Javelinas

MAGAZINE OF THE TEXAS WILDLIFE ASSOCIATION JULY 2023

Not all playgrounds

The outdoors is your sanctuary. It’s a place where you and your family can explore, relax, and simply live. What would make it all the more special is if the land you love to play on was your own. Capital Farm Credit can help you do just that. You see, we’re here for you with the knowledge, guidance and expertise in acquiring recreational land with loans that have competitive terms and rates. That way, whenever you have the urge to play, you have the perfect place to go do it. To learn more, visit CapitalFarmCredit.com.

NMLS493828

877.944.5500

2114 US-84 Goldthwaite, TX 76844 855.648.3341 hpolaris.com hcanam.com OUTDOOR SUPERSTORE We Ca r ry t he Utility Vehicles You N e e d and the brands you trust

JUSTIN DREIBELBIS

It’s hard to believe that it is already Convention time again, but here we are in July—the time of the year when TWA members from all around the state converge on San Antonio for a long weekend of fun, camaraderie, education, organizational business, and fundraising. We are gearing up for another great event!

The first Convention was held back in 1986 at the YO Hotel in Kerrville. I’ve had the good fortune to get my hands on some pictures from some of those early meetings (you will see a few later in this issue) and let me tell you, they are special.

There are photos of potluck dinners by the pool, lively auctions emceed by David Langford and Larry Weishuhn, and lots of networking events with a recognizable cast of members that may or may not have grayed a little since those photos.

Although the size of the convention and the hosting hotel has grown significantly over the years, the important things have remained consistent. The event is a family reunion where members show up to support each other, the organization, and Texas natural resources. I’m also excited to say that the children of several of the members in those original photos now serve in TWA leadership roles.

Convention is a heavy lift each year. From a staff perspective, we honestly start planning the next convention the day after the current one ends. I’m extremely proud of the hard work our team puts into planning and executing the event, but it is the members who blow wind into the sails and have made it work for 37 years.

It is inspiring to step back and think about the amount of time and resources invested into the event on an annual basis to ensure TWA can continue carrying out our mission. Our loyal sponsors generously underwrite the event and make it a revenue generator for the organization.

The Convention Committee works tirelessly to secure sponsorships and auction items. Advisory committees work to ensure the best educational resources are available through the Private Lands Summit, educational seminars and youth education programs. And finally, the members show up every year and open their checkbooks to purchase registrations and auction items that directly benefit the organization. Thank you all for your continued support.

In closing, I would like to thank our outgoing President Sarah Biedenharn for her leadership over the last two years. Her calm, thoughtful approach has had a positive impact on the organization in many ways and I very much appreciate her support and guidance during my first two years back with TWA.

During Sarah’s presidency, I was continually impressed by the way she made it a priority to show up for events all around the state to represent TWA. As my friend David K. Langford often says, “The world is run by those who show up.” TWA has a long track record of “showing up” to represent landowners and hunters and Sarah certainly embodied this mantra in the way she approached her presidency. Thank you, Sarah!

We look forward to seeing you all in San Antonio July 13-15 for WildLife 2023. Thanks for being a TWA member.

Texas Wildlife Association

Mission Statement

Serving Texas wildlife and its habitat, while protecting property rights, hunting heritage, and the conservation efforts of those who value and steward wildlife resources.

JULY 2023 4 TEXAS WILDLIFE TEXAS WILDLIFE is published monthly by the Texas Wildlife Association, 6644 FM 1102, New Braunfels, TX 78132. E-mail address: twa@texas-wildlife.org. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to Texas Wildlife Association, 6644 FM 1102, New Braunfels, TX 78132. The Texas Wildlife Association (TWA) was organized in 1985 for the purpose of serving as an advocate for the benefit of wildlife and

of wildlife managers, landowners and hunters in educational, scientific, political, regulatory and legislative arenas. TEXAS WILDLIFE is the

Texas

United States.

rights

No parts of these magazines may be reproduced or transmitted

publisher. Copyrighted 2023 Texas Wildlife Association. Views expressed by contributors are not necessarily

Texas Wildlife

Texas Wildlife Association 6644 FM 1102 New Braunfels, TX 78132 www.texas-wildlife.org (210) 826-2904 FAX (210) 826-4933 (800) 839-9453 (TEX-WILD)

for the rights

official TWA publication and has widespread circulation throughout

and the

All

reserved.

in any form or by any means without express written permission from the

those of the Texas Wildlife Association. Similarities between the name

Association and those of advertisers or state agencies are coincidental, and do not indicate mutual affiliation, unless clearly noted. TWA reserves the right to refuse advertising.

TEXAS WILDLIFE CEO COMMENTS

by DAVID BRIMAGER

33 Staff Spotlight

Meet Andrew Earl

by LARRY WEISHUHN

38 TAMU News

A Versatile Tool for Aquatic Vegetation Management by BRITTANY

CHESSER and TODD SINK

40 Out of Asia by WILL LESCHPER

KASSI SCHEFFER-GEESLIN

44 Phenotypic Variability in Feral Hogs by AARON SUMRALL, Ph.D.

48 A Prickly Subject Javelina Make Great Table Fare by KRISTIN BROOKE PARMA

by SALLIE LEWIS SCHNEIDER

The collard peccary or javelina is one of the most iconic big game animals in Texas, and perhaps the least understood. With it’s pig-like snout, it can be mistaken as just another pig, but the javelina is a species unto itself. And in spite of it’s musky smell it makes great table fare. For a detailed look at this unique animal, check out Joseph Richards’ article and photos beginning on page 8.

Cover Photo by Joseph Richards

WWW.TEXAS-WILDLIFE.ORG 5

Wildlife MAGAZINE OF THE TEXAS WILDLIFE ASSOCIATION 8 Javelina Status of a Texas Native by JOSEPH RICHARDS

Texas

VOLUME 39 H NUMBER 3 H 2023 JULY

Outdoor Traditions Reaching For the Moon

Photo by Joseph Richards

54

& Hunting Summer Time, Summer Time

16 Hunting Heritage State’s Top Big Game Showcased at WildLife 2023

34 Guns

Borderlands News Predicting Habitat Overlap Between Montezuma Quail and Feral Pigs by MAYA RESSLER, RYAN LUNA and JUSTIN FRENCH 30 18 Lessons From Leopold Biotic Pain

MAGAZINE OF THE TEXAS WILDLIFE ASSOCIATION JULY 2023 Javelinas

by STEVE NELLE

On the Cover MAGAZINE CORPS Justin Dreibelbis, Executive Editor David Brimager, Managing Editor Burt Rutherford, Consulting Publications Coordinator/Editor Lorie A. Woodward, Special Projects Editor Publication Printers Corp., Printing, Denver, CO Magazine Staff

20 Conservation Legacy Coming Together for Conservation Education

by

24 TWA Convention A Family Reunion from the Get-Go by LORIE A. WOODWARD

MEETINGS AND EVENTS

JULY

JULY 13-16

TWA’s 38th Annual Convention, WildLife 2023, San Antonio, JW Marriott San Antonio Hill Country Resort and Spa. For more information, visit www.texas-wildlife.org.

JULY 14

Texas Wildlife Association Foundation presents Shane Mahoney, guest luncheon speaker. JW Marriott San Antonio Resort and Spa, 12:00-1:30. Purchase tickets online at www.texas-wildlife.org. For information, contact TJ Goodpasture at tjgoodpasture@texas-wildlife.org.

JULY 22

Adult Learn to Hunt Program

Educational Sessions, TWA headquarters in New Braunfels. For information, contact Matt Hughes mhughes@texas-wildlife.org

JULY 29

Huntmaster Training, Sherman

FOR INFORMATION ON HUNTING SEASONS, call the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department at (800) 792-1112, consult the 2022-2023 Texas Parks and Wildlife Outdoor Annual, or visit the TPWD website at tpwd.state.tx.us.

AUGUST

AUGUST 4-6

Adult Learn to Hunt Program

Huntmaster, Volunteer Training, TBD. Contact Matt Hughes mhughes@texas-wildlife.org

AUGUST 8

Member Happy Hour, Corpus Christi. Contact Kristin Parma at kparma@texas-wildlife.org for more information.

AUGUST 16-18

Statewide Quail Symposium, Abilene

AUGUST 19

A Learn to Hunt Program Tamalada, TWA headquarters. Contact Kristin Parma at kparma@texas-wildlife.org for more information.

AUGUST 31

Member Happy Hour, Nacogdoches. For information, contact Matt Hughes at mhughes@texas-wildlife.org

SEPTEMBER

SEPTEMBER 21

Hunting Film Tour Austin

Hunting Film Tour San Antonio

Hunting Film Tour Dallas

Hunting Film Tour Houston

Contact Kristin Parma at kparma@texas-wildlife.org for more information.

OCTOBER

OCTOBER 10

Texas Outdoorsman Of The Year, San Antonio. For information, contact tjgoodpasture@texas-wildlife.org

OCTOBER 20-21

Panhandle Wildlife Conference, Lubbock. For more information, contact Kristin Parma, kparma@ texas-wildlife.org

DECEMBER

DECEMBER 11

7th Annual Houston Clay Shoot, Greater Houston Gun Club. Contact Kristin Parma at kparma@texas-wildlife.org for more information.

CONSERVATION LEGACY YOUTH PROGRAMMING

CONSERVATION LEGACY TEACHER WORKSHOPS

TWA’s Conservation Legacy team will conduct six Teacher Workshops this spring and summer. The workshops are 6-hour trainings that introduce attendees to TWA, in-class and outdoor lessons and activities, and how to incorporate natural resources into classrooms or programming. Lessons focus on teaching land stewardship, native wildlife, and water conservation and are Science TEKS-aligned for Grades K-8.

• Designed for Grade K-8 educators

• Open to all statewide formal and informal educators. The workshops are not restricted to a certain district or region.

• Workshops are offered at no cost

• Six, 6-hour workshops offer CPE credit

• Provides hands-on training for educators to incorporate natural resource and private land stewardship lessons into their teachings.

For more information, go to www.texas-wildlife.org/ educator-development-and-resources

JULY 2023 6 TEXAS WILDLIFE

TEXAS WILDLIFE

VISIT THE PROGRAM PAGES ONLINE AT https://www.texas-wildlife.org/youth-education/ for specifics and registration information.

TEXAS WILDLIFE

distinct

JULY 2023 8 TEXAS WILDLIFE JAVELINA

An adult javelina emerges from the South Texas brush. Javelinas are medium-sized, compact, and sport a

white collar circling the chest that contrasts with a dark salt-and-peppered hair coat.

JAVELINA

Status of a Texas Native

My ears were attuned to the chorus of sounds from the mesquite brush line. I sensed a presence in the thicket as the sound of approaching hoof steps echoed louder and louder. The dried leaves crackled beneath a large animal’s weight. I lifted my camera anticipating what might emerge. Within the span of a few seconds, the sounds of one animal turned into two, then three, and more.

Before I could catch a glimpse, I caught a hint of musk in the air. To my surprise, a herd—also called a squadron—of javelina rushed toward my corn feeder. With great determination, the javelina set up camp over the scattered corn—the sound of their munching filled the air.

Camouflaged and concealed, I witnessed the customs of javelina society unfold. The interactions between adult and

WWW.TEXAS-WILDLIFE.ORG 9

Article and photos by JOSEPH RICHARDS

juvenile javelinas seized my attention and were the highlight of my sit. Due to their limited range and elusive nature, very few people have first-hand experience observing javelinas in their environment. A wealth of buried knowledge pertaining to javelinas and their habits is destined to be revealed.

JAVELINA VS. WILD PIGS

Taking on the appearance of a pig, the collared peccary or javelina often suffers from mistaken identity. The javelina is one of three extant species of peccary that belong to the New World and are placed in the taxonomic family of Tayassuidae They are not true pigs which comprise the family Suidae and originated in the Old World.

Several physical characteristics distinguish pig-like peccaries from true pigs. Javelinas are medium-sized and compact. They sport a distinct white collar circling the chest that contrasts with a dark saltand-peppered hair coat. The neck and back harbor clusters of long, coarse bristles that can be erected voluntarily when excited. Wild pigs are medium to largesized animals that are highly variable in coloration. Male wild pigs are typically larger than females.

Atop the javelina’s back toward the rump is a large scent gland that can release a strong odor lending them the alternative names “musk hog” or “skunk pig.” They use this dorsal gland to mark or stain objects along territorial boundaries as a chemical message for other javelinas. The released odor can be detected by humans from several yards away. Wild pigs do not possess a dorsal scent gland.

Most notably, the javelina does not have a visible tail, making it easily distinguishable from wild pigs. The javelina has a single fused dewclaw on the hindfoot while pigs have two rear dewclaws which often appear in tracks.

The javelina’s spear-like upper and lower canines grow straight up and down and wear against each other to ensure razorsharp edges. The whole mouth holds 38 teeth. The upper tusks of a wild pig grow out and backward, and they possess 34 or 44 teeth depending on the species.

JULY 2023 10 TEXAS WILDLIFE JAVELINA

When on the move, young javelinas follow their parents closely and tend to stay right at their side.

Female javelinas only have four functional mammary glands and produce on average two young per litter. Far more prolific, wild pig sows have six to 20 mammary glands and can deliver more than 20 offspring at one time.

Less conspicuous features separating javelinas from wild pigs include a complex pouched stomach, a gallbladder and fusion of the foot and leg bones. Wild pigs possess a simple stomach, lack a gallbladder, and have unfused leg bones.

TPWD CALL FOR RESEARCH

A great deal of dramatized lore surrounds the mysterious javelina, resulting in many misconceptions and false notations about their character. However, fearsome stories told around the campfire have failed to generate enough interest in the management of the species. Today, the javelina represents to many the most neglected of Texas’ big game animals.

Limited research has gone into uncovering detailed information on javelina life history traits and population dynamics. In November 2022, the Texas Parks & Wildlife Department (TPWD) requested research proposals to help provide demographic information on javelina in South Texas.

“With whitetails, we have population models that we can plug in, observe numbers of does, bucks, and fawns so we can get population estimates. We can even manipulate those, given environmental variations,” said Dr. Whitney Gann, TPWD South

WWW.TEXAS-WILDLIFE.ORG 11 JAVELINA

Young javelinas have strong bonds with their parents. When not napping or foraging, they can often be observed rubbing and nose touching with siblings or other herd members.

Although they seem similar to wild pigs in appearance, the javelina belongs to its own family of Tayassuidae

JAVELINA

Texas ecosystem project leader at the Chaparral Wildlife Management Area, about the objectives of the proposed research. “Something like that does not exist for javelina.”

She explained that unlike other big game species such as white-tailed deer, there remains a lack of detailed harvest justification and recommendations for javelina. According to the TPWD proposal, the intended study will create a standardized survey methodology and a model for estimating populations that will be used by field biologists throughout the state.

“Hopefully through the process of developing the survey and model, the researchers will be able to give us the tools so that we can deploy the county biologists to evaluate exactly how far their [javelinas’] range is today and what the status of those herds are,” Gann said.

Javelina once occurred throughout two-thirds of the Lone Star State with historical accounts recorded as far north as the Red River and east toward the Brazos. The South Texas Brush Country and Trans-Pecos regions still boast high numbers of javelinas. In 2004, TPWD transplanted 29 javelinas into Mason Mountain Wildlife Management Area in attempt to restore the population in the Edwards Plateau. Outside of Texas, javelinas are also found in restricted pockets of Arizona and New Mexico with their range extending through Central America and as far south as Argentina.

“We are due now for an evaluation of which counties have them, how dense are their populations, and how often people are encountering them. All of these questions are worth answering,” she said.

Javelinas are often difficult to detect with traditional survey methods due to their preference for dense brush thickets,

chaparral, and mixed thorn-scrub woodlands. During the day, they spend long periods bedded in the brush with a heavy canopy for shade. In rocky terrain, javelinas will utilize caves and rock overhangs for cover. Most activity takes place in the early morning and late evening to avoid extreme temperatures.

“There’s a secondary factor associated with surveying javelina, and it’s the fact that they’re sexually monomorphic,” Gann said. “They look the same, and even between the juveniles and the adults it can be difficult to tell what you’re looking at.”

Relatively the same size, adult male and female javelinas are notoriously difficult to distinguish in the field, which makes it challenging during population surveys. Adults typically measure 3 to 4 feet long and weigh around 30 to 45 pounds. A very large javelina will tip the scale at more than 60 pounds with even larger sizes achieved in captivity.

Gann remarked that the call for research could not have come at a more appropriate time. Human population is growing across Texas, prompting more urban development. “The border is developing and growing, and there’s more instances of wildlife-human conflict as those urban centers expand and that can include a lot of different wildlife species, javelina being one of them,” she said.

Texas A&M University has been awarded the TPWD project to study population and spatial ecology of collared peccary across the western South Texas Plains. TAMU is working in collaboration with TPWD and the University of Montana.

“Collared peccary are unique critters adapted to more arid environments, and their study has largely been neglected, so this large-scale, five-year project will determine factors affecting population dynamics, movement, and habitat use while trying

JULY 2023 12 TEXAS WILDLIFE

Javelinas are often difficult to detect with traditional survey methods due to their preference for dense brush thickets, chaparral, and mixed thornscrub woodlands.

to develop more accurate and efficient survey techniques” said Dr. Stephen Webb, research assistant professor and principal investigator at TAMU.

The upcoming research will present a strategic chance to educate the public about javelina and the value in learning about one of our state’s unique and indigenous wildlife species, engendering pride.

“The conclusion of this study would be a prime opportunity to synthesize some of that information and use it as a starting point to begin an education program. . . Awareness, education and excitement about the species are ultimately where we’re hoping to end up,” she said.

JAVELINA BIOLOGY

Javelinas are gregarious, living together in squadrons averaging a dozen individuals with groups as large as 27 reported. The herd’s social structure consists of family members of mixed age and sex.

The herd maintains a territory with adults actively marking boundaries with scent from their dorsal glands. Within each territory, there are core areas of activity—bed grounds, feeding sites, waterholes, etc.—all connected by a network of trails. Javelinas travel along these trails in single file while continuously maintaining contact with members in the group. Use of these activity areas varies seasonally, but they remain important.

Observing a javelina herd can be an entertaining spectacle simply because of their modes of communicating with one another. Mutual rubbing is a common behavior that reinforces recognition and maintains herd cohesion. Head and neck nuzzling, nose touching, and licking are all mutual behavior patterns. Javelinas possess a keen sense of smell that is critical for exchanging scent between herd members. Their sense of smell is not only important for social behavior but also to detect predators and buried food.

In addition to tactile and chemical messages, javelinas communicate via vocalizations such as grunts, huffs, growls, and squeals. Low grunts are constantly emitted from a herd content in feeding. Huffs act as alerts for the whole herd to wait and lis-

ten for a possible disturbance. Aggressive calls like growls are loud and emitted between two javelinas during short squabbles. Rarely do adults squeal unless in distress, but young will squeal when they are separated or seek attention from their mother.

One of their more unique behaviors, javelinas clap their upper and lower canine teeth together making a “popping” or “clacking” sound as a sign of aggression. The level of speed and intensity varies, but the most impressive displays occur when an animal is cornered.

With bare tusks and raised manes, javelinas will confront predators to defend themselves or their young. High and coarsepitched game calls are known to bring in javelinas—probably with the intention of encountering whatever potential predator intrudes on their territory.

The javelina’s primary food is prickly pear cactus, which is a year-round food source for javelinas in the Southwest. Their complex, pouched stomachs create the conditions for breaking down the cactus pads—spines and all. How the spines dodge the inner vitals remains unknown. In areas lacking prickly pear, multiple species of cacti make up the food source, including lechuguilla, sotol, cholla, century plant, and other succulents that sustain their water needs during critical periods.

Javelinas also consume seasonal mast such as acorns, fruits, and mesquite beans. Forbs, grasses, rhizomes, tubers, bulbs, and occasional browse are also eaten. There is a substantial lack of evidence that javelinas regularly consume animal matter; however, they have been observed scavenging carcasses on occasion.

HUNTING JAVELINA

In 1939, javelinas gained status as a game animal in Texas, which protected them with harvest seasons and bag limits. Some

WWW.TEXAS-WILDLIFE.ORG 13 JAVELINA

An adult javelina raises its head to analyze the air—possibly to detect any chemical messages from other herd members or odors from predators.

The javelina’s neck and back harbor clusters of long, coarse bristles that can be erected voluntarily when excited.

landowners label javelinas as a range nuisance or deer corn guzzler; however, popularity for javelina hunting has grown, especially for youth hunters who haven’t yet seen this indigenous animal. The prime example of this is the annual Texas Youth Hunting Program’s (TYHP) Mother-Daughter Javelina Hunt in Maverick County.

“My favorite part about the Mother-Daughter hunt is watching the hunters and moms progress throughout the weekend together, sharing in the memories of getting to spend time outdoors together,” said TYHP Huntmaster and TWA Engagement Coordinator Kristin Parma. “Those relationships I know are so important. It is an exceptional weekend, and it is hard to put into words how impactful it has become in my life—all because of the collared peccary.”

During the week, participants receive instruction about hunter safety and lessons on various outdoor topics. One of the program’s major takeaways is emphasizing the important characteristics that make javelina a unique game animal.

“I believe that before hunting a particular animal, you should take a little time to learn about them,” she said. “I make a strong effort to highlight unique aspects about javelina—their history and decline in Texas, status as a regulated game animal, how they differ from feral hogs, their main diet consisting of succulent vegetation, their scent glands used to identify their herd members, and more.”

With game in hand, participants learn from Parma about the rewards of preparing javelina from field to table. Javelina, contrary to the impressions of the masses, offers fine table fare, Parma has embraced the mission of proving they are not only edible but delicious.

“I make a point to serve all wild game dishes on my hunts, especially javelina, since one of the biggest misconceptions about them

is that they aren’t edible,” she said. “As residents of the Southwest, it’s only natural that they are perfect for creating dishes like tamales, adobo, enchiladas, and more. I haven’t let that stop me from using javelina in ragus, lasagnas, soups, and even egg rolls.”

As a wild game chef whose renown is growing, Parma said, “I love cooking with javelina because creating a successful and delicious meal is so rewarding and an inspiring way to keep advocating for this native species.”

Given their potential to introduce youth to the outdoors and recruit new hunters, the javelina is being reassessed as a source for generating revenue for landowners interested in providing opportunities for paid hunts. TWA includes javelina in its Texas Big Game Awards program. Youth hunters can have their javelina scored and receive a first harvest certificate and award. Javelina numbers entered in the program have seen some increase since it is a required species to earn the Texas Slam Award.

Many of the program’s participants arrive on the hunt having never seen a javelina. However, by the end of the week they depart with a new appreciation for javelina and the outdoors.

“Every year I find that the girls on my hunts embrace the javelina in full force. I love it when they are just as excited to see them in the wild as I am,” Parma said. “This year, we completed our fifth year hosting the only Mother-Daughter Javelina hunt, and I am very proud of that.”

With every encounter in the photo blind, I observe and photograph something new that sparks my curiosity about javelina. As the sunlight dimmed, my javelina squadron trotted back into the spiny brush, leaving me with a collection of memories and photos detailing their antics. As our awareness of this species grows, so should our pride in having access to this unique Texas native.

JULY 2023 14 TEXAS WILDLIFE JAVELINA

A startled javelina makes a quick dash to the brush. Although they typically flee, javelinas will confront predators if cornered or to defend their young.

From the Piney Woods to the Panhandle, from the deserts of the Trans-Pecos to the barrier islands of the Coastal Bend, Texas is bountiful in beauty and rich in wildlife–and every last part of it is worth protecting. We take great pride in our great state, and that means we must invest in it and care for it. Since 1985, TWA has served as a strong voice for Texas private land stewards. We invite you to join us as a Corporate/Ranch Member to amplify that voice. Join TWA at the new Corporate/Ranch Membership Level • 12 issues of Texas Wildlife magazine a year • Stay up to date on the latest in hunting and conservation • Network with wildlife enthusiasts, ranch and business owners in your community • Personalized Gate Sign plus Agri-tourism Gate Sign • Showcased on the TWA website as a Corporate/Ranch Member - Complete with a link to your website - Showcased quarterly in the Texas Wildlife magazine Visit texas-wildlife.org/membership or call 210-826-2904 More than 95 percent of Texas land is privately owned. Texas wildlife depends on Texas landowners!

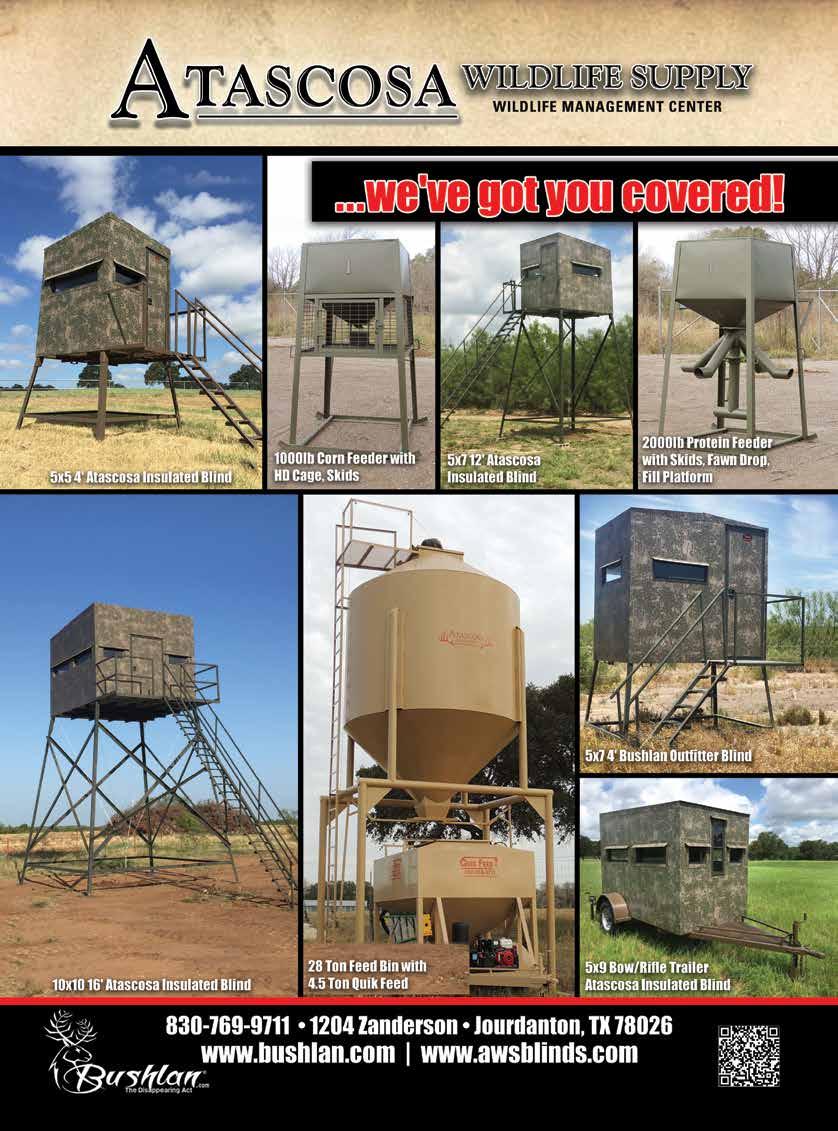

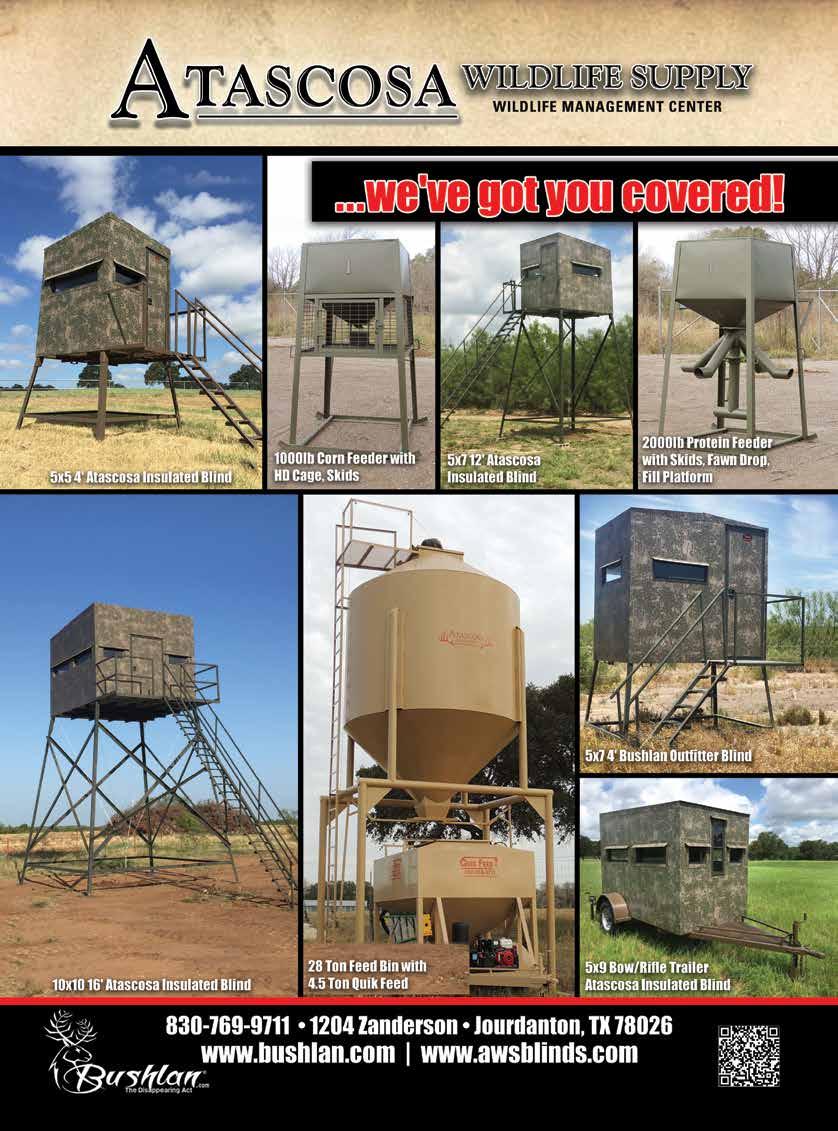

State’s Top Big Game Showcased at WildLife 2023

More than 30 of the biggest and best big game animals taken last season in Texas will be on display this month at the Texas Big Game Awards (TBGA) Statewide Sportsman’s Celebration held during your TWA’s Annual Convention, July 13-16 at the JW Marriott Hill Country Resort and Spa.

Annually, the TBGA recognizes the top three white-tailed deer, mule deer, javelina, and pronghorn during this special

awards presentation in different categories, as well as the landowners where the big game was harvested.

Eight Texas Slam awardees will also be recognized at the convention. The Texas Slam is an award given to hunters and landowners who harvest and produce all four TBGA qualifying big game species, meeting the minimum score for regional entry into the program.

Take a look at a few of the winners in this year’s TBGA!

JULY 2023 16 TEXAS WILDLIFE

Article by DAVID BRIMAGER Photos courtesy of AWARDEES

Texas Slam Awardees 2023

Keith Eason ...............................Double M Ranch

Corey Fearheiley .......................Double M Ranch

David Fluitt ...............................Sweetwater Ranch

Trey Maxwell ............................High Lonesome Ranch

Ali Ryan

Wyatt Sanchez ..........................Paloma Ranch

Wesley Tidwell ..........................Fraizer Ranch

Michael Wilson

WWW.TEXAS-WILDLIFE.ORG 17

TEXAS BIG GAME AWARDS 2022-2023 TOP ENTRIES

Place Region Name County High Fence High Fence Released Animal Category Net Score Ranch Name Best in Texas 3 Mason Schneider Tom Green Javelina 15 San Angelo State Park Second Best in Texas 1 Corey Fearheiley Hudspeth Javelina 14 12/16 Sweetwater Second Best in Texas 8 Braiden Meadows Maverick Javelina 14 12/16 Second Best in Texas 8 Sterling Meadows Maverick Javelina 14 12/16 Third Best in Texas 1 Ali Ryan Culberson Javelina 14 11/16 Best in Texas 2 Shane Maxwell Cochran Mule Deer NonTypical 201 7/8 Second Best in Texas 1 Trey Maxwell Hudspeth Mule Deer NonTypical 191 5/8 Sweetwater Ranch Third Best in Texas 1 Minka Sibert Jeff Davis Mule Deer NonTypical 190 4/8 CF Ranch Best in Texas 2 Matthew Crum Yoakum Mule Deer Typical 178 1/8 Second Best in Texas 2 Quynten Tarbet Gaines Mule Deer Typical 163 6/8 Third Best in Texas 2 David Fluitt Bailey Mule Deer Typical 160 6/8 Best in Texas 1 Gary Sitton Hudspeth Pronghorn 85 2/8 Second Best in Texas 1 Trey Maxwell Hudspeth Pronghorn 79 Double M Ranch Third Best in Texas 1 Jonathan McBride Hudspeth Pronghorn 78 4/8 Double U Ranch Best in Texas 3 Nathan Martin Cooke N Whitetail NonTypical 200 5/8 Martin Ranch Second Best in Texas 6 Zeb McGhee Harrison N Whitetail NonTypical 196 6/8 Third Best in Texas 6 Michael Posey Trinity N Whitetail NonTypical 192 Best in Texas 8 Juan Bailleres Zavala N Whitetail Typical 174 7/8 Second Best in Texas 8 TJ Gale Dimmit N Whitetail Typical 168 5/8 Faith Ranch Third Best in Texas 2 Ken Limbocker Sherman N Whitetail Typical 167 3/8 Best in Texas 8 Jerry Wascom Webb Y Whitetail NonTypical 200 4/8 Cactus Jack Ranch Second Best in Texas 8 Travis Carter Webb Y Whitetail NonTypical 198 3/8 Sombrerito Ranch Third Best in Texas 8 David Shashy Webb Y Whitetail NonTypical 193 4/8 Sombrerito Ranch Best in Texas 8 Michael Wascom Webb Y Whitetail Typical 174 6/8 Cactus Jack Ranch Second Best in Texas 8 David Shashy Webb Y Whitetail Typical 174 Cactus Jack Ranch Third Best in Texas 8 George Martin Webb Y Whitetail Typical 172 2/8 Sombrerito Ranch Best in Texas 3 Trey Maxwell Concho Y Y Whitetail Typical 168 2/8 High Lonesome Ranch Second Best in Texas 3 Michael Terry Stephens Y Y Whitetail Typical 167 4/8 Third Best in Texas 7 Elizabeth Erwin Jackson Y Y Whitetail Typical 166 4/8 Los Robles Ranch Best in Texas 7 Cade Teykl Victoria Y Y Whitetail NonTypical 232 Randy J Craft Second Best in Texas 4 Randy Stephens Menard Y Y Whitetail NonTypical 225 1/8 Starry Night Ranch Third Best in Texas 3 Trevor Rees-Jones Eastland Y Y Whitetail NonTypical 214 7/8 Cook Canyon Ranch

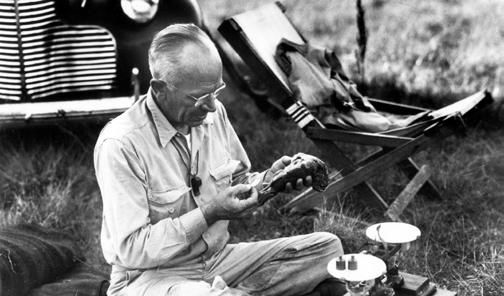

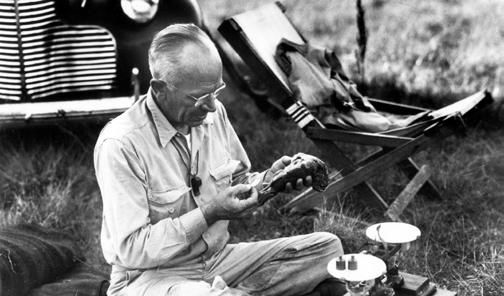

Biotic Pain

BY STEVE NELLE

“The practices we now call conservation are, to a large extent, local alleviations of biotic pain. They are necessary, but they must not be confused with cures. The art of land doctoring is being practiced with vigor, but the science of land health is yet to be born.”

Most of us are averse to pain. We don’t like it and we try to find ways to alleviate it. For some types of pain, we take pills for temporary relief, all the while knowing that these do not address the pain’s cause.

There are different degrees of pain and different responses. Hitting the finger hard with a hammer causes intense and immediate pain, but it only lasts for a short time. There is usually no long-term damage. Other forms of pain are chronic, perhaps subtle, and with gradual, cumulative damage.

There is also pain of the land; what Leopold calls “biotic pain.” As with human pain, some is brief, severe, and heals quickly while some is long lasting and slow to heal.

Physical pain or land pain can happen due to our own carelessness, the actions of others, or things beyond our control. Drought, wildfire, ice storm, insect plague, anthrax or EHD are “acts of God” outside of our control. Neighbors who over-pump shallow alluvial wells and reduce or eliminate creek and river flows cause pain for downstream landowners. However, much of the land pain we experience results from our own actions.

While none of us enjoy it, we understand that pain is the body’s signal that something is wrong and needs attention. Because it is often a sign of a deeper problem, the best course of action is figuring out what’s causing the pain, and not simply attempting short-term fixes.

In Leopold’s day, the common application of conservation was the band-aid approach. For example, flood control dams were installed to catch and slowly release floodwater and creeks were channelized to quickly transport floodwater. Neither of these addressed the cause of flooding and both have side effects that can cause additional problems downstream. Now we have learned there are other ways of reducing flood damage by addressing the cause.

Bare ground is a common and serious form of land pain. It can be caused by overgrazing, soil disturbance, wildfire, drought, termites, or a combination of these. Some of the cures are straightforward, such as stop overgrazing, while others may require more intensive remediation that can take many years before results are evident.

Poor habitat quality, poor body weights and antler development in deer is a type of biotic pain that is usually caused by maintaining too many deer and/or exotics. The solution is reducing deer numbers, but often we attempt to alleviate the pain by supplemental feeding. It is a quick fix that makes us feel good, but it does not address the underlying problem.

A lack of quail where there used to be abundance is painful. It can be caused by poor land management, natural causes, or a combination of these. But sometimes the causes of land pain are largely unknown and these are the most frustrating of all.

When Leopold penned the opening quote of this essay, he maintained that the science of land health had not yet been born. He noted that “land doctoring” was treating the visible symptoms of sick land but there was little interest in discovering the root causes.

Today, the science of land health is being practiced by a growing number of landowners and is being refined, honed, and adapted for specific and practical application. More people are striving to understand the principles and the underlying causes of landscape problems, then selecting a customized suite of treatments to address the deeper problems and achieve individual landowner goals and improved land health.

When we see bare ground, erosion, excessive runoff, declining plant or animal diversity, loss of plant vigor, a decline in reproduction, or other forms of land pain, we should pay attention. The lesson is clear: do not ignore pain. Work to discover the cause, and don’t just treat the symptoms.

JULY 2023 18 TEXAS WILDLIFE

~ Aldo Leopold, 1941

Photo Courtesy of the Aldo Leopold Foundation and University of Wisconsin-Madison Archives

WRITER’S NOTE: Aldo Leopold (1887-1948) is considered the father of modern wildlife management. This bi-monthly column will feature Leopold's thought-provoking philosophies as well as commentary.

THE WAY BANKING SHOULD BE MEMBER FDIC Call our team and let us help you bring your deal to life. ROGER PARKER 210.209.8474 NMLS# 794874 JOE PATTERSON 830.627.9335 NMLS# 612376 Ranch financing throughout Texas is our specialty. That means you enjoy the highest level of coordination, communication and execution throughout your financing process with our highly experienced Ranch Lending Team.

Coming Together for Conservation Education

Article by KASSI SCHEFFER-GEESLIN

Article by KASSI SCHEFFER-GEESLIN

As the programs of Conservation Legacy expand to reach Texans across the state, our network of conservation education partners continues to grow as well. These partners have served various roles—donors, hosts,

presenters—and our programs would not be the same without them. In 2023, these organizations, companies, individuals, schools, ranches, and their staff have provided invaluable impact and we thank them for working alongside us.

JULY 2023 20 TEXAS WILDLIFE

Women of the Land program at Welder Wildlife Foundation. Women of the Land Partners: Natural Resources Conservation Service; Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service; Texas State Comptroller’s Office; Texas Parks and Wildlife Department; Welder Wildlife Foundation.

Native Plant Expedition at TWA headquarters. Family Land, Water & Wildlife Expedition Partners are 5th Day Anglers; Austin Sunshine Camps; Bamert Seed Company; Blair Wildlife Consulting; Guadalupe River Trout Unlimited Foundation; Hershey Ranch; Inspiring Oaks Ranch; Line Cutterz; Long Acres Ranch; Lower Colorado River Authority; Native Backyards; Native Plant Society of Texas – New Braunfels Chapter; Texas A&M Forest Service; Texas Master Naturalists; Texas Parks and Wildlife Department; Travis Audubon; VetRecOutdoors.

Photo courtesy of TWA

Photo courtesy of Chad Timmons

their classrooms.

Center

Environmental Research; Biodiversity

Center (Coppell); Buescher State Park;

Park;

WWW.TEXAS-WILDLIFE.ORG 21 COMING TOGETHER FOR CONSERVATION EDUCATION

Student Expedition Day in Brenham. Student Land, Water & Wildlife Expedition Partners: Headwaters at the Comal; Kolkhorst Ranch; Lone Star Drone; Mustang Creek Ranch; Natural Resources Conservation Service; Northwest ISD Outdoor Learning Center; San Antonio River Authority; Spring Creek Ranch; Tarrant Regional Water District; Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service; Texas Master Naturalists; Texas Parks and Wildlife Department.

Photo courtesy of TWA

TWA Teacher Workshop, helping elementary teachers bring the outdoors indoors to

Teacher Workshop Partners: Austin Water

for

Education

Cleburne State

Delores Fenwick Nature Center; Discovery Gardens of Texas; Lake Houston Wilderness Park; Lewisville ISD Outdoor Learning Area; Long Acres Ranch; Quinta Mazatlan World Birding Center; Resaca De La Palma State Park; Sheldon Lake State Park; The Witte Museum.

TWA conservation educator presenting ‘Skins & Skulls’ at Natural Bridge Caverns. San Antonio Area Wildlife by Design Partners: Cibolo Center for Conservation, Natural Bridge Caverns, San Antonio Botanical Garden, San Antonio River Foundation at Confluence Park.

Photo courtesy of TWA

Photo courtesy of Natural Bridge Caverns

Small Acreage Big Opportunity workshop. Small Acreage, Big Opportunity (SABO) Partners: Bamert Seed Company; Natural Resources Conservation Service; Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service.

Photo courtesy of TWA

Texas Wil dl ife Association is pl eased to host its annual Private Lands Summit on Jul y 1 3 at the fabul ous J.W. Marriott in San Antonio, Texas This year's Summit wil l focus on innovative ways that Texas natural resource professional s are approaching some of the state's most pressing chal l enges--from species recovery and invasive management, to energy and the devel opment of our changing workforce

Notabl y, the 20 23 agenda wil l concl ude The East Foundation Three-Minute Thesis Competition, affording attendees the chance to hear from future l eaders in conservation on their research findings

TWA is proud the of the sl ate of experts coming together to share their l atest work with our membership. We hope to see you in Jul y!

Innovative Solutions

Complex

to

Conservation Challenges

1 3 J U L Y 2 0 2 3 | 9 A . M . - 4 P . M . $150 Register today www.texas-wildlife.org/wildlifeconvention 10TH ANNUAL PRIVATE LANDS SUMMIT

ANNUAL PRIVATE LANDS SUMMIT

SUMMIT SPONSORS

(Sponsors as July 1, 2023)

JOIN TODAY

PARTNER GOLD SILVER BRONZE

TWA Convention

A Family Reunion from the Get-Go

Article by LORIE A. WOODWARD Photos courtesy of TWA

Current Author’s Note: Sometimes it pays to be an information pack rat. As I was getting ready to visit with TWA co-founder Larry Weishuhn and CEO (retired) David K. Langford about TWA’s early conventions as part our ongoing look at TWA history, I ran across the following story.

It was written in 2003. Twenty years later, some of the characters, including co-founders Gary Machen and Murphy Ray Jr., as well as Fannie Grace Hindes and Carol Ray, have taken their places on the eternal stage. But memories of them and the early conventions are alive and well. The article is republished as it first appeared in April 2003. The additional information from Langford is new.

Original Author’s Note: This story was born one morning last November [2002]. I called early trying to catch Gary Machen at

home, but, instead, I got his wife, Barbara, who was in the middle of cleaning up breakfast dishes and getting ready for hunters to come in later that day. Fortunately, she wasn’t too busy to visit with me, and after a few conversational twists and turns, we got on the subject of the first TWA convention. As she began telling me about pickle jars, welcome wagons, and baking brownies for 300 people, I knew the story was too good to keep to myself.

Many big things start small. An oak from an acorn. Seven-foot, five-inch Houston Rocket Yao Ming from a diaper-clad baby. WildLife 2003 [and now WildLife 2023] from its humble beginnings in 1986.

Back then, the founding members of TWA were traveling around the state trying to drum up support. TWA was the new

JULY 2023 24 TEXAS WILDLIFE

Have a convention with people who wear cowboy boots and what do you get? A dance, of course. TWA members enjoyed dusting up the dance floor at the 1988 convention.

kid on the political block and members were double-timing it with legislators and agency heads trying to establish a good reputation in Austin.

The meetings were held at ranches around South Texas. Most advertising was word-of-mouth. The newsletter was four, type-written pages, “printed” on a copying machine. Money was tight…very, very tight. One “staff” member, who was actually Sid Lindsey’s full-time secretary, tried to keep up with it all.

In the midst of these growing pains, someone, most likely the directors, decided that TWA needed an annual meeting to assist in spreading the word about its mission, to attract new members, and to help fill the coffers. Plans were made and the first event was scheduled for April at the YO Ranch Hilton in Kerrville in 1986.

At the time, TWA was a very hands-on organization because the early members believed strongly in what they were creating—and it didn’t have the luxury of being anything else. Some of the busiest hands belonged to Barbara Machen of Pearsall, Carol Ray of Somerset, and Fannie Grace Hindes of Charlotte.

While these ladies are quick to give credit to their husbands, Gary Machen, Murphy Ray, Jr. and the late Roy Hindes, for the long-term success of TWA, it is obvious that these women are equally dedicated to the cause, and their hard work laid the foundation for what has become the best convention in Texas. Bottom line: these women know what makes a good party.

“We had a lot of fun then—and we have a lot of fun now,” Fannie Grace said. “I don’t think wild horses could keep me from coming because a lot of TWA members have become just like family to me.”

And the family feel that sets the TWA convention apart from the faceless, nameless hordes that define most convention experiences, got its start at the very beginning. Many of the first attendees were relatives of the early members, and those who weren’t kin were family friends.

“To get people to come, we got on the telephone and in our address books,” Fannie Grace said. “Everybody just issued

WWW.TEXAS-WILDLIFE.ORG 25 TWA CONVENTION

During the 1990 TWA Convention, Larry Weishuhn (left) and David K. Langford worked the crowd for just a few dollars more during the live auction.

a personal invitation to all the people they knew.”

Despite the personal attention and the relatively small circle of people, not everyone who attended the convention knew everyone else. The Ranch Gals, as Barbara, Fannie Grace, Carol, and their TWA girlfriends have dubbed themselves, wouldn’t allow anyone to feel like a stranger.

Barbara, who claims to have the ability to talk to a door, said, “We just appointed ourselves the unofficial welcome wagon with the goal of introducing everybody to everybody else. If we’d see someone standing apart, we’d go introduce ourselves and then introduce that person to one more.”

Fannie Grace said, “We never had trouble getting anyone to talk because everybody had so much in common. You know, ranchers and other people who love the land, are just a big family anyway.”

While the personal touch was important in getting people involved with one another, the name tags didn’t hurt. In those days, Carol, who spent a lot of time

at various registration tables, recalled that the name tags were not the computergenerated, beribboned behemoths that adorn TWA’ers lapels today. They were the “Hello, my name is…” labels, completed by hand when attendees registered.

“Instead of computers, we had markers. Instead of a mile-long registration table, we had a card table. Instead of preregistration forms, we had relatively short lines of people signing in when they arrived,” Carol said.

The newsletter account of the first annual meeting notes that 300 people attended. The Ranch Gals recall a slightly smaller crowd, more in the neighborhood of 100 people.

Barbara said, “It didn’t seem like there were 300 people there, but there might have been. Of course, in those days, the reported number might have reflected a little wishful thinking.”

Fannie Grace said, “To get 300 people, somebody must have counted us coming and going.”

Of course, the smaller crowd meant that there wasn’t a scramble for hotel

rooms, although the YO Ranch Hilton is a much smaller facility than the Hyatt Hill Country Regency Resort.

“I used to call two weeks in advance to reserve our hotel rooms—and I was one of the early ones,” Carol said. “It is amazing to me how things have changed. Recently, a friend of mine told me that she had made their reservations [at the Hyatt Hill Country Resort in San Antonio] for the convention back in December. I would have never imagined that people would be making reservations seven months in advance just to ensure that they’d have a place to stay during the TWA convention.”

While securing rooms was easy, feeding the crowd was an interesting proposition. Because the organizers were trying to attract people and keep the overhead down, they cut costs wherever they could. On Friday night, attendees had cocktails and botanas [finger foods] outside by the hotel pool instead of the full-blown Mexican buffet that is the tradition now.

The Saturday lunch was “catered” by the members themselves in concert with TPWD and private wildlife biologists. Barbecue pits and fish fryers were hauled in from ranches all over South Texas and the Hill Country and set up poolside, so members could cook the feral hog, cabrito, fish, and the other offerings that had been donated. A huge pot of pinto beans simmered over a fire. And platters of brownies, candy, and cookies, prepared by Barbara and Fannie Grace spilled over, testing the willpower of everyone.

“Making all those sweets was our idea,” Fannie Grace said. “The men said, ‘We don’t need any dessert,’ but we knew better. Every single crumb was eaten up.” It’s a good thing that everyone had a sweet tooth because delivering the “dessert cart” had been a logistical challenge.

“We made all that stuff at home and hauled it to the hotel. We had so many sweets that we all ran out of Tupperware and ended up using Cool Whip containers to hold them,” Fannie Grace recalled. “We had to store all those containers in our hotel rooms and divvy out the desserts onto trays that we got from the hotel staff. Barbara and I still laugh about sharing our rooms with all those cookies.”

JULY 2023 26 TEXAS WILDLIFE

TWA CONVENTION

Wildlife experts from many Texas universities were early TWA supporters. During the 1988 gathering, Judy “Possum” Steinbach, Dr. Don Steinbach, and Dr. Steve Demaris enjoyed catching up.

After lunch on Saturday, the members turned the kitchen duties back over to the hotel staff, so they could get ready for their big night.

People, then, like people now, dressed up to enjoy the festivities.

Carol said, “At the first convention, it was hard to be overdressed or underdressed. People just wore what made them feel comfortable for a social event. Over the years, the definition of ‘party clothes’ has gotten broader and more elaborate, just as the crowd has gotten bigger and more diverse.”

For the big party on Saturday night, convention attendees enjoyed a catered banquet, an auction and a raffle, which over the years has become the silent auction, and a dance. While the auction offerings were less exclusive and extensive than those available now, the biggest change can be found in the Silent Auction room. Instead of clipboards and bidding, the then-Silent Raffle used to involve gallon pickle jars and tickets.

Organizers situated the raffle offerings accompanied by empty gallon pickle

jars on tables throughout the lobby and attendees were encouraged to purchase raffle tickets, which they then placed in the pickle jars by the items the supporters hoped to win. During the evening’s festivities, tickets were drawn to see who would claim the prize.

The Ranch Gals recalled that the pickle jars were alarmingly empty at the start of Saturday night’s party. Gary [Machen] suggested that Barbara help remedy that by buying tickets, hopefully enticing more people to participate. She went on a buying and stuffing spree that eventually turned into an unprecedented winning streak.

“Almost every time the announcer drew a ticket, he would say, ‘Barbara Machen,’” Fannie Grace said. “I’ve never seen anybody win so much stuff in one night. We still tease her about it.”

Barbara added, “I donated everything back, so that other people would win and have a good time. But it really was funny how many times I marched up there.”

Raffle-winning Barbara is just one memory among thousands related to TWA that brings smiles to the faces of the

Ranch Gals. Since 1985, when TWA was born, the organization has been part of their families and part of their lives.

The convention, which started as a labor of love, is a reunion, allowing them to reconnect annually with their adopted family—the people who care about wild things and wild places as deeply as they do. While the event itself has changed, the inclusive spirit is still going strong.

“The convention continues in a different form and on a bigger scale, but all the important basics—like friends, family and fun—have remained the same,” said. Fannie Grace. “It’s just something you have to experience to understand.”

THE EVOLUTION OF THE GRAND AUCTION as told by CEO (retired)

David K. Langford

In the beginning, the Grand and Silent Auctions funded a lion’s share—almost 100 percent—of TWA’s operating budget. Today, proceeds from the convention weekend provide about 20 percent of

WWW.TEXAS-WILDLIFE.ORG 27

TWA CONVENTION

For the first few years of TWA’s history, the YO Hilton hosted the crowd. As time went on, however, and TWA grew in membership and reputation, the association had to find larger digs.

the annual budget. In 2022, the gross proceeds were upwards of $900,000. That wasn’t always the case…

“When I came to my first convention in the mid-80s, I’d been working as a livestock photographer for a lot of the big ranches across Texas and the country. As part of my duties, along with shooting cattle and horses for ads, I’d cover their big auctions, so I had a point of comparison for what I saw at TWA.

Frankly, it needed some help, especially since there were so many big ranches represented in the room. The only professional was Anthony Mihalski, the auctioneer. The ringmen were all volunteers. People had donated generously, but there was nothing particularly special about anything that was being offered.

I’m not even sure what the first auction I attended raised. Maybe $25,000-$30,000. I thought to myself, ‘Holy crap, it should be a lot better, especially with all these heavy hitters in the room.’

At the next executive committee meeting, I made the mistake of saying that out loud. Big Roy Hindes said, ‘Congratulations, you’re our next auction chairman.’

The next year it was back at the YO and the crowd was only slightly larger. Anthony Mihalski was back, and he brought some ringmen. Larry Weishuhn provided color commentary. But the big difference was in the auction items themselves.

I’d realized that many of our members had great hunting places that were only accessible to their family and invited friends. The phrase that I came up with for the auction catalog, which TWA still uses today, said it all, ‘Not available to the public.’

I, along with Larry [Weishuhn] and others, convinced 30-40 people to donate exclusive hunts or experiences. When the last gavel fell, we’d raised about $130,000.

Everybody almost fainted because we raised so much money. After that, the format was set and we just continued to improve on the basic model. TWA is still using it to great effect today. Every president and officer team draw on their networks to expand TWA’s circle of friends. The power of ‘not available to the public’ keeps the excitement alive every time someone new comes into the TWA family.”

THE POWER OF PLACE as told by

David K. Langford

Depending on who is asked, attendance at the earliest conventions was somewhere between 100 to 300 people. In 2022, more than 1,500 people converged on the JW Marriott San Antonio Hill Country Resort and Spa. While the convention moved through several hotels in San Antonio and even one in Austin before finding its home for 20 years at the Hyatt Regency Hill Country Resort and Spa in San Antonio, the convention grew into its potential at the Hill Country Hyatt…

“After a few years of holding the convention at the YO Hilton, we outgrew it primarily because of our ‘not available to the

public’ auction items. We bounced to a hotel in San Antonio, out by the airport, near Jones Maltsberger and Loop 410.

On the Thursday before our first convention at that San Antonio hotel, my phone rang sometime around 9 p.m. It was Fannie Grace Hindes asking, ‘David, how much potato salad do I need to make for Saturday?’ Somehow in all the discussions, nobody had informed the Ranch Gals that we were using caterers and they—and their Tupperware—were off the hook.

About that time, Charly [McTee] and I had come to run the office. We had one more convention at that San Antonio hotel and then we moved to Austin to provide easy access for legislators. It was at some Spanish-style hotel near the intersection of I-35 and US-290.

It was our first foray into big-time hotels and convention planning. We were green and didn’t know that you had to book every meeting room, ballroom, and hallway that you planned on using.

(Author’s Note: Next time you see Langford ask about the chaos that ensued when this oversight was brought to light late Saturday afternoon. As part of the “festivities” Langford had to convince a high school principal to move the school’s graduation party slated for the same Saturday night to the hotel bar so TWA would have all the space it needed.)

Then, if the challenge of moving everything around wasn’t enough, it came Noah’s flood. By Saturday, the Highland Lakes were overflowing, and dams were threatening to give way. Streets and highways were under water. Travel was almost impossible.

Incoming President Steve Lewis and I were beside ourselves because we just knew that nobody was going to be at the auction—and that TWA was going to be broke. Before the auction started, we peeked out from behind the curtains that surrounded the stage. There were no more than 75 people there and we had planned on 250-300. It was a literal washout.

Then it happened. There was a man and his wife who sat down at one of the front tables, most of which were conspicuously empty. Nobody knew them.

That night, there was not an auction item that came up that he didn’t raise his hand on—and he bought most of them. His generosity saved the night, the day—and TWA for that year.

The then-stranger was Jack Carmody, a contractor from Leander who specialized in heavy construction. He became a fast friend and one of TWA’s most solid supporters until his death in speed boat racing accident in Corpus Christi seven or eight years later.

We did another year in Austin, but it still didn’t feel like home. Incoming President Happy Rogers and his wife Elizabeth, both of whom were exceptionally involved in San Antonio’s high-visibility charitable organizations, changed that. Because of their experience with groups including the San Antonio Zoo and the Witte Museum, they understood the ambiance and amenities necessary for successful fundraising.

At the time, there was a new hotel being constructed out near Sea World. It preceded most of the development on that section of Loop 1604. Happy and Elizabeth insisted we move out there; nobody else was particularly enthused about the idea. Turns out that they knew better than the rest of us.

JULY 2023 28 TEXAS WILDLIFE TWA CONVENTION

When we arrived on the Thursday before the convention, there were still painters on tall ladders working. The smell of fresh paint was all over the hotel and almost overwhelming. TWA was the first convention ever held there.

On Friday morning just a couple of hours before registration opened, Jim Chesnut, our IT guy at the time, and Sharron Jay, who eventually became our CFO, had finished setting up our computer network.

Remember, this was the mid-90s and technology wasn’t what it is today. We had hauled all the equipment from our offices over to the hotel and cobbled together a remote network.

We were patting ourselves on the back and heaving a sigh of relief, when a bartender from Charley’s Long Bar, which was directly behind our registration area, thought it would be funny to unplug our computers. I thought I might go to jail for murder before we ever got started.

We had a few missteps here and there, but TWA staff and hotel staff learned together—and it turned out to be a perfect fit for 20 years. In fact, the staff baked TWA a huge 20th anniversary cake for the last banquet we held there.

Because of the facilities, we were able to create a destination event with something for the whole family. Every year after the convention was over, we’d gather the staff and volunteers to figure out what we could do better and differently.

The trade show grew as did the thank you and specialty parties. The Little Lonestars Kids’ Program was inspired by the space as was the TBGA Statewide Awards Celebration with the display of mounts and even TWA’s own awards banquet. I’m not sure we could have hosted master falconer John Karger and his Last Chance Forever birds of prey demonstrations anywhere else. And on and on and on…

By the time we outgrew the Hyatt, we had grown our annual WildLife gathering into a must-attend event. And we’d made a lot of memories, like the time the Longhorn steer donated by Lee and Ramona Bass for the auction, escaped onto the golf course…”

$45,000,000 | Whitehall, TX | 1,650± acres

Rare offering of outstanding beauty, agricultural production, and in the path of progress. Rolling improved pasture with irrigation, exceptional ranch infrastructure, existing venue opportunities, and scenic high-fenced game pasture.

$5,995,000 | Johnson City, TX | 302± acres

Cedar Ridge Ranch is 302± manicured acres located in Blanco County, 66 miles from Austin and 24 miles from Fredericksburg. Amenities include a nice home, electricity, well, pond, blinds/feeders, improved whitetails, and exotics.

VIEW MORE LISTINGS ONLINE AT

WWW.TEXAS-WILDLIFE.ORG 29 TWA CONVENTION

|

| FINANCE | APPRAISALS | MANAGEMENT WWW.HALLANDHALL.COM

SALES

AUCTIONS

CEDAR RIDGE RANCH

SEVEN-D RANCH

Predicting Habitat Overlap Between Montezuma Quail and Feral Pigs in the Davis Mountains of West Texas

Article by MAYA RESSLER, RYAN LUNA and JUSTIN FRENCH, Borderlands Research Institute, Sul Ross State University Photos courtesy of BORDERLANDS RESEARCH INSTITUTE

Montezuma quail inhabit the piñon-juniper woodlands of the southwestern United States and much of Mexico. Anecdotal reports suggest Montezuma quail historically had greater distribution throughout Texas. However, because they prefer rugged terrain and their diets and habits are similar to other quail, Montezuma quail are considered the most understudied quail species in the United States. As such, their populations have not been monitored in Texas outside of a relatively few dedicated studies.

Feral pigs are highly intelligent, adaptive ecological generalists, capable of surviving in a wide variety of habitats. In North America, feral pigs have been reported in 44 states and in portions of Mexico and Canada. In Texas, they have been documented in every county but one, El Paso County.

The movement of feral pigs into West Texas is fairly recent, beginning in the 1980s, and might have been caused by populations simply expanding their territories westward or by intentional introduction for hunting. Regardless, feral pigs

JULY 2023 30 TEXAS WILDLIFE BORDERLANDS NEWS BORDERLANDS RESEARCH INSTITUTE AT SUL ROSS STATE UNIVERSITY TEXAS WILDLIFE

BRI researchers conducting feral pig presence surveys at the Davis Mountains Preserve, owned by The Nature Conservancy.

are known for their destructive and system-altering nature and are especially destructive when they occur in high numbers in localized areas.

One of the biggest issues regarding feral pigs is the extensive damage they cause to natural and agricultural resources. Nationally, crop damage is estimated to cost producers about $800 million annually.

The damage is caused by rooting as they forage for food and is the most common sign of their presence. Through rooting, feral pigs disturb the soil, which potentially reduces plant cover, alters soil composition, and ultimately causes nutrient loss and altered vegetation communities that other native species depend on.

Although scientists predict that feral pig densities are relatively low in West Texas compared with the rest of the state, there is concern about the damage to sensitive resources, such as the limited, free water sources found throughout the Trans-Pecos. A previous study conducted in the Davis Mountains found that feral pigs preferred open-canopy evergreen woodlands, evergreen savannah grasslands, and sensitive riparian habitats. These sensitive ecosystems and water sources occur predominantly in the sky island mountain ranges of West Texas.

Sky islands are high-elevation mountainous habitats that are isolated from other nearby mountain ranges. Some of the mountain ranges found in the West Texas sky island complex include the Davis Mountains in Jeff Davis County, the Chisos Mountains in Brewster County, and the Guadalupe Mountains in Culberson County.

Sky islands generate topographically diverse habitats that occur along an elevational-climatic gradient. With the increase in elevation, there’s an increase in precipitation and generally cooler temperatures compared with the lower elevations, which in turn generates increased habitat variability.

There are plants and animals that thrive within specific spaces of this elevation gradient, like the Montezuma quail in the Davis Mountains. The woodland habitats in the Davis Mountains support a biodiverse ecosystem that creates what we believe to be some of the most contiguous habitat for Montezuma quail in Texas.

In West Texas, Montezuma quail occupy open evergreen and oak woodlands, savannahs, grasslands, and riparian habitats. Though they have been documented in hilly, desert grassland habitats in lower elevations around 4,000 feet, Montezuma quail tend to occur in higher densities in the elevations from 5,249 feet and higher with more tree and grass cover. They depend on sloped areas with dense herbaceous cover for general use and foraging.

Montezuma quail forage on roots, tubers, and bulbs of certain plants, as well as seeds, mast, insects, and green leaf material. Their diet composition highly depends on season and land use.

Across their range, overgrazing has been identified as one of the biggest contributing factors to population decline due to loss of ground cover and reduced forage availability. Increased feral pig densities may alter the plant communities in a similar way as overgrazing. This could reduce forage resources in addition to the ground cover that Montezuma quail utilize for nesting, temperature regulation, and predator avoidance.

Though these birds are assumed to be relatively “immune” to regular droughts and changes to their environment, Montezuma quail might be vulnerable to more aggressive, generalist competitors, like feral pigs, that alter their environment and change or reduce choice resources.

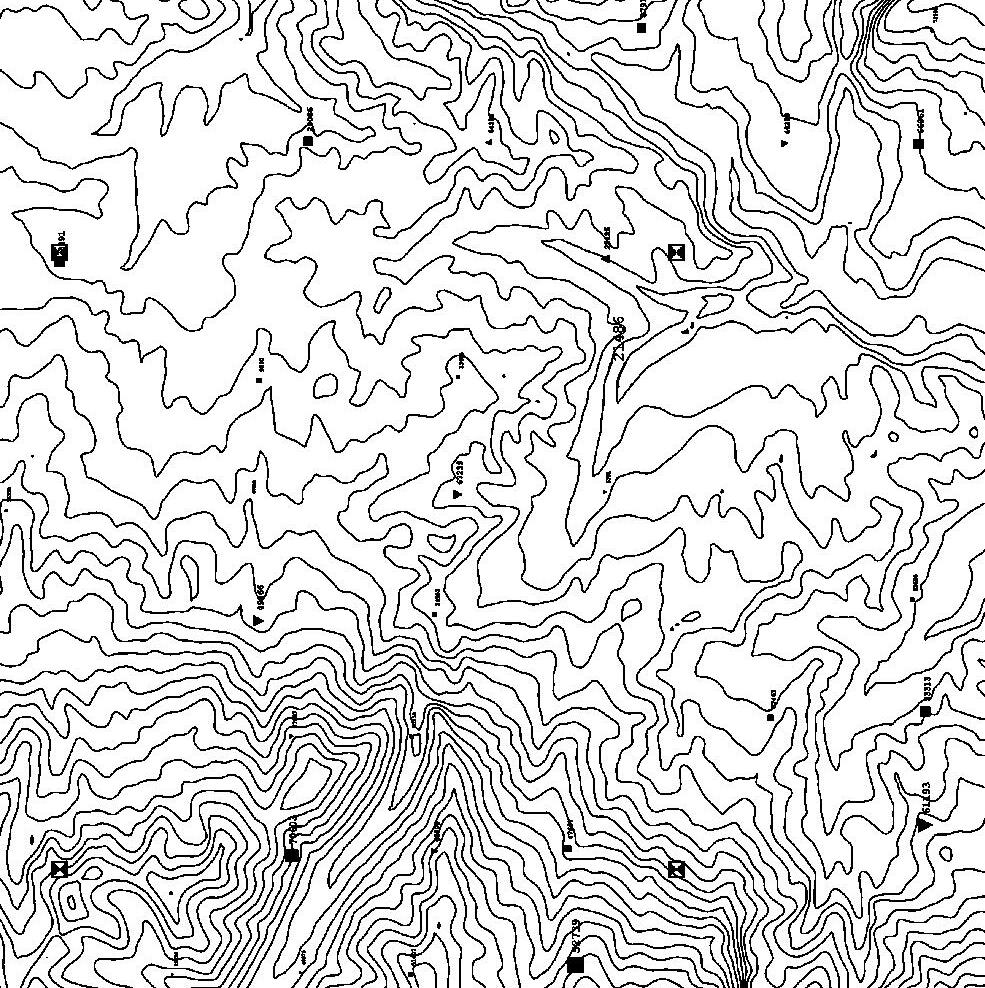

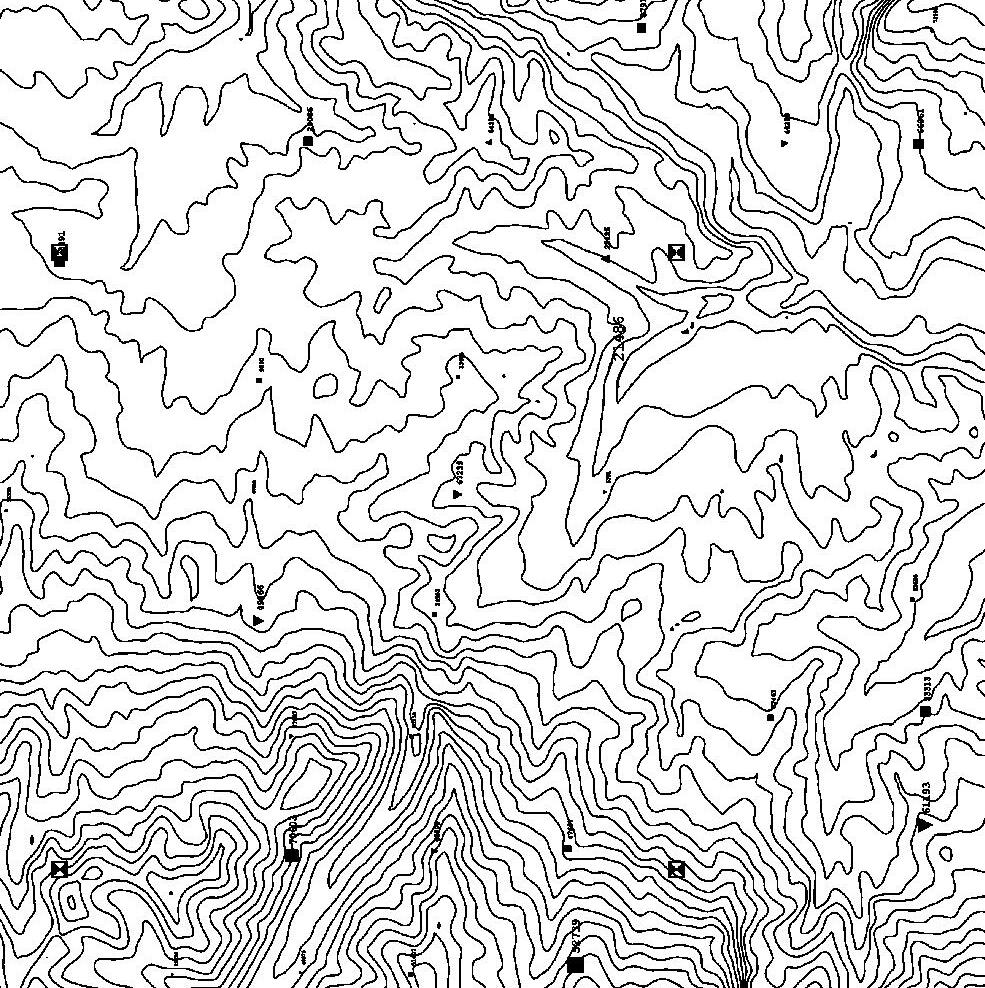

Through this study, we wanted to predict feral pig presence and then compare it with suitable habitat for Montezuma quail in the Davis Mountains. Examining where these species overlap is the first step in understanding whether feral pigs could be affecting Montezuma quail populations.

To estimate feral pig presence in the Davis Mountains, we surveyed 65 plots measuring 250 square meters across the southern portion of the Davis Mountains Preserve, owned by The Nature Conservancy. Each of the 65 plots had 25 sampling points at which any observation of feral pig presence was recorded.

WWW.TEXAS-WILDLIFE.ORG 31 BORDERLANDS NEWS

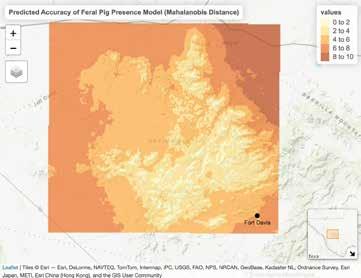

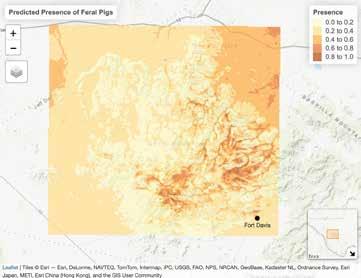

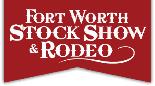

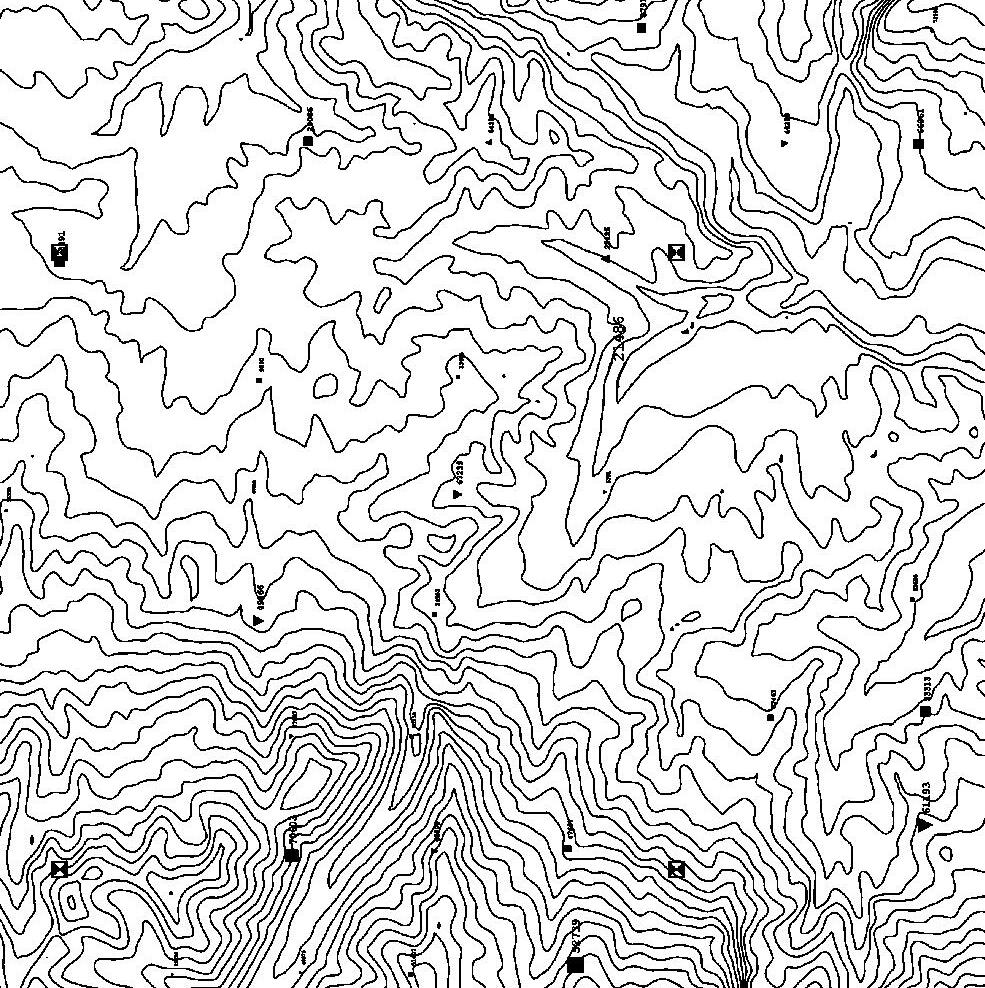

Figure 2. Predicted accuracy of feral pig presence map in the Davis Mountains, Jeff Davis County, Texas.

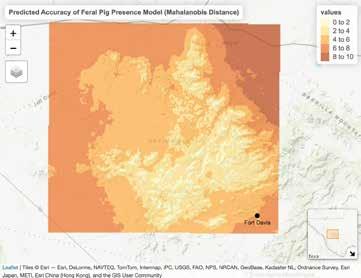

Figure 1. Map of predicted presence of feral pigs in the Davis Mountains, Jeff Davis County, Texas.

Long Term Hunters Wanted!

From these data, we fit a model to predict presence at other locations across the Davis Mountains Preserve. Elevation, slope, and tree cover had the most influence on the predicted presence of feral pigs. We then applied that model to the entire range of the Davis Mountains (Figure 1).

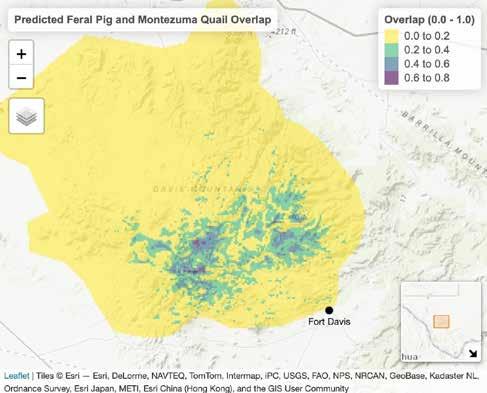

When we mapped this prediction outside of the Davis Mountains Preserve, we made inferences from the model, so the more dissimilar the environment is from the Preserve, the less confident our prediction is. This measure of confidence is mapped in Figure 2 where the lightest color indicates the most confidence.

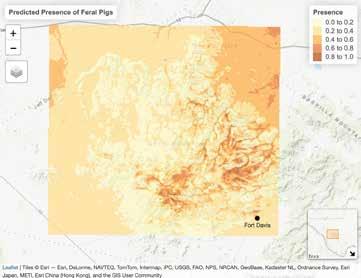

Once we created a map of predicted feral pig presence, we were able to calculate how that overlapped with predicted Montezuma quail habitat (Figure 3). Comparing these resulted in a predicted overlap of 51 percent for predicted feral pig presence and predicted Montezuma quail habitat in the mapped region.

Feral pig presence doesn’t completely overlap with predicted Montezuma quail habitat but occurs in areas that are considered critical for Montezuma quail when their populations are low and resources are scarce. This opens the door to question if feral pigs might have an effect on Montezuma quail resources and habitats.

Overall, researchers know very little about Montezuma quail, especially the populations in Texas. It’s recognized that habitat loss and reduced ground cover from overgrazing are potentially the main causes for population decline.

When resources become limited, it’s predicted that their range might be more restricted to higher elevations where our model showed higher overlap with feral pigs. In areas of overlap, feral pigs may affect the limited choices available to Montezuma quail for food and habitat, especially during periods of resource scarcity.

Further fine-scale research is required to better understand which Montezuma quail resources are being affected by feral pigs and if their foraging niches and habitat selection overlap at any capacity.

This project represents the first time researchers have studied Montezuma quail and feral pigs for potential habitat overlap in Trans-Pecos, Texas.

JULY 2023 32 TEXAS WILDLIFE BORDERLANDS NEWS

Figure 3. Map of predicted overlap between Montezuma quail habitat and feral pig presence in the Davis Mountains, Jeff Davis County, Texas.

• Rancho Rio Grande - Del Rio, TX MLD 3, $15.50/ac, Hwy 277 Frontage, water, electric. – 25,685 ac, Axis, Whitetail, Duck & Quail ο Some Improvements ο Live Water: Rio Grande River, Sycamore & San Felipe Creeks – 1,850 ac, SW Intersection 693 & 277, runs south along 277.

Meet Andrew Earl H

ello! My name is Andrew Earl, and I’m glad to have joined TWA as the director of conservation earlier this year. I come to the organization with roughly a decade of resource and sportsmen policy experience in the nation’s capital, and as the saying goes—I got to Texas as quickly as I could. In my short tenure with the organization, I’ve enjoyed working with not only my skilled colleagues at TWA, but also the powerful group of members and volunteers who inform the direction of our mission.

Previously, I served as the director of government relations with the Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Partnership in the nation’s capital, a national conservation group working to unify sportsmen voices on habitat and access issues. Before that, I managed natural resource and agricultural issues for a western U.S. Senator.

My love of the outdoors and passion for conservation took root digging for clams and fishing for striped bass off the south shore of Long Island. The Boy Scouts continued to drive me to the outdoors as I grew older. Recent years found me waterfowl hunting on the eastern shore of Maryland, and pursuing whitetailed deer in Virginia when opportunity allowed.

My role marries TWA’s policy work with our conservation curriculum, ensuring that the stated positions and values of the organization are represented in our expanding adult and family educational programs. As issues like land fragmentation, development, and water security continue to grow in Texas, I look forward to working with our team to ensure TWA remains a resource and voice of reason for lawmakers and landowners alike across the state.

JULY 2023 33 TEXAS WILDLIFE STAFF SPOTLIGHT TEXAS WILDLIFE

CONSIDER LEAVING A BEQUEST TO TWAF IN YOUR WILL Contact TJ Goodpasture for information | (800) 839-9453 HELP PROTECT AND PRESERVE FUTURE OUTDOOR EDUCATION.

Summer Time, Summer Time

Temptation often starts with a tiny itch, then transforms quickly to a constant gnawing.

I approached my wife to explain my itch for a couple of new hunting guns. She patiently listened, then commented with a sly smile, “Sure you didn’t get into chiggers?” I rolled my eyes, then continued trying to establish the necessity of purchasing a couple new guns.

“Think of all the delicious venison I can harvest…” She benignly nodded. I continued… “I need a new Mossberg 7mm PRC rifle and another Taurus Raging Hunter revolver in .454 Casull.” Her expression? Pure boredom.

Just when I thought she was not even listening, she smiled and said, “You’re going to get them anyway… Get pretty wood if you can.” She continued, “While you’re

at it, you might as well get another Trijicon AccuPoint scope for the new rifle and an SRO red dot sight for the revolver and Hornady ammo for both.” When I realized what she had said, I gave her a hug and immediately headed to our local gun shop.

It’s great to have an understanding wife. During our many years together, she has supported my decisions to hunt around the world and procure new guns even

JULY 2023 34 TEXAS WILDLIFE TEXAS WILDLIFE GUNS & HUNTING

Article by LARRY WEISHUHN Photos courtesy of LARRY WEISHUHN OUTDOORS

Summer is an ideal time to purchase a new rifle, scope and or ammunition. In this instance it was a Mossberg Patriot in .30-06, purchased the previous summer.

when I already had those appropriate for whatever I was about to hunt.

When asked the greatest attribute of my long career as a wildlife biologist, hunter/ conservationist, outdoor writer, television show host, podcaster, and other such things, I quickly and proudly proclaim, “My wife!”

Back to present. Summer is the ideal time to purchase a new rifle and scope, a new scope for an old rifle, or try different ammunition.

Me? I used to try to escape to the southern hemisphere during summer, but now spend my summers at the rifle range to learn the accuracy and capabilities of the guns I hunt with. It’s important to determine what my capabilities are with those guns shooting at the bench and from real-world hunting rests.

None of the places I hunt have a shooting bench positioned exactly where I need it when I find a buck or doe I want to harvest. With that said, I can get a good solid rest shooting from my Orion Hunting Products (www.huntorion.com) deer blind, aided by shooting sticks.

After determining how accurate my guns are at 100, 200, 300, and 400 yards from the bench, I am ready for some real-world shooting practice. If a gun is not capable of shooting 1-inch or smaller groups at 100 yards, it should not be shot at an animal much beyond 200 yards, and certainly not beyond 300.

Years ago, an outdoor writer friend, Dave Petzal, in a “Field & Stream” article, said, “Inaccurate rifles are boring!” I agree. I want my rifles shooting less than 1-inch, three-shot groups at 100 yards (i.e. 1 MOA, meaning 1 minute of angle). Then I know if I do things right, my rifles will shoot 6-inch or less groups at 400 yards. A 6-inch group is smaller than the average whitetail deer’s vitals, heart, and lungs.

I also want to know what the pointblank range is in the rifles and ammo I hunt with. Point blank is not up close. It is the distance at which a bullet will neither rise above a certain height, usually 3 inches, nor fall below 3 inches of a straight line out of the barrel. Point blank range varies with caliber, round, bullet design, and load.

WWW.TEXAS-WILDLIFE.ORG 35 GUNS & HUNTING

After hunting for a year with a .44 Mag Taurus Raging Hunter handgun, Weishuhn had a serious itch for a .454 Casull Taurus Raging Hunter.

With any new rifle, start out at the range to sight in at the bench and determine accuracy near and far.

Fast forward, I did indeed buy a new 7mm PRC Mossberg Patriot Predator. I scoped it with a Trijicon 4-16x50 AccuPoint; 4 to 16 meaning the magnification and 50 meaning the size in millimeters of the objective, or front lens. The Trijicon AccuPoint is built on a 30mm tube, as opposed to the traditional 1-inch tube most scopes were built on in the past. The 30mm tube along with the 50mm objective assist in gathering light, early or late.

The AccuPoint scope has ¼ MOA adjustments (“clicks”). This means the vertical and horizontal crosshair move the point of impact ¼-inch at 100 yards with each click. For the reticle to move 1 inch at 25 yards requires 16 clicks.

In my new 7mm PRC Mossberg/Trijicon combination I am shooting Hornady’s Precision Hunter, 175-gain ELDX loads. The bullet leaves the muzzle at 3,000 feet per second. The new 7mm PRC is in every way is a very efficient, effective, flat shooting, and hard hitting round.

For my upcoming Texas whitetail and mule deer hunts, I am sighted in 1.5-inches high at 100 yards. With that particular sight-in, my bullet strikes dead-on at 200-yards and 6 inches low at 300-yards. So I can hold dead-on out to 250 yards without holding over, or making a reticle turret adjustment.

I very rarely shoot at an animal farther than 300 yards. Remember, hold over does not mean holding over the deer’s back, but holding over an appropriate amount where you want your bullet to strike. On a deer at 300 yards, that means holding the horizontal crosshair immediately below the deer’s back, using guns like the 7mm PRC.

I know from shooting at the range my 7mm PRC bullet drops 18 inches at 400 yards. If for some reason a long shot is required, I can make an appropriate reticle dial up based on a ballistic chart. My goal is always to get as close as possible before squeezing the trigger.

Summer is also time to check deer stands, clear shooting lanes, make sure your hunting attire still fits after having “wintered well,” and start making serious fall hunting plans.

See you at the range.

JULY 2023 36 TEXAS WILDLIFE GUNS & HUNTING

The 7mm PRC, a new cartridge recently arrived on the scene, has garnered a lot of interest from Texas hunters.