Chasing the Jaguar

ARTICLE BY THE HON. KEN WISE

Looking at a photograph of Sam Houston from the mid-19th century, one is drawn to the flashy spotted vest under his traditional black coat. Houston liked to refer to it as a leopard vest, no doubt a nod to his famous quote, “A leopard never changes its spots.” But the vest is actually made from the pelt of a jaguar, a native cat of North America. Houston’s vest was unique because the jaguar started disappearing from the Texas in the 19th century.

A spotted pelt is where the similarity between the leopard and jaguar ends. The jaguar is distinct from its larger cousins, having a relatively compact, muscular build designed for an ambush-style attack rather than prolonged stalking or chasing. The muscles in its head and jaw give the jaguar an extreme amount of bite force relative to its size. They typically deliver one powerful killing bite to their prey. Jaguars can even swim and have been known to hunt

The Goldthwaite jaguar took out one dog and injured several others, and also killed a horse, before being shot after an long hunt in 1903.

turtles and fish or drown other prey in water. They easily adapt to a variety of habitats, from wetlands and riverine areas to dry forests or grasslands. Their ability to adapt to such varied geography made Texas a natural place for the jaguar to occupy.

Spanish explorers recorded encounters with the cats. On Coronado’s famed expedition through the American Southwest in 1541, he wrote the viceroy of encounters with jaguars in what is now New Mexico, referring to them as tigre. A priest named Ribas recorded the big cats in Sonora, Mexico, in the early 1600s. Then, in 1709, Fray Isidro de Espinosa led an expedition from the San Juan Bautista mission on the Rio Grande near present-day Guerrero, Mexico, into the central Texas area. Espinosa recorded seeing Jaguars south of present-day Austin between there and what would likely be the area around present-day

La Grange. Espinosa moved west from San Antonio toward the Frio River and recorded additional jaguar encounters.

When John James Audubon visited Texas in 1837, he visited President Sam in his residence at Houston, then the capital of the Republic. Houston told tales of seeing jaguars at multiple locations near the Rio Grande, Guadalupe and San Jacinto rivers.

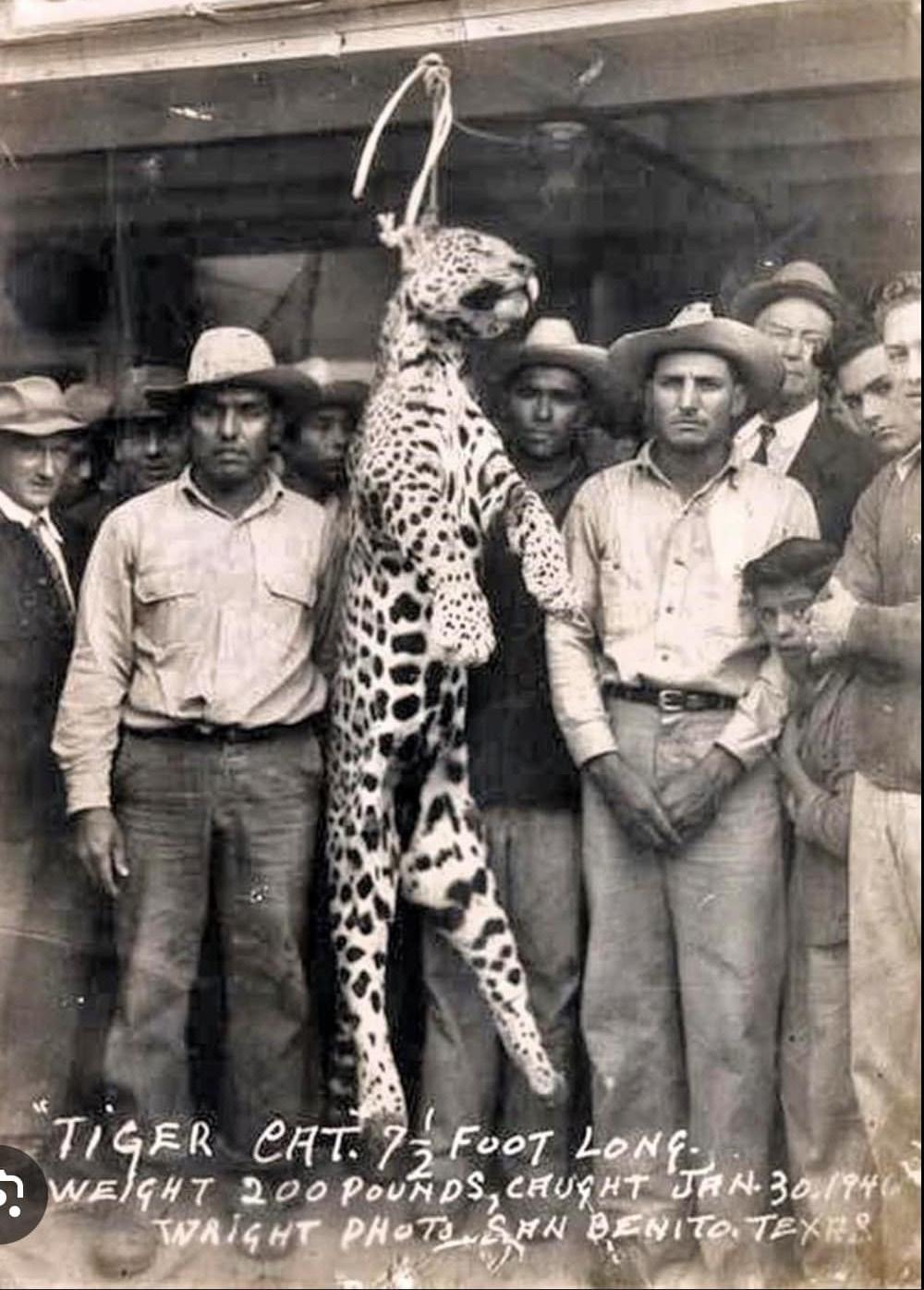

More modern accounts of jaguar encounters are recorded as occurring over a vast swatch of the state. Around the turn of the century, there were tales of jaguars as far east as Jasper, Beaumont and Conroe. Around the same time, there were reports of jaguars killed near Comstock and Carrizo Springs.

A lady named Eliza Johnson recalled an 1856 incident near Fort Mason in which what she describes as a “tiger cat” was spooked from the brush by a man practicing archery. San Antonio resident Gustave Duerler recalled seeing a jaguar in a tree near San Pedro springs in the 1860s. He called to his father, who killed the animal in what is now an area of San Antonio near downtown!

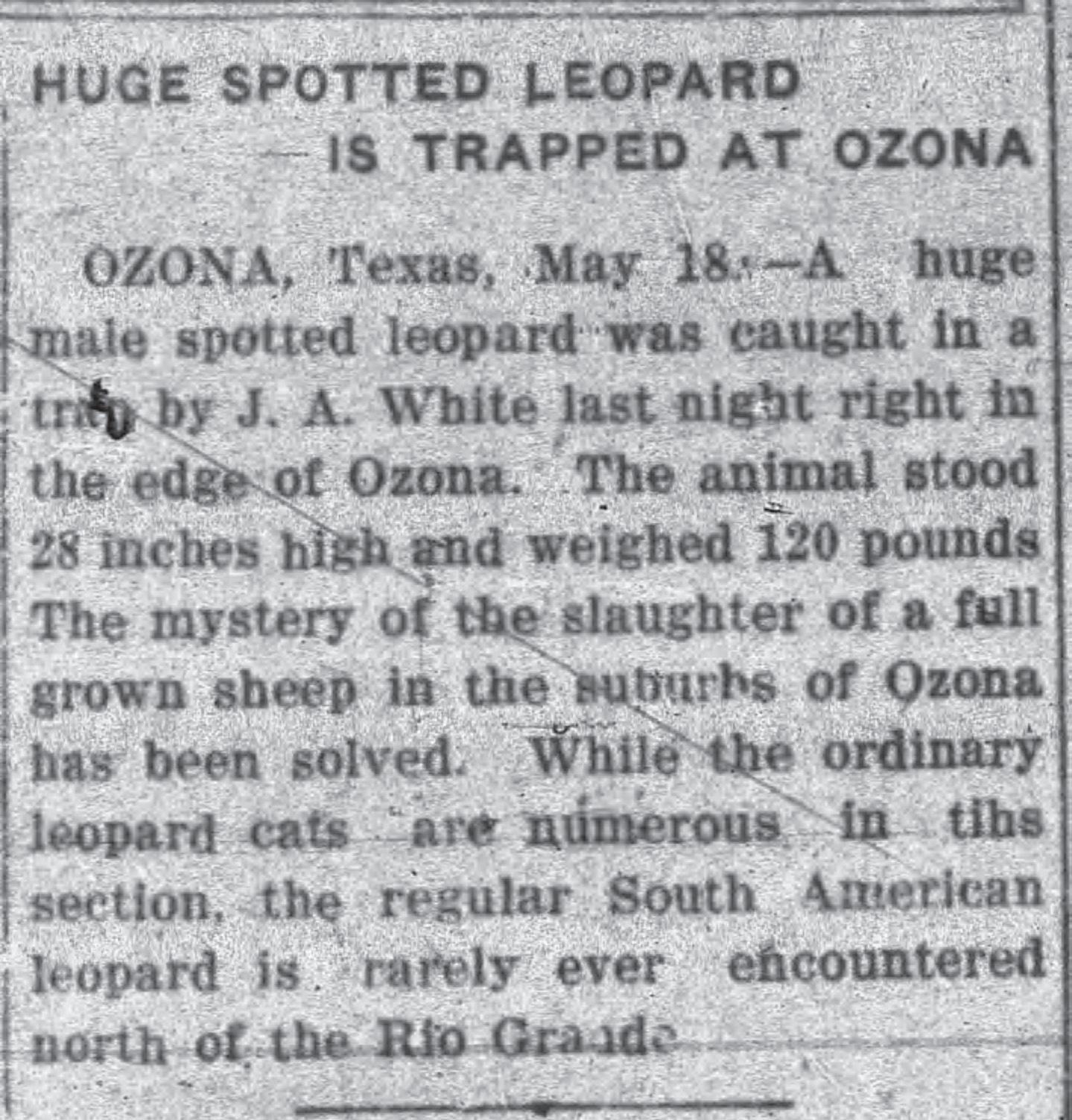

In 1903, a jaguar was taken near Center City, east of Goldthwaite, in the central part of the state. According to first-hand accounts, a group of men with hunting dogs set out at dusk to hunt a jaguar reported to be about

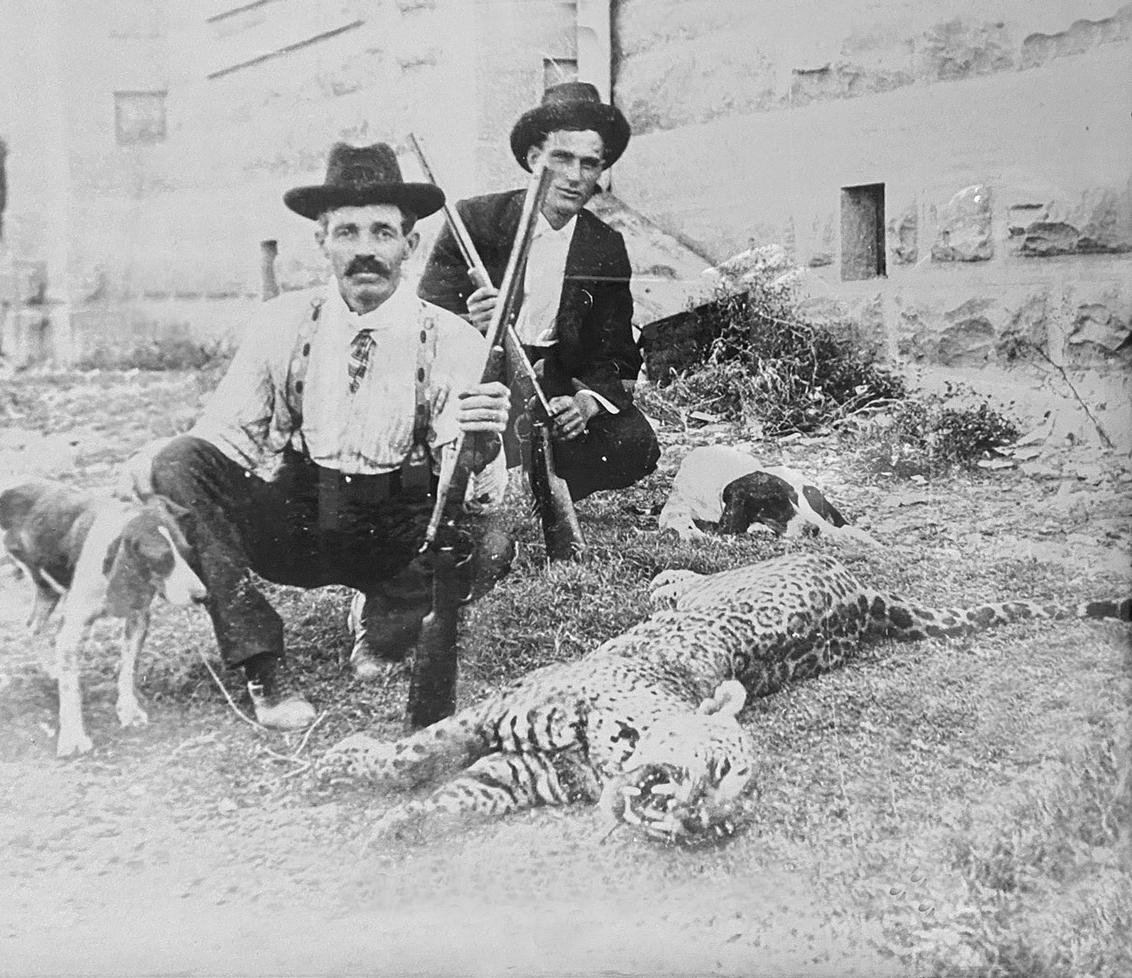

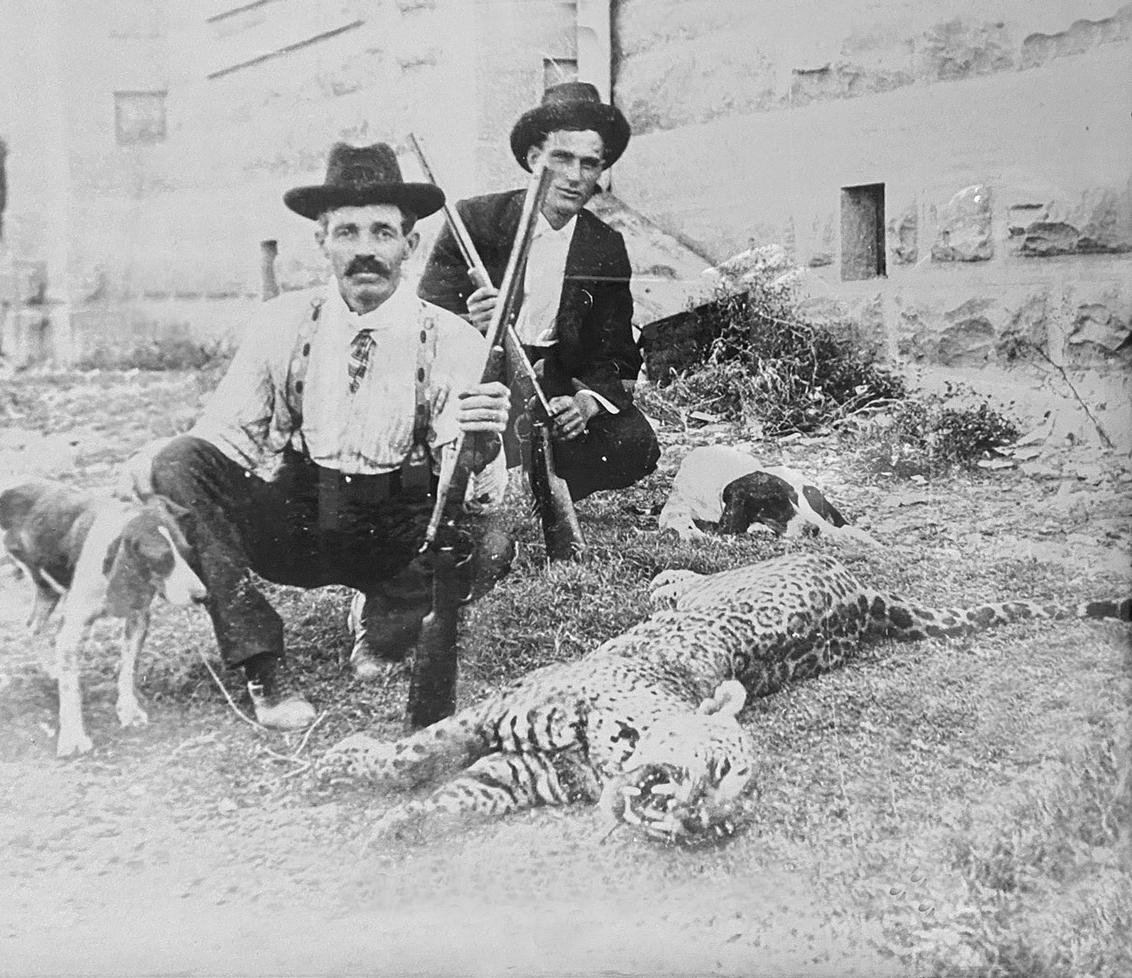

A brief mention of a jaguar trapped near Ozona was published in the May 18, 1915 edition of the Victoria Daily Advocate.

Weighing in at 140 pounds and measuring over 6 feet long, the skull and hide of the Goldthwaite jaguar now reside in the Smithsonian.

three miles from town. The dogs picked up the scent and gave chase, treeing the animal in a small oak. One of the hunters then shot the animal once with what he described as a “Colt .45.” The animal fell from the tree and took off running.

The dogs gave chase and bayed the animal. At this point, one of the hunters had to return 3 miles or so to Center City “for guns and ammunition.” There is no explanation for why the party set out after the state’s largest, perhaps the most dangerous, cat without adequate armaments and sufficient ammunition. After an hour and a half, the hunters were ready to set the dogs on the jaguar.

The hunters had to ride into the “shinnery” or oak brush to attempt to root out the big cat. Out it came. The hunters began their effort with 10 hunting dogs. By the time they killed the animal around midnight, there were only three dogs still in the fight, and one of those was wounded. The jaguar killed one dog and severely injured several others. Notably, the jaguar delivered a bite to one of the horses so severe that the horse later died of its wound. Ultimately, the jaguar measured over 6 feet long and weighed 140 pounds. Today, this jaguar’s skin and skull are in the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History collection under catalog number 123527, should the reader desire to see it.

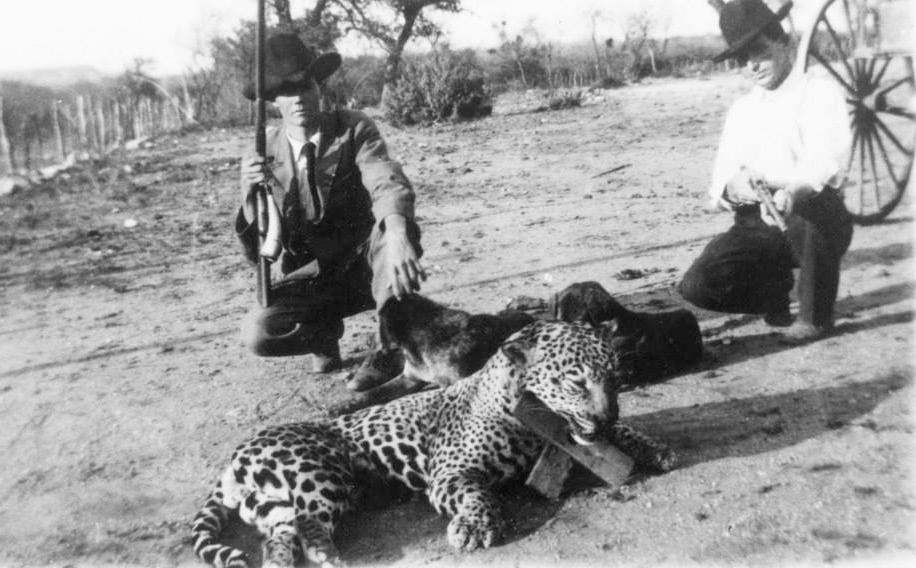

In 1909, another jaguar was killed near London, Texas. In that incident, two young boys took three hunting dogs to see if they could determine what had been causing the

In 1909 two young boys and their three hounds came across a jaguar near present-day Red Creek Cemetery Rd. and Hwy. 377 in Kimble County.

The last jaguar in Texas was killed near Kingsville in 1948 on the Ferguson Dairy Farm. One of the Ferguson boys posed with the big cat in a Kingsville neighborhood.

occasional sheep to go missing from the family ranch. While playing in some boulders on the side of a hill, the dogs began going crazy. It turns out the dogs had found a jaguar in a shallow cave. There was one significant problem—neither boy carried a gun.

The boys fled down the mountain to get help, which came in the form of an older boy named Dan and a double-barreled shotgun. Back up the mountain they went to confront the big cat. Doing their best under the circumstances, the younger boys took out their pocket knives to prepare for a wounded jaguar. Dan, no doubt nervous himself, let loose with both barrels into the cave—and missed.

The jaguar shot up the mountain, trailed by the three dogs, who managed to circle the cat back into the cave. This effort was not without incident when the jaguar swatted one dog so powerfully that it broke the dog’s hip. At that point, the boys decided to go in search of more firepower and enlisted the help of a neighbor who dispatched the cat with a .22 rifle. The cat’s hide was nailed to the side of a barn to dry, but the hunting dogs would have the last say. They shredded the hide of the jaguar overnight.

One of the more well-known jaguar encounters happened in Kingsville in 1948. On the Ferguson dairy farm, near presentday Dick Kleberg Park, ranch hand Reyes Cuevos went rabbit hunting with his .410 in the brush near the ranch house. He spotted a jaguar crouched on the ground behind a cactus. Perhaps not fully considering the situation, he fired with

However, when aerial deer surveys typically only reveal a fraction of an actual deer population, it might pay to keep your eyes peeled for any spotted “tiger cats.” It might also pay to carry a bigger gun.

his .410. The small shot may have blinded the cat because it started running in circles before seeing and taking advantage of the relative safety of a small tree nearby. In what seems to be a theme with these encounters, Cuevos went to fetch a larger gun and finished off his quarry. The biologist from the King Ranch, Val Lehman, inspected the animal, which measured over 5 feet, 10 inches long. When asked why he shot the jaguar with only the .410 he carried, Cuevos reportedly, “figured he could outrun the animal.” Fortunately for Cuevos, he didn’t have to learn a potentially harsh lesson.

That 1948 Kingsville cat is widely considered the last jaguar in Texas. Many varieties of felines still inhabit the state, including the smaller jaguarundi, ocelot, and the more prolific bobcat. However, when aerial deer surveys typically only reveal a fraction of an actual deer population, it might pay to keep your eyes peeled for any spotted “tiger cats.” It might also pay to carry a bigger gun.