CREATING THE EGALITARIAN METROPOLIS

Scholars and practitioners at Taubman College are working in, for, and with Detroit towards inclusive recovery and more equitably distributed prosperity

FALL 2022

Taubman College of Architecture and Urban Planning University of Michigan

(Above) As part of “The Detroit River Story Lab,” students from Detroit high schools, colleges, and youth-serving organizations ride the Inland Seas schooner along the Detroit River. (Below) The University of Michigan Architecture Preparatory Program (ArcPrep) is a semester-long immersive college preparatory course in architecture, urbanism, and studio design for Detroit Public School juniors.

(Above) As part of “The Detroit River Story Lab,” students from Detroit high schools, colleges, and youth-serving organizations ride the Inland Seas schooner along the Detroit River. (Below) The University of Michigan Architecture Preparatory Program (ArcPrep) is a semester-long immersive college preparatory course in architecture, urbanism, and studio design for Detroit Public School juniors.

A MESSAGE FROM THE DEAN

When Detroit communities gather to discuss new devel opment projects or neighborhood plans, residents fre quently express concerns about gentrification, the process through which economic development leads to the dis placement of long-standing residents by wealthier new comers. Yet by many measures, gentrification is far from the most salient issue facing the city, which has tens of thousands of abandoned properties, an infrastructure whose investment needs far outpace the revenue gener ated by its tax base, and is still losing population.

The Egalitarian Metropolis project goes to the heart of this tension. Funded by the Mellon Foundation, this research and teaching project follows a hypothesis: that the very extremity of Detroit’s challenges gives residents, allies, scholars, and practitioners the chance to develop and test recovery strategies that decouple investment and economic recovery from gentrification and displacement.

Detroit is a dire case of disinvestment and abandonment, processes that affected many cities. The magnitude of its rise and fall makes it exceptional — can this also be true of its revitalization? In an era of neoliberal redevelop ment, which all too often proceeds through privatization, can Detroit model pathways to greater prosperity that is more equitably distributed?

The city government of Detroit is pursuing an agenda of inclusive recovery, supported by Mayor Mike Duggan with city planning director Antoine Bryant and his predecessor, Maurice Cox. As our cover story illustrates, Taubman College faculty are at the forefront of this work, in part nership with other organizations and Detroit residents.

The Egalitarian Metropolis project has spurred numer ous additional research projects that are furthering and expanding on the original project’s aims. The Detroit River Story Lab is co-producing and disseminating historically nuanced, contextually aware, and culturally rooted narratives telling the story of the Detroit River in the lives of adjacent communities from an equitable, inclusive, and anti-racist perspective. Racializing Space — a project I have had the privilege of working on with fellow faculty and students — maps data from censuses and surveys to show how policies and processes of predatory exclusion and inclusion have linked race with housing inequality in Detroit and southeast Michigan. Students in our Systems Studio design proposals to

incorporate affordable housing into mixed, market-rate developments; their work sparks innovation among prospective developers and demonstrates how housing can contribute to the social and economic restructuring process of the city. And the Detroit as a Carceral Space initiative works alongside communities to create eco nomic opportunities, transform the justice system, and promote equitable and just cities. These are just a few examples of the many branches that have sprung from the roots of the Egalitarian Metropolis project.

Much of my own scholarship has concerned US singlefamily houses and homeownership as practices of citizen ship and self-fashioning, place-making and economic participation for individuals and families. For me, partici pating in the Racializing Space research project has been an opportunity to understand in detail, and in Detroit specificity, the processes of predatory exclusion and inclusion through which homeownership built white supremacy and racial inequities in wealth, educational outcomes, and life opportunities. This work feeds into the growing conversation about community-based repa rations, a domain that U-M colleague Earl Lewis is lead ing, with a large team and partners across the country, in another Mellon-funded project.

As the Egalitarian Metropolis project concludes, the work here at Taubman College continues. Our Michigan Architecture Prep Program provides Detroit Public School juniors with an immersive, semester-long college prepara tory program; they leave equipped to be city-makers, empowered in shaping this better future. Our AntiRacism Hiring Initiative project, Racial Justice and the Urban Humanities, has been awarded funding, and we are preparing to recruit new faculty who will advance the work in unforeseen ways. The March 2023 confer ence, The Egalitarian Metropolis: Towards an Inclusive Recovery for Detroit, will bring together leading thinkers in architecture, urban planning, history, geography, litera ture, economics, social work, and more, along with Detroit community members and civic organizations, to imagine an innovative and inclusive future for Detroit. Even as Robert Fishman retires, thanks to his collabora tive efforts we have the opportunity to recruit and support the next generation of scholars and practitioners as we seek to pilot an inclusive recovery in, for, and with Detroit.

Jonathan Massey, Dean Taubman College of Architecture and Urban Planning University of Michigan

2 FALL 2022 TAUBMAN COLLEGE AROUND THE COLLEGE / 04 04 News from the Art & Architecture Building and Beyond 08 Welcome New Faculty and Fellows FEATURE STORY / 10 10 Detroit’s Path to Inclusive Recovery Working toward a fairer future requires untangling legacies of displacement, segregation, and inequity in Detroit FACULTY & STUDENTS / 16 16 What Are You Thinking About? Jared Freeman, Joanne Huang, Maria Garcia Reyna, Odiso Obiora 18 A Day in the Life An In-Depth Exploration of Urban Centers / Learning Mexico City Through Its Built Environment 20 Global Lessons in Real Estate Development and Affordable Housing Professor Lan Deng encourages cities to learn from one another in order to find a more balanced approach to housing challenges 22 AI is Here, is Architecture Ready? Associate Professor Matias del Campo is ready for AI to change the way we build 24 ON AIR: Faculty Work 2020–2022 26 Work Spotlight Robotically Fabricated Structure (RFS): Assistant Professor of Architecture Arash Adel, ADR Laboratory CONTENTS 10

ON THE COVER:

The 1951 Sanborn fire insurance map of Black Bottom and Paradise Valley is georeferenced above the current geography. Nearly 50,000 people, upwards of 90% of whom were Black, were displaced over decades for land that is now mostly vacant, parking lot, or interstate highway. President Biden’s infrastructure package has set aside $100 million for the demolition of the highway interchange shown and the reconstruction of the neighborhood along principles of new urbanism.

28 Quotable Taubman College

29 Gradient Journal

An online platform for architecture and urbanism from Taubman College

ALUMNI / 32

32

Ensuring a More Equitable Future for Architecture

Randy Howder, B.S. Arch ’99, and his husband, Neal Conatser, are supporting the next generation of architects and critical thinkers with their $2.75 million pledge to the Howder-Conatser Architecture Scholarship Fund

34 Not the Only Player: Future-Focused Collaboration Kartik Desai, B.S. Arch ’99, works to foster interdis ciplinary thinking in architecture and real estate

36 Laying the Foundation for a New Generation of Change Makers

Brian Adelstein, B.S. Arch ’89, supports Taubman College students’ grand aspirations

37

Working With, Not Against, Nature Lizzie Yarina, B.S. Arch ’10, knows climate adaptation planning is full of trade-offs

38 Public Space, Personal Relationships

Kristen Conry, B.S. Arch ’99, M.Arch ’01, wants people to feel at home anywhere they work or travel

40 Living between Idea and Reality

Justin Mast, M.Arch ’12, is an entrepreneur who thinks like an architect

42 Community Conversation: Dignity through Design

Kyle Schertzing, B.S. Arch ’05, principal at Safdie Rabines Architects, in discussion with Taubman College student Mirabella Witte, B.S. Arch ’23

CLASS NOTES / 43

IN MEMORIAM / 47

CLOSING / 48

3

26

18 40

Addressing Brazil’s Affordable Housing Deficit

A team of Taubman College graduate students, led by Ana Paula Pimentel Walker, associate professor in urban and regional planning, collaborated with commu nity members in São Paulo, Brazil, this summer to help combat Brazil’s severe affordable housing deficit and promote environmental stewardship.

“These community members have built, over genera tions, a profound knowledge about the cities [they live in] and combining that knowledge with the professional background of our students is mutually beneficial. So we’ll advance both: the struggle for adequate housing and the careers of our students,” said Pimentel Walker.

4 FALL 2022 TAUBMAN COLLEGE AROUND THE COLLEGE

Agora Journal of Urban Planning and Design Wins Douglas Haskell Award

The Agora Journal of Urban Planning and Design has been awarded a Douglas Haskell Award for Student Journals from the American Institute of Architects (AIA). This prestigious award supports student journalism on architecture, planning, and related subjects and fosters regard for intelligent criticism among future professionals. “We are so honored that Agora received this recognition from the AIA. Agora is lucky to have an incredible, dedicated team of authors, staff, and photographers who helped make Agora 16 a success,” said Caroline Lamb and Laura Melendez, the publication’s editors-in-chief.

Peñarroyo Named Akademie Schloss Solitude Fellow

SPLAM Timber Pavilion Awarded AIA Small Project Award

A collaboration between architecture firm Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM) and Taubman College is one of thirteen architectural projects from across the United States honored as part of this year’s American Institute of Architects (AIA) Small Projects Awards. Wes McGee, associate professor of architecture, and Tsz Yan Ng, associate professor of architecture, collabo rated with SOM to design and build SPLAM Timber Pavilion utilizing robotic fabrication techniques for EPIC Academy in Chicago’s South Shore neighbor hood. The outdoor pavilion was constructed from sustainably sourced timber and showcases an optimized structural layout using spatial laminated timber to produce a more sustainable and efficient slab to inform design and con struction processes. Located at EPIC Academy, SPLAM also functions as an outdoor classroom and an event and performance space for students and teachers.

Cyrus Peñarroyo, assistant professor of architecture, has been named a 2022–2024 Akademie Schloss Solitude Fellow in the Spatial (architecture and design) category. Established in 1990, the fellowship supports young artists, scientists, and cul tural workers. Fellows complete a residency at Akademie Schloss Solitude, where they can devote themselves to their research with the benefit of material support and favorable intellectual condi tions. The wide-ranging fellowship program promotes the interrela tionship of art and science across disciplines. Peñarroyo is one of 58 fellows selected from a pool of 2,903 candidates for the 2022–2024 period. His work examines the urbanity of the Internet — how networked technologies shape urbanization and how media spheres influence built environments.

5

Trandafirescu Named Institute for the Humanities Fellow

Anca Trandafirescu, associate professor of architecture, has been named a 2022–23 Institute for the Humanities Faculty Fellow. Trandafirescu will spend September 1 to May 31 as a fellow pursuing her research titled “Constructed Revisionism: The Monumental Potentials of Past Mistakes.” Across the world, mon uments are torn down and cast away as if they never existed. Trandafirescu’s work asks what is lost when we choose to forget who we once were and what should be done with the monuments around us that no longer represent our col lective memory. In addition to her research and participating in the weekly seminar, she will present a lecture in the Institute for the Humanities’ FellowSpeak series.

— Anya Sirota, associate professor of architecture, on Acts of Urbanism (AOU)/Entre Actes d’Urbanisme. Held in June 2022, the week-long FrancoAmerican collaboration explored place-based approaches to urban activation in Banglatown, Detroit.

6 FALL 2022 TAUBMAN COLLEGE AROUND THE COLLEGE

Detroit is a city whose image precedes it. Visitors often come with strong ideas about its shape, challenges, and possibilities. Some arrive with preconceived solutions. Acts of Urbanism worked to deconstruct common public misconceptions and biases by inviting a range of urban actors and design professionals into a space of frank conversation and collective experimentation.”

“

Duggal Named Interim Director for Real Estate Development Activities and Weiser Center

Melina Duggal, ACIP, MUP ’95, will serve as the interim director for real estate development activities at Taubman College and the interim director for the Weiser Center for Real Estate at the Ross School of Business. Duggal is currently a visiting assistant professor of practice at Taubman College, where she teaches courses in real estate. She brings more than 25 years of real estate industry experience as a practitioner. She has also taught real estate courses at George Mason University and the University of Maryland. As President of Duggal Real Estate Advisors, Duggal conducts feasi bility studies, market analyses, financial analyses, and redevelop ment strategies for real estate projects and clients.

AIA College of Fellows Welcomes Five Taubman College Alumni

From left to right: AIA Fellows Amy Gilbertson M.Arch ’01, Jeff Hausman M.Arch ’81, Kurt Haapala M.Arch ’94, Tod Stevens M.Arch ’91, and Dorian Moore M.Arch ’88 pictured at the AIA Taubman College Alumni Reception in Chicago.

Goodspeed Wins 2022 Curriculum Innovation Award

Robert Goodspeed, associate professor of urban and regional planning, has been recognized by the Association of Collegiate Schools of Planning (ACSP) for his course Scenario Planning. Each year, the Curriculum Innovation Award honors four courses for designing accessible, engaging, and effective learning experiences for students in the urban planning field. Scenario Planning is a semester-long intensive on scenario planning methods, one of the only urban planning courses that combines the explicit teaching of the method with hands-on techniques. The course consists of a seminar series and a hands-on, collaborative project designed to mirror real-life scenario planning practices. It is structured to encourage students to take on a reflective practice toward urban planning and provide the technical skills for students to implement their ideas in a professional setting.

7

Welcome New Taubman College Faculty

Taubman College welcomes new faculty members who, along with established faculty, will offer students a wealth of learning and professional development opportunities.

Oksana Chabanyuk

Intermittent Lecturer, Architecture Chabanyuk’s academic interests include standardization and early industrialization in the USSR, the related influ ence of foreign specialists, prefabrication in industrial construction and housing, post-socialist housing, social housing, and regeneration of residential areas.

Emily Kutil, M.Arch ’13 Lecturer I, Architecture Kutil’s research investigates the intertwined social struc tures, material structures, and power structures that shape our world. She makes drawings, publications, installations, models, and other story-machines, often using collective, interdisciplinary processes.

Charlie O’Geen Lecturer I, Architecture O’Geen’s research investigates the utilization of existing site conditions for use as building systems, in opposition to conventional building practices which are materially consuming. Unconventionally, O’Geen’s work moves off paper and into the full-scale realities of site and material and looks to explore and expose the opportunities of existing material energy.

Gina Reichert

Lecturer III, Architecture Reichert is an artist, architect, and small-scale commu nity developer. Her practice is rooted in developing strat egies and self-initiated projects in her immediate Detroit neighborhood, defining opportunity in overlooked spaces, and using the resources at hand.

Torri Smith, M.Arch ’22 Intermittent Lecturer, Architecture Smith’s investigations span from environmental justice and design biology to storytelling and urban placemaking. She currently researches the intersection of environmen tal justice, urban activism, and design while simultane ously exploring the ways in which ecological regeneration can address systemic racial inequity.

Łukasz Stanek

Professor, Architecture Stanek’s scholarship seeks to understand worldwide urbanization processes since World War II beyond their reduction to the consequences of the colonial encounter with Western Europe and the impact of Westerndominated “globalization.” In particular, he studies how urbanization in post-independence West Africa and the Middle East was shaped and reshaped by resources circu lating in networks of socialist internationalism, the Non-Aligned Movement, and various forms of SouthSouth collaboration.

8 FALL 2022 TAUBMAN COLLEGE AROUND THE COLLEGE

(First row, from left) Oksana Chabanyuk, Emily Kutil, Charlie O’Geen, Gina Reichert, Torri Smith. (Second row, from left) Łukasz Stanek, John David Wagner, Elizabeth Gunden, Elisa Ngan, Jermaine Ruffin.

John David Wagner

Intermittent Lecturer, Architecture

Wagner is a design consultant, design researcher, and licensed architect with over a decade of experience cata lyzing change in the built environment through design, social advocacy, and material assemblies. From concep tual to visionary, his work has assisted clients to outline, prototype, and realize built projects that deliver innova tive, inclusive spatial designs, user experiences, and educational programs.

Elizabeth Gunden, M.U.R.P. ’19

Intermittent Lecturer

Gunden is a planner at Beckett & Raeder, Inc., a plan ning, landscape architecture, and civil engineering firm based in Ann Arbor, Michigan. Liz is a certified planner with the American Institute of Certified Planners (AICP). She also has a background in graphic design, and much of her work focuses on representing planning data and information in a visual and graphic way.

Elisa Ngan

Professor of Practice, Urban Technology Ngan’s research centers on creating data inter ventions for long-tail problems at the end of the product life cycle, cross-pollinating with topics of category theory, industrial cybernetics, and epistemic injustice to reveal the broken relationships of industrial maintenance and repair invisibly affecting the lives of marginalized persons and communities.

Jermaine Ruffin, M.U.R.P. ’17

Intermittent Lecturer, Urban & Regional Planning Ruffin is currently the vice president of neighborhoods with Invest Detroit. He has held various positions in the fields of community and economic development, includ ing roles with the Michigan State Housing Development Authority. Most recently, he was the associate director for equitable planning & legislative affairs (planning & development) with the City of Detroit.

Hello Fellows!

Welcome to our three new fellows joining us for the 2022–2023 academic year.

Stratton Coffman Architecture Fellow

Coffman uses the multi-facing tools of architecture to explore how capital, institutions, and design discourses conspire to produce material, social, and epistemic bod ies. They are co-instigator of the architecture research and design working group Proof of Concept with Isadora Dannin.

Salma Mozaffari

ADR Postdoctoral Research Fellow Mozaffari holds a Ph.D. in Structural Engineering from ETH Zurich. Her research experience includes computa tional structural design and optimization, algebraic geom etry, and signal processing for structural dynamics and health monitoring applications. She is interested in inter disciplinary research at the interface of digital fabrication and resource-aware construction.

Alina Nazmeeva Architecture Fellow

Nazmeeva examines entanglements and overlays between physical and digital spaces and objects and their cultural, economic, and political implications. Using gaming engines, CGI software, machinima, found footage, and installations, she exposes and examines the increasing oscillation between cities and video games, images and spaces, life and animation.

Salam Rida, M.Arch ’17

Michigan-Mellon Design Fellow

Rida’s research and practice, situated at the intersection of architecture and urban design, explores multidisci plinary approaches to tactical interventionism, environ ment sustainability, and equitable economic development.

9

(From left) Stratton Coffman, Salma Mozaffari, Alina Nazmeeva, Salam Rida.

Detroit’s Path to Inclusive Recovery

By Amy Crawford

EIGHT MILE ROAD MARKS the border between the city of Detroit and the suburbs of Oakland County. But this multilane thoroughfare, which carries traffic past sprawling shopping plazas and neighborhoods of modest single-family homes built during the prosperous years after World War II, represents more than a geo graphic boundary. It’s also a stark line between a Black city and its white suburbs, between a community with a median household income that hovers around half the national average and one of the wealthiest counties in the United States.

“When you see it on a map, you start to see how people in Detroit really lost out on building wealth,” says Larissa Larsen, associate professor and chair of Taubman College’s urban and regional planning program.

Detroit is an extreme example, but nationwide Black families still have about a tenth the wealth, on average, of their white counterparts, primarily because of a gap in rates of home ownership. “Certainly there’s structural racism baked right in there,” Larsen says. “And we, as architects and planners, worked for a century building American cities — so we’ve participated in making that happen.”

History shapes cities in myriad ways: through deliberate planning and government policy, the rise and fall of indus tries, war, disaster, and migration. The ways in which urban denizens are displaced, segregated, and cut off from resources today are also rooted in the past, and rectifying these inequities requires untangling those legacies. That need is at the heart of an emerging field of research known as urban humanities, which at Taubman College

has centered on a grant program called the MichiganMellon Project on the Egalitarian Metropolis. First funded by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation in 2013, the Egalitarian Metropolis was led since 2017 by Taubman College’s Robert Fishman, who retired in June as a profes sor of architecture and urban and regional planning, and by Angela Dillard, the Richard A. Meisler Collegiate Professor of Afroamerican and African Studies and cur rent chair of the history department at the College of Literature, Science and the Arts. Now in its concluding year, the project is evolving into an Urban Humanities Initiative at the University of Michigan, which will con tinue to connect humanities researchers, planners, and architects, along with community leaders outside the university, as they work toward a fairer future.

Robert Fishman grew up in Elizabeth, New Jersey, a train ride away from Manhattan, where the strata of history can often be found close to the surface.

“I was one of the bridge-and-tunnel people, as they’re called,” he says with a laugh. “For us, New York was even more of an ideal and a revelation than it was for the peo ple who were actually living within the city — I keep coming back to New York as my archetypal metropolis.”

As a teenager in the 1960s, Fishman took frequent trips into the city, spending long hours exploring its renowned art museums. But he also became fascinated by New York itself and by the extremes of wealth and poverty that were often on display. His curiosity led him to The City in History, a now-classic book by the historian Lewis Mumford, first published when Fishman was in high school. Mumford’s lyrical study of how the Western urban form has changed over time — from the ancient Greek

10 FALL 2022 TAUBMAN COLLEGE FEATURE STORY

Working toward a fairer future requires untangling legacies of displacement, segregation, and inequity in Detroit

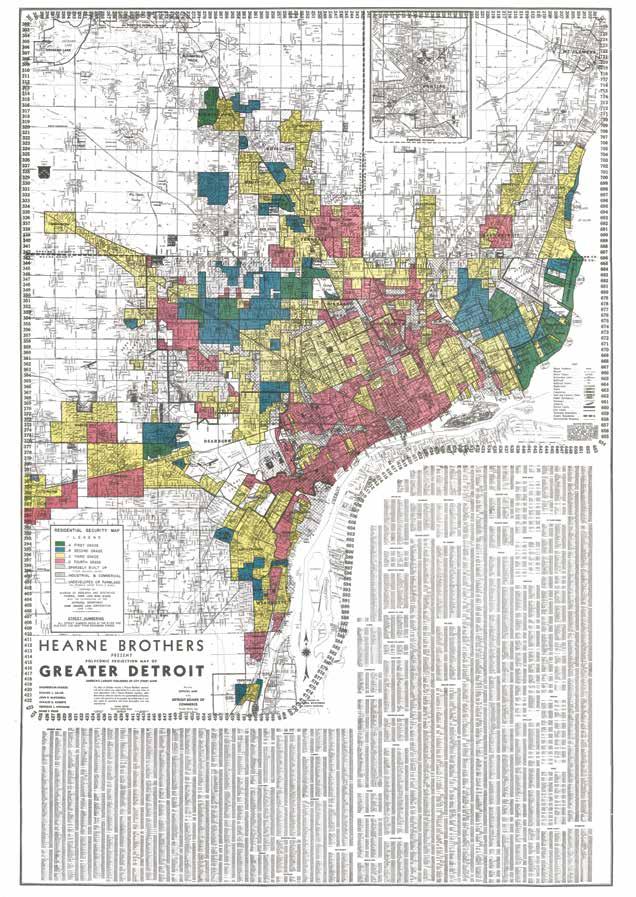

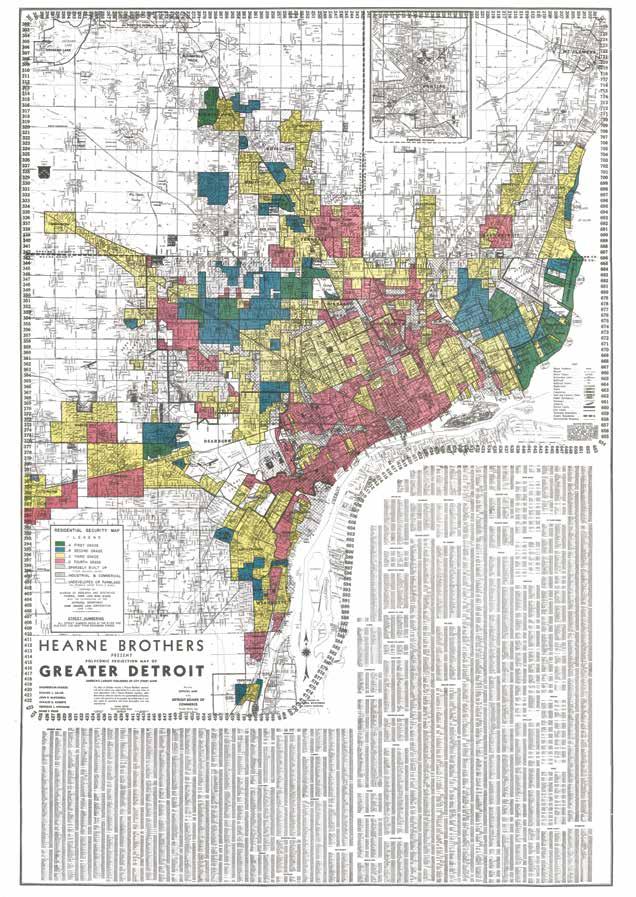

In this 1939 redlining map, green represents suburban and largely white neighborhoods that were considered safe investments for home mortgages. Red represents urban neighborhoods with Black, Jewish, and ethnic white communities.

11

Clockwise from top left: Ford Motor Company Highland Park plant, 1914. A Black family traveling during the Great Migration, 1940. Workers at the Ford Rouge plant, 1936. Black children standing in front of a wall near Eight Mile Road; this wall was built in August 1941 to separate the Black section from a white housing development going up on the other side.

12 FALL 2022 TAUBMAN COLLEGE

city-states and cathedral towns in medieval Europe to the modern capitalist metropolis — would prove a lifelong influence.

“I’ve assigned it in literally every course I’ve ever taught,” Fishman says. “Mumford’s way of looking at the city, his deep understanding of the impact of culture, has certainly shaped my work more than anyone else.”

Fishman went on to study history in college and graduate school, spending the first half of his teaching career in traditional history departments. When he came to the college in 2000, recruited as part of a new master’s pro gram in urban design, he found a student population eager to incorporate historical context into the study of design and planning.

“To be an urban designer, you really have to love the city, which means trying to grasp what is unique about each city,” Fishman explains, “and to understand what is unique about it you really have to look into the past, into the urban biography that has shaped every city.”

Fishman was part of the original team of faculty and students, led by Taubman College Associate Dean Milton Curry, who won the six-year, $1.3 million grant for the Michigan-Mellon Project on the Egalitarian Metropolis. Initially the project compared three cities — Detroit, Rio de Janeiro, and Mexico City — through a framework that assumed the inherent worth and equality of all the people who called each home. What were the most challenging contemporary issues facing these different communities, they asked, and how did their causes and solutions con nect to history, economic and political forces, architec ture, and urban design? The wide-ranging effort resulted in a series of courses, exhibitions, and symposia, which brought together academics with community leaders from the cities themselves.

In 2019, a second, $1 million grant allowed the project team to take a deeper look at a single city: Detroit, which — more than almost any other in the United States — has seen its fortunes rise and fall on the tide of larger historical forces. After Curry’s departure to be dean of architecture at USC, the project was now jointly headed by Fishman and LSA historian Angela Dillard. Fishman couldn’t imagine the Project without this close collabora tion. “I’m something of an outsider to Detroit. Angela grew up as a Black Detroiter, daughter of a prominent clergyman, and someone whose life and scholarship

A house located two blocks east of the long-abandoned Packard plant, 2014.

have been deeply engaged with Detroit. She brings a perspective that I couldn’t alone.”

“The Mellon Foundation,” he adds, “had observed that there is an unfortunate separation between schools of architecture and the humanities, and both architecture and humanities could benefit greatly by working more closely together,” Fishman says. “And the other part of the urban humanities concept was the need to include the diverse voices of the city itself, to really engage with the lives of our great cities.”

Detroit was first settled by French colonists in the early 1700s, but the history of the modern city begins in 1910 when Henry Ford opened his Highland Park plant and began churning out Model Ts on the world’s first automo tive assembly line. The growing automobile industry drew new populations of workers, including Black Americans, who fled the Jim Crow South as part of what became known as the Great Migration. By 1950, the city’s popula tion was eight times what it had been in 1900, and Detroit was among the most prosperous cities in the world. Over reliance on a single industry proved dangerous, however, and Detroit’s economy and population cratered beginning in the late 20th century as the auto industry decentral ized. Due to the legacies of white flight and redlining, the decline hit Black Detroiters especially hard.

“Detroit is an interesting case because the highs were high and the lows were so low,” says Larsen. “A 100 years ago, it was Silicon Valley, and the wealth is still there — it just went to the suburbs.”

Larsen, along with Fishman, Dean Jonathan Massey, and Josh Akers, an associate professor of geography and urban and regional studies at the University of Michigan-Dearborn, leads “Racializing Space: Housing and Inequality in Detroit, 1930–2020.” An outgrowth

13

FEATURE STORY

Inspiring Budding Architects, Shaping the Future of Cities

Michigan-Mellon’s renewed Egalitarian Metropolis cycle of funding focuses on the city of Detroit and ways that creative practice and the urban humanities can equitably address urban recovery. In tangible ways, The University of Michigan Architecture Preparatory Program (ArcPrep) is already doing just that: creating a sense of optimism and agency for Detroit public high school juniors interested in design and its affiliated fields.

Through an intensive, semester-long studio taught by our Mellon Fellows in Architecture, young designers learn to critically discern Detroit’s complex spatial histories as they explore ways to shape the city’s possible futures. The program takes the students’ talents, creativity, and expertise very seriously, nurturing an inclusionary pedagogical model based broadly on egalitarian educational ideals. In the process, we bring together a network of Taubman College faculty and students, Detroit institutions, community and government organizations, and professional enterprises into conversation and collaboration with students. In the past, ArcPrep has partnered with the Detroit Public Library, the Detroit Institute of Arts, the Detroit Cultivator Community Land Trust, and the Sidewalk Festival, to name a few. With each partnership, we situated culturally contingent, place-based design exercises for students to directly engage with the city and its leaders.

This year’s program promises to be very exciting. We will be working with Cornell University College of Architecture, Art and Planning, the Charles H. Wright Museum of African American History, and a group of Detroit-based artists to critically engage with the city’s cultural institutions and civic spaces in order to define what constitutes a new model for equitable cultural infrastructure. The students never cease to dazzle with their unbridled imaginaries, and I’m certain they will come up with inspiring takes on this instigation.

of the Egalitarian Metropolis, the effort involves mapping data from decades of censuses and surveys to show how Detroit’s regional segregation and racial wealth gaps developed.

Mapping plays a role in much of the research currently funded by or related to the Egalitarian Metropolis project. Doctoral student Christine Hwang, for example, is work ing on a dissertation that focuses on how the Catholic Church, with its parish-based organizational structure, influenced the development of Detroit’s neighborhoods.

“The Catholic parish was much more important in Detroit than in Catholic countries,” Hwang explains, “because it became a place of refuge for Catholics, as well as an ethni cally defined space. It was kind of a paradox — the parish was a place of refuge, but only people who spoke Polish or Italian, for example, really felt welcome in the neighbor hood that it defined.”

Black Americans, who were mostly Protestant, often sought to enroll their children in parochial schools because they were seen as offering a better chance at upward mobility. Hwang’s next big question is whether those parishes that welcomed Black families acted as an antidote to redlining (the phenomenon in which Black families were confined to the poorest neighbor hoods and denied mortgages when they tried to break the “color line”).

Myles Zhang, a Ph.D. candidate in architecture at Taubman College, has also studied religious institutions — specifically, medieval cathedrals. But his more recent research involves less lofty institutions, beginning with the architecture of prisons and extending to places of punishment that lie far beyond their walls.

“It’s looking at carceral spaces that do not at first glance look like carceral spaces,” Zhang says, referring to urban areas that “are spaces of confinement, perhaps through lack of access to resources, like good transportation or job programs, or histories of underinvestment, or stigma associated with those people and places.”

Such topics can make a person pessimistic, Zhang admits, but the Egalitarian Metropolis — indeed, the whole urban humanities approach — is concerned not only with the burdens of the past, but with how their lessons can shape the future.

“These historical questions don’t always point themselves toward solutions,” he says, “but they provide an impetus, a motivation, to use the built environment as a tool for social equity.”

14 FALL 2022 TAUBMAN COLLEGE

— Anya Sirota Associate Dean for Academic Initiatives / Associate Professor of Architecture

FEATURE STORY

The spirit of the Egalitarian Metropolis will continue at Taubman College, notably through the latest iteration of U-M’s Anti-Racism Hiring Initiative, which will fund three new faculty positions in the urban humanities, including one at the college focused on urban design, another in the Department of Afroamerican and African Studies in LSA, and a third position that the college will share with LSA’s Digital Studies Institute.

The culmination of the Michigan-Mellon Project, however, takes place next spring, with “The Egalitarian Metropolis: Toward an Inclusive Recovery for Detroit,” a symposium that will bring together U-M researchers and people who are working every day to make Detroit’s recovery equitable and inclusive.

“We need to look to history to understand where to go in the future, how to navigate similar issues, and how to avoid making similar mistakes,” says architectural historian Anna Mascorella, Taubman College’s current Fishman Fellow. “I think it’s critical to understand deeply how our cities came to be where they are today, and to ask ourselves who was — or wasn’t — at the table when these decisions were being made.”

To that end, the conference will be “a project of the urban humanities,” says Mascorella, who is working

Racial dot maps of Detroit, generated by Myles Zhang, show how the city remains racially and spatially segregated. More at racializingspace.org.

closely with Fishman to develop it. “It merges the aca demic disciplines of architecture, urban planning, history, geography, literature, economics, and social work with Detroit community members and civic organizations in order to truly foster critical conversations about Detroit’s future as an egalitarian metropolis.”

The path toward that future may not yet be clear, but Detroit is also not alone in its struggle to be a more inclusive place for humans to live, work, and grow.

“What happened to Detroit is profoundly engaged with deeper global forces,” says Fishman. “It’s these forces, including de-industrialization and changing global division of labor, that lead us to the divided metropolis, to increasing inequality all over the world.”

Global tides shift, however, and the college’s engagement with Detroit has revealed certain advantages — housing, for example, is “naturally affordable” in Detroit, even as other cities experience soaring home prices and rents.

“It was not too long ago when Detroit was seen as a warn ing about the future for every American city,” Fishman says. “But I think the very difficulties Detroit has faced might lead to better outcomes.”

After all, Detroit’s urban biography is far from complete. And whether the next chapter will be one of egalitarian ism or division is up to the next generation of architects, planners, policymakers, activists, and the everyday people who call cities home.

15

:

What Are You Thinking About?

A: Inclusivity as an architectural methodology.

Why is this interesting to you? My architectural education has been as much about understanding archi tecture as it has been understanding the design process. In my opinion, the most nuanced and innovative designs arrive from the pressure of various programmatic, environmen tal, and contextual constraints. We are being taught to design with intentionality and to have agency over our design choices in order to solve the design puzzle at hand.

My introduction to the study of inclusivity in architecture was through the lens of physical accessi bility. It is one thing to know about code compliance, but it is another to work accessibility into a space from its inception. We can improve our designs by thinking of accessibility (in all senses of the word) as a con straint and a principal design factor.

Jared Freeman B.S. Arch/B.A. International Studies ’23

Accessibility in architecture seems like the ultimate constraint. It is also the most fundamental. Architects are space makers, and what is the point of space making if people can’t access the space? Being able to enter a space is one of the most basic rights that all individuals should have.

Exclusivity in space making is hierar chical, discriminatory, and ableist. Whether intentional or not, we are making spaces that prevent people from entering, understanding, and feeling welcome in our architecture. Not only are we neglecting our responsibility as architects to be the patrons of space making, but at the same time, we are holding ourselves back from wonders of design that result from an inclusive design meth odology and the opportunities those constraints present to us.

A. How to bridge virtual and physical space with AR and VR.

Why is this interesting to you?

There is a fundamental disconnect between the virtual and physical space. The average American spends over seven hours looking at a screen each day. We might not remember the wall’s texture around us, but we remember the website’s brand color. Can virtual or physical space extend to the other to eliminate the gap?

What does the physical space for VR users look like? How can the physical space and VR experience design facilitate each other? Take Harry Potter and the Forbidden Journey, a ride in Universal Studios, as an example. Players sit in a pod, and the machine carries them flying through all the scenes. The path players go through is the spatial sequences we often use in architec

ture design, while the screens play ing enhance the emotional value of the spatial experience.

AR is an interactive experience that overlays digital content in the physical world. For architecture, this digital content can be used as a new element to provide information in the form of graphics and text. Some similar use cases we have already seen are video walls, signatures, and environmental graphics. Imagine all of these become intractable and floating in the air; how will this change the space design?

It’s fascinating to think about what space will be like in the next generation, especially integrating with powerful VR and AR tech nology. If you are interested in get ting in touch and learning more, feel free to visit my website: www.joannehuangdesign.com.

Joanne Huang M.Arch/MSI ’24

16 FALL 2022 TAUBMAN COLLEGE

Q

A. The evolution of technology in a world of digital divide.

Why is this interesting to you?

Digital technologies are advancing at a rapid (and sometimes alarming) rate. Meanwhile, there remains a rift between those who have access to newer technology and those who do not. Being a student during the pan demic opened my eyes to how dam aging a digital divide can be. Some students had access to the infra structure and resources that made distance learning easier. Other stu dents — especially those who lived in underserved communities — had to deal with additional barriers such as unreliable internet connections and outdated technology. These bar riers resulted in increased learning gaps that will impact students for years to come.

A. Resilience in cities starts with individuals.

Why is this interesting to you?

One of the biggest buzzwords cur rently part of the urban planning vernacular is “resilience,” specifically in reference to cities. Resilience against climate change, public health challenges, and political shifts requires the response from cities to adapt and grow. However, the term “resilience” results in a more zoomedout approach as it focuses on an overall city. Perhaps it doesn’t quite encapsulate the importance of look ing directly at people who are being forced to adapt, change, and, hope fully, grow. Every challenge is differ ent, and it’s clear that, even though everyone is affected, the distribution is uneven.

My strongest interest and focus, as reflected by my various forms of involvement within my communities, has always vacillated to and from a

big-picture approach. However, it is a zoomed-in level focus on individual people that I keep coming back to. It is a lens I take with me with each project I participate in and one that I hope to continue to take with me in my career as I prepare to graduate and enter the field full-time.

I have had the opportunity this past summer to see individuals do this firsthand: first, working with the City of Detroit’s Census recount challenge, and then seeing the small but mighty staff at Community Development Advocates of Detroit work to bring folks together to strengthen their communities. I have had the chance to see them distrib ute necessary information about resources and organizations that could mutually benefit from one another. These actions require patience and persistence. They are possibly the hardest thing a person in this field can practice, and it has the potential to result in resilience.

Urban technology will undoubtedly affect our future as well. However, since it is a relatively new discipline, it is difficult to predict what the future of urban technology looks like. How will these innovations be applied to a digitally divided society? Can technology respond effectively to the educational challenges and other issues exacerbated by the digital divide? During the Urban Technology spring intensive earlier this year, we examined how technol ogy can be used to improve cities, thereby improving the lives of resi dents. Hopefully, we can help build technology and infrastructure that improves the lives of all residents, regardless of where they may live.

17

FACULTY & STUDENTS

Odiso Obiora

B.S.

in Urban Technology

’25

Maria Garcia Reyna M.U.R.P. ’23

A DAY IN THE LIFE: An In-Depth Exploration of Urban Centers

The two-month Cities Intensive helps students in the Bachelor of Science in Urban Technology program understand cities in depth through trips to Detroit and other important urban centers. Between field trips, they complete hands-on design workshops to experi ment with how they see, shape, and experience urban life.

18 FALL 2022 TAUBMAN COLLEGE

FACULTY AND STUDENTS

A DAY IN THE LIFE: Learning Mexico City through Its Built Environment

Yojairo Lomeli’s spring travel course took students to Mexico City, a metropolis that offers unique, timely lessons for architects and producers of cities rethinking the scope and responsibility of architecture, planning, and design. Students learned from community organizations, designers, and architects working to address the metropolis’s complicated relationship to water and the various scales of challenges it faces.

19

Global Lessons in Real Estate Development and Affordable Housing

By Julie Halpert

LAN DENG HAS SPENT her academic career examin ing how government interventions work in improving housing affordability. Now, she’s completed the first paper that examines the changes in China’s real estate develop ment industry since 2000 and what that means for local housing production. Deng, a professor of urban and regional planning and the associate director for the Lieberthal-Rogel Center for Chinese Studies, is a leading researcher focused on better understanding how China’s housing system has evolved to create obstacles to afford able housing.

Deng explains that gaining a deeper understanding of how housing is produced and the dynamics of the Chinese housing markets “can help us identify the right strategies to address the country’s housing challenges.” She said that the real estate industry in China has “grown tremendously in the last two decades,” from a small sector dominated by state-owned enterprises to a “trillion-dollar industry” pop ulated by a large number of private firms, with recent evi dence pointing to a growing concentration of development activities among the country’s largest real estate develop ment firms. Deng recently finished a paper, co-authored with two Taubman College students and a colleague in China, which examines the factors that have been driving those industry changes and what these changes mean for local housing production.

The paper, currently under peer review, is one of the first to study the organization of China’s real estate develop ment industry. “There has been very little scholarly

20 FALL 2022 TAUBMAN COLLEGE

Professor of Urban and Regional Planning Lan Deng encourages cities to learn from one another in order to find a more balanced approach to housing challenges

FACULTY AND STUDENTS

research on how the real estate development industry works,” she said. “I argue that we need to look into how the industry works because the structure and behavior of the industry have consequences.” When their paper is published, Deng hopes it can open a whole new area of research.

Deng’s research shows how the organization of China’s real estate development industry has been shaped by the country’s public landownership system, which squeezes developers’ profits and prompts them to expand across markets. Since companies are expanding far across the country, the formulation of market monopoly and manip ulation of local housing markets aren’t occurring. Yet as real estate development has become less of a local busi ness, Deng is curious about what this means for local communities. She points to an oversupply of housing in less developed regions.

“There has been a phenomenon of ghost towns in China, where projects were built and few people moved in,” she said. “I am worried that it could turn into blight” like what Detroit has experienced, she said. Deng has been researching the factors that led to affordable housing issues in Detroit since 2010. “I feel that my Detroit research helps me see those problems, the issues that China is also likely to encounter in the future.”

There are many shared challenges among countries. Deng thinks it’s important for them to learn from each other. Last summer, she helped organize a panel on shrinking cities — former industrial cities in both the U.S. and China that are losing population. She brought together scholars from the two countries to “have a direct conversation on this global phenomenon and share expe riences on what works and what does not in the govern ment responses to it.”

Working with a colleague from Tsinghua University, Deng has recently co-edited a special issue in the journal Housing Policy Debate that looks at the recent shifts in Chinese housing policies. By showing how China has sought to rebalance social equity with economic develop ment in its housing policy-making, Deng and her coeditor hope that this special issue can help elevate the debate on what governments can do to address the chal lenges of housing affordability and rising social inequality that have become pervasive among cities across the world.

Deng believes that increasing the supply of housing while curbing the speculative demand from an oversupply of capital will be critical to addressing the housing afford ability challenge in the U.S. Housing construction in the last decade has not kept pace with demand, she said. Add to that supply chain issues, restrictive land use regu lations, and the low interest-rate environment and “it’s a perfect storm. There are so many factors that contribute to this crisis.”

On the horizon, Deng wants to conduct research that directly compares the housing policies and markets of the U.S. versus China. Housing policymaking in the two countries has been heavily influenced by their ideological context, she said. In the U.S., the culture is to reject gov ernment intervention. Yet in China, there’s too much state control. “The two countries can learn from each other to figure out a more balanced approach to these housing and urban challenges,” she said.

21

There has been very little scholarly research on how the real estate development industry works. I argue that we need to look into how the industry works because the structure and behavior of the industry have consequences.”

— Lan Deng, professor of urban and regional planning

“

AI is Here, is Architecture Ready?

Associate Professor of Architecture Matias del Campo is ready for AI to change the way we build

By Julie Halpert

MATIAS DEL CAMPO MADE productive use of his time when COVID put some of his projects on hold, writing one of the first books on the use of artificial intelli gence in architecture. As an associate professor at Taubman College and founder of the Architecture and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory, launched in January 2021, he’s considered a pioneer in bringing AI to the practice of architecture.

AI is “changing the design processes. It’s going to very likely change how we build.” He explains that AI lets architects harness the power of data to enhance the way they design spaces. The vast amounts of information gathered through AI can help architects to improve the planning of spatial layouts as much as the structural properties and aesthetics of their designs.

His book Neural Architecture: Design and Artificial Intelligence (ORO Editions, 2022), features several exam ples of how to use AI in architecture and discusses the cultural, political, and economic implications that archi tects need to consider as they use these new methods. He also explores how to address the fundamental shifts that AI will create. For example, if AI-assisted robots are used on construction sites, what happens to those who currently work on those sites?

“There’s a huge political implication,” he said. “Do we introduce universal basic income,” so working on the construction site isn’t necessary? Or should it become a collaboration between humans and machines?

Another major issue posed by the use of AI is how much agency architects have over their projects and the impli cations for copyrights. AI holds the possibility of entirely shifting the traditional concept of top-down architecture design methods. He suggests that there’s merit in moving away from the idea of the “architect as the genius who makes a napkin sketch that magically transforms into a built project.” Architecture, del Campo says, doesn’t operate that way; it’s a collaborative process.

“Now the question is: Do we open up to the idea that AI becomes a collaborator rather than thinking of it just as a tool?” He believes architects should view AI as help ing to expand their creativity — harnessing the power of data to make better architecture. Though the ultimate decision will remain with the architect, the advantage of AI is that it will provide hundreds of variations of plans in minutes, giving the architect far more choices in a short time.

Del Campo hopes his book will be pathbreaking in pro viding information on the opportunities that AI provides. Many, he said, view it just as a basic technology tool for architects. But he points out that AI is pervasive in every day life, including the way that Amazon learns to recom mend books for you based on your previous purchases. This technology “is so global, in terms of how it infuses so many parts of our life,” he said. “It has become an inte gral part of how we design and how we make art and how we make music even without us noticing. It is deeply ingrained in our contemporary age.”

22 FALL 2022 TAUBMAN COLLEGE

FACULTY AND STUDENTS

This summer, del Campo began working on a project with the University of Michigan Robotics team to evalu ate the use of machine vision for demolition at construc tion sites to allow the easy separation of materials for reuse. Separating materials like glass and concrete is a time- and labor-intensive process, and training a robot to separate the material would be far more affordable. He sees this as particularly advantageous in reducing the amount of waste generated during the lifecycle of a build ing. Speeding up the process and reducing the cost could help ensure that AI-driven building recycling would be widely used, he said.

Del Campo continues to encounter long-held skepticism and widespread suspicion of the tool from fellow archi tects. He believes that’s motivated by the fear that machines will displace humans. “They’re afraid they’re going to be out of a job or become obsolete or that they’re too old to get up to speed with technology”— none of which del Campo feels is true. He hopes more architects embrace AI instead of pushing it away since it can be a huge asset to the field.

“It is a train in motion,” he said. “If we as architects do not engage with this paradigm shift, somebody else will do it for us, robbing architecture of the opportunity to shape the trajectory that this development will take — and thus the impact it will have for the discipline.”

23

[AI] has become an integral part of how we design and how we make art and how we make music even without us noticing. It is deeply ingrained in our contemporary age.”

— Matias del Campo, associate professor of architecture

“

24 FALL 2022 TAUBMAN COLLEGE

ON AIR: Faculty Work 2020–2022

From March to September 2022, more than 60 examples of inspiration and innovation, including research, professional practice projects, publications, and other creative works, were on display in an exhibition of Taubman College faculty work from the past two years. The exhibition was planned and curated by Professor and Associate Dean for Research and Creative Practice Kathy Velikov. It featured a playful new event infra structure of large inflatables and stands designed by Taubman College Architecture Fellows Adam Miller and Leah Wulfman, in coordination with Velikov and a team of Taubman College architecture students. The new infrastructure was conceived as a deconstructed bounce house that can be played with and rearranged to serve future events, symposia, and exhibitions at Taubman College.

25

26 FALL 2022 TAUBMAN COLLEGE

Robotically Fabricated Structure (RFS): Assistant Professor of Architecture Arash Adel, ADR Laboratory

Robotically Fabricated Structure (RFS) is a robotically fabricated timber pavilion that explores responsible and precise methods contributing to sustainable and lowcarbon construction outlooks. This structure is designed with the help of custom algorithms developed specifically for this project and built through state-of-the-art humanrobot collaborative construction. Situated in the Matthaei Botanical Gardens in Ann Arbor, Michigan, it is designed for public engagement, acting as a defined gathering point located within the framework of a public conservatory while still maintaining an open-air condition.

27 WORK SPOTLIGHT

“

Quotable Taubman College

“

The reason that urban design keeps coming back to the linear city is that it really does have a functional logic.”

One financial [factor] that many people fail to take into consideration in choosing where to live is the cost of their commute. We become compla cent about long drives when gas is cheap. Then when gas prices spike, we find we can no longer afford to drive long dis tances yet we have no alternative means to get to work and other daily needs. The housing may be more expensive in walkable neighborhoods or close to transit and employment centers, but if you factor in transportation costs it may be more affordable to live in neighborhoods where you are not dependent on your car.”

— Kit Krankel McCullough, lecturer in architecture, in WalletHub article “2022’s Best States to Live In”

“

— Robert Fishman, professor of architecture and urban and regional planning, in Fast Company article “What’s the Point of Saudi Arabia’s Giant Sideways Desert Skyscraper?”

“

In order for the beach to stay the same, it has to be able to change. It has to be able to move and shift and grow and decrease over time as lake levels go up and down as conditions change. That’s the paradox of beach dynamics.”

— Richard Norton, professor of urban and regional planning, in Yahoo News article “As Lake Michigan Shoreline Vanishes, Wisconsinites Fight Waves with Walls”

While it’s popular, and maybe even accurate, to claim that architecture is for everyone, such claims find less acceptance when it comes to cultural institutions. No matter their location, collections, and entry fees (if any), the cultural cen ters of the world are not welcoming to every person; not everyone is comfortable in these spaces.”

— Craig Wilkins, associate profes sor of architecture, in Arch Daily article “Breaking the Dead Paradigm for Design Exhibitions”

“

The safer states have implemented a bundle of policies that are ori ented toward controlling the motor vehicle, while the dangerous states are more oriented toward accom modating it. The difference between the two suggests that policies that encourage driving make the trans portation system more dangerous simply by exposing people to more travel.”

— Jonathan Levine, professor of urban and regional planning, in the Midland Daily News article “Michigan Named Eighth-Worst State to Drive In”

28 FALL 2022 TAUBMAN COLLEGE

“

“

Gradient Journal

GRADIENT IS AN ONLINE PLATFORM for archi tecture and urbanism from the University of Michigan Taubman College. Organized in “feeds” rather than “issues,” the journal aspires to lean in to the potentials of digital media formats, elevating nascent disciplinary conversations at Taubman College and beyond. Feeds might be semi-defined topics, compelling misfits, or fragments of latent conversations: dim when first launched, but clarified over time. Each feed will remain active after its launch, welcoming responses and sub missions in any format — image, video, text, and more. Conversations will stay active until they resolve them selves, lose relevance, or just fade away into the endless digital ether — the Gradient. Gradient Feed #2: Inflections is a series of contributions on topics pertain ing to the role that technology plays in relation to how we conceive, build, experience, and teach architecture.

“

You can’t be a lone genius. That’s actually impossible. I think there’s something nice about being able to just escape that trap of thinking about any of us working in isolation, because it’s always been fiction.”

The 2019 hearings for the Right to Repair movement demonstrate how corporate exclusionary practices have a monopolistic agenda and, far from protecting the consumer, instead disrupt a pluralistic economy.”

“

Rocking Cradle: Interactive Urban Furniture for Environmental Attunement,” a vessel that acts as nursery planter for nascent seedlings, teeter-totter that provokes play, and mechanism for promoting stewardship between a community and its urban biome.

“

I think that ‘prototyping’ is a tricky word for me. I’d like to use the word ‘shaping.’ Because shaping refers not just to producing shapes, but also to producing impacts, having a relationship with things, having imprints toward matter and non physical things, having shaped one’s life and thecommunity around you.”

— DANA CUPKOVA , “Material Excerpts: A Conversation”

Read the latest Gradient feed: taubmancollege.umich.edu/ gradient-journal

29

Block West, AUAR Labs, 2020.

The IM_RU Pavilion addresses the relationship between architecture and public space, where an individual is simultaneously confronted with a multiplicity of individual and collective perceptions.

— JOSE SANCHEZ, “The Politics of Tectonics”

— SHELBY DOYLE, “Authorial Asymmetries: Computational Feminism, Access, and Cooperation in Digital Knowledge Creation”

30 FALL 2022 TAUBMAN COLLEGE

HELP US BUILD TOMORROW

“I went to a small high school and a small undergraduate program so I was eager to go to a larger school. When I’m designing things, I feel like my creativity is height ened when I’m surrounded by more voices,” says Iman Messado, M.Arch ’23. After studying economics and art as an undergraduate, she decided architecture was the ideal way to combine her artistic skills with interests like infrastructure development in West Africa and colo nialism and its latent effects. “I like the way art engages the average person to take more agency in crafting their built environment,” she explains.

Messado has found Taubman College welcoming and supportive. “I’d heard warnings about some schools’ studio culture, competition, and harsh criticism, but my time at Taubman has been full of patience and compas sion. And I don’t feel like I’ve sacrificed any skill or com petence. I’m intellectually challenged but not hurting myself to get there.”

As a mentor to high school students through the Equity in Architectural Education Consortium (EAEC), she’s helping the next generation succeed as well. She says, “I would have appreciated a mentor like me, and it was fun to interact with the students and see their perspec tive since they were new to architecture and design.”

As a Taubman scholar and the inaugural Cass A. Radecki and Cynthia Enzer Radecki Scholarship recipient, Messado has a solid foundation to pursue her studies. “The scholarships helped affirm my place here. They let me know people were looking out for me and were want ing me to succeed,” she says.

A gift to Taubman College supports the next generation of leaders in architecture and planning — including Iman.

taubmancollege.umich.edu/give

31

Ensuring a More Equitable Future for Architecture

Architecture Scholarship Fund

RANDY HOWDER HAS SPENT a great deal of time thinking about where people feel comfortable. He’s managing director and principal at Gensler’s San Francisco office, and, since the pandemic, he’s been considering what draws people back into public spaces after spending so much time at home.

“You go for the sensory excitement of the smells, the lighting, the din of the crowd, and getting out of your pajamas. You want to be around other people. I think the workplace is going through that same experience; people are gravitating to high-quality environments where they feel better having been there than if they hadn’t been there,” he says.

The San Francisco Gensler office has been strategic about finding new ways to facilitate in-person collaboration. Howder says, “Architecture is sometimes mythologized as this individual genius who comes up with these brilliant ideas, but in reality, it is a social activity designing a building or a space, anything that involves a lot of collab oration with colleagues. Every person on the team has something different to add.”

Returning to the office doesn’t mean a return to the status quo. Howder believes considering factors like the neuro and physical diversity of employees and making work accessible to employees from diverse locations, back grounds, and circumstances when balancing collaborative and individual work time is paramount. “I think architec ture is becoming a more sensitive profession, a more diverse profession. Remote work and having distributed teams helps us bring and keep more diverse participants in the profession,” he explains.

He sees Taubman College embracing and advancing the inclusiveness of the profession as well. “The college has really pushed forward diversity in a profession that has historically not been diverse in terms of gender, ethnicity, race, sexual orientation, all of the above. There’s definitely

been a shift from when I was at the college. I think stu dents being a part of that kind of diversity is making their work more interesting. They’re more aware and sensitive to some of the challenges facing the world, and it’s show ing up in their work, which is exciting.”

Howder and his husband, Neal Conatser, a successful Bay Area real estate agent, want to ensure that as many students as possible have the opportunity to experience the high-quality education they benefited from with the added diversity of thought Taubman College students are a part of today. In 2021, they established the HowderConatser Architecture Scholarship Fund at Taubman College as one way to make sure more people find their place in architecture. Now they’re reaffirming that com mitment with a pledge of $2.75 million through their estate to support Taubman College undergraduate architecture students, focusing on those with financial need and those who are the first in their families to go to college.

While Howder’s parents both went to college, Conatser was the first in his family to pursue higher education. Howder says what they shared is “the good fortune of being in these robust institutions that gave us a new per spective on the world and helped us see the world through others’ eyes.” Both see education as an answer to some of the world’s difficult challenges, like addressing climate change or transitioning to a more equitable economy.

“Income inequality is what’s driving a lot of political and social challenges in this country. I think it takes a college education to be really successful. It’s like table stakes now if you want to become part of the middle class or beyond. Someone who may not have the financial means to come to a world-class university like Michigan, if we can help however many people it is through the life of this scholar ship, that’s a small part we can play in helping the world, this country, and the state of Michigan be a better place,” Howder says.

32 FALL 2022 TAUBMAN COLLEGE

ALUMNI GIVING

Randy Howder, B.S. Arch ’99, and his husband, Neal Conatser, are supporting the next generation of architects and critical thinkers with their $2.75 million pledge to the Howder-Conatser

As an Alumni Council member, he has seen that Taubman College students are aware of and ready to tackle the world’s challenges. “They really value trying to solve some of these systemic issues that architecture, in particular, has often avoided because, historically, our clients are wealthy. Often people think don’t think architecture can affect those systemic issues, but it’s such a fundamental part of shaping society that it really does. Architecture communicates values.”

The tenacity and social consciousness of Taubman College students is one reason Howder and Conatser established their scholarship fund. “The experience at Taubman, no matter what your career track is, teaches that ability to learn how to follow a concept through to completion and then explain that clearly to others and bring them along; that’s the key to making the world a better place as far as we’re concerned,” says Howder.

He adds that he and his husband are thinking about the long term with their planned gift to Taubman College. “Our legacy, rather than being direct descendants, will be all of these architects and designers. Even if they’re not architects, they’ll be folks who can think critically and make progress on sticky issues and make the world a better place.”

He also hopes alumni realize gifts and support of all types and sizes make an impact on Taubman College students. “Giving back doesn’t always have to come as a large monetary amount. It can be volunteer time that helps graduating students find a job, being a guest critic at a studio, opening your office to students during spring break. No gift is too small. Give what you can when you can but stay connected to the college. Increasing the cohesiveness of the alumni network makes us all more valuable to the outside world and the profession.”

— Liz G. Fisher

33

Someone who may not have the financial means to come to a worldclass university like Michigan, if we can help however many people it is through the life of this scholarship, that’s a small part we can play in helping the world, this country, and the state of Michigan be a better place.”

— Randy Howder, B.S. Arch ’99

“

GIVING: KARTIK DESAI, B.S. ARCH ’99 Not the Only Player: Future-Focused Collaboration

KARTIK DESAI DOESN’T WANT to work in a silo.

“When you’re in architecture school, you’re very aware of the magic of creating and designing buildings. What you only have an inkling of is that you’re not the only player. There are owners, clients, engineers, and everyone else. I realized I was also interested in some of the other aspects of what makes a building a building,” says Desai.

When Desai founded D&A Companies in 2018, it was an opportunity to do a hybrid of real estate development and architectural design while leveraging the talent, skills, and cohesion of his longtime team of colleagues and friends.

“It’s incredibly rewarding to have written the recipe, baked it, and then served it up,” says Desai, who is a firm believer that understanding both real estate and architecture leads to a better built environment.

“What we aim to do is create places where people want to live, want to be, and want to work. We’re making places for people. It’s not just designing for design’s sake. To envision it, then to see it gradually come to reality over a number of years, and then to see people occupy it. There

are all these different thrills along the way. Of course, it’s interspersed with all the stresses, trials, and tribulations of getting a project done. But we get to conceive it, have a strong hand in designing it, and have a strong hand in actually executing it.”

Two such projects share a campus in Birmingham, Alabama. 2222 Arlington is the redevelopment of a modernist landmark into a class A office building. The Tramont is a luxury residential project — the city’s first concierge residence of its kind — with skyline views, a pool terrace, and a wellness facility.

Another project, Fall Park, is a mixed-use community in Gardiner, New York. A variety of houses and apartments, along with commercial, recreational, and agritourism facilities form clusters spread out over 100 acres to pre serve most of the picturesque Hudson Valley property. “It’s not often the right ingredients come together to build something special at this scale,” says Desai. “We love working with communities that believe in placemaking and investors who believe in the value of good design.”

Desai says his Taubman College education plays a role in what he’s doing today, “Taubman is where I learned how to design buildings. I learned an approach that’s very rigorous, thoughtful, and disciplined. They made me into the designer that I am still.”

Having found his success, Desai wants to help current and future Taubman College students do the same. He gives to Taubman College not just because of how the college shaped him but because of how Taubman College is growing now.

“I am really proud of Taubman for not just pioneering things like the urban technology program, but also colla borating across campus with the business school and Weiser Center to build a truly interdisciplinary real estate curriculum,” he says. “I want to do what I can, not just to help Taubman and to encourage young architects to take more of an interest in real estate development, but also to encourage business and real estate students to be more design literate. I want to foster that inter disciplinary model.” — Liz G. Fisher

34 FALL 2022 TAUBMAN COLLEGE

ALUMNI GIVING

Leave a Lasting Legacy

Including Taubman College in your estate or financial plans is one of the easiest ways to make a lasting impact. You can even generate income for yourself and your family while benefiting the college and generations of students. Types of planned gifts include gifts from a will or trust, beneficiary designations, and property.

Making a planned gift is a rewarding way to support your alma mater. Contact the Taubman College advancement team at taubmancollegeadvancement@umich.edu or 734.764.4720 to learn more about establishing a planned gift for Taubman College or to let us know if you already have included the college in your will or estate plans.

DEFERRED GIVING OPTIONS

GIFT TYPE BASIC DESCRIPTION

BEQUEST Transfer property (including cash, securities, or tangible property) through a will or trust. A bequest can be a specific dollar amount or a designated percentage of your estate.

• Legacy

Simple and flexible

HOW IT WORKS

BENEFICIARY OF RETIREMENT ACCOUNT(S)/ LIFE INSURANCE POLICY

Name Taubman College as a beneficiary of your retirement account(s) or life insurance policy.

• Legacy

• Simple and flexible

• Tax savings

CHARITABLE REMAINDER TRUST (CRT)

A life income gift that benefits you and Taubman College. You choose the fixed percentage rate of return and transfer cash, an appreciated asset, or other property to a trust that the university manages to generate payments to you.

Payout amount fluctuates based on market value of investment. Upon the passing of income beneficiaries, the balance comes to Taubman College.

Legacy

Tax savings

Lifetime income to donor

Variable payments

Irrevocable

CHARITABLE GIFT ANNUITY (CGA)

A life income gift that benefits you and Taubman College. Based on your age at the time of the gift, the university sets a fixed percentage rate of return. The university then invests your gift and makes fixed payments to you. Upon the passing of income beneficiaries, the balance comes to Taubman College.

Tax savings

Lifetime income to

Fixed payments

Irrevocable

35

BENEFITS

•

•

•

•

•

•

• Legacy •

•

donor •

•

DONOR DONOR DONOR DONOR HEIRS DONOR DONOR HEIRS Donor receives payments for life Donor receives payments for life Will $$$ $$$ receives remainder receives remainder RETIREMENT ACCOUNT(S)/LIFE INSURANCE POLICY ESTATE Fixed $ or Fixed % TRUST ANNUITY

GIVING: BRIAN ADELSTEIN, B.S. ARCH ’89

Laying the Foundation for a New Generation of Change Makers

DURING A RECENT TRIP TO Ann Arbor for his work on the Taubman College alumni council, Brian Adelstein was on a run through campus which ended up on the hill near Mary Markley Hall. He reflected on his time flipping burgers in the snack bar there as an undergraduate when he worked 30 hours a week to help pay for school.

Twenty-three years later, he’s still there, now leading a team of transaction managers in the completion of acquisitions and dispositions for a global financial services client. He’s invigorated by real estate, currently reaching a fever pace after some slower years due to the pandemic. And he’s happy to see Taubman College is now offering a real estate development minor and graduate certificate.

“I was energized to see an avenue within the school for people to test the waters in real estate and start really understanding what the industry can offer to them. I’ve been in that industry for 23 years, and every day I use something I learned at Taubman,” he says.

Now, with a successful career and his children in their teenage years, he’s in the position to give back to students who, just as he did, know that Taubman College is the best place for them.

“We can we do something for students like me who need financial help to go through this program,” he says. “It’s one of those things that you don’t really understand if you’ve never tried to go through college and wonder where the money is going to come from — what am I going to do to make sure I can afford that next semester or the supplies I need to complete a project?”

“I’m from Ohio. I could have gone to Ohio State or another state school and not have had to worry about money. But, in my mind, there was something important about going to a school like Michigan,” he says. “To be able to say, ‘I’m an alum of the University of Michigan. I’m an alum of Taubman College.’ It’s a badge of honor, and it says something about me to people with whom I’m having conversations or people who are considering me for jobs.”

It was a Taubman College classmate who recruited him to real estate company Cushman & Wakefield in 1999.

In addition to the Alumni Council’s fundraising work, Adelstein relishes the opportunity to engage with stu dents directly. Something struck him about the Taubman College students he spoke with.