hamiinat

As the President of the Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians, I extend my heartfelt gratitude to each of you for taking the time to read our magazine. Though our administration is small, we are indeed mighty, and your interest and engagement mean the world to us.

Through our publication, we aim to share not only our rich history and vibrant stories but also the cultural essence and the challenges and triumphs we experience as a community. The recognition of our Tribe is one of the oldest social justice issues in Los Angeles County, and all too often, we remain invisible.

With this magazine, we hope to shine a light on our existence and experiences, increasing our visibility for the next seven generations. Thank you for joining us on this journey. Together, we can ensure that our voices are heard and our stories are told.

A Native Sovereign Nation of Northern Los Angeles County with ties to Mission San Fernando and descent from the Simi, Santa Clarita, San Fernando, and Antelope Valleys.

All About Tarahát

published since 1990

Tarahát (The People) is a bi-annual publication that celebrates the stories, news, and culture of the Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians. With limited print distribution and a digital presence, Tarahát serves as a vital platform for connecting the Tribe’s citizens and sharing their rich history with a broader audience.

tarahát magazine

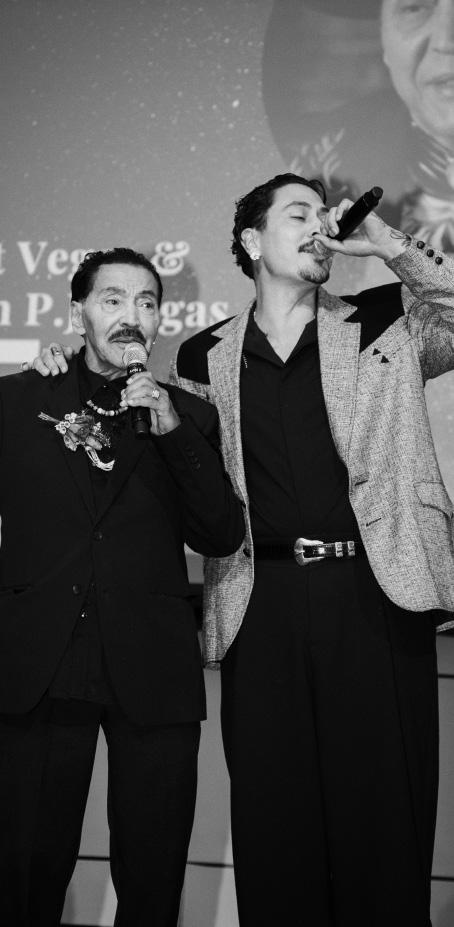

Rudy J. Ortega, Jr., L.H.D. Kimia Fatehi

HEAR ME BULLROAR: THE ART OF FERNANDEÑO WHISTLES

EXTRA- OARDINARY ACTS OF RESILIENCE: INSIDE FERNANDEÑO OAR-MAKING WORKSHOPS

tribal government

Rudy J. Ortega, Jr., L.H.D. President

Mark Villaseñor Vice President

Lucia Alfaro

Secretary

Elisa Ornelas Treasurer

Mary Acuña Senator

Jesus Alvarez Senator

Joe Bodle Senator

Crystal Crowe Senator

Stephanie Manriquez Senator

Cheryl Martin-Perez Senator

Jorge Salazar

Senator

tribal entities

pukúu cultural community services

Samantha Ortega Chair

R. Tolteka Cuauhtin

Nahua Xicanx, Vice Chair

Lauren Van Schilfgaarde Cochiti Pueblo, Secretary

Leon Worden Treasurer

Mary Acuña Fernandeño Tataviam

Cathy Salas Fernandeño Tataviam

Matthew Vasquez Fernandeño Tataviam

tataviam land conservancy

Jesus Alvarez Fernandeño Tataviam President

Lucia Alfaro Fernandeño Tataviam Vice President

Sarah Brewer Thompson Secretary

Katherine Pease

Alan Salazar Fernandeño Tataviam

Kevin Nuñez Gabrieleño Xaapchivit

tïuvac’a’ai tribal conservation corps

Miguel Luna Chair

Rudy J. Ortega, Jr. L.H.D Fernandeño Tataviam, Vice Chair

Julia Samaniego Fernandeño Tataviam

Bruce Saito native first lending

Severyn Aszkenazy

Ken Molina Fernandeño Tataviam, Elisa Ornelas Fernandeño Tataviam

Shawn Imitates Dog Oglala Lakota

paséki strategies corp

Rudy J. Ortega, Jr. L.H.D President

Mark Villaseñor Vice President

Elisa Ornelas Fernandeño Tataviam, Treasurer

Nicole Raphaely, J.D. Secretary

Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians

Time Immemorial Creation

Long before any settlers came to California, the Native Americans who became known as Fernandeño lived in their homeland of what is now known as Los Angeles County. They have been here since the beginning of time, before written history. The ancestors were taught by Creator how to live in harmony with the land, the animals, and the seasons.

Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians

SPANISH GOVERNMENT

The establishment of Mission San Fernando imposed a brutal regime of enslavement on the Native people who would come to be known as the Fernandeños. The Mission system brought profound disruption and devastation: families were separated, children were forcibly married, and sacred sites were desecrated. The Tribe’s rich cultural practices were systematically suppressed, and traditional lifeways—carefully honed over generations—were dismantled. The ecological balance of the land was further disturbed by invasive species introduced by settlers, leading to the depletion of vital food sources.

Under the authority of the Mission Padres, daily life was tightly controlled. Fernandeños required explicit permission to leave the Mission grounds and were subject to corporal punishment for dis-

obedience. Diseases, malnutrition, forced labor, and violence claimed countless lives. Yet, despite these oppressive and often fatal conditions, the Fernandeño Tataviam people endured.

Survival demanded both resistance and adaptation. Some community members preserved cultural traditions in secrecy, passing down knowledge and ceremony under threat of punishment. Others protected their families by concealing their Native identity, navigating a colonial system designed to erase them. The persistence of the Fernandeños through these genocidal policies is a testament to their resilience, strength, and unwavering commitment to their heritage.

acres held by the Tribe

M

1797 Mission San Fernando Rey de España is founded in Mission Hills, California.

1797

- 1820

1813 Misson San Fernando report that the Fernandeños still practice their culture and religion.

Spanish Period

Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians

18,000

MEXICAN GOVERNMENT

In 1821, Mexico gained independence from Spain, ushering in a new era of governance in California. With the secularization of the missions, a pivotal, yet precarious, opportunity arose for the Fernandeños. Approximately 50 surviving Tribal leaders stepped forward during this transitional moment, asserting their rights and negotiating land grants intended to secure a future for their families and descendants. In doing so, they reclaimed over 18,000 acres—roughly 10% of the San Fernando Valley—held in trust by the Mexican government. These land grants, which includ-

ed Rancho El Escorpión (Chatsworth), Rancho Encino (Encino), Rancho Cahuenga (Burbank), and Rancho Tujunga (Tujunga), were more than legal documents. They represented a bold assertion of sovereignty and a tangible effort by the Tribe to reestablish cultural continuity on their ancestral lands. The Fernandeños viewed this land not merely as property, but as a foundation for community resilience, spiritual renewal, and self-determination.

However, the shift in governance from Mexico to the United States would soon threaten these hard-

won gains. Maintaining legal ownership under new laws and colonial systems proved to be an ongoing battle—one that would define the Tribe’s struggle for recognition throughout the American period and beyond. Yet, the determination and foresight of Fernandeño leaders during this time laid the foundation for an enduring legacy: a continued fight for justice, cultural survival, and the restoration of what was taken.

acres held by the Tribe

1834 The Mexican republic’s secularization of the missions gave Fernandeños the right to organize village governments and petition for land.

Mexican Period

1846

1843

Over 50 Fernandeño families petition the Mexican governor for land, and in turn, receive over 18,000 acres of the San Fernando Valley by 1845.

1821 - 1847

After June 1846, San Fernando Mission ended Native enslavement and became Rancho Ex-Mission San Fernando, a farming and grazing site.

Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians

American GOVERNMENT

Throughout the 19th century, the United States advanced policies aimed at the erasure of Native nations, often through violent and systemic means. In California, this period was marked by state- and federally sanctioned acts of genocide targeting Native peoples. Within this hostile climate, the Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians—excluded from U.S. citizenship—fought tirelessly to defend their land in state courts, despite the overwhelming odds.

The passage of the 1851 Land Claims Act further imperiled their efforts. Under this law, any land not formally claimed within a two-year window

was transferred to the public domain. For the Fernandeños, many of whom were not literate in English and unfamiliar with the foreign legal systems imposed upon them, this law was catastrophic. The 18,000 acres of land attained under the Mexican government, rich in natural water sources andlong stewarded by Native families, became prime targets for settler encroachment and theft.

Though some Fernandeños pursued justice in court, including in cases such as Porter et al. v. Cota et al., the legal system consistently failed to recognize their claims. Courts routinely dismissed their

acres held by the Tribe

rights to land that, if protected, could have formed the basis for a reservation. By 1900, the Tribe had been entirely dispossessed, its citizens made refugees within their own ancestral homelands.

Despite this, Fernandeño leadership persisted. Tribal representatives sought legal aid, and advocates such as Assistant United States Attorney G. Wiley Wells and Special Indian Agent Frank D. Lewis made efforts to secure land for the displaced Tribe. Yet, despite their involvement, the federal government never granted the Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians the recognition afforded to other tribes— an enduring barrier in their fight for land and justice.

Today, over 900 descendants of the historic Fernandeño Indian Tribe survive through three core lineages: Ortega, Garcia, and Ortiz. These lineages remain rooted in Tataveaveat, the ancestral homeland that holds not only geographical significance, but a spiritual and cultural foundation that stretches back thousands of years. The land is remembered not simply as territory, but as a living archive of memory, language, and lifeways. Through continued stewardship and resistance, the Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians reaffirms its enduring connection to place, heritage, and identity, despite centuries of displacement and denial.

acres held by the Tribe

Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians

1848 The 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo promised land rights to Mission Indians, but the governor sold mission lands despite the Fernandeño having land grants.

1848 - TODAY

1892 Frank D. Lewis, Special Assistant U.S. Attorney, recognized the San Fernando Mission Indian community and advocated for the Fernandeños until 1897.

1876 On June 1, 1876, ex-Senator Maclay and Porter sued Fernandeños, including ancestor Antonio Maria Ortega, for occupying their homelands in the San Fernando Valley.

1886 U.S. Special Attorney

Guilford Wells represented Fernandeño captain Rogerio Rocha to stop eviction, but his 1885 petition was denied in court.

www.tataviam-nsn.us

1971 Late Tribal President Rudy Ortega Sr. formally requested land return from the U.S. government.

1995 - TODAY FTBMI submitted a petition for U.S. federal recognition, a process still ongoing today.

1980 The Fernandeños changed their government name from the San Fernando Band of Mission Indians to the Fernandeño Band. They would adopt “tataviam” in 2000.

American Period

Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians

Tribal

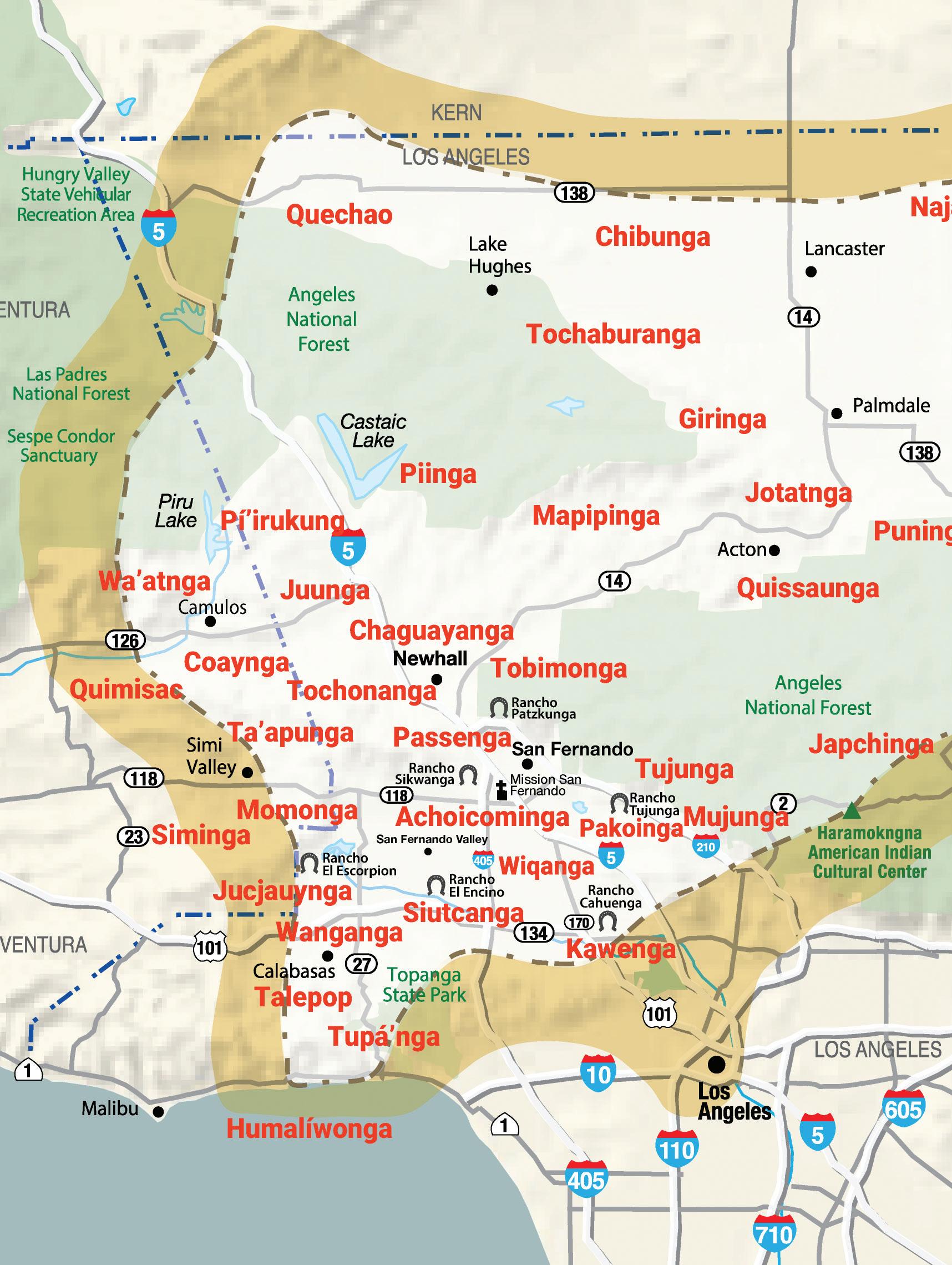

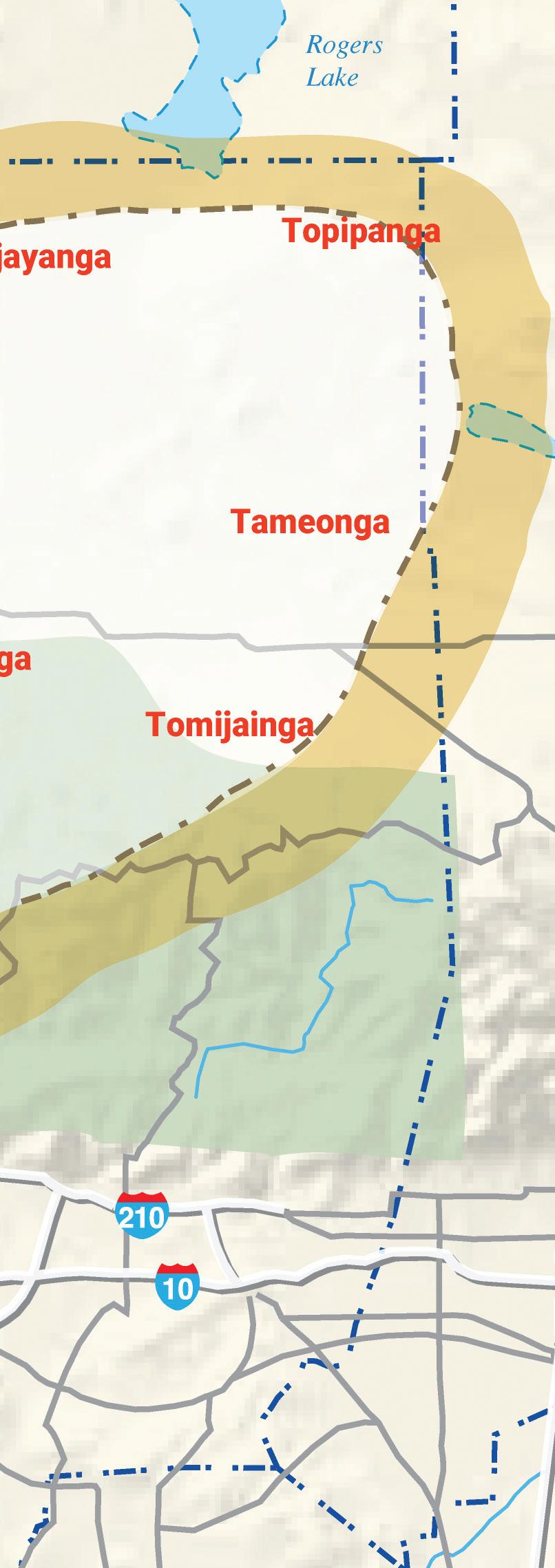

TERRITORY

The Official Tribal Boundary delineates the area of enslavement associated with Mission San Fernando, commencing in the year 1797. This boundary encompasses the villages situated within the four distinct ethno-linguistic valleys from which registered Tribal Citizens derive their ancestry.

Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians

Feature:

Preserving Fernandeño Heritage with David Casarez

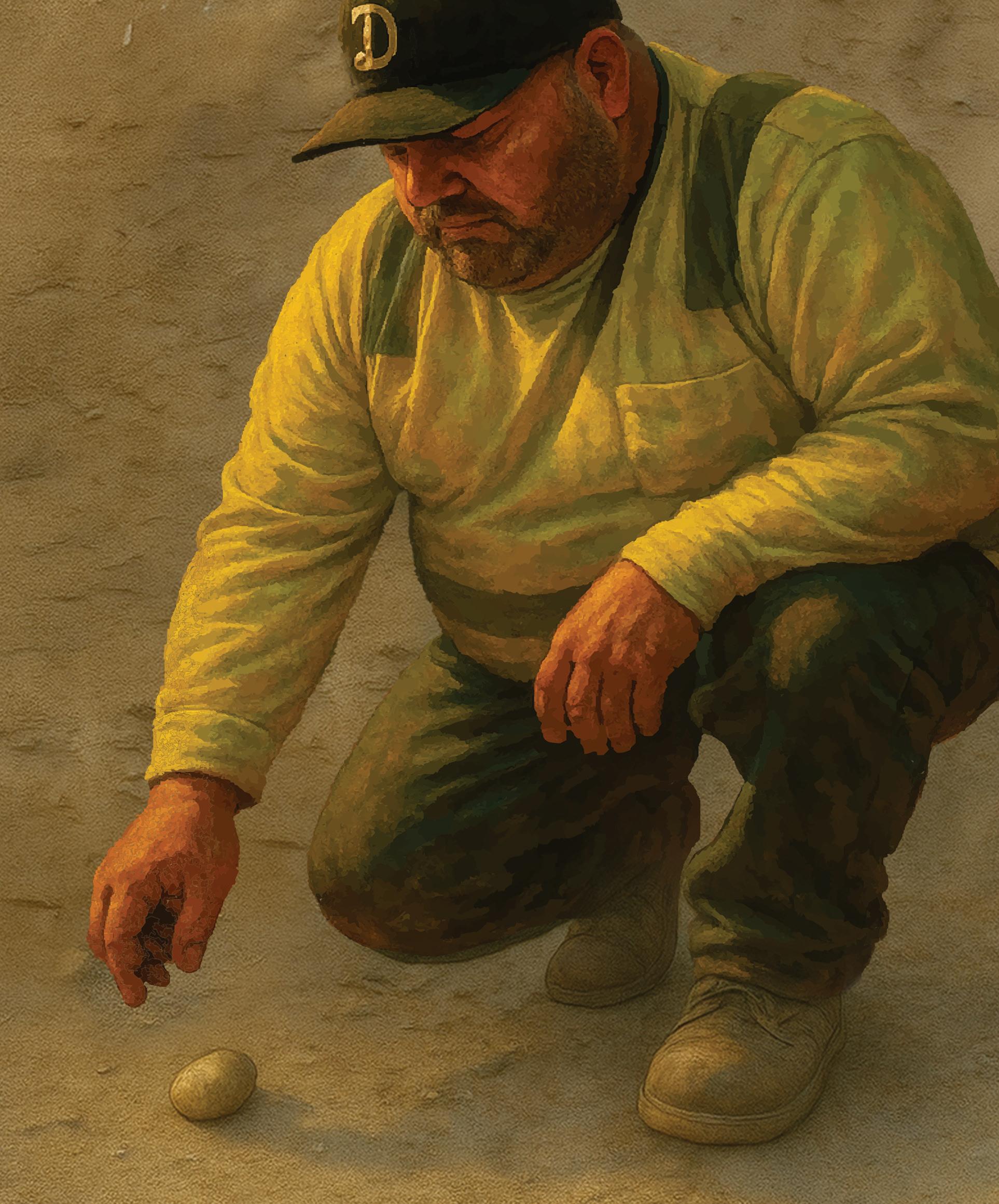

Before the morning traffic clogs the streets of Los Angeles County, David Casarez is already at work: boots in the soil, eyes scanning the ground for traces of his heritage.

As the Tribal Monitor Manager for the Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians, David doesn’t just oversee construction sites. He walks the same ancestral trails his people once traveled, searching for signs that the past still speaks beneath the surface.

each project’s potential impact on ancestral land. These consultations shape the protective measures put in place and determine whether monitors like David will be present on-site.

“Our parents did this labor for free. Now, it’s finally recognized as a profession.”

“It’s like walking the same path they stepped on,” he says. “Sometimes you’re in a ravine in the middle of a valley, and you just know they passed through. There’s evidence we findscrapers, ochre, flakes. They tell you: they were here.”

Tribal Monitoring: The Profession

For over a decade, David has led a team of Tribal Monitors across the Tribe’s ancestral homelands in northern Los Angeles County. His mission: to protect Tribal Cultural Resources from being lost to bulldozers or buried under new developments. These resources aren’t just artifacts - they’re pieces of living history. A single bead, a tool, even the view from a site can hold immense cultural significance.

But the work begins long before a monitor steps into the field. Through confidential, government-to-government consultations with city, county, and state agencies, the Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians assesses

“We’re the last line of defense,” David says. “We’re not preventing harm before it happens because we recognize that we can’t stop all development projects. We’re field operations for the Tribe’s Cultural Resources Management Division. He ensures every monitor is trained in both construction site safety and cultural protocol. It’s a role that demands vigilance, heart, and humility.

The work comes with risks- both physical and emotional. “Safety’s a huge challenge,” he says. “You never know if you can trust someone on a site. Once, a street collapsed right in front of us.”

Wildfires, unstable terrain, and extreme weather are constant threats. But so is skepticism.

“Sometimes people don’t believe in what we’re doing,” David explains. “But after four or five days, they come around. They start asking questions. I never shame them. I figure they’ve put their guard down. That’s when the learning starts.”

David doesn’t just lead, he teaches. He’s trained dozens of new monitors over the years.“I’ve taught 15 new monitors for our Tribe at once before. It was crazy. But even now, I’m still learning. You don’t know everything just because you’ve been doing it a while.”

Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians

One of his proudest moments came when he identified a seemingly ordinary stone as something far more critical.“They thought it was just a broken rock. But I saw it was a scrapersharp on one side, probably used for skinning. Stuff like that gives me chills.”

Another time, he unearthed a fragmented shell bead, stained with ochre, near a stream. “It didn’t have our cultural patterns. That tells you someone else passed through, someone from another tribe who traded with us. It reminds us that the land is alive with stories.”

A Legacy Passed Down

David’s path to this work wasn’t straightforward, but it was always rooted in family. His greatgrandmother, Mary Cooke Garcia, born in 1901, was a descendant of villages in the San Fernando, Santa Clarita, and Antelope Valleys. She passed her cultural pride to her granddaughter, Geraldine Lee Perez, who passed it on to David.

Growing up in the San Fernando Valley, he felt the pull of heritage, even if others didn’t recognize it.“In school, the kids would make fun of me because I didn’t ‘look’ Indian or Mexican,” he recalls. “Years later, when they found out I worked for the Tribe, they were

shocked. I said, ‘I told you! You just didn’t believe me.’”

He laughs, then adds, “School wasn’t for me. I took algebra four years in a row. I was done with it.” His turning point came during a chance conversation at the Tribal office.

“One time, you [Kimia F.] had me in the office, and we were looking at two different types of stone. You asked me if I’d be interested in a profession where I could do this for a living. Then my first job was near the village of Kawenga. I thought, ‘What an opportunity.’ It blended everything I love: being outdoors, working with my hands, and connecting with my heritage.”

The Work And Its Weight

Now, as Tribal Monitor Manager, David oversees all field operations for the Tribe’s Cultural Resources Management Division. He ensures

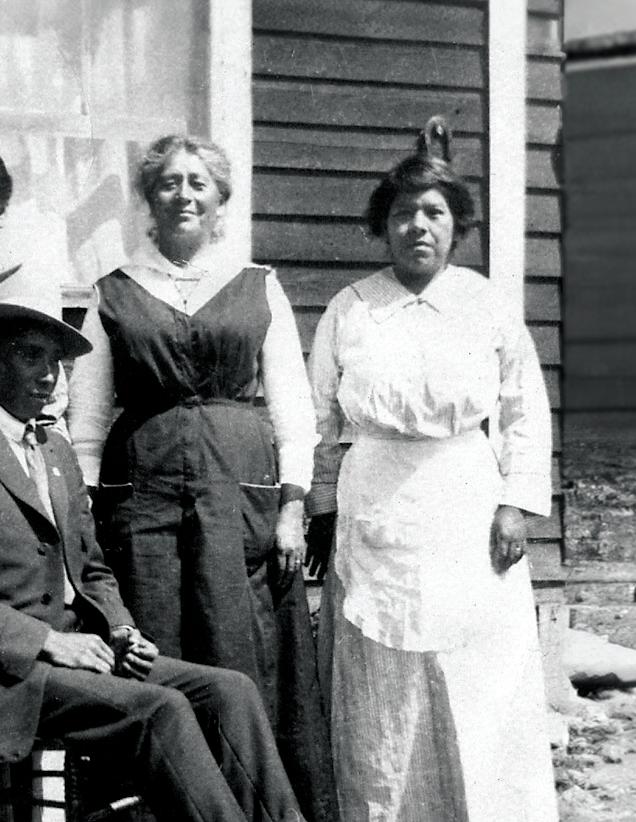

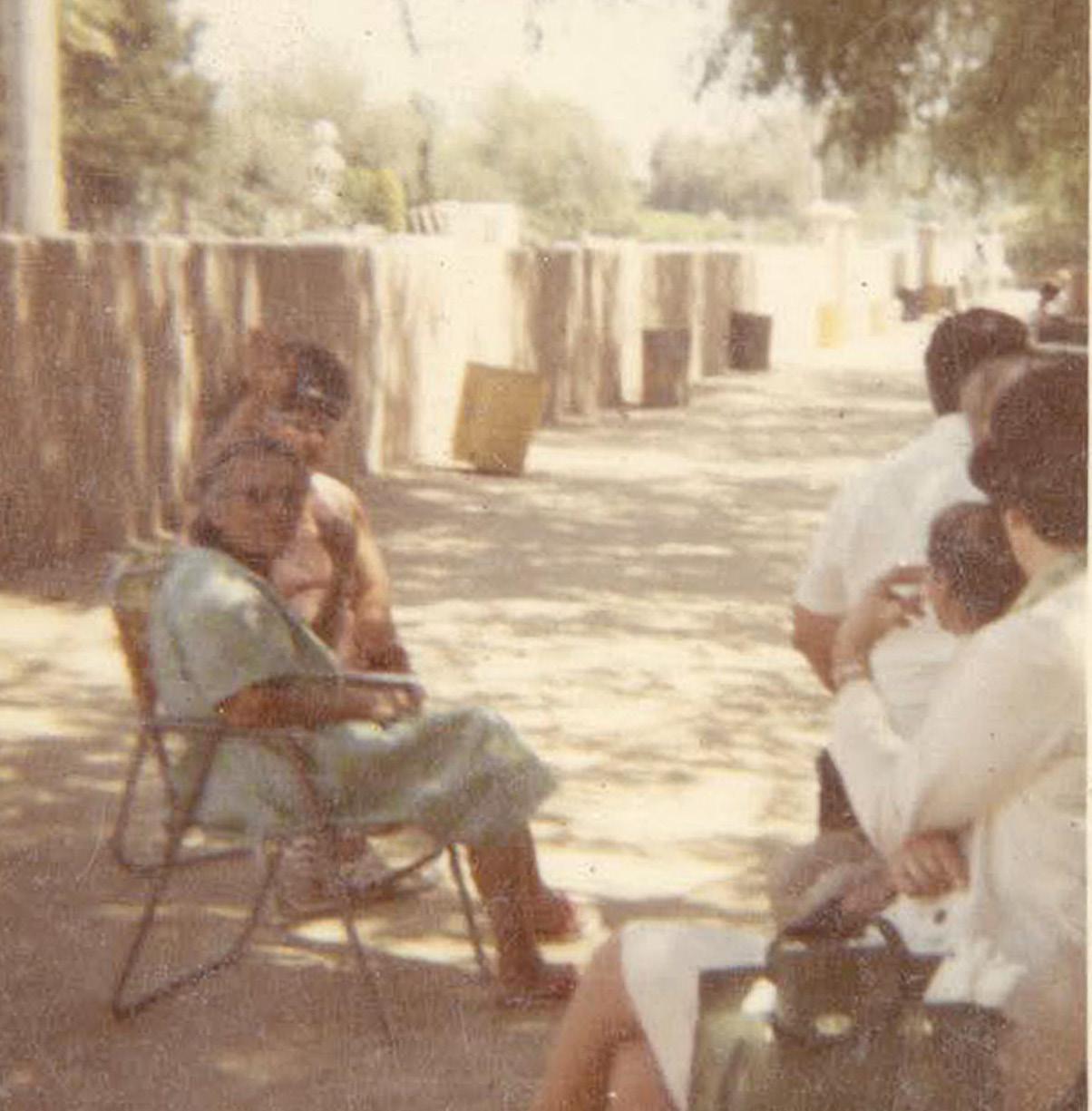

A MATERNAL LEGACY

A 1973 photo (bottom left) shows Mary Cooke Garcia (Dec. 12, 1901 – May 29, 1975), a revered Tribal headperson, with her granddaughter, the late Geraldine Lee Romero and great-grandson David Casarez Jr.

Portrait (bottom right) of David’s great grandmother, Mary Cooke Garcia, of the Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians.

“Sometimes

people on construction sites don’t believe in what we’re doing...But after four or five days, they come around. They start asking questions. I never shame them. I figure they’ve put their guard down. That’s when the learning starts.”

FTBMI Citizen David Casarez, Jr.

Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians

every monitor is trained in both construction site safety and cultural protocol. It’s a role that demands vigilance, heart, and humility.

The work comes with risks- both physical and emotional. “Safety’s a huge challenge,” he says. “You never know if you can trust someone on a site. Once, a street collapsed right in front of us.”

Wildfires, unstable terrain, and extreme weather are constant threats. But so is skepticism. “Sometimes people on construction sites don’t believe in what we’re doing,” David explains. “But after four or five days, they come around. They start asking questions. I never shame them. I figure they’ve put their guard down. That’s when the learning starts.”

David doesn’t just lead, he teaches. He’s trained dozens of new monitors over the years. “I’ve taught 15 new monitors for our Tribe at once before. It was crazy. But even now, I’m still learning. You don’t know everything just because you’ve been doing it a while.”

One of his proudest moments came when he identified a seemingly ordinary stone as something far more critical. “They thought it was just a broken rock. But I saw it was a scraper- sharp on one side, probably used for skinning. Stuff like that gives me chills.”

Another time, he unearthed a fragmented shell bead, stained with ochre, near a stream. “It didn’t have our cultural patterns. That tells you someone else passed through, maybe someone from another tribe who traded with us. It reminds us that the land is alive with stories.”

For David, every discovery is a kind of communion. “When I first started, I felt sorrow when I found something. It was like seeing a loved one’s belongings left behind. Over time, it became sacred. These items are conversations with our ancestors. They remind us they’re still among us.”

That reverence keeps him grounded.

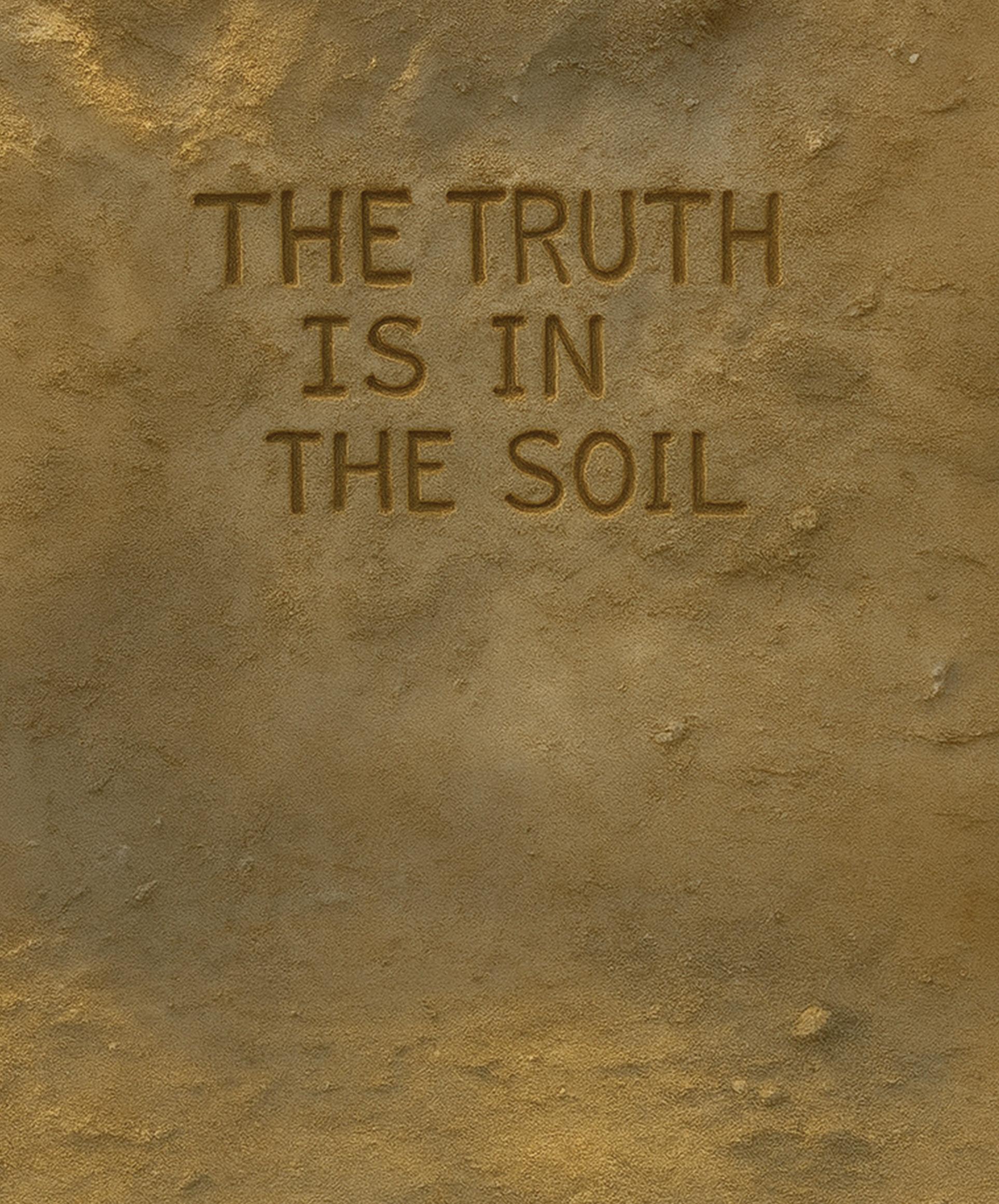

“We are here,” David says. “Even though we were evicted from this land, the truth is in the soil. We never left.”

“This work, it’s special. I get involved in a way most people don’t. When we find something, it’s something my ancestors held. It’s not just archaeology. It’s not academic. It’s presence.”

As Los Angeles continues to grow, so does the danger of erasure. But so too grows the quiet, persistent resistance of FTBMI Tribal Monitors like David Casarez. With each artifact they protect, each ancestral item that they honor, they reclaim more than history - they reclaim belonging.

To learn more about Tribal monitoring, please contact the FTBMI Tribal Historic & Cultural Preservation Department.

Ancestral Pathways

David Casarez Jr. (bottom) at Mission San Fernando, standing in the same area that his great grandmother is pictured (top left), in the

Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians

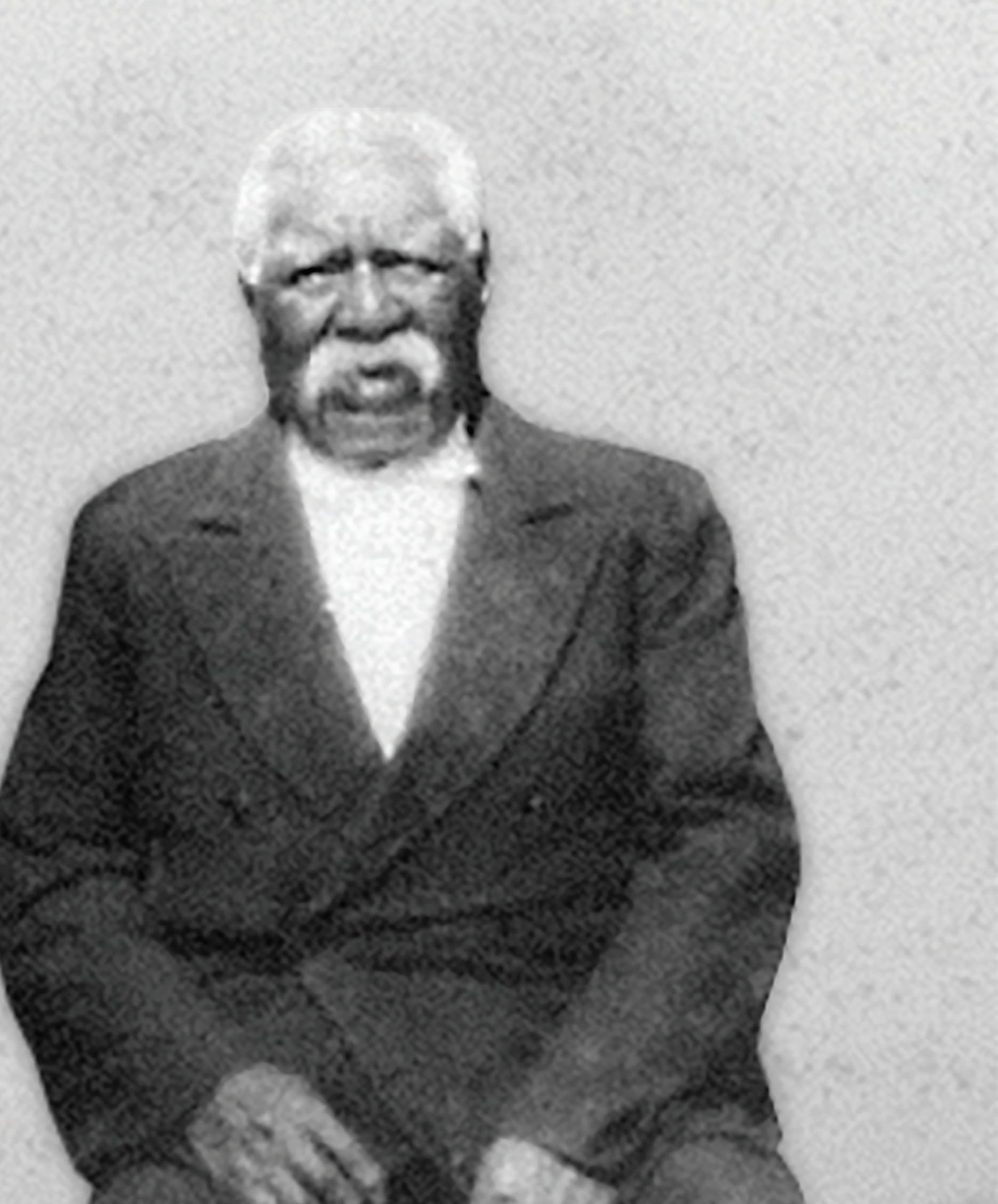

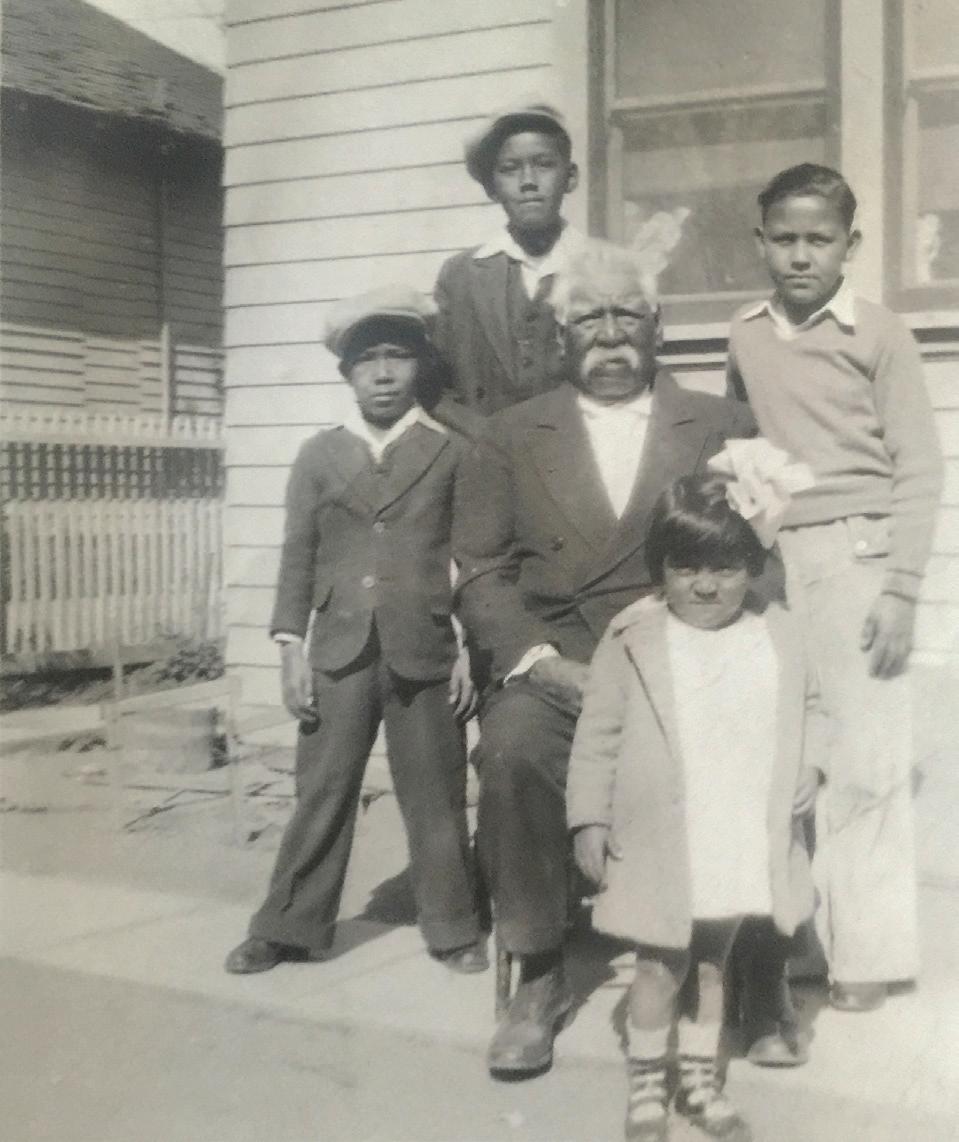

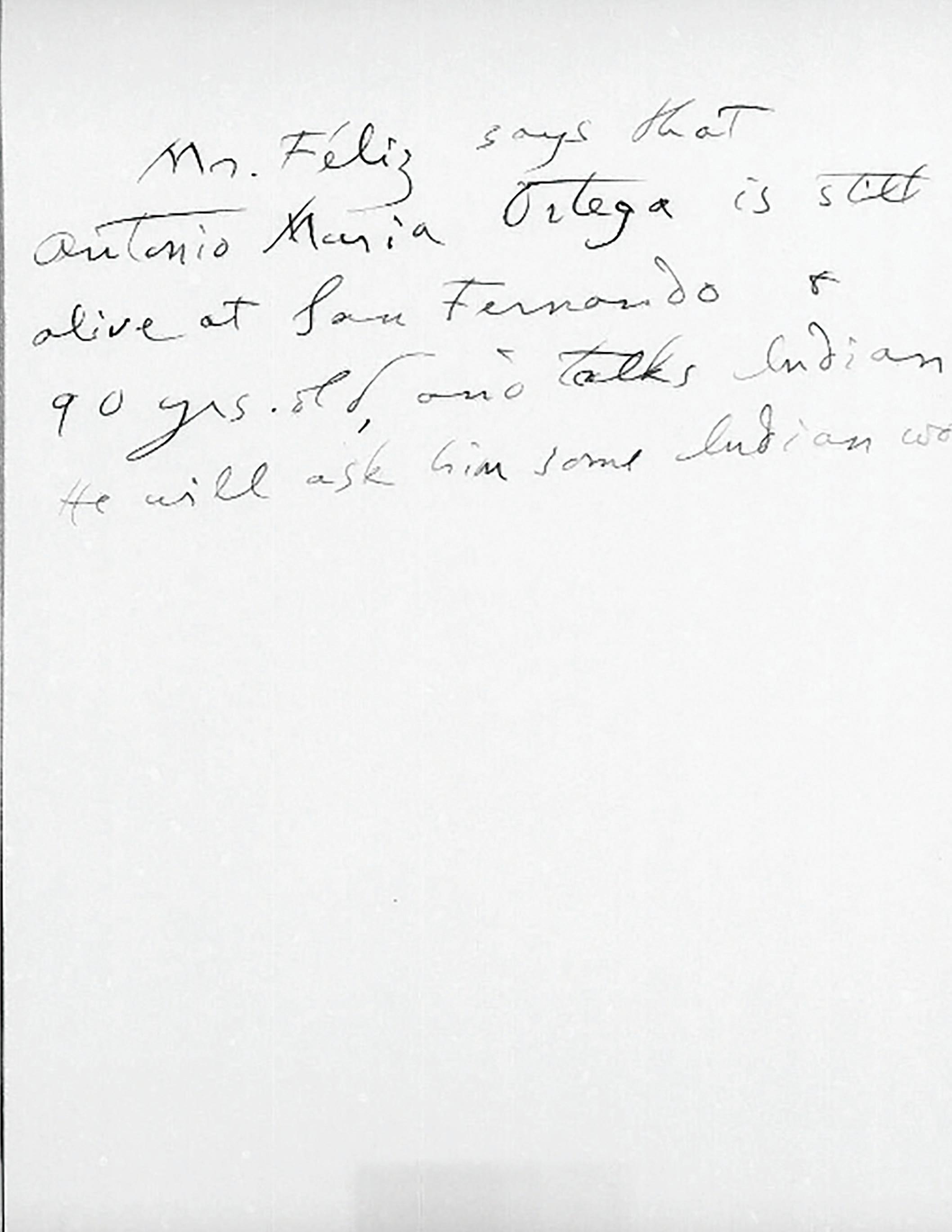

When Silence Spoke

Than Words

How One Fernandeño Man Demonstrated Resilience Through Silence.

The citizens of the Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians descend from the original inhabitants of the San Fernando, Santa Clarita, Simi, and Antelope Valleys. These homelands were once home to vibrant villages whose people spoke multiple languages and dialects. For the Fernandeños, language was not only a means of speaking, but also, a framework for understanding the world, deeply rooted in land, kinship, and cultural practice.

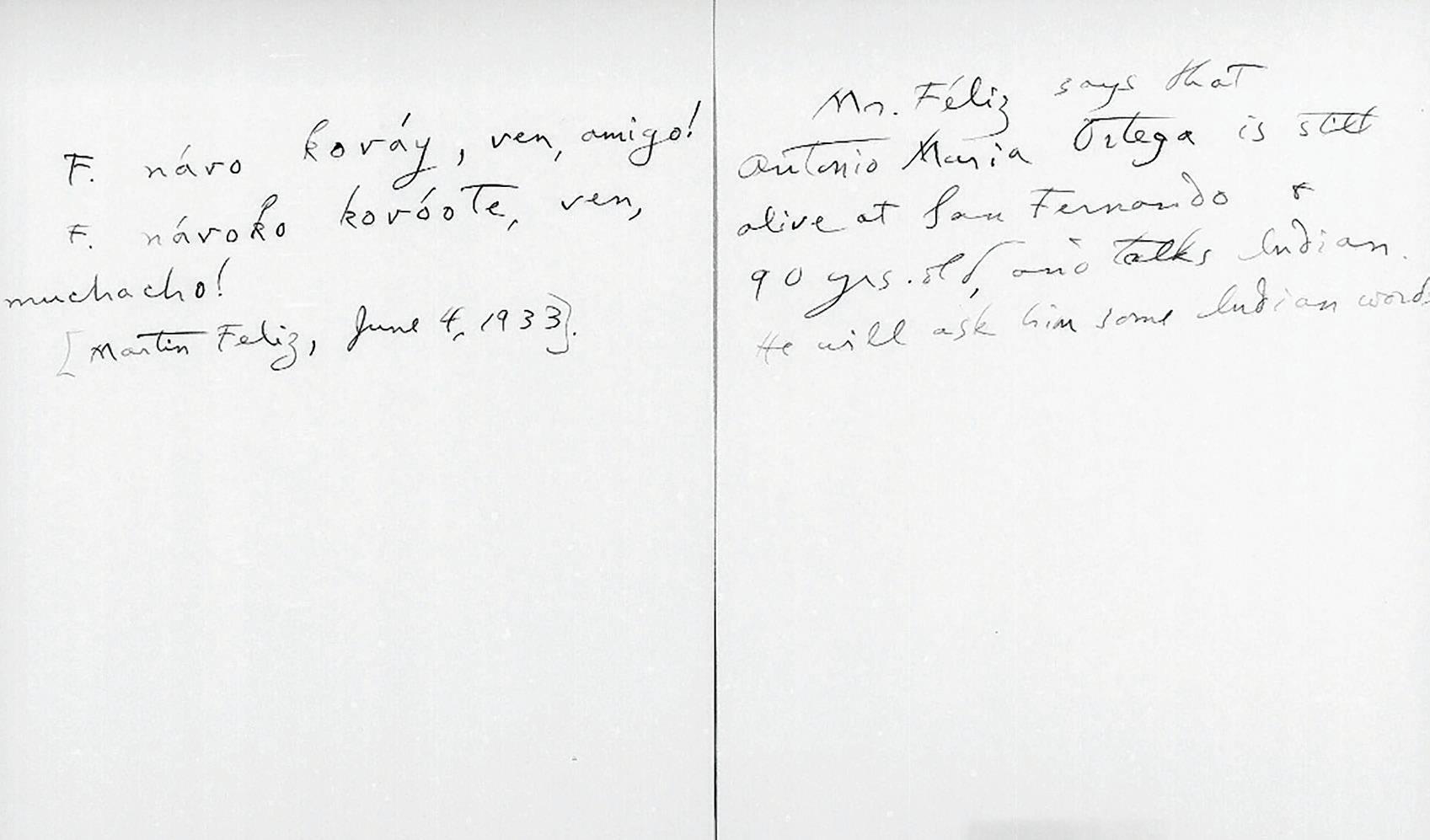

In the early 20th century, ethnologist John Peabody Harrington launched what he viewed as a race against time to document Native languages before they were lost forever. Working within the extractive model of salvage anthropology, he operated under the assumption that Native cultures were inevitably vanishing, and that they had to be preserved, or more precisely, captured, before they disappeared. But this sense of urgency, shaped by colonial thinking, ignored the true reasons these languages were endangered: land dispossession, forced assimilation, and the violent erasure of Native lifeways.

J.P.HARRINGTON’S

NOTES DOCUMENTING ANTONIO MARIA ORTEGA AS A FERNANDEÑO SPEAKER IN SAN FERNANDO, CALIFORNIA.

REEL 106. JUNE 4, 1933

Among those he hoped to interview was Antonio Maria Ortega, one of the last known speakers of the Fernandeño dialect. But Antonio would not speak.

His refusal was not just a matter of hesitation or mistrust. It was a reckoning with history. Antonio’s family traced their lineage to Siutcanga, where his mother was born—a

once-thriving village in what is now Encino. Their land, including Rancho Encino, was seized in the 1850s by a local settler expanding his estate. As a teenager, Antonio spent years in Los Angeles Superior Court fighting to reclaim his family’s stolen homeland.

He survived the legal battles, but he carried

deeper wounds: the loss of home, the betrayal of justice, and the constant arrival of outsiders who came not to support, but to take.

So when Harrington appeared in the San Fernando Valley with notebooks and questions, Antonio saw not a steward of language, but yet another representative of a system that had taken everything—land, history, trust.

His refusal was not silence. It was sovereignty. It was resistance and a deliberate act of protection. To Antonio, the Fernandeño language

“... Antonio Maria Ortega is still alive at San Fernando & 90 years olf. Antonio talks Indian.“

was not a dying relic for academic archives. It was alive. It was sacred. And it was not to be handed over to those who had failed to protect its people.

Today, the Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians is revitalizing its ancestral language on its own terms. Harrington’s notes offer fragments, but Antonio’s refusal speaks more clearly.

It was not the end of a language, but a refusal to let it be controlled by the very forces that tried to erase it.

In Antonio’s silence, there was strength.In his resistance, a legacy. And in his mistrust, a warning.

SAN FERNANDO, CA 1930S

John P. Harrington’s sparse Southern California/Basin subseries includes 1916 field notes on Fernandeño lifeways, largely from Setimo Lopez during trips through the San Fernando Valley. Additional insights came from Juana and Juan Melendrez and, in 1933, Martin Feliz.

ANTONIO MARIA ORTEGA

Hear

Hear Me

Listen to Alan Salazar’s bullroaring by scanning the QR code with your mobile device.

Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians

The Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians continues to walk in the footsteps of their ancestors, honoring sacred traditions passed down through generations. Among the most spiritually significant of their ceremonial instruments is the bullroareran object not just of sound, but of memory, power, and deep cultural meaning. Woven into the yucca fibers of their identity, the bullroarer holds a central place in the ceremonial life of Fernandeños.

Carefully crafted from elderberry wood, the bullroarer measures about nine inches in length. Its jagged, toothed edges give it a distinctive, sacred silhouette. Painted in bold, symbolic colors—

often red, representing vitality—it is tied to a cord, traditionally made of yucca, roughly two and a half feet long. When swung through the air, it releases a resonant, roaring hum, underscored by a high, whistling note that seems to come from the earth itself.

but to the fernandeños, the bullroarer is far more than an instrument. it is a vessel of spirit and an heirloom of ancestral wisdom.

Elders speak of its power and its role in spiritual life. While some ceremonial elements resemble those of neighboring coastal tribes such as the

Ventureño, each community maintains distinct meanings and practices. Historically, rites involving the bullroarer and deer-bone whistles were conducted within sacred circular enclosures, led by the Keepers of the Sacred - those entrusted with the care and continuation of ceremonial knowledge. These were not performances; they were acts of communion with the spirit world, rooted in place, lineage, and responsibility.

Today, they continue through the teachings of specific Fernandeño Knowledge Keepers that gather on the peaks of Mount Pinos, a place that lies at the spiritual heart of the Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians and local tribes. From this peak, the oldest

songs and teachings flow into the hearts of new generations. Young cultural singers begin by learning ancient songs in the dialects of their ancestors—songs that become prayers. Only when these songs are fully embodied are they guided into the next phase: learning the sound and purpose of the bullroarer.

This step-by-step journey is not simply instruction, it is initiation. It reflects a deepening relationship with the land, with the community, and with the ancestors who continue to dwell in spirit. Each note played, each word sung, carries the weight of generations. This practice becomes a sacred continuum, connecting past, present, and future.

At the core of Fernandeño Tataviam teachings is the story of earthquakes and serpentsancient memories that speak to the profound connection between people and the natural world. According to oral history, enlightened ancestors from coastal regions who held immense spiritual understanding held the power to communicate with the earth’s forces. Their songs were said to awaken the great earth serpents slumbering below.

when the serpents stir, their movements cause earthquakes.

When disturbed, these serpents would move, causing the land to shake in earthquakes. This belief is not merely a metaphor. It is an instruction. It reminds people of the balance that must be kept between humanity and the earth.

The bullroarer, then, is not just an instrument. It is a sacred voice that calls upon these

forces, invoking ancient memory, honoring a covenant between land and people. To wield it is to engage in a responsibility. The roar that echoes through the air is a reminder of that relationship: to live in balance, to listen deeply, and to carry forward knowledge with care and humility.

Through these traditions, young citizens of the FTBMI are not merely learning, they are being entrusted. As they sing the songs and eventually sound the bullroarer, they are not just remembering; they are continuing a dialogue between their people and the land. They are stepping into their roles as keepers of story, of ceremony, and of consequence.

And as we listen to the deep, rhythmic hum of the bullroarer in the distance, we are reminded of the enduring spirit of the Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians.

19th Century Bullroarer

Piru, California

Bullroarer

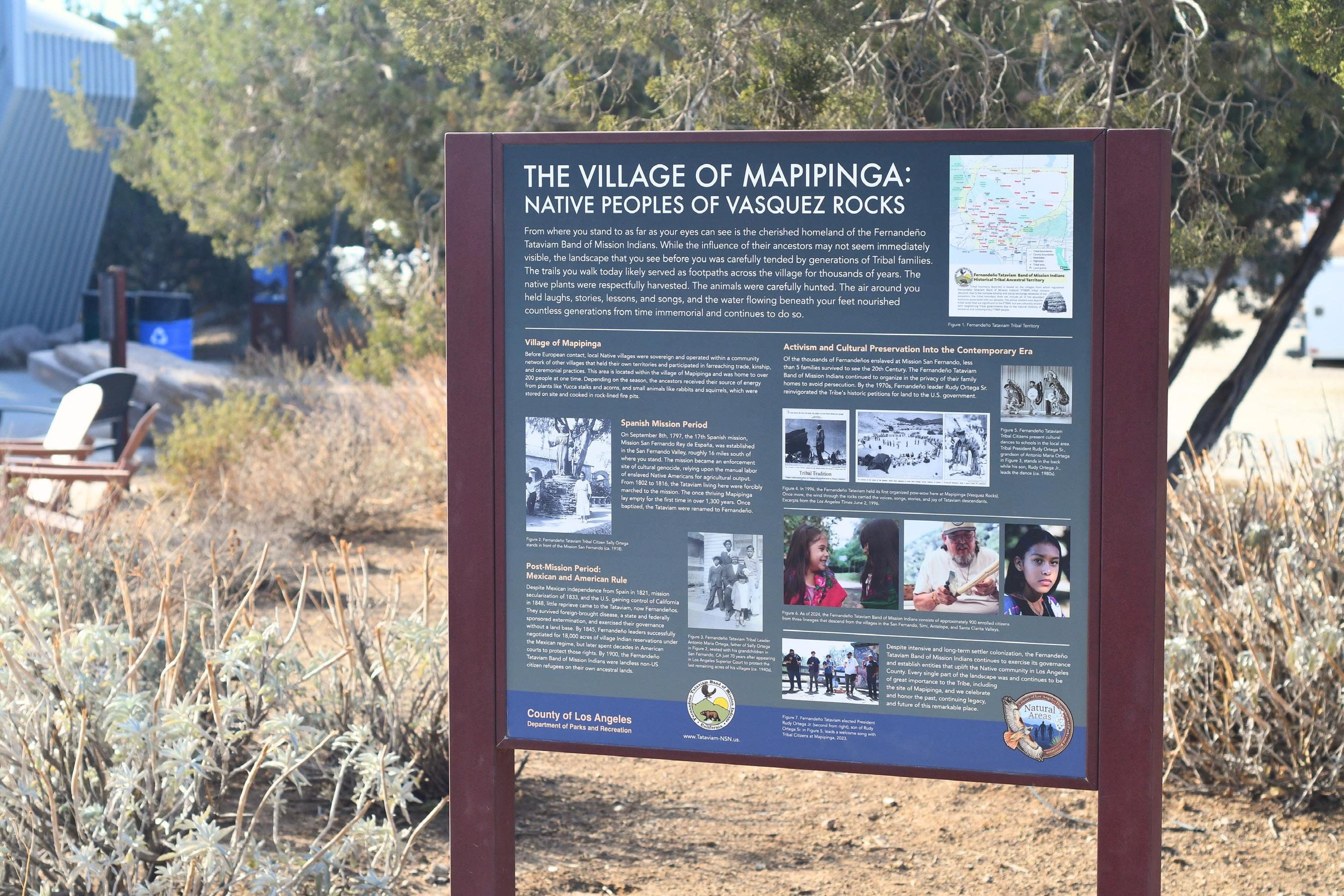

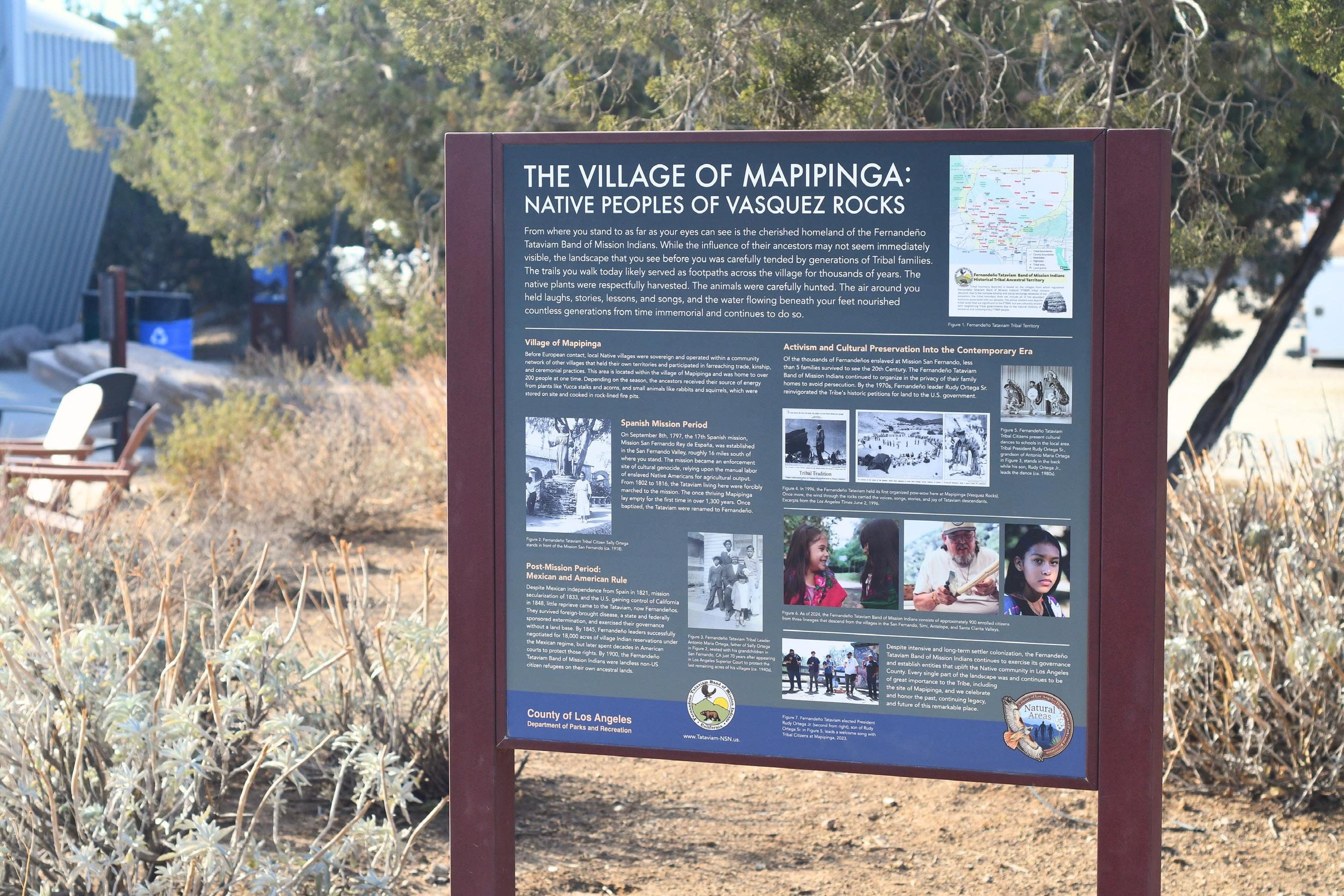

Horizon Signage on the

New Signs, Ancient Trails at Mapipinga Vasquez Rocks Natural Park

Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians

At Vasquez Rocks, the vibrant village of Mapipinga is undergoing a long-overdue transformation.

For the first time in the park’s 60-year history, this sacred site is beginning to speak in its own voice, through the language, leadership, and legacy of the Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians.

What visitors once regarded merely as a dramatic film backdrop or desert hiking destination is, in fact, an active cultural landscape. It is a village where the Tataviam ancestors prayed, hunted, held ceremonies, and were laid to rest. For generations, this truth was suppressed under layers of

colonial renaming and romanticized storytelling. Today, that silence is finally being broken.

Through a landmark collaboration with the Los Angeles County Department of Parks and Recreation and the Tribe, Mapipinga is now being recognized for what it truly is: a Native homeland rooted in sacred memory, language, and place.

The transformation began with what might seem like a simple change: signage. But these are no ordinary trail markers. They serve as ancestral acknowledgments and represent language returned to the land. Visitors will now encounter interpretive panels written in the voice of the Fernandeños, trail names restored in the ancestral

language, and culturally grounded information about ceremony, ecology, and geography.

For the Tribe, this effort is not about nostalgia. It is about visibility and the reclamation of space within their ancestral homelands. It is also, in a very real way, about safety and stewardship. Vasquez Rocks has long suffered from a fragmented and confusing trail system, resulting in frequent incidents where visitors were lost, injured, or required rescue. During summer months, emergency airlifts occurred as often as twice a week.

Yet since the first phase of the new signage was installed in April 2024, the park went six consecutive months without a single emergency rescue. These improvements demonstrate that culturally grounded wayfinding is not only informative. It is lifesaving.

This initiative marks the first time the Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians has been invited to shape public interpretation at such a scale. The results are profound.

The rocks have had their close-ups... Now it’s time you heard from the Tribe that never left the frame.

Working side by side with trail planners, ecologists, volunteers, and historians, the Tribe contributed ancestral names for three newly formalized trails and provided translations for existing English names. The Tribe offered Tribal ecological knowledge of native plants, animals, and geology; shared interpretive content on culture and ceremony; and developed a Land Acknowledgment and Elder’s Welcome Message to guide respectful visitation.

This is more than signage. It is story, presence, and legacy.

In honoring the past, the project is also paving the way for a more inclusive future. For the first time, ADA-accessible paths and interpretive areas now welcome elders, children, and individuals with mobility limitations. Trailhead kiosks, large print guides, and translated materials ensure that visitors of all backgrounds and abilities can learn from and connect with the land.

A handicap-accessible interpretive loop is currently in development, and printed trail booklets will soon be available for those unable to hike but still eager to engage with the site’s cultural history.

Mapipinga is not a relic of the past. It is a living village. The sandstone formations of Vasquez Rocks are not merely geological features. They are the Tribe’s archival memory, shaped by ceremony, carved by time, and walked by ancestors.

Each new sign, every name restored, and every story returned to the land is a prayer answered and a responsibility reclaimed.

This is only the beginning. From Vasquez Rocks to Eaton Canyon, the model established through this collaboration lays the foundation for a more respectful, informed, and inclusive park experience across all of Los Angeles County’s Natural Areas.

credit: fangirlquest.com

Far Right: FTBMI Tribal Citizens stand before the iconic sandstone peaks of Mapipinga.

Photo by Deniz Durmus. Courtesy of the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County.

Bottom: A scene from Star Trek featuring the sandstone peaks of Mapipinga in the background. Photo

Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians

FERN ANDO SAN FROM GUERNICA TO

A Tribal Citizen’s Mural Sparks

Reflection & Conversation

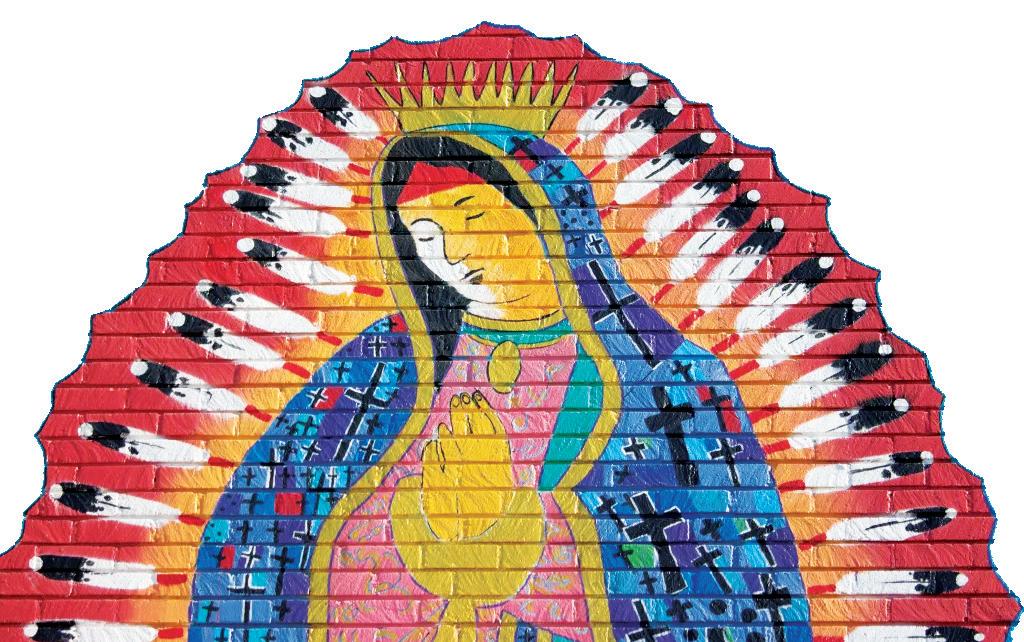

AT THE HEART of San Fernando, a powerful mural has transformed a corner of the city into a space for cultural reflection and conversation.

Installed just before Thanksgiving of 2023, Guernica to San Fernando spans 30 feet high and 100 feet long across a building near the U.S. post office and St. Ferdinand’s Catholic Church; two landmarks that hold personal significance for the artist.

The mural took two years to complete and represents wa deeply personal journey for Stanley Natchez, a citizen of the Fernandeño

Tataviam Band of Mission Indians. Through vivid imagery, the work explores the historical trauma experienced by his ancestors under the Mission system, portraying the suffering and forced labor they endured.

As the first mural of its size in San Fernando to center on Native history, it highlights not only Natchez’s personal story but broader issues affecting Native communities. However, the mural has also sparked controversy. One debated element is an aerosol can label “Warpaint,” which city officials saw as controversial due to its graffiti connotations. Natchez included it as a tribute to his son,

YOU KNOW?

The Mural faces the Lopez Adobe, where Fernandeño children, including Natchez’s great grandfather, worked in the 19th Century.

a graffiti artist who helped paint the mural, and stood firm on keeping the image.

Another point of contention centers on a 14-cent stamp in the mural, featuring the late Chief Rudy Ortega Sr., Natchez’s uncle and a prominent tribal leader. The stamp bears the word “Hostage” instead of “Postage,” a choice the city opposed. Natchez maintained that the wording was part of his original design and reflected the historical reality his ancestors faced. For Natchez, the mural is meant to

provoke thought and invite dialogue. He believes its power lies in encouraging viewers to reflect on their lives and the histories they may not have learned.

The mural also touches on broader themes such as environmental justice and cultural loss. Natchez includes imagery related to lost mineral rights and corporate extraction to illustrate the ongoing exploitation of Native lands.

Among the most symbolic elements is a reimagined Virgin of Guadalupe, encircled by eagle feathers rather than

Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians

golden rays. Natchez uses the eagle feather a sacred symbol of strength in Fernandeño culture, to honor traditional stories of sacrifice and protection.

Despite his critical view of the Catholic Church’s historic role in Native oppression, Natchez incorporates religious iconography as a nod to his upbringing and family’s connection to St. Ferdinand’s Church. He distinguishes between organized religion and Native spirituality, which he sees as more fluid and intuitive.

With its completion coinciding with Thanksgiving, the mural challenges the mainstream narrative of the holiday. Natchez sees it as a chance to confront myths and honor Native traditions of generosity and resilience.

Now living in New Mexico, Natchez

The Virgin of Guadelupe is encircled by eagle feathers to symbolize the Tribe’s strength.

continues to paint and run his gallery. He marked his 69th birthday perched on a cherry picker, finishing the mural, grateful for the strength to continue creating.

For Natchez, the mural is a time capsule, capturing both pain and persistence. He sees it as a reminder that history must be remembered and reckoned with, especially as humanity continues to grapple with the same struggles it has faced for centuries.

Photos: Semantha

Raquel Norris, San Fernando Sun

Extra Oardinary Acts of Resilience

Inside Fernandeño Oar-Making Workshops

On Sunday, March 9, 2025, citizens of the Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians came together for an immersive day of cultural reconnection. Hosted by the FTBMI’s Education and Cultural Learning Department, with special guest Elder Councilmember Alan Salazar, the oar-making workshop offered FTBMI citizens and descendants from the three lineages a chance to engage with ancestral knowledge through the hands-on construction of a traditional oar.

“We can’t lose these teachings. Doing this keeps our culture alive, not something stored on a library shelf.”

Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians

Spanning eight hours, the workshop welcomed participants of all ages, from toddlers and teens to parents and elders. Families representing the three Fernandeño lineages joined Salazar in a process that was part woodworking, part storytelling, and fully grounded in cultural identity. Under his guida nce, each family assembled and finished a handcrafted wooden oar, learning not only the techniques but also the meanings behind them.

For Salazar, who has dedicated over 25 years to revitalizing traditional

canoe building, the oar is not just a tool. It is a bridge to the past. His work with the tomol and tsá’atsh, traditional watercraft used by ancestral Fernandeño peoples, revives a history long threatened by colonial erasure. His own family’s ancestral territory spans the San Fernando, Santa Clarita, and Simi Valleys, reaching to Ta’apu, now Tapo Canyon, where his ancestors lived for generations.

Each workshop is an act of cultural continuity. Salazar’s teaching philosophy

centers on passing knowledge forward. He works closely with apprentices and community members to ensure that every piece of instruction, how to select materials, how to bind parts, how to listen to the wood, is rooted in Native values and responsibility.

At the end of the day, each family took home their oar. It was not a display piece, but a living symbol of connection to their ancestors. The hope is that future gatherings will lead to the construction of a community tomol.

With time, those who participated may use their oars to paddle the ocean and inland waters as their people once did, generations ago.

The oar-making workshop is part of a broader movement within the FTBMI to reclaim and renew traditional knowledge. Through the leadership of knowledge keepers like Alan Salazar and the commitment of families across generations, the Tribe is ensuring its culture continues. And that it is not only remembered, but practiced.

An Oar-some Time!

FTBMI Citizens and community members gather at Rudy Ortega Sr. Park to take part in the OarMaking workshop, presented by FTBMI Elder Alan Salazar and hosted by the Tribe’s Education & Cultural Learning Department.

This is about more than just making something with our hands. It’s about learning how our people moved across whater so that knowledge never dies.

Tribal Senator Jorge Salazar, District 2

Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians

HEAD ST

Glen Begay Ceremor

Victor Chavez, rea Director so Yanez, Head Man

Gracie Hernandez, Head W

van Bellingham, Head Young Man

Skye Padilla, oung Woman

Blue Starr, Host Northern Drum

Hale & Co., Host Southern Drum

Puhawvit Grows

A Native Plant

Nursery Takes Root In The San Fernando Valley

On Friday, February 28th, something extraordinary took root in the San Fernando Valley. Under clear skies and warm sunlight, the Tataviam Land Conservancy (TLC) welcomed the community to celebrate the grand opening of the Puhawvit Native Plant Nursery, a powerful symbol of renewal, resilience, and return.

What was once an abandoned, trash-strewn residential lot has transformed into a lush, living space dedicated to native flora, cultural heritage, and environmental education. Named Puhawvit, meaning “in the farm fields” in the Fernandeño Tataviam language, the nursery is the first Tribe-led native plant nursery in Los

NURTERING NATIVE FUTURES

FTBMI Leadership and Elders stand alongside a young Tribal Citizen as he joins Tribal President Rudy Ortega Jr. in cutting the ribbon at the groundbreaking ceremony.

Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians

A once-forgotten lot blooms into a vibrant space for native plants and Fernandeño restoration.

Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians

Angeles County, a historic first for the region and a landmark moment for Native environmental leadership.

Guests wandered through the blooming grounds, learning how native plants support local biodiversity and climate resilience. Children painted clay pots. Families shared tacos. Conversations buzzed with optimism and pride. But beyond the festivities, the event signaled the beginning of something deeper: a long-term vision rooted in Native land stewardship and Traditional Ecological Knowledge.

The nursery is the result of a powerful collaboration between TLC and the FTBMI, supported by CSUN, and funded through the USDA’s Urban and Community Forestry Program under the Sikwa’puhawam Urban Forestry Program. Together, these partners have created a space not only for growing plants—but for cultivating awareness, equity, and environmental justice.

The goal?

To empower local residents with the knowledge and plants needed to restore and reconnect with the land.

Representatives from local government, including Councilwoman Monica Rodriguez and Assemblywoman Celeste Rodriguez, presented certificates honoring the nursery’s launch recognizing its historic and cultural significance in reshaping how Los Angeles County approaches environmental justice.

The Puhawvit Native Plant Nursery is more than a place to grow trees—it’s a community hub, an educational platform, and a symbol of reclamation. Over the coming months, the nursery will host public workshops focusing on Traditional Ecological Knowledge, native tree cultivation, and sustainable practices rooted in Native knowledge.

Whether you’re interested in picking up a free native tree, learning about the power of native species, or simply want to support a groundbreaking community initiative, Puhawvit is a space to grow, in every sense of the word.

Returning Tribal Lands Back To Tribal Hands

Founded in 2018, the Tataviam Land Conservancy is committed to restoring the unceded ancestral homelands of the Fernandeño Tataviam by employing protective land management strategies, Traditional Ecological Knowledge, and innovative educational programs.

CULTURAL KNOWLEDGE SHARING

LAND-BASED EDUCATION

TRADITIONAL ECOLOGICAL KNOWLEDGE

HABITAT RESTORATION

CLIMATE JUSTICE

COMMUNITY LAND ACCESS

Our Community

, Together,

As One.

Since 1971, empowering American Indians through sustainable, culturally-rooted programs, today and for generations to come.

Emergency Services

Wellness Services

Fire Disaster Assistance

SCHOLARSHIPS ANNUAL ACADEMIC

Cultural Center

Scholarship Program

Youth Programs

“

I am deeply privileged to embark on my path as the first Medical Physician within my tribe. This role carries both honor and re sponsibility, allowing me to my fellow Native community mem bers in Southern California.

- Desirae B. Gabrieleno ‘24 Scholarship Recipient

How Pukuu’s Social Services

Uplift Native Self-Sufficiency

Transcription of the KCAL News CBS News

Community Member Spotlight: Francine Rosales

Rosales finds her spark again with help from Pukúu Cultural Community Services, the social services non-profit of the Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians

Now, most folks don’t realize it, but more Native Americans now live in Los Angeles than in any other county in the country. KCAL News’ Kara Finnstrom takes us to San Fernando, where a local tribe is working to make sure they’re seen and supported. “I’m doing things differently because I changed my life around.” We met Francine Rosales in what used to be a Native

Pukúu provides its services from the City of San Fernando, California - a traditional village of its founding Tribe, the Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians.

American village.

The Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians helps manage this historic San Fernando park. The tribe also started the nonprofit Pukúu Cultural Community Services, which has supported Rosales through huge challenges. “Homelessness, abuse, everything. And I came out of it.”

Pukúu is now helping Rosales pay her bills, go to cosmetology school, and dream again. “I’m going to be finishing in six months. And just opening my own business.”

She’s doing it for herself and her five-year-old son. She’s a single mom. “He’s special needs, nonverbal. But he’s doing good. He’s in their program.” He’s in a program because Pukúu’s says that this past year, they helped more than 500 people get everything from housing and food to clothing. The aid goes to anyone who qualifies.

But leaders say historical traumas continue to greatly impact Native Americans. “Some of the highest homeless rates, some of the highest incarcerated rates. That loss of history can really impact an individual,” says Mike Villaseñor, Case Manager, Pukúu Cultural Community Services, and also a Tribal Citizen of the FTBMI.

So Pukúu’s other mission is fostering unity and pride. Some of that happens here in Rudy Ortega Sr. Park. “We built a traditional house called a kich.”

The Fernandeño Tribe says their ancestors were living in Southland villages thousands of years before the first Spanish settlers arrived. “There used to be Indian reservations right here in Los Angeles. This was the village of

Francine with her five-yearold son, who is Pukúu’s program. More than 500 people have been assisted by Pukúu in the year 2024 alone.

Homelessness, abuse, everything... and I came out of it.

Francine Rosales

Patzkunga. And our families fought for this up until 1891 in court cases,” says Pamela Villaseñor, Executive Director of Pukúu and Tribal Citizen of the FTBMI.

Today, the FTBMI and the City of San Fernando co-manage

“I’m showing him his history.” Rosales brings her son to Pukúu’s events. The nonprofit started over 50 years ago, and she says this thriving community is strengthening her.

“Because it’s been a journey.”

Pukúu is helping her pay her bills, go to cosmetology school, and dream again.

these acres together. Pukúu uses them to restore cultural traditions. “Just a few weeks ago, we met with youth and families, gathered acorns, processed them, even ate it right there,” says Director Villaseñor.

When asked what’s been the most challenging part, Rosales replied, “Loving myself through Pukúu and through the community helping me. It’s… it’s been a blessing.”

SHELTER

• Homeless individuals may receive temporary shelter for approximately 1 week.

FOOD

• One-time food voucher for a local supermarket.

TRANSPORTATION

• One time emergency gas voucher for a local gas station

UTILITY

• Partial payment may be made directly to the utility company in order to prevent a utility from being turned off.

COUNSELING & REFERRAL

• Educational counseling to individuals in high school and college.

• Crisis counseling can also be provided as a secondary service.

• Referrals to agencies that can service emergency needs such as medical services, employment services and health needs.

CULTURE & RECREATIONAL

• Cultural Activities are organized throughout the year to provide social and communal celebrations of Native heritage and culture.

21th annual

November 7, 2025

Skirball Cultural Center

Los Angeles, California

Scholarship

Through our three Pukúu Scholarships, we work to help transform the educational systems upon our Indigenous lands for a healthier and more just world—for our ancestors, present, and future generations. Pukúu, we are one!

Tomiar Rudy Ortega Sr. Scholarship

In 1971, Pukuu’s founders Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians established a scholarship fund that provides awards to help American Indian students with higher education studies. Upon the passing of the Tribe’s Tomiar (traditional captain) and Tribal President, Pukúu’s board of directors named this fund in his honor: “Rudy Ortega Sr. Scholarship.”

Cultural Defender Caitlin Gulley Memorial Scholarship

Endowment established by FivePoint

Caitlin Gulley, a graduate of University of California Los Angeles, began her journey with the Tribe in 2014 as a Tribal Historic and Cultural Preservation officer. She was instrumental in defending and preserving the cultural resources of a non-federally recognized tribe and became determined to further her education in law due to the legal aspects intertwined with the practice of cultural resources protection.

Tribal Senator Austin Martin Memorial Scholarship

Endowment established by the Martin Family.

Tribal Senator Austin Martin served as a Tribal Senator on the legislative branch of the Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians. Senator Martin had the spirit for uplifting his people towards a bright future and was especially passionate about empowering Tribal youth.

Climate Health i s Human Health

Fernandeños Lead A Climate Resilient Future in

Los Angeles County.

In January 2024, the Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians released a bold and visionary document: the Tribal Climate Resiliency Plan. More than just a roadmap, it was a declaration of Indigenous strength and responsibility, a commitment to protect the land, its people, and the knowledge systems that have guided them for generations.

Now, months later, the Plan is not only alive but growing. Across the Tribe’s ancestral homelands from the chaparral hills of the Northeast Valley to the dense urban corridors of Los Angeles climate resilience is taking root, shaped by Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK), youth empowerment, and strategic alliances.

Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians

Greening Fields, Growing Futures Sikwa’puhawam

In the heart of this movement is the Sikwa’puhawam Urban Forestry Program, a transformative initiative seeded by a $5 million grant from the USDA. Meaning “greening fields” in the Tataviam language, the project is more than reforestation— it’s a return to relationship.

Led by the Tribe’s own Tataviam Land Conservancy and Tiüvac’a’ai Tribal Conservation Corps, and in partnership with CSUN, the program is cultivating a nursery of culturally significant native plants. From elderberry to oak, these species carry stories, medicines, and songs. With 750 trees slated for planting across Northeast Los Angeles, the program is also opening new green pathways for Tribal and local youth.

Through paid training and hands-on learning, TEK becomes both a tool of environmental restoration and a means of workforce wdevelopment.

Interested in Free Trees? Connect with our Cimate Ambassadors today!

As summers grow hotter and more dangerous, especially in L.A.’s most vulnerable neighborhoods, the Tribe is responding with education and care.Through a $3 million grant and in collaboration with UCLA’s Luskin Center for Innovation, Rising Communities, and L.A. County Public Health, the LARC-HEAT project is training Community Heat Ambassadors to deliver life-saving resources direct-

Protecting Health

Under Rising Temperatures

ly to residents in Palmdale, Lancaster, and the San Fernando Valley.

Through a Climate Ambassador Program, the ambassadors, grounded in cultural relevance and community trust, conduct outreach throughout the San Fernando and Antelope Valleys on the benefits of native trees. They are projected to reach over 9,000 people with tools for surviving extreme heat.

More than just data, this effort reflects the Tribe’s deeper goal: that no one, especially elders and those living without air conditioning, is left behind in the climate crisis.

Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians

Facing the Heat: How Climate Impacts Human Health

Rising temperatures—up to 7°F warmer by 2100—mean more than 38 extra days of dangerous heat and over 100 warm nights, increasing risks of heat-related illnesses and reducing nighttime recovery.

Worsening droughts threaten clean, affordable water supplies in Antelope Valley, putting vulnerable families at risk of dehydration and water insecurity.

Severe floods and debris flows following wildfires jeopardize homes and infrastructure, heightening injury and displacement risks.

Expanding fire zones increase exposure to toxic smoke and poor air quality, causing respiratory problems and long-term health effects for nearby communities.

Creating Places of Shade & Shelter Pasekinga

In San Fernando, another vision is taking shape- one centered on sanctuary. Pasekinga, meaning “place of shade,” is an ambitious network of climate resilience centers being developed in the parks that hold the community’s heartbeat: Las Palmas Park, Recreation Park, and Rudy Ortega Sr.

Park.

Funded by the CA Strategic Growth Council and in collaboration with the City of San Fernando, Climate Resolve, Paseki Strategies, and TTCC, Pasekinga will transform these public spaces into daily-use hubs that also serve as emergen-

cy shelters during climate disasters. Here, tradition and innovation meet: shade structures that echo the landscape’s past, cooling systems powered by sustainable energy, and programs that bridge ceremony and preparedness.

A Future In Motion

Each of these efforts represents a vital piece of the Tribe’s larger climate strategy. But they are also something more: a living testament to Tribal leadership, to the understanding that true resilience is rooted in land and community.

As the Tribe continues to implement its Climate Resiliency Plan, it does so not only to respond to climate change, but to honor those who came before and empower those who will come after.

Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians

Stay safe during Extreme Heat

Extreme heat is deadly and kills more people than any other weather event.

KNOW THE SYMPTOMS

Outdoor workers, older adults, pregnant people, children and people with chronic illnesses are at higher risk.

Heat Stroke

• Symptoms: Red, hot, dry skin; Confusion; Rapid pulse; Throbbing headache; Temperature above 104°F; Unconsciousness

• What to do: Call 911; Move to a cool place; Cool with water or ice

Heat Exhaustion

• Symptoms: Dizziness; Heavy sweating; Cramps; Nausea or vomiting

• What to do: Move to a cool place; Loosen clothes; Sip water

IF YOU ARE STAYING INSIDE

• Remember to drink more water

• Avoid alcohol and ca eine

• Do not use oven or stove

MONITOR HOW YOU’RE FEELING. GET HELP IF YOU FEEL SICK. For Immediate Help: Call 2-1-1 or text “LA” to 741741

• Take cool showers or put feet in cold water

• Look out for headaches, nausea, or dizziness

IF YOU ARE GOING OUTSIDE

• Bring a water bottle at all times

• Stay in the shade

• Pace yourself throughout the day

• Wear lightweight clothing and sunblock

• Cool o at libraries, malls, or free cooling centers

MENTAL HEALTH EFFECTS

Heat can cause irritability and depression, especially if you're struggling to sleep during the heat!

Remember

• Some medications increase heat-related illness risk.

Talk to your doctor.

• Reach out to family and friends for support. You are not alone in this!

Reach out to family and friends for support and look out for each other!