellowship

The Florey is grateful for the extraordinary philanthropy of Carl and Wendy Dowd in establishing the Carl and Wendy Dowd Professorial Fellowship – an example of the impact made possible through the Florey Future Fund. As a recipient of the fellowship, Professor Ross Bathgate has conducted groundbreaking research to develop new treatments for cardiovascular, neurological and gut disorders. With this support, he and his team have secured competitive funding and formed partnerships with industry leaders. The Dowd Fellowship has been instrumental in enabling these achievements.

The Florey Future Fund: ensuring a legacy of medical advancement

Established through the Dowds’ visionary philanthropy, the Florey Future Fund is an endowment that provides a perpetual stream of income to support our staff to build exceptional teams, conduct research in cuttingedge laboratories, and collaborate globally. It enables us to plan for a future free from the constraints of traditional medical research funding, providing security and allowing us to sustain projects in times of financial uncertainty.

An endowment fund operates by investing donated capital and using the returns to support ongoing activities – preserving the original gift while generating

a stable, long-term income stream. Through the Florey Future Fund, donors can contribute to a wide range of priorities, from research fellowships and laboratory innovation to international collaboration and gender equity in science.

In doing so, donors strengthen the Institute and provide researchers with the stability to pursue long-term, high-impact projects. These investments drive vital research into neurological and psychiatric conditions, advancing our understanding and developing better therapeutics and diagnostics.

Gifts of $100,000 or more are recognised in perpetuity, and supporters can contribute through cash donations or gifts in their Will.

Become a Florey supporter

Every donation to The Florey helps develop new treatments, advance our understanding of the brain and improve health outcomes.

Include a gift in your Will

Including a gift in your Will provides a legacy of hope. You can leave a total bequest, a residual bequest (what is left after loved ones are cared for), or a percentage of your estate. Our Philanthropy Team is here to support you and those who help with your estate planning.

Thank you to our donors

Thanks to the generous support of our donors, we are able to conduct our vital research. Your donations help us work towards more effective diagnostics, improved treatments, and better health outcomes. For further information, please contact our team.

Email: philanthropy@florey.edu.au

Phone: 1800 063 693

Find out more: www.florey.edu.au/support-us

Carl and Wendy Dowd

The Florey Institute of Neuroscience

Florey