Role Models Matter | National Biosecurity Network | The Marmoset Expert FALL 2023

Unlocking the Secrets to Aging Well

A publication of Texas Biomedical Research Institute

MEET DONNA LAYNE-COLON: MARMOSET COLONY MANAGER

RIGHT: Marmosets are an important research model to study aging processes.

COVER: Image of aging in action developed by Jeffrey Heinke with AI and other design tools.

2 PRESIDENT’S LETTER 4 BIOMED BRIEFS 8 ROLE MODELS MATTER 11 FACULTY NEWS 12 TEXAS BIOMED ADDS NEW ASSISTANT VP FOR RESEARCH 14 UNLOCKING THE SECRETS TO AGING WELL 21 TEXAS BIOMED NOW PART OF THE NATIONAL READINESS AND

NETWORK 24 COMMITMENT TO BUILDING HEALTH EQUITY 26 TEXAS BIOMED HOSTS STATEWIDE

28

PREPAREDNESS

TUBERCULOSIS RESEARCH CONFERENCE

Pardon our Progress

Levels and trim pieces and bulldozers, oh my! Texas Biomed is under construction. More than $60 million worth of capital projects are underway at the Institute, impacting every corner of campus. We are knocking down walls; adding lighting, flooring and new furniture; painting; and upgrading A/V and HVAC systems. We’ve also begun engineering Institute-wide upgrades to electrical and plumbing. Additionally, we are moving people across buildings in order to create operational efficiencies and opportunities for interaction when on campus.

Our team members have been moving science forward faster than ever before, but with that speed of discovery comes what I call “struggles of success.” Our campus is aged and needs new, modern spaces, so as we work on financing and fundraising for the new Global Center for Bioscience, which we highlighted in our 2022 Development Report, our

team has found ways to modernize what exists, providing safer, friendlier, more connected spaces. Additionally, more than $20 million of the changes happening on campus are in our animal facilities to ensure they have the best living environments. These projects are possible thanks to the enormous effort of Matt Majors, Vice President for Operations, and his team, which is leading the project management and implementation of these infrastructure upgrades while simultaneously managing daily facility operations of our unique enterprise. This is an incredibly important strategic undertaking.

While space and place are a critical piece of the Institute’s strategic plan, we also know that our people and programs are where science and community come together. This is where our mission is fulfilled, and we can realize our vision of a world free from the fear and effects of infectious diseases.

Texas Biomed President/CEO Larry Schlesinger and Vice President for Operations Matt Majors at the new Animal Care Complex site with construction partners from SpawGlass, including Project Manager Rex Cody and San Antonio Division President Jason Smith.

VISION

This fall’s COVER STORY is about the amazing research being done on aging here at the Institute. You might ask how aging and infectious disease are related, but as scientists, we are keenly aware that aging makes people more susceptible to infection. Understanding the aging process with the help of established research models is critical to treating infection and diseases of age while also identifying therapeutic interventions.

SPOTLIGHTS on our research include the big three: HIV, malaria and tuberculosis, as well as several innovations. In this issue, we FOCUS on Texas Biomed’s newest relationship with the national network for pandemic preparedness.

As our CATALYSTS are making their mark on our science program, our success is due to the exceptional team at Texas Biomed, and in this issue we PROFILE Donna Layne-Colon, who has worked with our marmoset colony from the beginning – 30 years ago.

From hosting statewide meetings and international collaborations to going out into the COMMUNITY and inspiring students, Texas Biomed continues to share its mission far and wide. We hope these stories help you understand the full impact we have on San Antonio and our world and encourage you to learn more and support us. Because, together, we can build healthier lives For All of Us.

Our team members have been moving science forward faster than ever before, but with that speed of discovery comes what I call “struggles of success.”

— Dr. Larry Schlesinger

Larry Schlesinger, MD President & CEO, Texas Biomed

3

SPOTLIGHT BIOMED BRIEFS

STRONG HEART STUDY IN 7TH PHASE

Launched in the 1980s, the Strong Heart Study is the longest-running study of cardiovascular health in American Indians. About every five years, local research centers work with tribes in Arizona, Oklahoma and the Dakotas to collect data from participants. The seventh phase is seeking to screen about 2,600 participants over two years, including all living members of the original cohort. “It is a very big undertaking, both for the field staff and for the participants,” says Texas Biomed Professor Shelley Cole, PhD, chair of the study steering committee. “We appreciate how participants are taking the time to provide their samples and trusting the researchers with them.” Along with a basic health exam, including height, weight, blood pressure, blood and urine samples, additional screenings aim to learn more about topics like mental health or microbiomes. Long-term studies like this provide valuable insights into how health is influenced by a wide range of factors, from genetics to environment.

CODE TOOL MAKES VACCINE DEVELOPMENT FASTER AND MORE ACCURATE

A new software tool developed by Texas Biomed Professor Luis Martinez-Sobrido, PhD, and collaborators in India and Spain can help scientists and vaccine developers quickly edit genetic blueprints of pathogens to make them less harmful. The tool, called CoDe – short for Codon Deoptimization – enables users to make precise edits to a genetic code to make genes less functional. Often, vaccine developers want to optimize or turn up expression of certain genes, and there are plenty of software tools to help with that. But for live attenuated vaccines that contain the full genetic sequence of a virus, it is critical to deoptimize, or turn down, certain genes to make the vaccines safe and effective.

“With CoDe we can precisely mutate thousands of nucleotides in a single gene,” Dr. Martinez-Sobrido says. “It also enables us to modulate gene expression of small sections, rather than knocking out entire genes completely. That is very helpful for vaccine design as well as basic research.” CoDe is freely available for other academic users and available to license by industry partners.

4

Exams for the 7th phase of the Strong Heart Study are underway.

THERAPY SHOWS PROMISE TO HELP CLEAR TUBERCULOSIS

A team of Texas Biomed and SNPRC scientists, led by Professor Smriti Mehra, PhD, have identified a promising way to help fight tuberculosis (TB), a disease that still kills nearly 2 million people annually. The research focuses on a potential host-directed therapy that can bolster the body’s ability to control infection. Specifically, the team found inhibiting an enzyme known as IDO – short for Indoleamine 2,3 dioxygenase – helped nonhuman primates better eliminate active TB infection. Blocking IDO for four weeks in conjunction with antibiotics led to improved health metrics compared with antibiotics alone. “This is exciting,” says Dr. Mehra. “We have promising results suggesting an IDO inhibitor could be a host-directed therapy that reduces the length of time and amount of antibiotics that TB patients have to take, especially those with multidrug resistance.”

SOLVING A PIECE OF THE TB PUZZLE

Like a biological trojan horse, Mycobacterium tuberculosis (M.tb), the pathogen responsible for tuberculosis, infects and hides inside macrophages, the immune system’s first responders. M.tb hijacks macrophages’ cell signaling pathways, evading detection and promoting its own growth. Texas Biomed Staff Scientist Chrissy Leopold Wager, PhD, has elucidated some of the mechanisms behind the bacteria’s prowess. Working with human macrophages, Dr. Leopold Wager and colleagues in Professor Larry Schlesinger’s lab identified the precise pathway M.tb uses to activate CREB, a critical protein involved with DNA transcription. CREB is like a conductor, deciding the time and level of expression of very specific genes, setting in motion precise cascades of reactions. They found that activation of CREB dampens the inflammatory response inside macrophages; specifically, it prevents the fusion of vesicles containing M.tb with lysosomes, little pockets of acids that would otherwise help destroy the bacteria. Excitingly, Dr. Leopold Wager found that inhibiting CREB allows fusion to proceed and helps control M.tb growth. The study, published in PLOS Pathogens, identifies CREB as a new and interesting target to combat tuberculosis.

5

A circular structure called a granuloma forms around TB bacteria. The immune system protein, IDO, is shown in pink.

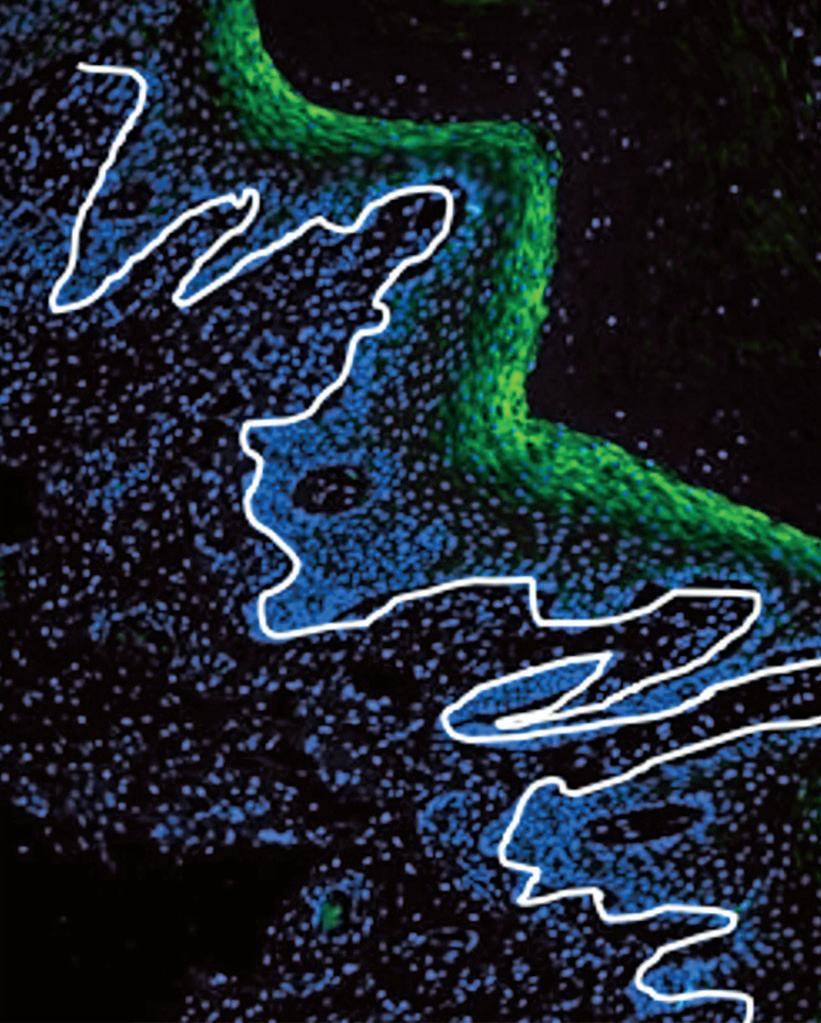

M.tb (red) appears inside lysosomes (green) thanks to CREB inhibition.

PRIOR DENGUE INFECTION MAY MAKE ZIKA OUTCOMES WORSE

Researchers at Texas Biomed and the Trudeau Institute in New York have discovered that female marmosets are more likely to transmit the Zika virus during pregnancy if they have been previously infected by a different virus, dengue. The research, published in Science Translational Medicine, may help unravel why the 2015 Zika outbreak led to thousands of miscarriages, stillbirths and cases of permanent birth defects. Texas Biomed Professor Corinna Ross, PhD, Professor Emeritus Jean Patterson, PhD, and their collaborators found that pregnant marmoset monkeys that had dengue previously passed 100,000 times the amount of Zika virus to their fetuses than marmosets that had never had dengue. The researchers suspect that Zika is using dengue antibodies to cross the placenta. Additional research is needed to fully understand the mechanisms and if the findings hold true for humans.

SECOND GENE IMPLICATED IN MALARIA DRUG RESISTANCE

The story of malaria’s resistance to the antimalarial drug chloroquine has long been thought to involve only one key gene. An international team led by Texas Biomed, University of Notre Dame, Seattle Children’s Hospital and the Medical Research Council Unit The Gambia, found a second gene is also involved. Researchers analyzed 600 genomes of Plasmodium falciparum, the deadliest species of malaria parasite, collected from 1984 to 2004. The dataset revealed mutations in another gene increased from 0% to 97% frequency over 30 years – clear signs of natural selection in action. A variety of additional analyses and experiments confirmed the mutations help confer drug resistance. “With drug-resistant pathogens on the rise, it is important to understand how treatments drive parasite evolution and how this evolution can vary in different parts of the world,” says Texas Biomed Professor Timothy J.C. Anderson, PhD. The research was published in Nature Microbiology.

6

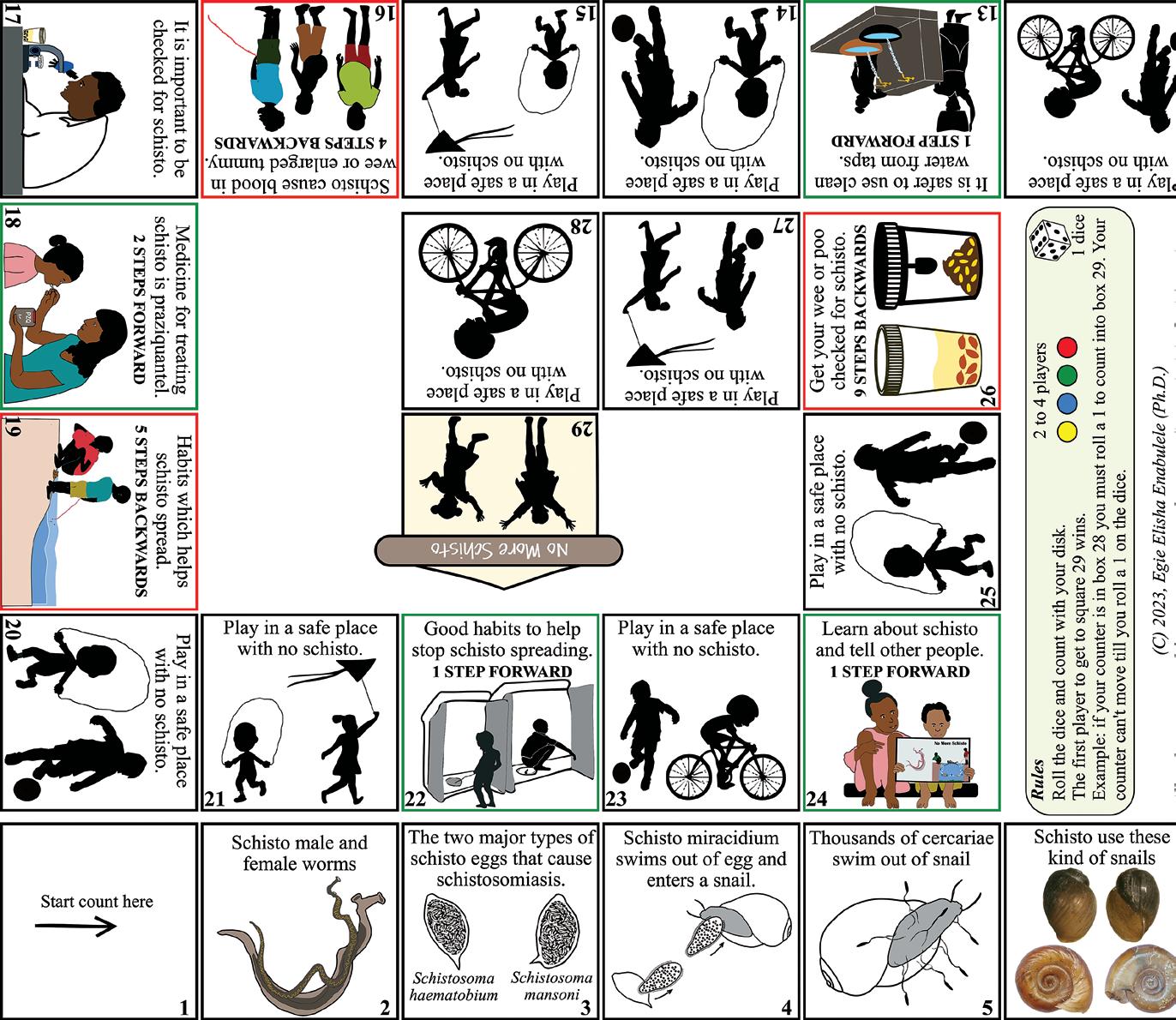

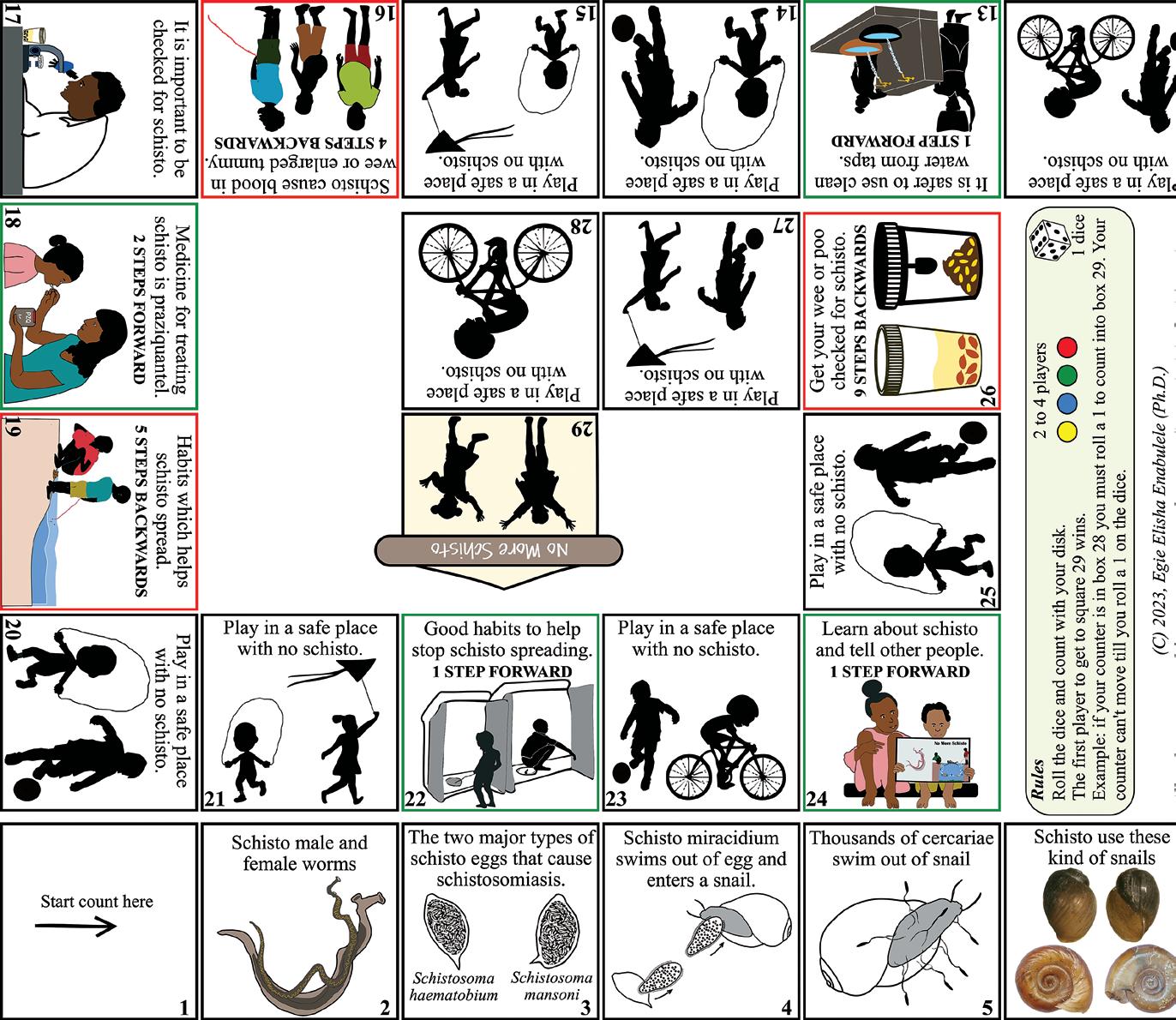

“NO MORE SCHISTO” GAME WINS INTERNATIONAL AWARD

Texas Biomed postdoctoral researcher Egie Enabulele, PhD, won an international award for a game he developed about the devastating parasitic disease, schistosomiasis, and how to avoid becoming infected. “No More Schisto” was recognized by The International Society of Neglected Tropical Diseases (ISNTD) with the ISNTD Festival 2023 Game Award. The board game can be printed on an A4 letter size piece of paper and is aimed at elementary school-aged children, who can become infected by swimming in lakes and rivers where the parasites and their snail vectors are present. “I wanted to design something that can be distributed and played in the field, and that could be easily translated into other languages,” says Dr. Enabulele, whose own kids and friends helped him test out and improve the game. Passionate about art and making science understandable for kids, he plans to make games about other diseases as well. “Education and behavior changes are a crucial strategy for eliminating many neglected tropical diseases,” he says.

HIV VACCINE CANDIDATE AIMS TO BLOCK VIRUS BEFORE IT TAKES ROOT

The National Institutes of Health awarded $3.8 million to Texas Biomed Professor Marie-Claire Gauduin, PhD, to further develop a promising HIV vaccine candidate over the next four years. An effective HIV vaccine has eluded the biomedical community for decades, in part because the virus spreads throughout the body within weeks of infection. Dr. Gauduin is aiming to stop HIV where it enters by designing a vaccine that specifically targets the interior lining of the vagina and rectum, called the mucosal epithelium. The vaccine stimulates the production of antibodies in these areas. Much like a bouncer checking for fake IDs just inside the door, or sentries along a castle wall, the antibodies are well positioned to quickly respond and block the virus from proceeding any further. The grant will allow Dr. Gauduin and her team to build on promising results in nonhuman primates and gather more data about mechanisms, safety, efficacy and different delivery methods. “I am excited to move forward and hope to get to the preclinical stage for human trials,” Dr. Gauduin says.

7

COMMUNITY MATTER ROLE MODELS

Texas Biomed’s new Scientist-in-Residence program is already leaving a positive mark on San Antonio students.

Health science teacher Sarah Hale speaks with Josué Méndez, a high schooler at Brooks Collegiate Academy, which partners with the Texas Biomed Scientist-in-Residence program.

Health science teacher Sarah Hale speaks with Josué Méndez, a high schooler at Brooks Collegiate Academy, which partners with the Texas Biomed Scientist-in-Residence program.

The day a scientist from Texas Biomed first visited his high school, 15-year-old Josué Méndez came home and told his parents all about it.

Eyes shining, Méndez recounted the story Israel Guerrero-Arguero had shared with the class about his own background. He was born in Mexico and his working-class parents taught him to value education while also encouraging his curiosity in science. After graduating from college in Monterrey, Guerrero moved to the United States and received his PhD in microbiology. Now, he is an infectious disease researcher at Texas Biomed.

“Before, I thought scientists were mostly born here in the United States and that their parents had been born here too,” says Méndez, who is interested in orthopedics and whose parents are from Mexico. “But I was so excited that day telling my parents because (Guerrero) showed me that you can be from anywhere and be a scientist.”

Such inspiration is at the heart of why Texas Biomed recently began the new Scientist-in-Residence Program as part of its Discovery and Learning Initiative, says Rosemary Riggs, PhD, Education Outreach Programs Manager. The initiative is dedicated to educating the next generation of STEM and bioscience leaders and advocates.

“These classroom visits are pivotal for students to learn about the diverse career opportunities within science research,” Dr. Riggs says. “The mission is to provide an innovative approach to connect students and teachers with scientists through in-person and virtual lessons and presentations.”

Dr. Guerrero’s time at Brooks Collegiate Academy, a PreK-12 campus in San Antonio, represents the beginning pilot of the Scientist-in-Residence Program, which will expand as funding and donations allow, Dr. Riggs says.

“We’ve designed it so our scientists can interact in an impactful manner with students and also collaborate with teachers to integrate bioscience research in the classroom,” she says.

Dr. Guerrero says that his “why” for volunteering stems from some parting words his dean had for him upon college graduation.

“He said something that really stuck with me, which was, ‘Now, you are a very privileged person. And you are in debt, so you need to pay back. So find where you can do that,’” Dr. Guerrero recalls.

The Scientist-in-Residence Program is that place, he says.

“Hearing stories like the one from Josué, it makes it all really worth it,” Dr. Guerrero says. “What I get back in return is the satisfaction of sharing what I know and communicating it to non-scientists so they can understand what’s going on. I really hope to inspire some young people to become scientists, so they can bring in their diverse perspectives and points of view to our world.”

9

Texas Biomed Staff Scientist Israel Guerrero-Arguero, PhD, hopes to inspire other young people to become scientists.

When you support Texas Biomed, you can impact the lives of young learners. Donate today and power the future of health!

SCAN TO DONATE

Research faculty promotions

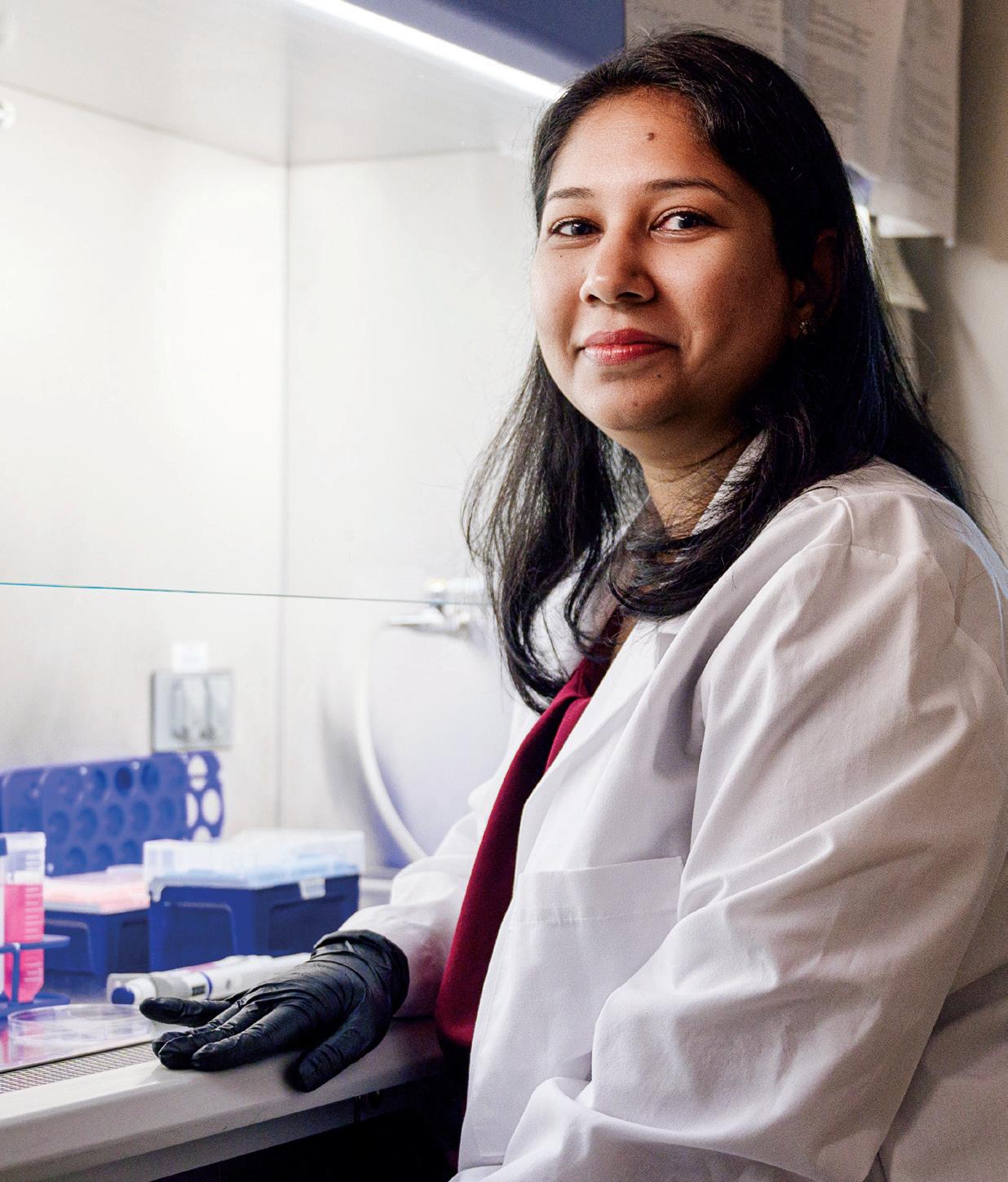

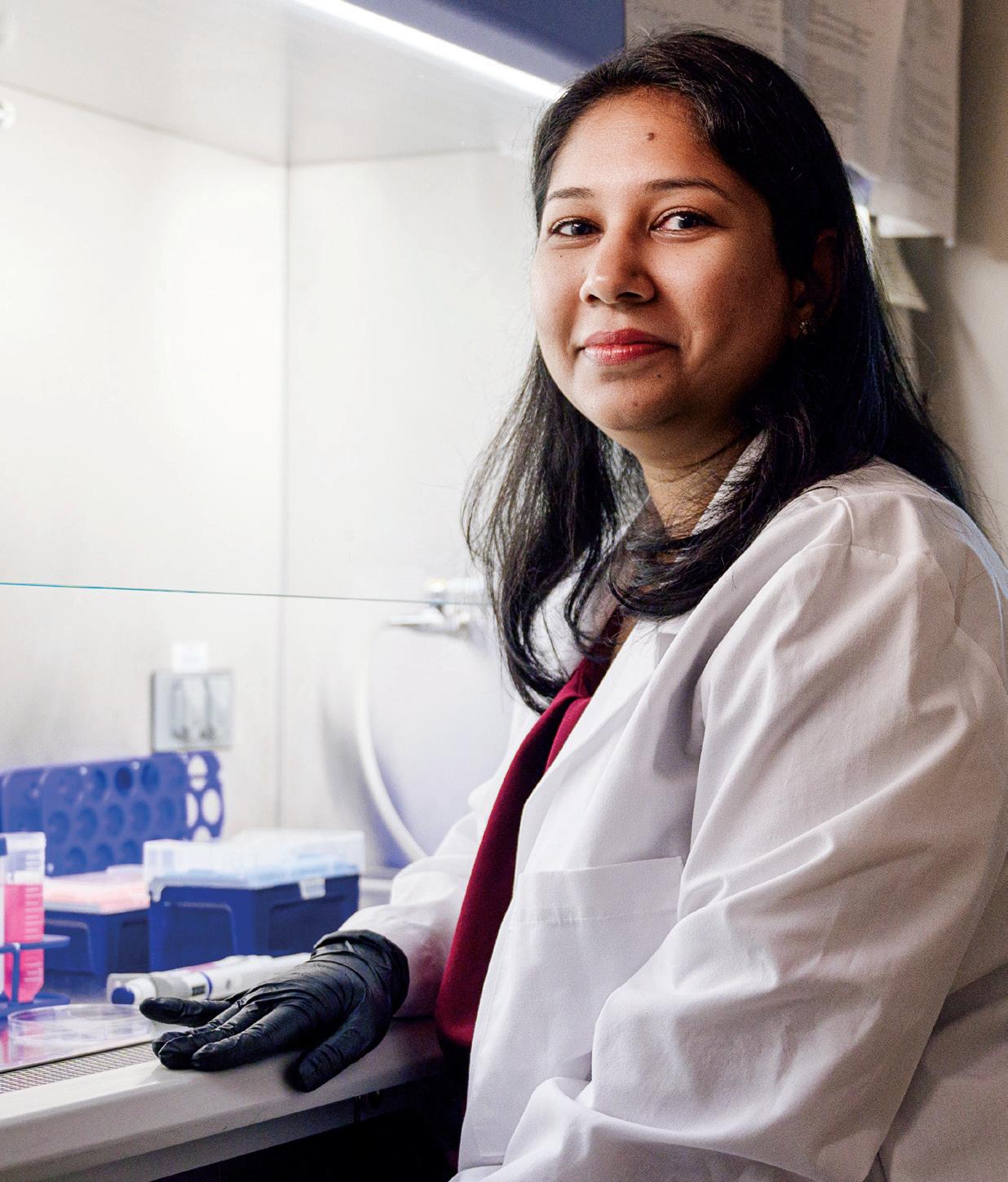

ASSISTANT PROFESSOR RITI SHARAN, PHD

Dr. Sharan came to Texas Biomed in 2019 as a postdoctoral researcher in Dr. Deepak Kaushal’s lab, becoming a Staff Scientist in 2021. She studies the interplay between tuberculosis (TB) and HIV and is especially interested in determining how latent TB infection is reactivated when a person becomes infected with HIV. She has received multiple research grants from the National Institutes of Health. She was recognized by the Texas Developmental Center for AIDS Research with the inaugural Robert Lanford Early-Stage Investigator Award for impactful contributions to HIV research. She is passionate about giving back through outreach to the community and inspiring the next generation, especially young girls, to pursue science.

11

CATALYSTS

Professor

Marie-Claire Gauduin, PhD

Professor Smriti Mehra, PhD

Professor

Binhua “Julie” Ling, MD, PhD

TEXAS BIOMED ADDS NEW ASSISTANT VP FOR RESEARCH

A Texas Biomed fan and collaborator, Amber Mallory, PhD, brings passion for service and expertise in biomedical research at the Department of Defense.

To help support expanding scientific faculty, staff and resources, Texas Biomed welcomes Amber Mallory, PhD, as Assistant Vice President for Research Resources & Strategic Initiatives.

“I have always had great respect for Texas Biomed,” says Dr. Mallory, who joined at the beginning of the year. “Texas Biomed is on the path to go up and up. I am enjoying learning from smart and accomplished scientists and supporting where I can to help the organization succeed.”

Dr. Mallory brings a wealth of experience in conducting and managing biomedical research for large organizations, having held research posts at Battelle, Los Alamos National Laboratory, the Food and Drug Administration, U.S. Navy and U.S. Air Force.

I am enjoying learning from smart and accomplished scientists and supporting where I can to help the organization succeed.

— Dr. Amber Mallory

12

CATALYSTS

Texas Biomed Executive Vice President for Research

Joanne Turner, PhD, is thrilled Dr. Mallory has joined her team through the newly created role for the Institute.

“We have oversight of more than a dozen programs at Texas Biomed and this position helps give our scientists the full support and attention they need,” Dr. Turner says.

At the outset, Dr. Mallory is helping oversee Texas Biomed’s Molecular, Microscopy and Biology Core Labs, which encompass shared equipment and research staff. She is also working with the directors of Texas Biomed’s biosafety level (BSL) 3 and 4 labs to support biocontainment research operations.

Before moving to Texas Biomed she worked just down the road at Lackland Air Force Base, directing trauma and clinical care research for the U.S. Air Force 59th Medical Wing’s Science and Technology Office. As a civilian scientist, she assisted physicians in designing preclinical studies and conducted her own research seeking ways to minimize infection in austere and combat settings using nanoparticles.

An Ohio native, Dr. Mallory’s scientific path began on a peach farm. The burgeoning organic movement sparked her curiosity about pesticides used on her family’s farm. She attended Youngstown State University, where she studied chemistry and biology while playing Division 1 volleyball.

She earned a master’s degree in microbiology at Texas Tech. She thought she would focus on environmental toxicology, but transitioned to infectious disease and biomedical research after working in biocontainment labs at Battelle. She completed her PhD at The Ohio State University in Integrated Biomedical Sciences, specializing in immunology, toxicology and nanomaterials. In particular, she studied quantum dots, air pollution and zeolites, a group of porous materials that can be modified for drug delivery and other applications. Her research demonstrated that silver nanoparticles embedded in a type of zeolite showed antimicrobial properties.

She specifically sought out postdoctoral positions in government labs, including Los Alamos National

Laboratory in New Mexico and the FDA in Washington, DC.

“I always wanted to work for the government and give back to the country in some way, that was important to me,” she says.

Dr. Mallory moved to San Antonio in 2013 to join the scientific team at The Henry M. Jackson Foundation for the Advancement of Military Medicine. There, she led mercury abatement research for the Navy. That led to opportunities to direct research programs for the Navy and Air Force primarily focused on combat casualty care.

While at the 59th Medical Wing, she regularly interacted with private, academic and industry sectors; one day, she received a cold call to collaborate with a company working on zeolites.

“It was my PhD mentor,” she says. “They had gone on to refine the zeolite compound that showed antimicrobial properties and patented it.”

When the COVID-19 pandemic began, Dr. Mallory received two grants to study different disinfection strategies in military settings, including one of those zeolite compounds. She immediately reached out to Texas Biomed to partner on the research. She worked with Professors Jordi B. Torrelles, PhD, and Luis Martinez-Sobrido, PhD, and Staff Scientist Israel Guerrero-Arguero, PhD, to evaluate how well the compound neutralized SARS-CoV-2 on a variety of surfaces, from tabletops to clothes.

That was such a positive experience that when the opportunity arose to join Texas Biomed full time, Dr. Mallory did not hesitate to apply.

“Research is a tiny sliver of the DOD’s mission,” Dr. Mallory says. “I love research and am excited to be part of an organization wholly dedicated to research.”

13

Dr. Mallory is helping oversee Texas Biomed’s Molecular, Microscopy and Biology Core Labs.

UNLOCKING THE SECRETS TO AGING WELL

What if instead of 80-year-old lungs, you could have 40-year-old lungs? Or younger versions of your own cells? Or age without frailty or dementia?

What if, rather than seeking a mythical fountain of youth, scientists could unlock the body’s secrets to aging with fewer illnesses and less inflammation? In other words, what if they could find viable ways to not live longer, but healthier?

“We are not trying to prolong life,” says Texas Biomed Professor Jordi B. Torrelles, PhD. “But for the years we are going to live, at least we are as healthy as possible. This is the mission.”

At Texas Biomed, aging research goes hand-in-hand with studying infectious diseases. Growing older makes people more vulnerable to infections. COVID-19 is a vivid example. Elderly populations were hit hard by the novel virus, while the majority of children and young adults were either asymptomatic or had relatively mild symptoms.

14

Improving healthspan – the number of years one can live relatively free from disease – is becoming increasingly important as more people around the world live into old age. According to the World Health Organization, the global population of people aged 60 years and older is approximately 1 billion and is projected to double by 2050. In the same timeframe, the number of people 80 years and older is expected to triple to reach 426 million.

“How do we keep people out of nursing homes? How do we prevent Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s and frailty – these long diseases that ravage the person and their families and cost a ton of money?” says Corinna Ross, PhD, Director of the Southwest National Primate Research Center (SNPRC).

Across Texas Biomed and SNPRC, researchers are striving to address these and other aging questions. The combination of expertise and resources located on one campus is profoundly unique. Texas Biomed is led by experts in lung immunology, genetics, respiratory illnesses and aging, and hosts SNPRC, one of seven federally-supported primate research centers. It’s home to the nation’s largest marmoset colony, including the largest geriatric marmoset population, and the pioneers who established marmosets as a prime research model for human aging.

“Aging is a really challenging topic to work on because there is so much variability,” says Texas Biomed Executive Vice President for Research Joanne Turner, PhD. “But it is so important to study. Everyone gets it. No one is immune.”

IF YOU COULD TURN BACK TIME

One of the key research areas for Texas Biomed is the lungs. Teams are seeking to understand the specifics of how older lungs, when compared to younger lungs, respond to illnesses such as flu, tuberculosis (TB) and COVID-19. These insights can be used to develop therapies to turn back the clock and keep lungs looking and behaving younger and healthier.

15

For example, Dr. Torrelles and his lab have found that with aging, pollution byproducts build up in the lungs. Specifically, they observe an increase in molecules called oxidants, which block proteins from doing their jobs correctly and cause tissue damage. This makes it harder to mount a functional immune response and fight disease.

The Torrelles lab is collaborating with Southwest Research Institute on an exciting innovation involving nanoparticles designed to deliver antioxidants to the lungs to protect against harmful pollution byproducts.

“The concept is to create a spray that you take once a month to help keep your lungs healthy as you age, so you are not as susceptible to respiratory illnesses like the flu,” Dr. Torrelles says. “It won’t prevent infection, but your lungs will be functional and control infections better.”

MITOCHONDRIA MYSTERIES

Dr. Turner is looking at ways to reinvigorate the aging lung environment by focusing on the powerhouse of the cell, mitochondria. She and a postdoctoral researcher put mitochondria from younger mice into older mice, specifically into a type of immune cell called T cells. Their studies showed that the elderly mice were able to fend off TB and flu just as well as younger mice, and far better than elderly mice with elderly mitochondria.

Likewise, Dr. Torrelles received a Texas Biomedical Forum pilot grant to study young versus old mitochondria in the lungs and explore ways to replace one’s own mitochondria with younger versions of themselves. He suspects that mitochondria are responsible for a lot of the pollution buildup observed in the lungs as people age.

“Within our cells, there are a lot of oxidative byproducts from making energy, which younger mitochondria clean up well,” he says. “We suspect that older cells are not as good about taking out the trash, and so then things start to get dirty and become dysfunctional. We’d like to find a way to help prevent this.”

16

We suspect that older cells are not as good about taking out the trash, and so then things start to get dirty and become dysfunctional. We’d like to find a way to help prevent this.

— Dr. Jordi B. Torrelles

Above: Angélica M. Olmo Fontánez is completing her PhD in Dr. Torrelles’ lab. She studies how age affects M.tb’s ability to replicate and spread.

Aging is

just everything in our body slowing down and dying,

WHAT’S INFLAMMATION GOT TO DO WITH IT?

When the immune system reacts to an illness, there is a fine line between mounting enough of a response to clear the illness and going into such overdrive that it causes damage throughout the body. Texas Biomed President/CEO Larry Schlesinger, MD, is especially interested in the interplay between the immune system, inflammation and aging.

“Aging is not just everything in our body slowing down and dying, but in fact, it creates a unique

baseline of inflammation that influences our ability to properly respond to infection, cancer and other insults,” Dr. Schlesinger says.

He and his lab study a particular immune cell called alveolar macrophages, which are present in the lining of the lung’s air sacs where air exchange occurs. They gobble up any particles that get past the nose and throat and into the deep lung, keeping the lungs healthy. Typically, macrophages are programmed to not be overzealous so they don’t cause excessive inflammation.

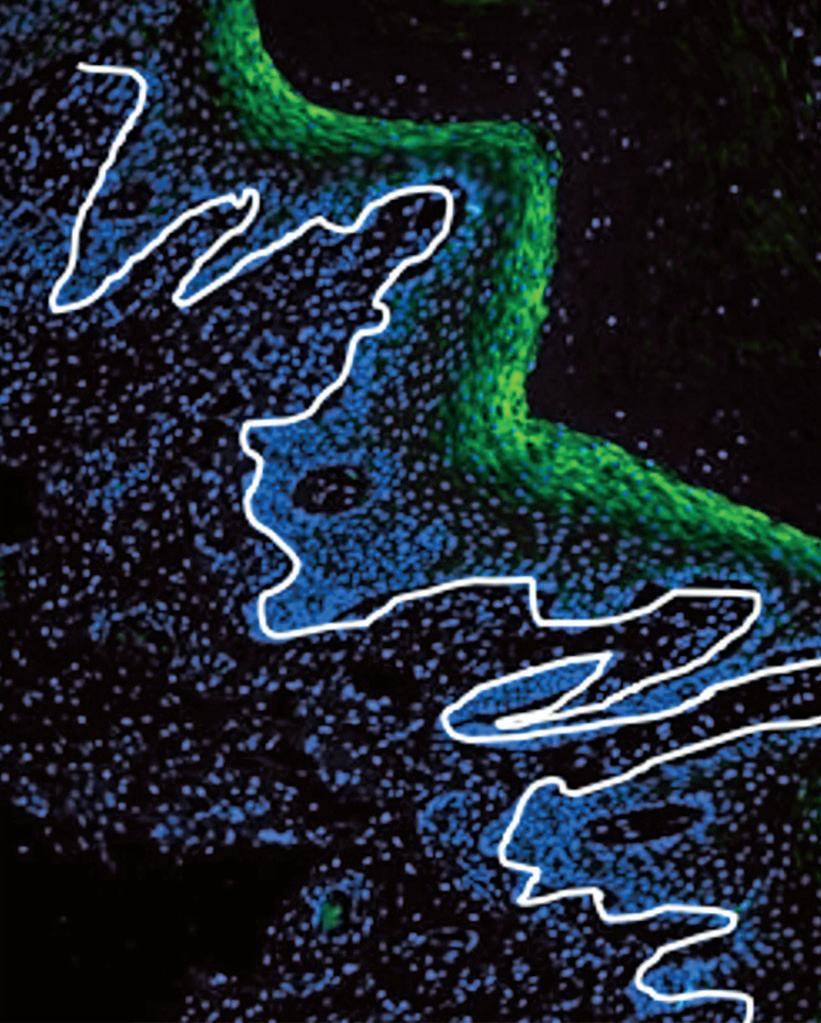

Dr. Schlesinger and postdoctoral researcher Susanta Pahari, PhD, developed a new way to generate the lung’s most important immune cell, the alveolar macrophage, in the lab. Human alveolar macrophages are challenging to study because they must be extracted from lung fluid samples, which are invasive, time-consuming and expensive to collect.

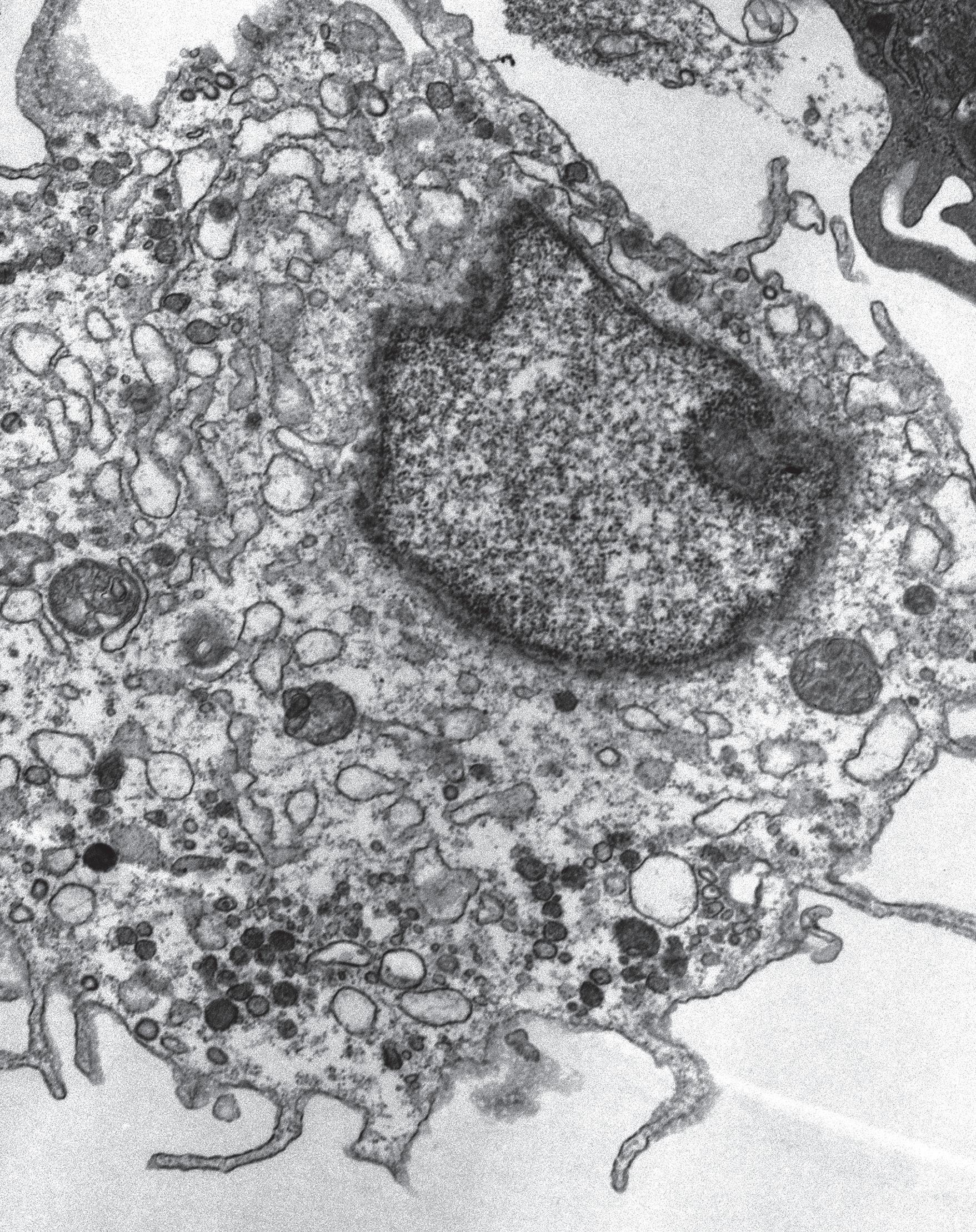

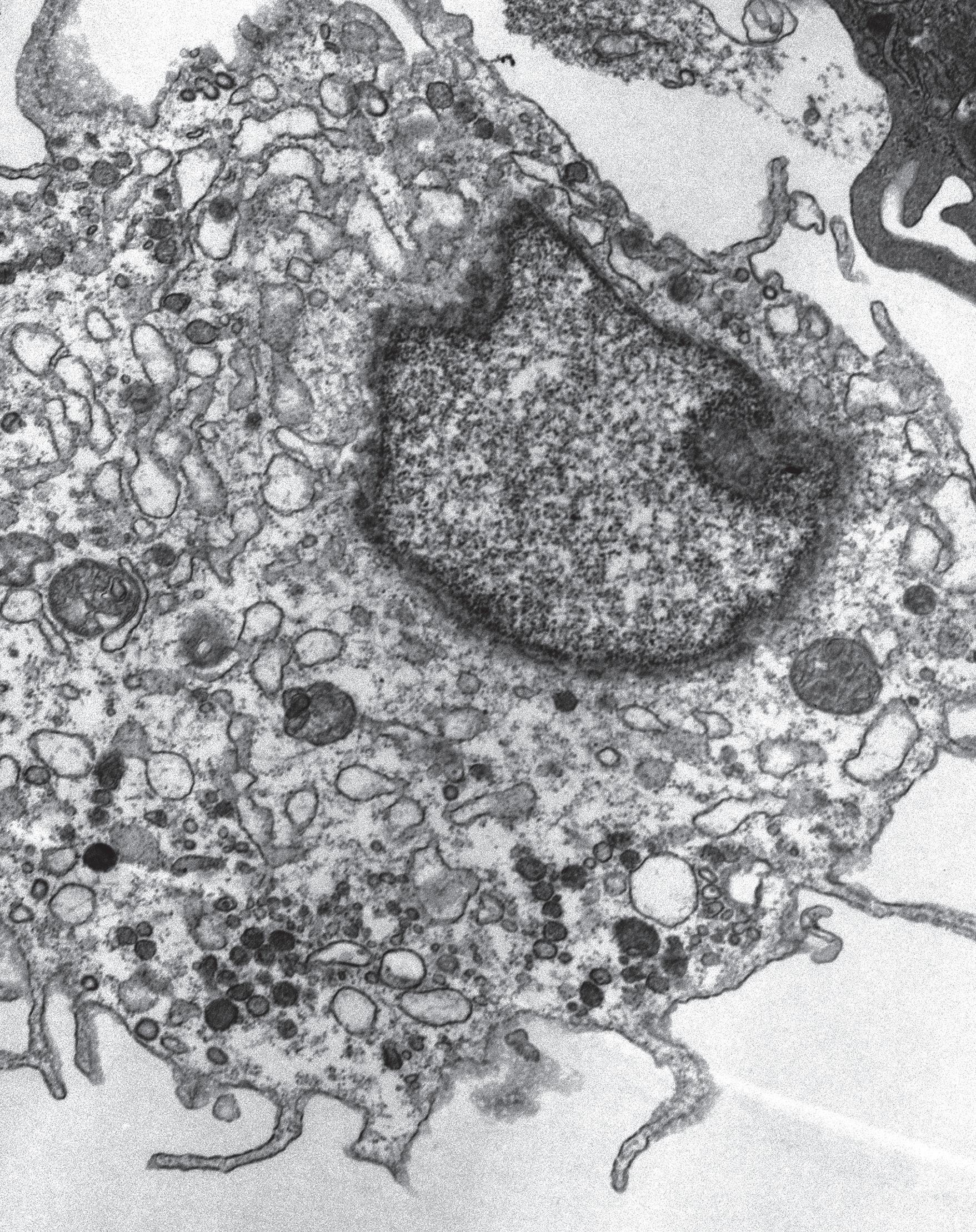

This new model starts with a simple blood draw. White blood cells are isolated and placed in Teflon jars with a “magic cocktail” containing four ingredients usually present inside our lungs. Within six days, the cells transform into alveolar macrophage-like cells (pictured) that are 94% genetically similar to alveolar macrophages collected from humans.

It took years of trial and error to determine the most effective combination for the cocktail. The patented model makes it much easier and less expensive to study respiratory diseases and screen potential therapies, including for COVID-19, TB, asthma, cystic fibrosis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

7

not

but in fact, it creates a unique baseline of inflammation that influences our ability to properly respond to infection, cancer and other insults.

— Dr. Larry Schlesinger

MAGIC COCKTAIL GENERATES CRITICAL IMMUNE CELL

An alveolar macrophage-like cell is seen in detail with transmission electron microscopy.

But he and his colleagues found that in aging mice and monkeys, as well as in healthy elderly humans, alveolar macrophages had much higher markers for inflammation, meaning they were poised to launch a scorched earth offensive at any sign of infection, such as TB.

“With inflammation turned way up, you would think these macrophages would fight off TB bacteria faster because they are primed and ready to respond,” Dr. Schlesinger says. “But it turned out to be the opposite. They were more susceptible to infection. It was bizarre. These are very different cells.”

The lab is working on understanding what’s at play here – such as what influences the cells to become more inflammatory and less effective. As part of this work, Dr. Schlesinger and his team have developed an innovative method to generate alveolar macrophages in a petri dish using cells from a simple blood draw. This new tool, now available to researchers around the world, is helping accelerate discoveries and screen potential therapies that target the lung.

MARMOSET PIONEERS

Along with the lungs, researchers are also studying how aging affects the brain and the gut, how those changes affect the ability to fight infection and how changes in one part of the body affect the other. To do that requires animal research.

Mice are the workhorse of aging studies because within 18 months to two years, they are the equivalent of 60- to 65-year-old humans. They provide critical insights that can then be verified in nonhuman primates, which are the gold standard for understanding how an entire complex system works. Or, in the case of aging, begins to stop working.

In the mid 2000s, the research community was looking for a primate with a relatively short lifespan that could help reveal the mechanisms of aging and potential interventions. At the time, 12-yearold marmosets were considered ancient; macaques,

18

An adult marmoset in the caring hands of Dr. Ross. SNPRC is home to more than 450 marmosets, the largest marmoset research colony in North America. Adult marmosets typically weigh less than one pound.

by comparison, typically live well into their mid-20s. While marmosets had been excellent for studying reproduction and genetics, it was unclear if they would also make a good model for human aging.

“There was a possibility that they didn’t die from the same things, that they didn’t have the same kind of deterioration with age, so we had to classify all of that,” says Dr. Ross.

Dr. Ross and her mentor, Professor Emeritus Suzette Tardif, PhD, documented how marmosets age. They found the small monkeys develop many, though not all, of the same conditions and disease as humans with age. It is notable that between Dr. Tardif, Dr. Ross and colony manager Donna Layne-Colon, Texas Biomed and SNPRC has had three of the world’s foremost experts in marmosets under one roof. (Read more about Donna, who has been with the colony since its inception 30 years ago, page 28.)

MARSHMALLOWS & MICROBIOMES

Cognitive decline is one of the aging metrics SNPRC scientists study. While some researchers test this using touch screens, Dr. Ross prefers a more “I Love Lucy” approach – think of Lucy at the chocolate factory, sneaking truffles off the conveyor belt as they pass. Similarly, as food comes down a conveyor belt,

19

Dr. Corinna Ross is particularly interested in studying how the gut microbiome affects aging.

Dr. Suzette Tardif and Dr. Ross established marmosets as a research model of aging.

marmosets have to use more control, or executive brain function, to let an unsavory turnip pass by and wait for a tastier treat; apples are good, marshmallows are best.

The scientists have documented that older animals with greater cognitive decline have a much harder time waiting for their preferred treat than their younger counterparts. This test helps the researchers measure the degree of cognitive decline, assess what factors may be contributing and test potential interventions.

Dr. Ross is particularly interested in studying how the gut microbiome affects aging, and if giving an older animal a younger microbiome makes a difference for a wide range of health metrics, from body condition and obesity, to cognition. To do this requires fecal transplants, which in marmosets is relatively easy to achieve.

“Thankfully, marmosets, they like poop,” Dr. Ross says. Through careful control of environment and diets, supplemented with shakes blended with feces from younger marmosets – savor that thought for a moment – the team is successfully transforming the gut microbiomes of elderly marmosets. Dr. Ross and researchers at UT Austin, Northwestern University, University of Idaho and Smithsonian Institution are collaborating on these studies to determine how altering gut microbiomes affect health outcomes.

The external partnerships complement ongoing internal collaborations between Drs. Schlesinger, Torrelles, Turner and Ross, which leverage immunology and

biochemistry methods to tease apart observations in animals on the cellular and molecular level.

“Interdisciplinary, team science like this brings diverse skillsets and perspectives together, and is critical to drive research forward and make impactful discoveries,” Dr. Schlesinger says.

LIVING LONGER

It turns out captive marmosets are living longer, especially when they go to the “nursing home” and get extra “TLC” and medical interventions, much like humans. SNPRC’s oldest marmoset reached 19, while Japan has reported a marmoset living to 22. While these added years may not seem ideal for research, it actually shows the model is robust.

“It’s that same kind of medical revolution that we went through with humans,” Dr. Ross says. “With the invention of antibiotics and vaccines, that means you’re living past these early life diseases, and you have a more stable life course until you’re older. Now, we’ve done that with the marmosets.”

While the studies to unlock secrets to aging well continue, researchers are often asked, what can we do to live healthier as we age? Dr. Turner notes there is no magic pill.

“Sorry… there’s no shortcut to this,” she says. “You have to be really mindful about taking care of yourself, eating well and exercising to reduce your inflammatory footprint. The less inflammation you have in your body, the more likely you will live longer and healthier.”

You

20

have to be really mindful about taking care of yourself, eating well and exercising to reduce your inflammatory footprint. The less inflammation you have in your body, the more likely you will live longer and healthier.

— Dr. Joanne Turner

TEXAS BIOMED NOW PART OF

NATIONAL READINESS AND PREPAREDNESS NETWORK

The federal agency that protects the nation against pandemics and bioterrorism has elevated Texas Biomed into the top ranks of its readiness and preparedness network. The move positions Texas as a leading source of medical countermeasures against 21st century health security threats.

The new designation as a prime contractor for the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) opens Texas Biomed to a portfolio of up to $100 million in funding over five years. BARDA, part of the Administration for Strategic Preparedness and Response within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services,

21 FOCUS

Veterinary research technician supervisor Laura Rumpf in the Texas Biomed BSL-4 lab.

oversees advanced research and development of medical countermeasures – vaccines, treatments and diagnostics – for public health emergencies stemming from infectious disease outbreaks, as well as chemical, biological, radiological and nuclear incidents and attacks.

Texas Biomed has long been a partner with BARDA through subcontractor status. Since 2015, the Institute has received about $46 million through subprime contracts. The promotion into its limited network of prime contractors now places the Institute in the upper echelons of global readiness and preparedness work, says Texas Biomed President/CEO Larry Schlesinger, MD.

“The significance of this cannot be overstated,” Dr. Schlesinger says. “We are now fully integrated into the federal fabric of preparedness. Texas Biomed is ideally and uniquely suited to be part of forwardthinking solutions for the growing infectious disease threats we face.”

Fewer than 15 labs nationwide – now including Texas Biomed as the only one in the state – are part of BARDA’s Nonclinical Biological Indefinite Delivery/Indefinite Quantity (IDIQ) Network. BARDA describes the purpose of these awards as building lab capability in the areas of “animal model development and analytical method development, qualification, validation and testing.”

“Texas Biomed’s new partnership with BARDA will improve our ability to prevent, assess, prepare for, and respond to biological threats,” says U.S. Rep. Tony Gonzales, R-San Antonio. “This move further expands Texas’ significance as a leader in military and community preparedness. The jobs and innovations that will be generated from this designation will boost San Antonio’s ability to compete globally in the biomedical and biotech realms.”

The network was developed in 2011 in order to better develop and bridge animal research study data to humans to provide evidence of therapy and vaccine effectiveness. It’s a key element in studying medical countermeasures since efficacy of many products surrounding such critical threats often cannot be verified using human clinical studies.

San Antonio Mayor Ron Nirenberg – referencing the recent City Council decision to award preparedness funding to the Institute – says the partnership is proof that “our investment in Texas Biomed is already paying off.”

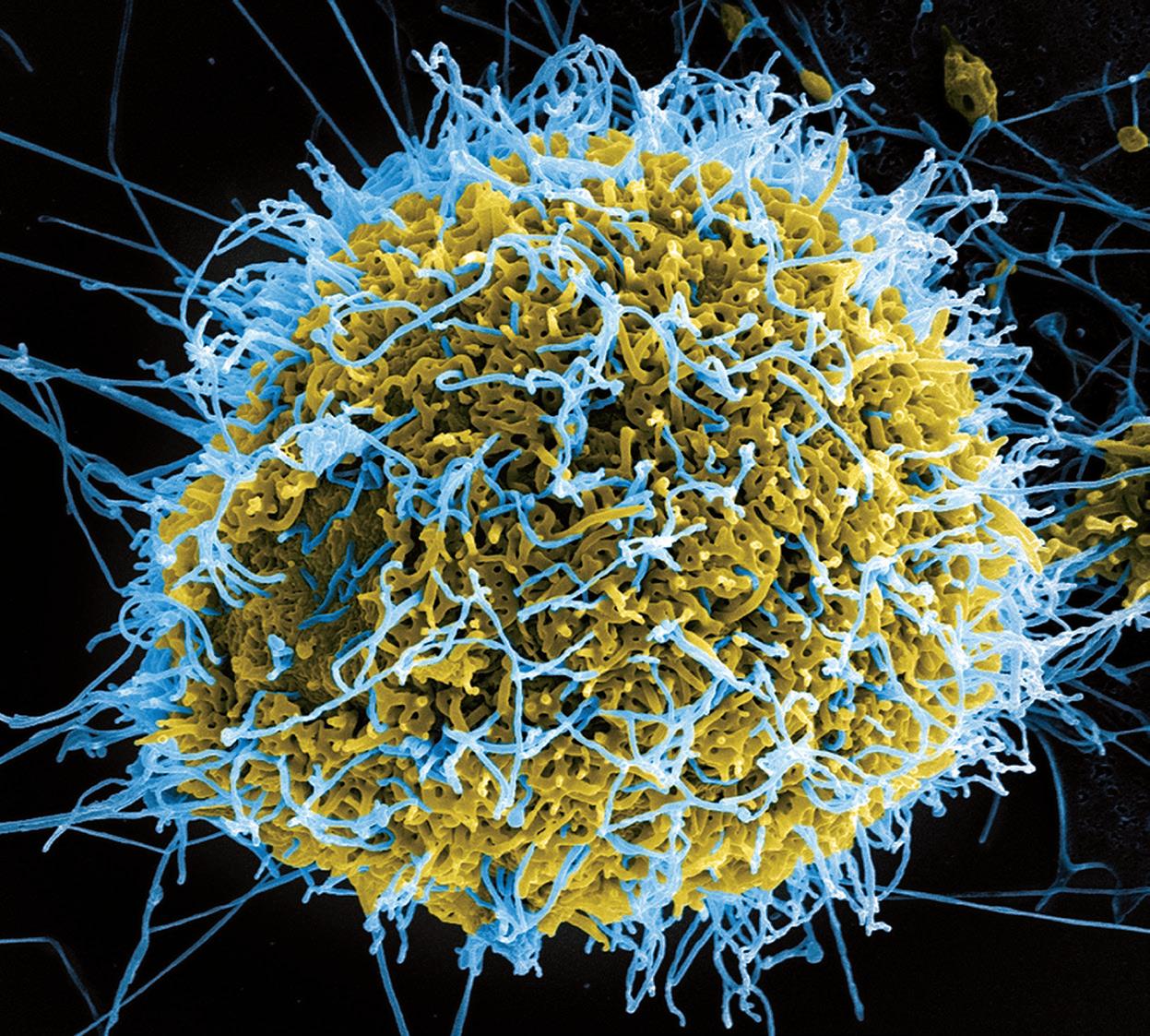

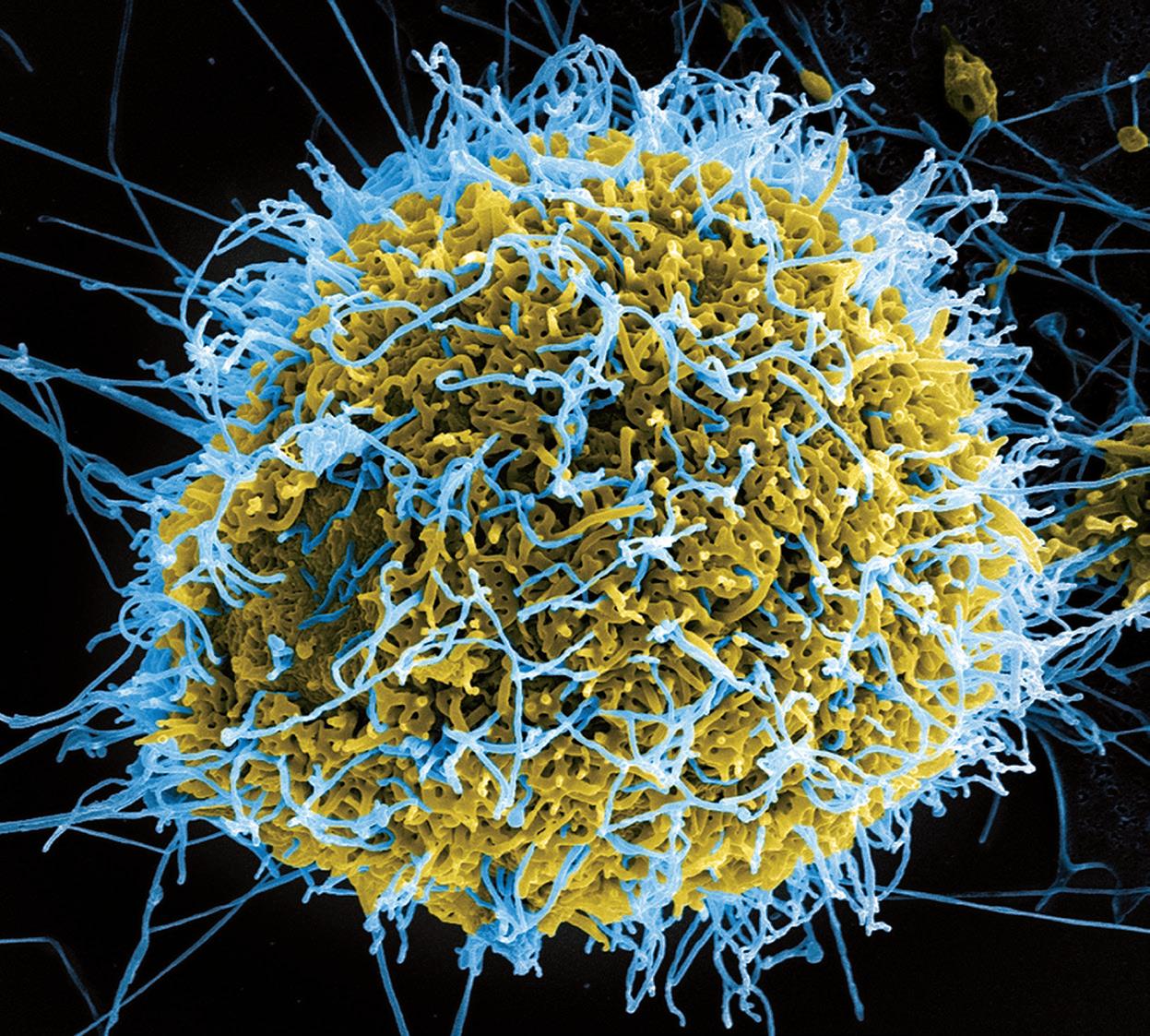

Since the opening of its high containment biosafety lab, known as a BSL-4, in 1999, Texas Biomed has worked closely with federal agencies on combatting national security bioterror threats. A recent example is its ongoing subcontract work with the Sabin Vaccine Institute through BARDA in developing a vaccine candidate for a variant of Ebola that caused an outbreak in Uganda in 2022 and 2023.

“Receiving the BARDA prime designation is proof that public/private partnerships produce high-value results,” says Texas Biomed Board of Trustees Chair Jamo Rubin, MD.

22

An Ebola microbe. Texas Biomed researchers are able to study such deadly pathogens in the high containment lab, known as a BSL-4.

Delivering Breakthroughs that Change Lives

Partnerships can save lives. We’re eager to work with innovators who share our values and our focus.

SCAN TO LEARN MORE

Commitment to Building Health Equity

Texas Biomed’s 3rd Global Health Symposium (GHS) convened health executives, healthcare providers, philanthropists, business leaders, scientists, educators and students from around the world to discuss how community, trust and science can help build health equity. Participants gathered online and at the San Antonio Botanical Garden May 18 and 19.

To cap off an invigorating two days of sessions, the closing keynote featured a discussion between Texas Biomed President/CEO Larry Schlesinger, MD and special guests Shirley Lacks and David Lacks, Jr., the daughter-in-law and grandson of Henrietta Lacks.

When Henrietta was alive, a swab of cervical cancer cells was collected without her knowledge, put in a petri dish and have not stopped multiplying since.

Henrietta died in 1951, yet her cells live on as the world’s first immortal human cell line. HeLa cells, as they are known, are routinely used to study and

develop vaccines and therapies for a wide variety of diseases, from polio to cancer to COVID-19.

“Unanimously, we are proud of what the HeLa cells have done for the world,” David Lacks, Jr. told the audience.

But, as Shirley Lacks commented, there is also deep mistrust of research and medical fields among AfricanAmerican communities – and members of their own family – because of this and other experiences. They are working to raise awareness about consent, equity and privacy in health research. Shirley Lacks shared that despite past wrongs, she encourages others to get involved in medical research, because you never know what impact it could have, like Henrietta’s.

Dr. Schlesinger acknowledged both the incredible contributions of HeLa cells and that equity must be incorporated into scientific research from the beginning.

24 IMPACT

Special guests David Lacks, Jr. and Shirley Lacks were interviewed by Dr. Larry Schlesinger at the 2023 Global Health Symposium.

“We’ve made mistakes, and there’s been quite a bit of mistrust out there, particularly for those individuals who are underserved or not seen enough,” he said. “I think we need to do better. I think this community understands that we need to do better.”

David Lacks, Jr. encouraged the audience to continue having conversations with diverse communities.

“Educate and communicate with people,” he said. “Speak on their level… to gain trust. We’ve got a long way to go, keep at it.”

Texas Biomed’s GHS is one way the Institute is fulfilling David Lacks’ wish. GHS 2023 welcomed more than 200 in-person guests and hundreds online for two days of conversations about the ways technology, philanthropy, public policy and science are impacting health equity across the globe. Scientists discussed how we are preparing for the next pandemic, while philanthropists and business

leaders discussed how to build trust in communities. Conversations on how to inspire future generations of scientists welcomed young leaders, as did discussions on the pathways for young investigators. With accessible topics, GHS aims to engage diverse voices and create a global network of change agents.

WATCH & LISTEN

Check out some of this year’s sessions on Texas Biomed’s YouTube Channel. Listen to Texas Public Radio’s Petrie Dish podcast “Reclaiming Henrietta Lacks” recorded at GHS: bit.ly/lacks

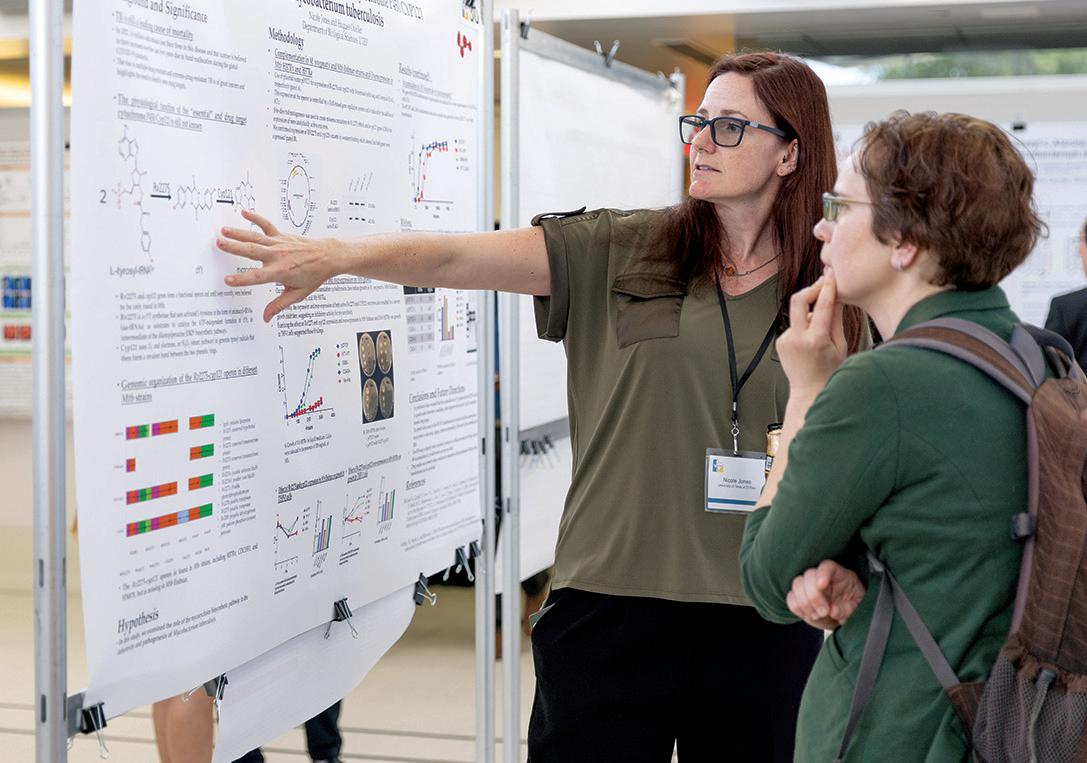

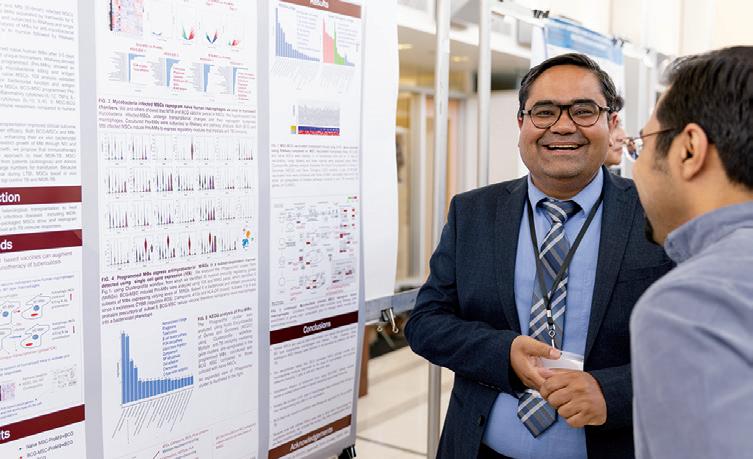

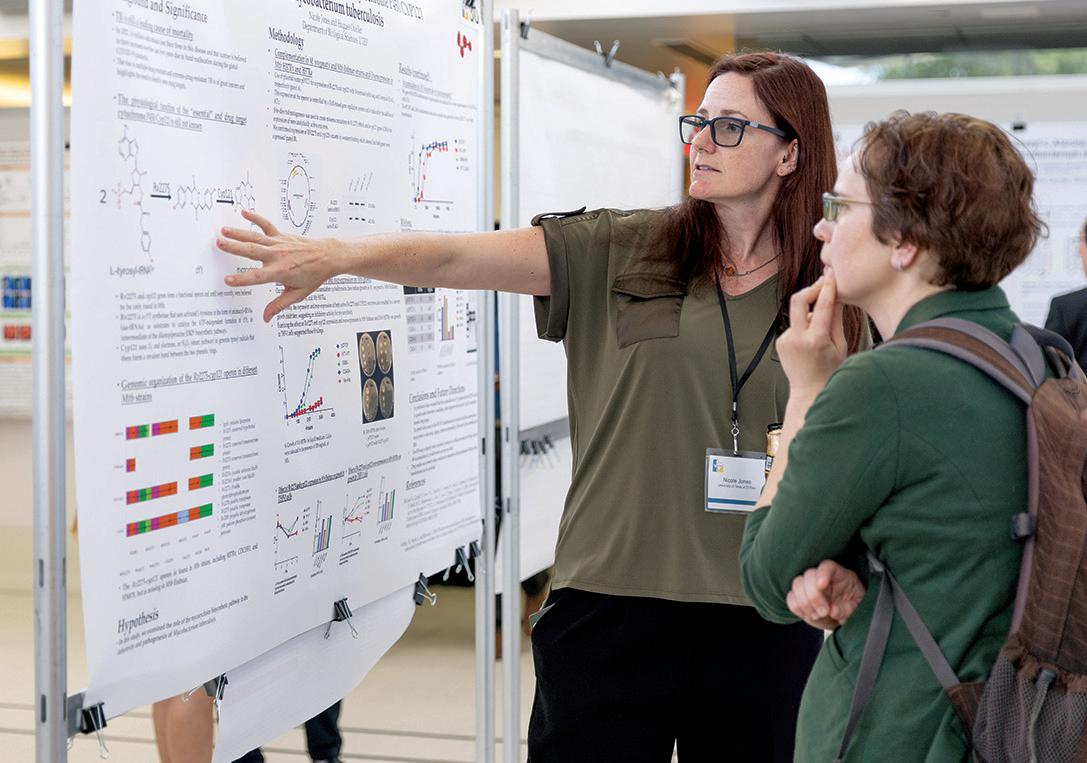

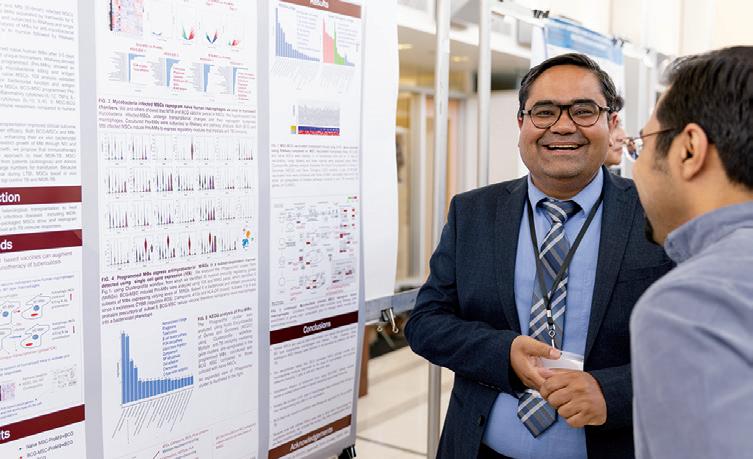

TEXAS BIOMED HOSTS

STATEWIDE TUBERCULOSIS RESEARCH CONFERENCE

Symposium featured recent discoveries from across Texas

Texas Biomed was proud to host the 6th Texas Tuberculosis Research Symposium in April, which brought more than 100 basic and translational scientists studying all aspects of TB together with clinicians who treat patients with TB.

“TB is one of the world’s oldest diseases that still claims more than 1.5 million lives every year,” says Texas Biomed Professor Jordi B. Torrelles, PhD, and symposium co-chair. “In the U.S., Texas has one of the highest incidence rates of TB. That is why it was so important to convene researchers and doctors from across Texas, so we could share our most recent discoveries in the lab and the field.”

The two-day conference featured more than 40 presentations, including many 3-minute lightning talks by students and early career investigators, as well as a poster session and tours. Participants hailed from across the state: UT Southwestern Medical Center, UT Tyler Health Science Center, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston Methodist, UT Medical Branch, UT El Paso, Texas Tech University Health Science Center El Paso, UT Health Houston at Brownsville and Texas A&M. They joined San Antonio-based scientists from the Heartland National TB Center, UT Health San Antonio, Southwest National Primate Research Center and Texas Biomed.

26 CONNECTIONS

The symposium brought together researchers from across the state, from experienced leaders in the field to graduate students presenting for the first time. Many applauded the organizers for providing numerous early career investigators the opportunity to present their research with 3-minute lightning talks and posters.

Representatives from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases opened the conference and University of Massachusetts Chan School of Medicine Professor Christopher M. Sassetti gave the closing keynote lecture.

“We were pleased to welcome experts from across the state and nation to exchange ideas, build collaborations and share what a powerful combination of resources we have to study TB here at Texas Biomed,” says Texas Biomed Professor Deepak Kaushal, PhD, and symposium co-chair.

Texas Biomed recently was named one of the nation’s premier training centers for TB researchers. The Interdisciplinary NexGen TB Research Advancement Center, better known as IN-TRAC, will provide “bench to bedside” training for up-and-coming TB researchers.

“San Antonio provides unparallel access to research and expertise in this field, with the only freestanding TB hospital in the nation, and study sites

at the Texas-Mexico border with people living into old age with TB,” says Texas Biomed Executive Vice President for Research Joanne Turner, PhD. “The region is truly one of the most diverse and dynamic places to study TB.”

The region is truly one of the most diverse and dynamic places to study TB.

— Dr. Joanne Turner

MEET DONNA LAYNE-COLON: MARMOSET COLONY MANAGER

Texas Biomed’s Southwest National Primate Research Center (SNPRC) houses more than 450 marmosets – the largest marmoset research colony in North America and second largest in the world.

Colony manager Donna Layne-Colon knows every single one. And, having been with the colony since its inception 30 years ago, she can tell you who each animal’s parents and grandparents were without a moment of hesitation.

“It’s astounding,” says Corinna Ross, PhD, SNPRC Director. “She has the entire marmoset pedigree database stored in her head.”

This is especially helpful because as colony manager, Layne-Colon decides which animals should be paired for breeding to maximize genetic diversity – not just at SNPRC, but also when collaborating with other institutes and their marmoset colonies.

“It also means when we have something show up clinically, she can track it back and say, ‘Oh, yeah, her sister had that or her great aunt to the second degree had that,’” Dr. Ross says.

Growing a healthy, robust colony is important because marmosets help researchers study a wide range of human and animal health conditions: reproduction and development, microbiomes and obesity, aging and neurological disorders. Common marmosets are

much smaller and shorter-lived than other nonhuman primates; about the size of guinea pigs, but with long, fluffy tails. The lifespan of a marmoset receiving around-the-clock care, like at SNPRC, ranges from 12 to 19 years.

Suzette Tardif, PhD, Texas Biomed Professor Emeritus and retired SNPRC Associate Director, established the colony at The University of Tennessee in 1993. At that time, Layne-Colon was an undergraduate majoring in zoology and anthropology, and worked as a research assistant caring for a wide variety of lab animals.

“It didn’t matter to me what species, I started off working with reptiles, amphibians and fish,” she says. “The herpetology lab had a boa constrictor that took three people to carry through the halls to be weighed once a year.”

When the opportunity arose to care for the marmosets as well, Layne-Colon happily took on the additional job – a decision that would shape the rest of her career.

“It will be 30 years this November,” she says. “Each time she moved, Suzette asked if I wanted to go with her. I said ‘yeah, of course.’”

Dr. Tardif, Layne-Colon and the marmosets moved from Tennessee to Kent State in Ohio in 1995 and then to Texas Biomed in 2001. Over the years, the

28 PROFILE

Donna Layne-Colon with the book she helped write and other marmoset memorabilia.

Donna Layne-Colon with the book she helped write and other marmoset memorabilia.

colony has grown from 45 to more than 450 through breeding and adding animals from other universities.

In the 2000s, Dr. Tardif, Dr. Ross and Layne-Colon led the efforts to establish marmosets as a research model for aging, documenting how they naturally develop most, though not all, of the same conditions and diseases as humans do in later years. The monkeys are also unique because they give birth to twins and triplets, providing a strong foundation for studying the interplay between genetics, environment, development and diseases. The marmosets have also been vital in learning more about how Zika virus passes from mother to fetus and test promising vaccine candidates.

Layne-Colon has been there for all of it, working alongside caretakers, veterinarians and researchers. She especially enjoys conducting ultrasounds to monitor mothers and offspring throughout pregnancies.

“I have seen them from in utero all the way through,” she says. “I’ve watched a lot of births, taken care of a lot of babies.”

Often, she stays overnight to observe the births, collect samples for tissue databases and document animal behavior. She prefers knowing exactly what happened versus coming in the next morning and having to guess. While she is well past the stage of providing basic care, such as daily feeding and cleaning, she is still always happy to help on the weekends when needed.

“She is the ultimate caretaker,” Dr. Ross says.

Layne-Colon’s love of animals began as a young girl growing up on a farm in Appomattox, Virginia.

“All of the kids, we kept turtles, lizards, snakes, baby bunnies, raised baby birds, raised baby deer, turkeys, you know, that sort of thing,” Layne-Colon says. “We had a few cows, but our friends ran a full dairy, so when we went to sleepovers with our friends, we were in the milk house at four in the morning.”

When she began caring for marmosets, there was no manual or how-to guide.

“There still isn’t,” she says.

30

Donna Layne-Colon regularly conducts ultrasounds to monitor mother and offspring health.

“The Common Marmoset in Captivity and Biomedical Research” – or “blue book” as it is known – is as close as the field gets. The two-inch-thick text was the first to summarize knowledge about the species. It was edited by Dr. Tardif; Layne-Colon wrote chapters on housing and husbandry; co-authors also include Dr. Ross and SNPRC veterinarian Anna Goodroe, DVM.

While Dr. Tardif is recognized as the pioneer of marmoset research in the U.S., and passed the leadership baton on to Dr. Ross, Layne-Colon is well-regarded as the go-to resource for all things marmosets. She receives calls and emails weekly from all over the world seeking advice on everything from medical care and breeding, to housing and research protocols.

“When I was a graduate student, long before I came to Texas Biomed, I was told to call Donna,” Dr. Ross says. “Though technically now I am her boss, she has been my mentor for more than 20 years.”

Layne-Colon is keen to share her knowledge so misconceptions can be dispelled and speciesappropriate care can be given. “Marmosets are not just little macaques,” she says, referring to another primate species used in biomedical research and at SNPRC.

Her office door, desk and walls are adorned with marmoset memorabilia, alongside art of other species she has worked with and anime drawings by her 14-year-old son. She is passionate about preserving the history of both the animals and the people working with them.

“I keep a ton of history about marmosets all over the country and the world. To me, it’s interesting,” she says. “A lot of the folks that remember the early years, they’re in the retirement group now, so that stuff will be lost.”

Dr. Tardif underscored how Layne-Colon is not one to sing her own praises, despite making such significant contributions to the field.

She has the capacity to get inside the animal, really understanding the animals’ perspective. That can be learned, but it is also – I think – a gift.

— Dr. Suzette Tardif

“She was an absolutely critical eye to me in terms of thinking about how to move research forward,” Dr. Tardif says. “She would always say, very politely, ‘Well, that’s an interesting idea, but here’s the thing, you know, I don’t think a marmoset would actually do that.’”

It’s all part of “what makes Donna, Donna,” colleagues say. Not just a compassionate and intelligent scientist with an incredible memory, but a one-of-a-kind individual.

“Donna is a what I would call a true naturalist,” says Dr. Tardif. “She gets animals in a way that’s both scientific but also real visceral. She has the capacity to get inside the animal, really understanding the animals’ perspective. That can be learned, but it is also – I think – a gift.”

31

A 6-day-old infant marmoset.

We extend heartfelt gratitude to supporters of our mission.

Together, we are building healthier lives FOR ALL OF US.

Larry Schlesinger, MD President and Chief Executive Officer

Bruce Edwards, MBA Executive Vice President, Finance and Administration Chief Financial Officer

Joanne Turner, PhD Executive Vice President, Research

Larry Schlesinger, MD President and Chief Executive Officer

Bruce Edwards, MBA Executive Vice President, Finance and Administration Chief Financial Officer

Joanne Turner, PhD Executive Vice President, Research

Jeffrey Heinke Designer

Photographers: Josh Huskin Katie Clementson

Jenae Escobar

Copyright ©2023 Texas Biomedical Research Institute P.O. Box 760549, San Antonio, Texas 78245

Under the microscope:

Macrophages are large immune cells that gobble up garbage throughout the body. These are alveolar macrophages, which specifically live in the lining of the lung’s air sacs where air exchange occurs. Alveolar macrophages are usually the first immune cells to encounter pathogens entering the deep lungs, such as SARS-CoV-2 or the bacteria that causes TB.

Lisa Cruz VP, Corporate Communications

Nicole Foy Director, Public Relations

Laura Petersen Senior Communications Specialist

Ruby Reyes-Hinojosa Marketing Manager

Madeleine Dionne Executive Assistant to the President/CEO

TxBiomed Magazine Editorial Team

Lisa Cruz VP, Corporate Communications

Nicole Foy Director, Public Relations

Laura Petersen Senior Communications Specialist

Ruby Reyes-Hinojosa Marketing Manager

Madeleine Dionne Executive Assistant to the President/CEO

TxBiomed Magazine Editorial Team

FROM YESTERDAY’S PIONEERS TO TODAY’S VISIONARIES

Texas Biomed founder Tom Slick, Jr. was an entrepreneur who in the 1940s dared to imagine a city of science in South Texas that could be a “great center for human progress through scientific research.”

Out of Slick’s ranchland grew a world-class research institute that today is tackling humanity’s biggest health challenges, from COVID-19 and chronic diseases to HIV and tuberculosis. Texas Biomed researchers are pioneering new ways to prevent and treat disease with next-generation vaccines and therapeutics. The legacy continues.

DONATE TODAY

Health science teacher Sarah Hale speaks with Josué Méndez, a high schooler at Brooks Collegiate Academy, which partners with the Texas Biomed Scientist-in-Residence program.

Health science teacher Sarah Hale speaks with Josué Méndez, a high schooler at Brooks Collegiate Academy, which partners with the Texas Biomed Scientist-in-Residence program.

Donna Layne-Colon with the book she helped write and other marmoset memorabilia.

Donna Layne-Colon with the book she helped write and other marmoset memorabilia.

Larry Schlesinger, MD President and Chief Executive Officer

Bruce Edwards, MBA Executive Vice President, Finance and Administration Chief Financial Officer

Joanne Turner, PhD Executive Vice President, Research

Larry Schlesinger, MD President and Chief Executive Officer

Bruce Edwards, MBA Executive Vice President, Finance and Administration Chief Financial Officer

Joanne Turner, PhD Executive Vice President, Research

Lisa Cruz VP, Corporate Communications

Nicole Foy Director, Public Relations

Laura Petersen Senior Communications Specialist

Ruby Reyes-Hinojosa Marketing Manager

Madeleine Dionne Executive Assistant to the President/CEO

TxBiomed Magazine Editorial Team

Lisa Cruz VP, Corporate Communications

Nicole Foy Director, Public Relations

Laura Petersen Senior Communications Specialist

Ruby Reyes-Hinojosa Marketing Manager

Madeleine Dionne Executive Assistant to the President/CEO

TxBiomed Magazine Editorial Team